Advancing Food Safety: Electrochemical Biosensor Protocols for Rapid Detection of Pesticide Residues in Fruits

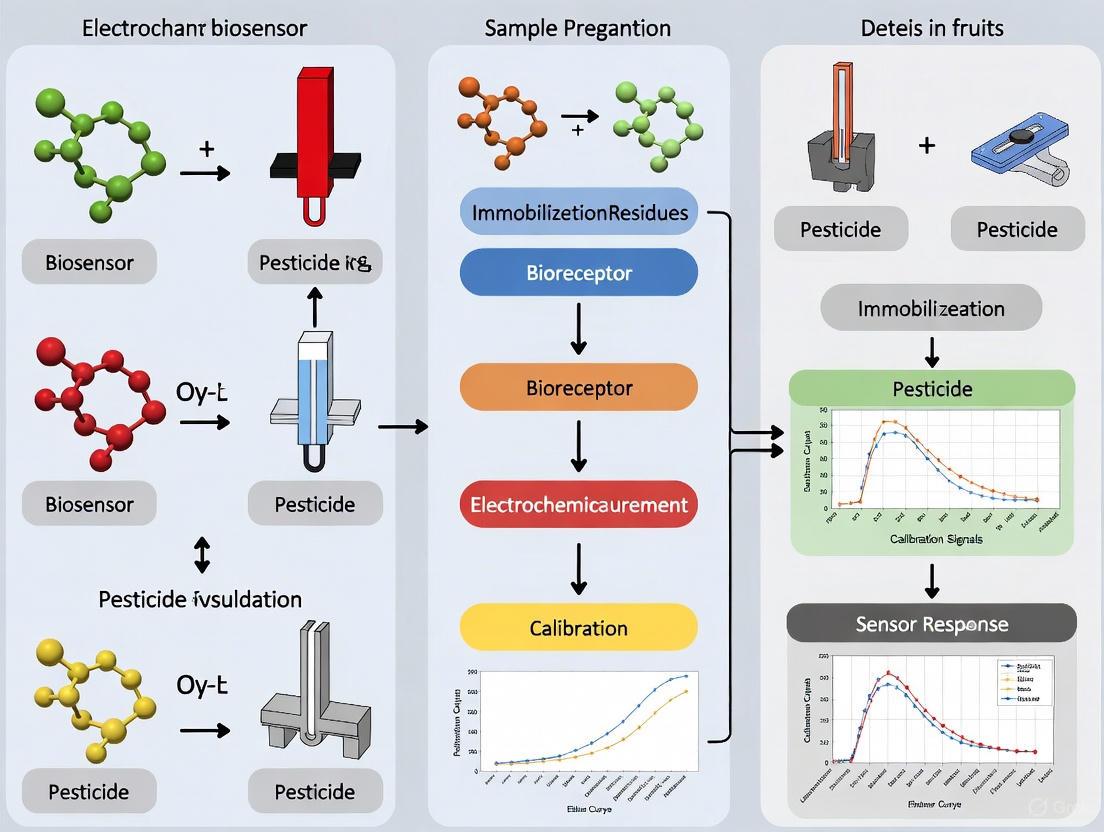

This article provides a comprehensive overview of electrochemical biosensor technology for the detection of pesticide residues in fruits, tailored for researchers and scientists in food safety and drug development.

Advancing Food Safety: Electrochemical Biosensor Protocols for Rapid Detection of Pesticide Residues in Fruits

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of electrochemical biosensor technology for the detection of pesticide residues in fruits, tailored for researchers and scientists in food safety and drug development. It covers the foundational principles of pesticide toxicity and biosensor operation, delves into detailed methodological protocols for sensor fabrication and application, addresses critical troubleshooting and optimization strategies for real-world samples, and presents a rigorous validation framework comparing biosensor performance against traditional chromatographic methods. The content synthesizes the latest advancements from 2024-2025, highlighting the transition toward portable, on-site analysis for enhanced food safety monitoring within a 'One Health' context.

The Urgent Need for Rapid Pesticide Detection: Principles and Public Health Imperatives

The widespread application of organophosphates (OPs), carbamates, and organochlorines in agriculture has made their residue detection in food products a critical public health concern. These compounds are designed to be biologically active and can inhibit essential nervous system enzymes in pests, but they pose significant risks to human health through the consumption of contaminated fruits and vegetables. Electrochemical biosensors have emerged as powerful tools for the rapid, sensitive, and cost-effective detection of these pesticide residues, offering a viable alternative to traditional chromatographic methods. This document provides detailed application notes and protocols for researchers developing these biosensing platforms, with a specific focus on assays for fruit samples.

Pesticide Classes: Mechanisms and Analytical Targets

The three pesticide classes of concern share a common neurotoxic mechanism but differ in their chemical structures, persistence, and specific modes of action. Understanding these differences is fundamental to designing specific detection protocols.

Table 1: Characteristics of Key Pesticide Classes

| Pesticide Class | Primary Mechanism of Action | Example Compounds | Key Structural/Functional Groups for Detection | Environmental Persistence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organophosphates (OPs) | Irreversible inhibition of acetylcholinesterase (AChE) [1] [2] | Chlorpyrifos, Parathion, Dichlorvos, Malathion [3] [2] | P=O (Oxon) or P=S (Thion) groups; P-O-C bonds [2] [4] | Low to moderate [2] |

| Carbamates | Reversible inhibition of acetylcholinesterase (AChE) [1] [2] | Carbaryl, Carbofuran, Methomyl, Aldicarb [1] [2] | Carbamate ester group (OC(O)N) [2] | Low [2] |

| Organochlorines | Disruption of sodium and potassium channels in neurons [5] | DDT, Endosulfan, Lindane [5] | Chlorinated cyclic hydrocarbons [5] | High (Persistent Organic Pollutants) [5] |

The following diagram illustrates the shared signaling pathway through which organophosphates and carbamates exert their neurotoxic effect, which is the basis for many enzyme-based biosensors.

A variety of biosensing platforms have been developed for pesticide detection, each with distinct performance characteristics. The table below summarizes the analytical performance of different transducer types as reported in recent literature.

Table 2: Comparison of Biosensor Platforms for Pesticide Detection

| Transducer Type | Target Pesticide (Example) | Reported Limit of Detection (LOD) | Linear Range | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electrochemical (AChE-based) | Carbofuran [6] | Not specified in excerpt | Not specified in excerpt | High sensitivity, cost-effective, portable [7] [6] |

| Piezoelectric (QCM) | Carbaryl [2] | 2 × 10⁻¹⁰ M [2] | Not specified in excerpt | Label-free, real-time output, high sensitivity [2] |

| Piezoelectric (QCM) | Diisopropylfluorophosphate [2] | 1 × 10⁻¹⁰ M [2] | Not specified in excerpt | Label-free, real-time output, high sensitivity [2] |

| Electrochemical (MIP-based) | Captan [8] | 1 × 10⁻¹⁴ M [8] | 1 × 10⁻¹⁴ to 9 × 10⁻¹⁴ M [8] | High selectivity, enzyme-free stability, reusability [8] |

| Cell-based (Bioelectric) | Chlorpyrifos & Carbaryl [1] | 1 ppb (approx. 10⁻⁹ M) [1] | Not specified in excerpt | Measures functional physiological response (cell membrane potential) [1] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

This section provides a step-by-step workflow for two primary electrochemical biosensor protocols: one based on enzyme inhibition and another utilizing molecularly imprinted polymers.

Protocol 1: AChE-based Electrochemical Biosensor for Fruit Samples

This protocol is adapted from established AChE-sensor methodologies for detecting organophosphate and carbamate pesticides [1] [6].

4.1.1 Workflow Diagram

4.1.2 Materials and Reagents

- Acetylcholinesterase (AChE): Enzyme biorecognition element, typically from electric eel [6].

- Acetylthiocholine (ATCh) or Acetylcholine (ACh): Enzyme substrate; hydrolysis produces electroactive product [1] [6].

- Working Electrode: Often Glassy Carbon Electrode (GCE), potentially modified with nanomaterials (e.g., carbon black) to enhance sensitivity [6].

- Chitosan/Nafion: Polymers used for enzyme immobilization and membrane formation on the electrode surface [6].

- Electrochemical Cell: Standard three-electrode setup (Working, Reference Ag/AgCl, Auxiliary Pt electrode) [8].

- Buffer Solutions: Phosphate or Tris buffer for maintaining optimal pH (e.g., pH 8 for AChE activity) [1].

- Extraction Solvent: Aqueous-organic mixture (e.g., water:acetone 1:3 v/v) for pesticide extraction from fruit [1].

4.1.3 Step-by-Step Procedure

- Sample Preparation: Homogenize fruit sample (e.g., apple, tomato). Extract pesticides using a suitable solvent like water:acetone (1:3 v/v). Evaporate acetone and use the aqueous supernatant for analysis [1] [8].

- Biosensor Fabrication: Immobilize AChE onto the surface of the working electrode. This can be done by drop-casting a mixture of the enzyme and a binder like chitosan or Nafion, followed by cross-linking with glutaraldehyde to stabilize the enzyme layer [6].

- Baseline Enzyme Activity Measurement: Immerse the biosensor in a buffer containing the substrate (e.g., acetylthiocholine). Measure the amperometric or voltammetric (DPV) current generated by the enzymatic product (thiocholine). This signal represents 100% enzyme activity [6].

- Inhibition/Incubation Step: Incubate the biosensor with the prepared fruit extract for a fixed time (e.g., 10-30 minutes). Any OPs or carbamates present will inhibit the AChE enzyme [1] [6].

- Post-Inhibition Activity Measurement: Re-immerse the sensor in the substrate solution and measure the electrochemical signal again. The signal will be lower due to enzyme inhibition [6].

- Quantification: Calculate the percentage of enzyme inhibition:

% Inhibition = [(I₀ - I₁) / I₀] × 100, where I₀ is the baseline current and I₁ is the current after exposure. The pesticide concentration is determined by comparing the % inhibition to a calibration curve prepared with known pesticide standards [6].

Protocol 2: Molecularly Imprinted Polymer (MIP)-based Electrochemical Sensor

This protocol details a non-enzymatic approach for specific pesticide detection, using Captan as an example [8].

4.2.1 Workflow Diagram

4.2.2 Materials and Reagents

- Template Molecule: The target pesticide (e.g., Captan) [8].

- Functional Monomer:

o-Phenylenediamine (o-PD) [8]. - Cross-linker & Electrolyte: Acetate buffer (pH 5.2) [8].

- Electrochemical Cell: Three-electrode system with GCE as working electrode [8].

- Extraction Solution: 1M HCl and Acetonitrile (ACN) mixture (7:3 v/v) [8].

- Redox Probe: Potassium ferrocyanide/ferricyanide ([Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻) in KCl [8].

4.2.3 Step-by-Step Procedure

- MIP Fabrication (Electropolymerization): Immerse a clean GCE in a solution containing the functional monomer (

o-PD), the template (Captan), and acetate buffer. Perform Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) for a set number of cycles (e.g., 10 cycles between -0.2 V and 0.8 V) to electropolymerize theo-PD around the template molecules [8]. - Template Extraction: Wash the polymer-coated electrode (MIP@o-PD/GCE) with a mixture of 1M HCl and acetonitrile to remove the Captan template molecules. This leaves specific recognition cavities in the polymer matrix [8].

- Analyte Rebinding: Incubate the MIP sensor in the prepared fruit extract. Captan molecules from the sample will selectively rebind to the cavities, changing the properties of the polymer layer [8].

- Electrochemical Measurement: Measure the Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) response of the sensor in a solution containing the [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻ redox probe. The rebinding of Captan impedes the access of the redox probe to the electrode surface, causing a decrease in the peak current [8].

- Quantification: The decrease in DPV peak current is proportional to the concentration of Captan in the sample. A calibration curve is constructed using standards to enable quantification [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Electrochemical Biosensor Development

| Item | Function/Application | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) | Primary biorecognition element for OP and carbamate detection via enzyme inhibition [1] [6]. | Electric eel AChE [6] |

| Acetylthiocholine (ATCh) / Acetylcholine (ACh) | Enzyme substrate; hydrolysis produces an electroactive product (thiocholine/choline) for signal generation [1] [6]. | Acetylthiocholine iodide (ATChI) [6] |

| Glassy Carbon Electrode (GCE) | Common working electrode substrate; provides a stable, conductive surface for enzyme/MIP immobilization [8]. | 3 mm diameter GCE [8] |

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymer (MIP) | Synthetic polymer with specific cavities for target analytes; offers enzyme-free, stable recognition [8]. | o-Phenylenediamine (o-PD) polymer for Captan [8] |

| Nanomaterial Modifiers (e.g., Carbon Black) | Enhance electrode surface area, improve electron transfer, and increase biosensor sensitivity [6]. | Conductive carbon black (Vulcan XC 72R) [6] |

| Immobilization Matrices (Chitosan, Nafion) | Form stable membranes on electrodes to entrap biorecognition elements (enzymes) [6]. | Chitosan & Nafion used for AChE immobilization [6] |

| Redox Probes (e.g., [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻) | Used with impedimetric or voltammetric techniques to monitor binding events or insulating layer formation on the electrode surface [8]. | Potassium ferrocyanide/ferricyanide [8] |

Critical Considerations for Assay Development

- Matrix Effects: The complex composition of fruit extracts can significantly interfere with sensor performance. Components like lipids, organic acids, or sugars can foul the electrode or non-specifically inhibit enzymes. Calibration curves should be constructed in the presence of a blank (pesticide-free) extract of the same fruit matrix to account for these effects [6].

- Sensor Regeneration: For reusable sensors, a regeneration step is required to remove the bound pesticide from the biorecognition element. For AChE-based sensors, this can be challenging due to the irreversible binding of OPs. For MIP sensors, the template extraction protocol can often be used for regeneration between measurements [8] [6].

- Multiplexed Detection: A significant challenge is detecting specific pesticides within a class or differentiating between OPs and carbamates. Using arrays of sensors with different biorecognition elements (e.g., AChE from different species, specific antibodies, or multiple MIPs) coupled with advanced data analysis is a promising approach to address this challenge [4].

Pesticide residues on agricultural products present a significant global public health challenge due to their potential to cause both immediate poisoning and long-term neurological damage. The widespread application of pesticides in modern agriculture has made residue exposure an unavoidable concern for consumers worldwide [9]. Understanding the dual-toxicity profile—acute effects following high-dose exposure and chronic neurodegenerative consequences from prolonged low-level exposure—is paramount for developing effective safety monitoring protocols. Electrochemical biosensors represent a transformative technology for quantifying these risks, offering rapid, sensitive, and field-deployable analysis of pesticide residues directly on food surfaces [10] [11]. This document provides detailed application notes and experimental protocols for assessing health risks from pesticide residues, with specific methodologies adapted for integration into electrochemical biosensing platforms for fruit analysis.

Health Risk Assessment of Pesticide Residues

Acute Toxicity Profiles of Major Pesticide Classes

Table 1: Acute Toxicity Mechanisms and Health Effects of Major Pesticide Classes

| Pesticide Class | Representative Compounds | Primary Mechanism of Action | Acute Health Effects | Detection Priority |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organophosphorus | Parathion, Dichlorvos, Malathion | Irreversible inhibition of acetylcholinesterase (AChE) [12] | Dyspnea, pulmonary edema, muscle spasms, dizziness, headache, bradycardia [12] | High (Enzyme Inhibition) |

| Carbamates | Carbaryl, Aldicarb, Carbofuran | Reversible inhibition of acetylcholinesterase (AChE) [12] | Dizziness, blurred vision, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, excessive sweating, tremors [12] | High (Enzyme Inhibition) |

| Neonicotinoids | Imidacloprid, Thiamethoxam | Continuous activation of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors [12] | Nausea, vomiting, headache, dizziness, insomnia, anxiety, consciousness disorders [12] | Medium (Receptor Binding) |

| Pyrethroids | Permethrin, Deltamethrin, Fenvalerate | Interference with sodium channels and GABA receptors [12] | Skin rashes, nausea, abdominal pain, headache, confusion, cough [12] | Medium (Biomimetic Assay) |

| Organochlorines | Hexachlorocyclohexane, Toxaphene | Inhibition of GABA receptors, ROS generation, endocrine disruption [12] | Similar to pyrethroids, plus endocrine disorders [12] | Low (Mostly Banned) |

Chronic Neurodegenerative Consequences

Beyond immediate toxicity, chronic exposure to certain pesticides, even at low concentrations, poses significant risks for neurodegenerative pathologies. The mechanisms involve complex interactions between genetic susceptibility and environmental exposures, where pesticides can act as neurotoxic stressors that accelerate or trigger pathological processes [13].

Key pathophysiological pathways include:

- Oxidative Stress: Many pesticides, including organochlorines, induce reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation, leading to neuronal oxidative damage and mitochondrial dysfunction [13] [12].

- Neuroinflammation: Chronic microglial activation by pesticide exposure creates a neuroinflammatory environment conducive to neurodegeneration [13].

- Protein Misfolding and Aggregation: Some pesticides can promote the misfolding and aggregation of proteins like α-synuclein and β-amyloid, hallmarks of Parkinson's and Alzheimer's diseases respectively [13].

- Epigenetic Modifications: Chronic exposure can alter DNA methylation and histone modification patterns, potentially leading to sustained changes in gene expression relevant to neuronal survival and function [13].

Epidemiological studies have consistently demonstrated associations between pesticide exposure and increased incidence of Parkinson's disease, Alzheimer's disease, and Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) [13]. The delayed onset and progressive nature of these conditions make early detection of exposure biomarkers particularly critical for preventive interventions.

Experimental Protocols for Risk Assessment Using Biosensors

Protocol 1: On-Glove Electrochemical Detection of Organophosphorus Pesticides on Fruit Peels

Principle: This protocol describes a direct, on-site method for detecting organophosphorus pesticides (e.g., dichlorvos) on fruit surfaces using an enzymatic inhibition biosensor integrated onto a glove fingertip [10].

Workflow Overview:

Materials and Reagents:

- Butyrylcholinesterase Enzyme: Biological recognition element whose inhibition is proportional to pesticide concentration [10].

- Prussian Blue and Carbon Black Nanomaterials: Electron-transfer mediators for enhanced electrochemical signal transduction [10].

- Screen-Printed Electrodes (SPEs): Miniaturized, disposable sensing platforms integrated onto glove fingertips [10].

- Acetylthiocholine or Butyrylthiocholine: Enzyme substrates that produce electroactive products upon hydrolysis [10].

- Portable Potentiostat: Miniaturized electrochemical analyzer for field-deployable measurements [10].

- Protective Nitrile Gloves: Base platform for sensor integration.

Procedure:

- Biosensor Preparation: Fabricate screen-printed electrodes modified with Prussian blue, carbon black, and butyrylcholinesterase enzyme on glove fingertips [10].

- Sampling: Directly scrub the fruit surface (e.g., apple, orange) for 10-15 seconds using the sensor-integrated glove fingertip [10].

- Inhibition Reaction: Allow 2-5 minutes for pesticide-enzyme interaction on the glove surface.

- Electrochemical Measurement: Transfer the glove to a portable potentiostat and perform chronoamperometry or square-wave voltammetry measurements in buffer solution containing enzyme substrate.

- Signal Analysis: Quantify the reduction in electrochemical current relative to a pesticide-free control. The signal inhibition is proportional to the pesticide concentration [10].

Performance Characteristics:

- Detection Limit: Nanomolar range (high ppt) for dichlorvos, below EU regulatory limits [10].

- Repeatability: <10% RSD [10].

- Analysis Time: <10 minutes total [10].

Protocol 2: Acetylcholinesterase-Based Inhibition Biosensor for Multi-Pesticide Screening

Principle: This protocol utilizes acetylcholinesterase (AChE) inhibition for detecting organophosphorus and carbamate pesticides in fruit extracts, suitable for laboratory-based high-throughput screening.

Workflow Overview:

Materials and Reagents:

- Acetylcholinesterase (AChE): Primary recognition element from electric eel or recombinant source.

- Acetylthiocholine Iodide: Enzyme substrate.

- Screen-Printed Carbon Electrodes: Disposable electrochemical platforms.

- Phosphate Buffer (0.1 M, pH 7.4): Reaction medium.

- Methanol or Acetonitrile: Extraction solvents.

- C18 Solid-Phase Extraction Cartridges: For sample clean-up.

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Homogenize 10 g fruit tissue with 20 mL methanol. Centrifuge at 5000 rpm for 10 minutes. Evaporate supernatant and reconstitute in buffer.

- Extract Clean-up: Pass fruit extract through C18 SPE cartridge to remove interfering compounds.

- Biosensor Assembly: Immobilize AChE on screen-printed carbon electrodes via cross-linking with glutaraldehyde.

- Inhibition Assay: Incubate AChE-modified electrode with 100 μL fruit extract for 10 minutes.

- Electrochemical Measurement: Transfer electrode to buffer containing 1 mM acetylthiocholine. Measure thiocholine oxidation current at +0.45 V vs. Ag/AgCl.

- Quantification: Calculate percentage inhibition relative to pesticide-free control: % Inhibition = [(Icontrol - Isample)/I_control] × 100.

Performance Characteristics:

- Detection Limits: 0.1-5 nM for most organophosphorus pesticides [9].

- Linear Range: 0.5-100 nM.

- Recovery: 85-110% for spiked fruit samples.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Pesticide Residue Biosensor Research

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) | Primary biorecognition element for organophosphorus and carbamate detection [9] | Electric eel AChE (Type VI-S), recombinant human AChE |

| Butyrylcholinesterase (BChE) | Broader substrate specificity biorecognition element [10] | Human serum BChE, recombinant expression |

| Screen-Printed Electrodes (SPEs) | Miniaturized, disposable transduction platforms [10] | Carbon, gold, or platinum working electrodes; Ag/AgCl reference |

| Prussian Blue Nanoparticles | High-efficiency electrocatalyst for hydrogen peroxide reduction [10] | Electrochemically synthesized, ~20-50 nm diameter |

| Carbon Black Nanomaterials | Enhanced electron transfer and surface area [10] | Vulcan XC-72, Super P Li |

| Acetylthiocholine Chloride | Enzyme substrate for electrochemical detection [12] | ≥98% purity, electrochemical generation of thiocholine |

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) | Synthetic biomimetic recognition elements [11] [12] | Methacrylic acid-based polymers imprinted with target pesticides |

| Aptamers | Nucleic acid-based recognition elements [11] [12] | Single-stranded DNA/RNA selected via SELEX process |

| Nanozymes (SAzymes) | Nanomaterial-based enzyme mimics with enhanced stability [12] | Single-atom catalysts (e.g., SACe-N-C) with peroxidase-like activity |

| Portable Potentiostats | Field-deployable electrochemical measurement [10] | PalmSens, EmStat Pico, ADI µPotentiostat |

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Quantitative Risk Assessment Metrics

Table 3: Key Analytical Parameters for Pesticide Risk Assessment Biosensors

| Analytical Parameter | Target Value | Regulatory Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Limit of Detection (LOD) | <1 nM (or lower than MRL) [10] | Enables detection below maximum residue limits (MRLs) |

| Analysis Time | <15 minutes [10] | Suitable for on-site decision making |

| Recovery Percentage | 85-115% [12] | Indicates minimal matrix effects |

| Repeatability (RSD) | <10% [10] | Ensures measurement reliability |

| Linear Dynamic Range | 3 orders of magnitude [12] | Covers sub-MRL to above-MRL concentrations |

Correlation with Health Risk Thresholds

Electrochemical biosensor data must be interpreted within the context of established health risk thresholds:

- Acute Risk Assessment: Compare measured concentrations with Acute Reference Doses (ARfDs) established by regulatory bodies. Sensor signals corresponding to concentrations exceeding 10% of ARfD should trigger immediate risk mitigation.

- Chronic Risk Assessment: For cumulative neurotoxicants, compare detected levels with Acceptable Daily Intakes (ADIs). Consistent detection even below MRLs but above ADI-equivalent levels warrants longitudinal exposure monitoring.

- Cumulative Risk Assessment: For pesticides with common mechanisms of toxicity (e.g., all AChE inhibitors), biosensor signals should be summed to assess aggregate risk, particularly important for multi-residue detection platforms.

Troubleshooting and Technical Notes

- Matrix Effects: Fruit peel matrices (oils, waxes, pigments) can interfere with detection. Always include matrix-matched calibration curves and consider solid-phase extraction for complex matrices [14].

- Enzyme Stability: Cholinesterase enzymes can denature under field conditions. Implement proper storage (lyophilized forms) and consider nanozymes or MIPs for improved stability [12].

- Cross-Reactivity: AChE-based biosensors cannot distinguish between different organophosphorus or carbamate pesticides. Confirm positive results with specific methods if compound identification is required [9].

- Sensor Regeneration: For reversible inhibitors (carbamates), sensors can be regenerated with oxime solutions (e.g., pralidoxime). Irreversible inhibitors (organophosphates) typically require sensor replacement [9].

Electrochemical biosensor technology continues to evolve toward multi-analyte detection, artificial intelligence-enhanced data processing, and integration with wireless connectivity for real-time food safety monitoring [11] [14]. These advances will further strengthen the correlation between detected residue levels and their potential health impacts, enabling more precise risk assessment and management across the food supply chain.

The One Health approach is defined as "a collaborative, multisectoral, and transdisciplinary approach — working at the local, regional, national, and global levels — with the goal of achieving optimal health outcomes recognizing the interconnection between people, animals, plants, and their shared environment" [15]. This perspective is particularly crucial for addressing the challenge of pesticide residues in food, a quintessential One Health issue that sits at the intersection of agricultural practices, environmental health, and human well-being [16] [15].

Foodborne diseases (FBDs), which can result from pesticide contamination, impose a significant global burden, causing over 100 million USD in annual preventable economic losses, with over 90% of this burden affecting low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) [16]. These diseases disproportionately impact children under five years of age, who experience 38% of all FBD incidence despite representing only 9% of the global population [16]. The interconnected issues of dwindling animal and plant health, food systems vulnerable to contamination, and pathogen threats necessitate a unified framework that concurrently addresses the health of humans, animals, and ecosystems [16].

Electrochemical biosensors have emerged as powerful tools within this framework, enabling the sensitive detection of pesticide residues in food matrices. These devices complement traditional chromatography methods like HPLC and GC-MS, which though highly accurate, require expensive equipment, extensive sample pretreatment, and highly skilled professionals [17]. Biosensors offer a viable alternative that simplifies or removes complex preparation steps, providing rapid, on-site analysis capabilities essential for monitoring the food supply chain [17].

Analytical Performance of Nanomaterial-Based Biosensors for Pesticide Detection

The integration of nanomaterials into biosensing platforms has significantly enhanced their analytical performance. The table below summarizes the detection capabilities of various nanomaterial-based biosensors for specific pesticides in food matrices, demonstrating limits of detection (LOD) well below the Codex Alimentarius maximum residue limits [17].

Table 1: Analytical Performance of Nanomaterial-Based Biosensors for Pesticide Detection in Food

| Nanomaterial | Biorecognition Element | Pesticide Detected | Limit of Detection (LOD) | Food Matrix | Transducer Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) | Organophosphorus (11 types) | 19–77 ng L⁻¹ | Apple, Cabbage | Electrochemical |

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) | Methomyl | 81 ng L⁻¹ | Apple, Cabbage | Electrochemical |

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | Aptamer | Chlorpyrifos | 36 ng L⁻¹ | Apple, Pak choi | Electrochemical |

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | Antibody | Chlorpyrifos | 0.07 ng L⁻¹ | Chinese cabbage, Lettuce | Electrochemical |

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | AChE | Carbamate | 1.0 nM | Fruit | Electrochemical |

| Nanohybrids | Various | Various | Varies (typically < 100 ng L⁻¹) | Various fruits, vegetables | Electrochemical, Fluorescent |

The data reveals that electrochemical transducers are the most prevalent (71.18% of studies), followed by fluorescent (13.55%) and colorimetric (8.47%) systems [17]. The exceptional sensitivity of these platforms, particularly those utilizing noble metal nanoparticles and carbon-based nanomaterials, enables detection at picomolar levels, ensuring food safety even for trace contaminants [17].

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials for Biosensor Development

The development of high-performance biosensors requires carefully selected materials and reagents. The following table details key components and their functions in constructing electrochemical biosensors for pesticide detection.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Biosensor Construction

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Nanomaterials | Enhance sensitivity, conductivity, and catalytic activity; provide high surface area for bioreceptor immobilization | AuNPs, AgNPs, Carbon NDs, MWCNTs, Nanohybrids [17] |

| Biorecognition Elements | Provide selective binding to target pesticide molecules | AChE enzyme, Aptamers, Antibodies, MIPs [17] |

| Transducer Materials | Convert biological recognition event into measurable electrical signal | Screen-printed electrodes (SPCE, SPWPE), Glassy Carbon Electrode (GCE) [17] |

| Chemical Reagents | Facilitate electrode modification, signal amplification, and experimental procedures | Tri-n-propylamine (TprA), Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA), Glutaraldehyde (for cross-linking) [17] |

| Buffer Solutions | Maintain optimal pH and ionic strength for biological components | Phosphate buffer saline (PBS) for enzyme stability and binding reactions |

Experimental Protocol: Development of an Acetylcholinesterase-Based Electrochemical Biosensor

Apparatus and Reagents

- Electrochemical Workstation: Potentiostat with capability for cyclic voltammetry (CV) and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS)

- Electrodes: Screen-printed carbon electrodes (SPCEs) or glassy carbon electrodes (GCE)

- Nanomaterials: Gold nanoparticles (AuNPs, 20nm diameter) and multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs)

- Biological Reagents: Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) enzyme, acetylthiocholine iodide (ATCh) substrate

- Buffer Solutions: Phosphate buffer saline (PBS, 0.1M, pH 7.4)

- Pesticide Standards: Chlorpyrifos, malathion, and paraoxon stock solutions (1000 ppm in methanol)

Electrode Modification and Biosensor Fabrication

- Electrode Pretreatment: Clean GCE with alumina slurry and perform cyclic voltammetry scans in 0.5M H₂SO₄ from -0.2V to +1.5V until stable response achieved.

- Nanomaterial Deposition: Prepare nanohybrid suspension (1mg/mL AuNPs-MWCNTs in DMF) and drop-cast 10μL onto electrode surface. Dry at room temperature for 2 hours.

- Enzyme Immobilization: Incubate modified electrode with 10μL AChE solution (0.5U/μL) in PBS at 4°C for 12 hours.

- Stabilization: Rinse electrode with PBS to remove unbound enzyme and stabilize in PBS for 1 hour before use.

Pesticide Detection Procedure

- Baseline Measurement: Record CV or EIS response in PBS containing 1mM ATCh as substrate.

- Inhibition Assay: Incubate biosensor with pesticide standard or sample solution for 10 minutes.

- Measurement: Record electrochemical response after incubation under identical conditions to baseline.

- Quantification: Calculate inhibition percentage using formula: % Inhibition = [(I₀ - I₁)/I₀] × 100 where I₀ is current before inhibition and I₁ is current after inhibition.

- Calibration: Generate standard curve using known pesticide concentrations and interpolate sample values.

Sample Preparation (Fruit Matrices)

- Extraction: Homogenize 10g fruit sample with 20mL acetonitrile in a blender for 2 minutes.

- Cleanup: Filter through Buchner funnel and concentrate extract under nitrogen stream.

- Reconstitution: Dilute concentrate 1:10 with PBS for analysis.

- Recovery Test: Perform standard addition method to validate accuracy.

Workflow Visualization: One Health Perspective in Pesticide Monitoring

Diagram 1: One Health pesticide monitoring workflow.

Biosensor Signaling Pathway for Pesticide Detection

Diagram 2: Biosensor signaling pathway with inhibition mechanism.

Data Analysis and Interpretation Guidelines

Calibration and Quantification

- Plot inhibition percentage versus pesticide concentration on a semi-log scale to generate calibration curves

- Determine linear range and limit of detection (LOD) using 3σ/slope criterion

- Calculate limit of quantification (LOQ) using 10σ/slope criterion

- For real samples, apply standard addition method to account for matrix effects

Validation Parameters

- Accuracy: Evaluate through recovery studies (85-115% acceptable range)

- Precision: Determine through relative standard deviation (RSD < 10% for replicates)

- Selectivity: Test against common interferents (heavy metals, other pesticides)

- Stability: Monitor biosensor response over 30-day period with proper storage

Comparison with Regulatory Standards

- Compare detected pesticide levels with Codex Alimentarius Maximum Residue Limits (MRLs)

- Reference WHO guidelines for acceptable daily intake (ADI) values

- Consider cumulative risk assessment for multiple pesticide residues

Electrochemical biosensors represent a transformative technology for operationalizing the One Health approach to pesticide monitoring. Their ability to provide rapid, sensitive, and on-site detection of harmful residues directly connects agricultural practices with human health outcomes through the shared environment [16] [15] [17]. The protocols outlined herein provide researchers with robust methodologies for developing these analytical tools, contributing to the broader goal of reducing the burden of foodborne diseases and promoting sustainable agricultural systems that respect the interconnected health of people, animals, and ecosystems.

The accurate detection of pesticide residues on fruits is a critical component of food safety monitoring, essential for protecting public health. For decades, the field has been dominated by conventional analytical techniques, primarily chromatography-based methods. While these methods are recognized for their accuracy and sensitivity, they possess significant drawbacks that limit their practical application for rapid, on-site screening. This document details the specific limitations of these conventional methods, focusing on their high cost, operational complexity, and lack of portability. Furthermore, it positions electrochemical biosensors as a promising alternative, outlining their working principles and advantages to provide researchers with a clear rationale for the paradigm shift in pesticide detection protocols.

Quantitative Analysis of Conventional Method Limitations

Conventional techniques for pesticide residue analysis, such as gas chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (GC-MS/MS) and liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS), while highly accurate, present substantial barriers to widespread and efficient use [18]. The following table summarizes the core limitations of these established methods.

Table 1: Core Limitations of Conventional Pesticide Detection Methods

| Limitation | Key Characteristics | Impact on Research & Deployment |

|---|---|---|

| High Cost [18] | - Significant initial capital investment for instruments (chromatographs, mass spectrometers).- Ongoing expenses for high-purity gases, solvents, and consumables.- Requirement for specialized laboratory infrastructure and maintenance. | Prohibits adoption in resource-limited settings, including field stations and smaller laboratories. Increases the per-sample cost of analysis. |

| Operational Complexity [18] | - Requires multi-step sample preparation (extraction, clean-up, pre-concentration).- Necessitates highly trained, specialized personnel for operation and data interpretation.- Time-consuming procedures, limiting sample throughput and delaying results. | Creates a bottleneck for high-volume screening. Results in a dependency on expert operators, increasing labor costs and limiting scalability. |

| Lack of Portability [18] | - Instruments are large, heavy, and require a stable laboratory environment.- Not suitable for on-site, at-line, or point-of-care testing at farms, markets, or border inspections. | Prevents real-time decision-making and rapid intervention. Requires sample transport, which can compromise integrity and increase time-to-result. |

In addition to these core limitations, traditional biorecognition elements like enzymes and antibodies, used in some sensors, can suffer from instability and complex preparation requirements [19]. The development of aptamer-based sensors (aptasensors) has emerged to overcome these issues, offering superior stability, reusability, and simpler production [19].

Experimental Protocols for Comparison

To illustrate the contrast between conventional and emerging methods, the following protocols detail a standard laboratory-based analysis versus a novel, portable biosensor approach.

Protocol A: Conventional LC-MS/MS Analysis for Multi-Pesticide Residues

This protocol is adapted from established methods for determining pesticide residues in complex food matrices like fruits [18].

1. Principle: Pesticides are extracted from a homogenized fruit sample, purified to remove interfering compounds, separated via liquid chromatography, and then identified and quantified by tandem mass spectrometry based on their mass-to-charge ratio.

2. Materials and Reagents:

- Homogenized fruit sample (e.g., apple, orange peel)

- Organic solvents (Acetonitrile, Methanol) of HPLC grade

- QuEChERS (Quick, Easy, Cheap, Effective, Rugged, and Safe) extraction kits

- Centrifuge tubes and vials

- High-performance liquid chromatography system coupled to a tandem mass spectrometer (LC-MS/MS)

- Analytical column (e.g., C18 reverse-phase)

3. Procedure: 1. Sample Preparation: Weigh 10 g of homogenized fruit sample into a 50 mL centrifuge tube. 2. Extraction: Add 10 mL of acetonitrile and shake vigorously for 1 minute. Use a QuEChERS salt packet to induce phase separation and centrifuge. 3. Clean-up: Transfer an aliquot of the upper acetonitrile layer to a dispersive Solid-Phase Extraction (d-SPE) tube containing sorbents. Shake and centrifuge to remove impurities. 4. Pre-concentration: Evaporate a portion of the clean extract to dryness under a gentle nitrogen stream and reconstitute in a smaller volume of initial mobile phase. 5. Instrumental Analysis: - Chromatographic Separation: Inject the reconstituted extract into the LC system. Pesticides are separated as they travel through the column under a specific gradient of aqueous and organic mobile phases. - MS Detection: Eluting compounds are ionized and fragmented in the mass spectrometer. Detection is based on monitoring unique precursor-product ion transitions for each pesticide. 6. Data Analysis: Quantify pesticide concentrations by comparing the peak areas of samples to those of a calibrated standard curve.

Protocol B: On-Glove Electrochemical Biosensor for Organophosphorus Pesticides

This protocol details a decentralized analysis method using a biosensor integrated directly onto a glove for sampling and detection on fruit peels [10].

1. Principle: A glove is fitted with an electrochemical biosensor containing the enzyme butyrylcholinesterase. Organophosphorus pesticides (e.g., dichlorvos) inhibit this enzyme. The degree of inhibition, measured via a change in electrochemical current, is proportional to the pesticide concentration.

2. Materials and Reagents:

- Glove with an integrated screen-printed electrode (SPE)

- Biosensor modification components: Prussian blue, Carbon black, Butyrylcholinesterase enzyme

- Portable potentiostat for electrochemical measurements

- Buffer solution

3. Procedure: 1. Sampling: The user wears the modified glove and simply scrubs the surface of the fruit (e.g., an apple) with the finger containing the biosensor. This direct contact transfers the pesticide residue from the peel to the sensor. 2. Measurement: The user places the sensor-finger into the portable potentiostat to perform an electrochemical measurement (e.g., chronoamperometry). 3. Detection: The system measures the enzymatic activity. A significant reduction in the current signal compared to a baseline indicates the presence of enzyme-inhibiting pesticides. 4. Analysis: The concentration of pesticide is quantified from the measured current using a pre-calibrated curve. The entire process, from sampling to result, is completed on-site in minutes.

Visualizing Workflows and Advantages

The fundamental differences in the workflows and capabilities of conventional methods versus portable biosensors are visualized below.

Diagram 1: A comparison of analytical workflows, highlighting the streamlined process of biosensors.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The development and operation of advanced electrochemical biosensors rely on key materials and reagents. The following table details essential components for constructing and using an on-glove biosensor for pesticide detection, as featured in the cited protocol [10].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for an On-Glove Electrochemical Biosensor

| Item | Function/Description | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Butyrylcholinesterase Enzyme | The biological recognition element that specifically reacts with its substrate; its activity is inhibited by organophosphorus pesticides. | The core of the biosensor's specificity. Requires stable immobilization on the electrode surface to maintain activity. |

| Screen-Printed Electrode (SPE) | A disposable, miniaturized electrochemical cell (working, counter, and reference electrodes) printed on a plastic or ceramic substrate. | Provides the platform for the biosensor. Ideal for mass production and integration into wearable devices like gloves. |

| Prussian Blue (PB) | An electron transfer mediator that shuttles electrons between the enzyme and the electrode, enhancing the current signal. | Often called an "artificial peroxidase," it improves the sensitivity and lowers the operating potential of the sensor. |

| Carbon Black | A nanomaterial used to modify the electrode surface, increasing its effective surface area and improving electron conductivity. | Enhances the electrochemical signal and provides a robust matrix for immobilizing the enzyme and mediator. |

| Portable Potentiostat | A compact, battery-powered electronic instrument that applies potential and measures the resulting current in an electrochemical cell. | Enables on-site and real-time measurements. Critical for moving analysis out of the centralized laboratory. |

Definition and Core Principle

An electrochemical biosensor is defined as a self-contained integrated device that converts a biological response into a quantifiable and processable electronic signal [20] [21]. These sensors utilize a biological recognition element (such as an enzyme, antibody, or nucleic acid) that is retained in direct spatial contact with an electrochemical transduction element [21]. The core principle involves the direct conversion of a biological event—such as an enzyme-substrate reaction or an antigen-antibody interaction—into an electrical signal (e.g., current, voltage, or impedance) [22]. This distinguishes true biosensors from bioanalytical systems that require additional processing steps like reagent addition [21].

Fundamental Components and Architecture

Electrochemical biosensors consist of five main components that work in sequence to detect and report analytical information [20] [23].

- Bioreceptor: This biological recognition element (e.g., enzyme, antibody, DNA, or whole cell) selectively binds to the target analyte. The specificity of the bioreceptor determines the sensor's selectivity [20] [22].

- Interface Architecture: This is the physical space where the specific biological event (e.g., binding or catalysis) occurs. The interface is often engineered with nanomaterials to enhance performance [20] [22].

- Transducer Element: Typically an electrode, this component transforms the biochemical signal resulting from the bioreceptor-analyte interaction into a measurable electrical signal [20] [23].

- Signal Processor: This detector circuit converts and amplifies the transducer's signal into an electronic signal that can be processed [20] [23].

- User Interface: Computer software and a display convert the electronic signal into a meaningful physical parameter (e.g., analyte concentration) that is presented to the operator [20] [23].

The performance of an electrochemical biosensor is heavily influenced by the surface architectures at the nanoscale that connect the sensing element to the biological sample, affecting both signal transduction and overall sensitivity [20] [22].

Classification of Electrochemical Biosensors

Electrochemical biosensors can be classified based on their transduction method and the type of biological recognition element used [24] [21]. The most common classification is by transduction principle, as detailed in the table below.

Table 1: Classification of Electrochemical Biosensors by Transduction Principle

| Transducer Type | Measured Parameter | Principle of Operation | Key Advantages | Example Application in Pesticide Detection |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amperometric [24] [25] | Current | Measures current from electrochemical oxidation/reduction of an electroactive species at a constant applied potential [24]. | High sensitivity, rapid response [24]. | Detection of organophosphorus pesticides using acetylcholinesterase inhibition [17]. |

| Voltammetric [24] | Current | Similar to amperometric, but the applied potential is ramped (e.g., cyclic or differential pulse voltammetry) and the resulting current is measured [24]. | Provides quantitative and qualitative data [24]. | Detection of chlorpyrifos using aptamer-based sensors on gold nanoparticles (LOD: 36 ng L⁻¹) [17]. |

| Potentiometric [24] [23] | Potential (Voltage) | Measures the accumulation of charge at an electrode (vs. a reference electrode) at zero current flow [24] [25]. | Small size, rapid response, resistant to color/turbidity [24]. | Often used with ion-selective electrodes for ion detection [25]. |

| Impedimetric [24] [25] | Impedance | Measures resistive and capacitive changes in the system by applying a small-amplitude AC potential. Can be label-free [24]. | Label-free, real-time monitoring of binding events [24]. | Label-free immunosensing for detection of dengue virus protein [24]. |

| Field-Effect Transistor (FET) [24] [26] | Current/Conductivity | Detects changes in source-drain channel conductivity caused by charged target species accumulating at the sensor surface [24]. | Label-free, miniaturization, mass production potential [24]. | Highly sensitive detection of Lyme disease antigens (LOD: 2×10⁻³ ng mL⁻¹) [24]. |

Operational Advantages

Electrochemical biosensors offer a compelling set of advantages that make them particularly suitable for on-site analysis, including the detection of pesticide residues in fruit [20] [23] [17].

- High Sensitivity and Low Detection Limits: These sensors can achieve excellent detection limits, often down to picomolar concentrations, due to the efficient transduction of biochemical events into electrical signals [25]. For example, biosensors for pesticides like chlorpyrifos have demonstrated limits of detection (LOD) as low as 70 × 10⁻³ ng L⁻¹, which is well below the maximum residue limits set by regulatory bodies [17].

- Instrumental Simplicity and Low Cost: They do not require complex or expensive optical components. Their design benefits from advances in low-cost microelectronic production, making the equipment affordable and easy to interface with standard readout systems [24] [23].

- Portability and Ease of Miniaturization: The electrochemical platform is inherently suitable for creating small, portable, and handheld devices, which is ideal for field-use and point-of-care testing [20] [23].

- Ability to Analyze Turbid Samples and Small Volumes: Unlike many optical methods, electrochemical sensors can function effectively in turbid biofluids and require only small volumes of analyte for analysis [20] [23].

- Rapid Response and Real-Time Analysis: These biosensors can provide results in minutes, allowing for real-time or near-real-time monitoring of analytes, which is crucial for quick decision-making in food safety [20] [17].

Experimental Protocol: Amperometric Biosensor for Organophosphorus Pesticide Detection

This protocol outlines the development and use of an amperometric biosensor for detecting organophosphorus pesticides in fruit samples, based on the inhibition of the enzyme acetylcholinesterase (AChE) [17].

Principle

Organophosphorus pesticides inhibit the activity of AChE. The biosensor measures the reduction in enzymatic activity by monitoring the amperometric current generated from the enzymatic reaction of AChE with its substrate, acetylthiocholine. The decrease in current is proportional to the pesticide concentration [17].

Materials and Reagents

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

| Item | Function/Description | Specifications/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) [17] | Biorecognition element; catalyzes substrate reaction. | From electric eel or recombinant source; immobilizable. |

| Acetylthiocholine [17] | Enzyme substrate; produces electroactive product upon hydrolysis. | Alternative to acetylcholine for more stable measurement. |

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) [17] [22] | Nanomaterial for electrode modification; increases surface area and enhances electron transfer. | ~10-20 nm diameter; can be synthesized or commercially acquired. |

| Screen-Printed Carbon Electrode (SPCE) [17] | Disposable electrochemical cell (working, counter, and reference electrodes). | Enables portability and single-use applications. |

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) | Electrolyte solution; provides optimal pH and ionic strength for enzymatic activity. | Typically 0.1 M, pH 7.4. |

| Fruit Sample Extract | Test matrix; requires pre-processing (blending, filtration, dilution). | Apple, cabbage, and other fruits have been successfully tested [17]. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Step 1: Electrode Modification and Enzyme Immobilization

- Prepare the working electrode: Clean the surface of the screen-printed carbon electrode (SPCE) according to manufacturer's instructions.

- Apply nanomaterial: Drop-cast 5-10 µL of a suspension of Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) onto the working electrode surface and allow it to dry at room temperature. This step increases the active surface area and improves electron transfer [17] [22].

- Immobilize the enzyme: Apply 5 µL of the AChE enzyme solution (e.g., 100 mU/µL in PBS) onto the AuNP-modified SPCE. Incubate in a humid chamber for 1 hour at 4°C to allow for physical adsorption or covalent binding.

- Rinse: Gently rinse the modified electrode with PBS buffer to remove any unbound enzyme.

Step 2: Apparatus Setup and Baseline Measurement

- Connect the biosensor: Place the modified SPCE into the potentiostat and connect the electrical contacts.

- Add electrolyte: Pipette 50 µL of PBS into the electrochemical cell.

- Measure baseline current: Add 10 µL of acetylthiocholine substrate solution (final concentration 1 mM) to the cell. Immediately apply a constant working potential of +0.5 V (vs. the Ag/AgCl reference electrode) and record the steady-state current (i_baseline). This current is generated by the oxidation of thiocholine, the product of the enzymatic hydrolysis of acetylthiocholine.

Step 3: Inhibition (Pesticide Detection)

- Expose to sample: Incubate a separate, identical AChE/AuNP/SPCE biosensor in 50 µL of the prepared fruit sample extract for 10 minutes.

- Rinse: Rinse the electrode gently with PBS to remove the sample while retaining the inhibited enzyme.

- Measure sample current: Add 10 µL of acetylthiocholine substrate as in Step 2.3 and record the steady-state current (i_sample).

Step 4: Data Analysis

- Calculate Inhibition: The percentage of enzyme inhibition is calculated as follows:

Inhibition (%) = [(i_baseline - i_sample) / i_baseline] * 100 - Quantify Pesticide: The percentage inhibition is correlated to the pesticide concentration by interpolating from a calibration curve previously constructed using standard solutions of known pesticide concentrations.

The following diagram illustrates the experimental workflow:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Electrochemical Biosensor Research in Pesticide Detection

| Category | Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| Biorecognition Elements | Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) [17] | Key enzyme for organophosphate/carbamate detection; inhibition is measured. |

| Nucleic Acid Aptamers [17] | Synthetic single-stranded DNA/RNA molecules that bind specific pesticides (e.g., chlorpyrifos). | |

| Monoclonal Antibodies [17] | Provide high specificity for immunoassays; used in immunosensors. | |

| Nanomaterials | Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) [17] [22] | Enhance electron transfer and provide a large surface area for biomolecule immobilization. |

| Carbon Nanotubes (SWCNTs/MWCNTs) [22] | Improve conductivity and catalytic activity; used to modify electrode surfaces. | |

| Graphene Oxide / Reduced GO [22] | 2D carbon material with high surface area and good dispersibility for sensor fabrication. | |

| Electrode & Instrumentation | Screen-Printed Electrodes (SPEs) [17] | Low-cost, disposable, and portable electrochemical cells ideal for on-site testing. |

| Potentiostat/Galvanostat | Core instrument for applying potential and measuring current in amperometric/voltammetric sensors. | |

| Supporting Reagents | Redox Probes (e.g., [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻) [24] | Used in impedimetric and voltammetric sensors to facilitate electron transfer and measure changes. |

| Blocking Agents (e.g., BSA) [17] | Used to cover non-specific binding sites on the sensor surface to reduce background noise. |

A Step-by-Step Protocol: From Biosensor Fabrication to On-Site Fruit Analysis

The accurate monitoring of pesticide residues in fruits is paramount for ensuring global food safety. Electrochemical biosensors have emerged as powerful analytical tools for this purpose, combining high sensitivity with the potential for rapid, on-site analysis. The performance of these biosensors is fundamentally governed by the biorecognition element (BRE) immobilized on the transducer surface, which dictates the sensor's selectivity, sensitivity, and operational stability [27]. This application note provides a detailed comparison of four principal classes of BREs—enzymes, aptamers, antibodies, and molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs)—within the context of developing robust electrochemical biosensors for fruit pesticide residue analysis. We summarize their characteristics in structured tables and provide detailed experimental protocols to guide researchers in the selection, optimization, and application of these critical components.

Comparative Analysis of Biorecognition Elements

The selection of a BRE involves balancing factors such as specificity, stability, cost, and ease of fabrication. Table 1 provides a quantitative comparison of these elements, while Table 2 outlines their suitability for detecting different pesticide classes.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Biorecognition Elements for Pesticide Biosensors

| Biorecognition Element | Affinity & Sensitivity | Stability & Lifetime | Development Cost & Time | Key Advantages | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enzymes | Moderate sensitivity; operates on inhibition principle [28] | Low; susceptible to denaturation, short lifetime [27] | Low to moderate cost; readily available [28] | "Biologically relevant" detection mechanism; reusable after reactivation [28] | Limited to pesticides that are enzyme inhibitors; susceptible to environmental conditions [27] |

| Aptamers | High affinity; detection limits down to femtomolar (fM) range [19] | High; stable over long-term storage and tolerant to harsh conditions [19] [27] | Moderate SELEX cost; inexpensive in vitro synthesis [19] | Small size, high stability, reusable, amenable to chemical modification [19] [27] | Susceptible to nuclease degradation in some environments; complex SELEX process for new targets [19] |

| Antibodies | Very high affinity and specificity [27] | Moderate; sensitive to temperature and pH [27] | High cost and time for development and production [27] | Well-established, high specificity validation protocols [27] | Animal-derived production; batch-to-batch variation; irreversible binding [19] [27] |

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) | High selectivity; comparable to antibodies ("artificial antibodies") [29] | Very high; robust thermal and chemical stability [29] | Low cost, rapid synthesis [29] | Excellent physical/chemical stability; reusable; suitable for harsh environments [27] [29] | Occasional incomplete template removal; heterogeneous binding sites [27] |

Table 2: Biorecognition Element Suitability for Major Pesticide Classes

| Pesticide Class | Example Pesticides | Suitable Biorecognition Elements | Detection Mechanism Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Organophosphates (OPs) | Dichlorvos, Malathion, Parathion [28] [10] | Enzymes (Cholinesterases), Aptamers, Antibodies, MIPs | Enzymatic inhibition is dominant for OPs and carbamates [28] [27]. Aptamers/MIPs allow specific compound identification [30]. |

| Carbamates | Carbofuran, Carbaryl, Aldicarb [28] | Enzymes (Cholinesterases), Aptamers, MIPs | Same neurotoxic mechanism as OPs allows use of same enzyme-based sensors [28]. |

| Triazines & Phenylureas | Atrazine, Diuron | Aptamers, Antibodies, MIPs, Photosynthetic Enzymes (e.g., PSII) | Detection often relies on direct binding. Photosystem II inhibition is a specific mechanism for herbicides [28]. |

| Organochlorines (OCPs) | DDT, Lindane | Antibodies, Aptamers, MIPs | Typically detected via direct binding assays due to their environmental persistence [18]. |

| Neonicotinoids | Thiamethoxam, Imidacloprid | Aptamers, Antibodies [19] | Direct binding is the primary mode of detection for these systemic insecticides [19]. |

The following diagram illustrates the strategic decision-making workflow for selecting the optimal biorecognition element based on research objectives and practical constraints.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Fabrication of an On-Glove Enzyme-Based Biosensor

This protocol details the construction of an innovative on-glove biosensor for the direct detection of organophosphorus pesticides (e.g., dichlorvos) on fruit peels, enabling decentralized analysis [10].

1. Reagents and Materials:

- Screen-printed carbon electrode (SPCE)

- Butyrylcholinesterase (BChE) enzyme

- Prussian blue (PB) and Carbon black (CB) nanoparticles

- Glove (e.g., nitrile)

- Phosphate buffer saline (PBS, 0.1 M, pH 7.4)

- Acetylthiocholine iodide (ATCh) substrate

- Dichlorvos standard

2. Sensor Fabrication Steps:

- Step 1: Preparation of Bio-hybrid Ink. Disperse Prussian blue and Carbon black nanoparticles in a suitable binder solution (e.g., Nafion) to form a stable carbon ink. Subsequently, mix the carbon ink with a solution of BChE enzyme to create a homogeneous bio-hybrid probe.

- Step 2: Integration onto Glove. Using a precision pipette, deposit a small volume (e.g., 5-10 µL) of the bio-hybrid ink onto the index finger of the glove and allow it to dry at room temperature. The SPCE is affixed to the glove's fingertip for connection to the potentiostat.

- Step 3: Electrochemical Characterization. Characterize the modified electrode using cyclic voltammetry (CV) in PBS to confirm the successful immobilization of the Prussian blue mediator and the enzyme.

3. Sample Analysis Workflow:

- Step 1: Sampling. The user scrubs the surface of the fruit (e.g., apple, orange) with the biosensor-integrated fingertip.

- Step 2: Inhibition. Any OPs present on the fruit peel will inhibit the BChE enzyme on the glove.

- Step 3: Measurement. The user adds a drop of ATCh substrate solution onto the sensor. The enzymatic conversion of ATCh produces thiocholine, which is electrochemically oxidized at the Prussian blue-modified electrode. The measured current is inversely proportional to the pesticide concentration due to the inhibition of BChE.

- Step 4: Quantification. The dichlorvos concentration is calculated from the percentage of enzyme inhibition using a pre-established calibration curve.

Protocol 2: Development of an Electrochemical Aptasensor for Carbendazim

This protocol outlines the construction of a highly sensitive aptasensor for the fungicide carbendazim (CBZ) using a dual-aptamer design and nanomaterial-enhanced signal amplification [19].

1. Reagents and Materials:

- Gold nanoparticles (Au NPs)

- Boron-doped electrode or SPCE

- CBZ-specific aptamer (CBZA) and its complementary strand (SH-cCBZA), thiol-modified

- Zirconium-based Metal-Organic Framework (MOF-808)

- Graphene nanoribbons

- Methylene blue (MB) redox reporter

- Carbendazim standard

2. Sensor Fabrication Steps:

- Step 1: Electrode Modification. Prepare a nanocomposite of graphene nanoribbons and MOF-808. Drop-cast this composite onto the electrode surface to create a high-surface-area platform. Electrodeposit Au NPs onto the modified electrode to facilitate subsequent aptamer immobilization via Au–S bonds.

- Step 2: Aptamer Immobilization. Co-immobilize the thiolated complementary DNA (SH-cCBZA) and the MB-labeled CBZ aptamer (CBZA) onto the Au NP surface. The two strands hybridize, forming a rigid double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) structure on the electrode.

3. Measurement and Detection Principle:

- Principle: In the absence of CBZ, the dsDNA structure keeps the MB reporter in a specific conformation, yielding a baseline electrochemical current.

- Step 1: Incubation. Incubate the aptasensor with the sample solution.

- Step 2: Binding-Induced Displacement. Upon introduction of CBZ, the aptamer has a stronger affinity for the target than for its complementary strand. It undergoes a conformational change, dissociates from the complementary strand, and binds to CBZ. This displacement leads to the removal of the MB-labeled complex from the electrode surface.

- Step 3: Signal Measurement. The change in the MB oxidation current (typically an increase) is measured using differential pulse voltammetry (DPV). The signal change is directly proportional to the CBZ concentration, achieving ultra-trace level detection.

Protocol 3: Construction of a MIP-Based Electrochemical Nanosensor

This protocol describes the creation of a robust and selective sensor using a Molecularly Imprinted Polymer as an artificial antibody for pesticide detection [29].

1. Reagents and Materials:

- Target pesticide molecule (template, e.g., chlorpyrifos)

- Functional monomers (e.g., acrylamide, pyrrole, o-phenylenediamine)

- Cross-linker (e.g., ethylene glycol dimethacrylate - EGDMA)

- Initiator (e.g., ammonium persulfate)

- Solvent (acetonitrile or water)

- Electrode (e.g., glassy carbon, SPCE)

2. Sensor Fabrication Steps:

- Step 1: Pre-Assembly. Mix the template molecule (pesticide) with the functional monomers in a solvent. Allow them to form a complex via non-covalent interactions (e.g., hydrogen bonding, van der Waals forces).

- Step 2: Electropolymerization. Place the electrode in the pre-assembled mixture. Using cyclic voltammetry (CV), apply a potential scan over a defined range to initiate the electrochemical polymerization of the monomers around the template. This process forms a thin, rigid polymer film on the electrode surface with cavities complementary in size, shape, and functionality to the target pesticide.

- Step 3: Template Removal. Thoroughly wash the electrode with a suitable solvent (e.g., methanol:acetic acid mixture) to extract the template molecules from the polymer matrix. This leaves behind specific recognition sites.

3. Measurement and Detection:

- Step 1: Rebinding. Incubate the MIP-modified electrode in the sample solution containing the target pesticide. The pesticide molecules selectively rebind to the imprinted cavities.

- Step 2: Electrochemical Readout. Measure the electrode's response using a technique such as differential pulse voltammetry (DPV) or electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS). The binding of the target pesticide hinders electron transfer, leading to a measurable change in current or impedance, which is correlated with the pesticide concentration.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Biosensor Fabrication

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Key Features & Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Screen-Printed Electrodes (SPEs) | Disposable, portable transducer platform; ideal for on-site testing [10] | Low-cost, mass-producible, integrated 3-electrode system (working, reference, counter) |

| Gold Nanoparticles (Au NPs) | Signal amplification; platform for immobilizing thiolated bioreceptors (aptamers, antibodies) [19] | High conductivity, large surface area, biocompatibility, facile surface chemistry (Au–S bonds) |

| Prussian Blue (PB) | Electron transfer mediator in enzyme-based sensors [10] | High electrocatalytic activity for H₂O₂ reduction, low working potential, "artificial peroxidase" |

| Graphene & Derivatives | Electrode nanomodifier to enhance conductivity and surface area [19] | Excellent electrical conductivity, high surface-to-volume ratio, functional groups for bioconjugation |

| Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) | Porous nanomaterial to increase immobilization capacity and pre-concentrate analytes [19] | Extremely high surface area, tunable porosity, enhances sensor loading and sensitivity |

| Methylene Blue | Redox-active reporter label in electrochemical aptasensors [19] | Intercalates with DNA; change in signal upon aptamer conformation/ displacement indicates binding |

| Nafion | Cation-exchange polymer; used as a permselective membrane and binder for biocomposite inks [10] | Prevents fouling, stabilizes enzyme layers, binds nanomaterials to electrode surfaces |

The strategic selection of a biorecognition element is the cornerstone of developing a successful electrochemical biosensor for pesticide analysis. Enzymes offer a biologically relevant mechanism for class-specific detection, while aptamers provide a versatile and stable platform for highly specific quantification. Antibodies remain the gold standard for immunoassays requiring extreme specificity, and MIPs present a robust, cost-effective biomimetic alternative. The protocols and comparisons detailed in this application note provide a framework for researchers to make informed decisions, balancing analytical requirements with practical constraints to advance the field of food safety monitoring.

Electrochemical biosensors have emerged as powerful analytical tools for the rapid and on-site detection of pesticide residues in fruits and vegetables, aligning with the growing need for food safety monitoring [31] [32]. The performance of these biosensors is critically dependent on the electrode materials and their modification with nanomaterials to amplify the electrochemical signal. Among the various nanomaterials available, gold nanoparticles (AuNPs), graphene and its derivatives, and carbon nanotubes (CNTs) belong to an elite group of nanomaterials that significantly enhance biosensor sensitivity, stability, and overall performance [33]. This protocol details the application of these nanomaterials in constructing high-sensitivity electrochemical biosensors specifically for detecting organophosphate and carbamate pesticides in fruit samples, providing a standardized methodology for researchers and scientists in the field of food safety and analytical chemistry.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Nanomaterial-Enhanced Electrochemical Biosensors

| Reagent/Material | Function/Description | Application in Biosensor Fabrication |

|---|---|---|

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | Colloidal solution with negative charge, large surface area, facile surface modification with thiols, low toxicity, and high biocompatibility [32]. | Provides a platform for biomolecule immobilization (antibodies, aptamers); enhances electron transfer and catalytic activity [33] [34]. |

| Graphene Oxide (GO) / Reduced GO (rGO) | Two-dimensional carbon nanomaterial with high surface area, excellent electrical conductivity, and abundant functional groups for bioconjugation [33] [35]. | Increases electroactive surface area; facilitates direct electron transfer; often used in nanocomposites to synergistically improve sensor performance [33] [34]. |

| Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes (MWCNTs) | Cylindrical carbon nanostructures with high electrical conductivity and mechanical strength; prone to agglomeration without functionalization [34] [35]. | Used as electrode modifiers to enhance electron transfer kinetics; often combined with other nanomaterials like rGO to form highly conductive networks [33] [34]. |

| Screen-Printed Electrodes (SPEs) | Disposable, low-cost, miniaturized electrochemical cells (working, reference, and counter electrode integrated) ideal for portable analysis [31] [36]. | Serve as the foundational substrate for nanomaterial modification and biosensor assembly; enable on-site testing with minimal sample volume [31] [37]. |

| Specific Aptamers/Antibodies | Biological recognition elements (single-stranded DNA/RNA or antibodies) with high affinity and specificity for target pesticide molecules [32]. | Immobilized on the nanomaterial-modified electrode to provide selective binding for the target analyte, forming the basis of the biosensing mechanism [31] [32]. |

| Chitosan (CS) | A biocompatible polymer with excellent film-forming ability and adhesion properties [34]. | Used as a dispersing agent for nanomaterials like MWCNTs and rGO and as a matrix for stable immobilization of biorecognition elements on the electrode surface [34]. |

Performance Comparison of Nanomaterial-Based Biosensors

The integration of nanomaterials into electrochemical biosensors has led to remarkable improvements in analytical performance for pesticide detection. The following table summarizes the reported efficacy of sensors utilizing different nanomaterial configurations.

Table 2: Analytical Performance of Nanomaterial-Enhanced Biosensors for Pesticide Detection

| Nanomaterial Configuration | Target Pesticide(s) | Detection Technique | Linear Range | Limit of Detection (LOD) | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) / c-MWCNT / Fe₃O₄-NP [32] | Malathion, Chlorpyrifos | Amperometry | Not Specified | 0.1 nM | High sensitivity; reusable >50 times; stable for 2 months. |

| Aptamer / Fe-Co MNPs / Fe-N-C Nanozyme [32] | Phorate, Profenofos | Colorimetry | Not Specified | 0.16 ng/mL (Phorate, Profenofos) | High specificity and stability; satisfactory recovery in vegetable samples. |

| MXene/Carbon Nanohorn/β-CD-MOF [32] | Carbendazim | Voltammetry | 0.003 to 10.0 μM | 1.0 nM | Excellent catalytic activity and high electronic conductivity. |

| MWCNTs-rGO-Chitosan [34] | Tau-441 Protein (Model Biomarker) | Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) | 0.5 - 80 fM | 0.46 fM | Signal multi-amplification via nanomaterial synergy and AuNP labels. |

| Au–Pd / rGO / MWCNTs Nanocomposite [31] | Pesticides (General) | Voltammetry | Not Specified | Not Specified | Enhanced electrocatalytic activity and surface area from noble metals and carbon nanomaterials. |

Experimental Protocol: Fabrication of a Nanocomposite-Based Electrochemical Aptasensor

Principle

This protocol describes the construction of an electrochemical aptasensor for the detection of organophosphorus pesticides (OPPs). The sensor is based on a glassy carbon electrode (GCE) modified with a multi-walled carbon nanotube-reduced graphene oxide (MWCNTs-rGO) nanocomposite to enhance the electrode surface area and conductivity. A specific aptamer against the target OPP is immobilized on this platform. The detection mechanism relies on the change in electrochemical signal, measured via Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV), when the aptamer binds to its target pesticide [31] [34] [32].

Materials and Equipment

- Electrochemical Workstation: Capable of performing Cyclic Voltammetry (CV), Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS), and DPV.

- Electrodes: Glassy Carbon Electrode (GCE, 3 mm diameter) or Disposable Screen-Printed Carbon Electrodes (SPCEs); Ag/AgCl reference electrode; Platinum counter electrode.

- Chemicals: Multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs), Graphene Oxide (GO) dispersion, Chitosan (CS), chloroauric acid (HAuCl₄), organophosphate pesticide (OPP) aptamer, potassium ferricyanide (K₃[Fe(CN)₆]), phosphate buffer saline (PBS, 0.1 M, pH 7.4).

- Lab Equipment: Ultrasonic bath, centrifuge, magnetic stirrer, pH meter, micropipettes.

Step-by-Step Procedure

Step 1: Synthesis of MWCNTs-rGO-Chitosan Nanocomposite

- Dispersion: Disperse 10 mg of MWCNTs and 10 mg of GO in 20 mL of deionized water separately. Sonicate both dispersions for 60 minutes until homogeneous.

- Mixing: Combine the MWCNTs and GO dispersions and continue sonication for an additional 60 minutes to form a uniform MWCNTs-GO mixture.

- Chemical Reduction: Add 100 µL of hydrazine hydrate (as a reducing agent) to the mixture and heat at 95°C for 2 hours under continuous stirring to reduce GO to rGO, resulting in an MWCNTs-rGO dispersion.

- Incorporation of Chitosan: Dissolve 0.5% (w/v) chitosan in 1% (v/v) acetic acid solution. Add 5 mL of this chitosan solution to the MWCNTs-rGO dispersion and stir for 30 minutes to form the final MWCNTs-rGO-CS nanocomposite. Store at 4°C when not in use [34].

Step 2: Electrode Pretreatment and Modification

- GCE Polishing: Polish the GCE sequentially with 1.0, 0.3, and 0.05 µm alumina slurry on a microcloth pad. Rinse thoroughly with deionized water between each polish and after the final polish.

- Electrochemical Cleaning: In a solution of 0.1 M H₂SO₄, perform cyclic voltammetry between -0.2 V and +1.0 V (vs. Ag/AgCl) at a scan rate of 100 mV/s until a stable voltammogram is obtained. Rinse the electrode with deionized water.

- Nanocomposite Coating: Deposit 8 µL of the MWCNTs-rGO-CS nanocomposite dispersion onto the clean, dry surface of the GCE. Allow it to dry under an infrared lamp or at room temperature to form a stable film. Label this as the GCE/MWCNTs-rGO-CS electrode.

Step 3: Aptamer Immobilization

- Aptamer Preparation: Dilute the synthetic OPP-specific aptamer to a concentration of 1 µM in 10 mM Tris-EDTA (TE) buffer, pH 8.0.

- Immobilization: Drop-cast 5 µL of the aptamer solution onto the surface of the GCE/MWCNTs-rGO-CS electrode.

- Incubation: Incubate the electrode in a humidified chamber at 4°C for 12-16 hours to allow for effective immobilization of the aptamer onto the nanocomposite film via electrostatic interactions and physical adsorption.

- Rinsing: Gently rinse the electrode with PBS (pH 7.4) to remove any unbound aptamer strands. The electrode is now functionalized and labeled as the Aptasensor (GCE/MWCNTs-rGO-CS/Apt).

Step 4: Electrochemical Measurement and Pesticide Detection

- Measurement Setup: Use a three-electrode system with the prepared aptasensor as the working electrode, Ag/AgCl as the reference, and a platinum wire as the counter electrode. The measurement solution is 5 mM [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻ in 0.1 M PBS (pH 7.4).

- Baseline Signal Record: First, record a DPV curve for the aptasensor in the measurement solution without the target pesticide. This serves as the baseline signal (I₀). The DPV parameters are: potential range from -0.1 V to +0.5 V, pulse amplitude of 50 mV, pulse width of 50 ms.

- Sample Incubation: Incubate the aptasensor in a sample solution (e.g., extracted fruit juice) spiked with a known concentration of the target OPP for 15 minutes at room temperature.

- Post-Incubation Measurement: Rinse the electrode gently with PBS to remove non-specifically bound molecules. Record the DPV signal again (I) under the same conditions as step 2.

- Signal Analysis: The binding of the target pesticide to the immobilized aptamer causes a steric hindrance, reducing the current signal. The signal decrease (I₀ - I) is proportional to the concentration of the target pesticide in the sample.

Data Analysis

- Calibration Curve: Measure the DPV signal for a series of standard solutions with known pesticide concentrations. Plot the signal decrease (ΔI = I₀ - I) against the logarithm of the pesticide concentration.

- Quantification: Fit the data points with a linear regression model (y = a + bx). The resulting calibration curve can be used to interpolate the concentration of unknown samples based on their measured ΔI.

- Validation: Validate the sensor's accuracy by testing spiked real samples (e.g., apple or cucumber extracts) and calculating the recovery rate [32].

Workflow and Signaling Visualization

Sensor Assembly and Measurement Flow