Regeneration and Reuse of Biosensor Platforms: Strategies for Sustainable and Cost-Effective Diagnostics

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the latest strategies for the regeneration and reuse of biosensor platforms, a critical focus for enhancing the sustainability and cost-effectiveness of diagnostic tools...

Regeneration and Reuse of Biosensor Platforms: Strategies for Sustainable and Cost-Effective Diagnostics

Abstract

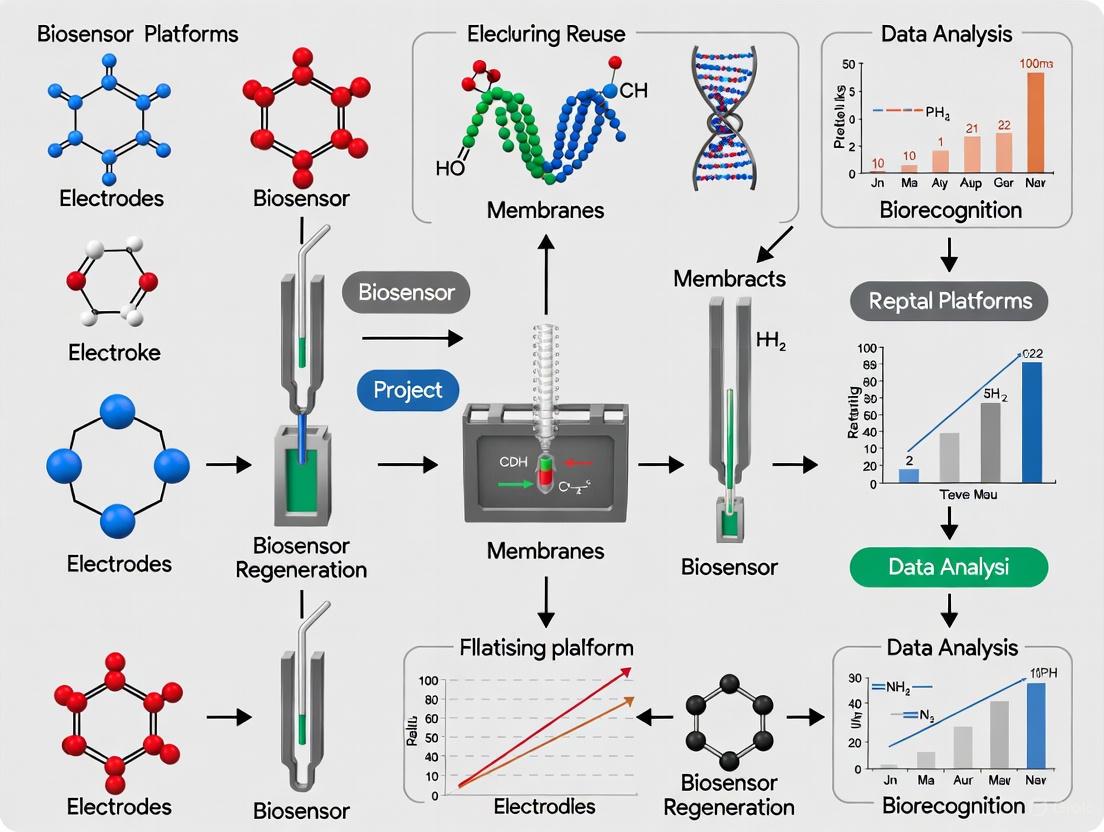

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the latest strategies for the regeneration and reuse of biosensor platforms, a critical focus for enhancing the sustainability and cost-effectiveness of diagnostic tools in biomedical research and drug development. It explores the fundamental principles driving the need for reusable biosensors, details cutting-edge methodological approaches—from chemical regeneration and surface engineering to the application of external stimuli and smart materials. The content further addresses key challenges in sensor stability and performance optimization, and offers a comparative analysis of validation techniques. Aimed at researchers and scientists, this review synthesizes current knowledge to guide the development of robust, long-lasting biosensing systems for clinical and point-of-care applications.

The Core Principles and Driving Need for Reusable Biosensors

Biosensor regeneration refers to the process of removing bound analytes from the recognition surface of a biosensor after a measurement cycle, restoring its functionality for repeated use. For researchers and drug development professionals, successful regeneration is crucial as it directly enhances cost-effectiveness by extending the operational lifespan of often expensive sensor platforms, increases experimental throughput, and reduces consumable waste, thereby supporting more sustainable laboratory practices.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting

Q: Why is my biosensor's signal degrading over multiple regeneration cycles?

- A: Signal degradation often indicates damage to the immobilized biorecognition elements (e.g., antibodies, aptamers) or the sensor surface itself. This can be caused by overly harsh regeneration conditions, such as an incorrect pH or excessive ionic strength. Refer to the optimization protocols below to systematically identify and rectify the issue [1].

Q: What does the "Biosensor Already in Use" or "Biosensor Incompatible" error mean?

- A: These error messages, common in commercial systems, can sometimes appear if a sensor is incorrectly flagged as expended by the software after a failed or incomplete regeneration cycle. Ensure all regeneration protocols are followed precisely and that the sensor is properly recalibrated before reuse. For specific devices, consulting the manufacturer's technical support is recommended [2].

Q: My regenerated biosensor shows a high background signal. What is the cause?

- A: A high background signal typically suggests incomplete removal of the analyte or contaminants from the previous assay cycle. This compromises the specificity of subsequent measurements. You may need to optimize the regeneration buffer composition or extend the washing duration. In some cases, a more rigorous cleaning procedure with a different buffer may be necessary [1].

Q: How can I keep my biosensor adhered for its full intended lifespan?

- A: Proper adhesion is critical for consistent performance, especially for wearable sensors. Issues with the sensor becoming loose or detaching prematurely can be mitigated by meticulously following the manufacturer's insertion and skin preparation guidelines. Using approved adhesive patches or secure mounting hardware can also enhance stability [3].

Troubleshooting Common Regeneration Issues

The table below summarizes specific problems, their potential causes, and actionable solutions.

| Problem | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low Binding Capacity After Regeneration | Bioreceptor denaturation or stripping from surface | Optimize regeneration buffer gentleness; validate immobilization stability [1] [4] |

| Poor Reproducibility Between Cycles | Inconsistent regeneration conditions | Automate fluid handling; strictly control buffer contact time, temperature, and flow rate [1] |

| Slow Binding Kinetics in Subsequent Runs | Partial, non-specific analyte retention | Increase stringency of wash steps; incorporate surfactant in regeneration buffer |

| Sensor Drift or Unstable Baseline | Surface fouling or gradual degradation | Implement a periodic, more rigorous "cleaning-in-place" protocol beyond standard regeneration |

Experimental Protocols for Regeneration Optimization

A systematic approach is essential for developing a robust regeneration protocol. The following methodology, based on Design of Experiments (DoE) principles, is far more efficient than optimizing one variable at a time, as it can reveal critical interactions between factors [1].

Systematic Optimization Using Design of Experiments (DoE)

Aim: To identify the optimal combination of regeneration buffer pH and contact time that maximizes signal recovery while minimizing baseline drift.

Materials:

- Biosensor platform (e.g., SPR chip, electrochemical cell)

- Target analyte and binding partner

- Regeneration buffer candidates (e.g., Glycine-HCl, NaOH)

- pH meter and precision pipettes

- Statistical software for DoE analysis

Method:

- Define Factors and Ranges: Select critical variables (e.g., pH (2-4), Contact Time (30-120 seconds)) [1].

- Choose Experimental Design: A Central Composite Design is ideal for modeling quadratic responses and finding a true optimum [1].

- Run Experiments: Execute the randomized experiments, measuring key responses like % Signal Recovery and Baseline Stability.

- Build Model & Analyze: Use software to build a predictive model and identify the optimal settings.

- Validate: Confirm the model's predictions by running experiments at the suggested optimum.

Multi-Objective Algorithm-Assisted Optimization

Aim: To concurrently optimize multiple sensor performance metrics (e.g., sensitivity, figure of merit) alongside regeneration potential, which is critical for single-molecule detection platforms [4].

Method:

- Identify Objectives: Define key performance metrics (e.g., Sensitivity (S), Figure of Merit (FOM), Signal-to-Noise ratio post-regeneration).

- Select Algorithm: Employ a Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) or similar algorithm to navigate the complex parameter space [4].

- Iterate and Converge: The algorithm iteratively tests parameter sets (e.g., incident angle, metal layer thickness) to find the configuration that best satisfies all objectives, ensuring the sensor design itself is robust to regeneration stresses [4].

Experimental Workflows and Signaling Pathways

The following diagrams illustrate the core logical workflows for the optimization strategies discussed.

Diagram: DoE Optimization Workflow

Diagram: Biosensor Analysis Lifecycle

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists essential materials and their functions in biosensor development and regeneration studies.

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in Biosensor Regeneration & Research |

|---|---|

| Aptamers / Antibodies | Serve as the primary biorecognition elements; their stability dictates regeneration potential [5]. |

| Glycine-HCl Buffer (low pH) | Common regeneration buffer that disrupts antibody-antigen bonds by altering protonation states. |

| Sodium Hydroxide (NaOH) | A harsh, high-pH regeneration agent effective for stripping tightly bound analytes. |

| Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) Chip | A common platform for real-time, label-free binding studies and rigorous regeneration testing [4]. |

| 2D Materials (e.g., Graphene) | Used to modify sensor interfaces; can enhance surface area and binding properties but require stability assessment during regeneration [4]. |

| Wax-Printed Paper Substrate | Provides a versatile, low-cost platform for disposable or limited-reuse biosensors, a benchmark for cost-comparison [6]. |

| Fluorescent Reporters | Used in platforms like ARTIST to transduce binding events into measurable signals, requiring stable output across cycles [5]. |

The Economic and Sustainability Imperative for Reusable Platforms in Diagnostics

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

This support center provides practical guidance for researchers working on the regeneration and reuse of diagnostic biosensor platforms. The following questions and answers address common experimental challenges within this field.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Why is there a systematic shift in my biosensor's electrochemical signal after several regeneration cycles?

- A: A reproducible shift in signals like Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) spectra is often not due to an increasing number of defects in the lipid bilayer itself. Research on regenerated tethered Bilayer Lipid Membrane (tBLM) biosensors points to physicochemical alterations in the submembrane reservoir—the 1–2 nm thick layer separating the membrane from the solid substrate. With each regeneration cycle, increased hydration of this layer can significantly decrease its resistance, leading to the observed spectral shifts. Ensuring analytical reproducibility requires controlling the properties of this submembrane reservoir [7].

Q2: What are the primary methods for regenerating a biosensor's surface?

- A: Biosensor regeneration strategies can be categorized by their underlying mechanism. Common methods include:

- Chemical Treatments: Using solutions to disrupt analyte-bioreceptor binding.

- Electrochemical Surface Regeneration: Applying a voltage to desorb Self-Assembled Monolayer (SAM) linkers and bound complexes from the electrode surface.

- Surface Engineering/Re-functionalization: Removing the old biological recognition layer and immobilizing a fresh one.

- Physical Methods: Using light (e.g., UV) to reset the sensor state, as seen in photopatterned silk biosensors [8] [9] [10].

- A: Biosensor regeneration strategies can be categorized by their underlying mechanism. Common methods include:

Q3: My reusable biosensor shows inconsistent performance after multiple uses. What could be the cause?

- A: Inconsistencies often stem from incomplete regeneration of the sensing surface. Key factors to investigate include:

- Re-adsorption: Detached molecules (e.g., SAMs) re-adsorbing onto the surface in a different orientation, interfering with subsequent immobilization cycles [10].

- Non-specific Adsorption: Target biomolecules bonding to empty spaces on an imperfectly formed SAM, which can cause false signals and reduce sensitivity over time [10].

- Degradation of Bioreceptors: The biological elements (enzymes, antibodies) may lose activity over multiple regeneration cycles, especially if harsh conditions are used [9].

- A: Inconsistencies often stem from incomplete regeneration of the sensing surface. Key factors to investigate include:

Q4: How can I visually confirm the success of my biosensor's regeneration process?

- A: For colorimetric biosensors, regeneration should result in a visible return to the baseline color. For instance, a silk-based glucose biosensor that turns pink upon activation should return to its uncolored state after the measurement and can be reset to pink with UV light for the next cycle. The number of such successful, visible cycles is a direct indicator of regeneration efficacy [9].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

The table below outlines specific problems, their potential causes, and recommended actions.

| Problem | Possible Cause | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|

| Decreasing sensitivity after regeneration | Bioreceptor denaturation or incomplete removal of previous analyte | Optimize regeneration buffer pH/ionic strength; validate bioreceptor activity after immobilization [8]. |

| High background signal/noise | Non-specific adsorption of proteins or other molecules | Use high-quality, densely packed short-chain SAMs to minimize empty spaces on the sensing surface [10]. |

| Poor reproducibility between cycles | Inconsistent SAM formation or surface roughness | Control gold electrode deposition rate and annealing to ensure consistent, low surface roughness [10]. |

| Slow dispensing of reagents | Particulates or crystallization in liquid lines | Flush lines with acetonitrile to remove crystallized amidites or replace kinked tubing [11]. |

| Liquid valve dripping constantly | Failing solenoid valve (common for acidic reagents) | Replace the liquid valve, ensuring proper torque (4-6 in-oz) during installation [11]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Biosensor Regeneration

Protocol 1: Electrochemical Regeneration of a Tethered Bilayer Lipid Membrane (tBLM)

This protocol is adapted from research on regenerating tBLMs for toxin detection [7].

- 1. Objective: To regenerate a protein-loaded phospholipid bilayer biosensor after exposure to a pore-forming toxin (e.g., α-hemolysin) for repetitive use.

- 2. Key Materials & Reagents:

- Substrate: Fluorine-doped tin oxide (FTO) electrodes.

- Molecular Anchors: Organic silane-based tethering molecules.

- Lipids: A mixture of dioleoylphosphatidylcholine and cholesterol.

- Regeneration Solutions: As specified by the two-step bilayer removal protocol (typically involving buffers and surfactants).

- 3. Methodology:

- Step 1 - Bilayer Removal: Subject the used tBLM to a two-step bilayer removal protocol. The specific solutions and conditions (e.g., flow rate, incubation time) must be optimized for your system.

- Step 2 - Re-assembly: Re-assemble the tBLM on the FTO substrate using the silane anchors and lipid mixture.

- Step 3 - Quality Control: After each regeneration cycle, assess membrane integrity and performance using Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS). Use inverse modeling of the EIS data to monitor key parameters like submembrane resistance and membrane capacitance, rather than just defect density.

- 4. Critical Notes: The electrochemical response may vary systematically due to changes in the submembrane reservoir. Focus on achieving a consistent submembrane layer rather than expecting identical EIS spectra across all cycles.

Protocol 2: Optical Regeneration of a Silk-Based Colorimetric Biosensor

This protocol is adapted from work on reusable glucose biosensors made from silk fibroin [9].

- 1. Objective: To regenerate a solid-state, enzyme-based colorimetric biosensor for multiple measurements of glucose.

- 2. Key Materials & Reagents:

- Substrate: Silk fibroin (SF) films from Bombyx mori cocoons.

- Enzymes: Glucose oxidase (GOx) and Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP).

- Mediator: 1,2-bis(5-carboxy-2-methylthien-3-yl)cyclopentene (DTE).

- Light Source: UV lamp (λ = 312 nm).

- 3. Methodology:

- Step 1 - Biosensor Production: Dope an aqueous SF solution with GOx, HRP, and the DTE mediator. Cast the solution and evaporate to form a stable, transparent film.

- Step 2 - Photopatterning: Irradiate the film through a photomask with UV light to isomerize the DTE from its uncolored to its pink, closed form, creating a visible pattern.

- Step 3 - Measurement & Reset:

- Detection: Upon exposure to glucose, the enzymatic cascade activates HRP, which selectively reduces the pink DTE to its uncolored form. The rate of color loss is proportional to glucose concentration.

- Regeneration: After measurement, expose the entire biosensor to UV light for ~30 seconds. This photoisomerizes the DTE back to its pink, closed form, resetting the biosensor for the next use.

- 4. Critical Notes: This platform has been demonstrated to withstand up to 5 measurement cycles with high stability. The silk matrix preserves enzyme functionality for extended periods, even when stored dried at room temperature.

Visualizing Biosensor Regeneration Pathways

tBLM Regeneration Workflow

Colorimetric Silk Biosensor Cycle

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The table below details essential materials and their functions in developing reusable biosensor platforms.

| Research Reagent | Function in Reusable Biosensors |

|---|---|

| Short-Chain Self-Assembled Monolayers (SAMs) | Act as linker molecules to immobilize bioreceptors. They offer higher detection sensitivity, lower steric hindrance, and faster formation/desorption cycles compared to long-chain SAMs, facilitating better regeneration [10]. |

| Tethered Lipid Mixtures | Form stable, regenerable bilayer membranes on solid substrates (e.g., FTO) that mimic cell membranes for detecting membrane-active compounds like toxins [7]. |

| Silk Fibroin (SF) | Provides a transparent, flexible, and biocompatible substrate that enhances the shelf-life of embedded enzymes and allows for the creation of biodegradable biosensors [9]. |

| Dithienylethene (DTE) Mediators | Photoelectrochromic molecules that act as optical mediators in enzymatic reactions. Their color state can be switched with light, enabling visual readout and UV-light-based regeneration of the biosensor [9]. |

| Fluorescent Protein/HaloTag FRET Pairs | Chemogenetic FRET pairs (e.g., ChemoG5) enable the design of highly sensitive, tunable biosensors for metabolites. The readout can be adapted for intensity, lifetime, or bioluminescence, offering flexibility in detection strategies [12]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the primary factors that cause bioreceptor instability? Bioreceptor instability is primarily caused by the physical and chemical degradation of the biological recognition elements (such as enzymes, antibodies, or aptamers) over time. This can result from denaturation, conformational changes, or oxidation when exposed to environmental factors like fluctuating temperature, pH, or repeated regeneration cycles [13] [14].

2. How does non-specific binding (NSB) interfere with biosensor measurements? NSB occurs when analytes or other molecules in a sample interact with the sensor surface through non-targeted interactions, such as hydrophobic or electrostatic forces. This can mask true specific binding events, lead to an overestimation of the analyte concentration, and cause inaccurate calculations of binding kinetics and affinity, ultimately compromising the biosensor's accuracy and reliability [15] [16].

3. Why is biofouling a particular problem for biosensors used in complex media? Biofouling refers to the non-specific adsorption of proteins, cells, or other biomolecules onto the sensing interface. In complex biological media like blood, saliva, or sweat, this fouling can passivate the electrode, significantly weaken electrochemical signals, lead to a loss of specificity, and promote bacterial colonization that can form biofilms and cause sensor failure [17].

4. Can biosensors be regenerated for multiple uses, and what are the common methods? Yes, a key focus of modern biosensor research is enabling regeneration for multiple uses to enhance cost-effectiveness and facilitate continuous monitoring. Common regeneration methods include chemical treatments (using acids or salts), the application of external energy (like heat or light to break bonds), and surface engineering that allows for the gentle removal and re-functionalization of the bioreceptor layer [18].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Rapid Degradation of Bioreceptor Activity

Potential Causes and Solutions

| Cause | Diagnostic Signs | Corrective Action & Preventive Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Denaturation | Gradual signal decay over time; reduced sensitivity. | Immobilize bioreceptors using stable covalent bonds [13] [14]. Include stabilizers (e.g., sugars, polymers) in storage buffer [14]. |

| Leaching | Complete loss of signal; inability to detect analyte. | Use physical entrapment in gels or polymers [14]. Apply protective coatings like membranes or nanomaterials [17] [14]. |

| Improper Storage | Inconsistent performance between different sensor batches. | Follow manufacturer's storage instructions [14]. Store in sealed, sterile packages away from light and moisture [14]. |

Experimental Protocol: Testing Bioreceptor Stability

- Objective: To quantify the operational stability of an immobilized enzyme bioreceptor.

- Materials: Biosensor, standard analyte solutions, appropriate assay buffer.

- Method:

- Calibrate the biosensor with standard analyte concentrations to establish a baseline response.

- Expose the biosensor to a fixed, moderate concentration of the analyte and record the signal.

- Gently wash the sensor with buffer to regenerate the surface.

- Repeat steps 2 and 3 for multiple cycles (e.g., 10-50 cycles).

- Plot the signal response versus the cycle number.

- Expected Outcome: A stable biosensor will show a less than 10% decrease in signal response over the tested cycles. A sharp decline indicates poor bioreceptor stability [19].

Issue 2: High Background Signal Due to Non-Specific Binding (NSB)

Potential Causes and Solutions

| Cause | Diagnostic Signs | Corrective Action & Preventive Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Electrostatic Interactions | High background with charged analytes or surfaces. | Adjust buffer pH to match protein isoelectric point (pI) [16] [20]. Increase salt concentration (e.g., 150-200 mM NaCl) to shield charges [16] [20]. |

| Hydrophobic Interactions | NSB with hydrophobic analytes or sensor surfaces. | Add non-ionic surfactants (e.g., 0.05% Tween 20) to running buffer [16] [20]. |

| Insufficient Surface Blocking | NSB from various sample proteins. | Include blocking additives like BSA (1%) in buffer and sample solutions [16] [20]. |

Experimental Protocol: Systematic NSB Mitigation using Design of Experiments (DOE)

- Objective: To efficiently identify the optimal buffer conditions to minimize NSB.

- Materials: Biosensor, analyte, solutions of pH modifiers, salts, surfactants, and blocking agents. DOE software (e.g., MODDE) is advantageous [15].

- Method:

- Identify Factors: Select critical factors to test (e.g., pH, NaCl concentration, %Tween-20, %BSA).

- Define Ranges: Set a high and low value for each factor based on literature and biomolecule compatibility.

- Run Experiments: Use the DOE software to generate a set of experimental conditions. Run a blank sample (analyte over a bare or non-specific sensor) for each condition and measure the background response.

- Analyze Data: The software will model the data to identify which factors and interactions most significantly reduce NSB.

- Verify Optimized Condition: Run a confirmation experiment using the predicted optimal buffer recipe [15].

Issue 3: Signal Drift and Inaccuracy from Biofouling

Potential Causes and Solutions

| Cause | Diagnostic Signs | Corrective Action & Preventive Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Fouling | Gradual signal drift in complex samples (e.g., serum, saliva). | Modify sensor interface with antifouling materials: Zwitterionic peptides (e.g., EKEKEKEK sequence) [17] or Polyethylene glycol (PEG) [17]. |

| Bacterial Adsorption | Sensor failure after prolonged use; biofilm formation. | Incorporate antibacterial agents: Integrate antimicrobial peptides (e.g., KWKWKWKW) into the sensor coating [17]. |

| Surface Roughness | Higher fouling propensity due to increased surface area. | Optimize electrode fabrication to achieve a smooth surface (roughness < 0.3 μm) [19]. |

Experimental Protocol: Evaluating Antifouling Performance with QCM-D

- Objective: To quantify the amount of non-specific protein adsorption on a modified sensor surface.

- Materials: Quartz Crystal Microbalance with Dissipation (QCM-D), sensor chips with modified and unmodified surfaces, protein solution (e.g., 1 mg/mL BSA in PBS).

- Method:

- Mount the sensor chip in the QCM-D and establish a stable baseline with buffer flow.

- Introduce the protein solution and monitor the frequency shift (ΔF). A larger decrease in frequency indicates more mass adsorption.

- Switch back to buffer flow to wash away loosely bound proteins.

- Compare the final frequency shift between the modified and unmodified surfaces.

- Expected Outcome: An effective antifouling surface will show a significantly smaller frequency shift (e.g., >90% reduction) compared to the control, demonstrating minimal non-specific adsorption [17].

Research Reagent Solutions

Essential materials for developing robust and regeneratable biosensors.

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experimentation |

|---|---|

| Zwitterionic Peptides (e.g., EKEKEKEK) | Serves as an antifouling layer on the sensor surface, forming a hydration layer that resists non-specific protein adsorption [17]. |

| Antimicrobial Peptides (e.g., KWKWKWKW) | Integrated into sensor coatings to kill adsorbed bacteria, preventing biofilm formation and maintaining function in complex media [17]. |

| BSA (Bovine Serum Albumin) | Used as a blocking agent in buffers (typically at 1%) to occupy non-specific sites on the sensor surface and tubing [16] [20]. |

| Non-ionic Surfactants (e.g., Tween 20) | Added to running buffers at low concentrations (e.g., 0.05%) to disrupt hydrophobic interactions that cause NSB [16] [20]. |

| Nafion Film | Acts as a buffering layer on transducers (e.g., graphene FETs), enabling gentle removal with ethanol for easy sensor re-functionalization and regeneration [18]. |

| GW Linker | A short peptide linker (Glycine-Tryptophan) fused to a biomediator like streptavidin; provides ideal flexibility and rigidity for optimal bioreceptor orientation and stability [19]. |

Experimental Workflows and System Relationships

Biosensor NSB Troubleshooting Logic

Regeneration Methods for Biosensors

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on Biosensor Regeneration

Q1: What are the key performance metrics for evaluating biosensor regeneration? The primary metrics for assessing biosensor regeneration are Regeneration Efficiency and Operational Lifespan. Regeneration Efficiency measures the sensor's ability to recover its original signal response after a regeneration cycle, while Operational Lifespan indicates the total number of reliable regeneration cycles a sensor can undergo before performance degrades. These metrics are tracked by monitoring signal sensitivity and consistency across multiple use cycles [18].

Q2: Why did my biosensor's signal drift after several regeneration cycles? Signal drift over repeated cycles can originate from physical changes in the sensor's sub-surface layers, not just the active surface. For instance, in tethered bilayer lipid membrane (tBLM) biosensors, electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) revealed that systematic signal shifts were due to increased hydration of the 1-2 nm thick submembrane reservoir, which changed its resistance, rather than damage to the membrane itself [7]. Ensuring consistent submembrane properties is key to reproducibility.

Q3: What is a typical operational lifespan for a reusable biosensor? The operational lifespan varies significantly by sensor design and regeneration method. The table below summarizes the lifespans reported for different biosensor platforms.

Table: Operational Lifespan of Various Regeneratable Biosensors

| Biosensor Platform | Target Analyte | Regeneration Method | Operational Lifespan (Number of Cycles) | Key Performance Metric |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Silk-based Colorimetric Biosensor [9] | Glucose | UV Light (312 nm) | 5 cycles | Visual distinction of glucose levels |

| Aptamer-based FET Biosensor [18] | Interferon-γ (IFN-γ) | Ethanol treatment | 80 cycles | Signal variation < 8.3% |

| Graphene-Nafion FET Biosensor [18] | Interferon-γ (IFN-γ) | Nafion film removal with Ethanol | 80 cycles | Consistent sensitivity |

| GMR DNA Biosensor [21] | DNA | 40% DMSO (at room temperature) | 14 orthogonal DNA pairs tested | Maintained probe DNA integrity |

| Electrochemical RNA Biosensor [22] | SARS-CoV-2 RNA | Not specified | Multiple uses demonstrated | 100% sensitivity and specificity |

Q4: Which regeneration method is most effective? No single method is universally best; the optimal choice depends on your biosensor's design and bioreceptors. Chemical denaturants like 40% DMSO are highly effective for DNA biosensors at room temperature [21]. Light-based regeneration (e.g., UV) is excellent for photoelectrochromic systems [9]. Chemical film removal (e.g., with ethanol) works well for sensors with a sacrificial buffering layer [18]. The choice involves trade-offs between regeneration efficiency, potential for sensor damage, and simplicity of the workflow.

Q5: How can I troubleshoot a complete loss of sensor signal after regeneration? A complete signal loss typically indicates a failure in the bioreceptor layer. This could be due to:

- Receptor Degradation: The regeneration process may have denatured the immobilized enzymes, antibodies, or aptamers beyond recovery [18].

- Layer Detachment: The entire functionalized interface may have delaminated from the transducer, especially in sensors that use a removable buffering film [18].

- Check the Integrity of Probe DNAs: For DNA-based sensors, verify that the probe DNA remains intact and covalently bonded to the surface after denaturation [21].

Troubleshooting Guide for Common Regeneration Issues

Table: Troubleshooting Biosensor Regeneration Problems

| Problem | Potential Causes | Solutions & Checks |

|---|---|---|

| Gradual Signal Decline | • Progressive denaturation of bioreceptors.• Fouling or non-specific buildup.• Physical changes in submembrane layers [7]. | • Optimize regeneration intensity/duration.• Incorporate a cleaning step with mild surfactants.• Characterize the submembrane resistance via EIS modeling. |

| Poor Regeneration Efficiency | • Incomplete removal of target analytes.• Inadequate regeneration conditions. | • Screen different denaturants (e.g., Urea, DMSO, TE buffer) [21].• Combine methods (e.g., chemical + thermal).• For affinity-based sensors, ensure binding reversibility is feasible. |

| High Signal Variability Between Cycles | • Inconsistent regeneration protocol.• Chip-to-chip fabrication variance. | • Automate the regeneration process using microfluidics [18].• Use the same sensor for sequential measurements to eliminate fabrication variance. |

| Complete Sensor Failure | • Harsh chemicals or physical damage to transducer.• Delamination of the sensing layer. | • Introduce a protective buffering layer (e.g., Nafion) [18].• Validate transducer functionality after fabrication. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Regeneration of a Silk-Based Colorimetric Glucose Biosensor using UV Light [9]

This protocol details the process for regenerating a solid-state biosensor made from silk fibroin doped with enzymes and a dithienylethene (DTE) mediator.

- Principle: The enzymatic reaction in the presence of glucose converts the pink, closed-form DTE to its uncolored, open form. UV light (312 nm) reverts the open-form DTE back to the closed, pink state, resetting the sensor.

- Key Reagents & Materials:

- Pre-fabricated silk film biosensor containing GOx, HRP, and DTE.

- Equipment:

- UV lamp (λ = 312 nm, 12 W power).

- Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Post-Measurement: After the colorimetric measurement of glucose, the silk film will have faded as DTE converts to its uncolored form.

- UV Irradiation: Expose the entire silk film biosensor to UV light for 30 seconds.

- Verification: Visually confirm that the pink color has fully returned to the film, indicating the reset of the DTE mediator.

- Storage: The sensor is now ready for the next measurement cycle. This cycle can be repeated up to 5 times.

Protocol 2: Regeneration of DNA Biosensors using a Chemical Denaturant [21]

This protocol uses 40% Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) to denature and remove hybridized target DNA from probe DNA on a giant magnetoresistive (GMR) biosensor, enabling reuse.

- Principle: 40% DMSO effectively disrupts the hydrogen bonding in DNA duplexes, denaturing the hybridized target DNA and removing it from the surface-bound probe DNA, without the need for heating and while preserving probe integrity.

- Key Reagents & Materials:

- Denaturant: 40% (v/v) DMSO in ultrapure water.

- Wash Buffer: Tris-EDTA buffer or ultrapure water.

- Equipment:

- GMR biosensor with integrated temperature control unit (optional).

- Microfluidic flow cell or pipettes for solution handling.

- Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Post-Detection: After completing the DNA hybridization and detection measurement, remove the sample from the sensor surface.

- Denaturant Injection: Gently flow or incubate the sensor surface with the 40% DMSO solution for a defined period (e.g., 10-15 minutes) at room temperature.

- Rinsing: Thoroughly rinse the sensor surface with a wash buffer (e.g., TE buffer or ultrapure water) to remove all traces of DMSO and the denatured target DNA.

- Re-equilibration: Equilibrate the sensor in the desired assay buffer.

- Validation: The biosensor is now regenerated and ready for a new measurement. The integrity of the probe DNA can be confirmed by testing with a known control target.

Research Reagent Solutions for Regeneration Experiments

Table: Essential Reagents for Biosensor Regeneration Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function in Regeneration | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) | A chemical denaturant that disrupts hydrogen bonding in biomolecules. | Effective for denaturing DNA duplexes on GMR and other planar biosensors at room temperature [21]. |

| Ethanol | A solvent that can dissolve sacrificial polymer layers and disrupt hydrophobic interactions. | Used to remove a Nafion film from a graphene FET, refreshing the surface for re-functionalization [18]. |

| Urea Solution | A chaotropic agent that denatures proteins and nucleic acids by disrupting non-covalent bonds. | Commonly tested as a denaturant for regenerating affinity-based biosensors [21]. |

| Tris-EDTA (TE) Buffer | A buffering solution; EDTA chelates metal ions, which can aid in disrupting biomolecular structures. | Used as a wash and denaturation buffer in nucleic acid sensor regeneration [21]. |

| Dithienylethene (DTE) | A photoelectrochromic molecule that switches states with light. | Acts as a mediator in enzymatic biosensors, enabling optical reset with UV light [9]. |

| Nafion | A sacrificial polymer film that protects the transducer and can be removed for regeneration. | Used as a buffering layer on graphene FETs, allowing sensor refresh by stripping and re-coating [18]. |

Biosensor Regeneration Workflow

The diagram below illustrates the core decision-making workflow and logical relationships for selecting and evaluating a regeneration strategy.

In biosensing, a bioreceptor is a biological or biomimetic molecule that specifically identifies and binds to a target analyte, forming the core of the sensor's selectivity [23]. The pursuit of regeneratable and reusable biosensor platforms is a significant research focus, driven by the goals of enhancing cost-effectiveness, enabling continuous monitoring, and establishing time-sequential biometric profiles in clinical diagnostics [18]. Regeneration typically involves refreshing the bioreceptors, either by cleaning and applying new receptors or, more challengingly, by detaching the target analytes from the existing receptors to restore their binding capability [18]. This technical support document provides a detailed overview of common bioreceptors—antibodies, aptamers, enzymes, and Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs)—within the context of biosensor regeneration and reuse, addressing common experimental challenges and providing practical solutions.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Different Bioreceptors

| Bioreceptor | Type | Key Feature | Primary Binding Mechanism | Stability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antibody | Natural | High specificity and affinity for antigens | Non-covalent interactions (hydrophobic, electrostatic) [24] | Moderate (susceptible to denaturation) [24] |

| Aptamer | Pseudo-natural | Synthetic oligonucleotide; target variety | Folds into 3D structure; hydrogen bonding, van der Waals [25] [24] | Moderate (susceptible to nuclease degradation) [25] |

| Enzyme | Natural | Catalytic conversion of substrate | Binding cavities with non-covalent interactions [24] | Moderate (dependent on environment) [24] |

| MIP | Synthetic | Artificial polymer with imprinted cavities | Size, shape complementarity, non-covalent interactions [25] [24] | High (resistant to harsh environments) [25] [26] |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions on Bioreceptor Selection and Use

Q1: What are the key factors when selecting a bioreceptor for a regeneratable biosensor? The selection hinges on the application's requirements for sensitivity, selectivity, reproducibility, and reusability [24]. For single-use disposable sensors, antibodies are excellent. For multiple uses, consider the inherent stability of MIPs or the reversible binding nature of aptamers. The required sensitivity may also guide the choice; for instance, MIP-aptamer combinations can achieve ultra-high sensitivity and selectivity [25]. The table below compares these performance characteristics to aid in selection.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Bioreceptors for Biosensing

| Performance Characteristic | Antibody | Aptamer | Enzyme | MIP | MIP-Aptamer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | High | Medium | High | Low | Ultrahigh [25] |

| Selectivity | High | High | High | Medium | Ultrahigh [25] |

| Reproducibility | Medium (batch variation) | High (synthetic) | Medium (batch variation) | High (synthetic) | High [25] |

| Reusability / Stability | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | High | High [25] |

| Binding Affinity | High | High | High | Low | High [25] |

Q2: Why is my biosensor signal declining over repeated regeneration cycles? Signal degradation is a common challenge in regeneration. Potential causes include:

- Incomplete Removal of Analyte: The regeneration method may not fully dissociate the target, leading to a cumulative blockage of binding sites [18].

- Damage to the Bioreceptor: Harsh regeneration conditions (e.g., extreme pH, solvents, or temperature) can denature antibodies or enzymes, or damage the polymer matrix of MIPs [18] [27].

- Loss of Bioreceptor from the Transducer Surface: Repeated chemical or physical treatments can cause the gradual desorption or cleavage of immobilized bioreceptors [18].

- Fouling or Nonspecific Adsorption: Contaminants from complex samples (like serum) can accumulate on the sensor surface, blocking access to the bioreceptors [28].

Q3: How can I reduce high background noise in my affinity-based biosensor? High background is often a result of nonspecific adsorption. To mitigate this:

- Optimize Blocking: Use an effective blocking agent (e.g., BSA, casein) for a sufficient time to cover all nonspecific binding sites on the sensor surface [29].

- Enhance Washing Stringency: Increase the number of wash cycles or incorporate detergents (e.g., Tween-20) in the wash buffer to remove loosely bound materials [29] [30].

- Verify Bioreceptor Purity: Ensure your immobilized antibodies or aptamers are pure and do not exhibit cross-reactivity with other components in the sample matrix [29].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Problems

Problem: Weak or No Signal in Affinity-Based Detection (e.g., ELISA or Aptasensor) This issue can occur even when the target analyte is present.

Table 3: Troubleshooting Weak or No Signal

| Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Reagent Degradation | Check expiration dates. Avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles of enzymes and antibodies [29]. |

| Insufficient Incubation Time/Temperature | Ensure each binding step meets the required time and temperature for the reaction to reach equilibrium [29]. |

| Improper Immobilization of Bioreceptor | Verify the coating procedure. For antibodies, ensure the correct buffer (e.g., PBS) and incubation time are used [30]. |

| Incorrect Pipetting or Dilution | Use calibrated pipettes and double-check dilution calculations. Ensure all reagents are at room temperature before use to avoid volume inaccuracies [29]. |

Problem: Poor Reproducibility Between Sensor Replicates or Regeneration Cycles Inconsistent results undermine the reliability of a biosensor.

Table 4: Troubleshooting Poor Reproducibility

| Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Inconsistent Technique | Establish a Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) for all steps, especially pipetting, washing, and incubation times [29]. |

| Edge Effects in Microplates or Chips | Use a proper plate sealer during incubations and avoid stacking plates to ensure uniform temperature across all wells [29] [30]. |

| Improper Mixing of Reagents | Gently vortex or invert all liquid reagents and samples before use to ensure homogeneity [29]. |

| Sensor-to-Sensor Variation | For regeneratable sensors, this can be mitigated by using a single sensor for continuous measurements rather than comparing different sensors [18]. |

Regeneration and Reuse of Biosensor Platforms

Fundamental Regeneration Methods

Regeneration strategies are broadly categorized into methods that refresh the bioreceptor and those that disrupt the analyte-bioreceptor bond.

Diagram 1: Biosensor Regeneration Strategies

Surface Re-functionalization

This method involves completely removing the old bioreceptor layer and applying a new one. A representative protocol involves a two-step cleaning process using cyclic voltammetry (CV) scans with sulfuric acid (H₂SO₄) and potassium ferricyanide (K₃Fe(CN)₆) under continuous flow to strip the electrode, followed by a fresh functionalization cycle with new bioreceptors [18]. While this ensures a consistent surface, it is time-consuming and requires manual intervention.

Target Dissociation via Chemical Treatment

This is the most common approach, using chemicals to break the bonds between the bioreceptor and analyte.

- For DNA-based Sensors (Aptamers, Genosensors): Chemicals like Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO), urea solution, or low ionic strength buffers (e.g., Tris-EDTA) can disrupt hydrogen bonding. A study showed that 40% DMSO at 25°C effectively denatured hybridized DNA on magnetic biosensors without damaging the covalently bound probe DNA, allowing for multiple reuse cycles [27].

- For Antibody-based Sensors: Solutions with extreme pH (e.g., Glycine-HCl pH 2.0-3.0) or high ionic strength are often used to disrupt antigen-antibody complexes. Caution is needed as these can denature the antibody over multiple cycles.

Target Dissociation via Physical and Field-Based Treatment

- Thermal Regeneration: Applying heat can denature the analyte or the bioreceptor's binding site. This is effective for nucleic acid-based receptors but can be damaging to protein-based bioreceptors.

- Electrical Field-Induced Regeneration: Applying an electric potential can induce redox reactions or electrostatic repulsion to desorb the target analyte. This method is promising for integrated and automated systems [18].

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Regeneration of a DNA Biosensor

The following protocol is adapted from studies on regenerating Giant Magnetoresistive (GMR) biosensors, which is applicable to other planar DNA biosensor systems [27].

Objective: To denature and remove hybridized target DNA from surface-immobilized probe DNA, allowing sensor reuse.

Materials:

- Functionalized biosensor with immobilized ssDNA probes.

- Denaturants: Ultrapure Water (UPW), Urea solution (8M), Tris-EDTA (TE) Buffer, or Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO).

- Wash Buffer (e.g., PBS with 0.05% Tween-20).

- Blocking Buffer (e.g., 1% BSA).

Procedure:

- Hybridization and Detection: Perform the initial hybridization of your target DNA and signal detection as per your standard protocol.

- Initial Rinse: Gently rinse the sensor chip with Wash Buffer to remove unbound materials.

- Denaturation:

- Option A (Chemical with DMSO): Incubate the sensor with 40% DMSO (diluted in UPW) for a defined period at 25°C. This concentration has been shown to be effective without requiring external heating [27].

- Option B (Chemical with Heat): Incubate the sensor with your chosen denaturant (e.g., UPW, Urea, TE buffer) and heat the chip to approximately 55°C for 10-60 minutes to accelerate denaturation.

- Post-Denaturation Wash: Thoroughly wash the sensor with Wash Buffer to remove the denaturant and any detached target DNA.

- Re-blocking: Incubate the sensor with Blocking Buffer (e.g., 1% BSA) for 30 minutes to passivate any nonspecific sites exposed during denaturation.

- Validation and Reuse: The sensor is now ready for a new round of hybridization. To validate regeneration efficiency, measure the signal from a positive control after the first regeneration cycle and compare it to the initial signal.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Biosensor Regeneration

Table 5: Key Research Reagents for Regeneration Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function in Regeneration | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| DMSO (Dimethyl Sulfoxide) | A polar aprotic solvent that disrupts hydrogen bonding networks. | Effective denaturant for dsDNA on biosensors without heating [27]. |

| Urea (8M Solution) | A chaotropic agent that disrupts the hydrophobic effect and hydrogen bonding. | Denaturation of proteins and nucleic acids [27]. |

| TE Buffer (Tris-EDTA) | A buffering agent; Tris maintains pH, EDTA chelates divalent cations. | Low ionic strength and cation chelation help destabilize DNA duplexes [27]. |

| Nafion | A proton-conducting polymer used as a buffering layer. | Can be removed with ethanol to refresh the sensor surface for aptamer re-functionalization [18]. |

| Glycine-HCl Buffer (low pH) | Creates an acidic environment to protonate key residues. | Disruption of high-affinity antibody-antigen interactions [18]. |

| BSA (Bovine Serum Albumin) | A blocking agent to passivate surfaces. | Re-blocking the sensor surface after regeneration to minimize nonspecific binding [27]. |

| EDC / NHS Chemistry | Crosslinking agents for covalent immobilization. | Used in the initial functionalization and during surface re-functionalization cycles [18]. |

The selection and management of bioreceptors are critical in advancing reusable biosensor platforms. While each bioreceptor type has distinct advantages, the hybrid MIP-aptamer approach and clever regeneration strategies involving chemical, thermal, or electrical stimuli show significant promise for creating robust, multi-use biosensing systems. Success hinges on careful optimization to balance the competing demands of sensitivity, selectivity, and the ability to withstand multiple regeneration cycles. The troubleshooting guides and protocols provided here offer a foundation for researchers to overcome common challenges in this dynamic field.

Cutting-Edge Techniques for Biosensor Regeneration and Real-World Applications

Troubleshooting Guides

Troubleshooting Guide: Chemical Regeneration of DNA Biosensors

Problem: Incomplete target denaturation and poor signal removal.

- Potential Cause 1: The chemical denaturant is ineffective or used at a sub-optimal concentration.

- Solution: Switch to or optimize the concentration of a proven denaturant like 40% Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO), which has demonstrated excellent performance in denaturing DNA hybrids on sensor surfaces without requiring heating [27]. Ensure fresh solutions are prepared for each regeneration cycle.

- Potential Cause 2: The denaturation conditions are too mild.

- Solution: For chemical-only methods, increase the contact time with the denaturant. Alternatively, combine chemical treatment with a mild thermal treatment (e.g., heating to 55°C) to disrupt hydrogen bonds more effectively [27].

- Potential Cause 3: The DNA sequence pair has very high hybridization stability.

- Solution: If possible, re-design probe sequences with moderate melting temperatures. Note that denaturation efficiency can vary with different DNA sequences, and a universal protocol may require optimization for specific pairs [27].

Problem: Loss of probe integrity and reduced sensitivity in subsequent measurements.

- Potential Cause 1: The regeneration conditions are too harsh, causing partial detachment or degradation of the immobilized probe molecules.

- Solution: Avoid using extreme pH or high temperatures for prolonged periods. The use of 40% DMSO at 25°C has been shown to effectively denature targets while preserving covalently bonded probe DNAs for reuse [27].

- Potential Cause 2: Repeated regeneration cycles lead to the accumulation of chemical or biological debris on the sensor surface.

- Solution: Incorporate a gentle washing step with a suitable buffer (e.g., SSC buffer with a surfactant like Tween-20) after denaturation and before the next hybridization to refresh the surface [27].

Problem: Inconsistent sensor performance after multiple regeneration cycles.

- Potential Cause 1: Gradual degradation of the transducer surface or its functionalization from repeated chemical exposure.

- Solution: Ensure the sensor's underlying platform is compatible with the chosen denaturants. Consider strategies like adding a protective buffering layer to the transducer that can be easily removed and reapplied, as demonstrated in some refunctionalization approaches [18].

- Potential Cause 2: Non-specific binding or biofouling on the sensor surface.

Troubleshooting Guide: Electrochemical Sensor Regeneration

Problem: Slow or inefficient regeneration of the detection platform.

- Potential Cause: Regeneration method relies on slow processes like long-term irradiation or chemical diffusion.

- Solution: Implement an electro-oxidation mediated regeneration strategy. Applying a controlled oxidative potential can dissociate host-guest complexes (e.g., ferrocene from cyclodextrin) in as little as 3 minutes, enabling a fast and reagentless regeneration [32].

Problem: Surface damage or shortened interface lifespan after regeneration.

- Potential Cause: The regeneration method uses harsh conditions that degrade the sensor's surface chemistry.

- Solution: Adopt milder regeneration triggers. Electro-oxidation, when precisely controlled, can be a gentler alternative to harsh chemical treatments or prolonged light exposure, helping to maintain surface integrity over multiple cycles [32].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the most effective chemical denaturant for regenerating DNA-based biosensors? A1: Recent research indicates that 40% DMSO is a highly effective denaturant for breaking the hydrogen bonds in DNA hybrids on biosensor surfaces. Its key advantage is that it performs excellently at room temperature (25°C) without a heating process, which helps preserve the integrity of the immobilized probe DNAs for subsequent detection cycles [27].

Q2: Why is probe integrity important for biosensor regeneration, and how can it be measured? A2: Probe integrity is crucial for maintaining the sensor's sensitivity and multiplexing capability for reuse. If probes are damaged or detached during regeneration, the sensor's response will be unreliable. Integrity can be evaluated by performing a fresh hybridization with a known target concentration after the regeneration process and comparing the signal output to that of the initial measurement [27].

Q3: Besides chemicals, what other methods can be used to regenerate biosensors? A3: Biosensor regeneration is a diverse field. Several other strategies include:

- Thermal Regeneration: Applying heat to melt DNA hybrids or denature protein complexes [18].

- Electro-oxidation: Applying a specific electric potential to induce the desorption of signal molecules or targets [32].

- Re-functionalization: Completely cleaning and reapplying a new layer of bioreceptors to the transducer surface [18].

- Light-Triggered Dissociation: Using light-sensitive molecules (e.g., azobenzene) that change structure upon irradiation, causing the release of the target [18].

Q4: What are common sources of error or false results in regenerated biosensors? A4: Errors can arise from several factors, including incomplete removal of the target (leading to false positives in the next cycle), degradation of the bioreceptor (leading to reduced sensitivity and false negatives), and non-specific binding or biofouling on the sensor surface [27] [33] [31]. A consistent and validated regeneration protocol is essential to mitigate these risks.

Experimental Protocol: Evaluating Denaturants for Planar DNA Biosensors

This protocol outlines a method to evaluate the effectiveness of different chemical denaturants for regenerating DNA-functionalized biosensors, based on a study using Giant Magnetoresistive (GMR) biosensors [27].

1. Principle The protocol involves hybridizing biotinylated target DNA to complementary probe DNA immobilized on a sensor surface. The hybridization is detected using streptavidin-coated magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs) that generate a quantifiable signal. A denaturant is then applied, and its efficiency is measured by the reduction in the MNP signal. The sensor's reusability is confirmed by re-hybridizing with a second set of targets.

2. Materials

- Biosensor Platform: GMR biosensor chip or other planar biosensor.

- DNA: Probe DNA (covalently immobilized on sensor), target DNA (biotinylated).

- Denaturants for Testing: e.g., Ultrapure Water (UPW), Urea solution, Tris-EDTA (TE) Buffer, Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) at various concentrations (20%, 30%, 40%, 60%, 80% in UPW).

- Other Reagents: Streptavidin-coated Magnetic Nanoparticles (MNPs), Saline-Sodium Citrate (SSC) Buffer, Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) with Tween-20, Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA), Biotinylated BSA.

- Equipment: Robotic spotter, temperature-controlled shaker and reader station, fluidic cartridge.

Diagram: Chemical Regeneration Workflow

3. Step-by-Step Procedure

- Sensor Preparation: Spot probe DNA solutions onto designated sensors on the chip. Incubate overnight in a humid chamber at 4°C.

- Assembly and Blocking: Assemble the chip with a fluidic cartridge. Wash with PBS-Tween buffer and block the surface with 1% BSA for 1 hour.

- Initial Hybridization: Introduce a mixture of biotinylated target DNAs in SSC buffer to the chip. Incubate for 1 hour at 25°C in a temperature-controlled shaker.

- Baseline Signal Measurement: Place the chip in a reader station and record a baseline signal.

- Signal Development: Replace the buffer with a solution of streptavidin-coated MNPs. Record the signal until saturation is reached. This is the pre-denaturation signal.

- Denaturation: Replace the MNP solution with the denaturant to be tested.

- For room temperature tests: Incubate at 25°C for 30 minutes while monitoring the signal in real-time [27].

- For heated tests: Heat the chip to ~55°C or place in a 90°C oven for varying durations.

- Post-Denaturation Wash: Wash the chip sequentially with washing buffer and SSC buffer.

- Post-Denaturation Signal Check: To quantify remaining MNPs, incubate with biotinylated BSA, followed by a fresh MNP solution, and record the signal. A significant drop indicates successful denaturation.

- Re-hybridization (Reusability Test): Introduce a second mixture of target DNAs to the chip. Repeat steps 4 and 5 to obtain the post-regeneration signal.

- Data Analysis: Calculate denaturation efficiency and the recovery of sensitivity by comparing the post-regeneration signal to the initial signal.

Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent | Function in Experiment | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) | Chemical denaturant that disrupts hydrogen bonding in DNA hybrids [27]. | Concentration is critical; 40% in UPW was identified as optimal in one study [27]. |

| Urea Solution | Chemical denaturant; disrupts hydrophobic interactions and hydrogen bonding [27]. | Typically used at high concentrations (e.g., 8M). |

| Tris-EDTA (TE) Buffer | A common buffer that can act as a mild denaturant; EDTA chelates Mg²⁺, destabilizing DNA [27]. | Less aggressive than other denaturants, which may be beneficial for probe integrity. |

| Streptavidin-coated MNPs | Signal generation agent for magnetic biosensors; binds to biotinylated target DNA [27]. | The core signal transducer in the referenced GMR protocol [27]. |

| SSC Buffer | Provides optimal ionic strength and pH for DNA hybridization [27]. | Standard buffer for nucleic acid hybridization and washing steps. |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | Blocking agent to reduce non-specific binding on the sensor surface [27]. | Essential for maintaining low background noise and assay specificity. |

4. Data Analysis and Interpretation The quantitative data from the protocol should be summarized and compared to identify the best-performing denaturant.

Denaturant Performance Comparison Table

| Denaturant | Typical Concentration | Conditions | Denaturation Efficiency | Probe Integrity Preservation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DMSO [27] | 40% (in UPW) | 25°C, no heat | Excellent | Excellent |

| Urea Solution [27] | e.g., 8M | 25°C or with heating | Variable (sequence-dependent) | Good |

| TE Buffer [27] | 10 mM Tris, 0.1 mM EDTA | 25°C or with heating | Lower than DMSO | Good |

| Ultrapure Water (UPW) [27] | N/A | 25°C | Low | High |

| Electro-oxidation [32] | N/A (Applied Potential) | ~3 minutes | High (for specific systems) | High (for platform) |

- Denaturation Efficiency: Calculated as

(1 - [Post-Denaturation Signal / Pre-Denaturation Signal]) * 100%. - Probe Integrity / Reusability: Calculated as

[Post-Regeneration Signal / Initial Signal] * 100%for a standardized target concentration. A value close to 100% indicates excellent preservation.

The development of regeneratable biosensor platforms is a critical frontier in diagnostic and drug development research, aiming to enhance cost-effectiveness and enable continuous biomarker monitoring. Central to this goal are advanced surface engineering strategies, particularly Self-Assembled Monolayers (SAMs) and polymer coatings. These interfacial layers serve as the foundational scaffold for biosensor operation, dictating performance through their control over bioreceptor immobilization, signal-to-noise ratio, and resilience to fouling in complex matrices. For a sensor to be reusable, this surface chemistry must not only facilitate robust initial functionalization but also allow for efficient regeneration—the complete removal of bound analyte while preserving the activity of the immobilized probe for subsequent detection cycles. This technical guide addresses the common challenges and solutions in working with these materials, providing a structured resource to support the development of reliable, reusable biosensing platforms.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary advantages of using SAMs in electrochemical biosensors? SAMs provide a well-ordered, nanoscale layer on surfaces, typically gold, via gold-thiol bonds. Their key advantages include reducing non-specific binding (biofouling), enhancing the stability of the electrochemical interface, and presenting functional groups (e.g., carboxyl or amine) for the controlled covalent immobilization of bioreceptors such as antibodies or DNA probes [34]. This order helps create a more reproducible and reliable sensing environment.

Q2: Why is regeneration a critical parameter in biosensor design? Regeneratable sensors mitigate potential errors from chip-to-chip variance during continuous measurements and address the need for highly accurate, cost-intensive transducers. This is crucial for establishing time-sequential biometric profiles in patients and significantly reduces the overall cost per test, making advanced diagnostics more accessible and sustainable [18].

Q3: My biosensor signal drifts over time. Could this be related to my SAM? Yes, baseline drift can be a sign of an insufficiently equilibrated sensor surface. While SAMs can improve stability, they can also be a source of baseline signal drift, which increases noise levels. It is sometimes necessary to allow the system to equilibrate extensively, even overnight, to minimize this drift [34] [35].

Q4: What is the fundamental challenge when designing antifouling polymer coatings for optical biosensors like SPR? The thickness of the polymer layer is a critical constraint. The evanescent field of a Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) sensor decays exponentially from the surface. Therefore, the antifouling layer must be thin enough (typically under 70 nm) to allow the sensitive detection of bound targets, while also being highly effective at repelling non-specific adsorption from complex fluids like blood serum [36].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

The following table summarizes common problems encountered when working with functionalized biosensor surfaces and their potential solutions.

Table 1: Troubleshooting Surface Functionalization and Regeneration

| Problem Category | Specific Issue | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline & Signal Stability | Baseline drift or noise [37] [35] | Improperly degassed buffer; unstable temperature; imperfect SAM formation leading to signal drift [34] [37]. | Degas buffers thoroughly; ensure a stable experimental environment; allow more time for surface equilibration; check SAM formation protocol. |

| No or weak signal change upon analyte injection [37] | Low ligand immobilization density; inactive target or ligand; inappropriate buffer conditions. | Optimize probe immobilization concentration and time; verify the activity of biological elements; check for compatibility between analyte and ligand. | |

| Surface Binding & Specificity | High non-specific binding [37] [38] | Inadequate antifouling properties of the SAM or polymer layer; non-optimal surface blocking. | Incorporate a blocking agent (e.g., BSA); use additives like surfactants in the running buffer; consider alternative antifouling polymers (e.g., PEG, zwitterions) [38] [36]. |

| Negative binding signals [38] | Buffer mismatch between sample and running buffer; volume exclusion effects. | Match the buffer composition of the analyte and the running buffer; test the suitability of the reference surface. | |

| Regeneration & Reusability | Incomplete analyte removal / carryover [37] [27] | Overly strong analyte-probe interaction; insufficiently harsh regeneration conditions. | Optimize regeneration solution (e.g., low/high pH, high salt, additives); increase regeneration time or flow rate [37]. For DNA biosensors, chemical denaturants like 40% DMSO can be highly effective [27]. |

| Loss of probe activity after regeneration [27] [18] | Regeneration conditions are too harsh, damaging the immobilized probes. | Gentler regeneration conditions or a different chemical agent. For a full refresh, a two-step clean/refunctionalization process can be used, though it is time-consuming [18]. | |

| Sensor surface degradation over multiple cycles [37] | Repeated exposure to harsh chemical or physical treatments. | Follow manufacturer guidelines for surface care; avoid extreme pH conditions; monitor surface performance over time. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Protocol 1: Two-Step Sensor Re-functionalization with SAMs

This protocol, adapted from a microfluidic electrochemical biosensor study, enables complete sensor regeneration through disassembly and reassembly of the sensing interface [18]. The entire process takes approximately four hours.

Step 1: Cleaning and Stripping the Surface

- Cleaning Solution: Continuously flow a solution of 0.5 M H2SO4 over the electrode surface.

- Electrochemical Cleaning: Perform multiple Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) scans while the acid is flowing. This step removes all previously immobilized molecules and cleans the underlying gold surface.

- Oxidizing Agent Rinse: Follow with a continuous flow of 10 mM K3Fe(CN)6 to further oxidize and remove any residual contaminants.

Step 2: Re-functionalization with a Fresh SAM and Bioreceptors

- SAM Formation: Flow a solution of 2 mM 11-mercaptoundecanoic acid (in ethanol) over the clean gold surface to form a new carboxyl-terminated SAM. Allow it to incubate to form a complete monolayer.

- Activation: Activate the terminal carboxyl groups on the SAM using a fresh mixture of EDC (1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide) and NHS (N-hydroxysuccinimide) to create amine-reactive succinimide esters.

- Probe Immobilization:

- For aptamer-based sensors: Immobilize amine-functionalized aptamers directly onto the activated SAM surface.

- For antibody-based sensors: First, bind streptavidin to the activated SAM. Then, introduce biotinylated antibodies which will capture onto the streptavidin layer via the strong SA-biotin interaction.

Protocol 2: Chemical Denaturation for DNA Biosensor Regeneration

This protocol evaluates denaturants for regenerating DNA biosensors by breaking the hydrogen bonds in double-stranded DNA (dsDNA), using a Giant Magnetoresistive (GMR) biosensor platform [27].

Key Reagents:

- Denaturants: Ultrapure Water (UPW), 8 M Urea solution, TE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0), and Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) at various concentrations (20-80%).

- Additive: 0.5% Tween-20 is added to each denaturant to improve wetting and efficiency.

Procedure:

- Hybridization: Hybridize the target DNA to the probe DNA immobilized on the sensor surface.

- Signal Generation: Introduce streptavidin-coated magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs) that bind to the hybridized DNA, generating a measurable signal.

- Denaturation: After signal saturation, replace the MNP solution with the chosen denaturant.

- Condition Testing: Test denaturation under different conditions:

- Room Temperature (25°C): Incubate for 30 minutes.

- Moderate Heat (~55°C): Monitor denaturation in real-time while heating.

- High Heat (90°C): Place the sensor in a 90°C oven for 10, 30, or 60 minutes.

- Regeneration Assessment: Wash the sensor and test its ability to re-hybridize with a fresh batch of target DNA. The integrity of the original probe DNA must be confirmed for true reusability.

Result: Among the tested denaturants, 40% DMSO at room temperature demonstrated excellent performance in denaturing target DNAs without damaging the covalently bonded probe DNAs, making it a strong candidate for regenerating planar DNA biosensors [27].

Data Presentation and Analysis

Comparison of Chemical Denaturants for DNA Biosensors

The following table synthesizes quantitative data from a systematic study that evaluated the effectiveness of various chemical denaturants for regenerating DNA-functionalized GMR biosensors [27].

Table 2: Performance of Chemical Denaturants for DNA Biosensor Regeneration

| Denaturant | Concentration | Temperature | Key Findings | Probe DNA Integrity Post-Denaturation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ultrapure Water (UPW) | N/A | 25°C, ~55°C, 90°C | Ineffective or very slow denaturation across all temperatures. | Preserved, but denaturation failed. |

| Urea Solution | 8 M | 25°C, ~55°C, 90°C | Required heating for significant denaturation; efficiency improved with temperature. | Moderate preservation; may vary with heating duration. |

| TE Buffer | 10 mM Tris, 0.1 mM EDTA | 25°C, ~55°C, 90°C | Similar to urea, required heating for efficient denaturation. | Moderate preservation. |

| Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) | 40% | 25°C | Excellent denaturation performance without any heating. | High - probe DNA successfully reused. |

| 20-30% | 25°C | Partial denaturation. | Preserved. | |

| 60-80% | 25°C | Effective denaturation, but potential risk to probe integrity. | May be compromised at very high concentrations. |

Performance of Refunctionalization and Polymer-Based Regeneration

This table summarizes data from studies on sensors regenerated through surface re-engineering and polymer manipulation, highlighting their long-term reusability potential [18] [39].

Table 3: Regeneration Performance of Re-functionalized and Polymer-Based Biosensors

| Biosensor Platform | Regeneration Method | Analyte | Regeneration Cycles Tested | Performance Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electrochemical Aptasensor [18] | Full SAM disassembly & re-functionalization (Protocol 1) | Cardiac Biomarker (CK-MB) | 5 cycles | Maintained consistent sensitivity across all cycles. |

| Graphene FET Biosensor [18] | Polymer (Nafion) removal with ethanol | Interferon-γ | 80 cycles | Signal variation < 8.3%; highly consistent performance. |

| Organic Electrochemical Transistor (OECT) [39] | Drug-mediated "Refreshing in Sensing" (RIS) | EGFR Protein | >200 cycles | Unprecedented reusability; recovery by soaking in drug solution. |

Visualization of Concepts and Workflows

Biosensor Re-functionalization Workflow

Diagram 1: Sensor re-functionalization workflow.

Drug-Mediated Regeneration (RIS) Concept

Diagram 2: Drug-mediated refreshing in sensing (RIS) mechanism.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Materials for Surface Functionalization and Regeneration

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| 11-Mercaptoundecanoic acid | Forms carboxyl-terminated SAMs on gold surfaces. | Enables covalent probe immobilization via EDC/NHS chemistry; facilitates sensor regeneration [34] [18]. |

| EDC & NHS | Crosslinking agents for covalent immobilization. | Activates carboxyl groups to form amine-reactive esters, crucial for attaching biomolecules to SAMs [34] [18]. |

| Streptavidin (SA) | Bridge for immobilization. | Binds to biotinylated surfaces; captures biotinylated probes (antibodies, DNA); offers high-affinity, stable binding [34]. |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | Blocking agent. | Reduces non-specific binding by occupying vacant sites on the sensor surface [37] [38] [36]. |

| Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) | Chemical denaturant for DNA biosensors. | Effectively denatures dsDNA at 40% concentration at room temperature, preserving covalently bound probes for reuse [27]. |

| Nafion | Cation-exchange polymer coating. | Serves as a regeneratable matrix for probe immobilization on FETs; can be stripped with ethanol for sensor reuse [18]. |

| Poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) | Antifouling polymer. | Forms a hydration layer that repels non-specific protein adsorption, improving signal fidelity in complex media [36]. |

| Gefitinib | Drug-based sensing probe. | Used in OECTs as a regeneratable, target-specific probe that enables a "Refreshing in Sensing" mechanism [39]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on Biosensor Regeneration

Q1: Why is regeneration important for modern biosensing platforms? Regeneration is crucial for making biosensing cost-effective and sustainable, especially for applications requiring continuous and real-time monitoring. It mitigates potential errors from chip-to-chip variance and reduces the overall cost per test, which is particularly important in healthcare diagnostics and long-term physiological monitoring [18].

Q2: My biosensor's signal drifts after several regeneration cycles. What could be the cause? Signal drift can originate from physical or chemical alterations to the sensor interface. For example, in tethered bilayer lipid membrane (tBLM) biosensors, a systematic shift in electrochemical impedance was traced to changes in the hydration and resistance of the submembrane reservoir, not the membrane itself. Ensuring consistent surface properties and employing gentle regeneration protocols can mitigate this [7].

Q3: What are the primary mechanisms for detaching target analytes during regeneration? The core mechanism involves overcoming the binding affinity between the target and the bioreceptor. This is commonly achieved by applying external stimuli that disrupt non-covalent interactions (e.g., hydrogen bonds, van der Waals forces, electrostatic interactions). The means vary widely and include changes in the chemical environment, application of temperature, light, or electric potentials [18].

Q4: I am using an aptamer-based biosensor. Which external stimuli are most suitable for its regeneration? Aptamers, being single-stranded DNA or RNA molecules, are highly suitable for regeneration via external triggers. Their reversible, non-covalent binding mechanisms allow for target dissociation using stimuli like temperature (heat) or light. Their conformational flexibility makes them ideal for creating regeneratable biosensors [18].

Troubleshooting Guides for Common Regeneration Challenges

Low Regeneration Efficiency

This occurs when the biosensor fails to recover its original signal baseline and sensitivity after a regeneration cycle.

- Potential Cause: Incomplete analyte-receptor dissociation.

- Potential Cause: Degradation or damage to the immobilized bioreceptor.

- Solution: Use a milder regeneration protocol. If using chemical treatments, ensure they are not damaging the receptors. For instance, a graphene-Nafion based FET biosensor was successfully regenerated over 80 cycles using ethanol, indicating the receptor's robustness to this specific chemical [18].

Poor Reproducibility Across Regeneration Cycles

This refers to inconsistent sensor performance (e.g., sensitivity, baseline signal) from one regeneration cycle to the next.

- Potential Cause: Inconsistent surface regeneration.

- Potential Cause: Alteration of the underlying sensor substrate.

- Solution: As highlighted in tBLM research, the problem may not be the bioreceptor but the underlying support structure. Using an inverse modeling approach for data analysis can help diagnose shifts in submembrane properties. Ensuring a stable and well-characterized substrate before receptor immobilization is key [7].

Non-Specific Binding Post-Regeneration

This involves unwanted signal from molecules other than the target analyte binding to the sensor surface after regeneration.

- Potential Cause: Residual analytes or contaminants on the sensor surface.

- Solution: Implement a more rigorous cleaning step. For electrochemical sensors, a two-step cleaning process with sulfuric acid and potassium ferricyanide has been used to refresh the electrode surface completely before re-functionalization [18].

- Solution: Use effective surface blocking agents (e.g., bovine serum albumin (BSA), casein, ethanolamine) after regeneration to occupy any remaining active sites on the sensor chip [40].

Quantitative Data on Regeneration Performance

The table below summarizes regeneration performance data from recent studies, providing benchmarks for expected outcomes.

| Biosensor Platform | Regeneration Method | Stimulus Category | Key Performance Metric | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aptamer-functionalized Graphene FET | Ethanol wash (Nafion film removal) | Chemical | Consistent sensitivity over 80 cycles (<8.3% signal variation) | [18] |

| Tethered Bilayer Lipid Membrane (tBLM) | Two-step bilayer removal protocol | Chemical | Effective regeneration after toxin exposure, but with systematic shift in EIS spectra | [7] |

| Microfluidic Electrode-based Biosensor | Acid & chemical clean + full re-functionalization | Chemical | Maintained sensitivity through 5 regeneration cycles (4-hour process) | [18] |

Experimental Protocols for Key Regeneration Techniques

Protocol 1: Chemical Regeneration and Re-functionalization of an Electrochemical Biosensor

This protocol is adapted from a method used for real-time biomarker measurement in organ-on-a-chip systems [18].

- Cleaning:

- Step 1: Subject the used sensor to continuous flow of 1M H₂SO₄ while performing cyclic voltammetry (CV) scans.

- Step 2: Follow with a continuous flow of 10 mM K₃Fe(CN)₆, also with CV scans.

- Purpose: These steps electrochemically clean the electrode surface, removing all immobilized molecules.

- Re-functionalization:

- Step 3: Form a fresh self-assembled monolayer (SAM) on the cleaned gold electrode.

- Step 4: For aptamer-based sensors, activate the surface with a solution of EDC (1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide) and NHS (N-hydroxysuccinimide).

- Step 5: Immobilize amine-functionalized aptamers onto the activated surface via EDC/NHS coupling chemistry.

- Note: The entire process is automated using integrated microfluidics and control software, taking approximately 4 hours.

Protocol 2: Light- or Heat-Induced Regeneration of an Aptamer-Based Biosensor

This protocol leverages the reversible nature of aptamer-target binding [18].

- Detection Cycle: First, complete the standard detection cycle where the aptamer binds to its target, causing a measurable signal change (e.g., electrochemical, optical).

- Regeneration Stimulus:

- Thermal Method: Increase the temperature of the sensor environment. The applied heat provides energy to break the non-covalent bonds (hydrogen bonds, van der Waals forces) between the aptamer and the target, causing dissociation.