Advanced Methods for Biosensor Calibration in Complex Samples: From Foundational Principles to Clinical Applications

Accurate biosensor calibration in complex biological matrices is paramount for reliable performance in biomedical research and drug development.

Advanced Methods for Biosensor Calibration in Complex Samples: From Foundational Principles to Clinical Applications

Abstract

Accurate biosensor calibration in complex biological matrices is paramount for reliable performance in biomedical research and drug development. This article comprehensively examines the entire calibration workflow, from foundational principles of biosensor operation and key performance metrics to advanced methodological approaches for handling sample complexity. We explore cutting-edge troubleshooting strategies to overcome interference, noise, and matrix effects, while providing rigorous validation frameworks and comparative analyses of different calibration techniques. By synthesizing current research and emerging trends, this resource equips scientists with the knowledge to implement robust calibration protocols that ensure data integrity across diverse applications, from therapeutic monitoring to diagnostic biomarker detection.

Core Principles and Performance Metrics for Biosensor Calibration

Core Concepts: Bioreceptor vs. Transducer

A biosensor is an analytical device that integrates a biological recognition element (bioreceptor) with a physicochemical transducer to detect a specific analyte [1] [2]. The bioreceptor is responsible for selective interaction with the target molecule, while the transducer converts this biological event into a measurable signal [3].

Bioreceptors provide the specificity of a biosensor. They are biological molecules or structures capable of recognizing a particular analyte with high affinity [1]. The transducer's role is to convert the biochemical response resulting from the bioreceptor-analyte interaction into an quantifiable output, such as an electrical or optical signal [1] [3].

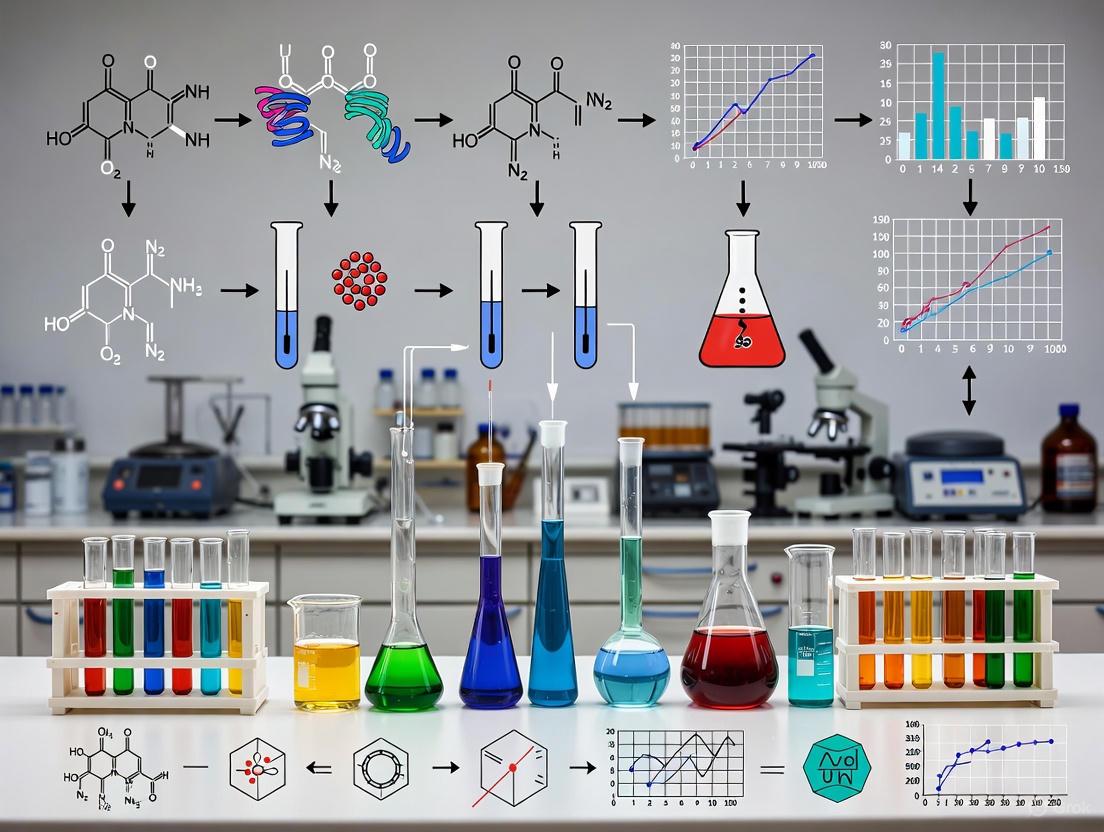

∎ Biosensor Architecture Diagram

Frequently Asked Questions & Troubleshooting Guides

∎ Biosensor Selection and Setup

What is the fundamental difference between a bioreceptor and a transducer? The bioreceptor is the biological component (e.g., enzyme, antibody, nucleic acid) that selectively binds to the target analyte. The transducer is the physical component (e.g., electrode, optical detector) that converts the binding event into a measurable signal [1] [3]. For example, in a glucose biosensor, the enzyme glucose oxidase is the bioreceptor, while the oxygen electrode is the transducer [1].

How do I select the appropriate bioreceptor for my target analyte? Choose a bioreceptor based on the required specificity and the nature of your analyte [4] [3].

- Enzymes: Ideal for substrates and catalytic reactions (e.g., glucose oxidase for glucose) [3].

- Antibodies: Excellent for specific antigen binding (e.g., immunosen sors for pathogens or proteins) [3].

- Nucleic Acids (DNA/RNA): Used for detecting complementary sequences, mutations, or specific genetic markers [3] [2].

- Whole Cells or Tissues: Provide complex responses for toxin detection or metabolic profiling [2].

What are the key characteristics of a high-performance biosensor? When selecting or designing a biosensor, optimize for these core characteristics [1]:

- Selectivity: The ability to measure the analyte in a sample containing adulterants.

- Sensitivity: The minimum amount of analyte that can be reliably detected (Limit of Detection, or LOD).

- Reproducibility: The precision and accuracy of repeated measurements.

- Stability: The susceptibility to ambient disturbances and the degradation rate of the bioreceptor.

- Linearity: The concentration range over which the sensor response is linearly proportional to analyte concentration.

∎ Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

My biosensor signal is unstable or drifting. What could be the cause? Signal drift often stems from bioreceptor instability or environmental factors [1] [2].

- Bioreceptor Degradation: Enzymes and antibodies can denature over time. Ensure proper storage conditions and check the shelf life of your bioreceptor components [1].

- Temperature Fluctuations: Many biological interactions are temperature-sensitive. Perform experiments in a temperature-controlled environment or use biosensors with built-in temperature compensation [1] [2].

- Calibration Error: Recalibrate the sensor regularly using fresh standard solutions. A common pitfall is using expired or contaminated buffer solutions for calibration [5].

- Fouling or Contamination: In complex samples (e.g., serum, wastewater), matrix components can non-specifically adsorb to the sensor surface. Use blocking agents or antifouling coatings to minimize this interference [2].

The sensitivity of my biosensor is lower than expected. How can I improve it? Low sensitivity can be addressed by enhancing the signal transduction or the biorecognition efficiency [2].

- Check Immobilization: The bioreceptor may be denatured or inaccessible. Optimize your immobilization method (e.g., covalent attachment, adsorption, entrapment) to maintain biological activity and orientation [2].

- Employ Nanomaterials: Integrate nanostructured materials (e.g., gold nanoparticles, graphene, MOFs) into your transducer. They increase the effective surface area, improving the loading of bioreceptors and enhancing the output signal [1] [2] [6].

- Verify Sample pH: The activity of the bioreceptor can be highly dependent on pH. Ensure the sample pH is within the optimal operating range for your specific bioreceptor [5].

- Amplification Strategies: For optical biosensors, use fluorescent labels or enzymes (e.g., horseradish peroxidase) that generate amplified products. For electrochemical sensors, consider using redox mediators [3] [2].

My biosensor shows poor selectivity in complex samples. What should I do? Poor selectivity is often due to non-specific binding or interference [1] [2].

- Optimize Blocking: After immobilizing the bioreceptor, block the remaining active surfaces on the sensor with inert proteins (e.g., BSA, casein) or other blocking agents to prevent non-specific adsorption [2].

- Sample Pre-treatment: Pre-filter, dilute, or desalt complex samples to reduce interferent concentration before analysis.

- Use a Ratiometric Design: Ratiometric biosensors, which measure the ratio of signals at two different wavelengths or potentials, provide an internal calibration that can correct for environmental interference and improve robustness in complex matrices [6].

- Check Bioreceptor Cross-reactivity: Validate the specificity of your antibody or aptamer against potential interfering compounds with similar structures.

∎ Systematic Troubleshooting Workflow

Experimental Protocols for Biosensor Calibration in Complex Samples

∎ Protocol 1: Calibration and Validation in a Simulated Complex Matrix

This protocol is designed to establish a calibration curve and validate biosensor performance in the presence of potential interferents, a critical step for research involving complex samples like serum or wastewater [2] [5].

1. Objective: To generate a standard calibration curve for the target analyte and determine the biosensor's Limit of Detection (LOD) and linear range in a controlled buffer system.

2. Materials:

- Biosensor system (with integrated bioreceptor and transducer)

- Stock solution of the pure analyte

- Appropriate assay buffer (e.g., PBS, pH 7.4)

- Standard solutions of known potential interferents

3. Methodology:

- Step 1: Preparation. Prepare a series of analyte standard solutions in assay buffer, covering the expected concentration range (e.g., from pM to μM).

- Step 2: Calibration. Measure the biosensor response for each standard solution. Perform measurements in triplicate.

- Step 3: Data Analysis. Plot the sensor response (e.g., current, fluorescence intensity) against the analyte concentration. Fit the data to determine the linear range, sensitivity (slope), and LOD (typically calculated as 3×standard deviation of the blank/slope).

4. Validation in Complex Matrix:

- Step 4: Spike-and-Recovery. Take a sample of the complex matrix (e.g., diluted serum) that is free of the analyte ("blank matrix"). Spike it with known concentrations of the pure analyte.

- Step 5: Measurement and Calculation. Measure the biosensor response for the spiked samples. Calculate the percentage recovery:

(Measured Concentration / Spiked Concentration) × 100%. Recoveries between 80-120% generally indicate good accuracy and minimal matrix interference [6].

∎ Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following reagents are essential for biosensor development and calibration experiments, particularly when working with complex samples.

| Reagent / Material | Function & Explanation |

|---|---|

| High-Affinity Bioreceptors (e.g., monoclonal antibodies, aptamers) | Provides the selectivity for the target analyte. High affinity reduces non-specific binding in complex matrices [1] [3]. |

| Blocking Agents (e.g., BSA, casein, synthetic blockers) | Reduces non-specific binding by adsorbing to unused sites on the sensor surface after bioreceptor immobilization, thereby lowering background noise [2]. |

| Nanomaterial Enhancers (e.g., gold nanoparticles, graphene, MOFs) | Increases signal strength and sensitivity by providing a high surface-to-volume ratio for greater bioreceptor loading and enhancing transduction efficiency (e.g., plasmonic effects, electrical conductivity) [1] [2] [6]. |

| Ratiometric Probes (e.g., dual-emission fluorescent dyes, reference electrodes) | Provides an internal calibration by measuring the ratio of two signals. This corrects for instrument fluctuations and environmental variability, improving accuracy in complex samples [6]. |

| Antifouling Coatings (e.g., PEG, zwitterionic polymers) | Prevents biofouling by creating a hydration layer that resists the non-specific adsorption of proteins, cells, and other biomolecules from complex samples like blood or wastewater [2]. |

In biosensor research, the accuracy and reliability of data generated from complex samples are paramount. Three fundamental metrics—Dynamic Range, Sensitivity, and Limit of Detection (LOD)—form the cornerstone of robust biosensor calibration and validation. Proper characterization of these parameters ensures that your biosensor can deliver selective, quantitative analytical information with the required precision for pharmaceutical and clinical applications [7]. The process of establishing these performance characteristics meets the requirements for the intended analytical application is often referred to as method validation [8]. This guide addresses frequent challenges researchers encounter during this critical process, providing targeted troubleshooting advice and experimental protocols to enhance your biosensor's performance.

Key Concepts and Definitions

What is the Limit of Detection (LOD) and how is it properly determined?

The Limit of Detection (LOD) is defined as the lowest concentration of an analyte in a sample that can be detected—though not necessarily quantified—with a stated probability under the stated experimental conditions [8]. It represents the smallest solute concentration that your analytical system can reliably distinguish from a blank sample (one without analyte) [8] [9].

Common Problem: Many researchers incorrectly calculate LOD by simply dividing the instrument resolution by the sensitivity, which can yield unrealistically low values that don't reflect actual performance [9].

Correct Approaches:

Method I: Using Blank Standard Deviation

- Make repeated measurements (n~20) of a blank sample to determine the mean signal (ȳB) and standard deviation (sB).

- The LOD is then calculated as: LOD = ȳB + k × sB, where k is a numerical factor chosen based on the desired confidence level [8] [9].

- For a factor of k=3, the probability of a false positive is approximately 7% [8]. IUPAC recommends this approach for LOD determination [9].

Method II: Using a Calibration Curve

- Prepare and measure a series of standard solutions at different concentrations, including some near the suspected LOD.

- Generate a linear calibration curve (y = aC + b, where 'a' is the sensitivity/slope).

- The LOD can be estimated as: LOD = 3 × sB / a, where sB is the standard deviation of the blank and 'a' is the slope of your calibration curve [10] [9].

Table 1: Comparison of LOD Determination Methods

| Method | Data Requirements | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blank Standard Deviation | 20+ blank measurements | Direct measurement of noise at zero concentration | Requires many replicates; may not account for matrix effects |

| Calibration Curve | Multiple low-concentration standards | Uses actual sensor response near LOD; more practical | Requires careful selection of low concentration standards |

How do I distinguish between Sensitivity and Limit of Detection?

Problem: Researchers often conflate sensitivity with LOD, leading to incorrect performance characterization.

Solution:

- Sensitivity is the analytical sensitivity defined as the slope (a) of your calibration curve (the change in sensor response per unit change in analyte concentration) [8] [9]. A steeper slope indicates higher sensitivity.

- LOD is the lowest concentration that can be reliably detected and depends on both sensitivity and the noise level of your measurement system [9].

A sensor can have high sensitivity but poor LOD if it has high background noise, or conversely, good LOD with moderate sensitivity if the system is very stable with low noise [9].

What defines the Dynamic Range of a biosensor and why is it crucial for complex samples?

The Dynamic Range (or working range) is the span of concentrations over which your biosensor provides accurate quantitative measurements. It is typically bounded at the lower end by the LOD and at the upper end by signal saturation [10].

Problem: In complex samples with unknown analyte concentrations, a narrow dynamic range may require extensive sample dilution or concentration, introducing error and increasing processing time.

Solution:

- The dynamic range is typically assessed by plotting sensor response against the logarithm of analyte concentration, which often produces a sigmoidal curve [10].

- The linear portion of this curve represents the working range where quantitative measurements are most accurate [10].

- For example, a novel GEM-based biosensor for heavy metal detection showed a linear dynamic range for Cd²⁺, Zn²⁺, and Pb²⁺ in the range of 1–6 ppb, making it suitable for detecting low concentrations of these metal ions [11].

Troubleshooting Common Calibration Issues

How can I improve my biosensor's Limit of Detection?

Problem: Unacceptably high LOD limits application for trace analysis.

Solutions:

- Signal Processing: Implement advanced signal processing techniques including noise reduction algorithms and signal amplification methods to enhance signal-to-noise ratio [10].

- Nanomaterials: Incorporate nanostructured materials (nanoparticles, nanowires) to increase surface area for biomolecule interactions and amplify sensing signals [10].

- Reference Sensors: Use a dual-sensor approach with a reference sensor to compensate for background interference, as demonstrated in fiber-optic systems where a reference oxygen optrode detected and compensated for response changes caused by bacterial growth or temperature fluctuations [7].

- Multi-Modal Sensing: Combine complementary sensing mechanisms (e.g., mechanical and optical resonances) to overcome limitations of individual techniques [10].

What strategies can extend the Dynamic Range of my biosensor?

Problem: Sensor response saturates at high analyte concentrations, requiring sample dilution.

Solutions:

- Multi-Modal Detection: Implement triple-mode biosensors that integrate three independent detection mechanisms, each covering different concentration ranges, to create an extended overall dynamic range [12].

- Surface Chemistry Optimization: Modify sensor architecture and surface chemistry to reduce steric hindrance and increase binding site availability [10].

- Array-Based Systems: Develop multiplexed resonant biosensor systems with different receptor affinities to cover a wider concentration spectrum [10].

- Data Processing: Utilize mathematical models and curve-fitting algorithms that can accurately interpret both linear and saturation regions of the sensor response [10].

How do I handle matrix effects in complex samples?

Problem: Sample matrix components interfere with biosensor response, causing inaccurate readings.

Solutions:

- Internal Standards: Use appropriate internal standard elements that are not found in your samples and don't spectrally interfere with analytes. Monitor their recovery rates to correct for matrix effects [13].

- Microfluidic Integration: Implement microfluidic systems for precise sample handling, controlled flow rates, and efficient mixing to reduce matrix interference [10].

- Sample Preparation: When possible, dilute samples to reduce concentration of interfering compounds while ensuring analytes remain above LOD [13].

Experimental Protocols for Metric Characterization

Standard Protocol for Determining LOD Using Calibration Curve Method

Prepare Solutions:

- Create a blank solution (without analyte)

- Prepare at least 5 standard solutions at concentrations spanning from below to above the expected LOD [8]

Measurement:

- Measure each solution in replicate (n ≥ 3)

- Record sensor responses for all measurements

- Maintain constant temperature, pH, and incubation time throughout [11]

Data Analysis:

The following workflow illustrates the complete LOD determination process:

Protocol for Characterizing Dynamic Range

Sample Preparation: Prepare standard solutions covering 3-5 orders of magnitude in concentration, from well below to above expected saturation point.

Measurement: Measure sensor response for each concentration in triplicate.

Data Processing:

- Plot sensor response (y-axis) against logarithm of concentration (x-axis)

- Identify the linear region where the coefficient of determination (R²) > 0.98

- Note the lower limit (typically LOD) and upper limit (where deviation from linearity exceeds 5%) [10]

Validation: Test samples with known concentrations within the dynamic range to verify accuracy.

Advanced Approaches for Enhanced Performance

Triple-Mode Biosensing for Self-Validation

Advanced triple-mode biosensors integrate three distinct detection mechanisms (e.g., colorimetric, fluorescent, and electrochemical) in a single platform. These systems provide built-in validation through cross-referencing of signals, significantly enhancing reliability in complex samples [12]. For example, combining photothermal, colorimetric, and fluorescence detection creates a robust system where each method covers different concentration ranges and provides validation for the others [12].

Microfluidic Integration for Consistent Performance

Integrating biosensors with microfluidic systems enables:

- Precise control of flow rates and sample volumes

- Reduced matrix effects through efficient mixing

- Automated calibration and sample introduction [10]

- Implementation of reference sensors to compensate for environmental fluctuations [7]

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Biosensor Calibration

| Reagent/Material | Function in Calibration | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Internal Standards (Y, Sc) | Correct for matrix effects & sample introduction variations [13] | ICP-OES analysis of environmental samples |

| Nanomaterials (Au nanoparticles, graphene) | Signal amplification; increased surface area for biorecognition [10] | Enhanced LOD in resonant biosensors |

| Enzyme Immobilization Matrices | Stabilize biological element; maintain activity over time [7] | Enzyme-based biosensors for continuous monitoring |

| Certified Reference Materials | Validate accuracy of calibration standards [8] | Method validation and quality control |

| Surface Functionalization Reagents | Control bioreceptor orientation and density | SPR and other label-free biosensors |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How many replicate measurements are sufficient for reliable LOD determination? For the blank measurement method, at least 20 replicates are recommended to obtain a statistically meaningful standard deviation. For the calibration curve method, a minimum of 5 concentrations with 3 replicates each is acceptable [8].

Q2: Why do I get different LOD values when using different calculation methods? This is expected, as each method accounts for different sources of error. The blank measurement method focuses on noise at zero concentration, while the calibration curve method incorporates errors across the low concentration range. Consistently report which method you used for transparency [9].

Q3: How often should I recalibrate my biosensor? Establish a regular calibration schedule based on:

- Manufacturer recommendations

- Regulatory requirements (for regulated industries)

- Observed signal drift in continuous monitoring

- When analyzing samples with markedly different matrices [7]

Q4: What acceptance criteria should I use for internal standard recovery? While some regulatory agencies suggest ±20% recovery compared to calibration solutions, the actual acceptable range should be determined based on your specific analysis requirements. More importantly, pay close attention to the precision of internal standard replicates—RSDs greater than 3% should be investigated [13].

Q5: How can I make my LOD and dynamic range characterization more reproducible?

- Always perform characterization under standardized conditions (temperature, pH, buffer composition) [10]

- Use the same reagent batches throughout characterization

- Document all instrumental parameters

- Follow established guidelines like IUPAC recommendations [9]

Proper characterization of dynamic range, sensitivity, and limit of detection is not merely a procedural requirement but a fundamental practice that determines the real-world applicability of your biosensor. By implementing these troubleshooting guidelines and experimental protocols, researchers can generate more reliable, reproducible data that stands up to scientific and regulatory scrutiny, ultimately advancing the field of biosensing in complex sample analysis.

Troubleshooting Guide & FAQs for Biosensor Calibration in Complex Samples

This technical support center addresses common challenges researchers encounter when calibrating biosensors for use in complex samples such as biological fluids, food homogenates, or environmental extracts. A deep understanding of the critical parameters—Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR), Selectivity, and Response Time—is essential for obtaining reliable data.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. How can I improve my biosensor's signal-to-noise ratio in turbid samples like blood serum?

A low SNR in complex matrices is often caused by light scattering (in optical sensors), fouling of the electrode surface (in electrochemical sensors), or non-specific binding. To address this:

- Use Permselective Membranes: Coat your sensor with a membrane like Nafion or cellulose acetate. These membranes block large, interfering molecules (like proteins) based on charge or size, while allowing the target analyte to pass through, thereby reducing background noise [14].

- Employ a Sentinel Sensor: Implement a reference sensor that is identical to your biosensor but lacks the biological recognition element (e.g., the enzyme is replaced with Bovine Serum Albumin). The signal from this "blank" sensor, which arises solely from matrix interferences, can be electronically subtracted from your biosensor's signal [14] [7].

- Leverage Machine Learning: Train machine learning models, such as Random Forests or Gaussian Process Regression, on the dynamic response data of your biosensor. These models can learn to distinguish the pattern of the specific analyte signal from the noise, significantly improving the fidelity of the extracted data [15] [16].

2. What are the most effective strategies to ensure selectivity for my target analyte when multiple interferents are present?

Selectivity is paramount in complex samples. Strategies can be categorized based on the biosensor generation and design.

- For First-Generation Biosensors: These are prone to interferences from electroactive compounds. The use of permselective membranes (e.g., charged polymers) is a primary defense mechanism [14].

- For Second/Third-Generation Biosensors: The use of mediators or direct electron transfer (DET) lowers the operational potential, minimizing the window for redox interferences [14] [17].

- Enzymatic Scavenging: Co-immobilize an enzyme that converts a common interferent into an inactive product. For example, ascorbate oxidase can be used to eliminate ascorbic acid interference [14].

- Multi-Sensor Arrays & Chemometrics: Use an array of sensors with slightly different specificities (e.g., enzymes from different sources or isoforms). The combined response pattern can be deconvoluted using machine learning (e.g., Linear Discriminant Analysis, Support Vector Machines) to quantify individual analytes in a mixture [14] [16] [18].

3. My biosensor has a long response time, delaying my readings. How can I speed it up without sacrificing accuracy?

Long response times can stem from slow mass transport to the sensing element or slow reaction kinetics.

- Optimize Immobilization: The enzyme immobilization method critically affects mass transfer. Ensure your 3D matrix is not too dense, which can trap the substrate and product. Physical entrapment in a porous hydrogel is often faster than thick, cross-linked polymers [17].

- Leverage Transient Response with AI: You do not need to wait for a steady-state signal. Machine learning models can be trained on the initial transient response of the biosensor to accurately predict the final analyte concentration, reducing the required data acquisition time by up to 50% or more [16].

- Use Mediators and Redox Polymers: In electrochemical biosensors, mediators shuttle electrons more efficiently from the enzyme's active site to the electrode, often resulting in a faster achievement of a measurable steady-state current [14] [17].

4. What calibration approach is best for biosensors with significant device-to-device variation, such as those based on graphene or other nanomaterials?

Variability is a known challenge in nanomaterial-based biosensors.

- High-Density Sensor Arrays: Instead of relying on a single sensor, fabricate or use chips with high-density arrays (e.g., 200+ sensing units). This provides massive redundancy [18].

- Profile-Matching Calibration: This method leverages sensor non-uniformity. Calibrate the entire array with a single, known standard solution. The unique response profile ("fingerprint") of the array to that standard can be used to calibrate subsequent measurements, eliminating the need for a full calibration curve for each sensor [18].

- Machine Learning for Inference: Train a model (e.g., Random Forest) on data from the entire array. The model will learn to ignore the variations of individual sensors and base its concentration prediction on the collective, statistically robust response of the array [18].

Performance Parameter Comparison and Methodologies

Table 1: Strategies for Optimizing Critical Biosensor Parameters

| Performance Parameter | Common Issue in Complex Samples | Recommended Solution | Key Reagents/Materials |

|---|---|---|---|

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio | Non-specific binding; sample turbidity; fouling. | Use of permselective membranes; sentinel sensors; machine learning signal processing. | Nafion; Cellulose acetate; Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) [14]. |

| Selectivity | Electroactive interferents (e.g., ascorbate, uric acid); compounds with similar structure to the analyte. | Permselective membranes; enzymatic scavenging (e.g., ascorbate oxidase); multi-sensor arrays. | Ascorbate oxidase; charged polymers (e.g., Nafion); cross-linkers (e.g., glutaraldehyde) for array fabrication [14] [15]. |

| Response Time | Slow mass transport through immobilization matrix; slow reaction kinetics. | Optimization of immobilization matrix density; use of mediators; AI analysis of transient response. | Redox mediators (e.g., ferrocene derivatives); porous hydrogels (e.g., PVA-SbQ); glutaraldehyde [14] [17] [16]. |

Table 2: Experimental Protocol for an AI-Enhanced Calibration to Reduce Response Time and False Results

| Step | Protocol Description | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Data Collection | Expose the biosensor to standard solutions of known analyte concentrations. Collect the full dynamic response (e.g., current vs. time, resonant frequency vs. time), not just the steady-state signal [16]. | To create a rich dataset that captures the unique kinetic "fingerprint" of the analyte binding process. |

| 2. Data Augmentation | Apply techniques like jittering, scaling, and magnitude warping to the collected dynamic response data [16]. | To artificially expand the dataset, addressing the common challenges of data sparsity and class imbalance, which improves subsequent machine learning model performance. |

| 3. Feature Engineering | Extract features from the dynamic data. Use both theory-guided features (e.g., initial rate of signal change, time constants from binding models) and traditional features (e.g., mean, variance, etc.) [16]. | To provide the machine learning model with meaningful inputs that are directly related to the underlying physico-chemical processes of sensing. |

| 4. Model Training & Validation | Train a classification model (e.g., Random Forest, Support Vector Machine) using the features from Step 3. The model learns to classify the dynamic response into the correct concentration bin [16] [18]. | To create a predictive tool that can identify the analyte concentration from a pattern of response, rather than a single point. Use k-fold cross-validation to ensure robustness. |

| 5. Deployment & Prediction | Use the trained model to predict the concentration of unknown samples based on their initial transient biosensor response. | To achieve accurate quantification with a significantly reduced data acquisition time, as the biosensor no longer needs to reach a steady-state signal [16]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Biosensor Development and Calibration

| Item | Function in Biosensor Research |

|---|---|

| Permselective Membranes (e.g., Nafion, Cellulose Acetate) | Coating that blocks interfering species based on charge (Nafion) or size (cellulose acetate), improving selectivity and reducing fouling [14]. |

| Enzymes for Scavenging (e.g., Ascorbate Oxidase) | Co-immobilized enzyme that converts a common electrochemical interferent (ascorbic acid) into a non-interfering product (dehydroascorbic acid) [14]. |

| Cross-linking Agents (e.g., Glutaraldehyde) | Bifunctional reagent used to covalently immobilize biorecognition elements (enzymes, antibodies) onto transducer surfaces, enhancing stability [17] [15]. |

| Redox Mediators (e.g., Ferrocene derivatives, Hexaammineruthenium(III) chloride) | Small molecules that shuttle electrons from the enzyme's active site to the electrode surface, lowering operating potential and often improving response time [14] [17]. |

| Ion-Selective Membranes (ISMs) | Lipophilic membranes containing ionophores, used to functionalize transistor-based sensors for selective ion detection (e.g., K+, Na+, Ca²⁺) in complex solutions like sweat or serum [18]. |

| Reference Sensor Components (e.g., BSA) | Used to create a "sentinel" or reference sensor that lacks specific biorecognition, allowing for signal subtraction of non-specific background effects [14]. |

Experimental Workflow and System Diagrams

The Impact of Sample Matrix Complexity on Calibration Accuracy

For researchers and scientists in drug development, achieving accurate biosensor measurements is paramount. The sample matrix—the environment in which the target analyte resides—introduces significant complexity that directly impacts calibration accuracy and reliability. Biosensors function by integrating a biological recognition element with a transducer to convert a biological event into a measurable signal [2]. However, in real-world applications, samples like blood, serum, wastewater, and food extracts are not pure solutions; they contain numerous interfering substances that can compromise the sensor's biorecognition elements, transducer signal, and overall performance [2] [19]. This technical resource center addresses the profound influence of matrix effects on biosensor calibration, providing targeted troubleshooting guidance, detailed experimental protocols, and material recommendations to enhance measurement validity for complex sample analysis within biosensor research.

FAQs: Core Principles of Matrix Effects on Calibration

1. What are "matrix effects" and why do they challenge biosensor calibration? Matrix effects refer to the phenomenon where components of a sample other than the target analyte influence the biosensor's signal output [2] [19]. In calibration, this is critical because a standard curve generated in a simple buffer may not accurately represent sensor behavior in a complex sample like blood or wastewater. These effects challenge calibration because they can alter the fundamental parameters of the sensor's response, including its sensitivity (gain), binding affinity, and signal stability, leading to inaccurate quantification of the analyte [20].

2. Which specific matrix variables most significantly impact calibration accuracy? Several key variables inherent to complex samples can derail calibration, as summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Key Matrix Variables Affecting Biosensor Calibration

| Variable | Impact on Biosensor Calibration | Common Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Temperature [20] | Alters binding affinity (K(_{1/2})), electron transfer rates, and signal gain. Mismatched temperatures between calibration and measurement cause significant quantification errors. | In-vivo measurements, environmental monitoring, process control. |

| pH & Ionic Strength [2] | Affects bioreceptor activity (e.g., enzyme denaturation) and binding equilibrium, shifting the calibration curve. | Blood, urine, fermented products, environmental waters. |

| Nonspecific Binding [2] | Proteins and other macromolecules adsorb to the sensor surface, causing signal drift and false positives. | Serum, plasma, whole blood, food homogenates. |

| Sample Age & Processing [20] | Degradation of sample components over time (e.g., in blood) can change the matrix and alter the sensor's response compared to fresh samples. | Stored clinical samples, environmental samples. |

| Interfering Chemicals | Redox-active species can interfere with electrochemical signals; auto-fluorescent compounds can obscure optical signals. | Biological fluids, food samples, industrial waste. |

3. How can I design a calibration protocol that accounts for matrix complexity? The most effective strategy is to perform calibration in a matrix that closely mimics the actual sample. For the highest accuracy in biological measurements, this means calibrating in freshly collected, undiluted whole blood at body temperature (37°C) [20]. When using a proxy calibration medium, its composition must be rigorously validated against the target matrix. Furthermore, employing a multi-point calibration curve within the expected analyte concentration range is superior to single-point calibration, as it can reveal non-linearities introduced by the matrix [20].

4. What is the role of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and advanced data processing in mitigating matrix effects? AI and machine learning (ML) can process complex biosensor outputs to correct for matrix-induced inaccuracies. For instance, Explainable AI (XAI) models can identify which design and environmental parameters most influence sensor performance, guiding robust design [21]. Advanced chemometric approaches, such as Least-Squares Support Vector Machines (LS-SVM), can model data from complex matrices like blood, correcting for interference and improving quantification accuracy compared to traditional calibration models [22].

Troubleshooting Guide: Addressing Common Calibration Failures

Table 2: Troubleshooting Common Calibration Issues in Complex Matrices

| Problem | Potential Root Cause | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Consistent over-/under-estimation | Mismatch between calibration matrix and sample matrix. | Re-calibrate using a matrix that matches the sample (e.g., fresh blood for in-vivo sensors) [20]. |

| High signal drift & poor repeatability | Nonspecific binding or biofouling of the sensor surface. | Implement improved surface chemistries: use blocking agents (e.g., BSA) or anti-fouling coatings like hydrogels [2]. |

| Low signal gain & sensitivity | Matrix components degrading the bioreceptor or inhibiting its function. | Optimize the immobilization method for the bioreceptor to enhance stability; incorporate a sample clean-up or filtration step [2]. |

| Poor reproducibility between sensors | Sensor-to-sensor fabrication variability exacerbated by matrix interference. | Use a standardized, out-of-set calibration curve validated for the specific sample type [20]. |

| Non-linear or distorted calibration curves | High cooperativity in analyte binding or environmental factors (pH, temp) affecting the bioreceptor. | Characterize sensor performance across the entire operating range (pH, temp); use multi-parameter calibration models (e.g., Hill-Langmuir isotherm) [20]. |

Experimental Protocols: Methodologies for Robust Calibration

Protocol: Calibration for In-Vivo or Whole Blood Measurements

This protocol is adapted from studies on Electrochemical Aptamer-Based (EAB) sensors for therapeutic drug monitoring (e.g., vancomycin) in whole blood [20].

1. Objective: To establish a calibration curve that enables accurate (<±10% error) quantification of an analyte in fresh, undiluted whole blood at body temperature.

2. Materials:

- Biosensors (e.g., EAB sensors with a known aptamer and redox reporter).

- Target analyte stock solutions.

- Freshly collected whole blood (e.g., rat or human). Note: Commercially sourced blood may yield different responses due to age and processing.

- Temperature-controlled electrochemical flow cell or chamber (maintained at 37°C).

- Potentiostat for square wave voltammetry (SWV) interrogation.

3. Methodology:

- Step 1: Sensor Interrogation. Immerse the sensor in fresh, body-temperature whole blood. Interrogate using SWV at two frequencies—one "signal-on" and one "signal-off"—to generate a Kinetic Differential Measurement (KDM) value, which corrects for drift.

- Step 2: Titration and Data Collection. Spike the blood with the target analyte at a minimum of 5 concentrations spanning the expected physiological range (e.g., for vancomycin: 6 to 42 µM). At each concentration, allow the signal to stabilize and record the KDM value.

- Step 3: Curve Fitting. Fit the averaged KDM values vs. concentration data to a Hill-Langmuir isotherm to derive the calibration parameters (KDMmin, KDMmax, K1/2, nH).

- Step 4: Validation. Test the calibrated sensor in separate samples of fresh, body-temperature blood dosed with known analyte concentrations. Calculate accuracy as the relative difference between expected and observed concentrations.

4. Visualization: Workflow for Optimal Biosensor Calibration The following diagram outlines the logical workflow for developing a matrix-robust calibration protocol.

Protocol: Mitigating Nonspecific Binding and Fouling in Optical Biosensors

This protocol is relevant for optical biosensors (e.g., Surface Plasmon Resonance imaging - SPRi) used in complex media like blood plasma or serum [23].

1. Objective: To validate biosensor selectivity and accuracy by minimizing nonspecific binding (NSB) from complex samples.

2. Materials:

- SPRi biosensor platform.

- Gold sensor chips.

- Bioreceptor (e.g., specific antibody).

- Cross-linkers (e.g., EDC/NHS protocol on thiol 11-MUA).

- Blocking agents (e.g., BSA, casein, or commercial blocking buffers).

- Complex samples (e.g., blood plasma from patients).

3. Methodology:

- Step 1: Surface Functionalization. Immobilize the specific bioreceptor (e.g., anti-YKL-40 antibody) onto the gold chip using a covalent chemistry like EDC/NHS.

- Step 2: Surface Blocking. Expose the functionalized sensor surface to a concentrated solution of a blocking protein (e.g., 1% BSA) to passivate any remaining active sites on the sensor surface.

- Step 3: Selectivity Test. Challenge the sensor with the complex sample (e.g., patient plasma) that does not contain the target analyte. A successful blocking step will result in a minimal change in the refractive index (or signal), indicating low NSB.

- Step 4: Accuracy Assessment. Test the blocked sensor with samples spiked with known concentrations of the analyte. The recovery rate (observed vs. expected concentration) should be close to 100%. High precision and a low coefficient of variation (CV) between measurements confirm the effectiveness of the protocol [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Matrix-Complex Calibration

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Fresh Whole Blood | Provides a physiologically relevant calibration matrix matching the sample environment. | Calibrating biosensors for in-vivo therapeutic drug monitoring (e.g., vancomycin) [20]. |

| Anti-Fouling Coatings (e.g., PEG, Hydrogels) | Form a physical barrier to prevent nonspecific adsorption of proteins and other macromolecules. | Modifying electrode or SPR chip surfaces for use in serum or plasma [2]. |

| Blocking Agents (e.g., BSA, Casein) | Passivate unused binding sites on the sensor surface after bioreceptor immobilization. | Reducing background noise in immunosensors and affinity-based sensors [23]. |

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) | Synthetic bioreceptors with high stability in harsh chemical environments (pH, organic solvents). | Detecting small molecules in environmental samples (e.g., brominated flame retardants) [24]. |

| Ionic Liquids & Nanomaterials (e.g., MWCNTs) | Enhance electron transfer, stabilize bioreceptors, and increase electrode surface area. | Improving sensitivity and stability of electrochemical biosensors in complex matrices [22]. |

| Chemometric Software (e.g., LS-SVM, PLS) | Advanced algorithms to deconvolute the target signal from matrix interference. | Extracting accurate analyte concentration from complex biosensor data outputs [22]. |

A biosensor is an analytical device that combines a biological recognition element with a physicochemical transducer to detect a specific analyte [2] [25]. The core components include a bioreceptor (enzyme, antibody, nucleic acid, cell, etc.) that provides specificity, a transducer (electrochemical, optical, piezoelectric, etc.) that converts the biological interaction into a measurable signal, and an electronic system for signal processing and display [2] [25]. Biosensors provide significant advantages for research in complex samples, including real-time analysis, high specificity, and the potential for miniaturization and portability [26]. This guide focuses on the three primary biological recognition systems—protein-based, nucleic acid-based, and whole-cell systems—to support your research and development efforts.

Biosensor Type Classifications and Characteristics

The table below summarizes the key features, advantages, and challenges of the three main biosensor classes.

Table 1: Comparison of Biosensor Classification by Biorecognition Element

| Biosensor Class | Bioreceptor Examples | Key Advantages | Common Transduction Methods | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein-Based | Enzymes (e.g., Glucose Oxidase), Antibodies, Allosteric Transcription Factors (aTFs) [2] [27] | High catalytic activity (enzymes); Exceptional specificity (antibodies); Can be engineered for novel functions [27] [25] | Electrochemical (amperometric, potentiometric) [2]; Optical (SPR, fluorescence) [26] | Medical diagnostics (e.g., glucose monitoring) [2] [28]; Drug discovery [29]; Environmental monitoring [27] |

| Nucleic Acid-Based | DNA, RNA, Aptamers, DNAzymes [27] [25] | High stability; Ease of synthesis and modification; Programmable (e.g., strand displacement) [30] | Fluorescence [30]; Electrochemical [31]; Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) [26] | Detection of nucleic acids, mutations [2]; Small molecule sensing [30]; In vitro diagnostics |

| Whole-Cell | Bacteria (e.g., E. coli), Yeast, Microalgae [2] [25] | Can detect global parameters (e.g., toxicity, stress); Provide functional/physiological response; Contains natural enzymatic pathways [25] | Optical (luminescence, fluorescence) [27]; Electrochemical (e.g., oxygen consumption) [25] | Toxicity and genotoxicity screening [2]; Environmental monitoring (e.g., herbicides, water pollution) [25]; Bioprocess monitoring |

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental architecture shared by all biosensors, highlighting the roles of the different biorecognition elements.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Protein-Based Biosensors

Q1: My protein-based biosensor shows a significant loss of sensitivity over time. What could be causing this, and how can I prevent it? A: Loss of sensitivity is often related to the instability of the biological component. To address this:

- Check Immobilization: Ensure your immobilization method (adsorption, covalent binding, entrapment) maintains the protein's native structure and active site accessibility. Poor immobilization can lead to denaturation or steric hindrance [2].

- Prevent Fouling: In complex samples (e.g., serum, wastewater), nonspecific binding of other proteins or molecules can foul the sensor surface. Use effective blocking agents (e.g., BSA, casein) or incorporate anti-fouling coatings like polyethylene glycol (PEG) on your transducer surface [2].

- Control Environment: Protein activity is highly dependent on pH and temperature. Use buffered solutions to maintain optimal pH and, if possible, conduct experiments in a temperature-controlled environment. Consider using engineered enzyme mutants designed for greater stability if available [2].

Q2: How can I improve the specificity of my immunosensor to reduce false positives from matrix effects? A: Improving specificity requires optimizing the biorecognition interface.

- Optimize Antibody Orientation: Random antibody immobilization can block antigen-binding sites. Use site-specific immobilization techniques, such as coupling via Fc regions using Protein A or G, to ensure proper orientation [25].

- Include Robust Controls: Always run controls with samples that do not contain the target analyte to quantify and correct for nonspecific binding signals.

- Introduce Wash Steps: Implement stringent wash steps after the sample incubation to remove weakly and non-specifically bound molecules from the sensor surface before reading the signal.

Nucleic Acid-Based Biosensors

Q3: The response time of my DNA strand displacement-based biosensor is slower than theoretical predictions. How can I optimize the reaction kinetics? A: The kinetics of strand displacement circuits are highly dependent on the design of the nucleic acid components.

- Optimize Toehold Design: The toehold region initiates the strand displacement reaction. Ensure the toehold length is sufficient (typically 6-8 nucleotides) and has minimal secondary structure to facilitate rapid binding [30].

- Check Invader Strand Structure: The secondary structure of the invading RNA or DNA strand can significantly hinder its ability to bind the toehold. Redesign the invader sequence to minimize self-dimerization or hairpin formation, which can dramatically improve reaction speed [30].

- Tune Reaction Conditions: Adjust factors like magnesium ion concentration and temperature, which are critical for nucleic acid hybridization and strand exchange kinetics.

Q4: My aptasensor shows poor reproducibility between experimental batches. What are the key factors to standardize? A: Batch-to-batch variability often stems from inconsistencies in the bioreceptor or its attachment.

- Standardize Aptamer Folding: Aptamers require a specific tertiary structure to function. Implement a strict protocol for thermal annealing (heating and slow cooling) in an appropriate buffer to ensure consistent folding before each experiment.

- Characterize Immobilization Density: Reproducibly control the density of aptamers on the sensor surface. Too high a density can cause steric crowding, while too low a density reduces signal. Use quantitative methods to verify surface coverage.

- Use High-Purity Reagents: Ensure the synthetic oligonucleotides and chemical modifiers used for surface functionalization are of high purity (e.g., HPLC-purified).

Whole-Cell Biosensors

Q5: The signal from my whole-cell biosensor is unstable and drifts during long-term monitoring. How can I improve stability? A: Signal drift is a common challenge with living systems due to changing metabolic states.

- Control Cell Physiology: Maintain a consistent and healthy cell population. Use cells in the same growth phase (e.g., mid-log phase) for all experiments, as metabolic activity varies significantly between phases.

- Ensure Nutrient Stability: For prolonged assays, ensure that the test environment provides adequate nutrients and removes waste products to prevent changes in cell viability and baseline signal over time.

- Use Constitutive Promoters: Include an internal control, such as a reporter gene under a constitutive promoter, to normalize the target signal against variations in cell number and metabolic activity.

Q6: The sensitivity of my bacterial biosensor is lower when testing real environmental samples compared to clean lab standards. How can I overcome this? A: Complex sample matrices can introduce interference and toxicity.

- Dilute the Sample: Diluting the sample can reduce the concentration of interfering substances or general toxins to a level that does not inhibit the biosensor cells, while still allowing detection of the target analyte.

- Implement Sample Pre-treatment: Simple pre-treatment steps, such as filtration to remove particulate matter or solid-phase extraction to concentrate the analyte and remove inhibitors, can significantly improve performance [2].

- Engineer Tolerant Strains: If a specific inhibitor is known, consider using or engineering bacterial strains with higher tolerance to that substance or to the general conditions of the sample matrix (e.g., salinity, pH).

Essential Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Developing a Protein-Based Biosensor Using Directed Evolution

This protocol outlines the key steps for enhancing biosensor performance through directed evolution of protein components, such as allosteric transcription factors (aTFs) or fluorescent protein pairs [27].

Workflow:

- Library Creation: Generate a diverse library of mutant genes for your protein of interest using error-prone PCR or other gene mutagenesis techniques.

- Selection/Screening System: Clone the mutant library into an appropriate host system (e.g., bacteria, yeast) linked to a selectable or screenable output. For example, fuse the mutated aTF to a green fluorescent protein (GFP) reporter [27].

- High-Throughput Screening: Use a method like Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) to screen millions of cells and isolate variants that show an improved response (e.g., higher fluorescence) in the presence of the target analyte [27].

- Characterization: Isplicate the genes from the best-performing clones, and characterize the kinetic parameters (sensitivity, specificity, dynamic range) of the new biosensor variant in vitro.

The following diagram visualizes this cyclical engineering process.

Protocol: Interfacing Cell-Free Transcription with Nucleic Acid Circuits

This protocol describes how to integrate a cell-free biosensing system with DNA strand displacement circuits to create programmable, "smart" diagnostics [30].

Workflow:

- System Assembly: Combine a cell-free transcription system (e.g., based on T7 RNA polymerase) with a DNA signal gate. The gate is a double-stranded DNA complex with a fluorophore and quencher on opposite strands.

- Sensor Configuration: Design a DNA template that includes a T7 promoter, an operator sequence for an allosteric transcription factor (aTF), and a sequence that encodes an "InvadeR" RNA strand.

- Target Detection: In the presence of the target ligand, the aTF activates transcription of the InvadeR RNA.

- Signal Generation: The synthesized InvadeR RNA binds to the DNA signal gate via toehold-mediated strand displacement, displacing the quencher strand and generating a fluorescent signal. The reaction kinetics can be tuned by optimizing the secondary structure of the InvadeR sequence [30].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Biosensor Development and Calibration

| Category | Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Immobilization Chemistry | N-Hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) / EDC | Covalent coupling of biomolecules (proteins, aptamers) to sensor surfaces via amine groups [26]. | Standard for SPR chip functionalization [26]. |

| Self-Assembled Monolayers (SAMs) | Create a well-defined, ordered molecular layer on transducer surfaces (e.g., gold) for precise bioreceptor attachment [2]. | Often use alkanethiols on gold surfaces. | |

| Signal Generation | Fluorescent Proteins (CFP, YFP, mScarlet) | Serve as donor/acceptor pairs in FRET-based biosensors to monitor conformational changes [27] [32]. | Critical for live-cell imaging and genetically encoded biosensors. |

| Fluorophore & Quencher Pairs | Label nucleic acid strands for real-time monitoring of strand displacement reactions (e.g., in molecular beacons, signal gates) [30]. | e.g., FAM/TAMRA, Cy3/BHQ-2. | |

| Calibration Standards | "FRET-ON" & "FRET-OFF" Standards | Genetically encoded constructs used to normalize FRET ratios, correcting for variations in laser intensity and detector sensitivity across experiments [32]. | Enables quantitative cross-experiment comparison [32]. |

| Nanomaterials | Gold Nanoparticles / Nanostructures | Enhance signal transduction in optical (LSPR) and electrochemical biosensors by increasing surface area and providing unique plasmonic properties [2] [26]. | Can be functionalized with antibodies or aptamers. |

| Biological Elements | Allosteric Transcription Factors (aTFs) | Engineered protein scaffolds that change conformation upon binding a target small molecule, regulating transcription in cell-free systems [27] [30]. | Can be evolved for new ligand specificity [27]. |

| DNAzymes & Aptamers | Nucleic acids with catalytic activity or specific binding properties; can be combined for target recognition and signal generation in a single molecule [25]. | Selected via SELEX; offer high stability. |

Practical Calibration Techniques for Complex Sample Matrices

Reference Standard Preparation and Traceability in Biological Matrices

FAQs: Core Concepts and Challenges

Q1: What is a "matrix effect" and why is it a major problem for biosensing in biological samples?

A matrix effect refers to the phenomenon where components within a complex biological sample (such as serum, urine, or saliva) interfere with the biosensor's ability to accurately detect and measure the target analyte. These interferences can distort the sensor's signal, leading to unreliable results [33] [34]. Matrix molecules can mask the target, suppress or augment the signal, cause nonspecific binding to the sensor surface, or alter the biorecognition element's activity [33] [34]. For example, variations in ionic strength or pH can severely affect sensors that rely on charge-based detection, while autofluorescence can interfere with optical methods [35].

Q2: Why is proper calibration with traceable standards non-negotiable for biosensor research?

Calibration with traceable standards is the definitive link between your biosensor's raw signal and a quantitatively meaningful result (e.g., concentration). It establishes accuracy, precision, and allows for comparison of data across different laboratories and over time. Without it, results are unverifiable and potentially misleading. For instance, a study on magnetic nanosensors demonstrated excellent chip-to-chip and sensor-to-sensor reproducibility only after implementing rigorous calibration protocols, which was crucial for validating their claims of matrix insensitivity [35].

Q3: What are the key differences between preparing standards in a simple buffer versus a complex biological matrix?

Preparing standards in a simple buffer (like PBS) is straightforward but fails to account for the complex reality of real-world samples. While it is useful for initial sensor characterization, this approach does not validate the sensor's performance in the presence of matrix interferences. Preparing standards in a matched biological matrix (e.g., human serum for a blood test) is critical for assessing and mitigating matrix effects. This process, often called "spiking," involves adding a known quantity of the pure analyte into the matrix. It verifies that the sensor can accurately quantify the analyte within the challenging sample environment, ensuring the method's true robustness [34] [35].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Issues and Solutions

| Problem Category | Specific Symptom | Potential Root Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensor Performance | Signal drift, increased noise, or loss of sensitivity. | Physical damage, fouling (e.g., biofilm, protein adsorption), or degradation of the biological recognition element [5] [34]. | Inspect sensor for damage. Clean with recommended solvents (e.g., distilled water). Implement antifouling surface coatings. Replace expired or degraded sensors [5]. |

| Calibration & Signal | Inaccurate quantification despite a clear signal. Improper standard preparation, sensor drift, or unaccounted matrix effects on calibration curve [5] [33]. | Calibrate regularly with fresh, matrix-matched standards if possible. Use stable, isotopically labeled internal standards (e.g., 13C, 15N) to correct for fluctuations and ionization effects in MS-based detection [33]. | |

| Sample Preparation | Inconsistent results, low recovery of the analyte. | Incomplete removal of matrix interferences (e.g., proteins, salts) or unintended reactivity of the analyte with matrix components [33]. | Optimize sample prep (e.g., Solid-Phase Extraction, filtration, centrifugation). For reactive analytes, use derivatization to "trap" the target molecule. Always use fresh, pH-matched buffers [33]. |

| Data Quality | High variability between replicates or unexpected results. | Non-specific binding, cross-reactivity, or improper data processing that ignores the impact of the complex sample design [33] [34] [36]. | Use appropriate blocking agents. Validate specificity in the target matrix. Apply specialized statistical software designed for complex sample data analysis [33] [36]. |

Experimental Protocol: Implementing a Matrix-Matched Standard Curve

This protocol outlines the methodology for generating a calibration curve in a biological matrix, a critical experiment for validating any biosensor intended for use with real samples. The following workflow visualizes the key stages of this process.

Detailed Methodology

Preparation of Primary Standard Stock Solution:

- Obtain a certified reference material (CRM) of the target analyte with a well-defined purity and concentration. This establishes traceability to international standards.

- Precisely weigh the CRM and dissolve it in an appropriate solvent to prepare a high-concentration stock solution (e.g., 1 mg/mL). This stock should be aliquoted and stored at the recommended temperature to maintain stability.

Serial Dilution and Spiking into Matrix:

- Perform a serial dilution of the primary stock solution using a compatible buffer (e.g., 0.1% BSA in PBS) to create a set of working standards covering the expected analytical range (e.g., from 1 pM to 100 nM) [35].

- Critical Step: Spike a fixed volume of each working standard into a constant volume of the biological matrix (e.g., pooled human serum, urine). The matrix should be as similar as possible to the intended test samples. This creates the matrix-matched calibration standards [35].

- Include a "blank" standard, which is the matrix spiked with only the buffer solvent.

Biosensor Analysis and Data Processing:

- Following the biosensor's standard operating procedure, analyze each matrix-matched standard (including the blank) in replicate (e.g., n=3 or more).

- Record the raw signal output for each standard.

- Plot the mean signal response (y-axis) against the known nominal concentration of the analyte in the matrix (x-axis).

- Apply a regression model (e.g., linear, logistic) to fit the data and establish the calibration function. The coefficient of determination (R²) should be >0.99 to indicate a robust fit [35].

Advanced Technique: Calibration Standards for FRET Biosensor Imaging

For live-cell imaging with FRET biosensors, traditional calibration is challenged by fluctuating imaging conditions. A robust solution is to use engineered calibration standards expressed in the cells themselves. The diagram below illustrates this calibration strategy.

- Generate Calibration Standards: Create cell lines expressing "FRET-ON" and "FRET-OFF" constructs. These are genetically encoded pairs of donor and acceptor fluorescent proteins locked in high-efficiency and low-efficiency FRET conformations, respectively.

- Barcode and Mix Cells: Use a barcoding method (e.g., with spectrally distinct blue or red fluorescent proteins targeted to specific organelles) to label cells expressing the calibration standards and cells expressing the biosensor of interest. Mix these populations for simultaneous imaging [32].

- Simultaneous Imaging and Normalization: In each imaging session, acquire the FRET signals from the biosensor cells and the calibration standard cells. Use the signals from the FRET-ON and FRET-OFF standards to normalize the biosensor's FRET ratio, compensating for variations in laser intensity and detector sensitivity. This yields a calibrated FRET ratio that is comparable across different experiments and over long durations [32].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Standard Preparation & Traceability |

|---|---|

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | The foundational source of traceability. These materials have certified purity and concentration values, providing an unbroken chain of comparison to a primary standard (e.g., from NIST) [35]. |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standards (e.g., 13C, 15N) | Added to both standards and samples to correct for analyte loss during preparation and signal suppression/enhancement during mass spectrometric detection. They are preferred over deuterated standards due to minimal chromatographic isotope effects [33]. |

| Antifouling Surface Coatings (e.g., PEG, zwitterionic polymers) | Applied to biosensor surfaces to minimize nonspecific adsorption of proteins and other matrix components. This is crucial for maintaining sensitivity and accuracy in complex biological fluids like serum [34]. |

| Matrix-Matched Pooled Biological Fluids (e.g., charcoal-stripped serum) | Used as the background for preparing calibration standards. Pooled fluids average out individual variations, and charcoal-stripping can remove endogenous analytes to create a "blank" matrix for spiking experiments [35]. |

| Genetically Encoded FRET Standards (FRET-ON/OFF) | Serve as internal calibrants for live-cell fluorescence imaging. They allow for normalization of the FRET ratio, making the quantitative readout independent of variable imaging parameters [32]. |

Standard Curve Generation and Dose-Response Characterization in Complex Media

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the most critical parameters to report from a dose-response curve for a biosensor assay? When publishing data from a biosensor assay in complex media, you should always report the potency (EC50 or IC50), the Hill Slope, and the upper (Top) and lower (Bottom) plateaus of the curve [37]. The EC50 (half-maximal effective concentration) or IC50 (half-maximal inhibitory concentration) represents the compound's potency. The Hill Slope describes the steepness of the curve. The Top and Bottom plateaus represent the maximum and minimum response levels, respectively [37]. For biosensors specifically, it is also critical to report the limit of detection (LOD) and any potential for false results, as biological components in complex media can interfere with the biorecognition elements [19].

FAQ 2: My dose-response curve is incomplete, lacking clear upper and lower plateaus. Can I still calculate an EC50 value? Yes, an EC50 can still be estimated, but you must be cautious about the type of value you report. For an incomplete curve, you can calculate a relative EC50 by fitting the data you have with a non-linear regression model (e.g., 4-parameter logistic (4PL)) and allowing the model to extrapolate the plateaus [37]. In contrast, an absolute EC50 requires the use of control values to define the minimum and maximum response and determines the concentration that gives a 50% inhibition from the maximum [37]. You should clearly state in your methods which approach was used.

FAQ 3: How many data points (concentrations) are sufficient for a reliable dose-response curve? It is generally recommended to use 5 to 10 concentrations distributed across a broad range [37]. This number of points allows for adequate characterization of the three critical parts of the curve: the bottom plateau, the top plateau, and the central, linear portion where the EC50 is located [37]. Using too few concentrations can lead to an unreliable fit and inaccurate parameter estimation.

FAQ 4: What are common sources of false results in biosensor-based dose-response experiments? False positives or negatives in biosensor assays can arise from multiple factors [19]. These include:

- Matrix Effects: Components in complex biological samples (e.g., serum, plasma) can non-specifically interact with the biosensor's bioreceptor or transducer, altering the signal [19].

- Sensor Fouling: Proteins or other macromolecules in the sample can adsorb to the biosensor surface, reducing its sensitivity and specificity [19].

- Cross-reactivity: The bioreceptor (e.g., antibody, aptamer) may bind to molecules structurally similar to the target analyte, generating a false positive signal [19].

- Signal Drift: Instabilities in the biosensor's physical or chemical properties over time can lead to inaccurate readings [19].

FAQ 5: How can I optimize my experimental design for dose-response studies? Statistical optimal design theory suggests that highly precise parameter estimates can be achieved with relatively few, strategically chosen dose levels. D-optimal designs for common models like the log-logistic or Weibull function often require only a control group and three distinct dose levels [38]. The optimal dose levels are typically placed near the anticipated EC10, EC50, and EC90, which maximizes the information gained about the curve's shape and parameters [38].

Troubleshooting Guides

Poor Curve Fit or Unreliable EC50

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Incomplete sigmoidal curve | The concentration range is too narrow. | Widen the concentration range to capture the lower and upper response asymptotes [37]. |

| EC50 at the extreme end of the concentration range | The concentration range is mispositioned. | Shift the tested concentration range up or down based on initial results to ensure the EC50 lies within the central part of your data [37]. |

| Shallow or too steep Hill Slope | High levels of non-specific binding or cooperativity in the system. | Check the assumptions of your model. For a system with low observations, consider constraining the Hill Slope to 1.0; for receptor-binding assays, a variable slope is often more appropriate [37]. |

| High variability in replicate measurements | Inconsistent sample preparation or biosensor fouling. | Standardize sample preparation protocols. Include control samples to assess and correct for background signal and matrix effects [19] [37]. |

High Background Signal or Noise in Complex Media

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Elevated signal in negative controls | Non-specific binding of matrix components to the biosensor surface. | Dilute the sample in a suitable buffer to reduce interference. Incorporate blocking agents (e.g., BSA, casein) in the running buffer. Perform a sample pre-treatment (e.g., filtration, extraction) to remove interferents [19]. |

| Signal drift over time | Fouling of the biosensor surface or instability of the biological element. | Implement more frequent calibration or standard addition protocols. Use regenerable biosensor surfaces if available. Ensure the biosensor is stored and operated within its specified environmental conditions [19]. |

| Inconsistent results between replicates | Heterogeneity of the complex sample or improper mixing. | Ensure samples are thoroughly homogenized before analysis. Increase the number of replicate measurements to account for sample variability [37]. |

Experimental Protocols

Standard Protocol for Generating a Dose-Response Curve

Principle: This protocol outlines the steps for treating a biological system with a serial dilution of a drug or analyte and fitting the resulting data to a four-parameter logistic (4PL) model to determine potency (EC50/IC50) and efficacy [37] [39].

Workflow Diagram:

Materials:

- Key Reagent Solutions:

- Stock Solution of Analyte/Drug: A highly concentrated, well-characterized solution of the test compound.

- Assay Buffer/Biological Media: The complex matrix in which the experiment is conducted (e.g., cell culture media, serum, artificial saliva).

- Standards/Controls: Solutions with known high and low (or zero) analyte concentration for signal normalization and quality control.

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Prepare Serial Dilutions:

- Create a serial dilution of the drug/analyte in the complex media of interest. It is recommended to use 5-10 concentrations spaced logarithmically (e.g., 1, 10, 100, 1000 nM) to adequately define the curve [37].

- Include a negative control (vehicle only) and a positive control if available.

Apply Dilutions and Incubate:

- Apply each dilution to your biological system (e.g., cells, tissue) or biosensor. Ensure the number of replicates (typically n=3-6) is sufficient for statistical power [38].

- Incubate for the predetermined time under appropriate physiological conditions (e.g., 37°C, 5% CO₂).

Measure Response:

- At the endpoint, measure the response using your biosensor or assay readout (e.g., fluorescence, luminescence, electrical impedance).

- Record the raw signal data for all concentrations and controls.

Data Transformation and Normalization:

- Normalization: Convert the raw response values to a percentage of the control response. The minimum and maximum plateaus are often set to 0% and 100%, respectively [37].

- Formula:

Normalized Response = (Raw Response - Min Response) / (Max Response - Min Response) * 100

- Formula:

- Transformation: The X-values (concentrations) are typically transformed using a base-10 logarithm to linearize the relationship and facilitate a better sigmoidal fit [37].

- Normalization: Convert the raw response values to a percentage of the control response. The minimum and maximum plateaus are often set to 0% and 100%, respectively [37].

Non-Linear Regression Analysis:

- Fit the normalized data (Y: Response, X: log(Concentration)) to a four-parameter logistic (4PL) model using curve-fitting software (e.g., GraphPad Prism, R).

- The standard 4PL equation is:

Y = Bottom + (Top - Bottom) / (1 + 10^((LogEC50 - X) * HillSlope))where Bottom and Top are the lower and upper asymptotes, X is the log(concentration), and HillSlope describes the steepness of the curve [37].

Evaluation and Interpretation:

Protocol for Biosensor Calibration in Complex Media

Principle: This protocol details the process of generating a standard curve with a biosensor in a complex sample matrix using the method of standard addition to account for matrix interference [19].

Workflow Diagram:

Materials:

- Key Reagent Solutions:

- High-Purity Analyte Standards: For preparing spiking solutions.

- Blank Complex Matrix: The same media as the unknown sample but confirmed to be free of the target analyte.

- Biosensor Regeneration Buffer: If using a reusable biosensor, a buffer that removes bound analyte without damaging the biological element.

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Sample Preparation:

- Prepare a consistent aliquot of the unknown sample in the complex media.

Standard Addition:

- Split the sample into multiple equal aliquots.

- Spike each aliquot with a known and increasing concentration of the analyte standard. Leave one aliquot unspiked (zero addition).

- The volume of the spike should be small enough to not significantly dilute the sample matrix.

Biosensor Analysis:

- Analyze each spiked sample with the biosensor according to the manufacturer's instructions or established lab protocol.

- Record the signal output for each spiked concentration.

Data Analysis:

- Plot the measured signal (Y-axis) against the concentration of the added standard (X-axis).

- Perform a linear regression on the data points.

- The absolute value of the X-intercept of the regression line corresponds to the concentration of the analyte in the original, unspiked sample. This method corrects for matrix effects that proportionally affect the signal [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Log-Logistic Model | A common non-linear regression model used to fit sigmoidal dose-response data. It estimates four parameters: Bottom, Top, EC50, and Hill Slope [38]. |

| Agonist/Antagonist | Agonists stimulate a response; Antagonists inhibit the action of an agonist. These are critical tools for probing pharmacological mechanisms in dose-response studies [37]. |

| Four-Parameter Logistic (4PL) Regression | The standard model for analyzing dose-response curves. It is synonymous with the Hill Equation and is used to quantify drug potency and efficacy [37]. |

| Nanoparticle-based Biosensors | Portable sensing platforms that use nanomaterials to enhance sensitivity and specificity. They are promising for point-of-care detection of biomarkers for diseases like diabetes and cancer [40]. |

| D-optimal Design | A statistical approach for designing efficient experiments. It helps determine the optimal number and placement of dose levels to maximize the precision of parameter estimates, often reducing the required number of experimental units [38]. |

Data Presentation Tables

Table 1: Key Parameters in Dose-Response Analysis

| Parameter | Symbol | Description | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Half-Maximal Effective Concentration | EC50 | The concentration that produces a response halfway between the baseline (Bottom) and maximum (Top) plateaus [37]. | A measure of potency. A lower EC50 indicates greater potency. |

| Half-Maximal Inhibitory Concentration | IC50 | The concentration that produces a response halfway between the maximum (Top) and minimum (Bottom) plateaus in an inhibitory curve [37]. | A measure of inhibitory potency. A lower IC50 indicates a more effective inhibitor. |

| Hill Slope | - | A parameter that reflects the steepness of the curve at its midpoint [37]. | A slope >1 suggests positive cooperativity; <1 suggests negative cooperativity or a heterogeneous system. |

| Top Plateau | Top | The maximum response asymptote of the curve [37]. | Represents the efficacy or maximal effect of the agonist. |

| Bottom Plateau | Bottom | The minimum response asymptote of the curve [37]. | Represents the baseline response in the absence of a stimulatory agonist. |

| Equilibrium Dissociation Constant | Kd | The molar concentration of a ligand at which 50% of the receptors are occupied [39]. | A measure of binding affinity. A lower Kd indicates a higher affinity for the receptor. |

Table 2: Comparison of Common Dose-Response Models

| Model | Function | Typical Application |

|---|---|---|

| Log-Logistic | ( f(x)=\frac{d-c}{1+\exp(b(\log(x)-\log(e)))}+c ) [38] | A versatile standard for many toxicological and pharmacological dose-response studies [38]. |