Fabrication and Applications of Silk Fibroin Hydrogel Film for Advanced Biosensor Strips

This article provides a comprehensive examination of silk fibroin (SF) hydrogel films as a premier material platform for biosensor strips, addressing the needs of researchers and drug development professionals.

Fabrication and Applications of Silk Fibroin Hydrogel Film for Advanced Biosensor Strips

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive examination of silk fibroin (SF) hydrogel films as a premier material platform for biosensor strips, addressing the needs of researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the fundamental properties of SF, including its exceptional biocompatibility, tunable biodegradability, and robust mechanical strength, which make it ideal for biomedical interfaces. The content details advanced fabrication methodologies, from chemical and physical cross-linking techniques to innovative 3D printing and functionalization with conductive materials. It further tackles critical troubleshooting and optimization strategies for gelation kinetics, mechanical stability, and sensor fidelity. Finally, the article covers rigorous validation protocols and comparative analyses with traditional synthetic polymers, positioning SF hydrogel films as a transformative technology for next-generation wearable, implantable, and point-of-care diagnostic devices.

Silk Fibroin Hydrogel Fundamentals: Why It's the Ideal Biosensor Material

Fundamental Properties of Silk Fibroin

Silk fibroin (SF) is a natural structural protein that constitutes the core filament of silk produced by the Bombyx mori silkworm. This versatile biopolymer has garnered significant scientific interest due to its exceptional combination of biological and mechanical properties, making it an ideal foundation for advanced biomedical applications, including hydrogel film biosensor strips [1] [2].

The primary structure of silk fibroin consists of a heavy chain (∼390 kDa) and a light chain (∼26 kDa) linked by a single disulfide bond. This H-L complex further associates with a glycoprotein, P25, via hydrophobic interactions [3] [2]. A key feature of the heavy chain is its organization into 12 hydrophobic repetitive domains, rich in glycine (Gly, ∼45%), alanine (Ala, ∼30%), and serine (Ser, ∼12%), which are interspersed with 11 hydrophilic non-repetitive domains. The hydrophobic GAGAGX sequences (where X is Ala, Ser, Tyr, or Val) self-assemble into crystalline β-sheets, which are fundamental to the protein's remarkable mechanical strength and stability [3] [2].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Silk Fibroin as a Biomaterial

| Property | Description | Significance for Biosensors |

|---|---|---|

| Biocompatibility | Excellent tissue compatibility with minimal immune response when sericin is removed [3] [2]. | Safe for potential implantable or skin-contact devices. |

| Biodegradability | Enzymatically degrades over time into amino acids; rate is tunable via β-sheet content [3] [2]. | Enables temporary sensors that do not require surgical removal. |

| Mechanical Properties | High tensile strength, toughness, and elasticity; properties are tunable in hydrogel form [2] [4]. | Allows fabrication of durable, flexible, and stretchable sensor strips. |

| Processability | Can be processed into various formats (hydrogels, films, fibers) using aqueous-based methods [5] [1]. | Facilitates the creation of thin, porous hydrogel films ideal for sensing. |

Fabrication Techniques for Silk Fibroin Hydrogels

The transformation of silk fibroin from its native fibrous state into a hydrogel involves a sol-gel transition process. This begins with the "degumming" of raw silk to remove the sericin coating, followed by dissolution of the purified fibroin fibers in high-concentration salt solutions (e.g., LiBr) [3] [6]. The resulting aqueous silk fibroin solution can then be induced to form a hydrogel through various cross-linking strategies, which determine the final hydrogel's microstructure and properties [7] [5].

Table 2: Common Cross-linking Methods for Silk Fibroin Hydrogels

| Method | Mechanism | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Cross-linking | Induced by sonication, vortexing, or altering temperature/pH to promote β-sheet formation [5] [2]. | Avoids chemical cross-linkers; high biocompatibility. | Can be slow; mechanical properties may be limited. |

| Chemical Cross-linking | Uses cross-linkers like genipin or enzymes (e.g., Horseradish Peroxidase) to form covalent bonds between SF chains [8] [5]. | Enhanced mechanical strength and stability. | Potential cytotoxicity from residual cross-linkers. |

| Photo-Cross-linking | Uses photosensitizers (e.g., Riboflavin) under UV light to create stable, covalent networks rapidly [8] [4]. | Rapid gelation (e.g., ≤15 min); high spatial control. | Requires optimization of photoinitiator concentration and light exposure. |

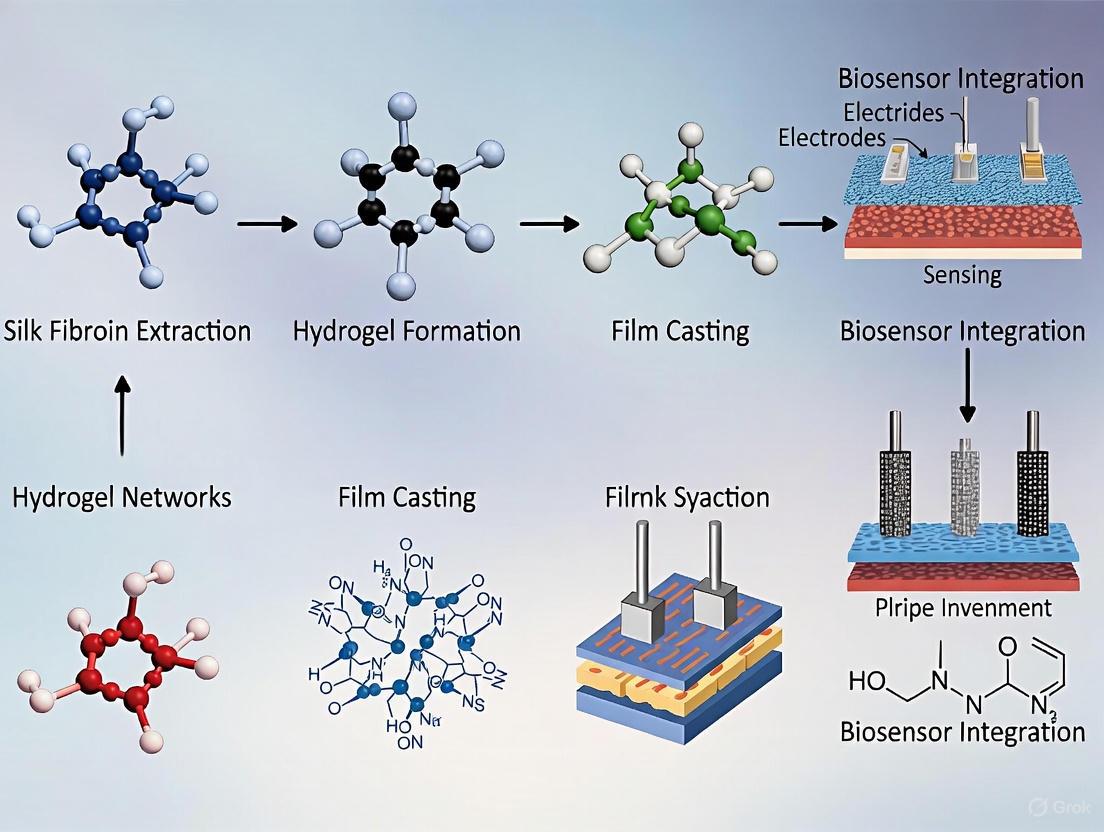

The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow from silkworm cocoon to a finished functional hydrogel.

Quantitative Performance of SF-Based Hydrogels in Sensing

Advanced SF composite hydrogels have been engineered to meet the demanding requirements of high-performance wearable sensors. These materials often combine SF with other polymers to create synergistic networks with enhanced properties.

Table 3: Performance Metrics of Advanced SF-Based Hydrogel Sensors

| Hydrogel Composition | Key Additives/Features | Mechanical & Electrical Performance | Sensing Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| SF/Poly-acrylic acid [9] | TA-Fe₃O₄@MXene catalytic system; biomimetic micro-architecture. | Stretchability: 946%; Sensitivity (Gauge Factor): 4.05; Stable for >100 cycles. | Wearable sensor for physiological signals. |

| SF/Polyacrylamide/Methyl Cellulose [4] | Triple-network; pH-pre-regulated precursor. | Hysteresis: 7.2%; Conductivity: 0.57 S/m; Elastic Modulus: 58.9 kPa. | Multi-channel wireless human motion, ECG, and EMG detection. |

| SF/Magnetic Nanoparticles [10] | Iron oxide nanoparticles (IONPs) for magnetic response. | Enables remote-controlled drug release under external magnetic field. | Intelligent drug delivery system. |

Experimental Protocol: Fabrication of a Photo-Cross-Linked SF-Sericin Hydrogel for pH Visualization

This protocol details the synthesis of a double-network SF-Sericin hydrogel integrated with a natural pH indicator, suitable for creating visual biosensor strips [8].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Reagents for SF-Sericin Hydrogel Fabrication

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| Bombyx mori Cocoons | Raw source material for silk fibroin and sericin. |

| Sodium Carbonate (Na₂CO₃) | Degumming agent for separating sericin from fibroin. |

| Riboflavin (Vitamin B₂) | Biocompatible photoinitiator for UV cross-linking. |

| Natural Anthocyanins | pH-responsive dye extracted from red cabbage; enables visual colorimetry. |

| Lithium Bromide (LiBr) | Electrolyte salt used to dissolve silk fibroin. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Solution Preparation (Day 1):

- Degumming and Co-extraction: In a 500 mL beaker, add 5.0 g of chopped silk cocoons to 250 mL of 0.02 M sodium carbonate solution. Boil for 30-60 minutes with constant stirring. Control the degumming time precisely to tune the final sericin content in the mixed solution.

- Purification: After cooling, rinse the degummed fibroin fibers thoroughly with copious amounts of ultrapure water (3 x 500 mL) to remove all traces of sericin and carbonate. Gently squeeze out excess water.

- Dissolution: Dissolve the washed, wet fibroin fibers in 25 mL of 9.3 M lithium bromide solution at 60°C for 1-2 hours until fully dissolved.

- Dialysis: Load the solution into a dialysis tube (MWCO 12-14 kDa) and dialyze against ultrapure water for 48 hours, changing the water every 6-8 hours, to remove the LiBr salt.

- Centrifugation & Concentration: Centrifuge the purified aqueous SF solution at 9,000 rpm for 20 minutes to remove impurities and aggregates. Decant the clear supernatant and concentrate it to a final concentration of 8-10% (w/v) using a centrifugal evaporator or by air-drying at 4°C.

Hydrogel Fabrication (Day 3):

- Mixing: To 5 mL of the concentrated SF-Serici mixed solution, add 100 µL of a 10 mM Riboflavin (RB) solution and 200 µL of anthocyanin extract (Cy). Mix the solution thoroughly by gentle vortexing for 2 minutes. Protect from light using aluminum foil.

- Photo-Cross-linking: Pipette the mixture into a polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) mold. Expose the mold to UV light (wavelength 365 nm, intensity 10 mW/cm²) for 15 minutes to initiate cross-linking and form the SF-Seri/RB@Cy hydrogel.

- Post-processing: Carefully demold the resulting hydrogel and store it in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at 4°C until use.

The logical workflow and responsive mechanism of the resulting smart hydrogel are summarized in the diagram below.

Application in Biosensor Strips: Mechanisms and Workflow

The integration of SF hydrogels into biosensor strips leverages their tunable mechanical properties, biocompatibility, and capacity for functionalization with conductive elements or molecular probes [9] [4]. For instance, a SF-based hydrogel can serve as both the sensing interface and the matrix for immobilizing recognition elements (e.g., enzymes, antibodies).

A typical biosensor fabrication workflow involves casting the prepared SF hydrogel solution onto a flexible substrate (e.g., polyester film), patterning it into a strip, and functionalizing it with specific receptors. When the strip encounters the target analyte (e.g., glucose, specific ions, or biomarkers), a change in the hydrogel's properties occurs—such as swelling, a shift in conductivity, or a colorimetric response—which is transduced into a measurable electrical or optical signal [9] [8]. The high water content and porous structure of the hydrogel facilitate rapid analyte diffusion, leading to faster response times.

Silk fibroin (SF), a natural protein derived from Bombyx mori silkworm cocoons, has emerged as a premier biomaterial for fabricating advanced hydrogel film biosensor strips. Its unique combination of properties allows for the creation of devices that are not only highly functional but also compatible with biological systems. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding and controlling these key physicochemical properties—biocompatibility, biodegradability, and mechanical robustness—is fundamental to developing reliable and effective biosensing platforms. This document details the core principles, quantitative relationships, and standardized protocols for optimizing these properties specifically for biosensor applications, providing a scientific framework for innovative research and development.

Fundamental Properties of Silk Fibroin Hydrogels

Molecular Basis of Key Properties

The exceptional properties of silk fibroin stem from its unique molecular architecture. The protein consists of a heavy chain (~390 kDa) and a light chain (~26 kDa) linked by a single disulfide bond [2] [11]. The heavy chain contains 12 hydrophobic repetitive domains rich in glycine (∼45%), alanine (∼30%), and serine (∼12%), which are interspersed with 11 hydrophilic non-repetitive domains [2]. The hydrophobic domains, particularly those with the GAGAGS peptide sequence, self-assemble into crystalline β-sheets that act as physical cross-links [12] [11]. This structure results in a natural block copolymer that provides mechanical strength through the β-sheet crystals, while the amorphous regions contribute to elasticity and toughness [11]. This hierarchical structure is the foundation for the tunable properties of SF hydrogels.

The table below summarizes the key physicochemical properties of silk fibroin hydrogels relevant to biosensor fabrication.

Table 1: Key Physicochemical Properties of Silk Fibroin Hydrogels for Biosensing

| Property | Molecular & Structural Basis | Typical Range/Value | Tunability Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biocompatibility | Purification via degumming to remove immunogenic sericin; natural protein structure [2] [13]. | Low immunogenicity; supports cell adhesion & proliferation [2] [12]. | Sericin removal efficiency [2]; cross-linking method (chemical residues can cause cytotoxicity) [14]. |

| Biodegradability | Enzymatic hydrolysis by proteases (e.g., protease XIV, α-chymotrypsin) cleaving protein backbone into amino acids [2] [12]. | Days to years, depending on β-sheet content and cross-linking density [2] [13]. | β-sheet content (higher content slows degradation) [2] [12]; cross-linking density [12]. |

| Mechanical Robustness | β-sheet crystallites acting as physical cross-links; nanofibrillar network [2] [11]. | Young's Modulus: ~0.01-0.1 MPa (conventional) up to 6.5 ± 0.2 MPa (high-strength formulations) [15]. | Protein concentration [15]; cross-linking method & density [14]; secondary structure content [12]. |

Experimental Protocols for Characterization

Protocol: Assessing In Vitro Biodegradation

This protocol determines the degradation profile of SF hydrogel films, which is critical for predicting biosensor functional lifetime.

Research Reagent Solutions & Materials:

- Silk Fibroin Hydrogel Film: Sample of known dimensions and mass.

- Protease XIV Solution: 1.0 U/mL protease XIV in 0.1 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.4 [2].

- Control PBS: 0.1 M PBS, pH 7.4, without enzymes.

- Water Bath: Maintained at 37°C.

- Analytical Balance.

Procedure:

- Initial Mass (W₀): Pre-weigh the dry SF hydrogel film sample accurately using an analytical balance.

- Incubation: Place the sample in a vial containing 10 mL of the pre-warmed Protease XIV Solution. For a negative control, incubate a separate sample in 10 mL of Control PBS.

- Agitation & Sampling: Place vials in the 37°C water bath with constant, gentle agitation. At predetermined time intervals (e.g., daily for the first week, then weekly), remove the sample from the enzymatic solution.

- Rinsing & Drying: Rinse the sample thoroughly with deionized water to halt enzymatic activity and remove salts.

- Dry Mass Measurement (Wₐ): Lyophilize or dry the sample to a constant weight and record the dry mass.

- Calculation: Calculate the remaining mass percentage at each time point: Remaining Mass (%) = (Wₐ / W₀) × 100.

- Data Analysis: Plot Remaining Mass (%) versus time to generate a degradation profile. The half-life of the film can be extrapolated from this curve.

Protocol: Determining Mechanical Properties via Uniaxial Compression

This protocol characterizes the mechanical robustness, specifically the compressive modulus, of SF hydrogel films.

Research Reagent Solutions & Materials:

- Hydrated SF Hydrogel Film: Cut into a standardized cylinder (e.g., 10 mm diameter, 5 mm height).

- Universal Mechanical Testing System equipped with a calibrated load cell and parallel plate geometry.

- PBS Buffer: To keep the sample hydrated during testing.

Procedure:

- Hydration: Equilibrate the SF hydrogel sample in PBS for at least 24 hours before testing to ensure full hydration.

- Mounting: Carefully center the hydrated sample on the lower plate of the testing system. Bring the upper plate into light contact with the sample surface to define zero position and preload.

- Compression Test: Compress the sample at a constant strain rate (e.g., 1 mm/min) until a predetermined strain (e.g., 60%) or failure is reached.

- Data Collection: Record the force and displacement data throughout the test.

- Analysis: Convert force-displacement data to a stress-strain curve.

- Stress (σ) = Force (F) / Original Cross-sectional Area (A₀)

- Strain (ε) = Change in height (ΔH) / Original height (H₀)

- Modulus Calculation: The Compressive Modulus (Young's Modulus) is determined from the slope of the initial linear region of the stress-strain curve (typically between 10-20% strain) [15].

Property Interrelationships and Biosensor Design

The three core properties are not independent; they are intrinsically linked through the underlying structure of the SF hydrogel. The following diagram illustrates the strategic balance between β-sheet content and these key properties, which is central to biosensor design.

Diagram 1: Property balance for biosensor design.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Cross-Linking Methods for Tunable Properties

The method used to induce gelation and form the SF hydrogel network is a critical design choice that directly impacts all key properties. The table below compares common techniques.

Table 2: Cross-Linking Methods for Silk Fibroin Hydrogels

| Method | Mechanism | Advantages | Disadvantages for Biosensing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical (e.g., Sonication, Shear) [14] | Induction of β-sheet formation via energy input (ultrasound, vortex) [14]. | Rapid; no chemical cross-linkers, high biocompatibility [14]. | Can be difficult to control uniformly; may produce weaker gels. |

| Chemical (e.g., Genipin) [14] | Covalent bonds between amino acid side chains. | Rapid gelation; stable, strong networks [12] [14]. | Potential cytotoxicity from residual cross-linkers [12] [14]. |

| Enzymatic (e.g., HRP) [8] [14] | Enzyme-mediated (e.g., Horseradish Peroxidase) radical coupling. | Highly biocompatible; mild reaction conditions; elastic gels [8] [14]. | Can be time-consuming; cost of enzymes [12]. |

| Photo-Crosslinking [8] [14] | Radical polymerization initiated by light and a photo-initiator (e.g., Riboflavin). | Rapid; excellent spatiotemporal control; efficient [8] [12]. | Potential cytotoxicity of photo-initiators (mitigated by using biocompatible ones like Riboflavin) [8] [12]. |

Advanced Functionalization for Biosensing

Moving beyond the base material, functionalization is key to creating a responsive biosensor. A core-shell architecture is a advanced strategy to decouple mechanical requirements from biosensing functions. The diagram below outlines the workflow for creating such a functionalized biosensor strip.

Diagram 2: Biosensor strip fabrication workflow.

Protocol: Fabrication of a Core-Shell SF Hydrogel Biosensor Strip

This protocol leverages a core-shell design to integrate mechanical robustness with high-sensitivity biosensing [16].

Research Reagent Solutions & Materials:

- Purified SF Solution: ≥15% w/v for core; ~4-6% w/v for shell [16].

- Functional Fusion Protein: e.g., BC-MAP (B and C domains of Protein A fused to a Mussel Adhesive Protein) [16].

- Photo-initiator: Riboflavin (Vitamin B2) solution [8].

- Antibody Solution: The specific immunoglobulin for the target analyte.

- UV Light Source: ~365-470 nm wavelength.

- Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) Mold: With micro-scale features for the biosensor strip.

Procedure:

- Core Hydrogel Precursor: Mix high-concentration SF solution (≥15% w/v) with Riboflavin photo-initiator.

- Core Molding & Cross-linking: Pour the core precursor into a PDMS mold. Expose to visible/UV light to form a physically robust, cross-linked core hydrogel.

- Shell Hydrogel Precursor: Mix lower-concentration SF solution (~4-6% w/v) with the BC-MAP fusion protein and Riboflavin.

- Shell Application & Bonding: Apply the shell precursor over the core structure. A second, brief photo-cross-linking step forms the shell and covalently bonds it to the core via di-tyrosine coupling facilitated by the MAP domain [16].

- Antibody Immobilization: Incubate the core-shell hydrogel strip in a solution of the specific antibody. The BC domains in the shell will immobilize the antibodies via high-affinity binding [16].

- Biosensor Operation: Upon exposure to the sample containing the target analyte, the analyte binds to the immobilized antibody, leading to a measurable signal (e.g., optical, electrochemical).

This structured approach to understanding, characterizing, and functionalizing silk fibroin hydrogels provides a solid foundation for developing the next generation of sophisticated and reliable biosensor strips.

Silk fibroin hydrogels have garnered significant interest in the biomedical field, particularly for advanced applications such as biosensor strip fabrication, due to their remarkable biocompatibility, tunable mechanical properties, and biodegradability [2]. The core process that transforms aqueous silk fibroin solutions into solid-like hydrogels is gelation, a phase transition critically governed by the formation of β-sheet structures and various cross-linking mechanisms [7] [2]. For biosensor films, precisely controlling this process is paramount, as it directly determines the film's mechanical integrity, porosity, and stability in aqueous environments. This document details the underlying gelation mechanisms and provides standardized protocols for fabricating silk fibroin hydrogels with properties tailored for biosensing applications, providing a vital resource for researchers and drug development professionals.

Gelation Mechanisms and Cross-linking Strategies

The gelation of silk fibroin can be initiated through physical, chemical, or enzymatic means, all of which ultimately promote the conformational transition of the protein chains from random coils or silk I structures to insoluble β-sheet crystallites [2] [17]. These β-sheet domains act as physical cross-links, anchoring the three-dimensional network of the hydrogel.

Table 1: Primary Gelation Mechanisms for Silk Fibroin Hydrogels

| Mechanism Type | Key Features | Impact on β-Sheet Formation | Advantages for Biosensors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Cross-linking (e.g., Sonication, Solvent Exchange, CO₂ Treatment) | Relies on non-covalent interactions; often initiated by altering pH, temperature, or ionic strength [2] [17]. | Induces self-assembly of hydrophobic domains into β-sheet crystallites that act as physical cross-links [2]. | High biocompatibility; avoids chemical residues; process can be mild and controllable [8]. |

| Chemical Cross-linking (e.g., Genipin, Glutaraldehyde) | Uses cross-linking agents to form covalent bonds between amino acid side chains (e.g., primary amines) [17]. | Can be designed to occur before or after β-sheet formation, significantly affecting final mechanics and morphology [17]. | Enhances mechanical strength and stability; allows for precise tuning of cross-link density [17]. |

| Photo-Cross-linking (e.g., Riboflavin) | A specific chemical method using a photo-initiator (e.g., Riboflavin) and light exposure to create covalent bonds [8] [18]. | The cross-linked network can template subsequent β-sheet formation, leading to a dual-network hydrogel [8]. | Enables spatial and temporal control; rapid gelation (e.g., ≤15 min); suitable for patterning sensor strips [8] [18]. |

| Enzymatic Cross-linking (e.g., Horseradish Peroxidase) | Uses enzymes to catalyze the formation of covalent bonds between tyrosine residues [8]. | Compatible with β-sheet formation; can be performed under physiological conditions. | High biocompatibility; gelation rate can be programmed [8]. |

The Role of β-Sheet Crystallites

The fundamental structural units of silk fibroin are β-sheet crystallites, primarily formed by the hydrophobic domains of the heavy fibroin chains rich in glycine, alanine, and serine repeats [2]. During gelation, these regions self-assemble through intermolecular and intramolecular interactions, including hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic effects, creating stable, water-insoluble nodes within the hydrogel network [2] [17]. The content and size of these β-sheet domains are the primary determinants of the hydrogel's mechanical properties, degradation rate, and swelling behavior. A higher degree of β-sheet crystallinity generally results in stiffer and more stable hydrogels but may also increase brittleness [2] [17].

Synergistic and Dual-Network Strategies

Advanced hydrogel designs for biosensors often employ synergistic or dual-network strategies to overcome the limitations of single-mechanism systems. A prominent example is the silk fibroin-sericin dual-network hydrogel. In this system, sericin, a hydrophilic protein naturally cocooned with fibroin, is incorporated to form a second network. Sericin's random coil structure and hydrophilic groups significantly improve the hydrogel's toughness and elasticity, mitigating the brittleness often associated with high β-sheet content fibroin networks [8] [18]. Furthermore, the chronology of cross-linking events can be engineered for precise property tuning. As demonstrated in [17], performing genipin-mediated chemical cross-linking after high-pressure CO₂-induced β-sheet gelation anchors the amorphous regions of the protein chains, resulting in a stiffer hydrogel compared to chemical cross-linking before gelation.

Quantitative Data on Hydrogel Properties

The properties of silk fibroin hydrogels can be finely tuned by varying the fabrication parameters, as illustrated by the following quantitative data extracted from recent studies.

Table 2: Tunable Properties of Silk Fibroin-Based Hydrogels

| Hydrogel System | Gelation Time | Maximum Stress / Young's Modulus | Strain at Break / Swelling | Key Tuning Parameter |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SF-Seri/RB Dual-Network [8] [18] | ≤ 15 minutes | 54 kPa (Stress) | 168% (Strain) | Sericin content; higher content accelerates gelation and improves toughness. |

| SH/SS Blend Hydrogel (Sulfhydrylated HA/SF) [19] | 0.4 to 32 hours | 1.2 - 10.9 kPa (Young's) | N/A | SH/SS mass ratio; higher SS content increases modulus and degradation resistance. |

| Genipin-Cross-linked SF [17] | N/A | Stiffness highly tunable | N/A | Order of cross-linking; Genipin after β-sheet formation yields a stiffer gel. |

| PVA/GL Dual-Network (Illustrative Composite) [20] | N/A | Tensile strength increased 3.18x | N/A | Glycerol (GL) content (50% optimal for strength). |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Fabrication of a Photo-Cross-linked SF-Seri Dual-Network Hydrogel for pH-Visual Sensing

This protocol is adapted from [8] [18] and is highly relevant for creating biosensor strips with a visual readout, such as for urine pH monitoring.

4.1.1 Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Photo-Cross-linked SF-Seri Hydrogel

| Reagent/Material | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| Bombyx mori Cocoons | Source of native silk proteins (fibroin and sericin). |

| Sodium Carbonate (Na₂CO₃) | Degumming agent for the controlled removal of sericin. |

| Riboflavin (RB) | Biocompatible photo-initiator; cross-links under visible light. |

| Natural Anthocyanin (Cy) | pH-responsive dye; extracted from red cabbage for visual color change. |

4.1.2 Step-by-Step Procedure

One-Step SF-Seri Mixed Solution Preparation:

- Degum Bombyx mori cocoons in a sodium carbonate solution (concentration and time are critical tuning parameters).

- Precisely control the degumming process to achieve a tunable sericin retention, resulting in an aqueous SF-Seri mixed solution without the need for separate extraction and purification [8] [18].

Precursor Solution Preparation:

- Adjust the concentration of the SF-Seri solution to the desired level (e.g., 10 wt% fibroin).

- Add Riboflavin (RB) to the solution. An RB concentration of at least 1 mM is typically required for effective cross-linking [18].

- Incorporate natural anthocyanin (Cy) extract, optimizing the loading process for a clear and distinct colorimetric response to pH changes.

- Systematically optimize parameters including sericin content, precursor solution pH, and RB concentration.

Photo-Induced Gelation:

- Pipette the precursor solution into the desired mold (e.g., a biosensor strip format).

- Expose the solution to visible light irradiation. Under optimized conditions, gelation can occur within 15 minutes [8].

- Control the irradiation time to fine-tune the cross-linking density and the resulting hydrogel's mechanical properties and swelling ratio.

Protocol 2: Tunable Gelation via Combined Physical and Chemical Cross-linking

This protocol, based on [17], highlights how the sequence of cross-linking events can be used to precisely control the viscoelastic properties of the final hydrogel, which is crucial for the mechanical flexibility of biosensor strips.

4.2.1 Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Materials for Genipin-Tuned SF Hydrogel

| Reagent/Material | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| Degummed Silk Fibroin Fibers | The primary structural protein polymer. |

| Lithium Bromide (LiBr) | Solvent for dissolving silk fibroin fibers. |

| Genipin | Biocompatible chemical cross-linker that reacts with primary amines. |

| High-Pressure CO₂ Reactor | Equipment for controlled physical gelation via pH reduction. |

4.2.2 Step-by-Step Procedure

Silk Fibroin Solution Preparation:

- Degum silk cocoons twice in Na₂CO₃ solution (e.g., 1.1 and 0.4 g/L) at 98°C to remove sericin completely [17].

- Dissolve the degummed silk fibroin fibers in 9.3 M LiBr at 65°C.

- Dialyze the solution against deionized water using a Slide-A-Lyzer cassette (3.5K MWCO) to remove the salt.

- Determine the protein concentration via spectrophotometry and adjust to the working concentration (e.g., 3-4% w/v).

Cross-linking Chronology Strategy:

- Path A: Chemical Cross-linking BEFORE Physical Gelation

- Add Genipin (e.g., 1 mM final concentration) to the fibroin solution and allow it to react. This increases the molecular weight of the protein in solution.

- Subsequently, induce physical gelation via high-pressure CO₂ treatment (e.g., 60 bar) to form β-sheet crystals. This pathway results in a hydrogel with altered gel morphology and a decreased stiffness response [17].

- Path B: Chemical Cross-linking AFTER Physical Gelation

- First, induce physical gelation by subjecting the pure fibroin solution to high-pressure CO₂ treatment to form the β-sheet network.

- Then, immerse the pre-formed physical hydrogel in a Genipin solution to covalently anchor the amorphous regions of the protein chains. This pathway yields a hydrogel with significantly increased stiffness [17].

- Path A: Chemical Cross-linking BEFORE Physical Gelation

Application in Biosensor Strip Fabrication: Concluding Remarks

The controlled formation of β-sheets and the strategic application of cross-linking methods are the cornerstones of engineering functional silk fibroin hydrogel films for biosensing. The protocols outlined herein provide a framework for fabricating hydrogels with bespoke mechanical properties, gelation kinetics, and integrated smart functions, such as visual pH response. The SF-Seri/RB dual-network system is particularly promising for disposable diagnostic strips due to its rapid gelation, robust mechanics, and ease of functionalization. For ongoing research, focusing on the long-term stability of these hydrogels in various biological fluids, the reproducibility of large-scale manufacturing, and the integration of additional sensing modalities (e.g., electrochemical detection) will be critical steps toward translating silk fibroin hydrogel biosensors from the laboratory to clinical and commercial applications.

Inherent Advantages over Collagen and Synthetic Polymers for Biosensing

Silk fibroin (SF), a natural protein polymer derived from Bombyx mori silkworm cocoons, has evolved from its traditional textile applications to become a leading material in the biomedical field. Its unique combination of remarkable mechanical properties, excellent biocompatibility, and flexible processability positions it as a superior alternative to both natural polymers like collagen and synthetic polymers for advanced biosensing applications [21] [2]. In the context of biosensor development, particularly for hydrogel film strip fabrication, SF's tunable molecular structure and abundant functional groups enable the creation of highly sensitive, stable, and adaptable sensing platforms that outperform conventional materials.

SF's structural backbone, comprised of hydrophobic repetitive domains rich in glycine, alanine, and serine that form stable β-sheet crystallites, and hydrophilic non-repetitive domains, is the origin of its exceptional material properties [2]. This hierarchical structure can be precisely engineered through various processing methods to yield hydrogels, films, and other morphologies ideal for biosensor fabrication. Unlike many synthetic polymers, SF is sustainable, biodegradable, and offers a robust clinical heritage through its long-standing use as an FDA-approved suture material [21]. For researchers and drug development professionals, these attributes translate into reliable, high-performance biosensing platforms capable of everything from point-of-care diagnostics to continuous physiological monitoring.

Comparative Material Advantages

The selection of a substrate material is fundamental to biosensor performance, influencing everything from signal transduction and bioreceptor immobilization to biocompatibility and operational lifetime. Silk fibroin presents a compelling set of advantages when directly compared to two widely used material categories: the natural polymer collagen and various synthetic polymers.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Biosensing Substrate Materials

| Property | Silk Fibroin (SF) | Collagen | Synthetic Polymers (e.g., PDMS, PANI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tensile Strength | High (up to 600 MPa in native fiber) [2] | Low (weak, gels easily) | Variable (PDMS: very low; PANI: moderate) [22] |

| Young's Modulus | Tunable, high toughness (70 MJ m⁻³) [2] | Low, soft | Variable |

| Biodegradability | Controllable (days to months) [21] [2] | Rapid, uncontrollable | Typically non-biodegradable [22] |

| Biocompatibility | Excellent, immunologically inert [2] | Good, but can elicit immune response | Varies, often poor (inflammatory responses) [22] |

| Structural Stability in Aqueous Environments | High (can be enhanced via oriented crystallization) [23] | Low (swells, mechanically weak) | Hydrophobic or unstable swelling |

| Processability & Functionalization | High (abundant -OH, -COOH groups for modification) [8] [2] | Moderate | Low to Moderate (often requires complex surface treatments) [22] |

| Optical Properties | Optically transparent, suitable for imaging [21] | Transparent | Often opaque |

| Cost & Source | Abundant, low-cost source [2] | High-cost, mammalian extraction | Low-cost, petroleum-based |

Advantages over Collagen

- Superior Mechanical Robustness: SF's mechanical strength and toughness far exceed those of collagen, which is typically weak and forms soft gels. This inherent strength allows for the fabrication of durable, freestanding biosensor strips that can withstand handling and operational stresses without deformation or failure [2]. This is a critical advantage for wearable or implantable sensor designs.

- Tunable and Predictable Degradation: A significant limitation of collagen is its rapid and relatively uncontrollable degradation profile. In contrast, the degradation rate of SF can be precisely engineered from days to months by modulating the crystalline β-sheet content during processing [21] [2]. This tunability ensures that the biosensor platform remains structurally intact for the required duration of its application, preventing premature functional failure.

- Enhanced Aqueous Stability: SF-based materials, particularly those engineered with oriented crystallization (OC), demonstrate remarkable stability in aqueous and in vivo environments, resisting the rapid swelling and structural disintegration that can plague collagen-based sensors [23]. This property is paramount for maintaining the integrity of the imprinted sensing cavities and conductive pathways in hydrogel film strips during operation.

Advantages over Synthetic Polymers

- Exceptional Biocompatibility and Biointegration: Unlike synthetic polymers like poly(dimethylsiloxane) (PDMS) or polyaniline (PANI), which can provoke inflammatory responses and fibrotic encapsulation, SF is highly biocompatible and immunologically inert [2] [22]. This promotes seamless integration with biological tissues, minimizes the foreign body response, and ensures accurate signal acquisition in vivo by reducing biofouling.

- Sustainable and Biodegradable Platform: SF is a natural, biodegradable polymer, addressing growing concerns about electronic waste and environmental sustainability associated with non-biodegradable synthetic polymers [22]. Its production from renewable resources aligns with green chemistry principles and is a key advantage for developing next-generation, environmentally responsible diagnostic devices.

- Facile Functionalization and ECM-Mimicry: SF's molecular structure presents abundant functional groups (e.g., hydroxyl, carboxyl) that facilitate straightforward chemical modification and covalent immobilization of biorecognition elements (e.g., antibodies, enzymes) [8] [2]. Furthermore, SF hydrogels can be engineered to closely mimic the biochemical and mechanical properties of the native extracellular matrix (ECM), providing a more physiologically relevant microenvironment for cell-based sensing than most synthetic substrates [21].

Application Notes for Biosensor Fabrication

SF Hydrogel Film Strip for Electrochemical Detection

The integration of SF hydrogel films with electrochemical transducers creates a powerful platform for label-free biosensing. Molecularly Imprinted Polymer (MIP) composites can be incorporated into the SF matrix to create highly selective recognition sites for specific analytes.

Table 2: Performance Metrics of a Representative SF-Based MIP Biosensor for Collagen Peptides

| Parameter | Performance Value |

|---|---|

| Detection Principle | Electrochemical (Current Response) |

| Target Analyte | Collagen Peptides |

| Linear Detection Range | 0.1 – 1000 µg/mL [24] |

| Limit of Detection (LOD) | 1.01 µg/mL [24] |

| Limit of Quantification (LOQ) | 4.46 µg/mL [24] |

| Sensitivity | 8.38 (Current vs. Concentration) [24] |

| Correlation Coefficient (R²) | 0.9436 [24] |

A key application is the detection of collagen peptides, which are critical biomarkers for degenerative musculoskeletal diseases [24]. An SF-MIP composite sensor demonstrated a wide detection range and high sensitivity, offering a rapid and cost-effective alternative to traditional methods like ELISA or HPLC.

Smartphone-Integrated Optical SF Biosensor

SF's optical transparency and capacity for functionalization make it an excellent material for optical biosensors that can be integrated with smartphone-based detection systems. These systems leverage the smartphone's camera as a detector and its processor for data analysis, enabling powerful point-of-care diagnostics [25].

A notable example is a pH-visualized SF-sericin composite hydrogel for urinary health monitoring [8]. This system uses natural anthocyanin extracted from red cabbage as a pH-responsive dye incorporated into the SF hydrogel. Upon contact with urine, the hydrogel displays distinct color changes corresponding to pH levels: green for the normal range, and reddish-purple or blue for abnormal acidity or alkalinity, serving as a visual warning [8]. This platform demonstrates excellent mechanical properties (maximum stress of 54 kPa, strain of 168%) and high water absorption (566%), making it ideal for integration into wearable products like smart diapers for vulnerable populations [8].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Fabrication of a Basic Silk Fibroin Hydrogel Film

This protocol details the foundational process for creating a stable, free-standing SF hydrogel film, which can serve as a substrate for various biosensing applications [2] [23].

Objective: To prepare a pure, biocompatible SF hydrogel film with tunable mechanical properties and degradation kinetics.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Material | Function/Note | Supplier Example |

|---|---|---|

| Bombyx mori Cocoons | Raw source of Silk Fibroin | Commercial supplier |

| Sodium Carbonate (Na₂CO₃) | Degumming agent to remove sericin | Sigma-Aldrich |

| Lithium Bromide (LiBr) | Chaotropic salt for dissolving degummed SF | Sigma-Aldrich |

| Slide-A-Lyzer Dialysis Cassettes (MWCO 3,500) | Removal of salts and small impurities | Pierce, Thermo Fisher |

| Riboflavin (Vitamin B₂) | Biocompatible photo-initiator for cross-linking | Sigma-Aldrich |

| Deionized Water | Solvent for all aqueous steps | N/A |

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Degumming: Boil 5 grams of Bombyx mori cocoons in 2 liters of 0.02 M sodium carbonate (Na₂CO₃) solution for 30 minutes to dissolve and remove the sericin gum. Rinse the resulting SF fibers thoroughly with copious amounts of deionized water and air-dry for 12 hours [2] [23].

- Dissolution: Dissolve the degummed SF fibers in a 9.3 M lithium bromide (LiBr) solution at 60°C for 4 hours with continuous stirring to achieve a complete dissolution of the SF protein [23].

- Dialysis: Transfer the SF/LiBr solution into a dialysis cassette (MWCO 3,500) and dialyze against deionized water for 48 hours to remove the LiBr salt. Change the water frequently. The solution will become slightly opaque during this process.

- Concentration & Purification: Centrifuge the dialyzed SF solution at 9,000 rpm for 20 minutes at 4°C to remove any aggregates and impurities. Collect the supernatant, which is the purified aqueous SF solution. The concentration can be determined by weighing the solid residue after drying a known volume and is typically adjusted to 6-8% (w/v) for film casting.

- Film Casting & Cross-linking: Pour the SF solution into a polystyrene Petri dish. For photo-cross-linking, add 0.1% (w/v) riboflavin to the solution and expose to visible light for 15-30 minutes to induce gelation and stabilize the hydrogel network [8]. Alternatively, physical cross-linking can be induced by leaving the cast solution in a fume hood for 24-48 hours, which promotes β-sheet formation.

- Post-processing: Once gelled, the SF hydrogel film can be carefully peeled from the mold. It may be further treated with methanol or autoclaving to increase β-sheet content and thus, mechanical strength and stability.

Protocol: Fabrication of an SF-Based MIP Electrochemical Biosensor Strip

This protocol builds upon the basic SF film fabrication to create a specific, sensitive biosensor for a target analyte, such as collagen peptides [24].

Objective: To fabricate a screen-printed electrode (SPE) modified with an SF-MIP composite for the electrochemical detection of collagen peptides.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Prepare Pre-polymer Mixture: In a microtube, combine the following to form a homogeneous pre-polymer solution:

- Monomer: Hydroxyproline and an amino acid standard (e.g., AAS18 from Sigma-Aldrich).

- Initiator: Azobisisobutyronitrile (AIBN), 1.5 mg (5 mg/mL).

- Cross-linker: N,N′-(1,2-dihydroxyethylene)bisacrylamide (DHEBA), 47 mg.

- Auxiliary Cross-linker: Glutaraldehyde (GA), 9.4 µL.

- Solvent: Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), 300 µL.

- Heat the mixture at 80°C for 30 minutes with stirring, then cool to room temperature [24].

- Modify the Working Electrode: Deposit a precise volume (e.g., 5 µL) of the pre-polymer solution onto the carbon working electrode surface of a commercial SPE, ensuring complete coverage.

- Template Imprinting: Add 1-2 µL of the target template (e.g., 1 mg/mL collagen peptide solution) onto the coated electrode.

- Polymerization: Place the modified SPE in a UVA chamber and expose to 365 nm wavelength light for 3 hours to complete the polymerization process and "lock in" the molecular imprints [24].

- Template Removal: Wash the polymerized SF-MIP/SPE thoroughly with a suitable buffer (e.g., Phosphate Buffered Saline, PBS) and a mild detergent solution to remove the embedded collagen peptide templates, thereby creating the specific recognition cavities.

- Sensor Validation: Characterize the sensor using electrochemical techniques such as Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) or amperometry by measuring the current response across a range of collagen peptide concentrations (e.g., 0.1–1000 µg/mL) to establish a calibration curve [24].

Visualization of the SF Biosensing Mechanism

The high performance of SF-based biosensors stems from the synergistic relationship between its material properties and the integrated sensing mechanism, as illustrated below.

From Solution to Sensor: Fabrication Techniques and Functional Applications

Regenerated silk fibroin (RSF) has emerged as a premier biomaterial for fabricating advanced biosensing platforms, such as hydrogel film-based biosensor strips, due to its exceptional biocompatibility, tunable mechanical properties, and excellent optical clarity [26] [27]. The performance of these biosensors is intrinsically linked to the molecular weight, structural integrity, and purity of the underlying RSF. This application note details a standardized workflow for the preparation of high-quality RSF, with a specific focus on methodologies that enhance the material's properties for biosensing applications. The protocols herein are designed to provide researchers with reliable and reproducible techniques to obtain RSF that forms robust, stable, and sensitive hydrogel films.

The journey from raw silk cocoons to a pure regenerated silk fibroin solution suitable for hydrogel film biosensors involves three critical stages: degumming, dissolution, and purification. The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow, highlighting key steps and decision points.

Detailed Protocols and Data Comparison

Degumming: Sericin Removal

The primary objective of degumming is to remove the sericin gum that binds silk filaments, which can cause immunogenic responses in biomedical applications [28]. The choice of degumming method significantly impacts the molecular weight and integrity of the final fibroin.

Protocol 1: Traditional Alkaline Degumming with Na₂CO₃ [29] [30]

- Procedure: Boil 5 g of raw silk cocoons in 500 mL of 0.02 M sodium carbonate (Na₂CO₃) solution for 30 minutes under constant stirring.

- Rinsing: Thoroughly rinse the degummed silk fibers with copious amounts of ultrapure water (≥ 5 times) to remove residual sericin and alkali.

- Drying: Air-dry the cleaned fibers overnight at room temperature.

- Output: The mass loss should be approximately 25-30%, corresponding to the sericin content. A higher mass loss (e.g., >30%) may indicate fibroin degradation.

Protocol 2: Rapid Microwave-Assisted Degumming [29]

- Reagent Preparation: Prepare a solution containing an anionic detergent like sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS).

- Procedure: Submerge raw silk in the SDS solution and subject it to repeated short-term cycles of microwave irradiation.

- Rinsing and Drying: As in Protocol 1, rinse thoroughly with ultrapure water and air-dry.

- Output: This gentler method yields a mass loss of ~32.8% and, crucially, preserves high-molecular-weight fibroin chains (evidenced by a distinct band at 350 kDa on SDS-PAGE), unlike the standard method which shows degradation.

Table 1: Comparison of Silk Fibroin Degumming Methods

| Method | Key Reagents | Conditions | Processing Time | Impact on SF | Key Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Alkaline [29] [30] | 0.02 M Na₂CO₃ | 100°C, 30-60 min | ~1-2 hours | Higher degradation; reduced MW | Mass loss ~35.6%; effective sericin removal |

| Rapid Microwave [29] | SDS, Microwave | Microwave irradiation, short cycles | < 1 hour | Minimal degradation; preserves high MW | Mass loss ~32.8%; superior fibroin integrity |

| Urea-Based [30] | Concentrated Urea | Moderate temperature | Varies | Higher MW and crystallinity | Gentler alternative to alkali |

| Enzymatic [30] | Protease | 50–65°C | Varies (often slow) | High specificity, minimal damage | Preserves native structure; slow degumming rate |

Dissolution: Solubilizing Degummed Fibroin

Dissolution breaks down the hydrogen-bonded crystalline structure of degummed silk fibroin to produce a regenerated silk fibroin (RSF) solution.

Protocol 1: Dissolution using Lithium Bromide (LiBr) [28] [30]

- Procedure: Dissolve 1 g of degummed silk fibers in 4 mL of 9.3 M lithium bromide (LiBr) solution.

- Incubation: Incubate the mixture at 60°C for 4 hours in a water bath with constant stirring until the fibers are completely dissolved.

- Output: A clear, viscous RSF-LiBr solution.

Protocol 2: Rapid Dissolution using Zinc Chloride (ZnCl₂) [29]

- Procedure: Incubate 1 g of degummed silk in 10 mL of a 56% (w/w) zinc chloride (ZnCl₂) solution.

- Incubation: Stir constantly at a lower temperature of 45°C for 1 hour until a clear solution is obtained.

- Output: A clear RSF-ZnCl₂ solution. This method can achieve concentrations up to 10% (w/v) and is notably faster and gentler.

Table 2: Comparison of Silk Fibroin Dissolution Systems

| Solvent System | Composition | Conditions | Processing Time | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lithium Bromide (LiBr) [28] [30] | 9.3 M LiBr in H₂O | 60°C, 4 hours | ~4 hours | Well-established, reliable |

| Zinc Chloride (ZnCl₂) [29] | 56% (w/w) ZnCl₂ in H₂O | 45°C, 1 hour | ~1 hour | Fast, low temperature, minimal degradation |

| Ajisawa's Reagent [29] [30] | CaCl₂ : EtOH : H₂O (1:2:8 molar ratio) | 65°C, 3 hours | ~3 hours | Effective for many applications |

| Calcium Nitrate/Methanol [29] | Ca(NO₃)₂ / CH₃OH | Not specified | Not specified | Alternative salt system |

| Phosphoric Acid [30] | Concentrated H₃PO₄ | Room temperature | Varies | Produces tunable nanostructures |

Purification: Desalting and Final Preparation

Purification removes the dissolution salts to yield a pure, aqueous RSF solution. This step is critical as residual salts can interfere with downstream processing, such as hydrogel cross-linking and biosensor function.

Protocol 1: Traditional Dialysis [28] [31]

- Setup: Load the viscous RSF-salt solution into a dialysis tubing (MWCO: 12-14 kDa).

- Dialysis: Dialyze against a large volume of ultrapure water for 2-3 days. Change the water frequently (e.g., every 6-8 hours for the first day, then every 12 hours) to ensure efficient salt removal.

- Concentration: The dialyzed RSF solution is often too dilute for direct use. Concentrate it using osmotic dehydration against polyethylene glycol (PEG) or via ultrafiltration to a desired concentration (e.g., 5-10% w/v) [26].

- Clarification: Centrifuge the concentrated solution at 8,911 × g for 10 minutes to remove any insoluble debris or aggregates [31]. The supernatant is the final purified RSF solution.

Protocol 2: Rapid Gel Filtration (Size Exclusion Chromatography) [29]

- Setup: Use a pre-packed desalting column or prepare a gel filtration matrix suitable for the sample volume.

- Procedure: Apply the RSF-salt solution to the column and elute with ultrapure water. The high-molecular-weight RSF protein elutes in the void volume, well-separated from the low-molecular-weight salt ions.

- Output: A desalted RSF solution can be obtained in minutes to a few hours, drastically reducing processing time. The solution can then be concentrated as needed.

Table 3: Comparison of RSF Purification Techniques

| Method | Principle | Processing Time | Throughput | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dialysis [28] [31] | Diffusion across a semi-permeable membrane | 2-3 days | Low | Time-consuming; consumes large volumes of water; standard method |

| Gel Filtration [29] | Size-based separation in a column | Minutes to a few hours | Medium to High | Fast and reliable; requires specialized equipment |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Reagents for RSF Fabrication

| Reagent | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Sodium Carbonate (Na₂CO₃) [29] | Traditional alkaline degumming agent | Effective sericin removal; can degrade fibroin if conditions are harsh. |

| Lithium Bromide (LiBr) [28] | Chaotropic salt for dissolving fibroin | High dissolving power; requires lengthy dialysis for removal. |

| Zinc Chloride (ZnCl₂) [29] | Rapid, mild solvent for fibroin dissolution | Enables low-temperature, quick dissolution; compatible with fast purification. |

| Dialysis Tubing (MWCO 12-14 kDa) [28] [31] | Purification via dialysis | Retains high-MW silk fibroin while allowing salts and small molecules to diffuse out. |

| Hydroxypropyl Methylcellulose (HPMC) [31] | Additive for bioprinting bioinks | Improves rheological properties and printability of RSF solutions. |

| Glycidyl Methacrylate (GMA) [27] | Chemical modifier for photocurable RSF | Introduces methacrylate groups for UV-induced cross-linking in DLP bioprinting. |

| Riboflavin (Vitamin B₂) [8] | Biocompatible photo-initiator | Enables visible light-induced cross-linking of RSF hydrogels. |

| Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP) [26] | Enzyme for cross-linking | Catalyzes oxidative coupling of tyrosine residues in SF to form stable, chemical-free hydrogels. |

A reproducible and efficient fabrication workflow is the cornerstone of high-quality regenerated silk fibroin for advanced biosensing applications. The protocols detailed in this note provide a clear path from raw silk to pure RSF solution. The choice between traditional and rapid methods allows researchers to balance processing time against the specific molecular weight and integrity requirements of their biosensor project. The rapid microwave degumming and ZnCl₂ dissolution followed by gel filtration is particularly recommended for workflows prioritizing speed and the preservation of high-molecular-weight fibroin, which is often linked to superior mechanical properties in final hydrogel films [29]. This standardized approach ensures a reliable foundation for the subsequent development of sensitive, robust, and consistent silk fibroin-based biosensor strips.

The fabrication of robust and biocompatible biosensor strips hinges on the precise engineering of the material matrix. For silk fibroin (SF) hydrogel film biosensors, the cross-linking strategy employed directly determines critical performance parameters such as mechanical strength, swelling behavior, diffusion kinetics, and biocompatibility [32] [14]. Silk fibroin, a natural protein renowned for its exceptional biocompatibility, tunable biodegradability, and impressive mechanical properties, provides an ideal foundation for biosensing applications [33] [14]. However, realizing its full potential requires careful selection and control of the gelation process.

Cross-linking methods can be broadly categorized into physical, chemical, and enzymatic approaches. Physical gelation relies on non-covalent interactions, such as hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic forces, to induce a sol-gel transition, often through the formation of β-sheet structures [32] [15]. Chemical gelation utilizes covalent cross-linking agents to create permanent, robust networks [32] [34]. Enzymatic gelation offers a middle ground, employing biological catalysts like transglutaminase to form covalent bonds under mild, cell-friendly conditions [35] [36]. The choice of method profoundly impacts the hydrogel's microstructure and final functionality within a biosensor strip, influencing factors like analyte diffusion, signal stability, and shelf life [32]. This document provides detailed application notes and protocols for these cross-linking strategies, specifically framed within the context of silk fibroin hydrogel film biosensor fabrication.

Physical Cross-Linking Strategies

Physical cross-linking methods form hydrogel networks through non-covalent interactions, offering the significant advantage of avoiding potential cytotoxicity associated with chemical cross-linkers [32] [14]. These methods are particularly valued for their simplicity and biocompatibility.

Mechanism and Workflow

The fundamental mechanism behind physical gelation of silk fibroin involves the induction of a conformational transition from a random coil to a β-sheet structure. This transition is driven by processes that increase molecular hydrophobicity and facilitate intermolecular association, such as hydrophobic interactions and hydrogen bonding [32] [15] [14]. The resulting β-sheet crystals act as physical cross-links that connect disparate protein chains into a continuous three-dimensional network [15].

The following workflow outlines the binary solvent-induced conformation transition (BSICT) strategy, a specific physical method for producing high-strength SF hydrogels.

Protocol: Binary Solvent-Induced Conformation Transition (BSICT)

This protocol is adapted from methods producing high-strength pristine SF hydrogels, suitable for applications requiring robust mechanical performance [15].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Silk Fibroin (SF): Regenerated aqueous solution (~6-8 wt%).

- Hexafluoroisopropanol (HFIP): High purity grade.

- Deionized Water: Nuclease-free recommended for biosensor use.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Pre-processing: Begin with an aqueous SF solution (~6-8 wt%). Freeze-dry this solution to obtain solid SF.

- SF Dissolution: Dissolve the freeze-dried SF in HFIP to achieve a final SF/HFIP concentration of 15% (w/v). Ensure complete dissolution to form a homogeneous solution.

- Solvent Addition: Gently add deionized water to the SF/HFIP solution. The H₂O/HFIP volume ratio is critical. A ratio of 1.5:3 (v/v) is a typical starting point. Note: The order of addition is crucial; adding SF/HFIP into water, or other variations, will result in precipitate formation rather than a uniform hydrogel [15].

- Gelation: Mix the solution thoroughly and transfer it to a mold. Incubate the solution at a controlled temperature (e.g., 37°C) to induce gelation. Gelation time is temperature-dependent, ranging from hours at 48°C to days at room temperature [15].

- Post-processing: Once gelation is complete, wash the resulting hydrogel thoroughly with copious amounts of deionized water to remove residual HFIP solvent.

Key Parameters for Biosensor Films:

- SF Concentration: A minimum SF/HFIP ratio of 15% (w/v) is required for effective gelation [15].

- H₂O/HFIP Ratio: This ratio controls the gelation rate and the final hydrogel's morphology and transparency. A systematic investigation is recommended to optimize for specific sensor needs [15].

- Temperature: Higher temperatures accelerate gelation but may affect the size of β-sheet crystallites and optical transparency [15].

Advantages and Limitations for Biosensing

Advantages:

- High Biocompatibility: Avoids chemical cross-linkers, reducing risk of cytotoxicity and preserving bio-recognition element activity [32] [15].

- Excellent Mechanical Properties: Can produce hydrogels with high Young's modulus (up to ~6.5 MPa) [15].

- Processability: Resulting hydrogels can be machined, laser-cut, or molded into complex structures [15].

Limitations:

- Limited Control: Can be difficult to precisely control the shape and detailed properties of the hydrogel [32].

- Potential Brittleness: Some physically cross-linked SF hydrogels can be brittle, though strategies like the BSICT method aim to overcome this [15] [14].

- Gelation Kinetics: Gelation time may be long and sensitive to environmental conditions.

Chemical Cross-Linking Strategies

Chemical cross-linking creates hydrogels through the formation of covalent bonds between polymer chains. This method typically yields hydrogels with superior mechanical strength, long-term stability, and better control over network structure compared to physical methods [32] [34].

Mechanism and Workflow

Chemical cross-linking involves activating silk fibroin's reactive amino acid side chains (e.g., tyrosine, lysine) to form permanent covalent linkages. A prominent strategy is photo-cross-linking, where a photo-initiator and specific wavelengths of light are used to trigger radical polymerization or coupling reactions [34] [8]. Common modifiers include glycidyl methacrylate (GMA), which introduces polymerizable vinyl groups onto the SF backbone [34]. This results in a stable network that is often resistant to dissolution and degradation.

The workflow below illustrates the process for creating a chemically modified, photo-cross-linked SF hydrogel.

Protocol: Photo-Cross-linking of Silk Fibroin with Riboflavin

This protocol describes the use of riboflavin (Vitamin B2), a biocompatible photo-initiator, for fabricating SF hydrogels, ideal for biosensors requiring high environmental stability [34] [8].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Silk Fibroin (SF) Solution: Regenerated aqueous solution.

- Riboflavin (RB): Prepare a stock solution in deionized water (e.g., 0.1-1 mM). Protect from light.

- Optional Modifier: Glycidyl Methacrylate (GMA) for methacrylate-functionalization.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- SF Modification (Optional but common): Functionalize the SF solution with GMA to introduce methacrylate groups, following established synthesis protocols [34].

- Solution Preparation: Mix the SF (or methacrylated SF) solution with the riboflavin photo-initiator. A typical riboflavin concentration ranges from 0.05% to 0.5% (w/v) [8]. Ensure homogeneous mixing under low-light conditions.

- Cross-linking: Pour the solution into a mold or coat it onto a substrate to form a film. Expose the solution to UV light (e.g., 365 nm wavelength) for a defined period. The irradiation time and intensity must be optimized; a range of 5-30 minutes is common [8].

- Post-processing: After cross-linking, rinse the hydrogel with deionized water to remove any unreacted components.

Key Parameters for Biosensor Films:

- Photo-initiator Concentration: Affects the cross-linking density and rate. Higher concentrations can accelerate gelation but may lead to network inhomogeneity [8].

- UV Intensity and Time: Directly control the degree of cross-linking, influencing the hydrogel's mechanical strength and mesh size.

- pH: The pH of the precursor solution can influence the cross-linking kinetics and must be controlled for reproducibility [8].

Advantages and Limitations for Biosensing

Advantages:

- Enhanced Mechanical Stability: Covalent networks provide excellent mechanical strength and durability for handling and use [32] [34].

- Environmental Stability: Hydrogels exhibit stable performance in ambient conditions, a key requirement for biosensor storage and operation [34].

- Precise Spatial and Temporal Control: Photo-cross-linking allows for patterning hydrogels with high resolution, enabling the fabrication of multi-analyte sensor arrays on a single strip [34] [14].

Limitations:

- Cytotoxicity Risk: Residual chemical cross-linkers or initiators can cause toxicity, which may be detrimental if live cells or sensitive biomolecules are incorporated [32].

- Reduced Biodegradability: The formation of non-degradable covalent bonds can limit the hydrogel's biodegradability [32] [8].

- Potential for Inhomogeneity: Rapid reaction kinetics can sometimes lead to heterogeneous network structures.

Enzymatic Cross-Linking Strategies

Enzymatic cross-linking uses biologically derived catalysts to form covalent bonds between protein chains. It is considered a safe and "green" method that operates under mild physiological conditions, making it suitable for incorporating labile bioactive compounds [35] [36].

Mechanism and Workflow

The enzyme transglutaminase (TGase) is widely used for gelation. It catalyzes an acyl-transfer reaction between the γ-carboxamide group of a protein-bound glutamine residue (acyl donor) and the ε-amino group of a protein-bound lysine residue (acyl acceptor), forming an ε-(γ-glutamyl)lysine isopeptide bond [35] [36]. This reaction creates stable, covalent cross-links without the need for harsh chemicals or radiation.

The following workflow diagrams the process of creating an enzyme-cross-linked SF composite hydrogel, which can be adapted for biosensor films.

Protocol: Transglutaminase-Induced Cross-Linking

This protocol is based on methods for constructing enzyme-induced emulsion gels, which can be translated to the fabrication of homogeneous SF or SF-composite hydrogel films [35].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Protein Solution: Silk fibroin solution. It can be used alone or blended with other TGase-substrate proteins like gelatin or Whey Protein Isolate (WPI) to enhance cross-linking density [35].

- Transglutaminase (TGase): Commercial microbial transglutaminase preparation. Dissute in buffer to create a stock solution.

- Buffer: A mild buffer (e.g., PBS) at a pH optimal for TGase activity (typically near neutral).

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Solution Preparation: Prepare a homogeneous aqueous solution of SF (and other optional biopolymers like gelatin/WPI). The total protein concentration should be optimized for film formation.

- Enzyme Addition: Add the TGase enzyme to the protein solution at a specified concentration. A common ratio is 10-20 enzyme units per gram of protein, but this requires optimization [35]. Mix gently but thoroughly to ensure uniform distribution without introducing excessive air bubbles.

- Gelation: Transfer the solution to a mold and incubate at 37°C to facilitate the enzymatic reaction. Gelation time can range from minutes to several hours, depending on enzyme concentration, protein substrate availability, and total solids content.

- Enzyme Deactivation: Once gelation is complete, the enzyme can be deactivated by a brief heat treatment (e.g., 75°C for 10 minutes) if necessary to prevent ongoing cross-linking.

Key Parameters for Biosensor Films:

- Enzyme Concentration: Directly influences the cross-linking density, gelation rate, and final gel stiffness [35] [36].

- Incubation Temperature and Time: Must be carefully controlled to achieve reproducible gelation kinetics and network structure.

- Protein Composition and Concentration: The availability of glutamine and lysine residues in the protein blend determines the extent of cross-linking.

Advantages and Limitations for Biosensing

Advantages:

- High Biocompatibility: The mild, chemical-free process preserves the activity of encapsulated biomolecules (e.g., enzymes, antibodies) [35].

- Safety: Enzymes are generally recognized as safe (GRAS), making this strategy suitable for implantable or transdermal sensors [35].

- Network Homogeneity: Can produce relatively homogeneous and fine-stranded networks favorable for consistent analyte diffusion [35] [36].

Limitations:

- Cost: Enzymes can be more expensive than some chemical cross-linkers.

- Specificity: Requires the presence of specific amino acid substrates in the protein.

- Kinetic Control: Gelation rate can be sensitive to environmental conditions like pH and temperature, requiring strict process control.

Comparative Analysis and Application in Biosensors

Selecting the appropriate cross-linking strategy is a critical design decision that dictates the performance of the final silk fibroin hydrogel biosensor strip. The table below provides a consolidated comparison of the key characteristics of each method.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Cross-linking Strategies for Silk Fibroin Hydrogel Biosensor Strips

| Parameter | Physical Cross-linking | Chemical Cross-linking | Enzymatic Cross-linking |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bond Type | Non-covalent (e.g., H-bond, hydrophobic) | Covalent | Covalent (isopeptide) |

| Typical Agents | Solvent (e.g., HFIP/Water), Sonication | GMA, Glutaraldehyde, Riboflavin/UV | Transglutaminase |

| Mechanical Strength | Can be very High (e.g., ~6.5 MPa Modulus) [15] | High | Moderate to High [35] |

| Biocompatibility | High | Low to Moderate (risk of cytotoxicity) [32] | High [35] |

| Gelation Control | Low to Moderate | High (spatial/temporal with photo) [34] | Moderate |

| Stability | Reversible/Sensitive to environment | High & Irreversible [34] | High & Irreversible |

| Biosensor Application | Structurally robust, non-toxic strips | Stable, patternable strips for e-skin [34] | Strips with encapsulated bioactive elements |

Selecting a Cross-linking Strategy for Biosensor Strips

The choice of gelation method should align with the specific requirements of the biosensor application.

- For High-Strength, Durable Strips: The BSICT physical method is ideal for creating sensor substrates that must withstand significant mechanical stress [15].

- For Patternable, Environment-Stable E-Skin: Photo-chemical cross-linking is the preferred choice. It enables the fabrication of high-resolution, micropatterned sensor arrays and produces hydrogels that maintain performance in ambient conditions, as demonstrated in electronic skin (e-skin) applications [34].

- For Strips with Encapsulated Bio-recognition Elements: Enzymatic cross-linking with transglutaminase is superior when the biosensor design relies on the incorporation of labile proteins, enzymes, or antibodies within the hydrogel matrix. The mild processing conditions help preserve the biological activity of these sensitive components [35].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Silk Fibroin Hydrogel Cross-linking

| Reagent | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Silk Fibroin (SF) | Primary structural polymer for hydrogel formation. | Molecular weight, concentration, and degree of degradation affect gelation and final properties. |

| Hexafluoroisopropanol (HFIP) | Solvent for physical cross-linking via BSICT strategy. | Highly volatile and toxic; requires use in a fume hood. Order of solvent addition is critical [15]. |

| Riboflavin (Vitamin B2) | Biocompatible photo-initiator for chemical cross-linking. | Concentration and UV exposure time control cross-linking density. Solutions are light-sensitive [8]. |

| Glycidyl Methacrylate (GMA) | Chemical modifier for introducing methacrylate groups onto SF. | Allows for photo-polymerization. Reaction conditions must be controlled to maintain SF solubility [34]. |

| Transglutaminase (TGase) | Enzyme catalyst for forming covalent isopeptide cross-links. | Activity is pH and temperature dependent. Requires specific glutamine/lysine residues on the protein substrate [35]. |

| Gelatin / Whey Protein Isolate (WPI) | Supplementary biopolymers for composite enzymatic gels. | Act as additional substrates for TGase, increasing cross-linking density and modifying network architecture [35]. |

Silk fibroin (SF), a natural protein derived from Bombyx mori silkworm cocoons, has emerged as a premier biomaterial for fabricating advanced hydrogel films due to its exceptional biocompatibility, tunable biodegradability, and remarkable mechanical properties [2]. Within the context of biosensor strip fabrication, SF hydrogel films provide an ideal platform for embedding sensing elements and facilitating interaction with biological analytes. Their high water content mimics the natural extracellular matrix, while their surface can be functionalized for specific molecular recognition, making them particularly suitable for diagnostic and monitoring applications in drug development [37] [13].

The transition to advanced manufacturing techniques like 3D printing and precision molding is revolutionizing the production of these biosensor platforms. These methods enable the creation of complex, patient-specific geometries with integrated microfluidic channels and precise spatial control over functional components—features essential for next-generation, multi-analyte sensing strips [38] [39]. This document outlines standardized protocols and application notes for the advanced manufacturing of SF hydrogel films, specifically tailored for biosensing applications.

Material Properties and Preprocessing

Silk Fibroin Extraction and Preparation

The foundational step in all SF hydrogel film manufacturing is the regeneration of SF into an aqueous solution. The following protocol ensures high-quality, reproducible SF solution.

Protocol 2.1.1: Preparation of Aqueous Silk Fibroin Solution

- Objective: To extract and purify silk fibroin from Bombyx mori cocoons for hydrogel formation.

- Materials and Reagents:

- Bombyx mori cocoons (5 g)

- Sodium carbonate (Na₂CO₃), 0.02 M solution (2 L)

- Lithium bromide (LiBr), 9.3 M solution

- Deionized (DI) water

- Dialysis cassette (3.5 kDa MWCO)

- Centrifuge tubes

Procedure:

- Degumming: Cut cocoons into small pieces and boil in 0.02 M Na₂CO₃ solution for 30-45 minutes to remove sericin [13].

- Rinsing: Remove the extracted silk fibers and rinse thoroughly with DI water at least four times to eliminate sericin residues [13].

- Drying: Squeeze out excess water and allow the fibers to dry completely in a fume hood [13].

- Dissolution: Dissolve the dried silk fibers in a 9.3 M LiBr solution at 60°C for 4 hours [13].

- Dialysis: Transfer the solution to a dialysis cassette and dialyze against DI water for 48 hours at 4°C, changing the water at least five times, to remove LiBr ions [40] [13].

- Purification: Centrifuge the resulting SF solution twice at 9000 rpm for 20 minutes to remove impurities and aggregates. Optionally, filter through a 5-μm membrane [13].

- Storage: Store the pure SF solution at 4°C to retard gelation [13].

Critical Parameters:

- Degumming time directly affects the molecular weight of SF. Longer degumming times (e.g., 2 hours vs. 0.5 hours) result in lower molecular weights (e.g., ~917 kDa vs. ~1590 kDa), which in turn slows the gelation rate [40].

- The final concentration of the SF solution can be increased by dialyzing against a hygroscopic polymer like polyethylene glycol (PEG) or by using ultrafiltration.

Functionalization for Advanced Manufacturing

For biosensor applications, SF often requires modification to introduce crosslinkable groups or enhance conductivity.

Protocol 2.1.2: Methacrylation of Silk Fibroin (Sil-MA) for Photopolymerization

- Objective: To modify SF with methacrylate groups, enabling rapid photochemical crosslinking for DLP 3D printing.

- Materials: Silk fibroin solution, Glycidyl methacrylate (GMA), Dialysis equipment.

- Procedure:

- Characterization: Confirm methacrylation success and degree of substitution (22-42%) using ¹H-NMR, identifying vinyl protons at δ = 6.2–6 and 5.8–5.6 ppm [27]. FT-IR can show characteristic peaks at 951 and 1165 cm⁻¹ [27].

Table 1: Characteristics of Silk Fibroin with Varying Degumming Times

| Degumming Time | Relative Molecular Weight (kDa) | Hydrodynamic Diameter (nm) | Impact on Gelation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5 hours | 1590 ± 244 | 651.7 ± 4.7 | Fastest gelation rate |

| 1 hour | 1280 ± 143 | 152.7 ± 0.4 | Intermediate gelation rate |

| 2 hours | 917 ± 38 | 73.8 ± 0.5 | Slowest gelation rate |

Source: Adapted from [40]

Advanced Manufacturing Techniques

3D Printing of SF Hydrogels

3D printing allows for the fabrication of biosensor strips with complex geometries, integrated channels, and multi-material capabilities.

Protocol 3.1.1: Digital Light Processing (DLP) 3D Printing of Sil-MA

- Objective: To fabricate high-resolution, complex 3D structures from Sil-MA bioink for sensor architecture.

- Materials and Reagents:

- Sil-MA bioink (e.g., 20-30% w/v)

- Photoinitiator (e.g., Lithium phenyl(2,4,6-trimethylbenzoyl) phosphinate (LAP), 0.5% w/v)

- Equipment: DLP 3D printer with UV light source (~405 nm).

- Printing Procedure:

- Bioink Preparation: Mix Sil-MA with LAP photoinitiator completely and protect from light [27].

- Printing Parameters: Set UV light intensity to ~3.5 mW/cm² with an exposure time of 3-10 seconds per layer [27].

- Printing: Execute the print job based on the sliced CAD model of the biosensor design (e.g., microfluidic lattice, microneedle array).

- Post-processing: Rinse the printed structure with sterile PBS to remove any uncrosslinked material.

- Critical Parameters:

Protocol 3.1.2: Extrusion-Based 3D Bioprinting of Composite SF Inks

- Objective: To create multi-material or cell-laden sensor scaffolds using extrusion printing.

- Bioink Formulation: Common composites include SF/Gelatin/Alginate or SF/Pluronic F-127/Alginate, with SF concentrations typically ranging from 1-5% w/v [41].

- Procedure:

- Load the composite bioink into a temperature-controlled syringe.

- Set printing parameters: Nozzle gauge (20-27G), pressure (15-50 kPa), printing speed (5-15 mm/s), and bed temperature (10-25°C).

- Print the structure layer-by-layer.

- Crosslink post-printing, typically using ionic crosslinkers (e.g., CaCl₂ for alginate) or vapor-induced β-sheet formation for SF.

- Critical Parameters: Bioink rheology (viscosity, shear-thinning behavior) is crucial for printability and shape fidelity [39] [41]. Increasing SF concentration can decrease the mechanical strength of some composite blends but improves bioactivity [41].

Table 2: Comparison of 3D Printing Techniques for SF Hydrogels

| Printing Technique | Key SF Bioink | Resolution | Key Advantages | Ideal Biosensor Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Digital Light Processing (DLP) | Sil-MA [27] | ~1 μm [27] | High speed, high resolution, excellent structural stability [27] | Complex microfluidics, high-density electrode arrays |