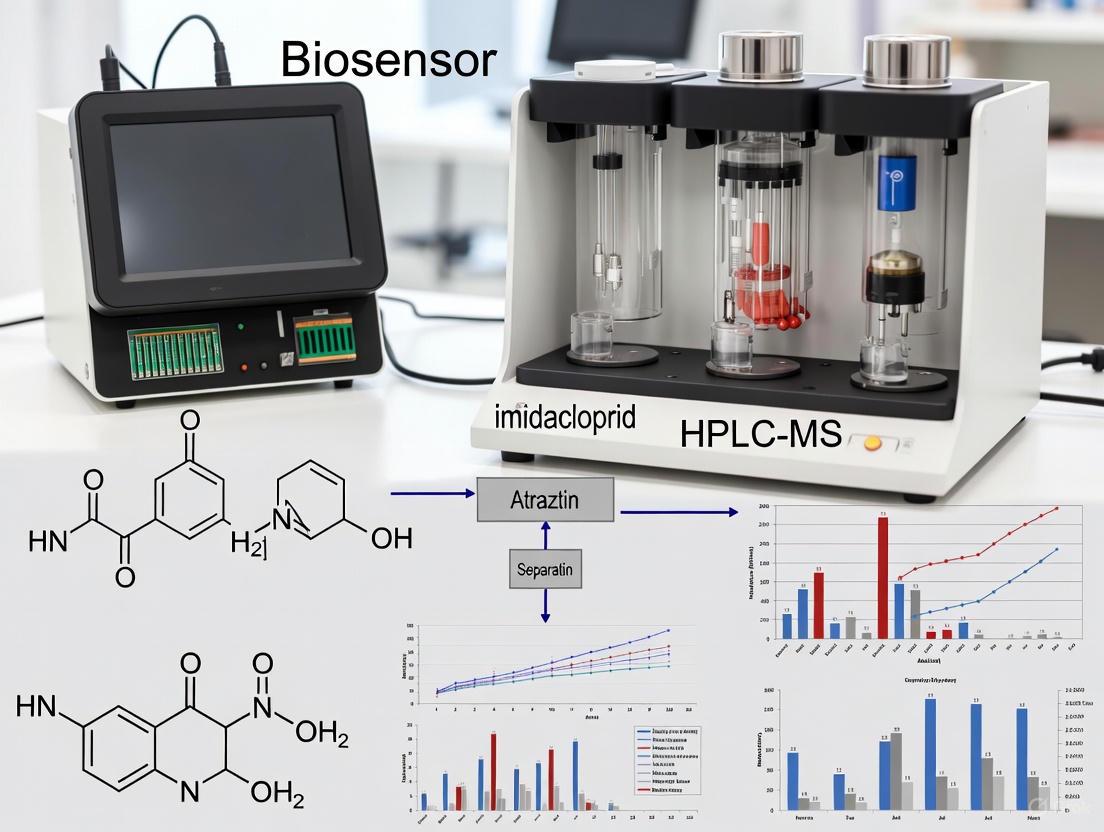

Biosensors vs. HPLC-MS for Pesticide Detection: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers

This article provides a systematic comparison for researchers and scientists evaluating analytical techniques for pesticide residue analysis.

Biosensors vs. HPLC-MS for Pesticide Detection: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a systematic comparison for researchers and scientists evaluating analytical techniques for pesticide residue analysis. It explores the foundational principles of biosensors and the established gold standard, HPLC-MS. The review delves into the operational mechanisms, diverse applications, and specific use-cases for each technology, from lab-on-a-chip biosensors to sophisticated multi-residue chromatographic methods. Critical challenges, including matrix interference, sensor stability, and method validation, are addressed with practical troubleshooting and optimization strategies. A direct, data-driven comparative analysis equips professionals to select the optimal methodology based on sensitivity, throughput, cost, and deployment context, concluding with a forward-looking synthesis on the convergent future of these technologies in food safety, environmental monitoring, and biomedical research.

The Analytical Landscape: Core Principles and Drivers for Pesticide Detection

The extensive global use of pesticides in modern agriculture is a critical intervention for protecting crop yields and ensuring food security for a growing population. However, this reliance on chemical pest control has created significant environmental and public health challenges due to the persistence of pesticide residues in soil, water, and food systems. These residues accumulate across environmental compartments, leading to bioaccumulation within food chains and ultimately resulting in human exposure through multiple pathways, including contaminated food and water [1] [2]. The public health implications are substantial, with epidemiological and toxicological studies consistently associating chronic pesticide exposure with increased risks of various cancers, neurological disorders, endocrine disruptions, and respiratory diseases [1]. The World Health Organization estimates that food contamination results in approximately $100 billion in healthcare costs annually in low- and middle-income nations alone, with pesticide residues representing a significant contributor to this burden [3].

Vulnerable populations, including agricultural workers, children, and pregnant women, face particularly elevated risks. Farmworkers experience high exposure during pesticide application, while consumers encounter residues through contaminated food products [2]. This widespread exposure scenario underscores the critical importance of effective pesticide monitoring systems throughout the agricultural supply chain—from production to consumption. Robust detection technologies are essential for enforcing food safety standards, protecting ecosystem health, and ultimately safeguarding public health from the detrimental effects of pesticide exposure.

Conventional versus Emerging Detection Paradigms

The landscape of pesticide detection is dominated by two distinct technological approaches: conventional laboratory-based instruments and emerging biosensing platforms. Each paradigm offers characteristic advantages and limitations that determine their suitability for different monitoring applications.

High-Performance Liquid Chromatography and Mass Spectrometry (HPLC-MS)

Chromatography-based techniques, particularly high-performance liquid chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS) and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS), represent the current gold standard for pesticide residue analysis [4] [5]. These conventional methods separate complex mixtures, identify individual pesticide compounds, and provide precise quantification at extremely low concentrations.

The analytical process involves sophisticated instrumentation that requires controlled laboratory environments, significant operational expertise, and substantial financial investment [6]. The typical workflow includes multiple stages: sample collection, transportation to centralized laboratories, intricate preparation (such as solid-phase extraction), chromatographic separation, mass spectrometric analysis, and data interpretation [7]. While these methods provide exceptional sensitivity, specificity, and multi-residue capability, their operational complexity and time-intensive procedures (often requiring hours to days) limit their effectiveness for rapid screening and on-site decision-making [8].

Biosensor Technologies

Biosensors represent an emerging technological paradigm that addresses several limitations of conventional methods. These devices integrate biological recognition elements (such as enzymes, antibodies, nucleic acid aptamers, or whole microbial cells) with physicochemical transducers that convert molecular interactions into measurable signals [6] [7]. This fundamental architecture enables rapid, cost-effective detection that can be deployed in field settings for real-time monitoring.

The diversity of biosensing platforms includes electrochemical, optical, microbial whole-cell, and paper-based devices [6] [8] [9]. These systems leverage specific biorecognition events, such as enzyme inhibition, antibody-antigen binding, or cellular stress responses, to generate detectable signals proportional to pesticide concentration. While traditionally characterized by lower sensitivity compared to HPLC-MS and potential susceptibility to matrix interference, recent technological advances have substantially improved their performance characteristics, making them increasingly viable for preliminary screening and complementary use alongside conventional methods [7].

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Pesticide Detection Technologies

| Characteristic | HPLC-MS | Biosensors |

|---|---|---|

| Principle | Chromatographic separation with mass spectrometric detection | Biological recognition element coupled with signal transducer |

| Sensitivity | Parts-per-trillion (ppt) to parts-per-billion (ppb) range | Parts-per-billion (ppb) to parts-per-million (ppm) range |

| Analysis Time | Several hours to days | Minutes to hours |

| Portability | Laboratory-bound; non-portable | Portable to handheld formats available |

| Operator Skill | Requires highly trained technicians | Minimal training required |

| Cost per Analysis | High equipment and reagent costs | Low to moderate cost |

| Multi-Residue Capacity | Excellent (can screen hundreds simultaneously) | Limited (typically single or few analytes) |

| Sample Preparation | Extensive and complex | Minimal to moderate |

Comparative Performance Data: Biosensors versus HPLC-MS

Empirical data from comparative studies provides critical insights into the operational performance characteristics of biosensors relative to the conventional HPLC-MS benchmark. This quantitative comparison reveals a trade-off between the exquisite sensitivity of traditional methods and the practical advantages of biosensing platforms.

Research demonstrates that HPLC-MS systems consistently achieve detection limits in the parts-per-trillion (ppt) to parts-per-billion (ppb) range, enabling precise quantification of trace-level pesticide residues even in complex sample matrices [4]. This exceptional sensitivity is essential for regulatory compliance testing against stringent maximum residue limits (MRLs). In contrast, biosensors typically operate in the parts-per-billion (ppb) to parts-per-million (ppm) range, though advanced platforms using nanomaterials and signal amplification strategies are progressively closing this sensitivity gap [6].

The temporal advantage of biosensors is particularly pronounced. While HPLC-MS analysis typically requires several hours to complete due to elaborate sample preparation and chromatographic separation, biosensors frequently generate results within minutes to hours [8] [9]. For instance, a paper-based sensor for detecting organophosphates, carbamates, and other pesticide classes in milk, cereal-based foods, and fruit juices demonstrated detection capabilities ranging from 1-50 ppb for most compounds with analysis times under 30 minutes [9]. This rapid response enables real-time decision-making in field settings—an capability beyond the practical scope of conventional methods.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Comparison for Selected Pesticide Detection Applications

| Technology | Target Pesticide/Class | Sample Matrix | Limit of Detection | Analysis Time | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GC-MS/MS | Organophosphorus pesticides | Biological matrices (blood, urine, viscera) | ppt to ppb range | Several hours (including sample preparation) | [5] |

| HPLC-MS | Multi-residue analysis | Food products, environmental samples | ppt to ppb range | Hours to days | [4] [6] |

| Paper-based biosensor | Organophosphates, carbamates | Milk, cereal foods, fruit juices | 1-50 ppb | < 30 minutes | [9] |

| Microbial Whole-Cell Biosensors | Broad-spectrum toxicity | Water, food samples | Varies by design; typically ppb range | 30-120 minutes | [3] [7] |

| Electrochemical biosensors | Organophosphates | Tea, agricultural products | ppb range | 5-30 minutes | [6] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standardized experimental protocols are essential for generating comparable and reliable data across different pesticide detection platforms. The following section outlines representative methodologies for both conventional and biosensor-based approaches.

HPLC-MS Protocol for Multi-Residue Pesticide Analysis

The conventional HPLC-MS protocol for multi-residue pesticide analysis involves a multi-stage workflow designed to extract, separate, and quantify diverse pesticide compounds from complex sample matrices [4] [6].

Sample Preparation:

- Extraction: Homogenize 10-15g of representative sample (food, soil, or biological tissue) with organic solvents (e.g., acetonitrile) containing 1% acetic acid.

- Clean-up: Purify extracts using dispersive solid-phase extraction (d-SPE) with primary-secondary amine (PSA) and C18 sorbents to remove interfering compounds like lipids and pigments.

- Concentration: Evaporate extracts under gentle nitrogen stream and reconstitute in injection solvent compatible with mobile phase.

Instrumental Analysis:

- Chromatographic Separation: Utilize reversed-phase C18 column (100 × 2.1 mm, 1.8 μm) with gradient elution using water/methanol mobile phases containing 0.1% formic acid.

- Mass Spectrometric Detection: Operate triple quadrupole mass spectrometer in multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) mode with electrospray ionization (ESI).

- Quantification: Generate external calibration curves using matrix-matched standards to compensate for ionization suppression/enhancement effects.

This method provides highly accurate and sensitive quantification of hundreds of pesticide residues simultaneously but requires 36-48 hours for complete analysis and sophisticated laboratory infrastructure [4].

Paper-Based Biosensor Protocol for Rapid Screening

The paper-based biosensor protocol leverages the inhibition of enzyme activity by pesticide compounds to generate rapid, colorimetric detection signals suitable for field deployment [8] [9].

Biosensor Preparation:

- Biorecognition Element Immobilization: Functionalize paper substrates with biological recognition elements (e.g., bacterial spores containing esterase enzymes, antibodies, or aptamers) using dispensing printers or dip-coating methods.

- Substrate Incorporation: Impregnate detection zones with chromogenic substrates (e.g., indoxyl acetate) that generate visible color changes upon enzymatic conversion.

- Device Assembly: Integrate sample flow paths, control zones, and absorption pads into laminated paper-based devices.

Sample Analysis:

- Extraction: Rapidly extract pesticides from food samples (e.g., milk, fruit juices) using simplified solvent extraction (e.g., 70% methanol in water).

- Application: Apply 50-100μL of extracted sample to the sample port of the paper device.

- Incubation: Allow lateral flow for 10-20 minutes at room temperature to enable complete reaction.

- Detection: Visually inspect color development in detection zones or use smartphone-based colorimetric analysis for semi-quantification.

This approach enables rapid screening (under 30 minutes) with minimal equipment but typically provides semi-quantitative results focused on specific pesticide classes rather than comprehensive multi-residue analysis [9].

Diagram 1: Pesticide Detection Workflow Comparison. The conventional HPLC-MS method (top) involves multiple complex steps, while biosensor approaches (bottom) utilize simplified procedures suitable for rapid screening.

Analytical Signaling Pathways and Detection Principles

The fundamental detection principles underlying HPLC-MS and biosensor technologies operate through distinctly different mechanisms, which ultimately determine their application suitability and performance characteristics.

HPLC-MS Detection Pathway

HPLC-MS detection relies on physical separation followed by mass-based detection in a coordinated two-stage process [4] [6]:

Chromatographic Separation:

- Liquid Chromatography: Dissolved sample components travel through a column packed with stationary phase at different rates based on their chemical affinity, separating them temporally.

- Elution: Pesticide compounds elute at characteristic retention times determined by their chemical properties and interaction with the stationary phase.

Mass Spectrometric Detection:

- Ionization: Eluted compounds are ionized in the interface region (typically using electrospray ionization) to create charged molecular species.

- Mass Filtering: Ions are separated based on their mass-to-charge (m/z) ratios using quadrupole mass filters.

- Fragmentation: Selected precursor ions undergo collision-induced dissociation to produce characteristic product ion patterns.

- Detection: Product ions strike the detector, generating signals proportional to analyte concentration that are used for both qualitative identification and quantitative measurement.

This orthogonal approach (separation + mass detection) provides exceptional specificity and forms the foundation of regulatory compliance testing worldwide.

Biosensor Signaling Pathways

Biosensors employ diverse biorecognition principles that translate molecular interactions into detectable signals through various transduction mechanisms [3] [6] [9]:

Enzyme Inhibition-Based Detection:

- Recognition: Pesticide compounds bind to and inhibit specific enzymes (e.g., acetylcholinesterase for organophosphates and carbamates).

- Signal Modulation: Enzyme inhibition reduces the conversion of substrates to detectable products.

- Transduction: The decreased reaction rate is measured electrochemically, optically, or colorimetrically.

Immunological Recognition:

- Molecular Recognition: Antibodies specifically bind to target pesticide molecules (antigens).

- Complex Formation: Antigen-antibody binding creates molecular complexes.

- Signal Generation: Labels (enzymatic, fluorescent, or nanoparticles) attached to antibodies generate measurable signals.

Whole-Cell Biosensing:

- Cellular Response: Genetically engineered microbial cells produce reporter proteins (e.g., fluorescent, luminescent) in response to pesticide exposure.

- Gene Expression: Specific promoters activate upon detecting pesticide-induced cellular stress.

- Signal Amplification: Cellular machinery amplifies the detection signal through natural biological processes.

Diagram 2: Biosensor Signaling Principle. Biosensors utilize biological recognition elements that interact with target pesticides, generating signals through various transduction mechanisms that can be electrical, optical, or colorimetric.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Implementing effective pesticide detection methodologies requires specific reagents, biological materials, and analytical components that form the foundation of reliable monitoring systems.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Pesticide Detection Research

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Chromatography Columns | Separation of pesticide mixtures | Reversed-phase C18 columns (100 × 2.1 mm, 1.7-1.8 μm) for HPLC-MS |

| Mass Spectrometry Standards | Instrument calibration and quantification | Isotope-labeled internal standards (e.g., deuterated pesticides) |

| Organic Solvents | Sample extraction and mobile phase preparation | HPLC-grade acetonitrile, methanol, acetone |

| Enzyme Preparations | Biosensor recognition elements | Acetylcholinesterase, organophosphorus hydrolase |

| Antibodies | Immunosensor development | Monoclonal antibodies specific to pesticide classes |

| Aptamers | Synthetic recognition elements | DNA/RNA aptamers selected for specific pesticide binding |

| Microbial Cells | Whole-cell biosensor development | Genetically engineered E. coli, Bacillus species with reporter genes |

| Nanomaterials | Signal amplification in biosensors | Gold nanoparticles, graphene oxide, quantum dots |

| Chromogenic Substrates | Visual detection in paper-based sensors | Indoxyl acetate, tetramethylbenzidine |

| Paper Substrates | Lateral flow and microfluidic devices | Nitrocellulose membranes, chromatographic paper |

The critical importance of pesticide monitoring for ensuring food safety and protecting public health necessitates a strategic approach that leverages the complementary strengths of both conventional and emerging detection technologies. Rather than positioning biosensors as direct replacements for established HPLC-MS methods, the evidence supports an integrated, tiered monitoring framework that utilizes each technology according to its respective advantages [7].

In this complementary model, biosensors serve as efficient frontline screening tools capable of processing large sample volumes rapidly and inexpensively under field conditions. Their portability, ease of use, and real-time capabilities make them ideal for identifying potential contamination hotspots and making preliminary safety determinations. Subsequently, HPLC-MS provides confirmatory analysis for samples that test positive in initial screening, delivering the precise, legally-defensible quantitative data required for regulatory compliance and enforcement actions [4] [5].

Future advancements in microfluidic integration, artificial intelligence-assisted data interpretation, and multiplexed detection capabilities will further enhance the utility of biosensors while complementary developments in miniaturized mass spectrometry and automated sample preparation may expand the application scope of conventional methods [6] [8]. This technological convergence, combined with robust regulatory frameworks and standardized validation protocols, will ultimately strengthen global capacity for pesticide monitoring—an essential requirement for protecting ecosystem integrity and ensuring public health in an era of increasing agricultural intensification.

In the ongoing research to ensure food and environmental safety, the comparison between biosensors and chromatography-mass spectrometry methods is a central thesis. While novel biosensors emerge as promising tools for rapid screening, High-Performance Liquid Chromatography and Gas Chromatography coupled with Mass Spectrometry (HPLC-MS and GC-MS) remain the undisputed gold standards for confirmatory analysis. This guide provides an objective comparison of their performance, supported by experimental data and detailed protocols.

Unmatched Confirmatory Power: Core Principles and Advantages

The status of HPLC-MS and GC-MS as reference methods is rooted in their exceptional sensitivity, specificity, and robust quantitative capabilities. Their core strength lies in coupling high-resolution chromatographic separation with the definitive identification power of mass spectrometry [10].

HPLC-MS is indispensable for analyzing non-volatile, thermally labile, and high-molecular-weight compounds, making it ideal for a broad range of pesticides, pharmaceuticals, and biomolecules [11]. Its operation at ambient temperature prevents the thermal degradation of sensitive analytes.

GC-MS, in contrast, excels in separating and identifying volatile and semi-volatile organic compounds. The high temperatures required for vaporization provide excellent separation efficiency for small molecules like many pesticides and environmental contaminants [11].

Recent advancements, including ultra-high-pressure systems (UHPLC), highly efficient columns, and hybrid mass analyzers (e.g., Q-TOF, Orbitrap), have further enhanced their speed, sensitivity, and resolution [10]. This allows for the study of complex and less abundant metabolites and contaminants in intricate matrices like food, biological specimens, and traditional Chinese medicine [10] [12].

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison of HPLC-MS and GC-MS

| Feature | HPLC-MS | GC-MS |

|---|---|---|

| Analytical Principle | Separation in liquid phase under high pressure; detection via mass spectrometry [11] | Separation in gas phase with temperature programming; detection via mass spectrometry [11] |

| Ideal Analytes | Non-volatile, thermally unstable, polar, and high molecular weight compounds (e.g., glyphosate, neonicotinoids) [11] [12] | Volatile and semi-volatile, thermally stable compounds (e.g., organochlorine pesticides, pyrethroids) [11] [12] |

| Key Advantage | Broad applicability without derivatization; superior for labile molecules [13] | Higher peak capacity and superior separation efficiency for volatiles [14] |

| Typical Sensitivity | Picogram to femtogram levels [10] | Picogram to femtogram levels [10] |

| Primary Role in Pesticide Analysis | Gold standard for multi-residue analysis of non-volatile and polar pesticides [4] [12] | Preferred method for volatile and semi-volatile pesticide residues [4] [12] |

Quantitative Performance: Sensitivity and Accuracy Data

The quantitative precision of HPLC-MS and GC-MS is the benchmark against which other technologies are measured. In practical applications, these methods consistently deliver the sensitivity and accuracy required for regulatory compliance and risk assessment.

Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) is hailed as the "gold standard for multi-residue analysis" with unparalleled sensitivity and selectivity for organic contaminants in complex matrices like traditional Chinese medicine [12]. In the pesticide detection market, methods based on liquid chromatography hold a significant share due to their high sensitivity and accuracy [4]. The technology can detect a broad spectrum of analytes at trace concentrations, with modern systems achieving detection limits in the picogram (pg) and even femtogram (fg) range [10].

The following table summarizes experimental performance data for contaminant detection in various sample types, demonstrating their application in real-world analysis.

Table 2: Experimental Performance Data for Contaminant Detection

| Application Context | Target Contaminant | Technique Used | Reported Performance (LOD/LOQ or Linearity) | Experimental Matrix |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmaceutical Impurity Profiling [14] | Drug degradants (e.g., M399, M416) | UHPLC-UV | High-sensitivity assays for trace impurities ~0.01% | Drug product (tablet) formulation |

| TCM Safety [12] | Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) | HPLC-FLD | Detection limit of ~1 ng/mL | 70 varieties of Traditional Chinese Medicine |

| TCM Safety [12] | Aflatoxin B1 (AFB1), Ochratoxin A (OTA) | HPLC-FLD | High selectivity and sensitivity for trace-level analysis | Traditional Chinese Medicine |

| Food & Environmental [10] | Veterinary drug residues, environmental pollutants | LC-MS / GC-MS | Detection at picogram and femtogram levels | Food products, environmental samples |

Experimental Protocols: The Basis for Reproducible Results

The reliability of HPLC-MS and GC-MS data stems from well-established, rigorous experimental protocols. Below is a detailed methodology for a typical multi-residue pesticide analysis, illustrating the comprehensive workflow.

Detailed Protocol: Multi-Residue Pesticide Analysis in Botanical Materials

This protocol is adapted from methodologies used for detecting exogenous contaminants in complex matrices like Traditional Chinese Medicine [12].

Sample Preparation and Extraction

- Homogenization: The botanical sample (e.g., leaves, roots) is freeze-dried and ground into a fine, homogeneous powder.

- Weighing: Precisely weigh 2.0 ± 0.1 g of the homogenized powder into a 50 mL centrifuge tube.

- Extraction: Add 10 mL of a solvent mixture, typically acetonitrile:water (80:20, v/v), to the tube. Vortex vigorously for 1 minute.

- Shaking: Place the tubes on a mechanical shaker and agitate for 30 minutes at 250 rpm to ensure complete extraction.

- Centrifugation: Centrifuge at 5,000 × g for 10 minutes to separate the solid residue from the extract. Collect the supernatant.

Extract Cleanup (to reduce matrix effects)

- Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE): Pass the supernatant through a pre-conditioned SPE cartridge (e.g., C18 or a specialized multi-mode cartridge).

- Elution: Elute the target analytes with a suitable solvent, such as 5 mL of methanol containing 0.1% formic acid.

- Concentration: Evaporate the eluate to dryness under a gentle stream of nitrogen at 40°C.

- Reconstitution: Reconstitute the dried extract in 1 mL of initial mobile phase (e.g., water:methanol, 95:5, v/v). Vortex and filter through a 0.22 µm membrane into an HPLC vial.

Instrumental Analysis (HPLC-MS/MS Example)

- Chromatography:

- Column: UHPLC C18 column (e.g., 100 mm × 2.1 mm, 1.7 µm).

- Mobile Phase: (A) 5 mM ammonium formate in water and (B) methanol.

- Gradient: Program from 5% B to 95% B over 15 minutes, hold for 3 minutes.

- Flow Rate: 0.3 mL/min. Injection Volume: 5 µL.

- Mass Spectrometry (Triple Quadrupole):

- Ionization: Electrospray Ionization (ESI), positive/negative switching mode.

- Data Acquisition: Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM). For each pesticide, one precursor ion > product ion transition is used for quantification, and a second for qualification.

- Source Conditions: Optimize for desolvation temperature, capillary voltage, and gas flows.

Data Analysis and Quantification

- Calibration: A matrix-matched calibration curve (e.g., 1-500 ng/mL) is prepared and analyzed to quantify residues in the samples, compensating for matrix effects.

- Identification: A pesticide is confirmed positive when (1) the retention time matches the standard within ±0.1 minute, and (2) the ion ratio (quantifier/qualifier) is within ±20% of the standard.

- System Suitability: Before sample analysis, a standard mixture is run to ensure chromatographic resolution, peak shape, and MS sensitivity meet predefined criteria.

The following diagram visualizes this multi-step analytical workflow.

Head-to-Head with Biosensors: An Objective Comparison

The emergence of biosensors presents a paradigm for rapid screening, but a direct comparison with chromatography-mass spectrometry reveals a clear distinction in their primary applications and capabilities.

Biosensors leverage biological recognition elements (enzymes, antibodies, aptamers) and are designed for speed, portability, and cost-effectiveness for on-site use [6] [15]. However, they often face challenges with stability, specificity in complex matrices, and simultaneous multi-residue analysis [16] [15]. In contrast, HPLC-MS and GC-MS are laboratory-based workhorses that sacrifice speed and portability for unmatched analytical depth, reproducibility, and multi-analyte scope.

Table 3: Objective Comparison: Chromatography-MS vs. Biosensors

| Parameter | Chromatography-MS (HPLC/GC-MS) | Biosensors |

|---|---|---|

| Analytical Speed | Minutes to hours per sample [15] | Seconds to minutes [6] [15] |

| Portability | Laboratory-bound, benchtop systems [6] | High potential for portable, on-site devices [6] [15] |

| Multi-Residue Analysis | Excellent (Can screen hundreds of analytes simultaneously) [4] [12] | Limited (Typically single or few analytes per sensor) [15] |

| Sensitivity & LOD | High (Trace-level, ppt/ppq range) [10] | Variable (Good to high, but can be inferior to MS) [6] |

| Specificity & Confirmatory Power | Very High (Separation + spectral fingerprint) [10] [14] | Moderate (Prone to cross-reactivity in complex matrices) [16] |

| Quantitative Precision | Excellent (High accuracy and reproducibility) [14] | Good, but can be less precise than MS [15] |

| Sample Throughput | High for automated systems, but requires prep time [14] | Very High for individual tests [15] |

| Cost | High capital and operational cost [13] [6] | Lower cost per test and potential for low-cost devices [6] |

| Primary Role | Confirmatory analysis and reference method [10] [12] | Rapid screening and preliminary on-site testing [6] [15] |

A key limitation of enzyme-based biosensors is the inhibition mechanism used for detection, which is illustrated below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The experimental workflow for chromatography-MS relies on a suite of high-purity reagents and specialized materials. The following table details key solutions and components essential for successful analysis.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Chromatography-MS

| Reagent/Material | Function & Role in Analysis | Example Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Chromatography Columns | Core component for analyte separation. | C18 UHPLC column (100mm x 2.1mm, 1.7µm) [14]; Capillary GC column (15-30m x 0.25mm, 0.25µm film) [11] |

| MS Ionization Sources | Ionizes analytes for mass analysis. | Electrospray Ionization (ESI) for HPLC-MS; Electron Impact (EI) for GC-MS [10] |

| High-Purity Solvents | Mobile phase and sample preparation. | LC-MS grade Acetonitrile, Methanol, Water; HPLC grade Hexane [11] |

| Volatile Buffers | Modifies mobile phase for improved separation and ionization. | Ammonium Formate, Ammonium Acetate (e.g., 5-20 mM) [14] |

| Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE) Cartridges | Cleanup and preconcentration of samples. | C18, Polymer-based, or Mixed-mode sorbents [12] |

| Analytical Standards | Identification and quantification of target analytes. | Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) for pesticides and metabolites [12] |

Biosensors are defined as analytical devices that integrate a biological recognition element (bioreceptor) with a physicochemical transducer to convert a biological event into a measurable signal [17] [18]. These systems provide exceptional specificity through their biorecognition components while offering sensitive detection via various transduction mechanisms. The first biosensor, developed over 55 years ago by Leland Clark, combined glucose oxidase with an amperometric oxygen sensor, establishing the foundational architecture for all subsequent biosensor developments [17].

In the context of pesticide detection, biosensors have emerged as viable alternatives to traditional chromatographic methods, addressing the need for rapid, on-site analysis without compromising sensitivity [6] [19]. While conventional techniques like high-performance liquid chromatography and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS and GC-MS) remain gold standards for laboratory-based pesticide residue analysis, they necessitate intricate pretreatment, substantial operational expenses, and are inadequate for swift on-site analysis [6]. Biosensors bridge this technological gap with their exceptional sensitivity, rapid response, and ease of operation, making them particularly valuable for preliminary screening and real-time monitoring in field conditions [6] [8].

The fundamental components of a biosensor include a biorecognition element that provides analyte specificity, a transducer that converts the biological response into a quantifiable signal, and a signal processing system that interprets the output [18]. This integrated approach allows biosensors to deliver analytical capabilities that support precision detection, high-throughput screening, and field-deployable monitoring across various applications including environmental surveillance, food quality control, and clinical diagnostics [18].

Core Principles of Biorecognition Elements

The biorecognition element is the cornerstone of biosensor specificity, designed to interact selectively with a target analyte through biochemical mechanisms. These elements can be categorized into several classes based on their biological origin and operational principles.

Natural Biorecognition Elements

Antibodies are naturally occurring 3D protein structures (~150 kDa) that form stable immunocomplexes with antigens through highly specific binding domains located on their "Y"-shaped arms [17]. This specific binding forms the basis of immunosensors, where antibody-antigen recognition is monitored using various transduction methods [17] [20]. Despite their excellent specificity, antibodies require animal experimentation for production, which is costly and time-consuming, and they can be unstable in solution, tending to aggregate with potential loss of activity [17].

Enzymes achieve bioanalyte specificity through binding cavities buried within their 3D structure, utilizing hydrogen-bonding, electrostatics, and other non-covalent interactions [17]. Enzymatic biosensors are typically biocatalytic, meaning the enzyme captures and catalytically converts the target bioanalyte to a measurable product [17]. For pesticide detection, enzymes such as acetylcholinesterase (AChE) are particularly valuable, as organophosphate and carbamate pesticides inhibit AChE activity, providing a reliable detection mechanism [19]. Enzymes are often embedded within surface structures to allow short diffusion pathways between the biorecognition element and transducer [17].

Synthetic and Engineered Biorecognition Elements

Aptamers are single-stranded oligonucleotides developed through a combinatorial selection process called Systemic Evolution of Ligands by Exponential Enrichment (SELEX) [17]. This iterative process screens large libraries of oligonucleotide sequences to identify those with strong binding affinities for target analytes, including metal ions, small molecules, proteins, and even whole cells [17]. Aptamers typically consist of 100 base pairs with a 20-70 randomized base pair binding region flanked by constant primer binding regions [17]. While the SELEX process can be costly, aptamers offer significant advantages in stability and application range compared to natural biorecognition elements.

Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) represent a fully synthetic approach to biorecognition, using a templated polymer matrix to achieve analyte specificity through patterns of non-covalent bonding, electrostatic interactions, or size inclusion/exclusion [17]. MIPs are synthetically fabricated for each unique target bioanalyte, with the polymer-based recognition element designed around the bioanalyte template [17]. This approach eliminates the need to biochemically identify specific biorecognition element-bioanalyte pairings, offering greater flexibility for novel targets.

Table 1: Comparison of Biorecognition Elements for Biosensors

| Biorecognition Element | Source | Binding Mechanism | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | Natural (biological) | Immunocomplex formation | High specificity and affinity | Production requires animals; costly and time-consuming; stability issues |

| Enzymes | Natural (biological) | Catalytic conversion or inhibition | High catalytic activity; reusable | Sensitivity to environmental conditions; limited to specific substrates |

| Aptamers | Synthetic (SELEX) | 3D structure complementary | Wide target range; high stability; modifiable | SELEX process costly; potential degradation by nucleases |

| Nucleic Acids | Natural/Synthetic | Complementary base pairing | High predictability; easy synthesis | Limited to nucleic acid targets; requires complementary sequence |

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) | Synthetic | Template-shaped cavities | High stability; customizable for any target | Possible non-specific binding; complex optimization |

Signal Transduction Mechanisms in Biosensors

The transducer component of a biosensor serves the critical function of converting the biological recognition event into a measurable signal. The choice of transduction mechanism significantly influences the sensitivity, detection limits, and practical applicability of the biosensor.

Electrochemical Transduction

Electrochemical biosensors represent the most common transduction method, comprising approximately 71% of reported biosensors for pesticide detection [19]. These systems measure electrical changes resulting from biochemical interactions at electrode surfaces, typically utilizing a three-electrode configuration (working electrode, counter electrode, and reference electrode) [20]. Electrochemical biosensors can be further categorized based on the specific electrical parameter measured:

- Amperometric sensors quantify current changes resulting from redox reactions occurring at the electrode surface, often measuring enzymatic conversion rates [18].

- Potentiometric sensors detect potential differences between working and reference electrodes when no significant current flows between them [18].

- Impedimetric sensors measure frequency-dependent resistance changes due to biomolecular binding at modified electrodes, monitoring changes in charge-transfer resistance (Rct) [18].

The integration of nanomaterials, particularly MXenes (two-dimensional transition metal carbides/nitrides), has significantly enhanced electrochemical biosensor performance [20]. MXenes provide abundant binding sites for effective immobilization of biorecognition elements while facilitating efficient electron transfer, resulting in improved sensitivity and lower detection limits [20].

Optical Transduction

Optical biosensors utilize various light-matter interactions to detect and quantify binding events, representing approximately 13.55% of biosensors for pesticide detection [19]. These systems offer superior multiplexing capabilities and are favored in research and high-resolution systems [18]. Major optical transduction approaches include:

- Fluorescence-based sensors employ fluorescent tags or labels that undergo intensity, lifetime, or anisotropy changes upon analyte binding, enabling single-molecule sensitivity and real-time monitoring [18].

- Colorimetric sensors detect visible color changes that can often be visualized without sophisticated instrumentation, making them suitable for point-of-care applications [19].

- Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) monitors changes in refractive index near a metal surface, enabling label-free detection of binding events in real-time [6].

- Luminescent sensors utilize light emission from excited states, with luminescent nanosensors emerging as promising tools for sensitive pesticide detection due to their portability, real-time monitoring capability, and potential for miniaturization [21].

Other Transduction Mechanisms

Piezoelectric and mechanical transducers detect mass changes on surfaces through shifts in resonance frequency when target analytes bind to functionalized interfaces [18]. Microelectromechanical systems (MEMS) and nanoelectromechanical systems (NEMS) transduce forces, deflections, or resonance frequency shifts, offering exceptional sensitivity to minute mass changes [18].

Thermal transducers monitor heat exchange from biochemical reactions, though these are less commonly employed for pesticide detection applications [18].

Diagram 1: Biosensor Architecture and Classification. This diagram illustrates the core components of a biosensor and the main categories of biorecognition elements and transduction mechanisms.

Biosensors Versus HPLC-MS for Pesticide Detection

The comparison between biosensors and HPLC-MS for pesticide detection reveals complementary strengths and limitations, with each approach serving distinct applications within the analytical workflow.

Analytical Performance Comparison

Table 2: Performance Comparison: Biosensors vs. HPLC-MS for Pesticide Detection

| Parameter | Biosensors | HPLC-MS |

|---|---|---|

| Detection Limit | nM to pM range [6] | Sub-ppb to ppt level [22] |

| Analysis Time | 5-30 minutes [6] | 30 minutes to several hours [6] |

| Sample Preparation | Minimal often required [19] | Extensive (SPE, microwave digestion) [6] |

| Portability | Excellent (lab-on-paper, portable devices) [8] | Limited to laboratory settings |

| Multi-residue Analysis | Limited multiplexing capability | Excellent (100+ compounds simultaneously) |

| Equipment Cost | Low to moderate [19] | High (>$1 million for ICP-MS) [6] |

| Operator Skill Required | Minimal training | Highly skilled technicians |

| Throughput | Moderate | High for multi-residue methods |

| Applications | Rapid screening, on-site testing | Regulatory compliance, reference methods |

Practical Implementation Considerations

The selection between biosensors and HPLC-MS depends heavily on the specific application requirements. Biosensors excel in scenarios requiring rapid results, field deployment, and high-frequency monitoring, with technologies such as lab-on-paper devices and lateral flow assays enabling point-of-care detection of pesticide residues [8]. These systems are particularly valuable for preliminary screening, allowing for immediate decision-making in field conditions without the need for sample transport to centralized laboratories.

HPLC-MS systems remain indispensable for regulatory compliance, method validation, and comprehensive multi-residue analysis where unambiguous identification and quantification of numerous pesticide compounds are required [22] [23]. These techniques offer exceptional precision, accuracy, and sensitivity for complex matrices, serving as reference methods for confirmatory analysis when legal or regulatory actions are contemplated [23].

The integration of nanomaterials has significantly enhanced biosensor performance, narrowing the sensitivity gap with traditional chromatographic methods. Noble metal nanoparticles (gold and silver), carbon-based nanomaterials, and nanohybrids (combining multiple nanomaterials) improve biosensor sensitivity by providing high surface area-to-volume ratios, enhanced electrical conductivity, and catalytic activity [19]. For instance, carbon quantum dot/AuNP-based aptasensors have achieved detection limits of 1.08 μg/L for acetamiprid in tomato, cucumber, and cabbage samples [21].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Representative Biosensor Experimental Protocol

Aptamer-Based Electrochemical Biosensor for Organophosphate Pesticides

Biorecognition Element Immobilization:

- Functionalize working electrode (gold or carbon) with MXene (Ti₃C₂Tₓ) dispersion to create a high-surface-area platform [20].

- Activate MXene surface through EDC/NHS chemistry to generate reactive groups for biomolecule conjugation.

- Incubate activated surface with thiol- or amine-modified aptamer specific to target pesticide (e.g., chlorpyrifos) for 2 hours at room temperature.

- Block non-specific binding sites with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 30 minutes.

Sample Preparation and Measurement:

- Prepare food samples (fruits, vegetables) through simple extraction using buffer solution, with minimal pretreatment [19].

- Incubate prepared sample with functionalized biosensor for 10-15 minutes.

- Perform electrochemical measurement using differential pulse voltammetry or electrochemical impedance spectroscopy.

- Quantify pesticide concentration based on changes in current or charge-transfer resistance relative to calibration curve.

Validation:

- Validate biosensor performance against reference HPLC-MS method for identical samples [19].

- Determine detection limit, linear range, and specificity against structurally similar compounds.

HPLC-MS Reference Method Protocol

Sample Preparation:

- Homogenize representative food sample (e.g., tea leaves, fruits, vegetables).

- Perform extraction using QuEChERS (Quick, Easy, Cheap, Effective, Rugged, Safe) method or solid-phase extraction (SPE) [22].

- Clean extracts using dispersive SPE to remove interfering compounds.

- Concentrate samples under gentle nitrogen stream.

Instrumental Analysis:

- Separate pesticides using liquid chromatography (UHPLC) with C18 reverse-phase column.

- Employ gradient elution with water and acetonitrile mobile phases, both modified with 0.1% formic acid.

- Interface with tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) using electrospray ionization in positive or negative mode.

- Monitor multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) transitions for target pesticides and their metabolites.

- Quantify against matrix-matched calibration curves with internal standards [22].

Diagram 2: Comparative Workflows: Biosensor vs. HPLC-MS. This diagram highlights the streamlined process for biosensors suitable for field testing versus the more rigorous laboratory-based HPLC-MS protocol.

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Successful development and implementation of biosensors for pesticide detection require specific reagents and materials that ensure optimal performance and reliability.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Biosensor Development

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Noble Metal Nanoparticles (Gold, Silver) | Signal amplification; enhanced conductivity; plasmonic effects | AuNPs for colorimetric aptasensors [19] |

| Carbon Nanomaterials (CNTs, Graphene, Carbon Dots) | Improved electron transfer; large surface area; quenching properties | CNT-based electrochemical sensors [19] |

| MXenes (Ti₃C₂Tₓ) | Biorecognition element anchoring; signal transduction | Electrochemical sensor platforms [20] |

| Enzymes (AChE, ChOx) | Biocatalytic recognition; inhibition-based detection | Organophosphate and carbamate detection [19] |

| Aptamers | Synthetic recognition elements; high stability | Chlorpyrifos detection in food matrices [19] |

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymers | Synthetic recognition cavities; custom design | Glyphosate detection in water [17] |

| Immobilization Matrices (Hydrogels, SAMs) | Bioreceptor stabilization; surface functionalization | Antibody attachment to transducers [18] |

| Signal Probes (Electroactive labels, Fluorophores) | Signal generation and amplification | Ferrocene derivatives for electrochemical detection [18] |

The evolution of biosensor technology continues to address the limitations of traditional pesticide detection methods, with emerging trends focusing on enhanced performance, practicality, and integration.

Miniaturization and portability represent a significant direction, with lab-on-paper devices and microfluidic systems enabling field-deployable analysis without compromising sensitivity [8]. These platforms utilize paper as a substrate, providing a low-cost, portable, and qualitative method for detecting pesticide residues in various samples [8]. The integration of smartphone-based readout systems further enhances the field applicability of these devices, allowing for real-time data analysis and sharing [8].

Multiplexing capabilities are being improved through the development of multi-analyte biosensors and array-based platforms, addressing a key advantage of chromatographic methods [6]. Recent advances have demonstrated simultaneous detection of chlorpyrifos, diazinon, and malathion in complex food matrices using quantum dot-based sensors with detection limits of 0.73, 6.7, and 0.74 ng/mL respectively [21].

Artificial intelligence and machine learning integration are creating intelligent sensing platforms that improve data interpretation, compensate for environmental variables, and enable predictive analysis [8]. These technologies enhance the reliability of biosensors in complex matrices and reduce false positive results through advanced pattern recognition.

Nanomaterial advancements continue to drive improvements in biosensor sensitivity, with novel structures such as metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) and MXenes providing unprecedented opportunities for biorecognition element immobilization and signal enhancement [6] [20]. MXenes, in particular, offer large specific surface area, tunable surface chemistry, and high conductivity, making them promising materials for next-generation biosensing applications [20].

In conclusion, while HPLC-MS remains the gold standard for confirmatory pesticide residue analysis in regulatory contexts, biosensors have established a crucial role in rapid screening, on-site monitoring, and resource-limited settings. The complementary application of both technologies provides a comprehensive approach to pesticide detection, balancing the need for expedient results with the requirement for definitive confirmation. Future advancements in biorecognition elements, transduction mechanisms, and material science will further narrow the performance gap between these platforms, ultimately expanding the capabilities for ensuring food safety and environmental protection.

Key Market and Regulatory Drivers Shaping Technology Adoption

The detection of pesticide residues in food and environmental samples represents a critical challenge at the intersection of public health, agricultural practice, and regulatory compliance. Within this domain, a significant technological divergence has emerged between established conventional methods and innovative biosensing approaches. High-performance liquid chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS) has long served as the gold standard for confirmatory laboratory analysis, offering exceptional sensitivity and multi-residue capability [24]. Conversely, biosensor technologies have rapidly advanced as viable alternatives that address the growing need for rapid, on-site screening with comparable sensitivity and significantly reduced operational complexity [6] [19]. This comparison guide objectively examines the competitive landscape between these technological paradigms, analyzing their respective performance characteristics, operational parameters, and positioning within a regulatory framework increasingly demanding both precision and practicality.

The global pesticide detection market, valued at approximately USD 1.50 billion in 2025 and projected to reach USD 2.43 billion by 2035, reflects the escalating emphasis on food safety and environmental monitoring [4]. This growth is primarily driven by stringent regulatory frameworks worldwide, such as the European Union's Regulation (EC) No 396/2005 and China's GB 2763-2021, which establish increasingly strict Maximum Residue Limits (MRLs) for pesticides in food commodities [6] [25]. These regulatory pressures compel producers and regulators to adopt more sophisticated monitoring technologies, creating a fertile environment for technological innovation that balances analytical rigor with operational feasibility.

Technology Comparison: Biosensors vs. HPLC-MS

Performance and Operational Characteristics

The selection between biosensor and HPLC-MS technologies involves critical trade-offs across multiple performance and operational parameters, as systematically compared in Table 1.

Table 1: Comprehensive Performance Comparison Between Biosensor and HPLC-MS Technologies

| Parameter | Biosensors | HPLC-MS |

|---|---|---|

| Detection Limit | nM to pM range [6]; LODs lower than Codex MRLs [19] | Ultra-trace detection (exact values method-dependent) [24] |

| Analysis Time | 5-30 minutes [6] | Several hours including preparation [26] [24] |

| Portability | High (field-deployable systems) [26] [8] | Low (laboratory-bound) [6] |

| Multiplexing Capability | Emerging for multi-residue detection [6] [19] | Excellent (established MRMs) [4] [24] |

| Sample Preparation | Minimal (often dilution/filtration only) [25] | Extensive (extraction, clean-up, concentration) [6] [26] |

| Cost Per Analysis | Low [24] | High [6] |

| Equipment Cost | Low to moderate [24] | High (>$1 million for ICP-MS) [6] |

| Operator Skill Required | Low to moderate [25] | High (specialized training) [25] [24] |

The data reveals complementary technological profiles. Biosensors excel in operational efficiency, offering rapid results with minimal sample preparation, which positions them ideally for high-throughput screening and field-deployment scenarios [6] [25]. Their limitations in specificity—often detecting pesticide classes rather than individual compounds—can be mitigated through strategic integration with confirmatory methods [25]. Conversely, HPLC-MS provides unparalleled analytical precision, enabling definitive identification and quantification of specific compounds in complex matrices, which remains indispensable for regulatory compliance and method validation [24]. This fundamental distinction informs their respective positions within the analytical ecosystem, with biosensors evolving as sophisticated screening tools and HPLC-MS maintaining its status as the definitive confirmatory technique.

Detection Principles and Workflows

The operational dichotomy between these technologies originates in their fundamentally different detection principles. HPLC-MS separates chemical compounds based on their interaction with a chromatographic column before ionizing and detecting them based on mass-to-charge ratio, providing structural identification [24]. In contrast, biosensors employ biological recognition elements (enzymes, antibodies, aptamers) that interact specifically with target analytes, transducing this interaction into a quantifiable electrical or optical signal [19].

The following diagram illustrates the core operational workflow for a widely used biosensor type based on the enzyme acetylcholinesterase (AChE), which detects organophosphorus and carbamate pesticides.

Diagram 1: Comparative Workflows of HPLC-MS and Biosensor Technologies

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Acetylcholinesterase-Based Biosensor Protocol

The experimental protocol for acetylcholinesterase (AChE)-based biosensors demonstrates the streamlined operational workflow characteristic of this technology. This method leverages the irreversible inhibition of AChE by organophosphorus pesticides (OPs) to achieve highly sensitive detection [25].

Materials and Reagents:

- Acetylcholinesterase enzyme (source: electric eel or recombinant)

- Acetylthiocholine chloride (ATCh) or acetylcholine (ACh) substrate

- Screen-printed electrodes (SPEs) with integrated working, reference, and counter electrodes

- Phosphate buffer saline (PBS, 0.1 M, pH 7.4)

- 5,5'-Dithio-bis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB) for chromogenic reaction (colorimetric detection)

- Portable potentiostat or dedicated readout device

Procedure:

- Electrode Modification: Immobilize AChE (e.g., 10 mU) onto the working electrode surface via physical adsorption or cross-linking with glutaraldehyde [26].

- Sample Preparation: For food matrices (e.g., pepper extracts, vegetable samples), homogenize and dilute with PBS. Filter if necessary to remove particulate matter. Minimal preparation is a key advantage [26] [25].

- Inhibition Phase: Incubate the AChE-modified electrode with the sample solution for a fixed period (typically 10-15 minutes). OPs present in the sample will inhibit the enzyme proportionally to their concentration.

- Substrate Addition & Measurement: Introduce substrate (ATCh) into the system. For electrochemical detection, apply a fixed potential (+0.5 V vs. Ag/AgCl) and measure the amperometric current generated by the enzymatic hydrolysis product (thiocholine) [26]. The percentage inhibition is calculated as (I₀ - I)/I₀ × 100%, where I₀ and I are the currents before and after exposure to OPs.

- Quantification: Determine pesticide concentration from a calibration curve of inhibition percentage versus standard pesticide concentration [26] [25].

Validation: The performance of this biosensor protocol was validated against HPLC-MS for pepper extracts, showing comparable results (biosensor: 184 μg/L vs. HPLC-MS confirmation) while significantly reducing analysis time and complexity [26].

HPLC-MS Reference Protocol

The HPLC-MS protocol represents the confirmatory method against which biosensor performance is often benchmarked, offering high accuracy and specificity at the cost of operational complexity [24].

Materials and Reagents:

- HPLC-grade solvents (acetonitrile, methanol)

- Pesticide analytical standards

- Formic acid or ammonium acetate for mobile phase modification

- Solid-phase extraction (SPE) cartridges (e.g., C18, QuEChERS)

- HPLC-MS system with electrospray ionization (ESI) or atmospheric pressure chemical ionization (APCI)

Procedure:

- Extraction: Homogenize the sample (e.g., 5 g) with an organic solvent (e.g., acetonitrile, 10 mL) [26] [24].

- Clean-up: Purify the extract using SPE or dispersive SPE (d-SPE) to remove co-extracted matrix interferents like lipids and pigments [24].

- Concentration: Evaporate the eluent to near-dryness under nitrogen stream and reconstitute in a solvent compatible with the HPLC mobile phase.

- Chromatographic Separation: Inject the extract onto a reversed-phase C18 column. Employ a gradient elution program (e.g., water/methanol with 0.1% formic acid) over 15-30 minutes to separate individual pesticide residues [24].

- Mass Spectrometric Detection: Analyze the column effluent using a mass spectrometer operated in multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) mode. Use optimized compound-specific parameters (precursor ion, product ion, collision energy) for identification and quantification [24].

- Data Analysis: Quantify residues by comparing analyte peak areas to a multi-point calibration curve of matrix-matched standards [24].

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The development and implementation of both biosensor and HPLC-MS technologies rely on specialized reagents and materials that define their operational capabilities and limitations. Table 2 catalogs these essential components, providing researchers with a foundational inventory for method establishment.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Pesticide Detection Technologies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Technology Application |

|---|---|---|

| Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) | Biological recognition element; inhibited by OPs/Carbamates | Biosensors [26] [25] |

| Nucleic Acid Aptamers | Synthetic recognition elements; high stability & specificity | Biosensors [6] [19] |

| Screen-Printed Electrodes (SPEs) | Disposable electrochemical transduction platform | Biosensors (Electrochemical) [26] |

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | Signal amplification; enhance electron transfer & optical properties | Biosensors (Multiple Types) [19] |

| Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) | Enzyme immobilization; improve stability & sensitivity | Biosensors [6] [25] |

| HPLC-MS Grade Solvents | Mobile phase & extraction; minimize background interference | HPLC-MS [24] |

| QuEChERS Extraction Kits | Sample preparation; rapid multi-residue extraction & clean-up | HPLC-MS [24] |

| Isotope-Labeled Internal Standards | Quantification accuracy; correct for matrix effects & loss | HPLC-MS [24] |

| Chromatographic Columns (C18) | Analytical separation; resolve complex pesticide mixtures | HPLC-MS [24] |

The strategic selection of these reagents directly influences analytical performance. For biosensors, the choice of recognition element (AChE, aptamers, antibodies) dictates specificity, while nanomaterials (AuNPs, MOFs) significantly enhance signal response and stability [19] [25]. For HPLC-MS, the quality of separation columns and extraction sorbents fundamentally determines resolution and sensitivity, while isotope-labeled standards are indispensable for accurate quantification in complex matrices [24].

Market Adoption Drivers and Future Outlook

The adoption dynamics for pesticide detection technologies are shaped by a complex interplay of regulatory requirements, economic considerations, and technological innovation. The global market valuation reflects a steady growth trajectory (CAGR of 4.9% from 2025-2035), underscoring the increasing prioritization of food safety and environmental monitoring [4]. A significant market trend involves the rising dominance of multi-residue methods (MRMs), projected to capture approximately 54% market share by 2025, as they provide efficient simultaneous detection of multiple pesticide residues in a single analysis, thereby reducing time and cost while improving accuracy [4].

The regulatory landscape functions as a primary technology adoption driver. Stringent MRLs established by international bodies (Codex Alimentarius) and national agencies (EU, U.S. EPA, China GB standards) continuously pressure the agricultural and food industries to implement more sensitive and reliable detection methods [6] [25]. This regulatory environment increasingly supports a collaborative "screening-confirmation" framework, where biosensors provide rapid, cost-effective initial screening to identify potential non-compliant samples, which are subsequently subjected to confirmatory analysis using definitive HPLC-MS techniques [25]. This integrated approach optimizes resource allocation by reducing the burden on expensive laboratory infrastructure while maintaining rigorous regulatory compliance.

Future developments will be shaped by several convergent technological trends. Miniaturization and portability will continue to enhance field-deployment capabilities, particularly for biosensors integrated with microfluidic platforms and smartphone-based readout systems [8]. Artificial intelligence and machine learning are poised to revolutionize data processing and interpretation, enabling intelligent sensing platforms that can compensate for environmental variables and improve prediction accuracy [8]. Furthermore, the integration of novel nanomaterials with tailored properties will persistently push the boundaries of sensitivity and multiplexing capability for both biosensor and chromatographic applications [6] [19] [25]. These advancements collectively signal a future where analytical technologies become increasingly accessible, intelligent, and integrated across the entire food production and environmental monitoring spectrum.

Inside the Technologies: Operational Mechanisms and Real-World Applications

The reliable detection of pesticide residues in food matrices represents a critical challenge for modern analytical chemistry, with significant implications for food safety, regulatory compliance, and public health. Within this field, high-performance liquid chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS) has emerged as the cornerstone technique for multiresidue analysis, capable of detecting hundreds of compounds in a single run at concentrations far below regulatory limits [27]. The technique's dominance stems from its exceptional sensitivity, selectivity, and ability to handle thermally labile and non-volatile pesticides that challenge other methodologies [4].

This guide examines the current state of HPLC-MS workflows for pesticide analysis, with particular focus on performance in complex matrices such as fruits, vegetables, and spices. We objectively compare emerging technological advancements against conventional approaches, providing experimental data to illustrate key performance differentiators. Furthermore, we contextualize these HPLC-MS methodologies within the broader research landscape of biosensor development, highlighting complementary strengths and applications in food safety monitoring.

HPLC-MS Workflow Components and Methodologies

Sample Preparation: QuEChERS as the Gold Standard

The Quick, Easy, Cheap, Effective, Rugged, and Safe (QuEChERS) method has become the predominant sample preparation technique for multiresidue pesticide analysis in complex matrices. This approach typically involves an acetonitrile-based extraction followed by a dispersive solid-phase extraction (d-SPE) clean-up step to remove matrix interferents [27] [28].

Recent optimizations have focused on matrix-specific clean-up protocols. For challenging matrices like chili powder—rich in pigments, oils, and capsinoids—researchers have systematically evaluated sorbents including primary secondary amine (PSA) for removing organic acids, C18 for lipids, and graphitized carbon black (GCB) for pigments [29]. The careful balancing of sorbent combinations is critical, as over-cleaning—particularly with GCB—can reduce recoveries of planar pesticide molecules [29].

Chromatographic Separation: The Shift to Micro-Flow LC

A significant advancement in HPLC-MS workflows is the transition from conventional analytical-flow liquid chromatography to micro-flow systems. While analytical-flow LC typically operates at 500-100 μL min⁻¹, micro-flow LC utilizes flow rates of 100-10 μL min⁻¹, offering substantial improvements in sensitivity and sustainability [30].

Table 1: Performance Comparison: Analytical-Flow vs. Micro-Flow LC-MS/MS

| Parameter | Analytical-Flow LC-MS/MS | Micro-Flow LC-MS/MS |

|---|---|---|

| Flow Rate | 500-100 μL min⁻¹ | 50 μL min⁻¹ |

| Solvent Consumption | Baseline (100%) | Reduced by >5-fold |

| Sensitivity (LOD) | 75-81% of compounds at 0.001-0.002 mg kg⁻¹ | 89% of compounds at 0.001-0.002 mg kg⁻¹ |

| Retention Time Stability | Not specified | <2.1 s deviation across 50 injections |

| Peak Area RSD | Not specified | 3.4% (tomato), 2.9% (orange) |

Micro-flow LC provides an optimal balance between the extreme sensitivity of nano-flow LC and the robustness of analytical-flow systems. The technology enhances electrospray ionization efficiency by producing smaller droplets, thereby improving desolvation and ion transmission into the mass spectrometer [30]. This results in significantly improved sensitivity for trace-level detection while dramatically reducing solvent consumption and waste generation, aligning with green analytical chemistry principles [30].

Mass Spectrometric Detection

Triple quadrupole mass spectrometers operating in multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) mode remain the workhorse for quantitative multiresidue pesticide analysis due to their excellent sensitivity and selectivity [30] [27]. Recent instrumental advancements focus on enhancing robustness and throughput. New systems feature improved ion sources, such as the PerkinElmer QSight series with StayClean technology and laminar flow ion guides, which reduce maintenance requirements when analyzing complex matrices [31] [4].

High-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) is gaining traction for non-targeted screening and metabolite identification, though its quantitative capabilities for routine analysis still generally trail those of triple quadrupole instruments [32].

Comparative Performance Analysis

Method Validation Metrics

Comprehensive method validation following established guidelines such as SANTE/11312/2021 demonstrates the exceptional performance of modern HPLC-MS workflows for multiresidue analysis [27] [28]. Key validation parameters include sensitivity, linearity, accuracy (recovery), precision, and matrix effects.

Table 2: Validation Data for HPLC-MS Methods in Different Matrices

| Matrix | Number of Pesticides | LOQ (mg kg⁻¹) | Recovery Range (%) | Precision (RSD%) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tomato | 349 | 0.01 | 70-120 | <20 | [27] |

| Various (fruits, vegetables, cereals) | 10 diamide insecticides | 0.005 | 76.6-108.2 | 1.0-13.4 (intra-day), 2.3-15.7 (inter-day) | [28] |

| Chili powder | 135 | 0.005 | 70-120 (per SANTE guidelines) | <15 | [29] |

| Tomato and orange | 257 | 0.001-0.002 | Not specified | 3.4% (tomato), 2.9% (orange) | [30] |

Throughput and Efficiency Considerations

A critical advantage of modern HPLC-MS workflows is their dramatically improved throughput. One study demonstrated the analysis of 349 pesticides in a single 15-minute chromatographic run, a significant improvement over previous methodologies that required multiple runs [27]. This enhancement directly translates to reduced analytical costs and faster turnaround times for monitoring programs.

Innovative approaches such as radial flow splitting columns can further increase throughput. This technology enables a threefold improvement in analytical throughput by splitting the total mobile phase flow and directing only the central portion to the MS, improving separation efficiency without compromising quantitative performance [33].

HPLC-MS in Context: Comparison with Biosensor Technologies

While HPLC-MS remains the gold standard for comprehensive multiresidue analysis, biosensor technologies represent an emerging alternative with distinct advantages for specific applications. The table below summarizes key differences between these complementary approaches.

Table 3: HPLC-MS vs. Biosensors for Pesticide Detection

| Parameter | HPLC-MS/MS | Biosensors |

|---|---|---|

| Detection Principle | Chromatographic separation with mass spectrometric detection | Biological recognition elements (enzymes, antibodies, nucleic acids, whole cells) coupled with transducers |

| Multiresidue Capability | Excellent (100+ compounds simultaneously) | Generally limited to single or few compounds per sensor |

| Sensitivity | Excellent (sub-ppb levels) | Good to excellent (varies by technology) |

| Analysis Time | Minutes to hours (including sample preparation) | Seconds to minutes |

| Portability | Laboratory-based | Portable and handheld options available |

| Cost per Analysis | High | Low to moderate |

| Operator Skill Requirements | High | Low to moderate |

| Applicability | Regulatory compliance, comprehensive monitoring | Rapid screening, field testing, point-of-care |

Biosensors typically utilize biological recognition elements such as enzymes, antibodies, nucleic acids, or whole cells integrated with transducers (electrochemical, optical, thermal) to convert molecular interactions into measurable signals [34]. Recent advancements have significantly improved their sensitivity, with electrochemical biosensors particularly promising due to their low detection limits and cost-effectiveness [34].

While biosensors excel in rapid, on-site screening applications, HPLC-MS maintains distinct advantages for comprehensive regulatory testing due to its unparalleled ability to simultaneously quantify hundreds of pesticide residues with exceptional sensitivity and confirmatory power [35] [34].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Representative Workflow: Multiresidue Analysis in Complex Matrices

(Diagram Title: HPLC-MS Workflow for Multi-Residue Analysis)

Detailed Extraction and Clean-up Protocol

For complex matrices like chili powder, the following optimized protocol has demonstrated robust performance [29]:

Extraction: Homogenize 10 g sample with 10 mL acetonitrile and shake vigorously for 1 minute. Add extraction salts (4 g MgSO₄, 1 g NaCl, 1 g trisodium citrate dihydrate, 0.5 g disodium hydrogen citrate sesquihydrate) and shake immediately for 1 minute. Centrifuge at 4000 rpm for 5 minutes.

Clean-up: Transfer 6 mL supernatant to a d-SPE tube containing 900 mg MgSO₄, 150 mg PSA, 150 mg C18, and 45 mg GCB. Shake for 30 seconds and centrifuge at 4000 rpm for 5 minutes.

Analysis: Transfer supernatant to an autosampler vial for HPLC-MS/MS analysis.

This protocol effectively minimizes matrix effects while maintaining high recovery rates for multiple pesticide classes [29].

HPLC-MS Instrumental Parameters

A validated method for 257 pesticides in tomato and orange matrices employs these conditions [30]:

- Chromatography: Micro-flow LC system with C18 column (1.0 × 100 mm, 1.7 μm) maintained at 40°C

- Mobile Phase: (A) Water with 0.1% formic acid and 5 mM ammonium formate; (B) Methanol with 0.1% formic acid and 5 mM ammonium formate

- Gradient: 5% B to 100% B over 14 minutes

- Flow Rate: 50 μL min⁻¹

- Injection Volume: 5 μL

- Mass Spectrometry: Triple quadrupole with ESI+ and ESI- switching

- Ion Source Temperature: 150°C

- Desolvation Temperature: 300°C

- Cone Gas Flow: 50 L hr⁻¹

- Desolvation Gas Flow: 1000 L hr⁻¹

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for HPLC-MS Pesticide Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Acetonitrile (LC-MS grade) | Primary extraction solvent | Preferred over methanol for better selectivity and lower co-extraction of non-polar interferents [29] |

| Primary Secondary Amine (PSA) | d-SPE sorbent | Removes fatty acids, sugars, and other organic acids [28] [29] |

| Graphitized Carbon Black (GCB) | d-SPE sorbent | Effective for pigment removal; use cautiously as it can adsorb planar pesticides [29] |

| C18 | d-SPE sorbent | Removes non-polar interferents like lipids and sterols [29] |

| Anhydrous MgSO₄ | Water removal | Essential for partitioning during QuEChERS extraction [28] |

| Ammonium formate/formic acid | Mobile phase additives | Enhance ionization efficiency and improve chromatographic peak shape [30] |

| Matrix-matched calibration standards | Quantification | Compensate for matrix effects; prepared in blank matrix extracts [29] |

| Isotopically labeled internal standards | Compensation for variability | Correct for losses during sample preparation and ionization suppression/enhancement [27] |

HPLC-MS technologies continue to evolve, with micro-flow LC systems representing a significant advancement that combines enhanced sensitivity with reduced environmental impact through dramatically lower solvent consumption [30]. These systems now enable reliable detection of hundreds of pesticide residues at concentrations as low as 0.001 mg kg⁻¹ in complex matrices, with robust performance meeting stringent regulatory requirements [30] [27].

While biosensor technologies offer compelling advantages for rapid screening applications, HPLC-MS maintains its position as the undisputed reference technique for comprehensive multiresidue analysis required for regulatory compliance and exposure assessment [35] [34]. The future landscape will likely see these technologies coexisting synergistically rather than competitively, with biosensors providing initial screening and HPLC-MS delivering definitive confirmation and quantification.

Ongoing advancements in instrumentation, sample preparation methodologies, and data processing capabilities will further strengthen the role of HPLC-MS in ensuring food safety and protecting public health from pesticide-related risks.

The quantitative analysis of chemical substances, particularly pesticides, is critical in environmental monitoring and food safety. For decades, high-performance liquid chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS) has been the gold standard technique for this purpose, offering high sensitivity, selectivity, and reliability for detecting a wide array of compounds [26] [36]. However, these traditional methods are characterized by their complexity, requiring extensive sample preparation, sophisticated and costly instrumentation, and highly skilled personnel, which limits their use for rapid, on-site screening [37] [36].

In this context, biosensors have emerged as powerful analytical devices that complement traditional methods. A biosensor integrates a biological sensing element with a physicochemical transducer to produce an electronic signal proportional to the concentration of a specific analyte [38]. The core components include a bioreceptor (e.g., enzyme, antibody, nucleic acid) that specifically interacts with the target compound, a transducer that converts this biological response into a measurable signal, and electronics for signal processing and display [38] [39]. Among the diverse transduction mechanisms available, electrochemical, optical, and piezoelectric systems represent three primary archetypes, each with distinct operating principles and advantages for pesticide detection in the framework of biosensor versus HPLC-MS research.

Biosensor Working Principle and Key Performance Parameters

The fundamental operation of a biosensor involves a series of coordinated steps. First, the target analyte (e.g., a pesticide molecule) binds to or interacts with the immobilized biological recognition element (the bioreceptor). This interaction produces a physical or chemical change, such as a shift in mass, electrical charge, or light absorption. The transducer then detects this change and converts it into an electrical signal, which is subsequently amplified, processed, and displayed in a user-readable format [38].

When selecting or developing a biosensor for a specific application like pesticide detection, several key performance parameters must be evaluated [38]:

- Sensitivity: The magnitude of the output signal change per unit change in analyte concentration.

- Selectivity: The ability to distinguish the target analyte from other interfering substances in the sample.

- Detection Limit: The lowest concentration of analyte that can be reliably detected.