Cross-Reactivity Assessment in Immunosensors and Aptasensors: Strategies, Challenges, and Future Directions

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of cross-reactivity, a critical performance parameter for biosensors used in biomedical research and clinical diagnostics.

Cross-Reactivity Assessment in Immunosensors and Aptasensors: Strategies, Challenges, and Future Directions

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of cross-reactivity, a critical performance parameter for biosensors used in biomedical research and clinical diagnostics. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the fundamental principles of antibody and aptamer interactions that underpin specificity in immunosensors and aptasensors. The scope spans from foundational concepts and methodological applications to advanced troubleshooting and rigorous validation protocols. By comparing the intrinsic factors and extrinsic optimization strategies that influence cross-reactivity in both sensor types, this review serves as a practical guide for the development of highly specific diagnostic tools, ultimately aiming to reduce false positives and enhance diagnostic accuracy.

Understanding Cross-Reactivity: Fundamental Concepts in Biorecognition

Cross-reactivity presents a fundamental challenge in the development of biosensors for diagnostic, environmental, and pharmaceutical applications. This phenomenon occurs when a biosensor's recognition element (e.g., an antibody or aptamer) binds not only to its intended target analyte but also to structurally similar molecules, potentially leading to false-positive results and inaccurate quantification [1] [2]. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding and minimizing cross-reactivity is crucial for developing reliable assays. The ideal scenario for any biosensor would be complete specificity for a single target with no cross-reactivity to structurally related analogs, thus guaranteeing accurate determination and avoiding false positives [3]. However, this ideal is rarely achieved in practice, as recognition elements often exhibit varying affinities for molecules sharing similar epitopes or structural motifs.

The clinical and analytical consequences of cross-reactivity can be significant. In diagnostic applications, cross-reactivity can lead to misdiagnosis or inaccurate disease monitoring. In food safety testing, it can result in false detections of antibiotic residues or other contaminants [3]. For pharmaceutical development, cross-reactivity with unintended targets can compromise drug safety profiles. Consequently, characterizing cross-reactivity has become an essential step in biosensor validation, requiring sophisticated experimental designs and careful interpretation of binding data across related compound panels [1] [2].

Comparative Analysis: Immunosensors vs. Aptasensors

Biosensors are primarily classified based on their biorecognition elements, with immunosensors (using antibodies) and aptasensors (using nucleic acid aptamers) representing two prominent technologies with distinct cross-reactivity profiles.

Fundamental Differences and Cross-Reactivity Mechanisms

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Immunosensors and Aptasensors

| Characteristic | Immunosensors | Aptasensors |

|---|---|---|

| Recognition Element | Antibodies (proteins) | Single-stranded DNA or RNA oligonucleotides |

| Production Process | Biological (in vivo) | Chemical (in vitro SELEX) |

| Binding Affinity | High (typically nM range) [3] | Variable (nM to μM range) [3] |

| Specificity Mechanism | Epitope recognition based on structural complementarity | 3D structure formation with target binding pockets |

| Cross-Reactivity Origin | Recognition of similar epitopes on related molecules [1] | Structural similarity between target and non-target molecules |

| Typical Cross-Reactivity | Often significant with close structural analogs [3] | Can be minimized through counter-selection [3] |

Immunosensors utilize antibodies as recognition elements, which are proteins produced by the immune system. Their cross-reactivity stems from the structural flexibility of antibody binding sites, which may accommodate molecules sharing similar molecular features with the target antigen [1]. This becomes particularly problematic when screening for small molecules like antibiotics, where antibodies may exhibit significant cross-reactivity with structurally related compounds [3]. For instance, immunosensors for sulfamethazine (SMZ) typically show high cross-reactivity with sulfamerazine (SMR), which differs by only one methyl group [3].

Aptasensors employ aptamers—single-stranded DNA or RNA molecules selected through Systematic Evolution of Ligands by Exponential Enrichment (SELEX)—as recognition elements [4] [3]. A key advantage of aptamer selection is the intentional incorporation of counter-selection steps, where potential aptamers that bind to structurally similar non-target molecules are deliberately discarded [3]. This process enables the development of aptamers with exceptional specificity, capable of differentiating between molecules differing by only a single functional group [3].

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Table 2: Experimental Cross-Reactivity Data for Antibiotics Detection

| Detection Platform | Target Analyte | Primary Cross-Reactant | Cross-Reactivity | LOD | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immunosensor | Sulfamethazine (SMZ) | Sulfamerazine (SMR) | 20-60% [3] | ~1 ng/mL | [3] |

| Immunosensor | Sulfonamides | Various sulfonamides | High (varies by assay format) [1] | - | [1] |

| Aptasensor | Sulfamethazine (SMZ) | 27 tested sulfonamides | Negligible (0%) [3] | 0.92 ng/mL | [3] |

| Multiplex Aptasensor | Imidacloprid | Other neonicotinoids | Minimal (excellent selectivity) [5] | 0.01 ng/mL | [5] |

The comparative data reveal a significant advantage for aptasensors in applications requiring high specificity. The chemiluminescence aptasensor for SMZ demonstrated negligible cross-reactivity with 27 tested sulfonamides, a level of specificity described as "impossible to achieve" with corresponding antibody-based approaches [3]. Similarly, a reduced graphene oxide-based electrochemical aptasensor for multiplex detection of neonicotinoid pesticides (imidacloprid, thiamethoxam, and clothianidin) showed excellent selectivity for all three analytes with minimal cross-reactivity [5].

Experimental Protocols for Cross-Reactivity Assessment

Standard Cross-Reactivity Determination Protocol

The most widely accepted method for quantifying cross-reactivity in competitive assay formats involves comparing the concentration of target analyte and cross-reactant required to produce the same analytical signal [1]. The standard protocol follows these steps:

Dose-Response Curves: Generate complete dose-response curves for both the target analyte and potential cross-reactants under identical assay conditions.

IC50 Determination: Calculate the concentration causing 50% inhibition of the detected signal (IC50) for both the target and cross-reactant.

Cross-Reactivity Calculation: Apply the formula: Cross-reactivity (CR) = [IC50(target analyte) / IC50(tested cross-reactant)] × 100% [1]

Validation: Test cross-reactivity against a comprehensive panel of structurally related compounds to fully characterize assay specificity.

This protocol applies to various biosensing platforms, including enzyme immunoassays, fluorescence polarization immunoassays, and electrochemical sensors [1]. The concentrations of immunoreactants and assay conditions significantly influence cross-reactivity measurements, with assays requiring lower reagent concentrations typically demonstrating higher specificity [1].

SELEX with Counter-Selection for High-Specificity Aptamer Development

The exceptional specificity of aptamers is achieved through intentional selection strategies during the SELEX process:

Library Preparation: Begin with a large library of random single-stranded DNA or RNA sequences (typically 10^14-10^15 different molecules) [4].

Target Immobilization: Immobilize the target molecule on solid supports such as magnetic beads (MB-SELEX) [3].

Positive Selection: Incubate the library with the immobilized target, retaining bound sequences.

Counter-Selection: Critically, incubate the enriched pool with non-target structural analogs to remove cross-reactive sequences [3].

Amplification: PCR amplify the specific binders for the next selection round.

Iteration: Repeat steps 3-5 for 8-15 rounds with increasing selection stringency.

Cloning and Sequencing: Identify individual aptamer sequences for characterization.

Affinity and Specificity Testing: Determine dissociation constants (Kd) and cross-reactivity profiles of selected aptamers [3].

This method yielded SMZ-specific aptamers with Kd values in the nanomolar range (79-274 nM) and negligible cross-reactivity with 27 other sulfonamides [3]. Molecular simulation and docking studies can further clarify the binding mechanism and explain the observed specificity at the structural level [3].

Technological Approaches to Minimize Cross-Reactivity

Assay Format and Condition Optimization

Cross-reactivity is not an intrinsic, fixed property of recognition elements but can be modulated by assay design and conditions [1]. Several strategies can enhance specificity:

Reagent Concentration Modulation: Implementing assays with sensitive detection and low concentrations of antibodies and competing antigens typically results in lower cross-reactivities and higher specificity [1]. Shifting to lower reagent concentrations can decrease cross-reactivities by up to five-fold [1].

Assay Format Selection: Different immunoassay formats (e.g., enzyme immunoassay vs. fluorescence polarization immunoassay) exhibit varying cross-reactivity profiles even when using the same antibodies [1].

Kinetic vs. Equilibrium Measurements: Varying the ratio of immunoreactants' concentrations and shifting from kinetic to equilibrium modes of antigen-antibody reaction can influence cross-reactivity measurements [1].

Heterologous Assay Designs: Using different antigen derivatives in analysis than those used in immunization can narrow specificity spectra in competitive immunoassays [1].

Emerging Technologies and Advanced Materials

Novel biosensing platforms and nanomaterials are providing new avenues for addressing cross-reactivity challenges:

Multiplexed Aptasensors: Advanced platforms like the reduced graphene oxide-based electrochemical aptasensor enable simultaneous detection of multiple analytes (imidacloprid, thiamethoxam, and clothianidin) with high specificity for each target, addressing a key limitation of traditional methods [5].

AI-Optimized Biosensors: Integration of artificial intelligence with electrochemical aptasensors has demonstrated significant improvements in specificity, increasing from 70-80% to 90-98% while reducing false positives and negatives from 15-20% to 5-10% [6].

High-Throughput Platforms: Technologies like the Sensor-Integrated Proteome On Chip (SPOC) enable large-scale kinetic screening of thousands of protein interactions with real-time label-free analysis, facilitating comprehensive cross-reactivity assessment during development [7].

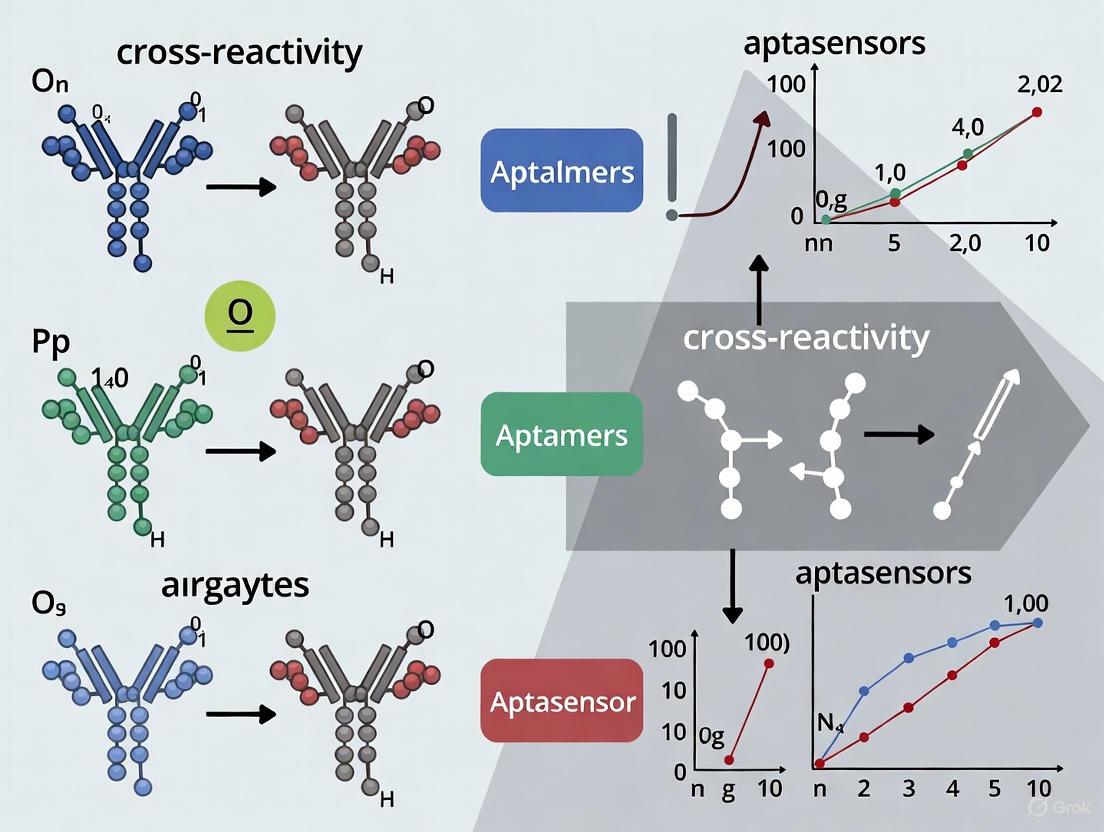

Visualization: Cross-Reactivity Mechanisms and Assessment

This diagram illustrates the fundamental differences in how immunosensors and aptasensors handle structurally similar molecules, along with the SELEX process that enables high-specificity aptamer development through intentional counter-selection against non-target analogs.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Cross-Reactivity Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function in Cross-Reactivity Assessment | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Structural Analogs | Panel of compounds similar to target for specificity testing | Essential for comprehensive cross-reactivity profiling; should include closest structural relatives [3] |

| Magnetic Beads (MB) | Immobilization support for SELEX targets | Used in MB-SELEX for aptamer selection; enable efficient separation of bound/unbound sequences [3] |

| Cross-linking Reagents | Covalent attachment of capture agents to sensor surfaces | BS3 and other homobifunctional crosslinkers used for antibody/aptamer immobilization [8] |

| Aminopropyltriethoxysilane (APTES) | Surface silanization for biosensor functionalization | Creates amine-reactive surfaces for subsequent biomolecule immobilization [8] |

| Reduced Graphene Oxide | Nanomaterial for enhanced electrochemical sensing | Increases surface area and electron transfer in electrochemical aptasensors [5] |

| Screen-Printed Electrodes | Disposable platforms for electrochemical detection | Enable cost-effective, portable biosensing; ideal for field-deployable sensors [5] |

| IVTT Lysate Systems | Cell-free protein expression for proteomic arrays | Enable in situ protein production for high-throughput interaction screening [7] |

Cross-reactivity remains a critical parameter in biosensor validation, with significant implications for diagnostic accuracy, regulatory compliance, and clinical decision-making. While immunosensors continue to play important roles in analytical applications, aptasensors offer distinct advantages in specificity through programmable selection processes and counter-selection strategies. The experimental data clearly demonstrate that aptasensors can achieve specificity levels that are challenging for antibody-based platforms, particularly for small molecule targets [3].

Future directions in addressing cross-reactivity challenges include the integration of artificial intelligence for biosensor optimization [6], development of multiplexed platforms for comprehensive specificity profiling [5] [7], and advancement of high-throughput methods for kinetic characterization of binding interactions [7]. As these technologies mature, researchers and drug development professionals will have increasingly powerful tools to ensure biosensor specificity while maintaining sensitivity, ultimately leading to more reliable analytical outcomes across diverse applications.

The development of robust immunosensors and emerging aptasensors is fundamentally shaped by the molecular recognition events between a bioreceptor and its target. For antibodies, these events are governed by the precise structural complementarity at the paratope-epitope interface. While high specificity is the goal, the inherent structural flexibility of antibodies and the existence of similar epitopes on different antigens can lead to cross-binding, a significant concern in diagnostic and therapeutic development [9]. Cross-binding can result in false positives in diagnostics or off-target effects in therapeutics, underscoring the need for rigorous early-stage assessment. Conversely, for aptasensors, cross-reactivity presents a similar challenge, though the synthetic nature and smaller size of aptamers offer distinct advantages and mechanisms for mitigation [10]. This guide objectively compares the experimental approaches and technologies used to quantify and mitigate cross-binding, providing researchers with a framework for evaluating the developability of their chosen bioreceptors.

Quantitative Comparison of Cross-Binding Assays and Performance

A critical step in biosensor development is the application of high-throughput assays to profile the cross-interaction propensity of candidate antibodies. The data below summarize key performance metrics of established assays and their correlation with downstream outcomes, providing a basis for comparison.

Table 1: Key Assays for Profiling Antibody Cross-Binding Propensity

| Assay Name | Principle of Measurement | Key Measurable Outputs | Reported Correlation with In Vivo Clearance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poly-Specificity Reagent (PSR) Binding [11] | Measures binding to a diverse mixture of non-cognate antigens (e.g., soluble membrane proteins) via ELISA or flow cytometry. | Median Fluorescence Intensity (MFI) | Strongest rank-order correlation (Spearman's ρ = 0.72); High predictive accuracy via ROC analysis [11]. |

| Cross-Interaction Chromatography (CIC) [11] | Evaluates weak cross-interaction by measuring retention time on a column coupled with human serum polyclonal antibodies. | Retention Time (minutes) | Significant rank-order correlation with mouse clearance rates [11]. |

| Affinity Capture Self-Interaction Nanoparticle Spectroscopy (AC-SINS) [11] | Detects self-association propensity by measuring plasmon wavelength shift of gold nanoparticles upon antibody clustering. | Δλmax (nanometers) | Forms a self-correlated cluster but did not directly correlate with clearance in a 16-mAb case study [11]. |

| Clone Self-Interaction Biolayer Interferometry (CSI-BLI) [11] | Real-time observation of mAb self-association and dissociation using BLI. | Binding Response (nm) | Correlated with other self-interaction assays but not with mouse clearance rate [11]. |

Table 2: Aptamer vs. Antibody: A Bioreceptor Comparison [10]

| Feature | Aptamers | Antibodies |

|---|---|---|

| Nature | Short ssDNA or RNA oligonucleotides | Large protein molecules (~150 kDa) |

| Production | Fully synthetic via SELEX | Biological (immunization, hybridoma, cell culture) |

| Development Time | Weeks | Months |

| Batch Consistency | High (chemical synthesis) | Variable (biological expression) |

| Stability | Stable to pH, heat; reversible folding | Sensitive to temperature, pH; irreversible denaturation |

| Immunogenicity | Very Low | May trigger immune responses |

| Target Range | Proteins, small molecules, ions, non-immunogenic targets | Mostly proteins and larger antigens |

| Tissue Penetration | Better (small size) | Limited (large size) |

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Assessing Cross-Binding

Protocol 1: Poly-Specificity Reagent (PSR) Binding Assay

The PSR assay is a high-throughput method to predict promiscuous cross-reactivity early in the discovery phase [11].

- PSR Preparation: A polyspecificity reagent is created, often comprising a cocktail of soluble membrane proteins (SMP) or other diverse non-cognate proteins to mimic a complex biological environment.

- Immobilization: The PSR is immobilized onto a solid support, such as an ELISA plate or the surface of a yeast cell.

- Antibody Incubation: The candidate monoclonal antibody (mAb) is added and allowed to bind. The mAb can be directly labeled or detected using a labeled secondary antibody.

- Signal Measurement: Binding is quantified via median fluorescence intensity (MFI) in a flow cytometry setup or by colorimetric/chemiluminescent readout in ELISA.

- Data Interpretation: A high MFI value indicates a "sticky" antibody with a high propensity for non-specific cross-binding. A cutoff value (e.g., MFI of 500) can be established to classify high- and low-risk candidates, with high-binders showing strong correlation to faster serum clearance in vivo [11].

Protocol 2: Cross-Interaction Chromatography (CIC)

CIC assesses weak cross-interactions under flowing conditions, predicting solubility issues [11].

- Column Preparation: A chromatography column is packed with a resin coupled to human serum polyclonal antibodies or other complex protein mixtures.

- Sample Injection: The candidate mAb is injected into the column using an HPLC system.

- Chromatographic Run: The mAb is eluted with an appropriate buffer, and its retention time is precisely measured.

- Data Interpretation: Late elution time indicates strong non-specific interaction with the immobilized proteins on the column. This prolonged retention is a key indicator of poor developability and has shown a significant correlation with faster clearance in mouse models [11].

Protocol 3: High-Throughput Kinetics Analysis with Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR)

Modern SPR systems like the Carterra LSA enable simultaneous kinetic screening of hundreds of interactions, moving beyond single-characterization analyses [12].

- Sample Expression: Candidate antibodies (e.g., Fab fragments) are expressed in a high-throughput system, such as Brevibacillus in 96-well plates.

- Immobilization: Antibodies from culture supernatants are captured in a multiplexed array on a sensor chip functionalized with nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA) for his-tagged proteins.

- Kinetic Injection: The antigen(s) of interest are flowed over the chip at multiple concentrations in a serial dilution.

- Data Analysis: The instrument measures association and dissociation in real-time, calculating the association rate constant (

k_on), dissociation rate constant (k_off), and equilibrium dissociation constant (K_D). - Cross-Reactivity Screening: This system can efficiently profile an antibody's binding kinetics not only against the intended target but also against related off-target proteins (e.g., mouse vs. human homologs), identifying variants with undesired cross-binding or improved cross-reactivity for translational research [12].

Protocol 4: SELEX and Post-SELEX Optimization for Aptamers

For aptasensors, minimizing cross-binding is engineered during the selection and optimization process [10].

- Library Incubation: A vast library of single-stranded DNA or RNA sequences (10^13–10^15 different molecules) is incubated with the target molecule.

- Partitioning: Target-bound sequences are separated from unbound sequences. Techniques like Capillary Electrophoresis (CE-SELEX) are highly efficient, separating complexes based on migration rates under a high-voltage electric field [10].

- Amplification: The bound sequences are amplified by PCR (for DNA) or RT-PCR (for RNA) to create an enriched pool for the next selection round.

- Counter-Selection: To reduce cross-binding, the library is pre-incubated with non-target molecules (e.g., structural analogs or sample matrix components) to remove sequences that bind non-specifically. This step is crucial for enhancing specificity.

- Post-SELEX Truncation: After selection, the full-length aptamer can be computationally and experimentally analyzed to identify the minimal functional sequence. This truncation often improves specificity and reduces synthesis cost without compromising affinity [10].

Workflow Visualization for Cross-Binding Assessment

The following diagram illustrates the integrated experimental workflow for evaluating antibody and aptamer cross-binding, from initial screening to structural analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Technologies

Successful assessment of cross-binding relies on a suite of specialized reagents and platforms.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Cross-Binding Analysis

| Reagent / Technology | Function in Cross-Binding Assessment |

|---|---|

| Poly-Specificity Reagent (PSR) [11] | A complex protein mixture used as a surrogate for non-specific interactions; high binding predicts poor developability. |

| Brevibacillus Expression System [12] | Enables high-throughput secretory expression of Fab antibodies in 96-well format for parallel kinetic and sequence analysis. |

| Carterra LSA SPR Platform [12] | A high-throughput SPR instrument capable of simultaneously immobilizing and measuring kinetics for up to 384 antibodies in a single run. |

| HRP-Streptavidin Conjugates | Common detection module for biotin-labeled aptamers in ELISA-style assays and lateral flow aptasensors. |

| Nitrilotriacetic Acid (NTA) Sensor Chip [12] | Used for his-tagged protein immobilization in SPR, enabling capture-based kinetics screening from crude supernatants. |

| Graphene Oxide (GO) [13] | A 2D nanomaterial used in fluorescent aptasensors; it quenches fluorophore-labeled aptamers and protects them from nuclease digestion. |

| RosettaDock Software [14] | A computational cross-docking suite for predicting antibody-antigen complex structures and discriminating cognate from non-cognate binders. |

| CRISPR-Cas12a System [13] | Integrated into aptasensors for signal amplification; upon target binding, Cas12a's collateral cleavage activity produces a fluorescent signal. |

The strategic assessment of cross-binding is a cornerstone of developing reliable biosensors. Experimental data demonstrates that high-throughput assays like PSR binding and CIC provide powerful, correlative predictions of in vivo antibody behavior, specifically clearance rates. The integration of advanced technologies such as high-throughput SPR and computational docking offers unprecedented depth in profiling kinetic parameters and structural determinants of cross-reactivity. For aptasensors, the SELEX process inherently incorporates counter-selection and post-SELEX optimization to engineer high specificity. By leveraging the comparative data and detailed protocols outlined in this guide, researchers can make informed, data-driven decisions to select and optimize lead bioreceptors, ultimately de-risking the path from laboratory discovery to a successful commercial biosensor.

The accuracy of a diagnostic test or the efficacy of a therapeutic agent is fundamentally governed by the specificity of its recognition element. For decades, antibodies have been the gold standard in molecular recognition, yet their inherent cross-reactivity with structurally similar molecules often compromises result accuracy. In recent years, nucleic acid aptamers have emerged as powerful alternatives, with their unique folding and recognition principles offering a pathway to unprecedented specificity. This guide provides a objective comparison between these two classes of recognition elements, focusing on their performance in scenarios demanding high specificity, with particular emphasis on cross-reactivity assessment in biosensor research.

Aptamers are single-stranded DNA or RNA oligonucleotides that bind to specific targets with high affinity and specificity through their unique three-dimensional structures [10]. Their binding to target molecules occurs through various forces, including van der Waals forces, hydrogen bonding, and electrostatic interactions [10]. Unlike antibodies, which are large protein molecules (~150 kDa) produced biologically, aptamers are typically short (20-80 nucleotides), fully synthetic molecules with better stability, lower production costs, and minimal batch-to-batch variability [10] [15]. Most significantly, the SELEX (Systematic Evolution of Ligands by Exponential Enrichment) process used for aptamer selection incorporates intentional counter-selection steps against non-target analogs, enabling the identification of receptors capable of distinguishing between molecules differing by only a single functional group [3].

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Aptamers and Antibodies

| Feature | Aptamers | Antibodies |

|---|---|---|

| Nature | Short ssDNA or RNA oligonucleotides | Large protein molecules (~150 kDa) |

| Production | Fully synthetic via SELEX | Biological (immunization and cell culture) |

| Development Time | Weeks | Months |

| Batch Consistency | High (chemical synthesis) | Variable (biological expression) |

| Size | Small (5-15 kDa) | Large (~150 kDa) |

| Target Range | Proteins, small molecules, ions, non-immunogenic targets | Mostly proteins and larger antigens |

| Stability | Stable to pH, heat; reversible folding | Sensitive to temperature, pH; irreversible denaturation |

| Modification | Easily and precisely modified | Modifications more limited and complex |

| Immunogenicity | Very low | May trigger immune responses |

| Specificity Engineering | Counter-SELEX enables discrimination of closely related analogs | Limited by immunological recognition |

Structural Foundations: How Folding Governs Specificity

Aptamer Folding and Binding Mechanisms

The exceptional specificity of aptamers originates from their ability to fold into defined three-dimensional structures that create complementary binding surfaces for their targets. This folding is characterized by the formation of secondary structure elements including hairpins, inner loops, pseudoknots, bulges, and G-quadruplexes [10]. The resulting three-dimensional conformation allows aptamers to adapt to target molecules of various sizes through distinct mechanisms. When binding small molecules, the aptamer typically wraps around and covers the target surface. For larger targets like proteins, aptamers form adaptive structures that fit into clefts and gaps on the target surface [10]. This flexible recognition mechanism stands in contrast to the more constrained paratope-epitope interaction of antibodies, contributing to the ability of aptamers to recognize subtle structural differences among target analogs.

The folding and stability of aptamer structures are influenced by environmental conditions, particularly the presence of monovalent or divalent cations in buffer solutions that can significantly reduce non-specific binding [10]. This environmental sensitivity represents both a challenge and an opportunity—while requiring optimized conditions for consistent performance, it also enables fine-tuning of aptamer specificity for particular applications through controlled buffer conditions.

Antibody Binding Structure

Antibodies recognize their targets through complementarity-determining regions (CDRs) within the Fab portion of the molecule, which form a binding pocket for specific epitopes on the antigen. While this system provides high affinity in many cases, the structural constraints of the immunoglobulin fold limit the ability to distinguish between closely related small molecules that share similar epitopes. This fundamental limitation manifests practically in the significant cross-reactivity observed with antibody-based sensors for small molecule targets, particularly problematic in applications like antibiotic residue detection in food samples [3].

Direct Performance Comparison: Experimental Specificity Data

Case Study: Sulfamethazine Detection

A compelling example of the specificity advantage of aptamers comes from the detection of sulfamethazine (SMZ), an antibiotic where accurate monitoring requires discrimination from numerous structurally similar sulfonamides. Researchers developed a chemiluminescence aptasensor using aptamers selected with an intentional counter-selection against other sulfonamides [3]. The results demonstrated remarkable specificity: the aptasensor achieved detection of SMZ with negligible cross-reactivity across 27 tested sulfonamides, a level of discrimination described as "impossible to achieve" with antibodies [3].

Table 2: Experimental Cross-Reactivity Comparison for Sulfamethazine Detection

| Parameter | Aptamer-Based Sensor | Typical Antibody-Based Sensors |

|---|---|---|

| Detection Limit | 0.92 ng/mL | Variable (typically similar sensitivity) |

| Cross-Reactive Compounds | 0 out of 27 sulfonamides | Multiple, especially sulfamerazine (SMR) |

| Differentiation Capability | Distinguishes single methyl group differences | High cross-reactivity with analogs sharing similar epitopes |

| Specificity Control in Production | Counter-SELEX during selection | Limited by immunological recognition |

| Recognition Element Affinity | Kd = 79-274 nM (nanomolar range) | Typically nanomolar affinity |

The fundamental difference lies in the production process: while antibody generation relies on biological immune responses that naturally recognize common structural motifs, the SELEX process allows for intentional counterselection against non-target analogs, actively eliminating candidates that cross-react with similar structures [3]. This systematic approach to specificity engineering enables aptamers to achieve discrimination between molecules differing by only a methyl group, a challenge that remains problematic for antibody-based approaches [3].

Broader Specificity Comparisons Across Targets

The specificity advantages extend beyond small molecules to complex targets. Aptamers selected against cellular targets demonstrate the ability to distinguish between closely related cell types based on subtle differences in surface marker expression [16]. Furthermore, in the detection of marine biotoxins, aptamers have shown the capability to distinguish chiral molecules and analogs with minimal structural differences, a level of specificity rarely achieved by antibodies [17]. This high specificity persists across various detection platforms, including colorimetric, fluorescence, electrochemical, and plasmonic aptasensors [18] [19].

Methodologies: Experimental Protocols for Specificity Assessment

Aptamer Selection with Specificity Engineering

The SELEX process can be modified to prioritize specificity through several methodological approaches:

MB-SELEX with Counter-Selection:

- Immobilization: Covalently conjugate the target molecule to magnetic beads using appropriate coupling chemistry (e.g., HATU for amine coupling) [3].

- Positive Selection: Incubate the random ssDNA library (typically 10-100 nmoles) with target-conjugated beads in selection buffer (e.g., HEPES with MgCl₂) for 30-60 minutes at controlled temperature [3].

- Washing: Remove unbound sequences with multiple buffer washes under increasingly stringent conditions.

- Elution: Heat elution (70-95°C) or competitive elution with free target to recover bound sequences.

- Counter-Selection: Incubate eluted sequences with beads conjugated to structural analogs (e.g., other sulfonamides for SMZ selection) and collect the unbound fraction [3].

- Amplification: PCR amplification of counter-selected pool using biotinylated or labeled primers for strand separation.

- Iteration: Typically 8-15 rounds with increasing stringency and alternating counter-selection targets.

Critical Parameters for Specificity:

- Counter-Selection Timing: Introduce counter-selection after 2-3 initial rounds to eliminate cross-reactive binders early [3].

- Stringency Control: Gradually decrease target concentration (from μM to nM) and increase wash stringency in later rounds.

- Analog Selection: Use the most structurally similar analogs for counter-selection to force discrimination of minimal differences.

Cross-Reactivity Testing Protocol

To objectively compare specificity between aptamer and antibody-based sensors:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare serial dilutions of primary target and structurally related analogs in relevant matrix (buffer, serum, milk, etc.).

- Dose-Response Curves: For each compound, measure sensor response across a concentration range (typically 0.1-100× KD value).

- Cross-Reactivity Calculation: Determine IC50 values for each compound and calculate % cross-reactivity as (IC50 target / IC50 analog) × 100%.

- Statistical Analysis: Perform replicates (n≥3) to establish significance of discrimination capability.

This protocol revealed that while antibody-based sensors for SMZ showed significant cross-reactivity with sulfamerazine (differing by one methyl group), aptamer-based sensors achieved negligible cross-reactivity across 27 sulfonamides [3].

Visualization: Specificity Engineering in Aptamer Development

Diagram 1: Specificity Engineering in SELEX. The SELEX process intentionally incorporates counter-selection rounds where potential aptamers binding to structural analogs are systematically discarded, enabling isolation of sequences with exceptional specificity.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Specificity Research

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Specificity Assessment

| Reagent/Material | Function in Specificity Research | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Structural Analogs | Counter-selection during SELEX; cross-reactivity testing | Critical for specificity engineering; purity essential |

| Magnetic Beads (Streptavidin/Carboxyl) | Target immobilization for SELEX | Enable efficient partitioning; various sizes available |

| HATU Coupling Reagent | Immobilization of small molecules on beads | Enables high coupling ratio for amine-containing targets |

| Modified Primers (Biotin/FAM) | Library amplification and detection | Biotin for bead separation; FAM for fluorescence detection |

| HEPES Buffer with Mg²⁺ | Folding buffer for aptamers | Divalent cations often crucial for proper aptamer structure |

| SPR/Chip Surfaces | Real-time binding kinetics measurement | Gold standard for affinity/specificity characterization |

| Next-Generation Sequencing | High-throughput pool characterization | Identifies enriched motifs; enables machine learning approaches |

The experimental evidence clearly demonstrates that while antibodies remain excellent recognition elements for many applications, aptamers offer distinct advantages in scenarios demanding exceptional specificity toward small molecules or the ability to discriminate between closely related structural analogs. The key differentiator lies in the production process: SELEX enables systematic engineering of specificity through counter-selection, while antibody production remains constrained by the biological immune response.

For researchers developing sensors for targets with many structural analogs (e.g., antibiotics, toxins, neurotransmitters) or requiring minimal cross-reactivity, aptamers provide a compelling alternative. The emerging integration of machine learning approaches with aptamer development further enhances this specificity advantage, enabling in silico prediction and refinement of aptamer sequences to optimize target discrimination [20]. As the field advances, the strategic selection between these recognition elements should be guided by the specific specificity requirements of the application, with aptamers representing the superior choice for the most challenging discrimination tasks.

Cross-reactivity, the binding of a recognition element to non-target molecules with structural similarities to the intended target, is a critical parameter in the development of sensitive and specific detection assays. This comparative analysis examines the inherent cross-reactivity profiles of antibodies and aptamers, two fundamental classes of binding reagents. Through evaluation of their respective development paradigms, structural characteristics, and experimental performances, this guide provides researchers with a structured framework for selecting appropriate reagents based on assay specificity requirements. Evidence from direct comparative studies indicates that while both reagents can exhibit cross-reactivity, the in vitro selection process of aptamers offers distinct advantages for engineering precise specificity profiles, particularly for challenging targets like small molecules and toxic compounds.

In the realms of diagnostics, therapeutics, and basic research, the accuracy of molecular detection hinges on the specificity of the binding reagents employed. Cross-reactivity occurs when a binding reagent, such as an antibody or aptamer, interacts with off-target analytes that share structural epitopes with the primary target [1]. This phenomenon can lead to false-positive signals, reduced assay sensitivity, and inaccurate research or clinical conclusions [1]. For researchers developing immunosensors (utilizing antibodies) or aptasensors (utilizing aptamers), understanding the inherent cross-reactivity profiles of these reagents is paramount.

The structural basis for cross-reactivity differs between antibodies and aptamers. Antibodies, developed in vivo, recognize specific epitopes on antigens, but conserved epitopes across related proteins or species can lead to cross-reactivity [21]. A single amino acid variation within a binding epitope can significantly alter binding affinity, though identical sequences do not guarantee cross-reactivity, as demonstrated in studies of ophthalmic antibody drugs [21]. Aptamers, selected in vitro through the Systematic Evolution of Ligands by EXponential enrichment (SELEX) process, form specific three-dimensional structures that bind their targets. Their selection process can be strategically designed to discriminate between closely related molecules by incorporating counter-selection steps against non-targets [21] [22].

This guide provides an objective comparison of antibody and aptamer cross-reactivity, supported by experimental data and methodological protocols, to inform reagent selection in sensor research and drug development.

Fundamental Differences Impacting Cross-Reactivity

The foundational differences in the origin, development, and physicochemical properties of antibodies and aptamers directly influence their propensity for cross-reactivity.

Origin and Development Paradigm

The development process is a primary factor dictating the specificity landscape of a binding reagent.

- Antibody Development (In Vivo): Traditional monoclonal antibody production requires immunization of a host animal, triggering a complex biological immune response [21]. This process inherently selects for antibodies that bind immunogenic epitopes under physiological conditions. Consequently, it is difficult to generate antibodies against non-immunogenic targets, such as small molecules (<600 Daltons) or highly toxic compounds, as they will not elicit a robust immune response [21]. The in vivo environment limits direct control over the fine specificity of the resulting antibodies.

- Aptamer Development (In Vitro): Aptamers are developed entirely in vitro via the SELEX process [22] [23]. This involves iterative rounds of selection against a target, amplification of binding sequences, and, crucially, counter-selection against non-targets. This allows researchers to actively shape the specificity profile by discarding aptamers that bind to structurally similar, non-target compounds [21]. The process can be performed under non-physiological conditions (e.g., specific pH, temperature, or buffer compositions), further enabling the selection of aptamers with tailored performance characteristics [21].

Structural and Physical Properties

The molecular structure of these reagents affects their interaction with targets.

- Size: A typical IgG antibody is large (~150-170 kDa), whereas an aptamer is significantly smaller (~12-30 kDa) [21] [22]. This size difference influences steric hindrance and access to sterically constrained epitopes.

- Stability and Renaturation: Antibodies are proteins susceptible to irreversible denaturation under harsh conditions (e.g., high temperature, extreme pH) [21] [22]. Once denatured, they typically cannot regain function. In contrast, aptamers are nucleic acid-based and can often be renatured after denaturation by reverting to permissive conditions, allowing for reagent reuse and more stringent elution protocols in assays [22].

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Antibodies and Aptamers

| Characteristic | Antibodies | Aptamers | Impact on Cross-Reactivity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Development Process | In vivo (Immune system) | In vitro (SELEX) | SELEX allows for positive/negative selection to enhance specificity [21]. |

| Development Time | ~4-6 months [21] | ~1-3 months [21] | Faster iteration for specificity optimization. |

| Minimum Target Size | ≥ 600 Daltons [21] | ≥ 60 Daltons [21] | Aptamers can be developed for small molecules, reducing need for cross-reactive assays. |

| Stability | Sensitive to heat/pH; irreversible denaturation [21] | Stable at ambient temperature; can be refolded if denatured [21] [22] | Enables use of harsh conditions to eliminate weak, cross-reactive binding. |

| Production | Biological (cell culture); risk of batch-to-batch variation [21] | Chemical synthesis; high batch-to-batch consistency [21] [22] | Consistent specificity across production lots. |

Experimental Data and Performance Comparison

Direct comparative studies and specific investigations highlight the practical implications of these fundamental differences on assay performance.

Evidence from Comparative Studies

A head-to-head comparison of aptamer-based (SOMAscan) and antibody-based (immunoassay) platforms for quantifying biomarkers in chronic kidney disease patients revealed variable correlations, dependent on the specific analyte [24]. For instance, out of eight immune biomarkers analyzed, four (IL-8, TNFRSF1B, TNFRSF1A, and suPAR) showed non-negligible to strong correlations (r = 0.23 to 0.93) between the two methods, while others (IFN-γ, IL-10, TNF-α) showed negligible correlation (r < 0.1) [24]. This suggests that the specificity and cross-reactivity profiles are target-dependent, and the choice of platform can significantly influence the resulting data.

Control and Modulation of Cross-Reactivity

Research demonstrates that cross-reactivity is not an immutable, intrinsic property of the binding reagent but can be modulated by assay conditions.

- For Antibodies: A study on immunoassays for sulfonamides and fluoroquinolones demonstrated that the cross-reactivity of the same antibodies could be altered by changing the assay format and reagent concentrations [1]. Assays with sensitive detection (utilizing low concentrations of antibodies and competing antigens) exhibited lower cross-reactivity and were more specific than assays requiring high reagent concentrations [1]. This indicates that careful optimization of immunoassay conditions can help mitigate undesirable cross-reactivity.

- For Aptamers: The evolutionary selection process of aptamers can be directly harnessed to engineer cross-reactivity profiles. A study successfully developed a sensor array from a pool of DNA sequences to achieve perfect classification of four different steroids [25]. The individual sensors were selected under pressure to interact with all four steroids, demonstrating that aptamer cross-reactivity can be intentionally optimized for applications requiring class-specific detection (e.g., detecting a family of related contaminants) rather than analyte-specific detection [25].

Table 2: Experimental Comparison of Cross-Reactivity Performance

| Aspect | Antibodies | Aptamers | Experimental Support |

|---|---|---|---|

| Specificity Control | Limited by immunogenicity; optimized via assay conditions [1]. | Directly engineered during SELEX via counter-selection [21]. | Selection against non-targets yields highly selective aptamers [21]. |

| Class vs. Analyte Specificity | Primarily analyte-specific; cross-reactivity can be an issue. | Can be designed for either class- or analyte-specificity [25]. | Sensor array built to discriminate steroid classes [25]. |

| Interference | Susceptible to heterophilic antibodies, HAMA, rheumatoid factor [21]. | No interference from endogenous antibodies [21]. | Eliminates a major source of false positives in clinical samples [21]. |

| Correlation with Alternate Platforms | Variable, analyte-dependent correlation with aptamer-based measurements [24]. | Strong correlation with immunoassays for some, but not all, targets [24]. | IL-8, TNFRSF1B showed strong correlation (r>0.9); TNF-α showed no correlation [24]. |

Methodological Protocols for Assessing Cross-Reactivity

Standardized experimental protocols are essential for rigorously evaluating the cross-reactivity of any binding reagent.

Standard Cross-Reactivity Testing

The established method for quantifying cross-reactivity in competitive assay formats (common for small molecule detection) uses the following formula [1]: Cross-reactivity (CR) = [IC₅₀ (Target Analyte) / IC₅₀ (Tested Cross-Reactant)] × 100% The IC₅₀ is the concentration of the analyte that causes a 50% reduction in the maximum assay signal. A lower CR percentage indicates higher specificity for the target over the cross-reactant.

Protocol: SELEX for High-Specificity Aptamers

The following methodology, adapted from a study selecting aptamers against an antibody target, minimizes non-specific binding and enhances specificity [26].

- Target Immobilization: Adsorb the target protein (e.g., 10 µg/mL in carbonate buffer) to the surface of a PCR tube for 1-2 hours at room temperature.

- Negative Selection (Counter-Selection): To eliminate non-specific binders, incubate the random ssDNA library (e.g., a 25-70 nt degenerate sequence flanked by primer sites) with a non-target surface or a mixture of related non-target proteins. Collect the unbound sequences.

- Positive Selection: Incubate the pre-cleared library with the immobilized target. Wash thoroughly to remove weakly bound or unbound sequences.

- Elution and Amplification: Elute specifically bound sequences. This can be achieved through denaturation (e.g., in the first PCR cycle) or competitive elution with the free target. Amplify the eluted sequences via PCR (for DNA aptamers) or RT-PCR (for RNA aptamers) to create a new, enriched library for the next round.

- Stringency Increase: Repeat steps 2-4 for 10-15 rounds, progressively increasing stringency by reducing incubation time, increasing wash stringency, and/or reducing target concentration.

- Characterization: Clone and sequence the final pool. Characterize individual aptamer candidates using techniques like fluorescence quenching, ELISA, and surface plasmon resonance (SPR) to determine affinity (Kd) and specificity [26].

Figure 1: The SELEX workflow for selecting high-specificity aptamers. Key steps like negative selection (counter-selection) are critical for minimizing cross-reactivity [22] [26] [23].

Protocol: Modifying Immunoassay Conditions to Reduce Cross-Reactivity

As demonstrated in [1], the cross-reactivity of an antibody can be optimized for the assay context.

- Reagent Concentration Titration: Implement a checkerboard titration of the capture and detection antibodies. Using the lowest possible concentrations of these reagents that still yield a robust signal can significantly improve specificity and reduce cross-reactivity [1].

- Assay Format Comparison: If possible, test the same antibody pair in different assay formats (e.g., ELISA vs. fluorescence polarization immunoassay). More sensitive formats that operate at lower reagent concentrations may inherently exhibit lower cross-reactivity [1].

- Kinetic vs. Equilibrium Measurements: The degree of cross-reactivity can vary between kinetic and equilibrium phases of the antigen-antibody reaction. Monitoring the assay signal at different time points can reveal optimal readout times for discriminating the target from cross-reactants [1].

Figure 2: A workflow for modulating antibody cross-reactivity through assay condition optimization. Shifting to lower reagent concentrations and more sensitive formats reduces cross-reactivity [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential materials and their functions for researchers working in this field.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Cross-Reactivity Assessment

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research and Development |

|---|---|

| Oligonucleotide Library | A synthetic pool of random-sequence ssDNA or RNA (typically 10^14-10^15 diversity) serving as the starting point for SELEX [22] [23]. |

| SELEX Counter-Targets | Structurally related non-target molecules used during negative selection to purge cross-reactive aptamers from the library [21]. |

| Immobilization Supports | Solid surfaces (e.g., PCR tubes, beads, chips) for immobilizing the target during SELEX or for assay development (ELASA, biosensors) [22] [26]. |

| Modified Nucleotides | Chemically altered nucleotides (e.g., SOMAmers) that introduce hydrophobic moieties, expanding the structural diversity and target range of aptamers, particularly for proteins [23] [24]. |

| Hapten-Carrier Conjugates | Conjugates of small molecules (haptens) to immunogenic carrier proteins, essential for generating antibodies against non-immunogenic targets [21]. |

| Anti-Animal Antibodies | Secondary antibodies used in immunoassays; a source of interference (e.g., HAMA) that can mimic cross-reactivity in clinical samples [21]. |

| Reference Cross-Reactants | Purified, structurally analogous compounds to the primary target, essential for empirical measurement of cross-reactivity percentages [1]. |

The choice between antibodies and aptamers involves a careful consideration of their inherent cross-reactivity profiles, guided by the specific application needs.

- Aptamers offer a superior level of control over specificity from the outset of development. The in vitro SELEX process, particularly with counter-selection, allows for the direct engineering of high-specificity binders, even for challenging targets like small molecules and toxins [21] [22]. Their chemical nature and small size also avoid common interference issues from endogenous antibodies [21].

- Antibodies remain powerful reagents, especially for in vivo applications where their longer circulating half-life can be beneficial. However, their in vivo production limits target scope and can make obtaining highly specific clones against conserved epitopes challenging [21]. While cross-reactivity can be mitigated through careful assay optimization [1], it is not as programmable as with aptamers.

Concluding Guidance for Researchers

For research and diagnostic applications where discriminating between highly homologous targets is critical (e.g., specific hormone isoforms, phosphorylated proteins, or specific drug metabolites), aptamers present a compelling choice due to the programmability of their specificity. Their lower cost, higher batch-to-batch consistency, and stability further support their use in standardized assays and biosensors [21] [22] [23].

For applications where the target is highly immunogenic and a class-specific response is acceptable, or where established, high-quality antibody reagents already exist, antibodies remain a viable option. However, researchers must rigorously validate antibodies for cross-reactivity within their specific assay system, acknowledging that this profile is not fixed but can vary with experimental conditions [1].

In conclusion, while both molecular recognition elements can exhibit cross-reactivity, the in vitro evolution of aptamers provides a more direct and controllable path to achieving high specificity, making them increasingly advantageous for the next generation of precise molecular detection tools.

The Impact of Cross-Reactivity on Diagnostic Accuracy and False Positives

Cross-reactivity represents a fundamental challenge in the development of precise diagnostic biosensors, directly impacting their accuracy and potential for generating false-positive results. This phenomenon occurs when a biorecognition element binds not only to its intended target but also to structurally similar molecules, leading to erroneous signals and compromised diagnostic reliability. In clinical and research settings, false positives stemming from cross-reactivity can trigger unnecessary treatments, patient anxiety, and increased healthcare costs, while false negatives may allow diseases to go undetected.

The selection between immunosensors (utilizing antibodies) and aptasensors (utilizing nucleic acid aptamers) represents a critical decision point in diagnostic development, with significant implications for cross-reactivity profiles. Antibodies, with their complex protein structures and biological origins, interact with targets through diverse molecular forces, while aptamers, as synthetically produced oligonucleotides, employ distinct binding mechanisms influenced by their three-dimensional folding. This guide objectively compares the cross-reactivity performance of these two prominent biosensing platforms, providing researchers with experimental data and methodological frameworks to inform their diagnostic development strategies.

Fundamental Differences Between Immunosensors and Aptasensors

Immunosensors and aptasensors differ fundamentally in their biorecognition elements, which directly influences their susceptibility to cross-reactivity. Antibodies are relatively large (∼150 kDa for whole IgG) Y-shaped proteins produced by the immune system, recognizing targets through their antigen-binding fragments [15]. Their binding interfaces are formed by complementarity-determining regions (CDRs) that create complex surfaces for molecular interaction. In contrast, aptamers are single-stranded DNA or RNA oligonucleotides (typically 15–100 bases) that fold into specific three-dimensional structures capable of binding targets with high specificity and affinity [27] [28]. These fundamental differences in composition, size, and origin establish distinct cross-reactivity profiles for each platform.

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Antibodies and Aptamers

| Characteristic | Antibodies (Immunosensors) | Aptamers (Aptasensors) |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Type | Proteins (IgG) | Single-stranded DNA or RNA |

| Size | ∼150 kDa (whole antibody) | 5–25 kDa |

| Production Method | Biological systems (hybridomas/animal hosts) | Chemical synthesis (SELEX in vitro) |

| Binding Mechanism | Surface complementarity via CDR regions | 3D structure folding & molecular affinity |

| Stability | Sensitive to temperature, prone to denaturation | Thermally stable, reversible denaturation |

| Modification | Limited, through protein engineering | Highly flexible (chemical modifications) |

| Cost & Reproducibility | Variable batch-to-batch, higher production costs | Excellent batch consistency, lower costs |

The production methodologies further differentiate these recognition elements. Antibodies are typically generated through biological systems, which can introduce variability between batches and limit the ability to fine-tune their specificity post-production [15]. Aptamers are developed through the Systematic Evolution of Ligands by Exponential Enrichment (SELEX) process, an in vitro selection technique that allows for precise control over selection conditions and target epitopes [28]. This synthetic production offers opportunities to manipulate cross-reactivity profiles by adjusting selection parameters, counter-selection steps, and using computational approaches to guide aptamer design [28].

Comparative Analysis of Cross-Reactivity Performance

Experimental Evidence from Diagnostic Applications

Direct comparisons of immunosensor and aptasensor performance reveal significant differences in cross-reactivity profiles across various diagnostic targets. In therapeutic drug monitoring, for instance, immunosensors for sulfonamide antibiotics demonstrate cross-reactivity patterns that vary substantially depending on assay format and reagent concentrations, with changes in reagent ratios altering cross-reactivity by up to five-fold [1]. This concentration-dependent cross-reactivity behavior represents a critical consideration for researchers optimizing immunoassay conditions.

A comprehensive review of electrochemical biosensors for small molecule detection revealed that immunosensors generally achieve limits of detection (LOD) two to three orders of magnitude lower than aptasensors for the same targets, attributed primarily to the superior binding affinities of high-quality antibodies [29]. However, this enhanced sensitivity does not necessarily correlate with improved specificity, as antibodies may exhibit broader cross-reactivity with structurally related compounds. For example, in sulfonamide and fluoroquinolone detection, immunoassay cross-reactivity profiles were demonstrably modulated by simply shifting reagent concentrations or transitioning between equilibrium and kinetic measurement modes [1].

Viral detection platforms further highlight these trade-offs. SPR-based aptasensors for virus detection have demonstrated promising performance with a pooled sensitivity of 1.89 (95% CI: 1.29, 2.78) across multiple studies, indicating robust detection capabilities despite potential cross-reactivity challenges in complex samples [27]. The synthetic nature of aptamers enables strategic selection approaches like Toggle-SELEX, which intentionally cycles between related targets to generate either highly specific or broadly cross-reactive aptamers depending on diagnostic needs [28].

Quantitative Comparison of Cross-Reactivity Performance

Table 2: Experimental Cross-Reactivity Comparison for Selected Targets

| Target Compound | Biosensor Platform | Cross-Reactivity Profile | Key Structural Analogs with Cross-Reactivity | Limit of Detection |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tetracycline | Immunosensor | High variability (5-fold changes with conditions) | Multiple tetracycline antibiotics | 6 pg/mL (13 pM) |

| Tetracycline | Aptasensor | More consistent across platforms | Primarily oxytetracycline | 0.3 nM (0.1 ng/mL) |

| Sulfonamides | Immunosensor (FPIA/EIA) | Concentration-dependent (up to 5-fold difference) | Various sulfonamide antibiotics | nM range |

| Ochratoxin A | Immunosensor | Lower LOD, broader cross-reactivity | Ochratoxin B & other mycotoxins | ~1 ng·mL−1 |

| Ochratoxin A | Aptasensor | Higher LOD, narrower cross-reactivity | Limited structural analogs | ~nM range |

| Dengue Virus | Aptasensor (Electrochemical) | Minimal cross-reactivity with CHIKV | Chikungunya virus (tested) | 0.1 μg/mL |

The data reveal that immunosensors generally achieve lower detection limits but often with more variable cross-reactivity that is highly dependent on assay conditions. Aptasensors typically show more consistent cross-reactivity profiles across different platforms but may sacrifice some sensitivity. The synthetic production of aptamers enables more predictable cross-reactivity behavior, while antibodies offer superior affinity in optimized conditions but with greater variability between assay formats.

Methodological Approaches to Assess and Minimize Cross-Reactivity

Standard Experimental Protocols for Cross-Reactivity Assessment

Establishing standardized protocols for cross-reactivity evaluation is essential for meaningful comparison between biosensing platforms. The widely accepted approach involves measuring the response of the biosensor to both the target analyte and potential cross-reactants, calculating cross-reactivity as the ratio of concentrations causing equivalent signals [1]. For competitive assay formats, this is typically determined using the IC50 values:

Cross-reactivity (CR) = IC50(target analyte)/IC50(tested cross-reactant) × 100% [1]

Rigorous cross-reactivity assessment should include:

- Selection of Structurally Related Compounds: Testing analogs with highest structural similarity to the target

- Dose-Response Curves: Generating full concentration-response curves for each compound

- Matrix Effects Evaluation: Testing in sample matrices identical to intended application

- Cross-Platform Validation: Comparing performance across different sensor configurations

For immunosensors, particular attention should be paid to reagent concentrations, as studies demonstrate that simply shifting to lower antibody and antigen concentrations can significantly reduce cross-reactivity [1]. This concentration-dependent effect stems from the differential impact on high-affinity versus low-affinity subpopulations of antibodies and their relative contributions to signal generation.

Strategic Selection of Biorecognition Elements

The selection process for both antibodies and aptamers offers opportunities to manage cross-reactivity. For antibodies, recombinant fragments (scFv, Fab') with molecular weights of 30–50 kDa allow for more dense immobilization and potentially improved specificity compared to whole antibodies (150 kDa) [15]. Oriented immobilization techniques using protein A/G, Fc-specific binding, or engineered tags (e.g., Avi-Tag, polyhistidine) can enhance binding site accessibility and reduce non-specific interactions [15].

For aptamers, advanced SELEX methodologies provide powerful tools for cross-reactivity control:

- Counter-Selection: Including negative selection steps against common cross-reactants

- Toggle-SELEX: Alternating between related targets to generate either specific or cross-reactive aptamers [28]

- Capture-SELEX: Particularly effective for small molecules, selecting for structure-switching aptamers with enhanced specificity [28]

- In Silico Maturation: Computational modeling of aptamer-target interactions to refine specificity before synthesis [28]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Cross-Reactivity Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Cross-Reactivity Assessment | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Structural Analogs | Serve as cross-reactivity probes | Select compounds with incremental structural changes |

| Reference Standards | Provide benchmark for specificity comparison | Use certified reference materials when available |

| Surface Chemistry Kits | Enable controlled immobilization | Thiol-based for gold, amine-reactive for other surfaces |

| Magnetic Beads | Facilitate separation in SELEX/sandwich assays | Streptavidin-coated for biotinylated capture probes |

| Signal Amplification Reagents | Enhance detection sensitivity | Enzymatic (HRP), nanomaterial-based, or catalytic |

| Blocking Buffers | Reduce non-specific binding | BSA, casein, or specialized commercial formulations |

| Regeneration Solutions | Allow biosensor surface reuse | Mild acids/bases or specific elution buffers |

Effective cross-reactivity management requires appropriate surface immobilization strategies. For immunosensors, oriented immobilization using protein A/G or fragment-based approaches (e.g., Fab' thiol coupling) significantly improves antigen accessibility compared to random adsorption [15]. For aptasensors, thiol-gold chemistry remains predominant, but hybrid approaches incorporating mixed self-assembled monolayers (SAMs) can further reduce non-specific binding [30]. Recent advances in computational modeling of both antibody-paratope and aptamer folding interactions have enabled more predictive approaches to cross-reactivity management before experimental validation [28].

Cross-reactivity remains an inescapable consideration in biosensor development, with both immunosensors and aptasensors offering distinct advantages and limitations. Immunosensors generally provide superior sensitivity and established validation protocols but exhibit more variable cross-reactivity that is highly dependent on assay conditions. Aptasensors offer more consistent cross-reactivity profiles, greater engineering flexibility, and the ability to strategically design specificity during the selection process, though sometimes at the cost of ultimate sensitivity.

The choice between these platforms should be guided by the specific diagnostic application. For targets requiring ultra-sensitive detection in controlled environments, immunosensors may be preferable. For applications demanding consistent performance across multiple sites or testing platforms, or when targeting molecules that poorly immunize animals, aptasensors offer significant advantages. Emerging approaches that combine both recognition elements in hybrid designs may ultimately provide the optimal balance of sensitivity and specificity, leveraging the strengths of both platforms while mitigating their respective limitations related to cross-reactivity and false positives.

Methodologies and Real-World Applications in Specificity Assessment

Cross-reactivity is a fundamental performance parameter in immunoassays, defined as the ability of an antibody to bind with structurally similar compounds other than its primary target analyte [1]. For researchers and drug development professionals, accurately measuring cross-reactivity is crucial because it determines an assay's specificity and selectivity, indicating whether it can detect a single compound with high precision or a class of related molecules [31] [1]. In competitive immunoassays, cross-reactivity is typically calculated as the ratio of the half-maximal inhibition concentration (IC50) of the target analyte to the IC50 of the cross-reactant, expressed as a percentage: CR = IC50(target analyte)/IC50(tested cross-reactant) × 100% [1].

The significance of cross-reactivity extends beyond being an undesirable property to avoid. Strategic exploitation of cross-reactivity can transform immunoassays, enabling them to function similarly to selective arrays for detecting a range of analytes, thus improving diagnostic capabilities and surveillance [31]. However, cross-reactivity is not a fixed parameter determined solely by antibody characteristics but is significantly influenced by assay format, reagent concentrations, and experimental conditions [1]. This guide provides an objective comparison of three principal techniques—ELISA, FPIA, and SPR—for measuring cross-reactivity, supported by experimental data and methodological protocols to inform selection for specific research applications in immunosensors and aptasensors.

Comparative Analysis of Technical Principles

The fundamental principles of ELISA, FPIA, and SPR dictate their respective capabilities and limitations in cross-reactivity assessment. ELISA operates on the principle of detecting antigen-antibody interactions using enzyme-labelled conjugates and substrates that generate measurable color changes [32]. It exists in multiple formats—direct, indirect, and competitive—with the competitive format being particularly relevant for cross-reactivity testing of small molecules [32] [33]. As a heterogeneous assay, ELISA requires multiple washing and separation steps, which can preferentially remove low-affinity binders, potentially affecting cross-reactivity profiles [34].

FPIA is a homogeneous competitive immunoassay that measures changes in fluorescence polarization when a fluorescently-labeled tracer bound to an antibody experiences rotational diffusion changes upon binding [35]. The key advantage of FPIA lies in its homogenous format, requiring no separation steps, making it particularly suitable for detecting low-affinity interactions that might be lost during ELISA washing procedures [35]. The technique is highly dependent on tracer design, with spacer length between the fluorescein label and antigen significantly affecting assay sensitivity and specificity [35].

SPR represents a label-free detection methodology that measures real-time changes in refractive index at a sensor surface where biomolecular interactions occur [34]. This technique provides direct observation of binding events without requiring secondary labels, enabling determination of both binding affinity (KD) and kinetics (ka, kd) [34]. The ability to monitor interactions in real-time offers distinct advantages for characterizing cross-reactive binding, as the kinetic parameters can reveal important details about the nature of cross-reactive interactions that endpoint assays like ELISA might miss [36] [34].

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of ELISA, FPIA, and SPR

| Parameter | ELISA | FPIA | SPR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Principle | Enzyme-based colorimetric detection | Fluorescence polarization changes | Refractive index changes |

| Assay Format | Heterogeneous (requires separation) | Homogeneous (no separation) | Heterogeneous (surface-bound) |

| Measurement Type | End-point | Equilibrium | Real-time kinetics |

| Label Requirement | Yes (enzyme-conjugate) | Yes (fluorescent tracer) | Label-free |

| Throughput | High (96/384-well plates) | Medium to High | Low to Medium (multiple flow cells) |

| Low-Affinity Interaction Detection | Limited (washed away) | Excellent | Excellent |

Figure 1: Fundamental Detection Principles Across Immunoassay Platforms - This diagram illustrates how competitive binding between antigens and cross-reactants is translated into measurable signals through different physical principles in ELISA, FPIA, and SPR platforms.

Experimental Data and Performance Comparison

Quantitative comparison of ELISA, FPIA, and SPR reveals significant differences in sensitivity, specificity, and cross-reactivity profiles. A study comparing ELISA and SPR for detecting anti-drug antibodies demonstrated that SPR identified a positivity rate of 4%, compared to only 0.3% by ELISA, with SPR consistently showing higher sensitivity in detecting low-affinity interactions [34]. This enhanced sensitivity for low-affinity binders makes SPR particularly valuable for comprehensive cross-reactivity profiling.

Experimental data from pesticide detection illustrates notable sensitivity differences. In clothianidin detection, a noncompetitive phage ELISA (P-ELISA) demonstrated exceptional sensitivity with a half saturation concentration (SC50) of 0.45 ± 0.02 ng/mL, significantly lower than competitive P-ELISA (IC50 of 3.83 ± 0.23 ng/mL) [33]. The noncompetitive format also showed superior specificity with no cross-reactivity with analogs like imidaclothiz, nitenpyram, and imidacloprid, whereas competitive P-ELISA showed 2.6–18.2% cross-reactivity with these compounds [33].

FPIA has demonstrated excellent performance in real-sample analysis. A recently developed FPIA for 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D) detection achieved detection limits of 8 ng/mL and 0.4 ng/mL in juice and water samples, respectively, with recovery rates of 95-120% in spiked samples [35]. The entire assay required only 20 minutes, significantly faster than traditional ELISA methods [35].

Table 2: Experimental Performance Comparison Across Applications

| Application Target | Assay Format | Sensitivity (LOD/IC50) | Cross-Reactivity Profile | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deoxynivalenol (DON) in Wheat | SPR | Matrix effects too high for reliable use | Not determinable due to interference | [36] |

| Deoxynivalenol (DON) in Wheat | ELISA | LOD: 233 μg/kg (wheat), 458 μg/kg (wheat dust) | Linear correlation (r=0.889) between wheat and dust | [36] |

| Clothianidin Pesticide | Competitive P-ELISA | IC50: 3.83 ± 0.23 ng/mL | 2.6-18.2% cross-reactivity with analogs | [33] |

| Clothianidin Pesticide | Noncompetitive P-ELISA | SC50: 0.45 ± 0.02 ng/mL | No cross-reactivity with analogs | [33] |

| 2,4-D Herbicide | FPIA | LOD: 0.4 ng/mL (water), 8 ng/mL (juice) | Not specified; recovery: 95-120% | [35] |

| Anti-Drug Antibodies | SPR | 4% positivity rate | Enhanced detection of low-affinity interactions | [34] |

| Anti-Drug Antibodies | ELISA | 0.3% positivity rate | Limited detection of low-affinity interactions | [34] |

Matrix effects present significant challenges in cross-reactivity assessment, particularly for SPR. In DON screening, SPR demonstrated substantial matrix interference from wheat and wheat dust, making the method unreliable without extensive sample cleanup [36]. In contrast, ELISA and BLI methods were successfully validated according to Commission Regulation 519/2014/EC and Commission Decision 2002/657/EC criteria, demonstrating better matrix tolerance [36].

The impact of assay format on cross-reactivity is further evidenced by research showing that cross-reactivity is not an intrinsic antibody property but varies significantly with assay format and reagent concentrations [1]. Studies with sulfonamides and fluoroquinolones demonstrated that shifting to lower reagent concentrations decreased cross-reactivities by up to five-fold, enabling modulation of immunodetection selectivity without changing binding reactants [1].

Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

ELISA Protocol for Cross-Reactivity Assessment

The standard protocol for competitive ELISA involves several critical steps. First, microplate coating is performed by adsorbing a known antigen (or antibody) to the solid phase, typically using 96-well polystyrene plates [32]. After overnight incubation at 4°C or 1-2 hours at 37°C, plates are washed with PBS-Tween buffer to remove unbound components [32]. A blocking step follows using proteins like BSA or casein to prevent nonspecific binding [32].

For the competitive reaction, a mixture of sample (or standard) and specific antibody is added to the wells and incubated for 1-2 hours at room temperature [32] [33]. After washing, an enzyme-labeled secondary antibody (e.g., horseradish peroxidase or alkaline phosphatase conjugate) is added for detection [32]. Following another wash, a chromogenic substrate (e.g., TMB for peroxidase or pNPP for phosphatase) is added, and the reaction is stopped after optimal color development [32]. The absorbance is measured at appropriate wavelengths (e.g., 450 nm for TMB), and data are analyzed by plotting a standard curve of absorbance versus analyte concentration to determine IC50 values for cross-reactivity calculation [32] [33].

FPIA Protocol for Cross-Reactivity Assessment

FPIA implementation begins with tracer preparation, where the target analyte is conjugated to a fluorescent dye (e.g., fluorescein) with carefully optimized spacer length [35]. The assay is performed by mixing fixed concentrations of antibody and tracer with varying concentrations of analyte or cross-reactants in appropriate buffers [35]. After a brief incubation period (typically 5-20 minutes), the fluorescence polarization is measured using a specialized reader [35].

The polarization values (mP units) are plotted against analyte concentration to generate a standard curve [35]. For cross-reactivity determination, the same procedure is repeated with structural analogs, and IC50 values are calculated for each compound [1]. Cross-reactivity percentages are then determined using the standard formula: (IC50 target analyte / IC50 cross-reactant) × 100% [1]. Sample preparation for FPIA typically involves simple dilution in buffer, though complex matrices may require additional cleanup [35].

SPR Protocol for Cross-Reactivity Assessment