Portable Biosensors for On-Site Organophosphate Detection: Current Technologies, Applications, and Future Directions

Organophosphate (OP) pesticides, while crucial for agriculture, pose severe health risks due to their acetylcholinesterase (AChE)-inhibiting neurotoxicity.

Portable Biosensors for On-Site Organophosphate Detection: Current Technologies, Applications, and Future Directions

Abstract

Organophosphate (OP) pesticides, while crucial for agriculture, pose severe health risks due to their acetylcholinesterase (AChE)-inhibiting neurotoxicity. The limitations of conventional detection methods have accelerated the development of portable biosensors for rapid, on-site analysis. This article provides a comprehensive review for researchers and drug development professionals, covering the foundational principles of OP detection mechanisms, the latest methodological advances in electrochemical and optical biosensors, critical troubleshooting and optimization strategies for real-world application, and a comparative validation of emerging technologies against gold-standard methods. The review synthesizes how these portable platforms are revolutionizing environmental monitoring, food safety, and clinical diagnostics.

The Urgent Need and Fundamental Principles of Organophosphate Biosensing

The Global Health Burden of Organophosphate Poisoning and Morbidity

Organophosphate (OP) compounds, primarily used as pesticides, represent a significant global public health challenge due to their high toxicity and widespread availability. Acute poisoning contributes substantially to global morbidity and mortality, particularly in developing countries and agricultural communities [1] [2]. The primary mechanism of toxicity involves irreversible inhibition of acetylcholinesterase (AChE), leading to accumulation of acetylcholine and overstimulation of muscarinic and nicotinic receptors [3] [2]. This application note synthesizes current epidemiological data on OP poisoning morbidity and outlines standardized experimental protocols for developing portable biosensors, which are crucial for rapid on-site detection and clinical intervention.

Epidemiological Profile of Organophosphate Poisoning

Global Burden and Demographic Characteristics

Table 1: Global Epidemiological Characteristics of Organophosphate Poisoning

| Epidemiological Parameter | Reported Value | Context and Population |

|---|---|---|

| Mean Age | 42.22 ± 9.29 years | Systematic review of 28,593 patients [1] |

| Gender Distribution | 70.4% Male (20,127/28,593) | Systematic review of 28,593 patients [1] |

| Mean Time to Hospital Arrival | 5.97 ± 2.48 hours | Systematic review of OP poisoning patients [1] |

| Complication Rate | 11.6% (3,331/28,593) | Systematic review of OP poisoning patients [1] |

| Mechanical Ventilation Requirement | 71.7% (2,387/3,331) | Among patients who developed complications [1] |

| Mortality Rate | 3.7% (1,059/28,593) | Systematic review of OP poisoning patients [1] |

| Global Age-Standardized Mortality Rate (2021) | 0.45 per 100,000 | For childhood poisoning (0-14 years), all causes [4] |

| Intentional Poisoning (Self-Harm) | 70.9% (285/402) | Hospital-based study in Nepal; pesticides were primary agent [5] |

The systematic review by Alva et al. (2025) provides comprehensive data on acute OP poisoning characteristics, highlighting a predominance of male patients and significant delays in hospital presentation, which is a critical factor in clinical outcomes [1]. The high rate of mechanical ventilation among complicated cases underscores the severe respiratory compromise typical of acute OP poisoning. While global mortality from unintentional poisoning has declined, the burden remains disproportionately high in low-resource settings [4] [5].

Regional Variations and Socioeconomic Disparities

Table 2: Regional and Socioeconomic Variations in Poisoning Burden

| Parameter | High-SDI Countries | Low-SDI Countries | Data Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age-Standardized Incidence Rate (ASIR) | Highest (e.g., Norway) | Lower | GBD Study 2021 [4] |

| Age-Standardized Mortality Rate (ASMR) | Lower | Highest (e.g., South Sudan) | GBD Study 2021 [4] |

| Age-Standardized DALY Rate (ASDR) | Lower | Highest | GBD Study 2021 [4] |

| Common Poisoning Agents | Therapeutic drugs, household chemicals | Pesticides (e.g., Organophosphates) | Hospital-based study, Nepal [5] |

| Primary Context | Unintentional | Intentional (self-harm) linked to mental health | Hospital-based study, Nepal [5] |

The Global Burden of Disease (GBD) 2021 study reveals significant health inequalities, with low-SDI countries bearing a disproportionately higher burden of fatal poisoning outcomes despite higher incidence rates in developed nations [4]. This disparity underscores the need for improved emergency response systems and medical infrastructure in developing regions. In Nepal, for instance, OP pesticides were the leading agent of poisoning, predominantly used for intentional self-harm, often related to family conflict and mental health issues [5].

Experimental Protocols for Organophosphate Detection

The following sections provide detailed methodologies for developing biosensing platforms for OP detection, with a focus on portability and applicability in resource-limited settings.

Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) Inhibition-Based Assay

Principle: This protocol leverages the enzymatic activity of AChE, which is selectively inhibited by OPs. The residual enzyme activity, inversely proportional to the OP concentration, is measured via colorimetric, fluorometric, or electrochemical readouts [3] [6].

Materials:

- Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) from electric eel or human recombinant

- Substrate: Acetylthiocholine (ATCh) or Acetylcholine (ACh)

- Colorimetric Indicator: 5,5'-Dithio-bis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB)

- Buffer: Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS, 0.1 M, pH 7.4)

- OP standard solutions (e.g., parathion, chlorpyrifos)

- Spectrophotometer, fluorometer, or potentiostat

Procedure:

- Enzyme Immobilization: Immobilize AChE (0.1-1 U/mL) on the sensor transducer surface (e.g., screen-printed electrode, paper strip). For electrochemical sensors, common substrates include graphene, carbon nanotubes (CNTs), or gold nanoparticles to enhance electron transfer [3] [7].

- Inhibition Phase: Incubate the immobilized AChE with the sample containing the target OP for a fixed period (e.g., 10-15 minutes) at room temperature.

- Washing: Gently rinse the sensor surface with buffer to remove unbound OP and potential interferents.

- Enzymatic Reaction: Introduce the substrate mixture.

- Colorimetric/Fluorometric Detection: Add ATCh and DTNB. The active AChE hydrolyzes ATCh to thiocholine, which reacts with DTNB to produce 2-nitro-5-thiobenzoate (TNB⁻), a yellow-colored anion, measurable at 412 nm [3]. The signal decrease correlates with OP concentration.

- Electrochemical Detection: Apply a fixed potential and monitor the amperometric current generated by the enzymatic hydrolysis of ACh or ATCh. The inhibition of AChE by OPs causes a decrease in the oxidation current [7].

- Quantification: Calculate the percentage of enzyme inhibition using the formula:

% Inhibition = [(I₀ - I)/I₀] × 100, where I₀ is the signal from the blank (no OP) and I is the signal from the sample. Determine the OP concentration by interpolating the % inhibition value against a standard calibration curve.

Voltammetric Detection of OPs Using Nanomaterial-Modified Electrodes

Principle: This non-enzymatic protocol detects OPs through their direct oxidation or reduction on an electrode surface. Nanomaterials are used to modify the electrode, enhancing its surface area, catalytic properties, and conductivity, thereby improving sensitivity and lowering the detection limit [7].

Materials:

- Working Electrode: Glassy carbon electrode (GCE) or screen-printed carbon electrode (SPCE)

- Nanomaterials: Multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs), graphene oxide (GO), gold nanoparticles (AuNPs), or metal oxides (e.g., CuO, ZrO₂)

- Supporting Electrolyte: PBS (0.1 M, pH 7.0) or acetate buffer

- Potentiostat/Galvanostat

- Standard OP solutions

Procedure:

- Electrode Modification:

- Polish the bare GCE with alumina slurry (0.05 µm) and sonicate in ethanol and deionized water.

- Disperse the nanomaterial (e.g., 1 mg/mL of MWCNTs) in a solvent like dimethylformamide (DMF) and deposit a fixed volume (e.g., 5-10 µL) onto the cleaned electrode surface. Allow it to dry under an infrared lamp [7].

- Electrochemical Measurement:

- Place the modified electrode in an electrochemical cell containing the supporting electrolyte and the OP sample.

- Utilize a voltammetric technique such as Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) or Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV). These methods enhance sensitivity by minimizing capacitive current.

- Scan the potential across a predetermined window (e.g., +0.5 V to +1.2 V for oxidation of certain OPs). The applied pulses in DPV and SWV help in achieving lower detection limits.

- Analysis: Record the current peak height/area, which is proportional to the concentration of the OP. Plot the calibration curve of peak current versus OP concentration for quantitative analysis.

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

AChE Inhibition Pathway in Organophosphate Toxicity

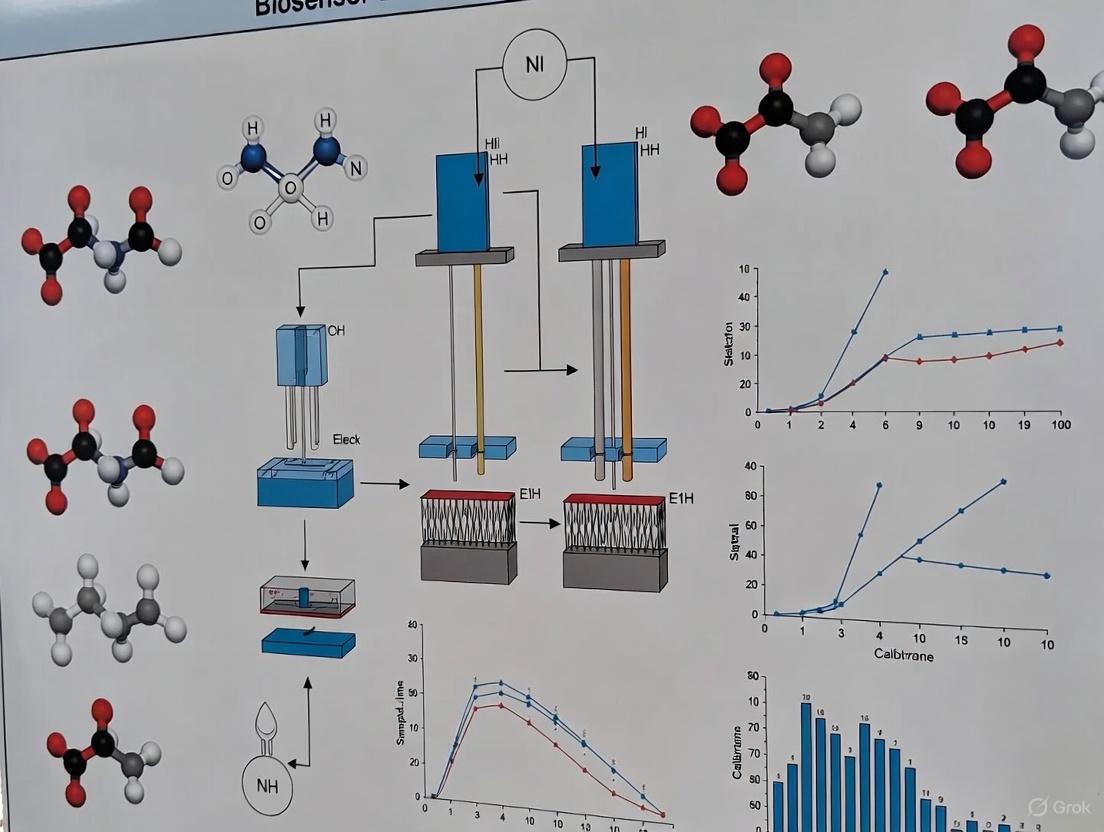

The following diagram illustrates the core biochemical mechanism of OP toxicity, which is exploited by AChE inhibition-based biosensors.

Biosensor Development Workflow

This workflow outlines the key stages in developing a portable biosensor for on-site OP detection.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for OP Detection Research

| Item | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) | Primary biorecognition element in inhibition-based sensors. Catalyzes substrate hydrolysis. | High specific activity, purity, and stability. Source (electric eel, human recombinant) can affect sensitivity [3] [8]. |

| Acetylthiocholine (ATCh) / Acetylcholine (ACh) | Enzymatic substrate. Hydrolysis product generates measurable signal. | ATCh is preferred for electrochemical/thiol-detecting colorimetric assays. Stability in solution is key [3]. |

| DTNB (Ellman's Reagent) | Colorimetric indicator. Reacts with thiocholine to produce yellow TNB⁻. | Allows for simple visual or spectrophotometric detection at 412 nm [3]. |

| Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) / Graphene | Electrode nanomaterial. Enhances electron transfer kinetics and surface area for sensor signal amplification. | High conductivity, functionalizable surface. CNTs can be carboxylated for better enzyme immobilization [2] [7]. |

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | Transducer nanomaterial. Facilitates electron transfer and serves as a platform for bioreceptor immobilization. | Excellent biocompatibility, tunable surface chemistry, and optical properties for colorimetric sensors [2] [6]. |

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) | Synthetic antibody mimics for non-enzymatic, selective OP recognition. | High chemical stability, reusable, tailored for specific OP molecules [2] [7]. |

| Screen-Printed Electrodes (SPEs) | Disposable, miniaturized electrochemical cell for portable sensor design. | Enable mass production, low cost, and integration into handheld devices for field testing [2] [7]. |

The widespread use of organophosphate (OP) and carbamate (CM) pesticides in agriculture poses significant health risks due to their inhibition of acetylcholinesterase (AChE), a crucial enzyme for neurological function [9] [2]. This application note details the core principle of AChE inhibition and presents standardized protocols for leveraging this mechanism in portable biosensors for on-site pesticide detection. Conventional methods like chromatography and mass spectrometry, while accurate, are costly, time-intensive, and require specialized facilities and personnel, making them unsuitable for rapid field testing [2] [10]. The protocols herein are designed for researchers and developers aiming to create accessible, efficient, and cost-effective biosensing platforms for public health protection and environmental monitoring [9].

Core Principle and Mechanism

The detection strategy is founded on the specific inhibition of AChE by OP and CM pesticides. AChE normally hydrolyzes the neurotransmitter acetylcholine, terminating its action at neuronal synapses. OPs and CMs irreversibly (OPs) or reversibly (CMs) bind to the serine hydroxyl group in the active site of AChE, preventing it from performing its catalytic function [2].

This inhibition is quantified indirectly by providing the enzyme with an artificial substrate, such as acetylthiocholine (ATCh). In an uninhibited system, AChE hydrolyzes ATCh to produce thiocholine (TCh) and acetate. The generated TCh can then be measured electrochemically or colorimetrically. In the presence of OP or CM pesticides, AChE activity is reduced, leading to a corresponding decrease in TCh production. This decrease in signal is quantitatively related to the concentration of the inhibiting pesticide [9] [11].

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow of this detection principle.

Quantitative Sensor Performance Data

The following tables summarize key performance metrics for AChE-based biosensors reported in recent literature, providing a benchmark for researchers.

Table 1: Detection Limits for Specific Pesticides

| Pesticide | Class | Sensor Platform | Limit of Detection (LOD) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mevinphos | Organophosphate | Personal Glucose Meter (PGM) | 0.138 ppm | [9] |

| Carbofuran | Carbamate | Personal Glucose Meter (PGM) | 0.113 ppm | [9] |

| Ethyl-paraoxon (Model OP) | Organophosphate | Paper-based (PesticidePAD) | 0.09 ppm | [11] |

Table 2: Comparison of AChE Substrate Performance

| Substrate | Assay Type | Apparent Km (mM) | Vmax (kat) | Advantage | Disadvantage | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indoxyl Acetate (IOA) | Colorimetric | 1.0 ± 0.2 | Not Specified | Superior sensitivity (Lower LOD) | Narrower detection range | |

| Acetylthiocholine (ATCh) | Electrochemical | 6.6 ± 3.2 | 123.8 ± 6.1 | Broader detection range (1.56–100 ppm) | Higher Km indicates lower affinity | [11] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol A: Personal Glucose Meter (PGM)-Based Detection

This protocol adapts ubiquitous personal glucose meters for pesticide detection by measuring thiocholine production electrochemically [9].

Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Specification | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Cholinesterase (ChE) | Cricket ChE or Human Whole Blood | Target enzyme whose inhibition is measured. |

| Acetylthiocholine Iodide (ATCh) | 15 mM solution in distilled water | Enzymatic substrate; hydrolysis produces thiocholine. |

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) | pH 7.4 or pH 8.0 | Reaction buffer to maintain optimal pH. |

| Personal Glucose Meter (PGM) | Sannuo Safe AQ smart | Portable device to read electrochemical signal from test strips. |

| Pesticide Standards | e.g., Mevinphos, Carbofuran | Analytes for calibration and validation. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Reagent Preparation:

- Sample Preparation:

- For blood samples, perform a 1:10 dilution by mixing 100 µL of whole blood with 900 µL of PBS [9].

- For vegetable samples, perform a standard extraction in PBS.

- Reaction Setup:

- Test Reaction: Combine 50 µL of sample (diluted blood or extract), 125 µL of PBS, and 25 µL of 15 mM ATCh solution [9].

- Sample Blank: Combine 50 µL of sample and 150 µL of PBS.

- Reagent Blank: Combine 175 µL of PBS and 25 µL of ATCh.

- Incubation:

- Incubate the test reaction at 25°C for a predetermined time (e.g., 5, 10, or 15 minutes) [9].

- Measurement & Data Analysis:

- Apply the incubated test reaction mixture directly to a PGM test strip and record the measured result.

- Calculate the Corrected PGM Readout using the formula:

Corrected PGM Readout (mg/dL) = Measured Result - Sample Blank - Reagent Blank[9]. - The corrected readout is proportional to AChE activity. Lower values indicate higher pesticide concentration and greater enzyme inhibition.

The workflow for this protocol, from sample preparation to data interpretation, is outlined below.

Protocol B: Paper-Based Colorimetric Biosensor (PesticidePAD)

This protocol describes a low-cost, colorimetric paper sensor for on-site screening of pesticide residues on vegetables [11].

Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Specification | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) | Electric eel or recombinant source | Recognition element; inhibition is measured. |

| Chromogenic Substrate | Indoxyl Acetate (IOA) or Acetylthiocholine (ATCh) | Hydrolyzed by AChE to produce a color change. |

| Paper Substrate | Chromatography or filter paper | Platform for reagent immobilization and reaction. |

| Stabilization Matrix | Sucrose/Trehalose Mix | Preserves enzyme and substrate activity during storage. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Sensor Fabrication:

- Immobilize AChE enzyme and the chromogenic substrate (IOA or ATCh) onto separate zones of a paper matrix.

- For long-term stability, use the Sandwich Method of Stabilization (SMS): layer the paper with enzyme and substrate between protective films, maintaining ~90% enzymatic activity for over five months at ambient conditions [11].

- Assay Execution:

- Crush or introduce a liquid sample (e.g., vegetable extract) directly onto the PesticidePAD.

- If pesticides are present, they inhibit the pre-immobilized AChE.

- Add a developer solution or rely on inherent moisture to dissolve and mix the substrate with the enzyme.

- Signal Acquisition:

- Incubate the sensor for a defined period to allow for color development.

- The color intensity generated is inversely proportional to the pesticide concentration.

- Read the result visually or by using a smartphone camera with color analysis software for semi-quantification.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table consolidates key materials required for developing and executing AChE-based biosensors.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for AChE-Based Biosensing

| Category | Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Enzyme | Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) | Primary recognition element. Source can be electric eel, cricket, or human blood [9] [11]. |

| Substrates | Acetylthiocholine (ATCh) | Electrochemical substrate; hydrolyzed to thiocholine [9] [11]. |

| Indoxyl Acetate (IOA) | Colorimetric substrate; offers higher sensitivity in colorimetric assays [11]. | |

| Buffer Systems | Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) | Maintains physiological pH (7.4-8.0) for optimal enzyme activity [9]. |

| Sensor Platforms | Personal Glucose Meter (PGM) | Low-cost, portable transducer for electrochemical detection [9]. |

| Paper-based Matrix | Low-cost substrate for building disposable, colorimetric sensors [11]. | |

| Screen-Printed Electrodes (SPEs) | Customizable electrodes for electrochemical biosensing [9]. | |

| Signal Mediators | Potassium Ferricyanide | Mediator in PGM test strips; oxidizes thiocholine [9]. |

| Stabilizers | Sucrose/Trehalose Matrices | Preserve enzyme and substrate activity in paper-based sensors during storage [11]. |

Limitations of Traditional Chromatography and Mass Spectrometry Methods for Field Use

For researchers and drug development professionals working on environmental monitoring and food safety, the detection of organophosphate (OP) compounds is a critical task. Traditional laboratory-based methods like gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) and high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) are considered reference techniques for their sensitivity and specificity [12] [13]. However, their applicability is severely limited in field settings, such as on-site farm testing or emergency response to potential pesticide exposure, where rapid, portable, and user-friendly detection is paramount. This application note details the specific limitations of these traditional methods and contrasts them with emerging biosensor technology, providing a framework for selecting appropriate detection strategies in field-based research on organophosphates.

Core Limitations of Traditional Analytical Methods

While powerful in the laboratory, traditional chromatography and mass spectrometry techniques face significant practical challenges that hinder their deployment for on-site organophosphate detection. The table below summarizes the key constraints.

Table 1: Key Limitations of Traditional Methods for Field-Based Organophosphate Detection

| Limitation Category | Chromatography (GC, HPLC) | Mass Spectrometry (MS) |

|---|---|---|

| Portability & Cost | Systems are large, benchtop-bound, and require significant laboratory space [14]. | MS systems are expensive to purchase and maintain, making them cost-prohibitive for many field applications [14] [15]. |

| Sample Preparation | Requires careful preparation, including extraction, cleanup, and derivatization, which is time-consuming and requires specialized expertise [12] [14]. | Sample preparation can be complex. The presence of a sample matrix can cause ion suppression or other interferences, affecting accuracy [14] [15]. |

| Analysis Time & Throughput | Analysis times can be long (minutes to hours), not including sample preparation, making true rapid on-site screening impossible [12] [16]. | The technology is highly complex and requires skilled operation, which is often incompatible with the workflow and personnel in field settings [13] [15]. |

| Operational Complexity | Operation and troubleshooting require a high level of technical expertise and are not suitable for novice users [16]. | Not a standalone technique; requires coupling with a separation technique like GC or LC, adding to system complexity [13]. |

| Sample Compatibility | GC is primarily suitable for volatile and semi-volatile compounds, requiring derivatization for many OPs [12] [14]. HPLC is incompatible with highly viscous or watery samples [14]. | Limited linear range, meaning it can only accurately measure analyte concentrations within a certain range without dilution [14]. |

| Environmental Robustness | Sensitive to environmental conditions like vibrations, temperature fluctuations, and power supply quality, which are common in field environments. | Requires high vacuum conditions and stable power, making it inherently non-portable and fragile for field use [13]. |

The Emergence of Biosensors as a Field-Compatible Alternative

In response to these limitations, biosensor technology has emerged as a promising solution for on-site organophosphate detection. These devices are designed to be fast, disposable, and cheap while maintaining a high degree of accuracy [17]. A prominent detection mechanism is the inhibition of the enzyme acetylcholinesterase (AChE), which is the same mechanism by which OP compounds exert their toxicity in organisms [18] [17].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the core principle of an AChE-based biosensor for OP detection.

AChE Biosensor Principle

Experimental Protocol: Potentiometric Biosensor for OP Detection

The following detailed protocol is adapted from research on developing a transducer-based biosensor with a small device potentiometer (SDP) for determining organophosphate pesticides [18].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Reagents

| Item | Function / Description | Source / Example |

|---|---|---|

| Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) | Biological recognition element; catalyzes the hydrolysis of the substrate. Inhibition is measured. | Electric eel, Sigma-Aldrich [18] [17] |

| Cellulose Acetate (CA) | Forms a membrane matrix for the immobilization of the AChE enzyme. | 15% (w/v) in acetone [18] |

| Glutaraldehyde (GA) | Cross-linking agent; stabilizes the enzyme within the cellulose acetate membrane. | 25% (v/v) in H₂O [18] |

| Acetylthiocholine Chloride (ATCl) | Enzyme substrate; hydrolysis product is measured potentiometrically. | Prepared in PBS solution (e.g., 10⁻³ M) [18] |

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) | Provides a stable pH environment (pH 8.0) for the enzymatic reaction. | 0.2 M Na₂HPO₄/NaH₂PO₄ [18] |

| Gold (Au) Electrode | Working electrode where the enzymatic reaction and inhibition occur. | Coated with CA/GA/AChE membrane [18] |

| Ag/AgCl Reference Electrode | Provides a stable and reproducible reference potential for measurements. | Can be prepared in-lab by electrolyzing Ag wire [18] |

| Small Device Potentiometer (SDP) | Transducer; measures the potential value generated from the biochemical reaction. | Portable potentiometric device [18] |

Step-by-Step Methodology

Part A: Biosensor Preparation

- Electrode Preparation: A gold (Au) electrode tip is immersed in a 15% (w/v) cellulose acetate (CA) membrane solution prepared in acetone.

- Cross-linking: The formed CA membrane is rinsed with distilled water and then dipped in 25% (v/v) glutaraldehyde (GA) solution for 6 hours to create a cross-linked matrix.

- Enzyme Immobilization: The electrode membrane (Em) is rinsed with distilled water and PBS (pH 8.0), then immersed in the AChE enzyme solution for 2 x 24 hours at 4°C to allow for immobilization.

- Curing: Before measurement, the biosensor components are stabilized at room temperature for approximately 2 hours to ensure a good response.

Part B: Measurement of Organophosphate Inhibition

- Baseline Measurement: The prepared Em is immersed in PBS (pH 8.0) for 10 minutes. It is then placed in a cell with the substrate solution (10⁻³ M ATCl), and the constant potential value is measured using the SDP.

- Inhibition Step: The Em is removed, rinsed, and immersed in the sample solution containing the organophosphate pesticide (e.g., diazinon or profenofos) for 30 minutes. During this time, the OP compound inhibits the AChE enzyme.

- Post-Inhibition Measurement: The Em is removed from the pesticide solution, rinsed with PBS (pH 8.0), and dipped again into the ATCl substrate solution.

- Signal Recording: The potential value is measured again. The difference between the baseline potential and the post-inhibition potential is correlated to the concentration of the OP inhibitor.

The entire experimental workflow, from biosensor preparation to signal measurement, is summarized below.

Biosensor Experimental Workflow

Performance Metrics of a Potentiometric Biosensor

Research has demonstrated that a well-optimized biosensor can achieve performance suitable for field analysis. The table below quantifies the performance for two common organophosphate pesticides.

Table 3: Exemplary Performance of an AChE-based Potentiometric Biosensor [18]

| Organophosphate Pesticide | Sensitivity (mV decade⁻¹) | Limit of Detection (LoD) | Accuracy (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diazinon | 21.204 | 10⁻⁷ mg L⁻¹ | 99.497 |

| Profenofos | 20.035 | 10⁻⁷ mg L⁻¹ | 94.765 |

The limitations of traditional chromatography and mass spectrometry methods—including their lack of portability, complex operation, and lengthy analysis times—render them unsuitable for rapid, on-site detection of organophosphate pesticides. For researchers developing field-deployable solutions, acetylcholinesterase-based biosensors present a viable and high-performance alternative. The provided experimental protocol and performance data illustrate that these sensors can be designed to be highly sensitive, accurate, and compatible with the demands of field use, offering a promising tool for enhancing environmental and food safety monitoring.

Biosensors are analytical devices that combine a biological recognition element with a physicochemical detector to provide quantitative or semi-quantitative analytical information. These systems have gained paramount importance in environmental monitoring, particularly for the on-site detection of organophosphate (OP) pesticides, which pose significant threats to human health and ecosystem balance through their inhibition of acetylcholinesterase (AChE) in the nervous system [3] [19]. The fundamental architecture of all biosensors consistently comprises three essential components: a bioreceptor that specifically interacts with the target analyte, a transducer that converts this biological recognition event into a measurable signal, and a readout system that displays the results in a user-interpretable form [20]. This application note delineates the core principles, components, and practical methodologies for developing and implementing biosensors within the context of portable devices for organophosphate detection, providing researchers with structured protocols and performance data to advance this critical field.

Core Components of a Biosensor

The Bioreceptor

The bioreceptor is the biological recognition element that imparts specificity to the biosensor by interacting selectively with the target analyte. In organophosphate detection, several classes of bioreceptors are employed, each with distinct mechanisms and advantages.

- Enzymes: Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) is a widely used bioreceptor for OP detection based on the inhibition principle. OPs irreversibly phosphorylate the serine residue in the active site of AChE, decreasing its enzymatic activity, which can be quantified to determine OP concentration [3] [19]. Alternatively, organophosphorus hydrolase (OPH) or methyl parathion hydrolase (MPH) enables direct detection by catalytically hydrolyzing OP compounds into measurable products [21].

- Antibodies: Immunosensors utilize antibodies as bioreceptors for specific OP antigens. The binding specificity is the primary characteristic, and the efficiency of the sensor depends on the antibody's specificity, stability, and sensitivity [19].

- Aptamers: These are single-stranded DNA or RNA oligonucleotides that bind to specific targets with high affinity. Aptamer-based sensors (aptasensors) are emerging for pesticides like malathion, offering advantages in stability and design flexibility [22].

- Whole Cells: Genetically engineered microorganisms expressing specific enzymes like OPH or MPH on their surface can serve as living bioreceptors, potentially offering cost-effective and regenerative sensing platforms [19].

The Transducer

The transducer transforms the biological recognition event into a quantifiable electronic signal. The choice of transducer depends on the nature of the biochemical change occurring at the bioreceptor layer.

- Electrochemical Transducers: These are highly prevalent in portable biosensor systems due to their sensitivity, low cost, and potential for miniaturization [20]. They encompass:

- Amperometric Sensors: Measure the current generated by the oxidation or reduction of an electroactive species at a constant potential.

- Potentiometric Sensors: Measure the potential difference between a working electrode and a reference electrode at zero current.

- Impedimetric Sensors: Monitor changes in the impedance (resistance to alternating current) at the electrode-electrolyte interface, often resulting from the binding of a target analyte [20].

- Optical Transducers: These measure changes in light properties. For OP detection, common optical methods include:

- Absorbance-based Sensors: Measure the concentration of a chromogenic product, such as the yellow p-nitrophenol produced from MP hydrolysis by MPH, by its light absorption at a specific wavelength [21].

- Fluorescence-based Sensors: Detect changes in fluorescence intensity, wavelength, or polarization. Quantum dots and other fluorescent materials are often employed as labels or signal reporters [3].

- Electrochemiluminescence (ECL): A combined electrochemical and optical method where an electrochemical reaction generates luminescent species. ECL-based aptasensors have been developed for ultrasensitive malathion detection [22].

- Other Transducers: These include piezoelectric (mass-sensitive) and thermal (enthalpy-sensitive) transducers, though they are less common for portable OP detection [3].

The Readout System

The readout is the final component that processes, interprets, and displays the signal from the transducer in a human-readable format. For portable biosensors, the readout system must be compact, low-power, and user-friendly.

- Electronic Displays: Simple liquid crystal displays (LCDs) or light-emitting diode (LED) screens integrated into the device can directly show numerical concentration values or qualitative results.

- Signal Interfaces: Portable systems often interface with smartphones or tablets via Bluetooth or wired connections, leveraging their powerful processors and displays for advanced data visualization, storage, and sharing [20] [3].

- Auditory or Visual Alarms: For field applications, simple LED color changes (e.g., green/red) or auditory beeps can provide immediate go/no-go results for pesticide contamination.

Table 1: Core Components of a Biosensor for Organophosphate Detection

| Component | Function | Common Types for OP Detection | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bioreceptor | Selective recognition of the target analyte | Enzymes (AChE, OPH/MPH), Antibodies, Aptamers | Defines specificity; Stability and immobilization are critical |

| Transducer | Converts biological event into measurable signal | Electrochemical, Optical (Absorbance, Fluorescence, ECL) | Defines sensitivity; Must be matched to the biorecognition event |

| Readout | Displays the processed result for the user | Integrated LCD/LED, Smartphone Interface, Visual Alarms | Should be intuitive and suitable for the deployment environment |

System Workflow and Logical Relationships

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow and logical relationships between the core components of a biosensor, from sample introduction to final result.

Experimental Protocol: Amperometric AChE-Based Biosensor for OP Detection

This protocol details the construction and operation of a disposable screen-printed amperometric biosensor for the detection of organophosphates based on acetylcholinesterase inhibition.

Principle

The sensor measures the amperometric current generated from the enzymatic hydrolysis of a substrate, acetylthiocholine. In the absence of OP, AChE catalyzes the hydrolysis of acetylthiocholine to thiocholine and acetate. Thiocholine is then oxidized at the electrode surface, producing a measurable current. When OP is present, it inhibits AChE, reducing the amount of thiocholine produced and consequently decreasing the oxidation current. The percentage of inhibition is proportional to the concentration of OP in the sample [3] [19].

Materials and Reagents

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

| Item | Function/Description | Specifications/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Screen-printed Carbon Electrode (SPCE) | Transducer platform | Disposable; typically features carbon working and counter electrodes and a silver/silver chloride reference. |

| Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) | Bioreceptor | Enzyme from Electrophorus electricus or recombinant source; specific activity >500 U/mg. |

| Acetylthiocholine chloride | Enzymatic substrate | Converted to electroactive thiocholine by AChE. |

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) | Electrolyte and dilution buffer | 0.1 M, pH 7.4, containing 0.1 M KCl. |

| Organophosphate Standard | Target analyte | Parathion-methyl or chlorpyrifos stock solution in methanol or acetonitrile. |

| Glutaraldehyde / BSA | Crosslinker / Stabilizer | For enzyme immobilization on the electrode surface. |

| Potentiostat | Readout Instrument | Portable potentiostat for amperometric measurements. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Part A: Electrode Modification and AChE Immobilization

- Surface Preparation: Clean the working electrode surface of the SPCE by cycling the potential in 0.1 M PBS (pH 7.4) between -0.5 V and +0.8 V until a stable voltammogram is obtained.

- Enzyme Immobilization: Prepare a 10 μL mixture containing 0.5 U of AChE and 0.25% (w/v) BSA in a small volume of PBS. Add 0.5 μL of 2.5% (v/v) glutaraldehyde to this mixture and vortex briefly.

- Drop-Casting: Immediately deposit 5 μL of the AChE/BSA/glutaraldehyde mixture onto the clean working electrode area. Allow it to dry at 4°C for 2 hours to complete the cross-linking process.

- Storage: Store the modified AChE-SPCEs at 4°C when not in use.

Part B: Amperometric Measurement and OP Detection

- Baseline Measurement: Place the AChE-SPCE into a portable potentiostat. Apply a constant potential of +0.5 V (vs. the on-chip Ag/AgCl reference) to the working electrode. After the background current stabilizes, inject 50 μL of 2 mM acetylthiocholine chloride (in PBS) into the electrochemical cell. Record the steady-state current (I₀) generated by the oxidation of thiocholine.

- Inhibition (Sample Exposure): Incubate the AChE-SPCE in 1 mL of the sample (or OP standard solution of known concentration) for 10 minutes. Rinse the electrode gently with PBS to remove unbound OP.

- Post-Inhibition Measurement: Repeat the amperometric measurement as in Step B1, injecting 50 μL of 2 mM acetylthiocholine chloride and recording the new steady-state current (I₁).

- Data Analysis: Calculate the percentage of enzyme inhibition using the formula: Inhibition (%) = [(I₀ - I₁) / I₀] × 100. The OP concentration in the sample is determined by interpolating the inhibition percentage against a calibration curve prepared with standard OP solutions.

Performance Data and Comparison of Biosensor Types

The performance of different biosensor configurations for OP detection varies significantly in terms of sensitivity, detection limit, and analysis time. The following table summarizes key performance metrics from recent developments.

Table 3: Performance Comparison of Biosensors for Organophosphate Detection

| Biosensor Type | Bioreceptor | Transducer | Target OP | Detection Limit | Linear Range | Analysis Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electrochemical (Inhibition) [3] [19] | AChE | Amperometry | Various OPs | ~ μg•L⁻¹ level | Varies | 15-20 min |

| Electrochemical (Aptasensor) [22] | DNA Aptamer | ECL | Malathion | 0.219 fM | 1.0×10⁻¹³ – 1.0×10⁻⁸ mol·L⁻¹ | Rapid |

| Optical (Direct) [21] | MPH | Absorbance | Methyl Parathion | 4 μM | Not Specified | Rapid |

| Immunosensor [19] | Antibody | Electrochemical | Specific OPs | Varies | Varies | Varies |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Key Reagents and Materials for Biosensor Development

| Item | Function | Critical Notes for Use |

|---|---|---|

| Nanomaterials (e.g., MWCNTs, ZnO, AuNPs) | Transducer enhancement | Increase electrode surface area, enhance electron transfer, and improve biosensor sensitivity and stability [20] [22]. |

| Methyl Parathion Hydrolase (MPH) | Catalytic Bioreceptor | Directly hydrolyzes methyl parathion to p-nitrophenol; can be immobilized via His-tag on Ni-NTA agarose for reusable sensor surfaces [21]. |

| Portable Potentiostat | Readout device | Essential for field-deployable electrochemical sensors; must be compact, low-power, and capable of connecting to mobile devices [20]. |

| Ni-NTA Agarose | Immobilization matrix | Provides oriented and stable immobilization of His-tagged recombinant enzymes (e.g., MPH), preserving activity and allowing for regeneration [21]. |

Biosensors represent a cornerstone technology for analytical detection, blending biology, chemistry, and engineering to convert specific biological responses into quantifiable signals. Within the strategic context of developing portable biosensors for on-site organophosphate (OP) detection, this document details the operational principles, key performance metrics, and standardized experimental protocols for three principal biosensor platforms: electrochemical, optical, and piezoelectric. The content is structured to serve researchers and scientists engaged in the design and implementation of biosensing systems for environmental monitoring and food safety, with a particular emphasis on miniaturized, on-site application. Data on sensitivity, linear range, and detection limits are summarized in comparative tables, and foundational methodologies for each platform are provided to ensure experimental reproducibility.

A biosensor is an analytical device that integrates a biological recognition element with a physicochemical transducer to detect a specific analyte [23] [24]. The core function of any biosensor relies on the specific binding or catalytic conversion of the target analyte by the biorecognition element (e.g., enzymes, antibodies, nucleic acids, or whole cells). This interaction produces a physical or chemical change that is converted by the transducer into an electronic signal, which is then processed and relayed to the user [24]. The general architecture and workflow of a biosensor are illustrated below.

The critical performance parameters for any biosensor, especially in the context of portable OP detection, include:

- Sensitivity: The magnitude of signal change per unit change in analyte concentration.

- Detection Limit: The lowest concentration of analyte that can be reliably distinguished from background noise.

- Selectivity: The ability to respond exclusively to the target analyte in complex sample matrices.

- Response Time: The time required to achieve a stable signal upon analyte exposure.

- Stability and Robustness: Essential for field-deployable devices, encompassing operational lifetime and resistance to environmental variations [23] [24].

Biosensor Platforms: Principles and Quantitative Comparison

Biosensors are primarily classified based on their transduction principle. The following sections and comparative table delineate the core attributes of the three major platforms relevant to portable biosensor development.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Major Biosensor Platforms

| Feature | Electrochemical | Optical | Piezoelectric |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transduction Principle | Measures electrical properties (current, potential, impedance) changes due to bio-recognition event [24]. | Measures changes in light properties (absorbance, fluorescence, FRET) [25]. | Measures change in resonant frequency or acoustic wave propagation due to mass adsorption on sensor surface [26]. |

| Common Sub-types | Amperometric, Potentiometric, Impedimetric [24]. | Fluorescence, FRET-based, Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR). | Quartz Crystal Microbalance (QCM), Surface Acoustic Wave (SAW) [26]. |

| Key Performance Metrics | Sensitivity (μA/mM), Limit of Detection (LOD), Linear Range. | Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR), Ratiometric Output (for FRET), LOD [27] [25]. | Frequency Shift (Hz), Mass Sensitivity (ng/cm²), Dissipation Factor [26]. |

| Typical LOD (General) | nM to fM range [23] | Varies with method; single molecules possible. | ng/cm² range [26] |

| Example LOD (OPs) | Glyphosate: 1.24 × 10⁻¹³ M [28] | Information not specified in search results. | Carbaryl: 0.14 ng/mL [26] |

| Advantages | High sensitivity, easy miniaturization, portable, low-cost, works in turbid solutions [24]. | High spatial resolution, multiplexing capability, real-time kinetic monitoring [25]. | Label-free, real-time monitoring, studies viscoelastic properties [26]. |

| Disadvantages | Susceptible to electrical interference, surface fouling. | Can be affected by ambient light, sample auto-fluorescence, requires sophisticated optics [27]. | Sensitive to environmental vibrations, viscosity and density of medium affect signal [26]. |

Electrochemical Biosensors

Electrochemical biosensors are among the most prevalent platforms for portable devices due to their high sensitivity, inherent capacity for miniaturization, and low power requirements [24]. Their operation is based on the detection of electrical signals generated from biochemical reactions at the sensor-solution interface.

The fundamental mechanism for enzyme-based OP detection involves the inhibition of acetylcholinesterase (AChE). The normal enzymatic hydrolysis of acetylcholine produces electroactive products, generating a measurable current. The presence of OPs inhibits AChE, reducing the catalytic current proportionally to the OP concentration [28].

Optical Biosensors

Optical biosensors transduce biological recognition events into changes in the properties of light, such as intensity, wavelength, polarization, or phase [25]. A prominent class for intracellular and quantitative sensing is the Genetically Encoded Fluorescent Biosensor (GEFB), which often uses Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET).

In a ratiometric FRET biosensor, the target analyte binding induces a conformational change in the sensor protein, altering the distance and/or orientation between a donor fluorophore and an acceptor fluorophore. This change modulates the efficiency of energy transfer, which is quantified as a ratio of the two emission intensities, making the measurement robust against variations in sensor concentration or excitation light intensity [25].

A critical performance parameter for optical biosensors is the Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR). A higher SNR facilitates faster and more accurate results [27]. SNR is calculated as the ratio of the average signal amplitude to the standard deviation of the noise. For optical measurements with DC signals: SNR = (Signal Average) / (Standard Deviation of Signal). This can also be expressed in decibels (dB) as SNR (dB) = 20 log₁₀(Signal Average / Noise Standard Deviation) [27].

Piezoelectric Biosensors

Piezoelectric biosensors, most commonly based on a Quartz Crystal Microbalance (QCM), are mass-sensitive devices that operate by measuring the decrease in resonant frequency of a piezoelectric crystal when a mass (such as a bound analyte) is adsorbed onto its surface [26]. This relationship is quantitatively described by the Sauerbrey equation for rigid, thin films in air/gas phase:

Δf = - (2 f₀² Δm) / (A (ρₐ μₐ)^½)

Where:

- Δf is the change in resonant frequency.

- f₀ is the fundamental resonant frequency of the crystal.

- Δm is the mass change.

- A is the active area of the crystal.

- ρₐ and μₐ are the density and shear modulus of the quartz, respectively [26].

When operating in a liquid environment, the frequency is also affected by the liquid's viscosity and density, and the adsorbed biolayers often have viscoelastic properties. Therefore, modern QCM systems often also measure the dissipation (D), which quantifies energy losses and provides information about the rigidity of the adsorbed layer [26].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Electrochemical Biosensor for Organophosphorus Pesticides (OPs)

This protocol outlines the procedure for developing a portable electrochemical biosensor for the detection of multiple OPs, based on the work by Wu et al. (2024) [28].

1. Sensor Fabrication:

- Working Electrode Preparation: Clean the gold working electrode surface with alumina slurry and sonicate in ethanol and deionized water.

- IMOF Modification: Deposit a suspension of the synthesized amino-modified ionic metal-organic framework (NH₂-IMOF) in chitosan (CS) solution onto the electrode surface. Dry at room temperature.

- Enzyme Immobilization: Drop-cast an acetylcholinesterase (AChE) solution onto the NH₂-IMOF@CS modified electrode and incubate in a humid chamber at 4°C to form the final NH₂-IMOF@CS@AChE biosensor. Rinse gently with buffer to remove unbound enzyme.

2. Measurement Setup (Portable Operation):

- Integrate the biosensor with a near-field communication (NFC) module and potentiostat for touchless, battery-free operation [28].

- Use a standard three-electrode system (fabricated working electrode, Ag/AgCl reference electrode, Pt counter electrode) connected to the portable potentiostat.

3. Detection Procedure (Differential Pulse Voltammetry - DPV):

- Baseline Acquisition: Immerse the biosensor in a stirred buffer solution and run the DPV method to obtain a stable baseline current.

- Inhibition Phase: Incubate the biosensor in a sample solution containing the target OP for a fixed period (e.g., 10-15 minutes). OPs will inhibit the AChE enzyme.

- Substrate Addition & Measurement: Transfer the biosensor to a buffer solution containing the substrate (acetylthiocholine). Record the DPV signal. The reduction in the oxidation current of the enzymatic product (thiocholine) is proportional to the OP concentration [28].

- Regeneration (for re-use): Regenerate the inhibited biosensor by incubating in a solution of a reactivator like pralidoxime (2-PAM).

Protocol: Piezoelectric (QCM) Immunosensor Operation

This protocol describes the steps for conducting a label-free affinity biosensing experiment using a QCM, adaptable for antibody-antigen interactions such as the detection of pesticide residues [26].

1. Sensor Preparation and Baseline Establishment:

- Mount a gold-coated QCM crystal (e.g., 10 MHz) in the flow cell.

- Establish a stable baseline by flowing a running buffer (e.g., phosphate-buffered saline) at a constant rate and temperature. Record the resonant frequency (f) and dissipation (D).

- For advanced characterization, use a QCM-D instrument that can monitor multiple overtones.

2. Surface Functionalization:

- Immobilization Layer: Flow a solution of the capture molecule (e.g., a specific antibody for a target OP) over the crystal surface. This can be done via direct adsorption or through a pre-formed self-assembled monolayer (SAM).

- Washing: Flush with running buffer to remove loosely bound molecules. A stable frequency shift (Δf) indicates successful immobilization.

3. Analyte Binding and Measurement:

- Sample Injection: Introduce the sample containing the target analyte (antigen) into the flow system.

- Real-time Monitoring: Monitor the decrease in resonant frequency (Δf) and increase in dissipation (ΔD) in real-time as the analyte binds to the immobilized capture molecule.

- Kinetic Analysis: The binding curve (Δf vs. Time) can be analyzed to extract association and dissociation rate constants.

4. Sensor Regeneration:

- After measurement, flow a regeneration solution (e.g., low pH glycine buffer) over the sensor surface to break the affinity bonds and remove the bound analyte, returning the frequency close to its post-immobilization value. The sensor can then be used for a new measurement cycle.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Biosensor Development

| Item | Function / Application | Example & Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Amino-modified Ionic Metal-Organic Frameworks (NH₂-IMOFs) | Electrochemical sensor substrate. Enhances electron transfer and provides a high-surface-area, charged matrix for stable enzyme immobilization [28]. | NH₂-IMOF used in a portable OP sensor; the framework's positive charge enhances electrostatic attraction for enzymes like AChE [28]. |

| Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) | Biorecognition element for organophosphate and carbamate pesticides. | The enzyme's catalytic activity is inhibited by OPs, providing the basis for detection in electrochemical and optical platforms [28]. |

| Gold Electrodes / QCM Crystals | Transducer surface. Provides an inert, conductive, and easily functionalizable platform for biomolecule immobilization. | Standard in electrochemical and piezoelectric (QCM) systems. Gold allows for strong thiol-based chemisorption for creating self-assembled monolayers (SAMs) [26] [24]. |

| Genetically Encoded FRET Biosensors | For intracellular, ratiometric quantification of ions, metabolites, and signaling molecules. | ABACUS (for ABA) and roGFP (for redox potential) are examples. They enable direct, real-time sensing in live cells with high spatiotemporal resolution [25]. |

| Chitosan (CS) | A biopolymer used for enzyme immobilization. Forms a biocompatible hydrogel matrix that entraps enzymes while allowing substrate and product diffusion. | Used in the NH₂-IMOF@CS@AChE biosensor to stabilize the enzyme layer on the electrode surface [28]. |

Advanced Biosensing Platforms and Their Real-World Deployment

Electrochemical biosensors for thiocholine detection represent a cornerstone technology in the development of portable, on-site analytical tools for organophosphate (OP) pesticide monitoring [3] [29]. These biosensors leverage the enzymatic hydrolysis of acetylthiocholine (ATCh) by acetylcholinesterase (AChE) to produce thiocholine, an electroactive compound whose measurement serves as the basis for detecting AChE-inhibiting neurotoxic agents [30] [31]. The inhibition of AChE by OPs provides the fundamental recognition mechanism, with the degree of inhibition correlating directly with pesticide concentration [3]. The selection of specific electrochemical transduction methods—amperometry, potentiometry, or impedimetry—determines critical sensor parameters including sensitivity, detection limit, and suitability for field deployment [32] [33]. This document provides detailed application notes and experimental protocols to guide researchers in developing and optimizing these biosensing platforms for environmental monitoring and food safety applications.

Core Principles and Signaling Pathways

The detection of organophosphates using AChE-based biosensors follows a consistent biochemical pathway, with variations occurring at the electrochemical transduction stage. The fundamental mechanism involves AChE catalyzing the hydrolysis of acetylthiocholine to produce thiocholine and acetate. The subsequent oxidation of thiocholine at the electrode surface generates the measurable electrochemical signal [31]. When OPs are present, they inhibit AChE activity, reducing thiocholine production and causing a corresponding decrease in the electrochemical signal that is proportional to the pesticide concentration [3].

The following diagram illustrates the core signaling pathway and the points of transduction for different electrochemical techniques:

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential materials and their specific functions in developing electrochemical biosensors for thiocholine detection.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents for Thiocholine Biosensor Development

| Reagent | Function and Application Notes |

|---|---|

| Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) | Biological recognition element; catalyzes ATCh hydrolysis to thiocholine. Source (electric eel, bovine erythrocytes) and immobilization method significantly impact biosensor stability and sensitivity [30] [3]. |

| Acetylthiocholine (ATCh) Chloride/Iodide | Enzymatic substrate. ATCh chloride is preferred for amperometry to avoid interference from iodide oxidation, whereas either salt can be used for potentiometric detection [31]. |

| Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) | Electrode nanomaterial; enhances electron transfer kinetics, increases effective surface area, and lowers thiocholine oxidation overpotential (~360 mV) [29] [31]. |

| Cobalt Phthalocyanine (CoPC) | Electron mediator; significantly reduces working overpotential for thiocholine oxidation to ~110 mV, minimizing interference from coexisting electroactive species [30] [31]. |

| Glutaraldehyde/BSA | Crosslinking system; standard mixture for enzyme immobilization on electrode surfaces via co-crosslinking, ensuring stable biorecognition layer formation [34] [31]. |

| Organophosphate Standards | Target analytes for inhibition-based detection (e.g., paraoxon, carbofuran). Used for biosensor calibration and evaluation of analytical performance [30] [3]. |

Detection Modalities: Principles and Protocols

Amperometric Detection

Amperometric biosensors measure the steady-state current generated by the electrochemical oxidation of thiocholine at a constant applied potential. The current magnitude is directly proportional to the thiocholine concentration, which in turn reflects AChE activity [30] [34].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Amperometric Biosensors

| Electrode Material | Applied Potential (vs. Ag/AgCl) | Detection Limit | Linear Range | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FePC-modified Carbon Paste | +0.35 V (for H₂O₂ detection) | 10⁻¹⁰ M Paraoxon | Not Specified | Low operating potential in bienzymatic system [30] |

| CoPC-modified SPE | ~+0.11 V | Not Specified | Not Specified | Very low overpotential for thiocholine oxidation [31] |

| CNT-modified SPE | ~+0.36 V | Not Specified | Not Specified | High sensitivity and good electrocatalysis [31] |

| Pt/Overoxidized Ppy-ChOx | +0.7 V (vs. SCE) | 0.5 U L⁻¹ BChE | Wide | Interference removal by polypyrrole layer [34] |

Protocol 1: Amperometric Biosensor for AChE Inhibition

- Objective: To fabricate an amperometric biosensor and measure AChE inhibition by organophosphates.

Materials: Screen-printed electrode (SPE, carbon, Pt, or Au); AChE enzyme; Acetylthiocholine chloride (ATCh-Cl); Glutaraldehyde (0.25%); Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA, 0.1%); Phosphate Buffer Saline (PBS, 0.1 M, pH 7.0-8.0) [34] [31].

Experimental Workflow:

- Critical Notes:

- Potential Optimization: The working potential must be optimized for each electrode type to maximize the signal-to-noise ratio for thiocholine oxidation while minimizing interference [31].

- Substrate Choice: Acetylthiocholine chloride is strongly recommended over the iodide salt to avoid parasitic currents from iodide oxidation, which can obscure the thiocholine signal and prevent observation of complete enzyme inhibition [31].

Potentiometric Detection

Potentiometric biosensors measure the potential difference between working and reference electrodes under conditions of negligible current flow. This potential change often results from ion fluxes generated by enzymatic activity, such as the production of protons during thiocholine hydrolysis [32].

Protocol 2: Potentiometric Transducer Setup

- Objective: To configure a potentiometric system for monitoring AChE-catalyzed reactions.

Materials: Ion-Selective Electrode (ISE) or Metal Electrode; High-Impedance Potentiometer; Reference Electrode (e.g., Ag/AgCl); Magnetic stirrer [32].

Procedure:

- Immobilize AChE on the surface of the ion-selective electrode or a conventional solid-contact electrode. This can be done via cross-linking with BSA/glutaraldehyde or entrapment within a polymer membrane (e.g., Nafion, chitosan) [32].

- Place the modified working electrode and the reference electrode in a stirred buffer solution containing the sample.

- Record the baseline potential until a stable reading is obtained.

- Inject a known concentration of acetylthiocholine substrate into the solution.

- Monitor the potential shift over time. The rate and magnitude of the potential change are related to the enzymatic activity.

- For inhibition assays, pre-incubate the biosensor with the OP sample before adding the substrate. The degree of inhibition is quantified by the reduced rate of potential change compared to the uninhibited control [32].

Critical Notes:

- Potentiometric sensors are highly sensitive to ionic strength and buffer capacity. Use a low-capacity buffer to maximize the pH shift signal from the enzymatic reaction.

- These sensors are susceptible to drift, requiring a stable reference electrode and temperature control for accurate measurements.

Impedimetric Detection

Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) detects changes in the charge transfer resistance (Rₑₜ) at the electrode-solution interface resulting from the enzymatic generation of thiocholine or the binding of inhibitors. EIS is a label-free technique that provides rich information about interfacial properties [35] [33].

Protocol 3: Label-Free Impedimetric Biosensing of AChE Inhibition

- Objective: To detect OPs by measuring impedance changes due to AChE inhibition.

Materials: SPE (Gold or carbon); Impedance Analyzer; Redox probe (e.g., [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻); AChE enzyme; ATCh-Cl; OPs standard [35] [29].

Procedure:

- Modify the Electrode: Immobilize AChE on the SPE surface.

- Record EIS Spectrum (Initial): Measure the impedance in a solution containing a redox probe (e.g., 5 mM [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻ in PBS) over a frequency range (e.g., 0.1 Hz to 100 kHz) at a fixed DC potential. Fit the data to a Randles equivalent circuit to extract the initial charge transfer resistance (Rₑₜ,ᵢₙᵢₜᵢₐₗ) [35].

- Incubate with Analyte: Expose the biosensor to the sample containing the target OP for a fixed period (e.g., 10 minutes).

- Record EIS Spectrum (Post-Inhibition): Wash the electrode and measure the impedance again in the fresh redox probe solution to obtain the new charge transfer resistance (Rₑₜ,ᵢₙₕᵢᵦᵢₜₑ𝒹).

- Data Analysis: The percentage of AChE inhibition can be calculated using the formula: % Inhibition = [ (Rₑₜ,ᵢₙₕᵢᵦᵢₜₑ𝒹 - Rₑₜ,ᵢₙᵢₜᵢₐₗ) / Rₑₜ,ᵢₙᵢₜᵢₐₗ ] × 100% This value is then correlated with the concentration of the inhibiting OP [29].

Amperometric, potentiometric, and impedimetric biosensors each offer distinct advantages for the detection of thiocholine and the monitoring of AChE-inhibiting organophosphates. The choice of technique involves a trade-off between sensitivity, simplicity, portability, and robustness. The ongoing integration of nanomaterials, novel immobilization strategies, and microfluidic platforms is steadily enhancing the performance of these biosensors, pushing detection limits to sub-nanomolar concentrations and making them increasingly viable for rigorous on-site environmental and food safety analysis [3] [29] [33]. The protocols outlined herein provide a foundational framework for researchers to develop and refine these critical analytical tools.

Ion-Sensitive Field-Effect Transistor (ISFET) biosensors represent a advanced class of electronic sensors that combine the sensitivity of field-effect transistors with the specificity of biological recognition elements. Initially pioneered in 1970, these devices substitute the traditional metal gate of a MOSFET with an ion-sensitive film and an electrolyte solution, creating a platform exquisitely sensitive to biochemical changes at its surface [36] [37]. The fundamental operating principle hinges on the modulation of the transistor's threshold voltage (Vth) when target analytes interact with the biologically sensitized gate region. This interaction alters the surface potential, subsequently changing the channel conductivity between the source and drain electrodes, thereby converting biological recognition events into quantifiable electrical signals [36].

The significance of ISFETs in modern biosensing stems from their numerous advantages, including label-free operation, miniaturization potential, high sensitivity, and rapid response times [36]. Their structure typically comprises a silicon semiconductor gate, an ion-selective membrane, a reference electrode, and an insulating layer. The gate region is functionalized with a recognition element (e.g., enzymes, antibodies, aptamers, or whole cells) tailored to the specific analyte of interest [36] [38]. This configuration allows ISFETs to detect a wide palette of targets, from ions and nucleic acids to proteins and cellular components, making them indispensable in fields ranging from clinical diagnostics to environmental monitoring [36].

Recent advancements have further propelled ISFET biosensors to the forefront of sensing technology. The integration of novel nanomaterials and microelectronic fabrication techniques has significantly enhanced sensor performance, steering their development toward higher sensitivity, seamless integration, and multifaceted detection capabilities [36]. These improvements are particularly relevant for applications in portable and on-site detection, such as the monitoring of organophosphorus pesticides (OPPs) in agricultural and environmental settings [39].

Application Note: ISFET Biosensor for Organophosphorus Pesticide Detection

Sensing Principle and Mechanism

The detection of organophosphorus pesticides (OPPs) using ISFET biosensors operates on the principle of enzyme inhibition [39]. A specific portable biosensor prototype utilizing the microalgae Chlorella sp. immobilized on a Ta₂O₅ ISFET has been developed for this purpose. In this system, the detection mechanism is based on the pesticide-induced inhibition of the enzyme alkaline phosphatase (AP) [39]. The enzymatic activity of AP typically leads to the production of ascorbic acid. When OPPs are present, they inhibit this enzyme, resulting in a measurable decrease in ascorbic acid production. This change in the concentration of the enzymatic product directly alters the local ionic environment at the gate surface of the ISFET, transducing the biochemical event into a potentiometric signal—a change in the output current or voltage—that is correlated with the pesticide concentration [39].

This mechanism is visually summarized in the following workflow:

Performance and Analytical Figures of Merit

The developed ISFET biosensor demonstrates exceptional performance for the detection of specific OPPs. The sensitivity, selectivity, and detection limit were rigorously evaluated for a range of pesticides, including acephate, triazophos, chlorpyrifos, and malathion [39]. The biosensor's performance metrics are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Analytical Performance of the ISFET Biosensor for Organophosphorus Pesticides

| Pesticide | Detection Limit | Linear Range | Response Time | Key Performance Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acephate | 10⁻¹⁰ M | 10⁻¹⁰ to 10⁻² M | 4 minutes | Remarkably high sensitivity and selectivity [39] |

| Triazophos | 10⁻¹⁰ M | 10⁻¹⁰ to 10⁻² M | 4 minutes | Remarkably high sensitivity and selectivity [39] |

| Chlorpyrifos | - | 10⁻⁷ to 10⁻² M | 4 minutes | - |

| Malathion | - | - | 4 minutes | Reduced sensitivity and inconsistent trends [39] |

The biosensor achieves an ultra-low detection limit of 10⁻¹⁰ M for acephate and triazophos, showcasing its capability to detect trace-level pesticide concentrations [39]. The linear response across a wide concentration range (from 10⁻¹⁰ M to 10⁻² M for some OPPs) ensures utility in both highly contaminated and lightly contaminated samples. The rapid response time of just 4 minutes facilitates near real-time monitoring, a critical feature for on-site applications [39]. Furthermore, the biosensor's accuracy was validated against the standard laboratory method of High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) using real-time soil samples, with an observed average deviation of less than 10%, confirming its reliability for real-world analysis [39].

Experimental Protocol

Biosensor Fabrication and Functionalization

This protocol details the procedure for fabricating a portable potentiometric biosensor using Chlorella sp. immobilized on a Ta₂O₅ ISFET for the detection of organophosphorus pesticides [39].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

| Item/Chemical | Function / Role in the Experiment | Specifications / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Ta₂O₅ ISFET Chip | Transducer platform; converts biological event to electrical signal. | Gate insulator sensitive to pH/ionic changes [39] [36]. |

| Chlorella sp. Culture | Whole-cell bio-recognition element; source of alkaline phosphatase enzyme. | Cultivated and harvested prior to immobilization [39]. |

| 2-Phospho-L-ascorbic acid (PAA) | Enzyme substrate for alkaline phosphatase. | Concentration optimized at 0.4 mL for the assay [39]. |

| Glutaraldehyde | Crosslinking agent for immobilizing algal cells on the ISFET gate. | Creates stable covalent bonds [39]. |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | May be used as a blocking agent to reduce non-specific binding. | - |

| Tris-HCl Buffer | Provides a stable pH environment for the biochemical reaction. | - |

| Magnesium Chloride (MgCl₂) | Enzyme activator for alkaline phosphatase. | - |

| Organophosphorus Pesticide Standards | Analytic targets for validation (e.g., acephate, triazophos). | Prepared in a range of concentrations from 10⁻¹⁰ to 10⁻² M [39]. |

Procedure:

- ISFET Preparation: Clean the surface of the Ta₂O₅ ISFET chip to ensure it is free from contaminants.

- Algal Immobilization: Mix 20 μL of the prepared Chlorella sp. suspension (optimal concentration) with a crosslinking agent such as glutaraldehyde. Apply this mixture to the gate region of the ISFET and allow it to immobilize, forming a stable bio-recognition layer [39].

- System Assembly: Integrate the functionalized ISFET into a portable potentiometric measurement device. This includes connecting the source, drain, and reference electrodes to the appropriate readout circuitry.

- Baseline Measurement: Introduce the substrate solution, 0.4 mL of PAA, in Tris-HCl buffer with MgCl₂ to the biosensor. Measure the initial output signal (current or voltage), which corresponds to the uninhibited enzymatic production of ascorbic acid [39].

Measurement and Detection Protocol

Procedure:

- Sample Introduction: Introduce the sample (e.g., extracted soil solution suspected to contain OPPs) to the biosensor chamber containing the substrate.

- Incubation and Reaction: Allow the sample to incubate for the optimized response time of 4 minutes. During this period, any OPPs present will inhibit the alkaline phosphatase enzyme in the immobilized Chlorella sp. cells [39].

- Signal Measurement: After the 4-minute response time, measure the final output signal from the ISFET. The difference from the baseline signal is inversely proportional to the enzymatic activity and, therefore, directly proportional to the concentration of the inhibiting pesticide [39].

- Quantification: Correlate the measured signal change (e.g., threshold voltage shift or drain current change) with pesticide concentration using a pre-established calibration curve plotted for known standard concentrations of the target OPP [39] [36].

- Validation (Optional): For research validation, compare the results obtained with the ISFET biosensor against a standard method like HPLC for the same sample to confirm accuracy and reliability [39].

The following diagram illustrates the key components and operational workflow of the ISFET biosensor:

Discussion and Comparative Analysis

The ISFET biosensor platform using Chlorella sp. presents a compelling alternative to conventional pesticide detection methods like spectrophotometry and chromatography, which are often constrained by complex procedures, high costs, and lack of portability [39]. The core strength of this technology lies in its use of whole algal cells as the bio-recognition element. Compared to biosensors relying on purified enzymes, whole-cell systems offer enhanced stability, viability, and functional robustness under in vitro conditions, maintaining consistent performance with less rigorous stabilization protocols [39].

The presented biosensor exemplifies the key trends in modern biosensing: portability, cost-effectiveness, and high reproducibility [39]. Its design aligns with the growing demand for point-of-care testing (POCT) and on-site environmental monitoring tools. When benchmarked against other enzymatic biosensors, this ISFET-based device stands out for its ultra-low detection limits and rapid analysis time [39]. The successful validation against HPLC for real soil sample analysis underscores its practical utility and trueness, moving it beyond a mere laboratory prototype [39].

Future advancements in this field may involve the integration of other novel biorecognition elements like aptamers or antibody fragments to expand the range of detectable analytes or improve specificity [40] [36]. Furthermore, the convergence of ISFET technology with smartphone-based readout systems and AI-powered data analytics, as seen in broader biosensor market trends, promises to create even more intelligent, proactive, and accessible diagnostic tools for environmental and agricultural monitoring [41] [42].

The detection and monitoring of organophosphorus pesticides (OPs) are critical for ensuring environmental safety and public health. Conventional techniques like chromatography, while sensitive, are laboratory-bound, costly, and time-consuming, making them unsuitable for rapid, on-site screening [39] [43]. Biosensors present a promising alternative, and among them, whole-cell biosensors utilizing microorganisms like the microalga Chlorella sp. offer distinct advantages in robustness, cost-effectiveness, and functional stability for field-deployable applications [39] [44] [45].

Whole-cell biosensors leverage intact living cells as the biorecognition element. Algal cells, in particular, provide a sustainable and resilient biological component, tolerating quasi-physiological conditions better than purified enzymes and maintaining consistent performance under variable conditions [39] [45]. Their ease of cultivation, extended lifespan, and high metabolic productivity make them ideal candidates for sensor modification [39]. This application note details the use of Chlorella sp.-based biosensors for OPs detection, providing validated protocols and analytical data tailored for researchers developing portable on-site detection systems.

Application Notes

Whole-cell algal biosensors primarily operate on two core principles: enzyme inhibition and photosystem disruption. The selection of the sensing mechanism depends on the target analyte and the desired sensor configuration.

- Enzyme Inhibition-Based Detection: This mechanism exploits the inhibitory effect of OPs on specific algal enzymes. A prominent example involves the inhibition of the enzyme alkaline phosphatase (AP). The detection is based on the pesticide-induced inhibition of AP activity, which leads to a measurable decrease in the production of ascorbic acid. This biochemical change is then transduced into an electrical signal, typically using a potentiometric Ion-Sensitive Field-Effect Transistor (ISFET) [39].

- Photosystem II (PS II)-Based Detection: This approach utilizes the inherent photosynthetic machinery of the algal cell. Organophosphorus pesticides can inhibit electron transport within PS II, typically by binding to the D1 protein. Under illumination, this disruption causes a measurable change (usually a decrease) in the photocurrent generated by the algal cells, which can be detected amperometrically [44].

The following diagram illustrates the two primary signaling pathways for algal whole-cell biosensors.

Algal whole-cell biosensors have been successfully configured into different formats, each with its own performance characteristics, as summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Performance comparison of suspended vs. immobilized Chlorella sp. biosensors.

| Parameter | Suspended Cell Configuration | Immobilized Cell Configuration |

|---|---|---|

| Immobilization Method | Cells free in solution | Glutaraldehyde cross-linking on electrode surface (e.g., Glassy Carbon Electrode) [44] |

| Detection Principle | Amperometric (PS II inhibition) [44] | Amperometric (PS II inhibition) [44] |

| Typical Algal Volume | 0.3 mL [44] | 25 µL [44] |

| Optimal pH | 7.0 [44] | 7.0 [44] |

| Response Time | Minutes [44] | Minutes [44] |

| Signal Trend (e.g., for Acephate) | Current decrease [44] | Current decrease [44] |

| Signal Trend (e.g., for Triazophos) | Current increase [44] | Current decrease [44] |

| Key Advantages | Simpler preparation, direct interaction with analyte [44] | Enhanced stability, reusability, consistent signal output, better suited for portable devices [44] [46] |

The core advantage of whole-cell systems lies in their robustness. Algal cells provide a more practical and stable alternative to biosensors relying on purified enzymes. They endure fluctuations in environmental conditions better, maintaining consistent performance and reducing the need for rigorous stabilization protocols [39]. Furthermore, the use of whole cells is often more cost-effective than isolating and purifying enzymes [45] [46].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: ISFET-Based Potentiometric Biosensor Using ImmobilizedChlorellasp.

This protocol describes the construction and use of a portable, potentiometric biosensor for OPs detection based on the inhibition of alkaline phosphatase in Chlorella sp. [39].

1. Materials and Reagents

- Algal Strain: Chlorella sp. culture

- Buffer: Tris-HCl buffer (reaction medium)

- Substrate: 2-Phospho-L-ascorbic acid (PAA)

- Enzyme Activator: Magnesium chloride (MgCl₂)

- Immobilization Reagents: Glutaraldehyde, Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA)

- Pesticide Standards: Acephate, triazophos, chlorpyrifos, malathion

- Equipment: Ta₂O₅-Ion Sensitive Field-Effect Transistor (ISFET), potentiometric measuring device, portable prototype setup

2. Algal Immobilization on ISFET 1. Harvest Chlorella sp. cells from a cultured medium during the logarithmic growth phase via centrifugation. 2. Wash the cell pellet with Tris-HCl buffer to remove residual growth medium. 3. Prepare an immobilization mixture containing 20 µL of algal suspension, BSA, and glutaraldehyde as a cross-linking agent. 4. Carefully deposit the mixture onto the open gate surface of the Ta₂O₅-ISFET and allow it to cross-link and dry, forming a stable biofilm on the transducer.