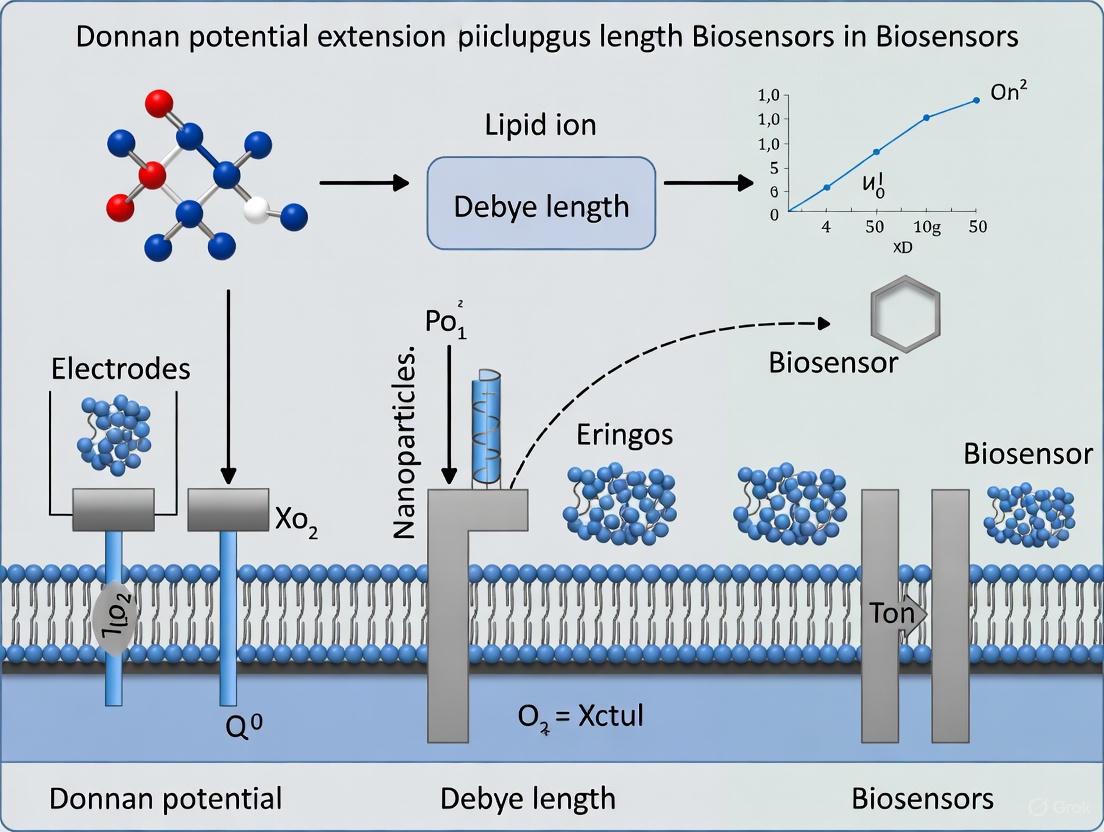

Overcoming the Debye Limit: How Donnan Potential Extends Biosensor Capabilities in Physiological Solutions

This article provides a comprehensive review of the Donnan potential effect as a transformative mechanism for extending the Debye length in field-effect transistor (FET) biosensors.

Overcoming the Debye Limit: How Donnan Potential Extends Biosensor Capabilities in Physiological Solutions

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive review of the Donnan potential effect as a transformative mechanism for extending the Debye length in field-effect transistor (FET) biosensors. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational electrostatics of the Donnan equilibrium, its practical implementation using advanced materials like polymer brushes and supported lipid bilayers, and systematic strategies for optimizing sensor performance. The content critically examines solutions for persistent challenges such as signal drift and steric hindrance, validates the approach through comparative analysis with experimental data, and discusses the implications for developing ultrasensitive, point-of-care diagnostic platforms capable of operating in biologically relevant ionic strength solutions.

The Donnan Equilibrium: Unraveling the Electrostatic Principle that Defeats Ionic Screening

The Fundamental Challenge: Debye Screening in Physiological Fluids

BioFETs are semiconductor-based devices that detect the electrical field generated by charged biomolecules, such as proteins, DNA, or ions, which bind to their sensitive surface. This binding event changes the local charge density, which in turn modulates the current flowing through the semiconductor channel, allowing for direct, label-free detection. The exceptional sensitivity, potential for miniaturization, and compatibility with complementary-metal-oxide-silicon (CMOS) processes make BioFETs promising platforms for ultra-sensitive, multiplexed diagnostics.

However, the operational principle of BioFETs is severely compromised in physiologically relevant media. Biological samples like serum, blood, or urine are high-ionic-strength solutions, containing a high concentration of mobile ions. When a charged biomolecule, such as a protein, approaches the sensor surface in such an environment, it attracts a cloud of counter-ions from the solution. This ion cloud electrically screens the charge of the target molecule, preventing its electric field from reaching and influencing the BioFET's channel.

The spatial range over which an electric field persists in an electrolyte is defined by the Debye screening length (λD). It is the characteristic distance at which the charge's influence drops by a factor of 1/e. The Debye length is inversely proportional to the square root of the ionic strength of the solution. In standard phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, ~0.165 M) or other physiological fluids, the Debye length is typically less than 1 nanometer [1] [2] [3]. This creates a critical dimensional mismatch: while the charge of a target biomolecule like an antibody (which can be 10-15 nm in size) must be detected, its electric field is effectively neutralized beyond a distance shorter than its own physical dimensions. Consequently, the sensitivity of conventional BioFETs is drastically reduced in high-ionic-strength environments, confining their operation to artificially diluted, low-ionic-strength buffers and limiting their practical application [1] [2].

The following diagram illustrates this fundamental screening problem.

Diagram 1: The Debye screening problem in BioFETs. The charge of a target biomolecule is screened by a cloud of counter-ions within the short Debye length, preventing its electric field from reaching the sensor surface.

Strategic Approaches to Overcome the Debye Length Limitation

Researchers have developed innovative strategies to circumvent the Debye screening problem. These methods can be broadly categorized into three approaches: electrostatic control of the interface, geometric and steric confinement, and the use of novel materials with inherent advantages.

Electrostatic and Donnan Potential Engineering

This strategy involves actively modifying the electrostatic environment at the solution-solid interface to reduce the local ion concentration and thereby extend the effective sensing range.

- Meta-Nano-Channel (MNC) BioFET: This novel design decouples the electrostatics of the double layer from the electrodynamics of the conducting channel. Fabricated in a CMOS process, it allows for the independent electrostatic tuning of the double layer. By applying specific potentials, the population of ions in the double layer is decreased, forcing the double layer ion concentration to match the bulk concentration and effectively increasing the screening length. This approach has been demonstrated to enhance the sensing signal for prostate-specific antigen (PSA) from 70 mV to 133 mV [4] [5].

- Exploiting Donnan Potentials in Soft Layers: When a charged, ion-permeable layer (like a polymer hydrogel or a polyelectrolyte multilayer (PEM)) is grafted onto the sensor surface, a Donnan potential is established at the interface between this layer and the bulk solution. The existence and magnitude of this potential depend on the properties of the layer. This modified interface can lead to a longer, intra-layer Debye screening length. The key condition is that the layer thickness must be significantly larger than this operative Debye length within the shell. The effective screening length inside such layers can be increased by an order of magnitude, allowing for charge detection beyond the conventional Debye limit [6] [2].

Geometric and Steric Confinement: The "Debye Volume" Concept

A more recent concept moves beyond the Debye length to consider the Debye volume—the total space available around a charge for ions to form a screening cloud.

- Nanostructured Surfaces: Concave geometries, such as those found in nanogaps, nanopores, or at the base of nanowires, inherently restrict the volume available for double layers to form. This spatial confinement introduces energetic constraints that reduce charge screening, making these geometries more sensitive than planar surfaces [2].

- Surface Grafting with Neutral Polymers: Coating the sensor surface with a dense, partially hydrated layer of large, neutral polymers like poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) physically limits the space into which screening ions can diffuse. The confined volume within the polymer brush extends the reach of electric fields from bound analytes. Studies have shown that this method can enable the detection of proteins like PSA and thyroid-stimulating hormone in undiluted serum, with reported sensitivity improvements of 3 to 5-fold [2].

Novel Material Platforms

Certain materials offer unique properties that can intrinsically mitigate screening effects.

- Epitaxial Graphene on SiC: Unlike exfoliated or chemically deposited graphene, single-crystal epitaxial graphene exhibits electrical characteristics that are nearly independent of the solution concentration. Its very low quantum capacitance may render the device less sensitive to the ionic strength of the solution, effectively creating a large effective screening length. This allows antibody-modified epitaxial graphene FETs to detect antigens without the need for sample desalting or complex device fabrication [3].

- Three-Dimensional Nanostructures: Using 3D crumpled graphene structures increases the effective sensing area and has been reported to effectively increase the Debye length, reducing charge screening and enabling ultrasensitive detection of small biomolecules like dopamine in complex media such as human urine and serum [7].

Table 1: Summary of Key Strategies for Overcoming the Debye Screening Length

| Strategy | Core Principle | Exemplar Technology/Method | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electrostatic Control [4] [5] | Actively manipulate surface potentials to deplete the double layer of ions. | Meta-Nano-Channel (MNC) BioFET | PSA detection signal increased from 70 mV to 133 mV. |

| Donnan Potential [6] [2] | Use a charged, porous layer to establish a constant potential that extends the sensing range. | Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) brushes; Polyelectrolyte Multilayers (PEM) | 3 to 5-fold sensitivity improvement for protein detection in serum; Order-of-magnitude increase in screening length predicted. |

| Geometric Confinement [2] | Restrict the physical volume (Debye volume) available for double-layer formation. | Nanogaps, nanopores, concave nanowire structures. | Enhanced sensitivity compared to planar sensor geometries. |

| Novel Materials [3] | Leverage intrinsic material properties that are less susceptible to ionic screening. | Epitaxial Graphene FETs on SiC | Successful antigen detection with antibodies in physiological buffers; Device characteristics independent of solution concentration. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Overcoming Screening with Polymer-Modified BioFETs

The following protocol provides a detailed methodology for functionalizing a BioFET sensor with a dense PEG brush to overcome Debye screening, based on strategies highlighted in the literature [2].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Reagents

| Item Name | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| BioFET Chip | The foundational sensor, e.g., a SiNW-FET, graphene FET, or MNC-BioFET. |

| Oxygen Plasma Cleaner | For cleaning and activating the sensor surface to enhance subsequent chemical binding. |

| Silane-PEG-NHS Ester | A heterobifunctional linker: silane group anchors to SiO₂ surfaces, while the NHS ester reacts with amine groups. The long PEG chain provides the steric barrier. |

| Aptamer or Antibody | The biological recognition element (probe) that specifically binds the target analyte. |

| Ethanolamine or BSA | Used to block any remaining reactive sites on the sensor surface after probe immobilization, reducing non-specific binding. |

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) | A standard buffer for preparing biological solutions and for conducting control experiments. |

| Target Analyte | The molecule of interest (e.g., a protein, hormone) to be detected. |

Step-by-Step Functionalization and Assay Procedure

Part A: Surface Preparation and PEGylation

- Surface Cleaning and Activation: Place the BioFET chip in an oxygen plasma cleaner. Treat it for 2-5 minutes at a medium power setting (e.g., 100 W). This step removes organic contaminants and creates a hydrophilic surface rich in hydroxyl (-OH) groups, which is crucial for the next step.

- Silane-PEG Coupling: Immediately after plasma treatment, prepare a 1-5 mM solution of Silane-PEG-NHS ester in anhydrous toluene. Immerse the activated chip in this solution and incubate for 4-12 hours at room temperature under an inert atmosphere (e.g., in a sealed vial with nitrogen gas). The silane group will covalently bind to the hydroxylated surface, forming a stable monolayer. The high-density PEG brush is established in this step.

- Washing and Curing: Remove the chip from the reaction solution and rinse it thoroughly with toluene followed by ethanol to remove any unbound molecules. Gently dry the chip with a stream of nitrogen gas. To ensure complete covalent bonding, cure the chip at 100-110 °C for 10-15 minutes.

- Probe Immobilization: Prepare a 1-10 µM solution of the amino-modified aptamer or antibody in a neutral buffer (e.g., 1x PBS, pH 7.4). Pipette this solution onto the PEGylated sensor surface and incubate in a humidified chamber for 1-2 hours at room temperature. The NHS ester group at the distal end of the PEG chain will react with primary amine groups on the probe, covalently tethering it to the surface.

- Surface Blocking: To passivate any remaining reactive NHS esters and minimize non-specific adsorption, incubate the sensor with a 1 M ethanolamine solution (or a 1% w/v BSA solution) for 30-60 minutes. After incubation, rinse the chip thoroughly with the running buffer (e.g., PBS) to remove any unbound blocking agents.

Part B: Biosensing Measurement and Data Acquisition

- Electrical Characterization: Integrate the functionalized BioFET chip into a liquid-gated measurement system with an Ag/AgCl reference electrode. Under a constant drain-source voltage (VDS), perform a gate voltage (VGS) sweep in pure buffer to obtain the baseline transfer characteristic (IDS vs. VGS).

- Analyte Introduction: Introduce the sample containing the target analyte at a known concentration into the measurement chamber. Allow the system to equilibrate for 10-20 minutes to ensure sufficient binding kinetics, as diffusion through the PEG layer can be slowed [2].

- Real-Time Monitoring: Continuously monitor the drain-source current (IDS) at a fixed, optimized gate voltage. The specific binding of the charged target to the immobilized probes will cause a shift in the IDS over time.

- Signal Quantification: After the signal stabilizes, perform another full transfer characteristic sweep. The shift in the threshold voltage (∆VTH) or the change in current (∆IDS) between the baseline and post-binding curves is the quantitative sensing signal.

- Control and Calibration: Repeat the process with solutions of different analyte concentrations to build a calibration curve, and use control experiments (e.g., with a non-complementary protein) to confirm specificity.

The experimental workflow for this protocol is summarized below.

Diagram 2: Workflow for BioFET functionalization and sensing.

The Debye screening problem represents a fundamental barrier to the widespread adoption of BioFETs in clinical and point-of-care settings. However, as outlined in this note, it is not an insurmountable one. Innovative strategies ranging from electrostatic engineering and the application of Donnan potentials in soft materials to the clever use of geometry and novel semiconductors provide a robust toolkit for overcoming this limitation. The successful demonstration of specific, label-free detection of biomarkers in undiluted, physiologically relevant fluids like serum, urine, and sweat signals a promising future for this technology. As these approaches mature and are integrated with wearable platforms, they will unlock the full potential of BioFETs for quantitative, real-time health monitoring and advanced diagnostic applications [4] [7] [8].

Field-effect transistor (FET)-based biosensors represent a powerful tool for label-free, rapid biological testing, with applications spanning from pathogen detection to biomarker quantification [9]. A significant challenge confronting these devices, especially when operating in physiologically relevant ionic strength solutions (e.g., 1X PBS), is the Debye screening effect [10]. In aqueous solutions, dissolved ions form an Electrical Double Layer (EDL) at charged surfaces. The characteristic thickness of this layer, the Debye length (λD), typically ranges from angstroms to a few nanometers in biological fluids [10]. This short length scale means that charged analyte molecules, such as antibodies (~10 nm in size), binding beyond this distance are electrically screened from the sensor surface, rendering them undetectable [10].

The Donnan potential phenomenon provides a mechanism to overcome this fundamental limitation. This principle is established when an ion-permeable layer (such as a polymer brush or a layer of immobilized bioreceptors) containing fixed structural charges is equilibrated with an electrolyte solution [6] [9]. A constant electrostatic potential, the Donnan potential (ΔφD), develops within this layer due to charge-driven accumulation of counterions and exclusion of co-ions [6]. This potential effectively extends the sensing distance beyond the native Debye length, enabling the detection of larger biomolecules in high ionic strength environments [10] [9]. This Application Note details the core principles and provides practical protocols for leveraging the Donnan potential to achieve effective Debye length extension in biosensor applications.

Theoretical Foundation

The Donnan Potential

The Donnan potential arises from a partitioning of ions between a bulk electrolyte solution and a charged, ion-permeable surface layer. The magnitude of this potential for a soft, charged layer is given by [9]:

$$\begin{array}{c}\Delta {\phi }{D}={\varphi }{th}\,ln\frac{(\sqrt{4{c}{s}^{2}+{c}{x}^{2}}+{c}{x})}{2{c}{s}}\end{array}$$

where:

- ΔφD is the Donnan potential.

- φth is the thermal voltage (≈ 26 mV at room temperature).

- cs is the bulk electrolyte concentration (ionic strength).

- cx is the effective charge concentration within the ion-permeable layer.

This equation shows that the Donnan potential increases with the charge density (cx) of the immobilized layer and decreases with increasing bulk ion concentration (cs). It is important to note that the existence of a stable Donnan potential is conditional. It requires that the thickness of the surface layer well exceeds the intra-particulate Debye screening length and that steric effects mediated by the sizes of the electrolyte ions and structural layer charges do not prevent its formation [6].

Debye Length and its Effective Extension

The Debye length (λD) in an aqueous solution can be approximated by [9]:

$$\begin{array}{c}\lambdaD ≈ \frac{0.3}{\sqrt{cs}} \text{ (in nanometers)}\end{array}$$

In a standard phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) solution, cs is high, resulting in a very short λD of about 0.7 nm. When a charged, ion-permeable layer like a polymer brush is immobilized on the sensor surface, the resulting Donnan potential creates a much larger region of electric field influence. From an electrical perspective, the system can be modeled with the bulk liquid as the gate of a transistor, and the combined Donnan region and the native Debye layer as the effective dielectric [9]. This effectively extends the sensing zone from a few nanometers to the entire thickness of the polymer layer, which can be tens of nanometers, thus overcoming the charge screening limitation [10].

Table 1: Key Parameters Governing Donnan Potential and Debye Length Extension.

| Parameter | Symbol | Description | Impact on Sensing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bulk Ion Concentration | cs | Ionic strength of the solution (e.g., PBS). | Higher cs reduces both λD and ΔφD, challenging detection. |

| Layer Charge Density | cx | Effective charge concentration within the immobilized layer. | Higher cx increases ΔφD, enhancing the sensing distance. |

| Layer Thickness | δ | Physical thickness of the ion-permeable polymer/bioreceptor layer. | Must significantly exceed the intra-layer Debye length for a stable Donnan potential to exist [6]. |

| Steric Factor | - | Finite sizes of ions and layer charges. | At high concentrations, can limit ion partitioning and prevent Donnan potential establishment [6]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Fabrication of a Graphene FET (gFET) Biosensor Platform

This protocol outlines the creation of a foundational gFET biosensor, which can subsequently be functionalized to exploit the Donnan effect.

1. Materials

- Pre-patterned wafer with source/drain electrodes (e.g., Au/Cr).

- High-quality graphene (CVD-grown).

- Transfer medium (e.g., PMMA).

- Etching solutions (e.g., FeCl3 for Au, APS for Cu).

- Deionized water and organic solvents (acetone, isopropanol).

- Photolithography or electron-beam lithography system.

- High-κ dielectric material (e.g., Al2O3, HfO2) for top-gating (optional).

2. Procedure

- Graphene Transfer: Transfer a monolayer of CVD graphene onto the pre-patterned electrode structures using a wet-transfer process with a PMMA support layer [9].

- Patterning: Use lithography and oxygen plasma etching to define the graphene channel dimensions.

- Dielectric Deposition (For top-gated devices): Deposit a thin layer of high-κ dielectric via atomic layer deposition (ALD).

- Passivation: Apply a passivation layer (e.g., SiO2 or SU-8 epoxy) to protect the contacts and define the active sensing area [10].

- Encapsulation: Implement encapsulation strategies to mitigate signal drift and leakage current, crucial for stable liquid gating [10].

- Electrical Characterization: Validate device performance in buffer solution by measuring the I-Vg transfer characteristics to determine carrier mobility and the Dirac point.

Protocol: Surface Functionalization for Debye Length Extension

This critical protocol details the application of a polymer brush layer to create the ion-permeable membrane necessary for the Donnan effect.

1. Materials

- Functionalized gFETs from Protocol 3.1.

- Poly(oligo(ethylene glycol) methyl ether methacrylate) (POEGMA) or similar PEG-based polymer.

- Initiator for polymer growth (e.g., for ATRP or photo-initiated polymerization).

- Suitable solvent (e.g., water, ethanol).

- Capture antibodies (cAb) or other bioreceptors (e.g., DNA aptamers).

- Crosslinkers (e.g., NHS-EDC chemistry).

2. Procedure

- Surface Activation: Clean and activate the gFET channel surface (e.g., with oxygen plasma) to generate functional groups for initiator attachment [10].

- Initiator Immobilization: Covalently anchor the polymerization initiator molecules to the activated surface.

- Polymer Brush Growth: Grow the POEGMA brush layer from the surface via a controlled polymerization technique (e.g., ATRP). Control polymerization time to achieve the desired brush thickness (≥ 10 nm is typical) [10].

- Prepare a degassed solution of POEGMA monomer and catalyst in solvent.

- Immerse the initiator-functionalized sensor into the solution.

- Allow polymerization to proceed for a controlled duration.

- Rinse thoroughly with solvent and DI water to remove unreacted monomer.

- Bioreceptor Immobilization: Print or spot the capture antibodies into the polymer brush matrix [10]. The brush can be designed to contain functional groups for covalent attachment via bio-orthogonal chemistry.

- Blocking: Incubate the functionalized sensor with a blocking agent (e.g., BSA, casein) to passivate any non-specific binding sites.

Protocol: Biosensing Measurement with the D4-TFT Workflow

This protocol describes a stable measurement methodology ("D4-TFT") for detecting biomarkers in high ionic strength solution [10].

1. Materials

- Functionalized gFET biosensor from Protocol 3.2.

- Assay buffer (e.g., 1X PBS).

- Sample containing the target analyte.

- Dissolvable trehalose layer containing detection antibodies (dAb) [10].

- Stable electrical testing setup with a pseudo-reference electrode (e.g., Pd) [10].

- Source-meter unit for DC sweeps.

2. Procedure

- Dispense (Baseline): Place a drop of assay buffer onto the sensor. Perform infrequent DC current-voltage (I-V) sweeps to establish a stable baseline current (Ibase). Avoid continuous DC measurement to minimize drift [10].

- Dispense (Sample): Replace the buffer with the sample solution containing the target analyte.

- Dissolve & Diffuse: The sample droplet dissolves the overlying trehalose layer, releasing the detection antibodies, which then diffuse to the sensor surface [10].

- Detect (Binding): If the target analyte is present, a sandwich complex (cAb-analyte-dAb) forms within the POEGMA brush. The associated change in charge density (Δcx) modulates the Donnan potential, leading to a measurable shift in the transistor's drain current (ΔI).

- Data Analysis: Calculate the sensor response as the percent change in current, %ΔI = [(I - Ibase) / Ibase] × 100. Compare against a negative control (a sensor without capture antibodies) to confirm specific binding [10].

Diagram 1: D4-TFT biosensing workflow for reliable biomarker detection.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key research reagents and materials for implementing Donnan-based biosensing.

| Item | Function/Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| CVD Graphene | High-mobility, chemically stable channel material for FETs. | Core transducer material in gFETs for sensitive charge detection [9]. |

| POEGMA Brush | Non-fouling polymer brush that establishes a Donnan potential. | Creates an ion-permeable layer to extend Debye length in 1X PBS [10]. |

| Palladium (Pd) Electrode | Stable pseudo-reference electrode for liquid gating. | Enables compact, point-of-care device design without bulky Ag/AgCl electrodes [10]. |

| Capture Antibodies | High-affinity bioreceptors immobilized in the polymer brush. | Specific capture of target biomarkers (e.g., viruses, cytokines) from solution [10]. |

| ATRP Initiator | Molecule to initiate controlled radical polymerization. | Covalently grafting POEGMA brushes from sensor surfaces [10]. |

| NHS-EDC Chemistry | Crosslinking reagents for covalent biomolecule immobilization. | Coupling antibodies or other bioreceptors to functionalized polymer brushes. |

Data Presentation & Analysis

The following table summarizes experimental data and performance metrics achievable with Donnan potential-based biosensing platforms, as reported in the literature.

Table 3: Performance summary of Donnan-enabled biosensing platforms.

| Sensor Platform / Assay | Target / Application | Key Performance Metric | Result | Reference Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNT-based D4-TFT | General Biomarker Detection | Detection Limit in 1X PBS | Sub-femtomolar (aM) | [10] |

| gFET Immunoassay | Infectious Disease Biomarker | Sensitivity in Serum | 500 ng/mL | [9] |

| gFET Immunoassay | Infectious Disease Biomarker | Sensitivity in Buffer | 18 ng/mL | [9] |

| POEGMA-functionalized FET | Debye Length Extension | Sensing Distance | Increased to ~10s of nm | [10] |

Diagram 2: Electrical model showing Donnan and Debye layer capacitances in a gFET.

The Critical Role of Ion-Impermeable and Ion-Permeable Layers

In the field of electrochemical biosensors, the interface between the biological recognition element and the transducer is critical for determining performance characteristics. The strategic application of ion-impermeable and ion-permeable layers at this interface provides a powerful mechanism for controlling the local ionic environment, directly addressing the fundamental challenge of Debye length screening in physiological solutions. When operating at biologically relevant ionic strengths, conventional biosensors suffer from limited detection capabilities because the electrical double layer (EDL) formed at the sensor surface screens charged analytes beyond a very short distance (typically <1 nm) [10].

The Donnan potential effect establishes an equilibrium at the interface between ion-permeable and ion-impermeable layers, creating a stable interfacial potential that can effectively extend the sensing distance beyond the traditional Debye length [10]. This principle enables the detection of larger biomolecules, such as antibodies (~10-15 nm), in high ionic strength solutions like blood or phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), where conventional field-effect transistor (FET) biosensors would normally fail [10]. This application note details the theoretical foundation, experimental protocols, and practical implementations of these critical layers for advancing biosensor research and development.

Theoretical Foundation: Donnan Potential and Debye Length Extension

Donnan Equilibrium Principles

The Donnan potential arises when an ion-impermeable layer containing fixed charges establishes equilibrium with an adjacent ion-permeable solution phase [11]. This phenomenon occurs extensively in ion-exchange membrane systems, where fixed charged groups attached to a polymer backbone create a selective barrier that excludes co-ions while allowing counter-ions to pass [11]. At thermodynamic equilibrium, the unequal distribution of ions between the hydrated membrane and aqueous phases generates an electrical potential at the interface—the Donnan potential—which can be described by:

EDon = RT/ziℱ ln(ais/aim) [11]

Where:

- EDon = Donnan electrical potential

- R = Ideal gas constant

- T = Temperature

- zi = Valence of ion i

- ℱ = Faraday constant

- ai = Activity of ion i in solution (s) or membrane (m) phase

Extension of the Debye Length in Biosensing

In biosensor applications, this Donnan equilibrium principle is leveraged by creating a structured interface where a polymer layer with specific ionic permeability characteristics is grafted onto the sensor surface. The poly(oligo(ethylene glycol) methyl ether methacrylate) (POEGMA) polymer brush has emerged as a particularly effective material for this purpose [10]. When functionalized with charged groups or biomolecular recognition elements, this layer establishes a Donnan potential that modulates the local ionic distribution, effectively extending the sensing distance beyond the native Debye length in high ionic strength solutions [10].

Table 1: Key Theoretical Parameters in Donnan Potential-Mediated Biosensing

| Parameter | Symbol | Typical Range/Value | Impact on Biosensing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed Charge Density | q | 0.1-2.0 eq/L [11] | Determines magnitude of Donnan potential and exclusion capability |

| Donnan Potential | EDon | Variable based on system | Creates interfacial potential that extends sensing distance |

| Debye Length | λD | ~0.7 nm in 1X PBS [10] | Native screening distance in physiological buffers |

| Effective Sensing Distance | - | Enhanced via Donnan effect [10] | Determines size of detectable biomolecules |

| Ionic Strength | I | 150 mM for physiological | Challenges conventional FET sensing without Donnan extension |

Experimental Protocols

Fabrication of POEGMA-Modified BioFETs with Donnan Extension Capability

This protocol details the creation of carbon nanotube-based BioFETs incorporating a POEGMA polymer brush to extend the Debye length via the Donnan potential effect [10].

Materials Required

- Semiconducting carbon nanotube (CNT) solution

- Poly(oligo(ethylene glycol) methyl ether methacrylate) (POEGMA)

- Atom transfer radical polymerization (ATRP) initiator

- High-κ dielectric substrate (e.g., Al2O3, HfO2)

- Phosphate buffered saline (PBS), 1X concentration

- Target-specific capture and detection antibodies

- Palladium (Pd) pseudo-reference electrode

- Trehalose excipient layer material

Procedure

CNT Thin-Film Transistor Fabrication

- Deposit CNTs onto high-κ dielectric substrate using solution-processing or printing techniques

- Pattern source and drain electrodes (typically Pd or Au) using photolithography or shadow masking

- Encapsulate device edges to minimize leakage current and enhance stability [10]

POEGMA Polymer Brush Growth

- Functionalize the CNT channel surface with ATRP initiator

- Grow POEGMA brush layer via surface-initiated ATRP

- Control polymer thickness (typically 10-100 nm) by adjusting monomer concentration and reaction time

- Verify polymer growth and uniformity using ellipsometry or AFM

Antibody Functionalization

- Inkjet-print capture antibodies (cAb) into the POEGMA matrix above the CNT channel

- Print detection antibodies (dAb) onto a dissolvable trehalose excipient layer on a separate pad

- Include control devices without antibodies printed over CNT channel for validation [10]

Device Integration and Packaging

- Integrate Pd pseudo-reference electrode to avoid bulky Ag/AgCl references

- Mount device on printed circuit board with automated testing capability

- Implement solution reservoir with growth medium for bacterial-based sensors if applicable [12]

Biosensing Operation Using D4-TFT Platform

The D4-TFT platform operates through four sequential steps that enable ultrasensitive detection in high ionic strength solutions [10]:

Dispense

- Dispense liquid sample onto the sensor cartridge

- Ensure contact with both the trehalose pad (containing dAb) and the POEGMA/antibody-functionalized CNT channel

Dissolve

- Allow the trehalose excipient layer to dissolve (typically 1-2 minutes)

- Release detection antibodies into the solution

Diffuse

- Detection antibodies and target analytes diffuse through the solution

- Form sandwich complexes (cAb-analyte-dAb) within the POEGMA layer above the CNT channel

- Incubate for sufficient time to allow binding (typically 5-15 minutes)

Detect

- Apply infrequent DC voltage sweeps (rather than static or AC measurements) to minimize signal drift

- Measure changes in CNT channel current resulting from antibody sandwich formation

- Compare signals between active and control devices to confirm specific detection

- Quantify analyte concentration based on calibrated current response

Figure 1: D4-TFT biosensing workflow illustrating the four operational steps that enable detection in high ionic strength solutions [10].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Donnan Potential-Based Biosensing

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| POEGMA Polymer Brush | Creates ion-permeable layer with Donnan potential [10] | Extends Debye length in physiological solutions; thickness critical for performance |

| Ion-Exchange Membranes | Provides fixed charge density for Donnan exclusion [11] | High charge density required for high-salinity systems; affects permselectivity |

| Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) | High-sensitivity transducer material [10] | High mobility in thin-film; chemical inertness; solution-phase processability |

| Palladium Pseudo-Reference Electrode | Stable potential measurement in miniaturized systems [10] | Enables point-of-care form factor without bulky Ag/AgCl electrodes |

| Trehalose Excipient | Stabilizes and contains detection antibodies [10] | Forms readily-dissolvable layer for controlled antibody release |

| Specific Antibodies | Biorecognition elements for target analytes | Printed into POEGMA matrix; form sandwich complexes with antigens |

Data Interpretation and Analysis

Electrical Characterization and Signal Validation

The critical advancement enabled by Donnan potential extension is the ability to operate in biologically relevant solutions (1X PBS) while maintaining sensitivity to sub-femtomolar biomarker concentrations [10]. Proper data interpretation requires:

Signal Drift Mitigation

- Use infrequent DC sweeps rather than continuous static measurements

- Monitor both active and control devices simultaneously

- Apply stable electrical testing configuration with proper passivation [10]

Specificity Validation

- Compare devices with and without antibodies printed over CNT channel

- Verify that signal shifts occur only in antibody-functionalized devices

- Confirm dose-response relationship across relevant concentration range

Performance Metrics

Table 3: Performance Comparison of Biosensing Platforms with and without Donnan Extension

| Performance Characteristic | Conventional BioFET | Donnan-Extended BioFET |

|---|---|---|

| Operating Ionic Strength | Requires dilution (e.g., 0.1X PBS) [10] | Native physiological strength (1X PBS) [10] |

| Effective Sensing Distance | Limited to native Debye length (~0.7 nm) [10] | Extended beyond Debye length via Donnan potential [10] |

| Detection Limit | Picomolar to nanomolar range [10] | Sub-femtomolar concentrations demonstrated [10] |

| Reference Electrode | Often requires bulky Ag/AgCl [10] | Compatible with Pd pseudo-reference electrodes [10] |

| Antibody Detection | Challenging due to size beyond Debye length [10] | Enabled via Donnan potential extension [10] |

Figure 2: Comparison of sensing mechanisms between conventional BioFETs and Donnan-extended BioFETs, highlighting the critical role of the ion-permeable polymer layer [10].

Troubleshooting and Optimization

Common Challenges and Solutions

Signal Drift Issues

- Problem: Temporal signal changes obscure biomarker detection

- Solution: Implement combination of sensitivity maximization through proper passivation, stable electrical testing configuration, and rigorous testing methodology with infrequent DC sweeps [10]

Insufficient Debye Length Extension

- Problem: Limited detection capability for large biomolecules

- Solution: Optimize POEGMA thickness and charge density; ensure proper polymer brush formation and antibody immobilization [10]

Non-Specific Binding

- Problem: False positive signals in control devices

- Solution: Utilize POEGMA's non-fouling properties; include rigorous control devices without antibodies above CNT channel [10]

Short Device Lifetime

- Problem: Degradation of biosensor performance over time

- Solution: Appropriate polymer immobilization techniques; stable encapsulation; optimized storage conditions [12]

The strategic implementation of ion-impermeable and ion-permeable layers represents a fundamental advancement in biosensor technology, directly addressing the critical challenge of Debye length screening in physiological environments. Through the establishment of a Donnan potential at carefully engineered interfaces, researchers can effectively extend the sensing distance in high ionic strength solutions, enabling detection of clinically relevant biomarkers at sub-femtomolar concentrations without sample dilution [10].

The protocols and methodologies detailed in this application note provide a foundation for developing next-generation biosensors capable of operating in biologically relevant conditions. The D4-TFT platform demonstrates how the integration of polymer brushes, appropriate transducer materials, and rigorous testing methodologies can overcome persistent limitations in the field, paving the way for truly practical point-of-care diagnostic devices [10]. As research in this area continues to evolve, further refinements in material selection, layer architecture, and signal processing algorithms will undoubtedly expand the capabilities and applications of Donnan potential-enhanced biosensing platforms.

Field-effect transistor (FET) based biosensors represent one of the most promising technologies for label-free, rapid, and sensitive detection of biomarkers, with applications ranging from clinical diagnostics to environmental monitoring [13]. A significant challenge encountered by these solution-gated devices is the Debye screening effect, wherein ions in a high ionic strength solution (such as physiological fluid) form an electrical double layer (EDL) that screens the charge of target biomolecules beyond a very short distance, typically less than 1 nm in 1X PBS [10]. Since most biorecognition elements (e.g., antibodies) are far larger than this distance, this screening severely limits the sensitivity of conventional FET biosensors in biologically relevant conditions.

The Donnan potential offers a mechanism to overcome this fundamental limitation. When a charged, ion-permeable layer (such as a polymer brush) is incorporated at the semiconductor/electrolyte interface, it establishes a Donnan equilibrium with the bulk solution. This equilibrium creates a constant electrostatic potential phase, which can effectively extend the sensing distance beyond the classical Debye length, enabling the detection of large biomolecules in high ionic strength environments [10]. This application note details the theoretical framework, experimental protocols, and key considerations for integrating the Donnan potential into FET sensor design.

Theoretical Framework

The Donnan Equilibrium in Soft Materials

The Donnan potential (ψDonnan) arises at the interface between an electrolyte solution and a charged, ion-permeable surface layer when the layer thickness significantly exceeds the local Debye screening length [6]. This potential is a consequence of the selective partitioning of ions between the bulk solution and the charged layer to satisfy electroneutrality, leading to an accumulation of counter-ions and exclusion of co-ions within the layer.

For a soft surface layer with a volume charge density n₀ (representing its structural charges) equilibrated with a symmetric z:z electrolyte (e.g., NaCl, where z is the ion valence), the Donnan potential can be derived from the Boltzmann distribution of ions and the local electroneutrality condition. The simplified expression is given by:

[ \psi{Donnan} = \frac{RT}{zF}\sinh^{-1}\left(\frac{n0}{2zFC_b}\right) ]

where R is the universal gas constant, T is the absolute temperature, F is the Faraday constant, and C_b is the bulk electrolyte concentration [6]. The existence of a stable Donnan potential is conditional and depends not only on the layer thickness but also on the charge density of the layer, the ionic strength, and steric effects related to the sizes of the ions and the structural charges of the layer [6].

Overcoming Debye Screening in FET Biosensors

In a standard electrolyte-gated FET (EG-FET), the total gate capacitance (C_TOT) is a series combination of the capacitance at the gate-electrolyte interface (C_GE) and the electrolyte-semiconductor interface (C_ES). In a biological solution, the EDL capacitance at the semiconductor surface is typically the limiting factor and is described by the Gouy-Chapman-Stern model, which includes a compact Helmholtz layer and a diffuse Gouy-Chapman layer [14].

The critical parameter is the Debye length (λD), which defines the characteristic decay length of the electrostatic potential from a charged surface. For a monovalent electrolyte, λD ≈ 0.3 nm in 1X PBS, making the FET insensitive to charged biomolecules like proteins located several nanometers away [10].

Integrating a charged polymer brush (e.g., POEGMA) onto the semiconductor surface creates a Donnan phase. The fixed charges on the polymer establish a Donnan potential that, at equilibrium, prevents the rapid decay of potential within the brush. The potential remains relatively constant throughout the polymer layer and only decays exponentially to zero within the bulk solution, starting from the brush-solution interface. This effectively shifts the plane of potential decay away from the semiconductor surface, increasing the distance over which the sensor can detect charges, as illustrated in the following diagram.

Diagram 1: Mechanism of Debye length extension via a charged polymer brush. The Donnan potential within the brush creates a constant potential region, shifting the exponential decay into the bulk solution and making distant biomolecular binding events detectable.

Quantitative Data and Material Properties

The efficacy of the Donnan potential in enhancing sensor response is governed by several key parameters. The tables below summarize the core relationships and the impact of different material and solution properties.

Table 1: Key Parameters Governing the Donnan Potential in FET Sensors

| Parameter | Symbol | Role in Donnan-Modulated Sensing | Typical Target Value/Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polymer Charge Density | n₀ | Determines the magnitude of the Donnan potential and the strength of the ion-partitioning effect. | Sufficiently high to counterbalance high salinity [11]. |

| Bulk Ionic Strength | Cb | Higher concentrations reduce the Donnan potential and the effective sensing distance. | 1X PBS (0.15 M) for physiological relevance [10]. |

| Ion Valence | z | Influences the Debye length and the sensitivity of ψDonnan to charge density. | 1 (for NaCl systems) [11]. |

| Polymer Layer Thickness | δ | Must be significantly larger than the intra-particulate Debye length to establish a stable Donnan phase [6]. | >> 1/κshell (internal Debye length) [6]. |

| Steric Factor | - | Accounts for the finite size of ions and polymer charges, limiting ion crowding and potential magnitude at high densities [6]. | Considered for non-dilute systems. |

Table 2: Impact of Material and Solution Properties on Sensor Performance

| Property / Condition | Effect on Donnan Potential | Consequence for FET Sensing | Experimental Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| High Fixed Charge Density (n₀) | Increases ψDonnan [11]. | Enhances permselectivity and signal for a given biomarker. | Must be balanced to avoid excessive ion congestion [6]. |

| Low Bulk Ionic Strength | Increases ψDonnan and λD. | Easiest condition for detection, but not physiologically relevant. | Useful for initial proof-of-concept experiments. |

| High Bulk Ionic Strength (e.g., 1X PBS) | Decreases ψDonnan and λD. | Challenges sensor sensitivity; necessitates high n₀ [11]. | Required for testing in clinically relevant media. |

| Use of POEGMA Brush | Creates a stable Donnan phase and reduces biofouling [10]. | Enables detection in 1X PBS and improves sensor stability. | A key enabling material for practical biosensors. |

| Asymmetric Ion Size/Valence | Alters the steric limit and the partition coefficients of ions [6]. | Can be used to tailor sensor response and selectivity. | Model with advanced Poisson-Boltzmann corrections. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Fabrication of a Donnan-Modulated CNT FET (D4-TFT) for Ultrasensitive Detection

This protocol outlines the procedure for creating a carbon nanotube-based FET biosensor that utilizes a POEGMA polymer brush to establish a Donnan potential for attomolar-level detection in 1X PBS [10].

Materials and Reagents

Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| Semiconducting Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) | Forms the conductive channel of the FET transducer. |

| Poly(oligo(ethylene glycol) methyl ether methacrylate) (POEGMA) | Polymer brush that forms the Donnan phase, extends sensing distance, and resists biofouling. |

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), 1X | High ionic strength solution simulating physiological conditions for testing. |

| Capture Antibodies (cAb) and Detection Antibodies (dAb) | Biorecognition elements for specific sandwich immunoassay. |

| Palladium (Pd) Pseudo-Reference Electrode | Provides a stable gate potential in a point-of-care form factor. |

| EDC/NHS Crosslinking Chemistry | Activates carboxyl groups for covalent attachment of bioreceptors. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

FET Fabrication:

- Fabricate source and drain electrodes (e.g., gold on Si/SiO₂) with a defined channel geometry.

- Deposit a thin film of semiconducting CNTs across the channel to form the conductive pathway [10].

Surface Passivation:

- Passivate the contact areas and defined regions of the channel to mitigate gate leakage currents and enhance electrical stability [10].

Polymer Brush Grafting:

- Grow a layer of POEGMA directly on the passivated CNT channel. This is a critical step, as the POEGMA forms the ion-permeable, charge-containing film that will establish the Donnan equilibrium [10].

Biofunctionalization:

- Print or spot capture antibodies (cAb) onto the POEGMA layer. The polymer brush should be functionalized to allow for covalent immobilization of the antibodies while retaining its non-fouling and Donnan potential properties [10].

- It is crucial to include control devices on the same chip where no antibodies are printed over the CNT channel.

Electrical Characterization and Biosensing:

- Integrate a Pd pseudo-reference electrode to complete the electrolyte-gated TFT setup.

- Use a stable electrical testing configuration, employing infrequent DC sweeps rather than continuous static or AC measurements to minimize signal drift [10].

- For the D4-TFT immunoassay, the "Dispense, Dissolve, Diffuse, Detect" steps are followed. The target analyte diffuses and binds to the cAb, followed by a detection antibody, forming a sandwich complex [10].

- Monitor the drain current (

I_D) over time. A positive shift inI_Din the test device, with no corresponding shift in the control device, confirms successful and specific detection.

The following workflow diagram summarizes the key fabrication and measurement steps.

Diagram 2: Key steps in the fabrication and operation of a Donnan-modulated D4-TFT biosensor.

Protocol: Measuring and Validating the Donnan Potential Effect

Objective

To experimentally confirm the presence of the Donnan potential and its role in extending the Debye length by comparing sensor response with and without the charged polymer layer.

Procedure

Device Comparison:

- Prepare two sets of identical FET devices. The experimental set is functionalized with the charged polymer brush (e.g., POEGMA), while the control set lacks this layer.

Solution Variation:

- Test both device sets in electrolytes of varying ionic strength (e.g., 0.1X PBS and 1X PBS). The Debye length is longer in 0.1X PBS, allowing the control device to potentially function.

Analyte Testing:

- Expose both devices to a model charged analyte, such as a protein or DNA, with a hydrodynamic size larger than the Debye length in 1X PBS (~0.7 nm).

Response Analysis:

- Measure the transfer characteristics (

I_Dvs.V_G) or the time-dependentI_Dresponse for both devices. - Validation: The control device will show a significant response in 0.1X PBS but a negligible response in 1X PBS due to screening. The experimental device (with polymer brush) will maintain a strong, stable response in both 0.1X PBS and 1X PBS, demonstrating the Debye-length-extension effect of the Donnan potential [10].

- Measure the transfer characteristics (

Discussion

Tackling Signal Drift and Stability

A major challenge in BioFETs is signal drift—the slow, unwanted change in baseline signal over time, which can obscure the specific response from biomarker binding. This drift is often caused by the slow diffusion of electrolytic ions into the sensing region, altering gate capacitance and threshold voltage [10]. The Donnan-potential-based sensor design must incorporate strategies to mitigate this:

- Stable Testing Configuration: Use infrequent DC sweeps instead of continuous static measurements to sample the device state without exacerbating drift [10].

- Effective Passivation: Robust passivation layers around the active channel are essential to prevent leakage currents [10].

- Non-Fouling Interfaces: The POEGMA brush itself acts as a bio-inert layer, reducing non-specific adsorption (biofouling) that can contribute to long-term signal instability [10].

Limitations and Advanced Considerations

While powerful, the Donnan model has limitations. At very high structural charge densities (n₀) and high ionic strengths, steric effects—the finite size of ions and polymer charges—become significant. These effects can limit the maximum achievable Donnan potential due to ion congestion, a deviation not captured by classical point-charge models [6]. Accurate modeling for such conditions requires corrections to the mean-field Poisson-Boltzmann theory that explicitly account for the excluded volume of ions and structural charges [6]. Furthermore, the permselectivity of the membrane or polymer layer is not absolute; a finite concentration of co-ions (C_co-ion) will always permeate the layer, an effect that is magnified at low fixed charge densities and high external salt concentrations [11].

Engineering the Interface: Materials and Methods for Implementing Donnan Potential Extension

The development of biosensors capable of operating in physiologically relevant ionic strength solutions represents a significant challenge in diagnostic medicine. A primary obstacle is the Debye screening effect, where ions in solution form an electrical double layer that screens the charge of target biomarkers, effectively limiting detection to molecules within a few nanometers of the sensor surface. This review details the application of poly(oligo(ethylene glycol) methyl ether methacrylate) (POEGMA) polymer brushes as a material strategy to overcome this limitation. By establishing a Donnan equilibrium potential at the biosensor interface, POEGMA brushes effectively extend the sensing distance, enabling the detection of sub-femtomolar biomarker concentrations in high ionic strength environments like 1X phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). This application note provides a comprehensive overview of the underlying mechanism, quantitative performance data, and detailed experimental protocols for implementing POEGMA brushes in field-effect transistor-based biosensors (BioFETs), framing this advancement within the broader context of Donnan potential-based Debye length extension for next-generation biosensing.

Biosensors that rely on field-effect transistors (BioFETs) are promising for point-of-care diagnostics due to their inherent simplicity, low cost, and high sensitivity [10]. However, when operating in solutions at biologically relevant ionic strengths, such as blood or 1X PBS, these devices face a fundamental physical constraint: the Debye screening effect [10] [15].

In physiological solutions, the Debye length—the characteristic distance over which electrostatic potentials decay—is typically less than 1 nanometer [15]. This is problematic because the biorecognition elements, such as antibodies, are often an order of magnitude larger (~10 nm). Consequently, any charged target biomarker binding to its receptor falls far outside the Debye length and its electrical signal is effectively screened, rendering it undetectable by conventional BioFETs [10].

Traditional workarounds, such as diluting the buffer to increase the Debye length, compromise biomarker stability and assay relevance, making the results physiologically irrelevant [10]. The integration of POEGMA polymer brushes addresses this problem directly by leveraging the Donnan equilibrium potential to create an extended sensing zone within the brush layer, permitting ultrasensitive detection in undiluted biological fluids [10] [15].

Mechanism of Action: Donnan Potential-Mediated Debye Length Extension

POEGMA brushes function as Debye length extenders not by physically altering the ionic composition of the bulk solution, but by creating a local environment at the sensor interface where a Donnan potential is established.

The brushes form a dense, highly hydrated layer with a significant volume fraction of polymer. The oligo(ethylene glycol) side chains are uncharged, making the brush layer charge-neutral [10]. When this neutral, porous brush is immersed in an ionic solution, the concentration of mobile ions within the brush differs from that in the bulk solution. This disparity in ion concentration creates a stable Donnan potential at the interface between the brush and the bulk electrolyte.

This potential extends the effective charge-sensing range of the biosensor far beyond the native Debye length in the bulk solution. When a charged target biomarker, such as a protein, binds to its capture antibody within the POEGMA brush, it introduces a fixed charge. The resulting perturbation of the local electrostatic environment is sensed by the underlying transducer (e.g., the channel of a carbon nanotube thin-film transistor) as a measurable change in current or threshold voltage [10]. This mechanism allows for the detection of charged biomolecules that bind at distances significantly greater than the traditional Debye length.

The diagram below illustrates the mechanistic difference between a standard biointerface and one functionalized with a POEGMA brush.

Quantitative Performance Data

The implementation of POEGMA brushes in biosensing platforms has led to remarkable improvements in sensitivity and performance, even in physiologically relevant conditions. The table below summarizes key quantitative findings from recent studies.

Table 1: Performance Summary of Biosensors Utilizing Polymer-Based Debye Length Extension

| Biosensor Platform | Target Analyte | Sensitivity (Limit of Detection) | Solution Conditions | Key Performance Metrics | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNT-based D4-TFT (POEGMA) | Model Biomarker | Sub-femtomolar (aM) | 1X PBS | Repeated and stable detection in point-of-care form factor | [10] |

| EGFET Immunosensor (PEG-like polymer) | p53 tumour suppressor | 100 pM | Physiological buffer | Sensitivity: 1.5 ± 0.2 mV/decade; Detection range: 0.1–10 nM | [15] |

| sSEBS-PEDOT/POEGMA Fibre Mat | Protein Fouling (BSA) | ~82% protein repellence | N/A | Antifouling efficiency with 30-mers POEGMA brushes; Cell viability >80% | [16] |

Experimental Protocols

This section provides detailed methodologies for fabricating and implementing POEGMA brush-modified interfaces for enhanced biosensing.

Protocol: Grafting POEGMA Brushes via Surface-Initiated ARGET ATRP

This protocol describes the functionalization of a conductive substrate (e.g., gold, carbon nanotube thin films) with POEGMA brushes to create a non-fouling, Debye-length-extending interface [16].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for SI-ATRP of POEGMA

| Reagent / Material | Function / Description | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| OEGMA Monomer | The primary building block of the polymer brush. Provides the antifouling and Donnan potential properties. | Oligo(ethylene glycol) methyl ether methacrylate (OEGMA, number of EG units can vary, e.g., n=3-19) [17]. |

| ATRP Initiator | A molecule that covalently attaches to the substrate surface and initiates the controlled radical polymerization. | EDOT-Br: An EDOT derivative with a bromopropanoate ATRP-initiating site, allows electropolymerization on conductive surfaces [16]. |

| Catalyst System | Mediates the atom transfer process during polymerization, controlling the reaction kinetics. | Copper(II) bromide with 2,2'-Bipyridine as a ligand. Cu^0 can be used for mediated (ARGET) ATRP to reduce catalyst concentration [16]. |

| Solvent | Dissolves the monomer and catalyst, enabling the polymerization reaction. | Anhydrous N,N-Dimethylformamide (DMF) or water/methanol mixtures [16] [17]. |

| Reducing Agent (for ARGET) | Regenerates the active Cu(I) catalyst from the Cu(II) deactivator, allowing for very low catalyst concentrations. | Ascorbic acid [16]. |

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Surface Preparation and Initiator Immobilization:

- For conductive surfaces like gold or CNTs, an ATRP initiator can be attached via self-assembled monolayers (e.g., from an ethanol solution of 2-bromo-2-methylpropionate) or electropolymerized.

- Electropolymerization Method: For conductive polymer-based substrates (e.g., PEDOT-infused fibre mats), electropolymerize a copolymer of EDOT and the ATRP-initiator functionalized EDOT-Br from an acetonitrile solution to create a uniform initlayer across the surface [16].

Polymerization Solution Preparation:

- In a Schlenk flask, dissolve the OEGMA monomer in a degassed solvent (e.g., a 1:1 v/v mixture of methanol and water, or DMF) to achieve a typical concentration of 1-2 M.

- Add the ligand (e.g., 2,2'-Bipyridine) and the copper(II) bromide catalyst. For ARGET ATRP, also add a stoichiometric amount of reducing agent (e.g., ascorbic acid) relative to the Cu(II). The goal is to achieve a very low concentration of the active Cu(I) catalyst for better control.

Surface-Initiated Polymerization:

- Transfer the degassed polymerization solution to a reaction vessel containing the initiator-functionalized substrate under an inert atmosphere (e.g., nitrogen or argon).

- Seal the vessel and place it in a temperature-controlled bath or oven. The polymerization is typically carried out at temperatures between 25°C and 40°C.

- Allow the reaction to proceed for a predetermined time (e.g., 1 to 24 hours) to control the brush thickness. The brush thickness and density can be tuned by varying the polymerization time and surface density of the active initiator [18].

Post-Polymerization Processing:

- After polymerization, carefully remove the substrate from the reaction mixture.

- Rinse the substrate thoroughly with copious amounts of the solvent and ethanol to remove any physisorbed monomer, catalyst, and untethered polymer.

- Dry the substrate under a stream of nitrogen or argon.

Validation and Characterization:

- Ellipsometry or AFM: Measure the dry thickness of the polymer brush layer.

- Water Contact Angle: Confirm increased hydrophilicity compared to the unmodified surface.

- Protein Assay (e.g., BCA Assay): Quantify the non-fouling properties by measuring the amount of adsorbed protein (e.g., Bovine Serum Albumin) from solution. Efficiency of >80% protein repellence has been demonstrated with 30-mers POEGMA brushes [16].

- Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS): Characterize the interfacial properties and the extension of the sensing distance.

Protocol: Biosensing with a POEGMA-Modified D4-TFT

This protocol outlines the use of a POEGMA-functionalized Carbon Nanotube Thin-Film Transistor (D4-TFT) for ultrasensitive biomarker detection [10].

Workflow Overview:

The following diagram outlines the complete experimental workflow for the D4-TFT biosensing assay, from surface preparation to electrical detection.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Device Fabrication and POEGMA Grafting:

- Fabricate a solution-gated thin-film transistor using semiconducting carbon nanotubes as the channel material.

- Graft a POEGMA brush layer directly above the CNT channel following the SI-ATRP protocol in Section 4.1.

Biofunctionalization:

- Printing Capture Antibodies: Using a non-contact inkjet printer or a microspotter, print capture antibodies (cAb) directly into the POEGMA brush layer above the CNT channel. A control device with no antibodies should be prepared on the same chip.

- Printing Detection Antibodies: Print detection antibodies (dAb), conjugated with a label if necessary, onto a readily dissolvable sugar layer (e.g., trehalose) patterned on a separate, facing substrate.

Assay Execution (D4 Protocol):

- Dispense: Dispense a small volume of the sample containing the target biomarker onto the device.

- Dissolve: The sample dissolves the trehalose layer, releasing the detection antibodies into the solution.

- Diffuse: All biomolecules (target and detection antibodies) diffuse to the sensor surface.

- Detect: A sandwich immunoassay complex forms on the sensor surface if the target biomarker is present.

Electrical Measurement and Data Analysis:

- Use a stable electrical testing configuration with a palladium (Pd) pseudo-reference electrode to avoid bulky Ag/AgCl electrodes.

- To mitigate signal drift, enforce a rigorous testing methodology that relies on infrequent DC sweeps rather than continuous static or AC measurements [10].

- Monitor the transistor's transfer characteristics (drain current, ID, vs. gate voltage, VG). The formation of the antibody-analyte sandwich complex within the POEGMA brush causes a measurable shift in the on-current or threshold voltage.

- Successful detection is confirmed by a significant signal shift in the active device compared to the control device with no antibodies.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Materials for POEGMA-based Biosensor Research

| Category | Item | Critical Function |

|---|---|---|

| Polymer & Monomers | OEGMA Monomer (n=3, 4, 5, 7, 9, 19) | Determines brush architecture, hydration, and final antifouling/Donnan potential performance [17]. |

| ATRP Initiator (e.g., EDOT-Br) | Covalently anchors the growing polymer chains to the substrate surface [16]. | |

| Catalysis & Synthesis | Copper(II) Bromide (CuBr₂) / 2,2'-Bipyridine | Catalyzes the surface-initiated ATRP reaction [16]. |

| Ascorbic Acid | Serves as a reducing agent in ARGET ATRP for better reaction control [16]. | |

| Sensor Components | Semiconducting Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) | Forms the high-sensitivity channel material for the BioFET transducer [10]. |

| Palladium (Pd) Wire | Acts as a stable, miniaturized pseudo-reference electrode for point-of-care device compatibility [10]. | |

| Biologicals | Capture & Detection Antibodies | Provide high-specificity recognition for the target biomarker in a sandwich assay format [10]. |

| Trehalose | Forms a dissolvable excipient layer for stable storage and controlled release of detection antibodies [10]. |

The integration of POEGMA polymer brushes into biosensor interfaces represents a transformative material strategy for overcoming the fundamental limitation of Debye screening. By establishing a localized Donnan potential, these brushes effectively extend the charge-sensing range, enabling direct, label-free, and ultrasensitive detection of biomarkers in physiologically relevant fluids. The detailed protocols and performance data provided herein offer researchers a clear pathway to implement this advanced functionality. When combined with robust sensing platforms like CNT-based TFTs and drift-mitigating electrical measurement schemes, POEGMA brushes pave the way for the development of reliable, high-performance point-of-care diagnostic devices that can function accurately in blood, serum, and other complex biological matrices.

A paramount challenge in the development of electronic biosensors is the severe charge screening effect in physiological environments, where the high ionic strength limits the electrostatic detection of biomarkers to distances shorter than 1 nm—the Debye length [2] [19]. This screening prevents the detection of larger biomolecules, such as antibodies, which can be 10–15 nm in size [2]. This Application Note details the use of Supported Lipid Bilayers (SLBs) as biomimetic platforms that, when functionalized with specific polymer brushes, can overcome this limitation by establishing a Donnan potential. This potential effectively extends the sensing range of biosensors, enabling highly sensitive detection in biologically relevant ionic strength solutions [10] [9].

Theoretical Framework: Donnan Potential and Debye Length Extension

The sensitivity of field-effect transistor (FET) based biosensors is traditionally limited by the formation of an Electrical Double Layer (EDL) at the sensor-solution interface. In high ionic strength solutions (e.g., 1X PBS), the EDL is compressed, resulting in a Debye length of only about 0.7 nm [10] [19]. Any charged biomarker beyond this distance from the sensor surface is electrically screened and undetectable.

The strategy outlined herein involves creating an ion-permeable layer atop the sensor, into which charged biomolecules can partition. This layer acts as a selective membrane, leading to an unequal distribution of ions between the layer and the bulk solution. This ion partitioning creates a Donnan potential, a constant electrostatic potential that extends throughout the entire ion-permeable layer [6] [9]. The Donnan potential (( \Delta \phiD )) can be quantitatively described by the following equation, where ( \varphi{th} ) is the thermal voltage, ( cs ) is the bulk ion concentration, and ( cx ) is the concentration of fixed charges within the permeable layer [9]: [ \Delta \phiD = \varphi{th} \, \ln \frac{(\sqrt{4{cs}^2 + {cx}^2} + {cx})}{2{cs}} ] This potential effectively pushes the sensing plane from the sensor surface to the outer boundary of the polymer layer, thereby overcoming the traditional Debye screening limitation [2] [9]. The schematic below illustrates this core concept.

Diagram 1: Conceptual framework of Donnan potential extending the sensing range beyond the Debye length.

Experimental Protocols

Fabrication of SLB-Based Biosensors (D4-TFT Platform)

This protocol describes the construction of an ultrasensitive Carbon Nanotube Thin-Film Transistor (CNT-TFT) biosensor, termed the D4-TFT, which integrates a Supported Lipid Bilayer (SLB) and a polymer brush to overcome Debye screening [10].

Key Materials:

- Substrate: Si/SiO₂ wafers with pre-patterned interdigitated gold source and drain electrodes.

- Semiconductor: Semiconducting carbon nanotubes (CNTs).

- Polymer Brush: Poly(oligo(ethylene glycol) methyl ether methacrylate) (POEGMA).

- Lipid Components: Soybean lecithin, phosphatidylethanolamine, and biotin-X DHPE (for functionalization).

- Biorecognition Elements: Target-specific capture antibodies (cAb) and biotinylated detection antibodies (dAb).

- Other Chemicals: EDC, S-NHS, phosphate-buffered saline (PBS).

Procedure:

- CNT-TFT Fabrication: Solution-processable CNTs are deposited onto the substrate to form the active channel between the source and drain electrodes [10].

- Surface Functionalization:

- The CNT surface is first functionalized with a plasma-deposited thin layer containing carboxylic acid (-COOH) moieties to promote subsequent binding [14].

- The surface is treated with a fresh EDC/S-NHS solution (100 mM each in PBS) for 1 hour at room temperature to activate the carboxyl groups.

- After rinsing, the POEGMA polymer brush is grafted onto the activated surface. This brush serves as the ion-permeable layer for Donnan potential extension and a non-fouling background [10].

- Supported Lipid Bilayer Formation via Vesicle Fusion: [20]

- Vesicle Preparation: Lipids (soybean lecithin, phosphatidylethanolamine, and biotin-X DHPE) are dissolved in chloroform. The solvent is evaporated under a nitrogen stream, and the lipid film is placed under vacuum for 60 minutes. The film is then rehydrated in PBS and sonicated on ice. The resulting multilamellar vesicle suspension is extruded through a polycarbonate filter (100 nm pore size) to form small unilamellar vesicles (SUVs).

- Vesicle Fusion: The freshly prepared SUV suspension is incubated overnight with the POEGMA-functionalized sensor surface under mild agitation. Vesicles adsorb, rupture, and merge to form a continuous SLB on the surface [20].

- Antibody Immobilization: Capture antibodies (cAb) are printed directly onto the POEGMA brush above the CNT channel. A control device with no antibodies is also prepared on the same chip for validation [10].

The overall workflow for sensor preparation and the D4 assay operation is summarized below.

Diagram 2: Workflow for SLB-based D4-TFT biosensor preparation and assay operation.

Electrical Measurement Protocol to Mitigate Signal Drift

Accurate measurement in ionic solutions is confounded by signal drift. The following protocol ensures stable readings [10].

Procedure:

- Stable Testing Configuration: Use a palladium (Pd) pseudo-reference electrode to avoid bulky Ag/AgCl electrodes. Ensure proper passivation of the device.

- Rigorous Measurement Methodology:

- Use infrequent DC current-voltage (I-V) sweeps instead of continuous static (DC) or alternating current (AC) measurements.

- Apply a single short pulse bias (e.g., 50 µs duration with a sampling rate of 10 ns) and integrate the measured current over the pulse period.

- Define the signal as a normalized change in the drain current (( \Delta I / I )) or as a current gain. This methodology minimizes ion drift and thermal noise, providing a stable baseline.

Key Experimental Data and Performance

The performance of the D4-TFT platform with the POEGMA polymer brush has been quantitatively evaluated. The table below summarizes key findings from the literature.

Table 1: Performance summary of SLB-based biosensors with Donnan potential extension.

| Sensor Platform | Target Analyte(s) | Sample Matrix | Detection Limit | Key Performance Feature | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D4-TFT (CNT, POEGMA) | Model biomarkers | 1X PBS | Sub-femtomolar (aM) | Achieved attomolar sensitivity in undiluted physiological buffer. | [10] |

| EDL AlGaN/GaN HEMT | HIV-1 RT, CEA, NT-proBNP, CRP | 1X PBS & Human Serum | Not specified | Direct detection in 5 minutes without sample dilution or washing. | [19] |

| Graphene FEB Sensor | Infectious disease biomarkers | Serum | 500 ng/mL | Demonstrated applicability in a commercially produced, foundry-fabricated device. | [9] |

Further characterization of the SLB itself is crucial for quality control. The table below outlines key parameters and common characterization techniques.

Table 2: Supported Lipid Bilayer characterization techniques and parameters.

| Characterization Method | Key Parameters Measured | Insight for SLB Quality |

|---|---|---|

| Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) | Lipid-phase separation, gel-phase domain formation and size (1-35 μm), bilayer thickness (~5 nm), fluidity. | Verifies successful bilayer formation, phase behavior, and lateral homogeneity [20]. |

| Fluorescence Microscopy | Lipid diffusion (Fluorescence Recovery After Photobleaching - FRAP), domain visualization via fluorescent tags. | Confirms bilayer fluidity and allows visualization of phase-separated domains [20]. |

| Electrical Impedance Spectroscopy | Membrane integrity, resistance, and capacitance. | Quantifies ion impermeability and confirms the formation of a continuous, defect-free bilayer. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential materials and reagents for SLB-based biosensor development.

| Item | Function/Description | Example/Catalog |

|---|---|---|

| Semiconducting CNTs | Forms the highly sensitive, solution-processable channel of the thin-film transistor. | Purity >98%, various diameters available. |

| POEGMA Polymer | Creates an ion-permeable, non-fouling brush layer that extends the Debye length via the Donnan effect. | Poly(oligo(ethylene glycol) methyl ether methacrylate). |

| Soybean Lecithin | A natural mixture of phospholipids used as the primary component for forming the SLB. | EPIKURON 200 [14]. |

| Biotin-X DHPE | A functionalized lipid that incorporates into the SLB, providing biotin handles for streptavidin-biotin based immobilization. | N-((6 (Biotinoyl)amino)hexanoyl)-1,2-Dihexadecanoyl-sn-Glycero-3-Phosphoethanolamine [14]. |

| Streptavidin/Avidin | Tetrameric protein that bridges biotinylated lipids and biotinylated detection antibodies. | From Streptomyces avidinii or egg white [14]. |

| EDC / S-NHS | Crosslinking agents for zero-length carbodiimide chemistry; activate carboxyl groups for covalent coupling to amine groups. | 1-Ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide / N-Hydroxysulfosuccinimide. |

Biosensor technology has emerged as a dynamic and rapidly evolving field, responding to the pressing need for precise, rapid, and cost-effective measurements in healthcare, environmental monitoring, and food safety [21]. The performance of these biosensors is fundamentally governed by the electrostatic conditions at the bio-interface, particularly the Donnan potential and its role in extending the effective Debye length within charged permeable layers [6]. This application note provides a detailed framework for the practical implementation of two cornerstone biosensing methodologies: the antibody-based sandwich assay and DNA-based detection via aptamers. We present structured quantitative data, step-by-step experimental protocols, and standardized visualization tools to guide researchers and drug development professionals in developing robust biosensing platforms that leverage these critical electrostatic phenomena.

Theoretical Framework: Donnan Potential and Debye Length in Biosensing

The electrostatics of charged bio-interfaces is pivotal for the reactivity and sensitivity of biosensors, influencing processes from colloid stability to the detection of biomolecular interactions [6]. In biosensors with ion-permeable, polyelectrolyte-like layers (such as polymer coatings or cellular membranes), a fundamental electrostatic phenomenon occurs.

When the thickness of a charged surface layer well exceeds the screening Debye length, a constant Donnan potential ((\Psi_D)) is established throughout that layer [6]. This potential arises from the charge-driven accumulation of counterions and exclusion of co-ions. The classical mean-field Poisson-Boltzmann theory describes this under the point-like charge approximation.

However, the existence and magnitude of the Donnan potential are conditional and highly dependent on steric effects mediated by the sizes of the electrolyte ions and the structural charges of the biosensor interface itself [6]. Modern corrections to the theory account for these steric effects, providing a more accurate rationale for the difference between the intra- and extra-particulate Debye screening lengths. This is crucial for biosensor design, as the Donnan potential directly affects the partitioning of ions and biomolecules (such as proteins or DNA) at the sensor surface, thereby influencing the binding efficiency and ultimate detection signal of an assay [6].

Biosensing Recognition Elements: A Quantitative Comparison

The choice of molecular recognition element is a primary determinant of biosensor performance. The following table summarizes the key characteristics of antibodies and nucleic acid aptamers, the two most prevalent biorecognition elements.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Antibodies and Aptamers as Biosensor Recognition Elements

| Feature | Aptamers | Antibodies |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Weight | 5 to 15 kDa [21] | 150 to 170 kDa [21] |

| Selection Process | SELEX (in vitro) [21] | Animal immune system (in vivo) [21] |

| Generation Time | Months [21] | Several months [21] |

| Production Scalability | Highly scalable (chemical synthesis) [21] | Limited scalability [21] |

| Batch-to-Batch Variation | Lower [21] | Higher [21] |

| Stability & Shelf Life | Long; renature after denaturation [21] | Short; sensitive to pH/temperature, irreversible denaturation [21] |

| Cost | Lower [21] | Higher [21] |

| Modifications | Easily modified for immobilization or detection [21] | Limited modification options [21] |