Electrochemical Biosensors in Agriculture: A Comprehensive Review of Principles, Applications, and Future Directions for Smart Farming

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the transformative role of electrochemical biosensors in modern agriculture.

Electrochemical Biosensors in Agriculture: A Comprehensive Review of Principles, Applications, and Future Directions for Smart Farming

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the transformative role of electrochemical biosensors in modern agriculture. It explores the foundational principles of these analytical devices, which combine a biological recognition element with an electrochemical transducer to convert a biological response into a quantifiable signal. The review details the diverse methodologies and specific applications in precision agriculture, including the real-time monitoring of plant health, early detection of devastating pathogens in key crops like oilseed rape and soybean, and analysis of soil and environmental conditions. It critically examines the technical challenges and optimization strategies for field deployment, such as overcoming matrix interference and improving sensor stability. Furthermore, the article offers a comparative analysis with traditional analytical methods, highlighting the superior portability, cost-effectiveness, and rapid response of biosensors. Finally, it discusses the integration of these sensors with emerging technologies like the Internet of Things (IoT), artificial intelligence (AI), and smartphone-based platforms, outlining a future roadmap for sustainable crop management and enhanced global food security.

The Fundamentals of Electrochemical Biosensors: Principles, Components, and Transduction Mechanisms

Electrochemical biosensors represent a powerful class of analytical devices that combine the specificity of biological recognition with the sensitivity of electrochemical transduction. These tools are transforming fields ranging from clinical diagnostics to environmental monitoring and, critically, agricultural research [1] [2]. For scientists engaged in agriculture, these biosensors offer the potential for real-time, on-site detection of pathogens, toxins, and stress biomarkers in crops and soil, enabling precision agriculture and early intervention strategies [3] [4]. The performance of any electrochemical biosensor hinges on the seamless integration of its core components: the bioreceptor, which provides molecular recognition, and the transducer, which converts the biological event into a quantifiable electrical signal [5] [6]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide to these fundamental elements, detailing their principles, configurations, and experimental implementation within an agricultural research context.

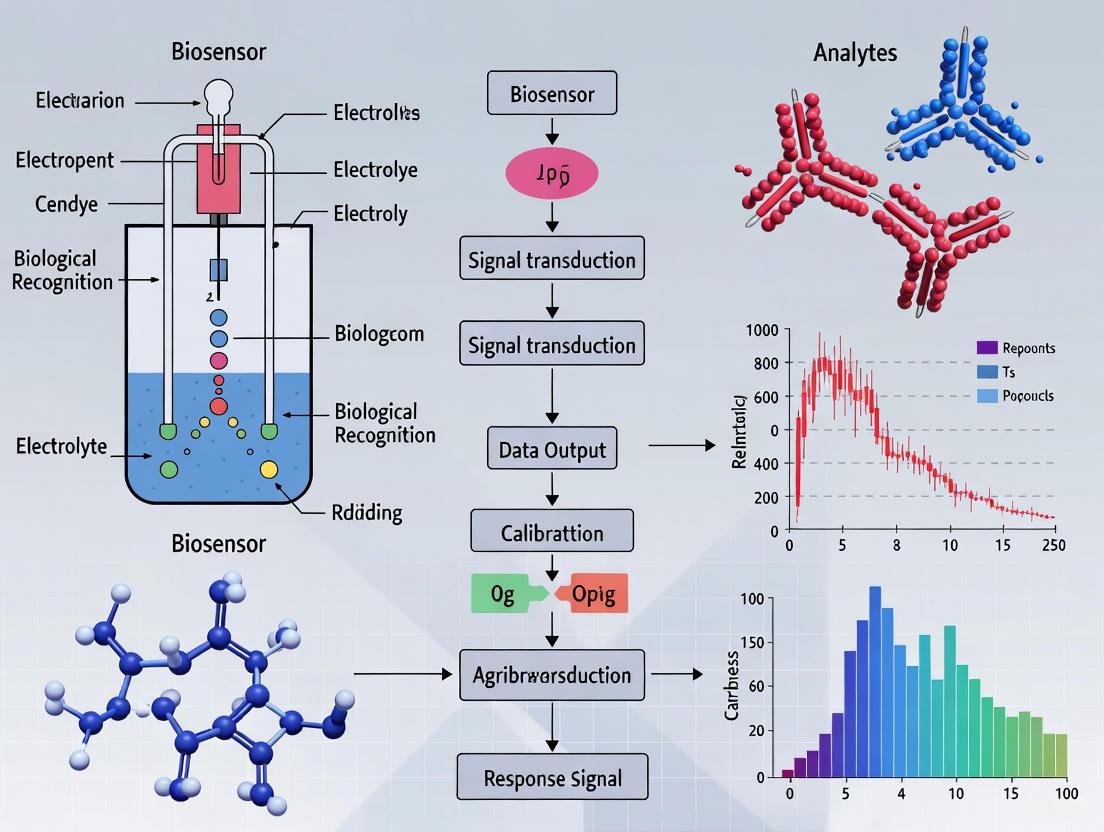

Core Components of an Electrochemical Biosensor

A typical electrochemical biosensor is an integrated device composed of five main elements: the bioreceptor, the interface, the transducer, detector electronics, and data output software [5] [6]. The central process involves the selective binding of the target analyte (e.g., a pathogen DNA sequence or a protein biomarker) by the bioreceptor immobilized on a sensor surface. This biological interaction produces a physicochemical change at the interface, which the transducer converts into an electrical signal. The detector circuit processes this signal, and software finally translates it into a meaningful physical parameter for the user [5]. The following diagram illustrates this workflow and the relationship between these core components.

The Bioreceptor: Engine of Molecular Recognition

The bioreceptor is the molecular recognition element of a biosensor, responsible for its high selectivity and specificity. It is a biological or biomimetic entity immobilized on the sensor surface that selectively binds to the target analyte [1] [5]. The choice of bioreceptor is dictated by the application and determines key sensor characteristics like stability, reproducibility, and susceptibility to interferences.

Common types of bioreceptors used in agricultural biosensing include:

- Enzymes: These biocatalysts recognize substrates and generate electroactive products (e.g., H₂O₂, O₂) whose concentration can be measured. They are widely used for detecting pesticides, which often act as enzyme inhibitors [5] [2].

- Antibodies: These immunoproteins form highly specific "lock-and-key" complexes with antigens (e.g., whole bacterial cells, viral proteins). Biosensors using antibodies are termed immunosensors and are central to pathogen detection [5] [7].

- Nucleic Acids (DNA/RNA): Single-stranded DNA or RNA probes hybridize with complementary target sequences, allowing for the detection of specific pathogen DNA (e.g., from Sclerotinia sclerotiorum) with high precision [1] [3].

- Whole Cells: Microorganisms (e.g., bacteria, yeast) or plant cells can serve as living bioreceptors, often engineered to produce an electrical signal in response to specific metabolic changes or environmental contaminants [5] [8].

- Aptamers: These are short, single-stranded oligonucleotides (DNA or RNA) selected in vitro for high-affinity binding to a target, from small molecules to whole cells. They are known as "chemical antibodies" and offer advantages in stability and synthesis [1] [3].

Table 1: Common Bioreceptors in Agricultural Electrochemical Biosensors

| Bioreceptor | Recognition Principle | Key Advantages | Agricultural Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enzymes | Catalytic substrate conversion | High turnover = signal amplification | Detection of organophosphate pesticides [5] |

| Antibodies | Affinity-based antigen binding | High specificity and affinity | Detection of E. coli O157:H7, Salmonella [7] [9] |

| Nucleic Acids | Base-pair hybridization | High specificity, stable receptors | Detection of fungal pathogen DNA [3] |

| Aptamers | 3D structure-based affinity | High stability, synthetic production | Detection of mycotoxins [1] |

| Whole Cells | Metabolic or stress response | Functional, multi-parameter response | Engineered cell sensors for bioactive compounds [8] |

The Transducer: Principle of Electrochemical Signal Conversion

The transducer is the component that converts the biological recognition event into a measurable electrical signal. In electrochemical biosensors, this occurs via electrodes that are in contact with the analytical sample [5] [2]. The design of the electrode and the electrochemical technique applied are critical for sensitivity, detection limits, and suitability for field use.

The most common electrochemical transduction techniques are:

- Amperometry: Measures the current generated by the electrochemical oxidation or reduction of an electroactive species at a constant applied potential. The current is directly proportional to the concentration of the species [5] [6]. It is widely used in enzyme-based biosensors.

- Potentiometry: Measures the potential difference (voltage) between a working electrode and a reference electrode when little to no current flows between them. Ion-selective electrodes (e.g., pH electrodes) are a common example [5] [6].

- Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS): Measures the impedance (resistance to current flow) of the electrode interface. The binding of a target analyte to the bioreceptor often alters the interfacial impedance, allowing for label-free detection [5].

- Voltammetry: Measures the current while the potential between the electrodes is swept and the redox behavior of electroactive species is analyzed. Techniques like Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) offer high sensitivity [5] [9].

- Conductometry: Measures the change in the electrical conductivity of a solution resulting from a biological reaction [5] [6].

Table 2: Core Electrochemical Transduction Techniques

| Technique | Measured Quantity | Principle | Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amperometry | Current | Redox reaction of electroactive species | High sensitivity, well-established |

| Potentiometry | Potential | Ion activity at electrode surface | Wide detection range, simple instrumentation |

| Impedimetry (EIS) | Impedance | Electrical resistance/ capacitance of interface | Label-free, real-time monitoring |

| Voltammetry | Current vs. Potential | Redox behavior during potential sweep | High sensitivity and selectivity (e.g., DPV) |

| Conductometry | Conductance | Ionic strength change in bulk solution | Simple, direct measurement |

The interplay between the bioreceptor and transducer, often enhanced with nanomaterials, defines the biosensor's mechanism. The following diagram details the operational principles of two common biosensor types: catalytic (e.g., enzyme-based) and affinity-based (e.g., antibody or aptamer-based).

Experimental Protocols for Biosensor Development

Protocol: Fabrication of a Nanomaterial-Modified Working Electrode

The sensitivity of modern biosensors is heavily dependent on the electrode's surface area and electronic properties. Nanomaterials are often used to modify the working electrode to enhance its performance [5] [3].

1. Aim: To fabricate a screen-printed carbon electrode (SPCE) modified with multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) and gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) to create a high-sensitivity platform for pathogen detection [7]. 2. Materials: * Screen-printed carbon electrode (SPCE) * Carboxyl-functionalized multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNT-COOH) * Chloroauric acid (HAuCl₄) * Phosphate buffer saline (PBS, 0.1 M, pH 7.4) * N,N-Dimethylformamide (DMF) * Eppendorf tubes and micropipettes 3. Procedure: * MWCNT Dispersion: Disperse 1 mg of MWCNT-COOH in 1 mL of DMF and sonicate for 30 minutes to obtain a homogeneous black suspension. * Electrode Modification: Drop-cast 5 µL of the MWCNT suspension onto the working electrode area of the SPCE and allow it to dry at room temperature. * AuNP Electrodeposition: Immerse the MWCNT/SPCE in a 0.1 M PBS solution containing 1 mM HAuCl₄. Perform cyclic voltammetry between -0.2 V and +1.0 V (vs. Ag/AgCl reference) for 10 cycles at a scan rate of 50 mV/s to electrodeposit AuNPs. * Rinsing and Storage: Rinse the modified electrode (MWCNT-AuNP/SPCE) thoroughly with deionized water and store dry at 4°C when not in use.

Protocol: Immobilization of an Aptamer Bioreceptor

Aptamers are a popular choice for bioreceptors due to their stability and specificity. This protocol describes their covalent immobilization on a nanomaterial-modified electrode [1] [3].

1. Aim: To covalently immobilize a thiol-modified DNA aptamer onto a gold nanoparticle-modified electrode surface for the detection of a specific pathogen. 2. Materials: * MWCNT-AuNP/SPCE (from Protocol 3.1) * Thiol-modified DNA aptamer (e.g., specific for E. coli O157:H7) * N-(3-Dimethylaminopropyl)-N′-ethylcarbodiimide (EDC) and N-Hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) * 6-Mercapto-1-hexanol (MCH) * Tris-EDTA (TE) buffer 3. Procedure: * Aptamer Preparation: Dilute the thiol-modified aptamer to 1 µM in TE buffer and reduce the thiol groups by incubating with Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP) for 1 hour. * Covalent Immobilization: Incubate the MWCNT-AuNP/SPCE with a mixture of 0.4 M EDC and 0.1 M NHS in water for 30 minutes to activate carboxyl groups on the MWCNTs. Then, drop-cast 10 µL of the reduced aptamer solution onto the activated surface and incubate in a humid chamber for 2 hours at 37°C. * Surface Blocking: To minimize non-specific binding, incubate the electrode with 1 mM 6-Mercapto-1-hexanol (MCH) for 30 minutes. This step passivates unoccupied gold sites. * Rinsing and Storage: Rinse the aptamer-functionalized biosensor with PBS to remove unbound aptamers. The biosensor can be stored in PBS at 4°C until use.

Protocol: Electrochemical Detection of Pathogen via Differential Pulse Voltammetry

This protocol outlines the use of the fabricated biosensor for the quantitative detection of a target pathogen using a sandwich assay format and DPV measurement [9].

1. Aim: To detect E. coli O157:H7 using an aptamer-based biosensor and a ferrocene-labeled reporter in a sandwich assay. 2. Materials: * Aptamer-functionalized biosensor (from Protocol 3.2) * Samples containing E. coli O157:H7 (concentration range 10² - 10⁸ CFU/mL) * Ferrocene-conjugated secondary aptamer or antibody * Electrochemical analyzer with DPV capability 3. Procedure: * Sample Incubation: Incubate the biosensor with 50 µL of the sample solution (or standard) for 20 minutes at room temperature to allow pathogen binding. * Sandwich Complex Formation: Rinse the sensor gently with PBS. Then, incubate it with 50 µL of the ferrocene-conjugated secondary detection probe for 15 minutes. * Electrochemical Measurement: After a final rinse, perform DPV measurement in a clean electrochemical cell containing 0.1 M PBS. The typical parameters are: potential window from 0 V to +0.5 V, pulse amplitude of 50 mV, and pulse width of 50 ms. * Data Analysis: The oxidation current peak of ferrocene (typically around +0.3 V) is measured. Plot the peak current against the logarithm of the pathogen concentration to generate a calibration curve for quantitative analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

The development and deployment of electrochemical biosensors for agricultural research rely on a specific set of reagents and materials. The following table details key components for building and experimenting with these devices.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Biosensor Development

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Screen-Printed Electrodes (SPEs) | Disposable, cost-effective sensor platforms with integrated working, reference, and counter electrodes. Ideal for field deployment [9]. |

| Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) | Nanomaterials used to modify electrodes. They provide a high surface area, enhance electron transfer, and can be functionalized for bioreceptor immobilization [5] [3]. |

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | Nanomaterials that improve conductivity and facilitate the stable immobilization of thiol-modified bioreceptors like antibodies or aptamers [7]. |

| Specific Bioreceptors | Engineered antibodies, aptamers, or DNA probes designed to bind with high affinity to a specific agricultural analyte (e.g., a fungal protein or mycotoxin) [1] [3]. |

| EDC & NHS Crosslinkers | Chemicals used for covalent immobilization of bioreceptors (especially those with carboxyl or amine groups) onto electrode surfaces [3]. |

| Electrochemical Redox Probes | Molecules such as Ferrocene or Hexaammineruthenium(III) chloride that act as labels to generate an amplified electrochemical signal in sandwich-type assays [9]. |

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) | A standard buffer used to maintain a stable pH and ionic strength during bioreceptor immobilization and electrochemical measurements [7]. |

Electrochemical biosensors have emerged as transformative analytical tools for precision agriculture, enabling the rapid, sensitive, and in-situ detection of vital plant nutrients, soil contaminants, and pathogen-derived biomarkers [10]. These sensors function at the interface of biology, chemistry, and material science, translating complex biological interactions into quantifiable electrical signals [11]. For agricultural researchers, the capability to monitor parameters such as soil contaminant levels or plant nitrogen status in real-time directly in the field represents a critical advancement over traditional laboratory-based methods, which are often hampered by complex pretreatment protocols and an inability to capture dynamic fluctuations [12] [13]. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of three foundational electrochemical detection techniques—amperometry, voltammetry, and impedance spectroscopy—detailing their principles, implementations, and specific applications within agricultural research to support the development of next-generation smart farming systems.

Core Technique Principles and Agricultural Applications

Amperometry

2.1.1 Principle and Mechanism Amperometric sensors operate by applying a constant potential to an electrochemical cell and measuring the resulting Faradaic current generated from the oxidation or reduction of electroactive species at the electrode surface [13] [11]. The measured current is directly proportional to the concentration of the target analyte. Key performance characteristics include sub-micromolar detection limits and sub-second response times, making this technique uniquely suited for capturing transient chemical events in biological systems [13]. A significant advantage of modern amperometric systems is their excellent RC time constant properties (less than 100 μs), which provides a high signal-to-noise ratio essential for monitoring rapid enzymatic reactions or nutrient uptake kinetics in plants [13].

2.1.2 Agricultural Implementation and Protocols In agricultural settings, amperometric sensors are particularly valuable for monitoring inorganic nitrogen species crucial for plant health, such as nitrate (NO₃⁻) and nitric oxide (NO) [13]. The experimental protocol typically involves polarizing a micro- or nano-scale working electrode at a predetermined potential specific to the target analyte. For in-situ plant monitoring, needle-type amperometric sensors can be inserted directly into plant stems or root zones to sample xylem and phloem sap, enabling real-time tracking of dynamic nitrogen fluxes during nutrient uptake and stress responses [13].

A standard methodology involves the following steps:

- Electrode Preparation: Modify working electrodes with nanomaterials (e.g., graphene, carbon nanotubes) or catalytic layers to enhance sensitivity and selectivity toward the target nitrogen species [13] [11].

- Potential Optimization: Determine the optimal working potential for the target analyte using preliminary cyclic voltammetry scans to identify the oxidation/reduction peak potentials.

- Calibration: Perform standard additions of the analyte to establish a linear relationship between current response and concentration.

- In-Situ Measurement: Deploy the calibrated sensor in the agricultural environment (e.g., inserted into plant tissue, immersed in soil leachate) while applying the constant potential and recording the steady-state current.

Voltammetry

2.2.1 Principle and Mechanism Voltammetry encompasses a group of techniques that measure current while systematically varying the applied potential between working and reference electrodes [13]. Different voltammetric methods offer unique capabilities for agricultural sensing:

- Cyclic Voltammetry (CV): applies a linear potential ramp that reverses direction at a set switching potential, providing information about redox potentials and reaction mechanisms of electroactive species [13].

- Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV): applies small amplitude potential pulses superimposed on a linear ramp, enhancing sensitivity through background current rejection, making it ideal for detecting low-concentration analytes in complex matrices like soil samples [13].

- Linear Sweep Voltammetry (LSV): employs a single linear potential sweep, useful for identifying redox signatures of nitrogenous analytes in plant systems [13].

2.2.2 Agricultural Implementation and Protocols Voltammetric techniques find extensive application in detecting pesticides, pharmaceutical contaminants, and heavy metals in soil and agricultural products [12] [14]. The redox-active characteristics of these contaminants make them particularly amenable to voltammetric analysis. For example, DPV has been successfully employed for the simultaneous determination of multiple neutral nitrogen compounds in complex environmental samples [13].

A representative experimental workflow for detecting soil contaminants involves:

- Sample Collection: Obtain soil cores or leachates from agricultural fields with minimal pretreatment to preserve native conditions.

- Electrode Modification: Fabricate nanostructured electrodes (e.g., with metal-organic frameworks or molecularly imprinted polymers) to enhance specificity toward target contaminants [12] [15].

- Electrochemical Analysis:

- For CV: Sweep potential between predetermined limits (e.g., -1.0 V to +1.0 V) at scan rates typically between 10-100 mV/s.

- For DPV: Apply pulses with amplitudes of 25-50 mV and durations of 50-100 ms.

- Data Interpretation: Identify target contaminants based on their characteristic peak potentials and quantify concentrations through calibration curves.

Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS)

2.3.1 Principle and Mechanism Impedimetric biosensors detect subtle changes in the electrical properties (resistance and capacitance) at the electrode-electrolyte interface upon binding of target analytes [11]. EIS measurements involve applying a small amplitude sinusoidal AC potential across a frequency range and measuring the resulting current response to determine impedance. These systems are broadly classified into two categories:

- Faradaic EIS: Utilizes redox mediators (e.g., ferro/ferricyanide) and monitors changes in charge transfer resistance (Rct) upon target binding [11].

- Non-Faradaic EIS: Operates without redox couples, relying instead on changes in double-layer capacitance (Cdl) and interfacial dielectric properties, making it particularly advantageous for detecting analytes in their native state without sample alteration [11].

2.3.2 Agricultural Implementation and Protocols EIS has demonstrated exceptional utility for the label-free detection of plant pathogens, toxins, and disease biomarkers in oilseed crops [15]. Its ability to monitor binding events without requiring redox labels or extensive sample preparation makes it ideal for field-deployable agricultural diagnostics. For example, EIS-based sensors have been developed for early detection of fungal pathogens like Sclerotinia sclerotiorum in oilseed rape, achieving ultra-low detection limits through appropriate electrode functionalization [15].

A standard EIS protocol for plant pathogen detection includes:

- Biorecognition Immobilization: Functionalize gold or carbon-based working electrodes with specific capture elements (aptamers, antibodies) using thiol-gold chemistry or carbodiimide crosslinking [15] [11].

- Impedance Measurement: Apply a small AC voltage (5-10 mV) across a frequency range (typically 0.1 Hz to 100 kHz) at the open circuit potential.

- Data Modeling: Fit obtained spectra to equivalent electrical circuits (e.g., Randles circuit) to extract specific parameters (Rct, Cdl) that correlate with target concentration.

- Quantification: Monitor the increase in Rct or change in Cdl resulting from the binding of target pathogens to the electrode surface.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Electrochemical Techniques in Agricultural Applications

| Technique | Detection Limit | Response Time | Key Agricultural Applications | Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amperometry | Sub-μM [13] | Sub-second [13] | Plant nitrogen species (NO₃⁻, NH₄⁺) monitoring | High temporal resolution, excellent for kinetic studies |

| Voltammetry | Variable (technique-dependent) | Seconds to minutes [13] | Pesticide detection, heavy metal screening in soils [12] | Identifies redox signatures, multi-analyte capability |

| Impedimetry | Femtomolar for pathogens [15] | Minutes [11] | Plant pathogen detection, soil contaminant monitoring [15] | Label-free detection, minimal sample preparation |

Experimental Design and Workflow

The successful implementation of electrochemical detection in agricultural research requires careful experimental design spanning from sensor fabrication to data interpretation. The following workflow diagram illustrates the integrated approach for real-time plant monitoring:

Figure 1: Integrated Workflow for Agricultural Electrochemical Sensing

Sensor Fabrication and Modification Strategies

Advanced sensor fabrication increasingly incorporates nanomaterials to enhance analytical performance. Nanostructured electrodes functionalized with graphene, carbon nanotubes, metal-organic frameworks, or metal nanoparticles provide increased surface area, improved electron transfer kinetics, and additional sites for immobilizing biorecognition elements [12] [11]. For agricultural applications requiring specificity toward biological targets, electrodes are modified with:

- Aptamers: Single-stranded DNA or RNA molecules that bind specific targets (pathogens, metabolites) with high affinity [15] [11].

- Antibodies: Immunorecognition elements for detecting plant pathogens or specific protein biomarkers [15].

- Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs): Synthetic polymers with tailor-made recognition sites for specific molecules, offering enhanced stability in harsh environmental conditions [11].

- Enzymes: Biological catalysts that provide specificity through substrate conversion to electroactive products [13].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Agricultural Electrochemical Sensing

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Electrode Materials | Gold microelectrodes, Screen-printed carbon, Platinum wire [11] | Signal transduction, providing conductive sensing platform |

| Nanomaterials | Graphene oxide, Carbon nanotubes, MXenes, Metal nanoparticles [12] [11] | Signal amplification, increased surface area, enhanced electron transfer |

| Biorecognition Elements | DNA aptamers, Antibodies, Enzymes (oxidoreductases) [15] [11] | Target specificity through molecular recognition |

| Redox Mediators | Ferro/ferricyanide, Methylene blue [11] | Facilitating electron transfer in faradaic systems |

| Stabilizing Matrices | Nafion, Chitosan, Self-assembled monolayers [15] | Biocompatible environments for biomolecule immobilization |

Signal Transduction Pathways in Electrochemical Biosensing

The fundamental signaling mechanisms in electrochemical biosensors involve a cascade of events from molecular recognition to measurable electrical outputs. The following diagram illustrates these transduction pathways:

Figure 2: Electrochemical Signal Transduction Pathways

Advanced Applications in Agricultural Research

Real-Time Plant Nutrient Monitoring

Electrochemical sensors have revolutionized precision nitrogen management by enabling real-time, in-situ detection of dynamically fluctuating nitrogen species in plants [13]. Breakthroughs in detection methodologies for inorganic nitrogen species (NO₃⁻, NH₄⁺, NO) have addressed critical gaps in traditional approaches limited by inadequate sensitivity and temporal resolution. Deployable miniaturized sensors now facilitate precision nitrogen management through direct integration with plant tissues or growth media, providing continuous data on nitrogen uptake kinetics and metabolic flux [13]. This capability is particularly valuable for optimizing fertilizer application schedules based on actual plant needs rather than predetermined regimens, significantly enhancing nitrogen use efficiency while reducing environmental pollution from agricultural runoff.

Case studies in maize and algal cultivation systems have demonstrated that electrochemical sensing technologies can support sustainable agricultural development by reducing excessive fertilizer use while maintaining or improving crop resilience and yield [13]. The integration of these sensor networks with Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Internet of Things (IoT) frameworks enables autonomous fertilization strategies tailored to real-time plant nitrogen demands, representing a paradigm shift in crop nutrient management [13].

Soil Contaminant Detection

Electrochemical sensors provide promising tools for rapid, sensitive, and selective detection of emerging contaminants (ECs) in soil, including pesticides, pharmaceuticals, heavy metals, and endocrine-disrupting compounds [12]. These contaminants pose significant threats to environmental and public health due to their diverse sources and complex environmental behaviors. Recent advances in electrochemical sensing have yielded enhanced detection limits, broader analyte ranges, and improved sensor stability under varying soil conditions [12].

Novel electrode materials and sensor designs have demonstrated particular effectiveness for monitoring soil pollution, with nanostructure-enhanced sensors showing remarkable improvements in specificity, sensitivity, and application potential [12]. The development of field-deployable electrochemical sensors for soil contaminant detection represents a critical advancement in environmental monitoring, enabling rapid assessment of soil health and prompt intervention when contamination is detected.

Plant Pathogen and Disease Diagnosis

Electrochemical biosensors have emerged as powerful tools for the early detection of diseases in economically important crops such as oilseed rape, soybean, and peanut [15]. Timely diagnosis is critical in agricultural management, as many pathogens exhibit latent infection phases or produce invisible metabolic toxins, leading to substantial yield losses before visible symptoms occur [15]. Innovations in nanomaterial-assisted electrochemical sensing have enabled the detection of pathogen DNA, enzymes, and toxins at ultra-low concentrations, providing a critical window for intervention before disease becomes established.

Specific applications include:

- Detection of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum (stem rot) in oilseed rape through identification of pathogen-specific biomarkers or secreted enzymes [15].

- Monitoring of Phakopsora pachyrhizi (soybean rust) infection by detecting effector proteins or changes in leaf physiology during the latent phase [15].

- Identification of aflatoxin-producing fungi in peanuts through toxin detection before visible symptoms manifest [15].

These applications demonstrate the transformative potential of electrochemical sensing for preventing crop losses and maintaining food security through early disease detection and targeted intervention.

Future Perspectives and Research Directions

The future development of electrochemical detection techniques for agricultural applications will likely focus on several key areas. Integration with artificial intelligence and machine learning algorithms will enhance data interpretation capabilities, enabling predictive analytics for plant health status and automated decision-making for agricultural management [13] [11]. Advances in wearable and minimally invasive sensor designs will facilitate long-term monitoring of plant physiological parameters without impairing growth or development [13]. The convergence of electrochemical sensing with wireless communication technologies and IoT networks will support the development of comprehensive agricultural monitoring systems capable of real-time, field-deployable disease surveillance and nutrient management [15].

Research efforts will also address current challenges in sensor stability, selectivity in complex matrices, and device miniaturization [15]. The exploration of biodegradable sensor materials represents an important direction for reducing environmental impact and ensuring sustainability in agricultural monitoring [15]. As these technologies mature, electrochemical detection techniques are poised to become cornerstone methodologies in smart agriculture, addressing global challenges in food security, environmental sustainability, and resource use efficiency.

In the rapidly evolving field of agricultural biotechnology, electrochemical biosensors have emerged as powerful analytical tools for monitoring pathogens, contaminants, and vital biomarkers across the food production chain. For researchers and drug development professionals implementing these technologies, a rigorous understanding of three fundamental performance metrics—sensitivity, selectivity, and limit of detection (LOD)—is paramount. These parameters collectively determine the reliability, accuracy, and practical utility of biosensing platforms in real-world agricultural applications, from precision farming to food safety monitoring [16] [17].

This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of these core metrics, establishing their theoretical foundations, practical measurement methodologies, and significance in agricultural research contexts. The content is structured to serve as both an educational resource for scientists new to biosensor development and a reference for experienced researchers validating analytical performance against regulatory standards.

Theoretical Foundations and Definitions

Sensitivity

Sensitivity quantifies the magnitude of signal change per unit change in analyte concentration. It represents the slope of the calibration curve, indicating how effectively a biosensor responds to minimal concentration variations of the target analyte [18]. In agricultural applications, high sensitivity is crucial for detecting trace-level contaminants like pesticides, mycotoxins, or bacterial pathogens in complex matrices such as soil, plant tissues, or food products [16].

Mathematically, sensitivity is defined as: [ S = \frac{\Delta S}{\Delta C} ] Where (S) is sensitivity, (\Delta S) is the change in sensor signal, and (\Delta C) is the change in analyte concentration.

Selectivity

Selectivity describes a biosensor's ability to distinguish the target analyte from interfering substances in a sample matrix. This characteristic is primarily determined by the specificity of the biological recognition element (enzyme, antibody, aptamer, or nucleic acid) toward its target [18]. In agricultural contexts with complex sample compositions, high selectivity ensures accurate measurements without false positives from chemically similar compounds or environmental interferents [19].

The related term specificity refers more narrowly to the capacity to identify an exact analyte in a mixture, while selectivity encompasses the broader ability to differentiate between multiple analytes [18].

Limit of Detection (LOD)

The Limit of Detection (LOD) is the lowest analyte concentration that can be reliably distinguished from a blank sample with a stated confidence level. It represents a fundamental parameter for assessing biosensor utility in early detection applications, such as identifying plant pathogens before visual symptoms appear [15] [20].

According to IUPAC definition, LOD is "the smallest solute concentration that a given analytical system can distinguish with reasonable reliability from a sample without analyte" [20]. The Limit of Quantification (LOQ), typically set at 10σ, represents the lowest concentration that can be quantitatively measured with acceptable precision and accuracy [18].

Table 1: Critical Performance Metrics for Electrochemical Biosensors

| Metric | Definition | Mathematical Expression | Agricultural Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | Change in signal per unit change in analyte concentration | ( S = \Delta S / \Delta C ) | Enables detection of low-level contaminants and pathogens |

| Selectivity | Ability to distinguish target from interfering substances | Not applicable | Ensures accuracy in complex matrices (soil, food, plant sap) |

| Limit of Detection (LOD) | Lowest detectable analyte concentration with statistical confidence | Typically ( 3\sigma_{blank}/S ) | Critical for early disease diagnosis and preventive intervention |

| Limit of Quantification (LOQ) | Lowest concentration measurable with acceptable precision | Typically ( 10\sigma_{blank}/S ) | Essential for quantitative monitoring of biomarkers |

Measurement Protocols and Methodologies

Determining Limit of Detection

The following procedural protocol outlines the standard method for determining LOD in label-free biosensors, adapted from international guidelines [20]:

Protocol: LOD Determination for Electrochemical Biosensors

Blank Measurement Preparation: Prepare a minimum of ( n_B ) replicates (typically ≥10) of blank solutions containing all components except the target analyte.

Signal Measurement: Measure the analytical response for each blank sample using the optimized biosensor platform.

Statistical Analysis: Calculate the mean (( \overline{yB} )) and standard deviation (( \sigma{blank} )) of the blank signals using Equations 1 and 2: [ \overline{yB} = \frac{\sum{j=1}^{nB} yj}{nB} ] [ \sigma{blank} = \sqrt{\frac{\sum{j=1}^{nB} (yj - \overline{yB})^2}{n_B - 1}} ]

Calibration Curve Construction: Prepare and analyze a minimum of 5 standard concentrations across the expected working range. Perform linear regression to establish the function ( y = aC + b ), where ( a ) is the sensitivity (slope) and ( b ) is the y-intercept.

LOD Calculation: Compute LOD using the formula: [ C{LOD} = \frac{3.3 \times \sigma{blank}}{a} ] The factor 3.3 corresponds to a 95% confidence level for both false positive and false negative rates [20].

The following diagram illustrates the statistical relationship between blank measurements, critical value, and LOD:

Assessing Sensitivity and Selectivity

Sensitivity Measurement Protocol:

- Generate a calibration curve with at least 5 concentration points across the analytical range

- Perform linear regression analysis to determine the slope (sensitivity) and correlation coefficient

- Report sensitivity with appropriate units (e.g., nA/μM, mV/decade) [18]

Selectivity Validation Protocol:

- Test biosensor response against structurally similar compounds and common matrix interferents

- Calculate selectivity coefficients for each potential interferent

- Evaluate performance in real samples with comparison to reference methods [19]

Performance Metrics in Agricultural Applications

Electrochemical biosensors in agricultural research must demonstrate robust performance across diverse and challenging environments. The table below summarizes reported performance metrics for various agricultural applications:

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Electrochemical Biosensors in Agricultural Applications

| Application | Target Analyte | Sensitivity | Selectivity Assessment | LOD | Reference Technique |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plant Pathogen Detection [15] | Sclerotinia sclerotiorum (Stem Rot) | Not specified | Demonstrated against other soil fungi | Early detection before vascular invasion | Visual inspection |

| Poultry Safety [21] | Salmonella spp., E. coli | Not specified | Differentiated from other enteric bacteria | Enables proactive flock management | Culture methods, PCR |

| GMO Screening [22] | EPSPS, PAT, Cry genes | Not specified | Specific DNA hybridization | Meets EU 0.9% threshold requirement | Multiplex qPCR |

| Viral Disease Monitoring [23] | Tobacco Mosaic Virus | Enhanced by AuNPs, MOFs | Minimal cross-reactivity | Significant improvement over ELISA | PCR, ELISA |

| Soil Nutrient Management [17] | Macronutrients (N, P, K) | Varies by ionophore | Ion-selective membranes | Sufficient for precision agriculture | Laboratory analysis |

Research Reagent Solutions for Biosensor Development

The following reagents and materials are essential for developing high-performance electrochemical biosensors for agricultural applications:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Biosensor Development

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | Enhance electron transfer, increase surface area for bioreceptor immobilization | Pathogen detection [24], viral disease monitoring [23] |

| Graphene Oxide (GO) | Provides large surface area with functional groups for stable probe immobilization | Contaminant monitoring, nutrient sensing [24] |

| Specific Antibodies | Immunological recognition elements for selective target binding | Pathogen detection [21], protein biomarker analysis |

| DNA/Aptamer Probes | Nucleic acid-based recognition with high specificity and stability | GMO detection [22], viral pathogen identification |

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) | Synthetic recognition elements with high stability | Pesticide detection, small molecule analysis [24] |

| Ion-Selective Membranes | Enable selective detection of specific ions | Soil nutrient monitoring [17] |

Technological Integration and Emerging Approaches

The convergence of electrochemical biosensing with advanced materials and digital technologies represents the future of agricultural monitoring. The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow from sensing to decision support:

Recent advances incorporate artificial intelligence and machine learning to enhance the interpretation of biosensor data, improving both the reliability of measurements and the predictive capabilities for agricultural management [16] [24]. The integration with Internet of Things (IoT) platforms enables real-time monitoring of crop health, soil conditions, and food contamination risks across distributed agricultural operations [16] [23].

Smartphone-integrated electrochemical devices represent a particularly promising development, combining laboratory-grade analysis with field-portable operation. These systems leverage the computational power, connectivity, and imaging capabilities of smartphones to create comprehensive mobile laboratories for on-site testing [24].

Sensitivity, selectivity, and limit of detection form the essential triad of performance metrics that dictate the practical utility of electrochemical biosensors in agricultural research and applications. As the field advances toward increasingly miniaturized, integrated, and intelligent monitoring systems, rigorous characterization and optimization of these parameters remains fundamental to transforming agricultural practices through precision management, early pathogen detection, and enhanced food safety assurance. The ongoing development of standardized protocols for evaluating these metrics will facilitate more meaningful comparisons between technologies and accelerate the translation of research innovations into practical agricultural solutions.

The Evolution from Laboratory Tools to Field-Deployable Agricultural Sensors

The transition of electrochemical biosensors from sophisticated laboratory instruments to robust field-deployable tools represents a paradigm shift in agricultural monitoring. This evolution is characterized by fundamental advances in nanomaterials engineering, bioreceptor stability, device miniaturization, and system integration, enabling direct detection of pathogens, toxins, and stress biomarkers in complex agricultural matrices. This whitepaper examines the technical trajectory of these sensing platforms, highlighting critical innovations in interface design, signal transduction, and data interoperability that support their integration within smart agricultural systems. The analysis further details standardized experimental protocols for performance validation and projects future development trajectories focused on artificial intelligence-driven interpretation and sustainable sensor architectures.

Fundamental Principles and Core Components

Electrochemical biosensors are analytical devices that integrate a biological recognition element with an electrochemical transducer to convert a biological event into a quantifiable electrical signal [5] [2]. The core architecture comprises bioreceptors (e.g., enzymes, antibodies, aptamers, nucleic acids) that provide selective binding to the target analyte, a transducer surface (typically an electrode) where the biochemical interaction occurs, and the electronic system that processes the signal into a readable output [5]. The significant advantage of electrochemical detection lies in its direct conversion of biological interaction to an electronic signal, enabling high sensitivity, minimal power requirements, and inherent compatibility with miniaturized, portable form factors [5] [25].

Table 1: Core Components of an Electrochemical Biosensor

| Component | Function | Common Materials & Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Bioreceptor | Provides selective binding to the target analyte | Enzymes (Glucose Oxidase), Antibodies, DNA/Aptamers, Whole Cells [16] [25] |

| Transducer | Converts the biological event into a measurable electrical signal | Gold, Carbon, or Platinum Electrodes; often nanomaterial-modified (e.g., Graphene Oxide, Gold Nanoparticles) [5] [25] |

| Electronics | Amplifies, processes, and displays the electrical signal | Potentiostats, custom ICs, integrated with microcontrollers and wireless communication modules [5] [25] |

The performance of these sensors is critically dependent on the precise control of the interface architecture at the nanoscale, where the interplay between surface functionalization, the chosen transducer principle, and the suppression of non-specific interactions determines ultimate sensitivity and specificity [5].

Figure 1: Core signaling pathway of an electrochemical biosensor, illustrating the conversion of a biological binding event into actionable data via a transducer.

Performance Metrics and Experimental Protocols

Validating sensor performance requires standardized methodologies to assess key metrics critical for both laboratory research and field application. The following protocols and metrics are essential for benchmarking.

Key Performance Metrics (KPIs)

Table 2: Key Performance Metrics for Agricultural Electrochemical Biosensors

| Metric | Definition | Target for Field Deployment |

|---|---|---|

| Limit of Detection (LOD) | The lowest analyte concentration that can be reliably distinguished from a blank | Ultra-low concentrations (e.g., pathogen DNA at femtomolar levels, toxins at μg/kg) [3] |

| Linear Range | The concentration interval over which the sensor response is linearly proportional to analyte concentration | Covers the clinically/agronomically relevant concentration span [3] |

| Selectivity/Specificity | The ability to detect the target analyte without interference from similar substances or matrix components | High specificity in complex matrices like soil extracts, plant sap, or food samples [16] |

| Stability | The ability to maintain performance over time and under storage conditions | Long-term stability (weeks to months) under variable temperature/humidity [16] |

| Reproducibility | The precision of measurements across different sensors or batches | Low coefficient of variation (<5-10%) between manufactured units [5] |

Detailed Experimental Protocol for Sensor Validation

The following protocol outlines a standard procedure for characterizing an electrochemical aptasensor for pathogen detection, adaptable for other targets.

Aim: To characterize the performance of a nanomaterial-modified electrochemical biosensor for the detection of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum DNA in a spiked plant extract sample.

Materials & Reagents:

- Working Electrode: Screen-printed carbon electrode (SPCE) modified with graphene oxide (GO) and gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) [25].

- Bioreceptor: DNA aptamer specific to S. sclerotiorum, thiol-modified for immobilization.

- Target Analyte: Synthetic oligonucleotide of the target pathogen DNA sequence.

- Electrochemical Probe: Potassium ferricyanide/ferrocyanide ([Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻) in buffer.

- Matrix: Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS, pH 7.4) for initial tests, followed by a filtered extract from healthy oilseed rape leaves to simulate a real sample matrix [3].

Methodology:

- Electrode Modification:

- Nanomaterial Deposition: Drop-cast 5-10 μL of a GO dispersion onto the SPCE surface and dry under nitrogen. Electrochemically reduce GO to conductive reduced graphene oxide (rGO) by performing cyclic voltammetry (CV) in a suitable buffer.

- AuNP Electrodeposition: Immerse the rGO/SPCE in a solution of HAuCl₄ and apply a constant potential to electrodeposit AuNPs, enhancing surface area and facilitating thiol binding [25].

- Aptamer Immobilization: Incubate the modified electrode with a 1 μM solution of the thiolated aptamer for 12-16 hours. Passivate any remaining gold surface with 6-mercapto-1-hexanol (MCH) to minimize non-specific binding.

Electrochemical Measurement:

- Perform electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) in the presence of the [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻ redox probe after each modification step (bare SPCE, rGO/SPCE, AuNP/rGO/SPCE, aptamer/MCH/AuNP/rGO/SPCE) to monitor the increase in electron transfer resistance (Rₑₜ), confirming successful layer-by-layer assembly.

- For quantitative detection, incubate the functionalized sensor with standard solutions of the target DNA (e.g., 1 pM to 100 nM) or spiked plant extracts for a fixed time (e.g., 20-30 minutes).

- Record the EIS or differential pulse voltammetry (DPV) signal after each incubation. The binding of the target DNA increases Rₑₜ or causes a change in current, which is proportional to the target concentration.

Data Analysis:

- Plot the change in Rₑₜ or current against the logarithm of the target concentration.

- Perform a linear regression analysis on the linear portion of the curve to establish the calibration plot.

- Calculate the LOD as 3.3 × (standard deviation of the blank/slope of the calibration curve).

The Trajectory from Laboratory to Field

The evolution of these sensors from lab to field is driven by specific technological breakthroughs that address the challenges of complexity, stability, and usability.

Miniaturization and Integration

Early laboratory biosensors relied on bulky, three-electrode systems connected to benchtop potentiostats. The adoption of screen-printed electrodes (SPEs), which integrate working, reference, and counter electrodes on a single, disposable chip, was a pivotal step toward portability and low-cost mass production [25]. Further integration with microfluidics (Lab-on-a-Chip, LoC) automates sample handling and reduces reagent volumes, making the device suitable for raw, minimally processed agricultural samples [25].

Nanomaterials for Enhanced Sensitivity

The incorporation of nanomaterials is a cornerstone of this evolution. Gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) and graphene oxide (GO) are engineered into electrode surfaces to provide a high surface-to-volume ratio for increased bioreceptor loading, enhanced electrical conductivity for faster electron transfer, and catalytic properties for signal amplification. This nanomaterial-driven enhancement allows for detection at ultra-low concentrations, which is crucial for identifying latent infections before symptoms appear [3] [25].

Connectivity and Data Interoperability

Modern field-deployable sensors transcend mere detection. Integration with smartphone-based potentiostats provides computational power, intuitive user interfaces, and cloud connectivity, transforming the sensor into a node in a larger Internet of Things (IoT) network [25]. This enables real-time data transmission to agricultural decision-support systems, facilitating immediate interventions and contributing to large-scale, data-driven pest and disease models [3] [16].

Figure 2: Workflow evolution from laboratory-based analysis to connected field-deployment.

Implementation Challenges and Material Solutions

Despite significant progress, the full deployment of electrochemical biosensors in agriculture faces several hurdles. The research community is actively developing innovative material and strategic solutions to address these challenges.

Table 3: Key Implementation Challenges and Emerging Solutions

| Challenge | Impact on Deployment | Emerging Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Matrix Interference | Complex agricultural samples (soil, sap) cause fouling and false signals, reducing accuracy. | - Use of robust antifouling membranes (e.g., hydrogels) [16].- Advanced surface chemistries to repel non-specific adsorption [5].- Integration of microfluidics for sample filtration/separation [25]. |

| Device Stability & Calibration | Sensitivity drifts over time due to bioreceptor denaturation, requiring frequent re-calibration. | - Development of synthetic bioreceptors (MIPs, engineered aptamers) with higher stability [25].- Exploration of reagent-free sensing mechanisms.- On-device calibration algorithms. |

| Standardization & Scalability | Lack of uniform manufacturing and testing protocols hinders regulatory approval and mass production. | - Adoption of scalable fabrication techniques like screen printing and inkjet printing [25].- Development of consensus performance standards and validation protocols for agri-food targets [16]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The development and implementation of advanced electrochemical biosensors rely on a suite of specialized reagents and materials.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Agricultural Biosensing

| Research Reagent | Function in Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|

| Screen-Printed Electrodes (SPEs) | Provide a disposable, miniaturized, and reproducible platform for sensor fabrication, forming the core of portable devices [25]. |

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) & Graphene Oxide (GO) | Nanomaterials used to modify electrode surfaces, enhancing sensitivity and signal-to-noise ratio by increasing surface area and facilitating electron transfer [25]. |

| Thiol-modified Aptamers | Serve as stable, synthetic bioreceptors. The thiol group allows for covalent, oriented immobilization on gold surfaces (e.g., AuNPs), improving binding efficiency and sensor consistency [3] [25]. |

| Redox Probes (e.g., [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻) | Used in electrochemical techniques like EIS and CV to monitor the success of electrode modification and to transduce the biorecognition event into a measurable electrical signal [5]. |

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) | Synthetic polymer scaffolds with tailor-made cavities for a specific analyte. They act as artificial antibodies, offering superior stability and lower cost than biological receptors for targets like pesticide residues [25]. |

The evolution of agricultural biosensors is continuing along several innovative trajectories. Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) are being integrated to handle complex data interpretation, compensating for sensor drift and environmental variability to improve prediction accuracy [3] [16]. A growing emphasis on sustainability is driving research into biodegradable sensor substrates and green manufacturing processes to minimize environmental impact [3]. Finally, the future lies in closed-loop systems, where sensor data automatically triggers agricultural actuators, such as initiating precision spraying or irrigation in real-time, fully realizing the promise of data-driven, sustainable precision agriculture [16].

In conclusion, the journey of electrochemical biosensors from laboratory tools to field-deployable assets is a testament to interdisciplinary innovation. Through advances in nanotechnology, materials science, and microelectronics, these sensors are poised to become ubiquitous tools for safeguarding crop health, optimizing resource use, and strengthening global food security.

From Lab to Field: Sensor Applications for Crop and Soil Monitoring in Precision Agriculture

Oilseed crops are vital components of global agriculture, supplying over 80% of edible oils and 40% of biofuel feedstock worldwide [3] [15]. However, their productivity is consistently threatened by devastating pathogens and the carcinogenic aflatoxins they can produce, leading to substantial economic losses and serious food safety concerns. Timely diagnosis is critical in disease management, as many pathogens exhibit latent infection phases where they colonize plant tissues without visible symptoms [3]. This technical guide explores the application of electrochemical biosensors as promising tools for early detection of oilseed pathogens and aflatoxins, focusing on their operational mechanisms, performance metrics, and implementation protocols within precision agriculture frameworks.

Major Oilseed Pathogens and Aflatoxins: Economic and Health Impacts

The following table summarizes the key pathogens affecting major oilseed crops, their detection windows, and the associated economic and health impacts.

Table 1: Major Oilseed Pathogens and Aflatoxins: Characteristics and Impacts

| Pathogen/Toxin | Primary Host(s) | Key Characteristics | Economic/Health Impact | Optimal Detection Window |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sclerotinia sclerotiorum (Stem Rot) | Oilseed Rape, Canola | Fungus survives in soil for years as sclerotia; produces ascospores dispersed by wind [3]. | Annual global yield loss: 15-20%; economic losses >$5 billion. In Canada (2022), led to 18% production decline in Manitoba [3]. | Early appearance of water-soaked lesions on stems, before hyphal invasion of vascular tissues [3]. |

| Phakopsora pachyrhizi (Soybean Rust) | Soybean | Airborne urediniospores can travel >1000 km/month; degrades thylakoid membranes within 72h [3]. | 2023 Brazil epidemic caused loss of 2.1M tons ($1.4B); latent infections can colonize 40% of leaf area before symptoms [15]. | Latent infection phase, before visible symptoms manifest [15]. |

| Sclerotium rolfsii (White Mold) | Peanut | Melanized sclerotia withstand 45°C soil temps, remain viable for 5-8 years; secretes cell-wall degrading enzymes [3] [15]. | Causes 20-50% yield loss in wet ecosystems; pod weight loss of 35-50% [3]. | Not specified in search results. |

| Aflatoxin B1 (AFB1) | Peanut, Soybean, Maize | Potent carcinogen produced by Aspergillus flavus and A. parasiticus; stable during processing [26] [27]. | Contributed to $320M in export rejections from India's Telangana region (2024); classified as Class 1 carcinogen; synergistically increases liver cancer risk with Hepatitis B [3] [26]. | Pre-harvest and post-harvest stages; critical in stored grains and edible oils [26]. |

Electrochemical Biosensors: Core Technologies and Performance

Electrochemical biosensors integrate a biological recognition element with an electrode transducer, converting a target-analyte interaction into a quantifiable electrical signal [16]. The performance of these sensors is significantly enhanced by nanomaterials and various biorecognition elements.

Table 2: Core Components and Performance of Nanomaterial-Based Electrochemical Biosensors

| Sensor Component | Function & Role | Key Innovations & Examples | Reported Performance Gains |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nanostructured Electrodes | Enhance surface area, conductivity, and electron transfer rates; improve loading capacity for bioreceptors [3] [7]. | Use of multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs), graphene, metal nanoparticles (e.g., gold), and metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) [7]. | Increased signal-to-noise ratio, lower limits of detection (LOD), and higher sensitivity in complex matrices [3] [7]. |

| Biorecognition Elements | Provide specificity by binding to the target analyte (pathogen DNA, toxin, enzyme) [3] [16]. | Aptamers: Single-stranded DNA/RNA oligonucleotides (e.g., structure-switching aptamer for AFB1) [28].Antibodies: Immunological recognition [3].Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs): Artificial antibody mimics [26]. | High specificity; aptamers offer advantages of stability and lower production cost compared to antibodies [26] [28]. |

| Signal Amplification | Augments the electrochemical response from the binding event, enabling ultra-low concentration detection [3] [7]. | Techniques include catalytic nanomaterials, enzymatic amplification, and cascading reactions [3]. | Enables detection of pathogen DNA, enzymes, and toxins at ultra-low concentrations (picomolar to femtomolar) [3]. |

Experimental Protocols for Biosensor Deployment

Protocol 1: Paper-based Ratiometric Aptasensor for Aflatoxin B1 Detection

This protocol outlines the procedure for constructing a disposable paper-based electrochemical biosensor for AFB1, leveraging a structure-switching aptamer for specificity and a ratiometric measurement for accuracy [28].

- Principle: The sensor uses a methylene blue (MB)-tagged DNA aptamer co-assembled with a ferrocene (Fc) internal reference on a paper-based electrode. In the presence of AFB1, the aptamer folds, distancing the MB tag from the electrode surface and reducing its current signal. The current ratio of MB to Fc provides a robust, internally-corrected measurement [28].

- Materials:

- Paper-based working electrode (e.g., screen-printed carbon electrode)

- AFB1-specific DNA aptamer tagged with Methylene Blue (MB)

- Internal reference probe tagged with Ferrocene (Fc)

- Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) apparatus

- Buffer solutions for immobilization and washing

- Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Electrode Co-assembly: Immobilize the MB-tagged aptamer and the Fc-tagged reference probe onto the paper-based electrode surface.

- Sample Incubation: Apply the sample extract (e.g., from groundnuts or edible oil) to the sensor surface and incubate to allow AFB1-aptamer binding.

- Electrochemical Measurement: Perform DPV measurements in a suitable buffer.

- Signal Analysis: Record the oxidation peak currents for both MB (IMB) and Fc (IFc).

- Quantification: Calculate the ratiometric signal (IMB / IFc). The signal decreases proportionally with increasing AFB1 concentration. Compare to a calibration curve for quantification.

- Performance Metrics: This sensor demonstrated a linear detection range of 20.0 to 1000.0 ng mL⁻¹ and a limit of detection (LOD) of 7.6 ng mL⁻¹. It showed high specificity and stability, with results correlating well with standard UPLC−MS/MS analysis in real samples [28].

Protocol 2: Smartphone-based Digital Image Colorimetry with Nanobiosensor

This protocol describes a colorimetric method integrating a bio-nanoparticle sensor with smartphone technology for sensitive AFB1 detection, suitable for resource-limited settings [29].

- Principle: Curcumin-functionalized ZnO nanoparticles form the sensing platform. AFB1 binding induces a color change in the nanoparticle-curcumin complex. Dispersive liquid-liquid microextraction (DLLME) pre-concentrates AFB1 from the sample. A smartphone camera in a portable light-box captures the color, which is analyzed via a colorimetric app [29].

- Materials:

- Bio-synthesized ZnO Nanoparticles functionalized with curcumin

- DLLME solvents: Chloroform (extraction solvent) and acetonitrile (disperser solvent)

- Smartphone with colorimetry application

- Portable colorimetric box with standardized LED lighting (45° angle, 4 LEDs recommended)

- Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Sample Pre-concentration: Perform DLLME on the liquid food sample (e.g., oil extract) using chloroform and acetonitrile to isolate and concentrate AFB1.

- Sensor Incubation: Re-dissolve the extracted AFB1 and mix with the ZnO-NPs/curcumin nano-biosensor complex at the optimized ratio (2:1 curcumin to NPs) and pH (9.44).

- Reaction: Allow the reaction to proceed for 2-3 minutes.

- Image Capture: Place the solution in the portable box and capture an image using the smartphone camera under standardized lighting.

- Color Channel Analysis: Analyze the image using the green (G) color channel intensity or the G/R ratio, which shows the best linear response to AFB1 concentration.

- Performance Metrics: This method achieved a remarkably low LOD of 0.09 μg/kg and a linear range of 0–1 μg/L, with high recoveries (89.8–94.2%) in baby food samples [29].

Visualizing Biosensor Workflows and Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and key decision points in developing and deploying an electrochemical biosensor for agricultural pathogens.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

This table catalogs key reagents and materials essential for developing and implementing electrochemical biosensors for oilseed pathogen detection.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Biosensor Development

| Item/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Biosensing |

|---|---|---|

| Biorecognition Elements | DNA/Aptamers (e.g., structure-switching aptamer for AFB1) [28]; Antibodies (vs. pathogens); Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) [26] | Provides high specificity and selectivity for the target analyte (pathogen, toxin). |

| Nanomaterials for Electrodes | Multi-walled Carbon Nanotubes (MWCNTs) [7]; Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) [7]; Graphene; Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) [7] | Enhances electrode conductivity, surface area, and signal amplification. Improves biosensor sensitivity and LOD. |

| Electrochemical Tags | Methylene Blue (MB) [28]; Ferrocene (Fc) [28] | Redox reporters that generate measurable current changes upon target binding in voltammetric sensors. |

| Sensor Substrates | Screen-Printed Electrodes (SPEs); Paper-based electrodes [28] | Provides a low-cost, disposable, and portable platform for single-use field-deployable sensors. |

| Signal Transduction Equipment | Potentiostat; Smartphone with colorimetry app [29] | Measures and interprets the electrochemical (current, impedance) or optical (color change) signal. |

Challenges and Future Research Directions

Despite significant advancements, the translation of laboratory biosensor prototypes to field-deployable tools faces several hurdles. A major challenge is the lack of real-world validation; a systematic review found that only 1 out of 77 studies tested biosensors on naturally contaminated food samples, with most relying on artificially spiked samples [7]. Other challenges include signal interference from complex plant matrices, limited device miniaturization, and the absence of standardized detection protocols [3] [16].

Future research should focus on:

- Validation and Standardization: Establishing protocols for testing with naturally contaminated samples and aligning performance metrics with international standards (ISO, FAO, FDA) [7].

- AI and IoT Integration: Leveraging artificial intelligence for data interpretation and integrating sensors into IoT networks for real-time, spatially-resolved disease surveillance in smart agriculture systems [3] [16].

- Material Innovation: Developing more stable bioreceptors and biodegradable sensor materials to enhance shelf-life and reduce environmental impact [3].

- Multiplexing: Creating sensors capable of simultaneously detecting multiple pathogens or toxins in a single assay to provide comprehensive crop health diagnostics [16] [4].

The transition to precision agriculture necessitates a shift from retrospective to real-time diagnostic tools for monitoring plant physiochemical signals. This whitepaper examines the principles and methodologies of sap analysis and nutrient solution monitoring, framing them within the advancing context of electrochemical biosensor technology. These tools provide a dynamic window into the plant's physiological status, enabling detection of active, soluble nutrients and signaling molecules with high temporal resolution. While sap analysis offers a snapshot of the mobile nutrients within the vascular system, electrochemical biosensors are emerging as a revolutionary technology for the in-situ and real-time detection of specific plant signaling molecules and stressors. This technical guide details standardized protocols, data interpretation frameworks, and the integration of these tools into a comprehensive sensor-based decision support system for research and development.

Plant health and productivity are governed by complex physiological processes influenced by environmental conditions and genetic makeup. Traditional plant analysis methods, such as tissue testing, provide a historical record of nutrient accumulation but lack the temporal resolution to capture dynamic changes in nutrient mobility and stress signaling. The limitations of tissue analysis have driven the development of advanced monitoring techniques that offer real-time or near-real-time insights [30].

Electrochemical biosensors represent a paradigm shift in this domain. These devices combine a biological recognition element with an electrochemical transducer, offering convenient methods for in-situ and real-time detection of plant signaling molecules due to their easy operation, high sensitivity, and high selectivity [31] [32]. This whitepaper explores how established sap analysis practices and cutting-edge electrochemical sensors collectively contribute to a deeper, more immediate understanding of plant physiochemistry, providing researchers with powerful tools for optimizing plant health and productivity.

Plant Sap Analysis: Principles and Methodologies

What is Plant Sap Analysis?

Plant sap analysis is a diagnostic technique that measures the concentration of soluble nutrients present in the vascular tissues (xylem and phloem) of a plant. Unlike traditional tissue analysis, which involves drying and grinding entire plant parts to measure total accumulated nutrients, sap analysis extracts the liquid component from fresh plant tissues to assess the nutrients that are actively circulating [33] [30]. This provides a near real-time assessment of nutrient availability within the plant, allowing for the detection of imbalances often weeks before visual symptoms manifest [33].

Comparative Analysis: Sap vs. Tissue Testing

The choice between sap analysis and traditional tissue testing depends on the specific research or monitoring objectives. The following table summarizes their key differences.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Sap Analysis and Standard Tissue Testing

| Aspect | Sap Analysis | Standard Tissue Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Type | Extracted sap from fresh plant tissues (e.g., leaves, petioles) | Dried and ground plant tissues (e.g., leaves, stems) |

| Nutrient Measurement | Measures nutrients in the plant's vascular system, reflecting current availability | Measures total accumulated nutrients, including those structurally bound in tissues |

| Turnaround Time | Rapid results, often within hours to a few days | Longer processing time, typically several days to a week |

| Detection Sensitivity | Can detect nutrient imbalances before visual symptoms appear | May not detect deficiencies until they manifest visibly |

| Data Interpretation | Requires expertise due to variability influenced by environmental factors | More standardized interpretation with established sufficiency ranges |

| Nutrient Mobility Insight | Provides information on nutrient mobility by comparing young and old leaves | Offers a cumulative view but less insight into real-time nutrient movement |

| Environmental Sensitivity | Results can be affected by time of day, plant hydration, and conditions | Less sensitive to immediate environmental fluctuations [30] |

Key Experimental Protocol for Sap Analysis

A reliable sap analysis protocol is critical for generating accurate and reproducible data. The following methodology outlines the key steps from sample collection to data interpretation.

1. Sample Collection:

- Selection: Identify the target crop and the specific plant part to be sampled (e.g., petioles, leaf midribs). Consistency in selection is paramount.

- Timing: Collect samples at the same time of day, typically in the early morning, to minimize diurnal fluctuations in nutrient concentrations.

- Handling: Use linear pressure-based sap extractors that avoid mastication, heat, acids, or solvents to maintain the integrity of the leaf and the sap's chemical profile [33]. Immediately place samples in sealed bags and store on ice.

2. Sample Preparation & Shipping:

- To preserve sample integrity, ship them overnight to the analytical laboratory using pre-arranged cool shipping programs [33].

- Laboratories typically extract sap through controlled linear pressure, applying different pressures for different crop types to ensure leaves and cellular structures remain intact [33].

3. Laboratory Analysis:

- The extracted sap is analyzed for a comprehensive suite of parameters. Standard analyses include:

- Macronutrients: Nitrogen (as Nitrate and Ammonia), Phosphorus (P), Potassium (K), Calcium (Ca), Magnesium (Mg), Sulfur (S)

- Micronutrients: Boron (B), Copper (Cu), Iron (Fe), Manganese (Mn), Molybdenum (Mo), Zinc (Zn)

- Other Elements: Sodium (Na), Chlorine (Cl), Aluminum (Al), Nickel (Ni)

- Physicochemical Indices: Brix (soluble sugar content), pH, and Electrical Conductivity (EC) [33]

4. Data Interpretation:

- New vs. Old Leaf Comparison: A powerful feature of sap analysis is comparing nutrient levels in new and old growth. For mobile nutrients (e.g., Nitrogen, Potassium), a higher concentration in new leaves indicates remobilization from older leaves, suggesting insufficient root uptake. Conversely, an excess is indicated by higher concentrations in old leaves [33].

- Contextualization: Results must be interpreted considering crop type, growth stage, and environmental conditions to make accurate nutrient management recommendations.

The workflow below summarizes the key steps involved in the sap analysis process.

Electrochemical Biosensors for Advanced Monitoring

Principles and Sensor Types

Electrochemical biosensors are ideal for bridging the gap between sap analysis and continuous, in-situ monitoring. These sensors integrate a biological recognition element (e.g., enzyme, antibody, DNA/aptamer, whole cell) with an electrochemical transducer that converts a biological interaction into a quantifiable electrical signal [16]. The development of in-situ and real-time detection capabilities for plant signaling molecules is considered a key breakthrough for botanical research and agricultural technology [31].

Plant signaling molecules detected by these sensors can be broadly categorized as:

- Plant Messenger Signaling Molecules: Calcium ions (Ca²⁺), hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂), Nitric oxide (NO) [31] [32].

- Plant Hormone Signaling Molecules: Auxin (IAA), salicylic acid, abscisic acid, cytokinin, jasmonic acid, gibberellins, brassinosteroids, strigolactone, and ethylene [31] [32].

Research Reagent Solutions for Biosensor Development

The fabrication of high-performance electrochemical biosensors relies on a suite of specialized materials and reagents. The following table details essential components used in this field.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Electrochemical Biosensor Development

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Nanomaterials | Enhance electrode surface area, electron transfer kinetics, and overall sensitivity/selectivity. | Various nanomaterials are applied to enhance electrode detection [31]. |

| Biorecognition Elements | Provide specificity by binding to the target analyte. | Enzymes [16], Antibodies (Ab) [16], DNA/Aptamers [16], Whole cells (e.g., engineered E. coli) [34]. |

| Immobilization Matrices | Entrap and stabilize biorecognition elements on the transducer surface. | Alginate-based hydrogels (for whole-cell immobilization) [34]. |

| Electrode Materials | Serve as the solid support and transducer. | Glassy Carbon Electrode (GCE), carbon fibers, stainless steel (SS) wire, Indium Tin Oxide (ITO), SS sheets [31]. |

| Electrochemical Mediators | Shuttle electrons between the biorecognition element and the electrode surface. | Non-enzymatic nanoceria tag [16]. |

Experimental Protocol for a Whole-Cell Biosensor

Whole-cell biosensors utilize living microorganisms, genetically engineered to produce a measurable signal in response to specific stimuli, such as volatile organic compounds (VOCs) emitted by stressed or infected plants [34]. The following is a detailed protocol for creating such a sensor for detecting crop spoilage.

1. Bacterial Strain Preparation:

- Obtain genetically engineered luminescent bioreporter bacterial strains (e.g., E. coli TV1061 or DnaK strain containing a plasmid with a promoter fused to the luxCDABE operon) [34].

- Streak bacterial stocks on Luria-Bertani (LB) agar plates supplemented with an appropriate antibiotic (e.g., 100 μg/mL ampicillin) and incubate for 24 hours at 37°C.

- Inoculate a single colony into 10 mL of LB medium with antibiotic and grow overnight at 37°C on a rotary shaker at 200 rpm.

- The following day, dilute the culture to ~10⁷ cells/mL and regrow without antibiotics to the early exponential phase (OD₆₀₀ ≈ 0.2) [34].

2. Cell Immobilization in Hydrogel:

- Harvest the bacterial cells via centrifugation.

- Mix the cell pellet 1:1 (v/v) with a 2.5% (w/v) sodium alginate solution.

- Load the cell-alginate mixture into custom cellulose tubes (e.g., 6 mm diameter).

- Immerse the tubes in a 0.25 M calcium chloride (CaCl₂) solution for 20 minutes to initiate polymerization and form stable calcium alginate tablets.

- Remove the alginate tubes and cut them into 3 mm tablets using a customized holder [34].

3. Biosensor Activation and Measurement:

- Expose the bacterial tablets to the air sample or headspace from the crop of interest (e.g., in a storage container).

- Monitor the bioluminescent response using a multi-mode plate reader or an imaging system like the IVIS Lumina LT.

- The induction of bioluminescence above a baseline threshold indicates the presence of target VOCs, signaling potential spoilage [34]. Lower temperatures (+4°C) have been shown to enhance sensor sensitivity and prolong bacterial viability, making this ideal for cold storage monitoring [34].

The logical relationship between the sensor components and the signal output is shown below.

Integration and Future Perspectives