Electrical Double Layer Capacitance and Signal Drift: Mechanisms, Measurement, and Mitigation in Biomedical Sensors

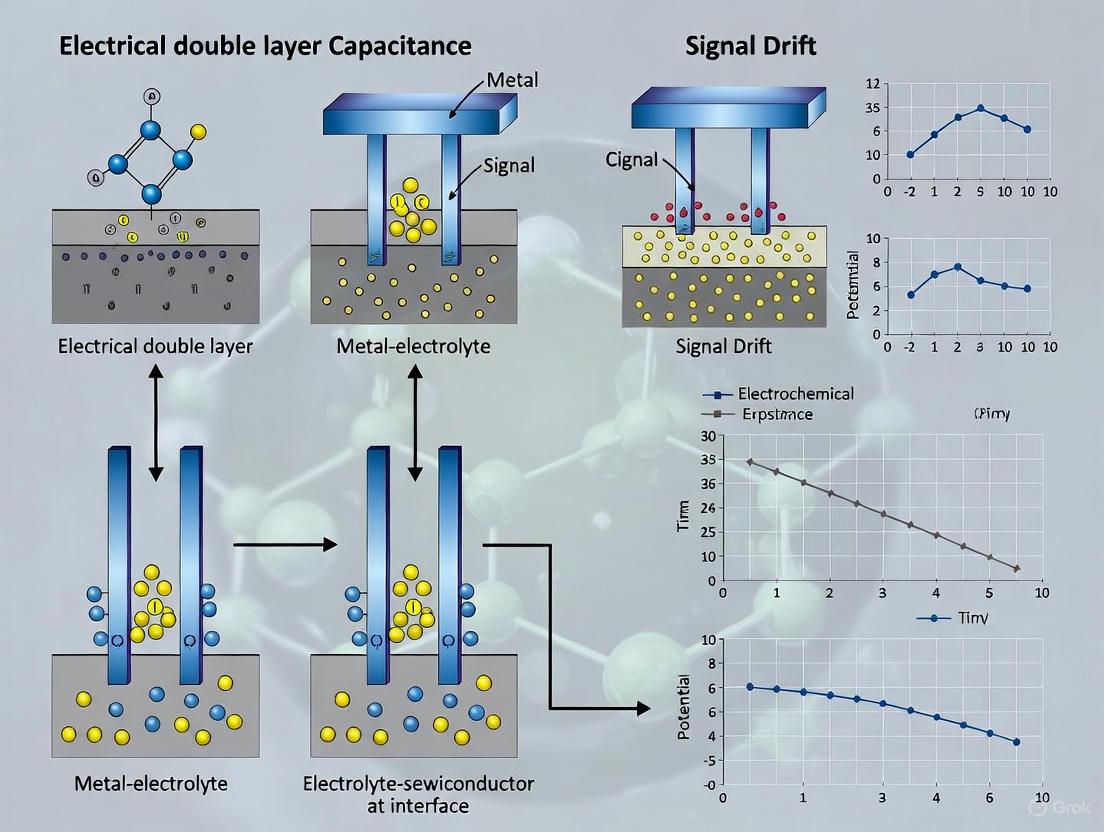

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the intricate relationship between electrical double layer capacitance (Cdl) and signal drift in electrochemical and transistor-based biosensors.

Electrical Double Layer Capacitance and Signal Drift: Mechanisms, Measurement, and Mitigation in Biomedical Sensors

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the intricate relationship between electrical double layer capacitance (Cdl) and signal drift in electrochemical and transistor-based biosensors. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the fundamental principles of the electrode-electrolyte interface, details advanced measurement techniques like EIS and CV, and systematically investigates the primary mechanisms behind signal degradation, including monolayer desorption and biofouling. The content further presents targeted strategies for drift mitigation and stabilization, evaluates the performance of various materials and sensor architectures, and discusses the implications for developing reliable, long-term in vivo monitoring and point-of-care diagnostic devices.

The Electrical Double Layer: Fundamental Principles and Its Role in Sensor Stability

The electrode-electrolyte interface is a critical region in electrochemical systems where charge carriers transition between electrons in a solid electrode and ions in an electrolyte solution. This interface governs performance across fields including biomedical sensing, energy storage, and neurostimulation [1] [2]. When a voltage is applied, charge distribution at this junction forms the electrical double layer (EDL), creating a capacitive effect known as the double layer capacitance (Cdl) [1].

Understanding Cdl is paramount for managing signal drift and stability in electrochemical devices. This in-depth technical guide examines the interface's fundamental principles, equivalent circuit models, characterization methods, and recent research advancements, providing researchers with the foundational knowledge needed to address challenges in signal integrity and measurement accuracy.

Core Theoretical Concepts

The Electrode-Electrolyte Interface and Double Layer Formation

The interface represents a phase boundary where charge carrier types change: electrons carry current in the electrode, while ions carry current in the electrolyte [1]. This transition imposes an impedance on current flow. The characteristics of this interface are crucial for recording high-quality signals such as electrocardiograms (ECGs) and for the operation of sensors and energy storage devices [1].

When a voltage is applied, a double layer of charge forms at the interface [1]. This structure comprises:

- Inner Helmholtz Plane (IHP): A monolayer of solvent molecules and anions adsorbed directly onto the electrode surface [1].

- Outer Helmholtz Plane (OHP): A layer of solvated cations attracted to the negatively charged electrode through the IHP [1].

This charge separation creates a capacitive effect, storing energy electrostatically much like a conventional capacitor, with the IHP acting as the dielectric [1].

Equivalent Circuit Model

The electrochemical properties of the interface are commonly described using an equivalent circuit model, which includes the double layer capacitance and other key components [1] [3].

Circuit Components and Their Significance:

- Double Layer Capacitance (Cdl): Represents the electrostatic charge storage at the interface. Its value depends on the electrode material, surface area, and electrolyte composition [1].

- Charge Transfer Resistance (Rct): Quantifies the resistance to current flow due to electrochemical reactions (Faradaic processes) at the interface. A lower Rct indicates easier charge transfer [1] [3].

- Spreading/Electrolyte Resistance (Rs): The series resistance from the electrolyte solution, leads, and contacts [1] [3].

- Half-cell Potential (Erev): The intrinsic equilibrium potential of the electrode material, measured relative to a standard reference electrode like the Standard Hydrogen Electrode (SHE) [1].

Frequency-Dependent Behavior of Cdl

The capacitive nature of the interface makes its impedance highly frequency-dependent [1]. At higher frequencies, the capacitive reactance of Cdl decreases, allowing current to pass more easily through this capacitive path. At lower frequencies, the higher capacitive reactance forces more current to pass resistively through Rct, which can lead to signal distortion in lower-frequency waveforms [1].

Signal Drift and Instability Mechanisms

Signal drift manifests as a gradual, unwanted change in the measured electrical signal over time, undermining measurement accuracy. Understanding its origins is essential for developing stable electrochemical devices.

- Charge Trapping in Substrate Defects: A primary cause of drift in devices like electrolyte-gated graphene field-effect transistors (EG-gFETs) is the trapping and slow release of charges at defect sites within the substrate material (e.g., silicon oxide) [2]. These trapped charges dope the channel electrostatically, shifting transfer characteristics.

- Unstable Half-Cell Potential: Electrodes with high or unstable half-cell potentials are prone to baseline wander (drift) and distortion. Any potential difference between electrodes is amplified along with the desired signal [1].

- Faradaic Leakage and Residual Voltage: In neurostimulation, even charge-balanced biphasic current pulses can leave a residual voltage across the interface due to the presence of the Faradaic impedance (Rct). This residual voltage can lead to continued electrochemical reactions and tissue damage [3].

The Critical Link Between Cdl and Drift

The stability of Cdl is intrinsically linked to signal drift. Changes in the interface properties—such as adsorption of species, surface oxidation, or ion intercalation—directly alter Cdl. This variability introduces a time-dependent element into the equivalent circuit, causing the measured signal to drift. Furthermore, the parallel Rct path allows for slow, persistent Faradaic currents that contribute to long-term drift by discharging the double layer or inducing DC offset voltages [2] [3].

Experimental Characterization and Protocols

Accurately measuring the properties of the electrode-electrolyte interface, particularly Cdl and Rct, is fundamental to research and development. The following section outlines standard and advanced experimental protocols.

Standard Bench Tests (AAMI EC12)

For patient monitoring electrodes, the ANSI/AAMI EC12 standard defines key tests to be performed in a gel-to-gel configuration [1]. The table below summarizes the core requirements.

Table 1: AAMI EC12 Standard Key Test Requirements for ECG Electrodes [1]

| Test Parameter | Standard Conditions | Acceptance Criteria | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| AC Impedance | 10 Hz sinusoidal current, ≤ 0.1 mA | Average of 12 pairs ≤ 2 kΩ; Single pair ≤ 3 kΩ | Ensures low interface impedance to minimize signal attenuation and interference. |

| DC Offset Voltage | - | - | Measures the steady-state potential difference between electrode pairs to predict baseline wander. |

| Combined Offset Instability & Internal Noise | - | - | Assesses low-frequency signal stability and inherent noise. |

| Defibrillation Overload Recovery | - | - | Verifies the electrode can recover functionality after a high-voltage defibrillation pulse. |

Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS)

Purpose: To characterize the electrode-electrolyte interface by measuring its impedance across a wide frequency range, enabling the extraction of circuit parameters like Cdl and Rct [1].

Detailed Protocol:

- Setup: Configure a standard three-electrode system (Working, Counter, and Reference electrodes) immersed in the electrolyte of interest.

- Measurement: Apply a small-amplitude AC voltage sinusoid (e.g., 10 mV) over a wide frequency range (e.g., 0.1 Hz to 1 MHz) and measure the phase and amplitude of the resulting current.

- Data Fitting: Fit the obtained impedance spectrum (often presented as a Nyquist or Bode plot) to the Randles circuit model [3]. The value of Cdl is a primary output of this fitting procedure. While the AAMI standard uses a single frequency (10 Hz), EIS provides a more in-depth analysis [1].

Protocol for Characterizing Drift in EG-gFETs

This protocol, adapted from research on electrolyte-gated graphene field-effect transistors, provides a method for quantifying drift [2].

Purpose: To comprehensively characterize the dynamic drift behavior of EG-gFETs under various measurement conditions.

Step-by-Step Workflow:

Key Parameters to Record:

- Primary Output: The Dirac point voltage (V_Dirac) from successive transfer curves [2].

- Environmental Factors: Temperature, electrolyte composition and pH [2].

- Electrical History: Gate voltage (V_GS) conditions and device's measurement history [2].

Advanced Research and Computational Methods

Overcoming the challenges of signal drift and interface instability requires advanced experimental and computational approaches.

Investigating Drift via Charge Trapping Models

Recent research on EG-gFETs demonstrates that charge trapping at substrate oxide defects is a dominant drift mechanism. Studies systematically rule out other factors (electrolyte type, surface functionalization, pH), pointing to electron transitions between graphene and oxide defects as the root cause [2]. This process is modeled using the non-radiative multiphonon (NPM) transition model, which accounts for how the graphene Fermi level, modulated by V_GS, influences electron capture/emission rates at defect sites [2].

Machine Learning-Accelerated Modeling

The HAML (Hybrid AIMD-MLP) framework combines ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) with machine learning potentials (MLP) to accurately simulate complex interface reactions over extended timescales that are prohibitively expensive for pure AIMD [4]. This method has been applied to model interfaces between Li metal and liquid/solid-state electrolytes, achieving speedups of over 10-20 times while maintaining high accuracy. This approach provides atomic-level insights into interfacial processes that drive drift and degradation [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Reagents for Electrode-Electrolyte Interface Research

| Item | Function / Purpose | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Silver/Silver Chloride (Ag/AgCl) Electrode | A common non-polarisable reference electrode with a stable, low half-cell potential [1]. | Used as a stable reference in three-electrode cell setups for EIS and other electrochemical measurements. |

| Sputtered Iridium Oxide Film (SIROF) Electrodes | A high-charge-capacity electrode material for electrical stimulation [3]. | Used in functional electrical stimulation of neural tissue (e.g., retinal implants) [3]. |

| Ionic Liquid Electrolytes | A medium with high ionic concentration, which can help reduce the half-cell potential and study drift mechanisms independent of evaporation [1] [2]. | Used in EG-gFET experiments to isolate charge trapping drift from other effects related to aqueous electrolytes [2]. |

| LPSC (Li₆PS₅Cl) Solid-State Electrolyte | A solid-state electrolyte for lithium metal batteries [4]. | Serves as a base material for studying the impact of element doping (Se, F, O) on interface stability and reaction kinetics in Li metal batteries [4]. |

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) | A standard, physiologically-relevant saline solution. | Used as a common electrolyte for testing biomedical sensors and simulating biological environments. |

The electrochemical interface, the boundary between an electrode and an ionic conductor such as an electrolyte, is characterized by a complex structural region where charge separation occurs. This region, known as the electrochemical double layer (EDL), is fundamental to numerous technological applications, including supercapacitors for energy storage, electrochemical sensors, and corrosion science [5] [6]. The operational conditions and performance of these devices are dictated by the physico-chemical phenomena taking place at this interface [6]. The EDL forms because charges on the electrode surface are balanced by a redistribution of ions in the electrolyte, creating a potential gradient that can exceed 10⁷ V cm⁻¹ [6]. Understanding the precise structure of this layer is critical for advancing research in electrical double layer capacitance and mitigating signal drift, a key challenge in precise electrochemical measurements and biosensor development.

The Grahame model, building upon earlier theories, provides the most comprehensive and widely accepted description of the EDL structure. This model is particularly indispensable for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals who utilize electrochemical systems, as it defines the specific locations and environments of ions at the interface, which directly influence capacitive behavior and signal stability. This technical guide will delve into the core principles of the Grahame model, its historical context, and its practical implications for modern electrochemical research.

Classical Theories of the Electrochemical Double Layer

The quest to understand the EDL began in the nineteenth century with macroscopic measurements under equilibrium conditions. The earliest quantitative studies were performed on mercury electrodes, favored for their reproducible, contaminant-free surfaces [6]. These experiments measured interfacial tension and capacitance as functions of applied potential and electrolyte activity.

The fundamental thermodynamic treatment stems from the concept of the ideally polarizable electrode, where no charge transfer occurs [6]. The system obeys the Lippmann equation, which forms the basis of interfacial thermodynamics [6]: [ \frac{\partial \gamma}{\partial \phi} = -\sigma ] where ( \gamma ) is the interfacial tension, ( \sigma ) is the surface charge density, and ( \phi ) is the Galvani potential. Differentiating this equation with respect to potential gives the expression for the specific differential capacitance, ( C{\text{diff}} ), of the electrode [6]: [ C{\text{diff}} = \frac{\partial \sigma}{\partial \phi} = - \frac{\partial^2 \gamma}{\partial \phi^2} ] The relationship between interfacial tension and potential produces an electrocapillary curve, the maximum of which corresponds to the potential of zero charge (PZC), where the net surface charge is zero [6]. The PZC is a critical parameter characterizing both the electrode material and the solution composition.

The Helmholtz Model

The first model to introduce the EDL concept was proposed by Helmholtz [6]. He envisaged the interface as a simple molecular capacitor, where the charge on the electrode (( \sigma )) is balanced by a monolayer of ions of opposite charge located adjacent to the surface. This compact layer is known as the Helmholtz layer [6]. In this model, the capacitance, ( C ), is given by ( C = \varepsilon / 4\pi d ), where ( \varepsilon ) is the relative permittivity of the dielectric and ( d ) is the distance between the "plates" [6]. While foundational, the Helmholtz model fails to account for the diffuse nature of the ion distribution in the electrolyte, which becomes significant at lower electrolyte concentrations or lower surface charges.

The Gouy-Chapman Model

The Gouy-Chapman model addressed the limitations of the Helmholtz model by considering the thermal motion of ions, which leads to a diffuse layer of charge extending from the surface into the electrolyte [5]. This model successfully predicted that the differential capacitance should increase with electrolyte concentration and vary with surface potential. However, it treated ions as point charges and neglected ion size and specific ion-surface interactions, leading to unrealistic predictions of infinite ion concentration at high surface potentials.

The Grahame Model: A Synthesis

David C. Grahame, in the mid-20th century, integrated the Helmholtz and Gouy-Chapman models into a single, more sophisticated framework. The Grahame model divides the electrochemical double layer into two distinct regions, resolving the inaccuracies of its predecessors.

Table 1: Core Components of the Grahame Double Layer Model

| Layer Name | Alternative Name(s) | Spatial Extent | Primary Characteristics | Governing Forces |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inner Helmholtz Plane (IHP) | Helmholtz Layer, Stern Layer | ~0.3-0.5 nm from electrode surface | Plane of closest approach for specifically adsorbed ions (may be partially or fully dehydrated); location of solvent dipoles. | Chemical (short-range), electrostatic. |

| Outer Helmholtz Plane (OHP) | Stern Layer | ~0.5-1.0 nm from electrode surface | Plane of closest approach for non-specifically adsorbed, |

hydrated ions; defines the boundary between the compact and diffuse layers. | Purely electrostatic (long-range). | | Diffuse Layer | Gouy-Chapman Layer | Extends from OHP into bulk electrolyte (nm to μm) | Region where ion distribution is governed by electrostatic forces and thermal motion; concentration decays to bulk value. | Electrostatic & thermal (Boltzmann distribution). |

The Inner Helmholtz Plane (IHP)

The Inner Helmholtz Plane (IHP) is defined as the locus of points occupied by the centers of specifically adsorbed ions. These ions are not fully solvated and have lost part or all of their hydration shell to contact the electrode surface directly. Adsorption into the IHP is driven by specific chemical interactions that go beyond pure electrostatics, such as covalent bonding, van der Waals forces, or hydrogen bonding [6]. This means that an ion can be adsorbed into the IHP even if it has the same charge sign as the electrode (anionic adsorption on a negatively charged surface, or cationic adsorption on a positively charged surface). The nature and population of ions in the IHP are critical as they directly affect the PZC and the total capacitance of the interface.

The Outer Helmholtz Plane (OHP)

The Outer Helmholtz Plane (OHP) is the plane of closest approach for non-specifically adsorbed ions. These ions remain fully solvated and are attracted to the electrode surface solely by long-range electrostatic forces. They cannot approach the electrode as closely as specifically adsorbed ions because they are separated by their hydration shells. The OHP represents the boundary between the compact, organized part of the double layer (comprising the IHP and OHP) and the diffuse layer.

The Diffuse Layer

Beyond the OHP lies the diffuse layer, as described by Gouy and Chapman. In this region, the ion distribution is governed by the balance between electrostatic attraction/repulsion and the randomizing effect of thermal motion. The potential drops exponentially from its value at the OHP (( \psi_0 )) to zero in the bulk solution. The thickness of this layer is characterized by the Debye length (( \kappa^{-1} )), which decreases with increasing electrolyte concentration and ionic strength.

The following diagram illustrates the structure of the EDL as described by the Grahame model, showing the relative positions of the IHP, OHP, and the diffuse layer, along with the corresponding potential decay.

Diagram 1: The structure of the electrochemical double layer according to the Grahame model, showing the IHP, OHP, and diffuse layer.

Experimental Protocols for Probing the Double Layer

Validating the Grahame model and characterizing the EDL in real systems requires sophisticated experimental techniques. The following methodologies are central to this field of research.

Electrochemical Capacitance Measurements

The primary method for investigating the EDL is through measurement of the differential capacitance (( C_{\text{diff}} )) as a function of applied potential and electrolyte concentration.

- Objective: To determine the capacitance of the electrode-electrolyte interface and observe how it changes with potential (to find the PZC) and electrolyte concentration.

- Protocol:

- Cell Setup: A standard three-electrode electrochemical cell is used, comprising a Working Electrode (the material under study, e.g., graphene, Hg), a Counter Electrode (e.g., Pt wire), and a Reference Electrode (e.g., Ag/AgCl, SCE) [6].

- Electrolyte Preparation: Prepare a series of aqueous electrolyte solutions (e.g., KCl, Na₂SO₄) with precisely known concentrations, typically ranging from 0.001 M to 1.0 M. Ensure high-purity reagents and degassing to remove oxygen.

- Impedance Spectroscopy: Apply a small-amplitude AC potential perturbation (e.g., 10 mV rms) over a range of frequencies (e.g., 10,000 Hz to 0.1 Hz) at a series of DC bias potentials. The DC potential is typically scanned step-wise across the electrochemical window of the working electrode.

- Data Analysis: At each DC potential, the impedance data is fit to an equivalent circuit model. The simplest relevant model is a series resistance (solution resistance, ( Rs )) with a double-layer capacitance (( C{dl} )). The inverse of the imaginary impedance at high frequency can often be used to approximate ( C{\text{diff}} ). Plotting ( C{\text{diff}} ) versus the DC potential yields a capacitance curve.

- Expected Outcome: In a dilute electrolyte, the capacitance curve will often show a "V" or "U" shape, with a minimum at the PZC, reflecting the dominance of the diffuse layer. At high concentrations, the curve flattens, indicating the increasing dominance of the compact Helmholtz layer, consistent with the predictions of the Grahame model [6].

In Situ Spectroscopy and Surface Analysis

To move beyond purely electrical measurements and gain direct structural information, advanced spectroscopic techniques are employed.

- Objective: To identify the chemical nature and bonding of specifically adsorbed ions and solvent molecules at the IHP.

- Protocol (e.g., In Situ Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy):

- Electrode Preparation: Use a working electrode with a nano-roughened surface (e.g., Au or Ag nanoparticles) to enhance the Raman signal from the interface.

- Spectroelectrochemical Cell: Use a cell with an optically transparent window, allowing a laser to be focused on the electrode surface in contact with the electrolyte.

- Measurement: While holding the working electrode at a controlled potential, acquire Raman spectra. The potential is systematically varied to observe the adsorption/desorption of species.

- Data Analysis: Changes in the Raman peak positions, intensities, and widths are correlated with the applied potential to identify the vibrational fingerprints of specifically adsorbed ions and interfacial water molecules.

The workflow for a comprehensive investigation integrating these techniques is summarized below:

Diagram 2: A generalized experimental workflow for probing the structure of the electrochemical double layer.

Quantitative Data and Modeling

The Grahame model can be expressed mathematically. The total differential capacitance is considered as a series combination of the Helmholtz capacitance (( CH )) and the diffuse layer capacitance (( C{diff} )): [ \frac{1}{C{\text{total}}} = \frac{1}{CH} + \frac{1}{C{diff}} ] where ( CH ) is typically considered constant, and ( C{diff} ) is potential and concentration-dependent, as derived from Gouy-Chapman theory: [ C{diff} = \frac{\varepsilon \kappa}{4\pi} \cosh\left(\frac{z e \psi0}{2 kB T}\right) ] where ( \varepsilon ) is the permittivity, ( \kappa^{-1} ) is the Debye length, ( z ) is the ion valence, ( e ) is the elementary charge, ( \psi0 ) is the potential at the OHP, ( kB ) is Boltzmann's constant, and ( T ) is the temperature.

Table 2: Characteristic Parameters and Values in EDL Research

| Parameter | Symbol | Typical Range/Value | Experimental/Model Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Potential of Zero Charge | PZC | Material and electrolyte specific (e.g., ~ -0.2 V vs. SCE for Hg in NaF) | Key output from electrocapillary or capacitance measurements [6]. |

| Helmholtz Capacitance | ( C_H ) | 10 - 40 μF cm⁻² | Represents the compact layer (IHP/OHP); relatively constant. |

| Debye Length | ( \kappa^{-1} ) | ~30 nm (0.001 M 1:1 electrolyte) to ~0.3 nm (1.0 M 1:1 electrolyte) | Characteristic thickness of the diffuse layer; dictates screening. |

| Diffuse Layer Capacitance | ( C_{diff} ) | Strongly dependent on potential and concentration. | Calculated from Gouy-Chapman theory; dominates total capacitance at low [ion] and near PZC. |

| Double Layer Capacitance | ( C_{dl} ) | 5 - 30 μF cm⁻² (for carbon materials) | Measured value; critical for supercapacitor energy storage calculations [5]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Double Layer Research

| Item Name | Function/Application | Critical Specifications | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Working Electrodes | The material whose interface is being studied. | Mercury: Historically ideal, atomically smooth [6]. Graphene: Modern 2D material, atomically smooth model surface [6]. Gold: For functionalized surfaces and in-situ spectroscopy. | |

| Inert Electrolytes | To study non-specific adsorption; provide ionic strength. | Alkali Metal Fluorides (e.g., NaF, KF): F⁻ ions show weak specific adsorption. Tetralkylammonium Salts (e.g., TBA PF₆): Large organic cations with low specific adsorption. | High purity, low water content for non-aqueous studies. |

| Specifically Adsorbing Electrolytes | To study chemical interactions at the IHP. | Halide Salts (e.g., KCl, NaBr): Cl⁻, Br⁻, I⁻ exhibit strong specific adsorption. | Concentration series to study adsorption isotherms. |

| Potentiostat/Galvanostat with EIS Module | The core instrument for applying potential/current and measuring electrochemical response. | Capability for Frequency Response Analysis (FRA), low-current measurement. | |

| Spectroelectrochemical Cell | Allows simultaneous electrochemical and spectroscopic measurement. | Optical transparency (e.g., quartz window), proper electrode alignment. |

The Grahame model, with its delineation of the IHP and OHP, remains the cornerstone of our understanding of the electrochemical double layer. It successfully integrates the concepts of specific chemical adsorption and electrostatic forces, providing a quantitative framework that accurately describes experimental observations from capacitance measurements and in-situ spectroscopy. For researchers focused on electrical double layer capacitance and signal drift, a deep understanding of this model is non-negotiable. Signal drift in sensors can often be traced to slow reorganization within the IHP or potential-dependent specific adsorption, highlighting the model's direct relevance. Future progress in this field, particularly with novel materials like graphene and ionic liquids, will rely on combining these classical theories with advanced computational simulations and high-resolution experimental techniques to further refine our atomic-level picture of the interface.

The interface between an electronic conductor (an electrode) and an ionic conductor (an electrolyte) is the site of all electrochemical processes. At this interface, a nanoscale region of separated charge forms, creating what is known as the Electrical Double Layer (EDL). The EDL is the electrochemical analogue of a capacitor, storing energy through the physical separation of charged species. Its structure and properties directly govern the performance of a vast array of technologies, from energy storage devices like batteries and supercapacitors to the latest generation of biosensors [7] [6]. A detailed understanding of the EDL as a nanoscale capacitor is therefore fundamental to advancements in electrochemistry and electronic device design.

This article establishes the theoretical basis of the EDL, framing it within the context of modern research challenges, particularly the critical issue of signal drift in sensitive electrochemical measurements. Accurate interpretation of the double-layer capacitance (C~dl~) is essential for distinguishing true analytical signals from temporal artifacts in applications such as field-effect transistor-based biosensors (BioFETs) [8] [7].

Classical Theoretical Models of the EDL

The evolution of EDL models represents a continuous effort to reconcile theoretical predictions with experimental electrochemical data. The following section outlines the key historical developments.

The Helmholtz Model

The simplest model, proposed by Helmholtz, envisions the double layer as a molecular dielectric capacitor [6]. In this concept, the charge on the electrode surface (σ) is balanced by a single layer of solvated ions of opposite charge located adjacent to the surface, known as the Helmholtz plane. The potential is predicted to drop linearly across this rigid, molecular layer.

- Capacitance Relationship: The Helmholtz capacitance (C~H~) is given by ( CH = \frac{\varepsilon \varepsilon0}{d} ), where ε is the relative permittivity of the dielectric, ε~0~ is the permittivity of free space, and d is the distance between the charge "plates," approximately equal to the ionic radius [6].

- Limitation: This model predicts a capacitance that is constant with applied potential, which contradicts experimental observations showing a strong potential dependence.

The Gouy-Chapman Model

The Gouy-Chapman model introduced a diffuse layer, accounting for the thermal motion of ions in the electrolyte. Instead of forming a rigid plane, the counter-ions are distributed diffusely in the solution, leading to a non-linear, exponential decay of potential with distance from the electrode.

- Capacitance Relationship: The diffuse layer capacitance (C~GC~) is described by ( C{GC} = \frac{\varepsilon \varepsilon0}{\lambdaD} \cosh\left(\frac{z e \psi0}{2 k_B T}\right) ), where λ~D~ is the Debye length, z is the ion valence, e is the elementary charge, ψ~0~ is the surface potential, k~B~ is Boltzmann's constant, and T is the temperature [6].

- Limitation: This model predicts a "V-shaped" capacitance curve and unrealistically high capacitance values at high potentials because it treats ions as point charges and ignores their finite size.

The Stern Model

Stern combined the two previous models, proposing that the EDL is composed of two distinct regions: an inner Helmholtz layer (including specifically adsorbed ions) and an outer Gouy-Chapman diffuse layer.

- Capacitance Relationship: The total differential capacitance (C~dl~) is treated as a series combination of the Helmholtz (C~H~) and Gouy-Chapman (C~GC~) capacitances: ( \frac{1}{C{dl}} = \frac{1}{CH} + \frac{1}{C_{GC}} ) [6].

- Significance: This hybrid model successfully explains the characteristic "U-shaped" capacitance curve observed for many electrode-electrolyte systems, with a minimum at the potential of zero charge (PZC).

The Grahame Model

Grahame further refined the Stern model by distinguishing between specifically adsorbed ions (which can contact the electrode surface by losing their solvation shell) in the Inner Helmholtz Plane (IHP), and non-specifically adsorbed ions that remain fully solvated in the Outer Helmholtz Plane (OHP) [9]. This model provides the most comprehensive classical description and is widely used as the basis for interpreting experimental data.

The following diagram illustrates the structure of the EDL and the corresponding potential decay according to the Grahame model:

Experimental Measurement of Double-Layer Capacitance

Accurately measuring C~dl~ is critical for characterizing the electrode-electrolyte interface. The most common techniques are Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) and Cyclic Voltammetry (CV).

Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS)

EIS is a powerful AC method that probes the interface over a range of frequencies. The system's response is modeled using an Equivalent Circuit Model (ECM) [10] [9].

- Equivalent Circuit: For a simple blocking electrode, the ECM consists of the solution resistance (R~s~) in series with a constant phase element (CPE) representing the double layer [9].

- The Constant Phase Element (CPE): Real electrodes often exhibit frequency dispersion, where the capacitance is not ideal. This is modeled by a CPE, with an impedance defined as ( Z_{CPE} = 1 / [Q (iω)^n] ), where Q is the CPE pre-factor, ω is the angular frequency, and n is the CPE exponent (0 ≤ n ≤ 1). A perfect capacitor has n = 1 [10] [9].

- Capacitance Calculation: The double-layer capacitance can be calculated from the CPE parameters at the characteristic frequency (ω~c~) of the interface: ( C{dl} = Q (\omegac)^{n-1} ) [9].

Cyclic Voltammetry (CV)

CV is a DC technique where the potential is scanned linearly and the current response is measured.

- Methodology: In a potential window where no Faradaic (charge-transfer) reactions occur, the current is primarily capacitive. The capacitive current (i~c~) is related to the scan rate (ν) and C~dl~ by ( ic = C{dl} \cdot ν ) [9].

- Analysis: By measuring the current in a non-Faradaic region and knowing the scan rate, C~dl~ can be estimated. For more complex systems with Faradaic contributions, the current from forward and backward sweeps at the open-circuit potential can be used: ( (Ia - Ic)/2 = C_{dl} \cdot (dE/dt) ) [9].

Table 1: Comparison of EIS and CV for Capacitance Measurement (Example: Iron in 0.1 M HCl)

| Technique | Measurement Principle | Key Parameter | Calculated C~dl~ | Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) | AC frequency response | CPE: Q = 6.3 µF·s^(n-1), n = 0.84 | 5.2 µF [9] | Deconvolutes charge transfer; models interface with ECM |

| Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) | DC current during potential scan | Scan rate: 40 mV·s⁻¹ | 4.3 µF [9] | Simple, fast experiment; directly probes kinetics |

Advanced Considerations and Research Challenges

The Interplay of Capacitance and Signal Drift

The interpretation of C~dl~ is not always straightforward and is often complicated by factors that lead to signal drift, a major challenge for stable electrochemical devices like BioFETs [7].

- Adsorption (Pseudo)capacitance: On non-ideal electrodes like platinum, the adsorption of species such as H~ads~ or OH~ads~ from water dissociation contributes an additional, potential-dependent "pseudo-capacitance" (C~ads~). This makes it difficult to deconvolute the true double-layer capacitance from the total measured capacitance, and this effect varies with the crystal facet of the metal [8].

- Temporal Instability: Slow processes such as the diffusion of ions into the sensing region or changes in the interface morphology can alter the gate capacitance and threshold voltage over time, causing signal drift that can obscure genuine analytical signals [7]. This is particularly debilitating for point-of-care biosensors.

Insights from Battery Research: Monitoring SEI Formation

Research in Li-ion batteries provides a clear example of the sensitivity of C~dl~. The formation of a Solid Electrolyte Interphase (SEI)—a passivating layer on the anode—can be monitored in situ through changes in the double-layer capacitance [10].

- Principle: The SEI physically grows on the electrode surface, effectively increasing the distance (d) between the electrode and the ions in the electrolyte. Since capacitance is inversely proportional to this distance (( C \propto 1/d )), a continuous decrease in C~dl~ measured via EIS directly indicates the formation and growth of the SEI layer [10].

- Application: This approach allows researchers to track interface changes within a few atomic layers and screen the effectiveness of different electrolytes for forming stable SEIs [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for EDL Studies

| Item | Function / Rationale | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Glassy Carbon Electrode | An atomically smooth, model electrode surface that provides reproducible and easily interpretable EIS data for fundamental studies [10]. | Used as a polished model electrode to study SEI formation in Li-ion batteries [10]. |

| Long-Chain Alkanethiols (e.g., 16-Mercaptohexadecanoic acid) | Used to form stable, self-assembled monolayers (SAMs) on gold electrodes. These layers act as well-defined insulating films for capacitive biosensors, minimizing signal drift [11]. | SAMs with ≥11 methylene groups showed significantly improved stability in aqueous solution and suppressed signal drift in capacitive sensors [11]. |

| Polymer Brushes (e.g., POEGMA) | A non-fouling polymer layer immobilized above a transistor channel. It extends the effective Debye length in high ionic strength solutions via the Donnan potential, enabling biomarker detection in physiological fluids [7]. | Used in D4-TFT BioFETs to overcome charge screening and detect sub-femtomolar biomarker concentrations in 1X PBS [7]. |

| Lithium Hexafluorophosphate (LiPF₆) in Carbonate Solvents | A standard, battery-grade electrolyte used to study electrochemical stability and SEI formation mechanisms on carbonaceous anodes [10]. | Used in combinations like EC-DMC to probe potential-dependent SEI formation on glassy carbon [10]. |

| Constant Phase Element (CPE) | A mathematical component used in equivalent circuit models to accurately fit the non-ideal, frequency-dependent capacitive behavior of real electrochemical interfaces [10] [9]. | Essential for extracting a meaningful capacitance value (C~dl~) from impedance data on real surfaces like iron [9]. |

The following workflow summarizes the key steps and decision points for characterizing the double layer as a nanoscale capacitor, integrating the core concepts and tools discussed.

From Ideal Capacitors to Constant Phase Elements (CPE) in Real Systems

In the realm of electrochemistry and biosensor development, the electrical double layer (EDL) is a fundamental concept governing the interaction between a conductive electrode and an ionic solution. The capacitance of this interface is central to the function of numerous devices, from supercapacitors for energy storage to transistor-based biosensors for biomarker detection [12] [7]. Theoretically, this interface is often modeled as an ideal capacitor, a component with a pure, frequency-independent capacitive impedance. However, in real-world systems, particularly in complex biological electrolytes, the EDL consistently deviates from this ideal behavior, exhibiting a phenomenon known as dispersion and behaving instead as a Constant Phase Element (CPE) [13]. This shift from ideal capacitive behavior to CPE-like response is not merely a theoretical curiosity; it has profound implications for the stability and accuracy of electrochemical measurements, directly impacting critical challenges such as signal drift in biosensing platforms [7]. Understanding this transition is therefore essential for researchers and scientists aiming to develop reliable point-of-care diagnostic tools and optimize energy storage systems. This guide frames the core principles of EDL capacitance and CPE within the context of ongoing research to mitigate signal drift, providing a technical foundation for drug development professionals and materials scientists navigating the complexities of interfacial electrochemistry.

Theoretical Foundations: The Electrical Double Layer and Its Capacitance

The Ideal Capacitor and the Electrical Double Layer

An ideal capacitor is a passive electrical component that stores energy in an electric field, characterized by a capacitance value, (C). Its impedance, (ZC), is purely imaginary and inversely proportional to frequency: [ ZC = \frac{1}{j\omega C} ] where (j) is the imaginary unit and (\omega) is the radial frequency [13]. In a perfect electrochemical capacitor, the EDL forms a rigid, atomic-scale charge separation at the electrode-electrolyte interface, akin to a perfect parallel-plate capacitor. This EDL stores electrostatic energy by modulating the spatial distribution of ions in the electrolytic solution [12]. The formation of the EDL is described by mean-field theories like Poisson-Bernst-Planck, which relate the electric potential (\phi(z,t)) to the ion densities (n_\pm(z,t)) [12]. For a symmetric electrolyte with ions of equal valence and diffusivity, the charging dynamics in the linear regime (small applied voltage) are well-understood, with characteristic relaxation times linked to the circuit's resistive-capacitive (RC) time constant [12].

The Constant Phase Element (CPE): Deviations from Ideality

In practice, the impedance of a real EDL rarely conforms to that of an ideal capacitor. Instead, it often behaves as a Constant Phase Element (CPE), an empirical circuit component whose impedance is given by: [ Z_{CPE} = \frac{1}{Q(j\omega)^\alpha} ] Here, (Q) is the CPE coefficient (in (S\cdot s^\alpha)), and (\alpha) is the CPE exponent (or phase angle), which is a dimensionless parameter between 0 and 1 [13]. The value of (\alpha) quantifies the degree of deviation from an ideal capacitor:

- (\alpha = 1): Ideal capacitor behavior.

- (\alpha = 0): Ideal resistor behavior.

- (0 < \alpha < 1): The system exhibits CPE behavior, characterized by a frequency-dependent phase angle that is constant, not equal to -90°.

This frequency dispersion results in a depressed semicircle on a Nyquist plot, rather than the perfect semicircle expected for a single ideal RC time constant [13]. The physical origins of CPE behavior are complex and multifaceted, often attributed to surface roughness, chemical heterogeneity, porosity, and non-uniform current distribution.

Signal Drift and Its Connection to Interfacial Instability

Signal drift is a pervasive challenge in solution-gated electrochemical devices, such as BioFETs. It manifests as a slow, undesired change in the measured signal (e.g., drain current or threshold voltage) over time, which can obscure the detection of target biomarkers [7]. This drift is intrinsically linked to the instability of the EDL. In high ionic strength solutions, electrolytic ions slowly diffuse into the sensing region, altering the gate capacitance and other interfacial properties over time [7]. The non-ideal, CPE-like nature of the EDL can exacerbate this issue, as the distributed time constants associated with surface heterogeneity create multiple, slow relaxation pathways. When a system is not at a steady state, standard impedance analysis tools can yield wildly inaccurate results, complicating the interpretation of sensor data and leading to false positives or negatives [13]. Therefore, mitigating signal drift requires strategies that address both the electrochemical stability of the interface and the underlying causes of CPE behavior.

Table 1: Key Parameters of an Ideal Capacitor vs. a Constant Phase Element

| Parameter | Ideal Capacitor | Constant Phase Element (CPE) |

|---|---|---|

| Impedance Formula | (Z = \frac{1}{j\omega C}) | (Z = \frac{1}{Q(j\omega)^\alpha}) |

| Phase Angle | Constant -90° | Constant (-(90 \times \alpha))° |

| Nyquist Plot | Perfect semicircle | Depressed semicircle |

| Physical Origin | Ideal charge separation | Surface roughness, heterogeneity, porosity |

| Impact on Drift | Predictable, minimal | Complex, can contribute to slow relaxations and drift |

Experimental Characterization and Analysis

Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS)

Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) is the primary technique for characterizing the EDL and identifying CPE behavior. EIS involves applying a small amplitude AC potential excitation to an electrochemical cell and measuring the current response across a wide frequency range [13]. The system must be pseudo-linear and at a steady state for the measurement to be valid, a particular challenge in biological systems prone to drift and biofouling [13]. The impedance data is typically presented in two ways:

- Nyquist Plot: The imaginary component of impedance ((-Z'')) is plotted against the real component ((Z')). A system with a single time constant and ideal capacitance produces a perfect semicircle. The presence of a CPE results in a depressed, "squashed" semicircle [13].

- Bode Plot: The magnitude of the impedance ((|Z|)) and the phase shift ((\phi)) are plotted against log frequency. A CBE causes the phase angle to plateau at a value other than -90° and the magnitude to have a slope other than -1 on the log-log plot [13].

Equivalent Circuit Modeling

EIS data is commonly analyzed by fitting it to an equivalent electrical circuit model, whose elements have a basis in the system's physical electrochemistry [13]. A simple model for a bare electrode in solution is the Randles circuit, which includes the solution resistance ((Rs)) in series with a parallel combination of the double-layer capacitance ((C{dl})) and the charge-transfer resistance ((R{ct})). In real systems, (C{dl}) is almost always replaced by a CPE to account for the observed dispersion. The quality of the fit, judged by the chi-squared value, validates the model's appropriateness, allowing researchers to extract quantitative parameters like the CPE exponent (\alpha) and correlate them with surface properties or performance metrics like signal drift.

A Research Focus: Mitigating Drift in Biosensing via Interfacial Control

The challenges of CPE behavior and signal drift are acutely felt in the development of ultra-sensitive biosensors. For example, carbon nanotube (CNT)-based BioFETs suffer from debilitating signal drift and charge screening when operating in biologically relevant ionic strengths, which can obscure actual biomarker detection [7]. Research has shown that overcoming these limitations requires direct intervention at the electrode-electrolyte interface.

One promising approach is the use of a poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG)-like polymer brush interface, such as poly(oligo(ethylene glycol) methyl ether methacrylate) (POEGMA) [7]. This interface serves a dual function:

- It acts as a Debye length extender by establishing a Donnan equilibrium potential, allowing for the detection of large antibodies that would otherwise be screened out in high ionic strength solutions like 1X PBS [7].

- It provides a non-fouling, homogenized surface that can reduce the interfacial heterogeneity that contributes to CPE behavior and signal drift.

Simultaneously, a rigorous testing methodology is required to mitigate drift, including:

- Maximizing sensitivity through appropriate passivation alongside the polymer brush coating [7].

- Using a stable electrical testing configuration with a stable pseudo-reference electrode [7].

- Enforcing a rigorous testing methodology that relies on infrequent DC sweeps rather than static or AC measurements to minimize the impact of slow, drift-related relaxations [7].

Table 2: Key Experimental Parameters and Their Impact on EDL Behavior and Signal Drift

| Experimental Parameter | Impact on EDL/CPE | Connection to Signal Drift |

|---|---|---|

| Ionic Strength | Higher strength decreases Debye length, increasing CPE effects from screening. | Increased drift due to higher ion flux and stronger EDL compression [7]. |

| Applied Voltage | Large voltages induce non-linear effects and asymmetric ion dynamics [12]. | Can accelerate drift by driving Faradaic processes or ion adsorption. |

| Surface Morphology | Roughness and chemical heterogeneity directly increase CPE exponent (\alpha). | Heterogeneous sites create multiple energy states, leading to slow, distributed relaxations (drift). |

| Polymer Brush (e.g., POEGMA) | Extends Debye length, creates a more uniform interfacial environment. | Mitigates biofouling and reduces charge screening, stabilizing the signal [7]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for EDL and Signal Drift Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| POEGMA (Poly(oligo(ethylene glycol) methyl ether methacrylate)) | A non-fouling polymer brush coating that extends the Debye length and creates a more homogeneous interface, reducing signal drift and CPE effects [7]. |

| PBS (Phosphate Buffered Saline) | A high ionic strength buffer (1X PBS) used to mimic physiological conditions, essential for testing drift and biosensor performance in relevant environments [7]. |

| PEG (Polyethylene Glycol) | Used in passivation layers to minimize non-specific binding and improve device stability, thereby reducing a source of signal drift [7]. |

| Palladium (Pd) Pseudo-Reference Electrode | Provides a stable, miniaturizable reference potential, bypassing the need for bulky Ag/AgCl electrodes in point-of-care device configurations [7]. |

| Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) | A high-sensitivity nanomaterial used as the channel in BioFETs; its interface with the electrolyte is a primary site for EDL formation and signal drift [7]. |

Experimental Protocol: Characterizing CPE and Drift in a BioFET

The following protocol outlines a methodology for evaluating the CPE behavior and signal drift of a CNT-based BioFET, incorporating key strategies from recent research.

Objective: To measure the interfacial impedance of a CNT-based BioFET in 1X PBS, extract CPE parameters, and monitor signal stability over time.

Materials:

- Fabricated CNT-based BioFET device with and without POEGMA functionalization [7].

- 1X PBS solution (pH 7.4).

- Potentiostat/Galvanostat with EIS capability.

- Pd pseudo-reference electrode [7].

- Environmental chamber for temperature control (e.g., 25°C).

Methodology:

- Device Preparation: Immobilize the POEGMA polymer brush on the CNT channel of the test device via surface-initiated polymerization. A control device should remain unfunctionalized [7].

- System Stabilization: Place the device in a Faraday cage and connect it to the potentiostat using the Pd pseudo-reference electrode. Introduce 1X PBS and allow the system to stabilize for 1 hour to approach a steady state, a critical prerequisite for valid EIS [13].

- EIS Measurement: Apply a small sinusoidal potential excitation (10 mV RMS) at the open circuit potential. Sweep the frequency from 100 kHz to 10 mHz, measuring the impedance spectrum for both the test and control devices.

- Equivalent Circuit Fitting: Fit the obtained Nyquist plots to a modified Randles circuit where the capacitor is replaced by a CPE. Use fitting software to extract the values for (Rs), (Q), (\alpha), and (R{ct}).

- Signal Drift Assessment: With a constant drain-source voltage applied, monitor the drain current ((I_d)) over a period of 4-8 hours. Use infrequent DC sweeps (e.g., every 15 minutes) instead of continuous monitoring to distinguish drift from the target signal [7].

- Data Analysis: Correlate the CPE exponent (\alpha) from step 4 with the magnitude of signal drift observed in step 5. Compare the functionalized and control devices to assess the efficacy of the POEGMA interface in promoting ideal capacitive behavior and improving signal stability.

Visualizing Concepts and Workflows

EDL Capacitance Evolution and Impact

BioFET Drift Mitigation Workflow

The journey from the theoretical simplicity of an ideal capacitor to the complex reality of the Constant Phase Element is a central narrative in interfacial electrochemistry. This deviation, driven by physical and chemical heterogeneity at the electrode surface, is not a minor artifact but a fundamental characteristic that has a direct and consequential impact on the pressing issue of signal drift in sensitive electrochemical devices like BioFETs. Addressing these challenges requires a multi-faceted approach, combining advanced materials like non-fouling polymer brushes to homogenize the interface, rigorous electrochemical characterization via EIS, and robust testing protocols designed to deconvolute signal from noise. For researchers in drug development and biosensing, a deep understanding of CPE behavior is no longer an esoteric specialty but a practical necessity. It provides the foundational knowledge required to design next-generation diagnostic platforms that are not only ultrasensitive but also stable and reliable, thereby bringing the vision of accurate point-of-care detection closer to reality.

Linking Cdl Variability to the Onset of Sensor Signal Drift

In the field of electrochemical sensing, signal drift presents a fundamental challenge to obtaining reliable, long-term measurements. This phenomenon, characterized by a gradual change in sensor output unrelated to the target analyte, is particularly debilitating for applications requiring high precision, such as continuous molecular monitoring in interstitial fluid or point-of-care diagnostic devices [14] [7]. Emerging research increasingly points to the variability of the double layer capacitance (Cdl) as a critical and often overlooked factor initiating and propagating this drift. The electrical double layer (EDL), which forms at the interface between a sensor electrode and an electrolyte solution, governs the charge distribution and potential gradients that are fundamental to electrochemical signal transduction. This technical guide explores the mechanistic relationship between Cdl variability and the onset of sensor signal drift, framing this link within a broader thesis on interfacial stability. It provides researchers and drug development professionals with the theoretical foundation, experimental protocols, and analytical frameworks necessary to diagnose, quantify, and mitigate Cdl-induced drift in their sensor systems.

The Fundamental Role of Cdl in Sensor Stability

The double layer capacitance (Cdl) is not merely a passive circuit element in an electrochemical system; it is a dynamic, responsive component that directly dictates the stability of the sensor's electrical environment. It represents the capacitance arising from the charge separation at the electrode-electrolyte interface, forming what is known as the Electrical Double Layer (EDL). The stability of this interface is paramount for sensors that rely on measuring potential or current changes, such as potentiometric ion-selective electrodes (ISEs) and field-effect transistor (FET) based biosensors [15] [7].

When Cdl is stable, it provides a consistent charge buffer, effectively decoupling the sensing element from minor fluctuations in the electrochemical cell. However, when Cdl is variable, it introduces instability in this critical region. In solid-contact ion-selective electrodes (SC-ISEs), a high Cdl is desirable because it acts as an internal charge reservoir, making the electrode potential less sensitive to external disturbances, such as changes in the sample composition or electrical noise. A low Cdl, conversely, results in a system highly susceptible to these disturbances, leading to significant potential drift and poor long-term stability [15]. For BioFETs, the EDL governs the gate capacitance. Drift in Cdl directly modulates the channel's threshold voltage, creating a background signal that can obscure the specific binding of target biomarkers. This is a primary reason why many highly sensitive BioFETs demonstrate exceptional performance in short-term tests but fail in prolonged deployments in biologically relevant ionic strengths [7].

Mechanisms Linking Cdl Variability to Signal Drift

The variability of Cdl is not a singular event but a consequence of several interfacial processes, which in turn become direct pathways to signal drift.

- Ion Migration and Adsorption: In solutions at biologically relevant ionic strengths, electrolytic ions from the solution can slowly diffuse into and interact with the sensing region. The progressive adsorption of ions or the formation of surface layers alters the effective dielectric properties and the thickness of the double layer, leading to a direct change in Cdl. This manifests as a continuous drift in the open-circuit potential of potentiometric sensors or the baseline current of transistor-based sensors [7].

- Electrode Surface Reconstruction and Fouling: The exposure of sensor electrodes to complex matrices like blood plasma or interstitial fluid can lead to the non-specific adsorption of proteins and other biomolecules, a process known as biofouling. This deposits an insulating or charge-screening layer on the electrode surface, physically changing the structure of the double layer and reducing Cdl. This fouling is a major contributor to signal degradation and drift in implantable and in vivo sensors [14].

- Changes in Material Properties: The transducer materials themselves can undergo changes. For example, the redox state of a conducting polymer like PEDOT or polyaniline in a SC-ISE can change over time, affecting its ionic and electronic conductivity and, consequently, its interfacial capacitance [15]. Similarly, in carbon nanotube networks, contamination or oxidation can alter the quantum capacitance of the material, a component in series with the double layer capacitance, leading to overall Cdl variability.

Quantitative Analysis of Cdl Impact on Sensor Performance

The influence of Cdl on sensor metrics can be quantified through key electrochemical parameters. Research demonstrates a direct correlation between high, stable Cdl values and superior sensor performance, particularly in terms of potential drift and signal-to-noise ratio.

Table 1: Impact of Transducer Material on Cdl and Potentiometric Sensor Drift

| Transducer Material | Key Feature | Impact on Cdl | Reported Potential Drift (ΔE/Δt) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes (MWCNTs) | High surface area; electronic & ionic conductivity | Significantly increases double-layer capacitance [15] | 34.6 µV/s [15] |

| Conducting Polymer (PEDOT/PANi) | Mixed ionic/electronic conduction; redox capacitance | Provides high redox capacitance [15] | Varies with polymer stability |

| Ferreocene | Reversible redox couple | Provides redox capacitance [15] | Generally higher than MWCNTs |

| Bare electrode (No SC) | No ion-to-electron transduction | Low double-layer capacitance | High drift and poor reproducibility [15] |

The data in Table 1 underscores why nanostructured carbon materials like MWCNTs are so effective; they drastically increase the double-layer capacitance and the interfacial contact area without changing the sensor's geometric footprint, resulting in significantly lower potential drift [15].

Beyond potentiometric sensors, the drift caused by Cdl variability is a universal problem in analytical chemistry. In Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS), signal intensity drift over long analytical sequences is a well-recognized issue that compromises quantification accuracy. While the underlying physics differs from electrochemical sensors, the conceptual parallel is that instrumental baselines can drift, requiring sophisticated software tools like QuantyFey that employ quality control-based bracketing and drift correction algorithms to maintain data quality [16].

Table 2: Comparative Drift Challenges and Mitigation Strategies Across Sensor Types

| Sensor / Technology | Primary Drift Manifestation | Role of Cdl / Interfacial Stability | Common Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Solid-Contact ISEs | Potential drift over time (mV/hr) | Central; low Cdl leads to high impedance and drift [15] | Use of high-surface-area SC materials (e.g., MWCNTs) [15] |

| CNT-Based BioFETs | Baseline current drift in solution | Critical; ion diffusion into sensing region alters gate C [7] | Polymer brush interfaces (e.g., POEGMA); stable electrical testing [7] |

| LC-MS Signal | Signal intensity drift over long sequences | Analogous to changing detector baseline | QC-based drift correction; external calibration bracketing [16] |

| Weigh-in-Motion Sensors | Systematic error increase over time | N/A (primarily mechanical) | Regular calibration against known reference [17] |

Experimental Protocols for Characterizing Cdl and Drift

A rigorous and standardized experimental approach is essential to reliably link Cdl variability to observed signal drift. The following protocols provide a framework for this characterization.

Protocol 1: Determining Cdl via Scan Rate-Dependent Cyclic Voltammetry

Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) is a primary technique for determining Cdl by measuring the non-Faradaic current response in a potential window where no redox reactions occur.

Methodology:

- Experimental Setup: Use a standard three-electrode configuration with the sensor as the working electrode, a stable reference electrode (e.g., Ag/AgCl), and a counter electrode. Ensure the electrolyte solution (e.g., 0.1 M KCl or PBS) is deaerated if necessary and that the potential window is carefully selected to avoid Faradaic processes.

- Data Collection: Acquire cyclic voltammograms at a series of scan rates (e.g., 10, 25, 50, 75, 100 mV/s). It is critical to ensure the measurements are performed at a constant temperature, as Cdl can be temperature-sensitive [18].

- Data Processing:

- At a fixed potential within the capacitive window, plot the absolute value of the charging current (Ic) on the Y-axis against the scan rate (v) on the X-axis.

- The Cdl is determined from the slope of this plot, based on the equation for capacitive current: Ic = Cdl * v. The use of allometric regression has been proposed as a more suitable model than linear regression for certain non-ideal systems [19].

- Reliability Checks: Adhere to established best practices to avoid misestimation. As outlined in the "Seven steps to reliable cyclic voltammetry," factors such as measurement settings (e.g., IR compensation), data collection parameters, and data processing choices can lead to substantial errors—sometimes exceeding 60% [19].

Protocol 2: Assessing Sensor Signal Drift via Chronopotentiometry

Chronopotentiometry (CP) is a direct method for evaluating the potential stability of a sensor under zero-current conditions, making it ideal for studying drift in potentiometric sensors like SC-ISEs.

Methodology:

- Baseline Recording: Immerse the sensor and a reference electrode in a stable, well-stirred electrolyte solution. Measure the open-circuit potential (EMF) over an extended period (e.g., 1-2 hours) to establish a baseline drift profile [15].

- Drift Quantification: The potential drift is calculated as the slope of the potential vs. time plot (ΔE/Δt), typically reported in microvolts per second (µV/s) or millivolts per hour (mV/hr). A lower absolute value indicates a more stable sensor. For example, a MWCNT-based SC-ISE demonstrated a low potential drift of 34.6 µV/s, correlating with its high Cdl [15].

Protocol 3: Comprehensive Interface Analysis via Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy

Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) is a powerful technique for deconvoluting the different resistive and capacitive components of an electrochemical interface, including the bulk resistance (Rb), charge transfer resistance (Rct), and Cdl.

Methodology:

- Measurement: Perform EIS over a wide frequency range (e.g., 100 kHz to 0.1 Hz) at the open-circuit potential with a small AC perturbation (e.g., 10 mV).

- Data Fitting: Fit the resulting Nyquist and Bode plots to an appropriate equivalent circuit model. A common model for a bare or solid-contact electrode is R(C(RW)), where the constant phase element (CPE) is often used instead of a pure capacitor to account for the non-ideal behavior of real surfaces.

- Extracting Cdl: The value of Cdl can be extracted from the fitted CPE parameters. By performing EIS over time on a sensor exposed to an operational environment, one can track the evolution of Cdl and directly correlate its increase or decrease with the onset of signal drift [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

A selection of key materials and their functions for developing drift-resistant electrochemical sensors is provided below.

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for Drift-Resistant Sensor Development

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in Managing Cdl and Drift |

|---|---|

| Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes (MWCNTs) | High surface-area transducer material that significantly increases double-layer capacitance (Cdl), stabilizing potential [15]. |

| Conducting Polymers (PEDOT, PANi) | Provide mixed ionic/electronic conductivity and high redox capacitance, acting as an efficient ion-to-electron transducer [15]. |

| Poly(OEGMA) Polymer Brush | A polyethylene glycol-like brush layer that extends the Debye length in high ionic strength solutions and reduces biofouling, stabilizing the interface and mitigating Cdl drift in BioFETs [7]. |

| Potassium Chloride (KCl) / PBS | Standard electrolyte solutions for electrochemical characterization and calibration. Maintaining consistent ionic strength is critical for stable Cdl measurements. |

| Tetrahydrofuran (THF) & PVC | Common solvent and polymer for preparing ion-selective membranes in SC-ISEs. The membrane composition directly affects ion transport to the underlying solid contact [15]. |

| Poly(vinyl chloride) (PVC) | A common polymer used as the matrix for the ion-selective membrane in potentiometric sensors [15]. |

| 2-Nitrophenyl octyl ether (o-NPOE) | A plasticizer used in PVC-based ion-selective membranes to ensure proper ionophore mobility and membrane conductivity [15]. |

Visualizing the Relationship: From Cdl Variability to Signal Drift

The following diagram illustrates the cascading relationship between the initial causes of Cdl variability, the resulting changes at the electrode-electrolyte interface, and the final manifestation as sensor signal drift.

Figure 1: Cdl Variability to Signal Drift Pathway

Mitigation Strategies and Future Directions

Understanding the link between Cdl and drift enables the development of targeted mitigation strategies. A multi-pronged approach is often most effective.

- Material Innovation: The cornerstone of drift mitigation is the use of transducer materials with high and stable capacitance. As demonstrated in Table 1, MWCNTs and certain conducting polymers are excellent choices for potentiometric sensors due to their high surface area and redox capacitance, which buffer against charge fluctuations [15]. For BioFETs, surface modification with polymer brushes like POEGMA creates a stable, non-fouling interface that resists Cdl variability by establishing a Donnan potential and extending the Debye length [7].

- Interface Engineering and Passivation: Robust device design that includes proper encapsulation is critical to prevent leakage currents and protect the sensitive electrode interface from environmental variables like humidity and contaminants, which are known causes of drift [7] [18].

- Rigorous Measurement Methodologies: The adoption of stringent testing protocols is essential. For BioFETs, this means relying on infrequent DC sweeps rather than continuous static measurements to distinguish true biomarker signal from temporal drift artifacts [7]. In all electrochemical characterizations, following standardized steps for techniques like CV ensures accurate and reproducible determination of Cdl, preventing misestimation that can obscure drift analysis [19].

- Data Processing and Correction Algorithms: In applications where physical mitigation is insufficient, computational approaches can be employed. As seen in LC-MS, software tools can implement drift correction algorithms based on quality control samples or bracketing methods to post-process data and compensate for baseline instability [16].

Future research will likely focus on the integration of machine learning for real-time drift prediction and correction, as well as the development of novel composite materials that combine high capacitance with inherent self-passivating properties. By anchoring sensor design and validation in a deep understanding of Cdl's role, researchers can advance the frontier of robust, reliable, and drift-free electrochemical sensing.

Quantifying Capacitance and Monitoring Drift in Biosensing Platforms

Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) for Cdl Determination

The electrical double layer (EDL) is a fundamental structure that forms at the interface between an electrode and an electrolyte. Its behavior is analogous to an electrical capacitor, leading to the concept of the double layer capacitance (Cdl) [9]. All electrochemical processes occur within this critical region, making accurate Cdl determination essential for understanding interface kinetics and properties [9]. The structure of this layer has been modeled by Helmholtz, Gouy-Chapman, Stern, and Grahame, describing it as two charged areas separated by a dielectric with a thickness corresponding to the ionic radius (approximately 50 nm) [9].

Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) serves as a powerful analytical technique for probing this interface. EIS measures the impedance of an electrochemical system over a range of frequencies, generating data that can be modeled using equivalent electrical circuits [13]. These circuits typically represent the double layer with a capacitive element, but real-world systems often exhibit non-ideal behavior that complicates direct Cdl extraction. The technique requires the system to be linear, time-invariant, and causal, with measurements conducted using a small excitation signal (typically 1-10 mV) to ensure pseudo-linear system response [13].

Theoretical Foundations

Equivalent Circuit Modeling

In an ideal scenario, the electrode-electrolyte interface can be modeled by a simple equivalent circuit consisting of the solution resistance (Rs) in series with a parallel combination of the double layer capacitance (Cdl) and the charge transfer resistance (Rct) [9]. This configuration, known as the Randles circuit, produces a perfect semicircle in the Nyquist plot representation [9]. However, experimentally obtained impedance spectra rarely display this ideal behavior. Instead, they often exhibit a depressed semicircle, indicating non-ideal capacitive behavior and surface inhomogeneity [9].

To account for this frequency dispersion, the Constant Phase Element (CPE) replaces the ideal capacitor in equivalent circuit models [9] [20]. The impedance of a CPE is defined as:

- Z

CPE= 1 / (Q(jω)ⁿ) - Z

CPE= (jω)⁻ⁿ / Q (alternative definition used in some commercial software) [20]

Where:

Qis the CPE constant (in Ω⁻¹sⁿ)nis the CPE exponent (0 ≤ n ≤ 1)jis the imaginary unitωis the angular frequency

The CPE exponent n quantifies the system's deviation from ideal capacitive behavior. When n = 1, the CPE behaves as an ideal capacitor; n = 0 represents a pure resistor; and n = 0.5 indicates diffusion-controlled behavior [9].

From CPE to Cdl: Correction Formulas

A significant challenge in EIS analysis lies in extracting the meaningful Cdl value from CPE parameters obtained through circuit fitting. The CPE parameter Q does not directly represent capacitance and requires mathematical correction [20]. Different correction approaches have been developed depending on the circuit configuration.

For a parallel CPE-Rct combination, the most accurate Cdl value is obtained using the Brug's formula:

- C

dl= Q¹/ⁿ × (Rs⁻¹ + Rct⁻¹)⁽ⁿ⁻¹⁾/ⁿ [20]

For cases where Rct >> Rs, this simplifies to:

- C

dl= (Q × Rs⁽¹⁻ⁿ⁾)¹/ⁿ

An alternative approach by Hsu and Mansfeld utilizes the frequency (ωmax) at which the imaginary impedance component reaches its maximum:

- C

dl= Q¹/ⁿ × (Rct)⁽¹⁻ⁿ⁾/ⁿ [20]

Table 1: Cdl Correction Formulas for Different Circuit Configurations

| Circuit Configuration | Correction Formula | Applicability |

|---|---|---|

| Parallel CPE-R | Cdl = Q¹/ⁿ × (Rs⁻¹ + Rct⁻¹)⁽ⁿ⁻¹⁾/ⁿ |

General case (Brug's formula) [20] |

Rct >> Rs |

Cdl = (Q × Rs⁽¹⁻ⁿ⁾)¹/ⁿ |

Simplified case [20] |

| Hsu & Mansfeld | Cdl = Q¹/ⁿ × (Rct)⁽¹⁻ⁿ⁾/ⁿ |

Uses ωmax at -Z'' peak [20] |

The choice of correction formula significantly impacts the calculated Cdl value, with potential for substantial errors if inappropriate methods are applied [20]. The discrepancy between fitted and corrected values depends on both n and R values, emphasizing the need for careful formula selection based on the specific circuit configuration [20].

Experimental Protocols

Standard EIS Procedure for Cdl Determination

A typical EIS experiment for Cdl determination follows a systematic protocol to ensure reliable results. The measurement usually employs a three-electrode setup: a working electrode (the material under investigation), a counter electrode (typically platinum), and a reference electrode (e.g., Saturated Calomel Electrode or Ag/AgCl) [9] [21].

Step-by-step protocol:

System Stabilization: Allow the electrochemical cell to reach a stable open circuit potential (OCP) before initiating measurements [22].

Parameter Configuration:

- Frequency range: 100 kHz to 100 mHz (or lower for diffusion-controlled processes) [9]

- AC amplitude: 10 mV (standard), though amplitudes as low as 3 mV may be used for sensitive systems [22] [23]

- DC bias: Typically set at OCP unless potential-dependent studies are performed [23]

- Points per decade: 5-10 points for initial surveys [22]

Data Acquisition: Perform impedance measurements across the specified frequency range. Modern potentiostats typically employ Fourier Transform-based methods to extract impedance from time-domain signals [13].

Data Validation:

- Assess data quality using Kramers-Kronig relations to check for linearity, stability, and causality

- Identify and potentially exclude low-frequency data points if system drift is observed [9]

Circuit Modeling:

- Select an appropriate equivalent circuit (e.g., R

s+ CPE/Rct) - Perform nonlinear least squares fitting to obtain circuit parameters

- Evaluate fit quality through chi-squared values and residual analysis

- Select an appropriate equivalent circuit (e.g., R

Cdl Calculation: Apply the appropriate correction formula to convert CPE parameters to meaningful C

dlvalues [20].

Diagram 1: EIS Experimental Workflow for Cdl Determination

Complementary Technique: Cyclic Voltammetry

While EIS provides detailed frequency-domain information, Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) serves as a complementary technique for Cdl estimation [9]. The CV approach involves:

Experimental Setup: Using the same three-electrode configuration as EIS measurements [9].

Parameter Selection:

Data Analysis:

- Calculate the current difference (I

a- Ic) at the OCP from anodic and cathodic sweeps - Apply the formula: C

dl= (Ia- Ic) / (2 × scan rate) [9]

- Calculate the current difference (I

CV-derived Cdl values typically show good agreement with EIS results when both measurements are performed under comparable conditions [9].

Advanced Methodological Considerations

Addressing Signal Drift in EIS Measurements

A critical challenge in EIS analysis, particularly for Cdl determination, is system non-stationarity or drift [22]. EIS theory assumes a time-invariant system, but real electrochemical systems often exhibit drift due to factors like adsorption processes, temperature fluctuations, or evolving surface morphology [22].

Drift correction methodologies:

Frequency-Domain Compensation: Modern instrumentation implements drift correction using adjacent frequency components in the Fourier spectrum [22]:

- Re

corr(fm) = Re(fm) - [Re(fm+1) + Re(fm-1)]/2 - Im

corr(fm) = Im(fm) - [Im(fm+1) + Im(fm-1)]/2

- Re

Data Acquisition Strategies:

Experimental Design:

- Control temperature precisely

- Use freshly prepared electrolytes to minimize contamination effects

- Ensure adequate purging with inert gas to remove dissolved oxygen [21]

Table 2: Troubleshooting Common Issues in EIS Cdl Determination

| Problem | Indicators | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| System Drift | Low-frequency scatter, poor Kramers-Kronig fit | Enable drift correction, exclude unstable data, ensure steady-state [22] |

| CPE Exponent n < 0.8 | Depressed semicircle, high fitting errors | Check surface roughness, heterogeneity; consider surface characterization [9] |

| Poor Circuit Fit | High chi-squared, systematic residuals | Validate circuit model, check for missing elements (Warburg, etc.) [24] |

| Inconsistent Cdl Values | Variable results between techniques/methods | Verify correction formula appropriateness, standardize experimental conditions [20] |

Novel Data Analysis Approaches

Recent advances in EIS data analysis offer promising alternatives to traditional equivalent circuit modeling:

The Loewner Framework (LF): This data-driven approach extracts the Distribution of Relaxation Times (DRT) directly from impedance data, facilitating identification of the most suitable equivalent circuit model without a priori assumptions [24]. The LF method provides unique DRTs that can distinguish between different circuit models yielding similar impedance spectra, addressing a fundamental challenge in traditional EIS analysis [24].

Time-Domain Modeling: Advanced computational approaches now enable modeling of CV responses using impedance-derived parameters through Fourier transformation [21]. This creates a bridge between frequency-domain and time-domain techniques, enhancing the consistency of Cdl values obtained through different methodologies [21].

Applications Across Research Fields

Battery Research