Optimizing Biosensor Fabrication for Maximum Specificity: Advanced Materials, Methodologies, and Machine Learning

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing biosensor fabrication to achieve maximum specificity, a critical parameter for clinical diagnostics and biomedical research.

Optimizing Biosensor Fabrication for Maximum Specificity: Advanced Materials, Methodologies, and Machine Learning

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing biosensor fabrication to achieve maximum specificity, a critical parameter for clinical diagnostics and biomedical research. It explores foundational principles of biorecognition and signal transduction, details advanced fabrication methodologies and novel materials like graphene and MXenes, and presents systematic troubleshooting and optimization strategies, including the use of machine learning. The content further covers rigorous validation protocols and comparative analysis of different biosensor configurations, offering a holistic framework for developing highly specific biosensing platforms for applications in precision medicine, point-of-care testing, and therapeutic monitoring.

Core Principles and Recognition Elements for High-Specificity Biosensing

The specificity of a biosensor is fundamentally determined by the selective interaction between its bioreceptor and the target analyte [1]. This biorecognition event is the critical first step in biosensor operation, initiating a process that ultimately generates a measurable signal proportional to the analyte concentration [2]. The fundamental principle can be represented by the following equation:

Analyte + Bioreceptor ⇌ Analyte-Bioreceptor Complex → Signal [1]

Achieving high specificity is paramount for developing reliable biosensors for complex applications in clinical diagnostics, environmental monitoring, and food safety, where distinguishing between structurally similar compounds is essential [3] [4]. The binding affinity and kinetic parameters of this interaction directly govern the biosensor's performance, including its detection limit, dynamic range, and selectivity against potential interferents [2]. Within the broader context of optimizing biosensor fabrication, engineering and immobilizing the bioreceptor to preserve its native binding capabilities is therefore a primary research focus [4].

Core Components Governing Specificity

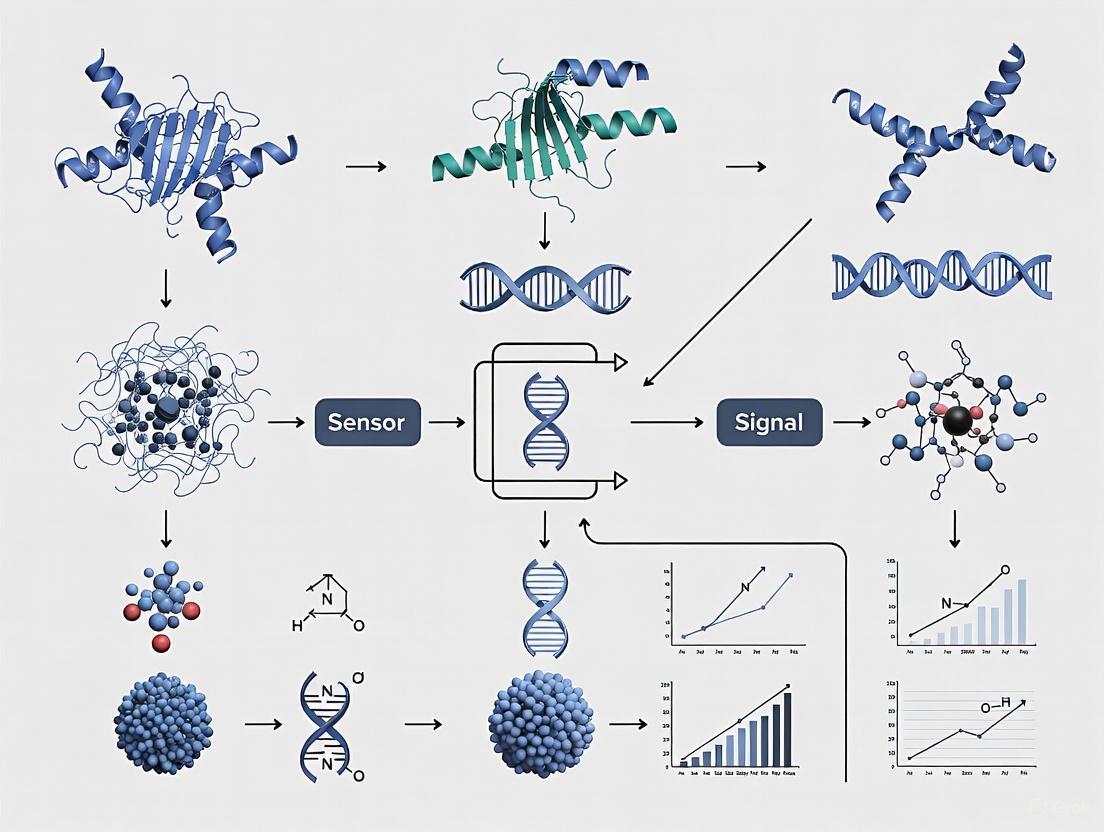

A biosensor is an integrated receptor-transducer device that converts a biological response into an analyzable signal [2]. The components most critical to specificity are the analyte and the bioreceptor, which participate in the biorecognition event, and the transducer, which converts this event into a measurable signal [1] [2].

Table 1: Core Biosensor Components Involved in Specificity

| Component | Description | Role in Specificity |

|---|---|---|

| Analyte | The substance of interest that is detected (e.g., glucose, pathogen, toxin) [2]. | The target whose unique structural features are recognized by the bioreceptor. |

| Bioreceptor | A biological molecule that recognizes the target analyte (e.g., enzyme, antibody, nucleic acid) [1] [2]. | Provides the binding site with high affinity and selectivity for the target analyte. |

| Transducer | Converts the biorecognition event into a measurable signal (e.g., electrochemical, optical) [1] [3]. | Must faithfully transduce the specific binding event without significant background noise. |

The design of a typical biosensor, highlighting the flow of information from analyte binding to signal output, is illustrated below.

Bioreceptor Types and Their Specificity Mechanisms

Bioreceptors can be classified into several major types, each with a distinct mechanism for achieving specificity [1] [3].

Enzymes as Bioreceptors

Enzymes are catalytic proteins that recognize specific substrates. Their specificity arises from the complementary three-dimensional structure of the active site, which binds the target substrate with high selectivity [1] [3]. The subsequent catalytic conversion of the substrate into a product provides the basis for the signal generation, as seen in the classic glucose biosensor using the enzyme glucose oxidase [1] [3].

Antibodies as Bioreceptors

Antibodies (immunosensors) are proteins generated by the immune system that possess exceptional specificity for a unique epitope on an antigen (the analyte) [1] [3] [4]. The strength of the antibody-antigen interaction (affinity) is a key determinant of biosensor sensitivity and specificity. Antibodies are widely used for detecting proteins, viruses, and whole bacterial cells [4].

Nucleic Acids as Bioreceptors

DNA or RNA probes function as bioreceptors through the principle of complementary base pairing (hybridization) [1] [3]. A single-stranded nucleic acid probe is immobilized on the sensor surface and selectively binds to its complementary target sequence, allowing for the detection of specific genetic markers or pathogens [3] [4].

Other Bioreceptors

Other bioreceptors include whole cells (which respond to analytes via integrated cellular pathways), aptamers (synthetic single-stranded DNA or RNA molecules that bind targets with high affinity), and biomimetic receptors like molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs), which are synthetic polymers with tailor-made cavities for specific analyte recognition [3] [4].

Table 2: Comparison of Bioreceptor Types for Specificity

| Bioreceptor | Mechanism of Specificity | Key Advantage | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enzyme | Lock-and-key fit in the active site; catalytic reaction [3]. | High specificity and catalytic signal amplification. | Limited to specific reactions; sensitivity to environmental conditions [3]. |

| Antibody | High-affinity binding to a specific antigenic epitope [3] [4]. | Exceptional specificity; wide range of available targets. | Costly production; potential for cross-reactivity with similar epitopes [3]. |

| Nucleic Acid | Watson-Crick base pairing with a complementary sequence [3]. | High specificity; ability to detect SNPs and genetic variations. | Requires knowledge of target sequence; susceptible to nuclease degradation [3]. |

| Aptamer | Folding into a 3D structure that binds the target with high affinity. | Chemical stability, in vitro selection, and modifiability. | Selection process can be complex; potential for nonspecific binding. |

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymer (MIP) | Size, shape, and functional group complementarity in a synthetic cavity [3] [4]. | High physical/chemical stability; simple synthesis. | Can have lower binding affinity and selectivity compared to biological receptors [3]. |

Experimental Protocol: Assessing Bioreceptor-Analyte Binding Kinetics

This protocol details the use of Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) to characterize the binding kinetics between an immobilized antibody (bioreceptor) and its soluble antigen (analyte). SPR is a label-free technique that provides real-time data on binding specificity, affinity, and rates.

Materials and Reagents

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Binding Kinetics Assay

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| SPR Instrument | Optical biosensor platform to monitor biomolecular interactions in real-time. |

| Sensor Chip (CM5) | Gold surface with a carboxymethylated dextran matrix for ligand immobilization. |

| Anti-Target Antibody | The purified bioreceptor to be immobilized on the sensor chip. |

| Target Antigen | The analyte for binding characterization; prepare a dilution series. |

| Running Buffer (e.g., HBS-EP) | Provides a consistent chemical environment (pH, ionic strength). |

| Amine Coupling Kit | Contains N-ethyl-N'-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide (EDC), N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS), and ethanolamine HCl for covalent immobilization. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Step 1: Surface Activation

- Dock the CM5 sensor chip in the SPR instrument.

- Prime the system with running buffer at a continuous flow rate (e.g., 10 µL/min).

- Inject a 1:1 mixture of EDC and NHS (from the amine coupling kit) for 7 minutes to activate the carboxyl groups on the dextran matrix, forming reactive ester groups.

Step 2: Ligand Immobilization

- Dilute the anti-target antibody in sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.0) to a concentration of 10-50 µg/mL.

- Inject the antibody solution over the activated surface for 5-10 minutes. The primary amines on the antibody will covalently couple to the activated matrix.

- Inject ethanolamine HCl for 7 minutes to deactivate and block any remaining activated ester groups.

Step 3: Data Acquisition (Binding Kinetics)

- Set the instrument temperature to 25°C.

- Prepare a series of antigen concentrations (e.g., 0, 3.125, 6.25, 12.5, 25, 50 nM) in running buffer.

- Program an automated cycle for each analyte concentration:

- Association Phase: Inject the antigen for 3-5 minutes to monitor binding.

- Dissociation Phase: Switch back to running buffer for 5-10 minutes to monitor complex dissociation.

- Regeneration: Inject a brief pulse (30 seconds) of a regeneration solution (e.g., 10 mM Glycine-HCl, pH 2.0) to remove all bound antigen without damaging the immobilized antibody.

Step 4: Data Analysis

- Subtract the signal from a reference flow cell (activated and blocked, but no antibody immobilized) to correct for bulk refractive index changes and non-specific binding.

- Fit the corrected, real-time sensorgram data to a 1:1 Langmuir binding model using the instrument's software to determine the association rate constant (ka), dissociation rate constant (kd), and the overall equilibrium dissociation constant (KD = kd/ka).

The experimental workflow for this protocol is summarized in the following diagram.

Transduction Methods for Monitoring Specific Interactions

The specific biorecognition event must be transduced into a quantifiable signal. The choice of transducer is critical for the overall performance of the biosensor [1] [3].

Table 4: Transduction Principles and Their Application to Specificity

| Transducer Type | Principle | How Specificity is Confirmed |

|---|---|---|

| Electrochemical | Measures changes in electrical properties (current, potential, impedance) due to the biorecognition event [1] [3] [4]. | Specific binding causes a change in interfacial electron transfer, which is measured against a control. |

| Optical (e.g., SPR, Fluorescence) | Measures changes in light properties (e.g., refractive index, wavelength, intensity) [1] [3]. | Real-time monitoring of binding; specific binding shows a characteristic association/dissociation curve. |

| Piezoelectric | Measures changes in the resonance frequency of a crystal due to mass change upon analyte binding [1]. | A frequency shift is directly linked to mass loading from the specific binding of the analyte. |

| Thermal | Measures the change in enthalpy (heat) from the biochemical reaction [1] [3]. | The specific binding event is exothermic or endothermic, producing a unique thermal signature. |

The foundation of biosensor specificity lies in the robust and selective interaction between the bioreceptor and its target analyte. A deep understanding of the kinetics and thermodynamics of this interaction is essential for researchers and engineers aiming to optimize biosensor fabrication. By systematically selecting the appropriate bioreceptor, carefully immobilizing it to preserve function, and employing precise transduction methods, it is possible to develop highly specific biosensors. These devices are crucial for advancing applications in drug development, clinical diagnostics, and environmental monitoring, where distinguishing target molecules in complex mixtures is paramount.

The performance of a biosensor is fundamentally dictated by the specificity and affinity of its biorecognition element. These biological molecules are responsible for the selective binding of the target analyte, forming the critical first step in the sensing mechanism. Within the context of optimizing biosensor fabrication for maximum specificity, the choice between antibodies, aptamers, and enzymes is paramount. Antibodies, with their well-established role in diagnostics, offer high specificity but present challenges in stability and production. Aptamers, as synthetic alternatives, provide superior stability and design flexibility, enabling the development of robust and reusable sensors. Enzymes, prized for their catalytic activity, facilitate the conversion of the recognition event into an amplifiable signal. This application note provides a detailed comparison of these biorecognition elements and outlines standardized protocols for their integration into biosensing platforms, with a specific focus on enhancing analytical specificity for research and drug development applications.

Comparative Analysis of Biorecognition Elements

The selection of an appropriate biorecognition element is a critical first step in biosensor design, directly impacting the sensor's sensitivity, specificity, stability, and practical applicability. Table 1 provides a quantitative comparison of the key characteristics of antibodies, aptamers, and enzymes.

Table 1: Comparative Properties of Biorecognition Elements

| Property | Antibodies | Aptamers | Enzymes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biochemical Nature | Proteins (Immunoglobulins) | Single-stranded DNA or RNA | Proteins |

| Molecular Size | ~150 kDa [5] [6] | ~15 kDa (5-10 times smaller than antibodies) [5] | Varies (e.g., Glucose Oxidase ~160 kDa) |

| Binding Affinity | Nanomolar range [5] | 1–1000 nM [5] | Defined by Michaelis-Menten constant (KM) |

| Target Range | Primarily immunogenic molecules [5] | Broad (ions, small molecules, proteins, cells) [7] [5] | Specific substrates and cofactors |

| Production Method | In vivo (animals) or in vitro (phage display) [5] [6] | In vitro (SELEX) [7] [8] | Microbial fermentation, extraction from tissues |

| Batch-to-Batch Variability | High (biologically derived) [5] | Negligible (chemically synthesized) [5] | Can be significant |

| Stability | Sensitive to temperature, pH; irreversible denaturation [5] | Thermally stable; can renature after denaturation [5] | Varies; generally sensitive to harsh conditions |

| Optimal pH Range | 5.0 - 9.0 [5] | DNA: 5.0 - 9.0; RNA: 6.0 - 8.5 [5] | Narrow, activity-specific range |

| Thermal Denaturation Point | 60–75 °C [5] | DNA: 40–80 °C; RNA: 40–70 °C [5] | Varies; often denatures below 70°C |

| Modification & Labeling | Limited, can affect binding [5] | Highly customizable (e.g., redox labels, thiol groups) [5] [8] | Can be engineered, but may affect activity |

| Typical Biosensor Role | Capture probe (Immunosensor) [6] | Capture probe and/or signal transducer (Aptasensor) [9] | Biological catalyst (Catalytic biosensor) |

Key Selection Criteria for Maximum Specificity

- Antibodies are the "gold standard" for specificity against immunogenic targets, making them ideal for clinical diagnostics where a vast library of validated antibodies exists. Their primary limitations include sensitivity to environmental conditions and the cold chain requirement for storage and shipping [5] [6].

- Aptamers excel in applications requiring detection of small molecules, toxins, or non-immunogenic targets. Their chemical synthesis ensures minimal batch-to-batch variation, and their small size allows for high-density immobilization on sensor surfaces, potentially increasing sensitivity. A significant advantage for electrochemical biosensors is their ability to be engineered to undergo conformational changes upon target binding, enabling reagentless, real-time detection [5] [9].

- Enzymes are indispensable for catalytic biosensors, where the signal is generated from the turnover of a substrate. They are key in detecting metabolites like glucose and lactate. Their specificity is high for their substrate, but they are generally not used for direct binding to a wide range of non-substrate analytes unlike antibodies and aptamers.

Application Notes & Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Aptamer Selection via Magnetic Bead-Based SELEX

This protocol describes the selection of single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) aptamers using magnetic bead-based SELEX (Systematic Evolution of Ligands by EXponential Enrichment), a widely used method for generating high-affinity aptamers against specific targets [7] [8].

Principle: A random ssDNA library is incubated with target molecules immobilized on magnetic beads. Bound sequences are separated from unbound ones using a magnetic field, eluted, and amplified by PCR. This iterative process enriches the pool with sequences having high affinity and specificity for the target.

Workflow Diagram: Magnetic Bead-Based SELEX

Materials:

- NHS-activated Magnetic Beads: Solid support for covalent target immobilization.

- Target Molecule (e.g., Paclitaxel, Leucovorin): The analyte for which an aptamer is desired.

- Random ssDNA Library: A diverse pool of ~10^14 unique sequences, typically 40-80 bases long with fixed primer regions.

- Binding Buffer (BB): Typically containing salts (e.g., NaCl, MgClâ‚‚) and buffering agents (e.g., Tris, HEPES) to promote binding.

- PCR Reagents: Taq polymerase, dNTPs, forward and reverse primers.

- Magnetic Separation Rack: For efficient partitioning of bead-bound complexes.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Target Immobilization: Covalently conjugate the target molecule (e.g., 1 mg/mL) to NHS-activated magnetic beads according to the manufacturer's protocol. Block any remaining active sites to prevent non-specific binding [8].

- Library Preparation: Denature the ssDNA library (e.g., 300 nmol) by heating to 90°C for 5-10 minutes, then rapidly cool on ice (4°C for 10 min) to allow proper folding. Equilibrate to room temperature for 5 minutes [8].

- Incubation and Binding: Incub the pre-folded ssDNA library with the target-conjugated beads in binding buffer for 1-2 hours under gentle rotation at room temperature [8].

- Partitioning and Washing: Place the tube in a magnetic rack to separate the beads. Carefully discard the supernatant containing unbound sequences. Wash the beads 3-5 times with binding buffer to remove weakly bound sequences [7] [8].

- Elution: Elute the specifically bound ssDNA by adding a small volume of elution buffer (e.g., 90°C TE buffer) and incubating for 10 minutes. Separate the eluate containing the bound sequences using the magnetic rack [8].

- Amplification: Amplify the eluted ssDNA by PCR using primers complementary to the fixed regions of the library. For DNA aptamers, this generates double-stranded DNA (dsDNA). For RNA aptamers, reverse transcription is required [7].

- ssDNA Regeneration: Purify the PCR product and generate ssDNA for the next selection round. This can be achieved via strand separation using streptavidin-coated beads (if a biotinylated primer was used) or asymmetric PCR [7].

- Counter-Selection (Negative Selection): Introduce counter-selection rounds after a few positive selection cycles. Incubate the enriched pool with "blank" beads (without target) or with related non-target molecules. Collect the unbound sequences to eliminate binders to the support matrix or non-target analytes [7] [8].

- Monitoring and Completion: Monitor the enrichment of binding sequences after each round, for example, by measuring the amount of recovered DNA. Typically, after 8-15 rounds, the pool is sufficiently enriched. The final pool is cloned, sequenced, and the resulting individual aptamer candidates are tested for affinity (Kd) and specificity [8].

Protocol 2: Fabrication of an Electrochemical Aptasensor

This protocol details the development of a "signal-on" electrochemical aptasensor (E-AB sensor) for the detection of a small molecule drug, such as a chemotherapeutic agent [9] [8].

Principle: A thiolated aptamer is immobilized on a gold electrode surface and labeled with a redox tag (e.g., Methylene Blue). In the absence of the target, the aptamer is flexible, keeping the tag distant from the electrode, resulting in a low electron transfer rate (low current). Upon target binding, the aptamer undergoes a conformational change that brings the redox tag closer to the electrode surface, facilitating electron transfer and producing a measurable increase in current ("signal-on") [5] [9].

Workflow Diagram: Electrochemical Aptasensor Operation

Materials:

- Screen-Printed Gold Electrodes (SPGEs): Disposable, cost-effective sensor platforms.

- Thiol-Modified Aptamer: The ssDNA aptamer, selected via SELEX, modified at the 5' or 3' end with a thiol (-SH) group.

- Redox Tag (e.g., Methylene Blue): A molecule that undergoes reversible reduction/oxidation, attached to the aptamer.

- Mercaptohexanol (MCH): A short-chain alkanethiol used to passivate the gold surface and create a well-oriented aptamer monolayer.

- Electrochemical Cell and Potentiostat: Instrumentation for performing electrochemical measurements.

- Binding Buffer (PBS, pH 7.4): Physiologically compatible buffer for the binding reaction.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Electrode Pretreatment: Clean the gold working electrode of the SPGE electrochemically (e.g., by cyclic voltammetry in sulfuric acid) or via plasma cleaning to ensure a clean, reproducible surface.

- Aptamer Immobilization: Incubate the gold electrode surface with a solution (e.g., 10 µL) of the thiolated aptamer (e.g., 1 µM) overnight at 4°C in a humidified chamber. This allows the formation of a stable Au-S bond, covalently tethering the aptamer to the electrode [8].

- Surface Passivation: Rinse the electrode with buffer to remove loosely bound aptamers. Subsequently, incubate the electrode with 1 mM MCH for 30-60 minutes at room temperature. MCH backfills the gold surface, displaces non-specifically adsorbed aptamers, and forces the remaining aptamers into an upright orientation, which minimizes non-specific adsorption and improves binding efficiency [8].

- Baseline Measurement: Wash the functionalized aptasensor with buffer. Place it in an electrochemical cell containing only the binding buffer. Perform electrochemical measurements, such as Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) or Cyclic Voltammetry (CV), to record the baseline signal (current or charge transfer resistance) [9].

- Target Detection: Incubate the aptasensor with a sample solution containing the target analyte (e.g., Paclitaxel) for a defined period (e.g., 15-30 minutes) to allow binding and conformational switching.

- Signal Measurement: Wash the sensor gently and perform the same electrochemical measurement in a clean buffer. The change in signal (e.g., increase in current in a "signal-on" sensor) is recorded.

- Calibration and Quantification: The magnitude of the signal change is correlated with the target concentration. A calibration curve is constructed using standard solutions of known concentration, enabling the quantification of the target in unknown samples [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2 lists key reagents and materials essential for the experiments described in these protocols.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function/Application | Example/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| NHS-activated Sepharose/Magnetic Beads | Solid support for target immobilization during SELEX. | Enables covalent coupling of target proteins or small molecules via primary amines for partitioning [7] [8]. |

| Thiol-Modified Oligonucleotides | Covalent immobilization of aptamers on gold surfaces. | The thiol group (-SH) forms a stable gold-sulfur (Au-S) bond, essential for creating stable aptasensors [8]. |

| Screen-Printed Electrodes (Gold, Carbon) | Disposable, miniaturized electrochemical sensor platforms. | Provide a cost-effective and reproducible base for developing electrochemical biosensors; ideal for prototyping [8]. |

| Mercaptohexanol (MCH) | Surface passivation agent. | Backfills gold surfaces after aptamer immobilization to create a well-ordered monolayer, reducing non-specific binding and improving aptamer orientation [8]. |

| Redox Reporters (Methylene Blue, Ferrocene) | Electroactive labels for signal transduction. | Tagged on aptamers; a change in their proximity to the electrode surface upon target binding generates the measurable electrochemical signal [5] [9]. |

| Systematic Evolution of Ligands by EXponential Enrichment (SELEX) | In vitro selection process for aptamer discovery. | A method to isolate high-affinity nucleic acid binders from a vast random sequence library against a specific target [7] [5]. |

| Phaeosphaone D | Phaeosphaone D, MF:C20H27N3O3S2, MW:421.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| D-Lyxose-13C-3 | D-Lyxose-13C-3, MF:C5H10O5, MW:151.12 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Biosensors are analytical devices that convert a biological response into a quantifiable and processable signal [10]. They are comprised of two main components: a bio-receptor that specifically binds to the target analyte (e.g., enzymes, antibodies, nucleic acids) and a transducer, which converts the biological recognition event into a measurable output signal [11] [10]. The transducer is a pivotal element, defining the fundamental classification, functionality, and compatibility of the biosensor, especially in wearable applications [11]. The collaboration between suitable bio-receptors and efficient signal conversion mechanisms enables the detection of a wide range of analytes from bodily fluids and the measurement of vital signs, thereby playing a crucial role in clinical diagnostics, environmental monitoring, and personal health tracking [11] [10].

This document details the operating principles, experimental protocols, and key optimization strategies for three major transducer platforms: electrochemical, optical, and surface plasmon resonance (SPR). The content is framed within a broader thesis on optimizing biosensor fabrication for maximum specificity, providing researchers and drug development professionals with practical application notes and methodologies.

Electrochemical Transduction Platforms

Platform Principles and Applications

Electrochemical biosensors, the first to be scientifically proposed and successfully commercialized, utilize electrodes to recognize and quantify alterations in the electrical characteristics of a biological sample following a biorecognition event [12] [11] [10]. The signal transduction occurs via a bio-electrochemical component that serves as the main transduction element, making these sensors robust, easily miniaturized, and capable of excellent detection limits even with small analyte volumes [10]. They are particularly advantageous for point-of-care testing due to their close link to low-cost microelectronic production [10].

The detection is typically based on an enzyme system that catalytically converts analytes into products that can be oxidized or reduced at a working electrode [10] [13]. These sensors are traditionally categorized based on the measured electrical property:

- Amperometric: Measures current generated by a redox reaction at the working electrode (held at a constant potential) [10].

- Potentiometric: Measures the accumulation of charge or potential difference between the working and reference electrodes when zero or negligible current flows between them [10].

- Impedimetric: Measures the impedance (both resistance and reactance) of a system, often to monitor binding events that alter the conductive properties at the electrode interface [10].

- Field-Effect Transistor (FET)-Based: Uses transistor technology where the potentiometric effect at a gate electrode modulates the current flow through the transistor channel [10].

A recent breakthrough demonstrates the significant enhancement of electrochemical signal amplification using Organic Electrochemical Transistors (OECTs). This method electronically couples enzymatic or microbial fuel cells with OECTs, amplifying weak electrical signals by three orders of magnitude (factors of 1,000 to 7,000) and improving the signal-to-noise ratio [14]. This approach overcomes challenges of direct biomolecule-sensor integration and opens doors for highly sensitive, low-power biosensors for applications like arsenite detection in water and lactate sensing in sweat [14].

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics for Electrochemical Transducers

| Transducer Type | Measured Quantity | Typical Applications | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amperometric | Current from redox reaction | Glucose monitoring, neurotransmitter detection | High sensitivity, well-established protocols |

| Potentiometric | Potential / charge accumulation | pH sensing, ion detection (Kâº, Naâº) | Simple instrumentation, wide dynamic range |

| Impedimetric | Impedance (Resistance & Reactance) | Pathogen detection, protein binding studies | Label-free, real-time kinetic evaluation |

| FET-Based | Modulated channel current | DNA hybridization, virus detection | Ease of miniaturization, high sensitivity |

| OECT-Amplified | Amplified current | Ultrasensitive medical diagnostics, environmental monitors (e.g., arsenite) | Extreme signal amplification (1000-7000x), low power, low noise [14] |

Experimental Protocol: Fabrication and Measurement of an OECT-Amplified Biosensor

This protocol details the methodology for creating a highly sensitive biosensor by integrating a microbial fuel cell with an Organic Electrochanical Transistor (OECT), based on recent research [14].

Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

Table 2: Essential Materials for OECT-Amplified Biosensor

| Item Name | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Organic Electrochemical Transistor (OECT) | Thin-film transistor acting as the signal amplifier; operates in aqueous environments with high sensitivity and low-voltage [14]. |

| Microbial Fuel Cell | Contains electroactive bacteria (e.g., engineered E. coli); metabolizes organic substrates to produce a current proportional to the target analyte [14]. |

| Electroactive Bacteria (e.g., engineered E. coli) | Biological recognition element. Can be engineered with specific responsive pathways (e.g., for arsenite) to generate electrical signals upon analyte presence [14]. |

| Channel Polymer Material (e.g., PEDOT:PSS) | Conductive polymer forming the OECT channel. Its properties are crucial for transistor performance and amplification efficiency [14]. |

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) or Synthetic Sweat | Electrolyte solution providing a stable ionic environment for the fuel cell and OECT operation, mimicking real-world conditions [14]. |

| Potentiostat/Galvanostat | Electronic instrument used to apply potentials and measure the resulting currents from the fuel cell and the OECT. |

| Microfabrication Equipment (e.g., spin coater, mask aligner) | For patterning and fabricating the miniaturized OECT and fuel cell components on a substrate (e.g., glass slide) [14]. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

OECT Fabrication:

- Pattern micro-electrodes (source, drain, gate) onto a glass slide using standard photolithography and metal deposition (e.g., Au) techniques.

- Spin-coat the channel polymer (e.g., PEDOT:PSS) onto the predefined channel area between the source and drain electrodes. Anneal as required to solidify the film.

Microbial Fuel Cell Preparation:

- Culture electroactive bacteria (e.g., Shewanella oneidensis or engineered E. coli) in a suitable growth medium.

- For analyte-specific detection, genetically engineer the bacteria to possess an electron transfer pathway responsive to the target (e.g., an arsenite-responsive promoter driving the expression of electron transfer genes).

- Immobilize the bacteria within the anode chamber of a miniaturized fuel cell.

Electronic Coupling:

- Connect the OECT and the microbial fuel cell in either a cathode-gate or anode-gate configuration using electrical wires. The cathode-gate configuration is recommended for superior amplification and to avoid potential device degradation [14].

- Place the coupled system in a controlled electrolyte environment (e.g., PBS).

Measurement and Data Acquisition:

- Use a potentiostat to apply a constant drain voltage (VD) to the OECT.

- The gate voltage (VG) is effectively defined by the potential generated by the microbial fuel cell.

- Introduce the target analyte (e.g., glucose, lactate, arsenite) to the microbial fuel cell chamber.

- The bacterial metabolism or specific response to the analyte will generate a current in the fuel cell. This small change modulates VG, causing a large, amplified change in the OECT's drain current (ID).

- Record the time-dependent change in ID

Optical Transduction Platforms

Platform Principles and Applications

Optical biosensors are a powerful class of sensors that use light as the transduction medium to detect the interaction between a biological recognition element and the target analyte [12] [13]. They are known for their high specificity, sensitivity, and capability for direct, real-time, and label-free detection [13]. The detection typically relies on measuring changes in optical properties such as absorbance, luminescence, fluorescence, polarization, or refractive index induced by the biorecognition event [13].

The first stage of optical transduction involves a chemical interaction between the analyte and an indicator phase to produce an optically detectable signal [15]. This interaction can take several forms:

- Direct Indicators: Reversible binding of the analyte to an indicator, commonly used in optical pH sensors [15].

- Integrating Reagents: Irreversible reaction with the analyte, requiring measurement of the product formation rate [15].

- Catalysis by Immobilized Enzymes: A steady-state measurement of an optically detectable substrate or product [15].

- Antibody-Based Recognition: High selectivity using competitive binding assays, though often with longer response times [15].

A prominent subtype is the nanomechanical optical biosensor, which uses a microcantilever. When molecules bind to one side of the cantilever, the induced differential surface stress causes a measurable deflection, which is typically detected by a reflected laser beam [13]. Another significant category is optical fiber sensors, where the indicator phase is often immobilized on the fiber, and the evanescent field is used for sensing [15].

Table 3: Key Performance Metrics for Optical Transducers

| Transducer Type | Measured Optical Property | Typical Applications | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Indicator-Based | Absorbance, Fluorescence | pH sensing, ion concentration (Kâº, Naâº) | Continuous measurements, reversible |

| Fluorescence-Based | Fluorescence Intensity / Quenching | Oxygen sensing, immunoassays | Very high sensitivity |

| Fiber Optic | Change in Evanescent Wave / Refractive Index | In-vivo physiological monitoring (pH, pOâ‚‚) | Miniaturization, safe for in-vivo use [15] |

| Nanomechanical (Microcantilever) | Deflection of a laser beam (Surface Stress) | Label-free DNA hybridization, protein recognition | Extreme sensitivity (femtomolar), real-time, label-free [13] |

Experimental Protocol: Fabrication of a Fluorescence-Based Optical Fiber pH Sensor

This protocol outlines the steps for creating a common optical biosensor: a fluorescence-based pH probe using an optical fiber [15].

Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

Table 4: Essential Materials for Optical Fiber pH Sensor

| Item Name | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Optical Fiber | Waveguide that transmits light to and from the sensing region. |

| Fluorescent pH Indicator Dye | The chemical indicator whose fluorescence properties (intensity or wavelength) change with pH [15]. |

| Polymer Matrix (e.g., porous polymer film) | A substrate for immobilizing the indicator dye on the fiber tip, permeable to H⺠ions but not to the indicator [15]. |

| Covalent Coupling Agents (e.g., silanes) | Used to chemically bond the indicator dye to the polymer matrix or directly to the fiber tip to prevent leaching [15]. |

| Fluorescence Spectrophotometer | Instrument containing a light source to excite the dye and a detector to measure the emitted fluorescence intensity. |

| Flow Cell or Sample Chamber | A holder that fixes the sensor probe in place during measurement in the sample solution. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Fiber Tip Preparation:

- Carefully cleave the end of an optical fiber to ensure a smooth, clean surface.

- Clean the fiber tip with suitable solvents (e.g., acetone, ethanol) and treat it with an oxygen plasma to create reactive hydroxyl groups on the surface.

Indicator Immobilization:

- Covalently immobilize the fluorescent pH indicator dye to the fiber tip. This can be achieved by:

- Silanizing the fiber tip with a reagent like 3-aminopropyltriethoxysilane (APTES).

- Subsequently reacting the amine-functionalized surface with an NHS-ester derivative of the fluorescent dye.

- Alternatively, the dye can be physically entrapped within a porous polymer film (e.g., polyacrylamide) that is then coated onto the fiber tip [15].

- Covalently immobilize the fluorescent pH indicator dye to the fiber tip. This can be achieved by:

Sensor Calibration:

- Connect the prepared sensor probe to the fluorescence spectrophotometer.

- Immerse the sensor tip in a series of standard buffer solutions with known pH values (e.g., from pH 6.0 to 8.5).

- For each buffer, record the fluorescence emission intensity at the characteristic wavelength upon excitation.

- Plot the fluorescence intensity versus pH to create a calibration curve.

Sample Measurement:

- Place the sensor probe into the unknown sample solution.

- Measure the fluorescence intensity under the same conditions used for calibration.

- Determine the pH of the sample by comparing the measured fluorescence intensity to the calibration curve.

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) Platforms

Platform Principles and Applications

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) biosensors are a highly sensitive and prominent class of optical biosensors that have emerged as a leading technology for label-free, real-time monitoring of biomolecular interactions [16] [17]. They function by detecting changes in the refractive index at the surface of a thin metal film (typically gold) upon binding of a target analyte to an immobilized biorecognition element [16]. The core principle involves the excitation of surface plasmons—collective oscillations of electrons at the metal-dielectric interface—by incident light at a specific angle. The binding of analyte molecules to the sensor surface alters the refractive index, leading to a shift in this resonance angle or wavelength, which is measured in real-time [16].

SPR sensors are extensively used to study kinetics, affinity, and specificity of interactions involving proteins, nucleic acids, hormones, cells, and other biomolecules [16]. A significant challenge has been detecting analytes at ultra-low concentrations, down to the single-molecule level. Recent advances employ multi-objective optimization algorithms to concurrently enhance multiple sensing parameters, leading to dramatically improved performance [16] [17]. One such study achieved a 230.22% increase in sensitivity, a 110.94% improvement in the Figure of Merit (FOM), and a 90.85% enhancement in the depth of the resonant dip, culminating in a limit of detection (LOD) as low as 54 ag/mL (0.36 aM) for mouse IgG, enabling single-molecule detection capabilities [16] [17].

Table 5: Key Performance Metrics for SPR Biosensors

| Performance Parameter | Description | Standard Performance | Algorithm-Optimized Performance [16] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity (S) | Shift in resonance signal per unit change in refractive index (nm/RIU) | ~7,415 nm/RIU (Baseline in cited study) | 24,482.86 nm/RIU (+230.22%) |

| Figure of Merit (FOM) | Ratio of Sensitivity to Resonance Dip Width (1/RIU) | ~17.41 1/RIU (Baseline) | 36.72 1/RIU (+110.94%) |

| Depth of Resonant Dip (DRD) | The magnitude of the reflectivity minimum | Baseline | +90.85% enhancement |

| Limit of Detection (LOD) | Lowest detectable concentration of analyte | > 1 fg/mL for single molecules | 54 ag/mL (0.36 aM) for mouse IgG |

Experimental Protocol: Algorithm-Assisted Optimization of an SPR Biosensor

This protocol describes a comprehensive method for optimizing the design parameters of a prism-coupled Kretschmann-configuration SPR biosensor using a multi-objective Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) algorithm [16].

Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

Table 6: Essential Materials for SPR Biosensor Optimization

| Item Name | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| SPR Prism Coupler | High-refractive-index prism (e.g., BK7) to couple incident light to the surface plasmons in the metal layer. |

| Metal Deposition System (e.g., e-beam evaporator) | For depositing thin, uniform layers of chromium (adhesive layer) and gold (active plasmonic layer) onto the prism. |

| Optical Setup | Includes a tunable laser light source, polarizer, and a high-resolution angular or spectral detector. |

| Bio-receptor Molecule | The specific capture agent (e.g., antibody, DNA strand) immobilized on the gold surface to bind the target analyte. |

| Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) Algorithm Software | Custom or commercial software to run the multi-objective optimization algorithm for designing the sensor parameters. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Define Optimization Objectives and Parameters:

- Set the key performance metrics to be optimized: Sensitivity (S), Figure of Merit (FOM), and Depth of Resonant Dip (DFOM).

- Define the design parameters to be tuned: incident angle, chromium adhesive layer thickness, and gold layer thickness.

Implement the Multi-Objective PSO Algorithm:

- Model the SPR system (prism/Cr/Au/analyte) as a multi-layer structure and use the transfer matrix method to compute its optical characteristics.

- Configure the PSO algorithm to iteratively search for the combination of design parameters (incident angle, Cr thickness, Au thickness) that maximizes the composite fitness function based on S, FOM, and DFOM.

- Run the algorithm for a sufficient number of iterations (e.g., 150) until the fitness function converges to a maximum value [16].

Sensor Fabrication Based on Optimized Parameters:

- Using the optimal parameters provided by the algorithm (e.g., specific Au and Cr thicknesses), fabricate the SPR chip.

- Clean the gold surface of the SPR chip via plasma treatment.

- Functionalize the gold surface by creating a self-assembled monolayer (e.g., using thiol chemistry) and immobilize the bio-receptor (e.g., anti-mouse IgG antibody) onto it.

Performance Validation:

- Set up the SPR instrument with the incident angle fixed at the optimized value.

- Flow a series of known concentrations of the target analyte (e.g., mouse IgG) over the sensor surface.

- Record the sensorgram (resonance shift vs. time) for each concentration.

- Plot the steady-state resonance shift against the logarithm of analyte concentration to establish a calibration curve and determine the Limit of Detection (LOD).

The integration of nanomaterials into biosensing platforms has marked a revolutionary advance in diagnostic technology, primarily by addressing the critical challenge of specificity. Specificity, the ability of a biosensor to selectively identify a target analyte within a complex biological matrix, is paramount for accurate diagnosis, environmental monitoring, and food safety. Traditional biosensors often struggle with cross-reactivity and insufficient selectivity. Nanomaterials such as graphene, carbon nanotubes (CNTs), and metal nanoparticles possess unique physicochemical properties—including an exceptionally high surface-to-volume ratio, tunable surface chemistry, and superior electronic properties—that make them ideal for enhancing specificity. Their functionalization with various biorecognition elements allows for precise molecular interactions, significantly reducing false-positive signals and enabling the detection of biomarkers at ultralow concentrations. This document, framed within a broader thesis on optimizing biosensor fabrication, provides detailed application notes and experimental protocols for employing these nanomaterials to achieve maximum specificity in research settings.

Performance Comparison of Nanomaterial-Enhanced Biosensors

The table below summarizes key performance metrics of biosensors utilizing graphene, carbon nanotubes, and metal nanoparticles, highlighting their role as specificity enhancers.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Nanomaterial-Based Biosensors for Specificity Enhancement

| Nanomaterial | Target Analyte | Biorecognition Element | Detection Limit | Linear Range | Key Advantage for Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Graphene (FET) | Ferritin (for anemia) | Anti-ferritin antibodies | Not Specified | Not Specified | Label-free, real-time response in complex saliva samples [18] |

| Graphene (SPR) | Hemoglobin | Not Specified | Not Specified | Not Specified | High-sensitivity, label-free clinical detection in blood [18] |

| CNT-FET | SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein | Antibodies | Not Specified | Not Specified | Rapid, accurate diagnostics via specific antibody conjugation [19] |

| CNT-FET | Salmonella enterica | Aptamer | Not Specified | Not Specified | High precision for single-pathogen detection [19] |

| Platinum NP (Electrochemical) | Glutamate | Glutamate Oxidase | 0.03 µM | 1–925 µM | Excellent selectivity for neurotransmitters in brain tissue [20] |

| Platinum NP (Electrochemical) | Organophosphorus Pesticides (Malathion) | Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) | 4.9 × 10â»Â¹âµ M | 4.9×10â»Â¹âµ to 1×10â»â¹ M | Specific enzyme inhibition mechanism [20] |

| Gold NP (Optical) | Cancer Biomarkers | Antibodies | Femto- to Picomolar | Not Specified | Strong LSPR enhances sensitivity in colorimetric assays [21] |

Application Notes and Experimental Protocols

Graphene-Based Field-Effect Transistor (FET) Biosensor

Application Note: Graphene's high carrier mobility and large surface area make it an excellent channel material for FET biosensors. Its atomically thin structure is exquisitely sensitive to electrostatic changes induced by the binding of a target biomolecule to a functionalized surface, enabling label-free, highly specific detection. This protocol details the fabrication of a GFET for the detection of ferritin in saliva, a non-invasive method for diagnosing iron deficiency anemia [18].

Experimental Protocol: Fabrication and Detection of Salivary Ferritin

- Objective: To construct a GFET biosensor functionalized with anti-ferritin antibodies for the specific, label-free detection of ferritin in human saliva.

Materials:

- Graphene film (synthesized via CVD or mechanical exfoliation)

- Silicon wafer with a SiOâ‚‚ layer (back-gate electrode)

- Photoresist and developer

- Electron beam evaporator for electrode deposition

- Gold (Au) and Chromium (Cr) source

- 1-Pyrenebutyric acid N-hydroxysuccinimide ester (PBASE) linker

- Anti-ferritin antibody solution (monoclonal, 100 µg/mL in PBS)

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), pH 7.4

- Ethanolamine solution (1M, pH 8.5) for blocking

- Saliva samples (centrifuged and filtered)

Procedure:

- Device Fabrication:

- Transfer a monolayer of graphene onto a pre-cleaned SiOâ‚‚/Si substrate.

- Pattern the graphene channel using photolithography and oxygen plasma etching.

- Deposit source and drain electrodes (typically 10/50 nm Cr/Au) using photolithography and an e-beam evaporator.

- Surface Functionalization:

- Incubate the GFET chip in a 2 mM solution of PBASE in dimethylformamide (DMF) for 1 hour. The pyrene group of PBASE non-covalently anchors to the graphene surface via π-π stacking.

- Rinse thoroughly with DMF and PBS to remove unbound linkers.

- Immerse the chip in the anti-ferritin antibody solution and incubate for 2 hours at 4°C. The NHS ester group of PBASE covalently binds to amine groups on the antibodies.

- Rinse with PBS to remove physically adsorbed antibodies.

- Block non-specific sites by incubating with 1M ethanolamine for 30 minutes.

- Electrical Measurement and Detection:

- Mount the functionalized GFET in a liquid-cell measurement setup.

- Apply a fixed drain-source voltage (Vds) and monitor the drain-source current (Ids) while applying a sweeping gate voltage (Vg) through a reference electrode in the solution to obtain the Dirac point transfer characteristic.

- Introduce the prepared saliva sample (calibrant or unknown) into the cell.

- Monitor the real-time shift in the Dirac point voltage (∆VDirac) upon binding of ferritin to the immobilized antibodies. This shift is proportional to the analyte concentration.

- Device Fabrication:

Data Analysis: Plot the ∆VDirac as a function of ferritin concentration to generate a calibration curve. The specificity can be validated by testing against other common salivary proteins.

Carbon Nanotube-Based FET (CNT-FET) Biosensor

Application Note: CNT-FETs leverage the exceptional electronic properties of semiconducting single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs). Functionalization of the CNT surface with specific biorecognition elements like aptamers or antibodies allows for the highly specific detection of pathogens and biomarkers through changes in conductance. This protocol describes the development of an aptamer-functionalized CNT-FET for detecting Salmonella enterica [19].

Experimental Protocol: Aptamer-Functionalized CNT-FET for Pathogen Detection

- Objective: To fabricate a CNT-FET biosensor functionalized with an aptamer for the specific, label-free detection of Salmonella enterica.

Materials:

- Semiconducting SWCNTs (aqueous suspension)

- SiOâ‚‚/Si substrate with pre-patterned Au/Cr electrodes

- PBASE linker

- Amino-terminated DNA aptamer specific to Salmonella enterica

- N-(3-Dimethylaminopropyl)-N′-ethylcarbodiimide (EDC) and N-Hydroxysuccinimide (NHS)

- 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid (MES) buffer

- Salmonella enterica culture (inactivated)

- Tris-EDTA (TE) buffer and PBS

Procedure:

- CNT Channel Formation:

- Deposit the SWCNT suspension onto the SiOâ‚‚/Si substrate between the pre-patterned source and drain electrodes, followed by rinsing and drying to form a random network CNT channel.

- Aptamer Immobilization:

- Incubate the CNT-FET device in a 5 mM PBASE solution in DMF for 2 hours. Rinse with DMF and MES buffer.

- Activate the PBASE's NHS ester by treating the device with a fresh mixture of EDC and NHS in MES buffer for 30 minutes.

- Rinse with MES buffer and immediately incubate with the amino-terminated aptamer solution (1 µM in TE buffer) for 3 hours. The activated NHS ester forms a stable amide bond with the aptamer's terminal amine group.

- Rinse with PBS to remove unbound aptamers.

- Electrical Measurement and Detection:

- Place the functionalized CNT-FET in a custom measurement setup.

- Apply a fixed Vds and record Ids while sweeping the liquid-gate voltage (Vg) to obtain the transfer characteristic.

- Introduce solutions containing varying concentrations of Salmonella enterica or control bacteria.

- Record the change in device conductance (or Ids at a fixed Vg) in real-time upon target binding.

- CNT Channel Formation:

Data Analysis: The specific binding of the pathogen to the aptamer induces a measurable shift in the transfer curve. The sensitivity and specificity are determined by the response to the target pathogen versus non-target bacteria.

Platinum Nanoparticle-Based Electrochemical Biosensor

Application Note: Platinum nanoparticles (Pt NPs) exhibit exceptional electrocatalytic properties, particularly towards the oxidation of hydrogen peroxide (Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚), a common byproduct of oxidase-based enzymatic reactions. This makes them ideal for enhancing the sensitivity and specificity of enzymatic electrochemical biosensors. This protocol outlines the construction of a Pt NP-based biosensor for the detection of L-glutamate, a key neurotransmitter [20].

Experimental Protocol: Pt NP/Enzyme Biosensor for Glutamate Detection

- Objective: To develop a highly sensitive and selective electrochemical biosensor for L-glutamate by immobilizing glutamate oxidase (GluOx) on a Pt NP-modified electrode.

Materials:

- Glassy carbon electrode (GCE)

- Platinum nanoparticle (Pt NP) colloid or precursors for electrochemical deposition

- Graphene oxide (GO) or reduced graphene oxide (rGO) dispersion

- Glutamate Oxidase (GluOx)

- EDC and NHS

- Chitosan solution (0.5% w/v in acetic acid)

- L-glutamate standard solutions

- PBS (pH 7.4)

Procedure:

- Electrode Modification:

- Polish the GCE with alumina slurry and sonicate in water and ethanol.

- Drop-cast a known volume of GO/rGO dispersion onto the GCE surface and dry.

- Electrodeposit or drop-cast Pt NPs onto the GO/rGO-modified GCE to form a Pt NP/rGO nanocomposite.

- Enzyme Immobilization:

- Activate the carboxylic groups on the nanocomposite by treating with EDC/NHS solution for 1 hour.

- Rinse and incubate the electrode with GluOx solution (2 mg/mL in PBS) overnight at 4°C.

- Alternatively, mix GluOx with a chitosan solution and drop-cast the mixture onto the modified electrode, allowing it to dry and form a stable hydrogel film.

- Amperometric Detection:

- Connect the biosensor to a potentiostat in a three-electrode configuration (biosensor as working electrode, Ag/AgCl reference, Pt wire counter).

- Immerse the electrode in stirred PBS and apply a constant potential of +0.7V (vs. Ag/AgCl) to oxidize Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚.

- Allow the background current to stabilize.

- Spike with successive additions of L-glutamate standard solution.

- Record the amperometric current-time (i-t) response. The steady-state current increase after each addition is proportional to the glutamate concentration.

- Electrode Modification:

Data Analysis: Plot the steady-state current versus glutamate concentration to obtain the calibration curve. The sensor's specificity is confirmed by testing against other amino acids like glutamine and aspartic acid, which should not generate a significant response.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents for Nanomaterial Biosensor Fabrication

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role in Specificity Enhancement | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| PBASE (1-pyrenebutyric acid N-hydroxysuccinimide ester) | A heterobifunctional crosslinker; pyrene group anchors to carbon nanomaterials via π-π stacking, NHS ester group covalently binds to amine groups on antibodies/aptamers. | Stable functionalization of Graphene FETs and CNT-FETs [19] [18]. |

| EDC & NHS Crosslinkers | Activate carboxylic acid groups on nanomaterials or support matrices to form stable amide bonds with amine-containing biomolecules. | Covalent immobilization of enzymes on Pt NP composites [20]. |

| Specific Aptamers | Single-stranded DNA/RNA oligonucleotides that bind to targets (proteins, cells) with high affinity and specificity; offer stability and design flexibility. | High-precision detection of pathogens like Salmonella on CNT-FETs [19]. |

| Monoclonal Antibodies | Provide high binding specificity and affinity to unique epitopes on target antigens, forming the primary recognition layer. | Detection of disease-specific biomarkers (SARS-CoV-2, ferritin) [19] [18]. |

| Chitosan | A natural biopolymer; forms a porous, biocompatible hydrogel matrix for entrapping enzymes and nanoparticles on electrode surfaces. | Immobilization of glutamate oxidase in Pt NP biosensors [20]. |

| Polyethyleneimine (PEI) | A polymer dopant; can modulate the conductivity and charge of CNTs, and provide primary amine groups for biomolecule conjugation. | Used in polymer doping strategies for CNT-FETs [19]. |

| GlcN-6-P Synthase-IN-1 | GlcN-6-P Synthase-IN-1, MF:C20H21N7S, MW:391.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Acetylcysteine-15N | Acetylcysteine-15N, MF:C5H9NO3S, MW:164.19 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Advanced Fabrication Techniques and Immobilization Strategies for Enhanced Specificity

Within the framework of optimizing biosensor fabrication for maximum specificity, the choice of enzyme immobilization strategy is a critical determinant of analytical performance. Enzyme-based biosensors rely on the precise confinement of biological catalysts on the transducer surface to facilitate specific analyte recognition and signal generation [22] [23]. Among the available techniques, cross-linking and entrapment represent two fundamentally different philosophies for enzyme stabilization. Cross-linking creates strong, covalent intermolecular bonds between enzyme molecules, often using a bifunctional reagent like glutaraldehyde, resulting in robust, carrier-free aggregates [22] [24]. In contrast, entrapment confines enzymes within the porous matrix of a polymer or silica gel, protecting them from the external environment while allowing substrate and product diffusion [22] [25]. This application note provides a comparative analysis of these two methods, detailing their principles, experimental protocols, and implications for biosensor specificity, stability, and sensitivity, to guide researchers and drug development professionals in selecting the optimal immobilization approach.

Principle and Comparative Analysis

The core distinction between the two methods lies in the nature of enzyme confinement. Cross-linking is a chemical immobilization method based on the formation of covalent bonds. It typically involves the use of bifunctional cross-linkers, most commonly glutaraldehyde, which react with free amino groups (e.g., from lysine residues) on the enzyme's surface to form stable, intermolecular cross-links [22] [26]. This can be performed with or without an inert carrier protein, such as Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA), to form Cross-Linked Enzyme Aggregates (CLEAs) or Cross-Linked Enzyme Crystals (CLECs) [24] [27].

Entrapment, conversely, is a physical method where enzymes are enclosed within a three-dimensional lattice. The enzyme is not bound to the matrix itself but is mechanically restricted within the pores of a polymer network, such as alginate, polyacrylamide, or silica gel, formed around it [25] [26]. This matrix permits the free diffusion of substrates and products while retaining the enzyme.

The following table summarizes the key characteristics of each method.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Cross-linking and Entrapment Immobilization Techniques

| Parameter | Cross-Linking | Entrapment |

|---|---|---|

| Bonding/Confinement | Covalent bonding between enzyme molecules [22] [26] | Physical enclosure within a polymer matrix [25] [27] |

| Required Enzyme Purity | High (often requires crystallized or highly pure enzymes) [24] | Moderate to Low |

| Impact on Enzyme Activity | High risk of activity loss due to conformational changes or modification of active sites [22] [24] | Generally minimal conformational change and activity loss [25] [26] |

| Stability & Reusability | High operational and storage stability; strong binding prevents enzyme leakage [22] [27] | Good stability; enzyme leaching is possible if pore size is too large [25] [27] |

| Mass Transfer Limitations | Low to Moderate | Can be significant; diffusion of substrates and products through the matrix can limit reaction rate [25] [28] |

| Method Simplicity & Cost | Simple procedure but can be expensive due to need for pure enzymes and cross-linking reagents [24] | Generally simple and cost-effective [26] |

| Best Suited for Biosensor Applications | Systems requiring high stability and minimal enzyme leakage, where activity loss can be tolerated or mitigated [23] | Systems with smaller substrates where diffusion is not a major constraint, and for preserving high enzyme activity [23] |

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental structural differences and process workflows for these two immobilization methods.

Figure 1: Workflow and structural comparison of cross-linking and entrapment methods. Cross-linking creates covalent bonds between enzyme molecules, while entrapment encapsulates them within a porous polymer network.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Enzyme Immobilization via Cross-Linking

This protocol describes the synthesis of Cross-Linked Enzyme Aggregates (CLEAs) using glutaraldehyde, a common and effective cross-linker [22] [27].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Enzyme Solution: Prepare a concentrated solution of the highly pure target enzyme in a suitable buffer (e.g., 0.1 M phosphate buffer, pH 7.0).

- Glutaraldehyde Solution: A 2-25% (v/v) solution of glutaraldehyde in the same buffer. The concentration must be optimized to balance stability and activity retention.

- Precipitant: A water-miscible organic solvent such as acetone, ethanol, or ammonium sulfate, selected based on compatibility with the enzyme.

- Washing Buffer: A standard buffer (e.g., 0.1 M phosphate buffer) to remove unreacted cross-linker and non-immobilized enzyme.

Procedure:

- Precipitation: To the enzyme solution, slowly add the precipitant with constant stirring at 4°C until the enzyme aggregates and precipitates out of the solution.

- Cross-Linking: Add the glutaraldehyde solution dropwise to the suspension of enzyme aggregates. The typical cross-linking reaction is allowed to proceed for 1-24 hours at 4°C with mild stirring.

- Quenching and Washing: Terminate the reaction by centrifugation and decanting the supernatant. Wash the resulting CLEAs thoroughly with large volumes of washing buffer to remove any unreacted glutaraldehyde and soluble enzyme.

- Storage: The final CLEA product can be stored in buffer at 4°C until use in biosensor fabrication [22] [23] [27].

Protocol for Enzyme Immobilization via Entrapment (Alginate Gel)

This protocol details a common entrapment method using calcium alginate, prized for its mild, non-denaturing conditions [25] [26].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Sodium Alginate Solution: 2-4% (w/v) sodium alginate dissolved in deionized water.

- Enzyme Solution: The target enzyme dissolved in a compatible, mild buffer.

- Gelling Bath: A 0.1-0.5 M solution of calcium chloride (CaClâ‚‚) in deionized water.

Procedure:

- Mixing: Gently mix the enzyme solution with the sodium alginate solution at room temperature to form a homogeneous enzyme-alginate mixture. Avoid introducing air bubbles.

- Droplet Formation: Using a syringe with a fine needle or a droplet generator, extrude the mixture dropwise into the stirred calcium chloride gelling bath.

- Gelation: Upon contact with Ca²⺠ions, each droplet instantly forms a spherical calcium alginate gel bead, entrapping the enzyme. Allow the beads to harden in the gelling bath for 30-60 minutes.

- Rinsing and Storage: Collect the beads by filtration or sieving, rinse with buffer to remove excess CaCl₂ and surface-bound enzyme, and store in a humidified buffer at 4°C until integration into the biosensor [25] [26].

Impact on Biosensor Performance and Specificity

The choice between cross-linking and entrapment directly influences key biosensor performance metrics critical for research and drug development.

Table 2: Impact on Key Biosensor Performance Parameters

| Performance Parameter | Impact of Cross-Linking | Impact of Entrapment |

|---|---|---|

| Specificity | Generally preserved, but chemical modification could potentially alter enzyme active site accessibility. | High, as the native enzyme conformation is largely undisturbed, maintaining intrinsic specificity [25]. |

| Sensitivity | May be reduced due to partial activity loss from the cross-linking process [29]. | Can be high initially, but apparent sensitivity may be lowered due to mass transfer resistance [28]. |

| Response Time | Typically fast, as there are minimal diffusion barriers for substrates and products. | Can be slowed due to the time required for substrates and products to diffuse through the polymer matrix [25] [28]. |

| Operational/Storage Stability | Very high; covalent bonds prevent enzyme leaching and denaturation, ideal for reusable sensors [22] [27]. | Moderate to good; the matrix offers protection, but enzyme leaching or matrix degradation can occur over time [25]. |

| Lifetime | Long, due to exceptional stability of the covalent linkages [23]. | Moderate; lifetime is limited by the integrity of the entrapping matrix and potential enzyme leakage. |

For biosensor fabrication aimed at maximum specificity, the immobilization method must ensure the enzyme's active site remains accessible and unaltered. Entrapment is advantageous when the enzyme is particularly sensitive to chemical modification, as it preserves the native structure. However, for analytes with larger molecular weights, diffusion limitations through the entrapment matrix can create a partitioning effect that inadvertently enhances specificity against larger interfering substances [25] [23]. Cross-linking, while riskier to activity, provides a stable, leaching-free environment that is crucial for the reproducibility and long-term reliability of biosensors in continuous monitoring applications, such as in bioprocess control or implantable medical devices [23] [30].

The relationship between the immobilization method and the resulting biosensor performance is summarized in the following decision pathway.

Figure 2: Decision pathway for selecting an immobilization method based on biosensor performance requirements and constraints.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for Enzyme Immobilization

| Reagent | Function | Example in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Glutaraldehyde | Bifunctional cross-linker that forms covalent Schiff base bonds with free amino groups on enzymes, creating a stable 3D network [22] [24]. | Cross-linking protocol, step 2. |

| Sodium Alginate | A natural polysaccharide polymer that, in the presence of divalent cations (e.g., Ca²âº), forms a hydrogel matrix for enzyme entrapment [25] [26]. | Entrapment protocol, step 1. |

| Calcium Chloride (CaCl₂) | Source of Ca²⺠ions that cross-link alginate chains, inducing gelation and forming the entrapping beads [25] [26]. | Entrapment protocol, gelling bath. |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | An inert protein often used as a supplement to cross-linking reactions to provide additional binding sites and form a more robust aggregate [23]. | Optional additive in cross-linking. |

| Acetone / Ethanol | Water-miscible organic solvents used to precipitate enzymes from aqueous solution prior to cross-linking [27]. | Cross-linking protocol, step 1. |

| trans-Hydroxy Praziquantel-d5 | trans-Hydroxy Praziquantel-d5, MF:C19H24N2O3, MW:333.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| cis-Dihydro Tetrabenazine-d7 | cis-Dihydro Tetrabenazine-d7, MF:C19H29NO3, MW:326.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The strategic selection between cross-linking and entrapment is fundamental to optimizing biosensor fabrication. This analysis demonstrates that there is no universally superior technique; the optimal choice is dictated by the specific constraints and goals of the application. Entrapment excels in scenarios demanding minimal enzyme modification, offering a gentle and often more specific confinement, ideal for sensitive enzymes and smaller analyte molecules. Cross-linking is the method of choice when the highest possible operational stability and prevention of enzyme leakage are paramount, even at the potential cost of some initial activity. For researchers and drug development professionals, the pathway to maximum biosensor specificity and performance lies in a careful evaluation of these trade-offs, guided by the experimental protocols and decision frameworks provided herein. Future advancements are likely to focus on hybrid strategies and the use of sophisticated nanomaterials to further mitigate the inherent limitations of each method [28] [30].

Maximizing Specificity with Nanomaterial-Enhanced Electrodes

In the field of biosensor fabrication, achieving high specificity is paramount for reliable detection of target analytes in complex biological matrices such as blood, serum, or saliva. Specificity refers to a biosensor's ability to accurately identify and measure a target biomarker while minimizing responses to interfering substances. Nanomaterial-enhanced electrodes have emerged as a powerful platform for maximizing specificity due to their unique physicochemical properties, including high surface-to-volume ratios, tunable surface chemistry, and enhanced electron transfer capabilities. The integration of nanomaterials such as gold nanoparticles (AuNPs), carbon nanotubes (CNTs), graphene, and silica nanoparticles (SNPs) provides strategic advantages for immobilizing biorecognition elements while maintaining their bioactivity and orientation, ultimately leading to significant improvements in analytical performance for clinical diagnostics, particularly in cancer biomarker detection [31] [32] [33].

Nanomaterial Selection for Enhanced Specificity

The choice of nanomaterial is crucial for optimizing biosensor specificity, as different materials offer distinct advantages for various sensing applications. The following table summarizes the key properties and contributions of prominent nanomaterials to biosensor specificity:

Table 1: Nanomaterial Properties and Their Contributions to Biosensor Specificity

| Nanomaterial | Key Properties | Contribution to Specificity | Exemplary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | Excellent conductivity, biocompatibility, facile functionalization | Enhanced electron transfer, controlled antibody orientation, reduced non-specific binding | CA125 immunosensors for ovarian cancer [33] |

| Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) | High aspect ratio, functionalizable surface, quantum effects | Increased bioreceptor loading, signal amplification, spatial organization of probes | DNA sensors for genetic biomarkers [34] |

| Graphene Oxide/Reduced Graphene Oxide | Large surface area, oxygen functional groups, tunable conductivity | Improved biomolecule immobilization, π-π interactions with probes, charge transfer mediation | Multiplexed cancer biomarker detection [31] [33] |

| Silica Nanoparticles (SNPs) | Tunable porosity, surface silanol groups, mechanical stability | Enzyme stabilization, reduced leaching, protection from denaturation | Horseradish peroxidase biosensors [35] |

| Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) | Ultrahigh porosity, crystalline structure, designable functionality | Molecular sieving effect, size-selective exclusion, enhanced signal-to-noise ratio | Epithelial cancer biomarker platforms [33] |

The exceptional properties of nanomaterials stem fundamentally from their high surface-to-volume ratio, which becomes dramatically more pronounced at the nanoscale. This increased surface area provides more sites for bioreceptor immobilization while enabling more efficient interaction with target analytes [32]. Furthermore, quantum confinement effects in nanomaterials can enhance electronic properties crucial for signal transduction in electrochemical biosensing platforms [32].

Experimental Protocols for Fabricating Nanomaterial-Enhanced Electrodes

Protocol 1: Fabrication of CNT Network-Based DNA Sensor via Inkjet Printing

This protocol describes the fabrication of a flexible, specific DNA sensor using carbon nanotube networks, adapted from research demonstrating successful detection of complementary DNA sequences with minimal non-specific binding [34].

Materials Required:

- Single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs), carboxylic acid functionalized (diameter: 4-5 nm, length: 0.5-1.5 µm)

- Polyethylene terephthalate (PET) flexible substrate

- Silver nanoparticle ink for electrode printing

- Single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) probes complementary to target sequence

- Phosphate buffer saline (PBS, 0.1 M, pH 7.4)

- Hybridization buffer (typically PBS with 0.1% SDS)

Procedure:

- Substrate Preparation: Clean PET substrate with sequential sonication in acetone, isopropanol, and deionized water (10 minutes each), then dry under nitrogen stream.

- Electrode Printing: Inkjet-print silver electrode array onto PET substrate using predetermined pattern. Cure at 120°C for 30 minutes.

- CNT Sensing Layer Deposition: Deposit functionalized SWCNT suspension (0.5 mg/mL in 0.1% SDS) onto electrode gap via inkjet printing. Dry at room temperature for 2 hours.

- Probe Immobilization: Incubate CNT network with 5 µM ssDNA probe solution in PBS for 16 hours at 4°C. Wash thoroughly with PBS to remove unbound probes.

- Hybridization Assay: Expose functionalized electrode to target DNA solution in hybridization buffer for 60 minutes at 37°C. Perform control experiments with non-complementary DNA to validate specificity.

- Signal Measurement: Measure electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) or differential pulse voltammetry (DPV) signals in appropriate redox mediator.

Validation: The reported limit of detection (LOD) for this sensor is 0.54 nM, with limit of quantification (LoQ) of 1.63 nM. Specificity should be confirmed using non-complementary DNA sequences, with signal difference >80% between complementary and non-complementary targets [34].

Protocol 2: Enzyme Electrode Fabrication Using Silica Nanoparticle Carriers

This protocol details the creation of highly specific enzyme electrodes with preserved catalytic activity using silica nanoparticles as enzyme carriers, significantly improving biosensor stability and operational lifetime [35].

Materials Required:

- Tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS) for silica nanoparticle synthesis

- (3-Aminopropyl)triethoxysilane (APTES) for surface functionalization

- Horseradish peroxidase (HRP) or other target enzyme

- Single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs)

- 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide (EDC) and N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) for covalent coupling

- Phosphate buffer (0.1 M, pH 7.0)

Procedure:

- Silica Nanoparticle Synthesis: Prepare SNPs via Stöber method by hydrolyzing TEOS (830 µL) in mixture of deionized H2O (13.5 mL), ethanol (24.5 mL), and concentrated NH3 (1.22 mL) with vigorous stirring (800 rpm) for 15 minutes. Age overnight on rotary mixer.

- SNP Functionalization: Wash SNPs by centrifugation (3000 rpm, 30 minutes) and resuspend in ethanol. Add APTES (200 µL) and react overnight to create amino-functionalized SNPs (SiO2-NH2). Convert to carboxylic groups by reacting with succinic acid (1% in anhydrous DMF with pyridine) overnight.

- Enzyme Immobilization: Activate carboxylic groups on SNPs with EDC/NHS mixture (0.1 M EDC, 25 mM NHS in phosphate buffer) for 60 minutes. Incubate with HRP solution (0.002 g/80 µL) for 2 hours at room temperature. Wash to remove unbound enzyme.

- Conductive Ink Preparation: Combine SNP-HRP conjugates with SWCNT ink in phosphate buffer. Sonicate to achieve homogeneous dispersion.

- Electrode Fabrication: Inkjet-print the SNP-HRP/SWCNT ink onto electrode substrate. Cure at room temperature for 4 hours.

- Biosensor Validation: Test sensor response to H2O2 using amperometry at -0.4 V vs. Ag/AgCl. Verify specificity against common interferents (ascorbic acid, uric acid, acetaminophen).

Performance Metrics: This approach preserves >90% enzyme activity after 3 months storage, demonstrating exceptional stability. The silica nanoparticle carriers reduce enzyme leaching and protect against denaturation during printing and operation [35].

Quantitative Performance Analysis of Nanomaterial-Enhanced Biosensors

Rigorous performance analysis is essential for validating biosensor specificity. The following table compiles quantitative data from recent studies on nanomaterial-enhanced electrodes for biomarker detection:

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Nanomaterial-Enhanced Biosensors for Biomarker Detection

| Target Analyte | Nanomaterial Platform | Detection Technique | Linear Range | Limit of Detection (LOD) | Specificity Validation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CA125 (Ovarian Cancer) | AuNPs/poly toluidine blue [33] | DPV | 1–500 U mL−1 | 1 mU mL−1 | <5% interference from other tumor markers |

| DNA Sequences | CNT network on inkjet-printed Ag electrodes [34] | EIS | 1–100 nM | 0.54 nM | >80% signal difference for non-complementary DNA |

| Hydrogen Peroxide | SNP-HRP/SWCNT [35] | Amperometry | 0.01–10 mM | 2.3 µM | Minimal interference from common electroactive species |

| Carcinoembryonic Antigen (CEA) | AuNPs/PEI/rGO [31] | DPV | 0.0001–100 ng mL−1 | 0.03 pg mL−1 | <6% cross-reactivity with similar antigens |

| Prostate-Specific Antigen (PSA) | Carbon nanoplatelets [31] | EIS | 0.1–100 ng mL−1 | 0.05 ng mL−1 | Tested against BSA, lysozyme, IgG |

The analytical hierarchy process (AHP) has been employed for quantitative performance analysis of flexible CNT biosensors, systematically evaluating factors influencing specificity before, during, and after mechanical bending [34]. This approach allows researchers to identify and quantify various performance indicators and noise factors that impact biosensor specificity in practical applications.

Research Reagent Solutions for Specificity Optimization