Addressing Acetaminophen Interference in Implantable Biosensors: Mechanisms, Mitigation Strategies, and Clinical Implications

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of acetaminophen interference in implantable biosensors, a critical challenge for researchers and drug development professionals in the field of continuous monitoring.

Addressing Acetaminophen Interference in Implantable Biosensors: Mechanisms, Mitigation Strategies, and Clinical Implications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of acetaminophen interference in implantable biosensors, a critical challenge for researchers and drug development professionals in the field of continuous monitoring. It explores the foundational electrochemical mechanisms underlying this interference, particularly in first-generation glucose oxidase-based sensors. The content reviews advanced methodological approaches for interference suppression, including membrane technologies and electrochemical techniques. Furthermore, it evaluates troubleshooting protocols, sensor optimization strategies, and comparative performance data across commercial biosensor platforms. This synthesis of current research and development offers valuable insights for creating more robust and reliable implantable diagnostic devices, ultimately enhancing patient safety in clinical applications involving polypharmacy.

The Acetaminophen Interference Problem: Foundational Science and Clinical Impact

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is electrochemical interference and why is it a problem for implantable biosensors? Electrochemical interference occurs when electroactive species other than the target analyte produce a false signal in a biosensor. In implantable glucose sensors, this is a significant problem because substances like acetaminophen and ascorbic acid are readily oxidized at the same potential used to detect hydrogen peroxide (the product of the glucose oxidase reaction). This leads to an overestimation of glucose concentration, which can be dangerous for patients, particularly those using the sensor for diabetes management [1] [2].

2. Why is acetaminophen a particularly serious interferent? Acetaminophen is a widely used over-the-counter pain and fever medication. It is electroactive and gets oxidized at the working electrode of first-generation amperometric biosensors, which typically operate at a high potential (e.g., +0.6 V vs. Ag/AgCl). Studies have shown that a clinically common plasma acetaminophen concentration of 200 μmol/L can cause a significant positive bias, leading to an underestimation of glucose concentration by approximately 6-7 mmol/L, which is a critical error [3] [2].

3. What are the main strategies to eliminate or reduce acetaminophen interference? Researchers have developed several key strategies to mitigate this interference:

- Permselective Membranes: Using composite membranes, such as cellulose acetate combined with Nafion, to create a charged barrier that selectively excludes interferents like acetaminophen while allowing hydrogen peroxide to pass [3] [1].

- Lowering Operating Potential: Employing second-generation biosensors that use artificial electron mediators, allowing the sensor to operate at a much lower potential where acetaminophen is not oxidized [4] [5].

- Electrode Design: Incorporating specific membrane "domains," such as interference membranes and bioprotective membranes, designed to reduce the flux of interfering substances to the electrode surface [4].

4. How do I test for interference in my sensor experiment? A standard in vitro protocol involves measuring the sensor's response to a target glucose concentration (e.g., 5 mmol/L) and then measuring the response after adding a physiological concentration of the interferent (e.g., 100-200 μmol/L acetaminophen). The bias is calculated as the difference in signal. For example, one study found that 100 μmol/L ascorbate introduced a minimal bias of ~0.4 mmol/L glucose, whereas 200 μmol/L acetaminophen introduced a ~7 mmol/L bias [2].

5. Are commercial Continuous Glucose Monitors (CGMs) affected by acetaminophen? Yes, many first-generation electrochemical biosensor-based CGMs are affected. Manufacturer labels for devices like the Dexcom G6/G7 and Medtronic Guardian Connect explicitly warn that taking higher-than-maximum dosages of acetaminophen may falsely raise sensor glucose readings. Some newer sensor models have incorporated design improvements, such as permselective membranes, to reduce this effect [4].

Troubleshooting Guide

Problem: High Background Signal or Inaccurate Readings in Complex Media

Potential Cause: Interference from electroactive species like acetaminophen, ascorbic acid, or uric acid.

Solution:

- Apply a Permselective Membrane: Spin-coat or dip-coat the sensor with a composite membrane. A proven methodology is:

- Prepare a solution of Cellulose Acetate (e.g., 2-5% w/v in acetone) and Nafion (e.g., 0.5-2% w/v in lower aliphatic alcohols/water).

- Apply this solution over the sensor's enzyme layer and allow it to dry, forming a thin film.

- Mechanism: Cellulose acetate acts as a size-exclusion layer, while Nafion, being negatively charged, repels anionic interferents like ascorbate and urate. For neutral molecules like acetaminophen, the composite structure creates a diffusion barrier, significantly slowing its response time. When combined with the drug's rapid clearance in the body, this minimizes its impact in vivo [3].

- Switch to a Mediated (Second-Generation) Biosensor Design:

- Immobilize both Glucose Oxidase and a mediator (e.g., ferrocene derivatives, ferricyanide) within a polymer matrix on the electrode.

- Mechanism: The mediator shuttles electrons from the reduced enzyme to the electrode, allowing the operating potential to be lowered to a range (e.g., 0.0 V to +0.2 V) where most common interferents are not electroactive [4] [5].

Problem: Sensor Signal Drift or Loss of Sensitivity Post-Implantation

Potential Cause: Biofouling, where proteins and cells adhere to the sensor surface, causing a foreign body response and limiting analyte diffusion.

Solution:

- Incorporate a Bioprotective Membrane: Use a outermost membrane designed for biocompatibility. Materials like poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG)-based hydrogels or polyurethane derivatives can reduce protein adsorption and cell adhesion, extending the functional life of the sensor in vivo [6] [4].

- Utilize Smart Biomaterials: Investigate the use of biodegradable and self-healing materials. These advanced materials can improve biocompatibility and device longevity, reducing the host's immune response over time [6] [7].

Quantitative Data on Interference

The table below summarizes the typical interference impact of key substances on first-generation amperometric glucose biosensors.

Table 1: Quantifying Interference in Glucose Biosensors

| Interfering Substance | Physiological Concentration Range | Approximate Signal Bias (vs. Glucose) | Key Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acetaminophen | Up to 200 μmol/L (therapeutic) | ~7 mmol/L glucose error [2] | Composite membranes (Cellulose Acetate/Nafion) [3] |

| Ascorbic Acid (Vitamin C) | 50-100 μmol/L | ~0.4 mmol/L glucose error (at 100 μmol/L) [2] | Nafion membrane, Ascorbate Oxidase [1] [5] |

| Uric Acid | 200-500 μmol/L | Varies | Nafion membrane [1] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Evaluating Interference with a Permselective Membrane

Objective: To test the effectiveness of a cellulose acetate/Nafion composite membrane against acetaminophen interference.

Materials:

- Fabricated glucose biosensor (Pt working electrode with immobilized Glucose Oxidase)

- Cellulose acetate (CA)

- Nafion perfluorinated resin solution

- Acetone

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), pH 7.4

- Glucose stock solution

- Acetaminophen stock solution

- Electrochemical workstation (e.g., potentiostat)

Procedure:

- Membrane Preparation: Prepare a 3% (w/v) solution of CA in acetone. Mix this 1:1 by volume with a 1% (w/v) Nafion solution.

- Sensor Modification: Dip-coat the fabricated glucose sensor into the CA/Nafion solution and withdraw it slowly. Allow the sensor to dry at room temperature for 1 hour.

- Amperometric Measurement:

- Set the potentiostat to apply a constant potential of +0.6 V vs. Ag/AgCl.

- Immerse the sensor in stirred PBS and record the baseline current.

- Add glucose to achieve a 5 mM concentration and record the steady-state current (Iglucose).

- Rinse the sensor and re-establish baseline in fresh PBS.

- Add acetaminophen to achieve a 200 μM concentration and record the steady-state current (Iacetaminophen).

- Data Analysis: Calculate the degree of interference by comparing I_acetaminophen to the current expected from an equimolar glucose solution. A well-functioning membrane will show a drastically reduced response to acetaminophen [3] [1].

Protocol 2: Testing a Mediated Biosensor at Low Potential

Objective: To demonstrate reduced acetaminophen interference by operating a biosensor at a low working potential.

Materials:

- Fabricated mediated biosensor (e.g., with Ferrocene carboxylic acid / Glucose Oxidase in a polymer matrix)

- PBS, pH 7.4

- Glucose stock solution

- Acetaminophen stock solution

- Electrochemical workstation

Procedure:

- Amperometric Measurement at Low Potential:

- Set the potentiostat to apply a constant potential of +0.2 V vs. Ag/AgCl.

- Repeat Step 3 from Protocol 1, measuring the sensor's response to 5 mM glucose and then to 200 μM acetaminophen.

- Data Analysis: The current response from acetaminophen at this low potential should be negligible compared to the response from glucose, confirming the success of the mediated approach in eliminating this interference [4] [5].

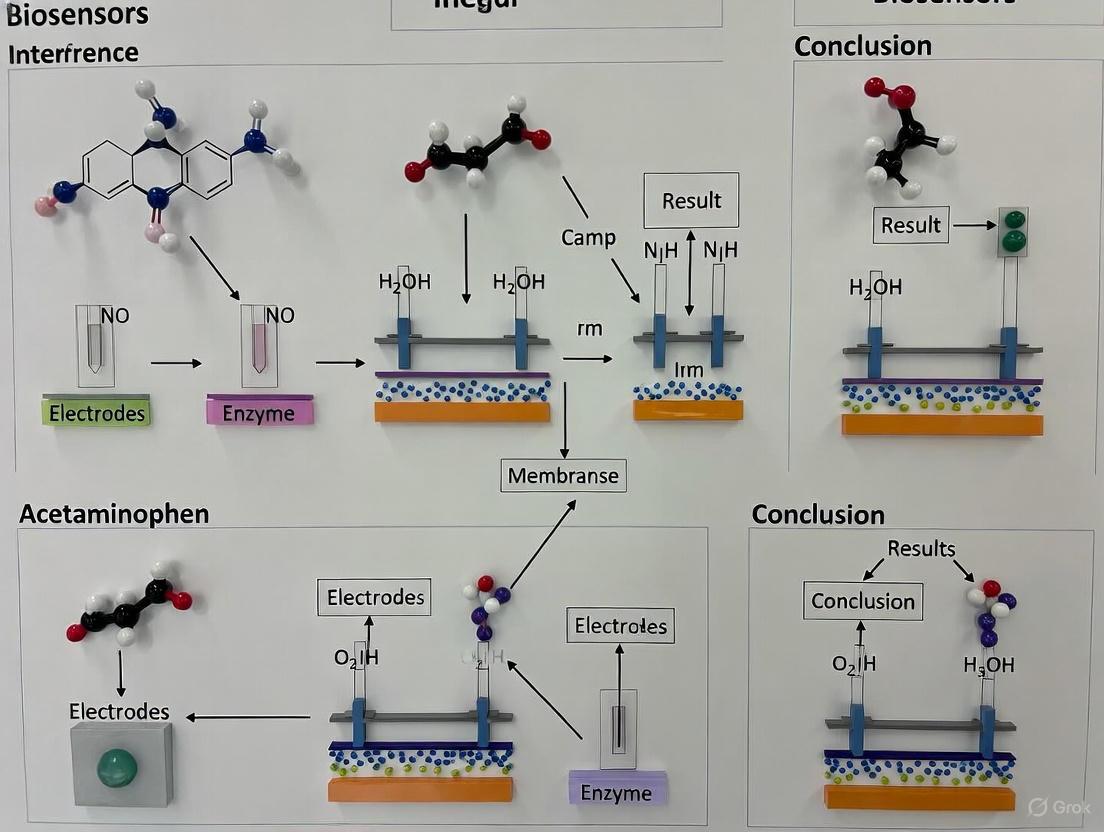

Visual Experimental Workflows

Interference Mechanism and Mitigation Pathways

In-Vitro Interference Testing Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Mitigating Acetaminophen Interference

| Reagent/Material | Function/Benefit | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Nafion | A cationic perfluorosulfonated polymer. Creates a negatively charged membrane that repels anionic interferents like ascorbate and urate [3] [5]. | Less effective against neutral interferents like acetaminophen alone; often used in composites. |

| Cellulose Acetate | A polymer that forms a size-selective hydrogel membrane. Restricts the diffusion of larger molecules towards the electrode surface [3] [1]. | The ratio with other polymers (e.g., Nafion) is critical for optimizing selectivity and Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ diffusion. |

| Ferrocene and Derivatives | Common redox mediators. Shuttle electrons from Glucose Oxidase to the electrode, enabling low-potential operation and minimizing interferent oxidation [4] [5]. | Must be immobilized effectively to prevent leakage from the sensor over time. |

| Polyurethane / PEG Hydrogels | Used as outer bioprotective membranes. Improve biocompatibility, reduce biofouling, and can also contribute to controlling analyte and interferent diffusion [6] [4]. | Mechanical properties and porosity must be tuned to match the implantation site. |

| Nicarbazin-d8 | Nicarbazin-d8, MF:C19H18N6O6, MW:434.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| ATM Inhibitor-2 | ATM Inhibitor-2|ATM Kinase Inhibitor|Research Compound | ATM Inhibitor-2 is a potent, selective ATM kinase inhibitor used in cancer research and DNA damage response (DDR) studies. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

Technical FAQ: Understanding and Troubleshooting Acetaminophen Interference

Q1: What is the fundamental mechanism by which acetaminophen interferes with CGM readings?

Acetaminophen interferes with the electrochemical sensing principle used by many continuous glucose monitors (CGMs), specifically those of a first-generation biosensor design [4]. These systems, including certain models from Dexcom and Medtronic, use the enzyme glucose oxidase (GOx) to detect glucose [4].

The interference occurs because the sensor does not perfectly distinguish the signal generated by glucose from that generated by other easily oxidized substances [8] [9]. When glucose in the interstitial fluid passes through the GOx membrane, it produces hydrogen peroxide (Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚). The sensor applies a voltage, causing the Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ to decompose and release electrons, which are then converted into a glucose reading [8] [9]. Acetaminophen is also easily oxidized at a similar voltage, causing it to generate an additional, non-glucose-related electrical current. The CGM system mistakenly interprets this combined signal as an elevated glucose level, resulting in a falsely high reading [8] [9].

Q2: How does the interference from intravenous (IV) acetaminophen differ from oral administration?

The route of administration significantly impacts the severity of interference. Intravenous acetaminophen leads to a higher and more rapid peak in blood concentration compared to oral administration, which in turn causes a greater and more acute overestimation of glucose levels by the CGM [8] [9].

The following table summarizes the key quantitative findings from a clinical case study on IV acetaminophen interference with a Medtronic Guardian 4 sensor [8] [9]:

| Parameter | Findings from IV Acetaminophen Case Study |

|---|---|

| Dosage | 15 mg/kg administered intravenously over 15 minutes [8] [9] |

| Time to Peak CGM Error | 29.2 ± 1.9 minutes (mean ± standard deviation) after administration [8] [9] |

| Magnitude of CGM Error | Estimated discrepancy of 55 to 114 mg/dL compared to capillary blood glucose measurements [8] [9] |

| Relationship to Glucose Level | Significant negative correlation; discrepancies were greater at lower blood glucose levels [8] [9] |

| Duration of Interference | Discrepancies persisted for more than 2 hours [8] [9] |

Q3: What specific risk does this interference pose in automated insulin delivery (AID) systems?

Falsely elevated CGM readings pose a critical safety risk in AID systems, also known as closed-loop systems [8] [9]. These systems rely on real-time CGM data to make automated decisions on insulin dosing. A falsely high glucose reading could trigger the system to deliver an unneeded "autocorrection" insulin bolus [8] [9]. This inappropriate insulin delivery, occurring when the patient's actual blood glucose is normal or low, significantly increases the risk of iatrogenic hypoglycemia [8] [9].

Q4: What is the recommended clinical troubleshooting protocol for patients requiring IV acetaminophen?

When a patient using a CGM requires IV acetaminophen, clinicians should adopt the following protocol to mitigate risk [8] [9]:

- Awareness and Recognition: Be aware that IV acetaminophen causes significant CGM interference, with errors potentially exceeding 100 mg/dL.

- Verify with Blood Glucose Meter: Do not rely on CGM readings during and for at least 2-3 hours after IV acetaminophen administration. Instead, use a blood glucose meter to guide therapy [8] [9].

- Suspend Automated Insulin Delivery: For patients on AID systems, switch the insulin pump to manual mode before administering IV acetaminophen to prevent automated correction boluses based on erroneous data [8] [9].

- Resume AID with Caution: Only switch the pump back to automated mode after confirming via blood glucose meter that the interference has subsided and the CGM readings have realigned with actual blood glucose levels [8] [9].

Experimental Insights for Research & Development

Experimental Protocol: Quantifying Acetaminophen Interference

The following methodology, adapted from a published case report, provides a framework for systematically evaluating sensor interference in a clinical or research setting [8] [9].

Objective: To quantify the magnitude, timing, and duration of CGM error induced by intravenous acetaminophen.

Materials & Reagents:

- CGM System: The sensor system under investigation (e.g., Medtronic Guardian 4) [8] [9].

- Blood Glucose Monitor (BGM): A validated, FDA-cleared device for reference capillary blood glucose measurements (e.g., ACCU-CHEK Guide Link) [8] [9].

- Intravenous Acetaminophen: Prepared at the standard dosage (e.g., 15 mg/kg) [8] [9].

- Data Extraction Software: Tool for extracting timestamped CGM data from the proprietary system (e.g., from the insulin pump) [8] [9].

- Statistical Software: For data analysis and linear regression (e.g., R software) [8] [9].

Procedure:

- Baseline Period: Ensure no oral intake or significant insulin boluses for at least 2 hours prior to acetaminophen administration to stabilize glucose levels [8] [9].

- Administration: Administer the IV acetaminophen dose over the specified duration (e.g., 15 minutes) [8] [9].

- Data Collection:

- Data Analysis:

- Peak Identification: Use CGM data to identify the peak glucose reading and the time to peak after administration [8] [9].

- Error Calculation: Calculate the discrepancy (CGM reading - BGM reading) at each time point.

- Linear Regression: Perform regression analysis to assess the relationship between the reference blood glucose level and the magnitude of the CGM discrepancy [8] [9].

Research Reagent Solutions & Materials

The table below lists key materials and reagents relevant to researching interference in implantable biosensors.

| Item | Function/Application in Research |

|---|---|

| Glucose Oxidase (GOx) | The primary enzyme used in first-generation electrochemical biosensors for glucose recognition; central to the interference mechanism [4]. |

| Acetaminophen (IV Formulation) | The interfering substance used to challenge sensor performance and quantify susceptibility in experimental protocols [8] [9]. |

| Platinum (Pt) Electrode | A common material for the working electrode in first-generation CGM designs where the oxidation reaction occurs [4] [10]. |

| Permselective Membrane | A sensor design feature (e.g., in Dexcom G6/G7) intended to reduce the flux of interfering substances like acetaminophen to the electrode surface [4]. |

| Hydrogen Peroxide (Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚) | The product of the glucose oxidase reaction; its electrochemical detection is the source of the signal that acetaminophen disrupts [4] [8]. |

| Biocompatible Polymers (e.g., Parylene-C) | Used for device insulation and encapsulation to improve biocompatibility and reduce the foreign body response in implantable sensors [10]. |

Biosensor Interference Pathway

The following diagram illustrates the core electrochemical mechanism by which acetaminophen causes interference in first-generation biosensors.

Acetaminophen (paracetamol) is one of the most well-documented and serious electrochemical interferences for oxidase-based amperometric biosensors. For researchers developing implantable glucose sensors, understanding and mitigating this interference is crucial for ensuring accurate physiological measurements. This technical guide examines the underlying mechanisms of acetaminophen interference, provides experimental methodologies for its investigation, and summarizes current strategies to eliminate its effects, providing a foundation for robust biosensor design.

The Electrochemical Mechanism of Interference

Core Sensing Principle of GOx-Based Sensors

Most continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) and implantable glucose sensors are amperometric biosensors that rely on glucose oxidase (GOx) as their molecular recognition element. The canonical reaction sequence is as follows [11] [12]:

- Enzymatic Reaction: Glucose oxidase catalyzes the oxidation of β-D-glucose to D-glucono-1,5-lactone, while simultaneously reducing the enzyme's cofactor, flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD), to FADH₂.

Glucose + GOx(FAD) → Gluconolactone + GOx(FADH₂) - Enzyme Re-oxidation: The reduced enzyme is re-oxidized by molecular oxygen (O₂), producing hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂).

GOx(FADH₂) + O₂ → GOx(FAD) + H₂O₂ - Electrochemical Detection: In first-generation sensors, H₂O₂ is oxidized at a positively polarized working electrode (typically +0.6 V to +0.7 V vs. Ag/AgCl), generating an electrical current proportional to the glucose concentration.

Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ → Oâ‚‚ + 2H⺠+ 2eâ»

Competitive Oxidation of Acetaminophen

The interference occurs at the final detection step. At the high working potential required for H₂O₂ oxidation, acetaminophen—which contains a readily oxidizable phenolic hydroxyl group—is also oxidized at the electrode surface [13] [11]. The electrochemical oxidation of acetaminophen produces N-acetyl-p-benzoquinone imine (NAPQI) and releases electrons [14] [11]:

Acetaminophen → NAPQI + 2H⺠+ 2eâ»

The critical issue is that the sensor's electronics cannot distinguish between the electrons generated from the target analyte (Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚, derived from glucose) and those from the interfering species (acetaminophen). Consequently, the oxidation current is additive, leading to a falsely elevated glucose reading [13] [14] [8].

The diagram below illustrates this competitive interference mechanism at the sensor electrode.

Quantitative Analysis of Interference Effects

The magnitude of acetaminophen interference is dose-dependent and can be significant, especially at lower glucose concentrations. The following table summarizes key quantitative findings from clinical and experimental studies.

Table 1: Quantified Impact of Acetaminophen on Glucose Sensor Readings

| Acetaminophen Dose & Route | Sensor Model(s) Tested | Observed Discrepancy (CGM vs. Reference) | Time to Peak Interference | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1,000 mg (Oral) | Dexcom G4 | Mean difference: 61 mg/dL (Upper 95% CI: 77 mg/dL) | 120 minutes | [13] |

| 1,000 mg (Oral) | Dexcom Seven Plus, Medtronic Guardian, Dexcom G4 Platinum | CGM readings: ~85 to 400 mg/dL (Reference BG: ~90 mg/dL) | Coincided with peak ISF acetaminophen | [14] |

| 15 mg/kg (IV) | Medtronic Guardian 4 | Estimated discrepancy: 55 to 114 mg/dL | 29.2 ± 1.9 minutes | [8] |

| 1,000 mg (Oral) | Guardian REAL-TIME | Increase from baseline: 21 mg/dL (at BG ~90 mg/dL) | Not Specified | [8] |

| 1,000 mg (Oral) | Dexcom G4 Platinum | Increase from baseline: 30 mg/dL (at BG ~90 mg/dL) | Not Specified | [8] |

A critical finding for patient safety is that the interference effect is inversely correlated with blood glucose levels. Analysis of IV acetaminophen administration showed a significant negative correlation, where the discrepancy between CGM readings and actual blood glucose was greater at lower glucose levels, thereby increasing the risk of masked hypoglycemia [8].

Experimental Protocols for Investigating Interference

Researchers can use the following methodologies to characterize and quantify acetaminophen interference in sensor systems.

In-Vitro Interference Challenge Protocol

This protocol is suitable for initial screening of sensor materials or designs.

- Objective: To quantify the amperometric response of a GOx sensor to acetaminophen in a controlled buffer system.

- Materials:

- Potentiostat and electrochemical cell.

- Working electrode (fabricated sensor), counter electrode, and reference electrode (Ag/AgCl).

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), pH 7.4.

- Stock solutions of D-glucose and acetaminophen in PBS.

- Procedure:

- Place the sensor in PBS under stirring conditions and apply the standard working potential (e.g., +0.65 V).

- Allow the background current to stabilize.

- Successively add aliquots of glucose stock solution to achieve desired concentrations (e.g., 50, 100, 200 mg/dL). Record the steady-state current after each addition.

- Rinse the sensor and cell. Re-stabilize the baseline current in fresh PBS.

- Successively add aliquots of acetaminophen stock solution across a physiological range (e.g., 0, 5, 10, 20 mg/L). Record the steady-state current after each addition.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the apparent "glucose-equivalent" signal generated by acetaminophen by comparing the current density per mg/dL of glucose to the current density per mg/L of acetaminophen.

In-Vivo Microdialysis and Sensor Correlation Protocol

This advanced method provides direct evidence of interference in a physiological context by simultaneously measuring interstitial fluid (ISF) drug concentrations and sensor performance [14].

- Objective: To correlate interstitial acetaminophen pharmacokinetics with the temporal profile of CGM sensor error.

- Materials:

- CGM systems (e.g., Dexcom, Medtronic Guardian).

- Microdialysis system with abdominal subcutaneous catheters.

- YSI analyzer or equivalent for reference plasma glucose.

- HPLC or COBAS c311 analyzer for plasma and microdialysate acetaminophen concentration.

- Procedure:

- In healthy volunteers or animal models, insert CGM sensors and microdialysis catheters in close proximity in abdominal subcutaneous tissue.

- After equilibration, administer a standard dose of acetaminophen (e.g., 1 g orally or 15 mg/kg IV).

- Collect serial blood and microdialysate samples at baseline and periodic intervals post-administration.

- Analyze samples for glucose and acetaminophen concentrations.

- Continuously record CGM glucose values.

- Data Analysis:

- Plot plasma glucose, ISF acetaminophen, and CGM glucose over time.

- The interference is directly demonstrated when CGM readings spike while plasma glucose remains constant, and this spike temporally aligns with the rise of acetaminophen in the ISF [14].

Mitigation Strategies: From Membranes to New Materials

Several strategies have been developed to minimize or eliminate acetaminophen interference, primarily focused on creating a selective barrier.

Permselective Membranes

The most established approach involves coating the sensor with a polymer membrane that selectively allows Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ to pass while blocking larger or differently charged molecules like acetaminophen.

- Cellulose Acetate and Nafion Composite: A classic and effective solution is a composite membrane of cellulose acetate and Nafion. The cellulose acetate layer acts as a size-exclusion barrier, while the charged Nafion layer can repel acetaminophen based on its ionic properties. This combination was shown to effectively eliminate acetaminophen interference in an implantable sensor while maintaining reasonable Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ diffusivity [3] [12].

- Electropolymerized Films: Membranes like polyphenylenediamine (PPD) can be electrochemically synthesized directly on the electrode surface. These films form dense, non-conducting layers with pore sizes that are tunable to exclude interferents like ascorbic acid and acetaminophen [12].

Advanced Material Strategies

Recent research explores novel materials and concepts to push the boundaries of interference rejection.

- Conductive Membrane Encapsulation: A novel strategy involves encapsulating the sensor with a conductive membrane (e.g., gold-coated track-etch membranes). A specific potential is applied to these outer membranes, electrochemically oxidizing and deactivating redox-active interferents like acetaminophen before they reach the inner sensing electrode. This approach has demonstrated a 72% reduction in redox-active interference [15].

- Carbon-Based Nanomaterials and Enzyme Engineering: Advances include using carbon nanomaterials (e.g., graphene, MXenes) to improve electrode conductivity and stability, coupled with chemical modification of GOx itself (mGOx) to enhance its performance and stability within the sensor [12].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Mitigating Acetaminophen Interference

| Research Reagent / Material | Function / Mechanism of Action | Key Findings / Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Cellulose Acetate | Hydrophobic polymer that creates a size-exclusion diffusion barrier. | Reduces access of larger interferent molecules to the electrode surface. Most effective when used in composites [3]. |

| Nafion | A sulfonated tetrafluoroethylene-based polymer. Creates a charged, permselective barrier that can repel acidic interferents. | The cellulose acetate/Nafion composite membrane effectively eliminated acetaminophen interference in an implantable sensor [3]. |

| Polyphenylenediamine (PPD) | An electrophymerized, non-conducting film deposited directly on the electrode. | Forms a dense film with tunable porosity that selectively removes ascorbic acid and other interferents [12]. |

| Gold-Coated Track-Etch Membranes | Conductive outer membrane. A potential is applied to electrochemically deactivate redox-active interferents before they reach the sensor. | Demonstrated a 72% reduction in redox-active interference and an 8-fold decrease in detection limit [15]. |

| MXene/GOx Polygel Nanocomposite (PGOx) | 2D MXene nanosheets provide a large surface area; polygels enhance enzyme stability. | Improves overall sensor stability and performance, which can indirectly improve selectivity. LOD of 3.1 μM for glucose [12]. |

Troubleshooting FAQs for Researchers

Q1: Our in-vitro sensor shows minimal interference, but significant discrepancy occurs in animal models. What could be the cause? A: This is a common issue. In-vitro tests often use buffers, while in-vivo, acetaminophen is metabolized. The primary metabolite in the interstitial fluid may be the actual interferent, not the parent compound. Implement an in-vivo microdialysis protocol [14] to directly measure the interferent profile in the ISF and correlate it with sensor error.

Q2: Why does the interference effect appear stronger at low glucose levels? A: The signal from the interferent is additive. At low glucose levels, the "background" current from glucose is small, so the fixed additional current from a given dose of acetaminophen constitutes a larger relative error, leading to a greater percentage overestimation of glucose [8].

Q3: We are using a Nafion coating, but interference persists. What are potential reasons? A: The thickness and morphology of the Nafion layer are critical. An overly thin or non-uniform coating may be incomplete. Consider using a composite membrane, such as cellulose acetate under Nafion, for a synergistic size-exclusion and charge-repulsion effect [3]. Also, validate that your working potential is optimized, as higher potentials exacerbate the issue.

Q4: Are there alternative sensing principles immune to acetaminophen interference? A: Yes. Second-generation sensors use redox mediators instead of Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ detection, often at lower operating potentials where acetaminophen is not oxidized. Third-generation sensors aim for direct electron transfer from the enzyme, also potentially avoiding this interference. Fluorescence-based sensors (e.g., Eversense) are inherently immune to electrochemical interferents [11] [12].

Acetaminophen interference in GOx-based sensors is a well-understood electrochemical phenomenon that remains a critical challenge for the development of robust implantable biosensors and the safe use of CGM systems. A deep understanding of the mechanism—competitive oxidation at the electrode surface—empowers researchers to select appropriate investigation protocols and implement effective mitigation strategies, such as advanced permselective membranes and novel conductive barriers. Continued research into these areas is essential for achieving the accuracy and reliability required for non-adjunctive glucose monitoring and closed-loop artificial pancreas systems.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is acetaminophen a particularly common interferent for implantable biosensors? Acetaminophen is a significant interferent for first-generation electrochemical biosensors because it is easily oxidized at the working electrode's applied voltage. These sensors measure glucose by detecting an electrical current from the oxidation of hydrogen peroxide (Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚), a byproduct of the glucose oxidase reaction. Acetaminophen competes in this reaction, generating an additional, non-glucose-related current that the sensor misinterpretes as a falsely high glucose concentration [8].

Q2: How does the route of administration (oral vs. intravenous) impact acetaminophen interference? The route of administration significantly affects the magnitude of interference. Intravenous (IV) administration can produce approximately twice the blood concentration of acetaminophen compared to oral intake. This higher concentration can lead to more severe and pronounced falsely elevated sensor readings. In one case, IV acetaminophen (15 mg/kg) caused a rapid spike in CGM readings, with an estimated discrepancy of 55 to 114 mg/dL compared to actual blood glucose, a larger effect than typically observed with oral doses [8].

Q3: What biosensor design features can help mitigate the effects of interferents like acetaminophen? Manufacturers incorporate several design features to reduce interference:

- Interference Membranes: Specialized permselective membranes are designed to limit the passage of common interfering substances to the working electrode [4].

- Bioprotective Membranes: These outer membranes provide biocompatibility and can also act as a barrier to interfering species [4].

- Nafion Coating: Applying a Nafion polymer coating to the electrode can improve sensor specificity by reducing the flux of interferents [16].

- Biosensor Generation: Second-generation biosensors use an artificial mediator, allowing for a lower operating potential that is less susceptible to oxidizing common interferents compared to first-generation (oxygen-dependent) systems [4].

Q4: Are there other common pharmaceutical substances known to interfere with biosensor performance? Yes, several other substances are known to cause interference, which is often detailed in manufacturer labeling. Common examples include:

- Ascorbic Acid (Vitamin C): Can falsely raise readings in some second-generation biosensor systems (e.g., FreeStyle Libre) [4].

- Hydroxyurea: Known to cause falsely elevated readings in first-generation systems from Dexcom and Medtronic [4].

- Salicylic Acid (in Aspirin): May slightly lower sensor glucose readings [4].

- Mannitol/Sorbitol: Can falsely elevate readings when administered intravenously [4].

- Tetracycline-class Antibiotics: May falsely lower sensor glucose readings in optical systems like the Senseonics Eversense [4].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing Unexplained Signal Spikes During In-Vitro Testing

Problem: During an in-vitro experiment with an implantable biosensor, you observe a rapid, unexplained increase in the sensor signal that does not correlate with the expected analyte concentration.

Possible Causes and Investigative Steps:

Review Recent Additives:

- Action: Immediately check the log of all pharmaceutical compounds or reagents introduced to the test solution.

- Investigation: Cross-reference these compounds against the known interferent list for your biosensor's technology (e.g., first-generation electrochemical). Acetaminophen, ascorbic acid, and hydroxyurea are primary suspects [4] [8].

Quantify the Interference:

- Action: If an interferent is suspected, design a controlled experiment to quantify its effect.

- Investigation: Spiked the test solution with the suspected interferent at a known, clinically relevant concentration while holding the glucose (or target analyte) concentration constant. Monitor the signal deviation. The table below summarizes quantitative interference data from a microneedle biosensor study, showing the relative impact of different substances [16]:

Table 1: Quantification of Interference on an Electrochemical Biosensor at 5 mM Glucose

| Interfering Substance | Concentration Tested | Interference (% Change in Signal) |

|---|---|---|

| Acetaminophen | Not Specified | Up to 150% |

| Ascorbic Acid | Not Specified | 4.5% - 17.8% |

| Urea | Not Specified | 4.2% - 11.3% |

- Verify Sensor Integrity:

- Action: Rule out sensor failure.

- Investigation: Perform a calibration check with a standard analyte solution free of any potential interferents. A stable and accurate reading suggests the spike was indeed due to chemical interference and not sensor drift.

Guide 2: Developing a Protocol for Systematic Interferent Screening

This guide provides a methodology for proactively evaluating the susceptibility of a biosensor to pharmaceutical interference, based on established practices in the field [4] [16].

Objective: To systematically test and quantify the effect of potential pharmaceutical interferents on the accuracy of an implantable biosensor in a controlled in-vitro environment.

Materials:

- Biosensor platform (e.g., functionalized microneedle array or other relevant design)

- Electrochemical analyzer (e.g., potentiostat)

- Standard analyte (e.g., D-glucose)

- Pharmaceutical interferents for testing (e.g., Acetaminophen, Ascorbic Acid, Hydroxyurea)

- Buffer solution (e.g., Phosphate Buffered Saline, PBS)

- Standard laboratory glassware and pipettes

Experimental Workflow:

Step-by-Step Protocol:

Baseline Establishment:

- Prepare a buffer solution with a known, physiologically relevant concentration of your target analyte (e.g., 5 mM glucose).

- Immerse the biosensor and measure the stable output signal. This is your baseline signal (I_glucose).

Interferent Introduction:

Signal Measurement and Analysis:

- Record the new sensor output (I_glucose+interferent).

- Calculate the percentage of signal interference using the formula:

- % Interference = [ (Iglucose+interferent - Iglucose) / I_glucose ] × 100

Data Compilation:

- Repeat steps 1-3 for all potential interferents and across a range of concentrations.

- Compile the results into an interference profile for the biosensor, similar to the example provided in Table 1.

Mitigation Strategy Testing:

- If a biosensor incorporates a special interference membrane or coating (e.g., Nafion), repeat the above protocol with and without the feature to quantitatively demonstrate its efficacy in reducing the interference effect [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Interference Studies in Biosensor Research

| Research Reagent | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Glucose Oxidase (GOx) | The biological recognition element immobilized on the working electrode. It catalyzes the oxidation of glucose, producing Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚, which is measured to deduce glucose concentration [16]. |

| Nafion | A perfluorinated polymer used as an electrode coating. It acts as a permselective layer to reduce the flux of negatively charged interferents like ascorbic acid and uric acid to the electrode surface, improving specificity [16]. |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) & Glutaraldehyde | Used together as a cross-linking system to immobilize and stabilize the glucose oxidase enzyme on the electrode surface, preserving its activity [16]. |

| Acetaminophen (Paracetamol) | A critical reagent used as a positive control for interference testing, especially for first-generation electrochemical biosensors, due to its well-documented propensity to cause falsely elevated signals [8] [16]. |

| Ascorbic Acid | Another common positive control interferent for testing the selectivity of biosensors, particularly relevant for second-generation systems [4]. |

| Hydroxyurea | A pharmaceutical compound used in interference testing, known to cause significant positive interference in specific CGM systems [4]. |

| Egfr-IN-38 | Egfr-IN-38, MF:C25H24ClN7O2, MW:490.0 g/mol |

| Cdk7-IN-16 | CDK7 Inhibitor Cdk7-IN-16 |

Technical Support Center

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the mechanism by which acetaminophen interferes with continuous glucose monitors?

Acetaminophen interferes with the electrochemical sensing principle of many CGM systems. Most CGM devices use a first-generation electrochemical biosensor design that relies on glucose oxidase enzyme reactions. When interstitial glucose passes through the enzyme membrane, hydrogen peroxide (Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚) is produced, which decomposes under applied voltage to release electrons that are converted into glucose readings [8]. However, acetaminophen's phenolic moiety is also oxidized at the electrode sensing surface, producing an additional electrochemical signal not related to glucose concentration [13] [8]. This results in falsely elevated CGM glucose values that do not correspond to actual blood glucose levels.

Q2: How does intravenous acetaminophen administration differ from oral administration in its interference effect?

Intravenous acetaminophen produces approximately twice the blood concentration of acetaminophen compared to oral administration and causes more significant CGM inaccuracies [8]. Clinical observations show IV administration (15 mg/kg over 15 minutes) causes a rapid increase in CGM readings, peaking at approximately 29.2 ± 1.9 minutes after administration, with estimated discrepancies of 55-114 mg/dL compared to capillary blood glucose measurements [8]. The intravenous route bypasses first-pass metabolism, leading to higher and more immediate serum concentrations that exacerbate the electrochemical interference effect.

Q3: Which CGM systems are most affected by acetaminophen interference?

First-generation electrochemical biosensor designs from Dexcom and Medtronic show significant susceptibility to acetaminophen interference [4]. Modern systems have implemented design improvements, but interference remains a concern. The specific affected models and their labeling are detailed in Table 1.

Q4: Why is acetaminophen interference particularly dangerous for Automated Insulin Delivery (AID) systems?

AID systems rely on accurate CGM readings to automatically calculate and deliver insulin doses. Falsely elevated CGM values can trigger unnecessary autocorrection boluses, potentially leading to dangerous hypoglycemic events [8]. This risk is amplified by the observation that acetaminophen interference produces greater discrepancies at lower blood glucose levels, creating a high-risk scenario where the system may administer insulin when actual glucose levels are already low or falling [8].

Q5: What design approaches are manufacturers implementing to reduce acetaminophen interference?

Manufacturers are employing multiple strategies to mitigate interference effects [4]:

- Permselective membranes: Designed to reduce the passage of interfering substances to the working electrode

- Multi-domain sensor designs: Incorporating interference membranes, bioprotective membranes, and diffusion resistance membranes

- Lower operating potentials: Newer systems reduce the applied voltage, minimizing oxidation of interfering substances

- Advanced biosensor generations: Movement toward second-generation (artificial mediator) and third-generation (direct electron transfer) designs

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Unexplained CGM Glucose Elevations Following Medication Administration

Symptoms: Rapid increase in CGM readings without corresponding blood glucose elevation; upward convex curve pattern; discrepancies lasting 2-8 hours.

Assessment Steps:

- Review recent medications: Identify any acetaminophen-containing products, including:

- Pain relievers (Tylenol)

- Cold and flu medications

- Fever reducers

- Note: Intravenous formulations pose highest risk [8]

Check CGM manufacturer specifications: Reference Table 1 for known interference patterns

Compare with blood glucose measurements: Conduct fingerstick testing to quantify discrepancy

Evaluate timing: Note that peak interference typically occurs 30 minutes-2 hours post-administration [13] [8]

Immediate Actions for AID Systems:

- Switch insulin pump to manual mode during acetaminophen effect window (2-8 hours post-administration) [8]

- Rely on blood glucose measurements rather than CGM values for treatment decisions

- Program temporary elevated glucose targets if system must remain in automated mode

- Increase blood glucose monitoring frequency during this period

Preventive Strategies:

- Identify acetaminophen-free alternative medications for pain/fever management

- Educate all healthcare providers about CGM interference risks

- Document interference events in patient records for future reference

- Consider CGM systems with lower acetaminophen susceptibility when available

Experimental Protocols for Interference Testing

In Vitro Assessment of Acetaminophen Interference

Objective: Quantify the effect of acetaminophen on CGM sensor accuracy under controlled conditions.

Materials:

- CGM sensors from multiple generations/manufacturers

- Acetaminophen stock solutions (varying concentrations)

- Glucose solutions spanning physiological range (40-400 mg/dL)

- Physiological buffer (pH 7.4)

- Electrochemical testing apparatus

- Statistical analysis software

Methodology:

- Sensor Calibration: Calibrate all sensors according to manufacturer specifications using glucose standards without interferents.

Interference Testing:

- Expose sensors to fixed glucose concentrations (100, 150, 200 mg/dL) while varying acetaminophen concentrations (0, 5, 10, 20 μg/mL)

- Measure sensor output at each combination

- Maintain constant temperature (37°C) and pH (7.4)

- Allow stabilization period between concentration changes

Data Collection:

- Record sensor readings at 1-minute intervals for 60 minutes

- Calculate mean absolute relative difference (MARD) for each condition

- Perform statistical analysis (ANOVA with post-hoc testing)

Dose-Response Characterization:

- Generate dose-response curves for acetaminophen interference

- Calculate interference magnitude as ΔGlucose = Sensor Reading - Actual Glucose

Clinical Validation Protocol

Objective: Evaluate acetaminophen interference in clinical setting with AID systems.

Study Design: Controlled crossover study with acetaminophen administration.

Participants: Type 1 diabetes patients using AID systems (n=20-40).

Intervention:

- Session 1: Oral acetaminophen (1000 mg)

- Session 2: Intravenous acetaminophen (15 mg/kg)

- Session 3: Placebo control

- Washout period: ≥7 days between sessions

Measurements:

- CGM readings every 5 minutes

- Reference blood glucose every 15 minutes (YSI or equivalent)

- Plasma acetaminophen levels at 0, 30, 60, 120, 240 minutes

- Insulin delivery data from AID system

Endpoint Analysis:

- Maximum CGM-blood glucose discrepancy

- Time to peak interference effect

- Duration of clinically significant interference (>20 mg/dL difference)

- Correlation between acetaminophen concentration and interference magnitude

Table 1: CGM System Interference Profiles and Manufacturer Labeling

| Manufacturer & Model | Biosensor Generation | Acetaminophen Interference | Other Labeled Interferents | Dose Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dexcom G6/G7/ONE/ONE+ | First-generation | Yes - may increase sensor readings | Hydroxyurea | >1000 mg every 6 hours in adults [4] |

| Medtronic Guardian 3/4/Sensor | First-generation | Yes - may falsely raise readings | Hydroxyurea | Any acetaminophen dose [4] |

| Medtronic Simplera | First-generation | Yes - may falsely raise sensor readings | Hydroxyurea | Medications containing acetaminophen [4] |

| Abbott FreeStyle Libre 2/3 | Second-generation | Not labeled | Ascorbic acid (Vitamin C) | >500 mg/day may affect readings [4] |

| Senseonics Eversense | Optical (Not electrochemical) | Not labeled | Tetracycline, Mannitol/Sorbitol | Unique interference profile [4] |

Table 2: Clinically Observed Acetaminophen Interference Magnitude

| Administration Route | Dose | Peak Discrepancy (mg/dL) | Time to Peak (minutes) | Duration of Effect | Study/Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oral | 1000 mg | 21-30 mg/dL | 60-120 min | Up to 8 hours [13] | Maahs et al. (2015) [13] |

| Intravenous | 15 mg/kg | 55-114 mg/dL | 29.2 ± 1.9 min | >2 hours [8] | Matsuyama et al. (2025) [8] |

| Oral (G6 System) | 1000 mg | 3.1 ± 4.8 mg/dL | Not specified | Not specified | Manufacturer data [8] |

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Diagram 1: Interference mechanism and testing workflow (Max Width: 760px)

Diagram 2: Clinical risk management protocol (Max Width: 760px)

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Interference Research

| Research Tool | Function/Application | Specifications/Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| First-generation CGM Sensors (Dexcom G6/G7, Medtronic Guardian) | Primary interference model systems; oxygen-dependent hydrogen peroxide detection | Use multiple lots; note membrane composition differences [4] |

| Second-generation CGM Sensors (Abbott FreeStyle Libre) | Control systems using artificial mediators; lower operating potential reduces interference [4] | Useful for comparative studies |

| Acetaminophen Reference Standards | Prepare precise concentrations for dose-response studies | Pharmaceutical grade; multiple solubility profiles (oral/IV simulations) [13] |

| Glucose Oxidase Enzyme | Understanding fundamental interference mechanism at molecular level | Multiple sources for reproducibility testing [8] |

| Electrochemical Testing Station | Controlled in vitro interference quantification | Capable of maintaining physiological temperature (37°C) and pH [17] |

| Physiological Buffer Systems | Simulate interstitial fluid environment for in vitro testing | pH 7.4; appropriate ionic composition [17] |

| HPLC/MS Equipment | Quantify acetaminophen concentrations in parallel with sensor testing | Validation of exposure concentrations [8] |

| Permselective Membrane Materials | Research on interference mitigation strategies | Various polymer compositions for flux control [4] |

| (R)-(+)-Pantoprazole-d6 | (R)-(+)-Pantoprazole-d6, MF:C16H15F2N3O4S, MW:389.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| MtTMPK-IN-4 | MtTMPK-IN-4|Inhibitor | MtTMPK-IN-4 is a potent M. tuberculosis thymidylate kinase inhibitor (IC50=6.1 µM). For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

Engineering Solutions: Biosensor Designs and Methodologies to Counteract Interference

This technical support center is designed for researchers working on implantable biosensors, with a specific focus on mitigating acetaminophen (APAP) interference through advanced permselective membrane systems. The guidance below provides troubleshooting, experimental data, and validated protocols to support your development efforts.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the primary mechanism of acetaminophen interference in electrochemical biosensors? Acetaminophen interferes with first-generation electrochemical biosensors because it is an easily oxidizable substance. These sensors operate at a high voltage to measure the hydrogen peroxide (Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚) produced from the glucose oxidase reaction. At this high potential, acetaminophen is also oxidized, generating a false additional current that is misinterpreted as higher glucose concentration [4] [8].

FAQ 2: How do permselective membranes function to exclude interferents? Permselective membranes are engineered domains within the sensor's layered architecture designed to be selectively permeable. They function as a physical and chemical barrier, strategically filtering molecules based on size, charge, or other properties before they reach the working electrode. This prevents electroactive interferents like acetaminophen from reacting at the electrode surface, while allowing glucose to pass through freely [4].

FAQ 3: Our in vitro interference screening shows promising results, but in vivo performance declines. What are potential causes? This common issue often relates to the biofouling process, which is not fully replicated in standard in vitro tests. After implantation, proteins and cells adhere to the sensor surface, forming a non-specific biofilm. This biofilm can alter the diffusion kinetics of both glucose and interferents, potentially reducing the effectiveness of the permselective membrane. Furthermore, the local inflammatory response can change the composition of the interstitial fluid, potentially concentrating interferents or creating new confounding factors [18]. Testing membranes with enhanced biocompatible coatings, such as specific hydrogels, may improve in vivo performance [18].

FAQ 4: Which biosensor generations are most susceptible to acetaminophen interference? Susceptibility varies by biosensor design generation [4]:

- First-Generation Biosensors (e.g., Dexcom G6/G7, Medtronic Guardian): Rely on oxygen and are highly susceptible to acetaminophen interference [4] [19].

- Second-Generation Biosensors (e.g., Abbott FreeStyle Libre): Use an artificial mediator and are less susceptible to acetaminophen but can be affected by high doses of ascorbic acid (Vitamin C) [4] [20].

- Third-Generation Biosensors (e.g., Sinocare iCan i3): Engineered for direct electron transfer and claim no interference from acetaminophen or vitamin C [4].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inconsistent interferent exclusion across sensor batches.

- Potential Cause 1: Inconsistent polymerization or cross-linking during membrane fabrication, leading to variations in pore size density.

- Solution: Implement more stringent quality control during polymer synthesis. Use techniques like scanning electron microscopy (SEM) to verify membrane morphology consistency. Ensure environmental conditions (temperature, humidity) are tightly controlled during fabrication.

- Potential Cause 2: Degradation of the polymer matrix during sterilization or storage.

- Solution: Evaluate alternative sterilization methods (e.g., gamma irradiation vs. ethylene oxide) and assess membrane performance post-sterilization. Optimize storage conditions to prevent polymer hydrolysis or oxidation.

Problem: Successful acetaminophen exclusion but significant oxygen limitation.

- Potential Cause: The permselective membrane's diffusion resistance to glucose is too low relative to oxygen, creating an oxygen-deficient environment around the glucose oxidase enzyme.

- Solution: Co-immobilize a custom oxygen reservoir material, such as perfluorocarbon, within the enzyme layer. Alternatively, engineer a composite membrane with a dedicated oxygen-rich domain to maintain a stable supply [4].

Experimental Data & Protocols

The following table summarizes quantitative data from a dynamic in vitro interference study, highlighting the response of different sensor types to various substances, including acetaminophen, at a stable glucose background of 200 mg/dL [19].

Table 1: Dynamic In-Vitro Interference Testing Results

| Substance Tested | Abbott Libre 2 (Max Bias) | Dexcom G6 (Max Bias) | Clinical Relevance Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acetaminophen | No significant bias | > +100% | Confirmed key interferent for first-gen sensors [4] [19] |

| Ascorbic Acid | +48% | No significant bias | Key interferent for second-gen sensors [4] |

| N-Acetyl-Cysteine | +11% | +18% | Relevant as an APAP antidote [21] |

| Galactose | > +100% | +17% | Sugar alcohol potential interferent |

| Hydroxyurea | No significant bias | > +100% | Pharmaceutical interferent |

| Uric Acid | No significant bias | +33% | Relevant endogenous interferent |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Chromatographic Analysis of APAP and Metabolites

This protocol allows for the simultaneous quantification of acetaminophen (APAP), its toxic metabolite NAPQI, and the antidote N-acetyl-cysteine (NAC) in plasma samples, useful for pharmacokinetic and toxicological studies [21].

1. HPLC Method for Simultaneous APAP, NAPQI, and NAC Analysis [21]

- Objective: To separate and quantify APAP, NAPQI, and NAC in a single analytical run.

- Equipment: HPLC system with a Photo-Diode Array (PDA) detector, Zorbax SB-C18 column (4.6 x 250 mm, 5 µm), pH meter, ultrasonic bath.

- Mobile Phase: Water, Methanol, and Formic acid in proportion (70:30:0.15, v/v/v).

- Flow Rate: 1.0 mL/min.

- Detection Wavelength: 254 nm.

- Injection Volume: 20 µL.

- Sample Preparation: Plasma samples should be protein-precipitated. Filter all samples through a 0.45 µm membrane filter before injection.

- Analysis: The total run time is approximately 5 minutes. Identify analytes by comparing retention times with pure standards.

2. HPTLC Method for Simultaneous APAP, NAPQI, and NAC Analysis [21]

- Objective: An alternative, cost-effective method for quantifying the same analytes.

- Equipment: HPTLC system with automatic sampler, silica gel 60 F254 plates (20 x 10 cm), twin-trough glass chamber, densitometer.

- Mobile Phase: Methanol, Ethyl Acetate, Glacial Acetic Acid (8:2:0.2, v/v/v).

- Sample Application: Apply samples as bands using an automatic sampler.

- Development: Saturate the chamber for 20 minutes. Allow mobile phase to ascend linearly to 9.0 cm.

- Detection: Air-dry plates and scan at 254 nm.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| N-Acetyl-Cysteine (NAC) | Used in studies as both a potential interferent and the primary antidote for APAP overdose; crucial for testing sensor specificity [21]. |

| Dithiothreitol (DTT) | A strong reducing agent used in interference studies; known to cause sensor fouling and failure, making it a stress-test agent for membrane robustness [19]. |

| Hydrogel Coatings | Polymers like polyethylene glycol (PEG) used to create a bioprotective domain; improve biocompatibility and reduce biofouling by creating a hydrophilic, protein-resistant surface [18]. |

| Permselective Polymers | Materials (e.g., polyurethanes, Nafion) used to form the interference domain; designed to be selectively permeable based on size and charge to exclude interferents [4]. |

| Glucose Oxidase | The core enzyme used in most CGM biosensors; catalyzes the oxidation of glucose, producing Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ that is measured electrochemically [4]. |

| Cdk1-IN-1 | Cdk1-IN-1|CDK1 Inhibitor|For Research Use Only |

| PROTAC IRAK4 degrader-2 | PROTAC IRAK4 degrader-2, MF:C57H68FN11O8S, MW:1086.3 g/mol |

Diagrams and Workflows

Biosensor Membrane Architecture

Dynamic Interference Testing Workflow

A significant challenge in the development and operation of continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) systems and other implantable biosensors is the distortion of signals caused by electroactive interfering substances, with acetaminophen being a primary culprit [4]. Accurate real-time monitoring is the cornerstone of effective diabetes management, especially for automated insulin delivery (AID) systems, which rely on precise sensor data to make dosing decisions [8]. Falsely elevated glucose readings due to acetaminophen interference can prompt these systems to deliver unneeded insulin, creating a serious risk of hypoglycemia for the user [8]. This technical support center document is designed to arm researchers and scientists with advanced electrochemical strategies, specifically the application of differential bias potentials, to identify, troubleshoot, and mitigate this critical interference in experimental settings.

Technical Background: Biosensor Design and Interference Mechanisms

Generations of Electrochemical Biosensors

Most commercially available CGM systems are based on first-generation electrochemical biosensor principles [4]. These sensors typically use glucose oxidase (GOx) as the recognition element. The core reaction involves the enzyme-catalyzed oxidation of glucose, which produces hydrogen peroxide (Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚) [8]. The sensor then applies a specific bias potential to the working electrode, which causes the Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ to oxidize. This reaction releases electrons, generating a current that is proportional to the glucose concentration [8].

Second-generation systems, like certain Abbott FreeStyle Libre models, employ an artificial mediator to shuttle electrons, which can allow for operation at lower potentials [4]. Third-generation systems aim for direct electron transfer from the enzyme to the electrode [4]. Each design presents a distinct profile of susceptibility to interfering substances.

The Acetaminophen Interference Mechanism

Acetaminophen is an electroactive compound that can be readily oxidized at the electrode surface. Critically, the oxidation potential for acetaminophen often overlaps with that of hydrogen peroxide in first-generation biosensors [8]. When a standard, single potential is applied, the sensor's transducer cannot distinguish between the electrons generated from the glucose-correlated Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ and those from the oxidation of acetaminophen. The sensor interprets the total current as stemming from glucose, leading to a falsely elevated reported value [22] [8].

The following diagram illustrates this core interference mechanism at the sensor's electrode interface.

Interference Mechanism at the Electrode

Quantitative Impact of Acetaminophen Interference

The magnitude of interference is dependent on dosage, route of administration, and the specific sensor design. The following table summarizes documented discrepancies across different scenarios.

Table 1: Documented Acetaminophen Interference Effects

| CGM Model | Acetaminophen Dose & Route | Observed Effect on Sensor Glucose | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Guardian 4 (Medtronic) | 15 mg/kg (IV) | Peak discrepancy of 55-114 mg/dL vs. blood glucose; peak at ~30 min post-dose. | [8] |

| Dexcom G6 | 1 g (Oral) | Mean increase in discrepancy of 3.1 mg/dL (±4.8 mg/dL) vs. plasma glucose. | [8] |

| Older Guardian REAL-TIME | 1 g (Oral) | Increase of ~21 mg/dL from baseline (at plasma glucose ~90 mg/dL). | [8] |

| Dexcom G4 Platinum | 1 g (Oral) | Increase of ~30 mg/dL from baseline (at plasma glucose ~90 mg/dL). | [8] |

| General Trend | N/A | Discrepancy is significantly greater at lower blood glucose levels. | [8] |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

This section addresses common experimental and technical challenges.

FAQ 1: Why does our lab-built biosensor show high background noise and signal drift in complex biological fluids like undiluted serum?

Answer: This is a classic symptom of biofouling and non-specific binding (NSB). Proteins and other biomolecules in the sample can adsorb onto the electrode surface, forming an insulating layer that increases charge-transfer resistance and degrades signal stability [23].

- Mitigation Strategies:

- Surface Passivation: Implement a robust permselective membrane. Common materials include Nafion (which is also cation-selective) or chitosan-based biopolymer films [4] [24]. These membranes create a physical and chemical barrier that limits the access of large, potentially interfering molecules to the electrode surface while allowing smaller analytes like Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ to pass.

- Hydrogel Layers: Incorporate a bioprotective hydrogel membrane (e.g., based on cross-linked poly(2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate)) [4]. This layer is designed to be biocompatible and to resist protein adhesion, thereby reducing biofouling over extended implantation periods.

- Low-Fouling Coatings: Modify the electrode surface with hydrophilic polymers like polyethylene glycol (PEG) or zwitterionic materials, which are highly resistant to protein adsorption.

FAQ 2: Our sensor successfully discriminates against acetaminophen in buffer, but performance degrades drastically in whole blood. What could be the cause?

Answer: This indicates that the interference rejection strategy is insufficient for real-world matrices. Whole blood contains a complex cocktail of electroactive interferents beyond acetaminophen, such as ascorbic acid (Vitamin C), uric acid, and lactate, which may oxidize at similar potentials [22] [20]. Your sensor's selectivity layer might be optimized for a single interferent but not for a complex mixture.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Systematic Interference Screening: Test your sensor not only with acetaminophen but also with a panel of common physiological interferents (ascorbic acid, uric acid, dopamine) both individually and in combination.

- Optimize the Interference Membrane: Re-evaluate the composition and thickness of your permselective membrane. A multi-domain membrane structure, as used in commercial sensors (e.g., Dexcom G6/G7), may be necessary to effectively screen out multiple classes of interfering molecules [4].

- Explore Advanced Materials: Consider incorporating molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs) designed to have specific cavities for acetaminophen, thereby trapping it before it reaches the electrode. Alternatively, the use of metallic nanoparticles or metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) can catalyze the specific oxidation of Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ at a lower potential, widening the window for discrimination [25].

FAQ 3: When testing differential potentials, how do we determine the optimal secondary potential for accurate signal discrimination?

Answer: Identifying the optimal secondary potential requires a systematic characterization of the current-potential (I-V) profiles for both your target analyte (Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚, correlated to glucose) and the primary interferent (acetaminophen).

- Experimental Protocol:

- Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) Scans: Perform CV in a standard solution containing only your electrolyte (e.g., PBS). This is your background.

- Analyte-Specific CV: Add a known concentration of Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ to the solution and run CV again. Identify the potential (or potential range) where the Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ oxidation current is maximal and stable.

- Interferent-Specific CV: In a fresh cell, run CV with a physiologically relevant concentration of acetaminophen. Identify its oxidation peak potential.

- Identify the "Silent" Window: Analyze the voltammograms to find a potential where the oxidation current for acetaminophen is minimal (i.e., it is not being oxidized), while a measurable, stable background current for Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ is still maintained. This potential often lies between the oxidation peaks of the two species or at a value below the interferent's oxidation onset.

- Validation: Calibrate your sensor using both the primary (measuring) potential and the secondary (discrimination) potential with solutions containing glucose only, acetaminophen only, and a mixture of both.

Experimental Protocols for Signal Discrimination

Protocol: Dual-Potential Amperometry for Acetaminophen Rejection

This protocol outlines a method to operate a biosensor at two different bias potentials to mathematically correct for acetaminophen interference.

Principle: The sensor is operated by rapidly toggling between a primary measuring potential and a secondary discrimination potential. The current at the primary potential contains signal from both glucose and acetaminophen. The current at the secondary potential is designed to be sensitive mainly to acetaminophen. A correction algorithm then subtracts the interferent contribution.

Workflow:

Dual-Potential Amperometry Workflow

Materials:

- Potentiostat/Galvanostat

- Custom-built or commercial 3-electrode system (WE: Pt; RE: Ag/AgCl; CE: Pt)

- GOx-modified working electrode

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), pH 7.4

- D-(+)-Glucose stock solution

- Acetaminophen stock solution

Procedure:

- Electrode Calibration: Immerse the sensor in stirred PBS at 37°C. Apply the primary potential (e.g., +0.6 V vs. Ag/AgCl) and record the background current until stable.

- Glucose Response: Add aliquots of glucose stock solution to achieve a range of known concentrations (e.g., 50-400 mg/dL). Record the steady-state current at the primary potential (IglucoseV1) for each concentration.

- Interferent Calibration at V1: Return to a baseline glucose level. Add acetaminophen to a clinically relevant concentration (e.g., 10-100 µM). Record the current increase at V1 (IacetV1).

- Identify Secondary Potential (V2): Using CV as described in FAQ 3, select a potential (V2, e.g., +0.3 V vs. Ag/AgCl) where Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ oxidation is minimal but acetaminophen still generates a significant current.

- Calibrate Interferent Response at V2: With acetaminophen present, switch the applied potential to V2 and record the steady-state current (IacetV2). Establish a correlation factor (k) between IacetV1 and IacetV2.

- Dual-Potential Operation & Validation: In a new solution containing both glucose and acetaminophen, rapidly pulse the applied potential between V1 and V2. Record ItotalV1 and IacetV2.

- Data Processing: Calculate the corrected glucose current: Icorrected = ItotalV1 - (k * IacetV2). Use the calibration curve from Step 2 to convert Icorrected to a glucose concentration.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Biosensor Interference Research

| Reagent/Material | Function in Experimentation | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Glucose Oxidase (GOx) | Biological recognition element; catalyzes glucose oxidation. | From Aspergillus niger. Ensure high specific activity (>200 U/mg). |

| Permselective Membranes | Reduces flux of interferents; enhances selectivity. | Nafion (cation exchanger), Poly-o-phenylenediamine (electropolymerized), Chitosan-based films [24]. |

| Bioprotective Membranes | Prevents biofouling; improves in vivo biocompatibility and longevity. | Cross-linked hydrogels (e.g., poly-HEMA). |

| Electrochemical Cell | Provides controlled environment for 3-electrode measurements. | Custom cell or commercial vessel (e.g., from Metrohm, BASi). |

| Potentiostat | Applies potential and measures resulting current. | Essential for amperometry, CV, and EIS. |

| Artificial Interstitial Fluid | Physiologically relevant testing matrix. | Contains key electrolytes (Na+, K+, Cl-, Ca2+) at physiological levels and pH (7.3-7.4). |

| Fak-IN-5 | Fak-IN-5, MF:C29H29ClF3N3O4, MW:576.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Hdac-IN-38 | HDAC-IN-38|HDAC Inhibitor|For Research Use | HDAC-IN-38 is a potent HDAC inhibitor for neuroscience research. It improves cerebral blood flow and cognitive function. This product is for research use only, not for human consumption. |

Advanced Experimental & Data Analysis Techniques

Protocol: Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) for Sensor Characterization

EIS is a powerful, non-destructive method for probing the interfacial properties of a modified electrode, which is crucial for diagnosing issues like biofouling or ineffective membrane deposition [23].

Principle: A small amplitude AC potential is applied across a range of frequencies, and the complex impedance (Z) of the system is measured. The data is often presented as a Nyquist plot.

Procedure:

- Setup: Configure the potentiostat for EIS mode. Set the DC potential to your sensor's operating point (e.g., +0.6 V). Set the AC voltage amplitude to 10 mV. Scan frequencies from 100 kHz to 0.1 Hz.

- Baseline Measurement: Run EIS on your bare or modified electrode in a clean electrolyte solution.

- Post-Modification Measurement: After applying a membrane (e.g., Nafion), run EIS again in the same solution. A successful coating will typically increase the charge-transfer resistance (Rct), visible as a larger diameter of the semicircle in the Nyquist plot.

- Post-Exposure Measurement: After exposing the sensor to a complex fluid (e.g., serum) or an interferent, run EIS again. An increase in Rct compared to the baseline often indicates successful fouling or binding events, which can be correlated with performance degradation.

Data Analysis: Machine Learning for Enhanced Discrimination

For complex datasets generated from multi-potential or multi-analyte experiments, machine learning (ML) can be a powerful tool to deconvolute signals.

- Approach: Use the currents from multiple applied potentials (not just two) as input features for a regression model (e.g., Random Forest, Support Vector Regression).

- Process:

- Feature Collection: For each sample, collect steady-state currents or integrated charge from a sequence of pulses to different potentials.

- Training Set: Create a large training set with known concentrations of glucose, acetaminophen, and other interferents, both alone and in mixtures.

- Model Training: Train the ML model to predict the reference glucose concentration based on the multi-potential current data.

- Validation: Test the model on a separate validation set not used in training. A well-trained model can effectively learn the unique "fingerprint" of each species' electrochemical behavior and provide a more robust glucose prediction in the presence of complex interference.

For researchers developing implantable biosensors, achieving accurate and selective measurements in complex biological matrices remains a significant challenge. A primary obstacle is signal interference from electroactive compounds that co-exist with the target analyte. Acetaminophen (APAP or paracetamol), a widely used over-the-counter analgesic and antipyretic, is a particularly problematic interferent for continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) systems and other implantable biosensors [4] [26].

This interference arises because acetaminophen oxidizes at electrochemical potentials that can overlap with those of target analytes, leading to falsely elevated readings [4] [27]. The consequences are not merely academic; they directly impact patient safety. For example, manufacturer labeling for leading CGM systems explicitly warns that taking higher than maximum dosage of acetaminophen (e.g., >1000 mg every 6 hours in adults) may falsely increase sensor glucose readings [4]. In the context of drug development and biomedical research, such interference can compromise data integrity and therapeutic monitoring.

This technical support article explores how biomimetic catalysts and nanozymes—nanomaterials with enzyme-like properties—offer innovative pathways to overcome these selectivity challenges. By providing alternative sensing mechanisms with enhanced specificity, these advanced materials present promising solutions for next-generation biosensing platforms where traditional enzymes fall short.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is acetaminophen such a prevalent interferent in electrochemical biosensors?

Acetaminophen's electrochemical behavior makes it particularly problematic. Its phenol group undergoes a two-electron, two-proton oxidation to form N-acetyl-p-benzoquinoneimine (NAPQI) at potentials that often overlap with those required to detect other important biomarkers [27]. This oxidation reaction is pH-dependent, with peak potential shifting to less positive values as pH increases [27]. In complex biological samples like serum, saliva, or interstitial fluid, acetaminophen can be present at therapeutic concentrations (0.01–0.05 mg/mL in saliva) [28], creating significant interference challenges for biosensors monitoring glucose, neurotransmitters, or other metabolites.

Q2: How do first-generation biosensors differ from later generations in their susceptibility to interference?

Biosensor generations are classified by their electron transfer mechanisms, which directly impact interference susceptibility:

- First-generation systems employ oxygen as a natural electron shuttle and typically require high operating potentials, making them highly susceptible to interference from electroactive compounds like acetaminophen and ascorbic acid [4] [26].

- Second-generation systems use artificial mediators to lower the required overpotential, thereby reducing interference from compounds that oxidize at higher potentials [26].

- Third-generation systems facilitate direct electron transfer between the enzyme and electrode, operating at near-physiological potentials where fewer interfering compounds are electroactive [26].

Q3: What advantages do nanozymes offer over natural enzymes in biosensing applications?

Nanozymes provide several distinct advantages that make them attractive for biosensing:

- Superior stability: They maintain catalytic activity under a wider range of temperature and pH conditions compared to natural enzymes [29] [30].

- Tunable activity: Their catalytic properties can be precisely engineered through surface modification, doping, or morphology control [31] [30].

- Cost-effectiveness: They can be produced at lower cost with more consistent quality than purified natural enzymes [29].

- Multi-enzyme mimicry: Single nanozyme systems can exhibit multiple enzyme-like activities, enabling complex cascade reactions [30].

Q4: What design strategies can improve the selectivity of biomimetic sensors?

Several innovative design strategies can enhance sensor selectivity:

- Biomimetic active sites: Designing nanozymes with atomic structures that mimic natural enzyme active sites (e.g., Fe-Nâ‚„ coordination) improves substrate specificity [30].

- Surface functionalization: Adding specific functional groups (e.g., phenolic hydroxyl groups) can create hydrogen-bonding sites that preferentially capture target molecules [32].

- Stimuli-responsive design: Creating nanozymes that activate only in response to specific microenvironmental cues (pH, redox conditions) enhances selective operation in complex biological environments [30].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges

| Challenge | Possible Causes | Solutions & Recommendations |

|---|---|---|