Modeling and Mitigating Temporal Drift in OECT Biosensors: From Theory to Reliable Biomedical Applications

Organic Electrochemical Transistors (OECTs) are a leading platform for biosensing due to their high sensitivity and biocompatibility.

Modeling and Mitigating Temporal Drift in OECT Biosensors: From Theory to Reliable Biomedical Applications

Abstract

Organic Electrochemical Transistors (OECTs) are a leading platform for biosensing due to their high sensitivity and biocompatibility. However, their widespread adoption in clinical and pharmaceutical settings is hindered by temporal signal drift, which compromises long-term accuracy and reliability. This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the theoretical underpinnings of drift phenomena in OECTs, exploring its origins in ion adsorption and diffusion dynamics. We review advanced device architectures, including dual-gate and three-dimensional designs, that effectively suppress drift. Furthermore, we present a suite of modeling, material, and operational strategies for drift mitigation and validation, offering researchers and drug development professionals a practical framework for developing stable, high-performance OECT-based biosensors capable of functioning in complex biological fluids like human serum.

Unraveling the Origins: The Fundamental Mechanisms of Temporal Drift in OECTs

Organic Electrochemical Transistors (OECTs) are three-terminal electronic devices that have emerged as a transformative technology for bioelectronic applications, including biosensing, neuromorphic computing, and real-time physiological monitoring [1] [2]. Their operation relies on the unique properties of organic mixed ionic-electronic conductors (OMIECs), which facilitate the simultaneous transport of both ions and electrons [3]. This dual conduction capability enables OECTs to efficiently transduce ionic fluctuations in biological environments into electronic signals, making them exceptionally suitable for interfacing with biological systems [4] [5].

A typical OECT comprises a channel (composed of an OMIEC), a gate electrode, and an electrolyte that bridges the two [5]. The most commonly used channel material is the conducting polymer poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) doped with poly(styrene sulfonate) (PEDOT:PSS), prized for its high transconductance, stability in aqueous environments, and biocompatibility [4] [6] [1]. The gate electrode can be made from polarizable materials (e.g., Au, Pt) or non-polarizable materials (e.g., Ag/AgCl) [3] [5]. When a voltage is applied to the gate electrode ((VG)), it drives ions from the electrolyte into the bulk of the OMIEC channel, thereby electrochemically modifying its doping state and modulating its electronic conductivity [4] [3]. This volumetric doping process is the source of the OECT's high transconductance ((gm)), a key figure of merit representing its signal amplification efficiency [4] [5].

Fundamental Operating Principles of OECTs

Operational Mechanism and Modes

The fundamental mechanism of an OECT involves the electrochemical doping and de-doping of the organic semiconductor channel via ion injection from the electrolyte, governed by the gate voltage [4]. In the most common example, a PEDOT:PSS-based OECT operates in depletion mode [4]. The channel is initially conductive (ON state) due to the presence of hole charge carriers (PEDOT+). When a positive gate voltage ((VG)) is applied, cations (e.g., Na+, K+) from the electrolyte are driven into the channel matrix. These cations associate with the immobilized PSS- anions, compelling the extraction of holes from the channel (to the drain electrode) to maintain charge neutrality. This process de-dopes the channel, reducing its hole density and thus its conductivity, which leads to a decrease in the drain current ((ID))—the OFF state [4]. The associated redox reaction is reversible and can be represented as:

[ n\left(\text{PEDOT}^{+}:\text{PSS}^{-}\right) + \text{M}^{n+} + n e^{-} \rightleftharpoons n \text{PEDOT}^{0} + \text{M}^{n+}:n\text{PSS}^{-} ]

Equation 1: The reversible redox reaction in a PEDOT:PSS OECT operating in depletion mode. Applying a positive gate voltage drives the reaction to the right (de-doping, OFF state), while removing the voltage allows it to return to the left (conductive, ON state) [4].

In contrast, OECTs can also be designed to operate in accumulation mode, typically using initially undoped (non-conductive) channel materials, which are OFF at zero gate voltage [4]. For an n-type accumulation-mode device, applying a positive (VG) injects cations into the channel, leading to its doping and an increase in (ID) (ON state) [4] [5]. Accumulation-mode devices are particularly advantageous for low-power applications [4].

Device Physics and Performance Metrics

The steady-state performance of OECTs is often described by the Bernards model [5] [7]. In this model, the drain current (I_D) in the saturation regime is given by:

[ ID = \frac{W d \mu C^*}{L} \left( VG - VT \right) VD ]

where:

- (W), (L), and (d) are the channel width, length, and thickness, respectively.

- (\mu) is the charge carrier mobility.

- (C^*) is the volumetric capacitance of the channel material.

- (V_T) is the threshold voltage.

- (V_D) is the drain voltage.

The most critical performance metric is the transconductance, (gm = \partial ID / \partial VG), which quantifies the amplification capability of the device. A high (gm) is essential for detecting weak biological signals [3] [5].

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics and Parameters for OECTs

| Parameter | Symbol | Description | Impact on Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transconductance | (g_m) | Efficiency of converting (VG) to (ID) change; (\partial ID / \partial VG) | Directly determines signal amplification and sensitivity [5]. |

| Volumetric Capacitance | (C^*) | Ability of the channel material to store charge per unit volume | A higher (C^*) enables stronger modulation of (ID) and higher (gm) [3]. |

| Charge Carrier Mobility | (\mu) | How quickly charge carriers move through the semiconductor | Higher (\mu) leads to faster switching and higher (g_m) [3]. |

| Response Time | (\tau) | Speed at which the device switches between ON and OFF states | Critical for capturing fast biological dynamics; limited by ion transport [1]. |

Diagram 1: OECT depletion mode operation, showing the OFF state with a positive gate voltage and the ON state with zero gate voltage.

The Signal Drift Challenge in OECTs

Origin and Mechanisms of Signal Drift

Signal drift is a critical challenge in OECTs, manifesting as a gradual, undesired change in the output signal (typically the drain current, (I_D)) over time, even when the target analyte concentration and all operational parameters remain constant [6]. This phenomenon severely compromises measurement accuracy, long-term stability, and the reliability of biosensors, leading to false positives/negatives and inaccurate quantification [6].

The primary physical origin of drift is the slow, continuous diffusion of ions from the electrolyte into the functional materials of the device, particularly the gate electrode or its modifying layers, even in the absence of a specific binding event [6]. This process can be modeled using first-order kinetics [6]. The rate of change of ion concentration within the gate's bioreceptor layer ((c_a)) is given by:

[ \frac{\partial ca}{\partial t} = c0 k+ - ca k_- ]

where:

- (c_0) is the ion concentration in the solution.

- (k+) and (k-) are the rate constants for ion absorption into, and desorption from, the gate material, respectively.

The ratio of these rate constants, (k+/k- = K = e^{(-\Delta G + \Delta V e0 z)/(kB T)}), determines the equilibrium ion partition and is influenced by the difference in the Gibbs free energy ((\Delta G)) and the electrostatic potential ((\Delta V)) [6]. The base rate constant (k0) is related to the diffusion constant (D) of ions in the material and its thickness (d), approximated by (k0 \sim D/d^2) [6]. This model confirms that the temporal current drift observed in experiments follows an exponentially decaying function, directly linked to ion accumulation [6].

Impact of Drift on Biosensing

In a biosensing context, this non-faradaic ion adsorption creates a shifting baseline, which can obscure the specific signal from the target biomolecule [6]. For instance, in a single-gate OECT (S-OECT) configured for immuno-sensing, a discernible drift in the output current is observed in control experiments with no analyte present, complicating data interpretation and reducing the sensor's limit of detection and accuracy over time [6]. The problem is exacerbated in complex biological fluids like human serum, which contain a multitude of ionic and biomolecular species that can interact non-specifically with the device surfaces [6].

Table 2: Factors Influencing Signal Drift in OECTs

| Factor | Impact on Drift | Supporting Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Gate Material & Thickness | Thicker or more porous gate materials can increase ion absorption capacity and prolong drift duration. | The drift rate constant (k_0) is inversely proportional to the square of the material thickness ((d^2)) [6]. |

| Bioreceptor Layer Properties | The chemical nature of the immobilization layer (e.g., PT-COOH, PSAA) affects ion absorption Gibbs free energy ((\Delta G)). | Different bioreceptor layers (PT-COOH, PSAA, SAL) showed distinct drift parameters in the kinetic model [6]. |

| Electrolyte Composition | Complex media like human serum cause more significant drift compared to simple buffers like PBS due to more non-specific interactions. | Drift was studied and successfully mitigated in both PBS and human serum, with the latter being a more challenging environment [6]. |

| Operation History | Previous voltage biases can precondition the channel and gate, altering their ion content and affecting subsequent drift. | Pre-biasing gate potential was shown to influence doping states in the channel, which correlates to ion content [2]. |

Theoretical Modeling of Drift

Accurately modeling drift is a cornerstone for developing effective compensation strategies. The first-order kinetic model provides a robust theoretical framework, treating the gate/functionalization layer as a reservoir that slowly accumulates ions [6].

The experimental protocol for characterizing and modeling drift typically involves:

- Device Preparation: Fabricate OECTs with the gate electrode functionalized with the bioreceptor layer of interest (e.g., a polymer like PT-COOH or a self-assembled monolayer) [6].

- Control Experiment: Place the functionalized OECT in the measurement electrolyte (e.g., 1X PBS or human serum) without the presence of the target analyte.

- Data Acquisition: Apply a constant gate voltage ((VG)) and drain voltage ((VD)) while monitoring the drain current ((I_D)) over an extended period to record its temporal drift.

- Model Fitting: Fit the acquired (ID) vs. time data to the solution of the first-order kinetic equation, which typically takes the form of an exponential decay function: (ID(t) = A e^{-t/\tau} + C), where (\tau) is the drift time constant [6].

- Parameter Extraction: Extract the fitting parameters ((A), (\tau), (C)), which quantify the magnitude and speed of the drift. These parameters can then be linked back to physical properties like ion diffusion coefficients and material thickness.

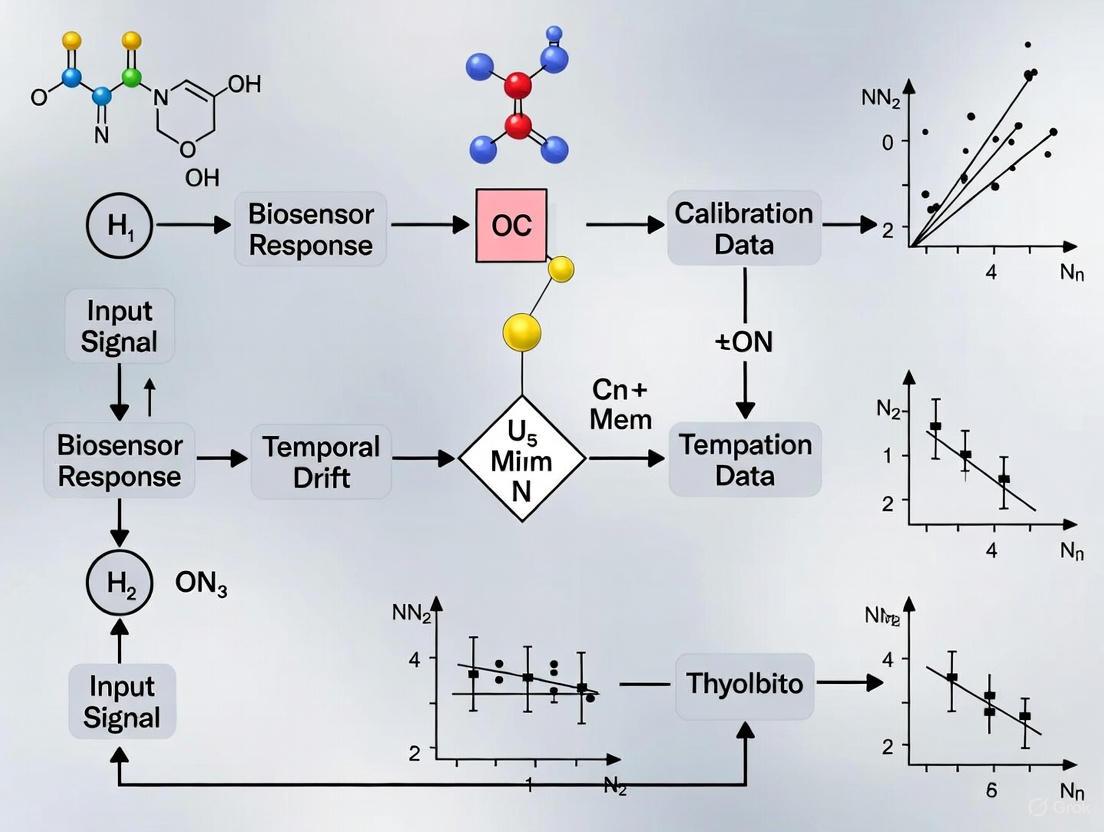

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for characterizing and modeling temporal drift in OECTs.

Mitigation Strategies and Advanced Device Architectures

Addressing the drift challenge requires innovative approaches at both the device architecture and circuit design levels.

Dual-Gate OECT (D-OECT) Architecture

A highly effective hardware-based solution is the dual-gate OECT (D-OECT) architecture [6]. This configuration employs two OECT devices connected in series. The gate voltage ((VG)) is applied to the bottom of the first device, and the drain voltage ((V{DS})) is applied to the second device. The transfer curves are measured from the second device [6]. This design fundamentally counteracts drift by preventing the accumulation of like-charged ions during measurement, a key driver of the phenomenon in single-gate setups (S-OECTs) [6]. Experimental results demonstrate that the D-OECT platform can largely cancel the temporal current drift observed in S-OECTs, thereby increasing the accuracy and sensitivity of immuno-biosensors, even in complex media like human serum [6].

Material and Design Engineering

Other strategies focus on the materials and operational paradigms of the OECT itself:

- Crystallinity Control: Engineering the channel material to have a mix of crystalline and amorphous domains can enable reconfigurable operation. Amorphous regions allow for volatile (fast) ion transport for sensing, while crystalline regions can trap ions, enabling non-volatile memory—which, if precisely controlled, can be used to counteract unwanted drift by stabilizing the device state [2].

- Vertical Architecture: Designing a vertical traverse OECT (v-OECT) with a very high channel thickness-to-length ratio (d/L) can flatten the electric potential gradient across the channel. This reduces the driving force for trapped ions to drift out of the channel after the gate voltage is removed, enhancing operational stability [2].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for OECT Drift Analysis

| Reagent / Material | Function in Drift Research | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| PEDOT:PSS | The most common OECT channel material; serves as a benchmark for studying ion injection and de-doping dynamics related to drift [4] [7]. | Used as the active channel in both single-gate and dual-gate OECT configurations to study baseline drift [6]. |

| PT-COOH (Poly(thiophene-3-carboxylic acid)) | A functionalized conducting polymer used as a bioreceptor layer on the gate electrode. Its interaction with ions is directly modeled in drift kinetics [6]. | Immobilized on gate electrodes to study the drift resulting from non-specific ion absorption in the absence of target analytes [6]. |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | A standard blocking agent used to passivate non-specific binding sites on the gate electrode. Incomplete blocking can contribute to drift. | Used in control experiments to investigate drift originating from ions and non-specifically bound biomolecules [6]. |

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) | A standard, well-defined ionic solution (containing Na+, K+, Cl-, PO4^3-) used for initial drift characterization and modeling. | Serves as a simpler system than biological fluids to quantify fundamental drift parameters of ion absorption [6]. |

| Human Serum | A complex biological fluid containing numerous ions, proteins, and other biomolecules. It represents a realistic and challenging environment for testing drift mitigation strategies. | Used to validate the effectiveness of the dual-gate (D-OECT) architecture in canceling drift in real-world conditions [6]. |

Signal drift, rooted in the slow, non-faradaic absorption of ions into the device's functional materials, presents a fundamental challenge to the long-term accuracy and reliability of OECT-based biosensors. A first-order kinetic model provides a robust theoretical framework for understanding and quantifying this phenomenon, directly linking it to physical material properties and operational conditions. While drift is pervasive, the development of innovative mitigation strategies—most notably the dual-gate OECT architecture—demonstrates a viable path forward. When combined with advanced material engineering and precise theoretical modeling, these approaches pave the way for the creation of robust, high-precision OECT biosensors capable of stable, long-term operation in complex biological environments, a critical requirement for their translation into real-world research and clinical applications.

In the field of bioelectronics, Organic Electrochemical Transistors (OECTs) have emerged as a versatile platform for biosensing, interfacing with biological systems, and neuromorphic computing [3] [8]. These devices uniquely transduce ionic signals from biological environments into electronic outputs, leveraging the mixed ionic and electronic conduction properties of organic materials [9] [3]. A persistent challenge in the practical deployment of OECT-based biosensors, however, is the phenomenon of temporal drift—a slow, monotonic change in the device's electrical characteristics, such as its threshold voltage, during prolonged operation [10] [11]. This instability leads to inaccuracies in both in vivo and in vitro measurements, limiting the reliability of continuous monitoring and long-term sensing applications [11].

The underlying mechanism of drift is intrinsically linked to the slow migration and redistribution of ions within the device's structure. This paper focuses on the First-Order Kinetic Model of Ion Adsorption as a fundamental theoretical framework to explain the origin of the drift phenomenon in OECTs, particularly those with functionalized gates [10]. Understanding and modeling this ion diffusion process is not merely an academic exercise; it is a critical step toward designing stable, accurate biosensors for demanding applications in medical diagnostics, drug development, and fundamental biological research. By framing ion adsorption and desorption as first-order processes, researchers can quantitatively describe and predict drift behavior, enabling the development of advanced device architectures, such as dual-gate OECTs, that actively mitigate its effects [10].

Theoretical Foundations of the First-Order Kinetic Model

Core Principles of Ion Kinetics in OECTs

The operation of an OECT hinges on the bulk coupling of ionic and electronic charges within the channel material, typically an organic mixed ionic-electronic conductor (OMIEC) like PEDOT:PSS [9] [8]. When a gate voltage is applied, ions from the electrolyte migrate into the channel, changing its doping level and hence its conductivity. The first-order kinetic model simplifies the complex dynamics of this ion exchange by treating the adsorption and desorption of ions into the gate or channel material as a reversible process with rate constants directly proportional to the concentration of the reacting species [10].

In this framework, the rate of change in the surface coverage of ions, θ, is given by the difference between the adsorption and desorption rates. The fundamental Langmuir rate equation, which has a general character for various sorption mechanisms, is expressed as:

dθ/dt = k_a * c * (1 - θ) - k_d * θ [12]

where k_a is the adsorption rate constant, k_d is the desorption rate constant, c is the ion concentration in the electrolyte, and (1 - θ) represents the available surface sites [12]. At equilibrium (dθ/dt = 0), this equation reduces to the Langmuir isotherm, defining the equilibrium coverage θ_eq [12]. The model's power lies in its ability to describe the temporal evolution of ion concentration within the sensing layer, which directly correlates to the observed electrical drift in the device output [10].

Relationship to Observable Drift Phenomena

The gradual adsorption of ions into the gate dielectric or the OMIEC channel creates an internal electric field that manifests as a slow shift in the device's threshold voltage (V_th). This is classically observed in Ion-Sensitive Field-Effect Transistors (ISFETs), a relative of OECTs, where the penetration of H+ ions into the oxide layer is a documented cause of long-term drift [11]. The electric field (E_diffusion) generated by the diffusion of ions with a concentration gradient dP/dx is given by:

E_diffusion = (q * D_p / σ) * (dP/dx) [11]

where D_p is the diffusion coefficient, σ is the conductivity, and q is the electronic charge. This field, in turn, influences the threshold voltage, leading to a measurable temporal drift [11]. In OECTs, this drift behavior has been successfully modeled using the first-order kinetic approach, showing excellent agreement with experimental data in both buffer solutions and complex biological media like human serum [10].

Table 1: Key Parameters in the First-Order Ion Adsorption Kinetic Model

| Parameter | Symbol | Unit | Description | Impact on Drift |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adsorption Rate Constant | k_a |

s⁻¹ or M⁻¹s⁻¹ | Speed of ion incorporation into the material | Higher k_a can lead to faster initial drift. |

| Desorption Rate Constant | k_d |

s⁻¹ | Speed of ion release from the material | Higher k_d can counteract drift, promoting stability. |

| Diffusion Coefficient | D_p |

m²/s | Measure of ion mobility within the material | Lower D_p can slow down the drift dynamics. |

| Equilibrium Constant | K = k_a / k_d |

Dimensionless | Ratio of adsorption/desorption, affinity of ions to the material | High K indicates strong binding, potentially leading to larger steady-state drift. |

| Volumetric Capacitance | C* or C_V |

F/cm³ | Ability of the channel material to store charge per unit volume | A higher C* amplifies the electrical impact of ion adsorption, affecting transconductance [9]. |

Experimental Validation and Protocols

Quantifying Drift in OECT Biosensors

Validating the first-order kinetic model requires precise experimental characterization of OECT drift under controlled conditions. The core methodology involves monitoring the temporal change in a key electrical parameter—typically the drain current (I_D) at a fixed gate voltage (V_G) or the threshold voltage (V_th)—while the device is immersed in an electrolyte [10] [3].

A standard protocol involves biasing the OECT in its operational regime (e.g., constant V_D and V_G) and measuring the drain current over an extended period (from several minutes to hours). To assess the efficacy of the first-order model, this experiment is conducted in both simple buffers, such as Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS), and complex biological fluids, like human serum, which presents a more challenging environment due to the presence of proteins and other interferents [10]. The experimental setup for such studies typically includes a source measure unit (SMU) or a potentiostat to control gate and drain voltages and precisely measure the resulting currents [3]. The extracted current or voltage drift data is then fitted to the solutions of the first-order kinetic equations to extract the rate constants k_a and k_d.

Key Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details essential reagents and materials used in experiments focused on ion adsorption kinetics and drift in OECTs.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for OECT Drift Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Description | Example in Context |

|---|---|---|

| PEDOT:PSS | The most widely used OMIEC for the OECT channel; provides a matrix for mixed ion-electron transport [9] [13]. | Serves as the active channel material whose conductivity is modulated by ion adsorption [10] [8]. |

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) | A standard buffer solution providing a stable ionic environment and pH for baseline characterization [10]. | Used as a well-defined electrolyte to study drift in a simple, controlled system [10]. |

| Human Serum | A complex biological fluid containing proteins, metabolites, and electrolytes [10]. | Used to test drift and biosensor performance in a realistic, clinically relevant medium [10]. |

| Ag/AgCl Gate Electrode | An unpolarizable reference electrode commonly used as the gate in OECTs due to its stable potential [3]. | Provides a stable gate voltage; its use helps isolate drift originating from the channel/electrolyte interface. |

| Venus Shell Biosorbent | An untreated, low-cost biosorbent material derived from waste venus shells [14]. | While not used in OECTs, its study for metal ion adsorption (e.g., Cu(II), Zn(II)) provides a validated model system for analyzing adsorption kinetics and isotherms, including pseudo-first and pseudo-second order models [14]. |

Data Analysis and Model Fitting

The experimental data for current drift over time is fitted to the integrated form of the first-order kinetic model. The model's agreement with data is a strong indicator that the underlying ion adsorption process is the rate-limiting step for the observed temporal drift [10]. Studies have successfully used this approach to not only describe drift but also to propose and validate solutions. For instance, research has demonstrated that a dual-gate OECT architecture can significantly mitigate the drift phenomenon, thereby increasing the accuracy and sensitivity of immuno-biosensors even in human serum [10]. This suggests that the model is not just descriptive but also predictive and instrumental in guiding device engineering.

Table 3: Experimental Drift Data Analysis in Different Media

| Electrolyte Medium | Observed Drift Behavior | First-Order Model Fit | Implications for Biosensing |

|---|---|---|---|

| PBS Buffer | Predictable, relatively stable drift dynamics [10]. | Shows very good agreement, allowing for parameter extraction [10]. | Provides a baseline for device characterization and model validation. |

| Human Serum | More complex and pronounced drift due to non-specific binding and interferents [10]. | Model still holds, demonstrating its robustness in complex media [10]. | Critical for validating biosensors intended for real-world clinical use. |

| Dual-Gate OECT Architecture | Temporal current drift is "largely mitigated" compared to standard single-gate design [10]. | The model helps explain the compensating effect of the second gate. | Enables higher accuracy and lower limit of detection in demanding applications [10]. |

Advanced Modeling Context: Nernst-Planck-Poisson Framework

While the first-order kinetic model provides a high-level, phenomenological description of ion adsorption, a more profound physical understanding requires advanced modeling that explicitly accounts for ion drift, diffusion, and the resulting electric fields. The Nernst-Planck-Poisson (NPP) framework is a cornerstone for such detailed simulations [9].

The NPP model self-consistently solves for ion concentration (Nernst-Planck equation) and the electrostatic potential (Poisson equation) throughout the device geometry. A critical insight from recent studies is the essential role of volumetric capacitance (C_V) in predictive 2D NPP simulations of OECTs [9]. Volumetric capacitance, which originates from electrostatic Stern layers formed between electronic and ionic charges throughout the material's volume, is a key material parameter that governs OECT performance, including transconductance (g_m = μ * C_V, where μ is the mobility) [9]. Neglecting C_V in OECT modeling is analogous to omitting conductivity in the description of a conductor—it overlooks a fundamental property required for accurate device behavior prediction [9].

This advanced framework is capable of accurately matching the measured output and transfer characteristics of OECTs, providing a deeper understanding of how parameters like diffusion coefficients and fixed charge concentration affect performance [9]. It bridges the gap between the simplified first-order kinetics of ion adsorption at a specific interface and the complex, coupled ion-electron transport dynamics occurring throughout the entire bulk of the OECT channel.

The first-order kinetic model of ion adsorption and desorption provides a powerful and accessible theoretical tool for understanding and quantifying the temporal drift in OECT biosensors. Its successful application, from simple buffer solutions to complex human serum, underscores its relevance in the practical development of reliable bioelectronic sensors [10]. By fitting experimental drift data to this model, researchers can extract meaningful kinetic parameters that inform material selection and device design.

The future of drift modeling and mitigation lies in the multi-scale integration of such simplified models with more comprehensive physical frameworks, like the Nernst-Planck-Poisson equations that incorporate critical parameters such as volumetric capacitance [9]. This combined approach will accelerate the optimization of OECTs, guiding the synthesis of new OMIECs with tailored ion-electron coupling and the development of innovative device architectures, such as the drift-compensating dual-gate design [10]. As the field progresses toward industrial-scale applications and higher device integration, a fundamental and quantitative grasp of ion diffusion kinetics will remain indispensable for advancing the stability and accuracy of OECTs in biomedical research and drug development.

Organic Electrochemical Transistors (OECTs) have emerged as a reliable platform for biomolecule detection due to their low operating voltage, high transconductance, and promising biosensing behavior [6] [4]. These devices operate through the application of a gate voltage that drives ions from an electrolyte into a conductive polymer channel, thereby altering its doping state and conductivity [6] [4]. However, a significant challenge in OECT biosensing is the temporal current drift observed even in control experiments without specific analyte binding, compromising measurement accuracy and reliability [6]. This drift originates fundamentally from the kinetic processes of ion diffusion into the gate functionalization layers, governed by the rate constants of ion adsorption (k⁺) and desorption (k⁻), and their equilibrium partition coefficient (K) [6]. Understanding and quantifying these parameters is thus essential for developing drift-mitigation strategies and enhancing the accuracy of OECT-based biosensors, particularly for applications in drug development and clinical diagnostics.

Theoretical Foundation of the Drift Phenomenon

The drift phenomenon in OECTs can be quantitatively explained by the diffusion of ions from the electrolyte into the gate material. In a typical biosensing environment like phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) or human serum, dominant ions such as Na⁺ and Cl⁻ migrate into the bioreceptor layer under an applied gate voltage [6].

First-Order Kinetic Model of Ion Diffusion

The core theoretical model describing this process is based on first-order kinetics [6]. The change in ion concentration within the bioreceptor layer ((ca)) over time is given by: [ \frac{\partial ca}{\partial t} = c0 k^+ - ca k^- ] where (c_0) represents the constant ion concentration in the bulk solution, (k^+) is the rate constant for ion adsorption from the solution to the gate material, and (k^-) is the rate constant for ion desorption from the material back to the solution [6].

Equilibrium Ion Partition and its Determinants

At equilibrium (( \frac{\partial ca}{\partial t} = 0 )), the ratio of the rate constants defines the equilibrium ion partition coefficient, K: [ \frac{k^+}{k^-} = K = e^{\frac{-\Delta G + \Delta V e0 z}{k_B T}} ] This equation reveals that the partition coefficient is governed by:

- (\Delta G): The difference in the Gibbs free energy of an ion between the bioreceptor layer and the solution, which corresponds to the difference in excess chemical potentials [6].

- (\Delta V): The difference in the electrostatic potential between the gate and the bulk solution [6].

- (e0 z): The charge of the ion, where (e0) is the unit charge and (z) is the ion valency [6].

- (k_B T): The thermal energy [6].

The base rate constant, (k0), which applies when (\Delta G = 0) and (\Delta V = 0), is estimated by the diffusion constant (D) of ions in the bioreceptor layer and the width of the layer (d), following the relation (k0 \sim D/d^2) [6].

Table 1: Key Parameters in the First-Order Kinetic Model of OECT Drift

| Parameter | Symbol | Description | Theoretical Determinants |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adsorption Rate Constant | (k^+) | Rate at which ions move from solution to the gate material. | Diffusion constant (D), gate material thickness (d), applied voltage ((\Delta V)). |

| Desorption Rate Constant | (k^-) | Rate at which ions move from the gate material back to the solution. | Binding affinity of ions to the material, Gibbs free energy change ((\Delta G)). |

| Equilibrium Partition Coefficient | (K) | Equilibrium ratio of ion concentration in the gate material to that in solution. | (K = k^+/k^- = e^{(-\Delta G + \Delta V e0 z)/kB T}) |

| Gibbs Free Energy Change | (\Delta G) | Difference in free energy of an ion between the gate material and solution. | Material composition, ion type, surface chemistry. |

Figure 1: Ion Exchange Dynamics. This diagram illustrates the first-order kinetic process governing ion exchange between the bulk solution and the gate material, driven by the rate constants k⁺ and k⁻, and the parameters ΔV and ΔG that determine the equilibrium partition coefficient K.

Experimental Protocols for Investigating Drift

To validate the theoretical model and extract the key parameters governing drift, controlled experiments are essential.

Protocol for Single-Gate OECT (S-OECT) Drift Measurement

The S-OECT platform, which features a single functionalized gate electrode, serves as the foundational setup for observing inherent drift behavior [6].

- Device Fabrication: Fabricate an OECT with source, drain, and gate terminals. The channel is typically made of a conductive polymer like PEDOT:PSS [6] [4]. The gate electrode is functionalized with a bioreceptor layer (e.g., PT-COOH, PSAA, or a Self-Assembly Layer (SAL)) and then blocked with a protein layer like Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) to minimize non-specific binding [6].

- Electrolyte Preparation: Prepare a 1X phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) solution, which provides a high-ionic-strength environment with known concentrations of Na⁺ and Cl⁻ ions [6].

- Electrical Measurement:

- Immerse the functionalized gate and channel in the electrolyte.

- Apply a constant gate voltage ((VG)) and drain voltage ((V{DS})).

- Measure the drain current ((I_D)) over time without introducing any specific analyte (e.g., human IgG). This constitutes the control experiment [6].

- Data Analysis: The recorded temporal decay in (ID) is the drift signal. This data is fitted to the solution of the first-order kinetic equation, ( \frac{\partial ca}{\partial t} = c0 k^+ - ca k^- ), which typically yields an exponentially decaying function. The fitting procedure extracts the experimental values for (k^+) and (k^-) [6].

Protocol for Dual-Gate OECT (D-OECT) Drift Mitigation

The dual-gate architecture is designed to actively counteract the drift phenomenon [6].

- Device Configuration: Construct a circuit with two OECT devices connected in series. The gate voltage ((VG)) is applied to the bottom of the first device, and the drain voltage ((V{DS})) is applied to the second device. Transfer curves are measured from the second device [6].

- Experimental Procedure: Follow the same fabrication and measurement steps as for the S-OECT, using identical functionalization layers (e.g., PT-COOH with immobilized IgG antibodies) and electrolytes (PBS or human IgG-depleted human serum) [6].

- Comparative Analysis: The output signal from the D-OECT platform is compared directly with that from the S-OECT. The D-OECT design prevents like-charged ion accumulation during measurement, which manifests as a significant reduction or cancellation of the temporal drift observed in the S-OECT configuration [6].

Table 2: Comparison of Single-Gate vs. Dual-Gate OECT Configurations for Drift Analysis

| Aspect | Single-Gate OECT (S-OECT) | Dual-Gate OECT (D-OECT) |

|---|---|---|

| Configuration | Single functionalized gate electrode. | Two OECTs connected in series. |

| Primary Purpose | Characterize inherent drift behavior. | Actively mitigate drift and improve signal accuracy. |

| Key Findings | Exhibits appreciable temporal current drift due to ion accumulation. | Drift is largely canceled; enables accurate detection in human serum. |

| Typical Experiment | Control experiment in PBS with BSA-blocked gate. | Detection of human IgG in PBS and human serum. |

| Impact on k⁺ and k⁻ | Allows direct measurement of intrinsic kinetic constants. | Architecture minimizes the net effect of k⁺ and k⁻ on the output signal. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful experimentation in OECT drift analysis requires a specific set of materials and reagents, each serving a critical function.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for OECT Drift Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function in Drift Investigation | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Conductive Polymer (Channel) | Forms the active channel of the OECT; its conductivity is modulated by ion injection. | PEDOT:PSS (most common), p(gNDI-g2T) [6] [4]. |

| Gate Functionalization Layers | Forms the interface for ion interaction; its properties directly influence k⁺, k⁻, and K. | PT-COOH, PSAA (insulating polymer), Self-Assembly Layers (SAL) [6]. |

| Blocking Agent | Passivates the gate surface to minimize non-specific binding of proteins or other biomolecules. | Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) [6]. |

| Electrolyte | Provides the ions (Na⁺, Cl⁻) whose diffusion into the gate material causes the drift phenomenon. | 1X PBS (for basic studies), Human Serum (for real-fluid validation) [6]. |

| Target Biomolecule | Used to validate biosensing performance in mitigated-drift platforms (e.g., D-OECT). | Human Immunoglobulin G (IgG) [6]. |

Advanced Modeling and Mitigation Strategies

The Role of Volumetric Capacitance and Advanced Modeling

Beyond the first-order kinetic model, accurate simulation of OECT operation is critical for predictive device design. The Nernst-Planck-Poisson (NPP) equations provide a robust framework, with the volumetric capacitance (CV) being a key parameter [9]. The performance of an OECT, including its sensitivity to drift, is directly linked to its transconductance ((gm)), which follows the relationship (gm = \mu CV), where (\mu) is the charge carrier mobility [9]. This highlights that the capacitance, which is influenced by ion dynamics, is central to device behavior. Advanced 2D models that incorporate this volumetric capacitance explicitly have shown perfect agreement with experimental OECT output currents, providing a powerful tool for optimizing device geometry and material parameters to minimize undesired effects like drift [9].

The Impact of Gel Electrolytes

Replacing liquid electrolytes with ion gels or hydrogels is a common strategy for improving device integration and stability [15]. The capacitance in these systems is governed by the Electrical Double Layer (EDL) at the electrolyte/channel interface, which consists of a Stern (Helmholtz) layer and a diffuse layer [15]. The total capacitance ((C^)) is a series combination of the Helmholtz capacitance ((C_H)) and the diffusion capacitance ((C_D)), where ( \frac{1}{C^} = \frac{1}{CH} + \frac{1}{CD} ) [15]. The diffusion capacitance, described by Gouy-Chapman theory as ( CD = \epsilon0 \epsilon_r \kappa \cosh(\frac{\varphi}{2}) ), depends on the ion concentration and the local electrical potential [15]. This refined understanding of how gel electrolyte properties affect capacitance, and thus transconductance and drift, provides a theoretical basis for selecting or designing optimal electrolytes for stable OECT operation.

Figure 2: Drift Influence Pathway. A causal diagram showing the relationship from the applied gate voltage to the final output current drift, highlighting the central role of ion dynamics and volumetric capacitance.

The Role of Electrostatic Potential (ΔV) and Material Properties in Drift Dynamics

Organic Electrochemical Transistors (OECTs) have established themselves as a premier platform for biosensing, capable of detecting targets from small molecules like glucose to larger proteins and DNA, often in complex biological fluids like blood serum [5]. A critical, persistent challenge that compromises the accuracy and reliability of these sensors is the temporal current drift observed even in the absence of the target analyte [6]. This drift phenomenon is not merely an experimental artifact but is fundamentally governed by the interplay between the electrostatic potential (ΔV) across the device and the intrinsic material properties of its constituent parts.

This whitepaper delves into the core physical principles underpinning drift dynamics, framing the discussion within the context of advanced theoretical modeling for OECT biosensors. Understanding and mitigating drift is not simply an engineering exercise; it is essential for achieving the high levels of accuracy and sensitivity required for applications in pharmaceutical research and clinical diagnostics [6] [16]. We will explore the theoretical models that describe these processes, present quantitative data on key parameters, outline experimental methodologies for investigation, and highlight device engineering strategies that successfully suppress drift.

Theoretical Foundations of Drift

The drift phenomenon in OECTs can be conceptualized as a consequence of the device's quest for a new electrochemical equilibrium under an applied bias. The following sections break down the key theoretical concepts that model this behavior.

The Electrochemical Potential and Ion Dynamics

At the heart of OECT operation and the associated drift is the concept of the electrochemical potential (μ'), defined as: [ \mu' \equiv \mu + q\phi ] where ( \mu ) is the chemical potential, ( q ) is the unit charge, and ( \phi ) is the electrostatic potential [17]. This sum dictates the direction of ion flow. The effective electric field (( \mathcal{E} )) that drives both electronic and ionic currents is proportional to the gradient of the electrochemical potential: [ \mathcal{E} = -\frac{\nabla \mu'}{q} = \pmb{\mathscr{E}} - \frac{\nabla \mu}{q} ] This equation highlights that ion movement is driven not only by the external electrostatic field (( \pmb{\mathscr{E}} )) but also by gradients in chemical potential (( \nabla \mu )), such as those arising from concentration differences [17]. In OECTs, the applied gate voltage creates a difference in the electrostatic potential (ΔV) between the gate and the channel, which is a key component of the electrochemical potential difference that drives ions into or out of the channel material.

First-Order Kinetic Model of Ion Adsorption

The temporal drift of the output current in a functionalized OECT can be quantitatively described using a first-order kinetic model for the adsorption and diffusion of ions into the gate material [6]. This model posits that the rate of change of ion concentration (( ca )) within the bioreceptor layer on the gate is given by: [ \frac{\partial ca}{\partial t} = c0 k+ - ca k- ] where ( c0 ) is the ion concentration in the solution, and ( k+ ) and ( k_- ) are the rate constants for ion movement into and out of the gate material, respectively [6].

The ratio of these rate constants defines the ion partition coefficient ( K ), which is exponentially dependent on the electrostatic potential and material properties: [ \frac{k+}{k-} = K = e^{-\frac{\Delta G + \Delta V e0 z}{kB T}} ] Here, ΔV is the difference in electrostatic potential between the gate and the bulk solution, a variable directly controlled by the applied gate voltage. ΔG is the difference in the Gibbs free energy of an ion between the bioreceptor layer and the solution at zero applied voltage, representing the intrinsic material property of the gate coating [6]. The other terms are the unit charge (( e0 )), ion valency (( z )), Boltzmann's constant (( kB )), and temperature (( T )).

Table 1: Key Parameters in the First-Order Kinetic Drift Model

| Parameter | Symbol | Description | Role in Drift Dynamics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electrostatic Potential Difference | ΔV | Voltage-driven potential between gate and channel | Primary driving force for ion injection; controlled by applied gate voltage. |

| Gibbs Free Energy Difference | ΔG | Intrinsic energy barrier for ion entry into gate material | Determines intrinsic material "affinity" for ions; a material property. |

| Ion Concentration in Solution | ( c_0 ) | Bulk concentration of ions in the electrolyte | Provides the source/sink for ions diffusing into the gate. |

| Rate Constant (in) | ( k_+ ) | Rate of ion absorption into gate material | Governs the speed of the initial drift response. |

| Rate Constant (out) | ( k_- ) | Rate of ion release from gate material | Governs the relaxation time and steady-state equilibrium. |

This model successfully fits experimental drift data with an exponentially decaying function, confirming its validity for describing the slow ion adsorption process that underlies current drift in single-gate OECTs (S-OECTs) [6].

Beyond Simple Models: The Role of Volumetric Capacitance and 2D Currents

While the first-order model is powerful, a comprehensive understanding requires considering device physics in greater detail. The volumetric capacitance (CV) is a critical material property that dictates OECT performance, directly influencing transconductance (( gm = \mu CV )) [9]. Accurate 2D models based on the Nernst-Planck-Poisson equations must explicitly include CV to predict device behavior, including transient and drift phenomena, as it couples the electron and ion phases [9].

Furthermore, traditional "capacitive models" that restrict ion movement to one dimension (vertical from the electrolyte into the channel) have been shown to be incomplete. A more accurate 2D drift-diffusion model reveals that lateral ion currents within the channel lead to an exponential distribution of ions, accumulating at the drain contact [18]. This accumulation creates an additional potential drop and alters the steady-state channel potential, a factor neglected in simpler models but crucial for a complete understanding of the equilibrium state and associated drift in OECTs [18].

Quantitative Data and Experimental Insights

The theoretical frameworks find strong support in experimental data, which also allows for the quantification of key parameters influencing drift.

Experimental Measurement of Drift

The investigation of drift often begins with a control experiment in a relevant buffer like phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) or a complex medium like human serum. The gate electrode is functionalized with a blocking layer (e.g., BSA) but not the specific antibody, ensuring no specific binding events occur. The temporal drift of the drain current (( I_D )) is then measured under a constant applied gate voltage [6].

Table 2: Experimentally Observed Drift Mitigation in Different OECT Architectures

| OECT Architecture | Key Feature | Impact on Drift & Performance | Test Medium |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single-Gate (S-OECT) | Standard three-terminal design | Exhibits appreciable temporal current drift due to uncontrolled ion adsorption. | PBS, Human Serum |

| Dual-Gate (D-OECT) | Two OECTs connected in series | Prevents like-charged ion accumulation, "largely mitigating" temporal drift [6]. | PBS, Human Serum |

| Potentiometric-OECT (pOECT) | Splits gate into sensing and gating electrodes; keeps sensing electrode at open circuit potential. | Higher accuracy, response, and stability vs. conventional OECTs; prevents gate current from damaging sensitive layers [16]. | Aqueous electrolyte |

The data shows that the dual-gate architecture can effectively operate in human serum, increasing the accuracy and sensitivity of immuno-biosensors compared to a standard single-gate design, even at a relatively low limit of detection [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

To conduct drift analysis and OECT biosensor development, the following materials and reagents are essential.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for OECT Drift Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Description | Role in Drift Investigation |

|---|---|---|

| PEDOT:PSS | Organic mixed ionic-electronic conductor (OMIEC); common channel material. | Its volumetric capacitance and morphology directly influence ion transport and dynamics [9] [19]. |

| PT-COOH | Functionalized semiconducting polymer (e.g., poly [3-(3-carboxypropyl)thiophene-2,5-diyl]). | Used as a bioreceptor layer on the gate; its thickness and chemical properties affect ion diffusion rates [6]. |

| Human Serum (IgG-depleted) | Complex biological fluid for realistic testing. | Provides a clinically relevant medium to validate drift mitigation strategies against non-specific binding and ion interference [6]. |

| BSA (Bovine Serum Albumin) | Protein used as a blocking agent. | Forms a blocking layer on the gate in control experiments to study drift from non-specific ion interactions [6]. |

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) | Standard buffer solution containing Na+, Cl- ions. | Used as a simple electrolyte for initial drift characterization and model fitting [6]. |

| CuxO Interlayer | Sol-gel derived thin film. | Modulates contact resistance at source/drain electrodes; reduced resistance minimizes parasitic losses, improving signal-to-noise and effective limit of detection [20]. |

Visualizing Drift Dynamics and Mitigation Strategies

The following diagrams illustrate the core concepts and experimental workflows related to drift dynamics in OECTs.

Ion Drift Dynamics in S-OECT vs. D-OECT

pOECT Configuration for Potentiometric Sensing

Protocols for Investigating Drift Dynamics

To systematically study drift dynamics, researchers can follow these detailed experimental protocols.

Protocol for Characterizing Drift in S-OECTs

This protocol is designed to quantify the intrinsic drift of a biosensor platform in the absence of specific binding.

- Device Fabrication: Fabricate a standard S-OECT with a gold gate electrode, a PEDOT:PSS channel, and source/drain electrodes. Use photolithography or printing techniques for defined geometries [9] [16].

- Gate Functionalization:

- Clean the gate electrode.

- Immobilize a bioreceptor layer (e.g., PT-COOH) or, for control experiments, a blocking layer like BSA.

- Characterize the modified surface using techniques like AFI or electrochemical impedance spectroscopy to confirm layer formation.

- Electrical Characterization Setup:

- Place the OECT in an electrochemical cell containing 1X PBS buffer or human serum as the electrolyte.

- Connect the source, drain, and gate to a source measure unit or potentiostat.

- Apply a constant drain voltage (( V_{DS} )) appropriate for the device's operational regime.

- Drift Measurement:

- Apply a constant gate voltage (( VG )).

- Measure the drain current (( ID )) continuously over a prolonged period (e.g., 30-60 minutes) with a high sampling rate.

- Ensure temperature and environmental conditions are stable throughout the measurement.

- Data Analysis:

- Plot the normalized ( I_D ) as a function of time.

- Fit the resulting drift curve to the first-order kinetic model or an exponentially decaying function to extract the rate constants ( k+ ) and ( k- ) [6].

Protocol for Validating Drift Mitigation with D-OECT/pOECT

This protocol validates the effectiveness of advanced architectures in suppressing drift.

- Device Preparation: Fabricate a D-OECT [6] or a pOECT [16] according to their respective designs. The pOECT requires a gate electrode split into a sensing gate (( GS )) and a gating gate (( GG )).

- Functionalization: Functionalize only the relevant sensing gate (( G_S ) in pOECT or the first gate in D-OECT) with the biorecognition element.

- System Configuration:

- For D-OECT: Connect the two OECTs in series, applying ( VG ) to the first device and ( V{DS} ) to the second. Measure the transfer curves from the second device [6].

- For pOECT: Connect the ( GS ) to the RE2 port and the ( GG ) to the CE2 port of the potentiostat, maintaining the ( G_S ) at open circuit potential [16].

- Comparative Measurement:

- Perform the same long-term ( I_D ) measurement as in Protocol 5.1 under identical buffer and bias conditions.

- In parallel, run a control experiment using a standard S-OECT.

- Performance Analysis:

The drift dynamics in OECT-based biosensors are a direct manifestation of fundamental physical processes, primarily the interplay between the electrostatic potential (ΔV) and the material properties of the gate and channel. The first-order kinetic model of ion adsorption provides a solid theoretical foundation, directly linking the drift rate to the Gibbs free energy difference (ΔG) of the gate material and the applied electrostatic potential (ΔV).

Moving forward, the focus for achieving high-accuracy, drift-resistant biosensors lies in the co-design of materials and device architecture. The development of novel organic mixed ionic-electronic conductors with tailored chemical properties and volumetric capacitance will continue to be crucial [9] [19]. Simultaneously, innovative device configurations like the dual-gate OECT and the potentiometric-OECT (pOECT) have demonstrated that architectural solutions can effectively mitigate the inherent drift problems of conventional single-gate designs. These strategies, grounded in a deep understanding of the underlying physics, are paving the way for the next generation of reliable OECT biosensors capable of meeting the stringent demands of drug development and clinical diagnostics.

Experimental Evidence of Drift in Control Studies using PBS and Human Serum

Organic Electrochemical Transistors (OECTs) are a leading platform for biomolecule detection due to their high transconductance, low operational voltage, and biocompatibility [21] [4]. A significant challenge in the practical deployment of OECT-based biosensors, especially for diagnostic applications in real biological fluids, is the temporal drift of the electrical signal. This drift can occur even in the absence of the target analyte, complicating data interpretation and reducing sensor reliability [21]. This whitepaper synthesizes experimental evidence and theoretical modeling of drift phenomena observed in control studies conducted in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and human serum, providing a framework for researchers developing robust biosensing assays.

Theoretical Modeling of the Drift Phenomenon

The temporal drift observed in OECT biosensors can be quantitatively explained by a first-order kinetic model describing the diffusion and adsorption of ions from the electrolyte into the gate material [21].

First-Order Kinetic Model

The model focuses on the dominant ions in the electrolyte (e.g., Na⁺ and Cl⁻ in PBS). The rate of change of the ion concentration within the gate's bioreceptor layer, (ca), is given by: [ \frac{\partial ca}{\partial t} = c0 k+ - ca k- ] where (c0) is the constant ion concentration in the solution, (k+) is the rate constant for ion absorption into the material, and (k_-) is the rate constant for ion release back into the solution [21].

The equilibrium ion partition coefficient, (K), is governed by the electrochemical potential difference between the gate and the bulk solution: [ \frac{k+}{k-} = K = e^{\frac{–\Delta G + \Delta V e0 z}{kB T}} ] where:

- (\Delta G) is the excess chemical potential difference,

- (\Delta V) is the electrostatic potential difference,

- (e_0) is the elementary charge,

- (z) is the ion valency,

- (k_B) is the Boltzmann constant,

- (T) is the absolute temperature [21].

This model shows excellent agreement with experimental drift data, confirming that non-Faradaic ion absorption and redistribution is a primary mechanism behind the observed current drift in control experiments.

Experimental Evidence of Drift in PBS and Human Serum

Drift in Single-Gate OECTs (S-OECTs)

Control experiments in 1X PBS using S-OECTs with various bioreceptor layers (PT-COOH, PSAA, SAL) consistently showed temporal current drift, despite the absence of specific antibody-antigen binding [21]. This drift is attributed to the gradual penetration of small ions into the gate material.

Key Experimental Observations:

- BSA Blocking Layer: Experiments with a gate electrode functionalized only with a BSA blocking layer (without antibodies) and exposed to human IgG in PBS still exhibited significant drift. This confirms that the drift originates from the interaction of small ions with the gate interface, not from specific biomolecular binding [21].

- Gate Material Thickness: The thickness of the gate material influences the ion diffusion dynamics, with thicker layers potentially leading to more prolonged drift behavior as ions penetrate deeper into the film [21].

Comparative Drift in Human Serum

Human serum presents a more complex environment than PBS, with a higher concentration of many metabolites and proteins [22]. This complexity can significantly influence sensor drift.

Differences Between PBS and Human Serum:

| Characteristic | Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS) | Human Serum |

|---|---|---|

| Composition | Simple salt solution (e.g., Na⁺, Cl⁻) | Complex mixture of proteins, metabolites, lipids |

| Metabolite Levels | Low and defined | Generally higher concentrations than in plasma [22] |

| Drift Contributors | Primarily small ions from buffer | Small ions, metabolites, and non-specific protein interactions |

| Experimental Complexity | Lower, ideal for initial validation | Higher, requires depletion of abundant analytes (e.g., IgG) for controlled studies [21] |

Studies show that the S-OECT platform exhibits drift in both PBS and human serum. However, the drift in serum is more complex due to potential non-specific binding of serum components and the presence of a wider variety of ionic species [21].

Mitigation Strategy: The Dual-Gate OECT (D-OECT) Architecture

A dual-gate OECT (D-OECT) architecture has been developed to mitigate the temporal current drift effectively [21]. This design features two OECT devices connected in series, where the gate voltage is applied to the first device and the drain voltage to the second device; the transfer curves are measured from the second OECT.

Mechanism of Drift Cancellation: The D-OECT configuration prevents the accumulation of like-charged ions during measurement, which is a primary cause of drift in the single-gate design [21]. Experimental results demonstrate that this architecture can largely cancel the drift phenomenon, leading to more stable and reliable biosensing signals. This stability is maintained even when operating in complex media like human serum, allowing for specific binding to be detected at a low limit of detection [21].

Experimental Protocols for Drift Analysis

Fabrication of S-OECTs and D-OECTs

Device Structure:

- S-OECT: A standard three-terminal device (source, drain, gate) with a functionalized gate electrode [21].

- D-OECT: Two OECTs connected in series, with a shared electrode configuration that allows for differential measurement [21].

Gate Functionalization:

- Bioreceptor Immobilization: The gate electrode is functionalized with a bioreceptor layer. Common materials include:

- Blocking: The functionalized gate is treated with a blocking agent, such as Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA), to minimize non-specific adsorption in subsequent steps [21] [23].

Control Experiment Protocol for Drift Measurement

- Baseline Establishment: The functionalized OECT (S-OECT or D-OECT) is immersed in the test solution (1X PBS or IgG-depleted human serum) [21].

- Gate Voltage Application: A fixed gate voltage ((VG)) is applied, and the resulting drain current ((ID)) is measured over time.

- Data Acquisition: The temporal drift of (I_D) is recorded in the absence of the target analyte (e.g., human IgG). For serum experiments, the serum is often depleted of the target analyte (e.g., human IgG) to establish a controlled baseline [21].

- Data Fitting: The recorded drift data is fitted using the first-order kinetic model to extract parameters such as (k+) and (k-) [21].

Workflow for Drift Characterization

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for conducting and analyzing drift in control experiments.

Diagram 1: Workflow for experimental characterization of drift in OECT biosensors.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

The table below lists essential materials used in the featured experiments for studying and mitigating drift in OECT biosensors.

| Item Name | Function / Role in Experiment |

|---|---|

| PEDOT:PSS | A widely used conductive polymer for the OECT channel; offers high transconductance and is the subject of drift studies [21] [4]. |

| PT-COOH | A functionalized conducting polymer used as a bioreceptor layer on the gate electrode for antibody immobilization [21]. |

| Poly(styrene–co–acrylic acid) (PSAA) | An insulating polymer used as a bioreceptor layer to study drift phenomena [21]. |

| Self-Assembly Layer (SAL) | A monolayer (e.g., on gold) used for functionalizing the gate electrode [21]. |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | A blocking agent used to cover non-specific binding sites on the functionalized gate surface [21] [23]. |

| IgG-depleted Human Serum | A controlled biological fluid used for testing biosensor performance and drift in a complex, real-world matrix [21]. |

| Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS) | A simple salt buffer solution used for initial device testing and drift characterization in a defined environment [21]. |

Implications for Biosensor Development in Drug Development

For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding and mitigating drift is critical for translating lab-based biosensors into clinical tools. The evidence indicates that:

- Modeling is Crucial: The first-order kinetic model provides a framework to quantify and predict drift, aiding in the design of more stable biosensors [21].

- Serum Compatibility is Key: Validating biosensor performance in human serum, not just buffer, is an essential step due to the matrix's complexity and its effect on drift [21] [22].

- Architectural Solutions Exist: The D-OECT platform presents a viable hardware-based solution to suppress drift, thereby increasing the accuracy and reliability of immuno-assays even in challenging biological fluids like serum [21].

Signaling Pathway of Ion Drift in an OECT

The core mechanism of operation and drift in an OECT involves the coupled movement of ions and electrons. The following diagram details this signaling pathway.

Diagram 2: Signaling pathway of ion drift in an OECT, showing the desired modulation and the parasitic drift effect.

Architectural and Theoretical Solutions for Drift Suppression

Organic Electrochemical Transistors (OECTs) have emerged as a leading platform for biomolecule detection due to their low operating voltage, high transconductance, and excellent biocompatibility [5] [24]. These devices efficiently transduce biological signals into amplified electrical outputs, making them particularly valuable for sensing applications in complex biological fluids like human serum [6] [21]. However, a significant challenge that impedes their reliability and accuracy is the temporal drift of the electrical signal—a phenomenon observed as a gradual change in output current even in the absence of the target analyte [6] [21]. This drift, consistently present in control experiments, introduces noise and reduces the fidelity of biosensing measurements, complicating data interpretation and compromising detection limits [6].

The drift phenomenon originates from the fundamental operating mechanism of OECTs. Their function relies on the electrochemical doping and dedoping of a channel material, typically a conductive polymer like PEDOT:PSS, via the injection or extraction of ions from an electrolyte [25] [24]. In a standard single-gate OECT (S-OECT) with a functionalized gate electrode, non-faradaic processes can lead to the gradual absorption and accumulation of ions from the electrolyte into the gate material itself [6] [21]. This slow ion diffusion process causes a time-dependent shift in the effective gate potential, manifesting as a drift in the drain current. This poses a particular problem for sensitive immuno-biosensing applications where specific binding events must be distinguished from non-specific background signals [6].

This technical guide explores the dual-gate OECT (D-OECT) architecture as a sophisticated circuit-based solution to cancel the drift phenomenon. Framed within a broader thesis on modeling temporal drift, this review details the theoretical foundation of drift, the operating principle of the D-OECT, experimental validation methodologies, and the key material solutions that enable its function.

Theoretical Modeling of Drift in Single-Gate OECTs

To effectively cancel drift, one must first understand its physical origin. Theoretical modeling reveals that drift can be explained by the diffusion of ions into the gate material [6] [21].

First-Order Kinetic Model of Ion Adsorption

The drift phenomenon in a single-gate, gate-functionalized OECT can be quantitatively described by a first-order kinetic model of ion adsorption [6] [21]. The model makes the following key assumptions:

- The dominant ions in a buffer solution like phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)—Na⁺ and Cl⁻—are absorbed into the bioreceptor layers on the gate electrode.

- The spatial distribution of ions within the material can be neglected for simplification.

- The ion concentration in the bulk solution (c₀) remains constant due to the high ionic strength of the environment.

The change in ion concentration within the gate material (cₐ) over time (t) is given by: ∂cₐ/∂t = c₀k₊ - cₐk₋ [6] [21]

Here, k₊ is the rate constant for ions moving from the solution to the gate material, and k₋ is the rate constant for the reverse process.

The equilibrium ion partition coefficient (K) between the solution and the gate material is determined by the ratio of these rate constants and is governed by the electrochemical potential: K = k₊ / k₋ = e^((-ΔG + ΔVe₀z)/(kBT)) [6] [21]

Where:

- ΔG is the difference in the Gibbs free energy of an ion between the gate material and the solution.

- ΔV is the difference in electrostatic potential between the gate and the bulk solution.

- e₀ is the elementary charge.

- z is the ion valency.

- kΒ is the Boltzmann constant.

- T is the absolute temperature.

This model fits experimental drift data exceptionally well, confirming that the slow, time-dependent adsorption of ions into the gate's functional layer is a primary driver of the drift phenomenon [6] [21]. The following diagram illustrates this ion adsorption process and its circuit-level impact in a single-gate configuration.

The Dual-Gate OECT (D-OECT) Architecture

The dual-gate OECT (D-OECT) is an elegant circuit-level innovation designed to actively counteract the drift inherent in single-gate configurations [6] [21] [26].

Architectural Principle and Configuration

The D-OECT platform employs two OECT devices connected in series [6]. In this setup:

- The gate voltage (V_G) is applied to the bottom of the first OECT device.

- The drain voltage (V_DS) is applied to the second OECT device.

- The transfer curves, which are critical for sensing, are measured from the second device in the series [6].

This specific configuration is fundamentally designed to prevent the accumulation of like-charged ions during the measurement process, which is a key source of drift in S-OECTs [6]. The architecture leverages a differential measurement principle, where drift signals common to both gates are rejected, while the specific sensing signal from the functionalized gate is amplified.

Mechanism of Drift Cancellation

The D-OECT operates by creating a symmetric environment where non-specific ion adsorption occurs similarly on both gates. However, only the sensing gate is functionalized with a biorecognition element (e.g., an antibody). When a target analyte binds specifically to the functionalized gate, it introduces a differential change that is not present on the reference gate. The series connection of the two OECTs allows the electronic circuit to subtract the common-mode drift signal, leaving behind a stable, amplified signal corresponding only to the specific binding event. This mechanism effectively separates the desired biosensing signal from the undesired low-frequency noise caused by ion diffusion.

The workflow below contrasts the signal pathways in single-gate and dual-gate architectures, highlighting how the D-OECT cancels the drift component.

Experimental Validation and Performance Data

The superiority of the D-OECT architecture has been experimentally demonstrated in both controlled buffers and complex biological fluids, validating its practical significance.

Key Experimental Protocols

A typical experiment to validate D-OECT performance involves the following steps [6] [21]:

- Device Fabrication: Fabricate both S-OECT and D-OECT devices. The channel is often made of PEDOT:PSS, while the gate is functionalized with a bioreceptor layer (e.g., PT-COOH for protein detection) [6].

- Bioreceptor Immobilization: For biosensing experiments, immobilize specific antibodies (e.g., against human IgG) onto the functionalized gate surface. A blocking layer like Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) is used to minimize non-specific binding [6] [21].

- Electrical Characterization: Measure transfer curves (drain current IDS vs. gate voltage VG) and time-dependent current drift for both S-OECT and D-OECT configurations.

- Drift Measurement in Buffer: Perform control experiments in PBS buffer without the target analyte to quantify the inherent temporal drift of each architecture.

- Sensing in Complex Media: Test the devices in a challenging, clinically relevant medium such as human IgG-depleted human serum [6] [21]. This allows for a controlled introduction of the human IgG target analyte while mimicking the background of real human serum.

- Data Analysis: Fit the S-OECT drift data to the first-order kinetic model. Compare the signal stability and sensitivity of S-OECT and D-OECT for detecting the target analyte (e.g., human IgG) in serum.

Quantitative Performance Comparison

The experimental results consistently show that the D-OECT architecture dramatically mitigates temporal drift and enhances sensing accuracy. The table below summarizes key performance comparisons derived from experimental studies.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of S-OECT vs. D-OECT Architectures

| Performance Metric | Single-Gate OECT (S-OECT) | Dual-Gate OECT (D-OECT) | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temporal Current Drift | Significant, described by first-order ion adsorption model [6] [21] | Largely mitigated [6] [21] | Measurement in PBS buffer and human serum [6] [21] |

| Limit of Detection (LOD) | Higher due to drift noise [6] | Relatively low LOD achievable [6] | Detection of human Immunoglobulin G (IgG) [6] |

| Accuracy in Complex Media | Compromised by drift and non-specific interactions [6] | Increased accuracy and sensitivity [6] [21] | Operation in human serum [6] [21] |

| Key Advantage | Simpler fabrication | Drift cancellation, improved signal fidelity [6] | Biosensing applications [6] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The experimental realization and optimization of D-OECTs rely on a specific set of materials and reagents. The following table details these key components and their functions in device fabrication and sensing.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for D-OECT Fabrication and Biosensing

| Material/Reagent | Function in D-OECT | Specific Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Channel Material | Forms the semiconducting channel between source and drain; its conductivity is modulated by ion injection from the electrolyte. | PEDOT:PSS is most widely used due to high transconductance and stability in water [6] [25] [27]. |

| Gate Electrode Material | Serves as the interface for applying the gate potential. Can be polarizable or non-polarizable. | Gold (Au), Platinum (Pt) [5]; Ag/AgCl is a common non-polarizable electrode [5] [26]. |

| Gate Functionalization Layer | Provides a matrix for immobilizing biorecognition elements and is the site where ion adsorption causing drift occurs. | PT-COOH (p-type semiconducting polymer), PSAA (insulating polymer), Self-Assembled Monolayers (SAL) [6] [21]. |

| Biorecognition Element | Imparts specificity to the biosensor by binding the target analyte. | Antibodies (e.g., anti-human IgG) [6]. |

| Blocking Agent | Reduces non-specific binding of non-target molecules to the gate surface. | Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) [6] [21]. |

| Electrolyte | Medium enabling ion transport between the gate and the channel. | Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS) for testing; Human serum for real-world validation [6] [21]. |

| Target Analyte | The molecule of interest to be detected. | Human Immunoglobulin G (IgG) is a common model protein target [6] [21]. |

The dual-gate OECT (D-OECT) architecture represents a significant advancement in the quest for stable and reliable OECT-based biosensors. By addressing the fundamental issue of temporal drift through a clever circuit-based design, it directly counters the limitations imposed by the first-order kinetics of ion adsorption in single-gate devices. Experimental data confirms that this architecture not only suppresses drift but also enables sensitive and accurate biomarker detection in clinically relevant, complex media like human serum. Integrating the D-OECT design with ongoing developments in novel organic semiconductors, fabrication techniques like stencil printing [27], and form factors like fiber-based devices [28] paves the way for a new generation of robust biosensors for point-of-care diagnostics, wearable health monitoring, and fundamental biological research.

Three-Dimensional and Electrolyte-Surrounded (3D ES) OECTs for Enhanced Ion Management

Organic Electrochemical Transistors (OECTs) have emerged as a transformative technology within the bioelectronics landscape, particularly for biosensing applications. Their operation relies on the mixed conduction of ionic and electronic charges within the channel material, typically an organic mixed ionic-electronic conductor (OMIEC) [3]. When a gate voltage is applied, ions from the electrolyte are driven into the channel material, modulating its conductivity by changing its doping state and enabling the transduction of biological signals into electronic outputs [1]. This unique mechanism grants OECTs exceptional signal amplification capabilities, biocompatibility, and operation in aqueous environments, making them ideal for interfacing with biological systems [3] [29]. However, a central challenge that impedes their performance, especially in biosensing, is the inefficient management of ion transport. Sluggish ion injection and migration within the bulk channel material often dictate the device's transient response, limiting its switching speed and creating a fundamental trade-off between gain and bandwidth [30] [29]. Furthermore, unintended temporal drift in the output current—a gradual shift in signal without a change in the target analyte—can severely compromise the accuracy and reliability of biosensors [21].

This guide focuses on a specific device architecture designed to overcome these limitations: the Three-Dimensional and Electrolyte-Surrounded (3D ES) OECT. The 3D ES design represents a paradigm shift from planar structures by maximizing the channel-electrolyte interfacial area and creating tailored pathways for ion ingress. This architecture surrounds the channel with electrolyte, facilitating volumetric ion charging from multiple directions rather than relying solely on vertical injection from the top. Enhanced ion management directly addresses the critical issues of response speed, transconductance, and temporal drift. By integrating the principles of 3D ES-OECTs into the broader context of theoretical modeling, particularly for temporal drift in biosensors, researchers can develop more robust and high-fidelity bioelectronic interfaces. The following sections provide a technical deep-dive into the device physics, architectural innovations, characterization methodologies, and theoretical frameworks essential for advancing this promising technology.

Device Physics and the Critical Role of Ion Transport

Fundamental Operating Principles

An OECT is a three-terminal device consisting of a semiconductor channel that connects a source and a drain electrode, with a gate electrode interfaced through an electrolyte. The fundamental operation involves applying a gate voltage (VG) to modulate the drain current (ID) by electrochemically doping or dedoping the channel material [1]. In a common p-type, depletion-mode OECT using PEDOT:PSS, the channel is highly conductive in its pristine state. Applying a positive gate voltage drives cations from the electrolyte into the channel, electrostatically compensating the PSS- sites and reducing the hole density in PEDOT+, thereby decreasing ID [31]. This electrochemical dedoping reaction can be represented as:

PEDOT+:PSS- + M+ + e- PEDOT0 + M+:PSS- [32]

Contrary to field-effect transistors where modulation occurs in a thin surface layer, the electrochemical doping/dedoping in OECTs is a volumetric process, occurring throughout the bulk of the channel material [3]. This bulk charging is responsible for the OECT's high transconductance (gm), a key figure of merit representing its amplification capability.

The Bernards-Malliaras Model and Ion Dynamics