Real-Time Biosensors for Pesticide Monitoring in Water: Advanced Technologies and Applications for Environmental Health

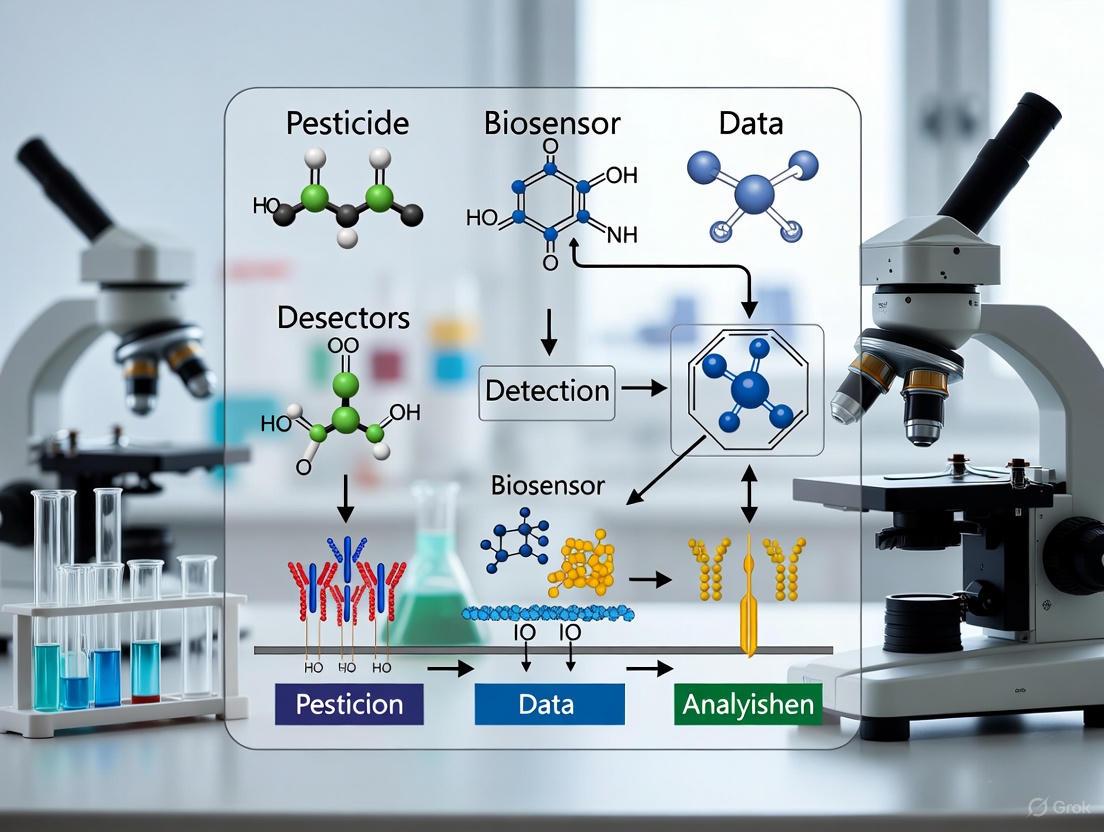

This article provides a comprehensive review of biosensor technologies for the real-time monitoring of pesticides in aquatic environments.

Real-Time Biosensors for Pesticide Monitoring in Water: Advanced Technologies and Applications for Environmental Health

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive review of biosensor technologies for the real-time monitoring of pesticides in aquatic environments. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of various biosensor platforms, including enzyme-based, antibody-based, aptasensors, and whole-cell biosensors. It delves into methodological applications for detecting specific pesticide classes, discusses critical challenges in sensor stability and real-world deployment, and offers a comparative analysis against traditional chromatographic techniques. The review synthesizes current advancements and future trajectories, highlighting the role of biosensors in enabling proactive environmental surveillance and protecting water resources.

Understanding Biosensor Platforms: Core Principles for Pesticide Detection

Emerging contaminants (ECs) represent a diverse group of chemical substances detected in environmental matrices at concentrations levels ranging from ng·mL⁻¹ to μg·mL⁻¹, raising concerns due to their potential ecological and human health impacts [1] [2]. These compounds are classified as "emerging" not necessarily because they are new, but because their presence is being identified in quantities and locations not previously recorded, often bypassing conventional monitoring programs and water treatment processes [3] [2]. The pervasive nature of ECs is exemplified by their detection in various urban water systems worldwide, including rivers, ponds, reservoirs, lakes, and groundwater [4].

Pesticides constitute a significant category of ECs that pose substantial monitoring challenges. These chemical substances are extensively used in agriculture to prevent, control, and eliminate pests, with over 1500 types currently employed worldwide [5]. While supporting crop yield and quality, their unscientific application has led to harmful residues persisting in plants, food, water, and soil, creating significant ecosystem risks [5]. Aquatic ecosystems serve as the main sink for these residues, with studies reporting pesticide concentrations between 7 ng·L⁻¹ and 121 μg·L⁻¹ in global surface waters [1].

The Critical Need for Pesticide Monitoring in Water

The imperative for advanced pesticide monitoring stems from several interconnected factors affecting environmental sustainability and public health.

Environmental and Health Impacts

Pesticides entering aquatic environments pose severe threats to ecosystem integrity and biodiversity. These compounds demonstrate remarkable persistence, with an estimated only 0.1% of applied pesticides reaching their target sites, while the majority migrates through spray drift, runoff, and accumulation in off-target locations [1]. This inefficient application leads to chronic contamination of water resources, with European surface waters showing higher median concentrations for fungicides (0.96 μg·L⁻¹) compared to herbicides (0.063 μg·L⁻¹) and insecticides (0.034 μg·L⁻¹) [1].

The health implications of pesticide exposure are equally concerning. Acute poisoning can cause respiratory difficulties, nausea, and vomiting, while long-term low-dose exposure associates with nervous system damage, reproductive system problems, and cancer [5]. Particularly vulnerable populations include children, pregnant women, and the elderly, who face heightened risks from even minimal exposure due to bioaccumulation effects [5].

Regulatory and Monitoring Gaps

Current regulatory frameworks struggle to address the complex challenge of pesticide monitoring. Legislation for pesticide limits in water remains scarce, with some countries establishing no maximum residue levels for surface or groundwater [1]. The European Union's Drinking Water Directive sets a maximum concentration of 0.1 mg·L⁻¹ for individual pesticides and 0.5 mg·L⁻¹ for total pesticides, but these standards represent exceptions rather than global norms [1].

Conventional analytical methods relying on gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) and liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) offer reliability and sensitivity with detection limits reaching ng·L⁻¹ [1]. However, these approaches present significant limitations including expensive and time-consuming laboratory analysis, extensive sample preparation requiring toxic solvents, and inability to provide real-time continuous surveillance [1]. These constraints delay timely interventions and complicate comprehensive monitoring programs, particularly in developing regions where resources are limited [2].

Biosensor Technology for Pesticide Detection

Fundamental Principles and Advantages

Biosensors represent integrated analytical devices incorporating biological recognition elements in direct spatial contact with transduction systems to detect target analytes [5] [1]. These systems offer transformative potential for pesticide monitoring by providing rapid, cost-effective, and disposable systems for high-throughput detection that can complement conventional methods [1].

The fundamental advantage of biosensors lies in their ability to enable real-time, on-site analysis without extensive sample preparation. This capability facilitates timely interventions when pesticide levels surpass acceptable limits and supports long-term monitoring trends to identify emerging concerns [1]. Biosensors are particularly valuable as an initial screening step in tiered assessment strategies, where positive results can trigger more comprehensive laboratory analysis [1].

Biosensor Classification and Mechanisms

Biosensors for pesticide detection employ diverse recognition elements and transduction mechanisms, each offering distinct advantages for specific application contexts. The major biosensor categories include:

Table 1: Classification of Biosensors for Pesticide Detection

| Classification Basis | Biosensor Type | Key Characteristics | Representative Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recognition Element | Enzymatic biosensors | Utilize enzyme inhibition or catalytic activity; high specificity | Organophosphate detection via acetylcholinesterase inhibition |

| Immunosensors | Employ antibody-antigen interactions; high sensitivity and selectivity | Herbicide detection using specific monoclonal antibodies | |

| Aptasensors | Use nucleic acid aptamers as recognition elements; tunable affinity | Various pesticides through selective aptamer binding | |

| Whole-cell biosensors | Incorporate living microorganisms or tissues; provide toxicity assessment | General toxicity screening of water samples | |

| Transduction Mechanism | Optical biosensors | Measure light signal changes (fluorescence, colorimetry, SPR) | Portable colorimetric strips for field testing |

| Electrochemical biosensors | Detect electrical signal changes (current, potential, impedance); high sensitivity | Miniaturized electrodes for in-situ pesticide quantification | |

| Thermal biosensors | Monitor temperature changes from biochemical reactions | Laboratory-based precision analysis | |

| Acoustic biosensors | Measure mass or viscosity changes through frequency variations | Specialized laboratory applications |

Biosensors function through coordinated processes beginning with selective binding between the biological recognition element and target pesticide molecules, followed by transduction of this interaction into a quantifiable signal proportional to analyte concentration [5] [1]. Advanced biosensors increasingly incorporate nanomaterials to enhance sensitivity, stability, and response kinetics, addressing previous limitations in field deployment [5].

Biosensor Operational Workflow

Advanced Biosensing Methodologies: Experimental Protocols

Metal-Organic Framework (MOF)-Based Biosensors

Protocol Title: Fabrication and Application of MOF-Enzyme Composite Biosensors for Pesticide Detection

Principle: This protocol leverages the synergistic combination of Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) and biological recognition elements for enhanced pesticide detection. MOFs provide exceptional tunability, efficient catalysis, and excellent selectivity while protecting enzymatic activity and enhancing stability [6].

Materials and Reagents:

- Metal precursors (e.g., Zn(NO₃)₂·6H₂O, ZrCl₄, Cu(NO₃)₂·3H₂O)

- Organic ligands (e.g., 2-methylimidazole, terephthalic acid, trimesic acid)

- Enzymes (e.g., acetylcholinesterase, organophosphorus hydrolase, tyrosinase)

- Buffer solutions (phosphate buffer, Tris-HCl)

- Pesticide standard solutions

- Signal probes (e.g., chromogenic substrates, electrochemical mediators)

Procedure:

Preparation of MOF-based enzyme/nanozyme composites:

- Select appropriate MOF composition based on target pesticide properties

- Employ one of three primary immobilization strategies:

- Surface immobilization: Covalently attach enzymes to pre-synthesized MOFs

- Pore encapsulation: Infiltrate enzymes into MOF pores during synthesis

- In-situ encapsulation: Co-crystallize MOFs around enzyme molecules

Biosensor fabrication:

- Deposit MOF-enzyme composites onto transducer surfaces (electrodes, optical fibers)

- Optimize composite loading to maximize sensitivity and reproducibility

- Characterize using SEM, XRD, and FTIR to verify successful integration

Detection procedure:

- Incubate biosensor with sample solution for predetermined time (typically 5-15 minutes)

- Measure signal response (electrochemical current, fluorescence intensity, color change)

- Compare response to calibration curve for quantitative analysis

- Regenerate sensor surface if applicable for reusable applications

Applications: MOF-based biosensors demonstrate particular efficacy for detecting organophosphates, carbamates, and neonicotinoid pesticides with significantly enhanced stability compared to free enzymes [6].

Electrochemical Biosensing Platform

Protocol Title: Electrochemical Detection of Pesticides Using Enzyme Inhibition-Based Biosensors

Principle: This method utilizes the inhibitory effect of specific pesticides on enzyme activity, with the inhibition level proportional to pesticide concentration. Measurable changes in electrochemical signals (current, potential, impedance) provide quantitative analysis [5].

Materials and Reagents:

- Working electrode (glassy carbon, gold, or screen-printed electrodes)

- Enzyme solutions (acetylcholinesterase, butyrylcholinesterase)

- Enzyme substrates (acetylthiocholine, butyrylthiocholine)

- Electrochemical mediators (e.g., ferricyanide, Prussian Blue)

- Electrolyte solutions (KCl, phosphate buffer)

- Electrochemical workstation with data acquisition software

Procedure:

Electrode modification:

- Clean electrode surface according to standard protocols

- Immobilize enzyme layer through cross-linking, entrapment, or adsorption

- Characterize modified electrode using cyclic voltammetry and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy

Measurement protocol:

- Record baseline electrochemical signal in substrate solution

- Incubate modified electrode with sample solution for 10 minutes

- Measure signal decrease relative to baseline due to enzyme inhibition

- Calculate inhibition percentage: Inhibition (%) = [(I₀ - I)/I₀] × 100 where I₀ is initial current and I is current after incubation

Quantification:

- Construct calibration curve using standard pesticide solutions

- Apply appropriate regression model for concentration determination

- Validate with control samples to ensure specificity

Performance Characteristics: Electrochemical biosensors typically achieve detection limits of 0.1-10 nM for organophosphate and carbamate pesticides, with complete analysis within 15-30 minutes [5].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Biosensor Technologies for Pesticide Detection

| Biosensor Technology | Detection Principle | Target Pesticides | Limit of Detection | Analysis Time | Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enzyme Inhibition-Based | Acetylcholinesterase inhibition | Organophosphates, Carbamates | 0.1-10 nM | 10-30 min | Broad detection spectrum, well-established |

| Immunosensors | Antibody-antigen interaction | Herbicides, Fungicides | 0.01-1 ng·mL⁻¹ | 15-45 min | High specificity, excellent sensitivity |

| Aptasensors | Aptamer conformational change | Various classes | 0.001-0.1 nM | 5-20 min | Tunable affinity, enhanced stability |

| Whole-cell Biosensors | Cellular response signaling | Broad-spectrum toxicity | Varies with toxicity | 30-120 min | Provides ecotoxicological relevance |

| MOF-Based Sensors | Enhanced recognition/catalysis | Organophosphates, Glyphosate | 0.001-0.1 nM | 5-15 min | Superior stability, multifunctionality |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of biosensor technologies for pesticide monitoring requires specific materials and reagents optimized for each detection platform.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Biosensor Development and Application

| Category | Specific Examples | Function in Biosensor Systems | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biological Recognition Elements | Acetylcholinesterase, Organophosphorus hydrolase, Antibodies, DNA aptamers | Target-specific molecular recognition | Selection depends on pesticide class; stability varies |

| Nanomaterials | Graphene oxide (GO), Metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), Molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs) | Signal enhancement, immobilization support, catalytic activity | MOFs offer exceptional tunability and protection [6] |

| Transduction Platforms | Screen-printed electrodes, Optical fibers, Quartz crystal microbalances, Field-effect transistors | Conversion of biological event to measurable signal | Choice depends on required sensitivity and portability |

| Signal Probes | Ferrocene derivatives, Prussian Blue, Fluorescent dyes, Enzymatic substrates | Generate detectable signals from molecular interactions | Must minimize background interference in complex matrices |

| Buffer Systems | Phosphate buffer, Tris-HCl, HEPES | Maintain optimal pH and ionic strength | Critical for preserving biological component activity |

Technological Integration and Future Perspectives

The effective deployment of biosensors for pesticide monitoring requires seamless integration into comprehensive environmental assessment frameworks. A tiered monitoring approach represents the most pragmatic strategy for implementation.

Tiered Monitoring Implementation Strategy

Future advancements in biosensor technology will focus on several critical areas to enhance practical implementation:

Multiplexing Capabilities: Developing sensors capable of simultaneous detection of multiple pesticide classes to provide comprehensive contamination profiles [5]

Advanced Materials: Engineering novel biocomposite materials with enhanced stability, sensitivity, and antifouling properties for real-world applications [6]

Integration with Digital Technologies: Incorporating Internet of Things (IoT) connectivity, artificial intelligence for data analysis, and cloud-based data management to enable smart monitoring networks [7]

Miniaturization and Portability: Creating increasingly compact, user-friendly devices capable of laboratory-comparable performance in field settings [1]

Despite significant progress, challenges remain in achieving long-term stability under variable environmental conditions, ensuring reproducibility across production batches, and reducing costs for widespread deployment [5] [6]. Addressing these limitations through continued research and development will further establish biosensors as indispensable tools for protecting water resources against pesticide contamination, ultimately supporting the achievement of Sustainable Development Goals related to clean water and ecosystem protection [2] [4].

Core Principles of Biosensor Design

A biosensor is an analytical device that converts a biological response into a measurable electrical signal [8]. Its core function is to detect a specific substance, or analyte, in a sample. The sophisticated operation of a biosensor relies on the seamless interplay of three fundamental components: the bioreceptor, the transducer, and the signal processor [8]. This integrated system allows for the sensitive, selective, and rapid detection of target compounds, making it invaluable for applications such as the real-time monitoring of pesticides in water [9] [10].

The bioreceptor is a biological molecular recognition element that interacts specifically with the target analyte [8]. This interaction, termed bio-recognition, is the first critical step and is the primary source of a biosensor's selectivity. The transducer then converts the physicochemical change resulting from the bioreceptor-analyte interaction into a quantifiable energy form [8]. Finally, the signal processor amplifies, conditions, and digitally converts this signal for clear presentation to the user on a display unit [8].

Table 1: Fundamental Components of a Biosensor

| Component | Function | Key Characteristics | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bioreceptor | Specifically recognizes and binds the target analyte [8]. | High selectivity and affinity for the analyte. | Enzymes, Antibodies, Nucleic Acids (Aptamers), Whole Cells [9]. |

| Transducer | Converts the bio-recognition event into a measurable signal [8]. | Sensitivity, robustness. | Electrodes (Electrochemical), Photodetectors (Optical), Piezoelectric Crystals [10]. |

| Signal Processor | Processes the transduced signal for interpretation [8]. | Amplification, filtering, and analog-to-digital conversion. | Electronic circuitry and microprocessors. |

| Display | Presents the final output to the user [8]. | User-friendly interface. | Liquid crystal display (LCD), direct printer, software interface. |

Quantitative Performance Metrics for Biosensors

The performance of a biosensor is evaluated against a set of critical metrics that determine its suitability for real-world applications, including environmental monitoring [8]. For the detection of trace-level pesticides in water, sensitivity and selectivity are particularly paramount [9].

- Sensitivity and Limit of Detection (LOD): The LOD defines the lowest concentration of an analyte that the biosensor can reliably detect [8]. In the context of emerging contaminants like pesticides, which can have toxic effects even at concentrations as low as ng/L, a low LOD is crucial [9]. For instance, amperometric enzyme-based biosensors have been developed for pollutants with LODs as low as 0.014 μg/L [10].

- Selectivity: This is the ability of a biosensor to measure the target analyte exclusively in a sample containing other interfering substances or contaminants [8]. The high specificity of bioreceptors, such as an antibody binding only to its corresponding antigen, is the key to achieving this [9] [8].

- Stability, Reproducibility, and Linearity: Stability refers to the sensor's susceptibility to ambient disturbances and its ability to maintain performance over time and during prolonged use [8]. Reproducibility is the precision and accuracy of obtaining identical results for repeated measurements [8]. Linearity indicates the accuracy of the sensor's response across a range of analyte concentrations, which defines its working range and resolution [8].

Table 2: Key Performance Metrics for Biosensors in Environmental Monitoring

| Performance Metric | Description | Significance for Pesticide Monitoring |

|---|---|---|

| Selectivity | Ability to detect a specific analyte in a sample containing admixtures and contaminants [8]. | Ensures accurate detection of a specific pesticide class (e.g., organophosphates) without cross-reactivity. |

| Sensitivity (LOD) | The minimum amount of analyte that can be reliably detected [8]. | Essential for detecting toxic pesticides present at trace levels (ng/L to μg/L) in water bodies [9]. |

| Reproducibility | Ability to generate identical responses for a duplicated experimental setup [8]. | Ensures reliable and comparable data across different monitoring events and locations. |

| Stability | Degree of susceptibility to ambient disturbances and signal drift over time [8]. | Critical for long-term, in-situ deployment in variable environmental conditions [10]. |

| Linearity | Accuracy of the measured response to a straight line over a concentration range [8]. | Allows for accurate quantification of pesticide concentration within a defined working range. |

Advanced Biosensor Typologies: Mechanisms and Applications

Biosensors are categorized based on the type of bioreceptor and the signal transduction method. Each typology offers distinct advantages for the detection of environmental pollutants [9] [10].

Bioreceptor-Based Classification

- Enzyme-Based Biosensors: These use enzymes as bioreceptors. The analyte can be a substrate that the enzyme metabolizes, or an inhibitor that reduces the enzyme's activity. The resulting change in the concentration of a product (e.g., a proton or electron) is measured [9]. They are widely used for detecting pesticides, many of which act as enzyme inhibitors [9].

- Antibody-Based Immunosensors: These leverage the high affinity and specificity of antigen-antibody binding [9]. They can be designed as label-free (detecting impedance or mass changes) or labeled (using fluorescent or enzymatic tags for signal generation) systems [9].

- Nucleic Acid-Based Aptasensors: These employ synthetic single-stranded DNA or RNA aptamers, selected for their high binding affinity to specific targets, including small molecules like pesticides [9] [10]. They offer high stability and are synthesized through chemical processes [9].

- Whole Cell-Based Biosensors: These utilize microorganisms (e.g., bacteria, algae) as integrated sensing elements. The cells can be engineered to produce a detectable signal (e.g., bioluminescence) in response to the presence of a target pollutant [9] [10]. They are robust and can self-replicate, but typically have a slower response time.

Transducer-Based Classification

- Electrochemical Biosensors: These measure the electrical properties (current, potential, impedance) change due to the biorecognition event. They are among the most common biosensors due to their portability, simplicity, and high sensitivity [9] [8].

- Optical Biosensors: These detect changes in light properties, such as absorbance, fluorescence, or chemiluminescence. A prominent example is a biosensor using Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET), where the binding event alters the energy transfer between two fluorophores [11].

- Piezoelectric Biosensors: These measure the change in mass on the sensor surface (e.g., a quartz crystal) by correlating it with a change in the crystal's oscillation frequency [10].

Experimental Protocols for Biosensor Development and Evaluation

Protocol 1: Fabrication of an Electrochemical Enzyme Biosensor for Pesticide Detection

Principle: This protocol outlines the steps for creating a biosensor based on enzyme inhibition. The target pesticide inhibits the immobilized enzyme, reducing its catalytic activity, which is measured as a decrease in electrochemical current [9] [10].

Materials:

- Glassy carbon or gold working electrode

- Enzyme (e.g., Acetylcholinesterase for organophosphate pesticides)

- Cross-linking agent (e.g., Glutaraldehyde)

- Nanoparticle suspension (e.g., Gold nanoparticles to enhance surface area and electron transfer [10])

- Phosphate buffer saline (PBS), pH 7.4

- Electrochemical workstation

- Substrate for the enzyme (e.g., Acetylthiocholine)

Procedure:

- Electrode Pretreatment: Polish the working electrode with alumina slurry (0.05 μm) on a microcloth to a mirror finish. Rinse thoroughly with deionized water and then with ethanol. Dry under a stream of inert gas (e.g., nitrogen).

- Nanomaterial Modification (Optional): To enhance sensitivity, deposit a suspension of nanomaterials (e.g., gold nanoparticles) onto the electrode surface and allow to dry [10].

- Enzyme Immobilization: Prepare a 10 μL droplet of enzyme solution. Mix it with a cross-linking agent. Deposit this mixture onto the pre-treated electrode surface and allow it to incubate in a humid chamber at 4°C for 2 hours.

- Rinsing and Storage: Gently rinse the modified electrode with PBS buffer to remove any unbound enzyme. Store the biosensor in PBS at 4°C when not in use.

- Measurement of Baseline Activity: Place the biosensor in an electrochemical cell containing PBS and the enzyme substrate. Measure the amperometric current generated by the enzymatic reaction over time. This serves as the baseline signal (I₀).

- Inhibition and Sample Measurement: Incubate the biosensor in a sample solution containing the target pesticide for a fixed period (e.g., 10 minutes). Re-measure the amperometric current in the substrate solution (Iᵢ).

- Quantification: The degree of inhibition is calculated as (I₀ - Iᵢ)/I₀ × 100%, which is correlated with the pesticide concentration using a pre-established calibration curve.

Protocol 2: Validation of Biosensor Performance in Real Water Samples

Principle: This protocol describes the validation of a developed biosensor using spiked real water samples to assess its accuracy and matrix effects [10].

Materials:

- Developed biosensor from Protocol 1

- Real water samples (e.g., river, lake, or tap water)

- Standard solution of target pesticide

- Filtration apparatus (0.45 μm filter)

- Reference analytical instrument (e.g., HPLC-MS, if available)

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Collect water samples from the target environment. Filter the samples through a 0.45 μm filter to remove particulate matter.

- Spiking: Spike the filtered water samples with known concentrations of the target pesticide standard to create a series of validation samples.

- Biosensor Analysis: Analyze the spiked samples using the developed biosensor following the measurement procedure from Protocol 1. Record the calculated concentration for each sample.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the recovery percentage for each spiked sample using the formula: Recovery (%) = (Measured Concentration / Spiked Concentration) × 100%. A recovery of 80-120% is generally considered acceptable, demonstrating the method's accuracy despite the sample matrix.

- Cross-Validation (Optional): If available, analyze the same set of spiked samples using a standard reference method (e.g., HPLC-MS) to cross-validate the results obtained from the biosensor.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Biosensor Research

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | Used to modify electrode surfaces to enhance electron transfer and increase the effective surface area for bioreceptor immobilization, thereby improving sensitivity [10]. |

| Glutaraldehyde | A common cross-linking agent for covalently immobilizing bioreceptors (e.g., enzymes, antibodies) onto transducer surfaces [9]. |

| Aptamers | Synthetic single-stranded DNA or RNA oligonucleotides selected via SELEX to bind specific targets; used as robust and versatile bioreceptors in aptasensors [9] [10]. |

| Allosteric Transcription Factors (aTFs) | Used in cell-free biosensing systems; they undergo a conformational change upon binding a target analyte (e.g., heavy metals), which can be linked to a reporter gene output [10]. |

| FRET-Compatible Fluorophores (e.g., edCerulean, edCitrine) | Paired donor and acceptor fluorescent proteins used in the construction of genetically encoded ratiometric biosensors for real-time monitoring of analytes like hormones or ions in living cells [11]. |

| Laccase Enzymes | Used in both detection and enzymatic detoxification of phenolic pollutants and dyes, catalyzing their oxidation and degradation [10]. |

| Engineered Microbial Cells (e.g., E. coli, Pseudomonas sp.) | Genetically modified whole-cell bioreceptors that can be designed to both detect pollutants (via bioluminescence) and express detoxifying enzymes [10]. |

Signaling Pathways and Workflow Visualizations

Biosensor Operational Workflow

FRET Biosensor Mechanism

Enzyme-based biosensors represent a transformative technology for the real-time monitoring of pesticides in water, leveraging the specificity and catalytic efficiency of enzymes to detect target analytes with high accuracy [12]. These analytical devices integrate a biological recognition element (an enzyme) with a physicochemical transducer to convert biochemical reactions into measurable signals [12]. Their unique ability to offer rapid, sensitive, and selective responses makes them indispensable tools for environmental monitoring, complementing conventional methods like chromatography and mass spectrometry [1].

The relevance of enzyme-based biosensors is particularly pronounced in the context of aquatic ecosystem protection. It is estimated that only 0.1% of applied pesticides reach their target site, with the majority accumulating in off-target environments like water bodies [1]. These biosensors provide a time- and cost-effective solution for screening large numbers of environmental samples, offering portability and real-time results that enable timely interventions when pesticide levels exceed acceptable limits [1].

Key Principles and Components

Fundamental Components

Enzyme-based biosensors consist of three primary components that work synergistically to detect target pesticides:

- Biological Recognition Element: Enzymes serve as biocatalysts that specifically interact with target analytes. Commonly used enzymes include acetylcholinesterase for neurotoxic insecticide detection, tyrosinase for phenolic compounds, and photosynthetic system enzymes for herbicide monitoring [12] [13].

- Transducer: This component converts the biochemical signal produced by the enzyme–analyte interaction into a quantifiable output. Transducers can be electrochemical (amperometric, potentiometric), optical (fluorescence, absorbance), thermistor, or piezoelectric [12].

- Immobilization Matrix: To ensure the enzyme remains stable and functional near the transducer, various immobilization techniques are employed, including physical adsorption, covalent bonding, entrapment in gels or polymers, or incorporation into nanoparticles [12].

Working Principles

The functional mechanism of enzyme-based biosensors for pesticide detection primarily operates through two distinct principles:

- Inhibition-Based Detection: For neurotoxic insecticides like organophosphates and carbamates, the detection relies on enzyme inhibition. These compounds suppress enzymatic activity, resulting in reduced or blocked signal generation [12] [13].

- Catalytic Detection: Alternatively, some biosensors exploit the direct catalytic activity of enzymes that utilize pesticides as substrates, though this approach is less common [14].

The resulting biochemical transformation is detected by the transducer, which produces an electrical or optical signal proportional to the analyte concentration [12].

Figure 1: Working principle of enzyme-based biosensors for pesticide detection, showing the sequential process from biological recognition to signal output.

Detection Mechanisms and Signaling Pathways

Enzyme Inhibition Mechanisms

The detection of neurotoxic insecticides primarily exploits their mechanism of toxicity, which involves inhibition of key enzymes:

- Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) Inhibition: Organophosphorus and carbamate insecticides inhibit AChE, preventing the hydrolysis of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine [13]. This inhibition forms the basis for numerous biosensors, where the decrease in enzymatic activity correlates with insecticide concentration [13].

- Photosynthetic System Inhibition: Herbicides like atrazine and diuron inhibit photosystem II (PSII) in the photosynthetic electron transport chain, particularly targeting the D1 protein [14]. This inhibition can be measured through changes in chlorophyll fluorescence or oxygen evolution [14].

Advanced Discrimination Techniques

To enhance selectivity for specific pesticides, advanced approaches using multiple enzyme variants and chemometric methods have been developed:

- Multi-Enzyme Arrays: Genetically engineered enzyme variants with different sensitivity patterns toward specific insecticides are employed in array formats [13].

- Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs): These computational models process signals from multiple biosensors to discriminate between different insecticides in mixtures [13]. For example, ANNs have successfully resolved binary mixtures of paraoxon and carbofuran with prediction errors of 0.4 μg L⁻¹ and 0.5 μg L⁻¹, respectively [13].

Figure 2: Advanced pesticide discrimination using enzyme arrays and artificial neural networks for identifying specific pesticides in mixtures.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential research reagents for enzyme-based biosensor development

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Biosensor | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enzymes | Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) [13], Tyrosinase [12], Glucose oxidase (GOx) [12], Urease [12], Lactate oxidase (LOx) [12] | Biological recognition element | High specificity, catalytic efficiency, stability |

| Transducer Materials | Graphene, Carbon nanotubes [12], Gold nanoparticles [13] | Signal transduction and amplification | Enhanced sensitivity, conductivity, surface area |

| Immobilization Matrices | Polymeric gels, Sol-gels, Nafion [12] | Enzyme stabilization and retention | Biocompatibility, porosity, chemical stability |

| Signal Probes | 5,5′-dithiobis(2-nitrobenzoic) acid (DTNB) [13], Red genetically encoded potassium indicators (RGEPOs) [15] | Signal generation and detection | High sensitivity, selectivity, and dynamic range |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Acetylcholinesterase-Based Biosensor for Neurotoxic Insecticides

Principle: This protocol describes the development of an amperometric biosensor for detecting organophosphorus and carbamate insecticides based on acetylcholinesterase (AChE) inhibition [13].

Materials:

- Acetylcholinesterase enzyme (from electric eel or genetically engineered variants)

- Transducer electrode (glassy carbon, gold, or screen-printed electrodes)

- Chitosan or Nafion for enzyme immobilization

- Acetylthiocholine iodide as substrate

- Phosphate buffer (0.1 M, pH 7.4)

- Standard solutions of target insecticides

Procedure:

- Electrode Modification: Clean the transducer electrode according to standard protocols (e.g., polishing with alumina slurry for solid electrodes) [13].

- Enzyme Immobilization: Prepare enzyme solution (2-4 U/μL AChE in phosphate buffer) and mix with immobilization matrix (e.g., 1% chitosan solution). Deposit 5-10 μL of the mixture onto the electrode surface and allow to dry at 4°C for 12 hours [13].

- Baseline Measurement: Immerse the biosensor in stirred phosphate buffer (0.1 M, pH 7.4) containing 0.5 mM acetylthiocholine iodide. Apply a detection potential of +0.7 V vs. Ag/AgCl and record the steady-state amperometric current (I₀) [13].

- Inhibition Phase: Incubate the biosensor in sample solution containing the insecticide for 10-15 minutes to allow enzyme inhibition.

- Post-Inhibition Measurement: Re-immerse the biosensor in substrate solution and record the steady-state current after inhibition (Iᵢ).

- Data Analysis: Calculate inhibition percentage using the formula: % Inhibition = [(I₀ - Iᵢ)/I₀] × 100. Determine insecticide concentration from a calibration curve prepared with standard solutions [13].

Troubleshooting Tips:

- If sensitivity is low, consider using genetically engineered AChE variants with enhanced sensitivity to specific insecticides [13].

- If reproducibility is problematic, optimize immobilization procedure and ensure consistent enzyme loading.

Protocol 2: Photosystem II-Based Biosensor for Herbicides

Principle: This protocol utilizes photosynthetic systems (algae, thylakoids, or chloroplasts) for detecting herbicides that inhibit photosystem II (PSII), such as atrazine and diuron [14].

Materials:

- Fresh spinach leaves or algal cultures (Chlorella, Scenedesmus)

- Isolation buffer (0.4 M sucrose, 50 mM HEPES, 10 mM NaCl, pH 7.5)

- Oxygen electrode or fluorescence measuring system

- Herbicide standard solutions

Procedure:

- Thylakoid/Chloroplast Isolation: Homogenize fresh spinach leaves in cold isolation buffer. Filter through muslin cloth and centrifuge at 2,000 × g for 5 min. Resuspend pellet in isolation buffer [14].

- Immobilization: Mix thylakoid/chloroplast preparation with bovine serum albumin (BSA) and glutaraldehyde. Deposit mixture on electrode surface or membrane support and allow to crosslink [14].

- Chlorophyll Fluorescence Measurement: For optical detection, immerse the biosensor in buffer and measure chlorophyll fluorescence parameters (Fv/Fm ratio) before and after exposure to sample [14].

- Amperometric Oxygen Detection: For electrochemical detection, immerse the biosensor in buffer saturated with CO₂. Illuminate with actinic light and measure the photocurrent generated by oxygen evolution [14].

- Inhibition Measurement: Expose the biosensor to sample solution for 5-10 minutes. Remeasure fluorescence parameters or photocurrent.

- Data Analysis: Calculate inhibition of photosynthetic activity by comparing signals before and after exposure. Quantify herbicide concentration using a calibration curve [14].

Troubleshooting Tips:

- If biosensor stability is low, prepare fresh thylakoid membranes and maintain at 4°C throughout the procedure.

- If signal-to-noise ratio is poor, optimize light intensity and ensure proper CO₂ saturation for amperometric detection.

Performance Data and Applications

Table 2: Performance characteristics of enzyme-based biosensors for pesticide detection

| Biosensor Type | Target Pesticides | Detection Principle | Linear Range | Detection Limit | Application Matrix |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acetylcholinesterase-based | Organophosphates, Carbamates [13] | Enzyme inhibition | 0–20 μg L⁻¹ [13] | 0.4–1.6 μg L⁻¹ [13] | Water, Food samples [13] |

| Photosystem II-based | Atrazine, Diuron [14] | Photosynthetic inhibition | 0.1–100 μg L⁻¹ [14] | 0.1–1 μg L⁻¹ [14] | Environmental water [14] |

| Tyrosinase-based | Phenolic herbicides [12] | Enzyme inhibition | Varies by compound | Varies by compound | Water samples [12] |

| Cell-based | Multiple herbicide classes [14] | Metabolic inhibition | 1–1000 μg L⁻¹ [14] | ~1 μg L⁻¹ [14] | Aquatic environmental samples [14] |

Enzyme-based biosensors represent promising tools for the real-time monitoring of pesticides in water, offering significant advantages in terms of sensitivity, portability, and cost-effectiveness compared to conventional analytical methods [1]. While challenges remain regarding enzyme stability, reproducibility, and potential interference from complex environmental matrices, recent advancements in nanotechnology, genetic engineering, and data analysis have substantially improved their performance and reliability [12] [13].

Future developments in this field are likely to focus on the integration of biosensors into automated monitoring systems, the creation of multi-analyte arrays for simultaneous detection of multiple pesticide classes, and the enhancement of operational stability through improved immobilization techniques and synthetic enzymes [12] [1]. As these technologies mature, enzyme-based biosensors are poised to become indispensable tools for comprehensive environmental monitoring programs, contributing significantly to the protection of aquatic ecosystems and human health.

Within the framework of developing biosensors for the real-time monitoring of pesticides in water, immunosensors emerge as a powerful analytical technology. These devices combine the exceptional specificity of antibody-antigen interactions with the sensitivity of physicochemical transducers, fulfilling an urgent need for cost-effective, high-throughput screening tools [1]. Conventional methods for pesticide detection, such as gas or liquid chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry (GC-MS/LC-MS/MS), are reliable but often time-consuming, expensive, and require well-trained personnel and laboratory settings [1] [16]. In contrast, immunosensors offer the potential for rapid, on-site analysis, making them ideal for an initial screening step in a tiered monitoring assessment, thereby complementing conventional methods [1]. This document provides application notes and detailed protocols for leveraging immunosensors, in both label-free and labeled formats, for the detection of currently-used pesticides in aquatic environments.

Immunosensor Working Principles and Classification

Immunosensors are affinity-based biosensors that rely on the specific binding between an antibody (Ab), immobilized on a transducer surface, and its target antigen (Ag), which can be a pesticide or its metabolite [17] [18]. This binding event generates a physicochemical change that is converted by the transducer into a measurable electrical or optical signal.

Transducer Types

The transducer is a core component defining the immunosensor's operational principle. Electrochemical transducers are the most prevalent due to their cost-effectiveness, portability, and high sensitivity [19] [18]. They can be further categorized based on the measured electrical property:

- Amperometric: Measures current resulting from a redox reaction at a constant potential.

- Potentiometric: Measures the potential difference between electrodes when no current flows.

- Impedimetric: Measures the impedance (resistance to current flow) of the electrode interface, often tracking the increase in electron transfer resistance upon antibody-antigen complex formation [19].

- Conductometric: Measures changes in the electrical conductivity of a solution.

Optical transducers, such as those based on Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) or whispering gallery mode (WGM) sensors, detect changes in the refractive index or light absorption properties upon analyte binding [20] [21]. Piezoelectric transducers measure the change in mass on the sensor surface through shifts in resonant frequency [17].

Assay Formats: Label-Free vs. Labeled

A critical distinction in immunosensor design is the use of labels.

Label-Free Immunosensors: These detect the physical or chemical changes resulting directly from the formation of the Ab-Ag complex, such as a change in mass or refractive index [19] [17]. The main advantage is the simplified assay procedure, as no additional labeling or washing steps are needed, enabling real-time monitoring of the binding event. A challenge, however, is the potential for non-specific adsorption of other proteins to the sensor surface, which can increase background signal and reduce sensitivity [17].

Labeled Immunosensors: These employ a signal-generating label (e.g., enzymes, nanoparticles, fluorescent dyes) attached to the antigen or antibody [19] [17]. The detection of this label correlates with the amount of target analyte. Labeled formats generally exhibit higher sensitivity and versatility, with a reduced effect from non-specific adsorption. Their drawbacks include higher development costs, more complex assay procedures, and the inability for real-time monitoring of the binding reaction [17].

Assay Formats: Competitive vs. Non-Competitive (Sandwich)

The choice of assay format is largely dictated by the molecular size of the target analyte.

Competitive Assays: Primarily used for small molecules, such as most pesticides, which have a low molecular weight and only one epitope (the antibody binding site) [22] [17]. In this format, the target analyte in the sample competes with a labeled version of the analyte for a limited number of antibody binding sites. The measured signal is inversely proportional to the concentration of the target in the sample [22].

Non-Competitive (Sandwich) Assays: This format is suitable for large molecules with multiple epitopes [22] [17]. It uses a capture antibody immobilized on the sensor and a second, labeled detector antibody that binds to a different epitope on the target antigen. The formation of this "sandwich" generates a signal that is directly proportional to the analyte concentration. This format is less common for small molecule pesticides [17].

The logical workflow for selecting and operating an immunosensor is summarized in the diagram below.

Application in Pesticide Monitoring

Immunosensors have been successfully developed for a range of environmentally relevant pesticides. Their application is particularly valuable for monitoring water sources, where pesticides accumulate due to runoff and spray drift [1].

Target Pesticides and Performance

The following table summarizes exemplary performance data of immunosensors for detecting specific pesticide classes in water samples.

Table 1: Representative Immunosensor Performance for Pesticide Detection in Water

| Pesticide Class / Example | Immunosensor Format | Transducer | Linear Range | Limit of Detection (LOD) | Sample Matrix |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organophosphates (e.g., Parathion, Methyl-parathion) [16] | Competitive, Label-based | Electrochemical | Not Specified | Low ng/L to µg/L range | Environmental Water |

| Neonicotinoids [16] | Competitive | Optical / Electrochemical | Not Specified | Low ng/L to µg/L range | Water, Food |

| Glyphosate [16] | Competitive | Electrochemical | Not Specified | Low ng/L to µg/L range | Water, Soil |

| Herbicides (e.g., Atrazine, Metolachlor) [1] | Various Immunosensors | Various | – | – | Surface Water |

| Fungicides (e.g., Tebuconazole, Carbendazim) [1] | Various Immunosensors | Various | – | – | Surface Water |

Addressing Specificity: Broad-Specificity Antibodies

A novel trend in pesticide immunosensing is the development of broad-specificity antibodies [16]. These are raised against a generic hapten designed from the common structure of a group of related pesticides. This allows a single immunosensor to detect multiple analytes simultaneously, making it a powerful tool for cost-effective multi-residue screening. For instance, a single broad-specificity monoclonal antibody has been reported for the detection of parathion, methyl-parathion, and fenitrothion [16].

Experimental Protocols

This section provides a generalized, step-by-step protocol for developing a competitive electrochemical immunosensor, a common format for detecting small-molecule pesticides in water.

Protocol: Competitive Electrochemical Immunosensor for Pesticides

Principle: The target pesticide (analyte) in a water sample competes with a fixed amount of enzyme-labeled pesticide (tracer) for binding sites on antibodies immobilized on the electrode surface. The enzyme label (e.g., Horseradish Peroxidase - HRP) catalyzes a reaction with its substrate, generating an electroactive product. The resulting current is inversely proportional to the pesticide concentration in the sample [22] [16].

Workflow Overview:

Materials and Reagents

- Working Electrode: Glassy Carbon Electrode (GCE), Gold Disk Electrode, or screen-printed carbon electrodes (SPCEs) for disposability.

- Nanomaterials: Gold nanoparticles (AuNPs), carbon nanotubes, graphene oxide, or metal oxides (e.g., MnO₂) to enhance surface area and conductivity [18] [23].

- Biorecognition Elements:

- Capture Antibody: Monoclonal or polyclonal antibody specific to the target pesticide.

- Tracer: Pesticide molecule conjugated to an enzyme (e.g., HRP) or a redox tag (e.g., Ferrocene).

- Chemical Reagents:

- Cross-linkers: Glutaraldehyde or BS³ (bis(sulfosuccinimidyl)suberate) for antibody immobilization [20].

- Blocking Agent: Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) or casein to prevent non-specific binding [17].

- Electrochemical Probe: [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻ in buffer for impedimetric or voltammetric measurements [19].

- Enzyme Substrate: e.g., H₂O₂ with a mediator like TMB (3,3',5,5'-Tetramethylbenzidine) for HRP [20].

- Buffers: Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS, 0.01 M, pH 7.4), acetate buffer.

Step-by-Step Procedure

Step 1: Electrode Surface Modification and Antibody Immobilization

- Electrode Pretreatment: Clean the working electrode (e.g., GCE) mechanically (polishing with alumina slurry) and electrochemically (via cyclic voltammetry in H₂SO₄ or probe solution) to ensure a fresh, active surface.

- Nanomaterial Deposition (Optional but Recommended): Deposit a suspension of nanomaterials (e.g., AuNPs, γ-MnO₂-Chitosan nanocomposite [23]) onto the electrode surface via drop-casting or electrodeposition. This step significantly increases the active surface area for antibody loading and enhances electron transfer.

- Antibody Immobilization:

- Physical Adsorption: Incubate the modified electrode with a solution of the capture antibody (e.g., 10-100 µg/mL in PBS) for several hours at 4°C or 1-2 hours at room temperature. Wash thoroughly with PBS to remove unbound antibodies.

- Covalent Binding (More Robust): For AuNP-modified surfaces, use thiol-based linkers like cysteamine, followed by glutaraldehyde, to create an aldehyde-functionalized surface. The amine groups of the antibody will then covalently attach to the aldehydes [24]. Alternatively, use cross-linkers like BS³ on aminated surfaces [20].

Step 2: Blocking

- Incubate the antibody-functionalized electrode with a blocking solution (e.g., 1% BSA or 1% casein in PBS) for 1-2 hours at room temperature.

- This critical step covers any remaining bare electrode surface to minimize non-specific adsorption of other molecules from the sample, thereby reducing background noise [17].

- Wash the electrode thoroughly with PBS or a mild detergent solution (e.g., Tween 20 in PBS).

Step 3: Competitive Immunoassay Incubation

- Prepare a mixture containing a fixed, known concentration of the enzyme-labeled pesticide tracer and a varying concentration of the target pesticide (either as a standard for calibration or the unknown environmental water sample).

- Incubate this mixture on the surface of the blocked immunosensor for a defined period (e.g., 15-30 minutes). During this time, the target pesticide and the tracer compete for the limited binding sites on the immobilized antibody.

- After incubation, perform a gentle washing step to remove unbound tracer and sample components.

Step 4: Electrochemical Measurement and Signal Readout

- Place the immunosensor into an electrochemical cell containing the appropriate substrate solution. For an HRP label, this would be a solution containing H₂O₂ and TMB.

- Apply the relevant electrochemical technique:

- The measured current signal is inversely proportional to the concentration of the target pesticide in the sample.

Step 5: Data Analysis

- Measure the current signals for a series of pesticide standards with known concentrations.

- Plot the signal (e.g., current in µA) versus the logarithm of the pesticide concentration to generate a calibration curve.

- Fit the data points with a four-parameter logistic (4PL) model, which is standard for competitive immunoassays.

- Interpolate the signal from the unknown sample on this calibration curve to determine its concentration.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Immunosensor Development

| Item / Reagent | Function / Application | Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Capture Antibodies | Biorecognition element; binds specifically to the target analyte. | Monoclonal (high specificity), Polyclonal (often higher affinity), Recombinant (engineered), Nanobodies (small, stable) [16]. |

| Electrode Materials | Platform for bioreceptor immobilization and signal transduction. | Glassy Carbon Electrode (GCE), Gold Electrode, Screen-Printed Electrodes (SPEs; disposable, portable) [18]. |

| Nanomaterials | Signal amplification; increases surface area for probe immobilization. | Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs), Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs), Graphene Oxide, Metal Oxide Nanocomposites (e.g., MnO₂) [18] [23]. |

| Cross-linking Chemicals | Covalently immobilizes bioreceptors onto the sensor surface. | Glutaraldehyde, BS³ (Bissulfosuccinimidyl suberate), EDC/NHS chemistry [20] [24]. |

| Blocking Agents | Reduces non-specific binding by occupying non-specific sites. | Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA), Casein, Milk Proteins, Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) [17]. |

| Electrochemical Labels/Probes | Generates or contributes to the measurable electrochemical signal. | Enzymes (HRP, Alkaline Phosphatase), Redox Molecules (Ferrocene, Thionine), Nanomimetic Enzymes [22] [19]. |

| Buffer Systems | Provides a stable pH and ionic environment for immuno-reactions. | Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), Acetate Buffer, Carbonate-Bicarbonate Buffer (for coating) [20]. |

Aptasensors, a class of biosensors that utilize synthetic DNA or RNA aptamers as recognition elements, represent a powerful technological advancement for the specific and sensitive detection of target analytes. Their application is particularly relevant for the real-time monitoring of pesticides in water, a critical need for environmental protection and public health [25] [26]. Aptamers are short, single-stranded oligonucleotides (typically 25-90 nucleotides) selected in vitro through a process called Systematic Evolution of Ligands by EXponential enrichment (SELEX) [27] [28]. They function as "chemical antibodies" by folding into unique three-dimensional structures that enable high-affinity and specific binding to a target molecule, ranging from small pesticides to entire cells [27] [29]. The binding mechanism relies on various molecular interactions, including hydrogen bonding, electrostatic interactions, van der Waals forces, and aromatic ring stacking [27].

Compared to traditional antibodies, aptamers offer significant advantages for environmental biosensing. They are characterized by high thermostability, protease resistance, and cost-effectiveness for in vitro production [25]. They also exhibit minimal batch-to-batch variation, are small in size, and are easy to modify and handle [25] [29]. Critically, for pesticide targets that are small molecules with low immunogenicity, aptamers can be developed where antibody generation is challenging or impossible [30]. These properties make aptamer-based biosensors exceptionally suitable for developing field-deployable devices that adhere to the ASSURED principles: Affordable, Sensitive, Specific, User-friendly, Rapid and robust, Equipment-free, and Deliverable to end-users [25].

The SELEX Process: Generating Target-Specific Aptamers

The generation of high-affinity aptamers is accomplished through the SELEX process, an iterative in vitro selection and amplification methodology. The following workflow and detailed protocol describe the key steps for selecting aptamers against a pesticide target.

Detailed SELEX Protocol for Pesticide Targets

Objective: To isolate single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) aptamers with high affinity and specificity for a target pesticide (e.g., Carbendazim).

Materials:

- Synthetic Oligonucleotide Library: A library containing a central random region (e.g., 40-70 nucleotides) flanked by fixed primer binding sites (e.g., 5'-GGGAGACAAGAATAAACGCTCAA-[N40]-TGGACACGGTGGCTTAGT-3').

- Target Pesticide: High-purity target molecule (e.g., Carbendazim).

- Immobilization Matrix: Streptavidin-coated magnetic beads if the pesticide is biotinylated, or a suitable chromatography resin for immobilization.

- Buffers: Binding buffer (e.g., PBS with Mg²⁺), washing buffer, and elution buffer.

- Enzymes: Taq DNA polymerase for PCR.

- Primers: Forward and reverse primers complementary to the fixed regions of the library.

- Equipment: Thermal cycler, magnetic rack, agarose gel electrophoresis system, and a spectrophotometer.

Procedure:

Library Preparation: Dilute the synthetic ssDNA library in the binding buffer. Denature the library at 95 °C for 5 minutes and immediately cool on ice for 10 minutes to allow the sequences to fold into their native structures [25].

Positive Selection (Binding): Incubate the pre-folded ssDNA library with the immobilized pesticide target. The incubation time and temperature should be optimized (e.g., 30 minutes at room temperature with gentle agitation) [25].

Partitioning (Washing): Separate the target-bound sequences from the unbound ones. If using magnetic beads, apply a magnetic field to retain the bead-aptamer-pesticide complexes and carefully remove the supernatant containing unbound sequences. Wash the beads multiple times with the washing buffer to remove weakly bound sequences [25].

Elution: Elute the specifically bound aptamers from the target. This can be achieved by heating the complex (e.g., 80 °C for 10 minutes) in an appropriate elution buffer or by using a denaturing agent [25].

Amplification: Amplify the eluted ssDNA sequences using asymmetric PCR or a similar method to generate a new, enriched ssDNA pool for the subsequent selection round. The PCR conditions must be optimized to minimize the formation of by-products [28].

Counter-Selection (Negative Selection): To enhance specificity, perform a counter-selection against the bare immobilization matrix (e.g., streptavidin beads without pesticide) in later rounds (e.g., rounds 3-4). Sequences that bind to the matrix are discarded, and the unbound fraction is used for the positive selection step [25].

Iteration: Repeat steps 1-6 for 8-15 rounds, progressively increasing the selection stringency by reducing the incubation time, increasing the number and volume of washes, or adding competing non-target molecules [25] [28].

Cloning and Sequencing: After the final selection round, clone the amplified PCR products into a plasmid vector and transform into bacteria. Pick multiple colonies for Sanger sequencing to identify the enriched aptamer sequences [31].

Binding Characterization: Synthesize the identified aptamer candidates and characterize their affinity for the target pesticide by determining the dissociation constant (Kd) using techniques like surface plasmon resonance (SPR) or isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC). Specificity should be tested against other structurally similar pesticides [25] [27].

Aptasensor Construction and Signaling Mechanisms

Once a high-affinity aptamer is secured, it is integrated into a biosensor platform. The binding event is transduced into a measurable signal through various mechanisms, each with distinct advantages for pesticide detection in water.

Signaling Modalities for Pesticide Detection

Table 1: Key Aptasensor Platforms for Pesticide Detection

| Sensor Type | Detection Principle | Advantages | Reported Performance (Example) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electrochemical [25] [27] | Measures change in electrical properties (current, impedance) upon aptamer-pesticide binding. | High sensitivity, portability, low cost, suitable for miniaturization. | Carbendazim (CBZ): LOD of 0.2 fM (femtomolar) using a dual-aptamer design with a metal-organic framework [27]. |

| Fluorescence [30] [29] | Measures change in fluorescence intensity/wavelength upon binding (e.g., using molecular beacons, FRET). | High sensitivity, suitability for multiplexing, real-time detection. | Tetrodotoxin (TTX): LOD of 3.07 nM using a fluorescent nanoscale metal-organic framework (NMOF) [29]. |

| Colorimetric [25] [30] | Measures visible color change, often due to aggregation/dispersion of gold nanoparticles (AuNPs). | Simplicity, low cost, equipment-free, result visible to the naked eye. | Generally more affordable; excellent for rapid, on-site screening [25]. |

| Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering (SERS) [27] [29] | Measures enhancement of Raman signal from a reporter molecule upon binding to a nanostructured metal surface. | Provides unique fingerprint spectra, ultra-high sensitivity, multiplexing capability. | Patulin (PAT): LOD of 0.0384 ng/mL using Au-Ag composite nanoparticles [29]. |

Protocol: Fabricating an Electrochemical Aptasensor for Carbendazim

Objective: To construct a voltammetric aptasensor for the ultrasensitive detection of the pesticide Carbendazim (CBZ) based on a published design [27].

Materials:

- Aptamer Sequence: CBZ-specific ssDNA aptamer (e.g., with a thiol modification at the 5' end for Au-S bonding).

- Electrode: Glassy carbon electrode (GCE) or gold electrode.

- Nanomaterials: Graphene nanoribbons, Gold Nanoparticles (Au NPs), Zirconium-based Metal-Organic Framework (MOF-808).

- Chemical Reagents: Methylene blue (redox probe), 6-mercapto-1-hexanol (MCH), potassium ferricyanide.

- Buffer: PBS (Phosphate Buffered Saline) for immobilization and washing.

- Equipment: Electrochemical workstation, cell for electrochemical measurement.

Procedure:

Electrode Modification:

- Polish the glassy carbon electrode (GCE) sequentially with alumina slurries (e.g., 1.0, 0.3, and 0.05 µm) and rinse thoroughly with deionized water.

- Deposit a nanocomposite suspension (e.g., graphene nanoribbons and MOF-808) onto the clean GCE surface and allow it to dry.

- Electrodeposit Au NPs onto the modified electrode to create a nano-structured surface for aptamer immobilization [27].

Aptamer Immobilization:

- Dilute the thiolated CBZ aptamer (CBZA) and its complementary strand (SH-cCBZA) in an immobilization buffer.

- Incubate the mixture on the Au NP-modified electrode overnight to allow the formation of a double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) structure and covalent bonding via Au-S chemistry.

- Rinse the electrode with buffer to remove unbound aptamers.

- Backfill the electrode with 1 mM 6-mercapto-1-hexanol (MCH) for 1 hour to block non-specific binding sites on the gold surface [27].

Measurement and Detection:

- Incubate the modified electrode with samples containing varying concentrations of CBZ for a fixed time (e.g., 30 minutes).

- Wash the electrode gently to remove unbound targets.

- Perform a square wave voltammetry (SWV) measurement in a solution containing a redox probe (e.g., methylene blue). The binding of CBZ to the aptamer causes a conformational change, releasing the complementary strand and altering the electron transfer efficiency, leading to a measurable increase in the oxidation current.

- Plot the change in current (ΔI) against the logarithm of CBZ concentration to generate a calibration curve [27].

Performance Data and Applications

The integration of aptamers with advanced nanomaterials and sensor designs has led to remarkable analytical performance for pesticide detection, often surpassing traditional methods in speed and sensitivity for on-site application.

Table 2: Comparative Performance of Selected Aptasensors for Pesticides

| Target Pesticide | Aptasensor Type | Linear Range | Limit of Detection (LOD) | Application in Real Samples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbendazim (CBZ) [27] | Electrochemical (Voltammetric) | 0.8 fM - 100 pM | 0.2 fM | Not specified in the source; suitable for ultra-trace analysis in water. |

| Thiamethoxam (TMX) [27] | Electrochemical | Not specified | Low pM range (enhanced by PrGO) | Demonstrated high sensitivity for on-site monitoring. |

| Atrazine [25] | Not specified (Various platforms) | Not specified | 0.62 nM (for a specific aptamer) | A model herbicide for aptasensor development. |

| Acetamiprid [25] | Not specified (Various platforms) | Not specified | 4.98 µM (for a specific aptamer) | An insecticide target for aptamer selection. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The development and deployment of pesticide aptasensors rely on a core set of reagents and materials.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Aptasensor Development

| Item | Function/Description | Key Utility |

|---|---|---|

| SELEX Library [25] [28] | A synthetic pool of ~10^15 unique ssDNA or RNA sequences with a central randomized region. | The starting point for in vitro selection of aptamers against any target pesticide. |

| Functionalized Aptamers [27] | Selected aptamers with 5' or 3' modifications (e.g., Thiol, Biotin, Amine, Fluorescent dyes). | Enables covalent immobilization on sensor surfaces (thiol, amine) or affinity capture (biotin). |

| Streptavidin-Coated Magnetic Beads [25] | Micron-sized beads functionalized with streptavidin for binding biotinylated molecules. | Crucial for target immobilization and efficient partitioning during the SELEX process. |

| Nanomaterial Composites [27] | Engineered materials like graphene derivatives, metal nanoparticles (Au, Pt), and MOFs. | Enhance electrode conductivity, increase surface area for aptamer loading, and amplify detection signals. |

| Electrochemical Redox Probes [27] | Molecules like Methylene Blue or Ferricyanide that undergo reversible redox reactions. | Generate the measurable current signal in electrochemical aptasensors upon target binding. |

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) [30] [29] | Colloidal gold nanoparticles (often ~20 nm diameter). | Serve as a colorimetric probe (color change upon aggregation) and as a platform for immobilization. |

Aptasensors, built upon the foundation of high-affinity DNA/RNA aptamers selected via SELEX, present a transformative approach for monitoring pesticide residues in water. Their superior stability, modifiability, and production simplicity compared to antibody-based systems make them ideal biorecognition elements. The integration of these aptamers with diverse transduction platforms—particularly electrochemical and optical methods—enables the creation of sensitive, specific, and portable devices. The provided protocols for SELEX and sensor fabrication offer a practical roadmap for researchers to develop and implement these advanced analytical tools. As the field progresses, the combination of novel SELEX methodologies, sophisticated nanomaterial engineering, and miniaturized readout systems will further solidify the role of aptasensors in achieving real-time, on-site water quality assessment, thereby contributing significantly to environmental safety and public health.

Application Notes: Environmental Monitoring of Pesticides

Whole-cell biosensors (MWCBs) are analytical devices that utilize living, genetically engineered microorganisms as the core sensing element to detect specific target analytes. They function by linking the cellular recognition of a chemical, such as a pesticide, to the production of a quantifiable reporter signal [32] [33]. For research on real-time pesticide monitoring in water, MWCBs present a cost-effective and biologically relevant alternative to conventional methods like gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) or liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS), which are expensive, time-consuming, and require extensive sample preparation [1].

A significant advantage of MWCBs is their ability to report on the bioavailable fraction of a contaminant—the portion that is actually accessible to living organisms and can thus elicit a biological effect [32] [34]. This is a crucial distinction from chemical methods that only provide total concentration, offering more physiologically relevant data for ecological risk assessment [1].

Recent advancements have focused on overcoming environmental challenges. For instance, traditional biosensors built on lab strains like Escherichia coli fail in high-salinity conditions. Pioneering work has created halotolerant biosensors using the chassis organism Halomonas cupida J9U, enabling the detection and degradation of organophosphate pesticides (OPs) in hypersaline ecosystems, such as saline-alkali soil and seawater [35]. The integration of biosensors with technologies like fiber-optic tips has also facilitated the development of portable systems for on-site, real-time toxicity assessment of water and sediment samples [34].

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Representative Whole-Cell Biosensors for Pesticide Detection

| Target Analyte | Chassis Organism | Sensing Element | Reporter Signal | Linear Detection Range | Limit of Detection (LOD) | Application Matrix |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Methyl Parathion (MP) / p-Nitrophenol (pNP) | Halomonas cupida J9U-mpd | PobR regulator & cognate promoter | Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) | 0.1–60 μM (pNP); 0.1–20 μM (MP) [35] | 0.1 μM (in water); 0.026 mg/kg (in soil) [35] | Seawater, high-salinity river water, saline-alkali soil [35] |

| General Cytotoxicity | Escherichia coli TV1061 | grpE promoter (heat shock response) | Bioluminescence (luxCDABE) | Dose-dependent response to stressors [34] | N/A (General stress response) | Water and sediment samples [34] |

Experimental Protocols

This section provides a detailed methodology for the application of a halotolerant, dual-functional whole-cell biosensor for the detection and degradation of p-nitrophenol-substituted organophosphate pesticides, as exemplified by recent research [35].

Protocol: Detection and Degradation of Methyl Parathion in Hypersaline Samples

Biosensor Preparation and Cultivation

- Strain: Use the genetically engineered biosensor strain Halomonas cupida J9U-mpd-pBBR-P3pobRA-gfp (or the P17 variant) [35]. This strain harbors a pNP-responsive transcriptional regulator (PobR) and its cognate promoter controlling GFP expression, along with a genomic mpd gene for methyl parathion degradation.

- Culture Conditions: Grow the biosensor cells in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium supplemented with appropriate antibiotics and 5-10% (w/v) NaCl to maintain halotolerance. Incubate at 30°C with shaking at 200-220 rpm [35].

- Cell Harvesting: In the late exponential growth phase, harvest the cells by centrifugation (e.g., 5,000 × g for 10 minutes). Wash the cell pellet and resuspend it in a saline buffer matching the salinity of the environmental samples to be tested.

Sample Preparation and Exposure

- Environmental Samples: Collect water (seawater, river water) or soil extracts from the monitoring site. For soil samples, create a slurry with a high-salinity buffer [35].

- Biosensor Assay: In a multi-well plate, combine the resuspended biosensor cells with the environmental sample or a standard solution of methyl parathion (MP) or p-nitrophenol (pNP) for calibration. A typical reaction volume is 200 μL per well.

- Incubation: Incubate the assay mixture at 30°C for a predetermined period (e.g., 80 minutes) to allow for both pesticide degradation and the induction of the GFP signal [35].

Signal Measurement and Data Analysis

- Fluorescence Measurement: Measure the fluorescence intensity using a microplate reader with excitation at 485 nm and emission at 510-520 nm.

- Quantification: Generate a standard dose-response curve using known concentrations of pNP or MP. Fit the fluorescence data to the standard curve to interpolate the concentration of the target analyte in the unknown environmental samples.

- Validation: Validate the biosensor's results by analyzing a subset of samples with a conventional method such as High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) to confirm accuracy [35].

Protocol: On-Site Toxicity Assessment Using a Fiber-Optic Biosensor

Bioreporter Immobilization

- Strain: Use E. coli TV1061, which contains the grpE promoter fused to the Photorhabdus luminescens luxCDABE operon [34].

- Encapsulation: Mix a concentrated suspension of the bioreporter cells with a sterile, low-viscosity sodium alginate solution (e.g., 1-2% w/v). Carefully dip the tip of an optical fiber into this mixture.

- Gel Formation: Expose the coated fiber tip to a calcium chloride solution (e.g., 100 mM) for several minutes to cross-link the alginate and form a stable, semi-permeable hydrogel matrix around the tip, entrapping the cells [34].

Field Measurement

- Setup: Connect the proximal end of the fiber-optic tip to a photon counter or luminometer housed within a light-proof, portable case.

- Testing: Directly submerge the biosensor tip into vials containing water or suspended sediment samples collected on-site [34].

- Data Acquisition: Record the bioluminescent signal continuously or at specific time intervals. The induction of bioluminescence above baseline levels indicates the presence of cytotoxic stressors in the sample.

Visualization: Signaling Pathways and Workflows

Signaling Pathway of a Transcription Factor-Based Whole-Cell Biosensor

Experimental Workflow for On-Site Sediment Toxicity Assessment

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for Whole-Cell Biosensor Construction and Application

| Item Name | Function/Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Halotolerant Chassis (Halomonas cupida J9U) | A robust microbial host that remains functional under high-salt stress, enabling biosensing in saline environments. | Detection of pesticides in seawater, saline-alkali soil, and high-salinity wastewater [35]. |

| Reporter Genes (e.g., gfp, luxCDABE) | Encodes for a measurable signal (fluorescence or bioluminescence) upon activation by the target analyte. | GFP for quantitative fluorescence detection; lux operon for self-sufficient bioluminescence without external substrate [35] [34]. |

| Transcriptional Regulator (e.g., PobR) | The sensing protein that specifically binds to the target analyte (e.g., pNP), triggering the expression of the reporter gene. | Core component of inducible biosensors for p-nitrophenol-substituted organophosphate pesticides [35]. |

| Calcium Alginate Hydrogel | A biocompatible polymer used to immobilize and protect bioreporter cells on surfaces like fiber-optic tips. | Creates a semi-permeable membrane for on-site biosensors, allowing toxin diffusion while retaining cells [34]. |

| General Stress Promoter (e.g., grpE) | A promoter sequence activated by cellular damage or metabolic stress, used for non-specific toxicity screening. | Drives reporter gene expression in response to a wide range of cytotoxicants for general toxicity assessment [34]. |

The escalating reliance on pesticides in global agriculture necessitates robust monitoring programs to protect aquatic ecosystems and human health. Conventional analytical techniques, while highly accurate, are often ill-suited for the demands of rapid, on-site screening due to their operational complexity and cost. Biosensor technology presents a transformative alternative, offering a powerful toolkit for decentralized water quality assessment. This application note details how the inherent advantages of biosensors—specifically their portability, cost-effectiveness, and rapid response—are being harnessed to advance the real-time monitoring of pesticides in water, framing these attributes within a broader thesis on innovative environmental surveillance.

The limitations of traditional methods are well-documented. Techniques such as high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-MS) require expensive instrumentation, often exceeding tens of thousands of dollars, necessitate complex sample preparation, and must be operated by trained personnel within laboratory settings [10] [9]. This centralized model leads to significant delays between sample collection and result acquisition, hindering timely decision-making. In contrast, biosensors integrate a biological recognition element (e.g., enzyme, antibody, aptamer) with a physicochemical transducer to create compact, self-contained analytical devices [36]. This fundamental design is the foundation for their critical advantages, enabling deployment at the point-of-need and providing actionable data with unprecedented speed.

Comparative Advantage: Biosensors vs. Conventional Analysis

The following table summarizes the performance and operational characteristics of biosensors in direct comparison to traditional laboratory methods, highlighting their suitability for on-site monitoring.

Table 1: Performance comparison of biosensors and conventional methods for pesticide detection.

| Feature | Biosensors | Conventional Methods (HPLC, GC-MS) |

|---|---|---|

| Analysis Time | Minutes to under an hour [10] | Hours to days, including sample preparation [9] |

| Portability | High; portable and handheld platforms available [9] [37] | Low; confined to laboratory settings |

| Equipment Cost | Low to moderate [9] | High (e.g., HPLC equipment can cost up to $100,000) [10] |

| Operational Skill | Minimal training required; designed for on-site use [38] | Requires trained technicians and specialized labs [38] |

| Sample Preparation | Minimal or none required [36] | Complex, time-consuming, and requires costly reagents [10] |

| Throughput | Ideal for single or few analytes; suitable for rapid screening [39] | High-throughput for multiple analytes in a single run |

| Sensitivity | High; capable of detection from ng/L to μg/L [9] | High (similar or better sensitivity) |

| Primary Use Case | Rapid screening, on-site monitoring, point-of-care testing [39] [37] | Confirmatory analysis, regulatory compliance, reference testing |