Enzyme-Based Biosensors for Organophosphate Detection: Mechanisms, Applications, and Future Frontiers

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of enzyme-based biosensors for detecting organophosphate pesticides (OPs), a critical need for environmental monitoring, food safety, and clinical diagnostics.

Enzyme-Based Biosensors for Organophosphate Detection: Mechanisms, Applications, and Future Frontiers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of enzyme-based biosensors for detecting organophosphate pesticides (OPs), a critical need for environmental monitoring, food safety, and clinical diagnostics. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of biosensor operation, focusing on the inhibition of acetylcholinesterase (AChE). It details current methodological advances, including novel nanomaterials and transduction mechanisms, while addressing key challenges in sensor stability and sensitivity. The content also covers rigorous validation protocols and comparative analyses with traditional methods, offering a holistic view of the technology's transition from laboratory innovation to real-world application.

The Core Principle: How Enzymes Enable Organophosphate Detection

Organophosphates (OPs) represent a class of phosphorous-containing compounds that have seen extensive global application as insecticides, herbicides, and chemical warfare agents. Their mechanism of action—targeting the nervous system of pests—also renders them exceptionally toxic to humans and non-target organisms. The intensive use of these intentionally toxic compounds has resulted in widespread environmental contamination, with serious consequences for ecosystem and human health. Worldwide pesticide usage reached approximately 3.42 million tons per year in 2015, with Europe accounting for 0.36 million tons [1]. The justification for their use relies on ensuring food and feed quantity and quality; however, only a minor fraction reaches intended targets while the remainder persists as environmental contaminants, with some compounds exhibiting half-lives of several decades [1].

The detection and monitoring of OPs present significant analytical challenges. Traditional chromatographic methods, while accurate and specific, suffer from drawbacks including high costs, lengthy analysis times, extensive sample preparation requirements, and the need for skilled personnel [1]. These limitations have prompted research into novel, performant analytical tools that are simultaneously cost-effective and rapid. In this context, enzyme-based biosensors have emerged as promising alternatives that leverage the biological relevance of OP toxicity mechanisms for detection purposes [1].

Toxicity Mechanisms of Organophosphates

Biochemical Basis of Toxicity

Organophosphates exert their toxic effects primarily through irreversible inhibition of acetylcholinesterase (AChE), a crucial enzyme in nervous system function. AChE normally catalyzes the hydrolysis of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine at synaptic junctions, terminating nerve impulse transmission [2]. When OPs enter the body through inhalation, ingestion, or dermal absorption, they phosphorylate the serine hydroxyl group in the active site of AChE, rendering the enzyme incapable of degrading acetylcholine [2].

This inhibition results in excessive accumulation of acetylcholine in synaptic clefts, leading to overstimulation of both muscarinic and nicotinic cholinergic receptors throughout the peripheral and central nervous systems [2] [3]. The consequent cholinergic toxidrome manifests through effects on multiple organ systems, with respiratory failure due to bronchorrhea and bronchospasm representing the leading cause of death in OP poisoning cases [2].

Clinical Manifestations and Health Impacts

The clinical presentation of organophosphate poisoning reflects the underlying cholinergic crisis and affects multiple physiological systems:

- Muscarinic effects: Include excessive salivation, lacrimation, urination, defecation, gastrointestinal upset, and emesis (SLUDGE syndrome); bronchorrhea; bronchospasm; bradycardia; and miosis [2] [3].

- Nicotinic effects: Manifest as muscle fasciculations, cramping, weakness, and flaccid paralysis; tachycardia; hypertension; and diaphoresis [2] [3].

- Central nervous system effects: Include confusion, restlessness, convulsions, coma, and respiratory depression [2] [3].

The severity and onset of symptoms vary based on the specific compound, exposure route, and dose received. Inhalation typically produces the most rapid symptom onset, while dermal absorption shows more variable systemic absorption depending on skin integrity and environmental factors [2]. Globally, mortality rates from organophosphate poisoning range from 2% to 25%, with prompt treatment being critical for positive outcomes [3].

Enzyme-Based Biosensors: Fundamental Principles

Enzyme-based biosensors represent a transformative analytical technology that leverages the specificity and catalytic efficiency of biological enzymes integrated with physicochemical transducers. These devices convert biochemical reactions into quantifiable signals, offering rapid, sensitive, and selective responses for target analytes [4].

Core Components and Working Mechanisms

Enzyme-based biosensors comprise three essential components that function synergistically:

- Biological recognition element: Enzymes such as acetylcholinesterase serve as biocatalysts that initiate specific reactions with target molecules (OPs) to produce detectable signals [4].

- Transducer: Converts the biochemical signal produced by enzyme-analyte interaction into a quantifiable electrical or optical output. Common transduction methods include electrochemical (amperometric, potentiometric), optical (absorbance, fluorescence, chemiluminescence), thermistor, and piezoelectric systems [4].

- Immobilization matrix: Stabilizes the enzyme in proximity to the transducer, enhancing stability and reusability. Techniques include physical adsorption, covalent bonding, entrapment in gels or polymers, and incorporation into nanomaterials [4].

For OP detection, most biosensors operate on an inhibition-based principle rather than direct substrate detection. In the presence of OPs, AChE activity is inhibited, reducing the enzymatic conversion of substrate to product and consequently diminishing the detectable signal [1] [4]. The degree of inhibition correlates with OP concentration, enabling quantitative analysis.

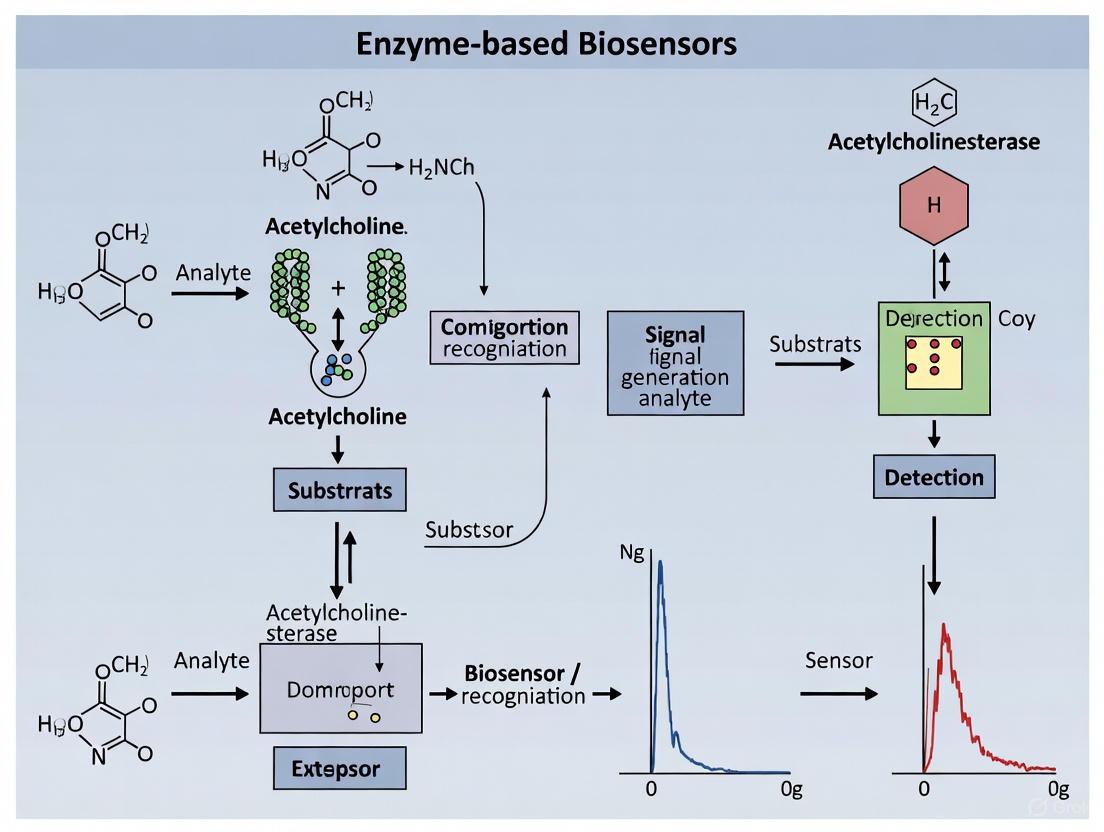

Figure 1: Enzyme Inhibition Mechanism of Organophosphate Detection. Organophosphates irreversibly inhibit acetylcholinesterase (AChE), preventing hydrolysis of acetylcholine and reducing measurable signals.

Acetylcholinesterase as Primary Recognition Element

Acetylcholinesterase serves as the predominant biological recognition element in biosensors for neurotoxic insecticides, including organophosphates and carbamates. The enzyme catalyzes the hydrolysis of acetylcholine to choline and acetate [1] [4]. When immobilized in biosensor systems, the inhibition of AChE by OPs provides a biologically relevant detection mechanism that directly correlates with the compound's toxicity [1].

Recent advances have focused on enhancing biosensor performance through the use of genetically engineered mutant enzymes with variable sensitivity patterns toward different insecticides [1]. These engineered enzymes enable the discrimination of specific OP compounds in mixtures when deployed in array-type sensor formats combined with chemometric analysis methods [1].

Advanced Detection Modalities and Materials

Transduction Mechanisms in OP Biosensing

Enzyme-based biosensors for OP detection employ diverse transduction mechanisms, each with distinct advantages and applications:

Table 1: Transduction Mechanisms in Enzyme-Based OP Biosensors

| Transduction Method | Detection Principle | Key Features | Reported Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electrochemical | Measures current or potential changes from redox reactions | High sensitivity, portable, cost-effective | Acetylcholinesterase inhibition-based sensors [1] [4] |

| Optical | Detects changes in light properties (absorbance, fluorescence) | High visibility, rapid response, versatile | Organophosphate hydrolase-based systems; colorimetric strips [5] [6] |

| Piezoelectric | Measures mass changes on sensor surface | Label-free detection, real-time monitoring | Quartz crystal microbalance biosensors [1] |

| Thermistor | Detects heat changes from enzymatic reactions | Insensitive to optical/electrical interference | Less common for OP detection [4] |

Nanomaterial-Enhanced Biosensing Platforms

The integration of nanomaterials has significantly advanced the performance characteristics of enzyme-based biosensors for OP detection. These materials enhance sensitivity, stability, and response times through various mechanisms:

Nanocellulose-based composites: Recent research has demonstrated the successful development of dialdehyde nanocellulose-modified silver nanoparticles (AgNP@DANC) as an efficient immobilization matrix for AChE. This nanocomposite, derived from rice husk agro-waste, provides a biocompatible and economical platform for ultrasensitive OP detection [7]. The sensing mechanism relies on AChE-catalyzed hydrolysis of acetylthiocholine to thiocholine, which induces aggregation of silver nanoparticles detectable via decreased absorption at 414 nm. In the presence of OPs, enzyme inhibition prevents nanoparticle aggregation, enabling detection of chlorpyrifos and malathion across remarkably broad linear ranges (10⁻³ to 10⁻¹⁹ M and 10⁻³ to 10⁻¹⁷ M, respectively) [7].

Nanozymes: Engineered nanomaterials with enzyme-like catalytic activity offer advantages including greater stability, tunable properties, and resistance to denaturation under harsh conditions [4]. These synthetic enzymes maintain functionality in environments where biological enzymes would degrade, extending operational lifespans for field-deployable sensors.

Striking advances in stability: Recent developments have produced biosensor systems with exceptional operational stability. Silk fibroin hydrogel films encapsulating AChE have demonstrated retention of significant sensitivity for over 18 months, even when stored at 37°C [5]. Such remarkable stability addresses a critical limitation in enzyme-based biosensing and facilitates practical deployment in resource-limited settings.

Innovative Form Factors and Detection Platforms

Distance-based paper biosensors: A novel enzyme inhibition-mediated distance-based paper (EIDP) biosensor has been developed for naked-eye visual detection of OPs in food samples [8]. This system utilizes a copper alginate (Cu-Alg) hydrogel that traps water within its matrix. During normal AChE activity on acetylthiocholine, generated thiocholine interacts with Cu²⁺ ions, altering the gel's structure and releasing trapped water to flow on pH paper. OP inhibition of AChE limits this water flow, enabling quantification via measured flow distance reduction [8]. This approach provides a simple, portable, instrument-free solution with a linear detection range of 18-105 ng/mL for malathion and successful application in pumpkin and rice samples [8].

Strip biosensors: Recent work has produced flexible, time-efficient biosensor strips incorporating AChE and pH test papers for visual detection of OPs [5]. These systems demonstrate limits of detection as low as 6.57 ng/mL for paraoxon and have been effectively applied to real samples of Chinese cabbage and peanuts, offering practical platforms for agricultural and food safety applications [5].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Representative Protocol: Nanocellulose-AgNP Biosensor

The development and application of nanocellulose-based biosensors follows a systematic methodology [7]:

Nanocomposite synthesis:

- Extract microcrystalline cellulose from agro-waste rice husk

- Functionalize cellulose via TEMPO-mediated oxidation to form nanocellulose

- Treat TEMPO-oxidized nanocellulose with sodium periodate to form dialdehyde nanocellulose (DANC)

- Use DANC as both reducing and stabilizing agent for silver nanoparticle formation

- Characterize resulting AgNP@DANC composite using SEM, FTIR, XRD

Biosensor fabrication:

- Immobilize AChE enzyme on AgNP@DANC nanocomposite matrix

- Optimize enzyme loading and stability parameters

- Incorporate into appropriate electrode or optical platform

Detection procedure:

- Incubate biosensor with acetylthiocholine (ATCh) substrate

- Measure baseline catalytic activity via UV-Vis spectroscopy (absorption at 414 nm)

- Expose biosensor to sample containing OPs

- Measure inhibition of AChE activity through reduced absorption decrease

- Quantify OP concentration based on inhibition percentage relative to calibration curve

Validation:

- Test biosensor with spiked real samples (fruits, vegetables)

- Compare results with standard chromatographic methods

- Evaluate stability over extended storage periods

Representative Protocol: Distance-Based Paper Biosensor

The enzyme inhibition-mediated distance-based paper (EIDP) biosensor employs the following methodology [8]:

Hydrogel preparation:

- Prepare copper alginate hydrogel by mixing sodium alginate (0.2 wt%) with Cu²⁺ solutions (0.5-2.5 mM)

- Characterize hydrogel properties via viscosity measurements and SEM

Biosensor assembly:

- Affix pH paper strips (60 × 5 mm) to PVC backing

- Apply optimized Cu-Alg hydrogel to paper platform

Detection protocol:

- Pre-incubate AChE (0.06 U/mL) with sample containing OPs for inhibition

- Add acetylthiocholine (3 mM) and incubate 10 minutes

- Apply reaction mixture to hydrogel on paper platform

- Measure water flow distance on pH paper after fixed time interval

- Quantify OP concentration based on reduced flow distance compared to inhibitor-free control

Optimization parameters:

- Systematically optimize AChE concentration (0-0.06 U/mL)

- Optimize ATCh concentration (0-3 mM)

- Determine optimal incubation times for enzyme-substrate and enzyme-inhibitor reactions

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Enzyme-Based OP Biosensor Development

| Reagent/Category | Function/Purpose | Specific Examples | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enzymes | Biological recognition element | Acetylcholinesterase (from Electric eel, Drosophila melanogaster) | Genetically engineered variants enhance selectivity [1] |

| Nanomaterials | Signal enhancement, enzyme stabilization | Silver nanoparticles, nanocellulose, graphene, carbon nanotubes | Improve sensitivity and stability [4] [7] |

| Immobilization Matrices | Enzyme stabilization on transducer | Silk fibroin hydrogels, polymer films, sol-gels | Critical for operational stability [5] |

| Substrates | Generate measurable signal product | Acetylthiocholine chloride, acetylcholine | Hydrolysis produces detectable products [7] [8] |

| Transduction Materials | Signal conversion and measurement | pH indicators, electrochemical mediators, fluorophores | Enable optical/electrochemical detection [4] [6] |

| Support Matrices | Biosensor platform | Chromatographic paper, PVC backings, electrodes | Provide structural support [8] |

Enzyme-based biosensors represent a rapidly advancing technology that addresses the critical need for rapid, sensitive, and field-deployable detection of organophosphates. By leveraging the biological relevance of acetylcholinesterase inhibition, these analytical devices provide toxicologically meaningful data that complements traditional analytical methods. Recent innovations in nanomaterial integration, stabilization strategies, and innovative form factors have substantially addressed historical limitations related to stability, sensitivity, and practicality.

Future development trajectories include the creation of multiplexed sensor arrays employing multiple enzyme variants with differential inhibition patterns, enabling discrimination between specific OP compounds in complex mixtures [1]. The integration with wearable technology and Internet of Things (IoT) platforms promises real-time environmental monitoring capabilities [4]. Additionally, the continued development of synthetic enzymes and nanozymes may ultimately overcome the fundamental stability limitations of biological recognition elements, further expanding the application scope of these biosensing platforms in resource-limited settings where OP exposure poses significant public health challenges.

The convergence of supramolecular chemistry, advanced materials science, and microengineering continues to propel the field of enzyme-based biosensing toward increasingly robust, multifunctional, and informative analytical tools that will enhance environmental monitoring, food safety assurance, and public health protection in the face of ongoing organophosphate contamination challenges.

Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) as the Primary Biorecognition Element

Acetylcholinesterase (AChE)-based biosensors represent a critical technological advancement in the detection of organophosphorus (OP) pesticides, leveraging the specific inhibition of the AChE enzyme as a transduction mechanism for analyte recognition [9] [1]. These analytical devices combine a biological recognition element (the AChE enzyme) with a physicochemical transducer, producing a measurable signal proportional to the concentration of neurotoxic insecticides such as OPs and carbamates [1] [4]. The operational principle hinges on the conversion of biochemical interactions—specifically, the inhibition of AChE enzymatic activity—into quantifiable electrical, optical, or thermal signals via appropriate transducers [4] [10]. Within the context of a broader thesis on enzyme-based biosensors for organophosphates, this whitepaper provides an in-depth technical examination of AChE's role as the primary biorecognition element, detailing the underlying biochemical principles, sensor fabrication methodologies, performance characteristics, and advanced applications incorporating machine learning and novel materials to enhance detection capabilities for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Biochemical Principles of AChE-Based Detection

Catalytic Function and Neurological Role

Acetylcholinesterase (AChE, EC 3.1.1.7) is a serine hydrolase enzyme concentrated at neuromuscular junctions and cholinergic brain synapses, where it plays a crucial role in terminating synaptic transmission by catalyzing the hydrolysis of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine (ACh) [9]. This enzymatic reaction proceeds at a remarkably high efficiency, cleaving ACh into choline and acetic acid within microseconds, thereby maintaining clear synaptic clefts and ensuring proper muscular responses [9]. The enzyme's active site consists of two key subsites—an anionic subsite responsible for substrate binding and an esteratic subsite containing a reactive serine residue that performs nucleophilic attack on the substrate's carbonyl carbon [9]. Under normal physiological conditions, this catalytic mechanism ensures precise regulation of cholinergic signaling, with the hydrolysis products being recycled by the body to maintain neurotransmitter reserves [9].

Inhibition Mechanism by Organophosphates

Organophosphorus pesticides exert their toxicity through irreversible inhibition of AChE, forming a stable covalent bond with the serine residue within the enzyme's active site [9] [11]. This inhibition prevents the hydrolysis of acetylcholine, leading to neurotransmitter accumulation in synaptic clefts, resulting in overstimulation of cholinergic nerves and causing a range of symptoms from headaches and confusion to respiratory failure and death in severe cases [9] [11]. The intensity of AChE inhibition demonstrates direct proportionality to the concentration of OP compounds, a relationship that forms the fundamental principle exploited in AChE-based biosensors for quantitative detection of these toxicants [9]. The covalent inhibition mechanism differentiates OPs from reversible inhibitors and underscores the irreversibility of the reaction, often necessitating enzyme reactivation or replacement for continuous monitoring applications [1].

Table: Comparative Analysis of Techniques for Organophosphorus Pesticide Detection

| Technique | Detection Principle | Limit of Detection | Analysis Time | Cost | Portability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AChE Biosensors | Enzyme inhibition | ng/mL to pg/mL [11] | Minutes [11] | Low | High |

| Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) | Mass separation and detection | pg/mL [11] | Hours [11] | High | Low |

| High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) | Liquid chromatography | ng/mL [11] | Hours [11] | High | Low |

| Capillary Electrophoresis (CE) | Electrophoretic separation | ng/mL [11] | 30-60 minutes [11] | Medium | Low |

Biosensor Architecture and Fabrication

Fundamental Biosensor Components

An AChE-based biosensor comprises three essential components that work synergistically to detect and quantify target analytes: (1) the biological recognition element (AChE enzyme), (2) a transducer that converts biochemical reactions into measurable signals, and (3) an immobilization matrix that stabilizes the enzyme while maintaining its accessibility to the analyte [4] [10]. The biological recognition element must exhibit high specificity toward the target analyte, with AChE serving as the biorecognition element specifically for detection of OP and carbamate pesticides through the inhibition mechanism [9] [4]. The transducer element—which may be electrochemical, optical, thermal, or piezoelectric—detects physicochemical changes resulting from the enzymatic reaction or its inhibition and transforms these changes into quantifiable signals [4] [10]. The immobilization matrix provides a stable microenvironment for the enzyme, preserving its catalytic activity while enabling proximity to the transducer surface, with the choice of matrix significantly influencing sensor stability, response time, and reproducibility [9] [4].

Enzyme Immobilization Strategies

Effective immobilization of AChE onto transducer surfaces represents a critical step in biosensor fabrication, with the chosen methodology profoundly impacting sensor performance, stability, and operational lifespan [9]. Physical adsorption, one of the simplest approaches, relies on weak interactions (Van der Waals forces, electrostatic interactions) between the enzyme and support material, offering advantages of simplicity and minimal enzyme activity compromise but suffering from potential enzyme leakage over time [9]. Physical entrapment confines AChE within gel matrices or membranes, providing a protective microenvironment while allowing substrate and product diffusion, though it may exhibit limited reproducibility and enzyme leaching [9]. Covalent coupling forms stable bonds between enzyme functional groups and activated support surfaces, preventing enzyme leakage and enabling direct analyte interaction but potentially causing enzyme denaturation and requiring complex procedures [9]. Advanced methods include self-assembled monolayers (SAMs) creating organized nanoscale structures with specific functional groups [9], oriented immobilization exploiting particular enzyme functional groups to position the active site optimally toward analyte flow [9], and electropolymerization using electrical fields to create polymer matrices for enzyme incorporation [9].

Transduction Mechanisms

AChE-based biosensors employ diverse transduction mechanisms to convert biochemical recognition events into quantifiable analytical signals, with electrochemical transducers representing the most prevalent approach due to their high sensitivity, simplicity, and compatibility with miniaturization [1] [4]. Amperometric transducers monitor current changes resulting from redox reactions of enzymatic products, typically operating at a fixed potential and offering excellent sensitivity with detection limits frequently reaching nanomolar or picomolar concentrations for OP compounds [4] [10]. Potentiometric sensors measure potential differences arising from ion accumulation or pH changes during enzymatic reactions, such as the production of acetic acid during acetylcholine hydrolysis [4] [10]. Optical transduction methods encompass absorbance, fluorescence, chemiluminescence, and surface plasmon resonance, detecting changes in optical properties resulting from enzymatic activity or its inhibition [1] [4]. Emerging transduction platforms include thermistor-based systems detecting heat emission or absorption during enzymatic reactions [10] and piezoelectric devices measuring mass changes on the sensor surface resulting from binding events [4].

Diagram 1: Core architecture of an AChE-based biosensor, illustrating the sequence from analyte recognition to signal output.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard Inhibition Assay Protocol

The fundamental experimental protocol for AChE-based biosensing involves an inhibition assay that quantifies the reduction in enzymatic activity following exposure to OP compounds [9] [1]. Begin by immobilizing AChE onto the selected transducer surface using an appropriate immobilization method (e.g., covalent binding to a functionalized electrode) [9]. Measure the initial enzymatic activity by incubating the biosensor with a substrate solution (typically acetylthiocholine or acetylcholine) and quantifying the generated signal—electrochemical current for thiocholine oxidation, pH change for potentiometric detection, or color change for optical systems [9] [1]. Subsequently, incubate the biosensor with the sample containing potential OP inhibitors for a predetermined period (typically 10-30 minutes) to allow enzyme-inhibitor complex formation [1]. Following incubation, re-measure the residual enzymatic activity using identical substrate concentration and detection conditions [9]. Calculate the percentage inhibition using the formula: % Inhibition = [(I0 - I1)/I0] × 100, where I0 represents the initial current (or signal) and I1 represents the current (or signal) after inhibition [9] [1]. Finally, correlate the inhibition percentage to OP concentration using a predetermined calibration curve generated with standard solutions [1].

Fabrication of Nanomaterial-Enhanced Biosensors

Incorporating nanomaterials into AChE biosensors significantly enhances their sensitivity, stability, and anti-interference capabilities [12] [11]. Begin by synthesizing or procuring appropriate nanomaterials such as graphene oxide, carbon nanotubes (CNTs), gold nanoparticles (AuNPs), metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), or MXenes [12] [11]. Functionalize the transducer surface (e.g., glassy carbon electrode, screen-printed electrode) with these nanomaterials to create a high-surface-area matrix—methods include drop-casting nanomaterial suspensions followed by solvent evaporation or electrochemical deposition for conductive materials [12]. Activate the nanomaterial-modified surface for enzyme attachment using appropriate cross-linkers (e.g., glutaraldehyde for amine-functionalized surfaces) or specific functional groups present on the nanomaterial [12]. Immobilize AChE onto the activated nanomaterial surface by incubating with enzyme solution (typically 0.1-1.0 U/μL concentration) for 1-2 hours at room temperature or 4°C overnight [11]. Rinse the modified biosensor thoroughly with buffer solution to remove unbound enzyme and store in appropriate conditions (typically pH 7-8 buffer at 4°C) until use [9] [11]. Validate the immobilization efficiency through electrochemical characterization (cyclic voltammetry, electrochemical impedance spectroscopy) or measurement of enzymatic activity compared to unmodified controls [13].

Diagram 2: AChE biosensor inhibition mechanism, showing the competitive pathways of substrate catalysis and inhibitor binding.

Sensor Validation and Data Analysis

Comprehensive validation of AChE biosensor performance requires characterization of multiple analytical parameters following fabrication and optimization [1] [11]. Determine the detection limit (LOD) and quantification limit (LOQ) by measuring the response to serially diluted standard OP solutions, typically calculating LOD as 3.3×σ/S and LOQ as 10×σ/S, where σ represents the standard deviation of the blank response and S represents the slope of the calibration curve [11]. Evaluate sensor linearity by analyzing the correlation coefficient (R²) across the working range of the biosensor, with acceptable values typically exceeding 0.990 [1]. Assess precision through repeatability (intra-assay) and reproducibility (inter-assay) experiments, calculating percent relative standard deviation (%RSD) for multiple measurements of the same sample [11]. Determine accuracy using spike-recovery experiments in real samples (fruits, vegetables, water) and comparison with standard chromatographic methods [11]. Evaluate biosensor stability by monitoring signal response retention over time (storage stability) and through multiple measurement cycles (operational stability) [9] [11]. For advanced applications, employ chemometric methods such as artificial neural networks (ANNs) or partial least squares (PLS) regression when using multiple enzyme variants to discriminate between different OP compounds in mixtures [1] [13].

Table: Performance Characteristics of Representative AChE-Based Biosensors

| Immobilization Matrix | Transducer Type | Target OP | Linear Range | Detection Limit | Stability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon Nanotubes [12] | Amperometric | Chlorpyrifos | 0.1-100 ng/mL [12] | 0.05 ng/mL [12] | 30 days [12] |

| Gold Nanoparticles [12] | Electrochemical | Methyl parathion | 0.01-1000 ng/mL [12] | 0.005 ng/mL [12] | 45 days [12] |

| Metal-Organic Frameworks [11] | Fluorescence | Paraoxon | 0.1-500 ng/mL [11] | 0.03 ng/mL [11] | 60 days [11] |

| Graphene Oxide [12] | Potentiometric | Malathion | 1-500 ng/mL [12] | 0.5 ng/mL [12] | 35 days [12] |

| Covalent Organic Frameworks [11] | Dual-mode | Dichlorvos | 0.05-200 ng/mL [11] | 0.02 ng/mL [11] | 50 days [11] |

Advanced Applications and Integration

Chemometric Methods for Enhanced Selectivity

A significant challenge in AChE-based biosensing involves discriminating between different OP compounds in complex mixtures, addressed through the integration of chemometric methods and multi-sensor arrays [1]. Artificial neural networks (ANNs) represent the most extensively applied approach, where biosensor arrays incorporating AChE from different biological sources or genetically engineered mutants with distinct inhibition profiles generate unique response patterns for various OPs [1]. For example, a system employing four AChE variants (electric eel, bovine erythrocytes, rat brain, and Drosophila melanogaster) successfully discriminated between paraoxon and carbofuran in binary mixtures at concentrations of 0-20 μg/L, with prediction errors of 0.9 μg/L for paraoxon and 1.4 μg/L for carbofuran [1]. Further refinement using genetically engineered Drosophila melanogaster AChE mutants (Y408F, F368L, F368H, F368W) improved discrimination capability for paraoxon and carbofuran mixtures at 0-5 μg/L concentrations, with prediction errors reduced to 0.4 μg/L and 0.5 μg/L, respectively [1]. Implementation in automated flow analysis systems enables simultaneous measurement with multiple enzyme variants, reducing analysis time and improving reproducibility compared to sequential measurements [1]. Alternative chemometric approaches include partial least squares (PLS) regression and radial basis function-artificial neural network (RBF-ANN) models, which have demonstrated efficacy in resolving pesticide mixtures in spectrometric detection systems [1].

Novel Materials and Portable Devices

Recent advances in AChE biosensor technology focus on developing field-deployable devices through innovative materials and miniaturization strategies [11] [14]. Metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) and covalent organic frameworks (COFs) provide exceptionally high surface areas and tunable pore structures that enhance enzyme loading capacity, stability, and mass transfer efficiency [11]. Two-dimensional materials such as MXenes (transition metal carbides, nitrides, and carbonitrides) offer outstanding electrical conductivity and surface functionality for improved electron transfer kinetics and enzyme immobilization [11]. Integration with microfluidic platforms enables automated sample handling, separation, and detection in compact "lab-on-a-chip" formats, significantly reducing reagent consumption and analysis time while improving reproducibility [4]. Smartphone-based detection systems leverage built-in cameras and processing capabilities for colorimetric or fluorescence measurements in point-of-need testing, with several reported applications for OP detection in food and environmental samples [11]. A notable development includes the Organophosphate Hydrolase (OPH)-based biosensor as an alternative to AChE, which directly hydrolyzes OPs rather than operating through an inhibition mechanism, enabling simplified operation without requirement for enzyme reactivation steps [14]. This OPH-based system demonstrated detection of OP residues in fruits and vegetables across a linear range from 100 ng/mL to 0.1 ng/mL, integrated with a field-portable high-throughput sensory system for on-spot analysis [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table: Essential Research Reagents for AChE-Based Biosensor Development

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Acetylcholinesterase Enzyme | Biorecognition element | Electric eel, Drosophila melanogaster, recombinant variants [9] [1] |

| Acetylthiocholine Chloride | Enzyme substrate | Produces electroactive thiocholine upon hydrolysis [9] |

| 5,5'-Dithiobis(2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB) | Chromogenic reagent for thiocholine detection | Ellman's reagent for optical detection [1] |

| Nanomaterials | Signal amplification, enzyme stabilization | CNTs, graphene, AuNPs, MOFs, COFs, MXenes [12] [11] |

| Cross-linking Agents | Enzyme immobilization | Glutaraldehyde, polyethyleneimine (PEI) [12] |

| Screen-Printed Electrodes | Disposable transducer platforms | Carbon, gold, or platinum working electrodes [9] |

| Standard OP Solutions | Calibration and validation | Paraoxon, chlorpyrifos, malathion in appropriate solvents [1] [11] |

AChE-based biosensors represent a mature yet continuously evolving technology that effectively bridges the gap between laboratory-based analytical methods and field-deployable detection systems for organophosphorus pesticides. The integration of novel nanomaterials, sophisticated immobilization strategies, and advanced computational approaches has addressed many historical limitations related to sensitivity, specificity, and operational stability. While challenges remain in standardization, reproducibility, and interference mitigation, current research directions focusing on engineered enzymes, multi-parameter sensing, and miniaturized platforms promise to further enhance the capabilities of these biosensors. For researchers and drug development professionals, AChE biosensors offer a biologically relevant detection platform that directly measures toxicity through enzyme inhibition rather than merely quantifying compound presence, providing valuable insights into the functional impact of organophosphates in both environmental and therapeutic contexts.

Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) is a critical enzyme in the nervous system, responsible for the rapid hydrolysis of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine at synaptic junctions, thereby ensuring proper nerve impulse termination and normal muscle function [15]. Organophosphorus pesticides (OPs) and nerve agents exert their acute toxicity primarily through the irreversible inhibition of AChE, leading to the accumulation of acetylcholine, overstimulation of cholinergic nerves, and potentially fatal consequences including respiratory failure [11] [15]. The detection of these inhibitors via enzyme-based biosensors leverages this specific biochemical interaction, transforming it into a quantifiable signal for environmental monitoring, food safety, and clinical diagnostics [16] [4]. This whitepaper details the molecular mechanism of irreversible inhibition and its application in modern biosensing technologies.

Molecular Mechanism of Irreversible Inhibition

Structural Architecture of the AChE Active Site

The catalytic efficiency of AChE is governed by its distinct structural architecture. The active site is located at the base of a 20 Å deep gorge [17]. The core catalytic machinery is the catalytic triad, composed of serine, histidine, and glutamate residues (specifically Ser-203, His-447, and Glu-334 in human AChE) [17] [15]. The hydrolysis of acetylcholine involves a two-step process: acylation and deacylation. The serine residue performs a nucleophilic attack on the substrate's carbonyl carbon, forming a transient acyl-enzyme intermediate, which is then rapidly hydrolyzed [17].

Adjacent to the catalytic triad is the catalytic anionic site (or alpha anionic site), which is responsible for orienting the quaternary ammonium group of acetylcholine substrate via cation-π interactions during hydrolysis [15]. A second, peripheral anionic site near the gorge entrance, rich in aromatic residues, facilitates substrate guidance and is a target for allosteric inhibitors [17].

Irreversible Inhibition by Organophosphorus Compounds

Organophosphorus compounds (OPs) act as irreversible mechanism-based inhibitors. Their mechanism involves:

- Nucleophilic Attack: The highly reactive serine hydroxyl group (Ser-203) within the catalytic triad performs a nucleophilic attack on the phosphorus atom of the OP molecule [18].

- Formation of a Covalent Bond: This results in the irreversible phosphorylation of the serine residue, forming a stable organophosphorus-serine conjugate [18]. This covalent modification is the definitive step of irreversible inhibition.

- Blocking of the Active Site: The phosphorylated serine residue is unable to participate in the hydrolysis of acetylcholine. The bulky phosphoryl group occupies the active site, sterically blocking substrate access and effectively halting enzyme function [11].

This covalent modification is exceptionally stable, rendering the enzyme permanently inactive. While nucleophilic reactivators like 2-pyridinealdoxime methochloride (PAM) can sometimes displace the phosphoryl group, they are often ineffective, and the inhibition is typically considered irreversible for practical purposes [19] [20].

The following diagram illustrates the key sites within AChE and the process of irreversible inhibition.

Biosensing Principles Based on AChE Inhibition

Fundamental Transduction Mechanisms

Biosensors convert the biochemical event of AChE inhibition into a measurable signal. The general principle is indirect: the degree of enzyme activity inhibition is correlated with the concentration of the OP inhibitor [11]. The operational principles of AChE-based biosensors are primarily divided into two main substrate-dependent pathways, both of which are disrupted upon inhibition, as shown in the workflow below.

The two main detection strategies are:

- Acetylcholine (ACh) as Substrate: AChE catalyzes the hydrolysis of ACh to choline and acetic acid. The choline is subsequently oxidized by choline oxidase (ChOx), producing hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂), which can be detected electrochemically. The production of acetic acid also causes a local pH change, which can be measured potentiometrically [11] [18].

- Acetylthiocholine (ATC) as Substrate: AChE hydrolyzes ATC to thiocholine and acetic acid. Thiocholine is easily oxidized at an electrode surface, generating a measurable amperometric current [20]. The presence of an OP inhibitor reduces the rate of thiocholine production, leading to a decrease in the observed electrochemical signal.

Advanced Sensing Modalities

Electrochemical biosensors are the most prevalent, prized for their sensitivity, portability, and cost-effectiveness [11] [16] [20]. To overcome the high overvoltage required for thiocholine oxidation, electrodes are often modified with mediators like carbon black, pillar[5]arenes, Methylene Blue, or thionine to enhance electron transfer and signal stability [20].

Optical biosensors, including colorimetric and fluorometric platforms, offer strong visual readability and are highly promising for on-site testing [16] [15]. These systems may utilize enzymes like chromogenic or fluorogenic substrates, or employ nanomaterials (e.g., gold nanoparticles) that undergo aggregation or changes in optical properties upon enzyme inhibition [16].

Emerging strategies to improve specificity include dual-recognition systems. For instance, a biosensor incorporating a Molecularly Imprinted Polymer (MIP) specific to non-phosphorus moieties of a target OP (e.g., acephate) can selectively preconcentrate the analyte. The captured OP subsequently inhibits AChE, allowing for specific quantification and reducing false positives from other cholinesterase inhibitors [18].

Quantitative Data and Performance of AChE Biosensors

The performance of AChE-based biosensors is quantified by their sensitivity, detection limit, and linear range. The following table summarizes representative data for the detection of organophosphorus pesticides using different transduction methods.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of AChE-Based Biosensors for OP Detection

| Transduction Method | Target OP / Inhibitor | Detection Limit | Linear Range | Key Material/Strategy | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amperometric (Flow-through) | Carbofuran | 10 nM | 10 nM – 0.1 μM | Enzyme reactor; CB/P[5]A/MB/Thionine modified electrode | [20] |

| Colorimetric / Fluorometric | Various OPs | Varies (μg•L⁻¹ level) | Not Specified | Smartphone-assisted platform | [16] |

| Dual-Recognition (MIP-AChE) | Acephate (AP) | Not Specified | Not Specified | Molecularly Imprinted Polymer for selective enrichment | [18] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Fabrication of a Flow-Through Amperometric AChE Biosensor

This protocol details the construction of a robust, flow-through biosensor with a replaceable enzyme reactor, suitable for the determination of reversible and irreversible inhibitors [20].

Sensor Fabrication and Electrode Modification:

- Produce screen-printed carbon electrode strips via a standard printing process.

- Modify the working electrode surface by applying a suspension of carbon black (CB) and pillar[5]arene (P[5]A) in DMF.

- Further modify the electrode by electropolymerizing a mixture of Methylene Blue (MB) and thionine onto the CB/P[5]A layer. This polymer film acts as a stable mediator for thiocholine oxidation.

Enzyme Immobilization:

- Fabricate a flow cell reactor using 3D printing with poly(lactic acid).

- Immobilize AChE from electric eel on the inner walls of the reactor cell. This can be achieved by physical adsorption or covalent bonding using cross-linkers like EDC/NHS.

- The immobilized enzyme reactor is then integrated with the modified screen-printed electrode into a flow-through system.

Inhibition Assay and Measurement:

- Continuously pump a substrate solution of acetylthiocholine (ATC) through the system in a phosphate buffer stream (e.g., 0.1 M, pH 8.0).

- Measure the steady-state amperometric current at -0.25 V (vs. Ag reference) generated by the oxidation of thiocholine.

- Introduce the sample containing the potential inhibitor (OP) into the flow stream for a fixed period (e.g., 5-10 minutes).

- Revert to the substrate buffer flow and measure the residual enzymatic activity. The percentage of inhibition is calculated as

(I₀ - I₁)/I₀ × 100%, where I₀ and I₁ are the steady-state currents before and after exposure to the inhibitor, respectively.

Protocol 2: Dual-Recognition Biosensor for Selective OP Detection

This protocol leverages a Molecularly Imprinted Polymer (MIP) for selective sample clean-up and enrichment prior to AChE inhibition detection, significantly improving specificity for a target OP like acephate (AP) [18].

MIP Preparation:

- Use acephate (AP) as the template molecule.

- Prepare the MIP on the surface of a microplate well via the self-polymerization of dopamine in a weak alkaline Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.5). This forms a polydopamine (PDA) film with imprinted cavities complementary to AP.

- Remove the template by washing with a methanol-acetic acid solution, leaving behind cavities that selectively recognize AP.

Selective Adsorption and Inhibition Assay:

- Incubate the sample solution (e.g., vegetable extract) in the MIP-coated well. AP and structurally similar compounds are selectively captured by the MIP.

- Wash the well thoroughly to remove non-specifically bound matrix interferents.

- Add a solution of AChE to the well. The AP captured by the MIP is still accessible to inhibit AChE, as the MIP is designed to bind moieties other than the phosphorus group responsible for enzyme inhibition.

- After an incubation period, transfer the AChE solution (now partially inhibited by the captured AP) to a separate well for activity measurement.

- Quantify the remaining AChE activity using a standard Ellman's assay (using acetylthiocholine iodide and DTNB) or a chemiluminescence assay. The degree of inhibition is directly correlated with the amount of AP selectively captured from the sample.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful research and development in AChE inhibition and biosensing rely on a suite of specialized reagents and materials.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for AChE Inhibition Studies and Biosensor Development

| Reagent / Material | Function and Role in Research | Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) | Primary biorecognition element; its inhibition is the basis of detection. | Electric eel AChE is commonly used; recombinant human AChE for specific mechanistic studies [17] [20]. |

| Organophosphorus (OP) Inhibitors | Target analytes used to study inhibition kinetics and sensor response. | Acephate, chlorpyrifos, paraoxon, carbofuran (carbamate) [18] [20]. |

| Enzyme Substrates | Used to measure baseline and residual enzyme activity. | Acetylthiocholine (ATC) for amperometric/colorimetric assays; Acetylcholine (ACh) for systems coupled with ChOx [18] [20]. |

| Signal Mediators & Transducers | Enhance signal transduction, particularly in electrochemical sensors. | Carbon black, Pillar[5]arenes, Methylene Blue, Thionine; used to modify electrodes for efficient thiocholine oxidation [20]. |

| Immobilization Matrices | Stabilize and confine the enzyme near the transducer surface. | Polydopamine films [18]; hydrogels; nanomaterials (e.g., MOFs, COFs) for enhanced stability [11]. |

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymer (MIP) | Artificial antibody for selective sample pre-treatment and analyte enrichment. | Polydopamine-based MIP selective to specific moieties of a target OP (e.g., acephate) [18]. |

| Enzyme Reactivators | Used in mechanistic studies to confirm irreversible covalent inhibition. | 2-PAM (Pralidoxime); used to attempt reactivation of phosphorylated AChE [19] [20]. |

Enzyme-based biosensors are analytical devices that integrate a biological recognition element with a physicochemical transducer to detect target analytes with high specificity and sensitivity [4] [21]. In the critical field of organophosphate (OP) pesticide research, these biosensors leverage the specific inhibition of cholinesterase enzymes (acetylcholinesterase, AChE, or butyrylcholinesterase, BuChE) by OP compounds [22] [7]. The core function of the biosensor rests on its signal transduction system, which converts the biochemical event of enzyme inhibition into a quantifiable electronic or optical signal that researchers can measure and correlate with OP concentration [4] [21]. This conversion is paramount for developing rapid, on-site detection methods that serve as alternatives to complex laboratory techniques like chromatography [7] [23].

The general workflow of an inhibition-based OP biosensor involves exposing the immobilized enzyme to a sample. If OPs are present, they bind to the active site of the enzyme, inhibiting its catalytic activity. Subsequently, the enzyme's substrate is introduced. The degree of inhibition, reflected in the reduced catalytic conversion of the substrate, is then transduced into a measurable signal [22] [7]. The following diagram illustrates this core principle and the subsequent transduction pathways.

Transduction Mechanisms and Methodologies

The transducer is the core component that defines the type of biosensor and its operational principles. For OP detection, the most prevalent transduction mechanisms are electrochemical and optical.

Electrochemical Transduction

Electrochemical biosensors measure the electrical current or potential generated from the enzymatic reaction [4] [21]. In a typical AChE-based sensor, the enzyme catalyzes the hydrolysis of its substrate, acetylthiocholine, producing thiocholine. Thiocholine is an electroactive species that can be oxidized at the surface of an electrode, generating a measurable current [7]. The presence of an OP inhibitor reduces the rate of thiocholine production, leading to a corresponding decrease in the electrochemical signal. This method is widely used due to its high sensitivity, low cost, and potential for miniaturization [4].

Optical Transduction

Optical biosensors transduce the inhibition event into a measurable change in light properties [4]. This can include changes in absorbance, fluorescence, or chemiluminescence. For instance, the chemiluminescence (CL) assay described in the search results utilizes a coupled enzyme system where the product of BuChE activity (choline) is oxidized by choline oxidase (ChOx), producing hydrogen peroxide [22]. The hydrogen peroxide then reacts with luminol in a peroxidase (HRP)-catalyzed reaction, emitting photons. Inhibition of BuChE by OPs reduces the photon count, allowing for quantitative detection [22]. Another optical approach involves colorimetric sensors based on localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) of noble metal nanoparticles like silver (Ag) or gold (Au) [7] [24]. The aggregation of these nanoparticles, induced by the products of the enzymatic reaction, causes a visible color shift. OP inhibition prevents this aggregation and color change, providing a visual or spectrophotometric readout [7] [24].

The following diagram details the specific experimental workflow for a chemiluminescence-based assay, illustrating the steps from sample preparation to signal measurement.

Quantitative Performance Data

The performance of different biosensor configurations for OP detection can be evaluated based on key analytical figures of merit such as detection limit, linear range, and stability. The following table summarizes quantitative data for selected methodologies from the search results.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Selected Enzyme-Based Biosensors for Organophosphate Detection

| Transduction Method | Target OPs | Linear Detection Range | Detection Limit | Stability / Reproducibility | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemiluminescence (BuChE inhibition) | Methyl Paraoxon (MPOx) | 0.005 – 50 μg·L⁻¹ | Not Specified | Mean recovery: 93.2–98.6%; RSD: 0.99–1.67% | [22] |

| Chemiluminescence (BuChE inhibition) | Methyl Parathion (MP), Malathion (MT) | 0.5 – 1,000 μg·L⁻¹ | Not Specified | Not Specified | [22] |

| Colorimetric / LSPR (AChE inhibition, AgNP@DANC) | Chlorpyrifos (CPF) | 1 × 10⁻³ to 1 × 10⁻¹⁹ M | Ultralow (from wide range) | Extensive stability for six months | [7] |

| Colorimetric / LSPR (AChE inhibition, AgNP@DANC) | Malathion (MLT) | 1 × 10⁻³ to 1 × 10⁻¹⁷ M | Ultralow (from wide range) | Extensive stability for six months | [7] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The development and execution of enzyme-based biosensors for OP research rely on a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The following table details key components and their functions in typical experimental setups.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for OP Biosensor Development

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role in Biosensing | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Cholinesterase Enzymes (AChE, BuChE) | Biological recognition element; its inhibition by OPs is the basis for detection. | Butyrylcholinesterase from equine serum used in a high-throughput chemiluminescence assay [22]. Acetylcholinesterase from Electrophorus electricus immobilized on a nanocomposite [7]. |

| Enzyme Substrates (Acetylthiocholine, Butyrylcholine) | Converted by the active enzyme into an electroactive or chromogenic product; the reaction rate is measured. | Butyrylcholine chloride used as a substrate for BuChE [22]. Acetylthiocholine chloride hydrolyzed by AChE to produce thiocholine [7]. |

| Signal-Generating Enzymes (Choline Oxidase, Horseradish Peroxidase) | Used in coupled enzyme systems to amplify the signal from the primary enzymatic reaction. | Choline oxidase and horseradish peroxidase used to generate a chemiluminescent signal from choline [22]. |

| Chemiluminescent Probes (e.g., Luminol) | Emits light upon chemical reaction (e.g., with H₂O₂ in the presence of HRP), providing the optical readout. | 5-amino-2,3-dihydro-1,4-phthalazinedione (Luminol) used as the CL substrate [22]. |

| Stabilizing Agents (e.g., Trehalose) | Protects enzymes during drying and storage, enhancing their shelf-life and operational stability at room temperature. | Dextrose and trehalose used to stabilize BuChE pre-loaded in microplates [22]. |

| Nanomaterial Composites (e.g., AgNP@DANC) | Serves as an advanced immobilization matrix; enhances enzyme stability, sensitivity, and can possess nanozyme activity. | Rice husk-derived dialdehyde nanocellulose capped silver nanoparticles (AgNP@DANC) used to immobilize and stabilize AChE [7]. |

| Immobilization Matrices (e.g., Silica Nanoparticles) | Provides a solid support for enzyme attachment, improving reusability and stability in flow-based systems. | Biomimetic silica nanoparticles used to encapsulate BuChE and OPH for continuous aerosol monitoring [23]. |

Enzyme-based biosensors represent a sophisticated class of analytical devices that integrate biological recognition elements with physicochemical transducers to detect specific analytes with high specificity and sensitivity. These devices function by immobilizing biological components onto transducer surfaces, enabling the detection of target substances without reagent addition to sample solutions [25]. The interaction between the target analyte and biological element produces physicochemical changes that transducers convert into measurable signals proportional to analyte concentration [25]. Within the specific context of organophosphate (OP) pesticide detection, enzyme-based biosensors have emerged as vital tools for environmental monitoring and food safety control, offering distinct advantages including high sensitivity and specificity, portability, cost-effectiveness, and potential for miniaturization and point-of-care diagnostic testing [25] [6].

This technical guide examines the three fundamental components constituting enzymatic biosensors for OP detection: the bioreceptor (biological recognition element), the transducer (signal conversion unit), and the immobilization matrix (enzyme stabilization framework). The precise integration of these components dictates biosensor performance metrics including sensitivity, selectivity, reproducibility, and operational stability [26] [27]. For organophosphate detection, specific enzymes including acetylcholinesterase (AChE) and organophosphate hydrolase (OPH) serve as primary biorecognition elements, enabling the development of biosensing systems that provide effective alternatives to traditional, time-consuming analytical methods [6] [28].

Core Component Analysis

Bioreceptor

The bioreceptor constitutes the biological recognition element of a biosensor, responsible for specific interaction with the target analyte. In enzymatic biosensors for organophosphate detection, the bioreceptors are enzymes that either directly catalyze OP hydrolysis or undergo inhibition by OPs, enabling quantitative detection [6].

- Acetylcholinesterase (AChE): This enzyme serves as the primary bioreceptor in inhibition-based biosensors for OP detection. Organophosphates specifically and irreversibly inhibit AChE activity by phosphorylating the serine residue within its active site [6] [28]. The detection mechanism relies on measuring decreased enzyme activity following exposure to OPs, where the inhibition level correlates with pesticide concentration.

- Organophosphate Hydrolase (OPH): Also known as paraoxonase, OPH acts as a catalytic bioreceptor that directly hydrolyzes OP compounds, including paraoxon, coumaphos, and diazinon [6]. The enzymatic reaction yields stoichiometric amounts of protons and chromophoric products, enabling detection through various transduction methods. OPH-based biosensors provide advantages of continuous monitoring and regenerability compared to inhibition-based approaches.

The operating principle of an enzyme-based biosensor involves detecting changes occurring during substrate consumption or product formation in enzymatic reactions, such as proton concentration, gas release/uptake, light emission/absorption, or heat emission [25]. These changes are converted by transducers into quantifiable electrical, optical, or thermal signals [25].

Transducer

The transducer functions as the signal conversion unit, transforming biochemical interactions occurring at the bioreceptor into measurable electronic signals. The choice of transducer significantly influences sensitivity, detection limits, and applicability for field use [25] [29].

Table 1: Transducer Types in Enzyme-Based Biosensors for OP Detection

| Transducer Type | Measurement Principle | Detection Method for OPs | Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electrochemical | Measures changes in electrical properties (current, potential, impedance) from redox reactions [25] | AChE inhibition: Measures thiocholine oxidation current [25] | Simplicity, portability, low cost, high sensitivity [25] |

| OPH catalysis: Measures pH change or hydrolytic product oxidation [25] | |||

| Optical | Detects changes in light properties (absorbance, fluorescence, luminescence) [25] [6] | AChE inhibition: Monitors colorimetric or fluorimetric substrate conversion [6] | High sensitivity, multiplexing capability, resistance to electromagnetic interference [6] |

| OPH catalysis: Tracks chromophoric product formation (e.g., p-nitrophenol from paraoxon) [6] | |||

| Thermal/Calorimetric | Measures heat emission from enzymatic reactions [25] | Monitors enthalpy changes from substrate hydrolysis | Label-free detection, applicable to various substrates |

| Piezoelectric | Detects mass changes on crystal surface through resonance frequency shifts [25] [29] | Measures mass loading from enzyme-OP binding or product formation | High sensitivity to mass changes, real-time monitoring |

Electrochemical biosensors represent the most extensively used transducer type, with amperometric systems being particularly common [25]. These systems apply a fixed potential to the working electrode and measure current generated from oxidation or reduction of electroactive species involved in the enzymatic reaction [25]. Optical biosensors have gained significant traction for OP detection due to advantages including high sensitivity and selectivity, simple operation, fast response, and relatively inexpensive instrumentation [6].

Immobilization Matrix

Enzyme immobilization represents a critical and essential step in biosensor design, profoundly affecting performance through influences on enzyme orientation, loading, mobility, stability, structure, and biological activity [27]. Effective immobilization maintains enzyme structure and function, ensures tight binding to the transducer surface, and preserves biological activity throughout biosensor operation [27].

Table 2: Enzyme Immobilization Methods for Biosensors

| Immobilization Method | Principle | Advantages | Disadvantages | Relevance to OP Detection |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adsorption | Physical attachment via weak bonds (Van der Waals, electrostatic, hydrophobic) [25] [27] | Simple, inexpensive, minimal enzyme modification [25] | Weak bonding sensitive to environmental changes (pH, temperature), potential leaching [25] | Limited use due to stability issues in field applications |

| Covalent Bonding | Formation of stable covalent bonds between enzyme and support [25] [27] | Strong binding, high stability, uniform surface coverage [25] | Potential enzyme activity loss, requires chemical modification [25] | Widely used; provides operational stability for AChE/OPH biosensors |

| Entrapment | Enzyme confinement within porous matrices (polymers, sol-gels, carbon paste) [25] [27] | No chemical modification, simultaneous deposition of enzymes/mediators [27] | Diffusion limitations for substrate/product, potential enzyme leakage [25] | Useful for OPH biosensors to retain cofactors; minimizes matrix effects |

| Cross-linking | Intermolecular covalent bonding between enzymes using bifunctional agents (glutaraldehyde) [25] [27] | Simple, strong chemical binding, high enzyme loading [25] [27] | Potential activity loss due to rigidification, possible diffusion limitations [25] | Enhances stability of immobilized AChE for reusable OP sensors |

| Affinity | Specific bioaffinity interactions (avidin-biotin, lectin-carbohydrate, antibody-antigen) [27] | Controlled orientation, preserves active site accessibility, minimizes denaturation [27] | Requires specific binding groups, more complex implementation [27] | Emerging approach for oriented AChE immobilization to enhance sensitivity |

The selection of appropriate immobilization strategy depends on enzyme characteristics, transducer properties, and intended application requirements. For organophosphate biosensors, covalent bonding and entrapment methods are frequently employed to enhance operational stability and maintain enzyme activity under various environmental conditions [27]. Recent approaches incorporate nanomaterials including carbon nanotubes, metal nanoparticles, and conducting polymer nanowires to create advanced immobilization matrices that increase surface area, enhance electron transfer, and improve biosensor sensitivity [27].

Integration for Organophosphate Detection

The effective integration of bioreceptor, transducer, and immobilization matrix enables the development of sophisticated biosensing platforms for organophosphate pesticide detection. The World Health Organization classifies OPs as extremely toxic compounds due to their specificity for acetylcholinesterase, causing irreversible harm to the nervous system [6] [28]. The excessive use of these pesticides, particularly in developing countries, has necessitated the development of easy, rapid, and sensitive detection methods for monitoring OP residues in food and water [6].

The logical relationship and workflow between core components in an enzyme-based biosensor for organophosphate detection can be visualized as follows:

This workflow illustrates how organophosphate compounds in sample solutions interact specifically with the enzyme bioreceptor (AChE or OPH), which is stabilized by the immobilization matrix. The biochemical recognition event generates physicochemical changes that the transducer converts into measurable signals, enabling quantitative OP detection.

Experimental Protocols for OP Detection

Acetylcholinesterase Inhibition-Based Protocol

This protocol details the procedure for detecting organophosphates using an AChE inhibition-based biosensor with electrochemical transduction [25] [6].

Principle: Organophosphates irreversibly inhibit AChE activity, reducing enzymatic conversion of substrates to electroactive products. The percentage inhibition correlates with OP concentration.

Materials:

- Acetylcholinesterase enzyme (Electric eel or recombinant source)

- Acetylthiocholine iodide or acetylcholine chloride substrate

- Phosphate buffer (0.1 M, pH 7.4)

- Organophosphate standards (paraoxon, parathion, malathion)

- Electrochemical cell with working, reference, and counter electrodes

- Immobilization matrix components (glutaraldehyde, BSA, Nafion, chitosan)

Procedure:

- Enzyme Immobilization: Immobilize AChE on electrode surface using preferred method:

Baseline Measurement: Incubate AChE biosensor in electrochemical cell with acetylthiocholine substrate (1 mM) in phosphate buffer. Apply +0.5V vs Ag/AgCl and record steady-state oxidation current (I₀).

Inhibition Phase: Incubate AChE biosensor with OP standard/sample for 10-15 minutes.

Post-Inhibition Measurement: Re-measure enzymatic activity with substrate as in step 2, record current (Iᵢ).

Quantification: Calculate percentage inhibition: % Inhibition = [(I₀ - Iᵢ)/I₀] × 100. Plot calibration curve using OP standards.

Organophosphate Hydrolase Catalytic Biosensor Protocol

This protocol describes OP detection using direct catalytic hydrolysis by OPH with optical transduction [6].

Principle: OPH catalyzes hydrolysis of organophosphates, generating colored or fluorescent products proportional to OP concentration.

Materials:

- Organophosphate hydrolase enzyme (recombinant source)

- Organophosphate standards (paraoxon, parathion)

- Buffer solution (Tris-HCl or HEPES, pH 8.5-9.0)

- Spectrophotometer or fluorimeter

- Immobilization support (agarose beads, sol-gel, polymer membranes)

Procedure:

- Enzyme Immobilization: Immobilize OPH on selected support:

Assay Setup: Add immobilized OPH to OP standards/samples in buffer.

Incubation: Incubate reaction mixture at 30-37°C for 5-15 minutes with agitation.

Product Measurement: Monitor hydrolytic product formation:

- Spectrophotometric: Measure absorbance at 400-405 nm for p-nitrophenol (ε = 17,000 M⁻¹cm⁻¹) from paraoxon hydrolysis [6].

- Fluorimetric: Monitor fluorescence change for coumaphos hydrolysis (excitation/emission: 360/454 nm).

Quantification: Calculate OP concentration from product standard curve.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Enzyme-Based OP Biosensors

| Reagent/Material | Function | Specification Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) | Bioreceptor for inhibition-based detection | Source: Electric eel (cheaper) or recombinant (higher purity); Specific activity: ≥500 U/mg [6] |

| Organophosphate Hydrolase (OPH) | Bioreceptor for catalytic detection | Recombinant from Pseudomonas diminuta or Flavobacterium; Specific activity: ≥1000 U/mg [6] |

| Acetylthiocholine iodide | Electrochemical substrate for AChE | Enzymatic product thiocholine oxidizes at electrode; Purity: ≥98% [25] |

| Paraoxon ethyl | Standard OP for calibration and inhibition studies | Model compound for OP detection; Purity: ≥95% [6] |

| Glutaraldehyde | Cross-linking agent for covalent immobilization | Creates stable enzyme linkages; Concentration: 2.5% v/v [25] [27] |

| Nafion polymer | Entrapment matrix for enzyme immobilization | Cation-exchange polymer; Protects electrode from fouling; Concentration: 0.5-1% w/v [27] |

| Sol-gel precursors (TMOS) | Silica matrix for enzyme entrapment | Forms porous network around enzyme; Tetraalkoxysilane precursors [27] |

| Screen-printed electrodes | Disposable electrochemical transducers | Carbon, gold, or platinum working electrodes; Enable mass production [25] |

The strategic selection and integration of these core components—specific bioreceptors, appropriate transducers, and effective immobilization matrices—enables researchers to develop sophisticated biosensing platforms for sensitive and selective detection of organophosphate pesticides. These systems continue to evolve through nanotechnology integration and immobilization strategy optimization, addressing the critical need for rapid environmental and food safety monitoring as emphasized by international health and agricultural organizations [6].

Advanced Sensing Platforms and Real-World Deployments

Electrochemical biosensors, particularly amperometric and potentiometric systems, are pivotal analytical tools that combine the specificity of biological recognition elements with the sensitivity of electrochemical transducers. These devices are integral to modern research, enabling the detection and quantification of various analytes. Within the specific context of organophosphate (OP) research, enzyme-based biosensors function primarily on the principle of enzyme inhibition [1] [30]. The core mechanism involves the interaction between the target OP and a specific enzyme, such as acetylcholinesterase (AChE) or organophosphate hydrolase (OPH). OP compounds irreversibly phosphorylate the serine hydroxyl group in the active site of AChE, leading to a decrease in enzymatic activity [16] [30]. This inhibition directly modulates the production of electroactive species (e.g., protons or electrons) in the enzyme-catalyzed reaction, which is then measured as a change in current (amperometry) or potential (potentiometry) at the transducer surface. This measurable signal is quantitatively related to the concentration of the toxic inhibitor, providing a powerful method for detecting these pesticides [1] [4].

Fundamental Principles and Transducer Mechanisms

Amperometric Biosensors

Amperometric biosensors operate by applying a constant potential and measuring the resulting current generated from the oxidation or reduction of an electroactive species involved in the biocatalytic reaction [31] [4]. The measured current is directly proportional to the concentration of the target analyte.

- Working Principle: In a typical enzyme-based system, the enzyme catalyzes a reaction that produces or consumes an electroactive product. For instance, AChE hydrolyzes acetylcholine to produce choline and acetic acid. The thiocholine produced from subsequent reactions can be oxidized at the electrode surface, generating a measurable anodic current. Inhibition of AChE by OPs reduces this current signal [30]. Alternatively, biosensors using organophosphate hydrolase (OPH) directly catalyze the hydrolysis of OPs, producing electroactive species like p-nitrophenol, which can be oxidized and detected amperometrically [14].

- Key Characteristics: These sensors are known for their high sensitivity, low detection limits, and excellent compatibility with miniaturized, portable devices for on-site analysis [31].

Potentiometric Biosensors

Potentiometric biosensors measure the change in potential (voltage) at an electrode surface under conditions of zero current. This potential change results from the accumulation of ions or charged molecules due to an enzymatic reaction [4].

- Working Principle: The most common approach involves the use of ion-selective electrodes (ISEs) or pH-sensitive field-effect transistors (FETs). An enzymatic reaction that generates or consumes ions (e.g., H⁺, NH₄⁺) leads to a change in the local ion concentration. This shift is measured as a potential difference relative to a reference electrode. For example, the hydrolysis of urea by urease increases the pH, which can be detected by a pH electrode [4]. While less common for OPs than amperometric systems, the inhibition of AChE can be monitored by tracking the reduced production of acetic acid, leading to a smaller pH change.

- Key Characteristics: Potentiometric sensors offer simplicity and low power consumption. However, they can be susceptible to interference from other ions in the sample matrix and may have a slower response time compared to amperometric sensors.

Table 1: Comparison of Amperometric and Potentiometric Transduction Principles

| Feature | Amperometric Biosensors | Potentiometric Biosensors |

|---|---|---|

| Measured Quantity | Current | Potential (Voltage) |

| Operating Condition | Constant applied potential | Zero current flow |

| Signal Dependency | Mass transport & reaction rate | Ionic activity (Nernst equation) |

| Typical Sensitivity | High (nano- to micro-ampere) | Moderate (millivolts per decade) |

| Response Time | Typically fast (seconds) | Can be slower |

| Common Interferences | Other electroactive species | Other ions in sample matrix |

Experimental Protocols for Organophosphate Detection

Protocol 1: Amperometric Biosensor Using Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) Inhibition

This protocol details the fabrication and operation of a classic inhibition-based biosensor for neurotoxic OPs and carbamates [1] [30].

1. Biorecognition Element Immobilization:

- Materials: Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) from electric eel or recombinant mutant enzyme; glutaraldehyde (cross-linker); bovine serum albumin (BSA); chitosan or carbon nanotube nanocomposite for the electrode matrix.

- Procedure: A mixture of AChE (0.5-2 U/µL) and BSA (1% w/v) is prepared in a phosphate buffer (0.1 M, pH 7.4). A 10 µL aliquot is deposited on the surface of a polished glassy carbon electrode (GCE). Then, 5 µL of glutaraldehyde (2.5% v/v) is added as a cross-linking agent to form a stable network. The electrode is dried for 1 hour at 4°C and then rinsed with buffer to remove any unbound enzyme [1].

2. Baseline Activity Measurement:

- Electrochemical Cell Setup: Use a three-electrode system with the AChE-modified GCE as the working electrode, an Ag/AgCl reference electrode, and a platinum wire counter electrode. The cell contains 10 mL of 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) with 0.1 M KCl as the supporting electrolyte.

- Amperometric Measurement: Apply a constant potential of +0.7 V vs. Ag/AgCl. Under stirring, inject a known concentration of the substrate acetylthiocholine iodide (ATCh, 1.0 mM final concentration). Monitor the oxidation current of the enzymatic product, thiocholine, until a stable steady-state current (I₀) is achieved [30].

3. Inhibition and Pesticide Detection:

- Incubation: Immerse the biosensor in a sample solution containing the target OP pesticide (e.g., paraoxon, chlorpyrifos-oxon) for a fixed incubation period (e.g., 10-15 minutes).

- Post-Inhibition Measurement: Wash the electrode gently with buffer and place it in a fresh electrochemical cell. Repeat the amperometric measurement with the same concentration of ATCh substrate (1.0 mM) and record the new steady-state current (Iᵢ).

- Quantification: The percentage of enzyme inhibition is calculated as % Inhibition = [(I₀ - Iᵢ) / I₀] × 100. This value is correlated with the pesticide concentration using a pre-established calibration curve [1].

Protocol 2: Potentiometric Biosensor Using Organophosphate Hydrolase (OPH)

This protocol utilizes OPH, which directly degrades OPs, making it a superior alternative for some applications by eliminating the incubation step required in inhibition-based assays [14].

1. OPH Enzyme Integration:

- Materials: Recombinant Organophosphate Hydrolase (OPH) expressed from the 'opd' gene; polyacrylamide gel or poly(carbamoyl sulfonate) hydrogel for entrapment; pH-sensitive field-effect transistor (FET).

- Procedure: The OPH enzyme (activity ~2.75 U/mL) is mixed with the hydrogel precursor solution. This mixture is spin-coated directly onto the gate surface of the pH-FET device and polymerized via UV exposure to form a thin, enzymatic film approximately 50-100 µm thick [14].

2. Direct Potentiometric Detection:

- Measurement Setup: The OPH-modified FET is integrated into a flow-cell or immersed in a stirred sample solution. A stable potential baseline (E₀) is recorded against a reference electrode.

- Analyte Introduction: The sample containing the OP analyte (e.g., paraoxon) is introduced. OPH catalyzes the hydrolysis reaction: Paraoxon + H₂O → p-Nitrophenol + Diethyl phosphate + H⁺.

- Signal Recording: The release of protons (H⁺) during the reaction causes a local decrease in pH at the FET gate surface. This is measured as a change in potential (∆E) relative to E₀. The rate and magnitude of this potential shift are proportional to the concentration of the OP pesticide in the sample [14].

Signaling Pathways and Workflow Visualization

AChE Inhibition Pathway for OP Detection

The following diagram illustrates the biochemical signaling pathway of AChE inhibition by organophosphates, which forms the basis for many amperometric biosensors.

Experimental Workflow for an Amperometric Biosensor

This workflow outlines the key steps in a typical experiment using an amperometric AChE-based biosensor for pesticide detection.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful development and deployment of electrochemical biosensors for OP research rely on a suite of key materials and reagents.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Enzyme-Based OP Biosensors

| Reagent/Material | Function/Role | Specific Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) | Primary biorecognition element; inhibition by OPs enables detection. | Electric eel, bovine erythrocyte, or genetically engineered mutants (e.g., from Drosophila melanogaster) for enhanced sensitivity/selectivity [1]. |

| Organophosphate Hydrolase (OPH) | Biorecognition element; directly catalyzes OP hydrolysis. | Recombinant enzyme expressed from the 'opd' gene; functions without an incubation step [14]. |