Advanced Biosensors for Environmental Water Monitoring: A Comprehensive Review of Technologies, Applications, and Future Directions

This review comprehensively examines the latest advancements in biosensor technologies for environmental water monitoring, addressing a critical need for researchers and scientists developing detection systems for emerging contaminants.

Advanced Biosensors for Environmental Water Monitoring: A Comprehensive Review of Technologies, Applications, and Future Directions

Abstract

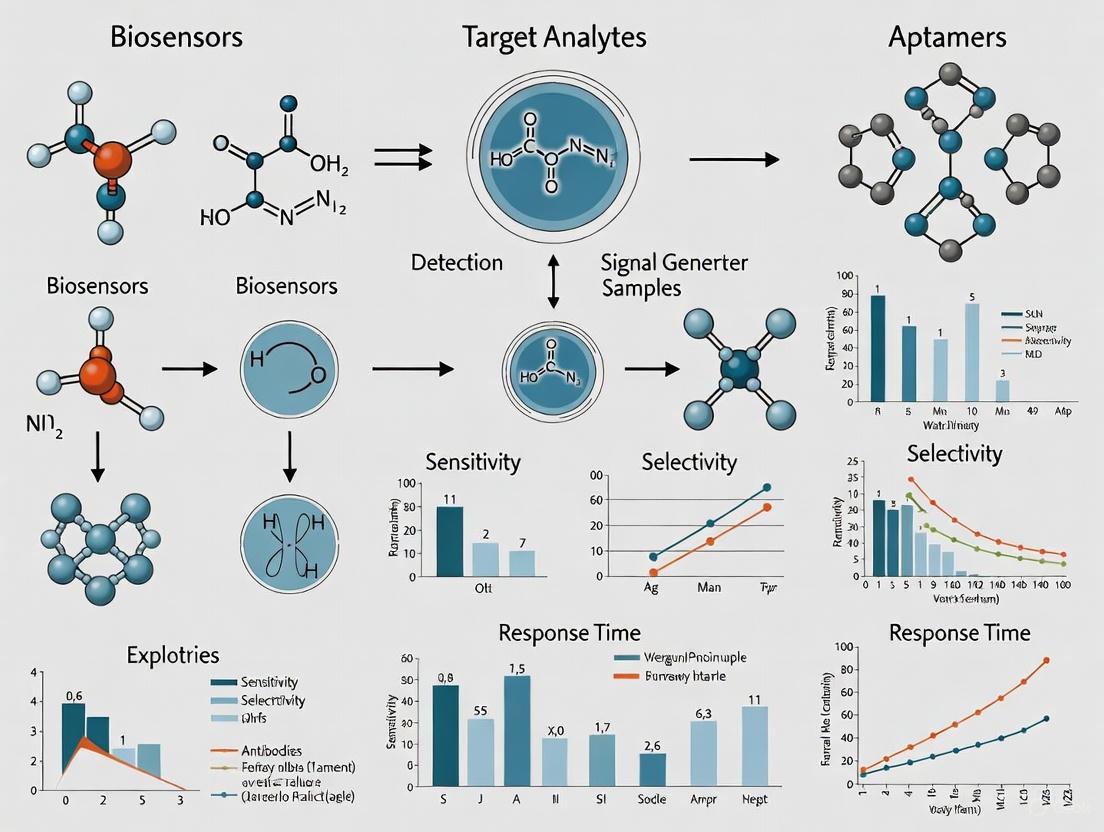

This review comprehensively examines the latest advancements in biosensor technologies for environmental water monitoring, addressing a critical need for researchers and scientists developing detection systems for emerging contaminants. The article explores the foundational principles and diverse classifications of biosensors, including electrochemical, optical, whole-cell, and nucleic acid-based platforms. It details methodological approaches for detecting pesticides, heavy metals, pharmaceuticals, and pathogens, while critically analyzing troubleshooting strategies for enhancing stability, sensitivity, and field deployment. Through validation case studies and comparative analysis with conventional techniques, we demonstrate how biosensors offer rapid, cost-effective, and real-time monitoring solutions that align with Sustainable Development Goals for water safety and environmental health.

Fundamental Principles and Biosensor Classifications for Water Quality Assessment

Biosensors are analytical devices that leverage biological recognition to detect specific analytes, playing an increasingly vital role in environmental water monitoring. They integrate a biological sensing element with a transducer, converting a biological event into a measurable signal [1]. Within the context of reviewing biosensors for environmental water research, understanding their core architecture is fundamental for developing effective tools to detect hazardous elements like pesticides, heavy metals, and pathogenic microorganisms [2] [3] [4]. These components work in concert to provide rapid, sensitive, and often portable alternatives to conventional analytical methods, addressing the urgent need for on-site and real-time water quality assessment [4]. This guide provides an in-depth technical examination of the three core components of a biosensor—the bioreceptor, the transducer, and the signal processor—with a specific focus on their application in monitoring aquatic environments.

Core Architectural Components of a Biosensor

The fundamental architecture of a biosensor consists of three integral components that function together to detect and quantify a target analyte. The bioreceptor is the biological recognition element that specifically interacts with the target. The transducer converts this biological interaction into a measurable signal. Finally, the signal processor amplifies, interprets, and displays this signal in a user-readable form [1]. The seamless integration of these components determines the sensor's overall performance, including its sensitivity, specificity, and reliability.

Bioreceptors: The Recognition Elements

Bioreceptors are the cornerstone of a biosensor's selectivity. They are biological or biologically-derived molecules that possess a high affinity for a specific target analyte. The interaction between the bioreceptor and the analyte is the critical first step in the sensing process [4].

- Enzymes: Enzyme-based biosensors rely on the catalytic transformation of the target analyte by an enzyme, leading to a measurable product. Alternatively, the analyte can act as an enzyme inhibitor, where its concentration is correlated with a reduction in enzymatic activity [4]. For instance, a sensor might use the enzyme β-glucuronidase, secreted by E. coli, to detect bacterial contamination in water [5].

- Antibodies: Antibodies are immunoglobulins that serve as powerful bioreceptors in immunosensors. They bind to target antigens (analytes) with high specificity and affinity. This binding event can be detected directly (label-free) or through a secondary label, such as a fluorescent dye or enzyme [4].

- Nucleic Acids (Aptamers): Aptasensors use synthetic single-stranded DNA or RNA oligonucleotides (aptamers) as recognition elements. These aptamers, selected through the SELEX process, fold into unique three-dimensional structures that bind to specific targets, including metal ions, organic compounds, and whole cells, through mechanisms like π-π stacking and hydrogen bonding [4].

- Whole Microbial Cells: Whole cells (bacteria, fungi, algae) function as integrated sensing systems, possessing both receptors and transducers. A key advantage is their ability to self-replicate, providing a renewable source of biorecognition elements. They are particularly robust and are often engineered to respond to specific environmental stimuli [4].

- Microorganisms: Used broadly for detecting toxic elements in water, these can provide a holistic response to environmental stress or specific pollutants [2].

Transducers: Converting Biological Events into Measurable Signals

The transducer is the component that transforms the biological response from the bioreceptor-analyte interaction into a quantifiable signal. The nature of this signal defines the primary classification of the biosensor [1].

- Electrochemical Transducers: These are among the most commonly used transducers due to their portability, simplicity, and rapid response [4]. They measure electrical changes resulting from the biological event.

- Amperometric: Measures current generated by a redox reaction at a constant potential.

- Potentiometric: Measures the change in potential (voltage) between a working electrode and a reference electrode.

- Impedimetric: Measures the change in electrical impedance due to the binding event on the electrode surface.

- Optical Transducers: These transducers detect changes in light properties. A prominent example is the Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET)-based biosensor, where the binding of the analyte induces a conformational change in the bioreceptor, altering the energy transfer between two fluorophores and resulting in a measurable change in fluorescence [6]. Other optical methods include surface plasmon resonance (SPR) and colorimetric detection, where a visible color change can be observed, sometimes even with the naked eye [5].

- Piezoelectric Transducers: These measure changes in mass on the sensor surface by detecting the variation in the frequency of oscillation of a crystal (e.g., quartz crystal microbalance) when the target analyte binds.

Signal Processors: Data Interpretation and Readout

The signal processor is the electronic component that conditions the raw signal from the transducer. It performs essential functions such as amplification, filtering of noise, and digital conversion. The processed signal is then displayed in an accessible format, such as a numerical value on a screen, a graph on a computer, or a simple color change on a fabric-based sensor that can be interpreted by a smartphone [5]. Advanced signal processing now frequently incorporates machine learning (ML) algorithms like Support Vector Machines (SVM) and Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) to analyze complex data, enhance accuracy, and distinguish between specific signals and background noise, which is particularly valuable in complex environmental samples [7].

Quantitative Comparison of Biosensor Components

The performance of a biosensor is quantified by its analytical characteristics. The following tables summarize key metrics and data for different biosensor types and their components as applied in environmental water monitoring.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Biosensors for Environmental Contaminants

| Target Contaminant | Bioreceptor Type | Transducer Type | Detection Limit | Detection Range | Reference Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli Bacteria | Enzyme (β-Glu) | Optical (Colorimetric) | 537 CFU/mL | 10² - 10⁶ CFU/mL | Fabric-based visual biosensor [5] |

| Auxin (Plant Hormone) | Engineered TrpR Protein | Optical (FRET) | ~3 µM (in protoplasts) | Multiple orders of magnitude | Direct visualization of auxin in plants [6] |

| Pesticides (General) | Various (Enzyme, Antibody, Cell) | Electrochemical / Optical | ng/L to µg/L | ng/L to g/L | Review on ECs in water [4] |

| Ciprofloxacin Antibiotic | Antibody (IgG) | Electrochemical (Impedimetric) | 10 pg/mL | Not Specified | Immunosensor for antibiotics [4] |

Table 2: Comparison of Bioreceptor and Transducer Pairings in Water Monitoring

| Bioreceptor | Transducer | Key Advantages | Common Targets in Water |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enzyme | Electrochemical | High specificity, rapid, portable | Pesticides (organophosphates), heavy metals [4] |

| Antibody | Optical (e.g., SPR, Fluorescence) | Very high affinity and specificity | Antibiotics, endocrine disruptors, toxins [4] |

| Aptamer | Electrochemical / Optical | High stability, synthetic, tunable | Heavy metals, pesticides, pathogens [4] |

| Whole Cell | Optical (Bioluminescence) | Robust, provides holistic toxicity | General toxicity, specific organic pollutants [4] |

Experimental Protocol: Development of a FRET-Based Biosensor

The development of "AuxSen," a FRET-based biosensor for the plant hormone auxin, provides a detailed methodological blueprint for biosensor engineering [6]. The following workflow and protocol outline the key stages.

Detailed Methodology

Base Protein Identification and Mutagenesis:

- The bacterial tryptophan repressor (TrpR) was selected as the scaffold due to its structural knowledge and low inherent affinity for the target molecule, indole-3-acetic acid (IAA).

- Mutagenesis: Focused mutagenesis was performed on residues surrounding the binding pocket (e.g., S88Y to block tryptophan binding and favor IAA). Successive rounds generated approximately 2,000 variants [6].

High-Throughput Screening:

- Variants were screened for an increase in FRET signal upon the addition of IAA. This identified mutants with improved response to the target ligand [6].

Affinity and Specificity Validation:

- Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC): Selected variants were analyzed using ITC to quantitatively confirm improvements in binding affinity (Kd) for IAA and to check for binding to similar compounds (e.g., indole-3 acetonitrile, IAN) [6].

Structural Analysis:

- X-ray Crystallography: The structures of key variants were solved to visualize the binding mode of IAA and guide subsequent rounds of rational mutagenesis (e.g., incorporating T44L and T81M to optimize hydrophobic interactions) [6].

Fluorophore and Linker Optimization:

- The final sensor composition was optimized by testing different fluorescent proteins (mNeonGreen and Aquamarine) and linker combinations to maximize the FRET signal change upon IAA binding [6].

In Planta Functional Validation:

- Transgenic Arabidopsis lines expressing the nuclear-localized sensor were generated.

- Kinetics Assay: Seedlings were treated with 10 µM IAA, and the FRET signal in root nuclei was recorded over time, showing a maximum signal reached within 2 minutes.

- Reversibility Test: After IAA incubation, the medium was changed to remove IAA, demonstrating the sensor's ability to monitor decreasing auxin levels, confirming its reversibility [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The development and application of biosensors require a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The following table details key items used in the featured experiments and the broader field.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Biosensor Development

| Item Name | Function / Description | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|

| mNeonGreen & Aquamarine | Donor and acceptor fluorescent proteins for FRET. | Fluorophore pair used in the final AuxSen biosensor design [6]. |

| Tryptophan Repressor (TrpR) | A dimeric bacterial transcription factor; base scaffold for engineering. | Engineered to create the auxin-specific FRET biosensor [6]. |

| 4-Methylumbelliferyl-β-D-glucuronide (MUG) | A fluorogenic enzyme substrate. | Used as the target molecule loaded onto a fabric-based biosensor; cleaved by β-glucuronidase (from E. coli) to produce a fluorescent signal [5]. |

| NHS/EDC Chemistry | (N-hydroxysuccinimide / N-(3-Dimethylaminopropyl)-N′-ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride) | A carbodiimide crosslinker chemistry used to covalently immobilize bioreceptors (e.g., antibodies, enzymes) onto transducer surfaces [5]. |

| Dexamethasone-inducible System | A chemically inducible gene expression system. | Used to control the expression of the AuxSen biosensor in transgenic Arabidopsis plants [6]. |

| Systematic Evolution of Ligands by Exponential Enrichment (SELEX) | An in vitro process to generate high-affinity nucleic acid aptamers. | Used to produce synthetic DNA/RNA aptamers for use as bioreceptors in aptasensors [4]. |

Biosensors represent a powerful class of analytical devices that integrate a biological recognition element with a physicochemical transducer to detect target analytes. In the context of environmental water monitoring, they have emerged as promising alternatives to conventional analytical techniques, offering advantages of portability, cost-effectiveness, and potential for real-time, on-site analysis [8] [9]. The core of a biosensor's specificity lies in its bioreceptor, the biological element that selectively interacts with the target contaminant. This technical guide provides an in-depth review of the four primary categories of biosensors classified by bioreceptor type: enzyme-based, antibody-based, nucleic acid-based, and whole-cell biosensors. The operating principles, characteristic performance data, and detailed experimental methodologies for each type are delineated, providing a foundational resource for researchers and scientists engaged in the development of biosensing platforms for the surveillance of emerging aquatic contaminants.

Core Principles and Comparative Performance of Biosensors

A biosensor functions by converting a biological recognition event into a quantifiable signal. The essential components include the bioreceptor, which is a biological molecule or system (e.g., enzyme, antibody, nucleic acid, whole cell) that specifically recognizes the target analyte, and the transducer, which converts the biological interaction into a measurable electrical, optical, or other physical signal [10] [11]. The transducer's output is then processed to provide information about the analyte's presence and concentration.

Biosensors are categorized based on their bioreceptor and transduction method. The major transduction mechanisms include:

- Electrochemical: Measures changes in current (amperometric), potential (potentiometric), or impedance (impedimetric) resulting from the biorecognition event [10] [11].

- Optical: Detects changes in light properties such as absorbance, fluorescence, luminescence, or refractive index (e.g., Surface Plasmon Resonance) [10] [11].

- Thermal: Measures the heat absorbed or released during a biochemical reaction [10].

- Piezoelectric: Detects changes in the mass on the sensor surface by measuring the shift in resonance frequency of a crystal [10].

The following sections and tables detail the specific mechanisms and performance of each bioreceptor type. The data summarized in Table 1 highlights the typical sensitivity, response times, and relative advantages of each biosensor class in detecting environmental pollutants in water.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Biosensor Types in Environmental Water Monitoring

| Biosensor Type | Typical Detection Limit | Key Analytes Detected | Response Time | Stability | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enzyme-Based | ng/L to µg/L [8] | Pesticides, Heavy Metals, Phenolic Compounds [12] [13] | Minutes [12] | Moderate (enzyme activity can degrade) [13] | High specificity and catalytic activity; wide range of analytes [8] [12] |

| Antibody-Based (Immunosensors) | pg/mL to ng/mL [8] | Antibiotics, Toxins, Pesticides [8] [14] | Minutes to Hours [8] | High (robust antibodies) | Exceptional specificity and affinity [8] |

| Nucleic Acid-Based (Aptasensors) | fM to pM [8] [10] | Heavy Metals, Organic Pollutants, Toxins [8] | Minutes | High (stable DNA/RNA) [8] | High affinity; synthetic production; design flexibility [8] |

| Whole-Cell-Based | ng/L to µg/L [8] | Heavy Metals, Pesticides, Organic Pollutants, General Toxicity [8] [9] | 30 mins to Several Hours [8] [9] | Variable (depends on cell viability) | Can report on bioavailability and toxicity; self-replicating [8] [9] |

Enzyme-Based Biosensors

Working Principle and Signaling Pathways

Enzyme-based biosensors utilize enzymes as bioreceptors that catalyze a reaction involving the target analyte. The detection mechanism can follow one of three primary pathways, as illustrated in the diagram below:

The catalytic reaction typically produces a measurable product (e.g., electrons, protons, light, or heat) that is proportional to the analyte concentration [8]. Electrochemical transducers are most common due to their portability and simplicity [8]. A prominent example is the use of acetylcholinesterase (AChE); its inhibition by organophosphorus pesticides reduces the enzymatic conversion of acetylcholine, leading to a measurable decrease in an electrochemical signal (e.g., current) [9] [12].

Experimental Protocol: Acetylcholinesterase-Based Sensor for Pesticides

Objective: To detect and quantify organophosphorus pesticides (e.g., paraoxon) in water samples using an inhibition-based acetylcholinesterase biosensor.

Materials:

- Bioreceptor: Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) enzyme.

- Transducer: Screen-printed gold electrode.

- Immobilization Matrix: Chitosan and gold nanoparticles [10].

- Substrate: Acetylthiocholine.

- Electrochemical Cell: Potentiostat for amperometric measurements.

Procedure:

- Electrode Modification: Immobilize AChE onto the surface of the screen-printed gold electrode using a composite film of chitosan and gold nanoparticles. This matrix enhances the enzyme's stability and electron transfer efficiency [10].

- Baseline Measurement: Place the modified electrode in a buffer solution and add a known concentration of the substrate, acetylthiocholine. Measure the steady-state amperometric current generated by the enzymatic production of thiocholine. This current represents the 100% activity baseline (I₀).

- Inhibition Phase: Incubate the biosensor with the water sample suspected to contain pesticides (e.g., paraoxon) for a fixed period (e.g., 10-15 minutes). The pesticide will bind to and inhibit the enzyme.

- Post-Inhibition Measurement: After incubation, re-measure the amperometric current (Iᵢ) following the addition of the same concentration of acetylthiocholine as in step 2.

- Quantification: The percentage of enzyme inhibition is calculated as (I₀ - Iᵢ)/I₀ × 100%. The analyte concentration in the sample is determined by interpolating this percentage against a calibration curve constructed from standards with known pesticide concentrations.

Performance: This method has been reported to achieve detection limits as low as 2 ppb for paraoxon and 5 fg mL⁻¹ for methyl parathion [10].

Antibody-Based Biosensors (Immunosensors)

Working Principle and Signaling Pathways

Antibody-based biosensors, or immunosensors, rely on the high affinity and specificity of antibodies (immunoglobulins) for their target antigens (analytes). The signal transduction can be categorized into label-free and labeled systems, as shown below:

In label-free configurations, the physical change (e.g., mass, refractive index, impedance) induced by the antigen-antibody binding is directly measured. For instance, an impedimetric immunosensor for ciprofloxacin detects the binding event through a change in electrical impedance, achieving detection limits as low as 10 pg/mL [8]. In labeled systems, a secondary molecule (e.g., a fluorescent dye, enzyme, or nanoparticle) is used to generate a signal. A classic example is a fluorescent immunoassay using quantum dots (QDs), where the formation of an antibody-QD complex produces a fluorescence signal for quantification [8].

Experimental Protocol: Impedimetric Immunosensor for Antibiotics

Objective: To detect ciprofloxacin (CIP) antibiotics in water samples using a label-free impedimetric immunosensor.

Materials:

- Bioreceptor: Anti-ciprofloxacin antibody.

- Transducer: Gold electrode or screen-printed electrode.

- Equipment: Electrochemical impedance spectrometer.

- Reagents: Phosphate buffer saline (PBS), redox probe (e.g., [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻).

Procedure:

- Antibody Immobilization: Covalently immobilize the anti-CIP antibodies onto the surface of a gold electrode. This can be achieved by creating a self-assembled monolayer (SAM) of linkers like cysteamine on the gold surface, followed by cross-linking the antibodies using glutaraldehyde.

- Blocking: Incubate the modified electrode with a blocking agent (e.g., bovine serum albumin, BSA) to cover any remaining non-specific binding sites on the electrode surface. This step is critical to minimize background noise.

- Baseline Impedance Measurement: Immerse the prepared immunosensor in a PBS solution containing a known concentration of the [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻ redox probe. Measure the electrochemical impedance spectrum (EIS) to establish a baseline charge-transfer resistance (Rcₜ).

- Antigen Binding: Expose the immunosensor to the water sample containing CIP for a fixed incubation time. The binding of CIP to the immobilized antibodies forms an immunocomplex on the electrode surface.

- Post-Binding Impedance Measurement: After incubation and a gentle washing step, re-measure the EIS in the fresh redox probe solution. The formation of the antibody-antigen complex acts as an insulating layer, hindering electron transfer to the electrode and resulting in an increase in the measured Rcₜ.

- Quantification: The change in Rcₜ (ΔRcₜ) is proportional to the concentration of CIP in the sample. The concentration is determined using a pre-established calibration curve of ΔRcₜ vs. log[CIP].

Nucleic Acid-Based Biosensors (Aptasensors)

Working Principle and Signaling Pathways

Aptasensors use synthetic single-stranded DNA or RNA oligonucleotides (aptamers) as recognition elements. These aptamers, selected through an in vitro process called SELEX (Systematic Evolution of Ligands by Exponential Enrichment), fold into unique 2D or 3D structures that bind to specific targets with high affinity [8]. The binding is stabilized by various forces, including π-π stacking, van der Waals forces, and hydrogen bonding [8]. The binding event induces a conformational change in the aptamer, which can be transduced into a measurable signal.

Experimental Protocol: Electrochemical Aptasensor for Heavy Metals

Objective: To detect mercury ions (Hg²⁺) in water using an electrochemical aptasensor.

Materials:

- Bioreceptor: DNA aptamer with specific sequence for Hg²⁺.

- Transducer: Electrode modified with single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs) to increase surface area and conductivity [10].

- Equipment: Potentiostat.

- Reagents: Methylene blue (redox label), buffer solution.

Procedure:

- Aptamer Immobilization: Chemically modify the DNA aptamer with a thiol group at one end. Immobilize the thiolated aptamer onto a SWCNT-modified gold electrode via a strong Au-S bond. The aptamer is designed to have a flexible, unfolded structure in the absence of the target.

- Signal-On vs. Signal-Off Design: In a common "signal-off" design, a redox label like methylene blue (MB) is attached to the end of the aptamer. When the aptamer is in its loose state, the MB is close to the electrode surface, facilitating electron transfer and producing a high electrochemical current.

- Target Binding and Signal Transduction: Upon introducing Hg²⁺, the aptamer binds to the ion and folds into a tight, hairpin-like structure (T-Hg²⁺-T configuration). This conformational change moves the MB label away from the electrode surface, hindering electron transfer and resulting in a measurable decrease in the amperometric or voltammetric signal.

- Quantification: The reduction in current signal is proportional to the concentration of Hg²⁺ in the sample. A calibration curve is constructed using standard solutions to quantify the unknown sample concentration.

Performance: Such aptasensors have demonstrated remarkably low detection limits for heavy metals, for instance, achieving 3 fM for Hg²⁺ [10].

Whole-Cell-Based Biosensors

Working Principle and Signaling Pathways

Whole-cell-based biosensors utilize living microorganisms (e.g., bacteria, algae, yeast) as the integrated biorecognition and transduction element. These sensors can be engineered to respond to specific contaminants or general toxicity. Their unique feature is the ability to self-replicate, potentially providing a renewable sensing element [8] [9].

The cellular response mechanisms are diverse. Specific biosensors are genetically engineered so that exposure to a target pollutant (e.g., cadmium, toluene) activates a specific promoter (e.g., from the cad operon or TOL plasmid), leading to the expression of a reporter gene like green fluorescent protein (GFP) or luciferase [9]. Nonspecific biosensors utilize general stress responses (e.g., heat shock, SOS response) to report on overall toxicity or the presence of hazardous conditions [9].

Experimental Protocol: Whole-Cell Biosensor for Pyrethroid Insecticide

Objective: To detect pyrethroid insecticides in water using a label-free, whole-cell optical biosensor.

Materials:

- Bioreceptor: Genetically engineered Escherichia coli (E. coli) cells containing a plasmid with an insecticide-responsive promoter fused to a reporter gene (e.g., gfp for GFP).

- Transducer: Fluorometer or microplate reader.

- Equipment: Sterile culture flasks, incubator shaker, centrifuge, cuvettes or microplates.

Procedure:

- Cell Culture and Preparation: Inoculate the recombinant E. coli strain in a suitable growth medium (e.g., LB broth) containing the appropriate antibiotic for plasmid selection. Grow the cells to the mid-logarithmic phase (OD₆₀₀ ~ 0.5-0.6) under controlled conditions (temperature, shaking).

- Exposure to Sample: Harvest the cells by gentle centrifugation, wash, and re-suspend them in a minimal buffer or medium. Aliquot the cell suspension into test tubes or wells of a microplate. Add the water sample (or a series of standard insecticide solutions for calibration) to the cells.

- Incubation and Induction: Incubate the cell-sample mixture for a predetermined period (e.g., 1-2 hours). During this time, if the target pyrethroid insecticide is present, it will enter the cell and trigger the specific promoter, leading to the expression and production of GFP.

- Signal Measurement: After the induction period, measure the fluorescence intensity of the sample using a fluorometer. The excitation and emission wavelengths are set according to GFP's properties (e.g., Ex ~488 nm, Em ~510 nm).

- Quantification: The fluorescence intensity is proportional to the concentration of the inducing insecticide. The concentration in the unknown sample is determined by comparing its fluorescence to a calibration curve generated from standards with known insecticide concentrations.

Performance: This approach has been successfully applied, for example, achieving a detection limit of 3 ng/mL for a pyrethroid insecticide [8].

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The development and deployment of biosensors require a specific set of biological and chemical reagents. The following table details key materials and their functions in biosensor construction and operation.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Biosensor Development

| Reagent/Material | Function in Biosensor Development | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) | Enzyme bioreceptor; its inhibition is used to detect organophosphorus and carbamate pesticides. | Enzyme-based sensors for pesticide monitoring in water [9] [12]. |

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | Nanomaterial used to enhance electrode surface area, improve electron transfer, and immobilize bioreceptors. | Used in electrochemical aptasensors and immunosensors to boost sensitivity [10]. |

| Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes (SWCNTs) | Nanomaterial for electrode modification; provides high conductivity and large surface area for bioreceptor immobilization. | Signal amplification in nucleic acid-based biosensors for heavy metal detection [10]. |

| Quantum Dots (QDs) | Semiconductor nanocrystals used as fluorescent labels in optical immunosensors and aptasensors. | Fluorescent signal generation in multiplexed detection of antibiotic residues [8]. |

| Chitosan | A natural biopolymer used as a hydrogel matrix for entrapping and stabilizing enzymes or whole cells on transducer surfaces. | Immobilization matrix in enzyme-based biosensors [10]. |

| Specific Aptamers | Synthetic single-stranded DNA/RNA oligonucleotides selected for high-affinity binding to a specific target analyte. | Recognition element in aptasensors for toxins, heavy metals, and pesticides [8]. |

| Genetically Engineered Microbial Cells | Whole-cell bioreceptors designed to produce a measurable signal (e.g., fluorescence) in response to a target pollutant or general stress. | Detection of bioavailable heavy metals, pesticides, and organic pollutants [8] [9]. |

| Screen-Printed Electrodes (SPEs) | Disposable, low-cost electrochemical transducers that facilitate mass production and field deployment of biosensors. | Platform for amperometric and impedimetric biosensors for on-site water testing [10] [11]. |

Biosensors have emerged as powerful analytical tools for environmental water monitoring, combining the specificity of biological recognition with the sensitivity of physicochemical detectors. Biosensors are defined as integrated devices that provide quantitative analytical information using a biological recognition element in direct spatial contact with a transducer [15]. The core function of a biosensor is to convert a biological interaction into a measurable signal proportional to the concentration of a target analyte. The selection of an appropriate transduction mechanism is paramount for developing effective biosensing platforms, as it directly influences key performance parameters including sensitivity, detection limit, operational feasibility, and suitability for field deployment [16] [15]. Within the specific context of environmental water monitoring, these devices must detect pollutants such as heavy metals, pesticides, pharmaceuticals, and pathogens at trace levels in complex matrices, often requiring capabilities for real-time, in-situ analysis [9] [2]. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of the four principal transduction mechanisms—electrochemical, optical, piezoelectric, and thermal—detailing their operational principles, implementation methodologies, and performance characteristics for application in environmental water research.

Fundamental Principles of Biosensor Operation

A biosensor functions through the coordinated operation of two distinct components: the bioreceptor and the transducer. The bioreceptor is a biological molecular species (e.g., enzyme, antibody, nucleic acid, whole cell) that interacts specifically with the target analyte [17]. This interaction produces a physicochemical change, which the transducer detects and converts into a measurable electronic signal [15]. The resulting output is processed to provide information about the analyte's identity and concentration.

The performance of all biosensors is evaluated against a standard set of metrics. Sensitivity refers to the magnitude of signal change per unit change in analyte concentration. The Limit of Detection (LOD) is the lowest analyte concentration that produces a signal distinguishable from background noise. Selectivity is the sensor's ability to respond exclusively to the target analyte amidst interfering substances. Dynamic range defines the span of analyte concentrations over which the sensor provides a quantifiable response. Finally, response time is the duration required for the sensor to generate a stable signal following exposure to the analyte [16] [15].

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics for Biosensor Evaluation

| Metric | Definition | Importance in Environmental Monitoring |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | Signal change per unit analyte concentration change | Determines ability to detect low pollutant levels |

| Limit of Detection (LOD) | Lowest distinguishable analyte concentration | Critical for detecting trace contaminants |

| Selectivity | Specificity for target versus interfering substances | Ensures accurate measurement in complex water matrices |

| Dynamic Range | Concentration span of quantifiable response | Defines operational scope for varying pollution levels |

| Response Time | Time to stable signal after analyte exposure | Enables real-time monitoring and rapid alerts |

| Stability | Consistency of performance over time and use | Determines shelf-life and field deployment viability |

Electrochemical Biosensors

Principle and Types

Electrochemical biosensors transduce biological recognition events into an electrical signal, typically current, potential, or impedance [15]. These sensors are classified based on the measured electrical parameter:

- Amperometric sensors measure current generated by the redox reactions of electroactive species at a constant applied potential. The measured current is directly proportional to the concentration of the electroactive species [15]. An example is the first-generation glucose biosensor, where the consumption of oxygen or production of H₂O₂ is monitored [15].

- Potentiometric sensors measure the potential difference between a working electrode and a reference electrode under conditions of zero current. The potential shift correlates with the ionic concentration or reaction activity at the electrode surface, often utilizing ion-selective membranes [15].

- Impedimetric sensors monitor changes in the impedance (resistance and capacitance) of the electrode-solution interface resulting from biorecognition events. The binding of biomolecules or cells alters the interface's electrical properties, allowing for label-free detection [15].

Experimental Protocol: Enzyme Inhibition-Based Heavy Metal Detection

A common application in environmental monitoring is detecting heavy metals via enzyme inhibition.

Materials and Reagents:

- Transducer: Glassy Carbon Electrode (GCE) or Screen-Printed Electrode (SPE) [9] [15]

- Enzyme: Glucose Oxidase (GOx) [15]

- Immobilization Matrix: Poly-o-phenylenediamine (electro-polymerized) or glutaraldehyde cross-linker [15]

- Buffer: Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), pH 7.4

- Substrate: D-Glucose solution

- Analyte: Standard solutions of target heavy metals (e.g., Cu²⁺, Hg²⁺, Cd²⁺)

Procedure:

- Electrode Preparation: Polish the GCE with alumina slurry, rinse with deionized water, and dry. For SPEs, use as received.

- Enzyme Immobilization: Immobilize GOx onto the electrode surface. This can be achieved via:

- Baseline Activity Measurement: Place the biosensor in a stirred PBS cell. Apply the operating potential (+0.7 V vs. Ag/AgCl for H₂O₂ oxidation). Inject a known concentration of glucose and record the steady-state amperometric current (I₀).

- Inhibition Phase: Incubate the biosensor in the sample containing the target heavy metal for a fixed period (e.g., 10-15 minutes).

- Post-Inhibition Activity Measurement: Rinse the biosensor and measure the amperometric current (Iᵢ) again under identical conditions as in step 3.

- Quantification: Calculate the percentage inhibition (% I) using the formula: I(%) = (I₀ - Iᵢ) / I₀ × 100 [15] The % I is correlated to the heavy metal concentration using a pre-established calibration curve.

Visualization of General Biosensor Operation

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental components and signal transduction pathway common to all biosensors.

Diagram 1: Core biosensor signal pathway.

Optical Biosensors

Principle and Types

Optical biosensors detect analytes by measuring changes in the properties of light, such as intensity, wavelength, polarization, or phase, resulting from a biorecognition event [16]. They are highly valued for their sensitivity and immunity to electromagnetic interference.

Key optical biosensor types include:

- Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR): This technique detects changes in the refractive index on a thin metal (typically gold) sensor surface. The binding of an analyte to an immobilized bioreceptor alters the mass on the surface, shifting the resonance angle or wavelength of the reflected light, which is measured in real-time without labels [16].

- Fluorescence-based Biosensors: These sensors rely on the emission of light from a fluorophore. The biological event can cause a change in fluorescence intensity, anisotropy, or lifetime. For instance, a GFP-labeled whole-cell biosensor can emit fluorescence upon encountering a specific pollutant [9] [16].

- Fiber Optic Biosensors: These use optical fibers as the transduction element. The bioreceptor is immobilized on the fiber's core or tip. An evanescent field on the fiber surface interacts with the analyte, modulating the light's properties (intensity, phase) as it propagates through the fiber [16].

- Interferometers and Resonators: These devices split light into two paths: one sensitive to the biorecognition event and one reference. The recombination of the beams creates an interference pattern, which shifts upon binding, allowing for highly sensitive detection [16].

Experimental Protocol: SPR-based Detection of Pathogens

SPR is effective for label-free detection of bacterial pathogens in water samples.

Materials and Reagents:

- Instrument: SPR spectrometer (e.g., Biacore system) [16]

- Sensor Chip: Gold-coated glass chip

- Bioreceptor: Specific antibodies against the target pathogen (e.g., E. coli O157:H7)

- Coupling Reagents: Carboxymethylated dextran matrix, N-ethyl-N'-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide (EDC), N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS)

- Running Buffer: HEPES-buffered saline (HBS-EP), pH 7.4

- Regeneration Solution: Glycine-HCl, pH 2.0-3.0

Procedure:

- Sensor Chip Functionalization:

- Mount the gold sensor chip in the SPR instrument.

- Inject a mixture of EDC and NHS to activate the carboxyl groups on the dextran matrix.

- Inject the antibody solution. Amine groups on the antibodies will covalently couple to the activated matrix.

- Inject ethanolamine to block any remaining activated groups.

- Baseline Establishment: Flow the running buffer over the sensor surface at a constant rate until a stable baseline resonance signal is achieved.

- Sample Injection: Inject the water sample (or standard) over the functionalized sensor surface for a fixed contact time (e.g., 5-10 minutes). The binding of the pathogen to the immobilized antibody will cause a shift in the SPR angle, recorded as a resonance units (RU) signal in real-time.

- Dissociation Phase: Switch back to running buffer to monitor the dissociation of weakly bound analytes.

- Surface Regeneration: Inject a short pulse of regeneration solution to remove all bound analyte from the antibody surface, restoring it for the next analysis cycle.

- Data Analysis: The sensorgram (RU vs. time plot) is analyzed. The response (RU shift) is proportional to the mass bound and is used for quantification against a calibration curve [16].

Piezoelectric Biosensors

Principle and Types

Piezoelectric biosensors are mass-sensitive devices based on the piezoelectric effect, where an electrical potential is generated across certain crystalline materials (e.g., quartz) upon mechanical stress, and vice-versa [18]. The most common platform is the Quartz Crystal Microbalance (QCM), which consists of a thin quartz disk sandwiched between two metal electrodes.

When an alternating voltage is applied, the crystal oscillates at its fundamental resonant frequency. The resonance frequency decreases linearly with an increase in mass on the electrode surface, as described by the Sauerbrey equation: Δf = -C_f · Δm [18] where Δf is the frequency shift, Δm is the mass change per unit area, and C_f is the sensitivity constant of the crystal. This makes QCM an effective tool for monitoring affinity interactions like antigen-antibody binding in real-time.

When operating in a liquid environment, the sensor also responds to the viscosity and density of the liquid, providing information about the viscoelastic properties of the adlayer. Advanced QCM with Dissipation monitoring (QCM-D) measures energy dissipation during oscillation, offering insights into the structural properties of soft, viscoelastic biolayers [18].

Experimental Protocol: QCM Immunosensor for Pesticide Detection

This protocol details the detection of a pesticide like carbaryl using a competitive immunoassay format on a QCM.

Materials and Reagents:

- Transducer: 10 MHz AT-cut quartz crystal with gold electrodes [18]

- Bioreceptor: Anti-carbaryl antibody

- Coating Antigen: Carbaryl conjugate (carbaryl linked to a carrier protein like BSA)

- Coupling Reagents: 11-mercaptoundecanoic acid (11-MUA), EDC, NHS

- Blocking Solution: Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA)

- Analyte: Carbaryl standards and samples

Procedure:

- Crystal Functionalization:

- Clean the QCM crystal with piranha solution (Caution: Highly corrosive) and rinse thoroughly.

- Immerse the crystal in an ethanolic solution of 11-MUA to form a self-assembled monolayer (SAM) with terminal carboxyl groups.

- Transfer the crystal to a flow cell. Inject EDC/NHS to activate the carboxyl groups.

- Immobilization of Coating Antigen: Inject the carbaryl-BSA conjugate. It will covalently attach to the SAM via amine coupling, leading to a frequency drop (Δf₁).

- Blocking: Inject a BSA solution to block non-specific binding sites on the gold surface.

- Competitive Assay:

- Pre-mix a fixed concentration of anti-carbaryl antibody with the sample/standard containing carbaryl.

- Inject this mixture over the sensor surface.

- Free carbaryl in the sample and the immobilized carbaryl-BSA compete for the limited antibody binding sites.

- The amount of antibody bound to the surface is inversely proportional to the carbaryl concentration in the sample, measured as a frequency shift (Δf₂).

- Regeneration: A mild acid or surfactant solution is used to remove bound antibody, regenerating the surface for the next run.

- Quantification: A calibration curve is constructed by plotting Δf₂ (or % inhibition) against the logarithm of carbaryl concentration [18].

Visualization of QCM Operational Principle

The following diagram illustrates the operational principle and mass-sensing mechanism of a Quartz Crystal Microbalance.

Diagram 2: QCM mass-sensing mechanism.

Thermal Biosensors

Principle

Thermal biosensors, or calorimetric biosensors, operate on the principle of detecting the enthalpy change (heat released or absorbed) during a biochemical reaction [15]. Most biological reactions, such as enzyme-catalyzed conversions, are exothermic. The core transducer is a thermistor, which measures the temperature change in the reaction chamber relative to a reference.

The total heat generated (ΔQ) is proportional to the total number of moles of product formed (N) and the molar enthalpy (ΔH) of the reaction: ΔQ = N · (-ΔH) [15]. Since the heat output is directly related to the substrate concentration, this allows for quantitative analysis. A key advantage is that they are largely unaffected by the optical or ionic properties of the sample, making them suitable for turbid or colored environmental samples.

Performance Comparison and Environmental Applications

The selection of a transduction mechanism is a critical decision in biosensor design, guided by the specific requirements of the environmental monitoring application. The following table provides a comparative summary of the four transduction mechanisms discussed.

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Biosensor Transduction Mechanisms

| Transducer | Measured Quantity | Typical LOD | Advantages | Limitations | Environmental Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electrochemical | Current, Potential, Impedance | ng/mL - µg/mL [15] | Highly sensitive, easily miniaturized, low cost, suitable for opaque samples [15] | Susceptible to interference from electroactive species, reference electrode instability | Heavy metal detection via enzyme inhibition [15] |

| Optical | Light Intensity, Wavelength, Phase | pg/mL - ng/mL (SPR) [16] | High sensitivity, immunity to electromagnetic interference, potential for multiplexing [16] | Bulky equipment, signal can be affected by ambient light and sample turbidity | Pathogen detection in water using SPR or fiber optics [16] [17] |

| Piezoelectric (QCM) | Resonant Frequency Shift | ng/cm² [18] | Label-free, real-time monitoring, provides viscoelastic information (QCM-D) [18] | Sensitive to environmental vibrations and temperature, performance in liquids is complex | Detection of pesticides and volatile organic compounds (VOCs) [18] |

| Thermal | Temperature Change / Heat | Varies with reaction enthalpy | Universal detection principle, works in turbid media [15] | Low specificity, requires excellent thermal insulation, slow response | Monitoring of enzymatic processes and total metabolic activity |

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful development and deployment of biosensors for environmental monitoring rely on a suite of specialized reagents and materials.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Biosensor Development

| Reagent / Material | Function in Biosensor | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Enzymes | Biorecognition element; catalyzes a reaction with the target analyte | Glucose Oxidase (for heavy metals via inhibition) [15], Acetylcholinesterase (for organophosphorus pesticides) [9] |

| Antibodies | High-affinity biorecognition element for specific antigens | Anti-E. coli antibodies (for pathogen detection) [16] [17], Anti-bisphenol A antibodies (for endocrine disruptors) [16] |

| Nucleic Acids (DNA/RNA) | Biorecognition element for complementary sequences or specific ligands (aptamers) | DNAzymes for heavy metal detection [9], Aptamers for pesticides and toxins [9] [16] |

| Whole Cells / Microorganisms | Living bioreporter; responds to toxicity or specific chemicals | Recombinant bacteria expressing GFP in response to pollutants [9] [16], Vibrio fischeri for toxicity monitoring (Microtox) [15] |

| Nanomaterials | Signal amplification, enhanced immobilization, improved electron transfer | Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) [9] [15], Graphene Oxide (GO) [9], Gold nanoparticles (for SPR and electrochemical signal enhancement) [16] |

| Immobilization Matrices | Stabilizes and confines the bioreceptor on the transducer surface | Silica gels, Poly-o-phenylenediamine (electropolymerized) [15], Self-Assembled Monolayers (SAMs) like 11-MUA [18], Nafion |

Electrochemical, optical, piezoelectric, and thermal transduction mechanisms each offer distinct advantages and face specific challenges for environmental water monitoring. The optimal choice is dictated by the target analyte, required sensitivity, and the operational context (lab vs. field). The current trend in biosensor research points toward miniaturization, multiplexing, and the integration of smart materials and nanotechnology to enhance performance. The development of robust, portable, and user-friendly biosensors that meet the ASSURED (Affordable, Sensitive, Specific, User-friendly, Rapid and robust, Equipment-free, and Deliverable) criteria defined by the WHO remains a primary objective [17]. As these technologies mature, they are poised to become indispensable tools for enabling real-time, on-site water quality assessment, thereby strengthening environmental protection and public health safety.

The Role of Biosensors in Achieving UN Sustainable Development Goals for Water Safety

Access to safe water is a fundamental human right, yet it remains a significant global challenge. The United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 6 (SDG 6) explicitly calls for ensuring "availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all" by 2030 [19]. Alarming statistics reveal that in 2024, approximately 2.2 billion people still lacked safely managed drinking water, highlighting the urgent need for innovative solutions to monitor and safeguard water quality [19]. Conventional analytical techniques for water quality assessment, such as high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and mass spectrometry,, while highly accurate, are often costly, time-consuming, and require complex sample preparation and trained personnel [20] [4]. These limitations restrict their widespread application for routine monitoring, particularly in resource-limited settings, thereby hindering progress toward SDG 6 targets.

Biosensor technology emerges as a transformative biotechnological alternative that can bridge this monitoring gap. Biosensors are defined as self-contained, integrated analytical devices that use a biological recognition element in direct contact with a signal transducer to provide precise quantitative or semi-quantitative analytical information [20]. Their cost-effectiveness, portability, capacity for real-time analysis, and high sensitivity make them exceptionally suitable for the decentralized monitoring of water quality [21] [4]. This review examines the role of biosensors in advancing water safety within the framework of the UN SDGs, providing a technical guide for researchers and scientists. It details the operating principles, performance metrics, and experimental protocols of various biosensor classes, underscoring their potential as sustainable tools for environmental water monitoring research.

Biosensors and Their Alignment with Sustainable Development

The deployment of biosensors directly supports the achievement of several SDG 6 targets, including Target 6.3, which aims to "improve water quality by reducing pollution, eliminating dumping and minimizing release of hazardous chemicals and materials" [19]. By enabling rapid, on-site detection of pollutants, biosensors facilitate timely interventions and pollution control. Furthermore, the development of biosensors using biodegradable components aligns with SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production) by minimizing waste [20]. Their low energy requirements compared to conventional laboratory techniques also contribute to SDG 13 (Climate Action), and their use in protecting aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems from pollutant toxicity advances SDG 14 (Life Below Water) and SDG 15 (Life on Land) [20].

Biosensors are typically classified based on their biorecognition element or their signal transduction method. The principal categories relevant to water monitoring are detailed below.

Classification by Biorecognition Element

Enzyme-Based Biosensors: These biosensors employ enzymes as bioreceptors to catalyze a reaction with the target analyte. The analyte concentration can be estimated either by measuring its catalytic transformation, the inhibition of the enzyme, or a change in the enzyme's characteristics [4]. They are among the earliest developed biosensors and are known for their high specificity and sensitivity. The biocatalytic reaction typically produces electrical, optical, or thermal signals, with electrochemical transducers being most common due to their rapidity, simplicity, and portability [4]. For instance, the enzyme lactate oxidase is used in biosensors where it catalyzes the oxidation of lactate, using oxygen as an electron acceptor, thus avoiding the need for additional reagents [22].

Antibody-Based Biosensors (Immunosensors): These leverage the high specificity and affinity of antibodies (e.g., IgG, IgM) for target recognition [4]. They can be categorized into label-free and labeled systems. Label-free immunosensors detect physical changes (e.g., in impedance, refractive index, or mass) resulting from the antigen-antibody binding event. In contrast, labeled systems use secondary molecules like fluorescent dyes or enzymes to generate a detectable signal [4].

Nucleic Acid-Based Biosensors (Aptasensors): These utilize synthetic single-stranded DNA or RNA aptamers, selected through the Systematic Evolution of Ligands by Exponential Enrichment (SELEX) process, as recognition elements [4]. Aptamers fold into specific 2D or 3D structures upon binding their target (e.g., metal ions, organic compounds) via mechanisms such as π-π stacking, van der Waals forces, and hydrogen bonding, which triggers signal transduction [20] [4].

Whole Cell-Based Biosensors: These use microbial cells (e.g., bacteria, algae) as the biorecognition element. The cells function as integrated machinery, containing both receptors and transducers [4]. A key advantage is their ability to self-replicate, which can enhance signal detection over time. They are generally more robust across various conditions and easier to handle. Microbial cells can be engineered through genomic editing or plasmid introduction to tailor the sensing system to specific requirements [4].

Classification by Transduction Mechanism

Electrochemical Biosensors: These represent one of the most extensively applied classes. Their design centers on electrodes suitable for immobilizing biomolecules, which then translate biochemical events into quantifiable electrical signals [20]. Their advantages include straightforward integration with existing electronics and suitability for mass production. Examples include amperometric, potentiometric, conductometric, and impedimetric biosensors [22] [20]. For example, a hybrid Pt NPs/SiO2–DNAzyme electrochemical biosensor has been reported to achieve ultralow limits of detection for heavy metals [20].

Optical Biosensors: These operate by utilizing the interaction between an optical field and the biorecognition element [20]. They are particularly useful for analyzing colored or turbid samples. Detection can be label-based (using colorimetric, fluorescent, or luminescent methods) or label-free (relying on direct analyte-transducer interactions, such as surface plasmon resonance (SPR)) [20]. An example is a sensor using nanocrystalline cellulose/PEDOT (NCC/PEDOT) thin films to enhance SPR sensitivity for mercury ions [20].

Mass-Based Biosensors: The fundamental operation of these biosensors centers on detecting mass changes that occur when the target analyte attaches to the biorecognition element fixed on the sensor's surface. This is typically measured using piezoelectric transducers like a quartz crystal microbalance (QCM), which converts mechanical stress into an electrical signal [20]. A QCM platform functionalized with homocysteine and nanoparticle coatings has been used to detect mercury ions with very high sensitivity [20].

The operational principle of a biosensor and its integration into a sensing system can be visualized as the following workflow:

Performance Metrics for Contaminant Detection

The effectiveness of biosensors for water monitoring is demonstrated by their performance in detecting various classes of pollutants. The following tables summarize representative quantitative data for the detection of heavy metals, pesticides, and other emerging contaminants.

Table 1: Performance of Biosensors for Heavy Metal Detection in Water

| Heavy Metal | Biosensor Type | Biorecognition Element | Limit of Detection (LOD) | Linear Range | Response Time | Sample Matrix |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lead (Pb²⁺) | Electrochemical (Aptasensor) | DNAzyme (FAM-Pb-14S) | 60.7 nM [20] | Information Missing | Information Missing | Lake Water [20] |

| Lead (Pb²⁺) | Electrochemical | DNAzyme (Pt NPs/SiO₂) | 0.8 nM [20] | ~1 - 50 nM [20] | < 19 s [20] | Not Specified |

| Cadmium (Cd²⁺) | Electrochemical | DNAzyme (Pt NPs/SiO₂) | 1 nM [20] | ~1 - 50 nM [20] | < 19 s [20] | Not Specified |

| Chromium (Cr³⁺) | Electrochemical | DNAzyme (Pt NPs/SiO₂) | 10 nM [20] | ~10 - 100 nM [20] | < 19 s [20] | Not Specified |

| Mercury (Hg²⁺) | Optical-SPR | Nanocrystalline Cellulose/PEDOT | 2 ppb (~10 nM) [20] | Information Missing | 30 min [20] | Not Specified |

| Mercury (Hg²⁺) | Piezoelectric (QCM) | Homocysteine/Nanoparticles | 0.1 ppb (~0.5 nM) [20] | 0.1 ppb - 1,355 ppm [20] | < 30 min [20] | Not Specified |

Table 2: Performance of Biosensors for Pesticides and Other Emerging Contaminants

| Target Analyte | Biosensor Type | Biorecognition Element | Limit of Detection (LOD) | Linear Range | Response Time | Sample Matrix |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Various Pesticides | Various (Enzymatic, Immuno-, Apta-) | Enzymes, Antibodies, Aptamers | General range: ng/L to g/L [4] | Information Missing | Information Missing | Environmental Water [21] [4] |

| Ciprofloxacin (Antibiotic) | Impedimetric Immunosensor | Antibody | 10 pg/mL [4] | Information Missing | Information Missing | Not Specified |

| Lactate (Indicator) | Amperometric | Lactate Oxidase (LOx) | Information Missing | Information Missing | Information Missing | Not Specified [22] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

To ensure reproducibility and provide a practical guide for researchers, this section outlines detailed protocols for biosensor fabrication and testing, focusing on two prominent types: electrochemical aptasensors for heavy metals and enzyme-based biosensors.

Protocol 1: Fabrication of an Electrochemical DNAzyme-based Biosensor for Heavy Metals

This protocol is adapted from the work on a hybrid Pt NPs/SiO2–DNAzyme biosensor that achieved ultralow detection limits for Pb²⁺, Cd²⁺, and Cr³⁺ [20].

Key Reagents and Materials:

- DNAzyme Sequence: A specific DNAzyme (e.g., for Pb²⁺) with catalytic and substrate strands.

- Platinum Nanoparticles (Pt NPs) and Silica Nanoparticles (SiO₂): For creating the hybrid nanocomposite to enhance the electrode surface area and DNA immobilization.

- Gold Electrode: A clean, polished gold disk electrode as the transducer substrate.

- MCH (6-Mercapto-1-hexanol): Used to form a self-assembled monolayer to block non-specific binding sites on the gold electrode [20].

- Buffer Solutions: e.g., Tris-HCl buffer for DNA dilution and hybridization; a specific buffer solution containing Co(NH₃)₆³⁺ may be used to stabilize G-quadruplex structures in certain DNAzyme designs [20].

Procedure:

- Electrode Pretreatment: Polish the gold electrode with alumina slurry (e.g., 0.3 μm and 0.05 μm) sequentially. Rinse thoroughly with deionized water and then with ethanol. Dry under a stream of inert gas (e.g., nitrogen).

- Nanocomposite Preparation: Synthesize or acquire Pt NPs and SiO₂ nanoparticles. Prepare a homogeneous suspension of the Pt NPs/SiO₂ hybrid material.

- DNAzyme Immobilization:

- Drop-cast the Pt NPs/SiO₂ hybrid suspension onto the clean gold electrode surface and allow it to dry.

- Incubate the modified electrode with a solution of the thiol-modified catalytic DNAzyme strand. This allows the DNA to form a self-assembled monolayer on the nanocomposite via Au-S bonding.

- Subsequently, incubate the electrode with a solution of MCH (e.g., 1 mM) for 30-60 minutes to passivate the remaining bare gold surface and prevent non-specific adsorption.

- Hybridize the immobilized catalytic strand with its complementary substrate strand by incubating in an appropriate hybridization buffer.

- Electrochemical Measurement:

- Use a standard three-electrode system (modified gold working electrode, Pt counter electrode, and Ag/AgCl reference electrode) connected to a potentiostat.

- Immerse the biosensor in the sample solution (or standard solution for calibration) containing the target metal ion.

- Record the electrochemical signal (e.g., differential pulse voltammetry or electrochemical impedance spectroscopy). The presence of the target metal ion will activate the DNAzyme, cleaving the substrate strand and leading to a measurable change in the electrochemical signal.

- Calibration and Analysis:

- Perform measurements with a series of standard solutions of known concentrations to create a calibration curve (e.g., 1, 2, 5, 10, 20, 50 nM for Pb²⁺ and Cd²⁺) [20].

- Plot the signal response against the logarithm of concentration to determine the concentration of the target in unknown samples.

Protocol 2: Development of a Lactate Oxidase-Based Amperometric Biosensor

This protocol details the construction of an amperometric biosensor for lactate, which can serve as a model for enzyme-based systems and as an indicator for microbial activity in water [22].

Key Reagents and Materials:

- Lactate Oxidase (LOx): The core biorecognition enzyme.

- Transducer: An amperometric transducer, typically a platinum or carbon-based working electrode.

- Enzyme Immobilization Matrix: Materials such as chitosan, Nafion, or sol-gels for entrapping and stabilizing the enzyme on the electrode surface.

- Glutaraldehyde: Often used as a cross-linking agent to covalently bind enzymes to the immobilization matrix or directly to the electrode.

- Phosphate Buffer Saline (PBS): For maintaining a stable pH during measurements.

Procedure:

- Transducer Preparation: Clean the working electrode surface as per manufacturer's or standard protocols (e.g., polishing for solid electrodes).

- Enzyme Immobilization:

- Prepare an enzyme cocktail by mixing a specific amount of LOx (e.g., 5-10 mg) with the immobilization matrix (e.g., 10 μL of 1% chitosan solution).

- Add a small volume of cross-linker (e.g., 0.1% glutaraldehyde) to the mixture and vortex gently.

- Drop-cast a precise volume (e.g., 5-10 μL) of this mixture onto the active surface of the working electrode and allow it to dry at room temperature or under mild desiccation.

- Experimental Setup and Measurement:

- Assemble the electrochemical cell with the biosensor as the working electrode, along with reference and counter electrodes, in a stirred PBS solution under a constant applied potential (e.g., +0.7 V vs. Ag/AgCl).

- Allow the background current to stabilize.

- Introduce standard lactate solutions or samples into the cell. LOx catalyzes the conversion of lactate to pyruvate and H₂O₂. The H₂O₂ produced is oxidized at the electrode surface, generating a current proportional to the lactate concentration.

- Record the steady-state current response.

- Data Processing:

- Plot the steady-state current versus lactate concentration to generate a calibration curve.

- The operational stability can be assessed by repeatedly measuring the response to a standard lactate solution over time or through continuous operation [22].

The following diagram illustrates the signaling pathway for an enzyme-based biosensor, using lactate oxidase as a specific example:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful development and fabrication of biosensors require a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The following table details key components and their functions in biosensor research.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Biosensor Development

| Item | Function/Application | Exemplar Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Lactate Oxidase (LOx) | Biorecognition element; catalyzes the oxidation of lactate to pyruvate and H₂O₂. | Core enzyme in amperometric lactate biosensors [22]. |

| DNAzymes | Synthetic, catalytic DNA strands used as biorecognition elements; cleave substrate strands in the presence of specific target ions. | Detection of heavy metals like Pb²⁺, Cd²⁺, and Cr³⁺ in electrochemical biosensors [20]. |

| Aptamers | Single-stranded DNA or RNA oligonucleotides selected for high-affinity binding to specific targets (ions, molecules, cells). | Used in aptasensors for a wide range of contaminants; e.g., for Pb²⁺ detection via G-quadruplex folding [20] [4]. |

| Platinum Nanoparticles (Pt NPs) | Nanomaterial used to modify electrode surfaces; enhances electrical conductivity and surface area for biomolecule immobilization. | Used in a hybrid Pt NPs/SiO₂ composite for ultrasensitive electrochemical DNAzyme biosensors [20]. |

| 6-Mercapto-1-hexanol (MCH) | Used to form self-assembled monolayers on gold surfaces; blocks non-specific binding and improves bioreceptor orientation. | Passivation agent in gold electrode-based aptasensors and DNAzyme sensors to reduce false signals [20]. |

| Glutaraldehyde | A common homobifunctional crosslinker; used to covalently immobilize biomolecules (e.g., enzymes) onto solid supports or matrices. | Cross-linking agent in enzyme-based biosensors for stable enzyme attachment on transducers [22]. |

| Quartz Crystal Microbalance (QCM) | Piezoelectric transducer that measures mass changes on its surface with high sensitivity. | Platform for mass-based biosensors; e.g., for Hg²⁺ detection functionalized with homocysteine [20]. |

Current Challenges and Future Research Directions

Despite their significant promise, several challenges must be addressed to enable the widespread deployment and commercialization of biosensors for water monitoring.

- Stability and Reproducibility: The biological components of biosensors (enzymes, antibodies, cells) can be sensitive to environmental factors such as temperature and pH, leading to degradation over time and affecting long-term stability and reproducibility [21] [4]. "Operational stability" refers to the retention of the biological element's activity during use and is a critical parameter [22].

- Interference from Environmental Matrices: Complex water samples may contain various interfering substances that can cause false positives or negatives, a challenge known as cross-sensitivity [21] [20].

- Mass Production and Regulatory Validation: Scaling up the fabrication of biosensors to ensure consistent quality and performance remains a hurdle. Furthermore, obtaining regulatory validation for these novel devices is necessary for their acceptance in official monitoring programs [20].

Future research is focused on overcoming these limitations through several innovative strategies:

- Advanced Immobilization Techniques and Nanomaterials: The use of hybrid nanomaterials and novel immobilization methods can significantly improve biosensor stability, sensitivity, and shelf life [4]. For example, incorporating nanoparticles can enhance signal transduction and provide a more robust matrix for bioreceptor attachment [20].

- Portable and Multifunctional Biosensors: The development of compact, user-friendly, and portable devices is crucial for on-site, real-time monitoring [4]. Future work also includes creating multiplexed biosensors capable of detecting multiple contaminants simultaneously in a single assay.

- Eco-Design and Sustainability: Aligning with SDG 12, there is a growing emphasis on developing eco-biosensors that utilize biodegradable components to minimize environmental impact [20].

A proposed framework for integrating biosensors into a comprehensive water safety plan, aligned with SDG 6, is outlined below:

Biosensors represent a paradigm shift in environmental monitoring, offering a powerful and sustainable technological pathway to support the achievement of UN SDG 6 for water safety. Their core advantages—cost-effectiveness, sensitivity, portability, and potential for real-time analysis—directly address the critical gaps left by conventional analytical methods, particularly for widespread screening and resource-limited scenarios. While challenges in long-term stability, reproducibility, and regulatory acceptance persist, ongoing research focused on nanomaterials, advanced immobilization techniques, and eco-design is rapidly advancing the field. For the research community, the continued development, refinement, and validation of biosensor platforms are imperative. By providing detailed protocols and performance metrics, this review aims to contribute to these efforts, fostering the development of robust biosensor technologies that will be integral to ensuring safe water for all, as envisioned by the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

The escalating challenge of environmental water pollution, particularly from emerging contaminants (ECs) and heavy metals, necessitates robust monitoring methodologies [8] [23]. Traditional analytical techniques, such as high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), gas chromatography (GC), and inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS), have long been the gold standard for pollutant quantification [9] [8]. While these methods offer high sensitivity and accuracy, they are characterized by significant limitations: they are laboratory-bound, require complex sample preparation, involve time-consuming protocols, and rely on expensive instrumentation and skilled personnel [8] [24] [25]. These constraints hinder their application for rapid, routine, and on-site monitoring, which is crucial for timely decision-making and effective environmental protection [9] [23].

Biosensors, analytical devices that integrate a biological recognition element with a physicochemical transducer, present a powerful alternative [26] [23]. This review, framed within a broader thesis on biosensors for environmental water monitoring, delineates their principal advantages over conventional methods. We focus on three transformative attributes: portability for on-site analysis, capability for real-time monitoring, and overall cost-effectiveness. The objective is to provide researchers and scientists with a technical guide that underscores how these features are addressing the urgent needs of modern environmental analysis and enabling a paradigm shift towards smarter, more sustainable water quality assessment.

Portability and On-Site Monitoring

The portability of biosensors is a cornerstone of their utility in environmental monitoring, effectively decentralizing analytical capabilities from centralized laboratories to the field.

Technical Basis for Portability

The miniaturization of biosensors is facilitated by advancements in microfabrication techniques and nanotechnology [26] [27]. A key innovation is the integration of microfluidic systems, which allow for the precise manipulation of small fluid volumes, thereby reducing reagent consumption and the overall footprint of the device [23]. Furthermore, the development of screen-printed electrodes (SPEs) and similar solid-state transducers has replaced bulky traditional electrodes, contributing to compact and robust sensor designs [9]. The convergence of these technologies enables the production of handheld or pocket-sized analytical devices that do not compromise on performance [26].

Comparison with Conventional Methods

Traditional instruments like GC-MS or ICP-MS are large, benchtop systems that require a stable laboratory environment with controlled temperature and humidity [25]. Transporting these instruments to the field is impractical. Moreover, the process of collecting water samples, preserving them to prevent analyte degradation, and transporting them to a laboratory introduces risks of sample contamination or changes in composition, potentially leading to inaccurate results [23]. Biosensors eliminate this pre-analytical uncertainty by performing analysis in situ.

Experimental Protocols for Field Deployment

A typical protocol for on-site water monitoring using a portable biosensor involves:

- Calibration: The biosensor is calibrated using standard solutions of the target analyte to establish a quantitative response curve.

- Sample Introduction: A small, minimally processed volume of the environmental water sample (often just filtration to remove particulates) is introduced into the biosensor's microfluidic chamber or onto its sensing surface [23].

- Incubation and Measurement: The sample interacts with the biorecognition element (e.g., enzyme, antibody, whole cell). The resulting biochemical change is transduced into a measurable electrical or optical signal.

- Data Readout: An integrated microprocessor converts the signal, providing a direct readout of the analyte concentration on a digital display within minutes [24].

Table 1: Comparison of Key Features Between Biosensors and Conventional Methods.

| Feature | Biosensors | Conventional Methods (HPLC, GC-MS, ICP-MS) |

|---|---|---|

| Portability | High (handheld, portable devices) [26] | Low (large, benchtop instruments) [25] |

| Analysis Speed | Minutes to hours [24] | Hours to days, including sample prep [8] |

| On-Site Capability | Yes, for real-time in situ analysis [23] | No, requires lab transport |

| Sample Preparation | Minimal (often just filtration) [23] | Extensive (extraction, purification, derivation) [25] |

| Operational Skill Requirement | Low to moderate | High, requires trained experts |

Figure 1: Workflow comparison of portable biosensor versus conventional lab-based analysis.

Real-Time and Continuous Monitoring

The ability to provide real-time or near-real-time data is a critical advantage of biosensors, enabling immediate response to pollution events.

Mechanisms Enabling Real-Time Sensing

Real-time capability is inherent to the design of many biosensors. Electrochemical biosensors, for instance, measure changes in current or potential that occur almost instantaneously upon the binding of the analyte to the bioreceptor [27]. Similarly, optical biosensors can detect changes in light properties in real-time [26]. The integration of biosensors with wireless communication technologies and the Internet of Things (IoT) allows for the continuous transmission of data from deployed sensors to central monitoring stations, facilitating the creation of early-warning systems [28] [24].

Contrast with Conventional Approach Limitations

Conventional methods are inherently discontinuous. They provide a "snapshot" of contamination levels only at the time of sample collection. For dynamic water systems, this can miss episodic pollution events, such as intermittent industrial discharges or pesticide runoff from agricultural fields after rainfall [23]. The delay between sample collection and the availability of results—often days or weeks—renders the data useless for immediate intervention.

Experimental Protocols for Continuous Monitoring

Protocols for deploying biosensors for continuous monitoring involve:

- Immobilization of Bioreceptor: The biological element (e.g., enzyme, antibody, whole cell) is stabilized and immobilized on the transducer surface to ensure long-term activity [23].

- System Integration and Calibration: The biosensor is integrated into a flow-through system or directly deployed in a water body, connected to a power source, and calibrated.

- Data Acquisition and Transmission: The sensor autonomously takes measurements at pre-set intervals. Data is processed by an on-board microcontroller and transmitted wirelessly (e.g., via GSM or LoRaWAN) [24].

- Alert Generation: Software algorithms analyze the incoming data stream and trigger automatic alerts if pollutant concentrations exceed predefined safety thresholds.

Table 2: Performance Data of Selected Biosensors for Real-Time Environmental Monitoring.

| Target Pollutant | Biosensor Type | Transduction Method | Detection Limit | Response Time | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hg²⁺ and Pb²⁺ | Cell-free, paper-based | Optical (aTF-based) | Hg²⁺: 0.5 nMPb²⁺: 0.1 nM | Not Specified | [24] |

| Organophosphorus Pesticides | Enzyme-based (AChE) | Electrochemical | Varies (ng/L range) | Minutes | [9] [8] |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Whole-cell-based | Optical (GFP) | N/A | Minutes | [23] |

| Polybrominated Diphenyl Ethers (PBDEs) | Enzyme-based (Glucose Oxidase) | Electrochemical (Amperometric) | 0.014 μg/L | Minutes to <1 hour | [24] |

Cost-Effectiveness

The economic argument for biosensors is compelling, encompassing not only the initial device cost but also operational and lifecycle expenses.

Analysis of Cost Components

- Initial Capital and Equipment Costs: Conventional analytical instruments represent a major capital investment, often exceeding tens of thousands of dollars per unit [24]. In contrast, biosensors, particularly disposable screen-printed variants or reusable portable units, are significantly less expensive to manufacture at scale [2].

- Operational and Consumable Costs: The cost-per-test for biosensors is low. They require minimal sample preparation, which reduces or eliminates the need for expensive solvents and reagents [8] [25]. Furthermore, they consume very little power, especially compared to energy-intensive instruments like ICP-MS [9]. This low operational cost makes frequent, large-scale screening economically feasible.

- Personnel and Infrastructure Costs: Operating a biosensor typically requires less specialized training than running and maintaining a GC-MS system. This reduces personnel costs and makes the technology accessible to a wider range of users, including field technicians and environmental health officers [23].

Quantitative Economic Impact