Electrochemical Biosensors: From Core Principles to Advanced Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of electrochemical biosensors, detailing the fundamental principles of how they transduce biological events into quantifiable electrical signals.

Electrochemical Biosensors: From Core Principles to Advanced Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of electrochemical biosensors, detailing the fundamental principles of how they transduce biological events into quantifiable electrical signals. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers the core components of these devices—bioreceptors and transducers—and explains key detection techniques such as amperometry and potentiometry. The content extends to advanced methodologies, including nanomaterial integration and multivariate optimization for enhanced sensitivity and selectivity. It further addresses critical challenges in sensor development, such as minimizing matrix interference and improving reproducibility, and offers a comparative analysis with other sensing technologies. The article concludes with a forward-looking perspective on the role of these biosensors in point-of-care diagnostics and personalized medicine.

The Building Blocks: Core Principles and Components of Electrochemical Biosensors

An electrochemical biosensor is an integrated analytical device that converts a biological event into a quantifiable electrical signal [1] [2]. These devices combine a biological recognition element (bioreceptor) with a physicochemical transducer, functioning as a self-contained analytical tool [3]. The fundamental principle involves the specific interaction between a target analyte and the bioreceptor, which generates a biochemical change. This change is then transduced by an electrochemical detector into a measurable electrical signal—such as current, potential, or impedance—that is proportional to the analyte concentration [4] [5].

The significance of electrochemical biosensors lies in their ability to provide rapid, sensitive, and selective analysis of complex biological samples, often without extensive pre-treatment [1]. Their close link to developments in microelectronic circuits enables easy interfacing with standard electronic read-out systems, facilitating miniaturization, portability, and cost-effective production [1]. These characteristics make them particularly valuable for point-of-care testing, environmental monitoring, food safety, and clinical diagnostics [2] [3].

Fundamental Principles and Components

The Biosensor Architecture

Every electrochemical biosensor consists of three essential components that work in sequence to detect and quantify an analyte [2] [3]:

- Biological Recognition Element (Bioreceptor): This component provides the specificity for the target analyte. Common bioreceptors include enzymes, antibodies, nucleic acids, aptamers, whole cells, and biomimetic polymers [1] [4] [3]. The bioreceptor is immobilized on the transducer surface and selectively interacts with the target molecule.

- Transducer: The transducer converts the biological interaction into a measurable electrical signal. In electrochemical biosensors, this is typically an electrode system that detects changes in electrical properties resulting from the biorecognition event [2].

- Signal Processor (Reader): This electronic component amplifies, processes, and displays the transducer signal in a user-readable format, enabling quantitative analysis [1] [3].

Key Electrochemical Transduction Techniques

The transducer detects the biological event using various electrochemical techniques, each with distinct measurement principles and applications [1] [6] [4].

Table 1: Fundamental Electrochemical Detection Techniques

| Technique | Measured Signal | Principle | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amperometry/ Voltammetry [6] | Current | Measures current generated from oxidation/reduction of electroactive species at a constant or varying potential. | Enzyme-based sensors (e.g., glucose), detection of redox markers. |

| Potentiometry [6] | Potential (Voltage) | Measures change in potential at an electrode surface versus a reference electrode under conditions of zero current. | Ion-selective electrodes, detection of enzyme-generated ions. |

| Impedimetry [6] [4] | Impedance | Measures the opposition to current flow (resistance and capacitance) when a small-amplitude AC voltage is applied. | Label-free immunosensors, detection of bacterial cells, DNA hybridization. |

| Conductometry [1] | Conductance | Measures the ability of a solution to conduct electricity, which changes with ionic strength. | Enzyme reactions that produce or consume ions. |

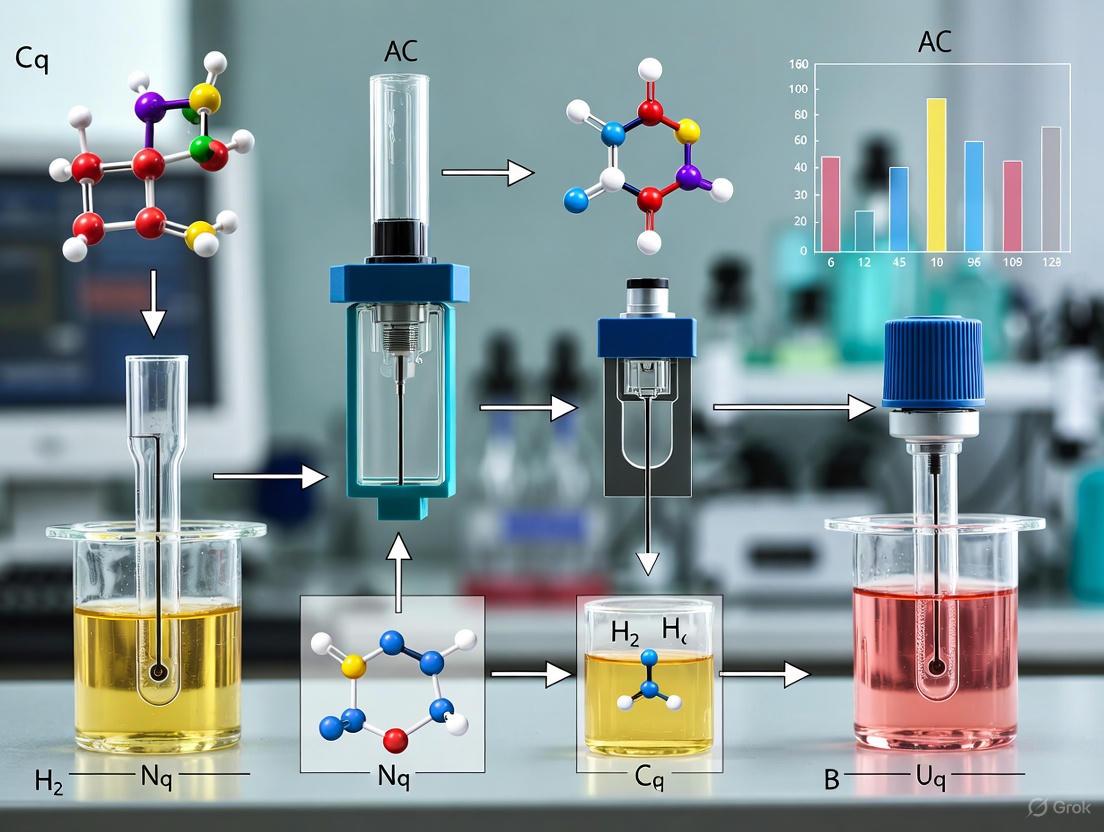

The following diagram illustrates the generalized workflow and signal transduction pathway common to most electrochemical biosensors.

Critical Research Reagents and Materials

The performance of an electrochemical biosensor hinges on the careful selection of its constituent materials, particularly for the bioreceptor and the electrode modification.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Biosensor Development

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function in Biosensor |

|---|---|---|

| Bioreceptors [4] [3] | Enzymes (e.g., Glucose Oxidase), Antibodies, Aptamers, DNA probes, Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) | Provides high specificity and selectivity for the target analyte. |

| Electrode Materials [1] [5] | Gold, Glassy Carbon, Screen-Printed Carbon, Indium Tin Oxide (ITO) | Serves as the solid support and base for electron transfer. |

| Nanomaterials for Enhancement [5] [3] | Carbon Nanotubes (SWCNTs/MWCNTs), Graphene/GO/rGO, Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs), Metal Oxides | Increases active surface area, improves electron transfer kinetics, and enhances loading of bioreceptors. |

| Immobilization Chemistries [5] | EDC-NHS, Thiol-gold (Au-S) bonding, Avidin-Biotin, APTES silanization | Anchors the bioreceptor to the transducer surface while maintaining its bioactivity. |

| Electrochemical Probes [6] | Ferricyanide ([Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻), Ferrocene derivatives, Methylene Blue | Acts as a redox mediator to facilitate electron transfer in certain sensor designs. |

Experimental Protocols: Methodologies for Biosensor Construction and Validation

Developing a robust electrochemical biosensor involves a multi-step process, from electrode modification to analytical validation.

Protocol 1: Fabrication of a Bioreceptor-Modified Electrode

This protocol outlines the general procedure for immobilizing a biological recognition element onto a transducer surface, a critical step for ensuring sensor specificity and stability [4] [5].

Electrode Pre-treatment:

- For glassy carbon electrodes (GCE), polish the surface sequentially with alumina slurries (e.g., 1.0, 0.3, and 0.05 µm) on a microcloth pad. Rinse thoroughly with deionized water between each polishing step and after the final polish.

- Perform electrochemical cleaning by cycling the potential in a suitable electrolyte (e.g., 0.5 M H₂SO₄) until a stable cyclic voltammogram is obtained [5].

Surface Functionalization:

- Depending on the electrode material and desired chemistry, apply a surface modification layer. For gold electrodes, form a self-assembled monolayer (SAM) by incubating in a solution of thiolated compounds (e.g., 1-6 hexanedithiol) for several hours [5].

- For carbon-based electrodes, surface activation can involve electrochemical oxidation to generate oxygen-containing groups or drop-casting of functional nanomaterials like MWCNTs or graphene oxide [5].

Bioreceptor Immobilization:

- Covalent Binding (for antibodies, enzymes): Activate carboxyl groups on the functionalized surface using a mixture of EDC (1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide) and NHS (N-hydroxysuccinimide) for 15-30 minutes. Then, incubate with the bioreceptor solution (typically in a phosphate buffer, pH 7.4) for 1-2 hours. Wash extensively to remove physically adsorbed molecules [5].

- Thiol-Gold Binding (for thiol-modified aptamers): Incubate the clean gold electrode directly with the thiolated aptamer solution overnight. Passivate the remaining gold surface with a backfiller like 6-mercapto-1-hexanol to minimize non-specific adsorption [3].

Blocking and Storage:

- To prevent non-specific binding of non-target molecules from samples, block the modified electrode surface with an inert protein like Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) or casein.

- Store the finished biosensor in a suitable buffer at 4°C when not in use [4].

Protocol 2: Analytical Validation using Impedimetric Detection

This protocol describes a common method for label-free detection of a target analyte, such as a protein or whole bacterium, using Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) [6] [4].

Experimental Setup:

- Use a standard three-electrode system: the bioreceptor-modified electrode as the working electrode, a Pt wire as the counter electrode, and an Ag/AgCl electrode as the reference.

- The electrochemical cell contains a solution of a redox probe, typically 5 mM K₃[Fe(CN)₆]/K₄[Fe(CN)₆] (1:1 mixture) in a neutral pH phosphate buffer saline (PBS).

EIS Measurement (Baseline):

- Record the electrochemical impedance spectrum at the modified electrode before exposure to the analyte. Apply a small amplitude sinusoidal AC voltage (e.g., 10 mV) over a frequency range from 100 kHz to 0.1 Hz, superimposed on a DC potential set to the formal potential of the redox probe.

- Fit the resulting Nyquist plot to a suitable equivalent circuit model (e.g., a modified Randles circuit) to determine the charge-transfer resistance (Rₑₜ), which is the key analytical signal.

Analyte Incubation and Detection:

- Incubate the working electrode with the sample containing the target analyte for a defined period (e.g., 15-30 minutes) at room temperature.

- Gently rinse the electrode with PBS to remove unbound material.

- Re-immerse the electrode in the redox probe solution and record a new EIS measurement under identical conditions.

Data Analysis:

- The binding of the target analyte (e.g., a protein or bacterial cell) to the surface-bound bioreceptor acts as an insulating layer, hindering the electron transfer of the redox probe. This results in an increase in the measured Rₑₜ value.

- The change in Rₑₜ (ΔRₑₜ) is calculated and plotted against the logarithm of the analyte concentration to generate a calibration curve, enabling quantitative analysis [6].

Current Research Trends and Future Perspectives

The field of electrochemical biosensing is continuously evolving, driven by advancements in nanotechnology and materials science [1]. A major focus is on integrating novel nanomaterials such as carbon nanotubes (CNTs), graphene, and metallic nanoparticles to enhance signal amplification, increase the immobilization surface area, and improve electron transfer rates [5]. These innovations are crucial for pushing the limits of detection (LOD) for various analytes. Furthermore, the combination of electrochemical transduction with optical techniques like electrochemiluminescence (ECL) or surface plasmon resonance (SPR) is creating powerful hybrid sensing platforms that offer complementary data and improved robustness [7].

Looking forward, the integration of electrochemical biosensors with portable, smartphone-based readers and the Internet of Things (IoT) is set to revolutionize decentralized diagnostics and real-time monitoring [2] [3]. The use of artificial intelligence and machine learning for data processing is also emerging as a key trend to improve the analysis of complex signals, differentiate between specific and non-specific binding events, and enable multi-analyte detection from a single sensor platform [7] [3]. The ultimate goal remains the development of fully integrated, automated, and highly reliable biosensors that can be deployed for real-world applications in clinical, environmental, and food safety sectors [7].

In the realm of electrochemical biosensors, which are analytical devices that convert a biological response into a quantifiable electronic signal, the precise function of the electrode system is paramount [1] [8]. These sensors are designed to be highly selective, often achieved by immobilizing biological recognition elements, such as enzymes, antibodies, or nucleic acids, onto the sensor substrate [1]. A typical biosensor comprises a bioreceptor, an interface architecture, a transducer, and electronic systems for signal processing [1] [8]. The transducer, which converts the biological event into a measurable electrical signal, is the core of the electrochemical biosensor, and its performance is critically dependent on a trio of electrodes: the working electrode, the reference electrode, and the counter electrode [1] [6]. This electrode configuration is fundamental to all electrochemical detection techniques, including amperometry, potentiometry, and impedance spectroscopy, which are used to probe a wide range of biological processes [1] [6] [9].

The delicate interplay between surface nano-architectures, surface functionalization, and the sensor transducer principle determines the ultimate sensitivity and specificity of the device [1]. This article provides an in-depth examination of the distinct roles, ideal characteristics, and common materials of these three essential electrodes, framing their operation within the context of how electrochemical biosensors detect analytes for applications in medical diagnostics, environmental monitoring, and drug development.

The Fundamental Principles of the Three-Electrode System

In an electrochemical cell, the three-electrode system establishes a controlled environment for investigating redox reactions. The system's configuration allows for the precise application of potential and the accurate measurement of current, which is the fundamental response in many biosensing applications [10] [6]. The working electrode is the stage where the action occurs, the reference electrode provides a stable benchmark for that action, and the counter electrode completes the electrical circuit, allowing charge to flow. Understanding the specific function of each is crucial for interpreting biosensor data and optimizing sensor design. The relationship and primary function of each electrode are summarized in the diagram below.

The Working Electrode (WE): The Sensor Stage

The working electrode (WE) is the cornerstone of the biosensor, serving as the platform where the specific biochemical recognition event is transduced into an electrical signal [1]. It is on the surface of this electrode that the biological recognition element (e.g., an enzyme, antibody, or DNA strand) is often immobilized [1] [8]. When the target analyte interacts with this bioreceptor, it triggers a biochemical reaction that either produces or consumes electrons, leading to a change in current or potential at the electrode-solution interface [10]. For example, in an enzymatic biosensor like the ubiquitous glucose sensor, the glucose oxidase enzyme catalyzes the oxidation of glucose, generating electrons that are subsequently measured as a current at the working electrode [1] [10]. The material and surface architecture of the working electrode are therefore critical, as they must facilitate efficient electron transfer and be amenable to functionalization with the chosen bioreceptor while minimizing non-specific binding [1].

The Reference Electrode (RE): The Stable Benchmark

The reference electrode (RE) functions as a stable, unchanging potential benchmark against which the potential of the working electrode is precisely controlled and measured [1] [10]. In electrochemical measurements, the applied potential is the difference between the working and reference electrodes. For this potential to be meaningful and reproducible, the reference electrode must maintain a constant potential, independent of the solution's composition or the current in the cell [1]. This is typically achieved by using an electrode immersed in a solution of fixed composition, such as the common Ag/AgCl (silver/silver chloride) electrode [1]. Its high stability is why it is described as being "kept at a distance from the reaction site in order to maintain a known and stable potential" [1]. Without a stable reference, the potential driving the electrochemical reaction at the working electrode would be poorly defined, leading to inaccurate and non-reproducible results.

The Counter Electrode (CE): Completing the Circuit

The counter electrode (CE), also known as the auxiliary electrode, completes the electrical circuit in the electrochemical cell [1]. When a potential is applied to the working electrode to drive a reaction (e.g., oxidation), a corresponding opposite reaction (e.g., reduction) must occur at the counter electrode to maintain charge balance and allow current to flow [1]. The primary function of the counter electrode is to conduct current without limiting the rate of the reaction occurring at the working electrode. It is designed to have a large surface area and be made from electrochemically inert materials, such as platinum or gold, to facilitate this current flow without itself becoming a source of significant overpotential or undergoing undesirable side reactions that could contaminate the solution [1].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of the Three-Electrode System

| Electrode | Primary Function | Key Characteristics | Common Materials |

|---|---|---|---|

| Working Electrode (WE) | Site of the biochemical recognition event; transduces reaction into measurable signal. | Functionalized with bioreceptors; signal sensitivity depends on its surface architecture and material. | Gold, Carbon (glassy carbon, graphite), Platinum [1] [11]. |

| Reference Electrode (RE) | Provides a stable, known potential benchmark for the working electrode. | Non-polarizable; maintains a constant potential regardless of solution conditions. | Ag/AgCl, Calomel (Hg/Hg₂Cl₂) [1]. |

| Counter Electrode (CE) | Completes the electrical circuit; facilitates current flow. | Large surface area; electrochemically inert to prevent undesired reactions. | Platinum, Gold [1]. |

Experimental Protocols in Electrochemical Biosensing

The trio of electrodes enables various electrochemical detection techniques that are central to biosensing. The specific experimental protocol depends on the transducer principle being employed. The following methodologies are widely used for quantitative analysis of target analytes.

Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) for Receptor Characterization

Objective: To characterize the redox properties of a bioreceptor (e.g., an enzyme) immobilized on the working electrode surface and to study the electron transfer kinetics.

Detailed Protocol:

- Sensor Fabrication: Immobilize the biological recognition element (e.g., glucose oxidase) onto the surface of the working electrode via physical adsorption, covalent bonding, or entrapment within a polymer matrix [1] [9].

- Instrument Setup: Place the functionalized working electrode, along with the reference and counter electrodes, into an electrochemical cell containing a buffer solution and the target analyte. Connect the electrodes to a potentiostat [10].

- Potential Sweep: Apply a linear potential sweep to the working electrode (vs. the reference electrode) between two set limits. For example, the potential may be swept from +0.6 V to -0.2 V and back to +0.6 V.

- Current Measurement: The potentiostat measures the resulting current at the working electrode as the potential is swept. The counter electrode completes the circuit, allowing this current to flow.

- Data Analysis: Plot the measured current (y-axis) against the applied potential (x-axis) to obtain a cyclic voltammogram. Characteristic peaks in the voltammogram indicate the redox potential of the immobilized receptor and can provide information about the reversibility of the reaction and the rate of electron transfer.

Chronoamperometry for Analytic Detection

Objective: To quantitatively measure the concentration of a target analyte by monitoring the Faradaic current generated from a biochemical reaction over time at a constant potential.

Detailed Protocol:

- Sensor Preparation: As in CV, a bioreceptor-modified working electrode is used.

- Baseline Stabilization: Immerse the electrode system in the buffer solution and apply a constant potential to the working electrode. Allow the background current to stabilize.

- Analyte Introduction: Introduce the sample containing the target analyte into the electrochemical cell under stirring (if required).

- Current Transient Measurement: Upon the enzymatic or binding reaction, electroactive species are produced or consumed, leading to a change in current. The potentiostat measures this current transient at the working electrode over time.

- Quantification: The steady-state current or the maximum change in current is proportional to the concentration of the analyte. A calibration curve is constructed using standards of known concentration to quantify the unknown sample [6].

Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) for Binding Detection

Objective: To monitor biomolecular binding events (e.g., antibody-antigen, DNA hybridization) in a label-free manner by measuring changes in the impedance at the electrode-solution interface.

Detailed Protocol:

- Electrode Modification: Immobilize the capture probe (e.g., an antibody or single-stranded DNA) onto the working electrode.

- Initial Impedance Measurement: In the presence of a redox probe like [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻, apply a small amplitude sinusoidal AC voltage over a range of frequencies to the working electrode. Measure the impedance spectrum, which provides a baseline of the interface's electrical properties.

- Incubation with Analyte: Expose the modified electrode to the sample solution containing the target analyte. The binding event occurs on the working electrode surface.

- Final Impedance Measurement: After washing, measure the impedance spectrum again under the same conditions.

- Data Interpretation: The binding of the target analyte insulates the electrode surface or hinders the redox probe's access, increasing the charge-transfer resistance (Rₑₜ). The change in Rₑₜ, often modeled using an equivalent circuit, is used to detect and quantify the analyte [6]. This principle has been successfully applied for detecting proteins like dengue NS1 in neat serum [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The development and operation of electrochemical biosensors rely on a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The table below details key components and their functions in a typical biosensor experiment.

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Electrochemical Biosensor Research

| Item | Function/Explanation |

|---|---|

| Biological Recognition Elements | Enzymes (e.g., Glucose Oxidase), antibodies, nucleic acids (DNA/RNA), or aptamers that provide high specificity by interacting selectively with the target analyte [1] [8]. |

| Redox Probes | Molecules such as Potassium Ferricyanide ([Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻) or Methylene Blue that facilitate electron transfer in techniques like EIS and voltammetry, acting as mediators to enhance signal [6]. |

| Potentiostat | The core electronic instrument that applies a controlled potential between the working and reference electrodes and measures the resulting current flowing between the working and counter electrodes. Modern versions include Source Measure Units (SMUs) with touchscreen interfaces [10]. |

| Screen-Printed Electrodes (SPEs) | Disposable, mass-producible electrode strips where the working, reference, and counter electrodes are printed on a plastic or ceramic substrate. They enable portable, low-cost, and single-use biosensing [10] [9]. |

| Surface Functionalization Reagents | Chemicals like self-assembled monolayers (SAMs) of alkanethiols on gold or polymers like Nafion. They are used to modify and functionalize the working electrode surface for optimal bioreceptor immobilization and to suppress non-specific binding [1] [6]. |

| Nanomaterials | Gold nanoparticles (AuNPs), carbon nanotubes, and graphene. Used to nanostructure the working electrode surface, increasing its effective surface area to enhance signal-to-noise ratio and improve biosensor sensitivity [1] [11]. |

The working, reference, and counter electrodes form an indispensable and synergistic trio in electrochemical biosensors. The working electrode acts as the transformative stage, the reference electrode provides the fundamental scale for measurement, and the counter electrode ensures the circuit is functionally complete. A deep understanding of their distinct yet interconnected roles, operational principles, and the experimental methods they enable is essential for researchers and scientists aiming to develop next-generation biosensors. As the field advances, driven by nanotechnology and new materials, the precise engineering and integration of these three electrodes will continue to be the foundation for creating highly sensitive, specific, and portable diagnostic devices for healthcare, environmental monitoring, and drug development.

In electrochemical biosensing, a bioreceptor serves as the biological recognition element that specifically interacts with a target analyte, while the transducer converts this biological event into a quantifiable electrochemical signal [12]. This combination of biological recognition and electrochemical detection forms the foundation of biosensing technology, enabling sensitive and selective detection of substances ranging from simple ions to complex biological entities like pathogenic bacteria [13] [1]. The bioreceptor's fundamental purpose is to provide high specificity for the target analyte, even within complex sample matrices such as blood, urine, saliva, or food products [13] [12].

The significance of bioreceptors extends across numerous fields including clinical diagnostics, environmental monitoring, food safety, and drug discovery [12] [14]. In clinical applications specifically, electrochemical biosensors incorporating appropriate bioreceptors can detect protein cancer biomarkers, pathogens, and other disease indicators in bodily fluids, often achieving detection limits as low as ng/ml or even fg/ml [12]. The selection of an appropriate bioreceptor is therefore paramount to achieving the desired sensitivity, selectivity, and overall performance characteristics required for a specific application.

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of an Effective Biosensor

| Characteristic | Description | Importance |

|---|---|---|

| Selectivity | Ability of a bioreceptor to detect a specific analyte in samples containing other admixtures and contaminants | Prevents false positives/negatives; ensures measurement accuracy |

| Sensitivity | Minimum amount of analyte that can be detected (Limit of Detection or LOD) | Determines applicability for trace analysis; critical for early disease detection |

| Reproducibility | Ability to generate identical responses for a duplicated experimental setup | Ensures reliability and robustness of measurements |

| Stability | Degree of susceptibility to ambient disturbances; retention of efficiency over time | Crucial for applications requiring long incubation or continuous monitoring |

| Linearity | Accuracy of measured response to a straight line over a concentration range | Defines analytical range and resolution of the biosensor |

Fundamental Principles of Biorecognition

Biorecognition relies on specific biochemical interactions between the bioreceptor immobilized on the sensor surface and the target analyte in solution. The specificity of this interaction is what distinguishes biosensors from other chemical sensors [8]. When the bioreceptor binds to its target, this molecular recognition event triggers a physicochemical change that the transducer detects and converts into a measurable electrochemical signal [12].

Electrochemical biosensors typically employ several measurement techniques to detect and quantify this biorecognition event. The most common include:

- Amperometry: Measures current generated by electrochemical oxidation or reduction at a constant potential [1]

- Potentiometry: Measures potential difference at zero current [1]

- Impedimetry: Measures impedance (both resistance and reactance) of the electrode interface [1]

- Voltammetry (including cyclic voltammetry, differential pulse voltammetry): Measures current while varying the applied potential [13] [15]

The resulting signals are processed by electronics and displayed in a user-friendly format, completing the journey from molecular interaction to analytical information [12].

Diagram 1: Biosensor signal transduction pathway (Title: Biosensor Architecture)

Major Bioreceptor Classes: Mechanisms and Characteristics

Enzyme-Based Bioreceptors

Enzymes function as bioreceptors through several mechanisms: (1) converting the analyte into an electrochemically detectable product, (2) undergoing inhibition or activation by the analyte, or (3) experiencing modified catalytic properties upon analyte interaction [8]. The catalytic activity of enzymes provides amplification, enabling lower limits of detection compared to binding-based techniques, while their specificity for substrates contributes to excellent selectivity [8]. A significant advantage of enzyme bioreceptors is that they are not consumed in reactions, allowing for continuous biosensor operation [8].

Common applications include glucose monitoring using glucose oxidase, detection of neurotransmitters using various oxidases, and environmental monitoring of pollutants like pesticides through inhibition mechanisms [14]. For example, the activity of tyrosinase enzyme can be inhibited by the herbicide atrazine, enabling detection at 0.3 ppm in water bodies [14]. Similarly, biosensors using lactate dehydrogenase, urease, acetylcholinesterase, and β-galactosidase have been developed for optical detection of milk quality and safety [14].

Antibody-Based Bioreceptors (Immunosensors)

Antibodies, or immunoglobulins, function as bioreceptors through their highly specific binding affinity for a specific compound or antigen [8]. The antibody-antigen interaction is analogous to a lock and key fit, where the antigen only binds to the antibody if it has the correct conformation [8]. This exceptional specificity makes antibodies ideal for detecting pathogens, biomarkers, and other complex molecules [13]. However, antibody binding capacity is strongly dependent on assay conditions such as pH and temperature, and the robust binding can be disrupted by chaotropic reagents, organic solvents, or ultrasonic radiation [8].

Immunosensors can be designed for direct antigen detection or for serological testing (detection of circulating antibodies in response to disease) [8]. Recent advances have focused on reducing incubation time, improving design, signal amplification, label-free detection, and controlling antibody placement [14]. For instance, a label-free immunosensor based on optical fiber coated with a thin film of titania-silica was successfully used for detecting Immunoglobin (IgG) and anti-IgG in human serum with very low limits of detection [14].

Nucleic Acid-Based Bioreceptors

Nucleic acid-based bioreceptors include both genosensors (based on complementary base pairing) and aptasensors (using nucleic acid-based antibody mimics called aptamers) [8]. Genosensors utilize the principle of complementary base pairing (adenine:thymine and cytosine:guanine in DNA) to detect specific DNA or RNA sequences [8]. If the target nucleic acid sequence is known, complementary sequences can be synthesized, labeled, and immobilized on the sensor to detect hybridization events [8].

Aptamers, in contrast, are single-stranded DNA or RNA molecules that fold into specific three-dimensional structures recognizing targets via specific non-covalent interactions and induced fitting [8]. These synthetic molecules can be generated against a wide range of targets including small molecules, proteins, cells, and viruses [8]. Aptamers offer advantages over antibodies including easier labeling with fluorophores or metal nanoparticles, superior stability, and compatibility with various detection platforms [8]. Additionally, aptamers can be combined with nucleic acid enzymes like RNA-cleaving DNAzymes, providing both target recognition and signal generation in a single molecule for multiplex biosensing applications [8].

Aptamers as Synthetic Recognition Elements

Aptamers deserve special attention as they represent a class of synthetic bioreceptors obtained through an in vitro selection process called SELEX (Systematic Evolution of Ligands by EXponential enrichment) [8]. These single-stranded DNA or RNA molecules fold into defined three-dimensional structures that bind to targets with high affinity and specificity, comparable to antibodies [8]. Aptamers offer several advantages over natural antibodies, including better stability, easier production and modification, reduced cost, and the ability to target molecules that don't elicit immune responses [8].

Aptamers can be engineered to undergo conformational changes upon target binding, enabling the development of signal-on and signal-off biosensing strategies [8]. They have been successfully developed against diverse targets including ions, small molecules, proteins, cells, and viruses [8]. When integrated into electrochemical biosensors, aptamers provide excellent sensitivity and selectivity while offering reversible binding behavior for reusable sensor platforms [8].

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Major Bioreceptor Types

| Bioreceptor | Recognition Mechanism | Key Advantages | Limitations | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enzymes | Catalytic activity and specific binding | Signal amplification; reusable; high catalytic activity | Stability limited by enzyme lifetime; sensitive to environment | Metabolite monitoring (glucose, lactate); environmental pollutants |

| Antibodies | Specific antigen-antibody binding | Very high specificity and affinity; well-established immobilization methods | Sensitive to assay conditions; binding can be irreversible; expensive production | Pathogen detection (Salmonella, E. coli); disease biomarkers; therapeutic drug monitoring |

| Nucleic Acids (DNA/RNA) | Complementary base pairing | High specificity; stable; predictable binding; easily synthesized | Requires sequence knowledge; may need amplification | Genetic disease markers; viral/bacterial DNA; gene expression monitoring |

| Aptamers | 3D structure-based recognition | Target versatility; thermal stability; reversible binding; cost-effective production | In vitro selection process can be complex; susceptible to nuclease degradation | Small molecule detection; proteins; cells; therapeutic applications |

Experimental Protocols: Bioreceptor Immobilization and Characterization

Bioreceptor Immobilization Techniques

Effective immobilization of bioreceptors onto transducer surfaces is critical for biosensor performance. The immobilization method must preserve bioreceptor activity while ensuring stable attachment. Common approaches include:

Covalent Immobilization: This traditional method uses bifunctional linkers with thiol end groups to bind gold surfaces and carboxylic or amino terminal groups to form covalent bonds with bioreceptors [15]. For antibody immobilization, carboxyl groups are typically activated with ethyl(dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide/N-hydroxysuccinimide (EDC/NHS) to form amide bonds, or amino groups are activated with glutaraldehyde to form imine bonds [15]. This approach provides stable, irreversible attachment but requires additional chemical reagents and processing steps.

Hydrogen Bonding Immobilization: Recent advances demonstrate that hydrogen bonding interactions can serve as an efficient alternative for bioreceptor immobilization [15]. This approach uses linkers with different terminal groups (COOH in cysteine or NH₂ in cysteamine) to promote hydrogen bonding with bioreceptors [15]. This method eliminates the need for additional chemical reagents, simplifies functionalization steps, and has shown improved repeatability and lower interference with serum matrices compared to covalent methods while achieving similar detection limits [15].

Physical Adsorption and Entrapment: Simple physical adsorption relies on non-specific interactions between bioreceptors and surfaces, but may result in unstable attachment [14]. Entrapment within polymer matrices or gels (e.g., polyvinyl alcohol) preserves bioreceptor activity while providing a stable microenvironment [14]. For example, spermine oxidase entrapped in polyvinyl alcohol gel on carbon electrodes modified with Prussian blue enabled detection of polyamines for food safety monitoring [14].

Electrochemical Characterization Methods

Following bioreceptor immobilization, comprehensive characterization ensures proper biosensor function:

Cyclic Voltammetry (CV): This technique scans the potential between two set values while measuring current, providing information about redox processes, electron transfer rates, and surface coverage [13] [15]. It is commonly used to verify successful bioreceptor immobilization by observing changes in redox peaks of tracer molecules like [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻ [15].

Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS): EIS measures the impedance of the electrode interface across a frequency range, detecting electrical changes resulting from variations in electrode composition [1] [15]. While highly sensitive, EIS requires several minutes per measurement and needs data fitting to equivalent circuits to calculate electron transfer resistance [15].

Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV): This pulsed voltammetric technique offers superior sensitivity and repeatability compared to EIS, with faster measurement times [15]. DPV has demonstrated excellent performance in label-free biosensing when combined with appropriate bioreceptor immobilization strategies [15].

Diagram 2: Bioreceptor immobilization workflow (Title: Immobilization and Testing Workflow)

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Bioreceptor Immobilization and Testing

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Cysteamine (CT) | Linker molecule with thiol end group for gold surface binding and amino terminal group for bioreceptor attachment | Antibody immobilization via hydrogen bonding or covalent binding [15] |

| Cysteine (CS) | Linker with thiol group for gold surface and carboxylic acid group for bioreceptor conjugation | Surface modification for subsequent bioreceptor immobilization [15] |

| EDC/NHS | Carbodiimide chemistry for activating carboxylic groups to form amide bonds with primary amines | Covalent immobilization of antibodies and other protein-based bioreceptors [15] |

| Glutaraldehyde | Homobifunctional crosslinker for activating amino groups to form imine bonds | Covalent immobilization of amine-containing bioreceptors [15] |

| [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻ | Redox probe for electrochemical characterization | Monitoring bioreceptor immobilization and target binding in label-free biosensors [15] |

| Prussian Blue | Electron transfer mediator and catalyst for hydrogen peroxide reduction | Enzyme-based biosensors for cholesterol, lactate, and other metabolites [14] |

| Gold Electrodes | Working electrode material with well-established surface modification chemistry | Preferred substrate for many biosensing applications due to conductivity and biocompatibility [15] |

| Screen-Printed Electrodes | Disposable, cost-effective electrode platforms | Commercial biosensor development; point-of-care testing devices [14] |

Advanced Applications and Future Perspectives

Bioreceptor-integrated electrochemical biosensors have enabled remarkable advancements across diverse fields. In clinical diagnostics, they facilitate detection of pathogenic bacteria such as Salmonella spp., Staphylococcus aureus, Campylobacter, Listeria, Shigella, or Escherichia coli O157:H7 with high sensitivity and selectivity [13]. Recent developments include wearable and implantable biosensors for continuous health monitoring, such as wireless graphene-based sensors for Staphylococcus aureus detection on tooth enamel with sensitivity down to a single bacterium [13].

In food safety applications, electrochemical biosensors with appropriate bioreceptors detect contaminants, pathogens, and spoilage indicators in meat, dairy products, fruits, and vegetables [13] [14]. For instance, biosensors for spermine and spermidine detection help monitor food freshness and safety [14]. Environmental monitoring applications include detection of herbicides like atrazine in water bodies using enzyme inhibition principles [14].

Future developments in bioreceptor technology focus on several key areas. Artificial binding proteins engineered from small protein scaffolds offer advantages over antibodies including smaller size, enhanced stability, lack of disulfide bonds, and high-yield expression in bacterial systems [8]. Biomimetic receptors such as molecularly imprinted polymers provide synthetic alternatives to biological recognition elements with superior stability and customizability [13]. Nanomaterial integration enhances biosensor performance through increased surface area, improved electron transfer, and novel signal transduction mechanisms [14]. Finally, multiplexing capabilities enable simultaneous detection of multiple analytes, addressing the growing need for comprehensive diagnostic information [16].

The convergence of bioreceptor engineering with advancements in electrochemistry, nanotechnology, and microfluidics continues to expand the capabilities of electrochemical biosensors. As these technologies mature, we can anticipate increasingly sophisticated biosensing platforms with enhanced sensitivity, specificity, and functionality for addressing complex analytical challenges across healthcare, environmental monitoring, and industrial applications.

Electrochemical biosensors have revolutionized the field of analytical chemistry by providing robust, sensitive, and often portable platforms for detecting a vast array of analytes, from small molecules like glucose to complex entities like whole bacterial cells [1]. These devices integrate a biological recognition element (such as an enzyme, antibody, or nucleic acid) with a transducer that converts a specific biological event into a quantifiable electronic signal [1] [17]. The core of this transduction lies in the electrochemical techniques of amperometry, potentiometry, and impedimetry. The selection of a specific transduction mechanism is pivotal, as it directly influences the biosensor's sensitivity, selectivity, limit of detection, and suitability for field deployment or point-of-care testing [18] [19]. This review provides an in-depth technical examination of these three principal electrochemical transduction mechanisms, detailing their fundamental principles, operational protocols, and key applications within modern biosensing.

Fundamental Principles and Comparative Analysis

The operational principles of amperometric, potentiometric, and impedimetric biosensors are distinct, leading to unique performance characteristics for each.

Amperometric biosensors operate by applying a constant potential to the working electrode and measuring the resulting current generated from the oxidation or reduction of an electroactive species involved in a biochemical reaction [1] [17]. The measured current is directly proportional to the concentration of the analyte. A classic example is the glucose biosensor, where the enzyme glucose oxidase (GOx) catalyzes the oxidation of glucose, and the subsequent reduction of oxygen or an artificial electron mediator generates a current [20].

Potentiometric biosensors measure the potential difference between a working electrode and a reference electrode under conditions of zero or negligible current flow [1] [21]. This potential develops across a selective membrane and is governed by the Nernst equation, relating the potential to the logarithm of the activity of the target ion [17]. Common potentiometric devices include ion-selective electrodes (ISEs) and field-effect transistors (FETs), where the binding of a charged analyte alters the potential at the electrode or gate surface [18] [22].

Impedimetric biosensors utilize electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) to monitor changes in the impedance (both resistance and reactance) at the electrode-electrolyte interface [17]. A small-amplitude AC voltage is applied over a range of frequencies, and the resulting current is measured to determine the impedance. Binding events, such as antibody-antigen interactions, alter the interfacial properties (e.g., charge transfer resistance, capacitance), allowing for label-free detection of analytes [17].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Electrochemical Transduction Mechanisms

| Feature | Amperometry | Potentiometry | Impedimetry |

|---|---|---|---|

| Measured Quantity | Current | Potential | Impedance (Z) |

| Applied Signal | Constant Potential | Zero Current | AC Voltage (multiple frequencies) |

| Key Relationship | Current ∝ Concentration | Potential ∝ log(Activity) | Fitting to Equivalent Circuit Models |

| Sensitivity | High (pM–nM) [18] | Moderate to High | High [17] |

| Selectivity | Achieved via enzyme specificity & applied potential | Achieved via ion-selective or biomimetic membranes | Achieved via specific biorecognition elements (e.g., antibodies) |

| Labeling | Often uses enzymes or mediators | Typically label-free | Label-free |

| Key Advantage | High sensitivity, well-established | Simple, compact, low power [18] | Label-free, monitors binding kinetics |

| Common Application | Glucose monitoring, neurotransmitter detection [23] | pH sensing, ion detection, DNA hybridization [18] [22] | Pathogen detection, biomarker quantification [17] |

Amperometric Detection

Principle and Workflow

Amperometric biosensors function by maintaining a constant potential at the working electrode relative to a reference electrode, which drives the oxidation or reduction of an electroactive species. The resulting faradaic current is measured and serves as the analytical signal. The biological recognition event, typically catalyzed by an enzyme, generates or consumes this electroactive species. For instance, the first-generation glucose biosensor relies on the production of hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂), which is oxidized at the electrode, or the consumption of oxygen [17]. Second-generation biosensors employ synthetic redox mediators (e.g., ferrocene) to shuttle electrons between the enzyme's active site and the electrode, improving efficiency and reducing the operating potential to minimize interferent effects [20].

Diagram 1: Amperometric biosensor signal pathway.

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Protocol: Fabrication and Testing of a Mediated Glucose Biosensor

This protocol outlines the steps for constructing a screen-printed, mediator-based amperometric biosensor for glucose detection, representative of common practices in the field [24] [20].

1. Electrode Preparation and Modification:

- Materials: Screen-printed carbon electrode (SPCE), glucose oxidase (GOx) enzyme, redox mediator (e.g., potassium ferricyanide or ferrocene derivatives), Nafion solution, chitosan, cross-linking agent (e.g., glutaraldehyde), phosphate buffer saline (PBS, pH 7.4) [20] [24].

- Procedure:

- Surface Activation: Clean the SPCE's working electrode surface by cycling the potential in a suitable electrolyte (e.g., 0.5 M H₂SO₄) until a stable cyclic voltammogram is obtained.

- Mediator/Enzyme Ink Preparation: Prepare a homogeneous ink by dissolving GOx (e.g., 100 U) and the redox mediator (e.g., 1% w/w) in a buffer solution. Add a biopolymer like chitosan (1% w/v) to form a viscous suspension that facilitates immobilization.

- Immobilization: Deposit a precise volume (e.g., 5 µL) of the prepared ink onto the working electrode area. Allow the solvent to evaporate at room temperature.

- Cross-linking and Stabilization: Expose the modified electrode to glutaraldehyde vapor for a few minutes to cross-link the enzyme and enhance operational stability.

- Membrane Casting: To prevent leaching of the bioactive layer and improve selectivity against interferents (e.g., ascorbic acid, uric acid), cast a thin layer of a permeslective membrane like Nafion (e.g., 2 µL of 0.5% solution) on top of the modified electrode and let it dry.

2. Electrochemical Measurement and Data Acquisition:

- Instrumentation: Potentiostat, data acquisition software, three-electrode system (modified SPCE as working electrode, integrated Ag/AgCl reference, and carbon counter electrode) [20].

- Procedure:

- System Setup: Connect the modified SPCE to the potentiostat. Place a drop of buffer or standard/sample solution onto the electrode array, ensuring all three electrodes are connected.

- Potential Application: Apply a constant DC potential optimal for the chosen mediator. For ferricyanide, a potential of +0.35 V vs. Ag/AgCl is typical to oxidize the reduced mediator (ferrocyanide) back to its oxidized form.

- Background Stabilization: Monitor the current until a stable baseline is achieved.

- Calibration and Sample Measurement:

- Add known concentrations of glucose standard solutions to the measurement cell.

- Record the steady-state current after each addition. The current will rise and plateau.

- Plot the steady-state current against glucose concentration to obtain a calibration curve.

- For unknown samples, measure the steady-state current and interpolate the concentration from the calibration curve.

Potentiometric Detection

Principle and Workflow

Potentiometric biosensors measure the accumulation of charge at an electrode interface without drawing significant current. The potential developed across a selective membrane is measured against a stable reference electrode [1] [21]. This mechanism is harnessed in Ion-Selective Electrodes (ISEs) and Field-Effect Transistor (FET)-based biosensors. In ISEs, the membrane potential changes in response to the activity of a specific ion [18]. In BioFETs, the binding of charged analytes to the gate dielectric modulates the conductance of the semiconductor channel, which is converted into a readable electrical signal [18] [22]. A significant advancement is the use of redox potentiometry, where the sensor detects the equilibrium potential of a redox couple, thereby overcoming issues like signal drift and charge screening in biological samples [22].

Diagram 2: Potentiometric biosensor signal pathway.

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Protocol: DNA Detection using a Potentiometric FET Biosensor Array

This protocol describes the use of a CMOS-compatible potentiometric sensor array for detecting DNA hybridization, a technique moving towards high-density, multi-analyte sensing [22].

1. Functionalization of the Extended-Gate Electrodes:

- Materials: CMOS sensor chip with gold extended-gate electrodes, 5'-thiol-modified probe DNA (e.g., 20-mer oligonucleotide), complementary and non-complementary target DNA sequences, phosphate buffer (1 mM, pH 7.0), ethanol for washing [22].

- Procedure:

- Surface Cleaning: Clean the gold extended-gate electrodes with oxygen plasma or piranha solution to remove organic contaminants, followed by rinsing with ethanol and deionized water. (Caution: Piranha solution is extremely dangerous and must be handled with extreme care.)

- Probe Immobilization: Incubate the sensor chip in a solution containing the thiol-modified probe DNA (e.g., 1 µM in phosphate buffer) for several hours (e.g., 12-16 hours) at room temperature. This allows the formation of a self-assembled monolayer (SAM) on the gold surface via gold-thiol bonds.

- Surface Blocking: Rinse the chip with buffer to remove physically adsorbed DNA. Subsequently, incubate in a solution of 6-mercapto-1-hexanol (e.g., 1 mM) for 1 hour to backfill any uncovered gold sites, which minimizes non-specific adsorption.

- Rinsing and Storage: Rinse the functionalized sensor chip thoroughly with phosphate buffer and store in a clean buffer at 4°C until use.

2. Potentiometric Measurement of Hybridization:

- Instrumentation: CMOS readout system, flow cell, precision syringe pump, data acquisition software [22].

- Procedure:

- Baseline Acquisition: Mount the functionalized sensor chip in a flow cell and connect it to the readout system. Flow a low-ion concentration buffer (e.g., 1 mM phosphate buffer) to establish a stable baseline potential for all sensor cells.

- Hybridization: Introduce the solution containing the complementary target DNA (e.g., 1 µM in buffer) into the flow cell at a controlled rate (e.g., 1 µL/s). Monitor the output voltage of each sensor cell in real-time.

- Control Experiment: Repeat the measurement using a non-complementary or reverse-complementary DNA sequence to confirm the specificity of the signal.

- Data Analysis: The specific hybridization event is indicated by a stable positive shift in the output voltage (e.g., 40 mV as reported) compared to the baseline and the control experiment. The magnitude of this shift can be correlated with target concentration.

Impedimetric Detection

Principle and Workflow

Impedimetric biosensors are label-free devices that monitor changes in the electrical impedance of the electrode-electrolyte interface due to a biorecognition event [17]. Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) involves applying a small sinusoidal AC voltage over a wide frequency range and measuring the phase-shifted current response. The data is often represented as a Nyquist plot and fitted to an equivalent electrical circuit model. Key parameters include the charge transfer resistance (R_ct), which typically increases when an insulating layer (like bound proteins or cells) forms on the electrode, hindering the access of a redox probe (e.g., [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻) to the surface [17]. This makes EIS exceptionally sensitive for directly detecting the binding of antibodies to antigens, DNA hybridization, and whole bacterial cells without any labeling.

Diagram 3: Impedimetric biosensor signal pathway.

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Protocol: Impedimetric Immunosensor for Pathogen Detection

This protocol details the development of a label-free EIS immunosensor for detecting whole bacterial cells, such as E. coli, using a gold electrode platform [19] [17].

1. Electrode Modification and Antibody Immobilization:

- Materials: Gold disk electrode, specific anti-E. coli antibodies, 11-mercaptoundecanoic acid (11-MUA), ethanolamine, N-(3-Dimethylaminopropyl)-N'-ethylcarbodiimide (EDC), N-Hydroxysuccinimide (NHS), PBS (pH 7.4) containing a redox probe (e.g., 5 mM [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻) [17].

- Procedure:

- Electrode Pretreatment: Polish the gold electrode with alumina slurries (e.g., 1.0, 0.3, and 0.05 µm) to a mirror finish. Clean electrochemically by cycling in 0.5 M H₂SO₄ until a reproducible cyclic voltammogram is obtained.

- SAM Formation: Incubate the clean gold electrode in a 1 mM solution of 11-MUA in ethanol for at least 12 hours to form a carboxyl-terminated self-assembled monolayer.

- Antibody Immobilization:

- Activate the terminal carboxyl groups of the SAM by immersing the electrode in a fresh solution of EDC (400 mM) and NHS (100 mM) in water for 1 hour.

- Rinse the electrode with PBS to remove excess EDC/NHS.

- Incubate the activated electrode in a solution of the specific antibody (e.g., 10 µg/mL in PBS) for 2 hours. The antibody covalently attaches to the SAM via amine coupling.

- Surface Blocking: Treat the electrode with 1 M ethanolamine (pH 8.5) for 30 minutes to deactivate any remaining activated ester groups and block non-specific binding sites. Rinse with PBS.

2. EIS Measurement and Data Analysis:

- Instrumentation: Potentiostat with EIS capability, three-electrode cell (functionalized Au working electrode, Pt counter electrode, Ag/AgCl reference electrode) [17].

- Procedure:

- Baseline Impedance: Place the modified electrode in a cell containing PBS with the redox probe. Run an EIS measurement with an AC voltage amplitude of 10 mV over a frequency range from 100 kHz to 0.1 Hz at the open circuit potential. This is the baseline spectrum (Rct, baseline).

- Antigen/Bacteria Incubation: Incubate the electrode with the sample containing E. coli cells (or a control buffer) for a fixed time (e.g., 30 minutes).

- Post-Incubation Impedance: Gently rinse the electrode with PBS and perform the EIS measurement again under identical conditions to obtain the spectrum after binding (Rct, sample).

- Data Fitting and Quantification:

- Fit both the baseline and sample Nyquist plots to a suitable equivalent circuit, typically a modified Randles circuit.

- The key parameter for analysis is the charge transfer resistance (Rct).

- The normalized signal is the change in Rct: ΔRct = Rct, sample - Rct, baseline.

- Plot ΔRct against the logarithm of the bacterial concentration to generate a calibration curve.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The development and implementation of electrochemical biosensors rely on a standardized set of reagents and materials. The table below catalogs key components essential for research in this field.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

| Item | Function/Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Screen-Printed Electrodes (SPEs) | Disposable, mass-producible platform for amperometric and impedimetric sensors. | Carbon, gold, or platinum ink working electrodes; often include integrated reference and counter electrodes [25]. |

| Glucose Oxidase (GOx) | Model enzyme for amperometric biosensor development and validation. | Used in conjunction with a mediator (e.g., ferrocene) for second-generation biosensors [20]. |

| Redox Mediators (e.g., Ferrocene, Potassium Ferricyanide) | Shuttle electrons between enzyme redox centers and the electrode surface. | Lower operating potential, reducing interference and improving sensitivity [22] [20]. |

| Ion-Selective Membranes | Core component of potentiometric sensors, provides selectivity for specific ions. | Materials include PVC-COOH, silicon nitride, or biomimetic membranes [18] [21]. |

| Self-Assembled Monolayer (SAM) Kits (e.g., Thiol- or Silane-based) | Create a well-defined, functionalizable interface on gold or oxide surfaces for bioreceptor immobilization. | Provides control over surface density and minimizes non-specific binding [22] [17]. |

| Cross-linking Agents (e.g., Glutaraldehyde, EDC/NHS) | Covalently immobilize bioreceptors (enzymes, antibodies) onto sensor surfaces. | Enhances the stability and longevity of the biosensing interface [24] [17]. |

| Permselective Membranes (e.g., Nafion) | Coating to reject interfering anions (e.g., ascorbate, urate) in amperometric sensors. | Improves selectivity in complex biological samples like blood [24]. |

| Redox Probes (e.g., [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻) | Essential for impedimetric biosensors to monitor changes in charge transfer resistance (R_ct). | The standard probe for characterizing electrode modifications and binding events [17]. |

Electrochemical biosensors have revolutionized analytical science by providing robust, sensitive, and selective platforms for detecting target analytes across healthcare, environmental monitoring, and food safety applications [26]. These devices integrate a biological recognition element with an electrochemical transducer to convert a biological event into a quantifiable electrical signal [27]. The evolution of these biosensors, particularly glucose sensors which dominate the commercial landscape, reflects a journey of scientific innovation aimed at overcoming limitations in sensitivity, selectivity, and operational practicality [28] [29]. This progression is categorized into distinct generations, each defined by fundamental improvements in electron transfer mechanisms between the biochemical recognition site and the physical transducer [28]. Understanding this evolution is crucial for researchers and drug development professionals designing the next generation of diagnostic and monitoring tools, framing the core thesis of how electrochemical biosensors detect analytes through increasingly sophisticated interfacial communication.

The Generational Shift in Biosensor Design

The development of electrochemical biosensors is historically classified into three generations, based primarily on the nature of the electron transfer pathway from the enzyme's active site to the electrode surface [28]. This framework charts a course from dependence on dissolved oxygen, through the introduction of artificial mediators, to the ideal of direct communication.

First-Generation Biosensors: The Oxygen-Based Paradigm

First-generation biosensors, pioneered by the work of Updike and Hicks following Clark's initial enzyme electrode concept, relied on the natural cosubstrates and products of the enzymatic reaction [28] [26]. The most established example is the glucose biosensor based on the enzyme Glucose Oxidase (GOx) [28].

- Working Principle: GOx catalyzes the oxidation of glucose, using the cofactor Flavin Adenine Dinucleotide (FAD) as the primary electron acceptor. The reduced form of the enzyme (GOx-FADH₂) is then re-oxidized by molecular oxygen (O₂), naturally present in the sample, which is reduced to hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) [28].

- Transduction Mechanism: The electrochemical detection is achieved by applying a relatively high potential (~0.6 V vs. Ag/AgCl) to a platinum electrode, where the generated H₂O₂ is oxidized, producing a measurable current signal proportional to the glucose concentration [28]. The fundamental reaction sequence is:

- Glucose + GOx-FAD → Gluconolactone + GOx-FADH₂

- GOx-FADH₂ + O₂ → GOx-FAD + H₂O₂

- H₂O₂ → 2H⁺ + O₂ + 2e⁻ (at the electrode surface) [28]

Table 1: Characteristics and Limitations of First-Generation Biosensors

| Feature | Description | Associated Challenge |

|---|---|---|

| Electron Transfer | Relies on natural oxygen diffusion and H₂O₂ detection [28]. | Signal dependent on variable oxygen concentration in the sample [28]. |

| Operating Potential | High (~0.6 V) for H₂O₂ oxidation [28]. | Attracts interfering species (e.g., ascorbic acid, uric acid), reducing selectivity [28]. |

| Historical Significance | Enabled the first commercial glucose biosensor (Yellow Springs Instrument Company, 1975) [28]. | Restricted to clinical labs due to expensive Pt electrodes and the above limitations [28]. |

Second-Generation Biosensors: The Mediator Era

To overcome the oxygen dependence of first-generation biosensors, the second generation introduced artificial redox mediators [28]. These synthetic molecules shuttle electrons directly from the reduced enzyme to the electrode surface, bypassing the natural oxygen pathway.

- Working Principle: The redox mediator (Mₒₓ), which is reduced (Mᵣₑd) by the enzyme FADH₂ center, diffuses to the electrode surface and is re-oxidized, generating the analytical current [28]. This decouples the sensor signal from fluctuating oxygen levels in the sample.

- Common Mediators: Ferrocene and its derivatives, ferricyanide, quinones, and methylene blue are commonly used mediators [28].

- Advantages: This approach allows for operation at a much lower applied potential, typically around the formal potential of the mediator (e.g., 0-0.2 V), which minimizes the electrochemical interference from other species in complex fluids like blood [28].

Despite their success, second-generation biosensors face challenges. There can be competition between the mediator and oxygen, and a persistent risk of mediator leaching from the sensor interface, which compromises long-term stability [28].

Third-Generation Biosensors: Direct Electron Transfer

Third-generation biosensors represent the ideal and most advanced design, characterized by the direct electron transfer (DET) between the enzyme's active site and the electrode, without any mediators [28]. This eliminates the need for both oxygen and artificial mediators, simplifying the system and enhancing its robustness.

- Working Principle: The deeply buried redox center of the enzyme (e.g., FAD in GOx) communicates directly with the electrode. Achieving this requires a sophisticated electrode design that can "wire" itself to the enzyme, often accomplished using engineered nanostructured materials like carbon nanotubes, graphene, or specific conductive polymers [28] [30].

- Challenges and Solutions: The major hurdle is the insulating protein shell of enzymes, which acts as a barrier to DET. Nanostructured electrodes have proven highly effective by providing a favorable microenvironment and orientation for immobilized enzymes, facilitating a more efficient electrical connection to the deeply buried active sites [28] [30]. Recent studies have proposed that electron transfer is physically accelerated within nanostructured electrodes due to reduced charge screening, which can yield a up to 24-fold increase in signal level [30].

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Biosensor Generations

| Feature | First Generation | Second Generation | Third Generation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electron Transfer Mechanism | Via natural cosubstrate (O₂/H₂O₂) [28] | Via artificial redox mediator [28] | Directly from enzyme to electrode [28] |

| Key Advantage | Simple concept, first to be commercialized [28] | Reduced O₂ dependence, lower operating potential [28] | No mediators, excellent selectivity, low potential [28] |

| Primary Limitation | O₂ tension fluctuations, interferents, enzyme deactivation by H₂O₂ [28] | Potential for mediator leaching, competition with O₂ [28] | Difficult to achieve for many enzymes due to insulated active sites [28] |

| Typical Electrode Material | Platinum [28] | Various (e.g., carbon, gold) [28] | Nanostructured (e.g., CNTs, graphene) [28] [30] |

Experimental Protocols for Investigating Electron Transfer

To validate the generation and performance of a biosensor, specific experimental protocols are essential. The following methodologies are foundational to the field.

Fabrication of a First-Generation Glucose Biosensor

This protocol outlines the construction of a classic first-generation biosensor for glucose detection [28].

- Objective: To immobilize Glucose Oxidase (GOx) on an electrode and detect glucose by measuring the hydrogen peroxide produced.

- Materials:

- Platinum (Pt) working electrode, Ag/AgCl reference electrode, Pt wire counter electrode.

- Glucose Oxidase (GOx) from Aspergillus niger.

- Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) and Glutaraldehyde for cross-linking.

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), pH 7.4.

- Glucose standard solutions.

- Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Electrode Pretreatment: Clean the Pt working electrode by polishing with alumina slurry and rinsing thoroughly with deionized water.

- Enzyme Immobilization: Prepare a mixture of 10 µL GOx (10 mg/mL), 5 µL BSA (10% w/v), and 2 µL glutaraldehyde (2.5% v/v). Spot 5 µL of this mixture onto the active surface of the Pt electrode and allow it to cure at 4°C for 1 hour.

- Electrochemical Measurement: Assemble the three-electrode system in an electrochemical cell containing PBS. Apply a constant potential of +0.6 V vs. Ag/AgCl.

- Calibration: Upon signal stabilization, sequentially add known aliquots of glucose stock solution to the stirred PBS. Record the steady-state current increase after each addition.

- Data Analysis: Plot the steady-state current versus glucose concentration to generate a calibration curve.

Protocol for Demonstrating Direct Electron Transfer

This protocol describes a method to observe direct electron transfer to a redox enzyme, a key requirement for third-generation biosensors [28] [30].

- Objective: To characterize the direct electrochemistry of an enzyme immobilized on a nanostructured electrode using Cyclic Voltammetry (CV).

- Materials:

- Nanostructured working electrode (e.g., Carbon Nanotube (CNT) modified glassy carbon electrode).

- Target enzyme (e.g., GOx, laccase, or cytochrome c).

- Deoxygenated PBS, pH 7.4.

- Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Electrode Modification: Deposit a well-dispersed suspension of CNTs onto a clean glassy carbon electrode and allow it to dry.

- Enzyme Adsorption/Immobilization: Immobilize the enzyme onto the CNT electrode via physical adsorption, covalent binding, or layer-by-layer assembly.

- Cyclic Voltammetry in Buffer: Place the modified electrode in deoxygenated PBS (no substrate or mediator). Record cyclic voltammograms at a slow scan rate (e.g., 10-50 mV/s) over a potential window that encompasses the expected redox potential of the enzyme.

- Data Interpretation: The appearance of a pair of stable, symmetric oxidation and reduction peaks in the absence of any mediator is a hallmark of direct electron transfer. The formal potential (E⁰') can be calculated as the midpoint between the anodic and cathodic peak potentials.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Successful development and analysis of electrochemical biosensors require a suite of specialized reagents and materials.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Biosensor Development

| Reagent/Material | Function in Biosensor Research | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Glucose Oxidase (GOx) | Model enzyme bioreceptor; catalyzes glucose oxidation [28]. | The foundational element for research and commercial glucose biosensors across all generations [28]. |

| Redox Mediators (e.g., Ferrocene) | Artificial electron shuttles; transfer electrons from enzyme to electrode [28]. | Enabling second-generation biosensors by replacing O₂ as the primary electron acceptor [28]. |

| Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) | Nanostructured electrode material; high conductivity and surface area facilitate direct electron transfer [28] [30]. | Used to create nanoelectrode ensembles (NEEs) for third-generation biosensors, enabling DET to buried enzyme active sites [28]. |

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | Nanomaterial for electrode modification; enhance surface area, conductivity, and biocompatibility [26]. | Used to immobilize biomolecules and improve electrochemical signal in affinity-based sensors (e.g., for DNA or proteins) [26]. |

| Glutaraldehyde | Cross-linking agent; forms stable covalent bonds between biomolecules and/or with the electrode surface [28]. | Used in enzyme immobilization protocols to create a robust, leak-proof biorecognition layer [28]. |

Visualization of Biosensor Evolution and Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the core concepts and experimental workflows discussed in this guide.

Electron Transfer Pathways Across Generations

Experimental Workflow for DET Characterization

The evolution from oxygen-dependent first-generation biosensors to the mediator-free ideal of third-generation devices represents a profound refinement in the fundamental interface between biology and electronics. This journey, driven by the need for more reliable, accurate, and user-friendly analytical tools, underscores a central thesis in sensor research: the mechanism of electron transfer is the critical determinant of performance. The ongoing integration of novel nanomaterials and a deeper understanding of bio-interfacial science continue to push the boundaries of what is possible [30] [29]. For researchers and drug development professionals, this generational perspective provides a crucial framework for designing the next wave of biosensing technologies, which will increasingly feature multiplexing, continuous monitoring, and seamless integration into digital health ecosystems [31] [29]. The future of biosensing lies in mastering the conversation between the biological recognition element and the transducer, a challenge that continues to inspire innovation across scientific disciplines.

Fabrication and Real-World Deployment: From Sensor Design to Biomedical Analysis

Electrochemical biosensors are analytical devices that combine a biological recognition element with a physicochemical transducer to detect specific analytes, converting a biological event into a quantifiable electronic signal [1] [2]. The core function of a biosensor relies on the precise integration of its components: the electrode serves as the fundamental transduction platform, the modified surface enhances its electronic and catalytic properties, and the immobilized bioreceptor provides the specific molecular recognition capability [32] [33]. This construction process is critical for determining the ultimate sensitivity, selectivity, and stability of the biosensor [1]. The widespread success of biosensors, most notably the glucose sensor, demonstrates the practical impact of optimizing these construction steps [1] [34]. This guide details the core technical procedures for building a robust electrochemical biosensor, framed within the broader research on how these devices detect analytes.

The general workflow for biosensor construction follows a logical sequence from a bare electrode to a functional sensing interface, as shown in the diagram below.

Electrode Preparation: Foundations of the Sensor Platform

The working electrode is the cornerstone of any electrochemical biosensor, where the biochemical recognition event is transduced into a measurable electrical signal. The choice of electrode material and its initial preparation are paramount for ensuring a reproducible and reliable sensor response [33].

Electrode Material Selection

Different electrode materials offer distinct advantages suited for various sensing applications.

Table 1: Common Electrode Materials and Their Properties

| Material | Key Advantages | Common Fabrication Methods | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gold (Au) | Easily functionalized with thiolated molecules; biocompatible; high conductivity [35] [36]. | Sputtering (PVD) [35]; Screen printing [35]; Laser cutting of gold leaf [35]. | Immunosensors [36]; DNA sensors [35]. |

| Glassy Carbon (GC) | Wide potential window; chemical inertness; smooth surface [33]. | Commercial polishing kits; surface activation via potential cycling [33]. | Detection of neurotransmitters, small molecules [33]. |

| Screen-Printed Electrodes (SPEs) | Disposable; low-cost; mass-producible; portable [35]. | Layering of conductive (carbon, gold, platinum) and insulating inks on ceramic or plastic substrates [35]. | Point-of-care testing; environmental monitoring [35] [34]. |

Electrode Cleaning and Activation Protocols

A clean and well-defined electrode surface is essential for achieving uniform modification and reproducible results. Contaminants can block electron transfer and lead to high background noise.

Glassy Carbon Electrode Polishing Protocol:

- Polish the electrode surface sequentially with alumina slurry of decreasing particle sizes (e.g., 1.0 µm, 0.3 µm, and 0.05 µm) on a microcloth pad [36] [33].

- Rinse thoroughly with deionized water between each polishing step to remove all alumina particles.

- Sonicate the electrode in ethanol and then in deionized water for 2-5 minutes each to remove any adhered particles [33].

- Electrochemically clean by performing cyclic voltammetry (CV) in 0.5 M H₂SO₄, scanning between -0.2 V and +1.2 V (vs. Ag/AgCl) until a stable voltammogram is obtained [33].

Gold Electrode Cleaning Protocol:

Electrode Surface Modification

Surface modification aims to enhance the electrode's properties by increasing its active surface area, improving electron transfer kinetics, and providing functional groups for the subsequent attachment of bioreceptors [33]. The choice of nanomaterial is critical for signal amplification.

Modification Materials and Their Functions

Table 2: Common Nanomaterials for Electrode Modification

| Nanomaterial | Key Function/Property | Impact on Biosensor Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | High conductivity, large surface-to-volume ratio, facile bioconjugation via thiol chemistry [32] [33]. | Increases electroactive surface area; catalyzes reactions; enhances signal sensitivity [32]. |

| Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) | Excellent electrical conductivity, high mechanical strength, and capacity for biomolecule adsorption [33]. | Promotes electron transfer; lowers overpotential; improves stability and detection limits [33]. |

| Graphene & Graphene Oxide | Very high electrical and thermal conductivity, large specific surface area [33]. | Similar to CNTs; its 2D structure provides an extensive platform for biomolecule immobilization [33]. |

| Conducting Polymers (e.g., PEDOT, Polypyrrole) | Combine electronic properties with mechanical flexibility and ease of processing [32]. | Can be electrodeposited; provide a 3D matrix for entrapment of bioreceptors; enhance biocompatibility [32]. |

Detailed Modification Methodologies

Several techniques can be employed to deposit these nanomaterials onto the electrode surface, each with its own advantages and limitations.

A. Drop-Casting Method (Most Common) [33]

- Procedure:

- Disperse the nanomaterial (e.g., AuNPs, graphene) in a suitable solvent (e.g., water, ethanol) to form a homogeneous suspension via sonication.

- Pipette a precise volume (e.g., 5-10 µL) of the suspension directly onto the pre-cleaned electrode surface.

- Allow the solvent to evaporate under ambient conditions or under an infrared lamp, leaving a thin film of the nanomaterial on the electrode.