Electrochemical vs. Optical Biosensors: A Comprehensive Comparison for Biomedical Research and Precision Diagnostics

This article provides a detailed comparative analysis of electrochemical and optical biosensor platforms, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Electrochemical vs. Optical Biosensors: A Comprehensive Comparison for Biomedical Research and Precision Diagnostics

Abstract

This article provides a detailed comparative analysis of electrochemical and optical biosensor platforms, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the fundamental principles, operational mechanisms, and distinct advantages of each technology. The scope extends to their methodological applications in disease diagnosis, therapeutic drug monitoring, and wearable sensors, alongside practical troubleshooting for sensitivity and real-world performance. A critical evaluation of clinical validation protocols and a direct performance comparison offer essential insights for selecting the optimal biosensing strategy to advance precision medicine and point-of-care diagnostics.

Core Principles and Working Mechanisms: Building a Foundation in Biosensing Technology

Biosensors are analytical devices that integrate a biological recognition element with a physicochemical transducer to produce a measurable signal proportional to the concentration of a target analyte. The fundamental operation of all biosensors relies on two essential components: a bioreceptor that selectively interacts with the target molecule and a transducer that converts this biological recognition event into a quantifiable signal. The specificity of biosensors stems from the selective binding of recognition elements to target molecules, minimizing interference from impurities and enabling ultra-low detection limits, typically in the nanomolar or picomolar range [1].

The transduction principle forms the core of biosensor functionality, determining key performance parameters including sensitivity, detection limit, dynamic range, and applicability to different experimental settings. This guide provides a systematic comparison of the two predominant biosensor transduction platforms: electrochemical and optical. Within the broader context of biosensor research, understanding these fundamental transduction principles enables researchers to select the optimal platform for specific applications in drug development, clinical diagnostics, and biomedical research.

Electrochemical Transduction Principles

Electrochemical biosensors transform biological recognition events into measurable electrical signals through changes in electrical properties at the electrode-solution interface. The high specificity of these systems stems from the selective binding of recognition elements to target molecules, which subsequently affects the electrochemical behavior of the electrode surface [1]. These sensors are categorized based on their specific signal transduction mechanism.

Amperometric/Voltammetric Sensors monitor current resulting from the electrochemical oxidation or reduction of an electroactive species at a constant or varying potential. The generated current has a linear relationship with the target analyte concentration. A notable application is a disposable thread-based electrochemical biosensor for lung cancer diagnosis, which demonstrated excellent sensitivity for biomarker detection [2].

Potentiometric Sensors measure the potential difference between working and reference electrodes when the net current is zero. This potential change occurs in response to the accumulation of charge or changes in ion concentration resulting from a biological recognition event.

Impedimetric Sensors analyze the resistance and reactance of a system to an applied alternating current. The binding of biomolecules to the electrode surface alters the interfacial electron transfer resistance, which can be quantified via electrochemical impedance spectroscopy.

Conductometric Sensors track changes in the electrical conductivity of a solution resulting from enzymatic reactions that generate or consume ions.

Table 1: Electrochemical Transduction Mechanisms and Applications

| Transduction Type | Measured Parameter | Detection Principle | Example Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amperometric/Voltammetric | Current | Redox current from electroactive species | Lung cancer biomarker detection [2] |

| Potentiometric | Potential | Ion concentration change | Ion-selective electrode sensors |

| Impedimetric | Impedance | Electron transfer resistance at electrode interface | Label-free protein detection |

| Conductometric | Conductivity | Ionic strength change from reaction | Enzyme-based metabolite sensors |

A key advantage of electrochemical biosensors is their performance enhancement through nanomaterial integration. Noble metal nanomaterials like gold nanoparticles provide large specific surface area and outstanding electrical conductivity, while carbon-based nanomaterials such as graphene and carbon nanotubes form conjugated π-electron networks granting exceptional electrical properties [1]. For instance, one study developed a biosensing system using gold nanofiber-modified screen-printed carbon electrodes that significantly enhanced electron transfer efficiency, achieving a detection limit of 0.28 ng/mL for prostate-specific antigen [1].

Optical Transduction Principles

Optical biosensors convert biological recognition events into measurable optical signals through changes in light properties including intensity, wavelength, polarization, or phase. These platforms have gained prominence due to their high sensitivity, capability for multiplexed detection, and non-invasive nature, though they may face limitations in portability and environmental resilience compared to electrochemical alternatives [3].

Fluorescence and FRET-based Biosensors utilize energy transfer between donor and acceptor fluorophores. When the donor fluorophore is excited, it transfers energy to the acceptor if they are in close proximity, resulting in acceptor emission. Biological events that alter the distance or orientation between fluorophores change the FRET efficiency. Genetically encoded FRET biosensors have revolutionized the monitoring of cellular processes, exemplified by the AuxSen auxin biosensor that employs mNeonGreen and Aquamarine fluorescent proteins coupled to a modified bacterial tryptophan repressor [4]. This sensor enables real-time monitoring of auxin concentrations at subcellular resolution with reversibility and high temporal resolution.

Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering (SERS) utilizes nanostructured metallic surfaces to enhance Raman scattering signals by several orders of magnitude. Sharp-tipped Au-Ag nanostars provide intense plasmonic enhancement due to their sharp-tipped morphology, enabling powerful SERS detection without dependence on Raman reporters [5]. One platform demonstrated sensitive detection of α-fetoprotein, a cancer biomarker, with a limit of detection of 16.73 ng/mL by exploiting the intrinsic vibrational modes of the target [5].

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) measures changes in the refractive index near a metal surface, typically gold or silver, resulting from biomolecular binding events. This label-free technique enables real-time monitoring of molecular interactions without requiring fluorescent labeling. SPR biosensors have been successfully employed for fragment-based drug discovery, with one study screening 930 fragment compounds against multiple drug targets including HIV-1 protease, thrombin, and carbonic anhydrase [6].

Photoelectrochemical Biosensors represent a hybrid category combining optical excitation with electrochemical detection. These systems use light to excite a photosensitive material, generating an electrical signal measured electrochemically. For example, an organic photoelectrochemical transistor biosensor based on BiVO₄-ZnIn₂S₄ material was developed for efficient and sensitive detection of MCF-7 cancer cells [7].

Table 2: Optical Transduction Mechanisms and Applications

| Transduction Type | Measured Parameter | Detection Principle | Example Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| FRET | Fluorescence intensity ratio | Energy transfer between fluorophores | Real-time auxin monitoring in plants [4] |

| SERS | Raman scattering intensity | Plasmonic enhancement on nanostructures | α-fetoprotein cancer biomarker detection [5] |

| SPR | Refractive index change | Biomolecular binding on metal surface | Fragment screening for drug discovery [6] |

| Photoelectrochemical | Photocurrent | Light-induced electron transfer | Cancer cell detection [7] |

Figure 1: Optical Biosensor Transduction Mechanisms. FRET biosensors (top) detect conformational changes through energy transfer between fluorophores. SPR biosensors (bottom) measure biomolecular binding via refractive index changes at a metal surface.

Comparative Performance Analysis

Direct comparison of electrochemical and optical biosensor platforms reveals distinct advantages and limitations for each technology. Performance evaluation encompasses sensitivity, specificity, detection limits, operational stability, cost-effectiveness, and suitability for point-of-care applications.

Electrochemical biosensors demonstrate exceptional performance for miniaturized, portable applications due to their low cost, adaptability to point-of-care formats, and compatibility with complex biological matrices. Recent advancements include a high-performance electrochemical biosensor comprising Mn-ZIF-67 conjugated with anti-O antibody for Escherichia coli detection, which achieved an impressive linear range of 10 to 10¹⁰ CFU mL⁻¹ with a detection limit of 1 CFU mL⁻¹, outperforming many optical sensors for the same analyte [8]. The sensor maintained >80% sensitivity over 5 weeks and successfully recovered 93.10–107.52% of E. coli spiked in tap water samples, demonstrating remarkable environmental robustness [8].

Optical biosensors, particularly SERS and SPR platforms, offer superior sensitivity and multiplexing capabilities but may face limitations in portability and environmental resilience [3]. The SERS-based immunoassay for α-fetoprotein detection achieved a limit of detection of 16.73 ng/mL using an Au-Ag nanostars platform, addressing current limitations in cancer biomarker detection such as low sensitivity and dependence on Raman reporters [5]. SPR biosensor technology has proven valuable for fragment-based lead discovery, enabling efficient screening of 930 compounds against multiple drug targets with minimal promiscuous binders [6].

Table 3: Direct Performance Comparison of Electrochemical vs. Optical Biosensors

| Performance Parameter | Electrochemical Biosensors | Optical Biosensors |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Detection Limit | 0.28 ng/mL (PSA) [1], 1 CFU/mL (E. coli) [8] | 16.73 ng/mL (α-fetoprotein) [5] |

| Sensitivity | High, enhanced by nanomaterials | Very high, particularly for SERS/SPR |

| Multiplexing Capability | Moderate | High (multiple wavelengths/channels) |

| Portability | Excellent for point-of-care | Limited for some platforms |

| Cost-Effectiveness | High (low-cost electrodes, simple instrumentation) | Moderate to high (may require expensive optics) |

| Environmental Robustness | Good to excellent | Moderate (may require controlled conditions) |

| Measurement Speed | Fast (seconds to minutes) | Fast (real-time for SPR) |

| Sample Throughput | Moderate | High for plate-based readers |

The selection between electrochemical and optical biosensor platforms ultimately depends on the specific application requirements. Electrochemical systems excel in field-deployable, cost-sensitive applications requiring robust performance, while optical platforms offer superior capabilities for laboratory-based applications demanding ultra-high sensitivity and multiplexed detection.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Electrochemical Biosensor Fabrication and Measurement Protocol

The development of a high-performance electrochemical biosensor for pathogen detection follows a systematic fabrication and characterization process, as demonstrated for the Mn-ZIF-67 based E. coli sensor [8]:

Electrode Modification Protocol:

- Material Synthesis: Prepare Mn-doped ZIF-67 by combining cobalt and manganese precursors with 2-methylimidazole ligand in solution. Manganese incorporation induces phase reconstruction, enhances surface area, and improves electron transfer.

- Physicochemical Characterization: Analyze crystallinity using XRD spectroscopy, functional groups via FTIR spectroscopy, and surface area/pore volume through N₂ adsorption-desorption measurements with Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) analysis.

- Bioreceptor Immobilization: Conjugate anti-O-specific antibodies to the Mn-ZIF-67 material. Antibody conjugation modulates wettability, introduces amide I and II vibrational modes, and selectively blocks electron transfer upon bacterial binding.

- Electrode Preparation: Deposit the functionalized material onto the working electrode surface and characterize using electrochemical cyclic voltammetry measurements to confirm enhanced electron transfer.

Measurement Procedure:

- Sample Incubation: Expose the modified electrode to sample solutions containing target bacteria for a specified period (typically 15-30 minutes).

- Electrochemical Analysis: Perform electrochemical measurements using techniques such as electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) or differential pulse voltammetry (DPV).

- Signal Measurement: Quantify the electron transfer resistance change or current response resulting from bacterial binding to the antibody-functionalized surface.

- Data Analysis: Generate calibration curves by plotting signal response against analyte concentration, achieving a wide linear detection range from 10 to 10¹⁰ CFU mL⁻¹.

Optical Biosensor Validation and Screening Protocol

Validation of optical biosensors, particularly for cellular applications, requires standardized methodologies to ensure reliability and reproducibility. A high-content assay for biosensor validation in a 96-well plate format using automated microscopy provides a robust framework [9]:

Biosensor Validation Protocol:

- Cell Preparation: Plate adherent cells in 96-well microplates and transfer with biosensor DNA (e.g., Rho GTPase FRET biosensors) along with upstream regulatory proteins.

- Titration Analysis: Co-express biosensors with increasing amounts of regulator DNA to determine saturation points and dynamic range. Include donor-only and acceptor-only controls for bleedthrough correction.

- Automated Imaging: Acquire images using an automated microscope with appropriate filter sets for FRET measurements. Maintain consistent environmental control (temperature, CO₂) throughout imaging.

- Image Analysis: Calculate FRET ratios and generate dose-response curves. Visually inspect images for cell health, biosensor localization, and potential artifacts.

SPR Biosensor Screening Protocol for Fragment-Based Drug Discovery [6]:

- Surface Preparation: Immobilize target proteins (HIV-1 protease, thrombin, carbonic anhydrase) on sensor chips via standard amine-coupling chemistry.

- Fragment Library Design: Select 930 compounds from commercially available sources using physicochemical and medicinal chemistry filters.

- Screening Conditions: Inject fragments under standardized conditions with appropriate buffer systems. Include reference surfaces and solvent correction cycles.

- Binding Assessment: Evaluate responses for specific binding, excluding promiscuous binders (interacting with stoichiometry ≥5:1 with all proteins).

- Hit Validation: Confirm specific binding through competition assays and dose-response measurements.

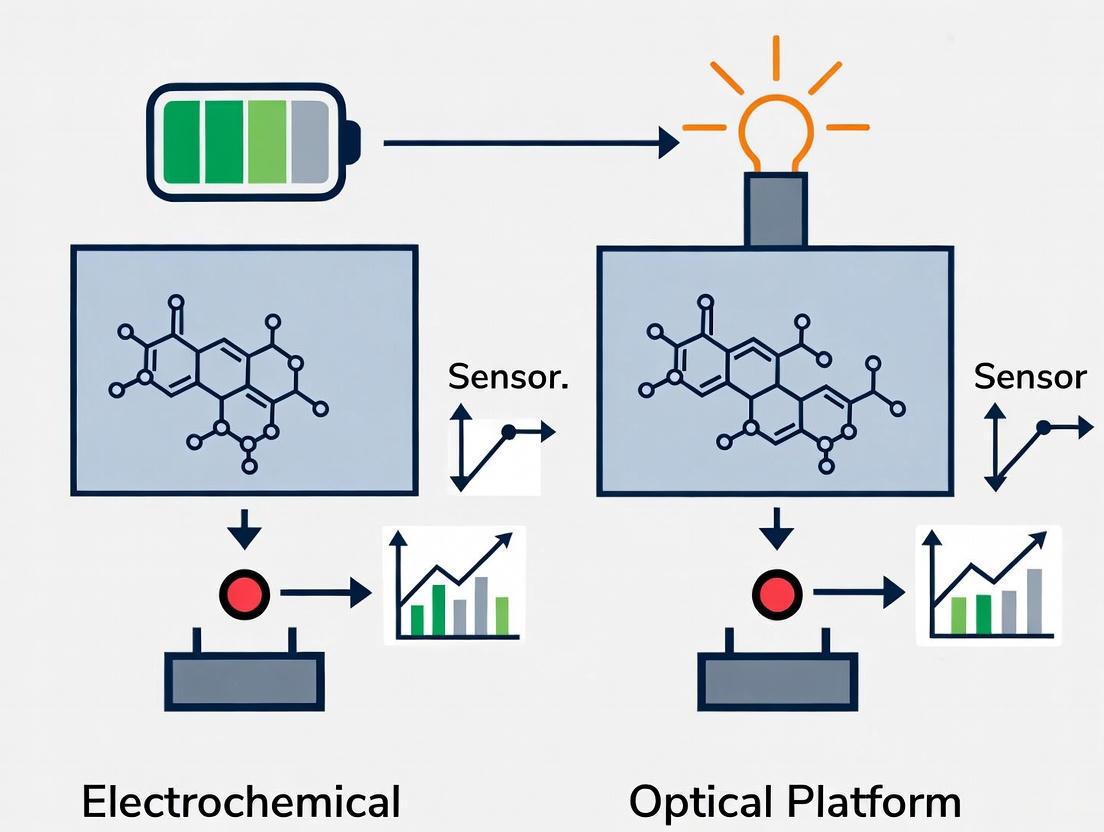

Figure 2: Experimental Workflows for Biosensor Development and Application. Electrochemical biosensors (top) rely on electrode modification and electrical signal measurement. Optical biosensors (bottom) utilize light-based detection of molecular recognition events.

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

The performance and reliability of biosensor platforms depend critically on the quality and appropriateness of research reagents and materials. The following table details essential components for biosensor development and implementation.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Biosensor Development

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | Signal amplification, electron transfer enhancement, biocompatible substrate | Prostate-specific antigen detection [1] |

| Metal-Organic Frameworks (ZIF-67) | Porous scaffold with large surface area, enhanced electrical conductivity | E. coli detection sensor [8] |

| Fluorescent Proteins (mNeonGreen, Aquamarine) | FRET donor-acceptor pairs for conformational biosensors | Auxin biosensor (AuxSen) [4] |

| Specific Antibodies (anti-O antibody) | Biorecognition element for selective target capture | E. coli O-polysaccharide detection [8] |

| Screen-Printed Carbon Electrodes (SPCEs) | Disposable, cost-effective electrode platform for point-of-care sensors | Lactate detection in sweat [1] |

| Aptamers | Nucleic acid-based recognition elements with high specificity and stability | NAD(H) detection [7] |

| Au-Ag Nanostars | Plasmonic nanoparticles for SERS enhancement | α-fetoprotein cancer biomarker detection [5] |

| Conductive Polymers (PEDOT) | Flexible, conductive substrates for wearable sensors | Sweat lactate sensor [1] |

Electrochemical and optical biosensing platforms offer complementary strengths for converting biological events into readable signals. Electrochemical systems provide robust, cost-effective solutions for field-deployable diagnostics with recent demonstrations achieving impressive detection limits for pathogens and disease biomarkers. Optical platforms deliver exceptional sensitivity and multiplexing capabilities for laboratory-based applications, with advanced FRET and SERS biosensors enabling real-time monitoring of cellular processes and ultrasensitive biomarker detection.

The continuing evolution of both platforms is being driven by nanomaterials innovation, improved bioreceptor engineering, and integration with automated systems. Future directions include developing multimodal sensing platforms that combine electrochemical and optical detection mechanisms, creating increasingly miniature and implantable form factors, and incorporating artificial intelligence for enhanced signal processing and data analysis. These advancements will further establish biosensors as indispensable tools across biomedical research, clinical diagnostics, and drug development.

Biosensors represent a critical convergence of biological specificity and analytical detection, serving pivotal roles in medical diagnostics, environmental monitoring, and food safety. The performance of these devices fundamentally depends on two key components: the biological recognition element that provides analyte specificity and the transducer interface that converts biological events into measurable signals. This comprehensive guide examines the operational principles, experimental methodologies, and performance characteristics of two dominant biosensor platforms: electrochemical and optical systems. By objectively comparing their respective advantages, limitations, and implementation requirements through structured data analysis and experimental protocols, this review provides researchers and development professionals with the foundational knowledge necessary to select appropriate biosensing architectures for specific applications.

Biosensors are analytically defined as self-contained integrated devices capable of providing specific quantitative or semi-quantitative analytical information using a biological recognition element retained in direct spatial contact with a transduction element [10]. This fundamental architecture enables the detection and quantification of target analytes across diverse fields including clinical diagnostics, environmental surveillance, food quality control, and bioprocess engineering [10] [11].

The core functionality of any biosensor relies on the synergistic operation of its two primary components: (1) the biological recognition element, which confers specificity through selective binding or catalytic interaction with the target analyte, and (2) the transducer interface, which transforms the biological response into a quantifiable signal [10]. Biological recognition elements encompass enzymes, antibodies, nucleic acids, aptamers, cellular receptors, or whole cells, each providing distinct binding affinities and operational mechanisms [10] [5]. The transducer component, typically classified as electrochemical, optical, piezoelectric, or thermal, defines the fundamental detection methodology and determines critical performance parameters including sensitivity, detection limits, and dynamic range [10] [12].

The escalating demand for decentralized diagnostics and real-time monitoring has accelerated refinement of both components, driven by advances in microfabrication, nanomaterials, and spectroscopic interrogation methods [10] [13]. This review systematically examines the implementation of these key components across electrochemical and optical biosensing platforms, providing comparative performance analysis and methodological protocols to guide platform selection for specific research and development applications.

Biological Recognition Elements: Specificity Foundations

Biological recognition elements form the molecular interface for selective analyte interaction, determining the fundamental specificity of biosensing systems. These elements operate through various mechanisms including catalytic transformation, affinity binding, or whole-cell responses, with selection dictated by target analyte properties and required assay conditions.

Element Classification and Operational Mechanisms

Enzyme-Based Recognition: Enzymes provide recognition through catalytic conversion of specific substrates, generating products detectable by transducers. Glucose oxidase exemplifies this approach, catalyzing glucose oxidation to gluconolactone while producing electrons measurable electrochemically [10] [14]. Enzyme sensors typically exhibit high turnover rates, amplifying detection signals, but may lack absolute specificity when facing structurally similar substrates.

Immunological Recognition Elements: Antibodies and antibody fragments enable detection through high-affinity binding to specific antigenic epitopes [10] [8]. Immunosensors provide exceptional specificity for proteins, pathogens, and high-molecular-weight compounds, though their non-catalytic binding mechanism typically requires labeling or secondary detection systems for signal generation. Recent advances incorporate monoclonal and recombinant antibodies to enhance reproducibility and stability [8].

Nucleic Acid-Based Recognition: DNA and RNA probes facilitate detection through complementary hybridization to target nucleic acid sequences, enabling genetic mutation identification, pathogen detection, and gene expression monitoring [10] [5]. Aptamers—engineered single-stranded oligonucleotides—fold into specific three-dimensional structures that bind molecular targets with antibody-like affinity, offering advantages of thermal stability and synthetic production [5].

Cellular and Tissue-Based Recognition: Whole cells, cellular receptors, or tissue sections provide recognition capability for complex analytes or functional responses [10]. These systems enable detection of biologically active compounds through metabolic pathway activation or receptor binding, though they typically exhibit slower response times and reduced operational stability compared to molecular recognition elements.

Immobilization Methodologies

Effective biosensor performance requires stable integration of biological recognition elements with transducer surfaces while maintaining biological activity. Common immobilization approaches include:

Adsorption: Physical attachment through van der Waals forces, ionic interaction, or hydrophobic binding provides simple implementation but may yield unstable bonding under varying pH or ionic strength conditions [10].

Covalent Attachment: Chemical bonding between functional groups on biological elements (amine, carboxyl, thiol) and activated transducer surfaces creates stable, irreversible immobilization [10] [8]. This approach often employs cross-linking agents like glutaraldehyde or EDC/NHS chemistry [5].

Entrapment: Physical confinement within polymeric matrices (e.g., hydrogels, sol-gels, conducting polymers) or behind semi-permeable membranes preserves biological activity while providing protective microenvironment [10] [13].

Affinity Binding: Specific biological interactions (e.g., avidin-biotin, protein A/G-antibody) enable oriented immobilization that optimizes binding site accessibility [10].

Transducer Interfaces: Signal Generation Mechanisms

Transducers constitute the signal conversion core of biosensors, transforming molecular recognition events into quantifiable electrical or optical outputs. The transduction mechanism fundamentally determines operational characteristics including sensitivity, response time, and instrumentation requirements.

Electrochemical Transduction

Electrochemical biosensors measure electrical signals generated from biochemical interactions, typically employing a three-electrode configuration (working, reference, and counter electrodes) to control potential and measure current [11] [14]. These systems are classified according to their measured electrical parameter:

Amperometric Sensors: Detect current generated from redox reactions at constant applied potential, with current magnitude proportional to analyte concentration [10] [15]. The extensively commercialized glucose biosensor exemplifies this approach, monitoring electron flow generated from enzymatic glucose oxidation [14].

Potentiometric Sensors: Measure potential difference accumulation at electrode surfaces under conditions of negligible current flow, typically using ion-selective membranes or field-effect transistors [10] [15].

Impedimetric Sensors: Monitor changes in system resistance and capacitance resulting from biomolecular binding events at modified electrode surfaces [10] [11]. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) provides label-free detection capability suitable for tracking binding kinetics [10].

Voltammetric Sensors: Apply potential sweeps or pulses while measuring resultant current, enabling discrimination of multiple electroactive species through their characteristic oxidation/reduction potentials [11] [14].

The following diagram illustrates the operational workflow of a typical electrochemical biosensing system:

Optical Transduction

Optical biosensors exploit light-matter interactions to detect binding events or concentration changes, utilizing parameters including absorbance, fluorescence, luminescence, refractive index, or reflectance [10] [13]. Major optical transduction platforms include:

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR): Measures refractive index changes at metal-dielectric interfaces during biomolecular binding, enabling label-free, real-time kinetic monitoring [10] [13]. Recent advances include SPR imaging for multiplexed analysis and smartphone-compatible miniaturization [13] [15].

Fluorescence-Based Detection: Utilizes light absorption and emission characteristics of fluorophores, providing exceptional sensitivity down to single-molecule detection under optimal conditions [10] [16]. Fluorescent biosensors employ intensity, lifetime, anisotropy, energy transfer (FRET), or quenching measurements to monitor molecular interactions [10].

Chemiluminescence and Bioluminescence: Detect light emission from chemical or enzymatic reactions without requiring excitation illumination, minimizing background signal [15]. These approaches offer exceptional sensitivity but typically require careful reagent integration and preservation.

Colorimetric Sensing: Monitors visible color changes from nanoparticle aggregation, enzyme-linked reactions, or pH indicators, enabling simple visual detection or smartphone quantification [15]. Lateral flow immunoassays represent widely deployed commercial applications of this principle [15].

Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS): Explores plasmonic nanoparticle enhancement of normally weak Raman scattering, providing vibrational "fingerprint" identification with single-molecule sensitivity in optimized configurations [5] [15].

The operational sequence for optical biosensing systems follows this generalized pathway:

Comparative Performance Analysis: Electrochemical vs. Optical Biosensors

The selection between electrochemical and optical transduction platforms involves balancing multiple performance parameters against application requirements. The following tables provide systematic comparison across critical operational characteristics.

Table 1: Fundamental operational characteristics comparison

| Parameter | Electrochemical Biosensors | Optical Biosensors |

|---|---|---|

| Detection Mechanism | Measurement of electrical signals (current, potential, impedance) from redox reactions [12] | Interaction of light with target molecules measuring optical property changes [12] |

| Transducer Element | Electrodes (Au, carbon, Pt) [11] [12] | Light sources, waveguides, photodetectors [12] [13] |

| Detection Dynamic Range | Limited [12] | Wide [12] |

| Multiplexing Capability | Limited support [12] | Excellent, enables simultaneous multi-analyte detection [12] [13] |

| Response Time | Fast (seconds) [12] | Slow (minutes) [12] |

| Contactless Measurement | Not available [12] | Available [12] |

| Electromagnetic Interference | Susceptible [12] | Immune [12] |

Table 2: Implementation and application considerations

| Parameter | Electrochemical Biosensors | Optical Biosensors |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Requirement | Works with complex, crude samples [12] | Often requires purified samples [12] |

| Instrumentation Size | Compact, easily miniaturized [11] [12] | Bulky, though miniaturization advancing [12] [13] |

| Cost | Relatively low, simple setup [12] | Generally higher, specialized optics required [12] |

| Lifetime | Minutes to days (biological component-dependent) [12] | Up to several years [12] |

| Primary Applications | Clinical diagnostics, food safety, environmental monitoring [11] [12] | Research, medical diagnostics, environmental monitoring [12] [13] |

Experimental Protocols and Performance Data

Electrochemical Biosensor Experimental Protocol: E. coli Detection

A recently developed high-performance electrochemical biosensor for Escherichia coli detection exemplifies contemporary methodology employing bimetallic metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) for signal enhancement [8].

Experimental Workflow:

- Electrode Modification: Glassy carbon electrodes are polished sequentially with 0.3 and 0.05 μm alumina slurry, followed by sonication in ethanol and deionized water [8].

- Mn-ZIF-67 Nanocomposite Synthesis: Mn-doped Co zeolitic imidazolate framework (ZIF-67) prepared through solvothermal reaction with varying Co:Mn molar ratios (10:1, 5:1, 2:1, 1:1) to optimize electron transfer properties [8].

- Bioreceptor Immobilization: Anti-E. coli O-specific antibody conjugated to Mn-ZIF-67 modified electrode surface via EDC/NHS chemistry, targeting O-polysaccharide antigen for selective recognition [8].

- Electrochemical Measurement: Amperometric detection performed in 0.1M PBS (pH 7.4) containing 5mM Fe(CN)₆³⁻/⁴⁻ as redox probe, monitoring current decrease following antigen-antibody binding [8].

Performance Metrics:

- Linear Detection Range: 10 to 10¹⁰ CFU mL⁻¹

- Limit of Detection: 1 CFU mL⁻¹

- Selectivity: Effectively discriminates non-target bacteria (Salmonella, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus)

- Stability: Maintains >80% sensitivity over 5 weeks

- Real Sample Recovery: 93.10–107.52% in spiked tap water samples [8]

Optical Biosensor Experimental Protocol: SERS-Based Immunoassay

A surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS) platform utilizing Au-Ag nanostars demonstrates advanced optical biosensing methodology for cancer biomarker detection [5].

Experimental Workflow:

- Nanostar Synthesis: Au-Ag nanostars prepared via seed-mediated growth, with sharp-tipped morphology optimized for plasmonic enhancement [5].

- Platform Optimization: Nanostar concentration tuned by centrifugation (10, 30, 60 minutes) with SERS performance evaluated using methylene blue and mercaptopropionic acid as probe molecules [5].

- Bioreceptor Functionalization: Optimized nanostars functionalized with mercaptopropionic acid (MPA), followed by EDC/NHS activation for covalent attachment of monoclonal anti-α-fetoprotein antibodies [5].

- SERS Detection: α-fetoprotein antigen detection across 500–0 ng/mL range using intrinsic vibrational modes without Raman reporters [5].

Performance Metrics:

- Linear Detection Range: 167–38 ng/mL (antibody), 500–0 ng/mL (antigen)

- Limit of Detection: 16.73 ng/mL for antigens

- Key Innovation: Aqueous, surfactant-free platform exploiting intrinsic AFP vibrational modes

- Application Potential: Sensitive and rapid cancer biomarker detection for early diagnostics [5]

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials

Table 3: Key research reagents and materials for biosensor development

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Flavin-adenine dinucleotide-dependent glucose dehydrogenase (FAD-GDH) | Oxygen-insensitive enzyme for glucose detection | Glucose biosensors, avoids oxygen interference [14] |

| Quinoline-5,8-dione (QD) mediator | Electron shuttle in enzymatic reactions | High-sensitivity glucose sensor strips [14] |

| Mn-doped ZIF-67 (Co/Mn ZIF) | Bimetallic MOF for enhanced electron transfer | Electrochemical E. coli biosensor [8] |

| Au-Ag nanostars | Plasmonic nanoparticles for signal enhancement | SERS-based immunoassays [5] |

| Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) | Flexible, transparent polymer substrate | Wearable optical biosensors [13] |

| Mercaptopropionic acid (MPA) | Linker molecule for surface functionalization | Antibody immobilization on SERS platforms [5] |

| EDC/NHS chemistry | Carboxyl-to-amine crosslinking | Covalent antibody immobilization [5] [8] |

| Anti-O-specific antibody | Bioreceptor for bacterial surface antigen | Selective E. coli detection [8] |

Electrochemical and optical biosensing platforms present complementary advantages that recommend them for distinct application environments. Electrochemical systems offer superior portability, rapid response, and compatibility with complex samples, making them ideal for point-of-care diagnostics and field deployment [11] [12] [15]. Optical platforms provide exceptional sensitivity, multiplexing capability, and resistance to electromagnetic interference, advantages that support research applications and laboratory-based diagnostic systems [16] [12] [13].

Future development trajectories indicate increasing convergence of these platforms with advanced materials (particularly nanomaterials), artificial intelligence for signal processing, and wireless connectivity for data transmission [11] [16] [13]. The integration of machine learning algorithms significantly enhances analytical performance in both platforms, enabling improved signal discrimination, drift correction, and multivariate analysis [16]. Selection between electrochemical and optical biosensing platforms ultimately depends on application-specific requirements including sensitivity thresholds, sample matrix complexity, operational environment, and resource constraints.

Electrochemical biosensors have emerged as powerful analytical tools that combine the specificity of biological recognition with the sensitivity of electrochemical transducers. These devices convert a biological response into a quantifiable electrical signal, enabling the detection of a wide range of analytes from clinical diagnostics to environmental monitoring [17]. The growing demand for point-of-care testing (POCT) systems has further accelerated development in this field, with electrochemical biosensors offering significant advantages including portability, low cost, rapid analysis, and compatibility with miniaturization [18] [15]. The fundamental operation of these sensors relies on the precise interplay between a biological recognition element (such as enzymes, antibodies, or nucleic acids) and an electrochemical transducer that detects the binding event or catalytic reaction [19].

Among the various transduction mechanisms, amperometric, potentiometric, and impedimetric techniques represent three foundational approaches that dominate both research and commercial applications. Each mechanism offers distinct operating principles, performance characteristics, and implementation considerations. Amperometric sensors measure current resulting from electrochemical oxidation or reduction, potentiometric sensors detect potential differences at zero current, and impedimetric sensors monitor changes in the electrical impedance of the electrode interface [20] [17]. The selection of an appropriate sensing mechanism depends on the specific application requirements, including target analyte, required detection limit, sample matrix, and necessary measurement throughput. This review provides a comprehensive comparison of these three electrochemical biosensing mechanisms, highlighting their fundamental principles, experimental implementations, and relative performance characteristics to guide researchers in selecting optimal sensing strategies for their specific applications.

The three primary electrochemical biosensing mechanisms operate on distinct physical principles, each with unique advantages and limitations. Understanding these fundamental differences is crucial for selecting the appropriate transduction method for specific applications.

Amperometric biosensors operate by applying a constant potential to an electrochemical cell and measuring the resulting current from the reduction or oxidation of an electroactive species involved in the biological recognition process [20]. The measured current is directly proportional to the concentration of the analyte, following the Cottrell equation: i = nFAc_j0√(D_j/πt), where i represents current, n is the number of electrons transferred, F is Faraday's constant, A is the electrode area, c_j0 is the initial concentration of the electroactive species, and D_j is its diffusion coefficient [20]. This technique is particularly sensitive to catalytic reactions, making it ideal for enzyme-based biosensors where the enzymatic reaction produces or consumes an electroactive species.

Potentiometric biosensors function differently by measuring the potential difference between working and reference electrodes under conditions of zero current flow [18] [20]. This potential develops as a result of specific sensor-analyte interactions that establish a local Nernstian equilibrium at the sensor interface. The measured potential relates to analyte concentration through the Nernst equation, with a theoretical sensitivity of 59 mV per decade of concentration change at 25°C [18]. These sensors can be implemented through various configurations including ion-selective electrodes (ISEs), coated-wire electrodes (CWEs), and field-effect transistors (FETs) [20]. Recent advances have demonstrated potentiometric sensors with exceptional performance, including pH sensors with sensitivities approaching the theoretical Nernstian limit and DNA detection systems capable of distinguishing single-nucleotide polymorphisms [18].

Impedimetric biosensors, also referred to as conductometric sensors, monitor changes in the impedance (both resistance and reactance) of the electrode-electrolyte interface resulting from specific biological recognition events [17]. This technique typically applies a small-magnitude alternating potential across a range of frequencies and measures the system's response in a steady state. The significant advantages of this approach include its ability to perform sensitive measurements that can be averaged over extended periods, theoretical treatment using generalized linear current-potential characteristics, and measurement capability across a broad frequency range [20]. Impedimetric biosensors are particularly valuable for label-free detection of binding events, such as antibody-antigen interactions or DNA hybridization, without requiring electroactive species.

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Electrochemical Biosensing Mechanisms

| Parameter | Amperometric | Potentiometric | Impedimetric |

|---|---|---|---|

| Measured Quantity | Current | Potential | Impedance (Resistance & Reactance) |

| Applied Signal | Constant potential | Zero current | Small AC potential with frequency sweep |

| Theoretical Basis | Cottrell equation | Nernst equation | Complex nonlinear least squares fitting |

| Detection Limit | Picomolar range [20] | Millimolar to micromolar [20] | Picomolar to femtomolar [17] |

| Dynamic Range | 3-6 orders of magnitude | 2-4 orders of magnitude | 3-5 orders of magnitude |

| Key Applications | Enzyme substrates, metabolic monitoring | Ions, pH, DNA hybridization, redox potential | Binding kinetics, cell growth, antibody-antigen interactions |

| Label Requirement | Often requires enzyme labels | Generally label-free | Typically label-free |

Figure 1: Fundamental operational principles of the three primary electrochemical biosensing mechanisms, showing the relationship between applied signals and measured outputs.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Amperometric Biosensor Implementation

Amperometric biosensors typically employ a three-electrode system consisting of working, reference, and counter electrodes immersed in an electrolyte solution containing the analyte of interest [20]. The fundamental instrumentation requires a controlled-potential system, often called a potentiostat, which applies a constant potential between the working and reference electrodes while measuring the current flowing between the working and counter electrodes [20] [17]. A critical requirement for controlled-potential measurements is the inclusion of a supporting electrolyte to prevent electromigration effects, lower solution resistance, and maintain constant ionic strength [20].

For enzyme-based amperometric biosensors, the experimental protocol typically involves immobilizing the enzyme on the working electrode surface, applying the predetermined operating potential, and monitoring the steady-state current or transient current response following analyte introduction. The working potential is carefully selected to maximize the signal-to-noise ratio for the specific electrochemical reaction of interest while minimizing interfering reactions from other electroactive species in the sample matrix. Microelectrodes have become particularly valuable in amperometric sensing due to their high mass transport density, small double-layer capacitance, and small ohmic drop, though careful design is required to prevent cross-talk between adjacent electrodes in array configurations [18].

Recent advances in amperometric sensing include the development of sophisticated switching circuits that enable high-speed multipoint measurement across microelectrode arrays. This approach addresses the inherent limitation of traditional systems that require seconds to minutes to reach steady-state conditions at each electrode, thereby enabling rapid spatial and temporal mapping of analyte distributions [18].

Potentiometric Biosensor Implementation

Potentiometric biosensor measurements are performed under conditions of zero current flow, requiring a high-impedance voltmeter to measure the potential difference between the working and reference electrodes without drawing significant current [20]. The experimental setup typically involves an ion-selective membrane or sensitive surface that generates a potential response specific to the target analyte. The reference electrode must maintain a stable and well-defined potential throughout the measurement, typically achieved through stable internal fill solutions and consistent junction potentials [20].

For integrated sensor arrays compatible with complementary metal-oxide semiconductor (CMOS) technology, specialized circuit designs such as the CMOS source-drain follower have been developed [18]. This configuration maintains both gate-source and gate-drain voltages of the sensor transistor at constant values, providing infinite input impedance for both DC and AC signals—a critical characteristic for potentiometric measurements that prevents loading of the sensing electrode [18]. This approach has been successfully implemented in large-scale arrays, with demonstrations including a million-sensor array on a single chip for genome sequencing applications [18].

A significant advancement in potentiometric sensing involves the transition from direct charge detection to redox potential detection methods. Direct charge detection suffers from limitations including charge screening by ions in solution, influence of molecular shape on charge distribution, and unstable floating electrode potentials [18]. In contrast, redox potential detection using modified electrodes (e.g., ferrocenyl-alkanethiol modified gold electrodes) detects the ratio of oxidizer to reducer concentration, providing improved stability and reduced drift compared to direct charge detection methods [18].

Impedimetric Biosensor Implementation

Impedimetric biosensor measurements utilize a small-amplitude alternating potential (typically 5-50 mV) applied across a range of frequencies (often 0.1 Hz to 100 kHz) to characterize the electrochemical impedance of the electrode-electrolyte interface [20] [17]. The measured impedance data is commonly presented as Nyquist plots (imaginary vs. real components) or Bode plots (magnitude and phase vs. frequency), with equivalent circuit modeling used to extract meaningful parameters related to specific biological recognition events.

The experimental protocol for impedimetric biosensing involves establishing a stable baseline measurement in the appropriate buffer system, followed by monitoring changes in specific impedance parameters (such as charge transfer resistance or double-layer capacitance) upon introduction of the target analyte or during the binding process. Non-Faradaic approaches monitor changes in the electrode double layer without redox mediators, while Faradaic approaches utilize reversible redox couples (such as ferro/ferricyanide) to enhance sensitivity to surface binding events [17].

Recent implementations have leveraged the label-free nature of impedimetric biosensing for continuous monitoring applications, including cell growth and proliferation studies, where increasing cell coverage on electrode surfaces produces quantifiable changes in the measured impedance [17]. The technique has proven particularly valuable for monitoring antibody-antigen interactions, DNA hybridization, and protein binding events without requiring enzymatic or fluorescent labels.

Table 2: Characteristic Performance Parameters of Electrochemical Biosensing Mechanisms

| Performance Metric | Amperometric | Potentiometric | Impedimetric |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose Detection Limit | ~2 mg/dL (0.1 mM) [18] | N/A | N/A |

| pH Sensitivity | N/A | 41-59 mV/pH [18] | N/A |

| DNA Detection Signal | N/A | 12-100 mV for hybridization [18] | N/A |

| Redox Potential Sensitivity | N/A | 57.9 mV/decade [18] | N/A |

| Typical Response Time | Seconds to minutes | Seconds to minutes | Minutes |

| Regeneration Potential | Limited | Good | Excellent |

| Stability | Moderate (enzyme degradation) | Good (membrane aging) | Excellent |

Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

The performance of electrochemical biosensors depends critically on the careful selection of materials and reagents that facilitate both biological recognition and electrochemical transduction. The following table summarizes key research reagents and their functions in developing effective biosensing platforms.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Electrochemical Biosensors

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Glucose Oxidase | Enzyme bioreceptor for glucose detection | Amperometric glucose biosensors [17] |

| 11-Ferrocenyl-1-undecanethiol (11-FUT) | Redox mediator for potential stabilization | Potentiometric redox sensors [18] |

| Cat-CVD Silicon Nitride | pH-sensitive membrane material | Potentiometric pH sensors and DNA detection [18] |

| Zeolitic Imidazolate Frameworks (ZIF-67) | Nanostructured porous sensing layer | Enhanced surface area for improved sensitivity [8] |

| Mn-doped ZIF-67 | Electron transfer enhancement | Improved conductivity in bimetallic MOF biosensors [8] |

| Anti-O Antibody | Biorecognition element for bacterial detection | E. coli immunosensors [8] |

| Thiol-modified Oligonucleotides | DNA probe immobilization | DNA hybridization sensors [18] |

| Polypyrrole | Conducting polymer for NH₃ sensing | Impedimetric gas sensors [20] |

| Hexacyanoferrate Mixture | Reversible redox couple | Electron transfer mediator in impedimetric sensors [18] |

| Au/Ag Nanostars | Plasmonic enhancement substrate | SERS-based biosensing platforms [5] |

Figure 2: Biosensor architecture showing the relationship between sample analytes, recognition elements, transducer materials, and resulting signal types.

Comparative Performance Analysis

When selecting an appropriate biosensing mechanism for specific applications, researchers must consider the relative advantages and limitations of each approach across multiple performance parameters. The following analysis provides a framework for this decision-making process based on characteristic performance data and implementation requirements.

Sensitivity and Detection Limits: Amperometric biosensors typically offer excellent sensitivity with theoretical detection limits extending to picomolar concentrations, attributable to the direct proportionality between analyte concentration and Faradaic current [20]. Practical implementations have demonstrated clinically relevant detection limits, such as glucose detection at 2 mg/dL in continuous flow systems [18]. Potentiometric biosensors generally provide slightly higher detection limits in the millimolar to micromolar range, though specialized implementations can achieve significantly better performance [20]. For example, DNA hybridization has been detected with signal changes of 12-100 mV, enabling discrimination of complementary and reverse-complementary sequences [18]. Impedimetric biosensors can achieve remarkably low detection limits, sometimes extending to femtomolar concentrations, due to their exceptional sensitivity to nanoscale surface modifications and binding events [17].

Dynamic Range and Linearity: Amperometric sensors typically provide the widest dynamic range, often spanning 3-6 orders of magnitude, making them suitable for applications requiring quantification across diverse concentration ranges [20]. The linearity of amperometric response is generally excellent within this range, following predictable diffusion-limited current relationships. Potentiometric sensors exhibit more limited dynamic range (typically 2-4 orders of magnitude) due to the logarithmic relationship between potential and concentration described by the Nernst equation [18] [20]. Impedimetric sensors demonstrate intermediate dynamic range capabilities, typically spanning 3-5 orders of magnitude, though this is highly dependent on the specific sensing interface and measurement frequency [17].

Response Time and Measurement Duration: Amperometric measurements can provide rapid response times ranging from seconds to minutes, depending on the diffusion path to the electrode surface and the kinetics of the electrochemical reaction [20]. Microelectrode designs significantly enhance response time by establishing rapid steady-state conditions [18]. Potentiometric sensors similarly achieve response times in the seconds to minutes range, though settling time can be significantly influenced by the sample matrix—with rapid settling in redox buffer solutions but potentially longer times in simple buffer systems [18]. Impedimetric measurements typically require longer acquisition times, particularly when full spectral analysis is performed across multiple frequencies, though single-frequency measurements can provide rapid monitoring capabilities for dynamic processes [20] [17].

Stability and Reproducibility: Long-term stability varies considerably between sensing mechanisms. Amperometric biosensors employing enzymatic recognition elements often suffer from limited stability due to enzyme degradation or inactivation, though this can be mitigated through sophisticated immobilization approaches [17]. Potentiometric sensors demonstrate good stability, with primary limitations arising from membrane aging or reference electrode drift [20]. Impedimetric sensors typically offer excellent long-term stability, as they often rely on robust recognition elements such as antibodies or DNA probes and do not consume reagents during measurement [17]. Reproducibility remains a challenge across all electrochemical biosensing platforms, with significant efforts focused on improving electrode-to-electrode and batch-to-batch consistency through standardized fabrication and functionalization protocols [11].

The comparative analysis of amperometric, potentiometric, and impedimetric biosensing mechanisms reveals a complex landscape of performance trade-offs that must be carefully considered for specific application requirements. Amperometric systems excel in sensitivity and wide dynamic range, making them ideal for detecting low concentrations of electroactive species, particularly in enzymatic sensing applications. Potentiometric approaches offer simplicity and direct relationship to thermodynamic parameters, providing robust platforms for ion detection and redox potential monitoring. Impedimetric techniques provide exceptional label-free capabilities and sensitivity to surface binding events, enabling detailed characterization of biomolecular interactions.

The ongoing convergence of electrochemical biosensing with advancements in nanomaterials science, micro fabrication technologies, and complementary detection modalities continues to expand the capabilities of all three sensing mechanisms [11]. Emerging trends include the development of multi-modal sensing platforms that combine complementary techniques, the integration of machine learning for enhanced data analysis, and the creation of increasingly miniaturized systems for point-of-care and wearable applications [11]. These advancements promise to further blur the traditional boundaries between sensing mechanisms while expanding the application space for electrochemical biosensors across clinical diagnostics, environmental monitoring, food safety, and biomedical research.

As the field continues to evolve, the optimal selection of biosensing mechanism will increasingly depend on the specific requirements of each application rather than inherent superiority of any single approach. Researchers are encouraged to consider the comprehensive performance characteristics outlined in this review when designing sensing strategies for their particular analytical challenges.

Optical biosensors represent a cornerstone of modern analytical science, combining the exquisite specificity of biological recognition elements with the high sensitivity of optical transduction mechanisms. These devices function by detecting changes in light properties—such as intensity, wavelength, polarization, or phase—resulting from interactions between a target analyte and an immobilized biological recognition element (e.g., antibody, aptamer, enzyme) immobilized on a transducer surface [21]. The evolution of optical biosensing has been remarkable, transitioning from laboratory-bound instruments to platforms amenable to point-of-care (POC) testing through integration with microfluidics, simplified manufacturing technologies, and portable detectors [21]. This progression aligns with the growing demand for diagnostic tools that meet the ASSURED criteria (Affordable, Sensitive, Specific, User-friendly, Rapid and robust, Equipment-free, and Deliverable) as defined by the World Health Organization, particularly in resource-limited settings [22].

Among the diverse optical transduction schemes available, four principal techniques have emerged as particularly impactful for biomedical and diagnostic applications: Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR), fluorescence, colorimetric, and Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS). Each technique operates on distinct physical principles and offers unique advantages and limitations in terms of sensitivity, multiplexing capability, equipment requirements, and suitability for quantitative analysis. SPR biosensors exploit the generation of charge-density oscillations at a metal-dielectric interface to monitor biomolecular interactions in real-time without labeling [23]. Fluorescence-based biosensors detect the light emitted by fluorophores following excitation, offering exceptional sensitivity and the potential for multiplexing [24]. Colorimetric biosensors translate molecular recognition events into visible color changes that can be interpreted by the naked eye or simple digital imaging [25]. SERS biosensors amplify the inherently weak Raman scattering signals of molecules adsorbed on nanostructured metallic surfaces, combining molecular fingerprint specificity with trace-level sensitivity [26]. This guide provides a comprehensive technical comparison of these four fundamental optical biosensing mechanisms, with particular emphasis on their operational principles, performance characteristics, experimental implementation, and relevance to drug development and clinical diagnostics.

Comparative Performance Analysis of Optical Biosensing Techniques

The selection of an appropriate biosensing technique for a specific application requires careful consideration of multiple performance parameters. The following table provides a systematic comparison of the key attributes of SPR, fluorescence, colorimetric, and SERS biosensing platforms, summarizing their relative advantages and limitations across critical performance metrics relevant to research and diagnostic applications.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Major Optical Biosensing Techniques

| Parameter | SPR | Fluorescence | Colorimetric | SERS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Limit of Detection (LOD) | pg/mL-fg/mL [23] | fg/mL [24] | ng/mL-µg/mL [25] | Single molecule [26] |

| Quantitative Capability | Excellent (real-time, label-free) | Excellent | Semi-quantitative to Quantitative (with instrumentation) | Excellent |

| Multiplexing Potential | Moderate | High | Moderate | Very High (sharp spectral peaks) |

| Real-time Monitoring | Yes | Yes | No | No (typically endpoint) |

| Throughput | Moderate | High (with microplates) | High (with lateral flow) | Moderate |

| Equipment Complexity | High | Moderate to High | Low | Moderate to High |

| Cost per Analysis | High | Moderate | Low | Moderate |

| Key Strength | Label-free kinetic analysis | Ultra-high sensitivity | Simplicity and portability | Molecular fingerprinting |

As evidenced in Table 1, no single technique is superior across all metrics; rather, each excels in specific domains. SPR stands out for its ability to monitor biomolecular interactions—such as antibody-antigen binding or protein-DNA interactions—in real-time and without labels, providing valuable kinetic parameters (association/dissociation rates) and affinity constants, which are crucial for basic research and drug development [23]. Fluorescence-based biosensors offer exceptional sensitivity, often achieving detection limits in the fg/mL range, and are highly amenable to multiplexing when combined with different fluorophores, making them ideal for high-throughput screening applications [24]. Colorimetric biosensors, while generally less sensitive, provide unmatched simplicity and are the foundation of many point-of-care tests (e.g., lateral flow immunoassays); their utility is enhanced when coupled with smartphone-based color analysis for semi-quantitative readouts [25]. SERS offers a unique combination of single-molecule sensitivity and molecular specificity due to its vibrational spectroscopy foundation, allowing for the identification of specific analytes in complex mixtures, which is valuable in both diagnostic and research settings [26].

Beyond the core parameters listed, practical considerations such as robustness in complex biological matrices, reagent stability, and development time also significantly influence technique selection. For instance, while colorimetric assays are highly robust and equipment-free, they can suffer from lower sensitivity and susceptibility to environmental interference compared to other methods [22] [25]. Conversely, the high sensitivity of fluorescence can be compromised by background autofluorescence from biological samples, and SERS requires careful design and fabrication of plasmonic substrates to ensure signal reproducibility [26] [15].

Principle and Protocol: Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR)

Mechanism and Signaling Pathway

SPR biosensors function by exploiting the electromagnetic surface plasmon waves generated at a thin metal film (typically gold)-dielectric interface when illuminated under total internal reflection conditions. The resonance phenomenon is highly sensitive to changes in the refractive index within the evanescent field extending a few hundred nanometers from the metal surface. When biomolecules bind to the functionalized sensor surface, the local refractive index increases, causing a measurable shift in the resonance angle or wavelength, which can be correlated to the mass concentration of the bound analyte in real-time [23]. This label-free nature is a significant advantage, as it avoids potential alterations to biomolecule activity that can occur with fluorescent or other tags.

Figure 1: SPR Biosensor Signaling Pathway

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Sensor Chip Functionalization: The foundational step involves preparing the gold sensor surface. This typically begins with a thorough cleaning protocol using oxygen plasma or piranha solution to remove organic contaminants. A self-assembled monolayer (SAM) is then formed on the gold surface using alkanethiols, creating a stable, ordered surface for subsequent immobilization. Carboxylated dextran polymers (e.g., in CM5 chips) are commonly used to provide a hydrophilic matrix that minimizes non-specific binding and offers high ligand loading capacity. The biorecognition element (e.g., antibody, receptor protein, DNA probe) is immobilized onto this matrix via standard amine-coupling chemistry: the dextran surface is activated with a mixture of N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) and N-ethyl-N'-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide (EDC), followed by injection of the ligand and subsequent deactivation of remaining active esters with ethanolamine [23].

Sample Analysis and Regeneration: Once the sensor surface is prepared, the analytical cycle begins. A continuous flow of running buffer is maintained over the sensor surface to establish a stable baseline. The sample containing the analyte is injected for a defined period (typically 1-5 minutes), during which the analyte binds to the immobilized ligand, resulting in an increasing signal (association phase). After sample injection, running buffer is flowed again, and the subsequent decrease in signal is monitored as the analyte dissociates from the ligand (dissociation phase). To reuse the sensor surface for multiple analyses, a regeneration solution (e.g., low pH glycine buffer, high salt, or mild detergent) is injected to disrupt the analyte-ligand interaction without denaturing the immobilized ligand. The sensor surface is then re-equilibrated with running buffer, ready for the next cycle. The entire process generates a sensorgram—a plot of response units (RU) versus time—from which kinetic rate constants (ka, kd) and the equilibrium dissociation constant (KD) can be extracted using appropriate fitting models [23].

Principle and Protocol: Fluorescence-Based Biosensing

Mechanism and Signaling Pathway

Fluorescence biosensors operate on the principle of detecting light emitted by a fluorophore when it returns from an excited electronic state to its ground state. The analyte concentration is quantified by measuring changes in fluorescence intensity, lifetime, polarization, or energy transfer. A key advantage is the potential for extremely high sensitivity, often down to the single-molecule level under optimal conditions. Recent advancements have focused on improving performance through strategies such as ratiometric measurements (using two inverse dynamic emissions for self-calibration), plasmon-enhanced fluorescence (PEF) to increase emission intensity, and the integration with smartphones for portable detection [24]. Ratiometric fluorescence is particularly reliable as it mitigates variations caused by environmental factors, probe concentration, and instrumental efficiency by measuring the ratio of fluorescence at two wavelengths [24].

Figure 2: Fluorescence Biosensor Signaling Pathway

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Ratiometric Fluorescence Assay: This protocol describes a general ratiometric detection strategy for enhanced accuracy. First, a fluorescence probe system with two emissive states is designed or selected. A common approach involves using two fluorescent dyes or a dye and a reference nanoparticle whose emissions change inversely in response to the target analyte. For example, a probe may exhibit an increase in emission at one wavelength (e.g., green) while simultaneously showing a decrease at another wavelength (e.g., red) upon binding the target. The assay is performed by adding the sample to a solution containing the ratiometric probe in a suitable buffer within a microplate or cuvette. After an appropriate incubation period for the reaction to reach equilibrium, the fluorescence intensities at the two emission wavelengths (I1 and I2) are measured sequentially or simultaneously using a spectrofluorometer or a custom-built fluorescence detector. The ratio R = I1 / I2 is calculated and plotted against the analyte concentration to generate a calibration curve. This ratiometric approach corrects for fluctuations in light source intensity, variations in probe concentration, and changes in environmental conditions, leading to more reliable and reproducible quantification [24].

Smartphone-Based Fluorescence Detection: For point-of-care applications, a portable fluorescence biosensor can be constructed using a smartphone. In this setup, the assay is typically performed on a lateral flow strip, in a microfluidic chip, or a multi-well plate. The smartphone, housed in a darkbox to exclude ambient light, is used as both the excitation source (via its LED flash) and the detector (via its CMOS camera). An additional lens might be used to focus the emission light, and inexpensive optical filters are placed in front of the camera to block the excitation light and only transmit the fluorescence emission. A dedicated mobile application controls the LED, captures the image, and analyzes the intensity of the fluorescence signal by quantifying the RGB (Red, Green, Blue) values of the image. The green channel intensity is often most sensitive for quantification. The app correlates this intensity with analyte concentration using a pre-loaded calibration curve, displaying the result on the screen [24]. This approach significantly reduces the cost and complexity of fluorescence detection, making it suitable for field use.

Principle and Protocol: Colorimetric Biosensing

Mechanism and Signaling Pathway

Colorimetric biosensors translate a biochemical reaction into a visible color change, which can be assessed qualitatively by the naked eye or quantitatively using simple spectrometers or smartphone cameras. The most common mechanisms include (1) the aggregation of plasmonic nanoparticles (e.g., gold nanoparticles), which causes a redshift in their Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance (LSPR) absorption band and a consequent color change from red to blue; (2) enzymatic reactions that produce colored products (e.g., horseradish peroxidase with TMB substrate); and (3) chemical reactions that alter the absorption properties of a chromophore [25]. The simplicity and minimal equipment requirements make colorimetric biosensors ideal for rapid, low-cost screening tests. The integration of nanomaterials has dramatically improved their sensitivity and versatility.

Figure 3: Colorimetric Biosensor Signaling Pathway

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Au-Nanoparticle (AuNP) Aggregation Assay: This protocol leverages the LSPR properties of gold nanoparticles for the detection of specific DNA sequences or proteins. Citrate-stabilized AuNPs (∼20 nm diameter, exhibiting a red color due to LSPR at ~520 nm) are synthesized or commercially obtained. The surface of the AuNPs is functionalized with probe molecules, such as thiol-modified DNA oligonucleotides or antibodies. In the absence of the target analyte, the functionalized AuNPs remain dispersed in a high-ionic-strength buffer due to electrostatic repulsion, and the solution remains red. Upon introduction of the target analyte (e.g., a complementary DNA strand or a multivalent protein), cross-linking occurs between the AuNPs, inducing their aggregation. This aggregation increases the inter-particle plasmonic coupling, shifting the LSPR peak to longer wavelengths (~650 nm) and causing a visible color change from red to purple or blue. The result can be visually interpreted or quantified by measuring the absorbance ratio (A650/A520) with a UV-Vis spectrophotometer, which increases with the degree of aggregation and target concentration [25].

Dipstick-Based Colorimetric Biosensor (e.g., for Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitors): This protocol details the construction of a simple cellulose-based dipstick biosensor. A cellulose membrane (e.g., Whatman filter paper) is cut into strips. The biorecognition element, Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) enzyme, is immobilized onto one end of the strip by applying a solution containing AChE and gelatin (as a stabilizing agent) and allowing it to dry. On the opposite end of the same strip, a chromogenic substrate, indoxylacetate, is deposited and dried. For the assay, the enzyme-containing end of the strip is immersed in the sample solution (e.g., water suspected to contain pesticides) and incubated. If an AChE inhibitor (e.g., paraoxon, carbofuran) is present in the sample, the enzyme is inhibited. The strip is then folded so that the substrate-containing end contacts the enzyme zone. In the absence of inhibitor, AChE hydrolyzes indoxylacetate to indoxyl, which spontaneously dimerizes to form indigo blue, producing an intense blue color. If the enzyme is inhibited, the color development is weak or absent. The intensity of the blue color, which is inversely proportional to the inhibitor concentration, can be scored visually using arbitrary units or quantified with a smartphone scanner [27].

Principle and Protocol: Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS)

Mechanism and Signaling Pathway

SERS biosensors combine the molecular fingerprinting specificity of Raman spectroscopy with the extreme sensitivity afforded by plasmonic enhancement. The mechanism involves two primary components: (1) an electromagnetic enhancement, where the local electric field is dramatically amplified by several orders of magnitude due to the excitation of LSPR on a nanostructured noble metal surface (e.g., gold or silver nanoparticles); and (2) a weaker chemical enhancement due to charge transfer between the analyte molecule and the metal surface. When a molecule is adsorbed on or in close proximity to such a nanostructured surface, its inherently weak Raman scattering signal can be enhanced by factors up to 10^10–10^11, enabling single-molecule detection [26]. This allows for the identification and quantification of specific analytes based on their unique vibrational spectra, even in complex biological matrices.

Figure 4: SERS Biosensor Signaling Pathway

Detailed Experimental Protocol

SERS-Based Lateral Flow Immunoassay (LFIA): This protocol describes a quantitative SERS-LFIA for detecting a protein biomarker, such as a viral antigen. First, SERS nanotags are synthesized by incubating gold nanoparticles (e.g., 60 nm) with a Raman reporter molecule (e.g., 4-mercaptobenzoic acid, 4-MBA) that has a strong, characteristic Raman signature and can bind to gold via a thiol group. The reporter-labeled nanoparticles are then conjugated with detection antibodies specific to the target analyte. A conventional lateral flow strip is prepared with a test line (coated with capture antibodies) and a control line. When the sample is applied, the target analyte binds to the SERS nanotags, and the complex migrates along the strip via capillary action. If the target is present, it is captured at the test line, immobilizing the SERS nanotags. The strip is then air-dried. For readout, the test line is illuminated with a portable or benchtop Raman spectrometer equipped with a laser (e.g., 785 nm to minimize fluorescence background). The intensity of the characteristic Raman peak of the reporter molecule (e.g., ~1585 cm⁻¹ for 4-MBA) is measured at the test line. This intensity is directly proportional to the amount of captured analyte, allowing for highly sensitive and quantitative analysis, a significant improvement over the qualitative or semi-quantitative readout of traditional colorimetric LFIAs [26] [15].

Label-Free SERS Detection in a Microfluidic Chip: For direct detection of small molecules or pathogens, a label-free SERS protocol can be employed. A SERS-active substrate, such as a silicon wafer coated with silver nanoparticles or an array of gold nanopyramids, is integrated into a microfluidic channel. The sample (e.g., bacterial lysate, serum) is injected into the microfluidic chip and allowed to interact with the SERS substrate, where analyte molecules are adsorbed. The chip is then placed under the Raman microscope. A laser is focused onto the substrate through an objective lens, and the Raman scattered light is collected and directed to the spectrometer. Multiple spectra are collected from different spots on the substrate to account for heterogeneity. The resulting spectra are processed (background subtraction, smoothing) and analyzed. Identification is achieved by matching the peak positions (Raman shifts) to reference spectra of the pure analyte. Quantification can be performed by measuring the intensity of a characteristic peak and comparing it to a calibration curve generated with known concentrations of the standard [26]. This approach is powerful for discovering biomarkers and studying complex biological mixtures without the need for extensive labeling.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The successful development and implementation of optical biosensors rely on a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The table below catalogs key solutions and their critical functions in the construction and operation of the biosensing platforms discussed in this guide.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Optical Biosensors

| Reagent/Material | Function | Primary Application(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | LSPR chromophores; signal labels in aggregation assays and SERS substrates. | Colorimetric (LSPR), SERS |

| Raman Reporter Molecules (e.g., 4-MBA, DTNB) | Provide unique, intense Raman signature for SERS nanotags. | SERS |

| Fluorescent Dyes & Quantum Dots | High-intensity emission labels for signal generation. | Fluorescence |

| Carboxymethylated Dextran Matrix | Hydrophilic matrix for ligand immobilization with low non-specific binding. | SPR |

| NHS/EDC Coupling Kit | Standard chemistry for covalent immobilization of biomolecules on carboxylated surfaces. | SPR, Fluorescence |

| Chromogenic Enzyme Substrates (e.g., TMB, Indoxylacetate) | Enzymatic conversion produces a visible color change. | Colorimetric (Enzymatic) |

| Plasmonic Nanostructures (e.g., Ag nanoparticles, nanorods) | Enhance electromagnetic field for signal amplification. | SERS, Plasmonic Fluorescence |

| Functionalized Microplates/Microfluidic Chips | Miniaturized platforms for high-throughput or automated analysis. | Fluorescence, SERS, Colorimetric |

The selection of appropriate reagents is paramount to the performance of the biosensor. For instance, the size and shape of AuNPs directly determine their LSPR wavelength and the resultant color in colorimetric assays [25]. Similarly, the choice of Raman reporter molecule in SERS impacts the magnitude of the enhancement and the specificity of the spectral fingerprint [26]. Furthermore, the immobilization strategy, such as the widely used NHS/EDC chemistry in SPR, must provide a stable and oriented presentation of the biorecognition element to ensure high activity and accessibility for the target analyte [23]. The ongoing development of novel nanomaterials and sophisticated surface chemistry protocols continues to push the boundaries of sensitivity, specificity, and robustness for all optical biosensing modalities.