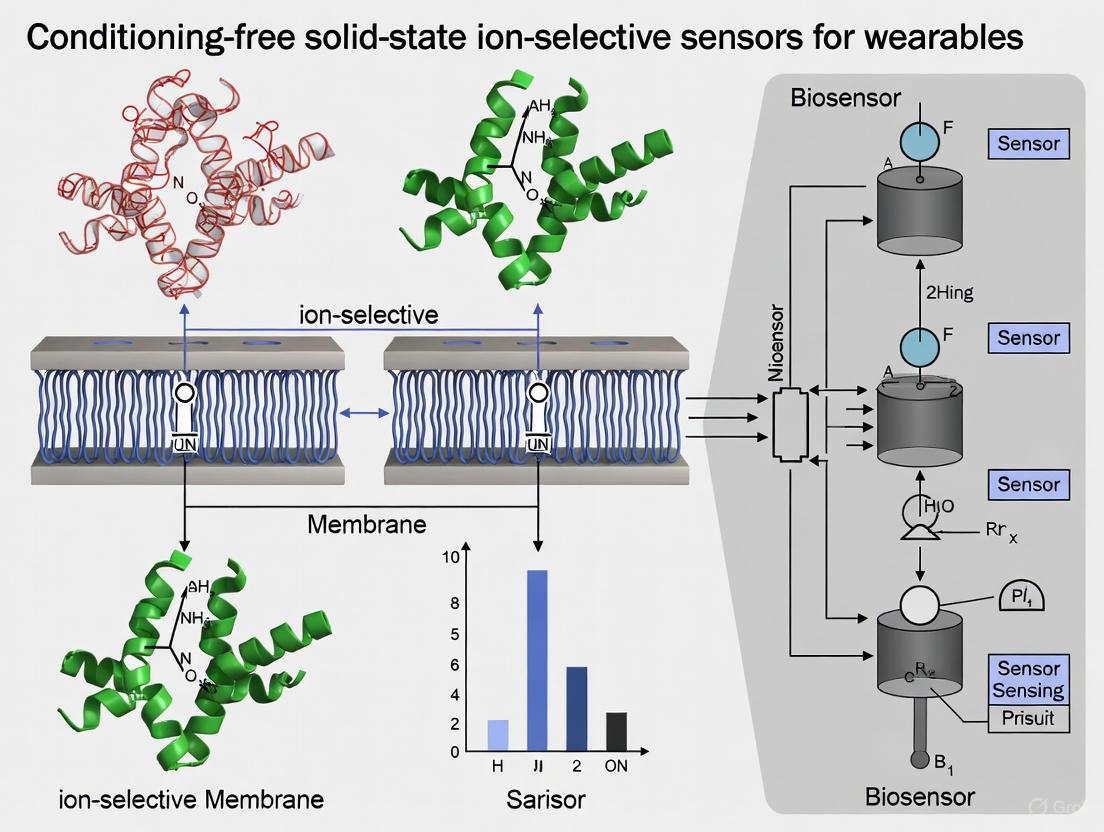

Conditioning-Free Solid-State Ion-Selective Sensors: The Future of Wearable Health Monitoring

This article explores the groundbreaking field of conditioning-free solid-state ion-selective electrodes (SC-ISEs) for wearable sensors.

Conditioning-Free Solid-State Ion-Selective Sensors: The Future of Wearable Health Monitoring

Abstract

This article explores the groundbreaking field of conditioning-free solid-state ion-selective electrodes (SC-ISEs) for wearable sensors. It covers the foundational principles driving the shift from traditional liquid-contact and conditioned solid-state sensors to advanced, ready-to-use platforms. The content details the latest methodologies in materials science, sensor fabrication, and integration with wearable systems for real-time monitoring of biomarkers in biofluids like sweat. It provides a critical analysis of persistent challenges—such as signal stability and reproducibility—and the innovative strategies being developed to overcome them. Through a comparative evaluation of sensor architectures and their validation in clinical scenarios, this review underscores the transformative potential of these sensors in enabling personalized medicine, therapeutic drug monitoring, and decentralized healthcare, ultimately aiming to make robust, lab-quality health diagnostics accessible anytime, anywhere.

The Paradigm Shift to Conditioning-Free Solid-State Sensors

Core Concepts and Advantages of SC-ISEs

What is a Solid-Contact Ion-Selective Electrode (SC-ISE)?

A Solid-Contact Ion-Selective Electrode (SC-ISE) is a potentiometric sensor that converts the activity of a specific ion in solution into an electrical potential, without using an internal liquid filling solution [1] [2]. Its core structure consists of a conductive substrate, a solid-contact (SC) layer that acts as an ion-to-electron transducer, and an ion-selective membrane (ISM) [2]. This all-solid-state design overcomes the key limitations of traditional liquid-contact ISEs (LC-ISEs), enabling significant advancements in miniaturization, stability, and integration into wearable devices [3] [1].

What are the primary advantages of SC-ISEs for wearable sensor research?

SC-ISEs offer several critical advantages that make them particularly suitable for wearable applications and conditioning-free operation:

- Easy Miniaturization and Chip Integration: The removal of the internal liquid solution allows for a simpler, more compact design that can be fabricated on a micro-scale and integrated into chips [2].

- Enhanced Physical Stability: Without an internal solution, the sensor is immune to issues like evaporation, permeation, and changes in osmotic pressure or orientation, which can cause drift in LC-ISEs [2].

- Potential for Rapid Conditioning and Long-Term Stability: Advanced solid-contact materials can be engineered to minimize water and ion fluxes, which is a key principle behind achieving sensors that require very short conditioning times and exhibit stable potentials over long durations [3]. Research has demonstrated prototypes with conditioning times as short as 30 minutes and high stability during continuous operation [3].

Table 1: Comparison of Liquid-Contact and Solid-Contact ISEs

| Feature | Liquid-Contact ISE (LC-ISE) | Solid-Contact ISE (SC-ISE) |

|---|---|---|

| Internal Structure | Contains an internal filling solution [4] [1] | No internal solution; uses a solid-contact layer [1] [2] |

| Miniaturization | Difficult to miniaturize [2] | Excellent for miniaturization and chip integration [2] |

| Stability | Sensitive to temperature, pressure, and osmotic changes [2] | Robust, stable in various environments [2] |

| Conditioning | Often requires long conditioning times (e.g., 16-24 hours) [5] | Potential for rapid conditioning with advanced materials [3] |

| Wearability | Cumbersome and impractical [1] | Ideal for flexible, wearable form factors [3] [1] |

Troubleshooting Common SC-ISE Experimental Challenges

Why does my SC-ISE show a slow response or signal drift?

Signal drift and slow response are among the most common challenges when developing SC-ISEs. The causes and solutions are often linked to the solid-contact layer and membrane.

Table 2: Troubleshooting Slow Response and Signal Drift

| Problem | Potential Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Slow Response Time | - Poor ion mobility in the membrane- Membrane thickness is excessive- Suboptimal conditioning | - Optimize plasticizer content in the ISM to improve ion mobility [2]- Tailor the thickness of the ion-selective membrane [3] |

| Signal Drift (Continuous potential change) | - Formation of a water layer between the SC and ISM [1]- Unstable redox capacitance in the SC layer- Swelling of the conducting polymer | - Use hydrophobic SC materials (e.g., PEDOT:TFPB) to hinder water and ion fluxes [3]- Ensure the SC layer has high capacitance and is chemically stable [1] |

| Poor Reproducibility | - Variations in SC layer deposition- Inconsistent ISM composition or thickness | - Standardize fabrication protocols for the SC and ISM layers [2]- Use high-purity materials and controlled environmental conditions during manufacturing |

How do I achieve a low detection limit and good selectivity with my SC-ISE?

Achieving a low detection limit and high selectivity is crucial for analyzing complex biological fluids like sweat.

Problem: High Detection Limit

Problem: Poor Selectivity (Interference from other ions)

- Cause: The ion-selective membrane is not perfectly specific and can respond to ions with similar properties [4] [7].

- Solution:

- Selective Ionophore: Use a high-quality, hydrophobic ionophore with a strong binding preference for your target ion [2].

- Ion Exchanger: Incorporate an appropriate lipophilic ion exchanger (e.g., NaTFPB, KTFPB) to enforce the Donnan exclusion effect, which helps repel interfering ions of the same charge [2].

- Matrix Matching: For calibration, use standards that closely mirror the ionic background of your sample to account for activity effects [5].

What are the best practices for storing SC-ISEs to maximize their lifetime?

Proper storage is critical for maintaining sensor performance and longevity.

- Short-Term Storage (between measurements): For polymer-based SC-ISEs, dry storage is typically recommended. Always refer to the manufacturer's specific instructions [7].

- Long-Term Storage: Store the sensors dry, with a protective cap on, to prevent physical damage and contamination of the sensing membrane [7].

- General Tip: The lifetime of a polymer membrane electrode is generally limited (e.g., about half a year) due to membrane aging, while crystalline membrane electrodes can last for several years [7].

Experimental Protocols for SC-ISE Development

What is a standard fabrication workflow for a SC-ISE?

The following diagram illustrates a generalized protocol for fabricating a solid-contact ion-selective electrode.

How do the response mechanisms in SC-ISEs work?

The solid-contact layer facilitates the conversion of an ionic signal in the membrane to an electronic signal in the conductor. This "ion-to-electron transduction" occurs primarily through two mechanisms.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for SC-ISE Research and Their Functions

| Material Category | Example Components | Function in SC-ISE |

|---|---|---|

| Solid-Contact Materials | PEDOT:TFPB [3], Polypyrrole (PPy) [1], Graphene, Carbon Nanotubes [1] [2] | Acts as an ion-to-electron transducer; critical for potential stability and preventing water layer formation. |

| Ion-Selective Membrane Components | Polymer Matrix: PVC, Polyurethane, Acrylic esters [2]Plasticizer: DOS, DOP, NOPE [2]Ionophore: Valinomycin (for K+) [4] [6]Ion Exchanger: NaTFPB, KTPCIPB [2] | The sensing element. The ionophore provides selectivity, while the polymer matrix and plasticizer give the membrane its physical and mechanical properties. |

| Conductive Substrates | Glassy Carbon, Gold, Screen-Printed Electrodes (SPE), FTO [1] [2] | Provides the electronic conduction base for building the SC-ISE. |

| Target Ions for Wearables | K⁺, Na⁺, Ca²⁺, NH₄⁺, Cl⁻, pH (H⁺) [7] | Key electrolytes and biomarkers detectable in biological fluids (e.g., sweat) using SC-ISEs. |

If you've ever worked with traditional Ion-Selective Electrodes (ISEs), you've undoubtedly encountered the mandatory, often lengthy, conditioning step before use. This pre-treatment is not merely a recommendation but a critical requirement for achieving stable and accurate measurements. Conditioning prepares the electrode's organic sensing membrane by allowing it to reach a state of equilibrium with an aqueous solution, a process fundamental to the electrode's function [5]. This guide explores the science behind this requirement, details the protocols for proper conditioning, and contrasts these traditional methods with the emerging generation of conditioning-free solid-state sensors designed for wearable applications.

The Science Behind Conditioning: A Technical Deep Dive

Establishing Electrochemical Equilibrium

The core function of an ISE is to measure the electrical potential that develops across a selective membrane when it contacts a solution containing target ions. This potential, described by the Nernst equation, is only reproducible and stable when the membrane is in a state of electrochemical equilibrium [8].

- For PVC (organic membrane) ISEs: The active sensing element is a plasticized PVC matrix containing a specialized ion-sensitive ligand (ionophore). This organic system must be soaked in an aqueous solution—typically a calibrating solution—for a significant period (recommended 16-24 hours) to establish this equilibrium fully [5].

- The Role of Water Layers: A primary challenge with traditional solid-contact ISEs is the formation of an undesired water layer between the ion-selective membrane (ISM) and the underlying solid-contact transducer. This water layer is a major source of potential drift and long-term instability, as it creates a secondary, poorly defined electrochemical environment [9]. Conditioning helps to stabilize this interface, though it does not eliminate the problem.

Consequences of Inadequate Conditioning

Skipping or shortening the conditioning step leads directly to performance issues:

- Drifting Readings: The electrode potential will not stabilize, making it impossible to obtain a steady, reliable measurement.

- Reduced Accuracy and Precision: The relationship between the measured potential and the logarithm of the ion activity (the Nernstian slope) will be sub-optimal, leading to inaccurate concentration calculations.

- Increased Response Time: The electrode will take longer to respond to changes in ion concentration.

Standard Conditioning and Calibration Protocols

Following a rigorous procedure is key to obtaining reliable data with traditional ISEs.

Step-by-Step Conditioning and Calibration Guide

The table below outlines a typical conditioning and calibration workflow for a traditional ISE, such as a calcium ISE [10].

| Step | Procedure | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Conditioning | Soak the ISE in the High Standard solution for 30 minutes to 24 hours. | Do not let the ISE rest on the container's bottom. Ensure reference contacts are immersed and no air bubbles are trapped [10]. |

| 2. Calibration Setup | Connect the sensor to the analyzer and initiate a two-point calibration. | Use fresh standard solutions that bracket your expected sample concentration, ideally not more than one decade apart [5]. |

| 3. First Point (High Standard) | Place the ISE in the High Standard, enter its concentration value, and wait for stability. | Keep the ISE still during measurement. Stirring can be used if sample measurements will be performed under stirring conditions [10]. |

| 4. Rinse | Remove the ISE from the High Standard, rinse thoroughly with distilled water, and gently blot dry. | Avoid rinsing with D.I. water between standards, as this dilutes the solution on the sensor surface and increases response time [5]. |

| 5. Second Point (Low Standard) | Place the ISE in the Low Standard, enter its concentration value, and wait for stability. | Validate the sensor's sensitivity (slope). A slope of 26 ± 2 mV/decade at 25°C is typical for a calcium ISE [10]. |

This workflow can be visualized as the following process:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for ISE Experiments

| Research Reagent | Function |

|---|---|

| Ion-Selective Electrode (ISE) | The core sensor with a membrane selective for a specific ion (e.g., Ca²⁺, Na⁺, K⁺) [8]. |

| High & Low Standard Solutions | Calibration solutions of known concentration used to establish the electrode's calibration curve [10]. |

| Ion Selective Membrane (ISM) | The polymer membrane (e.g., PVC-SEBS blend) containing ionophore that provides selectivity [9]. |

| Internal Reference Electrode | The stable internal reference system (e.g., Ag/AgCl) against which the membrane potential is measured [8]. |

| Carrier Ampholytes | In IEF, these create the pH gradient; in ISE context, analogous to ionic additives for membrane function. |

Troubleshooting Common Conditioning-Related Issues

Problem: Drifting or Unstable Readings During Calibration

- Cause: Inadequate conditioning time or formation of an unstable water layer [5] [9].

- Solution: Ensure the ISE has been conditioned for the full recommended duration. For persistent drift, verify the integrity of the membrane and reference electrode.

Problem: Slow Electrode Response Time

- Cause: The membrane has not fully hydrated or reached equilibrium. Rinsing with distilled water between standards can also slow response [5].

- Solution: Complete the full conditioning protocol. When moving between standard solutions, gently blot the electrode instead of extensively rinsing with water.

Problem: Calibration Slope is Outside Expected Range

- Cause: The ion-selective membrane may be degraded, contaminated, was conditioned improperly, or has reached the end of its lifespan.

- Solution: Re-condition the electrode. If the problem persists, replace the standard solutions and, if necessary, the electrode itself.

The Future: Conditioning-Free Solid-State ISEs for Wearables

The demanding pre-treatment of traditional ISEs is a major barrier for applications in point-of-care diagnostics and continuous monitoring, such as in wearable sweat sensors. Recent research is squarely focused on overcoming this limitation through innovative materials science.

New solid-contact ISEs (SC-ISEs) are being engineered to eliminate the need for conditioning by design. Key strategies include:

- Enhanced Hydrophobicity: Using highly hydrophobic materials like MXene/PVDF nanofiber mats and SEBS block copolymers in the membrane to prevent the formation of the troublesome water layer, which is a root cause of drift and the need for conditioning [9].

- Stable Solid-Contact Transducers: Employing advanced materials like laser-induced graphene (LIG) decorated with TiO₂ nanoparticles. This creates a robust, porous 3D electrode architecture with high electrical conductivity and excellent interfacial stability, reducing potential drift to ultra-low levels (e.g., < 0.04 mV/h for Na⁺) without pre-conditioning [9].

The logical progression from traditional to next-generation sensors is summarized below:

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Can I use my ISE without conditioning if I'm short on time? No. Using an ISE without proper conditioning will result in unreliable, drifting data and poor accuracy. The electrode membrane will not be in electrochemical equilibrium with the solution [5].

Q2: What is the real chemical reason conditioning is necessary? Conditioning allows the organic ion-selective membrane (a plasticized PVC matrix containing an ionophore) to become properly hydrated and pre-equilibrated with ions. This establishes a stable baseline potential across the membrane, which is essential for the Nernstian response [5].

Q3: How do new wearable sensors avoid this conditioning step? They use fundamentally different material designs. Advanced solid-contact ISEs incorporate highly hydrophobic membranes (e.g., with SEBS copolymer) and stable 3D transducer materials (e.g., laser-induced graphene) that inherently suppress water layer formation and potential drift, making extended pre-treatment unnecessary [9].

Q4: My calibrated ISE worked yesterday but is inaccurate today. Why? This is a classic symptom of a traditional ISE. The membrane may have dehydrated or the internal equilibrium may have shifted. Standard procedure is to re-condition the electrode by soaking it in a standard solution for at least 30 minutes before recalibrating [5] [10].

In solid-contact ion-selective electrodes (SC-ISEs), the solid-contact (SC) layer serves as the critical interface responsible for converting an ionic signal from the ion-selective membrane (ISM) into an electronic signal readable by the conductive substrate. This process, known as ion-to-electron transduction, is the fundamental core mechanism that enables the functioning of all-solid-state potentiometric sensors. Replacing the traditional internal filling solution with a solid-contact layer has paved the way for the miniaturization, integration, and development of robust sensors suitable for wearable applications [11]. The performance, stability, and reliability of SC-ISEs are predominantly determined by the efficacy of this transduction mechanism [12].

Two primary transduction mechanisms have been established, defined by the type of capacitance at the SC layer interface: redox capacitance and electric double-layer (EDL) capacitance [11]. The choice of transducer material directly influences which mechanism dominates and consequently determines key sensor characteristics such as potential drift, reproducibility, and long-term stability.

Transduction Mechanisms and Material Selection

Redox Capacitance-Type Transduction

This mechanism relies on conductive polymers (CPs) that undergo reversible redox reactions to facilitate charge transfer. These materials possess both electronic and ionic conductivity, often achieved through doping.

- Mechanism: When a potential is applied, the conducting polymer is oxidized or reduced. To maintain electroneutrality, ions from the ion-selective membrane are incorporated into or expelled from the polymer matrix. This reversible redox reaction provides a high redox capacitance that stabilizes the potential at the interface [11].

- Key Reaction:

- Exemplary Material: Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) (PEDOT) and its derivatives (e.g., PEDOT:TFPB) are considered template materials for this category [12] [3]. Their superhydrophobic nature can also hinder water and ion fluxes, improving stability and reducing conditioning time [3].

Electric Double-Layer (EDL) Capacitance-Type Transduction

This mechanism is characteristic of capacitive materials, primarily carbon-based nanomaterials, that do not undergo faradaic reactions. Instead, they operate through electrostatic attraction.

- Mechanism: A physical separation of charge occurs at the interface between the ISM and the SC layer. Ions from the ISM accumulate on one side of the interface, while charges of the opposite polarity (electrons or holes) accumulate in the solid-contact material. This creates a capacitor-like electric double-layer [12] [11].

- Key Feature: The transduction is non-faradaic, meaning no electrons are transferred across the interface. The capacitance is proportional to the effective surface area of the transducer material [12].

- Exemplary Materials: Multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs), graphene, and reduced graphene oxide (rGO). These nanostructured materials provide a large surface area, which significantly enhances the double-layer capacitance [12] [13].

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship and working principles of these two core transduction mechanisms.

Performance Comparison of Transducer Materials

The choice of transducer material directly impacts the electrochemical properties and analytical performance of the SC-ISE. The table below summarizes quantitative data for key transducer materials, as reported in recent studies.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Different Ion-to-Electron Transducer Materials

| Transducer Material | Slope (mV/decade) | Detection Limit (mol/L) | Capacitance (µF) | Potential Drift (µV/s) | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MWCNTs [12] | 56.1 ± 0.8 | 3.8 × 10⁻⁶ | Not Specified | 34.6 | Best electrochemical behavior in its study, low potential drift, excellent selectivity. |

| Graphene [13] | 61.9 ± 1.2 | ~3.2 × 10⁻⁶ | 383.4 ± 36.0 | 2.6 ± 0.3 | Highest capacitance, lowest drift, highest electroactive and hydrophobic surface. |

| PEDOT (e.g., PEDOT:PSS) [11] | Near-Nernstian | Varies with formulation | High (Redox) | Varies | High redox capacitance, stable potential, common benchmark material. |

| Polyaniline (PANi) [12] | Data not specified | Data not specified | Data not specified | Data not specified | Conducting polymer with redox capacitance; performance highly dependent on doping. |

| Ferrocene [12] | Data not specified | Data not specified | Data not specified | Data not specified | High redox capacitance; can suffer from leaching over time. |

Table 2: Electrochemical Properties from Chronopotentiometry (CP) Tests for Lithium SC-ISEs [13]

| Transducer Material | Total Resistance (kΩ) | Short-Term Drift (µV s⁻¹) | Long-Term Drift (mV h⁻¹) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Graphene | 216.1 ± 27.4 | 2.6 ± 0.3 | 0.5 |

| PEDOT | 321.0 ± 45.1 | 5.3 ± 0.7 | 1.4 |

| MWCNTs | 289.6 ± 33.2 | 4.1 ± 0.5 | 1.1 |

| Reduced Graphene Oxide (rGO) | 264.9 ± 31.8 | 3.5 ± 0.4 | 0.8 |

| Graphene Oxide (GO) | 598.3 ± 71.2 | 8.2 ± 1.1 | 2.1 |

Experimental Protocols for Fabrication and Characterization

Sensor Fabrication Workflow

A standardized protocol for fabricating and characterizing a SC-ISE is crucial for reproducibility. The following workflow outlines the key steps.

Detailed Methodologies

Protocol 1: Fabrication of PEDOT-based SC-ISEs via Electropolymerization

- Substrate Preparation: Clean the conductive substrate (e.g., glassy carbon, gold, or screen-printed carbon electrode) thoroughly according to standard electrochemical practices [13] [11].

- Electropolymerization: Prepare a monomer solution containing 0.01 M EDOT and 0.1 M supporting electrolyte (e.g., sodium poly(4-styrenesulfonate) - NaPSS). Deposit the PEDOT layer onto the substrate using cyclic voltammetry (e.g., scanning between -0.8 V and +1.0 V for 10 cycles) or chronoamperometry at a fixed potential [11].

- ISM Deposition: Prepare the ion-selective membrane cocktail by dissolving high molecular weight PVC, a plasticizer (e.g., o-NPOE or DOS), a target ion-selective ionophore, and a lipophilic ion exchanger (e.g., NaTFPB) in tetrahydrofuran (THF). Drop-cast a defined volume of this cocktail onto the PEDOT-modified electrode and allow the THF to evaporate slowly, forming a uniform membrane [12] [13].

Protocol 2: Fabrication of Carbon Nanomaterial-based SC-ISEs via Drop-Casting

- SC Layer Deposition: Prepare a stable dispersion of the carbon nanomaterial (e.g., MWCNTs, graphene) in a suitable solvent (e.g., ethanol, DMF). Sonicate the dispersion to achieve homogeneity. Drop-cast a specific volume of the dispersion onto the conductive substrate and allow the solvent to evaporate, forming the solid-contact layer [12] [13].

- ISM Deposition: Follow the same ISM deposition procedure as described in Protocol 1.

Protocol 3: Key Characterization Experiments

- Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS): Perform EIS in a frequency range from 100 kHz to 0.1 Hz at the open-circuit potential with a 10 mV AC amplitude. Use the resulting Nyquist plot to evaluate the bulk resistance (R₆) and geometric capacitance (Cg) of the ISM, as well as the charge transfer resistance and double-layer capacitance of the SC layer [12].

- Chronopotentiometry (CP): Apply a constant current pulse (e.g., ±1 nA for 60 s) and record the potential transient. The capacitance (C) of the SC layer can be calculated using the formula

C = i / (dE/dt), whereiis the applied current anddE/dtis the slope of the potential transient. The potential drift is also directly observed from this test [12] [13]. - Water Contact Angle Measurement: Use a goniometer to measure the static water contact angle on the surface of the SC layer. This quantifies the hydrophobicity of the transducer, which is critical for assessing its resistance to water layer formation [13].

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Why does my SC-ISE exhibit a high potential drift and unstable signal? A: This is one of the most common issues, often attributed to the formation of a water layer between the ISM and the SC layer. This thin aqueous film becomes an uncontrolled ionic reservoir, compromising the stability of the phase boundary potential [11]. To mitigate this:

- Use more hydrophobic transducer materials like graphene or PEDOT:TFPB, which have shown high water contact angles and superior performance [13] [3].

- Ensure the ISM components are highly lipophilic to prevent leaching and water uptake.

- Optimize the adhesion and interface between the ISM and the SC layer.

Q2: How can I reduce the long conditioning time required for my sensors? A: Traditional SC-ISEs can require hours of conditioning. Recent research demonstrates that conditioning time can be drastically reduced by engineering the SC layer to control water and ion transport.

- Strategy: Employ a superhydrophobic conducting polymer like PEDOT:TFPB. This material hinders water influx while maintaining high capacitance, allowing the sensor to function after a short conditioning time of ~30 minutes [3].

- Additional Tuning: The conditioning and stability performance can be further tuned by tailoring the thickness of the ISM and the polymerization charges of the CP [3].

Q3: My sensor's sensitivity (slope) is sub-Nernstian. What could be the cause? A: A sub-Nernstian slope indicates inefficient ion-to-electron transduction or high ohmic resistance.

- Check the integrity of the SC layer. Inhomogeneous coverage or low capacitance can lead to poor transduction.

- Verify the composition of the ISM. An incorrect ratio of ionophore to ion exchanger, or poor membrane plasticity, can reduce sensitivity.

- Ensure there are no air bubbles trapped in the sensing membrane or at the interfaces during fabrication [5].

Q4: How do I achieve a "calibration-free" and "ready-to-use" sensor for wearable applications? A: Achieving this requires a holistic approach combining materials and device engineering, as demonstrated by the r-WEAR system [14].

- Stable ISE: Use a superhydrophobic ion-to-electron transducer (e.g., PEDOT:TFPB) to stabilize the electromotive force.

- Stable Reference Electrode (RE): Implement a RE with a diffusion-limiting gelated salt bridge to regulate Cl⁻ flux and maintain a stable open-circuit potential (OCP).

- Electrical Shunting: Keep the sensor in a zero-bias (shunted) condition during storage until use. This maintains the OCP across the entire sensor in a pre-calibrated state, making it ready-to-use immediately upon unboxing [14].

Troubleshooting Guide

Table 3: Common Issues and Solutions in SC-ISE Development

| Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| High Potential Drift | Water layer formation; Low capacitance of SC layer; Unstable reference electrode. | Increase SC layer hydrophobicity (e.g., use graphene, PEDOT:TFPB); Use materials with higher capacitance (e.g., graphene: 383.4 µF) [13]; Validate RE stability [14]. |

| Slow Response Time | Thick ISM; High bulk resistance of ISM; Poor ion transduction kinetics. | Optimize ISM thickness [3]; Ensure adequate plasticizer and ion exchanger content; Use high-performance transducers (e.g., MWCNTs, PEDOT) [12]. |

| Poor Reproducibility | Inconsistent SC layer deposition; Inhomogeneous ISM; Air bubbles at interface. | Standardize deposition method (e.g., controlled drop-casting, electropolymerization); Ensure homogeneous membrane cocktail; Avoid D.I. water rinsing between calibrations, use sample instead [5]. |

| Sub-Nernstian Slope | Incomplete transduction; High circuit resistance; Incorrect ISM formulation. | Characterize SC layer with EIS/CP to ensure sufficient capacitance; Check all electrical connections; Re-optimize ISM component ratios. |

| Short Lifetime | Leaching of membrane components; Degradation of SC layer; Delamination of ISM. | Use more hydrophobic/lipophilic membrane components; Employ stable carbon-based or superhydrophobic CP transducers [13] [3]; Ensure good adhesion between layers. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Materials for SC-ISE Fabrication

| Material / Reagent | Function / Role | Example(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Conductive Substrate | Provides electronic conduction; Physical support for layers. | Glassy Carbon Electrode; Screen-Printed Carbon/Gold Electrodes [12] [13]. |

| Ion-to-Electron Transducer | Converts ionic current to electronic current; Stabilizes potential. | Redox Capacitance: PEDOT, PEDOT:TFPB, PANi [12] [3]. EDL Capacitance: MWCNTs, Graphene, rGO [12] [13]. |

| Polymer Matrix | Provides mechanical stability and backbone for the ISM. | Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC); Acrylic esters; Polyurethane [12] [11]. |

| Plasticizer | Imparts plasticity and mobility to ISM components; Influences dielectric constant. | 2-Nitrophenyl octyl ether (o-NPOE); Bis(2-ethylhexyl) sebacate (DOS) [12] [11]. |

| Ionophore | Selectively binds to the target ion; Imparts sensor selectivity. | Valinomycin (for K⁺); Sodium Ionophore X (for Na⁺); Custom synthetic ionophores [14] [11]. |

| Ion Exchanger | Introduces initial ionic sites; Facilitates ion exchange; Prevents interference. | Sodium tetraphenylborate (NaTPB); Sodium tetrakis[3,5-bis(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]borate (NaTFPB) [12] [11]. |

| Solvent | Dissolves ISM components for deposition. | Tetrahydrofuran (THF); Cyclohexanone [12] [14]. |

A technical resource for researchers developing the next generation of conditioning-free wearable biosensors.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Signal Instability and Potential Drift

Reported Symptom: The sensor output exhibits an unstable potential (drift) during continuous measurement, making accurate concentration readings difficult.

Potential Cause 1: Water Layer Formation.

- Diagnosis: Measure the potential drift over 48 hours. A significant deviation (e.g., >> 0.1 mV/h) suggests water uptake at the interface between the ion-selective membrane (ISM) and the solid-contact (SC) layer [2] [9].

- Solution: Implement a superhydrophobic SC layer. Using PEDOT:TFPB as the conducting polymer has been shown to hinder water and ion fluxes, resulting in a signal deviation of only 0.02 mV/h over 48 hours [3].

Potential Cause 2: Suboptimal Ion-Selective Membrane Hydrophobicity.

- Diagnosis: If the sensor requires long conditioning times (>30 minutes) or shows poor reversibility.

- Solution: Modify the ISM composition. Incorporating a block copolymer like SEBS (polystyrene-block-poly(ethylene-butylene)-block-polystyrene) into a conventional PVC/DOS membrane at a ratio of 30:30 wt% has been proven to mitigate water layer formation and reduce potential drift below 0.04 mV/h [9].

Potential Cause 3: Insufficient Capacitance of the Solid-Contact Layer.

- Diagnosis: The sensor exhibits slow response times or poor stability when not in use.

- Solution: Engineer the SC layer for high electric double-layer (EDL) capacitance. A composite electrode using a laser-induced graphene (LIG) and MXene/PVDF nanofiber mat (MPNFs/LIG@TiO2) provides excellent conductivity and high electrochemical surface area, leading to rapid response and minimal drift (0.04-0.08 mV/h) [9].

Guide 2: Resolving Challenges in Miniaturization and Integration

Reported Symptom: Sensor performance degrades upon miniaturization or integration into a flexible, wearable format.

Potential Cause 1: Poor Interfacial Adhesion on Flexible Substrates.

- Diagnosis: Cracking of the ISM or delamination from the electrode upon bending.

- Solution: Use flexible polymer blends for the ISM and robust electrode architectures. A PVC-SEBS blend membrane drop-cast onto a LIG electrode patterned on a flexible Ti3C2Tx-MXene/PVDF nanofiber mat ensures mechanical flexibility and skin conformity while maintaining sensor performance [9].

Potential Cause 2: Complex Wiring and Power Requirements for Wearables.

- Diagnosis: The wearable device is bulky, rigid, or requires frequent battery changes.

- Solution: Develop a battery-free, wireless sensing system. Integrate the ISE with a varactor diode into a resonant antenna circuit fabricated on a flexible PDMS substrate. This system converts interfacial potential changes into stable resonant frequency shifts, enabling power-free operation [15].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the significance of "conditioning-free" operation in wearable solid-contact ISEs (SC-ISEs)? A: Traditional ISEs require long hours of soaking (conditioning) in a solution to stabilize the potential signal before use and frequent recalibration. For wearables, this is highly impractical. Conditioning-free sensors are designed to function with minimal to no preparation, making them suitable for real-time, on-body monitoring. This is achieved by using materials and designs that inherently prevent the formation of unstable water layers, the primary cause of signal drift [3].

Q2: Our sensor readings for chloride ions are inconsistent. What are the typical voltage ranges we should expect during calibration? A: When calibrating a chloride ISE, the raw voltages for standard solutions should fall within a specific range. In a typical two-point calibration:

- The high standard (e.g., 1000 mg/L) should yield a voltage around 2.0 V.

- The low standard (e.g., 10 mg/L) should yield a voltage around 2.8 V. Significant deviations from these values may indicate a sensor or measurement setup issue [16].

Q3: Which solid-contact material is better for stability: conducting polymers or carbon-based materials? A: Both have shown success, and the choice depends on the specific design goals. Conducting polymers like PEDOT function via a redox capacitance mechanism and offer high capacitance and good transduction [2]. Carbon-based materials (e.g., graphene, carbon nanotubes) and composites often operate via an electric double-layer capacitance mechanism and can offer superior hydrophobicity, which is critical for suppressing water layer formation [9]. Recent trends favor engineered composites that combine the benefits of both, such as LIG with conductive polymers or hydrophobic nanoparticles [9] [15].

Q4: How can we achieve wireless, battery-free operation for our wearable sweat sensor? A: This can be accomplished by integrating the ISE into a passive resonant antenna (NFC/RFID) circuit. In this design, a varactor diode converts the potential change at the ISE into a capacitance change, which in turn shifts the circuit's resonant frequency. This frequency shift can be detected wirelessly by a reader, eliminating the need for onboard batteries or complex wiring [15].

Performance Data of Advanced SC-ISEs

The table below summarizes key performance metrics from recent studies on stable, wearable solid-contact ISEs.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Advanced Solid-Contact ISEs for Wearable Applications

| Ion Detected | Solid-Contact (SC) Layer | Key Innovation | Conditioning Time | Stability (Potential Drift) | Sensitivity (mV/decade) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Na⁺ / K⁺ [9] | LIG@TiO₂ on MXene/PVDF nanofiber | Hydrophobic composite with high EDL capacitance | Short (Not specified) | 0.04 mV/h (Na⁺); 0.08 mV/h (K⁺) | 48.8 (Na⁺); 50.5 (K⁺) |

| General (Cl⁻, Na⁺, K⁺) [3] | PEDOT:TFPB | Superhydrophobic conducting polymer | 30 minutes | 0.02 mV/h | Not specified |

| General (Cl⁻, Na⁺, K⁺) [15] | Integrated with varactor/antenna | Battery-free wireless resonant circuit | Not specified | Stable frequency output | Near-Nernstian |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Fabrication of a Highly Stable, Flexible Na⁺/K⁺ Patch Sensor

This protocol is adapted from research demonstrating sensors with ultralow potential drift [9].

1. Synthesis of MXene@PVDF Nanofibers (MPNFs) Mat:

- Step 1: Disperse multilayer Ti₂C₂Tx MXene powder (2.1 wt%) in a binary solvent of acetone and DMF (7:5 v/v) using probe sonication.

- Step 2: Add PVDF powder (12 wt% of total mass) to the dispersion and stir at 55°C for 2 hours to achieve a homogeneous solution.

- Step 3: Electrospin the solution at 18 kV, with a flow rate of 2.0 mL/h, and a tip-to-collector distance of 12 cm. Collect the nanofibers on aluminum foil.

- Step 4: Detach the nanofibers and dry them at 50°C for 3 hours.

2. Fabrication of Laser-Induced Graphene (LIG) Electrode:

- Step 5: Use a CO₂ laser to carbonize the electrospun MPNFs mat. This process creates the LIG electrode while simultaneously oxidizing MXene to form TiO₂ nanoparticles, resulting in the MPNFs/LIG@TiO₂ composite.

3. Preparation of Ion-Selective Membranes (ISMs) and Sensor Assembly:

- Step 6: Prepare the ISM cocktails. For example, for a K⁺ sensor, mix 51 mg PVC, 99 mg NPOE (plasticizer), 9.0 mg ionophore (e.g., Valinomycin), and 9.0 mg of the additive NaTFPB in 3.0 mL THF [17].

- Step 7: Drop-cast the ISM cocktail onto the prepared LIG electrode.

- Step 8: Condition the assembled sensor by immersing it in a 0.01 M KCl solution (for K⁺ sensor) before use.

Protocol 2: Integration of an ISE into a Battery-Free Wireless System

This protocol outlines the key steps for creating a wireless sensor as described in recent literature [15].

1. Fabricate the Resonant Antenna Circuit:

- Step 1: Pattern a copper coil antenna on a flexible PDMS substrate.

- Step 2: Solder a varactor diode (e.g., SMV1249–079LF) and a damping resistor into the antenna circuit.

2. Integrate the Ion-Sensing Unit:

- Step 3: Connect a custom solid-contact ISE (e.g., Ag/AgCl) as the working electrode to the varactor diode in the circuit.

- Step 4: The ISE is fabricated separately by depositing a conductive polymer (e.g., PEDOT:PSS) and an ion-selective membrane on a flexible electrode.

3. Data Acquisition:

- Step 5: Use a Vector Network Analyzer (VNA) with a reader coil to wirelessly measure the resonant frequency (S11 parameter) of the sensor circuit.

- Step 6: Correlate shifts in the resonant frequency to changes in ion concentration, which modulate the capacitance of the varactor diode via the ISE's potential.

Material Architectures and Signaling Pathways

Diagram: Architecture of a Conditioning-Free SC-ISE

The following diagram illustrates the multi-layered structure and ion-to-electron transduction mechanism in an advanced hydrophobic solid-contact ISE.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Materials for Fabricating Advanced Solid-Contact ISEs

| Material Category | Example Materials | Function | Key Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conducting Polymers | PEDOT:PSS, PEDOT:TFPB | Acts as an ion-to-electron transducer; PEDOT:TFPB offers superhydrophobicity. | [3] [17] |

| Carbon Nanomaterials | Laser-Induced Graphene (LIG), Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) | Provides a high-surface-area, conductive solid-contact layer with high double-layer capacitance. | [9] |

| 2D Materials & Composites | Ti₃C₂Tx MXene, MXene/PVDF nanofibers | Offers high conductivity and mechanical strength, forming a robust foundation for flexible electrodes. | [9] |

| Polymer Matrices | Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC), SEBS Block Copolymer | Forms the backbone of the ion-selective membrane; SEBS enhances hydrophobicity and flexibility. | [9] |

| Plasticizers | 2-Nitrophenyl octyl ether (NPOE), Bis(2-ethylhexyl) sebacate (DOS) | Imparts plasticity to the ISM and improves the solubility and mobility of ions within the membrane. | [17] |

| Ionophores | Valinomycin (for K⁺), ETH 129 (for Ca²⁺), Bis(12-crown-4) (for Na⁺) | The key component that selectively binds to the target ion, determining sensor selectivity. | [17] |

| Lipophilic Additives | Sodium Tetrakis [3,5-bis(trifluoromethyl)phenyl] borate (Na-TFPB) | Minimizes interference from lipophilic sample anions and reduces membrane resistance. | [17] |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs for Solid-Contact Ion-Selective Electrodes

This technical support center provides targeted guidance for researchers working with solid-contact ion-selective electrodes (SC-ISEs) in wearable applications. The content focuses on conditioning-free operation and addresses common experimental challenges.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My solid-contact K+ sensor shows significant potential drift during long-term monitoring. What could be causing this?

Potential drift in SC-ISEs can originate from several sources. First, check the solid-contact transducer layer between the ion-selective membrane and conducting substrate. This layer acts as the ion-to-electron transducer, and insufficient stabilization can cause drift [18]. For K+ sensors using advanced materials like PEDOT, ensure the redox capacitance mechanism is functioning properly, where the transducer converts ion concentration to electron signals through reversible oxidation/reduction reactions [18]. Also, verify that no slow water layers are forming at the substrate/membrane interface, which can destabilize potential readings over time.

Q2: Why does my Na+ sensor exhibit poor selectivity against K+ ions in sweat samples?

Selectivity issues typically originate from the ionophore in the selective membrane. For Na+ sensing, ensure you're using a highly selective ionophore like 4-tert-Butylcalix[4]arene (sodium ionophore X) [19]. The membrane composition is critical—use 2.10% (w/w) KTClPB, 3.3% (w/w) sodium ionophore X, 30.9% (w/w) PVC, and 63.7% (w/w) DOS dissolved in THF [19]. Also, validate that the conditioning step (30 minutes in 1 M NaCl) was properly completed, as insufficient conditioning can reduce membrane selectivity.

Q3: What is the typical response time I should expect for wearable K+ and Na+ sensors?

Response times vary based on design but aim for under 30 seconds for most applications. For example, engineered K+ biosensors like GINKO2 achieve rapid response suitable for real-time monitoring [20]. Na+ sensors in wearable microfluidic systems should provide stable readings within 20-60 seconds after sweat contact [19]. Slow response may indicate membrane thickness issues, inadequate transducer conductivity, or microfluidic delivery problems in wearable formats.

Q4: How do I validate the performance of my conditioning-free solid-state sensors against standard methods?

Performance validation should include several key parameters:

- Linearity: Check for Nernstian response (approximately 59 mV/decade for monovalent ions at 25°C)

- Detection limit: Determine via intersection of extrapolated linear regions

- Selectivity coefficients: Use separate solution method or fixed interference method

- Reproducibility: Multiple sensors from same batch should show <5% variation [5] Compare results with standard clinical analyzers or laboratory ISEs for correlation.

Q5: Can I use the same solid-contact platform for different target ions?

Yes, the solid-contact platform is adaptable across ions. The fundamental structure—conducting substrate, transducer layer, and ion-selective membrane—remains consistent. You would modify the ion-selective membrane components (ionophore, plasticizer, additive) specific to each target ion while potentially maintaining the same transducer material (e.g., PEDOT, carbon nanomaterials) and substrate [18].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Unstable Potentials in Wearable Sweat Sensors

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Tests | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Poor skin contact | Check electrode impedance; inspect skin-sensor interface | Improve conformal contact; use hydrogel or better adhesion |

| Air bubbles in microfluidics | Visual inspection; test with dye solution | Use paper-based microfluidics with capillary action [19] |

| Evaporation effects | Compare fresh vs stored samples | Implement closed microfluidics like butterfly designs [19] |

| Temperature fluctuations | Record simultaneous temperature data | Integrate temperature compensation; allow thermal equilibration |

Problem: Interference from Other Ions in Complex Biofluids

| Interferent | Affected Sensors | Mitigation Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Rb+ | K+ sensors | Use highly specific biosensors like GINKO2 [20] |

| Na+ | K+ sensors | Optimize ionophore concentration; add appropriate additives |

| Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺ | Na+, K+ sensors | Incorporate screening agents in membrane |

| pH variations | All sensors | Buffer samples; use pH-compensated membranes |

Problem: Short Sensor Lifetime in Continuous Monitoring

| Failure Mode | Root Cause | Prevention |

|---|---|---|

| Signal drift | Water layer formation | Use hydrophobic transducer materials (CBN220) [19] |

| Loss of sensitivity | Ionophore leaching | Optimize membrane polymerization; cross-linking |

| Physical damage | Mechanical stress | Use flexible substrates; strain-relief designs |

| Biofouling | Protein adsorption | Anti-fouling coatings; regular calibration checks |

Performance Specifications and Comparison

Table: Expected Performance Ranges for Solid-Contact ISEs in Wearable Applications

| Parameter | Na+ Sensors | K+ Sensors | pH Sensors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Linear Range | 10⁻⁴ - 10⁻¹ M | 10⁻⁴ - 10⁻¹ M | pH 4-9 |

| Slope | 55-59 mV/decade | 55-59 mV/decade | 50-59 mV/pH unit |

| Response Time | < 30 seconds | < 30 seconds | < 20 seconds |

| Lifetime | 2-4 weeks continuous | 2-4 weeks continuous | 4+ weeks continuous |

| Selectivity (log K) | ≤ -2.5 against K+ | ≤ -3.0 against Na+ | N/A |

Table: Comparison of Transducer Materials for SC-ISEs

| Material Type | Examples | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conducting Polymers | PEDOT, PPy | High capacitance, well-established | Potential drift in some formulations |

| Carbon Materials | Carbon black, graphene | Excellent stability, various forms | Sometimes lower capacitance |

| Nanomaterials | Au nanoparticles, MOFs | Tunable properties, high surface area | Complex fabrication, cost |

| Redox Molecules | Ferrocene derivatives | Simple mechanism, well-defined | Leaching potential |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Fabrication of Solid-Contact Na+ Selective Electrodes

This protocol details the creation of wearable Na+ sensors as demonstrated in recent research [19]:

- Substrate Preparation: Use flexible polyester films (Autostat HT5) as substrates.

- Electrode Printing: Print working and pseudo-reference electrodes using graphite ink (Electrodag 423 SS). Apply silver/silver chloride ink (Electrodag 6038 SS) for the pseudo-reference electrode.

- Insulation: Define the working electrode area (0.07 cm²) using a grey dielectric paste.

- Transducer Application: Modify the working electrode with 6 μL of Carbon Black N220 dispersion applied in three 2 μL steps, drying for 1 hour between steps.

- Membrane Formation: Prepare the ion-selective membrane containing 2.10% KTClPB, 3.3% sodium ionophore X, 30.9% PVC, and 63.7% DOS in THF. Drop-cast 7.5 μL onto the carbon-modified working electrode.

- Reference Membrane: Prepare a reference membrane with PVB and NaCl in methanol, then drop-cast 10 μL onto the pseudo-reference electrode.

- Conditioning: Condition the ion-selective membrane for 30 minutes in 1 M NaCl and the reference membrane for 18 hours in 3 M KCl.

Protocol 2: Validation of Sensor Performance in Sweat Analysis

- Calibration: Perform a 3-point calibration in relevant physiological ranges (e.g., 10-100 mM for Na+, 1-20 mM for K+).

- Selectivity Testing: Evaluate sensor response in artificial sweat containing Na+, K+, Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, and lactate ions.

- Stability Assessment: Monitor potential drift over 24 hours in constant ionic strength solutions.

- On-Body Testing: Validate with human subjects during controlled exercise, comparing against reference methods.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Materials for Solid-Contact ISE Research

| Reagent | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| 4-tert-Butylcalix[4]arene | Na+ ionophore | Selective Na+ recognition in membranes [19] |

| KTClPB | Lipophilic additive | Anion exclusion in cation-selective membranes [19] |

| PEDOT | Conducting polymer transducer | Ion-to-electron transduction in SC-ISEs [18] |

| Carbon Black N220 | Nanomaterial transducer | Solid-contact layer for wearable sensors [19] |

| PVC | Polymer matrix | Membrane structural component [19] |

| DOS plasticizer | Membrane plasticizer | Provides membrane mobility and stability [19] |

Technical Diagrams

Solid-Contact ISE Fabrication Workflow

Troubleshooting Decision Tree

Building the Lab-on-Skin: Fabrication and Real-World Applications

The advancement of solid-contact ion-selective electrodes (SC-ISEs) is pivotal for the next generation of wearable health monitors. These sensors must provide reliable, continuous data without the need for frequent conditioning or calibration, enabling their use in practical, user-friendly devices. The core challenge in creating such conditioning-free sensors lies in the meticulous design and integration of three key components: the ionophore (for target recognition), the polymer matrix (which houses the ionophore), and the solid-contact layer (which transduces the ionic signal into an electronic one). This technical support center addresses the specific experimental hurdles researchers face when developing these sophisticated material systems, providing troubleshooting guides and detailed protocols to facilitate robust sensor design [2] [21].

◉ The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The table below catalogues essential materials used in the fabrication of high-performance, conditioning-free solid-contact ISEs.

Table 1: Key Materials for Solid-State Ion-Selective Sensors

| Material Category | Specific Example | Function | Key Property for Conditioning-Free Operation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ionophore | Calcium Ionophore IV [22] | Selectively binds to target ions (e.g., Ca²⁺) | High hydrophobicity to prevent leaching [2]. |

| Ion Exchanger | Sodium tetrakis[3,5-bis(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]borate (NaTFPB) [22] | Imparts permselectivity and facilitates ion exchange | Creates a stable internal environment, reducing drift [2]. |

| Polymer Matrix | Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC) with plasticizer [2] | Provides the bulk of the ion-selective membrane | Traditional material, but susceptible to water uptake [22]. |

| Polymer Matrix | PMMA/PDMA Copolymer [22] | Water-repellent alternative to PVC | Significantly slows water pooling at the buried interface [22]. |

| Solid-Contact Layer | Poly(3-octylthiophene 2,5-diyl) (POT) [22] | Converts an ionic signal into an electronic current | Hydrophobic conducting polymer that eliminates water layer formation [22]. |

| Solid-Contact Layer | 3D-ordered Mesoporous Carbon [23] | Provides a high double-layer capacitance for stable potential | Creates a large interfacial area, resisting polarization [23]. |

⁇ Frequently Asked Questions & Troubleshooting Guides

General Sensor Performance

Q: Why does my solid-contact ISE show a continuous potential drift, even after 24 hours of conditioning?

A: A continuous drift typically indicates an unstable interface between the ion-selective membrane (ISM) and the solid-contact (SC) layer. This is often caused by a parallel process, such as the slow formation of a detrimental water layer. To troubleshoot:

- Verify Solid-Contact Hydrophobicity: Ensure your SC layer (e.g., POT) is highly hydrophobic and uniformly deposited [22].

- Check Membrane Composition: Use a water-repellent polymer matrix like PMMA/PDMA copolymer instead of standard plasticized PVC to drastically slow water ingress [22].

- Extend Characterization: Use electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) to monitor the capacitance and resistance of the SC layer over time to detect instabilities [23].

Q: How can I achieve high electrode-to-electrode reproducibility in a single batch?

A: High reproducibility requires rigorous control over the fabrication process and interface engineering.

- Standardized Deposition: Use precise, automated methods like drop-casting with controlled volumes and concentrations for the SC and ISM layers [22].

- Interface Scrutiny: Employ surface analysis techniques like X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) to ensure consistent SC surface chemistry before membrane application [23].

- Material Purity: Use high-purity, Selectophore-grade reagents to minimize batch-to-batch variability in membrane components [22].

Material Selection and Integration

Q: What is the "water layer" problem and how can my material choices solve it?

A: The water layer is a thin film of water that forms between the ISM and the SC layer. It acts as an uncontrolled electrolyte reservoir, causing slow response times, potential drift, and poor reproducibility [22] [23].

Table 2: Material Strategies to Mitigate the Water Layer

| Problem | Ineffective Material Choice | Recommended Solution | Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Water Pooling at Interface | Plasticized PVC (e.g., with DOS) [22] | Use PMMA/PDMA copolymer matrix [22] | The water-repellent nature of the copolymer prevents water accumulation. |

| Water Layer Formation on SC | Hydrophilic or imperfect SC surface [23] | Use hydrophobic POT as the SC layer [22] | Hydrophobicity prevents water from wetting the SC surface. |

| Overall Water Ingress | Single-layer material strategy | Combine PMMA/PDMA membrane with POT SC [22] | Synergistic effect creates a complete barrier against water. |

Q: My sensor works perfectly in buffer solutions but fails in complex bio-fluids like sweat. What could be wrong?

A: This is commonly due to interference from other ions or biofouling.

- Ion Interference: Re-check the selectivity coefficient of your ionophore. The presence of unexpected interfering ions (e.g., CN⁻, Br⁻ for Cl⁻ sensors) can skew readings [24]. Ensure your calibration standards mirror the ionic background of the target bio-fluid [5].

- Biofouling: Implement a protective Nafion layer or an anti-fouling hydrogel on top of your ISM to prevent protein adsorption and cell adhesion [21].

- pH Sensitivity: The performance of many ionophores is pH-dependent. Confirm your sensor's operational pH range and ensure the bio-fluid's pH falls within it, or integrate a parallel pH sensor for compensation [25] [5].

Experimental Protocols and Characterization

Q: What is a detailed protocol for fabricating a robust, water-layer-free SC-ISE?

A: The following protocol is adapted from methods proven to eliminate the water layer [22].

Experimental Protocol: Fabrication of a PMMA/PDMA and POT-Based Ca²⁺ SC-ISE

Objective: To fabricate a solid-contact Ca²⁺ selective electrode with minimized water layer formation.

Materials:

- Gold substrate electrode (3 mm diameter)

- POT cocktail: 0.94 mg POT in 20 mL chloroform [22]

- ISM cocktail: 1.0 wt% Calcium Ionophore IV, 1.1 wt% ETH 500, 0.5 wt% NaTFPB, 97.4 wt% PMMA/PDMA copolymer in dichloromethane [22]

Methodology:

- Substrate Preparation: Polish the gold electrode with alumina nanoparticles (300 nm). Rinse thoroughly with Milli-Q water and sequentially bath for 5 minutes each in acetone, dilute nitric acid, Milli-Q water, and dichloromethane. Air dry completely [22].

- Solid-Contact Deposition: Drop-cast 10 µL of the POT cocktail directly onto the clean gold electrode. Allow it to dry. Repeat this process for a total of six (6) layers to build a consistent and hydrophobic SC layer [22].

- Membrane Casting: Drop-cast 100 µL of the degassed PMMA/PDMA ISM cocktail directly onto the POT-coated electrode.

- Conditioning & Storage: Condition the completed electrode in a 0.1 M CaCl₂ solution for at least 24 hours before use to establish a stable equilibrium [22] [5].

Q: Which characterization techniques are most critical for diagnosing interface stability?

A: A multi-technique approach is essential to probe the buried interface.

- Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS): Used to monitor the capacitance of the SC layer and detect changes that indicate water layer formation [22] [23].

- In-situ Neutron Reflectometry/EIS (NR/EIS): Provides direct, molecular-level structural information about the SC/ISM interface in real-time and in a hydrated state, allowing you to observe water uptake and pooling directly [22].

- Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry (SIMS): Used to depth-profile the sensor and track the distribution of water and ions across the different layers after testing [22].

The following diagram illustrates the experimental workflow and the parallel characterization methods for developing a conditioning-free sensor.

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for sensor development with key characterization techniques.

FAQs: Core Concepts and Performance

Q1: What is the primary advantage of using superhydrophobic conducting polymers like PEDOT:TFPB in solid-contact ion-selective electrodes (SC-ISEs)?

The primary advantage is the significant reduction in conditioning time and enhanced long-term signal stability. These polymers hinder unwanted water and ion fluxes within the electrode, which minimizes the swelling of the conducting polymer and suppresses the formation of a detrimental water layer. This results in sensors that are functional after only about 30 minutes of conditioning and exhibit minimal signal deviation (e.g., 0.16% per hour or 0.02 mV/h) over 48 hours of continuous operation [3].

Q2: My flexible ISE shows potential drift during long-term measurements. What are the main causes and solutions?

Potential drift in flexible ISEs is often caused by water layer formation at the interface between the ion-selective membrane (ISM) and the transducer layer, insufficient hydrophobicity, and poor interfacial adhesion [9]. Solutions include:

- Interface Engineering: Using a 3D porous electrode architecture, such as laser-induced graphene (LIG) decorated with TiO2 nanoparticles on a MXene/PVDF nanofiber mat. This enhances hydrophobicity and electric double-layer capacitance, leading to ultra-low drift (as low as 0.04 mV/h) [9].

- Membrane Modification: Incorporating block copolymers like SEBS (polystyrene-block-poly(ethylene-butylene)-block-polystyrene) into traditional PVC-based ion-selective membranes. This improves hydrophobicity and mechanical strength, reducing ion pore leaching and water layer formation [9].

Q3: How do fabrication techniques like laser-induced graphene (LIG) contribute to better wearable sensors?

LIG fabrication, often using a CO2 laser on a polymer substrate, creates a patterned electrode directly on a flexible mat. This technique [9]:

- Enables High Conductivity: Creates a porous, graphene-based structure with a high electrochemical surface area.

- Ensures Flexibility and Conformability: The process is compatible with flexible substrates, allowing for skin-conformal patch sensors.

- Facilitates Robust Design: The LIG structure can be combined with other nanomaterials (e.g., MXene, TiO2) to create a robust, hierarchically porous architecture that enhances signal stability and ion transport.

Q4: What are the key considerations when moving a sensor from a rigid to a flexible substrate?

Key considerations include [26] [27]:

- Maintaining Electrical Performance: Ensuring that electrical conductivity and sensor precision are not compromised under mechanical deformation (bending, stretching).

- Material Biocompatibility: Using materials that are non-irritating for long-term skin contact or implantation.

- Mechanical Integrity: Developing materials and fabrication methods that ensure the device remains functional and reliable under repeated stress and strain.

- System Integration: Integrating high-performance electronic components on flexible substrates without compromising their flexibility or performance.

Troubleshooting Guides

Table 1: Common Fabrication and Performance Issues

| Problem Area | Specific Issue | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensor Stability | High potential drift (> 0.5 mV/h) | Water layer formation at the solid-contact/ISM interface; insufficient hydrophobicity [9]. | Employ superhydrophobic conducting polymers (e.g., PEDOT:TFPB) [3] or composite electrodes with enhanced capacitance and hydrophobicity (e.g., MPNFs/LIG@TiO2) [9]. |

| Sensor Stability | Long conditioning time required (>24 hrs) | Slow equilibration within the organic membrane system; high water uptake [5]. | Use a SC-ISE with a design that modulates water and ion transport, such as one with PEDOT:TFPB, to achieve rapid conditioning (~30 min) [3]. |

| Fabrication | Poor adhesion between layers (e.g., ISM delaminating) | Weak interfacial contact; incompatible surface chemistries [9]. | Engineer the electrode structure to induce strong π-π interactions within the composite (e.g., using LIG@TiO2). Optimize surface treatments before membrane casting. |

| Fabrication | Inconsistent sensor response (sensitivity, drift) | Non-uniform membrane thickness; variations in material composition during batch fabrication [9]. | Utilize scalable, low-cost laser engraving and solution casting techniques for reliable batch fabrication. Tailor ISM thickness and conducting polymer hydrophobicity/polymerization charges [3]. |

| Performance | Sub-Nernstian sensitivity | Inefficient ion-to-electron transduction; non-optimal ion-selective membrane composition [17]. | Ensure a high capacitance solid-contact layer (e.g., PEDOT:PSS) [17]. Verify ionophore and membrane component ratios during cocktail preparation [17]. |

Table 2: Quantitative Performance of Advanced Sensor Designs

| Sensor Design | Target Ion | Conditioning Time | Sensitivity (mV/decade) | Long-Term Stability (Potential Drift) | Key Innovation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEDOT:TFPB-based SC-ISE [3] | Not Specified | ~30 min | N/A | 0.02 mV/h (0.16%/h over 48h) | Superhydrophobic conducting polymer |

| MPNFs/LIG@TiO2 SC-ISE [9] | Na+ | N/A | 48.8 mV (Near-Nernstian) | 0.04 mV/h | Laser-induced graphene on MXene/PVDF nanofiber mat |

| MPNFs/LIG@TiO2 SC-ISE [9] | K+ | N/A | 50.5 mV (Near-Nernstian) | 0.08 mV/h | Laser-induced graphene on MXene/PVDF nanofiber mat |

| All-Solid-State with PEDOT:PSS [17] | Na+ | ~30 min (soak in standard) | Near-Nernstian | Stable operation in human saliva | Microfluidic integration for salivary monitoring |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Fabrication of a Flexible ISE Patch with LIG Electrode

This protocol outlines the creation of a highly stable, flexible ion-selective patch sensor based on a laser-induced graphene (LIG) electrode [9].

1. Synthesis of MXene@PVDF Nanofibers (MPNFs) Mat:

- Prepare Electrospinning Solution: Disperse multilayer Ti3C2Tx MXene powder in a binary solvent of acetone and DMF. Subject the dispersion to probe sonication for uniform exfoliation.

- Add Polymer: Add PVDF powder to the MXene dispersion and stir at 55°C to achieve a homogeneous, viscous solution.

- Electrospin Nanofibers: Load the solution into a syringe and electrospin through a metal needle at an applied voltage of 18 kV, with a specific flow rate and tip-to-collector distance. Collect the nanofibers on aluminum foil and dry.

2. Creation of Laser-Induced Graphene (LIG) Electrode:

- Laser Carbonization: Use a CO2 laser system to irradiate the electrospun MPNFs mat. This process converts the PVDF matrix into LIG and simultaneously oxidizes the MXene surface to generate TiO2 nanoparticles, forming an MPNFs/LIG@TiO2 composite.

- Pattern Electrodes: Directly pattern the LIG electrode onto the nanofiber mat using the laser system.

3. Sensor Assembly and Membrane Application:

- Prepare Ion-Selective Membrane (ISM): Prepare a cocktail using a blend of PVC and SEBS block copolymer, plasticizer, ionophore, and other required components dissolved in tetrahydrofuran (THF).

- Drop-Cast ISM: Drop-cast the prepared ISM cocktail onto the LIG working electrode and allow it to dry.

- Integrate into Patch: Use a double-sided PET tape substrate to assemble the sensor into a mechanically flexible and skin-conformal patch.

Protocol 2: Integration of All-Solid-State ISEs into a Microfluidic Device

This protocol describes integrating all-solid-state ISEs into a microfluidic platform for real-time, multi-ion salivary monitoring [17].

1. Fabricate All-Solid-State Sensors:

- Substrate Preparation: Clean a polyethylene terephthalate (PET) film with a pre-deposited gold electrode pattern.

- Apply Solid-Contact Layer: Drop-cast PEDOT:PSS onto the exposed gold electrode area and thermally cure to form the ion-to-electron transducer layer.

- Apply Ion-Selective Membrane: Drop-cast the specific ion-selective membrane cocktail (e.g., for Na+, K+, Ca2+) onto the PEDOT:PSS layer and dry.

2. Fabricate Microfluidic Flow Path:

- Create PDMS Channel: Use a mold to create a flow channel in a polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) layer. Typical channel dimensions are 3 mm wide and 0.5 mm high.

- Bond to Substrate: Attach the patterned PDMS layer to a glass substrate sputtered with gold and silver to form the complete flow cell, ensuring the sensor sites are aligned within the channel.

3. System Operation and Data Acquisition:

- Fluidic Handling: Connect the microfluidic device to a system for precise fluid handling and automated sample processing.

- Potentiometric Measurement: Use a system comprising a 16-bit analog-to-digital converter (e.g., ADS1115), a microcontroller (e.g., Arduino Pro Mini), and a wireless communication module (e.g., Xbee) for real-time data acquisition and transmission.

- Calibration: Calibrate the integrated sensors using standard solutions of known ion concentration.

Core Concepts and Workflows

Diagram: Strategy for Achieving Conditioning-Free ISEs

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Material / Reagent | Function in Fabrication | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| PEDOT:TFPB | A superhydrophobic conducting polymer that acts as the solid contact. Hinders water and ion fluxes, reducing conditioning time and improving potential stability [3]. | Used as the transducer layer in SC-ISEs to achieve rapid conditioning (30 min) and low drift (0.02 mV/h) [3]. |

| PEDOT:PSS | A conducting polymer dispersion used to form a hydrophilic solid-contact layer, facilitating ion-to-electron transduction [17]. | Drop-cast on gold electrodes to create a stable interface for the ion-selective membrane in all-solid-state sensors [17]. |

| Ti₃AlC₂ (MAX Phase) | Precursor for synthesizing MXene (Ti₃C₂Tₓ). Provides a 2D material with high conductivity and surface functionality [9]. | Etched to produce MXene, which is incorporated into electrospun nanofiber mats to enhance electrode conductivity [9]. |

| PVDF (Polyvinylidene fluoride) | A hydrophobic dielectric polymer used as a substrate or matrix. Provides mechanical flexibility and water-repellent properties [9]. | Electrospun with MXene to form a nanofibrous mat, which is later laser-carbonized to form LIG [9]. |

| SEBS Block Copolymer | A thermoplastic elastomer used as an additive in ion-selective membranes. Improves hydrophobicity and mechanical strength, suppressing water layer formation [9]. | Blended with PVC in ISMs to mitigate ion pore leaching and reduce potential drift in wearable patch sensors [9]. |

| Ionophores (e.g., Bis(benzo-15-crown-5), ETH 129) | Selective molecular recognition elements within the ISM that bind the target ion, determining sensor selectivity [17]. | Formulated into ISM cocktails to create sensors specific for ions like Na+, K+, and Ca²⁺ [17]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Connectivity and Pairing Issues

Problem: Unable to establish or maintain a stable Bluetooth connection between the sensor node and the host device (e.g., computer, smartphone).

- Possible Cause 1: Sensor is not in a discoverable or connectable state after a previous failed pairing attempt.

- Solution: Perform a hard reset on the sensor. Press and hold the power button for 10 seconds while the sensor is connected to a dedicated USB power source (if available). This also applies to coin cell-powered devices. Always reset the sensor after an unsuccessful pairing attempt [28].

- Possible Cause 2: Outdated device drivers or firmware on the host device or the sensor node.

- Solution:

- Ensure your operating system and the acquisition software (e.g., PASCO, LabVIEW) are updated to the latest version [28].

- For sensors with a USB port, connect them directly to a computer running the latest software. If a firmware update is available, you should be prompted to install it [28].

- Check the manufacturer's website for any BIOS or other hardware firmware updates for your computing device [28].

- Solution:

- Possible Cause 3: Poor radio frequency (RF) conditions and physical obstructions.

- Solution:

Data Synchronization and Accuracy Problems

Problem: Data acquired from multiple wireless sensor nodes is not accurately synchronized, leading to misaligned timestamps.

- Possible Cause 1: Use of standard wireless protocols like basic BLE or ZigBee that lack high-precision synchronization mechanisms.

- Solution: Implement a proprietary synchronization protocol designed for high accuracy. Research shows that Time-Division Multiple Access (TDMA)-based protocols can achieve sampling synchronization accuracy as low as 0.8 μs [29]. This is significantly more precise than standard protocols, which can have errors in the millisecond range [29].

- Possible Cause 2: Clock drift between independent sensor nodes.

- Solution: The system should incorporate a mechanism for frequent and automatic clock synchronization across all nodes in the network. The proposed TDMA-based protocol in the search results inherently manages this, ensuring all nodes are aligned to a common time source [29].

Problem: Data packets are being lost during transmission, resulting in incomplete datasets.

- Possible Cause 1: Low signal strength or poor link quality.

- Solution: Monitor the Link Quality Indicator (LQI) or similar metric provided by your wireless platform. Reposition nodes or add router nodes to improve the mesh network and signal path [30]. Increasing transmission power (TXPWR) can reduce the Packet Error Rate (PER); for example, one study achieved a PER of 0.18% at -4 dBm and 0.03% at 3 dBm [29].

- Possible Cause 2: Network congestion or collision of data packets.

- Solution: Adhere to recommended network topology guidelines. For instance, National Instruments suggests a maximum of 8 end nodes connecting directly to a single gateway or router to ensure reliability [30]. A TDMA-based protocol also prevents collisions by assigning specific time slots for each node's transmission [29].

Power and Performance Issues

Problem: Sensor node battery is depleting too quickly.

- Possible Cause 1: The default node behavior of transmitting every sample immediately to the gateway.

- Solution: Embed intelligence into the node using a platform like the LabVIEW WSN Module. Program the node to process data locally (e.g., averaging, applying threshold logic) and transmit only meaningful, summarized data. This drastically reduces the number of radio transmissions, which is the most power-intensive operation [30].

- Possible Cause 2: High sampling rate or continuous data streaming.

- Solution: Optimize the sampling interval for the application. For long-term monitoring, slower rates (e.g., one sample per minute) can extend battery life to over two years [30]. For high-speed acquisition, use local buffering on the node and transmit data in bursts during predefined, active time slots [29].

- Performance Reference Data: The following table summarizes key metrics from an ultra-low-power implementation [29]:

| Performance Metric | Achieved Value |

|---|---|

| Synchronization Accuracy | 0.8 μs |

| Power Consumption | 15 μW per 1 kb/s data throughput |

| CPU Load | < 2% (for sampling event handler below 200 Hz) |

| Packet Error Rate (PER) | ≤ 0.18% (for TXPWR ≥ -4 dBm) |

Sensor Integration and Calibration

Problem: The Ion-Selective Electrode (ISE) readings are unstable or inaccurate when integrated with the wireless data transmission system.

- Possible Cause 1: Electrical noise from the microcontroller or wireless system interfering with the analog sensor signal.

- Solution: Implement proper analog signal conditioning and shielding. Use a dedicated, high-resolution Analog-to-Digital Converter (ADC) and separate analog and digital grounds. Power the sensor's analog front-end with a low-noise linear regulator.

- Possible Cause 2: The need for frequent calibration of the ISE.

- Solution (Thesis Context): This is where conditioning-free solid-state ion-selective sensors provide a significant advantage. As part of your experimental protocol, document the long-term stability and drift characteristics of these sensors to establish their calibration-free operational lifetime. The core thesis of your research directly addresses this troubleshooting point by aiming to eliminate the need for repeated calibration [31].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the best wireless protocol to use for integrating ISEs with microcontrollers? There is no single "best" protocol; the choice depends on the application's requirements. For long-range, low-power applications with infrequent data updates, LoRaWAN is a strong candidate. For medium-range, mesh networking scenarios, ZigBee (based on IEEE 802.15.4) is reliable. For high-data-rate streaming where power is less of a concern, Wi-Fi is suitable. For a balance of data rate, power, and integration with existing IoT infrastructure, using MQTT-SN (MQTT for Sensor Networks) over a low-power physical layer like IEEE 802.15.4 is an excellent choice for seamless integration into larger IoT platforms [32].

Q2: How can I ensure the security of my transmitted ion concentration data? Security is a critical concern for WSNs. You can leverage security features built into your communication protocol. For ZigBee-based networks, reserved bits in the MAC header frame can be used to toggle between secure and insecure modes [33]. Research also suggests using lightweight block ciphers like RECTANGLE, Fantomas, and Camellia to provide alternative security solutions with good performance for different scenarios, balancing security, memory usage, and battery consumption [33].

Q3: My wireless sensor node is programmable. How can I use this to my advantage? Programmability allows you to move beyond simple data passthrough. You can:

- Extend Battery Life: Add local logic (e.g., in LabVIEW WSN Module) to transmit data only when a threshold is exceeded or to send averaged values instead of every raw sample [30].

- Improve Data Quality: Implement digital filters or data validation algorithms on the node before transmission.

- Enable Edge Computing: Perform initial data analysis and feature extraction directly on the node, reducing the data volume that needs to be transmitted.

Q4: What is an MQTT-SN Gateway and why do I need one? An MQTT-SN Gateway is a critical bridge that allows sensor nodes using the lightweight MQTT-SN protocol to connect to a standard MQTT broker. Since many low-power microcontrollers cannot run a full TCP/IP stack, they use MQTT-SN over simpler transport protocols like UDP or ZigBee. The gateway translates these MQTT-SN messages into standard MQTT messages for the broker, enabling your low-end devices to participate fully in an MQTT-based IoT network [32].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials

The following table details key materials and components used in the development of advanced, conditioning-free ion-sensing systems as discussed in the search results.

| Item | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| PEDOT:PSS | A conductive polymer used as the channel material in p-type Organic Electrochemical Transistors (OECTs). It offers excellent stability in aqueous environments and high transconductance, making it ideal for ion-to-electron transduction [31]. |

| BBL | Poly(benzimidazobenzophenanthroline), an n-type conductive polymer used in OECTs. It enables the creation of complementary amplifier circuits, which are crucial for high gain and low power consumption [31]. |

| OECT Complementary Amplifier | A circuit integrating a p-type and an n-type OECT. It functions as a sensitive ion-to-electron transducer and signal amplifier in a single device, overcoming the fundamental Nernst limit (59 mV/dec) and achieving sensitivities over 2000 mV/V/dec [31]. |