Porous Frameworks in Action: MOF and COF Biosensors for Advanced Pesticide Detection

This article comprehensively reviews the rapidly evolving role of Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) and Covalent Organic Frameworks (COFs) in constructing next-generation biosensors for pesticide monitoring.

Porous Frameworks in Action: MOF and COF Biosensors for Advanced Pesticide Detection

Abstract

This article comprehensively reviews the rapidly evolving role of Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) and Covalent Organic Frameworks (COFs) in constructing next-generation biosensors for pesticide monitoring. Tailored for researchers and scientists, we explore the foundational principles of these porous materials, detailing innovative synthesis strategies for creating enzyme composites and nanozymes. The scope extends to advanced application methodologies, including dual-modal sensing platforms for on-site analysis. We critically address key challenges such as material stability, biocompatibility, and toxicity, while providing a comparative validation of biosensor performance against conventional techniques. Finally, we synthesize future trajectories, highlighting the potential of these smart materials to revolutionize environmental monitoring and clinical diagnostics.

Unlocking the Architecture: Why MOFs and COFs are Ideal for Biosensing

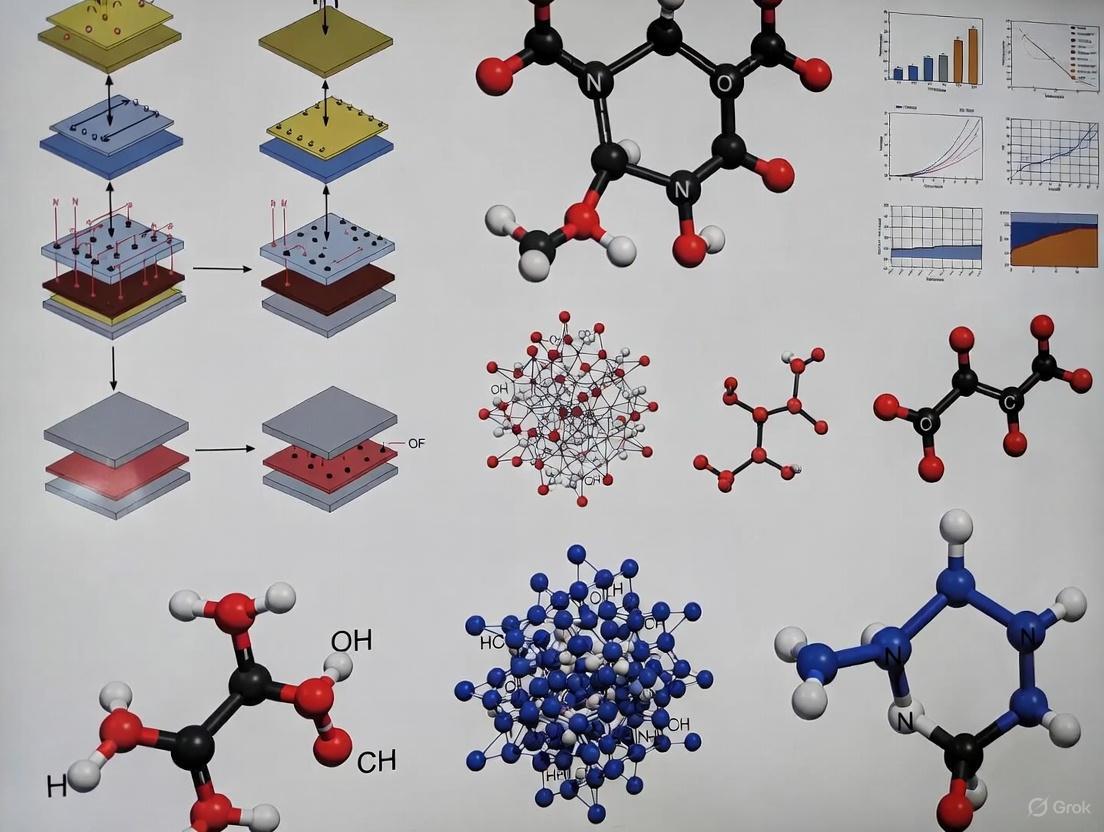

Metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) and covalent organic frameworks (COFs) represent two forefront classes of porous crystalline materials that have fundamentally transformed materials design for advanced applications. Their core structural principles are founded on reticular chemistry, which enables the precise assembly of molecular building blocks into predictable, porous network structures [1] [2]. In the specific context of biosensor construction for pesticide detection, the interplay between a material's porosity, surface area, and chemical tunability directly governs its performance in terms of sensitivity, selectivity, and stability.

MOFs are organic-inorganic hybrid structures formed via coordination bonds between metal ions or clusters (nodes) and organic linkers [3] [4]. In contrast, COFs are constructed entirely from organic molecules connected by strong covalent bonds (e.g., boronic esters, imines) to form rigid, typically two- or three-dimensional porous networks [5] [1]. A recent innovative hybrid, the covalent-metal organic framework (C-MOF), strategically integrates metal clusters as structural nodes (a MOF characteristic) with dynamic covalent linkages (a COF characteristic), aiming to synergize the robust stability of COFs with the rich catalytic activity of MOFs [1]. The following table summarizes the defining characteristics of these frameworks.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Porous Crystalline Frameworks

| Framework Type | Primary Bonding | Structural Components | Key Advantage | Common Challenge |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MOF (Metal-Organic Framework) | Coordination Bonds | Metal Ions/Clusters + Organic Linkers | High Catalytic Activity & Crystallinity | Moderate Chemical Stability [1] [6] |

| COF (Covalent Organic Framework) | Covalent Bonds | Organic Molecules | High Chemical & Thermal Stability | Lack of Innate Metal Active Sites [5] [1] |

| C-MOF (Covalent-MOF) | Covalent & Coordination Bonds | MOF-like SBUs + COF-like Linkers | Combined Stability & Catalytic Sites | Complex Synthesis [1] |

Core Properties and Their Quantification

The performance of MOFs and COFs in biosensing is largely dictated by three interconnected intrinsic properties: porosity, surface area, and tunability.

Porosity and Surface Area

Porosity refers to the presence of cavities or channels within the framework, which are critical for hosting biorecognition elements (e.g., enzymes), facilitating mass transfer of analytes, and providing space for signal transduction reactions. Surface area, typically measured in square meters per gram (m²/g), quantifies the total available interfacial space for molecular interactions.

The Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) method is the standard technique for determining the specific surface area of MOFs and COFs from gas adsorption isotherms [7]. MOFs are renowned for their record-breaking surface areas, which can exceed 7000 m²/g, while COFs have also demonstrated impressive values beyond 5000 m²/g [4]. This immense surface area allows for a high loading capacity of receptor molecules, directly enhancing the sensor's response signal.

Structural and Functional Tunability

Tunability is the cornerstone of reticular chemistry. The "de novo" design approach allows for the pre-selection of metal nodes and organic linkers with specific geometries and functionalities to create a framework with desired pore size, shape, and chemical environment [4]. A powerful extension of this is the multivariate (MTV) approach, where multiple, functionally distinct linkers are incorporated into a single, crystalline framework to create heterogeneous pore environments optimized for multi-analyte sensing or complex catalytic workflows [4].

Furthermore, post-synthetic modification (PSM) enables the chemical alteration of a pre-formed framework. This allows for the introduction of specific functional groups (e.g., -NH₂, -COOH) that enhance biocompatibility, improve binding affinity for target pesticides, or facilitate the immobilization of enzymes [3] [4].

Table 2: Quantitative Performance of MOF/COF-Based Biosensors for Pesticide Detection

| Material Platform | Target Pesticide | Detection Mode | Limit of Detection (LOD) | Key Stability Feature | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AChE@COF Capsule + Fe/Cu-MOF | Chlorpyrifos (CP) | Electrochemical | 0.3 pg/mL | Stable at 65°C, pH 4.0, organic solvents | [5] |

| AChE@COF Capsule + Fe/Cu-MOF | Chlorpyrifos (CP) | Colorimetric | 1.6 pg/mL | Stable at 65°C, pH 4.0, organic solvents | [5] |

| MOF-based Gated Nanoprobe | -- | Fluorescence (DNA-based) | 6.4 × 10⁻¹⁰ M | >90% detection accuracy | [3] |

| Zn-MOF Nanoparticles | -- | Photoluminescence (PSA Antigen) | 0.145 fg/mL | High thermal stability | [3] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Synthesis of a Hollow COF Capsule for Enzyme Encapsulation (AChE@COF)

This protocol details the synthesis of a hollow COF capsule using a sacrificial template to encapsulate and protect the enzyme acetylcholinesterase (AChE), a common biorecognition element in organophosphorus pesticide sensors [5].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for AChE@COF Synthesis

| Reagent/Material | Function/Description | Role in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| ZIF-8 Nanoparticles | Zeolitic Imidazolate Framework (a type of MOF) | Serves as a sacrificial template to define the hollow capsule structure. |

| Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) | Biological enzyme (from Electrophorus electricus) | The biorecognition element whose activity is inhibited by organophosphorus pesticides. |

| TFP and TAPB Monomers | 1,3,5-Triformylphloroglucinol (TFP) and 1,3,5-Tris(4-aminophenyl)benzene (TAPB) | Organic linkers that undergo polycondensation to form the COF (COFTFP-TAPB) shell. |

| Anhydrous Dichloroethane | Organic solvent | Reaction medium for the COF synthesis. |

| Acetic Acid (6 M) | Catalytic solution | Serves as a catalyst for the imine-based COF formation reaction. |

Procedure:

- Enzyme-loaded Template Preparation: First, immobilize the AChE enzyme onto pre-synthesized ZIF-8 nanoparticles. This is typically achieved by incubating an aqueous solution of AChE with a suspension of ZIF-8, allowing the enzyme to adsorb onto the MOF's surface and within its pores [5].

- COF Shell Growth: Re-disperse the resulting AChE@ZIF-8 composite in a mixture of anhydrous dichloroethane, the TFP and TAPB monomers. Subsequently, add a small quantity of 6 M acetic acid to catalyze the polycondensation reaction.

- Template Removal and Purification: Allow the reaction to proceed for a specified period to form a dense COF shell around the AChE@ZIF-8 core. Finally, the ZIF-8 template is selectively etched away using a mild acidic solution (e.g., EDTA), leaving the AChE enzyme encapsulated within a protective, hollow COF capsule (AChE@COF). The final product is collected via centrifugation, washed thoroughly, and stored in a suitable buffer [5].

Critical Step: The concentration of the enzyme and the ratio of the COF monomer precursors to the template must be optimized to ensure complete encapsulation while preserving enzymatic activity.

Protocol: Construction of an Electrochemical/Colorimetric Dual-Mode Sensor

This protocol outlines the assembly of a dual-mode sensor for organophosphorus pesticides (OPs), integrating the AChE@COF nanocapsule with a nanozyme to create a cascade system [5].

Diagram: Signaling Pathway in AChE-MOF Nanozyme Sensor

Procedure:

- Sensor Assembly: The synthesized AChE@COF nanocapsules are immobilized onto a solid electrode surface (e.g., glassy carbon or gold electrode). Separately, a peroxidase-like Fe/Cu-MOF nanozyme is synthesized and either co-immobilized on the electrode or added to the solution phase [5].

- Signal Generation Workflow:

- Introduce the substrate acetylthiocholine (ATCh) to the system.

- In the absence of OPs, the encapsulated AChE catalyzes the hydrolysis of ATCh to produce thiocholine (TCh).

- The generated TCh efficiently passivates the peroxidase-like activity of the Fe/Cu-MOF nanozyme.

- Consequently, when a peroxidase substrate like OPD or TMB is added, the nanozyme shows low activity, resulting in minimal production of electroactive oxOPD or colored oxTMB (Low Signal) [5].

- Analyte Detection Workflow:

- When an OP pesticide is present in the sample, it inhibits the activity of the encapsulated AChE.

- This leads to a significant reduction in TCh production.

- The Fe/Cu-MOF nanozyme remains highly active and catalyzes the oxidation of OPD or TMB, leading to a strong increase in electrochemical current or a vivid color change (High Signal) [5].

- Signal Measurement: The concentration of the OP pesticide is quantitatively determined by measuring the increase in electrochemical response (e.g., amperometric current) or the colorimetric intensity (absorbance), both of which are inversely proportional to AChE activity.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Reagent Solutions for MOF/COF-Based Biosensor Development

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function in Biosensor Construction |

|---|---|---|

| Metal Node Precursors | Zn(NO₃)₂, Cu(OAc)₂, ZrOCl₂, FeCl₃ | Source of metal ions for constructing MOF secondary building units (SBUs). |

| Organic Linkers | 2-Methylimidazole (for ZIFs), Terephthalic Acid, Trimesic Acid, TFP, TAPB | Molecular struts that connect metal nodes (MOFs) or form covalent networks (COFs). |

| Biorecognition Elements | Acetylcholinesterase (AChE), antibodies, aptamers, DNA strands | Provide selective binding and recognition for target pesticide molecules. |

| Signal Probes & Substrates | o-Phenylenediamine (OPD), TMB (3,3',5,5'-Tetramethylbenzidine), Acetylthiocholine (ATCh) | Enzymatic substrates that generate measurable (electro)chemical or colorimetric signals. |

| Nanozymes | Fe/Cu-MOF, Peroxidase-like MOFs | Mimic enzyme activity, often used as stable signal amplifiers in cascade systems. |

The intrinsic properties of MOFs and COFs—namely their vast porosity, immense surface area, and unparalleled chemical tunability—establish them as foundational materials for next-generation biosensors. By applying rational design and synthesis protocols, researchers can engineer these frameworks to create highly sensitive, stable, and versatile sensing platforms. The development of hybrid materials like C-MOFs and the strategic use of encapsulation techniques signal a promising trajectory for creating robust biosensors capable of reliable pesticide monitoring in complex, real-world environments.

The escalating global concern over pesticide contamination demands the development of advanced sensing technologies for precise detection and monitoring. Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) and Covalent Organic Frameworks (COFs) have emerged as forefront porous materials in constructing highly sensitive biosensors for pesticide detection. These materials offer exceptional structural tunability, high surface areas, and unique host-guest interactions that can be engineered specifically for recognizing neurotoxic pesticide compounds. This application note provides a systematic comparison of MOF and COF materials, focusing on their stability profiles and functional capabilities to guide researchers in selecting appropriate materials for specific pesticide sensing applications. We further present detailed experimental protocols for fabricating and characterizing these sensors, enabling reliable implementation in environmental monitoring and food safety applications.

Structural Fundamentals and Key Properties

MOFs are crystalline porous materials formed through coordination bonds between metal ions/clusters and organic linkers, while COFs are constructed entirely from light elements (H, B, C, N, O) connected via strong covalent bonds [2]. This fundamental structural difference dictates their contrasting properties and applications in sensing platforms.

Table 1: Comparative Structural Properties of MOFs and COFs

| Property | Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) | Covalent Organic Frameworks (COFs) |

|---|---|---|

| Bonding Type | Coordination bonds | Covalent bonds |

| Structural Components | Metal ions/clusters + Organic linkers | Light elements (H, B, C, N, O) |

| Porosity | Ultrahigh (>90% under physiological conditions) [8] | High, but typically lower than MOFs |

| Surface Area | Extremely high specific surface area [9] [10] | High specific surface area [9] |

| Electrical Conductivity | Generally poor, requires composites [11] [2] | Inherently higher due to conjugated structures |

| Active Sites | Open metal sites, functional organic linkers [12] | Predominantly functional organic groups |

Stability Analysis for Sensor Applications

Material stability under operational conditions is a critical determinant in sensor design, directly impacting device lifetime, reliability, and accuracy.

MOF Stability Considerations

MOFs face multiple degradation pathways in practical sensing environments [10]:

- Hydrolysis: Liquid water or high humidity can disrupt metal-ligand bonds, particularly in Zn, Cu-based MOFs

- Chemical Attack: Structural degradation under extreme pH (acids/bases) or coordinating anions

- Photodegradation: UV-visible light can induce photoreactive damage in some MOF structures

- Thermal Stress: Framework collapse at elevated temperatures

Stabilization strategies include using higher-valence metal clusters (e.g., Zr₆-cluster in UiO series), introducing hydrophobic substituents, and constructing MOF composites with protective matrices [13].

COF Stability Profile

COFs generally exhibit superior chemical stability compared to many MOFs due to their strong covalent bonding [9] [2]. They demonstrate enhanced resistance to hydrolysis and maintain structural integrity across wider pH ranges, making them suitable for sensing in aqueous environments.

Table 2: Stability Comparison for Sensor Design

| Stability Factor | MOFs | COFs |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrolytic Stability | Variable; Zr-based excellent, Zn/Cu-based poor [10] [13] | Generally superior to most MOFs [9] |

| Thermal Stability | Moderate to high | High |

| Chemical Stability | pH-dependent; can be limited | Broad pH tolerance |

| Long-term Operation | Requires stabilization strategies | Inherently more stable |

Functional Performance in Pesticide Sensing

Both MOFs and COFs can be functionalized to enhance their pesticide detection capabilities through incorporation of specific recognition elements, nanoparticles, or signal amplification components.

Signal Transduction Mechanisms

Electrochemical Sensors leverage the redox activity of pesticides, where MOF/COF modifiers enhance electrode sensitivity. The high surface area enables pesticide preconcentration, while framework functionalities promote specific interactions [9] [11].

Optical Sensors utilize fluorescence quenching/enhancement upon pesticide binding. MOFs offer diverse luminescence origins (metal-/ligand-centered), while COFs provide conjugated platforms for energy/electron transfer [10].

Enhancing Sensing Performance

MOF-Specific Strategies: Utilization of open metal sites (OMS) for strong analyte binding [12]; Integration with conductive nanomaterials (graphene, CNTs) to overcome inherent electrical limitations [2] [13].

COF-Specific Strategies: Leveraging inherent π-conjugated systems for signal transduction; Functionalization with specific recognition units via pre- or post-synthetic modification.

Composite Approaches: MOF@COF hybrid structures combine MOF's catalytic activity with COF's stability, creating synergistic sensing platforms [9] [2].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Fabrication of MOF-Based Electrochemical Sensor for Organophosphorus Pesticides

Principle: ZIF-8 provides high surface area for pesticide adsorption, while AuNPs enhance electron transfer and serve as immobilization matrix for acetylcholinesterase enzyme [11] [2].

Materials:

- Glassy Carbon Electrode (GCE, 3 mm diameter)

- ZIF-8 MOF (synthesized via solvothermal method)

- N,N-Dimethylformamide (DMF, HPLC grade)

- Hydrogen tetrachloroaurate(III) trihydrate (for AuNP electrodeposition)

- Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) from Electrophorus electricus

- Phosphate buffer saline (PBS, 0.1 M, pH 7.4)

Procedure:

- Electrode Pretreatment: Polish GCE sequentially with 1.0, 0.3, and 0.05 µm alumina slurry. Rinse thoroughly with ethanol and deionized water. Dry under nitrogen stream.

- Suspension Preparation: Disperse 2.0 mg of ZIF-8 in 1.0 mL DMF. Sonicate for 30 minutes to obtain homogeneous suspension.

- Electrode Modification: Drop-cast 5.0 µL of ZIF-8 suspension onto GCE surface. Dry at 60°C for 15 minutes.

- Nanoparticle Decoration: Immerse modified electrode in 1 mM HAuCl₄ solution containing 0.1 M KNO₃. Perform electrodeposition at -0.2 V for 60 seconds.

- Enzyme Immobilization: Incubate ZIF-8/AuNP/GCE with 10 µL AChE solution (0.5 U/µL) for 12 hours at 4°C. Rinse gently with PBS to remove unbound enzyme.

Characterization: Confirm successful modification using cyclic voltammetry in 5 mM [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻ solution. Monitor increased peak currents and decreased peak-to-peak separation, indicating enhanced electron transfer.

Protocol 2: Construction of COF-Based Fluorescent Sensor for Triazine Herbicides

Principle: A π-conjugated COF serves as fluorescent reporter, whose emission is quenched via photoinduced electron transfer (PET) upon triazine herbicide binding [10].

Materials:

- TpBD-COF (composed of triformylphloroglucinol and benzidine)

- Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, spectroscopic grade)

- Triazine herbicide standards (atrazine, simazine)

- Quartz cuvette (1 cm path length)

Procedure:

- COF Dispersion: Prepare 0.1 mg/mL TpBD-COF dispersion in DMSO. Sonicate for 20 minutes until achieving clear, non-turbid suspension.

- Sample Preparation: Mix 2.0 mL COF dispersion with 10 µL pesticide standard at varying concentrations (0.1-100 µM).

- Incubation: Vortex mixture for 30 seconds, then incubate for 5 minutes at room temperature for complete interaction.

- Fluorescence Measurement: Transfer solution to quartz cuvette. Record fluorescence emission spectrum (λex = 380 nm, λem = 400-600 nm).

- Calibration: Plot fluorescence intensity at λ_max versus pesticide concentration. Typically follows Stern-Volmer relationship.

Characterization: Verify COF structure by powder X-ray diffraction before sensing experiments. Monitor fluorescence lifetime changes to confirm PET mechanism.

Sensing Mechanisms and Performance

Table 3: Analytical Performance of MOF/COF Sensors for Pesticide Detection

| Material Type | Target Pesticide | Detection Mechanism | Linear Range | Detection Limit | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZIF-8/AuNP Composite | Organophosphates | Electrochemical (Enzyme inhibition) | 0.1-100 nM | 0.05 nM | [11] |

| Cu-based MOF | Paraoxon | Fluorescence quenching | 0.01-10 µM | 3.2 nM | [10] |

| Zr-MOF | Methyl parathion | Electrochemical (Redox) | 0.001-10 µM | 0.3 nM | [14] |

| Imine COF | Atrazine | Fluorescence (PET) | 0.05-50 µM | 8.2 nM | [9] |

| β-ketoenamine COF | Chlorpyrifos | Electrochemical | 0.01-5 µM | 2.1 nM | [2] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Reagents for MOF/COF Sensor Development

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Examples/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| ZIF-8 | MOF with zeolitic structure, high surface area | Zn²⁺ nodes, 2-methylimidazole linker; excellent for enzyme immobilization [11] |

| UiO-66 | Zr-based MOF, exceptional chemical stability | Zr₆O₄(OH)₄ clusters, terephthalic acid; stable in water [13] |

| MIL-101 | Cr-based MOF, large pore size | Cr³⁺ nodes, terephthalic acid; good for large pesticide molecules [10] |

| TpBD-COF | Fluorescent COF for optical sensing | Triformylphloroglucinol + benzidine; keto-enol tautomerism [9] |

| Au Nanoparticles | Enhance conductivity, facilitate immobilization | Electrodeposited or pre-synthesized; bio-conjugation with enzymes [2] |

| Acetylcholinesterase | Enzyme recognition element for OPs | Inhibition-based detection; from electric eel or recombinant [11] |

| Carbon Nanotubes | Conductive additive for MOF composites | Improve electron transfer in electrochemical sensors [2] |

MOFs and COFs each present distinct advantages for pesticide sensor design, with selection dependent on specific application requirements. MOFs offer superior structural diversity, open metal sites for specific interactions, and excellent electrocatalytic properties, though with variable stability concerns. COFs provide enhanced chemical stability, predictable porosity, and inherent π-conjugation for optical sensing, but with more challenging synthesis. The emerging trend of MOF@COF hybrid materials represents a promising direction, combining the strengths of both material classes [9] [2]. Future research should focus on improving conductivity, enhancing selectivity through molecular imprinting, developing smartphone-integrated portable sensors, and advancing sustainable synthesis routes to facilitate commercial application of these advanced sensing platforms.

The Role of Metal Nodes and Organic Linkers in Target-Specific Pesticide Recognition

Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) and Covalent Organic Frameworks (COFs) have emerged as highly versatile crystalline porous materials for constructing advanced biosensors, particularly for pesticide detection in environmental and food safety applications. The structural and chemical tunability of these frameworks allows for precise design of materials with specific recognition capabilities toward target analytes. MOFs, composed of inorganic metal nodes coordinated with organic linkers, and COFs, built from light elements connected by covalent bonds, feature extremely large specific surface areas, tunable nanoporosity, and unique surface chemistry that make them ideal for sensing platforms [2]. The intrinsic properties of these materials, managed through strategic selection of metal nodes and organic linkers, directly influence their sensing performance through mechanisms such as host-guest interactions, electron transfer, and molecular sieving effects [15] [2]. This application note details how specific combinations of metal nodes and organic linkers in MOFs and COFs enable target-specific pesticide recognition, providing structured protocols and data for researchers developing next-generation agricultural biosensors.

Fundamental Principles of MOF/COF-Based Pesticide Recognition

Key Recognition Mechanisms

The exceptional sensing capabilities of MOFs and COFs for pesticide detection originate from multiple synergistic mechanisms that can be tailored through framework design:

Host-Guest Interactions: The tunable pore structures and surface chemistry of frameworks enable selective adsorption of pesticide molecules based on size, shape, and chemical affinity [2]. The pore environment can be engineered to provide optimal van der Waals forces, hydrogen bonding, and π-π interactions with specific pesticide classes.

Electron Transfer Processes: Metal nodes with redox activity facilitate electron transfer reactions with electroactive pesticide compounds, enabling electrochemical detection [16]. The semiconductor properties of certain MOFs also allow for photoinduced electron transfer mechanisms in optical sensors [17].

Molecular Sieving Effect: Precisely controlled pore apertures (0.5-2 nm) in frameworks can selectively exclude interfering molecules while permitting access to target pesticides, significantly enhancing detection selectivity [2] [18].

Signal Amplification: The high surface area and porosity provide numerous active sites for pesticide binding, while framework structures can enhance signal transduction through mechanisms like fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) and surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS) [19] [17].

Design Considerations for Target-Specific Recognition

Achieving target-specific pesticide recognition requires strategic design considerations across multiple framework aspects:

Metal Node Selection: The choice of metal center (e.g., Zn²⁺, Cu²⁺, Zr⁴⁺, Fe³⁺) determines coordination geometry, Lewis acidity, redox activity, and catalytic properties that influence pesticide binding and signal transduction [16] [18].

Organic Linker Functionalization: Linkers with specific functional groups (-NH₂, -COOH, -OH, -SH) can be tailored for hydrogen bonding, acid-base interactions, or coordination with particular pesticide molecules [15] [20].

Pore Engineering: Control over pore size, shape, and volume enables size-selective recognition, while hydrophobic/hydrophilic balance affects partitioning of pesticides from aqueous environments [18] [20].

Structural Flexibility: Flexible MOFs (FMOFs) exhibit stimuli-responsive "breathing" behavior that can enhance selectivity through induced-fit mechanisms for specific pesticide geometries [20].

Table 1: Key Recognition Mechanisms and Their Design Parameters

| Recognition Mechanism | Governing Design Parameters | Target Pesticide Classes |

|---|---|---|

| Coordination Interaction | Metal Lewis acidity, Coordination geometry, Oxidation state | Organophosphates, Carbamates |

| Hydrogen Bonding | Functional group density, Polarity, Spatial arrangement | Triazines, Ureas, Carbamates |

| π-π Stacking | Aromatic content, Electron density, Interplanar distance | Neonicotinoids, Pyrethroids |

| Hydrophobic Interaction | Pore hydrophobicity, Surface functionalization | Organochlorines, Pyrethroids |

| Size/Shape Selectivity | Pore aperture, Framework flexibility, Channel dimensionality | All classes (molecular sieving) |

Metal Node Selection for Pesticide Recognition

Transition Metal Nodes

Transition metals provide diverse coordination geometries and redox activity that facilitate specific interactions with pesticide molecules:

Copper (Cu) Nodes: Cu-based MOFs (e.g., HKUST-1) exhibit excellent electrocatalytic activity toward organophosphorus pesticides due to the accessible Cu²⁺/Cu⁺ redox couple and Lewis acid sites that coordinate with phosphoryl oxygen atoms [16]. The open metal sites in Cu-MOFs strongly adsorb and catalytically degrade organophosphates through coordination bonding.

Zinc (Zn) Nodes: Zn-based MOFs (e.g., ZIF-8) offer tunable porosity and good chemical stability for sensing applications. While Zn centers typically lack redox activity, they provide well-defined coordination environments that can be combined with functional linkers for selective pesticide recognition through size exclusion and host-guest interactions [19] [17].

Iron (Fe) Nodes: Fe-based MOFs possess peroxidase-like catalytic activity that enables enzyme-free catalytic assays for pesticide detection. Fe³⁺/Fe²⁺ redox cycling facilitates electron transfer with pesticide molecules, while the magnetic properties of certain Fe-MOFs allow easy sensor regeneration [16].

Zirconium (Zr) Nodes: Zr-based MOFs (e.g., UiO-66 series) exhibit exceptional chemical and thermal stability, making them suitable for sensing in harsh environmental conditions. The high-valence Zr⁴⁺ centers provide strong Lewis acidity for coordinating with electron-rich functional groups on pesticides [2] [16].

Lanthanide and Multimetal Nodes

Advanced sensing platforms utilize lanthanide metals and mixed-metal clusters to enhance recognition capabilities:

Lanthanide Nodes: Eu³⁺ and Tb³⁺-based MOFs exhibit characteristic luminescence emissions with long lifetimes and large Stokes shifts, enabling sensitive fluorescence-based detection through pesticide-induced quenching or enhancement effects [17]. The antenna effect in lanthanide MOFs amplifies signals for ultra-trace detection.

Bimetallic Systems: Mixed-metal MOFs combine the advantages of different metal centers, creating synergistic effects for pesticide recognition. For example, Cu/Zn-MOFs integrate the redox activity of Cu with the structural stability of Zn, enhancing both sensitivity and sensor longevity [16].

Table 2: Metal Node Characteristics for Specific Pesticide Classes

| Metal Node | Coordination Geometry | Key Properties | Optimal Pesticide Targets | Detection Limits Reported |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cu²⁺ | Octahedral, Paddle-wheel | Redox activity, Open metal sites, Lewis acidity | Organophosphates, Carbamates | 0.05-2 nM [16] |

| Zn²⁺ | Tetrahedral, Octahedral | Structural stability, Tunable porosity | Neonicotinoids, Triazines | 0.1-5 nM [19] |

| Zr⁴⁺ | Octahedral, Cubic | High stability, Strong Lewis acidity | Broad-spectrum | 0.01-1 nM [2] |

| Fe²⁺/Fe³⁺ | Octahedral | Peroxidase-mimetic, Magnetic, Redox activity | Organochlorines, Phenoxy | 0.5-10 nM [16] |

| Eu³⁺/Tb³⁺ | Varied (8-9 coordinate) | Luminescence, Long lifetime, Antenna effect | Pyrethroids, Carbamates | 0.005-0.1 nM [17] |

Organic Linker Design for Enhanced Specificity

Linker Functionalization Strategies

Organic linkers serve as primary recognition elements through strategic functionalization that complements metal node properties:

Amino-Functionalized Linkers: Linkers containing -NH₂ groups (e.g., 2-aminoterephthalate) provide hydrogen bond donors and basic sites for interacting with electrophilic functional groups on pesticides. Amino groups also enhance fluorescence properties for optical sensing and can be further modified with recognition elements [2] [17].

Carboxylate-Rich Linkers: Multidentate carboxylate linkers (e.g., benzene tricarboxylic acid) not only stabilize framework structures but also offer hydrogen bond acceptors and acidic sites for binding basic pesticide molecules. The charge density on carboxylates influences electrostatic interactions with charged pesticide species [16].

Thiol-Functionalized Linkers: Linkers containing -SH groups provide soft Lewis basic sites for coordinating with heavy metal-containing pesticides or creating affinity for sulfur-containing pesticide compounds. Thiol groups can also be oxidized to create more reactive sulfonic acid groups [20].

Aromatic Systems: Extended π-conjugated linkers (e.g., pyrene, porphyrin-based) enable strong π-π stacking interactions with aromatic rings in pesticides like neonicotinoids and pyrethroids. The conjugated systems also facilitate charge transfer and luminescence signaling [2] [17].

Biomimetic and Customized Linkers

Advanced linker designs incorporate biomimetic recognition elements and customized geometries:

Biomimetic Linkers: Linkers incorporating molecularly imprinted polymers or biomimetic recognition elements (e.g., cyclodextrin, calixarene) create specific binding pockets for target pesticides, mimicking enzyme-substrate specificity [19].

Click Chemistry Functionalization: Post-synthetic modification using click chemistry allows introduction of specialized recognition groups (triazoles, tetrazoles) that provide specific interactions with pesticide molecules while maintaining framework integrity [2] [20].

Redox-Active Linkers: Linkers with inherent electrochemical activity (e.g., ferrocene, quinone-based) provide additional redox centers that enhance electron transfer processes in electrochemical sensing of pesticides [16].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Synthesis of ZIF-8 with Varied Organic Linkers for Neonicotinoid Sensing

Principle: Zeolitic Imidazolate Framework-8 (ZIF-8) provides excellent chemical stability and tunable functionality for pesticide sensing. This protocol details the synthesis of ZIF-8 with modified linkers for enhanced neonicotinoid recognition.

Materials:

- Zinc nitrate hexahydrate (Zn(NO₃)₂·6H₂O, 99%)

- 2-Methylimidazole (Hmim, 99%)

- Functionalized imidazole linkers (2-aminobenzimidazole, 2-chlorobenzimidazole)

- Methanol (anhydrous, 99.8%)

- N,N-Dimethylformamide (DMF, HPLC grade)

Procedure:

- Precursor Solutions: Dissolve 2.93 g Zn(NO₃)₂·6H₂O in 40 mL methanol (Solution A). Dissolve 3.24 g 2-methylimidazole and 0.25 g functionalized imidazole linker in 40 mL methanol (Solution B).

- Mixing and Reaction: Rapidly pour Solution A into Solution B under vigorous stirring (500 rpm). Continue stirring for 1 hour at room temperature.

- Aging and Crystallization: Transfer the mixture to a sealed container and age for 24 hours at room temperature without disturbance.

- Product Isolation: Collect the white crystalline product by centrifugation at 8,000 rpm for 10 minutes.

- Washing: Wash the product three times with fresh methanol (20 mL each) to remove unreacted precursors.

- Activation: Dry the product under vacuum at 120°C for 12 hours to remove guest molecules from pores.

- Characterization: Confirm successful synthesis by PXRD, BET surface area analysis, and FT-IR spectroscopy.

Application in Sensing: The synthesized ZIF-8 variants are composited with carbon electrodes for electrochemical detection of imidacloprid and thiamethoxam. The amino-functionalized ZIF-8 shows enhanced sensitivity due to hydrogen bonding with nitro groups in neonicotinoids.

Protocol 2: Construction of Cu-Based MOF Electrochemical Sensor for Organophosphorus Pesticides

Principle: Cu-MOFs with open metal sites provide excellent electrocatalytic activity for organophosphorus pesticide (OPP) detection. This protocol details electrode modification for sensitive OPP determination.

Materials:

- HKUST-1 ([Cu₃(BTC)₂], Basolite C300)

- Chitosan (medium molecular weight)

- Acetic acid (glacial, 99.7%)

- Phosphate buffer saline (PBS, 0.1 M, pH 7.4)

- Screen-printed carbon electrodes (SPCEs)

- Dichlorvos, malathion, parathion standards

Electrode Modification Procedure:

- MOF Dispersion: Disperse 5 mg HKUST-1 in 1 mL chitosan solution (0.5% w/v in 1% acetic acid) and sonicate for 30 minutes to form homogeneous suspension.

- Electrode Modification: Drop-cast 5 μL HKUST-1/chitosan suspension onto the working electrode surface of SPCE and dry under infrared lamp for 15 minutes.

- Sensor Activation: Cyclically scan the modified electrode in 0.1 M PBS (pH 7.4) between -0.2 V and +0.6 V (vs. Ag/AgCl) at 50 mV/s for 20 cycles to stabilize the electrochemical response.

- Pesticide Detection: Incubate the activated electrode in sample solution containing OPPs for 5 minutes with gentle stirring. Transfer to electrochemical cell containing 0.1 M PBS (pH 7.4) for measurement.

- Electrochemical Measurement: Perform square wave voltammetry from +0.2 V to +0.8 V with amplitude 25 mV and frequency 15 Hz. Measure the oxidation peak current at approximately +0.55 V, which decreases proportionally with OPP concentration due to inhibition of electron transfer.

Performance Parameters: The sensor typically shows linear ranges of 0.1-100 nM for dichlorvos with detection limits of 0.05 nM. The Cu²⁺ open metal sites specifically coordinate with phosphoryl oxygen, while the large surface area preconcentrates OPPs at the electrode interface.

Protocol 3: Luminescent Ln-MOF-Based Sensor for Pyrethroid Detection

Principle: Lanthanide MOFs (Ln-MOFs) exhibit strong characteristic emission that is quenched by energy transfer or electron transfer with pesticide molecules, enabling highly sensitive detection.

Materials:

- Europium nitrate hexahydrate (Eu(NO₃)₃·6H₂O, 99.9%)

- Terbium nitrate pentahydrate (Tb(NO₃)₃·5H₂O, 99.9%)

- 1,3,5-Benzenetricarboxylic acid (H₃BTC, 95%)

- N,N-Dimethylformamide (DMF, anhydrous)

- Ethanol (absolute)

- Acetone (HPLC grade)

Synthesis Procedure:

- Reaction Mixture: Dissolve 0.5 mmol Eu(NO₃)₃·6H₂O and 0.5 mmol H₃BTC in 15 mL DMF/ethanol mixture (2:1 v/v) in a 25 mL Teflon-lined autoclave.

- Solvothermal Reaction: Heat at 120°C for 24 hours, then cool slowly to room temperature at 5°C/hour.

- Crystal Collection: Collect the crystalline product by filtration and wash with DMF (3 × 5 mL) and acetone (3 × 5 mL).

- Activation: Soak crystals in acetone for 24 hours with solvent change every 8 hours, then activate under vacuum at 150°C for 12 hours.

- Characterization: Confirm structure by PXRD and analyze luminescence properties by fluorescence spectroscopy (excitation 330 nm, emission 590-620 nm for Eu-MOF).

Sensing Application:

- Sensor Fabrication: Immobilize 2 mg activated Eu-MOF on quartz substrate using transparent polymer matrix.

- Measurement: Expose sensor to sample solutions containing pyrethroids (cypermethrin, deltamethrin) for 10 minutes.

- Detection: Measure luminescence intensity at 612 nm (Eu³⁺ emission). The intensity decreases proportionally with pyrethroid concentration due to energy transfer from excited Eu³⁺ to pesticide molecules.

- Calibration: Construct calibration curve with linear range typically 0.01-10 μM and detection limit of 3 nM for cypermethrin.

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for MOF/COF-Based Pesticide Sensors

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Sensor Development | Supplier Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metal Precursors | Zn(NO₃)₂·6H₂O, Cu(NO₃)₂·2.5H₂O, ZrOCl₂·8H₂O, Eu(NO₃)₃·6H₂O | Provide metal nodes for framework construction with specific coordination and electronic properties | Use high purity (>99%) from Sigma-Aldrich or Alfa Aesar |

| Organic Linkers | 1,3,5-Benzenetricarboxylic acid, 2-Methylimidazole, 2-Aminoterephthalic acid, Terephthalaldehyde | Build framework structure and provide functional groups for pesticide recognition | Custom synthesis often required for specialized linkers |

| Solvents | N,N-Dimethylformamide (DMF), Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), Methanol, Acetonitrile | Medium for MOF/COF synthesis and processing | Anhydrous grades recommended for reproducible crystallization |

| Electrode Materials | Screen-printed carbon electrodes, Glassy carbon electrodes, Gold electrodes, FTO glass | Platforms for electrochemical sensor construction | BASi, Metrohm, or DropSens for consistent quality |

| Pesticide Standards | Chlorpyrifos, Imidacloprid, Atrazine, Glyphosate, Cypermethrin | Method development, calibration, and validation | Certified reference materials from Dr. Ehrenstorfer or AccuStandard |

| Characterization Reagents | Potassium ferricyanide, Ferrocenemethanol, Naphthol AS-D chloroacetate | Electrochemical and optical characterization of sensor performance | ACS grade for reproducible electrochemical responses |

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Diagram 1: Signaling pathways in MOF-based pesticide sensors, showing how molecular recognition events are transduced into measurable signals through various mechanisms.

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for developing MOF-based pesticide sensors, showing key steps and decision points in the sensor development process.

The strategic selection of metal nodes and organic linkers in MOFs and COFs provides an powerful approach for developing target-specific pesticide recognition platforms. The synergistic combination of metal coordination sites, functional organic groups, and tunable porosity enables precise molecular recognition across diverse pesticide classes. Current research demonstrates exceptional sensitivity with detection limits reaching nanomolar to picomolar levels for various pesticides including organophosphates, neonicotinoids, and pyrethroids [2] [16] [19].

Future developments in this field will likely focus on several key areas: (1) Multi-functional frameworks that integrate recognition, signal transduction, and self-calibration capabilities; (2) Biomimetic designs incorporating molecularly imprinted binding pockets for enhanced specificity; (3) Flexible MOFs that exhibit adaptive pore structures for selective capture of specific pesticide geometries [20]; (4) Integration with portable platforms and smartphone-based detection for field-deployable sensors; and (5) Machine learning approaches to guide optimal metal-linker combinations for previously unaddressed pesticide targets [21] [18]. As synthetic methodologies advance and our understanding of structure-property relationships deepens, MOF and COF-based sensors are poised to become indispensable tools for comprehensive pesticide monitoring in agricultural, environmental, and food safety applications.

Metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) and covalent organic frameworks (COFs) have revolutionized the construction of biosensors for pesticide detection, evolving from mere enzyme supports to sophisticated nanozymes with inherent catalytic activity. These porous coordination polymers, formed through metal ions/clusters and organic linkers, provide exceptional structural tunability, high surface areas, and remarkable catalytic properties that make them ideal for sensing applications [11] [22]. The integration of these materials into biosensing platforms addresses critical challenges in pesticide monitoring, including the need for rapid, sensitive, and on-site detection capabilities that traditional laboratory methods cannot provide [11] [23]. This application note details the advanced catalytic functionalities of MOF/COF materials and provides detailed protocols for their implementation in pesticide biosensing research, framed within the broader context of developing next-generation agricultural monitoring systems for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Quantitative Performance Metrics of MOF/COF-Based Sensors

The exceptional performance of MOF and COF-based sensors is demonstrated through their quantitative detection capabilities for various pesticide targets. The following tables summarize key performance metrics reported in recent studies.

Table 1: Detection Performance of MOF/COF-Based Sensors for Organophosphorus Pesticides

| Material Platform | Target Pesticide | Detection Limit | Linear Range | Detection Mode | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AChE@COFTFP-TAPB/Fe/Cu-MOF | Chlorpyrifos | 0.3 pg/mL (electrochemical), 1.6 pg/mL (colorimetric) | Not specified | Electrochemical/Colorimetric dual-mode | [5] |

| GQD/AChE/CHOx nanozyme | Dichlorvos | 0.778 μM | Not specified | Fluorescence | [23] |

| AuNPs/PDDA/CBZ aptamer | Carbendazim (CBZ) | 2.2 nmol L⁻¹ | 2.2–500 nmol L⁻¹ | Colorimetric | [24] |

| Acetamiprid aptamer/AuNPs | Acetamiprid | 62 pmol L⁻¹ | Not specified | Chemiluminescent | [24] |

| PEDOT/carboxylated MWCNT aptasensor | Malathion | 4 pmol L⁻¹ | Not specified | Electrochemical | [24] |

Table 2: Environmental Tolerance of Enzyme-Encapsulated COF Systems

| Parameter | Free AChE Performance | AChE@COFTFP-TAPB Performance | Application Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature | Deactivated at 65°C | Maintained high activity at 65°C | Enables field use in varied climates |

| pH Stability | Compromised at pH 4.0 | High catalytic activity at pH 4.0 | Functions in diverse environmental samples |

| Organic Solvents | Significant activity loss | Maintained structural integrity and function | Direct analysis of food extracts possible |

| Storage Stability | Limited shelf-life | Enhanced long-term stability | Reduced reagent replacement costs |

Advanced Nanozyme Architectures and Their Catalytic Mechanisms

MOF-Based Peroxidase Mimics

MOF nanozymes exhibit exceptional peroxidase-like activity that enables highly sensitive detection systems. The Fe-N-C single-atom nanozyme (SAN), composed of atomically dispersed Fe─Nx moieties hosted by MOF-derived porous carbon, demonstrates unprecedented catalytic efficiency with a specific activity of 57.76 U mg⁻¹ – nearly comparable to natural horseradish peroxidase (HRP) while offering superior storage stability and robustness against harsh environments [25]. The catalytic mechanism involves the facilitation of electron transfer between substrates and H₂O₂, generating reactive oxygen species that oxidize chromogenic substrates like TMB (3,3',5,5'-tetramethylbenzidine) [25].

Recent advancements in microenvironmental modulation have further enhanced nanozyme performance. By confining poly(acrylic acid) (PAA) within the mesoporous channels of PCN-222-Fe NPs, researchers successfully lowered the microenvironmental pH, enabling optimal peroxidase-like activity at physiological pH (7.4) instead of the traditional acidic optimum (pH 3.0-4.5). This innovation resulted in a 4-fold increase in catalytic activity at neutral pH, overcoming a fundamental limitation in nanozyme applications [26].

COF-Encapsulated Bio-Enzyme Systems

COF-based encapsulation technology represents a breakthrough in enzyme stabilization for sensing applications. The AChE@COFTFP-TAPB nanocapsule system, fabricated using ZIF-8 as a sacrificial template, creates a hollow COF structure that encapsulates acetylcholinesterase (AChE) within a rigid, protective shell [5]. This architecture preserves enzymatic conformational freedom while providing exceptional protection against non-mild environments, including high temperatures (up to 65°C), acidic conditions (pH as low as 4.0), and organic solvents [5]. The spacious hollow COF microenvironment maintains high catalytic activity while facilitating efficient mass transfer of substrates and products, addressing key limitations of traditional enzyme immobilization approaches.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Fabrication of AChE@COF Nanocapsules for Enhanced Environmental Tolerance

Principle: This protocol describes the encapsulation of acetylcholinesterase (AChE) within hollow COF nanocapsules using ZIF-8 as a sacrificial template, significantly improving enzyme stability under harsh conditions for pesticide detection [5].

Materials:

- Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) from Electrophorus electricus

- 2-methylimidazole (2-MeIM)

- Zinc nitrate hexahydrate (Zn(NO₃)₂·6H₂O)

- TFP (1,3,5-triformylphloroglucinol) and TAPB (1,3,5-tris(4-aminophenyl)benzene) for COF synthesis

- Methanol, acetic acid, and other organic solvents

- Centrifugal filters (100 kDa MWCO)

Procedure:

- ZIF-8 Template Synthesis:

- Dissolve 2.97 g of Zn(NO₃)₂·6H₂O in 80 mL methanol (Solution A)

- Dissolve 6.49 g of 2-methylimidazole in 80 mL methanol (Solution B)

- Rapidly mix Solution A and Solution B with vigorous stirring at room temperature for 24 hours

- Collect white precipitate by centrifugation (10,000 × g, 10 min) and wash three times with methanol

AChE Encapsulation in ZIF-8:

- Redisperse 100 mg of ZIF-8 nanoparticles in 20 mL of 10 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4)

- Add 5 mg of AChE dissolved in 2 mL of the same buffer dropwise under gentle stirring

- Incubate the mixture at 4°C for 12 hours with continuous mixing

- Recover AChE@ZIF-8 by centrifugation (8,000 × g, 10 min)

COF Encapsulation:

- Prepare 10 mL of 0.2 mM TFP in acetonitrile

- Prepare 10 mL of 0.3 mM TAPB in acetonitrile

- Suspend 50 mg of AChE@ZIF-8 in the TFP solution and sonicate for 10 minutes

- Add TAPB solution and 200 μL of acetic acid (6 M) as catalyst

- React at room temperature for 24 hours with continuous shaking

Template Removal:

- Collect the AChE@ZIF-8@COF by centrifugation (6,000 × g, 8 min)

- Treat with 0.1 M EDTA solution (pH 5.5) for 12 hours to dissolve ZIF-8 template

- Wash three times with 10 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4)

- Characterize by SEM/TEM to confirm hollow capsule structure

Validation:

- Verify enzyme activity using Ellman's assay with acetylthiocholine as substrate

- Confirm enhanced stability by testing activity after incubation at 65°C for 1 hour

- Compare performance with free AChE in acidic conditions (pH 4.0)

Protocol 2: Construction of a Dual-Mode Electrochemical/Colorimetric Sensor

Principle: This protocol outlines the integration of AChE@COF nanocapsules with peroxidase-like Fe/Cu-MOF nanozymes to create a dual-mode sensor for organophosphorus pesticides (OPs) based on enzyme inhibition [5].

Materials:

- Synthesized AChE@COF nanocapsules (from Protocol 1)

- Fe/Cu-MOF nanozyme (prepared separately)

- Acetylthiocholine (ATCh) iodide

- 3,3',5,5'-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB)

- o-phenylenediamine (OPD)

- H₂O₂ (30%)

- Screen-printed carbon electrodes (SPCE)

- Phosphate buffer (0.1 M, pH 7.4)

- Acetate buffer (0.2 M, pH 4.0)

Procedure:

- Fe/Cu-MOF Nanozyme Synthesis:

- Dissolve 0.5 mmol FeCl₃ and 0.5 mmol Cu(NO₃)₂ in 20 mL DMF

- Add 1 mmol of 1,3,5-benzenetricarboxylic acid dissolved in 10 mL DMF

- Transfer to Teflon-lined autoclave and heat at 120°C for 24 hours

- Cool to room temperature, collect precipitate by centrifugation

- Wash three times with DMF and ethanol, then activate at 150°C under vacuum

Sensor Assembly:

- For electrochemical mode: Modify SPCE with 5 μL of Fe/Cu-MOF suspension (2 mg/mL in water) and dry at room temperature

- For colorimetric mode: Prepare Fe/Cu-MOF suspension in acetate buffer (0.1 mg/mL)

Detection Procedure:

- Inhibition Phase: Incubate AChE@COF nanocapsules with pesticide sample for 15 minutes at 35°C

- Reaction Phase: Add ATCh (final concentration 1 mM) and incubate for 10 minutes to generate thiocholine (TCh)

- Electrochemical Detection:

- Transfer reaction mixture to Fe/Cu-MOF modified SPCE

- Add OPD (0.5 mM) and record differential pulse voltammetry (DPV) from 0 to 0.8 V

- Measure oxidation peak current at ~0.4 V

- Colorimetric Detection:

- Mix reaction mixture with Fe/Cu-MOF in acetate buffer

- Add TMB (0.2 mM) and H₂O₂ (0.1 mM)

- Incubate for 5 minutes and measure absorbance at 652 nm

Quantification:

- Calculate % inhibition = [(I₀ - I)/I₀] × 100, where I₀ and I are signals without and with pesticide

- Generate calibration curve using pesticide standards

Validation:

- Test sensor with chlorpyrifos standards (0.001-100 ng/mL)

- Verify dual-mode correlation between electrochemical and colorimetric signals

- Assess sensor performance in real samples (apple extracts) with standard addition method

Signaling Pathways and Sensing Mechanisms

The detection mechanisms for pesticides using MOF/COF-based platforms primarily operate through enzyme inhibition and nanozyme-catalyzed signal amplification, as illustrated in the following diagrams.

Diagram 1: Enzyme Inhibition-Based Pesticide Detection Mechanism. This diagram illustrates the signaling pathway for pesticide detection based on AChE inhibition. Organophosphorus pesticides (OPs) inhibit AChE, reducing thiocholine (TCh) production. Less TCh results in reduced passivation of Fe/Cu-MOF nanozyme, leading to increased production of electroactive oxOPD and colored oxTMB [5].

Diagram 2: Single-Atom Nanozyme Synthesis and Catalytic Mechanism. This workflow illustrates the fabrication of Fe-N-C single-atom nanozyme (SAN) through Fe-doped ZIF-8 pyrolysis and its peroxidase-mimicking mechanism. The atomically dispersed Fe─Nx sites provide exceptional catalytic activity comparable to natural HRP enzyme [25].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for MOF/COF-Based Pesticide Sensing

| Reagent/Category | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| MOF Precursors | Framework construction | ZIF-8 (Zn²⁺ + 2-methylimidazole), PCN-222 (Zr₆ clusters + Fe-TCPP), Fe/Cu-MOFs |

| COF Building Blocks | Porous organic frameworks | TFP (1,3,5-triformylphloroglucinol), TAPB (1,3,5-tris(4-aminophenyl)benzene) |

| Enzymes | Biorecognition elements | Acetylcholinesterase (AChE), Butyrylcholinesterase (BChE), Choline Oxidase (CHOx) |

| Nanozyme Substrates | Signal generation | TMB (colorimetric), OPD (electrochemical), Amplex Red (fluorescent) |

| Polymer Modifiers | Microenvironment tuning | Poly(acrylic acid) (PAA, Mw 2kDa), Poly(ethylene imine) (PEI) for pH modulation |

| Aptamers | Specific recognition | Nucleic acid aptamers for carbendazim, acetamiprid, malathion |

| Detection Substrates | Sensor platforms | Screen-printed carbon electrodes (SPCE), paper-based strips, microfluidic chips |

The construction of high-performance biosensors for pesticide detection represents a critical frontier in environmental monitoring and food safety. Within this field, Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) and Covalent Organic Frameworks (COFs) have emerged as particularly promising porous materials. Their integration into composite materials creates synergistic effects that substantially enhance the key performance parameters of biosensors: sensitivity enables the detection of target analytes at minimal concentrations, while selectivity allows the sensor to distinguish the target analyte amidst a complex background of interfering substances [14]. These synergistic effects, achieved through the rational design of composite materials, are paving the way for a new generation of reliable, rapid, and on-site detection tools for organophosphorus pesticides (OPs) and other toxic compounds [5] [27].

Quantitative Performance of MOF/COF-Based Sensors

The enhanced performance of composite materials is clearly demonstrated by the quantitative improvements in key sensor metrics. The following table summarizes the performance of recent MOF/COF-based sensors for pesticide detection.

Table 1: Performance metrics of recent MOF/COF-based sensors for pesticide detection.

| Sensor Material | Target Analyte | Detection Mode | Limit of Detection (LOD) | Key Enhancement | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AChE@COF(TFP-TAPB) / Fe/Cu-MOF | Chlorpyrifos (CP) | Electrochemical | 0.3 pg/mL | COF encapsulation for enzyme protection | [5] |

| AChE@COF(TFP-TAPB) / Fe/Cu-MOF | Chlorpyrifos (CP) | Colorimetric | 1.6 pg/mL | COF encapsulation for enzyme protection | [5] |

| Pr6O11/Zr-MOF | Organophosphorus Pesticides | Colorimetric / Smartphone RGB | 1.47 μg/mL | Zr-MOF prevents nanozyme aggregation and enriches OPs | [27] |

The data illustrates the exceptional sensitivity achievable with composite materials. The AChE@COF/Fe-Cu-MOF sensor achieves detection limits as low as 0.3 pg/mL, which is attributed to the synergistic combination of a protected enzyme and a highly active nanozyme [5]. Furthermore, the development of sensors compatible with smartphone detection, such as the Pr6O11/Zr-MOF nanozyme, highlights a parallel synergy aimed at enhancing accessibility and practical deployment in the field [27].

Experimental Protocols for Key Sensor Platforms

Protocol 1: Fabrication of an AChE@COF(TFP-TAPB)-Based Dual-Mode Sensor

This protocol details the construction of an electrochemical/colorimetric dual-mode sensor for organophosphorus pesticides (OPs) utilizing acetylcholinesterase (AChE) encapsulated in a hollow COF capsule [5].

Materials and Reagents

- Acetylcholinesterase (AChE)

- ZIF-8 sacrificial template

- Organic ligands for COF(TFP-TAPB) synthesis

- Fe/Cu-MOF nanozyme

- Acetylthiocholine (ATCh) substrate

- Organophosphorus pesticide standard (e.g., chlorpyrifos)

- Electrochemical probe (e.g., o-phenylenediamine, OPD) or chromogenic substrate (e.g., 3,3’,5,5’-tetramethylbenzidine, TMB)

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Synthesis of AChE@ZIF-8: Immobilize AChE enzyme onto/within ZIF-8 nanoparticles under mild aqueous conditions.

- Encapsulation via COF Growth: Use the AChE@ZIF-8 composite as a sacrificial template. Grow a COF(TFP-TAPB) shell around it through a solvothermal reaction. Subsequently, etch away the ZIF-8 core to create a hollow COF capsule (AChE@COF(TFP-TAPB)) with the enzyme confined inside [5].

- Sensor Assembly: Integrate the AChE@COF(TFP-TAPB) composite with the peroxidase-like Fe/Cu-MOF nanozyme on the working electrode of an electrochemical cell or in a solution-based colorimetric assay.

- Detection Procedure:

- a. Incubate the sensor with the sample solution containing the target OPs.

- b. Add the substrate acetylthiocholine (ATCh).

- c. For electrochemical detection, also add OPD and measure the generated electrical signal. The inhibition of AChE by OPs leads to less TCh production, which in turn reduces the passivation of Fe/Cu-MOF and results in more oxOPD and a higher electrochemical signal [5].

- d. For colorimetric detection, add TMB and measure the color change (e.g., absorbance). The inhibition of AChE leads to less TCh, which reduces passivation of Fe/Cu-MOF, resulting in more oxTMB and a more pronounced colorimetric signal [5].

Critical Notes

- The hollow COF capsule is crucial for protecting the enzymatic activity from harsh environmental conditions (e.g., high temperature up to 65°C, pH as low as 4.0, organic solvents) [5].

- The dual-mode capability allows for mutual verification of results, significantly improving detection reliability.

Protocol 2: Smartphone-Based Colorimetric Detection using Pr6O11/Zr-MOF Nanozyme

This protocol describes a rapid, accessible method for detecting OPs in food samples using a nanozyme composite and a smartphone for result interpretation [27].

Materials and Reagents

- Pr6O11/Zr-MOF nanozyme composite

- TMB or other suitable chromogenic substrate

- Buffer solution (e.g., acetate buffer)

- Food samples (e.g., cucumber, lettuce)

- Smartphone with a color analysis application (e.g., an RGB analysis app)

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Nanozyme Synthesis: Synthesize the Pr6O11/Zr-MOF composite via an in-situ growth method where the Zr-MOF is formed anchored onto Pr6O11 particles. This prevents aggregation of the nanozyme and provides sites for enriching OPs [27].

- Sample Preparation: Homogenize the food sample and extract the pesticides using a suitable solvent.

- Detection Reaction:

- a. In a test tube, mix the sample extract (or standard), Pr6O11/Zr-MOF nanozyme, and TMB substrate in buffer.

- b. Incubate the mixture for approximately 40 minutes at room temperature [27].

- c. Observe the resulting color development.

- Signal Acquisition and Analysis:

- a. Use a smartphone to capture an image of the solution under consistent lighting conditions.

- b. Utilize a dedicated smartphone application to perform a Red-Green-Blue (RGB) analysis of the image color intensity.

- c. Quantify the OP concentration by correlating the RGB values to a pre-established calibration curve.

Critical Notes

- The Zr-MOF component significantly enhances the oxidase-like activity of Pr6O11 and enriches OPs via coordination, improving sensitivity [27].

- This method is designed for accessibility, requiring no sophisticated laboratory instrumentation for the final readout.

Signaling Pathways and Workflow Visualizations

AChE Inhibition-Based Sensing Mechanism

Diagram 1: AChE inhibition-based sensing mechanism.

Workflow for Smartphone-Based Nanozyme Detection

Diagram 2: Workflow for smartphone-based pesticide detection.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key materials used in the construction of advanced MOF/COF-based biosensors, along with their specific functions.

Table 2: Essential research reagents and materials for MOF/COF-based biosensor construction.

| Material/Reagent | Function in Sensor Construction | Key Properties & Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Zr-MOF | Porous support for nanozymes (e.g., Pr6O11) or direct sensing element. | High surface area, structural versatility, and ability to enrich target analytes like OPs through coordination [27]. |

| COF(TFP-TAPB) Capsule | Encapsulation and protection of biological enzymes (e.g., AChE). | Provides a rigid, hollow shell with ordered pores that protects enzymes from harsh environments while preserving conformational freedom and allowing mass transfer [5]. |

| Fe/Cu-MOF Nanozyme | Signal generator with peroxidase-like activity. | Catalyzes the oxidation of chromogenic substrates (TMB/OPD), producing a measurable colorimetric or electrochemical signal [5]. |

| Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) | Biorecognition element for organophosphorus pesticides. | Its activity is selectively inhibited by OPs, providing the basis for the detection mechanism [5]. |

| Acetylthiocholine (ATCh) | Enzymatic substrate for AChE. | Hydrolyzed by AChE to produce thiocholine, which interacts with the nanozyme to modulate its activity [5]. |

| ZIF-8 | Sacrificial template for hollow COF formation. | Used as a temporary scaffold during COF synthesis to create a spacious hollow microenvironment for enzyme encapsulation [5]. |

Building the Sensor: Synthesis Strategies and Cutting-Edge Applications

Application Notes

The Critical Role of Encapsulation in Biosensing

In the realm of biosensor construction for pesticide detection, enzymes like acetylcholinesterase (AChE) are pivotal biocatalysts. Their activity is often inhibited by organophosphorus pesticides (OPs), providing a reliable mechanism for detection. However, the inherent fragility of enzymes—their susceptibility to deactivation under non-mild conditions such as high temperature, extreme pH, or organic solvents—severely limits the reliability and field-deployability of biosensors [5] [28]. Encapsulation within Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) and Covalent Organic Frameworks (COFs) has emerged as a powerful strategy to armor enzymes, significantly enhancing their environmental tolerance while maintaining high catalytic activity [5] [29]. This armor protects the enzyme's delicate three-dimensional structure from denaturation, thereby ensuring the performance and accuracy of biosensing platforms in complex, real-world agricultural environments.

Performance Comparison of Encapsulation Techniques

The encapsulation of enzymes within MOFs and COFs can be achieved through various strategies, each offering distinct advantages and trade-offs in terms of protection, catalytic efficiency, and ease of synthesis. The performance of these strategies is summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Comparison of Enzyme Immobilization Strategies via MOFs/COFs

| Immobilization Strategy | Level of Protection | Mass Transfer Efficiency | Key Advantages | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surface Attachment [30] | Low | High | Simple procedure; preserves enzyme conformation; broad compatibility. | Limited protection; potential for enzyme leakage. |

| Pore Infiltration [30] | Medium | Medium | Effective protection; utilizes pre-synthesized MOFs/COFs. | Requires mesoporous supports with large enough pores. |

| Encapsulation (in situ) [5] [30] | High | Low to Medium | Superior protection in harsh environments; facile one-pot synthesis. | Can restrict enzyme conformation and substrate diffusion. |

Recent research has led to significant advancements in the performance of enzyme@MOF and enzyme@COF composites. The following table quantifies the enhanced stability and sensing capabilities achieved through these encapsulation techniques.

Table 2: Enhanced Performance of Enzyme-MOF/COF Composites in Biosensing

| Composite Material | Enzyme | Application | Enhanced Stability / Performance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AChE@COFTFP-TAPB (Hollow Capsule) | Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) | Electrochemical/Colorimetric detection of OPs | Withstood 65°C, pH 4.0, and organic solvents; LOD for chlorpyrifos: 0.3 pg/mL (electrochemical) | [5] |

| Phytase@MIL-88A (Spray Dried) | Phytase | Enhanced stability for industrial use | Thermal stability improved from 4% to 95% after MOF encapsulation | [31] |

| Lipase–ZIF-8 (Ultrasound-treated) | Lipase | Biocatalysis | Enzymatic activity boosted by up to 5.3-fold compared to native enzyme | [28] |

| Enzyme–MOF Composites (General) | Various | Biosensing & Biocatalysis | Enhanced stability against denaturants, high temperatures, and extreme pH | [28] [30] |

Strategic Insights for Biosensor Development

For researchers developing biosensors for pesticides, the choice of encapsulation strategy and framework is critical. The following insights are drawn from recent applications:

- Strengthening Environmental Tolerance: Encapsulating AChE into a hollow COF capsule using ZIF-8 as a sacrificial template has proven highly effective. This rigid COF shell protects the enzyme from denaturation at high temperatures (up to 65°C) and in acidic media (as low as pH 4.0), while its spacious hollow microenvironment preserves the enzyme's conformational flexibility and catalytic activity. This allows the biosensor to perform reliably in non-mild environments where free enzymes would fail [5].

- Constructing Robust Sensing Platforms: Integrating armored enzymes with nanozymes creates powerful cascade systems. For instance, combining AChE@COF with a peroxidase-like Fe/Cu-MOF nanozyme enables the construction of dual-modal (electrochemical/colorimetric) sensors. This provides mutual verification of results, overcoming the limitations and potential false signals of single-mode sensing, thereby significantly improving detection reliability [5].

- Enhancing Catalytic Activity Beyond Protection: While protection is crucial, encapsulation can also boost activity. Strategies such as ultrasound treatment during immobilization can "lock" enzymes in an activated conformation, leading to a multi-fold increase in activity. Modifying the enzyme's surface charge can also accelerate the encapsulation process and improve biofunctionality [28].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Encapsulation of AChE in a Hollow COF Capsule for Pesticide Sensing

This protocol details the synthesis of a hollow COF capsule for encapsulating acetylcholinesterase (AChE), resulting in a composite with superior environmental tolerance for use in pesticide biosensors [5].

Principle

A zeolitic imidazolate framework (ZIF-8) is first synthesized as a sacrificial template around the AChE enzyme. The covalent organic framework (COF) is then grown around the AChE@ZIF-8 composite. Finally, the ZIF-8 core is selectively etched away, leaving the enzyme encapsulated within a protective, hollow COF capsule with ample space for conformational flexibility and efficient mass transfer.

Reagents and Equipment

- Enzyme Solution: Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) in a suitable buffer (e.g., phosphate buffer saline, PBS).

- ZIF-8 Precursors: Zinc nitrate hexahydrate (Zn(NO₃)₂·6H₂O) and 2-Methylimidazole.

- COF Monomers: TFP (Triformylphloroglucinol) and TAPB (1,3,5-Tris(4-aminophenyl)benzene).

- Solvents: Methanol, deionized water, and an organic solvent for COF synthesis (e.g., a mixture of mesitylene and dioxane).

- Etching Solution: Diluted acidic solution or a competing agent to dissolve ZIF-8.

- Key Equipment: Centrifuge, vacuum oven, scanning electron microscope (SEM), transmission electron microscope (TEM).

Step-by-Step Procedure

Diagram Title: Hollow COF Capsule Synthesis Workflow

Synthesis of AChE@ZIF-8 Core:

- Dissolve Zn(NO₃)₂·6H₂O and 2-methylimidazole in separate vials using methanol.

- Rapidly mix the enzyme solution (containing AChE) with the zinc nitrate solution.

- Immediately pour this mixture into the 2-methylimidazole solution under vigorous stirring.

- Allow the reaction to proceed for a defined period (e.g., 15-30 minutes) at room temperature.

- Collect the resulting AChE@ZIF-8 nanoparticles by centrifugation, and wash several times with methanol to remove unreacted precursors.

Growth of the COF Shell (COFTFP-TAPB):

- Re-disperse the purified AChE@ZIF-8 particles in a solvent mixture suitable for COF synthesis.

- Add the TFP and TAPB monomers to the suspension.

- Perform the COF synthesis under solvothermal conditions (e.g., at 120°C for 72 hours) to grow a crystalline COF layer around the AChE@ZIF-8 core.

- Recover the composite material (AChE@ZIF-8@COF) by centrifugation and wash thoroughly.

Etching of the ZIF-8 Sacrificial Template:

- Treat the AChE@ZIF-8@COF composite with a mild etching solution (e.g., a diluted acidic buffer) for a specific duration. This selectively dissolves the ZIF-8 core without damaging the COF shell or the enzyme.

- Centrifuge and wash the resulting hollow AChE@COF capsules extensively with buffer to remove etching agents and ZIF-8 debris.

Characterization and Biosensor Integration:

- Characterize the final AChE@COF material using SEM and TEM to confirm the hollow capsule morphology.

- The composite is now ready for integration into a biosensor platform, for example, by depositing it onto an electrode surface alongside a Fe/Cu-MOF nanozyme to construct a dual-modal sensor [5].

Protocol 2: Biomimetic Mineralization for One-Pot Enzyme@MOF Encapsulation

This protocol describes a one-pot biomimetic mineralization method to encapsulate enzymes in ZIF-8, a common and highly protective MOF, without the need for toxic organic solvents or additional capping agents [28].

Principle

Enzyme molecules act as nucleation points for the crystallization of the MOF. In an aqueous solution, the metal ions (Zn²⁺) and organic ligands (2-methylimidazole) coordinate around the enzyme, spontaneously forming a protective ZIF-8 framework that encapsulates the enzyme in a single step.

Reagents and Equipment

- Enzyme Solution: Target enzyme (e.g., Horseradish Peroxidase, Lipase, etc.) in a mild buffer.

- ZIF-8 Precursors: Zinc acetate dihydrate (Zn(CH₃COO)₂·2H₂O) and 2-Methylimidazole.

- Buffer: 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid (MES) buffer or PBS.

- Key Equipment: Benchtop centrifuge, vortex mixer, analytical balance.

Step-by-Step Procedure

Diagram Title: One-Pot Enzyme@ZIF-8 Synthesis

- Prepare Ligand Solution: Dissolve 2-methylimidazole in MES buffer (e.g., 0.1 M, pH 6.5) to create a concentrated solution.

- Introduce the Enzyme: Add the enzyme solution to the 2-methylimidazole solution and mix gently by vortexing.

- Initiate Mineralization: Add an aqueous solution of zinc acetate to the enzyme-ligand mixture. The final molar ratio of zinc to ligand is typically 1:4 to 1:8.

- Crystallization: Allow the reaction mixture to incubate at room temperature with gentle shaking for 1-2 hours. The formation of a cloudy suspension indicates the successful synthesis of Enzyme@ZIF-8 particles.

- Recovery and Washing: Collect the particles by centrifugation. Wash the pellet several times with the buffer to remove unencapsulated enzyme and excess precursors. The final Enzyme@ZIF-8 composite can be re-suspended in buffer for immediate use or stored at 4°C.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table lists key materials and reagents essential for developing and working with MOF/COF-based enzyme encapsulation systems.

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for Enzyme Encapsulation Research

| Reagent/Material | Function and Role in Encapsulation | Example in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Zeolitic Imidazolate Framework-8 (ZIF-8) | A MOF with excellent biocompatibility; used as a protective matrix or sacrificial template for encapsulation. | Serves as the core in hollow COF synthesis and the direct encapsulation matrix in biomimetic mineralization [5] [28]. |

| COF Monomers (e.g., TFP, TAPB) | Building blocks for constructing highly ordered, stable, and porous covalent organic frameworks. | Used to grow the protective hollow shell around the AChE@ZIF-8 composite [5]. |

| 2-Methylimidazole | Organic ligand used in the synthesis of ZIF-8; coordinates with metal ions to form the framework. | A key precursor in both the sacrificial template and one-pot encapsulation protocols [5] [28]. |

| Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) | A model enzyme for pesticide detection biosensors; its activity is inhibited by organophosphorus pesticides. | The enzyme of interest being encapsulated to enhance its stability for pesticide residue monitoring [5]. |

| Fe/Cu-MOF Nanozyme | A MOF with peroxidase-like activity; used in cascade systems with enzymes to generate detectable signals. | Integrated with AChE@COF to construct a dual-modal electrochemical/colorimetric sensor [5]. |

Designing MOF-based Nanozymes for Robust, Enzyme-Free Pesticide Detection

Metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) and covalent organic frameworks (COFs) represent a revolutionary class of porous materials in biosensor construction, offering exceptional tunability, high surface area, and structural diversity. Their integration into nanozyme design has opened new frontiers in pesticide detection, particularly for developing robust, enzyme-free sensing platforms that overcome the limitations of natural enzyme-based systems. These natural enzymes suffer from instability under extreme conditions, complex preparation protocols, and sensitivity to environmental factors such as pH and temperature [32] [5]. MOF-based nanozymes address these challenges by providing superior stability, cost-effectiveness, and customizable catalytic activities that mimic natural peroxidases and oxidases [32] [33]. This application note details recent advances and methodologies for constructing these sophisticated biosensing platforms, focusing on their application within pesticide monitoring for agricultural and food safety. The transition to enzyme-free detection represents a significant paradigm shift, simplifying sensing systems while enhancing their reliability for real-world applications [32].

Performance Metrics of MOF-based Nanozymes for Pesticide Detection

The following table summarizes the performance characteristics of recently developed MOF-based nanozymes for detecting specific pesticide classes.

Table 1: Performance of Representative MOF-based Nanozymes in Pesticide Detection

| MOF-Nanozyme Composition | Target Pesticide (Class) | Detection Mechanism | Limit of Detection (LOD) | Linear Range | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fe@PCN-224 NCs | Propiconazole (Triazole) | Peroxidase-like activity inhibition via triazole-Fe coordination | ( 8 \times 10^{-9} ) mol L⁻¹ | ( 0.03 \times 10^{-6} ) to ( 0.90 \times 10^{-6} ) mol L⁻¹ | [32] |

| Pr₆O₁₁/Zr-MOF | Organophosphorus (OPs) | Oxidase-like activity; OPs enrichment via coordination | 1.47 μg mL⁻¹ | Not Specified | [34] |

| Fe/Cu-MOF (Dual-mode Sensor) | Chlorpyrifos (OPs) | Electron transfer passivation by thiocholine | 0.3 pg mL⁻¹ (Electrochemical), 1.6 pg mL⁻¹ (Colorimetric) | Not Specified | [5] |

Experimental Protocols for Nanozyme Synthesis and Sensing

This protocol describes the synthesis of iron-integrated porphyrinic MOF nanozymes with peroxidase-like activity.

Principle: A highly stable porphyrinic MOF (PCN-224) is synthesized from Zr₆ clusters and tetrakis(4-carboxyphenyl)porphyrin (TCPP) linkers. Coordinatively unsaturated Fe(III) ions are subsequently introduced into the porphyrin units, creating the active Fe@PCN-224 nanozyme. The triazole ring of propiconazole specifically coordinates with the Fe active site, inhibiting peroxidase-like activity and enabling colorimetric detection.

Materials:

- Metal Precursor: Zirconyl (IV) chloride octahydrate (ZrOCl₂·8H₂O)

- Organic Linker: Tetrakis(4-carboxyphenyl)porphyrin (TCPP)

- Iron Source: Ferric chloride (FeCl₃)

- Solvents: N,N-Dimethylformamide (DMF), Benzoic acid

- Substrate for Activity: 3,3′,5,5′-Tetramethylbenzidine (TMB), Hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂)

Procedure:

- Synthesis of PCN-224: Dissolve ZrOCl₂·8H₂O (50 mg) and TCPP (20 mg) in 15 mL of DMF containing benzoic acid (1.2 g) in a Teflon-lined autoclave. Heat the mixture at 90°C for 24 hours. After cooling to room temperature, collect the resulting purple precipitate by centrifugation. Wash the solid sequentially with DMF and ethanol, then activate under vacuum drying.

- Preparation of Fe@PCN-224 NCs: Disperse the as-synthesized PCN-224 nanocubes (NCs) in an aqueous solution of FeCl₃. Stir the mixture for 12 hours at room temperature to incorporate Fe(III) ions into the porphyrin rings. Centrifuge the product and wash thoroughly with deionized water to remove unreacted Fe³⁺ ions.

- Colorimetric Detection of Propiconazole:

- Incubate the Fe@PCN-224 NCs with a sample solution containing propiconazole for a specific duration to allow coordination and inhibition.

- Add the chromogenic substrate TMB and H₂O₂ to the mixture.