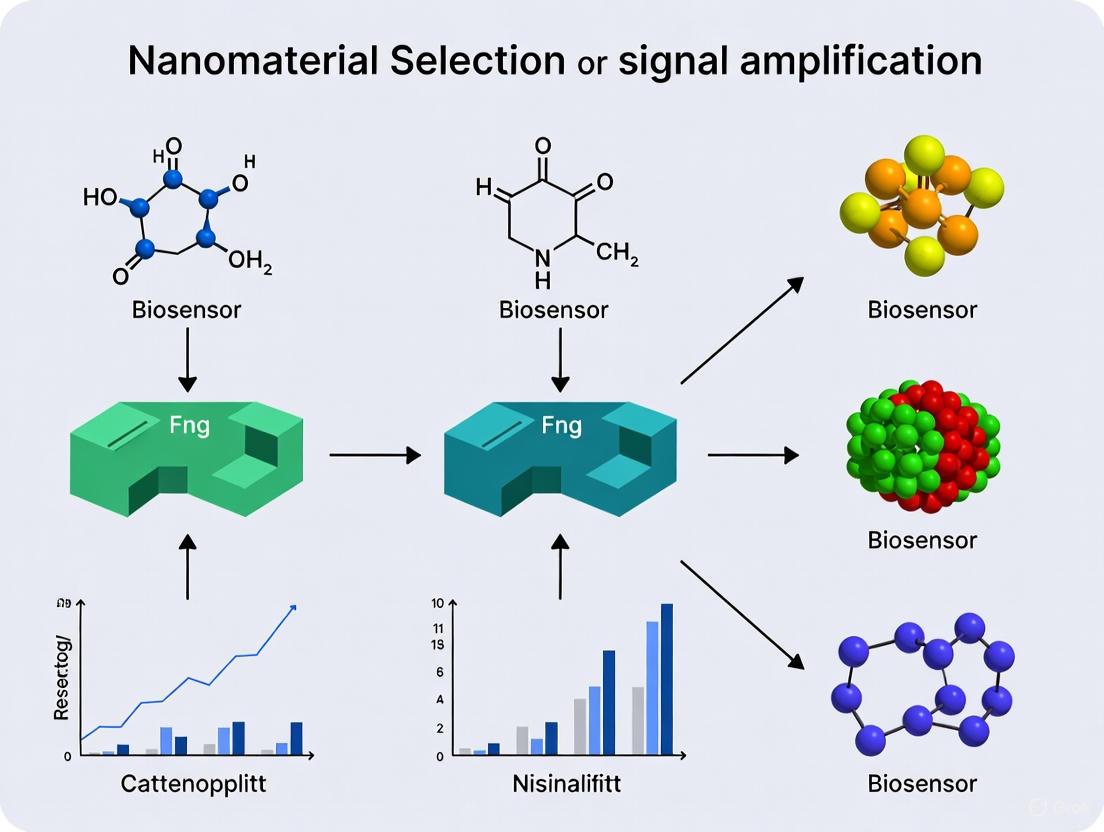

Strategic Nanomaterial Selection for Advanced Signal Amplification in Biosensing and Diagnostics

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on selecting nanomaterials to enhance signal amplification in biosensors.

Strategic Nanomaterial Selection for Advanced Signal Amplification in Biosensing and Diagnostics

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on selecting nanomaterials to enhance signal amplification in biosensors. It covers the foundational principles of how nanomaterials like gold nanoparticles, graphene, MOFs, and COFs improve detection sensitivity and specificity. The scope extends to methodological applications in electrochemical, photoelectrochemical, and Raman-based sensors; troubleshooting for real-world sample analysis; and a comparative validation of material performance. By synthesizing current research and future trends, this resource aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to design highly sensitive and specific detection platforms for clinical diagnostics, environmental monitoring, and therapeutic development.

Nanomaterial Fundamentals: Core Mechanisms and Properties for Signal Enhancement

FAQs: Nanomaterial-Enhanced Signal Amplification

What are the primary advantages of using nanomaterials for signal amplification in biosensing?

Nanomaterials are game-changers in biosensing due to their unique physical and chemical properties that directly enhance key sensor performance metrics [1].

- Enhanced Sensitivity and Lower Detection Limits: Their high surface-to-volume ratio provides a greater area for immobilizing biomarker recognition elements (like antibodies or DNA), effectively concentrating the target and amplifying the detected signal [1].

- Improved Signal Transduction: Many nanomaterials, such as gold nanoparticles and carbon nanotubes, exhibit excellent electrical conductivity. This property is crucial for electrochemical biosensors, as it facilitates electron transfer, leading to stronger and more easily detectable electrical signals [1].

- Versatile Signal Generation: Certain nanomaterials possess intrinsic optical properties. For instance, gold nanoparticles undergo a visible color change (e.g., red-to-purple) upon aggregation, enabling simple colorimetric detection. Quantum dots are highly fluorescent and resistant to photobleaching, making them superior probes for fluorescence-based assays [1].

What is the biggest challenge when incorporating nanomaterials into a sensing system, and how can it be overcome?

The biggest challenge is achieving compatibility between the nanoparticle and the final product or system [2].

Nanomaterials must remain stable and functional within the specific chemical environment of the biosensor, which includes factors like pH, solvent composition, and the presence of other additives. Incompatibility can lead to nanoparticle agglomeration, loss of function, or interference with other system components, resulting in poor performance and unreliable data [2]. To overcome this:

- Adopt a Co-Design Approach: Work iteratively with your nanomaterial supplier, providing them with detailed information about your system's chemistry and processing conditions. This allows for the custom design of nanoparticles with optimized surface chemistry (e.g., using specific capping agents like silanes or thiols) for perfect compatibility [2].

- Avoid "Off-the-Shelf" Pitfalls: Catalog nanomaterials are useful for early proof-of-concept work but are often not formulated for specific system chemistries and may not be scalable for commercial production [2].

My electrochemical biosensor signal is weak. What nanomaterial-based strategies can I use to amplify it?

Weak signals in electrochemical biosensors can be addressed with several nanomaterial strategies designed to enhance electron transfer and increase the active surface area of the electrode [1].

- Use Metallic Nanoparticles: Incorporate gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) onto your electrode surface. Their high conductivity facilitates electron transfer during redox reactions, significantly boosting the current signal even when low amounts of the target biomarker are present [1].

- Employ Carbon Nanomaterials: Modify your electrode with carbon nanotubes (CNTs) or graphene. The tubular structure of CNTs provides an extremely high surface area, increasing the electrode's active area for biomarker binding and electron transfer. Graphene offers similar advantages with added flexibility, making it ideal for wearable sensors [1].

- Explore Hybrid Methods: Combine different amplification strategies. For example, you can use enzymatic amplification (e.g., with alkaline phosphatase) in conjunction with a nanoparticle-modified electrode to create a cascade effect that dramatically enhances the output signal [3] [4].

How does nanoparticle size affect biosensor performance, and how can size be controlled?

Particle size is a critical parameter that directly influences performance [2].

- Impact on Performance:

- Smaller Sizes (typically < 20 nm): Are better for applications requiring high transparency and low haze, such as in optical coatings or displays. They can also have higher catalytic activity [2].

- Larger Sizes: May be necessary if particles need to be embedded within a matrix or if a higher refractive index is desired [2].

- Control During Synthesis: Precise size control is achieved by fine-tuning the synthetic process. Key factors include:

- Capping Agents: These molecules bind to the nanoparticle surface during growth, controlling and limiting crystal size [2].

- Reaction Conditions: Parameters like reaction time, temperature, and concentration of precursors are adjusted to nucleate and grow crystals to a specific size [2].

- It is crucial to agree on the sizing method (e.g., Dynamic Light Scattering for hydrodynamic size, TEM for core size) with your material supplier to ensure you are measuring the same property [2].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Nanoparticles are aggregating in the final biosensor formulation.

Possible Cause & Solution:

- Chemical Incompatibility: The solvent, pH, or ionic strength of your formulation is incompatible with the nanoparticle's surface chemistry [2].

- Solution: Re-formulate the nanoparticles with a custom capping agent that is stable in your specific solvent system (aqueous, organic, polymeric). A provider can functionalize the surface with specific chemical groups (e.g., using silanes for oxide particles) to ensure compatibility [2].

- Insufficient Stabilization: The repulsive forces between particles are not strong enough to overcome van der Waals attraction.

- Solution: Introduce or optimize dispersants and other stabilizers into the formulation. In some cases, a simple solvent shift may be sufficient [2].

Problem: High background noise in an optical biosensor using quantum dots.

Possible Cause & Solution:

- Non-Specific Binding: Quantum dots may be adhering to non-target areas of the sensor.

- Solution: Improve the surface functionalization of the quantum dots. Ensure they are conjugated with high-affinity, specific biorecognition elements like antibodies or aptamers. Also, incorporate rigorous blocking steps with agents like BSA during your assay protocol to minimize non-specific binding [1].

- Unwashed Excess Probes: Unbound quantum dots remain in the solution.

- Solution: Include additional washing steps in your experimental workflow to remove any un-conjugated quantum dots before the detection phase.

Problem: Low signal-to-noise ratio in an electrochemical DNA sensor.

Possible Cause & Solution:

- Inefficient Electron Transfer: The transducer surface is not optimally configured to pick up the electrochemical signal.

- Solution: Redesign the electrode surface with a nanomaterial that enhances electron transfer. A highly effective strategy is to create a nanocomposite electrode using multi-walled carbon nanotubes to increase the active surface area and gold nanoparticles to improve conductivity [1].

- Non-optimized Assay Conditions: The chemical environment is not ideal for the reaction.

- Solution: Systematically optimize reaction conditions such as buffer pH, ionic strength, and incubation times. The use of advanced signal amplification strategies like CRISPR-based systems or enzymatic catalysis can also be explored to magnify the specific signal over the background noise [4].

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: Enhancing an Electrochemical Immunosensor with Gold Nanoparticles

This protocol details the modification of a screen-printed carbon electrode (SPCE) with AuNPs to improve sensitivity for detecting a protein biomarker.

1. Electrode Pretreatment:

- Clean the SPCE by cycling the potential in 0.5 M H₂SO₄ between 0 and +1.0 V (vs. Ag/AgCl) until a stable voltammogram is achieved.

- Rinse thoroughly with deionized water and dry under a nitrogen stream.

2. AuNP Electrode Deposition (Electrodeposition Method):

- Prepare a solution of 1 mM HAuCl₄ in 0.5 M H₂SO₄.

- Immerse the cleaned SPCE and a platinum counter electrode in the solution.

- Apply a constant potential of -0.4 V for 60-120 seconds to reduce Au³⁺ ions to Au⁰, forming a layer of AuNPs on the SPCE surface.

- Rinse the AuNP/SPCE with deionized water to remove loosely bound particles.

3. Antibody Immobilization:

- Activate the AuNP surface by incubating with a 10 mM cysteamine solution for 1 hour to form a self-assembled monolayer.

- Use cross-linkers like EDC/NHS to covalently bind the capture antibodies to the amine-terminated monolayer.

- Block non-specific sites by incubating with 1% BSA for 1 hour.

- The sensor is now ready for use in a standard sandwich or competitive immunoassay format.

Key Reagent Solutions:

| Research Reagent | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Screen-printed Carbon Electrode (SPCE) | Low-cost, disposable transducer platform. |

| Hydrogen Tetrachloroaurate (HAuCl₄) | Source of gold ions for nanoparticle synthesis. |

| Cysteamine | Forms a self-assembled monolayer on gold, providing functional groups for bioconjugation. |

| EDC/NHS Cross-linkers | Activates carboxyl groups, enabling covalent attachment of antibodies to the sensor surface. |

| Capture Antibody | The biorecognition element that specifically binds to the target biomarker. |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | A blocking agent used to cover non-specific binding sites and reduce background noise. |

Protocol 2: Developing a Colorimetric Viral Sensor using Aggregation of Gold Nanoparticles

This method leverages the color-shift property of AuNPs for the naked-eye detection of a viral target, such as SARS-CoV-2.

1. Functionalization of AuNPs:

- Synthesize or obtain ~20 nm spherical citrate-capped AuNPs.

- Incubate the AuNP solution with thiol-modified DNA aptamers (or antibodies) specific to the target viral surface protein for 24 hours. The thiol group chemisorbs onto the gold surface.

- Add a passivating agent (e.g., mercaptohexanol) to cover any remaining bare gold surfaces and ensure the probes stand upright.

- Purify the functionalized AuNPs via centrifugation to remove unbound aptamers.

2. Assay Execution:

- Prepare two tubes: one with a control solution (buffer only) and one with the sample containing the viral target.

- Add an equal volume of the functionalized AuNP solution to both tubes.

- Incubate at room temperature for 15-30 minutes.

- Add a predetermined, sub-optimal concentration of salt to both tubes.

3. Result Interpretation:

- Negative Sample: In the absence of the virus, the salt will screen the repulsive forces between AuNPs, causing them to aggregate and the solution color to change from red to purple.

- Positive Sample: The virus particles bind multiple AuNPs, preventing salt-induced aggregation. The solution remains red.

- A red color in the sample tube, against a purple control, indicates a positive detection.

Workflow: Colorimetric Viral Detection

The Scientist's Toolkit: Nanomaterials for Signal Amplification

The table below summarizes key nanomaterials and their functions in biosensing, providing a quick reference for material selection.

| Nanomaterial | Key Function in Signal Amplification | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | High electrical conductivity; Color change upon aggregation. | Electrochemical signal enhancement; Colorimetric detection of viruses (e.g., SARS-CoV-2) [1]. |

| Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) | High surface area; excellent electron transfer properties. | Quantifying multiplex cancer biomarkers in serum; increasing electrode active area [1]. |

| Graphene | High conductivity, flexibility, and biocompatibility. | Electrodes for wearable biosensors for real-time tracking of inflammation or diabetes markers [1]. |

| Quantum Dots (QDs) | Bright, tunable, photostable fluorescence. | Fluorescent probes in assays for cardiovascular disease, tuberculosis, and cancer [1]. |

| Magnetic Nanoparticles | Enable target separation and concentration from complex mixtures. | Isolating target biomarkers (e.g., for Ebola virus) from blood before detection, reducing background noise [3]. |

| Enzymes (e.g., Alkaline Phosphatase) | Catalyze reactions to produce many detectable molecules from a single binding event. | Enzymatic signal amplification in infectious disease detection (e.g., tuberculosis, HIV) [3]. |

Logical Relationships in Nanomaterial Selection

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why are nanomaterial properties like surface area so critical for signal amplification?

Nanomaterials exhibit unique, size-dependent properties that differ dramatically from their bulk counterparts. The two primary factors are quantum confinement effects and significantly increased surface-to-volume ratios [5]. A high surface area provides a massive platform for immobilizing biomolecules (e.g., antibodies, DNA probes) or carrying a large number of signal tags (e.g., redox molecules, enzymes), which directly increases the signal generated per binding event [6] [7]. This is foundational to their role as nanocarriers and electrode modifiers in amplification strategies [8].

FAQ 2: How does the catalytic activity of nanomaterials enhance detection sensitivity?

Many nanomaterials possess intrinsic catalytic properties or can serve as supports for catalytic substances. They can catalyze electrochemical reactions or act as nanocatalysts to accelerate signal-producing reactions [7] [8]. For instance, they can enhance enzymatic reactions or facilitate the decomposition of substrates in an electrochemiluminescence (ECL) system, leading to a substantial amplification of the output signal and allowing for the detection of ultralow analyte concentrations [6] [7].

FAQ 3: In what ways does improved conductivity benefit an electrochemical biosensor?

Enhanced conductivity, often achieved by modifying electrodes with nanomaterials like gold nanoparticles (Au NPs), graphene derivatives, or carbon nanotubes (CNTs), promotes efficient electron transfer between the biorecognition element and the transducer surface [6] [8]. This minimizes background noise and maximizes the faradaic current from redox reporters, resulting in a stronger, cleaner signal, a lower detection limit, and improved signal-to-noise ratios [6].

FAQ 4: Can a single nanomaterial possess all three key properties?

Yes, many advanced nanomaterials are multifunctional. For example, metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) and covalent organic frameworks (COFs) combine an ultrahigh surface area with tunable catalytic sites and the potential for good electrical conductivity, especially when composited with other materials like graphene [6]. Similarly, graphene oxide offers a large surface area, can be catalytically active, and is an excellent conductor, making it a versatile tool for signal amplification [9] [10].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Low Signal Amplification Despite Using Nanomaterials

| Potential Cause | Investigation Questions | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Sub-optimal Nanomaterial Concentration | Is the concentration too low (insufficient effect) or too high (may cause aggregation or inhibition)? | Perform a dose-response experiment to determine the optimal concentration for your specific assay [9] [10]. |

| Insufficient Immobilization | Is the nanomaterial's surface properly functionalized for biomolecule attachment? | Ensure appropriate surface modification (e.g., with carboxyl or amine groups) to enhance biomolecule loading and stability [9] [7]. |

| Aggregation of Nanomaterials | Have the nanoparticles settled or aggregated in the storage buffer or reaction mix? | Sonicate nanomaterial dispersions before use and use surfactants or surface coatings to improve stability [5]. |

| Incorrect Nanomaterial Selection | Does the chosen nanomaterial have the required catalytic or conductive properties for your detection method? | Re-evaluate material choice. For electrochemical sensors, use high-conductivity materials like Au NPs or CNTs; for catalytic amplification, consider oxide nanoparticles [6] [8]. |

Issue 2: High Background Noise or Non-Specific Signal

| Potential Cause | Investigation Questions | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Non-Specific Adsorption | Are biomolecules or reporters adsorbing non-specifically to the nanomaterial or electrode surface? | Include a blocking agent (e.g., BSA, casein) in the assay buffer to passivate unoccupied surfaces [9]. |

| Unstable Nanomaterial Luminophores | In ECL sensors, is the luminophore (e.g., Ru(bpy)₃²⁺) leaking or degrading? | Use core-shell structures or porous nanomaterials (like MOFs) to encapsulate and protect ECL luminophores [7]. |

| Surface Charge Interference | Is the surface charge of the nanomaterial causing unwanted electrostatic interactions with assay components? | Modify the surface charge through functionalization to reduce non-specific binding [9] [5]. |

Issue 3: Poor Reproducibility Between Experimental Replicates

| Potential Cause | Investigation Questions | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Inconsistent Nanomaterial Synthesis/Batch | Are you using nanomaterials from different synthesis batches? | Characterize each new batch (size, zeta potential, concentration) and source materials from a reliable, consistent supplier [5]. |

| Improper Pipetting and Mixing | Are nanomaterial dispersions being mixed thoroughly before use? | Use calibrated pipettes and positive-displacement tips. Mix all solutions thoroughly and consistently during preparation [11]. |

| Nanomaterial Adhesion Issues | Is the nanomaterial layer on the electrode uneven or unstable? | Standardize the electrode modification protocol (e.g., drop-casting volume, electrodeposition time) and validate surface coverage with a technique like SEM [8]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Optimizing Nanoparticle Concentration for PCR Amplification

This protocol is used to determine the ideal concentration of nanoparticles (e.g., Au NPs, graphene oxide) to enhance the specificity and yield of a Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) [9] [10].

Methodology:

- Prepare Master Mix: Create a standard PCR master mix containing buffer, dNTPs, primers, DNA polymerase, and template DNA.

- Spike with Nanoparticles: Aliquot the master mix into a series of PCR tubes. Spike each tube with a known volume of your nanoparticle stock solution to create a concentration gradient (e.g., 0 nM, 10 nM, 50 nM, 100 nM, 200 nM). Include a negative control (no nanoparticles) and a positive control (a known effective concentration if available).

- Run PCR Amplification: Perform thermal cycling using your standard PCR protocol.

- Analyze Results: Analyze the PCR products using agarose gel electrophoresis.

- Assess amplification yield by the intensity of the correct product band.

- Assess specificity by the absence of non-specific bands (e.g., primer-dimers).

- The optimal concentration is the one that produces the strongest specific product band with the cleanest background [9].

Protocol 2: Electrode Modification with Gold Nanoparticles for Enhanced Conductivity

This protocol details the modification of a glassy carbon electrode (GCE) with Au NPs to create a high-surface-area, conductive platform for immobilizing biomolecules in an electrochemical biosensor [6] [8].

Methodology:

- Electrode Pre-treatment: Polish the GCE with alumina slurry (e.g., 0.3 and 0.05 µm) on a microcloth. Ruminate thoroughly with deionized water and then ethanol. Dry under a stream of nitrogen gas.

- Electrochemical Cleaning: Perform cyclic voltammetry (CV) in a 0.5 M H₂SO₄ solution from -0.2 to 1.5 V until a stable CV profile is obtained.

- Nanoparticle Deposition: Deposit Au NPs onto the clean GCE surface via electrodeposition by cycling the potential in a solution containing HAuCl₄ (e.g., 0.5 mM in 0.1 M KNO₃) between -0.2 and +1.0 V for a set number of cycles. Alternatively, drop-cast a known volume (e.g., 5 µL) of synthesized Au NP solution onto the GCE surface and allow it to dry.

- Characterization: Characterize the modified electrode (GCE/Au NPs) using CV and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) in a standard redox probe solution (e.g., 5 mM [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻). A successful modification is indicated by a decreased electron transfer resistance and increased peak current compared to a bare GCE.

Properties and Performance of Key Nanomaterials

The following table summarizes the properties and optimal concentrations of commonly used nanomaterials for signal amplification, as reported in the literature.

Table 1: Key Nanomaterials for Signal Amplification: Properties and Experimental Conditions

| Nanomaterial | Key Amplifying Properties | Exemplary Optimal Concentration & Size | Primary Role(s) in Amplification |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gold Nanoparticles (Au NPs) | Excellent conductivity, catalytic activity, biocompatibility, facile surface modification [9] [8] | ~13 nm diameter at 1.3 nM [9] | Nanocatalyst, Electrode Modifier, Nanocarrier [9] [8] |

| Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) | High aspect ratio & surface area, excellent electrical conductivity, mechanical strength [9] [6] | Single-walled CNTs (SWCNTs) at ~3 µg/µL; PEI-modified MWCNTs at 0.39 mg/L [9] | Electrode Modifier, Nanocarrier, Electrocatalyst [9] [6] |

| Graphene Oxide (GO) | Very high surface area, tunable functional groups, good water dispersibility, catalytic properties [9] [10] | Specific concentration varies by synthesis and application [9] | Nanocarrier, Concentrator, Electrode Modifier [9] [6] |

| Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) | Ultrahigh surface area, tunable porosity, designable catalytic sites [6] | Specific concentration varies by type and application [6] | Nanocarrier (high probe loading), Nanocatalyst [6] |

| Quantum Dots (QDs) | Size-tunable optical & electronic properties, high redox activity, electrocatalytic properties [9] [7] | Specific concentration varies by composition and size [9] | Nanoreporter, Nanocatalyst, Luminophore [9] [7] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Nanomaterial-Based Signal Amplification Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiments | Key Considerations for Use |

|---|---|---|

| Gold Nanoparticles (Au NPs) | Used to enhance electron transfer in electrochemical sensors, quench or generate signals in optical assays, and carry multiple redox tags [9] [8]. | Surface functionalization (e.g., with thiolated DNA or antibodies) is often required. Optimal size and concentration are critical [9]. |

| Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) | Serve as scaffolds for biomolecule immobilization on electrodes, significantly increasing surface area and improving electrical conductivity [9] [6]. | Require dispersion and functionalization (e.g., carboxylation) to prevent aggregation and facilitate biomolecule attachment [9]. |

| Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) | Act as porous nanocarriers to encapsulate a high density of signal reporters (enzymes, redox molecules) or electrocatalysts, providing massive signal amplification per binding event [6]. | Stability in the desired aqueous or buffer solution must be verified. Postsynthetic modification is often used for bioconjugation [6]. |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | A common blocking agent used to passivate unoccupied surfaces on nanomaterials and electrodes, thereby reducing non-specific binding and background noise [9] [11]. | Typically used at 1-5% (w/v) concentration. Ensure it is compatible with other assay components. |

| Electrochemical Redox Probes | Molecules such as [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻ or Methylene Blue are used to characterize electrode modifications and serve as reporters in signal-generation systems [8]. | Solution concentration and pH must be consistent. The probe should be stable and not interfere with the biorecognition event. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges

This section addresses frequent issues encountered during the synthesis, conjugation, and application of gold nanoparticles.

Troubleshooting Gold Nanoparticle Experiments

| Problem Category | Specific Issue | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Synthesis & Stability | Particle aggregation [12] [13] | - Contaminated glassware- High ionic strength- Incorrect pH- Old or degraded reagents | - Clean glassware thoroughly with aqua regia [13].- Use stabilizers (e.g., citrate, tannic acid) [12].- Ensure reagents are fresh (e.g., ascorbic acid, silver nitrate) [13]. |

| Poor control over nanorod aspect ratio [13] | - Incorrect silver nitrate concentration- Inconsistent seed amount- Ostwald ripening over time | - Adjust AgNO₃ concentration for aspect ratios up to ~850 nm LSPR [13].- Use a binary surfactant system (e.g., CTAB + BDAC) for higher aspect ratios [13].- Document and track reagent lots for consistency [13]. | |

| Optical Properties | Shift in plasmon resonance peak [12] [14] | - Change in local refractive index [14]- Particle aggregation [14]- Ostwald ripening in nanorods [12] | - Characterize the environment (solvent, coatings) [14].- Check for aggregation via UV-Vis (shoulder or peak broadening) [14] [13].- Use nanorods promptly after synthesis [12]. |

| Low shape purity in nanorods [12] | - Synthetic method limitations- Low seed quality | - Source nanorods with high shape purity (e.g., >90% for 800 nm rods) [12].- Optimize seed-mediated growth protocols [13]. | |

| Bioconjugation & Application | Low conjugation efficiency [15] | - Sub-optimal pH- Incorrect antibody-to-nanoparticle ratio- Non-specific binding | - Use pH 7-8 conjugation buffer for antibodies [15].- Optimize the antibody-nanoparticle ratio [15].- Use blocking agents like BSA or PEG [15]. |

| Cytotoxicity of gold nanorods [12] | - Presence of cytotoxic CTAB surfactant | - Source CTAB-free nanorods [12].- Use specialized surface exchange protocols to replace CTAB with citrate [12]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

A. Synthesis and Stability

Q1: Can I obtain truly "bare" gold nanoparticles? No. All nanoparticles require a capping agent or stabilizer to prevent irreversible aggregation. Surfaces like citrate or tannic acid can be displaced by other molecules for functionalization, but a stabilizing agent is always present [12].

Q2: How can I prevent my gold nanorods from aggregating? Aggregation can be identified by a color change from red to blue/purple or a "shoulder" in the UV-Vis spectrum. Prevent it by using high-purity water (18.2 MΩ·cm), fresh reagents, and maintaining clean glassware. Run small pilot studies regularly to verify reagent quality [13].

Q3: Why is the peak resonance of my nanorods different from the specification sheet? A slight blue-shift over time can occur due to Ostwald ripening, where atoms reorganize to a more thermodynamically stable shape, reducing the aspect ratio. Use particles promptly after synthesis [12].

B. Optical Properties

Q4: Why does the color of my spherical gold nanoparticle solution change? The intense red color of a stable solution comes from the Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR). If the solution turns blue/purple, it indicates particle aggregation, which red-shifts the SPR peak. A clear solution with black precipitates suggests severe aggregation and precipitation [14].

Q5: How does the local environment affect the optical properties of my AuNPs? An increase in the local refractive index (e.g., transferring nanoparticles from water to oil or coating them with silica or biomolecules) causes the extinction peak to red-shift. This property is leveraged in many sensing applications [14].

Q6: What is the difference between the optical properties of small and large spherical AuNPs? Smaller nanospheres (e.g., < 20 nm) primarily absorb light, with a peak near 520 nm. Larger spheres exhibit significantly increased scattering, and their extinction peaks broaden and shift to longer wavelengths [14].

Experimental Protocols for Key Techniques

A. Seed-Mediated Growth of Gold Nanorods

This is a common method for producing anisotropic gold nanorods with tunable optical properties [13].

Detailed Methodology:

Preparation of Gold Seed Solution:

- Reduce chloroauric acid (HAuCl₄) using sodium borohydride (NaBH₄) in an aqueous solution of cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) or citrate.

- The solution should change from yellow to brownish, indicating the formation of small gold nanoparticle seeds.

- Allow the seed solution to age for a specified time (e.g., 30 minutes to 2 hours) before use [13].

Preparation of Growth Solution:

- Prepare a solution containing CTAB, silver nitrate (AgNO₃), and HAuCl₄ in water. For longer nanorods, a co-surfactant like benzyldimethylammonium chloride (BDAC) may be added.

- Add ascorbic acid to the growth solution. This mild reducing agent converts Au³⁺ ions (from HAuCl₄) to Au¹⁺, changing the solution from yellow to colorless. Ascorbic acid alone cannot reduce Au¹⁺ to metallic gold (Au⁰) [13].

Initiation of Nanorod Growth:

- Add the prepared gold seed solution to the growth solution.

- The seeds catalyze the reduction of Au¹⁺ to Au⁰. CTAB and Ag act to break symmetry by preferentially adsorbing to specific crystal facets ({110} and {100}), inhibiting growth in those directions and promoting anisotropic growth along the {001} plane, resulting in rod-shaped particles [13].

- Let the reaction proceed undisturbed for several hours to allow complete growth.

B. Plant-Mediated Green Synthesis of Spherical AuNPs

This environmentally friendly method uses plant extracts as reducing and stabilizing agents [16] [17].

Detailed Methodology (using Green Tea Extract):

Preparation of Plant Extract:

- Boil deionized water and steep green tea leaves for 5-10 minutes.

- Filter the cooled extract to remove solid particles.

Synthesis of AuNPs:

- Prepare a 1 mM aqueous solution of chloroauric acid (HAuCl₄).

- Mix the green tea extract with the HAuCl₄ solution under constant stirring. The volume ratio of extract to gold solution will determine the reduction rate and final particle size (e.g., a 1:9 ratio is a common starting point).

- The solution will gradually change color from yellow to deep purple or ruby red, indicating the formation of AuNPs. The catechins and polyphenols in the tea act as both reducing and capping agents [17].

- Continue stirring for a set period (e.g., 1 hour) to ensure complete reaction.

Purification:

- Purify the synthesized nanoparticles by repeated centrifugation and redispersion in deionized water to remove any unreacted plant metabolites.

Synthesis Selection and Optimization Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the decision-making process for selecting and optimizing a gold nanoparticle synthesis method, a critical step for signal amplification research.

Research Reagent Solutions

This table details key materials and their functions for working with gold nanoparticles in diagnostic and signal amplification applications [15].

Essential Materials for Diagnostic Assay Development

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Citrate-capped AuNPs | Standard spherical nanoparticles; provide a negatively charged surface for physisorption of biomolecules [12]. | Stable in higher ionic strength solutions; surface can be easily modified [12]. |

| CTAB-free Gold Nanorods | Anisotropic particles for photothermal therapy and imaging; tunable NIR absorption [12]. | Essential for bio-applications; avoids cytotoxicity associated with CTAB [12]. |

| Conjugation Buffers (pH 7-8) | Maintain optimal pH for efficient binding of biomolecules (e.g., antibodies) to AuNP surfaces [15]. | Critical for binding efficiency; use dedicated conjugation buffers for stable pH [15]. |

| Blocking Agents (BSA, PEG) | Reduce non-specific binding in diagnostic assays, preventing false-positive results [15]. | Added after conjugation to block unused surface areas on the nanoparticle [15]. |

| Stabilizing Agents | Enhance the shelf life of nanoparticle conjugates, ensuring consistent performance over time [15]. | Particularly important for commercial diagnostic kits [15]. |

| High-Purity HAuCl₄ | The most common gold precursor for the synthesis of AuNPs via reduction [13]. | The source and lot of gold salt can impact the size and LSPR of the final product [13]. |

| Silver Nitrate (AgNO₃) | Used as a shape-directing agent in the seed-mediated growth of gold nanorods [13]. | Concentration is a key parameter for controlling the final aspect ratio of the nanorods [13]. |

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guide

Q1: My carbon nanotube (CNT)-modified electrode shows inconsistent electrical conductivity and poor signal output. What could be the cause?

A: Inconsistent conductivity often stems from impurities and structural variability in the CNTs.

- Cause 1: Metallic vs. Semiconducting Chirality. CNTs can be metallic or semiconducting depending on their chiral structure (how the graphene sheet is rolled). A mixture of both types, common in most syntheses, leads to inconsistent electrode behavior [18].

- Solution: Source pre-purified CNTs that are enriched with either metallic or semiconducting types, depending on your application's need for high conductivity or transistor-like behavior.

- Cause 2: Defects and Impurities. Commercial CNT samples may contain residual metal catalysts or structural defects that disrupt electron transport [19] [18].

- Solution: Repurify CNTs using established methods like acid treatment and filtration. Always characterize the material's properties (e.g., with Raman spectroscopy) upon receipt, rather than relying solely on manufacturer specifications [19].

Q2: Why is the signal from my graphene-based biosensor unstable and decaying over time in complex biological samples?

A: Signal decay often results from nonspecific adsorption and biofouling.

- Cause: The high surface area of graphene, while excellent for biomolecule immobilization, can also passively adsorb other proteins or molecules from the sample matrix (e.g., serum). This fouling insulates the electrode surface, increasing impedance and degrading the electrochemical signal [20] [6].

- Solution: Implement a surface passivation strategy. Coimmobilize inert proteins like bovine serum albumin (BSA) or create a hydrophilic polymer brush layer on the graphene surface to block nonspecific binding sites.

Q3: The dispersion of my carbon nanomaterial in aqueous buffer is unstable; it aggregates and settles quickly, leading to poor film formation on my electrode.

A: Achieving a stable, homogeneous dispersion is a critical and common challenge.

- Cause: Pristine graphene and CNTs are hydrophobic and tend to agglomerate in water due to strong van der Waals forces [6].

- Solution: Functionalize the nanomaterials to introduce hydrophilic groups.

- Covalent Functionalization: Treat with strong acids to create carboxylic acid (-COOH) groups on the surface. These groups impart a negative charge and improve water solubility [18].

- Non-covalent Functionalization: Use surfactants (e.g., sodium dodecyl sulfate) or polymers to wrap around the nanotubes, providing steric or electrostatic stabilization without altering their electronic structure.

Table 1: Electronic and Physical Properties of Carbon-Based Nanomaterials

| Property | Graphene | Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes (SWCNTs) | Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes (MWCNTs) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electrical Conductivity | Very high (electron mobility > 15,000 cm²/V·s) | Metallic or semiconducting based on chirality; ropes have resistivity ~10⁻⁴ Ω·cm [18] | Complex interwall conduction; generally metallic [18] |

| Current Density | High (theoretically ~10⁸ A/cm²) | Extremely high; up to 10⁷ A/cm² demonstrated, 10¹³ A/cm² theoretical [18] | High |

| Thermal Conductivity | Excellent (~3000-5000 W/m·K) | The best known; >3000 W/m·K [18] | High |

| Young's Modulus (Stiffness) | ~1 TPa | ~1 TeraPascal (TPa), can be higher [18] | High, depends on wall disorder [18] |

| Specific Surface Area | High (theoretical ~2600 m²/g) | Very high (~1000 m²/g) [18] | High (lower than SWCNTs) |

Table 2: Performance Comparison in Electrochemical Sensing Applications

| Characteristic | Graphene & Derivatives | Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Role in Signal Amplification | Promotes direct electron transfer, increases electroactive surface area [21] | High aspect ratio facilitates electron tunneling; acts as "nanoneedles" to access redox sites [21] |

| Biomolecule Immobilization | Strong π-π stacking and hydrophobic interactions [6] | Can entrap biomolecules in the nanotube mesh; can be functionalized for covalent attachment [6] |

| Typical Limit of Detection (LOD) | Attomolar to femtomolar range possible [20] [6] | Attomolar to femtomolar range possible [20] [6] |

| Key Advantage | High conductivity, large 2D surface area, facile modification [21] | High aspect ratio provides percolation networks at low loadings [18] |

| Key Challenge | Restacking of sheets, variable quality [6] | Control of chirality, metallic vs. semiconducting mixture [18] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Fabrication of a CNT-based Electrochemical Immunosensor

This protocol details the construction of an electrode using carbon nanotubes for ultrasensitive detection of a target antigen [20] [6].

Workflow Overview:

Materials:

- Glassy Carbon Electrode (GCE)

- Carboxylated Multi-walled Carbon Nanotubes (MWCNTs-COOH)

- N-(3-Dimethylaminopropyl)-N'-ethylcarbodiimide (EDC)

- N-Hydroxysuccinimide (NHS)

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), pH 7.4

- Specific Capture Antibody

- Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA)

- Ethanol, Ultrapure water

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Electrode Pretreatment: Polish the GCE with alumina slurry (0.05 µm) on a microcloth. Rinse thoroughly with ethanol and water, then dry under nitrogen gas.

- CNT Dispersion: Disperse 1 mg of MWCNTs-COOH in 1 mL of water via 30 minutes of probe ultrasonication to create a homogeneous black suspension.

- Electrode Modification: Drop-cast 5 µL of the CNT dispersion onto the clean GCE surface and allow it to dry at room temperature, forming a uniform CNT film.

- Antibody Immobilization:

- Prepare a fresh activation solution containing 2 mM EDC and 5 mM NHS in PBS. Activate the CNT/GCE by applying 10 µL of this solution for 30 minutes to convert carboxyl groups to amine-reactive esters.

- Rinse the electrode gently with PBS to remove excess EDC/NHS.

- Incubate the electrode with 10 µL of the capture antibody solution (e.g., 10 µg/mL in PBS) for 1 hour at 37°C. The antibodies will covalently attach to the activated CNT surface.

- Blocking: Treat the electrode with 10 µL of 1% BSA solution for 30 minutes to block any remaining nonspecific binding sites on the CNT surface. Rinse with PBS.

- Target Capture: Incubate the immunosensor with the sample containing the target antigen for 40 minutes at 37°C. Rinse thoroughly with PBS to remove unbound material.

- Electrochemical Detection: Perform voltammetric measurement (e.g., Differential Pulse Voltammetry) in a solution containing a redox probe (e.g., 5 mM [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻). The binding of the antigen will hinder electron transfer to the probe, resulting in a measurable change in current, which is proportional to the antigen concentration.

Protocol 2: Functionalization of Graphene for Enhanced Biomolecule Loading

This protocol describes the chemical activation of graphene oxide (GO) for efficient conjugation of biomolecules [6].

Workflow Overview:

Procedure:

- Prepare a 1 mg/mL dispersion of Graphene Oxide (GO) in a suitable buffer (e.g., MES, pH 6.0) via ultrasonication.

- Add EDC and NHS to the GO dispersion to final concentrations of 2 mM and 5 mM, respectively.

- Allow the reaction to proceed with gentle shaking for 15-30 minutes at room temperature.

- Add the target biomolecule (e.g., an antibody or enzyme) to the activated GO solution and incubate for 2 hours at room temperature or overnight at 4°C.

- Purify the GO-biomolecule conjugate via centrifugation and washing to remove unreacted reagents.

- The conjugate can be used as a sensitive signal tag, where the GO serves as a high-capacity carrier for multiple enzyme molecules or redox labels, significantly amplifying the detection signal [20] [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Carbon Nanomaterial-based Sensing

| Reagent / Material | Function and Rationale |

|---|---|

| Carboxylated CNTs/Graphene | Provides readily available functional groups (-COOH) for covalent immobilization of biomolecules via EDC/NHS chemistry, ensuring stable and oriented binding [6] [18]. |

| EDC and NHS Crosslinkers | Act as coupling agents. EDC activates carboxyl groups, and NHS stabilizes the intermediate ester, facilitating efficient amide bond formation with amine-containing biomolecules [6]. |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | Used as a blocking agent to passivate unused surface areas on the nanomaterial and electrode, minimizing nonspecific binding and reducing background noise [20] [6]. |

| Electrochemical Redox Probes | Molecules like [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻ or [Ru(NH₃)₆]³⁺ are used to probe the electron transfer efficiency at the modified electrode interface. Changes in their voltammetric signal indicate binding events [20]. |

| Enzymatic Labels (e.g., HRP) | Horseradish Peroxidase is often conjugated to a detection antibody. In the presence of H₂O₂ and a substrate, it generates an amplified electrochemical signal, pushing detection limits to the attomolar range [20] [6]. |

FAQ: Frameworks and Material Selection

Q1: What are the core advantages of using MOFs and COFs for immobilization over traditional porous materials?

MOFs and COFs offer significant advantages due to their highly tunable structures. Unlike traditional porous materials like activated carbon or mesoporous silica, which often have poorly defined pore architectures, MOFs and COFs provide precise control over pore size, shape, connectivity, and surface functionality through their modular construction [22]. This results in exceptionally high internal surface areas—up to approximately 7839 m² g⁻¹ for MOFs and 5083 m² g⁻¹ for COFs—which are crucial for high-capacity immobilization of enzymes, biomarkers, or other guest molecules [22].

Q2: How does the choice between a MOF and a COF impact my sensor's performance?

The choice hinges on the required properties for your application. MOFs, being metal-organic, often provide redox activity and catalytic sites, which are beneficial for electrochemical sensors [23]. COFs, constructed entirely with strong covalent bonds, typically offer higher thermal and chemical stability [22]. For enhanced performance, MOF@COF composites are emerging, which combine the functional versatility of MOFs with the robust stability of COFs, creating synergistic effects for biosensing and other applications [24].

Q3: What are the common degradation issues with MOFs in practical applications, and how can I stabilize them?

MOFs can face several degradation pathways, including:

- Hydrolysis: Liquid water or high humidity can break coordination bonds, destroying the framework [25].

- Attack by Acids/Bases and Anions: The pH and presence of coordinating anions can displace ligands or dissolve metal clusters [25].

- Photodegradation and Redox Processes: Light exposure and redox-active substances can damage the framework [25].

Stabilization strategies include using more stable metal-ligand pairs (e.g., Zr⁴⁺-based UiO series), introducing hydrophobic functional groups on pore surfaces to repel water, and constructing MOF-based composites to shield the framework from harsh environments [25].

Q4: What signal amplification strategies can I implement with these frameworks?

MOFs and COFs are excellent for signal amplification. Their primary roles include:

- Increasing Immobilization Capacity: Their ultrahigh surface area allows for high-density loading of signal tags like enzymes or electroactive molecules [6].

- Enhancing Electron Transfer: When combined with conductive materials, they facilitate better charge transport, leading to faster and stronger electrochemical signals [23] [6].

- Promoting Preconcentration: Their tunable porosity can be designed to selectively adsorb and concentrate target analytes within the pores, amplifying the detectable signal [23].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Table 1: Troubleshooting Immobilization and Stability Issues

| Problem Symptom | Potential Root Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low immobilization efficiency or uneven distribution of biomolecules. | Pore size mismatch; non-optimal surface chemistry. | Perform de novo design to tailor linker length/functionality [22] or apply post-synthetic modification (PSM) to graft specific binding groups [22]. |

| Poor electron transfer in electrochemical sensing. | Inherently low electrical conductivity of the pristine framework. | Form composites with conductive materials (e.g., carbon nanotubes, graphene) [23] [6] or create conductive MOFs using redox-active metal centers/linkers [23]. |

| Framework degradation in aqueous or biological media. | Hydrolysis of coordination bonds (especially for water-sensitive MOFs). | Select stable metal nodes (e.g., Zr⁴⁺, Fe³⁺); incorporate hydrophobic moieties via mixed-linker synthesis or PSM [25]. |

| Non-specific binding, leading to high background noise. | Lack of selectivity in the pore environment. | Engineer pore surfaces with functional groups that have high affinity for the target analyte (e.g., S, N, O for heavy metals) [23]. |

| Leakage of encapsulated enzymes or catalysts. | Pore apertures are too large, or encapsulation is physical. | Utilize a "ship-in-a-bottle" approach, synthesizing the framework around the enzyme, or choose a framework with a pore size that sterically confines the biomolecule [26]. |

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Determining Enzyme Orientation and Dynamics within MOFs/COFs

Understanding how an enzyme is oriented and moves within a porous framework is critical for explaining catalytic performance [26].

Methodology:

- Site Selection: Obtain the crystal structure of your target enzyme. Identify representative surface residues (e.g., on α-helices or β-strands) for spin labeling, ensuring they cover most of the protein surface.

- Cysteine Mutation: Use site-directed mutagenesis to introduce cysteine mutations at the selected sites.

- Spin Labeling: React the mutated enzyme with a spin label (e.g., HO-225) to attach a nitroxide sidechain (R1) to the thiol group of the cysteine.

- Encapsulation: Encapsulate the spin-labeled enzyme into the MOF or COF.

- EPR Measurement & Analysis: Acquire Electron Paramagnetic Resonance (EPR) spectra. Analyze the spectra to extract dynamics parameters and determine the relative orientation of the enzyme in respect to the pore surfaces [26].

Protocol 2: Synthesis of MOF@COF Core-Shell Composites

Creating composites can synergize the properties of MOFs and COFs [24].

General Workflow:

- Synthesis of MOF Core: Synthesize MOF crystals (e.g., HKUST-1, ZIF-8) using standard solvothermal methods.

- Surface Functionalization: Activate the surface of the pre-formed MOF crystals to provide nucleation sites for COF growth.

- COF Shell Growth: Immerse the functionalized MOFs in a solution containing COF monomers (e.g., aldehydes and amines). Under controlled solvothermal conditions, the COF shell will crystallize on the MOF surface, forming a core-shell structure [24].

- Characterization: Confirm the composite structure using techniques like PXRD, BET surface area analysis, and electron microscopy.

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for selecting a framework and the subsequent immobilization and signal detection process.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents for MOF/COF-based Immobilization and Sensing

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role in Experiment | Example Framework / System |

|---|---|---|

| Zr₆O₄(OH)₄ clusters | Stable metal-node for MOFs; provides high chemical stability. | UiO-66, UiO-67 [25] |

| 1,3,5-Benzenetricarboxylic acid (H₃BTC) | Trifunctional organic linker for MOF synthesis. | HKUST-1 [25] |

| 2-Methylimidazole | Nitrogen-containing organic linker for zeolitic frameworks. | ZIF-8 [25] |

| Terephthalic Acid (H₂BDC) | Linear dicarboxylate linker for MOF synthesis. | MOF-5, UiO-66 [22] [25] |

| Site-Directed Spin Label (e.g., HO-225) | Labels cysteine residues on proteins for EPR studies of orientation/dynamics in pores [26]. | Protocol for enzyme encapsulation [26] |

| Conductive Nanomaterials (CNTs, Graphene) | Enhances electron transfer in MOF composites for electrochemical sensors [23] [6]. | MOF-conductive polymer composites [23] |

| Redox-active molecules (Ferrocene, Methylene Blue) | Acts as signal tags; can be loaded into MOF/COF pores for amplified electrochemical detection [6]. | Various electrochemical immunosensors [6] |

The integration of quantum dots (QDs) with metal oxides represents a frontier in designing advanced functional materials for optoelectronics and catalysis. This synergy leverages the unique properties of QDs—such as their size-tunable band gaps and efficient light-harvesting capabilities—with the stability and charge-transport properties of metal oxides. For researchers and drug development professionals, mastering the selection and troubleshooting of these nanomaterials is crucial for developing highly sensitive biosensors, efficient photocatalytic systems, and advanced optoelectronic devices. This technical support center addresses specific, frequently encountered experimental challenges, providing practical guidance to streamline your research and development process.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary advantages of using carbon quantum dots (CQDs) over traditional semiconductor quantum dots (SQDs) in biosensing and photocatalysis? CQDs offer several distinct benefits for sensitive applications. Their high aqueous solubility, excellent biocompatibility, and low toxicity make them particularly suitable for biomedical sensing and drug development contexts [27]. Furthermore, CQDs exhibit superior photostability and resistance to photo-bleaching compared to many SQDs, ensuring consistent performance over time [27]. Their surface is rich in functional groups, which facilitates easy functionalization with biomolecules (e.g., aptamers, enzymes) and integration with metal oxide substrates [28] [27].

Q2: How does the quantum confinement effect in QDs influence the performance of a QD-metal oxide composite? The quantum confinement effect, which becomes prominent when the particle size is reduced to the nanometer scale, allows for precise tuning of the QD's bandgap by varying its size [29] [30]. This enables researchers to tailor the optical absorption and emission properties of the composite material for a specific application. For instance, a smaller QD size results in a wider bandgap, which can be leveraged to enhance light absorption efficiency and modify the redox potential for photocatalytic reactions [30].

Q3: What is the role of a molecular linker in functionalizing a metal oxide with colloidal QDs? Molecular linkers, such as bifunctional organic molecules, are often used to anchor ex-situ synthesized colloidal QDs to metal oxide surfaces (e.g., TiO₂, ZnO) [29]. These linkers form a chemical bridge between the QD and the oxide, improving the stability and adhesion of the hybrid structure. Critically, the chemical nature of this linker creates an energy barrier at the interface and fundamentally determines the mechanism of electron transfer, influencing whether it occurs via tunneling through the barrier or hopping through states within the bridging molecule [29].

Q4: Why is charge recombination a major challenge in g-C₃N₄, and how does integrating with metal oxide QDs mitigate this? Graphitic carbon nitride (g-C₃N₄), while a promising metal-free photocatalyst, suffers from the rapid recombination of photogenerated electron-hole pairs, which limits its efficiency [30]. Integrating it with metal oxide QDs (e.g., TiO₂, ZnO) to form a 0D-2D heterostructure promotes the separation of these charges. The combined interface and band alignment facilitate the transfer of electrons from g-C₃N₄ to the metal oxide QDs, thereby spatially separating electrons and holes and reducing the probability of recombination [30].

Troubleshooting Guides

Low Photocatalytic Degradation Efficiency

Problem: Your QD-metal oxide photocatalyst shows poor performance in degrading organic dye pollutants. Potential Causes and Solutions:

Cause 1: Rapid Charge Carrier Recombination

- Solution: Introduce CQDs as an electron mediator. In systems with a narrow bandgap, CQDs can accept and shuttle electrons, preventing them from recombining with holes. In wide-bandgap semiconductors, CQDs can act as spectral converters via up-conversion luminescence, enabling visible-light activity [28]. Constructing a Z-scheme heterostructure, where CQDs facilitate the transfer of electrons between two semiconductors, can also significantly reduce recombination [28].

Cause 2: Insufficient Visible Light Absorption

- Solution: Decorate wide-bandgap metal oxides (like TiO₂) with visible-light-active QDs. QDs such as CdS or CQDs can act as photosensitizers, absorbing visible light and injecting excited electrons into the conduction band of the metal oxide, thereby extending the photocatalytic activity into the visible spectrum [27] [31].

Cause 3: Poor Interaction with Target Pollutants

Poor Signal Response in Electrochemical Biosensing

Problem: Your aptamer-based electrochemical biosensor utilizing QDs and metal oxides has low sensitivity and a high detection limit for target miRNA or proteins. Potential Causes and Solutions:

Cause 1: Inefficient Electron Transfer

- Solution: Enhance the electrode's electroactive surface area and conductivity. Modify the electrode with a nanocomposite of metal oxides and carbon nanomaterials. For example, using a composite of reduced graphene oxide (rGO) with TiO₂ or thorn-like Au@Fe₃O₄ nanostructures can significantly improve electron transfer kinetics and provide a larger surface area for immobilizing biorecognition elements [32] [33].

Cause 2: Inadequate Signal Amplification

- Solution: Integrate nucleic acid-based amplification strategies with your nanomaterial platform. Techniques such as Hybridization Chain Reaction (HCR) or Catalytic Hairpin Assembly (CHA) can be employed on the sensor surface. These methods create large DNA structures that can be labeled with multiple QD tags, leading to a dramatic amplification of the electrochemical signal upon target binding [32].

Cause 3: Non-Specific Binding

- Solution: Optimize the surface passivation and the orientation of aptamers. Ensure that the metal oxide-QD substrate is properly functionalized with the aptamer probes and that any unbound sites are blocked with inert proteins or chemicals to minimize background noise [33].

Instability and Aggregation of Nanocomposites

Problem: The QD-metal oxide nanocomposites aggregate in solution or lose activity over multiple uses. Potential Causes and Solutions:

Cause 1: Lack of a Stabilizing Capping Layer

- Solution: Use appropriate molecular ligands during the synthesis of colloidal QDs. Ligands like oleic acid or mercaptopropionic acid not only control QD growth but also act as an electronic passivation layer, reducing surface recombination centers and providing steric or electrostatic stabilization to prevent aggregation [29].

Cause 2: Weak Attachment Between QDs and Metal Oxide

- Solution: For ex-situ hybridization, employ robust functionalization strategies. Instead of relying on physical adsorption, use covalent coupling methods. For carbon-based materials, oxidation can introduce carboxyl groups, which can then be linked to aminated aptamers or metal oxide surfaces via amide bond formation [33].

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Protocol: Synthesis of CQDs/g-C₃N₄ Nanocomposite for Photocatalysis

This protocol describes a common method for creating a visible-light-active photocatalyst for organic pollutant degradation [27] [30].

1. Synthesis of g-C₃N₄:

- Precursor: Place 10g of melamine or urea in an alumina crucible with a lid.

- Thermal Polymerization: Heat in a muffle furnace at 550°C for 4 hours with a ramp rate of 5°C/min.

- Product Collection: After cooling to room temperature, collect the resulting pale-yellow solid and grind it into a fine powder.

2. Synthesis of Carbon Quantum Dots (CQDs) via Bottom-Up Method:

- Precursor: Use a natural carbon source such as citric acid.

- Hydrothermal Treatment: Dissolve 2g of citric acid in 100mL of deionized water. Transfer the solution to a Teflon-lined autoclave and heat at 180°C for 8 hours.

- Purification: After cooling, centrifuge the resulting CQD solution at high speed (e.g., 12,000 rpm) to remove large particles. Filter the supernatant through a 0.22 μm membrane.

3. Formation of CQDs/g-C₃N₄ Nanocomposite:

- Mixing: Disperse 500mg of as-synthesized g-C₃N₄ powder in 100mL of the CQD solution.

- Sonication and Stirring: Sonicate the mixture for 1 hour followed by vigorous stirring for 12 hours to allow adsorption of CQDs onto the g-C₃N₄ sheets.

- Drying: Separate the composite by centrifugation and dry in a vacuum oven at 60°C overnight.

Table 1: Key Properties and Performance of Selected QD-Metal Oxide Composites in Photocatalysis

| Composite Material | Target Pollutant | Light Source | Degradation Efficiency | Key Enhancement Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CQDs/TiO₂ [28] [27] | Methylene Blue | Visible Light | >90% (in 60 min) | CQDs act as electron reservoirs & photosensitizers |

| CQDs/g-C₃N₄ [27] [30] | Rhodamine B | Simulated Sunlight | ~85% (in 90 min) | Enhanced charge separation, extended light absorption |

| Au-TiO₂ NWs [31] | -- | UV Light | -- | Surface plasmon resonance, reduced charge recombination |

Protocol: Fabricating an Electrochemical miRNA Biosensor with HCR Amplification

This protocol outlines the steps for creating a highly sensitive biosensor for microRNA detection, integrating a metal oxide substrate and a nucleic acid amplification strategy [32] [33].

1. Electrode Modification:

- Substrate Preparation: Prepare a nanocomposite of reduced graphene oxide and titanium dioxide (rGO-TiO₂) to enhance the electrode surface area and conductivity.

- Electrode Coating: Drop-cast 10 μL of the rGO-TiO₂ suspension onto a polished glassy carbon electrode (GCE) and allow it to dry.

2. Aptamer Immobilization:

- Probe Attachment: Incubate the modified electrode with 5'-aminated capture DNA probes complementary to a segment of the target miRNA. Use EDC/NHS chemistry to form covalent amide bonds between the probe's amine group and carboxyl groups on the rGO-TiO₂ surface.

- Blocking: Treat the electrode with a 1% BSA solution for 1 hour to block non-specific binding sites.

3. Target miRNA Capture and Signal Amplification:

- Hybridization: Incubate the sensor with the sample containing target miRNA for 60 minutes at 37°C.

- HCR Initiation: Expose the electrode to a solution containing two species of fluorescently tagged or enzyme-linked DNA hairpins (H1 and H2). The captured miRNA initiates a cascade of hybridization events between H1 and H2, forming a long double-stranded DNA polymer on the sensor surface.

- Signal Generation: If using enzyme labels (e.g., Horseradish Peroxidase), add an electrochemical substrate (e.g., H₂O₂) and measure the current. The large HCR polymer carries numerous labels, leading to a significantly amplified signal.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Amplification Strategies in Electrochemical miRNA Biosensing

| Amplification Strategy | Detection Limit (approx.) | Linear Range | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hybridization Chain Reaction (HCR) [32] | ~fM (femtomolar) | 0.1 - 1000 pM | Enzyme-free, isothermal, simple operation | Probe design complexity |

| Rolling Circle Amplification (RCA) [32] | ~aM (attomolar) | 1 fM - 10 nM | High amplification efficiency, can be combined with CRISPR | Requires circular template, longer time |

| Catalytic Hairpin Assembly (CHA) [32] | ~fM | 0.01 - 100 pM | Enzyme-free, catalytic, autonomous | Susceptible to non-specific opening |

| Nanomaterial (e.g., AuNP) Enhancement [33] | ~pM - nM | 0.001 - 100 nM | Increases surface area, improves conductivity | Signal amplification less than nucleic acid methods |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for QD-Metal Oxide Research

| Category / Item | Specific Examples | Primary Function in Experiments |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum Dots | Carbon QDs (CQDs), CdS QDs, PbS QDs | Photosensitizers, electron mediators, spectral converters, signal tags. |

| Metal Oxides | TiO₂, ZnO, SnO₂, Fe₃O₄ | Charge transport matrices, photocatalytic substrates, magnetic separation. |

| Carbon Nanomaterials | Graphene (GR), Reduced Graphene Oxide (rGO), Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) | Enhancing electrode conductivity, providing high surface area for immobilization. |

| Linkers & Functionalization | (3-Aminopropyl)triethoxysilane (APTES), Mercaptopropionic acid (MPA) | Covalently anchoring QDs to metal oxide surfaces; surface passivation. |

| Biosensing Elements | DNA aptamers, miRNAs, specific antibodies | Biorecognition of target analytes (ions, proteins, cells). |

| Amplification Reagents | DNA hairpins (for HCR/CHA), DNA polymerases (for RCA), Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP) | Enzymatic and non-enzymatic amplification of detection signals. |

Signaling Pathways and Workflow Visualizations

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why is my plasmonic signal amplification inconsistent or weak, even with confirmed nanoparticle formation?

Inconsistent amplification often stems from poorly controlled hot carrier dynamics or inefficient charge transfer at the interface. Recent studies reveal that ultrafast, nonthermal electron transfer directly from gold nanoparticles to a semiconductor substrate (like GaN) can occur without energy losses from electron-electron scattering, but this requires strong interfacial interactions and intimate contact [34]. Verify your system's interface quality and energy band alignment. Furthermore, the polarization of incident light can dynamically modulate charge generation and energy distribution; optimizing this parameter is crucial for controlling electron relaxation and improving injection efficiency over the Schottky barrier [34].

FAQ 2: How does nanoparticle size and shape affect hot electron transfer and 'hot spot' efficiency?

The size and electronic structure of plasmonic nanoparticles are critical and have complex effects:

- Size Dependence: Theoretical studies on silver nanoclusters show that while the probability of direct hot electron transfer may decrease with increasing cluster size, the net electron transfer is not simply size-dependent. It is governed by the interplay between the electronic structures of the nanocluster and the acceptor molecule [35].

- Shape Dependence: Morphology directly determines the number and quality of "hotspots." Gold nanostars, for instance, are highly efficient for Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering (SERS) due to the extreme near-field enhancement at their sharp tips and branches, creating more intrinsic hotspots per particle compared to spherical nanoparticles [36].

FAQ 3: What are the key differences between thermal and nonthermal electron transfer processes?

The distinction lies in the energy distribution and pathway of the electrons involved:

- Nonthermal Electron Transfer: This is an ultrafast, direct injection process where electrons are transferred before undergoing energy-wasting electron-electron scattering. This facilitates efficient charge separation and produces a nonthermal distribution of transferred electrons, maximizing energy utilization [34].

- Thermal Electron Transfer: In this conventional pathway, photoexcited carriers first thermalize through electron-electron scattering, forming a hot Fermi-Dirac distribution within hundreds of femtoseconds. This process involves substantial energy dissipation, constraining the overall efficiency of energy conversion devices [34] [37].

FAQ 4: How can I experimentally verify the mechanism of charge transfer in my plasmonic system?

A combination of advanced spectroscopic and microscopic techniques is required:

- Femtosecond Time-Resolved Spectroscopy: Techniques like transient absorption (TA) and time-resolved two-photon photoemission (TR-2PPE) can probe ultrafast hot electron relaxation and charge transfer dynamics on the relevant timescales (e.g., within 40 fs) [34] [38].

- Nanoscale Surface Analysis: Surface photovoltage microscopy (SPVM) with nanometer resolution allows direct visualization of photogenerated charge transfer at the spatial positions of nanoparticles [34].

- Theoretical Modeling: Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations can complement experimental data to confirm a purely electron transfer-mediated mechanism and illustrate the establishment of high-speed electron transfer channels in heterostructures [38].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low Photocatalytic or Photocurrent Efficiency in a Plasmonic Metal/Semiconductor Heterostructure

Possible Causes and Solutions:

| Problem Area | Specific Issue | Diagnostic Method | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Interface Quality | Weak interfacial interaction leading to suppressed charge transfer. | XPS to check for binding energy shifts indicating strong interaction (e.g., Au 4f peak shifts) [34]. | Engineer intimate interface contact. Compare nanoparticles to flat films; nanoparticles often exhibit stronger interactions [34]. |

| Energy Alignment | Schottky barrier is too high for hot electrons to surmount. | Conductive AFM (CAFM) to measure nanoscale current-voltage curves and determine Schottky barrier height [34]. | Select a semiconductor with a more favorable conduction band position or use a co-catalyst to extract charges [38]. |

| Carrier Recombination | Rapid recombination of photogenerated electron-hole pairs before charge separation. | Time-resolved spectroscopy (e.g., TR-2PPE, TA) to measure carrier lifetimes [34] [38]. | Introduce a charge extraction layer or form a heterojunction (e.g., Ni3S4/ZnCdS) to spatially separate electrons and holes [38]. |

| Excitation Source | Sub-optimal excitation of the localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR). | Absorption spectroscopy to confirm overlap between light source and LSPR peak [34] [36]. | Tune the excitation wavelength to match the LSPR. Experiment with light polarization to modulate charge generation [34]. |

Problem: Inconsistent or Low SERS Signal from Plasmonic Substrate

Possible Causes and Solutions:

| Problem Area | Specific Issue | Diagnostic Method | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hotspot Reliability | Poor control over the formation and distribution of electromagnetic hotspots. | SEM/TEM to analyze nanoparticle morphology and aggregation [36]. Dark-field spectroscopy to check for consistent LSPR [36]. | Use nanoparticles with sharp features like nanostars. Employ a polymer matrix (e.g., phospholipid nanogel) to control particle aggregation and distribution uniformly [36]. |

| Substrate Stability | Inconsistent analyte distribution or poor stability of colloidal substrates. | Micro-Raman mapping to check for signal uniformity across the substrate [36]. | Use solid substrates or pseudo-immobilize nanoparticles in a reversible thermoresponsive nanogel within a microfluidic channel for more reliable and reproducible analysis [36]. |

| LSPR-Laser Match | Laser excitation wavelength is not optimally resonant with the LSPR. | Extinction spectroscopy to measure LSPR [36]. | Synthesize nanoparticles (e.g., gold nanostars) with a LSPR wavelength maximum (λmax) specifically aligned to resonate with your laser excitation (e.g., 638 nm) [36]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Probing Ultrafast Nonthermal Electron Transfer using Time-Resolved Spectroscopy

This protocol is based on methodologies used to reveal direct nonthermal electron transfer in Au NP/GaN systems [34].

- Sample Preparation: Deposit plasmonic nanoparticles (e.g., ~7 nm Au NPs) on a suitable substrate (e.g., n-type GaN). Ensure the substrate has a wide bandgap to avoid direct photogeneration of electron-hole pairs by the pump light.

- Pump-Probe Setup: Utilize a femtosecond laser system.

- Pump Pulse: Tune the wavelength (e.g., ~520 nm) to excite the Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) of the nanoparticles.

- Probe Pulse: Use a time-delayed UV pulse for the photoemission probe.

- TR-2PPE Measurement:

- Measure the energy and momentum of photoemitted electrons as a function of the time delay between pump and probe pulses.

- Track the emergence and evolution of electron populations in the semiconductor conduction band with femtosecond resolution.

- Data Analysis:

- Identify a nonthermal distribution of electrons in the GaN conduction band appearing within the laser pulse duration (<40 fs) as evidence of direct, nonthermal transfer.

- Compare the measured occupation lifetimes of these electrons to predictions from the Fermi liquid model; significantly extended lifetimes support the nonthermal transfer mechanism.

Protocol 2: Synthesis of High-Hotspot-Density Gold Nanostars for SERS

This protocol is adapted from a synthesis method for creating reliable SERS substrates [36].

- Seed Solution Preparation: First, synthesize citrate-capped gold nanospheres (~13 nm diameter) using the Turkevich method.

- Growth Solution:

- In a 20 mL glass vial with a magnetic stir bar, add 10 mL of ultrapure water and stir at 600 rpm.

- Under ambient conditions, add 492 µL of gold chloride solution (5.08 mM) and mix for 10 s.

- Add 20 µL of HCl (1.0 N) and mix for 10 s.

- Immediately add 140 µL of the pre-formed gold nanosphere seed solution and mix for 10 s.

- Nanostar Growth:

- Add 34 µL of AgNO3 (3.0 mM) and mix for 5 seconds. A color change indicates the initiation of nanostar formation.

- Immediately add 100 µL of ascorbic acid (100 mM) and mix for 60 s to reduce the gold and promote branch growth.

- Stabilization: For long-term stability, functionalize the synthesized nanostars with mPEG-SH (2000 Da).

- Characterization: Use UV-Vis-NIR spectroscopy to confirm the LSPR peak is at the desired wavelength (e.g., ~638 nm). Use TEM to verify the star-like morphology with sharp branches.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

| Item | Function / Application in Research |

|---|---|

| Gold Nanostars | Plasmonic nanoparticles with multiple sharp tips that create intense electromagnetic "hotspots," making them superior substrates for SERS and sensing applications [36]. |

| Gallium Nitride (GaN) | A wide-bandgap semiconductor substrate used in plasmonic heterostructures. Its accessible conduction band states allow for plasmonic electron injection, and its transparency enables visible light excitation of SPR without intrinsic absorption [34]. |

| Phospholipid Nanogel (DMPC/DHPC) | A thermally responsive polymer matrix. It can pseudo-immobilize plasmonic nanoparticles in microfluidic channels for reproducible SERS analysis and be flushed out for device reuse, enhancing reliability [36]. |

| Ni3S4 Co-catalyst | A non-noble metal co-catalyst used in heterojunctions (e.g., with ZnCdS). It acts as an electron extractor, establishing high-speed electron transfer channels to promote reactions like H₂ production while leaving holes for oxidation reactions [38]. |

| Covalent/Metal-Organic Frameworks (COFs/MOFs) | Porous nanomaterials with ultrahigh surface areas and tunable porosity. They serve as excellent carrier platforms in electrochemical sensors, enhancing electron transfer, biomolecular loading capacity, and signal amplification [39]. |

Visualizing Plasmonic Electron Transfer Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the key processes involved in plasmonic hot carrier generation and transfer.

Diagram 1: Plasmonic hot carrier pathways. Upon light excitation, a plasmon decays via Landau damping, generating initial non-thermal hot carriers (electrons and holes). These can follow one of two primary pathways: 1) Direct Non-thermal Transfer, an ultrafast, efficient injection into an acceptor's conduction band without energy loss to scattering, or 2) Thermalization, where carrier-carrier scattering creates a thermalized electron distribution, followed by slower, less efficient thermal transfer [34] [37].

The following diagram outlines a key experimental workflow for creating and analyzing a plasmonic nanocomposite for SERS sensing.

Diagram 2: SERS substrate workflow. This workflow details the process for creating a reusable, thermoresponsive plasmonic nanocomposite for microfluidic SERS sensing. Gold nanostars are synthesized and characterized before being embedded in a phospholipid nanogel. This composite can be loaded into a microfluidic channel, immobilized by heating for analysis, and then flushed out by cooling, allowing the device to be reused [36].

Application in Biosensing: Integrating Nanomaterials into Electrochemical, Optical, and PCR Platforms

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges and Solutions

This guide addresses frequent issues encountered when developing electrochemical biosensors for miRNA and protein detection, providing targeted solutions to enhance sensitivity, specificity, and reliability.

Table 1: Troubleshooting Common Biosensor Performance Issues

| Problem Category | Specific Symptom | Potential Root Cause | Recommended Solution | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low Sensitivity | High detection limit, weak signal for low-abundance targets (e.g., <1 pM miRNA). | Insufficient signal amplification; inefficient electron transfer. | Integrate nanomaterials (MXenes, AuNPs) or enzymatic cascades (ALP, HRP). Implement enzyme-free amplification (HCR, TRA). | [40] [41] [42] |

| Poor signal-to-noise ratio in complex samples (e.g., serum). | Non-specific adsorption; electrode fouling. | Use conformational change-based probes (E-AB, E-DNA) that are fouling-resistant. Improve surface passivation with MCH or BSA. | [43] [40] | |

| Poor Specificity | False positives from closely related sequences (e.g., miRNA family members). | Inadequate probe selectivity; cross-hybridization. | Optimize probe length and sequence. Use competitive or sandwich assays to enhance recognition specificity. | [43] [44] |

| Signal interference from sample matrix (e.g., proteins in serum). | Non-specific binding of non-target biomolecules. | Incorporate rigorous washing steps. Use nanostructured interfaces (GO, MOFs) that favor specific binding. | [6] [44] | |

| Signal Instability | Signal drift over time or between measurements. | Unstable biorecognition element immobilization; mediator leakage. | Employ covalent binding for probe immobilization. Use solid-state mediators or label-free detection schemes. | [45] [44] |

| High batch-to-batch variation in sensor response. | Inconsistent nanomaterial synthesis or electrode modification. | Standardize synthesis and functionalization protocols. Use characterization techniques (SEM, EIS) for quality control. | [6] [46] | |

| Bioreceptor Activity | Loss of antibody/aptamer binding capability after immobilization. | Harsh immobilization chemistry denatures bioreceptor. | Use oriented immobilization strategies (e.g., protein A for antibodies). Employ gentle cross-linkers and verify activity after each step. | [44] |

| Reduced activity of enzymatic labels (e.g., ALP, HRP). | Enzyme inactivation due to environmental factors. | Ensure proper storage conditions. Use nanozymes (catalytic nanomaterials) as stable alternatives. | [40] [42] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)