Biorecognition Elements in Pesticide Biosensors: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers and Developers

This article provides a detailed examination of the biorecognition elements that form the core of modern pesticide biosensors.

Biorecognition Elements in Pesticide Biosensors: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers and Developers

Abstract

This article provides a detailed examination of the biorecognition elements that form the core of modern pesticide biosensors. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles, operational mechanisms, and real-world applications of enzymes, antibodies, aptamers, whole cells, and molecularly imprinted polymers. The scope extends from fundamental selection criteria and binding mechanisms to advanced optimization strategies, performance validation, and comparative analysis. By synthesizing current research and future trajectories, this review serves as a critical resource for the strategic selection and development of biorecognition elements to advance biosensor technology for environmental and food safety monitoring.

The Building Blocks of Specificity: Understanding Biorecognition Elements

Defining Biorecognition Elements and Their Role in Biosensor Architecture

In the evolving landscape of analytical science, biosensors have emerged as powerful diagnostic tools that seamlessly integrate biological recognition with physicochemical detection [1] [2]. The architectural foundation of any biosensor rests upon two critical components: a biorecognition element responsible for target specificity, and a transducer that converts the biological binding event into a quantifiable signal [3] [2]. This biological element, often termed a "bioreceptor" or "biorecognition element," provides the molecular intelligence that enables the sensor to identify and capture specific analytes within complex sample matrices [4].

Within the specific domain of pesticide detection, the strategic selection and implementation of biorecognition elements has transformed monitoring capabilities, moving analysis from centralized laboratories to field-deployable systems [5] [6]. This technical guide examines the core principles, operational mechanisms, and practical implementation of biorecognition elements, with particular emphasis on their architectural role in constructing robust pesticide biosensors for environmental and food safety applications.

Core Principles and Classification of Biorecognition Elements

Biorecognition elements are biological or biomimetic molecules that exhibit specific, high-affinity binding to target analytes [3]. The quality of the interaction between the biorecognition element and its target dictates the fundamental performance characteristics of the resulting biosensor, including its sensitivity, specificity, and operational stability [3] [7]. These elements can be broadly categorized into three classes based on their origin: natural, synthetic, and pseudo-natural modalities [3].

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Major Biorecognition Element Classes

| Biorecognition Element | Classification | Binding Mechanism | Primary Target(s) | Key Advantage | Inherent Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antibodies [3] | Natural | 3D structural complementarity, immunocomplex formation | Proteins, peptides, small molecules, cells [4] | High specificity and affinity | Animal production required; costly and time-consuming to develop [3] |

| Enzymes [3] [6] | Natural | Catalytic conversion of substrate; inhibition by analyte | Substrates, inhibitors (e.g., organophosphates) [6] | Signal amplification via catalysis | Stability issues; susceptible to environmental conditions [3] |

| Nucleic Acids [3] [4] | Natural | Watson-Crick base pairing | Complementary DNA/RNA sequences [3] | High predictability and design flexibility | Limited to nucleic acid targets [3] |

| Aptamers [3] | Pseudo-natural | 3D structure-mediated binding (via SELEX selection) | Ions, small molecules, proteins, whole cells [3] | Synthetic production; thermal stability | SELEX discovery process can be costly [3] |

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) [3] | Synthetic | Templated cavities with structural memory | Small molecules, pesticides [5] | High stability and tunability | Complex optimization of polymer chemistry [3] |

The operational mechanism varies significantly across these classes. Affinity-based sensors (e.g., using antibodies, aptamers, or nucleic acids) generate a signal when the binding event itself occurs, often monitored through changes in mass, refractive index, or electrical properties [3] [2]. In contrast, catalytic sensors (e.g., using enzymes) detect the products of a catalytic reaction, typically monitored via electrochemical or optical transducers [3] [6]. The choice between these mechanisms is application-dependent, with catalytic systems offering inherent signal amplification, while affinity-based systems typically provide broader target range [3].

Biorecognition Elements in Pesticide Biosensing

The application of biosensors for pesticide detection represents a paradigm shift from conventional chromatographic methods, which despite their precision, require sophisticated instrumentation, extensive sample preparation, and are ill-suited for field deployment [5] [8]. Biorecognition-based sensors address these limitations by offering rapid, sensitive, and potentially portable analytical capabilities [5] [6].

Enzyme-Based Recognition for Neurotoxic Insecticides

Enzymes serve as particularly relevant biorecognition elements for detecting neurotoxic pesticides, especially organophosphates (OPs) and carbamates (CBs), which function by inhibiting the enzyme acetylcholinesterase (AChE) in nervous tissues [5] [6]. An AChE-based biosensor reproduces this inhibition mechanism in vitro, where the percentage of enzyme inhibition correlates directly to the concentration of the neurotoxic insecticide present in the sample [6].

The experimental protocol typically involves:

- Immobilization: AChE is immobilized onto a transducer surface (e.g., an electrode) using methods such as adsorption, covalent attachment, or entrapment within a polymer matrix [6].

- Baseline Measurement: The enzymatic activity is measured by introducing a substrate, typically acetylcholine. The enzymatic conversion produces electroactive or colored products, establishing a baseline signal [6].

- Inhibition Phase: The sensor is exposed to the sample containing the pesticide. OP or CB compounds inhibit AChE, reducing its catalytic activity.

- Signal Measurement: The substrate is reintroduced, and the decreased signal (current or absorbance) is measured relative to the baseline. The signal reduction is proportional to the pesticide concentration [6].

To overcome the limitation of detecting only total inhibition rather than specific compounds, researchers have developed sophisticated arrays using AChE from different biological sources or genetically engineered mutants with varying sensitivities to specific insecticides [6]. These arrays, when coupled with chemometric tools like artificial neural networks (ANNs) or partial least squares (PLS), enable the discrimination and simultaneous quantification of multiple insecticides in a mixture, such as paraoxon and carbofuran [6].

Antibodies and Aptamers for Specific Pesticide Recognition

Immunosensors and aptasensors leverage the high specificity of antibodies and aptamers, respectively, for direct pesticide capture. These are affinity-based sensors where the binding event itself is transduced into a signal [3] [9].

For antibody-based detection (immunosensors), the protocol generally follows these steps:

- Surface Preparation: A solid surface (e.g., gold for SPR, electrode for electrochemical detection) is functionalized.

- Antibody Immobilization: Specific monoclonal or polyclonal antibodies against the target pesticide (e.g., atrazine, acetamiprid) are immobilized on the functionalized surface [1] [8].

- Blocking: The surface is treated with a blocking agent (e.g., bovine serum albumin) to minimize non-specific adsorption from the sample matrix [2].

- Sample Incubation: The sample is introduced. The target pesticide (antigen) binds to the immobilized antibody, forming an immunocomplex.

- Signal Transduction: The formation of the immunocomplex alters the physical properties at the sensor interface. In electrochemical sensors, this change affects electron transfer, measurable as a change in current (amperometry), potential (potentiometry), or impedance (impedimetry) [1] [7]. In optical sensors like Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR), the binding causes a change in the refractive index, leading to a shift in the resonance angle [5] [2].

Aptamer-based sensors follow a similar workflow but use synthetic oligonucleotides selected through the SELEX process. Aptamers against pesticides like acetamiprid and atrazine have been successfully isolated and deployed in both electrochemical and optical platforms [3] [9]. A key advantage is the ability to design aptamer sequences that undergo conformational changes upon target binding, which can be directly linked to signal generation [3].

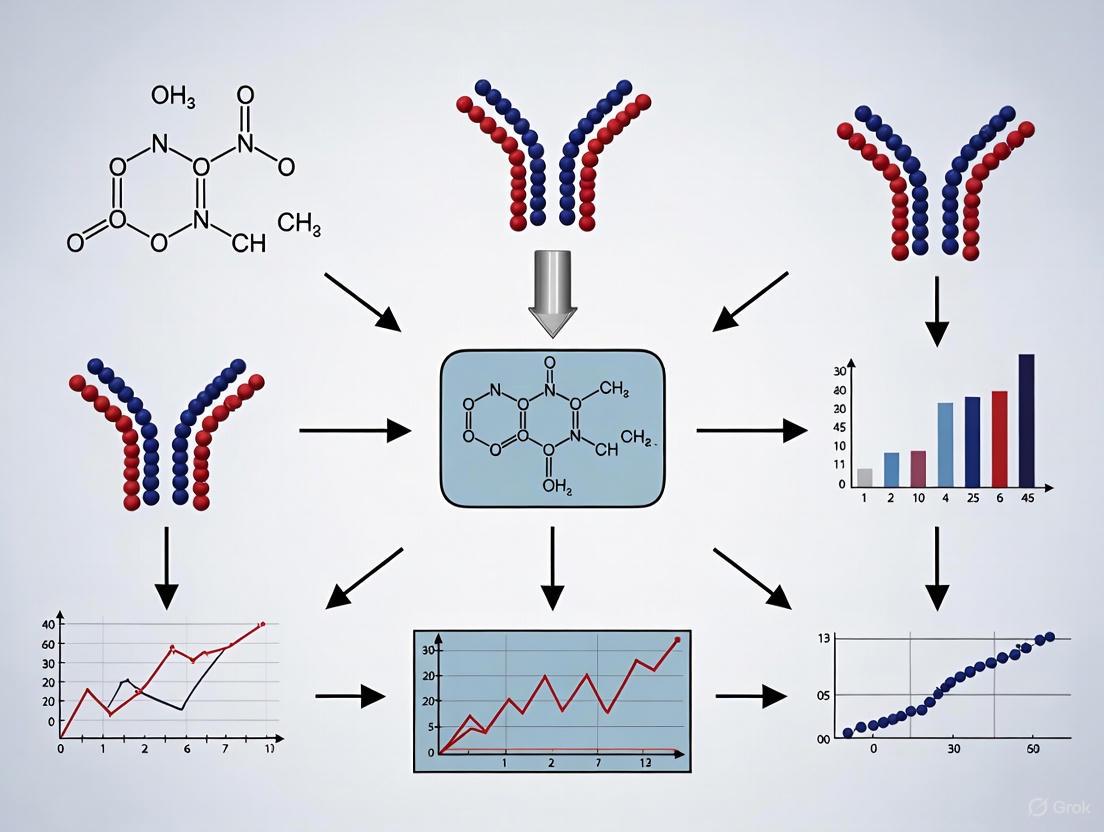

Diagram 1: Biosensor assembly and signal transduction workflows.

Advanced Architectures and Emerging Trends

Biorecognition-Element-Free Sensors

A frontier in biosensing involves developing sensors that forego traditional biorecognition elements. These platforms rely on the intrinsic physical or electrochemical properties of nanomaterials that undergo measurable changes upon interaction with target pesticides [5] [10]. For instance, nanoparticles can be functionalized to undergo aggregation in the presence of a specific pesticide, resulting in a visible color change detectable by colorimetric methods [5]. Similarly, gold interdigitated microelectrodes (IDμE) can directly measure changes in the impedance or capacitance of a sample solution caused by the presence of bacterial cells or other analytes, without any immobilized biorecognition layer [10]. While these approaches can simplify sensor fabrication and enhance stability, a significant challenge remains in achieving high selectivity in complex sample matrices without a specific capture element [5].

Integration with Advanced Transduction Platforms

The performance of a biorecognition element is profoundly influenced by its integration with the transducer. Nanomaterials have been pivotal in this regard, enhancing sensitivity by increasing the surface area for immobilization and facilitating electron transfer in electrochemical sensors [5] [1]. A prominent example is the integration of biorecognition elements with Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS). SERS provides exceptional sensitivity through massive signal amplification of Raman scattering from molecules adsorbed on plasmonic nanostructures. By functionalizing SERS substrates with antibodies or aptamers, the platform gains the required specificity, creating a powerful SERS biosensor that can detect trace levels of pesticides with fingerprint identification capability [9].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Biosensor Development

| Reagent / Material | Function in Biosensor Assembly | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) [5] [9] | Signal amplification; Colorimetric reporter; SERS substrate; Electrode modifier | Colorimetric aggregation assays; SERS biosensor platforms [5] |

| Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) [6] | Biorecognition element for organophosphate/carbamate pesticides | Enzyme inhibition-based electrochemical sensors [6] |

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) [5] [3] | Synthetic bioreceptor with templated cavities for target capture | Label-free sensors for small molecule pesticides [5] |

| Aptamers (selected via SELEX) [3] | Synthetic oligonucleotide bioreceptor with high affinity and stability | Electrochemical or optical aptasensors for acetamiprid, atrazine [3] |

| Monoclonal Antibodies [4] [8] | High-specificity capture agent for immunoassays | Immunosensors for pyrethroids, atrazine [8] |

| Carbon Nanotubes / Graphene [5] | Electrode nanomaterial for enhanced electron transfer and surface area | Nanocomposite-based electrochemical biosensors [5] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Experimental Considerations

Immobilization Strategies

The method used to tether the biorecognition element to the transducer surface is critical for biosensor performance. Immobilization must preserve the biological activity of the element while ensuring stability over repeated uses [2]. Common techniques include:

- Adsorption: Physical attachment based on hydrophobic or ionic interactions. Simple but can lead to leaching and unstable coatings [2].

- Covalent Binding: Chemical linkage to activated surface groups (e.g., via amine, carboxyl, or thiol functionalities). Provides stable, oriented immobilization but requires more complex surface chemistry [3] [2].

- Entrapment: Encapsulation within a polymer matrix (e.g., silica sol-gel, conducting polymers). Protects the bioreceptor but can introduce diffusion barriers [6].

- Affinity Binding: Use of high-affinity pairs like biotin-streptavidin. Allows for controlled, oriented immobilization [3].

Troubleshooting and Pitfall Management

Translating biosensor theory into reliable laboratory practice requires awareness of common challenges [2]:

- Biological Stability: Antibodies and enzymes can denature over time. Mitigation strategies include careful storage, use of stabilizing additives, or employing more robust synthetic receptors like aptamers or MIPs [3].

- Matrix Interference: Complex samples like food extracts or soil suspensions can cause non-specific binding and signal fouling. The use of blocking agents, sample dilution, or pre-filtration steps is often necessary [2].

- Sensor Drift: Gradual signal change over time due to bioreceptor degradation or environmental fluctuations. Regular recalibration against reference standards is essential [2].

- Reproducibility: Achieving consistent fabrication across multiple sensors is challenging. Automation of immobilization steps and rigorous characterization of nanomaterials can improve batch-to-batch consistency [3].

Biorecognition elements constitute the foundational intelligence of a biosensor, defining its analytical specificity and enabling the detection of target pesticides amidst complex environmental and food matrices. The architectural integration of these elements—from classical enzymes and antibodies to emerging aptamers and synthetic MIPs—with advanced transduction platforms and nanomaterials, continues to push the boundaries of sensitivity, portability, and multiplexing capabilities. Future developments will likely focus on harnessing artificial intelligence for data analysis, creating more robust and stable synthetic bioreceptors, and engineering fully integrated, miniaturized systems for real-time, on-site monitoring across the entire "farm-to-fork" continuum. The strategic selection and optimization of the biorecognition element remain, therefore, the most critical step in the design of effective biosensor architectures for pesticide detection and beyond.

Biorecognition elements (BREs) are the cornerstone of biosensor technology, conferring specificity and selectivity by interacting with target analytes. In the specific field of pesticide biosensors, the choice of BRE directly dictates the sensor's performance, including its sensitivity, stability, and applicability in complex matrices. The evolution of these elements from natural biological molecules to sophisticated synthetic constructs has significantly advanced the capabilities of modern biosensing platforms. This guide provides a comprehensive technical overview of the major BRE classes, framing their principles, performance, and practical implementation within pesticide detection research. The continuous innovation in this domain, from the refinement of natural molecules to the rational design of fully synthetic systems, is paving the way for a new generation of robust, field-deployable analytical tools for environmental and food safety monitoring [4].

Foundational Classes of Biorecognition Elements

The performance of a biosensor is fundamentally linked to the properties of its biorecognition element. The following sections detail the core classes of BREs, with their operational mechanisms, strengths, and limitations summarized in Table 1 for direct comparison.

Table 1: Core Biorecognition Element Classes in Pesticide Biosensors

| Biorecognition Element | Recognition Principle | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Example Pesticide Targets |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enzymes | Catalytic activity or inhibition | High catalytic turnover; well-established immobilization protocols; reusable | Susceptible to denaturation; limited by inherent enzyme stability; can be inhibited non-specifically | Organophosphates, Carbamates [11] [12] |

| Antibodies | Affinity-based binding (Antigen-Antibody) | Exceptional specificity and high affinity; wide range of available targets | Susceptible to permanent binding; large size can limit density; animal-derived production | Pyrethroids, Herbicides [8] [9] |

| Nucleic Acid Aptamers | 3D structure-complementary binding | Synthetic production; small size for high density; stability across temperatures | Susceptible to nuclease degradation; complex, expensive selection process (SELEX) | Various chemical classes [4] [9] |

| Engineered Whole Cells | Cellular response (e.g., transcription factor activation) | Can detect bioavailable fractions; provide toxicity data; inherently amplified signals | Longer response times; complex maintenance and storage; less specific for single compounds | Heavy metals, Broad-spectrum toxins [13] [14] |

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) | Shape-complementary cavities in a synthetic polymer | High physical/chemical robustness; reusable; no biological source required | Challenging elution of template molecules; can suffer from heterogeneity | Customizable for various pesticides [4] |

Natural and Bio-Derived Elements

Enzymes: Enzymes are among the most traditional BREs. Their application in pesticide detection often relies on inhibition-based mechanisms. For instance, acetylcholinesterase (AChE) and organophosphorus hydrolase (OPH) are widely used for detecting organophosphorus (OP) and carbamate pesticides. AChE-based sensors operate on the principle that the target pesticide inhibits the enzyme's activity, reducing the catalytic conversion of its substrate and leading to a measurable decrease in signal (e.g., amperometric or colorimetric) [11]. In contrast, OPH-based sensors utilize a direct catalytic mechanism, where OPH hydrolyzes specific OP compounds, generating a detectable product [11]. The main challenges include the inherent instability of enzymes under operational conditions and potential interference from other cholinesterase-inhibiting chemicals in complex samples.

Antibodies: Antibodies, particularly monoclonal and recombinant antibodies, offer exquisite specificity for a single pesticide or a closely related group. This makes them ideal for immunosensors and immunoassays, such as enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) and immunochromatographic test strips (ICTS) [8] [4]. The high affinity of the antibody-antigen interaction allows for very low detection limits. However, their production can be costly, they are susceptible to irreversible binding, and their performance can be compromised in harsh environmental conditions (e.g., extreme pH or temperature) [4].

Synthetic and Engineered Elements

Nucleic Acid Aptamers: Aptamers are single-stranded DNA or RNA oligonucleotides selected in vitro through the Systematic Evolution of Ligands by EXponential enrichment (SELEX) process to bind specific targets with high affinity. They are often called "synthetic antibodies" but offer distinct advantages: they are chemically synthesized, providing excellent batch-to-batch reproducibility, and are generally more stable than proteins [4] [9]. Their small size allows for high-density immobilization on sensor surfaces. Aptamers can undergo conformational changes upon target binding, which can be transduced into a signal, making them versatile for various biosensor platforms [9].

Whole-Cell Biosensors: These systems use living microorganisms (e.g., bacteria, yeast) engineered with synthetic gene circuits to detect target analytes. Upon exposure to a specific pesticide or class of pesticides, a cellular response is triggered, such as the activation of a promoter linked to a reporter gene (e.g., for green fluorescent protein (GFP) or luciferase) [13] [14]. This approach is valuable for assessing the cumulative toxicity or bioavailable fraction of a sample. A key advancement is their integration into Engineered Living Materials (ELMs), where cells are encapsulated in hydrogels or other polymers, enhancing their stability and practicality for field use [14].

Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs): MIPs are fully synthetic polymeric materials that contain tailor-made recognition sites complementary in shape, size, and functional groups to a target molecule (the "template"). After synthesizing the polymer around the template, the template is removed, leaving behind cavities that can selectively rebind the target analyte [4]. MIPs are highly robust, capable of withstanding extreme pH, temperature, and organic solvents, making them suitable for harsh environmental sampling. Their primary challenge is achieving the same level of specificity and binding affinity as biological receptors.

Experimental Protocols for BRE Development and Integration

To illustrate the practical application of these BREs, detailed protocols for key experimental procedures are provided below.

Protocol: SELEX for Aptamer Selection against a Pesticide Target

This protocol outlines the process for selecting a specific DNA aptamer capable of binding to a target pesticide, such as a common organophosphate [4] [9].

- Library Preparation: Begin with a synthetic single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) library containing a central random sequence region (e.g., 40 nucleotides) flanked by constant primer binding sites.

- Incubation with Immobilized Target: Immobilize the target pesticide molecule on a solid support (e.g., sepharose beads or a microplate). Incubate the ssDNA library with the immobilized target in a binding buffer to allow for the formation of target-aptamer complexes.

- Partitioning and Washing: Remove unbound and weakly bound DNA sequences through extensive washing with the binding buffer.

- Elution of Bound Sequences: Elute the specifically bound DNA sequences from the target. This can be achieved by denaturing the complex, for example, by using a high-temperature incubation or an elution buffer containing a high concentration of the free target molecule to compete for binding.

- Amplification: Amplify the eluted DNA sequences using the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with primers corresponding to the constant regions.

- Generation of ssDNA Library for Next Round: Convert the double-stranded PCR product back into a single-stranded DNA library, ready for the next selection round.

- Repetition and Counter-SELEX: Repeat steps 2-6 for 8-15 rounds, progressively increasing the selection stringency (e.g., by increasing wash stringency or incorporating counter-SELEX steps with non-target molecules to eliminate cross-reactive binders).

- Cloning and Sequencing: After the final round, clone the enriched DNA pool and sequence individual clones to identify the dominant aptamer sequences.

- Characterization: Chemically synthesize the identified aptamer candidates and characterize their affinity (dissociation constant, Kd) and specificity against structurally similar pesticides.

Protocol: Development of an Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) Inhibition Biosensor

This protocol details the construction of an electrochemical biosensor for detecting organophosphate and carbamate pesticides based on AChE inhibition [11] [15].

- Electrode Modification: Prepare the working electrode (e.g., glassy carbon or screen-printed carbon electrode). To enhance sensitivity, the electrode surface may be modified with nanomaterials such as carbon nanotubes or gold nanoparticles to increase the electroactive surface area and facilitate electron transfer.

- Enzyme Immobilization: Immobilize AChE onto the modified electrode surface. This can be achieved through cross-linking with glutaraldehyde, entrapment within a polymer matrix (e.g., Nafion or chitosan), or physical adsorption.

- Baseline Signal Measurement: Place the modified electrode in an electrochemical cell containing a buffer solution with a known concentration of the enzyme's substrate, acetylthiocholine. Measure the amperometric current generated by the enzymatic reaction. The product, thiocholine, is oxidized at the electrode surface, producing a measurable baseline current (I₀).

- Inhibition (Sample Assay): Incubate the biosensor with a sample solution suspected to contain the pesticide inhibitor for a fixed period (e.g., 10-15 minutes).

- Post-Inhibition Signal Measurement: After incubation, wash the electrode and measure the amperometric current (Iᵢ) again under the same conditions as in step 3.

- Quantification: The degree of enzyme inhibition is calculated as a percentage: Inhibition (%) = [(I₀ - Iᵢ) / I₀] × 100. This percentage is then correlated with the concentration of the inhibiting pesticide in the sample using a pre-established calibration curve.

Protocol: Constructing a Whole-Cell Biosensor in a Hydrogel ELM

This protocol describes the encapsulation of an engineered bacterial biosensor within a hydrogel to create a stable material for pesticide detection [14].

- Genetic Circuit Engineering: Genetically engineer a bacterial strain (e.g., E. coli or B. subtilis) to contain a sensing module. This typically involves a promoter that is activated by a specific stress response (e.g., oxidative stress from herbicides) or directly by a transcription factor that binds the target pesticide. This promoter is fused to a reporter gene, such as gfp (green fluorescent protein).

- Cell Culture and Preparation: Grow the engineered bacteria to the mid-logarithmic phase. Harvest the cells by centrifugation and resuspend them in a sterile buffer or nutrient-poor medium to arrest growth.

- Hydrogel Precursor Preparation: Prepare a sterile solution of the hydrogel precursor. Common materials include alginate, agarose, or synthetic polymers like polyacrylamide.

- Cell-Polymer Mixing: Gently mix the concentrated bacterial suspension with the hydrogel precursor solution to achieve a homogeneous cell-polymer mixture.

- Polymerization/Casting: Induce gelation to form the ELM. For alginate, this is done by extruding the mixture into a solution containing calcium ions (e.g., CaCl₂) to form stable cross-linked beads or films. For thermosensitive polymers like agarose, gelation occurs upon cooling.

- Sensor Validation and Use: Validate the sensor by exposing the ELM to samples with known concentrations of the target pesticide. The cellular response, typically fluorescence, can be quantified using a plate reader, microscope, or a portable fluorometer. The stability of the sensor can be assessed by monitoring its response over days or weeks under storage conditions.

The logical workflow for developing and applying these biosensors, from design to readout, is visualized in the following diagram.

Advanced Sensing Mechanisms and Characterization

Integration with Advanced Transduction Platforms

The performance of a BRE is fully realized through its integration with a sensitive transducer. Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS) platforms exemplify this synergy. In a typical SERS biosensor, a BRE like an aptamer or antibody is immobilized on a plasmonic nanostructure (e.g., gold or silver nanoparticles). When the BRE captures the target pesticide, it brings the molecule into the "hot spots" of the nanostructure, resulting in a dramatic enhancement of its characteristic Raman signal, allowing for fingerprint identification and ultra-sensitive detection, potentially down to single-molecule levels [9]. This combination provides the specificity of the BRE with the exceptional sensitivity and rich spectroscopic information of SERS.

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Rigorous characterization of BRE-based biosensors is essential. Key performance metrics are consolidated in Table 2 below, providing a benchmark for comparing sensor efficacy as reported in recent literature.

Table 2: Representative Performance Metrics of Biosensors Using Different Biorecognition Elements

| Biorecognition Element | Transduction Method | Target Pesticide | Limit of Detection (LOD) | Linear Range | Reference Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) | Electrochemical (Amperometric) | Organophosphates / Carbamates | pM - nM range | Up to 4-5 orders of magnitude | Inhibition-based soil/water screening [11] [15] |

| Antibody | Immunochromatographic Test Strip (ICTS) | Various (e.g., Pyrethroids) | ~ ng/mL range | Visual and semi-quantitative | Rapid on-site tea leaf testing [8] |

| Aptamer | Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering (SERS) | Specific chemical classes | fM - pM range | Wide dynamic range | Highly sensitive multi-residue detection [9] |

| Organophosphate Hydrolase (OPH) | Electrochemical (Potentiometric) | Organophosphates | ~ 1 × 10⁻¹¹ μM (reported) | Not specified | Direct catalytic detection [11] |

| Engineered Whole Cell | Optical (Fluorescence) | Broad-spectrum stressors | Compound-dependent | Variable, based on promoter | Toxicity assessment in water [14] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The development and deployment of pesticide biosensors require a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The following table lists key components and their functions as derived from the reviewed research.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Biosensor Research

| Item Name | Function / Application in Research | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) | Core biorecognition element for inhibition-based detection of OPs and carbamates. | Source (electric eel, human recombinant) and purity significantly impact sensitivity and stability [11]. |

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | Signal amplification and labeling; component of SERS substrates and electrochemical transducers. | Functionalized with BREs (antibodies, aptamers); size and shape tune plasmonic properties [13] [9]. |

| Screen-Printed Electrodes (SPEs) | Disposable, miniaturized electrochemical cells for portable biosensor development. | Enable low-cost, mass-produced sensor platforms for field testing [11] [15]. |

| SELEX Kit | In vitro selection of high-affinity DNA/RNA aptamers against target pesticide molecules. | Streamlines the complex and iterative process of aptamer development [4] [9]. |

| Alginate Hydrogel | Biopolymer for encapsulating and protecting whole-cell biosensors in ELMs. | Forms a biocompatible, porous matrix via ionic cross-linking with Ca²⁺ [14]. |

| CRISPR-Cas System (e.g., Cas12a, Cas13a) | Provides nucleic acid detection with single-base specificity; used for signal amplification. | Enables ultrasensitive, amplification-free detection when combined with aptamers or other BREs [16]. |

| Plasmonic Nanostructures | Form the core of SERS biosensors, generating intense electromagnetic fields for signal enhancement. | Typically made of gold or silver; geometry (nanorods, nanostars) is critical for performance [9]. |

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymer (MIP) Pre-polymerization Mix | Synthetic cocktail for creating biomimetic recognition sites for target pesticides. | Contains functional monomers, cross-linkers, and the template (pesticide) molecule [4]. |

The landscape of biorecognition elements for pesticide biosensors is rich and diverse, spanning from highly specific natural molecules to robust, designable synthetic systems. Each class of BRE—enzymes, antibodies, aptamers, whole cells, and MIPs—offers a unique set of advantages and constraints, making them suitable for different application scenarios. The ongoing convergence of synthetic biology, nanotechnology, and materials science is pushing the boundaries of what is possible, leading to the development of intelligent, portable, and highly sensitive biosensing platforms. Future research will likely focus on enhancing the stability and reusability of BREs in real-world environments, developing multi-analyte detection systems, and seamlessly integrating these sensors with data analytics and decision-support systems to create a truly responsive and sustainable agri-food monitoring network.

In the realm of pesticide biosensors, analyte selectivity is the cornerstone of reliable detection. This specificity is governed by the biorecognition element, a biological or biomimetic component that selectively interacts with a target pesticide, and the transduction mechanism that converts this binding event into a measurable signal [5] [17]. The choice and engineering of this biorecognition layer directly determine the sensor's performance, including its sensitivity, robustness, and applicability in complex matrices like food and environmental samples [18]. This guide examines the fundamental binding mechanisms and design principles that underpin selectivity, providing a technical framework for researchers and scientists developing next-generation biosensing platforms. Within the broader thesis on biorecognition elements, understanding these core principles is essential for innovating beyond traditional methods and addressing the limitations of conventional chromatography-based techniques [19] [8].

Fundamental Binding Mechanisms

The selective capture of target analytes by biorecognition elements is driven by a combination of structural compatibility and intermolecular forces. The following diagram illustrates the core binding interactions and signal transduction pathways common across different biosensor platforms.

The high-affinity binding between a biorecognition element and its target pesticide is stabilized by a synergistic combination of several non-covalent interactions [18]:

- Hydrogen Bonding: Directional interactions between hydrogen atoms bound to electronegative atoms (like N or O) and other electronegative atoms. Crucial for orienting the target within the binding pocket.

- Electrostatic Interactions: Attractive forces between oppositely charged ionic groups on the bioreceptor and the pesticide molecule (e.g., between a carboxylate and an ammonium group).

- van der Waals Forces: Weak, non-specific attractive forces that become significant when the shapes of the bioreceptor and target are highly complementary, maximizing surface contact.

- Hydrophobic Effects: The driving force that sequesters non-polar regions of the pesticide away from the aqueous environment and into hydrophobic pockets of the bioreceptor.

- π-π Stacking: Interactions between aromatic rings in the bioreceptor (e.g., nucleobases in an aptamer) and aromatic structures in certain pesticides.

The specific combination and relative contribution of these forces vary with the biorecognition element and the target's chemical structure, ultimately defining the selectivity profile of the biosensor.

Biorecognition Elements and Their Selectivity

The core of a biosensor's selectivity lies in its biorecognition element. The table below provides a comparative overview of the four primary types used in pesticide detection.

Table 1: Key Biorecognition Elements in Pesticide Biosensors

| Biorecognition Element | Origin & Composition | Primary Mechanism for Selectivity | Typical Targets (Pesticides) | Key Advantages | Inherent Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aptamers [18] | Synthetic single-stranded DNA/RNA (ssDNA, RNA); 25-90 bases. | Folding into unique 3D structures that form binding pockets; selectivity via SELEX in vitro. | Carbendazim, Thiamethoxam, Acetamiprid [18] [8] | High thermal/chemical stability; small size for high density; reusability; modifiable with functional groups. | In vitro selection (SELEX) can be complex; susceptibility to nuclease degradation (RNA). |

| Antibodies [5] [17] | Immunoglobulins (e.g., IgG); produced in vivo. | Molecular recognition via the paratope (antigen-binding site); high-affinity lock-and-key fit. | Pyrethroids, Organophosphates (e.g., Malathion) [18] [8] | Exceptional specificity and high affinity; well-established conjugation protocols. | Susceptible to denaturation in harsh conditions; batch-to-batch variation; animal use required for production. |

| Enzymes [5] [17] | Proteins (e.g., Acetylcholinesterase, AChE). | Catalytic activity inhibition or activation by the target; specificity for the enzyme's active site. | Organophosphates, Carbamates [5] [19] | Natural catalytic amplification; direct functional readout (inhibition). | Limited to enzyme-inhibiting pesticides; stability issues over time. |

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) [5] [20] | Synthetic polymers with tailor-made cavities. | Shape complementarity and chemical functionality memory from the polymerization process. | Various, depending on the template molecule used [5] | High robustness in extreme pH/temperature; cost-effective production; long shelf-life. | Challenges with template leakage; sometimes lower affinity compared to biological elements. |

Experimental Protocols for Evaluating Selectivity

Rigorous experimental validation is required to confirm a biosensor's specificity. The following workflow outlines a standard protocol for selectivity assessment, particularly for an electrochemical aptasensor.

Detailed Protocol: Selectivity Testing for an Electrochemical Aptasensor

This protocol details the steps to confirm that an aptamer-based sensor specifically binds its target pesticide (e.g., carbendazim) and minimizes response to interfering substances.

1. Bioreceptor Immobilization:

- Functionalization: Prepare a gold disk working electrode by cleaning via polishing and electrochemical cycling. Incubate with a 2 mM solution of 6-mercapto-1-hexanol (MCH) in ethanol for 1 hour to form a self-assembled monolayer (SAM) [18].

- Immobilization: Inject a solution of thiol-modified DNA aptamer (e.g., 1 µM in Tris-EDTA buffer with Mg²⁺) onto the MCH-modified electrode. Allow 16 hours for covalent Au-S bond formation. Rinse thoroughly to remove physically adsorbed strands [18].

2. Baseline Signal Acquisition:

- Using a potentiostat, perform Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) in a 5 mM [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻ redox solution.

- Record the charge transfer resistance (Rₑₜ) as the baseline signal before analyte introduction [18].

3. Target Analyte Exposure:

- Incubate the functionalized electrode with the target pesticide (carbendazim) at a known concentration (e.g., 1 nM in a suitable buffer) for a fixed time (e.g., 30 minutes).

- Rinse the electrode gently to remove unbound molecules.

4. Specificity Test (Interferents):

- Repeat Step 3 independently using a suite of potential interferents. These should include:

- Structurally similar pesticides (e.g., thiabendazole for a carbendazim sensor).

- Pesticides of different classes commonly found in the sample matrix (e.g., organophosphates like chlorpyrifos).

- Common ions (e.g., K⁺, Ca²⁺, NO₃⁻).

- For complex samples like tea, include matrix components like tea polyphenols and catechins [8].

5. Signal Measurement & Analysis:

- After each incubation (target and each interferent), perform EIS again under identical conditions and record the new Rₑₜ value.

- Calculate the signal change (e.g., ΔRₑₜ = Rₑₜ(after) - Rₑₜ(baseline)).

- Quantify selectivity by calculating a selectivity coefficient (k) for each interferent (I) relative to the target (T): k = ΔRₑₜ(I) / ΔRₑₜ(T). A sensor is highly selective for the target when k << 1 for all interferents.

6. Regeneration Test (Optional for Reusability):

- To test aptamer reversibility, expose the sensor to a regeneration buffer (e.g., 1 mM NaOH or a solution with EDTA) for 1-2 minutes to dissociate the bound target.

- Re-measure the EIS signal in the redox solution. A return to the baseline Rₑₜ value indicates successful regeneration and aptamer stability [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The development and fabrication of selective biosensors rely on a suite of specialized reagents and materials.

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for Biosensor Development

| Item | Function/Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Gold Nanoparticles (Au NPs) [5] [20] | Signal amplification; enhance electron transfer in electrochemical sensors; used in colorimetric and SERS-based sensors. | Functionalized with thiolated aptamers or antibodies. High conductivity and tunable optical properties. |

| Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) [18] | Increase electrode surface area; improve electron transfer kinetics in electrochemical aptasensors. | Can be single-walled (SWCNT) or multi-walled (MWCNT). |

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) [5] [20] | Synthetic bioreceptors; provide robust, stable recognition cavities for pesticides in harsh environments. | Created using a template (target pesticide), functional monomers, and a cross-linker. |

| Thiol Linkers (e.g., MCH) [18] | Form self-assembled monolayers (SAMs) on gold surfaces; orient and stabilize immobilized aptamers; reduce non-specific binding. | Creates a well-ordered interface crucial for consistent sensor performance. |

| Methylene Blue[ [18]] | Electroactive label; often tethered to aptamers in "signal-on" or "signal-off" electrochemical sensors. | Redox behavior changes upon aptamer folding/target binding. |

| Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs, e.g., MOF-808) [18] | Porous nanomaterials; used to immobilize bioreceptors and pre-concentrate target analytes, boosting sensitivity. | High surface area and modular chemistry. |

| Streptavidin/Biotin System [18] | High-affinity coupling; used to immobilize biotinylated aptamers or antibodies onto sensor surfaces. | Provides a stable and oriented immobilization method. |

| Systematic Evolution of Ligands by EXponential enrichment (SELEX) Kits [18] | In vitro selection of high-affinity aptamers against specific pesticide targets. | The foundational process for generating new DNA/RNA recognition elements. |

The path to achieving high selectivity in pesticide biosensors is multifaceted, relying on a deep understanding of intermolecular binding forces, the strategic selection and engineering of biorecognition elements, and rigorous experimental validation against realistic interferents. The ongoing convergence of nanotechnology, materials science, and synthetic biology promises to yield even more robust and specific sensing platforms. Future advancements will likely involve the rational design of aptamers with pre-defined binding pockets, the creation of more sophisticated MIPs, and the integration of AI to guide material selection and optimize sensor design [20]. These innovations will be critical for meeting the growing demand for rapid, on-site detection of pesticide residues, thereby strengthening global food safety and environmental monitoring protocols.

Biosensors are analytical devices that integrate a biological recognition element with a transducer to produce a signal proportional to the concentration of a target analyte [21]. The performance of these devices, particularly in the critical field of pesticide detection, is governed by a set of core metrics that determine their reliability and applicability in real-world scenarios [8] [22]. Within pesticide biosensors research, the choice of biorecognition element—be it enzymes, antibodies, aptamers, or whole cells—fundamentally influences these performance parameters [17] [23]. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of the four cornerstone biosensor performance metrics, with specific emphasis on their interplay with biorecognition elements in pesticide detection platforms. The optimization of these metrics is paramount for transitioning laboratory prototypes into robust field-deployable tools for environmental monitoring, food safety, and public health protection [8] [23].

Core Performance Metrics: Definitions and Significance

The analytical performance of biosensors is quantified through standardized figures of merit. These metrics provide objective criteria for evaluating and comparing different biosensing platforms, guiding the development process, and establishing confidence in the generated data [24]. For pesticide biosensors, stringent performance standards are essential due to the low regulatory limits and complex sample matrices involved [8] [23].

Table 1: Core Performance Metrics for Biosensors

| Metric | Technical Definition | Significance in Pesticide Detection |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | Slope of the analytical calibration curve; the minimum amount of analyte that can be reliably detected [21] [24]. | Determines capability to detect trace pesticide residues at regulatory levels (often ng/mL or lower) [21] [8]. |

| Selectivity | Ability of a bioreceptor to detect a specific analyte in samples containing admixtures and contaminants [21] [24]. | Ensures accurate measurement despite interference from structurally similar pesticides or complex sample matrices (e.g., tea, soil) [8]. |

| Reproducibility | Closeness of agreement between measurements under different conditions (operators, apparatus, laboratories) [21] [24]. | Guarantees reliability across different testing scenarios and locations for regulatory compliance monitoring [21]. |

| Reusability | Ability of a biosensor to be regenerated and reused multiple times while maintaining performance. | Reduces cost-per-test and enables continuous monitoring applications; highly dependent on bioreceptor stability [22]. |

The Interplay Between Biorecognition Elements and Performance Metrics

The biological recognition component is the cornerstone of any biosensor, defining its fundamental interaction with target analytes. In pesticide detection, different classes of biorecognition elements offer distinct advantages and challenges that directly impact the core performance metrics [17].

Enzymes as Biorecognition Elements

Enzyme-based biosensors primarily operate on inhibition or catalytic principles. Enzymes such as acetylcholinesterase (AChE) are inhibited by organophosphorus and carbamate pesticides, enabling detection through measurable decreases in enzymatic activity [17]. Alternatively, some enzymes directly metabolize pesticides, with the catalytic transformation providing the measurable signal [17].

Impact on Performance:

- Sensitivity: Enzyme sensors can achieve high sensitivity due to catalytic amplification, but inhibition-based approaches may suffer from limited sensitivity against certain pesticide classes [22].

- Selectivity: A significant challenge as enzymes may be inhibited by multiple compounds, leading to false positives from sample matrices [8].

- Reproducibility: Subject to variability due to enzyme instability under different environmental conditions (pH, temperature) [21].

- Reusability: Generally low as enzyme inhibition is often irreversible, requiring fresh enzyme for each test [22].

Antibodies as Biorecognition Elements

Immunosensors exploit the high specificity of antigen-antibody interactions. Antibodies can be engineered for specific pesticide epitopes or classes, functioning in either label-free or labeled formats [17] [24].

Impact on Performance:

- Sensitivity: Excellent sensitivity with detection limits reaching pg/mL for some targets, suitable for trace pesticide detection [17].

- Selectivity: High specificity for target analytes, though cross-reactivity with structurally similar compounds can occur [8].

- Reproducibility: Generally good with monoclonal antibodies, though storage stability and batch-to-batch variability can affect performance [21].

- Reusability: Moderate; regeneration of antibody binding sites is possible but may gradually reduce binding capacity [22].

Aptamers as Biorecognition Elements

Aptamers are synthetic single-stranded DNA or RNA oligonucleotides selected through SELEX (Systematic Evolution of Ligands by Exponential Enrichment) to bind specific targets with high affinity [17]. They fold into specific three-dimensional structures upon target binding.

Impact on Performance:

- Sensitivity: Can achieve nM to pM detection limits, competitive with antibody-based systems [17].

- Selectivity: High specificity, capable of distinguishing between closely related pesticide analogs [8].

- Reproducibility: Excellent due to synthetic production with minimal batch-to-batch variation [17].

- Reusability: High; aptamers can undergo denaturation-renaturation cycles, allowing multiple regeneration cycles [22].

Whole Cells as Biorecognition Elements

Whole cell biosensors utilize microorganisms (bacteria, fungi, algae) as integrated sensing elements, typically employing metabolic activity, stress responses, or genetic regulation mechanisms [17] [23].

Impact on Performance:

- Sensitivity: Variable; some systems can detect pesticides at ng/mL levels, though generally less sensitive than molecular recognition elements [17].

- Selectivity: Often lower as cells may respond to multiple stressors; useful for class-level detection rather than specific compounds [23].

- Reproducibility: Challenging due to biological variability and maintenance requirements of living systems [17].

- Reusability: Moderate; cells can self-replicate but require careful maintenance of viability and consistent physiological state [17].

Table 2: Comparative Performance of Biorecognition Elements in Pesticide Biosensors

| Biorecognition Element | Sensitivity | Selectivity | Reproducibility | Reusability | Best Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enzymes | Moderate to High | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Broad-spectrum screening, inhibition-based detection |

| Antibodies | High | High | High | Moderate | Targeted, specific pesticide quantification |

| Aptamers | High | High | High | High | Reusable sensors, harsh environments |

| Whole Cells | Moderate | Low to Moderate | Low | Moderate | Toxicity assessment, class-level detection |

Methodologies for Performance Evaluation

Standardized experimental protocols are essential for reliable evaluation and cross-comparison of biosensor performance. This section details key methodologies for quantifying each core metric.

Sensitivity and Limit of Detection (LOD) Determination

Experimental Protocol:

- Prepare a dilution series of the target pesticide in appropriate buffer across at least 5-6 concentration points.

- For each concentration, measure the biosensor response in triplicate.

- Plot the mean response against pesticide concentration to generate a calibration curve.

- Fit the data using linear regression (y = mx + c, where y is signal, x is concentration).

- Calculate sensitivity as the slope (m) of the linear range.

- Determine LOD using the formula: LOD = 3.3 × σ/S, where σ is the standard deviation of the blank signal and S is the sensitivity [21] [24].

Key Considerations:

- Matrix-matched calibration is essential for real-sample analysis to account for matrix effects.

- The linear range defines the operational concentration window for quantitative analysis.

- For optical biosensors, LOD values for pesticides have been reported in the range of 10 fM to 1 nM, while electrochemical methods can achieve even lower detection limits in some cases [22].

Selectivity and Cross-Reactivity Assessment

Experimental Protocol:

- Test the biosensor response against the target pesticide at a fixed concentration (typically near the middle of the linear range).

- Under identical conditions, test the biosensor against potential interferents individually, including:

- Structurally similar pesticides

- Common environmental contaminants (heavy metals, PAHs)

- Matrix components (for tea sensors: polyphenols, caffeine, pigments) [8]

- Calculate cross-reactivity percentage for each interferent: (Signalinterferent/Signaltarget) × 100%.

- A selectivity coefficient <5% is generally acceptable for most applications [24].

Key Considerations:

- For antibody-based sensors, cross-reactivity profiling is particularly important due to potential recognition of similar epitopes.

- Aptamers generally exhibit lower cross-reactivity than antibodies for closely related compounds [17].

Reproducibility and Repeatability Evaluation

Experimental Protocol:

- Repeatability (intra-assay precision): Perform 10-20 replicate measurements of the same pesticide sample using a single biosensor in one session. Calculate the relative standard deviation (RSD).

- Reproducibility (inter-assay precision): Prepare multiple identical biosensors (n ≥ 5). Measure the same pesticide sample with each sensor on different days or by different operators. Calculate RSD across sensors.

- Intermediate precision: Assess variation between different batches of bioreceptor immobilization or different production lots.

Acceptance Criteria:

- For quantitative analysis, RSD should generally be <10-15% depending on application requirements [21] [24].

- Document all conditions (temperature, pH, sample preparation) that may contribute to variability.

Reusability and Stability Testing

Experimental Protocol:

- Operational stability: Perform repeated measurement-regeneration cycles with the same biosensor. After each measurement, regenerate according to the appropriate protocol:

- Plot the response versus cycle number to determine the maximum number of uses before signal degradation >10%.

- Storage stability: Store biosensors under recommended conditions and test performance at regular intervals over days to months.

- Real-time stability: Continuously operate the biosensor in buffer or complex matrix to assess signal drift over time.

Key Considerations:

- The regeneration method must effectively dissociate the analyte without damaging the bioreceptor.

- Stability is highly dependent on bioreceptor immobilization method and storage conditions [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Pesticide Biosensor Development

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Biosensor Development |

|---|---|---|

| Biorecognition Elements | Acetylcholinesterase (AChE), anti-chlorpyrifos antibodies, organophosphate-binding aptamers, E. coli reporter cells [17] [23] | Target recognition and signal initiation through specific binding or catalytic activity |

| Nanomaterials | Gold nanoparticles, graphene oxide (GO), carbon nanotubes (CNTs), metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) [22] [25] [24] | Signal amplification, increased surface area for bioreceptor immobilization, enhanced electron transfer |

| Immobilization Matrices | Chitosan, Nafion, polyaniline, sol-gels, self-assembled monolayers (SAMs) [22] | Secure bioreceptors to transducer surface while maintaining bioactivity and accessibility |

| Signal Generation Reagents | Horseradish peroxidase (HRP), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), quantum dots, electrochemical mediators (ferrocene derivatives) [17] [24] | Produce measurable signals (colorimetric, fluorescent, electrochemical) upon target recognition |

| Regeneration Buffers | Glycine-HCl (pH 2.0-3.0), NaOH (10-100 mM), EDTA (1-10 mM), SDS (0.1-1%) [22] | Dissociate analyte from bioreceptor between measurements for sensor reusability |

Advanced Optimization Strategies

Nanomaterial-Enhanced Performance

The integration of nanomaterials has revolutionized biosensor performance by addressing multiple metrics simultaneously [25] [24]. Gold nanoparticles provide exceptional signal amplification, with studies demonstrating up to 50-fold improvement in detection limits when incorporated into immunosensors [24]. Carbon nanotubes and graphene oxide enhance electron transfer kinetics in electrochemical biosensors while providing high surface area for bioreceptor immobilization [22] [25]. Metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) offer tunable porosity for both pesticide capture and signal enhancement, with particular utility in both detection and removal applications [22].

Immobilization Techniques for Enhanced Stability

The method of bioreceptor immobilization directly impacts stability, reusability, and overall performance. Covalent immobilization via glutaraldehyde or EDC/NHS chemistry provides stable linkage but may reduce bioactivity. Physical entrapment in polymer matrices (e.g., chitosan, sol-gels) preserves activity but may limit analyte diffusion. Affinity-based immobilization (e.g., streptavidin-biotin) offers oriented attachment that maximizes binding site availability. Recent advances include DNA-directed immobilization for aptasensors and bioorthogonal chemistry for minimal interference with binding sites [22].

Technological Implementation and Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the core operational workflow and logical relationships in a generalized pesticide biosensor system, highlighting how the biorecognition element connects to the measurable signal through the transduction mechanism:

The rigorous characterization of sensitivity, selectivity, reproducibility, and reusability provides the fundamental framework for evaluating and advancing pesticide biosensor technologies. These interdependent metrics collectively determine the practical utility of biosensors for real-world applications in environmental monitoring, food safety, and public health protection. The strategic selection of biorecognition elements—enzymes, antibodies, aptamers, or whole cells—establishes the foundational performance ceiling, while advanced nanomaterial integration and immobilization techniques enable progressive optimization toward this potential. Future developments will likely focus on multi-analyte detection platforms, enhanced field-deployability, and intelligent biosystems incorporating machine learning for data analysis, ultimately creating more robust and accessible monitoring solutions for pesticide residues across the agricultural and environmental sectors.

The accurate detection of pesticide residues is a critical challenge in ensuring food safety, protecting environmental health, and complying with global regulatory standards [26] [27]. Biosensor technology, which integrates a biorecognition element with a transducer, offers a powerful solution for specific, sensitive, and rapid pesticide monitoring [8] [17]. The core of a biosensor's analytical performance lies in the biorecognition element—the biological or biomimetic component that selectively interacts with the target pesticide [5] [28]. The strategic selection of an appropriate biorecognition element, tailored to the chemical class and mode of action of the target pesticide, is therefore paramount to developing a successful detection platform [6] [22]. This guide provides an in-depth technical framework for researchers and scientists to systematically match biorecognition elements to major pesticide classes, detailing the underlying principles, experimental protocols, and advanced material solutions that drive modern pesticide biosensing.

Pesticide Classification and Recognition Principles

Pesticides are categorized based on their chemical structure and biological target, which directly inform the choice of biorecognition element. The four most prevalent classes are organophosphates, carbamates, neonicotinoids, and pyrethroids [5] [27].

Organophosphates (OPs) and carbamates both exert their toxicity through the inhibition of the enzyme acetylcholinesterase (AChE) in the nervous system of target pests. This shared mechanism makes AChE an ideal biorecognition element for their detection [6]. The inhibition is reversible for carbamates and irreversible for most OPs, a difference that can be exploited in sensor design [6].

Neonicotinoids are synthetic insecticides that act as agonists on the nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) in the insect central nervous system [26]. Their detection can leverage these native receptors or engineered versions, as well as antibodies and aptamers selected for high affinity.

Pyrethroids are synthetic derivatives of natural pyrethrins that disrupt voltage-gated sodium channels in nerve membranes [8]. While their detection often employs antibodies in immunoassays, enzyme-based sensors that detect oxidative metabolites are also used.

The principle of "bioactivity-guided" detection is particularly powerful for OPs and carbamates, where the inherent toxicity of the pesticide (enzyme inhibition) is directly translated into a measurable signal [6] [22]. For other classes, "bioaffinity-guided" detection, which relies on selective binding without catalytic transformation, is more common, utilizing elements like antibodies and aptamers [22].

Biorecognition Elements: A Comparative Analysis

The selection of a biorecognition element involves a careful trade-off between specificity, stability, cost, and ease of production. The main types of elements used in pesticide biosensors are enzymes, antibodies, nucleic acid aptamers, and whole cells [17] [28].

- Enzymes: Catalytic proteins that recognize a substrate or inhibitor. AChE is the most prominent example for neurotoxic insecticides [6]. Other enzymes, such as alkaline phosphatase, tyrosinase, and peroxidases, are also used [6].

- Antibodies: Immunoglobulins that bind to a specific antigen (e.g., a pesticide molecule) with high affinity. They are the basis of immunosensors [17] [28].

- Aptamers: Short, single-stranded DNA or RNA oligonucleotides selected in vitro for high-affinity binding to a specific target. They are synthetic alternatives to antibodies [17] [22].

- Whole Cells: Microorganisms (e.g., bacteria, algae) that act as integrated sensing elements, often through engineered genetic circuits that respond to the presence of a pollutant [17] [23].

Table 1: Comparative Profile of Biorecognition Elements for Pesticide Detection

| Biorecognition Element | Key Feature | Primary Detection Mechanism | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enzymes (e.g., AChE) | Catalytic activity | Inhibition of activity (for OPs, carbamates) [6] | High sensitivity, biologically relevant signal [6] | Limited to enzyme-inhibiting pesticides, stability issues [6] |

| Antibodies | High-affinity binding | Binding event (Immunoassay) [17] [28] | Excellent specificity, wide applicability [28] | Animal-derived, batch-to-batch variation, cross-reactivity [5] |

| Aptamers | In vitro selected oligonucleotides | Conformational change upon binding [17] | Chemical synthesis, high stability, modifiable [17] [22] | Susceptibility to nuclease degradation, complex selection process [17] |

| Whole Cells | Self-replicating, integrated metabolism | Stress response, metabolic activity, genetic regulation [17] | Robustness, cost-effective, detects bioavailability [17] [23] | Longer response time, lower specificity, complex signal interpretation [17] |

Matching Biorecognition Elements to Pesticide Classes

The optimal pairing between a biorecognition element and a pesticide is determined by the pesticide's chemical properties and its biochemical mechanism of action. The following section provides detailed matching criteria and experimental workflows.

Table 2: Strategic Matching of Biorecognition Elements to Target Pesticide Classes

| Target Pesticide Class | Exemplary Actives | Recommended Biorecognition Element(s) | Rationale for Matching |

|---|---|---|---|

| Organophosphates | Parathion, Chlorpyrifos, Malathion [5] | Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) [6], Organophosphorus hydrolase (OPH) [22], Aptamers [17] | AChE is the primary biological target; inhibition provides a direct, toxicologically relevant signal [6]. |

| Carbamates | Aldicarb, Carbofuran, Oxamyl [5] | Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) [6] | Shares the AChE inhibition mechanism with OPs, allowing for detection with the same element [6]. |

| Neonicotinoids | Imidacloprid, Dinotefuran [26] [8] | Antibodies [8], Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) [26], Aptamers [22] | Antibodies and aptamers can be selected for high specificity to the stable neonicotinoid structure [8] [22]. |

| Pyrethroids | Bifenthrin, Fenpropathrin, Fenvalerate [8] | Antibodies [8], E. coli-based whole cells [17] | Immunoassays are highly effective for this structurally diverse class; whole cells can be engineered for a response [8] [17]. |

| Triazines & Herbicides | Atrazine [5] | Antibodies, Aptamers, Photosynthetic System II (PSII) [6] | PSII is the direct target for many herbicides, enabling activity-based detection [6]. |

| Organochlorines | DDT, Lindane [27] | Antibodies, Aptamers [22] | While largely banned, their persistence necessitates monitoring via highly specific affinity elements [27] [22]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: AChE-based Electrochemical Sensor for Organophosphates

This protocol details the development of a standard amperometric biosensor for detecting organophosphate (OP) pesticides based on the inhibition of acetylcholinesterase [6].

1. Principle: The enzyme acetylcholinesterase (AChE) catalyzes the hydrolysis of the substrate acetylthiocholine (ATCh) to produce thiocholine and acetate. Thiocholine is then oxidized at the surface of an electrode, generating a measurable amperometric current. The presence of an OP pesticide inhibits AChE activity, leading to a reduction in the enzymatic product and a corresponding decrease in the electrochemical signal. The degree of inhibition is proportional to the pesticide concentration [6].

2. Reagents and Materials:

- Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) from Electric Eel or recombinant source

- Acetylthiocholine (ATCh) chloride or iodide salt

- Phosphate Buffer Saline (PBS, 0.1 M, pH 7.4)

- Target organophosphate pesticide (e.g., chlorpyrifos-oxon, paraoxon)

- Glutaraldehyde (for cross-linking immobilization)

- Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA)

- Screen-printed carbon electrodes (SPCEs) or Gold electrodes

3. Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Electrode Pretreatment: Clean the working electrode of the SPCE according to the manufacturer's instructions (e.g., electrochemical cycling in sulfuric acid or gentle polishing).

- Enzyme Immobilization: Prepare an immobilization mixture containing 5 μL of AChE (2 U/mL) and 2 μL of BSA (1% w/v) in PBS. Add 1 μL of glutaraldehyde (0.25% v/v) as a cross-linker. Spot 5 μL of this mixture onto the working electrode and allow it to dry at 4°C for 1 hour.

- Baseline Measurement: Place the modified electrode in an electrochemical cell containing 10 mL of PBS with 0.1 M ATCh substrate. Apply a constant potential of +0.5 V (vs. Ag/AgCl reference) and record the steady-state amperometric current (I₀). This represents the uninhibited enzyme activity.

- Inhibition/Incubation Step: Incubate the AChE-modified electrode in a sample solution containing the target OP pesticide for a fixed time (e.g., 10-15 minutes). Rinse gently with PBS to remove unbound pesticide.

- Post-Inhibition Measurement: Re-immerse the electrode in the fresh ATCh/PBS solution and record the steady-state current again (Iᵢ).

- Data Analysis: Calculate the percentage of enzyme inhibition using the formula: Inhibition (%) = [(I₀ - Iᵢ) / I₀] × 100. The pesticide concentration in an unknown sample can be determined by interpolating the % inhibition value against a calibration curve constructed with standard solutions.

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Immunosensor for Pyrethroid Detection

This protocol outlines the key steps for developing a competitive immunoassay for pyrethroids using a lateral flow assay (LFA) format [8] [29].

1. Principle: A competitive format is used for detecting small molecules like pesticides. In this setup, pesticide molecules in the sample compete with a labeled pesticide analog (conjugate) for a limited number of binding sites on immobilized antibodies. The signal is inversely proportional to the pesticide concentration in the sample [29].

2. Reagents and Materials:

- Monoclonal antibody specific to the target pyrethroid (e.g., bifenthrin)

- Bifenthrin-protein conjugate (e.g., BSA-Bifenthrin)

- Gold nanoparticles (AuNPs, 20-40 nm) or fluorescent latex microspheres

- Nitrocellulose membrane, sample pad, conjugate pad, and absorbent pad

- Phosphate Buffer Saline (PBS) and blocking buffer (e.g., PBS with 1% BSA)

3. Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Conjugate Pad Preparation: Conjugate the anti-bifenthrin antibody to the AuNPs. Dispense the antibody-AuNP conjugate onto the glass fiber conjugate pad and dry.

- Test Line and Control Line Preparation: Dispense the bifenthrin-BSA conjugate at the test line (T-line) and a species-specific anti-IgG antibody at the control line (C-line) of the nitrocellulose membrane.

- Assembly: Assemble the LFA strip by attaching the sample pad, conjugate pad, nitrocellulose membrane, and absorbent pad in sequential order on a backing card with ~2 mm overlaps.

- Assay Execution: Apply 100 μL of the liquid sample (extract) to the sample pad. The sample migrates via capillary action, rehydrating the conjugate pad.

- Reaction and Signal Development: As the sample flows, the free pesticide in the sample and the pesticide-protein conjugate at the T-line compete for binding to the limited antibody-AuNP conjugates. After 10-15 minutes, the result can be visually read.

- Result Interpretation: A colored T-line indicates a negative result (no pesticide in sample). The absence of a T-line color indicates a positive result. The presence of a C-line confirms the test is valid. For quantitative analysis, a smartphone-based reader can be used to measure the color intensity of the T-line [29].

Visualization of Biosensor Selection and Operation

The following diagrams illustrate the logical workflow for selecting a biorecognition element and the operational mechanisms of the key biosensor types described in the experimental protocols.

Diagram 1: Biorecognition Element Selection Workflow.

Diagram 2: Key Biosensor Signaling Mechanisms.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The development and implementation of pesticide biosensors require a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The following table details key components and their functions in a typical research setting.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Pesticide Biosensor Development

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) | Biorecognition element for organophosphate and carbamate insecticides [6]. | Source (electric eel, bovine, recombinant) and enzyme variant impact sensitivity and selectivity to different inhibitors [6]. |

| Acetylthiocholine (ATCh) | Enzymatic substrate for AChE; product (thiocholine) is electroactive [6]. | Preferred over acetylcholine for electrochemical sensors due to the electroactivity of its hydrolysis product. |

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | Optical label (colorimetric) or electrochemical tag in lateral flow immunoassays and aptasensors [29] [22]. | Provide a vivid red color for visual detection; size and surface functionalization are critical for performance. |

| Screen-Printed Electrodes (SPEs) | Disposable, miniaturized electrochemical transducers for field-deployable sensors [6]. | Enable low-cost, mass-produced sensor platforms. Carbon, gold, and carbon nanotube-based inks are common. |

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) | Synthetic, biomimetic recognition elements with high stability [22]. | "Plastic antibodies" that offer an alternative to biological elements in harsh environments [22]. |

| Monoclonal Antibodies | High-specificity biorecognition elements for immunoassays targeting a single pesticide [17]. | Provide superior consistency and specificity compared to polyclonal antibodies. |

| Nucleic Acid Aptamers | Synthetic, single-stranded DNA/RNA recognition elements selected via SELEX [17]. | Chemically synthesized, thermally stable, and easily modified, making them versatile bioreceptors [17]. |

The strategic matching of biorecognition elements to target pesticide classes is a fundamental determinant of success in biosensor research. As detailed in this guide, the selection process must be guided by the pesticide's biochemical mode of action, leading to logical pairings such as AChE for neurotoxic organophosphates and carbamates, or high-affinity antibodies and aptamers for structurally distinct pyrethroids and neonicotinoids. Current research is pushing the boundaries of this field through the use of engineered mutant enzymes for enhanced specificity [6], the integration of nanomaterials like graphene oxide and metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) for signal amplification [8] [22], and the application of advanced data analytics like artificial neural networks (ANNs) to resolve signals from complex pesticide mixtures [6] [29]. By adhering to the systematic selection criteria and experimental frameworks outlined herein, researchers can develop next-generation biosensing platforms with the specificity, sensitivity, and robustness required for effective environmental monitoring and food safety assurance.

From Principle to Practice: Operational Mechanisms and Real-World Deployments

Enzyme-based biosensors represent a critical technological advancement in the detection of neurotoxic pesticides, offering a unique combination of biological specificity and analytical precision. Framed within the broader context of biorecognition elements—which include antibodies, nucleic acids, and whole cells—enzyme-based systems are particularly distinguished by their catalytic activity, which enables both substrate transformation and signal amplification [17]. This technical guide focuses on biosensors that leverage enzyme inhibition mechanisms, a highly relevant approach for detecting organophosphorus (OP) and carbamate (CB) pesticides designed to disrupt biological processes in target pests [6] [30].

The fundamental advantage of inhibition-based biosensors lies in their ability to translate a pesticide's inherent toxicity into a quantifiable analytical signal. Unlike conventional chromatographic methods, which are accurate but labor-intensive and ill-suited for rapid screening, these biosensors provide a "biologically relevant" assessment of contamination by measuring the functional inhibition of enzymes such as acetylcholinesterase (AChE) [6]. This guide details the core principles, experimental methodologies, and advanced applications of these systems, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive resource for developing and implementing these powerful analytical tools.

Core Principles and Enzyme Mechanisms

Fundamental Biosensor Architecture

An enzyme-based biosensor is an integrated analytical device comprising three essential components: a biological recognition element (the enzyme), a transducer, and an immobilization matrix [31]. The enzyme serves as a highly specific biocatalyst, initiating a reaction with its target substrate. This biochemical reaction produces a measurable change in a physicochemical parameter—such as electron flow, light emission, or mass change—which is then converted by the transducer into a quantifiable electrical or optical signal [31] [17].

The operational principle bifurcates into two primary detection modes for pesticides:

- Substrate Detection: The enzyme metabolizes its specific substrate, and the resulting product concentration is measured.

- Inhibition Detection: The target analyte (e.g., a pesticide) suppresses the enzyme's catalytic activity, leading to a measurable reduction in product formation, which correlates with the inhibitor's concentration [17].

For neurotoxic pesticides, the inhibition mode is most pertinent. The percentage of inhibited enzyme (I%) is quantitatively related to the inhibitor concentration and the incubation time, meaning the residual enzyme activity is inversely proportional to the amount of toxicant present [30].

Key Enzymes for Neurotoxic Pesticide Detection

Several enzymes are exploited in inhibition biosensors, but acetylcholinesterase (AChE) is the most significant for neurotoxic insecticides.

Acetylcholinesterase (AChE): This enzyme catalyzes the hydrolysis of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine into choline and acetate. Organophosphorus and carbamate pesticides exert their toxicity by covalently binding to the serine residue in the enzyme's active site, forming a stable complex that inhibits its function [6] [31]. This inhibition prevents the breakdown of acetylcholine, leading to neurotransmitter accumulation and continuous nerve firing, which is fatal to insects and toxic to humans. AChE-based biosensors measure this inhibition as a drop in enzymatic activity, providing a detection mechanism for these pesticides [31].

Other Relevant Enzymes: While AChE predominates, other enzymes like tyrosinase, laccase, and alkaline phosphatase are also used to detect pesticides from different chemical classes based on their specific inhibition mechanisms [6].

Table 1: Key Enzymes Used in Inhibition Biosensors for Pesticide Detection

| Enzyme | Target Pesticide Classes | Inhibition Mechanism | Typical Transducer |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) | Organophosphates, Carbamates | Irreversible (OP) or reversible (CB) binding to active site serine | Electrochemical, Optical [6] [31] |