Advanced Strategies to Minimize Non-Specific Adsorption in Biosensors: From Antifouling Coatings to Machine Learning

Non-specific adsorption (NSA) remains a critical barrier to the reliability and clinical adoption of biosensors, causing signal interference, false results, and reduced sensitivity in complex matrices like blood and serum.

Advanced Strategies to Minimize Non-Specific Adsorption in Biosensors: From Antifouling Coatings to Machine Learning

Abstract

Non-specific adsorption (NSA) remains a critical barrier to the reliability and clinical adoption of biosensors, causing signal interference, false results, and reduced sensitivity in complex matrices like blood and serum. This article provides a comprehensive overview of innovative strategies to combat biosensor fouling, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. We explore the fundamental mechanisms of NSA and its impact on analytical signals, detail the latest material and surface chemistry solutions—including zwitterionic peptides, conductive polymers, and 2D materials like graphene. The discussion extends to practical optimization protocols, high-throughput evaluation methods, and comparative analyses of antifouling performance across electrochemical, SPR, and combined EC-SPR platforms. Finally, we examine the path toward clinical validation and the transformative role of machine learning in designing next-generation, fouling-resistant biosensors.

Understanding the Foe: The Fundamental Mechanisms and Impacts of Non-Specific Adsorption

Non-specific adsorption (NSA), often termed biofouling, represents a fundamental challenge in biosensing that significantly compromises analytical performance across healthcare diagnostics, environmental monitoring, and biotechnology [1]. NSA occurs when non-target molecules—such as proteins, lipids, or other matrix components—adhere to biosensor surfaces through physisorption, generating background signals often indistinguishable from specific analyte binding [1] [2]. This phenomenon persistently degrades key analytical figures of merit including sensitivity, specificity, and reproducibility, ultimately increasing false-positive rates and limiting detection capabilities, especially when analyzing complex biological samples like blood, serum, or milk [1] [2] [3].

The underlying mechanisms driving NSA primarily involve physisorption rather than chemical bonding [1]. This process is facilitated by a combination of intermolecular forces including hydrophobic interactions, ionic attractions, van der Waals forces, and hydrogen bonding [2]. The cumulative effect of these interactions results in the irreversible adsorption of non-target molecules to sensing interfaces, transducer surfaces, and even the bioreceptors themselves [1] [2].

Impact on Biosensor Performance and Signal Integrity

The consequences of NSA manifest differently across biosensing platforms but consistently impair analytical performance. In electrochemical biosensors, fouling layers disrupt electron transfer kinetics at electrode surfaces and can passivate the interface, leading to signal drift and degraded performance over time [2]. For optical biosensors utilizing surface plasmon resonance (SPR), non-specifically adsorbed molecules produce refractive index changes virtually identical to those generated by specific binding events, making discrimination impossible without sophisticated reference systems [2] [4]. Particularly problematic is that NSA can simultaneously cause both false-positive signals (when non-target adsorption is measured as analyte) and false-negative results (when fouling blocks analyte access to recognition elements) [2].

The economic and practical implications are substantial. As noted in a perspective on clinical implementation, "Avoidance of this phenomenon has not figured prominently, at least as it pertains to operation on real clinical samples" despite being a "major critical factor in ensuring the clinical relevance of a biosensor's data" [3]. This underscores the critical need for effective NSA mitigation strategies to enable translation of biosensors from research laboratories to real-world applications.

Quantitative Comparison of NSA Reduction Methods

Table 1: Performance Comparison of NSA Reduction Strategies

| Method Category | Specific Approach | Key Performance Metrics | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Passive Physical | Protein blocking (BSA, casein) | Rapid implementation; well-established for ELISA | Potential immunogenicity; can mask binding sites [1] |

| Passive Chemical | PEG/SAM coatings | Protein resistance reduced by 75% with optimized long-chain SAMs [5] | Sensitive to surface roughness and crystallization [5] |

| Surface Engineering | Zwitterionic materials | High hydration capacity; superior antifouling in complex media | Requires specialized synthesis protocols [6] |

| Material Innovation | Molecularly imprinted polymers + surfactants | LOD for sulfamethoxazole: 6 ng/mL in milk/water [7] | Optimization required for different analyte classes [7] |

| Active Removal | Electrochemical desorption | Applied voltage: 0.9 V in PBS; enables surface regeneration [8] | Limited compatibility with delicate bioreceptors [1] |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Reagents for NSA Research and Their Functions

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blocking Proteins | BSA, casein, milk proteins | Occupies vacant surface sites to prevent non-target adsorption [1] | Cost-effective but can introduce interference in some assays [1] |

| Polymer Coatings | Polyethylene glycol (PEG), polydopamine, zwitterionic polymers | Creates hydrophilic, neutral boundary layer resistant to protein adhesion [1] [6] | Thickness and grafting density critically impact performance [6] |

| Self-Assembled Monolayers | Alkanethiols (varying chain lengths), OEG-SH | Forms dense, ordered molecular barriers against fouling [5] [4] | Performance depends on incubation time, surface roughness (0.8-4.4 nm RMS optimal) [5] |

| Surfactants | SDS, CTAB | Electrostatic modification to eliminate NSA in MIPs [7] | Concentration must be optimized to avoid disrupting specific binding [7] |

| Nanomaterials | Graphene, carbon nanotubes, gold nanoparticles | High surface-area-to-volume ratio for dense bioreceptor immobilization [6] | Can introduce own nonspecific adsorption without proper functionalization [6] |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Surfactant Modification of Molecularly Imprinted Polymers

Background and Principle

Molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs) function as synthetic antibodies with specific recognition cavities, but often suffer from NSA due to functional groups located outside these cavities [7]. This protocol describes electrostatic modification of MIPs using surfactants to eliminate non-specific binding while preserving specific recognition capabilities, with demonstrated application for detecting sulfamethoxazole (SMX) in milk and water samples [7].

Materials and Equipment

- Polymers: Poly(4-vinylpyridine) or polymethacrylic acid-based MIPs

- Surfactants: Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) for positive MIPs; cetyl trimethyl ammonium bromide (CTAB) for negative MIPs [7]

- Target Analyte: Sulfamethoxazole (SMX) standard

- Chemical Reagents: Ethanol (99.9%), dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO), hydrochloric acid, sodium hydroxide

- Equipment: Ultrasonic water bath, incubation system with agitation, spectrophotometer or HPLC system for detection

Step-by-Step Procedure

- MIP Preparation: Synthesize MIPs using standard bulk or precipitation polymerization with SMX as template molecule [7].

- Template Removal: Extract template molecules thoroughly using appropriate solvents to create specific recognition cavities.

- Surfactant Modification:

- For poly(4-vinylpyridine) MIPs: Incubate with SDS solution (concentration optimized empirically)

- For polymethacrylic acid MIPs: Treat with CTAB solution

- Equilibration: Wash modified MIPs extensively with buffer to remove unbound surfactant while retaining electrostatic modifications.

- Binding Assay:

- Incubate modified MIPs with sample containing SMX (standards or unknown samples)

- Use appropriate binding time (typically 30-60 minutes) with continuous agitation

- Detection and Quantification:

- Measure bound SMX using spectrophotometric, chromatographic, or electrochemical methods

- Construct calibration curve with SMX standards (typical range: 0-100 ng/mL)

Critical Notes and Troubleshooting

- Surfactant Concentration Optimization: Excess surfactant can disrupt polymer structure, while insufficient amounts provide incomplete NSA protection [7].

- Specificity Validation: Test against structural analogs (sulfadiazine, sulfamerazine) to confirm maintained specificity post-modification [7].

- Stability Assessment: Validate thermal and operational stability; properly modified MIPs maintain performance even at elevated temperatures [7].

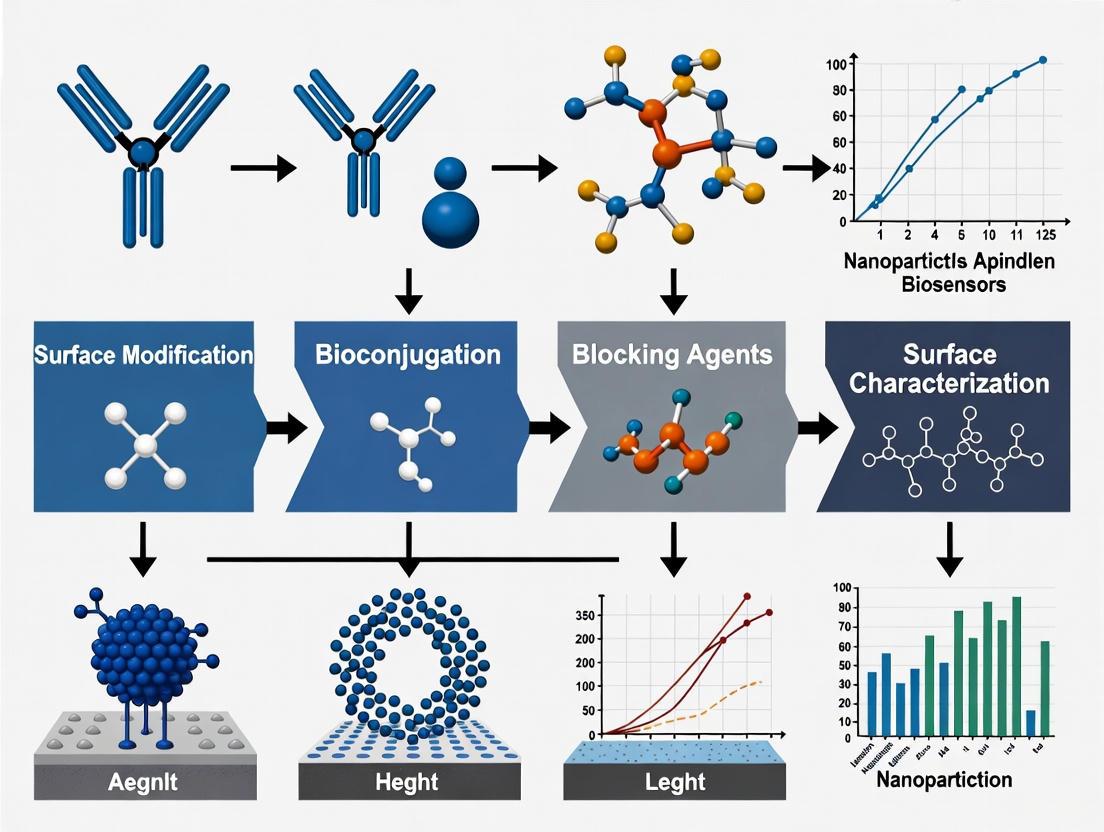

Experimental Workflow and Method Selection Guide

Experimental Workflow for NSA Mitigation

This workflow outlines a systematic approach for selecting and validating NSA reduction strategies based on sample complexity and methodological considerations [1] [2] [7].

Emerging Solutions and Future Perspectives

Innovative approaches continue to emerge addressing NSA challenges. Artificial intelligence and machine learning are increasingly applied to optimize surface functionalization strategies, predict material-analyte interactions, and design novel antifouling coatings with enhanced performance [6]. AI-driven models can analyze complex relationships between surface properties and sensor performance, accelerating the development of NSA-resistant interfaces [6].

Cell-free biosensing systems represent another promising approach, eliminating constraints associated with living cells while maintaining biological recognition capabilities [9]. These systems have demonstrated particular utility in environmental monitoring applications, detecting targets including heavy metals and organic pollutants with limits of detection meeting regulatory requirements [9].

The integration of advanced materials with tailored surface properties continues to yield improved NSA resistance. Zwitterionic coatings, biomimetic membranes, and hybrid nanomaterials offer enhanced antifouling performance while maintaining bioreceptor functionality [2] [6]. As these technologies mature, they promise to expand the applicability of biosensors to increasingly complex sample matrices and challenging analytical environments.

Non-specific adsorption remains a pivotal challenge in biosensor development, particularly for applications involving complex sample matrices. A comprehensive understanding of NSA mechanisms and a systematic approach to mitigation combining passive surface engineering, active removal methods, and emerging AI-driven optimization is essential for advancing biosensor capabilities. The experimental protocols and analytical frameworks presented here provide researchers with practical tools for addressing NSA challenges in their specific applications, ultimately contributing to the development of more robust, reliable, and clinically relevant biosensing platforms.

Non-specific adsorption (NSA), or biofouling, poses a significant challenge in the development of reliable biosensors. It occurs when unintended molecules adsorb onto the biosensing interface, leading to elevated background signals, reduced sensitivity, false positives, and compromised analytical performance [1] [2]. These phenomena are primarily driven by three fundamental physical interactions: electrostatic, hydrophobic, and van der Waals forces. In complex biological samples, these interactions operate concurrently, facilitating the adhesion of proteins, cells, and other biomolecules to sensor surfaces [10]. Understanding these mechanisms is crucial for devising effective strategies to suppress fouling, which is a persistent barrier to the widespread clinical adoption of biosensors, particularly for applications involving direct analysis of serum, blood, or other complex media [3]. This document outlines the core fouling mechanisms, presents quantitative data on their effects, and provides detailed protocols for implementing advanced antifouling surface modifications, specifically focusing on zwitterionic peptides and surfactant-integrated molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs).

Fundamental Fouling Mechanisms

The adsorption of biomolecules to sensor surfaces is a complex process governed by a combination of non-covalent interactions. The following table summarizes the key characteristics of the primary fouling mechanisms.

Table 1: Fundamental Mechanisms Driving Non-Specific Adsorption

| Mechanism | Physical Origin | Impact on Biosensor Performance | Influencing Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electrostatic Interactions | Attraction between oppositely charged groups on the surface and the biomolecule [10]. | Can cause significant signal drift and false positives by concentrating charged interferents near the sensing area [2]. | pH, ionic strength, surface charge density, biomolecule's isoelectric point [11]. |

| Hydrophobic Interactions | Entropy-driven association of non-polar regions to minimize contact with water molecules [10] [12]. | Leads to irreversible protein denaturation and passivation of the electrode surface, degrading sensor function over time [12]. | Surface hydrophobicity, protein characteristics, temperature [12]. |

| Van der Waals Forces | Weak, short-range attractions from induced dipole-dipole interactions [10]. | Provides a universal, attractive force that contributes to the initial adhesion of nearly all biomolecules to surfaces [1] [10]. | Polarizability of the interacting molecules, distance between surfaces [10]. |

These interactions rarely act in isolation. In a typical biofluid, the combined effect of these forces results in the formation of a fouling layer that masks the sensing element, sterically hinders analyte access, and can directly interfere with the transduction signal [2] [3]. For instance, in electrochemical biosensors, fouling can insulate the electrode surface, severely inhibiting electron transfer kinetics [2].

Quantitative Analysis of Fouling and Mitigation Efficacy

Evaluating the performance of antifouling strategies requires quantitative metrics. The following table summarizes data from recent studies demonstrating the effectiveness of two advanced materials: zwitterionic peptides and modified MIPs.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance of Advanced Antifouling Strategies

| Antifouling Strategy | Target Analyte | Key Performance Metric | Result | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zwitterionic Peptide (EKEKEKEKEKGGC) | Lactoferrin (in GI fluid) | Limit of Detection (LOD) / Signal-to-Noise | >10x improvement over PEG-passivated sensor [11] [13]. | |

| Zwitterionic Peptide (EKEKEKEKEKGGC) | Proteins & Cells | Non-specific Adsorption | < 0.2 ng cmâ»Â² protein adsorption; 99.3% reduction in bacterial adsorption [11]. | |

| SDS-Modified Polyaniline MIP | Tryptophan | Limit of Detection (LOD) | 6.7 μM [14]. | |

| SDS-Modified Polyaniline MIP | Tryptophan | Selectivity | High selectivity maintained against diverse interferents [14]. | |

| Agarose Gel-Coated Nanochannel | Prostate-Specific Antigen (PSA) | LOD in Human Serum | 1 ng mLâ»Â¹ (equivalent to commercial ELISA) [15]. |

The data underscores that effective surface engineering can suppress fouling to levels compatible with clinical diagnostics. The zwitterionic peptide's performance is particularly notable, offering broad-spectrum protection against both molecular and cellular fouling [11].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 4.1: Fabrication of a Zwitterionic Peptide-Modified Porous Silicon (PSi) Biosensor

This protocol details the modification of a PSi biosensor surface with a zwitterionic peptide to impart robust antifouling properties, enabling reliable detection in complex biological fluids like gastrointestinal fluid or serum [11] [13].

Research Reagent Solutions

- Porous Silicon (PSi) substrates: The high-surface-area transducer platform.

- Zwitterionic Peptide (EKEKEKEKEKGGC): The active antifouling agent; the lysine (K) and glutamic acid (E) motifs create a charge-neutral, hydrophilic surface, while the C-terminal cysteine enables covalent anchoring [11].

- (3-Aminopropyl)triethoxysilane (APTES): A silane coupling agent used to introduce primary amine groups onto the PSi surface.

- N-(3-Dimethylaminopropyl)-N′-ethylcarbodiimide (EDC): A carbodiimide crosslinker for activating carboxyl groups.

- N-Hydroxysuccinimide (NHS): Stabilizes the EDC-activated intermediate to form an amine-reactive NHS ester.

- Ethanolamine (1 M, pH 8.5): A blocking solution to deactivate and quench any remaining active ester groups after peptide immobilization.

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS, 10 mM, pH 7.4): A standard buffer for washing steps and as a solvent.

Procedure

- PSi Surface Activation: Clean and thermally oxidize the PSi films to establish a consistent surface hydroxide layer.

- Aminosilanzation: Incubate the PSi substrates in a 2% (v/v) solution of APTES in anhydrous toluene for 4 hours at room temperature. Rinse thoroughly with toluene and ethanol, then cure at 110°C for 15 minutes. This results in an amine-terminated surface.

- Peptide Solution Preparation: Dissolve the zwitterionic peptide in degassed PBS (10 mM, pH 7.4) to a final concentration of 0.2 mg mLâ»Â¹. Add a 10-fold molar excess of EDC and NHS to the peptide solution and allow it to activate for 15 minutes.

- Peptide Immobilization: Incubate the amine-functionalized PSi substrates in the activated peptide solution for 2 hours at room temperature under gentle agitation.

- Quenching: Rinse the substrates with PBS and subsequently incubate in 1 M ethanolamine (pH 8.5) for 30 minutes to block any unreacted NHS esters.

- Final Rinse and Storage: Rinse the modified PSi biosensors thoroughly with PBS and store in fresh PBS at 4°C until use.

Workflow Visualization

Protocol 4.2: Suppressing Non-Specific Adsorption in MIPs via Surfactant Immobilization

This protocol describes the integration of the surfactant sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) into conductive molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs) to minimize non-specific binding, thereby enhancing sensor selectivity for target analytes like tryptophan and tyramine [14].

Research Reagent Solutions

- Monomer (Aniline or Pyrrole): The building block for the conductive polymer matrix (e.g., polyaniline or polypyrrole).

- Template Molecule (e.g., Tryptophan): The target analyte around which the polymer is formed, creating specific recognition cavities.

- Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS): An anionic surfactant electrostatically immobilized within the polymer to shield non-specific binding sites and reduce interference [14].

- Lithium Perchlorate (LiClOâ‚„): The supporting electrolyte for the electrochemical polymerization process.

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS): Used for template removal (extraction) and subsequent washing steps.

Procedure

- Electrode Preparation: Clean the working electrode (e.g., glassy carbon or gold) according to standard electrochemical procedures.

- Polymerization Solution: Prepare a solution containing the monomer (e.g., aniline, 0.1 M), the template molecule (e.g., tryptophan, 5 mM), and the supporting electrolyte (LiClOâ‚„, 0.1 M) in a suitable solvent.

- Electropolymerization: Using cyclic voltammetry (CV), deposit the MIP film directly onto the electrode surface. Typical parameters include 10-15 scan cycles between a suitable potential range (e.g., -0.2 V to +0.8 V) at a scan rate of 50 mV/s.

- SDS Immobilization: Immerse the MIP-coated electrode in an aqueous solution of SDS (e.g., 10 mM) for 30 minutes. The SDS molecules will electrostatically bind to the conductive polymer network.

- Template Removal: Thoroughly rinse the MIP-sensor with PBS (or a PBS-ethanol mixture) to completely remove the embedded template molecules, thereby creating the specific recognition cavities.

- Sensor Validation: The resulting MIP-sensor is now ready for analytical performance evaluation, demonstrating enhanced selectivity due to reduced non-specific adsorption from the SDS treatment [14].

Workflow Visualization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Antifouling Research

Table 3: Key Reagents for Developing Antifouling Biosensors

| Reagent / Material | Function / Mechanism | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Zwitterionic Peptides (EK repeats) | Forms a strong, neutral hydration layer via electrostatic and hydrogen bonding; minimizes all three fouling interactions [11]. | Covalent surface modification of optical and electrochemical transducers (PSi, SPR chips) [11] [13]. |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | Forms a hydrated steric barrier that entropically excludes biomolecules; the historical "gold standard" [11]. | Physical adsorption or covalent grafting onto various sensor surfaces; being superseded by more stable alternatives. |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | A blocker protein that passively adsorbs to unoccupied surface sites, preventing further non-specific protein binding [1] [12]. | Common blocking step in immunoassays and immunosensors (e.g., ELISA-style formats) [12]. |

| Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS) | An anionic surfactant that electrostatically shields functional groups on polymers to reduce non-specific binding [14]. | Integration into conductive polymer-based MIPs to enhance selectivity [14]. |

| Agarose Gel | A neutral, highly hydrophilic polymer that forms a porous physical hydrogel barrier, resisting protein adsorption and pore clogging [15]. | Coating for nanochannel/nanopore biosensors to enable detection in whole blood [15]. |

| Carbodiimide Crosslinkers (EDC/NHS) | Activates carboxyl groups for covalent coupling to primary amines, enabling stable immobilization of biorecognition elements [11]. | Standard chemistry for attaching peptides, antibodies, or other biomolecules to sensor surfaces. |

| Sudocetaxel | Sudocetaxel Zendusortide | Sudocetaxel is a peptide-drug conjugate for cancer research, targeting sortilin receptors. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary use. |

| Mt KARI-IN-2 | Mt KARI-IN-2|KARI Inhibitor|For Research Use | Mt KARI-IN-2 is a potent KARI inhibitor for tuberculosis research. It targets the bacterial branched-chain amino acid biosynthesis pathway. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

Mitigating fouling driven by electrostatic, hydrophobic, and van der Waals interactions is paramount for advancing biosensor technology from research laboratories to clinical settings. The strategies detailed here—particularly the use of zwitterionic peptides to create a neutrally charged hydration layer and the integration of surfactants into MIPs to block non-specific sites—provide robust, quantifiable improvements in sensor performance. The experimental protocols offer a clear roadmap for researchers to implement these advanced antifouling coatings. As the field progresses, the high-throughput screening of new materials, supported by molecular simulations and machine learning, promises to further expand the toolkit available for developing next-generation biosensors capable of reliable operation in the most complex biological environments [2].

Non-specific adsorption (NSA) is a fundamental challenge that critically compromises the performance and reliability of biosensors. NSA refers to the undesirable accumulation of non-target molecules (e.g., proteins, cells, other biomolecules) from a sample onto the biosensor's sensing interface [2] [16]. This phenomenon, also known as biofouling, directly leads to performance degradation by causing signal drift, false positives, false negatives, and surface passivation [2] [16]. The negative effects are particularly pronounced when analyzing complex biological samples such as blood, serum, or milk, which contain a high concentration of potential interferents like proteins and lipids [2]. This Application Note delineates the operational impacts of NSA and provides detailed, actionable protocols for its quantitative evaluation and minimization, framed within the context of advanced biosensor research.

The Operational Impact of Non-Specific Adsorption

The deleterious effects of NSA manifest through several interconnected mechanisms, each degrading a key performance metric of the biosensor.

Signal Drift and Instability

NSA is a dynamic, time-dependent process. The continuous accumulation of non-target molecules on the sensing interface causes a baseline signal that shifts over time, known as signal drift [2]. This drift complicates signal interpretation, necessitates sophisticated background correction algorithms, and ultimately limits the biosensor's operational lifespan. Over short time spans, correction measures might be effective, but prolonged exposure leads to irreversible surface degradation and persistent drift [2].

False Positives and False Negatives

- False Positives: Occur when the signal from non-specifically adsorbed molecules is indistinguishable from the signal generated by the specific binding of the target analyte. This leads to an overestimation of the analyte concentration and incorrect diagnostic conclusions [2] [16].

- False Negatives: NSA can block or sterically hinder bioreceptors (e.g., antibodies, aptamers), preventing the target analyte from binding. Furthermore, adsorbed passivating molecules can inhibit the function of enzymatic bioreceptors. In both cases, the specific signal is suppressed, leading to an underestimation of the analyte concentration or a failure to detect its presence entirely [2].

Surface Passivation

Passivation describes the loss of biosensor function due to the formation of an irreversible, non-conductive layer of foulants on the transducer surface [2]. This layer can dramatically reduce the efficiency of electron transfer in electrochemical biosensors and degrade the performance of optical sensors by changing the refractive index properties of the interface [2].

Quantitative Evaluation of NSA Impact

Robust evaluation is crucial for diagnosing NSA and validating the efficacy of antifouling strategies. The following table summarizes key analytical parameters and techniques used for NSA assessment.

Table 1: Analytical Techniques for Quantifying NSA and its Effects

| Analytical Parameter | Technique | Measurement Principle | Impact of NSA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surface Fouling Degree | Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) | Measures change in refractive index at a metal surface [2] | Increase in resonance units (RU) proportional to adsorbed mass |

| Quartz Crystal Microbalance (QCM) | Measures mass change via oscillation frequency shift of a piezoelectric crystal [16] | Decrease in resonant frequency (ΔF) indicates mass loading | |

| Interfacial Electron Transfer | Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) | Measures charge transfer resistance (Rct) at electrode interface [14] | Significant increase in Rct indicates passivating layer formation |

| Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) | Measures current response during a potential sweep [14] [17] | Decrease in peak current and increased peak potential separation (ΔEp) | |

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) | Amperometry / Voltammetry | Ratio of specific analyte signal to non-specific background [2] | Decreased SNR compromises limit of detection (LOD) |

| Sensor Response Drift | Continuous / Real-time Monitoring | Slope of baseline signal over time under constant conditions [2] | Non-zero drift rate indicates progressive fouling |

Experimental Protocol: Evaluating NSA using EIS and SPR

This protocol outlines a coupled approach to assess NSA on a gold sensor surface, such as one used in electrochemical or SPR biosensors.

Aim: To quantify the extent of NSA from a complex sample (e.g., 10% serum) and evaluate the effectiveness of an antifouling coating.

Materials:

- Biosensor Substrate: Gold-coated SPR chip or electrochemical electrode.

- Antifouling Reagent: Zwitterionic peptide solution (e.g., EKEKEKEKEKGGC, 1 mg/mL in PBS) [11].

- Control Reagent: Polyethylene glycol (PEG) solution (e.g., 750 Da, 1 mg/mL) [11].

- Foulant Solution: Undiluted fetal bovine serum (FBS) or human serum.

- Buffer: Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), pH 7.4.

- Instrumentation: SPR instrument and/or Potentiostat with EIS capability.

Procedure:

- Baseline Establishment:

- Mount the bare gold sensor.

- For SPR: Flow PBS at a constant rate (e.g., 10 µL/min) until a stable baseline is achieved. Record the baseline reflectivity.

- For EIS: Immerse the electrode in PBS containing 5 mM [Fe(CN)6]3-/4-. Acquire an EIS spectrum (e.g., 0.1 Hz to 100 kHz, 10 mV amplitude). Record the charge transfer resistance (Rct).

Surface Functionalization (Test Surface):

- Passivate the sensor surface by flowing or incubating with the zwitterionic peptide solution for 1 hour at room temperature.

- Rinse thoroughly with PBS and DI water.

- Re-establish the PBS baseline in the instrument.

NSA Challenge:

- Expose the sensor to 100% FBS for 30 minutes.

- For SPR: Monitor the reflectivity shift in real-time. The total shift (in RU) after serum exposure is a direct measure of adsorbed protein mass.

- For EIS: After serum exposure, rinse the electrode and acquire a new EIS spectrum in the same [Fe(CN)6]3-/4- solution. Measure the new Rct.

Data Analysis:

- SPR: Calculate the total frequency or angular shift (ΔResponse) after serum injection and rinsing.

- EIS: Calculate the percentage increase in Rct: % Increase = [(Rctpost - Rctinitial) / Rct_initial] × 100.

- Compare the results from the zwitterionic peptide-coated sensor with a PEG-coated control and a bare gold surface.

Strategies to Mitigate NSA: A Focus on Antifouling Materials

Developing effective surface chemistries to prevent NSA is a primary research focus. The following table compares advanced antifouling materials.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Advanced Antifouling Materials

| Material / Strategy | Mechanism of Action | Reported Performance (in Complex Media) | Key Advantages | Limitations / Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zwitterionic Peptides (e.g., EKEKEKEK) | Forms a strong, neutrally charged hydration layer via electrostatic and hydrogen bonding [11] | >90% reduction in protein adsorption from GI fluid vs. bare surface; superior to PEG [11] | High stability, commercial availability, tunable sequences, resists cell adhesion [11] | Requires covalent surface immobilization; optimal sequence may be target-dependent |

| Zwitterionic Polymers (e.g., poly(sulfobetaine)) | Net-neutral charge with mixed positive/negative moieties; binds water molecules strongly [16] [11] | Effective for reducing protein NSA in blood and serum [16] | Strong hydration layer; good stability; can be grafted as brushes | Polymerization process can be difficult to control [11] |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | Forms a hydrophilic, steric barrier that resists protein adhesion [16] [11] | Historically the "gold standard"; performance depends on molecular weight and density | Well-established chemistry; widely available | Prone to oxidative degradation in biological media [11] |

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) with Surfactant | Creates specific cavities for the analyte; surfactants block non-specific sites [14] | SDS immobilization eliminated NSA for tryptophan sensing [14] | High selectivity and stability; "plastic antibodies" | Optimization of polymer and surfactant is critical to avoid template leaching |

Experimental Protocol: Functionalizing a Porous Silicon Biosensor with a Zwitterionic Peptide

This protocol details the procedure for creating a robust antifouling surface on a porous silicon (PSi) transducer, a high-surface-area substrate highly susceptible to fouling [11].

Aim: To covalently immobilize a zwitterionic peptide onto a PSi surface to minimize NSA for biosensing in complex fluids.

Materials:

- Substrate: Oxidized PSi thin film.

- Zwitterionic Peptide: EKEKEKEKEKGGC, synthesized and purified (>95%).

- Crosslinker: (3-Aminopropyl)triethoxysilane (APTES).

- Coupling Agents: N-(3-Dimethylaminopropyl)-N′-ethylcarbodiimide (EDC) and N-Hydroxysuccinimide (NHS).

- Solvents: Anhydrous toluene, dimethylformamide (DMF), ethanol.

- Buffers: 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid (MES) buffer (0.1 M, pH 6.0), PBS (0.1 M, pH 7.4).

Procedure:

- PSi Surface Activation:

- Hydrate the oxidized PSi film in ethanol.

- Activate the surface by immersing in a 2% (v/v) solution of APTES in anhydrous toluene for 2 hours under an inert atmosphere to form an amine-terminated monolayer.

- Rinse thoroughly with toluene and ethanol to remove physisorbed silane.

- Cure the silane layer at 110°C for 10 minutes.

Peptide Immobilization:

- Prepare a 1 mM solution of the EKEKEKEKEKGGC peptide in MES buffer.

- Activate the carboxylic acid groups on the peptide by adding EDC (400 mM) and NHS (100 mM) to the peptide solution. Allow to react for 15 minutes.

- Incubate the APTES-functionalized PSi chip in the activated peptide solution for 3 hours at room temperature.

- Rinse the chip sequentially with MES buffer, PBS, and DI water to remove any unbound peptide.

Blocking:

- To cap any remaining unreacted amine sites on the surface, incubate the chip in a 1 M ethanolamine solution (pH 9.0) for 1 hour.

- Rinse thoroughly with PBS and store in PBS at 4°C until use.

Validation:

- The success of the functionalization can be validated using Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) to confirm the presence of amide bonds.

- The antifouling performance must be validated using the evaluation protocol in Section 3.1, challenging the sensor with a relevant complex sample like serum or GI fluid.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for NSA Research

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Antifouling Biosensor Development

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Zwitterionic Peptides (EK repeats) | Forms a stable, charge-neutral hydration layer to prevent molecular and cellular adhesion [11] | Primary antifouling coating for PSi, SPR chips, and electrochemical sensors [11] |

| Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS) | Anionic surfactant used to block charged sites on conductive polymers to minimize NSA [14] | Post-polymerization treatment of MIPs (e.g., polypyrrole, polyaniline) to enhance selectivity [14] |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | Hydrophilic polymer that forms a steric barrier against protein adsorption [16] [11] | Common blocking agent and passivation layer; a benchmark for comparing new materials [11] |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | Protein blocker used to passivate uncoated surface sites after bioreceptor immobilization [16] | Standard blocking step in immunosensor and aptasensor fabrication protocols [16] |

| Ethanolamine | Small molecule used to deactivate and block unreacted functional groups on the sensor surface [11] | Capping reactive esters on NHS-activated surfaces after bioreceptor immobilization [11] |

| (3-Aminopropyl)triethoxysilane (APTES) | Silane coupling agent used to introduce primary amine groups onto oxide surfaces (e.g., SiOâ‚‚, PSi) [11] | Creates a functional layer for subsequent covalent immobilization of bioreceptors or antifouling layers [11] |

| Millmerranone A | Millmerranone A, MF:C27H28O9, MW:496.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Atr-IN-19 | Atr-IN-19, MF:C18H19N7OS, MW:381.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The direct impact of NSA on biosensor performance is a critical barrier to the deployment of reliable devices for clinical and environmental monitoring. Signal drift, false results, and surface passivation are direct consequences of fouling that can be systematically evaluated using techniques like EIS and SPR. The development of advanced antifouling materials, such as zwitterionic peptides, represents a significant leap forward, demonstrating superior performance over traditional blockers like PEG in challenging biological media. Integrating these materials with robust surface functionalization protocols, as detailed herein, provides a clear path toward developing next-generation biosensors capable of functioning accurately in real-world samples.

Non-specific adsorption (NSA) is a pervasive challenge that critically compromises the sensitivity, specificity, and reproducibility of biosensors. This phenomenon occurs when non-target molecules, such as proteins or lipids, physisorb onto the biosensing interface, leading to elevated background signals, false positives, and reduced dynamic range [1]. The detrimental impact of NSA is amplified when analyzing complex biological samples like blood, serum, or milk, which contain numerous interfering components [2]. This application note delineates the effects of NSA across three principal biosensor types—electrochemical, surface plasmon resonance (SPR), and enzyme biosensors—and provides detailed, actionable protocols to mitigate these effects, thereby enhancing biosensor performance for research and diagnostic applications.

Case Studies & Data Analysis

The following case studies quantitatively demonstrate the impact of NSA and the efficacy of various antifouling strategies.

Table 1: Analytical Performance of Biosensors Before and After NSA Mitigation

| Biosensor Type | Target Analyte | Sample Matrix | Key Antifouling Strategy | Limit of Detection (LOD) / Performance Metric | Signal Change due to NSA | Reference / Case Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electrochemical | Lysophosphatidic Acid (LPA) | Goat Serum | Silane-based interfacial chemistry | LOD: 0.7 µM | Significant signal drift and degradation over time without coating | [18] |

| Electrochemical | General Performance | Complex Media | Novel thiolated-PEG linker (DSPEG2) on gold | N/A | Albumin adsorption suppressed by ~90% compared to unmodified gold | [19] |

| SPR | Protein Interactions | Blood, Serum | Zwitterionic materials, PEG-based coatings | N/A | NSA causes indistinguishable signal shifts from specific binding | [1] [2] |

| Enzyme | Glucose | Buffer/Complex Media | Not Specified | Linear range: 1-50 mM; Sensitivity: 7.06 µA/mM | Non-specific adsorption leads to enzyme inhibition and passivation | [20] |

Table 2: Comparison of Common Antifouling Materials and Their Properties

| Material Class | Example Materials | Mechanism of Action | Compatibility | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polymer Brushes | Poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) | Forms a hydrated, steric barrier that resists protein adsorption | Electrochemical, SPR | Well-established, effective | Stability in flow systems [19] |

| Zwitterions | Carboxybetaine, Sulfobetaine | Creates a hydr ated layer via strong electrostatically-induced hydration | SPR, Optical | Highly effective antifouling properties | Can be sensitive to pH and ionic strength [2] |

| Proteins | Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA), Casein | Blocks vacant surface sites through pre-adsorption | Electrochemical, ELISA | Easy to implement, low cost | Potential desorption and instability [1] |

| Self-Assembled Monolayers (SAMs) | Silane-based (e.g., MEG-Cl), Thiolated PEG | Creates a dense, oriented, hydrophilic surface layer | Electrochemical, SPR (on Au) | Highly ordered and stable films | Substrate-specific (e.g., Au for thiols, SiO2 for silanes) [1] [18] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Developing an Antifouling Electrochemical Biosensor Using Silane Chemistry

This protocol outlines the development of an electrochemical biosensor for detecting Lysophosphatidic Acid (LPA) in serum, utilizing a silane-based monolayer to minimize NSA [18].

Step 1: Electrode Preparation and Cleaning

- Utilize medical-grade stainless steel or gold electrodes.

- Clean the electrode surface thoroughly via plasma treatment or piranha solution (a 3:1 mixture of concentrated sulfuric acid and 30% hydrogen peroxide). Caution: Piranha solution is highly corrosive and must be handled with extreme care. Rinse extensively with deionized water and dry under a stream of nitrogen.

Step 2: Formation of the Antifouling Monolayer

- Prepare a 1-2 mM solution of the silane-based molecule (e.g., 3-(3-(trichlorosilyl)propoxy) propanoyl chloride, MEG-Cl) in an anhydrous toluene solvent.

- Immerse the cleaned electrodes in the silane solution for 1-2 hours at room temperature under an inert atmosphere.

- Remove the electrodes, rinse with toluene followed by ethanol, and cure at 110-120°C for 10-15 minutes to facilitate cross-linking and stabilize the monolayer.

Step 3: Immobilization of the Biorecognition Element

- The specific biorecognition system in this case study is the gelsolin-actin system.

- Actin is immobilized onto the silanized surface. This can be achieved through covalent coupling (e.g., using EDC/NHS chemistry to target carboxylic acid groups on the silane layer and amine groups on the protein) or affinity-based binding.

- Subsequently, gelsin (the first three domains of gelsolin, G1-3) is introduced, which binds to the surface-immobilized actin.

Step 4: Electrochemical Measurement and NSA Validation

- Employ a standard three-electrode system for measurements.

- Use Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) and Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) with a redox couple (e.g., [Fe(CN)₆]³â»/â´â») to characterize the electrode after each modification step. A successful modification will show increased electron transfer resistance.

- Validate antifouling performance by incubating the biosensor in pure serum (e.g., goat serum) for 30-60 minutes. Measure the signal before and after incubation. A stable signal indicates effective NSA suppression.

- For LPA detection, monitor the electrochemical signal (e.g., impedance change) upon introduction of the sample. LPA severs the gelsolin-actin complex, producing a quantifiable signal.

Protocol 2: Fabricating a Low-NSA SPR Biosensor with a Thiolated-PEG Coating

This protocol describes the use of a novel thiolated-PEG linker (DSPEG2) on gold SPR chips to create a surface resistant to non-specific protein adsorption [19].

Step 1: SPR Chip Cleaning

- Clean the gold SPR chip surfaces with a fresh "piranha" solution (3:1 Hâ‚‚SOâ‚„:Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚) for 5-10 minutes. Warning: Piranha is extremely dangerous and should not be stored in closed containers. Rinse thoroughly with absolute ethanol and deionized water. Dry under a stream of nitrogen or argon.

Step 2: Self-Assembly of the DSPEG2 Monolayer

- Prepare a 0.1-1.0 mM solution of the DSPEG2 linker in a suitable solvent (e.g., ethanol or DMSO).

- Incubate the clean gold chips in the DSPEG2 solution for a minimum of 12 hours (overnight) at room temperature.

Step 3: Surface Characterization

- Remove the chips from the solution and rinse copiously with the pure solvent to remove physisorbed molecules.

- Characterize the modified surface using techniques such as Cyclic Voltammetry (CV), Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS), X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS), or Time-of-Flight Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry (TOF-SIMS) to confirm the formation of a dense, uniform monolayer.

Step 4: NSA Testing via SPR

- Mount the modified SPR chip in the instrument.

- Establish a stable baseline with a running buffer (e.g., PBS).

- Inject a concentrated solution of a model foulant protein (e.g., Bovine Serum Albumin, BSA, at 1 mg/mL in PBS) over the sensor surface for 5-10 minutes.

- Monitor the resonance unit (RU) signal. A minimal change in RU indicates successful suppression of NSA.

- Compare the signal response on the DSPEG2-modified surface to an unmodified gold surface or a surface modified with a control linker.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for NSA Mitigation in Biosensor Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role in NSA Reduction | Example Application / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) | Forms a hydrated, sterically repulsive layer that prevents protein fouling. | Thiolated-PEG (e.g., DSPEG2) for gold surfaces [19]. Silane-PEG for oxide surfaces. |

| Zwitterionic Compounds | Creates a super-hydrophilic surface via electrostatically-induced water binding, resisting protein adsorption. | E.g., Carboxybetaine, sulfobetaine; particularly effective for SPR sensors [2]. |

| Blocking Proteins (BSA, Casein) | Passive method that adsorbs to vacant surface sites, reducing available area for non-specific binding. | Commonly used in ELISA and immunoassays; potential for desorption [1]. |

| Silane-Based Linkers (MEG-Cl) | Forms a stable, covalently attached self-assembled monolayer (SAM) on oxide surfaces, providing a non-fouling base layer. | Used on stainless steel and silicon oxide surfaces for electrochemical biosensors [18]. |

| Functionalized Nanomaterials | Provides a high surface area for bioreceptor immobilization; some materials (e.g., GO) can be modified with antifouling polymers. | Carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs/MWCNTs), graphene oxide (GO). Note: Pristine CNTs are prone to NSA [20]. |

| Triclabendazole sulfoxide-d3 | Triclabendazole sulfoxide-d3, MF:C14H9Cl3N2O2S, MW:378.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| AChE-IN-21 | AChE-IN-21|Potent Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitor|RUO | AChE-IN-21 is a potent acetylcholinesterase inhibitor for neurology research. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

Mechanisms of NSA and Antifouling Strategies

Understanding the physical mechanisms behind NSA is crucial for selecting the appropriate mitigation strategy. NSA is primarily driven by physisorption, resulting from a combination of hydrophobic interactions, electrostatic (ionic) interactions, van der Waals forces, and hydrogen bonding [1] [2]. Antifouling materials function by creating a physical and thermodynamic barrier that makes adsorption unfavorable.

Passive methods, such as coating surfaces with blocker proteins (BSA, casein) or engineered polymers (PEG, zwitterions), aim to prevent NSA by creating a non-adsorptive boundary layer [1]. In contrast, active removal methods use external energy (e.g., acoustic, electromechanical, or hydrodynamic shear forces) to physically desorb weakly bound molecules after they have adhered to the sensor surface [1]. The protocols detailed in this document focus on passive methods, which are the most widely adopted and easily integrated into standard biosensor fabrication workflows.

The Antifouling Toolkit: Material Innovations and Surface Functionalization Strategies

Nonspecific adsorption (NSA) is a fundamental challenge compromising the performance of biosensors across biomedical diagnostics, environmental monitoring, and food safety applications. When proteins, cells, or other biomolecules inadvertently adhere to sensing interfaces, they generate false-positive signals, reduce sensitivity, and impair reproducibility [1] [2]. This phenomenon, known as biofouling, is particularly problematic when biosensors operate in complex matrices like blood, serum, or food samples, where non-target molecules vastly outnumber the analytes of interest [2] [21].

For decades, polyethylene glycol (PEG) has been the gold standard for creating antifouling surfaces. PEG's effectiveness stems from its hydrophilicity and capacity to form a hydration barrier that sterically hinders protein adsorption [22]. However, PEG suffers from significant limitations: it undergoes autoxidation degradation in the presence of oxygen or metal ions, leading to compromised long-term stability [21] [11]. This vulnerability has driven the search for more robust alternatives, with zwitterionic peptides emerging as particularly promising candidates [11] [23].

Zwitterionic peptides, composed of alternating positively and negatively charged amino acids (such as lysine and glutamic acid), create a superhydrophilic surface that strongly binds water molecules through electrostatic interactions [21] [11]. This creates a dense hydration layer that effectively prevents fouling while offering superior stability compared to PEG. Their peptide-based structure provides additional advantages, including precise sequence control, ease of functionalization, and excellent biocompatibility [11] [23].

PEG vs. Zwitterionic Peptides: A Quantitative Comparison

The transition from PEG to zwitterionic peptides is supported by numerous studies demonstrating superior antifouling performance across multiple metrics. The table below summarizes key comparative studies quantifying this advantage.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of PEG and Zwitterionic Peptide Antifouling Performance

| Material | Specific Composition | Key Performance Metrics | Results | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEG | PEG (750 Da) | Used as a reference standard on PSi surfaces. | Baseline performance for comparison. | [11] |

| Zwitterionic Peptide | EKEKEKEKEKGGC peptide on PSi | Non-specific adsorption from GI fluid and bacterial lysate; Lactoferrin detection sensitivity. | Superior antifouling vs. PEG; >10x improvement in LOD and signal-to-noise ratio. | [11] |

| Zwitterionic Peptide | CFEFKFC hydrogel-based electrochemical biosensor | Detection of Prostate Specific Antigen (PSA) in human serum. | Low fouling; LOD of 5.6 pg mLâ»Â¹; Linear range: 0.1 - 100 ng mLâ»Â¹. | [23] |

| Hybrid Coating | Hyaluronic Acid + p-EK peptide on Au surface | Protein adsorption resistance measured by SPR and QCM. | 2x enhancement of antifouling performance compared to HA-modified surface alone. | [24] |

| Egfr-IN-37 | Egfr-IN-37|Potent EGFR Kinase Inhibitor|RUO | Egfr-IN-37 is a potent, selective EGFR inhibitor for cancer research. It blocks tyrosine kinase activity to suppress tumor cell growth. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. | Bench Chemicals | |

| Dhfr-IN-2 | Dhfr-IN-2, CAS:331942-46-2, MF:C14H13NO2, MW:227.26 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The data consistently shows that zwitterionic peptides not only match but significantly exceed PEG's capabilities. For instance, the EK peptide sequence applied to porous silicon (PSi) biosensors achieved over an order of magnitude improvement in both the limit of detection and signal-to-noise ratio compared to PEG-passivated sensors [11]. Furthermore, zwitterionic peptide hydrogels have enabled sensitive detection of clinically relevant biomarkers like prostate-specific antigen in undiluted human serum, demonstrating robust antifouling performance in one of the most challenging analytical environments [23].

Antifouling Mechanism: The Role of Superhydrophilicity

The exceptional antifouling performance of zwitterionic peptides originates from their unique mechanism of action, which centers on the formation of an impenetrable hydration layer.

Electrostatically Induced Hydration: Zwitterionic peptides contain equimolar positive and negative charges within their molecular structure. This creates a strong dipole moment that interacts vigorously with water molecules through ionic solvation [21]. The resulting hydration layer is more dense and tightly bound than that formed by PEG, which relies primarily on hydrogen bonding [21]. This tightly bound water layer creates a physical and energetic barrier that proteins must disrupt before they can adsorb to the surface, an energetically unfavorable process [11] [23].

Spatial Steric Effects: The molecular structure of surface-grafted zwitterionic peptides provides a steric barrier that repels approaching biomolecules. Achieving optimal grafting density is crucial—too low, and proteins can penetrate the coating; too high, and it may hinder the immobilization of biorecognition elements [21]. When properly engineered, this combination of strong hydration and steric hindrance effectively resists adsorption of a broad spectrum of foulants, from proteins and lipids to whole cells and bacteria [21] [11].

The following diagram illustrates the multifaceted antifouling mechanism of zwitterionic peptides, highlighting how their superhydrophilic nature provides a barrier against different types of foulants.

Experimental Protocols: Application on Biosensing Interfaces

Protocol: Functionalization of Porous Silicon with Zwitterionic Peptides

This protocol, adapted from Awawdeh et al., details the modification of PSi biosensors for enhanced antifouling performance in complex biological fluids [11].

Table 2: Key Reagents for PSi Functionalization

| Reagent/Material | Specifications | Function/Role |

|---|---|---|

| Porous Silicon (PSi) | Thin films, thermally oxidized or hydrosilylated | High-surface-area transducer substrate |

| Zwitterionic Peptide | EKEKEKEKEKGGC, >95% purity, lyophilized | Primary antifouling agent |

| Ethanolamine | 1M solution in water | Blocking agent for unreacted sites |

| Coupling Buffer | Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), 10 mM, pH 7.4 | Medium for peptide immobilization |

| Washing Buffers | PBS + 0.05% Tween 20; Deionized Water | Removal of unbound peptides and contaminants |

Procedure:

- PSi Substrate Preparation: Fabricate PSi thin films via electrochemical anodization of silicon wafers. For enhanced stability, perform thermal oxidation (e.g., 800°C for 1 hour) or thermal hydrosilylation to create a homogeneous Si-H terminated surface.

- Surface Activation: For oxidized PSi, activate the surface with (3-Aminopropyl)triethoxysilane (APTES) to generate amine groups. For hydrosilylated PSi, this step may be omitted if direct peptide coupling is possible.

- Peptide Immobilization: a. Prepare a 1.0 mg/mL solution of the EKEKEKEKEKGGC peptide in degassed coupling buffer (e.g., PBS, pH 7.4). b. Incubate the activated PSi substrates in the peptide solution for 2 hours at room temperature or overnight at 4°C under gentle agitation. c. The terminal cysteine residue of the peptide facilitates covalent attachment to the surface via Au–S bonds (on gold-coated surfaces) or other coupling chemistries.

- Blocking: Rinse the functionalized surfaces with coupling buffer to remove physically adsorbed peptides. Incubate with 1M ethanolamine solution for 30 minutes to quench any remaining reactive groups on the substrate.

- Washing and Storage: Wash the substrates thoroughly with PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20, followed by deionized water. Store the modified PSi sensors under nitrogen or in buffer at 4°C until use.

Validation: The successful modification and antifouling performance can be validated using Quartz Crystal Microbalance with Dissipation (QCM-D) and Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) by exposing the sensor to complex media like GI fluid or 100% serum and measuring frequency or resonance angle shifts [11].

Protocol: Constructing an Electrochemical Biosensor with Zwitterionic Peptide Hydrogel

This protocol, based on the work of Du et al., describes the fabrication of an electrochemical biosensor for the detection of protein biomarkers in human serum with minimal biofouling [23].

Table 3: Key Reagents for Electrochemical Biosensor Construction

| Reagent/Material | Specifications | Function/Role |

|---|---|---|

| Zwitterionic Peptide | CFEFKFC, >95% purity | Self-assembling antifouling hydrogel |

| EDOT Monomer | 3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene, 10 mM | Monomer for conductive polymer PEDOT |

| HAuClâ‚„ | Chloroauric acid, 1% w/v | Source for electrodepositing gold nanoparticles |

| PSS | Poly(sodium 4-styrenesulfonate), 0.1 M | Dopant for PEDOT electrodeposition |

| Anti-PSA Antibody | Monoclonal, 100 μg/mL | Biorecognition element for specific detection |

Procedure:

- Electrode Pretreatment: Clean the glassy carbon electrode (GCE) sequentially with 0.3 and 0.05 μm alumina slurry on a microcloth. Rinse thoroughly with deionized water and dry under nitrogen.

- Conductive Polymer Deposition: a. Prepare an electrodeposition solution containing 10 mM EDOT and 0.1 M PSS in water. b. Perform electropolymerization on the GCE using cyclic voltammetry (CV) from -0.8 to 0.9 V (vs. Ag/AgCl) for 10 cycles at a scan rate of 50 mV/s, forming a PEDOT:PSS film.

- Gold Nanoparticles Modification: a. Transfer the PEDOT-modified electrode into a solution of 1% HAuCl₄ (in 0.1 M KNO₃). b. Perform constant potential amperometry at -0.2 V for 30 seconds to electrodeposit AuNPs onto the PEDOT surface.

- Peptide Hydrogel Immobilization: a. Prepare the zwitterionic peptide hydrogel by dissolving the CFEFKFC peptide in deionized water (e.g., 5 mg/mL) and allowing it to self-assemble. b. Incubate the AuNP-modified electrode with the peptide hydrogel solution for 2 hours at room temperature. The thiol groups of the terminal cysteine residues will form stable Au–S bonds.

- Antibody Immobilization: a. Activate the carboxylic acid groups on the peptide hydrogel using a mixture of EDC (400 mM) and NHS (100 mM) in MES buffer (pH 6.0) for 30 minutes. b. Rinse the electrode and incubate it with a solution of anti-PSA antibody (100 μg/mL in PBS, pH 7.4) for 2 hours, forming covalent amide bonds.

- Blocking and Storage: Block any remaining active sites with 1% BSA for 30 minutes. The biosensor is now ready for use and can be stored in PBS at 4°C when not in use.

Validation: The biosensor's performance is tested by measuring varying concentrations of PSA in human serum using electrochemical techniques like CV or electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS). A successful fabrication will show a low limit of detection (e.g., 5.6 pg mLâ»Â¹) and minimal signal interference from the complex serum matrix [23].

The workflow for constructing such a biosensor, integrating both the antifouling layer and the biorecognition element, is illustrated below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful implementation of zwitterionic peptide-based antifouling strategies requires a specific set of reagents and materials. The following toolkit summarizes the essential components.

Table 4: Research Reagent Toolkit for Zwitterionic Peptide Applications

| Category/Reagent | Example Specifications | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Zwitterionic Peptides | ||

| › EK-repeat peptide | EKEKEKEKEKGGC, MW ~1563 Da | Primary antifouling agent for PSi and other surfaces [11] |

| › Hydrogel-forming peptide | CFEFKFC, purified, lyophilized | Forms 3D antifouling hydrogel matrix for electrochemical sensors [23] |

| › Short zwitterionic peptide | p-EK (commercial sequence) | Enhances existing coatings (e.g., HA) for hybrid antifouling surfaces [24] |

| Surface Coupling Agents | ||

| › (3-Aminopropyl)triethoxysilane (APTES) | ≥98%, for silicon/glass surfaces | Creates amine-terminated surface for peptide coupling [11] |

| › EDC/NHS kit | 400 mM EDC, 100 mM NHS | Activates carboxyl groups for covalent antibody immobilization [23] |

| Blocking Agents | ||

| › Ethanolamine | 1M solution, pH 8.5 | Quenches unreacted sites on sensor surfaces [11] |

| › Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | 1% solution in PBS | Blocks nonspecific binding sites on functionalized biosensors [23] |

| Characterization Tools | ||

| › QCM-D sensors | Gold-coated quartz crystals | Real-time, label-free monitoring of peptide adsorption and antifouling performance [22] [24] |

| › SPR chips | Gold film on glass substrate | Label-free analysis of binding kinetics and nonspecific adsorption [24] |

| Piracetam-d8 | Piracetam-d8|Deuterated Nootropic | Piracetam-d8 is a deuterium-labeled Piracetam used in neurological and pharmacokinetic research. For Research Use Only. Not for human consumption. |

| Sos1-IN-8 | Sos1-IN-8|SOS1 Inhibitor|For Research Use | Sos1-IN-8 is a potent SOS1 inhibitor for cancer research. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO) and is not intended for diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

Zwitterionic peptides represent a transformative advancement in the design of antifouling interfaces, effectively addressing the long-standing limitations of PEG. Their superhydrophilic nature, driven by electrostatically induced hydration, creates a physical and energetic barrier superior to traditional materials. As demonstrated in numerous applications—from PSi optical biosensors to electrochemical immunosensors—these peptides enable reliable operation in clinically and environmentally relevant complex media by drastically reducing nonspecific adsorption [11] [23].

Future research will likely focus on several key areas:

- High-Throughput Screening: Expediting the discovery of novel peptide sequences with optimized antifouling properties [2].

- Stability Optimization: Designing peptides with charged groups possessing high pKa values to maintain performance across varying pH and ionic strength conditions [21].

- Universal Functionalization: Developing robust, generalizable methods for immobilizing zwitterionic peptides onto diverse transducer materials [2] [21].

The integration of zwitterionic peptides brings biosensing closer to the goal of direct, reliable measurement in real-world samples, paving the way for more accurate diagnostics, improved environmental monitoring, and enhanced food safety surveillance.

Non-specific adsorption (NSA), the undesirable adhesion of non-target molecules like proteins and cells to a biosensor's surface, remains a significant barrier to the reliable application of biosensors in complex biological samples such as blood and serum [1] [2]. This phenomenon, also known as biofouling, compromises key analytical figures of merit by reducing sensitivity and specificity, increasing background noise, and causing false-positive responses [1] [25]. The development of advanced materials that can intrinsically resist fouling while maintaining excellent electrochemical activity is therefore a critical focus in biosensor research.

Conductive polymers (CPs) have emerged as a premier material class for addressing this dual challenge. Their unique conjugated electron systems endow them with metal-like conductivity, which can be precisely tuned through doping, while their polymeric nature allows for flexible structural design and the incorporation of antifouling motifs [26] [27]. This application note details how engineered conductive polymer networks integrate robust antifouling properties with electrochemical function, providing structured protocols and data to guide their implementation in biosensing platforms aimed at minimizing NSA.

Antifouling Conductive Polymer Architectures and Their Properties

The integration of antifouling properties into conductive polymers is achieved through several material design strategies. The table below summarizes the key classes of antifouling conductive polymers, their structural features, and their performance characteristics.

Table 1: Antifouling Conductive Polymer Architectures and Performance

| Material Class | Key Components | Antifouling Mechanism | Reported Performance | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEGylated CPs [1] [25] | Poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) grafted to PANI or PPy | Formation of a highly hydrated steric barrier; chain repulsion [25]. | Retained 92% of signal after incubation in undiluted human serum [25]. | Nucleic acid biosensor for BRCA1 gene [25]. |

| Zwitterionic CPs [25] [2] | Polypeptides or polymers with mixed charged groups (e.g., pCBMA). | Forms a strong electrostatically-induced hydration layer [25]. | Detection of 10 ng mLâ»Â¹ BSA in 100% bovine serum [25]. | Protein microarrays [25]. |

| Hydrogel-CP Hybrids [28] | PAA-SCMC double-network hydrogel. | Highly hydrated 3D network providing a physical and chemical barrier. | Conductivity of 2.25 S/m; strain of 1675% [28]. | Multifunctional wearable strain and sweat sensors [28]. |

| Functional Peptide-CP Composites [29] | Designed peptide with PEDOT. | Peptide provides specific recognition and antifouling; PEDOT enhances signal. | LOD of 22 cells mLâ»Â¹ in 25% human blood [29]. | Detection of MCF-7 circulating tumor cells (CTCs) [29]. |

Experimental Protocols

This section provides detailed methodologies for fabricating and characterizing two prominent antifouling conductive polymer-based biosensors.

Protocol: Fabrication of an Antifouling Peptide/PEDOT Biosensor for CTC Detection

This protocol outlines the construction of an electrochemical biosensor for the direct detection of circulating tumor cells (CTCs) in blood, using a designed functional peptide and the conducting polymer PEDOT [29].

1. Materials and Reagents

- Working Electrode: Gold disk electrode or glassy carbon electrode (GCE).

- Monomer: 3,4-Ethylenedioxythiophene (EDOT).

- Dopant: Polystyrene sulfonate (PSS).

- Functional Peptide: A custom-synthesized peptide sequence containing:

- A cell-binding motif (e.g., for MCF-7 breast cancer cells).

- An antifouling motif (e.g., a zwitterionic peptide sequence).

- A terminal cysteine residue for gold-thiol chemistry.

- Buffer: Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), pH 7.4.

- Blood Samples: Human whole blood or serum, acquired per ethical guidelines.

2. Sensor Fabrication Workflow

3. Step-by-Step Procedure

- Step 1: Electrode Pretreatment

- Polish the gold electrode with 0.3 and 0.05 µm alumina slurry sequentially. Rinse thoroughly with deionized water.

- Clean the electrode via electrochemical cycling in 0.5 M Hâ‚‚SOâ‚„ until a stable cyclic voltammogram is obtained. Dry under a nitrogen stream.

Step 2: Electrodeposition of PEDOT:PSS

- Prepare an aqueous solution containing 0.01 M EDOT and 0.1% PSS.

- Using the cleaned electrode as the working electrode, perform electrochemical deposition via chronoamperometry at a fixed potential of +1.0 V (vs. Ag/AgCl) for 100-300 seconds.

- Rinse the modified electrode (now GCE/PEDOT:PSS) gently with water to remove unreacted monomer.

Step 3: Peptide Immobilization

- Prepare a 1 µM solution of the functional peptide in PBS.

- Incubate the GCE/PEDOT:PSS electrode in the peptide solution for 2 hours at room temperature to allow the cysteine thiol group to bind to the polymer surface.

- Rinse the electrode with PBS to remove physically adsorbed peptide. The sensor (GCE/PEDOT:PSS/Peptide) is now ready.

Step 4: Electrochemical Characterization

- Characterize the sensor after each modification step using Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) and Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) in a 5 mM [Fe(CN)₆]³â»/â´â» solution.

- A successful modification will show a decrease in electron transfer resistance (Rₑₜ) after PEDOT deposition, followed by a controlled increase after peptide immobilization.

Step 5: Cell Capture and Detection in Complex Media

- Incubate the sensor with 50 µL of whole blood sample spiked with a known concentration of MCF-7 cells for 15-30 minutes.

- Rase gently with PBS to remove unbound cells.

- Transfer the sensor to a clean electrochemical cell containing PBS. Measure the EIS signal.

- The increase in Rₑₜ is correlated with the number of captured cells on the sensor surface.

4. Troubleshooting and Notes

- Low Conductivity: Ensure the EDOT monomer is fresh and the electrodeposition solution is deoxygenated with nitrogen.

- High Non-Specific Adsorption: Verify the synthesis and purity of the functional peptide. Optimize the immobilization time and concentration.

- Signal Instability: Ensure the PEDOT film is uniformly deposited and thoroughly rinsed.

Protocol: Synthesis of a PEGylated Polyaniline (PANI/PEG) Nanofiber Biosensor

This protocol describes the synthesis of PEG-grafted polyaniline nanofibers and their application in a DNA biosensor for operation in serum [25].

1. Materials and Reagents

- Aniline monomer.

- Ammonium persulfate (APS) as an oxidant.

- Poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) with a reactive terminal group (e.g., NHS-PEG-COOH).

- 1-Ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide (EDC) and N-Hydroxysuccinimide (NHS).

- DNA capture probe with a 5'-amine modification.

- Target DNA and non-complementary DNA for specificity tests.

2. Step-by-Step Procedure

- Step 1: Synthesis of PANI Nanofibers

- Dissolve aniline (0.1 M) in 1 M HCl. Initiate polymerization by rapidly adding an equal volume of APS (0.1 M) in 1 M HCl.

- Stir the reaction mixture for 2-4 hours. Collect the resulting dark green PANI nanofibers by centrifugation, and wash repeatedly with deionized water until the supernatant is neutral.

Step 2: Grafting of PEG onto PANI

- Activate the terminal carboxyl group of NHS-PEG-COOH using EDC/NHS chemistry in MES buffer (pH 6.0) for 30 minutes.

- Add the activated PEG to a dispersion of PANI nanofibers in PBS (pH 7.4). React for 4 hours at room temperature.

- Purify the PANI/PEG conjugate via dialysis against water for 24 hours to remove unreacted PEG and by-products.

Step 3: Electrode Modification and DNA Probe Immobilization

- Drop-cast 5 µL of the PANI/PEG nanofiber dispersion onto a polished GCE and allow it to dry.

- Activate the carboxylic groups on the grafted PEG on the GCE/PANI/PEG surface with EDC/NHS.

- Incubate the electrode with a 1 µM solution of the amine-modified DNA capture probe for 2 hours, forming an amide bond.

- Rinse the sensor (GCE/PANI/PEG/DNA) and store in PBS before use.

Step 4: Hybridization and Detection

- Incubate the biosensor with target DNA in buffer or diluted serum for 1 hour.

- Use Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) with methylene blue (MB) as an electrochemical indicator. MB signal decreases upon DNA hybridization.

- The linear range and LOD can be determined by measuring the MB signal decrease against a series of target DNA concentrations.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table catalogs key materials required for developing antifouling conductive polymer biosensors.

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Antifouling Conductive Polymer Biosensors

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Conductive Polymer Monomers | Forms the conductive backbone of the sensing layer. | EDOT: For PEDOT synthesis, offers high stability [25] [29]. Aniline: For PANI synthesis, tunable conductivity [25] [27]. |

| Antifouling Co-Monomers/Polymers | Imparts resistance to non-specific adsorption. | PEG derivatives: Gold standard; grafted to CPs [25]. Zwitterionic monomers: e.g., CBMA; superior hydration [25]. |

| Crosslinkers & Activators | Enables covalent immobilization of biorecognition elements. | EDC/NHS: Activates carboxyl groups for amide bond formation with proteins or peptides [25] [29]. |

| Electrochemical Probes | Used for transducer characterization and signal generation. | [Fe(CN)₆]³â»/â´â»: Redox probe for EIS/CV characterization [29]. Methylene Blue: Intercalating redox label for nucleic acid detection [25]. |

| Blocking Agents | Passivates any remaining reactive sites. | Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA), Casein: Common physical blockers; used after bioreceptor immobilization [1]. |

| Acremonidin A | Acremonidin A | Acremonidin A is a polyketide-derived antibiotic for research use only (RUO). It is not for diagnostic or personal use. |

| (-)-Fucose-13C-3 | (-)-Fucose-13C-3|Stable Isotope | (-)-Fucose-13C-3 is a 13C-labeled stable isotope for glycosylation and metabolic pathway research. This product is for Research Use Only. Not for human or therapeutic use. |

Data Analysis and Performance Validation

Rigorous validation in complex media is essential to demonstrate the efficacy of an antifouling strategy. The following diagram and table summarize the key performance metrics and validation workflow.

Table 3: Key Performance Metrics for Antifouling Validation

| Metric | Calculation / Method | Target Performance | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Signal Retention | (Signalpostexposure / Signal_initial) × 100% | >90% in target biofluid over assay duration. | 92% current retained in serum for PANI/PEG DNA sensor [25]. |

| Limit of Detection (LOD) in Matrix | 3.3 × (Standard Deviation of Blank / Slope of Calibration Curve) | As low as possible; minimal deviation from LOD in buffer. | LOD of 22 cells/mL in 25% blood for peptide/PEDOT sensor [29]. |

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) | Mean Signalanalyte / Standard Deviationblank | Maximize; high SNR indicates low fouling-induced noise. | PEDOT improves SNR by enhancing electron transfer [29]. |

| Analytical Recovery | (Measured Concentration / Spiked Concentration) × 100% | 85-115% in complex samples. | Successful analysis of serum from cancer patients vs. healthy controls [25]. |

Non-specific adsorption (NSA) of biomolecules onto sensor surfaces remains a significant obstacle in the development of reliable biosensors. This phenomenon leads to false-positive signals, reduced sensitivity, and compromised diagnostic accuracy. Two-dimensional (2D) nanomaterials, particularly graphene and its derivatives, offer a powerful platform to address this challenge through precise surface engineering. Their unique tunable surface chemistry and exceptional electrical conductivity enable the creation of biosensing interfaces that maximize specific molecular recognition while minimizing background interference [30] [31].

Graphene's atomic thickness, high surface-to-volume ratio, and versatile chemical functionality provide unprecedented control over the bio-interface. Researchers can exploit these properties to design surfaces that preferentially bind target analytes through specific biorecognition elements while effectively repelling non-target species. The following sections detail the fundamental properties, quantitative performance, and practical protocols for leveraging graphene's capabilities to overcome NSA challenges in biosensor research and development [32] [33].

Fundamental Properties of Graphene for Biosensing

Structural and Electrical Characteristics

Graphene consists of a single layer of sp²-hybridized carbon atoms arranged in a hexagonal honeycomb lattice. This structure confers exceptional electrical properties, including ultra-high charge carrier mobility (exceeding 200,000 cm²/V·s) and excellent electrical conductivity [31]. The delocalized π-electron system extending above and below the atomic plane facilitates efficient electron transfer, which is crucial for sensitive electrochemical and field-effect transistor-based biosensing [30].

Table 1: Fundamental Properties of Graphene and Derivatives Relevant to Biosensing

| Material Property | Graphene | Graphene Oxide (GO) | Reduced GO (rGO) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electrical Conductivity | Excellent (semimetal) | Insulating | Good (restored) |

| Surface Functional Groups | Minimal (pristine) | Abundant oxygen-containing | Reduced oxygen content |

| Dispersibility in Water | Poor | Excellent | Moderate |

| Biocompatibility | High | High | High |

| Functionalization Versatility | Covalent and non-covalent | Primarily covalent | Covalent and non-covalent |

| Transparency (~2.3% absorption per layer) | High | High | Moderate-High |

Tunable Surface Chemistry

The graphene surface can be modified through both covalent and non-covalent approaches to control its interaction with biological molecules. Covalent functionalization involves creating permanent chemical bonds with oxygen-containing groups or other moieties, while non-covalent functionalization exploits π-π stacking, van der Waals forces, or electrostatic interactions [30] [32]. This tunability enables researchers to engineer surfaces with specific affinity for target biomarkers while incorporating passivation layers that resist NSA [34].

Graphene derivatives offer complementary properties: Graphene Oxide (GO) contains abundant oxygen functional groups (carboxyl, hydroxyl, epoxy) that facilitate further chemical modification and biomolecule immobilization. Reduced Graphene Oxide (rGO) balances restored electrical conductivity with residual functional groups for bioconjugation [30] [35].

Quantitative Analysis of Graphene-Based Biosensing Platforms

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Graphene-Based Biosensors for Various Applications

| Target Analyte | Sensor Platform | Functionalization Strategy | LOD/ Sensitivity | Selectivity/ NSA Reduction | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast Cancer Biomarkers | ML-optimized Gr-FET | Ag-SiOâ‚‚-Ag architecture with graphene spacer | 1785 nm/RIU | Parametric optimization via machine learning | [36] |

| Cardiac Troponin-I | SnSâ‚‚-MWCNT/Gr composite | Explainable ML framework | Ultra-sensitive | OVSA-ML enhanced specificity | [36] |

| H. pylori | Electrochemical | Antibody immobilization on GO | Not specified | Passivation layer implementation | [37] |

| General Biomarkers | GFET | PEG passivation layer | ~90% signal:noise improvement | ~80% NSA reduction | [30] [34] |

| Multiplexed Targets | Optical (SPR) | Graphene-enhanced plasmonic | >10x SERS enhancement | Functionalization-controlled specificity | [30] [32] |

Experimental Protocols for Surface Functionalization

Standard Graphene Surface Preparation Workflow

The following protocol outlines the essential steps for preparing graphene surfaces with minimized non-specific adsorption, adapted from established methodologies in the literature [30] [32] [34].

Protocol Title: Standard Graphene Surface Functionalization for NSA Minimization