Aptasensors vs. Immunosensors: A Modern Guide to Agrochemical Analysis

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of aptasensors and immunosensors for the detection of agrochemicals, catering to researchers and scientists in the field.

Aptasensors vs. Immunosensors: A Modern Guide to Agrochemical Analysis

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of aptasensors and immunosensors for the detection of agrochemicals, catering to researchers and scientists in the field. It covers the foundational principles of both technologies, explores diverse methodological approaches and their practical applications in food and environmental safety, discusses key challenges and optimization strategies for real-world use, and delivers a critical, evidence-based comparison of their analytical performance. The review synthesizes recent advancements to guide the selection and development of the most suitable biosensing platform for specific agrochemical monitoring needs.

Core Principles: Understanding Aptasensors and Immunosensors

Biosensors are sophisticated analytical devices that combine a biological recognition element with a physical transducer to detect and quantify a specific substance, or analyte [1]. The core principle of a biosensor is to convert a biological response into a quantifiable and processable signal [2]. Since the development of the first biosensor by Leland C. Clark, Jr. in 1956 for oxygen detection, these devices have become powerful tools with applications spanning clinical diagnostics, environmental monitoring, food safety, and drug discovery [3] [1]. The success of a biosensor hinges on the integrated performance of its two primary components: the biorecognition element, which provides specificity, and the transducer, which converts the biological interaction into a measurable output [3] [4]. This guide details these core components within the context of modern research on aptasensors and immunosensors for agrochemicals.

Core Components of a Biosensor

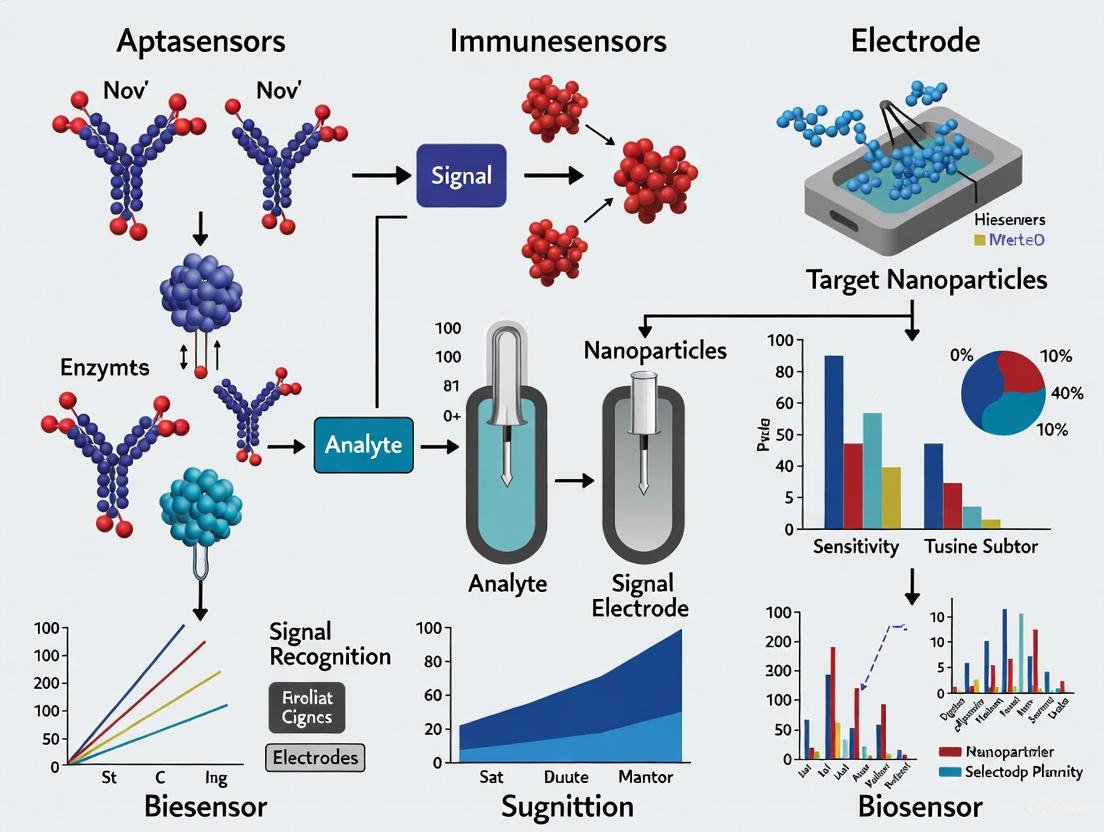

A typical biosensor consists of five main elements that work in sequence to detect and report on an analyte (Figure 1).

- Analyte: The substance of interest that needs to be detected (e.g., a specific pesticide, glucose, or a protein biomarker) [4] [1].

- Bioreceptor (or Biorecognition Element): A biological molecule that specifically recognizes and binds to the analyte. Examples include antibodies, nucleic acids, and aptamers [4] [1]. The interaction between the bioreceptor and the analyte is termed bio-recognition.

- Transducer: The component that converts the biological recognition event into a measurable signal, a process known as signalisation. Transducers can transform energy from one form to another, such as converting a binding event into an electrical or optical signal [4] [1].

- Electronics: The electronic circuitry that processes the transduced signal. This often involves signal conditioning, such as amplification, filtering, and conversion from analog to digital form [4] [1].

- Display: The user interface that presents the final result in a user-friendly format, which can be numerical, graphical, or tabular [4].

The following diagram illustrates the workflow and logical relationships between these core components.

Figure 1: The fundamental workflow of a biosensor, from sample introduction to result display.

Biorecognition Elements

The biorecognition element is the cornerstone of a biosensor's specificity. It is a molecule that selectively interacts with the target analyte, ensuring that the sensor responds only to the substance of interest while ignoring potential interferents in a sample [3] [1]. Several classes of biorecognition elements are available, each with distinct characteristics, advantages, and limitations. The selection of an appropriate biorecognition element is a critical first step in biosensor design, as it directly influences key performance metrics such as sensitivity, selectivity, and stability [3].

Table 1: Comparison of Common Biorecognition Elements

| Biorecognition Element | Type | Binding Mechanism | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antibody [3] [4] | Natural (Biological) | Affinity-based; forms a 3D immunocomplex with the antigen. | High specificity and affinity. | Production requires animals; costly and time-consuming to produce; can be unstable. |

| Enzyme [3] [4] | Natural (Biological) | Biocatalytic; captures and converts the analyte to a measurable product. | High catalytic activity; can amplify signal. | Activity can be dependent on environmental conditions (pH, temperature). |

| Nucleic Acid (DNA) [3] [4] | Natural (Biological) | Complementary base-pairing (hybridization). | High specificity for genetic targets; stable. | Limited to applications targeting nucleic acids. |

| Aptamer [3] [5] [6] | Pseudo-natural (Synthetic) | Folds into a 3D structure for high-affinity binding to a target. | High stability; cost-effective synthesis; easily modified; targets diverse analytes (ions, cells, pesticides). | Discovery process (SELEX) can be costly and time-consuming. |

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymer (MIP) [3] [4] | Synthetic | A synthetic polymer matrix with cavities templated for the target analyte. | High chemical/thermal stability; no need for biological discovery. | Can suffer from lower selectivity compared to biological receptors. |

For agrochemical detection, such as monitoring pesticide residues, aptamers and antibodies are the most prominent biorecognition elements used in modern biosensors [5] [7]. Immunosensors, which use antibodies, have been a long-standing tool. However, aptasensors, which use aptamers, are increasingly favored due to aptamers' superior stability, easier modification, and more cost-effective production [5]. Aptamers are engineered through an in vitro process called SELEX (Systematic Evolution of Ligands by EXponential enrichment), which selects specific DNA or RNA sequences that bind with high affinity to a target molecule [3] [6].

Transducers

The transducer is the component responsible for converting the biorecognition event into a measurable signal. The choice of transducer depends on the nature of the biological interaction and the desired output signal [2]. The main classes of transducers and their mechanisms are detailed below.

Table 2: Comparison of Common Transducer Types in Biosensors

| Transducer Type | Measurable Signal | Mechanism of Action | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electrochemical [8] [2] | Current, Potential, Impedance | Measures changes in electrical properties due to the biorecognition event (e.g., electron transfer in a redox reaction). | Glucose monitors, detection of pesticides like neonicotinoids [7]. |

| Optical [2] [1] | Fluorescence, Absorbance, Light Intensity | Detects changes in the properties of light (e.g., intensity, wavelength) caused by the binding of the analyte. | Fluorescent aptasensors for mycotoxins and pathogens [6]. |

| Piezoelectric [2] | Mass Change | Measures the change in mass on the sensor surface due to analyte binding, often by a change in the resonance frequency of a crystal. | Quartz crystal microbalance (QCM) immunosensors. |

| Thermal [2] | Temperature / Heat | Measures the heat generated or absorbed during the biochemical reaction. | Enzyme thermistors for metabolite detection. |

The selection of an appropriate transducer is a key element in biosensor development, influencing the device's sensitivity, portability, and cost [8]. For point-of-care and on-site applications, such as testing for pesticide residues on a farm or in a food processing facility, electrochemical transducers are particularly advantageous due to their potential for miniaturization, low cost, high sensitivity, and fast response times [5] [8] [6].

Performance Characteristics of Biosensors

The effectiveness of a biosensor is evaluated based on a set of key performance characteristics [2] [1]. Understanding these metrics is essential for researchers to design, validate, and compare different biosensing platforms.

- Selectivity/Specificity: The ability of the biosensor to detect only the target analyte in a sample containing other admixtures and contaminants. This is primarily determined by the biorecognition element [3] [1].

- Sensitivity & Limit of Detection (LOD): The minimum amount of analyte that can be reliably detected by the biosensor. A lower LOD indicates higher sensitivity, which is crucial for detecting trace-level contaminants like pesticides [2] [1].

- Reproducibility: The ability of the biosensor to generate identical responses for a duplicated experimental setup, reflecting the precision and reliability of the device and its fabrication process [3] [1].

- Stability: The degree to which the biosensor maintains its performance over time and under various storage and operating conditions. This can be affected by the degradation of the biorecognition element [1].

- Linearity and Dynamic Range: The range of analyte concentrations over which the sensor's response is linearly proportional to the concentration. A wide dynamic range is desirable for applications where analyte concentrations can vary significantly [1].

Experimental Focus: A Multiplexed Aptasensor for Agrochemicals

To illustrate the integration of a biorecognition element and a transducer in a practical research context, consider a recent study developing a multiplexed electrochemical aptasensor for the detection of three neonicotinoid pesticides: imidacloprid, thiamethoxam, and clothianidin [7].

Research Objective and Rationale

Neonicotinoids are widely used insecticides, but their residues pose significant environmental and health risks. There is a need for cost-effective, sensitive, and on-site methods to monitor their presence in food and environmental samples, moving beyond traditional, lab-bound techniques like chromatography [7].

Methodology and Workflow

The experimental protocol for fabricating and testing this aptasensor is outlined below and summarized in Figure 2.

- Aptamer Selection and Truncation: Amine-labeled aptamers specific to each pesticide were selected. The aptamer for imidacloprid was rationally truncated to a shorter sequence, which improved its binding affinity (KD = 12.8 nM) and reduced production costs [7].

- Transducer Functionalization: Screen-printed electrodes (the transducer base) were coated with graphene oxide (GO), which was subsequently electrochemically reduced to form reduced GO (rGO). This nanomaterial enhances the electrode's surface area and electrical conductivity [7].

- Bioreceptor Immobilization: The rGO-coated electrodes were functionalized with 1-pyrenebutyric acid, which acts as a linker. The amine-labeled aptamers were then covalently immobilized onto this activated surface [7].

- Electrochemical Measurement: The binding of the target pesticides to their respective immobilized aptamers was monitored using Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV). The measurement was performed in a solution containing a redox probe ([Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻). The binding event causes a change in the electrochemical impedance and current at the electrode surface, which is quantifiable and proportional to the analyte concentration [7].

- Validation: The aptasensor's performance was validated by testing spiked tomato and rice samples and comparing the results with a standard liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) method, demonstrating high recovery rates and excellent agreement [7].

Figure 2: Experimental workflow for the development of a multiplexed electrochemical aptasensor for neonicotinoid pesticides [7].

Key Research Reagent Solutions

This experiment relied on several critical reagents and materials, whose functions are detailed in the following table.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Their Functions in the Multiplexed Aptasensor Experiment

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Screen-Printed Electrode (SPE) | Serves as the portable and disposable electrochemical transducer platform. |

| Graphene Oxide (GO) / Reduced GO (rGO) | Nanomaterial that increases the electrode's surface area and enhances electron transfer, boosting sensitivity. |

| Amine-labeled DNA Aptamers | Act as the synthetic biorecognition elements, specifically binding to imidacloprid, thiamethoxam, and clothianidin. |

| 1-Pyrenebutyric Acid (Linker) | Functionalizes the rGO surface to enable the covalent attachment of the amine-labeled aptamers. |

| Redox Probe (K₃[Fe(CN)₆]/K₄[Fe(CN)₆]) | Provides the electrochemical signal that changes upon aptamer-pesticide binding, which is measured by DPV. |

| Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) | The specific electrochemical technique used for highly sensitive measurement of the concentration-dependent signal. |

Results and Significance

The developed biosensor demonstrated excellent sensitivity with a linear detection range from 0.01 ng/mL to 100 ng/mL for all three pesticides, with high selectivity against other interfering substances [7]. This study exemplifies the power of combining highly specific aptamers with a robust electrochemical transducer and signal-enhancing nanomaterials to create a practical tool for agrochemical analysis.

Biosensors are defined by the synergistic operation of their two core components: the biorecognition element, which provides molecular specificity, and the transducer, which generates a measurable signal. As research advances, the trend is toward designing biosensors that are not only highly sensitive and selective but also portable, cost-effective, and capable of multiplexed detection. The integration of novel synthetic bioreceptors like aptamers with versatile electrochemical transducers and nanomaterials is paving the way for the next generation of biosensors. These devices are poised to make significant contributions to fields like agrochemical research, enabling rapid on-site monitoring of pesticide residues to ensure environmental safety and food security.

Aptamers are short, single-stranded DNA or RNA oligonucleotides that bind to specific target molecules with high affinity and specificity [9] [10]. The term "aptamer" originates from the Latin word "aptus" (to fit) and the Greek word "meros" (particle), reflecting their role as fitting ligand particles [10] [11]. These synthetic molecules, typically comprising 20-100 nucleotides, fold into defined three-dimensional structures through base-pair interactions, creating surfaces that enable them to recognize and bind to their targets via shape complementarity, hydrogen bonds, van der Waals interactions, electrostatic forces, and planar group stacking [9] [10]. Aptamers can be generated against a diverse range of targets, from small molecules like pesticides and toxins to complex structures including proteins, whole living cells, viruses, and bacteria [12] [10].

Referred to as "chemical antibodies," aptamers share functional similarities with monoclonal antibodies but possess several distinctive advantages that position them as promising tools in biomedicine, environmental monitoring, and therapeutic applications [9] [13]. Their unique characteristics include higher specificity, stronger binding affinity, superior stability, easier chemical modification, and more cost-effective production compared to traditional antibodies [9] [14]. The clinical potential of aptamers was first realized in 2004 with the FDA approval of pegaptanib (Macugen) for treating age-related macular degeneration, followed by avacincaptad pegol (Izervay) in 2023 for geographic atrophy, demonstrating their growing therapeutic relevance [9].

The SELEX Selection Process

Fundamental Principles

The Systematic Evolution of Ligands by Exponential Enrichment (SELEX) is the foundational in vitro selection process used to identify specific aptamers from vast oligonucleotide libraries [9] [15]. First established in 1990 by Tuerk and Gold, who screened RNA aptamers binding to bacteriophage T4 DNA polymerase, SELEX has since evolved into numerous variants while maintaining its core iterative principle of selecting high-affinity ligands through repeated binding, partitioning, and amplification cycles [9] [11]. The process begins with the synthesis of an oligonucleotide library containing an enormous diversity of random sequences (typically >10^15 different sequences), each consisting of a central random region (20-50 nucleotides) flanked by constant primer binding regions for amplification [10] [13]. This library is incubated with the target molecule, allowing high-affinity aptamers to bind while unbound sequences are removed through partitioning techniques such as nitrocellulose filtration, affinity chromatography, or magnetic bead separation [9] [15]. The bound aptamers are then amplified via PCR (for DNA aptamers) or reverse transcription-PCR (for RNA aptamers), creating an enriched pool for subsequent selection rounds [10]. This cycle typically repeats 8-15 times, progressively enriching the pool with sequences exhibiting the highest target affinity [11]. Following the final selection round, the enriched pool undergoes high-throughput sequencing and bioinformatics analysis to identify individual aptamer candidates with optimal binding properties [15].

SELEX Methodologies and Variations

Several SELEX methodologies have been developed to enhance selection efficiency, specificity, and applicability to different target types. The following table summarizes the key SELEX variants and their applications:

Table 1: Comparison of Major SELEX Methodologies

| SELEX Method | Target Type | Key Features | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In Vitro SELEX | Purified proteins, small molecules | Controlled environment (temperature, pH, buffers) | Rapid screening, high throughput, simplified workflow | Artificial conditions may not reflect physiological relevance |

| Cell-SELEX | Whole living cells | Uses native cell surface targets in physiological conformation | Identifies aptamers for cell-specific biomarkers, no prior target knowledge required | Complex procedure, potential for off-target binding |

| In Vivo SELEX | Living organisms | Selection within physiological environment | Enhances physiological relevance, identifies aptamers that overcome biological barriers | Resource-intensive, ethical considerations, biological variability |

| Immobilized Target SELEX | Small molecules, pesticides | Target molecules immobilized on solid support | Efficient partitioning for small targets | Immobilization chemistry may affect target structure |

| Hybrid/Crossover SELEX | Proteins, cell surface markers | Combines cell-SELEX and protein-SELEX | Enhanced specificity, validates binding in multiple contexts | More complex workflow requiring multiple selection strategies |

Cell-SELEX deserves particular emphasis as it enables aptamer selection against complex targets in their native conformations [13]. Introduced in 1998 using human red blood cell membrane preparations, this approach has evolved to use whole, living cells as selection targets, preserving the natural folding, distribution, and post-translational modifications of cell surface biomarkers [13]. A critical aspect of cell-SELEX is the incorporation of counter-selection steps using control cells (e.g., mock-transfected or non-target cells) to filter out sequences binding to common surface molecules, thereby enhancing the specificity for the target cell phenotype [13]. Hybrid or crossover SELEX represents another significant advancement, combining the advantages of different SELEX approaches. For instance, researchers may begin with cell-SELEX to enrich for aptamers recognizing a target in its native conformation, followed by protein-SELEX against the purified recombinant target to further enhance specificity [13]. This dual approach proved effective in isolating high-affinity tenascin-C (TNC) aptamers, first enriching the pool on glioblastoma cells overexpressing TNC, then further selecting against the recombinant protein [13].

Aptamer Structure and Binding Mechanisms

Structural Characteristics

Aptamers undergo folding into specific three-dimensional configurations that enable target recognition, with structures ranging from simple stems and loops to complex G-quadruplexes, pseudoknots, and bulges [10]. The folding is driven by nucleobase interactions, creating complementary surfaces that fit their targets with remarkable precision [10]. DNA and RNA aptamers differ in their structural capabilities; RNA molecules offer greater flexibility and folding complexity due to the presence of 2'-hydroxyl groups, while DNA aptamers exhibit superior innate stability and simpler amplification protocols [13]. Typical aptamers have an optimal length of 15-45 nucleotides after optimization, with molecular weights ranging from 5-15 kDa—significantly smaller than the ~150 kDa of full-sized monoclonal antibodies [10] [13]. This compact size (20-25 times smaller than antibodies) facilitates better tissue penetration and allows higher density immobilization on sensor surfaces [13] [14]. The binding affinities of aptamers vary from picomolar to micromolar ranges, with typical dissociation constants (Kd) in the low nanomolar range, comparable to or even exceeding those of antibodies [13].

Molecular Recognition Mechanisms

Aptamer-target binding occurs through multiple molecular interactions, including hydrogen bonding, electrostatic interactions, van der Waals forces, aromatic ring stacking, and shape complementarity [12]. The binding mechanism is facilitated by the aptamer's ability to fold around small molecular targets or adapt to crevices and indentations on larger target surfaces [10]. For small molecules like pesticides, aptamers often form binding pockets that encapsulate the target, while for protein targets, they typically interact with specific epitopes or structural domains [12] [11]. The distinctive folding capability enables aptamers to achieve exceptional specificity, often discriminating between closely related targets, such as different pesticide analogs or protein isoforms with minimal structural variations [12]. This molecular recognition flexibility allows aptamers to be developed for diverse targets that challenge antibody production, including toxins, non-immunogenic molecules, and highly conserved proteins [12] [14].

Diagram 1: Aptamer binding involves folding and multiple molecular forces.

Advantages Over Antibodies

Comparative Analysis

Aptamers offer significant advantages over traditional antibodies, making them attractive alternatives for various applications in research, diagnostics, and therapeutics. The following table provides a comprehensive comparison of their key characteristics:

Table 2: Aptamers vs. Antibodies: Comparative Analysis

| Characteristic | Aptamers | Antibodies |

|---|---|---|

| Production Process | In vitro selection (SELEX), <1 month | In vivo immunization, 3-6 months |

| Production Cost | Low-cost chemical synthesis | Expensive biological production |

| Batch-to-Batch Variation | Minimal (synthetic production) | Significant (biological production) |

| Size | 5-15 kDa (20-25x smaller than antibodies) | ~150 kDa (full-sized monoclonal) |

| Stability | Thermally stable, reversible denaturation | Heat-sensitive, irreversible denaturation |

| Modification | Easy chemical modification with various functional groups | Complex conjugation chemistry |

| Target Range | Toxins, small molecules, non-immunogenic targets | Primarily immunogenic targets |

| Immunogenicity | Low to non-immunogenic | Can trigger immune responses |

| Shelf Life | Long-term stability at room temperature | Limited, requires cold chain |

| Tissue Penetration | Excellent due to small size | Limited due to large size |

Key Operational Advantages

Beyond the comparative characteristics, aptamers exhibit several operational advantages that enhance their practical utility. Their superior stability allows aptamers to withstand harsh conditions, including extreme pH, organic solvents, and elevated temperatures, without permanent functional loss [12] [14]. Aptamers can undergo reversible denaturation, regaining their active configuration after heat treatment that would permanently denature antibodies [12]. This attribute enables aptamer reuse in multiple assay cycles and reduces storage and transportation constraints. The ease of modification represents another significant advantage, as aptamers can be chemically synthesized with various functional groups (e.g., amines, thiols, biotin) at precise positions without affecting their binding properties [13]. This facilitates oriented immobilization on sensor surfaces, tagging with detection molecules, and conjugation with therapeutic agents [16]. Furthermore, aptamers demonstrate remarkable target versatility, capable of binding to targets that challenge antibody development, including small molecules, toxins, and non-immunogenic compounds [12] [11]. This flexibility has enabled aptamer development against various pesticides, despite their small molecular size and structural simplicity [12] [11].

Applications in Agrochemical Research

Aptasensors for Pesticide Detection

The application of aptamers in biosensors (aptasensors) for pesticide detection represents a rapidly advancing field addressing the critical need for monitoring environmental contamination and food safety [12] [11]. Conventional pesticide analysis relying on chromatographic methods (HPLC, GC/MS, LC/MS), while highly accurate, requires expensive instrumentation, lengthy processing times, and specialized technical expertise, limiting their suitability for rapid on-site screening [12] [11]. Aptasensors integrate aptamers as recognition elements with various transduction mechanisms, including electrochemical, fluorescent, colorimetric, electrochemiluminescent, and surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS) platforms [12]. Electrochemical aptasensors have demonstrated exceptional sensitivity for pesticide detection, often achieving detection limits in the femtomolar range through signal amplification strategies incorporating nanomaterials like carbon nanotubes, metal nanoparticles, and graphene derivatives [12]. For example, a dual-signal electrochemical aptasensing platform for carbendazim (CBZ) detection employed a specific aptamer combined with zirconium-based metal-organic frameworks (MOF-808) and graphene nanoribbons, achieving an remarkably low detection limit of 0.2 fM [12]. Colorimetric aptasensors offer alternative advantages of simplicity, visual detection capability, and minimal equipment requirements, making them suitable for field testing and resource-limited settings [11].

Research Reagent Solutions

The development and implementation of aptamer-based technologies for agrochemical research requires specific reagents and materials. The following table outlines essential research reagent solutions and their functions:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Aptamer Development and Application

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Oligonucleotide Library | Source of sequence diversity for selection | SELEX initialization with 10^14-10^16 random sequences |

| Modified Nucleotides | Enhance stability and binding properties | 2'-fluoro, 2'-amino RNA for nuclease resistance |

| Magnetic Beads | Solid support for target immobilization | Partitioning bound and unbound sequences |

| PCR Reagents | Amplification of selected sequences | Library enrichment between selection rounds |

| Nanomaterials | Signal amplification and immobilization | CNTs, AuNPs, graphene in electrochemical aptasensors |

| Immobilization Chemistries | Surface functionalization | Maleimide-thiol, streptavidin-biotin, amine coupling |

| Capillary Electrophoresis | Separation and analysis | Partitioning aptamer-target complexes |

Experimental Protocols

SELEX Protocol for Small Molecule Targets

The following detailed protocol outlines the SELEX procedure for selecting aptamers against small molecule targets such as pesticides, adapted from established methodologies with an emphasis on critical steps that influence selection success [11] [15].

Initial Library Preparation: Begin with synthesizing a single-stranded DNA library featuring a central random region (30-40 nucleotides) flanked by constant primer binding sequences (18-22 nucleotides each). For the initial library, use approximately 10^14-10^16 DNA molecules dissolved in binding buffer (typically containing NaCl, MgCl2, and pH-stabilizing agents like Tris-HCl) [13] [11]. Denature the library at 95°C for 5 minutes and immediately cool on ice for 10 minutes to ensure proper folding before selection.

Target Immobilization: For small pesticide targets, immobilize the target molecules on solid supports to facilitate efficient partitioning. Covalently conjugate target molecules to magnetic beads using appropriate crosslinkers (e.g., EDC/sulfo-NHS chemistry for carboxylated beads) [11]. Alternatively, conjugate pesticides to carrier proteins like BSA before immobilization to enhance presentation. Include control beads without target molecules for counter-selection steps.

Selection Rounds:

- Pre-clearing: Incubate the DNA library with control beads (without target) for 30-60 minutes at room temperature with gentle rotation. Discard beads to remove sequences binding non-specifically to the solid support or carrier matrix.

- Positive Selection: Transfer the pre-cleared library to target-immobilized beads and incubate for 30-60 minutes under optimal binding conditions.

- Washing: Separate bead-bound complexes using magnetic separation and wash with binding buffer to remove weakly bound sequences. Gradually increase washing stringency (e.g., add mild detergents or reduce salt concentration) in subsequent selection rounds.

- Elution: Elute specifically bound sequences using denaturing conditions (e.g., 95°C heat, 7M urea, or elevated pH) or competitive elution with free target molecules.

- Amplification: Amplify eluted sequences using PCR with appropriate primers. For DNA SELEX, use symmetric PCR; for RNA SELEX, include in vitro transcription steps. Monitor amplification carefully to prevent over-amplification that can favor parasitic sequences.

- Purification: Purify the amplified product and regenerate single-stranded DNA for the next selection round. For RNA aptamers, include reverse transcription and transcription steps.

Progress Monitoring: Monitor selection progress by measuring the enrichment of bound sequences after each round using quantitative PCR or other appropriate methods. Typically, significant enrichment is observed after 5-8 rounds, with the process continuing for 10-15 total rounds until binding saturation is achieved.

Clone Sequencing and Characterization: After the final selection round, clone the enriched pool and sequence individual clones (typically 50-100). Identify candidate aptamers based on sequence redundancy and structural motifs. Synthesize these candidates and characterize their binding affinity (Kd) using methods like surface plasmon resonance (SPR) or fluorescence anisotropy, and assess specificity against related molecules [11].

Aptamer Immobilization for Biosensing

Effective aptamer immobilization on sensor surfaces is critical for developing high-performance aptasensors. The following protocol details a robust method for thiol-modified aptamer immobilization on gold surfaces, commonly used in electrochemical and SPR-based biosensors [12] [14].

Surface Preparation: Clean gold sensor surfaces using oxygen plasma treatment or piranha solution (3:1 H2SO4:H2O2 - EXTREME CAUTION REQUIRED), followed by thorough rinsing with deionized water and ethanol. Alternatively, perform electrochemical cleaning in 0.5M H2SO4 by cycling between -0.2V and +1.5V until a stable voltammogram is obtained.

Aptamer Immobilization:

- Dilute thiol-modified aptamers (typically 1-10 µM) in immobilization buffer (e.g., 10 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA, 50 mM NaCl, pH 7.4) containing a reducing agent like TCEP (50-100 µM) to cleave potential disulfide bonds.

- Incubate the aptamer solution on the cleaned gold surface for 2-16 hours at room temperature in a humidified chamber to prevent evaporation.

- Rinse the surface thoroughly with immobilization buffer to remove physically adsorbed aptamers.

- Block the surface with 1-6 mM mercaptohexanol (MCH) in immobilization buffer for 1-2 hours to displace non-specifically adsorbed aptamers and create a well-oriented monolayer.

- Rinse with binding buffer and store in appropriate buffer until use.

Quality Control: Assess immobilization quality using electrochemical methods (e.g., redox capacitance measurements), SPR, or quartz crystal microbalance (QCM). Successful immobilization typically results in surface densities of 1-5 × 10^12 molecules/cm², with higher densities potentially leading to steric hindrance and reduced binding efficiency.

Diagram 2: SELEX is an iterative process of binding and amplification.

Aptamers represent a powerful class of recognition elements with significant advantages over traditional antibodies in terms of production efficiency, stability, modification flexibility, and target versatility. The SELEX process, while conceptually straightforward, has evolved into sophisticated methodologies that enable the selection of high-affinity aptamers against diverse targets, including challenging small molecules like pesticides. Their unique properties position aptamers as ideal recognition elements for developing advanced biosensing platforms, particularly in agrochemical research where rapid, sensitive, and field-deployable detection methods are urgently needed. As selection methodologies continue to advance and our understanding of structure-function relationships deepens, aptamers are poised to play an increasingly prominent role in biosensing, diagnostics, and therapeutic applications, potentially transforming how we detect and monitor environmental contaminants and ensuring food safety through innovative analytical technologies.

Antibodies, also known as immunoglobulins, are sophisticated glycoproteins that function as the primary recognition elements of the adaptive immune system, specifically binding to foreign substances known as antigens. In the context of biosensor technology, particularly immunosensors, antibodies serve as critical biorecognition receptors that provide the foundation for detection systems. Their ability to selectively identify and bind to specific molecular targets with high affinity makes them invaluable tools for detecting a wide array of analytes, from pathogens and disease biomarkers to environmental contaminants such as agrochemicals. Within the framework of agrochemicals research, understanding the fundamental properties of antibodies—their precise specificity, production methodologies, and inherent limitations—is essential for developing effective immunosensing platforms and for appreciating the emerging role of alternative recognition elements like aptamers in aptasensors. This review examines the core principles of antibody specificity, the evolution of antibody production technologies, and the practical constraints that impact their application in environmental monitoring and food safety.

The Molecular Basis of Antibody Specificity

Antibody specificity refers to the precise molecular recognition and binding between an antibody and its target antigen. This interaction is a fundamental property that enables antibodies to identify and eliminate specific pathogens while ignoring the body's own cells and benign substances [17].

Structural Determinants of Specificity

The specific binding capability of an antibody resides in its variable region, which forms a unique three-dimensional structure called the paratope that is complementary to a specific portion of the antigen known as the epitope [17] [18]. This precise lock-and-key fit, supplemented by an induced-fit model where both molecules may adjust their conformations, enables one antibody to recognize a specific antigen while ignoring others [18]. Because one antibody only recognizes a specific antigen, antibodies designed to attack cancer cells, for example, do not attack normal cells—demonstrating the remarkable specificity of this interaction [17].

The binding is stabilized by multiple non-covalent forces, including hydrogen bonds, electrostatic interactions, van der Waals forces, and hydrophobic interactions [18]. The strength of this binding, known as affinity, is quantified by the dissociation constant (Kd), with lower values indicating higher affinity [18]. It is crucial to note that absolute specificity is thermodynamically impossible; no antibody exhibits infinite affinity or perfect discrimination [18]. Antibodies can demonstrate varying degrees of cross-reactivity with structurally similar molecules, which can be either a limitation or an advantage depending on the application context [18] [19].

Practical and Biological Implications of Specificity

In practical applications, the observed specificity of an antibody is not solely determined by its paratope-epitope interaction but is influenced by multiple factors. Biological specificity refers to the ability of an antibody to trigger a specific immune response (e.g., cell activation or complement cascade) upon binding, which may not always directly correlate with binding affinity measurements [18]. Furthermore, the context of the antigen—whether it is displayed as a monovalent form or in a multivalent, multideterminant array on a cell surface—significantly impacts an antibody's ability to discriminate between different targets [18].

For immunosensors in agrochemical research, antibody specificity determines the sensor's ability to distinguish between structurally similar pesticides or their metabolites, directly impacting the reliability and accuracy of detection [12] [20]. This is particularly challenging when detecting small molecules, where slight structural differences must be discerned to avoid false positives or negatives in complex matrices like food and environmental samples [20].

Antibody Production Methodologies

The production of antibodies for research, diagnostic, and therapeutic applications has evolved significantly, with different methods offering distinct advantages and limitations. The choice of production method depends on the required specificity, quantity, consistency, and application context.

Polyclonal Antibody Production

Polyclonal antibodies represent a heterogeneous mixture of antibodies produced by different B-cell clones in an animal in response to an antigen. Each antibody within the mixture recognizes different epitopes on the same antigen [19].

- Production Protocol: The production process begins with immunizing a host animal (e.g., rabbit, goat, or sheep) with the target antigen, typically emulsified in an adjuvant to enhance the immune response. This is followed by several booster immunizations at 2-4 week intervals to increase the titer and affinity of antigen-specific antibodies. Blood is then collected from the immunized animal, and the serum (containing the polyclonal antibody mixture) is separated. The antibodies may be used in their crude form or purified further using methods like antigen-affinity purification to enhance specificity [19].

- Advantages and Limitations: Polyclonal antibodies produce a strong signal in detection assays due to the recognition of multiple epitopes and are relatively inexpensive and quick to produce. However, they are limited in supply, exhibit significant batch-to-batch variation, and have a higher risk of cross-reactivity due to the presence of antibodies that may bind to similar epitopes on unrelated proteins [19].

Monoclonal Antibody Production via Hybridoma Technology

Monoclonal antibodies are homogenous antibodies derived from a single B-cell parent clone, recognizing a single epitope on an antigen. The hybridoma technology, developed by Köhler and Milstein in 1975, enables their production [21] [19].

- Experimental Workflow:

- Immunization: A mouse (or other host) is immunized with the target antigen following a schedule similar to polyclonal production.

- Cell Fusion: Antibody-producing B-cells are harvested from the spleen of the immunized animal and fused with immortal myeloma cells using a fusogen like polyethylene glycol (PEG).

- Selection and Screening: The fused cells (hybridomas) are cultured in a selective medium (e.g., HAT medium) that allows only the hybridomas to survive. The supernatant from each hybridoma culture is screened for antibody production and specificity against the target antigen.

- Cloning and Expansion: Positive hybridomas are single-cell cloned (e.g., by limiting dilution) to ensure monoclonality. The selected clone is then expanded in culture flasks or injected into the peritoneal cavity of mice to produce antibody-rich ascites fluid [19].

- Advantages and Limitations: Monoclonal antibodies offer defined specificity to a single epitope, minimal cross-reactivity, and an unlimited supply from a stable hybridoma cell line. However, the production process is time-consuming, expensive, and requires specialized expertise. A significant limitation is that hybridoma-derived monoclonal antibodies are prone to genetic drift over time, potentially leading to variations in the antibody produced from the same cell line years later [19].

Diagram 1: Monoclonal antibody production workflow using hybridoma technology.

Recombinant Antibody Production

To overcome the limitations of hybridoma technology, recombinant antibody production methods have been developed. These involve cloning the antibody-coding genes into expression vectors and producing antibodies in vitro using host cell lines [19].

- Production from Hybridomas: The variable region genes of a selected hybridoma are sequenced and cloned into expression vectors containing constant region genes. These vectors are then transfected into mammalian cell lines (e.g., HEK 293 or CHO cells) for large-scale antibody production [19].

- Phage Display: This in vitro technology bypasses animal immunization. A library of bacteriophages, each expressing a different antibody fragment (e.g., scFv or Fab) on its surface, is panned against the immobilized target antigen. Phages that bind specifically are retained, eluted, and amplified through multiple rounds to enrich high-affinity binders. The antibody sequences from selected phages are then isolated and used to produce full-length recombinant antibodies [19].

- Advantages: Recombinant antibodies offer superior consistency with minimal batch-to-batch variation, a secured long-term supply, and the potential for engineering to improve properties like affinity, specificity, and solubility [19]. They also facilitate the creation of chimeric (murine variable domains fused to human constant domains) and humanized (murine hypervariable loops grafted onto a human antibody framework) antibodies to reduce immunogenicity in therapeutic applications [21].

Table 1: Comparison of Antibody Production Platforms

| Production Method | Key Characteristics | Specificity Profile | Scale of Production | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polyclonal [19] | Heterogeneous antibody mixture from serum | Recognizes multiple epitopes; higher risk of cross-reactivity | Small to medium | Batch-to-batch variation; limited supply |

| Monoclonal (Hybridoma) [22] [19] | Homogeneous antibodies from a single clone | Single epitope recognition; high specificity | Small to large scale | Time-consuming; genetic drift; animal use |

| Recombinant [19] | Antibodies produced from synthetic genes in host cells | Defined single epitope; can be engineered | Large scale; most consistent | Technically complex; requires sequence knowledge |

Inherent Limitations of Antibodies in Sensing Applications

Despite their widespread use and success, antibodies possess several inherent limitations that can constrain their effectiveness, particularly in the context of biosensor development for agrochemicals.

Immunogenicity and Stability Issues

Early therapeutic monoclonal antibodies were murine-derived and often elicited a Human Anti-Mouse Antibody (HAMA) response when administered to patients, leading to accelerated clearance and reduced efficacy [21]. While engineering chimeric, humanized, and fully human antibodies has mitigated this issue, immunogenicity remains a consideration [21]. Furthermore, antibodies are susceptible to degradation under non-physiological conditions. They can undergo oxidation, deamidation, and aggregation when exposed to reactive oxygen species, extreme temperatures, or organic solvents, compromising their binding ability and shelf life [23]. This lack of robustness can be a significant drawback for field-deployable sensors in agricultural settings.

Production and Batch Consistency Challenges

The production of high-quality antibodies, especially monoclonals, is a resource-intensive process. It requires significant time (several months), specialized facilities, and high costs, particularly for in vitro production which needs optimization by highly skilled personnel [22]. Even with hybridoma technology, ensuring long-term stability is challenging due to genetic drift, where the antibody produced by a cell line changes over successive generations [19]. While recombinant technology solves the consistency problem, it introduces complexity and cost. For polyclonal antibodies, batch-to-batch variation is a major concern, as the immune response can differ between animals and even in the same animal over time [19].

Limitations in Targeting Small Molecules and Toxins

Generating antibodies against small molecules, such as many pesticides and toxins, is particularly challenging. These molecules are often not inherently immunogenic because they are too small to be recognized by the immune system on their own (haptens). They must first be chemically conjugated to a larger carrier protein (e.g., BSA or KLH) to elicit an immune response [20]. This process is complex, and the resulting antibodies may not always possess the required affinity or specificity. There are also risks associated with handling toxic compounds during the immunization process [12].

Antibodies versus Aptamers: Implications for Agrochemical Research

The limitations of antibodies have accelerated the exploration of alternative recognition elements, with aptamers emerging as a powerful tool, especially for constructing aptasensors for food safety and environmental monitoring [20].

Aptamers are short, single-stranded DNA or RNA oligonucleotides selected in vitro through the Systematic Evolution of Ligands by Exponential Enrichment (SELEX) process to bind specific targets with high affinity and specificity [12] [23]. Their unique properties offer several advantages in the context of agrochemical detection, as summarized in the table below.

Table 2: Comparison of Antibodies and Aptamers as Biorecognition Elements

| Property | Antibodies | Aptamers | Implication for Agrochemical Sensor Development |

|---|---|---|---|

| Production & Cost [23] [20] | Animal/hybridoma required; months to produce; high cost; batch variation | Chemical synthesis; weeks to produce; lower cost; high batch consistency | Enables rapid, cost-effective development of sensors for a wide pesticide panel. |

| Size [12] | ~10-15 nm (larger, potential steric hindrance) | ~1-2 nm (fits within Debye length for FET sensors) | Aptamers allow for higher density immobilization and are better suited for miniaturized electronics. |

| Stability [23] [20] | Sensitive to heat, pH; irreversible denaturation; limited shelf-life | Thermally stable; reversible denaturation; long shelf-life | Aptasensors are more robust for field use and can withstand harsh regeneration conditions. |

| Modification [23] | Limited sites for chemical modification; complex | Easy chemical modification with functional groups/ labels | Simplifies sensor construction with flexible immobilization and signaling strategies. |

| Target Range [12] [20] | Difficult for small molecules, toxins, non-immunogenic targets | Broad, including ions, small molecules, toxins | Aptamers can be developed for targets where antibody generation fails or is risky. |

| Immunogenicity | Can evoke immune response (therapeutics) | Low or no immunogenicity | Reduced risk of interference in in vivo or therapeutic applications. |

For agrochemical research, the advantages of aptamers are particularly relevant. Electrochemical aptasensors have been successfully developed for pesticides like carbendazim (CBZ) and thiamethoxam (TMX), demonstrating remarkable sensitivity with detection limits reaching femtomolar (fM) levels [12]. The small size of aptamers allows for higher density immobilization on electrode surfaces, enhancing sensor sensitivity. Furthermore, their stability and reusability make them ideal for developing robust, field-deployable sensors for on-site monitoring of pesticide residues in food and water samples [12] [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents for Antibody-Based Research

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Antibody Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function and Application |

|---|---|

| Adjuvants (e.g., Freund's) [19] | Boosts immune response during animal immunization for polyclonal and monoclonal antibody production. |

| Myeloma Cells [19] | Fusion partner for B-cells to create immortal hybridoma cell lines for monoclonal antibody production. |

| HAT Selection Medium [19] | Selective medium (Hypoxanthine, Aminopterin, Thymidine) that eliminates unfused myeloma cells, allowing only hybridomas to proliferate. |

| Protein A/G/L Beads [18] | Used for affinity purification of antibodies from serum or culture supernatant based on binding to Fc regions. |

| ELISA Plates & Substrates [18] | Standard tool for screening antibody titer, specificity, and cross-reactivity. |

| BIAcore/SPR Systems [18] | Label-free technology for real-time analysis of antibody-antigen binding kinetics (association/dissociation constants). |

| CHO or HEK 293 Cell Lines [19] | Mammalian expression hosts for recombinant antibody production, ensuring proper glycosylation and folding. |

Antibodies remain cornerstone bioreceptors in immunosensor technology due to their well-characterized specificity and reliable production pipelines. A thorough understanding of their specificity mechanisms, production methodologies, and inherent limitations—including immunogenicity, stability issues, and challenges in targeting small molecules—is critical for researchers developing detection platforms for agrochemicals. While antibodies continue to be powerful tools, the emergence of aptamers presents a compelling alternative, offering advantages in production simplicity, stability, and engineering flexibility that are particularly beneficial for environmental monitoring and food safety applications. The future of sensing in agrochemical research likely lies in leveraging the strengths of both recognition elements—and potentially their conjugates, such as antibody-oligonucleotide conjugates (AOCs)—to create next-generation biosensors with enhanced sensitivity, specificity, and field-deployability for ensuring food security and environmental health.

The accurate detection of agrochemicals is paramount for ensuring food security, environmental safety, and public health. Within this field, biosensors utilizing highly specific biorecognition elements have emerged as powerful analytical tools. Two primary categories of these biosensors are aptasensors, which employ synthetic oligonucleotide aptamers, and immunosensors, which rely on immunological antibodies [14] [24]. Although both can be designed to detect the same target analyte, their characteristics differ significantly. This technical guide provides an in-depth comparison of these two platforms, focusing on the core aspects of cost, stability, synthesis, and modification ease, providing researchers and scientists with a foundational framework for selection and application in agrochemicals research.

Core Comparative Analysis: Aptasensors vs. Immunosensors

The selection between an aptasensor and an immunosensor hinges on a clear understanding of their intrinsic properties. The table below summarizes a direct comparison of their key characteristics, drawing from experimental studies and theoretical reviews.

Table 1: Direct comparison of aptasensor and immunosensor properties

| Characteristic | Aptasensors | Immunosensors |

|---|---|---|

| Production Cost | Low; chemical synthesis [25] | High; biological production in animals or cell cultures [25] |

| Thermal Stability | High; can undergo repeated denaturation/renaturation [12] | Low; susceptible to irreversible denaturation and aggregation [12] |

| Chemical Stability | Robust; stable under various pH and organic solvent conditions [12] | Moderate; vulnerable to chemical degradation (e.g., oxidation, deamidation) [12] |

| Synthesis & Production | In vitro (SELEX process); not reliant on animals [14] [26] | In vivo (immune system); requires animal hosts or recombinant systems [14] |

| Batch-to-Batch Variation | Low; high-degree purification and synthetic process [12] | Can be significant; inherent to biological production [12] |

| Modification Ease | Easy; terminal functionalization (e.g., biotin, thiol, amine) during synthesis [25] [26] | Complex; requires chemical conjugation that may affect binding affinity [14] |

| Size (Approx.) | 1–2 nm [12] | ~10–15 nm for whole antibodies [12] |

| Renewability/Reusability | High; multiple regeneration cycles demonstrated (e.g., 7 cycles for AFB1 detection) [27] | Limited; fewer regeneration cycles (e.g., 1 cycle for AFB1 detection) [27] |

In-Depth Discussion of Comparative Advantages

Cost and Synthesis Efficiency: The production pathway is a major differentiator. Aptamers are developed entirely in vitro via the Systematic Evolution of Ligands by Exponential Enrichment (SELEX) process, selecting sequences from a synthetic library [14] [26]. This process is controllable and does not involve animals. In contrast, antibody production is an in vivo process, requiring immunization of animals for polyclonal antibodies or complex hybridoma techniques for monoclonals, making it more costly and time-consuming [14] [25]. The chemical synthesis of aptamers is also more scalable and cost-effective than the biological production of antibodies.

Stability and Reusability: Aptamers demonstrate superior robustness. Their oligonucleotide nature allows them to withstand harsh conditions, including elevated temperatures and organic solvents, and to be regenerated after denaturation by simple cooling [12]. Antibodies, being proteins, are prone to irreversible denaturation under similar stresses, which permanently impairs their function [12]. This directly translates to better sensor reusability, as evidenced by a comparative study for aflatoxin B1 (AFB1) detection where the aptasensor endured seven regeneration cycles without performance loss, while the immunosensor was limited to a single cycle [27].

Ease of Modification and Immobilization: Aptamers can be precisely engineered with functional groups (biotin, thiol, amine) at a specific terminus (5'- or 3'-end) during their synthesis [25] [26]. This enables highly controlled, oriented immobilization on sensor surfaces (e.g., via Au-S bonds on gold or biotin-streptavidin affinity), maximizing target accessibility [14] [12]. Antibody immobilization is often more challenging; while fragments like Fab' can be used for oriented attachment, conventional methods frequently result in random orientation, which can block a significant portion of antigen-binding sites and reduce sensing efficiency [14].

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Sensor Development

To illustrate the practical application of these principles, this section outlines detailed methodologies for constructing representative aptasensors and immunosensors, as cited in recent literature.

This protocol describes the development of a reusable aptasensor for the ultrasensitive detection of a mycotoxin in foodstuffs.

- Objective: To develop a direct, label-free SERS aptasensor for AFB1 using a silver-impregnated porous silicon (Ag-pSi) substrate.

- Materials & Reagents:

- SERS Substrate: Silver-coated porous silicon (Ag-pSi).

- Bioreceptor: Specific anti-AFB1 DNA or RNA aptamer.

- Raman Reporter: 4-Aminothiophenol (4-ATP).

- Buffers: Binding buffer (e.g., PBS or Tris-HCl with Mg²⁺), washing buffer.

- Procedure:

- Substrate Functionalization: Modify the Ag-pSi SERS substrate with the Raman reporter molecule, 4-ATP.

- Aptamer Immobilization: Incubate the 4-ATP-modified substrate with the specific anti-AFB1 aptamer, allowing it to chemisorb onto the surface.

- Target Capture & Measurement: Introduce the sample containing AFB1 to the functionalized substrate. The binding of AFB1 to the aptamer induces a change in the SERS signal of the 4-ATP reporter, which is measured using a portable Raman spectrometer.

- Regeneration: To reuse the sensor, rinse the substrate with a mild denaturing buffer (e.g., low pH or EDTA-containing buffer) to dissociate the AFB1-aptamer complex, then re-equilibrate with binding buffer. The study showed this could be done for at least 7 cycles.

- Key Analytical Performance:

- Linear Range: 0.2–200 ppb

- Limit of Detection (LOD): 0.0085 ppb

This protocol details the construction of a highly stable dual-channel immunosensor for a tumor marker, illustrating advanced electrode design and signal validation strategies.

- Objective: To create a dual-channel, label-free electrochemical immunosensor for the sensitive detection of CEA.

- Materials & Reagents:

- Sensing Platform: Gold-copper co-doped vertical graphene (Au–AuCu-VG) electrode.

- Bioreceptor: Anti-CEA antibody (whole mAb or fragment).

- Electrochemical Probe: [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻ redox couple.

- Crosslinker: N-hydroxysuccinimide/1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide (NHS-EDC) for antibody immobilization on carboxylated surfaces.

- Procedure:

- Electrode Fabrication: Synthesize the AuCu-VG nanosheets on a titanium substrate using electron-assisted hot-filament chemical vapor deposition (EA-HF-CVD).

- Nanoparticle Decoration: Electrodeposit Au nanoparticles (Au NPs) onto the AuCu-VG electrode to enhance the surface area and provide binding sites for antibodies.

- Antibody Immobilization: Covently immobilize anti-CEA antibodies onto the Au NPs/AuCu-VG surface, typically using amine-coupling chemistry facilitated by NHS-EDC or via direct affinity binding to Au.

- Blocking: Incubate the electrode with Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) to block non-specific binding sites.

- Dual-Channel Detection: Incubate the immunosensor with the CEA sample. Monitor the binding event by measuring the changes in both the oxidation and reduction peak currents of the [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻ probe using differential pulse voltammetry (DPV) or electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS). The dual signals are averaged to improve reliability.

- Key Analytical Performance:

- Linear Range: 0.001 – 30,000 pg mL⁻¹

- Limit of Detection (LOD): 0.28 fg mL⁻¹

Diagram 1: General sensor development and regeneration workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The development of high-performance biosensors relies on a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The following table details key components and their functions in sensor fabrication.

Table 2: Key reagents and materials for biosensor development

| Reagent/Material | Function in Biosensor Development | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Gold Nanoparticles (Au NPs) | Signal amplification; platform for bioprobe immobilization via Au–S bonds [12] [25]. | Electrochemical and SERS-based aptasensors/immunosensors [25]. |

| Graphene Quantum Dots (GQDs) | Enhance electron transfer; provide high surface area for biomolecule loading [25]. | Composite electrodes for electrochemical detection [25]. |

| NHS/EDC Chemistry | Activates carboxyl groups for covalent immobilization of biomolecules (e.g., antibodies) onto surfaces [28]. | Antibody attachment on carbon-based electrodes [28]. |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | Blocks uncovered sites on the sensor surface to minimize non-specific adsorption [28]. | A standard step in immunosensor and some aptasensor protocols [28]. |

| Magnetic Nanoparticles (MNPs) | Separation and concentration of targets from complex matrices; signal amplification [29]. | Isolation of foodborne pathogens or contaminants in aptasensors [29]. |

| 4-Aminothiophenol (4-ATP) | Acts as a Raman reporter molecule in SERS-based sensing platforms [27]. | Label-free detection of AFB1 in a SERS aptasensor [27]. |

Signaling Pathways and Transduction Mechanisms

The interaction between the bioreceptor and the target analyte is converted into a measurable signal through various transduction mechanisms. The following diagram illustrates the primary signaling pathways employed in aptasensors and immunosensors.

Diagram 2: Biosensor signal transduction pathways.

The choice between an aptasensor and an immunosensor for agrochemical research is application-dependent. Aptasensors offer compelling advantages in terms of lower cost, superior stability, straightforward chemical synthesis, and ease of modification and regeneration, making them highly suitable for routine, on-site monitoring in potentially harsh environmental or agricultural settings [27] [12]. Immunosensors, leveraging the exquisite specificity of antibodies, remain a powerful platform, particularly where an established, high-affinity antibody exists and laboratory-based analysis is feasible. The ongoing development of portable sensing platforms and novel nanomaterial composites continues to enhance the performance of both systems. Ultimately, this comparative analysis provides a foundational framework to guide researchers in selecting the most appropriate biosensing technology for their specific agrochemical detection needs.

The safety of global food supply chains is continuously challenged by the presence of hazardous agro-chemical contaminants, primarily pesticides, mycotoxins, and heavy metals. These substances originate from intensive agricultural practices and environmental pollution, entering the food chain through contaminated raw materials and posing significant risks to human health. Pesticides, including organophosphates, neonicotinoids, and herbicides, are extensively used to protect crops but leave persistent residues that can exceed maximum residue limits (MRLs). Mycotoxins, such as aflatoxins and ochratoxins, are toxic metabolites produced by fungi that contaminate various agricultural commodities, especially under favorable climatic conditions. Heavy metals, including cadmium, lead, and arsenic, accumulate in crops through contaminated soil and water, presenting long-term toxicity concerns due to their non-biodegradable nature and bioaccumulation potential [30] [31] [32].

The conventional analytical techniques for monitoring these contaminants, including high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS), and inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS), offer precision and sensitivity but present significant limitations for rapid screening. These methods require sophisticated instrumentation, skilled operators, extensive sample preparation, and are often time-consuming and laboratory-bound, rendering them unsuitable for on-site or high-throughput analysis [12] [31] [33]. This technological gap has accelerated the development of biosensors as promising alternatives, with aptasensors and immunosensors emerging as frontrunners in the field of agro-chemical detection [6].

This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical examination of these key agro-chemical targets, framed within the context of biosensor research. It explores the fundamental principles of aptasensors and immunosensors, presents detailed experimental protocols, and synthesizes performance data to guide researchers and scientists in the development of next-generation detection platforms for food safety and environmental monitoring.

Fundamental Principles: Aptasensors vs. Immunosensors

Biosensors are analytical devices that integrate a biological recognition element with a transducer to produce a measurable signal proportional to the target analyte concentration. In the detection of agro-chemicals, immunosensors and aptasensors represent two dominant architectures, differentiated by their core biorecognition elements.

Immunosensors

Immunosensors employ antibodies as capture probes. These are proteins produced by the immune system that bind to specific target molecules (antigens) with high affinity and specificity. The analytical performance of an immunosensor is heavily influenced by antibody selection and immobilization strategy.

- Antibody Types: Immunosensors can utilize whole monoclonal antibodies (mAbs, ~150 kDa), polyclonal antibodies, or engineered fragments such as antigen-binding fragments (Fab', ~50 kDa) and single-chain variable fragments (scFv, ~30 kDa). Smaller fragments enable higher immobilization density and can improve sensitivity [14].

- Immobilization and Orientation: A critical aspect of immunosensor design is the controlled immobilization of antibodies onto the transducer surface. Random orientation through adsorption or amine coupling can block antigen-binding sites. Oriented immobilization strategies, such as coupling via thiol groups in Fab' fragments or using affinity proteins like Protein A/G that bind the Fc region of antibodies, ensure optimal presentation and maximize binding capacity [14].

- Detection Formats: Common formats include direct detection (measuring the signal change upon antigen binding), sandwich assays (using a second antibody for enhanced specificity and signal amplification, suitable for larger analytes), and competitive assays (often used for small molecules like pesticides, where the analyte competes with a labeled analog for a limited number of antibody binding sites) [14].

Aptasensors

Aptasensors utilize aptamers as recognition elements. Aptamers are short, single-stranded DNA or RNA oligonucleotides (typically 25-90 bases) selected in vitro through a process called Systematic Evolution of Ligands by EXponential enrichment (SELEX). They fold into defined three-dimensional structures that confer high affinity and specificity for targets ranging from small molecules to whole cells [12] [6].

- Binding Mechanism and Advantages: Aptamer-target binding is driven by non-covalent interactions, including hydrogen bonding, electrostatic interactions, van der Waals forces, and aromatic ring stacking [12]. Key advantages over antibodies include:

- * Superior Stability*: Aptamers are stable under a wide range of temperatures and pH conditions, can undergo repeated denaturation/renaturation cycles, and have a longer shelf life [12] [27].

- Ease of Synthesis and Modification: They are produced by chemical synthesis, ensuring batch-to-batch consistency. Functional groups (e.g., thiol, amine, biotin) can be easily incorporated during synthesis for directed immobilization [12] [6].

- Small Size: Their compact size (1-2 nm) allows for high surface density and makes them ideal for devices where binding must occur within a short distance from the transducer surface, such as field-effect transistors [12].

- Immobilization Strategies: Common methods include covalent bonding (e.g., Au-S bonds between thiolated aptamers and gold electrodes), affinity attachment (e.g., biotin-streptavidin bridging), and physical adsorption. The choice of strategy impacts aptamer density, orientation, and stability [12].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Aptasensors and Immunosensors for Agro-Chemical Detection

| Feature | Aptasensors | Immunosensors |

|---|---|---|

| Biorecognition Element | Single-stranded DNA/RNA oligonucleotide (Aptamer) | Antibody (IgG, Fab', scFv, etc.) |

| Production Process | In vitro chemical synthesis (SELEX) | In vivo (animal hosts) or recombinant expression |

| Size | ~1-2 nm | ~10-15 nm (whole IgG) |

| Stability | High thermal stability; can be regenerated | Susceptible to permanent denaturation at high temperatures |

| Modification | Easy chemical modification with functional groups | More complex modification process |

| Cost | Relatively low-cost synthesis | Can be expensive to produce and purify |

| Typical Assay Format | Target-induced structure switching, competitive, sandwich | Direct, sandwich, competitive |

Technical Performance and Experimental Data

The performance of biosensors is quantified by several key parameters, including limit of detection (LOD), dynamic range, sensitivity, selectivity, and reusability. Recent advancements, particularly the integration of nanomaterials, have significantly enhanced these metrics.

Performance Comparison for Specific Targets

Direct comparative studies provide the most insightful data for evaluating sensor platforms.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Aptasensors and Immunosensors from Direct Studies

| Target | Sensor Platform | LOD | Dynamic Range | Key Findings | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aflatoxin B1 (AFB1) | SERS Aptasensor (Ag-pSi) | 0.0085 ppb | 0.2–200 ppb | Achieved 7 regeneration cycles without performance loss. | [27] |

| Aflatoxin B1 (AFB1) | SERS Immunosensor (Ag-pSi) | 0.0110 ppb | 0.2–200 ppb | Achieved only 1 regeneration cycle. | [27] |

| Prostate Specific Antigen (PSA) | Electrochemical Aptasensor (GQDs-AuNRs/SPE) | 0.14 ng/mL | Not Specified | Demonstrated better stability, simplicity, and cost-effectiveness. | [25] |

| Prostate Specific Antigen (PSA) | Electrochemical Immunosensor (GQDs-AuNRs/SPE) | 0.14 ng/mL | Not Specified | Comparable LOD but lower stability and higher cost. | [25] |

Illustrative Experimental Protocols

This protocol details the development of a highly sensitive and reusable SERS aptasensor.

- 1. Substrate Preparation: A porous silicon (pSi) interferometer is fabricated via anodization. Silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) are impregnated into the porous scaffold through immersion plating to create the Ag-pSi SERS substrate, which is characterized for pore dimensions, metal distribution, and enhancement factor (>10^7).

- 2. Aptamer Immobilization: The Ag-pSi substrate is modified with a Raman reporter molecule (4-aminothiophenol, 4-ATP). A thiol- or amino-terminated anti-AFB1 aptamer is then immobilized onto the substrate.

- 3. Detection Mechanism: The binding of AFB1 to the aptamer induces a conformational change or direct interaction that alters the local environment of the 4-ATP reporter, resulting in a quantifiable change in the SERS signal intensity (ratiometric response).

- 4. Measurement: SERS spectra are collected using a portable Raman spectrometer. The ratio of two characteristic peak intensities is plotted against the AFB1 concentration for quantification.

- 5. Regeneration: The sensor surface is regenerated by a mild washing procedure that dissociates the AFB1-aptamer complex, allowing for repeated use.

This protocol exemplifies a sophisticated approach for simultaneous detection.

- 1. Electrode Modification: A glassy carbon electrode is modified with a nanocomposite (e.g., functionalized reduced graphene oxide and NF/HP-UiO66-NH2) to increase the effective surface area and electron transfer rate.

- 2. Antibody Immobilization: Antibodies specific for acetamiprid (AD) and malathion (ML) are immobilized on the modified electrode surface, often using EDC/NHS chemistry for covalent bonding.

- 3. Signal Probe Preparation: Two distinct signal probes are synthesized. For example, one probe uses methylene blue (MB) loaded on a metal-organic framework (MOF235) and conjugated to a complementary DNA strand for AD. The other uses ferrocenecysteine (FcCys) on Au nanoparticles conjugated to a different complementary DNA for ML.

- 4. Competitive Assay: The immobilized antibodies are saturated with a mixture of the two pesticides. The signal probes are then added. In a competitive format, the presence of the pesticide prevents the binding of the signal probe. The higher the pesticide concentration, the lower the electrochemical signal from MB and FcCys when measured via techniques like differential pulse voltammetry (DPV).

- 5. Data Analysis: The reduction peaks for MB and FcCys are measured simultaneously. The decrease in current for each probe is proportional to the concentration of its respective target pesticide.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The development of high-performance aptasensors and immunosensors relies on a suite of specialized reagents and nanomaterials.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Biosensor Development

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Use Cases |

|---|---|---|

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | Signal amplification, electrode modification, SERS substrate, facile bioconjugation via Au-S chemistry. | Electrodeposited on electrodes for aptamer immobilization [12]; used in lateral flow immunosensors [27]. |

| Graphene Derivatives (GQDs, GO, rGO) | Enhance electrical conductivity, provide large surface area for bioreceptor loading, improve catalytic activity. | GQDs-AuNRs composite for electrochemical PSA detection [25]; rGO in multi-pesticide sensors [6]. |

| Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) | High surface area for signal tag loading, catalytic activity, often used to encapsulate redox probes. | MOF-808 and Zn-MOF used for loading signaling molecules in electrochemical sensors [12] [6]. |

| Specific Aptamers | Biorecognition element for aptasensors; selected for specific targets like pesticides, mycotoxins, or heavy metal ions. | Anti-carbendazim aptamer [12]; anti-AFB1 aptamer [27]; anti-S. aureus aptamer [6]. |

| Specific Antibodies | Biorecognition element for immunosensors; monoclonal or polyclonal antibodies against target analytes. | Anti-AFB1 antibody [27]; anti-Malathion antibodies [6]. |

| Raman Reporters (e.g., 4-ATP) | Molecules with strong Raman spectra used as labels in SERS-based sensors. | 4-ATP used as a label in SERS aptasensor for AFB1 [27]. |

| Redox Probes (e.g., Methylene Blue, Ferrocene) | Generate electrochemical signals in voltammetric/amperometric sensors; signal changes upon target binding. | MB and FcCys used as distinct labels for simultaneous detection of two pesticides [6]. |

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Mechanisms of Key Contaminants

Understanding the toxicological mechanisms of agro-chemical contaminants is crucial for assessing health impacts and can inform the design of functional biosensors.

The diagram above illustrates the primary molecular pathways through which these contaminants exert their toxic effects:

- Organophosphorus Pesticides: These compounds, such as chlorpyrifos, act as irreversible inhibitors of acetylcholinesterase (AChE), an enzyme critical for breaking down the neurotransmitter acetylcholine (ACh) in synaptic clefts. This inhibition leads to ACh accumulation, resulting in hyperstimulation of cholinergic nerves and causing acute symptoms like headaches and seizures. Chronic exposure is linked to an increased risk of neurodegenerative disorders like Parkinson's disease [31] [33].

- Heavy Metals: Metals like cadmium and arsenic induce toxicity through multiple interconnected pathways. They trigger oxidative stress by generating reactive oxygen species (ROS), cause direct DNA damage, and disrupt mitochondrial function. These insults can lead to genomic instability and are established mechanisms of carcinogenesis [30] [32].

- Mycotoxins: Aflatoxin B1 (AFB1), a Group 1 carcinogen, requires metabolic activation in the body. The activated form binds to DNA, forming bulky adducts (primarily in the liver) that cause mutations in critical genes, such as the tumor suppressor gene p53. This process is a primary driver of AFB1-induced hepatocarcinogenesis (liver cancer) [30] [27].

Experimental Workflow for Biosensor Development and Application

The process of creating and deploying a biosensor for agro-chemical analysis involves a series of methodical steps, from surface functionalization to final quantification.

The workflow for a typical biosensor involves two main phases:

- Sensor Fabrication:

- Transducer Modification: The base transducer (e.g., gold electrode, glass slide) is modified with nanomaterials (e.g., graphene, metal nanoparticles, MOFs) to enhance its electrical, optical, or catalytic properties and provide a high-surface-area platform [12] [25].

- Bioreceptor Immobilization: The specific aptamer or antibody is immobilized onto the modified surface. This step is critical and often uses covalent chemistry (e.g., Au-S bonds, EDC/NHS) or affinity interactions (e.g., biotin-streptavidin) to ensure stable and oriented attachment [12] [14].

- Surface Blocking: The remaining reactive sites on the sensor surface are blocked with inert proteins (e.g., Bovine Serum Albumin - BSA) or other agents to minimize non-specific adsorption of non-target molecules from the sample, which is crucial for achieving a high signal-to-noise ratio in complex matrices [6].

- Assay and Analysis:

- Sample Introduction & Incubation: A pre-treated food sample, potentially diluted or extracted, is introduced to the sensor surface and incubated to allow the target analyte to bind to the immobilized bioreceptor.

- Signal Transduction: The binding event is converted into a measurable signal. This could be a change in current (electrochemical), a shift in wavelength or intensity (optical/fluorescent), or an alteration in Raman scattering (SERS) [12] [27] [6].