Signal Over Noise: Advanced Strategies for Enhancing SNR in Selective Biosensing

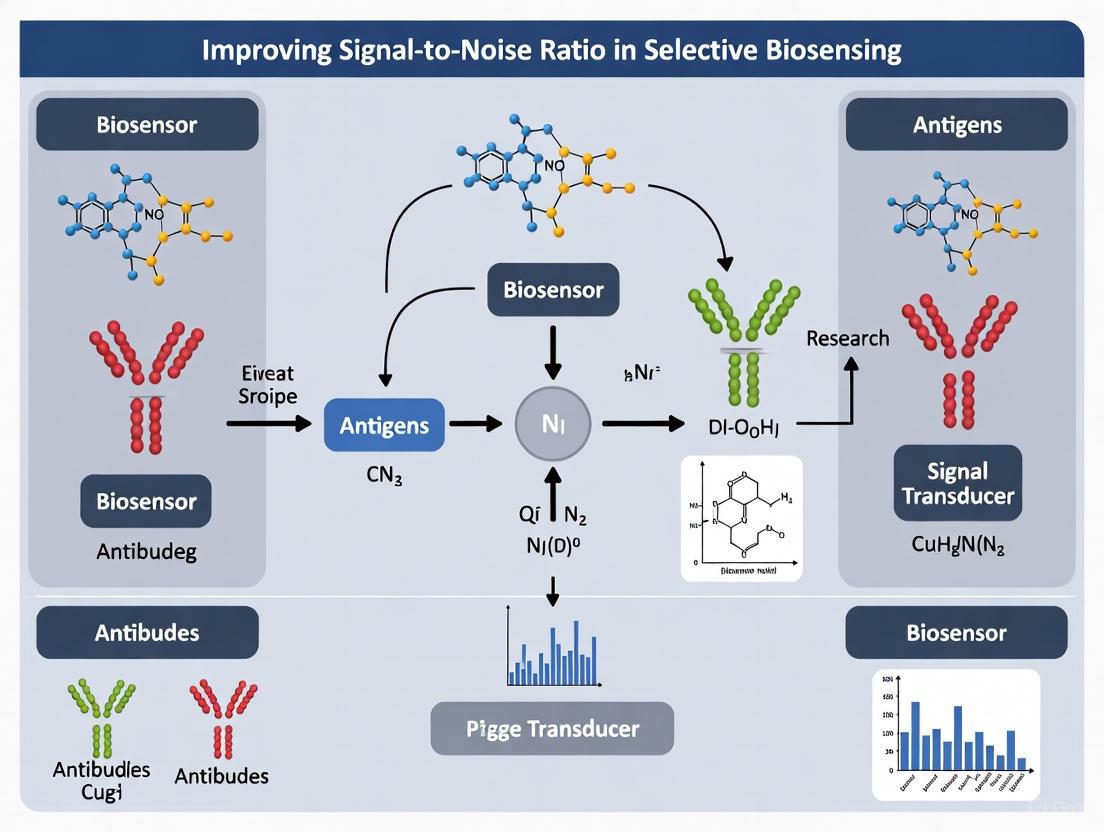

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of strategies to improve the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) in selective biosensing, a critical performance metric for researchers and drug development professionals.

Signal Over Noise: Advanced Strategies for Enhancing SNR in Selective Biosensing

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of strategies to improve the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) in selective biosensing, a critical performance metric for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the fundamental principles defining SNR and its impact on detection sensitivity and accuracy. The scope extends to cutting-edge methodological advances, including novel sensor architectures, machine learning-based noise reduction, and material innovations. It further offers practical guidance on troubleshooting and optimization, and concludes with validation frameworks and comparative performance analysis of emerging technologies, providing a holistic resource for developing next-generation, high-fidelity biosensing platforms.

The Critical Foundation: Understanding SNR and Its Role in Biosensing Performance

The Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) is a fundamental measure used in science and engineering that compares the level of a desired signal to the level of background noise. It is a critical parameter for evaluating the performance and quality of systems that process or transmit signals, including all types of biosensors. A high SNR indicates a clear, easily detectable signal, whereas a low SNR means the signal is corrupted or obscured by noise, making it difficult to distinguish or recover. In the context of selective biosensing research, improving SNR is paramount for developing reliable, sensitive, and accurate detection systems for medical diagnostics, environmental monitoring, and drug development [1] [2].

The ability to maximize SNR directly impacts key biosensor performance metrics, including detection limit, sensitivity, and the speed at which results can be reported. For biosensors, noise originates from multiple sources, such as electrical, thermal, optical, and environmental interference. Effectively managing these factors to enhance SNR is a primary focus of biosensor design and optimization [2].

Core Concepts and Definitions

What is Signal-to-Noise Ratio?

SNR is defined as the ratio of the power of a meaningful signal to the power of background noise. It is mathematically represented as:

SNR = Psignal / Pnoise

where P is the average power. Both signal and noise power must be measured at the same or equivalent points in a system and within the same system bandwidth. When the signal and noise are measured as amplitudes (e.g., voltage or current), the relationship becomes:

SNR = (Asignal / Anoise)²

where A is the root mean square (RMS) amplitude [1].

SNR in Decibels (dB)

Because signals often have a very wide dynamic range, SNR is frequently expressed using the logarithmic decibel (dB) scale. This simplifies the comparison of large and small ratios.

- For power measurements: SNR_dB = 10 log₁₀(SNR)

- For amplitude measurements: SNRdB = 20 log₁₀(Asignal / A_noise)

Expressing SNR in decibels is particularly useful for quantifying the performance gains from various signal enhancement strategies in biosensing research [1].

Alternative Definition for DC Signals and Imaging

An alternative definition of SNR uses the ratio of the mean (μ) to the standard deviation (σ) of a signal or measurement, expressed as SNR = μ / σ. This definition is particularly relevant for measurements like optical biosensing of DC signals, where the signal amplitude can be calculated as the average of the measured signal, and the noise amplitude can be calculated as its standard deviation [2] [3].

In imaging applications, the Rose criterion states that an SNR of at least 5 (14 dB) is needed to distinguish image features with certainty. This principle can be extended to biosensing, where a minimum SNR is required to unambiguously detect a binding event [1].

The Relationship Between SNR and Dynamic Range

SNR is closely related to, but distinct from, dynamic range. Dynamic range measures the ratio between the strongest undistorted signal a channel can handle and the minimum discernible signal, which is often the noise level. SNR, on the other hand, measures the ratio between an arbitrary signal level (not necessarily the most powerful possible) and the noise at that specific operating point [1].

Calculating SNR: Methods and Formulas

General Calculation Methods

The appropriate method for calculating SNR depends on the nature of the signal and the biosensing platform.

Table 1: Common SNR Calculation Formulas

| Method | Formula | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Power Ratio | ( SNR = \frac{P{signal}}{P{noise}} ) | Fundamental definition; used when signal and noise power can be directly measured [1]. |

| Amplitude Ratio | ( SNR = \left( \frac{A{signal}}{A{noise}} \right)^2 ) | Used when signal and noise are measured as amplitudes (e.g., voltage) [1]. |

| Decibel Scale | ( SNR{dB} = 10 \log{10}\left( \frac{P{signal}}{P{noise}} \right) ) OR ( SNR{dB} = 20 \log{10}\left( \frac{A{signal}}{A{noise}} \right) ) | Standard for reporting and comparing wide dynamic ranges [1]. |

| Mean/Std. Dev. (DC) | ( SNR = \frac{\mu}{\sigma} ) | Ideal for DC signals or measurements where the signal can be represented by an average value and noise by the standard deviation [2]. |

| Fluorescence (SQRT) | ( SNR = \frac{Peak\ Signal - Background\ Signal}{\sqrt{Background\ Signal}} ) | Used with photon-counting detectors in spectrometry/fluorometry; assumes Poisson noise statistics [4]. |

| Fluorescence (RMS) | ( SNR = \frac{Peak\ Signal - Background\ Signal}{RMS_{noise}} ) | Used with analog detectors; RMS_noise is measured from a kinetic scan of the background [4]. |

| Boolean Biosensing | ( SNR{dB} = 20 \log{10}\frac{ \mid \log{10}(\mu{g,true} / \mu{g,false}) \mid }{ 2 \cdot \log{10}(\sigma_g) } ) | For biological computations where outputs follow a log-normal distribution [3]. |

Workflow for SNR Calculation in Optical Biosensing

The following diagram outlines a generalized workflow for measuring SNR in an optical biosensor system, such as one based on photoplethysmography (PPG) or fluorescence:

Step 1: Stabilize Experimental Setup. Place the biosensor on a stable, vibration-free surface like an optical bench. For optical sensors, use a fixed reflector and cover the setup with a black box or sheet to block ambient light, which is a significant source of noise [2].

Step 2: Acquire Raw Signal Data. Collect data from the sensor under the desired configuration. For example, in an optical sensor, this would be the raw ADC (Analog-to-Digital Converter) counts, which are linearly dependent on the received optical signal [2].

Step 3: Separate AC & DC Components (for signals like PPG). For biosignals such as a photoplethysmogram (PPG), which contains both AC (pulsatile) and DC (baseline) components, a frequency-domain filter can be applied. The signal below 20 Hz is typically isolated as the biological signal, while the higher-frequency content is treated as noise [2].

Step 4: Calculate Signal Amplitude.

- For DC signals: Signal amplitude is the average (mean) of the measured ADC counts or signal output over a stable period [2].

- For AC+DC signals: After filtering, the signal amplitude is derived from the filtered data.

Step 5: Calculate Noise Amplitude.

- For DC signals: Noise amplitude is the standard deviation of the measured signal [2].

- For AC+DC signals: The noise amplitude is the standard deviation of the high-frequency components separated by the filter [2].

Step 6: Compute Final SNR Value. Use the appropriate formula from Table 1. For many biosensor applications, this is: SNR = (Average Signal) / (Standard Deviation of Noise) [2].

SNR Troubleshooting Guide and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is an acceptable SNR for detecting a peak in chromatography or spectroscopy? A signal-to-noise ratio of 3:1 is generally considered the minimum for confirming that a peak is real and detectable. For reliable quantification, a higher ratio of 10:1 is typically required [5].

Q2: My biosensor has a high signal but also high noise. What are the first things I should check? Begin with these steps:

- Check the sensor: Inspect for physical damage, clean it with distilled water or a suitable solvent to remove contaminants or biofilm, and ensure it has been stored correctly in the recommended storage buffer [6].

- Stabilize the setup: Ensure the sensor and any reflectors are on a stable surface. Distance variations between a reflector and a photodiode, for example, can manifest as noise [2].

- Block ambient light: For optical sensors, even small amounts of ambient light can skew results. Always cover the test setup with a black box or sheet [2].

Q3: How can I improve my biosensor's SNR without changing the hardware?

- Increase signal averaging: Acquiring more data points or scans (increasing the number of excitations, Nex) and averaging them can reduce random noise [2] [5].

- Optimize integration time: Increasing the time the detector collects signal at each step can improve SNR, but this trades off with measurement speed [4].

- Post-processing filtering: Apply digital filters (e.g., low-pass filters) to the acquired data to suppress out-of-band noise, as demonstrated with human PPG signals [2].

Q4: Why is my calculated SNR different when using various methods? Different formulas make different assumptions about the nature of the noise. The "Mean/Std. Dev." method is simple but may not account for all noise types. The "SQRT" method assumes noise follows Poisson statistics (common in photon counting). The "RMS" method is more general for analog systems. Always use the same calculation method when comparing results between different systems or experiments [4].

Advanced Technique: Site-Selective Immobilization

A powerful method for improving SNR in label-free biosensors like those based on Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance (LSPR) is to ensure that target molecules bind only to the most sensitive regions of the sensor. The electromagnetic (EM) field in metal nanostructures is often most intense at edges and gaps, not on flat top surfaces.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for SNR Enhancement

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Gold Nano-truncated Cone (GNTC) Array | The LSPR transducer structure. The 40nm height maximizes the side surface area with high EM field intensity for biomolecule immobilization [7]. |

| SiO₂ Capping Layer | A 5nm oxide layer deposited to physically block the top surface of the GNTC, preventing the immobilization of receptor molecules on this low-sensitivity area [7]. |

| α-fetoprotein (AFP) Antibodies | The receptor molecules in the model assay, selectively immobilized on the exposed, high-sensitivity sidewalls of the GNTCs [7]. |

| Enzyme-precipitation Reaction Reagents | Used to amplify the signal change after the sandwich immunoreaction, counteracting the low penetration depth of the LSPR evanescent field [7]. |

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship and experimental outcome of this site-selective approach:

This methodology resulted in a six-fold enhancement in detection sensitivity in serum samples compared to uncapped nanostructures where molecules could bind to the less-sensitive top surface [7].

A deep understanding of Signal-to-Noise Ratio—from its fundamental definitions and calculations to its practical optimization in complex biosensing environments—is indispensable for researchers aiming to push the boundaries of detection limits and accuracy. As biosensors become increasingly critical in diagnostics and drug development, strategies such as careful experimental design, systematic troubleshooting, and advanced techniques like site-selective immobilization will be key to achieving the high SNR required for reliable and impactful results.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) in the context of biosensing?

A: In biosensing, the Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) is a critical performance metric that compares the power of a desired analytical signal (e.g., a fluorescence change upon target binding) to the power of the background noise. It quantifies how clearly the target signal can be distinguished from irrelevant interference [1] [8]. A higher SNR means the signal is clearer and more detectable, which directly enhances the reliability of your data [1].

Q2: How does a low SNR directly impact my biosensing experiments?

A: A low SNR can severely compromise your experimental results in several ways [9]:

- Reduced Limit of Detection (LoD): Noise raises the baseline fluctuation, masking low-concentration analyte signals and imposing a hard floor on the sensor’s minimum detectable concentration.

- Loss of Precision and Repeatability: A high level of signal noise results in a high coefficient of variation (CV) across repeated measurements, making results inconsistent.

- False Positives and Negatives: Cross-reactivity or electrical interference can produce spurious signal changes that are mistaken for a true positive or that obscure a weak positive signal. This is especially problematic in complex biological matrices like serum or saliva.

A: The main sources of noise in biosensors can be categorized as follows [9]:

- Electronic Noise: This includes thermal (Johnson) noise from the random motion of charge carriers and 1/f (flicker) noise, which is prevalent at low frequencies and is often related to imperfections in electrode materials.

- Environmental Interference: This includes Electromagnetic Interference (EMI) from power lines or wireless communication devices, which can capacitively or inductively couple into the sensor system.

- Biological Noise: This refers to cross-reactivity with non-target molecules in a sample matrix, leading to non-specific signals.

Q4: How can I quickly estimate the SNR from a chromatogram or similar output?

A: A common method for estimating SNR involves measuring the peak-to-peak amplitude of the baseline noise (N) over a defined period and the height of the analyte signal (S) from the middle of the baseline.

- Standard Calculation: SNR = S / N

- Pharmacopoeia (USP/EP) Calculation: SNR = 2H / h, where H is the signal height and h is the peak-to-peak noise. Note that this definition yields a value twice as large as the standard calculation [10].

Q5: What SNR value is considered "good" for a reliable connection or detection?

A: While the acceptable SNR varies by application, the following is a general guideline in wireless communications, which provides a useful analogy [11]:

- Below 10 dB: Below the minimum level to establish a reliable connection.

- 10 - 15 dB: The accepted minimum for an unreliable connection.

- 15 - 25 dB: Minimally acceptable level, poor connectivity.

- 25 - 40 dB: Good.

- 41 dB or higher: Excellent.

Troubleshooting Guide: Improving SNR in Biosensor Experiments

Problem: High Baseline Noise Obscuring Signal

| Symptoms | Possible Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Erratic baseline fluctuations; poor signal clarity at low analyte concentrations [9]. | Electronic Thermal Noise: Inherent in all conductive materials, worsened by high temperature or resistance [9]. | - Use materials with higher conductivity (e.g., novel carbon nanomaterials) to reduce resistance.- For extreme sensitivity, consider cryogenic cooling of circuitry [8]. |

| 1/f (Flicker) Noise: More dominant at low frequencies, often due to electrode material defects [9]. | - Use electrodes made from materials with fewer grain boundaries and defects.- Implement nanostructured materials (e.g., highly porous gold, graphene) designed for reduced flicker noise [12] [9]. | |

| Environmental EMI: Noise from power lines, motors, or wireless devices [9]. | - Use shielded cables and enclosures.- Place the experimental setup inside a Faraday cage if possible.- Use a stable, filtered power supply. |

| Symptoms | Possible Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Weak output signal even when the target is present at significant concentrations. | Low Sensitivity of Transducer: The sensor design does not efficiently transduce the biological event into a measurable signal [12] [13]. | - Engineer the transducer surface with nanomaterials (e.g., Au-Ag nanostars, Pt nanoparticles) to increase active surface area and enhance signal [12].- Amplify the signal using techniques like Rolling Circle Amplification (RCA) [12]. |

| Signal Attenuation: The signal is weakened before detection. | - Ensure proper gain settings on your detector/instrument.- Check for any obstructions or issues in the optical or electrical path. | |

| Biofouling: Non-specific adsorption of proteins or cells creates a barrier, reducing the signal [9]. | - Apply antifouling coatings (e.g., polyethylene glycol, BSA-based composites).- Use novel carbon nanomaterials with innate antifouling properties [9]. |

Problem: Slow Sensor Response Time

| Symptoms | Possible Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| The sensor takes too long to reach a maximum signal after analyte introduction, hindering real-time monitoring [13]. | Inherently Slow Sensor Kinetics: The biochemical recognition or transduction mechanism is slow. | - Explore hybrid approaches that combine stable systems with faster-acting components, such as riboswitches or toehold switches [13].- Use directed evolution or high-throughput screening (e.g., via FACS) to select for mutant biosensors with improved response times [13]. |

Key Performance Metrics for Biosensor Evaluation

When developing or selecting a biosensor, it is crucial to characterize its performance using the following standardized metrics, which are interdependent and often involve trade-offs [13].

| Metric | Definition | Impact on Performance & Relationship to SNR |

|---|---|---|

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) | Ratio of the power of the desired signal to the power of background noise [1]. | A high SNR is foundational, enabling a low LoD, high precision, and reliable detection. |

| Dynamic Range | The span between the minimal and maximal detectable signal concentrations [13]. | A wide dynamic range is necessary, but a high SNR is required to accurately distinguish signals across that entire range. |

| Limit of Detection (LoD) | The lowest concentration of analyte that can be reliably distinguished from zero [9]. | Directly limited by SNR. A higher SNR allows for a lower LoD by making weaker signals discernible from noise [9]. |

| Response Time | The speed at which the biosensor reacts to a change in analyte concentration [13]. | A slow response time can hinder real-time control. For dynamic systems, both a fast response and a high SNR are needed for accuracy and speed [13]. |

Experimental Protocol: Quantifying SNR in Imaging Systems

This protocol, adapted from methodologies used in Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), provides a practical approach to measuring SNR that can be conceptually applied to other imaging-based biosensing platforms [14].

Objective: To accurately quantify the spatially varying SNR in an image acquired with a multi-channel detector and parallel imaging reconstruction.

Principle: The method involves acquiring a standard "anatomical" image followed by a fast "noise scan" with radiofrequency pulses disabled. This noise scan captures the thermal noise statistics of the system, which are used to calculate SNR at any location in the anatomical image [14].

Materials:

- Imaging system (e.g., MRI, fluorescence imager).

- Phantom or biological sample.

- Data analysis software (e.g., Python, MATLAB, ImageJ).

Procedure:

- Acquire Anatomical Image: Perform your standard imaging sequence with the sample in place.

- Acquire Noise Scan: Immediately after, run an identical sequence but with all RF excitation pulses and magnetic field gradients disabled. Cardiac or respiratory triggering should also be disabled. This scan can be very short (e.g., 30 seconds for a 10-minute MRI scan) [14].

- Reconstruct Images: Reconstruct both the anatomical and noise datasets using the same linear reconstruction algorithm. Non-linear filters should be avoided as they can alter noise statistics differently.

- Define Regions of Interest (ROIs): Select ROIs in the anatomical image for signal measurement.

- Measure Signal and Noise:

- Signal (S): Calculate the mean pixel value within an ROI on the anatomical image.

- Noise (N): Copy the ROI to the identical location on the noise image. Calculate the standard deviation (SD) of the pixel values in this ROI. For magnitude images, multiply this SD by a correction factor of

2 / sqrt(4 - π) ≈ 1.526to account for the Rayleigh distribution of noise [14].

- Calculate SNR: Compute the SNR for each ROI using the formula: SNR = S / N.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key materials and reagents used in advanced biosensing research to improve SNR and sensitivity [12] [13] [9].

| Research Reagent | Function & Utility in Biosensing |

|---|---|

| Au-Ag Nanostars | A plasmonic nanomaterial used as a substrate in Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering (SERS). Its sharp-tipped morphology provides intense signal enhancement, enabling highly sensitive, label-free detection of biomarkers like α-fetoprotein [12]. |

| Novel Carbon Nanomaterials (e.g., Gii) | Engineered carbon-based transducer materials that offer high conductivity (reducing thermal noise), a large active surface area (increasing signal), and innate antifouling properties (reducing biological noise) [9]. |

| Genetically-Encoded Fluorescent Biosensors | Recombinant proteins (e.g., for cAMP, Ca²⁺) expressed in live cells. They transduce the concentration of a specific signaling molecule into a change in fluorescence intensity, allowing real-time, kinetic monitoring of GPCR signaling and other pathways [15]. |

| Polydopamine/Melanin-like Coatings | Bio-inspired coatings that mimic mussel adhesion proteins. They are used for versatile, biocompatible surface modification of electrodes, which can help in immobilizing recognition elements and potentially reducing non-specific binding [12]. |

| Riboswitches & Toehold Switches | RNA-based biosensors. They undergo conformational changes upon binding a target (ligand or RNA sequence), regulating gene expression. They are compact, tunable, and enable rapid, logic-gated control of metabolic pathways in synthetic biology [13]. |

| Rolling Circle Amplification (RCA) Reagents | An isothermal DNA amplification technique used for signal amplification. It generates a long, repetitive DNA product that remains localized, making it ideal for single-molecule counting assays and in situ detection with high specificity [12]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What are the most common consequences of noise in biosensing experiments? Noise fundamentally impairs a biosensor's ability to generate accurate data. Key consequences include an increased Limit of Detection (LoD), where noise masks low-concentration analyte signals; reduced precision and repeatability across measurements; a higher risk of false positives and false negatives, especially in complex biological matrices like blood or saliva; and the need for increased calibration and sophisticated signal processing to compensate for drift [9].

My resonant biosensor's performance degrades at room temperature. What can I do? This is a common challenge, as thermal noise becomes a dominant factor at the nanoscale and at ambient conditions [16]. A traditional approach is to suppress thermal noise by operating in a vacuum or at cryogenic temperatures, but this is often impractical [16]. A recent, counterintuitive paradigm shift is to design sensors that harvest thermal noise as the driving force instead of fighting it. Using highly compliant, lightly damped nano-structures (like specific cantilevers) allows their resonant response to ambient thermal noise to be used for detection, creating simpler, low-power sensors that function effectively at room temperature [16].

How can I reduce optical interference in my wearable PPG biosensor? Optical biosensors like those used for Photoplethysmography (PPG) are highly susceptible to environmental noise. To mitigate this:

- Ambient Light: Use a front-end circuit that captures the ambient light level when the sensor's LED is off and subtracts this DC component from the signal before sampling to prevent photodetector saturation [17].

- Flickering Light: Employ advanced correlated sampling techniques in your integrated circuit (e.g., PPG ICs like the MAX30112) designed to attenuate 50Hz/60Hz flicker from indoor lighting [17].

- Motion Artifacts: This is a significant challenge. Solutions range from using simple moving averages to complex adaptive filtering algorithms. Incorporating external references, such as inertial measurement units (IMUs) to detect motion or a third light wavelength to track optical path changes, can also help qualify and correct for motion-induced errors [17].

Which biosensor materials can help minimize noise and biofouling? Material selection is critical for performance. Carbon-based nanomaterials are increasingly favored over traditional noble metals like gold and platinum. These materials offer high conductivity (reducing thermal noise), large surface-to-volume ratios (increasing sensitivity), and some exhibit innate antifouling properties. This inherent resistance to non-specific adsorption from complex matrices like blood or serum reduces biological noise without the need for additional coatings that can slow analyte access and reduce signal strength [9].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide: Diagnosing and Mitigating Electrical Noise

Electrical noise can manifest as a fluctuating baseline or erratic signals in your output data.

Step 1: Identify the Source

- Thermal (Johnson-Nyquist) Noise: This is intrinsic and arises from the random motion of charge carriers in conductive components. It is present in all materials and is proportional to temperature and resistance. It is particularly problematic for ultra-low signal levels (e.g., femtomolar detection) [9].

- 1/f (Flicker) Noise: This is most prevalent at low frequencies and is introduced by imperfections in electrode materials, such as defects and grain boundaries. Nanostructured transducers can have amplified flicker noise due to their high surface area [9].

- Electromagnetic Interference (EMI): This originates from external sources like power lines and wireless communication devices, coupling capacitively or inductively into the sensor system [9].

Step 2: Apply Mitigation Strategies

- Material Selection: Use high-conductivity, low-resistance materials to minimize Johnson noise. Carbon nanomaterials like graphene or specific commercial variants (e.g., Gii) can offer high conductivity and reduced flicker noise due to fewer grain boundaries [9].

- Shielding: Use proper electromagnetic shielding for cables and the sensor housing to block EMI.

- Filtering: Implement electronic filters (e.g., low-pass filters) in your readout circuitry to suppress high-frequency noise.

Guide: Addressing Thermal Noise in NEMS/MEMS Resonant Sensors

Thermal noise can overwhelm the signal in high-precision mechanical sensors.

Step 1: Evaluate Your Operating Requirements

- Determine if your application allows for operation in a controlled environment or must function in ambient conditions.

Step 2: Choose a Sensing Paradigm

- Option A: Conventional External Drive

- Methodology: Use an external actuator to drive the resonator at its resonant frequency. Detect the frequency or amplitude shift caused by the target analyte.

- Noise Challenge: Thermal noise sets a fundamental limit on the Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR).

- Mitigation Protocol: To suppress thermal noise, operate the resonator under high vacuum conditions and/or at cryogenic temperatures. This requires specialized, often cumbersome equipment [16].

- Option B: Noise-Driven Sensing (Emerging Paradigm)

- Methodology: Eliminate the external drive. Design the sensor as a lightly damped, highly compliant nano-structure (e.g., a high-aspect-ratio cantilever) that dynamically amplifies its own inherent thermal noise at resonance. Use the properties of this amplified response (e.g., resonant frequency, peak magnitude) for detection.

- Advantages: Self-powered by the environment, simpler, lower power consumption, and inherently turns a key limitation into a core component [16].

- Experimental Protocol:

- * Fabricate* a nano-cantilever with low stiffness (k) and low damping per unit mass (μ).

- Place the sensor in the measurement environment (e.g., ambient air or liquid).

- Use a motion transducer (e.g., optical readout) to measure the resonator's power spectral density (PSD).

- Track changes in the resonant peak's properties (frequency, magnitude) in the PSD, which correlate with the target stimulus (e.g., pressure, temperature, adsorbed mass) [16].

- Option A: Conventional External Drive

Guide: Correcting for Biological and Environmental Confounders

Non-specific binding and environmental changes can cause drift and false signals.

Step 1: Characterize the Interference

- Biological Noise: This includes biofouling—the non-specific adsorption of proteins, cells, or other molecules not being targeted onto the sensing surface. This can block binding sites and change the surface properties [9].

- Environmental Noise: For optical biosensors, this includes changes in ambient light and temperature, which can alter the optical path and sample properties [17].

Step 2: Implement Surface and System Design Solutions

- Antifouling Coatings: Apply coatings such as polyethylene glycol (PEG) or nanocomposites (e.g., BSA/prGOx/GA) to create a bio-inert surface that repels non-specific adsorption [9].

- Innate Antifouling Materials: Utilize novel carbon nanomaterials that possess inherent antifouling properties, eliminating the need for extra coatings that can sometimes hinder sensor response [9].

- Environmental Control: For optical systems, use housings that block ambient light. Implement temperature control circuits if necessary. For wearable sensors, use algorithms that can reference data from other sensors (e.g., accelerometers for motion) to correct for confounders [17].

The following table summarizes key noise sources and their quantitative impact on biosensor performance.

Table 1: Characteristics of Common Biosensor Noise Sources

| Noise Category | Specific Type | Root Cause | Impact on Signal | Typical Mitigation Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electrical | Thermal (Johnson) | Random charge carrier motion [9] | Raises baseline, limits ultra-low concentration detection [9] | Use high-conductivity materials; reduce operating temperature [9] |

| Electrical | 1/f (Flicker) | Material imperfections & defects [9] | Low-frequency signal drift & instability [9] | Engineer electrodes with fewer grain boundaries; use carbon nanomaterials [9] |

| Environmental | Electromagnetic Interference (EMI) | External power lines, wireless devices [9] | Capacitive/inductive coupling causes baseline fluctuations [9] | Implement electromagnetic shielding; use twisted-pair cables [9] |

| Environmental | Ambient Light (Optical) | DC or AC (flicker) from room lighting [17] | Photodetector saturation; offset errors in signal [17] | DC subtraction circuits; correlated sampling for AC flicker rejection [17] |

| Fundamental | Thermomechanical | Molecular agitation in resonator [16] | Limits SNR & resolution in NEMS/MEMS [16] | Operate in vacuum/cryogenic conditions; or adopt noise-driven sensing paradigm [16] |

| Biological | Biofouling | Non-specific adsorption in complex matrices [9] | Signal drift, false positives/negatives, reduced accuracy [9] | Apply antifouling coatings (e.g., PEG); use innate antifouling materials [9] |

Experimental Protocol: Validating a Noise-Driven Resonant Sensor

This protocol outlines the methodology for implementing a thermal noise-driven sensor, as referenced in the troubleshooting guide [16].

Aim: To detect a target analyte (e.g., pressure change, adsorbed mass) by characterizing the shift in the resonant frequency of a microstructure driven solely by ambient thermal noise.

Principle: A nano/micro-scale cantilever in a thermal bath at room temperature experiences constant thermomechanical noise. This noise is "colored" by the resonator, resulting in a dynamically amplified response at its natural resonant frequency. The binding of a target mass or application of a stimulus (e.g., pressure) shifts this resonant frequency, which can be tracked without any external actuation.

Materials and Reagents:

- Sensor Chip: A microcantilever fabricated from silicon or a polymer, designed for high compliance (low stiffness,

k) and low damping [16]. - Optical Readout System: A laser Doppler vibrometer or an interferometric setup to transduce the cantilever's motion without electrical contact, minimizing additional noise [16].

- Signal Analyzer: A spectrum analyzer or high-speed data acquisition card with Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) software to compute the Power Spectral Density (PSD).

- Fluidic Chamber & Calibration Samples: A microfluidic chamber to introduce samples and controlled pressure/analyte streams.

Procedure:

- Sensor Preparation: Mount the microcantilever chip inside the fluidic chamber, ensuring it is secure but mechanically isolated from external vibrations.

- Baseline Acquisition: With the chamber containing only the background medium (e.g., air or buffer), use the optical readout to measure the cantilever's displacement over time.

- Data Processing: Compute the Power Spectral Density (PSD) of the displacement signal. This will reveal a Lorentzian-shaped peak centered at the natural resonant frequency (

f₀). Record the baseline resonant frequency and the peak magnitude. - Sample Introduction: Introduce the test sample or apply the target stimulus (e.g., a specific gas for pressure change, a solution with target analytes for mass detection) into the fluidic chamber.

- Sample Measurement: Repeat step 2 and 3 while the sensor is exposed to the sample.

- Data Analysis: Compare the PSD from the sample measurement to the baseline. A successful detection is indicated by a measurable shift in the resonant frequency (

Δf = f_sample - f₀). The magnitude of this shift is proportional to the applied stimulus or adsorbed mass.

Experimental Workflow and Signaling Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for selecting a noise mitigation strategy based on the primary noise source identified in a biosensing experiment.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Materials for Advanced Biosensor Fabrication and Noise Mitigation

| Material / Reagent | Function in Biosensing | Key Property for Noise Reduction |

|---|---|---|

| Carbon Nanomaterials (e.g., Gii, Graphene) [9] | Electrode/transducer material | High conductivity reduces thermal & flicker noise; innate antifouling reduces biological noise [9]. |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) [9] | Antifouling coating | Forms a hydrated, bio-inert layer to minimize non-specific binding of biomolecules [9]. |

| Nitrogen-Vacancy (NV) Nanodiamonds [18] | Quantum sensing platform | Highly sensitive to elusive bio-signals (forces, free radicals) with enhanced precision, useful for intracellular sensing [18]. |

| Gold Nanoparticles / Nanostructures [19] | Transducer for LSPR biosensors | Enable label-free, real-time detection via local refractive index changes; sensitivity depends on size, shape, and arrangement [19]. |

| Screen-Printed Electrodes (SPE) | Disposable sensor substrate | Enable mass-produced, portable biosensors. When made with carbon nanomaterials, combine low cost with low-noise properties [20]. |

For researchers in selective biosensing, achieving an excellent signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) is a fundamental objective for detecting low-concentration analytes with high fidelity. However, this pursuit is perpetually balanced against the constraints of power consumption, especially in portable or implantable devices. This technical support guide addresses the core trade-offs between SNR, power, and sensor design, providing troubleshooting advice and methodologies to help you optimize your experimental biosensing systems for both performance and efficiency.

↑ FAQs: Core Trade-offs and Design Principles

1. What is the fundamental relationship between SNR and power consumption in a biosensor's analog front-end (AFE)?

In the analog front-end of a biosensor, particularly in the readout circuitry, a higher Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) often requires higher power consumption. This is because achieving a clean signal from weak, noisy physiological data (like EEG or ECG) necessitates high-gain, low-noise amplifiers. Designing these amplifiers for lower inherent noise typically requires higher bias currents, which directly increases power dissipation [21]. Furthermore, techniques like oversampling, which is used to improve effective resolution and shape quantization noise, require the circuit to operate at a frequency much higher than the signal's native bandwidth, also increasing power usage [21].

2. How does the choice of Analog-to-Digital Converter (ADC) impact the SNR and power budget?

The ADC is a critical component where the SNR-power trade-off is explicitly managed. Sigma-Delta (Σ-Δ) ADCs are particularly suited for biosensing applications because they use oversampling and noise-shaping to push quantization noise out of the signal band, achieving high effective resolution (high SNR) for low-frequency signals [21]. The power consumption of a Σ-Δ ADC depends on its architecture:

- Operational Amplifier (Op-Amp) Design: The op-amps in the modulator are primary power consumers. For instance, a folded-cascode op-amp might consume 250 μW to achieve a 76 dB gain, whereas a two-stage amplifier can achieve a similar gain with only 72 μW, offering a significant power saving for a slight trade-off in other specifications [21].

- Quantizer Design: Replacing an op-amp-based quantizer with a dynamic comparator circuit can further reduce power consumption [21].

The table below summarizes key performance parameters from a low-power Σ-Δ ADC design for biomedical applications [21].

Table 1: Performance Summary of a Low-Power Sigma-Delta ADC for Biomedical IoT

| Parameter | Value | Significance for Biosensing |

|---|---|---|

| Power Consumption | 0.498 mW | Ideal for battery-operated, portable, or implantable devices. |

| Effective Number of Bits (ENOB) | 13.995 bits | Enables high-resolution digitization of subtle physiological signals. |

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) | 84.8 dB | Reflects a high-fidelity signal with low noise floor. |

| Figure of Merit (FOM) | 20.41 fJ/conversion | A composite metric indicating high energy efficiency. |

| Oversampling Ratio (OSR) | 128 | Determines the degree of noise shaping and resolution enhancement. |

3. Beyond electronics, what biosensor properties influence SNR and how can they be optimized?

The biological and chemical elements of the biosensor are equally crucial for a good SNR.

- Bioreceptor Affinity and Stability: The selectivity and affinity of your bioreceptor (e.g., antibody, enzyme, aptamer) for the target analyte directly influence the strength of the signal. A high-affinity interaction produces a stronger signal, improving SNR [22]. Furthermore, the stability of the bioreceptor impacts long-term SNR; degradation over time can lead to signal drift and increased noise [22].

- Immobilization Technique: The method used to affix the bioreceptor to the transducer surface (physical adsorption vs. chemical covalent bonding) affects its activity and orientation. Optimal immobilization preserves bioactivity and minimizes non-specific binding, which is a significant source of experimental noise [23] [24].

- Dynamic Range and Operating Range: Ensure your biosensor's dynamic range (the span between minimal and maximal detectable signals) and operating range (the concentration window for optimal performance) are suited to your target analyte concentrations. Operating outside this range can lead to signal saturation or a response buried in noise [13].

↑ Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Poor Signal-to-Noise Ratio in Electrochemical Measurements

Problem: The output signal is weak and noisy, making it difficult to distinguish the true response from the background.

Possible Causes and Solutions:

Cause: Excessive Electronic Noise.

- Solution A: Check for proper shielding of cables and the measurement setup. Ensure all connections are secure.

- Solution B: Verify that your AFE is designed for low-noise operation. This may involve using components that consume slightly more power to achieve lower noise figures [21].

Cause: Non-Specific Binding.

- Solution A: Optimize your sample preparation and the composition of your buffer solution. Include blocking agents (e.g., BSA) to minimize non-specific interactions.

- Solution B: Re-evaluate your bioreceptor immobilization strategy. A more controlled, covalent immobilization method may reduce random orientation and denaturation, improving specificity over simple adsorption [24].

Cause: Suboptimal Bioreceptor Performance.

- Solution A: Characterize your bioreceptor's affinity and stability. A bioreceptor with low affinity or one that is degrading will produce a weak signal [22].

- Solution B: For synthetic biology approaches, consider engineering the biosensor. The response sensitivity and dynamic range can often be tuned by modifying genetic parts such as promoters and ribosome binding sites (RBS) [13].

Issue: High Power Consumption in Continuous Monitoring Systems

Problem: The biosensor device depletes its battery too quickly for practical long-term monitoring.

Possible Causes and Solutions:

Cause: Inefficient Data Conversion.

- Solution: Adopt an energy-efficient ADC architecture like the Sigma-Delta modulator. Explore design optimizations such as using a two-stage amplifier in the integrator or a dynamic comparator in the quantizer, as these choices can reduce power consumption by over 40% [21].

Cause: Always-On, High-Frequency Sampling.

- Solution: Implement adaptive sampling protocols. Instead of continuously sampling at the highest rate, design the system to increase the sampling rate only when a signal of interest is detected. This can dramatically reduce the average power consumption.

Cause: Power-Hungry Digital Filtering.

- Solution: Optimize the digital signal processing chain. For example, in a Cascaded Integrator Comb (CIC) filter used with a Σ-Δ ADC, replacing traditional adder-based integrators with counter-based integrators can reduce the filter's power dissipation by up to 30% [21].

↑ Experimental Protocols for Characterizing SNR and Power

Protocol 1: Characterizing Biosensor Dose-Response and Dynamic Range

Objective: To map the biosensor's output signal against analyte concentration and determine its key performance metrics [13].

Materials:

- Biosensor platform with functional bioreceptor.

- Stock solutions of the target analyte at known, varying concentrations.

- Buffer for dilution and control measurements.

- Data acquisition system (e.g., potentiostat for electrochemical sensors).

Methodology:

- Baseline Measurement: Record the sensor's output signal in the presence of only the buffer (blank solution) to establish the baseline and noise level.

- Dose-Response: Sequentially expose the biosensor to a series of analyte solutions with concentrations spanning several orders of magnitude (e.g., from pM to μM). Allow the signal to stabilize at each concentration.

- Data Analysis:

- Plot the steady-state signal (or rate of signal change) against the logarithm of the analyte concentration.

- Fit a curve (e.g., sigmoidal) to the data.

- Calculate the Dynamic Range: The concentration range between the lower and upper detection limits.

- Calculate the Limit of Detection (LOD): Typically the concentration corresponding to the baseline signal plus three times the standard deviation of the baseline noise.

- Assess Linearity: The range over which the response is linear with concentration [22].

Protocol 2: Measuring Power Consumption of Readout Circuitry

Objective: To accurately measure the power consumption of the biosensor's analog front-end and ADC.

Materials:

- Biosensor readout circuit (AFE and ADC).

- DC power supply.

- Digital multimeter or a current-sensing module (e.g., a sense resistor and an oscilloscope).

- Load resistor/capacitor to simulate the sensor.

Methodology:

- Setup: Connect the DC power supply to the circuit's VDD and ground. Break the VDD line and insert a low-value, high-precision sense resistor.

- Voltage Measurement: Measure the voltage drop across the sense resistor using a multimeter. The current draw (I) is calculated by I = Vsense / Rsense.

- Power Calculation: Total power consumption is P = V_supply * I.

- Dynamic Power: For circuits with dynamic power (like clocks in ADCs), use an oscilloscope to measure the current waveform across the sense resistor to capture average and peak power.

- Correlation with SNR: Perform this measurement while the circuit is processing a known input signal. Record the output and calculate the SNR. Repeat under different operating conditions (e.g., different sampling rates, amplifier biases) to build a profile of the SNR vs. Power trade-off.

↑ Visualizing the Trade-offs and Solutions

The following diagram illustrates the core conflict and the primary design strategies used to manage the trade-off between SNR and power consumption in biosensor design.

Diagram: Managing SNR and Power Trade-off

↑ The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Biosensing Experiments

| Item | Function in Research | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Bioreceptors (Antibodies, Aptamers, Enzymes) | The molecular recognition element that provides selectivity by binding the target analyte [22] [24]. | Affinity, specificity, and stability are paramount. Choose between natural (e.g., antibodies) and synthetic (e.g., aptamers, MIPs) based on application [24]. |

| Immobilization Chemicals (e.g., EDC/NHS, Glutaraldehyde) | Enable covalent attachment of bioreceptors to the transducer surface, creating a stable sensing interface [24]. | The chosen chemistry must preserve bioreceptor activity and minimize non-specific binding. |

| Blocking Agents (e.g., BSA, Casein) | Used to passivate unused sites on the transducer surface after bioreceptor immobilization [22]. | Critical for reducing background noise caused by non-specific adsorption of non-target molecules. |

| Sigma-Delta ADC Evaluation Board | A development platform to prototype and test high-resolution, energy-efficient analog-to-digital conversion [21]. | Allows researchers to empirically validate the power/performance trade-offs of different ADC configurations before custom IC design. |

| Low-Noise Amplifier (LNA) IC | Provides the first stage of signal conditioning, amplifying weak sensor signals while adding minimal noise [21]. | Key specifications include input-referred noise voltage, gain, and power consumption. |

Methodological Breakthroughs: Sensor Design and AI for Enhanced SNR

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

This technical support center provides troubleshooting guidance for researchers working with advanced biosensing architectures, with a specific focus on methodologies to improve the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) in selective biosensing.

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) Troubleshooting

FAQ: My SPR baseline is unstable or drifting. What could be the cause and solution?

- Cause: Baseline drift is often a sign of a system that is not optimally equilibrated. This can be caused by improperly degassed buffer (leading to bubbles), leaks in the fluidic system, buffer contamination, or significant temperature fluctuations [25] [26].

- Solution:

- Ensure the running buffer is properly degassed to eliminate air bubbles [25].

- Check the fluidic system for any leaks that could introduce air [25].

- Use a fresh, clean, and filtered buffer solution [25].

- Allow the system more time to equilibrate; it can sometimes be necessary to run the buffer overnight or perform several buffer injections before the experiment [26].

- Place the instrument in a stable environment with minimal temperature variations and vibrations [25].

FAQ: I observe no signal change or a very weak signal upon analyte injection. How can I enhance the response?

- Cause: This can result from low analyte concentration, insufficient ligand immobilization level, inactive ligand, or non-optimal flow conditions [25] [27] [28].

- Solution:

- Verify the activity and integrity of your ligand and analyte [25] [28].

- Increase the analyte concentration, if feasible [25].

- Optimize the ligand immobilization density to achieve a higher level [25].

- Confirm the ligand's coupling method; if the binding pocket is obstructed, try alternative immobilization strategies such as capture experiments or coupling via thiol groups [27] [28].

- Extend the association time or adjust the flow rate [25].

FAQ: How can I resolve issues with high non-specific binding on my SPR sensor chip?

- Cause: The analyte is binding to the sensor surface itself, rather than specifically to the immobilized ligand [27] [28].

- Solution:

- Block the sensor surface with a suitable agent like BSA or ethanolamine before ligand immobilization [25].

- Supplement your running buffer with additives such as surfactants, BSA, dextran, or polyethylene glycol (PEG) to minimize non-specific interactions [27] [28].

- Optimize the regeneration step to efficiently remove any non-specifically bound material between analysis cycles [25].

- Consider changing the sensor chip type to one more suitable for your specific interaction [27].

FAQ: My sensor surface is not regenerating completely, leading to carryover effects. What should I do?

- Cause: The regeneration conditions are not strong enough to fully remove the bound analyte without damaging the ligand [25] [27].

- Solution:

- Systematically optimize the regeneration conditions. Test different solutions including acidic conditions (e.g., 10 mM Glycine pH 2.0), basic conditions (e.g., 10 mM NaOH), or high-salt conditions (e.g., 2 M NaCl) [27].

- Increase the regeneration flow rate or contact time [25].

- For capture experiments, ensure both the target and analyte are efficiently removed [27].

- Adding 10% glycerol to the regeneration solution can sometimes help with target stability [27].

The table below summarizes common SPR issues and their solutions.

| Issue Category | Specific Problem | Proposed Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline Issues [25] [26] | Baseline drift | Degas buffer; check for leaks; use fresh buffer; extend system equilibration time. |

| Noisy or fluctuating baseline | Place instrument in stable environment; use filtered buffer; clean sensor surface. | |

| Signal Issues [25] [27] [28] | No signal or weak signal | Increase analyte concentration; optimize ligand density; check ligand activity; alter coupling chemistry. |

| High non-specific binding | Use blocking agents (BSA); add buffer additives (surfactants, PEG); optimize regeneration; change chip type. | |

| Sensorgram saturation | Reduce analyte concentration or injection time; use lower ligand density; increase flow rate. | |

| Regeneration Issues [25] [27] | Incomplete analyte removal | Optimize regeneration solution (e.g., pH, salt); increase flow rate/contact time; add 10% glycerol for stability. |

Silicon Nanowire Field-Effect Transistor (SiNW-FET) Troubleshooting

FAQ: How can I significantly enhance the signal-to-noise ratio for detecting low-abundance DNA targets with my SiNW-FET biosensor?

- Solution: Implement a signal amplification strategy such as Rolling Circle Amplification (RCA). This technique can be integrated with your SiNW-FET biosensor to dramatically improve the SNR and lower the detection limit [29].

- Experimental Protocol (RCA on SiNW-FET):

- Immobilization: Immobilize the probe DNA on the surface of the silicon nanowire.

- Hybridization: Perform a sandwich hybridization by introducing the target DNA, which is perfectly matched to the probe, followed by an RCA primer.

- Amplification: The RCA primer hybridizes to a circular DNA template and initiates the RCA reaction. This reaction generates a long, single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) product that possesses numerous repeating units.

- Detection: The extensive negative charge of the long ssDNA RCA product causes a significant conductance change in the SiNW, thereby enhancing the electronic signal far beyond what the single target molecule would produce.

- Outcome: This method has been shown to achieve a signal-to-noise ratio of >20 for 1 fM DNA detection, implying an ultra-low detection floor of around 50 aM. It also offers high selectivity, effectively discriminating perfectly matched DNA from one-base mismatched sequences [29].

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key reagents and materials used in the featured biosensor experiments and explains their critical functions.

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| CM5 Sensor Chip (SPR) [28] | A carboxymethylated dextran matrix commonly used for the immobilization of ligands via amine coupling. |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) [25] [27] | Used as a blocking agent to cover unused reactive groups on the sensor surface, reducing non-specific binding. |

| Glycine-HCl (pH 2.0-3.0) [27] | A low-pH regeneration solution used to disrupt protein-protein interactions and remove bound analyte from the ligand. |

| Sodium Hydroxide (e.g., 10-50 mM) [27] | A common basic regeneration solution for SPR surfaces. |

| Rolling Circle Amplification (RCA) Kit [29] | An isothermal enzymatic DNA amplification technique used with SiNW-FET to create long ssDNA products for substantial signal enhancement. |

| Silicon-on-Insulator (SOI) Wafer [30] | A substrate used for fabricating microfluidic chips and sensors. It provides an exceptionally flat surface, which is critical for reducing background noise in fluorescence-based and other optical detection systems. |

Experimental Workflow Visualizations

SPR Regeneration Optimization Workflow

SiNW-FET with RCA Signal Enhancement

FAQs: Core Concepts for Researchers

Q1: What makes 2D nanomaterials particularly effective for signal amplification in biosensors?

2D nanomaterials provide exceptional properties for signal amplification, including an ultra-high surface-to-volume ratio for superior biomolecule loading, excellent electrical conductivity for efficient electron transfer, and tunable surface chemistry for easy functionalization with biorecognition elements. Their atomic-level thickness and planar structure make them ideal for constructing highly sensitive field-effect transistor (FET) biosensors, enabling low detection limits, real-time monitoring, and label-free diagnosis [31] [32].

Q2: How can I select the most suitable 2D material for my specific biosensing application?

Material selection should be guided by the transducer principle and the required electronic properties. The table below summarizes key 2D materials and their primary amplification roles [31] [32]:

Table 1: Guide to Selecting 2D Materials for Signal Amplification

| Material | Electronic Property | Key Role in Signal Amplification | Exemplary Biosensing Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Graphene/GO/rGO | Metallic/Semi-metallic | High carrier mobility; electrochemical catalyst; efficient transducer in FETs | DNA sensing; pathogen detection; wearable sensors |

| MXenes (e.g., Ti₃C₂Tₓ) | Metallic | Excellent electrical conductivity; facilitates electron transfer in electrochemical sensors | Detection of small molecules, proteins, and cancer biomarkers |

| Transition Metal Dichalcogenides (e.g., MoS₂) | Semiconducting | Intrinsic bandgap allows for high current on/off ratio; catalytic activity | FET-based immunosensors; nucleic acid detection |

| Black Phosphorus (Phosphorene) | Semiconducting | Tunable bandgap; high charge-carrier mobility | Flexible and wearable bio-FETs |

| 2D Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) | Varies | Ultra-high porosity and surface area for target preconcentration | Enzyme-based biosensors; environmental monitoring |

Q3: What are the primary signal amplification strategies employed with 2D materials?

Strategies can be categorized as target-based or signal-based. Target-based amplification (e.g., loop-mediated isothermal amplification - LAMP) increases the number of target analyte molecules before detection. Signal-based amplification enhances the signal generated per binding event and includes nanomaterial-enabled electrocatalysis, enzymatic labeling, and the use of 2D materials as a scaffold for other signal-generating elements like enzymes or metal nanoparticles [33] [34].

Q4: My biosensor shows poor electron transfer and low sensitivity. What material should I consider?

Metallic 2D materials like MXenes (e.g., Ti₃C₂Tₓ) are highly recommended. They possess excellent electrical conductivity that facilitates rapid electron transfer, thereby directly amplifying the electrochemical signal. Their rich surface chemistry also allows for easy immobilization of biorecognition elements [31].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Low Sensitivity and High Limit of Detection

Table 2: Troubleshooting Low Sensitivity

| Observation | Potential Root Cause | Corrective Action & Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Weak electrochemical signal | Poor electron transfer kinetics between bioreceptor and electrode | Protocol: Integrate a highly conductive 2D material like MXene or reduced Graphene Oxide (rGO). Drop-cast a dispersion of the material onto the electrode surface and anneal. |

| Low loading density of bioreceptors (e.g., antibodies, aptamers) | Protocol: Utilize a 2D material with a high surface area, such as a 2D MOF or functionalized graphene. Activate the surface with EDC/NHS chemistry before incubating with the bioreceptor. | |

| High background noise | Non-specific adsorption of interferents on the sensor surface | Protocol: Implement a blocking step after bioreceptor immobilization. Use 1% BSA or a similar blocking agent for 1 hour. Functionalize the 2D material with polyethylene glycol (PEG) chains to create an anti-fouling layer. |

| Inconsistent signal between replicates | Inhomogeneous dispersion of 2D material on transducer | Protocol: Ensure proper exfoliation and stabilization of the 2D material in solvent (e.g., using surfactants or solvent exchange). Characterize the modified surface using techniques like SEM or AFM. |

Guide 2: Resolving Reproducibility and Stability Issues

Table 3: Troubleshooting Reproducibility and Stability

| Observation | Potential Root Cause | Corrective Action & Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Signal drift over time | Degradation of the 2D material (e.g., oxidation of Black Phosphorus) | Protocol: For air-sensitive materials, perform all fabrication steps in a glove box. Apply a thin protective coating (e.g., aluminum oxide via atomic layer deposition). Store the biosensor in an inert atmosphere. |

| Variation in Cq values > 0.5 cycles in qPCR-based assays | Pipetting error or insufficient mixing of 2D nanomaterial-enhanced reagents [35] | Protocol: Calibrate pipettes regularly. Use positive-displacement pipettes and filtered tips. Mix all solutions thoroughly during preparation. Hold pipette vertically when aspirating. |

| Poor functionalization efficiency | Inadequate surface chemistry of the 2D material | Protocol: Optimize the functionalization protocol (e.g., concentration of coupling agents, pH, reaction time). Use characterization techniques like XPS or Raman spectroscopy to confirm successful functionalization. |

| Jagged or noisy amplification plot | Poor amplification efficiency or mechanical error [35] | Protocol: Ensure a sufficient amount of probe is used. Try a fresh batch of probe. Mix primer/probe/master solution thoroughly. Contact equipment technician to check the instrument. |

Experimental Protocols for Signal Amplification

Protocol 1: Universal Gold Enhancement for Nanoprobe-Based Biosensing

This enzyme-free protocol rapidly enhances the signal from various nanoprobes (e.g., gold, silver, silica, iron oxide) by depositing a gold layer, increasing light scattering and enabling visual detection of even low nanoprobe densities [36].

Workflow Diagram:

Detailed Methodology:

- Assay Completion: First, complete your standard biosensing assay (e.g., microarray, lateral flow) using your chosen nanoprobe for detection.

- Prepare Enhancement Solution: Freshly prepare a solution containing 5 mM Chloroauric acid (HAuCl₄·3H₂O), 50 mM MES buffer (pH 6.0), and 1.027 M Hydrogen Peroxide (H₂O₂).

- Apply Enhancement Solution: Gently apply the enhancement solution to the biosensing substrate (e.g., the paper array or electrode) containing the captured nanoprobes.

- Incubate and Rinse: Allow the reaction to proceed for 2-5 minutes at room temperature. The MES buffer and H₂O₂ will reduce Au(III) to Au(0), depositing it onto the existing nanoprobes and enlarging them. Terminate the reaction by rinsing thoroughly with deionized water and drying.

- Signal Acquisition: The enlarged nanoprobes will scatter light more efficiently. Acquire the signal visually, with a tabletop scanner, or via UV-Vis spectroscopy. This method can achieve a 100-fold improvement in the signal-to-noise ratio [36].

Protocol 2: Integrating Isothermal Amplification with 2D Material-Based Electrochemical Detection

This protocol combines the target-copying power of LAMP with the sensitive transduction of 2D material-modified electrodes for ultra-sensitive nucleic acid detection [33].

Workflow Diagram:

Detailed Methodology:

- Nucleic Acid Extraction: Extract and purify the target nucleic acid (DNA/RNA) from your sample.

- LAMP Amplification: Perform LAMP amplification on the target sequence using a standard kit or protocol. This isothermal step rapidly generates a large number of double-stranded DNA amplicons.

- Electrochemical Detection:

- Electrode Preparation: Modify a screen-printed or glassy carbon electrode with a dispersion of an electrocatalytic 2D material like MoS₂ or rGO.

- Measurement: Transfer a small volume of the LAMP amplicon to the electrode. Add a redox-active DNA intercalator, such as Methylene Blue.

- The intercalator binds to the double-stranded LAMP products, and a change in the electrochemical signal (e.g., in Differential Pulse Voltammetry - DPV) is measured. The 2D material enhances this signal by improving electron transfer.

- Data Analysis: The measured current is proportional to the amount of amplicon, which correlates with the initial target concentration.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Key Reagents for 2D Material-Based Signal Amplification

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Methylene Blue | Electroactive intercalator for nucleic acid detection [33] | Redox probe; signal decreases upon intercalation into dsDNA. |

| Chloroauric Acid (HAuCl₄) | Gold precursor for signal enhancement protocol [36] | Source of Au(III) ions for reduction to Au(0) on nanoprobes. |

| EDC / NHS Crosslinkers | Surface functionalization of 2D materials [31] | Activates carboxyl groups for covalent attachment of bioreceptors. |

| MES Buffer | Reduction and pH control in enhancement solution [36] | Reduces Au(III) to Au(0); maintains optimal pH for reaction. |

| BSA or Casein | Blocking agent to minimize non-specific binding [35] | Proteins that occupy non-specific binding sites on the sensor surface. |

| TMB (3,3',5,5'-Tetramethylbenzidine) | Chromogenic substrate for horseradish peroxidase (HRP) [36] | Yields a blue color upon enzymatic oxidation; can be used in HRP-labeled assays. |

Technical FAQs: Core Concepts and System Setup

FAQ 1: What is the principle behind using a 1D-CNN for noise reduction in biosensing, and how does it outperform traditional filters?

Traditional digital filters, such as low-pass or moving average filters, operate on fixed frequency cutoffs and linear principles. They often struggle with non-linear, time-varying noise common in biosensor signals, which can lead to the inadvertent removal of critical signal components, reducing sensitivity [37] [38]. A 1D Convolutional Neural Network (1D-CNN) is a deep learning model that performs adaptive, non-linear filtering. It learns complex noise patterns directly from the data through training, allowing it to distinguish and filter out noise while preserving the essential characteristics of the biosignal. This results in higher fidelity signal recovery in complex, noisy environments [37] [39].

FAQ 2: Why is an FPGA the preferred hardware for accelerating 1D-CNNs in real-time biosensing applications?

Field-Programmable Gate Arrays (FPGAs) are integrated circuits that can be reconfigured to create custom hardware architectures. For 1D-CNN inference, FPGAs offer three key advantages over general-purpose processors:

- High Parallelism: FPGAs can execute multiple mathematical operations, such as convolutions, simultaneously, drastically speeding up processing [40].

- Low Latency: The parallel architecture and custom data paths enable deterministic, low-latency processing, which is critical for real-time detection and feedback [37] [41].

- Power Efficiency: FPGAs can achieve high computational throughput at relatively low power consumption, making them ideal for portable and point-of-care diagnostic devices [37] [42].

FAQ 3: Our biosensor's signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) is insufficient after basic amplification. How can this system help?

This system employs a two-stage approach to significantly enhance SNR. First, a high-gain analog front-end, such as a folded-cascode amplifier, provides initial hardware-based amplification, boosting the raw signal [37] [38]. Second, the FPGA-accelerated 1D-CNN performs advanced, adaptive noise reduction on this pre-amplified signal. In a simulated study for a viral detection biosensor, this combined approach achieved an SNR of approximately 70 dB with the amplifier and an additional 75% noise reduction across a broad frequency range using the 1D-CNN [37]. The table below summarizes the performance improvements from a representative study.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of an FPGA-based 1D-CNN Biosensing System (Simulation Results)

| Performance Metric | Value | Context / Method |

|---|---|---|

| Final Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) | ~70 dB | After folded-cascode amplifier and 1D-CNN processing [37] |

| Noise Reduction | ~75% | Achieved by the 1D-CNN across a broad frequency range [37] |

| Processing Latency | 221 ms per frame | For a lightweight U-Net CNN on FPGA for ultrasound imaging [41] |

| Power Consumption | 0.918 W | For a 32-channel ultrasound system with FPGA-CNN reconstruction [41] |

| Classification Accuracy | 90.1% | For a 1DCNN-GRU hybrid model on FPGA for plant signal classification [42] |

Troubleshooting Guides: Implementation and Optimization

Problem 1: Model accuracy is poor after deployment on FPGA, despite good performance in software simulation.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Precision Loss from Quantization. Floating-point models (32-bit) trained in software are often quantized to fixed-point (e.g., 8-bit or 16-bit) for efficient FPGA implementation. Aggressive quantization can lead to significant accuracy loss.

- Solution: Implement Quantization-Aware Training (QAT). Train the model while simulating the effects of quantization, allowing it to adapt. Consider mixed-precision quantization, where critical layers retain higher precision (e.g., 16-bit) while others are lowered (e.g., 8-bit) [41].

- Cause: Overfitting on Limited Training Data. The model has memorized the training dataset and fails to generalize to real-world signals.

- Cause: Domain Shift. The data distribution of the real-world target signals differs from the source data used for training.

- Solution: Employ transfer learning or domain adaptation techniques. For example, use Correlation Alignment (CORAL) to minimize the distribution discrepancy between features extracted from your source (training) and target (real-world) data [43].

Problem 2: The 1D-CNN model exceeds the FPGA's available resources (DSPs, BRAM).

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Excessively Large Model. The CNN architecture may have too many parameters or layers for the target FPGA.

- Cause: Inefficient Hardware Mapping. The model's computational graph is not optimized for the hardware.

- Solution: Perform hardware-software co-design. Optimize the data flow (e.g., loop unrolling, tiling) to maximize data reuse and minimize memory bandwidth bottlenecks. Utilize the FPGA's parallel processing capabilities effectively by designing a custom accelerator architecture tailored to your specific 1D-CNN [40].

Problem 3: The system experiences high latency, failing to meet real-time processing requirements.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Memory Bandwidth Bottleneck. The computational units are frequently idle, waiting for data from off-chip memory.

- Solution: Optimize the memory hierarchy. Use the FPGA's on-chip Block RAM (BRAM) as a cache for weights and intermediate feature maps to reduce access to external DRAM. Design data pipelines that ensure a continuous flow of data to the processing elements [40].

- Cause: Non-optimized Processing Pipeline. Operations are executed sequentially rather than in parallel.

- Solution: Increase the parallelism in your hardware design. This can involve instantiating multiple processing engines to handle different filters or parts of the input signal concurrently. Pipelining the operations (convolution, activation, pooling) can also ensure that different stages of the network are processing data simultaneously [40] [42].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol: Implementing a 1D-CNN for Denoising Biosensor Time-Series Data

This protocol outlines the key steps for developing and deploying a 1D-CNN noise filter, based on methodologies used in successful implementations [37] [39] [42].

1. Data Acquisition and Preprocessing:

- Signal Collection: Collect raw time-series data from your biosensor (e.g., SiNW-FET, electrochemical sensor) under various conditions, including clean (if possible) and noisy environments. The signal should be sampled at a frequency sufficiently higher than its bandwidth.

- Data Labeling: For supervised learning, you need clean "ground truth" signals. This can be achieved by:

- Recording signals in a controlled, low-noise laboratory setting.

- Using high-precision, benchtop instrumentation to obtain reference signals.

- Applying advanced signal processing techniques (e.g., wavelet transforms) to generate a cleaner version of the signal.

- Dataset Creation: Segment the continuous signal into fixed-length windows. Split the data into training, validation, and test sets.

2. Model Design and Training:

- Network Architecture: Design a 1D-CNN. A typical denoising architecture may include:

- Input Layer: Accepts a 1D vector of the raw signal.

- Convolutional Layers: Use 1D kernels to extract local temporal features. Multiple kernels of different sizes can capture multi-scale patterns [39].

- Activation Functions: Use non-linear functions like ReLU (Rectified Linear Unit) after convolutions.

- Pooling Layers (Optional): For classification, pooling reduces dimensionality. For denoising, they may be omitted to preserve signal resolution.

- Fully Connected / Output Layer: Produces the denoised signal of the same length as the input.

- Training Configuration:

3. FPGA Deployment:

- Model Conversion: Convert the trained model (e.g., from PyTorch or TensorFlow) to a format suitable for FPGA implementation using tools like Xilinx Vitis AI or Intel OpenVINO.

- Hardware Acceleration Design: Develop the custom hardware logic in HDL (e.g., VHDL, Verilog) or High-Level Synthesis (HLS - e.g., C++). Key design considerations include parallelism, pipelining, and memory management [40].

- Integration and Testing: Integrate the CNN accelerator block with the rest of the system (e.g., analog-to-digital converter interfaces, communication modules). Perform rigorous on-device testing with live data to validate performance and latency.

Diagram 1: 1D-CNN based biosignal denoising workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Components for an FPGA-Accelerated 1D-CNN Biosensing System

| Component / Tool | Category | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| High-Gain Amplifier | Analog Front-End | Boosts the weak electrical signal from the biosensor before digitization, improving the initial SNR. Example: Folded-cascode amplifier [37]. |

| ADC (Analog-to-Digital Converter) | Data Acquisition | Converts the amplified analog biosignal into a digital time-series for processing by the 1D-CNN. |

| Altera DE2 FPGA Board | Hardware Platform | A specific example of an FPGA development board used to implement and accelerate the 1D-CNN model for real-time processing [37]. |

| PyTorch / TensorFlow | Software Framework | Open-source machine learning libraries used to design, train, and validate the 1D-CNN model in software before hardware deployment [39]. |

| Vitis AI / OpenVINO | Development Tool | Toolkits provided by FPGA vendors (Xilinx/Intel) to convert trained models into optimized code for deployment on their hardware platforms [40]. |

| Quantization-Aware Training (QAT) | Optimization Technique | A method that simulates lower numerical precision (e.g., INT8) during training, ensuring model accuracy is maintained after deployment on resource-constrained FPGAs [41]. |

| Correlation Alignment (CORAL) | Algorithm | A domain adaptation algorithm used to align the statistical properties of features from different datasets, improving model robustness against domain shift [43]. |

For researchers and scientists in drug development, achieving a high signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) is a fundamental challenge in the pursuit of sensitive and reliable biosensors. The operational regime of a field-effect transistor (FET) within the sensor is not merely a technical detail; it is a critical determinant of performance. Operating the FET in its subthreshold region—where the gate-to-source voltage is below the threshold voltage—can yield exponential enhancements in sensitivity and a significantly improved SNR [44]. This guide provides targeted troubleshooting and FAQs to help you successfully implement and optimize this powerful technique in your selective biosensing research.

## FAQs on Subthreshold Operation

1. Why does subthreshold operation fundamentally improve sensor sensitivity?

In the subthreshold, or weak inversion, regime, the current between the drain and source (IDS) exhibits an exponential dependence on the gate voltage (VGS) [45]. This exponential relationship makes the sensor's conductance exceptionally responsive to minor surface potential changes induced by the binding of charged target molecules.

When a sensor operates in the strong inversion (linear or saturation) region, the charge carriers in the channel strongly screen the electric field from bound charges. This limits the field's influence to a thin surface layer defined by the Debye screening length [44]. In the subthreshold regime, the carrier density is much lower, significantly increasing the screening length. This allows the electric field from a single bound biomolecule to gate the entire cross-section of the nanoscale sensor, leading to a maximal relative change in conductance (ΔG/G) [44].

2. We need high throughput; will subthreshold operation slow down our sensing measurements?

There is a trade-off to consider. The absolute current levels in the subthreshold regime are lower than in strong inversion, which can inherently limit the sensor's speed and maximum operating frequency [45]. For many biosensing applications involving the detection of proteins, DNA, or ions, the binding kinetics are often the rate-limiting step, not the electronic readout speed. Therefore, the profound sensitivity gain frequently outweighs the speed limitation. The suitability of this trade-off should be evaluated based on the specific temporal resolution requirements of your assay.

3. Our sensor response is unstable. How does subthreshold operation affect variability?