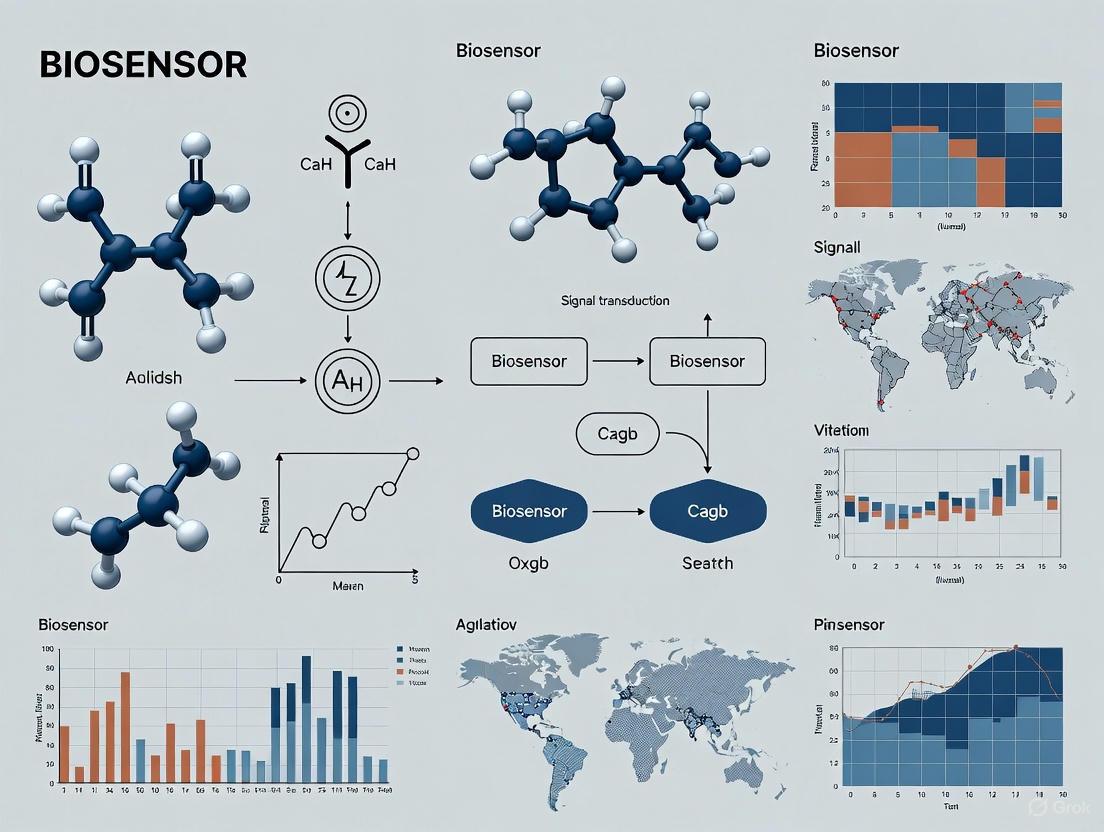

Strategies for Enhancing Biosensor Selectivity and Specificity: From Foundational Concepts to Advanced Applications

This article provides a comprehensive examination of the latest strategies for improving the selectivity and specificity of biosensors, a critical challenge for their application in clinical diagnostics, drug development, and...

Strategies for Enhancing Biosensor Selectivity and Specificity: From Foundational Concepts to Advanced Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive examination of the latest strategies for improving the selectivity and specificity of biosensors, a critical challenge for their application in clinical diagnostics, drug development, and environmental monitoring. Aimed at researchers and scientists, the content explores the fundamental principles governing biosensor performance, details innovative methodological approaches including nanomaterial integration and novel sensing mechanisms, addresses troubleshooting for complex sample matrices, and discusses rigorous validation protocols. By synthesizing current research and emerging trends, this review serves as a strategic guide for the development of next-generation, high-fidelity biosensing platforms.

The Fundamentals of Biosensor Fidelity: Defining Selectivity and Specificity

Core Definitions and Conceptual Framework

In the field of biosensing, the terms selectivity and specificity are often used interchangeably, but they describe fundamentally different concepts. Understanding this distinction is critical for designing robust experiments, interpreting data accurately, and advancing biosensor research.

- Specificity refers to the ability of a biosensor to assess an exact, single analyte in a mixture, unequivocally, and without cross-reactivity from other components that are expected to be present. A perfectly specific sensor, much like a single key designed to open one specific lock, responds to only one target. This is the ideal principle behind many recognition elements such as highly optimized antibodies, enzymes in lock-and-key mechanisms, and specific aptamers [1] [2].

- Selectivity, in contrast, is the ability of a biosensor to differentiate and quantify multiple different analytes within a mixture simultaneously. Rather than focusing on one target, a selective approach aims to identify all components present. Using the key analogy, selectivity requires identifying all keys in a bunch, not just the one that opens the lock. This is often achieved using cross-reactive sensor arrays that generate a unique response pattern or "fingerprint" for a complex sample [1] [2].

The table below summarizes the key differences:

| Feature | Specificity | Selectivity |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | "One-to-one" binding; unequivocal identification of a single analyte [2]. | "One-to-many" differentiation; recognizes multiple distinct analytes in a mixture [2]. |

| Analytical Goal | Confirm the presence and/or concentration of a predefined target. | Generate a pattern to classify a sample or measure multiple components at once [1]. |

| Common Sensor Design | Single, highly specific bioreceptor (e.g., antibody, aptamer) [1]. | Array of cross-reactive sensors (a "chemical nose/tongue") [1]. |

| Data Output | Direct, quantitative data for one analyte. | Multidimensional data requiring pattern recognition analysis [1]. |

Diagram 1: Decision workflow for choosing between specificity and selectivity.

Quantitative Metrics and Performance Evaluation

Evaluating a biosensor's performance requires quantifying its specificity and selectivity using standardized metrics. The following table outlines key parameters and their definitions [3].

| Metric | Definition & Calculation | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Limit of Detection (LoD) | The lowest analyte concentration that can be reliably detected. Typically, Signal-to-Noise (S/N) > 3 or signal > 3 × standard deviation of the blank [3]. | Lower LoD indicates higher sensitivity. Essential for detecting trace amounts. |

| Limit of Quantification (LoQ) | The lowest analyte concentration that can be quantitatively measured with acceptable precision. Typically, S/N > 10 or signal > 10 × standard deviation [3]. | Defines the lower end of the analytical range where the sensor is precise. |

| Sensitivity | The change in sensor signal per unit change in analyte concentration (e.g., nA/mM for an amperometric glucose sensor) [3]. | The slope of the calibration curve. A steeper slope means a larger signal change for a small concentration change. |

| Response Time (T90) | The time required for the sensor output to reach 90% of its final value after a change in analyte concentration [3]. | Critical for real-time and continuous monitoring applications. |

| Signal Resolution | The ability to discern a signal difference between two analyte concentrations. Requires a signal change ≥ 3 × standard deviations [3]. | Determines the smallest concentration difference the sensor can reliably report. |

Case Study: SERS-Based Immunoassay

A recent study developing a SERS-based immunoassay for the α-fetoprotein (AFP) cancer biomarker demonstrates a specific sensing approach. The sensor used Au-Ag nanostars functionalized with monoclonal anti-α-fetoprotein antibodies (AFP-Ab). This design resulted in a Limit of Detection (LoD) of 16.73 ng/mL for the AFP antigen, showcasing high specificity and sensitivity for a single, predefined target [4].

Experimental Protocols for Assessment

Protocol: Demonstrating Specificity in a Single-Analyte Sensor

This protocol is designed to validate the specificity of a sensor, such as an antibody-based electrochemical biosensor.

- Sensor Preparation: Immobilize your specific bioreceptor (e.g., antibody, aptamer) onto the transducer surface using your established functionalization protocol [5].

- Calibration: Record the sensor's response (e.g., current, voltage, frequency shift) in the presence of a series of standard solutions with known concentrations of the target analyte. This creates the calibration curve.

- Interference Test:

- Prepare a mixture containing the target analyte at a concentration near the middle of its analytical range.

- Spike this mixture with high, physiologically relevant concentrations of potential interferents (e.g., structurally similar molecules, common matrix components).

- Expose the sensor to this spiked solution and record the response.

- Control Test: Expose a separate, identical sensor to a solution containing only the potential interferents, with no target analyte present.

- Data Analysis:

- The sensor response in step 3 should closely match the response expected for the target analyte alone (from the calibration curve). A significant change indicates cross-reactivity and poor specificity.

- The sensor response in step 4 should be negligible, confirming no false positive signal from the interferents [2].

Protocol: Demonstrating Selectivity via a Cross-Reactive Array

This protocol outlines the creation and validation of a selective sensor array for complex sample discrimination.

- Array Design: Select a set of sensing elements (e.g., various lectins, functionalized nanoparticles, or synthetic receptors) known to have differential, cross-reactive responses to the class of analytes of interest (e.g., glycans, proteins, volatile organic compounds) [1].

- Immobilization: Pattern or immobilize each sensing element into a distinct region on a solid support, creating the array [1].

- Training Phase:

- Expose the array to a set of known, purified analytes or characterized complex samples (the "training set").

- Collect the multidimensional response pattern from all elements in the array for each sample.

- Use statistical or machine learning methods (e.g., Linear Discriminant Analysis, Principal Component Analysis) to create a classification model that links response patterns to sample identity [1].

- Validation Phase:

- Expose the array to a new set of "unknown" samples (the "test set").

- Use the classification model from step 3 to predict the identity or class of the unknowns.

- The accuracy of these predictions quantifies the selectivity and discriminatory power of the array [1].

Diagram 2: Workflow for a selective, array-based sensor.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

FAQ 1: My sensor shows a strong signal for my target, but I also get a significant signal from a known interferent. How can I improve specificity?

- Problem: Cross-reactivity with structurally similar molecules or matrix components.

- Solution:

- Bioreceptor Screening: Screen a library of different bioreceptors (e.g., different clone antibodies or aptamer sequences) to find one with higher affinity and specificity for your target.

- Surface Engineering: Modify the sensor surface with blocking agents (e.g., BSA, specific polymer brushes like POEGMA) or create a physical barrier (hydrogel) to reduce non-specific binding of interferents [6].

- Sample Pre-treatment: Introduce a purification or separation step (e.g., filtration, centrifugation) to remove the interferent from the sample matrix before analysis.

- Multistep Assay Design: Implement a sandwich-type assay format (e.g., using two different antibodies that bind to separate epitopes on the target) to enhance specificity [6].

FAQ 2: The response patterns from my selective sensor array are inconsistent, leading to poor sample classification. What could be wrong?

- Problem: Poor reproducibility in the sensor array's response.

- Solution:

- Immobilization Check: Ensure the bioreceptors in your array are immobilized in a stable, reproducible, and uniform manner across different batches. Optimize your functionalization protocol for consistency [5].

- Environmental Control: Tightly control experimental conditions such as temperature, pH, and humidity, as these can affect the interaction kinetics and lead to pattern drift.

- Signal Drift Correction: Implement a referencing strategy or internal standard to correct for baseline signal drift over time [3] [6].

- Data Processing Review: Re-examine your data preprocessing steps (normalization, scaling) and ensure your training set is large and diverse enough to build a robust classification model [1].

FAQ 3: My biosensor works perfectly in buffer but fails in complex biological samples like blood serum. How can I recover performance?

- Problem: Matrix effects and biofouling in complex media.

- Solution:

- Antifouling Coatings: Apply advanced antifouling coatings to your sensor surface. Recent research shows that polymer brushes like poly(oligo(ethylene glycol) methacrylate) (POEGMA) can physically prevent non-specific binding, eliminating the need for blocking and lengthy wash steps [6].

- Dilution: Dilute the complex sample with a compatible buffer to reduce the concentration of interfering substances. This must be validated to ensure it does not dilute the target below the LoD.

- Standard Addition Method: Use the method of standard additions to calibrate the sensor directly in the sample matrix, which can help account for matrix-related signal suppression or enhancement.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table lists key materials used in advanced biosensing research, as highlighted in recent literature.

| Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Au-Ag Nanostars | A plasmonic material used as a substrate for Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering (SERS). Their sharp-tipped morphology provides intense signal enhancement, enabling highly sensitive detection of biomarkers [4]. |

| Polymer Brushes (e.g., POEGMA) | Used to create antifouling surfaces on sensors. These brushes minimize non-specific binding in complex samples like blood serum, greatly improving assay robustness and specificity [6]. |

| Magnetic Beads | Solid supports used in assay design. They can be grafted with antifouling polymers and capture antibodies, facilitating easy separation and concentration of targets, which simplifies workflows and reduces interference [6]. |

| CMOS (Complementary Metal-Oxide-Semiconductor) Chips | Integrated circuits used as the base for highly miniaturized, scalable, and sensitive biosensor platforms. They allow for the development of portable, multi-analyte devices for point-of-care testing [6]. |

| Graphene | A two-dimensional nanomaterial used in electrochemical and THz SPR biosensors. Its excellent electrical conductivity, large surface area, and tunable properties enhance sensitivity and enable active performance modulation (e.g., via magnetic field) [4] [5]. |

| Polydopamine | A melanin-related, biocompatible polymer that mimics mussel adhesion proteins. It is used for simple, environmentally friendly surface modification of electrodes, improving the stability and functionalization of electrochemical sensors [4]. |

In biosensor development, the choice of biorecognition element fundamentally dictates analytical performance, particularly selectivity and specificity. These biological molecules—including enzymes, antibodies, aptamers, and functional nucleic acids—serve as the molecular interface that differentiates target analytes from complex sample matrices. This technical resource center examines the mechanistic origins of selectivity across different biorecognition classes and provides practical troubleshooting guidance for researchers optimizing biosensor platforms for clinical diagnostics, drug development, and environmental monitoring. Understanding these principles is essential for advancing biosensor technology beyond laboratory settings into real-world applications.

Performance Comparison of Biorecognition Elements

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Major Biorecognition Elements

| Biorecognition Element | Source/Production | Binding Mechanism | Key Advantages | Primary Limitations | Optimal Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aptamers | In vitro selection (SELEX) [7] | 3D structure folding (helices, loops, G-quadruplexes) via van der Waals forces, hydrogen bonding, electrostatic interactions [7] | High thermal stability, chemical synthesis, easy modification, low batch-to-batch variability, small size [8] [7] [9] | Susceptibility to nuclease degradation, requires optimized hybridization conditions [8] [10] | Point-of-care diagnostics, targeted delivery, environmental monitoring [11] [7] |

| Antibodies | Animal immune systems (in vivo) [11] | Specific antigen-antibody interaction recognizing distinct epitopes [10] | High specificity and sensitivity, mature commercial production protocols [10] [9] | Resource-intensive production, batch-to-batch variability, poor thermal stability, high cost [11] [10] | Clinical immunodiagnostics, therapeutic applications [11] [9] |

| Enzymes | Biological organisms or recombinant expression | Active site catalysis with exceptional substrate specificity [10] | Catalytic signal amplification, high efficiency, application versatility [10] | Stringent operational requirements (temperature, pH), high production/purification costs [10] | Metabolic sensing, food quality control, environmental monitoring [10] |

| Nucleic Acids | Chemical synthesis | Programmable complementary base-pair hybridization [10] | Structural predictability, molecular recognition fidelity, superior thermal stability [10] | Requires strict hybridization condition control, complex selection process for high-affinity probes [10] | Genetic testing, pathogen detection, miRNA profiling [10] |

Table 2: Analytical Performance Metrics in Biosensing Applications

| Biorecognition Element | Typical Detection Limit | Assay Time | Stability & Shelf Life | Susceptibility to Interference | Reproducibility |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aptamers | Femtomolar (fM) to attomolar (aM) range [8] | Rapid (minutes to hours) [11] | Excellent (can be stored long-term) [7] | Low to moderate (depends on folding) [8] | High (chemical synthesis ensures consistency) [7] |

| Antibodies | Picomolar (pM) to nanomolar (nM) range | Moderate to long (hours) | Moderate (sensitive to denaturation) [11] | Moderate (cross-reactivity possible) [9] | Variable (batch-to-batch differences) [11] [10] |

| Enzymes | Nanomolar (nM) range [10] | Rapid (minutes) [10] | Moderate (dependent on conditions) [10] | High (sensitive to inhibitors, temperature, pH) [10] | Moderate to high (with purification) [10] |

| Nucleic Acids | Attomolar (aM) for amplified assays [10] | Moderate (hybridization time required) [10] | Excellent (stable at room temperature) [10] | Moderate (affected by sample contaminants) [10] | Very high (sequence-defined) [10] |

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQ for Researchers

Aptamer-Related Issues

Q1: Our aptamer-based sensor shows decreased specificity in complex biological samples. What optimization strategies can we implement?

Decreased specificity typically stems from non-specific interactions or aptamer unfolding in complex matrices. Implement these solutions:

- Chemical Modification: Incorporate locked nucleic acids (LNAs) or 2'-fluoro ribose substitutions into aptamer sequences to enhance nuclease resistance and stabilize binding conformations [8].

- Pre-negative Selection: Incubate your aptamer library with the sample matrix lacking the target to remove sequences binding to non-target components [7].

- Buffer Optimization: Introduce monovalent or divalent cations (e.g., Mg²⁺) that promote proper aptamer folding and reduce non-specific binding [7].

- Surface Passivation: Use polyethylene glycol (PEG) or bovine serum albumin (BSA) coatings on sensor surfaces to minimize biofouling [9].

Q2: The SELEX process for developing new aptamers is time-consuming and inefficient. Are there advanced selection methods to improve this?

Traditional SELEX can require 8-15 rounds over several months, but advanced techniques significantly streamline this:

- Capillary Electrophoresis SELEX (CE-SELEX): Separates bound and unbound sequences based on migration rates under high voltage, typically achieving high-affinity aptamers in 1-4 rounds [7].

- One-round Pressure Controllable Selection (OPCS): Incubates nucleic acid libraries with two competitive target proteins simultaneously, with separation via capillary electrophoresis, enhancing selection efficiency through competitive pressure [7].

- Microfluidic SELEX: Automates selection processes using minimal reagents and enables precise control over binding conditions, improving selection stringency [7].

Antibody-Related Issues

Q3: Our antibody-based biosensors exhibit significant batch-to-batch variability. How can we improve consistency?

Batch variability originates from the biological production system. Mitigation strategies include:

- Hybridoma Cell Line Validation: Ensure stable hybridoma cells by single-cell cloning and extensive validation of secretion consistency [10].

- Quality Control Assays: Implement multiple characterization techniques (Western blot, ELISA, surface plasmon resonance) to assess binding affinity and specificity across batches [10].

- Alternative Recognition Elements: Consider switching to recombinant antibodies or aptamers for applications requiring high batch consistency [11] [9].

Q4: Antibody degradation is affecting our biosensor shelf life. What preservation methods are most effective?

Antibody instability often relates to thermal denaturation or protease activity:

- Stabilization Formulations: Add trehalose or sucrose as cryoprotectants in storage buffers to prevent thermal denaturation [11].

- Controlled Environment: Maintain cold chain (4°C or -20°C) with desiccation to minimize degradation [11].

- Oriented Immobilization: Use Fc-specific binding proteins (e.g., Protein A/G) to consistently orient antibodies on sensor surfaces, protecting antigen-binding sites [9].

General Performance Optimization

Q5: Our biosensor shows insufficient signal intensity for low-abundance targets. What signal amplification strategies can we employ?

Enhancing detection sensitivity requires strategic amplification:

- Nanomaterial Integration: Utilize gold nanoparticles (AuNPs), graphene oxide, or carbon nanotubes to enhance electron transfer in electrochemical sensors and provide high surface area for probe immobilization [8].

- Enzymatic Amplification: Employ horseradish peroxidase (HRP) or glucose oxidase (GOx) systems that generate electroactive products for signal multiplication [8] [10].

- Hybridization Chain Reaction (HCR): Implement enzyme-free nucleic acid amplification through triggered self-assembly of DNA hairpins for exponential signal enhancement [10].

- CRISPR/Cas Systems: Leverage CRISPR-associated proteins for highly specific nucleic acid detection with collateral cleavage activity that amplifies detection signals [10].

Q6: We're experiencing significant non-specific binding in complex samples. How can we improve selectivity?

Non-specific binding (biofouling) is a common challenge in complex matrices:

- Reference Sensors: Incorporate reference electrodes functionalized with scrambled or non-functional sequences to measure and subtract background signals [9].

- Blocking Agents: Use casein, BSA, or salmon sperm DNA to block non-specific binding sites on sensor surfaces [9].

- Wash Stringency Optimization: Increase salt concentration or add mild detergents (e.g., Tween-20) in wash buffers to disrupt weak non-specific interactions while preserving specific binding [9].

- Sample Pretreatment: Implement filtration, dilution, or centrifugation steps to remove interfering components from samples before analysis [8].

Experimental Protocols for Enhanced Selectivity

Protocol 1: Aptamer Truncation and Optimization for Improved Performance

Purpose: Minimize aptamer sequences to essential binding regions to reduce synthesis costs and improve binding efficiency [7].

Materials:

- Full-length aptamer sequence

- PCR reagents and thermal cycler

- Gel electrophoresis equipment

- Target analyte for binding validation

- Predictive modeling software (e.g., Mfold, NUPACK)

Procedure:

- Sequence Analysis: Use predictive algorithms to simulate aptamer-target interactions and identify minimal functional sequences through structural mapping [7].

- Systematic Truncation: Design truncated variants focusing on conserved regions and predicted secondary structures (stems, loops, G-quadruplexes) [7].

- Binding Affinity Validation: Compare truncated and full-length aptamers using:

- Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) for real-time kinetics

- Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) to measure binding-induced interfacial changes [8]

- Fluorescence Anisotropy for solution-phase binding assessments

- Selectivity Testing: Challenge optimized aptamers against structurally similar analogs to confirm specificity retention.

- Sensor Integration: Incorporate validated truncated aptamers into biosensing platforms and compare performance metrics with full-length versions.

Protocol 2: Oriented Antibody Immobilization for Enhanced Antigen Accessibility

Purpose: Maximize antibody binding capacity and consistency through controlled surface orientation.

Materials:

- Purified antibodies

- Gold sensor surface or functionalized electrodes

- Protein A or Protein G solution

- Cross-linking agents (e.g., NHS/EDC)

- Blocking buffer (BSA or casein-based)

Procedure:

- Surface Preparation: Clean gold surfaces with oxygen plasma or piranha solution (Caution: hazardous).

- Fc-Receptor Coating: Immerse sensor in Protein A or Protein G solution (10-50 μg/mL) for 1 hour to create an oriented capture layer [9].

- Antibody Immobilization: Incubate with specific antibody solution (10-50 μg/mL) for 2 hours, allowing Fc-domain binding to Protein A/G.

- Cross-Linking (Optional): Apply mild cross-linking (e.g., DSS) to stabilize the antibody-receptor complex.

- Blocking: Treat surface with blocking buffer for 30 minutes to passivate unoccupied sites.

- Validation: Quantitate surface binding capacity using ELISA or SPR against standardized antigen preparations.

Protocol 3: SELEX Modification for Enhanced Selectivity Against Complex Targets

Purpose: Improve aptamer selectivity for targets in complex environments like whole blood or cell lysates.

Materials:

- Single-stranded DNA or RNA library

- Target molecule/cells

- Negative selection matrix (without target)

- PCR/RT-PCR reagents

- Partitioning system (magnetic beads, filters, or capillary electrophoresis apparatus)

Procedure:

- Counter-Selection: Pre-incubate nucleic acid library with negative selection matrix to remove non-specific binders [7].

- Positive Selection: Incubate pre-cleared library with target under conditions mimicking final application (e.g., in diluted serum).

- Stringent Partitioning: Use capillary electrophoresis or magnetic separation to efficiently isolate target-bound sequences [7].

- Amplification: PCR amplify bound sequences with appropriate controls to prevent amplification bias.

- Progressive Stringency: Increase selection stringency over rounds by:

- Reducing target concentration

- Decreasing incubation time

- Adding specific competitors for off-target sites

- Clone and Sequence: After 5-15 rounds, clone individual sequences and characterize binding properties.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Biorecognition Element Research and Development

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| SELEX Components | ssDNA/RNA library, Taq polymerase, magnetic beads with target immobilization [7] | In vitro selection of high-affinity aptamers | Use modified nucleotides (2'-F, 2'-O-methyl) for enhanced nuclease resistance [7] |

| Stabilization Agents | Trehalose, glycerol, BSA, LNAs (Locked Nucleic Acids) [8] | Enhance bioreceptor stability and shelf life | LNAs improve aptamer binding affinity and thermal stability [8] |

| Immobilization Matrices | Gold nanoparticles, graphene oxide, carbon nanotubes, metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) [8] | Provide high surface area scaffolds for bioreceptor attachment | Nanomaterials enhance electron transfer and signal amplification [8] |

| Signal Amplification Systems | Horseradish peroxidase (HRP), gold nanoparticles, hybridization chain reaction (HCR) components [10] | Enhance detection sensitivity for low-abundance targets | Enzyme-free systems like HCR offer improved stability [10] |

| Surface Passivation Agents | Polyethylene glycol (PEG), casein, Tween-20 [9] | Reduce non-specific binding on sensor surfaces | PEGylation creates a non-fouling surface background [9] |

Selection Workflow and Signaling Mechanisms

dot: Biorecognition_Selection_Workflow.dot

dot: Signaling_Mechanisms_Comparison.dot

The selective capabilities of biosensors originate from the fundamental properties of their biorecognition elements. Aptamers offer synthetic versatility and stability, antibodies provide well-established specificity, enzymes enable catalytic amplification, and nucleic acids deliver programmable predictability. Successful biosensor implementation requires matching these intrinsic properties to application-specific requirements while implementing appropriate optimization strategies to overcome limitations. Future advances will likely focus on hybrid systems combining multiple recognition elements, improved stabilization technologies for challenging environments, and integration with artificial intelligence for predictive modeling of binding interactions. As the field progresses, the systematic approach outlined in this technical resource will enable researchers to make informed decisions in biorecognition element selection and troubleshooting, ultimately accelerating the development of more reliable and specific biosensing platforms.

Complex biological matrices such as blood, serum, and food present significant challenges for biosensor accuracy and reliability. These samples contain numerous interfering substances—including proteins, lipids, salts, and other biomolecules—that can foul sensor surfaces, reduce signal-to-noise ratios, and generate false positives or negatives [12] [13]. Overcoming these matrix effects is crucial for developing biosensors with the selectivity and specificity required for precision medicine, diagnostic applications, and food safety monitoring.

The dynamic interplay of diverse microbial communities in food systems exemplifies these challenges, where detection platforms must distinguish between beneficial microbes (e.g., Lactobacillus spp.) and pathogens (e.g., Listeria spp., Escherichia coli) within intricate backgrounds [12]. Similarly, in clinical diagnostics, protein biosensors must detect specific biomarkers in blood or serum amid a complex milieu of other proteins and cellular components [13].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the most common sources of interference in complex matrices? The primary interference sources include:

- Protein Fouling: Non-specific adsorption of proteins like albumin on sensor surfaces, which can block active sites and reduce sensitivity [13].

- Cross-reactivity: Recognition elements (antibodies, aptamers) interacting with structurally similar molecules rather than the target analyte [13].

- Matrix Effects: Components in the sample that alter the physicochemical environment (pH, ionic strength, viscosity), affecting bioreceptor binding kinetics and transducer signal [12].

- Endogenous Compounds: Substances in biological samples (e.g., ascorbic acid, urea, lipids) that may undergo redox reactions at electrode surfaces in electrochemical biosensors [13].

Q2: What strategies can improve biosensor specificity in food samples? Effective strategies include:

- Sample Pre-treatment: Implementing filtration, centrifugation, or dilution to remove particulate matter and reduce complexity [12].

- Surface Modification: Using nanomaterials (graphene, polyaniline, gold nanoparticles) and antifouling coatings (hydrogels, PEG) to minimize non-specific binding [12] [13].

- Advanced Recognition Elements: Employing nucleic acid aptamers, molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs), or synthetic antibodies with enhanced selectivity for specific targets in food matrices [12] [13].

Q3: How can I validate that my biosensor's performance isn't compromised by matrix effects? Validation should include:

- Spike-and-Recovery Experiments: Adding known quantities of the target analyte to the natural matrix and measuring recovery efficiency [13].

- Comparison with Gold Standard Methods: Running parallel analyses with established reference methods (e.g., ELISA, PCR, chromatography) [12] [13].

- Calibration in Actual Matrix: Preparing calibration standards in the same matrix as the test samples rather than in simple buffer solutions [12].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: High Background Signal or Noise

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Cause: Non-specific Binding

Cause: Matrix-induced Signal Drift

Problem: Inconsistent Results Between Buffer and Real Samples

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Cause: Biofouling

- Solution: Modify electrode surfaces with antifouling nanomaterials such as graphene, polyaniline, or zwitterionic polymers [13].

- Solution: Apply nanostructured coatings (e.g., highly porous gold, vertically aligned graphene) that can physically prevent fouling agents from reaching the transducer surface [4] [13].

Cause: Recognition Element Instability

Problem: Signal Loss or Deterioration Over Time

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Cause: Sensor Surface Passivation

Cause: Interferent Accumulation

Experimental Protocols for Addressing Matrix Effects

Protocol for Nanomaterial-Based Antifouling Coatings

Objective: Enhance biosensor selectivity and specificity in complex matrices using nanomaterial coatings.

Materials:

- Graphene oxide dispersion

- Gold nanoparticles (5-20 nm)

- Polyaniline solution

- Cross-linking agents (e.g., EDC/NHS)

- Substrate electrodes (gold, glassy carbon, or screen-printed electrodes)

Methodology:

- Electrode Pretreatment: Clean electrode surfaces according to standard protocols (e.g., polishing, plasma treatment).

- Nanomaterial Deposition:

- Apply graphene oxide dispersion via spin-coating or drop-casting.

- Alternatively, electrodeposit gold nanoparticles by cycling potential in HAuCl₄ solution.

- Bioreceptor Immobilization:

- Activate surface functional groups using EDC/NHS chemistry.

- Incubate with specific bioreceptors (antibodies, aptamers, enzymes) for 2-4 hours.

- Block remaining active sites with BSA or other blocking agents.

- Validation:

- Characterize modified surfaces using SEM, AFM, or electrochemical impedance spectroscopy.

- Test antifouling properties by exposing to complex matrices (e.g., serum, food homogenates) and measuring non-specific adsorption.

Protocol for Sample Pre-treatment Optimization

Objective: Develop standardized sample preparation methods to minimize matrix effects.

Materials:

- Centrifugation equipment

- Filtration membranes (0.22-0.45 µm)

- Solid-phase extraction (SPE) cartridges

- Dilution buffers (PBS, Tris-HCl)

Methodology:

- Sample Homogenization:

- For food samples, homogenize in appropriate buffer (1:2 to 1:10 w/v ratio).

- For blood/serum, allow complete clotting and separate serum by centrifugation.

- Interferent Removal:

- Centrifuge samples at 10,000 × g for 10 minutes to remove particulate matter.

- Pass supernatant through appropriate filtration membranes.

- For lipid-rich samples, consider liquid-liquid extraction or SPE.

- Optimization:

- Test different dilution factors (1:2 to 1:100) to identify optimal concentration that minimizes matrix effects while maintaining detectable analyte levels.

- Validate recovery rates using spiked samples across the calibration range.

Quantitative Data on Biosensor Performance in Complex Matrices

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Biosensors in Complex Matrices

| Biosensor Type | Target Analyte | Matrix | Detection Limit | Recovery Rate | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electrochemical Aptasensor | Salmonella spp. | Fresh Produce | 10² CFU/mL | 95-102% | [12] |

| SPR Biosensor | Listeria spp. | Dairy Products | 10³ CFU/mL | 89-105% | [12] |

| Microelectrode Array | E. coli O157:H7 | Meat | 10¹ CFU/mL | 92-98% | [12] |

| QCM Biosensor | Staphylococcus spp. | Meat | 10² CFU/mL | 85-96% | [12] |

| Nanostructured Electrode | Glucose | Interstitial Fluid | 95.12 ± 2.54 µA mM⁻¹ cm⁻² | N/A | [4] |

Table 2: Comparison of Interference Mitigation Strategies

| Strategy | Mechanism of Action | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nanomaterial Coatings | High surface area; enhanced electron transfer; physical barrier | Improved sensitivity; antifouling properties | Complex fabrication; potential toxicity |

| Sample Pre-treatment | Removal of interferents before analysis | Simple; cost-effective | Potential analyte loss; additional steps |

| Surface Functionalization | Chemical modification to reduce non-specific binding | Highly specific; customizable | Requires optimization for each matrix |

| Advanced Bioreceptors | Higher specificity (aptamers, MIPs) | Stable; reproducible production | Limited repertoire for some targets |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Biosensor Development

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Biosensor Development |

|---|---|---|

| Nanomaterials | Graphene, polyaniline, carbon nanotubes, gold nanoparticles | Enhance signal transduction; provide large surface area for bioreceptor immobilization; improve electron transfer rates [4] [13] |

| Recognition Elements | Antibodies, DNA aptamers, enzymes, molecularly imprinted polymers | Provide specificity for target analytes through biological or synthetic recognition mechanisms [12] [13] |

| Cross-linking Agents | EDC/NHS, glutaraldehyde, sulfo-SMCC | Facilitate covalent immobilization of bioreceptors to transducer surfaces [13] |

| Blocking Agents | BSA, casein, milk powder, salmon sperm DNA | Reduce non-specific binding by occupying unused sites on the sensor surface [13] |

| Signal Transduction Materials | Ferrocene derivatives, methylene blue, quantum dots, electrochemical mediators | Amplify and convert biological recognition events into measurable signals [13] |

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Biosensors are analytical devices that combine a biological recognition element with a physical transducer to detect specific analytes. The evolution of biosensor technology, particularly glucose biosensors, is categorized into distinct generations, each marked by significant improvements in selectivity, sensitivity, and practical applicability [15]. These advancements primarily address the critical challenge of eliminating interfering signals by refining the electron transfer pathway between the enzymatic recognition element and the transducer surface [13] [16]. Understanding this generational shift is fundamental for researchers aiming to design experiments with enhanced specificity and reduced cross-reactivity in complex matrices like blood or interstitial fluid.

The table below summarizes the core characteristics of each biosensor generation.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Biosensor Generations

| Generation | Electron Transfer Mediator | Key Feature | Primary Challenge |

|---|---|---|---|

| First | Oxygen (natural mediator) [15] | Detection of consumed oxygen or produced hydrogen peroxide [15] | Signal dependence on ambient oxygen concentration, leading to quantification errors [15] |

| Second | Artificial redox mediators (e.g., Ferrocene) free in solution [15] | Reduced oxygen dependence, improved reproducibility [15] | Unsuitable for implantable devices; potential mediator toxicity and decaying sensitivity [15] |

| Second.5 | Artificial redox mediators bonded to the electrode [15] | Constant mediator concentration; enabled wearable/implantable biosensors [15] | Not a full paradigm shift from the 2nd generation principle [15] |

| Third | Direct Electron Transfer (DET); no mediator [15] | Direct communication between enzyme's active site and electrode [15] | Enzyme's catalytic center is often buried, making electron transfer difficult [15] |

Experimental Protocols: Methodology for Investigating Electron Transfer Mechanisms

Protocol for First-Generation Biosensor Characterization

This protocol outlines the evaluation of a first-generation glucose biosensor based on the amperometric detection of hydrogen peroxide.

- Objective: To measure the sensitivity and oxygen dependence of a first-generation biosensor.

- Materials:

- Glucose Oxidase (GOx): The biological recognition element [16].

- Platinum or Carbon Electrode: The transducer surface [13].

- Buffer Solutions: Phosphate buffer saline (PBS) at physiological pH (7.4) [16].

- Glucose Standard Solutions: A series of concentrations (e.g., 0-20 mM) prepared in PBS.

- Dissolved Oxygen Probe: To monitor oxygen levels in the test solution.

- Procedure:

- Electrode Modification: Immobilize GOx onto the electrode surface using a method such as cross-linking with glutaraldehyde or physical adsorption.

- Apparatus Setup: Place the modified electrode in an electrochemical cell containing PBS under constant stirring. Apply a potential of +0.7 V vs. Ag/AgCl to oxidize hydrogen peroxide.

- Calibration: Inject increasing concentrations of glucose standard solutions and record the amperometric current response.

- Oxygen Interference Test: Repeat the calibration in a deoxygenated buffer (bubbled with nitrogen) and compare the current response to the one obtained in an oxygen-saturated buffer.

- Troubleshooting: If the signal is unstable, ensure the enzyme immobilization protocol is robust and that the applied potential is optimized to avoid interfering species. Linearity loss at high glucose concentrations may indicate oxygen depletion [15].

Protocol for Second-Generation Biosensor with Mediator Integration

This protocol details the incorporation of a soluble redox mediator to overcome oxygen limitation.

- Objective: To construct and test a second-generation biosensor using ferrocene as a redox mediator.

- Materials:

- Procedure:

- Mediator Introduction: Add a fixed concentration (e.g., 1 mM) of the ferrocene derivative to the glucose standard solutions.

- Electrochemical Measurement: Place the GOx-modified electrode in the solution. Apply a lower potential (e.g., +0.2 V vs. Ag/AgCl) sufficient to oxidize the reduced mediator.

- Data Analysis: Record the current generated from the mediator's oxidation. The current is proportional to the glucose concentration as it reflects the rate of the enzymatic reaction.

- Troubleshooting: Signal drift can occur if the mediator is not stable or diffuses away from the electrode surface. Testing different mediator concentrations and applying protective membranes (e.g., Nafion) can improve stability [15].

Protocol for Third-Generation Direct Electron Transfer (DET) Studies

This advanced protocol investigates DET, the hallmark of third-generation biosensors.

- Objective: To achieve and characterize direct electron transfer between an enzyme and an electrode.

- Materials:

- Procedure:

- Electrode Nanostructuring: Modify the electrode surface with a nanostructured material like a MXene (Ti₃C₂Tₓ) to enhance its surface area and electron transfer properties [17].

- Enzyme Immobilization: Carefully immobilize the engineered enzyme onto the nanostructured surface, preserving its activity and orientation.

- Cyclic Voltammetry in Absence of Substrate: Perform CV in a blank buffer. The observation of distinct, stable redox peaks confirms direct electron transfer between the enzyme's active site and the electrode.

- Amperometric Sensing: Upon adding glucose, measure the catalytic current at the formal potential of the enzyme without any exogenous mediator.

- Troubleshooting: The absence of a DET signal is common. Ensure the enzyme is not denatured during immobilization. Experiment with different electrode nanomaterials and surface functionalization techniques to optimize enzyme orientation [15].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting

Q1: My biosensor's signal drifts significantly during calibration. What could be the cause?

- A: Signal drift is often related to an unstable biorecognition layer or mediator. For first-generation sensors, check for oxygen depletion in poorly stirred solutions. For second-generation sensors, the soluble mediator may be diffusing away. Consider switching to a immobilized mediator system (2.5th generation) or applying a stabilizing membrane. Also, verify the stability of your reference electrode [15] [16].

Q2: Why does my third-generation biosensor not show the expected Direct Electron Transfer (DET) response in cyclic voltammetry?

- A: DET is highly dependent on the distance and orientation between the enzyme's redox center and the electrode surface. The failure to observe a DET signal typically indicates that the enzyme's active site is still too deeply buried. Troubleshoot by: 1) Using a different, more DET-compatible enzyme; 2) Re-engineering your electrode surface with different nanostructures (e.g., MXenes, porous gold) to better "wire" the enzyme; 3) Optimizing the immobilization method to promote a more favorable orientation [17] [15].

Q3: How can I improve the selectivity of my biosensor against common interferents like ascorbic acid and uric acid?

- A: Selectivity is improved by moving to later generations. First-generation sensors operating at high potentials (+0.7V) are susceptible to these interferents. Second-generation sensors, using mediators like ferrocene, allow operation at much lower potentials (e.g., +0.2V), where interferents are not electroactive. The most selective are third-generation DET sensors, which operate at the intrinsic potential of the enzyme. Additionally, the use of permselective membranes (e.g., Nafion or poly-o-phenylenediamine) can block anionic interferents [13] [15].

Q4: My continuous biosensor readings do not match my reference benchtop analyzer. What should I check?

- A: This is a common issue when transitioning from lab buffers to complex samples [18] [16]. First, ensure proper calibration of both systems. For wearable sensors, note that they measure glucose in interstitial fluid, which has a physiological lag (5-15 minutes) behind blood glucose [18]. Check for biofouling on the sensor surface, which can attenuate the signal over time. Finally, always validate your sensor against a reference method using the same sample matrix (e.g., blood, serum) to account for matrix effects [16] [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Reagents for Biosensor Research and Development

| Item Name | Function/Application | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Glucose Oxidase (GOx) | Model enzyme for biorecognition of glucose [15] [16] | Inexpensive, rapid turnover, and highly stable at physiological conditions; the benchmark for biosensor research [16] |

| Ferrocene & Derivatives | Artificial redox mediator for 2nd generation biosensors [13] [15] | Efficiently shuttles electrons from the reduced enzyme to the electrode, eliminating oxygen dependence [15] |

| MXenes (e.g., Ti₃C₂Tₓ) | Nanostructured electrode material for 3rd gen biosensors [17] | High electrical conductivity, large surface area, and tunable surface chemistry promote Direct Electron Transfer [17] |

| Nafion Membrane | Permselective coating to enhance selectivity [16] | Cation-exchange polymer that repels common anionic interferents (e.g., ascorbate, urate) while allowing analyte diffusion [16] |

| Gold Nanoparticles | Nanomaterial for signal amplification and enzyme immobilization [4] [13] | Excellent biocompatibility and conductivity; used to functionalize electrodes and enhance electrochemical signals [4] |

Workflow and Signaling Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the core electron transfer mechanisms that define each generation of electrochemical biosensors.

Diagram 1: Electron transfer pathways across biosensor generations. The 3rd generation pathway represents the ideal, most selective configuration for biosensor research.

Advanced Engineering and Material Strategies for High-Fidelity Biosensing

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges and Solutions

Researchers often encounter specific challenges when developing nanomaterial-enhanced biosensors. This guide addresses frequent issues, their potential causes, and validated solutions to help you optimize your experiments.

How can I reduce non-specific binding in my nanomaterial-based biosensor?

Problem: High background signal or false positives caused by non-target molecules adsorbing to the sensor surface.

Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Inadequate surface blocking on the sensor chip.

- Solution: Use effective blocking agents such as ethanolamine, casein, or Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) to occupy any remaining active sites on the sensor surface after ligand immobilization [20].

- Cause: Suboptimal surface chemistry for your specific analyte.

- Solution: Select a sensor chip with tailored chemistry. For example, use CM5 chips with carboxymethylated dextran or C1 chips with minimal modification to prevent undesired adsorption [20].

- Cause: Buffer composition promotes non-specific interactions.

- Solution: Optimize your buffer by adding surfactants like Tween-20 and adjust ionic strength to minimize unwanted binding without destabilizing your target interactions [20].

- Cause: Lack of a controlled-assembly surface.

- Solution: Employ specific linker chemistries. The PBASE (1-pyrenebutyric acid N-hydroxysuccinimide ester) linker has been widely used for the stable and efficient attachment of biomolecules onto Carbon Nanotube (CNT) surfaces, ensuring oriented immobilization and reducing non-specific interactions [21].

What should I do if my electrochemical biosensor has low signal intensity?

Problem: Weak output signal, leading to poor sensitivity and high limits of detection.

Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Insufficient density of biorecognition elements (e.g., antibodies, aptamers) on the transducer surface.

- Solution: Optimize ligand immobilization density. Perform titrations during immobilization to find an optimal surface density that maximizes signal without causing steric hindrance [20].

- Cause: Inefficient electron transfer between the biorecognition element and the electrode.

- Cause: Use of inappropriate nanomaterials for signal amplification.

- Solution: Incorporate high-efficacy signal amplifiers. The integration of metal nanoparticles, such as gold nanoparticles (Au-NPs), onto CNT or graphene surfaces facilitates superior electron transport and can provide localized surface plasmon resonance effects, significantly boosting the signal response [21] [24].

- Cause: The analyte concentration is too low for the sensor's native sensitivity.

- Solution: Employ enzymatic amplification strategies. Using enzyme-labeled detector antibodies in a sandwich immunoassay format can catalyze a reaction that produces a large amount of electroactive product, thereby amplifying the signal [24].

How can I improve the reproducibility and stability of my biosensor?

Problem: High variability between sensor batches or a rapid decline in sensor performance over time.

Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Inconsistent synthesis or functionalization of nanomaterials.

- Cause: Unstable immobilization of the biorecognition layer.

- Solution: Use robust immobilization strategies. Covalent immobilization via EDC/NHS chemistry provides a stable bond, while non-covalent methods like streptavidin-biotin interactions offer controlled orientation and good stability [20].

- Cause: Degradation of the biological element (enzyme, antibody) under operational conditions.

- Solution: Utilize composite materials to enhance stability. Integrating nanomaterials like carboxylated graphene quantum dots (cGQDs) with CNTs has been shown to improve the operational stability of the sensing interface [21]. For enzymatic sensors, immobilizing enzymes on nanoporous materials can enhance their stability [23].

- Cause: Variation in experimental setup and handling.

- Solution: Implement strict quality control measures. Use control samples in every run, ensure consistent surface activation protocols, and perform experiments in a temperature-controlled environment to minimize drift and improve reproducibility [20].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What are the key advantages of using graphene over CNTs in electrochemical sensors, and vice versa?

Both are carbon-based nanomaterials with exceptional properties, but their optimal applications can differ.

- Graphene offers a very high surface area (theoretically 2630 m²/g) that is entirely accessible for functionalization and analyte interaction, which is beneficial for loading high amounts of biorecognition elements. Its 2D planar structure often makes it easier to process and integrate into uniform thin-film electrodes. Graphene demonstrates excellent electrical conductivity and facilitates fast electron transfer, which is crucial for high-sensitivity electrochemical detection [23].

- Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs), particularly single-walled CNTs (SWCNTs), exhibit unique 1D quantum wire characteristics that enable ballistic electron transport and extremely high carrier mobility. Their high aspect ratio is advantageous for creating conductive networks in composites. A distinct advantage of CNTs is the ease of creating vertically aligned forests, which can significantly increase the functional surface area of an electrode [21]. The choice often depends on the specific transducer design and the need for a 1D versus 2D nanomaterial.

How can I validate that the signal amplification is due to the nanomaterial and not other experimental factors?

Proper control experiments are essential for validation.

- Baseline Control: Perform the same assay using an electrode fabricated identically but without the nanomaterial coating. A significantly lower signal confirms the nanomaterial's role in amplification.

- Selectivity Control: Use a "sentinel" sensor, which is a sensor that contains the same immobilization matrix and nanomaterial but lacks the specific biorecognition element (e.g., coated with an inert protein like BSA). Any signal generated from a sample on this control sensor is due to non-specific binding or interference, which can then be subtracted from the main biosensor's signal [22].

- Material Characterization: Use techniques like Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) and Raman spectroscopy to confirm the successful integration, morphology, and quality of the nanomaterials on your electrode surface, correlating these physical characteristics with electrochemical performance.

What is the best strategy to functionalize CNTs for achieving high specificity in a complex biological sample?

Achieving specificity requires covalently or non-covalently attaching highly specific biorecognition molecules to the CNT surface.

- Aptamer Functionalization: Aptamer-functionalized CNT-FETs have demonstrated remarkable potential for the specific detection of single pathogens, such as Salmonella enterica [21]. Aptamers offer high stability and can be engineered for specific targets.

- Antibody Conjugation: Antibody-conjugated CNT biosensors facilitate the detection of disease-specific biomarkers, such as the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, with high specificity [21].

- Linker-Assisted Immobilization: Using a bifunctional linker like PBASE is a widely employed strategy. The pyrene group adsorbs non-covalently onto the CNT sidewall via π-π stacking, while the NHS ester end reacts with amine groups on antibodies or proteins, providing a stable and oriented immobilization platform [21].

Performance Data and Experimental Protocols

Comparative Performance of Nanomaterial-Enhanced Biosensors

The table below summarizes key performance metrics from recent studies to provide a benchmark for your own experiments.

| Target Analyte | Nanomaterial Used | Sensor Platform | Detection Limit | Key Advantage | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein | CNTs with PBASE linker | CNT-FET | Not Specified | Rapid, label-free detection; high specificity via antibody conjugation. | [21] |

| Salmonella enterica | Aptamer-functionalized CNTs | CNT-FET | Not Specified | Single-pathogen detection with high precision. | [21] |

| Glucose | Graphene / Metal Oxides | Non-enzymatic Electrochemical | Varies by design | High stability, avoids oxygen dependence of enzymatic sensors. | [23] |

| Organophosphate Pesticides | SWCNT-modified GCE | Amperometric Immunosensor | Low detection limits achieved | Rapid, sensitive detection without labeling; suitable for on-site use. | [24] |

| Bacterial Toxins | cGQD-coupled CNTs | CNT-FET | Enhanced sensitivity | Improved sensitivity and selectivity through synergistic coupling. | [21] |

Detailed Protocol: Constructing a CNT-FET Biosensor for Protein Detection

This protocol outlines the key steps for fabricating a carbon nanotube-based field-effect transistor for detecting specific proteins, such as viral antigens or disease biomarkers [21].

Principle: The biosensor utilizes semiconducting single-walled CNTs (SWCNTs) as the channel material. The binding of a target biomolecule to receptors functionalized on the CNT surface alters the local electrostatic environment, which in turn modulates the conductivity of the CNT channel. This change in electrical signal (e.g., drain current) is measured in real-time for label-free detection.

Materials:

- Nanomaterials: High-purity semiconducting SWCNTs.

- Substrate: Heavily doped silicon wafer with a thermal oxide layer (acts as a back gate).

- Electrodes: Source and drain electrodes (e.g., gold/chromium) defined by photolithography.

- Functionalization Reagents: PBASE (1-pyrenebutyric acid N-hydroxysuccinimide ester), suitable buffer (e.g., phosphate buffer saline, PBS).

- Biorecognition Element: Specific antibodies or aptamers against your target protein.

- Blocking Agent: Ethanolamine or Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA).

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Device Fabrication:

- Pattern source and drain electrodes on the SiO₂/Si substrate using standard lithography and metal deposition (e.g., e-beam evaporation) techniques.

- Deposit a network of SWCNTs between the electrodes, typically via solution-based methods like drop-casting or spin-coating, followed by rinsing to remove excess material.

Surface Functionalization:

- Incubate the CNT-FET device with a solution of PBASE linker (e.g., 1 mM in an organic solvent like dimethylformamide) for several hours. This allows the pyrene group to adsorb onto the CNTs.

- Thoroughly rinse the device with solvent and then PBS buffer to remove unbound linker.

- Activate the NHS ester end of the linker by incubating with a solution containing your antibody or aptamer (e.g., 10-100 µg/mL in PBS, pH ~7.4) for a few hours. This forms a stable amide bond.

- Rinse again with buffer to remove unbound biorecognition elements.

Surface Blocking:

- Incubate the functionalized sensor with a blocking solution (e.g., 1% BSA or 1 M ethanolamine in PBS) for 30-60 minutes to passivate any remaining reactive sites and minimize non-specific binding.

- Rinse with buffer to prepare the sensor for measurement.

Measurement and Detection:

- Mount the sensor in a measurement cell with liquid gate capability.

- Apply a constant drain-source voltage (Vds) and a liquid gate voltage (Vlg) using an electrolyte (e.g., PBS).

- Continuously monitor the drain current (Ids).

- Introduce the sample solution. The specific binding of the target protein to the immobilized receptors will cause a measurable shift in the Ids vs. Vlg transfer characteristics or a change in Ids at a fixed Vlg.

Troubleshooting Tip: If the signal-to-noise ratio is poor, ensure that the CNT network is not too dense (which can short the channel) and that all washing steps are thorough to remove any loosely adsorbed contaminants. Using a dual-gated architecture can also help improve sensitivity and reduce noise [21].

Signaling Pathways and Workflows

Direct Electron Transfer in Third-Generation Biosensors

This diagram illustrates the superior electron transfer mechanism in third-generation biosensors, which is facilitated by nanomaterials and eliminates the need for mediators.

Diagram Title: Direct Electron Transfer Pathway

This direct "wiring" of the enzyme to the electrode, enabled by the nanomaterial's properties, reduces interference from electroactive species that might oxidize at the higher potentials required by first-generation biosensors, thereby enhancing selectivity [22] [23].

Experimental Workflow for Biosensor Development and Validation

This workflow outlines the critical stages in developing and validating a nanomaterial-enhanced biosensor, from material preparation to real-sample testing.

Diagram Title: Biosensor Development Workflow

This systematic approach ensures that the biosensor is not only sensitive but also specific, reproducible, and fit for its intended application in complex matrices like blood, serum, or environmental samples [21] [20] [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The table below lists key reagents and materials used in the development of nanomaterial-enhanced biosensors, along with their primary functions.

| Reagent / Material | Function / Purpose | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| PBASE Linker | A bifunctional linker for stable immobilization of biomolecules on CNT/graphene surfaces via π-π stacking and amine coupling. | Functionalizing CNT-FETs with antibodies for specific antigen detection [21]. |

| Gold Nanoparticles (Au-NPs) | Signal amplification tags; enhance electron transfer and can be used in labeled assays. | Conjugated with detection antibodies in electrochemical immunosensors for organophosphates [24]. |

| Nafion & Cellulose Acetate | Permselective membranes that block interferents (e.g., ascorbic acid, uric acid) based on charge or size. | Used in implantable glucose biosensors to improve selectivity in biological fluids [22]. |

| Carboxylated Graphene Quantum Dots (cGQDs) | Nanomaterial used to couple with CNTs to enhance sensitivity and selectivity. | cGQD-coupled CNTs for bacterial toxin detection [21]. |

| Ethanolamine | A blocking agent used to deactivate and cap unreacted NHS ester groups on sensor surfaces. | Preventing non-specific adsorption after amine-coupling immobilization on SPR chips [20]. |

| Screen-Printed Electrodes (SPEs) | Disposable, low-cost, mass-producible electrodes ideal for portable biosensing. | Base transducers for on-site electrochemical detection of pesticides [24]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental principle behind E-DNA and E-AB biosensors? These biosensors rely on a binding-induced conformational change in an electrode-tethered, redox-tagged DNA probe (for E-DNA) or aptamer (for E-AB). When the target analyte binds, the probe changes its shape, altering the electron transfer efficiency of the redox tag. This change produces a measurable electrochemical signal without the need for reagents or additional amplification steps [26] [27].

Q2: Why are these sensors particularly resistant to signal fouling in complex media? The signal generation depends on a specific conformational change. Non-specific adsorption of proteins or other molecules onto the sensor surface does not induce this specific structural rearrangement. Therefore, while fouling may occur, it does not produce the same electrochemical signature as the target binding, making the signal robust even in challenging samples like undiluted serum [26] [28].

Q3: My sensor shows a significant signal drop after modification. Is this normal? Yes, this is often expected. A successful modification with a dense monolayer of DNA probes can lead to electrostatic repulsion or steric hindrance, which increases the electron transfer resistance. The subsequent signal upon target binding is a function of the conformational change, not the absolute current value. Focus on the relative signal change (e.g., % signal suppression) upon target introduction [27].

Q4: How can I improve the stability of the self-assembled monolayer on my gold electrode? The traditional Au-S bond can be susceptible to displacement by biothiols in complex samples. A promising alternative is using a Pt-S interaction for biomolecule immobilization. Density functional theory calculations and experimental data confirm that Pt-S bonds offer superior chemical stability, with one study showing less than 10% signal degradation over 8 weeks compared to faster degradation with Au-S [28].

Q5: My biosensor lacks sensitivity for my low-abundance target. What optimization strategies can I try?

- Probe Truncation: Systematically shorten the oligonucleotide probe while maintaining its binding core. Smaller probes can improve target accessibility and reduce steric hindrance, enhancing sensitivity [27].

- Antifouling Co-Modification: Incorporate blocking molecules like polyethylene glycol (PEG) or zwitterionic materials into the self-assembled monolayer. This minimizes non-specific adsorption, reducing background noise and improving the signal-to-noise ratio in complex samples [27].

- Nanomaterial Enhancement: Integrate functional nanomaterials like graphene or metallic nanoparticles at the electrode interface. These materials can increase the active surface area and enhance electron transfer, leading to signal amplification [29].

Q6: How do I validate sensor performance for a specific complex matrix like human serum? Perform a spike-and-recovery experiment. Spike known concentrations of your target analyte into the matrix (e.g., serum) and measure the concentration detected by your sensor. Excellent recovery rates (e.g., ±10%) indicate high accuracy and minimal matrix interference [26].

Troubleshooting Guide

Table 1: Common Experimental Issues and Proposed Solutions

| Problem | Potential Cause | Troubleshooting Steps |

|---|---|---|

| Low Signal Change | Non-optimal probe density | Dilute probe concentration during immobilization; use a co-adsorbent like PEG or MCH to create a mixed monolayer [27]. |

| Incorrect probe design | For E-AB, re-truncate the aptamer; ensure the probe is designed to undergo a significant conformational change upon binding [27]. | |

| High Background Noise | Electrode fouling | Improve cleaning protocol (electrochemical polishing); incorporate robust antifouling layers (PEG, peptides) [28] [27]. |

| Non-specific adsorption | Include negative control sequences; optimize the composition and density of the blocking layer on the electrode [26]. | |

| Poor Reproducibility | Inconsistent electrode surface | Standardize electrode polishing and cleaning procedures; use electrochemical characterization (e.g., CV in Ferricyanide) to verify surface quality [27]. |

| Unstable biomolecule attachment | Switch from Au-S to more stable immobilization chemistry like Pt-S bonds [28]. | |

| Loss of Signal Over Time | Degradation of the recognition probe | Ensure proper storage conditions (nuclease-free buffers, cold temperature); test sensor stability over desired timeframe [28]. |

| Desorption of the probe monolayer | As above, employ more stable Pt-S chemistry for immobilization to enhance operational longevity [28]. |

Experimental Protocols & Performance Data

Core Protocol: Fabrication of a Conformational Change-Based Biosensor

This protocol outlines the key steps for creating an E-DNA or E-AB sensor on a gold electrode, based on established methodologies [26] [27].

Electrode Pretreatment:

- Polish the gold working electrode sequentially with alumina slurries (e.g., 1 μm, 0.3 μm, and 0.05 μm) on a microcloth for 5 minutes each.

- Sonicate the electrode in deionized water and then in ethanol to remove any residual alumina particles.

- Perform electrochemical cleaning in 0.05 M H₂SO₄ via cyclic voltammetry (CV) until a stable voltammogram characteristic of a clean gold surface is obtained.

Probe Preparation:

- Reduce disulfide bonds in thiol-modified oligonucleotide probes by incubating with 10 mM Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP) for 1 hour at room temperature.

Self-Assembled Monolayer (SAM) Formation:

- Incubate the clean gold electrode overnight in a solution containing the reduced, redox-tagged (e.g., Methylene Blue) DNA probe (typically 0.1 - 1 μM) in a high-salt buffer (e.g., 10 mM Tris-HCl, 1.5 M NaCl, 1 mM MgCl₂, pH 7.4). The high ionic strength facilitates probe packing.

Surface Blocking:

- Rinse the electrode and subsequently incubate in a solution of an antifouling molecule. This could be:

- This step creates a mixed monolayer that minimizes non-specific adsorption.

Sensor Measurement:

- Perform electrochemical measurements in a suitable measurement buffer (e.g., PBS, pH 7.4) using Square-Wave Voltammetry (SWV). The faradaic current from the redox tag (MB) is recorded.

- Measure the signal before and after exposure to the target analyte. The relative change in current (often a decrease due to tag displacement) is correlated to target concentration.

Key Experimental Data and Performance

Table 2: Summary of Quantitative Performance from Literature

| Sensor Type | Target | Detection Range | Limit of Detection (LOD) | Matrix Tested | Key Performance Metric | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E-DNA | miRNA-29c | 0.1 - 100 nM | Not Specified | Undiluted Human Serum | Excellent recovery (±10%); High selectivity vs. mismatched sequences | [26] |

| E-AB | Serotonin (ST) | 0.1 - 1000 nM | 0.14 nM | Human Serum & Artificial Cerebrospinal Fluid | High selectivity over interferents (DA, AA); Enhanced by PEG | [27] |

| Peptide-based | ErbB2 | Not Specified | Not Specified | Undiluted Human Serum | <10% signal degradation over 8 weeks (Pt-S bonding) | [28] |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Materials and Their Functions in Sensor Development

| Reagent | Function/Benefit | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Thiolated, Redox-Tagged DNA Probes/Aptamers | The core recognition element. Thiol group enables gold surface attachment; redox tag (MB) provides electrochemical signal. | E-DNA sensor for miRNA [26]; E-AB sensor for serotonin [27]. |

| Polyethylene Glycol Thiol (PEG) | A "gold standard" antifouling polymer. Creates a hydrophilic barrier that resists non-specific protein adsorption via steric repulsion. | Blocking agent to enhance performance in serum [27]. |

| Platinum Nanoparticles (PtNP) | Provides a platform for robust Pt-S bonding with biomolecules, offering superior stability over traditional Au-S chemistry. | Interface for immobilizing branched-cyclopeptides in fouling-resistant biosensors [28]. |

| Truncated Aptamers | Shortened versions of selected aptamers that maintain binding affinity. Smaller size can improve binding kinetics and sensitivity. | Enhancing sensitivity of serotonin E-AB sensor [27]. |

| Functional Nanomaterials | Enhance electrode performance by increasing surface area, improving conductivity, and facilitating signal amplification. | Graphene for neural signal detection; MXenes for reduced impedance [29]. |

Signaling Pathway and Experimental Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the foundational signaling mechanism of conformational change-based biosensors and a generalized experimental workflow.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary functions of a permselective membrane in an electrochemical biosensor? Permselective membranes serve two critical functions: they act as a physical barrier that reduces fouling by macromolecules (like proteins) and, more importantly, they selectively filter out electroactive interferents based on size and charge. For instance, a conductive membrane can allow the target analyte to pass through while electrochemically deactivating unwanted redox-active interferents, thus drastically improving signal-to-noise ratio [30].

Q2: My sensor's calibration is accurate in buffer solution, but the signal is skewed in real samples. What could be the cause? This is a classic symptom of matrix effects from complex samples. Components in the sample matrix, such as proteins, lipids, or other electroactive species (e.g., ascorbic acid, uric acid), can cause non-specific adsorption or generate competing signals. This underscores the necessity of using a permselective membrane and validating sensor performance in the actual sample matrix (e.g., serum, blood) rather than just in buffer solutions [31] [32].

Q3: How can I differentiate between a loss of sensitivity and increased interference as the cause of signal drift? A systematic troubleshooting approach is needed:

- Check Calibration Slope: A consistent decrease in signal amplitude across all calibration points typically indicates a loss of sensitivity, often due to bioreceptor degradation or sensor fouling.

- Assess the Baseline Signal: A rising or unstable baseline in the absence of the target analyte strongly suggests an increase in non-specific interference. Techniques like electrochemical impedance spectroscopy can help characterize fouling [33].

- Validate with Spiked Samples: If the measured concentration in a spiked sample is off, but the sensor recovers well when the same sample is analyzed with a standard method (e.g., ELISA), the issue is likely interference specific to your sensor [34].

Q4: What is a "sentinel" sensor and how does it improve specificity? A sentinel sensor is a reference sensor that lacks the specific bioreceptor or has it blocked. It is deployed alongside the active working sensor. Any signal generated at the sentinel sensor is attributed to non-specific binding, matrix effects, or interferents. By subtracting the sentinel signal from the working sensor's signal, you can isolate the specific response attributable only to the target analyte, thereby significantly improving measurement accuracy [32].

Q5: Why is my molecularly imprinted polymer (MIP) membrane exhibiting high background noise? High background noise in MIP sensors often stems from incomplete template removal after synthesis, leading to "leaching" and false positives. It can also be caused by a non-specific binding to low-affinity sites within the polymer matrix. Ensure rigorous template washing protocols during MIP fabrication and consider incorporating a sentinel non-imprinted polymer (NIP) membrane to account for non-specific binding [35] [36].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Poor Selectivity Against Redox-Active Interferents

Symptoms:

- High background current.

- Inaccurate readings in complex matrices like blood or urine compared to buffer.

- Non-linear response at low analyte concentrations.

Solutions:

- Implement a Conductive Membrane: Use a membrane that is permeable to your target analyte but can electrochemically deactivate common interferents like ascorbate, urate, or acetaminophen. The membrane allows redox-inactive species to pass while degrading interferents [30].

- Apply a Charge-Blocking Layer: Coat your sensor with a thin, negatively charged membrane (e.g., Nafion). This will repel negatively charged interferents (e.g., ascorbic acid, uric acid) while attracting positively charged targets, if applicable [33].

- Use Complexometric Masking: For metal ion detection, introduce a chelating agent that binds more strongly to the interfering metal ion than to your target. For example, ammonia can be used as a ligand to mask Cu(II) interference during the anodic stripping voltammetry detection of As(III) [34].

Validation Experiment:

- Objective: Confirm the membrane's effectiveness.

- Protocol: Compare the amperometric or voltammetric response of your sensor in a solution containing a physiologically relevant concentration of a common interferent (e.g., 0.1 mM ascorbic acid) before and after membrane application. A significant reduction (>80%) in the interferent's signal confirms successful blocking.

Problem: Signal Instability and Drift

Symptoms:

- Gradual signal decrease or increase over time during a single measurement.

- Poor reproducibility between consecutive measurements.

Solutions:

- Optimize Membrane Cross-linking: If using a polymer-based membrane, insufficient cross-linking can lead to swelling, dissolution, or instability. Increase cross-linker concentration or curing time to enhance mechanical and chemical stability [36].

- Ensure Proper Storage: Store sensor elements in an appropriate buffer at 4°C to prevent dehydration or degradation of biological components (enzymes, aptamers). Molecularly Imprinted Polymer (MIP)-based sensors are generally more stable and can often be stored dry [35] [33].

- Inspect the Reference Electrode: A unstable reference electrode potential is a major cause of drift. Ensure your reference electrode (e.g., Ag/AgCl) is properly filled and not contaminated.

Problem: Inconsistent Performance Between Sensor Batches

Symptoms:

- Variations in sensitivity and dynamic range when a new batch of membranes or sensors is fabricated.

Solutions:

- Standardize Fabrication Protocols: Ensure all chemical purification steps, polymer mixing times, speeds, and environmental conditions (temperature, humidity) are strictly controlled and documented.

- Implement Rigorous Quality Control: For each new batch, characterize key parameters such as membrane thickness, porosity, and electrochemical impedance to ensure consistency [37] [36].

- Utilize Functional Nucleic Acids: Consider using aptamers or DNAzymes as bioreceptors. They are synthesized chemically, leading to much higher batch-to-batch consistency compared to biologically-derived receptors like antibodies [32].

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Protocol: Complexometric Masking for Heavy Metal Detection

This protocol is adapted from a method to mitigate copper interference in arsenic detection [34].

1. Reagents and Materials:

- Working electrode (e.g., Gold Nanoparticle modified Glassy Carbon Electrode).

- Standard solutions of your target metal ion (e.g., As(III)) and the interferent (e.g., Cu(II)).

- Complexing agent (e.g., Ammonia solution for Cu(II) masking).

- Supporting electrolyte (e.g., KNO₃).

- Electrochemical workstation.

2. Procedure:

- Step 1: In the sample solution containing both the target and the interferent, add the complexing agent. For example, add ammonia to a final concentration of 0.1 M to form stable [Cu(NH₃)₄]²⁺ complexes.

- Step 2: Proceed with your standard electrochemical detection method (e.g., Anodic Stripping Voltammetry).

- Step 3: The complexation prevents the interferent (Cu(II)) from being electrochemically reduced and deposited on the electrode surface during the pre-concentration step, thereby eliminating its stripping signal.