Fluorescence and Surface Plasmon Resonance: Principles and Advancements in Optical Biosensing

This article provides a comprehensive review of the principles and applications of fluorescence- and surface plasmon resonance (SPR)-based optical biosensors, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Fluorescence and Surface Plasmon Resonance: Principles and Advancements in Optical Biosensing

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive review of the principles and applications of fluorescence- and surface plasmon resonance (SPR)-based optical biosensors, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational physics behind label-free SPR detection and sensitive fluorescence signaling, detailing their methodologies in drug discovery, clinical diagnostics, and environmental monitoring. The content addresses key challenges such as sensitivity limits and sample matrix interference, offering optimization strategies and comparative analyses of emerging technologies. Finally, it synthesizes future trajectories, including the integration of artificial intelligence, nanotechnology, and IoT for next-generation point-of-care diagnostic systems.

The Fundamental Physics of Optical Biosensors: From Light-Matter Interactions to Signal Generation

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) is a label-free optical biosensing technology that enables real-time, quantitative analysis of biomolecular interactions [1] [2]. When implemented in analytical instrumentation, SPR provides researchers with the ability to monitor binding events without requiring fluorescent or radioactive labels, making it indispensable for investigating interactions between proteins, nucleic acids, lipids, and small molecules [3]. The technology's core strength lies in its exceptional sensitivity to minute changes in refractive index (RI) occurring at a metal-dielectric interface, which correspond directly to mass changes caused by molecular binding [4]. This physical principle has established SPR as a cornerstone technique in drug discovery, where it is extensively used for characterizing antibody-antigen recognition, fragment-based screening, and kinetic evaluation of therapeutic candidates [3].

The fundamental SPR phenomenon involves the collective oscillation of free electrons at the surface of a thin metal film when excited by incident light under specific conditions [4]. These charge density waves, known as surface plasmons, generate an evanescent electromagnetic field that extends approximately 200 nanometers from the metal surface into the adjacent medium [4] [3]. This decaying field makes the resonance exquisitely sensitive to alterations in the local refractive index, forming the physical basis for refractometric sensing in SPR biosensors [2]. The resonance condition depends critically on the angle, wavelength, and polarization of incident light, as well as the optical properties of both the metal film and the dielectric medium in contact with it [5].

Fundamental Principles of Refractometric Sensing

The Physical Phenomenon of SPR

Surface Plasmon Resonance occurs when energy from incident photons is transferred to collective oscillations of free electrons at a metal-dielectric interface [4]. This energy transfer happens only at a specific combination of incident angle and wavelength, satisfying the momentum-matching condition between the incoming light and the surface plasmons [5]. The resulting resonance manifests as a sharp dip in the intensity of reflected light, as energy is absorbed by the metal film to excite the surface plasmons [3]. The precise resonance condition is highly sensitive to the refractive index of the dielectric medium within the evanescent field, enabling detection of molecular adsorption events in real-time [4].

The underlying physics can be described by the dispersion relation for surface plasmon polaritons:

$$ k(\omega) = \frac{\omega}{c} \sqrt{\frac{\varepsilon1 \varepsilon2 \mu1 \mu2}{\varepsilon1 \mu1 + \varepsilon2 \mu2}} $$

Where $k(\omega)$ represents the wave vector of the surface plasmon, $\omega$ is the angular frequency of light, $c$ is the speed of light in vacuum, $\varepsilon$ denotes dielectric functions, and $\mu$ represents permeability [4]. For biosensing applications, the critical parameter is the resonance condition's dependence on the refractive index of the dielectric medium adjacent to the metal surface.

Refractometric Sensing Mechanism

SPR biosensors function as refractometers, detecting changes in the local refractive index resulting from molecular binding at the sensor surface [4]. When target molecules (analytes) in solution bind to their immobilized interaction partners (ligands) on the sensor chip, the accumulated mass increases the refractive index in the region probed by the evanescent field [3]. This alteration shifts the SPR resonance condition, which can be monitored as a change in either the resonance angle (angle interrogation) or resonance wavelength (wavelength interrogation) [5]. The magnitude of this shift is directly proportional to the mass concentration of bound analyte, allowing for quantitative measurements of binding kinetics and affinity [3].

The exceptional sensitivity of SPR biosensors stems from the enhanced electromagnetic field associated with surface plasmon excitation. Traditional SPR configurations can detect refractive index changes on the order of 10⁻⁵ to 10⁻⁷ refractive index units (RIU), corresponding to picogram amounts of bound protein per square millimeter [1]. This sensitivity can be further enhanced by several orders of magnitude through techniques such as surface plasmon-enhanced fluorescence spectroscopy (SPFS), which combines the field enhancement of SPR with fluorescence detection [6] [7].

The Kretschmann Configuration: Theory and Implementation

Fundamental Architecture

The Kretschmann configuration represents the most widely adopted and practical implementation of SPR for biosensing applications [5] [4]. In this arrangement, a thin metal film (typically gold) is directly deposited onto the base of a high-refractive-index prism [3]. Polarized light is directed through the prism and undergoes total internal reflection at the prism-metal interface, generating an evanescent wave that penetrates through the metal film [8]. When the momentum of this evanescent wave matches that of the surface plasmon at the outer metal-dielectric interface, resonance occurs, resulting in a characteristic drop in reflected light intensity [4].

This configuration effectively overcomes the momentum mismatch between incident photons and surface plasmons by utilizing the prism to increase the wave vector of the excitation light [5]. The Kretschmann configuration provides more efficient plasmon generation compared to the alternative Otto configuration, where an air gap exists between the prism and the metal layer [5]. This efficiency advantage, combined with practical implementation benefits, has established the Kretschmann configuration as the foundation for most commercial SPR instruments, including widely used systems such as Cytiva's Biacore platforms [3].

Technical Implementation

In a standard Kretschmann configuration setup, several optical and mechanical components work in concert to generate and measure the SPR phenomenon. A monochromatic, polarized light source (typically a laser diode) is directed through a prism toward the metal-coated interface [8]. The prism material is selected for its high refractive index (commonly fused silica or BK7 glass) to enable efficient momentum matching [8]. The metal film, generally comprising a 50-nanometer layer of gold, provides the conductive surface necessary for plasmon generation while offering excellent chemical stability for biological applications [9]. A detector, such as a position-sensing device (PSD) or charged-coupled device (CCD), measures the intensity of reflected light across a range of angles [4].

The following visualization represents the fundamental components and light path in the Kretschmann configuration:

Diagram 1: Kretschmann configuration setup for SPR sensing.

The detection mechanism relies on monitoring the reflectivity of the prism-metal interface as a function of incident angle. At the specific resonance angle where SPR occurs, reflected light intensity reaches a minimum [8]. Molecular binding at the sensing surface increases the local refractive index, shifting this resonance angle to higher values [3]. By tracking this angular shift in real-time, researchers can obtain quantitative information about binding kinetics, including association and dissociation rates [3].

Performance Metrics and Quantitative Comparison of SPR Platforms

The performance of SPR biosensors is evaluated using several key metrics that quantify their detection capabilities and overall efficiency. Wavelength sensitivity (WS), expressed in nanometers per refractive index unit (nm/RIU), measures the spectral shift in resonance wavelength for a given refractive index change [9]. Amplitude sensitivity (AS), reported in RIU⁻¹, quantifies changes in resonance intensity [9]. The figure of merit (FOM), also measured in RIU⁻¹, combines spectral and amplitude characteristics to provide a comprehensive performance indicator [9]. Additionally, the quality factor (QF) represents another important parameter for assessing sensor resolution and detection limits [8].

Recent advances in SPR platform development have yielded significant improvements in these performance metrics, particularly through innovative materials and structural designs. The table below summarizes the performance characteristics of various state-of-the-art SPR sensing platforms as reported in recent literature:

Table 1: Performance comparison of advanced SPR biosensor platforms

| SPR Platform | Sensing Structure | Sensitivity | Figure of Merit (FOM) | Refractive Index Range | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D-shaped PCF with Au/TiO₂ [9] | Photonic crystal fiber | 42,000 nm/RIU (WS) | 1393.128 RIU⁻¹ | 1.3-1.4 | Multi-cancer cell detection |

| Ag-ZnSe layered structure [8] | Kretschmann prism | 451 °/RIU | 173.46 RIU⁻¹ (QF) | 1.2-1.36 | Broad-range detection |

| Graphene-integrated Otto [10] | Terahertz SPR | 3.1043×10⁵ °/RIU (phase) | N/R | N/R | Liquid and gas sensing |

| Ag/Au membrane SPR [10] | Conventional SPR | 8x enhancement vs. Au | N/R | N/R | Human Immunoglobulin G detection |

| Dual Au/MgF₂ [9] | D-shaped PCF | 31,800 nm/RIU | N/R | 1.27-1.43 | Broad-range sensing |

These performance metrics demonstrate the remarkable progress in SPR sensor technology, with modern platforms achieving sensitivities orders of magnitude higher than traditional configurations. The development of photonic crystal fiber-based sensors and the integration of novel materials like TiO₂ and graphene have been particularly instrumental in these advancements [9] [10].

Experimental Protocols for SPR Analysis

Sensor Surface Preparation and Ligand Immobilization

A typical SPR experiment begins with careful preparation of the sensor surface and immobilization of the ligand molecule. The gold sensor chip is first cleaned using plasma treatment or piranha solution to remove organic contaminants and ensure a uniform surface [3]. For protein immobilization, the gold surface is often functionalized with a carboxymethylated dextran matrix that provides a hydrophilic environment and facilitates covalent coupling through amine, thiol, or other specific chemistries [3]. The ligand (typically at concentrations of 10-100 μg/mL in low-salt buffer at optimal pH) is then injected over the sensor surface, either directly or via capture-based methods such as antibody-mediated immobilization [3]. Unreacted groups on the surface are subsequently blocked using ethanolamine or other suitable capping agents to minimize non-specific binding during analyte exposure.

Binding Kinetics Measurement

The core application of SPR technology involves quantifying the binding kinetics between immobilized ligands and analytes in solution. The experimental workflow follows a well-defined sequence that generates a characteristic sensorgram. The following diagram illustrates the key phases of an SPR binding experiment and the corresponding processes occurring at the molecular level:

Diagram 2: SPR sensorgram phases and molecular events.

The experiment initiates with a baseline phase, where buffer alone flows across the sensor surface to establish a stable reference signal [3]. The association phase begins at time t=0 when analyte solution is introduced into the flow system, resulting in binding to the immobilized ligand and a corresponding increase in SPR response [3]. From this binding phase, the association rate constant (kₐₙ) can be determined. The system may reach a steady state where association and dissociation rates equalize, allowing calculation of the equilibrium dissociation constant (K_D) [3]. Subsequently, during the dissociation phase, buffer flow is restored, and the decrease in signal as complexes dissociate provides the dissociation rate constant (kₒff) [3]. For tight-binding interactions with slow dissociation, a regeneration phase using solutions with altered pH or high salt concentration may be necessary to remove bound analyte and prepare the surface for subsequent analysis cycles [3].

Data Analysis and Kinetic Parameter Extraction

Analysis of SPR sensorgram data enables quantification of key kinetic and affinity parameters that characterize the molecular interaction. The equilibrium dissociation constant KD is calculated as the ratio of dissociation to association rate constants (KD = kd/ka) [4]. Modern SPR instruments include sophisticated software that performs global fitting of the entire binding curve to appropriate interaction models (1:1 Langmuir, bivalent, heterogeneous, etc.), extracting parameters with high precision and statistical validation [3]. For quality control, replicates at multiple analyte concentrations are essential to confirm the binding model and obtain reliable kinetic parameters.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of SPR biosensing requires careful selection of materials and reagents optimized for specific experimental requirements. The following table catalogizes essential components for SPR experiments, along with their functions and typical specifications:

Table 2: Essential research reagents and materials for SPR biosensing

| Component | Function | Common Types/Specifications | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensor Chips [3] | Platform for ligand immobilization | Dextran-based, carboxymethylated, NTA, SA | Choice depends on ligand properties and coupling chemistry |

| Gold Film [9] | Plasmon-active metal layer | 50 nm thickness, chromium or titanium adhesion layer | High purity (>99.99%) ensures sharp resonance |

| Coupling Prism [8] | Optical component for light coupling | Fused silica, BK7 glass, SF10 | Higher index prisms enable wider angular scans |

| Immobilization Reagents [3] | Covalent attachment of ligands | EDC/NHS chemistry, amine coupling, thiol coupling | pH optimization critical for efficient coupling |

| Regeneration Solutions [3] | Remove bound analyte without damaging ligand | Glycine-HCl (pH 1.5-3.0), high salt, NaOH | Must be optimized for each ligand-analyte pair |

| Running Buffers [3] | Maintain physiological conditions during analysis | HBS-EP, PBS with surfactant | Minimize non-specific binding; ensure compatibility |

Gold remains the predominant metal for SPR biosensing due to its favorable optical properties, chemical stability, and well-established surface chemistry for biomolecule immobilization [9]. Recent innovations have explored enhancements using materials like TiO₂, graphene, and zinc selenide to improve sensitivity and functionality [9] [8] [10]. The choice of sensor chip matrix directly impacts ligand activity, accessibility, and non-specific binding propensity, requiring careful matching to the specific experimental system.

Advanced SPR Configurations and Emerging Applications

Alternative SPR Platforms

While the Kretschmann configuration remains the workhorse of commercial SPR systems, several alternative platforms offer unique advantages for specialized applications. Grating-coupled sensors replace the prism with a diffraction grating etched into the substrate, enabling more compact device architectures [5]. Optical fiber SPR sensors utilize the evanescent field at the core-cladding interface of a fiber waveguide, facilitating miniaturization and remote sensing capabilities [5]. Waveguide-coupled SPR systems guide light through thin-film waveguides, allowing control of both transverse electric (TE) and transverse magnetic (TM) modes for simultaneous measurement of density and thickness of adsorbed layers [5].

Enhanced SPR Modalities

Several enhanced SPR modalities have been developed to address specific limitations of conventional SPR. Surface Plasmon Resonance Microscopy (SPRM) combines SPR with high-resolution imaging to visualize binding events across the sensor surface with micrometer-scale spatial resolution [2]. Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance (LSPR) utilizes metallic nanoparticles rather than continuous films, generating highly localized plasmon fields with sensitivity to single-molecule binding events [2]. Electrochemical SPR (EC-SPR) integrates electrochemical control with SPR detection, enabling simultaneous monitoring of binding events and redox processes [2]. Most notably, Surface Plasmon-Enhanced Fluorescence Spectroscopy (SPFS) dramatically enhances detection sensitivity by leveraging the intensified electromagnetic field of SPR to excite fluorophore-labeled molecules, achieving detection limits several orders of magnitude lower than conventional SPR [6] [7].

Cutting-Edge Applications in Medical Diagnostics

SPR biosensors have found particularly significant applications in medical diagnostics, where their label-free detection capability and real-time monitoring enable rapid and precise analysis of clinically relevant biomarkers. Recent developments have demonstrated SPR platforms capable of detecting cancer cells (including Basal, MDA-MB-231, Jurkat, PC-12, and HeLa lines) with exceptional sensitivity by monitoring refractive index changes in cell cytoplasm [9]. SPR immunosensors have been configured for detection of pathogens, viruses, and bacteria, with applications in point-of-care diagnostics [1]. The technology has also been successfully applied to monitoring therapeutic antibodies, nucleic acid biomarkers, and exosomes in complex biological matrices [1]. These applications highlight the translation of SPR principles from basic research tools to clinically implemented diagnostic platforms.

Surface Plasmon Resonance biosensing based on the Kretschmann configuration represents a mature yet continuously evolving technology that has revolutionized the study of biomolecular interactions. The fundamental principles of refractometric sensing through excitation of surface plasmons provide a robust physical foundation for label-free, real-time monitoring of binding events with exceptional sensitivity. Ongoing advancements in materials science, particularly the integration of novel nanomaterials like graphene and TiO₂, alongside innovative optical designs such as photonic crystal fibers, continue to push the detection limits of SPR platforms. These developments ensure that SPR technology remains at the forefront of biomedical research, drug discovery, and clinical diagnostics, enabling increasingly sophisticated analysis of the molecular interactions underlying biological function and disease pathology.

Optical biosensors represent a powerful class of analytical tools that transduce biological binding events into measurable optical signals, with fluorescence-based techniques standing at the forefront due to their exceptional sensitivity and versatility [11]. These biosensors have revolutionized biomarker identification by enabling researchers to detect and quantify specific analytes—from small ions to complex proteins and pathogens—with unprecedented precision in diverse matrices including biological fluids, environmental samples, and food products [12] [13]. The fundamental principle governing fluorescence-based detection lies in the photophysical properties of fluorophores, which are molecular entities that absorb light at specific wavelengths and subsequently emit light at longer wavelengths through a process known as photoluminescence [12]. This absorption-emission cycle provides a detectable signal that can be quantitatively correlated to the concentration of a target biomarker, forming the basis for a wide array of diagnostic and research applications.

The significance of fluorescence-based biosensors extends across multiple domains, including clinical diagnostics, drug discovery, environmental monitoring, and food safety [12] [14]. Their integration into point-of-care (POC) devices has been particularly transformative, facilitating rapid detection at the patient's bedside or in field settings without the need for sophisticated laboratory infrastructure [12]. This transition from laboratory-based techniques to portable platforms has been enabled by advancements in miniaturization, smartphone-based readout systems, and the development of novel fluorescent materials with enhanced optical properties [12]. As we delve deeper into the mechanisms of light absorption and emission, it becomes evident that the strategic design of these biosensing platforms hinges on a thorough understanding of photophysical principles and their practical implementation for specific biomarker recognition.

Fundamental Photophysics of Fluorescence

Light Absorption and Emission Mechanisms

The process of fluorescence begins when a fluorophore absorbs a photon of specific energy, typically in the ultraviolet or visible region of the electromagnetic spectrum, promoting an electron from its ground state (S₀) to a higher vibrational level of an excited singlet state (S₁, S₂, etc.) [12]. This absorption event occurs on an extremely fast timescale (approximately 10⁻¹⁵ seconds), and the excited electron rapidly relaxes to the lowest vibrational level of S₁ through internal conversion (10⁻¹² to 10⁻¹⁴ seconds) [14]. The molecule resides in this excited state for a characteristic period known as the fluorescence lifetime (typically 1-10 nanoseconds), after which the electron returns to the ground state, emitting a photon with energy lower than that of the absorbed photon—a phenomenon described as the Stokes shift [12].

The magnitude of the Stokes shift is crucial for practical applications as it enables the separation of excitation light from emitted fluorescence, thereby improving signal-to-noise ratio in detection systems [13]. Several deactivation pathways compete with fluorescence emission, including non-radiative relaxation (heat dissipation) and intersystem crossing to triplet states, which can lead to phosphorescence or photobleaching [14]. The efficiency of fluorescence emission is quantified by the quantum yield (Φ), defined as the ratio of photons emitted to photons absorbed, with ideal fluorophores for biosensing applications possessing high quantum yields and photostability [14].

Molecular Design Strategies for Fluorescent Probes

The development of effective fluorescent probes requires careful molecular engineering to optimize aqueous solubility, binding affinity, and optical properties [13]. Key design strategies include the incorporation of hydrophilic functional groups (e.g., sulfonates, carboxylates, quaternary ammonium salts) to ensure water compatibility while maintaining sufficient lipophilicity for cell membrane permeation when intracellular imaging is desired [13]. The absorption and emission characteristics can be tuned through extended π-conjugation systems, electron-donating or withdrawing substituents, and structural rigidity to reduce non-radiative decay pathways [13].

Recent advances have produced probes with emission tailored to the "biological window" (650-900 nm) where tissue absorption and autofluorescence are minimal, thereby enhancing penetration depth and signal clarity for in vivo applications [13]. Additionally, environmental sensitivity can be engineered into fluorophores such that their emission intensity, lifetime, or spectral position changes in response to specific physicochemical parameters (pH, viscosity, polarity) or the presence of target analytes [12]. These designed responses form the mechanistic basis for sensing applications and are frequently mediated through photoinduced electron transfer (PET), intramolecular charge transfer (ICT), excited-state intramolecular proton transfer (ESIPT), or aggregation-induced emission (AIE) processes [13].

Table 1: Key Photophysical Mechanisms in Fluorescent Probe Design

| Mechanism | Process Description | Signal Change | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Photoinduced Electron Transfer (PET) | Electron transfer between fluorophore and receptor quenches fluorescence | Turn-on upon analyte binding | Ion and small molecule detection |

| Intramolecular Charge Transfer (ICT) | Change in dipole moment upon excitation alters emission energy | Spectral shift | Polarity sensing, molecular recognition |

| Excited-State Intramolecular Proton Transfer (ESIPT) | Proton transfer in excited state creates tautomer with distinct emission | Dual emission, large Stokes shift | Microenvironment monitoring |

| Aggregation-Induced Emission (AIE) | Restriction of intramolecular rotation reduces non-radiative decay | Emission enhancement in aggregate state | Biomarker assembly detection |

| Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) | Non-radiative energy transfer between donor and acceptor fluorophores | Ratio metric response | Molecular interactions, proximity assays |

Key Fluorescence Mechanisms in Biosensing

Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET)

FRET represents a powerful sensing mechanism based on the non-radiative transfer of energy from an excited donor fluorophore to a proximal acceptor molecule through dipole-dipole interactions [14]. This process occurs when several conditions are met: (1) the emission spectrum of the donor significantly overlaps with the absorption spectrum of the acceptor (typically >30%), (2) the donor and acceptor transition dipoles are favorably oriented, and (3) the molecules are within a characteristic distance known as the Förster radius (R₀), typically ranging from 1-10 nanometers [14]. The efficiency of FRET (E_FRET) exhibits an inverse sixth-power dependence on the distance between donor and acceptor (R), as described by the equation:

E_FRET = R₀⁶ / (R₀⁶ + R⁶) [14]

where R₀ represents the distance at which energy transfer efficiency is 50% [14]. This strong distance dependence makes FRET exceptionally sensitive to molecular-scale displacements, conformational changes, and binding events, rendering it ideal for monitoring biomolecular interactions in real-time [14]. In practice, FRET-based biosensors translate molecular recognition events into measurable changes in fluorescence intensity, lifetime, or emission ratios, enabling quantitative detection of targets ranging from ions and small molecules to proteins and nucleic acids [14] [15].

The design of FRET biosensors requires careful selection of donor-acceptor pairs with appropriate spectral overlap, quantum yields, and photostability [14]. Common pairs include cyan fluorescent protein (CFP)/yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) for genetically encoded sensors, and organic dyes such as fluorescein (FAM)/tetramethylrhodamine (TAMRA) or cyanine dyes (Cy3/Cy5) for in vitro applications [15]. Recent advancements have incorporated nanomaterials like quantum dots, graphene oxide, and MoS₂ nanosheets as either donors or acceptors, leveraging their broad absorption spectra and high quenching efficiencies to enhance sensitivity [15] [16].

Fluorescence Quenching Mechanisms

Fluorescence quenching encompasses processes that decrease the emission intensity of a fluorophore through various deactivation pathways [15]. In biosensing applications, two primary quenching mechanisms are exploited: dynamic (collisional) quenching and static (complex formation) quenching [12]. Dynamic quenching occurs when the excited-state fluorophore interacts with a quencher molecule through collisions, facilitating non-radiative energy transfer, while static quenching involves the formation of a non-fluorescent ground-state complex between fluorophore and quencher [15]. Both mechanisms result in a reduction of fluorescence intensity and lifetime, though the specific photophysical signatures differ.

The Stern-Volmer equation describes the relationship between fluorescence intensity and quencher concentration:

F₀/F = 1 + K_SV[Q]

where F₀ and F represent fluorescence intensities in the absence and presence of quencher, respectively, [Q] is the quencher concentration, and K_SV is the Stern-Volmer quenching constant [15]. This relationship forms the basis for quantitative sensing applications, particularly in "turn-off" assays where analyte binding enhances quenching. More sophisticated "turn-on" sensors utilize the displacement or separation of quencher from fluorophore upon analyte recognition, resulting in fluorescence recovery [15]. Nanomaterial quenchers like graphene oxide (GO) and MoS₂ nanosheets have gained prominence due to their exceptional quenching efficiencies through energy transfer processes and their large surface areas for biomolecular assembly [15] [16].

Table 2: Comparison of Fluorescence Quenching Materials in Biosensing

| Quenching Material | Quenching Mechanism | Advantages | Limitations | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Graphene Oxide (GO) | FRET, π-π stacking | High quenching efficiency, water dispersibility | Non-specific binding | CRP detection [15] |

| MoS₂ Nanosheets | FRET, charge transfer | High surface area, tunable properties | Complex synthesis | Parasite detection [16] |

| Gold Nanoparticles | Nanometal surface energy transfer | Tunable plasmonics, versatile conjugation | Potential cytotoxicity | Pathogen detection [12] |

| Carbon Nanomaterials | FRET, photoinduced electron transfer | Low cost, chemical stability | Batch variability | Ion sensing [12] |

| Organic Dyes | FRET, inner filter effect | Well-characterized, commercial availability | Photobleaching | Cellular imaging [14] |

Additional Fluorescence Sensing Mechanisms

Beyond FRET and quenching, several other photophysical mechanisms contribute to the diverse toolbox of fluorescence-based biosensing. Photoinduced Electron Transfer (PET) involves the transfer of an electron from a receptor moiety to the excited fluorophore (or vice versa), resulting in fluorescence quenching until analyte binding disrupts this pathway and restores emission [13]. This mechanism forms the basis for many small-molecule sensors, particularly for metal ions and pH detection, where coordination or protonation alters the redox properties of the receptor [13].

Intramolecular Charge Transfer (ICT) occurs in fluorophores with separated electron donor and acceptor groups, leading to a large change in dipole moment upon excitation [13]. The emission characteristics of ICT fluorophores are highly sensitive to local environment polarity, enabling their use as molecular reporters for solvation, membrane potential, and binding events that alter microenvironment polarity [13]. Ratiometric measurements based on ICT can provide internal calibration, improving quantification accuracy by mitigating artifacts from probe concentration variations or instrumental fluctuations [13].

Aggregation-Induced Emission (AIE) represents a more recent development where fluorophores that are non-emissive in molecularly dispersed states become highly fluorescent upon aggregation [13]. This phenomenon contrasts with traditional aggregation-caused quenching and has been exploited for sensing applications where analyte binding induces fluorophore assembly, such as in the detection of proteins, nucleic acids, and enzymatic activities [13]. AIE-based sensors often exhibit significant signal amplification and excellent photostability, making them attractive for high-sensitivity applications.

Experimental Implementation and Protocols

FRET-Based Aptasensor for C-Reactive Protein Detection

The following protocol details the implementation of a FRET-based aptasensor for ultrasensitive detection of C-reactive protein (CRP), an important inflammatory biomarker, utilizing graphene oxide (GO) as a quenching platform [15]. This method exemplifies the integration of fluorescence principles with biomolecular recognition elements for specific analyte detection.

Materials and Reagents:

- FAM-labeled aptamer (sequence: 5'-FAM-GGC AGG AAG ACA AAC ATA TAA TTG AGA TCG TTT GAT GAC TTT GTA AGA GTG TGG AAT GGT CTG TGG TGC TGT-3')

- Graphene oxide (GO) suspension (4 mg/mL in Milli-Q water)

- CRP protein standards

- Phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4)

- Bovine serum albumin (BSA)

- Interfering substances for selectivity testing (TNF-α, hemoglobin, herceptin)

- Human serum samples (positive and negative)

- 300-μL quartz cuvette

Instrumentation:

- Fluorescence spectrophotometer (e.g., Hitachi F-7000)

- Ultrasonic bath

- NanoDrop UV-Vis spectrophotometer

- TEM for GO characterization

- XRD for GO structural analysis

Procedure:

GO Synthesis and Characterization (Hummers' Method):

- Oxidize natural graphite powder with NaNO₃, KMnO₄, and concentrated H₂SO₄ under controlled temperature [15].

- Terminate reaction with H₂O₂, then wash and exfoliate through ultrasonication to obtain GO suspension.

- Characterize GO by XRD (peak at 2θ = 11.6°), UV-Vis (λ_max = 230 nm), and TEM to confirm morphology [15].

Aptamer-GO Complex Preparation:

- Dilute FAM-aptamer stock to 330 nM in Milli-Q water.

- Mix 1 μL aptamer with 0.5 μL GO suspension (0.03 mg/mL final concentration).

- Dilute mixture to 300 μL with Milli-Q water.

- Incubate for 5 minutes at room temperature to allow π-π stacking between aptamer nucleobases and GO surface [15].

Fluorescence Quenching Verification:

- Transfer aptamer-GO complex to quartz cuvette.

- Measure fluorescence intensity with excitation at 450 nm, emission at 520 nm.

- Confirm >90% quenching efficiency compared to free aptamer.

CRP Detection Assay:

- Add CRP standards (concentration range: 33-207 fg/mL) to aptamer-GO complex.

- Incubate for 5 minutes with gentle shaking.

- Measure fluorescence recovery at 520 nm.

- Generate calibration curve from fluorescence intensity versus CRP concentration.

Selectivity Assessment:

- Repeat assay with potential interferents (TNF-α, hemoglobin, herceptin).

- Compare fluorescence response to CRP-specific signal.

Real Sample Analysis:

- Dilute human serum samples 1:100 in assay buffer.

- Apply 1 μL to detection system.

- Quantify CRP concentration from calibration curve.

Data Analysis: The assay exhibits two linear ranges (33-82 fg/mL and 114-207 fg/mL) with a limit of detection (LOD) of 2.27 fg/mL [15]. Calculate CRP concentration in unknown samples using the regression equation derived from the standard curve. The exceptional sensitivity stems from the high quenching efficiency of GO and the specific conformational change in the aptamer upon CRP binding, which displaces the FAM label from the GO surface, restoring fluorescence [15].

Research Reagent Solutions for Fluorescence-Based Detection

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Fluorescence-Based Biomarker Detection

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Assay | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fluorophores | 6-Carboxyfluorescein (FAM), Cyanine dyes (Cy3, Cy5), BODIPY derivatives, Quantum dots | Signal generation | High quantum yield, photostability, appropriate excitation/emission profiles [14] [15] |

| Quenching Materials | Graphene oxide (GO), MoS₂ nanosheets, Gold nanoparticles, Carbon nanomaterials | Signal modulation | High quenching efficiency, biocompatibility, surface functionalization capability [15] [16] |

| Biological Recognition Elements | Aptamers, Antibodies, Enzymes, Molecularly imprinted polymers | Target recognition | High affinity and specificity, stability, reproducible production [15] |

| Signal Amplification Components | Recombinase polymerase amplification (RPA), Horseradish peroxidase (HRP), Alkaline phosphatase (AP) | Sensitivity enhancement | Efficient signal multiplication, compatibility with detection system [16] |

| Sample Matrix Modifiers | Bovine serum albumin (BSA), Surfactants (Tween-20), Protease inhibitors | Reduction of non-specific binding | Blocking interference, stabilizing delicate components [15] |

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

The evolution of fluorescence-based detection systems continues to expand their application domains and technical capabilities. In clinical diagnostics, FRET-based biosensors have enabled real-time monitoring of disease biomarkers with exceptional sensitivity, as demonstrated by the CRP detection assay achieving attomolar sensitivity [15]. Similarly, pathogen detection platforms have been developed for bacterial infections including Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pyogenes, Escherichia coli, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa with detection limits below 50 CFU/mL, leveraging the differential affinities of various fluorescent nanoclusters to bacterial cell wall components [12].

The integration of CRISPR/Cas systems with fluorescence detection methodologies represents a cutting-edge advancement, particularly for nucleic acid detection [16]. For instance, the combination of MoS₂ nanosheets as quenching platforms with CRISPR/Cas12a has enabled attomolar sensitivity for food-borne parasite detection within 35 minutes, showcasing the potential for rapid, on-site diagnostics [16]. This platform utilizes the collateral cleavage activity of Cas12a, which is activated upon target recognition and cleaves reporter DNA molecules, leading to fluorescence dequenching and signal amplification [16].

Future directions in fluorescence-based detection focus on enhancing multiplexing capabilities, improving quantification accuracy through ratiometric measurements, and developing increasingly portable platforms for point-of-care applications [12] [14]. The synthesis of novel fluorescent materials with enhanced brightness, photostability, and environmental responsiveness will further push detection limits, while machine learning approaches for signal analysis may enable more robust interpretation of complex fluorescence signatures in heterogeneous samples [12]. As these technologies mature, fluorescence-based detection will continue to serve as a cornerstone methodology in biomarker identification, enabling fundamental biological discoveries and transformative diagnostic applications.

The investigation of molecular interactions—the fundamental language of biological processes—relies heavily on biosensing technologies capable of translating these subtle biochemical conversations into quantifiable signals. Within this domain, a fundamental methodological divide exists between label-free and label-based sensing approaches, each offering distinct pathways to observe molecular behavior. Label-free biosensors detect target analytes in their natural, unmodified state by directly transducing binding events into measurable signals through various physical principles [17] [18]. In contrast, label-based methods rely on chemical tags—such as fluorescent dyes, enzymes, or radioactive isotopes—attached to the target molecule to generate a detectable signal [19] [20]. This distinction is particularly crucial for research focused on understanding native molecular states, where the very act of observation should ideally introduce minimal perturbation to the system under study.

The core principle of label-free optical biosensing rests on detecting changes in the physical properties of the sensing interface—typically the refractive index—when a target analyte binds to its immobilized receptor [21]. As most biological molecules have a higher refractive index (1.45–1.55 RIU) than the aqueous buffers they are typically dissolved in (1.33 RIU), molecular binding increases the refractive index in a thin surface layer, which optical transducers can detect with remarkable sensitivity [21]. Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR), a cornerstone of label-free sensing, exemplifies this principle by exploiting collective electron oscillations at a metal-dielectric interface to probe binding events in real-time without any molecular modification [22] [21].

Within the context of optical biosensor research, the choice between label-free and label-based strategies represents more than a technical preference; it embodies a philosophical approach to experimental design that balances the desire for native-state observation against practical considerations of sensitivity and multiplexing capability. This review examines the advantages and limitations of both paradigms, providing researchers with a framework for selecting the optimal sensing strategy for investigating molecular interactions in their most natural form.

Core Principles and Technological Foundations

Label-Free Sensing: Direct Detection of Molecular Presence

Label-free biosensing technologies operate by directly transducing the physical presence of molecules at a sensing interface into an analyzable signal. The primary advantage of this approach lies in its ability to monitor molecular interactions in real-time without requiring additional labeling steps that might alter molecular function or binding characteristics [17] [18]. Various physical principles are harnessed for this purpose:

Optical Transducers: These represent the most mature category of label-free biosensors. Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) and its localized counterpart (LSPR) detect binding-induced changes in the local refractive index through shifts in resonance conditions [22] [21]. Interferometric methods, such as Interference Scattering Microscopy (iSCAT), leverage the interference between light scattered by a biomolecule and a reference wave to achieve single-molecule sensitivity [22]. Photonic crystal structures and whispering gallery mode resonators confine light to create highly sensitive electromagnetic fields that respond to molecular binding [21].

Mechanical Transducers: Devices like microcantilevers and quartz crystal microbalances (QCM) detect the mass change associated with molecular binding. As molecules accumulate on the sensor surface, they induce measurable changes in resonance frequency or deflection [19].

Electrical Transducers: Field-effect transistors (FETs) functionalized with specific receptors can detect the charge perturbations associated with molecular binding, enabling direct electronic readout of binding events [23].

The fundamental workflow of label-free detection involves immobilizing a molecular recognition element (e.g., an antibody, aptamer, or receptor) on the transducer surface, establishing a baseline signal, introducing the analyte sample, and monitoring the signal change in real-time as binding occurs [17]. This process enables the determination of binding kinetics (association and dissociation rates) and affinity constants without any secondary detection steps.

Label-Based Sensing: Amplification Through Molecular Tags

Label-based sensing employs molecular tags to generate a detectable signal, transforming the challenge of direct detection into one of specific recognition followed by amplified reporting [19] [20]. This approach typically requires a sandwich assay format where the target analyte is captured between a surface-immobilized receptor and a solution-phase detection reagent that carries the label [17]. Several classes of labels dominate current methodologies:

Fluorescent Labels: These include small organic dyes, fluorescent proteins, and quantum dots that absorb light at specific wavelengths and re-emit it at longer wavelengths [19] [22]. Fluorescence detection offers exceptional sensitivity and multiplexing capability through different spectral signatures but may suffer from photobleaching and relatively large label size that can perturb molecular function [22].

Enzymatic Labels: Enzymes such as horseradish peroxidase (HRP) and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) catalyze the conversion of substrates into detectable products, providing significant signal amplification through enzymatic turnover [20]. These systems enable highly sensitive colorimetric, chemiluminescent, or electrochemical detection but introduce additional washing and substrate addition steps [19] [20].

Nanoparticle Labels: Gold nanoparticles, quantum dots, and other nanomaterials provide versatile labeling platforms offering unique optical, electrochemical, or magnetic properties [19] [20]. Their high surface-area-to-volume ratio allows for multi-valent labeling and significant signal enhancement, though conjugation chemistry and potential non-specific binding require careful optimization [20].

Isotopic Labels: Radioisotopes such as ³²P and ¹²⁵I provide extremely sensitive detection through radiation measurement but present safety concerns and regulatory hurdles that limit their widespread adoption [19].

Label-based methods typically involve more complex experimental workflows than label-free approaches, including multiple incubation and washing steps to ensure specific signal generation. However, they often achieve superior sensitivity and are more readily adaptable to multiplexed detection formats [19] [20].

Comparative Analysis: Advantages and Limitations

Quantitative Comparison of Sensing Modalities

The choice between label-free and label-based sensing involves trade-offs across multiple performance parameters. The table below summarizes key characteristics of each approach:

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Label-Free and Label-Based Sensing Methods

| Parameter | Label-Free Sensing | Label-Based Sensing |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Preparation | Simpler, less time-consuming [24] [25] | More complex, requires labeling/conjugation steps [19] [25] |

| Cost | Lower, no labeling reagents needed [24] [25] | Higher, due to labeling reagents and additional chemicals [24] [25] |

| Native-State Preservation | Excellent, no molecular modifications [22] [18] | Poor, labels may alter function/behavior [22] |

| Real-Time Kinetics | Yes, enables monitoring of association/dissociation [17] [21] | Limited, typically endpoint measurements [17] |

| Multiplexing Capability | Limited with conventional SPR, improving with new platforms [19] [18] | Excellent, through different spectral signatures [19] [20] |

| Sensitivity (Traditional) | Moderate (nM-pM range) [21] | High (pM-fM range) [20] |

| Sensitivity (Advanced) | Single-molecule level with latest innovations [22] [21] | Single-molecule level with fluorescence [22] |

| Throughput | Medium | High [25] |

| Dynamic Range | Wider [25] | Narrower [25] |

| Susceptibility to Matrix Effects | Higher, due to direct detection [17] | Lower, washing steps remove interferents [17] |

Advantages and Limitations for Native-State Studies

When investigating molecular interactions in their native state, label-free sensing offers distinct advantages that have established it as the preferred method for fundamental biophysical studies:

Minimal Perturbation: By avoiding molecular modifications, label-free approaches preserve natural conformation, dynamics, and interaction interfaces [22]. Fluorescent labels, particularly those comparable in size to the molecule being studied (e.g., with small molecules), can significantly alter binding affinities or interfere with native conformational dynamics [22].

Real-Time Kinetic Monitoring: The ability to continuously monitor binding events provides direct access to association (kₐₙ) and dissociation (kₐₚₚ) rate constants, enabling a more complete understanding of interaction mechanisms than equilibrium endpoint measurements [17] [21]. This is particularly valuable for characterizing transient complexes or multi-step binding processes.

Simplified Experimental Workflow: The elimination of labeling and associated purification steps reduces preparation time and potential artifacts [24] [25]. This simplicity also facilitates the study of interactions that might be disrupted by labeling procedures.

Despite these advantages, traditional label-free sensing faces limitations that have restricted its broader adoption:

Sensitivity Limitations: Conventional SPR and related techniques have struggled to match the sensitivity of well-established label-based methods, particularly for detecting low-abundance analytes [21]. This limitation becomes critical when studying rare biological species or working with limited sample volumes.

Limited Multiplexing: Traditional label-free platforms have offered limited capability for parallel detection of multiple analytes, though recent developments in imaging SPR and photonic crystal arrays are addressing this limitation [18].

Vulnerability to Non-Specific Binding: Without the specificity conferred by secondary recognition elements and washing steps, label-free sensors may be more susceptible to interference from non-specific binding, particularly in complex biological matrices [17].

Label-based methods, while potentially perturbing native molecular states, continue to offer compelling advantages for specific applications:

Signal Amplification: Enzymatic labels provide substantial signal amplification through catalytic turnover, while fluorescent nanoparticles offer high brightness per binding event [20]. This amplification enables detection of rare species that might otherwise escape notice.

Spatial Resolution: Fluorescent labeling enables super-resolution localization far beyond the diffraction limit, providing nanoscale spatial information about molecular distribution and interaction [22].

Established Protocols: Well-characterized labeling chemistry and detection protocols reduce method development time and facilitate cross-laboratory reproducibility [19] [20].

Recent Technological Advances

Overcoming Sensitivity Barriers in Label-Free Sensing

Recent innovations have substantially addressed the historical sensitivity limitations of label-free sensing, with several platforms now achieving single-molecule detection capability:

Plasmonic Phase Sensing: Traditional SPR monitors intensity changes (reflectance dips), but newer approaches exploit phase singularities that occur at points of minimum reflectance where the optical phase undergoes an abrupt jump [21]. This phase response can be up to 1000× more sensitive than conventional intensity-based measurements, enabling detection limits below 1 fg/mm² and making single-protein detection routine [21].

Interferometric Scattering Microscopy (iSCAT): This technique interferes light scattered from a nanoparticle or biomolecule with a reference wave reflected from a substrate, creating contrast proportional to particle mass [22]. With optimized illumination and detection, iSCAT can detect single proteins as small as 60 kDa and track their motion in real-time, effectively serving as an "optical mass spectrometer" for quantitative single-molecule imaging [22].

Metamaterial-Enhanced Sensing: Engineered materials with optical properties not found in nature, such as hyperbolic metamaterials and coupled plasmonic nanostructures, concentrate electromagnetic fields into nanoscale volumes, dramatically enhancing light-matter interactions [21]. These platforms have demonstrated detection of attomolar concentrations of analytes, rivaling the most sensitive label-based assays [21].

Nanoparticle-Enhanced Sensing: The combination of label-free transducers with nanoparticles as signal enhancers creates hybrid approaches that preserve real-time monitoring while boosting sensitivity [18]. For example, antibody-conjugated gold nanoparticles binding to captured viral proteins can amplify SPR signals, enabling direct detection of viruses at clinically relevant concentrations [18].

Emerging Applications and Methodologies

These technological advances have unlocked new application areas previously inaccessible to label-free sensing:

Digital Detection of Single Molecules: By partitioning samples into femtoliter volumes where the presence or absence of single molecules creates a digital readout, researchers can achieve absolute quantification without calibration curves [18]. This approach has been applied to protein biomarkers and nucleic acids with sensitivities approaching those of digital PCR.

Direct Virus Detection and Enumeration: Unlike PCR-based methods that detect genomic material or immunoassays that detect viral proteins, advanced label-free imaging techniques can directly count intact virus particles as diffraction-limited spots [18]. This capability provides a more direct measure of infectious potential and has been demonstrated for SARS-CoV-2 and influenza viruses.

Single-Molecule Dynamics and Heterogeneity: Label-free techniques now enable observation of individual biomolecules without averaging across populations, revealing transient intermediate states, conformational fluctuations, and molecular heterogeneities that are masked in ensemble measurements [22].

Experimental Considerations and Protocols

Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of sensing experiments requires careful selection of recognition elements, surfaces, and detection components:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Molecular Sensing Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Recognition Elements | Antibodies, aptamers, recombinant proteins, peptide arrays [19] [26] | Molecular specificity for target capture; immobilized on sensor surface |

| Sensor Substrates | Gold films (SPR), functionalized glass, graphene, nano-structured metasurfaces [21] | Transducer surface for immobilization; determines sensitivity and noise characteristics |

| Labeling Reagents | Fluorescent dyes (Cy3, Cy5, FITC), enzymes (HRP, ALP), gold nanoparticles, quantum dots [19] [20] | Signal generation in label-based approaches; selected based on detection modality |

| Surface Chemistry | SAMs (alkanethiols), PEG layers, carboxylated dextran, biotin-streptavidin systems [19] | Controlled immobilization of recognition elements; minimizes non-specific binding |

| Signal Generation | Chemiluminescent substrates, enzymatic substrates, electrochemical mediators [19] [20] | Convert molecular recognition into detectable signals in label-based formats |

| Reference Materials | Isotopically labeled standards (SILAC), purified target analytes [24] [19] | Quantification standards and internal controls for assay validation |

Method Selection Workflow

The following diagram illustrates a systematic approach for selecting between label-free and label-based sensing strategies based on experimental objectives and sample characteristics:

Diagram 1: Method Selection Workflow for Molecular Sensing Studies

Detailed Protocol: Real-Time Binding Kinetics Using Surface Plasmon Resonance

The following protocol provides a detailed methodology for characterizing molecular interactions using label-free SPR technology:

I. Sensor Surface Preparation

- Substrate Selection: Use a commercially available SPR sensor chip with a gold film (≈50 nm) on a glass substrate with an adhesion-promoting chromium or titanium layer (≈2 nm).

- Surface Functionalization: Create a self-assembled monolayer (SAM) of carboxylated alkanethiols (e.g., 16-mercaptohexadecanoic acid) by immersing the gold substrate in a 1 mM ethanol solution for 24 hours [21].

- Receptor Immobilization: Activate the carboxyl groups with a mixture of 0.4 M EDC (1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide) and 0.1 M NHS (N-hydroxysuccinimide) for 7 minutes. Dilute the capture molecule (antibody, receptor) to 10-50 μg/mL in 10 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.0) and inject until desired immobilization level is reached (typically 5-15 kRU). Deactivate remaining esters with 1 M ethanolamine-HCl (pH 8.5) [17].

II. Binding Kinetics Measurement

- System Preparation: Prime the SPR instrument with running buffer (e.g., HBS-EP: 10 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, 3 mM EDTA, 0.005% surfactant P20, pH 7.4). Maintain constant temperature (±0.03°C) and flow rate (typically 30 μL/min).

- Analyte Injection: Dilute analytes in running buffer spanning a concentration range of 0.1-10 × expected K({}_{D}). Inject samples for 2-5 minutes (association phase) followed by running buffer for 5-30 minutes (dissociation phase). Include blank buffer injections for double-referencing.

- Surface Regeneration: Remove tightly bound analyte using a 30-second pulse of regeneration solution (e.g., 10 mM glycine-HCl, pH 2.0) that does not damage the immobilized receptor. Verify surface stability through repeated control injections.

III. Data Analysis

- Reference Subtraction: Subtract signals from reference flow cells and blank injections to remove bulk refractive index changes and systematic artifacts.

- Kinetic Modeling: Fit processed sensorgrams to appropriate interaction models (1:1 Langmuir, two-state reaction, conformational change, etc.) using global fitting algorithms that simultaneously analyze multiple concentrations.

- Affinity Determination: Calculate equilibrium dissociation constant (K({}{D})) both from kinetic rate constants (K({}{D}) = k({}{d})/k({}{a})) and from steady-state response levels at different concentrations.

Critical Considerations: Include concentration series spanning at least a 10-fold range above and below K({}_{D}). Verify mass transport limitations are not affecting measured rates. Perform experiments in triplicate to ensure reproducibility. Include control surfaces to assess specificity [17] [21].

The historical divide between label-free and label-based sensing is narrowing as technological innovations address their respective limitations. Label-free methods, once considered insufficiently sensitive for many applications, now approach single-molecule detection through advanced photonic approaches that exploit phase measurements, interference phenomena, and engineered metamaterials [22] [21]. Similarly, label-free platforms are gaining multiplexing capabilities through spatial encoding and imaging detection schemes [18]. Meanwhile, label-based methods continue to evolve through brighter fluorophores, more efficient enzymatic systems, and novel nanomaterials that reduce the size and potential perturbance of labels while maintaining excellent sensitivity [20].

For researchers investigating native molecular states, label-free sensing remains the preferred approach when real-time kinetic information and minimal perturbation are paramount. The choice between these paradigms should be guided by specific experimental requirements rather than preconceived preferences, with hybrid approaches offering a middle ground that leverages the advantages of both strategies [18]. As both technologies continue to mature, their convergence promises a future where researchers can routinely observe molecular interactions with unprecedented spatial and temporal resolution while preserving the native state of the system under study.

The ongoing integration of these sensing technologies with microfluidics, automated sample processing, and advanced data analytics will further transform their capabilities, potentially enabling comprehensive characterization of molecular interactions in contexts that more closely resemble their native physiological environments. This evolution will continue to enhance our fundamental understanding of biological processes and accelerate the development of novel therapeutic interventions.

The performance of an optical biosensor is fundamentally determined by its biorecognition element, the biological component that confers specificity for the target analyte. These elements interact specifically with targets such as pathogens, proteins, or DNA sequences, and this binding event is transduced into a quantifiable optical signal [27] [28]. In the context of optical biosensors, particularly those based on fluorescence and surface plasmon resonance (SPR), the choice and proper implementation of the biorecognition element are critical for achieving high sensitivity, specificity, and reliability [29] [28]. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of the three primary classes of biorecognition elements—enzymes, antibodies, and nucleic acids—framed within the principles of optical biosensing.

Biorecognition elements function as the exquisite "locks" designed to fit specific molecular "keys." Their inherent biological specificity allows for the precise detection of target analytes, even within highly complex sample matrices like blood, serum, or environmental samples [27]. When this specific binding occurs on the surface of an optical transducer, it alters the local refractive index or generates a fluorescent signal, enabling real-time, label-free detection in the case of SPR, or highly sensitive detection in fluorescence-based systems [29] [28]. The effectiveness of these devices is highly dependent on their biorecognition capabilities, which must combine selective and potent affinity towards the bioanalyte with stability and suitability for immobilization on sensor surfaces [27].

Fundamental Principles of Optical Biosensing

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) Biosensing

Surface Plasmon Resonance is a powerful label-free detection technique that has emerged as a cornerstone for studying biomolecular interactions in real-time. The principle relies on the excitation of surface plasmons—coherent oscillations of free electrons at a metal-dielectric interface, typically a thin gold film [29]. In the common Kretschmann configuration, a polarized light source is directed through a prism onto the metal film. At a specific angle of incidence, the energy of the photons couples with the electron oscillations, resulting in a sharp drop in the intensity of the reflected light, known as the resonance angle [29].

This resonance angle is exquisitely sensitive to changes in the refractive index within the evanescent field, which extends a few hundred nanometers from the metal surface. When a biorecognition event, such as an antibody binding to its antigen, occurs on the sensor surface, it increases the local refractive index, causing a measurable shift in the resonance angle [29]. This shift is monitored in real-time, providing a direct measure of binding kinetics—including association (k_on) and dissociation (k_off) rate constants—and affinity without the need for fluorescent or radioactive labels [29]. The technique's versatility allows it to monitor a wide range of interactions, including protein-protein, protein-DNA, receptor-drug, and cell-virus-protein interactions [29].

Fluorescence-Based Biosensing

Fluorescence biosensing employs a different principle, relying on the detection of light emitted by a fluorophore following its excitation at a specific wavelength. In biosensor design, fluorescence can be generated or modulated through several mechanisms, including Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET), where energy is transferred from a donor fluorophore to an acceptor molecule when they are in close proximity [30]. The efficiency of this transfer is highly dependent on the distance between the donor and acceptor, making FRET an exceptionally powerful mechanism for reporting conformational changes in biorecognition elements upon analyte binding [30].

Genetically Encoded Fluorescent Biosensors (GEFBs) represent a sophisticated application of this principle, where a sensory domain is fused to one or more fluorescent proteins (FPs). Upon binding the target analyte, a conformational change alters the FP's emission properties or FRET efficiency between two FPs [30]. This design enables intrinsic, ratiometric sensing, allowing for the quantification of analytes like hormones, calcium ions, or reactive oxygen species in living cells with high spatiotemporal resolution, while controlling for optical artefacts [30]. The high sensitivity of fluorescence detection, capable of reaching single-molecule levels, makes it particularly valuable for detecting low-abundance biomarkers [28].

Comparative Analysis of Key Biorecognition Elements

The selection of an appropriate biorecognition element is a critical design decision that directly impacts biosensor performance. The table below provides a structured comparison of the three primary biorecognition elements across key technical parameters relevant to optical biosensor design.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Key Biorecognition Elements for Optical Biosensors

| Characteristic | Enzymes | Antibodies | Nucleic Acids (Aptamers & DNAzymes) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Mechanism | Catalytic turnover & substrate conversion | High-affinity antigen-binding | Sequence-specific hybridization (DNA/RNA) or 3D structure-based binding (aptamers) |

| Key Advantage | Signal amplification through catalysis | Exceptional specificity & commercial availability | High chemical stability, reusability, & tailorability via SELEX |

| Common Immobilization Methods | Covalent bonding, entrapment in polymers | Adsorption, covalent attachment to SAMs | Thiol-gold chemistry, biotin-streptavidin, covalent bonding |

| Typical Targets | Substrates, inhibitors, cofactors | Proteins, pathogens, hormones | Ions, small molecules, proteins, whole cells |

| Stability | Moderate (sensitive to T, pH) | Moderate (can denature) | High (robust to T, long shelf-life) |

| Development Time/Cost | Low (if commercially available) | High (animal immunization required) | Moderate (in vitro selection) |

| Susceptibility to Matrix Effects | High (inhibitors may be present) | High (nonspecific binding) | Lower (can be engineered for robustness) |

Enzymes as Biorecognition Elements

Enzymes are biocatalysts that accelerate specific biochemical reactions. In biosensors, their inherent specificity for their substrate is leveraged for detection. Enzyme-based biosensors typically operate by measuring the consumption of a reactant or the generation of a product, which can be optically detected [28]. A classic example is the use of glucose oxidase in electrochemical glucose sensors, a principle that can be adapted for optical detection using fluorescent or chemiluminescent products [28].

The principal advantage of enzymes is catalytic signal amplification. A single enzyme molecule can convert millions of substrate molecules to a detectable product, significantly enhancing sensitivity [27]. Furthermore, the catalytic activity can be modulated by inhibitors, allowing for the development of biosensors for toxins, pesticides, or heavy metals [28]. However, the practical application of enzyme-based optical biosensors can be limited by the stability of the enzyme, which is often sensitive to temperature, pH, and denaturing agents in the sample matrix. Additionally, the requirement for a detectable product often adds steps to the assay protocol [27].

Antibodies as Biorecognition Elements

Antibodies, or immunoglobulins, are proteins produced by the immune system that bind to specific antigens with high affinity. Biosensors utilizing antibodies are termed immunosensors and represent a dominant technology in clinical diagnostics, such as for the detection of cardiac biomarkers, pathogens, and cytokines [27] [28]. The antibody-antigen interaction is highly specific and strong, making it ideal for detecting analytes in complex mixtures like blood or serum.

Immunosensors can be configured in various formats. In direct SPR immunosensors, the binding of the antigen to the surface-immobilized antibody causes a direct change in the refractive index, which is measured in real-time [29]. In fluorescent immunoassays, the signal may be generated by a labeled secondary antibody (sandwich format) or through competitive binding assays for smaller molecules [28]. A significant challenge with antibodies is their susceptibility to nonspecific adsorption of other proteins from the sample, which can lead to false-positive signals. This necessitates careful surface chemistry and the use of blocking agents [28]. Furthermore, the production of antibodies involves animal systems, making it a time-consuming and costly process, and the resulting molecules can be prone to batch-to-batch variation and degradation [27].

Nucleic Acids as Biorecognition Elements

Nucleic acid-based biorecognition encompasses both natural oligonucleotides and engineered molecules. Traditional DNA biosensors rely on the principle of complementary base pairing (hybridization) to detect specific DNA or RNA sequences, which is crucial for genetic mutation analysis, pathogen identification, and gene expression profiling [27] [29].

More recently, engineered nucleic acids like aptamers and DNAzymes have gained prominence. Aptamers are single-stranded DNA or RNA oligonucleotides selected in vitro (via SELEX) to bind specific targets, from small molecules to proteins and whole cells, with affinity and specificity rivaling antibodies [27] [29]. DNAzymes are catalytic DNA molecules that can perform specific chemical reactions, such as cleavage of a RNA substrate, upon binding a co-factor like a metal ion [27]. The key advantages of nucleic acid-based receptors include their high chemical stability, ease of synthesis and modification, and reusability (as they can often be denatured and regenerated) [27]. Their robustness and lower production cost make them attractive alternatives to antibodies, especially for use in rugged or resource-limited settings [27].

Experimental Protocols for Biosensor Development

Protocol: Fabrication of a Pedestal High-Contrast Grating (PHCG) for Label-Free Detection

High-contrast gratings (HCGs) are dielectric sensing structures that support guided-mode resonances with narrow linewidths, making them highly sensitive to refractive index changes. The following protocol details the fabrication of a pedestal HCG (PHCG), which has demonstrated enhanced sensitivity over conventional designs [31].

- Substrate Preparation: Begin with a 500 µm thick Si ⟨100⟩ wafer. Perform a standard RCA cleaning procedure to remove organic and ionic contaminants.

- Thermal Oxidation: Oxidize the wafer in a furnace using a wet oxidation process (H₂O at 1100 °C) to grow a 1.1 µm thick SiO₂ layer.

- Amorphous Silicon Deposition: Deposit a 500 nm thick layer of amorphous silicon (aSi) via Low-Pressure Chemical Vapor Deposition (LPCVD) using silane (SiH₄) at 560 °C, creating a custom silicon-on-insulator (SOI) structure.

- Patterning via Deep-UV Lithography:

- Spin-coat the wafer with a 65 nm bottom anti-reflective coating (BARC) and a 360 nm layer of positive photoresist.

- Bake, expose (dose of 240 J/m²) using a photomask defining a 1D periodic pattern (e.g., period Λ = 820 nm, bar width w = 340 nm), and develop the resist.

- Deep Reactive Ion Etching (DRIE): Etch the exposed pattern through the aSi layer using a DRIE process (e.g., SPTS Pegasus) with SF₆ chemistry. Maintain the process at 0 °C and 10 mTorr. Follow with an O₂ plasma step to remove residual resist.

- Pedestal Formation (Isotropic Etching): Use vapor-phase hydrofluoric acid (HF) etching (e.g., Primaxx uEtch tool) to isotropically and controllably under-etch the SiO₂ layer beneath the silicon grating bars. An etch time of 600 seconds creates the pedestal structure, which increases the surface area interacting with the analyte's electric field.

- Characterization: Inspect the final PHCG structure using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) to confirm critical dimensions and etch profile.

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for PHCG Fabrication

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| Si ⟨100⟩ Wafer | Primary substrate material. |

| RCA Clean Chemicals | Standard mixture of SCI and SC2 solutions for ultra-cleaning. |

| Silane (SiH₄) Gas | Precursor for LPCVD of amorphous silicon. |

| Deep-UV Photoresist & BARC | Light-sensitive polymer and anti-reflective layer for patterning. |

| SF₆ and O₂ Gases | Etchant and cleaning gases for the DRIE process. |

| Vapor-Phase HF | Isotropic etchant for silicon dioxide to create the pedestal. |

Protocol: Development of an Aptamer-Based SPR Biosensor

This protocol outlines the steps for creating a biosensor by immobilizing a DNA aptamer on an SPR gold chip for the detection of a specific protein target, such as a disease biomarker.

- Surface Pre-conditioning: Rinse the bare gold sensor chip with absolute ethanol and deionized water, then dry under a stream of nitrogen. Clean the surface with an oxygen plasma treatment for 2-5 minutes to remove any organic contaminants.

- Formation of a Self-Assembled Monolayer (SAM): Immerse the clean chip in a 1 mM solution of a thiolated alkane, such as 6-mercapto-1-hexanol (MCH), in ethanol for 12-24 hours at room temperature. This forms a dense, ordered SAM that passivates the surface against non-specific binding.

- Aptamer Immobilization:

- Design: Use an aptamer with a 5' or 3' modification, typically a thiol (-SH) or biotin group.

- Activation: If using a thiolated aptamer, dilute it in a suitable buffer (e.g., Tris-EDTA with Mg²⁺) to a concentration of 0.5-1 µM. For biotinylated aptamers, proceed to step 4.

- Incubation: Inject the aptamer solution over the SAM-functionalized SPR chip surface for 30-60 minutes. The thiol group will covalently bind to the gold, displacing some MCH molecules and tethering the aptamer to the surface.

- Alternative: Streptavidin-Biotin Immobilization:

- First, immobilize a streptavidin layer on the chip (e.g., via amine coupling to a carboxymethylated dextran surface).

- Then, inject the biotinylated aptamer solution, which will bind with high affinity to the immobilized streptavidin.

- Surface Blocking: Rinse the chip with buffer to remove loosely bound aptamers. Inject a solution of a blocking agent, such as bovine serum albumin (BSA, 1% w/v) or casein, for 30 minutes to cover any remaining gold surface and minimize non-specific adsorption.

- Binding Kinetics Analysis:

- Set the SPR instrument temperature to a constant value (e.g., 25 °C).

- Use a continuous flow of running buffer (e.g., HEPES buffered saline).

- Inject a series of concentrations of the target protein (e.g., 10, 25, 50, 100 nM) for 3-5 minutes each (association phase), followed by running buffer for 5-10 minutes (dissociation phase).

- Regenerate the surface between cycles with a mild regeneration solution (e.g., 10 mM glycine-HCl, pH 2.0) to dissociate the bound target without damaging the aptamer.

- Data Analysis: Fit the resulting sensorgrams (response vs. time) globally using a 1:1 Langmuir binding model or a more complex model if needed to determine the kinetic rate constants (

k_a,k_d) and the equilibrium dissociation constant (K_D).

Advanced Concepts and Emerging Trends

The field of biorecognition is continuously evolving, with research pushing the boundaries of sensitivity, multiplexing, and application scope. SPR imaging (SPRI) is a powerful extension of conventional SPR that enables high-throughput, multiplexed analysis. Instead of monitoring a few flow cells, SPRI uses a coherent light source and a CCD camera to visualize molecular binding events across a large biochip formatted as a microarray [29]. This allows for the simultaneous screening of hundreds of biomolecular interactions, such as an entire library of drug candidates against a protein target or the profiling of multiple disease biomarkers in a single sample [29].

Another significant trend is the integration of computational and omics data for biosensor development. Tools like OmicSense represent a paradigm shift by using entire omics datasets (e.g., transcriptome, metabolome) as a comprehensive "biosensor" [32]. This method constructs a probability distribution from a library of simple regression models between a target physiological state and each variable in the omics dataset. The resulting mixture of Gaussian distributions yields the most likely prediction of the target state, effectively using the entire molecular profile of a sample as a biomarker assemblage, which is highly robust against data noise and multidimensionality [32].

Furthermore, the development of Genetically Encoded Fluorescent Biosensors (GEFBs) has revolutionized the quantitative analysis of dynamic processes in living cells. Unlike indirect transcriptional reporters, direct GEFBs, such as the ABACUS sensor for abscisic acid, consist of a sensory domain fused between two fluorescent proteins that undergo a change in FRET efficiency upon analyte binding [30]. This allows for ratiometric, real-time quantification of hormones, second messengers, and enzyme activities with high spatiotemporal resolution, independent of the cell's transcriptional/translational machinery [30]. This provides robust data for mathematical modeling of complex biological systems.

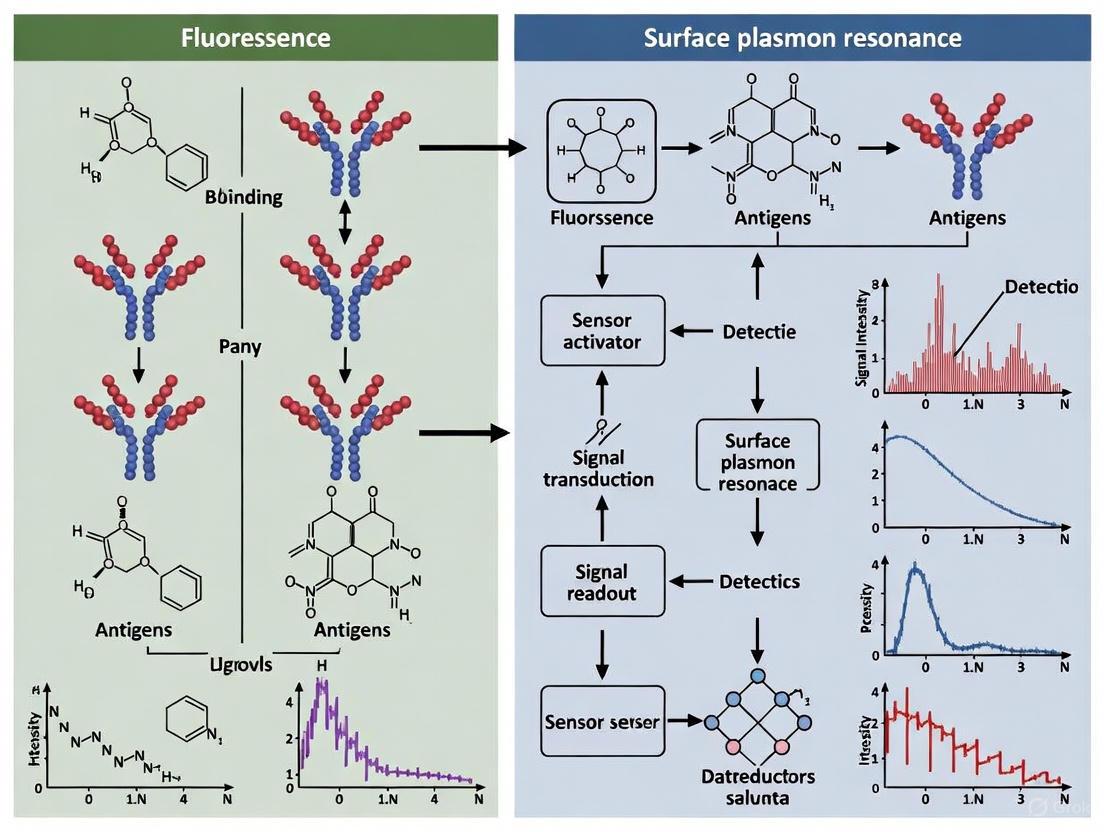

Diagram 1: Optical Biosensing Mechanisms. The top section illustrates the principle of a direct, FRET-based fluorescent biosensor, where analyte binding induces a conformational change that alters energy transfer between two fluorophores. The bottom section depicts the label-free detection principle of SPR, where binding of an analyte to an immobilized bioreceptor changes the local refractive index (RI), shifting the resonance angle of reflected light.