Strategies for Enhancing Biosensor Stability and Shelf Life: From Fundamental Mechanisms to Commercial Applications

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the latest strategies and materials developed to improve the stability and shelf life of biosensors, a critical factor for their commercial success and...

Strategies for Enhancing Biosensor Stability and Shelf Life: From Fundamental Mechanisms to Commercial Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the latest strategies and materials developed to improve the stability and shelf life of biosensors, a critical factor for their commercial success and reliability in clinical and research settings. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational mechanisms of biosensor degradation, advanced methodological approaches for interface stabilization, practical troubleshooting and optimization techniques, and rigorous validation frameworks. By synthesizing current research trends and real-world applications, this review serves as a strategic guide for overcoming stability challenges and developing next-generation, durable biosensing platforms.

Understanding Biosensor Degradation: The Fundamental Mechanisms Limiting Stability and Shelf Life

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the difference between operational stability and shelf life for a biosensor? Operational stability refers to the retention of the biosensor's activity during use, indicating how long it can continuously or repeatedly provide accurate measurements in its working environment. In contrast, shelf life is the total time a biosensor can be stored and remain functional when it is not in use, typically under specified storage conditions [1] [2].

Q2: My biosensor signals are unstable and show significant drift. What could be the cause? Baseline drift is often a sign of a poorly equilibrated sensor surface or buffer incompatibility. It can be minimized by thoroughly equilibrating the surface with running buffer, sometimes overnight, and ensuring the flow buffer and analyte buffer are perfectly matched to avoid bulk shifts. Other common causes include inefficient regeneration of the sensor surface between measurements or a buildup of contaminants [3] [4].

Q3: How can I improve the reusability of my biosensor? Effective surface regeneration is key to reusability. This involves using a specific buffer to dissociate the analyte from the immobilized ligand without damaging the biorecognition element. The optimal regeneration buffer and protocol (e.g., contact time, pH) must be determined experimentally for each specific ligand-analyte pair to maintain sensor performance over multiple cycles [3].

Q4: What strategies can extend the operational stability of an implantable biosensor? A primary strategy is the use of smart biocompatible coatings. These advanced materials help reduce the Foreign Body Response (FBR)—an immune reaction to the implanted device—which is a major factor limiting sensor lifetime. Such coatings have been shown to extend the functional life of implantable sensors beyond three weeks [5].

Troubleshooting Common Biosensor Stability Issues

Problem 1: Rapid Loss of Signal Intensity

- Potential Cause: Degradation or inactivation of the biological recognition element (e.g., enzyme, antibody) on the sensor surface.

- Solution:

- Check Storage Conditions: Ensure biosensors are stored in the recommended buffer at the correct temperature. Allowing a sensor to dry out or storing it in inappropriate conditions can cause irreversible damage [6].

- Optimize Immobilization: The method used to attach the biorecognition element to the transducer is critical. Explore different immobilization strategies (e.g., covalent binding, cross-linking, encapsulation in polymers) to enhance stability and maintain bioactivity [3] [2].

- Use Stabilizing Additives: Incorporate stabilizers like sugars (e.g., trehalose) or proteins (e.g., BSA) in the storage buffer or during immobilization to protect sensitive biomolecules from denaturation [7].

Problem 2: Poor Reproducibility Between Measurement Cycles

- Potential Cause: Incomplete or harsh surface regeneration, or gradual fouling of the sensor surface.

- Solution:

- Systematic Regeneration Scouting: Test a panel of regeneration solutions (e.g., low pH, high salt, mild surfactants) to find the mildest condition that effectively removes the analyte without damaging the immobilized ligand [3].

- Include Control Cycles: Regularly run a control sample with a known concentration to monitor the sensor's performance over time and identify any decline in reproducibility [3].

- Implement a Cleaning-in-Place Protocol: For systems with significant fouling, a periodic, more rigorous cleaning step may be necessary to restore surface performance.

Problem 3: Short Shelf Life

- Potential Cause: Instability of the biorecognition element over time.

- Solution:

- Lyophilization (Freeze-Drying): For many biosensors, especially those using enzymes or cell-free systems, lyophilization in a stabilizing matrix can dramatically extend shelf life at ambient temperatures [7].

- Advanced Materials: Utilize stabilizing nanomaterials or polymeric matrices during sensor fabrication. Inorganic nanoparticles, conductive polymers, and self-assembled monolayers (SAMs) can create a more protective microenvironment for the biological component [2].

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Stability Metrics

Protocol 1: Quantifying Operational Stability for a Reusable Biosensor

This protocol assesses how many times a biosensor can be used while maintaining its performance.

- Initial Calibration: Calibrate the biosensor using standard solutions with known analyte concentrations to establish a baseline response curve.

- Measurement Cycle:

- Assay: Expose the sensor to a test sample with a known, mid-range analyte concentration.

- Regeneration: Apply the optimized regeneration solution to dissociate the analyte from the sensor surface.

- Wash: Rinse with running buffer to re-equilibrate the surface.

- Repetition: Repeat Step 2 for a defined number of cycles (e.g., 50-100 cycles).

- Data Analysis: After every 10 cycles, re-calibrate the sensor. Plot the sensor's response (e.g., signal intensity, calculated concentration) against the cycle number. Operational stability is often reported as the number of cycles after which the sensor signal degrades to a certain percentage (e.g., 80% or 50%) of its initial value [1].

Protocol 2: Determining Shelf Life

This protocol evaluates the long-term stability of stored biosensors.

- Sensor Fabrication & Initial Testing: Fabricate a large batch of identical biosensors. Randomly select and test a subset (e.g., n=5) to determine initial performance (sensitivity, response time).

- Storage: Store the remaining biosensors under controlled conditions (specified temperature, humidity, and storage buffer).

- Periodic Testing: At regular time intervals (e.g., 1 month, 3 months, 6 months, 1 year), retrieve a subset of sensors (e.g., n=5) from storage.

- Performance Evaluation: Calibrate and test the retrieved sensors using a standard protocol. Compare their performance metrics (sensitivity, limit of detection, response time) to the initial values.

- Data Analysis: Shelf life is defined as the storage time after which the sensor's performance falls below pre-defined acceptance criteria [2].

Quantitative Data on Biosensor Stability

The following table summarizes stability metrics reported in recent research for different types of biosensors.

Table 1: Reported Stability Metrics for Various Biosensor Platforms

| Biosensor Type / Target | Key Stability Feature | Reported Metric | Context / Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lactate Biosensor [1] | Operational Stability (Modeled) | Marginal stability with potential for limit cycle behavior | Model based on Michaelis-Menten kinetics with discrete delays. |

| Implantable Electrochemical Biosensor [5] | Operational Lifetime | >3 weeks | In vivo, achieved using smart coatings to mitigate Foreign Body Response. |

| General Electrochemical Biosensors [2] | Target Lifetime | Months to years | Goal for commercial applications; depends on materials and immobilization. |

| Cell-Free Biosensors [7] | Shelf Life (Post-Lyophilization) | Extended stability at ambient temperatures | Enabled by lyophilization (freeze-drying) of the sensing system on paper or other substrates. |

Research Reagent Solutions for Stability Enhancement

Table 2: Essential Materials for Improving Biosensor Stability

| Item | Function in Stability Research | Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Biocompatible Polymers [5] | Coatings to reduce biofouling and Foreign Body Response in implantable sensors. | Hydrogels, smart biodegradable materials. |

| Stabilizing Agents [7] | Protect biorecognition elements (enzymes, antibodies) from denaturation during storage and use. | Sugars (trehalose), proteins (BSA), polymers. |

| Nanomaterials [2] | Enhance electrochemical properties and provide a high-surface-area, stable matrix for biomolecule immobilization. | Inorganic/organic nanoparticles, conductive polymers, graphene. |

| Surface Chemistry Kits [3] | For controlled and stable immobilization of ligands on sensor chips. | Amine-coupling kits (EDC/NHS), streptavidin-biotin systems, NTA chips for His-tagged proteins. |

| Lyophilization Reagents [7] | Enable long-term, ambient-temperature storage of biosensors by removing water. | Cryoprotectants (e.g., trehalose, PEG) used in paper-based and cell-free biosensors. |

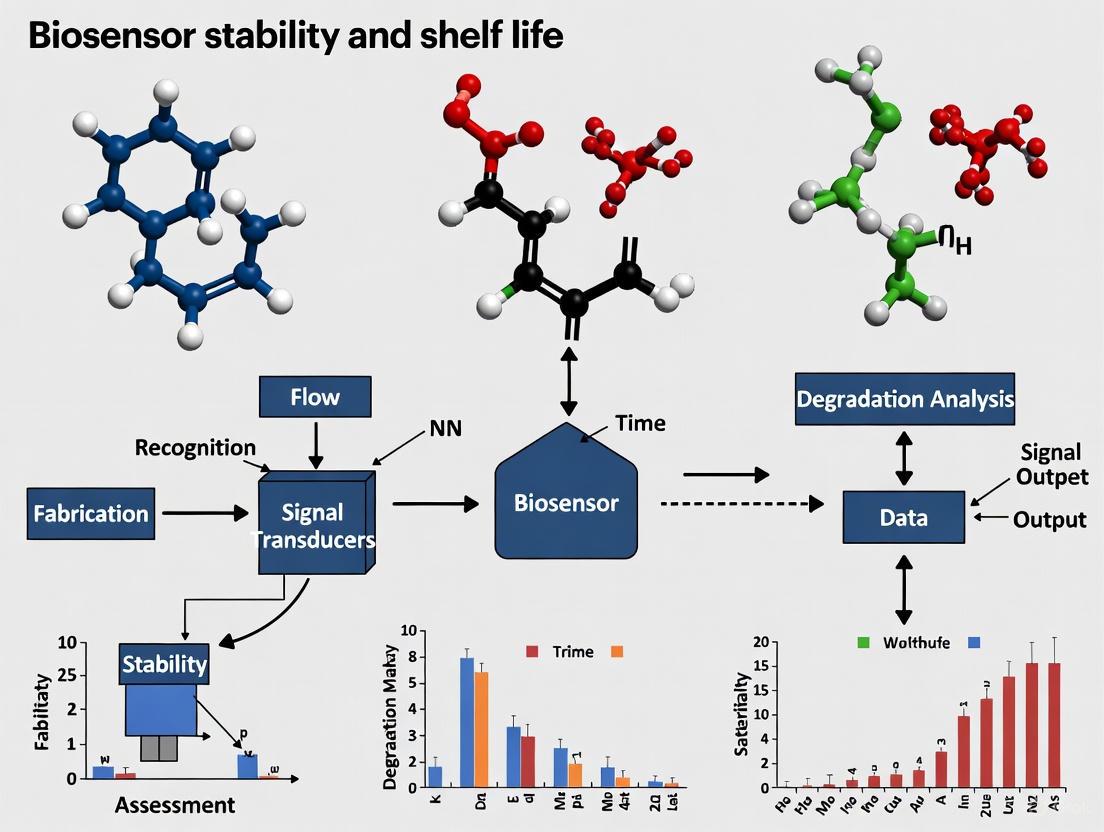

Biosensor Stability Analysis Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between different stability concepts, common problems, and strategic solutions in biosensor development.

Core Mechanisms of Biosensor Aging and Signal Drift

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is biosensor signal drift and why is it a critical issue for long-term experiments?

A1: Signal drift is a gradual, unintended change in a biosensor's output signal over time, even when the concentration of the target analyte remains constant. [8] It represents a temporal instability in the sensor's readings, leading to systematic errors that can compromise data integrity. [8] [9] For researchers, this is critical because unaccounted drift can lead to inaccurate conclusions, flawed dose-response data, and reduced reliability in diagnostic or monitoring applications. [10] [11] [8] In long-term continuous monitoring scenarios—such as tracking metabolite concentrations in bioreactors or drug levels in live subjects—drift can obscure true biological signals, making effective process control or physiological interpretation difficult. [11] [12]

Q2: What are the primary physical and chemical mechanisms that cause sensor aging and drift?

A2: The mechanisms are multifaceted and can be categorized as follows:

- Environmental Stressors: Exposure to temperature fluctuations, varying humidity, or chemical components in the sample matrix can induce physical and chemical changes in sensor materials. [8]

- Component Aging and Degradation: The biological and electronic components of a biosensor can degrade over time. [8] This includes:

- Dissociation of Biorecognition Elements: The gradual loss of immobilized antibodies, enzymes, or analyte-analogue molecules from the sensor surface, which reduces the available binding sites and signal-generating capacity. [11]

- Material Degradation: Corrosion, oxidation, or fouling of the transducer material (e.g., the gate oxide layer in a FET sensor) can alter its electrical properties. [8] [9]

- Biofouling: The nonspecific adsorption of proteins or other biomolecules from complex samples (like blood or serum) onto the sensor surface, which can block binding sites and insulate the sensor, leading to signal attenuation. [10] [12]

- Ion Diffusion and Electrochemical Effects: In electrochemical sensors, ions from the solution can slowly diffuse into sensitive regions or interact with the sensing surface, altering capacitance, threshold voltage, and drain current. [10] [9]

Q3: How can I experimentally determine if my observed signal change is due to a real analyte binding event or just sensor drift?

A3: A rigorous testing methodology is required to decouple drift from a true signal. Key approaches include:

- Use a Control Channel: Integrate a control sensor on the same chip that is functionally identical but lacks the specific biorecognition element (e.g., an antibody). [10] A true positive detection event will show a significant signal change in the active sensor but not in the control, whereas drift will affect both channels similarly.

- Monitor Temporal Patterns: Distinguish between the rapid signal change typically associated with specific binding and the slow, gradual shift characteristic of drift. [11]

- Employ a Referencing Scheme: Use a self-referencing system that can switch between a sensing mode and a reference mode where the target analyte is transparent, using the reference state to compensate for the drift in the sensing signal. [13]

- Validate with Standard Solutions: Periodically introduce a calibration standard with a known analyte concentration to check the sensor's response and recalibrate if necessary.

The following workflow outlines a systematic approach to diagnose signal drift:

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Rapid Signal Changes in a Particle-Based Biosensor

This problem is often observed in sensors that rely on biofunctionalized particles switching between bound and unbound states. [11]

- Symptoms: Signal instability on short timescales (minutes to a few hours), inconsistent binding/unbinding rates.

- Underlying Mechanism: The leading hypothesis is multivalent interactions between the particle and the sensing surface, where a single particle forms multiple non-specific or specific bonds, leading to unstable and complex motion patterns. [11]

- Solutions:

- Optimize Surface Blocking: Ensure all non-specific binding sites on both the particles and the sensing surface are thoroughly blocked with appropriate blockers (e.g., BSA, biotin-PEG, or other inert proteins/polymers). [11]

- Improve Bioconjugation: Use site-specific and controlled conjugation techniques to attach biorecognition elements (e.g., antibodies) to prevent random orientations that promote multivalent binding.

- Adjust Ionic Strength: Modify the salt concentration in the buffer to alter electrostatic interactions that may contribute to non-specific multivalent binding.

Problem: Slow, Gradual Signal Decay Over Hours or Days

This is a common aging phenomenon affecting a wide range of biosensors during extended operational lifetimes. [11]

- Symptoms: A continuous, slow decline in signal output or sensitivity when measuring a constant analyte concentration or a blank solution.

- Underlying Mechanism: The primary cause is often the gradual dissociation (or "bleeding") of immobilized molecules from the sensor surface. This includes capture antibodies, analyte-analogue molecules, or even the enzyme cofactors in enzymatic sensors. [11]

- Solutions:

- Enhance Immobilization Stability: Use covalent binding chemistry (e.g., EDC/NHS coupling) instead of physical adsorption. Explore stronger affinity pairs (e.g., streptavidin-biotin).

- Stabilize with Polymer Brushes: Graft non-fouling polymer layers like poly(oligo(ethylene glycol) methyl ether methacrylate) (POEGMA) onto the sensor surface. These brushes can provide a stable, hydrogel-like matrix for immobilizing biorecognition elements, reducing dissociation. [10]

- Protective Coatings: Apply bioinspired protective coatings, such as a synthetic mucosa layer, to shield the sensing elements from degradation, mimicking the protective mechanism of the gut. [12]

Problem: Significant Signal Drift in FET-based Biosensors in High Ionic Strength Solutions

This is a classic challenge for BioFETs operating in physiological buffers like PBS. [10] [9]

- Symptoms: Large, continuous shifts in threshold voltage or drain current when the sensor is exposed to biological solutions, making stable, quantitative measurement difficult.

- Underlying Mechanisms:

- Debye Screening: In high ionic strength solutions, the electrical double layer (Debye length) is very short (angstroms to nanometers), screening the charge from target biomarkers and preventing their detection. [10]

- Ion Influx: Undesirable ions from the solution slowly diffuse and interact with the gate oxide layer, changing its surface charge and electrical characteristics. [10] [9]

- Solutions:

- Extend the Debye Length: Use a polymer brush interface (e.g., POEGMA) to create a Donnan potential that effectively increases the sensing distance, allowing detection of larger biomarkers in physiological buffers. [10]

- Surface Passivation: Chemically modify the gate oxide layer (e.g., with APTES and succinic anhydride) to create a stable, well-defined surface that minimizes undesirable ion reactions. [9]

- Optimize Measurement Protocol: Rely on infrequent DC sweeps rather than continuous static measurements to reduce the impact of drift, and use a stable pseudo-reference electrode to replace bulky Ag/AgCl references. [10]

Quantitative Data on Signal Drift

The following table summarizes experimental data on signal drift from recent studies, providing a benchmark for comparison.

| Sensor Type | Key Intervention | Drift Performance | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| ISFET Biosensor [9] | Bare SnO₂ Gate Oxide | 21.5 mV / 5 min (4.3 mV/min) in 0.01x PBS | Measurement of voltage drift (ΔVdf) in diluted buffer. |

| ISFET Biosensor [9] | Surface-treated SnO₂ Gate Oxide (with antibodies) | ~11.4 mV / 5 min in 0.01x PBS | Chemical passivation of the gate oxide layer significantly reduced drift. |

| CNT-based BioFET (D4-TFT) [10] | POEGMA polymer brush & stable measurement configuration | Drift mitigated to enable attomolar-level detection in 1x PBS | Achieved stable, drift-free performance in undiluted physiological buffer. |

| Magnetic Biosensor [13] | Self-referencing resonant circuit | Two-orders-of-magnitude improvement in drift cancellation | CMOS-based system using a reference frequency to compensate for thermal drift. |

Key Experimental Protocols for Drift Mitigation

Protocol 1: Mitigating Drift in a FET Biosensor via Surface Passivation

Based on strategies to minimize sensing voltage drift error in an ISFET biosensor. [9]

- Gate Oxide Preparation: Deposit a thin film of SnO₂ (e.g., 80 nm via RF sputtering) on an ITO glass substrate.

- Surface Hydroxylation: Treat the GOL with oxygen plasma to form OH functional groups on the surface.

- Aminosilanation: Quickly add a 5% solution of 3-aminopropyltriethoxysilane (APTES) to the GOL to form NH₂ functional groups. Incubate for 1 hour in the dark, then sonicate in ethanol and dry with N₂ gas.

- Carboxylation: Add a 5% solution of succinic anhydride in dimethylformamide (DMF) to convert NH₂ groups to COOH groups. Incubate overnight at 37°C.

- Antibody Immobilization: Activate the carboxylated surface using EDC and NHS chemistry. Subsequently, incubate with the desired antibody (e.g., 100 nM solution).

- Blocking: Add 1M ethanolamine to deactivate unreacted cross-linkers, followed by a 10% Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) solution to block against non-specific binding for 1 hour.

Protocol 2: Enhancing Stability via Polymer Brush Functionalization

Adapted from the D4-TFT platform for carbon nanotube-based BioFETs. [10]

- Substrate Preparation: Fabricate your transducer (e.g., a CNT thin-film).

- Polymer Brush Grafting: Grow a non-fouling polymer brush layer, such as poly(oligo(ethylene glycol) methyl ether methacrylate) (POEGMA), from the sensor surface. This is typically done via surface-initiated atom transfer radical polymerization (SI-ATRP).

- Bioreceptor Immobilization: Inkjet-print or spot capture antibodies (cAb) directly into the POEGMA matrix above the active sensing channel. The POEGMA layer serves both to extend the Debye length and to provide a stable hosting matrix for the antibodies.

- Control Sensor Preparation: On the same chip, ensure there is a control region where POEGMA is present but no antibodies are printed. This is crucial for differentiating drift from specific binding.

- Stable Electrical Readout: Use a measurement setup with a stable pseudo-reference electrode (e.g., Pd) and acquire data using infrequent DC sweeps from a semiconductor parameter analyzer to minimize drift-inducing continuous bias stress.

This workflow visualizes the core steps of this protocol:

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key materials used in the featured experiments to combat biosensor aging and drift.

| Reagent / Material | Function in Drift Mitigation | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| POEGMA (Poly(oligo(ethylene glycol) methyl ether methacrylate)) | Extends Debye length via Donnan potential; provides a non-fouling, stable matrix for bioreceptor immobilization. [10] | Carbon nanotube BioFETs for detection in undiluted PBS. [10] |

| Redox-Active Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) | Acts as a nanoscale "wire" for efficient electron transfer, improving enzyme stability and preventing leaching in electrochemical biosensors. [14] | Enzyme-based electrochemical sensors for healthcare and environmental monitoring. [14] |

| APTES (3-Aminopropyltriethoxysilane) | Provides a stable amine-functionalized layer on oxide surfaces for subsequent covalent biomolecule immobilization. [9] | Surface passivation of SnO₂ gate oxide in ISFET biosensors. [9] |

| EDC / NHS Chemistry | Standard carbodiimide crosslinking chemistry for covalent conjugation of carboxyl- and amine-containing molecules, creating stable bonds. [15] [9] | Antibody immobilization on sensor surfaces. [15] [9] |

| Nanoporous Gold with Protective Polymer Coating | Creates a 3D protective structure that shields molecular recognition elements from biofouling and degradation in complex fluids. [12] | SENSBIT system for long-term molecular monitoring in live rats. [12] |

The Impact of Biological Component Degradation (Enzymes, Antibodies, Nucleic Acids)

Biosensors are analytical devices that integrate a biological recognition element (such as an enzyme, antibody, or nucleic acid) with a transducer to convert a biological event into a measurable signal [16]. The stability of the biological component is a critical factor influencing the overall performance, commercial success, and translational potential of a biosensor [17]. Degradation of these biological elements leads to a loss of sensitivity and accuracy over time, manifesting as a drop in the output signal [17]. This technical support center provides troubleshooting guides and experimental protocols framed within the broader context of academic research aimed at improving biosensor stability and shelf life.

Core Degradation Mechanisms & Characteristics

Understanding the specific degradation profiles of different biorecognition elements is the first step in diagnosing stability issues. The table below summarizes the stability characteristics and primary degradation triggers for common biological components.

Table 1: Stability Characteristics of Common Biorecognition Elements

| Biorecognition Element | Primary Stability Challenges | Key Degradation Triggers | Impact on Biosensor Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enzymes [18] [19] | Loss of catalytic activity over time; denaturation; leaching from immobilization matrix. | Temperature, pH extremes, proteolytic cleavage, deactivation by inhibitors. | Decrease in VMAX (indicating fewer active enzymes) and reduced sensitivity (Lower LRS) [19]. |

| Antibodies [20] [18] | Denaturation leading to loss of binding affinity and specificity; aggregation. | Repetitive freeze-thaw cycles, elevated temperatures, surface immobilization stress. | Reduced selectivity, increased non-specific binding, and a drop in signal intensity. |

| Nucleic Acids (Aptamers/DNA) [20] [18] | Nuclease-mediated cleavage; chemical degradation (e.g., depurination); denaturation of secondary structures (for aptamers). | Temperature, pH, presence of nucleases in the sample matrix. | Loss of hybridization efficiency or target-binding capability, leading to false negatives. |

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between a biosensor's core components and the primary factors that lead to the degradation of its biological element.

Experimental Protocols for Stability Assessment

Rigorous and standardized testing is essential to quantify biosensor stability. The following protocols are foundational for any thesis research focused on shelf-life improvement.

Protocol: Thermally Accelerated Ageing for Shelf-Life Prediction

This protocol provides a rapid method to determine long-term shelf life, based on established models [17].

- Principle: Ageing is accelerated at elevated temperatures, and the degradation rate is modeled to predict stability under normal storage conditions.

- Materials:

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), 100 mM, pH 7.4.

- Analyte stock solution (e.g., 1 M Glucose).

- Biosensors to be tested.

- Controlled temperature incubators (e.g., +4°C, +25°C, +40°C, +60°C).

- Electrochemical workstation or relevant signal readout system.

- Method:

- Baseline Measurement: At day zero, calibrate all biosensors (n ≥ 3 per group) by measuring the signal response across a range of analyte concentrations.

- Accelerated Ageing: Divide the biosensors into groups and store them at different elevated temperatures (e.g., +25°C, +40°C, +60°C). A control group should be stored at the recommended temperature (e.g., +4°C).

- Periodic Testing: At predefined intervals (e.g., 24h, 48h, 96h), remove a set of biosensors from each storage condition and perform a full calibration.

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate the sensitivity (e.g., Linear Region Slope - LRS) for each biosensor at each time point.

- For each temperature, plot the normalized sensitivity (%) against time.

- Fit the data using both Arrhenius (exponential) and linear models. Research indicates a linear degradation model often provides a better fit for biosensor ageing [17].

- Use the linear model to extrapolate the time required for a 10% loss in sensitivity at the recommended storage temperature.

Protocol: Operational Stability (Reusability & Continuous Use)

This protocol assesses stability under active use conditions, which is critical for sensors intended for semi-integrated devices [17].

- Principle: The biosensor is subjected to repeated measurement cycles or continuous exposure to the analyte to simulate in-use ageing.

- Materials: As per Protocol 3.1.

- Method:

- Reusability Testing:

- Perform a calibration measurement.

- Gently rinse the biosensor with buffer.

- Repeat the measurement cycle multiple times (e.g., 10-20 cycles) over a single day.

- Plot the signal response against the cycle number to determine the loss per use.

- Continuous Use Testing:

- Immerse the biosensor in a constant, physiologically relevant concentration of the analyte.

- Monitor the signal output continuously or at very short intervals (e.g., every minute) for an extended period (e.g., 24-72 hours).

- Plot the signal against time to observe the decay profile.

- Reusability Testing:

Table 2: Key Quantitative Parameters for Stability Assessment

| Parameter | Description | Interpretation | Experimental Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| VMAX [19] | The maximum enzymatic reaction rate when saturated with substrate. | Indicates the number of active enzyme molecules on the biosensor surface. A drop signals enzyme degradation. | Full calibration curve analysis. |

| KM [19] | The Michaelis constant; substrate concentration at half of VMAX. | Reflects the enzyme's affinity for the substrate. Significant changes suggest alterations in the enzyme's binding site or micro-environment. | Full calibration curve analysis. |

| LRS (Linear Region Slope) [19] | The slope of the response in the linear detection range. | The primary analytical parameter for sensitivity. The most direct indicator of performance degradation. | Linear regression of the low-concentration data points. |

| Signal Decay Rate [17] | The rate of signal loss over time under continuous use. | Quantifies operational stability. A slower decay rate indicates a more robust biosensor for prolonged monitoring. | Continuous use testing. |

Material & Immobilization Solutions

The choice of materials and how the biological component is anchored to the transducer are paramount for stability. The following table details key research reagents that can mitigate degradation.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Enhanced Stability

| Reagent / Material | Function / Explanation | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) [14] | Porous crystalline structures that can encapsulate enzymes, preventing leaching and denaturation while allowing substrate access. Act as a "wire" for efficient electron transfer. | Used to create highly efficient and stable enzyme-based electrochemical biosensors for long-term measurements [14]. |

| MXenes [21] | Emerging two-dimensional nanomaterials with unique electrochemical properties and a layered structure that provides a high surface area for stable immobilization. | Ideal material for developing high-sensitivity, high-stability, and multifunctional biosensors [21]. |

| Glutaraldehyde (GTA) [19] | A crosslinking agent that creates strong covalent bonds between enzymes and carrier proteins (e.g., BSA), forming a stable, non-leaching network. | Used in a final layer with BSA to create a robust containment net for glucose and lactate biosensors, improving shelf-life [19]. |

| Polyurethane (PU) [19] | A polymer used to form a permeable containment membrane over the biological layer, offering physical protection and reducing leaching. | Applied as a final dip-coating layer to entrap the enzyme layer on a biosensor, an alternative to GTA crosslinking [19]. |

| Polydopamine [15] | A melanin-like polymer that forms a universal, biocompatible, and adhesive coating on various surfaces, simplifying and stabilizing immobilization. | Used for surface modification of electrodes in environmental and food monitoring sensors, providing a versatile platform for bioreceptor attachment [15]. |

The workflow below summarizes the strategic decision process for selecting a stabilization method, based on the diagnostic information gathered.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the most critical factor for maximizing the shelf-life of my biosensors? A: Consistent and correct low-temperature storage is paramount. Studies show that storage at -80 °C can not only preserve but, in some cases, unexpectedly improve the performance (VMAX and LRS) of enzyme-based biosensors over a 120-day period, significantly outperishing storage at +4 °C or -20 °C [19]. Always store biosensors in dry, airtight conditions to prevent humidity and ice damage.

Q2: My biosensor signal drops significantly after a few uses. What is the most likely cause? A: This typically points to an operational stability issue. The most common causes are:

- Poor Immobilization: The biological component (e.g., enzyme) is leaching out from the sensor surface. Re-evaluate your immobilization strategy, considering stronger crosslinking (e.g., Glutaraldehyde/BSA) or entrapment in polymers or MOFs [14] [19].

- Handling Damage: Physical stress during rinsing or handling between measurements can damage the active layer. Standardize and gentle handling procedures [17].

- Fouling: Sample matrix components (e.g., proteins, cells) are adsorbing to the sensor surface, blocking access to the biorecognition element. Implement anti-fouling coatings or membrane layers [16].

Q3: How can I quickly estimate the long-term shelf-life of my new biosensor design during my PhD? A: Employ a thermally accelerated ageing protocol. By storing your biosensors at multiple elevated temperatures (e.g., +40°C, +60°C) and measuring the signal decay over a few days, you can use a linear model to extrapolate the long-term shelf-life at your desired storage temperature (e.g., +4°C). This method can predict stability over months or years in a matter of days [17].

Q4: Are there more stable alternatives to traditional antibodies for my immunosensor? A: Yes, aptamers (single-stranded DNA or RNA oligonucleotides) are a powerful alternative. They are selected in vitro (via SELEX) for high affinity and specificity, and often exhibit superior thermal stability and lower immunogenicity compared to antibodies [20] [18]. Furthermore, they can be chemically synthesized with high reproducibility.

Troubleshooting Guide: Material and Signal Failures

This guide addresses common material-level failures that impact the stability and function of transducers and biological signal mediators within biosensors.

Q1: How do I diagnose a pressure transducer that provides no output or an unexpected signal?

A systematic electrical diagnostic approach can identify common failures in transducer systems.

- Prerequisite Knowledge and Tools: The individual performing troubleshooting must have sound knowledge of the equipment and be able to use a digital multimeter to measure resistance, current, and voltage. Access to a 24 VDC power source is also required [22].

- Procedure for a 2-Wire Transducer (Connected to Pipeline): First, verify the power connections: ensure -24 VDC is connected to the common terminal and +24 VDC is connected to the +excitation terminal. Then, disconnect the wire connecting the control circuit to the transducer’s +signal terminal. Place the negative lead of a voltmeter on the common terminal and the positive lead on the +signal terminal of the transducer. Check if the voltage output matches the specifications in the transducer's data sheet. If it does, the transmitter is operational [22].

- Procedure for a 3-Wire or 4-20mA Transducer: For a 3-wire system with no signal, remove the transmitter from the control unit and pipeline. Identify all terminals using the model's operating instructions. Apply power and place the voltmeter's positive lead on the +signal terminal and the negative lead on the common terminal. An expected reading indicates proper function [22]. For a 4-20mA transducer, connect 24 VDC to the red wire, disconnect the control unit wire, and connect the lead to the negative terminal of a digital milliamp meter. Connect the meter's positive lead to the transducer's black wire. A 4mA output signal with no pressure applied confirms basic operation [22].

Q2: What are the common analytical methods to identify material failure in a transducer component?

Failure analysis of a component is a systematic process to determine the root cause of failure. The approach can range from a visual examination to a full laboratory analysis, often involving the following techniques [23] [24]:

Table: Key Analytical Methods for Material Failure Analysis

| Method Category | Specific Technique | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Visual Examination | Macroscopic examination, Optical/Digital microscopy | To identify macroscopic damage features, cracks, and flaws; provides initial diagnosis [23] [24]. |

| Non-Destructive Testing (NDE) | Dye penetrant inspection, Phased array ultrasonics | To identify surface and sub-surface anomalies without damaging the component [24]. |

| Chemical Analysis | Composition analysis, Residual/Contaminant analysis | To verify material is within specification and identify environmental contaminants that cause corrosion or stress cracking [23] [24]. |

| Mechanical Testing | Hardness testing, Tensile testing | To determine if material properties (e.g., hardness, strength, ductility) meet specifications [23] [24]. |

| Microstructural Evaluation | Metallography, Fractography | To assess microstructure, degradation, and fracture characteristics (e.g., crack path, rupture features) using SEM and other microscopes [23] [24]. |

| Surface Characterization | Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDS), X-ray Diffraction (XRD) | To identify the elemental and chemical composition of oxides, deposits, and corrosion products [24]. |

Q3: What material instabilities can lead to the degradation of a biosensor's bioreceptor or transducer?

Instability can arise from the chemical nature of the materials themselves or from their interaction with the environment.

- Chemical Instability of Materials: Reactive substances in the biosensor's construction can undergo undesired reactions, such as thermal decomposition or polymerization, if they are exposed to conditions outside their safe operating window (e.g., excessive temperature, pressure, or incompatible chemicals). This can degrade the bioreceptor's function or damage the physical transducer [25].

- Environmental and Operational Factors: Factors like humidity, extreme temperature, and vibration can lead to material failure. For instance, surface oxides or corrosive deposits can cause direct wall loss or attack of a metal transducer component. The presence of contaminants, either from manufacturing or the operating environment, can initiate failure mechanisms like stress corrosion cracking [22] [24].

- Microstructural Degradation: Over time and under operational stress, the microstructure of materials can change. This includes effects like spheroidization, graphitization, or creep cavitation, which weaken the component and ultimately lead to failure [24].

Q4: What experimental protocols can be used to study chemical instability in sensor materials?

Chemical instability studies investigate conditions that lead to unsafe and uncontrolled reactions, which is crucial for predicting sensor shelf life and failure modes [25].

- Objective: To understand the behavior of reactive substances, identify their reactivity limits, and determine the conditions (temperature, pressure, concentration) that may lead to hazardous reactions or performance degradation [25].

- Methodology: The study typically involves a combination of laboratory tests (e.g., thermal analysis), literature reviews, and chemical compatibility assessments. Computer modeling may also be used to simulate potential reactions, estimate reaction rates, and predict products [25].

- Data Application: The results guide the safe design and optimization of the sensor by establishing boundaries for safe operation. This includes defining storage and handling precautions, selecting compatible materials, and implementing engineering controls to prevent accidents [25].

Chemical Instability Study Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Materials for Failure Analysis and Stability Research

| Reagent/Material | Function in Experimentation |

|---|---|

| Digital Multimeter | Measures electrical parameters (voltage, current, resistance) to diagnose transducer power and signal integrity [22]. |

| 24 VDC Power Source | Provides standardized excitation power for testing and troubleshooting various transducer types [22]. |

| Optical & Scanning Electron Microscopes (SEM) | Enables visual examination, fractography, and microstructural evaluation to identify fracture origins and mechanisms [23] [24]. |

| Hardness Tester | Indicates the metallurgical condition and mechanical properties (e.g., tensile strength) of a material [24]. |

| Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectrometer (EDS) | Characterizes the elemental composition of oxides, deposits, and corrosion products on failed surfaces [24]. |

| Chemical Reagents for Analysis | Used in investigative and residual chemical analysis to identify unspecified elements or contaminants that contribute to failure [23] [24]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Our biosensor gives inconsistent readings. Could this be a material-level issue, and how do we investigate?

Yes, inconsistent readings often point to material-level instability. The investigation should follow a structured failure analysis process [23] [24]:

- Data Collection: Gather all information on the circumstances of failure, including sensor design, manufacturing methods, material specifications, and service history.

- Non-Destructive Testing (NDE): Perform a visual examination and techniques like dye penetrant inspection to identify surface flaws without damaging the sensor.

- Destructive Testing: If possible, conduct tests on failed units to determine material composition, mechanical properties, and the presence of environmental contaminants.

- Analysis of Data: Correlate all findings to identify the root failure mechanism (e.g., corrosion, fatigue, chemical degradation).

Q2: What are the primary reasons for a complete lack of signal from a transducer?

The most common causes for no signal are related to the electrical system and installation [22]:

- Inadequate Power Supply: The transducer may not be receiving the correct voltage (e.g., 24 VDC).

- Improper Wiring or Incorrect Polarity: Check that all wires are connected to the correct terminals and that the polarity is not reversed.

- Short Circuits or Multiple Grounds: These can disrupt the electrical pathway and prevent signal generation.

Q3: How often should we perform stability studies on the materials used in our biosensors?

Stability studies are not a one-time event. They should be conducted [25]:

- During the initial design phase of the biosensor.

- Whenever new chemicals or material mixtures are introduced.

- When significant changes occur in the manufacturing process or operating conditions.

- Regularly reviewed and updated to ensure ongoing process safety and product reliability.

Q4: Can material failures be predicted and prevented?

While not all failures can be predicted with absolute certainty, risk can be significantly minimized through proactive measures [25] [24]:

- Chemical Instability Studies: Actively assess reactive substances under various conditions to identify hazardous reaction potentials before they occur [25].

- Proper Material Selection: Choose materials that are chemically compatible and suitable for the intended service environment (e.g., resistant to corrosion, humidity) [22] [25].

- Implementation of Safety Controls: Use the data from instability studies and failure analyses to design processes and housing that keep operating conditions within safe boundaries [25].

Common Material Failure Causes

This technical support center provides evidence-based troubleshooting guides and FAQs to support researchers investigating and improving the stability and shelf life of biosensors. The performance of biosensors is intrinsically linked to their operating environment. Fluctuations in temperature and pH, along with exposure to complex sample matrices, can significantly impact the stability of the biological recognition elements and the reliability of the signal transduction. This resource, framed within the broader context of biosensor stability research, consolidates current knowledge and practical protocols to help scientists identify, understand, and mitigate these environmental challenges during their experiments.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs): Core Concepts

Q1: Why are biosensor readings so sensitive to ambient temperature fluctuations?

Biosensor sensitivity to temperature stems from its dual impact on both the biochemical recognition element and the physicochemical transduction process. Temperature changes alter the kinetics of enzyme-catalyzed reactions or probe-target binding (hybridization, antibody-antigen interaction), directly affecting the rate at which the measurable signal is generated [26]. Furthermore, the electron transfer rate at the transducer surface, which is the basis for electrochemical biosensors, is itself temperature-dependent [26]. Even for robust commercial systems, high accuracy requires operation within specified temperature ranges.

Q2: How does pH influence the performance of enzyme-based biosensors?

The activity of enzyme biorecognition elements is highly dependent on the pH of the sample matrix. Each enzyme has an optimal pH at which its catalytic activity is maximized. Deviations from this pH can lead to enzyme denaturation (irreversible loss of function) or a reversible decrease in activity, resulting in a diminished and inaccurate signal [27] [28]. For instance, the common enzyme Glucose Oxidase (GOx) loses performance when the pH falls below 2 or rises above 8 [28].

Q3: What is meant by "complex matrices" and how do they interfere with biosensing?

Complex matrices are real-world samples—such as blood, serum, urine, sweat, or food extracts—that contain not only the target analyte but also a multitude of interfering substances. These can include proteins, lipids, salts, and other biomolecules. Interferences manifest as:

- Non-specific Binding: Other molecules adsorbing to the sensor surface, causing a false positive signal [29] [16].

- Fouling: Physical blockage of the sensor's active surface, reducing sensitivity and response time [30] [16].

- Chemical Interference: Endogenous compounds that are electrochemically active or that react with signaling reagents, skewing the results [31].

Q4: What are the primary strategies for improving biosensor shelf life?

Improving shelf life focuses on stabilizing the biological component. Key strategies include:

- Advanced Immobilization: Using nanostructured materials or covalent bonding techniques to secure bioreceptors more effectively, preventing denaturation [30] [27].

- Stabilizing Formulations: Incorporating sugars, polyols, or other excipients in storage buffers to protect enzymes and proteins from dehydration and degradation [29].

- Use of Robust Bioreceptors: Exploring synthetic alternatives like aptamers or engineered nanozymes, which offer greater stability than their natural counterparts [27] [28].

- Proper Storage Conditions: Ensuring consistent, low-temperature storage without humidity fluctuations is critical for maintaining activity over time [31].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Signal Drift and Inaccuracy Under Variable Temperature

This is a common challenge when moving biosensors from controlled lab environments to real-world applications.

Potential Causes:

- Temperature-dependent changes in hybridization/binding kinetics of DNA-based probes [26].

- Variation in the electron transfer rate constant of electrochemical sensors [26].

- Denaturation of temperature-sensitive biological components (e.g., enzymes, antibodies).

Step-by-Step Diagnostic Protocol:

- Baseline Stability Check: Characterize your sensor's performance in a buffer solution at a constant temperature (e.g., 25°C). Establish a stable baseline signal.

- Controlled Temperature Ramp: Place the sensor in a temperature-controlled chamber (or water bath). Measure the sensor's response to a fixed analyte concentration while systematically varying the temperature (e.g., from 20°C to 40°C in 5°C increments).

- Data Analysis: Plot the signal output (e.g., current, voltage) against temperature. A strong correlation indicates high temperature sensitivity.

- Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV) Optimization (For Electrochemical Sensors): As demonstrated in recent E-DNA sensor research, explore different SWV frequencies. Higher frequencies can sometimes decouple the signal from temperature-dependent kinetic effects, enabling more temperature-independent signaling [26].

Corrective Actions:

- Implement On-Site Calibration: Develop a temperature-correction algorithm based on your diagnostic data. Integrate a digital thermometer (e.g., a Pt1000 sensor) into your device to enable real-time signal compensation [28] [32].

- Sensor Architecture Optimization: For DNA-based sensors, select probe architectures with fast hybridization kinetics, which have been shown to be less susceptible to temperature-induced fluctuations [26].

- Use Thermostable Receptors: Whenever possible, employ engineered enzymes or aptamers selected for stability across a wider temperature range.

Issue 2: Loss of Sensitivity and Selectivity in Complex Samples

A sensor that works perfectly in buffer may fail in blood, sweat, or food samples due to matrix effects.

Potential Causes:

- Biofouling from proteins or cells [30].

- Non-specific adsorption of interfering molecules to the sensor surface [29].

- Chemical interference from electroactive species (e.g., ascorbic acid, uric acid in biological fluids) [31].

Step-by-Step Diagnostic Protocol:

- Spike-and-Recovery Test: Spike a known concentration of your analyte into the complex matrix (e.g., serum) and measure the sensor's response. Compare the measured value to the result obtained from a buffer solution spiked with the same concentration. A lower recovery rate indicates matrix interference.

- Control Experiment: Run the complex matrix without the target analyte. Any signal generated is due to non-specific interference or matrix components.

- Surface Characterization: Use techniques like electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) or scanning electron microscopy (SEM) to inspect the sensor surface before and after exposure to the complex matrix for evidence of fouling [30].

Corrective Actions:

- Surface Passivation: Coat the sensor with an antifouling polymer membrane such as Nafion [28] or create a hydrogel layer to create a physical and charge-based barrier against interferents.

- Use of Blocking Agents: During sensor fabrication, incubate the surface with inert proteins (e.g., bovine serum albumin - BSA) or detergents to block sites prone to non-specific binding [29].

- Sample Pre-treatment: For some applications, simple dilution, filtration, or centrifugation of the sample can reduce interference sufficiently without compromising the detection of the analyte.

- Membrane Selection (for lateral flow assays): Carefully choose the porosity and protein-binding capacity of nitrocellulose membranes to optimize flow and minimize non-specific binding [29].

Experimental Protocols for Stability Assessment

Protocol 1: Quantifying Temperature Dependence

Objective: To systematically evaluate the effect of temperature on biosensor signal output and determine the optimal operating range.

Research Reagent Solutions:

| Reagent/Material | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Temperature-controlled Chamber | Provides a stable and adjustable thermal environment for testing. |

| High-Precision Thermometer (e.g., Pt1000) | Accurately monitors and validates the actual temperature at the sensor interface. |

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) | Provides a consistent, defined ionic background for baseline measurements. |

| Standardized Analyte Solution | A solution of the target molecule at a known, fixed concentration. |

Methodology:

- Setup: Place the biosensor and reference thermometer in the temperature-controlled chamber.

- Initial Reading: Set the chamber to a baseline temperature (e.g., 22°C). Allow the system to equilibrate for 15 minutes.

- Measurement: Introduce the standardized analyte solution and record the sensor's signal output (e.g., peak current in µA, voltage in mV).

- Temperature Ramp: Increase the chamber temperature to the next pre-set point (e.g., 25°C, 30°C, 35°C, 37°C). For each step, allow for thermal equilibration before repeating the measurement with a fresh aliquot of analyte solution.

- Data Analysis: Plot the signal intensity (Y-axis) against temperature (X-axis). Calculate the coefficient of thermal influence, which can be used for software-based calibration correction in future applications.

The workflow for this quantitative assessment is outlined below.

Protocol 2: Testing for Matrix Interference

Objective: To diagnose and quantify the extent of signal suppression or enhancement caused by a complex sample matrix.

Research Reagent Solutions:

| Reagent/Material | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Complex Sample Matrix (e.g., serum, urine) | The real-world sample to be tested for interference effects. |

| Synthetic Analog of Matrix (e.g., artificial sweat, urine) | A defined control solution that mimics the salt/composition of the real matrix. |

| Standard Reference Material (Analyte) | Pure form of the target molecule for spiking. |

| Blocking Buffer (e.g., with BSA or casein) | A solution used to passivate the sensor surface and reduce non-specific binding. |

Methodology:

- Prepare Samples:

- Sample A (Buffer Control): Spike a known amount of analyte into a clean buffer. Measure the signal (Sbuffer).

- Sample B (Matrix Spike): Spike the same amount of analyte into the undiluted complex matrix. Measure the signal (Smatrix).

- Sample C (Matrix Blank): Run the complex matrix without any added analyte. Measure the signal (S_blank).

- Calculate Key Metrics:

- Signal Suppression/Enhancement: = (Smatrix - Sblank) / Sbuffer. A value of 1 indicates no interference; <1 indicates suppression; >1 indicates enhancement.

- Percent Recovery: = [(Smatrix - Sblank) / Sbuffer] * 100%.

- Interpretation: A low percent recovery (e.g., <80% or >120%) confirms significant matrix interference and indicates a need for surface modification or sample preparation.

The logical process for testing and calculation is summarized in the following diagram.

Advanced Materials and Engineering Solutions for Robust Biosensor Design

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Rapid Signal Degradation and Loss of Sensitivity

- Problem Description: A biosensor experiences a significant drop in signal output and fails to detect target analytes at its initial sensitivity within a short period.

- Root Cause Analysis:

- Biofouling: Accumulation of proteins, cells, or other biological molecules on the sensor interface, creating a physical barrier that hinders analyte access [33].

- Nanomaterial Leaching: Detachment of immobilized gold nanoparticles or metal oxides from the electrode surface due to weak adhesion or unstable functionalization [34].

- Surface Passivation: Oxidation or chemical modification of the nanomaterial surface, reducing its electrocatalytic activity, particularly for non-enzymatic sensors [35].

- Solutions:

- Implement Anti-Fouling Coatings: Modify the interface with polyethene glycol (PEG), zwitterionic polymers, or self-assembled monolayers (SAMs) to create a hydrophilic, bio-inert barrier [33].

- Optimize Immobilization Chemistry: Use stronger cross-linkers or covalent bonding strategies to anchor nanomaterials firmly to the transducer surface [36].

- Employ Electrochemical Cleaning: Apply periodic electrochemical pulses or potentials to desorb fouling agents from the electrode surface without damaging the nanomaterial coating [33].

Problem 2: Poor Reproducibility and High Batch-to-Batch Variability

- Problem Description: Biosensors fabricated in different batches show inconsistent performance metrics, such as variable sensitivity and detection limits.

- Root Cause Analysis:

- Inconsistent Nanomaterial Synthesis: Variations in the size, shape, or functional groups of synthesized nanomaterials (e.g., graphene oxide, AuNPs) due to non-standardized protocols [35] [37].

- Non-Uniform Interface Deposition: Inhomogeneous dispersion or aggregation of nanomaterials during the electrode modification process, leading to uneven active sites [34].

- Solutions:

- Standardize Synthesis Protocols: Strictly control reaction parameters (temperature, precursor concentration, reaction time) and employ characterization techniques (TEM, DLS) to validate each batch [35].

- Improve Deposition Techniques: Use controlled methods like electrodeposition, spin-coating, or spray-coating to achieve uniform films. Incorporate dispersing agents to prevent nanomaterial aggregation in solutions [37].

Problem 3: Low Selectivity and Interference from Complex Matrices

- Problem Description: The biosensor produces false-positive signals or shows cross-reactivity when tested in real samples like blood, serum, or environmental water.

- Root Cause Analysis:

- Non-Specific Adsorption (NSA): Undesired binding of interfering molecules (e.g., ascorbic acid, uric acid, proteins) to the nanomaterial surface [35] [33].

- Insufficient Bioreceptor Orientation: Poorly controlled immobilization of antibodies or aptamers on the nanomaterial, blocking their active binding sites [36].

- Solutions:

- Engineer a Mixed SAM Layer: Co-immobilize the bioreceptor with ethylene glycol or zwitterionic molecules to create a non-fouling background that resists NSA [33].

- Site-Specific Bioconjugation: Utilize click chemistry or site-directed mutagenesis to attach bioreceptors (e.g., antibodies, enzymes) in a specific orientation, ensuring maximum antigen-binding site availability [36].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the primary mechanisms by which gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) enhance biosensor performance?

AuNPs improve biosensors through several mechanisms. They provide a high surface-area-to-volume ratio for immobilizing a large number of bioreceptor molecules, enhancing the capture of target analytes [36]. Their excellent electrical conductivity facilitates faster electron transfer in electrochemical sensors, leading to amplified signals [38] [36]. Furthermore, their unique optical properties enable strong signal generation in colorimetric and surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS)-based biosensors [15].

FAQ 2: How does graphene oxide contribute to the stability of a biosensor interface compared to pure graphene?

While both offer a large surface area, Graphene Oxide (GO) contains oxygen-rich functional groups (e.g., -COOH, -OH) on its basal plane and edges. These groups are crucial for two key stability functions: they enable strong covalent immobilization of bioreceptors, preventing leaching, and they confer high hydrophilicity, which helps form a hydration layer that resists biofouling by proteins and cells [33]. Reduced Graphene Oxide (rGO) finds a balance between the superior conductivity of graphene and the easier functionalization of GO [35].

FAQ 3: We are developing a non-enzymatic glucose sensor using metal oxides. What is the fundamental detection mechanism?

Non-enzymatic glucose sensors using metal oxides (e.g., NiO, Co3O4) rely on the direct electrocatalytic oxidation of glucose on the nanomaterial surface. Two primary models explain this [35]:

- Activated Chemisorption Model: Glucose molecules adsorb onto the metal oxide surface, where direct electron transfer occurs, oxidizing glucose to gluconolactone.

- Incipient Hydrous Oxide Adatom Mediator (IHOAM) Model: The metal oxide surface undergoes a reversible oxidation to form a higher-valent oxy-hydroxide species, which then acts as a chemical mediator to oxidize the glucose molecule.

FAQ 4: What are the best practices for storing nanomaterial-functionalized biosensors to maximize shelf life?

For long-term stability, store the biosensors in a dry, inert environment. A dark vacuum desiccator at 4°C is ideal. This protects the interface from moisture-induced degradation, oxidation, and the growth of biological contaminants. Avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles, which can cause delamination or cracking of the nanomaterial layer [33].

Performance Data and Experimental Protocols

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Selected Nanomaterial-Enhanced Biosensors

| Nanomaterial | Target Analyte | Sensor Type | Limit of Detection (LOD) | Linear Range | Key Stability Finding | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Au-Ag Nanostars | α-Fetoprotein | Optical (SERS) | Not Specified | Not Specified | Platform addresses limitations in cancer biomarker detection [15]. | |

| Porous Au/PANI/Pt | Glucose | Electrochemical | High Sensitivity: 95.12 µA mM⁻¹ cm⁻² | Not Specified | Excellent stability in interstitial fluid; surpasses conventional electrodes [15]. | |

| Graphene-based | Lead (Pb²⁺) | Electrochemical | 0.01 ppb | Not Specified | High resistivity and stability in water [39]. | |

| Gold Nanoparticles | Mercury (Hg²⁺) | Electrochemical | 0.005 ppb | Not Specified | Exhibits high sensitivity to mercury ions [39]. | |

| Nanocomposite Electrode | Glucose | Electrochemical (Non-enzymatic) | High Sensitivity | Not Specified | Superior stability and shelf life vs. enzymatic sensors [35]. |

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Nanomaterial-Enhanced Biosensing

| Reagent / Material | Function / Explanation | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | Signal amplification (electrical/optical); Bioreceptor immobilization. | Tunable size (20-100 nm) and shape (spheres, rods, nanostars) for optimizing performance [15] [36]. |

| Graphene Oxide (GO) | 2D platform for immobilization; enhances hydrophilicity to resist fouling. | Degree of oxidation impacts conductivity and available functional groups for chemistry [35] [33]. |

| Transition Metal Oxides (e.g., NiO) | Direct electrocatalysis for non-enzymatic sensors (e.g., glucose). | Operational stability can be compromised by surface poisoning from reaction intermediates [35]. |

| Zwitterionic Polymers | Form ultra-low fouling surfaces to resist non-specific protein adsorption. | More stable and resistant to oxidation compared to traditional PEG coatings [33]. |

| Cross-linkers (e.g., EDC/NHS) | Form covalent bonds between nanomaterial functional groups (-COOH) and bioreceptors (-NH₂). | Reaction pH and time must be optimized to prevent nanoparticle aggregation [36]. |

Protocol 1: Fabrication of a Stable, Anti-Fouling Graphene Oxide-Based Electrochemical Interface

- Objective: To create a reproducible and biofouling-resistant electrode surface using graphene oxide for the detection of biomarkers in complex biological fluids.

- Materials: Glassy Carbon or Gold Electrode, Graphene Oxide (GO) dispersion (1 mg/mL in DI water), EDC, NHS, specific antibody or aptamer, Zwitterionic polymer (e.g., poly(sulfobetaine methacrylate)), Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS).

- Methodology:

- Electrode Pretreatment: Polish the electrode with alumina slurry (0.05 µm), rinse with DI water, and perform electrochemical cleaning via cyclic voltammetry in a suitable electrolyte (e.g., 0.5 M H₂SO₄) until a stable voltammogram is obtained.

- GO Immobilization: Deposit 5-10 µL of the GO dispersion onto the clean electrode surface and allow it to dry under ambient conditions. Alternatively, use electrophoretic deposition for a more uniform film.

- Bioreceptor Immobilization:

- Activate the carboxyl groups on GO by incubating the electrode with a mixture of 20 mM EDC and 50 mM NHS in MES buffer for 30 minutes.

- Rinse the electrode and incubate it with a solution of your antibody or amine-modified aptamer (10-50 µg/mL) for 2 hours at room temperature.

- Anti-Fouling Coating: Incubate the functionalized electrode with a 1% w/v solution of zwitterionic polymer for 1 hour. This step passivates any remaining active sites, creating a non-fouling background [33].

- Storage: Store the final biosensor in a vacuum desiccator at 4°C until use.

Protocol 2: Enhancing Sensor Stability via Electrochemical Cleaning Regeneration

- Objective: To restore sensor performance after exposure to complex, fouling-prone samples without damaging the nanomaterial interface.

- Materials: Functionalized biosensor, Potentiostat, appropriate buffer (e.g., PBS, pH 7.4).

- Methodology:

- Post-Measurement Rinse: Gently rinse the sensor with a stream of clean buffer to remove loosely adsorbed contaminants.

- Application of Cleaning Pulses:

- Place the sensor in a fresh, clean buffer solution.

- Apply a series of short, high-potential pulses (e.g., +1.2 V for 5 ms, followed by -0.5 V for 5 ms) for 30-60 seconds. The exact potentials should be optimized to be strong enough to oxidize/desorb foulants but not so strong as to damage the underlying nanomaterial or bioreceptor [33].

- Stability Check: Re-calibrate the sensor in standard solutions to verify that sensitivity has been restored to within 90% of its original value.

Diagrams and Workflows

Sensor Enhancement and Degradation Pathways

Non-Enzymatic Glucose Sensing Mechanism

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How can I improve the electrical conductivity of my chitosan-based composite films without compromising their biocompatibility? Incorporating conductive nanofillers is a highly effective strategy. You can use polyaniline/graphene (PAG) nanocomposites or single-wall carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs). For PAG, a low loading of 2.5 wt.% in a chitosan/gelatin matrix has been shown to provide a suitable balance, significantly enhancing conductivity while maintaining proper biocompatibility for nerve tissue engineering [40]. For SWCNTs, incorporating 0.1–3.0 wt.% into a chitosan matrix can dramatically increase conductivity from 10⁻¹¹ S/m (pure chitosan) to 10 S/m, which effectively supports the electrical stimulation of human dermal fibroblasts [41].

Q2: What are the critical factors affecting the shelf life of biosensors utilizing these polymer composites? The stability of the biological recognition element (e.g., enzymes, antibodies) is often the limiting factor. Shelf-life estimation can be performed via accelerated aging studies, which involve exposing the biosensors to elevated temperatures and using a mathematical model to extrapolate stability under standard storage conditions [42]. More broadly, challenges include the need for enhanced stability and reliability of the biosensing interface, which requires ongoing research into new biometric components and sensor materials [43] [44].

Q3: My hydrogel scaffolds lack the required mechanical strength for tissue engineering. How can I reinforce them? Forming graft copolymers or interpenetrating networks with synthetic polymers can significantly enhance mechanical properties. For instance, creating a chitosan-polyacrylamide graft copolymer hydrogel has been demonstrated to improve mechanical strength, with reported tensile and compression strengths of 37 kPa and 19 kPa, respectively, for samples swollen at pH 6.8. Using N, N′-Methylene-bis-acrylamide as a crosslinker for polyacrylamide helps form a robust three-dimensional network [45].

Q4: How can I monitor and optimize the performance of my composite materials during fabrication? Biosensors integrated into the manufacturing process can provide real-time monitoring of key biochemical parameters and metabolite concentrations, enabling precise control and optimization [43] [44]. Furthermore, for the final biosensor device design, machine learning (ML) and explainable AI (XAI) can be employed to rapidly predict performance metrics and identify the most influential design parameters (e.g., gold thickness, pitch in SPR biosensors), significantly accelerating the optimization process compared to conventional simulation-heavy methods [46].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low Electrical Conductivity in Chitosan Composite Films

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient dispersion of conductive filler | Perform SEM/AFM imaging to check for agglomerates; measure conductivity across multiple sample points. | Subject filler dispersions (e.g., SWCNT) to prolonged ultrasound treatment (e.g., 15-30 min at 25-30 kHz) before mixing with the polymer solution [41]. |

| Filler content below percolation threshold | Create a conductivity vs. filler concentration plot to identify the threshold. | Systematically increase the filler content. For SWCNT, aim for 0.5-3.0 wt.% [41]; for PAG, a low amount of 2.5 wt.% can be effective [40]. |

| Poor ionic/electronic connectivity | Use FTIR to confirm chemical interactions between polymer and filler; check for excessive porosity. | Ensure a homogeneous mixture by stirring for extended periods (e.g., 6 hours) and deaerating in a vacuum chamber before film casting [41]. |

Problem: Poor Mechanical Integrity of Hydrogel Scaffolds

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Inadequate crosslinking | Measure the equilibrium swelling ratio; a very high ratio suggests low crosslink density. | Optimize the concentration of crosslinkers like N, N′-Methylene-bis-acrylamide or glutaraldehyde [40] [45]. |

| Unbalanced polymer blend ratio | Conduct mechanical testing (tensile/compression) on blends with varying ratios. | Adjust the ratio of natural and synthetic polymers (e.g., chitosan to acrylamide) to find an optimum for your application [45]. |

| Excessive porosity or pore size | Use Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) to characterize the scaffold's microstructure. | Adjust the fabrication parameters (e.g., freezing temperature, solvent concentration) to control pore size and wall thickness [40]. |

Problem: Inconsistent Cell Response on Electrically Stimulated Scaffolds

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Inhomogeneous surface charge distribution | Map surface potential with Kelvin Probe Force Microscopy (KPFM). | Improve filler dispersion to create a uniform conductive network [41]. |

| Current density too high or too low | Model the electric field across the scaffold; perform a cell viability assay (e.g., MTT) at different stimulation parameters. | Systematically titrate the applied current strength and frequency to find the optimal window for your specific cell type, as excessive current can cause cell death [41]. |

| Unstable electrochemical interface | Monitor pH changes in the culture medium during stimulation. | Use materials with stable electrochemical characteristics or consider using capacitive stimulation to minimize faradaic reactions and pH shifts [41]. |

Table 1: Properties of Chitosan-Based Conductive Composites with Different Fillers

| Filler Material | Filler Content (wt.%) | Matrix Polymer | Key Property Improvements | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polyaniline/Graphene (PAG) | 2.5 | Chitosan/Gelatin | Enhanced electrical & mechanical properties; suitable porosity & biocompatibility for neural tissue engineering. | [40] |

| Single-Wall Carbon Nanotubes (SWCNT) | 0.5 | Chitosan | Tensile strength increased to ~180 MPa; strain at break ~60%. | [41] |

| Single-Wall Carbon Nanotubes (SWCNT) | 0.1 - 3.0 | Chitosan | Electrical conductivity increased from 10⁻¹¹ S/m to 10 S/m. | [41] |

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Advanced Biosensors

| Biosensor Type | Target Analyte | Key Performance Metric | Value | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCF-SPR (ML-optimized) | Refractive Index (General) | Wavelength Sensitivity | 125,000 nm/RIU | [46] |

| PCF-SPR (ML-optimized) | Refractive Index (General) | Amplitude Sensitivity | -1422.34 RIU⁻¹ | [46] |

| SERS Immunoassay | α-Fetoprotein (AFP) | Limit of Detection (LOD) | 16.73 ng/mL | [15] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Fabrication of Conductive Chitosan/Gelatin/PAG Scaffolds

This protocol is adapted from the synthesis of porous conductive scaffolds for nerve tissue engineering [40].

Key Research Reagent Solutions:

- Chitosan Solution: Prepare a 2% (w/v) solution of medium molecular weight chitosan in dilute acetic acid.

- Gelatin Solution: Prepare a 2% (w/v) solution of gelatin (Type A) in deionized water.

- PAG Nanocomposite: Synthesize polyaniline/graphene nanocomposite in advance via in-situ polymerization of aniline in the presence of graphene nanosheets.

Methodology:

- Solution Preparation: Mix the chitosan and gelatin solutions in a desired mass ratio (e.g., 1:1) under vigorous stirring.

- Filler Incorporation: Gradually add the PAG nanocomposite powder to the polymer blend to achieve the target concentration (e.g., 0.5 - 5 wt.%). Continuously stir and sonicate to ensure homogeneous dispersion.

- Crosslinking: Add a crosslinking agent, such as a diluted glutaraldehyde solution (e.g., 1% w/w), to the mixture and stir.

- Porogen Introduction: Add a porogen (e.g., salt crystals, ice crystals) if needed, to create a porous structure.

- Casting and Freezing: Pour the mixture into a mold and freeze at a defined temperature (e.g., -20°C to -80°C).

- Freeze-Drying: Transfer the frozen construct to a freeze-dryer to sublime the solvent and create a porous scaffold.

- Post-processing: Wash the scaffold to remove residual crosslinker and porogen. Neutralize if necessary (e.g., with NaOH solution for chitosan).

Protocol: Machine Learning-Optimized Design of a PCF-SPR Biosensor

This protocol outlines the hybrid approach for designing highly sensitive biosensors [46].

Methodology:

- Initial Design and Simulation:

- Propose an initial design for the Photonic Crystal Fiber (PCF), defining parameters like pitch, air hole diameter, and gold layer thickness.

- Use simulation software (e.g., COMSOL Multiphysics) to model the sensor's performance (effective index, confinement loss) over a range of wavelengths and analyte refractive indices.

- Dataset Generation:

- Systematically vary the design parameters within a defined range using a design-of-experiments approach.

- Run simulations for each parameter set and record the resulting optical properties. This forms your training dataset.

- Machine Learning Model Training:

- Import the dataset into an ML environment (e.g., Python with scikit-learn).

- Train multiple regression models (e.g., Random Forest, Gradient Boosting, Artificial Neural Networks) to predict optical properties (output) from design parameters (input).

- Evaluate model performance using metrics like R² score and Mean Squared Error (MSE).

- Performance Prediction and XAI Analysis:

- Use the best-performing ML model to rapidly predict sensor performance metrics like wavelength and amplitude sensitivity for new, untested design combinations.

- Apply Explainable AI (XAI) methods, such as SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP), to the model to identify which design parameters (e.g., gold thickness, pitch) most significantly influence sensitivity.

- Validation:

- Select the optimal design predicted by the ML model.

- Validate its performance by running a final, conventional simulation to confirm the predicted results.

Workflow and Pathway Visualizations

Troubleshooting Common Immobilization Issues

FAQ: Why is my immobilized enzyme losing activity much faster than the free enzyme?

This is often due to an unsuitable immobilization strategy or suboptimal binding conditions. A poorly designed protocol can lead to uncontrolled multi-point interactions that distort the enzyme's active conformation [47]. To troubleshoot:

- Check enzyme-support orientation: Ensure the active site isn't sterically blocked. For covalent binding, consider site-specific immobilization using engineered tags [47].

- Evaluate mass transfer limitations: For entrapment/encapsulation systems, verify that pore sizes allow adequate substrate and product diffusion [47] [48].

- Assess conformational changes: Use spectroscopic methods (e.g., CD spectroscopy, fluorescence) to monitor structural integrity post-immobilization.

FAQ: How can I prevent enzyme leakage from my entrapment system?

Enzyme leakage occurs when the matrix pore size is too large or the polymer network is unstable [48].

- Optimize polymer concentration and cross-linking density: Increasing polymer concentration or cross-linker percentage can reduce pore sizes.

- Characterize matrix morphology: Use SEM to visualize the fiber network and pore structure of electrospun nanofibers or other matrices [48].

- Consider composite materials: Incorporate materials like iron (II, III) oxide (Fe₃O₄) into polymers (e.g., PMMA) to enhance structural stability, which has been shown to prevent leakage and retain 90% activity after 40 days [48].

FAQ: My covalently immobilized enzyme shows low activity recovery. What could be wrong?

Low activity recovery typically stems from excessive multi-point binding or inappropriate coupling chemistry.

- Review your coupling chemistry: The functional groups on your support should not react with amino acids critical for catalysis. Avoid coupling near the active site [49].

- Control activation level: Over-activation of the support (e.g., with too much glutaraldehyde or EDC/NHS) can lead to excessive, conformation-distorting bonds [49].

- Optimize immobilization time and pH: Shorter times and pH values far from the enzyme's isoelectric point can reduce multi-point attachment intensity.

- Use spacer arms: Incorporate flexible linkers between the support and enzyme to provide greater conformational freedom [49].

FAQ: My 3D-printed biosensor has poor signal output. How can I improve it?

This can result from inefficient enzyme incorporation into the 3D structure or material incompatibility.

- Check material-enzyme compatibility: Ensure the printing material (e.g., photopolymer, PLA) and any post-processing treatments do not denature the enzyme [50] [51].

- Optimize printing parameters: For extrusion-based printing, nozzle temperature, printing speed, and layer height can affect the microporous structure that houses the enzyme [50] [51].