Nanomaterial-Modified Screen-Printed Electrodes for Advanced Pesticide Analysis: From Fundamentals to Biomedical Applications

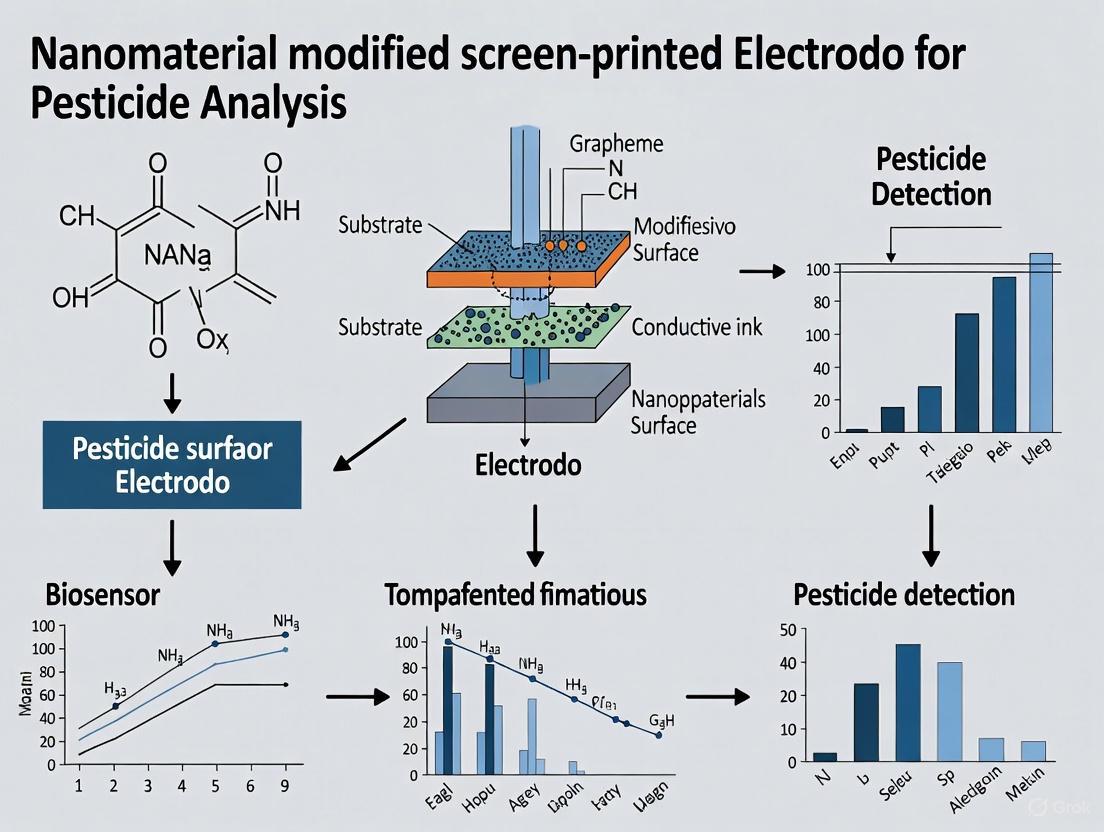

This comprehensive review explores the cutting-edge development and application of nanomaterial-modified screen-printed electrodes (SPEs) for pesticide analysis, addressing critical needs in food safety, environmental monitoring, and biomedical research.

Nanomaterial-Modified Screen-Printed Electrodes for Advanced Pesticide Analysis: From Fundamentals to Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This comprehensive review explores the cutting-edge development and application of nanomaterial-modified screen-printed electrodes (SPEs) for pesticide analysis, addressing critical needs in food safety, environmental monitoring, and biomedical research. The article systematically examines the foundational principles of SPE design and nanomaterial enhancement, detailed methodologies for electrode modification and pesticide detection, optimization strategies for improving sensor performance, and rigorous validation against conventional analytical techniques. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this work highlights how these portable, cost-effective biosensors enable rapid, sensitive, and selective detection of various pesticide classes including organophosphates, carbamates, and neonicotinoids, with significant implications for public health protection and clinical diagnostics.

Fundamentals of SPEs and Nanomaterial Enhancement for Pesticide Sensing

Screen-printed electrodes (SPEs) represent a transformative technology in electrochemistry, enabling the mass production of disposable, cost-effective, and portable sensing platforms. These miniaturized electrochemical cells have become fundamental tools for decentralized analysis across numerous fields, including environmental monitoring, clinical diagnostics, and food safety [1] [2]. Their significance is particularly pronounced in the context of pesticide analysis, where on-site detection capabilities offer a compelling alternative to traditional laboratory-based methods [1] [3]. SPEs integrate working, counter, and reference electrodes onto a single, compact substrate through a scalable printing process, making sophisticated electrochemical analysis accessible outside centralized laboratories [4] [2]. This application note details the design principles, fabrication methodologies, and inherent advantages of SPEs, with specific consideration to their application in pesticide detection research utilizing nanomaterial modifications.

Design and Structural Features of Screen-Printed Electrodes

The architecture of a typical screen-printed electrode is designed for functional completeness and miniaturization. A standard SPE comprises three primary components printed on a single, non-conductive substrate: a working electrode (WE), a counter electrode (CE), and a reference electrode (RE) [4] [2]. This integrated design creates a full electrochemical cell that is both compact and ready-to-use.

- Substrate Materials: The foundation of an SPE is a non-conductive material that provides mechanical stability. Common substrates include polyvinyl chloride (PVC), polyester, ceramics, and polycarbonate [5] [4]. The choice of substrate influences flexibility, chemical resistance, and overall durability.

- Conductive Inks: The electrode components are formed using conductive inks. The working electrode is often fabricated from carbon-based inks (e.g., graphite, graphene, carbon nanotubes) due to their wide potential window, chemical stability, and low cost [4]. The reference electrode is commonly made from silver/silver chloride (Ag/AgCl) ink, while the counter electrode is typically carbon or sometimes platinum [4].

- Design Flexibility: SPE designs are highly customizable. Using software like CorelDraw, researchers can create specific templates to guide the printing process, allowing for customization of electrode size, geometry, and layout to suit particular experimental or device integration needs [4].

The following diagram illustrates the typical layered structure and components of a standard screen-printed electrode.

Fabrication Process

The fabrication of SPEs is a multi-step, additive manufacturing process that allows for high-volume production. The process is valued for its simplicity, cost-effectiveness, and versatility [4] [2].

- Ink Preparation: The process begins with the formulation of conductive inks. These are viscous pastes composed of a conductive material (e.g., graphite, silver), a binder to control viscosity and adhesion, and organic solvents to create a homogeneous mixture [4]. The ink's rheological properties are critical for successful printing.

- Screen Printing: A mesh screen, patterned with the desired electrode design, is placed over the substrate. Conductive ink is forced through the open areas of the mesh onto the substrate using a squeegee. This step is performed sequentially for each ink type (e.g., carbon for WE/CE, then Ag/AgCl for RE) [5] [4].

- Curing and Drying: After printing, the electrodes are cured in an oven to evaporate solvents and solidify the ink, ensuring strong adhesion to the substrate and optimal electrical conductivity. Curing temperatures and times vary; for example, carbon inks may be dried at 60°C for 30 minutes, while silver inks might require 120°C for 60 minutes [5].

- Insulation and Final Assembly: A final insulating layer is often applied to cover the contact leads, leaving only the active electrode areas and terminal contacts exposed [4]. This step defines the electrochemical active area and protects the conductive tracks.

Table 1: Key Fabrication Steps and Parameters for Screen-Printed Electrodes

| Fabrication Step | Key Parameters | Common Materials/Examples | Impact on Final Product |

|---|---|---|---|

| Substrate Selection | Flexibility, chemical inertness, surface energy | PVC, polyester, polycarbonate, ceramic [4] | Determines mechanical robustness and application suitability (e.g., rigid vs. flexible) |

| Ink Formulation | Conductive material, binder ratio, solvent, viscosity | Graphite, graphene, carbon nanotubes, Ag/AgCl paste [6] [4] | Defines electrical conductivity, electrochemical window, and modifiability |

| Printing Process | Mesh size, squeegee pressure, printing speed | Manual or automated screen-printing systems [5] | Controls pattern resolution, thickness of deposited layer, and manufacturing throughput |

| Curing/Drying | Temperature, time, atmosphere | Oven drying: 60°C for carbon, 120°C for silver [5] | Ensures ink adhesion, solvent removal, and final electrical properties |

Advantages for Decentralized Analysis

SPEs offer a compelling set of advantages that make them ideally suited for decentralized analytical applications, such as on-site pesticide detection [1] [7].

- Portability and Miniaturization: The small size and lightweight nature of SPEs allow them to be integrated into handheld, portable potentiostats, enabling field-deployable analysis outside of traditional laboratories [8] [2].

- Low Cost and Disposability: The mass-production capability of screen printing dramatically reduces the per-unit cost of electrodes. This disposability is critical for avoiding cross-contamination between samples, which is a significant concern in pesticide analysis of complex agricultural or food matrices [1] [4].

- Ease of Use and Mass Production: SPEs are pre-configured, user-friendly devices that require no polishing or pre-treatment before use, simplifying the analytical workflow. The screen-printing technique supports the high-volume, reproducible manufacturing of sensors with consistent performance [1] [8].

- Simplified System Integration: The three-electrode system on a single chip simplifies connection to potentiostats and is readily integrated with fluidic systems for automated analysis, as demonstrated in systems for heavy metal detection [7].

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The functionality of SPEs, particularly for specialized applications like pesticide sensing, is often enhanced through surface modifications. The following table catalogizes key reagents and materials used in the fabrication and modification of SPEs.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for SPE Fabrication and Modification

| Material Category | Specific Examples | Function in SPE Development |

|---|---|---|

| Conductive Inks | Graphite ink, Silver/Silver Chloride (Ag/AgCl) ink, Carbon nanotube (CNT) ink, Graphene ink [5] [4] | Forms the conductive pathways for the working, counter, and reference electrodes; foundation for electron transfer. |

| Nanomaterials | Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs), Graphene & its derivatives, Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs), Metal Oxides (e.g., CuO) [9] [4] [3] | Enhances electrochemical sensitivity and surface area; can provide catalytic activity or serve as an immobilization platform. |

| Biorecognition Elements | Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) enzyme, Antibodies, Aptamers, Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) [1] [3] | Provides high selectivity for the target analyte (e.g., pesticides) by leveraging specific biological or biomimetic interactions. |

| Polymers & Binders | Chitosan, Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), Nafion, Polyethylene oxide (PEO) [6] [5] | Used as substrates, hydrogel matrices for entrapment, or binders to improve adhesion and stability of the modified layer. |

| Chemical Modifiers | Prussian Blue, Meldola's Blue, Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) polystyrene sulfonate (PEDOT:PSS) [6] [2] | Acts as electrocatalysts or electron mediators to lower working potentials and improve signal-to-noise ratio. |

Experimental Protocol: Fabrication and Modification of SPEs for Pesticide Detection

This protocol provides a detailed methodology for the in-house fabrication of carbon-based SPEs and their subsequent modification with a nanocomposite for the electrochemical detection of organophosphorus pesticides. The workflow is summarized in the diagram below.

Materials and Equipment

- Materials: Polyvinyl chloride (PVC) sheet as substrate; graphite conductive ink (e.g., SC-1010 from ITK); silver/silver chloride (Ag/AgCl) ink (e.g., NT-6307-2 from PERM TOP); chitosan (medium molecular weight); graphene nanoplatelets; acetylcholinesterase (AChE) enzyme; acetylthiocholine (ATCh) iodide; phosphate buffer saline (PBS, 0.1 M, pH 7.4) [5] [4] [3].

- Equipment: Screen-printing apparatus (e.g., Model NSP-1A, YULISHIH INDUSTRIAL Co., Ltd.); precision oven; laboratory potentiostat/ galvanostat; ultrasonic bath.

Step-by-Step Procedure

Part A: Fabrication of Carbon Screen-Printed Electrodes

- Substrate Cleaning: Clean the PVC substrate sheet with dichloromethane (DCM) or ethanol to remove any organic contaminants and ensure good ink adhesion. Allow to dry completely [4].

- Screen Alignment: Secure the patterned screen (designed with a three-electrode layout) over the clean PVC substrate.

- Printing Working and Counter Electrodes: Apply graphite ink to the screen and use a squeegee to spread it evenly, forcing ink through the mesh onto the substrate to form the working and counter electrodes. Repeat this step to ensure a smooth, uniform layer [4].

- Intermediate Curing: Transfer the printed substrate to an oven and cure at 60°C for 30 minutes to dry the carbon ink [5].

- Printing Reference Electrode: Using a clean screen patterned for the reference electrode, apply Ag/AgCl ink to form the reference electrode.

- Final Curing: Cure the complete SPE at a higher temperature of 120°C for 60 minutes to ensure all inks are fully dried and adhered [5].

Part B: Surface Modification with Nanocomposite for Pesticide Sensing

- Nanocomposite Ink Preparation: Prepare a composite ink by dispersing 2 mg/mL of graphene nanoplatelets in a 0.5% chitosan solution (dissolved in 0.1 M acetic acid). Sonicate for 60 minutes to achieve a homogeneous suspension [6].

- Enzyme Solution Preparation: Prepare a solution of AChE enzyme (1 U/μL) in chilled 0.1 M PBS, pH 7.4.

- Electrode Modification: Deposit 5 μL of the graphene-chitosan nanocomposite ink onto the surface of the carbon working electrode and allow it to dry at room temperature. Subsequently, deposit 3 μL of the AChE enzyme solution onto the modified surface and allow it to immobilize under refrigeration (4°C) for 12 hours [3].

Electrochemical Characterization and Validation

- Cyclic Voltammetry (CV): Characterize the modified SPE by performing CV in a 5 mM solution of potassium ferricyanide in 0.1 M KCl. Scan between -0.2 V and +0.6 V at a scan rate of 50 mV/s. A well-modified electrode should show a well-defined, reversible redox peak with an increase in peak current compared to an unmodified electrode, indicating enhanced surface area and electron transfer [4].

- Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS): Further characterize the electrode in the same redox probe solution. Apply a DC potential at the formal potential of the redox couple with a 10 mV AC perturbation across a frequency range of 0.1 Hz to 100 kHz. A significant decrease in the charge transfer resistance (Rₑₜ) observed in the Nyquist plot confirms improved electron transfer kinetics due to the nanocomposite modification [4].

Screen-printed electrodes provide a robust, versatile, and economically viable platform for decentralized analytical sensing. Their design, which integrates all necessary electrodes on a single chip, combined with a scalable fabrication process, makes them indispensable for modern applications ranging from clinical diagnostics to environmental monitoring. As the demand for on-site analysis grows, particularly in fields like pesticide residue monitoring, the role of SPEs is set to expand. Future advancements will likely focus on the development of novel nanomaterial composites and biorecognition elements to further enhance the sensitivity, selectivity, and stability of these devices, solidifying their position as a cornerstone of decentralized analytical science.

The accurate and sensitive detection of pesticide residues is a critical challenge in ensuring food safety, environmental health, and public safety. Traditional analytical methods, while effective, often require sophisticated laboratory equipment, trained personnel, and are time-consuming, limiting their use for rapid, on-site screening [10] [11]. Within the context of a broader thesis on nanomaterial-modified screen-printed electrodes (SPEs) for pesticide analysis, this document establishes the foundational role of specific nanomaterial classes.

Electrochemical biosensors have emerged as predominant tools, offering rapid, sensitive, and cost-effective analysis [12]. The core of these sensors is the transducer, with SPEs being particularly advantageous due to their low cost, portability, ease of mass production, and minimal sample volume requirements [10] [13] [14]. However, the performance of SPEs is substantially enhanced through strategic surface modification with nanomaterials [11]. The integration of noble metals, carbon nanostructures, and metal oxides confers unique physicochemical properties—such as high electrical conductivity, large surface area, and superior catalytic activity—that collectively increase sensor sensitivity, selectivity, and stability [12] [15] [11]. This application note provides a detailed overview of these critical nanomaterials, their properties, and standardized protocols for their application in advanced electrochemical sensing platforms for pesticide detection.

Critical Nanomaterial Classes: Properties and Functions

The enhancement of electrochemical sensors relies on the synergistic properties of various nanomaterials. The table below summarizes the key characteristics and primary functions of the three critical nanomaterial classes in pesticide sensor applications.

Table 1: Critical Nanomaterial Classes for Electrode Modification in Pesticide Sensing

| Nanomaterial Class | Key Properties | Primary Functions in Pesticide Sensing | Common Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Noble Metals | High electrical conductivity, excellent catalytic activity, biocompatibility, surface plasmon resonance [12] [11]. | Signal amplification, electrocatalysis of redox reactions, facilitation of electron transfer, label for biorecognition elements [12] [10]. | Gold (Au), Silver (Ag), Platinum (Pt), Palladium (Pd) nanoparticles; Au-Pd bimetallic nanoparticles [10] [16]. |

| Carbon Nanostructures | High surface area, excellent electrical conductivity, mechanical strength, chemical stability, good biocompatibility [17] [12]. | Providing a high-surface-area scaffold, enhancing electron transfer kinetics, increasing biomolecule adsorption, serving as a conductive support [12] [11]. | Graphene, Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs), Carbon Nanofibers (CNFs), Reduced Graphene Oxide (rGO) [17] [12] [10]. |

| Metal Oxides | Catalytic activity, high surface area, tunable electronic properties, semiconducting nature, photocatalytic properties [12]. | Electrocatalysis, signal enhancement for specific analytes, improving sensor stability and selectivity [12]. | Iron Oxide (Fe₃O₄), Titanium Oxide (TiO₂), Zinc Oxide (ZnO) [12]. |

The synergistic combination of these materials in hybrid nanocomposites often yields superior performance. For instance, the hybridization of carbon nanotubes with metal oxide nanoparticles can significantly enhance electron transfer kinetics and sensor sensitivity [12]. Similarly, combining graphene with metal nanoparticles provides a highly conductive and catalytically active platform ideal for immobilizing biological recognition elements [12].

Experimental Protocols for Electrode Modification and Characterization

Standardized Protocol for Nanomaterial Modification of SPEs

The following protocol outlines a generalized procedure for modifying screen-printed electrodes (SPEs) with nanomaterials, which can be adapted for specific material types.

Table 2: The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials for Electrode Modification

| Item Name | Function/Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Screen-Printed Electrode (SPE) | A miniaturized, disposable electrochemical cell; serves as the foundational transducer [10] [13]. | The base platform for all modifications, typically with carbon, gold, or silver working electrodes. |

| Nanomaterial Suspension | A stable, homogeneous dispersion of the selected nanomaterial in a suitable solvent (e.g., water, ethanol). | The active modifier used in drop-casting to enhance the electrochemical properties of the SPE surface. |

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) | A buffer solution used to maintain a stable pH during electrochemical measurements and biomolecule immobilization. | Provides a consistent chemical environment for reliable and reproducible electrochemical analysis. |

| Biopolymer (e.g., Chitosan, Nafion) | A polymeric matrix used to entrap and stabilize nanomaterials and biomolecules on the electrode surface [13]. | Acts as a binder and stabilizing agent, preventing nanomaterial leaching and improving film adhesion. |

| Electrochemical Workstation | Instrument for applying controlled potentials and measuring resulting currents for sensor characterization [18]. | Used for Cyclic Voltammetry (CV), Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS), and analytical measurements. |

Procedure:

- SPE Pretreatment: Clean the working electrode surface of the SPE by cycling the potential in a suitable electrolyte (e.g., 0.1 M H₂SO₄ or PBS) using Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) until a stable voltammogram is obtained. This removes any contaminants.

- Suspension Preparation: Disperse the desired nanomaterial (e.g., 1-5 mg) in a solvent (e.g., deionized water, ethanol) to a final volume of 1-10 mL. Sonicate the mixture for 30-60 minutes to achieve a homogeneous suspension [16].

- Modification via Drop-Casting:

- Pipette a precise volume (typically 2-10 µL) of the nanomaterial suspension directly onto the pre-cleaned working electrode surface.

- Allow the electrode to dry under ambient conditions or under a gentle infrared lamp [16]. For more uniform films, controlled drying under a nitrogen stream is recommended to mitigate the "coffee-ring" effect [15].

- Stabilization (Optional): To enhance the stability of the modification layer, apply a thin layer of a biopolymer (e.g., 2-5 µL of 0.5% Nafion or Chitosan solution) over the dried nanomaterial film and allow it to dry.

Alternative Methods: For higher precision and uniformity, other deposition techniques can be employed:

- Electrodeposition: The nanomaterial or metal nanoparticles are deposited onto the SPE surface by applying a constant potential or cycling the potential in a solution containing metal ion precursors (e.g., HAuCl₄, PdCl₂) [15] [16].

- Spin Coating: A small volume of suspension is placed on the electrode, which is then spun at high speed to create a thin, uniform film [15].

- Spray Coating: The suspension is sprayed onto the electrode surface using a carrier gas, allowing for the coating of larger areas [15].

Protocol for Electrochemical Characterization of Modified Electrodes

Characterizing the modified electrode is crucial to confirm successful modification and assess its electrochemical performance.

Materials:

- Potentiostat/Galvanostat (Electrochemical Workstation)

- Modified and unmodified (control) SPEs

- Redox probe solution (e.g., 5 mM [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻ in 0.1 M KCl)

- Phosphate Buffer Saline (PBS, 0.1 M, pH 7.4)

Procedure:

- Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) in a Redox Probe:

- Immerse the modified SPE in a solution of 5 mM [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻ in 0.1 M KCl.

- Record a CV scan within a potential window of -0.2 V to 0.6 V (vs. the on-chip reference) at a scan rate of 50 mV/s.

- A successful modification is indicated by an increase in the peak current and a decrease in the peak-to-peak separation (ΔEp) compared to the bare SPE, signifying enhanced electron transfer kinetics [10].

- Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS):

- Using the same redox probe solution, perform EIS at a DC potential corresponding to the formal potential of the redox couple, with a small AC voltage amplitude (e.g., 5-10 mV) over a frequency range from 100 kHz to 0.1 Hz.

- The diameter of the semicircle in the Nyquist plot represents the charge transfer resistance (Rₑₜ). A decrease in Rₑₜ after modification confirms improved conductivity and electron transfer efficiency [10] [16].

The following workflow diagram summarizes the key stages from electrode modification to sensor characterization.

Diagram 1: Workflow for electrode modification and characterization. The process begins with electrode pretreatment, proceeds through one of several modification paths, and concludes with electrochemical validation.

Analytical Performance and Application in Pesticide Detection

The true value of nanomaterial-modified SPEs is demonstrated through their analytical performance in detecting specific pesticides. The following table compiles representative data from the literature showcasing the efficacy of different nanomaterial composites.

Table 3: Analytical Performance of Nanomaterial-Modified Electrodes for Pesticide Detection

| Target Pesticide | Electrode Modification | Detection Technique | Linear Range | Limit of Detection (LOD) | Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organophosphorus (e.g., Paraoxon) | Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) enzyme immobilized on CNT/Nafion-SPE [10] | Amperometry (Enzymatic Inhibition) | Not Specified | Low µM range | Water and Food Samples [10] |

| Organophosphorus & Carbamate | Multi-enzyme system (AChE, BChE, Tyrosinase) on SPE [10] | Amperometry (Enzymatic Inhibition) | Not Specified | Not Specified | Multi-analyte Screening [10] |

| Fenobucarb | Graphene Nanoribbons-Ionic Liquid-Cobalt Phthalocyanine/SPE [11] | Flow Injection Analysis | Not Specified | High Sensitivity Reported | Not Specified [11] |

| Diclofenac Sodium (Model Drug) | Au-Pd Bimetallic NPs/Halloysite/PGE [16] | Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) | 1 – 100 µM | 0.047 µM | Proof of Concept for Sensor Design [16] |

The primary sensing mechanisms for pesticides include:

- Enzymatic Inhibition: The most common route, where pesticides like organophosphates and carbamates inhibit enzymes such as acetylcholinesterase (AChE). The decrease in enzymatic activity, measured electrochemically, is proportional to the pesticide concentration [10].

- Direct Electrochemical Detection: Electroactive pesticides can be directly oxidized or reduced on the catalytically active surface of the modified electrode, with the current response being proportional to concentration [10] [11].

The integration of noble metals, carbon nanostructures, and metal oxides into screen-printed electrodes represents a powerful strategy for advancing electrochemical sensor technology for pesticide analysis. The protocols and data summarized in this application note provide a framework for researchers to fabricate and characterize high-performance, nanomaterial-modified sensing platforms. The demonstrated enhancements in sensitivity, selectivity, and portability make these devices compelling tools for on-site monitoring, addressing critical needs in food safety and environmental protection.

Future developments in this field are likely to focus on several key areas:

- Advanced Nanocomposites: Designing more sophisticated multi-functional nanocomposites that leverage synergistic effects for even greater analytical performance [12] [11].

- Integration with Smart Technology: Coupling these sensors with smartphone-based readouts and data transmission for real-time, geographically tagged analysis [11].

- Lab-on-a-Chip (LOC) Systems: Incorporating modified SPEs into fully integrated microfluidic LOC devices that automate sample preparation and analysis, enhancing usability and reliability for field deployment [11].

- Machine Learning (ML): Employing ML algorithms to analyze complex electrochemical data, predict sensor performance based on fabrication parameters, and improve the accuracy of multi-analyte detection [18].

By continuing to refine these materials and methodologies, the scientific community can develop next-generation analytical devices that are not only highly effective but also accessible and practical for widespread use.

The escalating need for global food production has led to the extensive use of pesticides, including organophosphates (OPs), carbamates, and neonicotinoids [19]. While effective for crop protection, their persistence in the environment and subsequent contamination of food and water sources pose significant health risks to humans, ranging from neurological disorders to carcinogenic effects [10] [20]. This has spurred the development of rapid, sensitive, and cost-effective detection methods, moving beyond traditional techniques like chromatography and mass spectrometry [10].

Electrochemical sensing, particularly using nanomaterial-modified screen-printed electrodes (SPEs), has emerged as a powerful analytical tool for pesticide monitoring [1] [10]. These sensors leverage the distinct electrochemical properties of different pesticide classes, enabling the design of highly specific and sensitive detection platforms. This application note details the electrochemical behaviors of major pesticide classes and provides standardized protocols for their analysis using modified SPEs, serving as a practical guide for researchers developing advanced electrochemical sensors.

Electrochemical Properties and Detection Mechanisms by Pesticide Class

The detection strategy for a pesticide is fundamentally guided by its molecular structure and intrinsic electrochemical properties. The following sections delineate the characteristics and sensing mechanisms for the three primary insecticide classes.

Organophosphates (OPs)

Mechanism of Toxicity: OPs irreversibly inhibit the enzyme acetylcholinesterase (AChE), leading to the accumulation of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine and resulting in neurotoxicity [21] [22].

Detection Mechanisms:

- Enzyme Inhibition-Based Sensing: This is the most common strategy for OP detection. The principle involves immobilizing AChE on the electrode surface. The active enzyme hydrolyzes its substrate, acetylthiocholine (ATCh), producing an electroactive product, thiocholine, which generates a measurable current. Upon exposure to OPs, the enzyme is inhibited, leading to a reduction in the catalytic current that is proportional to the OP concentration [10] [23].

- Enzymatic Catalysis-Based Sensing: Certain OPs can be directly hydrolyzed by enzymes like organophosphate hydrolase (OPH). The hydrolysis of OPs like paraoxon and parathion produces p-nitrophenol (p-NP), an electroactive species that can be detected amperometrically [21] [22].

Table 1: Electrochemical Detection of Select Organophosphates.

| Pesticide | Detection Mechanism | Electrode Modification | Linear Range | Limit of Detection (LOD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chlorpyrifos | AChE Inhibition | CuNWs/rGO on SPCE [23] | 10 - 200 µg/L | 3.14 µg/L |

| Paraoxon | OPH Catalysis | Engineered Microbial System [22] | Sub-µM range | Not Specified |

| Methyl Parathion | OPH Catalysis | MPH/Silica-Gold-CNT Composite [21] | Refer to [21] | Refer to [21] |

Carbamates

Mechanism of Toxicity: Similar to OPs, carbamates are AChE inhibitors, but their action is reversible, which generally makes them less toxic to mammals than OPs [20] [24].

Detection Mechanisms:

- Enzyme Inhibition-Based Sensing: Analogous to OPs, carbamates can be detected by measuring their inhibitory effect on the activity of AChE or other enzymes like tyrosinase immobilized on the electrode [10].

- Direct Electrochemical Detection: Some carbamates, or their hydrolysis products, are electroactive. For instance, the carbamate carbaryl can be directly oxidized on suitably modified electrodes, allowing for direct quantification without an enzyme [20].

Table 2: Electrochemical Detection of Select Carbamates.

| Pesticide | Detection Mechanism | Electrode Modification | Linear Range | Limit of Detection (LOD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbofuran | AChE Inhibition | AuNPs/MWCNT on SPCE [20] | 0.5 - 100 µM | 0.21 µM |

| Carbaryl | Direct Oxidation | Molecularly Imprinted Polymer (MIP) [20] | 1 - 100 µM | 0.8 µM |

| Aldicarb, Propoxur | Voltammetric Analysis | Glassy Carbon Electrode (GCE) [20] | Varies by compound | Varies by compound |

Neonicotinoids

Mechanism of Toxicity: Neonicotinoids act as agonists on the nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChR) in the central nervous system of insects, causing overstimulation and death. They exhibit selective toxicity towards insects over mammals due to higher affinity for insect nAChRs [19] [24].

Detection Mechanisms:

- Direct Electrochemical Detection: This is the predominant strategy for neonicotinoids. Many, such as imidacloprid and acetamiprid, contain electroactive functional groups (e.g., nitro groups) that can be directly reduced or oxidized on the electrode surface. The resulting current is directly proportional to concentration [19] [24].

- Aptasensors and Immunosensors: Specific aptamers or antibodies are used as recognition elements for neonicotinoids. The binding event is then transduced into an electrochemical signal, often using EIS, providing high specificity [24].

Table 3: Electrochemical Detection of Select Neonicotinoids.

| Pesticide | Detection Mechanism | Electrode Modification | Linear Range | Limit of Detection (LOD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Imidacloprid | Direct Reduction | Fe-rich FeCoNi-MOF [24] | 0.005 - 20 µM | 0.26 nM |

| Acetamiprid | Aptasensor | rGO/β-cyclodextrin polymer [24] | 1 pM - 1 µM | 0.34 pM |

| Thiamethoxam | Direct Detection | Boron-Doped Diamond [24] | 0.49 - 7.36 µM | 0.12 µM |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Detection of Organophosphates via an AChE Inhibition Biosensor

This protocol details the construction of a biosensor for chlorpyrifos detection using an AChE enzyme inhibition approach on a CuNWs/rGO-modified SPCE [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

| Reagent / Material | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Screen-Printed Carbon Electrode (SPCE) | Disposable, portable electrochemical transducer platform. |

| Reduced Graphene Oxide (rGO) | Enhances electrical conductivity and provides a large surface area for biomolecule immobilization. |

| Copper Nanowires (CuNWs) | Improves electrocatalytic activity and electron transfer, particularly for thiocholine oxidation. |

| Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) | Biological recognition element; its inhibition is measured. |

| Acetylthiocholine (ATCh) | Enzyme substrate; hydrolysis produces electroactive thiocholine. |

| Phosphate Buffer Saline (PBS) | Provides a stable pH environment for the enzymatic reaction. |

| Glutaraldehyde | Crosslinking agent for enzyme immobilization on the electrode surface. |

Procedure:

- Electrode Modification:

- Prepare a homogeneous dispersion of CuNWs/rGO nanocomposite in a suitable solvent (e.g., DMF).

- Drop-cast a precise volume (e.g., 5 µL) of the nanocomposite dispersion onto the working electrode area of the SPCE.

- Allow the solvent to evaporate completely at room temperature to form a stable modified film.

- Enzyme Immobilization:

- Prepare a solution of AChE (e.g., 0.5 U/µL) in a mild phosphate buffer (pH 7.4).

- Apply the AChE solution onto the modified SPCE surface.

- Use glutaraldehyde vapor to cross-link and stabilize the enzyme layer.

- Rinse the electrode gently with PBS to remove any unbound enzyme.

- Electrochemical Measurement (Baseline):

- Place the modified SPCE in an electrochemical cell containing PBS (pH 7.4) and ATCh.

- Record a cyclic voltammogram (CV) or a chronoamperogram. A clear oxidation peak or steady-state current corresponding to the enzymatic production of thiocholine should be observed. This is the baseline signal (I₀).

- Inhibition (Pesticide Detection):

- Incubate the biosensor in a sample solution containing the target organophosphate (e.g., chlorpyrifos) for a fixed time (e.g., 10-15 minutes).

- Gently rinse the electrode with PBS to remove the pesticide solution.

- Electrochemical Measurement (Post-Inhibition):

- Record the CV or chronoamperogram again under the same conditions as in Step 3. The measured current (I) will be lower due to enzyme inhibition.

- Quantification:

- The percentage of enzyme inhibition is calculated as: Inhibition (%) = [(I₀ - I) / I₀] × 100.

- The inhibition percentage is proportional to the logarithm of the pesticide concentration and can be plotted to create a calibration curve.

The following workflow illustrates the key steps in this biosensing protocol:

Diagram 1: AChE Inhibition Biosensor Workflow.

Protocol 2: Direct Electrochemical Detection of a Neonicotinoid

This protocol outlines the direct voltammetric detection of imidacloprid, leveraging the electrochemical reduction of its nitro group on a nanomaterial-modified electrode [19] [24].

Procedure:

- Electrode Modification:

- Modify the SPCE or GCE with the selected nanomaterial (e.g., Fe-rich FeCoNi-MOF, graphene oxide, or boron-doped diamond).

- The modification can be achieved via drop-casting or electrodeposition to form a uniform catalytic layer.

- Electrochemical Measurement:

- Prepare standard solutions of imidacloprid in a supporting electrolyte (e.g., Britton-Robinson buffer, pH 7.0).

- Transfer the analyte solution to the electrochemical cell.

- Using the modified working electrode, apply a square-wave voltammetry (SWV) or differential pulse voltammetry (DPV) potential sweep in a negative direction (e.g., from -0.4 V to -1.0 V).

- The reduction of the nitro group (-NO₂) to the hydroxylamine group (-NHOH) will produce a characteristic cathodic peak.

- Calibration and Quantification:

- Record voltammograms for a series of standard solutions with increasing imidacloprid concentrations.

- Plot the peak current intensity against the concentration to generate a calibration curve for quantitative analysis of unknown samples.

The logical relationship between the analyte's structure and the detection signal is as follows:

Diagram 2: Direct Detection Signaling Logic.

The distinct electrochemical properties of different pesticide classes dictate the design and application of effective sensing strategies. Organophosphates and carbamates are predominantly detected via enzyme inhibition pathways, while neonicotinoids are often quantified through direct electron transfer involving their nitro group. The use of nanomaterial-modified SPEs is a cornerstone of modern electrochemical pesticide analysis, providing enhanced sensitivity, selectivity, and portability. The protocols outlined herein offer a foundational framework for researchers to develop and optimize robust electrochemical sensors for environmental monitoring and food safety assurance. Future perspectives point towards the increased integration of novel biorecognition elements like aptamers, the development of multi-analyte arrays, and the creation of fully integrated, field-deployable devices.

The core of any advanced electrochemical (bio)sensor is its recognition element, a biological or biomimetic molecule designed to interact specifically with a target analyte. The selectivity and sensitivity of the sensor are fundamentally determined by the affinity and properties of this element. For the analysis of pesticides using nanomaterial-modified screen-printed electrodes (SPEs), four primary classes of recognition elements are predominantly employed: enzymes, antibodies, aptamers, and Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs). Screen-printed electrodes serve as an ideal platform for such sensing due to their cost-effectiveness, portability for on-site analysis, and ease of modification with various nanomaterials and recognition elements [25] [13]. The integration of nanomaterials like gold nanoparticles, carbon nanotubes, and graphene oxide further enhances the electrochemical performance by improving electron transfer, increasing surface area, and providing a scaffold for the immobilization of these recognition elements [26] [27] [28]. This document provides detailed application notes and experimental protocols for the integration of these four key recognition elements within the context of a thesis focused on nanomaterial-modified SPEs for pesticide analysis.

The choice of recognition element dictates the design, performance, and application range of the sensor. The following table offers a structured comparison of these elements to guide selection.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Recognition Elements for Pesticide Sensing on SPEs

| Recognition Element | Mechanism of Action | Key Advantages | Inherent Limitations | Typical Electrochemical Technique |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enzymes | Catalytic transformation or inhibition of the target pesticide. | High catalytic activity; Well-established protocols; Reusable sensors. | Susceptible to environmental conditions (pH, T); Limited enzyme stability; Broad specificity for inhibitor classes. | Amperometry, Chronoamperometry [25] |

| Antibodies | Specific immunochemical binding (antigen-antibody). | Exceptional specificity and affinity; Wide variety commercially available. | Animal-derived production; Batch-to-batch variability; Sensitive to denaturation; Irreversible binding. | Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) [25] [26] |

| Aptamers | Conformational change upon binding to a specific target. | Synthetic production (low cost, high stability); Reversible binding; Modifiable chemistry. | In vitro selection process (SELEX) can be complex; Susceptibility to nuclease degradation in biofluids. | EIS, Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV), Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV) [27] [29] |

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) | Selective rebinding to synthetic, template-shaped cavities. | High physical/chemical robustness; Applicable to a wide range of targets; Long shelf-life. | Risk of incomplete template removal; Heterogeneous binding sites; Optimization can be complex. | DPV, Cyclic Voltammetry (CV), EIS [30] [31] |

Detailed Application Notes & Experimental Protocols

Enzymatic Sensors: Acetylcholinesterase-based Inhibition Assay

Principle: This protocol is based on the inhibition of the enzyme acetylcholinesterase (AChE) by organophosphorus and carbamate pesticides. The active enzyme hydrolyzes its substrate, producing an electroactive product. The presence of the pesticide inhibits AChE, leading to a measurable decrease in the electrochemical signal, which is proportional to the pesticide concentration [25].

Experimental Protocol:

SPE Nanomaterial Modification:

- Clean the bare carbon SPE by performing 10 cycles of Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) in 0.1 M H₂SO₄ from 0 V to +1.2 V (vs. Ag/AgCl reference).

- Deposit 5 µL of a graphene oxide (GO) dispersion (1 mg/mL) onto the working electrode and allow it to dry at room temperature.

- Electrochemically reduce the GO to rGO by performing CV in 0.1 M phosphate buffer saline (PBS), pH 7.4, for 15 scans.

Enzyme Immobilization:

- Prepare an immobilization mixture containing 5 µL of AChE (2 U/µL), 5 µL of bovine serum albumin (BSA, 1% w/v), and 2 µL of glutaraldehyde (0.25% v/v).

- Deposit 8 µL of this mixture onto the rGO/SPE and incubate at 4°C for 1 hour.

- Rinse the modified electrode thoroughly with PBS (pH 7.4) to remove any unbound enzyme.

Pesticide Incubation (Inhibition Step):

- Immerse the AChE/rGO/SPE in a solution containing the target pesticide (e.g., chlorpyrifos) for 15 minutes.

- Rinse gently with PBS.

Electrochemical Measurement:

- Transfer the sensor to an electrochemical cell containing 10 mL of PBS (pH 7.4) with 1.0 mM acetylthiocholine (ATCh), the enzyme substrate.

- Perform Chronoamperometry at an applied potential of +0.5 V for 60 seconds.

- The current generated from the oxidation of the enzymatic product (thiocholine) is recorded. The percentage of inhibition is calculated as:

% Inhibition = [(I₀ - I)/I₀] × 100, where I₀ and I are the currents before and after incubation with the pesticide, respectively.

Diagram 1: AChE Inhibition Assay Workflow

Immunosensors: Antibody-based Detection with Nanomaterial Labels

Principle: This protocol describes a sandwich-type electrochemical immunosensor. A capture antibody is immobilized on the SPE. The target pesticide (acting as an antigen) is bound, and is subsequently recognized by a second detection antibody conjugated to a nanomaterial label, such as gold nanoparticles (AuNPs). The electrochemical signal from the AuNP label is quantified via anodic stripping voltammetry, providing high sensitivity [26].

Experimental Protocol:

SPE Functionalization and Capture Antibody Immobilization:

- Modify the SPE working electrode with a dispersion of multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) to enhance surface area and conductivity.

- Activate the surface by applying a potential of +1.7 V in 0.1 M NaOH for 60 seconds.

- Deposit 10 µL of a solution containing the capture antibody (e.g., anti-atrazine IgG, 10 µg/mL in PBS, pH 7.4) and incubate for 12 hours at 4°C.

- Block non-specific binding sites by applying 10 µL of BSA (1% w/v) for 1 hour at room temperature. Rinse with PBS.

Immunoassay Procedure:

- Incubate the modified SPE with 50 µL of the sample containing the target pesticide for 30 minutes at 37°C. Rinse.

- Incubate the sensor with 50 µL of the AuNP-labeled detection antibody solution for 30 minutes at 37°C. Rinse thoroughly.

Electrochemical Detection:

- Place the immunosensor in an electrochemical cell containing 0.1 M HCl.

- Apply a pre-concentration potential of +1.0 V for 120 seconds to oxidize and dissolve the AuNPs into AuCl₄⁻ ions.

- Perform Anodic Stripping Voltammetry (ASV) by scanning from +0.2 V to +1.0 V.

- The sharp oxidation peak current at ~+0.65 V is directly proportional to the concentration of Au³⁺ ions, which in turn is proportional to the concentration of the captured pesticide.

Aptasensors: Label-free Impedimetric Detection

Principle: This protocol utilizes an aptamer that undergoes a conformational change upon binding to its target pesticide. This change alters the interfacial properties of the electrode surface, which is measured as a change in charge transfer resistance (Rcₜ) using Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) [27] [29].

Experimental Protocol:

SPE Modification and Aptamer Immobilization:

- Modify the SPE with a nanocomposite of gold nanoparticles and reduced graphene oxide (AuNP-rGO) to create a highly conductive platform with ample sites for thiol-binding.

- Prepare a 1 µM solution of the thiolated aptamer specific to the target (e.g., tetracycline) in Tris-EDTA buffer.

- Deposit 10 µL of the aptamer solution onto the AuNP-rGO/SPE and incubate overnight at 4°C to form a self-assembled monolayer via Au-S bonds.

- Rinse and then block the surface with 6-mercapto-1-hexanol (1 mM) for 1 hour to passivate unbound gold sites.

Target Binding and EIS Measurement:

- Record the EIS spectrum of the aptasensor in a 5 mM [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻ redox probe solution (in 0.1 M KCl) as a baseline. Parameters: DC potential of +0.22 V, amplitude of 5 mV, frequency range from 0.1 Hz to 100 kHz.

- Incubate the aptasensor with the sample solution containing the pesticide for 20 minutes.

- Rinse the sensor gently and record the EIS spectrum again under identical conditions.

- The increase in the diameter of the semicircle in the Nyquist plot, corresponding to an increase in Rcₜ, is used to quantify the pesticide concentration.

Diagram 2: Aptamer-based EIS Sensing Workflow

Molecularly Imprinted Polymer Sensors

Principle: MIPs are synthetic polymers with cavities complementary in shape, size, and functional groups to the target molecule (the template). This protocol involves the in-situ electropolymerization of a monomer around the template pesticide on the SPE surface. After template removal, the resulting cavities selectively rebind the pesticide from samples [30] [31].

Experimental Protocol:

SPE Pre-treatment and MIP Formation:

- Clean the carbon SPE via CV in 0.5 M H₂SO₄.

- Prepare a polymerization solution containing the template (e.g., 5 mM paraoxon), the functional monomer (e.g., 20 mM o-phenylenediamine), and 0.1 M PBS (pH 7.0).

- Deposit 15 µL of this solution onto the working electrode.

- Perform Electropolymerization by applying CV between -0.2 V and +0.8 V for 15 cycles at a scan rate of 50 mV/s.

Template Removal:

- Carefully wash the polymerized SPE with a mixture of methanol and acetic acid (9:1, v/v) under gentle stirring for 15 minutes to extract the template molecules, leaving behind specific cavities.

- Rinse extensively with PBS until a stable background CV signal is obtained.

Rebinding and Detection:

- Incubate the MIP/SPE in the sample solution for 15 minutes to allow the pesticide to rebind to the cavities.

- Rinse the sensor to remove non-specifically bound molecules.

- Transfer the sensor to a clean electrochemical cell containing a redox probe (e.g., 5 mM [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻).

- Perform DPV. The binding of the non-electroactive pesticide into the MIP cavities hinders the diffusion of the redox probe to the electrode surface, resulting in a decrease in the peak current, which is correlated to the pesticide concentration.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Sensor Development

| Item Name | Function / Application | Example Specifications / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Screen-Printed Electrodes (SPEs) | Disposable, miniaturized electrochemical cell transducers. | Ceramic or plastic substrates with carbon, gold, or silver ink working electrodes. |

| Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) | Enzyme for inhibition-based detection of OPs and carbamates. | Source: Electric eel; Activity: >1000 U/mg. Store at -20°C. |

| Anti-pesticide Antibodies | Capture and detection elements for immunosensors. | Monoclonal antibodies preferred for specificity. Requires cold chain storage. |

| DNA/RNA Aptamers | Synthetic recognition elements for aptasensors. | Thiol- or amino-modified for surface immobilization. HPLC purified. |

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | Nanomaterial for electrode modification and as an electrochemical label. | ~20 nm diameter, functionalized with streptavidin or antibodies. |

| Graphene Oxide / Reduced Graphene Oxide | Nanomaterial to enhance electrode conductivity and surface area. | Aqueous dispersion, 1-5 mg/mL. |

| o-Phenylenediamine | Functional monomer for electropolymerization of MIP films. | Used in molecular imprinting for phenolic or aromatic targets. |

| Electrochemical Redox Probes | Mediators for signal generation in EIS, DPV, and CV. | 5 mM Potassium ferri/ferrocyanide ([Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻) in 0.1 M KCl. |

| Glutaraldehyde | Crosslinking agent for covalent immobilization of proteins. | Typically used as a 0.25-2.5% (v/v) solution. Handle with care. |

| 6-Mercapto-1-hexanol | Backfiller molecule for Au surfaces to minimize non-specific binding. | Used in aptamer-based sensors to create a well-ordered SAM. |

Performance Data and Analysis

The following table summarizes representative performance metrics achievable with different recognition elements on nanomaterial-modified SPEs, as reported in the literature.

Table 3: Exemplary Performance Metrics for Pesticide Detection

| Recognition Element | Target Pesticide | Nanomaterial Used | Detection Limit | Linear Range | Reference Technique |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AChE (Enzyme) | Chlorpyrifos | Reduced Graphene Oxide | 0.5 ng/L | 1-1000 ng/L | Chronoamperometry [25] |

| Anti-atrazine Antibody | Atrazine | Gold Nanoparticles / CNTs | 0.01 µg/L | 0.05–10 µg/L | ASV [26] |

| Tetracycline Aptamer | Tetracycline | AuNP-rGO nanocomposite | 0.1 nM | 1 nM - 1 µM | EIS [28] [29] |

| MIP (o-PDA polymer) | Paraoxon | Prussian Blue / Carbon Black | 0.8 nM | 5 nM - 5 µM | DPV [31] |

The integration of enzymes, antibodies, aptamers, and MIPs with nanomaterial-modified SPEs provides a powerful and versatile toolbox for advanced pesticide analysis. The choice of the optimal recognition element depends on the specific requirements of the analysis, including the target pesticide, required sensitivity and specificity, sample matrix, and intended use (e.g., one-time field testing vs. continuous monitoring). Enzymes offer a well-understood, catalytic approach ideal for class-specific screening. Antibodies provide unparalleled specificity for individual compounds in a sandwich format. Aptamers present a synthetic, stable, and flexible alternative, excellent for label-free and reversible sensing. MIPs deliver extreme robustness and are suitable for harsh environments and a wide range of targets. A key trend in this field is the development of hybrid systems, such as MIP-aptamer composites, which aim to harness the synergistic advantages of multiple recognition elements to create sensors with superior performance, moving laboratory research closer to real-world deployment [30] [31].

The accurate detection of pesticide residues in food and environmental samples represents a critical challenge in analytical chemistry, directly impacting public health and food safety. Traditional methods, such as chromatography, are often constrained by the need for costly equipment, specialized laboratory settings, and lengthy analysis times [3] [32]. Within this context, electrochemical biosensors based on screen-printed electrodes (SPEs) have emerged as a powerful alternative, offering portability, cost-effectiveness, and the potential for rapid, on-site analysis [1] [2]. The integration of nanomaterials into these sensing platforms has been pivotal in overcoming limitations of sensitivity and selectivity, leading to a transformative leap in their analytical performance [32] [33]. This application note details the fundamental mechanisms through which nanomaterials enhance sensor function, provides a validated experimental protocol for electrode modification and pesticide detection, and outlines the essential toolkit for researchers in this field. The content is specifically framed within ongoing thesis research focused on developing advanced nanomaterial-modified SPEs for pesticide analysis.

Core Enhancement Mechanisms of Nanomaterials

Nanomaterials enhance biosensor performance through several interconnected physical and chemical mechanisms. Their unique properties, such as high surface area-to-volume ratio and quantum effects, directly improve the critical parameters of sensor function.

Table 1: Core Enhancement Mechanisms of Nanomaterials in Electrochemical Sensors

| Enhancement Mechanism | Key Nanomaterials Involved | Primary Effect on Sensor Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Increased Electroactive Surface Area | Carbon nanotubes (CNTs), Graphene, Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | Enhances analyte loading and reaction sites, boosting signal intensity and sensitivity [32] [33]. |

| Enhanced Electron Transfer Kinetics | CNTs, Graphene, Metal Nanoparticles | Acts as an electron "bridge" or conduit, facilitating faster electron shuttling between the biorecognition element and the electrode surface [1] [34]. |

| Catalytic Activity | Metal Oxides (e.g., CuO), Nanozymes, Single-Atom Catalysts (SACs) | Lowers oxidation/reduction overpotentials, improves reaction efficiency, and enables signal amplification [3]. |

| Biorecognition Immobilization | AuNPs, CNTs, Nanohybrids | Provides a stable and favorable microenvironment for anchoring enzymes, antibodies, or aptamers, preserving their bioactivity [3] [32]. |

The synergy of these mechanisms is illustrated in the following diagram, which maps the logical pathway from nanomaterial properties to the final sensor performance metrics.

Quantitative Performance of Nanomaterial-Based Sensors

The practical impact of these enhancement mechanisms is reflected in the superior analytical performance of nanomaterial-based sensors. The following table compiles data from a systematic review of recent research, showcasing the low detection limits achieved for various pesticides in food matrices.

Table 2: Analytical Performance of Selected Nanomaterial-Based Biosensors for Pesticide Detection in Food [32]

| Nanomaterial | Biorecognition Element | Pesticide | Limit of Detection (LOD) | Food Matrix |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) | Organophosphorus (class) | 19–77 ng L⁻¹ | Apple, Cabbage |

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | AChE | Methomyl | 81 ng L⁻¹ | Apple, Cabbage |

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | AChE | Carbamate (class) | 1.0 nM | Fruit |

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | Aptamer | Chlorpyrifos | 36 ng L⁻¹ | Apple, Pak choi |

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | Antibody | Chlorpyrifos | 0.07 ng L⁻¹ | Chinese cabbage, Lettuce |

| Nanohybrids | Various | Various | < Maximum Residue Limits | Various fruits/vegetables |

Experimental Protocol: AChE-based Sensor for Organophosphorus Pesticides

This protocol provides a detailed methodology for fabricating a nanomaterial-enhanced acetylcholinesterase (AChE) biosensor for the detection of organophosphorus pesticides (OPs) in fruit juice samples, based on established procedures in the literature [35] [3] [32].

Principle

The sensor operates on an enzyme inhibition mechanism. The immobilized AChE enzyme catalyzes the hydrolysis of acetylthiocholine (ATCh), producing thiocholine. Thiocholine is then electrochemically oxidized at the nanomaterial-modified SPE surface, generating a measurable amperometric current. The presence of OPs inhibits AChE activity, leading to a reduction in the generated thiocholine and a consequent decrease in the electrochemical signal, which is proportional to the pesticide concentration.

Reagents and Materials

- Screen-Printed Electrodes (SPEs): Carbon-based three-electrode systems.

- Nanomaterial Dispersion: e.g., multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs, 1 mg/mL in DMF) or graphene oxide (GO, 1 mg/mL in water).

- Biorecognition Element: Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) from Electrophorus electricus.

- Enzyme Substrate: Acetylthiocholine chloride (ATCh) or iodide (ATCHI).

- Buffer: Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS, 0.1 M, pH 7.4).

- Crosslinker: Glutaraldehyde solution (0.25% v/v).

- Standard Solutions: Parathion, chlorpyrifos, or malathion standards for calibration.

- Real Samples: Fruit juice (e.g., apple juice) filtered and diluted 1:1 with PBS.

Procedure

Step 1: Electrode Modification and Nanomaterial Deposition

- Pretreatment: Activate the bare carbon SPE by cycling the potential in a suitable redox couple or by applying a constant potential in acidic solution to generate oxygenated functional groups [34].

- Modification: Pipette 5 µL of the well-dispersed nanomaterial suspension (e.g., MWCNTs) directly onto the working electrode surface.

- Drying: Allow the electrode to dry at room temperature for 45-60 minutes, forming a uniform film. Rinse gently with distilled water to remove loosely bound material.

Step 2: Enzyme Immobilization

- Preparation: Mix 10 µL of AChE solution (5 U/mL) with 10 µL of a 0.25% glutaraldehyde solution.

- Immobilization: Immediately deposit 5 µL of the AChE-glutaraldehyde mixture onto the nanomaterial-modified working electrode.

- Curing: Let the electrode sit for 1 hour at 4°C to allow for complete cross-linking and enzyme immobilization.

- Storage: Store the prepared biosensors at 4°C in PBS when not in use.

Step 3: Electrochemical Measurement and Pesticide Detection

- Baseline Signal: Place the modified AChE-biosensor in an electrochemical cell containing 10 mL of PBS and 1 mM ATCh. Record the steady-state amperometric current (i₀) at a fixed potential (typically +0.7 V vs. Ag/AgCl reference).

- Inhibition: Incubate the biosensor for 10 minutes in a sample solution (standard or real sample) containing the target OP pesticide.

- Post-Inhibition Signal: Rinse the electrode gently with PBS and measure the amperometric current (i₁) again under the same conditions as in Step 3.1.

- Analysis: The percentage of enzyme inhibition is calculated as: % Inhibition = [(i₀ - i₁) / i₀] × 100. The pesticide concentration is determined by interpolating this value into a pre-established calibration curve.

The workflow for this experimental protocol is summarized in the following diagram:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful development of a nanomaterial-modified SPE biosensor requires a carefully selected set of materials. The following table lists key reagents and their specific functions within the experimental workflow.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Sensor Fabrication

| Item | Function / Role in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Screen-Printed Electrodes (SPEs) | Disposable, portable, and mass-producible platform integrating working, reference, and counter electrodes [1] [2]. |

| Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) / Graphene | High-conductivity nanomaterials that provide a large surface area for enzyme loading and facilitate electron transfer, significantly enhancing signal response [32] [34]. |

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | Excellent biocompatibility and conductivity; often used to immobilize biomolecules via Au-S bonds and to enhance electrochemical signals [32] [36]. |

| Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) Enzyme | The primary biorecognition element whose activity is inhibited by organophosphorus and carbamate pesticides, forming the basis of the detection mechanism [3] [32]. |

| Acetylthiocholine (ATCh) | Enzyme substrate; its hydrolysis by AChE produces thiocholine, which is electrochemically oxidized to generate the analytical signal [3]. |

| Glutaraldehyde | A crosslinking agent used to create stable covalent bonds between the enzyme (AChE) and the nanomaterial-modified electrode surface [32]. |

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) | Provides a stable pH and ionic strength environment for maintaining enzyme activity and for all electrochemical measurements [32]. |

Fabrication Techniques and Detection Methodologies for Practical Pesticide Analysis

The functionalization of transducer surfaces is a critical step in the development of highly sensitive and selective electrochemical sensors. Within the context of screen-printed electrode (SPE)-based platforms for pesticide analysis, the method of applying nanomaterials and biorecognition elements directly governs the analytical performance of the resulting biosensor [9] [10]. SPEs provide a versatile and disposable foundation, but their inherent capabilities are substantially enhanced through deliberate modification strategies that increase effective surface area, improve electron transfer kinetics, and allow for the stable immobilization of specific bioreceptors [34] [10].

This protocol details three cornerstone modification techniques—electrodeposition, drop-casting, and chemical immobilization—tailored for the construction of nanomaterial-enhanced biosensors for pesticide detection. These methods facilitate the creation of a sensitive transduction interface and ensure the robust attachment of biological components such as enzymes, antibodies, or aptamers, which are essential for selective target recognition [32] [10]. The strategic integration of nanomaterials like gold nanoparticles (AuNPs), carbon nanotubes (CNTs), and graphene oxide (GO) is emphasized, as they are pivotal in amplifying the electrochemical signal and lowering detection limits to clinically and environmentally relevant concentrations [9] [32].

Theoretical Foundations of Modification Techniques

The choice of modification technique is governed by the desired properties of the nanomaterial film and the nature of the biological element to be immobilized. Each method presents distinct advantages regarding film uniformity, adhesion strength, processing time, and compatibility with sensitive biomolecules.

Electrodeposition leverages electrochemical principles to precisely control the nucleation and growth of a material onto the electrode surface from a precursor solution. Applying a controlled potential or current density allows for the controlled reduction of metal ions (e.g., Au³⁺, Ag⁺) to form a nanostructured layer. This method typically yields films with strong adhesion and excellent electrical connectivity to the electrode surface, which is crucial for efficient electron transfer [37]. The morphology, particle size, and density of the deposited nanomaterial can be finely tuned by varying key parameters such as the applied potential, deposition time, and the composition of the electrolyte solution [10].

Drop-Casting is a straightforward physical adsorption technique where a small, defined volume of nanomaterial dispersion is pipetted directly onto the working electrode surface and allowed to dry. Its primary advantages are simplicity and minimal equipment requirements. However, the resulting film can be heterogeneous, with a potential for "coffee-ring" effects, and the adhesion is primarily physical (van der Waals forces) rather than chemical [37]. The homogeneity and thickness of the film are highly dependent on the dispersion quality of the nanomaterial, the surface wettability of the electrode, and the ambient drying conditions. Despite its simplicity, a comparative study on AuNP-modified SPEs found that the drop-casting method could produce a higher peak current and a lower charge-transfer resistance (2.534 kΩ) than other methods like spray coating, making it a robust choice for many applications [37].

Chemical Immobilization involves forming strong, covalent bonds between the electrode surface (often pre-modified with a nanomaterial) and the biorecognition element. A common strategy involves leveraging the strong Au-S chemistry between gold nanoparticles and thiolated DNA probes or antibodies [37]. This method provides a stable, oriented, and dense layer of bioreceptors, which enhances the sensor's specificity, reproducibility, and resistance to fouling. The formation of a self-assembled monolayer (SAM) through thiol chemistry is a quintessential example of this approach, creating a well-ordered interface for subsequent biomolecular conjugation [37].

The workflow below illustrates the decision-making process for selecting and implementing these key modification strategies.

Materials and Reagents

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table catalogues the essential materials required for the modification of screen-printed electrodes and the subsequent development of electrochemical biosensors.

Table 1: Essential Reagents and Materials for Electrode Modification

| Item Name | Function / Purpose | Specific Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Screen-Printed Electrodes (SPEs) | Disposable, miniaturized electrochemical cell substrate. | Carbon-based working electrode is most common [34] [10]. |

| Gold Chloride (HAuCl₄) | Precursor salt for synthesizing gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) [37]. | Used in electrodeposition and chemical synthesis [37]. |

| Carbon Nanomaterials | Enhance conductivity and surface area; serve as a scaffold [9]. | Graphene Oxide (GO), Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) [9] [38]. |

| Thiolated DNA Probes | Biorecognition element; forms covalent Au-S bonds on AuNPs [37]. | Used for immobilization in aptasensors and genosensors [37]. |

| Specific Antibodies | Biorecognition element for immunosensors; detects target antigens [10] [38]. | e.g., cTnI antibodies for cardiac monitoring [38]. |

| Enzymes (e.g., AChE) | Biorecognition element for enzymatic biosensors [10]. | Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) used for organophosphate pesticide detection [10]. |

| Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP) | Reducing agent; cleaves disulfide bonds in thiolated probes [37]. | Ensures free thiol groups are available for Au-S binding [37]. |

| Saline-Sodium Citrate (SSC) Buffer | Hybridization buffer for DNA/RNA-based sensors [37]. | Provides optimal ionic strength and pH for biomolecular interactions [37]. |

| Potassium Ferricyanide/K Ferrocyanide | Redox probe for electrochemical characterization [34] [37]. | [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻ used in EIS and CV to monitor electrode modification [34] [37]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Electrodeposition of Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs)

Principle: This protocol uses electrochemical reduction to deposit a layer of AuNPs directly onto the carbon working electrode of an SPE. This creates a nanostructured surface with high conductivity and a large active area, which is also ideal for subsequent chemical immobilization of thiolated bioreceptors [37].

Materials:

- Screen-printed carbon electrode (SPCE)

- Chloroauric acid (HAuCl₄) solution (e.g., 0.5 - 1 mM in 0.1 M KCl or H₂SO₄)

- Electrochemical workstation

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS, 0.1 M, pH 7.4) or other supporting electrolyte

Procedure:

- Electrode Pre-treatment: Place the SPCE in an electrochemical cell containing a supporting electrolyte like 0.1 M H₂SO₄. Perform cyclic voltammetry (CV) between 0 V and +1.0 V (vs. Ag/AgCl reference on the SPE) for 5-10 cycles until a stable voltammogram is obtained. This step cleans and activates the carbon surface [34].

- Preparation of Deposition Solution: Transfer a known volume (e.g., 50-100 µL) of the 0.5 mM HAuCl₄ solution in 0.1 M KCl onto the electrode surface, covering the entire working electrode.

- Electrodeposition: Use amperometry (chronoamperometry) to apply a constant reduction potential. A potential of -0.4 V (vs. Ag/AgCl) for a duration of 60-300 seconds is typical, but this should be optimized [37]. The deposition process reduces Au³⁺ ions to metallic Au⁰, forming nanoparticles on the electrode surface.

- Rinsing and Drying: After deposition, carefully rinse the modified SPCE (now SPCE/AuNP) with deionized water to remove any unreacted precursors and salts. Gently dry under a stream of inert gas (e.g., nitrogen) or air.

Critical Parameters:

- Applied Potential and Time: These directly control the size, density, and morphology of the AuNPs. More negative potentials and longer times generally yield larger, denser particles [37].

- Precursor Concentration: Higher HAuCl₄ concentrations can lead to thicker and more continuous films.

Protocol 2: Drop-Casting of Nanomaterial Inks

Principle: A dispersion of pre-synthesized nanomaterials is physically applied to the electrode surface. This is a versatile method for applying a wide range of nanomaterials, including graphene derivatives and carbon nanotubes [39] [37].

Materials:

- SPE

- Nanomaterial dispersion (e.g., 1 mg/mL graphene oxide in water)

- Micropipette

- Heated plate or lamp for controlled drying

Procedure:

- Dispersion Preparation: Prepare a homogeneous dispersion of the nanomaterial (e.g., GO, CNTs) in a suitable solvent (often water or ethanol). Sonication for 30-60 minutes is typically required to achieve a stable, non-aggregated dispersion.

- Surface Modification: Using a precision micropipette, deposit a specific volume (e.g., 2 - 10 µL) of the nanomaterial dispersion directly onto the working electrode area.

- Drying: Allow the solvent to evaporate under ambient conditions or under a mild heat source (e.g., 40°C on a hotplate) to form a thin film. Uniform drying can be promoted by placing the electrode in a covered petri dish.

Critical Parameters:

- Dispersion Quality: Incomplete sonication leads to aggregation, resulting in a non-uniform film and poor sensor performance.

- Volume and Concentration: These factors directly determine the thickness of the modified layer. Excess material can lead to a thick, resistive film that hinders electron transfer.

- Drying Control: Uncontrolled drying can cause the "coffee-ring" effect, where material accumulates at the edges of the droplet.

Protocol 3: Chemical Immobilization of Thiolated DNA Probes

Principle: This protocol leverages the strong, covalent Au-S bond to immobilize thiol-modified DNA probes onto a gold nanoparticle-modified SPE (from Protocol 1 or commercial Au-SPEs), creating a stable and organized recognition layer for genosensors or aptasensors [37].

Materials:

- SPCE/AuNP (from Protocol 1 or commercial source)

- Thiolated single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) probe sequence

- Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP, e.g., 0.1 M)

- Saline-sodium citrate (SSC) buffer, pH 7.0

- Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS, 0.1%)

Procedure:

- Probe Activation: Incubate the thiolated ssDNA probe (e.g., at 0.5 µg/mL) with a 10-20x molar excess of TCEP for 1 hour at room temperature. This step reduces any disulfide bonds that may have formed, ensuring the thiol groups are free and reactive [37].

- Immobilization: Dilute the TCEP-treated probe in SSC buffer. Apply a precise volume (e.g., 5-10 µL) of this solution to cover the SPCE/AuNP surface. Incubate in a humidified chamber for a predetermined time (e.g., 22 minutes at room temperature) to allow the formation of a self-assembled monolayer (SAM) [37].

- Rinsing: After immobilization, rinse the electrode thoroughly with SDS solution (0.1%) followed by SSC buffer to remove any physisorbed DNA probes.

- Surface Blocking (Optional but Recommended): To minimize non-specific adsorption, incubate the electrode with a blocking agent like 6-mercapto-1-hexanol (1-2 mM) for 15-30 minutes. This step passivates any uncovered gold sites.

Critical Parameters:

- Probe Concentration and Immobilization Time: These must be optimized to achieve an optimal probe density. Overcrowding can sterically hinder target binding [37].

- Ionic Strength of Buffer: SSC buffer provides the appropriate ionic strength to facilitate the interaction between the DNA backbone and the gold surface, promoting a well-ordered SAM.

- Thiol Reduction: Incomplete reduction with TCEP will significantly decrease immobilization efficiency.

Performance Comparison and Data Analysis

The modification strategy profoundly impacts the sensor's analytical figures of merit. The following table summarizes the expected outcomes and performance characteristics of the different methods.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Electrode Modification Strategies

| Modification Strategy | Typical Nanomaterials Used | Key Advantages | Limitations / Challenges | Reported Performance (LOD Example) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electrodeposition | AuNPs, AgNPs, PtNPs [37] | Strong adhesion, excellent electrical contact, controllable morphology [37]. | Requires potentiostat, optimization of deposition parameters [37]. | SARS-CoV-2 RNA: 1 copy/μL [37] |

| Drop-Casting | GO, CNTs, rGO, pre-formed NPs [39] [37] | Simplicity, speed, no specialized equipment, versatile [37]. | Risk of non-uniform film ("coffee-ring"), weaker physical adhesion [37]. | Amaranth dye: 30.0 nM [39] |

| Chemical Immobilization | Thiolated DNA/RNA, Antibodies (on AuNPs) [37] | Stable, dense, and oriented binding; high specificity and reproducibility [37]. | Requires functionalized ligands (e.g., -SH); multi-step procedure [37]. | SARS-CoV-2 RNA: 0.1664 μg/mL [37] |

Analytical Validation

Following modification and bioreceptor immobilization, the sensor must be validated.

- Electrochemical Characterization: Use Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) and Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) with a standard redox probe like [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻ to monitor each modification step. A successful AuNP electrodeposition or carbon nanomaterial drop-cast will typically show an increase in peak current and a decrease in charge-transfer resistance (Rct) in EIS Nyquist plots [34] [37]. Subsequent immobilization of an insulating biological layer (e.g., DNA SAM) will increase Rct, confirming successful surface modification [37].

- Analytical Performance: The sensor's performance is evaluated by measuring the electrochemical response (e.g., via DPV, amperometry) to varying concentrations of the target analyte (e.g., a specific pesticide). The Limit of Detection (LOD), linear dynamic range, selectivity, and reproducibility should be determined. For instance, nanomaterial-based biosensors for pesticides have consistently demonstrated LODs lower than the maximum residue limits (MRLs) defined by regulatory bodies [32] [10].

Troubleshooting

Problem: High Background Noise or Unstable Baseline.

- Cause: Incomplete rinsing after modification, leading to residual salts or unbound reagents.

- Solution: Implement more rigorous washing steps with appropriate buffers and deionized water.

Problem: Low or No Signal.

- Cause (Drop-Casting): The nanomaterial film is too thick, creating a resistive barrier.

- Solution: Optimize the volume and concentration of the nanomaterial dispersion cast onto the electrode.

- Cause (Chemical Immobilization): Inefficient thiol reduction or probe denaturation.

- Solution: Ensure fresh TCEP is used for reduction and avoid harsh conditions for biomolecules.

Problem: Poor Reproducibility Between Sensors.

- Cause: Inconsistent modification procedures, particularly in manual drop-casting or drying.

- Solution: Standardize all parameters (volumes, times, temperatures) and use automated dispensers if available. Characterize multiple electrodes at each step using EIS to ensure consistency.

Electrochemical detection has emerged as a powerful analytical technique for pesticide analysis, offering a complementary approach to traditional chromatographic methods like HPLC and MS. These conventional techniques, while highly sensitive, are often characterized by high operational costs, lengthy analysis times, and requirements for sophisticated laboratory infrastructure and qualified personnel [10]. In contrast, electrochemical methods provide reliable, simple, and cost-effective analytical tools that enable rapid, in-situ measurements and screening with minimal sample volumes [10]. The growing need for on-site pesticide monitoring in environmental, agricultural, and food safety contexts has significantly increased the importance of these techniques.

The fundamental principle of electrochemical detection involves measuring electrical signals generated from oxidation (loss of electrons) and reduction (gain of electrons) reactions [40]. These processes occur in an electrochemical cell containing conductive electrodes and an electrolyte solution that facilitates electricity conduction [40]. When applied to pesticide analysis, particularly using nanomaterial-modified screen-printed electrodes (SPEs), these methods demonstrate exceptional sensitivity, portability, and operational efficiency. Screen-printed electrodes, constructed through thick film deposition onto plastic or ceramic substrates, have revolutionized electrochemical detection by enabling simple, inexpensive, and rapid on-site analysis with high reproducibility and accuracy [41]. The integration of nanomaterials into SPEs further enhances their analytical performance through increased surface area, improved electron transfer kinetics, and tailored recognition properties.

Table 1: Advantages of Electrochemical Detection for Pesticide Analysis

| Feature | Electrochemical Methods | Traditional Chromatographic Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Cost | Low-cost equipment and operation | Expensive instrumentation and maintenance |

| Analysis Time | Rapid (minutes) | Lengthy (potentially hours) |

| Sample Volume | Microliter range | Milliliter range |

| Portability | High (suitable for field use) | Low (laboratory-bound) |