Multiplex Biosensors for Pesticide Residues: Advanced Nanomaterial-Driven Detection Strategies

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of multiplex biosensors for the simultaneous detection of multiple pesticide residues, a critical need for modern food safety and environmental monitoring.

Multiplex Biosensors for Pesticide Residues: Advanced Nanomaterial-Driven Detection Strategies

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of multiplex biosensors for the simultaneous detection of multiple pesticide residues, a critical need for modern food safety and environmental monitoring. It explores the foundational principles of optical and electrochemical sensing platforms driven by advanced nanomaterials, including noble metal nanoparticles, carbon-based materials, and metal-organic frameworks. The review details methodological innovations in fluorescence, surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS), colorimetry, and electrochemical sensing, alongside their practical applications in complex matrices. It further addresses key challenges in real-sample analysis, sensitivity, and selectivity, offering troubleshooting and optimization strategies. Finally, the article presents a comparative validation of these emerging technologies against traditional chromatographic methods, highlighting their potential for rapid, on-site screening and paving the way for next-generation diagnostic tools in biomedical and clinical research.

The Rise of Multiplex Biosensing: Addressing the Urgent Need for Multi-Residue Pesticide Analysis

Pesticide contamination represents a critical global environmental challenge, with significant implications for ecosystem stability and public health. The extensive reliance on synthetic chemicals for agricultural and public health purposes has led to the pervasive presence of pesticide residues in aquatic ecosystems, where they adversely affect non-target organisms and contribute to biodiversity loss [1]. Current monitoring approaches primarily depend on conventional analytical techniques such as gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) and liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS), which, while highly sensitive and reliable, present limitations for rapid environmental screening due to their time-consuming processes, requirement for sophisticated laboratory infrastructure, and extensive sample pretreatment [1] [2]. These challenges highlight the pressing need for innovative monitoring solutions that can provide rapid, on-site, and cost-effective detection of multiple pesticide residues across diverse environmental matrices.

The development and implementation of multiplex biosensors offer a transformative approach to pesticide monitoring by enabling simultaneous detection of multiple analytes with high specificity and sensitivity. This application note details the operational principles, experimental protocols, and implementation frameworks for advanced biosensing platforms designed to address the global challenge of pesticide contamination, with particular emphasis on their application within environmental water quality assessment and agricultural product safety.

Biosensor Platforms for Pesticide Detection

Biosensors integrate biological recognition elements with physicochemical transducers to produce measurable signals proportional to target analyte concentration. The diversity of biosensor platforms enables tailored approaches for specific monitoring applications and detection requirements. The table below summarizes the principal biosensor types employed in pesticide residue detection, along with their respective characteristics and common applications.

Table 1: Classification and Characteristics of Biosensors for Pesticide Detection

| Biosensor Type | Recognition Element | Transducer Principle | Key Advantages | Representative Pesticides Detected |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enzymatic Biosensors | Enzymes (e.g., acetylcholinesterase, organophosphorus hydrolase) | Electrochemical, Optical | High catalytic activity, substrate specificity | Organophosphates, carbamates, methyl parathion [1] [3] |

| Immunosensors | Antibodies | Optical (SPR, TIRF), Electrochemical | High specificity and affinity, versatile format | Herbicides (atrazine), insecticides (chlorpyrifos) [1] [4] |

| Aptasensors | Nucleic acid aptamers | Electrochemical, Fluorescent | Thermal stability, chemical synthesis, small size | Various insecticides and herbicides [1] |

| Whole-Cell Biosensors | Microorganisms or plant cells | Electrochemical, Bioluminescent | Functional toxicity assessment, viability | Broad-spectrum detection [1] |

| Wearable Biosensors | Enzymes or antibodies | Electrochemical | In-situ, real-time, non-destructive analysis | Organophosphorus pesticides on crops [3] |

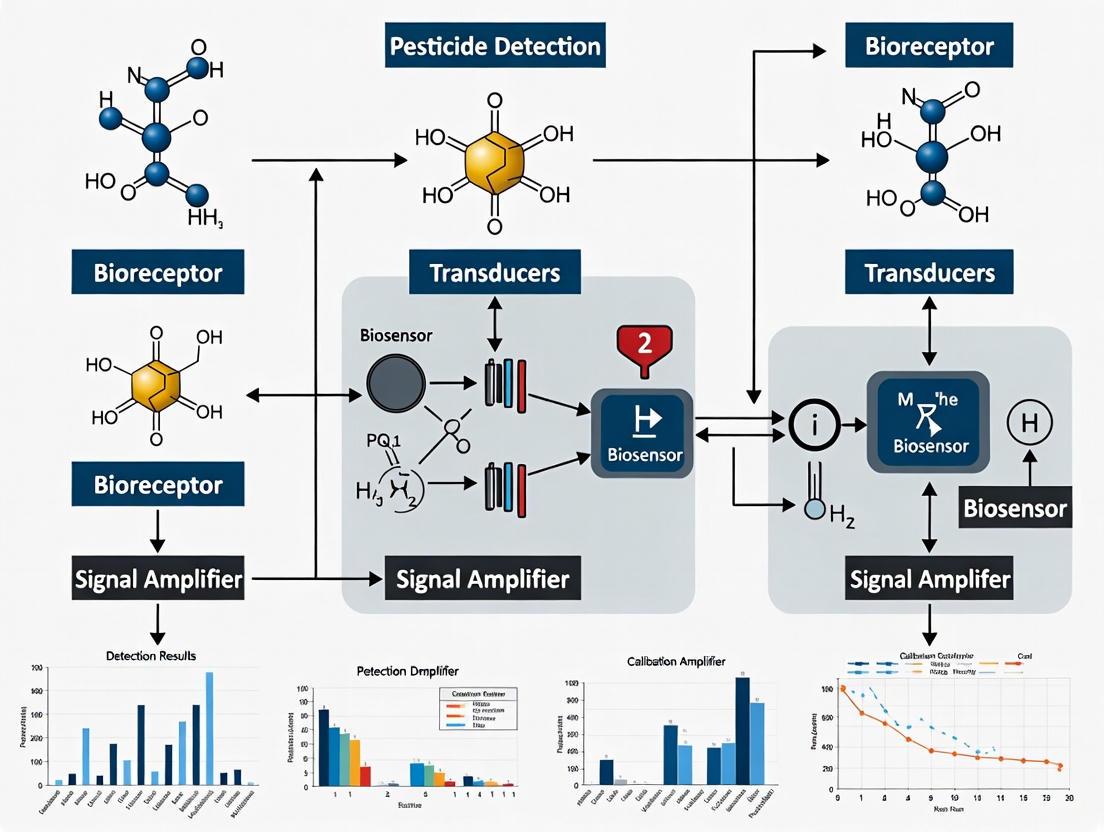

The operational principle of multiplex biosensor detection relies on the parallel integration of multiple biological recognition elements onto a single platform, each specifically targeting a different pesticide compound. This configuration allows for the simultaneous quantification of several analytes in a single sample, significantly enhancing screening efficiency. Transducer elements convert the specific binding events into quantifiable signals, typically electrochemical, optical, or acoustic, which are subsequently processed and correlated to analyte concentration [1] [4].

Figure 1: Fundamental principle of multiplex biosensor operation for parallel pesticide detection.

Research Reagent Solutions

The development and implementation of effective biosensing platforms require specific research-grade reagents and materials to ensure analytical reliability and performance. The following table details essential reagents and their functional roles in biosensor fabrication and operation.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Biosensor Development and Application

| Reagent/Material | Functional Role | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Organophosphorus Hydrolase (OPH) | Enzyme recognition element; catalyzes hydrolysis of organophosphorus pesticides. | Selective capture and recognition of methyl parathion and related OPs in wearable and enzymatic biosensors [3]. |

| Nucleic Acid Aptamers | Synthetic oligonucleotide recognition elements; high-affinity binding to specific pesticide targets. | Aptasensor development; stable alternatives to antibodies for various insecticides and herbicides [1]. |

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | Signal amplification; enhance electron transfer in electrochemical sensors and optical properties. | Modification of electrode surfaces (e.g., LIG) to improve sensitivity in wearable and other biosensors [2] [3]. |

| Laser-Induced Graphene (LIG) | Porous, high-surface-area electrode material; provides conductive substrate for sensor fabrication. | Flexible, stretchable three-electrode systems for plant-wearable and other electrochemical biosensors [3]. |

| Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) | Flexible, biocompatible polymer substrate; allows sensor conformability to irregular surfaces. | Transfer and encapsulation of LIG electrodes for plant-wearable applications [3]. |

| Specific Monoclonal Antibodies | Immunological recognition elements; high specificity for target pesticide antigens. | Immunosensors (e.g., SPR, array biosensors) for herbicides like atrazine and insecticides [1] [4]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Fabrication of a Plant-Wearable Serpentine Electrode Biosensor

This protocol describes the fabrication and application of a flexible, plant-wearable biosensor for in-situ detection of organophosphorus pesticides on crop surfaces [3].

Materials Required:

- Commercial polyimide (PI) film (25 μm thickness)

- CO₂ laser induction system

- Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS)

- Ag/AgCl ink

- Organophosphorus hydrolase (OPH)

- Gold(III) chloride trihydrate (HAuCl₄·3H₂O)

- Phosphate buffer (0.1 M, pH 7.4)

- Semisolid electrolyte (e.g., gelatin-based)

- Hand-held potentiostat with Bluetooth capability

Procedure:

- Laser-Induced Graphene (LIG) Patterning:

- Mount the PI film securely on the laser processing stage.

- Utilize computer-controlled laser writing to pattern a serpentine three-electrode system (working, counter, and reference electrodes) directly onto the PI surface.

- Optimize laser power (e.g., 3.6 W) and scan speed to achieve a 3D porous graphene structure with high conductivity and mechanical integrity [3].

Electrode Transfer and Functionalization:

- Apply a PDMS layer to transfer and encapsulate the LIG electrode, conferring flexibility and stretchability.

- Modify the working electrode surface by electrodepositing gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) from a HAuCl₄ solution to enhance electrochemical performance and surface area.

- Immobilize the OPH enzyme onto the AuNP-modified working electrode using a cross-linking agent or physical adsorption, followed by rinsing with phosphate buffer to remove unbound enzyme.

Sensor Integration and Calibration:

- Apply a biocompatible semisolid electrolyte layer over the three-electrode system.

- Connect the flexible sensor to a hand-held potentiostat.

- Calibrate the biosensor by measuring the amperometric response (e.g., chronoamperometry) to standard solutions of methyl parathion in phosphate buffer across a concentration range (e.g., 0.1-100 μM).

- Establish a calibration curve correlating pesticide concentration to electrochemical signal.

In-Situ Application on Crops:

- Gently attach the functionalized biosensor directly to the surface of a leaf or fruit.

- Initiate measurement via the potentiostat; the OPH enzyme catalyzes the hydrolysis of methyl parathion, generating an electroactive product detected amperometrically.

- Wirelessly transmit the resulting data in real-time to a smartphone device for analysis and interpretation.

Figure 2: Workflow for plant-wearable biosensor fabrication and deployment.

Protocol 2: Multiplex Array Biosensor for Water Monitoring

This protocol outlines the procedure for utilizing a planar array biosensor based on the NRL (Naval Research Laboratory) platform for simultaneous detection of multiple pesticides in water samples [4].

Materials Required:

- Planar waveguide chip (e.g., glass slide)

- Avidin coating solution

- Biotinylated capture antibodies (specific to target pesticides, e.g., atrazine, chlorpyrifos)

- Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) flow channel block

- Fluorescently labeled tracer antibodies (e.g., Cy5 or AlexaFluor 647 conjugates)

- Diode laser (635 nm) and CCD detection system

- Water samples (filtered if containing particulate matter)

- Regeneration buffer (e.g., low pH glycine buffer)

Procedure:

- Waveguide Functionalization:

- Coat a clean planar waveguide with an avidin layer.

- Immobilize biotinylated capture antibodies in distinct columns on the waveguide surface using a PDMS flow channel block to create a patterned array.

Sample Preparation and Assay:

- Pre-mix the environmental water sample with a solution containing fluorescently labeled tracer antibodies.

- Perpendicularly orient the PDMS flow channel block to the immobilized antibody columns and introduce the sample mixture.

- Allow the sample to flow through the channels, enabling pesticides in the sample to compete with immobilized haptens or directly bind to capture antibodies in a sandwich format.

Signal Detection and Analysis:

- Launch 635 nm light from a diode laser into the waveguide edge, creating an evanescent wave that excites surface-bound fluorophores.

- Capture the fluorescent pattern emitted from the array using a CCD camera.

- Quantify the fluorescence intensity at each capture spot, which is inversely proportional to the pesticide concentration in competitive assays or directly proportional in sandwich assays.

Regeneration and Reuse:

- Regenerate the biosensor surface by flowing a regeneration buffer to dissociate bound analytes and antibodies.

- Recalibrate with standard solutions before subsequent sample analyses to ensure quantitative accuracy.

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Biosensor data analysis requires conversion of raw signal outputs (electrical current, fluorescence intensity, spectral shift) into quantitative analyte concentrations based on established calibration models. For multiplex detection, data deconvolution is essential to accurately attribute signals to specific targets within a mixture.

Table 3: Typical Performance Metrics of Advanced Biosensor Platforms

| Biosensor Platform | Target Analytic | Sample Matrix | Detection Limit | Detection Time | Multiplexing Capacity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plant-Wearable (Electrochemical) | Methyl parathion | Crop surface (in-situ) | Low μM range [3] | Minutes [3] | Single analyte |

| NRL Array Biosensor (Optical) | Toxins, small molecules | Water, food crude extracts | ng/L to μg/L range [4] | 5 - 15 minutes [4] | Multiple (e.g., 4-6 analytes) |

| SPR-based Immunosensor | Herbicides, antibiotics | Water, milk | ng/L level [4] | Real-time (< 5 min) [4] | Moderate (4-16 spots) |

| CL-based Microarray | Antibiotics | Milk | ng/L level [4] | ~5 minutes [4] | High (dozens of spots) |

| Fluorescent Aptasensor | Various pesticides | Processed tea extracts | pM to nM range [2] | 5 - 30 minutes [2] | Moderate |

Statistical analysis, including replicate measurements (n ≥ 3) and appropriate controls (negative, positive), is crucial for ensuring data reliability. The limit of detection (LOD) is typically calculated as the mean signal of the blank plus three times its standard deviation. Cross-reactivity assessments are particularly important for multiplex assays to verify minimal interference between parallel detection channels.

Troubleshooting and Optimization

Successful implementation of biosensor protocols often requires optimization and problem-solving. Common challenges and recommended solutions include:

- Low Signal-to-Noise Ratio: Optimize recognition element density on the sensor surface. For electrochemical sensors, ensure proper electrode cleaning and surface renewal. For optical sensors, check laser alignment and fluorescence background.

- Poor Selectivity/Cross-Reactivity: Re-evaluate the specificity of biological recognition elements (antibodies, aptamers). Implement additional blocking steps during surface preparation (e.g., with BSA or casein) to minimize non-specific binding.

- Signal Drift or Instability: Verify the stability of the reference electrode in electrochemical systems. Ensure constant temperature and pH during measurements, as these factors significantly affect biorecognition kinetics and stability.

- Reproducibility Issues: Standardize the immobilization chemistry for biological elements across different sensor batches. Implement rigorous quality control using standard reference materials for each experimental run.

- Matrix Interference: For complex samples like tea, incorporate sample clean-up steps such as dilution, filtration, or solid-phase extraction to remove interfering compounds like polyphenols and alkaloids [2]. Utilize standard addition methods for quantification to compensate for matrix effects.

Biosensor technology represents a paradigm shift in environmental monitoring, offering rapid, sensitive, and potentially on-site detection capabilities that complement traditional analytical methods. The protocols outlined herein for wearable and multiplex biosensors provide researchers with practical frameworks for detecting pesticide residues in various environmental and agricultural contexts. Future developments in this field are anticipated to focus on enhanced multiplexing capabilities for a broader spectrum of pesticides, integration with microfluidic systems for automated sample handling, incorporation of artificial intelligence for data analysis and pattern recognition, and the development of increasingly robust and stable biorecognition elements for prolonged field deployment [1] [2]. The ongoing convergence of nanotechnology, materials science, and biotechnology will continue to propel the evolution of biosensors, ultimately contributing to more effective global management of pesticide contamination and the mitigation of associated health risks.

The accurate monitoring of pesticide residues in food products is a critical component of ensuring global food safety and protecting public health. Traditional analytical techniques, particularly High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC), Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS), and Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA), have long served as the cornerstone of residue analysis in regulatory and quality control settings [5]. These methods are renowned for their accuracy, sensitivity, and reliability in quantifying specific analytes at trace levels.

However, in the context of modern agricultural practices, which involve the use of hundreds of different pesticide compounds, these traditional methods face significant challenges. The demand for analyzing multiple pesticide residues simultaneously—driven by the need for comprehensive food safety assessments—has exposed inherent limitations in these conventional platforms [5]. This application note details the specific constraints of HPLC, GC-MS, and ELISA, framing their shortcomings within the pressing need for advanced, multiplexed detection solutions such as biosensors. By examining performance metrics, operational complexities, and practical bottlenecks, this analysis provides a scientific rationale for the transition towards next-generation analytical technologies.

Performance Limitations and Comparative Analysis

The limitations of traditional methods become evident when their key operational characteristics are systematically compared. The following table summarizes the principal constraints of each technique, highlighting the factors that hinder their efficiency in modern multi-residue analysis.

Table 1: Comparative Limitations of Traditional Detection Methods

| Method | Key Limitations | Typical Sample Throughput | Multiplexing Capability | Approximate Cost Factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HPLC | Complex sample prep, high solvent consumption, requires skilled technicians, limited to lab use [2] [5] | Low to Moderate | Low (Single or few analytes per run) | High (Equipment & Consumables) |

| GC-MS | Extensive sample cleanup needed, derivatization for non-volatile compounds, matrix effects, sophisticated instrumentation [6] [5] [7] | Low to Moderate | Moderate (with advanced MS) | Very High (Equipment & Maintenance) |

| ELISA | Susceptible to matrix/solvent interference, single-analyte focus, limited dynamic range, antibody cross-reactivity [8] [9] | High (per analyte) | Very Low (Typically single-analyte) | Low to Moderate (per test) |

Quantitative data further underscores these limitations. For instance, a study validating an HPLC-MS/MS method for 121 pesticides in rice reported a sample preparation and analysis workflow that is inherently time-consuming and complex, despite achieving excellent recoveries of 70-119% [10]. Similarly, a GC-MS method for 12 pesticides in cucumbers, while achieving a satisfactory recovery range of 80.6-112.3%, required meticulous calibration and cleanup procedures that are not amenable to rapid, on-site analysis [6]. ELISA kits, though simpler, show their own constraints in sensitivity and specificity, as seen in an ELISA for dinotefuran, where the working range was 1.0–30 ng/mL and cross-reactivity with clothianidin was a notable 184% [8].

Detailed Experimental Protocols Highlighting Operational Complexity

Protocol: Multi-Residue Analysis by GC-MS Using QuEChERS

This protocol, adapted from a method for determining 208 pesticides in plant-derived foods, exemplifies the intricate and multi-step nature of traditional chromatographic analysis [7].

1. Reagent Preparation:

- Extraction Solvent: Acetonitrile with 1% acetic acid.

- Standard Solutions: Prepare a series of matrix-matched calibration standards (e.g., 10–500 µg/L) from pesticide stock solutions in ethyl acetate. An internal standard (e.g., Heptachloride B) is added for quantification.

2. Sample Preparation (QuEChERS):

- Extraction: Weigh 10 g of homogenized sample (e.g., apple) into a 50 mL centrifuge tube. Add 10 mL of extraction solvent and a commercial QuEChERS salt packet (containing MgSO₄, NaCl, trisodium citrate, disodium hydrogen citrate). Shake vigorously for 1 minute and centrifuge.

- Cleanup: Transfer 6 mL of the supernatant to a dSPE tube containing cleanup sorbents (e.g., PSA, C18, and MgSO₄). Vortex and centrifuge. Transfer a portion of the cleaned extract, evaporate to near dryness under a nitrogen stream, and reconstitute in a solvent compatible with GC injection [7].

3. GC-MS Analysis:

- Injection: Inject 1–2 µL of the final extract in splitless mode.

- GC Conditions: Use a temperature-programmed run (e.g., initial 75°C, ramping to 300°C) on a non-polar or mid-polar capillary column (e.g., HP-5ms).

- Detection: Operate the mass spectrometer in multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) mode for high selectivity and sensitivity. Identify and quantify pesticides by comparing retention times and ion ratios to those of the matrix-matched calibration standards.

This workflow, while robust, involves numerous manual steps, requires significant solvent use, and depends on expensive, laboratory-bound instrumentation.

Protocol: Residue Analysis by ELISA

This protocol for the fungicide azoxystrobin demonstrates the comparative simplicity of ELISA but also its targeted, single-analyte nature [9].

1. Sample Extraction:

- Homogenize the agricultural sample.

- Extract the analyte with a water-miscible solvent like methanol or acetonitrile. For some matrices (e.g., rice), methanol extracts can be directly analyzed after dilution, as they show no significant matrix interference [8].

2. Assay Procedure:

- Add the standard or sample extract to the wells of a microplate pre-coated with capture antibody (direct competitive ELISA) or antigen (indirect ELISA).

- Add the enzyme-conjugated tracer (hapten or antibody) and incubate to allow competitive binding.

- Wash the plate to remove unbound materials.

- Add a colorimetric enzyme substrate and incubate for a defined period.

- Stop the reaction and measure the absorbance of each well with a plate reader.

3. Data Analysis:

- Construct a standard curve by plotting absorbance against the logarithm of the standard concentration.

- Interpolate the concentration of the analyte in the sample extracts from the standard curve. Recovery rates for a well-optimized ELISA, such as the one for azoxystrobin, can range from 96-109% [9].

The limitation is fundamental: each well or test is designed for one specific analyte, making the comprehensive screening of a sample for multiple pesticides prohibitively time-consuming and resource-intensive.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The execution of traditional methods relies on a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The following table details essential items and their functions in the analytical workflow.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Traditional Methods

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| QuEChERS Extraction Kits | Standardized salts and tubes for pesticide extraction and partitioning from food matrices [7]. | GC-MS, LC-MS sample prep |

| dSPE Cleanup Tubes | Dispersive Solid-Phase Extraction tubes containing sorbents (PSA, C18, GCB) to remove matrix interferences like fatty acids and pigments [6] [7]. | GC-MS, LC-MS sample prep |

| Chromatography Columns | GC (e.g., HP-5) and HPLC (e.g., C18) columns for the physical separation of analyte mixtures. | GC-MS, HPLC |

| MS-Grade Solvents | Ultra-pure solvents (acetonitrile, methanol, ethyl acetate) with minimal impurities to avoid background noise in detection. | HPLC, GC-MS, ELISA |

| Antibodies (Monoclonal/Polyclonal) | Biological recognition elements that provide high specificity and sensitivity for a target analyte in immunoassays [8] [9]. | ELISA |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standards | Standards used in MS for precise quantification, correcting for matrix effects and recovery losses. | GC-MS, LC-MS |

Workflow Visualization of Traditional Methods

The following diagram illustrates the complex, multi-stage processes involved in chromatographic methods (HPLC/GC-MS) and the simpler, yet single-plex, process of ELISA, highlighting their operational bottlenecks.

The limitations of traditional detection methods—operational complexity, low throughput for multi-analyte screening, high cost, and lack of portability—are inherent to their fundamental design principles [2] [5]. While HPLC, GC-MS, and ELISA remain gold standards for confirmatory, single-analyte quantification, their shortcomings create a significant technological gap in the face of the growing need for comprehensive pesticide residue profiling.

This analysis underscores the necessity for a paradigm shift in food safety monitoring. Multiplex biosensor technology emerges as a promising solution, potentially integrating the specificity of biological recognition with transducers capable of generating simultaneous, multi-analyte signals. By overcoming the key limitations outlined in this document, such advanced systems are poised to enable rapid, on-site, and high-throughput screening of multiple pesticide residues, thereby enhancing the efficacy of food safety control systems and better protecting public health.

Biosensors are analytical devices that integrate a biological recognition element with a physicochemical transducer to convert a biological event into a measurable signal [11]. These devices have become indispensable tools across various fields, including medical diagnostics, environmental monitoring, and food safety control, particularly for detecting pesticide residues in agricultural products [12] [11]. The core principle of biosensor operation involves three essential components: a biorecognition element that specifically interacts with the target analyte, a transducer that converts the biological interaction into a quantifiable signal, and a signal processing system that interprets and displays the results [13] [11]. This application note examines the fundamental principles of recognition elements and transduction mechanisms, framed within the context of multiplex biosensor detection for multiple pesticide residues research.

Fundamental Components and Principles

Core Biosensor Architecture

All biosensors share a common architectural framework consisting of three fundamental components that work in sequence to detect and quantify target analytes [13] [11]. The arrangement and integration of these elements determine the biosensor's performance characteristics, including sensitivity, specificity, and operational stability.

Recognition Elements

Recognition elements form the molecular interface that provides biosensors with their exceptional specificity. These biological or biomimetic components are selected for their ability to bind particular target molecules with high affinity while minimizing interactions with non-target substances in complex sample matrices [12] [13]. The choice of recognition element significantly influences the sensor's selectivity, stability, and application potential.

Table 1: Common Recognition Elements in Biosensors for Pesticide Detection

| Recognition Element | Composition | Detection Principle | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enzymes (e.g., AChE, BChE) | Proteins | Enzyme inhibition or catalytic activity | High catalytic activity, signal amplification | Sensitivity to environment, limited stability [12] |

| Antibodies | Immunoglobulin proteins | Antigen-antibody binding | High specificity, commercial availability | Animal-derived, batch variability [14] |

| Aptamers | Single-stranded DNA/RNA oligonucleotides | Folding into target-specific 3D structures | Chemical stability, thermal stability, modifiable [15] | |

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) | Synthetic polymers with template-shaped cavities | Molecular recognition via shape complementarity | Robustness, stability in harsh conditions [12] |

Transduction Mechanisms

Transduction mechanisms form the critical interface between biological recognition events and measurable physical signals. These systems convert molecular interactions into quantifiable outputs that can be processed, analyzed, and interpreted [13] [11]. The transduction principle employed determines key performance parameters including sensitivity, detection limit, and compatibility with different measurement environments.

Table 2: Transduction Mechanisms in Biosensors

| Transduction Type | Measurable Signal | Detection Method | Sensitivity Range | Applications in Pesticide Detection |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electrochemical | Current, potential, or impedance changes | Amperometric, potentiometric, impedimetric | nM to fM | Organophosphorus, carbamate detection [11] [15] |

| Optical | Light absorption, emission, or scattering | Fluorescence, luminescence, colorimetry, SPR | pM to fM | Multiplex pesticide detection [12] [16] |

| Piezoelectric | Mass change | Frequency shift | ng-level mass detection | Gas phase pesticide detection [11] |

| Thermal | Heat change | Temperature measurement | - | Enzyme-based pesticide sensors [11] |

Experimental Protocols for Pesticide Detection

Protocol 1: Acetylcholinesterase-Based Electrochemical Biosensor for Organophosphorus Pesticides

Principle: This protocol utilizes the inhibition of acetylcholinesterase (AChE) enzyme activity by organophosphorus pesticides (OPs). The decrease in enzymatic conversion of acetylthiocholine to thiocholine is measured amperometrically, with the signal reduction correlating to pesticide concentration [12].

Materials:

- Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) from electrophorus electricus

- Acetylthiocholine chloride (ATCh) substrate

- Phosphate buffer saline (PBS, 0.1 M, pH 7.4)

- Screen-printed carbon electrodes (SPCEs)

- Potentiostat for electrochemical measurements

- Chitosan for enzyme immobilization

- Glutaraldehyde for cross-linking

Procedure:

- Electrode Modification: Clean SPCEs by cycling in 0.5 M H₂SO₄ between -1.0 V and +1.0 V until stable voltammogram is obtained.

- Enzyme Immobilization: Prepare AChE solution (0.5 U/μL) in chitosan matrix (0.5% w/v). Deposit 5 μL of enzyme solution on electrode surface. Cross-link with 2% glutaraldehyde vapor for 30 minutes.

- Baseline Measurement: Incubate modified electrode in PBS containing 1 mM ATCh. Record amperometric current at +0.7 V for 2 minutes. This current (I₀) represents uninhibited enzyme activity.

- Inhibition Phase: Incubate biosensor in sample containing suspected OPs for 15 minutes. Rinse gently with PBS to remove unbound pesticides.

- Post-Inhibition Measurement: Measure amperometric current (Iᵢ) again under identical conditions as step 3.

- Calculation: Calculate inhibition percentage as: % Inhibition = [(I₀ - Iᵢ)/I₀] × 100

- Quantification: Compare inhibition percentage to calibration curve prepared with standard OP solutions.

Performance Parameters:

- Detection limit: 0.38 pM for specific OPs [12]

- Linear range: 0.1-100 nM

- Total analysis time: 25 minutes

- Recovery in spiked apple samples: 95-105%

Protocol 2: Aptamer-Based Optical Biosensor for Neonicotinoid Pesticides

Principle: This protocol employs fluorescently-labeled DNA aptamers that undergo conformational changes upon binding to neonicotinoid pesticides, resulting in measurable fluorescence alterations [15].

Materials:

- Fluorescently-labeled aptamer specific to imidacloprid

- Tris buffer (10 mM, pH 7.4 with 5 mM MgCl₂)

- Quencher-labeled complementary DNA (for quenching-based detection)

- Fluorometer or fluorescence microplate reader

- Solid support for aptamer immobilization (e.g., magnetic beads)

- Washing buffer (Tris with 0.05% Tween-20)

Procedure:

- Aptamer Preparation: Denature aptamer solution at 95°C for 5 minutes, then slowly cool to room temperature for proper folding.

- Immobilization: Immobilize thiol-modified aptamers on gold surfaces or magnetic beads via gold-thiol chemistry. Block nonspecific sites with 1% BSA for 1 hour.

- Sample Incubation: Incubate immobilized aptamers with sample solutions for 20 minutes with gentle shaking.

- Washing: Remove unbound analytes by washing three times with washing buffer.

- Signal Measurement: Measure fluorescence intensity at excitation/emission wavelengths specific to the fluorophore used.

- Quantification: Generate calibration curve by plotting fluorescence intensity against pesticide concentration.

Performance Parameters:

- Detection limit: 0.1 nM for imidacloprid

- Specificity: Minimal cross-reactivity with other pesticides

- Analysis time: 30 minutes

- Applicable to fruit and vegetable samples

Research Reagent Solutions for Multiplex Pesticide Detection

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Biosensor Development

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Biosensor | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recognition Elements | Acetylcholinesterase, Anti-parathion antibodies, DNA aptamers | Molecular recognition of specific pesticide classes | Determines specificity, shelf life, operating conditions [12] [15] |

| Signal Transducers | Screen-printed electrodes, Gold SPR chips, Quantum dots, Carbon nanotubes | Convert binding events to measurable signals | Determine sensitivity, detection limit, signal-to-noise ratio [12] [11] |

| Immobilization Matrices | Chitosan, Nafion, Sol-gels, Self-assembled monolayers | Stabilize recognition elements on transducer surface | Affect bioreceptor activity, sensor stability, response time [11] |

| Signal Amplifiers | Enzymes (HRP, AP), Metal nanoparticles, Polymer beads | Enhance detection signals for lower detection limits | Improve sensitivity, enable visual detection, reduce instrument requirements [12] [16] |

| Sample Preparation Kits | QuEChERS kits, Solid-phase extraction cartridges | Extract and clean up pesticides from complex matrices | Improve accuracy, reduce matrix effects, concentrate analytes [17] |

Advanced Signaling Pathways in Biosensor Detection

The fundamental principles of biosensors revolve around the sophisticated integration of biological recognition elements with appropriate transduction mechanisms. For multiplex pesticide detection, the strategic selection and combination of these components determines the analytical performance, including sensitivity, specificity, and multiplexing capability. Current research trends indicate a movement toward miniaturized, portable devices incorporating artificial intelligence for data interpretation, wearable formats for continuous monitoring, and Internet of Things (IoT) integration for real-time environmental surveillance [14] [15]. The convergence of nanotechnology, materials science, and biotechnology continues to push the boundaries of what's possible in biosensing, promising increasingly sophisticated solutions for the complex challenge of multiple pesticide residue detection in food and environmental samples. As these technologies mature, standardization of fabrication protocols and validation under real-world conditions will be essential for translating laboratory developments into practical analytical tools that can effectively safeguard public health and environmental quality.

The monitoring of multiple pesticide residues in food and environmental samples is a critical challenge for ensuring public health and safety. Multiplexing technologies, which enable the simultaneous detection and quantification of numerous analytes in a single assay, have emerged as powerful tools to address this need. These strategies offer significant advantages over traditional single-analyte methods, including reduced analysis time, lower sample volume requirements, decreased cost per analyte, and higher throughput capabilities [18]. This article explores the fundamental strategies and practical protocols for implementing multiplex detection systems, with particular focus on applications within pesticide residue analysis for research and development professionals.

Core Multiplexing Strategies

Multiplex biosensing platforms primarily employ two distinct strategic approaches: recognition element-based methods and inherent characteristic-based methods [18]. Each strategy offers unique advantages for specific application requirements in multi-analyte detection.

Recognition Element-Based Strategies

This approach relies on biological or biomimetic recognition elements with broad specificity toward multiple target compounds. The three primary categories include:

Broadly Specific Antibodies: These can be generated through four main methods: (1) generic antibodies prepared using "general-structure" immunogens that preserve common features of an entire analyte class; (2) broad-spectrum antibodies generated with multi-hapten immunogens; (3) bispecific antibodies composed of two different heavy/light chains; and (4) combinations of multiple analyte-specific antibodies [18]. Computer-assisted molecular modeling and quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) studies have significantly improved the design of haptens for generating antibodies with desired broad specificity profiles [18].

Aptamers: These single-stranded DNA or RNA molecules offer advantages of thermal stability, simple production, and ease of modification compared to antibodies.

Molecular Imprinted Polymers (MIPs): These synthetic polymers contain tailor-made recognition sites that mimic natural antibodies, offering excellent stability and customizability.

Inherent Characteristic-Based Strategies

This alternative approach leverages the innate physical or chemical properties of target analytes without requiring specific recognition elements. Key methodologies include:

- Enzymatic inhibition-based sensors

- Near-infrared (NIR) spectroscopy

- Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering (SERS) spectroscopy [18]

Experimental Protocols

Multiplex Immunochip Assay for Pesticide Detection

This protocol describes a membrane-based colorimetric immunochip assay for simultaneous detection of seven pesticides from six different chemical groups [19].

Materials and Reagents

- Nitrocellulose (NC) membrane

- Goat anti-mouse IgG and rabbit anti-goat IgG

- Pesticide standards (triazophos, methyl-parathion, fenpropathrin, carbofuran, thiacloprid, chlorothalonil, carbendazim)

- 2-(N-morpholino) ethanesulfonic acid (MES) buffer

- Bovine serum albumin (BSA)

- Chloroauric acid

- Nanogold enhancement solution

- Primary secondary amine (PSA) and C18 sorbents

Procedure

Chip Fabrication:

- Spot seven pesticide antigens as capture probes on designated positions of the NC membrane

- Include rabbit anti-goat IgG as a positive control position

- Allow spots to dry completely at room temperature for 1 hour

- Block the membrane with 1% BSA in PBS for 1 hour at 37°C to prevent nonspecific binding

Immunoassay Procedure:

- Apply 10 μL of standard or sample extract to each antigen spot

- Immediately add 10 μL of primary antibody mixture (containing specific antibodies for all seven pesticides)

- Incubate at 37°C for 30 minutes in a humidified chamber

- Wash the membrane three times with PBS containing 0.05% Tween-20 (PBST)

Signal Development:

- Add nanogold-labeled secondary antibody solution (gold-conjugated anti-species IgG)

- Incubate at 37°C for 20 minutes

- Wash with PBST followed by deionized water

- Apply nanogold enhancement solution for signal amplification

- Terminate the reaction by rinsing with deionized water after optimal color development (typically 4-8 minutes)

Signal Detection:

- Capture chip images using a flatbed scanner or digital camera

- Analyze spot intensity using image analysis software (e.g., ImageJ)

- Generate calibration curves for each pesticide by plotting normalized intensity (B/B₀) against logarithm of concentration

- Calculate sample concentrations using the established calibration curves

Performance Characteristics: The immunochip assay demonstrates detection limits of 0.02–6.45 ng mL⁻¹ for the seven pesticides, with visual detection limits ranging from 1 to 100 ng mL⁻¹ [19]. Recovery tests in spiked vegetable and fruit samples validate the method's accuracy and precision for multi-residue screening applications.

Quantitative Performance Data

Table 1: Analytical Performance of Multiplex Detection Platforms for Pesticide Residues

| Detection Platform | Number of Analytes | Detection Limit Range | Analysis Time | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immunochip Assay [19] | 7 pesticides | 0.02–6.45 ng mL⁻¹ | < 60 minutes | Vegetables, fruits |

| Fluorescent LFIA [18] | 7 β-agonists | Not specified | Rapid screening | Food safety |

| icELISA [18] | 5 antibacterial synergists | 0.067–0.139 μg/L | Standard ELISA time | Food analysis |

| dcELISA [18] | 5 antibacterial synergists | 0.208–9.24 μg/L | Shorter than icELISA | Food analysis |

| Chemiluminescence ELISA [18] | 21 FQs | 0.10–33.83 ng/mL | Standard ELISA time | Milk samples |

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Multiplex Biosensor Development

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Assay |

|---|---|---|

| Recognition Elements | Generic antibodies, Aptamers, MIPs [18] | Target capture and specificity |

| Signal Transducers | Colloidal gold nanorods, Fluorochromes [20] [21] | Signal generation and amplification |

| Solid Supports | Nitrocellulose membrane, Modified glass slides [19] | Platform for probe immobilization |

| Blocking Agents | BSA, Casein, Skim milk [19] | Minimize nonspecific binding |

| Enhancement Reagents | Nanogold enhancers, Silver stains [19] | Signal amplification |

| Biological Buffers | MES, PBS, Carbonate-bicarbonate [19] | Maintain optimal assay conditions |

Visual Workflows

Multiplex Strategy Selection Workflow - This diagram illustrates the decision pathway for selecting appropriate multiplex detection strategies based on sample characteristics and analytical requirements.

Immunochip Experimental Protocol - This workflow details the step-by-step procedure for performing multiplex pesticide detection using the membrane-based immunochip platform with nanogold signal enhancement.

Multiplex biosensors represent a transformative advancement in analytical technology, enabling the simultaneous detection and quantification of multiple analytes in a single assay. Within the critical field of pesticide residue research, these systems address fundamental limitations of traditional methods by integrating high-throughput capabilities with portable design. The core advantages of multiplex biosensors—exceptional speed, significant cost-reduction, and true on-site operational capability—are revolutionizing monitoring approaches across the "tea garden-to-cup" supply chain and other agricultural sectors [2]. This Application Note delineates the quantitative benefits of these technologies and provides detailed protocols for their implementation in pesticide residue detection, framed within a broader thesis on advanced detection methodologies.

Core Advantages: A Quantitative Comparison

The transition from conventional, single-analyte techniques to multiplexed platforms offers demonstrable and significant improvements in key performance metrics. The following table summarizes the comparative advantages of multiplex biosensors over traditional detection methods.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Pesticide Residue Detection Technologies

| Technology Feature | Traditional Methods (GC-MS/LC-MS) | Multiplexed Biosensors | Practical Implication for Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Analysis Time | 30 minutes to several hours per sample [2] | 5–30 minutes per multi-analyte profile [2] | High-throughput screening; rapid iteration for kinetic studies |

| Detection Limit | ~0.002–0.5 mg/kg (GC-MS) [22] | < 0.0012 μM (for pesticides) [23] | Ultra-sensitive detection for trace-level residue analysis |

| Multiplexing Capacity | Typically single-analyte or targeted MRM | Simultaneous detection of 7+ pesticides [23] | Identification of mixed contamination profiles with a single test |

| Portability | Laboratory-bound, benchtop systems | Portable, handheld devices enabled | True on-site analysis in fields and processing facilities |

| Cost per Data Point | High (equipment > $1M, skilled operator) [2] | Significantly lower, minimal reagent use [24] | Enables large-scale spatial and temporal monitoring studies |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Nanozyme-Based Colorimetric Sensor Array for Multi-Pesticide Detection

This protocol details the creation of a colorimetric sensor array using self-assembled copper-amino acid (Cu-AC) nanozymes, capable of discriminating seven different pesticides with limits of detection below 0.0012 μM [23].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Cu-AC Nanozymes: Sensing units with tunable laccase-mimic activity, self-assembled from Cu²⁺ ions and amino acids (L-leucine, L-isoleucine, L-phenylalanine) [23].

- Chromogenic Substrate: A solution containing 2,4-dichlorophenol (2,4-DP) and 4-aminoantipyrine (4-AP) [23].

- Pesticide Standards: Analytical-grade target pesticides in a suitable solvent (e.g., methanol).

- Buffer Solution: Acetate buffer (0.1 M, pH 4.5) for optimal nanozyme activity.

Procedure:

- Sensor Array Fabrication:

- Prepare three distinct Cu-AC nanozyme suspensions (Cu-Leu, Cu-Ile, Cu-Phe) in acetate buffer.

- Dispense 50 μL of each nanozyme suspension into separate wells of a 96-well microplate to form the three-element sensor array.

- Assay Execution:

- Add 50 μL of the chromogenic substrate solution (2,4-DP + 4-AP) to each well.

- Introduce 100 μL of the sample (or pesticide standard) into each well.

- Incubate the microplate at 25°C for 15 minutes to allow the colorimetric reaction to proceed.

- Signal Acquisition:

- Capture an image of the entire microplate using a standard flatbed scanner or a smartphone under controlled lighting conditions.

- Extract the Red-Green-Blue (RGB) values from each well using image processing software (e.g., ImageJ).

- Data Analysis:

- Compile the RGB values from the three sensing units for each sample to create a unique fingerprint.

- Input the fingerprint data into a pre-trained Linear Discriminant Analysis model for pesticide classification.

- For automated, high-confidence identification, use a YOLOv8 deep learning algorithm trained on LDA plot images, achieving a mean average precision of up to 0.99 [23].

- Sensor Array Fabrication:

Protocol 2: Multiplexed Electrochemical Biosensor for High-Specificity Detection

This protocol outlines a multiplexed sensing platform using metal nanoparticles and Y-shaped DNA structures, exemplifying a strategy that can be adapted for the specific detection of pesticide residues [25].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Metal Nanoparticles (MNPs): AgNPs, PtFeNPs, and AuNPs, functionalized with specific molecular recognition elements (e.g., antibodies or aptamers) [25].

- Y-shaped DNA Probes: Synthetic DNA structures designed for simultaneous target capture and signal amplification [25].

- Electrode Chip: A multi-working electrode system (e.g., screen-printed carbon or gold electrodes).

- Buffer Solutions: PBS (10 mM, pH 7.4) for immobilization and assay steps.

Procedure:

- Probe Immobilization:

- Immobilize the Y-shaped DNA structures onto the predefined working electrodes of the chip.

- Conjugate the different metal nanoparticles (AgNPs, PtFeNPs, AuNPs) with their respective detection probes (e.g., antibodies against specific pesticides).

- Assay Execution:

- Apply the sample to the electrode chip and incubate for 20 minutes to allow the target pesticides to bind to the Y-DNA and form sandwich complexes with the MNP-labeled probes.

- Wash the chip thoroughly with PBS buffer to remove unbound reagents.

- Signal Transduction and Readout:

- Place the chip in an electrochemical reader containing an appropriate electrolyte solution.

- Perform square wave voltammetry (SWV) or differential pulse voltammetry (DPV).

- Measure the distinct redox currents from each metal nanoparticle (e.g., Ag⁺, Pt²⁺, Au³⁺) at their characteristic oxidation potentials.

- Data Analysis:

- The magnitude of each specific current peak is directly proportional to the concentration of the corresponding pesticide target, enabling simultaneous quantification [25].

- Probe Immobilization:

Technology Workflow and Data Integration

The operational pipeline of a multiplex biosensor, from sample to result, integrates material science, biorecognition, and advanced data analytics. The following diagram visualizes this integrated workflow.

Diagram 1: Integrated Workflow of a Multiplex Biosensor Platform. This diagram illustrates the seamless integration of sample introduction, biorecognition, signal transduction, and intelligent data processing that characterizes modern multiplex biosensor systems.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful implementation of multiplex biosensors relies on a suite of specialized materials and reagents. The following table catalogues the core components central to the experimental protocols and the broader field.

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Multiplex Biosensor Research and Development

| Research Reagent | Core Function | Exemplar Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Nanozymes (e.g., Cu-AC) | Mimics natural enzyme activity; serves as a highly tunable and stable sensing unit for colorimetric reactions. | Core element in colorimetric sensor arrays for discriminating multiple pesticides via unique activity profiles [23]. |

| Functionalized Metal Nanoparticles (Au, Ag, PtFe) | Acts as an electrochemical label; provides distinct, resolvable redox signals for multiplexed detection. | Used as labels in electrochemical biosensors for simultaneous discrimination of multiple targets [25]. |

| Biological Recognition Elements (Antibodies, Aptamers) | Provides high specificity and affinity for binding to target analytes (e.g., a specific pesticide). | Immobilized on sensor surfaces or nanoparticles to capture specific targets from a complex sample matrix [26] [24]. |

| Y-shaped DNA Nanostructures | Provides a programmable scaffold for simultaneous target capture and signal probe attachment, enhancing assay efficiency. | Used in electrochemical biosensors to create a structured platform for forming detection complexes [25]. |

| Cell-Free Protein Expression Systems | Enables on-chip synthesis of functional protein arrays directly from DNA, bypassing costly protein purification. | Facilitates high-throughput, label-free kinetic screening of thousands of protein interactions on platforms like SPOC [27]. |

Nanomaterial-Enhanced Sensing Platforms: From Fluorescence to Electrochemical Detection

The detection of multiple pesticide residues represents a significant challenge in ensuring food safety and environmental health. Optical biosensing technologies have emerged as powerful tools to address this challenge, offering rapid, sensitive, and specific detection capabilities that are essential for monitoring the complex mixtures of pesticides found in agricultural products [2] [28]. These sensing strategies leverage the interactions between light and matter to transduce molecular recognition events into measurable signals, enabling the quantification of trace-level contaminants [29]. The integration of these technologies with advanced nanomaterials has dramatically enhanced their performance, pushing detection limits to parts-per-billion or even parts-per-trillion levels while enabling multiplexed analysis of several pesticides simultaneously [28] [12]. This application note provides a detailed overview of four principal optical biosensing strategies—fluorescence (including FRET and MEF), Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS), colorimetry, and Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR)—within the context of multiplex detection platforms for pesticide residue analysis. We present standardized protocols, analytical performance comparisons, and implementation guidelines to facilitate the adoption of these methodologies in research and development settings focused on agricultural safety monitoring.

Fundamental Principles and Signaling Mechanisms

Core Sensing Modalities

Fluorescence-based sensing operates on the principle that certain molecules (fluorophores) absorb light at specific wavelengths and subsequently emit light at longer wavelengths. This process can be modulated through mechanisms such as FRET (Förster Resonance Energy Transfer), where energy non-radiatively transfers from a donor fluorophore to an acceptor molecule through dipole-dipole coupling, and MEF (Metal-Enhanced Fluorescence), where fluorophores interacting with plasmonic metallic nanostructures exhibit significantly enhanced emission intensities [29] [30]. These mechanisms are particularly valuable for pesticide detection as they can signal binding events or enzymatic activity inhibition with high sensitivity.

Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS) leverages the enormous enhancement of Raman scattering signals (typically 10⁶-10⁸ fold) observed when target molecules are adsorbed onto or in close proximity to nanostructured noble metal surfaces (primarily Au and Ag) [28]. This enhancement arises from electromagnetic mechanisms (localized surface plasmon resonances) and chemical mechanisms (charge transfer), enabling the acquisition of distinct molecular "fingerprint" spectra even at trace concentrations, which is ideal for identifying specific pesticide compounds in complex mixtures [28].

Colorimetric sensing relies on visually detectable color changes induced by the interaction between target pesticides and recognition elements, often mediated by functional nanomaterials such as gold and silver nanoparticles [31]. These color changes can result from various mechanisms including nanoparticle aggregation, redox reactions, or enzyme-mediated chromogenic reactions, providing a simple yet effective detection method suitable for point-of-care testing [31] [28].

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) detects changes in the refractive index occurring at the surface of a thin metal film (typically gold) when target molecules bind to immobilized recognition elements [29] [28]. This interaction alters the angle or wavelength at which surface plasmons are excited, enabling real-time, label-free monitoring of binding kinetics and affinity, which is valuable for characterizing pesticide-receptor interactions [29].

Visualizing Biosensing Mechanisms

The following diagrams illustrate the fundamental working principles and signaling pathways of the four optical biosensing strategies discussed.

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents for Optical Biosensing of Pesticides

| Category | Specific Materials | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nanomaterials | Gold nanoparticles (AuNPs), Silver nanoparticles (AgNPs), Quantum Dots (QDs) [31] [12] | Signal generation/enhancement; Colorimetric, fluorescence, and SERS probes | Tunable LSPR properties; High extinction coefficients; Size/shape-dependent optical properties |

| Recognition Elements | Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) enzyme, Antibodies, Aptamers, Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) [12] | Target-specific binding; Enzyme inhibition assays | High specificity and affinity; Stability under varying conditions; Reusability for MIPs |

| Signal Amplification Reagents | Nanozymes (e.g., CuO NPs), Single-Atom Nanozymes (SAzymes), Catalytic nanoparticles (Au/Pt) [12] [30] | Signal amplification; Enhanced detection sensitivity | Peroxidase-like activity; Higher stability than natural enzymes; Tunable catalytic properties |

| Substrate Materials | SPR gold chips, SERS-active substrates (Au/Ag nanostructures), Microfluidic chips, Filter paper [31] [28] | Sensor platform; Sample containment and flow | Low autofluorescence; Controlled surface chemistry; Reproducible nanostructuring |

| Detection Reagents | Chromogenic substrates (TMB, OPD), Fluorogenic substrates, Enzyme substrates (acetylthiocholine) [12] [30] | Signal generation in presence of target | High turnover rates; Distinct color/fluorescence changes; Low background interference |

Comparative Performance Analysis of Optical Biosensing Techniques

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Comparison of Optical Biosensing Techniques for Pesticide Detection

| Technique | Detection Limit | Analysis Time | Multiplexing Capability | Key Advantages | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fluorescence (FRET/MEF) | pM-fM range [30] | 10-60 minutes [12] | Moderate to High | Ultra-high sensitivity; Real-time monitoring; Ratiometric capabilities | Photobleaching potential; Background autofluorescence interference |

| SERS | Single-molecule to nM range [28] | 5-30 minutes [2] | High | Molecular fingerprinting; Multiplex detection; Minimal sample preparation | Substrate reproducibility; Signal uniformity challenges |

| Colorimetry | nM-µM range [31] [12] | 5-30 minutes [2] [31] | Low to Moderate | Visual detection; Instrument-free potential; Cost-effectiveness | Lower sensitivity compared to other methods; Matrix interference in complex samples |

| SPR | pM-nM range [29] [28] | Real-time (minutes) | Moderate | Label-free detection; Kinetic parameter measurement; High specificity | Bulk refractive index sensitivity; Nonspecific binding interference |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Fluorescence-Based Detection Protocol for Organophosphorus Pesticides

Principle: This protocol utilizes enzyme inhibition-based fluorescence detection, where organophosphorus pesticides inhibit acetylcholinesterase (AChE) activity, reducing the production of fluorescent products [12].

Materials and Reagents:

- Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) enzyme solution (0.5 U/mL)

- Acetylthiocholine (ATCh) substrate solution (5 mM)

- Quantum dots (CdTe) or fluorogenic substrate

- Phosphate buffer (0.1 M, pH 7.4)

- Standard pesticide solutions for calibration

- Microfluidic device or 96-well microplate [12]

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Homogenize agricultural samples (fruits, vegetables) and extract pesticides using appropriate solvent systems (e.g., acetonitrile). Filter through 0.22 µm membrane.

- Enzyme Inhibition: Mix 50 µL of sample extract with 50 µL of AChE solution in buffer. Incubate at 37°C for 20 minutes.

- Substrate Addition: Add 50 µL of ATCh substrate solution and incubate for additional 10 minutes at 37°C.

- Signal Development: Introduce 50 µL of quantum dot solution or fluorogenic substrate. For QD-based detection, thiocholine produced from ATCh hydrolysis quenches QD fluorescence, while pesticides inhibit AChE, preventing fluorescence quenching [12].

- Measurement: Record fluorescence intensity using microplate reader or microfluidic detector (Ex/Em: 360/450 nm for common fluorogenic substrates).

- Quantification: Generate calibration curve with pesticide standards (0.1-1000 ppb). Calculate unknown concentrations from the standard curve.

Notes: This method achieved LOD of 0.38 pM for organophosphorus pesticides in apple samples [12]. For enhanced sensitivity, metal-enhanced fluorescence (MEF) substrates can be incorporated to boost signal intensity [30].

SERS-Based Multiplex Detection Protocol for Pesticide Residues

Principle: This protocol employs SERS-active substrates to enhance Raman signals of pesticide molecules, enabling simultaneous detection of multiple residues through their unique spectral fingerprints [28].

Materials and Reagents:

- SERS-active substrate (Au or Ag nanostructures on silicon/silica)

- Portable Raman spectrometer with 785 nm or 633 nm laser

- Standard solutions of target pesticides

- Extraction solvents (methanol, acetonitrile)

- Centrifugal filtration devices (3 kDa MWCO)

Procedure:

- Substrate Preparation: Fabricate SERS substrates using electron beam lithography, nanoimprinting, or chemical synthesis of Au/Ag nanoparticles on solid supports.

- Sample Extraction: Extract pesticides from agricultural products using QuEChERS method or solid-phase extraction. Concentrate extracts using nitrogen evaporation.

- Sample Application: Apply 2-5 µL of concentrated extract to SERS substrate. Allow to dry at room temperature.

- SERS Measurement: Focus laser spot on sample area. Acquire spectra with integration time of 10-30 seconds. Collect multiple spectra from different spots for statistical analysis.

- Spectral Processing: Preprocess spectra by subtracting background, smoothing, and vector normalization.

- Multiplex Analysis: Employ chemometric methods (PCA, PLS-DA) to deconvolute overlapping peaks from multiple pesticides. Develop multivariate calibration models using reference standards.

Notes: Key to this method is substrate reproducibility and signal uniformity. Core-shell nanoparticles (Au@Ag) can provide enhanced stability and SERS activity. Integration with microfluidics enables automated sample delivery and washing steps [28].

Colorimetric Nanozyme-Based Detection Protocol

Principle: This protocol utilizes nanozymes (nanomaterial-based enzyme mimics) that catalyze color-changing reactions, with pesticides modulating this catalytic activity [31] [12].

Materials and Reagents:

- Copper oxide nanoparticles (CuO NPs) or other nanozymes

- Colorimetric substrate (TMB, ABTS)

- Hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) solution

- Acetate buffer (0.1 M, pH 4.0)

- Paper-based analytical devices

- Smartphone with color analysis app

Procedure:

- Nanozyme Synthesis: Prepare CuO NPs through chemical precipitation: mix copper chloride with NaOH, collect precipitate by centrifugation, wash, and resuspend in water [12].

- Device Fabrication: Create paper-based microfluidic devices by wax printing or cutting. Spot nanozyme solution onto detection zones.

- Sample Preparation: Extract pesticides from tea leaves or other crops using simplified extraction procedure.

- Assay Assembly: Mix 10 µL sample extract with 10 µL H₂O₂ solution and 10 µL TMB substrate solution. Apply to sample pad of paper device.

- Color Development: Allow reaction to proceed for 10 minutes at room temperature. Pesticides inhibit nanozyme activity, reducing color intensity proportionally to concentration.

- Signal Detection: Capture device image using smartphone camera. Analyze RGB values using ImageJ or custom app. Calculate pesticide concentration from standard curve.

Notes: This system achieved LOD of 0.08 mg/L for malathion with ~10 minute analysis time [12]. For quantitative precision, include color reference standards on each device to correct for lighting variations.

SPR-Based Binding Assay for Pesticide Detection

Principle: This protocol employs SPR to monitor direct binding between pesticides and immobilized recognition elements (antibodies, aptamers) in real-time without labeling [29] [28].

Materials and Reagents:

- SPR instrument with gold sensor chips

- Carboxymethyl dextran-coated sensor chips

- EDC/NHS crosslinking reagents

- Recognition elements (antibodies, aptamers)

- Running buffer (HEPES with surfactant)

- Regeneration solution (glycine-HCl, pH 2.5)

Procedure:

- Surface Functionalization: Activate carboxymethyl dextran sensor chip surface with EDC/NHS mixture for 7 minutes.

- Ligand Immobilization: Dilute recognition element (antibody/aptamer) in sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.0). Inject over activated surface for 15-30 minutes to achieve desired immobilization level.

- Blocking: Deactivate remaining active esters with ethanolamine-HCl injection.

- Equilibration: Condition surface with multiple injections of regeneration solution until stable baseline achieved.

- Sample Analysis: Dilute pesticide samples in running buffer. Inject samples over functionalized surface at flow rate of 30 µL/min for 3-5 minutes association phase.

- Dissociation Monitoring: Continue buffer flow for 5-10 minutes to monitor dissociation.

- Surface Regeneration: Inject regeneration solution for 30 seconds to remove bound analytes.

- Data Analysis: Determine binding response in resonance units (RU). Calculate kinetic parameters (kₐ, kḍ, Kᴅ) using appropriate binding models.

Notes: SPR enables real-time monitoring of pesticide-antibody interactions with pM-nM sensitivity [29]. Reference flow cell should be similarly prepared without recognition element to correct for bulk refractive index changes and nonspecific binding.

Implementation Workflow for Multiplexed Detection

The following diagram illustrates a comprehensive experimental workflow integrating multiple optical biosensing strategies for multiplexed pesticide detection, from sample preparation to data analysis.

Optical biosensing strategies offer powerful approaches for multiplex detection of pesticide residues, each with distinct advantages and optimal application scenarios. Fluorescence techniques provide ultra-sensitive detection, SERS enables specific molecular identification, colorimetry offers simplicity and field-deployment potential, and SPR permits label-free binding characterization. The integration of these complementary techniques within a unified analytical framework, supported by advanced nanomaterials and AI-enhanced data processing, represents the future of pesticide monitoring technology [28] [32]. Emerging trends include the development of smartphone-integrated portable detection systems, self-validating dual-mode sensors, and AI-optimized nanomaterial designs that collectively promise to transform pesticide residue analysis from laboratory settings to point-of-need applications across the food supply chain [28]. As these technologies continue to mature, their implementation in standardized monitoring protocols will significantly enhance our capability to ensure food safety and protect public health through comprehensive pesticide residue surveillance.

Electrochemical biosensors represent a powerful class of analytical devices that combine the specificity of biological recognition elements with the sensitivity of electrochemical transducers. These systems are particularly valuable for detecting pesticide residues in complex matrices due to their robustness, potential for miniaturization, excellent detection limits, and ability to function in turbid biofluids [33]. Within this domain, potentiostatic and impedimetric detection methods have emerged as prominent techniques for quantifying biochemical interactions. Potentiostatic methods, such as amperometry and cyclic voltammetry, operate by applying a constant potential to an electrochemical cell and measuring the resulting current generated from redox reactions. In contrast, impedimetric techniques monitor changes in the electrical impedance at the electrode-solution interface, providing a label-free approach to detecting binding events [34]. The integration of these detection principles with advanced nanomaterials and biorecognition elements has significantly enhanced the performance of biosensing platforms, enabling the sensitive, selective, and multiplexed detection required for comprehensive pesticide residue analysis in environmental and food safety monitoring [35] [22].

Theoretical Foundations and Detection Mechanisms

Potentiostatic Detection Principles

Potentiostatic detection methods encompass a range of techniques where the potential between the working and reference electrodes is maintained at a constant value while the current is measured. The most common potentiostatic methods include amperometry, chronoamperometry, and cyclic voltammetry (CV). In amperometric biosensors, the current resulting from the electrochemical oxidation or reduction of an electroactive species is monitored at a constant applied potential. This current is directly proportional to the concentration of the analyte. A prime example is the glucose biosensor, where the enzymatic reaction produces hydrogen peroxide, which is then oxidized at the electrode surface, generating a measurable current [33]. Cyclic voltammetry involves scanning the potential linearly with time while measuring the current, providing information about redox potentials and reaction kinetics of electrochemical processes. These techniques are widely employed in biosensing due to their high sensitivity, relatively simple instrumentation, and well-established theoretical foundations [33].

Impedimetric Detection Principles

Impedimetric biosensors function by monitoring changes in the electrical impedance of the electrode-solution interface, which comprises both resistive and capacitive components. Electrical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) serves as the primary technique for these measurements, applying a small amplitude AC potential across a range of frequencies and analyzing the system's response [34]. Impedimetric biosensors are broadly categorized into faradaic and non-faradaic systems. Faradaic impedimetric biosensors utilize a redox probe in the solution, such as ferro/ferricyanide, and measure changes in charge transfer resistance (Rct) upon target binding. Non-faradaic systems operate without redox reactions, instead relying on changes in the electrical double-layer capacitance (Cdl) caused by binding events [34]. This label-free approach is particularly advantageous for detecting biomolecular interactions in their native state, preserving sample integrity while enabling real-time monitoring of binding events. The exceptional versatility of impedimetric biosensors supports various recognition elements, including antibodies, aptamers, enzymes, and molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs), making them highly adaptable for pesticide residue detection [34].

Comparative Analysis of Detection Techniques

Table 1: Comparison of Electrochemical Detection Techniques for Biosensing Applications

| Parameter | Amperometric/Potentiostatic | Impedimetric |

|---|---|---|

| Detection Principle | Measures current from redox reactions at constant potential | Measures changes in electrical impedance (resistance and capacitance) |

| Sensitivity | High (nM-pM range) | Very High (pM-fM range demonstrated) |

| Label Requirement | Often requires enzyme labels or redox mediators | Label-free detection possible |

| Measurement Complexity | Moderate | Requires frequency analysis in EIS |

| Real-time Monitoring | Limited for some configurations | Excellent for real-time, label-free monitoring |

| Impact on Sample | May require sample modification with redox probes | Minimal sample preparation; measures native state |

| Primary Applications | Enzyme-based sensors, metabolic markers | Affinity-based detection (immunosensors, DNA sensors), kinetic studies |

Experimental Protocols for Pesticide Detection

Protocol 1: Impedimetric Aptasensor for Organophosphorus Pesticides

This protocol details the development of a faradaic impedimetric biosensor for the detection of chlorpyrifos and other organophosphorus pesticides using a gold electrode platform with aptamer recognition elements [22] [34].

Materials and Reagents:

- Gold working electrode (2 mm diameter)

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS, 0.1 M, pH 7.4)

- [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻ redox probe (5 mM in PBS)

- Thiol-modified aptamer specific to target pesticide (100 μM stock in TE buffer)

- 6-Mercapto-1-hexanol (MCH, 1 mM in PBS)

- Pesticide standards for calibration

- Ethanol (absolute) for cleaning

- Deionized water (18.2 MΩ·cm)

Experimental Procedure:

Electrode Pretreatment:

- Polish the gold electrode with 0.3 μm and 0.05 μm alumina slurry sequentially on a microcloth pad.

- Rinse thoroughly with deionized water between polishing steps.

- Electrochemically clean in 0.5 M H₂SO₄ by cycling the potential between 0 V and 1.5 V (vs. Ag/AgCl) until a stable cyclic voltammogram is obtained.

- Rinse with deionized water and dry under nitrogen stream.

Aptamer Immobilization:

- Incubate the cleaned gold electrode with 100 μL of 1 μM thiol-modified aptamer solution in PBS at 4°C for 16 hours.

- Rinse with PBS to remove loosely bound aptamers.

- Backfill with 1 mM MCH for 1 hour to block uncovered gold surfaces.

- Wash thoroughly with PBS to remove excess MCH.

Impedance Measurements:

- Record EIS spectra in 5 mM [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻ solution with frequency range from 0.1 Hz to 100 kHz at open circuit potential.

- Use amplitude of 10 mV for AC perturbation.

- Measure charge transfer resistance (Rct) from Nyquist plot fittings.

- Establish calibration curve by measuring Rct changes with varying pesticide concentrations (0.1 pg/mL to 100 ng/mL).

Data Analysis:

- Fit EIS data using appropriate equivalent circuit model.

- Plot ΔRct (Rct after binding - Rct before binding) versus logarithm of pesticide concentration.

- Calculate limit of detection (LOD) using 3σ/slope method.

Protocol 2: Multiplexed Potentiostatic Sensor for Azole Fungicides

This protocol describes the development of a multiplexed potentiostatic biosensor for simultaneous detection of multiple azole-containing fungicides using enzyme inhibition principles, suitable for integration into microfluidic platforms for field testing [35] [33].

Materials and Reagents:

- Screen-printed carbon electrode (SPCE) arrays

- Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) enzyme solution (5 U/mL in PBS)

- Chitosan solution (1% w/v in 1% acetic acid)

- Gold nanoparticles (20 nm diameter)

- Substrate solution: Acetylthiocholine iodide (ATCH, 5 mM in PBS)

- Detection solution: 5,5'-Dithiobis(2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB, 0.1 mM in PBS)

- Azole fungicide standards (triadimefon, propiconazole, etc.)

- Bovine serum albumin (BSA, 1% w/v in PBS)

Experimental Procedure:

Electrode Modification:

- Deposit 5 μL of chitosan-gold nanoparticle composite onto each SPCE working electrode.

- Dry at room temperature for 2 hours.

- Immobilize AChE by depositing 3 μL of enzyme solution onto modified electrodes.

- Cross-link with 2 μL of 2.5% glutaraldehyde solution for 30 minutes.

- Block non-specific sites with 5 μL of 1% BSA for 1 hour.

Inhibition Assay:

- Incubate modified electrodes with 50 μL of pesticide standards of varying concentrations for 15 minutes at 25°C.

- Rinse gently with PBS to remove unbound pesticides.

- Add 50 μL of substrate detection mixture (ATCH + DTNB) to each electrode.

- Incubate for 10 minutes for enzymatic reaction.

Amperometric Measurement:

- Apply constant potential of +0.5 V (vs. Ag/AgCl reference) to working electrodes.

- Measure steady-state current generated from thiocholine oxidation.

- Record current values after stabilization (typically 60 seconds).

- Calculate inhibition percentage: % Inhibition = [(I₀ - I)/I₀] × 100, where I₀ is current without inhibitor and I is current with inhibitor.

Multiplexed Detection:

- Functionalize different electrodes in array with varying enzyme isoforms for differential detection.

- Employ statistical pattern recognition for identifying specific azole compounds.

- Generate heat maps of inhibition profiles for pesticide mixture analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Electrochemical Biosensor Development

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Gold Electrodes | Working electrode substrate; enables thiol-based bioconjugation | 2 mm diameter, polished to 0.05 μm finish |

| Screen-Printed Electrodes (SPCEs) | Disposable, cost-effective sensor platforms; ideal for field testing | Carbon working, silver reference, carbon counter electrodes |

| Thiol-modified Aptamers | Biorecognition elements for specific pesticide binding | 25-40 nucleotides, 5'- or 3'-thiol modification, HPLC purified |

| Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) | Enzyme for inhibition-based pesticide detection | 500-1000 U/mg protein, electric eel source |

| [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻ Redox Probe | Electron mediator for faradaic impedance measurements | 5 mM in PBS, equimolar mixture |

| Chitosan | Biopolymer for enzyme immobilization and nanocomposite formation | Medium molecular weight, >75% deacetylation |

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | Nanomaterial for signal amplification and electrode surface enhancement | 20 nm diameter, OD₁ ≈ 1 in aqueous solution |

| 6-Mercapto-1-hexanol (MCH) | Backfilling agent to form well-ordered self-assembled monolayers | 97% purity, prepared in ethanol or PBS |

Application in Multiplex Pesticide Residue Detection