Biosensors for Pesticide Detection: A Comprehensive Guide to Principles, Applications, and Emerging Technologies

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the latest advancements in biosensor technology for pesticide detection, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Biosensors for Pesticide Detection: A Comprehensive Guide to Principles, Applications, and Emerging Technologies

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the latest advancements in biosensor technology for pesticide detection, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of different biosensor types, including enzyme-based, immunosensors, aptasensors, and whole-cell biosensors. The scope extends to detailed methodologies, leveraging nanomaterials like metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) and nanozymes, and covers practical applications in food safety and environmental monitoring. The review also addresses key challenges in sensor stability and specificity, offers comparative analyses with traditional chromatographic methods, and discusses future trajectories involving AI integration and multimodal sensing for enhanced on-site detection capabilities.

The Principles and Urgent Need for Biosensing in Pesticide Monitoring

The global population has surpassed 8 billion, presenting a monumental challenge in securing the global food supply [1]. Pesticides play an indispensable role in enhancing crop yields and maintaining quality by controlling pests and diseases; however, their excessive or improper use leads to persistent environmental contamination and poses significant health risks to consumers, including links to cancer, neurological disorders, and endocrine disruptions [2]. This creates a critical tension between the need for agricultural productivity and the imperative of food safety. Traditional pesticide detection methods, such as gas chromatography (GC) and high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), while accurate, are labor-intensive, time-consuming, and require sophisticated laboratory settings [3] [2]. Consequently, there is an urgent need for advanced, field-deployable analytical tools. Biosensor technology has emerged as a viable and efficient solution, offering rapid, sensitive, and on-site detection capabilities that are crucial for modern food safety control and environmental monitoring [3] [4].

Biosensing Fundamentals and Relevance

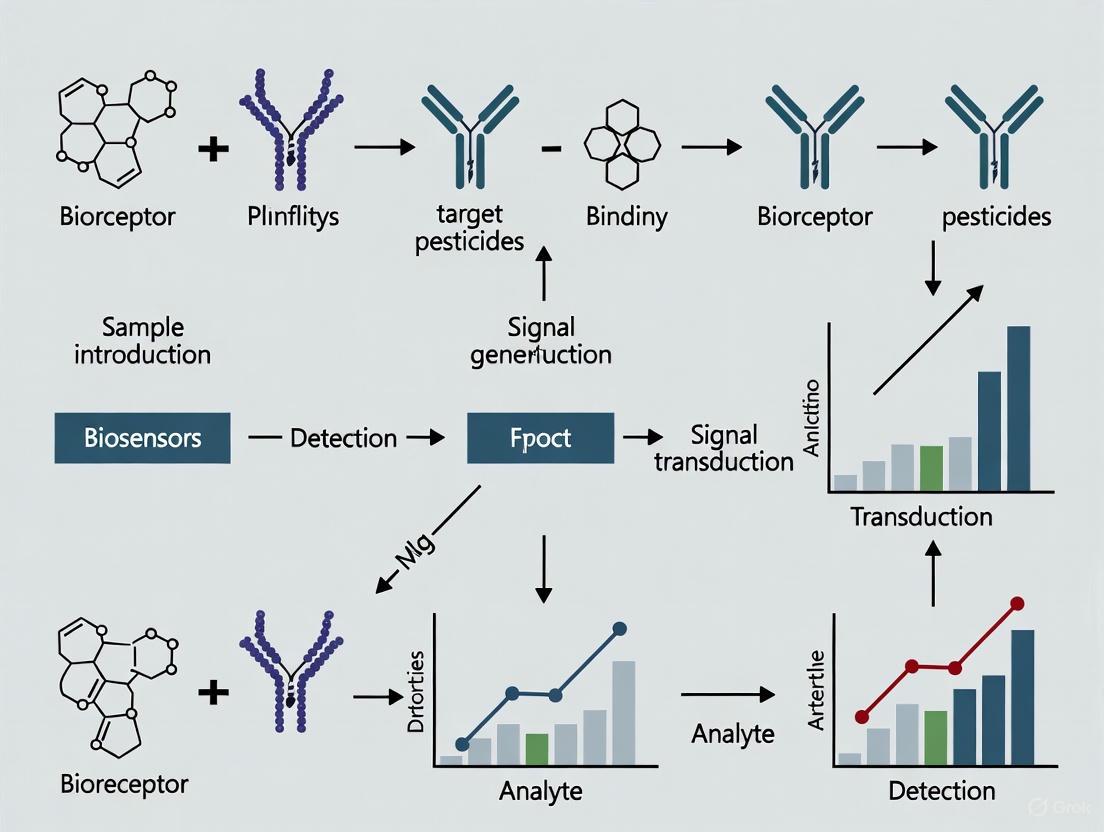

A biosensor is an analytical device that integrates a biological recognition element (such as an enzyme, antibody, or aptamer) with a physicochemical transducer (optical, electrochemical, etc.) to convert a biological interaction into a quantifiable signal [2]. The effectiveness of biosensors for pesticide detection hinges on their design, which leverages specific biological interactions with pesticide molecules.

Table 1: Core Components of a Biosensor

| Component | Description | Common Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Biological Recognition Element | Provides specificity by interacting with the target analyte | Acetylcholinesterase (AChE), antibodies, aptamers, whole cells [5] [2] |

| Transducer | Converts the biological response into a measurable signal | Electrode (electrochemical), photodetector (optical), piezoelectric crystal [3] [6] |

| Signal Processor | Amplifies and displays the output signal | Potentiostat, spectrophotometer, computer interface [2] |

For pesticide detection, biosensors often exploit specific mechanisms, most notably enzyme inhibition. Enzymes like acetylcholinesterase (AChE) are strongly inhibited by organophosphorus (OP) and carbamate pesticides. The degree of inhibition is proportional to the pesticide concentration, allowing for quantitative detection [5]. Alternative strategies involve direct binding using immunochemical reactions with antibodies or specific oligonucleotide sequences (aptamers) [2].

Diagram 1: Enzyme inhibition biosensor principle. The core mechanism of an enzyme inhibition-based biosensor. The target pesticide molecule inhibits the enzyme, reducing its catalytic activity and leading to a measurable decrease in signal output.

Current Biosensor Technologies for Pesticide Detection

Recent advancements have led to the development of highly sensitive and specific biosensing platforms. The performance of these technologies varies based on their underlying principle and configuration.

Table 2: Analytical Performance of Major Biosensor Platforms

| Biosensor Platform | Detection Principle | Typical Detection Limit | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electrochemical | Measures change in electrical properties (current, potential) due to biorecognition event [3] | pM-nM range [3] | High sensitivity, portability, cost-effectiveness [3] |

| Fluorescence | Quantifies change in fluorescence intensity/quenching upon analyte binding [3] [4] | Nanomolar range (e.g., paraoxon) [4] | High spatial resolution, visual detection potential |

| Colorimetric | Detects color change visible to the eye or via a smartphone [2] | ~0.08 mg/L for malathion [2] | Simplicity, user-friendliness, no complex instrumentation |

| Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) | Monitors refractive index change on a sensor surface [3] [6] | Real-time pathogen detection [6] | Label-free, real-time monitoring |

| Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering (SERS) | Enhances Raman signal of molecules on nanostructured surfaces [3] | High sensitivity for trace analysis [3] | Fingerprint molecular identification |

The integration of nanomaterials has been a key driver in enhancing biosensor performance. Materials such as metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), quantum dots, and gold nanoparticles provide high surface areas for enzyme immobilization, improve electron transfer in electrochemical sensors, and enhance optical signals [1] [2]. For instance, MOFs can serve as protective "armor" for natural enzymes, boosting their stability, or function as nanozymes themselves, mimicking catalytic activity while offering superior robustness [1].

Detailed Experimental Methodologies

Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) Inhibition-Based Detection

This is a classic and widely adopted protocol for detecting organophosphorus and carbamate pesticides [5].

- Principle: Target pesticides inhibit the activity of AChE, reducing its catalytic hydrolysis of the substrate acetylthiocholine (ATCh). This leads to a decreased production of thiocholine, which is correlated to the pesticide concentration [5] [2].

- Materials:

- Enzyme: Acetylcholinesterase (from electric eel or genetically modified variants).

- Substrate: Acetylthiocholine (ATCh).

- Chromogenic Agent: 5,5′-Dithiobis(2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB), which reacts with thiocholine to produce a yellow-colored product [5].

- Buffer: Phosphate buffer saline (PBS), pH ~7.4.

- Procedure:

- Enzyme Inhibition: Incubate a standard amount of AChE with the sample containing the target pesticide for a fixed time (e.g., 10-15 minutes).

- Substrate Addition: Add ATCh and DTNB to the mixture.

- Signal Measurement: The active AChE hydrolyzes ATCh to thiocholine, which reacts with DTNB to form 2-nitro-5-thiobenzoate (TNB⁻), a yellow anion. The intensity of the color is measured spectrophotometrically at 412 nm.

- Quantification: The absorbance is compared to a control without pesticide. The percentage of enzyme inhibition is calculated as

(1 - A_sample/A_control) × 100%and correlated to pesticide concentration via a calibration curve.

Fluorescence-Based Biosensor using Thermostable Esterase

This method, reported for sensitive organophosphate detection, uses fluorescence quenching [4].

- Principle: A thermostable esterase (EST2) is labeled with a fluorescent probe. Upon binding to specific organophosphate pesticides (e.g., paraoxon), a change in the local environment of the probe causes fluorescence quenching, which is quantitatively measured.

- Materials:

- Biological Receptor: Double mutant of thermostable esterase-2 (EST2).

- Fluorescent Probe: A suitable fluorophore.

- Buffer: Optimal pH buffer for EST2 activity.

- Procedure:

- Labeling: The EST2 enzyme is covalently labeled with the fluorescent probe.

- Incubation: The labeled enzyme is incubated with the sample containing the pesticide.

- Measurement: Fluorescence intensity is measured (excitation/emission at specific wavelengths). A decrease in fluorescence (quenching) indicates the presence of the pesticide.

- Analysis: The degree of quenching is proportional to the pesticide concentration, allowing for detection in the nanomolar range, even in complex food matrices like fruits and juices [4].

Diagram 2: Enzyme inhibition assay workflow. A generalized flowchart for a standard enzyme inhibition assay, illustrating the key steps from sample preparation to data analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The development and operation of advanced biosensors rely on a suite of specialized reagents and materials.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Their Functions in Biosensor Development

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in Biosensor Development |

|---|---|

| Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) | Biorecognition Element: The primary biological component in inhibition-based sensors for neurotoxic insecticides [5]. |

| Aptamers | Biorecognition Element: Synthetic single-stranded DNA/RNA molecules that bind targets with high specificity; offer advantages in stability and production over antibodies [2]. |

| Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) | Nanomaterial Support/ Nanozyme: Porous crystals used to immobilize and stabilize enzymes, or act as enzyme mimics (nanozymes) with high catalytic activity [1]. |

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | Signal Amplification/Tranducer: Used for colorimetric detection or to enhance electrochemical signals due to their excellent conductivity and optical properties [3]. |

| Quantum Dots (QDs) | Fluorescent Probe: Semiconductor nanocrystals used as fluorescent labels in optical sensors due to their bright and stable fluorescence [2]. |

| 3,3',5,5'-Tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) | Enzyme Substrate: A chromogenic substrate that produces a blue color when oxidized by peroxidase-like enzymes (e.g., nanozymes), used in colorimetric assays [2]. |

The field of biosensors is rapidly evolving toward multiplexing (detecting multiple analytes simultaneously), intelligent microdevices, and deeper integration with artificial intelligence (AI) for data processing [3] [6]. The incorporation of CRISPR/Cas technology has already demonstrated breakthroughs in sensitivity and specificity for nucleic acid detection, and its principles are being expanded to other domains [7]. Furthermore, the rise of wearable and implantable biosensors points toward a future of continuous, real-time monitoring of environmental contaminants [7]. However, challenges remain in standardizing these devices for commercial use, ensuring their robustness in diverse and complex food matrices, and reducing costs for widespread adoption [7] [8].

In conclusion, the global challenge of balancing population-driven food production with safety necessitates a paradigm shift in monitoring technologies. Biosensors, with their exceptional sensitivity, rapid response, and potential for portability, are poised to revolutionize pesticide residue analysis. By providing advanced technical support for on-site monitoring and source management across the entire "farm-to-fork" supply chain, biosensors offer a powerful tool to safeguard public health and ensure the sustainable development of the global food industry.

A biosensor is an analytical device that converts a biological response into a quantifiable electrical or optical signal [2]. It integrates a biological recognition element with a physicochemical transducer to detect a specific analyte [9]. In the context of pesticide detection, biosensors have emerged as a viable alternative to conventional techniques like gas chromatography (GC) and mass spectrometry, addressing the need for swift on-site analysis with their exceptional sensitivity, rapid response, and ease of operation [3] [10]. This guide details the core architecture, functioning, and experimental protocols of biosensors, providing a technical foundation for research and development professionals.

Core Components of a Biosensor

Every biosensor comprises three fundamental components that work in concert to achieve detection.

Biorecognition Element

This is the biological part of the sensor that provides specificity by interacting selectively with the target analyte. Common types used in pesticide detection include:

- Enzymes: Proteins that catalyze biochemical reactions. Biosensors for organophosphorus and carbamate pesticides often use enzymes like acetylcholinesterase (AChE) or butyrylcholinesterase (BChE), whose activity is inhibited by these pesticides [2] [11].

- Antibodies: Immunoglobulins with high binding affinity for specific antigens. Antibody-based biosensors (immunosensors) can be designed to detect a wide array of pesticide molecules [10] [9].

- Nucleic Acid Aptamers: Synthetic single-stranded DNA or RNA oligonucleotides selected for their high affinity to specific targets, such as pesticides or proteins related to pesticide exposure [2] [9].

- Whole Cells: Microbial cells, such as bacteria or fungi, that function as integrated sensing systems. They can be engineered for specific responses to environmental pollutants, including pesticides [9].

- Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs): Synthetic polymers with tailor-made recognition sites that mimic biological receptors, offering high stability for detecting pesticide residues [10] [2].

Transducer

The transducer converts the biological interaction between the biorecognition element and the analyte into a measurable signal. The principal types are:

- Electrochemical Transducers: Measure electrical changes (current, potential, impedance) resulting from the biochemical reaction. They are prominent in pesticide detection due to their simplicity, low cost, and potential for portability [10] [11].

- Optical Transducers: Measure changes in light properties, such as fluorescence [3] [2], colorimetry [3] [10], or Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) [3].

- Other Transducers: Include piezoelectric (measuring mass changes) and thermal transducers (measuring heat changes) [10].

Signal Processing System

This electronic component amplifies, processes, and displays the signal from the transducer in a user-interpretable format, often quantitative [2].

Table 1: Core Components of a Biosensor

| Component | Function | Common Examples in Pesticide Detection |

|---|---|---|

| Biorecognition Element | Provides specificity by binding the target analyte | Acetylcholinesterase (AChE), antibodies, aptamers, whole cells, Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) |

| Transducer | Converts the biological event into a measurable signal | Electrode (electrochemical), photodetector (optical), piezoelectric crystal |

| Signal Processor | Amplifies and displays the output signal | Potentiostat, smartphone detector, digital display |

Working Mechanisms and Signaling Pathways

The operational principle of a biosensor hinges on the specific interaction between the bioreceptor and the target pesticide, which modulates a biochemical or physical signal captured by the transducer.

Enzyme Inhibition Mechanism

This is a prevalent mechanism for detecting organophosphorus (OP) and carbamate pesticides. The enzyme acetylcholinesterase (AChE) normally catalyzes the hydrolysis of its substrate, acetylthiocholine (ATCh), producing thiocholine and acetic acid. In the presence of OP pesticides, AChE is inhibited, reducing the production of thiocholine. This reduction is measured electrochemically or optically [2] [11]. The following diagram illustrates the signaling logic for this inhibition-based detection.

Affinity-Based Detection

This mechanism relies on the specific binding of a pesticide to a bioreceptor without causing inhibition.

- Immunosensors: Rely on the binding of a pesticide (antigen) to its specific antibody, which can directly cause a measurable change in mass or refractive index (label-free) or be measured using a secondary antibody tagged with an enzyme or fluorescent marker (labeled) [9].

- Aptasensors: Aptamers undergo a conformational change upon binding their target pesticide, which can be transduced into an optical or electrochemical signal [9].

Experimental Protocols for Key Biosensor Types

Protocol: Paper Strip Biosensor for Multi-Pesticide Screening

This protocol is adapted from a study detecting pesticides in animal feed, milk, and soil [12].

1. Bioreceptor Preparation:

- Microbial Culture: Revive Bacillus megaterium (MTCC 2949) in nutrient broth at 37°C for 24 hours.

- Spore Production: Inoculate the revived culture into a sporulation medium and incubate at 37°C for 42 hours.

- Spore Harvesting: Centrifuge the culture at 10,000 rpm for 10 minutes at 10°C. Wash the pellet containing spores twice with potassium phosphate buffer (pH 6.8, 10 mM) and resuspend in the same buffer.

2. Sample Preparation:

- Extract samples (e.g., feed, soil) using appropriate organic solvents.

- Add PSA (Primary Secondary Amine) and MgSO4 at a 1:2 ratio to remove pigments and other interferences that could affect the color development on the strip.

3. Assay Execution:

- Apply the processed sample to the paper strip functionalized with bacterial spores and a chromogenic substrate.

- The presence of pesticides inhibits specific marker enzymes from the spores.

- Observe the color change: a reduction in color intensity indicates pesticide presence.

4. Detection and Analysis:

- The assay is semi-quantitative. The developed technology can detect various pesticides (e.g., organochlorine, organophosphate, carbamate) at limits of detection (LOD) ranging from 1 to 500 μg/L, suitable for screening under field conditions [12].

Protocol: Electrochemical On-Glove Biosensor for Fruit Peel Analysis

This protocol describes a wearable biosensor for direct detection of organophosphorus pesticides on fruit surfaces [11].

1. Biosensor Fabrication:

- Electrode Modification: Engineer a screen-printed electrode on a glove finger by modifying it with a bio-hybrid probe. The probe consists of:

- Prussian blue and Carbon black (electron mediators to enhance electrochemical signal).

- Butyrylcholinesterase (BChE) enzyme (the biorecognition element).

2. Sample Collection and Analysis:

- Direct Sampling: The end-user simply scrubs the surface of the fruit (e.g., apple, orange) with the sensor strip on the glove finger.

- Electrochemical Reading: Perform an electrochemical measurement on the glove-integrated system. The principle is based on the inhibition of BChE by the pesticide (dichlorvos).

3. Signal Measurement:

- The degree of enzyme inhibition correlates with the reduction in electrochemical signal (e.g., current), which is quantified.

- The system achieved a detection limit for dichlorvos in the nanomolar range (high ppt), which is lower than the maximum residue limits established by the EU, with a repeatability of less than 10% [11].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Material | Function in the Experiment | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) / Butyrylcholinesterase (BChE) | Biorecognition element; its inhibition is measured to detect pesticides. | Detection of organophosphorus and carbamate pesticides [2] [11]. |

| Bacterial Spores (e.g., B. megaterium) | Source of marker enzymes that are inhibited by pesticides; used as a robust bioreceptor. | Broad-spectrum pesticide detection in paper strip sensors [12]. |

| Aptamers | Synthetic nucleic acid bioreceptors with high affinity for specific targets. | Detection of various pesticides via optical or electrochemical aptasensors [9]. |

| Prussian Blue & Carbon Black | Redox mediators that enhance electron transfer in electrochemical sensors. | Signal amplification in on-glove electrochemical biosensors [11]. |

| Primary Secondary Amine (PSA) | Clean-up sorbent; removes pigments and fatty acids from samples during extraction. | Reducing matrix interference in analysis of complex samples like feed [12]. |

| Chromogenic Substrate (e.g., o-dianisidine) | Changes color upon enzymatic action; allows for visual or colorimetric detection. | Color development in paper-based optical sensors [2]. |

Biosensors represent a powerful convergence of biology and transducer technology, defined by their core components: a biorecognition element, a transducer, and a signal processor. Their working mechanisms, particularly enzyme inhibition and affinity-based binding, provide the specificity and sensitivity required for modern pesticide detection. The experimental protocols for paper strip and on-glove biosensors highlight the trend towards portability, rapid analysis, and user-friendly application in field settings. As research progresses, the integration of advanced nanomaterials, microfluidic systems, and artificial intelligence is poised to further enhance the capabilities and application scope of biosensors in ensuring agricultural and environmental safety [3] [10].

Biosensors are analytical devices that combine a biological recognition element with a physicochemical detector to measure the presence or concentration of a target analyte [13]. The biorecognition element is the cornerstone of a biosensor, responsible for the specific and selective interaction with the target molecule. In the context of pesticide detection, which is crucial for environmental protection and food safety, these elements enable the identification of trace amounts of hazardous substances [14] [15]. The integration of biological sensing elements with transducers has led to the development of highly sensitive and selective biosensors that provide rapid, real-time, and often portable means of analysis, addressing the limitations of conventional methods like gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) and high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) [14] [3].

The performance of a biosensor is fundamentally governed by the properties of its biorecognition element. Key parameters include sensitivity (the ability to detect low analyte concentrations), specificity (the ability to distinguish the target from interfering substances), affinity (the strength of binding), and stability under operational conditions [13]. This guide provides an in-depth technical examination of the four primary classes of biorecognition elements—enzymes, antibodies, aptamers, and whole cells—framed within the specific application of pesticide detection research.

Enzymes

Enzymes are biocatalysts that accelerate specific biochemical reactions. In biosensors, their catalytic activity is harnessed for the detection of target analytes, which may be the enzyme's substrate, an inhibitor, or a co-factor.

Mechanism of Action and Key Characteristics

Enzyme-based biosensors typically operate on one of two principles. The first is substrate detection, where the enzymatic reaction with the target analyte produces a measurable product (e.g., a change in pH, electron transfer, or light emission). The second, more common for pesticides, is inhibition-based detection. Many pesticides, such as organophosphates (OPs) and carbamates, are potent acetylcholinesterase (AChE) inhibitors [14]. The mechanism involves the pesticide binding to the active site of AChE, inhibiting its function in hydrolyzing the neurotransmitter acetylcholine. The degree of inhibition is proportional to the pesticide concentration, which can be measured electrochemically or optically [14].

A key advantage of enzymes is their catalytic nature, which provides signal amplification as a single enzyme molecule can turn over many substrate molecules, enhancing sensitivity. However, a significant limitation is their susceptibility to environmental factors such as pH, temperature, and ionic strength, which can denature the protein and lead to irreversible loss of activity, thereby reducing sensor shelf-life [14] [13].

Experimental Protocol for an Acetylcholinesterase Inhibition Assay

This protocol is commonly used for detecting organophosphorus and carbamate pesticides [14].

- Step 1: Sensor Preparation. Immobilize acetylcholinesterase (AChE) enzyme onto a transducer surface (e.g., a screen-printed carbon electrode). Common immobilization methods include cross-linking with glutaraldehyde, entrapment within a polymer matrix like Nafion, or covalent binding to a functionalized surface.

- Step 2: Baseline Measurement. Incubate the sensor with a standard solution of the enzyme's substrate, acetylthiocholine. Measure the initial rate of enzymatic reaction by detecting the product, thiocholine, typically via its electrochemical oxidation current.

- Step 3: Inhibition (Sample Exposure). Incubate the sensor with the sample solution containing the target pesticide for a fixed period (e.g., 10-15 minutes). During this time, the pesticide inhibitor binds to the active site of AChE, reducing its activity.

- Step 4: Residual Activity Measurement. Re-introduce the substrate solution and measure the rate of the enzymatic reaction again. The signal will be lower than the baseline due to enzyme inhibition.

- Step 5: Quantification. The percentage of enzyme inhibition is calculated as

(1 - I/I₀) × 100%, where I₀ and I are the currents before and after inhibition, respectively. The pesticide concentration is determined by interpolating the inhibition percentage against a pre-established calibration curve.

Diagram 1: Acetylcholinesterase inhibition assay workflow for pesticide detection.

Antibodies

Antibodies, or immunoglobulins, are Y-shaped proteins produced by the immune system that bind to a unique molecular structure, known as an antigen, with high specificity.

Mechanism of Action and Key Characteristics

Antibody-based biosensors, known as immunosensors, rely on the specific antigen-antibody binding event. The antibody serves as the capture probe, and its binding to the target pesticide (or a pesticide derivative) generates a signal. This signal transduction can be achieved through various methods, including label-free techniques like Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) or by using enzyme-linked labels (e.g., in an ELISA-style format) that produce an optical or electrochemical signal upon binding [13] [16].

The primary strength of antibodies is their exceptional specificity and high binding affinity, which minimizes cross-reactivity and allows for precise target identification. They are well-established in clinical diagnostics. However, their production is a significant drawback, as it requires animal hosts, making it a time-consuming and costly process [17]. Furthermore, antibodies are large proteins sensitive to their environment; denaturation is often irreversible, leading to limited shelf-life and stability, particularly under harsh conditions [17] [13].

Experimental Protocol for a Competitive Immunoassay

This is a common format for detecting small molecules like pesticides, which may not be large enough to bridge two antibodies simultaneously.

- Step 1: Surface Functionalization. Immobilize a pesticide-protein conjugate or a capture antibody onto the sensor surface (e.g., a gold chip for SPR or an electrode).

- Step 2: Incubation with Sample and Label. Mix the sample with a known concentration of a labeled (e.g., with an enzyme or nanoparticle) pesticide or antibody. This mixture is then introduced to the functionalized sensor surface. The target pesticide in the sample and the labeled analyte compete for a limited number of binding sites on the capture probe.

- Step 3: Washing. Remove unbound molecules by washing with a buffer solution to reduce non-specific binding and background signal.

- Step 4: Signal Detection. Measure the signal generated from the bound label. In a competitive assay, a higher concentration of the target pesticide in the sample will result in less labeled analyte binding, leading to a lower final signal.

- Step 5: Data Analysis. The signal is inversely proportional to the pesticide concentration in the sample. A calibration curve is generated using standards of known concentration to quantify the target.

Aptamers

Aptamers are short, single-stranded DNA or RNA oligonucleotides that are engineered in vitro to bind to a specific target molecule with high affinity.

Mechanism of Action and Key Characteristics

Aptamers are identified through an in vitro process called Systematic Evolution of Ligands by Exponential Enrichment (SELEX) [17] [18]. Through iterative rounds of selection and amplification, aptamers that bind tightly to a target pesticide are enriched from a vast random sequence library. In a biosensor (an aptasensor), the aptamer undergoes a conformational change upon binding the target. This structural shift can be directly measured if it alters the aptamer's distance from a transducer surface, or it can be linked to a signal-generating probe [17] [19].

Aptamers offer several distinct advantages over antibodies. They are produced by chemical synthesis, leading to low batch-to-batch variation and lower production costs. They are also highly stable under a wide range of temperatures and pH conditions, and their denaturation is often reversible [17]. Furthermore, they can be easily chemically modified to enhance stability or for immobilization. A key limitation is that RNA aptamers are susceptible to nuclease degradation in biological fluids, though this can be mitigated using modified nucleotides [17].

Experimental Protocol for a SELEX Procedure

The SELEX process is used to develop novel aptamers for specific targets, such as a new pesticide.

- Step 1: Library Preparation. Synthesize a large single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) or RNA library containing a central random sequence region (e.g., 30-50 nucleotides) flanked by constant primer regions for PCR amplification.

- Step 2: Incubation and Binding. Incubate the oligonucleotide library with the immobilized target pesticide.

- Step 3: Partitioning. Wash away unbound and weakly bound sequences. The tightly bound sequences are then eluted.

- Step 4: Amplification. The eluted sequences are amplified by PCR (for DNA) or reverse transcription-PCR (for RNA) to create an enriched pool for the next selection round.

- Step 5: Iteration. Repeat steps 2-4 for multiple rounds (typically 8-15) under increasingly stringent conditions (e.g., higher wash volumes, shorter incubation times, or the addition of counter-targets) to select for the highest-affinity binders.

- Step 6: Cloning and Sequencing. After the final round, the enriched pool is cloned, sequenced, and the individual aptamer candidates are characterized for their binding affinity and specificity.

Diagram 2: SELEX workflow for aptamer development against a pesticide target.

Whole Cells

Whole-cell biosensors utilize living microorganisms (e.g., bacteria, yeast, or microalgae) as the biorecognition element. The cells respond to the presence of a target analyte through their inherent metabolic or genetic pathways.

Mechanism of Action and Key Characteristics

Whole-cell biosensors can be designed to be either constitutive or inducible [15]. In an inducible system, the exposure to a specific pesticide or class of pesticides triggers a cellular response. This is often achieved by using genetically engineered cells where a promoter sequence, activated by the pesticide or its metabolic byproduct, is linked to a reporter gene (e.g., for green fluorescent protein (GFP), luciferase, or β-galactosidase). The presence of the pesticide induces the expression of the reporter protein, generating a measurable signal.

The primary advantage of whole-cell biosensors is their ability to report on the bioavailability and overall toxicity of a sample, rather than just the concentration of a single compound. They can detect a class of pollutants simultaneously. However, they have a slower response time compared to molecular biosensors due to the time required for gene expression and protein synthesis. They also require strict control of growth conditions (nutrients, temperature, pH) to maintain cell viability, which complicates their use in the field [15].

Experimental Protocol for a Genetically Engineered Whole-Cell Biosensor

This protocol describes the use of a bacterial cell engineered to express a reporter protein in response to pesticide stress.

- Step 1: Cell Culture and Preparation. Grow the engineered bacterial strain (e.g., E. coli) to the mid-logarithmic phase in an appropriate culture medium under sterile conditions.

- Step 2: Sample Exposure. Harvest the cells and expose them to the environmental water sample or a solution containing the target pesticide. A negative control (no pesticide) and positive control (known pesticide concentration) must be run in parallel.

- Step 3: Incubation. Incubate the cell-sample mixture for a predetermined period (e.g., 1-2 hours) to allow for the induction of the genetic circuit and the expression of the reporter protein.

- Step 4: Signal Measurement. Measure the signal from the reporter. For luminescent reporters like luciferase, add the substrate and measure light emission with a luminometer. For fluorescent reporters like GFP, measure the fluorescence intensity at specific excitation/emission wavelengths.

- Step 5: Data Interpretation. The magnitude of the signal is correlated with the level of pesticide-induced stress. The signal from the sample is compared to the calibration curve generated from the positive controls to estimate the pesticide's toxic equivalent concentration.

Comparative Analysis of Biorecognition Elements

The choice of biorecognition element depends on the specific requirements of the application, such as the need for portability, sensitivity, specificity, or robustness. The tables below summarize the key properties and performance metrics of the four elements in the context of pesticide detection.

Table 1: Characteristic Comparison of Biorecognition Elements

| Property | Enzymes | Antibodies | Aptamers | Whole Cells |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Nature | Protein (Catalyst) | Protein (Binding) | Nucleic Acid (DNA/RNA) | Living Microorganism |

| Production | Isolation/Recombinant | Animal Hosts | Chemical Synthesis (SELEX) | Cell Culture |

| Specificity | Moderate | Very High | Very High | Low to Moderate (Class-specific) |

| Stability | Low (Irreversible denaturation) | Moderate (Irreversible denaturation) | High (Reversible denaturation) | Low (Require viable conditions) |

| Modification | Difficult | Moderate | Easy (Chemical synthesis) | Genetic Engineering |

| Key Advantage | Catalytic Signal Amplification | Well-established, High Specificity | Stability, Cost, Design Flexibility | Reports on Bioavailability & Toxicity |

| Key Limitation | Susceptible to Inhibitors | Cost, Production Time, Stability | Susceptibility to Nucleases (RNA) | Slow Response, Complex Maintenance |

Table 2: Performance Metrics in Pesticide Detection

| Biorecognition Element | Example Target | Detection Mechanism | Reported Detection Limit | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enzyme (AChE) | Organophosphates, Carbamates | Electrochemical Inhibition | Varies by specific sensor | [14] |

| Antibody | Chlorpyrifos | Fluorescence Immunoassay | Varies by specific sensor | [15] |

| Aptamer | Chlorpyrifos | Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) | 0.051 ng/mL | [19] |

| Whole Cell | General Toxicity | Luminescence Induction | Varies by specific sensor and test organism | [15] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The development and application of biosensors for pesticide detection rely on a suite of specialized reagents and materials.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Biosensor Development

| Reagent / Material | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) | Biorecognition element for inhibition-based detection of OPs and carbamates. | Electrochemical biosensor for organophosphate pesticides [14]. |

| Nucleic Acid Aptamer | Synthetic biorecognition element selected for a specific pesticide. | Fluorescence aptasensor for chlorpyrifos detection [19]. |

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | Signal amplification; Quencher in FRET assays; Platform for immobilization. | Used as a quencher in a FRET-based aptasensor [19]. |

| SELEX Kit | Contains reagents and protocols for the systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment. | In vitro selection of a novel DNA aptamer against a pesticide target [17]. |

| Nafion Polymer | Cation-exchange polymer used for enzyme immobilization on electrode surfaces. | Entrapment of AChE on an electrode for enhanced stability [14]. |

| Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) Chip | Gold-coated glass chip for label-free, real-time monitoring of biomolecular interactions. | Characterization of antibody-pesticide binding kinetics [13] [16]. |

Biosensors are analytical devices that combine a biological recognition element with a physicochemical transducer to detect target analytes. In the critical field of pesticide detection, biosensors provide a powerful alternative to conventional chromatographic methods, offering the potential for rapid, cost-effective, and on-site monitoring of harmful residues ( [15] [5] [10]). The core of any biosensor is its signal transduction platform, which converts the specific biological recognition event into a quantifiable electrical or optical signal. The choice of transduction method—electrochemical, optical, or piezoelectric—profoundly influences the sensor's sensitivity, selectivity, portability, and practical applicability. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide to these three principal signal transduction platforms, detailing their fundamental principles, experimental protocols, and performance in the context of pesticide detection research. The ongoing development of these biosensing technologies is essential for safeguarding environmental and public health against pesticide contamination ( [15] [20]).

Electrochemical Biosensors

Working Principle

Electrochemical biosensors detect pesticides by measuring electrical signals—such as current, potential, or impedance—that arise from a biochemical reaction or binding event at the surface of an electrode ( [10]). The biological recognition element, often an enzyme like acetylcholinesterase (AChE), is immobilized on the electrode. Upon exposure to a sample, several mechanisms can generate a signal:

- Inhibition-Based Detection: For neurotoxic organophosphates (OPs) and carbamates (CBs), the operational principle is often the inhibition of AChE. The enzyme's normal activity converts its substrate, acetylcholine, into products that can be electrochemically detected (e.g., thiocholine, which oxidizes at a certain potential). When the enzyme is inhibited by a pesticide, this catalytic activity decreases, leading to a reduction in the electrochemical signal that is proportional to the pesticide concentration ( [5]).

- Affinity-Based Detection: Other biosensors rely on the direct binding of a pesticide to a recognition element (e.g., an antibody, aptamer, or whole cell), which alters the interfacial properties of the electrode. This change can be measured as a shift in potential (potentiometric), a change in the current at a fixed potential (amperometric), or a modification of the electrical impedance at the electrode surface (impedimetric) ( [10]).

Experimental Protocol: Enzyme-Inhibition Based Amperometric Sensor

Objective: To detect organophosphorus and carbamate pesticides via inhibition of acetylcholinesterase.

Materials and Reagents:

- Acetylcholinesterase (AChE): Enzyme from electric eel or genetically engineered variants from Drosophila melanogaster for tailored sensitivity ( [5]).

- Acetylthiocholine (ATCh): Enzyme substrate.

- 5,5'-dithiobis(2-nitrobenzoic) acid (DTNB): Chromogenic reagent for Ellman's assay, used in spectrophotometric calibration.

- Working Electrode: Often glassy carbon or gold electrode, modified with nanomaterials (e.g., graphene oxide, carbon nanotubes) to enhance surface area and electron transfer ( [10]).

- Pesticide Standards: Analytical grade paraoxon, carbofuran, etc.

Procedure:

- Electrode Modification: Prepare a suspension of the nanomaterial (e.g., graphene oxide) and deposit a fixed volume onto the polished surface of the working electrode. Allow to dry.

- Enzyme Immobilization: Immobilize AChE onto the modified electrode surface. This can be achieved via drop-casting, followed by cross-linking with glutaraldehyde, or through layer-by-layer assembly.

- Baseline Activity Measurement:

- Place the modified electrode in an electrochemical cell containing a suitable buffer (e.g., 0.1 M phosphate buffer, pH 7.4) and the substrate acetylthiocholine.

- Apply a fixed potential (e.g., +0.5 V vs. Ag/AgCl) and record the steady-state oxidation current of the enzymatic product (thiocholine). This is the initial current, ( I_0 ).

- Inhibition Step: Incubate the biosensor in the sample solution containing the target pesticide for a fixed period (e.g., 10-15 minutes).

- Inhibited Activity Measurement: Rinse the electrode and measure the electrochemical current again under identical conditions as in step 3. This is the inhibited current, ( I_i ).

- Data Analysis: Calculate the percentage of enzyme inhibition using the formula: [ \%\text{Inhibition} = \frac{(I0 - Ii)}{I_0} \times 100 ] The inhibition percentage is then correlated with pesticide concentration using a calibration curve prepared with standard solutions.

Table 1: Performance of Selected Electrochemical Biosensors for Pesticide Detection

| Recognition Element | Transducer | Target Pesticide(s) | Linear Range | Limit of Detection (LOD) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) | Amperometric | Paraoxon, Carbofuran | 0–20 μg L⁻¹ | 0.9 μg L⁻¹ (Paraoxon) | [5] |

| Genetically engineered AChE variants | Amperometric | Paraoxon, Dichlorvos | 0–5 μg L⁻¹ | 0.4 μg L⁻¹ (Paraoxon) | [5] |

| Antibodies (Immunosensor) | Electrochemical | Various | Varies by design | ~nM to pM | [10] |

| Aptamers (Aptasensor) | Electrochemical | Various | Varies by design | ~nM to pM | [10] |

Research Reagent Solutions

- AChE Enzymes: Wild-type and mutant forms (e.g., from Drosophila melanogaster) for tuning sensitivity and selectivity in inhibitor mixtures ( [5]).

- Nanomaterial Modifiers: Graphene oxide (GO), carbon nanotubes, and metal nanoparticles to enhance electrode conductivity and enzyme loading ( [10]).

- Cross-linking Agents: Glutaraldehyde and BS³ for stable enzyme immobilization on electrode surfaces.

Optical Biosensors

Working Principle

Optical biosensors transduce the binding or inhibition event into a measurable change in light properties. These changes can include intensity, wavelength, polarization, or phase ( [10]). Several modalities are prominent in pesticide detection:

- Fluorescence: Measures the change in fluorescence intensity, anisotropy, or lifetime. This can be based on the intrinsic fluorescence of a recognition element, fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET), or the use of fluorescently labeled molecules ( [10]).

- Colorimetry: Involves a visual or spectrophotometric color change, often using enzyme-catalyzed reactions (e.g., with horseradish peroxidase) or aggregation of metal nanoparticles like gold ( [3] [10]).

- Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR): Detects changes in the refractive index on a thin metal (typically gold) surface, allowing for real-time, label-free monitoring of binding interactions (e.g., between an antibody and a pesticide) ( [3] [10]).

Experimental Protocol: Whole-Cell Colorimetric Biosensor for Chlorpyrifos

Objective: To visually detect chlorpyrifos (CPF) and its toxic metabolite, TCP, using an engineered bacterial cell system.

Materials and Reagents:

- Biosensor Strain: E. coli cells engineered to harbor the ChpR transcriptional regulator and the pigment-producing vioABCE gene cluster on a plasmid (e.g., pET-21a backbone) ( [20]).

- LB Growth Medium: For cell culture.

- CPF and TCP Standards: Analytical grade.

- Induction Agent: Isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) to induce the biosensing system.

- Spectrophotometer or Plate Reader: For quantitative colorimetric measurement.

Procedure:

- Cell Culture and Induction: Inoculate the engineered biosensor strain into LB medium with appropriate antibiotics. Grow to mid-log phase and induce with a predetermined optimal concentration of IPTG.

- Sample Exposure: Aliquot the induced cells into multi-well plates. Add a series of concentrations of CPF or TCP to the test wells. Use a negative control (no pesticide) and a positive control if available.

- Incubation and Color Development: Incubate the plate with shaking at a specified temperature (e.g., 30°C or 37°C) for several hours to allow for color development. The presence of CPF/TCP triggers the ChpR regulator, which activates the vioABCE operon, leading to the production of a violet pigment.

- Signal Acquisition:

- Visual Inspection: Observe the wells for a visible color change from colorless/pale to violet. This provides a qualitative yes/no result.

- Quantitative Measurement: Measure the absorbance of the solution at a specific wavelength (e.g., 550-580 nm for the violet pigment) using a plate reader.

- Data Analysis: Plot the absorbance against the logarithm of the pesticide concentration to generate a calibration curve. The limit of detection (LOD) and linear range can be determined from this curve. The reported LOD for this system is 0.8 μM for CPF and 7.813 nM for TCP ( [20]).

Table 2: Performance of Selected Optical Biosensors for Pesticide Detection

| Recognition Element | Transducer | Target Pesticide(s) | Linear Range | Limit of Detection (LOD) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Engineered E. coli (ChpR/vioABCE) | Colorimetric | Chlorpyrifos (CPF) | 1.6–12.5 μM | 0.8 μM | [20] |

| Engineered E. coli (ChpR/vioABCE) | Colorimetric | TCP (metabolite) | 15.6–125 nM | 7.813 nM | [20] |

| Antibodies | SPR | Various | Varies by design | ~nM to pM | [3] [10] |

| Enzymes (e.g., HRP) | Fluorescence | Various | Varies by design | ~nM to pM | [10] |

Figure 1: Workflow of a whole-cell colorimetric biosensor for detecting chlorpyrifos.

Research Reagent Solutions

- ChpR/vioABCE Plasmid System: Genetic construct for building whole-cell biosensors specific to chlorpyrifos and TCP ( [20]).

- Fluorescent Dyes/Tags: Such as green fluorescent protein (GFP) variants for constructing fluorescence-based reporter systems.

- Gold Nanoparticles: For colorimetric sensors, where analyte-induced aggregation causes a visible color shift from red to blue ( [3] [10]).

Piezoelectric Biosensors

Working Principle

Piezoelectric biosensors are mass-sensitive devices based on quartz crystal microbalance (QCM) technology. The core component is a quartz crystal disc sandwiched between two metal electrodes. An alternating voltage applied across the electrodes induces a shear deformation of the crystal at its resonant frequency. The fundamental principle, described by the Sauerbrey equation, states that the resonant frequency decreases linearly with an increase in mass adsorbed on the crystal surface ( [21]). The equation is: [ \Delta f = -\frac{2f0^2 \Delta m}{A \sqrt{\rhoq \muq}} = -C \Delta m ] where ( \Delta f ) is the frequency change, ( f0 ) is the fundamental resonant frequency, ( \Delta m ) is the mass change, ( A ) is the active area, and ( \rhoq ) and ( \muq ) are the density and shear modulus of quartz, respectively. ( C ) is a constant for the specific crystal ( [21]). In liquid environments, the frequency is also affected by the viscosity and density of the liquid, requiring more complex analysis, sometimes including the dissipation factor (D) to account for viscoelastic effects (QCM-D) ( [21]).

Experimental Protocol: QCM Immunosensor for Pesticide Detection

Objective: To detect a specific pesticide (e.g., carbaryl) using an antibody-based QCM immunosensor.

Materials and Reagents:

- PZ Crystals: AT-cut quartz crystals with gold electrodes (e.g., 10 MHz fundamental frequency).

- Oscillator Circuit: To drive the crystal and monitor frequency changes (e.g., based on a 74LS320 integrated circuit) ( [21]).

- Frequency Counter: A high-resolution (≥1 Hz) device connected to a computer for data acquisition.

- Anti-pesticide Antibody: Specific to the target analyte.

- Cross-linkers: Such as carbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC) and N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) for antibody immobilization.

- Flow Cell: To facilitate controlled introduction of samples and buffers.

Procedure:

- Crystal Functionalization: Clean the gold electrode surface of the PZ crystal. Immobilize a self-assembled monolayer (SAM) of a linker molecule (e.g., 11-mercaptoundecanoic acid) onto the gold surface to provide functional groups for antibody attachment.

- Antibody Immobilization: Activate the carboxyl groups on the SAM using a mixture of EDC and NHS. Then, expose the crystal to a solution of the specific antibody, allowing covalent amide bond formation to immobilize the antibodies on the sensor surface.

- Baseline Establishment: Mount the crystal in a flow cell and perfuse with a stable running buffer. Monitor the resonant frequency until a stable baseline (( f_0 )) is achieved.

- Sample Injection: Inject the sample or standard solution containing the target pesticide. The binding of the pesticide to the immobilized antibody increases the mass on the crystal surface, leading to a frequency shift (( \Delta f )).

- Regeneration (Optional): For reusability, inject a regeneration solution (e.g., a low-pH glycine buffer) to dissociate the antibody-pesticide complex, returning the frequency close to its original baseline.

- Data Analysis: The frequency shift is recorded in real-time. The magnitude of ( \Delta f ) is proportional to the mass of bound analyte. A calibration curve of ( \Delta f ) vs. pesticide concentration is used for quantification. Advanced signal analysis, such as phase-shift measurement, can significantly improve the LOD ( [21]).

Table 3: Performance and Characteristics of Piezoelectric Biosensors

| Parameter | Specifications / Performance | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Mass Sensitivity | ~4.4 ng/cm² per 1 Hz frequency shift for a 10 MHz crystal | [21] |

| Detection Method | Active (oscillator-based) or passive (impedance analysis) | [21] |

| Target Pesticide | Carbaryl (as an example) | [21] |

| LOD (Phase Shift Method) | 0.14 ng/mL (with 100 MHz resonator) | [21] |

| Key Advantage | Label-free, real-time monitoring of binding events | [21] |

Figure 2: Operating principle of a piezoelectric quartz crystal microbalance (QCM) biosensor.

Research Reagent Solutions

- QCM Crystals & Chips: AT-cut quartz crystals with gold electrodes, available in various resonant frequencies (e.g., 5-20 MHz) ( [21]).

- Surface Chemistry Kits: Containing thiol-based linkers (e.g., 11-mercaptoundecanoic acid) and cross-linkers (EDC, NHS) for biomolecule immobilization.

- QCM-D Instruments: Commercial systems (e.g., from QSense/Biolin Scientific) for simultaneous monitoring of frequency (f) and dissipation (D) to characterize soft, viscoelastic layers ( [21]).

Electrochemical, optical, and piezoelectric transduction platforms each offer distinct advantages for pesticide detection. Electrochemical methods, particularly amperometry, are prized for their high sensitivity, portability, and cost-effectiveness, making them ideal for on-site screening ( [5] [10]). Optical biosensors, including colorimetric and fluorescence-based systems, provide versatility, the potential for multiplexing, and, in the case of whole-cell sensors, biologically relevant detection of toxic metabolites ( [20] [10]). Piezoelectric QCM sensors offer the unique benefit of real-time, label-free monitoring of binding kinetics and mass deposition ( [21]). The future of biosensing lies in the integration of these platforms with advanced nanomaterials, microfluidics, and artificial intelligence for data analysis. Furthermore, the development of multi-parameter sensor arrays, using engineered enzymes or different transducer types in combination, will be crucial for discriminating between complex mixtures of pesticides in real-world environments ( [15] [5] [10]).

The Critical Role of Biosensors in Smart Agriculture and Public Health Protection

Biosensors are analytical devices that combine a biological recognition element with a physicochemical transducer to detect specific analytes. In the context of pesticide detection, these systems leverage bioreceptors such as enzymes, antibodies, nucleic acids, and whole cells to identify residue contaminants with high specificity and sensitivity [9]. The global expansion of agricultural and industrial activities has intensified the challenge of controlling pesticide residues, making the development of rapid, accurate, and on-site detection technologies a critical research focus [3] [10]. This whitepaper examines the transformative impact of biosensing technologies in enabling smart agriculture practices and protecting public health from pesticide-related hazards, framing this discussion within the broader thesis of biosensor research for pesticide detection.

Fundamental Principles of Biosensors for Pesticide Detection

Biosensors operate on the principle of converting a biological interaction into a quantifiable signal. The core components include a biorecognition element that specifically interacts with the target pesticide and a transducer that converts this interaction into a measurable output [9]. The analytical performance of these devices is characterized by several key parameters: sensitivity (ability to detect low analyte concentrations), specificity (selectivity for target analytes), dynamic range (span between minimal and maximal detectable signals), response time, and signal-to-noise ratio [22].

The detection mechanisms vary significantly based on the bioreceptor and transducer employed. Enzyme-based biosensors often rely on the inhibition of enzyme activity by pesticides, where the reduction in catalytic activity correlates with pesticide concentration [9]. Immunosensors utilize the specific binding between antibodies and pesticide antigens, generating signals through label-free or labeled approaches [9]. Aptasensors employ synthetic single-stranded DNA or RNA aptamers selected through Systematic Evolution of Ligands by Exponential Enrichment (SELEX) to bind specific targets through various electrostatic and intramolecular mechanisms [9]. Whole cell-based biosensors use microorganisms as integrated sensing elements, leveraging their metabolic activity, stress responses, or genetic regulation mechanisms to detect pesticide presence [9].

Table 1: Fundamental Biosensor Types for Pesticide Detection

| Biosensor Type | Biorecognition Element | Detection Principle | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enzyme-based | Enzymes (e.g., acetylcholinesterase) | Enzyme inhibition or metabolism of analyte | High specificity, rapid response for specific pesticide classes |

| Antibody-based | Monoclonal or polyclonal antibodies | Antigen-antibody binding | High affinity and specificity, adaptable to various formats |

| Nucleic acid-based | DNA or RNA aptamers | Aptamer-target binding with structural change | Chemical synthesis, stability, programmable |

| Whole cell-based | Microorganisms (e.g., bacteria, algae) | Metabolic activity or stress response | Robustness, self-replication, detects bioavailable fraction |

Figure 1: Fundamental Architecture of Biosensors for Pesticide Detection

Biosensing Technologies in Smart Agriculture

Monitoring Pesticide Residues in Crops

The application of biosensors in agriculture has revolutionized pesticide monitoring, enabling real-time detection directly in field conditions. For high-value crops like tea, which face significant export restrictions due to stringent pesticide regulations, biosensors offer a viable alternative to conventional techniques such as gas chromatography (GC) and inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) [3]. These traditional methods, despite their high precision, require intricate pretreatment, incur substantial operational expenses, and are inadequate for swift on-site analysis [3].

Recent research has demonstrated the successful application of various biosensing platforms for detecting pesticide residues in crops. Electrochemical biosensors have shown particular promise for portable, on-site use owing to their enhanced sensitivity, cost-effectiveness, and adaptability to intricate plant matrices [3]. Similarly, fluorescence-based biosensors provide high sensitivity with detection limits ranging from nM to pM, while being resistant to interference from plant compounds like polyphenols and alkaloids [3].

Detection of Genetically Modified Traits

Beyond pesticide detection, biosensors play a crucial role in characterizing genetically modified (GM) crops. Recent developments include portable, paper-based biosensors for identifying GM traits in corn and soybean using loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) [23]. This technology offers a fast and less expensive alternative to conventional molecular tools, with test reactions costing approximately $2.90 each compared to $8-9 for other LAMP techniques [23].

A significant advantage of this approach is its compatibility with crude leaf extracts, eliminating the need for purified DNA. As Verma et al. reported, "We use that crude extract directly with our biosensor. Our biosensor with the leaf extract is as good as purified DNA" [23]. This feature dramatically simplifies field applications, allowing farmers to perform testing without laboratory infrastructure.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Pesticide Detection Technologies

| Detection Method | Detection Limit | Analysis Time | Cost per Test | Portability | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biosensors (General) | nM to pM range [3] | 5-30 minutes [3] | Low [9] | High | On-site screening, routine monitoring |

| Electrochemical Biosensors | Very low (varies by target) [10] | Rapid (minutes) [10] | Low [10] | High | Field detection of organophosphates, carbamates |

| Optical Biosensors | nM range [10] | Moderate (15-30 min) [3] | Moderate [10] | Moderate to High | Laboratory and field applications |

| Chromatography (GC, HPLC) | Very low (ppt-ppb) [3] | Hours to days [3] | High [3] | Low | Reference laboratory confirmation |

| Spectrometry (ICP-MS) | Very low (ppt) [3] | Hours [3] | Very High [3] | Low | Regulatory testing, research |

Advanced Materials and Sensing Mechanisms

Innovative Biomaterials in Biosensor Design

The performance of biosensors heavily depends on the materials used in their construction. Recent advancements have introduced various nanomaterials and functional biomaterials that significantly enhance detection capabilities. These include graphene oxide (GO), molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs), graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4), and metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) [10].

These advanced materials contribute to lower detection limits, excellent selectivity, and in some cases, large adsorption capacities for pesticide removal applications [10]. For instance, metal-organic frameworks offer high surface areas and tunable porosity, making them ideal for both sensing and removing pesticide contaminants [10]. The integration of these materials with biological recognition elements creates sophisticated sensing platforms capable of detecting multiple pesticide residues simultaneously—a significant advantage for comprehensive environmental monitoring.

Engineering Biosensor Performance

Strategic engineering of biosensor components allows fine-tuning of performance characteristics critical for agricultural applications. Key parameters such as dynamic range (the span between minimal and maximal detectable signals) and operating range (the concentration window where the biosensor performs optimally) can be optimized through various approaches [22].

Engineering methods include "exchanging promoters and ribosome binding site number and position of the operator region" [22]. Additionally, "the chimeric fusion of the DNA and ligand binding domains have also been used to engineer the specificity of the biosensor" [22]. High-throughput techniques like cell sorting, combined with directed evolution strategies, can lead to improved sensitivity and specificity of the engineered biosensor [22].

Figure 2: Generalized Workflow for Pesticide Detection Using Biosensors

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standardized Testing Procedures

Implementing biosensor technology requires standardized protocols to ensure reproducibility and reliability across different applications. For pesticide residue detection in agricultural products, a typical experimental workflow involves several critical stages:

Sample Preparation: For plant materials like tea leaves, this involves extraction using appropriate solvents followed by potential cleanup steps to remove interferents. Recent advancements have enabled the use of crude extracts, as demonstrated in GM crop detection where researchers "homogenized [the sample] as a liquid, then diluted to one part extract and seven parts water" [23].

Assay Procedure: The specific protocol varies by biosensor type. For enzyme-based detection cards, a representative method involves: "Using a detection card, add two or three drops of the test solution and set it in an incubator at 37°C for 10 min to initiate a pre-reaction. After the pre-reaction, half-fold the detection card and maintain 37°C at a steady temperature for three minutes" [24].

Signal Measurement and Analysis: Depending on the biosensor platform, this may involve electrochemical measurements, optical readings (colorimetric, fluorescent, etc.), or other transduction methods. For colorimetric sensors, "image recognition technology is used to extract the color information RGB eigenvalues from the detection results" [24].

Quantitative Analysis Models

Advanced data processing techniques enhance the accuracy of biosensor outputs. Research has compared multiple regression models for quantifying pesticide residue concentrations from detection cards, including:

- Linear regression model

- Quadratic polynomial regression model

- Exponential regression model

- RBF neural network model [24]

Studies found that "the exponential regression model is superior at predicting the pesticide residue concentration indicated by the rapid detection card" with a correlation value of 0.900 and root mean square error of 0.106 [24]. This approach prevents negative prediction values when the expected concentration is near zero, addressing a common limitation in quantitative analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Biosensor Development

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Applications | Performance Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) | Enzyme bioreceptor for organophosphate and carbamate detection | Enzyme inhibition-based biosensors | High sensitivity to specific pesticide classes; detection limits down to nM range [9] |

| Nucleic Acid Aptamers | Synthetic DNA/RNA recognition elements | Aptasensors for various pesticides | Selected via SELEX; high affinity and specificity; tunable through chemical modification [9] |

| Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) | Nanostructured sensing/adsorption platform | Signal enhancement and pesticide removal | High surface area; tunable porosity; functionalizable with biorecognition elements [10] |

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) | Artificial antibody mimics | Bionic-guided detection strategies | High stability; customizable for specific pesticide molecules; reusable [10] |

| Gold Nanoparticles | Signal amplification and transduction | Colorimetric and electrochemical biosensors | Enhanced sensitivity; color change properties; excellent conductivity [3] |

| Whole Microbial Cells | Living bioreporters for bioavailable contaminants | Cell-based biosensors for environmental monitoring | Detect functional toxicity; self-replicating; can report via bioluminescence or fluorescence [9] |

Public Health Protection through Environmental Monitoring

Water Quality Assessment

Biosensors play a crucial role in safeguarding public health by monitoring pesticide contamination in water systems. The detection of emerging contaminants (ECs) in water environments has become a growing concern due to their high toxicity even at minimal concentrations [9]. Traditional analytical techniques like HPLC, GC, MS, and ICP-MS, while accurate, face limitations for routine monitoring due to high costs, complex sample preparation, and labor-intensive processes [9].

Biosensors address these challenges by offering highly sensitive, selective, low-cost, and simple-to-use alternatives for detecting hazardous elements in water [25]. Their portability enables on-site monitoring of water sources, providing real-time data for rapid response to contamination events. This capability is particularly valuable for assessing pesticide runoff from agricultural areas, where timely detection can prevent broader environmental dissemination and human exposure.

Integration with Public Health Surveillance

The application of biosensor technologies extends beyond environmental monitoring to direct public health protection. As demonstrated during the COVID-19 pandemic, biosensing platforms can be adapted for various health threats, showcasing their versatility [26]. This adaptability is equally relevant for pesticide surveillance, where exposure biomarkers in biological samples can be detected using similar principles.

The integration of biosensors with data analytics and wireless communication technologies creates comprehensive monitoring networks that can track pesticide exposure pathways from agricultural applications through environmental distribution to potential human exposure. These systems provide critical data for public health authorities to identify at-risk populations, implement targeted interventions, and evaluate the effectiveness of regulatory measures.

Future Perspectives and Research Directions

The future of biosensors in smart agriculture and public health protection will be shaped by several emerging trends and technological advancements. Research is increasingly focusing on multi-analyte detection platforms that can simultaneously screen for multiple pesticide residues and other contaminants [3]. The integration of microfluidic systems enhances the portability and automation of biosensing devices, while artificial intelligence improves data analysis and interpretation [3].

Future biosensor development will also leverage advances in synthetic biology to create more sophisticated biological recognition elements. As noted in recent research, "Dynamic control circuits in biosensors are typically characterized by input–output dose–response curves, but their dynamic performance—such as the response speed and signal-to-noise ratios—should also be key metrics of their evaluation" [22].

The growing emphasis on sustainability in agriculture will further drive biosensor innovation, with research focusing on devices that support integrated pest management and precision farming practices. Ultimately, these advancements will contribute to the development of comprehensive monitoring networks spanning the entire "tea garden-to-cup" supply chain and analogous systems for other agricultural products [3].

Biosensors represent a transformative technology for addressing the dual challenges of agricultural productivity and public health protection in the context of pesticide use. Their exceptional sensitivity, portability, and cost-effectiveness position them as indispensable tools for advancing smart agriculture practices through real-time monitoring and precision application of agrochemicals. Simultaneously, their application in environmental surveillance and exposure assessment provides critical data for protecting population health from pesticide-related risks.

As research continues to enhance the performance, reliability, and accessibility of these technologies, biosensors are poised to become increasingly integrated into agricultural management systems and public health protection frameworks. The ongoing convergence of biosensing with developments in materials science, data analytics, and wireless connectivity will further expand their capabilities, ultimately contributing to more sustainable agricultural systems and enhanced health security.

Cutting-Edge Biosensor Platforms and Their Real-World Applications

Enzyme-based biosensors have emerged as transformative analytical tools that leverage biological recognition for detecting specific analytes. Within this domain, biosensors utilizing the inhibition mechanism of acetylcholinesterase (AChE) represent a particularly significant technology for environmental monitoring and food safety, specifically for detecting neurotoxic pesticides [27] [28]. These biosensors combine the exceptional specificity of enzymatic reactions with the sensitivity of physical transducers, offering a robust alternative to conventional chromatographic methods such as gas chromatography (GC) and high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), which are often hampered by high operational costs, intricate sample pretreatment, and lack of portability for on-site analysis [27] [3] [10].

The core principle of AChE-based biosensors hinges on the enzyme's vital role in the nervous system. AChE catalyzes the hydrolysis of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine (ACh) into choline and acetic acid, a process crucial for terminating synaptic transmission [27] [29]. Organophosphorus (OP) and carbamate pesticides inhibit AChE by covalently binding to the serine residue in its active site, leading to enzyme inactivation and accumulation of ACh, which causes neurological dysfunction and other toxic effects [27] [30] [28]. The degree of enzyme inhibition is directly proportional to the pesticide concentration, forming the fundamental detection mechanism for AChE-based biosensors [27].

This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of AChE inhibition mechanisms, detailed experimental protocols, and advanced biosensing architectures, framed within the broader context of biosensor research for pesticide detection.

Inhibition Mechanism and Biochemical Principle

Acetylcholinesterase is a serine hydrolase concentrated at neuromuscular junctions and cholinergic brain synapses. Its primary function is to catalyze the breakdown of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine (ACh) into choline and acetic acid, thereby terminating synaptic transmission and ensuring proper muscular response [27] [29]. The catalytic efficiency of AChE is extraordinarily high, hydrolyzing ACh within microseconds to maintain clear synaptic communication [27].

The enzyme's active site consists of two key subsites: the anionic site, which attracts and positions the positively charged quaternary ammonium group of acetylcholine, and the esteratic subsite, which contains a catalytic triad of serine, histidine, and glutamate residues that mediate the hydrolysis of the ester bond [27]. In the absence of inhibitors, AChE efficiently converts its substrate, acetylthiocholine (AChI), into electrochemically active thiocholine and acetic acid [27] [30].

Organophosphorus (OP) and carbamate pesticides exert their toxicity through a common inhibition mechanism. These compounds structurally resemble the natural ACh substrate and are attracted to the enzyme's active site. Once bound, the electrophilic phosphorus atom (in OPs) or carbonyl carbon (in carbamates) undergoes a nucleophilic attack by the serine hydroxyl group in the catalytic triad. This reaction results in the formation of a stable, covalent phosphorylated or carbamylated enzyme complex, which effectively blocks the active site and prevents further catalysis [27] [30] [28]. The intensity of AChE inhibition is quantitatively proportional to the concentration of the inhibiting pesticide, forming the fundamental principle for biosensor-based detection [27]. While both classes inhibit AChE, phosphorylated enzymes are generally more stable, leading to longer-lasting inhibition compared to carbamylated complexes.

The following diagram illustrates the core biochemical workflow of the AChE inhibition mechanism used in pesticide detection.

Biosensor Fabrication and Immobilization Strategies

The performance of an AChE biosensor—including its sensitivity, stability, and reproducibility—is critically dependent on the method used to immobilize the enzyme onto the transducer platform. Effective immobilization preserves enzymatic activity, prevents leakage, and often enhances stability by restricting conformational changes [27] [31]. The choice of support material and immobilization technique must therefore be carefully considered.

Immobilization Techniques

Several well-established methods are available for AChE immobilization, each with distinct advantages and limitations [27]:

- Physical Adsorption: This method relies on weak interactions such as Van der Waals forces, hydrogen bonding, or electrostatic attractions between the enzyme and the support material. It is simple, economical, and avoids harsh chemical conditions that could denature the enzyme. However, the binding is weak, often resulting in enzyme leakage from the electrode surface over time, especially in variable pH or ionic strength conditions [27].

- Covalent Coupling: This approach forms stable covalent bonds between functional groups on the enzyme (e.g., amino, carboxyl, or hydroxyl groups) and chemically activated groups on the support surface. It strongly prevents enzyme leaching and allows for direct analyte-enzyme interaction, leading to a fast response time. The drawbacks include complex procedures, potential for enzyme denaturation if harsh coupling agents are used, and high enzyme consumption [27] [30].

- Entrapment/Encapsulation: The enzyme is physically confined within a porous matrix or membrane, such as a polymer gel (e.g., polysaccharides, polyacrylamide) or an inorganic silica network. This method is a simple, one-step procedure that is gentle on the enzyme. A significant challenge is the potential for leaching of smaller enzyme molecules, along with possible diffusion barriers for the substrate that can increase response time and cause lower reproducibility [27].

- Self-Assembled Monolayers (SAMs): This technique involves the spontaneous organization of molecules with a specific head group (e.g., thiols on gold) and a functional tail group into an ordered, nanoscale layer. The AChE enzyme is then attached to this monolayer. SAMs provide a well-defined and ordered structure. Their drawbacks include difficulties in reproduction and susceptibility to fouling over time as interactions weaken [27].

- Cross-Linking: Enzymes are interconnected via bi- or multi-functional reagents (e.g., glutaraldehyde), often forming a robust network. While this method effectively prevents leaching, it can lead to a loss of activity due to the potential for creating diffusion barriers and rigidifying the enzyme structure [30].

Advanced Support Materials

The selection of the support material is equally critical for biosensor performance. Recent research has focused on nanomaterials and novel composites to enhance electron transfer, increase surface area, and improve biocompatibility.

- Renewable Carbon (RC): Derived from biomass pyrolysis, RC is a sustainable, carbon-rich material with moderate surface area and porosity. It can be functionalized with acid treatments to introduce surface groups that enhance enzyme binding. RC represents a low-cost and environmentally friendly alternative to more complex carbon nanomaterials [30] [32].

- Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs): These are crystalline porous materials formed by metal ions and organic linkers. MOFs can serve as excellent immobilization matrices due to their ultra-high surface area and tunable pore size. They can physically protect the enzyme, enhancing its stability against harsh conditions [1].

- Nanoparticles: The incorporation of nanoparticles, such as gold and carbon nanotubes, has been widely reported to significantly improve biosensor efficiency. They provide a large surface area for enzyme loading, facilitate electron transfer, and can be functionalized to promote oriented enzyme immobilization, making the biosensor more reliable and robust [27] [28].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

This section details specific protocols for AChE inhibition assays, ranging from high-throughput screening formats to applications with real food samples.

Cell-Based AChE Inhibition Assay (qHTS Format)

This protocol uses a human neuroblastoma cell line (SH-SY5Y) to provide a physiological environment for detecting AChE inhibition [29].

Key Reagents and Materials:

- Human neuroblastoma cell line (SH-SY5Y)

- Customized DMEM/F-12 cell assay medium (without choline and phenol red)

- Positive controls: Chlorpyrifos-oxon (potent AChE inhibitor) or BW284c51

- Detection Kit: Amplite Red Fluorimetric Acetylcholinesterase Assay Kit

- Assay Plates: 1536-well black wall/clear-bottom plates

Procedure: