From Lab to Reality: A Comprehensive Guide to Validating Biosensors in Complex Biological Samples

This article provides a systematic guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the critical process of validating biosensors for use with real-world biological samples.

From Lab to Reality: A Comprehensive Guide to Validating Biosensors in Complex Biological Samples

Abstract

This article provides a systematic guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the critical process of validating biosensors for use with real-world biological samples. Covering foundational principles to advanced applications, it details the significant challenges posed by sample matrix effects, the necessity of robust optimization strategies like Design of Experiments (DoE), and the implementation of rigorous clinical validation protocols. By synthesizing recent advances and practical methodologies, this resource aims to bridge the gap between promising laboratory biosensor research and their reliable, clinically relevant deployment, ultimately accelerating the translation of these technologies into tools that improve diagnostics and therapeutic monitoring.

The Biosensor Blueprint: Core Principles and The Real-Sample Challenge

Biosensors represent a convergence of biological recognition and physicochemical detection, forming analytical devices indispensable in modern research, clinical diagnostics, and drug development. The international union of pure and applied chemistry (IUPAC) defines a biosensor as a self-contained integrated device that provides specific quantitative or semi-quantitative analytical information using a biological recognition element (bioreceptor) in direct spatial contact with a transducer [1]. The fundamental architecture of any biosensor comprises three core components: a bioreceptor for selective target recognition, a transducer for converting the biological event into a measurable signal, and signal processing electronics for interpreting and displaying the output [2] [3].

The validation of these components within real biological matrices—such as serum, blood, or environmental samples—presents the ultimate test for their analytical robustness. Performance characteristics including sensitivity, selectivity, and stability must be rigorously evaluated against complex backgrounds of interfering substances [4] [5]. This guide deconstructs the biosensor architecture, comparing the performance of various component alternatives and providing experimental methodologies for their validation, framed within the critical context of real-sample analysis.

Core Components of a Biosensor

Bioreceptors: The Molecular Recognition Elements

The bioreceptor is the biological sensing element that confers specificity to the biosensor by interacting selectively with the target analyte. The choice of bioreceptor fundamentally determines the sensor's application potential and limitations in complex samples [1].

Table 1: Comparison of Major Bioreceptor Types

| Bioreceptor Type | Recognition Principle | Key Advantages | Limitations in Real Samples | Exemplary Analytic Targets |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enzymes | Catalytic activity converting substrate to product [3] | High catalytic turnover amplifies signal; wide range of substrates [1] | Stability affected by pH, temp., inhibitors in sample [3] | Glucose, Urea, Pesticides, Heavy Metals [1] |

| Antibodies | High-affinity binding to a specific antigen (lock-and-key fit) [3] | Exceptional specificity; robust immunoassay formats [1] | Binding capacity depends on assay conditions (pH, T); can be disrupted [3] | Pathogens, Proteins, Hormones, Toxins [1] |

| Nucleic Acids (DNA/RNA) | Complementary base pairing (hybridization) [3] [1] | High predictability of interactions; aptamers can bind diverse targets [3] | Susceptible to nucleases in biological fluids | DNA/RNA sequences, Aptamer-binding molecules [1] |

| Whole Cells | Metabolic or stress response of living cells [1] [6] | Provides functional/toxicity info; no enzyme purification needed [1] | Longer response time due to transport barrier; less specific [1] | Biological Oxygen Demand (BOD), Toxicity, Heavy Metals [1] [6] |

| Artificial Binding Proteins | Engineered protein scaffolds (e.g., from phage display) [3] | Small size, high stability, can be expressed in bacterial cytoplasm [3] | Relatively new technology; limited commercial availability | Various protein targets [3] |

Transducers: Converting Biological Events into Measurable Signals

The transducer serves as the core signal conversion unit, transforming the biorecognition event into a quantifiable electrical, optical, or mechanical output. The transducer's selection directly impacts the sensor's sensitivity, miniaturization potential, and compatibility with point-of-care formats [7] [4].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Major Transducer Types

| Transducer Type | Signal Measured | Detection Limit | Response Time | Key Challenges in Real-sample Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electrochemical | ||||

| Amperometric [1] | Current from redox reactions | Very Low (nM-pM) [8] | Seconds to Minutes [8] | Electrode fouling; interference from electroactive species |

| Potentiometric [1] | Potential change at electrode surface | Low (µM-nM) | Seconds to Minutes | Sensitivity to ionic strength; reference electrode stability |

| Conductometric [1] | Change in ionic conductivity | Moderate (µM) | Minutes | Non-specific conductivity changes from sample matrix |

| Optical | ||||

| Fluorescence [1] [9] | Light emission intensity/wavelength | Extremely Low (pM-fM) [9] | Seconds to Minutes | Autofluorescence of sample components; light scattering |

| Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) [1] | Change in refractive index | Low (nM) [1] | Real-time (seconds) [1] | Non-specific adsorption to gold surface |

| Piezoelectric [1] [4] | Change in mass (frequency) | High for mass change (~pg) [4] | Minutes | Viscosity and density of sample affect frequency |

| Thermal [4] | Heat absorption/generation (temperature) | Moderate (µM) | Minutes | Requires excellent thermal insulation; background heat |

Experimental Validation in Real Biological Samples

Case Study: Validating a GEM Biosensor for Heavy Metal Detection

A 2023 study on a Genetically Engineered Microbial (GEM) biosensor for detecting Cd²⁺, Zn²⁺, and Pb²⁺ provides a robust template for validation protocols. The sensor was based on a redesigned CadA/CadR operon from Pseudomonas aeruginosa coupled with an enhanced Green Fluorescent Protein (eGFP) reporter in E. coli BL21 [6].

1. Experimental Protocol: Specificity and Cross-Reactivity Assessment

- Objective: To confirm the biosensor's response is specific to Cd²⁺, Zn²⁺, and Pb²⁺ and to rule out interference from other metals.

- Methodology:

- Prepare 100 ppm stock solutions of target metals (Cd²⁺, Pb²⁺, Zn²⁺) and non-specific metals (Ni²⁺, Fe³⁺, AsO₄³⁻) using analytical grade salts dissolved in ddH₂O [6].

- Confirm exact concentrations using Microwave Plasma-Atomic Emission Spectrometry (MP-AES) [6].

- Culture the GEM biosensor cells and expose them to a series of metal solutions (both targets and non-targets) at a range of concentrations (e.g., 0.1 - 5.0 ppm).

- Incubate under optimal physiological conditions (e.g., 37°C, pH 7.0) for a predetermined period.

- Measure the fluorescent output (eGFP intensity) using a fluorometer or microplate reader.

- Validate reporter gene expression via Quantitative PCR (qPCR) [6].

- Data Analysis:

- Plot fluorescence intensity against metal concentration for each metal.

- Calculate the linear regression (R²) for each dose-response curve. High R² values for target metals (e.g., 0.9809 for Cd²⁺) and low R² for non-specific metals (e.g., 0.0373 for Fe³⁺) confirm specificity [6].

- Determine the Limit of Detection (LOD) from the linear calibration graph.

2. Experimental Protocol: Analytical Recovery in Complex Matrices

- Objective: To evaluate the accuracy and precision of the biosensor measurement in a complex, real-world sample.

- Methodology:

- Select a relevant real sample matrix (e.g., water from a potential contamination site, processed food samples, or synthetic biological fluids).

- Spike the sample with known, quantified concentrations of the target analyte (e.g., Cd²⁺ at 1, 2, and 3 ppb).

- Process the sample with the biosensor and measure the resulting signal.

- Use the pre-established calibration curve to calculate the measured concentration of the analyte.

- Compare the measured concentration to the known spiked concentration.

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate the % Recovery for each spike level: (Measured Concentration / Spiked Concentration) × 100.

- Acceptable recovery typically falls between 80-120%, demonstrating that the matrix does not significantly interfere with the assay [6].

- Calculate the coefficient of variation (CV) for replicate measurements (n≥3) to determine precision.

Case Study: Europium Complex-Loaded Nanoparticles for Immunoassay

A 2025 study on immunosensors utilized albumin nanoparticles loaded with luminescent europium complexes for the detection of human IgG, demonstrating key validation steps for an optical biosensor [9].

Experimental Protocol: Assessing Reproducibility and Clinical Concordance

- Objective: To validate the biosensor's performance against a gold-standard clinical method.

- Methodology:

- Functionalize nanoparticle surface with streptavidin for specific binding in a sandwich immunoassay format [9].

- Test the biosensor on a panel of human serum samples with varying IgG levels, diluted up to 1:100,000 [9].

- Employ time-resolved detection to reduce background fluorescence by two orders of magnitude [9].

- Run the same set of samples in parallel using a commercial immunoassay (e.g., ELISA).

- Data Analysis:

- Perform a correlation analysis (e.g., Pearson correlation) between the signals from the new biosensor and the commercial assay.

- Assess intra-assay reproducibility by calculating the CV for replicate measurements of the same sample. The study noted CVs >20% in some sera, highlighting a key area for improvement [9].

- Test cross-reactivity with related analytes (e.g., IgA, IgM), where the reported immunosensor showed minimal cross-reactivity (~2%) [9].

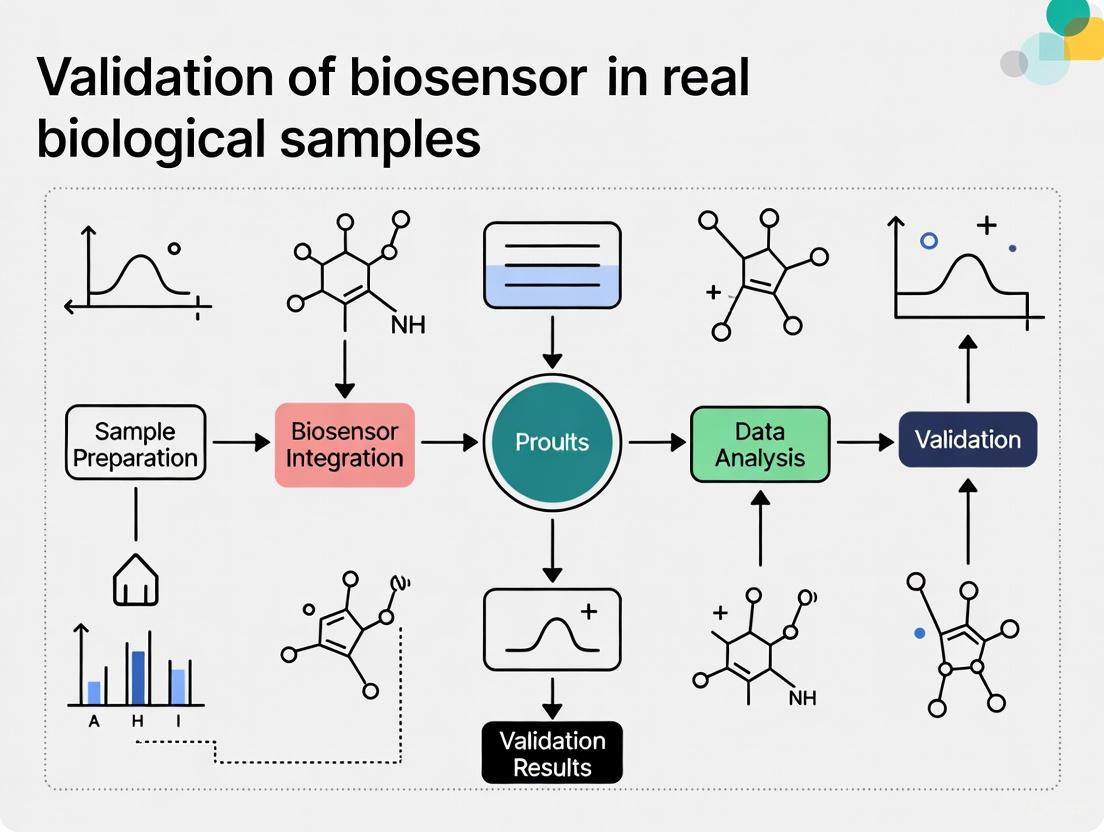

Schematic Representations

Architectural and Validation Workflow

(Biosensor Signal Flow Architecture)

GEM Biosensor Experimental Workflow

(GEM Biosensor Validation Workflow)

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The development and validation of biosensors require a curated set of high-quality reagents and materials. The following toolkit details essentials for constructing and testing biosensor systems, drawing from the cited experimental studies.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Biosensor Validation

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Exemplary Use Case & Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| pJET1.2 Plasmid | Cloning vector for genetic circuit | Used in GEM biosensor [6] to host the synthetic CadA/CadR-eGFP circuit; provides high copy number and selection. |

| Enhanced Green Fluorescent Protein (eGFP) | Reporter gene for optical detection | Provides a strong, quantifiable fluorescent signal in GEM biosensors upon activation by target analytes [6]. |

| Gold Nanoparticles | Transducer enhancement platform | Used as a substrate for immobilizing bioreceptors (e.g., glucose oxidase) to enhance electron transfer and signal in electrochemical biosensors [2] [8]. |

| Screen-Printed Electrodes (SPEs) | Disposable electrochemical transducers | Provide a ready-to-use, miniaturized three-electrode system (working, reference, counter) for portable amperometric or potentiometric sensing [1]. |

| Streptavidin | Immobilization and binding bridge | Used to functionalize sensor surfaces; binds biotinylated antibodies or DNA, enabling stable and oriented immobilization of bioreceptors [9]. |

| Cadmium Chloride (CdCl₂), Lead Nitrate (Pb(NO₃)₂) | Standard solutions for validation | Prepare stock solutions of target analytes (e.g., heavy metals) for calibration curves and spiking experiments to validate sensor response [6]. |

| Laccase Enzyme | Bioreceptor for organic pollutants | Used in enzymatic biosensors for detecting and degrading phenolic compounds and dyes; catalyzes oxidation reactions [8]. |

| BSA (Bovine Serum Albumin) | Blocking agent | Minimizes non-specific adsorption (fouling) on the transducer surface, a critical step for maintaining specificity in complex samples [9]. |

The systematic deconstruction of biosensor architecture reveals a tightly interconnected relationship between bioreceptor selectivity, transducer sensitivity, and the imperative of robust signal processing. Validation in real biological samples remains the critical gateway for transitioning laboratory biosensor designs into reliable analytical tools for research, clinical diagnostics, and drug development. The experimental frameworks and comparative data presented here provide a roadmap for researchers to rigorously benchmark new biosensor technologies against established alternatives, focusing on the key performance metrics that define analytical utility in real-world conditions. Future advancements will likely hinge on the continued integration of novel nanomaterials [2], engineered biomolecules [3], and sophisticated data analytics to overcome persistent challenges in stability, specificity, and reproducibility.

The transition of biosensors from controlled laboratory settings to real-world clinical applications represents one of the most significant challenges in diagnostic development. While biosensors frequently demonstrate exceptional performance in purified buffer solutions, their accuracy, sensitivity, and reliability can be dramatically compromised when confronted with the complex composition of real biological samples. This phenomenon, known as the matrix effect, arises from the myriad of components in blood, serum, and urine that can interfere with molecular recognition events and signal transduction. The validation of biosensors against these complex matrices is not merely a final checkbox before deployment but constitutes the ultimate test of their true analytical robustness and clinical utility. This guide systematically compares biosensor performance across different biological matrices, provides experimental protocols for evaluating matrix effects, and details strategies to overcome these challenges, framing the discussion within the broader thesis that rigorous validation in real samples is fundamental to advancing biosensor research.

Defining the Problem: The Nature of Matrix Complexity

Biological matrices such as blood, serum, and urine present a complex and variable mixture of components that can interfere with biosensor function through multiple mechanisms:

- Enzymatic Degradation: Nucleases and proteases present in clinical samples can degrade biological recognition elements (e.g., RNA, DNA, protein) essential for biosensor operation [10].

- Optical Interference: The autofluorescence of sample components or their optical absorption can severely impact the signal-to-noise ratio in fluorescence-based and colorimetric detection systems [11].

- Electrochemical Interference: Variations in ionic strength, pH, and the presence of electroactive species can distort signals in electrochemical biosensors [11] [12].

- Fouling and Non-Specific Binding: Proteins, lipids, and other biomolecules can adsorb to sensor surfaces, blocking binding sites and generating false positive signals [13].

The composition of these matrices varies not only between sample types but also between individuals and within the same individual under different physiological conditions, adding another layer of complexity to biosensor validation.

Comparative Analysis of Matrix Effects Across Sample Types

Quantitative Impact on Cell-Free Biosensor Performance

Research has systematically quantified the inhibitory effects of various clinical samples on biosensor performance. In a 2022 study evaluating cell-free transcription-translation (TX-TL) systems, clinical samples added at 10% of the final reaction volume demonstrated substantial inhibition of reporter production [10] [14].

Table 1: Matrix Inhibition on Cell-Free Biosensor Reporter Production

| Sample Type | Inhibition of sfGFP Production | Inhibition of Luciferase Production | Key Interfering Components |

|---|---|---|---|

| Serum | >98% | >98% | Nucleases, proteases, lipids |

| Plasma | >98% | >98% | Nucleases, proteases, anticoagulants |

| Urine | >90% | >90% | Metabolites, salts, variable pH |

| Saliva | 40% | 70% | Bacteria, food debris, enzymes |

Performance Variation Across Sensing Modalities

Different biosensor technologies exhibit varying susceptibility to matrix effects based on their transduction mechanisms. The table below compares the performance of several biosensor platforms when challenged with complex biological samples.

Table 2: Biosensor Technology Comparison in Biological Matrices

| Biosensor Technology | Sample Type | Key Matrix Challenges | Mitigation Strategies | Performance Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell-Free TX-TL Systems [10] [14] | Serum, Plasma, Urine, Saliva | RNase degradation, protease activity, glycerol inhibition | Engineered RNase inhibitor strains, buffer optimization | 40-70% signal recovery with RNase inhibition |

| Magnetic Nanosensors [11] | Serum, Urine, Saliva, Lysates | Minimal interference | Magnetic detection (no optical/charge limitations) | Attomolar sensitivity, 93-107% recovery in spiked tap water |

| Electrochemical Biosensors [15] | Tap water, complex media | Fouling, non-specific binding | Mn-doped ZIF-67 MOF coating, antibody functionalization | 1 CFU/mL detection limit, >80% sensitivity over 5 weeks |

| Lab-on-Paper Devices [16] | Urine, Blood | Complex composition, viscosity | Sample filtration, separation membranes | Successful ALB, CRE, and protein detection |

Experimental Protocols for Matrix Effect Evaluation

Standardized Protocol for Assessing Matrix Interference

To systematically evaluate matrix effects, researchers can implement the following standardized protocol adapted from studies on cell-free biosensors and other platforms:

1. Sample Collection and Preparation:

- Collect clinical samples (serum, plasma, urine, saliva) using standardized protocols [10]. For serum and plasma, blood should be collected in appropriate vacuum tubes and centrifuged to obtain the respective fractions.

- Minimize preprocessing to maintain matrix integrity; avoid additional purification unless specifically testing pretreatment methods.

- Aliquot and store samples at -80°C if not used immediately to preserve component stability.

2. Biosensor Reaction Setup:

- Prepare biosensor reactions according to established protocols. For cell-free systems, mix plasmids constitutively expressing reporters (e.g., sfGFP, luciferase) with cell-free extract and optimized buffer containing necessary building blocks, salts, and energy sources [10].

- Add clinical samples to constitute 10% of the final reaction volume, maintaining consistent proportions across experiments.

- Include control reactions without clinical samples to establish baseline signal levels.

- For electrochemical biosensors, functionalize electrodes with recognition elements (e.g., anti-O antibody for E. coli detection) prior to sample exposure [15].

3. Signal Measurement and Analysis:

- Quantify reporter production using appropriate instrumentation (fluorometry for sfGFP, luminometry for luciferase, electrochemistry for electrochemical sensors).

- Calculate percentage inhibition relative to control reactions:

% Inhibition = [(Signal_control - Signal_sample)/Signal_control] × 100 - Evaluate inter-patient variability by testing samples from multiple donors (recommended n≥10) [10].

Mitigation Strategy Testing Protocol

1. Inhibitor Screening:

- Test categories of inhibitors including RNase inhibitors, protease inhibitors (both bacterial and mammalian), and combination approaches.

- Use commercial inhibitors initially, but account for potential buffer-derived interference (e.g., glycerol in RNase inhibitor preparations) [10].

- For electrochemical platforms, evaluate antifouling coatings and blocking agents to reduce non-specific binding.

2. Signal Recovery Quantification:

- Calculate percentage signal recovery for each mitigation strategy:

% Recovery = [(Signal_mitigation - Signal_no mitigation)/(Signal_control - Signal_no mitigation)] × 100 - Compare mitigation effectiveness across different sample types and biosensor platforms.

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for systematic evaluation of matrix effects in biological samples

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Matrix Effect Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Application | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNase Inhibitors | Protect RNA components from degradation | Cell-free biosensors in serum/plasma | Commercial preparations may contain glycerol which can inhibit reactions [10] |

| Protease Inhibitors | Prevent protein degradation | Biosensors with protein recognition elements | Test both bacterial and mammalian-specific formulations [10] |

| Engineered E. coli Strains | Produce native RNase inhibitors | Avoid glycerol inhibition in cell-free systems | No additional steps required in extract preparation [10] [14] |

| Magnetic Nanoparticles | Enable matrix-insensitive detection | Magnetic nanosensor platforms | No magnetic background in biological samples reduces interference [11] |

| Zeolitic Imidazolate Frameworks | Enhance sensor surface area and electron transfer | Electrochemical biosensors | Mn-doping improves conductivity and catalytic performance [15] |

| Sample Separation Membranes | Filter complex samples | Lab-on-paper devices | Integrated into microfluidic devices for on-chip separation [16] |

Technological Solutions for Matrix Challenges

Matrix-Insensitive Sensing Platforms

Certain biosensor technologies demonstrate inherent advantages in complex biological matrices:

Magnetic Nanosensors: Giant magnetoresistive (GMR) sensors detect magnetic nanoparticle tags bound to target analytes. Since biological matrices lack a detectable magnetic background, these platforms achieve exceptional sensitivity (down to attomolar concentrations) with minimal matrix interference across diverse media including serum, urine, and saliva [11]. Performance remains stable across varying pH (4-10) and temperature conditions that would compromise other sensing modalities.

Engineered Cell-Free Systems: The development of E. coli strains that produce endogenous RNase inhibitors during extract preparation represents a significant advancement. This approach eliminates the need for commercial inhibitors with detrimental glycerol buffers, improves protein production yields, and reduces inter-patient variability in biosensor response [10] [14].

Metal-Organic Framework (MOF)-Enhanced Electrochemical Sensors: Mn-doped ZIF-67 composites increase sensor surface area and electron transfer efficiency while providing a stable platform for antibody functionalization. These materials enable extremely low detection limits (1 CFU/mL for E. coli) and maintain >80% sensitivity over 5 weeks in complex samples [15].

Diagram 2: Comprehensive strategies for mitigating matrix effects in biosensor applications

Methodological Approaches to Matrix Challenges

Sample Pretreatment Integration: Microfluidic lab-on-paper devices increasingly incorporate on-sample pretreatment steps including separation membranes for plasma isolation from whole blood, extraction pads for target analytes, and filtration zones to remove interfering components [16]. These integrated approaches minimize the need for external sample processing while improving biosensor performance.

Context-Aware Biosensor Design: Implementing Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycles that characterize biosensor performance across different environmental conditions (media, supplements, carbon sources) enables the development of context-aware systems with more predictable behavior in variable matrices [17].

The complexity of biological matrices presents a formidable but not insurmountable challenge in biosensor development. Systematic evaluation across sample types reveals consistent patterns of interference, with serum and plasma typically causing the most severe inhibition, followed by urine and saliva. Successful navigation of these challenges requires both technological innovations—such as magnetic detection platforms and engineered biological components—and methodological advances in sample handling and pretreatment. The ultimate validation of any biosensor must occur in the complex, variable, and often unforgiving environment of real clinical samples, as this remains the only meaningful test of its true diagnostic utility. As the field advances, the integration of matrix mitigation strategies directly into biosensor design will be essential for translating promising laboratory technologies into clinically viable diagnostic tools.

The transition of biosensors from research prototypes to reliable clinical tools hinges on rigorous validation against standardized analytical figures of merit. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding and accurately determining these parameters is crucial for evaluating biosensor performance in complex biological matrices such as blood, serum, and urine [18]. These metrics—sensitivity, specificity, limit of detection (LOD), and limit of quantitation (LOQ)—form an interconnected framework that dictates whether a biosensor can deliver the precision, reliability, and accuracy required for clinical decision-making [19] [20]. In the context of real biological samples, where interferents abound and analyte concentrations can span from abundant to trace levels, these figures of merit provide the objective criteria needed to assess a biosensor's clinical viability [18] [21]. This guide systematically compares these critical parameters, provides experimental protocols for their determination, and contextualizes their significance for biosensor validation in pharmaceutical and clinical research environments.

Defining the Key Figures of Merit

Conceptual Definitions and Clinical Significance

The analytical performance of biosensors is quantified through specific figures of merit, each measuring a distinct aspect of performance. The table below summarizes their core definitions, clinical implications, and determination methods.

Table 1: Core Analytical Figures of Merit for Biosensor Validation

| Figure of Merit | Definition | Clinical Significance | Typical Determination Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | The change in analytical signal per unit change in analyte concentration [18]. | Dictates the biosensor's ability to detect clinically relevant concentration changes (e.g., small increases in cardiac troponin) [19]. | Slope of the analytical calibration curve [18]. |

| Specificity | The ability to detect a specific analyte in a sample containing other admixtures and contaminants [19]. | Ensures accurate diagnosis by minimizing false positives from interfering substances in biological samples [20]. | Confusion matrix analysis; cross-reactivity testing with structurally similar compounds [20]. |

| Limit of Detection (LOD) | The lowest analyte concentration that can be reliably distinguished from a blank sample [22]. | Determines early disease detection capability (e.g., detecting low ng/ml levels of cancer biomarkers) [19]. | LOD = 3σ/S, where σ is the standard deviation of the blank and S is the sensitivity [20] [23]. |

| Limit of Quantitation (LOQ) | The lowest analyte concentration that can be quantified with acceptable precision and accuracy [22]. | Essential for monitoring disease progression or drug levels where precise concentration values are critical [20]. | LOQ = 10σ/S, where σ is the standard deviation of the blank and S is the sensitivity [20]. |

Interrelationships and Technical Nuances

These figures of merit are not independent; optimizing one can impact another. For instance, enhancing a biosensor's sensitivity often involves using nanomaterials like gold nanoparticles or carbon nanotubes, which provide a larger surface area for bioreceptor immobilization and improve electron transfer rates, thereby amplifying the signal per unit concentration [18]. However, such modifications must be engineered without compromising specificity, which is the bioreceptor's inherent ability to bind only to the target analyte even in complex samples like blood or serum [19]. The high-affinity interaction between an antibody and antigen is a classic example of this specificity [19].

The relationship between LOD and LOQ is fundamentally statistical. The LOD is the point at which a signal can be trusted as real (not noise), while the LOQ is the point at which the measurement becomes quantitatively meaningful [22]. The factor of three standard deviations for LOD provides a 99% confidence level for a true detection, while the ten standard deviations for LOQ ensures a low enough relative standard deviation for accurate quantification [20] [22]. In a clinical setting, the required LOD is directly tied to the physiological or pathological concentration range of the target analyte. For example, a biosensor designed to detect prostate-specific antigen (PSA) must achieve an LOD of at least 4 ng/ml to be clinically relevant for prostate cancer risk assessment [19].

Experimental Protocols for Determination

Protocol for Determining Sensitivity and Calibration Curve

Objective: To construct a calibration curve and determine the analytical sensitivity of a biosensor. Materials: Biosensor platform, purified analyte standard, buffer matrix, data acquisition system. Procedure:

- Standard Preparation: Prepare a series of standard solutions covering the expected clinical range (e.g., 0.1-100 nM) in a matrix that mimics the biological sample (e.g., buffer with 1% serum albumin).

- Measurement: For each standard concentration, measure the biosensor's response (e.g., current in nA, frequency shift in Hz, or optical shift in nm).

- Data Analysis: Plot the measured signal (y-axis) against the analyte concentration (x-axis). Using linear regression, fit a line to the data points. The slope of this calibration curve (e.g., in nA/nM) is the analytical sensitivity [18]. The linearity of this plot across the working range is also a critical performance parameter [19].

Protocol for Determining Limit of Detection (LOD) and Limit of Quantitation (LOQ)

Objective: To calculate the LOD and LOQ of a biosensor. Materials: Biosensor platform, blank sample (analyte-free matrix), low-concentration analyte standards. Procedure:

- Blank Measurement: Analyze the blank sample (e.g., pure buffer) at least 10 times to establish the baseline signal.

- Calculation: Calculate the standard deviation (σ) of the blank measurements. Determine the sensitivity (S) from the calibration curve as described in Section 3.1.

- Determination: Calculate LOD as 3σ/S and LOQ as 10σ/S [20] [23]. For example, a microRNA biosensor with a blank standard deviation of 0.05 nA and a sensitivity of 500 nA/nM would have an LOD of (3 × 0.05) / 500 = 0.0003 nM (or 300 fM) [21].

Protocol for Evaluating Specificity and Selectivity

Objective: To verify the biosensor's specificity towards the target analyte in the presence of potential interferents. Materials: Biosensor platform, target analyte, structurally similar compounds, and common interferents found in the biological sample (e.g., ascorbic acid, uric acid for blood analysis). Procedure:

- Interferent Preparation: Prepare solutions of the target analyte and individual interferents at physiologically relevant concentrations.

- Cross-reactivity Test: Measure the biosensor's response for each interferent solution separately.

- Data Analysis: The response from interferents should be negligible compared to the response from the target analyte at an equivalent concentration. Specificity is often presented via a confusion matrix, showing the rate of true positives and false positives [20]. A biosensor detecting a specific malaria DNA sequence, for instance, should not show a significant signal when exposed to DNA from other pathogens [24].

Comparative Performance Data in Clinical Applications

The practical application of these figures of merit is evident when comparing biosensor performance across different clinical targets. The following table compiles recent data from the literature to illustrate achievable performance benchmarks.

Table 2: Comparative Performance of Biosensors for Various Clinical Targets

| Target Analyte | Biosensor Type | Sensitivity | LOD | LOQ | Specificity/Selectivity Notes | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR-21 (Cancer) | Electrochemical (MWCNT) | Not specified | 1.2 × 10⁻¹⁸ M | Not specified | Demonstrated performance in human serum. | [21] |

| SARS-CoV-2 | Metasurface Optical | 400 GHz/RIU | Not specified | Not specified | Machine learning enhanced; label-free. | [25] |

| P. fluorescens | RAA-Test Strip | Not specified | 37 CFU/mL (gyrB gene) | Not specified | No cross-reactivity with 19 other bacteria. | [26] |

| Malaria (Schizont) | SPR | 263.26 °/RIU | Not specified | Not specified | Stage-specific differentiation. | [24] |

| Various Flavonoids | Whole-Cell (TtgR-based) | Not specified | 0.01 mM | Not specified | Engineered TtgR variants for tailored ligand response. | [26] |

| Lidocaine HCl | Dissolvable Microneedles | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | Significant analgesia in mice within 5 min. | [26] |

CFU: Colony Forming Unit; MWCNT: Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotube; RAA: Recombinase-Aided Amplification; RIU: Refractive Index Unit; SPR: Surface Plasmon Resonance.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key reagents and materials critical for developing and validating biosensors, along with their primary functions.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Biosensor Development

| Reagent/Material | Function in Biosensor Development | Example Use Cases |

|---|---|---|

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | Signal amplification; enhanced electron transfer; large surface area for bioreceptor immobilization. | Used in electrochemical DNA sensors to achieve fM detection limits [18]. |

| Graphene | Transducer component; high electrical conductivity and surface area; enhances plasmonic fields in optical sensors. | Integrated into SPR platforms to improve sensitivity for malaria detection [24] [25]. |

| Carbón Nanotubes (CNTs) | Transduction element; facilitate electron transfer in electrochemical biosensors. | Detection of proteins, neurotransmitters, and cancer biomarkers [18]. |

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) | Artificial bioreceptors; synthetic recognition sites for selective target binding. | Used as stable, synthetic alternatives to antibodies in sensors for small toxic molecules [27]. |

| Thiol-tethered ssDNA | Bioreceptor; provides stable, oriented binding to sensor surfaces for specific DNA/RNA detection. | Functionalization of graphene surfaces for specific malaria DNA sequence detection [24]. |

| CRISPR/Cas systems | Biorecognition and signal amplification; provides high specificity for nucleic acid targets. | Used in immobilized assays for unamplified miRNA quantification with femtomolar sensitivity [27]. |

Visualizing the Validation Workflow and Relationships

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for validating a biosensor, connecting the key experimental procedures with the figures of merit they determine.

Diagram 1: Biosensor Validation Workflow. This chart outlines the key experimental steps (green and red nodes) for determining the core figures of merit (blue nodes).

The conceptual relationship between the blank measurement, LOD, and LOQ is fundamental, as shown in the following probability distribution diagram.

Diagram 2: Statistical Relationship of Blank, LOD, and LOQ. This diagram visualizes the statistical definitions of LOD and LOQ based on the distribution of the blank signal, highlighting the differing levels of confidence for detection versus quantification [22].

The rigorous characterization of sensitivity, specificity, LOD, and LOQ is non-negotiable for the validation of biosensors intended for clinical use. As demonstrated, these parameters are interdependent, and their optimization must be balanced to meet the specific demands of detecting target analytes in complex biological samples. The experimental protocols and performance benchmarks outlined here provide a framework for researchers to systematically evaluate their biosensing platforms. The ongoing integration of advanced materials like nanomaterials and CRISPR-based recognition elements continues to push the boundaries of these figures of merit, enabling detection of clinically significant targets at previously unattainable concentrations. Ultimately, a thorough understanding and precise determination of these key analytical metrics are foundational to developing biosensors that are not only scientifically innovative but also clinically reliable and impactful.

The transition from analytical validation in simple buffer solutions to clinical application in complex biological fluids represents a critical "valley of death" in biosensor development. While academic literature reports countless biosensors with exceptional analytical performance in controlled buffer systems, only a minute fraction successfully translates to commercialized diagnostic products [28] [29]. This translational gap persists despite continuous advancements in sensing modalities, nanomaterials, and biorecognition elements. The core challenge lies in the dramatic performance deterioration that occurs when biosensors encounter the complex, heterogeneous, and variable matrix of biological samples [12] [30]. Even biosensors exhibiting picomolar detection limits for specific biomarkers in buffer may fail to function in blood, saliva, or urine due to a multitude of interference mechanisms that are often overlooked during early-stage development. This review systematically analyzes the common failure points at this critical transition, providing researchers with a framework for anticipating and addressing these challenges through robust experimental design and validation strategies.

Systematic Analysis of Failure Points in Complex Matrices

Matrix Effects and Interfering Substances

Biological fluids contain numerous components that can interfere with biosensor function through various mechanisms. Blood plasma, for instance, contains human serum albumin (35–60 mg mL⁻¹), immunoglobulin G (6–16 mg mL⁻¹), and fibrinogen (2 mg mL⁻¹), which collectively account for significant nonspecific binding that can reduce sensor sensitivity and specificity [30]. Saliva, while less complex than blood, still contains mucins, food debris, and variable ionic strength that can affect sensor performance [30]. The key interfering substances and their mechanisms of action are detailed in the table below.

Table 1: Common Interfering Substances in Biological Fluids and Their Impact on Biosensor Performance

| Biological Fluid | Key Interfering Substances | Interference Mechanism | Impact on Biosensor Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blood/Plasma/Serum | Albumin, Immunoglobulins, Fibrinogen | Nonspecific adsorption, surface fouling | Reduced sensitivity, increased background noise, false positives |

| Red/white blood cells | Physical blockage, release of intracellular components | Sensor fouling, additional redox reactions | |

| Lipids, Bilirubin | Optical interference, viscosity changes | Signal quenching in optical sensors, diffusion limitations | |

| Saliva | Mucins, Glycoproteins | Surface fouling, increased viscosity | Reduced bioreceptor accessibility, slowed diffusion |

| Food debris, Bacteria | Particulate blockage, enzymatic degradation | Physical obstruction, bioreceptor degradation | |

| Variable pH, Ionic strength | Altered bioreceptor conformation/activity | Reduced binding affinity, changed electrochemical properties | |

| Urine | Urea, Creatinine | Chemical interference, high ionic strength | Denaturation of biological recognition elements, high background current |

| Urinary sediments | Physical deposition on sensor surface | Blocked active sites, reduced signal generation |

Biomarker Accessibility and Stability Issues

Beyond matrix effects, the intrinsic properties of target biomarkers themselves present significant challenges in real samples. Circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA), for example, appears in blood as short fragments (<200 bp) with a half-life of less than 2.5 hours, requiring rapid processing and highly sensitive detection methods [31]. The ctDNA-to-circulating free DNA (cfDNA) ratio varies considerably (0.1–5%) depending on disease stage and tumor type, meaning the abundant non-target cfDNA can vastly overwhelm the target signal [31]. For protein biomarkers, stability issues are paramount; many proteins degrade rapidly in collected samples unless specific stabilization protocols are implemented [30]. Furthermore, biomarkers may exist in multiple forms – free, protein-bound, or encapsulated in extracellular vesicles – each with different accessibility to biosensor recognition elements [31].

Electrode Fouling and Surface Passivation

Electrode fouling represents one of the most significant failure points for electrochemical biosensors transitioning to biological samples. The nonspecific adsorption of proteins, lipids, and other biomolecules onto electrode surfaces creates an insulating layer that impedes electron transfer, increases impedance, and reduces sensitivity [28] [30]. This fouling phenomenon occurs rapidly upon exposure to complex biological matrices and is often irreversible without stringent surface regeneration protocols. The problem is particularly acute for continuous monitoring applications where fouling accumulates over time, leading to signal drift and eventual sensor failure. While antifouling coatings such as hydrophilic polymers, zwitterionic materials, and biomimetic membranes have been developed, their integration often involves trade-offs between fouling resistance and sensor sensitivity [28].

Comparative Performance Analysis: Buffer vs. Biological Samples

The performance gap between idealized buffer systems and real biological matrices can be quantified across multiple analytical parameters. The following table compiles experimental data from published studies demonstrating this performance degradation.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Comparison of Selected Biosensors in Buffer vs. Biological Fluids

| Biosensor Platform | Target Analyte | Limit of Detection (Buffer) | Limit of Detection (Biological Fluid) | Signal Reduction in Biological Matrix | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electrochemical immunosensor | Cardiac troponin | 20 pg mL⁻¹ | 100 pg mL⁻¹ | 5-fold | [28] |

| Au-Ag nanostars SERS platform | α-Fetoprotein (AFP) | Not specified | 16.73 ng mL⁻¹ | Not reported | [32] |

| Mn-ZIF-67 electrochemical sensor | E. coli | Not specified | 1 CFU mL⁻¹ (in spiked tap water) | 93.10–107.52% recovery | [15] |

| DNA-based electrochemical sensor | KRAS mutations | Sub-femtomolar (buffer claims) | Only detected in patient serum after wild-type sequence sequestration | Required specialized sample pre-treatment | [31] |

| Aptamer-modified gold test strip | SARS-CoV-2 | Not reported | Demonstrated in clinical samples | Not quantified | [28] |

The data reveal several consistent trends: limits of detection typically degrade by 5-10 fold in biological matrices, assay variability increases substantially, and many platforms require significant sample pre-treatment to function in complex media. Notably, the Mn-ZIF-67 sensor for E. coli demonstrates exceptional performance retention in tap water, though performance in more complex biological fluids like blood or serum remains unverified [15].

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Matrix Effects

Standardized Matrix Challenge Protocol

To systematically evaluate biosensor robustness against matrix effects, researchers should implement a standardized matrix challenge protocol:

Sample Collection and Processing: Collect biological samples (blood, saliva, urine) from at least 5-10 different donors to account for biological variability. Process samples following standardized protocols (e.g., double centrifugation for plasma separation) [31].

Spike-and-Recovery Experiments: Spike known concentrations of the target analyte into both buffer and biological matrix. Calculate percent recovery using the formula: Recovery (%) = (Measured concentration in matrix / Measured concentration in buffer) × 100. Acceptable recovery typically falls between 85-115% [15].

Interference Testing: Test potential interfering substances individually and in combination at physiologically relevant concentrations. Common interferents include ascorbic acid, uric acid, acetaminophen (for electrochemical sensors), albumin, immunoglobulins, and lipids [12].

Cross-Reactivity Assessment: For multiplexed detection or specific identification, test against structurally similar molecules or non-target analytes that may be present in the sample (e.g., different bacterial species for pathogen sensors) [15].

Surface Characterization and Fouling Assessment

Comprehensive surface analysis is essential for understanding and mitigating fouling phenomena:

Pre- and Post-Exposure Surface Analysis: Characterize sensor surfaces before and after exposure to biological fluids using techniques including electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) [15].

Quantitative Fouling Metrics: Calculate fouling parameters using electrochemical methods: Fouling Ratio = (Signal after exposure / Initial signal) × 100. Monitor signal drift over time during continuous exposure.

Antifouling Coating Efficacy: Evaluate antifouling strategies using fluorescence labeling of adsorbed proteins or quartz crystal microbalance with dissipation monitoring (QCM-D) for real-time adsorption quantification.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Addressing Translational Challenges

| Reagent/Category | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Biomimetic antifouling coatings | Reduce nonspecific adsorption | Zwitterionic polymers, polyethylene glycol derivatives, hydrophilic surfaces |

| Plasma/serum from diseased populations | Validate clinical relevance | Testing biosensors against real patient samples rather than spiked healthy samples |

| Stabilized collection devices | Preserve biomarker integrity | EDTA tubes with stabilizers for ctDNA, protease inhibitors for protein biomarkers |

| Matrix-matched calibration standards | Account for matrix effects | Calibrants in artificial or pooled natural matrices rather than pure buffer |

| Blocking agents | Minimize nonspecific binding | Bovine serum albumin, casein, synthetic blocking peptides |

| Signal amplification reagents | Enhance sensitivity in complex media | Enzymatic amplification, nanomaterials, redox mediators |

Workflow and Strategic Approaches

The transition from buffer to biological samples requires a systematic workflow that anticipates failure points and implements mitigation strategies at each development stage.

Case Studies: Lessons from Success and Failure

Success Story: Glucose Monitoring Systems

The glucose sensor represents the most successful commercial biosensor platform, with its triumph owing to several key factors: the enzyme glucose oxidase exhibits remarkable stability at physiological pH and temperature, high catalytic turnover provides signal amplification, and sophisticated electrode engineering minimizes interference from ascorbic acid, uric acid, and other electroactive compounds in blood [29]. Modern glucose sensors incorporate multiple membranes – an inner enzyme layer for specificity, an interference rejection layer to exclude electroactive compounds, and a biocompatible outer layer that controls glucose diffusion while limiting protein fouling [29]. This multi-layered approach to addressing matrix effects provides a template for other biosensor platforms.

The Challenge of Protein Biomarker Detection

In contrast to glucose monitoring, biosensors for protein biomarkers like cardiac troponin or PSA have faced significant translational hurdles. For instance, while numerous electrochemical immunosensors demonstrate picomolar detection limits for troponin in buffer, performance typically degrades to 100 pg mL⁻¹ or worse in serum or blood [28]. This degradation stems primarily from nonspecific binding of abundant proteins like albumin and immunoglobulins, which can constitute >99% of total protein content in samples, effectively masking the rare target biomarker [30]. Successful platforms increasingly employ dual-strategy approaches combining surface chemistries that minimize nonspecific binding with signal amplification methods that enhance specific signals above the background noise.

The journey from buffer to biological fluid remains fraught with challenges, but systematic assessment of failure points enables researchers to develop more robust biosensing platforms. Key strategies for success include: (1) early and continuous testing in relevant biological matrices rather than postponing these validation steps; (2) implementation of multi-faceted antifouling strategies that address both nonspecific binding and signal interference; (3) adoption of signal processing approaches that can distinguish specific signals from matrix-derived background; and (4) design of sample handling protocols that preserve biomarker integrity while minimizing complexity. By learning from both successful and failed translation attempts, and by embracing a holistic design philosophy that prioritizes robustness alongside sensitivity, the biosensing community can narrow the translational gap and deliver on the promise of point-of-care diagnostics for precision medicine.

Biosensors in Action: Methodologies and Breakthrough Applications Across Medicine

Electrochemical biosensors have revolutionized metabolic monitoring by converting biological information into quantifiable electrical signals such as current, voltage, or impedance [33] [34]. The driving force behind this field has been the global need for improved diabetes management, with 530 million adults affected worldwide and regular glucose monitoring being crucial for reducing the risks of hypo- and hyperglycemia [35]. These sensors combine a biological recognition element (enzymes, antibodies, DNA, or aptamers) with an electrochemical transducer, offering advantages including high sensitivity, rapid response times, portability, and cost-effectiveness [33] [36].

The evolution has progressed from single-analyte glucose sensors to multi-analyte platforms for continuous metabolic tracking [35]. This expansion is supported by advancements in nanomaterials, manufacturing technologies, and the integration of artificial intelligence, enabling these biosensors to provide comprehensive physiological profiles for personalized healthcare [33] [34]. The validation of these sensors in complex biological matrices—from blood and serum to sweat, saliva, and tears—remains a critical focus, ensuring their transition from laboratory innovation to reliable clinical and point-of-care applications [37] [35].

Performance Comparison of Electrochemical Biosensors

The performance of electrochemical biosensors varies significantly based on their transduction mechanism, biorecognition element, and target analyte. The following tables summarize the key performance metrics for various biosensor types and their applications in detecting different classes of analytes.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Electrochemical Transduction Techniques

| Transduction Method | Measured Signal | Key Applications | Detection Limit | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amperometric | Current from redox reactions | Glucose, lactate, cholesterol, neurotransmitters [34] | Nanomolar to micromolar range [34] | High sensitivity, compatibility with miniaturization [34] | Signal can be affected by electrode fouling [33] |

| Potentiometric | Potential difference at zero current | Electrolytes (K⁺, Na⁺), pH, ion concentration [34] | Micromolar range [34] | Simple, compact, low power, resistant to interference [34] | Slower response time compared to amperometric sensors |

| Voltammetric | Current as a function of applied potential | Cancer biomarkers, cardiac biomarkers, heavy metals [34] | Picomolar to nanomolar (e.g., 27 pM for dopamine) [36] | Low-noise, capable of multi-analyte detection [34] | Can require complex data interpretation |

| Impedimetric (EIS) | Impedance change at electrode interface | Pathogen detection, antibody-antigen binding, cell growth [34] | High sensitivity for label-free detection [34] | Label-free, real-time monitoring [34] | Complex data representation (Nyquist plots) |

Table 2: Performance of Biosensors for Different Analytic Classes

| Analyte Class | Bioreceptor | Target Example | Linear Range | Detection Limit | Real Sample Tested |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proteins | Immunosensor | Prostate-Specific Antigen (PSA) [36] | 0 to 100 ng/mL [36] | 0.28 ng/mL (8.78 fM) [36] | Not specified |

| Proteins | Immunosensor | Tau-441 (Alzheimer's) [38] | 1 fM – 1 nM [38] | 0.14 fM [38] | Human serum [38] |

| Neurotransmitters | Non-enzymatic | Dopamine [36] | 50 pM – 15 nM [36] | 27 pM [36] | Not specified |

| Toxins | Aptasensor | Endotoxin [36] | 1 fg/mL – 100 ng/mL [36] | 0.55 fg/mL [36] | Not specified |

| Metabolites (Sweat) | Enzyme (Lactate Oxidase) | Lactate [36] | Not specified | 0.083 mmol/L [36] | Human sweat [36] |

Experimental Protocols for Biosensor Validation

Validating biosensor performance in real biological samples requires rigorous and standardized experimental protocols. Key methodologies for different sensor types and validation steps are detailed below.

Fabrication of a Wearable Sweat Lactate Sensor

Objective: To develop a flexible electrochemical biosensor for monitoring lactate in human sweat [36].

- 1. Electrode Modification: Screen-printed carbon electrodes (SPCEs) serve as the base platform. A large-area, ordered poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) (PEDOT) film is synthesized via interfacial polymerization and deposited onto the SPCE to enhance conductivity and provide a stable substrate.

- 2. Enzyme Immobilization: Lactate oxidase (LOX) is immobilized onto the PEDOT-modified electrode surface. This is achieved through a cross-linking method, typically using glutaraldehyde or a similar cross-linker, which traps the enzyme in a polymer matrix (e.g., polyvinyl alcohol) to ensure stability and reusability.

- 3. Calibration: The sensor is calibrated using standard lactate solutions in a physiologically relevant buffer (e.g., phosphate buffer saline, pH 7.4). Amperometric measurements (current response at a fixed potential) are recorded at varying lactate concentrations to establish a calibration curve.

- 4. Real-Sample Validation: The sensor is integrated into a wearable patch and deployed for on-body testing. Sweat is induced through exercise, and the lactate concentration measured by the sensor is compared against a gold-standard method (e.g., high-performance liquid chromatography) to validate accuracy.

Electrochemical Immunosensor for Protein Biomarkers

Objective: To create a highly sensitive immunosensor for the detection of Tau-441 protein in human serum for Alzheimer's disease diagnosis [38].

- 1. Electrode Functionalization: A commercial 3D graphene foam (GF) electrode is carboxyl-functionalized (COOH-GF) via π–π non-covalent interactions to preserve conductivity while introducing carboxyl groups for biomolecule conjugation.

- 2. Antibody Immobilization: Anti-Tau antibodies are covalently immobilized onto the COOH-GF surface using EDC/NHS (1-Ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide/N-Hydroxysuccinimide) carbodiimide chemistry. This reaction activates the carboxyl groups, forming stable amide bonds with primary amines on the antibodies.

- 3. Immunoassay and Detection: The functionalized electrode is incubated with samples (standard solutions or diluted human serum). After washing, the binding of Tau-441 is quantified using Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) in the presence of a redox probe (e.g., [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻). The charge transfer resistance increases proportionally with the amount of bound antigen.

- 4. Specificity Testing: The sensor's selectivity is validated by testing against a panel of potential interferents, including other proteins like tau-217, tau-181, amyloid beta, and bovine serum albumin (BSA) [38].

General Procedure for Sensor Calibration and Characterization

Objective: To standardize the assessment of key biosensor performance parameters.

- 1. Selectivity/Interference Study: The sensor's response to the target analyte is compared to its response against structurally similar compounds or common interferents found in the biological matrix (e.g., ascorbic acid, uric acid, acetaminophen in blood).

- 2. Limit of Detection (LOD) and Quantification (LOQ): The LOD is typically calculated as 3.3 × σ/S, and LOQ as 10 × σ/S, where σ is the standard deviation of the blank signal and S is the slope of the calibration curve.

- 3. Reproducibility and Stability: The intra-assay and inter-assay precision (relative standard deviation, RSD) are determined from multiple measurements. Long-term stability is assessed by storing the sensor under defined conditions and periodically testing its response over days or weeks.

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

The core functionality of electrochemical biosensors relies on specific signaling pathways and logical workflows, from molecular recognition to data output. The following diagrams visualize these critical processes.

Diagram 1: The core pathway of an electrochemical biosensor shows the conversion of a biological event into a quantifiable electrical signal.

Diagram 2: The workflow for developing and validating an electrochemical biosensor for use in real biological samples emphasizes testing in complex matrices.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The advancement and fabrication of high-performance electrochemical biosensors rely on a suite of specialized materials and reagents. The table below details key components and their functions in sensor development.

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for Electrochemical Biosensor Research

| Material/Reagent | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | Signal amplification; enhance electron transfer; immobilization platform [36]. | Used in a PSA immunosensor to form a conductive gold nanofiber network on SPCE [36]. |

| Graphene & Carbon Nanotubes | High surface area; excellent electrical conductivity; mechanical strength [36]. | Fe/N-doped graphene used for dopamine detection to improve electron transfer and expose active sites [36]. |

| EDC/NHS Chemistry | Cross-linker for covalent immobilization of biomolecules onto carboxylated surfaces [38]. | Used to anchor anti-Tau antibodies onto carboxyl-functionalized 3D graphene electrodes [38]. |

| Ion-Selective Membranes | Provide selectivity for specific ions in potentiometric sensors [34]. | Key component of ion-selective electrodes (ISEs) for measuring electrolytes like Na⁺, K⁺ in blood [34]. |

| Conductive Polymers (e.g., PEDOT) | Flexible, conductive substrates for wearable sensors; biocompatible [36]. | Served as a matrix for immobilizing lactate oxidase in a flexible sweat sensor [36]. |

| Enzymes (e.g., Glucose Oxidase) | Biorecognition element; provides high specificity for catalytic biosensors [37] [35]. | The core of most commercial glucose biosensors, catalyzing the oxidation of glucose [37]. |

| Aptamers | Synthetic bioreceptors with high specificity and stability; alternative to antibodies [36]. | Employed in a sandwich-type electrochemical aptasensor for ultrasensitive endotoxin detection [36]. |

Future Perspectives: AI Integration and Multimodal Sensing

The future of electrochemical biosensors lies in their convergence with advanced data science and materials engineering. Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) are now being deployed to manage the complex, multidimensional data these sensors produce, enhancing sensitivity and specificity by identifying patterns imperceptible to traditional analysis [33] [34]. AI-powered systems facilitate early detection, personalized treatment plans, and real-time health monitoring, as seen in systems that classify pathogens with over 85% accuracy [39] [34].

Simultaneously, the exploration of novel materials like covalent organic frameworks (COFs) and liquid metal composites is paving the way for a new generation of wearables [38] [36]. These materials offer high surface areas, tunable pores, and intrinsic stretchability, which are critical for comfortable, long-term metabolic tracking. The ultimate goal is the development of fully integrated, self-powered, and multimodal sensing systems that can continuously track a panel of metabolic markers (e.g., glucose, lactate, cortisol) from easily accessible biofluids like sweat, providing a holistic view of an individual's metabolic health in real-time [37] [35].

Cancer remains a leading cause of mortality worldwide, with early detection being a critical factor in improving patient survival rates [40]. The detection of protein biomarkers such as Prostate-Specific Antigen (PSA) and α-Fetoprotein (AFP) in biological fluids provides a promising pathway for non-invasive cancer diagnosis and monitoring [41] [42]. Conventional detection methods like enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), polymerase chain reaction (PCR), and computed tomography (CT) scans, while effective, often suffer from limitations including high cost, time-consuming procedures, and the need for sophisticated laboratory infrastructure [40] [43]. These challenges are particularly acute in resource-limited settings, where the majority of cancer deaths occur [40].

In response to these limitations, optical and plasmonic biosensing technologies have emerged as powerful analytical tools capable of rapid, sensitive, and label-free detection of cancer biomarkers [44] [45]. These biosensors translate biomolecular binding events into quantifiable optical signals through various mechanisms, including surface plasmon resonance (SPR), localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR), fluorescence, and colorimetric detection [41] [45]. The integration of nanomaterials and advanced plasmonic structures has further enhanced biosensor performance, enabling the detection of clinically relevant biomarkers at ultralow concentrations in complex biological samples such as blood, serum, and cerebrospinal fluid [46] [45] [42]. This review provides a comprehensive comparison of emerging optical and plasmonic platforms, detailing their operational principles, experimental validation, and performance in detecting key cancer biomarkers like PSA and AFP within real biological matrices.

Performance Comparison of Optical and Plasmonic Biosensing Platforms

The performance of biosensing platforms is primarily evaluated based on sensitivity, limit of detection (LOD), and linear dynamic range. These parameters determine a sensor's ability to detect clinically relevant concentrations of biomarkers in complex biological samples. The following tables provide a comparative analysis of various optical and plasmonic platforms for detecting PSA and AFP.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Biosensors for α-Fetoprotein (AFP) Detection

| Sensing Platform | Detection Mechanism | Linear Range | Limit of Detection (LOD) | Real Sample Tested |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hybridization Chain Reaction (HCR) Assembly | Colorimetric (TMB oxidation) | 0.1 – 50 ng/mL | 1.95 pg/mL (instrument)5 pg/mL (naked eye) | Not Specified [41] |

| AuNPs/Bi₂Se₃ Nanosheets | Colorimetric (Catalytic switching) | 1 ng/mL – 10 μg/mL | 39 pg/mL | Not Specified [41] |

| Graphene Oxide (GO) co-adsorbed with HRP and anti-IgG | Signal-amplified Immunosensing | Information Missing | Information Missing | Information Missing [41] |

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Biosensors for Prostate-Specific Antigen (PSA) and Other Cancer Biomarkers

| Sensing Platform | Target Analyte | Sensitivity | Limit of Detection (LOD) | Real Sample Tested |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dual-channel SPR with fPSA@Au nanoparticles | Free PSA | Linear range: 0.010 – 0.40 ng/mL | Information Missing | Serum [42] |

| LSPR with Au nanoparticles conjugated with anti-PSA | PSA | Calibration Sensitivity: 43.75 nm/(ng/mL) | Information Missing | Serum [42] |

| BK7/BaTiO₃/Ag/Black Phosphorus | Cancer Cells (via RI) | 334 deg/RIU (General)271.25 – 290.714 deg/RIU (Specific Cells) | Information Missing | Six cancer cell lines (Jurkat, HeLa, PC-12, MDA-MB-231, MCF-7, Basal) [40] |

| BK7/ZnO/Ag/Si₃N₄/WS₂ | Blood Cancer Cells (Jurkat) | 342.14 deg/RIU | Information Missing | Blood cancer, cervical cancer, and skin cancer cells [42] |

| Figure-eight-shaped MXene/BP/Graphene Metasurface | Protein Biomarkers | 395 GHz/RIU | Information Missing | Neurological disorder biomarkers [46] |

Table 3: Comparison of Fundamental Biosensing Mechanisms and Their Characteristics

| Biosensing Mechanism | Key Principle | Advantages | Common Transducer Materials |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) | Collective oscillation of electrons at a metal-dielectric interface; resonance angle shifts with refractive index change [40] [45]. | Label-free, real-time monitoring, high sensitivity. | Gold (Au), Silver (Ag), BaTiO₃, 2D materials (Graphene, BP) [40] [42]. |

| Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance (LSPR) | Coherent oscillation of conduction electrons in metal nanostructures; LSPR peak shift with local dielectric environment change [45]. | Enhanced local electromagnetic field, label-free, simpler instrumentation than SPR. | Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs), Silver Nanoparticles (AgNPs) [45]. |

| Colorimetric | Measurement of visible color change due to aggregation of nanoparticles or catalytic reaction [41] [45]. | Simplicity, low cost, potential for naked-eye detection without complex equipment. | AuNPs, AgNPs, Catalytic Nanocomposites (e.g., AuNPs/Bi₂Se₃) [41]. |

| Fluorescence | Measurement of light emission from excited fluorophores; intensity changes with biomarker binding [47]. | High sensitivity, multiplexing capability. | Quantum Dots, Fluorescent Dyes [47]. |

Experimental Protocols for Biosensor Validation

To ensure the reliability and clinical relevance of biosensing data, rigorous experimental protocols must be followed. These procedures cover the fabrication of the sensor chip, its functionalization for specific biomarker capture, the actual measurement process, and subsequent data analysis.

Sensor Fabrication and Functionalization

The foundation of a high-performance biosensor is a meticulously fabricated and functionalized sensing surface.

- Prism-Coated Multilayer Fabrication (for SPR/LSPR): A common method involves using a BK7 glass prism as a coupling element. Thin films are sequentially deposited on the prism. For instance, a BaTiO₃ layer (e.g., 6 nm) can be deposited first to enhance field confinement, followed by a silver (Ag) layer (e.g., 36 nm) as the primary plasmonic material, and finally a black phosphorus (BP) layer (e.g., 0.7 nm) to enhance biomolecular interaction. Each layer's thickness is optimized using frameworks like the Transfer Matrix Method (TMM) to maximize performance metrics such as sensitivity and quality factor [40].

- Nanomaterial Synthesis for Colorimetric Sensors: For a catalytic colorimetric sensor, materials like Bi₂Se₃ nanosheets may be synthesized and then decorated with gold nanoparticles (AuNPs). This creates a nanocomposite (Au/Bi₂Se₃) with high catalytic activity for reactions like the reduction of 4-nitrophenol, a signal that can be "switched off" upon binding of the target biomarker [41].

- Surface Biofunctionalization: The transducer surface must be modified to capture the target biomarker specifically. This is typically achieved by immobilizing a capture antibody specific to the target antigen (e.g., anti-AFP or anti-PSA) onto the sensor surface. Immobilization can occur through physical adsorption, covalent bonding, or via linker molecules like streptavidin-biotin interactions [41] [42]. This step is critical for ensuring the sensor's specificity.

Measurement and Detection Protocols

The protocol for measuring biomarker concentration varies depending on the detection mechanism.

Angular Interrogation SPR Measurement:

- The functionalized sensor chip is integrated into a microfluidic system to control the flow of samples.

- P-polarized light from a monochromatic source (e.g., a laser) is directed through the prism at a range of incident angles.

- The intensity of reflected light is measured by a photodetector. A sharp dip in reflectivity at a specific SPR angle is observed.

- A baseline reading is established by flowing a buffer solution over the sensor.

- The sample (e.g., serum spiked with the biomarker or a clinical sample) is injected over the sensor surface.

- The binding of biomarkers to the capture probes causes a local increase in the refractive index (RI), leading to a measurable shift in the SPR angle.

- The angular shift (Δθ) is recorded in real-time and is proportional to the biomarker concentration [40] [42].

Colorimetric Detection Protocol:

- The antibody-functionalized nanomaterial (e.g., Au/Bi₂Se₃) is incubated with the sample containing the target biomarker [41].

- Binding of the biomarker to the surface often alters the catalytic activity of the nanomaterial or causes aggregation of metal nanoparticles.

- A substrate solution (e.g., TMB/H₂O₂ for HRP-based systems or 4-NP/NaBH₄ for catalytic sensors) is added.

- The resulting color change or intensity is quantified using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer to measure absorbance at a specific wavelength. The change in absorbance is correlated with the biomarker concentration [41].

Data Processing and Analysis

For advanced sensors, particularly those generating complex datasets, sophisticated data analysis is employed.

- Machine Learning Integration: Sensor responses, such as transmission spectra at different refractive indices or biomarker concentrations, can be used to train machine learning models. For example, Bayesian Ridge Regression has been demonstrated to effectively predict refractive index variations (R² ≈ 86%) and angular dependencies (R² ≈ 96%), enhancing the accuracy and robustness of the quantification [46].

- Real-Time Binding Kinetics: SPR sensors directly generate sensorgrams (response vs. time), which can be analyzed to extract association and dissociation rate constants (kₐ and kḍ), providing insights into the affinity and kinetics of biomolecular interactions [45].

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow and signal transduction principles of an SPR biosensor.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The development and validation of high-performance optical biosensors rely on a specific set of advanced materials and reagents. The table below details key components, their functions, and examples of their application in the cited research.

Table 4: Essential Research Toolkit for Optical and Plasmonic Biosensor Development

| Material/Reagent | Function in Biosensor | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| BK7 Glass Prism | Optical coupler that enables excitation of surface plasmons in the Kretschmann configuration. | Used as the base coupling element in multiple SPR sensors [40] [42]. |

| Silver (Ag) and Gold (Au) | Plasmonic metals that support surface plasmon waves. Ag offers higher sensitivity; Au provides better stability and biocompatibility. | Ag used as the primary plasmonic layer in a BaTiO₃/Ag/BP sensor [40]. |

| 2D Materials (Black Phosphorus, Graphene, TMDCs like WS₂) | Enhance sensitivity and field confinement due to high surface area and strong light-matter interactions. Promote biomolecule adsorption. | BP used to enhance biomolecular interaction [40]. WS₂ identified as the top-performing 2D material in a ZnO/Ag/Si₃N₄/WS₂ sensor [42]. |

| High-Index Dielectrics (BaTiO₃, ZnO, Si₃N₄) | Improve electric field confinement and reduce reflectance curve width, leading to higher sensitivity and detection accuracy. | BaTiO₃ used to enhance optical confinement and sensitivity [40]. ZnO and Si₃N₄ used in a multilayer sensor for cancer cell detection [42]. |

| Capture Antibodies (e.g., anti-AFP, anti-PSA) | Biological recognition element that provides specificity by binding to the target biomarker. | Immobilized on sensor surfaces for specific capture of AFP and PSA [41] [42]. |

| Enzyme Labels (e.g., Horseradish Peroxidase - HRP) | Used in signal amplification strategies. Catalyzes a chromogenic reaction to produce a measurable color change. | Used in a colorimetric AFP biosensor based on HCR assembly and TMB oxidation [41]. |

| Chromogenic Substrates (e.g., TMB, ABTS) | Produce a visible color change when oxidized by an enzyme label like HRP, enabling colorimetric detection. | TMB used for instrumental and visual detection of AFP [41]. |

Optical and plasmonic biosensing platforms represent a significant advancement in the detection of cancer biomarkers, offering performance characteristics that are increasingly competitive with, and in some aspects superior to, conventional methods. The integration of novel materials like 2D semiconductors and high-index dielectrics, coupled with sophisticated structural designs, has pushed the sensitivity of these sensors to new heights, enabling the detection of subtle refractive index changes associated with low biomarker concentrations. The ongoing integration of machine learning for data analysis further enhances their accuracy and potential for real-world application.

Validation in complex biological matrices remains the critical benchmark for clinical translation. The promising results demonstrated by various SPR, LSPR, and colorimetric sensors in detecting PSA, AFP, and entire cancer cells in serum and other samples underscore the viability of this technology. Future research will likely focus on enhancing multiplexing capabilities for parallel detection of biomarker panels, improving sensor stability and reproducibility for point-of-care use, and conducting larger-scale clinical validation studies. As these platforms continue to mature, they hold the strong potential to become indispensable tools in the clinical arsenal for the early diagnosis, prognosis, and monitoring of cancer.

Lab-on-a-Chip (LoC) technology represents a pioneering amalgamation of fluidics, electronics, optics, and biosensors that performs various laboratory functions on a miniaturized scale, typically on a single chip ranging from millimeters to a few square centimeters [48]. These systems process small volumes of fluids, typically from 100 nL to 10 μL, consolidating multiple laboratory processes including sampling, pretreatment, chemical reactions, separation, detection, and data analysis onto a single platform [48]. The concept of miniaturizing laboratory processes began with the development of microelectromechanical systems (MEMS) in the 1960s, with the first actual LoC created in 1979 at Stanford University for gas chromatography [49] [50]. The field gained prominent recognition after the conceptual work on miniaturized total analysis systems (μTAS) by Manz et al. in 1990, with a groundbreaking advancement achieved in 1993 with the pioneering discovery of on-chip capillary electrophoresis [48].

The fundamental principle behind LoC technology is microfluidics—the science of manipulating and controlling fluids at a microscale, typically involving channels with dimensions ranging from tens to hundreds of micrometers [50]. At this scale, fluid behavior differs significantly from macro-scale flows, with laminar flow dominating and parameters like surface forces, shear forces, diffusion, and viscosity becoming crucial while gravitational forces become less significant [48]. This technology has evolved from a novel concept to a powerful tool with broad applications across diagnostics, drug discovery, and environmental monitoring, leveraging the principles of microfluidics and integration of various laboratory functions to offer compact, efficient, and versatile solutions for rapid analysis [50].

Key Materials and Fabrication Techniques

Materials for LoC Devices

The selection of materials for LoC devices significantly influences their intrinsic properties, fabrication methods, and overall functionality. Key considerations include flexibility, air permeability, electrical conductivity, solvent compatibility, optical transparency, and biocompatibility [48].

Table 1: Comparison of Key Materials Used in Lab-on-a-Chip Devices

| Material | Advantages | Limitations | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|