Advanced Strategies for Optimizing Biosensor Surface Modification to Maximize Selectivity

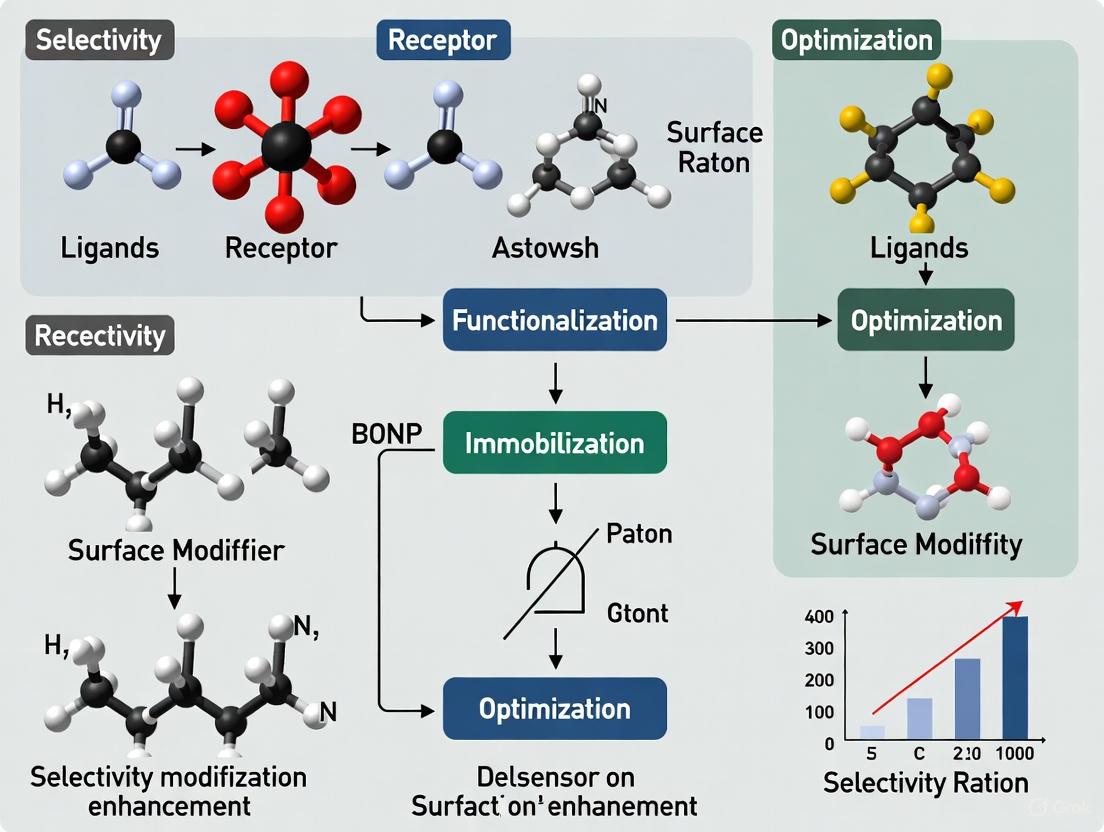

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing biosensor surface modification to achieve high selectivity, a critical parameter for accurate diagnostics and reliable data.

Advanced Strategies for Optimizing Biosensor Surface Modification to Maximize Selectivity

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing biosensor surface modification to achieve high selectivity, a critical parameter for accurate diagnostics and reliable data. We explore the fundamental principles of interfacial chemistry and probe immobilization that form the basis of selective recognition. The review details advanced methodological strategies, including the use of DNA nanostructures, molecularly imprinted polymers, and nanozymes, supported by recent application case studies. A dedicated section addresses common challenges like non-specific adsorption and stability, offering practical troubleshooting and AI-driven optimization techniques. Finally, we present a comparative analysis of surface modification methods and validation protocols, equipping scientists with the knowledge to design biosensors with exceptional specificity for demanding biomedical and clinical applications.

The Fundamentals of Selective Biosensor Interfaces: Principles, Challenges, and Surface Chemistry

The Critical Role of Interfacial Chemistry in Biosensor Selectivity

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the most effective surface functionalization strategies to minimize non-specific binding in complex samples?

Non-specific binding (NSB) is a primary cause of reduced selectivity. Effective strategies involve creating a well-defined, oriented, and stable bioreceptor layer while using antifouling coatings to block non-target interactions.

- Covalent Immobilization vs. Non-covalent Adsorption: Covalent grafting (e.g., using EDC/NHS chemistry with carboxylated surfaces) provides a stable, ordered layer that reduces random bioreceptor orientation and desorption, a common source of NSB [1] [2]. In contrast, non-covalent physisorption often leads to heterogeneous and unstable layers.

- Use of Zwitterionic Materials and PEG: Surfaces modified with zwitterionic polymers or polyethylene glycol (PEG) create a hydration layer that effectively repels proteins and other biomolecules, preventing fouling from complex matrices like blood or serum [1].

- Engineered Monolayers: Ultrathin, well-ordered monolayers, such as those formed by diazonium salt electrografting, offer superior control over surface density and functionality compared to disordered multilayers, which can trap contaminants and inhibit analyte access [2].

FAQ 2: How can I improve the sensitivity of my biosensor without compromising its selectivity?

Sensitivity and selectivity are interdependent. The key is to increase the number of available recognition sites while ensuring they remain specific to the target analyte.

- Employ 3D Nanostructured Materials: Using materials like highly porous gold, 3D graphene, metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), or hydrogels drastically increases the surface area available for probe immobilization. This higher probe loading capacity enhances the signal without sacrificing the inherent specificity of the biorecognition element [3] [4].

- Leverage Nanomaterials for Signal Amplification: Integrating nanomaterials such as gold nanoparticles (AuNPs), carbon nanotubes (CNTs), or graphene enhances electron transfer in electrochemical sensors and provides plasmonic enhancement in optical sensors. This amplifies the signal generated from each binding event, allowing detection of lower analyte concentrations [1] [4].

- Ensure Oriented Immobilization: Techniques that control the orientation of bioreceptors (e.g., antibodies) ensure their active binding sites are fully accessible to the analyte. This maximizes the efficiency of the recognition event, directly boosting both sensitivity and selectivity [1].

FAQ 3: My biosensor performance degrades rapidly. What interfacial factors affect stability and how can I improve it?

Operational stability is critically dependent on the robustness of the functionalized interface.

- Covalent Grafting for Long-Term Stability: Covalently bound layers (e.g., via diazonium electrografting or silanization) are significantly more resistant to desorption under flow or in variable ionic strength conditions compared to layers reliant on non-covalent interactions (e.g., electrostatic or hydrophobic adsorption) [1] [2].

- Biomolecule Denaturation at Interfaces: The native structure and function of immobilized proteins can be compromised by harsh surface chemistry. Using biocompatible coatings and immobilization buffers that mimic physiological conditions helps preserve bioreceptor activity over time [1].

- Precise Control of Grafting Conditions: The formation of dense, passivating multilayers during functionalization can inhibit electron transfer and reduce sensor responsiveness. Optimizing parameters like grafting potential and time to form controlled monolayers is essential for maintaining performance [2].

FAQ 4: How is Artificial Intelligence (AI) transforming the optimization of biosensor interfaces?

AI is revolutionizing the design process, moving it from traditional trial-and-error to a predictive, data-driven science.

- Predictive Modeling: Machine learning (ML) models can analyze vast datasets to predict the optimal surface compositions, topographies, and bioreceptor configurations for a specific analyte, dramatically reducing development cycles [1].

- Analysis of Characterization Data: AI algorithms can process complex spectroscopic and imaging data (e.g., from SEM, FTIR) at high throughput to characterize surface properties and predict how they will influence sensor performance metrics like limit of detection and response time [1].

- Molecular Dynamics Simulations: AI-guided simulations provide atomic-level insights into the interactions between the bioreceptor, the functionalized surface, and the target analyte. This allows for the rational design of high-affinity binding surfaces and effective antifouling coatings before any physical experiment is conducted [1].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem 1: High Background Signal or Low Signal-to-Noise Ratio

This is a classic symptom of non-specific binding or inefficient signal transduction.

- Potential Cause 1: Inadequate blocking of the sensor surface.

- Solution: Implement a rigorous blocking protocol. After immobilizing the capture probe, incubate the surface with a suitable blocking agent (e.g., BSA, casein, or synthetic blocking peptides) to cover any remaining reactive sites. The choice of blocker should be optimized for your specific sample matrix [1].

- Potential Cause 2: Disordered or multilayer functionalization leading to probe heterogeneity and trapped contaminants.

- Solution: Optimize your functionalization protocol to form a controlled monolayer. For diazonium grafting, this may involve reducing grafting cycle numbers or concentration. Techniques like X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) can be used to characterize layer thickness and homogeneity [2].

- Potential Cause 3: Suboptimal choice of nanomaterial or its functionalization.

- Solution: Ensure nanomaterials are properly functionalized with the correct linkers (e.g., MPA/EDC/NHS for Au surfaces, APTES for SiOâ‚‚) to create a uniform probe layer. Aggregation of nanomaterials can also increase background noise [3].

Problem 2: Poor Reproducibility Between Sensor Batches

Inconsistency points to a lack of control over the surface modification process.

- Potential Cause 1: Uncontrolled functionalization conditions.

- Solution: Standardize all reaction parameters, including temperature, pH, ionic strength, concentration of modifying agents, and reaction time. Automated liquid handling systems can significantly improve reproducibility for coating and immobilization steps [2].

- Potential Cause 2: Inconsistent surface pretreatment.

- Solution: Establish a strict and validated protocol for cleaning and activating the transducer surface (e.g., oxygen plasma for gold, piranha solution for oxides) before any functionalization. Surface wettability tests can be a quick quality check.

- Potential Cause 3: Variability in bioreceptor quality.

- Solution: Source bioreceptors (antibodies, aptamers) from reliable suppliers and characterize their activity and concentration before use. Avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles.

Problem 3: Low Sensitivity and Slow Response Time

The sensor fails to detect low analyte concentrations or reacts too slowly.

- Potential Cause 1: Low density or improper orientation of capture probes.

- Solution: Shift from 2D to 3D immobilization platforms. Use nanostructured electrodes or porous scaffolds like hydrogels or MOFs to increase the probe loading capacity [4]. Employ site-specific immobilization techniques (e.g., using Fc-specific antibodies or engineered tags) to ensure oriented probe presentation [1].

- Potential Cause 2: Inefficient mass transport of the analyte to the sensing surface.

- Solution: For flow-based systems, optimize the flow rate to balance between sufficient analyte delivery and incubation time. Incorporating mixing or stirring in batch systems can also enhance mass transport.

- Potential Cause 3: A passivating or disordered interfacial layer that hinders electron or signal transfer.

- Solution: As demonstrated in studies comparing mono- and tri-carboxylated diazonium layers, an ultrathin, well-ordered monolayer (e.g., from ATA) provides superior accessibility and signal compared to a disordered multilayer (e.g., from PAB). Re-optimize your grafting chemistry to avoid over-functionalization [2].

Experimental Protocols for Key Surface Modifications

Protocol 1: Creating a Well-Defined Covalent Interface via Diazonium Electrografting

This protocol is adapted from research on engineering grafted adlayers for electrochemical detection and provides a method for creating a stable, carboxyl-functionalized surface for subsequent biomolecule immobilization [2].

Principle: Electrochemical reduction of an aryl diazonium salt generates reactive aryl radicals that form robust covalent bonds with carbon-based electrodes, creating a uniform monolayer.

Key Research Reagent Solutions:

- 3,4,5-Tricarboxybenzenediazonium (ATA) salt solution (2 mM): Prepared in 0.5 M Hâ‚‚SOâ‚„ for electrografting.

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), pH 7.4: For washing and subsequent steps.

- MES buffer, pH 5.0: For EDC/NHS activation.

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Electrode Preparation: Clean the electrode substrate (e.g., HOPG, glassy carbon) according to standard procedures (e.g., polishing, plasma cleaning).

- Electrochemical Grafting: Place the electrode in a cell containing the ATA solution. Perform 1-3 cyclic voltammetry (CV) scans between +0.5 V and -0.5 V (vs. Ag/AgCl) at a scan rate of 50 mV/s. A characteristic irreversible reduction peak will appear in the first cycle and diminish in subsequent cycles, indicating monolayer formation.

- Rinsing: Rinse the grafted electrode thoroughly with PBS and deionized water to remove any physisorbed species.

- Surface Activation: Incubate the carboxyl-functionalized surface with a fresh mixture of EDC and NHS (e.g., 400 mM / 100 mM) in MES buffer for 30-60 minutes to activate the carboxyl groups to NHS esters.

- Bioreceptor Immobilization: Rinse the activated surface and immediately incubate with the solution containing your amine-terminated bioreceptor (antibody, aptamer, etc.) for 1-2 hours.

- Blocking: Finally, block any remaining active esters and non-specific sites with a 1% BSA solution for 1 hour.

Expected Outcomes:

- A stable, covalently grafted carboxylic acid monolayer.

- Successful immobilization should lead to a significant enhancement in sensitivity and selectivity for the target analyte, as demonstrated for epinephrine detection [2].

Protocol 2: Constructing a 3D Immobilization Matrix Using a Hydrogel Scaffold

This protocol outlines the general steps for creating a 3D sensing interface to dramatically increase probe loading, based on strategies for influenza virus detection [4].

Principle: A hydrogel matrix provides a highly porous, biocompatible, and hydrophilic 3D environment that allows for high-density immobilization of capture probes while maintaining their functionality and reducing non-specific adsorption.

Key Research Reagent Solutions:

- Polyethylene glycol diacrylate (PEGDA) precursor solution.

- Photoinitiator: e.g., 2-Hydroxy-4'-(2-hydroxyethoxy)-2-methylpropiophenone.

- Capture Probe Solution: e.g., thiol- or amine-modified DNA aptamers or antibodies.

- EDC/NHS solution in MES buffer.

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Surface Priming: Functionalize the transducer surface with reactive groups (e.g., acrylate or vinyl groups) to enable covalent attachment of the hydrogel.

- Hydrogel Formation: Mix the PEGDA precursor with the photoinitiator and the capture probes. Deposit the mixture onto the primed surface and expose to UV light (e.g., 365 nm) for several minutes to initiate cross-linking polymerization, entrapping the probes within the 3D network.

- Post-Assembly Processing: After polymerization, rinse the hydrogel-modified sensor thoroughly with PBS to remove unreacted monomers and unbound probes.

- Optional Surface Activation: If probes are not incorporated during polymerization, the hydrogel can be functionalized with carboxyl or other reactive groups post-formation and activated with EDC/NHS for subsequent probe coupling.

- Blocking: Incubate the sensor with a blocking solution suitable for the hydrogel chemistry (e.g., BSA, ethanolamine) to minimize non-specific binding.

Expected Outcomes:

- Formation of a uniform, hydrated 3D layer on the sensor surface.

- A significant increase in analytical signal and lower limit of detection due to higher probe density, as evidenced in biosensors for virus detection [4].

Table 1: Comparison of Surface Functionalization Strategies

| Strategy | Key Reagents | Advantages | Limitations | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covalent Grafting | Diazonium salts, EDC/NHS, APTES, Glutaraldehyde | High stability, controlled orientation, robust in variable conditions [1] [2] | Can require complex synthesis/optimization, may reduce conductivity [2] | Long-term sensing, harsh environments |

| Non-covalent Adsorption | Au-Thiol SAMs, Protein A/G, Polyelectrolytes | Simple, preserves biomolecule activity, fast [1] [5] | Lower stability, random orientation, prone to desorption [1] | Rapid prototyping, sensitive biomolecules |

| 3D Matrices | Hydrogels, porous Au, MOFs, 3D Graphene | High probe density, enhanced sensitivity, biocompatible [3] [4] | Slower diffusion, more complex fabrication, potential for batch variation [4] | Ultra-sensitive detection, single-molecule counting |

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Advanced Biosensor Platforms

| Biosensor Platform / Technique | Target Analyte | Key Performance Metric (e.g., LOD, Sensitivity) | Key Interfacial Design Feature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Au-Ag Nanostars SERS Platform [3] | α-Fetoprotein (AFP) | LOD: 16.73 ng/mL [3] | Spiky morphology for plasmonic enhancement; MPA/EDC/NHS antibody immobilization |

| Graphene THz SPR Sensor [3] | Liquid/Gas Analytes | Phase Sensitivity: 3.1x10âµ deg RIUâ»Â¹ (liquid) [3] | Magneto-optically tunable graphene layer in an Otto configuration |

| Diazonium-Grafted HOPG [2] | Epinephrine (EP) | Sub-micromolar detection, enhanced signal [2] | Ultrathin, well-ordered ATA monolayer with accessible COOH groups |

| Rolling Circle Amplification [3] | Various (Single Molecule) | Enables single molecule detection without compartmentalization [3] | Spatially resolved DNA amplification for localized signal enhancement |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Materials for Interfacial Engineering

| Reagent / Material | Function in Biosensor Development | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Diazonium Salts (e.g., ATA) [2] | Covalently grafts specific functional groups (e.g., -COOH) to carbon-based electrodes to create stable, well-defined adlayers. | Engineering a carboxylated interface on HOPG for electrostatic capture of epinephrine [2]. |

| EDC / NHS | Crosslinker system that activates carboxyl groups to form amide bonds with amine-containing biomolecules (e.g., antibodies, aptamers). | Covalent immobilization of anti-AFP antibodies onto a MPA-modified Au-Ag nanostar surface [3]. |

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) & Nanostars | Provide high surface area, enhance electron transfer, and generate strong plasmonic effects for signal amplification. | Core of a SERS platform for sensitive, label-free cancer biomarker detection [3]. |

| Polydopamine (PDA) | Forms a universal, adherent coating that mimics mussel adhesion, enabling secondary functionalization on virtually any surface. | Used for eco-friendly surface modification in electrochemical sensors for environmental monitoring [3]. |

| 3D Graphene Foams | Offer an extremely high surface-to-volume ratio and excellent conductivity for immobilizing a high density of biorecognition elements. | Used as a scaffold in electrochemical biosensors to increase probe loading and sensitivity [4]. |

| Mercaptopropionic Acid (MPA) | Forms a self-assembled monolayer on gold surfaces, presenting terminal carboxyl groups for EDC/NHS coupling. | Creating a functional base layer on Au and Ag nanostars for antibody conjugation [3]. |

Experimental and Troubleshooting Workflows

Troubleshooting Logic Flow

Surface Modification Workflow

Troubleshooting Guide

Table 1: Troubleshooting Common Biosensor Performance Challenges

| Observed Problem | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution | Underlying Principle |

|---|---|---|---|

| High background signal; false positives. | Non-specific adsorption (NSA) of non-target molecules to the sensor surface [6]. | Implement passive blocking (e.g., BSA, casein) or active removal methods (e.g., electromechanical shear) [6]. | Passive methods create a hydrophilic, non-charged boundary; active methods use force to shear away adhered molecules [6]. |

| Low signal intensity; inconsistent results between sensor batches. | Poor probe orientation or denaturation upon surface immobilization [1]. | Use oriented immobilization strategies (e.g., streptavidin-biotin, His-tag on Ni-NTA SAMs, covalent site-specific binding) [1]. | Controlled orientation maximizes the availability of active binding sites, improving consistency and signal strength [1]. |

| Low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR); difficulty distinguishing target signal. | 1. High non-specific adsorption [6].2. Suboptimal probe density [7].3. Electronic or optical system noise [8]. | 1. Apply antifouling coatings (e.g., PEG, zwitterionic materials) [6] [1].2. Optimize probe surface density to balance accessibility and steric hindrance [7].3. Characterize and optimize SNR vs. power consumption (e.g., LED current in optical sensors) [8]. | A balance must be found where surface attraction concentrates targets without permanently adsorbing them, and probe spacing allows for efficient hybridization [7]. Increasing signal power improves SNR but at the cost of higher system power [8]. |

| Low hybridization efficiency despite high probe density. | Steric hindrance and repulsive forces between densely packed probes [7]. | Dilute probe density so that inter-probe spacing is greater than the length of the target DNA strand [7]. | Hybridization becomes severely hindered when inter-probe spacing is less than or equal to the target DNA length due to crowding [7]. |

| Sensor signal degrades over time or in complex samples. | Biofouling; denaturation of immobilized bioreceptors [1]. | Employ cross-linking strategies during immobilization and use highly stable, engineered bioreceptors (e.g., mutant enzymes, nanobodies) [1] [9]. | Cross-linking stabilizes the 3D structure of the bioreceptor. Engineered proteins can have enhanced stability and selectivity for specific substrates [9]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the most effective methods to reduce non-specific adsorption (NSA) in microfluidic biosensors?

NSA can be addressed through two primary approaches:

- Passive Methods: These involve coating the surface to prevent undesired adsorption. Common techniques include using blocker proteins like Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) or casein, and chemical coatings that create a thin, hydrophilic, and non-charged boundary layer (e.g., polyethylene glycol (PEG) or zwitterionic materials) [6].

- Active Methods: These are more recent and involve dynamically removing adsorbed molecules after they have attached. This is achieved by generating surface shear forces, either through electromechanical transducers, acoustic devices, or hydrodynamic fluid flow, to overpower the adhesive forces of the physisorbed molecules [6]. The choice between passive and active methods depends on the sensor design and the compatibility of the coating with the sensing mechanism.

Q2: How does probe density affect my electrochemical DNA biosensor's performance?

Probe density is a critical factor that directly impacts hybridization efficiency and sensor signal. Computational and experimental studies show a non-linear relationship:

- Low Density: Provides ample space for target molecules to access probes, minimizing steric hindrance.

- High Density: Can lead to two issues: 1) Steric Hindrance: When the spacing between probes is less than the length of the target DNA strand, it physically blocks the target from binding [7]. 2) Electrostatic Repulsion: Neighboring DNA probes, which are negatively charged, can create a repulsive barrier that hinders the approach of the target DNA [7]. Therefore, finding an optimal probe density that maximizes surface coverage without causing steric or electrostatic blockage is crucial for high sensitivity.

Q3: How can I quantitatively measure and improve the Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) in my optical biosensor?

SNR is a key metric for evaluating sensor performance. For an optical biosensor with a DC signal like a photodiode current, SNR can be calculated as the ratio of the average signal amplitude to the standard deviation of the signal noise [8].

- Formula:

SNR = (Mean of ADC Counts) / (Standard Deviation of ADC Counts)[8]. Improvement strategies involve a trade-off: - Increase Signal: This can be done by increasing LED drive current, pulse width, or sample rate to get more light to the photodetector [8].

- Reduce Noise: Ensure a stable test setup free from environmental vibrations, block ambient light, and use signal processing techniques like frequency-domain filtering to separate the desired signal from noise [8]. A key consideration is that aggressively increasing signal (e.g., LED power) also increases system power consumption, so an optimal balance must be found for the specific application [8].

Q4: What advanced surface functionalization strategies can improve probe orientation and stability?

Traditional physical adsorption often leads to random orientation and denaturation. Advanced strategies include:

- Covalent Immobilization: Provides a stable, irreversible attachment. Site-specific covalent binding can be achieved using click chemistry or other bioorthogonal reactions, which help control orientation [1].

- Affinity-Based Immobilization: This is highly effective for ensuring uniform orientation. Common pairs include:

- Nanomaterial-Assisted Immobilization: Using materials like graphene, carbon nanotubes, or gold nanoparticles can provide a high surface-to-volume ratio and unique chemistries for dense and oriented probe immobilization [1].

Q5: Can artificial intelligence (AI) help optimize biosensor surfaces?

Yes, AI and machine learning (ML) are revolutionizing biosensor design. They can be used to:

- Predict Optimal Surface Architectures: ML models can analyze complex relationships between surface properties (e.g., hydrophobicity, charge) and performance metrics (e.g., limit of detection, sensitivity) to predict the best surface compositions and topographies [1].

- Accelerate Material Discovery: AI can design novel nanomaterials with tailored properties for signal amplification [1].

- Provide Atomic-Level Insight: AI-guided molecular dynamics simulations can model how bioreceptors interact with substrates, helping to design high-affinity and antifouling surfaces [1]. This data-driven approach reduces development time and moves beyond traditional trial-and-error methods.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Optimizing DNA Probe Density on a Gold Surface via Self-Assembled Monolayers (SAMs)

This protocol outlines a method to create and characterize a SAM with a controlled density of ssDNA probes, based on simulation-validated principles [7].

1. Principle: The performance of a DNA biosensor depends on the surface density of the probe DNA. This protocol uses alkanethiols to form a SAM on a gold surface, into which thiol-modified DNA probes are inserted. By varying the ratio of a spacer thiol (e.g., 6-mercapto-1-hexanol) to the DNA-thiol during formation, the probe density can be systematically controlled to minimize steric hindrance and maximize hybridization efficiency [7].

2. Materials:

- Gold substrate (e.g., sensor chip or slide)

- Thiol-modified ssDNA probe (e.g., 5'-Thiol-C6- [probe sequence])

- Spacer thiol (e.g., 6-mercapto-1-hexanol, MCH)

- Ultrapure water and molecular biology-grade buffers (e.g., PBS, TE)

- UV-Vis Spectrophotometer or Flurometer for DNA concentration quantification

- Electrochemical or SPR setup for characterization

3. Procedure:

- Step 1: Substrate Cleaning. Clean the gold substrate thoroughly with Piranha solution (Caution: Highly corrosive) or via oxygen plasma treatment, followed by rinsing with water and ethanol.

- Step 2: Prepare DNA/Alkanethiol Solution. Co-dissolve the thiol-modified DNA and the spacer thiol (MCH) in a suitable buffer (e.g., 10 mM PBS, pH 7.4) at a molar ratio of 1:100 for a low-density surface. For higher densities, use ratios of 1:50 or 1:10. A DNA-only solution (no MCH) can be used as a high-density control.

- Step 3: SAM Formation. Incubate the cleaned gold substrate in the prepared DNA/MCH solution for a defined period (typically 12-24 hours) at room temperature in a sealed container to prevent evaporation.

- Step 4: Rinsing and Drying. After incubation, rinse the substrate extensively with buffer and ultrapure water to remove physisorbed molecules. Gently dry under a stream of nitrogen or argon.

4. Characterization and Validation:

- Electrochemical Validation: Use electrochemical method like electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) or cyclic voltammetry (CV) with a redox couple (e.g., [Fe(CN)₆]³â»/â´â») to confirm SAM formation and estimate surface coverage.

- Hybridization Test: Expose the functionalized sensor to a solution of complementary target DNA. The hybridization event can be measured using the sensor's native transduction method (e.g., change in electrochemical current, SPR angle shift). The density that yields the highest signal change indicates the optimal probe density for that system [7].

Protocol 2: Measuring SNR for an Optical Biosensor

This protocol provides a standardized method to characterize the SNR of an optical biosensor, such as those used in photoplethysmography (PPG) [8].

1. Principle: SNR is a quantitative measure of how well a desired signal can be distinguished from background noise. For a stable, DC optical signal, it is calculated as the ratio of the average signal (in ADC counts) to the standard deviation of the noise.

2. Materials:

- Optical biosensor evaluation board or device

- Stable, reflective surface (e.g., a white styrene high-impact plastic card)

- Black box or sheet to block ambient light

- Data acquisition software and connection cables

- Computer with data analysis software (e.g., MATLAB, Python)

3. Procedure:

- Step 1: Stable Setup. Place the biosensor device on a stable, vibration-free optical bench. Position the white reflector at a fixed distance from the sensor's LED and photodiode. Cover the entire setup with a black box to eliminate ambient light.

- Step 2: Data Acquisition. Power on the device and configure it to the desired LED current, pulse width, and sampling rate. Acquire a stream of raw optical data (ADC counts) for a sufficient duration (e.g., 10-30 seconds) to capture a stable signal.

- Step 3: Data Analysis.

- Import the ADC count data into your analysis software.

- Calculate the mean (µ) of the ADC counts over the acquisition period. This is your Signal Amplitude.

- Calculate the standard deviation (σ) of the ADC counts over the same period. This is your Noise Amplitude.

- Compute the SNR using the formula: SNR = µ / σ.

- Step 4: Power Sweep. Repeat steps 2 and 3 for different LED current settings to generate a plot of SNR vs. Input Current. This helps identify the optimal operating point that balances SNR performance with power consumption [8].

4. Advanced Note for AC Signals (e.g., PPG): For signals like PPG that contain both AC and DC components, the conventional method is insufficient. A more advanced approach involves:

- Applying a Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) to the signal.

- Separating the signal power (contained in frequencies below 20 Hz for PPG) from the noise power (frequencies above 20 Hz).

- Calculating SNR as the ratio of signal power to noise power in the frequency domain [8].

Essential Visualizations

Diagram 1: Biosensor Optimization Strategy Logic

Biosensor Optimization Logic Flow

Diagram 2: Probe Density & Steric Hindrance

Probe Density Impact on Hybridization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Biosensor Surface Optimization

| Item | Function / Application | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | A common blocking agent used to passivate surfaces and reduce non-specific adsorption by occupying vacant sites [6]. | Effective and low-cost, but can be susceptible to displacement in some complex media [6]. |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | A polymer used to create antifouling surfaces. Its high hydrophilicity and flexibility form a hydrated barrier that repels proteins [6] [1]. | Chain length and density on the surface critically determine its antifouling performance. |

| Zwitterionic Materials | Surfaces with mixed positive and negative charges (e.g., carboxybetaine) that strongly bind water, creating an ultra-low fouling layer [1]. | Often considered superior to PEG in stability and antifouling performance in complex biological fluids [1]. |

| Self-Assembled Monolayers (SAMs) | Well-ordered molecular assemblies (e.g., alkanethiols on gold) that provide a tunable platform for controlling surface chemistry, charge, and probe density [7] [1]. | The tail group (e.g., OH, COOâ», CH₃) defines surface properties and is key for oriented probe immobilization [7]. |

| Streptavidin & Biotin | A high-affinity binding pair used for oriented immobilization. Biotinylated probes (DNA, antibodies) bind uniformly to streptavidin-coated surfaces [1]. | Provides nearly irreversible binding and excellent orientation, but the streptavidin layer itself may require passivation. |

| His-Tag & NTA Functionalized Surfaces | A method for oriented immobilization of recombinant proteins. A hexahistidine (His) tag on the probe binds to Ni²âº-Nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA) on the surface [1]. | Ideal for immobilizing engineered proteins and enzymes. Chelation strength can be influenced by buffer conditions. |

| MXenes (e.g., Ti₃C₂Tₓ) | Two-dimensional nanomaterials with high electrical conductivity and surface area, used to enhance signal transduction in electrochemical biosensors [10]. | Improves electron transfer and allows for high probe loading. Challenges include stability and biocompatibility, which require surface modification [10]. |

| Engineered Enzymes (e.g., DAAO variants) | Bioreceptors with enhanced selectivity and stability through protein engineering (e.g., point mutations) [9]. | Can be tailored to discriminate between very similar substrates (e.g., D-serine vs. D-alanine), drastically improving biosensor selectivity [9]. |

| Ac-hMCH(6-16)-NH2 | Ac-hMCH(6-16)-NH2, MF:C58H99N21O13S3, MW:1394.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Tubulin inhibitor 18 | Tubulin inhibitor 18, MF:C22H26O5, MW:370.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

FAQs: Core Concepts and Strategy Selection

Q1: What are the fundamental differences between covalent and non-covalent surface functionalization, and when should I choose one over the other?

Covalent and non-covalent strategies differ primarily in the strength, stability, and reversibility of the bonds formed between the biorecognition element (ligand) and the transducer surface.

- Covalent Immobilization involves forming strong, irreversible chemical bonds (e.g., amide, ether, or thioether bonds). Common techniques include amine coupling using EDC/NHS chemistry, thiol-based coupling, and click chemistry [1] [11].

- When to use: When high operational stability and long-term durability of the biosensor are required. It is ideal for applications requiring a robust, non-reversible surface that will not leach ligands [1].

- Non-Covalent Immobilization relies on weaker, reversible interactions such as electrostatic adsorption, affinity binding (e.g., streptavidin-biotin), hydrophobic interactions, or van der Waals forces [1] [11].

Q2: How do nanomaterials enhance biosensor surface functionalization?

Nanomaterials act as superior transducer interfaces due to their unique physical and chemical properties [1] [13]. Their enhancement mechanisms include:

- High Surface-to-Volume Ratio: Provides a significantly larger area for biomolecule immobilization, leading to higher ligand density and enhanced signal amplification [1].

- Tunable Surface Chemistry: Their surfaces can be easily modified with various functional groups (e.g., -COOH, -NHâ‚‚) to facilitate covalent or non-covalent immobilization strategies [11].

- Unique Opto-electronic Properties: Materials like graphene, carbon nanotubes (CNTs), and gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) exhibit excellent electrical conductivity, quantum confinement, and surface plasmon resonance, which directly improve transduction mechanisms in electrochemical and optical biosensors [1] [13].

Q3: What are the most common causes of non-specific binding (NSB), and how can it be minimized?

Non-specific binding occurs when analytes or other molecules in the sample interact with the sensor surface through unintended means, leading to elevated background noise and false positives [14] [12].

- Common Causes:

- Electrostatic or hydrophobic interactions with unblocked areas of the sensor chip.

- Inefficient surface blocking after ligand immobilization.

- Sample-related issues, such as impurities or aggregate formation [12].

- Minimization Strategies:

- Effective Surface Blocking: Use blocking agents like Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA), casein, or ethanolamine to passivate unreacted active sites on the surface [14] [12].

- Buffer Optimization: Add surfactants (e.g., Tween 20) to the running buffer, or use additives like dextran or polyethylene glycol (PEG) to reduce hydrophobic interactions [14].

- Surface Chemistry Selection: Choose a sensor chip with a surface chemistry that minimizes interactions with your specific analyte. Using a well-designed reference channel is also critical for subtracting NSB effects [14] [12].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Non-Specific Binding (NSB)

| Observation | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High response signal on the reference surface or inconsistent data. | Inadequate surface blocking after immobilization. | Incorporate a blocking step with a suitable agent like BSA, casein, or ethanolamine [14] [12]. |

| Electrostatic/hydrophobic attraction between analyte and surface. | Optimize buffer conditions (pH, ionic strength). Introduce non-ionic surfactants (e.g., Tween 20) to the running buffer [14]. | |

| Sample impurities or aggregates. | Ensure sample purity via centrifugation or filtration. Use a fresh, properly prepared sample [12]. |

Experimental Protocol for Minimizing NSB:

- Immobilize your ligand using standard procedures.

- Block the surface by injecting a solution of 1% BSA or 1 M ethanolamine (for amine coupling) for 5-7 minutes.

- Wash extensively with running buffer.

- Test for NSB by injecting your analyte over a blank, functionalized reference surface. A significant signal indicates NSB is present.

- Iterate by adjusting buffer additives or blocking agents until the reference channel signal is minimized [14] [12].

Issue 2: Low Signal Intensity

| Observation | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Weak binding response upon analyte injection, making kinetic analysis difficult. | Low ligand immobilization density. | Increase the concentration of the ligand during the immobilization step to achieve a higher density on the surface [12]. |

| Poor immobilization efficiency or incorrect surface chemistry. | Ensure the surface activation (e.g., EDC/NHS for amine coupling) is fresh and efficient. Consider alternative coupling chemistries that better suit your ligand's functional groups [12]. | |

| Analyte concentration is too low. | Increase the analyte concentration, if feasible. Perform a concentration series to find the optimal range for detection [12]. |

Issue 3: Baseline Drift or Instability

| Observation | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| The baseline signal gradually increases or decreases over time before analyte injection. | Buffer mismatch between running buffer and sample. | Ensure the sample is prepared in the running buffer or is thoroughly dialyzed against it to minimize bulk refractive index shifts [15] [16]. |

| Bubbles in the fluidic system or improper buffer degassing. | Degas all buffers thoroughly before use. Check the instrument for leaks and prime the system properly [15]. | |

| Slow equilibration of the sensor surface. | Allow more time for the baseline to stabilize before starting the experiment. A longer initial buffer flow can help [16]. |

Issue 4: Poor Reproducibility Between Experiments

| Observation | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Significant variation in binding responses or kinetics across replicate experiments. | Inconsistent ligand immobilization levels. | Standardize the immobilization procedure carefully, monitoring the coupling response in Real-Time (RU) to achieve a consistent density for each experiment [12]. |

| Sensor surface degradation or carryover from incomplete regeneration. | Optimize the regeneration solution and contact time to fully remove bound analyte without damaging the immobilized ligand. Validate with a control injection [15] [12]. | |

| Variation in sample quality or handling. | Use consistent sample preparation and handling techniques. Verify sample stability over time [15]. |

Comparative Data Tables

Table 1: Comparison of Immobilization Strategies

| Strategy | Mechanism | Advantages | Limitations | Ideal Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covalent | Forms strong, irreversible chemical bonds (e.g., amide, thioether) [1]. | High stability; Durable surface; Prevents ligand leaching [1]. | Complex protocols; Potential for random orientation; Can denature sensitive biomolecules [1]. | Long-term biosensors; Stable bioassays; Harsh operating conditions [1]. |

| Non-Covalent (Electrostatic) | Relies on attraction between oppositely charged surfaces [11]. | Simple; Fast; Reversible; Tunable via pH/ionic strength [1] [11]. | Sensitivity to environmental changes (pH, salt); Lower stability [11]. | Reusable sensors; Immobilization of charged biomolecules (DNA, some proteins) [11]. |

| Non-Covalent (Affinity) | Uses high-affinity pairs (e.g., streptavidin-biotin, His-tag-NTA) [1]. | Controlled, oriented immobilization; High activity preservation [1]. | Requires genetic or chemical modification of the ligand; Can be expensive [1]. | Kinetic studies requiring specific orientation; Capturing tagged proteins [1] [12]. |

| Nanomaterial-Assisted | Utilizes enhanced properties of nanomaterials (e.g., graphene, AuNPs) for adsorption or coupling [1] [13]. | High surface area for loading; Intrinsic signal amplification; Tunable chemistry [1] [13]. | More complex characterization; Potential for batch-to-batch variation in nanomaterial synthesis [1]. | Ultra-sensitive detection; Signal-enhanced biosensing platforms [1] [13]. |

Table 2: Properties of Common Nanomaterials for Functionalization

| Nanomaterial | Key Properties | Functionalization Methods | Role in Biosensing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR), excellent biocompatibility, high conductivity [1]. | Thiol-gold chemistry, electrostatic adsorption, polymer wrapping [1] [11]. | Signal amplification in optical and electrochemical biosensors [1]. |

| Graphene & Graphene Oxide | High electrical conductivity, large surface area, tunable oxygen-containing groups (-COOH, -OH) [1] [11]. | Covalent modification via -COOH/-OH, non-covalent π-π stacking, polymer coatings [11]. | Transducer in electrochemical sensors; Quencher in fluorescence-based assays [13]. |

| Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) | High aspect ratio, ballistic electron transport, functionalizable sidewalls [1]. | Acid oxidation to introduce -COOH, polymer wrapping, π-π stacking with aromatic molecules [1] [11]. | Enhancing electron transfer in electrochemical sensors; Scaffold for biomolecule immobilization [1]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

| Item | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| CM5 Sensor Chip | A gold chip coated with a carboxymethylated dextran matrix that facilitates covalent immobilization via amine coupling [12]. | General-purpose protein immobilization for kinetic and affinity studies. |

| EDC / NHS | Cross-linking reagents used to activate carboxyl groups on the sensor surface for covalent coupling to primary amines on ligands [12]. | Standard amine coupling for proteins and peptides. |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | A common blocking agent used to passivate unreacted active sites on the sensor surface, thereby reducing non-specific binding [14] [12]. | Blocking after immobilization to minimize background noise. |

| Biotinylated Ligand & SA Chip | A highly specific affinity pair. The ligand is conjugated with biotin, which is captured by the streptavidin (SA) coated on the sensor chip [12]. | Site-directed, oriented immobilization of antibodies or other biomolecules. |

| Polyethylenimine (PEI) | A cationic polymer used to wrap nanoparticles or surfaces, imparting a strong positive charge for electrostatic adsorption of negatively charged biomolecules like DNA [11]. | Creating a stable, positively charged layer for nucleic acid capture. |

| (3-Aminopropyl)triethoxysilane (APTES) | A silane coupling agent used to introduce primary amine groups onto silica or metal oxide surfaces, enabling subsequent covalent functionalization [1] [11]. | Functionalizing silica nanoparticles or SPR chips for covalent attachment. |

| Microtubule inhibitor 4 | Microtubule inhibitor 4, MF:C25H23FN4O3, MW:446.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Topoisomerase II inhibitor 10 | Topoisomerase II inhibitor 10, MF:C27H20N6O7S, MW:572.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Experimental Workflows and Strategy Selection

Surface Functionalization Strategy Selection

Covalent Immobilization via Amine Coupling

The Impact of Probe Density and Spatial Orientation on Target Binding Efficiency

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

FAQ: My biosensor shows high non-specific binding. How might probe density and orientation be contributing, and how can I address this?

High non-specific binding often results from suboptimal probe density. Excessively high density can cause steric hindrance, forcing probes into unfavorable conformations that reduce specific binding and increase non-specific interactions. Furthermore, random probe orientation can bury active binding sites, exacerbating the issue.

- Solutions:

- Optimize Probe Density: Systematically vary the surface density of your probes. Use experimental design (DoE) methodologies to efficiently find the optimum, which maximizes specific binding while minimizing non-specific adsorption [17].

- Implement Oriented Immobilization: Transition from passive adsorption to chemical methods that control orientation. For antibody probes, use Protein A, Protein G, or site-specific covalent immobilization via engineered cysteine residues or carbohydrate moieties to ensure the antigen-binding sites are exposed to the solution [18] [19].

FAQ: I have confirmed that target molecules are present in the sample, but my biosensor shows low binding signal. What could be wrong?

This issue, potentially low binding efficiency, is frequently caused by low probe density or poor accessibility of the binding sites due to incorrect orientation or steric crowding.

- Solutions:

- Characterize and Adjust Density: Use surface characterization techniques (e.g., XPS, ellipsometry) to verify probe density. Computational studies indicate that hybridization efficiency is severely hindered when inter-probe spacing is less than or equal to the length of the target DNA, confirming the need for an optimal density [7].

- Ensure Proper Orientation: As demonstrated with odorant-binding proteins, a genetically added cysteine residue enabled controlled orientation on the chip, making the binding pocket more accessible and favoring specific interactions, which significantly enhanced selectivity [18].

FAQ: My biosensor performance degrades rapidly. Could the probe immobilization method be a factor?

Yes. Simple physical adsorption, while easy, often results in random orientation and weak attachment, leading to probe leaching and unstable sensor performance [19].

- Solutions:

- Use Covalent Immobilization: Create a stable, covalently bound monolayer. For SiOâ‚‚ surfaces, silane chemistry (e.g., using APDMS or APTES) provides a robust foundation for subsequent probe attachment [20].

- Employ Cross-linkers: Use bifunctional linkers like glutaraldehyde after silanization to create strong covalent bonds between the surface and probes, ensuring long-term stability [21] [20].

Experimental Protocols for Optimization

Protocol: Optimizing DNA Probe Density on a Gold Surface Using Self-Assembled Monolayers (SAMs)

This protocol is adapted from computational and experimental studies on electrochemical nucleic acid biosensors [7].

- Objective: To create a well-defined SAM with a controlled surface density of ssDNA probes to maximize hybridization efficiency with complementary targets.

- Materials:

- Gold substrate/sensor

- Alkanethiols (e.g., hydrophobic CH₃-terminated, polar OH-terminated, or anionic COOâ»-terminated)

- Thiol-modified ssDNA probes

- Appropriate buffer (e.g., phosphate buffer with Mg²âº)

- Procedure:

- Clean the Gold Surface: Thoroughly clean the gold transducer using oxygen plasma or piranha solution to remove organic contaminants.

- Prepare Mixed SAM Solutions: Co-immobilize thiol-modified DNA probes with spacer alkanethiols (e.g., 6-mercapto-1-hexanol). Vary the molar ratio of DNA-thiol to spacer-thiol in solution (e.g., 1:100, 1:1000) to achieve different surface densities.

- Form the SAM: Incubate the clean gold substrate in the prepared solutions for a set period (typically 12-24 hours).

- Rinse and Dry: Rinse the substrate extensively with solvent and buffer to remove physisorbed molecules and dry under a stream of inert gas.

- Characterize Density: Use electrochemical methods (e.g., measurement of redox charge from a bound marker) or surface plasmon resonance (SPR) to quantify the resulting surface density of the DNA probes.

- Test Hybridization: Expose the functionalized sensor to a solution containing the complementary DNA target. Measure the binding kinetics and saturated signal to determine the optimal probe density for the highest hybridization efficiency.

Protocol: Achieving Oriented Antibody Immobilization on a Silica (SiOâ‚‚) Surface

This protocol is based on a detailed study for MMP9 biosensing that highlights the use of specific silanes for reproducible monolayer formation [20].

- Objective: To covalently immobilize antibodies in an oriented "end-on" manner to maximize the availability of antigen-binding sites.

- Materials:

- SiOâ‚‚ substrate/sensor

- (3-Ethoxydimethylsilyl)propylamine (APDMS) or (3-Aminopropyl)triethoxysilane (APTES)

- Glutaraldehyde (GA)

- Antibody of interest (e.g., Anti-MMP9)

- Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA)

- Dry toluene

- Procedure:

- Surface Activation: Clean SiOâ‚‚ chips by sonication in acetone, ethanol, and dichloromethane. Activate the surface by oxygen plasma treatment for 15 minutes to generate a high density of surface hydroxyl (-OH) groups.

- Silanization: Immediately transfer the activated chips to a solution of 1% (v/v) APDMS in dry toluene. Stir overnight under an argon atmosphere. APDMS is preferred over APTES for its tendency to form ordered monolayers with minimal polymerization [20].

- Washing: Sonicate the chips to remove any polymerized silane and dry with nitrogen. Cure in an oven at 110 °C for 1 hour to stabilize the silane layer.

- Surface Activation with Linker: Incubate the aminosilanized surface with a glutaraldehyde solution (e.g., 2.5% in PBS) for 1 hour. Glutaraldehyde reacts with the surface amine groups to provide an aldehyde-functionalized surface.

- Antibody Immobilization: Incubate the aldehyde-activated surface with a solution of the target antibody for 1-2 hours. The antibody covalently attaches primarily via amine groups on its Fc region, leading to an oriented "end-on" immobilization.

- Quenching and Blocking: Quench unreacted aldehyde groups with a solution of BSA or ethanolamine. Use BSA as a blocking agent to passivate any remaining surface areas against non-specific binding.

Key Data and Performance Metrics

Table 1: The Impact of Probe Density on Hybridization Efficiency

| Probe Surface Density (probes/nm²) | Inter-Probe Spacing | Observed Hybridization Efficiency | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.002 | > Target DNA length | High | Efficient; balance of attraction and accessibility [7] |

| Very High | ≤ Target DNA length | Severely Hindered | Steric and energetic crowding blocks access [7] |

| Low | N/A | Low | Low probability of target-probe encounter [7] |

Table 2: Comparison of Common Functionalization Methods

| Immobilization Method | Orientation Control | Stability | Experimental Complexity | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Adsorption | Poor (Random) | Low | Low | Initial proof-of-concept studies [19] |

| Streptavidin-Biotin | Good | High | Medium | Well-established systems; high stability required [21] |

| Covalent (e.g., APTES-GA) | Medium to Good | High | Medium | General purpose; SiOâ‚‚ surfaces [21] [20] |

| Site-Specific (e.g., Cysteine) | Excellent | High | High (requires protein engineering) | Maximum performance applications [18] |

| Protein A/G | Excellent (for Antibodies) | Medium | Medium | Oriented antibody immobilization [19] |

Essential Signaling Pathways and Workflows

Optimization Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Materials for Surface Functionalization

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| APDMS (Aminosilane) | Forms a uniform, ordered monolayer on SiOâ‚‚ surfaces, providing amine groups for subsequent bioconjugation. Preferred for its consistency over APTES [20]. |

| Glutaraldehyde (GA) | A homo-bifunctional crosslinker used to link amine-functionalized surfaces to amine groups on proteins/antibodies [21] [20]. |

| Protein A / Protein G | Bacterial proteins that bind specifically to the Fc region of antibodies, enabling oriented immobilization on various surfaces [19]. |

| 6-Mercapto-1-hexanol (MCH) | A spacer alkanethiol used in mixed SAMs on gold to dilute probe density, reduce non-specific binding, and orient DNA probes [7]. |

| Thiol-modified DNA | Allows for covalent attachment to gold surfaces via gold-thiol chemistry, forming the basis of many electrochemical DNA biosensors [7]. |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | Used as a blocking agent to passivate unreacted surface areas, thereby minimizing non-specific adsorption of non-target molecules [20] [22]. |

| Btk-IN-16 | Btk-IN-16, MF:C15H14N4O2, MW:282.30 g/mol |

| Hbv-IN-24 | Hbv-IN-24, MF:C23H27NO6, MW:413.5 g/mol |

This technical support center provides targeted troubleshooting guides and FAQs for researchers utilizing Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM), Ellipsometry, and Time-of-Flight Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry (ToF-SIMS). The content is framed within the context of optimizing biosensor surface modification, focusing on resolving specific experimental issues to enhance the selectivity and performance of sensing interfaces.

AFM Troubleshooting Guide

Table 1: Common AFM Imaging Issues and Solutions

| Problem | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Unexpected, repeating patterns in images [23] | Tip artefacts (broken or contaminated tip) [23] | Replace the probe with a new, guaranteed-sharp one [23]. |

| Difficulty imaging vertical structures or deep trenches [23] | Low aspect ratio or pyramidal tip geometry [23] | Switch to a high aspect ratio (HAR) conical tip [23]. |

| Blurry, out-of-focus images [24] | False feedback from surface contamination layer [24] | Increase tip-sample interaction: decrease setpoint in vibrating mode or increase it in non-vibrating mode [24]. |

| Blurry, out-of-focus images [24] | False feedback from electrostatic forces [24] | Create a conductive path between cantilever and sample; if not possible, use a stiffer cantilever [24]. |

| Repetitive lines across the image [23] | Electrical noise (often at 50/60 Hz) or laser interference [23] | Image during quieter times (e.g., early morning); use a probe with a reflective coating to mitigate laser interference [23]. |

| Streaks on images [23] | Environmental noise and vibration [23] | Ensure anti-vibration table is functional; post signs to minimize activity near the instrument; relocate to a quieter room [23]. |

| Streaks on images [23] | Loose particles or contamination on the sample surface [23] | Improve sample preparation protocols to minimize loosely adhered material [23]. |

Ellipsometry FAQ

What do the primary measured values, Ψ and Δ, represent? Ellipsometry measures the change in the polarization state of light after it reflects from a sample surface. This change is expressed by two values: Psi (Ψ) and Delta (Δ). Tan(Ψ) represents the amplitude ratio change between the p- and s-polarized light components, while Δ represents their phase difference [25].

Why is data analysis always necessary for ellipsometry? The raw Ψ and Δ values are not directly informative of material properties. Data analysis, which involves fitting the data to a optical model, is required to determine properties of interest such as film thickness, refractive index, and surface roughness [25].

What are the advantages of using multiple wavelengths (Spectroscopic Ellipsometry)? Spectroscopic Ellipsometry (SE) offers several key advantages over single-wavelength measurements [25]:

- Unique Answers: It resolves the periodicity problem, providing a single, unambiguous solution for film thickness.

- Improved Sensitivity: It enhances sensitivity to a wider range of material properties, such as conductivity and crystallinity.

- Application-Specific Data: It provides optical constants at the specific wavelengths relevant to your application.

What is the typical thickness range measurable by Spectroscopic Ellipsometry? SE is highly sensitive to surface layers down to a fraction of a nanometer. The maximum thickness depends on the measurement wavelength, but with visible-to-near-infrared light, the preferred limit is typically under 5 microns. Thicker films (up to 50 microns) can be measured using longer infrared wavelengths [25].

Table 2: Ellipsometry Capabilities for Thin Films

| Parameter | Detail | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Minimum Thickness | A fraction of a nanometer (sub-nm) [25] | For ultra-thin films, assume a known refractive index to determine thickness accurately [25]. |

| Maximum Thickness | Up to ~50 µm (dependent on wavelength) [25] | Near-IR or Mid-IR extends the range; uniformity becomes critical for thick films [25]. |

| Film Types | Dielectrics, semiconductors, metals, organics, multilayers [25] | The coating must be smooth enough to reflect the probe beam to the detector [25]. |

| Key Advantage | Non-contact, highly precise for thickness and optical constants [25] [26] | Particularly useful for characterizing functionalization layers and polymer coatings on biosensors [26]. |

ToF-SIMS Troubleshooting Guide

What is the "static limit" and why is it critical? The static limit is the maximum primary ion dose (typically 1 × 10^13 ions/cm² for organic materials) that a surface can receive before it becomes significantly damaged and no longer provides data representative of the original surface chemistry. For reliable analysis, data should be collected at doses at or below 1 × 10^12 ions/cm² [27].

My spectra are highly complex with many fragments. Is this normal? Yes. The high primary ion energies used in ToF-SIMS cause significant fragmentation. While molecular ions are detected, the intensity of fragment ions is often higher. This fragmentation pattern is a source of valuable chemical information and can act as a built-in MS/MS capability for identifying species [27].

What are common causes of poor mass resolution or high background?

- Instrumental Tuning: The instrument must be properly tuned for optimal mass resolution.

- Surface Charging: Analyzing insulating samples can cause surface charging, which distorts the mass analysis. Using an electron flood gun for charge compensation is essential.

- Metastable Ions: Ions that break up in the flight tube can contribute to the background noise. Modern instruments use a "reflectron" to filter many of these out [27].

Table 3: Essential ToF-SIMS Terminology

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Primary Ion | The energetic ion (e.g., Bi₃âº, Arâ‚₀₀₀âº) used to bombard the surface and generate secondary ions [27]. |

| Secondary Ions | Ions generated from the surface due to primary ion impact; can be atoms, molecules, or fragments [27]. |

| Static SIMS | Analysis performed while keeping the primary ion dose below the static limit, preserving surface chemistry [27]. |

| Mass Resolution (m/Δm) | A measure of the instrument's ability to distinguish between peaks of similar mass; higher values allow for more accurate peak assignment [27]. |

| UHV (Ultrahigh Vacuum) | The required operating pressure for ToF-SIMS (typically 10â»â¸ – 10â»â¹ mbar) to prevent surface contamination and allow secondary ions to travel to the detector [27]. |

Experimental Workflow for Biosensor Surface Characterization

The following workflow integrates AFM, Ellipsometry, and ToF-SIMS to systematically optimize a biosensor surface, from initial substrate preparation to final functional layer validation.

Research Reagent Solutions for Surface Functionalization

Table 4: Key Materials for Biosensor Surface Engineering

| Material | Function in Surface Functionalization | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| (3-Aminopropyl)triethoxysilane (APTES) | A silane coupling agent that introduces reactive amine (-NHâ‚‚) groups onto oxide surfaces (e.g., glass, silicon) [1]. | Provides a covalent linker for immobilizing biomolecules via carboxyl groups using EDC/NHS chemistry [1]. |

| EDC and NHS | Cross-linking agents that activate carboxyl groups to form stable amide bonds with primary amines [1] [3]. | Critical for covalent and oriented immobilization of proteins and antibodies on sensor surfaces [1] [3]. |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | A polymer used to create hydrophilic, non-fouling surfaces that resist non-specific protein adsorption [1] [26]. | Used as a spacer or background layer on biosensors to improve selectivity by reducing false signals [1] [26]. |

| Polydopamine | A versatile bio-adhesive polymer that forms a thin, functional coating on virtually any material surface [1] [3]. | Used for surface modification and as a universal platform for secondary reactions and biomolecule immobilization [1] [3]. |

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | Nanomaterials with high surface-to-volume ratio and unique optoelectronic properties [1]. | Used to functionalize transducer interfaces to enhance signal amplification and increase bioreceptor loading [1]. |

| Mercaptopropionic Acid (MPA) | A thiol-containing molecule that forms self-assembled monolayers (SAMs) on gold surfaces [3]. | Used to create a well-ordered functional layer on gold electrodes/surfaces, presenting carboxyl groups for bioconjugation [3]. |

Methodologies for Enhanced Selectivity: From DNA Nanostructures to Molecular Imprinting

Tetrahedral DNA Nanostructures (TDNs) for Controlled Probe Presentation and Reduced Background Noise

FAQ: TDN Synthesis and Characterization

What are the critical factors for achieving high yield in TDN synthesis? High yield in TDN synthesis is achieved through precise oligonucleotide design, appropriate buffer conditions, and a controlled thermal annealing process. The four single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) strands must be designed with complementary domains that facilitate the formation of the pyramidal structure. Unpaired "hinge" bases are incorporated at the vertices to provide the necessary flexibility for assembly. The synthesis is typically performed in TM buffer (10 mM Tris, 20 mM MgCl₂, pH 8.0), as the magnesium ions are crucial for stabilizing the DNA structure. The standard thermal annealing process involves heating the equimolar mixture of strands to 95°C for 10 minutes to denature any secondary structures, followed by a rapid cooling to 4°C to facilitate precise self-assembly. This one-step process can achieve yields as high as 95% [28].

How can I verify the successful assembly and structural integrity of my TDNs? A combination of analytical techniques is required to confirm successful TDN assembly and structural integrity:

- Native Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (PAGE): This is used to analyze the molecular weight and purity of the assembled TDNs. A single, distinct band with lower mobility than the individual ssDNA strands indicates successful formation of a higher-order structure [28].

- Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) and Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM): These imaging techniques provide direct visualization of the tetrahedral morphology and allow for assessment of structural uniformity [28] [29].

- Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS): DLS measures the hydrodynamic diameter and size distribution of the TDNs in solution, while zeta-potential analysis confirms the negative surface charge characteristic of DNA nanostructures [28].

My TDN-based biosensor shows high background noise. What could be the cause? High background noise often stems from non-specific adsorption (NSA) or improper probe orientation. TDNs are designed to mitigate this by presenting capture probes in a consistent, upright orientation, which minimizes uncontrolled interactions with the sensor surface. Ensure your TDN is correctly anchored and that the surface passivation is complete. Using a rigid TDN scaffold with optimal probe length (typically 40-60 bases for the constituent strands) reduces random probe distribution and prevents the probes from lying flat on the sensor surface, a common cause of NSA [30].

FAQ: Functionalization and Application

What are the primary strategies for functionalizing TDNs with probes or other molecules? TDNs offer multiple sites for functionalization, providing significant flexibility:

- Vertex Modification: Functional molecules (e.g., aptamers, fluorescent dyes) can be attached by extending one of the four oligonucleotide strands with a complementary sequence or via chemical crosslinking during synthesis [28].

- Edge Modification: The double-helical edges of the TDN can be functionalized by incorporating functional groups into the staple strands or through intercalation of small molecules into the duplex DNA [28].

- Cage Encapsulation: Small molecules or drugs can be physically encapsulated within the internal cavity of the TDN cage structure [28].

Can TDNs be used for applications in live cells? Yes, TDNs possess several inherent properties that make them suitable for live-cell applications. They exhibit excellent biocompatibility and can autonomously enter a wide variety of mammalian cells in large quantities without the need for transfection reagents. Their rigid, stable structure provides resistance to nuclease degradation, increasing their circulation time inside cells compared to linear DNA. Studies have shown that TDNs can remain intact within a living cell for over an hour, whereas linear DNA constructs may degrade within 20 minutes [28].

What makes TDNs superior to other surface modifications for nucleic acid biosensors? TDNs provide a rigid, three-dimensional scaffold that ensures probes are presented with controlled density and consistent upright orientation. This defined spatial organization maximizes probe accessibility for target binding and dramatically reduces non-specific adsorption (NSA) by minimizing random, flat interactions with the sensor surface. This leads to enhanced hybridization efficiency, lower background noise, and improved overall sensitivity and specificity compared to traditional methods like physical adsorption or random covalent immobilization [30].

Troubleshooting Guides

Table 1: Troubleshooting TDN Synthesis and Characterization

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low assembly yield or multiple bands in PAGE | Incorrect strand stoichiometry, inadequate buffer conditions (low Mg²âº), or inefficient denaturing during annealing. | Ensure equimolar mixing of strands, use TM buffer (20 mM MgClâ‚‚), and verify the thermal cycler program includes a 95°C denaturing step [28]. |

| Unstable TDNs in biological fluids | Degradation by nucleases. | Ensure structural integrity is optimal; TDNs are inherently more stable than linear DNA, but complex biological matrices may require further optimization of buffer conditions [28]. |

| Poor cellular uptake | Incorrect TDN size or morphology. | Verify TDN structure via AFM/TEM. TDNs in the range of several tens of nanometers are typically internalized efficiently due to their pyramid structure that minimizes electrostatic repulsion [28]. |

| High background in biosensing | Non-specific adsorption or random probe orientation. | Confirm successful TDN anchoring and use the TDN's rigid structure to enforce upright probe presentation. Optimize probe length to avoid steric hindrance [30]. |

Table 2: Quantitative Performance of TDN-based Biosensing

| Application | Target | Sensing Performance | Key Advantage | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial Transcriptomics (TDDN-FISH) | ACTB mRNA | ~8x faster than HCR-FISH; stronger signal than smFISH with only 3 probes vs. 48. | Enzyme-free, exponential signal amplification enabling high-speed, sensitive RNA detection [29]. | |

| miRNA Detection | miRNA (e.g., miR-141) | Ultrasensitive electrochemical analysis for prostate cancer diagnosis. | High specificity to distinguish target miRNA from interfering miRNAs with slightly different sequences [28]. | |

| Ion Detection | Zn²⺠| Detection range: 0.5–10 μM; LOD: 345 nM. | Capability for in vivo sensing due to biocompatibility and stability of DNAzyme-integrated nanostructures [31]. | |

| Protein Detection | Alpha-fetoprotein, miRNA-122 | Used in biosensor for hepatocellular carcinoma diagnosis. | Multi-analyte detection on a single platform using TDN's multiple modification sites [30]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Standard TDN Synthesis and Purification

This protocol describes the one-step self-assembly of TDNs from four single-stranded DNA oligonucleotides [28].

Materials:

- Oligonucleotides: Four specially designed ssDNA strands (typically 63-mer for common sizes), dissolved in TE buffer or nuclease-free water.

- TM Buffer: 10 mM Tris, 20 mM MgClâ‚‚, pH 8.0.

- Equipment: Thermal cycler or heat block, microcentrifuge, equipment for native PAGE.

Procedure:

- Design and Dilution: Design the four oligonucleotides such that each strand contains three domains complementary to segments of the other three strands. Dilute the strands to a final concentration of 1-10 µM in TM buffer. The total reaction volume is typically 50-100 µL.

- Annealing: Mix the four strands in equimolar ratios in TM buffer.

- Thermal Annealing: Place the mixture in a thermal cycler and run the following program:

- 95°C for 10 minutes (denaturation)

- Rapid cooling to 4°C over 20 minutes (annealing)

- Verification and Storage: Analyze 5 µL of the product using 8% native PAGE to confirm a single band of lower mobility. The assembled TDNs can be stored at 4°C for several weeks.

Protocol 2: Constructing a TDN-Modified Electrode for Biosensing

This protocol outlines the functionalization of a gold electrode with TDNs for electrochemical biosensing applications [30].

Materials:

- Gold Electrode

- Thiolated TDNs: TDNs where one vertex strand is synthesized with a 5' or 3' thiol modification.

- Cleaning Solutions: Piranha solution (Caution: highly corrosive) or oxygen plasma cleaner.

- MCH (6-Mercapto-1-hexanol): 1 mM solution in water or buffer.

Procedure:

- Electrode Cleaning: Clean the gold electrode thoroughly to remove organic contaminants. This can be done using piranha solution (handle with extreme care) or oxygen plasma treatment.

- TDN Immobilization: Incubate the clean gold electrode with a solution of thiolated TDNs (e.g., 100-500 nM in TM buffer) for 2-4 hours at room temperature. The thiol groups will form covalent bonds with the gold surface.

- Surface Blocking: Rinse the electrode gently with buffer to remove unbound TDNs. Then, incubate the electrode with 1 mM MCH for 30-60 minutes. MCH fills any uncovered gold sites, creating a well-ordered self-assembled monolayer that minimizes non-specific adsorption.

- Biosensor Use: The TDN-modified electrode is now ready for hybridization with target nucleic acids or further functionalization for specific sensing applications.

Experimental Workflow and Signaling

TDN-Enhanced Biosensor Workflow

Mechanism of Reduced Background Noise

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for TDN Research

| Item | Function in Experiment | Specification Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Synthesized Oligonucleotides | Building blocks for TDN self-assembly. | HPLC-purified; typically 40-63 nt; designed with three complementary domains per strand [28] [30]. |

| TM Buffer | Provides optimal ionic conditions for TDN folding and stability. | 10 mM Tris, 20 mM MgCl₂, pH 8.0. Mg²⺠is critical for stabilizing DNA structure [28]. |

| Thiol Modifier | Enables covalent immobilization of TDN on gold surfaces. | Added as C6-S-S or C3-SH at 5' or 3' end of one oligonucleotide strand during synthesis [30]. |

| 6-Mercapto-1-hexanol (MCH) | Backfilling agent to form a dense self-assembled monolayer, reducing non-specific adsorption. | 1 mM solution in buffer or water; used after TDN immobilization [30]. |

| Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) | Direct visualization of TDN morphology and structural integrity. | Requires a mica substrate for sample preparation [28] [29]. |

| Native PAGE Gel | Verifies successful TDN assembly and purity based on molecular weight and shape. | Typically 8% polyacrylamide; run in non-denaturing conditions with Mg²⺠in buffer [28]. |

Self-Assembled Monolayers (SAMs) as Tunable Platforms for Reproducible Immobilization

Self-Assembled Monolayers (SAMs) provide one of the most elegant and convenient approaches to functionalize electrode surfaces by forming organized organic films of molecular thickness [32] [33]. These highly ordered unimolecular films resemble the biomembrane microenvironment, making them particularly useful for immobilizing biological molecules in biosensor applications [32]. The exceptional versatility of SAMs stems from their tunable properties—by selecting organic molecules with specific anchor groups (thiols, disulfides, amines, silanes, or acids) and varying their chain length and terminal functionality, researchers can precisely control surface characteristics for optimal biomolecule immobilization [32] [34] [33]. This tunability enables tremendous flexibility in designing biosensing interfaces with customized hydrophilicity, distance-dependent electron transfer behavior, and specific biorecognition capabilities [32] [35].

For researchers and drug development professionals working on biosensor selectivity, SAMs offer distinct advantages. Their minimal resource requirements (approximately 10â»â· moles/cm²) facilitate easy miniaturization, while their dense, ordered nature provides exceptional stability for immobilized biomolecules such as antibodies, enzymes, nucleic acids, and even whole cells [32]. The simple preparation method—typically involving substrate immersion in dilute precursor solutions followed by solvent washing—makes SAMs accessible while providing sophisticated control over the molecular architecture of sensing interfaces [32] [33]. This technical resource center addresses the key experimental challenges and considerations for leveraging SAMs as tunable platforms in biosensor development.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common SAMs Experimental Challenges

Table 1: Troubleshooting Common SAMs Fabrication and Performance Issues

| Problem | Potential Causes | Solutions | Prevention Tips |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-specific binding | Inadequate SAM packing density; improper terminal group selection; insufficient blocking steps | Use longer-chain alkanethiols (e.g., NAATS vs APTES); implement optimized blocking agents (e.g., hexylamine); employ mixed SAMs with inert terminal groups [35] [36]. | Characterize SAM quality with AFM/XPS; optimize solution concentration and immersion time [36]. |

| Poor reproducibility | Inconsistent substrate cleaning; variable solution concentrations; environmental contamination | Standardize substrate preparation protocol; use fresh SAM solutions; control ambient humidity (for silane-based SAMs) [32] [35]. | Implement quality control checks with contact angle measurements; use controlled environment for SAM formation. |

| Low immobilization efficiency | Improper activation of terminal groups; insufficient density of functional groups; steric hindrance | Ensure fresh preparation of EDC/NHS activation solutions; optimize molar ratio in mixed SAMs (e.g., 10:1 dilution:anchor); test different spacer arm lengths [35] [36]. | Characterize surface functional groups after SAM formation; validate activation protocol with control experiments. |

| SAM instability | Weak head-group binding; chemical degradation; oxidation of anchor groups | Choose appropriate head group for substrate (thiols for Au, silanes for oxides); store SAM-modified substrates in inert atmosphere; avoid extreme pH conditions [32] [33]. | Test SAM stability under experimental conditions; use freshly prepared substrates for SAM formation. |

| Inconsistent electrochemical response | Poor electronic coupling; excessive tunnel distance; heterogeneous SAM formation | Optimize alkyl chain length for electron transfer; ensure complete substrate coverage; characterize with electrochemical methods [32] [37]. | Standardize chain length based on application (electron transfer vs. inert layer). |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

SAMs Design and Selection

Q1: What factors should guide my choice between thiol-based and silane-based SAMs? The substrate material is the primary consideration. Thiol-based SAMs (e.g., alkanethiols) form strong S-Au bonds with gold surfaces and are ideal for electrochemical biosensors [33]. Silane-based SAMs (e.g., APTES, NAATS) react with hydroxylated surfaces like silicon, silicon dioxide, and other metal oxides, making them suitable for SiGe MEMS resonators and semiconductor-based devices [36] [37]. Consider your transduction method—thiol-on-gold is preferred for electrochemical detection, while silane-on-oxide is better for semiconductor-based or optical transduction systems.