Chemometrics for Biosensor Selectivity Enhancement: Strategies, Applications, and Future Outlook in Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive overview of chemometrics as a powerful, cost-effective toolkit for enhancing the selectivity and analytical performance of biosensors.

Chemometrics for Biosensor Selectivity Enhancement: Strategies, Applications, and Future Outlook in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of chemometrics as a powerful, cost-effective toolkit for enhancing the selectivity and analytical performance of biosensors. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of key chemometric methods like Principal Component Analysis (PCA), Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression, and Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs). The scope extends to methodological applications in pharmaceutical monitoring and therapeutic drug sensing, troubleshooting for interference effects and real-world deployment, and comparative validation against standard analytical techniques. By synthesizing these facets, the article serves as a guide for leveraging data-driven analytics to develop more reliable, accurate, and intelligent biosensing systems for complex biomedical matrices.

Understanding Chemometrics: The Data Science Foundation for Advanced Biosensing

Defining Chemometrics and Its Role in Modern Biosensor Technology

Chemometrics is the science of extracting meaningful chemical information from complex data sets by applying mathematical and statistical methods. In the context of biosensing, chemometric tools are essential for interpreting the rich, high-dimensional data generated by modern sensor systems, moving beyond simple univariate regression to multivariate analysis that can handle complex sample matrices and interference effects [1]. This data-centric approach is pivotal for enhancing the performance of biosensors, which are analytical devices that combine a biological recognition element (such as an enzyme, antibody, aptamer, or peptide) with a physicochemical transducer to produce a measurable signal proportional to the concentration of a target analyte [2] [3].

The integration of chemometrics is a response to the growing sophistication of biosensor technology, which now includes a diverse array of transducer principles—electrochemical, optical, thermal, and piezoelectric [4]. These systems, particularly those employing voltammetric techniques or multi-sensor arrays, generate complex response patterns that are ideal for multivariate analysis [2] [5]. The core challenge in biosensing, especially for applications in complex biological fluids like blood or serum, is to maintain high selectivity—the ability of a method to distinguish the target analyte from other components in the sample matrix [6]. Selectivity is a cornerstone of analytical chemistry, directly impacting the accuracy, reliability, and overall validity of results. High selectivity ensures measurements are specific to the analyte, reducing false positives/negatives, which is critical in pharmaceuticals, clinical diagnostics, and environmental monitoring [6]. Chemometrics provides the computational framework to achieve this specificity, transforming biosensors from simple detectors into intelligent, decision-making analytical platforms.

The Chemometric Toolkit for Selectivity Enhancement

The fundamental role of chemometrics in boosting biosensor selectivity is to mathematically resolve target analyte signals from a background of interference and noise. This is accomplished through several key classes of algorithms, each suited to different types of data and analytical objectives.

Dimensionality Reduction and Unsupervised Learning: Techniques like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) are foundational. PCA reduces the dimensionality of complex data sets while preserving the most significant variance, allowing researchers to visualize natural clustering of samples and identify potential outliers [1] [5]. This is often the first step in data exploration to assess the inherent discriminative power of a sensor array.

Supervised Classification and Regression: When the goal is to assign unknown samples to predefined categories (e.g., diseased vs. healthy) or to quantify analyte concentration, supervised methods are employed. Partial Least Squares Discriminant Analysis (PLS-DA) is a powerful regression-based technique that finds a linear relationship between sensor data (X) and class membership (Y), maximizing the covariance between them. It has been successfully used in optical biosensors, achieving high sensitivity and specificity in detecting SARS-CoV-2 antibodies [7]. Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) is another classic method that maximizes the separation between classes. Studies have compared its performance against PCA, with PCA load analysis sometimes demonstrating superior accuracy for specific tasks like detecting milk adulteration [5].

Advanced Machine Learning (ML) and Deep Learning: The incorporation of Artificial Neural Networks (ANN), Support Vector Machines (SVM), and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) has brought new opportunities to handle non-linear data and further improve detection performance in complex samples [2] [5]. These models can learn intricate patterns from large training datasets, making them exceptionally robust for real-world applications where sensor responses are not perfectly linear. For instance, ANN algorithms have demonstrated the highest accuracy (95.51%) in detecting adulteration in olive oil samples compared to other methods [5].

Table 1: Key Chemometric Methods for Biosensor Data Analysis

| Method Category | Specific Algorithm | Primary Function | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dimensionality Reduction | Principal Component Analysis (PCA) | Exploratory data analysis, visualization | Identifies natural clustering and trends without prior knowledge of sample classes [5]. |

| Supervised Classification | Partial Least Squares Discriminant Analysis (PLS-DA) | Classification and quantitative regression | Maximizes covariance between sensor data and class labels; ideal for collinear data [7]. |

| Supervised Classification | Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) | Classification | Maximizes separation between known classes [5]. |

| Machine Learning | Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) | Classification and regression | Models complex, non-linear relationships; high accuracy in various applications [2] [5]. |

| Machine Learning | Support Vector Machine (SVM) | Classification | Effective in high-dimensional spaces; robust against overfitting [5]. |

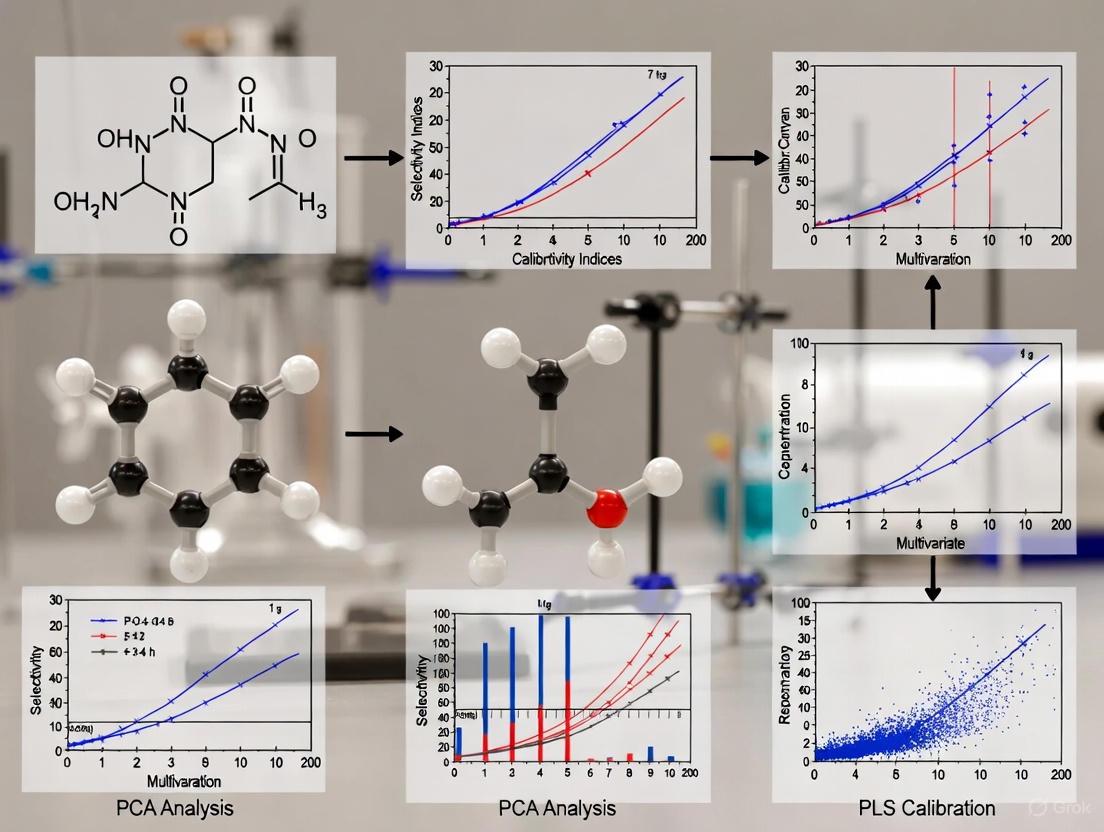

The following diagram illustrates the standard workflow for applying these chemometric tools to biosensor data, from signal acquisition to final classification or regression outcome.

Experimental Protocols for Chemometrics-Enhanced Biosensing

This section provides a detailed, reproducible protocol for developing a peptide-based electrochemical biosensor, incorporating chemometric analysis to achieve variant-specific detection of antibodies, as exemplified in recent research [7].

Protocol: Peptide-Based Electrochemical Biosensor for Antibody Detection

1. Objective: To fabricate a biosensor for the ultrasensitive and specific detection of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in human serum using peptide-functionalized electrodes and Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) with PLS-DA modeling.

2. Materials and Reagents:

- Synthetic Peptides: Immunodominant peptide P44 (wild-type sequence: TGKIADYNYKLPDDF) and its mutated analogs (e.g., P44-T, P44-N) [7].

- Electrode Substrate: Glassy carbon electrode (GCE) [7].

- Chemical Linker: 4-mercaptobenzoic acid (MBA) or similar cross-linker [7].

- Redox Probe: Potassium ferricyanide/ferrocyanide ([Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻) solution [8].

- Biological Sample: Human serum samples (from convalescent patients and pre-pandemic controls) [7].

- Buffer Solutions: Phosphate buffer saline (PBS, 10 mM, pH 7.4) for dilution and measurements [7].

3. Experimental Workflow:

Step 1: Electrode Functionalization

- Begin by meticulously polishing the glassy carbon electrode with alumina slurry (e.g., 0.3 µm and 0.05 µm) to create a clean, reproducible surface. Rinse thoroughly with deionized water and dry.

- Immerse the polished electrode in a solution containing the cross-linker (e.g., MBA) to form a self-assembled monolayer. This layer provides functional groups for subsequent peptide immobilization.

- Incubate the modified electrode in a solution of the specific synthetic peptide (P44-WT or a variant) for a predetermined time (e.g., 2 hours) to allow covalent attachment. Wash the electrode gently with buffer to remove any physically adsorbed peptides.

Step 2: Data Acquisition via Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS)

- Use a standard three-electrode system (functionalized GCE as working electrode, Pt counter electrode, and Ag/AgCl reference electrode).

- Prepare a solution of the redox probe (e.g., 10 mM [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻ in PBS).

- Record EIS spectra for the functionalized electrode first in the presence of negative control serum, and then after incubation with serum samples containing target antibodies. The antibody binding event insulates the electrode surface, increasing the electron transfer resistance (Rₑₜ), which is measured.

- Perform all measurements in triplicate to ensure statistical robustness.

Step 3: Chemometric Data Analysis with PLS-DA

- Construct a data matrix where each row represents a sample and each column represents a feature extracted from the EIS spectrum (e.g., Rₑₜ at different frequencies, charge transfer resistance, solution resistance, Warburg impedance).

- Code the class labels (e.g., "Positive" or "Negative") numerically.

- Split the data set into a training set (e.g., 70-80%) and a test set (e.g., 20-30%).

- Use the training set to build the PLS-DA model, which will find the latent variables that best separate the classes.

- Validate the model's performance by using it to predict the classes of the unseen test set. Calculate performance metrics such as sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Biosensor Development

| Reagent/Material | Function in the Experiment | Exemplification from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | Signal amplification platform; enhances surface area for biorecognition element immobilization. | Used in SERS and electrochemical biosensors for SARS-CoV-2 antibody detection [7]. |

| Synthetic Peptides (e.g., P44) | Biorecognition element; specifically binds to target antibodies. | P44 peptide used for variant-specific detection of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies [7]. |

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) | Synthetic bioreceptor with tailor-made binding cavities for a specific analyte. | Used in solid-phase extraction (SPE) to selectively capture analytes from complex matrices [6]. |

| Magnetic Beads (MBs) | Solid support for immobilizing biorecognition elements; enables easy separation and preconcentration of analyte. | Applied in biosensors for pathogen detection (e.g., Salmonella, Listeria); enhances sensitivity and selectivity [8]. |

| 4-Mercaptobenzoic Acid (MBA) | Raman reporter and chemical linker; facilitates attachment of peptides to gold surfaces via thiol groups. | Used as a stabilizer and linker for functionalizing AuNPs with peptides [7]. |

The following workflow summarizes the key experimental and computational steps in this protocol.

Case Studies and Quantitative Performance

The efficacy of chemometrics in enhancing biosensor performance is best demonstrated through specific, real-world applications. The following case studies highlight the quantitative improvements achieved.

Case Study 1: Variant-Specific SARS-CoV-2 Antibody Detection A recent 2025 study developed a biosensor platform using the immunodominant peptide P44 and its mutants to detect variant-specific antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 [7]. The platform utilized two transduction methods:

- Optical Biosensing (SERS): The SERS biosensor, when analyzed with PLS-DA, achieved 100% sensitivity and 76% specificity in classifying serum samples (n=104) [7].

- Electrochemical Biosensing (EIS): This method provided exceptionally low detection limits for the different peptide variants: 0.43 ng mL⁻¹ for P44-WT, 4.85 ng mL⁻¹ for P44-T, and 8.04 ng mL⁻¹ for P44-N [7]. This demonstrates the platform's high sensitivity and its ability to differentiate based on minor peptide mutations.

Case Study 2: Pathogen Detection in Food Safety A 2025 study presented a cost-effective, label-free biosensor using gold leaf electrodes (GLEs) and magnetic beads (MBs) for the quantitative detection of food-borne pathogens [8]. The integration of MBs allowed for efficient target capture and preconcentration, significantly enhancing the sensor's selectivity and sensitivity in the complex food matrix. The study successfully detected Salmonella typhimurium and Listeria monocytogenes, showcasing the practical application of such systems for public health protection [8].

Case Study 3: Overcoming Cross-Sensitivity in Gas Sensing While not a biosensor in the strictest sense, the principles are analogous. Chemiresistive gas sensors are notoriously plagued by cross-sensitivity. Research has shown that employing sensor arrays combined with pattern recognition methods like PCA, LDA, and ANN can effectively overcome this limitation [5]. For example, using an ANN algorithm led to a high accuracy of 95.51% in detecting adulteration in olive oil samples, transforming a non-selective sensor into a highly discriminative tool [5].

Table 3: Quantitative Performance of Chemometrics-Enhanced Biosensors

| Application & Technique | Chemometric Tool | Reported Performance Metrics |

|---|---|---|

| SARS-CoV-2 Antibody Detection (SERS) [7] | Partial Least Squares Discriminant Analysis (PLS-DA) | Sensitivity: 100%, Specificity: 76% |

| SARS-CoV-2 Antibody Detection (EIS) [7] | Not Specified (Quantitative Regression) | Limit of Detection (LOD): 0.43 - 8.04 ng mL⁻¹ |

| Olive Oil Adulteration Detection [5] | Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) | Classification Accuracy: 95.51% |

| Milk Adulteration Detection [5] | PCA Load Analysis | Accurate detection of formalin, H₂O₂, NaOCl at 0.01% |

| Health State Classification [5] | Principal Component Analysis (PCA) | Successful classification of 4 health states (CKD, diabetes, healthy) |

The integration of chemometrics is no longer an optional enhancement but a fundamental component of modern biosensor technology, particularly for achieving the high selectivity required in complex real-world samples. By leveraging multivariate algorithms like PLS-DA and ANN, biosensors can transcend the limitations of their individual physical components, transforming from simple detectors into intelligent analytical systems capable of sophisticated pattern recognition.

The future of this synergistic field is bright, driven by several key trends. Advances in nanomaterials and synthetic bioreceptors like molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs) will provide more stable and selective recognition surfaces, whose complex outputs will necessitate robust chemometric analysis [6]. The drive towards point-of-care testing (POCT) and the use of smartphones as portable analysis platforms creates a direct need for embedded, efficient chemometric models that can provide real-time, on-site decision-making capabilities [2]. Finally, the ongoing revolution in data analysis, including the adoption of more powerful deep learning architectures, promises to further improve the interpretation of biosensor data, enabling the resolution of increasingly subtle analytical challenges in medical diagnostics, environmental monitoring, and food safety [2] [5]. The continued collaboration between sensor developers, chemometricians, and end-users will be crucial in realizing the full potential of these intelligent analytical systems.

The integration of chemometrics—the application of mathematical and statistical methods to chemical data—has become a cornerstone of modern biosensing research. While biosensors are renowned for their high selectivity, achieved through specific biorecognition elements like enzymes, antibodies, or aptamers, real-world sample matrices often introduce complexities such as interferences, non-linear responses, and signal overlap [9] [10]. The prevailing philosophy that "math is cheaper than physics" provides a compelling motivation for employing sophisticated data processing techniques to enhance biosensor performance, rather than solely relying on complex and costly physical sensor redesigns [9] [10]. This application note details the protocols for three core chemometric tools—Principal Component Analysis (PCA), Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression, and Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs)—and demonstrates their application within a research program aimed at biosensor selectivity enhancement.

The following table summarizes the primary functions and biosensing applications of the three core chemometric tools discussed in this document.

Table 1: Core Chemometric Tools for Biosensor Research

| Tool | Primary Function | Key Biosensing Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| PCA (Principal Component Analysis) | Unsupervised exploration, visualization, and dimensionality reduction of multivariate data [9] [10]. | - Identifying patterns and grouping in samples based on biosensor array responses [9] [10].- Optimizing sensor array configuration by identifying the most informative sensors [9].- Objective analysis of multi-harmonic data from acoustic sensors like QCM [11]. |

| PLS (Partial Least Squares) | Multivariate regression for relating biosensor responses to analyte concentrations or sample properties [9] [12]. | - Quantifying analytes in complex matrices where signals interfere [9].- Predicting sample quality parameters (e.g., Biochemical Oxygen Demand) from biosensor array data [9] [10].- Modeling data from designed experiments to understand factor effects [12]. |

| ANN (Artificial Neural Network) | Non-linear modeling for complex classification and regression tasks [9] [13]. | - Analyzing mixtures of compounds using biosensor outputs [13].- Discriminating between similar analytes and estimating their concentrations in a mixture [13].- Handling highly non-linear biosensor responses and complex data patterns [14]. |

Protocol for Principal Component Analysis (PCA) in Biosensor Array Optimization

Background and Principle

PCA is an unsupervised technique that reduces the dimensionality of multivariate data while preserving the majority of its variance. It transforms the original variables into a new set of orthogonal variables called Principal Components (PCs), where the first PC (PC1) captures the greatest variance, the second PC (PC2) the next greatest, and so on [9] [10]. This allows for the visualization of complex, multi-dimensional biosensor data in a 2D or 3D score plot, where similar samples cluster together and dissimilar samples are separated [9].

Experimental Protocol

Objective: To identify the minimal and most effective combination of sensors in a biosensor array for discriminating between different water quality types.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Data Collection: Acquire response data from an array of biosensors (e.g., eight enzyme-based platinum sensors). For each sample, collect readings at multiple time channels to create a rich, multivariate data set [9] [10].

- Data Structuring: Organize the data into a matrix X (samples × variables), where the variables are the response readings from all sensors and time points.

- Data Pre-processing: Pre-process the data by mean-centering and scaling (e.g., unit variance scaling) to ensure all variables contribute equally to the model.

- PCA Model Calculation: Perform PCA on the full data matrix X to extract the principal components and their corresponding scores and loadings.

- Visualization and Initial Analysis: Generate a PCA score plot (e.g., PC1 vs. PC2) to visualize the natural grouping of all water samples (e.g., untreated, alarm, alert, normal, pure water) using the entire sensor array.

- Sensor Contribution Analysis: Examine the loadings plot to identify which sensors contribute most significantly to the PCs that separate the sample classes.

- Iterative Sensor Selection: Systematically perform new PCA models using subsets of sensors (e.g., a combination of just two key sensors) [9] [10].

- Performance Evaluation: Compare the score plots from different sensor subsets. The optimal subset is the one that yields distinct, well-separated clustering according to the known water types, as achieved with a specific two-sensor combination in the referenced study [9].

Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Biosensor Array-Based Analysis

| Material/Reagent | Function in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| Platinum Sensor Array | Platform for immobilizing different bioreceptors; provides the multivariate response signal. |

| Enzyme Cocktails (e.g., Glucose Oxidase, Urease) | Biorecognition elements that provide complementary and overlapping sensitivity patterns for different analytes. |

| Standard Water Samples | Samples with known quality classifications (e.g., normal, alert) used to build and validate the PCA model. |

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for using PCA to optimize a biosensor array.

Protocol for Partial Least Squares (PLS) Regression for Quantifying Biochemical Oxygen Demand (BOD)

Background and Principle

PLS regression is a supervised multivariate technique used to model the relationship between a set of predictor variables (biosensor responses) and one or more response variables (analyte concentrations or sample properties) [9] [12]. Unlike PCA, which only considers the variance in the predictor X-block, PLS finds components that simultaneously maximize the variance in X and the correlation with the response Y-block [9] [12]. This makes it exceptionally powerful for analyzing noisy, collinear data from biosensor arrays.

Experimental Protocol

Objective: To develop a rapid PLS calibration model for predicting 7-day Biochemical Oxygen Demand (BOD₇) in wastewater using a biosensor array, replacing the time-consuming standard method.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Reference Analysis: Determine the reference BOD₇ values for a set of calibration wastewater samples using the standard 7-day method [9] [10].

- Biosensor Measurement: For the same set of calibration samples, collect the multivariate response from the biosensor array.

- Data Set Preparation: Split the data into a calibration set (for model training) and a validation set (for model testing).

- PLS Model Calibration: Build a PLS model that regresses the biosensor array data (X) onto the reference BOD₇ values (Y). Use cross-validation on the calibration set to determine the optimal number of latent variables to avoid overfitting.

- Model Validation: Apply the calibrated PLS model to the independent validation set. Predict the BOD values (BOD_pred) for these samples.

- Performance Evaluation: Construct a "measured vs. predicted" plot. Calculate the Root-Mean-Square Error of Prediction (RMSEP) to quantify the model's accuracy [9] [10]: ( RMSEP = \sqrt{\frac{\sum{(y{i,ref} - y{i,pred})^2}}{n}} ) where ( y{i,ref} ) and ( y{i,pred} ) are the reference and predicted values for the ith sample, and n is the number of samples.

Performance Metrics

Table 3: Performance of a PLS Model for BOD Prediction [9]

| Sample Type | Performance |

|---|---|

| All Simulated Wastewater Samples | PLS-predicted BOD differed from reference BOD₇ by < 5.6% |

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram outlines the key steps in developing and validating a PLS regression model for biosensing.

Protocol for Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) in Mixture Analysis

Background and Principle

ANNs are a group of powerful, non-linear modeling tools inspired by the biological brain's structure [9] [13]. They are capable of learning complex, non-linear relationships between inputs and outputs, making them ideal for tasks where biosensor responses to analyte mixtures are highly intertwined and not separable by linear methods. A basic ANN consists of an input layer, one or more hidden layers, and an output layer, with interconnected nodes (neurons) that apply activation functions [9].

Experimental Protocol

Objective: To use an ANN to discriminate and quantify individual components in a mixture from the combined response of an amperometric biosensor.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Data Generation (Simulation): Generate a comprehensive set of biosensor calibration and test data using a validated mathematical model of the biosensor. The model should be based on diffusion equations and Michaelis-Menten kinetics to simulate the response to mixtures of compounds [13].

- Data Preprocessing and Optimization: Perform PCA on the simulated data to reduce dimensionality and optimize the input structure for the ANN [13].

- ANN Architecture Definition: Design the network architecture:

- Input Layer: Number of nodes equals the number of features from the PCA-reduced data.

- Hidden Layer(s): Start with one or two hidden layers and a trial number of neurons (e.g., 5-15). This must be optimized.

- Output Layer: Number of nodes equals the number of compounds in the mixture to be quantified.

- ANN Training: Train the ANN using a backpropagation algorithm (e.g., Levenberg-Marquardt) on the simulated calibration data. The network's weights and biases are iteratively adjusted to minimize the error between the predicted and true concentrations.

- Model Testing: Evaluate the trained ANN's performance on the independent, simulated test data set that was not used during training.

- Performance Evaluation: Report the recovery rates for each analyte in the mixture, calculated as (Predicted Concentration / True Concentration) × 100%.

Performance Metrics

Table 4: Performance of an ANN for Mixture Analysis [13]

| Analysis Mode | Model Performance |

|---|---|

| Flow Injection Analysis | Prediction recovery for each mixture component > 99% |

| Batch Analysis | Prediction recovery for each mixture component > 99% |

Workflow Visualization

The workflow for developing an ANN model for biosensor data analysis, particularly with simulated data, is shown below.

The strategic application of PCA, PLS, and ANNs provides a powerful chemometric toolkit for overcoming significant challenges in biosensing, particularly in enhancing effective selectivity in complex matrices. As demonstrated in the protocols above, these tools enable researchers to extract maximal information from biosensor data, from exploratory analysis and array optimization to robust quantitative modeling and the deconvolution of complex mixtures. The integration of these chemometric methods is pivotal for advancing biosensor technology from laboratory prototypes to reliable analytical solutions for real-world problems in drug development, environmental monitoring, and clinical diagnostics. Future trends point towards the deeper integration of these classical methods with advanced machine learning and explainable AI (XAI) frameworks, further augmenting the power and interpretability of biosensor data analysis [14] [15].

The paradigm that highly selective bioreceptors alone guarantee accurate biosensing is being fundamentally re-examined. While bioreceptors such as antibodies, aptamers, and enzymes provide exceptional molecular recognition, their performance in complex real-world matrices is frequently compromised by non-specific binding, signal drift, and interfering substances. This application note demonstrates how chemometric data processing transforms raw, interference-prone biosensor signals into reliable analytical measurements. We present experimental protocols and data analysis workflows that enable researchers to deploy biosensors for precise quantification in biomedical diagnostics, environmental monitoring, and food safety applications, even in challenging matrices.

Biosensors combine a biological recognition element (bioreceptor) with a physicochemical transducer to detect specific analytes. The exceptional selectivity of bioreceptors like antibodies, aptamers, enzymes, and nucleic acids originates from their precise molecular complementarity with target analytes [10] [16]. This inherent specificity suggests that a perfectly selective bioreceptor should require only simple univariate calibration to relate sensor response to analyte concentration.

However, this theoretical ideal collapses in practice when biosensors encounter complex real-world samples such as blood, wastewater, or food products. In these matrices, even the most specific bioreceptors face significant challenges:

- Matrix Effects: Complex samples contain numerous components that can cause non-specific binding or alter the transducer signal.

- Signal Non-linearity: The relationship between analyte concentration and sensor response often deviates from ideal linearity.

- Instrumental Noise and Drift: Environmental factors and electronic noise introduce signal artifacts, especially in prolonged monitoring.

The conventional approach to these challenges involves refining the bioreceptor or sensor platform, which demands substantial investments of time and resources [10] [17]. Chemometrics offers an alternative paradigm: rather than eliminating all interference through physical means, advanced mathematical and statistical techniques extract the relevant analytical information from complex, multivariate sensor signals [10]. As noted in recent literature, "math is cheaper than physics" in overcoming these analytical challenges [10] [17].

The Chemometric Advantage: From Raw Data to Reliable Information

Chemometric techniques enhance biosensor performance by treating the output not as a single value, but as a rich, multivariate dataset containing both analytical information and various noise components.

Key Chemometric Tools for Biosensing

Table 1: Essential Chemometric Methods for Enhanced Biosensor Selectivity

| Method | Primary Function | Application Example in Biosensing | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Principal Component Analysis (PCA) | Unsupervised pattern recognition and data visualization | Identifying inherent clustering of samples based on biosensor array responses to different water quality levels [10] | Reveals natural groupings in data without prior knowledge of sample classes |

| Partial Least Squares Regression (PLS) | Multivariate calibration relating sensor response to analyte concentration | Predicting biochemical oxygen demand (BOD) in wastewater from biosensor array data, achieving <5.6% error compared to standard 7-day method [10] | Handles correlated variables and noisy data better than ordinary least squares |

| Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) | Non-linear modeling for classification and prediction | Processing complex electrochemical signals for multi-analyte detection in presence of overlapping responses [10] [18] | Capable of learning complex, non-linear relationships in data |

| Multiple Linear Regression (MLR) | Modeling relationship between multiple independent variables and a dependent variable | Quantifying propionaldehyde concentration from chronoamperometric biosensor data [18] | Simple, interpretable models for less complex data structures |

Quantitative Evidence of Enhanced Performance

Table 2: Performance Comparison: Univariate vs. Chemometric Analysis of Biosensor Data

| Analysis Method | Analyte | Sensor Type | Key Performance Metric | Result with Univariate Analysis | Result with Chemometric Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chronoamperometric data analysis [18] | Propionaldehyde | Screen-printed dehydrogenase biosensor | Coefficient of variation | 33% | 15% |

| Array-based sensing [10] | Biochemical Oxygen Demand (BOD) | Multi-sensor biosensor array | Prediction error vs. reference method | Not feasible (single sensor) | <5.6% error for all sample types |

| Electronic tongue system [10] | Wastewater quality parameters | 8-sensor enzyme array | Discrimination of water types (untreated, alert, normal, pure) | Poor separation | Distinct clustering by water quality |

The transformation from univariate to multivariate analysis represents a fundamental shift in biosensor data interpretation. Rather than relying on a single data point (e.g., current at a fixed time), chemometric approaches utilize the entire response profile, extracting more information and significantly improving reliability.

Figure 1: Chemometric Data Processing Workflow. This diagram illustrates the transformation of raw biosensor signals into reliable analytical information through sequential chemometric processing steps.

Experimental Protocol: Implementing Chemometric Analysis for Biosensor Data

This section provides a detailed protocol for applying chemometric analysis to biosensor data, using a case study of screen-printed biosensors for aldehyde detection [18].

Materials and Reagents

Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function/Biological Role | Specifications/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Aldehyde Dehydrogenase (EC 1.2.1.5) | Bioreceptor: Catalyzes oxidation of propionaldehyde | From Saccharomyces cerevisiae, 1 IU mg−1 solid |

| β-Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide (NAD+) | Coenzyme: Electron acceptor in enzymatic reaction | Essential for dehydrogenase-based biosensors |

| Meldola Blue-Reinecke's Salt | Electron mediator: Shuttles electrons from NADH to electrode | Insoluble salt form provides stable immobilization |

| Propionaldehyde | Target analyte: Substrate for dehydrogenase enzyme | Prepare fresh standards in appropriate buffer |

| Photocrosslinkable Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA) | Immobilization matrix: Entraps enzyme and mediator on electrode surface | "Bio" form, polymerization degree 1700 |

| Screen-printed Dual-electrode Systems | Transducer platform: Graphite working and counter electrodes | Mass-producible, disposable sensor platform |

Sensor Preparation and Data Acquisition

Procedure:

Electrode Modification:

- Prepare mediator-modified screen-printed graphite electrodes by incorporating Meldola Blue-Reinecke's salt into the ink formulation.

- Coat electrodes with enzyme solution containing aldehyde dehydrogenase (1 IU mg−1) in photocrosslinkable PVA matrix.

- Photocrosslink the enzyme layer using UV exposure (365 nm) for 5 minutes to create a stable biorecognition layer.

Chronoamperometric Measurements:

- Apply a fixed potential of +0.1 V vs. Ag/AgCl reference.

- Record current transient at 100 ms intervals for 30 seconds following sample introduction.

- Use propionaldehyde standards in concentration range of 0.2-1.2 mM for calibration.

- Perform triplicate measurements for each concentration.

Data Export and Formatting:

- Export entire chronoamperometric curves (300 data points each) rather than single time-point measurements.

- Arrange data in matrix format with samples as rows and time points as columns.

- Include reference concentrations as separate vector for calibration.

Chemometric Data Processing Protocol

Software Requirements: MATLAB, Python (with scikit-learn, pandas), or specialized chemometric software.

PLS Model Implementation:

Data Preprocessing:

- Apply baseline correction to remove capacitive current contributions.

- Normalize data using standard normal variate (SNV) transformation to minimize sensor-to-sensor variations.

- Split data into calibration (70%) and validation (30%) sets.

Model Training:

- Perform cross-validation to determine optimal number of latent variables.

- Build PLS regression model using non-linear iterative partial least squares (NIPALS) algorithm.

- Validate model using root mean square error of cross-validation (RMSECV).

Concentration Prediction:

- Apply trained PLS model to predict unknown sample concentrations.

- Calculate prediction uncertainty using confidence intervals based on model residuals.

Critical Step: Avoid overfitting by ensuring the number of latent variables is significantly less than the number of calibration samples. Typically, 4-7 latent variables are sufficient for chronoamperometric data [18].

Advanced Applications and Case Studies

Bioelectronic Tongues for Complex Matrix Analysis

The concept of "bioelectronic tongues" utilizes arrays of biosensors with partially overlapping selectivity patterns, combined with multivariate analysis, to resolve complex mixtures [10]. In one implementation, an eight-enzyme biosensor array successfully classified wastewater into five distinct quality categories (untreated, alarm, alert, normal, and pure water) using PCA [10]. The optimal configuration required only two carefully selected sensors from the original eight, demonstrating how chemometrics can guide sensor selection while maintaining classification accuracy.

Real-time Monitoring with Drift Compensation

Implantable biosensors for continuous health monitoring face particular challenges with signal drift and biofouling. Chemometric approaches can distinguish between true analytical signals and drift artifacts. Recent research highlights adaptive calibration models that continuously update using reference measurements, enabling reliable in vivo monitoring of biomarkers like glucose and tryptophan [19].

High-Sensitivity Pathogen Detection

Advanced biosensor platforms combining novel materials with chemometrics achieve remarkable sensitivity in complex samples. A recently developed electrochemical biosensor utilizing Mn-doped ZIF-67 metal-organic framework functionalized with anti-O antibody demonstrated detection of E. coli at 1 CFU mL⁻¹ in tap water, with 93.10–107.52% recovery [20]. PLS analysis enabled discrimination from non-target bacteria (Salmonella, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus) despite potential cross-reactivities.

Figure 2: The Selectivity Enhancement Paradigm. This diagram illustrates how chemometric processing resolves the fundamental challenge of extracting specific analytical signals from interference-prone biosensor responses.

The integration of chemometric analysis with biosensing platforms represents a fundamental advancement in analytical science, transforming devices from simple detectors to intelligent analytical systems. The experimental protocols and case studies presented demonstrate that even biosensors employing highly specific bioreceptors benefit substantially from multivariate data processing.

Key Implementation Recommendations:

Data Quality Precedes Model Complexity: Ensure consistent sensor fabrication and measurement protocols before applying advanced chemometrics. No algorithm can compensate for fundamentally flawed data.

Model Validation is Critical: Always validate chemometric models with independent test sets not used in model building. Report both calibration and prediction errors.

Balance Complexity and Interpretability: While neural networks can model complex non-linear relationships, simpler methods like PLS often provide sufficient accuracy with greater transparency and easier implementation.

Consider Computational Requirements: For point-of-care applications, select chemometric methods that can be implemented within the computational constraints of the intended platform.

The synergy between sophisticated bioreceptor engineering and advanced data processing represents the future of biosensing. As one review notes, this approach "shifts the complexity of the analysis from the physical domain to the digital processing domain" [19], enabling reliable analysis in increasingly complex real-world environments from clinical diagnostics to environmental monitoring.

Biosensor technology has fundamentally transformed analytical science, enabling the precise detection of specific analytes in complex biological matrices. A biosensor is defined as a self-contained analytical device that integrates a biological recognition element with a physicochemical transducer to produce a measurable signal proportional to the concentration of a target analyte [21]. The core components of any biosensor include the bioreceptor (e.g., enzyme, antibody, nucleic acid), the transducer (electrochemical, optical, piezoelectric, thermal), and the signal processing system that converts raw data into actionable analytical information [22].

The calibration of these instruments—the process of establishing a relationship between the sensor's response and the analyte concentration—has undergone a significant evolution. Traditional univariate calibration methods, which model a single sensor output against concentration, are often insufficient for modern applications where interfering substances, environmental fluctuations, and matrix effects complicate measurements [23]. This has driven a paradigm shift toward multivariate calibration, which utilizes multiple variables or sensor responses simultaneously, harnessing the power of chemometrics to enhance accuracy, robustness, and selectivity [23] [24].

This paradigm shift is particularly critical within the context of chemometrics for biosensor selectivity enhancement. By employing multivariate algorithms, researchers can deconvolute the specific signal of the target analyte from background noise and cross-reactivities, thereby significantly improving the reliability of biosensors in real-world applications such as medical diagnostics, food safety, and environmental monitoring [23] [22].

Theoretical Background: Calibration Methodologies

Univariate Calibration

Univariate calibration represents the most fundamental calibration approach, establishing a direct relationship between a single input variable (analyte concentration) and a single output variable (the sensor's response) [23]. This method typically results in a simple linear calibration curve. For instance, in a glucose biosensor, the measured current (amperometric signal) is directly plotted against glucose concentration to create a standard curve used for predicting unknown concentrations [25].

The primary limitation of univariate models is their inability to account for interfering factors that influence the sensor signal. Factors such as temperature variations, pH fluctuations, the presence of chemically similar interferents, and sensor drift can introduce significant errors, compromising the analytical accuracy [24] [25]. The assumption of a singular relationship between one signal and one analyte often breaks down in complex sample matrices.

Multivariate Calibration

Multivariate calibration constitutes a more sophisticated approach that models the relationship between multiple input variables (e.g., intensities at multiple wavelengths, responses from sensor arrays, or features from a single complex signal) and the analyte concentration or property of interest [23]. The core advantage is its ability to handle and model interferents explicitly, thereby enhancing selectivity and robustness.

Several key algorithms form the backbone of multivariate calibration in biosensing:

- Partial Least Squares (PLS): A widely used method that projects the predicted variables and the observable variables to a new space, maximizing the covariance between the sensor data and the analyte concentrations [23].

- Multiple Linear Regression (MLR): Used to model the linear relationship between two or more independent variables and a dependent variable by fitting a linear equation to the observed data [23].

- Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs): Powerful non-linear algorithms inspired by the human brain, capable of learning complex patterns in data. While highly effective for fitting data from a single sensor, they can be susceptible to deviations between different sensor units [24].

Comparative Analysis: Univariate vs. Multivariate Approaches

The following table summarizes the fundamental differences between the two calibration paradigms, highlighting the advantages of multivariate methods.

Table 1: Comparative analysis of univariate and multivariate calibration methodologies for biosensors.

| Feature | Univariate Calibration | Multivariate Calibration |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Models a single sensor response against a single analyte concentration [23]. | Models multiple sensor responses/variables against analyte concentration(s) [23] [24]. |

| Handling of Interferents | Poor; interferents can cause significant errors. | Excellent; can model and correct for known and unknown interferents. |

| Data Structure Used | A single data stream (e.g., current at one potential). | Multi-dimensional data (e.g., full spectrum, multi-sensor array data). |

| Complexity & Cost | Low complexity and computational cost. | Higher complexity and computational cost. |

| Robustness | Low; highly susceptible to environmental and matrix effects [24]. | High; more resilient to noise and variable conditions [23]. |

| Selectivity | Relies on the intrinsic specificity of the biorecognition element. | Enhanced selectivity is achieved mathematically through chemometrics [23]. |

| Best-Suited For | Simple matrices, well-understood systems, low-cost deployment. | Complex samples (serum, food, environmental), advanced diagnostics. |

Quantitative studies demonstrate the superiority of multivariate models. For example, in the calibration of low-cost particulate matter (PM) sensors, a univariate model using raw PM1 sensor output achieved an R² of approximately 0.81 against a reference instrument. This fitting quality was improved to R² ≈ 0.87 with a multivariate model that incorporated additional variables such as temperature and relative humidity [24]. Similarly, in a nitrate biosensor, multivariate calibration was essential to correct for heterogeneity in reagent deposition and variations in light sources, factors that would severely compromise a univariate model [23].

Experimental Protocol: Implementing Multivariate Calibration for a Paper-Based Nitrate Biosensor

The following detailed protocol is adapted from a study on a paper-based enzymatic biosensor for nitrate determination in food samples, which effectively combines digital image processing with multivariate calibration [23].

Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

Table 2: Essential reagents and materials for the paper-based nitrate biosensor experiment.

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| Nitrate Reductase | Biological recognition element; enzyme that selectively reduces nitrate to nitrite [23]. |

| Griess Reagent | Colorimetric agent; produces a red azo dye upon reaction with nitrite. Composition: 3-nitroaniline, 1-naphthylamine, HCl in DDW/ethanol [23]. |

| Whatman Filter Paper | Platform (substrate) for the paper-based biosensor [23]. |

| Sodium Nitrate Stock Solution | Source of nitrate ions for preparing standard solutions and calibration curves [23]. |

| Digital Image Capture System | System (e.g., smartphone with high-resolution camera) for capturing color change on the biosensor platform [23]. |

| MATLAB with PLS Toolbox | Software environment for digital image processing and multivariate calibration analysis [23]. |

Step-by-Step Workflow

Step 1: Biosensor Fabrication Cut rectangular pieces from Whatman filter paper to serve as the biosensor platform. Immerse these papers into the Griess reagent solution, ensuring complete impregnation. Allow the papers to dry at room temperature. Finally, micropipette a solution of nitrate reductase (10 U mL⁻¹) onto the surface of the prepared sensor [23].

Step 2: Sample Preparation and Data Acquisition

- Prepare a series of standard nitrate solutions covering the desired concentration range for calibration.

- For real samples (e.g., potato, onion), extract nitrate by stirring crushed samples in deionized water at 70°C for 10 minutes, followed by filtration [23].

- Drop a distinct volume (e.g., 100 µL) of each standard or sample solution onto the surface of the biosensor. The enzymatic reaction will produce a red color, the intensity of which is correlated with the nitrate concentration.

- Place the biosensor in a standardized image capture system. This system should include a fixed smartphone camera, a sample holder to ensure consistent positioning, and controlled LED lighting to provide uniform illumination [23].

- Capture an image of the biosensor surface before applying the sample to serve as a blank. Then, capture images of each biosensor after sample application.

Step 3: Digital Image Processing

- Transfer the captured images to a computer running MATLAB.

- In MATLAB, each image is represented as a 3D array (e.g., 2160 × 3840 × 3) corresponding to the intensity of red, green, and blue (RGB) colors.

- Subtract the blank image array from each sample image array to correct for background and unevenness.

- Extract the red color intensity matrix (size 2160 × 3840) from the corrected array, as this channel is most sensitive to the color change.

- Convert this 2D matrix into a one-dimensional vector (size 1 × 3840) and normalize it. This normalized vector serves as the multivariate input for the calibration algorithms [23].

Step 4: Multivariate Model Building and Optimization

- Split the dataset of normalized vectors and known concentrations into a training set (e.g., 70%) for model building and a validation set (e.g., 30%) for testing [23] [24].

- Use the training set to build calibration models using various algorithms such as PLS-1, continuum power regression (CPR), or multiple linear regression (MLR).

- Optimize the parameters for each model. For instance, for PLS, the critical parameter is the number of latent variables (LVs). This is typically done by minimizing the root mean squared error of cross-validation (RMSECV) [23].

- Validate the optimized models using the independent validation set by calculating figures of merit like the root mean square error of prediction (RMSEP) and the relative error of prediction (REP) [23].

The entire experimental and analytical workflow is summarized in the diagram below.

Data Presentation and Model Performance

The effectiveness of the multivariate calibration is evaluated by comparing the performance metrics of different algorithms. The following table presents a simplified representation of such a comparative analysis.

Table 3: Exemplary performance metrics of different multivariate calibration models for a nitrate biosensor. Model parameters are optimized for each algorithm [23].

| Calibration Algorithm | Key Parameters Optimized | R² (Validation) | RMSEP | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLS-1 | Number of Latent Variables (LVs) | ~0.84 | Value | Robust and widely applicable [23]. |

| CPR | LVs, Power Parameter (PP) | ~0.85 | Value | Adds flexibility with a power parameter [23]. |

| MLR | Number of LVs | ~0.82 | Value | Simple linear model, computationally efficient [23]. |

| Artificial Neural Network (ANN) | Network Architecture | ~0.90 (for single unit) | Value | Excellent for complex non-linear data [24]. |

Successful implementation of multivariate calibration requires both wet-lab reagents and dry-lab computational resources.

Table 4: Essential toolkit for developing multivariate-calibrated biosensors.

| Category | Item | Specific Function |

|---|---|---|

| Biological Reagents | Nitrate Reductase [23] | Enzyme for selective biorecognition of nitrate. |

| Antibodies [22] | Biorecognition element for immunosensors. | |

| Glucose Oxidase [22] | Model enzyme for glucose biosensors. | |

| Chemical Materials | Griess Reagent Components [23] | 3-nitroaniline, 1-naphthylamine for colorimetric detection. |

| Nanomaterials (e.g., COFs, Graphene) [26] [22] | Enhance transducer signal and immobilize bioreceptors. | |

| Signal Transduction | Smartphone/High-Res Camera [23] | Optical signal capture for colorimetric/fluorescent sensors. |

| Potentiostat | For applying potential and measuring current in electrochemical sensors. | |

| Software & Algorithms | MATLAB with PLS Toolbox [23] | Platform for image processing and multivariate algorithm implementation. |

| Python (Scikit-learn, TensorFlow) | Open-source platform for machine learning and chemometric analysis. | |

| Multivariate Algorithms | PLS, PCR, MLR [23] | Core linear multivariate calibration algorithms. |

| Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) [24] | For modeling highly complex, non-linear systems. |

The transition from univariate to multivariate calibration represents a fundamental and necessary evolution in biosensor science. While univariate methods offer simplicity, they are inherently limited when dealing with the complexities of real-world biological samples. Multivariate calibration, powered by advanced chemometrics, directly addresses these limitations by enhancing selectivity, robustness, and accuracy. The detailed protocol for the nitrate biosensor demonstrates a practical implementation of this paradigm shift, integrating digital image capture with multivariate modeling. As biosensors continue to evolve toward higher complexity, miniaturization, and deployment in challenging environments, multivariate calibration will remain an indispensable tool in the scientist's arsenal, ensuring that biosensor data is not just available, but also accurate and reliable.

Methodologies in Action: Implementing Chemometrics for Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Sensing

Designing Effective Biosensor Arrays and Bioelectronic Tongues

Biosensor arrays and bioelectronic tongues are advanced analytical systems that merge the principles of biosensing with multivariate data analysis. A bioelectronic tongue is defined as an analytical instrument comprising an array of non-specific, low-selective chemical sensors with high stability and cross-sensitivity to different species in solution, coupled with an appropriate method of pattern recognition and/or multivariate calibration for data processing [27]. These systems are fundamentally inspired by biological recognition, where arrays of non-specific sensors (like those in taste buds) gather information that is processed collectively to generate a distinct fingerprint for complex samples [27].

The core motivation for integrating chemometrics—the application of mathematical and statistical methods to chemical data—with biosensing is succinctly captured by the principle that "math is cheaper than physics" [10]. Instead of solely relying on increasingly sophisticated and expensive physical sensor design to achieve perfect selectivity, chemometric tools extract the required information from the complex, overlapping signals of simpler sensor arrays. This digital approach alleviates matrix effects, interference, signal drift, and non-linearity, thereby enhancing the effective selectivity and reliability of the biosensing system [10] [19]. This review details the design, operation, and practical application of these powerful tools within the context of enhancing biosensor selectivity through chemometrics.

Key Components and Working Principles

Sensor Array Architectures

The sensor array forms the hardware core of a bioelectronic tongue. Its design is critical for generating rich, multivariate data.

- Sensor Types and Transduction Principles: A wide variety of electrochemical sensors are commonly employed, including potentiometric, amperometric, voltammetric, and impedimetric sensors [27] [28]. Optical techniques, such as absorbance and luminescence, are also used [27]. The choice of transducer depends on the target analytes; for instance, voltammetry is suitable for redox-active species, while potentiometric sensors respond to charged molecules [27].

- Bioreceptor Integration: To form a true biosensor array, these transducers are integrated with biological or bio-mimetic recognition elements. Common bioreceptors include enzymes (e.g., galactose oxidase, urease), antibodies, aptamers, and whole cells or bioreporters [10] [29] [28]. For example, in a dairy analysis bioelectronic tongue, enzymes were covalently linked to a sensor surface to improve selectivity for compounds like lactose, urea, and lactic acid [28].

- Material Science and Nanomaterial Enhancement: The sensitivity and stability of sensors can be significantly improved by modifying them with nanomaterials. A prominent example is the incorporation of gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) into polymeric membrane matrices. Research has demonstrated that sensors with a higher percentage of AuNPs show markedly higher sensitivities towards target compounds in complex samples like milk [28].

Chemometric Data Processing Workflow

The signals from the sensor array are processed through a chemometric pipeline to translate raw data into meaningful analytical information. The following diagram illustrates the core workflow of a bioelectronic tongue, from sample introduction to result interpretation.

The process involves several key stages. First, the liquid sample is introduced to the sensor array, where each sensor generates a response based on its interaction with the sample's chemical components [27] [30]. These individual responses are collected to form a multivariate raw data vector for the sample [10]. The raw data then undergoes preprocessing, which may include normalization, filtering, and extraction of kinetic parameters to reduce noise and correct for baseline drift [27] [30]. Finally, the preprocessed data is analyzed using chemometric tools such as Principal Component Analysis (PCA) for sample classification and discrimination, or Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression and Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) for quantifying analyte concentrations or predicting sample properties [10] [28].

Performance Benchmarking of Representative Systems

The performance of bioelectronic tongues is demonstrated through their application in diverse fields. The table below summarizes the key performance metrics from recent research and commercial applications.

Table 1: Performance Benchmarking of Bioelectronic Tongue Systems

| Application Field | System Description | Key Performance Metrics | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dairy Analysis | Potentiometric array with AuNPs and enzymes (Lactose, urea, lactic acid) | PCA classification of milk by fat content; PLS prediction of acidity (R²P=0.85), proteins (R²P=0.84), lactose (R²P=0.88) | [28] |

| Wastewater Toxicity Assessment (TOXLAB) | Array of 8 bioreporter cells | Correlation with urban WWTP microbiome effects; Lack of correlation (r²=0.033) with industrial site microbiome, highlighting need for site-specific biosensors | [29] |

| Wastewater Quality Monitoring | Amperometric array of 8 enzyme-modified Pt sensors | Successful discrimination of 5 water quality types (untreated, alarm, alert, normal, pure) using PCA | [10] |

| Industrial Wastewater BOD Assessment | Biosensor array | PLS-predicted BOD values differed from reference BOD₇ by <5.6% | [10] |

| Umami Substance Detection | Electrochemical / Bioelectronic Tongue | Presented as a viable alternative to traditional methods due to specificity, sensitivity, and rapid analysis | [31] |

| Commercial System (ASTREE II) | 7 ISFET sensors | Applied in quality control, food recognition, taste assessment, and pharmaceutical industry | [27] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Development of a Potentiometric Bioelectronic Tongue for Milk Analysis

This protocol is adapted from a study that developed a gold nanoparticle-modified bioelectronic tongue for the discrimination and prediction of parameters in milk [28].

1. Sensor Fabrication

- Supports Preparation: Prepare solid conducting supports using silver-epoxy. Allow to cure according to the manufacturer's instructions.

- Polymeric Membrane Formulation: For each sensor in the array, prepare a unique polymeric membrane. A typical composition includes:

- Poly(vinyl chloride) (PVC) as the base polymer.

- A plasticizer (e.g., bis(1-butylpentyl) adipate, tris(2-ethylhexyl)phosphate, or 2-nitrophenyl-octylether).

- An additive (e.g., oleyl alcohol).

- Gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) at varying percentages (e.g., 0%, 0.5%, 1.0% w/w) to enhance sensitivity.

- Membrane Casting: Dissolve the membrane components in tetrahydrofuran (THF). Drop-cast the resulting solution onto the silver-epoxy supports and allow the THF to evaporate slowly, forming a uniform membrane.

- Biosensor Functionalization (Optional): To create specific biosensors, covalently immobilize enzymes (e.g., galactose oxidase, urease, lactate dehydrogenase) onto the surface of selected PVC/AuNP membranes using standard cross-linking protocols.

2. Electronic Tongue Assembly and Data Acquisition

- Array Construction: Integrate the fabricated sensors (e.g., 9-27 sensors) into an array alongside an Ag/AgCl reference electrode.

- System Connection: Connect the sensor array to a high-impedance data acquisition system or multiplexer.

- Sample Preparation: Obtain commercial milk samples with varying nutritional content (e.g., whole, semi-skimmed, skimmed). Dilute samples in a defined buffer if necessary.

- Signal Measurement: Immerse the sensor array and reference electrode in each milk sample. Record the potentiometric response (mV) of each sensor until a stable signal is achieved. Rinse the sensors thoroughly with a background electrolyte solution between measurements to prevent carry-over.

3. Data Processing and Model Building

- Data Preprocessing: Compile the stable potentiometric signals from all sensors for each sample into a data matrix. Mean-center or autoscale the data if necessary.

- Exploratory Analysis (PCA): Input the data matrix into a PCA algorithm. Examine the resulting score plot (typically PC1 vs. PC2) to visualize the natural clustering of the different milk types based on their nutritional content.

- Quantitative Model (PLS): If reference data for chemical parameters (e.g., fat, lactose, protein content) is available, use PLS regression to build a quantitative model. Correlate the sensor response matrix (X-block) with the reference chemical data (Y-block). Validate the model using cross-validation or an independent test set.

Protocol: Application of a Bioelectronic Tongue for Toxicity Assessment in Wastewater

This protocol is based on a 2025 study that designed a bioelectronic tongue (TOXLAB) to estimate the toxicological intensity of pollutants in wastewater treatment plants [29].

1. Selection and Preparation of Bioreporters

- Strain Selection: Select a panel of microbial bioreporter strains (e.g., 8 strains) that are representative of, and sensitive to, the stressors expected in the target environment. The selection is crucial and may require specific sets for different industrial sites.

- Cell Cultivation: Culture each bioreporter strain to the mid-logarithmic growth phase under optimal conditions.

- Sample Exposure: In a microtiter plate, expose each bioreporter to a series of wastewater samples. Include appropriate controls (e.g., negative control with no toxicant, positive control with a known toxicant).

2. Signal Acquisition and Data Compilation

- Response Measurement: Monitor the physiological response of the bioreporters. This could be:

- Inhibition of metabolic activity measured by a colorimetric assay like MTT or Alamar Blue.

- Expression of a reporter gene (e.g., bioluminescence, fluorescence) if genetically modified strains are used.

- Other viability indicators.

- Data Matrix Formation: For each sample, compile the response data from all bioreporters into a multivariate data vector.

3. Data Analysis and Toxicity Index Calculation

- Algorithm Processing: Feed the multivariate response data into a custom algorithm or a multivariate calibration model (e.g., PLS) designed to generate a composite Toxicological Intensity value.

- Validation: Compare the TOXLAB results with those from standard toxicity tests (e.g., tests based on marine bioluminescent bacteria) and, importantly, with the effects observed on the autochthonous microbial community from the specific wastewater treatment plant.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table lists key materials and reagents essential for the development and operation of bioelectronic tongues, as derived from the cited protocols and applications.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Bioelectronic Tongue Development

| Item Name | Function / Application | Specific Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | Nanomaterial enhancer to increase sensor sensitivity. | Incorporated into PVC membranes at 0.5-1.0% w/w; shown to significantly boost signal response [28]. |

| Poly(vinyl chloride) (PVC) | Base polymer for forming the ion-selective membrane matrix. | Combined with plasticizers and additives to create the sensing layer [28]. |

| Plasticizers | Provides mobility for ion exchange within the polymer membrane and determines permselectivity. | Bis(1-butylpentyl) adipate, tris(2-ethylhexyl)phosphate, 2-nitrophenyl-octylether [28]. |

| Enzymes | Biorecognition elements that confer selectivity to specific substrates. | Galactose oxidase (for galactose), urease (for urea), lactate dehydrogenase (for lactic acid) [28]. |

| Bioreporter Cells | Living microbial sensors used to assess overall toxicity or metabolic impact. | A panel of 8 different bioreporters used to create a holistic toxicity profile of wastewater [29]. |

| Chemometric Software | Software platform for multivariate data analysis and model building. | Used for executing PCA, PLS, ANN, and other pattern recognition techniques [10] [27]. |

Visualizing the Chemometric Enhancement of Selectivity

The fundamental challenge that chemometrics addresses is the non-ideal, overlapping responses of individual sensors in an array. The following diagram illustrates how multivariate analysis transforms these cross-sensitive signals into a selective and informative output.

The process begins when a complex sample containing multiple analytes and potential interferents interacts with the sensor array. Each sensor in the array is cross-sensitive, meaning it responds to several components in the sample, but with varying degrees of affinity [10] [27]. The collective, overlapping responses from all sensors form a unique multivariate data pattern, which serves as a "fingerprint" for that specific sample or analyte concentration profile [27]. This composite fingerprint is then processed by a chemometric model (such as PLS or ANN). The model is trained to recognize the underlying correlation patterns between the complex input signal and the desired output (e.g., analyte concentration), effectively filtering out noise and interference to produce a selective and accurate result [10] [19].

Voltammetric Techniques (DPV, SWV) and Data-Rich Fingerprinting for Complex Samples

The accurate analysis of complex biological and environmental samples represents a significant challenge in analytical chemistry. Traditional methods that rely on highly specific sensor elements for individual targets can be constrained by cost, complexity, and a lack of prior knowledge about all relevant analytes. Voltammetric techniques, particularly Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) and Square-Wave Voltammetry (SWV), have emerged as powerful tools that generate rich, multidimensional electrochemical data ideal for profiling complex mixtures. When these data-rich fingerprinting approaches are combined with chemometric analysis, they create a robust framework for enhancing biosensor selectivity and performing hypothesis-free sample classification. This application note details the protocols and methodologies for leveraging DPV and SWV to generate electrochemical fingerprints and analyzes how these data can be processed to extract meaningful information for research and drug development.

Pulse voltammetric techniques like DPV and SWV were developed to minimize non-Faradaic (charging) currents and maximize the Faradaic current related to redox reactions, thereby significantly improving analytical sensitivity [32] [33]. The table below compares the core parameters of these two techniques.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of DPV and SWV

| Parameter | Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) | Square-Wave Voltammetry (SWV) |

|---|---|---|

| Waveform | Series of small-amplitude pulses superimposed on a linear staircase base potential [34] | Combined square wave and staircase potential [35] |

| Current Sampling | Measured twice per pulse (before and after the pulse); the difference is plotted [33] [34] | Measured at the end of each forward and reverse potential pulse; the difference (net current) is often plotted [32] [33] |

| Key Strengths | Excellent peak resolution for closely spaced signals; high analytical sensitivity; reduced capacitive current [36] [34] | Very fast scan speeds; exceptional sensitivity; provides kinetic and mechanistic insights [33] [37] |

| Typical Applications | Trace metal analysis [34], detection of organic molecules in complex matrices [38] | Analysis in complex media like blood serum [37], conformation switching sensors [32] |

Fundamental Principles and Waveforms

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and key differentiators of the DPV and SWV techniques.

Diagram 1: Workflow comparison of DPV and SWV techniques.

Experimental Protocols

This section provides detailed methodologies for implementing DPV and SWV to generate high-quality, reproducible electrochemical fingerprints from complex samples.

Protocol 1: DPV for Fingerprinting Medicinal Plant Extracts

This protocol is adapted from a study that successfully identified closely related species of Anoectochilus roxburghii using DPV fingerprints and machine learning [38].

Research Reagent Solutions Table 2: Essential Materials for DPV-based Fingerprinting

| Item | Function/Description | Example/Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Working Electrode | Platform for electron transfer and signal generation. | Bare Glassy Carbon Electrode (GCE) [38] |

| Reference Electrode | Provides a stable, known reference potential. | Ag/AgCl (3 M KCl) [38] [37] |

| Counter Electrode | Completes the electrical circuit in the cell. | Graphite rod or platinum wire [38] [37] |

| Buffer Solutions | Provide a conductive, pH-controlled electrolyte medium. | Phosphate Buffer Saline (PBS, pH 7.0) and Acetic Acid Buffer Solution (ABS, pH 4.5) [38] |

| Sample Material | Source of electroactive compounds for fingerprinting. | Dried and powdered plant material (e.g., Anoectochilus roxburghii) [38] |

| Solvent | Medium for compound extraction from the sample. | Absolute Ethanol or other suitable solvent [38] |

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Electrode Preparation: Polish the bare glassy carbon working electrode with an alumina (Al₂O₃) slurry on a microcloth pad. Rinse thoroughly with purified water and dry in air [38] [37].

- Sample Preparation: Extract the powdered plant sample (e.g., 0.5 g) with an appropriate solvent (e.g., 10 mL of ethanol) using sonication for 30 minutes. Centrifuge the mixture and collect the supernatant for analysis [38].

- Instrument Setup: Transfer 10 mL of the supporting electrolyte (e.g., PBS or ABS) into the electrochemical cell. Insert the three-electrode system. Decorate the solution with nitrogen or argon for 10 minutes to remove dissolved oxygen.

- DPV Parameter Optimization: Set the DPV parameters on the potentiostat. Typical initial settings are [36] [34]:

- Pulse Amplitude: 10-50 mV

- Pulse Duration: 50-100 ms

- Step Potential: 2-10 mV

- Scan Rate: Determined by step potential and duration (e.g., 10-50 mV/s)

- Background Measurement: Run a DPV scan in the pure supporting electrolyte over the desired potential window (e.g., 0.0 V to +0.8 V vs. Ag/AgCl) to record a background voltammogram.

- Sample Measurement: Add a known volume of the plant extract (e.g., 50-100 µL) to the cell. Stir and decorate briefly. Run the DPV scan under the same parameters as the background measurement.

- Data Collection: Record the DPV voltammogram. Repeat measurements in multiple buffer solutions to enrich the fingerprint data [38]. The final signal used for analysis is the sample voltammogram, often with the background subtracted.

Protocol 2: SWV for Direct Analysis of Blood Serum Biomarkers

This protocol is based on a study that directly detected uric acid, bilirubin, and albumin in human blood serum using SWV without any sample pre-treatment or electrode modification [37].

Research Reagent Solutions Table 3: Essential Materials for SWV-based Serum Analysis

| Item | Function/Description | Example/Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Working Electrode | Electrocatalytic surface for competitive adsorption of biomolecules. | Edge-plane Pyrolytic Graphite Electrode (EPGE) [37] |

| Reference Electrode | Provides a stable, known reference potential. | Ag/AgCl (3 M KCl) [37] |

| Counter Electrode | Completes the electrical circuit in the cell. | Graphite rod [37] |

| Buffer Solution | Dilution medium and supporting electrolyte. | 0.1 M Phosphate Buffer (pH 7.34) [37] |

| Human Blood Serum | The complex sample matrix for analysis. | Stored at -5 °C after separation from whole blood [37] |

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Electrode Preparation: Clean the EPGE by gently rubbing the surface on abrasive paper followed by alumina slurry. Rinse thoroughly with purified water in an ultrasonic bath and air-dry [37].

- Sample Preparation: Dilute the human blood serum sample in a 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.34). A typical dilution factor is 1:10 (e.g., 100 µL serum in 900 µL buffer) [37].

- Instrument Setup: Place the diluted serum sample into the electrochemical cell. Insert the three-electrode system (EPGE as WE). Decoration is often not required for this specific application [37].

- SWV Parameter Optimization: Set the SWV parameters. The high speed and differential nature of SWV are crucial for resolving signals in complex media [37]. Key parameters include:

- Frequency: 10-50 Hz

- Amplitude: 10-50 mV

- Step Potential: 1-5 mV

- Voltammetric Scanning: Run the SWV scan over the optimal potential window. For serum analysis, a window from -0.4 V to +0.9 V vs. Ag/AgCl can reveal well-defined peaks for uric acid, bilirubin, and albumin in a single experiment [37].

- Data Collection: Record the net SWV voltammogram, which shows separated and intense peaks corresponding to different electroactive serum components.

Data Analysis and Chemometric Integration

The voltammetric fingerprints generated by DPV or SWV are multivariate data sets, where current is a function of applied potential. Analyzing these rich data requires chemometric tools to move from simple fingerprinting to reliable classification and identification.

From Fingerprints to Classification: A Machine Learning Workflow

The process of transforming raw electrochemical data into a validated classification model follows a structured pipeline, as illustrated below.

Diagram 2: Chemometric workflow for electrochemical fingerprint classification.

Key Chemometric Techniques

- Dimensionality Reduction: Techniques like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) are used to visualize sample clustering and identify the most significant patterns in the data by reducing the number of variables while preserving variance [39].

- Supervised Classification: Methods such as Partial Least Squares-Discriminant Analysis (PLS-DA) and Support Vector Machines (SVM) are employed to build predictive models. For instance, a nonlinear SVM model achieved a 94.4% accuracy in identifying closely related medicinal plant species based on the slopes of their DPV responses in different buffers [38].

- Advantage of Multidimensionality: The power of this approach lies in leveraging the cross-reactivity of sensor elements. Unlike a specific sensor that binds a single target, a few cross-reactive sensors can generate a unique fingerprint pattern ("chemical nose/tongue") that discriminates between many more analytes or sample types than there are sensing elements [40]. This allows for hypothesis-free analysis of samples where all relevant biomarkers may not be known.

Application in Biosensor Selectivity Enhancement

Within the context of a thesis on chemometrics for biosensor selectivity, DPV and SWV fingerprinting offer a powerful alternative or complement to traditional specific sensing.

The paradigm shifts from engineering perfect specificity for a single analyte to intentionally collecting a cross-reactive response and deconvoluting it computationally. This is particularly advantageous for:

- Conformation-Sensing Biosensors: Techniques like continuous Square-Wave Voltammetry (cSWV) can dynamically monitor aptamer conformation changes, providing a multitude of voltammograms from a single sweep and enabling rapid sensor calibration [32].

- Complex Disease Diagnosis: Where diseases are characterized by fluctuations in multiple biomarkers, a fingerprinting approach can detect the overall pattern without requiring specific sensors for every individual marker [40] [37].

- System-Level Analysis: This methodology aligns with the goal of moving from single-analyte detection to a more holistic, systems-level understanding of complex samples, effectively using chemometrics to "encode" selectivity in software rather than solely in the hardware of the sensor [40] [38].