Evaluating Biosensor Sensitivity and Specificity: From Foundational Concepts to Clinical Validation

This article provides a comprehensive evaluation of biosensor sensitivity and specificity, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Evaluating Biosensor Sensitivity and Specificity: From Foundational Concepts to Clinical Validation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive evaluation of biosensor sensitivity and specificity, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the fundamental principles defining sensor performance, including key metrics like limit of detection (LOD), wavelength sensitivity, and figure of merit (FOM). The scope extends to advanced methodological applications across biomedical fields, such as cancer cell detection and therapeutic monitoring, alongside emerging optimization strategies leveraging machine learning and novel materials. The content further addresses critical troubleshooting for real-world performance and outlines rigorous clinical validation protocols and comparative analyses essential for regulatory approval and successful translation into clinical and research settings.

Defining Performance: Core Principles and Metrics for Biosensor Sensitivity and Specificity

In the development and evaluation of biosensors, specific analytical parameters are used to quantitatively assess performance, ensure reliability, and validate results for clinical or research use. For scientists and professionals in drug development, a precise understanding of these Figures of Merit (FOMs) is not merely academic; it is critical for selecting appropriate diagnostic tools, interpreting experimental data accurately, and ultimately making decisions that can accelerate drug discovery and ensure patient safety.

This guide provides a structured comparison of these fundamental concepts—Sensitivity, Specificity, Limit of Detection (LOD), and related metrics—framed within the context of biosensor research. We will define these terms, outline standard protocols for their determination, present comparative performance data from real-world studies, and provide a toolkit for their practical application in the laboratory.

Core Definitions and Mathematical Foundations

The performance of a biosensor or diagnostic test is fundamentally characterized by its ability to correctly identify the presence and quantity of an analyte. The following parameters form the cornerstone of this evaluation.

2.1 Sensitivity and Specificity: Diagnostic Accuracy

Sensitivity and Specificity are statistical measures used to evaluate the clinical or diagnostic accuracy of a binary classification test, such as distinguishing between diseased and healthy states [1].

- Sensitivity, or the true positive rate, measures the proportion of actual positives that are correctly identified. A test with high sensitivity effectively rules out the disease when the result is negative (often summarized as "SnOut").

- Specificity, or the true negative rate, measures the proportion of actual negatives that are correctly identified. A high specificity effectively rules in the disease when the result is positive ("SpIn") [1].

These concepts are intrinsically linked to the Confusion Matrix and the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve. The ROC curve plots the true positive rate (Sensitivity) against the false positive rate (1-Specificity) at various threshold settings. The Area Under the Curve (AUC) of the ROC curve provides a single measure of overall accuracy, where an AUC of 1.0 represents a perfect test, and 0.5 represents a test no better than chance [1].

2.2 Limit of Detection (LOD) and Limit of Quantification (LOQ): Analytical Sensitivity

While diagnostic sensitivity refers to the rate of true positives, the term "sensitivity" in an analytical context often relates to the smallest detectable amount of an analyte. This is formally defined by the LOD and LOQ [1] [2].

- Limit of Detection (LOD): The lowest quantity of an analyte that can be reliably distinguished from its absence. According to the widely accepted IUPAC definition, for a signal to be deemed detectable, it must be greater than the signal from a blank sample by three times the standard deviation of the blank (S > 3σ) [1] [2]. This provides a 99% confidence level for a false positive.

- Limit of Quantification (LOQ): The lowest concentration of an analyte that can be quantitatively determined with stated acceptable precision and accuracy. It is typically defined as a signal ten times greater than the noise level (S > 10σ) [1].

It is crucial to distinguish between analytical sensitivity (LOD) and diagnostic sensitivity (true positive rate), as they address different aspects of a test's performance [1] [3].

2.3 Selectivity vs. Specificity

Although sometimes used interchangeably, selectivity and specificity have distinct meanings in biosensor science. Specificity refers to the ability of a bioreceptor (e.g., an antibody) to assess an exact analyte in a mixture. In contrast, selectivity is the broader ability of the biosensor to differentiate the target analyte from other interfering substances or contaminants in a sample matrix [1] [3].

Table 1: Summary of Key Figures of Merit in Biosensor Evaluation

| Figure of Merit | Definition | Typical Benchmark | Primary Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity (Diagnostic) | Proportion of true positives correctly identified [1]. | Varies by application; e.g., ≥80% for SARS-CoV-2 LFDs per WHO [4]. | Ability to rule out a disease (SnOut). |

| Specificity | Proportion of true negatives correctly identified [1]. | Varies by application; e.g., ≥97% for SARS-CoV-2 LFDs per WHO [4]. | Ability to rule in a disease (SpIn). |

| Limit of Detection (LOD) | Lowest analyte concentration distinguishable from a blank [1] [2]. | Signal-to-Noise > 3 (S > 3σ) [1]. | Measure of analytical sensitivity. |

| Limit of Quantification (LOQ) | Lowest analyte concentration that can be accurately measured [1]. | Signal-to-Noise > 10 (S > 10σ) [1]. | Lower limit of the quantitative range. |

| Selectivity | Ability to differentiate target analyte from interferents in a mixture [1] [3]. | N/A | Resistance to false signals from sample matrix. |

Experimental Protocols for Determining FOMs

Standardized experimental protocols are essential for the consistent and accurate determination of these FOMs. Below are detailed methodologies for key assays.

3.1 Protocol for Determining Limit of Detection (LOD)

The following procedure outlines a general method for establishing the LOD for an amperometric biosensor, which can be adapted for other transducer types [1].

- Signal Measurement: Perform repeated measurements (n ≥ 10) of a blank sample (a sample without the analyte) to establish the baseline signal and its standard deviation (σ).

- Calibration Curve: Prepare and analyze a series of standard solutions with known analyte concentrations across the expected range. Plot the signal response against concentration to generate a calibration curve.

- LOD Calculation: Apply the formula derived from the calibration curve. The LOD is calculated as the concentration corresponding to the mean blank signal plus three times the standard deviation of the blank. Mathematically, if the calibration curve is

y = ax + b, whereyis the signal andxis the concentration, then:

3.2 Protocol for Evaluating Diagnostic Sensitivity/Specificity

Evaluating diagnostic sensitivity and specificity requires a clinical study comparing the test device against a reference standard [4].

- Sample Collection: Obtain well-characterized clinical samples (e.g., surplus patient samples from a healthcare setting) that include both positive and negative cases for the condition of interest.

- Blinded Testing: Analyze all samples using the biosensor or test device under evaluation. The operators should be blinded to the reference results to prevent bias.

- Reference Method Comparison: Compare the results from the test device with those from a validated reference method (e.g., RT-PCR for viral detection, or culture for bacterial detection).

- Statistical Analysis: Construct a 2x2 confusion matrix to classify results into True Positives (TP), False Positives (FP), True Negatives (TN), and False Negatives (FN).

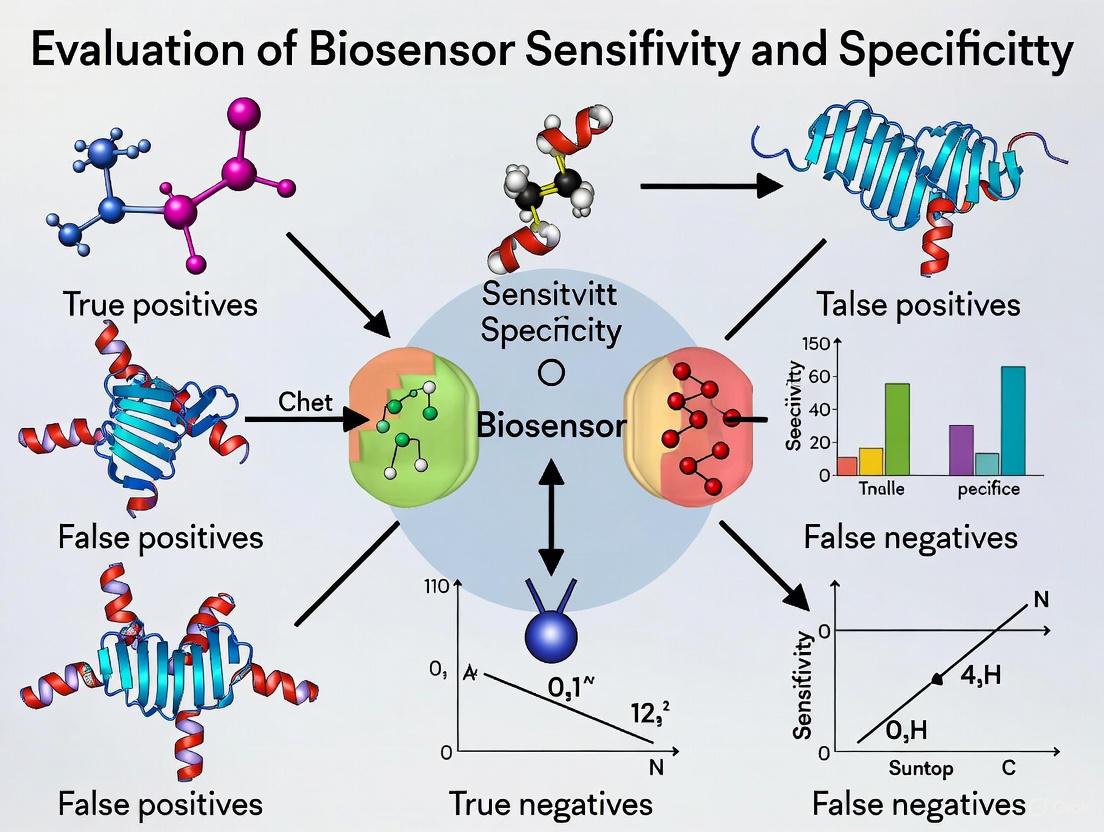

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and calculations involved in this validation process.

Comparative Performance Data in Practice

Independent, real-world evaluations often reveal performance variations that may differ from manufacturer claims. This is critical for professionals making procurement or deployment decisions.

4.1 Independent Evaluation of SARS-CoV-2 Lateral Flow Devices (LFDs)

A large-scale independent evaluation by the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) of 86 SARS-CoV-2 LFDs highlights this discrepancy.

- Claimed vs. Actual Performance: The study found that while 73 of the 86 LFDs claimed clinical sensitivity ≥85% in their instructions for use, the UKHSA-determined sensitivity ranged from 32% to 83% [4].

- Lack of Correlation: The analysis found "no evidence of correlation between manufacturer-reported test sensitivity and UKHSA determined test sensitivity," underscoring the necessity of independent verification for critical performance metrics [4].

4.2 Comparison of Molecular vs. Antigen Tests for Strep A

A 2025 comparative study of Group A Streptococcus (GAS) tests provides a clear example of how different technologies yield different LODs, directly impacting analytical sensitivity.

- Study Design: The study compared the LoD of one molecular point-of-care test (ID NOW Strep A 2) and three lateral flow immunoassays (BD Veritor, Sofia, OSOM) using serial dilutions of bacterial isolates [5].

- Results: The molecular test demonstrated a significantly lower LoD (3.125 × 10³ to 2.5 × 10⁴ CFU/mL) compared to the lateral flow assays (1 × 10⁶ to 1.5 × 10⁷ CFU/mL), confirming its higher analytical sensitivity [5].

Table 2: Comparative Analytical Sensitivity of Diagnostic Tests for Group A Streptococcus

| Test Name | Technology | Limit of Detection (LoD) Range (CFU/mL) | Relative Sensitivity |

|---|---|---|---|

| ID NOW Strep A 2 | Molecular (POC) | 3.125 × 10³ to 2.5 × 10⁴ [5] | Highest |

| Sofia Strep A+ | Lateral Flow (FIA) | 1 × 10⁶ to 1 × 10⁷ [5] | Medium |

| BD Veritor Plus | Lateral Flow | 1 × 10⁷ to 1.5 × 10⁷ [5] | Low |

| OSOM Strep A | Lateral Flow | 1 × 10⁷ [5] | Low |

The LOD Paradox: Contextualizing the Need for Sensitivity

A critical consideration in biosensor research is that a lower LOD is not always synonymous with a better biosensor. This is known as the "LOD paradox" [6].

- Clinical Relevance over Pure Sensitivity: The primary goal should be to detect analytes within their clinically significant range. A biosensor capable of detecting a biomarker at picomolar levels is technologically impressive, but if the biomarker's pathological concentration is in the nanomolar range, that ultra-sensitivity may be redundant. It can even be detrimental, adding unnecessary complexity, cost, and potential for interference without improving clinical outcomes [6].

- Balancing Performance Characteristics: The pursuit of an ultra-low LOD can sometimes compromise other vital features, such as the dynamic range, robustness, ease of use, and cost-effectiveness. A holistic approach that balances sensitivity with real-world applicability, regulatory compliance, and user needs is essential for developing impactful biosensors [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key materials and reagents commonly used in the development and validation of biosensors, particularly those based on electrochemical or immunoassay principles.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Biosensor Development

| Material/Reagent | Function in Biosensor Development | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Bioreceptors (Antibodies, Aptamers, Enzymes) | The biological recognition element that binds specifically to the target analyte [3]. | Immobilized on a transducer surface to capture glucose (enzyme) or a viral antigen (antibody). |

| Silicon Nanowire Chips | A transducer platform that converts a bio-recognition event into an electrical signal [7] [8]. | Used in platforms like ASG's sensors for highly sensitive, multiplexed detection of host cell proteins [7] [8]. |

| Electrochemical Cell/Buffer | Provides the controlled chemical environment necessary for electrochemical measurements [1]. | Used in amperometric biosensors to maintain stable pH and ionic strength during signal measurement. |

| Reference Material (ATCC isolates) | Well-characterized samples used as a gold standard for determining LoD and validating assay accuracy [5]. | Serial dilution of S. pyogenes ATCC isolates to establish the LoD of a Strep A test [5]. |

| Lateral Flow Test Strips | A porous substrate that enables capillary flow for the separation and detection of analytes in rapid tests [4]. | The core component of SARS-CoV-2 antigen tests and home pregnancy tests. |

The evaluation of biosensor performance hinges on a set of core, quantifiable metrics that allow researchers to objectively compare technologies and predict their behavior in real-world applications. Wavelength sensitivity (WS), amplitude sensitivity (AS), and resolution are three such parameters, forming a critical triad for assessing a sensor's ability to detect minute biological events. Within the broader thesis of biosensor evaluation, understanding the practical interplay and trade-offs between these metrics is paramount for selecting the appropriate technology for specific applications, from early disease diagnostics to drug discovery. This guide provides a comparative analysis of contemporary biosensor technologies by synthesizing experimental data and detailed methodologies from recent, high-impact research.

Core Quantitative Metrics and Performance Comparison

Defining the Metrics

- Wavelength Sensitivity (WS) is a measure of the shift in the resonance wavelength (typically in nanometers, nm) per unit change in the refractive index (RI) of the surrounding medium. It is expressed in nm/RIU (Refractive Index Unit). A higher WS indicates that the sensor can produce a larger, more easily measurable signal for a small molecular binding event.

- Amplitude Sensitivity (AS) quantifies the change in the intensity or amplitude of the reflected or transmitted light at a fixed wavelength for a unit change in RI. It is expressed in RIU⁻¹. A sensor with high AS is adept at detecting intensity variations, which can be advantageous for certain detection schemes.

- Resolution defines the smallest detectable change in refractive index. It is inversely related to sensitivity and is expressed in RIU. A lower resolution value signifies a finer ability to distinguish between minute changes in analyte concentration.

Comparative Performance of Advanced Biosensors

The table below synthesizes experimental and simulation data from recent studies, providing a direct comparison of these metrics across different biosensor architectures.

Table 1: Comparative Performance Metrics of Contemporary Biosensors

| Biosensor Technology | Target Application | Wavelength Sensitivity (nm/RIU) | Amplitude Sensitivity (RIU⁻¹) | Resolution (RIU) | Figure of Merit (RIU⁻¹) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D-shaped PCF-SPR (Gold-TiO₂) [9] | Multi-cancer detection | 42,000 | -1,862.72 | Not Specified | 1,393.13 |

| ML-optimized PCF-SPR [10] | Chemical & cancer sensing | 125,000 | -1,422.34 | 8.00 × 10⁻⁷ | 2,112.15 |

| PCF-SPR (Dual-core) [11] | Basal cancer cell detection | 10,000 | Not Specified | Not Specified | Not Specified |

| Reflection-type GMR Metasurface [12] | Gastric cancer biomarker (CK8/18) | 420.33 | Not Specified | Not Specified | Not Specified |

| Graphene-Silver Metasurface [13] | COVID-19 detection | 400 (GHz/RIU)* | Not Specified | Not Specified | 5.000 |

Note: *This value is in GHz/RIU; conversion to nm/RIU is wavelength-dependent and not directly comparable.

The data reveals that photonic crystal fiber surface plasmon resonance (PCF-SPR) sensors currently push the boundaries of raw wavelength sensitivity, with machine learning (ML)-optimized designs achieving exceptional performance [10]. The incorporation of oxide layers like TiO₂ alongside gold has also proven highly effective for sensitivity enhancement [9]. In contrast, metasurface-based sensors, while demonstrating high figures of merit and excellent integration potential, often report more modest sensitivity values [13] [12].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

The high performance of modern biosensors is underpinned by rigorous design and validation protocols. The following workflows are foundational to the field.

Machine Learning-Enhanced Sensor Design and Optimization

The integration of machine learning represents a paradigm shift from traditional, computationally expensive iterative simulation methods.

Diagram 1: ML-driven biosensor optimization workflow.

Detailed Workflow:

- Parametric Design Definition: The process begins with defining the initial biosensor geometry and material properties. Key parameters include air hole diameter in PCFs, pitch distance, thickness of plasmonic layers (e.g., gold), and analyte layer thickness [10].

- Computational Modeling: The designed sensor is modeled using finite-element method (FEM) software, primarily COMSOL Multiphysics. This step simulates the sensor's optical behavior, such as mode propagation and the excitation of surface plasmons, across a range of refractive indices (e.g., 1.33 to 1.40) to generate data on effective index and confinement loss [11] [10].

- Dataset Generation: Data from thousands of simulations are compiled into a structured dataset, where the input features are the design parameters and the output targets are the performance metrics (effective index, confinement loss).

- Machine Learning Model Training: Regression models like Gradient Boosting (GBR), Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBR), and Random Forest (RF) are trained on this dataset. These models learn the complex relationships between design parameters and sensor performance, achieving high predictive accuracy (R² > 0.99) [11] [10].

- Explainable AI Analysis: Techniques like SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) are applied to interpret the ML models. This identifies the most influential design parameters (e.g., gold thickness, pitch, wavelength) on sensitivity and loss, providing actionable insights for optimization [10].

- Performance Validation: The optimized design parameters identified by the ML and XAI pipeline are validated through final simulations, confirming the predicted enhancements in sensitivity, resolution, and figure of merit [10].

Fabrication and Experimental Validation of Metasurface Biosensors

For metasurface sensors, sophisticated nanofabrication techniques are required to translate the design into a functional device.

Diagram 2: Metasurface biosensor fabrication and testing.

Detailed Workflow:

- Substrate Preparation: A silicon dioxide (SiO₂) substrate is rigorously cleaned using standard semiconductor cleaning protocols (e.g., RCA cleaning) to remove organic and metallic contaminants [13].

- Graphene Transfer: A high-quality monolayer of graphene is synthesized via chemical vapor deposition (CVD) on a copper foil and then transferred onto the SiO₂ substrate using a polymer support layer (e.g., PMMA), followed by etching and annealing [13].

- Metasurface Patterning: The intricate metasurface pattern (e.g., circular rings, rectangular resonators) is defined using high-resolution electron beam lithography (EBL). A layer of electron-sensitive resist is spin-coated, exposed to the electron beam according to the design, and developed [13].

- Metal Deposition and Lift-off: A thin film of plasmonic metal (silver or gold) is deposited onto the patterned substrate using electron beam evaporation. A subsequent lift-off process in acetone removes excess metal, leaving behind the precise metasurface structures [13].

- Surface Functionalization: The sensor surface is bio-functionalized by immobilizing specific biorecognition elements, such as monoclonal antibodies. This often involves chemical linkers like EDC/NHS to covalently bind antibodies to the sensor surface [14] [15].

- Optical Characterization and Sensing: The fabricated sensor is integrated into an optical setup. A tunable laser source emits light, which is polarized and coupled into the sensor. The output spectrum is recorded by an optical spectrum analyzer as analytes are introduced, allowing for the measurement of wavelength or amplitude shifts corresponding to binding events [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The development and operation of high-performance biosensors rely on a suite of specialized materials and reagents.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions in Biosensor Development

| Item | Function in Biosensor Development | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Plasmonic Materials | Generate surface plasmon waves for highly sensitive detection. | Gold (Au), Silver (Ag) [13] [9] |

| 2D Materials & Coatings | Enhance field confinement, improve sensitivity, and provide functionalization sites. | Graphene, TiO₂, MoS₂, MXene [13] [11] [9] |

| Biorecognition Elements | Provide specificity by binding to the target analyte. | Monoclonal Antibodies, Aptamers [14] [15] |

| Coupling Reagents | Facilitate covalent immobilization of biorecognition elements onto the sensor surface. | EDC, NHS [14] |

| Optical Substrates | Serve as the mechanical support and optical platform for the sensor. | Silicon Dioxide (SiO₂), Photonic Crystal Fiber (PCF) [13] [9] |

The quantitative comparison of wavelength sensitivity, amplitude sensitivity, and resolution reveals a clear trajectory in biosensor development: complex architectures like PCF-SPR, particularly when enhanced with machine learning and novel materials, are achieving unprecedented sensitivity. However, the choice of biosensor must align with the specific application requirements, considering not only raw sensitivity but also factors like portability, cost, and ease of fabrication. Metasurface and other miniaturized platforms offer a compelling balance for point-of-care applications. As the field progresses, the standardized reporting of this core set of metrics, derived from rigorous and openly shared experimental protocols, will be crucial for advancing the broader thesis of robust biosensor evaluation and accelerating their translation from the research lab to the clinic.

In the pursuit of higher sensitivity and specificity for biosensors, the strategic selection of materials forms the very foundation of signal generation. Plasmonic metals and two-dimensional (2D) materials have emerged as particularly powerful components in the biosensor engineer's toolkit. These materials excel at transducing a biological binding event—such as an antibody attaching to a viral antigen—into a quantifiable, often optical, signal that can be detected with remarkable precision [16]. The operational principle of many advanced optical biosensors, including the widely used surface plasmon resonance (SPR), relies on exciting electron oscillations at a metal-dielectric interface. When the refractive index of the local environment changes due to a molecular binding event, it alters the resonance conditions, producing a detectable signal shift [16] [17]. The integration of 2D materials like graphene, transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDCs) such as MoS₂, and black phosphorus (BP) into these systems has further enhanced performance. Their exceptional surface-to-volume ratios and unique optical properties significantly improve the sensitivity and robustness of biosensing platforms [18] [19] [20]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these critical materials, underpinned by experimental data, to inform their selection for applications ranging from viral detection to cancer diagnostics.

Comparative Analysis of Material Performance

The performance of a biosensor is quantified through key metrics such as sensitivity, figure of merit (FoM), and limit of detection (LOD). The tables below consolidate recent experimental and simulation data to facilitate a direct comparison between different material configurations.

Table 1: Performance comparison of SPR biosensors using different plasmonic metals and 2D materials.

| Sensor Configuration | Sensitivity (deg/RIU) | Figure of Merit (FoM) (/RIU) | Key Applications Demonstrated | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BK7/SiO₂/Cu/BaTiO₃ | 568 | 134.75 | Detection of basal, Jurkat, and HeLa cancer cells | [17] |

| BK7/Ag/MoS₂/Graphene | 175% improvement over graphene-only sensor | Not Specified | DNA hybridization detection | [20] |

| CaF₂/TiO₂/Ag/WS₂ (bilayer) | 240.10 | 78.46 | General biochemical sensing | [20] |

| SF10/Cu/Graphene (multiple layers) | Increase with layer count | Not Specified | DNA detection | [20] |

| BK7/Au/WSe₂/PtSe₂/BP | ~200 | 17.70 | General biochemical sensing | [20] |

Table 2: Performance of advanced metasurface and field-effect transistor (FET) biosensors incorporating 2D materials.

| Sensor Type & Configuration | Sensitivity | Limit of Detection (LOD) | Key Advantages | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Graphene-Ag Metasurface | 400 GHz/RIU | Not Specified | Machine learning-enhanced predictive accuracy (R²=0.90) for COVID-19 detection | [13] |

| SERS Platform (Au-Ag Nanostars) | Not Applicable | 16.73 ng/mL (for α-Fetoprotein) | Label-free cancer biomarker detection using intrinsic vibrational modes | [14] |

| 2D Material-based Bio-FETs (e.g., Graphene, TMDCs, BP) | Very High (general claim) | Very Low (general claim) | Label-free diagnosis, real-time monitoring, portability for point-of-care | [19] |

| SERS Substrate (Ag NPs on Si nanowires) | Not Applicable | 10⁻¹¹ M | Signal amplification by orders of magnitude | [16] |

Fundamental Mechanisms of Signal Generation

The Plasmonic Effect and 2D Material Enhancement

The signal generation in plasmonic biosensors begins with the excitation of surface plasmons. In the most common Kretschmann configuration, a light source is directed through a prism onto a thin plasmonic metal film (e.g., Gold or Silver). At a specific angle of incidence, the energy of the photons is transferred to the electrons in the metal, creating coherent electron oscillations known as surface plasmon polaritons (SPPs). This results in a sharp dip in the reflected light intensity, measured as the resonance angle [16] [17]. When target analyte molecules bind to recognition elements on the sensor surface, they cause a local increase in the refractive index (RI). This RI change directly alters the propagation constant of the SPPs, leading to a measurable shift in the resonance angle or wavelength, which is the core signal of an SPR biosensor [17].

2D materials enhance this process through several mechanisms. Firstly, their large surface area provides abundant sites for biomolecule immobilization, increasing the number of binding events and thus the magnitude of the RI change [19]. Secondly, materials like graphene can act as field enhancers. Their unique electronic properties can intensify the electromagnetic field at the interface, making the sensor more responsive to minute RI variations [20]. Some 2D materials, like TMDCs, also have a high absorption coefficient, leading to more efficient interaction with incident light and a sharper resonance curve, which can improve the detection accuracy [20].

Experimental Workflow for Biosensing

The following diagram illustrates the standard workflow for conducting an experiment and generating a signal using a prism-coupled SPR biosensor, showcasing the integration of plasmonic metals and 2D materials.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To achieve the reported data, rigorous experimental protocols for sensor fabrication and characterization must be followed. This section outlines the methodologies cited in the comparative tables.

Fabrication of a High-Sensitivity SPR Biosensor

The protocol for a multi-layered SPR sensor, as described in [17], involves precise thin-film deposition and optical characterization.

- Substrate Preparation: Begin with a BK7 prism as the coupling element. Clean the prism surface thoroughly using standard protocols (e.g., RCA cleaning) to remove organic and ionic contaminants [13].

- Layer-by-Layer Deposition:

- SiO₂ Layer: Deposit a 5 nm thick silicon dioxide (SiO₂) layer onto the prism. This layer can be deposited via techniques like sputtering or electron-beam evaporation and acts to enhance sensitivity and protect the metal layer [17].

- Plasmonic Metal Layer: Deposit a 50 nm thick copper (Cu) film onto the SiO₂ layer. The thickness is critical and must be optimized; the deposition is typically performed via thermal or electron-beam evaporation under high vacuum [17].

- Perovskite Layer: Deposit a 15 nm thick layer of barium titanate (BaTiO₃) over the copper. This high-refractive-index material significantly enhances the electromagnetic field, boosting sensitivity [17].

- Functionalization: For specific detection (e.g., of cancer cells), the sensor surface (BaTiO₃) must be functionalized with appropriate biorecognition elements, such as antibodies, using chemical linkers like EDC/NHS chemistry [14].

- Optical Characterization (Angular Interrogation):

- Setup: Use a monochromatic light source (e.g., a 650 nm laser diode). The light must be p-polarized. Mount the sensor on a goniometer to control the angle of incidence precisely [17] [20].

- Measurement: For a range of analyte refractive indices (e.g., 1.33 to 1.335), scan the incident angle and measure the intensity of the reflected light using a photodetector.

- Data Analysis: Plot reflectance versus angle for each analyte. The resonance angle is identified as the angle at which reflectance is minimum. Sensitivity is calculated as the shift in resonance angle per unit change in refractive index (deg/RIU) [17].

Fabrication of a SERS-Based Immunosensor

The protocol for a SERS-based platform for biomarker detection, as in [14], focuses on nanostar synthesis and functionalization.

- Substrate Synthesis: Synthesize Au-Ag nanostars using a wet-chemical method. Their sharp-tipped morphology is crucial for generating intense local electromagnetic "hot spots" [14].

- Nanostar Concentration: Concentrate the nanostars via centrifugation at different durations (e.g., 10, 30, and 60 minutes) to tune their density and SERS performance [14].

- Surface Functionalization:

- Activation: Incubate the nanostars with mercaptopropionic acid (MPA), which forms a self-assembled monolayer via Au-S bonds.

- Conjugation: Activate the carboxyl groups of MPA with a mixture of EDC and NHS. This creates an amine-reactive ester.

- Antibody Immobilization: Add monoclonal anti-α-fetoprotein antibodies (AFP-Ab) to the activated nanostars. The antibodies covalently attach to the MPA layer [14].

- SERS Measurement and Detection:

- Incubation: Incubate the functionalized nanostars with a sample containing the target antigen (AFP).

- Measurement: Use a Raman spectrometer to acquire spectra of the liquid-phase platform. Unlike conventional SERS, this platform detects the intrinsic Raman signal of the captured antigen itself, eliminating the need for a separate Raman reporter [14].

- Quantification: The intensity of the characteristic Raman peaks of the antigen is correlated with its concentration. The LOD is determined from the calibration curve, following statistical guidelines (e.g., EP17 protocol which involves measuring the limit of blank and low concentration samples) [16] [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key materials and their functions for developing and working with plasmonic biosensors.

Table 3: Essential materials and reagents for plasmonic biosensor research.

| Item Name | Function / Role in Experiment | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Plasmonic Metal Films | Serves as the active layer for generating surface plasmon polaritons (SPPs). | Gold (Au), Silver (Ag), Copper (Cu) [17] [20] |

| 2D Nanomaterials | Enhances sensitivity, provides high surface area for bioreceptor immobilization, and protects the metal layer. | Graphene, MoS₂, WS₂, Black Phosphorus (BP), WSe₂ [18] [19] [20] |

| Prism Couplers | Optical component to enable the phase-matching condition for SPR excitation via attenuated total reflection (ATR). | BK7 glass, SF10 glass [17] [20] |

| Biorecognition Elements | Provides specificity by binding to the target analyte, inducing the measurable refractive index change. | Antibodies, Aptamers, DNA strands [16] [14] [19] |

| Chemical Linkers | Facilitates the covalent immobilization of biorecognition elements onto the sensor surface. | EDC, NHS, MPA (Mercaptopropionic Acid) [14] |

| High-Refractive-Index Layers | Used in hybrid designs to further concentrate the electromagnetic field and boost sensitivity. | Barium Titanate (BaTiO₃), Silicon (Si) [17] [20] |

The drive for more sensitive and specific biosensors is fundamentally linked to the innovative use of materials. While traditional plasmonic metals like gold and silver remain the workhorses for signal generation, the data clearly demonstrates that hybrid configurations combining these metals with 2D materials (e.g., BK7/SiO₂/Cu/BaTiO₃) or perovskites yield superior performance [17]. The future of signal generation lies in this synergistic approach, where each material is selected to play a specific role—be it transduction, enhancement, or protection. Furthermore, the integration of these advanced material platforms with machine learning algorithms for data analysis is poised to push the boundaries of predictive accuracy and diagnostic reliability, paving the way for the next generation of point-of-care and clinical-grade biosensors [13].

Biosensor technology is undergoing a transformative evolution, driven by two parallel revolutions: the adoption of cell-free synthetic biology and the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) for data analysis and system optimization. Cell-free biosensors, which utilize biological machinery without maintaining living cells, offer advantages in stability, customization, and deployment in resource-limited settings [21]. Concurrently, AI and machine learning (ML) enhance biosensor capabilities by improving signal processing, pattern recognition, and predictive modeling, thereby boosting sensitivity, specificity, and reliability [22] [23]. This guide objectively compares the performance of these emerging systems, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a critical evaluation of their experimental performance, underlying mechanisms, and practical applications.

Performance Comparison of AI-Integrated and Cell-Free Biosensors

The convergence of cell-free biosensing and AI has led to significant advancements in detection capabilities. The table below provides a comparative overview of the performance of various biosensing systems as documented in recent experimental studies.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Advanced Biosensing Systems

| Biosensor Type / Platform | Target Analyte | Detection Limit | Specificity / Key Feature | Experimental Data Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell-Free (CRISPR-based) | Pathogens/Viral RNA | Single-base specificity | Ultrasensitive, programmable | [24] |

| Cell-Free (Plasmonic Coffee-Ring) | PSA (for cancer) | 3 pg/mL | Asymmetric plasmonic pattern, smartphone readout | [25] |

| Cell-Free (Plasmonic Coffee-Ring) | Procalcitonin (for sepsis) | <10 pg/mL (in saliva) | Detects sepsis-relevant levels in human saliva | [25] |

| Cell-Free (aTF-based) | Lead (Pb²⁺) | 0.1 nM (≈20.7 ppt) | High selectivity in real water samples | [21] |

| Cell-Free (Riboswitch-based) | Tetracyclines | 0.079 - 0.47 µM | Broad-spectrum detection in milk | [21] |

| AI-Enhanced Optical | Disease biomarkers | Enhanced over non-AI counterparts | Improved multiplexing, noise reduction | [22] [23] |

| AND-Gate Peptide (Cell-Free) | Protease Activity (Cancer) | N/A (Boolean logic) | Distinguishes treated vs. untreated tumors in vivo | [26] |

| ML-Predicted Electrochemical | Glucose | RMSE = 0.143 (Model) | Stacked ensemble ML for signal prediction | [27] |

Analysis of Comparative Data

The data reveals distinct trends. Cell-free biosensors consistently achieve remarkably low detection limits across diverse targets, from metals to proteins, making them suitable for early disease diagnosis and environmental monitoring [21] [25]. A key differentiator is their functional specificity, achieved through various mechanisms: allosteric transcription factors (aTFs) for metals, riboswitches for antibiotics, and Boolean logic (AND-gates) for complex cellular events [21] [26]. AI's primary role is performance enhancement, using models like deep neural networks to extract quantitative data from complex outputs (e.g., smartphone images) or to predict and optimize sensor responses, thereby improving accuracy and reliability [27] [25].

Experimental Protocols for Key Biosensing Platforms

Reproducibility is fundamental to biosensor research. Below are detailed methodologies for two representative and high-performance platforms.

Protocol: Plasmonic Coffee-Ring Biosensor for Ultra-Sensitive Protein Detection

This protocol details the procedure for detecting low-abundance proteins like Procalcitonin (PCT) or Prostate-Specific Antigen (PSA) using a coffee-ring effect-based pre-concentration and plasmonic signal generation [25].

Primary Materials:

- Thermally treated nanofibrous membrane: Serves as the substrate for droplet evaporation.

- Protein sample: Prepared in a suitable buffer (e.g., 5 µL volume).

- Plasmonic droplet: Contains gold nanoshells (GNShs) functionalized with specific antibodies (e.g., 2 µL volume).

- Smartphone with camera: For image capture of the final pattern.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Sample Deposition and Pre-concentration: Pipette a 5 µL sample droplet onto the right side of the nanofibrous membrane. Allow it to dry completely at room temperature. During evaporation, the coffee-ring effect pre-concentrates the target proteins at the edge of the droplet.

- Plasmonic Signal Generation: Pipette a 2 µL droplet of functionalized GNShs onto the left side of the dried first droplet, ensuring a partial overlap. Allow this second droplet to dry completely.

- Pattern Formation: The evaporation-induced flow of the second droplet carries GNShs over the pre-concentrated protein coffee-ring. Specific antibody-protein interactions cause GNShs to form a dispersed 2D pattern in the overlap zone, while nonspecific aggregation occurs elsewhere, creating a visible asymmetric pattern.

- Data Acquisition and Analysis: Capture an image of the asymmetric plasmonic pattern using a smartphone. Analyze the image using a trained deep neural network (e.g., integrating generative and convolutional networks) to correlate the pattern with biomarker concentration quantitatively.

Protocol: AND-Gate Protease Biosensor for In Vivo Cancer Monitoring

This protocol outlines the application of a cell-free, nanoparticle-based biosensor that uses Boolean logic to detect specific protease activities associated with tumor cell death [26].

Primary Materials:

- Cyclic peptide-based nanosensors: Composed of iron oxide nanoparticles and engineered cyclic peptides that are substrates for both granzyme B (from immune cells) and matrix metalloproteinase (from cancer cells).

- Animal model: Mice with established tumors.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Sensor Administration: Intravenously inject the cyclic peptide-based nanosensors into the animal model.

- In Vivo Activation: The nanosensors circulate and accumulate in the tumor microenvironment. The sensor signal is activated only upon the simultaneous presence and cleavage by both granzyme B and matrix metalloproteinase (AND-gate logic). This dual-protease requirement ensures high specificity for immune activity against tumors.

- Signal Detection and Readout: Monitor the activated sensor signal using an appropriate in vivo imaging modality. The signal intensity correlates with the degree of immune-mediated tumor cell killing.

- Validation: Correlate the sensor signal with treatment efficacy, such as distinguishing between tumors that respond to immune checkpoint blockade therapy from those that are resistant.

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the core operational logic of two advanced biosensor types, highlighting the integration of biological components and computational analysis.

AND-gate Biosensor Logic

Diagram 1: AND-gate Biosensor Logic. This diagram illustrates the Boolean logic required for signal activation in advanced biosensors like the protease-activated nanosensor. The biosensor (center) only produces a readable output when both required input proteases are present and active [26].

AI-integrated Biosensing Workflow

Diagram 2: AI-integrated Biosensing Workflow. This workflow shows how raw data from a biosensor is processed by AI/ML algorithms to generate an enhanced, more reliable output. Key applications of AI in this process include complex pattern recognition (e.g., from smartphone images), signal noise filtration, and quantitative analyte prediction [22] [23] [25].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The development and deployment of advanced biosensors rely on a core set of biological and synthetic components.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Advanced Biosensing

| Reagent / Material | Function in Biosensing | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Allosteric Transcription Factors (aTFs) | Biological recognition element that changes structure upon binding a target analyte, triggering a signal. | Detection of heavy metals (e.g., Hg²⁺, Pb²⁺) in water [21]. |

| CRISPR-Cas Systems | Provides ultra-specific nucleic acid recognition and can be coupled to signal amplification. | Precision detection of pathogen DNA/RNA with single-base specificity [24]. |

| Riboswitches / RNA Aptamers | Synthetic RNA sequences that bind to a target molecule, regulating reporter gene expression. | Detection of small molecules like tetracycline antibiotics in food samples [21]. |

| Gold Nanoshells (GNShs) | Plasmonic nanoparticles that undergo visible aggregation or color change upon binding events. | Signal generation in ultra-sensitive protein detection platforms [25]. |

| Cyclic Peptides | Engineered synthetic molecules that can be designed as substrates for specific proteases. | Core sensing element in AND-gate logic biosensors for in vivo monitoring [26]. |

| Cell-Free Protein Synthesis (CFPS) Systems | Purified cellular machinery that enables protein expression without whole cells, allowing for tunable reactions. | The core reaction environment for many cell-free biosensors; enables production of reporter proteins [21]. |

| Nanofibrous Membranes | Porous substrate that facilitates controlled droplet evaporation and pre-concentration of analytes. | Used to create the coffee-ring effect for signal enhancement [25]. |

Advanced Sensing Modalities and Their Application in Biomedical Research

Optical biosensors have revolutionized the field of biomarker detection by enabling label-free, real-time analysis of molecular interactions. Among the most prominent technologies are Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR), Photonic Crystal Fiber-SPR (PCF-SPR), and Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS), each offering distinct mechanisms and advantages for scientific research and drug development. SPR biosensors detect refractive index changes at a metal-dielectric interface, while PCF-SPR incorporates microstructured fibers to enhance light-matter interaction and sensitivity [28] [29]. SERS utilizes plasmonic nanostructures to amplify Raman scattering signals by several orders of magnitude, enabling single-molecule detection in some configurations. These platforms have become indispensable tools for researchers studying biomolecular interactions, disease mechanisms, and therapeutic candidate screening, particularly as the demand for high-sensitivity, point-of-care diagnostic technologies continues to grow [28] [30].

The evaluation of biosensor performance relies on several key parameters. Sensitivity quantifies the detectable change in signal per unit change in analyte concentration or refractive index, often reported as nm/RIU (refractive index unit) for wavelength-based detection or RIU⁻¹ for amplitude-based detection [29]. Specificity refers to the sensor's ability to distinguish target analytes from similar molecules in complex biological samples. Figure of Merit (FOM) combines sensitivity and resonance sharpness to provide a comprehensive performance metric, while resolution indicates the smallest detectable refractive index change [31] [29]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these three biosensing platforms, supported by experimental data and methodologies from recent research advances.

The following table summarizes the fundamental characteristics, operating principles, and typical applications of each biosensing platform:

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Optical Biosensing Platforms

| Parameter | SPR | PCF-SPR | SERS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Detection Principle | Refractive index change at metal-dielectric interface [29] | Enhanced light-matter interaction in microstructured fibers [28] [29] | Raman signal amplification via plasmonic nanostructures |

| Key Materials | Gold, silver with dielectric layers (e.g., ZnO, Si₃N₄) [30] | Gold, silver, novel plasmonic materials (ZrN, TMDCs) [29] [32] | Gold, silver nanoparticles, nanostructured substrates |

| Typical Applications | Biomolecular interaction analysis, kinetic studies [28] | Cancer detection, environmental monitoring, chemical sensing [28] [29] | Pathogen detection, chemical imaging, single-molecule spectroscopy |

| Label-Free | Yes | Yes | Yes (indirect enhancement) |

| Throughput | Moderate | High (multi-analyte potential) | High (multiplexing capability) |

Recent advances in PCF-SPR sensors have demonstrated remarkable performance improvements through innovative design strategies. The bowtie-shaped PCF-SPR biosensor achieves a wavelength sensitivity of 143,000 nm/RIU and amplitude sensitivity of 6,242 RIU⁻¹ across a broad refractive index range (1.32-1.44) [31]. Machine learning-optimized PCF-SPR designs report similarly high performance with 125,000 nm/RIU wavelength sensitivity and 2,112.15 FOM [33] [10]. Comparative studies show that PCF-SPR sensors consistently outperform conventional SPR platforms in sensitivity metrics while offering greater design flexibility and miniaturization potential [28] [29].

Quantitative Performance Comparison

The table below summarizes experimental performance data for various biosensor configurations reported in recent literature:

Table 2: Experimental Performance Metrics of Recent Biosensor Designs

| Sensor Type | Configuration/Materials | Sensitivity | FOM | Resolution (RIU) | Detection Range (RIU) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCF-SPR | Bowtie-shaped, Gold | 143,000 nm/RIU (WS), 6,242 RIU⁻¹ (AS) | 2,600 | 6.99×10⁻⁷ | 1.32-1.44 | [31] |

| PCF-SPR | ML-optimized, Gold | 125,000 nm/RIU (WS), -1,422.34 RIU⁻¹ (AS) | 2,112.15 | 8×10⁻⁷ | 1.31-1.42 | [33] [10] |

| SPR | BK7/ZnO/Ag/Si₃N₄/WS₂ | 342.14 deg/RIU | 124.86 | N/R | 1.33-1.40 | [30] |

| PCF-SPR | V-shaped, ZrN | 6,214.28 nm/RIU (TM, breast cancer) | N/R | N/R | 1.39-1.41 | [32] |

| PCF-SPR | Cylindrical vector modes, Gold | 13,800 nm/RIU (WS), 2,380 RIU⁻¹ (AS) | N/R | ~10⁻⁶ | 1.29-1.34 | [34] |

WS: Wavelength Sensitivity; AS: Amplitude Sensitivity; N/R: Not Reported

For cancer detection applications, SPR biosensors with specialized architectures have demonstrated remarkable capabilities. A layered structure incorporating WS₂ (BK7/ZnO/Ag/Si₃N₄/WS₂/sensing medium) achieved sensitivity of 342.14 deg/RIU and FOM of 124.86 RIU⁻¹ for blood cancer (Jurkat) detection, outperforming other configurations for cervical cancer (HeLa) and skin cancer (Basal) detection [30]. The integration of transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDCs) like MoS₂, MoSe₂, WS₂, and WSe₂ has proven particularly effective for enhancing sensitivity in cancer biomarker detection [30].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Sensor Design and Optimization Protocols

Finite Element Method (FEM) Simulation: Researchers typically employ COMSOL Multiphysics or similar platforms to model sensor architectures [31] [34]. The process involves creating a geometric model of the proposed sensor, defining material properties (including wavelength-dependent refractive indices for metals using Drude-Lorentz model and for silica using Sellmeier equation), applying appropriate boundary conditions (Perfectly Matched Layer, PML, for radiation absorption), and performing mesh convergence analysis to ensure numerical accuracy [31] [34]. For PCF-SPR sensors, key parameters including pitch (Λ), air hole diameters (d₁, d₂, d₃), plasmonic layer thickness (t_g), and core-to-metal distance are systematically varied to optimize performance metrics [31].

Machine Learning Optimization: Recent approaches integrate ML algorithms to accelerate sensor optimization [33] [10]. The standard protocol involves: (1) generating comprehensive datasets through parametric sweeps using FEM simulations; (2) training multiple regression models (Random Forest, Gradient Boosting, etc.) to predict optical properties based on design parameters; (3) applying explainable AI (XAI) methods like SHAP analysis to identify critical design parameters; and (4) iteratively refining designs based on ML predictions to maximize sensitivity and FOM while minimizing confinement loss [33] [10]. This approach significantly reduces computational costs compared to traditional optimization methods.

Performance Characterization Methodology

Sensitivity Measurement: For wavelength interrogation, researchers track the resonance wavelength shift (Δλ) corresponding to variations in analyte refractive index (Δna), calculating wavelength sensitivity as Sλ = Δλ/Δna (nm/RIU) [29]. For amplitude interrogation, sensitivity is calculated as SA = (1/α(λ)) × (∂α(λ)/∂n_a) (RIU⁻¹), where α(λ) represents transmission loss [29] [34]. Measurements are typically performed across the target refractive index range (e.g., 1.31-1.44 for biological analytes) with incremental steps of 0.01-0.03 RIU [31].

Figure of Merit and Resolution Calculation: FOM is determined as the ratio of wavelength sensitivity to the full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the resonance peak: FOM = Sλ/FWHM (RIU⁻¹) [31]. Sensor resolution represents the smallest detectable refractive index change and is calculated as R = Δna × (Δλmin/Δλ), where Δλmin is the minimum resolvable wavelength shift (typically 0.1 nm for standard spectrometers) [31].

Figure 1: PCF-SPR Experimental Setup and Sensing Mechanism

Operational Principles and Signaling Pathways

The fundamental operating principle of SPR and PCF-SPR biosensors relies on the excitation of surface plasmon polaritons (SPPs) at the metal-dielectric interface [29]. When incident light strikes the metal surface under total internal reflection conditions, it generates an evanescent field that penetrates the dielectric medium. At a specific resonance wavelength or angle, the wave vector of the incident light matches that of the surface plasmons, resulting in resonant energy transfer and a sharp dip in the reflected or transmitted light spectrum [29] [34]. This resonance condition is extremely sensitive to changes in the local refractive index at the metal surface, enabling detection of biomolecular binding events in real-time without labels.

In PCF-SPR sensors, the photonic crystal fiber provides enhanced light confinement and flexible design options to optimize plasmonic excitation [28] [29]. The microstructured air holes can be arranged in various configurations (hexagonal, bowtie, V-shaped, etc.) to control light propagation characteristics and maximize overlap between the guided mode and analyte medium [31] [32]. The strategic placement of plasmonic materials (external coating, internal deposition, or selective infiltration) further enhances the coupling efficiency between core-guided modes and surface plasmon modes [29].

Figure 2: Biosensing Principle and Signal Transduction Pathway

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Optical Biosensors

| Category | Specific Materials | Research Function | Performance Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plasmonic Materials | Gold (Au), Silver (Ag), Zirconium Nitride (ZrN) [29] [32] | Generate surface plasmon waves for signal transduction | Au: High stability, strong resonance; Ag: Sharper resonance but oxidation-prone; ZrN: High melting point, CMOS compatibility [32] |

| 2D Enhancement Materials | Graphene, TMDCs (MoS₂, WS₂), Black Phosphorus [28] [30] | Enhance light-matter interaction, protect metallic layers, provide binding sites | TMDCs: Strong field confinement, biocompatibility; Graphene: High adsorption for biomolecules [30] |

| Dielectric Layers | ZnO, Si₃N₄, TiO₂, SiO₂ [30] [32] | Adhesion layers, optical coupling, surface functionalization | ZnO: Enhances electric field; Si₃N₄: Improved sensitivity and FOM [30] |

| Computational Tools | COMSOL Multiphysics, MATLAB, Python ML libraries [33] [31] | Sensor design, simulation, data analysis, optimization | FEM: Accurate electromagnetic modeling; ML: Rapid design optimization and prediction [33] [10] |

| Substrate Materials | BK7 prism, Silica (SiO₂), Photonic Crystal Fibers [30] [29] | Light coupling, structural foundation, guidance mechanism | PCFs: Flexible design, enhanced light confinement; Prism: Conventional SPR coupling [29] |

The comparative analysis of SPR, PCF-SPR, and SERS platforms reveals a dynamic landscape of optical biosensing technologies with distinct advantages for different research applications. Conventional SPR systems offer well-established operation and reliability for biomolecular interaction analysis, while PCF-SPR platforms provide superior sensitivity and design flexibility through microstructured fiber optics. SERS delivers exceptional molecular fingerprinting capability through Raman signal enhancement.

Future research directions focus on addressing current limitations including fabrication complexity, detection range constraints, and material costs [28]. The integration of machine learning and artificial intelligence for sensor optimization and data analysis represents a promising avenue for enhancing detection efficiency and accuracy [28] [33] [10]. Additionally, the development of novel plasmonic materials, multi-analyte detection capabilities, and point-of-care miniaturization will further expand the applications of these powerful biosensing platforms in biomedical research, clinical diagnostics, and drug development [28] [29]. As these technologies continue to evolve, they will play an increasingly crucial role in advancing personalized medicine and improving healthcare outcomes through sensitive, specific, and rapid biomarker detection.

Electrochemical biosensors have emerged as powerful tools in modern healthcare, enabling the sensitive and specific detection of metabolites and disease-associated biomarkers. These sensors function by incorporating a biological recognition element, such as an enzyme or antibody, in direct spatial contact with an electrochemical transducer, which converts a biological reaction into a quantifiable electrical signal such as current or potential [35]. This operational principle allows for the rapid, cost-effective, and highly sensitive analysis of target analytes in complex biological matrices like blood, sweat, and saliva [36].

The focus of biosensor research has increasingly shifted towards achieving ultra-high sensitivity and specificity, which are critical for the early diagnosis of diseases where biomarkers are present at ultralow concentrations [36]. Recent innovations have been fueled by the integration of advanced nanomaterials, novel transducer designs, and the development of wearable and point-of-care (POC) devices. These advancements are systematically overcoming traditional limitations of electrochemical sensors, such as signal instability and insufficient sensitivity for macromolecular biomarkers, paving the way for their broader clinical and commercial application [35] [37].

Performance Comparison: Sensor Platforms for Metabolites and Protein Biomarkers

The performance of electrochemical biosensors varies significantly based on their design, the biomarker target, and the materials used for electrode modification. The tables below provide a comparative analysis of documented sensor performances for key metabolite and clinical protein biomarkers.

Table 1: Performance comparison of electrochemical sensors for metabolite detection.

| Target Analyte | Associated Condition | Sensor Type / Recognition Element | Linear Range | Limit of Detection (LOD) | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose | Diabetes Mellitus | Enzymatic (e.g., Glucose Oxidase) | Not Specified | 0.159 μM | 2021 |

| Glucose | Diabetes Mellitus | Enzymatic | Not Specified | 3.35 μM | 2021 |

| Lactate | Diabetes Mellitus | Enzymatic (e.g., Lactate Oxidase) | Not Specified | 0.41 mM | 2021 |

| Urea | Diabetes Mellitus | Enzymatic | Not Specified | 0.14 nM | 2020 |

| Dopamine | Parkinson's Disease | Affinity-based | Not Specified | 10 pM | 2021 |

| Dopamine | Alzheimer's Disease | Affinity-based | Not Specified | 8.75 pM | 2020 |

| H₂O₂ | Neurodegenerative Disease | Catalytic Material | Not Specified | 0.02 μM | 2020 |

| Branched-Chain Amino Acids | Metabolic Syndrome | Wearable Molecularly Imprinted Polymer [38] | Not Specified | Trace levels in sweat [38] | 2022 |

Table 2: Performance comparison of electrochemical immunosensors for protein biomarkers.

| Target Analyte | Associated Condition | Sensor Design | Linear Range | Limit of Detection (LOD) | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α-Fetoprotein (AFP) | Liver Cancer | Au@Pd NPs, MoS₂@MWCNTs [37] | Not Specified | 3.57 pM (≈0.60 ng/mL)* | 2009 |

| α-Fetoprotein (AFP) | Liver Cancer | Cu-Ag NPs, Polydopamine [37] | Not Specified | 4.27 pg/mL | Recent |

| Prostate-Specific Antigen (PSA) | Prostate Cancer | Immunosensor | Not Specified | 29.4 pM | 2017 |

| CYFRA 21-1 | Lung Cancer | Immunosensor | Not Specified | 57.5 fM | 2016 |

| Amyloid-β Oligomer | Alzheimer's Disease | Immunosensor | Not Specified | 1.0 aM (atto-molar) | 2020 |

| t-Tau | Alzheimer's Disease | Immunosensor | Not Specified | 1.59 fM | 2020 |

Note: Calculated using molecular weight of AFP (~67 kDa).

Experimental Protocols: Methodologies for High-Performance Sensing

Protocol for a Nanomaterial-Enhanced Immunosensor

The high sensitivity required for detecting low-abundance protein biomarkers, such as Alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), is often achieved through sophisticated nanomaterial-based electrode modifications. The following protocol, derived from recent research, outlines a representative methodology [37].

- 1. Electrode Substrate Preparation: A glassy carbon electrode (GCE) is typically polished to a mirror finish with alumina slurry, followed by sequential sonication in ethanol and deionized water to create a clean, reproducible surface.

- 2. Synthesis of Composite Nanomaterial: Polydopamine (PDA)-modified cellulose nanofibers (CNFs) are synthesized. Subsequently, bimetallic Cu-Ag nanoparticles (NPs) are deposited onto the PDA/CNF substrate. The PDA provides a universal adhesion layer and a platform for nanoparticle reduction and anchoring.

- 3. Electrode Modification: The synthesized nanocomposite (e.g., Cu-Ag/PDA/CNF) is dispersed in a solvent like ethanol and drop-cast onto the cleaned GCE surface, followed by drying.

- 4. Antibody Immobilization: A capture antibody (e.g., anti-AFP) is immobilized onto the modified electrode surface. This can be achieved through cross-linkers like glutaraldehyde or via direct adsorption facilitated by the nanomaterial's high surface area and biocompatibility.

- 5. Immunoassay Procedure: The functionalized electrode is incubated with the sample containing the target antigen (AFP). In a sandwich-type assay, a secondary antibody (Ab2), which is often conjugated with a signal-amplifying label (e.g., enzymatic or nanoparticle-based), is added. The specific binding of the antigen creates an immunocomplex on the electrode.

- 6. Electrochemical Measurement: The electrocatalytic activity of the Cu-Ag NPs is utilized for signal transduction. The electrode is placed in a solution containing H₂O₂, and the reduction current of H₂O₂, which is catalyzed by the NPs and whose magnitude is proportional to the amount of captured immunocomplex, is measured using techniques like amperometry or chronoamperometry. The decrease in current upon the formation of the insulating immunocomplex can also be monitored in some label-free setups.

Protocol for a Wearable Metabolite Sensor

For continuous monitoring of metabolites like amino acids and vitamins in sweat, wearable sensors employ a different set of protocols, as exemplified by a reported graphene-based platform [38].

- 1. Sensor Fabrication: Graphene electrodes are fabricated on a flexible substrate. These electrodes are functionalized with metabolite-specific molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs), which act as synthetic, antibody-like recognition elements. Redox-active reporter nanoparticles are integrated into the MIP matrix.

- 2. System Integration: The functionalized sensor is integrated with a wearable platform that includes modules for sweat induction (e.g., iontophoresis), microfluidic sweat sampling, signal processing, calibration, and wireless data transmission.

- 3. On-Body Operation and Sensing: The wearable device is applied to the skin. Iontophoresis induces sweat, which is channeled through the microfluidic system to the sensor array. Binding of the target metabolite to the MIPs causes a change in the electrochemical signal (e.g., in the voltammetric peak of the reporter nanoparticles), which is measured and wirelessly transmitted.

- 4. In-situ Regeneration: A key feature of this platform is its ability to be regenerated in situ. A low-pH elution buffer is delivered via the integrated microfluidics to disrupt the metabolite-MIP binding, refreshing the sensor for subsequent measurements.

Diagram 1: Workflow of a wearable metabolite sensor with in-situ regeneration.

Signaling Pathways and Sensor Operational Logic

The core functionality of electrochemical biosensors relies on specific signaling pathways and logical operational principles. The diagram below illustrates the general signaling pathway for an electrochemical immunosensor and the logical flow of a machine learning-enhanced optimization process, which is increasingly used to improve sensor performance [27].

Diagram 2: Signaling pathway for a label-free electrochemical immunosensor.

Diagram 3: Logic of machine learning-driven biosensor optimization.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The development of high-performance electrochemical sensors relies on a specific toolkit of materials and reagents. The table below details key components and their functions in sensor fabrication.

Table 3: Key research reagents and materials for electrochemical biosensor development.

| Material/Reagent | Category | Primary Function in Sensor Development | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gold Nanoparticles (Au NPs) | Zero-dimensional (0D) Nanomaterial [37] | Enhances electron transfer, provides high surface area for biomolecule immobilization, and can be used as an electrocatalyst or label [37]. | Functionalizing graphene oxide substrates to create highly sensitive immunosensors [37]. |

| Graphene & Derivatives | Carbon Nanomaterial | Provides excellent electrical conductivity, large specific surface area, and facilitates charge transfer. Used in substrates and wearable electrodes [38]. | Base material for flexible electrodes in wearable sweat sensors [38]. |

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) | Plastic Antibody / Synthetic Receptor [37] | Provides synthetic, stable, and selective recognition sites for target molecules, serving as an antibody alternative [38]. | Recognition element for amino acids and vitamins in wearable sweat sensors [38]. |

| Glutaraldehyde | Crosslinking Agent | Creates covalent bonds to stably immobilize biomolecules (enzymes, antibodies) onto sensor surfaces. | Crosslinking glucose oxidase or antibodies to nanomaterial-modified electrodes. |

| Enzymes (e.g., GOx, Lactate Oxidase) | Biological Recognition Element | Provides high specificity for the catalytic conversion of a target metabolite, generating an electroactive product (e.g., H₂O₂) [35]. | Key component in amperometric glucose and lactate sensors [36]. |

| Monoclonal Antibodies | Biological Recognition Element | Provides high specificity and affinity for protein biomarkers (antigens) via immunoreaction, forming the basis of immunosensors [37]. | Capture and detection antibody in a sandwich assay for Alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) [37]. |

| Electroactive Reporters (e.g., Methylene Blue) | Redox Probe | Acts as a signaling molecule; changes in its electrochemical behavior (e.g., peak current) indicate the binding of a target analyte. | Used in aptamer-based sensors where binding-induced folding alters electron transfer. |

| Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) | Porous Nanomaterial | Provides an ultra-high surface area for biomolecule loading, can enhance stability, and some exhibit catalytic activity. | Used to immobilize enzymes while maintaining their activity, improving sensor stability. |

Precision medicine aims to tailor medical treatment to the individual characteristics of each patient, and in oncology, this hinges on the ability to detect cancer-specific biomarkers with high sensitivity and specificity. Biosensor technology has emerged as a powerful platform for achieving this goal, enabling the rapid, accurate, and often non-detection of molecular signatures associated with different cancer types. The performance of these biosensors is critically dependent on their design, which dictates their analytical sensitivity, specificity, and overall utility in clinical decision-making. This guide provides a comparative evaluation of leading biosensor architectures, with a focused analysis on their application in detecting multiple cancer types and profiling protein interactions. We objectively compare the performance of surface plasmon resonance (SPR), photonic crystal fiber (PCF)-SPR, and microfluidic-integrated biosensors, presenting experimental data to illustrate their respective capabilities and limitations within the context of precision oncology.

Comparative Performance Analysis of Biosensing Platforms

The evolution of biosensor technology has yielded a diverse array of platforms, each with distinct operational principles and performance characteristics. The following comparative analysis synthesizes data from recent studies to provide a clear overview of their capabilities in multi-cancer detection.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Biosensor Platforms in Cancer Detection

| Biosensor Platform | Key Materials / Configuration | Detection Method | Cancer Types Detected | Reported Sensitivity | Specificity / FOM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prism-based SPR [30] | BK7/ZnO/Ag/Si3N4/WS2 | Angular Interrogation | Blood (Jurkat), Cervical (HeLa), Skin (Basal) | 342.14 deg/RIU (Jurkat) | FOM: 124.86 RIU⁻¹ (Jurkat) |

| D-Shaped PCF-SPR [39] | Gold/TiO₂ on silica PCF | Wavelength Interrogation | Basal, HeLa, Jurkat, PC-12, MDA-MB-231 | 42,000 nm/RIU | FOM: 1393.128 RIU⁻¹ |

| Electrochemical Microfluidic [40] | Gold Nanoparticles, Graphene, CNTs | Electrochemical Signal | Various (via biomarkers like ctDNA, proteins) | Enhanced for low-concentration biomarkers | High Selectivity |

| Multi-Cancer Detection (MCD) Tests [41] | cfDNA mutation analysis & protein biomarkers | Blood-based Liquid Biopsy | Ovarian, Liver, Esophageal, Pancreatic, Stomach, Colorectal, Lung, Breast | 62.3% (overall), 49.9% (Stage I), 70.2% (Stage III) | 99.1% |

The data reveals a clear performance trade-off between different sensing principles. The D-Shaped PCF-SPR sensor demonstrates exceptionally high wavelength sensitivity and the highest Figure of Merit (FOM), which is a composite metric reflecting overall sensor quality [39]. This is attributed to its optimized Gold/TiO₂ layers and the efficient light-analyte interaction within the PCF structure. In contrast, the conventional prism-based SPR sensor, while highly sensitive in angular interrogation units, operates on a different scale but is notable for its direct comparison of multiple two-dimensional materials, identifying WS₂ as the most effective for sensitivity enhancement [30].

Meanwhile, blood-based MCD tests like CancerSEEK represent a different class of technology, reporting performance in clinical terms of sensitivity and specificity for detecting a cancer signal from a panel of biomarkers [41]. Their strength lies in the ability to screen for multiple cancers concurrently from a single, non-invasive blood draw, though their sensitivity is currently highest for later-stage cancers.

Detailed Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol for Prism-Based SPR Biosensing

The experimental setup and methodology for conventional SPR biosensors, as used for cancer cell detection, typically involves the following steps [30]:

- Sensor Chip Functionalization: A BK7 prism is coated with successive layers of ZnO, Ag, Si3N4, and a 2D material (e.g., WS₂) to form the sensing interface. The architecture (e.g., BK7/ZnO/Ag/Si3N4/WS₂) is designed to enhance the electromagnetic field and light absorption.

- Baseline Establishment: A polarized light source is directed through the prism to excite surface plasmons in the metal layer. The reflected light is measured with a detector, establishing a baseline resonance angle (or curve) using a buffer solution.

- Analyte Introduction: A solution containing the target cancer cells (e.g., Jurkat for blood cancer, HeLa for cervical cancer) is flowed over the sensor surface.

- Real-Time Monitoring: The binding of cancer cells to the sensing surface causes a local change in the refractive index. This shift is detected in real-time as a change in the resonance angle.

- Data Analysis: The angular shift (in degrees/RIU) is quantified and correlated to the concentration of bound cells. The sensitivity is calculated from this shift, and the Full Width at Half Maximum (FWHM) of the resonance curve is used to calculate the Figure of Merit (FOM = Sensitivity / FWHM).

Protocol for D-Shaped PCF-SPR Biosensing

The methodology for PCF-based sensors differs significantly due to the fiber-optic platform [39]:

- Fabrication and Coating: A D-shaped photonic crystal fiber is fabricated, and its flat surface is polished. This surface is then coated with a uniform layer of gold, followed by a layer of TiO₂.

- Optical Setup: A broadband light source (visible to near-infrared) is launched into one end of the PCF. An analyte (e.g., a solution simulating cancer cell cytoplasm) is brought into contact with the metal-coated surface of the PCF.

- Spectral Analysis: The output light from the other end of the PCF is captured by an optical spectrum analyzer. The excitation of surface plasmons at the metal-analyte interface causes a characteristic loss band in the transmission spectrum.

- Refractive Index Perturbation: As the refractive index of the analyte changes (due to the presence of different cancer cell types or concentrations), the wavelength of this loss peak shifts.

- Sensitivity Calculation: The wavelength sensitivity (WS) is calculated as the shift in the resonance wavelength (in nanometers) per unit change in the refractive index (RIU), expressed as nm/RIU. The amplitude sensitivity (AS) and FOM are also derived from the spectral data.

<100 chars: D-Shaped PCF-SPR Workflow

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Interactions in Cancer Biosensing

Biosensors detect cancer by interacting with specific biomolecules and pathways that are deregulated in cancer cells. SPR and other label-free sensors typically detect these interactions directly through mass or refractive index changes.

<100 chars: Cancer Biomarker Detection Pathway

The fundamental principle involves the specific binding of target biomarkers present in or on cancer cells to recognition elements (e.g., antibodies, aptamers) immobilized on the sensor surface [30] [40]. For instance:

- Protein Interaction Analysis: Sensors can be functionalized with antibodies against cancer-specific proteins (e.g., CA15-3 for breast cancer [30] or CYFRA 21-1 for esophageal cancer [42]). The binding kinetics and affinity can be analyzed in real-time using SPR.

- Nucleic Acid Detection: For mutations in genes like BRCA1, BRCA2, or TP53, the sensor surface is coated with complementary DNA probes. The hybridization of target ctDNA from liquid biopsies is detected [30] [41].

- Whole Cell Detection: The sensor can be designed to capture entire cancer cells (e.g., Jurkat, HeLa) by targeting unique surface antigens, with the resulting bulk refractive index change being measured [30] [39].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The performance of advanced biosensors is critically dependent on the materials and reagents used in their fabrication and operation. The table below details key components referenced in the studies.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Biosensor Development

| Material / Reagent | Function in Biosensor | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Gold (Au) & Silver (Ag) [30] [39] | Plasmonic metal layer; generates surface plasmons for signal transduction. | Standard in SPR and PCF-SPR sensors. Gold preferred for chemical stability. |

| Transition Metal Dichalcogenides (WS₂, MoS₂) [30] | 2D material overlayer; enhances light-matter interaction and sensitivity. | Used in BK7/ZnO/Ag/Si3N4/WS₂ configuration for cancer cell detection. |

| Titanium Dioxide (TiO₂) [39] | Dielectric overlayer; enhances sensitivity and coupling efficiency in SPR. | Combined with gold in D-shaped PCF-SPR for high sensitivity (42,000 nm/RIU). |

| Graphene & Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) [40] | Nanomaterial with high surface area and conductivity; enhances signal in electrochemical and optical sensors. | Integrated into microfluidic biosensors for capturing and detecting low-concentration biomarkers. |

| Zinc Oxide (ZnO) [30] | Interface layer; improves adhesion and performance of the plasmonic metal film. | Used as a layer between the BK7 prism and Ag layer in SPR configurations. |

| Specific Antibodies & DNA Probes [30] [41] [40] | Biorecognition elements; provide specificity by binding to target biomarkers (proteins, ctDNA). | Anti-PSA for prostate cancer, probes for BRCA1/2 mutations, anti-HER2 for breast cancer. |

| Photonic Crystal Fiber (PCF) [39] | Waveguide platform; allows efficient light-analyte interaction in a compact, flexible format. | Base structure for D-shaped SPR sensors, enabling high-sensitivity, multi-analyte detection. |

The comparative data presented in this guide underscores the rapid advancement in biosensor technology for precision oncology. Platforms like the D-shaped PCF-SPR and 2D-material-enhanced SPR show remarkable analytical performance in terms of sensitivity and FOM, making them powerful research tools. Concurrently, the clinical translation of biosensor principles into blood-based MCD tests represents a significant stride toward population-level screening. The future of this field lies in the continued integration of technologies, such as combining microfluidics for sample handling with SPR or electrochemical detection for high sensitivity [40]. Furthermore, the incorporation of artificial intelligence and machine learning for data analysis is poised to enhance the ability of these biosensors to deconvolute complex signals, identify subtle patterns, and improve diagnostic accuracy, ultimately solidifying their role in the era of personalized cancer medicine.

Cell-free biosensors represent a transformative approach in analytical science, harnessing the core molecular machinery of cells for detection without the constraints of maintaining cell viability. These systems utilize purified cellular components—such as transcription and translation factors, ribosomes, and energy sources—to perform complex biochemical reactions in vitro, enabling highly sensitive and specific detection of diverse analytes [21]. By eliminating the cell membrane barrier and viability requirements, cell-free biosensors overcome significant limitations of traditional whole-cell biosensors, including slow response times, susceptibility to environmental stressors, and cell-wall transport inhibition [21] [43]. This technology has rapidly advanced through integration with synthetic biology, materials science, and microengineering, creating powerful platforms for addressing two critical global challenges: monitoring environmental toxins and enabling point-of-care diagnostics in resource-limited settings [21] [44].