Benchmarking Biosensor Stability in High Ionic Strength Environments: Strategies for Reliable Biomedical and Clinical Applications

The performance and reliability of biosensors in biologically relevant ionic strengths are critical for their translation from research to clinical and point-of-care diagnostics.

Benchmarking Biosensor Stability in High Ionic Strength Environments: Strategies for Reliable Biomedical and Clinical Applications

Abstract

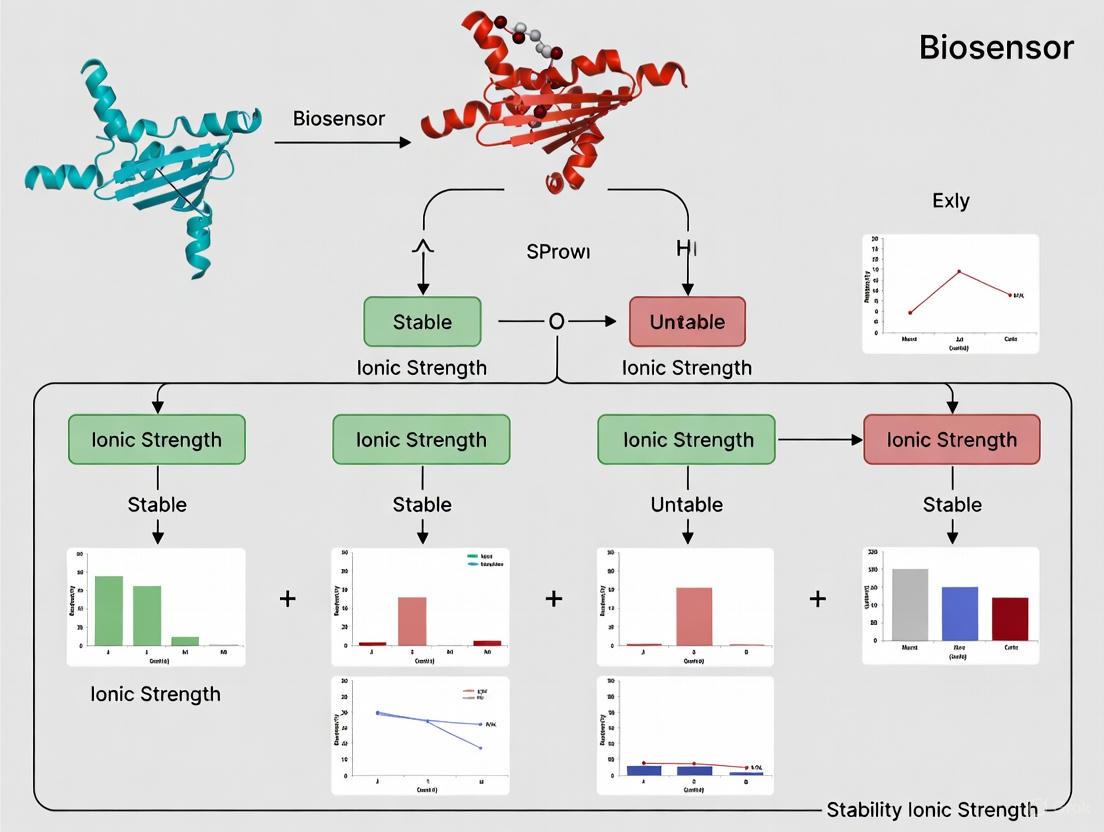

The performance and reliability of biosensors in biologically relevant ionic strengths are critical for their translation from research to clinical and point-of-care diagnostics. This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the key challenges, including signal drift and Debye length screening, that compromise biosensor stability in high ionic strength solutions like blood and interstitial fluid. Drawing on the latest research, we explore foundational principles, advanced materials and interface designs, practical optimization methodologies, and standardized validation frameworks. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes actionable strategies to enhance biosensor robustness, ensuring accurate and stable performance in real-world biomedical applications.

The Stability Challenge: Foundational Principles of Biosensor Performance in High Ionic Strength Environments

For biosensors to function effectively in point-of-care diagnostics and real-time monitoring, they must operate directly in complex biological fluids such as blood, serum, or saliva. These environments present two fundamental physical obstacles that compromise measurement accuracy: the Debye screening effect and signal drift. The Debye screening effect limits the ability to detect biomarkers in high-ionic-strength solutions, while signal drift causes the sensor's baseline output to change over time, independent of the target analyte. Overcoming these intertwined challenges is critical for developing reliable biosensors for physiological applications. This guide objectively compares the performance of current technologies addressing these limitations, providing a framework for benchmarking biosensor stability in biologically relevant conditions.

Defining the Problems: Mechanisms and Impact

The Debye Screening Effect

The Debye screening effect, or charge screening, is a fundamental limitation for label-free biosensors operating in physiological buffers. In high-ionic-strength solutions (e.g., 1X PBS), dissolved ions form a dense Electrical Double Layer (EDL), also known as the Debye layer, at the sensor-solution interface. This layer electrically screens charges beyond its very short range.

- Physical Principle: The EDL has a characteristic thickness called the Debye length (κ⁻¹), which is inversely proportional to the square root of the ionic strength. In physiological saline (1X PBS), the Debye length is approximately 0.7 nm [1].

- Impact on Sensing: Most biorecognition elements (e.g., antibodies, which are 10–15 nm in size) and their binding events are located far beyond this Debye length. Consequently, the electric field from a charged target biomarker is effectively screened, preventing it from influencing the transducer and causing a severe loss of sensitivity [2] [1]. Conventional field-effect transistor (FET) biosensors are particularly affected, often necessitating sample dilution or washing steps that are impractical for point-of-care use.

Signal Drift

Signal drift refers to the slow, non-random change in a biosensor's output signal over time under constant conditions. In physiological buffers, this is primarily caused by the slow, non-specific interaction of electrolytic ions and biomolecules with the sensor surface.

- Primary Causes:

- Ion Diffusion: Ions from the solution can gradually diffuse into the sensing region or the dielectric layers of the sensor, altering the local capacitance and threshold voltage [2].

- Biofouling: Non-specific adsorption of proteins or other biomolecules onto the sensor surface modifies interface properties and contributes to a drifting baseline [3].

- Impact on Sensing: Drift obscures the specific signal from target-receptor binding, convolutes results, and can lead to false positives, especially if the drift direction mimics the expected sensor response. This is particularly critical for long-term or continuous monitoring applications [2].

The following diagram illustrates the combined negative impact of these two phenomena on a biosensor's signal over time.

Technological Solutions and Performance Comparison

Researchers have developed innovative material, electrical, and design strategies to overcome Debye screening and signal drift. The following sections compare the most prominent solutions.

Strategies to Overcome the Debye Length Limitation

Table 1: Comparison of Debye Length Extension Strategies

| Strategy | Mechanism | Key Performance Data | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polymer Brush Interface (e.g., POEGMA) [2] | Establishes a Donnan equilibrium potential, effectively increasing the sensing distance (Debye length) in high ionic strength solutions. | Enabled sub-femtomolar (aM) detection of biomarkers in 1X PBS [2]. | - Functions in undiluted physiological buffers.- Reduces biofouling.- Compatible with antibody-based detection. | - Requires sophisticated surface chemistry.- Polymer layer thickness and uniformity must be controlled. |

| Electric Double Layer (EDL) FETs [1] | Uses a separated gate electrode. A short pulse bias induces EDL formation, pulling ions towards the gate and channel, which modulates conductance beyond the static Debye length. | Direct detection of proteins (e.g., HIV-1 RT, CEA) in 1X PBS and human serum in 5 minutes with no dilution [1]. | - No reference electrode needed.- Fast detection.- Insensitive to target charge. | - Requires precise pulse timing.- Device design and fabrication are more complex than standard FETs. |

| High-Frequency AC Sensing [1] | Applies high-frequency alternating current to "break down" the EDL, allowing the electric field to penetrate deeper into the solution. | Reported operational frequencies vary widely (1 kHz–50 MHz), and direct detection in serum is not consistently demonstrated [1]. | - Can be applied to various FET geometries. | - Mechanism is not fully understood.- Performance is highly dependent on sensor geometry and frequency.- Role of reference electrode is ambiguous. |

Strategies to Mitigate Signal Drift

Table 2: Comparison of Signal Drift Mitigation Strategies

| Strategy | Mechanism | Key Performance Data | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rigorous DC Testing Methodology [2] | Uses infrequent DC sweeps instead of continuous static or AC measurements to minimize ion migration and polarization effects that cause drift. | Achieved a stable, repeatable baseline, allowing reliable measurement of attomolar-level on-current shifts [2]. | - Effective for highly sensitive, endpoint measurements.- Simpler electronics than high-frequency AC. | - Not suitable for real-time, continuous monitoring.- Requires careful timing and protocol design. |

| Stable Material Platforms (e.g., GaN) [1] | Uses chemically inert semiconductors where ions cannot easily diffuse, preventing the internal field formation that causes drift in materials like SiO₂. | AlGaN/GaN HEMTs demonstrated excellent repeatability and a stable baseline in ionic solutions [1]. | - High intrinsic stability in harsh environments.- Long-term reliability. | - Limited to compatible semiconductor processes.- May be higher cost than silicon-based sensors. |

| Pre-equilibrium Sensing [4] | Quantifies target concentration kinetically using the rate of receptor binding (dy/dt) before equilibrium is reached, circumventing drift that occurs over longer timescales. |

Theoretical framework shows potential for tracking rapid physiological changes, such as continuous insulin monitoring, which is impossible with slow equilibrium sensors [4]. | - Enables real-time monitoring of fast concentration changes.- Relaxes requirement for ultra-stable receptors. | - Algorithmically complex.- Requires high signal-to-noise ratio to accurately measure binding rates.- Susceptible to noise if kinetics are too slow. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To benchmark new biosensor platforms, the following experimental protocols, derived from the cited literature, are essential.

Protocol: Evaluating Debye Screening Mitigation with Polymer Brushes

This protocol is adapted from the D4-TFT (thin-film transistor) development [2].

- 1. Sensor Functionalization:

- Surface Coating: Grow or deposit a poly(oligo(ethylene glycol) methyl ether methacrylate) (POEGMA) polymer brush layer on the transducer surface (e.g., CNT channel). This serves as the Debye-length-extending and anti-fouling layer.

- Antibody Immobilization: Pattern or immobilize capture antibodies (cAb) into the POEGMA matrix.

- Control Preparation: Fabricate control devices on the same chip with POEGMA but no antibodies over the active channel.

- 2. Measurement in Physiological Buffer:

- Prepare samples containing the target biomarker in 1X PBS (ionic strength ~150 mM) to mimic physiological conditions.

- Introduce the sample to the sensor. A dissolvable trehalose layer can be used to pre-position detection antibodies (dAb) for an automated "D4" (Dispense, Dissolve, Diffuse, Detect) workflow.

- Allow the sandwich immunoassay (cAb-target-dAb) to form directly in the high-ionic-strength buffer.

- 3. Data Acquisition and Analysis:

- Use a stable electrical testing configuration (e.g., infrequent DC sweeps) to measure the device's electrical property (e.g., on-current,

I_on). - The signal is the shift in this property (

ΔI_on) upon target binding. - Validation: A successful experiment shows a significant

ΔI_onfor the functionalized device and no significant change in the control device, confirming detection is specific to antibody-antigen binding and not a solution artifact.

- Use a stable electrical testing configuration (e.g., infrequent DC sweeps) to measure the device's electrical property (e.g., on-current,

The workflow for this protocol is summarized below:

Protocol: Assessing Signal Drift via Electrical Measurement Strategies

This protocol compares DC and pulsed methods for drift assessment [2] [1].

- 1. Baseline Stability Test:

- Immerse the biosensor in 1X PBS or another relevant high-ionic-strength buffer without any target analyte.

- Monitor the output signal (e.g., drain current

I_dfor FETs, capacitance for EIS sensors) over an extended period (e.g., 30-60 minutes).

- 2. Signal Application Methods:

- Method A: Continuous DC Bias: Apply a constant gate and drain bias and record

I_dcontinuously. This typically exhibits significant drift. - Method B: Infrequent DC Sweeps [2]: Hold the sensor at a low, non-perturbing bias. Periodically (e.g., every few minutes), apply a full voltage sweep (e.g., Vg sweep) to acquire the transfer characteristic, then return to the low-bias hold state. The key parameter (e.g.,

I_onat a specific Vg) is extracted from each sweep. - Method C: Short-Pulse EDL FETs [1]: Use a pulsed gate bias (e.g., +0.5 V for 50 µs) with a constant drain bias. Integrate the transient drain current over the pulse duration to obtain a total charge value, which is used as the stable output signal.

- Method A: Continuous DC Bias: Apply a constant gate and drain bias and record

- 3. Drift Quantification:

- Plot the output signal (from any method) versus time.

- Calculate the percentage change or slope of the signal over the test duration. A superior method will show a near-zero slope and minimal deviation from the initial value.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successfully developing and benchmarking biosensors for physiological buffers requires a specific set of materials and reagents.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Biosensor Development

| Category / Item | Specific Examples | Function in Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Sensor Substrate | Semiconducting Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) [2], AlGaN/GaN HEMTs [1] | Forms the core transducer; chosen for high electrical sensitivity and stability in liquids. |

| Debye Length Extender | POEGMA (Poly(oligo(ethylene glycol) methyl ether methacrylate)) [2] | Polymer brush coating that extends the sensing distance via the Donnan potential, enabling detection in PBS. |

| Biorecognition Element | Monoclonal/Polyclonal Antibodies [2] [5], DNA Aptamers [6] | Provides specific binding to the target analyte; immobilized on the sensor surface. |

| Anti-Fouling Agent | POEGMA [2], Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) [1], Poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) | Reduces non-specific adsorption of proteins and other biomolecules, mitigating signal drift and noise. |

| Physiological Buffer | 1X Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), Simulated Serum [1] | Provides a biologically relevant, high-ionic-strength testing environment (Debye length ~0.7 nm). |

| Reference Electrode | Pd pseudo-reference electrode [2], Ag/AgCl electrode | Provides a stable, known potential in the solution; pseudo-reference electrodes aid device miniaturization. |

| Signal Processing Unit | Source Meter Unit, Potentiostat with high-speed sampling | Applies electrical signals (DC sweeps, AC frequencies, short pulses) and measures the sensor's response. |

The journey toward robust biosensors for use in physiological buffers hinges on directly confronting the dual challenges of Debye screening and signal drift. As evidenced by the data, no single solution is universally superior; each presents a distinct set of trade-offs.

Technologies like polymer brushes (POEGMA) and EDL-FETs have demonstrated proven success in overcoming Debye screening to achieve ultraselective, direct detection in undiluted serum and PBS. For combating signal drift, innovative measurement methodologies (infrequent DC sweeps, short pulses) and inherently stable materials (GaN) have shown the most concrete results in providing the stable baseline required for sensitive measurements. The emerging concept of pre-equilibrium sensing offers a paradigm shift for real-time monitoring by circumventing drift entirely, though it demands high-quality data and sophisticated kinetics analysis.

Benchmarking new biosensor platforms requires rigorous testing in high-ionic-strength buffers against the standards outlined here. The choice of strategy ultimately depends on the application's specific requirements: attomolar sensitivity for endpoint diagnostics, long-term stability for implantable sensors, or second-scale resolution for real-time physiological tracking. Future progress will likely involve the clever integration of these materials, design, and algorithmic approaches to create a new generation of drift-resistant, charge-screening-immune biosensors.

The pursuit of reliable biosensing in complex biological fluids represents a significant challenge in diagnostic medicine and biomedical research. A core obstacle is maintaining sensor sensitivity and stability in environments with high ionic strength, such as blood, serum, or saliva. The performance of electrochemical and field-effect transistor (FET) biosensors in these milieus is predominantly governed by two interrelated interfacial phenomena: the Electrical Double Layer (EDL) and the Donnan Potential. The EDL refers to the structured layers of ions that form at the electrode-electrolyte interface, while the Donnan Potential is an equilibrium potential that arises from the unequal distribution of ions between a charged membrane or surface and the surrounding solution. This guide objectively compares how these mechanisms influence biosensor performance, providing a foundational framework for benchmarking biosensor stability in physiologically relevant conditions.

Fundamental Principles and Direct Comparative Analysis

The EDL and Donnan Potential define the operational window for biosensors, controlling the distance over which an electrical field can exert influence and thereby detect a binding event. Their behavior in high-ionic-strength environments is a critical determinant of sensor efficacy.

Electrical Double Layer (EDL) and Debye Length: When an electrode is immersed in an electrolyte solution, charged species align at the interface, forming the EDL. The innermost region, known as the compact Helmholtz plane or Stern layer, consists of solvent molecules and specifically adsorbed ions. Beyond this is the diffuse layer, where ions are distributed by a balance of electrostatic forces and thermal motion [3]. The characteristic thickness of this diffuse layer is the Debye length, which dictates the distance from the electrode surface within which charge sensing is effective. In high-ionic-strength solutions like bodily fluids, the Debye length is compressed to just a few nanometers [3]. This severely limits the sensitivity of biosensors that rely on field effects, such as silicon nanowire FETs (SiNW-FETs), as the binding of a target biomarker may occur beyond this screened range [7].

Donnan Potential: The Donnan Potential (ΨD) arises at the interface between a solution and a charged, permselective membrane or surface, such as an ion-exchange membrane or a biomolecular layer with fixed charges. Due to the presence of these fixed charges, an unequal distribution of mobile ions (counter-ions and co-ions) exists between the two phases to maintain electroneutrality, generating the Donnan Potential [8]. This potential acts to exclude co-ions from entering the charged layer; a larger absolute Donnan Potential leads to stronger co-ion exclusion [8]. The magnitude of this potential is not fixed; it depends on the concentration of the external solution and the valence of the counter-ions. When the external solution concentration is low relative to the fixed charge concentration, the absolute value of the Donnan Potential is high, and vice-versa [8].

Table 1: Comparative Influence of EDL and Donnan Potential on Biosensing

| Feature | Electrical Double Layer (EDL) | Donnan Potential |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Role | Governs charge distribution & electric field extension at electrode-electrolyte interface [3] | Governs ion distribution & exclusion at charged membrane/ polymer-solution interface [8] |

| Primary Impact on Sensing | Determines the Debye length; defines distance for field-effect detection [3] [7] | Establishes a permselective barrier; enhances selectivity by excluding co-ions [8] |

| Effect of High Ionic Strength | Compresses Debye length (to ~1 nm), reducing sensing range and signal-to-noise ratio [3] | Reduces the magnitude of the potential, weakening co-ion exclusion and lowering selectivity [8] |

| Key Tuning Parameters | Ionic strength of buffer, size of counterions, electrode geometry [3] [7] | Density of fixed charges on the surface/membrane, counter-ion valence [8] |

Visualizing the Interfacial Potentials

The following diagram illustrates the structure of the EDL and the origin of the Donnan Potential at a functionalized biosensor interface.

Diagram 1: Interfacial structure showing the Electrical Double Layer (Stern and Diffuse layers) and the Donnan Potential at a charged biosensor interface.

Experimental Methodologies for Investigation

A comprehensive understanding of these core mechanisms requires diverse experimental techniques, ranging from direct potential measurement to indirect sensing performance evaluation.

Direct Measurement of the Donnan Potential

For decades, the Donnan Potential was indirectly estimated but never directly measured until the recent application of tender ambient pressure X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (tender-APXPS).

- Protocol Summary: A commercial cation exchange membrane (CR-61, poly(p-styrene sulfonate-co-divinylbenzene)) is equilibrated with aqueous salt solutions (e.g., NaCl, MgCl₂) of varying concentrations (0.001 to 1 M). Using the "dip and pull" method, a thin solution layer (~17-21 nm) is formed on the membrane surface. The interface is then probed with tender-APXPS at a photon energy of 4.0 keV [8].

- Key Measurements: At thermodynamic equilibrium, the electric potential of the bulk electrolyte is zero. The Donnan Potential is measured by tracking the binding energy (BE) shift of membrane-related core levels, such as the sulfur 1s (S 1s) peak originating from the fixed sulfonate groups. The shift in binding energy is directly related to the Donnan Potential by ΔBE = ΔΨD eV. The measured BE shifts are converted to Donnan potentials by aligning the system to a known reference point, typically where the external salt concentration matches the fixed ion concentration in the membrane, resulting in a near-zero Donnan Potential [8].

- Data Interpretation: This method directly revealed that the Donnan Potential decreases in magnitude as the external NaCl concentration increases. Furthermore, it confirmed that for a given concentration, the Donnan Potential is lower for membranes that have sorbed divalent counter-ions (Mg²⁺) compared to monovalent ones (Na⁺), leading to reduced co-ion exclusion [8].

Optimization of Sensing Buffer Ionic Concentration

The ionic strength of the sensing buffer is a critical parameter that balances biological hybridization efficiency with the constraints of the EDL.

- Protocol Summary: To detect miRNA-21 using a SiNW-FET biosensor, a systematic study tested Bis-Tris propane (BTP) buffers with varying ionic strengths (10 mM, 50 mM, and 150 mM). The surface functionalization was optimized via a 30-minute silanization reaction at room temperature, followed by acetic acid rinsing to ensure a uniform surface. Hybridization efficiency was evaluated using fluorescence microscopy, while the structural stability of DNA/RNA hybrids was confirmed by Grazing-incidence small-angle X-ray scattering (GISAXS) across all ionic strengths. The sensor's performance was assessed by measuring voltage shifts upon miRNA-21 binding [7].

- Key Measurements: Fluorescence microscopy showed the highest hybridization amount at the highest ionic strength (150 mM). However, the SiNW-FET electrical measurements found that 50 mM BTP buffer yielded the highest voltage shifts and optimal sensitivity. This concentration was identified as the best compromise, providing sufficient ionic strength for efficient hybridization while maintaining a Debye length long enough for effective signal transduction [7].

- Data Interpretation: The study highlights the critical trade-off governed by the EDL: high ionic strength favors biomolecular interactions but compresses the Debye length, hampering field-effect detection. An intermediate ionic strength can optimally balance these competing effects.

Performance Benchmarking of Advanced Materials

Novel materials can enhance sensor performance by modulating interfacial properties. The following table benchmarks a select set of recently reported biosensors, highlighting their operating mechanisms and performance metrics.

Table 2: Performance Benchmarking of Select Biosensors Addressing Interfacial Challenges

| Biosensor Platform | Core Mechanism / Material | Target Analyte | Key Performance Data | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mn-ZIF-67 Electrochemical Sensor | Bimetallic MOF; enhanced surface area & electron transfer [5] | E. coli O157 | LOD: 1 CFU mL⁻¹Linear Range: 10 – 10¹⁰ CFU mL⁻¹Stability: >80% sensitivity over 5 weeks [5] | [5] |

| SiNW-FET with BTP Buffer | EDL tuning using large counterions [7] | miRNA-21 | Optimal buffer: 50 mM BTPSignal improvement over PBS due to reduced ion accumulation [7] | [7] |

| SERS Au-Ag Nanostars | Signal enhancement via plasmonics [9] | α-Fetoprotein (AFP) | LOD: 16.73 ng/mLLinear Range: 0 – 500 ng/mL (antigen) [9] | [9] |

| PNA-Based Electrochemical Sensor | Donnan effect reduction via neutral probe backbone [6] | DNA/RNA | Stronger hybridization vs. DNA probes;Stable geometry across ionic strengths [6] | [6] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Advancing research in this field relies on a specific set of materials and reagents designed to engineer the sensor interface.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Interfacial Engineering

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Experimental Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Bis-Tris Propane (BTP) Buffer | A sensing buffer with larger counterions [7]. | Reduces surface accumulation of ions compared to PBS, leading to a more favorable EDL structure and enhanced signal transduction in FET sensors [7]. |

| Peptide Nucleic Acid (PNA) Probes | Synthetic DNA analogue with an uncharged backbone [6]. | Eliminates the negative electrostatic barrier present in DNA probes, enabling stronger hybridization and operation under low ionic strength to mitigate Debye screening [6]. |

| Ionic Liquids (ILs) & Polymeric ILs (PILs) | Tunable electrolytes for electrochemical biosensors [10] [11]. | Offer high thermal stability, low volatility, and wide electrochemical windows. PILs can be integrated into hydrogels for flexible sensors and wound dressings [10] [11]. |

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | Nanomaterial for electrode modification [12]. | Provides a large surface area, good biocompatibility, and high conductivity, improving the adsorption of biomolecules and signal response [12]. |

| Cation Exchange Membrane (e.g., CR-61) | Model charged surface for fundamental studies [8]. | Used for direct measurement and fundamental study of the Donnan Potential at a defined polymer-solution interface [8]. |

Workflow for Evaluating Buffer Ionic Strength

A typical experimental workflow for optimizing and evaluating the ionic strength of a sensing buffer is summarized below.

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for determining the optimal ionic concentration of a sensing buffer.

The Electrical Double Layer and Donnan Potential are not merely abstract concepts but are foundational to the practical design and benchmarking of stable, sensitive biosensors. The EDL defines the physical limits of field-effect sensing via the Debye length, while the Donnan Potential governs the permselectivity and interfacial charge environment. Direct measurement techniques like tender-APXPS have demystified these potentials, providing quantitative data to validate theoretical models. The performance benchmarks and reagent toolkit provided here underscore that overcoming the challenges of high-ionic-strength environments requires a multi-faceted strategy. This includes optimizing buffer composition, employing novel non-charged probes like PNA, and engineering advanced materials such as bimetallic MOFs and ionic liquids. For researchers benchmarking biosensor stability, a rigorous evaluation of these core interfacial mechanisms is indispensable for transitioning laboratory innovations into robust diagnostic and pharmaceutical applications.

The Impact of Biofouling on Sensor Longevity and Signal Integrity

The accumulation of microorganisms, plants, algae, or animals on submerged surfaces, known as biofouling, presents a fundamental constraint on the deployment of sensors in marine, freshwater, and biological environments. For electrochemical biosensors operating in biologically relevant ionic strengths, biofouling is not merely a nuisance but a core determinant of analytical performance, impacting everything from signal integrity to operational longevity [13]. The formation of biofilms on sensor surfaces introduces a dynamic, living interface that directly interferes with measurement principles, whether optical, electrochemical, or mechanical. This review synthesizes current understanding of biofouling impacts on sensor systems, providing a comparative analysis of protection strategies and their efficacy in preserving sensor function under challenging conditions.

The biofouling process progresses through distinct, sequential stages that determine the severity of impact on sensor systems. Initially, a conditioning film of organic molecules forms on the sensor surface within seconds to minutes of immersion [14]. This is followed by the attachment of bacteria and microorganisms within hours, forming a primary biofilm. Over days, this develops into a complex microfilm containing spores of macroalgae and protozoa [14]. Finally, in the stage most detrimental to sensor function, macrofouling occurs with the attachment of larger organisms such as barnacles and mussels, which can permanently damage sensor elements and housings [15] [14]. Understanding this progression is essential for implementing targeted antifouling strategies at appropriate intervention points.

Quantitative Analysis of Biofouling Impacts on Sensor Performance

Biofouling directly compromises sensor function through multiple physical and biochemical mechanisms. The following table summarizes the documented impacts of biofouling on critical sensor parameters across different measurement technologies.

Table 1: Quantified Impacts of Biofouling on Sensor Performance Parameters

| Sensor Type | Performance Metric | Impact of Biofouling | Experimental Conditions | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dissolved Oxygen | Response Time | Increased due to reduced gas diffusion through fouled membranes | Field deployment; biofilm on membrane surface | [14] |

| pH Electrodes | Response Time | Significantly increased due to thickened diffusion layer | Laboratory testing with cultivated biofilm | [14] |

| Conductivity-Temperature (CT) Sensors | Data Accuracy | Errors >30% in biofouled sensors at depths up to 50m | 202-day offshore deployment in Bay of Bengal and Arabian Sea | [14] |

| Optical Sensors (Turbidity) | Signal Transmittance | Marked decline in transmittance through biofouled optical windows | PMMA surfaces at 4700m depth in Cayman Trough | [15] |

| Wave Buoys | Data Accuracy | >30% increase in data errors due to biofouling | Field observations of operational buoys | [15] |

| All Sensor Types | Operational Lifetime | 50% of operational budgets attributed to biofouling management | Cost analysis for coastal deployments | [13] |

The economic implications of these performance impacts are substantial. The Alliance for Coastal Technologies estimates that up to 50% of operational budgets for deployed aquatic instrumentation are directly attributable to biofouling management, including shorter deployment periods, loss of data due to sensor drift, frequent maintenance requirements, and reduced instrument lifespan [13]. With biofouling recognized as a primary factor limiting deployment duration, particularly in long-term continuous monitoring applications, development of effective antifouling strategies becomes essential for both research and commercial sensor applications.

Experimental Methodologies for Assessing Biofouling Impact

Electrochemical Sensor Testing Under Controlled Ionic Strength

Understanding biofouling impacts on electrochemical biosensors requires standardized testing methodologies that replicate operational conditions. The following protocol, adapted from recent research on DNA-based sensors, provides a framework for evaluating biofouling resistance under biologically relevant ionic strengths [16]:

Figure 1: Experimental Workflow for Biofouling Impact Assessment

Electrode Preparation Protocol:

- Surface Polishing: Electrodes are polished with 0.05 μm alumina slurry for 3 minutes followed by sonication in ethanol/water (1:1) for 5 minutes to achieve uniform surface area [16].

- Electrochemical Cleaning: Cyclic voltammetry in 0.5 M H₂SO₄ from -0.35 to +1.5 V vs. Ag|AgCl at 0.1 V/s for 5 cycles removes surface impurities [16].

- Self-Assembled Monolayer (SAM) Formation: Incubate freshly cleaned electrodes in reduced thiolated DNA solution (1.25 μM in HEPES/NaClO₄ buffer, pH 7.0) for 1 hour at room temperature in darkness [16].

- Non-Specific Binding Prevention: Transfer SAM-modified electrodes to 3 mM 6-mercaptohexanol (MCH) solution for 1 hour to block uncovered gold surfaces [16].

Measurement Conditions:

- Electrochemical Technique: Square-wave voltammetry (SWV) with step size of 1 mV, pulse height of 25 mV, frequency of 100 Hz over potential range from -0.45 to 0 V [16].

- Ionic Strength Variations: Testing across physiological range (0.125 M to 1.00 M NaClO₄) to simulate different biological fluids [16].

- Kinetic Monitoring: Regular SWV measurements over 125 minutes to track signal degradation due to initial biofouling [16].

Field-Based Sensor Performance Evaluation

For validation under real-world conditions, field deployment studies provide critical performance data:

Methodology:

- Multi-Depth Deployment: Moored sensor arrays positioned at varying depths (surface to 50m) to assess depth-dependent biofouling impacts [14].

- Long-Term Monitoring: Extended deployment periods (typically 60-200 days) with periodic sensor calibration and data validation [14].

- Environmental Correlation: Measurement of local water quality parameters (temperature, nutrient levels, chlorophyll) to correlate fouling severity with environmental conditions [14].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Biofouling Impact Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Context | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thiolated DNA Probes | SAM formation on gold electrodes | Electrochemical biosensor development | Requires TCEP reduction of dithiol to monothiol before SAM formation [16] |

| 6-Mercaptohexanol (MCH) | Backfilling agent for non-specific binding prevention | Surface passivation in biosensors | Critical for maintaining probe accessibility and reducing non-specific adsorption [16] |

| HEPES/NaClO₄ Buffer | Controlled ionic strength environment | Electrochemical measurements under physiological conditions | NaClO₄ preferred over NaCl for reduced corrosion in electrochemical systems [16] |

| Alumina Slurry (0.05 μm) | Electrode surface polishing | Electrode preparation for reproducible surfaces | Creates uniform surface topography essential for consistent SAM formation [16] |

| Boron-Doped Diamond (BDD) Electrodes | Alternative electrode material | Capacitive sensing in high-ionic-strength solutions | Enhanced stability and reduced background interference in complex fluids [3] |

Signal Interference Mechanisms at the Biofilm-Sensor Interface

The detrimental effects of biofouling on sensor signal integrity manifest through multiple physical and biochemical pathways. The following diagram illustrates the primary interference mechanisms at the biofilm-sensor interface.

Figure 2: Biofouling Signal Interference Mechanisms

Diffusion-Limited Signal Response

Biofilm formation directly impedes analyte transport to the sensing interface, particularly critical for gas-sensing membranes. Research demonstrates that thicker biofilms reduce gas diffusion through membranes, significantly increasing sensor response time [14]. For dissolved oxygen sensors, fouling caused by microorganism accumulation on membrane surfaces directly affects oxygen molecule movement from the bulk solution to the electrode surface [14]. Similarly, pH electrodes exhibit prolonged response times as biofilms increase the thickness of the stagnant layer at electrode surfaces, extending the diffusion path length for ions [14].

Interfacial Chemistry Alteration

The biofilm-sensor interface represents a dynamic biochemical environment that directly interferes with measurement accuracy. Sulfate-reducing bacteria (SRB) within biofilms participate in sulfur cycling via anaerobic respiration, reducing sulfate to H₂S and creating localized anaerobic microenvironments [15]. These heterogeneous biofilms exacerbate local corrosion and alter interfacial electrochemistry through several mechanisms:

- Micro-battery Formation: Potential differences between anaerobic biofilm zones and surrounding aerobic areas create galvanic corrosion cells [15].

- Metabolite Interference: SRB-produced H₂S combines with dissolved Fe²⁺ to form FeS, which acts as micro-batteries with the metal matrix to accelerate corrosion [15].

- Ion Adsorption: The viscous biofilm matrix, primarily composed of extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) with strong complexing ability, adsorbs seawater Cl⁻ which damages metal passive films [15].

Ionic Strength Considerations for Biosensor Stability

The performance degradation of sensors in high-ionic-strength environments presents particular challenges for biological applications. Capacitive sensors, which enable label-free, real-time detection at low non-perturbing voltages, experience significantly compromised sensitivity in high-ionic-strength solutions such as bodily fluids due to reduced Debye length and non-specific interactions [3]. The Debye length, representing the effective region within which an electric field can recognize analyte-sensor interactions, becomes compressed to just a few nanometers in physiological fluids, severely limiting signal transduction for target-receptor interactions occurring beyond this narrow electrical double layer [3].

DNA-based electrochemical sensors exhibit particularly strong dependence on ionic environment. Studies varying the position of double-stranded DNA segments relative to the electrode surface under different ionic strengths (0.125 to 1.00 M) revealed significant interferences with DNA hybridization closer to the surface, with more substantial interference at lower ionic strength [16]. This manifests as slowed reaction kinetics and diminished efficiency for toehold-mediated strand displacement reactions near the electrode surface [16]. Strategic placement of DNA binding sites away from the electrode surface improves reaction rates and yields, highlighting the critical importance of considering both salt concentration and probe positioning when designing DNA-based electrochemical sensors for biologically relevant conditions [16].

Comparative Analysis of Antifouling Strategies for Sensor Protection

Multiple approaches have been developed to mitigate biofouling impacts on sensor systems, each with distinct mechanisms, advantages, and limitations. The following table provides a comparative analysis of established and emerging antifouling technologies.

Table 3: Antifouling Strategy Comparison for Sensor Applications

| Strategy | Mechanism of Action | Sensor Integration | Limitations | Efficacy Data |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Silicone-Based Fouling-Release Coatings | Low surface energy prevents strong adhesion | Compatible with various sensor housings | Limited effectiveness in low-flow environments | >80% reduction in macrofouling adhesion strength [17] |

| Ultrasonic Antifouling Systems | Sound waves interfere with biofilm formation | Integrated into sensor housings | Power-intensive for long-term deployments | Effective for biofilm prevention; limited data on macrofouling [17] [18] |

| Biomimetic Microtextured Surfaces | Topographical features prevent settlement | Direct application to sensor surfaces | Fabrication complexity for non-planar surfaces | 70-90% reduction in diatom adhesion demonstrated [14] |

| UV-C Light Treatment | Microbicidal effect on settling organisms | Optical sensor protection | Limited penetration; requires clear windows | >95% reduction in biofilm formation on optical surfaces [18] |

| Enzyme-Based Biofilm Prevention | Degradation of adhesive polymers | Co-immobilization with sensing layers | Specificity to particular biofilm components | Limited field validation data available [13] |

| Electrochemical Chlorine Generation | In situ production of biocidal compounds | Particularly effective for marine sensors | Potential sensor surface damage; byproduct formation | Effective but requires careful optimization [13] |

Mechanical and Physical Protection Methods

In-water grooming represents an emerging approach where proactive, scheduled maintenance prevents fouling accumulation before it becomes problematic. Unlike traditional cleaning that occurs only after fouling becomes visible, grooming maintains surface smoothness and coating performance while avoiding aggressive techniques that damage sensor elements [17]. Robotic grooming systems operating autonomously in port settings can identify early-stage fouling and remove it with minimal impact to sensitive sensor components [17]. These systems also reduce the risk of discharging debris into the water, addressing environmental concerns particularly relevant in invasive species-sensitive areas [19].

Ultrasonic antifouling systems utilize sound waves at specific frequencies to interfere with the attachment and development of microorganisms on sensor surfaces. These systems operate by generating ultrasonic waves that create microscopic bubbles in the water adjacent to protected surfaces [17] [18]. The continuous formation and collapse of these bubbles disrupt the settlement process of fouling organisms while preventing the production of biofilms in their early stages. This approach offers the advantage of continuous protection without chemical releases or physical contact with sensor surfaces, making it particularly suitable for optical elements and delicate sensing membranes.

Advanced Materials and Surface Engineering

Superhydrophobic and superhydrophilic surfaces inspired by natural antifouling organisms represent a promising direction for sensor protection. These surfaces leverage extreme wettability to prevent organism attachment through either complete water repellency or complete wetting that minimizes interfacial points for adhesion [14]. Surface wettability, governed by both chemical composition and topographic features at multiple scales, directly influences antifouling performance through modulation of interfacial energy [14]. The complexity of coating materials, including chemical composition and surface free energy, plays a key role in determining antifouling efficacy, with lower surface energy generally correlating with reduced biofouling adhesion strength [14].

Slippery Liquid-Infused Porous Surfaces (SLIPS) technology has emerged as a particularly effective approach for optical sensors where transparency maintenance is critical. These surfaces create a molecularly smooth, liquid interface that presents no stable anchor points for adhering organisms [14]. The continuous liquid layer prevents both initial biofilm formation and attachment of larger fouling organisms while maintaining optical clarity essential for photometric measurements. Additionally, these surfaces can demonstrate self-healing properties where the infused liquid fills in minor scratches or defects that might otherwise provide footholds for fouling organisms.

The impact of biofouling on sensor longevity and signal integrity represents a multifaceted challenge requiring integrated solutions combining materials science, surface engineering, and intelligent monitoring. As sensor technologies advance toward longer deployment periods and operation in increasingly challenging environments, the development of effective antifouling strategies becomes essential for data reliability and operational efficiency. The progression from reactive biofouling management to proactive, data-driven approaches represents the most promising direction for next-generation sensor systems [17].

Future research directions should focus on multi-disciplinary coupling technologies that address biofouling across its progression stages, from initial molecular conditioning to macroscopic organism settlement [15]. The integration of AI-driven fouling prediction models with real-time sensor performance monitoring will enable condition-based maintenance strategies optimized for specific deployment environments [15] [18]. Additionally, the development of standardized testing protocols and cross-scenario evaluation systems will accelerate the translation of antifouling technologies from laboratory validation to field deployment [15]. As the economic and operational costs of biofouling continue to drive innovation, sensors capable of maintaining signal integrity over extended deployments in fouling-prone environments will unlock new possibilities in environmental monitoring, biomedical sensing, and oceanographic research.

Biosensor stability, characterized by a decrease in signal response over time, is a paramount determinant of commercial success and practical utility across diverse fields, from medical diagnostics to environmental monitoring [20] [21]. This degradation is a complex phenomenon, arising from the sum of changes affecting the biological recognition element (e.g., enzymes, antibodies), the signal transducer, and the protective matrices within the sensor architecture [20]. For researchers and professionals in drug development and biomedical science, benchmarking stability is not merely a procedural step but a critical evaluation of a biosensor's reliability under biologically relevant conditions. This guide provides a structured framework for this essential benchmarking process, focusing on three core operational metrics: shelf-life, reusability, and continuous use stability.

A significant challenge in this domain is achieving consistent performance in physiologically relevant, high-ionic-strength environments. Conventional biosensors often suffer from charge-screening effects in these conditions, which can severely limit their sensitivity and accuracy [22]. Therefore, modern stability assessments must extend beyond idealized buffer systems to include testing in complex matrices like blood serum or phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to ensure real-world applicability [23] [22]. This guide synthesizes current research and experimental data to objectively compare stability performance, providing a foundational resource for rigorous biosensor evaluation.

Comparative Analysis of Biosensor Stability Metrics

The following section distills experimental data into a structured comparison of how different biosensor designs and materials perform across the key stability metrics. This quantitative overview aids in identifying architectures suited for specific application needs, whether for single-use diagnostics or long-term implantable monitors.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Biosensor Stability Architectures

| Biosensor Architecture / Strategy | Shelf-Life Stability | Reusability Performance | Continuous Use Stability | Key Findings & Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose Oxidase Biosensor (Model System) | Signal loss is temperature-dependent; can be modeled for prediction [20]. | Poor correlation due to unpredictable handling effects [20]. | Determined in less than 24 hours via accelerated ageing [20]. | A linear ageing model was found more suitable than an exponential (Arrhenius) model for predicting shelf-life [20]. |

| Flexible Trihexylthiol Anchor (E-DNA Sensor) | Retained 75% of original signal after 50 days in aqueous buffer storage [23]. | Demonstrated excellent robustness to repeated electrochemical interrogation [23]. | N/A | Provided significantly enhanced stability compared to mono-thiol anchors without sacrificing electron transfer efficiency [23]. |

| Rigid Adamantane Anchor / Mono-thiol (E-DNA Sensor) | Significant signal loss (>60%) upon wet storage or thermocycling [23]. | Similar poor stability performance as mono-thiol anchors [23]. | N/A | Stability was similar to conventional mono-thiol anchors, highlighting the importance of anchor flexibility [23]. |

| Enhanced EDL FET Biosensor | N/A | N/A | High sensitivity maintained in high-ionic-strength solution (1X PBS) [22]. | Overcomes the Debye length limitation, enabling direct protein detection in physiological samples in 5 minutes without dilution [22]. |

| PNA-Based Biosensors | High inherent stability due to nuclease-resistant, neutral backbone [6]. | Strong and stable hybridization with DNA/RNA supports potential reusability [6]. | Maintains structural integrity under low ionic strength conditions [6]. | The neutral PNA backbone prevents enzymatic degradation and enables stable performance across varying ionic conditions [6]. |

Experimental Protocols for Determining Stability Characteristics

To ensure reproducibility and meaningful cross-comparison between studies, standardized experimental protocols are essential. Below are detailed methodologies for assessing the three key stability metrics, derived from established research practices.

Protocol for Shelf-Life Estimation via Thermally Accelerated Ageing

This protocol provides a rapid method for determining long-term shelf-life, circumventing the need for real-time storage studies [20].

- Objective: To predict the long-term shelf-life of a biosensor under standard storage conditions within a short timeframe (e.g., 4 days).

- Materials:

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), 100 mM, pH 7.4.

- Thermally controlled ovens or water baths (e.g., set at 40°C, 50°C, 60°C).

- Standard analyte solutions for performance validation.

- Method:

- Fabricate multiple identical batches of the biosensor.

- Divide the sensors into groups and store them in PBS at elevated temperatures (e.g., 40°C, 50°C, 60°C). A control group should be stored at the target storage temperature (e.g., 4°C or 25°C).

- At regular intervals (e.g., 0, 12, 24, 48, 96 hours), remove a subset of sensors from each temperature condition.

- Measure the analytical signal (e.g., current, voltage) for each sensor using a standard concentration of the target analyte.

- Plot the normalized signal (%) against time for each temperature.

- Data Modeling: A linear degradation model is often more suitable than an exponential one. The degradation rate at each temperature is determined from the slope. An overall model is then built to correlate degradation rate with temperature, allowing for extrapolation to standard storage temperatures [20].

Protocol for Assessing Reusability and Handling Robustness

This protocol evaluates a sensor's ability to withstand repeated use and regeneration cycles, a key metric for cost-effective diagnostics [20] [23].

- Objective: To quantify the signal retention and performance consistency of a biosensor over multiple cycles of use, regeneration, and storage.

- Materials:

- Biosensors, analyte solution, regeneration buffer (e.g., deionized water, low-pH buffer).

- Electrochemical or optical workstation for signal measurement.

- Method:

- Measure the initial signal response of the biosensor to a known analyte concentration.

- Regenerate the sensor surface according to the established protocol (e.g., a 30-second wash in deionized water for E-DNA sensors) [23].

- Re-measure the signal in a blank solution to confirm a return to the baseline.

- This cycle of Measurement → Regeneration → Baseline Check constitutes one reuse cycle.

- Repeat this process for a defined number of cycles (e.g., 10, 20, 50) while tracking the signal attenuation from the initial value.

- Note: Reusability is highly dependent on handling and the harshness of the regeneration method, leading to more variable and unpredictable outcomes compared to shelf-life studies [20].

Protocol for Continuous Use Stability

This metric is critical for biosensors intended for implanted or online monitoring applications, where the sensor is constantly operational [20].

- Objective: To evaluate the signal drift and performance decay of a biosensor during prolonged, uninterrupted operation in a relevant matrix.

- Materials:

- Flow-cell system or stirred solution to maintain constant analyte contact.

- Continuous monitoring equipment (e.g., potentiostat for electrochemical sensors).

- Test matrix (e.g., buffer, simulated body fluid, serum).

- Method:

- Immerse the biosensor in the chosen test matrix under operational conditions (e.g., at applied voltage, in flow).

- Continuously or intermittently monitor the output signal over a set period (e.g., 8, 24, 72 hours).

- The analyte concentration can be held constant or periodically spiked to assess response consistency.

- The rate of signal drift or the percentage of signal loss over time is the key metric for continuous use stability. This can also be accelerated at elevated temperatures to obtain data more rapidly [20].

Research Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful stability testing relies on a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The following table outlines key components referenced in the studies cited in this guide.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Biosensor Stability Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function in Stability Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Screen-Printed Electrodes (SPEs) | Low-cost, disposable substrate for rapid prototyping and testing of electrochemical biosensors. | Used as a model for glucose oxidase biosensor fabrication in accelerated ageing studies [20]. |

| Gold Electrodes & Alkane Thiols | Form self-assembled monolayers (SAMs) for precise immobilization of biorecognition elements. | Platform for studying the effect of anchor chemistry (mono-thiol vs. tri-thiol) on E-DNA sensor stability [23]. |

| Peptide Nucleic Acid (PNA) Probes | Synthetic, neutral backbone probes offering superior chemical and enzymatic stability over DNA. | Used in biosensors for strong, stable hybridization with DNA/RNA, especially under low ionic strength conditions [6]. |

| Nafion Membranes | A protective polymer membrane used to coat biosensors, improving selectivity and potentially enhancing stability by reducing fouling. | Used as a component in the immobilization cocktail for model glucose biosensors [20]. |

| Reduced Graphene Oxide (rGO) | A nanomaterial used to enhance electron transfer, sensitivity, and stability in electrochemical biosensors. | Identified as a major research cluster in bibliometric analysis of biosensor stability [21]. |

| Field-Effect Transistors (FETs) | Provide high signal amplification. When combined with EDL modulation, they enable sensing in physiological ionic strength. | Core component of EnEDL FET biosensors that overcome Debye screening for direct detection in PBS/serum [22]. |

Stability Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Understanding the conceptual and experimental flow is key to robust stability research. The following diagrams map the core concepts and a standard experimental workflow.

Biosensor Ageing Pathways

This diagram visualizes the primary factors and mechanisms that contribute to biosensor ageing and signal degradation.

Accelerated Ageing Experimental Workflow

This diagram outlines the standard step-by-step protocol for conducting a thermally accelerated ageing study to predict biosensor shelf-life.

Benchmarking biosensor stability is a multifaceted process that requires careful consideration of the intended application, whether it demands long-term storage (shelf-life), repeated measurements (reusability), or uninterrupted operation (continuous use). The experimental data and protocols presented herein demonstrate that strategic choices in material science—such as employing flexible tri-thiol anchors, stable PNA probes, or innovative EDL FET architectures—can dramatically enhance biosensor robustness [23] [6] [22]. A critical finding for researchers is that a linear model for thermally accelerated ageing can provide reliable shelf-life predictions more effectively than traditional exponential models [20]. Ultimately, integrating stability testing under biologically relevant conditions, particularly at physiological ionic strengths, is no longer optional but a fundamental requirement for the development of biosensors that are reliable, commercially viable, and truly fit for purpose in modern therapeutics and diagnostics.

Engineering Stable Interfaces: Advanced Materials, Designs, and Sensing Methodologies

A central challenge in modern biosensing is maintaining high performance and stability in biologically relevant media, such as blood, serum, or saliva. These high-ionic-strength environments screen electrical fields, promote non-specific binding, and can destabilize the bioreceptor layer, leading to signal drift and reduced sensor lifespan [3]. This guide benchmarks three key material classes—nanocomposites, conducting polymers, and advanced immobilization matrices—objectively comparing their performance in enhancing biosensor stability for research and drug development applications. The comparative analysis focuses on quantitative metrics critical for applications in point-of-care diagnostics and continuous monitoring, where operational stability is as crucial as sensitivity.

Performance Benchmarking of Innovative Material Classes

The table below provides a comparative analysis of three core material categories based on recent experimental findings, highlighting their respective contributions to sensor stability and performance.

Table 1: Performance Benchmarking of Innovative Material Classes for Biosensing

| Material Class | Key Representatives | Impact on Stability & Performance | Reported Experimental Data | Limitations & Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nanocomposites | Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs), Au-Ag Nanostars, Graphene, WS₂ | Enhance signal-to-noise ratio and sensitivity. WS₂ in SPR sensors increased sensitivity for cancer cell detection [24]. Nanocomposites enable reagent-free operation ideal for continuous monitoring [3]. | SPR biosensor with WS₂: Sensitivity of 342.14 deg/RIU for blood cancer cell detection [24]. Porous Au/Polyaniline/Pt NP glucose sensor: Sensitivity of 95.12 ± 2.54 µA mM⁻¹ cm⁻² and stable performance in interstitial fluid [9]. | Can be susceptible to biofouling; requires additional antifouling strategies. Reproducibility in large-scale fabrication can be challenging [3] [25]. |

| Conducting Polymers | PEDOT:PSS, Polypyrrole (PPy), Polyaniline (PANI) | Provide a soft, biocompatible interface that reduces mechanical mismatch with tissue, improving in vivo stability. Enable direct, label-free electrochemical detection [26] [27] [28]. | PPy demonstrates high versatility in biosensors and bioelectrical stimulation [28]. Sensors using these polymers have effectively detected viruses like SARS-CoV-2 [27]. | Can suffer from electrical and environmental instability in moist, ion-rich conditions. Mechanical rigidity compared to biological tissues can lead to poor integration [28]. |

| Advanced Immobilization Matrices | Self-Assembled Monolayers (SAMs), Polyethylene Glycol (PEG), Zwitterionic Coatings, Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) | Directly address the core stability challenge by providing a robust, ordered layer for bioreceptor attachment. Reduce non-specific binding and prevent desorption or denaturation [29]. | Covalent immobilization strategies significantly enhance operational longevity versus physical adsorption [29]. Zwitterionic coatings and MIPs mimic biological surroundings to minimize fouling [29]. | Optimal surface architecture is complex to design. Traditional methods are often trial-and-error, though AI is accelerating optimization [29]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Surface Functionalization via Self-Assembled Monolayers (SAMs)

Objective: To create a stable, ordered, and low-fouling interface on a gold transducer surface for the covalent immobilization of bioreceptors (e.g., antibodies).

- Step 1: Surface Cleaning. Gold substrate is cleaned via oxygen plasma treatment or piranha solution (3:1 mixture of concentrated H₂SO₄ and 30% H₂O₂) to remove organic contaminants.

- Step 2: SAM Formation. The clean substrate is immersed in a 1-10 mM ethanolic solution of an alkanethiol (e.g., 11-mercaptoundecanoic acid) for 12-24 hours to form a dense, oriented monolayer.

- Step 3: Activation. The terminal carboxylic acid groups of the SAM are activated using a fresh mixture of N-(3-Dimethylaminopropyl)-N′-ethylcarbodiimide (EDC) and N-Hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) (typically 400 mM / 100 mM in water) for 15-60 minutes.

- Step 4: Bioreceptor Immobilization. The activated surface is rinsed and incubated with a solution of the bioreceptor (e.g., 10-100 µg/mL antibody in a suitable buffer) for 1-2 hours, forming stable amide bonds.

- Step 5: Deactivation & Blocking. Unreacted sites are deactivated with ethanolamine. The surface is then treated with a blocking agent (e.g., 1% BSA or PEG-based compounds) to passivate any remaining surface against non-specific binding [3] [29].

Capacitive Sensing in High-Ionic-Strength Solutions

Objective: To measure changes in the dielectric properties at the electrode-solution interface upon biomolecular binding, without the use of redox probes.

- Step 1: Sensor Preparation. An IDE or potentiostatic electrode is functionalized with a capture probe following a protocol similar to Section 3.1. A thin, insulating layer is critical to prevent Faradaic currents.

- Step 2: Baseline Measurement. The functionalized sensor is immersed in a buffer solution. Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) is performed at a low, non-perturbing AC voltage (e.g., 10 mV) over a frequency range (e.g., 0.1 Hz to 100 kHz). The double-layer capacitance (Cdl) is extracted from the impedance data, often by fitting to an equivalent circuit model.

- Step 3: Analyte Exposure. The target analyte in a high-ionic-strength solution (e.g., PBS, simulated serum) is introduced to the sensor surface.

- Step 4: Signal Measurement. The EIS measurement is repeated after a fixed incubation period. The binding of the target analyte increases the thickness of the dielectric layer, leading to a measurable decrease in capacitance (ΔCdl).

- Step 5: Data Analysis. The normalized change in capacitance (ΔCdl/Cdl) is plotted against analyte concentration to generate a calibration curve [3].

Strategic and Experimental Pathways

The following diagrams map the logical relationship between the core biosensor challenge and the material solutions, as well as a typical experimental workflow.

Material Strategies to Overcome Biosensor Instability

Workflow for Stable Biosensor Surface Fabrication

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Developing Stable Biosensors

| Item | Function / Role | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| EDC/NHS Chemistry | Crosslinkers for covalent immobilization of biomolecules via carboxylate and amine groups. | Immobilizing antibodies or DNA probes on SAM-coated gold surfaces [29]. |

| Alkanethiols (e.g., 11-Mercaptoundecanoic acid) | Form Self-Assembled Monolayers (SAMs) on gold, providing a tunable, ordered interface. | Creating a stable foundation for subsequent bioreceptor attachment [3] [29]. |

| PEDOT:PSS Dispersion | A commercially available, aqueous-processable conducting polymer for electrode modification. | Fabricating flexible, transparent, and biocompatible electrochemical sensors [28]. |

| Zwitterionic Compounds (e.g., SBAA) | Form ultra-low-fouling surfaces that resist non-specific protein adsorption. | Coating sensor surfaces to enhance performance in complex media like blood and serum [29]. |

| Carboxylated Carbon Nanotubes | Nanomaterials for enhancing electrode surface area and electron transfer kinetics. | Signal amplification in electrochemical biosensors for proteins or nucleic acids [25]. |

| Polyaniline (PANI) Emeraldine Salt | A conducting polymer with tunable redox states, useful for abiotic (enzyme-free) sensing. | Developing stable, non-enzymatic glucose sensors [27] [9]. |

| Transition Metal Dichalcogenides (e.g., WS₂) | 2D nanomaterials for enhancing sensitivity in optical biosensors like SPR. | Improving the performance of SPR biosensors for the detection of cancer cells [24]. |

The quest for biosensor stability in biologically relevant conditions is driving interdisciplinary innovation. As evidenced by the experimental data, no single material offers a perfect solution; rather, a synergistic combination of these classes shows the greatest promise. The future of stable biosensing lies in hybrid platforms, such as nanocomposites embedded within conducting polymer hydrogels, which are further stabilized by advanced antifouling immobilization matrices [29] [28]. Furthermore, the integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and machine learning is emerging as a powerful tool to accelerate the rational design of these complex interfaces, moving beyond traditional trial-and-error methods to predict optimal material compositions and surface architectures [29]. For researchers in drug development, this progression towards more robust, stable, and reliable biosensing platforms will be instrumental in enabling accurate, long-term biomarker monitoring and facilitating the transition from laboratory research to clinical point-of-care applications.

The performance and reliability of a biosensor are fundamentally dictated by the design and properties of its interface—the thin layer that separates the biological recognition elements from the physical transducer. A well-engineered interface must simultaneously achieve multiple critical functions: it must provide a stable environment for biomolecule immobilization, facilitate efficient signal transduction, and crucially, resist the nonspecific adsorption of interfering substances from complex samples, a phenomenon known as biofouling. The stability of this interface is paramount, as its degradation directly compromises key sensing performance parameters such as sensitivity, limit of detection, and reproducibility.

A significant challenge in deploying biosensors for real-world clinical or environmental monitoring is operating reliably in solutions of high ionic strength, such as blood, serum, or interstitial fluid. These environments screen electrical fields, drastically reducing the effective sensing range of electrochemical and capacitive transducers to a scale of nanometers, and promote nonspecific fouling through electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions. This review provides a comparative guide to modern interface architectures—specifically monolayer techniques, 3D constructions, and polymer brush coatings—focusing on their performance and stability in biologically relevant ionic strengths.

Comparative Analysis of Interface Architectures

The following section objectively compares the key characteristics, experimental performance data, and material requirements of different interface architectures. The data is synthesized from recent research to facilitate direct comparison.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Interface Architectures for Biosensing

| Interface Architecture | Key Material Examples | Optimal Biofouling Resistance (Complex Fluid) | Reported Sensitivity / Performance Metric | Key Advantage | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polymer Brushes (Zwitterionic) | Poly(sulfobetaine methacrylate) (PSBMA), EK-peptides [30] [31] | Yes (GI fluid, bacterial lysate) [31] | >1 order of improvement in LOD and SNR vs. PEG [31] | Superior hydration layer; resistance to oxidative degradation [30] [31] | Can be overly hydrophilic for easy functionalization [32] |

| Polymer Brushes (PEG-like) | POEGMA [33] [32] | Yes (whole blood, serum, plasma) [32] | High analytical sensitivity for POC immunoassays [32] | Established "gold standard"; tunable thickness [33] [32] | Susceptible to anti-PEG antibodies and oxidation [32] |

| 2D Material Monolayers | Graphene, MoS₂, WS₂ [12] [34] | Not Primary Focus | 203 deg./RIU (SPR sensitivity for ssDNA) [34] | Excellent electrical conductivity & large surface area [12] [34] | Susceptible to biofouling without passivation [31] |

| 3D Nanomaterial Constructions | Nanoporous Gold, Carbon Nanotubes, Nanoporous Silica [12] [3] | Not Primary Focus | High signal response speed and adsorption capacity [12] | Extremely high surface area for biomolecule loading [12] | High surface area can increase susceptibility to fouling [31] |

Table 2: Summary of Material and Reagent Solutions for Featured Experiments

| Category | Specific Item / Reagent | Function in Experiment / Application |

|---|---|---|

| Polymer Brush Synthesis | Oligo(ethylene glycol) methacrylate (OEGMA), Sulfobetaine methacrylate (SBMA) [33] [32] | Monomers for forming protein-resistant polymer brushes via SI-ATRP. |

| Zwitterionic Peptides | EKEKEKEKEKGGC peptide sequence [31] | Provides antifouling via a stable, charge-neutral hydration layer; cysteine enables surface anchoring. |

| Surface Initiation | (3-aminopropyl)triethoxysilane (APTES), α-bromoisobutyryl bromide (BiB) [32] | Silane and initiator for functionalizing glass/SiO₂ surfaces to enable surface-initiated ATRP. |

| Polymerization Catalysis | Copper(I) bromide, HMTETA [32] | Catalyst and ligand system for Atom Transfer Radical Polymerization (ATRP). |

| Nanomaterial Synthesis | Chitosan, Graphene Oxide (GO), Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) [12] | Form composite interfaces to enhance biomolecule immobilization, stability, and signal transduction. |

Detailed Architectures and Experimental Protocols

Polymer Brush Coatings: POEGMA and Polyzwitterions

Polymer brushes are dense arrays of polymer chains tethered by one end to a surface. They confer stability and antifouling properties by forming a hydrated, steric barrier that repels proteins and other biomolecules.

POEGMA (Poly(oligo(ethylene glycol) methacrylate)): POEGMA brushes are a comb-shaped polymer system where the side chains are oligoethylene glycol groups. Their antibiofouling action stems from the formation of a tightly bound hydration layer and significant steric hindrance [33] [32]. The grafting density (ρ), main-chain length (n), and side-chain length (m) can be tuned to control the "molecular sieving" property of the coating, creating dynamic pores that exclude large molecules (like antibodies) while permitting access to smaller molecules (like substrates for enzymatic sensors) [33]. However, a key limitation is the prevalence of anti-PEG antibodies in the human population, which can bind to POEGMA brushes and cause nonspecific background signals [32].

Polyzwitterions: Zwitterionic polymers, such as poly(sulfobetaine methacrylate) (PSBMA) or surface-tethered zwitterionic peptides, possess both positive and negative charges within a single monomer unit, resulting in a net-neutral and superhydrophilic structure [30] [31]. Their exceptional antifouling performance arises from an even stronger hydration layer bound via electrostatic interactions, which creates a greater energy barrier for protein adsorption than PEG-based materials [30]. A study on porous silicon (PSi) biosensors demonstrated that a zwitterionic peptide with the sequence EKEKEKEKEKGGC provided broad-spectrum protection against proteins, bacteria, and mammalian cells. Sensors functionalized with this peptide showed over an order of magnitude improvement in both the limit of detection (LOD) and signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) compared to traditional PEGylated sensors when detecting lactoferrin in gastrointestinal fluid [31].

Diagram 1: Polymer brush architecture and function.

Experimental Protocol: SI-ATRP of POEGMA and PSBMA on Glass/Silica

This protocol outlines the formation of a polymer brush via surface-initiated atom transfer radical polymerization (SI-ATRP), a common method for creating dense, well-defined brushes [32].

Surface Preparation and Initiator Immobilization:

- Clean glass or silicon wafer substrates thoroughly.

- Immerse the substrates in a 10% (v/v) solution of (3-aminopropyl)triethoxysilane (APTES) in ethanol for 4 hours to form an amine-terminated monolayer.

- Rinse with ethanol and deionized (DI) water, then cure at 120°C.

- React the aminated surfaces with a solution of α-bromoisobutyryl bromide (BiB) (1% v/v) and triethylamine (1% v/v) in dichloromethane for 30 minutes. This step tethers the ATRP initiator to the surface.

- Rinse with dichloromethane, ethanol, and DI water, then cure at 120°C.

Polymerization:

- For POEGMA: Prepare a degassed aqueous solution containing the OEGMA monomer, Cu(I)Br catalyst, and the ligand HMTETA. Immerse the initiator-functionalized substrates in this solution under an argon atmosphere for a controlled duration (e.g., 1-4 hours) to grow brushes of specific thickness [32].

- For PSBMA: Prepare a degassed solution of SBMA monomer in methanol/water with Cu(I)Br and Cu(II)Br (for deactivator) and HMTETA. Place the substrates in this solution for the desired time [32].

- The thickness of the brush is directly proportional to the polymerization time.

Post-Polymerization Processing:

- Remove the substrates from the polymerization solution and rinse extensively with DI water and relevant solvents to remove physisorbed monomers and catalyst.

- Dry the substrates with nitrogen or by centrifugation.

Monolayer Techniques and 3D Constructions

2D Material Monolayers

Monolayers of two-dimensional (2D) materials like graphene and transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDCs) such as MoS₂ and WS₂ are used to enhance the sensitivity of optical biosensors like Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR). Their high surface-to-volume ratio and exceptional optical properties allow for strong field confinement and enhanced interaction with biomolecules.

- Experimental Protocol (SPR Biosensor for ssDNA): A typical fabrication process involves [34]:

- A BK-7 glass prism is coated with a 44 nm silver (Ag) film by vacuum thermal evaporation.

- A monolayer of graphene, synthesized by chemical vapor deposition (CVD), is transferred onto the silver layer.

- A thin (e.g., 4 nm) gold (Au) layer is deposited on the graphene via thermal evaporation.

- Layers of TMDCs (e.g., WS₂, MoS₂) are subsequently transferred onto the gold layer.

- Finally, a monolayer of single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) probes is immobilized on the 2D material surface to capture the target analyte. This hybrid metallic-2D material structure was shown to achieve a theoretical sensitivity of 203°/RIU, significantly higher than conventional SPR sensors [34].

3D Nanomaterial Constructions

Three-dimensional nanostructures leverage high porosity and an immense surface area to increase the loading capacity of capture probes and enhance signal transduction.

- Materials and Methods: Common 3D materials include nanoporous gold, nanoporous silicon, carbon nanotubes, and nanocomposites like graphene-chitosan [12] [31]. For example, a capacitive biosensor might use a 3D nanoporous gold electrode to increase the effective surface area and enhance charge accumulation capabilities [3].

- Challenge of Fouling: A critical caveat of 3D constructions is that their high surface area, while beneficial for loading, also makes them more susceptible to biofouling. The porous silicon (PSi) biosensor is a prime example, where its inherent high surface area was identified as a major contributor to nonspecific binding, necessitating the use of advanced passivation strategies like zwitterionic peptides [31].

Diagram 2: 3D nanostructure interface and fouling challenge.

The selection of an interface architecture is a critical determinant of biosensor stability and performance in high-ionic-strength environments. As the comparative data shows, no single solution is universally superior; each presents a set of trade-offs. POEGMA brushes offer tunable molecular sieving but face challenges from anti-PEG antibodies. Zwitterionic polymers and peptides demonstrate superior antifouling and stability, pushing the limits of detection in complex fluids, but may require hybrid strategies for easy functionalization. While 2D monolayers and 3D nanostructures can dramatically enhance sensitivity, their high surface area often makes passivation with advanced antifouling coatings like zwitterionics a necessity, not an option.

Future research directions will likely focus on developing hybrid and smart interfaces that combine the strengths of different materials. This includes creating charge-tunable zwitterionic-cationic brushes for easier inkjet printing of antibodies [32], or further optimizing the grafting density and chain length of comb-polymer brushes like POEGMA via predictive in-silico models to achieve precise size-selective permeability [33]. The ultimate goal is the creation of next-generation biosensor interfaces that are intrinsically stable, resistant to the complex biofouling landscape of bodily fluids, and capable of reliable, long-term operation for point-of-care diagnostics and continuous monitoring.

Biosensors are powerful analytical tools that combine a biological recognition element with a physicochemical detector. Among the most promising architectures are Biological Field-Effect Transistors (BioFETs) and electrochemical biosensors, which offer label-free detection, high sensitivity, and potential for miniaturization. However, their widespread adoption, particularly for point-of-care diagnostics, faces a significant challenge: maintaining stability and performance in biologically relevant ionic strengths.

Physiological fluids, such as blood, serum, and peritoneal dialysis effluent, have high ionic strengths (e.g., ~1X PBS). This environment severely compromises biosensor performance through two primary mechanisms: Debye screening, which limits the detection range of charged biomolecules, and signal drift, which causes unreliable readings over time [2]. This article provides a comparative analysis of recent device-level innovations in BioFETs and electrochemical biosensors designed to overcome these stability barriers, offering a benchmark for researchers developing next-generation diagnostic platforms.

Performance Comparison of Stable Biosensing Platforms

The table below compares three advanced biosensing platforms documented in recent literature, highlighting their designs, operational contexts, and key performance metrics relevant to stability.

Table 1: Comparison of Recent Stable Biosensing Platforms