Advanced Strategies to Minimize Electrochemical Interference in Biosensors for Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of strategies to reduce electrochemical interference, a critical challenge that compromises the sensitivity, specificity, and reliability of biosensors.

Advanced Strategies to Minimize Electrochemical Interference in Biosensors for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of strategies to reduce electrochemical interference, a critical challenge that compromises the sensitivity, specificity, and reliability of biosensors. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational sources of noise, from electronic and environmental to biological origins. The scope extends to methodological innovations in materials science, bioreceptor engineering, and system design, alongside advanced troubleshooting techniques leveraging artificial intelligence and multi-mode sensing for optimization. Finally, the article covers validation frameworks and performance comparisons, establishing a pathway for developing robust, clinically viable biosensing platforms for precision medicine and point-of-care diagnostics.

Understanding the Enemy: A Deep Dive into the Sources and Impact of Electrochemical Interference

In the pursuit of robust and reliable electrochemical biosensors, researchers and developers must contend with a spectrum of interference signals, or "noise," that can obfuscate the target analytical signal. This noise, if unmitigated, compromises sensitivity, selectivity, and the overall accuracy of a biosensor, particularly in complex matrices like blood, serum, or saliva. Effectively classifying and understanding these interferences is the first critical step in developing strategies to suppress them. This guide frames the challenge of interference within the broader thesis of advancing biosensor research, providing a practical toolkit for troubleshooting the most common issues encountered during experimental development. The content is structured to directly address the problems faced by researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, offering clear FAQs, detailed protocols, and actionable solutions to enhance the performance of their electrochemical platforms.

Noise Classification and Troubleshooting FAQs

Electrochemical biosensors are susceptible to various interferences that can be systematically categorized into electronic, environmental, and biological noise. The table below summarizes these key interference types, their sources, and their impact on the sensor signal.

Table 1: Classification of Interferences in Electrochemical Biosensors

| Noise Category | Type of Interference | Source / Cause | Effect on Sensor Signal |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electronic | Thermal Noise | Random thermal motion of charge carriers in the electrode and electronic components [1]. | Increases baseline current/voltage fluctuations, raising the limit of detection. |

| Electronic | Flicker Noise (1/f) | Imperfections and heterogeneity on the electrode surface [1]. | Causes low-frequency signal drift, obscuring slow or small Faradaic processes. |

| Environmental | Electromagnetic Interference (EMI) | External electromagnetic fields from power lines, radio transmitters, or other lab equipment [2]. | Introduces erratic, high-frequency spikes or an unstable baseline in the measured signal. |

| Biological | Biofouling | Non-specific adsorption of proteins, cells, or other biomolecules onto the electrode surface [1] [2]. | Passivates the electrode, reducing electron transfer kinetics and signal amplitude over time. |

| Biological | Cross-reactivity | Lack of perfect specificity in the biorecognition element (e.g., antibody, aptamer) [3]. | Generates a false positive signal from structurally similar molecules that are not the target analyte. |

Electronic Noise: Thermal and Flicker

Q1: My baseline current shows significant random fluctuations, even in a pure buffer solution. What could be the cause and how can I minimize it?

A: This is a classic symptom of electronic noise, primarily Thermal (Johnson-Nyquist) noise. This inherent noise arises from the random thermal motion of electrons in the electrochemical cell and the circuitry of your potentiostat. Its magnitude is proportional to the square root of the resistance and temperature.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Control Temperature: Perform experiments in a temperature-controlled environment (e.g., an incubator or Faraday cage with temperature regulation) to minimize thermal drift.

- Check Connections: Ensure all cables and electrode connections are secure and clean, as poor contacts increase resistance and noise.

- Shield the System: Use a Faraday cage to enclose your electrochemical setup. This will not directly reduce thermal noise but is crucial for isolating the system from external electromagnetic interference (EMI), which often compounds the problem.

- Signal Averaging: Employ multiple scans and use the averaged signal in your measurements. Thermal noise is random, so averaging multiple runs can help cancel it out.

Q2: I observe a persistent low-frequency drift in my baseline during long-term or slow-scan measurements. How can I address this?

A: This signal drift is typically characteristic of Flicker Noise (1/f noise), which is dominant at low frequencies. In electrochemical systems, this is often related to surface phenomena and heterogeneity on the electrode.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Electrode Polishing: Ensure your solid working electrode (e.g., Glassy Carbon Electrode, GCE) is meticulously polished to a mirror finish using progressively finer alumina slurry. A reproducible and smooth surface minimizes 1/f noise [4].

- Surface Characterization: Use techniques like Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) or Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) to verify the homogeneity of your electrode surface or the nanomaterial coating you have applied.

- Electrode Modification: Employ nanomaterials like graphene or carbon nanotubes that provide a large, uniform electroactive surface area. This can help distribute the electrochemical processes more evenly, reducing noise originating from surface defects [1].

Environmental Noise: Electromagnetic Interference (EMI)

Q3: My voltammograms show unpredictable, sharp spikes that are not reproducible. What is the likely source?

A: These erratic spikes are a hallmark of Electromagnetic Interference (EMI). Your setup is likely picking up ambient electromagnetic radiation from sources like AC power lines, fluorescent lights, switches, or motors in nearby equipment.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Use a Faraday Cage: This is the most effective solution. Always conduct sensitive electrochemical measurements inside a properly grounded Faraday cage.

- Check Grounding: Ensure your potentiostat and all other instruments are connected to a common, proper ground.

- Isolate Power Sources: Run the instrument on battery power if possible, or use a line conditioner to filter AC power noise. Move cell phones and other wireless devices away from the setup.

Biological Noise: Biofouling and Cross-reactivity

Q4: The sensitivity of my biosensor decreases significantly after exposure to complex biological samples like serum or blood. Why?

A: This loss of sensitivity is most likely due to Biofouling. Proteins, lipids, and cells non-specifically adsorb onto your electrode surface, forming an insulating layer that blocks electron transfer and access to the biorecognition elements [1] [2].

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Surface Passivation: Co-modify your electrode with anti-fouling agents. Common solutions include:

- Poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) and its derivatives: Form a hydrophilic, steric barrier that repels proteins [2].

- Self-Assembled Monolayers (SAMs): Dense, well-ordered monolayers (e.g., of alkanethiols on gold) can reduce non-specific adsorption.

- Hydrogels: Create a hydrated physical barrier against fouling agents.

- Use Nanomaterials: Certain nanomaterials like reduced Graphene Oxide (rGO) can offer improved biocompatibility and reduced fouling compared to bare electrodes [1].

- Sample Dilution or Pre-treatment: If compatible with your detection limit, dilute the sample in a clean buffer or use centrifugal filters to remove large fouling agents.

- Surface Passivation: Co-modify your electrode with anti-fouling agents. Common solutions include:

Q5: My sensor shows a positive signal for a non-target molecule that is structurally similar to my analyte. How can I improve specificity?

A: This is the challenge of Cross-reactivity, where your biorecognition element (e.g., antibody, aptamer) interacts with non-target analytes.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Biorecognition Element Engineering: Screen for and use high-affinity aptamers or monoclonal antibodies with higher specificity. For enzymes, ensure substrate specificity is high.

- Use a Dual-Recognition System: Design a sandwich-type assay that requires two separate recognition events to generate a signal, which dramatically increases specificity.

- Optimize Assay Conditions: Fine-tune the pH, ionic strength, and incubation time of your assay. Suboptimal conditions can promote weak, non-specific binding.

- Introduce Blocking Agents: During the immobilization and assay steps, use blocking buffers containing inert proteins (e.g., Bovine Serum Albumin - BSA) or casein to occupy any non-specific binding sites on the electrode surface.

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Mitigating Interferences

Protocol: Minimizing Interference from Ascorbic Acid using a BDD Electrode and Mediator Selection

This protocol is adapted from a study demonstrating low-interference detection of glucose and lactate [5]. It provides a concrete methodology for tackling a common source of environmental interference in enzymatic biosensors.

1. Objective: To detect glucose or lactate in human serum with minimal interference from ascorbic acid (AA) by using a Boron-Doped Diamond (BDD) working electrode and the electron mediator menadione (MD).

2. Principle: The BDD electrode exhibits a high overpotential for the oxidation of AA, resulting in a slow reaction rate and lower background current. Furthermore, menadione has a lower formal potential than AA, leading to a slow redox reaction rate between them. This synergistic combination minimizes the signal contribution from the interfering species [5].

3. Materials and Reagents:

- Working Electrode: Boron-Doped Diamond (BDD) electrode.

- Control Electrodes: Au, Glassy Carbon (GC), or Indium Tin Oxide (ITO) electrodes for comparison.

- Electron Mediators: Menadione (MD), Ru(NH₃)₆³âº, 4-amino-1-naphthol, 1,4-naphthoquinone.

- Enzymes: Glucose oxidase (GOx) for glucose detection; Lactate oxidase (LOx) for lactate detection.

- Biochemicals: D-glucose, L-lactate, Ascorbic Acid (AA).

- Buffer: Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), pH 7.4.

4. Experimental Procedure:

- Step 1: Electrode Preparation. Clean the BDD electrode according to the manufacturer's instructions (e.g., sonicate in ethanol and DI water).

- Step 2: Immobilization. Prepare an enzyme-mediator mixture. For the glucose sensor, mix GOx and MD in a suitable buffer. Deposit a precise volume (e.g., 5 µL) of this mixture onto the active area of the BDD electrode and allow it to dry under ambient conditions or a gentle nitrogen stream [5] [4].

- Step 3: Electrochemical Measurement.

- Use a standard three-electrode system (BDD working, Pt counter, Ag/AgCl reference).

- Immerse the electrode in a stirred PBS solution (pH 7.4).

- Apply the required potential for the redox cycling (e.g., 0.2 V vs. Ag/AgCl for MD-based detection).

- Record the amperometric current (i-t curve).

- Successively add aliquots of the glucose/lactate standard solution to the cell and record the steady-state current after each addition.

- Step 5: Interference Test. Repeat the above measurement in the presence of a physiologically relevant concentration of Ascorbic Acid (e.g., 0.1 mM) to demonstrate the minimal interference effect.

5. Expected Results: The combination of BDD electrode and menadione should yield a highly linear response to the target analyte (glucose/lactate) with a low detection limit (e.g., ~3 µM for glucose in ENN redox cycling), while the current response from the addition of AA will be negligible compared to other electrode-mediator combinations [5].

Protocol: Constructing a Carbon Nanotube-Based Impedimetric Biosensor to Combat Biofouling and Enhance Sensitivity

This protocol outlines the construction of a biosensor using carbon nanotubes to increase surface area and improve signal-to-noise ratio, while also incorporating strategies to reduce biofouling [1].

1. Objective: To fabricate a label-free impedimetric biosensor with enhanced sensitivity and reduced biofouling for the detection of a specific DNA sequence or protein.

2. Principle: Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes (SWCNTs) provide a large surface area for immobilizing biomolecules (e.g., ssDNA probes or antibodies) and facilitate efficient electron transfer. The porous, nanoscale structure can help mitigate some fouling, and further passivation can be applied. The binding of the target analyte increases the charge-transfer resistance (Rct), which is measured using Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) [1] [6].

3. Materials and Reagents:

- Working Electrode: Glassy Carbon Electrode (GCE) or screen-printed gold electrode.

- Nanomaterial: Carboxylated Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes (SWCNTs-COOH).

- Cross-linker: 1-Ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide (EDC) and N-Hydroxysuccinimide (NHS).

- Biorecognition Element: Amino-modified ssDNA probe or specific antibody.

- Anti-fouling Agent: Poly(ethylene glycol) Thiol (SH-PEG) for gold surfaces, or BSA for blocking.

- Redox Probe: 5 mM [Fe(CN)₆]³â»/â´â» in PBS.

4. Experimental Procedure:

- Step 1: Electrode Modification with SWCNTs.

- Polish the GCE and clean it.

- Disperse SWCNTs-COOH in DI water (e.g., 1 mg/mL) and sonicate to create a stable suspension.

- Deposit a known volume (e.g., 10 µL) of the SWCNT suspension onto the GCE surface and let it dry under ambient conditions (drop-coating) [4].

- Step 2: Functionalization with Biorecognition Element.

- Activate the carboxyl groups on the SWCNTs by incubating the modified electrode in a solution of EDC and NHS for 1 hour.

- Rinse the electrode to remove excess EDC/NHS.

- Incubate the electrode with a solution containing the amino-modified ssDNA probe or antibody for several hours to allow covalent immobilization via amide bond formation [1].

- Step 3: Anti-fouling Passivation.

- Incubate the functionalized electrode in a solution of SH-PEG (for gold) or BSA (for general use) to block any remaining non-specific binding sites.

- Rinse thoroughly with buffer.

- Step 4: EIS Measurement.

- Perform EIS in the redox probe solution over a frequency range (e.g., 0.1 Hz to 100 kHz) at a fixed DC potential.

- Record the Nyquist plot. The diameter of the semicircle corresponds to the Rct.

- Incubate the biosensor with the target analyte and measure the EIS again. An increase in Rct indicates successful target binding.

5. Expected Results: The SWCNT-modified electrode will show a significantly lower initial Rct compared to a bare electrode, indicating enhanced electron transfer. Upon target binding, a clear and measurable increase in Rct will be observed. The passivated sensor should maintain its performance with a minimal change in baseline Rct when exposed to a complex, fouling-rich sample like diluted serum [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Materials and Reagents for Interference Mitigation

| Item | Function / Application | Example in Use |

|---|---|---|

| Boron-Doped Diamond (BDD) Electrode | Working electrode material with a wide potential window, low background current, and low susceptibility to fouling. | Used with menadione mediator for low-interference detection of glucose and ascorbic acid [5]. |

| Menadione | An electron mediator with a low formal potential, reducing its reactivity with common interfering species like ascorbic acid [5]. | Synergistic use with BDD electrode in enzymatic (EN) redox cycling biosensors. |

| Carbon Nanotubes (SWCNTs/MWCNTs) | Nanomaterial used to modify electrode surfaces; provides a large surface area, enhances electron transfer, and increases biomolecule loading capacity [1]. | Covalent immobilization of DNA probes for enhanced sensitivity in impedimetric detection [1]. |

| Graphene Oxide (GO) & Reduced GO (rGO) | 2D nanomaterial with high surface area and excellent conductivity. rGO, in particular, is favorable for electrochemical biosensing [1]. | SERS-based biosensor platform; acts as a binding layer and signal enhancer when combined with metallic nanoparticles [7]. |

| EDC & NHS Cross-linkers | Carbodiimide chemistry agents used to activate carboxyl groups for covalent immobilization of biomolecules (with primary amines) onto electrode surfaces [1] [3]. | Creating stable, covalently bonded layers of antibodies or DNA on COOH-functionalized nanomaterials. |

| Poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) | Anti-fouling polymer used to create a hydrophilic, steric barrier on surfaces, minimizing non-specific protein adsorption [2]. | Incorporated into self-assembled monolayers (SAMs) on gold electrodes to improve performance in serum. |

| Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) | Porous crystalline materials that can be used for signal amplification and to enhance selectivity in sensing interfaces [2]. | Used in advanced surface engineering to lower detection limits for specific disease biomarkers. |

| Shanciol B | Shanciol B, MF:C25H26O6, MW:422.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Isoprocarb-d3 | Isoprocarb-d3, MF:C11H15NO2, MW:196.26 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

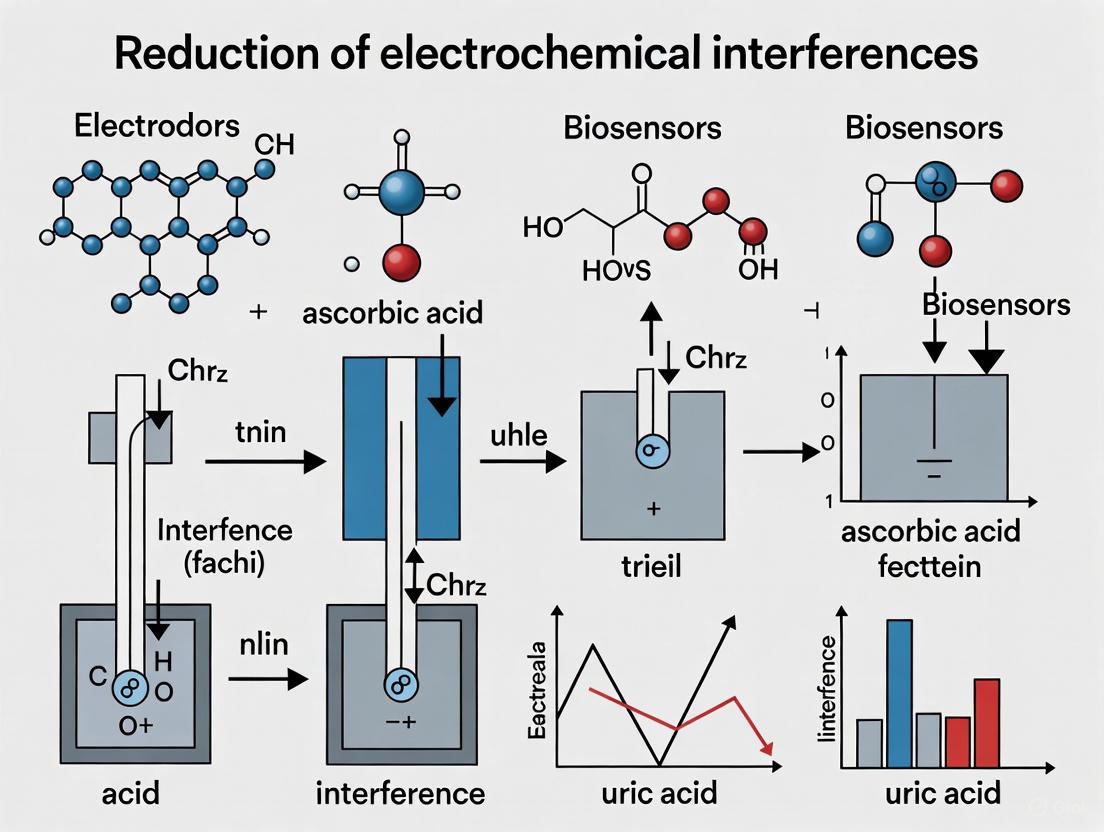

Visualizing Experimental Workflows

Interference Mitigation Strategy Diagram

BDD Electrode Experimental Workflow

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the most common sources of interference in electrochemical biosensors? In complex real samples, electrochemical sensors are susceptible to several types of interference that can degrade performance. Key sources include:

- Chemical Interference: Signals from non-target substances with similar redox potentials can cause signal overlap and cross-interference, especially when detecting biomarkers in biological fluids like blood or saliva [8].

- Matrix Effects: The complex physiological environment itself can cause non-specific binding and electrode fouling, where proteins and other molecules adsorb to the sensor surface, blocking the active sites and reducing signal strength over time [9].

- Environmental Factors: Changes in temperature, humidity, and long-term usage can lead to signal drift, where the baseline signal changes, making accurate calibration difficult [8].

2. How does interference lead to a higher Limit of Detection (LoD)? Interference elevates the baseline noise of the sensor system. At low analyte concentrations, the target signal can be obscured by this noise, making it indistinguishable. This low signal-to-noise ratio makes it difficult for the sensor to reliably confirm the presence of trace amounts of the analyte, thereby increasing the practical LoD [8]. For instance, without strategies to mitigate interference, a sensor might fail to detect a biomarker at clinically relevant low concentrations [9].

3. What mechanisms cause false positives and false negatives?

- False Positives occur when interference from other substances generates a signal that the sensor misinterprets as the target analyte. For example, in complex samples, other electroactive compounds can be misjudged as the biomarker of interest [9].

- False Negatives happen when interference masks the signal from the actual target. This can be due to signal suppression from electrode fouling, where the sensor surface is blocked, or when the target is present at a concentration too close to the elevated noise floor caused by interference [8] [10].

4. Can AI/ML truly help overcome these interference issues? Yes, Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) offer powerful, data-driven approaches to combat interference. They do not eliminate the physical/chemical interference but can mathematically separate the desired signal from the noise [8] [9].

- Feature Extraction and Noise Reduction: ML algorithms can process raw, complex sensor data to identify and extract the unique "fingerprint" of the target analyte while suppressing noise and signals from interferents [8] [9].

- Modeling Complex Relationships: They can learn the nonlinear relationship between the sensor's signal and the target concentration, even in the presence of drift or multiple interferents, leading to more accurate calibration models [8].

- Multiplexed Signal Decoding: For sensors designed to detect multiple targets at once, ML is particularly effective at deconvoluting overlapping signals, significantly enhancing selectivity and accuracy [8].

5. What are some experimental strategies to minimize interference?

- Surface Engineering: Using three-dimensional (3D) immobilization materials like hydrogels, metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), or porous carbon can increase probe density and improve binding efficiency, which helps enhance sensitivity and selectivity against interferents [11].

- Material Selection: Incorporating advanced nanomaterials like polydopamine-based coatings or violet phosphorene can improve biocompatibility, reduce fouling, and increase the signal-to-noise ratio [8] [12].

- Sensor Design: Employing mediators or specific electrode modifications can create a more selective electron transfer pathway, reducing the influence of other electroactive species [8].

Experimental Protocols & Troubleshooting Guides

Protocol 1: Assessing and Mitigating Signal Drift

Objective: To evaluate and correct for signal drift caused by environmental factors and sensor aging.

Materials:

- Electrochemical workstation (e.g., potentiostat)

- Your biosensor system (working, reference, and counter electrodes)

- Standard buffer solutions

- Temperature and humidity control chamber (optional but recommended)

Methodology:

- Baseline Recording: Immerse the sensor in a stable standard solution. Record the baseline current or potential over an extended period (e.g., 1-2 hours) under constant, controlled conditions.

- Drift Characterization: Plot the baseline signal over time. The slope of this plot indicates the drift rate.

- ML-Assisted Compensation:

- Collect a dataset of sensor signals alongside reference measurements (e.g., from a standard lab technique) taken at multiple time points.

- Train a machine learning model (e.g., a time-series forecasting model like ARIMA or a recurrent neural network) to learn the relationship between the drifting sensor signal and the true reference value.

- Integrate this model into your data processing pipeline to predict and subtract the drift component from future sensor readings [8].

Troubleshooting Tip: If drift is excessive, investigate the stability of your reference electrode and the consistency of your sensor's surface modification. A poorly fabricated or aged reference electrode is a common source of drift.

Protocol 2: Enhancing Selectivity in Complex Samples

Objective: To improve sensor accuracy when detecting a specific target in a mixture of interfering substances.

Materials:

- Functionalized biosensor

- Target analyte standard

- Potential interfering substances (e.g., ascorbic acid, uric acid, acetaminophen for biological samples)

- Buffer for sample dilution

Methodology:

- Individual Calibration: Measure the sensor's response to the target analyte across a range of concentrations in a clean buffer to establish a standard curve.

- Interference Test: Spike a constant, physiologically relevant concentration of the target analyte into samples that also contain high concentrations of potential interferents. Measure the sensor response for each mixture.

- Data Processing with ML:

- Use techniques like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to visualize if the data from target and interference clusters can be separated.

- Train a classification or regression model (e.g., Support Vector Machine or Artificial Neural Network) on the raw or pre-processed voltammetric/impendence data. The model will learn to recognize the complex pattern unique to the target, even against a noisy background [8] [9].

- Validation: Test the ML-enhanced sensor on a blind set of complex samples (e.g., diluted serum) and compare its performance against a standard method.

Troubleshooting Tip: If selectivity remains low, consider refining the feature extraction step for your ML model or re-evaluating the specificity of your biorecognition element (e.g., antibody or aptamer).

Table 1: Common Interference Types and Their Impact on Sensor Performance

| Interference Type | Primary Cause | Effect on LoD | Effect on False Results | Primary Mitigation Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Interference [8] [9] | Similar redox potentials of non-target molecules | Increases | Increases both False Positives & Negatives | Machine Learning signal deconvolution; Use of selective mediators |

| Signal Drift [8] | Environmental changes (temp, humidity); sensor aging | Increases | Increases False Positives over time | ML-based drift compensation; Environmental control; Robust reference electrodes |

| Matrix Effects / Fouling [9] [11] | Non-specific adsorption of proteins/lipids | Increases | Increases False Negatives (signal suppression) | 3D surface engineering (e.g., hydrogels, MOFs); Anti-fouling coatings (e.g., polydopamine) |

| Low Signal-to-Noise at Trace Levels [8] | Weak target signal obscured by system noise | Defines the fundamental LoD | Increases False Negatives | Nanomaterial-enhanced signal amplification; ML for noise reduction |

Table 2: Performance of AI/ML Models in Addressing Sensor Challenges

| Sensor Challenge | ML Algorithm Applied | Key Performance Outcome | Reference Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nonlinear Signal-Concentration Relationship | Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) | Accurate modeling of saturation behavior, expanding dynamic range | [8] |

| Signal Drift Compensation | Time-Series Forecasting Models | Corrected for long-term signal decay, improving accuracy from >10% to <3% error | [8] |

| Multiplexed Detection & Cross-Talk | Support Vector Machines (SVM) | Enabled simultaneous quantification of multiple biomarkers with high selectivity | [8] |

| Low-Concentration Accuracy | Combined with optimized nanomaterials (e.g., BiFeO3/MXene) | Achieved ultra-sensitive Pb2+ detection with a significantly lowered LoD | [8] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Developing Interference-Resistant Biosensors

| Material / Reagent | Function | Example in Application |

|---|---|---|

| Metal Nanoparticles (e.g., Au, Pt) [11] | Enhance electrical conductivity and provide a high-surface-area scaffold for probe immobilization. | Gold nanoparticles used in a BiFeO3/Ti3C2 MXene platform for sensitive Pb2+ detection [8]. |

| Carbon-Based Nanomaterials (Graphene, CNTs) [11] | Improve electron transfer kinetics and increase the electroactive surface area. | 3D graphene oxide structures used to enhance performance in influenza virus sensors [11]. |

| Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) [11] | Provide ultra-high porosity and tunable chemistry for efficient 3D capture of target molecules. | MOFs used in trimetallic sensors for detecting p-Nitrophenol in soil [8]. |

| Hydrogels [11] | Create a biocompatible, hydrated 3D matrix that reduces non-specific adsorption and increases probe loading. | Used as a matrix for biomolecule capture in 3D-based biosensors [11]. |

| Aptamers [8] | Serve as synthetic, stable recognition elements that can be selected for high specificity to a target. | Used in platforms for detecting mycophenolic acid and THC/CBD, overcoming cross-interferences [8]. |

| Machine Learning Algorithms [8] [9] | Process complex electrochemical data to extract features, reduce noise, and model nonlinear relationships. | Used to distinguish biomarkers in complex mixtures and compensate for signal drift [8]. |

| (Rac)-Ruxolitinib-d9 | (Rac)-Ruxolitinib-d9, MF:C17H18N6, MW:315.42 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Antitubercular agent-13 | Antitubercular agent-13|Pks13 Inhibitor|For Research | Antitubercular agent-13 is a potent Pks13 inhibitor for tuberculosis research. It targets mycolic acid biosynthesis. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

Visualized Workflows and Relationships

Diagram 1: Interference Impact Pathway

Diagram 2: AI-Enhanced Sensor Workflow

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My electrochemical biosensor shows inconsistent results between measurements. What could be causing this?

Inconsistent results often stem from instability at the electrode-electrolyte interface. Key factors include:

- Self-Assembled Monolayer (SAM) Instability: Repeated electrochemical interrogation, such as cyclic voltammetry (CV) scans, can cause reorganization or degradation of thiolated nucleic acid and mercapto alcohol monolayers on gold surfaces. This leads to changes in packing density and false changes in charge-transfer resistance (R~ct~) [13].

- Electrode Fouling: Non-specific adsorption of proteins or other molecules from complex samples (e.g., blood, serum) can block active sites and increase background noise [14].

- Redox Mediator Degradation: Partial degradation of common redox mediators like

[Fe(CN)~6~]^(3−/4−)can produceCN−anions, which contribute to etching the gold electrode surface, permanently altering its properties [13].

Q2: Why is the sensitivity of my sensor lower than expected when detecting low analyte concentrations?

A lower-than-expected sensitivity is frequently a problem of signal-to-noise ratio.

- High Background Noise: Electronic noise (e.g., thermal noise, 1/f flicker noise from electrode material imperfections) and environmental electromagnetic interference can mask the weak signal from low-concentration analytes [14].

- Suboptimal Electron Transfer Kinetics: Slow electron transfer kinetics at the electrode surface can dampen the Faradaic signal. This can be influenced by the electronic structure of the electrode material, including its density of states near the Fermi level and quantum capacitance [15].

- Inefficient Probe Immobilization: Low or uneven packing density of biorecognition elements (e.g., aptamers) on the transducer surface reduces the number of available binding sites, leading to a weaker signal [13].

Q3: I am observing a high rate of false positives. How can I improve the selectivity of my biosensor?

False positives are typically caused by interference from non-target molecules.

- Non-Specific Adsorption: Interferents present in complex sample matrices can adsorb onto the sensor surface or the molecularly imprinted polymer (MIP), producing a signal that mimics the target [16].

- Cross-Reactivity: The biorecognition element (e.g., an aptamer) may have affinity for molecules structurally similar to the target analyte.

- Solution: Employ a differential sensing strategy. Using a pair of sensors—such as two molecularly imprinted polymer (MIP) sensors for different analytes—allows you to subtract the signal contribution from non-specific adsorption common to both, significantly enhancing selectivity [16].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Drifting Baseline and Signal Instability

This problem manifests as an unstable baseline current or impedance, making it difficult to distinguish the true signal.

| Troubleshooting Step | Action / Protocol | Key Parameters & Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Inspect SAM Stability [13] | Characterize the monolayer pre- and post-CV using EIS. Fit data to a modified Randles circuit to track R~ct~ and capacitance. | Protocol: Immobilize thiolated DNA on Au electrode, then backfill with MCH. Run 10 CV cycles (0.8 V to -0.15 V, 100 mV/s). Measure EIS after cycles 1, 5, and 10. Outcome: A stable SAM shows <5% change in R~ct~ after 10 cycles. |

| Verify Electrode Cleaning [13] | Clean the gold electrode to remove adsorbed contaminants and oxide layers before SAM formation. | Protocol: Electrochemically clean in 0.5 M H~2~SO~4~ or 0.1 M KOH via CV until a stable voltammogram for a clean Au surface is achieved. Outcome: A clean, reproducible Au surface voltammogram. |

| Check Redox Mediator [13] | Use a fresh redox mediator solution and avoid repeated use. | Protocol: Prepare [Fe(CN)~6~]^(3−/4−) solution daily in degassed buffer. Outcome: Improved signal stability and reduced electrode etching. |

The following workflow outlines the systematic approach to diagnosing and resolving baseline drift:

Problem 2: Poor Signal-to-Noise Ratio in Low Concentration Detection

A poor signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) obscures the detection of low-concentration analytes, raising the limit of detection.

| Troubleshooting Step | Action / Protocol | Key Parameters & Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Assess Electronic Noise [14] | Use a Faraday cage to shield the setup. Use twisted-pair cables and ensure proper grounding. | Protocol: Place electrochemical cell inside a grounded Faraday cage. Outcome: Significant reduction in 50/60 Hz power line noise and environmental EMI. |

| Evaluate Electrode Material [14] [15] | Switch to advanced carbon nanomaterials with high conductivity and innate antifouling properties. | Protocol: Fabricate electrodes using novel carbon nanomaterials (e.g., LIG, N-doped graphene). Outcome: Reduced thermal/flicker noise and higher sensitivity due to tunable electronic structure. |

| Apply Antifouling Coatings [14] | Apply a coating to reduce non-specific binding in complex matrices. | Protocol: Form a nanocomposite antifouling layer (e.g., BSA/prGOx/GA) or use PEG. Outcome: Reduced false positives from serum/blood components, leading to a cleaner signal. |

Problem 3: Low Selectivity and Specificity

The sensor responds to interferents, leading to false positives and inaccurate quantification.

| Troubleshooting Step | Action / Protocol | Key Parameters & Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Implement a Differential Strategy [16] | Use a dual-sensor system to correct for non-specific adsorption. | Protocol: Fabricate two MIP sensors for different analytes (e.g., AP and SMR). Use the current difference between them as the signal indicator. Outcome: Interference from non-specific adsorption is reduced by an order of magnitude. |

| Optimize Probe Packing Density [13] | Systematically vary the concentration of thiolated probe DNA during SAM formation to find the optimal density. | Protocol: Immobilize thiolated DNA at concentrations from 0.1 to 5 µM. Characterize with chronocoulometry and EIS. Outcome: A packing density that maximizes signal for target binding while minimizing non-specific adsorption. |

| Validate with Controls [13] | Always run control experiments with non-complementary targets or on NIP surfaces. | Protocol: Test sensor response against a panel of structurally similar molecules. Outcome: Confirmation that the signal change is due to specific target-probe interaction. |

The diagram below illustrates the core principle of the differential sensing strategy for enhancing selectivity:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential materials and their functions for developing robust electrochemical biosensors, as derived from the cited research.

| Item | Function / Rationale | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Thiolated Nucleic Acids (Aptamers) | Forms the biorecognition SAM on gold surfaces. The thiol group provides a stable Au-S bond for immobilization [13]. | Affinity-based detection of specific targets (proteins, small molecules) [17] [13]. |

| Mercaptohexanol (MCH) | A short-chain alkanethiol used as a diluent in mixed SAMs. It minimizes non-specific adsorption and helps orient the nucleic acid probes upright [13]. | Backfilling SAMs to create a well-ordered, low-fouling sensing interface on gold electrodes [13]. |

| Potassium Hexacyanoferrate(II/III) | A common outer-sphere redox probe for characterizing electrode kinetics and interface integrity via EIS and CV [13] [15]. | Quantifying charge-transfer resistance (R~ct~) and monitoring SAM formation and stability [13]. |

| Ruthenium Hexamine (RuHex) | A cationic redox probe used in chronocoulometry to determine the surface coverage of anionic DNA probes [13]. | Measuring the surface density (molecules/cm²) of immobilized nucleic acid probes [13]. |

| Ni~2~P Nanoparticles | A noble-metal-free electrocatalyst used to modify the electrode surface, enhancing sensitivity and electron transfer [16]. | Serving as an electrode modifier in molecularly imprinted polymer (MIP) sensors for small molecules [16]. |

| Laser-Induced Graphene (LIG) | A 3D porous graphene material with high conductivity and abundant edge defects that enhance electroactivity and electron transfer kinetics [15]. | Fabricating high-sensitivity, flexible electrodes for sensing and energy storage applications [15]. |

| Polypyrrole (PPy) | A conductive polymer used for electropolymerization to create MIP membranes. It offers strong adherence and rapid response [16]. | Creating synthetic recognition cavities for specific molecules in MIP-based sensors [16]. |

| Anti-Influenza agent 3 | Anti-Influenza agent 3, MF:C16H22ClNOS, MW:311.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Tiropramide-d5 | Tiropramide-d5, MF:C28H41N3O3, MW:472.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Engineering Solutions: Material, Design, and Immobilization Strategies for Cleaner Signals

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the key advantages of using carbon nanostructures in electrochemical biosensors? Carbon nanostructures like graphene, carbon nanotubes (CNTs), and carbon nanofibers offer high electrical conductivity, a large surface area, and good biocompatibility [18]. Their extended sp² hybridized network facilitates rapid electron transfer during redox reactions, which is crucial for enhancing sensor sensitivity and achieving a low limit of detection [18].

Q2: How do Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) improve biosensor performance? MOFs possess a high surface area and tunable porosity [19]. This allows for selective adsorption and release of biomolecules, significantly enhancing the sensitivity and selectivity of the sensor. Their structure can be tailored by changing metal ions and organic linkers to optimize them for specific sensing tasks [19].

Q3: Why are metallic nanoparticles like gold and silver used in biosensors? Metallic nanoparticles provide high catalytic activity and ease of functionalization [18]. Their nano-dimensional size contributes to enhanced synergy and catalytic activity, which allows for improved signal amplification and selectivity. They can also act as carriers for biomolecules, increasing the loading capacity of recognition elements [18].

Q4: What is a common challenge when working with carbon-based materials, and how can it be mitigated? Some carbon materials can be hydrophobic, which may limit their compatibility with biomolecules [18]. This challenge can be addressed through surface modifications and functionalization with specific chemical groups to improve hydrophilicity and biocompatibility [18].

Q5: How can I verify if the signal from my biosensor electrode is functioning correctly? A good practice is to test your electronics independently of the sensor. You can short the reference (RE) and counter (CE) electrodes together, and then short the working electrode (WE) to that connection via a large resistor (e.g., 1 MΩ). Applying a series of bias voltages and measuring the resulting output can help verify if the electronics are producing sensible signals [20].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Poor Electrical Conductivity in Nanomaterial-Based Electrodes

Problem: The modified electrode exhibits insufficient electrical conductivity, leading to a weak or noisy signal.

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cause 1: Inadequate Dispersion of Nanomaterials.

Agglomerated nanoparticles or carbon nanotubes can create poor electrical pathways.

- Solution: Implement more rigorous sonication protocols during nanomaterial preparation. Use appropriate surfactants or solvents to improve dispersion stability [21].

- Cause 2: Non-optimized Nanomaterial Loading.

Excessive loading of insulating components (e.g., certain metal oxides or ligands in MOFs) can hinder electron transfer.

- Solution: Titrate the concentration of the nanomaterial in the composite. Refer to established data, such as that for nanodiamond-enhanced fluids, where a 0.0338 volume fraction resulted in a 98-fold increase in conductivity, to find the optimal balance between surface area and conductivity [21].

- Cause 3: Incompatible Surface Chemistry.

The functional groups on the nanomaterial may not facilitate efficient electron transfer to the biorecognition element.

- Solution: Explore different surface modification techniques. For carbon nanotubes, functionalization with groups that improve biocompatibility and electron transfer kinetics is often necessary [18].

Guide 2: Managing Non-Specific Binding and Electrochemical Interferences

Problem: The biosensor shows a high background signal or responds to non-target analytes, reducing its selectivity.

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cause 1: Ineffective Electrode Surface Passivation. Uncovered areas of the electrode are susceptible to non-specific adsorption of proteins or other interfering species.

- Cause 2: Interference from Redox-Active Species in the Sample. Molecules like ascorbic acid or uric acid in biological samples can be oxidized at similar potentials as the target analyte.

Guide 3: Ensuring Stability and Reproducibility

Problem: Sensor performance degrades over time or varies between different fabrication batches.

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cause 1: Leaching of Biorecognition Elements. Enzymes, antibodies, or DNA may not be stably immobilized on the sensor surface.

- Cause 2: Poor Mechanical Stability of the Nanocomposite Film.

The nanomaterial coating may detach from the transducer surface during operation or washing.

- Solution: Enhance the adhesion between the nanolayer and the electrode. This can be achieved by using linker molecules or employing in-situ synthesis techniques, such as directly growing MOFs on the flexible substrate of a wearable sensor [19].

Table 1: Electrical Conductivity Enhancement from Selected Nano-enhanced Fluids

This table provides a reference for the scale of conductivity improvement achievable with different nanomaterials, which is directly relevant to electrode modification [21].

| Base Fluid | Nanoparticle Type | Observation on Electrical Conductivity | Relevance as a Conductive Fluid |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ethylene Glycol | Nanodiamond (0.0338 vol frac.) | 98 times higher than base fluid | Yes |

| Ethylene Glycol | In₂O₃ (0.0081% at 333.15 K) | 27,300% growth | Yes |

| Ethylene Glycol | Graphene | Enhancement up to 220% | Yes |

| Water | Al₂O₃ (0.2% at 25.9 °C) | Highest value: 2370 µS/cm | Yes |

| Water | Fe₃O₄ | Considerable enhancement with concentration/temperature increase | Yes |

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Nanomaterial-Enhanced Biosensors

This table lists key materials and their functions in developing these advanced biosensors [18] [19] [23].

| Material Category | Example Reagents | Primary Function in Biosensor Development |

|---|---|---|

| Carbon Nanomaterials | Graphene, CNTs, Carbon Black | High surface area conductive support; enhances electron transfer kinetics and biomolecule immobilization. |

| Metal/Metal Oxide NPs | Gold NPs, Platinum NPs, ZnO, Fe₃O₄ | Electrocatalysts for signal amplification; carriers for biomolecules; improve sensitivity and selectivity. |

| MOFs | 2D MOFs (e.g., C-MOF) | Tunable porous structure for selective analyte adsorption; scaffold for creating synergistic composites. |

| Surface Modifiers | Alkane-thiolates (for SAM) | Create a defined interface on electrodes; reduce non-specific binding; allow for bioreceptor attachment. |

| Permselective Membranes | Nafion | Coating to repel charged interfering substances (e.g., ascorbic acid) in complex samples like blood. |

Experimental Protocol: Constructing a Carbon Nanotube/MOF-Modified Biosensor Electrode

Aim: To fabricate a working electrode with enhanced conductivity and surface area for sensitive electrochemical detection of a target biomarker (e.g., glucose).

Materials:

- Glassy Carbon Electrode (GCE)

- Carboxylated Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes (MWCNTs)

- Precursors for a specific MOF (e.g., Zn²⺠ions and 2-methylimidazole for ZIF-8)

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), pH 7.4

- Enzyme (e.g., Glucose Oxidase, GOx)

- Cross-linking agent (e.g., EDC/NHS chemistry)

- Nafion solution (~0.5% in alcohol)

Methodology:

- Preparation of MWCNT Dispersion: Disperse 1 mg of carboxylated MWCNTs in 1 mL of dimethylformamide (DMF) and sonicate for 30-60 minutes to obtain a homogeneous, black dispersion.

- Electrode Pre-treatment: Polish the bare GCE with alumina slurry (0.05 µm) on a microcloth, followed by rinsing with distilled water and drying.

- Modification with MWCNTs: Drop-cast 5 µL of the MWCNT dispersion onto the clean GCE surface and allow it to dry under ambient conditions. This forms a highly conductive base layer.

- In-situ Growth of MOF Layer: Immerse the MWCNT/GCE into an aqueous solution containing the MOF precursors (e.g., 50 mM Zn(NO₃)₂ and 100 mM 2-methylimidazole) for a predetermined time (e.g., 2-4 hours) at room temperature to grow a porous MOF film directly on the nanostructured surface.

- Enzyme Immobilization: Activate the carboxylic groups on the MOF or CNT surface using EDC/NHS. Then, incubate the electrode with a solution of the enzyme (e.g., 10 mg/mL GOx) for several hours to covalently bind the biorecognition element.

- Application of Nafion Membrane: Finally, drop-cast 3 µL of a 0.5% Nafion solution to form a thin protective layer that minimizes fouling and rejects anionic interferents.

Validation: The performance of the modified electrode should be validated using Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) and Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) in a standard redox probe like [Fe(CN)₆]³â»/â´â». A decrease in electron transfer resistance and an increase in peak current, compared to the bare electrode, indicate successful modification. The biosensing capability is then tested by measuring the amperometric response upon the addition of the target analyte (e.g., glucose) [24] [23].

Workflow and Troubleshooting Diagram

The following diagram outlines a logical workflow for developing and troubleshooting a nanomaterial-based biosensor.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

This technical support center provides solutions for researchers working with advanced biorecognition elements to mitigate electrochemical interferences in biosensor development.

Frequently Encountered Experimental Issues

Q1: My electrochemical biosensor shows high non-specific binding in complex samples like serum, leading to inaccurate readings. How can I improve specificity?

A: High non-specific binding is a common challenge. Implement a dual-recognition system to enhance selectivity.

- Recommended Action: Integrate Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) with an aptamer on your sensor platform. The MIP provides robust, shape-complementary cavities, while the aptamer offers high biological affinity. This synergistic combination creates two independent recognition events that must both occur for a signal, drastically reducing false positives from matrix interferents [25] [26].

- Protocol Enhancement: When fabricating the MIP via electropolymerization (e.g., using dopamine as a monomer), ensure thorough template removal by performing multiple cycles of cyclic voltammetry in a suitable washing buffer. Incomplete template removal is a primary cause of high background signal and reduced binding capacity [25].

Q2: The sensitivity of my aptamer-based sensor is lower than expected. What strategies can I use to amplify the signal?

A: Low sensitivity often stems from poor electron transfer kinetics at the electrode interface.

- Recommended Action: Functionalize your electrode with conductive nanomaterials. A highly effective approach is to electrodeposit bimetallic nanoparticles, such as Platinum-Gold Nanoparticles (PtAuNPs), onto a covalent organic framework (COF) modified electrode [25].

- Protocol Enhancement: The COF structure, for example, COFWOTA synthesized from N, N, N', N'-tetrakis(4-aminophenyl)-1, 4-phenylenediamine and 2, 5-dimethoxyterephthalaldehyde, provides a vast surface area and a hierarchical network. The deposited PtAuNPs significantly enhance conductivity and facilitate electron transfer, leading to a lower detection limit and higher signal-to-noise ratio [25].

Q3: The reproducibility of my MIP-based sensor is poor between different production batches. How can I achieve more consistent results?

A: Reproducibility issues in MIPs often arise from inconsistencies during the polymerization process.

- Recommended Action: Strictly control the monomer-to-template ratio, polymerization time, and temperature. Automating the electropolymerization step can minimize operator-induced variability [27].

- Protocol Enhancement: Utilize a standardized protocol with purified reagents. Characterize each batch of MIPs using electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) to ensure consistent charge-transfer resistance (Rct) values for a control solution before proceeding with target analyte testing [28].

Q4: What is the best way to immobilize an aptamer on a gold electrode surface to ensure optimal binding activity?

A: Proper immobilization is crucial for maintaining aptamer conformation and function.

- Recommended Action: Use a thiolated aptamer to form a self-assembled monolayer on the gold electrode via a stable Au-S bond. This provides a well-oriented and dense surface coverage [25] [27].

- Protocol Enhancement: After immobilization, backfill the electrode with a short-chain mercaptan (e.g., 6-mercapto-1-hexanol) to passivate unreacted gold sites. This step minimizes non-specific adsorption and helps to orient the aptamer for better target accessibility [25].

Performance Data of Advanced Biorecognition Systems

The following table summarizes the analytical performance of state-of-the-art biosensors utilizing dual-recognition elements, demonstrating their superiority in mitigating interference.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Advanced Biosensors for Specificity and Sensitivity

| Target Analyte | Biorecognition Strategy | Electrode Modification | Linear Range | Detection Limit | Application in Real Samples |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chlorpyrifos (CPF) [25] | MIP & Aptamer (Dual-recognition) | PtAuNPs/COFWOTA/GCE | 10.0 fM to 1.0 nM | 9.34 fM | Vegetables and fruits (Recovery: 96.67–100.33%) |

| Progesterone [25] | MIP & Aptamer (Dual-recognition) | SnO₂–graphene/AuNPs | 10.0 pM to 10.0 μM | 1.73 fM | Not Specified |

| Gatifloxacin (GTX) [25] | MIP (Single-recognition) | Not Specified | 1.00 × 10â»Â¹â´ to 1.00 × 10â»â· M | 2.61 × 10â»Â¹âµ M | Antibiotic pollutants |

Experimental Protocol: Fabrication of a Dual-Recognition MIP-Aptamer Sensor

This detailed protocol is for constructing an ultrasensitive chlorpyrifos sensor, adaptable for other targets [25].

1. Electrode Modification with Conductive COF and Nanoparticles:

- Synthesize COFWOTA via Schiff base condensation between N, N, N', N'-tetrakis(4-aminophenyl)-1, 4-phenylenediamine and 2, 5-dimethoxyterephthalaldehyde.

- Deposit the COF onto a clean Glassy Carbon Electrode (GCE) surface.

- Electrochemically deposit bimetallic PtAuNPs onto the COF/GCE to form a PtAuNPs/COFWOTA/GCE. This nanocomposite layer enhances the interfacial surface area and electron transport.

2. Aptamer Immobilization:

- Immobilize the terminal amine-modified aptamer onto the PtAuNPs/COFWOTA/GCE via covalent bonding. The PtAuNPs serve as an excellent anchor for the biorecognition element.

3. Molecular Imprinting via Electropolymerization:

- Immerse the Apt/PtAuNPs/COFWOTA/GCE in a solution containing the template molecule (CPF) and the functional monomer (dopamine).

- Perform electropolymerization using cyclic voltammetry to form a polydopamine film embedded with CPF molecules around the aptamer.

- Carefully remove the CPF template molecules from the polymer matrix by cycling in a washing buffer, leaving behind specific complementary cavities.

4. Electrochemical Measurement:

- Perform square wave voltammetry (SWV) or EIS measurements in the presence of the target analyte.

- The binding of CPF to both the MIP cavity and the aptamer causes a measurable change in current or impedance, which is proportional to its concentration.

The workflow for this protocol is summarized in the following diagram:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Materials and Their Functions in Advanced Biosensor Development

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment | Key Characteristic |

|---|---|---|

| Covalent Organic Frameworks (COFs) [25] | High-surface-area platform for immobilizing receptors and nanomaterials. | Enhanced interfacial surface area, tunable pore dimensions, and predictable functional properties. |

| Platinum-Gold Nanoparticles (PtAuNPs) [25] | Signal amplification; enhances electron transport kinetics and anchors biorecognition elements. | Excellent electrical conductivity and catalytic activity. |

| Thiolated or Amine-Modified Aptamers [25] [27] | High-affinity biological recognition element. | Allows for stable covalent immobilization on electrode surfaces (Au-S bond or amide linkage). |

| Dopamine (Functional Monomer) [25] | Forms the Molecularly Imprinted Polymer (MIP) matrix via electropolymerization. | Forms a robust polymer film (polydopamine) with good adhesion and biocompatibility. |

| Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) [28] | Label-free transduction method to monitor binding events at the electrode surface. | Sensitive to subtle changes at the electrode-electrolyte interface (e.g., charge-transfer resistance). |

| 2-Deoxy-D-glucose-13C | 2-Deoxy-D-glucose-13C, MF:C6H12O5, MW:165.15 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| H-Trp-Phe-Tyr-Ser(PO3H2)-Pro-Arg-pNA | H-Trp-Phe-Tyr-Ser(PO3H2)-Pro-Arg-pNA, MF:C49H59N12O13P, MW:1055.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

This technical support guide addresses the critical challenge of reducing electrochemical interferences in biosensors through the strategic design of three-dimensional (3D) probe immobilization scaffolds. For researchers and scientists in drug development, achieving high capture efficiency of biorecognition probes (such as antibodies, oligonucleotides, or enzymes) is paramount for developing sensitive, specific, and reliable diagnostic devices. This resource provides targeted troubleshooting and methodologies for working with hydrogel, graphene oxide, and porous silica—three key scaffold materials that enhance biosensor performance by increasing probe loading capacity and optimizing signal transduction.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Why should I use a 3D scaffold instead of a traditional 2D surface for my electrochemical biosensor? 3D scaffolds provide a significantly larger surface area for the immobilization of capture probes compared to flat, two-dimensional (2D) surfaces. This increased area allows for a higher density of biorecognition elements, which directly enhances the binding capacity for target analytes and improves the sensor's sensitivity. The 3D architecture also positively influences electrode reaction kinetics and reduces the diffusion time of analytes to the immobilized probes, leading to faster response times and a lower limit of detection [29]. Furthermore, 3D structures can be engineered from flexible and biocompatible materials, making them superior for implantable biosensor applications [29].

2. How does moving to a 3D scaffold help mitigate electrochemical interferences? The use of 3D scaffolds can contribute to interference mitigation in several ways. Firstly, the high probe-loading capacity can improve the specific signal relative to non-specific background noise. Secondly, conductive 3D materials like graphene can enhance electron transfer efficiency, which is beneficial for signal clarity [30] [31]. More direct strategies include functionalizing the scaffold with selective membranes or using the material's inherent properties. For instance, one innovative approach uses a conductive membrane that can be held at a specific potential to electrochemically deactivate redox-active interferents before they reach the underlying sensor, while allowing the target analyte to pass through unaltered [32].

3. My hydrogel scaffold is mechanically weak. How can I improve its stability? Pure hydrogels can indeed be mechanically weak, which limits their utility. A common and effective strategy is to form composite materials by doping the hydrogel network with reinforcing nanomaterials. For example, incorporating two-dimensional (2D) materials like graphene or its derivatives (graphene oxide, reduced graphene oxide) into the 3D hydrogel network has been shown to significantly improve the composite's mechanical strength and electrical conductivity without sacrificing biocompatibility [30]. This synergy creates a more robust and functional scaffold for biosensing.

4. What is the advantage of using porous silica in a biosensor scaffold? Porous silica is an attractive material due to its tunable pore size, high surface area, and chemical stability. Its well-defined and controllable 3D porous structure provides an excellent platform for immobilizing a large number of probes. Additionally, the silica surface can be readily functionalized with various chemical groups (e.g., silanes) to facilitate the covalent attachment of biorecognition elements, enhancing the stability of the immobilized layer [33] [29].

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Scaffold Preparation and Immobilization Issues

Table 1: Troubleshooting Probe Immobilization on 3D Scaffolds

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low Probe Loading | Scaffold pore size is too small for probe diffusion. | Optimize synthesis parameters to create larger, interconnected pores. For silica, use a template to control pore architecture [29]. |

| Poor Signal Output | Inadequate conductivity of the scaffold matrix. | Dope hydrogel with conductive materials like graphene or metal nanoparticles to enhance electron transfer [30] [31]. |

| Non-Specific Binding | Scaffold surface is not sufficiently bio-inert. | Implement blocking agents (e.g., BSA) or modify surface chemistry with antifouling polymers like PEG [24]. |

| Probe Leaching | Weak attachment between probe and scaffold. | Shift from physical adsorption to stronger covalent bonding strategies using cross-linkers like EDC/NHS or glutaraldehyde [29]. |

| Inconsistent Results | Non-uniform scaffold fabrication or uneven probe immobilization. | Use controlled deposition methods like electrodeposition or layer-by-layer assembly to ensure homogeneity [33]. |

Guide 1: Mitigating Electrochemical Interferences

Objective: To minimize the impact of redox-active species in complex samples (e.g., blood, urine) that can cause false positives or elevated background signals.

Workflow: The following diagram illustrates a strategic workflow for integrating interference mitigation into your 3D biosensor design.

Key Strategies:

- Material Selection: Opt for 3D scaffold materials known for their selective electrochemical properties. Graphene-based composites, for instance, offer excellent electrical conductivity that can be tuned for specific sensing applications [30] [31].

- Conductive Membrane Integration: A highly effective method involves encapsulating the sensor with a conductive membrane, such as a gold-coated track-etch membrane. By applying a specific potential to this membrane, redox-active interferents can be electrochemically deactivated before they reach the sensing element. Research has demonstrated this can reduce interference by up to 72% [32].

- Surface Passivation: Ensure that all non-active areas of the biosensor are thoroughly blocked with a passivating agent to minimize non-specific adsorption of interfering compounds.

Guide 2: Optimizing Capture Probe Density

Objective: To maximize the number of active biorecognition probes immobilized within the 3D scaffold, thereby enhancing the sensor's sensitivity.

Workflow: A multi-faceted approach is required to maximize the density and activity of your capture probes.

Methodology:

- Scaffold Characterization: Begin by quantifying the specific surface area and pore size distribution of your scaffold material using techniques like BET analysis. This data is crucial for understanding its theoretical loading capacity.

- Surface Functionalization:

- Graphene Oxide: Rich in oxygen-containing groups (carboxyl, epoxy) that can be activated with EDC/NHS chemistry for covalent coupling to amine-containing probes [30] [31].

- Porous Silica: Silanol groups allow for functionalization with silane coupling agents (e.g., APTES) to introduce amine, thiol, or other functional groups for subsequent probe attachment [29].

- Hydrogel: Functional monomers (e.g., with carboxyl groups) can be incorporated during polymerization. Alternatively, hydrogels can be doped with functionalized nanomaterials like graphene oxide to provide anchor points for probes [30] [34].

- Validation: Use fluorescently labeled probes to visually confirm uniform distribution within the 3D matrix. Quantify immobilization efficiency by measuring probe concentration in solution before and after immobilization (e.g., via UV-Vis spectroscopy).

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Fabrication of a 3D Graphene Oxide-Hydrogel Composite Scaffold

This protocol outlines the synthesis of a hybrid scaffold that combines the high water content and biocompatibility of a hydrogel with the enhanced electrical conductivity and mechanical strength of graphene oxide [30] [34].

Materials:

- Graphene oxide (GO) aqueous dispersion

- Pyrrole monomer

- Cross-linker (e.g., poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate)

- Initiator system (e.g., Ammonium persulfate (APS) and Tetramethylethylenediamine (TEMED))

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), pH 7.4

Step-by-Step Method:

- Hydrogel Pre-Mixture: Prepare your standard hydrogel monomer solution (e.g., based on acrylamide or alginate) in PBS.

- GO Incorporation: Add a calculated volume of GO dispersion (e.g., 1 mg/mL) to the hydrogel pre-mixture and vortex thoroughly to achieve a homogeneous blend.

- Gelation: Add the cross-linker and initiator to the GO-hydrogel mixture according to your established hydrogel protocol. Pipette the solution onto your electrode surface and allow it to polymerize under controlled conditions (e.g., 37°C for 30 minutes).

- Post-Assembly (Optional): For enhanced conductivity, the composite can be subjected to a mild chemical or thermal reduction step to convert graphene oxide to reduced graphene oxide (rGO) within the hydrogel network [34].

- Equilibration: Rinse the polymerized scaffold with PBS to remove any unreacted reagents and to hydrate it fully before probe immobilization.

Protocol 2: Probe Immobilization via Covalent Coupling

This is a general protocol for covalently attaching amine-containing probes (e.g., antibodies, amino-modified DNA) to a carboxyl-functionalized scaffold (such as GO-hydrogel or functionalized porous silica).

Materials:

- Carboxylated 3D scaffold on electrode

- Capture probe (antibody, DNA, etc.)

- EDC (1-Ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide) and NHS (N-Hydroxysuccinimide)

- MES buffer (0.1 M, pH 5.5) and PBS buffer (0.1 M, pH 7.4)

Step-by-Step Method:

- Activation: Prepare a fresh solution of EDC (e.g., 40 mM) and NHS (e.g., 10 mM) in MES buffer. Incubate the scaffold with the activation solution for 30-60 minutes at room temperature with gentle shaking to convert the carboxyl groups to NHS esters.

- Rinsing: Thoroughly rinse the scaffold with MES buffer to remove excess EDC/NHS.

- Immobilization: Immediately incubate the activated scaffold with a solution of your capture probe (typically 10-100 µg/mL in PBS, pH 7.4) for 2-4 hours at room temperature or overnight at 4°C.

- Quenching and Blocking: Rinse the scaffold with PBS to remove physically adsorbed probes. Incubate with a blocking solution (e.g., 1% BSA in PBS) for at least 1 hour to deactivate any remaining active esters and to block non-specific binding sites.

- Storage: The functionalized biosensor can be stored in PBS at 4°C until use.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for 3D Probe Immobilization

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Graphene Oxide (GO) | Provides a high-surface-area 2D nanomaterial with functional groups for covalent probe attachment; enhances conductivity when reduced [30] [31]. | Used in a 3D porous rGO-PPy composite to immobilize B. subtilis via coordination and electrostatic interactions for a BOD biosensor [34]. |

| EDC / NHS Cross-linker | Activates carboxyl groups on the scaffold surface, enabling stable covalent bond formation with amine-containing probes [29]. | A standard chemistry for creating amide bonds to immobilize antibodies and enzymes on functionalized surfaces. |

| Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA) / Alginate | Forms biocompatible hydrogel matrices that can entrap probes and cells; allows for diffusion of analytes and substrates [29]. | Common hydrogel materials used for immobilizing microorganisms and biomolecules in biosensors. |

| (3-Aminopropyl)triethoxysilane (APTES) | Functionalizes silica and metal oxide surfaces with primary amine groups, creating a linker layer for probe conjugation [29]. | Used to modify porous silica and other metal oxides to facilitate the covalent attachment of biomolecules. |

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | Used in electrodeposition to create 3D nano-structured surfaces on electrodes; increases conductive surface area for probe immobilization [33]. | Electrodeposited on 3D scaffolds to enhance electrical conductivity and provide a platform for thiol-based probe immobilization. |

| Ferricyanide Mediator | Serves as an artificial electron acceptor in mediated biosensors, shuttling electrons from biochemical reactions to the electrode surface [32] [34]. | Used in a mediated BOD biosensor with immobilized B. subtilis to facilitate electrochemical detection [34]. |

| Nlrp3-IN-4 | NLRP3-IN-4|Potent NLRP3 Inflammasome Inhibitor | |

| Bace1-IN-12 | Bace1-IN-12, MF:C29H28Cl2N6O, MW:547.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Table 3: Performance Comparison of 3D Scaffold Materials

| Scaffold Material | Key Advantage | Demonstrated Performance Metric | Consideration for Interference Reduction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogel-Graphene Composite | High biocompatibility & enhanced conductivity | 72% reduction in redox interference with conductive membrane [32]. | Can be integrated with conductive membranes; doping with graphene improves electrical signal quality. |

| 3D Porous Graphene-Polypyrrole | Large surface area & tunable surface chemistry | Linear BOD detection range of 4-60 mg/L [34]. | Inherent conductivity allows for potential strategies to selectively bias the scaffold. |

| Porous Silica | High mechanical stability & well-defined porosity | Excellent platform for high-density probe loading [29]. | Non-conductive nature may require incorporation of conductive elements for electrochemical sensing. |

| Metal Nanoparticle Coatings | Significant increase in electroactive surface area | Enables ultra-sensitive detection; improves signal-to-noise ratio [33]. | The metal surface itself must be chosen and potentially protected to avoid non-specific adsorption. |

Microfluidic biosensors represent a powerful synergy of microfluidic technology and biosensing elements, creating miniaturized "lab-on-a-chip" systems that automate the entire process from sample input to analytical result [35]. This system-level integration is pivotal for automating sample processing and, crucially, for reducing interferences in electrochemical biosensing. By enabling precise fluid control at microscopic scales (handling volumes from 10â»â¹ to 10â»Â¹â¸ liters), microfluidic systems mitigate key challenges such as fouling, non-specific binding, and diffusion limitations that traditionally plague electrochemical detection in complex matrices [36] [37]. The inherent characteristics of microfluidics—including laminar flow, high surface-to-volume ratios, and rapid heat transfer—directly enhance biosensor performance by improving reaction yields, conversion efficiencies, and signal-to-noise ratios [35]. For researchers focused on minimizing electrochemical interferences, the controlled microenvironment within microfluidic channels provides an unparalleled platform for implementing sophisticated interference-filtering strategies directly within the analytical workflow.

Technical Support Center: FAQs and Troubleshooting

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How does microfluidic integration specifically reduce interferences in electrochemical biosensors? Microfluidics reduces interferences through several integrated mechanisms. First, the precise spatial and temporal control over fluids allows for on-chip sample preparation steps like separation, purification, and washing, which can isolate the analyte from interferents before it reaches the detection chamber [35]. Second, the laminar flow regime (low Reynolds number) dominant at the microscale enables predictable fluid behavior, allowing for the design of channels that strategically remove interfering substances via diffusion-based sorting or by creating chemical gradients [35]. Third, integration facilitates miniaturized detection volumes, which localize the electrochemical reaction, confine the diffusion of redox species, and thereby enhance the signal relative to background noise [37].

Q2: What are the key considerations when selecting a material for my microfluidic biosensor? The choice of material is critical and involves trade-offs between performance, fabrication complexity, and cost, especially for electrochemical applications. The following table summarizes the key characteristics of common materials:

Table: Key Materials for Microfluidic Chip Fabrication

| Material | Advantages | Disadvantages | Best for Electrochemical Sensing? |

|---|---|---|---|

| PDMS (Elastomer) | High optical clarity, gas permeability for cells, easy prototyping [35] | Hydrophobic, prone to analyte absorption, can leach uncured oligomers [38] | Caution advised; surface modification often needed to prevent interference [38] |

| Glass | Excellent optical properties, high chemical resistance, rigid, low intrinsic fluorescence [39] [35] | Brittle, higher cost, complex and hazardous fabrication (e.g., HF etching) [39] | Excellent, due to inertness and established surface chemistry [39] |

| PMMA (Thermoplastic) | Good optical clarity, low cost, amenable to mass production [39] | Susceptible to organic solvents, lower chemical resistance [39] | Good, with proper surface passivation to minimize non-specific binding |

| Paper | Very low cost, self-pumping via capillarity, disposable [39] [40] | Lower sensitivity, susceptible to evaporation, limited flow control [39] | Promising for low-cost, single-use POC sensors; may have higher background [39] |

| Silicon | High thermal conductivity, excellent fabrication precision [35] | Opaque, high cost, complex fabrication [35] | Limited; opacity hinders some detection methods, but can be used with embedded electrodes |

Q3: My electrochemical signal is unstable. Could this be related to fluidic flow in the chip? Yes, unstable flow is a common culprit. To diagnose and resolve this:

- Check for Bubbles: Bubbles are a major cause of signal noise and drop-out. Degas your buffers before use and ensure all fluidic connections are tight. Incorporating bubble traps into your chip design can be highly effective.

- Verify Pump Performance: Ensure your syringe or peristaltic pump is calibrated and functioning correctly. pulsations from the pump can cause regular signal fluctuations. Dampeners can help smooth the flow.

- Inspect Channel Integrity: Clogs or damaged channels can create turbulent flow and backpressure, leading to signal drift. Flush the system with a cleaning solution and inspect under a microscope.

Q4: What are the best practices for immobilizing biorecognition elements (e.g., aptamers, antibodies) inside a microchannel to ensure stability and minimize non-specific binding? Effective immobilization is key to sensor stability and selectivity.

- Surface Activation: For glass, PDMS, or PMMA, use an oxygen plasma treatment to create hydroxyl groups, followed by silane chemistry (e.g., (3-Aminopropyl)triethoxysilane, APTES) to create a functional linker layer [37].

- Covalent Binding: Immobilize your biorecognition elements (antibodies, aptamers) via covalent bonds to the linker layer. For example, use EDC/NHS chemistry to crosslink amino-modified aptamers to an APTES-functionalized surface [37]. This prevents leakage and ensures a stable, dense receptor layer.

- Surface Passivation: After immobilizing your capture probe, passivate the remaining surface area with an inert protein (e.g., Bovine Serum Albumin - BSA) or a commercial blocking solution (e.g., SuperBlock). This is a critical step to minimize non-specific adsorption of interferents, a major source of false positives and background noise [37].

Troubleshooting Guide

Table: Common Experimental Issues and Solutions

| Problem | Potential Causes | Diagnostic Steps | Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| High Background Noise (Electrochemical) | 1. Non-specific binding of sample matrix components.2. Adsorption of redox mediators or reaction products.3. Electronic interference from pumping system. | 1. Run a negative control (sample without analyte).2. Test with buffer alone.3. Check signal with pump temporarily off. | 1. Optimize surface passivation protocol (e.g., use different blocking agents).2. Increase stringency of wash steps (e.g., more volumes, add mild detergent).3. Use electrical shielding and ground the system properly [41]. |

| Signal Drift Over Time | 1. Fouling of the electrode or channel surface.2. Evaporation from reservoirs (especially in open systems).3. Gradual degradation of the immobilized biorecognition element. | 1. Inspect electrode surface microscopically.2. Measure fluid volume in waste reservoir.3. Test a freshly prepared chip. | 1. Incorporate a periodic, gentle cleaning cycle (e.g., low-pH buffer).2. Seal reservoirs or use oil overlays to prevent evaporation.3. Ensure stable storage conditions (e.g., buffer, temperature) for chips. |

| Poor Reproducibility Between Chips/Runs | 1. Inconsistent surface chemistry/immobilization.2. Manufacturing variability in channel dimensions.3. Inaccurate fluidic control (flow rate variations). | 1. Use a fluorescent tag to quantify immobilization density.2. Measure channel dimensions under a microscope.3. Calibrate pumps and check for leaks. | 1. Standardize and rigorously control the immobilization protocol (time, temperature, concentration).2. Move to a more reproducible fabrication method (e.g., injection molding over soft lithography).3. Use high-precision pumps and verify flow rates regularly. |

| Low Sensitivity / Signal | 1. Inefficient transport of analyte to the sensor surface.2. Loss of bio-recognition element activity.3. Channel clogging. | 1. Measure analyte concentration in waste vs. input.2. Test the activity of the bio-recognition element in solution.3. Visually inspect channels for clogs. | 1. Use mixing structures (e.g., serpentine channels, herringbone mixers) to enhance mass transport [38].2. Optimize immobilization chemistry to preserve activity; avoid harsh conditions.3. Pre-filter complex samples and use channels with appropriate dimensions. |

Essential Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Fabrication of a PDMS Microfluidic Chip with Integrated Electrodes via Soft Lithography

This protocol outlines the creation of a reusable microfluidic chip suitable for integrating screen-printed or thin-film electrodes.

1. Master Mold Creation:

- Design: Create your channel network design (typically a single inlet, serpentine mixing/detection channel, and outlet) using CAD software. Feature widths should be >50 µm for ease of fabrication and to reduce clogging [42].

- Printing: Print the design as a high-resolution transparency mask.

- Alternative (Low-Cost): As demonstrated in recent work, a positive master can be created by laser-engraving a self-adhesive paper sheet (e.g., ~900 µm thick) and affixing it to a glass slide [42].