Acetylcholinesterase Inhibition Biosensors: Principles, Advances, and Applications in Biomedical Research and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive overview of acetylcholinesterase (AChE) inhibition biosensors, a critical technology in biomedical and environmental monitoring.

Acetylcholinesterase Inhibition Biosensors: Principles, Advances, and Applications in Biomedical Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of acetylcholinesterase (AChE) inhibition biosensors, a critical technology in biomedical and environmental monitoring. It covers the foundational principle of detecting inhibitors by measuring decreased enzymatic activity, which is pivotal for diagnosing neurological conditions and screening therapeutic agents. The content explores cutting-edge methodological advances, including electrochemical, fluorometric, and colorimetric platforms enhanced by nanomaterials like MOFs and MXenes. It addresses key challenges in sensor optimization, such as improving specificity and reproducibility, and provides a comparative analysis of validation techniques. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes recent progress (2020-2025) to guide the development of next-generation, high-performance biosensing systems.

The Core Principle: How AChE Inhibition Forms the Basis of Modern Biosensing

Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) is a critical serine hydrolase enzyme responsible for the rapid termination of impulse transmission at cholinergic synapses by hydrolyzing the neurotransmitter acetylcholine (ACh) [1]. This enzyme is a primary target for two major classes of synthetic compounds: organophosphorus (OP) compounds and carbamates. While both act as AChE inhibitors, their mechanisms and clinical implications differ significantly. OPs, found in pesticides and nerve agents, irreversibly inhibit AChE, leading to potentially fatal cholinergic crisis [2] [1]. Certain carbamates also exhibit pseudoirreversible inhibition and are used therapeutically in neurodegenerative diseases [3] [1]. Understanding the fundamental mechanism of irreversible AChE inhibition is crucial for developing effective biosensors, medical countermeasures, and therapeutic drugs. This technical guide details the biochemical principles, kinetic characteristics, and experimental methodologies relevant to researchers and drug development professionals working in this field.

Biochemical Mechanism of AChE Inhibition

Catalytic Function of Acetylcholinesterase

AChE exhibits extraordinarily high catalytic activity, hydrolyzing approximately 25,000 molecules of acetylcholine per second, which approaches a diffusion-controlled reaction rate [1]. The enzyme's active site contains a catalytic triad composed of serine (Ser200), histidine (His440), and glutamate (Glu327) [1]. The hydrolysis reaction proceeds through a two-step mechanism: First, the serine hydroxyl group undergoes nucleophilic attack on the substrate's carbonyl carbon, forming a transient tetrahedral intermediate that collapses into an acetyl-enzyme conjugate and releases choline. Second, the acetyl-serine undergoes nucleophilic attack by a water molecule, regenerating the free enzyme and releasing acetate [1].

The active site is positioned at the base of a deep, narrow gorge approximately 20Å long, lined with 14 conserved aromatic amino acids that facilitate substrate guidance and binding [1].

Figure 1: Catalytic Mechanism of Acetylcholinesterase

Molecular Mechanism of Irreversible Inhibition

Organophosphorus compounds and carbamates act as mechanism-based inhibitors that exploit the native catalytic function of AChE. Both classes form covalent adducts with the active site serine, but with dramatically different stability profiles [1].

Organophosphorus Compounds (e.g., pesticides like paraoxon, methamidophos; nerve agents like sarin, soman) contain a pentavalent phosphorus atom that serves as an electrophilic target for the catalytic serine. The inhibition proceeds through phosphorylation (for oxon forms) or phosphonylation (for nerve agents) of the serine hydroxyl group, resulting in a phosphoryl-enzyme conjugate [1] [4]. The stability of the phosphorus-serine bond makes this inhibition effectively irreversible, with spontaneous reactivation occurring extremely slowly over days to weeks [1].

Carbamate Inhibitors (e.g., carbofuran, physostigmine, rivastigmine) also target the catalytic serine, forming a carbamyl-enzyme conjugate. While this bond is technically covalent, it is significantly less stable than the phosphoryl-enzyme bond. The carbamylated enzyme undergoes spontaneous hydrolysis over periods of hours, making carbamate inhibition "pseudoirreversible" or reversible on a practical timescale [1] [5].

The structural orientation of the inhibitor within the active site gorge is critical for inhibition efficiency. Molecular modeling studies show that effective inhibitors position their leaving group opposite the serine Oγ atom to facilitate nucleophilic attack [4].

Figure 2: Comparative Inhibition Pathways for OPs and Carbamates

Experimental Characterization and Kinetics

Kinetic Analysis of Progressive Inhibition

The inhibition of AChE by OPs follows a time- and concentration-dependent progressive inhibition pattern characterized by a two-step mechanism: initial reversible complex formation followed by irreversible phosphorylation [4].

The overall reaction can be represented as: E + I ⇌ E·I → E-I Where E is the enzyme, I is the inhibitor, E·I is the reversible complex, and E-I is the phosphorylated enzyme.

The kinetic constants for progressive inhibition of human AChE (hAChE) and human butyrylcholinesterase (hBChE) by selected OP pesticides are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Inhibition Kinetic Constants of Human Cholinesterases by Organophosphorus Pesticides [4]

| Pesticide | Cholinesterase | kᵢ (m⁻¹min⁻¹) | kmax (min⁻¹) | Kᵢ (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethoprophos | hAChE | 21,200 ± 1,600 | - | - |

| Fenamiphos | hAChE | 1,300 ± 100 | 0.20 ± 0.01 | 76 ± 6 |

| Methamidophos | hAChE | 690 ± 50 | - | - |

| Phosalone | hAChE | 710 ± 60 | - | - |

| Ethoprophos | hBChE | 15,800 ± 1,500 | - | - |

| Fenamiphos | hBChE | 28,600 ± 2,100 | - | - |

| Methamidophos | hBChE | 320 ± 30 | - | - |

| Phosalone | hBChE | 6,800 ± 500 | - | - |

The second-order rate constant of inhibition (kᵢ) reflects the overall efficiency of inhibition, with ethoprophos showing the highest potency against hAChE. For fenamiphos inhibition of hAChE, a saturation curve was observed, enabling determination of the first-order inhibition constant (kmax) and enzyme-inhibitor dissociation constant (Kᵢ) [4].

Reactivation Kinetics

Unlike carbamate inhibition, which reverses spontaneously, OP-inhibited AChE requires specific reactivators, primarily oxime compounds that act as nucleophiles to displace the phosphoryl group from the active site serine [1] [4]. Reactivation efficiency varies significantly based on the specific OP compound and oxime structure, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2: Reactivation Kinetics of Human AChE Inhibited by Phosphoramidate Pesticides [4]

| Oxime | Inhibitor | k₂ (min⁻¹) | KOX (mM) | kr (m⁻¹min⁻¹) | Reactmax (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14A | Methamidophos | 0.32 ± 0.02 | 0.024 ± 0.006 | 13,300 ± 2,000 | 91 ± 2 |

| 14A | Fenamiphos | 0.11 ± 0.01 | 0.15 ± 0.04 | 730 ± 120 | 83 ± 3 |

| RS194B | Methamidophos | 0.26 ± 0.01 | 0.013 ± 0.002 | 20,000 ± 2,000 | 92 ± 1 |

| RS194B | Fenamiphos | 0.10 ± 0.01 | 0.09 ± 0.03 | 1,100 ± 200 | 85 ± 2 |

| 2-PAM | Methamidophos | 0.06 ± 0.01 | 0.9 ± 0.2 | 67 ± 10 | 74 ± 3 |

| 2-PAM | Fenamiphos | 0.03 ± 0.01 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 75 ± 15 | 70 ± 4 |

The zwitterionic oxime RS194B shows remarkable reactivation potential, particularly due to its ability to cross the blood-brain barrier and reactivate AChE in the central nervous system [4].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for AChE Inhibition Studies

| Reagent | Function/Application | Examples/Specific Types |

|---|---|---|

| Acetylcholinesterase | Primary enzyme for inhibition studies | Human recombinant AChE, Electric eel AChE, Erythrocyte-derived AChE [4] [5] |

| Butyrylcholinesterase | Secondary cholinesterase for selectivity studies | Human plasma BChE, Serum-derived BChE [4] |

| Organophosphorus Inhibitors | Progressive irreversible inhibition | Paraoxon, Soman, Sarin, Methamidophos, Fenamiphos [2] [4] |

| Carbamate Inhibitors | Pseudoirreversible inhibition | Carbofuran, Physostigmine, Rivastigmine [1] [5] |

| Oxime Reactivators | Reactivation of OP-inhibited AChE | 2-PAM, Obidoxime, HI-6, RS194B [4] |

| Cholinesterase Substrates | Activity assays | Acetylthiocholine iodide, Acetylcholine [5] |

| Electrochemical Sensors | Biosensor development | AChE-modified electrodes, Carbon black/Vulcan XC 72R-based sensors [5] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Progressive Inhibition Kinetics Assay

Objective: Determine the bimolecular rate constant of inhibition (kᵢ) for an OP compound against AChE [4].

Materials:

- Purified AChE (human recombinant or electric eel)

- OP inhibitor stock solution in appropriate solvent

- Substrate solution (acetylthiocholine iodide, 1-10 mM in buffer)

- DTNB (Ellman's reagent, 0.3-0.5 mM in buffer)

- Phosphate buffer (0.1 M, pH 7.4-8.0)

- Spectrophotometer or plate reader

Procedure:

- Prepare inhibitor dilutions in phosphate buffer across a concentration range (typically 0.1-100 μM)

- Pre-incubate AChE with each inhibitor concentration at 25°C

- At timed intervals, remove aliquots and transfer to substrate/DTNB mixture

- Measure residual enzyme activity by monitoring absorbance at 412 nm

- Plot residual activity versus pre-incubation time for each inhibitor concentration

- Determine the rate constant of inhibition (kobs) for each concentration from the slope of semilogarithmic plots

- Plot kobs versus inhibitor concentration; the slope represents kᵢ

Data Analysis: For inhibitors showing saturation kinetics (e.g., fenamiphos with hAChE), fit data to the equation: kobs = kmax × [I] / (Kᵢ + [I]) where kmax is the maximum inhibition rate constant and Kᵢ is the dissociation constant [4].

Protocol 2: Reactivation Kinetics of Inhibited AChE

Objective: Determine reactivation kinetics parameters for oxime-mediated recovery of OP-inhibited AChE [4].

Materials:

- OP-inhibited AChE preparation

- Oxime reactivators at various concentrations (0.01-1 mM)

- Substrate and detection reagents

- Temperature-controlled spectrophotometer

Procedure:

- Pre-inhibit AChE with OP compound (>95% inhibition)

- Remove excess inhibitor by dialysis, gel filtration, or dilution

- Incubate inhibited enzyme with various oxime concentrations

- Monitor restoration of enzymatic activity over time (up to 24 hours)

- Calculate reactivation rate constants (kobs) for each oxime concentration

- Determine maximum reactivation rate (k₂) and oxime dissociation constant (KOX) from nonlinear regression

Data Analysis: Fit reactivation data to the equation: kobs = k₂ × [oxime] / (KOX + [oxime]) The second-order reactivation rate constant (kr) is calculated as k₂/KOX [4].

Implications for Biosensor Research

Understanding the fundamental mechanisms of irreversible AChE inhibition directly enables the development of advanced biosensing platforms. AChE-based biosensors typically operate on the principle of measuring enzyme inhibition to detect OP and carbamate compounds [3] [5]. Recent advances include electrochemical sensors utilizing immobilized AChE on modified electrodes, where pesticide detection is achieved by measuring the reduction in enzymatic activity when exposed to inhibitors [5].

Key considerations for biosensor design include:

- Enzyme immobilization techniques that preserve catalytic activity while ensuring stability

- Matrix effects from real samples that may interfere with inhibition measurements [5]

- Synergistic inhibition phenomena observed in complex matrices like vegetable oils [5]

- Regeneration strategies using oxime reactivators to create reusable sensor platforms

The detailed kinetic parameters and mechanistic insights provided in this guide serve as fundamental knowledge for optimizing biosensor sensitivity, specificity, and operational stability in environmental monitoring, food safety, and clinical diagnostics.

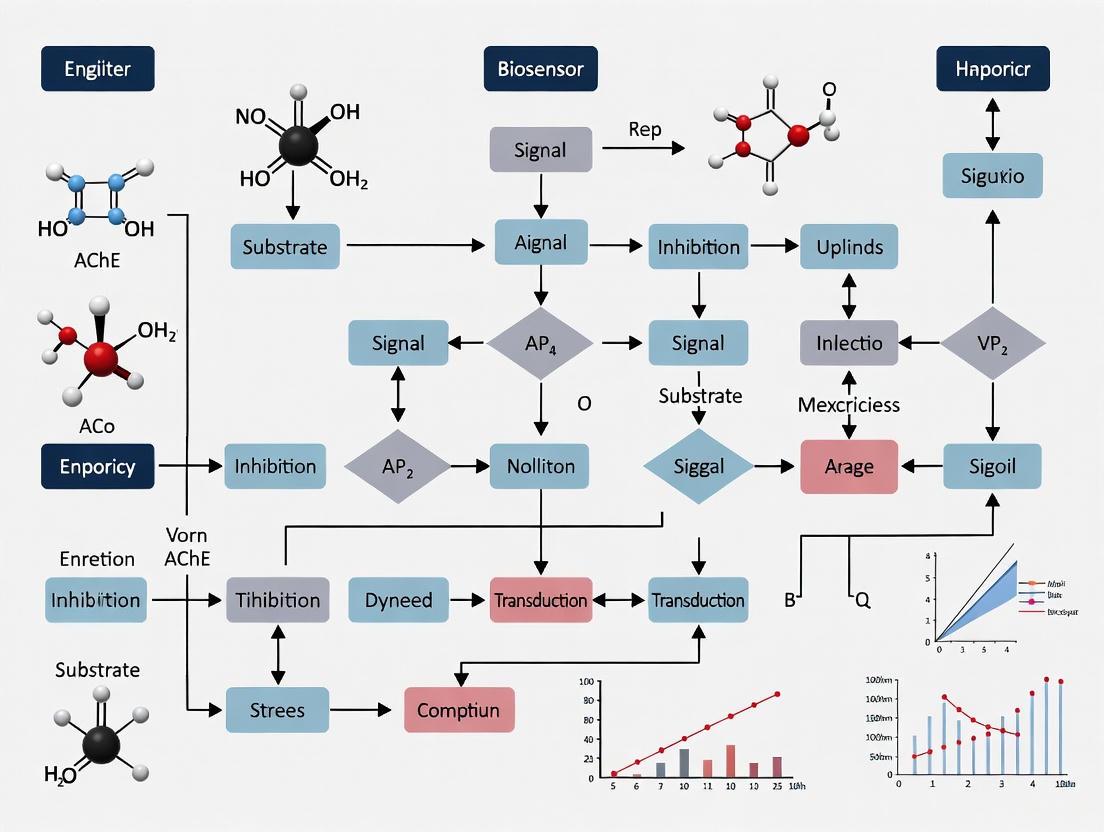

Figure 3: AChE-Based Biosensor Workflow for Inhibitor Detection

Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) inhibition biosensors represent a sophisticated convergence of enzymology, electrochemistry, and materials science. These analytical devices exploit the exquisite specificity of AChE, an enzyme crucial for neurological function, to detect and quantify substances that modulate its activity. The core principle hinges on translating the biochemical hydrolysis of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine into a quantifiable electrical signal, which is subsequently altered in the presence of inhibitors. This technical guide delineates the fundamental pathway from molecular recognition to signal transduction, providing a foundational framework for researchers and drug development professionals working in environmental monitoring, clinical diagnostics, and pharmaceutical research [6] [3].

The operational premise of these biosensors is that neurotoxic compounds, such as organophosphate and carbamate pesticides, as well as certain therapeutic drugs, act as AChE inhibitors. By monitoring the inhibition of AChE activity, these biosensors can indirectly detect and measure the concentration of these biologically significant analytes. The integration of immobilized AChE with physical transducers combines the specificity of biological recognition with the precision and speed of physical measurement, offering a promising alternative to more cumbersome analytical techniques like chromatography or mass spectrometry [6].

The Fundamental Biochemical Pathway of Acetylcholine Hydrolysis

Catalytic Mechanism of Acetylcholinesterase

Acetylcholinesterase is a serine hydrolase that catalyzes the cleavage of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine (ACh) into choline and acetic acid. This reaction is paramount for terminating synaptic signals in cholinergic systems, thereby ensuring discrete neurotransmission [7] [8]. AChE is one of the most efficient enzymes known, operating at a rate approaching the diffusion-controlled limit, with a single molecule hydrolyzing approximately 10,000 acetylcholine molecules per second [3] [9].

The catalytic process occurs within a deep gorge in the enzyme and proceeds through a multi-step mechanism involving a catalytic triad and an oxyanion hole, as detailed in Table 1. The mechanism can be conceptually divided into two primary stages: acylation and deacylation, as illustrated in Figure 1 [9] [10].

Table 1: Key Components of the AChE Active Site and Their Roles

| Component | Role in Catalysis |

|---|---|

| Catalytic Triad | Serine-203, Histidine-447, Glutamate-334 (mouse AChE numbering) [9] [10]. |

| Ser-203 | Serves as the nucleophile, becoming covalently attached to the substrate during the reaction [10]. |

| His-447 | Acts as a general acid/base, activating Ser-203 and the catalytic water molecule [10]. |

| Glu-334 | Modifies the pKa of His-447 and stabilizes the transition state electrostatically [10]. |

| Oxyanion Hole | Comprised of the backbone NH groups of Gly-121, Gly-122, and Ala-204 [9] [10]. |

| Function | Stabilizes the negatively charged tetrahedral intermediate and transition states during catalysis [9]. |

Figure 1: The Catalytic Cycle of Acetylcholine Hydrolysis by AChE. The process involves acylation (formation and breakdown of the first tetrahedral intermediate) and deacylation (hydrolysis of the acetyl-enzyme complex) stages [9] [10].

Stages of the Hydrolysis Reaction

- Acylation Stage: The reaction initiates with the nucleophilic attack by the oxygen atom of Ser-203 on the carbonyl carbon of acetylcholine. This step is concerted with a proton transfer from Ser-203 to His-447, facilitated by Glu-334, leading to the formation of a short-lived, tetrahedral intermediate (TI1). This intermediate is stabilized by hydrogen bonds within the oxyanion hole. The intermediate then collapses, resulting in the cleavage of the ester bond, release of the choline molecule, and formation of a covalent acetyl-enzyme intermediate [9].

- Deacylation Stage: A water molecule, activated by the now protonated His-447, performs a nucleophilic attack on the carbonyl carbon of the acetyl-enzyme intermediate. This forms a second tetrahedral intermediate (TI2), which is also stabilized by the oxyanion hole. The subsequent collapse of TI2 results in the release of acetic acid and the regeneration of the free enzyme, which is then available for another catalytic cycle [9] [10].

This efficient hydrolysis is the critical biochemical event that AChE biosensors harness and monitor.

Transduction of Hydrolysis into a Measurable Signal

To convert the biochemical reaction into a quantifiable signal, biosensors employ synthetic substrates and sophisticated transducer interfaces. The most common strategy involves using acetylthiocholine (ATCh) as a substrate analogue.

From Biochemical to Electrochemical Reaction

In a typical electrochemical AChE biosensor, the native substrate acetylcholine is replaced by acetylthiocholine iodide (ATCh). The immobilized AChE catalyzes the hydrolysis of ATCh, producing thiocholine and acetate [11] [12]. Thiocholine is an electroactive species, unlike choline, which allows for its direct detection.

The transduction pathway, from inhibitor presence to signal output, is summarized in the following workflow:

Figure 2: Workflow of an AChE Inhibition Biosensor. The presence of an inhibitor reduces the production of thiocholine, leading to a measurable decrease in the amperometric signal [6] [12].

Electrochemical Detection and Signal Enhancement

The generated thiocholine (TCh) can be oxidized at the surface of an electrode: 2 TCh → Dithio-bis-choline + 2 H⁺ + 2 e⁻ [12]. The resulting anodic current is directly proportional to the enzyme activity. In the presence of an AChE inhibitor, less TCh is produced, leading to a reduction in the measured current. The degree of current inhibition is quantitatively related to the concentration of the inhibitor [6] [13].

A significant challenge is the high overpotential required for the direct oxidation of TCh on bare electrodes, which can lead to poor sensitivity and electrode fouling. To overcome this, biosensor designs frequently incorporate mediators and nanomaterials to enhance electron transfer, as detailed in Table 2.

Table 2: Common Mediators and Nanomaterials in AChE Biosensors

| Material/Mediator | Function | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Redox Dyes | Electropolymerized to form stable, mediating films on the electrode surface. | Thionine, Methylene Blue [12]. |

| Macrocyclic Molecules | Act as electrocatalysts, lowering the overpotential for thiocholine oxidation. | Pillar[5]arene (P[5]A) [12]. |

| Carbon Nanomaterials | Increase the effective surface area and enhance electron transfer kinetics. | Carbon black, reduced graphene oxide, carbon nanotubes [6] [12]. |

| Metallic Nanoparticles | Improve conductivity and can catalyze electrochemical reactions. | Gold (Au) nanoparticles [6] [12]. |

| Composite Matrices | Used to entrap and stabilize the enzyme on the transducer surface. | Chitosan, Nafion [13] [12]. |

Experimental Protocols for Biosensor Construction and Interrogation

This section provides a detailed methodology for fabricating a representative AChE biosensor and utilizing it for inhibitor detection.

Protocol: Fabrication of a Flow-Through AChE Biosensor with a Modified Electrode

This protocol is adapted from recent work on flow-through systems with replaceable enzyme reactors [12].

Objective: To construct an amperometric biosensor for the detection of AChE inhibitors using a screen-printed carbon electrode (SPCE) modified with carbon black-pillar[5]arene and electropolymerized mediators, coupled with a 3D-printed enzyme reactor.

Materials & Reagents:

- Acetylcholinesterase (AChE): From electric eel (e.g., 518 U/mg, Sigma-Aldrich) [12].

- Screen-printed carbon electrodes (SPCEs)

- Carbon Black (CB) N220 and Pillar[5]arene (P[5]A)

- Mediators: Thionine acetate, Methylene Blue (MB)

- Cross-linkers: N-(3-Dimethylaminopropyl)-N′-ethylcarbodiimide (EDC), N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS)

- Substrate: Acetylthiocholine iodide (ATCh)

- Poly(lactic acid) for 3D printing the flow cell

- Buffer: 0.1 M Phosphate Buffer Saline (PBS), pH 7.0-8.0, with 0.1 M KCl

Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Acetylthiocholine (ATCh) | Synthetic substrate; its hydrolysis generates electroactive thiocholine [12]. |

| Butyrylthiocholine (BuTCh) | Alternative substrate for butyrylcholinesterase (BuChE)-based sensors [11]. |

| Thionine / Methylene Blue | Redox dyes; electropolymerized to create a mediating layer on the electrode [12]. |

| Pillar[5]arene (P[5]A) | Synthetic macrocycle; acts as an electrocatalyst for thiocholine oxidation [12]. |

| Carbon Black (CB) | Nanostructured carbon material; increases electrode surface area and adsorption of mediators [12]. |

| Chitosan (CS) | Biopolymer; used as a biocompatible matrix for enzyme immobilization [13]. |

| Glutaraldehyde | Cross-linking agent; used to covalently immobilize enzymes on support surfaces [13]. |

| Nafion | Cation-exchange polymer; used to form permselective membranes and stabilize the sensing layer [13]. |

| EDC / NHS | Carbodiimide cross-linkers; activate carboxyl groups for covalent enzyme immobilization [12]. |

Procedure:

- Electrode Modification: a. Prepare a dispersion of Carbon Black (CB) and P[5]A in a suitable solvent (e.g., water/ethanol). b. Deposit the CB-P[5]A suspension onto the working area of the SPCE and allow to dry. c. Electropolymerize a mixture of thionine and Methylene Blue onto the modified SPCE by performing cyclic voltammetry (e.g., 15 cycles between -0.6 and +1.0 V at 50 mV/s) in a solution containing the dyes.

- Enzyme Reactor Preparation: a. Fabricate the flow cell body, including a reactor chamber, using a 3D printer and poly(lactic acid) filament. b. Immobilize AChE on the inner wall of the reactor chamber. This can be achieved by physical adsorption or covalent binding after activating the surface. For example, incubate the reactor with an AChE solution (e.g., in pH 7.3 phosphate buffer) for a defined period (e.g., 25 minutes), then wash and dry [12].

- Biosensor Assembly: a. Assemble the flow-through cell by connecting the modified SPCE and the AChE-loaded reactor. b. Integrate the cell with a peristaltic pump for buffer and sample delivery and connect to a potentiostat.

Protocol: Measurement of AChE Inhibition for Inhibitor Detection

Objective: To quantify reversible and irreversible AChE inhibitors using the fabricated biosensor.

Principle: The rate of thiocholine production, and thus the measured amperometric current, is inversely proportional to the degree of enzyme inhibition caused by the target analyte.

Procedure:

- Baseline Activity Measurement: a. Pump a stream of phosphate buffer (e.g., 0.1 M PBS, pH 8.0) through the assembled biosensor at a constant flow rate. b. Inject a known concentration of the substrate ATCh into the flow stream. c. Measure the steady-state amperometric current (at an applied potential of e.g., -0.25 V vs. Ag/AgCl) generated by the oxidation of thiocholine. This current (I₀) represents the uninhibited enzyme activity [12].

- Inhibition (Incubation) Step: a. Expose the AChE reactor to a solution containing the inhibitor (e.g., pesticide or drug) for a fixed incubation time (e.g., 5-15 minutes). This can be done by injecting the sample into the buffer stream and stopping the flow, or by continuous flow of the inhibitor solution.

- Inhibited Activity Measurement: a. Thoroughly rinse the system with clean buffer to remove any unbound inhibitor. b. Re-inject the same concentration of ATCh and measure the new steady-state current (Iᵢ).

- Data Analysis: a. Calculate the percentage of enzyme inhibition (I%) using the formula: I% = [(I₀ - Iᵢ) / I₀] × 100 [11] [12]. b. The inhibitor concentration in an unknown sample is determined by interpolation from a calibration curve plotting I% against the logarithm of standard inhibitor concentrations.

Table 3: Example Analytical Performance for Various Inhibitors

| Inhibitor | Type | Linear Range | Application in Real Samples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carbofuran (Carbamate Pesticide) | Irreversible | 10 nM – 0.1 µM | Detection in spiked peanut samples [12]. |

| Donepezil (Anti-Alzheimer's Drug) | Reversible | 1.0 nM – 1.0 µM | Determination in spiked artificial urine [12]. |

| Nerve Agents (e.g., Sarin, VX) | Irreversible | ~ 0.001 µg/mL in water (visual detection) | Detection in water [11]. |

The pathway from acetylcholine hydrolysis to a measurable signal is a elegant example of bioanalytical chemistry. The core enzymatic reaction, optimized over millennia of evolution, provides the specificity. Materials science and electrochemistry provide the means to transduce this molecular event into a reliable, quantifiable signal through the strategic use of synthetic substrates, engineered interfaces, and signal mediators. Understanding this pathway in depth—from the atomic-level details of the catalytic gorge to the practical considerations of electrode modification—is fundamental for researchers aiming to develop next-generation AChE biosensors with enhanced sensitivity, stability, and applicability for on-site monitoring and precise clinical diagnostics. Future directions will likely focus on further miniaturization, multiplexing capabilities, and improving robustness against complex sample matrix effects [6] [13].

Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) is a pivotal enzyme in cholinergic neurotransmission, serving as a critical biorecognition element in biosensing technologies. Its primary biological role involves terminating impulse transmission at cholinergic synapses through rapid hydrolysis of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine (ACh) into choline and acetic acid [14] [1]. This specific catalytic activity, combined with its sensitivity to inhibition by various compounds, makes AChE an exceptionally powerful biological recognition component for detecting both therapeutic agents and neurotoxic substances [15] [6].

The fundamental significance of AChE-based biosensing lies in its dual applicability across therapeutic monitoring and toxicological screening. In therapeutic contexts, these biosensors enable precise quantification of anti-Alzheimer's drugs that act as reversible AChE inhibitors [16]. In environmental and food safety applications, they provide sensitive detection platforms for organophosphorus (OP) and carbamate pesticides that irreversibly inhibit AChE activity [17] [6]. This versatility, grounded in the enzyme's specific biochemical interactions, positions AChE-based biosensing as an indispensable technology across clinical, environmental, and industrial domains.

Structural and Functional Basis for AChE Specificity

Molecular Architecture and Catalytic Mechanism

AChE possesses a remarkably efficient catalytic architecture characterized by a deep, narrow gorge that penetrates halfway into the enzyme [1] [18]. This unique structural feature contains several functionally distinct subsites that collectively enable AChE's exceptional catalytic proficiency, with each molecule capable of degrading approximately 25,000 acetylcholine molecules per second – a rate approaching diffusion-controlled limits [1].

The catalytic triad forms the biochemical core of AChE's hydrolytic function, consisting of serine, histidine, and glutamate residues (specifically Ser203, His447, and Glu334 in human AChE) [1] [18]. This triad operates through a sophisticated mechanism where histidine facilitates proton transfer, enabling nucleophilic attack by serine on the substrate's carbonyl carbon. The reaction proceeds through a tetrahedral transition state that decomposes to release choline, followed by rapid hydrolysis of the acetyl-enzyme intermediate to regenerate free AChE and release acetate [1].

Beyond the catalytic triad, AChE's specificity is further refined by complementary structural elements. The anionic subsite, comprising 14 conserved aromatic residues, provides optimal binding orientation for acetylcholine's quaternary ammonium group through cation-π interactions rather than electrostatic forces [1]. The peripheral anionic site (PAS), located near the gorge entrance, contributes to substrate guidance and allosteric modulation of catalytic activity [18]. This intricate architectural organization ensures both remarkable catalytic efficiency and exceptional substrate specificity.

Inhibition Mechanisms

The specificity of AChE as a biorecognition element derives substantially from distinct inhibition mechanisms exhibited by different classes of compounds:

Irreversible Inhibition: Organophosphorus compounds (nerve agents, pesticides) phosphorylate the catalytic serine residue, forming covalently modified enzyme that cannot hydrolyze acetylcholine [1] [6]. This inhibition requires strong nucleophiles (oximes) for reactivation and underlies AChE's utility in detecting neurotoxic pesticides.

Reversible Inhibition: Therapeutic agents for Alzheimer's disease (donepezil, rivastigmine, galantamine) competitively inhibit AChE through non-covalent interactions, primarily within the active site gorge [1] [16]. These inhibitors increase synaptic acetylcholine levels to compensate for cholinergic deficit in neurodegenerative conditions.

The following diagram illustrates the catalytic and inhibition mechanisms of AChE:

Figure 1: AChE Catalytic and Inhibition Mechanisms. This diagram illustrates acetylcholine hydrolysis and the distinct mechanisms of reversible versus irreversible inhibition.

AChE Biosensing Modalities and Transduction Mechanisms

Electrochemical Biosensors

Electrochemical AChE biosensors represent the most extensively developed modality, leveraging the enzyme's catalytic activity to generate measurable electrical signals. These systems typically employ acetylthiocholine as a synthetic substrate, which AChE hydrolyzes to produce thiocholine and acetate [6]. Thiocholine is then electrochemically oxidized at the transducer surface, generating a quantifiable amperometric or voltammetric signal proportional to enzyme activity.

Inhibition-based detection follows a straightforward principle: when AChE inhibitors (therapeutics or toxins) are present, they reduce enzymatic activity, consequently decreasing thiocholine production and diminishing the electrochemical signal [6] [16]. The magnitude of signal reduction correlates directly with inhibitor concentration, enabling precise quantification. This approach has demonstrated exceptional sensitivity, with detection limits for organophosphorus pesticides reaching nanomolar to picomolar ranges in optimized systems [17].

Recent advancements in electrochemical biosensing have focused on enhancing sensitivity and anti-interference capabilities through nanomaterial integration. Gold nanoparticles, carbon nanotubes, graphene, metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), and MXenes have been successfully incorporated to increase electrode surface area, improve electron transfer kinetics, and facilitate more efficient enzyme immobilization [17] [6]. These nanomaterials significantly boost biosensor performance while enabling miniaturization for field-deployable applications.

Optical Biosensors

Optical AChE biosensors translate enzymatic activity into measurable optical signals through various mechanisms, with colorimetric and fluorometric approaches being most prevalent.

Colorimetric biosensors typically exploit chromogenic substrates that produce visible color changes upon enzymatic hydrolysis. The Ellman's method represents the historical standard, utilizing acetylthiocholine and DTNB to generate yellow-colored 2-nitro-5-thiobenzoate, detectable at 412 nm [19] [20]. Recent innovations have introduced alternative substrates like indoxylacetate, which produces blue indigo upon hydrolysis, offering improved stability and visual detection capabilities [19] [20]. These systems are particularly valuable for rapid, field-based screening applications where sophisticated instrumentation is unavailable.

Fluorometric biosensors offer enhanced sensitivity through fluorescent signal detection. These systems often employ substrates that generate fluorescent products upon enzymatic hydrolysis or utilize fluorescence quenching mechanisms [18] [21]. Advanced approaches incorporate quantum dots, carbon dots, and other nanomaterials to amplify signals and improve detection limits. Ratiometric fluorescence techniques, which measure intensity ratios at two wavelengths, provide internal calibration that minimizes environmental interference and improves quantification accuracy [18].

Emerging and Hybrid Platforms

The evolving landscape of AChE biosensing includes several promising technological developments:

Dual-Mode Sensors: Integrated platforms combining multiple detection principles (e.g., colorimetric and fluorometric, electrochemical and photothermal) enable cross-validation and enhanced reliability [18]. These systems particularly benefit complex sample analysis where matrix effects may compromise single-mode detection.

Smartphone-Integrated Biosensors: Leveraging smartphone cameras as detectors in conjunction with paper-based assays or 3D-printed platforms represents a growing trend toward decentralized testing [20]. These systems facilitate rapid, point-of-care analysis without requiring specialized instrumentation, making AChE-based sensing accessible in resource-limited settings.

Nanozyme-Based Sensors: Engineered nanomaterials with enzyme-mimicking properties (nanozymes) offer superior stability than natural enzymes while maintaining high catalytic efficiency [15] [18]. These synthetic alternatives address limitations associated with biological enzyme instability under harsh operational conditions.

The following table summarizes the principal AChE biosensing modalities and their characteristics:

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of AChE Biosensing Modalities

| Transduction Mechanism | Detection Principle | Typical Substrates | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electrochemical | Measurement of current or potential changes from enzymatic products | Acetylthiocholine | High sensitivity, portability, cost-effectiveness, quantitative precision | Signal interference in complex matrices, enzyme instability on electrodes |

| Colorimetric | Visual detection of color changes from chromogenic reactions | Indoxylacetate, DTNB/acetylthiocholine | Simplicity, low cost, visual readout, suitability for field testing | Moderate sensitivity, subjective interpretation, sample turbidity interference |

| Fluorometric | Fluorescence intensity measurement from enzymatic reactions | Fluorescent probes, quantum dots | Exceptional sensitivity, low detection limits, quantitative accuracy | Instrumentation cost, photobleaching potential, background fluorescence |

| Multi-Mode Platforms | Combined transduction mechanisms | Varies by platform | Cross-validation, enhanced reliability, complementary information | Increased complexity, higher development costs, optimization challenges |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Enzyme Immobilization Strategies

Effective AChE immobilization is crucial for biosensor performance, directly influencing stability, sensitivity, and operational lifespan. The selected immobilization method must preserve enzymatic activity while ensuring secure attachment to the transducer surface. The following table outlines essential reagents and materials for AChE biosensor development:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for AChE Biosensor Development

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Examples/Specific Types |

|---|---|---|

| Acetylcholinesterase | Biorecognition element | Electric eel AChE, human recombinant AChE, erythrocyte-derived AChE |

| Enzyme Substrates | Signal generation | Acetylthiocholine, acetylcholine, indoxylacetate, acetylthiocholine chloride |

| Immobilization Matrices | Enzyme support and stabilization | Gelatin, cellulose membranes, chitosan, MOFs, COFs, MXenes, graphene |

| Crosslinking Agents | Covalent enzyme attachment | Glutaraldehyde, bovine serum albumin (BSA)-glutaraldehyde mixtures |

| Nanomaterials | Signal amplification and electrode modification | Gold nanoparticles, carbon nanotubes, graphene oxide, metal-organic frameworks |

| Inhibitor Standards | Calibration and validation | Paraoxon, carbofuran, donepezil, rivastigmine, galantamine |

Common immobilization approaches include:

Physical Adsorption: Simple deposition of enzyme solution onto transducer surfaces followed by drying. While straightforward, this method often suffers from enzyme leaching and unstable performance.

Covalent Binding: Chemical conjugation of AChE to functionalized surfaces using crosslinkers like glutaraldehyde. This approach minimizes enzyme leakage and enhances operational stability but may reduce specific activity due to random orientation or active site modification.

Entrapment/Encapsulation: Incorporation of AChE within polymeric matrices (e.g., gelatin, chitosan) or porous nanomaterials (e.g., MOFs, COFs). Gelatin entrapment on cellulose matrices has demonstrated exceptional stability, preserving activity for over four months with minimal performance degradation [19].

Affinity Immobilization: Oriented attachment using specific biological interactions. This approach can optimize catalytic efficiency by positioning the active site advantageously toward substrate solution.

The following workflow diagram illustrates a typical AChE biosensor fabrication and application process:

Figure 2: AChE Biosensor Experimental Workflow. This diagram outlines the key steps in biosensor fabrication and application for inhibitor detection.

Representative Experimental Protocols

Colorimetric Cellulose-Based Biosensor

This protocol describes the construction of a simple, cost-effective biosensor for inhibitor screening [19]:

Enzyme Immobilization: Prepare AChE solution (5 U in phosphate buffered saline) and mix with 2% (w/w) gelatin. Apply 20 μL aliquots to cellulose filter paper strips (5 × 50 mm) and dry at 37°C in a humidified incubator.

Substrate Integration: Impregnate the opposite end of cellulose strips with 20 μL of 100 mmol/L indoxylacetate in ethanol. Air-dry at room temperature protected from light.

Assay Procedure: Apply 40 μL of sample solution to the enzyme-containing zone and incubate for 15 minutes. Fold the strip to bring substrate and enzyme zones into contact. Incubate for 30 minutes and assess blue color development visually or via smartphone camera.

Quantification: For semi-quantitative analysis, compare color intensity to calibration standards using arbitrary units (no coloring, + light blue, ++ azure blue, +++ dark blue). For quantitative analysis, use smartphone colorimetry applications measuring RGB channel intensities, with the red channel typically providing optimal sensitivity.

This biosensor format demonstrates excellent stability, retaining full activity for over four months when stored desiccated in darkness at room temperature. The system effectively detects organophosphorus pesticides, carbamates, and therapeutic inhibitors with detection limits in the nanomolar range [19].

Electrochemical Biosensor with Nanomaterial Enhancement

This protocol details the development of a sensitive electrochemical platform for precise inhibitor quantification [17] [6]:

Electrode Modification: Deposit nanomaterials (e.g., graphene oxide, gold nanoparticles, MOFs) on electrode surfaces through drop-casting, electrodeposition, or in-situ synthesis approaches.

Enzyme Immobilization: Apply AChE solution (concentration optimized for specific nanomaterial) to modified electrodes. Crosslink with 0.1-2.5% glutaraldehyde vapor or solution for 30-60 minutes. Alternatively, employ entrapment within polymer matrices like chitosan or Nafion.

Electrochemical Measurement: Incubate the biosensor in sample solution containing potential inhibitors for a fixed time (typically 10-15 minutes). Transfer to electrochemical cell containing acetylthiocholine substrate in appropriate buffer.

Signal Detection: Apply optimal detection potential (typically +0.7-0.8 V vs. Ag/AgCl for thiocholine oxidation) and record amperometric response. Alternatively, employ cyclic voltammetry or differential pulse voltammetry for enhanced specificity.

Data Analysis: Calculate inhibition percentage as (I₀ - I)/I₀ × 100%, where I₀ and I represent current signals before and after inhibitor exposure, respectively. Generate calibration curves using standard inhibitor solutions for quantitative analysis.

Nanomaterial-enhanced biosensors routinely achieve detection limits below 10⁻⁹ M for organophosphorus pesticides and therapeutic agents, with linear ranges spanning 2-3 orders of magnitude [17] [6]. The incorporation of multiple nanomaterials in hybrid structures can further improve performance through synergistic effects.

Applications in Therapeutic and Toxicological Sensing

Therapeutic Drug Monitoring

AChE biosensors have gained significant importance in monitoring anti-Alzheimer's disease medications, particularly reversible AChE inhibitors like donepezil, rivastigmine, and galantamine [16]. These therapeutic agents ameliorate cognitive symptoms by increasing synaptic acetylcholine levels through AChE inhibition. Therapeutic drug monitoring is essential for optimizing dosage regimens and minimizing side effects while ensuring efficacy.

Electrochemical AChE biosensors demonstrate particular utility for therapeutic monitoring due to their quantitative precision, rapid analysis capability, and compatibility with complex biological matrices [16]. Biosensors employing human AChE provide clinically relevant data on drug-enzyme interactions, enabling personalized dosing strategies based on individual metabolic variations. Recent advances focus on multiplexed platforms capable of simultaneous measurement of multiple cholinesterase inhibitors and metabolites, offering comprehensive pharmacokinetic profiling.

Environmental and Food Safety Monitoring

The extensive application of organophosphorus and carbamate pesticides in agriculture creates significant requirements for monitoring food and environmental contamination [17] [6]. AChE biosensors provide ideal solutions for field-based screening, offering rapid, cost-effective detection without requiring sophisticated laboratory infrastructure.

Modern AChE biosensing platforms achieve detection limits surpassing conventional analytical techniques for certain pesticides, with capabilities for identifying OPs at concentrations as low as 10⁻¹¹ M in optimized systems [17]. The integration of smartphone-based detection with paper microfluidics represents a particularly promising approach for democratizing pesticide monitoring, enabling widespread deployment among agricultural workers and food safety inspectors [20].

Emerging Diagnostic Applications

Beyond established applications, AChE biosensing platforms are expanding into novel diagnostic domains:

Neurodegenerative Disease Biomarkers: Altered AChE activity in blood components may serve as biomarker for early neurodegenerative disease detection, with biosensors enabling convenient monitoring of disease progression and therapeutic response [18] [16].

Liver Function Assessment: Butyrylcholinesterase (BChE), often measured concurrently with AChE, serves as indicator of hepatic synthetic function, with depressed activity signaling impaired liver performance [20] [21].

Chemical Threat Detection: Military and homeland security applications utilize AChE biosensors for detecting chemical warfare agents (sarin, soman, VX), providing early warning capabilities in defense and counterterrorism operations [19] [16].

Current Challenges and Future Perspectives

Despite significant advances, AChE-based biosensing faces several persistent challenges that guide future research directions:

Specificity Limitations: AChE biosensors respond to all inhibitors rather than specific compounds, complicating identification in complex samples. Future approaches may incorporate sensor arrays with multiple enzyme variants or complementary recognition elements to improve discriminatory capability.

Matrix Interference: Complex sample matrices (food extracts, biological fluids) can interfere with signal transduction. Advanced sample preparation methodologies, including integrated microfluidics and membrane-based filtration, are being developed to address this limitation [17].

Enzyme Stability: Maintaining AChE activity during storage and operation remains challenging, particularly for field-deployable devices. Solutions include engineered enzyme variants with enhanced stability, improved immobilization strategies, and alternative recognition elements like nanozymes [15] [18].

Future development trajectories point toward several promising directions:

Multimodal Sensing Platforms: Integrated systems combining multiple detection principles will enhance reliability through signal complementarity and redundancy [18].

Point-of-Care Devices: Miniaturized, user-friendly platforms incorporating smartphone connectivity will expand accessibility beyond specialized laboratories [20].

High-Throughput Screening: Automated microarray and lab-on-chip formats will enable rapid pharmaceutical screening and environmental monitoring [17] [15].

Intelligent Sensing Systems: Integration with artificial intelligence for data analysis and interpretation will improve analytical accuracy and predictive capability.

The evolving landscape of AChE biosensing continues to leverage advances in nanotechnology, materials science, and biotechnology to overcome existing limitations while expanding application horizons. As these technologies mature, AChE-based biosensors are poised to play increasingly vital roles in therapeutic monitoring, environmental protection, and public health safety.

The principles of Michaelis-Menten kinetics serve as the fundamental framework for understanding and quantifying enzyme activity, forming the cornerstone of modern acetylcholinesterase (AChE) inhibition biosensors research. These biosensors represent a critical technology for rapid detection of enzyme inhibitors, including pesticides, nerve agents, and therapeutic drugs for conditions like Alzheimer's disease [22] [23]. At the core of these analytical devices lies the immobilized AChE enzyme, which catalyzes the hydrolysis of its substrate, and whose alteration in kinetic behavior in the presence of inhibitors provides the measurable signal for detection [23].

The Michaelis-Menten model describes the relationship between enzyme reaction velocity (v) and substrate concentration ([S]) through the equation v = (Vmax × [S]) / (Km + [S]), where Vmax represents the maximum reaction rate when the enzyme is fully saturated with substrate, and Km (the Michaelis constant) is the substrate concentration at which the reaction rate is half of Vmax [24] [25]. In biosensor applications, Km provides a crucial measure of the enzyme's affinity for its substrate—a lower Km value indicates higher affinity, meaning the enzyme can achieve half-maximal velocity at lower substrate concentrations [22] [25]. This relationship generates a characteristic hyperbolic curve when reaction velocity is plotted against substrate concentration, demonstrating saturation kinetics where further increases in substrate concentration beyond a certain point do not increase reaction rate [25].

For AChE inhibition biosensors, understanding these kinetic parameters is essential for optimizing sensor design, interpreting inhibition data, and calculating inhibitor potency through metrics like IC50 values (the concentration of inhibitor required to reduce enzyme activity by 50%) [26] [27]. The accurate determination of Km and Vmax values enables researchers to distinguish between different types of inhibition mechanisms and develop highly sensitive detection systems for environmental monitoring, food safety testing, and drug discovery [22] [23].

Michaelis-Menten Constants and Their Significance in Inhibition Studies

Theoretical Foundation of Kinetic Parameters

The Michaelis constant (Km) and maximum velocity (Vmax) serve as fundamental indicators of enzyme-substrate interactions and catalytic efficiency. Km reflects the enzyme's affinity for its substrate, with lower values indicating stronger binding between enzyme and substrate [25]. In practical terms, an enzyme with a low Km value reaches half its maximum catalytic efficiency at lower substrate concentrations, making it more efficient at low substrate levels. Vmax represents the theoretical maximum rate of the enzymatic reaction when all available enzyme molecules are saturated with substrate [24] [28]. This parameter is determined by the turnover number (kcat) of the enzyme, which defines the number of substrate molecules converted to product per enzyme molecule per unit time when the enzyme is fully saturated [24].

In biosensor design, the Km value directly informs the operational range of the device. The linear relationship between substrate concentration and reaction rate typically holds up to approximately the Km value, guiding researchers in determining the optimal substrate concentration ranges for quantitative measurements [28]. Furthermore, the stability of these kinetic parameters provides a benchmark for assessing whether enzyme immobilization procedures have maintained the functional integrity of the biological recognition element, a critical consideration in biosensor development [23] [27].

Quantitative Determination of Kinetic Constants

The Lineweaver-Burk plot, a double-reciprocal transformation of the Michaelis-Menten equation, provides a classical method for determining Km and Vmax values. By plotting 1/v versus 1/[S], researchers obtain a straight line with a slope of Km/Vmax, a y-intercept of 1/Vmax, and an x-intercept of -1/Km [28]. This linear transformation allows for more accurate estimation of kinetic parameters from experimental data, though it can be sensitive to measurement errors at low substrate concentrations [28].

Contemporary research employs additional analytical methods for determining kinetic parameters, including nonlinear regression analysis directly applied to the hyperbolic Michaelis-Menten curve [27]. These computational approaches often provide more reliable estimates by avoiding the distortion of experimental error inherent in linear transformations. For AChE inhibition studies specifically, the determination of Km values under both inhibited and uninhibited conditions provides crucial information for classifying inhibition mechanisms and calculating inhibitor constants (Ki) [26].

Table 1: Experimentally Determined Michaelis-Menten Constants for Acetylcholinesterase in Various Biosensor Configurations

| Immobilization Method | Substrate | Km Value | Vmax | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oriented-immobilized enzyme microreactor (AuNPs@Con A@AChE) | ATCh | 0.061 mmol/L | 6040.566 mmol/L/min | [27] |

| Electrochemically induced porous graphene oxide network | ATCl | 0.45 mmol/L | Not specified | [23] |

| Purified human erythrocyte AChE (solution) | Acetylthiocholine iodide | 0.08 mM | Not specified | [26] |

Types of Enzyme Inhibition and Their Kinetic Signatures

Classification of Inhibition Mechanisms

Enzyme inhibitors can be categorized based on their binding site, mechanism of action, and the resulting kinetic effects on Km and Vmax values. Understanding these distinctions is crucial for interpreting inhibition data from AChE biosensors and designing effective therapeutic agents [29] [30].

Competitive inhibition occurs when an inhibitor molecule directly competes with the substrate for binding to the enzyme's active site. This type of inhibition is characterized by an increase in apparent Km value while Vmax remains unchanged [29] [30]. The inhibitor typically exhibits structural similarity to the substrate, allowing it to bind reversibly to the active site but not undergo catalysis [29]. In the context of AChE biosensors, competitive inhibition can often be overcome by increasing substrate concentration, as the substrate can outcompete the inhibitor when present at sufficiently high levels [29].

Non-competitive inhibition occurs when an inhibitor binds to an allosteric site (a site other than the active site) on the enzyme, inducing conformational changes that reduce catalytic activity [29] [30]. This mechanism results in decreased Vmax while Km remains unchanged [29]. Unlike competitive inhibition, increasing substrate concentration does not reverse non-competitive inhibition because the substrate and inhibitor bind to different sites [30]. Non-competitive inhibitors are particularly significant in drug development as they can effectively regulate enzyme activity regardless of substrate concentration [31].

Uncompetitive inhibition involves binding of the inhibitor exclusively to the enzyme-substrate complex rather than the free enzyme [30]. This unique mechanism leads to a simultaneous decrease in both Km and Vmax [30]. Uncompetitive inhibition becomes more pronounced at higher substrate concentrations, as the increased formation of enzyme-substrate complexes provides more binding opportunities for the inhibitor [30].

Mixed inhibition represents a combination of competitive and non-competitive characteristics, where the inhibitor can bind to both the free enzyme and the enzyme-substrate complex, but with different affinities for each [30]. This complex interaction affects both Km and Vmax values, with the specific changes depending on the relative binding affinities [30].

Diagram 1: Competitive vs. non-competitive inhibition mechanisms. Competitive inhibitors bind to the active site, while non-competitive inhibitors bind to allosteric sites.

Kinetic Signatures of Different Inhibition Types

Each inhibition mechanism produces distinctive patterns when visualized through kinetic plots, enabling researchers to identify the nature of enzyme-inhibitor interactions through experimental data.

Lineweaver-Burk plots (double-reciprocal plots) are particularly valuable for distinguishing inhibition types. In competitive inhibition, these plots show lines with different x-intercepts but the same y-intercept, indicating changing Km values with constant Vmax [29]. For non-competitive inhibition, the lines converge on the x-axis but have different y-intercepts, reflecting constant Km with varying Vmax [29]. Uncompetitive inhibition produces parallel lines with different intercepts on both axes [30].

Michaelis-Menten plots of reaction velocity versus substrate concentration also reveal characteristic patterns for each inhibition type. Competitive inhibition shows a decreased initial slope but the same maximum velocity at high substrate concentrations [29]. Non-competitive inhibition exhibits a lower maximum velocity at all substrate concentrations, with the curve maintaining the same general shape but reaching a lower plateau [29]. Uncompetitive inhibition manifests as a series of curves with both reduced slopes and lower plateaus [30].

Table 2: Kinetic Parameter Changes in Different Types of Enzyme Inhibition

| Inhibition Type | Binding Site | Effect on Km | Effect on Vmax | Reversibility by Increased [S] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Competitive | Active site | Increases | Unchanged | Yes |

| Non-competitive | Allosteric site | Unchanged | Decreases | No |

| Uncompetitive | Allosteric site (ES complex only) | Decreases | Decreases | No |

| Mixed | Allosteric site (both E and ES) | Increases or decreases | Decreases | Partially |

Experimental Methodologies for Kinetic Analysis in AChE Biosensors

Biosensor Fabrication and Enzyme Immobilization Protocols

The development of reliable AChE biosensors requires sophisticated enzyme immobilization strategies that maintain enzymatic activity while ensuring stability and reproducibility. Recent advances have demonstrated the effectiveness of nanomaterial-based immobilization platforms for enhancing kinetic performance.

Electrochemically Induced Porous Graphene Oxide Network (e-pGON) Method: This protocol involves depositing graphene oxide (GO) onto an electrode surface followed by electrochemical reduction using successive cyclic voltammetry scans in 0.5 M H₂SO₄ solution [23]. The process creates a porous network with high surface area that facilitates electron transfer and substrate access to enzyme active sites. Acetylcholinesterase is then immobilized onto this e-pGON matrix through physical adsorption or covalent binding, resulting in a biosensor with high sensitivity to carbamate pesticides like carbaryl, demonstrating a Km value of 0.45 mM for acetylthiocholine chloride substrate [23].

Oriented-Immobilized Enzyme Microreactor (OIMER) with Gold Nanoparticles: This sophisticated approach utilizes the specific affinity between concanavalin A (Con A) and glycosyl groups on AChE to achieve oriented immobilization [27]. The protocol begins with functionalizing gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) with Con A, followed by binding AChE through specific glycosyl recognition [27]. These functionalized nanoparticles (AuNPs@Con A@AChE) are then assembled onto a positively charged capillary inlet through electrostatic interactions, creating an oriented-immobilized enzyme microreactor [27]. This method significantly enhances enzyme loading and activity, yielding an exceptionally low Km value of 0.061 mM, indicating high substrate affinity [27].

Diagram 2: AChE biosensor development workflow from fabrication to inhibitor screening.

Kinetic Characterization and Inhibition Assay Procedures

Standardized protocols for kinetic characterization ensure reproducible determination of Michaelis-Menten parameters and reliable screening of AChE inhibitors.

Michaelis-Menten Constant Determination: To determine Km and Vmax values, researchers measure reaction rates at varying substrate concentrations [27] [28]. For AChE biosensors, this typically involves injecting acetylthiocholine (ATCh) solutions at concentrations ranging from 0.05-0.30 mM while measuring the production of thiocholine electrochemically [27]. The current response, proportional to reaction rate, is recorded for each substrate concentration. Data are then fitted to the Michaelis-Menten equation using nonlinear regression or linearized using Lineweaver-Burk plots to extract Km and Vmax values [27] [28].

Inhibition Assays and IC50 Determination: For inhibitor screening, biosensors are first incubated with varying concentrations of the test inhibitor for a fixed period (typically 10-15 minutes) [23] [27]. The remaining enzyme activity is then measured by adding substrate at a known concentration, usually near the Km value for optimal sensitivity [23]. The percentage inhibition is calculated as (1 - (Ai/A0)) × 100%, where A0 is the activity without inhibitor and Ai is the activity with inhibitor [27]. IC50 values are determined by plotting inhibition percentage against inhibitor concentration and fitting the data to a logistic function [26] [27].

Validation and Reproducibility Testing: Reputable studies include rigorous validation procedures such as testing operational stability through multiple assay cycles (e.g., 100 consecutive runs), assessing reproducibility between different biosensor batches (reported as relative standard deviation), and verifying storage stability over time [23] [27]. These quality control measures ensure that kinetic parameters remain consistent throughout the study and that inhibition data are reliable for comparative analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for AChE Inhibition Kinetics Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) | Enzyme source for biosensor fabrication | Electric eel AChE (Type C3389) [23], Human erythrocyte AChE [26] |

| Enzyme Substrates | Compounds hydrolyzed by AChE to measure activity | Acetylthiocholine (ATCh) [23] [27], Acetylthiocholine iodide [26] |

| Reference Inhibitors | Positive controls for inhibition studies | Donepezil [27], Physostigmine [26], Phenserine [26] |

| Nanomaterials | Enzyme immobilization platforms | Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) [27], Graphene Oxide (GO) [23] |

| Immobilization Reagents | Facilitate enzyme attachment to sensor surfaces | Concanavalin A (Con A) [27], Hexadimethrine bromide (HDB) [27] |

| Buffer Systems | Maintain optimal pH for enzyme activity | Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS, pH 7.4) [23] |

| Electrochemical Cell Components | Enable amperometric or voltammetric detection | Working electrode (e.g., glassy carbon), Reference electrode (e.g., Ag/AgCl), Counter electrode [23] |

Case Studies and Research Applications

Kinetic Analysis of Novel Therapeutic Candidates

Research on tolserine, an experimental Alzheimer's therapeutic agent, demonstrates the application of Michaelis-Menten kinetics in drug development. Detailed kinetic studies using purified human erythrocyte AChE revealed that tolserine acts as a partial non-competitive inhibitor with an IC50 value of 8.13 nM and a Ki (inhibition constant) of 4.69 nM [26]. Dixon and Lineweaver-Burk plots confirmed the non-competitive nature of inhibition, indicating that tolserine binds to an allosteric site rather than competing with the substrate for the active site [26]. These detailed kinetic analyses allowed researchers to compare tolserine's potency with structural analogues physostigmine and phenserine, establishing its superior inhibitory efficacy [26].

Environmental Monitoring Applications

AChE biosensors have been successfully applied to pesticide detection in environmental samples. In one study, an AChE biosensor based on an electrochemically induced porous graphene oxide network demonstrated sensitive detection of the carbamate pesticide carbaryl, with a detection limit of 0.15 ng/mL and a linear range from 0.3 to 6.1 ng/mL [23]. The biosensor exhibited a Km value of 0.45 mM for acetylthiocholine chloride, indicating favorable substrate affinity after immobilization [23]. This application highlights how kinetic parameters can be used to optimize biosensor performance for specific analytical targets, with the low Km value contributing to high sensitivity for inhibitor detection.

Advanced Immobilization Strategies

The development of oriented-immobilized enzyme microreactors (OIMER) represents a significant advancement in AChE biosensor technology. By utilizing gold nanoparticles functionalized with concanavalin A to achieve oriented immobilization through specific glycosyl recognition, researchers created a system with enhanced kinetic performance [27]. This approach increased the peak area of the enzymatic product by 52.6% compared to randomly immobilized enzymes and achieved an exceptionally low Km value of 0.061 mM, indicating high substrate affinity [27]. The system maintained excellent reproducibility (RSD of 1.3% for 100 consecutive runs) and was successfully applied to screen inhibitors from Chinese medicinal plants, demonstrating the practical benefits of optimized kinetic properties [27].

The integration of Michaelis-Menten kinetics with advanced biosensor technologies has created powerful analytical platforms for studying AChE inhibition. The precise determination of Km and Vmax values provides critical insights into enzyme-inhibitor interactions, enabling the development of highly sensitive detection systems for therapeutic drugs, environmental contaminants, and potential neurotoxins. As immobilization strategies continue to evolve, particularly through oriented attachment approaches and nanomaterial enhancements, the kinetic performance of AChE biosensors will further improve, expanding their applications in drug discovery, environmental monitoring, and clinical diagnostics. The ongoing refinement of these biosensing platforms underscores the enduring relevance of Michaelis-Menten principles in advancing both fundamental enzymology and practical analytical technologies.

Advanced Sensing Modalities and Their Real-World Applications in Research and Diagnostics

Electrochemical biosensors have emerged as powerful analytical tools that combine the specificity of biological recognition elements with the sensitivity of electrochemical transducers. Among these, biosensors based on the inhibition of acetylcholinesterase (AChE) represent a particularly significant category due to their broad applications in environmental monitoring, food safety, and clinical diagnostics [6]. These sensors operate on the principle that certain analytes, such as neurotoxic pesticides and pharmaceuticals, inhibit AChE activity, which can be quantitatively measured through various electrochemical transduction methods [32] [17].

The fundamental working principle of AChE-based biosensors involves the enzymatic hydrolysis of acetylcholine or its analogs, producing electroactive species that generate measurable signals. When inhibitors are present, they reduce enzyme activity, consequently altering the electrochemical response in a concentration-dependent manner that enables quantitative detection [17] [33]. This technical guide comprehensively examines the three primary electrochemical transduction techniques—amperometric, potentiometric, and impedimetric—within the context of AChE inhibition biosensors, providing researchers with detailed methodologies, performance comparisons, and implementation frameworks.

Fundamental Principles of AChE Inhibition Biosensors

Biochemical Basis

Acetylcholinesterase is a crucial enzyme in cholinergic neurotransmission, catalyzing the hydrolysis of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine into choline and acetic acid [32]. This reaction terminates nerve signal transmission across synaptic clefts. AChE inhibitors, including organophosphorus and carbamate pesticides, nerve agents, and certain pharmaceuticals, covalently modify or block the enzyme's active site, leading to enzyme inactivation [17] [6].

The inhibition mechanism enables AChE biosensors to function effectively. The degree of enzyme inhibition correlates directly with inhibitor concentration, providing the quantitative basis for detection. For biosensing applications, the native substrate acetylcholine is often replaced by acetylthiocholine, which undergoes similar enzymatic hydrolysis to produce thiocholine—an electroactive product that can be oxidized at electrode surfaces [32] [33]:

[ \text{Acetylthiocholine} + H_2O \xrightarrow{\text{AChE}} \text{Thiocholine} + \text{Acetic acid} ]

[ 2\text{Thiocholine} \rightleftharpoons \text{Dithio-bis-choline} + 2H^+ + 2e^- ]

The detection of AChE inhibitors thus relies on measuring the decrease in this electrochemical signal relative to the uninhibited enzyme activity [33].

Signaling Pathways and Operational Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the core signaling pathway and operational workflow for AChE inhibition biosensors:

Transduction Methodologies

Amperometric Transduction

Amperometric biosensors measure current resulting from the electrochemical oxidation or reduction of an electroactive species at a constant applied potential. This technique has gained widespread adoption in AChE biosensing due to its inherent sensitivity, simplicity, and compatibility with miniaturized systems [32].

Working Principle: In amperometric AChE biosensors, the enzymatic hydrolysis of acetylthiocholine produces thiocholine, which is oxidized at the working electrode surface upon application of a specific potential (typically +0.6 to +0.8 V vs. Ag/AgCl) [33]. The resulting current is directly proportional to the enzyme activity. In the presence of AChE inhibitors, less thiocholine is produced, leading to a measurable decrease in oxidation current that correlates with inhibitor concentration [33].

Advanced Catalytic Systems: Recent innovations include the use of organocatalysts like nortropine-N-oxyl (NNO), which catalyzes the oxidation of choline generated from acetylcholine hydrolysis [34]. This approach eliminates the need for additional enzymes such as choline oxidase, simplifying the sensing system:

[ \text{Acetylcholine} \xrightarrow{\text{AChE}} \text{Choline} + \text{Acetic acid} ]

[ \text{Choline} + \text{NNO}{(\text{ox})} \rightarrow \text{Betaine} + \text{NNO}{(\text{red})} ]

[ \text{NNO}{(\text{red})} \xrightarrow{\text{Electrode}} \text{NNO}{(\text{ox})} + e^- ]

This NNO-mediated system enables direct real-time monitoring of AChE activity with a linear range of 50–2000 U L⁻¹ and a detection limit of 14.1 U L⁻¹ [34].

Experimental Protocol for Amperometric AChE Biosensor:

- Electrode Modification: Electropolymerize 4,7-di(furan-2-yl)benzo thiadiazole (FBThF) on a glassy carbon electrode surface via cyclic voltammetry (typically 15 cycles between 0 and +1.2 V at 50 mV/s) [33].

- Nanocomposite Integration: Deposit Ag-rGO-NH₂ nanocomposite suspension (2 μL) onto the polymer-modified electrode and dry at room temperature [33].

- Enzyme Immobilization: Apply AChE solution (0.5 μL, 5 U/μL) cross-linked with glutaraldehyde vapor (2.5% for 30 minutes) to create a biocompatible sensing interface [33].

- Amperometric Measurement: Conduct measurements in stirred phosphate buffer (0.1 M, pH 7.4) at an applied potential of +0.65 V vs. Ag/AgCl. Record the steady-state current following successive additions of acetylthiocholine substrate or sample solutions [33].

- Inhibition Assay: Incubate the biosensor with inhibitor samples for 10-15 minutes, then measure residual enzyme activity. Calculate percentage inhibition relative to the baseline activity [33].

Impedimetric Transduction

Impedimetric biosensors monitor changes in the electrical properties of the electrode-electrolyte interface, including charge transfer resistance and double-layer capacitance, without requiring electroactive species or applied redox potentials [35] [36].

Working Principle: Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) measures the impedance response of an electrochemical system across a frequency range. For AChE biosensors, enzyme inhibition typically increases the charge transfer resistance (Rct) due to reduced enzymatic generation of conductive products or structural changes at the electrode interface [35]. This increase in Rct quantitatively correlates with inhibitor concentration.

Experimental Protocol for Impedimetric AChE Biosensor:

- Electrode Functionalization: Incubate a gold electrode overnight in 10 mM 16-mercaptohexadecanoic acid ethanol solution to form a self-assembled monolayer (SAM) [35].

- Surface Activation: Activate carboxyl terminals using EDC/NHS mixture (0.1 M each) for 1 hour to form amine-reactive esters [35].

- Enzyme Immobilization: Deposit 10 μL of enzyme solution (AChE 5%, BSA 5%, glycerol 10% in phosphate buffer) onto the activated surface. Cross-link with glutaraldehyde vapor for 30 minutes [35].

- EIS Measurement: Perform impedance analysis in 5 mM K₃[Fe(CN)₆]/K₄[Fe(CN)₆] solution with a frequency range of 0.1 Hz to 100 kHz and amplitude of 10 mV at the formal potential of the redox couple [35].

- Data Analysis: Fit impedance spectra using the Randles equivalent circuit model. Monitor increases in charge transfer resistance (Rct) following exposure to inhibitors [35].

Potentiometric Transduction

Potentiometric biosensors measure the potential difference between working and reference electrodes under conditions of zero current flow. This transduction method responds to ionic species generated or consumed in enzymatic reactions [32].

Working Principle: The hydrolysis of acetylcholine by AChE produces acetic acid, leading to a localized pH decrease near the electrode surface [32]. Potentiometric transducers, such as ion-sensitive field effect transistors (ISFETs) or pH electrodes, detect this pH change. Inhibition of AChE reduces acid production, resulting in a smaller pH shift that correlates with inhibitor concentration [32].

While potentiometric biosensors offer advantages of simple instrumentation and compatibility with integrated circuit technology, they typically exhibit lower sensitivity compared to amperometric and impedimetric methods due to the logarithmic relationship between potential and analyte concentration described by the Nernst equation [32].

Performance Comparison of Transduction Methods

The table below summarizes the key performance characteristics of the three electrochemical transduction methods for AChE inhibition biosensors:

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Electrochemical Transduction Methods for AChE Biosensors

| Parameter | Amperometric | Impedimetric | Potentiometric |

|---|---|---|---|

| Measured Quantity | Current | Impedance/Charge Transfer Resistance | Potential |

| Detection Principle | Oxidation/Reduction Current of Electroactive Products | Changes in Electron Transfer Resistance | pH Change from Acetic Acid Production |

| Sensitivity | High (nano to pico-molar) [33] [37] | Moderate to High (nano-molar) [35] | Moderate (micro-molar) [32] |

| Linearity | Wide linear range [33] | Limited linear range | Logarithmic response (Nernstian) [32] |

| Label Requirement | Often requires natural enzymatic products | Label-free | Label-free |

| Implementation Complexity | Moderate | High (requires modeling) | Low |

| Key Applications | Pesticide detection, Drug monitoring [33] [38] | Toxin screening, Protein interactions [35] | Pharmaceutical analysis [32] |

Advanced Materials and Nanocomposites

The performance of electrochemical AChE biosensors has been significantly enhanced through the integration of advanced functional materials and nanocomposites:

Carbon and Metal Nanomaterials: Graphene derivatives, particularly amine-functionalized reduced graphene oxide (rGO-NH₂), provide exceptional electrical conductivity and large surface areas for enzyme immobilization [33]. Silver nanoparticles (Ag NPs) contribute catalytic activity and facilitate electron transfer, while silver-reduced graphene oxide nanocomposites (Ag-rGO-NH₂) demonstrate synergistic effects that enhance biosensor sensitivity [33].

Two-Dimensional Materials: MXenes, especially Ti₃C₂Tₓ MXene quantum dots (MQDs), represent a recent advancement with exceptional conductivity, quantum confinement effects, and abundant surface functional groups that promote enzyme stabilization [37]. Biosensors incorporating MQDs have achieved unprecedented detection limits as low as 1 × 10⁻¹⁷ M for organophosphorus pesticides like chlorpyrifos [37].

Conjugated Polymers: Polymers such as poly(4,7-di(furan-2-yl)benzo thiadiazole) provide electrical conductivity, homogeneous film formation, and biocompatibility, serving as effective matrices for enzyme integration while facilitating electron transfer [33].

Biopolymer Matrices: Natural polymers like sodium alginate offer biocompatible microenvironments that preserve enzyme activity through hydrophilic networks and functional groups for covalent immobilization [35].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for AChE Biosensor Development

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Enzymes | Acetylcholinesterase (AChE from Electrophorus electricus) [33] [34] | Primary biorecognition element that catalyzes substrate hydrolysis |

| Substrates | Acetylthiocholine chloride (ATCl) [33], Acetylcholine chloride [34] | Enzyme substrates that generate electroactive/products upon hydrolysis |

| Cross-linking Agents | Glutaraldehyde (GA) [33] [37] | Forms covalent bonds with enzyme amino groups for stable immobilization |

| Nanomaterials | Ag-rGO-NH₂ nanocomposite [33], Ti₃C₂Tₓ MXene QDs [37] | Enhance electron transfer, increase surface area, improve sensitivity |

| Polymers/Matrices | Sodium alginate [35], Chitosan [37], Poly(FBThF) [33] | Provide biocompatible environment for enzyme stabilization |

| Electrochemical Mediators | Nortropine-N-oxyl (NNO) [34] | Organocatalyst that facilitates choline oxidation, simplifying detection |

| Blocking Agents | Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) [35] [36] | Reduces non-specific binding on sensor surfaces |

Applications in Research and Development

Environmental Monitoring and Pesticide Detection

AChE biosensors have found extensive application in detecting organophosphorus and carbamate pesticides in environmental samples. The amperometric biosensor based on poly(FBThF)/Ag-rGO-NH₂ nanocomposite demonstrates excellent sensitivity for malathion (LOD 0.032 μg L⁻¹) and trichlorfon (LOD 0.001 μg L⁻¹) [33]. Similarly, impedimetric biosensors employing lipases from Candida rugosa can detect diazinon with a detection limit of 10 nM, offering an alternative enzymatic approach for organophosphate monitoring [36].

Pharmaceutical Research and Neurodegenerative Disease