SERS Biosensor Platforms for Pesticide Residue Detection: Principles, Advances, and Biomedical Applications

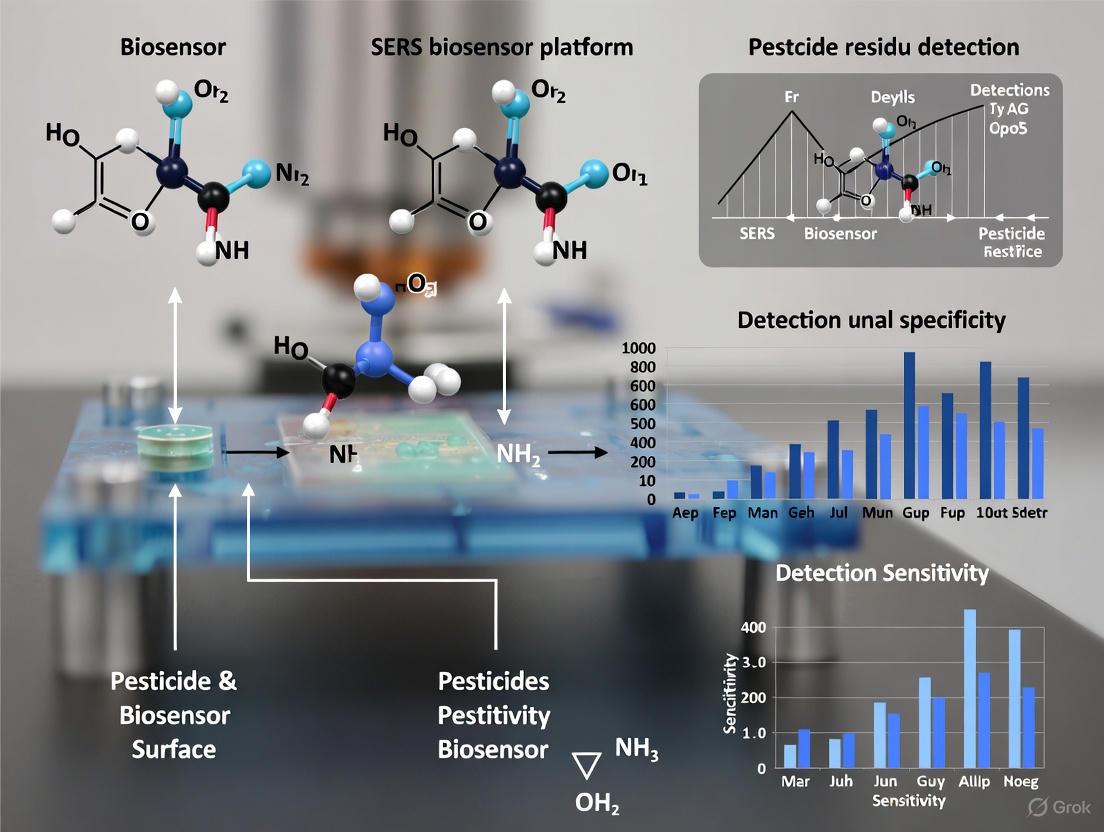

This article comprehensively reviews the development and application of Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS) biosensor platforms for detecting pesticide residues.

SERS Biosensor Platforms for Pesticide Residue Detection: Principles, Advances, and Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article comprehensively reviews the development and application of Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS) biosensor platforms for detecting pesticide residues. It covers the foundational principles of SERS technology and its enhancement mechanisms, explores the integration with biological recognition elements like antibodies and aptamers, and details the design of novel substrates and portable sensors for field application. The content addresses key challenges in selectivity and real-sample analysis, provides comparative validation against traditional chromatographic methods, and discusses the transformative potential of these platforms for ensuring food safety, protecting public health, and their promising future in clinical diagnostics and biomedical research.

Unlocking SERS Technology: Core Principles and the Urgent Need for Advanced Pesticide Detection

Global Pesticide Usage: Scale and Trends

Pesticides are integral to modern agriculture, with global usage patterns revealing significant regional variations in volume and application intensity. The following tables synthesize the most current quantitative data on global pesticide consumption.

Table 1: Top 10 Countries by Total Agricultural Pesticide Use (2023) [1]

| Country | Agricultural Use (tons) | Use per Capita (kg) | Use per Area of Cropland (kg/ha) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brazil | 800,700 | 3.79 | 12.6 |

| United States | 429,500 | 1.25 | 2.78 |

| Indonesia | 294,900 | 1.05 | 6.68 |

| Argentina | 262,500 | 3.87 | 6.33 |

| China | 218,000 | 0.15 | 1.71 |

| Australia | 182,300 | 3.94 | 5.81 |

| Vietnam | 161,900 | 1.61 | 13.9 |

| Russia | 97,000 | 0.67 | 0.78 |

| Canada | 95,600 | 2.43 | 2.5 |

| France | 65,400 | 0.98 | 3.65 |

Table 2: Countries with Highest Application Intensity per Area (2023) [1]

| Country | Use per Area of Cropland (kg/ha) | Agricultural Use (tons) |

|---|---|---|

| Suriname | 38.8 | 2,100 |

| Costa Rica | 17.4 | 9,500 |

| Israel | 17.1 | 6,400 |

| Panama | 14.5 | 9,800 |

| Vietnam | 13.9 | 161,900 |

| South Korea | 13.5 | 20,400 |

| Taiwan | 13.5 | 10,500 |

| Brazil | 12.6 | 800,700 |

| Japan | 10.6 | 45,600 |

| Chile | 9.23 | 17,700 |

The market for agricultural pesticides continues to expand, projected to grow by USD 24.62 billion from 2025 to 2029, with a compound annual growth rate of 4.1% [2]. This growth is fragmented across herbicide, insecticide, and fungicide product types, with herbicides representing a significant segment. Asia-Pacific leads in market contribution at 42%, with Brazil, the U.S., and China among key countries [2].

Human Health Risks: From Acute Toxicity to Chronic Diseases

Pesticide exposure poses significant health threats through multiple pathways, including dietary residue ingestion, occupational exposure, and environmental contamination. The health effects are broadly categorized into acute and chronic manifestations.

Table 3: Health Effects of Major Pesticide Classes [3] [4]

| Pesticide Class | Mechanism of Action | Acute Health Effects | Chronic Health Effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Organophosphates & Carbamates | Inhibit acetylcholinesterase enzyme, disrupting nerve signal transmission | Headaches, nausea, dizziness, vomiting, chest pain, muscle twitching; Severe: convulsions, respiratory failure, coma, death | Neurological damage, developmental disorders, possible links to Parkinson's disease |

| Pyrethroids | Disrupt sodium channels in nerve cells | Tremors, salivation, fatigue, stinging and itching skin, involuntary twitching | Genetic damage, reproductive harm, cardiovascular disease (from biomonitoring data) |

| Soil Fumigants | Broad-spectrum biocides that form toxic gases in soil | Skin, eye, and lung irritation; severe respiratory distress | Cancer, reproductive harm, increased premature birth rates in high-use areas |

| Various | Endocrine disruption | Often asymptomatic at time of exposure | Cancers (leukemia, lymphoma, breast, prostate), birth defects, infertility, developmental disorders |

Vulnerable populations experience disproportionate risks. Children are particularly susceptible due to developing organ systems, higher metabolic rates, increased skin surface area relative to body size, and behaviors that increase exposure [4]. Farm workers and pesticide applicators face elevated exposure risks, with acute pesticide poisoning affecting hundreds of thousands globally each year [4].

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency emphasizes that health risk depends on both pesticide toxicity and exposure level [3]. Regulatory assessments aim for "reasonable certainty of no harm" from pesticide residues on food, establishing usage limits and protective equipment requirements [3].

SERS Biosensor Platform: Principles and Components

Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering (SERS) biosensing has emerged as a powerful analytical technique that combines molecular fingerprint specificity with exceptional sensitivity, detecting trace analytes at the single-molecule level [5]. This technology is particularly suited for pesticide residue detection in complex food matrices, offering significant advantages over traditional chromatographic methods.

Enhancement Mechanisms

SERS operation relies on two primary enhancement mechanisms:

Electromagnetic Enhancement (EM): This mechanism dominates SERS effects, arising from localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) when plasmonic nanostructures interact with electromagnetic radiation [5]. The enhanced electromagnetic fields near nanoparticle surfaces dramatically increase Raman scattering cross-sections, with enhancement factors (EF) reaching 10^10-10^11 for optimal substrates [6].

Chemical Enhancement (CM): This secondary mechanism involves charge transfer between the analyte molecule and substrate surface, which changes the polarizability of the system and increases Raman scattering probability [5].

The overall SERS enhancement factor is proportional to the fourth power of the local field enhancement (EF ∝ |E|^4), explaining the extraordinary sensitivity achievable with optimized substrates [5].

SERS Biosensor Design and Fabrication

SERS biosensors for pesticide detection typically employ a labeled approach using SERS tags, which provide high specificity and semi-quantitative analysis capabilities [5]. These tags are engineered systems with specific functional components:

SERS Tag Fabrication Workflow

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for SERS Biosensor Development [7] [6] [5]

| Component Category | Specific Examples | Function and Properties |

|---|---|---|

| Plasmonic Nanomaterials | Gold nanoparticles (AuNPs), Silver nanoparticles (AgNPs), Gold nanostars (AuNSs), Gold nanorods (AuNRs), Au@Ag core-shell structures | Generate enhanced electromagnetic fields for signal amplification; Noble metals provide tunable plasmon resonance |

| Raman Reporters | Rhodamine derivatives, Crystal Violet, 4-aminothiophenol, Malachite Green, Alkyne-tagged molecules | Provide strong, characteristic Raman fingerprints; Molecules with large Raman cross-sections enhance sensitivity |

| Biorecognition Elements | Acetylcholinesterase (AChE), Antibodies, Aptamers, Molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs) | Provide specific binding to target pesticide molecules; Enzyme-inhibition based detection for organophosphates/carbamates |

| Protective Coatings | Silica shells, Polyethylene glycol (PEG), Alumina coatings, Bovine serum albumin (BSA) | Improve stability in complex matrices; Prevent nonspecific binding; Enhance biocompatibility |

| Signal Transduction Systems | Electrochemical interfaces, Fluorescent-quencher pairs, Colorimetric substrates, Microfluidic chips | Convert molecular recognition into measurable signals; Enable multiplexed detection and point-of-care applications |

Nanomaterial selection significantly influences biosensor sensitivity. Noble metals in isolation (gold: 8.47%; silver: 6.68%) and carbon-based nanomaterials (20.34%) are commonly employed, but nanohybrids (47.45%) that combine multiple materials demonstrate superior performance by leveraging synergistic properties [7].

Experimental Protocols for Pesticide Detection

Protocol: SERS-Based Detection of Organophosphates Using Acetylcholinesterase Inhibition

Principle: Organophosphate and carbamate pesticides inhibit acetylcholinesterase (AChE) activity. This protocol detects pesticide concentration by measuring decreased enzymatic activity with SERS signaling [7].

Materials:

- Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) from electric eel or human recombinant

- Acetylthiocholine iodide or acetylcholine as substrate

- Gold nanoparticles (50-60 nm) synthesized by citrate reduction

- Raman reporter (DTNB or 4-ATP)

- Phosphate buffer (0.1 M, pH 7.4)

- Malathion, chlorpyrifos, or paraoxon as standard organophosphate pesticides

- Food samples: apple, cabbage, fruit juices

Procedure:

SERS Substrate Preparation:

- Synthesize gold nanoparticles by trisodium citrate reduction method (30-60 nm diameter)

- Functionalize AuNPs with Raman reporter (4-ATP, 1 mM, 2h incubation)

- Conjugate AChE enzyme to functionalized AuNPs via EDC-NHS chemistry

- Purify AChE-AuNP conjugates by centrifugation (8,000 rpm, 10 min)

Sample Preparation:

- Homogenize food samples (5 g) in 10 mL acetonitrile

- Extract pesticides by vortexing (2 min) and sonication (15 min)

- Centrifuge at 5,000 rpm for 10 min and collect supernatant

- Evaporate solvent under nitrogen stream and reconstitute in buffer

Inhibition Assay:

- Incubate AChE-AuNP conjugates with sample extract (or standard) for 15 min at 37°C

- Add substrate solution (acetylthiocholine, 2 mM)

- Incubate for 20 min at 37°C

SERS Measurement:

- Transfer reaction mixture to microcuvette or paper-based SERS substrate

- Acquire spectra with Raman spectrometer (785 nm laser, 5s integration)

- Measure characteristic Raman peak intensity (e.g., 4-ATP at 1078 cm⁻¹)

Data Analysis:

- Calculate inhibition percentage: % Inhibition = [(I₀ - I)/I₀] × 100

- Generate calibration curve with pesticide standards (0.1-1000 ppb)

- Determine pesticide concentration in unknown samples

Validation: Compare results with LC-MS/MS reference method. This approach achieves LODs of 19-77 ng L⁻¹ for organophosphates in apple and cabbage matrices [7].

Protocol: Aptamer-Based SERS Detection of Specific Pesticides

Principle: This protocol utilizes pesticide-specific aptamers as recognition elements, offering high specificity for individual pesticides like chlorpyrifos [7].

Aptamer-Based SERS Detection

Materials:

- Chlorpyrifos-specific aptamer (5'-/ThioMC6-D/CCA CGG CGG GTC TTC CGG CGG TGT GGT GTC GTC CGC GTA C-3')

- Gold nanostars (for enhanced hot spots)

- Raman reporter (Malachite Green isothiocyanate)

- Capture DNA complementary to aptamer sequence

- Magnetic beads for separation (optional)

- Food matrices: apple, pak choi, lettuce

Procedure:

SERS Tag Fabrication:

- Synthesize gold nanostars by seed-mediated growth

- Immobilize Raman reporter (10 µM, 12h)

- Passivate with PEG-thiol (1 mM, 1h)

- Conjugate thiolated aptamer to SERS tags via gold-thiol chemistry

Assay Assembly:

- Immobilize capture DNA on solid support or magnetic beads

- Hybridize aptamer-SERS tags with capture probe (30 min, RT)

- Incubate assembled system with sample extract (1h, RT with shaking)

Signal Detection:

- In competitive format, pesticide binding displaces SERS tags

- Measure remaining SERS signal on solid support

- Alternatively, use signal enhancement approach upon binding

Quantification:

- Construct standard curve with chlorpyrifos standards (0.01-100 ppb)

- Calculate concentration in samples from calibration curve

- Achieve LOD of 36 ng L⁻¹ in apple and pak choi [7]

Analytical Performance Comparison

Table 5: Performance Metrics of SERS Biosensors for Pesticide Detection [7]

| Detection Method | Nanomaterial | Biorecognition Element | Target Pesticide | LOD | Food Matrix |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electrochemical | AuNPs | AChE | 11 Organophosphorus + Methomyl | 19-81 ng L⁻¹ | Apple, Cabbage |

| Fluorescent | AuNPs | AChE | Carbamate | 1.0 nM | Fruit |

| Electrochemical | AuNPs | Aptamer | Chlorpyrifos | 36 ng L⁻¹ | Apple, Pak choi |

| Electrochemical | AuNPs | Antibody | Chlorpyrifos | 0.07 ng L⁻¹ | Chinese cabbage, Lettuce |

| Colorimetric | AuNPs | AChE | Organophosphates | 2.48 μg L⁻¹ | Fruit, Vegetables |

All developed biosensors demonstrate limits of detection (LODs) significantly lower than the Codex Alimentarius maximum residue limits, confirming their efficacy for food safety monitoring [7]. Electrochemical transduction dominates applications (71.18%), followed by fluorescent (13.55%) and colorimetric (8.47%) methods [7].

SERS biosensor platforms represent a transformative approach to addressing the global pesticide problem, offering rapid, sensitive, and specific detection capabilities that complement traditional analytical methods. The integration of advanced nanomaterials with biological recognition elements has enabled detection limits meeting stringent food safety requirements while providing potential for field-deployable analysis.

Future developments will focus on multiplexed detection platforms for simultaneous screening of multiple pesticide residues, enhanced field-portability for point-of-care testing, and integration with smartphone-based readout systems for widespread monitoring applications. The combination of SERS technology with emerging artificial intelligence and machine learning algorithms for spectral analysis will further improve detection accuracy and reliability in complex food matrices.

As global pesticide usage continues to evolve, advanced monitoring technologies like SERS biosensors will play an increasingly critical role in protecting human health, ensuring food safety, and promoting sustainable agricultural practices worldwide.

The accurate detection of pesticide residues is a cornerstone of environmental safety, food security, and public health. For decades, the analytical landscape has been dominated by traditional techniques, primarily chromatography-based methods and immunoassays. While these are considered reference standards, they possess inherent limitations that hinder their efficacy for rapid, on-site, and high-throughput screening. This application note delineates the critical constraints of Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS), Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS), and Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA), thereby framing the necessity for advanced sensing platforms like Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering (SERS) biosensors in modern pesticide residue analysis.

Quantitative Comparison of Traditional vs. SERS Methods

The following table summarizes the key performance metrics and limitations of traditional methods alongside the emerging potential of SERS biosensors.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Pesticide Residue Detection Methods [8] [9]

| Method | Typical Detection Limit | Analysis Time | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GC-MS / LC-MS | 0.001 - 0.01 μg·kg⁻¹ [9] | Several hours [9] | High accuracy and sensitivity; Reliable for a wide range of pesticides [9] | Expensive, bulky instrumentation; Requires skilled technicians; Time-consuming sample preparation; Not portable [9] |

| ELISA | Varies (e.g., ~300-500 PFU mL⁻¹ for LFA) [10] | < 15 min (LFA) to hours (ELISA) [10] | Cost-effective; Rapid; Suitable for high-throughput screening [11] | Can produce false-positive results [11]; Insufficient sensitivity for early-stage infection/detection [10]; Limited multiplexing capability |

| SERS | Ultralow concentrations (e.g., 10 pg mL⁻¹ for aflatoxin) [11] | Minutes to rapid prediction (30-50 ms) [11] | High sensitivity and specificity; Rapid analysis; Portable; Molecular "fingerprint" specificity; Potential for multiplexing [12] [13] | Faces reproducibility challenges; Requires robust substrate fabrication and data processing [8] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

This protocol is adapted for detecting multi-class pesticides (e.g., triazophos, carbofuran) in complex botanical samples like Chuanxiong rhizoma.

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Extraction Solvent: Acetonitrile or Acetonitrile/Acetone mixture.

- Purification Sorbent: Primary Secondary Amine (PSA), C18, or Graphitized Carbon Black (GCB).

- Mobile Phases: (A) High-purity water with 0.1% Formic Acid; (B) Methanol or Acetonitrile with 0.1% Formic Acid.

- Analytical Standards: Certified reference standards for target pesticides.

Procedure:

- Homogenization: Precisely weigh 2.0 g of the homogenized herbal medicine sample into a 50 mL centrifuge tube.

- Extraction: Add 10 mL of acetonitrile and shake vigorously for 1 minute. Add a salt mixture (e.g., MgSO₄, NaCl) for partitioning, shake immediately, and centrifuge at 4000 rpm for 5 minutes.

- Purification (dSPE): Transfer 1.5 mL of the supernatant extract to a 2 mL micro-centrifuge tube containing 150 mg MgSO₄ and 25 mg PSA. Vortex for 1 minute and centrifuge.

- Concentration: Transfer the purified supernatant to a new vial and evaporate under a gentle nitrogen stream. Reconstitute the residue in 1 mL of initial mobile phase (e.g., water/methanol, 95:5) and filter through a 0.22 μm membrane.

- LC-MS/MS Analysis:

- Column: C18 reversed-phase column (e.g., 2.1 x 100 mm, 1.8 μm).

- Gradient: 5% B to 95% B over 15 minutes.

- Flow Rate: 0.3 mL/min.

- Ionization: Electrospray Ionization (ESI), positive mode.

- Detection: Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM). Quantify against a 5-point calibration curve of analytical standards.

This protocol outlines a stable and rapid SERS strategy for pesticide detection, integrating multi-dimensional data and supervised learning.

Research Reagent Solutions:

- SERS Substrate: Three-dimensional (3D) gold nanotrees electrodeposited on ITO slides [11] or silver nanoflower-based substrates [8].

- Raman Reporter: Not applicable for direct, label-free detection of pesticides.

- Extraction Solvent: Ethyl acetate or QuEChERS-based extraction mix.

- Chemometrics Software: Python with Scikit-learn, MATLAB, or proprietary PLS toolboxes.

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Extract the pesticide from a 1 g food/herbal sample using a suitable solvent. A simplified QuEChERS method can be employed, with or without a cleanup step, depending on the matrix complexity.

- SERS Substrate Immersion: Deposit 2 μL of the purified extract onto the 3D gold nanotree SERS substrate and allow it to dry at room temperature.

- SERS Mapping Data Acquisition:

- Instrument: A Raman microscope system with a 785 nm or 633 nm laser.

- Settings: Laser power: 1-10 mW; Integration time: 1-5 seconds; Grating: 600-1200 lines/mm.

- Acquisition: Collect SERS spectra in mapping mode over a predefined area (e.g., 20 x 20 μm) to generate a comprehensive dataset comprising both 1D spectral data and 2D mapping images [11].

- Data Pre-processing: Preprocess the raw spectral data using Standard Normal Variate (SNV) normalization to correct for scattering effects, followed by Savitzky-Golay smoothing.

- Model Building and Prediction:

- Data Fusion: Integrate the normalized 1D spectral and 2D mapping data.

- Variable Selection: Apply variable selection algorithms like Variable Combination Population Analysis-Iteratively Retaining Informative Variables (VCPA-IRIV) to compress the variable space and retain key information [11].

- Quantification: Build a predictive model using Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression on the selected variables. The optimized model can achieve rapid prediction within 30-50 ms for unknown samples [11].

Workflow and Signaling Visualization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Materials for SERS-Based Pesticide Detection Research [11] [10] [13]

| Item | Function/Description | Research Context |

|---|---|---|

| 3D Gold Nanotrees | SERS substrate with high hotspot uniformity, fabricated via electrodeposition. | Provides stable and reproducible signals for quantitative analysis [11]. |

| Core-Satellite Nanotags (CS@SiO₂) | Functional SERS nanotags with controllable internal "hot spots" for intense, reproducible signals. | Used in highly sensitive, indirect SERS-based immunoassays [10]. |

| QuEChERS Kits | Quick, Easy, Cheap, Effective, Rugged, Safe. A standardized sample preparation method. | For efficient extraction and clean-up of pesticides from complex food/herbal matrices [9]. |

| Raman Microscope System | Instrument for acquiring SERS spectra and mapping images. Typically equipped with 785 nm laser. | Enables collection of multi-dimensional SERS data (1D spectra + 2D maps) [11]. |

| Machine Learning Toolboxes | Software libraries (e.g., in Python, MATLAB) for chemometric analysis. | Used for spectral preprocessing, feature selection (e.g., VCPA-IRIV), and predictive modeling (e.g., PLS) [11] [13]. |

The limitations of chromatography and ELISA—including their lack of portability, prolonged analysis time, complex operation, and in the case of ELISA, limited sensitivity and potential for false positives—create a significant analytical gap. Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering (SERS) biosensor platforms emerge as a powerful alternative, offering a path toward rapid, sensitive, and on-site detection. By integrating advanced nanomaterials, portable instrumentation, and machine learning for data analysis, SERS technology holds the promise of transforming pesticide residue monitoring, ensuring greater efficacy and safety across the agricultural and pharmaceutical supply chains.

Surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS) has evolved over fifty years into a powerful analytical technique that dramatically amplifies the inherently weak Raman scattering signal from molecules adsorbed on or near nanostructured surfaces [14]. The exceptional sensitivity of SERS, capable of detecting molecules at trace levels relevant for pesticide residue analysis, originates from two primary enhancement mechanisms: the electromagnetic enhancement (EM) and the chemical enhancement (CM) [15] [16]. These mechanisms can operate independently or synergistically to boost the Raman signal by several orders of magnitude, enabling the detection of organophosphorus pesticides (OPPs) at concentrations as low as the sub-μg L−1 to low μg L−1 range in complex food matrices [15]. A profound understanding of both EM and CM is fundamental to designing effective SERS biosensor platforms for agricultural and food safety monitoring.

Electromagnetic Enhancement (EM) Mechanism

The electromagnetic enhancement mechanism is universally acknowledged as the dominant contributor, responsible for the majority of the signal intensity gain in SERS, often providing enhancement factors of 10^6 or higher [15] [16].

Physical Basis and Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance (LSPR)

The EM mechanism is rooted in the localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) phenomenon exhibited by noble metal nanostructures, typically of gold (Au), silver (Ag), and copper [15]. When incident laser light illuminates these nanostructures, its frequency matches the collective oscillation frequency of the conduction electrons at the metal surface. This resonance drives the coherent oscillation of these electrons, generating intensely localized electromagnetic fields, particularly at sharp edges, tips, and within nanoscale gaps between particles [17] [18]. These regions of concentrated field are famously termed "hot spots" [15].

Enhancement Factor and "Hot Spots"

The Raman scattering intensity for a molecule located within such a hot spot is proportional to the fourth power of the local electric field enhancement (E/E₀) [17]. This relationship is expressed as EF_EM ∝ |E/E₀|^4. Consequently, even a modest increase in the local electric field can produce an enormous enhancement of the Raman signal. The primary goal of SERS substrate engineering is to create substrates with a high density of reproducible and stable hot spots. For instance, nanogaps as small as 6-8 nanometers fabricated on wafer-scale substrates have demonstrated a maximum analytical enhancement factor (AEF) of 6.9 × 10^6 due to plasmonic resonances concentrated at these narrow gaps [18].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of the Electromagnetic Enhancement Mechanism

| Feature | Description | Implication for SERS Substrate Design |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Source | Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance (LSPR) | Use materials with strong LSPR (Ag, Au, Cu) |

| Enhancement Factor | Proportional to the fourth power of the local field, ∣E/E₀∣⁴ | Focus on creating high local field intensities |

| Enhancement Range | Long-range (1-10 nm); does not require direct chemical contact | Molecules need only be proximal to the metal surface |

| "Hot Spots" | Regions of intense field confinement (nanogaps, sharp tips) | Engineer nanostructures with narrow gaps and sharp features |

| Material Dependence | Noble metals (Ag typically shows the strongest effect) [19] | Ag is often the material of choice for maximum sensitivity |

Chemical Enhancement (CM) Mechanism

The chemical enhancement mechanism, while generally contributing a smaller effect (typically 10-10^3-fold), provides crucial molecular specificity and complements the EM mechanism [16].

Charge Transfer and Resonance Effects

The CM mechanism involves a short-range, chemical interaction that requires the target molecule to be directly adsorbed onto the metal surface or a suitable semiconducting material [16]. It is primarily governed by a charge-transfer (CT) process. Upon adsorption, a complex is formed between the molecule and the substrate, leading to the creation of new electronic states. When the incident light resonates with the energy required for electron transfer between the Fermi level of the substrate and the molecular orbitals, the polarizability of the adsorbed molecule changes, resulting in enhanced Raman scattering [16]. This process is sometimes referred to as photo-induced charge transfer (PICT) [16].

Molecular Specificity and Functional Group Interactions

The CM mechanism is highly dependent on the specific chemical identity of the analyte and its interaction with the substrate. In the context of pesticide detection, specific functional groups in organophosphorus pesticides—such as P=O and P=S groups, aromatic rings, and halogen substituents—play a critical role [15]. These groups can form coordination bonds or engage in π–π stacking with the substrate, leading to a stronger CM contribution and more distinct spectral fingerprints [15]. Two-dimensional materials like MXene (e.g., Ti₃C₂Tₓ) are particularly effective at inducing CM due to their ability to form specific complexes with many molecules, facilitating strong charge transfer [16].

Diagram 1: CM involves charge transfer between molecule and substrate.

Synergistic Enhancement and Combined Substrates

The most powerful SERS substrates are those that effectively harness both EM and CM simultaneously, leading to a synergistic effect where the total enhancement is greater than the sum of the individual contributions.

Hybrid Substrates for Maximum Sensitivity

A prime example of this synergy is the Ti₃C₂Tₓ/AgNPs composite substrate [16]. In this system:

- The Ag nanoparticles (AgNPs) provide a strong electromagnetic enhancement through their LSPR, creating abundant hot spots.

- The MXene (Ti₃C₂Tₓ) nanosheets contribute a significant chemical enhancement due to their high affinity for target molecules and efficient charge transfer capability.

This combination resulted in an extraordinary total enhancement factor of 3.8 × 10⁸ for the probe molecule rhodamine 6G (R6G). The study quantified the synergistic interaction through a "coupling factor (CF)" of 33.6%, demonstrating that the integration of both mechanisms is a highly effective strategy for developing ultra-sensitive SERS platforms [16].

Table 2: Comparison of SERS Enhancement Mechanisms

| Aspect | Electromagnetic (EM) | Chemical (CM) |

|---|---|---|

| Enhancement Factor | 10⁶ - 10⁸ (Dominant) | 10 - 10³ (Supplementary) |

| Range of Action | Long-range (1-10 nm) | Short-range (requires chemisorption) |

| Material Dependence | Noble metals (Ag, Au, Cu) | Metals & semiconductors (e.g., MXene) |

| Molecular Specificity | Low; any molecule in hot spot is enhanced | High; depends on chemical bonding |

| Primary Mechanism | Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance | Charge Transfer & Resonance |

| Key for Pesticides | General signal amplification | Fingerprinting via P=O, P=S groups [15] |

Experimental Protocols for SERS Substrate Evaluation

Protocol: Fabrication and Testing of a Ti₃C₂Tₓ/AgNPs Hybrid Substrate

This protocol outlines the creation of a synergistic SERS substrate for ultra-sensitive detection, adapted from recent research [16].

1. Reagents and Materials:

- Ti₃C₂Tₓ MXene nanosheet solution (commercially available)

- Silver nitrate (AgNO₃), Sodium borohydride (NaBH₄)

- Cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB)

- Rhodamine 6G (R6G) or target analyte (e.g., pesticide standard)

- High-purity water and ethanol

2. Synthesis of CTAB-capped Ag Nanoparticles (AgNPs): a. Prepare an aqueous solution of AgNO₃ (0.1 M) and keep it on ice. b. In a separate flask, dissolve CTAB (0.1 M) in warm water. c. Rapidly add the ice-cold AgNO₃ solution to the CTAB solution under vigorous stirring (1200 rpm). d. Immediately add a freshly prepared, ice-cold NaBH₄ solution (0.1 M) dropwise. The solution will turn bright yellow. e. Continue stirring for 10 minutes. The resulting positively charged AgNPs are stable for weeks.

3. Electrostatic Self-Assembly of Ti₃C₂Tₓ/AgNPs Composite: a. Step 1: Dilute the commercially acquired Ti₃C₂Tₓ solution (negatively charged) to a concentration of 0.1 mg/mL. b. Step 2: Mix the Ti₃C₂Tₓ solution with the positively charged AgNPs solution in a 1:1 volume ratio. c. Step 3: Stir the mixture gently for 2 hours at room temperature to allow electrostatic self-assembly. The composite can be drop-casted onto a silicon wafer or glass slide and dried under nitrogen for use as a solid substrate.

4. SERS Measurement Procedure: a. Apply 1-2 µL of the analyte solution (e.g., R6G or extracted pesticide) onto the dry Ti₃C₂Tₓ/AgNPs substrate. b. Allow the droplet to air-dry completely. c. Place the substrate under the Raman microscope. d. Acquisition Parameters: Use a 633 nm laser excitation wavelength, 1-10 seconds integration time, and 1-5 accumulations. Laser power should be optimized to avoid sample degradation. e. Collect spectra from at least 10 random spots on the substrate to assess homogeneity and signal reproducibility.

Protocol: Standardized SERS Analysis of Complex Samples

Lack of standardization is a major challenge in SERS. This protocol provides a framework for consistent analysis of complex samples like serum or food extracts, based on a comparative study [20].

1. Sample Pre-treatment:

- Option A (Direct Mixing): Mix the liquid sample (e.g., fruit juice) 1:1 with a concentrated colloidal AgNP or AuNP solution. Vortex for 30 seconds and proceed to measurement.

- Option B (Deproteinization for complex biofluids): Add acetonitrile (2:1 ratio to sample) to precipitate proteins. Centrifuge at 10,000 rpm for 10 minutes. Use the supernatant for SERS analysis via Option A.

2. Substrate and Measurement Consistency:

- Substrate: Use a single, well-characterized batch of nanoparticles or a solid substrate to minimize batch-to-batch variability.

- Internal Standard: For quantitative analysis, consider spiking the sample with a known compound (e.g., 4-mercaptobenzoic acid) that provides a stable Raman peak, to normalize variations.

- Laser Power: Keep laser power consistent across all measurements (typically 0.1-5 mW for bio/sensitive samples) to prevent thermal damage.

- Calibration: Perform a daily calibration of the Raman spectrometer using a silicon wafer (peak at 520.7 cm⁻¹).

3. Data Collection and Analysis:

- Collect a minimum of 20 spectra per sample from different spots.

- Pre-process spectra: subtract background fluorescence (e.g., polynomial fitting), normalize, and smooth if necessary.

- Use multivariate statistical analysis, such as Principal Component Analysis (PCA), to identify spectral patterns and assess repeatability [20].

Diagram 2: Workflow for evaluating SERS substrate performance.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for SERS Biosensor Development

| Reagent/Material | Function in SERS Experiment | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Gold (Au) Nanoparticles | Provides EM enhancement; highly stable and biocompatible. | Commonly used with 633 nm or 785 nm lasers. Functionalized with aptamers for specificity [19]. |

| Silver (Ag) Nanoparticles | Provides the strongest EM enhancement; highest sensitivity. | Can oxidize over time. Often used with a 532 nm laser for maximum enhancement [19]. |

| MXene (Ti₃C₂Tₓ) | 2D material providing strong CM; enables charge transfer. | Negatively charged surface allows electrostatic assembly with metal NPs [16]. |

| Aptamers | Single-stranded DNA/RNA recognition elements for specific pesticide binding. | Selected via SELEX; offer high stability and specificity for target pesticides [19]. |

| Rhodamine 6G (R6G) | Standard probe molecule for evaluating SERS substrate performance. | Provides a strong, characteristic Raman signal; used to calculate Enhancement Factor (EF). |

| Cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) | Surfactant and stabilizing agent for nanoparticle synthesis. | Forms a bilayer on AgNPs, conferring a positive charge for self-assembly [16]. |

The formidable detection power of SERS in pesticide residue analysis stems from the nuanced interplay between the electromagnetic and chemical enhancement mechanisms. The EM mechanism, driven by plasmonic nanostructures and their generated hot spots, provides the bulk of the signal amplification. The CM mechanism, arising from specific chemical adsorption and charge transfer, adds a critical layer of molecular specificity, which is essential for identifying target functional groups in pesticides like OPPs. The future of SERS biosensors lies in the rational design of hybrid substrates that synergistically combine both mechanisms, as demonstrated by the Ti₃C₂Tₓ/AgNPs composite. When coupled with standardized experimental protocols and innovative recognition elements like aptamers, these advanced substrates are poised to transition SERS from a powerful laboratory technique into a reliable, robust, and practical platform for ensuring food safety and protecting public health.

Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS) has emerged as a powerful analytical technique that combines molecular fingerprint specificity with trace-level sensitivity, making it particularly valuable for detecting pesticide residues in complex food and environmental matrices [12] [21]. This technique leverages plasmonic nanostructures to amplify the Raman signal of target molecules by many orders of magnitude, enabling the detection of chemical species at ultralow concentrations [22]. The resulting SERS spectrum provides a unique vibrational fingerprint that allows for precise identification of molecular structures, even in mixed analyte environments [23].

The fundamental principle underlying SERS involves the excitation of localized surface plasmon resonances in metallic nanostructures, typically gold or silver, when illuminated with visible or near-infrared light [21]. This phenomenon creates intensely localized electromagnetic fields at "hot spots" - nanoscale gaps between nanoparticles - where the Raman signal of molecules positioned within these regions can be enhanced by factors of 10⁴ to 10¹⁰ [22] [21]. This extraordinary sensitivity, coupled with the inherent molecular specificity of Raman spectroscopy, positions SERS as an ideal platform for biosensor development in food safety applications, particularly for monitoring hazardous substances like pesticides [22].

Recent advancements in SERS biosensing have focused on integrating biological recognition elements such as antibodies, aptamers, and molecularly imprinted polymers with plasmonic nanosystems to create platforms with enhanced selectivity and affinity for target pesticides [22] [21]. These developments are driving the transformation of SERS technology from a laboratory technique to a practical tool for point-of-care testing and environmental monitoring outside specialized labs [12].

The Molecular Fingerprint Advantage of SERS

Fundamental Principles of Spectral Specificity

The exceptional molecular specificity of SERS stems from its basis in Raman spectroscopy, which probes the vibrational energy levels of molecules. When light interacts with a molecule, a tiny fraction (approximately 1 in 10⁷ photons) undergoes inelastic scattering, with energy shifts corresponding to the molecule's vibrational modes [23]. These energy shifts create a spectral pattern unique to each chemical compound, serving as a molecular fingerprint that enables definitive identification [12].

SERS magnifies this inherently weak Raman effect by leveraging the plasmonic properties of metallic nanostructures. The enhancement mechanism operates through two primary pathways: electromagnetic enhancement and chemical enhancement. The electromagnetic mechanism, which accounts for the majority of the signal intensification (up to 10⁸-fold), results from the localized surface plasmon resonance effect when incident light couples with conduction electrons in noble metal nanostructures [21]. The chemical mechanism, contributing enhancement factors of 10-10⁴, involves charge transfer between the analyte molecules and the metal surface, which can alter the polarizability of the molecules and further enhance the Raman signal [21].

Table 1: Comparison of SERS with Other Common Analytical Techniques for Pesticide Detection

| Technique | Detection Principle | Sensitivity | Molecular Specificity | Analysis Time | Equipment Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SERS | Inelastic light scattering enhanced by plasmonics | Very High (single molecule possible) | Very High (fingerprint spectra) | Minutes | Moderate |

| HPLC/GC | Chromatographic separation with various detectors | High | Moderate | Hours | High |

| ELISA | Antibody-antigen recognition | High | High | Hours | Low-Moderate |

| Fluorescence | Light emission from excited states | High | Moderate | Minutes | Moderate |

SERS Biosensor Platforms for Pesticide Detection

The integration of SERS with biological recognition elements has led to the development of sophisticated biosensor platforms specifically designed for pesticide residue detection [22]. These platforms combine the unmatched sensitivity and fingerprinting capability of SERS with the molecular recognition properties of bioreceptors, creating systems capable of selectively identifying and quantifying specific pesticides in complex sample matrices [22] [21].

Common biological recognition elements employed in SERS biosensors include:

- Antibodies: Immunoglobulin proteins that bind specifically to target pesticides or pesticide classes with high affinity [22]

- Aptamers: Single-stranded DNA or RNA oligonucleotides that fold into specific three-dimensional structures capable of binding target molecules with antibody-like specificity [22] [23]

- Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs): Synthetic polymers containing tailor-made binding sites complementary to the target pesticide molecules in shape, size, and functional groups [23]

- Enzymes: Biological catalysts whose activity is inhibited by specific classes of pesticides, enabling indirect detection [23]

The synergy between these recognition elements and SERS detection creates a powerful analytical platform. The biological component provides selective capture and concentration of the target pesticide from complex samples, while the SERS substrate enables sensitive, multiplexed detection based on the unique vibrational fingerprints of the captured analytes [22].

Diagram Title: SERS Enhancement Mechanism

Quantitative Performance of SERS in Pesticide Detection

Analytical Sensitivity and Detection Limits

SERS has demonstrated exceptional performance in the detection of various pesticide classes, consistently achieving detection limits at parts-per-billion (ppb) or even parts-per-trillion (ppt) levels, which surpass regulatory requirements for many agricultural commodities [24] [25]. The remarkable sensitivity of SERS platforms enables the monitoring of pesticide residues at concentrations significantly below the maximum residue limits (MRLs) established by food safety authorities worldwide.

Recent developments in substrate engineering and detection strategies have further pushed the boundaries of SERS sensitivity. For instance, a novel SERS imaging approach utilizing borohydride-reduced silver nanoparticles achieved detection of pesticide residues at levels below 1 picogram per milliliter (pg/mL) [25]. Another study reported an enhancement factor of 10⁸ and a detection limit lower than 10⁻¹⁰ M (0.1 ppb) for various pesticides dispersed in colloids [24].

Table 2: SERS Detection Performance for Various Pesticide Classes

| Pesticide Class | Example Compounds | Detection Limit | SERS Substrate | Linear Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organophosphates | Chlorpyrifos, Dimethoate | 0.1-1 ppb | Ag@BOCMNPs [24] | 0.1-1000 ppb |

| Carbamates | Thiram, Carbaryl | 0.05-0.5 ppb | Ag NPs [24] | 0.05-500 ppb |

| Pyrethroids | Cypermethrin, Permethrin | 0.1-2 ppb | Au/Ag NPs [25] | 0.1-2000 ppb |

| Neonicotinoids | Acetamiprid, Imidacloprid | 0.01-0.1 ppb | Ag NPs [24] | 0.01-100 ppb |

| Benzimidazoles | Thiabendazole | 0.05 ppb | Ag@BOCMNPs [24] | 0.05-800 ppb |

Multiplex Detection Capability

A significant advantage of SERS over many other analytical techniques is its capacity for multiplex detection - simultaneously identifying and quantifying multiple pesticide residues in a single analysis [22]. This capability stems from the narrow spectral bandwidths of Raman peaks (typically 1-10 cm⁻¹), which minimizes peak overlap and enables clear discrimination between different pesticides even in complex mixtures [22].

Studies have successfully demonstrated the simultaneous detection and quantitative analysis of mixed pesticides using SERS, with excellent linearity (r² = 0.9983) across concentration ranges relevant to food safety monitoring [24]. The fingerprint specificity of SERS spectra allows for the deconvolution of spectral contributions from multiple pesticides, enabling comprehensive screening of agricultural products for compliance with food safety regulations [22] [24].

The combination of SERS with advanced chemometric methods such as vertex component analysis (VCA) and Euclidean distance (ED) methods further enhances the ability to identify and quantify multiple pesticide residues in complex sample matrices [24]. These computational approaches facilitate the extraction of meaningful information from SERS spectral data, enabling accurate identification of pesticide residues even in the presence of interfering compounds from the food matrix [24].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: SERS-Based Detection of Multiplex Pesticide Residues on Crop Surfaces

This protocol describes a method for detecting and visualizing multiple pesticide residues on the surface of fruits and vegetables using a sprayable SERS substrate and Raman imaging [24].

Materials and Reagents

- Silver nitrate (99.9%)

- Sodium borohydride (99.99%)

- Methanol (HPLC grade)

- Target pesticides (thiabendazole, thiram, acetamiprid, chlorpyrifos)

- Fresh produce (apples, grapes, pears, oranges, cucumbers, tomatoes)

- Deionized water (18.2 MΩ·cm)

SERS Substrate Preparation

- Add 5 mL of 0.35 M sodium borohydride to 490 mL deionized water in a clean glass container.

- Stir the mixture vigorously at 500 rpm using a magnetic stirrer while maintaining temperature at 25°C.

- Slowly add 5 mL of 0.1 M silver nitrate solution dropwise to the stirring mixture over 5 minutes.

- Continue stirring for an additional 30 minutes until a homogeneous pale yellow colloidal suspension forms.

- Characterize the nanoparticles using TEM to confirm size distribution (expected range: 20-50 nm) and UV-Vis spectroscopy to verify plasmon resonance peak (~400 nm).

Sample Preparation and SERS Measurement

- Prepare standard solutions of individual pesticides and pesticide mixtures in methanol at concentrations ranging from 0.1 ppb to 1000 ppb.

- For real samples, collect fruits/vegetables from local markets and rinse gently with deionized water to remove surface debris.

- Apply pesticide standards or naturally contaminated samples to crop surfaces and allow to dry for 15 minutes.

- Spray the Ag nanoparticle substrate uniformly onto the crop surfaces using an atomizer from a distance of 15 cm.

- Allow the substrate to dry for 5 minutes under ambient conditions.

- Acquire SERS spectra using a Raman spectrometer with the following parameters:

- Laser wavelength: 785 nm

- Laser power: 10 mW

- Integration time: 10 seconds

- Spectral range: 400-1800 cm⁻¹

- For SERS imaging, set the mapping resolution to 1 μm step size and collect spectra at each position.

Data Analysis

- Preprocess spectra by subtracting background fluorescence using asymmetric least squares algorithm.

- Normalize spectra to the most intense peak for comparative analysis.

- For multiplex detection, use vertex component analysis (VCA) to identify spectral contributions from different pesticides.

- Apply Euclidean distance (ED) methods to classify and visualize pesticide distribution on crop surfaces.

- Generate quantitative models using partial least squares regression (PLSR) for concentration prediction.

Diagram Title: SERS Imaging Workflow

Protocol 2: SERS Biosensor for Selective Pesticide Detection Using Aptamer Recognition

This protocol describes the development of a SERS biosensor that incorporates aptamers as biological recognition elements for selective pesticide detection [22] [23].

Materials and Reagents

- Gold nanoparticles (20 nm diameter)

- Thiol-modified aptamers specific for target pesticides

- Magnesium chloride (MgCl₂)

- Phosphate buffered saline (PBS, 10 mM, pH 7.4)

- Raman reporter molecules (e.g., 4-aminothiophenol, malachite green isothiocyanate)

- Target pesticides and structurally similar analogs for selectivity testing

Aptamer Functionalization of SERS Substrate

- Dilute thiol-modified aptamers to 1 μM concentration in PBS buffer containing 1 mM MgCl₂.

- Heat the aptamer solution to 95°C for 5 minutes, then gradually cool to room temperature over 30 minutes to facilitate proper folding.

- Mix the folded aptamers with gold nanoparticle suspension at a molar ratio of 200:1 (aptamer:nanoparticle).

- Incubate the mixture for 16 hours at 4°C with gentle shaking to allow self-assembly of aptamers on gold surface.

- Centrifuge the functionalized nanoparticles at 12,000 rpm for 15 minutes to remove unbound aptamers.

- Resuspend the pellet in PBS buffer and characterize using dynamic light scattering to verify functionalization.

SERS Detection Procedure

- Incubate the aptamer-functionalized SERS substrate with samples containing target pesticides for 30 minutes at room temperature.

- For competitive assays, pre-incubate aptamers with Raman reporter molecules before introducing target pesticides.

- Wash the substrate gently with PBS buffer to remove non-specifically bound molecules.

- Acquire SERS spectra using a Raman microscope with the following parameters:

- Laser wavelength: 633 nm

- Laser power: 5 mW

- Integration time: 5 seconds

- Accumulations: 3

- Measure signal intensity at characteristic peaks specific to the Raman reporter or the pesticide molecules.

Data Interpretation

- Plot calibration curves of SERS intensity versus pesticide concentration.

- Calculate detection limit based on 3σ/slope, where σ is the standard deviation of blank measurements.

- Evaluate selectivity by testing against structurally similar pesticides and calculating cross-reactivity.

- Determine recovery rates by spiking known pesticide concentrations into real samples (e.g., fruit extracts).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for SERS Biosensor Development

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Specifications | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gold Nanoparticles | Plasmonic substrate for SERS enhancement | 20-60 nm diameter, OD₁ = 1 in aqueous suspension | Tunable plasmon resonance based on size and shape [21] |

| Silver Nanoparticles | High enhancement SERS substrate | 30-50 nm diameter, citrate stabilized | Higher enhancement than Au but less stable [24] |

| Aptamers | Biological recognition elements | Thiol-modified, HPLC purified, >80% purity | Require proper folding in binding buffer [22] |

| Antibodies | Immunorecognition elements | Monoclonal, pesticide-specific, >95% purity | Orientation control crucial for binding efficiency [22] |

| Raman Reporters | Signal generation in indirect assays | 4-MBA, 4-ATP, MGITC, >95% purity | Must have strong affinity for metal surface [21] |

| Magnetic Nanoparticles | Sample preconcentration | Fe₃O₄@SiO₂@Au core-shell, 100-200 nm | Enable separation and concentration from complex matrices [21] |

The molecular fingerprint specificity of SERS spectra represents a powerful advantage for pesticide residue detection in complex food matrices. By providing unique vibrational signatures for each chemical compound, SERS enables precise identification and quantification of multiple pesticide residues simultaneously, addressing a critical need in food safety monitoring. The integration of SERS with biological recognition elements creates biosensor platforms that combine unmatched sensitivity with high selectivity, capable of detecting pesticides at concentrations significantly below regulatory limits.

Recent advancements in substrate design, imaging capabilities, and data analysis methods have further enhanced the practical utility of SERS for pesticide monitoring. The development of sprayable substrates, portable instruments, and robust computational algorithms is transforming SERS from a laboratory technique to a practical tool for field-deployable pesticide detection [24] [25]. These innovations, coupled with the inherent advantages of fingerprint specificity, sensitivity, and multiplexing capability, position SERS as a transformative technology that will continue to advance food safety and environmental monitoring.

Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS) represents a powerful analytical technique that combines molecular fingerprint specificity with the capability to detect trace amounts of analytes [12]. The integration of SERS with highly specific biological recognition elements, such as antibodies and aptamers, has given rise to a new generation of biosensors that are revolutionizing detection capabilities across multiple fields, including biomedical diagnostics, food safety, and environmental monitoring [22]. These SERS biosensors leverage the unique properties of plasmonic nanomaterials to significantly enhance Raman signals while incorporating the exceptional selectivity of biological binding molecules, creating platforms capable of identifying and quantifying target substances with unprecedented sensitivity and specificity [12] [22]. This application note explores the fundamental principles, recent advancements, and practical implementation of SERS biosensors incorporating antibodies and aptamers, with a specific focus on applications in pesticide residue detection research.

Principles of SERS Biosensing

SERS Enhancement Mechanisms

The remarkable sensitivity of SERS stems from two primary enhancement mechanisms: electromagnetic enhancement and chemical enhancement [26]. The electromagnetic mechanism (EM), regarded as the dominant contributor, is driven by localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) occurring on metallic nanostructures, typically gold or silver [26]. When plasmonic nanoparticles are illuminated with light at appropriate wavelengths, collective oscillations of conduction electrons are excited, generating intensely localized electromagnetic fields known as "hot spots" [26]. These hot spots, particularly those occurring in nanoscale gaps between particles, can enhance Raman signals by factors of 10⁶–10⁸, enabling single-molecule detection under optimal conditions [26]. The chemical mechanism (CM), contributing a smaller but significant enhancement (10²–10³), arises from charge-transfer complexes formed when analyte molecules directly adsorb to or chemically bond with the metal surface [26].

Biological Recognition Elements

The specificity of SERS biosensors is conferred by biological recognition elements that selectively capture target analytes. Antibodies provide exceptional specificity through immunoaffinity interactions, forming the basis for numerous commercial diagnostic assays [22]. Aptamers, short single-stranded DNA or RNA molecules selected through Systematic Evolution of Ligands by EXponential enrichment (SELEX), offer a promising alternative to antibodies [27]. Aptamers demonstrate several advantageous properties, including superior stability, synthetic production capabilities, ease of modification, and the ability to be selected against a wide range of targets from small molecules to entire cells [27]. The combination of these biological recognition elements with SERS detection creates biosensors that simultaneously offer high sensitivity, specificity, and the capability for multiplexed analysis [22].

Table 1: Comparison of Biological Recognition Elements for SERS Biosensors

| Feature | Antibodies | Aptamers |

|---|---|---|

| Production | Biological systems (animals/hybridomas) | Chemical synthesis |

| Stability | Moderate (sensitive to temperature, pH) | High (thermal stability, can be regenerated) |

| Modification | Limited, primarily through amino groups | Versatile, precise positioning of functional groups |

| Cost | Relatively high | Lower, scalable production |

| Target Range | Primarily immunogenic molecules | Broad (ions, small molecules, proteins, cells) |

| Development Time | Months | Weeks (after SELEX establishment) |

SERS Biosensor Platforms for Pesticide Residue Detection

SERS-Antibody Biosensors

The integration of antibodies with SERS platforms has created highly specific sensors for pesticide detection. These biosensors typically employ a sandwich immunoassay format where capture antibodies immobilized on a solid support selectively bind target pesticides, followed by detection with antibody-conjugated SERS tags [22]. This approach leverages the well-established specificity of immunoassays while overcoming the sensitivity limitations of traditional methods like ELISA through the signal amplification provided by SERS nanotags [22]. The SERS nanotags typically consist of gold or silver nanoparticles functionalized with Raman reporter molecules and detection antibodies, creating highly sensitive probes that accumulate at test lines or detection zones in the presence of target analytes [28].

Recent innovations in this area include the development of paper-based SERS immunoassays that offer point-of-care capabilities. For instance, lateral flow assays (LFA) combined with SERS detection provide user-friendly platforms that meet WHO ASSURED criteria (Affordable, Sensitive, Specific, User-friendly, Rapid/Robust, Equipment-free, and Deliverable) [28]. These SERS-LFA platforms maintain the simplicity of conventional lateral flow tests while adding the quantitative capabilities and enhanced sensitivity of SERS detection, making them suitable for on-site pesticide screening in agricultural settings [28].

SERS-Aptamer Biosensors

Aptamer-based SERS biosensors, or aptasensors, represent an emerging technology with significant potential for pesticide residue detection. Aptamers offer several advantages for SERS biosensing, including their small size, ease of modification with thiol groups for gold surface attachment, and compatibility with various signal transduction mechanisms [27] [22]. These biosensors typically operate through one of two mechanisms: (1) "signal-on" approaches where aptamer-target binding induces conformational changes that bring Raman reporters closer to metallic surfaces, or (2) "signal-off" approaches where target displacement reduces SERS signals [22].

A notable application involves the detection of organophosphorus pesticides, where aptamers selected against specific pesticide molecules are immobilized on SERS-active substrates. Upon target binding, the structural reorganization of the aptamer can either enhance or quench the SERS signal of associated reporter molecules, enabling quantitative detection [22]. The stability and reusability of aptamer-based sensors further enhance their practical utility for environmental monitoring and food safety applications [27] [22].

Advanced SERS Substrate Engineering

Recent advancements in substrate engineering have significantly improved the performance of SERS biosensors. A notable development is the flexible cellulose nanofiber (CNF)/gold nanorod@Ag (GNR@Ag) SERS sensor, fabricated using vacuum filtration methods [29]. This substrate leverages the high absorbency of CNF combined with the plasmonic properties of core-shell nanostructures to create a highly sensitive detection platform. The optimization of silver shell thickness on gold nanorod cores enables the precise engineering of electromagnetic hot spots, maximizing SERS enhancement factors [29].

An innovative feature of this platform is the incorporation of a localized evaporation enrichment effect using hydrophilic CNF and hole-punched hydrophobic polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) [29]. This design creates a microfluidic flow that concentrates analyte molecules within confined areas, enhancing SERS sensitivity by up to 465% and enabling detection limits for pesticides like Thiram as low as 10⁻¹¹ M on fruit surfaces [29]. The flexibility of this sensor allows direct application to non-planar surfaces like fruits and vegetables, making it particularly suitable for real-world pesticide screening in agricultural products [29].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Fabrication of Flexible CNF/GNR@Ag SERS Sensor

This protocol describes the preparation of a highly absorbent and sensitive flexible SERS sensor for on-site pesticide detection [29].

Materials and Reagents

- Cellulose nanofiber (CNF) suspension

- Gold nanorod (GNR) solution

- Silver nitrate (AgNO₃) solution

- Ascorbic acid (reducing agent)

- 4-aminothiophenol (4-ATP, Raman probe molecule)

- Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) kit

- Whatman filter paper or similar filtration membrane

- Vacuum filtration apparatus

- Pesticide standards (e.g., Thiram, carbendazim, nitrofurazone)

Step-by-Step Procedure

Synthesis of GNR@Ag Core-Shell Nanostructures

- Begin with prepared gold nanorods (approximately 50 nm length, 15 nm diameter).

- Add 1 mL of GNR solution to 20 mL of ultrapure water under gentle stirring.

- Sequentially add 100 μL of 10 mM AgNO₃ and 100 μL of 10 mM ascorbic acid.

- Monitor color change from brown to greenish-gray, indicating silver shell formation.

- Optimize silver thickness by varying AgNO₃ concentration (0.1-1 mM) to maximize SERS enhancement.

Fabrication of CNF/GNR@Ag Composite Substrate

- Prepare 0.5% CNF suspension in water and homogenize using a high-shear mixer.

- Mix CNF suspension with GNR@Ag solution at 3:1 volume ratio.

- Assemble vacuum filtration system with 0.2 μm pore size membrane.

- Filter the CNF/GNR@Ag mixture under vacuum to form uniform thin film.

- Air-dry the composite film at room temperature for 12 hours.

- Carefully peel the flexible CNF/GNR@Ag substrate from the filtration membrane.

Preparation of Hydrophobic PDMS Mask

- Mix PDMS base and curing agent at 10:1 ratio.

- Degas the mixture under vacuum until bubbles disappear.

- Pour PDMS into custom mold with cylindrical pillars (1-2 mm diameter).

- Cure at 70°C for 2 hours.

- Punch holes corresponding to pillar positions to create penetration channels.

Sensor Assembly and Optimization

- Attach PDMS mask to CNF/GNR@Ag substrate, aligning holes with detection zones.

- Validate SERS performance using 4-ATP as probe molecule.

- Optimize laser power and integration time for target pesticides.

Protocol: SERS-Based Detection of Pesticides on Fruit Surfaces

This protocol describes the application of the flexible SERS sensor for on-site detection of pesticide residues on agricultural produce [29].

Materials and Reagents

- Flexible CNF/GNR@Ag SERS sensor

- Portable Raman spectrometer (785 nm laser)

- PDMS mask with hole-punched pattern

- Methanol or ethanol (HPLC grade)

- Ultrasonic bath

- Centrifuge

- Pesticide standard solutions

Step-by-Step Procedure

Sample Collection from Fruit Surfaces

- Cut flexible SERS sensor to appropriate size (e.g., 1 × 1 cm).

- Gently press sensor against fruit surface (e.g., apple, chili pepper) for 30 seconds.

- Alternatively, swab fruit surface with methanol-dampened cotton tip, then transfer to sensor.

Evaporation-Enrichment Concentration

- Attach PDMS mask to pesticide-exposed sensor surface.

- Apply 10 μL of methanol to each hole in PDMS mask.

- Allow solvent to evaporate completely (5-10 minutes at room temperature).

- The evaporation process creates microfluidic flow that concentrates pesticides within hole areas.

SERS Measurement and Data Acquisition

- Position sensor under portable Raman spectrometer.

- Set laser wavelength to 785 nm with power adjusted to 5-50 mW.

- Set integration time to 1-10 seconds.

- Collect spectra from multiple points within each enrichment zone.

- For each sample, acquire at least 10 spectra from different positions.

Data Analysis and Quantification

- Preprocess spectra: subtract background, remove cosmic rays, normalize.

- Identify characteristic pesticide peaks (e.g., Thiram: 560 cm⁻¹, 1385 cm⁻¹).

- Generate calibration curve using standard solutions (10⁻⁶ to 10⁻¹¹ M).

- Calculate pesticide concentration on fruit surface using peak intensity.

Table 2: Characteristic SERS Bands for Common Pesticides

| Pesticide | Class | Characteristic SERS Bands (cm⁻¹) | Reported LOD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thiram | Dithiocarbamate | 560, 1145, 1385, 1515 | 10⁻¹¹ M [29] |

| Carbendazim | Benzimidazole | 730, 1020, 1225, 1275, 1465 | Not specified |

| Nitrofurazone | Nitrofuran | 1335, 1570 | Not specified |

| Organophosphates | Phosphate esters | 630, 880, 1090, 1340 | Varies by compound |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for SERS Biosensor Development

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | Plasmonic substrate for SERS enhancement | Colloidal SERS assays, LFA conjugates | Size (20-80 nm), shape (spherical, rods), surface chemistry |

| Silver Nanoparticles (AgNPs) | High enhancement SERS substrate | Paper-based SERS, colloidal aggregates | Higher enhancement than Au but more susceptible to oxidation |

| Raman Reporters | Generate characteristic SERS fingerprints | SERS nanotags, direct detection | Strong affinity for metal surface, distinct fingerprint region |

| Antibodies | Biological recognition element | Immunoassays, SERS-LFA | Specificity, affinity, cross-reactivity, immobilization method |

| Aptamers | Nucleic acid-based recognition element | Aptasensors, competitive assays | SELEX selection, modification (thiol, amine), stability |

| Cellulose Nanofibers | Flexible substrate matrix | CNF/GNR@Ag flexible sensors | Porosity, purity, mechanical strength [29] |

| PDMS | Hydrophobic masking material | Evaporation enrichment chambers | Ease of fabrication, hydrophobicity, flexibility [29] |

The integration of biological recognition elements with SERS technology has created powerful biosensing platforms that combine exceptional sensitivity with high specificity. Antibody-based SERS biosensors leverage well-established immunoaffinity principles while aptamer-based sensors offer advantages in stability, production, and design flexibility [27] [22]. The development of innovative substrate designs, such as flexible CNF/GNR@Ag sensors with evaporation enrichment capabilities, has further enhanced detection sensitivity and practical applicability for real-world scenarios like pesticide screening on agricultural products [29].

Future developments in this field will likely focus on several key areas: (1) improving reproducibility and standardization of SERS substrates to enable reliable quantitative analysis; (2) expanding multiplexing capabilities for simultaneous detection of multiple pesticide residues; (3) enhancing portability and automation for field-deployable systems; and (4) integrating nucleic acid amplification techniques to achieve ultra-sensitive detection of biomarkers and contaminants [26]. As these technologies mature, SERS biosensors incorporating antibodies and aptamers are poised to become indispensable tools for ensuring food safety, protecting environmental health, and advancing biomedical diagnostics.

Engineering Advanced SERS Platforms: Substrate Design, Biosensor Integration, and Real-World Applications

Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering (SERS) has emerged as a powerful analytical technique for the detection of low-concentration molecules, including pesticides, due to its exceptional sensitivity, rapid response, and unique molecular fingerprinting capability [30] [5]. The core of SERS technology lies in its substrates—nanostructured materials that amplify the inherently weak Raman signals by many orders of magnitude, enabling detection down to the single-molecule level [31] [32]. For pesticide residue analysis in complex food matrices, the design of the SERS substrate is paramount, dictating the sensitivity, selectivity, and reproducibility of the biosensor [7].

The enhancement of Raman signals primarily arises from two synergistic mechanisms: the electromagnetic enhancement (EM) and the chemical enhancement (CM) [5] [33]. EM, which typically accounts for the majority of the signal boost (enhancement factors of 10^6-10^12), results from the excitation of localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) on the surfaces of noble metals and some other nanomaterials when irradiated with light [34] [35]. CM, contributing a more modest enhancement (typically 10-10^3), involves charge transfer (CT) between the analyte molecules and the substrate, which alters the polarizability of the adsorbed molecules [35] [33]. The "hot spots"—nanoscale gaps, sharp tips, or pores within these substrates—are critical regions where the electromagnetic field is intensely localized, leading to the greatest signal amplification [31]. The recent trend in SERS substrate design moves beyond traditional noble metals to include sophisticated composites and non-metal materials, which offer improved stability, selectivity, and biocompatibility, making them particularly suitable for detecting pesticides in food [7] [34] [35].

Types and Performance of SERS Substrates

SERS substrates can be broadly categorized based on their material composition. The following sections and tables detail the characteristics, advantages, and limitations of noble metal, composite, and non-metal substrates, with a specific focus on their applicability in pesticide sensing.

Noble Metal Substrates

Noble metals, particularly gold (Au) and silver (Ag), are the most traditional and widely used SERS substrates. Their high free electron density enables strong LSPR effects under visible light excitation, yielding very high enhancement factors [5] [33]. Silver often provides the highest enhancement but can suffer from oxidation and poor chemical stability. Gold offers excellent biocompatibility and stability, making it a preferred choice for many biosensing applications [5].

Table 1: Performance of Noble Metal-Based SERS Substrates in Pesticide Detection

| Nanomaterial | Target Pesticide(s) | Reported LOD | Food Matrix | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) [7] | Chlorpyrifos | 70 × 10⁻³ ng L⁻¹ | Chinese cabbage, Lettuce | Excellent biocompatibility & stability |

| AuNPs [7] | 11 Organophosphorus & Methomyl | 19–81 ng L⁻¹ | Apple, Cabbage | High sensitivity for multi-residue detection |

| Silver Nanoparticles (AgNPs) [7] | Various | N/A | Food Matrices | Very high EM enhancement |

| Silver Nanostars (AgNSs) [31] | Various | N/A | N/A | High density of sharp tips for "hot spots" |

Composite Substrates

Composite substrates integrate two or more distinct materials to create a synergistic system that overcomes the limitations of individual components. A common strategy is combining noble metals with functional non-metal materials like graphene, semiconductors, or metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) [30] [33]. These hybrids benefit from the strong EM of the metals and additional CM or molecular enrichment capabilities of the functional materials.

Table 2: Performance of Composite SERS Substrates

| Composite Material | Component Roles | Enhancement Factor (EF) | Key Advantage for Pesticide Detection |

|---|---|---|---|

| Au NPs/CNT [34] | EM from Au, CM & large surface area from CNT | N/A | Efficient charge transfer; analyte enrichment |

| CNF-Cu₂O/Ag [34] | EM from Ag, CM & selectivity from Cu₂O | N/A | Improved stability and selectivity |

| GQD–Mn₃O₄ [30] | Fluorescence quenching by Mn₃O₄, substrate from GQD | N/A | Suppressed fluorescence background |

| Cellulose/Metal NPs [36] | Flexible substrate from cellulose, EM from Metal NPs | Up to 10¹¹ | Low-cost, flexible, biodegradable substrate |

Non-Metal Substrates

Non-noble metal substrates are an emerging class of SERS-active materials that include carbon-based nanomaterials (e.g., graphene, carbon nanotubes), transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs like MoS₂), metal oxides, and MXenes [34] [35]. Their enhancement is predominantly driven by the chemical mechanism (CM), specifically charge transfer, which can exhibit high molecular selectivity. They offer superior economy, stability, and biocompatibility compared to noble metals [35].

Table 3: Performance of Non-Metal SERS Substrates

| Material Class | Example Materials | Key Enhancement Mechanism | Advantage for Biosensing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon-Based [30] [35] | Graphene, GO, rGO, CQDs | Chemical Enhancement (Charge Transfer) | Excellent uniformity, biocompatibility, fluorescence quenching |

| Transition Metal Dichalcogenides (TMDs) [35] | MoS₂, WS₂ | Strong Chemical Enhancement | Tunable bandgap, layer-dependent properties |

| Metal Oxides [34] [35] | ZnO, TiO₂, WO₃ | Charge Transfer induced by defects/doping | Good chemical stability, customizable surface chemistry |

| MXenes [34] [35] | Ti₃C₂Tₓ | High electronic conductivity, CM | Large surface area, versatile surface functionalization |

Experimental Protocols for SERS Substrate Fabrication and Pesticide Detection

This section provides detailed, step-by-step protocols for fabricating key types of SERS substrates and applying them to the detection of pesticide residues.

Protocol 1: Fabrication of Citrate-Reduced Gold Nanoparticle (AuNP) Substrates

Application: This protocol produces a stable colloidal suspension of AuNPs, which is a versatile and widely used substrate for the SERS detection of various organophosphate and carbamate pesticides [7].

Materials:

- Hydrogen tetrachloroaurate(III) trihydrate (HAuCl₄·3H₂O)

- Trisodium citrate dihydrate (Na₃C₆H₅O₇·2H₂O)

- High-purity deionized (DI) water (18.2 MΩ·cm)

- Round-bottom flask

- Condenser

- Hot plate with magnetic stirrer

- Heating mantle

Procedure:

- Solution Preparation: Prepare a 1 mM HAuCl₄ solution by dissolving 39.4 mg of HAuCl₄·3H₂O in 100 mL of DI water. Prepare a 38.8 mM trisodium citrate solution by dissolving 114 mg in 10 mL of DI water.

- Reduction and Nucleation: Add 50 mL of the 1 mM HAuCl₄ solution to the round-bottom flask equipped with a condenser. Bring the solution to a vigorous boil while stirring on a hot plate.

- Rapid Injection: Quickly inject 0.5 mL of the 38.8 mM trisodium citrate solution into the boiling gold solution.

- Reaction and Cooling: Continue heating and stirring for 10 minutes. The solution color will change from pale yellow to deep red. After 10 minutes, remove the flask from the heat and allow the colloidal solution to cool slowly to room temperature while continuing to stir.

- Characterization: Characterize the synthesized AuNPs using UV-Vis spectroscopy (should show a plasmon peak at ~520-530 nm) and dynamic light scattering (DLS) to confirm size and monodispersity (typical diameter ~50-60 nm).

Protocol 2: Functionalization of AuNPs with Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) for Pesticide Detection

Application: This protocol describes the immobilization of the AChE enzyme on AuNPs to create a biosensor for organophosphate and carbamate pesticides, which act as AChE inhibitors [7].

Materials:

- Synthesized AuNP colloid from Protocol 1

- Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) enzyme

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), 10 mM, pH 7.4

- Centrifugation tubes

- Microcentrifuge

Procedure:

- pH Adjustment: Adjust the pH of the AuNP colloid to approximately 7.4 using a dilute solution of NaOH or HCl. This pH is optimal for maintaining enzyme activity and stability.

- Enzyme Immobilization: Add a calculated volume of AChE stock solution (e.g., 1 mg/mL in PBS) to the AuNP colloid to achieve a final enzyme concentration of 10 µg/mL. Gently mix the solution on a rotator for 2 hours at 4°C to allow for physical adsorption of the enzyme onto the AuNP surface.

- Purification: Centrifuge the AChE-AuNP conjugate at 10,000 rpm for 15 minutes to remove any unbound enzyme. Carefully decant the supernatant.

- Resuspension: Resuspend the soft pellet of AChE-AuNP conjugates in 1 mL of PBS buffer (pH 7.4). The functionalized substrate is now ready for use in inhibition assays.

Protocol 3: SERS-Based Detection of Chlorpyrifos Using AChE-Functionalized AuNPs

Application: This protocol outlines the specific steps for quantifying an organophosphorus pesticide (e.g., Chlorpyrifos) by measuring its inhibitory effect on the AChE enzyme immobilized on AuNPs [7].

Materials:

- AChE-AuNP conjugates from Protocol 2

- Chlorpyrifos standard solutions (in a suitable solvent like methanol) at known concentrations

- Acetylthiocholine (ATCh) iodide substrate

- 5,5'-Dithio-bis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB, Ellman's reagent)

- PBS buffer (10 mM, pH 7.4)

- Raman spectrometer with a 532 nm or 785 nm laser

Procedure:

- Inhibition Reaction: Incubate 100 µL of the AChE-AuNP conjugate with 50 µL of different concentrations of Chlorpyrifos standard (or sample extract) for 20 minutes at 37°C.

- Enzymatic Reaction: Add 50 µL of a mixture containing ATCh (final concentration 1 mM) and DTNB (final concentration 0.5 mM) to the inhibition mixture. Incubate for 10 minutes at 37°C.

- SERS Measurement: Place a 10 µL droplet of the final reaction mixture on an aluminum slide or in a well plate. Focus the Raman laser on the droplet and acquire spectra.

- Data Analysis: Monitor the SERS intensity of the characteristic peak of the reaction product between thiocholine (from ATCh hydrolysis) and DTNB, which appears at ~1330 cm⁻¹ [7]. The intensity of this peak is inversely proportional to the pesticide concentration. Generate a calibration curve by plotting the SERS intensity (or the inhibition percentage) against the logarithm of Chlorpyrifos concentration to determine the Limit of Detection (LOD) and quantify unknown samples.

Protocol 4: Fabrication of Graphene Oxide/Gold Nanoparticle (GO/AuNP) Composite Substrate

Application: This protocol creates a paper-based composite SERS substrate that combines the EM of AuNPs with the CM and large surface area of GO, suitable for the adsorption and detection of aromatic pesticide molecules.

Materials:

- Graphene Oxide (GO) dispersion in water (1 mg/mL)

- Synthesized AuNP colloid from Protocol 1

- Filter paper (e.g., cellulose nitrate membrane)

- Filtration apparatus

- Oven

Procedure:

- Mixing: Combine 10 mL of the AuNP colloid with 1 mL of the GO dispersion (1 mg/mL). Sonicate the mixture for 30 minutes to ensure homogeneity.