Nanoparticles in Biosensor Design: Enhancing Sensitivity, Specificity, and Clinical Translation

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the latest advancements and applications of nanoparticles in biosensor technology, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Nanoparticles in Biosensor Design: Enhancing Sensitivity, Specificity, and Clinical Translation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the latest advancements and applications of nanoparticles in biosensor technology, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of various nanoparticles, including quantum dots, gold nanoparticles, and graphene-based structures, detailing their unique optical and electrochemical properties. The scope extends to methodological innovations in disease diagnosis, drug monitoring, and environmental sensing, while also addressing critical challenges in sensor stability, specificity, and scalable manufacturing. Furthermore, the article offers a comparative evaluation of emerging trends, such as AI-integrated and biodegradable nanosensors, validating their performance against conventional diagnostic tools and discussing their future impact on precision medicine and point-of-care diagnostics.

The Building Blocks: How Nanoparticles Revolutionize Biosensing Fundamentals

The integration of nanotechnology into biosensor design has revolutionized the field of diagnostic sensing, enabling the development of devices with exceptional sensitivity, specificity, and portability. These advancements are critically important for managing global health challenges, particularly in the context of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) like diabetes, cardiovascular disorders, and cancer, as well as for the detection of infectious diseases [1] [2]. The core functional properties of these biosensors—optical, electrochemical, and magnetic—are fundamentally enhanced by the unique physicochemical characteristics of nanomaterials. Nanoparticles provide a high surface-to-volume ratio, superior catalytic efficiency, and tunable properties that can be meticulously engineered to improve biorecognition and signal transduction [3] [4] [5]. This technical guide delves into the mechanisms by which these core properties are leveraged, providing a detailed analysis for researchers and scientists engaged in the development of next-generation biosensing platforms. By framing this discussion within the broader thesis of nanoparticle applications, this review underscores how nanomaterial integration is pivotal in creating point-of-care (POC) diagnostic tools that are affordable, sensitive, and suitable for use in resource-limited settings, thereby aligning with the World Health Organization's ASSURED criteria [2].

Nanotechnology in Biosensing: Fundamental Concepts

Biosensors are analytical devices that combine a biological recognition element (such as an enzyme, antibody, or strand of DNA) with a physicochemical transducer [4]. The primary function of the transducer is to convert the biological interaction into a quantifiable signal. The integration of nanomaterials into these systems bridges the dimensional gap between the bioreceptor and the transducer, both of which operate at the nanoscale [3] [5]. This synergy significantly enhances biosensor performance by improving characteristics such as the detection limit, sensitivity, selectivity, and response time [4].

Nanomaterials used in biosensors are categorized based on their dimensions. These include zero-dimensional structures like solid and hollow nanoparticles and quantum dots (QDs); one-dimensional structures such as nanowires (NWs), nanotubes (NTs), and carbon nanotubes (CNTs); two-dimensional structures like films and sheets; and three-dimensional structures including nanocomposites and polycrystals [5]. The synthesis of these nanomaterials follows either a "top-down" approach (involving the mechanical milling of bulk materials) or a "bottom-up" approach (building structures atom-by-atom or molecule-by-molecule through methods like chemical vapor deposition and sol-gel techniques) [5]. The choice of nanomaterial and synthesis method allows researchers to precisely engineer the properties of the biosensing interface, tailoring it for specific applications and thereby pushing the boundaries of detection capabilities.

Optical Biosensing Modalities

Optical biosensors transduce a biological binding event into a measurable optical signal, such as a change in light absorption, fluorescence intensity, or color. Nanoparticles dramatically enhance these signals due to their unique optical properties.

Fluorescence and FRET-Based Sensors

Fluorescent nanoparticles, particularly quantum dots (QDs), are widely used due to their high quantum yield, photostability, and size-tunable emission spectra [3] [4]. A advanced application involves Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET), where energy is transferred from a donor fluorophore to an acceptor fluorophore when they are in close proximity.

A groundbreaking development is the ChemoX platform, which employs a engineered, reversible interaction between a fluorescent protein (FP) and a synthetic fluorophore-labeled HaloTag (HT7) to achieve near-quantitative FRET efficiency (≥94%) [6]. This chemogenetic design allows for the creation of biosensors for analytes like calcium, ATP, and NAD+ with unprecedented dynamic ranges. The spectral properties of the biosensor can be easily tuned by changing the FP donor (e.g., eGFP, eBFP2, mCerulean3) or the synthetic fluorophore acceptor (e.g., JF525, TMR, SiR, JF669), enabling multiplexed detection [6].

Colorimetric and Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) Sensors

Gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) are the cornerstone of colorimetric biosensors due to their intense Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR)-derived colors and high extinction coefficients [7]. A notable example is a sensor for the direct detection of unamplified Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) RNA [7]. This assay induces the aggregation of citrate-capped AuNPs, which are decorated with an HCV-specific nucleic acid probe, using positively charged cationic AuNPs (cysteamine or CTAB-capped). The aggregation event causes a distinct color shift from red to blue, allowing for visual detection without sophisticated instrumentation. This platform is simple, rapid, and cost-effective, achieving a detection limit of 4.57 IU/µl in clinical samples [7].

The table below summarizes the performance of selected optical biosensing platforms.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Selected Optical Biosensors

| Technique / Target | Detection Mechanism | Limit of Detection (LOD) | Assay Time | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FRET-based (ChemoG5) [6] | FRET between FP and rhodamine-labeled HaloTag | N/A (High dynamic range) | N/A | Near-quantitative FRET (~96%); Highly tunable colors; Suitable for live-cell imaging |

| AuNP Aggregation / HCV RNA [7] | Aggregation-induced color shift (SPR) | 4.57 IU/µl | Rapid | Direct detection of unamplified RNA in clinical samples; 93.3% sensitivity |

| Fluorescence Polarization / Salmonella spp. [2] | Fluorescence polarization change | 1 CFU | 20 min | Differentiates between bacterial species in blood samples; Cost: ~$1 |

| Localized SPR / Influenza Virus [2] | LSPR shift using AuNP-alloyed QDs | H1N1: 0.03 pg/mL (in water) | 5 min | Differentiates between influenza strains in serum |

Figure 1: Generalized workflow for optical biosensing, highlighting the key stages from sample introduction to signal readout.

Electrochemical Biosensing Modalities

Electrochemical biosensors detect biological interactions by measuring electrical signals such as current (amperometric), potential (potentiometric), or impedance (impedimetric). The integration of nanomaterials like graphene, carbon nanotubes (CNTs), and metal nanoparticles greatly enhances the electroactive surface area, facilitates electron transfer, and improves catalytic activity, leading to superior sensitivity [4] [5].

These biosensors are particularly valued for POC applications due to their miniaturization potential, portability, low cost, and fast response times [4]. A significant advancement in this field is the move towards non-biological recognition elements, such as transition metal oxides (MXenes), to overcome the limitations of biological elements like enzymes and antibodies, which can be unstable under varying environmental conditions (pH, temperature) and have complex immobilization procedures [4]. MXenes and similar nanomaterials offer outstanding stability, high selectivity, and sensitivity, making them robust alternatives for continuous monitoring and harsh environments [4].

Table 2: Key Characteristics of Electrochemical Biosensing Modalities

| Transduction Method | Measured Quantity | Role of Nanomaterials | Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amperometric | Current from redox reactions | Enhance electron transfer kinetics; Increase electrode surface area; Catalyze reactions | High sensitivity; Low detection limits |

| Potentiometric | Potential difference at equilibrium | Act as ion-to-electron transducers; Provide Nernstian response | Simple instrumentation; Wide detection range |

| Impedimetric | Electrical impedance/conductivity | Increase surface area for bioreceptor immobilization; Amplify conductivity changes | Label-free detection; Real-time monitoring |

Magnetic Biosensing Modalities

Magnetic biosensors utilize magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs), typically based on iron oxides like magnetite (Fe₃O₄), as labels or capture agents. The detection is based on measuring the magnetic properties of these particles, which are highly stable and minimally affected by the biological matrix, thus reducing background interference [2].

The primary applications of MNPs in biosensing include:

- Sample Preparation and Concentration: MNPs functionalized with specific antibodies or DNA probes can selectively bind to target analytes (e.g., pathogens, biomarkers) in a complex sample. An external magnetic field is then used to separate and concentrate the bound targets, thereby purifying and enriching the analyte before detection [2].

- Signal Transduction: The magnetic field generated by the MNPs can be measured directly using sophisticated detectors like giant magnetoresistance (GMR) or superconducting quantum interference device (SQUID) sensors. This allows for the highly sensitive and direct detection of the target molecule without the need for optical labels or enzymatic amplification [2].

Magnetic biosensors are particularly promising for detecting pathogens in blood, sputum, or environmental samples because their signal is not obscured by the inherent opacity or autofluorescence of these complex media [2].

Experimental Protocols and Reagent Solutions

Detailed Protocol: Gold Nanoparticle-Based HCV RNA Detection

This protocol details the experimental workflow for the direct, colorimetric detection of unamplified HCV RNA using gold nanoparticle (AuNP) aggregation [7].

1. Synthesis and Functionalization of Citrate-Capped AuNPs (Nanoprobes):

- Synthesis: Prepare citrate-capped AuNPs via the sodium citrate reduction method of tetrachloroauric acid (HAuCl₄). Heat a boiling HAuCl₄ solution and rapidly add trisodium citrate under vigorous stirring. Continue heating until the solution turns deep red, indicating nanoparticle formation. Characterize the AuNPs using UV-Vis spectroscopy (SPR peak ~520 nm), Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) for size, and Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) for morphology [7].

- Functionalization: Functionalize the citrate AuNPs with an alkanethiol-modified DNA probe specific to the conserved region of the HCV 5'UTR using the salt-aging process. Incubate the AuNPs with the thiolated probe and gradually increase the salt concentration (e.g., with NaCl) to stabilize the nanoparticles against aggregation during probe conjugation. Purify the functionalized "nanoprobes" from excess unbound probes using centrifugation or size-exclusion chromatography [7].

2. Synthesis of Cationic AuNPs (Aggregation Inducers):

- Cysteamine AuNPs: Synthesize using a sodium borohydride reduction method. Mix HAuCl₄ with cysteamine hydrochloride, then add ice-cold NaBH₄ under vigorous stirring. The cysteamine cap provides a positive surface charge [7].

- CTAB AuNPs: Synthesize using a seed-mediated growth method. A seed solution is prepared by adding NaBH₄ to a mixture of CTAB and HAuCl₄. This seed solution can be used directly. CTAB forms a bilayer on the AuNP surface, conferring a strong positive charge [7].

- Characterize both cationic AuNPs using DLS for size and zeta potential measurements to confirm positive surface charge [7].

3. RNA Extraction and Assay Execution:

- RNA Extraction: Extract total RNA from clinical serum samples using a commercial kit (e.g., Promega SV-total RNA isolation system or QIAamp viral RNA kit) [7].

- Aggregation Assay: Mix the functionalized citrate nanoprobes with the extracted RNA sample. Then, add the cationic AuNPs (cysteamine or CTAB-capped) to the mixture. If the target HCV RNA is present, it binds to the nanoprobes. The cationic AuNPs then electrostatically induce the aggregation of the RNA-nanoprobe complexes.

- Detection and Quantification: The positive result is indicated by a visible color change from red (dispersed) to blue/purple (aggregated). Quantification can be achieved by measuring the absorbance ratio (A₅₂₀/A₆₅₀) via UV-Vis spectroscopy, which correlates with the degree of aggregation and thus the target concentration [7].

Figure 2: Experimental workflow for the AuNP-based HCV RNA detection assay.

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists essential materials and their functions for the nanoparticle-based biosensing experiments cited.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Featured Biosensing Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role in Experiment | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) [7] | Signal transducer; Colorimetric label based on SPR aggregation. | HCV RNA detection [7] |

| Thiol-Modified DNA/RNA Probes [7] | Biorecognition element; Covalently anchors to AuNP surface for target capture. | Functionalizing AuNPs for HCV RNA binding [7] |

| Cysteamine / CTAB [7] | Capping agents for synthesizing positively charged cationic AuNPs. | Inducing aggregation of probe-decorated AuNPs [7] |

| HaloTag Protein (HT7) [6] | Self-labeling protein module; enables specific, covalent labeling with synthetic fluorophores. | Chemogenetic FRET biosensors (ChemoX platform) [6] |

| Silicon Rhodamine (SiR) / TMR [6] | Synthetic fluorophore; serves as FRET acceptor with superior photophysical properties. | Labeling HaloTag in ChemoG5 for high-efficiency FRET [6] |

| Fluorescent Proteins (eGFP, mScarlet) [6] | Genetically encoded FRET donors. | Constituting the donor side of the ChemoX FRET pairs [6] |

| Transition Metal Oxides (MXenes) [4] | Non-biological recognition element; provides high stability and electrical conductivity. | Electrochemical biosensing in complex media [4] |

The strategic leveraging of optical, electrochemical, and magnetic properties through nanotechnology represents the forefront of biosensor development. The core modalities discussed—each enhanced by the unique advantages of nanomaterials—enable the creation of powerful diagnostic tools that meet the stringent demands of modern healthcare and environmental monitoring. Optical sensors offer versatility and high sensitivity; electrochemical sensors provide portability and ease of miniaturization; and magnetic sensors allow for robust operation in complex matrices. The continuous refinement of these platforms, guided by detailed experimental protocols and a deep understanding of nanomaterial interactions, is paving the way for a new generation of biosensors. These devices promise not only to improve early disease detection and monitoring of non-communicable diseases but also to make advanced diagnostic capabilities accessible on a global scale, ultimately transforming patient outcomes and public health.

The integration of nanotechnology has fundamentally transformed the landscape of biosensor design, enabling unprecedented levels of sensitivity, specificity, and portability for diagnostic applications. This whitepaper provides a comprehensive technical analysis of four critical nanoparticle classes—quantum dots, metallic nanoparticles, carbon-based nanomaterials, and polymeric nanocomposites—detailing their unique properties, functional mechanisms, and experimental protocols for biosensor integration. Designed for researchers and drug development professionals, this guide synthesizes current advancements to facilitate the rational selection and application of these materials in next-generation biosensing platforms. The convergence of these nanomaterials is pushing the frontiers of diagnostic science, creating powerful tools for precise medical diagnostics, environmental monitoring, and food safety analysis [1] [8].

Nanoparticles, defined by their nanoscale dimensions (typically 1-100 nm), exhibit unique physical and chemical properties that differ fundamentally from their bulk counterparts. These properties—including high surface area-to-volume ratio, quantum confinement effects, tunable surface chemistry, and enhanced catalytic activity—make them ideal transducers and signal amplifiers in biosensing systems [9]. The strategic incorporation of nanomaterials into biosensors has addressed critical limitations of conventional diagnostic platforms, particularly in achieving rapid, sensitive, and accurate detection of biomarkers at point-of-care settings [1] [10]. This section establishes the fundamental principles governing nanoparticle behavior in biological detection systems and their role in advancing analytical science.

The global push toward personalized medicine and decentralized testing has accelerated the demand for biosensors that combine laboratory-grade accuracy with field-deployable convenience. Nanoparticles are pivotal to this paradigm shift, enabling the development of portable devices that perform complex analyses in resource-limited environments [1]. For instance, nanoparticle-enabled portable biosensors have demonstrated remarkable capabilities in early detection and monitoring of non-communicable diseases such as diabetes, cardiovascular disorders, and cancer, providing a cost-effective solution for improving healthcare outcomes worldwide [1]. The following sections explore the distinct advantages and implementation strategies for each major class of nanoparticles in modern biosensor design.

Quantum Dots (QDs) in Biosensing

Properties and Classification

Quantum dots are luminescent semiconductor nanocrystals (typically 2-10 nm) characterized by quantum confinement effects that govern their exceptional optical and electronic properties [11] [12]. The size-tunable fluorescence of QDs allows precise control over their emission spectra—a single excitation source can simultaneously activate QDs of different sizes, emitting distinct, narrow, and symmetric fluorescence bands. This property makes them exceptionally valuable for multiplexed detection systems. QDs are primarily classified into two categories: semiconductor QDs (e.g., CdSe, CdTe, PbS) and carbon-based QDs (graphene quantum dots and carbon nanodots), each offering distinct advantages for biosensing applications [11] [12].

Semiconductor QDs exhibit high molar extinction coefficients, remarkable photostability, and high quantum yield, outperforming conventional organic dyes that suffer from rapid photobleaching. Carbon-based QDs, while generally less luminescent, offer superior biocompatibility, lower toxicity, and abundant surface functional groups (-COOH, -OH) that facilitate bioconjugation [11] [10]. The versatile surface chemistry of QDs allows functionalization with various biomolecular recognition elements (antibodies, aptamers, enzymes), creating robust probes for specific target detection in complex biological matrices [12].

Biosensing Mechanisms and Applications

QDs function primarily as signal transducers in biosensors, converting molecular recognition events into measurable optical or electrical signals. In fluorescence-based detection, QD emission intensity, lifetime, or energy transfer efficiency changes upon binding with the target analyte. Common mechanisms include fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET), photoinduced electron transfer (PET), and fluorescence quenching/enhancement [12]. For electrochemical detection, QDs serve as electrocatalysts or electrochemical labels, with their quantum confinement properties influencing electron transfer kinetics [11].

Table 1: Quantum Dots Biosensing Applications and Performance Metrics

| Analyte Category | Specific Target | QD Type | Biosensing Mechanism | Limit of Detection | Linear Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antibiotics | Various classes | CdTe, GQDs | FL quenching/immunoassay | Low nM range | nM-μM |

| Pesticides | Organophosphates | CdSe/ZnS | Enzyme inhibition | Sub-nM to pM | pM-nM |

| Pathogens | E. coli, Salmonella | Carbon dots | Electrochemical aptasensor | 10-100 CFU/mL | 10²-10⁶ CFU/mL |

| Cancer Biomarkers | PSA, CEA | Graphene QDs | EIS, DPV | Femtomolar | fM-pM |

Recent applications demonstrate the exceptional capabilities of QD-based biosensors. In food safety analysis, QD-FRET sensors have detected antibiotic residues with limits of detection in the nanomolar range, significantly below regulatory thresholds [12]. For pathogen detection, carbon dot-integrated electrochemical aptasensors have achieved sensitivity as low as 10 CFU/mL for E. coli and Salmonella in contaminated food samples [12]. In cancer diagnostics, graphene quantum dots functionalized with aptamers have enabled femtomolar detection of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) in serum samples using electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) and differential pulse voltammetry (DPV) [8].

Experimental Protocol: QD-Aptasensor Fabrication for Protein Detection

Objective: Develop a fluorescence-based QD-aptasensor for specific protein detection (e.g., thrombin) using FRET mechanism.

Materials:

- CdSe/ZnS core-shell QDs (emission 550 nm)

- Cy3-labeled aptamer specific to target protein

- 1-Ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide (EDC)/N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS)

- Phosphate buffer saline (PBS, 0.01 M, pH 7.4)

- Purification columns (e.g., Sephadex G-25)

- Spectrofluorometer

- Centrifugation equipment

Procedure:

- QD Functionalization: Activate carboxylated QDs (2 nM in PBS) with EDC (50 mM) and NHS (25 mM) for 30 minutes with gentle shaking.

- Aptamer Conjugation: Purify activated QDs using centrifugation filters (10 kDa MWCO) and resuspend in PBS. Add Cy3-labeled aptamer (200 nM) to QD solution and incubate for 2 hours at room temperature with continuous mixing.

- Purification: Remove unbound aptamers using gel filtration chromatography (Sephadex G-25 column) with PBS as eluent. Collect the colored fraction containing QD-aptamer conjugates.

- Sensor Characterization: Measure fluorescence emission spectrum (excitation at 450 nm) of the QD-aptamer conjugate to establish baseline FRET efficiency (QD emission at 550 nm, Cy3 emission at 570 nm).

- Target Detection: Incubate QD-aptamer conjugate with varying concentrations of target protein (0-100 nM) for 30 minutes. Measure fluorescence emission spectrum after each incubation.

- Data Analysis: Calculate FRET efficiency as the ratio of Cy3 acceptor emission (570 nm) to QD donor emission (550 nm). Plot FRET efficiency against protein concentration to generate calibration curve.

Validation: Confirm specificity using non-target proteins (e.g., BSA, lysozyme) and assess reproducibility through triplicate measurements.

Metallic Nanoparticles in Biosensing

Types and Properties

Metallic nanoparticles, including noble metals (gold, silver, platinum) and transition metals (copper, iron), possess exceptional physicochemical properties that render them invaluable for biosensing applications. Their most distinctive feature is surface plasmon resonance (SPR), a collective oscillation of conduction electrons upon interaction with specific wavelengths of light, resulting in intense absorption and scattering [9] [13]. Gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) exhibit tunable SPR in the visible range (520-580 nm) with vibrant color changes based on size, shape, and interparticle distance, forming the basis for colorimetric detection systems. Silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) display stronger plasmonic effects but lower stability, often incorporated into polymer matrices to enhance functionality [13].

Recent emphasis on sustainable nanotechnology has promoted green synthesis approaches using biological sources (plant extracts, fungi, bacteria) as reducing and stabilizing agents [9] [14]. These methods offer eco-friendly, cost-effective alternatives to conventional chemical synthesis, producing nanoparticles with enhanced biocompatibility and diverse morphologies. Green-synthesized metal nanoparticles (G-MNPs) have demonstrated excellent performance in biomedical applications while minimizing environmental impact [14]. Magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs), particularly iron oxide (Fe₃O₄), provide additional functionality through remote manipulation using external magnetic fields, enabling sample concentration and separation to enhance sensitivity [15].

Biosensing Mechanisms and Applications

Metallic nanoparticles enhance biosensing through multiple mechanisms. AuNPs and AgNPs serve as excellent colorimetric labels due to distance-dependent aggregation that induces visible color changes from red to blue [9]. They also function as electrochemical catalysts, enhancing electron transfer in redox reactions and significantly lowering detection limits. MNPs enable efficient magnetic separation and concentration of target analytes from complex matrices, reducing background interference and improving signal-to-noise ratio [15]. The high surface area of metallic nanoparticles allows dense immobilization of recognition elements (antibodies, aptamers), increasing binding capacity and sensor response.

Table 2: Metallic Nanoparticles in Biosensing: Applications and Performance

| Nanoparticle Type | Synthesis Method | Functionalization | Analyte | Detection Method | LOD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gold (AuNPs) | Citrate reduction | Anti-PSA antibody | PSA | Colorimetric/LSPR | 0.1 ng/mL |

| Silver (AgNPs) | Green synthesis (plant extract) | Aptamer | Thrombin | Electrochemical (DPV) | 5 pM |

| Iron Oxide (Fe₃O₄ MNPs) | Co-precipitation | Streptavidin | E. coli | Fluorescence (after separation) | 10 CFU/mL |

| Au-Fe₃O₄ (Hybrid) | Thermal decomposition | DNA probe | miRNA-21 | SERS & Electrochemical | 0.1 fM |

In practice, MNP-based aptasensors have revolutionized pathogen detection for food safety. A recent platform for monitoring foodborne bacteria employed MNPs conjugated with specific aptamers against Salmonella and Listeria, achieving detection limits of 10-100 CFU/mL in contaminated samples through magnetic concentration followed by optical or electrochemical detection [15]. For medical diagnostics, AgNP-polymer nanocomposites (AgNP-PNCs) have been integrated into electrochemical biosensors for cancer biomarker detection, leveraging their catalytic properties to amplify signals and achieve femtomolar sensitivity [13]. The antimicrobial properties of AgNPs also provide self-sterilizing capabilities to biosensor surfaces, preventing biofilm formation and enhancing operational stability in complex biological fluids [13].

Experimental Protocol: Green Synthesis of AgNPs and Sensor Fabrication

Objective: Eco-friendly synthesis of silver nanoparticles using plant extract and application in electrochemical biosensor for cancer biomarker detection.

Materials:

- Fresh plant leaves (Azadirachta indica or similar)

- Silver nitrate (AgNO₃) solution (1 mM)

- Whatman filter paper No. 1

- Phosphate buffer (0.1 M, pH 7.4)

- Anti-CEA antibody and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) standards

- Glassy carbon electrode (GCE)

- Electrochemical workstation

Procedure:

- Plant Extract Preparation: Wash 10 g of fresh leaves thoroughly with distilled water, dry, and grind with 100 mL of distilled water. Filter the mixture through Whatman filter paper and collect the supernatant.

- Green Synthesis of AgNPs: Mix 10 mL of plant extract with 90 mL of 1 mM AgNO₃ solution. Heat at 60°C for 30 minutes with continuous stirring. Observe color change from pale yellow to reddish-brown, indicating AgNP formation.

- Nanoparticle Characterization: Confirm AgNP synthesis by UV-Vis spectroscopy (SPR peak at ~420 nm), TEM (size and morphology), and FTIR (identifying capping biomolecules).

- Electrode Modification: Polish GCE with alumina slurry (0.05 μm), rinse with distilled water, and dry. Drop-cast 10 μL of AgNP solution onto GCE surface and dry at room temperature.

- Antibody Immobilization: Incubate AgNP-modified GCE with 10 μL of anti-CEA antibody (100 μg/mL) for 2 hours at 4°C. Wash with PBS to remove unbound antibodies.

- Electrochemical Measurement: Employ differential pulse voltammetry (DPV) in [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻ solution. Measure current decrease after incubating with CEA standards (0-100 ng/mL) for 30 minutes, due to immunocomplex formation hindering electron transfer.

- Calibration: Plot current response versus CEA concentration to establish standard curve.

Validation: Assess cross-reactivity with other cancer biomarkers (e.g., AFP, PSA) and test real serum samples spiked with known CEA concentrations.

Carbon-Based Nanomaterials in Biosensing

Types and Properties

Carbon nanomaterials (CNMs) represent a versatile class of nanostructures with exceptional electrical, mechanical, and thermal properties ideal for biosensing applications. This family includes graphene and its derivatives (graphene oxide, reduced graphene oxide), carbon nanotubes (single-walled and multi-walled), carbon nanodots, graphitic carbon nitride, and fullerenes [10]. Graphene exhibits remarkable electrical conductivity (∼200,000 cm² V⁻¹ s⁻¹), high theoretical specific surface area (2630 m² g⁻¹), and exceptional mechanical strength, making it an excellent transducer material [10]. Carbon nanotubes combine unique one-dimensional tubular structure with high aspect ratio, facilitating electron transfer and providing large surface area for biomolecule immobilization.

The versatile surface chemistry of CNMs enables covalent and non-covalent functionalization with various biomolecular recognition elements. Oxygen-containing functional groups (carboxyl, hydroxyl, epoxy) on graphene oxide facilitate further modification with proteins, nucleic acids, and polymers through EDC/NHS chemistry or π-π stacking interactions [10]. Carbon nanodots and graphene quantum dots exhibit photoluminescence with high quantum yield and excellent photostability, serving as effective alternatives to semiconductor quantum dots with potentially lower toxicity [10]. The rich surface chemistry and biocompatibility of CNMs have established them as fundamental building blocks in modern electrochemical and optical biosensors.

Biosensing Mechanisms and Applications

CNMs enhance biosensing performance through multiple mechanisms. In electrochemical biosensors, they facilitate electron transfer between redox species and electrode surfaces, increase electroactive surface area, and can be functionalized with electrocatalytic elements to enhance signal amplification [10]. For optical biosensors, CNMs serve as efficient quenchers in FRET-based assays, fluorescent labels, or signal amplifiers in surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS). Their large surface area allows high-density immobilization of recognition elements, improving binding capacity and detection sensitivity.

A prominent application of CNMs is in neurodegenerative disease diagnostics. Recent advances in carbon nanomaterial-based electrochemical biosensors have demonstrated exceptional capability for detecting Alzheimer's disease biomarkers (Aβ, tau protein) in clinical samples [10]. For instance, an aptamer-functionalized graphene platform achieved limits of detection in the femtomolar to picogram per milliliter range for Aβ oligomers in human serum, with high selectivity against interferents like BSA, glucose, uric acid, and dopamine [10]. CNM-based biosensors typically exhibit linear ranges spanning 2-3 orders of magnitude (e.g., from femtomolar to picomolar), covering clinically relevant concentrations for early disease detection [10].

Experimental Protocol: CNT-Based Electrochemical Aptasensor for Alzheimer's Biomarker

Objective: Develop a carbon nanotube-based electrochemical aptasensor for ultrasensitive detection of amyloid-beta (Aβ) biomarker.

Materials:

- Carboxylated multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs)

- 1-pyrenebutanoic acid succinimidyl ester (PBSE)

- Amine-modified aptamer specific to Aβ

- N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF)

- Screen-printed carbon electrode (SPCE)

- Electrochemical workstation

- Aβ peptide standards and control proteins

Procedure:

- MWCNT Functionalization: Disperse carboxylated MWCNTs (1 mg/mL) in DMF by sonication for 30 minutes. Add PBSE (2 mM) and incubate for 2 hours to form π-π stacking.

- Aptamer Immobilization: Separate MWCNT-PBSE complex by centrifugation and resuspend in PBS. Add amine-modified aptamer (1 μM) and incubate overnight at 4°C to form amide bonds.

- Electrode Modification: Drop-cast 5 μL of MWCNT-aptamer suspension on SPCE and dry at room temperature.

- Sensor Blocking: Treat electrode with 1% BSA for 1 hour to block non-specific binding sites.

- Electrochemical Measurement: Incubate modified electrode with Aβ standards (0-1000 pg/mL) for 30 minutes. Perform electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) in 5 mM [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻ solution with frequency range 0.1-100,000 Hz.

- Data Analysis: Calculate charge transfer resistance (Rct) from Nyquist plots. Plot ΔRct versus Aβ concentration to generate calibration curve.

Validation: Test sensor specificity with control proteins (α-synuclein, tau), reproducibility with 5 different electrodes, and stability over 4-week period with storage at 4°C.

Polymeric Nanoparticles and Nanocomposites

Types and Properties

Polymeric nanoparticles and nanocomposites combine the versatility of polymers with the enhanced functionality of nanomaterials, creating sophisticated systems for biosensing applications. This category includes natural polymers (chitosan, alginate, cellulose), synthetic polymers (polyaniline, polypyrrole, polylactic acid), and their composites with other nanomaterials [13]. Polymeric matrices provide mechanical stability, controlled porosity, and abundant functional groups for biomolecule immobilization. When integrated with functional nanoparticles like AgNPs, they form nanocomposites with synergistic properties—the polymer ensures structural integrity and biocompatibility, while the embedded nanoparticles contribute catalytic, optical, or electrical enhancements [13].

Silver nanoparticle-polymer nanocomposites (AgNP-PNCs) represent a particularly advanced class of materials, combining the potent antimicrobial properties of AgNPs with the structural versatility of polymers [13]. These composites enable controlled release of silver ions, mitigate cytotoxic effects associated with free AgNPs, and prevent nanoparticle aggregation. The polymer matrix acts as a stabilizing medium, allowing functional modifications to tailor mechanical, chemical, and biological properties for specific biomedical applications [13]. Other notable polymeric nanocomposites include chitosan-gold nanoparticles for electrochemical sensing and polypyrrole-carbon nanotube hybrids for conductive biosensing platforms.

Biosensing Mechanisms and Applications

Polymeric nanocomposites enhance biosensing through multiple mechanisms. Conducting polymers like polyaniline and polypyrrole facilitate electron transfer in electrochemical detection, while their swelling properties can be exploited in gravimetric sensors. The tunable porosity of polymeric matrices enables size-selective detection, excluding interferents while allowing analyte access to recognition elements. In AgNP-PNCs, the silver nanoparticles provide catalytic activity for signal amplification in electrochemical sensors and plasmonic properties for optical detection [13].

These materials have found significant applications in wearable biosensors and implantable devices. Recent advances in implantable sensor technologies have leveraged flexible, bioresorbable, and multimodal polymeric nanocomposites for chronic monitoring of physiological parameters [16]. For example, internal ion-gated organic electrochemical transistors (IGTs) integrated with flexible polymers have enabled precise neural interfacing with minimal tissue damage [16]. In cancer diagnostics, AgNP-PNCs have been employed in electrochemical biosensors for detecting prostate-specific antigen (PSA) and cytokeratin fragment antigen 21-1 (CYFRA 21-1), achieving detection limits in the femtomolar range through signal amplification [8] [13]. The antimicrobial properties of AgNP-PNCs also prevent biofilm formation on implantable sensors, extending their functional lifetime in biological environments [13].

Comparative Analysis and Research Reagents

Performance Comparison Across Nanoparticle Classes

The optimal selection of nanoparticles for specific biosensing applications requires careful consideration of their respective advantages and limitations. Quantum dots excel in multiplexed optical detection due to their size-tunable fluorescence and photostability but may present toxicity concerns for in vivo applications. Metallic nanoparticles offer versatile colorimetric detection and strong plasmonic effects but can suffer from aggregation and stability issues. Carbon nanomaterials provide exceptional electrical conductivity and large surface area for electrochemical biosensing but may exhibit reproducibility challenges due to difficulties in achieving homogeneous dispersion [10]. Polymeric nanocomposites offer outstanding biocompatibility and functional flexibility but may have limited conductivity unless combined with other nanomaterials.

Table 3: Comprehensive Comparison of Nanoparticle Classes for Biosensing

| Parameter | Quantum Dots | Metallic NPs | Carbon Nanomaterials | Polymeric Nanocomposites |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Strengths | Multiplexing, high photostability | Strong plasmonic effects, colorimetric detection | High conductivity, large surface area | Biocompatibility, controlled release |

| Detection Limits | pM-fM (optical) | fM-pM (colorimetric), pM (electrochemical) | fM-pM (electrochemical) | nM-pM (varies with composite) |

| Stability | Moderate (potential degradation) | Moderate (aggregation issues) | High (chemical inertness) | High (tunable polymer properties) |

| Biocompatibility | Variable (depends on composition) | Moderate (cytotoxicity concerns) | High (carbon dots, graphene) | Excellent (especially natural polymers) |

| Functionalization Ease | Moderate (surface chemistry dependent) | Excellent (thiol, amine binding) | Excellent (abundant functional groups) | Excellent (versatile chemistry) |

| Cost Considerations | Moderate to high | High (precious metals) | Moderate (scalable production) | Low to moderate |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table summarizes key reagents and materials essential for experimental work with nanoparticle-based biosensors, compiled from methodologies across the cited research.

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Nanoparticle Biosensor Development

| Reagent/Material | Supplier Examples | Key Applications | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carboxylated QDs (CdSe/ZnS) | Thermo Fisher, Sigma-Aldrich | Fluorescence sensing, FRET assays | Suspend in PBS, avoid freeze-thaw cycles, protect from light |

| Citrate-capped AuNPs (20 nm) | nanoComposix, Cytodiagnostics | Colorimetric assays, LFA, electrode modification | Store at 4°C, characterize by UV-Vis (SPR ~520-530 nm) |

| Carboxylated MWCNTs | Sigma-Aldrich, Cheap Tubes | Electrode modification, aptasensors | Sonicate >30 min for proper dispersion, functionalize via EDC/NHS |

| AgNP-Polymer Composite | Specific research formulations | Antimicrobial coatings, electrochemical sensors | Characterize silver ion release profile for consistent performance |

| EDC/NHS Coupling Kit | Thermo Fisher, Sigma-Aldrich | Biomolecule immobilization on NPs | Fresh preparation recommended, optimize molar ratio for each NP |

| Screen-Printed Electrodes (SPEs) | Metrohm, DropSens, PalmSens | Electrochemical biosensing | Pre-treatment improves reproducibility, check batch consistency |

| Aptamer Sequences | Integrated DNA Technologies, Sigma | Specific target recognition | HPLC purification, verify secondary structure for functionality |

Visualization of Biosensor Design Principles

Workflow for Nanoparticle-Based Biosensor Development

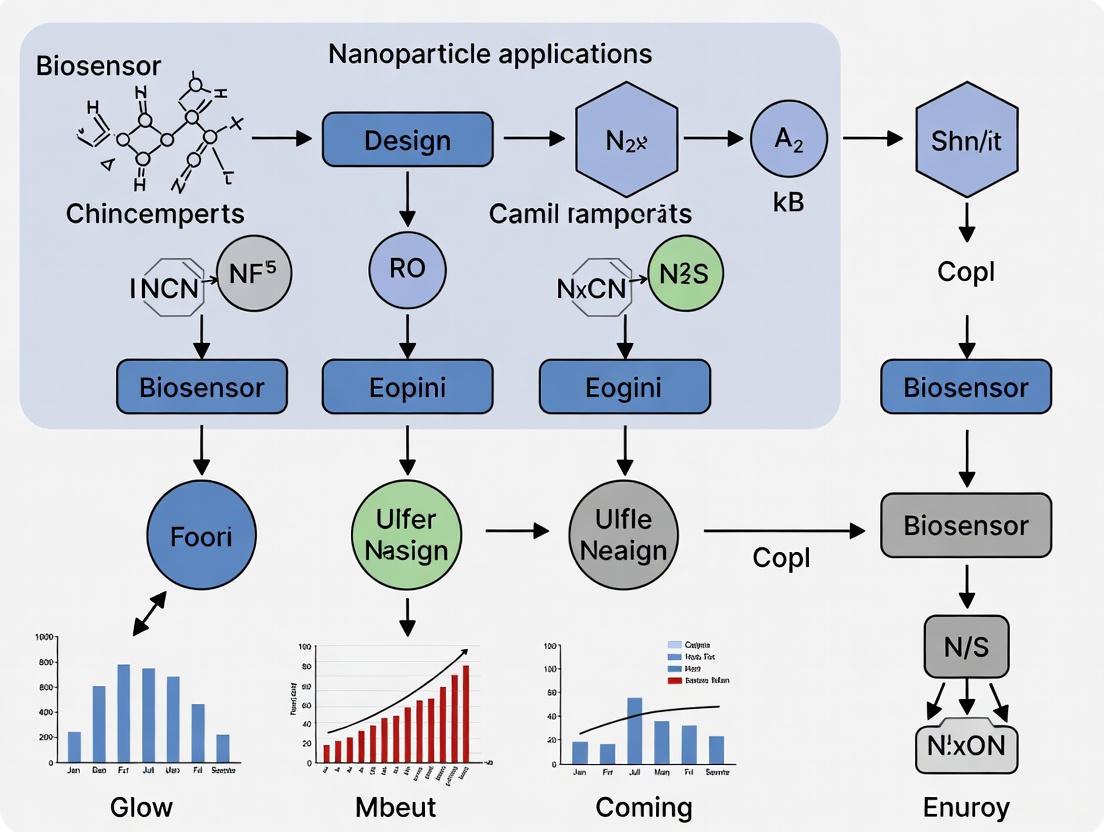

The diagram below illustrates the systematic development process for nanoparticle-based biosensors, from material selection to performance validation.

Nanoparticle Functionalization Mechanisms

This diagram details the primary chemical strategies for functionalizing nanoparticles with biological recognition elements.

The strategic integration of quantum dots, metallic nanoparticles, carbon-based nanomaterials, and polymeric variants has created a powerful toolkit for advancing biosensor technology. Each class offers unique advantages that address specific challenges in sensitivity, specificity, multiplexing, and point-of-care applicability. The continuous refinement of synthesis methods, particularly green approaches for metallic nanoparticles and functionalization strategies for carbon nanomaterials, promises enhanced performance and biocompatibility. Future developments will likely focus on multimodal nanoparticles that combine advantageous properties from different classes, intelligent sensors with built-in signal processing, and increasingly sophisticated point-of-care devices for personalized medicine. As characterization techniques improve and standardized protocols emerge, nanoparticle-based biosensors will play an increasingly vital role in global healthcare, environmental monitoring, and food safety systems.

In the pursuit of advanced biosensors, nanoparticles have emerged as unparalleled transducers, capable of converting molecular recognition events into quantifiable optical signals. The core of this capability lies in two dominant transduction mechanisms: plasmon resonance and fluorescent signal amplification. These mechanisms leverage the unique physicochemical properties of nanomaterials to achieve detection sensitivity that often surpasses conventional analytical methods. Plasmonic phenomena, arising from the collective oscillation of electrons at metal-dielectric interfaces, provide exquisitely sensitive detection of refractive index changes in the local nanoenvironment [17] [18]. Complementarily, fluorescent mechanisms utilize precise nanomaterial engineering to generate highly amplified, specific signals through various energy transfer pathways [19]. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these mechanisms is paramount for designing next-generation biosensors with applications ranging from point-of-care diagnostics to single-molecule detection. This technical guide examines the fundamental principles, experimental implementations, and cutting-edge advancements that define the current state of nanomaterial-powered biosensing platforms, with particular emphasis on their integration within biomedical research and therapeutic development.

Fundamentals of Plasmonic Transduction Mechanisms

Plasmonic transduction mechanisms exploit the unique interactions between light and free electrons in metallic nanostructures to detect biological binding events. The foundational principle involves the excitation of surface plasmons—coherent oscillations of conduction electrons at metal-dielectric interfaces—which generate intense electromagnetic fields highly sensitive to minute changes in their local environment [18]. This sensitivity forms the basis for label-free detection of biomolecular interactions.

Two primary plasmonic configurations dominate biosensing applications: Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) and Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance (LSPR). SPR occurs at continuous metal films (typically gold or silver) and generates propagating electromagnetic waves along the metal-dielectric interface. The resonance condition is highly dependent on the refractive index of the dielectric medium adjacent to the metal surface, following the relationship: √εₚ sin θᵣₑₛ = √[(εₘε𝒹)/(εₘ + ε𝒹)], where εₚ, εₘ, and ε𝒹 represent the dielectric constants of the prism/m substrate, metal, and dielectric layer, respectively [18]. In contrast, LSPR occurs in discrete metallic nanoparticles, where electrons oscillate locally rather than propagating along a surface. LSPR exhibits intense, size- and shape-dependent absorption and scattering spectra, providing enhanced spatial resolution and simpler instrumental requirements compared to SPR [17].

The practical implementation of these mechanisms has spawned several advanced spectroscopic techniques. Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering (SERS) amplifies the inherently weak Raman signals by many orders of magnitude when analyte molecules are adsorbed onto roughened metal surfaces or nanoparticles, enabling single-molecule detection [20]. Surface-Enhanced Fluorescence (SEF) utilizes the plasmonic near-field to enhance both excitation rates and emission quantum yields of fluorophores positioned at optimal distances from metal surfaces [17]. Surface-Enhanced Infrared Absorption (SEIRA) similarly exploits plasmonic enhancement to strengthen the typically weak signals in infrared spectroscopy [17]. The following diagram illustrates the fundamental working principle of an SPR biosensor.

The exceptional utility of plasmonic biosensors in viral diagnostics exemplifies their practical significance. These sensors have been successfully configured to detect various viral targets using multiple recognition elements, including antibodies, DNA aptamers, whole antigens, infected cells, and molecularly imprinted polymers [18]. This versatility, combined with their label-free operation and real-time monitoring capabilities, positions plasmonic transduction as a cornerstone technology in modern biosensor design, particularly for applications requiring high sensitivity and minimal sample preparation.

Fluorescent Signal Amplification Mechanisms

Fluorescent transduction mechanisms in nanobiosensors employ fundamentally different principles than plasmonic methods, relying on the emission of light from excited states rather than scattering or absorption. The core of a fluorescent probe consists of three integral components: a recognition unit that specifically binds to the target analyte, a fluorescence unit (fluorophore) that generates the optical signal, and a connector/linker that spatially organizes these elements [19]. The sophisticated engineering of these components enables detection limits reaching the single-molecule level, making fluorescence amplification particularly valuable for early disease diagnosis where biomarker concentrations are extremely low.

Four primary mechanisms govern fluorescent signal amplification in nanobiosensors, each with distinct operational principles and application domains. Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) involves non-radiative energy transfer between two light-sensitive molecules (donor and acceptor) through dipole-dipole interactions. The efficiency of this transfer exhibits an inverse sixth-power dependence on the distance between donor and acceptor, typically requiring separation under 10 nanometers for effective operation [19]. FRET-based probes employ various strategic designs, including target-induced alteration of acceptor properties, spatial blocking to increase donor-acceptor distance, disruption of donor-acceptor connection upon target binding, or direct utilization of the target as the energy acceptor.

Photoinduced Electron Transfer (PET) operates through electron exchange between the fluorophore (donor) and a recognition unit (acceptor). This mechanism manifests in two distinct forms: reductive PET, where electrons transfer from the recognizer's highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) to the fluorophore's HOMO, and oxidative PET, where electrons transfer from the fluorophore's lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) to the recognizer's LUMO [19]. In practical operation, fluorescence remains quenched until target binding occurs, which restricts electron transfer and restores emission—a mechanism particularly effective for detecting metal ions that coordinate with electron-donating atoms.

Intramolecular Charge Transfer (ICT) utilizes a "push-pull" electronic system comprising an electron donor and acceptor connected through a conjugated bridge. Modifying the electron-donating or withdrawing capabilities of these components directly influences the energy gap between HOMO and LUMO orbitals, resulting in predictable shifts in absorption and emission wavelengths [19]. This sensitivity to electronic perturbations makes ICT-based probes exceptionally responsive to environmental changes and binding events.

Aggregation-Induced Luminescence (AIE) represents a more recently discovered phenomenon where certain fluorophores exhibit weak emission in dispersed states but intense fluorescence upon aggregate formation. This mechanism counters the traditional aggregation-caused quenching effect and provides particularly robust signaling for targets that induce nanoparticle aggregation [17]. The following diagram illustrates the key fluorescent amplification mechanisms.

The implementation of these mechanisms relies heavily on advanced fluorescent nanomaterials including quantum dots (QDs), metal nanoclusters (MNCs), carbon dots (CDs), and metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) [19]. Each material offers distinct advantages: QDs provide size-tunable emission and exceptional photostability; MNCs offer molecule-like properties with enhanced biocompatibility; CDs deliver low toxicity and straightforward functionalization; MOFs present extraordinary surface areas and structural diversity. By manipulating parameters such as morphology, size, and surface chemistry, researchers can optimize these nanomaterials for specific amplification mechanisms and application requirements, creating a versatile toolkit for fluorescent biosensor design.

Comparative Analysis of Transduction Mechanisms

The selection of an appropriate transduction mechanism represents a critical design consideration that directly influences biosensor performance, application suitability, and implementation requirements. The quantitative performance metrics across different transduction mechanisms reveal distinct operational profiles, as summarized in the following table.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Plasmonic and Fluorescent Transduction Mechanisms

| Transduction Mechanism | Typical Detection Limit | Key Advantages | Inherent Limitations | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPR | ~1 pg/mm² [18] | Label-free, real-time kinetics, reusable | Mass transport limitations, steric hindrance | Biomolecular interaction analysis, antibody characterization |

| LSPR | nM-pM range [17] | Label-free, simpler instrumentation, higher spatial resolution | Lower sensitivity than SPR for bulk RI changes | Point-of-care diagnostics, environmental monitoring |

| SERS | Single-molecule [20] | Exceptional specificity, molecular fingerprinting | Substrate reproducibility, complex spectral interpretation | Pathogen identification, toxicology analysis |

| SEF | Enhanced up to 1000-fold [17] | Combines specificity of fluorescence with plasmonic enhancement | Precise distance requirements (~10-20 nm) | Cellular imaging, high-throughput screening |

| FRET | Concentration-dependent | High spatial resolution, ratiometric measurements | Spectral crosstalk, limited donor-acceptor pairs | Molecular beacons, protein conformational studies |

| PET | Varies with probe design | High signal-to-noise ratio, reversible sensing | Susceptible to interferents, complex probe design | Ion sensing, small molecule detection |

Beyond these fundamental metrics, practical implementation considerations significantly influence mechanism selection. Plasmonic techniques generally excel in label-free scenarios where monitoring binding kinetics in real-time is prioritized, while fluorescent mechanisms typically provide superior sensitivity and specificity for detecting low-abundance analytes, albeit often requiring more complex probe design [17] [18] [19]. The recent trend toward multimodal sensing platforms that combine multiple transduction mechanisms in a single device leverages the complementary strengths of different approaches, enabling more comprehensive analytical characterization and cross-validation of results.

The physical properties of nanomaterials themselves play a determining role in transduction efficiency. For plasmonic mechanisms, nanoparticle composition, size, shape, and local environment dramatically influence resonance wavelength and field enhancement factors [21]. For fluorescent mechanisms, quantum yield, photostability, and emission profile determine detection sensitivity and practical utility [19]. This structure-function relationship underscores the importance of nanomaterial engineering in optimizing biosensor performance, with advanced synthesis techniques enabling precise control over these critical parameters.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Implementation of SPR-Based Viral Detection

The application of SPR biosensing for viral detection exemplifies a well-established methodology with clearly defined protocols. The experimental workflow begins with sensor chip functionalization, typically employing a gold-coated glass substrate thoroughly cleaned with oxygen plasma or piranha solution to ensure uniform surface properties [18]. The gold surface is subsequently modified with a self-assembled monolayer (SAM)—often using alkane thiols with terminal functional groups such as carboxyl, amino, or hydroxyl—which provides attachment points for biorecognition elements. Virus-specific antibodies or DNA aptamers are then immobilized onto the functionalized surface using covalent coupling strategies such as EDC-NHS chemistry for carboxyl groups or glutaraldehyde cross-linking for amino groups [18].

The analytical measurement phase employs a microfluidic system to deliver samples and buffers across the sensor surface with precise flow control. In the classic Kretschmann configuration, polarized light passes through a high-index prism and reflects off the gold-sample interface, with a CCD detector monitoring the reflected intensity across a range of incident angles [18]. The critical measurement parameter—the resonance angle where reflected intensity reaches a minimum—shifts in response to changes in refractive index caused by biomolecular binding at the sensor surface. This angular shift (Δθ) relates directly to mass accumulation through the equation: Δθ ≈ (dn/dc) × ΔC × L, where dn/dc represents the refractive index increment, ΔC denotes the surface concentration change, and L corresponds to the characteristic electromagnetic field decay length [18].

For viral particle detection, diluted serum or buffer samples containing virus particles are injected across the functionalized sensor surface, followed by a buffer wash to remove unbound material. The resulting sensorgram—a plot of resonance angle versus time—provides quantitative information about binding kinetics (association and dissociation rates) and equilibrium binding constants, enabling both qualitative detection and quantitative characterization of viral loads [18]. Regeneration of the sensor surface for reuse typically involves injecting a mild acidic or basic solution (e.g., 10 mM glycine-HCl, pH 2.0-3.0) to disrupt antibody-antigen interactions without damaging the immobilized recognition elements.

Fabrication and Testing of HUNPs for Tumour Imaging

The development of Hydrophobic core-tunable Ultra-pH-sensitive NanoProbes (HUNPs) represents a sophisticated example of fluorescent nanosensor engineering for biomedical applications. The synthetic protocol begins with the precise copolymerization of amphiphilic block copolymers (mPEG-b-P(Ri-r-Rn)) using reversible addition-fragmentation chain-transfer (RAFT) polymerization [21]. The hydrophobic block comprises two monomer types: tertiary amine-containing ionizable monomers (Ri) such as 2-(diisopropylamino) ethyl methacrylate (iDPA-MA) and non-ionizable hydrophobic monomers (Rn) including butyl methacrylate (BMA) or hydroxyethyl methacrylate (HEMA). Systematic variation of the Ri:Rn ratio (e.g., from 100:0 to 50:50) enables precise tuning of the pH transition point (pHt) across the physiological range (pH 4.0-7.4) [21].

Nanoparticle self-assembly proceeds through the dialysis method, where the synthesized copolymer (typically 10 mg) is first dissolved in a water-miscible organic solvent (e.g., DMSO, 1 mL), then dialyzed against deionized water (1 L) using a membrane with appropriate molecular weight cutoff (e.g., 3.5-7 kDa) for 24-48 hours with multiple water changes [21]. During this process, the polymers spontaneously assemble into core-shell nanoparticles with the hydrophobic block forming the core and hydrophilic PEG chains constituting the shell. Fluorescent labeling incorporates near-infrared dyes such as indocyanine green (ICG) or Cy5 via NHS ester coupling to terminal amino groups on the PEG chain, achieving dye-to-polymer ratios of approximately 1:1 [21].

Characterization and validation employ multiple analytical techniques: dynamic light scattering (DLS) confirms nanoparticle size (typically ~30 nm at pH 7.4) and monodispersity; atomic force microscopy (AFM) measures mechanical stiffness (typically 90-130 MPa); fluorescence spectroscopy quantifies ON/OFF ratio (>100-fold) and sharpness of pH response (ΔpH10-90% < 0.25) [21]. In vitro validation includes incubation with cell cultures (e.g., 4T1 tumor cells) for 2-24 hours followed by confocal microscopy and flow cytometry to assess cellular uptake and intracellular activation. For in vivo tumor imaging, HUNPs (20 mg kg⁻¹) are administered intravenously to tumor-bearing mice, with fluorescence imaging systems capturing real-time biodistribution and tumor-specific activation over 48 hours, achieving tumor-to-normal tissue ratios of 10-27 [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The experimental implementation of plasmonic and fluorescent transduction mechanisms requires specialized materials and reagents meticulously selected for their specific functionalities. The following table catalogues essential components from recent research developments, providing researchers with a practical resource for experimental design.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Nanobiosensor Development

| Category/Reagent | Specific Examples | Function in Biosensor Design | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plasmonic Materials | Gold nanoparticles (20-100 nm), Silver nanostructures, Gold-silver alloys | LSPR substrates, SERS enhancement, SPR chip fabrication | Tunable resonance wavelength, high stability, biocompatibility |

| Fluorescent Nanomaterials | Quantum dots (CdSe/ZnS), Carbon dots, Metal nanoclusters (Au, Ag), Upconversion nanoparticles | Signal generation in fluorescent probes, FRET donors/acceptors, bioimaging | High quantum yield, photostability, size-tunable emission |

| Surface Functionalization | Polyethylene glycol (PEG) thiols, Alkane thiols (COOH, NH₂ terminated), Silane coupling agents | Biocompatibility enhancement, bioreceptor immobilization, non-fouling surfaces | Specific terminal functional groups, molecular self-assembly |

| Biorecognition Elements | Monoclonal antibodies, DNA aptamers, Peptide nucleic acids (PNAs), Molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs) | Target-specific binding, molecular recognition, sensor specificity | High affinity and selectivity, stability, reproducible production |

| Polymeric Matrix Components | mPEG-b-P(iDPA-r-BMA), PLGA, PEG-PLGA copolymers, pH-sensitive polymers | Nanoparticle formation, controlled release, environmental responsiveness | Biocompatibility, tunable degradation, stimulus-responsive properties |

| Signal Amplification Agents | Enzyme conjugates (HRP, AP), Catalytic nanoparticles, Dendrimers, Rolling circle amplification materials | Signal enhancement, detection limit improvement, multiplexing | High catalytic efficiency, structural uniformity, modular design |

This reagent toolkit enables the construction of sophisticated biosensing platforms highlighted in recent literature. For instance, the development of HUNPs specifically requires mPEG-b-P(Ri-r-Rn) copolymers with precisely controlled Ri:Rn ratios, fluorophore-conjugated derivatives for imaging, and characterization tools including DLS and fluorescence spectroscopy [21]. Similarly, SPR-based viral detection platforms utilize gold sensor chips, thiol-based coupling chemistry, virus-specific antibodies or aptamers, and microfluidic delivery systems [18]. The strategic selection and combination of these components underpin the successful implementation of transduction mechanisms in cutting-edge biosensor research.

Emerging Trends and Future Perspectives

The evolution of transduction mechanisms in biosensing continues to advance toward increasingly sophisticated, integrated, and intelligent systems. Several emerging trends highlight the future trajectory of this field, with orthogonal signal amplification representing a particularly promising approach. This strategy employs multiple complementary transduction mechanisms to achieve exponential signal enhancement, as demonstrated by hydrophobic core-tunable ultra-pH-sensitive nanoprobes (HUNPs) that combine environmental responsiveness with enhanced cellular internalization [21]. The incorporation of high-content hydrophobic monomers (e.g., 50% butyl methacrylate) in nanoparticle cores dramatically enhances cellular association by more than ten-fold, leading to significantly improved fluorescence activation in target tissues [21].

The integration of advanced nanomaterials with novel optical configurations continues to push detection boundaries. Two-dimensional materials including graphene, transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDCs), MXene, and black phosphorus (BP) are increasingly incorporated into sensors to substantially enhance sensitivity and detection performance [22]. Similarly, the development of high-throughput microplate biosensors based on 3D nanocup array structures enables rapid screening with reduced costs and increased speed compared to conventional methods [22]. These material innovations synergize with instrumental advancements in miniaturization and portability, particularly through optical fiber sensing platforms with composite sensitive membranes that offer high sensitivity and selectivity for point-of-care applications [22].

The growing incorporation of artificial intelligence and machine learning represents a paradigm shift in signal processing and data interpretation for nanobiosensors. AI-assisted signal analytics address critical challenges in complex data interpretation, particularly for techniques like SERS that generate multidimensional spectral information [20]. Machine learning algorithms enable pattern recognition in noisy datasets, improve quantification accuracy, and facilitate the development of multimodal sensing platforms that integrate multiple transduction mechanisms for comprehensive analyte characterization [5]. These computational approaches complement hardware innovations in wearable and implantable biosensors, creating closed-loop systems for continuous health monitoring and personalized medicine applications [1] [23].

Future developments will likely focus on addressing remaining challenges in signal reproducibility, biocompatibility, fabrication scalability, and long-term stability [20]. The convergence of nanotechnology, biotechnology, and information technology promises to yield increasingly sophisticated biosensing platforms with transformative potential for biomedical research, clinical diagnostics, and therapeutic development. As these technologies mature, they will undoubtedly expand the boundaries of detectable biomarkers, reduce detection limits further toward single-molecule sensitivity, and enable unprecedented insights into biological systems at the nanoscale.

Bioconjugation chemistry serves as the foundational pillar for advanced biosensor design, enabling the precise assembly of hybrid nanostructures that integrate the molecular recognition capabilities of biomolecules with the unique physicochemical properties of nanoparticles. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical examination of contemporary bioconjugation methodologies for immobilizing antibodies, aptamers, and enzymes onto nanomaterial surfaces. Within the context of biosensor research, these strategies are critical for developing devices with enhanced sensitivity, specificity, and stability for applications spanning medical diagnostics, environmental monitoring, and food safety. The guide presents structured comparisons of conjugation techniques, detailed experimental protocols, and visualization of complex relationships, providing researchers with a comprehensive framework for designing effective nano-bio interfaces.

The integration of biological recognition elements with signal transducers represents the core principle of biosensor technology. Bioconjugation—the covalent or high-affinity attachment of biomolecules to other molecules, surfaces, or particles—enables the creation of these critical interfaces [24]. In nanoparticle-powered biosensors, the conjugation strategy directly influences analytical performance by determining orientation, stability, and accessibility of immobilized biomolecules [25]. The strategic selection of anchoring methods allows researchers to preserve biological activity while maximizing signal transduction, creating sophisticated sensing platforms capable of detecting targets from small molecules to entire pathogens [26] [5].

This technical guide examines bioconjugation strategies within the broader research context of functional nanomaterial applications, focusing specifically on the immobilization of three key biorecognition elements: antibodies for immunodetection, aptamers for versatile targeting, and enzymes for catalytic signal generation. The convergence of these bioconjugation methods with nanomaterial science has catalyzed the development of biosensors with unprecedented capabilities, including single-molecule detection, real-time monitoring of cellular processes, and point-of-care diagnostic devices [27] [5].

Bioconjugation Chemistry Fundamentals

Covalent Coupling Strategies

Covalent bioconjugation forms stable, permanent linkages between biomolecules and functionalized surfaces. The efficacy of these strategies depends on the availability of specific functional groups and the reaction conditions that preserve biological activity.

Table 1: Covalent Bioconjugation Strategies

| Strategy | Reaction Mechanism | Functional Groups | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amide Coupling | Carbodiimide (EDC)-mediated amide bond formation | Carboxyl (-COOH) to primary amine (-NH₂) | Requires N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) to stabilize intermediate; may cause uncontrolled cross-linking |

| Thiol-Maleimide | Michael addition of thiol to maleimide | Thiol (-SH) to maleimide | Highly specific; maleimide hydrolysis can limit efficiency; optimal at pH 6.5-7.5 |

| Click Chemistry | Copper-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition (CuAAC) | Azide (-N₃) to alkyne (-C≡CH) | High specificity, bioorthogonal; copper catalyst may cause toxicity in biological systems |

| Glutaraldehyde Crosslinking | Schiff base formation between aldehydes and amines | Aldehyde to primary amine (-NH₂) | Simple protocol; can form heterogeneous multimers; stability concerns in aqueous solutions |

| Oxidative Coupling | Periodate oxidation of glycans followed by imine formation | Oxidized diols (sugars) to hydrazides or amines | Particularly useful for antibody Fc region conjugation; may affect glycosylation-dependent epitopes |

Amide coupling via carbodiimide chemistry represents one of the most established methods, utilizing EDC (1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide) to activate carboxyl groups for nucleophilic attack by primary amines, forming stable amide bonds [24]. This approach is particularly effective for conjugating biomolecules to carboxyl-functionalized nanoparticles, though control over orientation remains challenging. Thiol-maleimide chemistry offers superior specificity by targeting cysteine residues, which are less abundant than lysines in most proteins, enabling more controlled conjugation [25]. The emergence of bioorthogonal click chemistry, particularly copper-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition (CuAAC), has revolutionized bioconjugation by providing exceptional specificity under physiological conditions, though copper-free variants are preferred for in vivo applications to avoid potential metal toxicity [24].

Affinity-Based Conjugation Methods

Non-covalent affinity interactions provide an alternative conjugation approach that leverages biological recognition pairs. These methods often yield uniformly oriented biomolecules with preserved activity.

Table 2: Affinity-Based Bioconjugation Systems

| System | Components | Binding Affinity | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Avidin-Biotin | Streptavidin/biotin | Kd ~ 10⁻¹⁵ M | Extraordinarily strong; versatile; amplifiable signal | Endogenous biotin can cause interference; large size of streptavidin |

| Protein A/G | Bacterial proteins/antibody Fc | Kd ~ 10⁻⁸-10⁻¹⁰ M | Uniform antibody orientation; preserves antigen binding | Limited to antibodies; potential immunogenicity |

| His-Tag/NTA | Polyhistidine/Ni-NTA | Kd ~ 10⁻⁶-10⁻⁹ M | Small tag minimally affects protein function; reversible with imidazole | Metal chelation can be unstable in reducing environments |

| DNA Hybridization | Complementary oligonucleotides | Kd dependent on length and sequence | Programmable; precise spatial control; thermally reversible | Requires oligonucleotide modification; nuclease sensitivity |

The avidin-biotin system remains the gold standard for affinity-based conjugation due to its exceptionally high binding affinity (Kd ≈ 10⁻¹⁵ M), approximately 1-3 orders of magnitude stronger than typical antigen-antibody interactions [25]. This system enables signal amplification through biotin's four binding sites and facilitates the creation of complex multi-component assemblies. For antibody-specific orientation, Protein A/G conjugations leverage the natural interaction between these bacterial proteins and the antibody Fc region, ensuring proper presentation of antigen-binding domains [24]. Polyhistidine-Ni-NTA coordination chemistry provides a smaller, less obstructive tagging system that is particularly valuable for membrane protein studies and enzyme immobilization where orientation and active site accessibility are paramount.

Biomolecule-Specific Conjugation Approaches

Antibody Immobilization Strategies

Antibodies require precise orientation on nanoparticle surfaces to maximize antigen-binding capacity. Random immobilization through lysine residues often leads to heterogeneous populations with compromised activity, making site-specific conjugation preferable.

Experimental Protocol: Site-Specific Antibody Conjugation via Reduced Disulfides

- Antibody Reduction: Incubate 1 mg/mL antibody with 10-20 mM 2-mercaptoethylamine (MEA) or tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP) in PBS (pH 7.4) for 1-2 hours at 37°C under inert atmosphere.

- Purification: Remove reducing agents using desalting columns (e.g., Zeba Spin Columns) equilibrated with degassed conjugation buffer (PBS, pH 7.0-7.4 with 1 mM EDTA).

- Maleimide Activation: Functionalize nanoparticles with maleimide crosslinkers (e.g., SMCC) at 5-10× molar excess for 30 minutes at room temperature.

- Conjugation: Combine activated nanoparticles with reduced antibodies at 1:3-1:5 molar ratio and incubate for 2-4 hours at 4°C with gentle agitation.

- Quenching: Add 10× molar excess of L-cysteine relative to maleimide groups and incubate for 15 minutes to block unreacted sites.

- Purification: Remove unconjugated antibodies through centrifugal filtration or dialysis [25].

This protocol typically yields 60-80% conjugation efficiency while preserving >90% antigen-binding capacity compared to random conjugation methods. The controlled orientation minimizes steric hindrance and prevents Fab region denaturation that commonly occurs with lysine-based chemistries.

Aptamer Functionalization Methods

Aptamers, single-stranded DNA or RNA oligonucleotides that bind specific targets with antibody-like affinity, offer distinct advantages for biosensing applications, including superior stability, easier modification, and lower production costs [26]. However, their susceptibility to nuclease degradation requires strategic chemical modification.

Experimental Protocol: Thiol-Gold Aptamer Conjugation for Nanozyme Biosensors

- Aptamer Design: Incorporate a 5' or 3' alkylthiol modification (C6-SH) during oligonucleotide synthesis with a poly-A/T spacer (10-15 bases) to minimize steric interference.

- Activation: Reduce thiolated aptamers (100-500 μM) with 10 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 8.0) for 1 hour at room temperature.

- Purification: Remove DTT using desalting columns or ethanol precipitation and resuspend in degassed immobilization buffer (10 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.4).

- Gold Nanoparticle Functionalization: Incubate citrate-stabilized gold nanoparticles (10-20 nm) with activated aptamers at 100:1 molar ratio in 0.1× PBS for 16-24 hours at room temperature with gentle shaking.

- Aging: Add NaCl to final concentration of 0.1-0.5 M in stepwise increments over 4-6 hours to stabilize nanoparticles against salt-induced aggregation.

- Blocking: Treat with 1-5 μM 6-mercapto-1-hexanol (MCH) for 1 hour to passivate unoccupied gold surfaces and upright aptamer orientation.

- Purification: Remove unbound aptamers by repeated centrifugation (14,000 × g, 20 minutes) and resuspension in storage buffer [26] [25].

This procedure typically achieves surface densities of 50-200 aptamers per 20 nm gold nanoparticle, with binding affinity retention of 70-90% compared to free aptamers. The MCH backfilling step is critical for displacing non-specifically adsorbed aptamers and creating a well-ordered monolayer that enhances target accessibility.

Enzyme Immobilization Techniques

Enzyme conjugation requires particular attention to preserving catalytic activity while enabling stable attachment. The conjugation site must avoid active centers and maintain structural integrity for optimal function.

Experimental Protocol: Click Chemistry-Mediated Enzyme Immobilization

- Enzyme Modification: Incubate enzyme (1-5 mg/mL) with 10× molar excess of NHS-ester azide linker in 50 mM bicarbonate buffer (pH 8.5) for 2 hours at 4°C.

- Purification: Remove excess linker using desalting columns equilibrated with reaction buffer (PBS, pH 7.4).

- Nanoparticle Functionalization: React alkyne-modified nanoparticles with 5× molar excess of azide-modified enzyme in the presence of 1 mM CuSO₄, 2 mM THPTA ligand, and 2 mM sodium ascorbate for 2-4 hours at room temperature.

- Catalyst Removal: Purify conjugates using size exclusion chromatography or centrifugal filtration to remove copper catalysts.

- Activity Assessment: Measure specific activity compared to free enzyme using standard spectrophotometric assays [24].

This approach typically yields 40-70% retention of enzymatic activity with conjugation efficiencies exceeding 80%. The bioorthogonal nature of click chemistry minimizes side reactions that could compromise enzyme function, making it particularly suitable for delicate enzymes with complex tertiary structures.

Impact of Bioconjugation on Nanozyme Activity

The conjugation of biomolecules to nanozymes—nanomaterials with enzyme-like activities—introduces unique considerations as these interactions occur at the catalytic interface. Adsorbed biomolecules can significantly modulate nanozyme activity through multiple mechanisms, including surface blocking, electrostatic effects, and conformational changes [25].

Table 3: Effects of Bioconjugation on Nanozyme Performance

| Nanozyme Type | Conjugation Method | Impact on Activity | Potential Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Iron Oxide NPs (Peroxidase-like) | Antibody adsorption | 40-60% decrease | Steric hindrance of substrate access to active surface sites |

| Gold NPs (Glucose Oxidase-like) | Aptamer conjugation | 70-90% inhibition | Surface passivation and altered electronic properties |

| Cerium Oxide NPs (Oxidase-like) | PEGylation | 20-30% decrease | Reduced substrate diffusion to surface; minimal electronic effects |

| Carbon Nanozymes (Peroxidase-like) | Avidin-biotin | 10-30% decrease | Moderate steric blocking with maintained electron transfer capability |

The substantial inhibition observed in gold nanoparticles with aptamer conjugation demonstrates the critical importance of surface accessibility in nanozyme function. Interestingly, in some cases, biomolecule adsorption can enhance specificity by reducing non-specific substrate binding, particularly in complex biological matrices [25]. Optimization requires empirical adjustment of binding density and orientation to balance recognition element accessibility with catalytic efficiency.