Calibration Methods for In-Vivo Biosensing: A Comprehensive Accuracy Comparison for Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of calibration method accuracy for in-vivo biosensors, a critical determinant of reliability for researchers and drug development professionals.

Calibration Methods for In-Vivo Biosensing: A Comprehensive Accuracy Comparison for Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of calibration method accuracy for in-vivo biosensors, a critical determinant of reliability for researchers and drug development professionals. We explore the foundational challenges necessitating calibration, from sensor drift to biological variability. A detailed comparison of methodological approaches—including one-point, two-point, dual-frequency, and kinetic calibration—is presented, followed by troubleshooting strategies for environmental interference and signal attenuation. The review culminates in validation techniques and direct accuracy comparisons across biosensor platforms, including continuous glucose monitors and electrochemical aptamer-based sensors, offering evidence-based guidance for method selection to enhance data integrity in biomedical research.

The Critical Role and Fundamental Challenges of Biosensor Calibration

Why Calibration is a Significant Hurdle in Clinical Biosensor Adoption

For researchers and scientists developing in-vivo biosensing platforms, calibration is not merely a procedural step but a central determinant of clinical viability. Biosensors, defined as analytical devices that combine a biological recognition element with a physicochemical detector, have shown transformative potential for real-time monitoring of therapeutics and biomarkers directly in the living body [1]. The translation of this potential from laboratory prototypes to clinically adopted tools, however, faces a critical bottleneck: the establishment of robust, reliable calibration methods that maintain accuracy under physiologically dynamic conditions.

The clinical biochemistry laboratory represents an environment where diagnostic accuracy is paramount, with an estimated 75% of medical decisions relying on laboratory results [2]. In this context, any variance in calibration can have profound implications for patient diagnosis and treatment. This review systematically examines calibration as a significant adoption hurdle by comparing the performance of different calibration methodologies under experimental conditions relevant to in-vivo biosensing research, providing researchers with objective data to inform sensor development strategies.

Fundamental Calibration Challenges in Complex Biological Environments

The Clinical Accuracy Imperative

The transition of biosensors from research tools to clinical applications demands rigorous validation against established diagnostic standards. Clinical laboratories typically process millions of assays annually across diverse specialties including biochemistry, microbiology, and molecular biology [2]. For a biosensor to gain acceptance in this environment, its calibration must demonstrate uncompromising reliability when analyzing real clinical samples such as serum, saliva, and urine—matrices known for complex composition and potential interference factors.

A primary challenge lies in minimizing non-specific adsorption (NSA), a phenomenon where biomolecules adhere indiscriminately to sensor surfaces, potentially distorting calibration curves and compromising measurement accuracy [2]. This issue is particularly acute for in-vivo applications where sensors interface directly with complex biological fluids. Furthermore, the conservative nature of clinical adoption means that new biosensing technologies must demonstrate not just equivalence but superiority over entrenched methods from a cost-per-assay standpoint, placing additional pressure on calibration robustness as a key differentiator [2].

Environmental and Biological Matrix Effects

The calibration of biosensors for in-vivo applications must account for dynamic physiological variables that significantly impact sensor performance. Experimental studies have demonstrated that temperature differentials between calibration and measurement conditions introduce substantial error. Research on electrochemical aptamer-based (EAB) sensors revealed that calibration curves differ significantly between room and body temperature, with interrogation at 25 and 300 Hz showing up to 10% higher signal at room temperature across vancomycin's clinical concentration range [3]. This temperature dependency stems from its influence on both binding equilibrium coefficients and electron transfer rates, fundamentally altering sensor response characteristics.

Beyond temperature, the biological matrix itself introduces variability that challenges conventional calibration approaches. Studies comparing calibration in freshly collected versus commercially sourced blood have identified marked differences in sensor response. For vancomycin-detecting EAB sensors, commercially sourced bovine blood yielded lower signal gain compared to freshly collected blood, leading to potential overestimation of drug concentrations [3]. Even blood age significantly impacts sensor response, with 14-day-old blood producing different calibration curves, particularly at target concentrations above the clinical range [3]. These findings underscore the critical importance of matching calibration media to the intended measurement environment—a challenging requirement for in-vivo applications where physiological conditions constantly fluctuate.

Table 1: Impact of Environmental Variables on Biosensor Calibration

| Variable | Experimental Impact | Consequence for Calibration |

|---|---|---|

| Temperature | 10% higher KDM signal at room temperature vs. body temperature [3] | Underestimation of concentrations if calibrated at different temperature |

| Matrix Age | Lower signal gain in aged blood vs. fresh blood [3] | Overestimation of target concentrations |

| Matrix Composition | Differing responses in commercial vs. freshly collected blood [3] | Requires media-specific calibration curves |

| Electron Transfer Rate | Increases with temperature, shifting peak charge transfer [3] | Alters optimal signal-on/off frequency selection |

Comparative Analysis of Calibration Methods for In-Vivo Applications

One-Point In Vivo Calibration

The pursuit of simplified calibration methodologies has led to investigation of one-point calibration approaches, particularly for continuous monitoring applications. Early foundational research on "wired" glucose oxidase electrodes implanted in jugular veins of rats demonstrated the feasibility of one-point in vivo calibration during periods of rapid glucose fluctuation [4]. This method achieved clinically acceptable accuracy with regression analysis yielding a slope of 0.97 ± 0.07 and intercept of 0.3 ± 0.3 mM, with correlation coefficient (r²) of 0.949 ± 0.020 across the 2-22 mM range [4].

The one-point approach leverages a single reference measurement to establish baseline sensor response, assuming stable sensor sensitivity over the monitoring period. This method offers practical advantages for clinical implementation by reducing the need for multiple blood draws or reference measurements. However, its accuracy depends critically on understanding and modeling transient physiological differences between measurement compartments—such as between subcutaneous tissue and blood glucose concentrations—and assumes minimal sensor drift during the monitoring period [4]. For researchers, this approach represents a compromise between practicality and precision, suitable for applications where trends matter more than absolute values.

Multi-Point and Media-Matched Calibration

For applications requiring higher analytical precision, multi-point calibration using media-matched conditions represents the current gold standard. Research with EAB sensors for vancomycin monitoring demonstrates that calibration using freshly collected, undiluted whole blood at body temperature achieves remarkable accuracy of better than ±10% across the drug's clinical concentration range (6-42 µM) [3]. This methodology involves generating a full calibration curve across the expected concentration range using the exact media and temperature conditions encountered during measurement.

The experimental protocol for this approach involves several critical steps: (1) collection of fresh whole blood, (2) maintenance of blood at body temperature (37°C) throughout calibration, (3) sequential dosing with target analyte across the clinically relevant concentration range, and (4) fitting of the response to a Hill-Langmuir isotherm to extract calibration parameters [3]. The resulting calibration curve accounts for matrix effects, temperature dependencies, and binding characteristics specific to the measurement environment. While this approach is logistically challenging, it currently represents the most accurate method for quantifying in vivo biosensor performance in research settings.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Calibration Methods for In-Vivo Biosensing

| Calibration Method | Experimental Accuracy | Precision | Implementation Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|

| One-Point In Vivo | Slope: 0.97 ± 0.07 [4] | r²: 0.949 ± 0.020 [4] | Low |

| Multi-Point (Media-Matched) | Better than ±10% in clinical range [3] | ≤14% coefficient of variation [3] | High |

| Out-of-Set Calibration | No significant change vs. individual calibration [3] | Slight reduction in precision [3] | Medium |

| Proxy Media Calibration | Varies with media similarity [3] | Dependent on media matching | Medium |

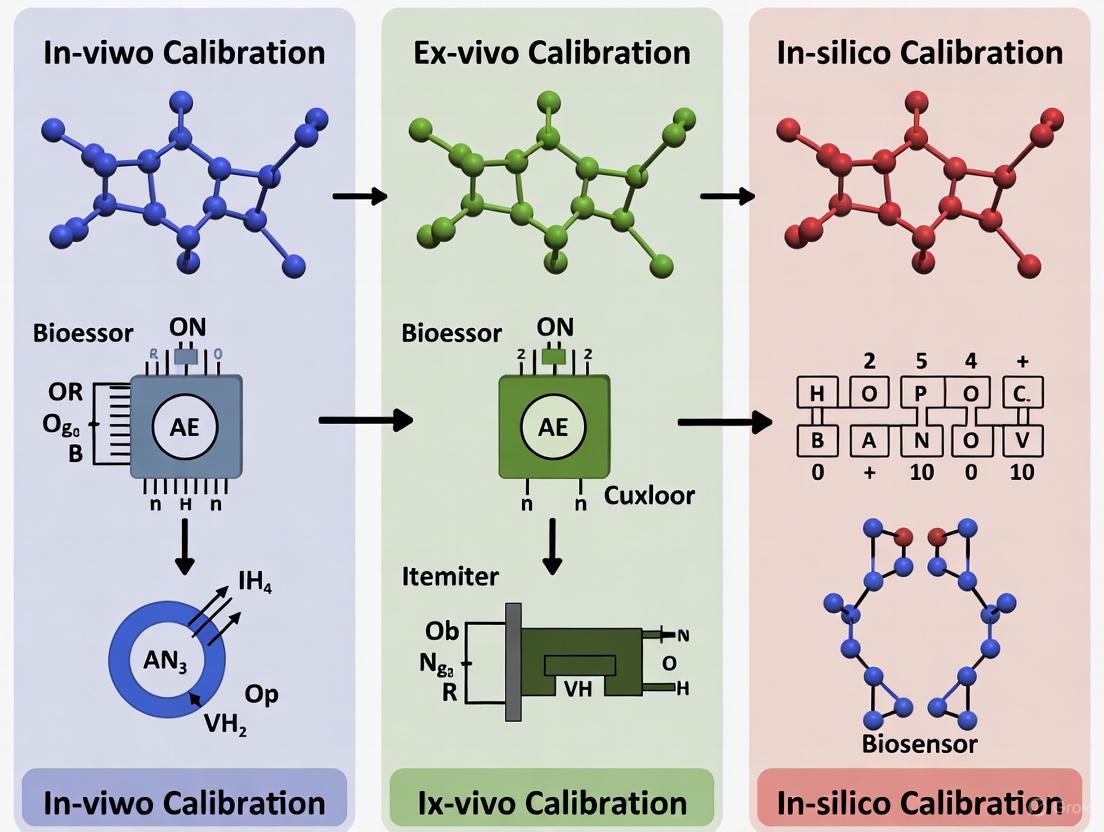

Diagram 1: Media-Matched Calibration Workflow

Advanced and Emerging Calibration Approaches

Kinetic Differential Measurement

The Kinetic Differential Measurement (KDM) approach represents a significant advancement in calibration methodology for addressing signal drift in electrochemical biosensors. This technique involves collecting voltammograms at multiple square wave frequencies—typically both "signal-on" and "signal-off" frequencies—and converting them into normalized KDM values [3]. The mathematical transformation involves subtracting the normalized peak currents observed at signal-on and signal-off frequencies, then dividing by their average [3]. This approach effectively corrects for drift and enhances gain during in vivo measurements by focusing on the kinetic aspects of the sensor response rather than absolute signal magnitude.

The experimental implementation requires careful frequency selection, as temperature changes can alter the optimal signal-on and signal-off frequencies. Research has demonstrated that a frequency functioning as a weak signal-on at room temperature may transition to a clear signal-off frequency at body temperature [3]. The resulting KDM values are fitted to a Hill-Langmuir isotherm to generate calibration parameters according to the equation:

Where nH is the Hill coefficient, K1/2 is the binding curve midpoint, and KDMmin and KDM_max represent the minimum and maximum KDM values [3]. This mathematical framework enables researchers to extract quantitative concentration data from complex in vivo environments.

Calibration-Free and AI-Enhanced Approaches

Emerging research directions focus on reducing or eliminating the need for traditional calibration through innovative technological approaches. Electrochemical DNA-based biosensors are exploring calibration-free operational strategies that leverage predictable binding kinetics and signal patterns to infer concentration without explicit calibration curves [5]. These approaches typically require extensive characterization of sensor behavior across diverse conditions to establish robust computational models.

The integration of artificial intelligence with biosensing represents a promising frontier for addressing calibration challenges. AI algorithms can process complex biosensor outputs and recognize patterns that would be difficult to discern manually, potentially compensating for calibration drift and matrix effects through computational correction [1]. Machine learning approaches can model the relationship between sensor response and target concentration while simultaneously accounting for confounding variables such as temperature fluctuations, pH changes, and interfering substances [6]. These advanced methodologies remain primarily in the research domain but offer potential pathways to simplify calibration requirements for clinical adoption.

Experimental Protocols for Biosensor Calibration

Media-Matched Calibration Protocol

For researchers requiring high-accuracy quantification in vivo, the following experimental protocol for media-matched calibration has demonstrated superior performance in controlled studies [3]:

Fresh Blood Collection: Draw whole blood immediately before calibration (or use preservative-treated blood validated for minimal signal impact). Commercial blood sources should be avoided or validated due to observed differences in sensor response.

Temperature Equilibrium: Maintain blood at 37°C throughout calibration using a precision-controlled heating block or water bath. Temperature control should extend to all fluid handling components.

Sensor Pre-conditioning: Condition sensors in the target matrix without analyte for 30-60 minutes to establish stable baseline signals before calibration.

Sequential Dosing: Introduce target analyte sequentially across the clinically relevant concentration range, allowing sensor stabilization at each concentration point. For vancomycin, this typically spans 0-100 μM.

Signal Acquisition: Collect square wave voltammograms at both signal-on and signal-off frequencies. Optimal frequency pairs should be determined empirically at the calibration temperature.

KDM Calculation: Convert voltammogram peak currents to KDM values using the formula: KDM = (Isignal-off - Isignal-on) / ((Isignal-off + Isignal-on)/2) [3].

Curve Fitting: Fit averaged KDM values to a Hill-Langmuir isotherm to extract KDMmin, KDMmax, K_1/2, and nH parameters.

Validation: Validate calibration parameters using out-of-set samples not included in the original curve fitting.

This protocol, while resource-intensive, has demonstrated accuracy better than ±10% for drug monitoring applications when both calibration and measurement are performed under matched conditions [3].

One-Point Calibration Validation Protocol

For researchers validating one-point calibration approaches, the following methodology provides rigorous assessment:

Reference Measurement: Obtain a precise reference measurement of target concentration using established laboratory methods.

Sensor Measurement: Concurrently record sensor output at the known concentration.

Sensitivity Calculation: Determine sensor sensitivity (signal per unit concentration) from the single point.

Assumption of Linearity: Assume linear response across the clinical range, validated through previous characterization.

Tracking Application: Apply the calculated sensitivity to subsequent sensor measurements.

Accuracy Assessment: Compare sensor estimates with periodic reference measurements to assess calibration stability.

This approach requires thorough preliminary characterization of sensor linearity and drift properties but offers practical advantages for extended monitoring applications.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Biosensor Calibration

| Reagent/Material | Function in Calibration | Critical Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Fresh Whole Blood | Physiologically relevant calibration matrix | Collected same day, anticoagulant-treated [3] |

| Temperature-Controlled Chamber | Maintain physiological temperature during calibration | ±0.5°C stability at 37°C [3] |

| Target Analytic Standards | Generation of concentration response curve | Pharmaceutical grade (>95% purity) [3] |

| Hill-Langmuir Fitting Software | Extraction of calibration parameters | Nonlinear regression capabilities [3] |

| Electrochemical Station | Signal acquisition and processing | Square wave voltammetry capability [3] |

| Anti-fouling Coatings | Reduction of non-specific adsorption | PEG-based or zwitterionic polymers [2] |

Calibration remains a significant adoption hurdle for clinical biosensors due to the complex interplay between sensor elements and dynamic physiological environments. The comparative analysis presented here demonstrates that while media-matched multi-point calibration achieves the highest accuracy (>90% in clinical range), it presents substantial practical challenges for routine clinical implementation [3]. One-point calibration offers simplified workflow but depends critically on sensor stability and well-characterized response patterns [4].

For researchers and drug development professionals, the selection of calibration methodology involves balancing analytical requirements with practical constraints. Emerging approaches including kinetic differential measurement, calibration-free strategies, and AI-enhanced signal processing offer promising pathways to reduce the calibration burden while maintaining analytical validity [5] [6] [1]. The ultimate resolution of the calibration hurdle will likely involve continued sensor development alongside computational innovation, creating systems that either resist environmental interference or automatically compensate for it through integrated intelligence.

As biosensor technology continues its trajectory toward clinical adoption, calibration methodologies must evolve from specialized laboratory procedures to robust, standardized protocols that ensure reliability across diverse patient populations and clinical settings. Through continued research focusing on the fundamental challenges outlined in this review, the scientific community can overcome this significant adoption hurdle and realize the full potential of in-vivo biosensing for therapeutic monitoring and personalized medicine.

Addressing Sensor-to-Sensor Fabrication Variation and Signal Drift

For researchers and drug development professionals, achieving high-fidelity data from in-vivo biosensing is often hampered by two persistent technical challenges: sensor-to-sensor fabrication variation and signal drift. Fabrication variation introduces inconsistencies between sensors, compromising the reproducibility of data, while signal drift causes a sensor's output to change over time independently of the target analyte, leading to inaccurate readings. The choice of calibration method is critical to overcoming these hurdles and ensuring data accuracy. This guide objectively compares the performance of emerging calibration strategies—from sophisticated hardware designs to innovative software and material-based approaches—framed within the broader thesis that effective calibration is the cornerstone of reliable in-vivo biosensing research.

Comparative Analysis of Calibration Methods

The table below summarizes the quantitative performance data and key characteristics of contemporary calibration methods designed to mitigate fabrication variation and signal drift.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Biosensor Calibration Methods

| Calibration Method | Reported Performance Metric | Target Application | Key Advantage for Drift/Fabrication Variation | Experimental Limit of Detection |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-Calibration PEC Platform [7] | Improved stability & anti-interference | In-vitro trypsin detection | Dual-channel differential measurement eliminates common-mode background signal and drift. | Not Specified |

| Skin Surface pH Calibration [8] | MARD decreased from 34.44% to 14.78% | Non-invasive ISF glucose detection | Compensates for drift in ISF extraction caused by variable skin surface pH. | - |

| FRET Standards Calibration [9] | Enables cross-experimental and long-term studies | Live-cell molecular activity imaging | Calibrated FRET ratio is independent of imaging conditions (laser power, detector sensitivity). | - |

| D4-TFT with Rigorous Testing [10] | Achieved attomolar (aM) detection in 1X PBS | Ultrasensitive biomarker detection in point-of-care format | Mitigates signal drift via a stable electrical configuration and infrequent DC sweeps. | Sub-femtomolar to attomolar |

| Calibration-Free eDNA Sensors [5] | Advancements in TDM and personalized therapy | Continuous in-vivo molecular monitoring | Eliminates the need for repeated calibration in complex biological environments. | - |

| Carbon Nanomaterial Platform [11] | Improved signal precision and stability | General biosensor performance | High manufacturability reduces sensor-to-sensor variation; stable signal minimizes drift. | Ultra-low (e.g., femtomolar) |

Detailed Experimental Protocols and Data

Self-Calibration Photoelectrochemical (PEC) Biosensing

This method employs a hardware-based, self-calibration system to address baseline drift and background signal interference simultaneously [7].

- Core Principle: The platform uses two independent PEC test channels—a test channel and a blank channel—processed by a dual-channel data acquisition unit. The signal difference between the two channels is used for quantification, effectively subtracting the background and drift common to both [7].

- Protocol Workflow:

- Probe Preparation: A peptide-recognition element is assembled onto a carbon-rich plasmonic hybrid (C–Mo2C) probe.

- Sensor Assembly: The probe is anchored onto a TiO₂ nanoparticle substrate to form the photoanode. Identical photoanodes are used in both test and blank channels.

- Target Incubation: The target analyte (e.g., trypsin) is introduced only to the test channel. Its interaction causes a change in the probe on the electrode.

- Signal Acquisition & Calibration: Under NIR light, the PEC signals from both channels are recorded simultaneously. The final, calibrated signal is the difference between the blank channel (background/drift) and the test channel (background/drift + target response) [7].

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship and workflow of this self-calibration system:

Drift Mitigation in Carbon Nanotube (CNT) BioFETs

This approach combines material science with a stringent testing methodology to achieve ultra-stable sensing in biologically relevant ionic strength solutions [10].

- Core Principle: Signal drift in CNT-based field-effect transistors (BioFETs) is mitigated by maximizing sensitivity through passivation, using a stable testing configuration, and relying on infrequent DC sweeps instead of continuous static measurements [10].

- Protocol Workflow:

- Device Fabrication: Create a thin-film transistor using printed CNTs. A non-fouling polymer brush interface (POEGMA) is grown above the device to act as a Debye length extender, allowing detection in high ionic strength solutions [10].

- Antibody Printing: Capture antibodies are printed into the POEGMA layer.

- Control Design: A control device with no antibodies printed over the CNT channel is fabricated and tested alongside the active sensor to confirm specific detection [10].

- Stable Measurement: The D4-TFT device uses a palladium pseudo-reference electrode and a printed circuit board for automated testing. The key to drift mitigation is collecting data via infrequent DC voltage sweeps rather than continuous monitoring at a fixed voltage [10].

Calibration Using FRET Standards

This method is critical for optical biosensors, where fluctuations in imaging parameters can mimic or obscure genuine biosensor responses [9].

- Core Principle: The FRET ratio (acceptor-to-donor signal) is calibrated by imaging engineered "FRET-ON" and "FRET-OFF" standard cells under the same conditions as the experimental biosensor cells [9].

- Protocol Workflow:

- Sample Preparation: A mixed population of cells is prepared, expressing either the biosensor of interest or the calibration standards (FRET-ON and FRET-OFF) [9].

- Cell Barcoding: Cells are labeled with distinct pairs of barcoding proteins (e.g., blue or red FPs targeted to different locations) to allow for multiplexed identification during imaging [9].

- Simultaneous Imaging: All cells—biosensor and both standards—are imaged simultaneously in the same session.

- Signal Normalization: The FRET ratio from the biosensor cells is normalized against the signals obtained from the FRET-ON and FRET-OFF standards. This calibration produces a value independent of laser intensity and detector sensitivity, enabling accurate cross-experimental comparisons [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential materials and their functions for implementing the discussed calibration methods.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Advanced Biosensor Calibration

| Item Name | Function in Experiment | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| C–Mo2C Carbon-Rich Plasmonic Hybrid [7] | Acts as a photoactive element; enables NIR-driven sensing and provides signal amplification via plasmonic and photothermal effects. | Self-calibration PEC biosensing. |

| Poly(OEGMA) Polymer Brush [10] | Coated on the sensor surface to extend the Debye length and reduce biofouling, enabling detection in physiological fluids. | CNT-BioFETs for point-of-care diagnostics. |

| FRET-ON/FRET-OFF Standard Cells [9] | Genetically encoded calibration standards used to normalize the FRET ratio against variations in imaging conditions. | Live-cell imaging with FRET biosensors. |

| Palladium (Pd) Pseudo-Reference Electrode [10] | Provides a stable reference potential in a miniaturized form factor, replacing bulky Ag/AgCl electrodes. | Portable and point-of-care electrochemical sensors. |

| Bipolar Silica Nanochannel Array Film [12] | Used to stably immobilize ECL emitters like Ru(bpy)₃²⁺, enhancing the stability of solid-phase electrochemiluminescence sensors. | Enzyme-based solid-phase ECL sensors. |

| High-Performance Carbon Nanomaterial [11] | A 3D porous carbon scaffold that provides high surface area, conductivity, and manufacturability, improving sensitivity and reducing sensor-to-sensor variation. | General platform for high-performance electrochemical biosensors. |

The accurate comparison of calibration methods reveals that no single solution is universally superior; the optimal choice is dictated by the specific biosensing platform and research question. Hardware-level self-calibration [7] is powerful for direct drift rejection but adds system complexity. Material-driven approaches [10] [11] address the root causes of variation and drift, offering a more foundational solution that enhances multiple performance metrics simultaneously. For optical biosensors, the use of internal standards [9] is indispensable for quantitative accuracy.

Future research is poised to integrate artificial intelligence to dynamically model and correct for drift in real-time [5] [1]. Furthermore, the convergence of advanced biofabrication techniques [13] with high-precision nanomaterials [11] promises to minimize fabrication variation at the source, ultimately leading to a new generation of robust, calibration-free, and highly reliable biosensors for demanding in-vivo research and drug development applications.

In the field of in-vivo biosensing, the selection of a biological matrix is a fundamental decision that directly influences the accuracy, relevance, and temporal resolution of measurements. Blood has traditionally been the gold standard for clinical diagnostics, providing a direct window into systemic circulation. However, the quest for continuous monitoring and minimally invasive techniques has brought interstitial fluid (ISF) and other biofluids like sweat to the forefront [14] [15]. This guide objectively compares the performance of blood and ISF as biological matrices, focusing on their metabolite dynamics and the implications for sensor calibration and data interpretation. Understanding the kinetic equilibrium and physiological lag between these compartments is critical for developing reliable biosensors for applications ranging from diabetes management to therapeutic drug monitoring and athletic performance [14] [16].

Comparative Analysis of Biological Matrices

The following table summarizes the core characteristics of blood and interstitial fluid as matrices for biosensing.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Blood vs. Interstitial Fluid for Biosensing

| Characteristic | Blood | Interstitial Fluid (ISF) |

|---|---|---|

| Physiological Role | Systemic transport of gases, nutrients, hormones, and waste products [17]. | Bathes and nourishes cells; medium for exchange between blood and cells [14]. |

| Primary Sampling Method | Venipuncture or fingerprick (invasive) [15]. | Minimally invasive (e.g., subcutaneous sensors, microneedles) [14] [16]. |

| Metabolite Correlation | Gold standard reference [15]. | High correlation for many analytes, but with a physiological time lag [14] [16]. |

| Representativeness | Reflects systemic, whole-body concentration. | Reflects local, tissue-level concentration [17]. |

| Key Advantage | Direct measurement, established clinical reference. | Enables comfortable, continuous monitoring. |

| Key Challenge | Invasiveness limits frequency; unsuitable for real-time tracking. | Dynamic equilibrium with blood introduces calibration complexity [14] [3]. |

Experimental Evidence of Analyte Dynamics

The relationship between blood and ISF glucose has been extensively studied, particularly in the context of Continuous Glucose Monitoring (CGM). Research consistently shows that ISF glucose levels are correlated with blood glucose but exist in a kinetic equilibrium, resulting in a measurable time and magnitude gradient [14].

Table 2: Experimentally Measured Lag Times Between Blood and Interstitial Fluid Glucose

| Study (First Author, Year) | Estimated Lag Time (Minutes) | Study Population | IF Sampling Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shichiri M, 1986 [14] | 5 | People with diabetes (n=5) | Transcutaneous sensor |

| Sternberg F, 1996 [14] | 2–12 | People with diabetes (n=40) | Microdialysis |

| Rebrin K, 2000 [14] | 5–12 | Anaesthetised dogs | Transcutaneous sensor |

| Boyne MS, 2003 [14] | 4–10 | People with type 1 diabetes (n=14) | Transcutaneous sensor |

| Steil GM, 2005 [14] | 3–8 | Healthy subjects (n=10) | Transcutaneous sensor |

| Kulcu E, 2003 [14] | 5 | People with type 1 or 2 diabetes (n=51) | Reverse iontophoresis |

For other metabolites, the dynamics can differ. A study on lactate monitoring during aerobic exercise found a strong correlation (ρ = 0.93) between ISF lactate and blood lactate, positioning ISF as a reliable proxy for systemic lactate levels. In contrast, sweat lactate showed a much weaker correlation (ρ = 0.36), highlighting the importance of matrix selection for specific analytes [16].

Metabolomic studies further reveal that ISF can provide a unique signature that differs from blood. An NMR-based analysis of patients with arterial hypertension identified nine potential metabolomic biomarkers in ISF that were distinct from those found in plasma or urine. These ISF-specific biomarkers primarily reflected alterations in lipid and amino acid metabolism and indicated increased levels of local oxidative stress and inflammation [17].

Experimental Protocols for Matrix Comparison

To ensure the accuracy and reliability of comparative data, rigorous experimental protocols must be followed. The following workflow outlines a standardized approach for validating ISF sensor readings against blood references.

Detailed Methodology

Participant Selection and Sample Collection

Studies should recruit a well-defined population (e.g., healthy adults, diabetic patients, or athletes) with approved ethical oversight and informed consent [17] [16]. For dynamic monitoring, samples are collected at synchronized timepoints.

- Blood Collection: Venous or capillary blood is drawn using standard phlebotomy procedures. Plasma is isolated by centrifugation (e.g., 3000× g for 10 min at 4°C) for analysis [17] [3].

- ISF Collection: ISF can be accessed via:

- Continuous Subcutaneous Sensors: Commercial or research-grade CGM systems are implanted according to manufacturer protocols [14].

- Microdialysis: A probe is inserted into the subcutaneous tissue and perfused with a buffer to harvest analytes [14].

- Microneedle Arrays: Patches containing micron-scale needles penetrate the skin barrier to access ISF, often functionalized with biosensing elements [16].

Sample Processing and Metabolite Analysis

- Blood/Plasma: Processed plasma and ISF samples are often analyzed using high-resolution techniques like 1H NMR spectroscopy for broad metabolomic profiling [17]. For specific analytes, targeted biosensing is employed.

- Biosensor Calibration: Electrochemical biosensors, such as Electrochemical Aptamer-Based (EAB) sensors, require careful calibration. A common method involves generating a calibration curve by measuring the sensor response (e.g., Kinetic Differential Measurement values) across a range of target concentrations in a relevant medium (e.g., fresh whole blood). The data is fitted to a Hill-Langmuir isotherm to determine parameters like the binding curve midpoint (K~1/2~) and signal gain, which are used to convert sensor output into concentration estimates [3].

Critical Factors in Experimental Design

- Temperature Control: Sensor response and binding equilibria are temperature-sensitive. Calibration should be performed at the intended measurement temperature (e.g., 37°C for in-vivo studies) to avoid significant quantification errors [3].

- Media Freshness and Composition: The age and source of calibration media (e.g., blood) can impact sensor performance. Using freshly collected blood is superior to aged, commercially sourced blood, as it better replicates the in-vivo environment [3].

- Data Synchronization: Accurate timestamping of all samples is crucial for calculating physiological lag times between blood and ISF analyte changes [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists essential materials and their functions for conducting research on blood and ISF metabolite dynamics.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Matrix Comparison Studies

| Item | Function/Application | Representative Example |

|---|---|---|

| Potentiometric Sensor | Measures ion concentration (e.g., H+, Na+, K+) by detecting changes in electrical potential; commonly used for pH and electrolyte sensing in sweat and ISF [15] [16]. | Ionselective electrodes in wearable patches. |

| Amperometric Sensor | Measures current generated by the redox reaction of an analyte; used for continuous monitoring of metabolites like glucose and lactate [14] [16]. | Enzyme-based (e.g., glucose oxidase) subcutaneous sensors. |

| Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes (SWCNT) | Nanomaterial scaffold for near-infrared (NIR) optical biosensors; offers high biocompatibility and stable fluorescence for long-term implantable sensing [18]. | NIR fluorescence-based nitric oxide sensors. |

| Electrochemical Aptamer-Based (EAB) Sensor | Combines a target-specific aptamer with an electrochemical reporter; enables real-time measurement of specific molecules (e.g., drugs, metabolites) in undiluted whole blood [3]. | Vancomycin-detecting sensors for therapeutic drug monitoring. |

| Microneedle Array | Minimally invasive platform to access ISF; can be fabricated from polymers (e.g., SU-8) and integrated with biosensing elements for continuous monitoring [16]. | Lactate-sensing microneedle patches for athletic monitoring. |

| High-Resolution NMR Spectroscopy | Non-destructive analytical technique for unambiguous identification and quantification of a wide range of metabolites in biofluids like plasma, ISF, and urine [17]. | 600 MHz NMR for metabolomic fingerprinting of hypertension. |

The choice between blood and interstitial fluid as a biological matrix is not a matter of identifying a superior option, but of selecting the most appropriate one for the specific research or clinical application. Blood remains the indispensable gold standard for definitive, point-in-time measurements. However, for the future of continuous, real-time health monitoring, ISF offers a minimally invasive and information-rich alternative. The key to its successful utilization lies in a deep understanding of the analyte-specific dynamics and time delays that exist between these compartments. Robust, temperature-matched calibration protocols are critical to translate ISF sensor signals into accurate physiological data. As biosensing technologies like microneedles and advanced electrochemical sensors continue to evolve, the simultaneous monitoring of multiple matrices will provide a more holistic and dynamic picture of human physiology, revolutionizing personalized healthcare and athletic performance optimization.

The Impact of Temperature, pH, and Ionic Strength on Sensor Response

For researchers and drug development professionals, the pursuit of accurate, continuous molecular monitoring in vivo represents a significant frontier in biomedical science. A critical, yet often underexplored, challenge in this domain is the susceptibility of biosensors to fluctuations in their immediate physiological environment. Parameters such as temperature, pH, and ionic strength—while tightly regulated in the mammalian body—can vary sufficiently across different tissue types and physiological states to compromise sensor accuracy. This guide provides a comparative analysis of how these environmental factors impact various biosensor platforms, evaluates the performance of different calibration strategies to mitigate these effects, and presents supporting experimental data to inform robust sensor selection and deployment in research.

Comparative Impact of Environmental Factors on Sensor Platforms

The stability and accuracy of biosensors are not uniform; their performance under stress is a function of their underlying design, materials, and transduction mechanisms. The following comparison outlines the tolerance of different sensor types to environmental variations.

Table 1: Comparative Stability of Capped Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) under Environmental Stress [19]

| Capping Agent | Temperature Tolerance | pH Tolerance | Ionic Strength Tolerance (Saline) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glutathione (AuNPs-II) | Stable up to 70°C for 144 h | Wide range (pH 3–11) | High (up to 1600 mM) |

| Citrate (AuNPs-I) | Less stable than AuNPs-II | Less stable than AuNPs-II | Less stable than AuNPs-II |

| Ascorbic Acid (AuNPs-III) | Susceptible to slight variation | Narrow range | Low (only up to 80 mM) |

Table 2: Impact of Physiological-Scale Variations on Electrochemical Aptamer-Based (EAB) Sensors [20]

| Environmental Parameter | Physiological Range Tested | Impact on EAB Sensor Accuracy | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ionic Strength & Cations | 152 mM to 167 mM (Na+, K+, Mg2+, Ca+) | Minimal; Mean Relative Error (MRE) clinically acceptable (<20%) | No correction typically needed |

| pH | 7.35 to 7.45 | Minimal; MRE clinically acceptable (<20%) | No correction typically needed |

| Temperature | 33°C to 41°C | Significant error induced | Requires measurement and correction |

Key Insights from Comparative Data

- Nanoparticle Stability: Glutathione-capped AuNPs demonstrate exceptional colloidal stability under extreme conditions, making them superior for applications requiring high ionic strength, variable pH, or elevated temperatures [19]. In contrast, Ascorbic Acid-capped AuNPs are highly susceptible to even mild environmental changes.

- In Vivo Sensor Robustness: EAB sensors, a leading platform for continuous in vivo monitoring, show remarkable resilience to physiologically relevant variations in ionic composition and pH. This is largely because these parameters are under tight homeostatic control in blood and interstitial fluid [20].

- The Primary Challenge - Temperature: Across platforms, temperature fluctuation is the most significant environmental confounder. For EAB sensors, physiologically plausible changes (e.g., from 33°C skin temperature to 41°C core fever) induce substantial measurement errors that must be corrected for accurate readings [20].

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Environmental Impact

To systematically evaluate sensor performance, standardized experimental protocols are essential. The methodologies below are derived from cited studies and can serve as templates for validation.

- Objective: To determine the tolerance levels of differentially capped AuNPs to temperature, pH, and ionic strength.

- Synthesis: AuNPs are synthesized via chemical reduction methods. Citrate-capped AuNPs (AuNPs-I) are prepared by the trisodium citrate reduction method. Glutathione-capped (AuNPs-II) and Ascorbic Acid-capped (AuNPs-III) are synthesized by ligand exchange and direct reduction, respectively.

- Characterization: Synthesized AuNPs are characterized using UV-Vis spectroscopy (to monitor the Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance (LSPR) peak), Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) for size and zeta potential, and Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) for morphology.

- Stress Testing:

- Temperature: AuNP colloidal solutions are incubated at temperatures ranging from 4°C to 70°C for up to 144 hours. Aliquots are taken at intervals for LSPR measurement and visual inspection for aggregation.

- pH: The pH of AuNP solutions is adjusted from pH 2 to 12 using dilute HCl or NaOH. Changes in LSPR and solution color are monitored after a set equilibration time.

- Ionic Strength: Increasing concentrations of NaCl (from 0 mM to 1600 mM) are added to AuNP solutions. The stability is assessed by tracking the LSPR peak and observing color changes indicative of aggregation.

- Data Analysis: The specific conditions under which the LSPR peak broadens, shifts, or disappears—or the solution color changes—are identified as the tolerance limits.

- Objective: To quantify the accuracy of EAB sensors against target analytes under physiological variations in cation concentration, pH, and temperature.

- Sensor Calibration:

- Calibrate sensors in a standard buffer (e.g., 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.4) containing midpoint concentrations of physiological cations (Na+, K+, Mg2+, Ca2+) at 37°C.

- Perform titrations of the target analyte (e.g., vancomycin, phenylalanine) and fit the data to a Langmuir isotherm model to generate a standard calibration curve.

- Validation Testing:

- Challenge new sensors with a test set of analyte concentrations under "out-of-calibration" conditions.

- Cation/Ionic Strength: Use buffers where all four cations are simultaneously at the lower or upper end of their physiological range.

- pH: Use buffers at pH 7.35 and 7.45.

- Temperature: Perform measurements across a range from 33°C to 41°C.

- Use the standard-condition calibration curve to estimate the analyte concentration in these non-standard conditions.

- Challenge new sensors with a test set of analyte concentrations under "out-of-calibration" conditions.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the Mean Relative Error (MRE) for each condition. Compare the MRE under test conditions to the MRE achieved under standard calibration conditions to assess the degradation in accuracy.

Diagram 1: Environmental impact pathways and calibration corrections for biosensors.

Calibration Methods for Accuracy Optimization

When environmental factors degrade sensor performance, calibration strategies are essential to restore accuracy. The following methods are currently employed in research settings.

Table 3: Comparison of Calibration Methods for In-Vivo Biosensing

| Calibration Method | Principle | Experimental Workflow | Impact on Accuracy | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Point-of-Care (POC) Blood Glucose Calibration [21] | Uses intermittent fingerstick blood glucose measurements to recalibrate a continuous glucose monitor (CGM). | 1. POC BG measurement is taken.\n2. Value is entered into the CGM device if the sensor reading is outside a validation threshold (e.g., ±20%).\n3. Sensor recalibrates its output. | MARD reduced from 25% at calibration event to ~9.6% after 6 hours. | Most effective when calibration is timely (within 5-10 minutes of POC test). |

| Temperature-Aware Correction Algorithms [20] | Measures ambient temperature and applies a mathematical correction to the sensor signal based on pre-characterized temperature sensitivity. | 1. Characterize sensor's dose-response curve at multiple temperatures.\n2. Develop a model (e.g., using ANN) that maps signal and temperature to analyte concentration.\n3. In deployment, co-measure temperature and apply the model in real-time. | Corrects substantial errors induced by physiological temperature variations (33-41°C). | Requires integrated temperature sensor and robust model trained on high-quality data. |

| AI-Enhanced Signal Processing [22] [23] | Uses machine learning (e.g., Artificial Neural Networks) to process complex signal data (e.g., fluorescence lifetime) and decouple analyte concentration from environmental noise. | 1. Train a model (e.g., ANN, Spiking GNN) on a large dataset of sensor outputs under varied analyte and environmental conditions.\n2. Deploy the trained model to interpret raw sensor signals in real-time. | Improves precision, enables faster readouts, and enhances robustness against interference. | Dependent on the quality and breadth of the training dataset; can be computationally intensive. |

Diagram 2: Workflow for selecting calibration correction methods.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Materials and Reagents for Sensor Stability and Calibration Research

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Glutathione (GSH) | Capping agent for gold nanoparticles to confer high colloidal stability against aggregation under extreme ionic, pH, and temperature stress [19]. | Creating stable nanoparticle platforms for sensing in complex biological environments like waste water or physiological fluids. |

| Electrochemical Aptamer-Based (EAB) Sensor | A biosensor platform where a target-binding, redox-tagged aptamer is immobilized on a gold electrode, enabling real-time, reversible molecular monitoring in vivo [20]. | Continuous measurement of drugs (e.g., vancomycin) or metabolites (e.g., phenylalanine) in live animal models. |

| Chromatic Nanoswitchers (CNSs) | Fluorescent nanothermometers comprising a dye in a thermoresponsive matrix, providing high-sensitivity lifetime-based temperature reading resistant to environmental interference [23]. | Accurate, remote thermal sensing at the nanoscale (e.g., for cellular thermodynamics or microelectronic devices). |

| Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) | Machine learning models for advanced processing of complex sensor signals (e.g., from FET sensors or fluorescent nanoswitchers) to improve accuracy and speed of readouts [22] [23]. | Predicting sensor sensitivity categories from material properties; enabling fast, robust thermal readouts from fluorescence lifetime data. |

| Phase Change Material (PCM) Matrix | A material (e.g., eicosane/docosane mixture) that undergoes a solid-to-liquid phase transition at a specific temperature, used to modulate a fluorescent dye's emission properties [23]. | Serving as the core of CNSs to create a highly temperature-sensitive fluorescent reporter around physiological temperatures (~37°C). |

Distinguishing Between In-Vivo and Ex-Vivo Calibration Requirements

In the field of biosensing, the accuracy and reliability of measurements are paramount, particularly when these sensors are deployed in complex biological environments. The calibration requirements for biosensors diverge significantly depending on whether they are intended for use within a living organism (in vivo) or outside of it in controlled laboratory settings (ex vivo). This guide objectively compares the performance and calibration methodologies for these two distinct application domains, framing the discussion within a broader thesis on accuracy comparison for calibration methods in biosensing research. The calibration approaches are shaped by fundamentally different challenges: in vivo calibration must contend with a dynamic, closed-loop biological system, whereas ex vivo calibration operates in controlled, accessible environments. Understanding these distinctions is critical for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals who rely on precise measurements for diagnostic, therapeutic, and research applications.

Comparative Analysis of Calibration Environments

The table below summarizes the core distinctions between in vivo and ex vivo biosensor calibration, highlighting how the deployment environment dictates calibration strategy, challenges, and technological solutions.

Table 1: Fundamental Requirements for In-Vivo vs. Ex-Vivo Biosensor Calibration

| Aspect | In-Vivo Calibration | Ex-Vivo Calibration |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Objective | Continuous, real-time monitoring in a dynamic, closed system [5] [18] | Precise, endpoint or intermittent measurement in a controlled, open system [9] [24] |

| System Accessibility | Limited or no physical access post-implantation; often a closed-loop system [18] | Full physical and operational access; an open system allowing for direct manipulation [9] |

| Key Challenges | Biofouling, signal drift, dynamic physiological changes, biocompatibility, and limited recalibration opportunities [18] [25] | Controlling experimental parameters (e.g., pH, temperature), correcting for instrumentation drift, and sample handling [9] [26] |

| Calibration Strategy | Emphasis on calibration-free operation, internal reference standards, and reversible sensing elements [5] [18] | Reliance on external calibration curves using standard solutions and control samples [9] [24] |

| Common Techniques | Self-referencing sensors, multi-parameter correction, in-situ background measurement [5] [27] | Pre- and post-measurement calibration with known analyte concentrations, signal normalization [9] |

| Data Reliability | Vulnerable to long-term signal drift and biofouling; requires robust sensor design [25] | Generally high and can be verified repeatedly; susceptible to acute instrumental error [9] |

Experimental Protocols and Performance Data

In-Vivo Calibration: Towards Calibration-Free Operation

The gold standard for in vivo sensing is a calibration-free or self-calibrating sensor that maintains accuracy over long durations within the body. A prominent example is the use of electrochemical DNA (eDNA) biosensors for continuous therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM).

Table 2: Performance of Selected In-Vivo Biosensing Platforms

| Biosensor Platform | Target Analyte | Key Calibration Feature | Reported Performance / Challenge |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electrochemical DNA (eDNA) Sensors [5] | Drugs, Neurochemicals | Calibration-free strategies; reversible binding for continuous equilibrium | Advances personalized drug therapy; challenges in long-term stability & selectivity [5] |

| Genetically Encoded FRET Biosensor (R-eLACCO2.1) [27] | Extracellular L-lactate | Use of internal FRET standards ("FRET-ON/OFF") for signal normalization | Enables multiplexed imaging with neural activity sensors (e.g., GCaMP) in awake mice [27] |

| Microneedle (MN) Biosensors [25] | Glucose, Lactate, Hormones | Pre-use calibration; challenge with signal drift due to biofouling & electrode degradation | Long-term stability (>24h) is challenging; strategies include antifouling coatings [25] |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: FRET Biosensor Calibration for In-Vivo Imaging [9] [27]

- Sensor Design and Expression: Utilize a genetically encoded biosensor (e.g., R-eLACCO2.1 for lactate) expressed in the target tissue of a live animal model (e.g., mouse somatosensory cortex).

- Introduction of Calibration Standards: Co-express or co-introduce engineered "FRET-ON" and "FRET-OFF" standard proteins in a subset of cells. These standards provide reference signals for high and low FRET efficiency, independent of the actual analyte concentration.

- In-Vivo Image Acquisition: Perform multiplexed fluorescence imaging (e.g., using two-photon microscopy) on awake, behaving subjects. Simultaneously capture signals from the biosensor and the calibration standards.

- Signal Normalization: Normalize the acquired acceptor-to-donor FRET ratio from the biosensor against the signals from the FRET-ON and FRET-OFF standards within the same imaging session. This corrects for fluctuations in laser intensity, optical path, and tissue scattering.

- Data Validation: The calibration process should restore the expected reciprocal changes in donor and acceptor signals, validating the observed biosensor responses against instrumentation artifacts.

In-Vivo FRET Biosensor Calibration Workflow

Ex-Vivo Calibration: Precision Through Controlled Referencing

Ex vivo calibration relies on constructing a reliable relationship between sensor signal and analyte concentration in a controlled medium, which is then applied to interpret measurements in biological samples like serum, urine, or tissue extracts.

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Aptamer-Based Fluorescent Detection of ATP in Body Fluids [24]

- Probe Fabrication: Construct a fluorescent nanoprobe by adsorbing a ROX-tagged ATP-aptamer onto the surface of titanium carbide (TC) nanosheets. The TC acts as a quencher, initializing the probe in an "off" state.

- Construction of Calibration Curve:

- Prepare a series of standard ATP solutions in a buffer, spanning the expected physiological range (e.g., 0 μM to 1.5 mM).

- Incubate a fixed concentration of the TC/Apt probe with each standard solution.

- Measure the fluorescence recovery at 610 nm upon excitation at 545 nm. The fluorescence intensity increases as ATP binds the aptamer, releasing it from the quencher.

- Plot fluorescence intensity versus ATP concentration to generate a standard calibration curve.

- Sample Measurement and Quantification:

- Dilute the ex vivo sample (e.g., mouse serum, human serum, or urine) appropriately.

- Incubate the sample with the same concentration of TC/Apt probe under identical conditions.

- Measure the fluorescence signal and use the pre-established calibration curve to determine the ATP concentration in the unknown sample.

Table 3: Performance of an Ex-Vivo ATP Biosensor in Body Fluids [24]

| Body Fluid Sample | Linear Detection Range | Limit of Detection (LOD) | Key Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mouse Serum | 1 μM to 1.5 mM | 0.2 μM | Monitoring metabolic status and disease biomarkers [24] |

| Human Serum | 1 μM to 1.5 mM | 0.2 μM | Diagnostic detection of diseases linked to abnormal ATP [24] |

| Mouse Urine | 1 μM to 1.5 mM | 0.2 μM | Non-invasive metabolic monitoring [24] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table lists key reagents and materials critical for implementing the calibration methods discussed in this guide.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Biosensor Calibration

| Reagent / Material | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| FRET Standard Plasmids (FRET-ON, FRET-OFF) [9] | Provide internal reference signals for normalizing imaging conditions and calculating FRET efficiency in vivo. | Calibrating genetically encoded biosensors (e.g., R-eLACCO2.1) in live cell or animal imaging [9]. |

| Titanium Carbide (TC) Nanosheets [24] | Act as a highly efficient fluorescence quencher in a FRET-based assay configuration. | Core component of the ex vivo ATP detection probe; quenches ROX-aptamer fluorescence [24]. |

| ROX-tagged ATP Aptamer [24] | The biological recognition element that binds ATP specifically, coupled to a fluorescent reporter. | Sensing element in the ex vivo ATP probe; fluorescence recovers upon target binding [24]. |

| Analyte Standard Solutions | Used to create the primary calibration curve, defining the relationship between signal and concentration. | Preparing known concentrations of ATP, glucose, or lactate for ex vivo sensor calibration [25] [24]. |

| Antifouling Coatings (e.g., Zwitterionic polymers) [25] | Coating material applied to sensor surfaces to minimize non-specific protein adsorption and biofouling. | Extending the functional lifetime and stability of implantable microneedle sensors in vivo [25]. |

The calibration requirements for in vivo and ex vivo biosensing are fundamentally distinct, each presenting a unique set of challenges and necessitating specialized technological solutions. Ex vivo calibration achieves high accuracy through controlled external referencing and calibration curves, offering precision for diagnostic and research applications. In contrast, in vivo calibration is evolving toward calibration-free and self-referencing paradigms to overcome the constraints of dynamic, inaccessible biological systems. The choice of calibration strategy directly impacts the validity and reliability of the resulting data. As the field advances, the integration of robust internal standards, antifouling materials, and artificial intelligence for data correction will be crucial to bridging the gap between the precision of ex vivo methods and the imperative for reliable, long-term in vivo monitoring.

Comparative Analysis of Calibration Techniques and Algorithms

Calibration is a fundamental process in scientific measurement, serving as the critical bridge between a sensor's raw signal and a meaningful, quantitative result. In the context of in-vivo biosensing research, where accurate measurement of biological analytes is essential for both research conclusions and drug development, the choice of calibration methodology directly impacts data reliability. The two primary approaches—one-point and two-point calibration—differ significantly in their underlying principles, implementation complexity, and ultimately, their measurement accuracy.

A one-point calibration assumes a proportional relationship between the sensor's signal and the analyte concentration, effectively presuming that the calibration line passes through the origin (zero signal corresponds to zero concentration). This method calculates the sensor's sensitivity (S) from a single reference measurement: S = I/G, where I is the sensor current and G is the reference glucose concentration. The concentration at any time is then estimated as G(t) = I(t)/S [28]. In contrast, a two-point calibration incorporates an additional parameter to account for the sensor's background current (Io), which represents a glucose-nonspecific signal caused by interfering substances in the interstitial fluid such as ascorbic acid, acetaminophen, and uric acid. This method determines both sensitivity and background current using two reference measurements: S = (I₂ - I₁)/(G₂ - G₁) and Io = I₁ - (S × G₁). The subsequent concentration estimation is given by G(t) = (I(t) - Io)/S [29] [30].

The ongoing debate surrounding these methods centers on a fundamental trade-off: whether the theoretical advantage of accounting for background current in the two-point approach outweighs the potential error amplification from measurement uncertainties in practical applications. This article objectively compares these calibration strategies specifically for in-vivo biosensing, examining their relative accuracy through published experimental data, detailing their implementation protocols, and providing practical guidance for researchers in the field.

Theoretical Foundations and Practical Trade-offs

Core Conceptual Differences

The mathematical distinction between these calibration methods has profound practical implications. The one-point calibration model operates on a single-parameter system (sensitivity only), while the two-point calibration establishes a two-parameter system (sensitivity and background current). This additional parameter in the two-point method aims to enhance accuracy by accounting for the sensor's baseline signal, but it also introduces a potential vector for error propagation [30]. Measurement uncertainties, inherent in both reference glucose measurements and sensor signal acquisition, can significantly impact the calculated values of both S and Io. These uncertainties often manifest as a negative correlation between the estimated sensitivity and background current, sometimes resulting in physiologically implausible negative values for Io [30].

A significant challenge in two-point calibration arises from the physiological time lag between blood glucose (BG) and interstitial glucose (IG) concentrations. Since continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) sensors measure glucose in the interstitial fluid, not directly in blood, a variable gradient exists between BG and IG, particularly during non-steady-state conditions like dropping hypoglycemia or post-meal spikes. This lag causes a fundamental mismatch when calibrating ISIG values (which reflect IG) against BG values, leading to substantial error in estimating the sensor background current, especially when calibration points are taken during these dynamic periods [29].

Table 1: Core Characteristics of One-Point and Two-Point Calibration

| Feature | One-Point Calibration | Two-Point Calibration |

|---|---|---|

| Underlying Principle | Assumes negligible background current (Io); linear relationship through origin [28]. | Accounts for non-zero background current (Io); defines both slope and intercept [29]. |

| Mathematical Complexity | Simple: G(t) = I(t)/S [28]. | More complex: G(t) = (I(t) - Io)/S [29]. |

| Key Assumption | Background current (Io) is negligible or constant [28]. | Background current can be accurately estimated from two points [29]. |

| Primary Advantage | Simplicity, reduced error propagation from fewer measurements, user-friendly [28]. | Theoretically more comprehensive by accounting for baseline signal [29]. |

| Primary Limitation | Inaccurate if background current is significant and unaccounted for [29]. | Highly sensitive to measurement errors in reference values and physiological time lag [29] [30]. |

| User Workload | Lower (requires one reference measurement per calibration) [28]. | Higher (requires two reference measurements per calibration) [29]. |

Experimental Data and Performance Comparison

Clinical Evidence from Glucose Monitoring Studies

Substantial clinical evidence, particularly from continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) research, demonstrates a counterintuitive finding: despite its simpler model, one-point calibration often delivers superior accuracy in practice. A comprehensive study involving 132 type 1 diabetes patients directly compared a real-time CGM algorithm using two-point calibration against its updated version using one-point calibration. The results were revealing: the one-point calibration approach improved overall CGM accuracy, with the most significant enhancement observed in the critical hypoglycemic range. The Median Absolute Relative Difference (MARD) in hypoglycemia was 12.1% for one-point calibration compared to 18.4% for the two-point method [29].

Furthermore, the one-point calibration increased the percentage of sensor readings in the clinically accurate Zones A+B of the Clarke Error Grid Analysis across the entire glycemic range and enhanced hypoglycemia sensitivity, a crucial safety parameter for diabetic patients [29]. A separate, earlier study that implanted glucose sensors in nine diabetic patients for 3-7 days found congruent results. It reported that the percentages of points in zones A and B of the Clarke Error Grid were significantly higher when the system was calibrated using the one-point method compared to the two-point method [28].

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Table 2: Summary of Key Performance Metrics from Clinical Studies

| Performance Metric | One-Point Calibration Performance | Two-Point Calibration Performance | Study Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| MARD in Hypoglycemia | 12.1% [29] | 18.4% [29] | 132 type 1 diabetes patients [29]. |

| Points in Clarke Error Grid A+B | Significantly higher percentage [28] | Lower percentage [28] | 9 diabetic patients, 3-7 day implantation [28]. |

| Hypoglycemia Sensitivity | Enhanced [29] | Reduced [29] | 132 type 1 diabetes patients [29]. |

| Impact of Reference Measurement Error | Less sensitive [28] | Highly sensitive; causes miscalculation of S and Io [30] | Theoretical analysis and patient trials [30] [28]. |

The superior performance of the one-point method is largely attributed to its robustness against measurement uncertainties. Every reference blood glucose measurement carries a potential error (e.g., ±10% for commercial meters), and every sensor signal is subject to electronic noise. The two-point calibration process magnifies these errors. As noted in research, "a measurement error on the current, linked for instance to electric noise, and/or on capillary blood glucose measurement... contributed to the generation of a value of Io which could be either positive or negative" [30]. The one-point method, by avoiding the calculation of this additional parameter, sidesteps this source of error amplification.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol for a One-Point Calibration Study

The following protocol is adapted from methodologies used in clinical CGM research [29] [28]:

- Sensor Deployment: Implant the biosensor (e.g., a subcutaneous enzymatic glucose sensor) into the target tissue (e.g., abdominal subcutaneous tissue) of the study subject (e.g., human or animal model).

- Reference Measurement Collection: At predetermined time points (e.g., before meals), obtain a reference measurement of the analyte (e.g., capillary blood glucose) using a validated reference method (e.g., clinical glucose meter). Ensure the measurement is performed in duplicate for confirmation.

- Signal Recording: Simultaneously record the raw signal output (e.g., current in nA) from the biosensor.

- Calculation of Sensitivity (S): For each calibration instance, calculate the sensor's sensitivity as the ratio of the sensor signal (I) to the reference concentration (G): S = I / G.

- Conversion to Estimated Concentration: To convert subsequent sensor signals I(t) into estimated analyte concentrations G(t), apply the formula: G(t) = I(t) / S.

- Recalibration Schedule: Recalibrate the sensor periodically (e.g., once or twice daily) to account for potential changes in sensor sensitivity over time.

Protocol for a Two-Point Calibration Study

This protocol outlines the steps for a two-point calibration, incorporating elements from both biosensing and other scientific fields [29] [31]:

- Sensor Deployment: Implant the biosensor as described in Section 4.1.

- Two-Point Reference Collection: Obtain two separate reference measurements (G₁, G₂) and their concomitant sensor signals (I₁, I₂). These measurements should be taken at different concentration levels and distant by a sufficient time interval (e.g., at least 1 hour) to ensure a meaningful difference.

- Parameter Calculation:

- Calculate the sensor sensitivity: S = (I₂ - I₁) / (G₂ - G₁).

- Calculate the background current: Io = I₁ - (S × G₁).

- Conversion to Estimated Concentration: For all subsequent sensor signals I(t), calculate the analyte concentration using: G(t) = (I(t) - Io) / S.

- Error Handling: Implement procedures to handle potential calculation errors, such as negative Io values, which can arise from measurement uncertainties [30].

Protocol for a Comparative Accuracy Study

To objectively compare both methods, a within-subject design is optimal [29]:

- Study Population: Recruit a sufficient number of subjects (e.g., 100+ type 1 diabetic patients) to ensure statistical power.

- Data Collection: Collect a large dataset of paired sensor signals and high-quality reference measurements over several days.

- Post-Hoc Analysis: Apply both one-point and two-point calibration algorithms to the same sensor data stream offline.

- For one-point calibration, use reference points from, for instance, pre-meal times.

- For two-point calibration, use pairs of reference points, such as those before breakfast.

- Accuracy Assessment: Compare the output of both calibrated signals against the reference measurements using standardized metrics:

- Median Absolute Relative Difference (MARD): Calculated for the overall range and specific glycemic ranges (hypoglycemia, euglycemia, hyperglycemia).

- Clarke Error Grid Analysis (EGA): To assess clinical accuracy.

- Hypoglycemia Sensitivity and Specificity.

Diagram 1: Workflow for a Comparative Calibration Accuracy Study. This diagram illustrates the parallel application of one-point and two-point calibration algorithms on the same dataset for a direct performance comparison.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for In-Vivo Calibration Research

| Item Name | Function/Description | Relevance to Calibration Research |

|---|---|---|

| Subcutaneous Glucose Sensor (e.g., SCGM1, Roche) [29] | Microdialysis-based or enzymatic sensor for continuous glucose measurement in interstitial fluid. | The primary data source. Its raw signal (ISIG) is the input for all calibration procedures. |

| High-Accuracy Blood Glucose Meter (e.g., Glucotrend) [30] [28] | Provides reference capillary blood glucose measurements for calibration and validation. | Serves as the "ground truth." Its measurement error is a key source of uncertainty in calibration [30]. |

| MCT Inhibitors (e.g., AR-C155858, AZD3965) [31] | Pharmacological blockers of monocarboxylate transporters. | Used in advanced two-point calibration protocols (e.g., for FRET sensors) to manipulate intracellular metabolite levels and determine the sensor's dynamic range (RMAX). |

| MPC Inhibitor (e.g., UK-5099) [31] | Pharmacological blocker of the mitochondrial pyruvate carrier. | Used in conjunction with MCT inhibitors to induce intracellular pyruvate saturation for sensor calibration. |

| FRET-based Genetically Encoded Indicator (e.g., Pyronic) [31] | A fusion protein that changes fluorescence upon binding a specific metabolite (e.g., pyruvate). | A modern biosensing tool whose fluorescence signal requires calibration for quantitative assessment, often via a two-point method to determine its full dynamic range in each cell. |

The body of evidence from in-vivo biosensing research challenges the intuitive appeal of the more complex two-point calibration. For researchers and drug development professionals, the choice between one-point and two-point calibration is not merely theoretical but has direct consequences for data integrity.

The consensus from multiple studies indicates that one-point calibration often provides superior accuracy, particularly in dynamic physiological states like hypoglycemia. This is primarily because it is less vulnerable to the error amplification inherent in calculating a background current (Io) from noisy real-world measurements. The two-point method, while theoretically more comprehensive, is highly sensitive to physiological time lags and reference measurement errors, often leading to greater overall deviation [29] [30] [28].

Recommendations for Practice

Based on the analyzed evidence, the following recommendations are proposed:

- Prioritize One-Point Calibration for Routine CGM: For most in-vivo glucose monitoring applications, a one-point calibration protocol, performed once or twice daily before meals, is recommended as the starting point for its robustness and simplicity [28].

- Reserve Two-Point Calibration for Specific Cases: Two-point calibration remains valuable in scenarios where the background current is known to be significant and stable, or in specialized research requiring absolute quantification of novel biomarkers using advanced sensors like FRET-based indicators, where its protocol is well-established [31].

- Acknowledge and Minimize Reference Error: Regardless of the method chosen, researchers must recognize that the accuracy of the reference measurement is a fundamental limiter of calibration quality. Using highly precise reference methods and duplicate measurements is crucial [30].

- Contextualize the "Best" Method: The optimal calibration strategy is use-specific. Researchers should conduct pilot studies to compare both methods on their specific sensor platform and target analyte to make a data-driven decision.

In conclusion, within the critical field of in-vivo biosensing, the simpler one-point calibration method frequently offers a more favorable trade-off, yielding not just greater usability but also higher measurement accuracy than its two-point counterpart.

Dual-Frequency and Ratiometric Approaches for Calibration-Free Operation

The need for frequent calibration remains a significant hurdle limiting the widespread clinical adoption of continuous biosensors. Conventional biosensors require calibration against reference samples to correct for sensor-to-sensor fabrication variations and signal drift experienced in complex biological environments. This process is cumbersome, increases the risk of user error, and is particularly problematic for measuring endogenous biomarkers where "zero-concentration" reference points are unavailable [32] [33]. In response to these challenges, dual-frequency and ratiometric approaches have emerged as transformative strategies that enable calibration-free operation while maintaining high accuracy in vivo.

These innovative methods leverage inherent signal properties rather than external references to generate measurement outputs that are largely independent of the absolute number of sensing elements or the microscopic surface area of electrodes. By producing a unitless ratiometric signal, these approaches effectively cancel out common noise sources and fabrication variances that plague traditional single-output sensors [32] [33]. This capability is particularly valuable for applications such as therapeutic drug monitoring and tracking of disease biomarkers in live animals and humans, where conventional calibration is impractical or impossible after sensor deployment [5].

This guide provides a systematic comparison of these calibration-free methodologies, focusing on their operational principles, experimental implementation, and performance characteristics. By presenting quantitative data and detailed protocols, we aim to equip researchers and drug development professionals with the necessary information to select and implement appropriate calibration-free strategies for their specific in vivo biosensing applications.

Comparative Performance Analysis of Calibration-Free Methods

The table below summarizes the key performance characteristics of major calibration-free biosensing approaches, highlighting their relative advantages in real-world applications.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Calibration-Free Biosensing Methods

| Method | Target Analytes | Dynamic Range | Reported Accuracy | Key Advantages | Implementation Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dual-Frequency EAB | Vancomycin, Phenylalanine, Cocaine | Up to 100-fold | Within ±20% across dynamic range | Drift correction in vivo, eliminates single-point calibration | Medium (requires frequency optimization) |

| Ratiometric EAB | Vancomycin, Phenylalanine | Not specified | Effectively indistinguishable from KDM | Simple signal calculation, robust performance | Low (simple current ratio calculation) |

| Dual-Comb Biosensing | SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein | Detection to sub-fM level | High precision via RF conversion | Exceptional sensitivity, active temperature compensation | High (specialized optical setup required) |

| Ratiometric Fluorescence | Various small molecules, ions | Varies by probe design | Improved reliability via self-calibration | Built-in reference signal, visual detection capability | Medium (requires dual-emission probes) |

Table 2: In Vivo Performance of Electrochemical Aptamer-Based Sensors

| Sensor Type | Analysis Method | Test Environment | Baseline Recovery | Drift Correction | Calibration Requirement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional EAB | Single-frequency SWV | Live rats | Poor without calibration | Limited | Single-point calibration essential |

| Dual-Frequency EAB | rKDM (Equation 2) | Live rats | Accurate | Excellent | None |

| Dual-Frequency EAB | Ratiometric (Equation 3) | Live rats | Accurate | Excellent | None |

Experimental Protocols for Key Calibration-Free Methods

Dual-Frequency Electrochemical Aptamer-Based (EAB) Sensing

Principle of Operation: This method exploits the square-wave frequency dependence of electron transfer kinetics in electrochemical aptamer-based sensors. When target molecules bind to electrode-bound aptamers, they alter electron transfer rates, producing measurable current changes. The approach uses two specific square-wave frequencies: one that is highly responsive to target binding and another that is minimally responsive [32] [33].

Protocol Details:

- Sensor Fabrication: Thiol-modified redox reporter-labeled aptamers are co-immobilized onto gold electrodes through self-assembled monolayer formation, typically using a 1:1000 ratio of aptamer to 6-mercapto-1-hexanol to achieve optimal packing density and sensor response [32].

- Frequency Selection: Prior to testing, identify optimal frequency pairs through preliminary experiments. For cocaine detection, 500 Hz (responsive) and 40 Hz (non-responsive) have been used effectively [33].

- Measurement: Interrogate sensors simultaneously or sequentially at both selected frequencies using square wave voltammetry.