Smartphone-Integrated Biosensors for Visual Pesticide Detection: A New Paradigm for On-Site Food Safety and Environmental Monitoring

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the latest advancements in smartphone-integrated biosensors specifically designed for the visual detection of pesticide residues.

Smartphone-Integrated Biosensors for Visual Pesticide Detection: A New Paradigm for On-Site Food Safety and Environmental Monitoring

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the latest advancements in smartphone-integrated biosensors specifically designed for the visual detection of pesticide residues. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of these portable analytical platforms, delves into novel methodologies such as ratiometric fluorescent probes and molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs), and addresses critical challenges in sensor calibration and real-world deployment. The scope extends to rigorous performance validation against traditional chromatographic methods and discusses the transformative potential of integrating artificial intelligence (AI) and IoT connectivity for enhancing diagnostic accuracy and enabling widespread, decentralized monitoring in agricultural, clinical, and environmental contexts.

The Science Behind Smartphone Biosensors: Principles, Components, and Recognition Elements

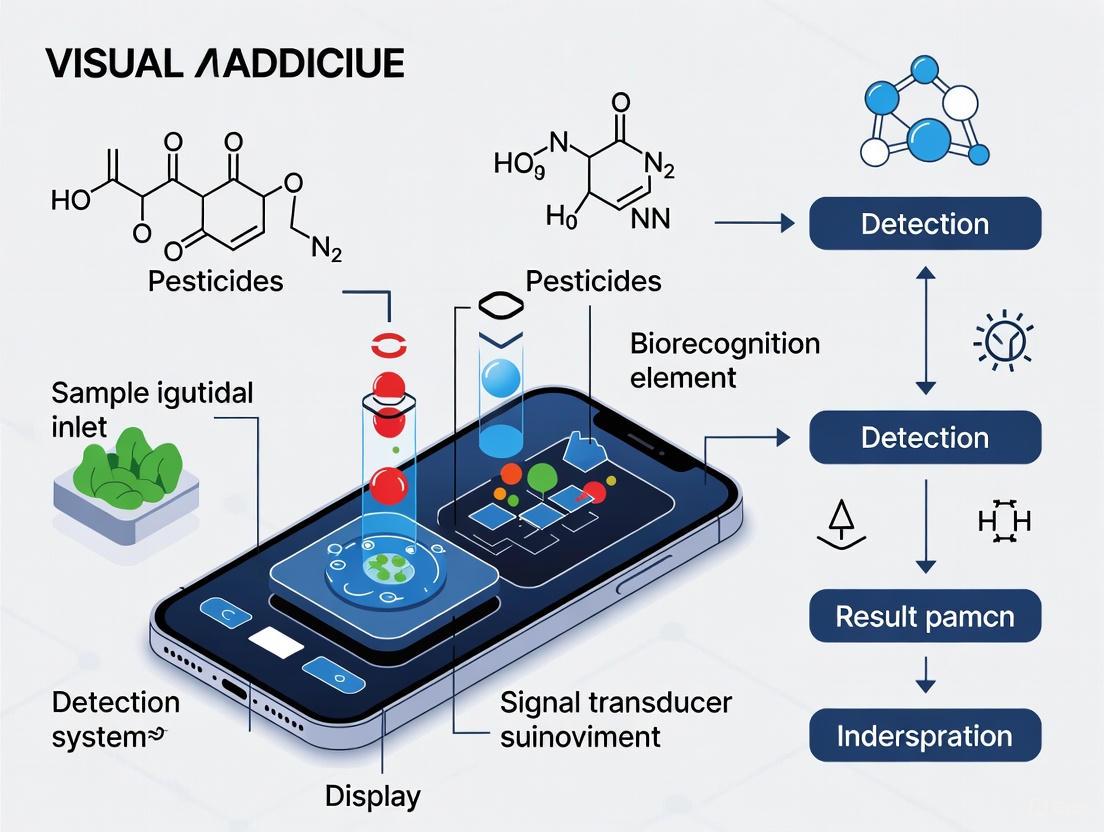

Smartphone-integrated biosensors represent a transformative approach for the on-site detection of pesticides, merging the specificity of biological recognition with the ubiquity and processing power of mobile devices. These systems are particularly valuable for environmental and food safety monitoring, such as detecting organophosphorus and carbamate pesticides in tea and other agricultural products [1]. The core working principle involves a sequential process: a biorecognition element first selectively binds to the target pesticide, this binding event is transduced into a measurable optical signal, and the smartphone then captures and processes this signal to provide a quantitative readout [2] [3] [4]. This document details the application notes and experimental protocols underlying this technology, providing a framework for researchers and scientists engaged in its development and application.

Core Principles and Biosensor Architecture

The operation of a smartphone-integrated biosensor for visual pesticide detection rests on three foundational pillars: biorecognition, signal transduction, and smartphone-based readout.

Biorecognition Elements

The specificity of the biosensor is determined by its biorecognition element, which selectively interacts with the target analyte. Common types include:

- Enzymes: Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) is widely used for detecting organophosphorus and carbamate pesticides. These pesticides inhibit AChE activity, reducing the rate of enzymatic hydrolysis of its substrate (e.g., acetylthiocholine). The subsequent reduction in a colored or electroactive product formation serves as the basis for detection [1] [4].

- Antibodies: These proteins offer high affinity and specificity for a wide range of pesticide targets. Immunosensors utilize the antibody-antigen binding event, which can be detected through label-based or label-free methods [4].

- Nucleic Acid Aptamers: Single-stranded DNA or RNA molecules that fold into specific three-dimensional structures to bind target molecules with antibody-like affinity. They are synthetic, stable, and easily modified, making them emerging tools for biosensing [4].

- Biomimetic Receptors: This category includes Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs), which are artificial receptors containing tailor-made binding sites complementary to the target pesticide. They are prized for their high stability and cost-effectiveness [4].

Signal Transduction and Transduction

Following biorecognition, the binding event must be converted into a quantifiable signal. For visual detection, optical transduction is paramount:

- Colorimetric Transduction: The most common method for smartphone-based visual detection. It often involves nanoparticles, such as gold nanoparticles (AuNPs), which exhibit intense colors due to surface plasmon resonance. A reaction between the bioreceptor and the target analyte can induce a color change or a shift in the absorption spectrum of the AuNPs [1] [5]. For instance, AChE inhibition can be coupled to a reaction that prevents the aggregation of AuNPs, resulting in a distinct color change from red to blue [6].

- Fluorescence Transduction: Some biosensors use fluorescent dyes or materials (e.g., quantum dots, metal-organic frameworks). The presence of the pesticide may quench or enhance the fluorescence intensity, which can be captured by the smartphone camera [1] [5].

Smartphone Readout and Data Processing

The smartphone serves as a portable spectrophotometer and data processor [2] [3]. The core steps are:

- Image Acquisition: The smartphone camera captures an image of the colorimetric reaction under controlled lighting conditions, often using a custom attachment to ensure consistency [6].

- Image Pre-processing: Algorithms correct for variable lighting conditions (e.g., using the gray world algorithm or a reference color card), segment the region of interest (the test strip), and extract color values (typically in RGB, HSV, or LAB color spaces) [6].

- Data Analysis and Quantification: Machine learning models, such as Support Vector Machines (SVM) for classification and Support Vector Regression (SVR) for continuous concentration prediction, are deployed on the smartphone to map the extracted color features to pesticide concentration [6]. This process mitigates the subjectivity of visual interpretation and enhances accuracy.

The following diagram illustrates the complete integrated workflow from sample to result.

Performance Comparison of Biosensing Technologies

The analytical performance of biosensors varies significantly based on the detection technique and the biorecognition element employed. The table below summarizes key performance metrics for common biosensor types used in pesticide detection, compared to traditional methods.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Biosensor Performance for Pesticide Detection

| Detection Technique | Biorecognition Element | Typical Detection Limit | Assay Time | Key Advantages | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electrochemical [1] [3] | Enzymes (AChE), Antibodies | nM - pM | 5 - 30 min | High sensitivity, portability, cost-effectiveness | Signal drift, electrode fouling |

| Fluorescence [1] [5] | Aptamers, Antibodies | pM range (MOF-enhanced) | 15 - 60 min | Very high sensitivity, multiplexing potential | Requires light source, can be complex |

| Colorimetric (Smartphone) [1] [6] | Enzymes (AChE), Antibodies | nM - µM | 10 - 30 min | Simplicity, true portability, low cost | Susceptible to ambient light interference |

| Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) [1] | Antibodies | nM range | 10 - 20 min | Label-free, real-time monitoring | Expensive instrumentation, bulky |

| Chromatography (GC/HPLC) [1] | N/A | nM - pM | Hours | Gold standard, high accuracy & precision | Lab-bound, expensive, requires trained personnel |

Experimental Protocol: Smartphone-Based Colorimetric Detection of Pesticides using an Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) Biosensor

This protocol provides a detailed methodology for detecting organophosphorus pesticides using an AChE-inhibited reaction on a test strip, with quantification via a smartphone application.

Principle

The assay is based on the inhibition of AChE. In the absence of pesticide, AChE hydrolyzes acetylthiocholine to thiocholine, which reduces a chromogen (e.g., Ellman's reagent) to produce a yellow color. When pesticides are present, they inhibit AChE, reducing the generation of thiocholine and resulting in a diminished color intensity. This color change is inversely proportional to the pesticide concentration and is quantified by a smartphone app [1] [6].

Materials and Equipment

- Smartphone with custom-built analysis application (e.g., built with Flutter framework) [6].

- Test strips impregnated with AChE and substrate/chromogen system [6].

- Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs): Can be used as colorimetric probes in alternative assay designs [6].

- Reference color card (for illumination correction).

- Sample solutions: Pesticide standards and unknown samples.

- Pipettes and microcentrifuge tubes.

Procedure

Sample Preparation:

- Prepare a series of pesticide standard solutions in a suitable buffer (e.g, phosphate buffer saline) to generate a calibration curve.

- Prepare unknown samples by extracting and filtering, if necessary.

Assay Execution:

- Apply a fixed volume (e.g., 50 µL) of standard or sample solution onto the test strip.

- Incubate the test strip at room temperature for a defined period (e.g., 10-15 minutes) to allow for the enzyme inhibition reaction to complete.

- After incubation, initiate the color development reaction if required by the specific test strip design.

Image Acquisition:

- Place the developed test strip and the reference color card in a well-lit area, avoiding shadows and glare.

- Open the smartphone application. Use the in-app guide to align the test strip and color card within the camera's field of view.

- Ensure stable exposure and capture the image.

Data Analysis:

- The application will automatically pre-process the image: correct illumination using the reference card, and segment the region of interest on the test strip.

- The application will extract color features (e.g., RGB values) from the segmented area.

- A pre-trained machine learning model (SVM/SVR) will analyze the color features and output the predicted pesticide concentration [6].

The specific data processing workflow within the smartphone is detailed below.

Data Interpretation

- The application provides a numerical value of the pesticide concentration.

- Results can be categorized into "safe," "warning," or "hazardous" based on predefined regulatory thresholds (e.g., from GB 2763-2021 or EU MRLs) [1].

- Data, along with timestamp and geolocation, can be optionally uploaded to a cloud database for large-scale environmental monitoring [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The development and execution of smartphone-based biosensors rely on a core set of reagents and materials. The following table catalogues key components and their functions.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Biosensor Development

| Item | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) [1] [4] | Primary biorecognition element for organophosphorus/carbamate pesticides. Enzyme inhibition is the basis of detection. | High specific activity, purity, and stability. |

| Polyclonal/Monoclonal Antibodies [4] | Biorecognition element for specific pesticide targets in immunosensors. | High affinity and specificity. Monoclonal offers better reproducibility. |

| Nucleic Acid Aptamers [4] | Synthetic biorecognition element; can be selected for various targets via SELEX. | High thermal stability, easily synthesized and modified. |

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) [5] [6] | Colorimetric signal probe; color changes upon aggregation or interaction with analyte. | High extinction coefficient, tunable surface chemistry. |

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) [4] | Biomimetic synthetic receptor; template-shaped cavities for pesticide binding. | High chemical/thermal stability, low-cost production. |

| Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) [1] [5] | Fluorescence signal amplification; can be used to enhance sensor sensitivity. | High porosity, tunable structure, and strong luminescence. |

Key Components of a Smartphone-Integrated Biosensing System

Smartphone-integrated biosensing systems represent a convergence of specific biological recognition elements and the versatile data processing, connectivity, and imaging capabilities of modern smartphones. These systems are primarily designed for point-of-care (POC) and point-of-need testing, enabling the decentralized detection of analytes such as pesticide residues in food and environmental samples [7] [8]. Their architecture is defined by the location of the biosensing function (on- or off-phone) and the locus of data processing (local on the smartphone or remotely on a server) [7]. For visual pesticide detection, systems leveraging the smartphone's built-in camera for optical readout are particularly prominent, functioning as portable spectrophotometers or fluorimeters [9]. This document outlines the key components, performance metrics, and detailed experimental protocols for assembling and utilizing such systems, with a specific focus on applications in food safety and environmental monitoring.

Core System Components and Their Functions

A fully functional smartphone-integrated biosensor comprises several integrated subsystems: the biological recognition element, the transducer, the smartphone with its hardware and software, and, for some configurations, external accessories and data servers.

Table 1: Key Components of a Smartphone-Integrated Biosensing System

| Component Category | Specific Element | Function & Description |

|---|---|---|

| Biological Recognition | Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) | Enzyme inhibited by Organophosphorus (OP) pesticides; basis for enzymatic biosensors [10]. |

| Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP) | Enzyme used in enzyme-linked assays; its inhibition can be correlated to pesticide concentration [11]. | |

| Antibodies & Aptamers | Provide high specificity for immunoassays and aptamer-based sensors [1] [9]. | |

| Transducer & Signal Conversion | Polyaniline Nanofibers (PAnNFs) | Conducting polymer; conductance changes with proton doping during ACh hydrolysis, enabling resistive sensing [10]. |

| Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) | Nanomaterial used in nanocomposite films to enhance conductivity and sensor performance [10]. | |

| Fluorescent Markers (e.g., DFQ) | Molecule produced in enzymatic reactions; its fluorescence intensity, when excited, is measured quantitatively [11]. | |

| Smartphone Hardware & Software | CMOS Camera | Acts as a optical detector for colorimetric, fluorescence, or label-free assays [7] [9]. |

| Mobile Application (App) | Controls data acquisition, processing, analysis, visualization, and sharing of results [10] [8]. | |

| CPU/Connectivity (Bluetooth, USB) | Provides processing power and a link to external sensors or cloud servers for data handling [7] [12]. | |

| External Accessories | Portable Fluorescence Device | Custom attachment with LEDs and filters to create a controlled environment for fluorescence excitation and emission [11]. |

| Cradle Attachment with Diffraction Grating | Converts the smartphone camera into a spectrometer for wavelength-specific measurements [9]. | |

| Microfluidic Paper-Based Device (μPAD) | Provides a low-cost, disposable platform with hydrophilic/hydrophobic channels to conduct assays [3]. |

Performance Metrics of Representative Systems

The analytical performance of developed systems is critical for assessing their applicability. The following table summarizes data from recent research on smartphone-based biosensors for pesticide detection.

Table 2: Analytical Performance of Smartphone-Based Biosensors for Pesticide Detection

| Detection Principle | Target Analyte | Linear Range | Limit of Detection (LOD) | Real-Sample Application | Citation Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fluorescence Biosensor (ALP-based) | Malathion (Organophosphorus) | 0.1 - 1 ppm | 0.05 ppm | Vegetable samples | [11] |

| Resistive Biosensor (AChE/PAnNF/CNT) | Paraoxon-Methyl (Organophosphate) | 1 ppt - 100 ppb | 0.304 ppt | Food and environmental water | [10] |

| Electrochemical Biosensor (General) | Various Pesticides | Not Specified (High Sensitivity) | nM to pM levels | Tea leaves | [1] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Fluorescence-Based Detection of Organophosphorus Pesticides

This protocol is adapted from a study detailing a smartphone-based fluorescence biosensor for malathion [11].

I. Research Reagent Solutions

- L-Ascorbic Acid 2-phosphate sesquimagnesium salt hydrate (AAP) Solution: Serves as the enzyme substrate.

- Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP) Enzyme Solution: The enzyme whose activity is inhibited by the target pesticide.

- o-Phenylenediamine (OPD) Solution: Reacts with ascorbic acid to form the fluorescent product DFQ.

- Organophosphorus Pesticide Standard Solutions: (e.g., Malathion) in a range of known concentrations for calibration.

- Sample Extraction Buffer: Suitable for extracting pesticides from vegetable matrices.

II. Procedure

- Sample Preparation: Homogenize the vegetable sample (e.g., 1 g) and extract the analyte using a suitable buffer. Centrifuge and filter the supernatant to obtain a clear test solution.

- Reaction Incubation: In a microcentrifuge tube, mix the following:

- A fixed volume of the sample extract or pesticide standard.

- A known activity of ALP enzyme solution.

- Incubate the mixture for 10 minutes at 37°C to allow for potential enzyme inhibition by the pesticide.

- Fluorescent Product Generation: To the same tube, add:

- AAP substrate solution.

- OPD solution.

- Incubate for another 20 minutes at 37°C. In the absence of inhibitor, ALP converts AAP to ascorbic acid, which then reacts with OPD to yield the fluorescent molecule DFQ. The presence of pesticide inhibits ALP, reducing DFQ formation proportionally.

- Smartphone Measurement:

- Transfer the reaction solution to a cuvette or a well in a microtiter plate.

- Place the container into the portable fluorescence device attachment, which is equipped with an appropriate excitation LED.

- Use the smartphone app to capture an image of the fluorescence emission or to record the RGB values of the solution.

- Data Analysis: The smartphone app converts the fluorescence intensity (via RGB values) into a concentration. A calibration curve, generated from standards of known concentration, is used for interpolation.

Protocol 2: Resistive Biosensor for Organophosphate Pesticides

This protocol is based on an integrated smartphone/resistive biosensor for sensitive OP pesticide monitoring [10].

I. Research Reagent Solutions

- Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) Enzyme Solution: The biological recognition element.

- Polyaniline Nanofibers (PAnNFs) Suspension: The conductive transducer material.

- Carbon Nanotube (CNT) Suspension: Used to form a conductive nanocomposite.

- Chitosan Solution: A biopolymer for forming a stable nanocomposite film.

- Acetylcholine (ACh) Substrate Solution: The hydrolyzed substrate.

- Pesticide Standard Solutions: (e.g., Paraoxon-Methyl) for calibration.

II. Procedure

- Biosensor Fabrication:

- Prepare a nanocomposite by mixing AChE, PAnNFs, CNTs, and chitosan in a defined ratio.

- Deposit a small volume of the nanocomposite onto a gold interdigitated electrode (IDE).

- Allow the film to dry and crosslink, forming the functional resistive biosensor.

- Baseline Measurement:

- Connect the IDE to a readout circuit that can communicate with the smartphone (e.g., via USB or Bluetooth).

- Using the smartphone app, measure the initial conductance of the biosensor film.

- Inhibition and Measurement:

- Expose the biosensor to a sample solution (extracted from food or water) containing the target pesticide for a fixed time (e.g., 10 minutes).

- Wash the sensor gently to remove unbound molecules.

- Introduce the substrate, acetylcholine (ACh), to the sensor.

- The smartphone app records the change in conductance over time. In a pesticide-free sample, AChE hydrolyzes ACh, releasing protons that dope the PAnNFs and cause a large conductance increase. If AChE is inhibited by pesticides, the conductance change is proportionally smaller.

- Data Processing: The smartphone app analyzes the rate of conductance change or its absolute value. The degree of inhibition is calculated relative to a negative control and correlated to the pesticide concentration via a pre-loaded calibration curve.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Smartphone-Based Pesticide Biosensors

| Reagent/Material | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) | Core biorecognition element for OP pesticides; its inhibition is the basis for quantification in enzymatic sensors [10]. |

| Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP) | Enzyme used in alternative enzyme-inhibition assays; its activity is modulated by the presence of inhibitors [11]. |

| Polyaniline Nanofibers (PAnNFs) | Conducting polymer transducer; its electronic properties (conductance) change in response to biochemical reactions (proton doping) [10]. |

| Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) | Nanomaterial used to enhance electron transfer and improve the sensitivity and stability of electrochemical/resistive biosensors [10]. |

| L-Ascorbic Acid 2-phosphate (AAP) | Enzyme substrate that is converted by ALP to ascorbic acid, a key reactant in a subsequent fluorescence-generating reaction [11]. |

| o-Phenylenediamine (OPD) | Chemical compound that reacts with ascorbic acid to produce a fluorescent product (DFQ), enabling optical detection [11]. |

| Gold Interdigitated Electrodes (IDEs) | The physical transducer platform where the biosensing film is immobilized and electrical (resistive) measurements are taken [10]. |

| Specific Antibodies/Aptamers | High-affinity recognition elements for designing immunosensors or aptasensors with high specificity for target pesticide molecules [1] [9]. |

The development of robust, selective, and sensitive biosensors hinges on the performance of their molecular recognition elements. These components are responsible for the specific binding and identification of target analytes within complex sample matrices. Within the specific context of developing smartphone-integrated biosensors for the visual detection of pesticides, the choice of recognition element dictates the sensor's overall applicability, sensitivity, and potential for field deployment. This document provides detailed application notes and protocols for four primary classes of advanced recognition elements—Enzymes, Antibodies, Aptamers, and Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs)—framed within the demands of modern, portable biosensing platforms. The convergence of these elements with smartphone-based detection heralds a new era of on-site analysis, enabling rapid and quantitative monitoring of pesticide residues for environmental and food safety [1].

Performance Comparison of Advanced Recognition Elements

The selection of an appropriate recognition element requires a balanced consideration of its inherent properties. The following table summarizes the key characteristics of each element type, providing a guide for selection based on the requirements of a specific biosensing application, particularly for pesticide detection.

Table 1: Comparative analysis of advanced recognition elements for biosensing.

| Recognition Element | Affinity & Specificity | Stability & Production | Key Advantages | Primary Limitations | Common Transduction Methods |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enzymes | Moderate; specificity for substrate catalysis | Low thermal/operational stability; complex purification | Natural catalytic activity; signal amplification | Susceptible to inhibition; limited target scope | Electrochemical, Optical (Colorimetric, Fluorescent) |

| Antibodies | High (pM-nM); high specificity for a single epitope | Moderate stability; sensitive to conditions; requires animal hosts | Well-established, commercial availability; high specificity | Batch-to-batch variation; expensive production; animal use | ELISA (Colorimetric, Chemiluminescent), SPR, Fluorescent |

| Aptamers | High (nM-pM); high specificity for small molecules | High thermal/chemical stability; chemical synthesis | Small size; tunable affinity; label-free detection possible | Susceptible to nuclease degradation; complex SELEX process | Fluorescent (FRET), Electrochemical, SPR, Colorimetric |

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) | Moderate to High; specificity mimics antibodies | Excellent stability (thermal, pH, solvent); chemical synthesis | Robustness; low-cost; reusability; long shelf-life | Occasional heterogeneity in binding sites | Electrochemical, Optical, SPR |

Detailed Element Analysis and Protocols

Antibodies and the Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

Antibodies are immunoglobulins that bind to specific molecular epitopes with high affinity. The sandwich ELISA is a premier format for achieving high sensitivity and specificity, making it a gold standard for protein detection [13] [14]. In this format, a capture antibody is immobilized on a surface to bind the target antigen from a sample, after which a second, enzyme-conjugated detection antibody is added to complete the "sandwich." The enzyme, such as Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP), then catalyzes the conversion of a substrate into a colored, fluorescent, or chemiluminescent product, enabling quantification [15].

Table 2: Key research reagents for antibody-based biosensing.

| Reagent / Solution | Function in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| Capture Antibody | Immobilized on the microplate to specifically bind the target pesticide or its derivative. |

| Enzyme-Conjugated Detection Antibody | Binds a different epitope on the captured target and provides the signal via enzyme catalysis. |

| Blocking Buffer (e.g., BSA or Skim Milk) | Blocks unsaturated binding sites on the microplate to minimize non-specific adsorption. |

| Coating Buffer (e.g., Carbonate-Bicarbonate, pH 9.4) | Provides optimal pH and ionic conditions for passive adsorption of the capture antibody to the plate. |

| Enzyme Substrate (e.g., ABTS for HRP) | Converted by the enzyme into a measurable product, generating the detection signal. |

Protocol: Sandwich ELISA for Pesticide Detection

- Coating: Dilute the capture antibody in a carbonate-bicarbonate coating buffer (pH 9.4) to a concentration of 2–10 µg/mL. Add 100 µL per well to a 96-well microplate and incubate for 16 hours at 4°C [15].

- Blocking: Wash the plate three times with PBS containing 0.1% Tween 20 (wash buffer). Add 200 µL of blocking buffer (e.g., 5% skim milk or BSA in PBS) to each well and incubate for 1–2 hours at room temperature. Wash three times.

- Sample Incubation: Add 100 µL of the sample or pesticide standard to each well. Incubate for 1–2 hours at 37°C to allow antigen binding. Wash thoroughly to remove unbound material.

- Detection Antibody Incubation: Add 100 µL of the enzyme-conjugated detection antibody (diluted in blocking buffer) to each well. Incubate for 1–2 hours at 37°C. Wash extensively.

- Signal Development & Smartphone Readout: Add 100 µL of the appropriate substrate solution (e.g., ABTS for HRP). Incubate in the dark for 15–30 minutes. Terminate the reaction if necessary. Instead of a plate reader, place the plate on a uniform light source and capture an image using a smartphone. Analyze the color intensity of each well using image processing software (e.g., ImageJ) to generate a quantitative standard curve and determine analyte concentration [1].

Aptamers and Fluorescent Biosensing

Aptamers are single-stranded DNA or RNA oligonucleotides selected in vitro to bind specific targets with high affinity and specificity, earning them the moniker "chemical antibodies" [16] [17]. Their utility in biosensors is extensive, with fluorescent aptasensors being particularly suitable for integration with smartphone optics. A common mechanism involves a "signal-on" configuration based on Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET), where an aptamer is labeled with a fluorophore whose emission is quenched by a nearby nanomaterial (e.g., graphene oxide) or quencher. Upon binding the target, the aptamer undergoes a conformational change, separating the fluorophore from the quencher and restoring fluorescence [16].

Table 3: Key research reagents for aptamer-based biosensing.

| Reagent / Solution | Function in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| Fluorophore-Labeled Aptamer | The core recognition element; its target-induced conformational change modulates the fluorescence signal. |

| Quencher or Nanomaterial (e.g., Graphene Oxide) | Initially quenches the fluorophore's emission; signal is generated upon displacement. |

| Binding Buffer | Provides optimal ionic strength and pH to facilitate correct aptamer folding and target binding. |

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | Used for signal amplification and enhancement in various optical and electrochemical sensors [17]. |

Protocol: 'Signal-On' Fluorescent Aptasensor for Pesticide Detection

- Aptamer Preparation: Reconstitute the fluorophore-labeled aptamer (e.g., specific for a pesticide like ochratoxin A) in the appropriate binding buffer. Anneal the aptamer by heating and slowly cooling to ensure proper folding [16].

- Sensor Assembly & Quenching: Incubate the folded aptamer with the quencher (e.g., graphene oxide) for a fixed time (e.g., 30 minutes) to allow adsorption and fluorescence quenching.

- Target Binding & Signal Recovery: Introduce the sample containing the target pesticide to the aptamer-quencher mixture. Incubate for 30-60 minutes. Target binding will cause the aptamer to change conformation, releasing the fluorophore from the quencher and restoring fluorescence.

- Smartphone Fluorescence Detection: Transfer the solution to a low-volume cuvette or a microfluidic chip designed for smartphone attachment. Using a simple smartphone adapter equipped with a complementary filter set, illuminate the sample with the excitation wavelength and capture the emitted fluorescence. The intensity of the green fluorescence is proportional to the pesticide concentration and can be quantified using a smartphone application [16] [1].

Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs)

MIPs are synthetic polymers that possess tailor-made recognition sites complementary to a target molecule in shape, size, and functional groups. They are fabricated by polymerizing functional monomers around a template molecule (the target analyte). Subsequent removal of the template leaves behind cavities that exhibit high specificity for the original molecule, functioning as artificial antibodies [18]. Their exceptional physical and chemical stability makes them ideal for harsh environments and reusable sensors.

Table 4: Key research reagents for MIP-based biosensing.

| Reagent / Solution | Function in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| Template Molecule (Target Pesticide) | Serves as the mold around which the complementary cavity is formed during polymerization. |

| Functional Monomer | Contains functional groups that form reversible interactions with the template. |

| Cross-linker | Creates a rigid polymer network that stabilizes the imprinted cavities after template removal. |

| Electrochemical Probe (e.g., [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻) | Used in electrochemical MIP sensors; its signal is perturbed upon target rebinding. |

Protocol: Electrochemical MIP Nano-sensor for Pesticide Detection

- MIP Synthesis on Electrode: Mix the target pesticide (template), functional monomer (e.g., acrylic acid), and cross-linker (e.g., ethylene glycol dimethacrylate) in a solvent. Add an initiator and deposit the pre-polymerization mixture onto the surface of a working electrode (e.g., glassy carbon or screen-printed electrode). Polymerize via UV irradiation or thermal initiation to form a thin polymer film [18].

- Template Removal: Carefully wash the polymer-coated electrode with a solvent mixture (e.g., methanol:acetic acid) to extract the template molecules from the polymer matrix, leaving behind specific recognition sites.

- Rebinding and Measurement: Incubate the MIP-modified electrode in the sample solution containing the pesticide. The target molecules will selectively rebind to the imprinted cavities. For electrochemical detection, monitor the current of a redox probe (e.g., ferricyanide) using differential pulse voltammetry (DPV) or electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS). The binding of the pesticide hinders electron transfer, leading to a measurable change in current, which is proportional to the pesticide concentration [18].

- Smartphone Integration: Connect the electrochemical sensor to a miniaturized, smartphone-operated potentiostat. The smartphone can control the measurement parameters and record the electrochemical signal. The data is processed by a dedicated app to provide a quantitative result on-screen, enabling fully portable electrochemical detection [18] [1].

The integration of advanced recognition elements with smartphone-based detection platforms creates powerful tools for on-site pesticide monitoring. Antibodies offer proven sensitivity, aptamers provide versatility and stability, and MIPs deliver unmatched robustness and low-cost potential. The choice of element is application-dependent, but the ongoing trend is toward the development of MIPs and aptamers that match the affinity of antibodies while offering superior stability for field use. The future of this field lies in the fusion of these elements with nanomaterials for signal enhancement, microfluidics for automated sample handling, and IoT platforms for real-time data geolocation and sharing, ultimately creating a connected network for environmental and food safety surveillance [18] [1].

Biosensors are analytical devices that combine a biological recognition element with a transducer to produce a measurable signal proportional to the concentration of a target analyte. The transduction mechanism is a fundamental component that defines the sensor's characteristics, performance, and suitability for specific applications. In the context of developing smartphone-integrated biosensors for visual pesticide detection, the choice between optical and electrochemical transduction is particularly critical. This application note provides a comparative overview of these two dominant transduction mechanisms, focusing on their operational principles, performance parameters, and implementation protocols for pesticide detection applications. The integration of these biosensing platforms with smartphone technology represents a frontier in point-of-care testing, enabling rapid on-site analysis for environmental monitoring and food safety.

Fundamental Principles and Mechanisms

Optical Transduction Mechanisms

Optical biosensors detect targets by recognizing changes in optical properties and converting them into readable signals [19]. These sensors employ various optical phenomena including fluorescence, colorimetry, surface plasmon resonance (SPR), and surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS) [19]. For pesticide detection, the enzyme inhibition principle is commonly employed, where organophosphorus pesticides inhibit acetylcholinesterase activity, leading to measurable changes in optical signals [20].

Fluorescence-based sensing operates on principles such as Förster Resonance Energy Transfer, where energy transfer occurs between a donor fluorophore and an acceptor quencher. Target-induced conformational changes alter donor-quencher proximity, terminating FRET and restoring fluorescence [19]. Nanomaterials like graphene oxide have been extensively utilized in FRET-based aptasensors due to exceptional photoelectric properties that enable fluorescence quenching [19].

Colorimetric sensing detects color changes visible to the naked eye or through smartphone cameras. Nanozyme-based colorimetric strategies have gained prominence, where nanomaterials with enzyme-like activity catalyze chromogenic reactions [21] [20]. For instance, hydrogen-bonded organic framework nanozymes with peroxidase-like activity can catalyze the oxidation of 3,3',5,5'-tetramethylbenzidine, producing a color change measurable via smartphone [20].

Surface-enhanced Raman scattering provides fingerprint molecular identification through significant enhancement of Raman signals when analytes are adsorbed on nanostructured metal surfaces, enabling highly sensitive detection [21].

Electrochemical Transduction Mechanisms

Electrochemical biosensors measure electrical signals resulting from biochemical interactions at the electrode-solution interface [22]. These sensors encompass techniques including voltammetry, amperometry, potentiometry, electrochemical impedance spectroscopy, and electrochemiluminescence [22].

In amperometric sensors, current is measured at a constant potential applied to the working electrode, with the magnitude proportional to analyte concentration [23]. For organophosphorus pesticide detection, this typically involves measuring changes in cholinesterase activity through substrate hydrolysis [23].

Voltammetric techniques apply a potential sweep and measure resulting current, providing information about redox reactions. The strategic design of electrode surfaces with nanomaterials enhances electron transfer characteristics and loading efficacy of biorecognition elements [22].

Impedimetric sensors monitor changes in electrical impedance resulting from binding events at modified electrode surfaces, often enabling label-free detection [22].

Electrochemiluminescence combines electrochemical and optical methods, whereelectrochemical reactions generate luminescent species, offering high sensitivity with low background signals [22].

Comparative Performance Analysis

The table below summarizes key performance characteristics of optical and electrochemical transduction mechanisms for biosensing applications, particularly focused on pesticide detection.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Optical and Electrochemical Transduction Mechanisms

| Parameter | Optical Transduction | Electrochemical Transduction |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | High (e.g., LOD of 3.04 ng/mL for chlorpyrifos using HOF nanozyme) [20] | High (e.g., detection limits of 0.11 U/mL for AChE) [23] |

| Selectivity | High (molecular recognition via enzymes, antibodies, aptamers) [19] [20] | High (bioreceptor specificity combined with electrochemical selectivity) [22] |

| Multiplexing Capability | Moderate to high (multiple wavelengths, spatial resolution) [24] | Moderate (multiple electrode arrays, different potentials) [22] |

| Sample Volume | Microliter to milliliter range [20] | Microliter range (miniaturized electrochemical cells) [22] |

| Detection Time | Seconds to minutes (rapid color development) [20] | Seconds to minutes (rapid electron transfer) [23] [22] |

| Instrumentation Complexity | Moderate to high (light sources, detectors) [21] | Low to moderate (potentiostats, readout circuits) [22] |

| Cost | Moderate to high (optical components) [21] | Low (miniaturized electronics) [22] |

| Smartphone Integration | Excellent (built-in cameras for colorimetric/fluorescent detection) [23] [20] | Good (requires external interface circuitry) [23] |

| Reproducibility | Moderate (nanomaterial batch variations) [20] | Moderate to high (electrode surface reproducibility challenges) [22] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Optical Biosensor (Colorimetric Nanozyme-based Detection)

This protocol describes the development of a smartphone-integrated colorimetric biosensor for organophosphorus pesticide detection using HOF nanozymes [20].

Materials and Reagents:

- Acetylcholinesterase (220 U/mg)

- 6,6',6'',6'''-(Pyrene-1,3,6,8-tetrayl) tetrakis(2-naphthoic acid) (H4PTTNA)

- Acetylthiocholine iodide

- 3,3',5,5'-Tetramethylbenzidine

- Hemin

- Sodium alginate

- Calcium chloride

- Organophosphorus pesticide standards (chlorpyrifos, acephate, fenthion)

- Hydrogen peroxide

- Phosphate buffer saline (PBS, 0.1 M, pH 7.4)

Procedure:

Synthesis of Hemin@HOF Nanozyme:

- Dissolve H4PTTNA (5 mg) in DMSO (1 mL) by sonication for 10 minutes

- Add bovine serum albumin (50 mg) to phosphate buffer (10 mL, 10 mM, pH 7.4)

- Mix H4PTTNA solution with BSA solution under vigorous stirring

- Add Hemin solution (2 mg/mL in DMSO) dropwise to the mixture

- Incubate at room temperature for 12 hours with continuous stirring

- Centrifuge at 12,000 rpm for 15 minutes and wash three times with deionized water

- Resuspend in PBS and store at 4°C until use

Hydrogel Biosensor Preparation:

- Prepare sodium alginate solution (3% w/v) in deionized water

- Mix Hemin@HOF nanozyme suspension with sodium alginate solution at 1:4 volume ratio

- Add AChE enzyme (0.5 U/mL final concentration) to the mixture

- Dropwise add the mixture into CaCl₂ solution (5% w/v) to form hydrogel beads

- Incubate for 30 minutes to complete cross-linking

- Wash hydrogel beads with PBS and store at 4°C in moist conditions

Pesticide Detection Assay:

- Place hydrogel biosensor in microcentrifuge tube

- Add pesticide sample (100 μL) and incubate for 15 minutes at 37°C

- Add ATCh substrate (200 μL, 5 mM) and incubate for 10 minutes

- Add TMB solution (200 μL, 2 mM) and H₂O₂ (50 μL, 10 mM)

- Incubate for 5 minutes to allow color development

- Capture image using smartphone camera under controlled lighting

- Analyze RGB values using color analysis application

Data Analysis:

- Measure blue channel intensity from smartphone images

- Plot intensity versus pesticide concentration for quantification

- Calculate limit of detection using 3σ/slope method

Protocol for Electrochemical Biosensor (Resistive Nanosensor Platform)

This protocol describes the development of a smartphone-integrated resistive nanosensor for organophosphorus pesticide detection via cholinesterase activity monitoring [23].

Materials and Reagents:

- Multiwalled carbon nanotubes

- Polyaniline nanofibers

- Chitosan solution (1% in acetic acid)

- Gold interdigitated electrodes

- Acetylcholinesterase from human erythrocytes

- Butyrylcholinesterase from human serum

- Acetylcholine chloride

- Butyrylcholine chloride

- BW284c51 (AChE-specific inhibitor)

- Magnesium chloride

- Calcium chloride

- Phosphate buffer saline (0.1 M, pH 7.4)

- Finger-stick blood samples

Procedure:

Preparation of CS/MWCNT/PAnNF Nanocomposite:

- Synthesize polyaniline nanofibers via interfacial polymerization

- Functionalize MWCNTs by acid treatment (3:1 H₂SO₄:HNO₃) for 4 hours

- Prepare chitosan solution (1% w/v) in acetic acid (1% v/v)

- Disperse MWCNTs (2 mg/mL) in chitosan solution by probe sonication

- Mix MWCNT/chitosan suspension with PAnNF dispersion at 1:1 volume ratio

- Stir for 2 hours to form homogeneous nanocomposite

Electrode Modification:

- Clean gold interdigitated electrodes with oxygen plasma treatment

- Drop-cast CS/MWCNT/PAnNF nanocomposite (5 μL) onto electrode surface

- Dry at room temperature for 4 hours followed by 40°C for 30 minutes

- Characterize modified electrode using SEM and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy

Reagent Pad Preparation:

- Prepare outer pretreatment pad by soaking glass fiber pad (Ø 4 mm) in inhibitor solution (BW284c51 for AChE specificity)

- Prepare inner signal generation pad with acetylcholine (for AChE) or butyrylcholine (for BChE) substrate

- Dry pads under vacuum for 2 hours and store with desiccant

Pesticide Detection Assay:

- Apply whole blood sample (10 μL) to outer pretreatment pad

- Assemble sensor with reagent pads in contact with modified electrode

- Connect electrode to Bluetooth resistance meter paired with smartphone

- Measure conductance change over 5-minute interval

- Calculate cholinesterase activity from conductance slope

- Determine pesticide concentration from enzyme inhibition percentage

Data Analysis:

- Transmit resistance measurements to smartphone via Bluetooth

- Calculate cholinesterase activity using calibration curve

- Determine pesticide exposure level based on enzyme inhibition

- Store results with timestamp and geolocation data

Signaling Pathways and Mechanisms

The following diagrams illustrate the signaling pathways and mechanisms for optical and electrochemical biosensors used in pesticide detection.

Diagram 1: Optical transduction signaling pathway for pesticide detection based on enzyme inhibition and nanozyme-catalyzed color development.

Diagram 2: Electrochemical transduction signaling pathway for pesticide detection based on enzyme inhibition and proton-mediated conductance changes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Biosensor Development

| Category | Item | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biological Elements | Acetylcholinesterase | Primary recognition element for OPs | Enzyme inhibition assays [23] [20] |

| Aptamers | Nucleic acid-based recognition elements | Target-specific molecular recognition [19] | |

| Antibodies | Immunoaffinity recognition | Molecular imprinting and immunoassays [25] | |

| Nanomaterials | Graphene Oxide | Fluorescence quenching in FRET assays | Optical aptasensors [19] |

| HOF Nanozymes | Peroxidase-mimicking activity | Colorimetric detection [20] | |

| MWCNT/PAnNF | Conductance-based sensing | Electrochemical biosensors [23] | |

| Gold Nanoparticles | Signal amplification, SERS substrates | Enhanced detection sensitivity [26] | |

| Signal Probes | TMB | Chromogenic substrate | Colorimetric detection [20] |

| Acetylthiocholine | Enzyme substrate | Electrochemical and optical assays [23] [20] | |

| Methylene Blue | Electrochemical redox probe | Voltammetric sensing [26] | |

| Support Materials | Sodium Alginate | Hydrogel matrix formation | Biosensor immobilization [20] |

| Chitosan | Biocompatible polymer matrix | Nanocomposite formation [23] | |

| Gold Interdigitated Electrodes | Transduction platform | Resistive/conductive measurements [23] |

Optical and electrochemical transduction mechanisms offer complementary advantages for smartphone-integrated biosensors targeting pesticide detection. Optical methods, particularly colorimetric approaches using nanozymes, provide visual readouts ideally suited for smartphone camera detection with sensitivity meeting practical requirements. Electrochemical techniques offer inherent advantages for miniaturization and direct electronic integration with smartphone platforms. The choice between these mechanisms depends on specific application requirements including sensitivity needs, sample matrix, instrumentation constraints, and intended user operation. Future developments will likely focus on hybrid approaches combining the visual simplicity of optical detection with the electronic interface capabilities of electrochemical systems, further enhanced by artificial intelligence for signal processing and result interpretation.

The field of biosensing is undergoing a transformative shift, driven by the convergence of artificial intelligence (AI), the Internet of Things (IoT), and cloud connectivity. This synergy is particularly impactful in the development of smartphone-integrated biosensors, creating powerful, decentralized diagnostic and monitoring platforms [27] [7]. These systems are moving analytical capabilities from centralized laboratories directly to the point-of-need, enabling rapid, on-site detection of analytes like pesticides [23] [28] [10]. For researchers focused on visual pesticide detection, this integration addresses critical challenges in sensitivity, specificity, and data management, while opening new avenues for real-time environmental and health monitoring. This document outlines the key technological trends, provides structured experimental data, and details protocols for developing and validating these advanced biosensing systems.

The Converging Technological Landscape

The modern biosensor is no longer a simple transducer but a sophisticated system that leverages advances in multiple domains. The core of this evolution lies in the seamless integration of sensing, computation, and connectivity.

AI-Enhanced Biosensing

Artificial intelligence, particularly machine learning (ML) and deep learning, dramatically improves the analytical performance of optical biosensors. AI algorithms are adept at processing complex, multivariate signal data to enhance sensitivity and specificity [27].

- Intelligent Signal Processing: AI can differentiate target signals from background noise and correct for environmental interferences or matrix effects in complex samples like food [27] [28].

- Multiplexing and Pattern Recognition: For sensors detecting multiple pesticides, AI models can deconvolute overlapping optical signals (e.g., fluorescence, colorimetric) from array-based sensors, enabling simultaneous identification of several analytes [27].

- Predictive Analytics: ML models can predict calibration drift or sensor degradation, prompting recalibration and ensuring data reliability over time [27].

IoT and Connectivity Frameworks

The IoT ecosystem provides the infrastructure for biosensors to become interconnected nodes in a larger network. Billions of connected IoT devices form a foundation for widespread biosensor deployment, with key connectivity technologies including Wi-Fi (32%), Bluetooth (24%), and Cellular IoT (22%) [29].

Smartphone-based biosensors fit into system architectures defined by the location of the biosensing function and data processing [7]:

- Architecture A: On-phone biosensing with local data processing.

- Architecture B: On-phone biosensing with server/cloud processing.

- Architecture C: Off-phone biosensing with local processing (on a dedicated device or smartphone).

- Architecture D: Off-phone biosensing with server processing.

The choice of architecture involves trade-offs between portability, sensing capability, processing power, and data storage [7]. The integration of IoT enables features like real-time data tracking, sharing of results with healthcare providers or regulatory bodies, and large-scale environmental biomonitoring [23].

Edge Computing and Cloud Synergy

A key trend is the move towards edge computing, where data is processed on the device itself or a local gateway rather than being sent entirely to the cloud [30]. For biosensors, this means:

- Ultra-Low Latency: Critical for real-time decision-making, such as immediate alerts for toxic pesticide levels [30].

- Bandwidth and Cost Savings: Only processed results or relevant data subsets are transmitted to the cloud, reducing data transmission loads [30].

- Enhanced Data Privacy: Sensitive information can be analyzed locally, minimizing external data transmission [30].

The cloud complements the edge by providing vast storage for historical data, powerful resources for training complex AI models, and a platform for aggregating data from multiple sensors for large-scale analytics [27] [7].

Quantitative Data in Modern Biosensing

The performance of emerging biosensing platforms is quantified through key analytical parameters. The tables below summarize data from recent implementations relevant to pesticide detection and associated technologies.

Table 1: Analytical Performance of Selected Smartphone-Integrated Biosensors for Pesticide and Contaminant Detection

| Target Analyte | Sensing Platform | Detection Mechanism | Linear Range | Limit of Detection (LOD) | Test Duration | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organophosphate Pesticides (e.g., Paraoxon-Methyl) | Smartphone/Resistive Nanosensor | AChE inhibition; Conductance change of PAnNF/CNT film | 1 ppt – 100 ppb | 0.304 ppt | ~10 minutes | [10] |

| Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) Activity (OP Exposure Biomarker) | Smartphone/Resistive Nanosensor | Substrate hydrolysis; Conductance change | 2.0–18.0 U/mL | 0.11 U/mL | ~10 minutes | [23] |

| Butyrylcholinesterase (BChE) Activity (OP Exposure Biomarker) | Smartphone/Resistive Nanosensor | Substrate hydrolysis; Conductance change | 0.5–5.0 U/mL | 0.093 U/mL | ~10 minutes | [23] |

| Various Pesticides & Antibiotics | Smartphone/Fluorescent Probe (UOFs) | Ratiometric Fluorescence | N/S (Well below regulatory thresholds) | N/S | ~10 seconds | [28] |

Table 2: IoT Connectivity Landscape Relevant for Distributed Biosensor Networks (2025 Data) [29]

| Connectivity Technology | Share of Global IoT Connections | Key Characteristics & Relevance to Biosensing |

|---|---|---|

| Wi-Fi | 32% | High bandwidth; suitable for fixed or powered sensors in homes, clinics, or labs. |

| Bluetooth | 24% | Low power; ideal for short-range communication between a biosensor and a smartphone. |

| Cellular IoT (5G, LTE-M, NB-IoT) | 22% | Wide area coverage; enables remote biosensing in agricultural or environmental fields. |

| Other (LPWAN, etc.) | 22% | Very low power, long range; for sensors in remote locations with infrequent data transmission. |

Experimental Protocols

This section provides detailed methodologies for implementing and validating key aspects of AI- and IoT-enhanced biosensors for pesticide detection.

Protocol: Development of a Smartphone-Based Resistive Nanosensor for Organophosphate Pesticides

Application: On-site rapid detection of organophosphate pesticides in food and water samples [10].

Principle: The sensor leverages the inhibition of acetylcholinesterase (AChE). In the absence of pesticide, AChE hydrolyzes acetylcholine, releasing protons that dope polyaniline nanofibers (PAnNFs) and increase film conductance. OP pesticides inhibit AChE, reducing the rate of proton generation and the resultant conductance change, which is quantitatively measured [10].

Materials:

- Gold interdigitated electrodes (AuIDEs)

- Chitosan (CS), Multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs), Polyaniline nanofibers (PAnNFs)

- Acetylcholinesterase (AChE)

- Acetylcholine (ACh) substrate

- Phosphate buffer saline (PBS, 0.1 M, pH 7.4)

- Smartphone with custom-developed application

- Bluetooth-enabled portable resistance meter

Procedure:

- Nanosensor Fabrication:

- Clean AuIDEs with oxygen plasma.

- Prepare a composite suspension of CS, MWCNTs, PAnNFs, and AChE in acetic buffer.

- Drop-cast the suspension onto the active area of the AuIDE and allow it to dry.

- Integrate reagent pads: an outer glass fiber pad pre-loaded with anti-interference reagents and an inner pad pre-loaded with the ACh substrate [23] [10].

Measurement Setup:

- Connect the fabricated nanosensor to the portable resistance meter.

- Pair the resistance meter with the smartphone app via Bluetooth.

- For calibration, apply 20 μL of standard solutions (or sample extracts) with known pesticide concentrations to the sensor.

- The app initiates resistance measurement and records the data in real-time.

Data Acquisition and Analysis:

- The smartphone app records the resistance change over a fixed period (e.g., 5-10 minutes).

- The rate of resistance change is inversely proportional to AChE activity and directly proportional to pesticide concentration.

- A calibration curve is established within the app by measuring standard solutions.

- Unknown sample concentrations are calculated by the app by interpolating the measured signal against the calibration curve.

Validation:

- Validate the sensor's performance against a standard method like liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) using spiked food and water samples [10].

- Calculate recovery rates (target: ~98%) and reproducibility (RSD <5%).

Protocol: Implementing AI for Signal Processing in Optical Biosensors

Application: Enhancing the sensitivity and specificity of smartphone-based colorimetric or fluorescent pesticide sensors [27] [28].

Principle: AI models, particularly convolutional neural networks (CNNs), can be trained to analyze images captured by the smartphone camera. They learn to correlate specific visual patterns (hue, intensity, texture) with analyte concentration, compensating for variable lighting conditions and sample impurities.

Materials:

- Smartphone with integrated camera

- A uniform lighting enclosure (to minimize external light variation)

- Trained AI/ML model (e.g., TensorFlow Lite model)

- Sample holder compatible with the smartphone attachment

Procedure:

- Data Collection for Model Training:

- Capture images of the sensor output (e.g., colorimetric test strip, fluorescent probe) across a wide range of known analyte concentrations.

- Vary lighting conditions and use different smartphone models to build a robust dataset.

- Annotate each image with the true concentration.

Model Training and Deployment:

- Pre-process images (e.g., crop region of interest, color space conversion).

- Train a CNN model for regression (to predict concentration) or classification (e.g., safe/unsafe).

- Convert the trained model to a mobile-friendly format (e.g., TFLite) and integrate it into the smartphone application.

In-Field Analysis:

- The user places the reacted sensor in the designated holder.

- The smartphone app automatically captures an image.

- The integrated AI model processes the image and outputs the predicted concentration or classification in real-time.

- Results, along with timestamp and geolocation, can be stored locally or uploaded to a cloud database via IoT connectivity.

Protocol: Deployment and Data Management via IoT/Cloud Architecture

Application: Enabling large-scale, distributed monitoring and real-time data tracking for pesticide exposure or environmental contamination [23] [7].

Principle: Biosensor data is transmitted from the smartphone to a cloud platform, where it is aggregated, stored, and made accessible for visualization and further analysis, facilitating remote monitoring and population-level studies.

Materials:

- Smartphone-integrated biosensor

- Cloud computing service (e.g., Google Cloud Platform, AWS)

- Database (e.g., SQL, NoSQL)

- Web interface for data visualization

Procedure:

- System Architecture Setup (Architecture D [7]):

- Configure the smartphone app to transmit results (measurement, timestamp, device ID, location) to a cloud database via a secure API upon test completion. Connectivity can be Wi-Fi or cellular [29].

- Set up the cloud database to receive and store data from multiple users/devices.

Data Processing and Storage:

- Implement cloud functions to validate incoming data and trigger alerts if measurements exceed predefined thresholds (e.g., pesticide regulatory limits).

- Store raw and processed data in a structured format for long-term access.

Visualization and Sharing:

- Develop a web-based dashboard that displays aggregated data, trends over time, and geographic distribution of results.

- Implement secure, role-based access to the dashboard for researchers, public health officials, or individual users.

- The system can be designed to automatically generate and share reports with relevant stakeholders [23].

Signaling Pathways and Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the logical workflow of an integrated biosensing system and the molecular signaling principle of a common pesticide detection method.

Diagram 1: Integrated AIoT Biosensing Workflow

Diagram 2: AChE Inhibition Biosensing Principle

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Smartphone-Based Resistive Biosensor Development

| Item / Reagent | Function / Role in the Experiment | Exemplary Specifications / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) | Biological recognition element; catalyzes substrate hydrolysis. | Source: Electric eel or recombinant. Activity >1000 U/mg. Stability under storage conditions is critical. |

| Polyaniline Nanofibers (PAnNFs) | Transducer material; conductance is modulated by proton doping from the enzymatic reaction. | High surface-to-volume ratio enhances sensitivity. Synthesized via oxidative polymerization [23] [10]. |

| Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) | Nanomaterial enhancing electron transfer and providing a high-surface-area matrix for enzyme immobilization. | Multi-walled (MWCNTs) or single-walled (SWCNTs). Functionalized (e.g., carboxylated) for better dispersion and biocompatibility [23] [10]. |

| Gold Interdigitated Electrode (AuIDE) | Platform for the nanosensor film; interdigitated structure maximizes contact area for sensitive resistance measurement. | Standard finger width/spacing of 10 μm. Requires cleaning (e.g., oxygen plasma) before modification. |

| Chitosan (CS) | Biopolymer used for enzyme immobilization; provides a biocompatible, porous matrix. | High degree of deacetylation. Forms a stable hydrogel in mild acidic conditions for encapsulating AChE/CNT/PAnNF [23] [10]. |

| Acetylcholine (ACh) / Acetylthiocholine (ATCh) | Enzyme substrate; hydrolysis produces protons (ACh) or thiocholine (ATCh), leading to the measurable signal. | ACh for resistive sensors; ATCh for electrochemical sensors. Stability and purity are important for reproducible kinetics. |

| Smartphone & Mobile App | Serves as the user interface, data processor, and communication hub. | App developed in Android/iOS to control measurement, run AI models, display results, and manage IoT data transmission [23] [7]. |

| Portable Resistance Meter | Measures the conductance change of the nanosensor film. | Bluetooth-enabled for wireless communication with the smartphone. Requires stable baseline and high-resolution measurement. |

Implementing Visual Detection: From Probe Design to Real-World Application

The detection of pesticide residues in food and environmental samples is a critical global challenge, necessitating the development of rapid, sensitive, and field-deployable analytical technologies. Traditional methods, such as gas chromatography and high-performance liquid chromatography, offer high precision but are hampered by their high cost, operational complexity, and lack of portability for on-site analysis [1]. In response, smartphone-integrated biosensors have emerged as a transformative platform for point-of-need testing, combining the powerful processing, imaging, and connectivity of consumer devices with advanced biochemical sensing principles [31] [32].

Among the most promising advancements in this field are probe technologies based on uranium-organic frameworks (UOFs) and ratiometric fluorescence. UOFs are a class of metal-organic frameworks that leverage uranyl ions as the metal center, offering exceptional water stability, strong luminescence, and unique photocatalytic properties [28] [33]. Concurrently, ratiometric fluorescence sensing employs the ratio of fluorescence intensities at two different wavelengths, providing a built-in calibration that minimizes environmental interference and significantly enhances measurement accuracy and sensitivity compared to single-intensity probes [31] [34]. The synergy of these technologies with smartphone-based detection creates a powerful tool for the visual, quantitative, and on-site screening of hazardous pesticides, paving the way for a new generation of food safety monitoring systems [28] [35].

Uranium-Organic Frameworks (UOFs) as Sensing Probes

Uranium-organic frameworks are a specific type of MOF characterized by their unique photophysical and structural properties. The uranyl ions (UO₂²⁺) impart several key advantages for sensing applications:

- Enhanced Rigidity and Luminescence: The incorporation of uranium centers and a heterometallic design in UOFs results in enhanced structural rigidity, defined pore structures, and strong luminescence, which are crucial for sensitive detection [28].

- Photoactive Properties: Uranyl ions possess a high oxidation potential (

E₀ = 2.6 V) and can participate in ligand-to-metal charge transfer (LMCT) processes. This allows UOFs to act not only as sensors but also as photocatalysts for the degradation of pollutants, a property explored in environmental remediation [33]. - Tailorable Specificity: Researchers can synthesize UOFs with specific structures and luminescent properties by selecting appropriate organic linkers and synthesis conditions. For instance, three distinct heterometallic UOFs were tailored to respond to different pesticides and antibiotics through unique fluorescence responses, enabling selective detection [28].

Principles of Ratiometric Fluorescence Sensing

Ratiometric fluorescence is a self-referencing technique that significantly improves the reliability of fluorescence-based assays. Its core principle and advantages are:

- Self-Calibration Mechanism: This method uses the change in fluorescence intensity at two different emission wavelengths. The ratio of these two intensities (

I₁ / I₂) is used as the analytical signal, which automatically corrects for variations in experimental conditions such as probe concentration, excitation light intensity, and environmental noise [28] [31]. - Superior Sensitivity and Accuracy: Probes designed with two emissions that change in opposite directions (one increasing and the other decreasing) in response to an analyte provide the highest sensitivity. This opposite response amplifies the change in the ratiometric signal, leading to lower limits of detection [31].

- Visual and Qualitative Analysis: The distinct color changes under UV light that often accompany ratiometric sensing allow for qualitative analysis by the naked eye, which can then be quantified precisely using a smartphone's camera and a dedicated application [36] [34].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Synthesis of Heterometallic UOFs for Pesticide Detection

This protocol is adapted from the work of Yang et al., which focused on developing a smartphone-integrated sensor for pesticides and antibiotics [28].

- Objective: To synthesize heterometallic uranium-organic frameworks (UOFs) with strong luminescence and tailored specificity for use as fluorescent probes.

- Materials:

- Metal Precursors: Uranyl salt (e.g.,

UO₂(NO₃)₂·6H₂O) and salts of secondary metals (e.g.,Ca²⁺,Sr²⁺,Ba²⁺). - Organic Linkers: Tricarboxylic acid ligands (e.g., imidazole-based ligands).

- Solvent:

N,N'-Dimethylformamide (DMF), deionized water.

- Metal Precursors: Uranyl salt (e.g.,

- Procedure:

- Dissolution: Dissolve the uranyl salt, the secondary metal salt, and the organic linker in a mixture of DMF and water in a defined molar ratio.

- Solvothermal Reaction: Transfer the solution to a Teflon-lined autoclave. Heat the autoclave to 120-150 °C and maintain this temperature for 24-48 hours to allow for slow crystal growth.

- Product Recovery: After the reaction vessel has cooled to room temperature, collect the resulting crystalline product via centrifugation.

- Purification: Wash the crystals repeatedly with fresh DMF and ethanol to remove unreacted precursors and impurities.

- Activation: Finally, dry the purified UOF crystals under vacuum at an elevated temperature (e.g., 100 °C) for 12 hours to remove solvent molecules from the pores, activating them for sensing applications.

- Key Notes: The specific structure and luminescent properties of the UOF are highly dependent on the reaction temperature, time, and the metal-to-ligand ratio. These parameters must be optimized for the target analytes.

Protocol 2: Smartphone-Based Ratiometric Fluorescence Detection of Pesticides

This protocol details the use of a synthesized UOF probe for the actual detection of pesticides, integrated with a smartphone for readout [28] [34].

- Objective: To quantitatively detect pesticide residues in food samples using a UOF-based ratiometric fluorescent probe and a smartphone-based fluorospectrophotometer.

- Materials:

- Probe: Synthesized UOF particles (from Protocol 1), suspended in a suitable buffer.

- Samples: Food extracts (e.g., from vegetables, fruits).

- Equipment: Custom smartphone fluorospectrophotometer (SBS), UV light source (365 nm), cuvette.

- Software: Custom Android application (e.g., SBS-App) for spectral analysis [34].

- Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Homogenize the food sample (e.g., 1.0 g of apple or cabbage) and extract pesticides using a solvent like acetonitrile. Filter the extract to remove particulate matter.

- Detection Reaction: In a cuvette, mix 100 µL of the filtered food extract with 900 µL of the UOF probe suspension. Allow the mixture to react for 10 seconds.

- Signal Acquisition: Place the cuvette in the holder of the smartphone-based fluorospectrophotometer. Irradiate the mixture with a 365 nm UV LED. Use the smartphone's camera and the SBS-App to capture the fluorescence emission spectrum across the visible range (380-760 nm).

- Data Processing: The SBS-App automatically converts the captured image into a fluorescence spectrum and calculates the intensity ratio (

I₁ / I₂) at two predetermined emission wavelengths. - Quantification: The concentration of the target pesticide in the sample is determined by interpolating the measured intensity ratio against a pre-established calibration curve.

- Key Notes: The entire process, from sample reaction to quantitative result, can be completed in under 30 seconds. The smartphone app is critical for converting raw images into spectral data and performing the ratiometric calculation, which minimizes user-induced errors [28] [34].

Signaling Pathways and Workflows

The detection mechanism for pesticides, particularly organophosphorus pesticides (OPs), can be based on enzyme inhibition. The following diagram illustrates the signaling pathway for this type of sensor.

The experimental workflow, from probe preparation to final analysis, is a multi-step process that integrates chemistry, materials science, and smartphone technology, as outlined below.

Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

The following table details key reagents and materials essential for developing and implementing UOF-based ratiometric fluorescence sensors.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for UOF-based Ratiometric Sensing

| Item Name | Function/Description | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

Uranyl Salts (e.g., UO₂(NO₃)₂·6H₂O) |

Metal precursor for UOF synthesis | Provides the photoactive UO₂²⁺ center; defines framework topology and luminescence [28] [33]. |

| Tricarboxylic Acid Ligands | Organic linker for UOF synthesis | Connects metal nodes to form porous frameworks; functional groups influence specificity and stability [28] [33]. |

Heterometallic Salts (e.g., CaCl₂, Sr(NO₃)₂) |

Co-metal precursor for UOF synthesis | Enhances structural rigidity and tailors the luminescent response to specific analytes [28]. |

| Smartphone Fluorospectrophotometer (SBS) | Portable detection device | Custom attachment with UV LED, diffraction grating, and cuvette holder; uses smartphone CMOS for spectral capture [34]. |

| SBS-App | Data processing software | Custom Android/iOS application for converting camera images to spectra and calculating ratiometric values [34]. |

| Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) | Biological recognition element | Enzyme whose inhibition by OPs is the basis for the sensing mechanism in many ratiometric assays [36] [34]. |

Performance Data and Comparison

The performance of UOF and other ratiometric probes for pesticide detection is quantified by parameters such as detection limit, linear range, and recovery rate in real samples. The data below summarizes the capabilities of these advanced sensors.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Ratiometric Fluorescence Sensors for Pesticide Detection

| Detection Platform / Probe | Target Pesticide | Linear Range | Detection Limit | Application in Real Samples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heterometallic UOFs [28] | Multiple antibiotics & pesticides | Not specified | Below regulatory thresholds | Vegetables, animal products |

| FRET-based Aptasensor (MWCNTs/AuNPs) [37] | Acetamiprid (ACE) | 4 – 40 pM | 2.8 pM | Bell pepper |

| MnO₂ Nanosheet Sensor (SC & AR) [36] | Organophosphorus (e.g., DDVP) | 5.0 pg/mL – 500 ng/mL | 1.6 pg/mL | Apple, cabbage |

| Smartphone Fluorospectrophotometer (CDs & QDs) [34] | Chlorpyrifos | 0.5 – 50 ng/mL | 0.42 ng/mL | Apple, cabbage |

The high sensitivity and selectivity of these sensors are further validated through recovery studies in complex food matrices. For instance, the smartphone fluorospectrophotometer (SBS) achieved recovery rates of 94.6% to 105.8% for chlorpyrifos in apple and cabbage samples, demonstrating accuracy comparable to the standard GC-MS method [34]. Similarly, the FRET-based aptasensor for acetamiprid showed efficient performance in bell pepper samples, confirming its applicability in agricultural products [37].

Colorimetric and Fluorometric Assay Development for Pesticide Sensing

The increasing use of organophosphorus (OP) and carbamate (CM) pesticides in modern agriculture poses significant threats to human health and environmental safety. These compounds function by inhibiting acetylcholinesterase (AChE), an enzyme crucial for proper nervous system function, leading to potential neurological dysfunction and other health issues upon chronic exposure [38] [39]. While conventional methods like gas chromatography and high-performance liquid chromatography offer high sensitivity, they require sophisticated instrumentation, extensive sample preparation, and lack suitability for rapid on-site screening [1] [39]. Consequently, developing simple, rapid, and reliable detection methods has become imperative for environmental monitoring and food safety control.

Biosensing technologies, particularly colorimetric and fluorometric assays, have emerged as viable alternatives to conventional methods, offering exceptional sensitivity, rapid response, and ease of operation [1]. The integration of these assays with smartphones further enhances their potential for point-of-care testing, enabling real-time, on-site detection of pesticide residues [20] [28]. This application note details the development of robust colorimetric and fluorometric assays for pesticide sensing, framed within a broader research context focused on smartphone-integrated biosensors for visual pesticide detection.

Key Sensing Mechanisms and Performance Comparison

Contemporary research has explored various sensing mechanisms for pesticide detection, primarily based on enzyme inhibition principles or nanozyme-enhanced catalysis. The table below summarizes the key characteristics and analytical performance of different assay types.

Table 1: Comparison of Colorimetric and Fluorometric Assays for Pesticide Detection

| Assay Type | Sensing Mechanism | Target Pesticide | Limit of Detection (LOD) | Analysis Time | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colorimetric (Nanozyme-enhanced) [38] | Enhancement of oxidase-mimicking activity of cube-shape Ag₂O | Dimethoate (Organophosphorus) | 14 μg·L⁻¹ | < 10 minutes | Simple, rapid, reliable; Does not require H₂O₂ |

| Colorimetric (Enzyme Inhibition) [39] | Inhibition of cricket cholinesterase | Organophosphates & Carbamates | 0.002–0.877 ppm | Optimized at 5 min | Low-cost, uses widely available cricket enzyme |

| Fluorometric/Colorimetric Bimodal [40] | Enzyme-triggered decomposition of AuNCs-MnO₂ nanocomposite | Carbaryl (Carbamate) | 0.125 μg·L⁻¹ | - | Dual-output for self-verification; High sensitivity and anti-interference |

| Smartphone-assisted Hydrogel Biosensor [20] | HOF nanozyme-based inhibition assay | Chlorpyrifos (Organophosphorus) | 3.04 ng/mL | - | Portable, on-site detection; Robust stability |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Colorimetric Detection of Dimethoate Using Cube-Shape Ag₂O Nanozyme

This protocol outlines a strategy based on enhancing the oxidase-mimicking activity of cube-shape Ag₂O for rapid dimethoate detection [38].

Materials and Reagents

- AgNO₃ powder

- NaOH

- 3,3′,5,5′-Tetramethylbenzidine (TMB)

- Dimethoate standard

- Acetate buffer (0.2 M, pH 4.0)

- Absolute ethanol

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Synthesis of Cube-Shape Ag₂O Particles: Prepare cube-shape Ag₂O particles according to the previously reported method. Briefly, mix solutions of AgNO₃ and NaOH, then stir vigorously at room temperature. Collect the resulting cube-shape Ag₂O particles by centrifugation, wash with ethanol and water, and dry [38].

- Preparation of Detection System: In a standard cuvette or microplate well, mix the following:

- Acetate buffer (0.2 M, pH 4.0): 500 μL

- TMB solution (2.0 mM): 100 μL

- Cube-shape Ag₂O suspension (50 μg·mL⁻¹): 100 μL

- Varying concentrations of dimethoate standard or sample extract.

- Catalytic Reaction and Measurement: Incubate the reaction mixture at 35 °C for 10 minutes. The presence of dimethoate enhances the oxidase-mimicking activity of Ag₂O, catalyzing the oxidation of TMB to a blue product (oxTMB).

- Signal Acquisition: Measure the absorbance of the solution at 652 nm using a spectrophotometer or a smartphone-based colorimetric detection system. The increase in absorbance is directly proportional to the dimethoate concentration.

Signaling Pathway Workflow

Protocol 2: Fluorometric/Colorimetric Bimodal Detection of Carbaryl Using AuNCs-MnO₂ Nanocomposite