Coupled Multi-Enzyme Systems for Selective Detection: Strategies, Applications, and Biosensing Advancements

This article explores the rapidly evolving field of coupled multi-enzyme systems for selective detection, addressing the needs of researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Coupled Multi-Enzyme Systems for Selective Detection: Strategies, Applications, and Biosensing Advancements

Abstract

This article explores the rapidly evolving field of coupled multi-enzyme systems for selective detection, addressing the needs of researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational principles of enzyme coupling for enhancing biosensor selectivity and signal amplification. The scope extends to methodological designs, including nano-engineered assemblies and scaffold-mediated complexes, and their applications in biomedical diagnostics and environmental monitoring. The content also provides critical troubleshooting and optimization strategies to overcome practical challenges like enzyme coordination and interference. Finally, it examines validation protocols and performance comparisons with standard analytical methods, synthesizing key takeaways and future directions for clinical and biomedical research.

Fundamental Principles of Enzyme Coupling for Enhanced Selectivity and Signal Amplification

Biosensors, which integrate a biological recognition element with a physicochemical transducer, are powerful analytical tools. However, a persistent challenge limiting their broader application, especially in point-of-care and real-time monitoring, is selectivity—the ability to accurately identify and quantify a specific target analyte within a complex sample matrix without interference from co-existing substances.

This challenge is particularly acute in clinical diagnostics, environmental monitoring, and food safety, where samples like blood, sweat, wastewater, or food extracts contain numerous interfering compounds. These interferents can be structurally similar to the target, cause non-specific binding, or foul the sensor surface, leading to false positives or negatives. Enzyme-based biosensors offer a powerful solution to this problem by leveraging the inherent specificity of enzymes as biological catalysts. This application note, framed within thesis research on coupled multi-enzyme systems, defines the selectivity problem and details a protocol for developing a highly selective multi-enzyme biosensor.

The selectivity challenge in biosensing arises from several key sources, which are summarized in the diagram below.

- Structural Analogues: Compounds with molecular structures similar to the target analyte (e.g., uric acid vs. xanthine in sweat) can bind to the recognition site, generating a confounding signal [1].

- Non-Specific Adsorption: Proteins, lipids, and other biomolecules can physically adsorb onto the sensor surface without a specific binding event, altering the interface's properties and signal output [2].

- Electroactive Interferents: In electrochemical biosensors, substances like ascorbic acid, urea, or acetaminophen can be oxidized or reduced at the working electrode potential, contributing directly to the current and obscuring the signal from the target analyte [3].

- Sensor Surface Fouling: The accumulation of non-target materials on the sensor surface can block active sites, reduce mass transport, and degrade sensor performance over time, a phenomenon known as biofouling [4].

Enzyme-Based Solutions: A Protocol for a Multi-Analyte Sweat Sensor

Enzymes provide a solution through their high catalytic efficiency and specificity for their substrate. A state-of-the-art approach involves coupling multiple enzymes with advanced nano-material substrates and protective frameworks to create sensors capable of selective, multi-analyte detection.

The following workflow outlines the key stages in fabricating such a sensor, from electrode preparation to final validation.

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Fabrication of B,NMCNS/rGO Sensing Electrode

- Objective: To create a highly conductive and porous sensing substrate that enhances electron transfer and provides a large surface area for enzyme immobilization.

- Materials:

- Reduced Graphene Oxide (rGO) dispersion

- Resorcinol, Boric Acid (H₃BO₃), Cetyltrimethylammonium Bromide (CTAB), Formaldehyde (HCHO), Tetraethyl Orthosilicate (TEOS)

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), pH 7.4

- Procedure:

- Synthesis of Boron-Nitrogen co-doped porous Carbon Nanospheres (B,NMCNS): Dissolve resorcinol (1.0 g) and boric acid (1.0 g) in a mixture of deionized water and ethanol. Add CTAB as a soft template and formaldehyde as a cross-linker. Stir vigorously and then hydrothermally treat the mixture at 100°C for 24 hours. Carbonize the resulting polymer in a tube furnace at 800°C under a nitrogen atmosphere. Etch the silica template (from TEOS) with HF solution to obtain the porous nanospheres [5].

- Preparation of B,NMCNS/rGO Composite: Disperse the synthesized B,NMCNS and rGO in ethanol by sonication for 1 hour to form a homogeneous ink.

- Electrode Modification: Deposit 5 µL of the B,NMCNS/rGO ink onto the surface of a pre-treated screen-printed carbon electrode. Allow it to dry at room temperature. The electrode should be rinsed with DI water before further modification [5].

Biomimetic Mineralization of Enzymes in MOF-74/Argdot

- Objective: To co-encapsulate multiple enzymes within a metal-organic framework (MOF) alongside carbon dots to enhance stability and activity.

- Materials:

- Glucose Oxidase (GOx), Lactate Oxidase (LOx), Xanthine Oxidase (XOD)

- Zinc nitrate hexahydrate (Zn(NO₃)₂·6H₂O), 2,5-Dihydroxyterephthalic acid

- Arginine-derived Carbon Dots (Argdot) – synthesized from arginine precursor

- Sodium Acetate Buffer (10 mM, pH 4.5)

- Procedure:

- Synthesis of Argdot: Heat arginine powder at 200°C for 2 hours. The resulting brown solid is dissolved in water and filtered to obtain the Argdot solution [1].

- Co-encapsulation via One-Pot Biomimetic Mineralization: For each enzyme (GOx, LOx, XOD), prepare a separate solution containing the enzyme (2 mg/mL) and Argdot (1 mg/mL) in a sodium acetate buffer (10 mM, pH 4.5).

- Add 2,5-dihydroxyterephthalic acid (the organic linker) and Zn(NO₃)₂·6H₂O (the metal ion source) to each enzyme/Argdot solution. Gently stir the mixture at 30°C for 6 hours.

- Centrifuge the solution to collect the MOF-74/Enzyme/Argdot composite. Wash the precipitate three times with sodium acetate buffer and re-disperse it for electrode modification [1] [5].

Biosensor Assembly and Measurement

- Objective: To integrate the recognition element with the transducer and perform electrochemical detection.

- Procedure:

- Drop-cast 3 µL of each MOF-74/Enzyme/Argdot composite suspension onto separate, designated B,NMCNS/rGO working electrodes. Allow to dry.

- For electrochemical measurement, use a standard three-electrode system with the modified electrode as the working electrode, an Ag/AgCl reference electrode, and a platinum wire counter electrode.

- Perform Amperometric detection at a defined potential (e.g., +0.55 V vs. Ag/AgCl) while spiking known concentrations of the analytes (glucose, lactate, xanthine) into a stirred PBS solution.

- Record the steady-state current response and plot it against analyte concentration to generate a calibration curve [1] [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential materials and reagents for fabricating the multi-enzyme biosensor.

| Reagent/Material | Function in the Protocol | Key Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| B,NMCNS/rGO Composite | Sensing electrode substrate | Enhances electron transfer, provides large active surface area, reduces background noise [5]. |

| MOF-74 (Metal-Organic Framework) | Enzyme immobilization matrix | Protects enzymes from denaturation, increases loading capacity, enhances thermal/pH stability [1] [5]. |

| Arginine-derived Carbon Dots (Argdot) | Co-immobilization agent | Acts as a peroxidase mimic, stabilizes enzyme structure, facilitates Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ catalysis at lower voltage [1] [5]. |

| Glucose Oxidase (GOx) | Biorecognition element for Glucose | Catalyzes glucose oxidation to gluconolactone and Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚, providing a specific and amplifiable signal [5] [6]. |

| Lactate Oxidase (LOx) | Biorecognition element for Lactate | Catalyzes L-lactate oxidation to pyruvate and Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚, enabling tracking of metabolic fatigue [1] [6]. |

| Xanthine Oxidase (XOD) | Biorecognition element for Xanthine | Catalyzes xanthine oxidation to uric acid and Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚, associated with oxidative stress levels [1] [5]. |

| Hpk1-IN-24 | Hpk1-IN-24, MF:C19H14FN5, MW:331.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Steroid sulfatase-IN-4 | Steroid sulfatase-IN-4, MF:C19H17ClN2O5S, MW:420.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Performance Data and Validation

The performance of the described multi-enzyme biosensor was rigorously validated. The following table quantifies its key analytical figures of merit for the detection of three target analytes.

Table 2: Analytical performance of the MOF-74/Enzyme/Argdot biosensor for multi-analyte detection in sweat [1] [5].

| Analyte | Detection Sensitivity | Linear Range | Stability (60-day storage) | Selectivity Validation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose | 182.4 nA µMâ»Â¹ cmâ»Â² | Fully covers physiological sweat levels | >94% response retained | No interference from lactate, xanthine, uric acid, or ascorbic acid |

| Lactic Acid | 386.6 nA mMâ»Â¹ cmâ»Â² | Fully covers physiological sweat levels | >94% response retained | Specific to lactate; no cross-talk from other analytes |

| Xanthine | 207.6 nA µMâ»Â¹ cmâ»Â² | Fully covers physiological sweat levels | >94% response retained | High specificity against common sweat interferents |

The sensor's selectivity was further confirmed by challenging it with potential interfering substances commonly found in sweat, such as ascorbic acid and uric acid. The observed current response was negligible, confirming the high specificity conferred by the enzyme-based recognition layers and the effectiveness of the MOF-74/Argdot encapsulation in mitigating non-specific interactions [1] [5].

The selectivity challenge in biosensing is a critical barrier that can be effectively overcome through sophisticated enzyme-based strategies. The detailed protocol for the MOF-74/Argdot biomimetic mineralization sensor demonstrates a viable path toward achieving highly selective, stable, and multi-analyte detection in complex matrices. This approach, central to research on coupled multi-enzyme systems, validates that the inherent specificity of enzymes, when augmented by advanced materials, provides a robust framework for the next generation of reliable biosensors for research, clinical, and environmental applications.

In metabolic pathways, enzymes catalyzing sequential reactions often organize into multi-enzyme complexes. This spatial arrangement facilitates two fundamental mechanisms that enhance metabolic efficiency: substrate channeling and metabolic compartmentalization. Substrate channeling describes the direct transfer of an intermediate from one enzyme's active site to the next without its release into the bulk cellular solution [7]. Metabolic compartmentalization involves segregating multi-enzyme systems within specialized compartments or organelles, often bounded by semi-permeable membranes [8]. For researchers developing coupled multi-enzyme systems for selective detection, mastering these mechanisms is crucial for creating highly sensitive, specific, and efficient biosensors and diagnostic platforms. These systems minimize cross-talk, protect unstable intermediates, and accelerate response times, which is paramount in analytical applications.

Core Mechanisms and Their Biotechnological Advantages

Substrate Channeling

Substrate channeling is a process where the product of one enzyme is transferred to an adjacent cascade enzyme as its substrate without equilibrating with the bulk phase [7]. This direct transfer can occur through two primary mechanisms:

- Direct Transfer (Tunneling): The intermediate is physically passed through a molecular tunnel or via electrostatic channels connecting the active sites [8] [9].

- Proximity Effect (Leaky Channeling): Enzymes are positioned sufficiently close so that an intermediate released from the first enzyme has a high probability of being captured by the second enzyme before it diffuses away [7].

This mechanism offers several advantages for detection systems, summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Advantages of Substrate Channeling in Biotechnological Applications

| Advantage | Description | Relevance to Detection Systems |

|---|---|---|

| Enhanced Reaction Rate | Reduces the transient time (lag phase) to reach steady-state flux in a cascade reaction [9]. | Decreases response time of biosensors, enabling faster detection. |

| Protection of Unstable Intermediates | Shields reactive or labile metabolites from degradation by the bulk solvent [7]. | Increases signal yield and reliability for detection assays involving fragile intermediates. |

| Circumvention of Unfavorable Equilibrium | Prevents intermediates from equilibrating with the bulk phase, bypassing thermodynamic constraints [7]. | Can drive reactions toward product formation, enhancing signal intensity. |

| Mitigation of Substrate Competition | Isolates intermediates, making them unavailable for competing side reactions [7] [9]. | Improves specificity and reduces false positives in complex samples like blood serum. |

| Forestallment of Toxic Metabolite Inhibition | Prevents the accumulation of inhibitory intermediates in the bulk medium [7]. | Maintains high enzyme activity and extends the functional lifespan of a biosensor. |

Metabolic Compartmentalization

Compartmentalization involves isolating multi-enzyme systems within a confined space, such as a synthetic vesicle or a protein-based bacterial microcompartment, through a semi-permeable membrane [8]. This strategy offers distinct benefits:

- Creation of a Specialized Microenvironment: The compartment can maintain conditions (e.g., pH, ion concentration) optimal for the encapsulated enzyme cascade, which may differ from the external environment [9].

- Enzyme Stabilization and Protection: The physical barrier protects enzymes from proteolytic degradation and denaturing factors in the external solution [8].

- Concentration of Intermediates: By confining substrates and enzymes to a small volume, the effective local concentration is increased, which can boost reaction rates.

Experimental Protocols for Constructing and Analyzing Multi-enzyme Complexes

This section provides detailed methodologies for creating and characterizing synthetic multi-enzyme complexes, with a focus on applications for selective detection.

Protocol 1: Construction of a Scaffold Protein-Mediated Multi-enzyme Complex

This protocol outlines the assembly of a multi-enzyme complex using a synthetic scaffold protein, inspired by natural cellulosomes, for a coupled enzymatic assay [8] [7].

Principle: A non-catalytic scaffold protein is engineered to contain multiple divergent protein-protein interaction domains (e.g., cohesins). Enzymes of interest are fused to complementary interaction domains (e.g., dockerins). The scaffold recruits these enzymes into a predefined complex via specific, high-affinity interactions.

Materials:

- Research Reagent Solutions: See Table 4 in Section 5.

- Purified scaffold protein (e.g., with 3x cohesin modules).

- Purified enzyme-fusion proteins (e.g., Enzyme A-dockerin, Enzyme B-dockerin, Enzyme C-dockerin).

- Assembly buffer (e.g., 50 mM Tris-HCl, 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM CaClâ‚‚, pH 7.5).

- Size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) column.

- SDS-PAGE and native-PAGE equipment.

Procedure:

- In Vitro Assembly:

- Mix the scaffold protein and enzyme-fusion proteins at a stoichiometric ratio (e.g., 1:1:1:1 for a three-enzyme complex) in assembly buffer.

- Incubate the mixture for 1-2 hours at 4°C with gentle agitation to allow for complex formation.

- Purification and Validation:

- Purify the assembled complex from unbound enzymes using size-exclusion chromatography. The complex will elute at a higher molecular weight than individual components.

- Analyze the fractions using SDS-PAGE (denaturing, confirms protein presence) and native-PAGE (non-denaturing, confirms intact complex).

- Functional Assay for Detection:

- Prepare a reaction mixture containing the substrate for the first enzyme in the cascade.

- Initiate the reaction by adding the purified multi-enzyme complex.

- Monitor the generation of the final detectable product (e.g., a fluorophore or chromophore) spectrophotometrically or fluorometrically over time.

- Compare the lag time and initial reaction rate against a control mixture of non-complexed, free enzymes at the same concentration.

Protocol 2: Kinetic Analysis of Substrate Channeling

This protocol describes a kinetic method to experimentally confirm substrate channeling in a constructed multi-enzyme complex using a competing reaction [7].

Principle: If an intermediate is channeled, it should be inaccessible to a competing enzyme present in the bulk solution. A lack of inhibition or diversion of the intermediate by the competitor suggests channeling.

Materials:

- Assembled multi-enzyme complex (from Protocol 1).

- Free enzyme mixture (control).

- Substrate for the first enzyme.

- Competing enzyme that utilizes the intermediate produced by the first enzyme.

- Detection reagents for the final product of the cascade.

Procedure:

- Setup: Prepare two identical reaction mixtures containing the substrate for the first enzyme and the detection system for the final product.

- Addition of Competing Enzyme: To the experimental tube, add the assembled multi-enzyme complex and the competing enzyme. To the control tube, add the free enzyme mixture and the competing enzyme.

- Reaction and Monitoring: Monitor the formation of the final product in both tubes over time.

- Analysis:

- A significant decrease in the final product formation in the control tube (free enzymes) indicates the competing enzyme is successfully intercepting the intermediate from the bulk solution.

- A markedly smaller reduction (or no reduction) in the final product formation in the experimental tube containing the scaffolded complex provides strong evidence for substrate channeling, as the intermediate is protected from the competitor.

The workflow for this kinetic analysis is outlined below.

Quantitative Data and Performance Metrics

The performance of engineered multi-enzyme complexes is quantitatively evaluated against free enzyme systems. Key metrics are consolidated in the tables below.

Table 2: Kinetic Performance Metrics of Engineered Multi-enzyme Complexes

| Enzyme System / Complex Type | Reported Lag Time Reduction | Reported Flux Increase | Key Experimental Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fusion Protein (Aldolase-Kinase) [8] | Not specified | Overall reaction rate "much higher" than native non-fused enzymes | Demonstrated facilitated substrate channeling via a short peptide linker. |

| Natural Cellulosome Complex [7] | Not applicable | Hydrolysis rates "several times higher" than simple enzyme mixtures | Proximity effect enhances synergistic degradation of solid cellulose. |

| Glucose Oxidase-Horseradish Peroxidase (GOx-HRP) on DNA Scaffold [9] | Not specified | Initial reaction rate several-fold higher than free enzymes | Rate enhancement attributed to shortened lag phase and altered local microenvironment. |

| GOx-HRP in DNA Nanocage [9] | Not specified | Activity 4x higher than freely diffusing enzymes | Confinement in a tailored microenvironment positively alters enzyme kinetics. |

Table 3: Key Advantages of Different Assembly Strategies

| Assembly Strategy | Key Advantage | Consideration for Detection Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Scaffold Proteins | High degree of control over enzyme stoichiometry and spatial organization [8]. | Ideal for complex cascades requiring specific enzyme ratios for maximal flux. |

| Fusion Proteins | Genetically encoded; simple construction at the genetic level [8]. | Risk of protein misfolding or inclusion body formation; linker optimization is critical. |

| DNA/RNA Scaffolds | Highly programmable and addressable for precise nanometer-scale positioning [9]. | Can create a local microenvironment (e.g., altered pH) that enhances kinetics [9]. |

| Compartmentalization | Provides a protective barrier against external proteases and inhibitors [8]. | Excellent for assays in complex, crude samples (e.g., whole blood, lysate). |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Reagents for Multi-enzyme Complex Research

| Reagent / Material | Function and Description | Application in Protocols |

|---|---|---|

| Synthetic Scaffold Protein | A non-catalytic protein backbone containing repeating protein-binding domains (e.g., cohesins). Serves as an assembly platform. | Core component for assembling enzyme complexes in Protocol 1. |

| Enzyme-Dockerin Fusion | Catalytic enzyme fused to a dockerin domain, which binds specifically and tightly to cohesin modules on the scaffold. | The "building block" that is recruited to the scaffold in Protocol 1. |

| Assembly Buffer (with Ca²âº) | Provides optimal ionic strength and pH for protein interactions. Ca²⺠is often crucial for stabilizing cohesin-dockerin binding. | Used in the in vitro assembly step in Protocol 1. |

| Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) Column | Also known as gel filtration. Separates molecules based on size, allowing purification of the large, assembled complex from smaller, unbound proteins. | Critical for purifying and validating the assembled complex in Protocol 1. |

| Competing Enzyme | An enzyme that catalyzes the conversion of the metabolic intermediate to an alternate, non-detectable product. | Used as a probe to test for substrate channeling in Protocol 2. |

| Hpk1-IN-21 | Hpk1-IN-21, MF:C22H25ClFN5O2, MW:445.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Targeting the bacterial sliding clamp peptide 46 | Targeting the bacterial sliding clamp peptide 46, MF:C47H64N8O11, MW:917.1 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

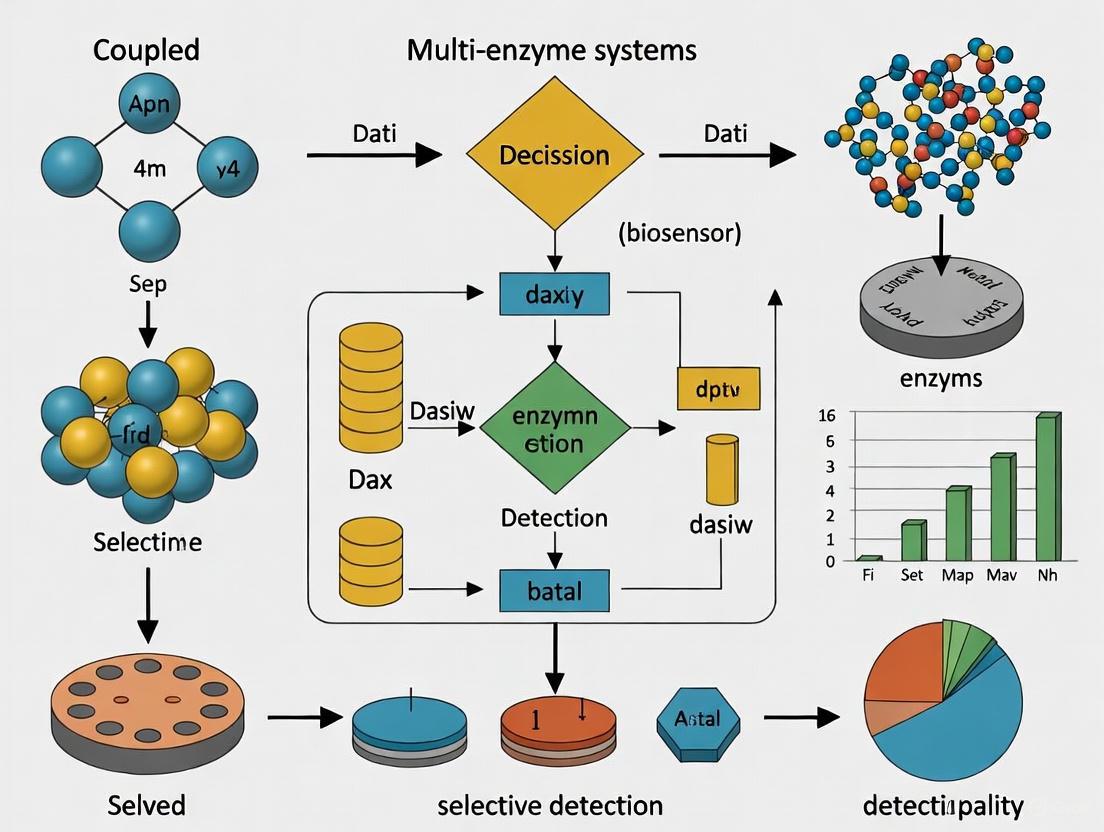

Visualization of Multi-enzyme Complex Mechanisms

The following diagrams illustrate the core concepts and experimental workflows discussed in this document.

Core Mechanisms of Multi-enzyme Systems

This diagram contrasts the traditional diffusion-based model with substrate channeling and compartmentalization strategies.

Experimental Workflow for Complex Assembly & Testing

This diagram provides an overview of the complete process for constructing and validating a functional multi-enzyme complex.

Coupled multi-enzyme systems represent a transformative approach in biocatalysis and biosensing, enabling complex chemical transformations and selective detection schemes that are impossible with single enzyme reactions. These systems integrate multiple enzymatic steps into coordinated cascades, often relying on efficient cofactor recycling to maintain thermodynamic feasibility and economic viability. For detection applications, the strategic coupling of enzymes facilitates signal amplification and enhances selectivity, particularly in complex biological matrices like blood. This article provides a comprehensive introduction to the key enzyme classes and cofactor recycling systems that form the foundation of these sophisticated detection cascades, with detailed protocols for their implementation in research settings.

Key Enzyme Classes in Detection Cascades

Oxidoreductases

Oxidoreductases, particularly alcohol dehydrogenases (ADHs), play a pivotal role in stereoselective syntheses of chiral building blocks and detection systems. These enzymes typically require nicotinamide cofactors (NAD+/NADH), making their application in biotechnology economically feasible only with appropriate cofactor regeneration systems [10]. The oxidation of a co-substrate (e.g., benzyl alcohol) generates the reduced cofactor while producing a co-product (e.g., benzaldehyde) that can be strategically utilized in coupled reactions.

Transferases

O-phospho-L-serine sulfhydrylase (OPSS) is a pyridoxal 5'-phosphate (PLP)-dependent transferase that catalyzes nucleophilic substitution reactions for synthesizing non-canonical amino acids (ncAAs). This enzyme demonstrates remarkable versatility, accepting various nucleophilic reagents including allyl mercaptan, potassium thiophenolate, and 1,2,4-triazole to produce corresponding ncAAs with C-S, C-Se, and C-N side chains [11]. The enzyme operates via a ping-pong bi-bi mechanism where a lysine residue in the active site forms an internal Schiff base with PLP, facilitating the reaction through an α-aminoacrylate intermediate.

Multi-enzyme Cascade Systems

Sophisticated detection and synthesis platforms often integrate multiple enzyme classes into coordinated systems. A representative 2-step enzymatic cascade combines a thiamine diphosphate (ThDP)-dependent carboligase with an alcohol dehydrogenase [10]. In this system, the carboligase catalyzes the formation of chiral 2-hydroxy ketones from aldehydes, which are subsequently reduced by ADH to 1,2-diols. The ingenuity of this design lies in configuring the co-product of the ADH-catalyzed step (benzaldehyde) to serve as substrate for the carboligation step, creating an efficient recycling system.

Table 1: Key Enzyme Classes in Detection Cascades

| Enzyme Class | Representative Enzymes | Cofactor Requirements | Primary Functions in Cascades |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oxidoreductases | Alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH), Glucose dehydrogenase (GDH), Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) | NAD+/NADH, NADP+/NADPH | Stereoselective reductions/oxidations, cofactor recycling, signal generation |

| Transferases | O-phospho-L-serine sulfhydrylase (OPSS), Transaminases | Pyridoxal 5'-phosphate (PLP) | Nucleophilic substitutions, amino acid synthesis, group transfer reactions |

| Lyases | Tyrosine phenol-lyase (TPL), Tryptophan synthase (TrpB) | Pyridoxal 5'-phosphate (PLP) | C-C bond formation, elimination reactions |

| Multi-enzyme Systems | Carboligase-ADH cascades, GDH-LDH pairs | Multiple cofactors | Complex substrate transformations, coordinated reaction sequences |

Cofactor Recycling Systems

NADH/NAD+ Recycling Systems

Efficient NADH regeneration is crucial for dehydrogenase-dependent detection systems. Glucose dehydrogenase (GDH) provides an effective mechanism for NAD+ reduction to NADH while oxidizing glucose to gluconolactone. Recent research demonstrates that assembling GDH on nanoparticle scaffolds enhances cofactor recycling efficiency approximately 5-fold compared to free enzymes [12]. When coupled with NADH-dependent LDH conversion of lactate to pyruvate, the joint assembly of both enzymes on quantum dot-based nanoclusters increased the coupled reaction rate by a similar magnitude.

ATP Regeneration Systems

For enzymatic cascades requiring ATP, polyphosphate kinase (PPK) provides an efficient regeneration mechanism by transferring phosphate groups from polyphosphate to ADP [11]. This system is particularly valuable in multi-enzyme synthesis platforms where ATP-dependent kinases are employed, such as in the conversion of d-glycerate to d-3-phosphoglycerate by d-glycerate-3-kinase (G3K).

Integrated Cofactor Recycling Networks

Advanced detection cascades often employ sophisticated cofactor recycling networks. A prime example integrates glutamate dehydrogenase (gluGDH) to regenerate NAD+ and L-glutamate from NADH and 2-oxoglutarate, effectively recycling byproducts into substrates [11]. This approach maintains cofactor balance while minimizing accumulation of inhibitory byproducts.

Table 2: Cofactor Recycling Systems for Detection Cascades

| Recycling System | Key Enzymes | Cofactor Regenerated | Energy Source | Reported Enhancement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Substrate-Coupled | Alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) | NADH | Benzyl alcohol oxidation | Enables >100 mM product concentrations [10] |

| Enzyme-Nanoparticle Assemblies | Glucose dehydrogenase (GDH) | NADH | Glucose oxidation | ~5-fold rate enhancement [12] |

| Polyphosphate-Based | Polyphosphate kinase (PPK) | ATP | Polyphosphate | Enables sustainable ATP-dependent reactions [11] |

| Integrated Network | Glutamate dehydrogenase (gluGDH) | NAD+ | 2-Oxoglutarate/glutamate | Recycles byproducts into substrates [11] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Two-Step Cofactor and Co-Product Recycling Cascade

This protocol describes the implementation of a carboligase-ADH cascade for selective synthesis of chiral 1,2-diols with integrated cofactor regeneration [10].

Materials:

- ThDP-dependent carboligase

- Alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH)

- Thiamine diphosphate (ThDP)

- NAD+ cofactor

- Acetaldehyde substrate

- Benzyl alcohol (co-substrate for cofactor regeneration)

- Appropriate buffer system (e.g., phosphate or Tris buffer, pH 7.0-8.0)

Procedure:

- Prepare reaction mixture containing 50 mM buffer, 2 mM ThDP, 0.5 mM NAD+, and 100 mM benzyl alcohol

- Add acetaldehyde to final concentration of 150 mM

- Initiate reaction by adding carboligase (0.1-0.5 mg/mL) and ADH (0.2-0.8 mg/mL)

- Incubate at 30°C with continuous mixing

- Monitor reaction progress by HPLC or GC analysis

- Terminate reaction after 24 hours or when substrate depletion reaches >95%

Expected Outcomes: This system typically yields >100 mM concentrations of (1R,2R)-1-phenylpropane-1,2-diol with optical purities up to 99% ee. The cascade design overcomes benzaldehyde solubility limitations in aqueous systems and optimizes atom economy by minimizing waste production.

Protocol 2: Nanozyme-Based Multi-Analyte Detection System

This protocol details the implementation of a nanozyme system for selective detection of multiple analytes in complex biological samples [13].

Materials:

- Gold nanorod core nanoparticles with carbon shell (nanorod dimensions: 93±16 nm length, 53±7 nm width; carbon shell thickness: 5.8±2.3 nm)

- Phosphate buffer (pH 7.4)

- Whole blood samples

- Electrochemical cell with three-electrode configuration

Procedure:

- Immobilize nanozymes onto electrode surface following standard drop-casting protocols

- Place modified electrode in electrochemical cell containing blood sample

- For dopamine detection:

- Apply reductive potential of -0.7 V for 0.2 s to expel chloride and remove fouling proteins

- Immediately apply potential of 0.3 V for 0.2 s for dopamine oxidation

- Repeat pulse sequence 90-200 times, summing current measurements

- For glucose detection:

- Apply reductive potential to split water and increase local pH within nanochannels

- Apply oxidative potential for glucose oxidation at elevated pH

- Measure resulting current response

- Construct calibration curves using standard additions

Expected Outcomes: This system enables selective detection of both dopamine (linear range: 10 nM to 60 μM) and glucose in unadulterated whole blood by exploiting temporal control of solution environment within substrate channels through electrochemical potential manipulation.

Protocol 3: Modular Multi-Enzyme Cascade for ncAA Synthesis

This protocol describes a sustainable approach for non-canonical amino acid synthesis from glycerol using a modular multi-enzyme system [11].

Materials:

- Module I Enzymes: Alditol oxidase (AldO), Catalase

- Module II Enzymes: d-glycerate-3-kinase (G3K), d-3-phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase (PGDH), phosphoserine aminotransferase (PSAT), polyphosphate kinase (PPK), glutamate dehydrogenase (gluGDH)

- Module III Enzyme: O-phospho-L-serine sulfhydrylase (OPSS)

- Substrates: Glycerol, nucleophiles (thiols, azoles, selenols)

- Cofactors: ATP, NAD+, PLP, polyphosphate

- Buffer components

Procedure:

- Prepare reaction mixture containing 100 mM glycerol, ATP regeneration system (PPK + polyphosphate), and NAD+ regeneration system (gluGDH + 2-oxoglutarate)

- Add Module I enzymes (AldO + catalase) to initiate glycerol oxidation to d-glycerate

- Incorporate Module II enzymes (G3K, PGDH, PSAT) sequentially to convert d-glycerate to O-phospho-L-serine

- Add selected nucleophile and Module III enzyme (OPSS) for ncAA synthesis

- Incubate at 37°C with mixing for 24-48 hours

- Monitor reaction progress by LC-MS or NMR

- Purify products using appropriate chromatography methods

Expected Outcomes: This system enables gram- to decagram-scale production of 22 different ncAAs with C-S, C-Se, and C-N side chains in a 2L reaction system with water as the sole byproduct and atomic economy >75%.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Enzyme Cascade Development

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Detection Cascades | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Key Enzymes | Alcohol dehydrogenases, Carboligases, Glucose dehydrogenase, Lactate dehydrogenase, OPSS | Catalyze specific transformation steps, enable cofactor recycling | Select thermostable variants for extended operational stability; consider immobilized forms for reusability |

| Cofactors | NAD+/NADH, NADP+/NADPH, ATP, ThDP, PLP | Essential electron carriers and cosubstrates | Implement recycling systems to reduce costs; protect from degradation |

| Nanoparticle Scaffolds | Gold nanorods with carbon shells, Quantum dots | Enzyme immobilization, activity enhancement, channeling facilitation | Gold core: 93±16 nm length, 53±7 nm width; Carbon shell: 5.8±2.3 nm thickness [13] |

| Nucleophilic Substrates | Allyl mercaptan, Potassium thiophenolate, 1,2,4-triazole | ncAA synthesis through OPSS-catalyzed nucleophilic substitution | Screen multiple nucleophiles to expand product diversity |

| Sustainable Substrates | Glycerol | Low-cost, renewable substrate for multi-enzyme cascades | Use biodiesel-derived glycerol for improved sustainability profile |

| Csf1R-IN-7 | Csf1R-IN-7|Potent CSF1R Inhibitor|For Research Use | Csf1R-IN-7 is a potent CSF1R inhibitor for cancer and neuroscience research. This product is For Research Use Only and is not intended for diagnostic or therapeutic use. | Bench Chemicals |

| Mrtx-EX185 | Mrtx-EX185, MF:C33H33FN6O2, MW:564.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Schematic Representations

Cofactor Recycling in a 2-Step Enzyme Cascade

Cofactor and Co-product Recycling in a 2-Step Enzyme Cascade: This diagram illustrates the integrated recycling system where the benzaldehyde co-product from the ADH reaction serves as substrate for the carboligase reaction, while NADH/NAD+ cycling links the two enzymatic steps [10].

Modular Multi-Enzyme Cascade for ncAA Synthesis

Modular Multi-Enzyme Cascade for ncAA Synthesis: This workflow depicts the three-module system converting glycerol to non-canonical amino acids, with integrated ATP and NAD+ recycling systems [11].

Nanozyme-Based Multi-Analyte Detection Mechanism

Nanozyme-Based Multi-Analyte Detection Mechanism: This diagram shows the sequential detection of dopamine and glucose in whole blood using potential pulses to control the local solution environment within nanochannels [13].

Spatial organization, the precise arrangement of enzymes within a cellular or synthetic environment, is a fundamental principle governing metabolic efficiency in biological systems. In nature, enzymes are not randomly dispersed but often assembled into multi-enzyme complexes or metabolons that facilitate substrate channeling and enhance pathway flux [14]. This organization prevents the loss of volatile intermediates, reduces cross-talk with competing metabolic pathways, and shields the cell from toxic reaction products. The field of synthetic biology has increasingly embraced this paradigm, developing innovative biomimetic strategies to co-localize enzymes in microbial chassis for applications ranging from metabolic engineering to biosensing [15] [16]. For researchers focused on coupled multi-enzyme systems in selective detection, mastering spatial organization is paramount; it directly influences the sensitivity, specificity, and response time of biosensor platforms by controlling the local concentrations of enzymes, substrates, and intermediates [17] [14].

The limitations of traditional, unorganized systems are particularly apparent in complex heterologous pathways. Without proper organization, cells experience crosstalk between pathways, degradation of vital intermediates, and accumulation of toxic by-products, all of which severely impact the efficiency and yield of the desired product or signal [15]. Consequently, translating the blueprint of natural enzyme complexes into synthetic designs offers a powerful route to overcome these roadblocks and enhance the performance of engineered biological systems.

Natural Paradigms and Synthetic Strategies

Natural Examples of Spatial Organization

Natural systems employ a variety of sophisticated mechanisms to compartmentalize biochemistry. Eukaryotes discretize their metabolism into membrane-bound organelles, creating distinct chemical environments that separate incompatible processes [14] [16]. Furthermore, enzyme complexes like polyketide synthases and other metabolons bring sequential enzymes into close proximity to facilitate channeling of intermediates [14]. Even in prokaryotes, which lack many membrane-bound organelles, spatial organization is pervasive. Bacteria utilize protein-based bacterial microcompartments (BMCs), such as the 1,2-propanediol utilization (Pdu) microcompartment and carboxysomes, to encapsulate metabolic pathways [14]. These compartments consist of a protein shell that encloses enzymes and intermediates, functioning both to protect the cell from toxic metabolites and to increase the local concentration of substrates for enhanced kinetic performance [14].

Synthetic Organization Strategies

Inspired by nature, synthetic biologists have developed a toolkit of strategies to impose spatial organization on heterologous enzyme pathways, each with distinct advantages and implementation considerations (Table 1).

Table 1: Comparison of Major Spatial Organization Strategies

| Strategy | Core Mechanism | Key Advantages | Common Applications & Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Enzyme Fusion [15] | Genetic fusion of enzyme coding sequences into a single polypeptide. | Simple design; ensures 1:1 enzyme stoichiometry and proximity. | Fusion of two to three enzymes for resveratrol or α-farnesene production [15]. |

| Protein Scaffolds [15] [16] | Recruitment of enzyme-fusion proteins to a centralized protein via high-affinity interactions (e.g., SH3, PDZ, GBD domains). | Tunable enzyme ratios; modular design. | Up to 77-fold improvement in mevalonate production in E. coli [15] [16]. |

| Nucleic Acid Scaffolds [15] | Attachment of enzyme-fusion proteins (e.g., via zinc fingers) to DNA or RNA scaffolds with programmable sequences. | Highly predictable and programmable geometry; theoretically unlimited size. | ~5-fold enhancement in resveratrol and mevalonate production; 48-fold increase in hydrogen production [15]. |

| Bacterial Microcompartments [14] | Encapsulation of enzyme pathways within a self-assembling protein shell. | Creates a physically segregated environment; protects the host and intermediates. | Modeling of native Pdu metabolism and heterologous mevalonate pathway for flux enhancement [14]. |

The following workflow diagram illustrates the decision-making process for selecting and implementing these different strategies.

Quantitative Analysis of Organization Benefits

The theoretical benefits of spatial organization are substantiated by quantitative metrics, including significant enhancements in product titers and pathway flux. The performance gain is highly dependent on the chosen strategy and the specific pathway.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Enhancements from Spatial Organization

| Organization Strategy | Pathway/System | Host Organism | Performance Enhancement | Key Metric |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Scaffold [15] [16] | Mevalonate Biosynthesis | E. coli | Up to 77-fold increase | Production titer |

| Protein Scaffold [15] | Glucaric Acid Biosynthesis | E. coli | ~5-fold increase | Production titer |

| RNA Scaffold [15] | Hydrogen Production ([Fe-Fe] hydrogenase) | E. coli | 48-fold increase | Production efficiency |

| RNA Scaffold [15] | Succinate Synthesis | E. coli | 88% improvement | Productivity |

| DNA Scaffold [16] | Resveratrol, Mevalonate, 1,2-Propanediol | E. coli | Up to 5-fold enhancement | Production titer |

| Direct Enzyme Fusion [16] | Resveratrol Production | Yeast/Human Cells | 15-fold enhancement | Production titer |

| Bacterial Microcompartment (Model) [14] | Native Pdu Metabolism | Salmonella (model) | 4 orders of magnitude | Pathway flux |

Modeling studies suggest that the benefit of encapsulation in bacterial microcompartments can be commensurate with substantial enzyme kinetic improvements achieved through protein engineering, highlighting the profound impact of physical organization on pathway flux [14]. Furthermore, the optimal spatial organization strategy for a given pathway is not universal; it depends on pathway-intrinsic factors (e.g., enzyme kinetics, intermediate toxicity) and extrinsic factors (e.g., culture conditions, substrate influx) [14].

Application Notes & Protocols for Biosensor Development

The principles of spatial organization are directly applicable to the engineering of sophisticated multi-enzyme biosensors. The following section provides detailed protocols for implementing these strategies.

Protocol: Assembling a Bi-Enzymatic Biosensor on a DNA Scaffold

This protocol details the construction of a glucose-sensing system using glucose oxidase (GOx) and horseradish peroxidase (HRP) assembled on a DNA scaffold, a classic configuration for analyte detection [17] [15].

Principle: The DNA scaffold brings GOx and HRP into close proximity. Glucose oxidase catalyzes the oxidation of glucose, producing hydrogen peroxide (Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚). Horseradish peroxidase then uses Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ to oxidize a chromogenic substrate, generating a detectable colorimetric signal. Spatial co-localization significantly enhances the local concentration of Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚, improving the sensor's sensitivity and response time [17] [15].

Materials:

- Enzymes: Glucose Oxidase (GOx), Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP)

- DNA Scaffold: Designed single-stranded DNA scaffold containing specific docking sequences.

- Fusion Proteins: GOx and HRP genetically fused to zinc finger proteins (ZFPs) that bind the DNA docking sequences.

- Buffers: Immobilization buffer (e.g., 10 mM PBS, pH 7.4).

- Substrates: D-Glucose, Chromogenic HRP substrate (e.g., TMB or ABTS).

Procedure:

- Scaffold Preparation: Synthesize and purify the designed single-stranded DNA scaffold. Dilute to a working concentration of 1 µM in immobilization buffer.

- Enzyme-ZFP Mixing: Combine the GOx-ZFP and HRP-ZFP fusion proteins in a 1:1 molar ratio. Incubate on ice for 10 minutes.

- Complex Assembly: Add the enzyme-ZFP mixture to the DNA scaffold solution at a molar ratio ensuring all docking sites are occupied. Incubate at room temperature for 1 hour.

- Immobilization: Deposit the assembled complex onto a clean electrode surface or other solid support. Allow adsorbing for 2 hours in a humidified chamber.

- Washing & Validation: Rinse the sensor surface gently with immobilization buffer to remove unbound enzymes. Validate assembly via electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) or fluorescence labeling.

- Detection Assay: Introduce the sample containing glucose and the chromogenic substrate. Monitor the colorimetric or amperometric signal generation over time.

Protocol: Enhancing a Multi-Enzyme Pathway via Protein Scaffolding

This protocol describes the use of a synthetic protein scaffold to enhance a three-enzyme biosynthetic pathway, such as for the detection of a metabolite that is a pathway intermediate.

Principle: A central scaffolding protein engineered with multiple peptide interaction domains (e.g., SH3, PDZ, GBD) recruits pathway enzymes fused to their cognate ligand peptides. This creates a metabolon that channels intermediates, increasing local substrate concentrations and reducing loss to diffusion or competing reactions [15] [16].

Materials:

- Plasmids: Expression vectors for:

- The scaffold protein (e.g., with GBD-SH3-PDZ domains).

- Enzyme A fused to the GBD ligand.

- Enzyme B fused to the SH3 ligand.

- Enzyme C fused to the PDZ ligand.

- Host Strain: Competent E. coli or yeast cells.

- Media: Selective growth media with appropriate antibiotics.

- Inducer: Depending on the expression system (e.g., IPTG, arabinose).

Procedure:

- Strain Engineering: Co-transform the four plasmids (scaffold + three enzyme fusions) into the microbial host. Plate on selective media and incubate.

- Culture & Induction: Pick a single colony and grow a starter culture. Dilute into fresh, selective medium and grow to mid-log phase. Induce protein expression with the appropriate inducer.

- Titration (Optional): To optimize the system, vary the inducer concentration or use plasmids with different copy numbers to titrate the relative expression levels of the scaffold and the enzymes.

- Harvest & Analysis: Harvest cells by centrifugation. Analyze pathway performance by measuring the titer of the final product or the consumption of the primary substrate using HPLC or GC-MS.

- Comparison: Compare the product titer and flux to a control strain expressing the unfused enzymes without the scaffold.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of spatial organization strategies requires a suite of specialized molecular tools and reagents.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Spatial Organization

| Reagent / Material | Function / Description | Key Application |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Interaction Domains (e.g., SH3, PDZ, GBD) [15] | Engineered into scaffold proteins to recruit ligand-fused enzymes with high specificity. | Building synthetic protein scaffolds for metabolic pathways. |

| Zinc Finger Proteins (ZFPs) [15] [16] | DNA-binding proteins fused to enzymes; allow precise positioning on DNA scaffolds. | Assembling enzyme complexes on programmable DNA nanostructures. |

| RNA Aptamers [15] | Structured RNA motifs that bind specifically to protein adaptors fused to enzymes. | Constructing one-, two-, or three-dimensional RNA scaffolds in vivo. |

| SpyCatcher/SpyTag System [16] | A protein tag-peptide pair that forms an irreversible isopeptide bond upon interaction. | Covalently and irreversibly crosslinking enzymes to scaffolds or to each other. |

| Inducible Dimerization Systems (e.g., FKBP-FRB) [16] | Small molecule-induced protein-protein interaction domains. | Enabling dynamic, temporal control over enzyme complex assembly. |

| Targeting Sequences (e.g., mitochondrial, peroxisomal) [16] | Short peptide sequences that direct protein localization to specific organelles. | Recruiting pathway enzymes to pre-existing cellular compartments. |

| 19,20-Epoxycytochalasin D | 19,20-Epoxycytochalasin D, MF:C30H37NO7, MW:523.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Chitin synthase inhibitor 6 | Chitin Synthase Inhibitor 6 | Chitin synthase inhibitor 6 is a potent, broad-spectrum antifungal research compound. It targets CHS for infection research. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

Visualization and Analysis of Organized Systems

Advanced visualization tools are critical for analyzing the effects of spatial organization, especially when dealing with multi-omics data from engineered systems. Tools like the Cellular Overview in Pathway Tools (PTools) enable researchers to paint up to four different types of omics data (e.g., transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, reaction flux) simultaneously onto an organism-specific metabolic network diagram [18]. This allows for a metabolism-centric analysis, revealing how spatial organization impacts pathway activation and metabolic flux across the entire network, which is indispensable for diagnosing bottlenecks in complex, engineered multi-enzyme systems [18].

Design Strategies and Real-World Applications in Diagnostics and Monitoring

Application Notes

The spatial organization of multi-enzyme systems is a critical frontier in biocatalysis, particularly for developing sensitive detection platforms. Table 1 summarizes the performance of advanced assembly methodologies, demonstrating how precise control over enzyme placement enhances catalytic efficiency, stability, and signal generation in biosensing and diagnostic applications.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Multi-Enzyme Assembly Methodologies

| Assembly Method | Key Components | Reported Performance Metrics | Primary Application in Detection |

|---|---|---|---|

| Keratin Self-Assembly Platform [19] | RK86 microparticles, RK31 fusion tags (variable length) | 33% increase in Vmax; 22% reduction in Km for GOX/HRP cascade [19]. | Biosensing via enhanced reaction kinetics. |

| TRAP Protein Scaffolds [20] | TRAP1/TRAP3 domains, Peptide-tagged enzymes (e.g., FDH1, AlaDH3) | Up to 5-fold higher specific productivity; Enhanced NADH channeling [20]. | Cell-free biosynthesis of amino acids and amines. |

| SpyCatcher/SpyTag Immobilization [21] | SpyCatcher003/SpyTag003, Galectin-3 CRD, Fluorescent protein (eYFP) | Covalent immobilization; Micromolar binding affinity (KD) to glycoproteins [21]. | Targeted binding and imaging for diagnostic microgels. |

| Nano-fibrillated Cellulose Scaffolds [22] | 3D-printed NFC/CMC/citric acid scaffold, Zbasic2 fusion enzymes | ~65 mg protein/g carrier; Recyclable for 5 consecutive reactions [22]. | Natural product glycosylation for assay reagent synthesis. |

The core principle uniting these methodologies is the creation of biomimetic metabolons—synthetic analogues of the multi-enzyme complexes found in nature. By co-localizing enzymes, these systems facilitate substrate channeling, where the intermediate of a cascade reaction is directly transferred to the next enzyme without diffusing into the bulk solution. This minimizes the loss of labile intermediates, reduces cross-talk with other cellular components, and can shift reaction equilibria, leading to the significantly improved kinetics observed in Table 1 [20].

For detection systems, this spatial organization is paramount. The keratin platform demonstrates that even the nanometric distance between enzymes, adjusted by the length of the keratin tags, can be used to fine-tune the kinetic parameters of a cascade, directly impacting the sensitivity and output signal of a biosensor [19]. Furthermore, the TRAP system shows that scaffolds can do more than just position enzymes; they can be engineered with positively charged surfaces to electrostatically sequester reaction intermediates like NADH, further increasing their local concentration and driving reaction flux toward the desired product [20].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assembling a Multi-Enzyme System via the Keratin Self-Assembly Platform

This protocol details the creation of a glucose oxidase (GOX) and horseradish peroxidase (HRP) cascade system immobilized on keratin microparticles for use in biosensing applications [19].

Principle: A type II keratin (RK86) forms stable microparticles. Enzymes are genetically fused to tags derived from its pairing partner, type I keratin (RK31). The specific self-assembly between RK86 and RK31 tags facilitates spontaneous immobilization and allows spatial regulation by varying tag length [19].

Materials:

- Recombinant Proteins: RK86 microparticles; GOX and HRP enzymes fused with RK31 tags (e.g., RK31-(P2α-15), RK31-(2α-30)) [19].

- Buffers: PBS (pH 7.4) or other suitable physiological buffer.

- Equipment: Microcentrifuge, shaking incubator or rotator, spectrophotometer or plate reader.

Procedure:

- Expression and Purification: Express the RK31-tagged GOX and HRP fusion proteins in E. coli (e.g., using pET-22b(+) vector). Purify the proteins using standard affinity chromatography methods (e.g., His-tag purification) [19].

- Preparation of RK86 Microparticles: Synthesize and purify RK86 protein. Induce self-assembly into microparticles under appropriate buffer conditions as characterized in the original study [19].

- Immobilization Reaction:

- Mix RK86 microparticles with the purified RK31-tagged GOX and HRP in a suitable buffer.

- Incubate the mixture for 1-2 hours at room temperature with gentle agitation to allow for heterotypic self-assembly.

- Washing and Recovery:

- Centrifuge the mixture to pellet the immobilized enzyme complexes.

- Carefully remove the supernatant and wash the pellet with buffer to remove any unbound enzymes.

- Repeat the washing step 2-3 times.

- Resuspend the final immobilized multi-enzyme complex in storage or reaction buffer.

- Validation and Activity Assay:

- Confirm immobilization and spatial arrangement using techniques like FITC fluorescent labeling and SEM characterization [19].

- Assess cascade activity by measuring the oxidation of a chromogenic substrate (e.g., ABTS) in the presence of glucose. Compare the Vmax and Km of the immobilized system to the free enzyme system.

Protocol 2: Co-Immobilization of Glycosyltransferases on 3D-Printed NFC Scaffolds

This protocol describes the use of a modular, charged polysaccharide scaffold for the directed co-immobilization of Leloir glycosyltransferases [22].

Principle: A 3D-printed scaffold composed of nano-fibrillated cellulose (NFC), carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC), and citric acid presents a negatively charged surface. Enzymes fused with the cationic module Zbasic2 are immobilized via strong electrostatic interactions [22].

Materials:

Procedure:

- Scaffold Preparation: Fabricate the porous scaffold using direct-ink-writing 3D printing of the NFC-based ink, followed by cross-linking and washing [22].

- Enzyme Preparation: Express and purify the Zbasic2-tagged enzymes from a suitable host.

- Directed Co-Immobilization:

- Incubate the 3D scaffold with a solution containing the Zbasic2 fusion enzymes.

- Allow binding to proceed for 1 hour at 4°C with gentle shaking.

- Washing: Thoroughly wash the scaffold with buffer to remove any non-specifically bound enzyme until no protein is detected in the flow-through.

- Activity Assay:

- Use the co-immobilized system for cascade reactions (e.g., synthesis of nothofagin from phloretin and sucrose).

- Monitor reaction conversion (e.g., by HPLC). The system should be recyclable for multiple batches [22].

Visualized Workflows and Signaling Pathways

Multi-Enzyme System Assembly and Channeling

SpyCatcher/SpyTag Protein Immobilization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Multi-Enzyme System Assembly

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role | Example Application / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Keratin Tags (RK31) [19] | Genetically fused to enzymes for directed self-assembly onto keratin platforms. | Tag length (e.g., 2α-15 vs. 2α-30) can regulate inter-enzyme distance and cascade kinetics [19]. |

| TRAP Domains (TRAP1/TRAP3) [20] | Engineered protein scaffolds for orthogonal, high-affinity binding of peptide-tagged enzymes. | Allows nanometric organization and can be designed with charged surfaces for intermediate/cofactor channeling [20]. |

| SpyCatcher003/SpyTag003 [21] | Protein-peptide pair forming a spontaneous, covalent isopeptide bond for irreversible immobilization. | Enables modular and oriented conjugation of functional proteins (e.g., galectins) to surfaces or other biomolecules [21]. |

| Zbasic2 Module [22] | Cationic binding module for immobilizing enzymes onto negatively charged polysaccharide scaffolds. | Enables directed, affinity-like immobilization on 3D-printed NFC/CMC composites without chemical treatment [22]. |

| Nano-fibrillated Cellulose (NFC) Scaffold [22] | 3D-printed, macro-porous polysaccharide-based carrier for enzyme co-immobilization. | Provides a tunable, sustainable, and biocompatible solid support with high surface area for biocatalysis [22]. |

| Entecavir-d2 | Entecavir-d2, MF:C12H15N5O3, MW:279.29 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Dyrk1A-IN-4 | Dyrk1A-IN-4|Potent DYRK1A Kinase Inhibitor |

The integration of natural enzymes with nanozymes within Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) represents a paradigm shift in the design of coupled multi-enzyme systems for selective detection research. This approach synergistically combines the unparalleled specificity and catalytic efficiency of biological enzymes with the superior stability, tunability, and multifunctionality of MOF-based nanozymes [23] [24]. MOFs are crystalline porous materials formed by metal ions/clusters and organic ligands, offering ultrahigh surface areas, ordered networks, and tunable pore sizes that make them ideal scaffolds for immobilizing biological components and hosting catalytic sites [25] [26] [23]. The confinement effect within MOF architectures enhances catalytic efficiency by spatially isolating active sites and allowing high local substrate concentrations, enabling the creation of sophisticated biomimetic systems that overcome the limitations of traditional multi-enzyme complexes, which often suffer from instability, high cost, and complex fabrication procedures [24].

This convergence is particularly valuable for developing advanced biosensing platforms that require precise catalytic sequencing and robust performance in complex biological environments. By rational design of these hybrid systems, researchers can create tailored platforms for detecting biomarkers, pathogens, and other analytes with high sensitivity and specificity, addressing critical needs in biomedical diagnostics, environmental monitoring, and therapeutic development [23].

Fundamental Concepts and Design Principles

MOF Nanozymes: Active Sites and Catalytic Diversity

MOFs serve as exceptional nanozyme platforms due to their ability to mimic natural enzymatic active sites through metal nodes, organic linkers, or a combination of both [26]. The modular construction of MOFs enables precise control over their catalytic properties, allowing researchers to tailor nanozymes for specific detection applications. MOF nanozymes can exhibit a wide spectrum of enzyme-mimetic activities, including oxidase (OXD), peroxidase (POD), catalase (CAT), superoxide dismutase (SOD), and glutathione peroxidase (GPx) activities [24]. These catalytic capabilities can be further enhanced through strategic transformation of MOFs into derivatives such as porous carbon materials and nanostructured metal compounds, which often demonstrate improved stability and catalytic performance [26].

The classification of MOF-based nanozymes generally falls into two main categories based on their redox functions: pro-oxidant nanozymes (e.g., OXD, POD) that typically generate reactive oxygen species (ROS) for signaling or antimicrobial applications, and anti-oxidant nanozymes (e.g., CAT, SOD, GPx) that primarily scavenge ROS for therapeutic purposes or to maintain redox homeostasis in detection systems [24]. Advanced systems can incorporate multiple enzymatic activities within a single platform, enabling complex cascade reactions that mirror natural metabolic pathways.

Integration Strategies for Natural Enzymes and Nanozymes in MOFs

The construction of hybrid enzyme-MOF systems employs several strategic approaches, each offering distinct advantages for specific applications:

Embedding/Encapsulation: Natural enzymes are physically entrapped within the porous matrix of MOFs during synthesis, providing protection against denaturation and proteolytic degradation while maintaining enzymatic activity [27]. This approach creates a nanoconfined environment that can enhance stability and substrate channeling.

Surface Immobilization: Pre-synthesized enzymes are attached to the external surfaces or pore openings of MOFs through covalent bonding, affinity binding, or physical adsorption [27]. This method facilitates better mass transfer of substrates and products while still offering stability improvements.

MOF-based Nanozyme Composites: MOFs themselves function as nanozymes while also serving as carriers for natural enzymes, creating synergistic systems that leverage both biological and biomimetic catalysis [27]. This integrated approach enables complex multi-step reactions where the nanozyme and natural enzyme activities complement each other.

Biomimetic Co-localization: Multiple enzyme types (both natural and nanozymes) are strategically positioned within the MOF architecture to mimic metabolic pathway organization, enabling efficient substrate channeling and reduced diffusion limitations [24].

Table 1: Comparison of Integration Strategies for Enzyme-MOF Hybrid Systems

| Integration Strategy | Key Advantages | Potential Limitations | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Embedding/Encapsulation | Maximum enzyme protection; minimized leaching; enhanced stability | Potential diffusion limitations; more complex synthesis | Biosensing in complex media; therapeutic delivery systems |

| Surface Immobilization | Simpler fabrication; better substrate access; easier orientation control | Reduced protection from external environment; potential stability issues | Flow-through systems; large substrate detection |

| MOF-Nanozyme Composites | Synergistic catalysis; multifunctionality; tunable activities | Potential interference between activities; more complex optimization | Cascade reaction systems; theranostic applications |

| Biomimetic Co-localization | Efficient substrate channeling; reduced diffusion limitations; metabolic pathway mimicry | Highly complex design and fabrication requirements | Multi-analyte detection; complex biomarker profiling |

Applications in Selective Detection Systems

Advanced Biosensing Platforms

The integration of natural enzymes with MOF nanozymes has enabled significant advancements in biosensing capabilities, particularly for detecting clinically and environmentally relevant analytes. These hybrid systems leverage the complementary strengths of both components: the high specificity of natural enzymes for target recognition and the enhanced stability and signal amplification provided by MOF nanozymes [23].

For pesticide detection, MOF-enzyme composites have been successfully developed where the MOF matrix protects hydrolytic enzymes (such as organophosphorus hydrolase) while simultaneously providing peroxidase-like activity for signal generation [27]. This dual functionality enables sensitive detection of pesticide residues through enzyme inhibition assays or direct catalytic conversion, with detection limits often surpassing traditional methods. Similarly, for pathogen detection, MOF platforms functionalized with aptamers or antibodies can selectively capture microbial targets, while their intrinsic nanozyme activity facilitates colorimetric, fluorescent, or electrochemical signal transduction [23].

A particularly innovative application involves the detection of multiple analytes in complex samples. Recent research has demonstrated that a single nanozyme platform can be engineered to selectively detect different targets by controlling the local electrochemical environment within nanoconfined spaces, mimicking the substrate channeling found in natural enzymes [28]. This approach was used to successfully detect both glucose and dopamine in the same unadulterated whole blood sample by strategically altering applied potentials to create conditions favorable for oxidizing each analyte sequentially [28].

Therapeutic and Diagnostic Applications

Beyond environmental and food safety monitoring, enzyme-MOF hybrid systems show tremendous promise in biomedical applications. Their unique properties enable novel approaches for disease treatment and diagnosis, particularly in managing oxidative stress-related conditions and inflammatory diseases.

MOF-based nanozymes with multiple antioxidant activities (SOD, CAT, and GPx mimics) can effectively scavenge reactive oxygen species and mitigate oxidative damage in pathological conditions [24]. For instance, cerium oxide-based nanozymes have demonstrated therapeutic efficacy in dry eye disease models by reducing oxidative damage and restoring corneal and conjunctival integrity through regenerative ROS scavenging mechanisms [23]. Similarly, in acute lung injury (ALI), MOF nanoplatforms have been engineered for pulmonary drug delivery, leveraging their anti-inflammatory and antioxidant functions while responding to the inflammatory microenvironment through smart release mechanisms triggered by pH, ROS, or enzymatic activity [29].

The integration of natural enzymes with MOF nanozymes also opens possibilities for sophisticated theranostic platforms that combine therapeutic and diagnostic functions. Glucose oxidase (GOx) immobilized in MOFs can efficiently consume glucose while generating hydrogen peroxide, which can subsequently be catalyzed by the peroxidase-like activity of the MOF to produce cytotoxic radicals for cancer therapy or signal molecules for monitoring therapeutic response [24].

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Representative Enzyme-MOF Hybrid Detection Systems

| Target Analyte | MOF Platform | Enzyme/Nanozyme Component | Detection Mechanism | Limit of Detection | Linear Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organophosphate Pesticides | ZIF-8 | Acetylcholinesterase + MOF POD-like activity | Enzyme inhibition with colorimetric readout | 0.05 nM | 0.1-100 nM |

| Glucose | AuNR@Carbon Nanochannel | Intrinsic OXD-like activity | Electrochemical (potential pulse) | 3.2 μM | 10-500 μM |

| Dopamine | AuNR@Carbon Nanochannel | Intrinsic electrocatalytic activity | Electrochemical (potential pulse) | 0.8 μM | 1-100 μM |

| Pathogenic Bacteria | Fe-MIL-88 | Aptamer + POD-like activity | Colorimetric sandwich assay | 10 CFU/mL | 10^1-10^5 CFU/mL |

| H2O2 | FePPOP-1 | POD-like activity | TMB oxidation colorimetry | 0.2 μM | 0.5-100 μM |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Encapsulation of Natural Enzymes in MOF Matrices

Principle: This protocol describes the co-precipitation method for encapsulating hydrolytic enzymes (e.g., organophosphorus hydrolase) within zeolitic imidazolate framework-8 (ZIF-8) for pesticide detection applications [27].

Materials:

- Zinc nitrate hexahydrate (Zn(NO3)2·6H2O)

- 2-Methylimidazole (2-MIM)

- Organophosphorus hydrolase (OPH) enzyme

- MOPS buffer (10 mM, pH 7.0)

- Centrifugal filters (MWCO 50 kDa)

Procedure:

- Prepare aqueous solutions of 25 mM Zn(NO3)2 and 50 mM 2-Methylimidazole separately in MOPS buffer.

- Dissolve OPH enzyme (2 mg/mL) in the zinc nitrate solution.

- Rapidly mix the enzyme-zinc solution with the 2-Methylimidazole solution in a 1:1 volume ratio.

- Vortex the mixture for 30 seconds and allow crystallization to proceed at room temperature for 1 hour.

- Collect the enzyme-embedded ZIF-8 crystals by centrifugation at 8,000 × g for 5 minutes.

- Wash the precipitate three times with MOPS buffer to remove unencapsulated enzyme.

- Resuspend the final product in MOPS buffer and store at 4°C for further use.

Validation: Successful encapsulation can be confirmed by measuring enzyme activity using paraoxon as substrate and comparing to free enzyme. The encapsulated enzyme should retain >80% activity while demonstrating significantly improved stability against thermal denaturation and protease digestion [27].

Protocol 2: Electrochemical Detection Using Nanozyme Channels

Principle: This protocol details the application of gold nanorod-carbon nanochannel structures for selective detection of multiple analytes (glucose and dopamine) in whole blood samples [28].

Materials:

- Gold nanorod-carbon nanozyme electrodes

- Phosphate buffer saline (PBS, 0.1 M, pH 7.4)

- Whole blood samples (heparinized)

- Potentiostat with standard three-electrode configuration

- Ag/AgCl reference electrode

- Platinum counter electrode

Procedure:

- Prepare the nanozyme-modified working electrode according to established synthesis protocols [28].

- Set up the electrochemical cell with 1 mL of whole blood sample diluted 1:10 in PBS.

- For dopamine detection:

- Apply a reductive potential of -0.7 V for 0.2 seconds to remove fouling agents.

- Immediately step to an oxidative potential of 0.3 V for 0.2 seconds.

- Measure the oxidation current at the end of the pulse.

- For glucose detection:

- Apply a highly reductive potential of -1.85 V for 5 seconds to split water and create basic conditions within nanochannels.

- Step to an oxidative potential of -0.25 V for 0.2 seconds.

- Measure the oxidation current at the end of the pulse.

- Generate calibration curves using standard additions of dopamine and glucose to whole blood samples.

Validation: The method should demonstrate linear responses for both analytes in the physiologically relevant range with minimal cross-talk between measurements. Selectivity can be verified by testing against common interferents such as ascorbic acid and uric acid [28].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Enzyme-MOF Hybrid Systems

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Key Characteristics | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| ZIF-8 | Enzyme encapsulation matrix; nanozyme platform | Biocompatible; mild synthesis conditions; high surface area | OPH@ZIF-8 for pesticide detection [27] |

| MIL-series MOFs | Nanozyme platforms; drug delivery carriers | Iron-based; tunable porosity; biodegradable | MIL-100(Fe) as peroxidase mimic [23] |

| UiO-66 | Stable enzyme carrier; nanozyme scaffold | Exceptional chemical stability; zirconium-based | UiO-66-NH2 for antibody immobilization [23] |

| PCN-333 | Large-pore enzyme encapsulation | Mesoporous structure; huge cage size | Multi-enzyme encapsulation for cascade reactions |

| Gold Nanorod-Carbon Nanochannels | Electrochemical sensing platform | Nanoconfinement effects; tunable surface chemistry | Multi-analyte detection in whole blood [28] |

| TMB Substrate | Chromogenic substrate for peroxidase activity | Color change (colorless to blue); high sensitivity | H2O2 detection; oxidase-coupled assays [23] |

| Reactive Oxygen Species Sensors | Monitoring oxidative activity in nanozyme systems | Fluorescent or colorimetric readouts; specific to ROS type | H2DCFDA for general ROS; Amplex Red for H2O2 |

| Selexipag-d6 | Selexipag-d6, MF:C26H32N4O4S, MW:502.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| D-Glucose-13C2,d2 | D-Glucose-13C2,d2, MF:C6H12O6, MW:184.15 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Signaling Pathways and System Workflows

Cascade Catalysis in Hybrid Systems

The diagram illustrates the fundamental signaling pathway in integrated enzyme-MOF nanozyme systems for detection applications. The process begins with specific substrate recognition by the natural enzyme component, which generates a reaction intermediate. This intermediate then activates the MOF nanozyme component, ultimately producing a detectable signal output through various transduction mechanisms.

Multi-Analyte Detection Workflow

This workflow demonstrates the sequential detection of multiple analytes in a single blood sample using potential pulse manipulation. The system leverages nanoconfinement effects to create distinct local environments favorable for specific detection reactions, enabling measurement of both dopamine and glucose with a single nanozyme platform.

The engineering of multi-enzyme systems presents a formidable challenge in synthetic biology and biocatalysis. Traditional directed evolution approaches, which optimize individual enzymes in a sequential manner, often result in enhanced single-enzyme catalytic efficiencies at the cost of coordination within the enzymatic cascade [30]. This limitation becomes particularly problematic in industrial biocatalysis and biosensing, where the efficient channeling of intermediates between coupled enzymes is crucial for overall system performance. The emerging paradigm of system-wide directed evolution addresses this fundamental challenge by simultaneously optimizing multiple enzymes and their genetic regulatory elements to enhance both catalytic efficiency and coordination.

This Application Note provides a comprehensive framework for implementing simultaneous directed evolution in coupled multi-enzyme systems, with a specific focus on applications in selective detection research. We present detailed protocols, quantitative performance data, and visualization tools to enable researchers to effectively implement these strategies for optimizing complex enzymatic cascades.

Key Strategies for System-Wide Optimization

Simultaneous Directed Evolution of Coupled Enzymes

The core principle of system-wide optimization involves subjecting all enzymes in a pathway to evolutionary pressure concurrently, rather than sequentially. This approach mimics natural evolutionary processes where multiple proteins co-evolve to maintain functional harmony [30]. In practice, this is achieved by:

- Creating combinatorial libraries that randomize genes encoding all target enzymes simultaneously

- Implementing screening methodologies that select for overall pathway performance rather than individual enzyme activities

- Optimizing inter-enzyme coordination through adjustments in expression levels, spatial organization, and kinetic parameters

A representative study demonstrated the power of this approach in a coupled system containing glutamate dehydrogenase (PmGluDH) and glucose dehydrogenase (EsGDH) for the asymmetric biosynthesis of L-phosphinothricin. Through simultaneous evolution, researchers introduced a beneficial A164G mutation in PmGluDH that boosted catalytic efficiency from 1.29 sâ»Â¹ mMâ»Â¹ to 183.52 sâ»Â¹ mMâ»Â¹, while concurrently optimizing the ribosomal binding site for EsGDH to enhance expression levels [30]. The resulting system showed a dramatic increase in total turnover numbers from 115 to 33,950, with coupling efficiency improving from approximately 30% to 83.3% [30].

Spatial Organization Using DNA Nanostructures

Beyond genetic optimization, the spatial arrangement of enzymes significantly impacts cascade efficiency. DNA-assembled architectures provide nanometer-scale precision in enzyme positioning, enabling optimized substrate channeling and reduced intermediate diffusion [31]. These structures can be engineered as:

- One-dimensional linear arrays controlling inter-enzyme distance

- Two-dimensional geometric patterns regulating enzyme stoichiometry

- Three-dimensional confined structures creating favorable microenvironments

The programmable nature of DNA nanotechnology allows precise control over inter-enzyme distances and stoichiometries, directly addressing kinetic bottlenecks in multi-enzyme cascades [31]. This approach has demonstrated particular value in biosensing applications, where it significantly enhances detection sensitivity by mimicking the substrate channeling observed in natural metabolic pathways.

Machine Learning-Guided Protein Engineering

Recent advances integrate machine learning with directed evolution to navigate complex sequence-function landscapes more efficiently. Active Learning-assisted Directed Evolution (ALDE) represents a particularly promising approach that combines wet-lab experimentation with iterative model training to predict beneficial mutations [32]. This methodology is especially valuable for addressing epistatic interactions – non-additive effects between mutations – that complicate traditional directed evolution.

In one application, ALDE was used to optimize five epistatic residues in the active site of a protoglobin for a non-native cyclopropanation reaction. Within just three rounds of experimentation, the product yield increased from 12% to 93%, successfully navigating a fitness landscape that proved challenging for conventional directed evolution [32].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Simultaneous Directed Evolution of a Two-Enzyme System

Application: Optimizing coupled enzyme systems for biosynthetic pathways or detection cascades.

Materials:

- pETDuet-1 vector or similar bicistronic expression system

- Error-prone PCR kit (commercial systems recommended)

- E. coli BL21(DE3) or similar expression host

- MnClâ‚‚ for mutagenesis rate control

- Selection substrates and detection reagents

Procedure:

Library Construction:

- Amplify target genes (e.g., pmgludh and esgdh) using error-prone PCR with varying MnClâ‚‚ concentrations (0.10-0.20 mM) to control mutation rates [30].

- Clone mutated genes into expression vector using standard molecular biology techniques.

- Transform library into expression host; aim for library size >10â´ variants.

Primary Screening:

- Plate transformed colonies on selective media and incubate until colonies appear.

- Pick individual colonies into 96-well plates containing growth medium.

- Induce expression with IPTG and incubate for enzyme production.