Strategies for Troubleshooting and Minimizing False Positives in Biosensor Assays

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on identifying, troubleshooting, and preventing false positives in biosensor assays.

Strategies for Troubleshooting and Minimizing False Positives in Biosensor Assays

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on identifying, troubleshooting, and preventing false positives in biosensor assays. Covering foundational principles to advanced technological integrations, it explores the multifaceted origins of false signals—from bioreceptor selection and sample matrix effects to transducer limitations. The content details systematic troubleshooting workflows, highlights the role of machine learning and dual-mode sensing for enhanced validation, and offers comparative analyses of optimization strategies. By synthesizing current research and practical methodologies, this resource aims to equip professionals with the knowledge to improve assay robustness, reliability, and clinical translatability.

Understanding the Core Principles and Common Pitfalls of Biosensor Assays

Defining Biosensor Components and Their Role in Signal Generation

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the core components of a biosensor? A biosensor is a self-contained analytical device consisting of five main components [1]:

- Analyte: The specific substance targeted for detection (e.g., glucose, a virus, or a protein biomarker).

- Bioreceptor: A biological element (e.g., enzyme, antibody, aptamer, or nucleic acid) that specifically recognizes and binds to the analyte. This interaction is called biorecognition.

- Transducer: The part that converts the biorecognition event into a measurable signal (e.g., optical or electrical). This energy conversion is called signalization [1].

- Electronics: The circuitry that processes the transducer's signal (e.g., amplifying it or converting it from analog to digital).

- Display: The interface that presents the final result in a user-comprehensible format, such as a numerical value or graph on a screen [1].

Why is understanding biosensor components critical for troubleshooting false positives? False positives occur when a biosensor indicates the presence of a target analyte when it is not actually there. The root cause of such errors can almost always be traced to a problem or interference at one of the core components [1]:

- Bioreceptor Issues: Loss of specificity, for instance from antibody cross-reactivity with similar molecules in a sample, can lead to false signals.

- Transducer & Electronics Issues: Environmental interference, electrical noise, or signal drift can be misinterpreted as a positive result.

- Overall System Design: Inadequate shielding from complex sample matrices (like blood or serum) can cause non-specific adsorption onto the sensor surface, generating a false signal.

What are some emerging technologies to reduce false results? Researchers are developing advanced biosensor designs to improve reliability:

- Dual-Modality Biosensors: These sensors integrate two independent detection methods (e.g., electrochemical and optical) into a single device. The two signals can cross-validate each other, significantly reducing the risk of false positives and negatives [2].

- Bio-Inspired Protection: New designs, like the SENSBIT system, mimic the human gut's protective mechanisms. A 3D nanoporous gold surface and a protective polymer coating shield the sensitive bioreceptor from interference and degradation in complex environments like flowing blood, enhancing signal stability and reliability [3].

- AI-Enhanced Biosensors: Artificial intelligence algorithms can process complex data from biosensors to identify patterns and distinguish specific signals from background noise, though they also require careful validation to avoid new sources of error from biased data or algorithms [1].

Troubleshooting Guide: False Positives

This guide helps you systematically diagnose and address the causes of false positive results. The following table outlines common issues and their solutions related to each biosensor component.

Table 1: Troubleshooting False Positives by Biosensor Component

| Faulty Component | Potential Cause of False Positive | Troubleshooting & Resolution Steps |

|---|---|---|

| Bioreceptor | Cross-reactivity with non-target molecules in the sample matrix [1]. | • Validate bioreceptor specificity against a panel of structurally similar interferents.• Switch to a higher-affinity or more specific bioreceptor (e.g., an aptamer). |

| Transducer | Non-specific adsorption of molecules to the transducer surface, generating a signal [4]. | • Improve the antifouling properties of the sensor interface with coatings like polyethylene glycol (PEG) or melanin-like polydopamine [5] [4].• Use a ratiometric measurement technique that internally corrects for background drift [4]. |

| Sample & Assay | Interfering substances in the complex sample matrix (e.g., proteins in blood) [4]. | • Dilute the sample or implement a sample purification/pre-treatment step.• Use standard addition methods to account for matrix effects. |

| System Design | Inability to self-validate the result due to a single measurement modality [2]. | • Adopt a dual-modality biosensor design that uses two different physical principles (e.g., electrochemical and optical) to detect the same analyte, providing built-in cross-validation [2]. |

Experimental Protocols for Diagnosis

Protocol 1: Validating Specificity via Cross-Reactivity Screening Purpose: To confirm that your biosensor's bioreceptor does not respond to molecules structurally related to your target analyte. Materials: Purified target analyte, structurally similar potential interferents, biosensor, buffer. Procedure:

- Prepare separate solutions of your target analyte and each potential interferent at physiologically relevant concentrations.

- Measure the biosensor's response to the buffer alone (blank).

- Measure the response to each interferent solution individually.

- Compare the signal generated by the interferents to the signal from the target. A significant response to an interferent indicates cross-reactivity. Interpretation: A specific biosensor should show a strong signal only for the target analyte and negligible signals for interferents.

Protocol 2: Assessing Matrix Effects with Standard Addition Purpose: To determine if components of the sample matrix itself are contributing to the false positive signal. Materials: Test sample (e.g., serum, blood), purified target analyte, buffer. Procedure:

- Measure the biosensor's response to the unspiked sample (this is your background signal).

- Spike the sample with a known, low concentration of the purified target analyte.

- Measure the biosensor's response to the spiked sample.

- Calculate the recovery:

(Measured concentration in spiked sample - Measured concentration in unspiked sample) / Known spiked concentration * 100%. Interpretation: A recovery value significantly different from 100% indicates substantial matrix interference, which may be causing false positives [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential materials used in modern biosensor development and troubleshooting.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Biosensor Development

| Item | Function in Biosensor Development | Specific Example & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Aptamers | Synthetic single-stranded DNA or RNA molecules that act as bioreceptors; offer high specificity and stability [5]. | Used for detecting hazards in food; can be selected via SELEX to bind diverse targets from small molecules to whole cells [5]. |

| Nanoporous Gold Electrodes | A nanostructured material providing a high surface area for bioreceptor immobilization, enhancing signal strength and stability [3]. | Used as a 3D scaffold in the SENSBIT system to protect molecular recognition elements and enable long-term monitoring in blood [3]. |

| Organic Electrochemical Transistors (OECTs) | Signal transducers that provide massive signal amplification (1000-7000x) and improve the signal-to-noise ratio [7]. | Used to amplify weak signals from enzymatic or microbial fuel cells for highly sensitive detection of targets like lactate or arsenite [7]. |

| Melanin-like Coatings (e.g., Polydopamine) | Versatile, biocompatible coatings that improve surface adhesion and provide antifouling properties [5]. | Used to modify electrode surfaces, reducing non-specific binding in environmental and food monitoring sensors [5]. |

| CRISPR/Cas Systems | Provides an enzymatic mechanism for signal amplification, enabling extremely high sensitivity and specificity for nucleic acid detection [4]. | Integrated into lateral flow assays for attomolar-level detection of viral genomic DNA or RNA, as demonstrated during the COVID-19 pandemic [4]. |

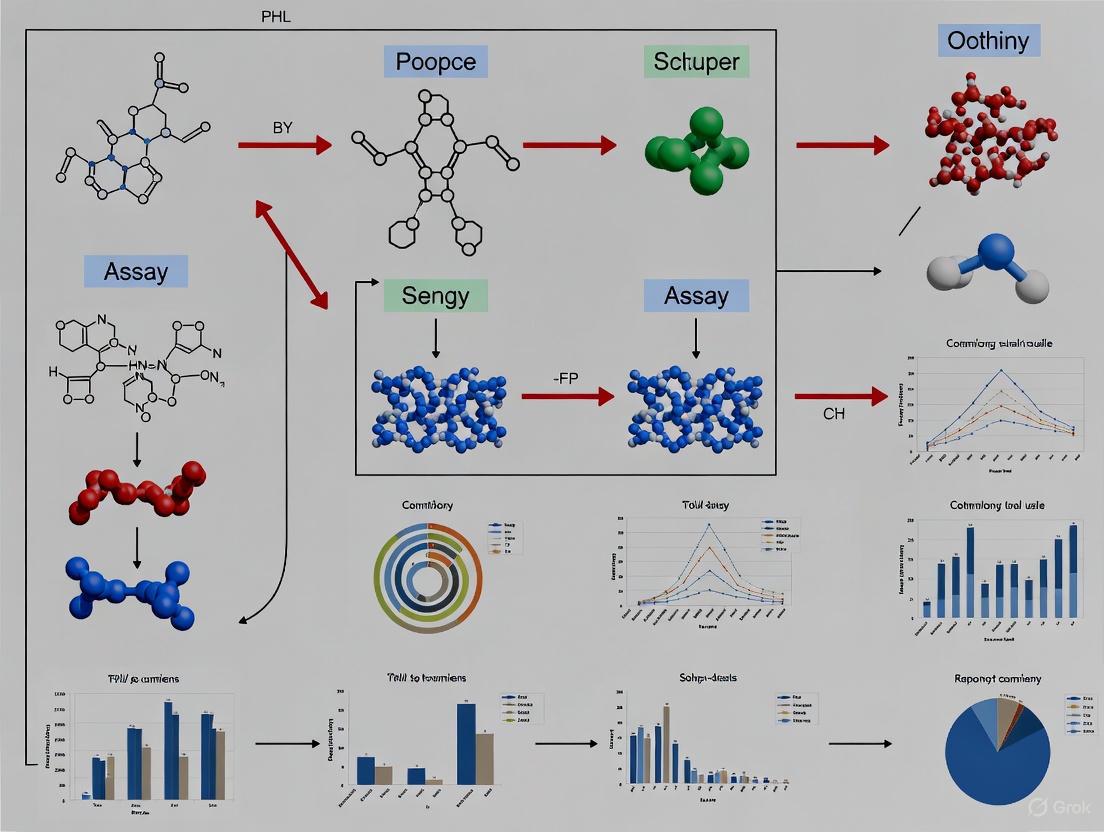

Technical Diagrams

Diagram 1: Biosensor Core Components and False Positive Triggers

This diagram illustrates the signal flow through the core components of a biosensor and pinpoints where specific failures can lead to a false positive result.

Diagram 2: Dual-Modality Biosensor Cross-Validation Workflow

This workflow shows how a dual-modality biosensor provides built-in cross-validation. An interferent may trigger one signal path, but the lack of a corresponding signal from the second, independent path flags the result as a potential false positive.

Systematic Classification of False Positive Triggers and Root Causes

False positive results present a significant challenge in biosensor applications, potentially leading to incorrect diagnostic, environmental, or research conclusions. Understanding their triggers and root causes is essential for developing robust analytical systems. False positives occur when a biosensor incorrectly indicates the presence of a target analyte, and they can arise from multiple sources including biological recognition elements, transducer systems, sample matrix effects, and operational protocols [1].

The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the critical implications of false results in diagnostic systems, underscoring that no diagnostic tool is infallible [1]. Both conventional and AI-powered biosensors remain susceptible to these inaccuracies, which can stem from various causes including cross-reactivity, environmental interference, signal noise, calibration difficulties, and non-specific binding events [1] [2].

Classification of False Positive Triggers

Biological Recognition Elements

Biological recognition elements form the foundation of biosensor specificity, yet they represent a primary source of false positive triggers.

Antibody-Based Recognition Issues: Antibodies, while highly specific, can generate false positives through several mechanisms. Cross-reactivity with structurally similar molecules represents a major concern, particularly when antibodies bind to epitopes shared among different analytes. Batch-to-batch variability in antibody production can also lead to inconsistent sensitivity and specificity between production lots. Furthermore, degradation of antibodies during storage or use compromises their binding specificity, potentially increasing non-specific interactions [8].

Nucleic Acid Recognition Challenges: DNA-based recognition systems, including hybridization probes and aptamers, face distinct false positive triggers. Non-specific hybridization can occur when probe sequences interact with partially complementary targets under suboptimal hybridization conditions. The susceptibility of DNA to nuclease degradation in complex sample matrices can generate fragments that produce detectable signals. Additionally, variations in temperature, pH, or ionic strength significantly impact hybridization efficiency and specificity [8].

Enzyme-Related False Positives: Enzyme-based biosensors can produce false positives when endogenous enzymes in samples catalyze similar reactions to the recognition enzyme, or when sample components interfere with the enzymatic reaction. Enzymes also require strict environmental control, particularly precise temperature regulation, to maintain catalytic specificity [8].

Table: Classification of False Positives by Biological Recognition Element

| Recognition Element | Primary False Positive Triggers | Common Analytical Contexts |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | Cross-reactivity, Batch variability, Degradation | Clinical diagnostics, Food safety |

| Nucleic Acids | Non-specific hybridization, Degradation, Suboptimal conditions | Genetic testing, Pathogen detection |

| Enzymes | Interfering substrates, Environmental sensitivity, Endogenous enzymes | Metabolite monitoring, Environmental sensing |

Transducer and Signal Generation Mechanisms

The transducer component converts biological recognition events into measurable signals, and its limitations constitute another major category of false positive sources.

Optical Biosensor Artifacts: In surface plasmon resonance (SPR) systems, non-specific adsorption of materials to the sensor surface can generate signals indistinguishable from specific binding events. Contamination of optical components or light source instability may create baseline drift or spurious signals. For fluorescence-based systems, autofluorescence from sample components or container materials can produce background signals misinterpreted as positive results [9] [10].

Electrochemical Biosensor Interferences: Electroactive compounds present in samples can undergo oxidation or reduction at electrode surfaces, generating currents mistaken for target detection. Electrode fouling through protein adsorption or other matrix components alters electrode properties and response characteristics. Additionally, reference electrode potential drift leads to miscalibration and incorrect signal interpretation [2] [8].

Piezoelectric and Thermal Transducers: Mass-based sensors like cantilevers respond non-specifically to viscosity changes or non-target adsorption. Thermal biosensors detect heat from non-specific biochemical reactions or environmental temperature fluctuations [11].

Sample Matrix and Environmental Factors

Complex sample matrices introduce numerous interferents that can trigger false positive responses across various biosensor platforms.

Table: Sample Matrix Interferents and Their Effects

| Interferent Category | Example Interferents | Biosystems Affected |

|---|---|---|

| Biomolecules | Proteins, Lipids, Carbohydrates | Optical, Electrochemical, Mass-based |

| Small Molecules | Medications, Metabolites, Antioxidants | Electrochemical, Enzyme-based |

| Ionic Components | High salt concentrations, Metal ions | Electrochemical, Nucleic acid-based |

| Particulate Matter | Cells, Debris, Bubbles | Optical, Mass-based |

Biosensor performance is also compromised by improper storage conditions, temperature fluctuations during analysis or transport, and humidity variations that affect reagent stability [1] [12]. In resource-limited settings, additional challenges include inadequate cold chain maintenance, power supply instability affecting electronic components, and limited quality control infrastructure [12].

Troubleshooting Guide: Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: How can I distinguish true TLR4 activation from false positives in cell-based biosensor assays?

Challenge: Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) from different bacterial sources can produce varying signaling patterns that may be misinterpreted. For instance, LPS from E. coli and S. minnesota induce distinct dynamic mass redistribution (DMR) profiles in TLR4 biosensors [9].

Solution: Implement a multi-pronged verification approach:

- Include control experiments with TLR4-specific antagonists like TAK-242 to confirm receptor-specific signaling

- Use multiple LPS chemotypes to compare response patterns

- Employ cytoskeletal inhibitors (cytochalasin B, latrunculin A, nocodazole) to verify that signals depend on cellular structural reorganization

- Validate findings in control cell lines lacking TLR4 expression to identify non-specific responses

Experimental Protocol: TLR4 Signaling Specificity Verification

- Culture HEK293 TLR4/MD-2/CD14 reporter cells in antibiotic-free media

- Passage cells every 48-72 hours, maintaining ≤80% confluence to prevent background FRET

- Plate cells in 96-well plates at 20,000 cells/well 24 hours before treatment

- Prepare LPS dilutions in Opti-MEM and equilibrate to room temperature

- Mix samples with Lipofectamine 2000 (1.5μl reagent + 28.5μl Opti-MEM, 5min incubation)

- Combine LPS and transfection mixtures, incubate 30min at room temperature

- Divide mixtures among 3 replicate wells

- After 48 hours, trypsinize and fix cells in 2% PFA for flow cytometry analysis

- Include TAK-242 controls and TLR4-negative cell lines in each experiment [9]

FAQ 2: What strategies can reduce false positives in nucleic acid detection using SPR biosensors?

Challenge: Non-specific DNA adsorption and reflective angle misinterpretation can generate false positives in SPR-based DNA detection [10].

Solution: Apply machine learning classification to differentiate specific binding from non-specific adsorption:

- Collect comprehensive reflective angle data across multiple gold surface thicknesses

- Utilize feature selection algorithms (t-SNE) to identify patterns associated with true binding events

- Implement random forest classifiers that achieve 94% accuracy in DNA classification tasks

- Normalize data using min-max normalization before analysis to improve classifier performance

Experimental Protocol: ML-Enhanced DNA Detection Validation

- Prepare gold surfaces with varying thicknesses for SPR analysis

- Measure reflective angles of 632.8nm light at 0.05° intervals from 40°-89°

- Collect data at three binding stages: bare surface, immobilized ssDNA, and hybridized dsDNA

- Apply min-max normalization to reflective angle data

- Implement t-SNE feature extraction to reduce dimensionality and identify clustering patterns

- Train random forest classifiers on labeled datasets of known true and false positive outcomes

- Validate model performance using 10-fold cross-validation

- Deploy optimized classifier to distinguish specific DNA binding from non-specific adsorption [10]

FAQ 3: How can I minimize cross-reactivity in antibody-based biosensors for mycotoxin detection?

Challenge: Antibodies against mycotoxins like aflatoxins, ochratoxin A, and zearalenone may cross-react with structurally similar compounds in food samples [8].

Solution: Implement dual modality biosensing with cross-validation:

- Combine electrochemical and optical detection methods to verify results through two independent mechanisms

- Incorporate aptamer-based recognition elements as they offer higher batch-to-batch consistency

- Use sample pre-treatment to remove interfering compounds

- Employ signal amplification strategies with nanomaterials that improve specificity

Experimental Protocol: Dual Modality Mycotoxin Detection

- Functionalize electrode surface with anti-mycotoxin antibodies or aptamers

- For optical channel, integrate SERS-active nanoparticles functionalized with same recognition element

- Apply sample to biosensor and record both electrochemical impedance and SERS signals

- Process signals independently through separate transduction pathways

- Compare results from both modalities - concordant signals indicate true positives

- Discordant signals suggest interference or cross-reactivity requiring further investigation

- Validate against chromatographic standards for confirmation [2] [8]

FAQ 4: What approaches can identify instrument-generated false positives versus true biological signals?

Challenge: Signal drift, electronic noise, and transducer artifacts can mimic true biological responses [11].

Solution: Implement theory-guided deep learning to distinguish instrument artifacts from biological signals:

- Record dynamic biosensor responses rather than single endpoint measurements

- Apply data augmentation to address sparsity in calibration datasets

- Use cost function supervision incorporating biosensor theory to guide machine learning models

- Validate with known standards across the concentration range to establish signal patterns

Experimental Protocol: Artifact Identification Using Dynamic Signals

- Collect time-series data from biosensor during analyte detection

- Augment dataset through synthetic data generation to address class imbalance

- Train recurrent neural networks (RNN) with theory-guided constraints

- Incorporate domain knowledge of binding kinetics into model cost function

- Use theory-guided RNN classifiers to identify signal patterns characteristic of instrument artifacts

- Achieve up to 98.5% accuracy in distinguishing true signals from false positives

- Implement continuous monitoring with dynamic signal analysis to reduce time delay [11]

Research Reagent Solutions for False Positive Mitigation

Table: Essential Reagents for False Positive Control

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in False Positive Control |

|---|---|---|

| Specific Inhibitors | TAK-242 (TLR4), Cytochalasin B (actin) | Confirm pathway-specific signaling and cytoskeletal dependence |

| Cytoskeletal Inhibitors | Latrunculin A, Nocodazole | Verify morphological changes in whole-cell biosensors |

| Binding Blockers | BSA, Casein, Synthetic blocking peptides | Reduce non-specific adsorption to surfaces |

| Reference Materials | LPS from different bacterial species | Distinguish specific response patterns from non-specific effects |

| Surface Chemistry | PEG-based coatings, Zwitterionic polymers | Minimize non-specific binding in optical and electrochemical sensors |

| ML Training Standards | Labeled datasets of true/false positives | Train classifiers for automatic artifact recognition |

Visualization of False Positive Mitigation Workflows

Comprehensive False Positive Diagnosis Pathway

Dual Modality Biosensor Verification System

Systematic classification of false positive triggers enables researchers to develop targeted mitigation strategies that enhance biosensor reliability. The integration of dual modality sensing, theory-guided machine learning, and comprehensive troubleshooting protocols provides a multifaceted approach to false positive reduction. As biosensor technologies evolve toward greater sensitivity and automation, robust false positive identification and management will remain essential for research validity, clinical diagnostics, and environmental monitoring applications.

Analyzing the Impact of Bioreceptor-Antigen Interactions on Specificity

Core Concepts: Bioreceptors and Specificity

What are bioreceptors and why are they critical for biosensor specificity?

Bioreceptors are biological or biomimetic molecules immobilized on a biosensor that specifically recognize and bind to a target analyte (antigen). This specific interaction is the foundation of biosensor specificity, as the bioreceptor determines which molecules will be detected. Common bioreceptors include antibodies, enzymes, nucleic acids, aptamers, and whole cells [1] [13].

The specificity of a biosensor refers to its ability to accurately detect and measure a target analyte while ignoring interfering substances in a sample. This characteristic is primarily determined by the selective binding affinity between the bioreceptor and its target antigen [14].

What are the most common types of bioreceptors used in diagnostic assays?

Table 1: Common Bioreceptor Types and Their Characteristics

| Bioreceptor Type | Description | Key Advantages | Common Sources of False Positives |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antibodies [14] | Y-shaped proteins produced by the immune system that bind to specific antigens. | High specificity and affinity; well-established immobilization methods. | Cross-reactivity with similar epitopes; non-specific adsorption. |

| Engineered Antibody Fragments [14] (e.g., scFv, Fab, nanobodies) | Genetically modified fragments of full antibodies. | Smaller size can improve binding site access and signal; often more stable. | Similar to full antibodies, though reduced Fc region can minimize some non-specific binding. |

| Enzymes [1] | Proteins that catalyze specific biochemical reactions. | Signal amplification via catalytic activity. | Cross-talk with similar substrates or inhibitors in sample. |

| Nucleic Acids [1] [13] (DNA, RNA, aptamers) | Strands with specific sequences that bind complementary strands (hybridization) or specific targets (aptamers). | High stability; synthetic production; aptamers can be selected for a wide range of targets. | Non-specific hybridization; secondary structure formation in aptamers. |

| Whole Cells [1] | Microorganisms or eukaryotic cells used as sensing elements. | Can report on functional responses (e.g., toxicity). | Often lack the selectivity of enzyme- or antibody-based sensors. |

Troubleshooting False Positives: FAQs and Guides

Our assay consistently produces false positives. How can we determine if the cause is bioreceptor-related?

A systematic investigation is required to isolate the variable of the bioreceptor-antigen interaction. The following workflow diagram outlines a recommended diagnostic process.

Experimental Protocol: Diagnosing Bioreceptor-Related False Positives

- Blank Solution Test: Run the biosensor assay using the complete protocol with a sample matrix that is identical to your test samples but is guaranteed to contain zero target analyte. A positive signal indicates significant non-specific binding or interference from the sample matrix [15].

- Cross-Reactivity Test: Repeat the assay with a sample containing a known, structurally similar compound (an interferent) that is not the target analyte. A positive signal confirms the bioreceptor lacks sufficient specificity and is cross-reacting [14].

- Bioreceptor Batch Test: Repeat the original assay with a fresh, properly validated batch of the bioreceptor. If the false positive signal disappears, the original bioreceptor batch may have been degraded, denatured, or contaminated [1].

We use antibody bioreceptors. What are the primary causes of false positives in immunosensors?

False positives in immunosensors (antibody-based biosensors) often stem from the following issues:

- Cross-Reactivity: The antibody binds to epitopes on non-target molecules that are structurally similar to the intended antigen [14]. This is a primary failure mode of specificity.

- Non-Specific Adsorption (NSA): Proteins or other components in the sample matrix adhere to the sensor surface or parts of the antibody (like the Fc region) through non-specific interactions (e.g., hydrophobic, ionic), generating a signal indistinguishable from the specific binding event [14] [15].

- Incomplete Washing: Failure to adequately remove unbound or loosely bound molecules after the binding step can leave behind non-specifically trapped analytes or interferents [1].

- Antibody Degradation: Improper storage or handling can lead to antibody aggregation, denaturation, or fragmentation, which can expose hydrophobic regions and increase non-specific binding [1].

How can antibody engineering help minimize false positives?

Antibody engineering creates optimized fragments that can enhance specificity and reduce non-specific binding. The following table details common engineered formats.

Table 2: Engineered Antibody Fragments for Enhanced Biosensing

| Engineered Format | Description | Mechanism for Reducing False Positives | Common Application in Biosensors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single-Chain Variable Fragment (scFv) | The variable regions of the heavy and light chains linked by a peptide linker. | Smaller size allows for denser immobilization and better orientation, reducing nonspecific binding from the Fc region. | Electrochemical and optical immunosensors for small molecules [14]. |

| Antigen-Binding Fragment (Fab) | A fragment containing one constant and one variable domain of both the heavy and light chains. | Lacks the Fc region, eliminating a major source of non-specific adsorption. | Diagnostic assays requiring high stability [14]. |

| Nanobodies (VHH) | Single-domain antibodies derived from heavy-chain-only antibodies in camellids. | Extremely small size and simple structure improve stability and access to concave epitopes, enhancing specificity. | Detection of complex targets like viruses and cancer biomarkers [14]. |

| Bispecific Antibodies | Antibodies engineered to have two different antigen-binding sites. | Can be designed for "AND-gate" logic, requiring two antigens for a signal, drastically increasing specificity. | Highly specific cell detection and targeted therapies [14]. |

Beyond the bioreceptor itself, what other factors can lead to false signals?

The bioreceptor is only one component of the system. The following factors are also critical:

- Transducer Limitations: The physical transducer (e.g., FET, electrode) may be sensitive to environmental changes like pH, temperature, or ionic strength, producing a signal shift that can be misinterpreted [1] [15]. Sensor design and surface topology can also limit the probability of target molecules adsorbing to the active detection area [15].

- Assay Conditions: Suboptimal pH, ionic strength, or temperature can disrupt the precise binding kinetics of the bioreceptor-antigen interaction, promoting non-specific binding [1] [16].

- Sample Matrix Effects: Complex samples (e.g., blood, serum, food homogenates) contain numerous proteins, lipids, and other molecules that can foul the sensor surface or interfere with the binding reaction [13].

Advanced Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Surface Passivation to Minimize Non-Specific Adsorption

Objective: To block reactive sites on the sensor surface surrounding the immobilized bioreceptor to prevent non-specific binding of sample components.

Reagent Solutions:

- Blocking Agent: Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) at 1-5% w/v, casein, or commercial blocking buffers.

- Wash Buffer: Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) with a mild detergent (e.g., 0.05% Tween-20).

Methodology:

- After immobilizing the bioreceptor on the sensor surface, rinse the surface three times with wash buffer.

- Incubate the sensor with the blocking solution for 30-60 minutes at room temperature.

- Thoroughly wash the sensor surface with wash buffer to remove any unbound blocking agent.

- The sensor is now ready for use. Validate the passivation by testing with a blank sample.

Protocol: Using Isotype Controls for Immunosensors

Objective: To distinguish specific signal from non-specific background signal in antibody-based assays.

Reagent Solutions:

- Isotype Control: An antibody of the same isotype (e.g., IgG1, IgG2a) and from the same host species as your primary bioreceptor antibody, but with no specificity for your target antigen.

Methodology:

- Run your assay in parallel on two identical sensor platforms.

- On the test sensor, immobilize the specific primary antibody.

- On the control sensor, immobilize the isotype control antibody at the same concentration.

- Expose both sensors to the same sample and run the identical protocol.

- The signal generated by the isotype control sensor represents the non-specific background. Subtract this value from the signal of the test sensor to obtain the specific signal.

Protocol: Assessing Binding Kinetics and Specificity using a SOI-FET Biosensor

Objective: To theoretically model and understand the probabilistic nature of detection and how it impacts accuracy, particularly at low analyte concentrations.

Background: The adsorption of "antibody + antigen" (AB+AG) complexes on a sensor surface like a Silicon-on-Insulator Field-Effect Transistor (SOI-FET) is a random event influenced by diffusion, concentration, and temperature. The probability of a target molecule hitting the sensor surface is described by the Poisson distribution [15]. At very low concentrations (e.g., femtomolar), this probability becomes very low, leading to false negatives. Conversely, non-specific binding of background particles can lead to false positives [15].

Methodology & Visualization: The logical flow of the detection process and its failure points can be modeled as follows:

Key Consideration: This model highlights that achieving a reliable signal requires not only specific bioreceptors but also a system design that maximizes the probability of correct complex adsorption. Using a larger number of biosensors on a single chip can improve accuracy and reduce detection time by increasing the total capture area and statistical probability of detection [15].

Assessing Sample Matrix Effects and Interfering Substances in Complex Fluids

Matrix effects present a significant challenge in the translation of biosensors from controlled laboratory settings to clinical use. These effects refer to the interference caused by the complex components of biological samples, which can alter the sensor's response and lead to inaccurate results, including false positives and negatives [17]. The core of the problem lies in the fact that while a biosensor may demonstrate exceptional sensitivity and a low limit of detection (LOD) under pristine buffer conditions, this performance often degrades when the sensor is applied to real-world samples such as serum, urine, sputum, or saliva [17] [18]. Molecules present in these matrices can interact with the analyte, the sensor surface, or the biorecognition elements, causing nonspecific adsorption, signal suppression, signal enhancement, or cross-reactivity [17] [19]. Overcoming these effects is therefore not merely an optimization step but a fundamental requirement for developing reliable diagnostic biosensors.

FAQs on Matrix Effects and Interference

Q1: What are the most common sources of interference in complex biological fluids? Interference in complex fluids can arise from a wide variety of sources, which can be broadly categorized as follows [19]:

- Analyte-Independent Interference: This includes factors related to sample handling and general composition, such as hemolysis (rupture of red blood cells), lipemia (high lipid content), the choice of anticoagulants in blood samples, and the overall viscosity of the sample.

- Analyte-Dependent Interference: This involves specific compounds within the sample that actively interfere with the assay's biochemistry. Key examples include:

- Human Anti-Animal Antibodies (HAAA): Such as Human Anti-Mouse Antibodies (HAMA), which can bind to assay antibodies and create a signal.

- Autoantibodies: Like the rheumatoid factor, which targets the Fc portion of immunoglobulin G (IgG).

- Cross-reactivity: Occurs when the biorecognition element (e.g., an antibody) binds to molecules structurally similar to the target analyte.

- Exogenous Interference: This category covers external factors, including:

- Drugs and Metabolites: Common examples are biotin supplements (which interfere with streptavidin-biotin systems) and certain corticosteroids.

- Sample Carryover: Contamination from previous runs in automated systems.

- Assay Conditions: Suboptimal pH or ionic strength of the assay buffer.

Q2: How does the sample matrix lead to false positives and false negatives? The matrix causes inaccurate results through several distinct mechanisms [1] [19]:

False Positives are typically caused by:

- Nonspecific Binding: Matrix proteins or other molecules adsorbing to the sensor surface, creating a background signal.

- Cross-reactivity: The capture agent binding to non-target molecules with similar epitopes.

- Interfering Antibodies: HAAAs can bridge capture and detection antibodies in a sandwich assay, mimicking the presence of the target analyte.

False Negatives are often the result of:

- Signal Suppression: Matrix components can sterically hinder access to the sensor surface or quench the output signal (e.g., in optical assays).

- The "Hook Effect": In sandwich assays, extremely high analyte concentrations can saturate both the capture and detection antibodies, preventing the formation of the "sandwich" complex and leading to a falsely low signal.

- Analyte Degradation: Enzymes in the sample may break down the target analyte before it can be detected.

Q3: Why do some biosensors work perfectly in buffer but fail with patient samples? This failure is primarily due to the "matrix effect," a term that encapsulates all the ways a complex sample differs from a simple buffer [17] [18]. Biological fluids contain a high and variable concentration of proteins, lipids, salts, and cells. These components can foul the sensor surface, change the local pH or ionic environment at the sensor interface (critically affecting charge-based sensors like nanowires or electrochemical sensors), or contribute to a high background signal in optical assays due to autofluorescence or turbidity [17] [20]. In essence, the controlled, "clean" environment of the buffer is replaced by a "dirty" and unpredictable one in a clinical sample.

Q4: What are the best strategies to identify and mitigate matrix effects? A systematic approach is required to identify and overcome matrix interference [19]:

Identification:

- Spike-and-Recovery Experiments: This is a cornerstone validation test. A known amount of analyte is spiked into the sample matrix, and the measured concentration is compared to the expected value. Recovery outside the 80-120% range indicates interference.

- Parallel Analysis: Comparing results with a reference method (e.g., LC-MS or a different immunoassay format) helps verify accuracy.

- Linearity-of-Dilution: Diluting the sample and assessing if the measured analyte concentration decreases linearly can reveal matrix effects.

Mitigation:

- Sample Pre-treatment: Dilution, filtration, or extraction can reduce the concentration of interferents.

- Surface Blocking: Using blockers like BSA, casein, or normal serum to saturate non-specific binding sites on the sensor surface.

- Improved Assay Design: Using matched antibody pairs to reduce cross-reactivity, or switching assay formats (e.g., to mitigate the hook effect).

- Choice of Biosensor Technology: Label-free optical sensors like Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) are sensitive to matrix effects, while magnetic nanosensors have been shown to be largely matrix-insensitive, as they are unaffected by sample turbidity, pH, or ionic strength within a broad range [20].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Problems and Solutions

The table below outlines common symptoms, their potential causes, and actionable solutions.

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Troubleshooting Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High background signal/noise | Nonspecific adsorption of matrix proteins to sensor surface. | Improve surface blocking with BSA, casein, or commercial blockers; include a reference sensor; use more stringent wash buffers [21] [19]. |

| Signal drift during measurement | Sensor surface not equilibrated; bulk refractive index shifts (SPR). | Equilibrate the sensor surface with running buffer overnight or with multiple injections; match the composition of the sample and running buffers [21]. |

| Low signal recovery in spiked samples | Matrix components suppressing signal or degrading analyte. | Dilute the sample to reduce interferent concentration; add enzyme inhibitors; use a sample purification step [19]. |

| Inconsistent results between replicates | Sample carryover or dispersion; heterogeneous or viscous sample. | Increase wash steps between runs; ensure proper sample mixing and homogenization; implement a sample liquefaction step for sputum/mucus [21] [22]. |

| Falsely low signal at high analyte concentration (Hook Effect) | Saturation of both capture and detection antibodies in a sandwich assay. | Test sample at multiple dilutions; switch to a competitive assay format or an assay design with a larger dynamic range [19]. |

| Poor sensitivity compared to buffer tests | Fouling of sensor surface, limiting analyte access. | Implement robust antifouling surface chemistries (e.g., PEGylation); use nanostructured surfaces to minimize fouling [17]. |

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Interference

Protocol: Spike-and-Recovery Experiment

This protocol is a fundamental test to quantify matrix interference [19].

Objective: To determine whether components in a sample matrix are suppressing or enhancing the detected signal of the target analyte.

Materials:

- Neat (unspiked) sample matrix (e.g., pooled human serum)

- Assay buffer

- Pure analyte standard

- Standard equipment for your biosensor (plate reader, etc.)

Method:

- Prepare three sets of samples in duplicate or triplicate:

- Neat Matrix: The sample matrix with no added analyte.

- Spiked Buffer (Control): A known concentration of analyte spiked into the standard assay buffer.

- Spiked Matrix (Test): The same known concentration of analyte spiked into the sample matrix.

- It is recommended to test at least three different analyte concentrations (low, medium, and high).

- Run all samples according to your established biosensor assay protocol.

- Calculation: Determine the percentage recovery using the formula:

- % Recovery = ( [Spiked Matrix] - [Neat Matrix] ) / [Spiked Buffer] × 100

Interpretation of Results:

| % Recovery | Interpretation |

|---|---|

| 80% - 120% | Acceptable, minimal interference. |

| < 80% | Signal suppression (indicative of matrix interference). |

| > 120% | Signal enhancement (possible interference or cross-reactivity). |

Case Study: Overcoming Sputum Matrix Effects with a Paper Biosensor

Background: Detecting pyocyanin (PYO) in sputum for diagnosing Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections is challenging due to the highly viscous and complex sputum matrix, which causes significant variability in traditional competitive ELISAs [22].

Innovative Solution: A paper-based biosensor was developed to mitigate these effects.

Workflow Diagram:

Key Advantages and Outcomes:

- Rapid Results: The entire assay is completed within 6 minutes, compared to 2 hours for ELISA.

- Reduced Matrix Effects: The paper platform and mild enzymatic liquefaction (using hydrogen peroxide) minimized the variability caused by the sputum matrix, leading to a lower relative standard deviation than ELISA.

- Point-of-Care Applicability: The simplicity and speed make it a strong candidate for bedside testing [22].

Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential reagents used to combat interference in biosensor assays, as discussed in the cited research.

| Research Reagent | Function in Troubleshooting | Brief Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | Blocking Agent | Used to saturate non-specific binding sites on the sensor surface, reducing background noise from protein adsorption [19] [22]. |

| Casein Buffer | Blocking Agent | An effective alternative to BSA for blocking, often used in immunoassays to prevent non-specific binding [19]. |

| Heterophilic Blocking Reagents | Interference Blocker | Specifically designed to bind and neutralize Human Anti-Mouse Antibodies (HAMA) and other heterophilic antibodies, preventing false positives [19]. |

| Polystyrene sulfonate (PSS) | Sensor Platform Material | Used to functionalize paper in biosensors, creating a reservoir for reagents like antibody-conjugated nanoparticles [22]. |

| Streptavidin-Coated Magnetic Nanoparticles | Signal Generation & Separation | Used in matrix-insensitive assays (e.g., GMR sensors). The magnetic tag is detected without interference from optical properties of the sample, and magnetic fields facilitate washing and separation [20]. |

| PC1-BSA Bioconjugate | Competing Antigen | A synthesized molecule used in competitive assays (e.g., for pyocyanin detection) where it competes with the analyte for binding sites on the detection antibody [22]. |

Comparison of Biosensor Technologies and Matrix Effects

Different biosensor transduction principles exhibit varying degrees of susceptibility to matrix effects. The table below summarizes the advantages and disadvantages of several common technologies in this context.

| Biosensor Technology | Key Advantage | Susceptibility to Matrix Effects | Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) [17] [18] | Real-time, label-free kinetic data. | High. Sensitive to bulk refractive index changes from sample matrix; surface fouling. | Reference channel subtraction; extensive buffer matching; advanced antifouling coatings. |

| Electrochemical (Amperometric) [17] [18] | Simple design, highly miniaturizable. | High. Sensitive to pH and ionic strength; surface fouling limits access. | Use of mediators; protective membranes; sample dilution. |

| Magnetic Nanosensor (GMR) [20] | Highly matrix-insensitive. | Very Low. Unaffected by sample turbidity, autofluorescence, pH (4-10), or ionic strength. | Requires minimal sample pre-treatment; no complex mitigation needed. |

| Lateral Flow Assays (LFA) [17] | Low cost, rapid, simple use. | Medium. Viscosity affects flow; non-specific binding can occur. | Optimized sample pad chemistry; inclusion of detergent in buffers. |

| Biolayer Interferometry (BLI) [23] | Label-free, "dip-and-read", real-time kinetics. | Medium. Can be sensitive to nonspecific binding and refractive index shifts. | Includes onboard shake to reduce nonspecific binding; reference sensor subtraction. |

The Role of Transducer Stability and Non-Specific Binding in Signal Noise

Troubleshooting Guide: Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What are the primary sources of signal noise and false positives in biosensor assays?

The main sources are non-specific binding (NSB) of molecules to the sensor surface and transducer instability caused by environmental factors. NSB occurs when biomolecules interact with the sensor through means other than the intended specific biorecognition, creating a false signal that is indistinguishable from a true positive [1] [24]. Transducer instability can arise from temperature fluctuations, electromagnetic interference, or poor power supply regulation, which introduce noise and drift into the measurement signal [25] [26] [27].

Q2: How can I experimentally confirm that my signal is caused by non-specific binding and not a true positive?

You can employ a dielectrophoretic (DEP) repulsion method. This technique uses a calibrated electric field to apply a controlled physical force to bound particles or molecules. Specifically bound analytes, which have stronger binding affinity, will remain attached, while non-specifically bound entities, with weaker interactions, will be detached [24]. A significant drop in signal post-DEP application confirms the presence of NSB. Alternatively, using surface plasmon resonance (SPR) or similar techniques to monitor binding kinetics in real-time can help, as NSB often shows fast, nonsensical on/off rates compared to the characteristic kinetics of specific binding.

Q3: What practical steps can I take to reduce non-specific binding in my assay?

The following table summarizes key reagents and their functions for minimizing NSB [28]:

Table: Research Reagent Solutions for Minimizing Non-Specific Binding

| Reagent | Function/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|

| Betaine | Organic additive that disrupts secondary structure formation in primers and templates, improving assay specificity. |

| Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) | Helps in strand separation of DNA and inhibits nonspecific primer interactions. |

| Uracil-DNA-Glycosylase (UDG) | Enzyme that degrades uracil-containing DNA from previous amplification reactions, effectively controlling carry-over contamination. |

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | Can be used to create a hot-start effect, suppressing enzyme activity until the optimal temperature is reached, thus reducing nonspecific amplification. |

| PEG (Polyethylene Glycol) | Used in surface backfilling to create a dense, inert layer that sterically hinders non-specific adsorption of proteins and other biomolecules. |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | A common blocking agent that occupies potential non-specific binding sites on the transducer surface. |

Q4: My biosensor signal is unstable and drifts over time. How can I troubleshoot the transducer's stability?

Follow this systematic approach:

- Verify the Power Supply: Use a multimeter to ensure the power source provides a stable, clean voltage that matches the transducer's specifications. Noise or voltage fluctuations from the supply can directly manifest as signal noise [25].

- Inspect for Environmental Interference: Ensure the transducer is properly shielded and grounded. Keep it away from sources of electromagnetic interference (EMI) such as motors, power cables, and radio transmitters [25] [26].

- Analyze Environmental Conditions: Check that the operating temperature and humidity are within the sensor's specified limits. Temperature extremes and rapid cycling can cause significant accuracy drift and mechanical stress [26].

- Check Physical Connections: Inspect all wiring and terminals for loose connections, damage, or corrosion, which can cause intermittent signals and noise [25].

Q5: How can I optimize the Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) in my optical biosensor readings?

Optimizing SNR involves maximizing your desired signal while minimizing noise sources.

- For the Signal: Ensure your biorecognition elements (e.g., antibodies, aptamers) are fresh and properly immobilized. For optical sensors, you can increase the excitation light intensity, but this must be balanced against power consumption and potential photobleaching [27].

- For the Noise: Implement the stability measures listed above. Furthermore, when analyzing data such as photoplethysmography (PPG) signals, you can apply band-pass filtering in the frequency domain to isolate the biologically relevant signal (e.g., below 20 Hz) from higher-frequency electronic and environmental noise [27]. The optimal configuration is a balance between high SNR and acceptable system power consumption.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Discriminating Specific from Non-Specific Binding Using Dielectrophoretic (DEP) Forces

This protocol is adapted from Liu et al. and is designed for on-chip magnetic bio-assays [24].

1. Objective: To apply a controlled rupture force via DEP to remove non-specifically bound magnetic particles while leaving specifically bound particles intact.

2. Materials:

- Functionalized biosensor chip with integrated electrodes and magnetoresistive (e.g., GMR) sensors.

- Streptavidin-coated magnetic particles (MPs).

- Target analyte (e.g., biotinylated molecules for specific binding).

- Non-functionalized or PEG-coated surface for NSB control.

- Function generator for creating AC electric fields.

- Buffer solution.

3. Methodology:

- Step 1: Surface Preparation. Functionalize different regions of the sensor chip with specific capture molecules (e.g., biotin) and non-specific blocking agents (e.g., PEG).

- Step 2: Incubation. Incubate the chip with a solution containing the target analyte and the magnetic particles. Allow binding to occur.

- Step 3: Baseline Measurement. Use the magnetoresistive sensors to measure the initial magnetic signal, which represents total binding (specific + non-specific).

- Step 4: DEP Force Application. Apply a non-uniform AC electric field across the integrated electrodes to generate a repulsive DEP force. The frequency and voltage must be optimized to exert a force strong enough to break weaker non-specific bonds but not stronger specific ones.

- Step 5: Post-DEP Measurement. Re-measure the magnetic signal. A significant decrease indicates the removal of non-specifically bound MPs.

4. Data Analysis: Compare the magnetic signals before and after DEP application. The remaining signal is attributed to specific binding. The percentage signal loss quantifies the level of non-specific binding in the assay.

Protocol 2: Reducing False-Positives in Amplification-Based Biosensors Using UDG Enzyme

This protocol is for loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) assays but can be adapted for other nucleic acid amplification techniques [28].

1. Objective: To eliminate false-positive results caused by carry-over contamination of amplicons from previous reactions.

2. Materials:

- LAMP reaction mix (Bst DNA polymerase, primers, dNTPs, etc.).

- Uracil-DNA-Glycosylase (UDG).

- dUTP (incorporated in place of dTTP during amplification).

- Template DNA.

3. Methodology:

- Step 1: Reaction Setup. Prepare the LAMP master mix, substituting dTTP with dUTP. Add UDG enzyme to the mix before the template is added.

- Step 2: Contamination Degradation. Incubate the reaction mix (without Bst polymerase, or at a low temperature where Bst is inactive) for a short period (e.g., 10-30 minutes at 25-37°C). During this step, UDG will actively degrade any uracil-containing contaminating DNA from previous runs, breaking the DNA backbone and rendering it unamplifiable.

- Step 3: Enzyme Inactivation & Amplification. Heat the reaction to the LAMP operating temperature (60-65°C). This heat step simultaneously inactivates UDG (which is thermolabile) and activates the hot-start Bst DNA polymerase, allowing only the intended, pristine template to be amplified.

4. Data Analysis: Compare results from UDG-treated and untreated reactions. A reduction in false-positive amplification in negative controls for the UDG-treated reactions confirms the effectiveness of the method.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Comparison of Physical Forces for Discriminating Non-Specific Binding

| Force Method | Mechanism | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dielectrophoretic (DEP) Repulsion [24] | Applies electric field gradient to exert force on bound particles. | Easy electrode fabrication; availability of repulsive forces; low thermal dissipation. | Requires specialized chips with integrated electrodes; optimization of voltage/frequency is needed. |

| Fluidic Shear Forces | Uses buffer flow to create a washing force. | Conceptually simple; can be integrated into microfluidics. | Can be less controllable; may not generate sufficient localized force for strong discrimination. |

| Magnetic Forces | Uses magnetic field gradient to pull magnetic particles. | Highly specific to magnetic labels. | Force generation can be poor due to size mismatch; requires magnetic particles and equipment. |

Table 2: Methods for Confirming True vs. False-Positive Signals Post-Amplification

| Confirmation Method | Analyte | Principle | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR/Cas System | Nucleic Acids | Uses guide RNA to specifically recognize and cleave target LAMP amplicons, generating a signal only for specific products. | [28] |

| DNAzyme Formation | Nucleic Acids | LAMP amplicons with a G-quadruplex sequence react with hemin to form a DNAzyme that causes a colorimetric change, distinguishing it from nonspecific products. | [28] |

| Lateral Flow Immunoassay (LFA) | Nucleic Acids/Proteins | Uses hybridized probes to accurately recognize and bind to specific LAMP amplicons, providing a visual readout on a test strip. | [28] |

Diagram Specifications

Diagram Title: Biosensor Workflow and Noise Source Map

Diagram 2: DEP Force Discrimination Workflow

Diagram Title: DEP Force NSB Discrimination Protocol

Diagram 3: Signal-to-Noise Optimization Logic

Diagram Title: SNR Troubleshooting Decision Tree

Leveraging Advanced Technologies and Assay Designs for Enhanced Specificity

Integrating Machine Learning for Signal Pattern Recognition and Noise Reduction

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

General ML Integration

Q1: What are the most suitable machine learning algorithms for reducing noise in biosensor signals? The choice of algorithm depends on your data type and the nature of the noise. For supervised tasks with labeled data, Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) are highly effective for processing signal and image data from platforms like lateral flow assays, as they can learn to ignore noise and extract robust features. [29] Support Vector Machines (SVMs) and Random Forests are also widely used for classification tasks, such as distinguishing true positive signals from false positives. [30] [29] For unlabeled data or discovering hidden patterns in signal datasets, unsupervised learning methods like clustering can be valuable. [31] [30]

Q2: How can I quickly check if my ML model is suffering from overfitting during biosensor signal analysis? A primary indicator of overfitting is a significant performance gap between your training and validation datasets. If your model achieves high accuracy on the training data but performs poorly on the separate validation data, it has likely memorized the training data instead of learning generalizable patterns. [29] To mitigate this, ensure you use a rigorous data splitting protocol, typically 60% for training, 20% for validation, and 20% for blind testing. [29]

Q3: What is the role of data preprocessing in improving ML-based biosensor signal analysis? Data preprocessing is a critical step that dramatically improves ML model performance. It involves:

- Data denoising and background subtraction to enhance the signal-to-noise ratio. [29]

- Data normalization to reduce variability from different sensors or experimental conditions. [29]

- Data augmentation to artificially expand your dataset, which can improve model robustness. [29] These steps help minimize the impact of outlier samples and the inherent variabilities present in raw biosensor signals. [29]

Troubleshooting False Positives

Q4: My ML-powered optical biosensor is producing false positives. What are the common causes? False positives can arise from multiple sources, which should be investigated systematically. The following table outlines common causes and their respective troubleshooting actions.

| Cause | Troubleshooting Action |

|---|---|

| Nonspecific Binding | Review bioreceptor specificity (e.g., antibody/aptamer cross-reactivity); optimize blocking conditions and wash steps. [1] |

| Contaminated Reagents | Implement fresh reagent controls; ensure proper storage of critical components like enzymes and antibodies. [1] |

| Insufficient Model Training | Increase training dataset size, ensuring it includes adequate negative samples and examples of common interferents. [1] [30] |

| Signal Noise Misinterpretation | Apply advanced signal processing filters (e.g., digital smoothing); re-train the model with noisier data to improve robustness. [30] [29] |

| Inconsistent Sample Matrix | Standardize sample preparation protocols; include matrix-matched calibration standards in your experiments. [1] |

Q5: What experimental controls are essential for validating an ML-integrated biosensor and minimizing false results? Robust validation requires several key controls [32]:

- Donor-only and Acceptor-only controls: Essential for calculating and correcting for bleed-through in optical signals (e.g., FRET biosensors).

- Biosensor mutant controls: Use biosensors with inactivating mutations to establish a baseline for non-specific signals.

- Non-specific regulator controls: Co-express proteins that do not regulate your target activity to confirm the specificity of the biosensor's response.

- Positive and negative regulator controls: For dynamic biosensors, co-express known activators and inhibitors to confirm the sensor's expected response range.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: High Signal Noise in Electrochemical Biosensor Data

Symptoms: Unstable baseline, erratic signal output, poor signal-to-noise ratio that obscures the target analyte signal.

Investigation and Resolution Protocol:

Verify Experimental Conditions:

- Check the stability and purity of your buffer solutions. Prepare fresh solutions if necessary.

- Confirm that all electrical connections are secure and that the instrument is properly grounded.

Apply Signal Processing Techniques:

- Implement Digital Filtering: Apply a moving average filter or a low-pass filter to the raw signal data to smooth out high-frequency noise. [29]

- Utilize Machine Learning: Train a model, such as a denoising autoencoder, on a dataset of clean and noisy signals. The model can learn to map noisy input to a clean output, effectively filtering the signal. [30]

Optimize Biosensor Design (if possible):

Problem 2: False Positives in a Colorimetric Lateral Flow Assay Analyzed by a CNN

Symptoms: The convolutional neural network incorrectly classifies a negative sample as positive.

Investigation and Resolution Protocol:

Inspect Test Line Characteristics:

- Visually inspect the false positive test line. Is it a faint, diffuse band versus a sharp, solid band in true positives? This could indicate non-specific binding.

Augment and Re-train the ML Model:

- Expand Training Dataset: Systematically collect more negative samples that produce these faint, non-specific lines.

- Implement Data Augmentation: Artificially create variations of your existing negative sample images (e.g., by adjusting brightness, contrast, or adding slight blur) to teach the model to ignore these artifacts. [29]

- Review Model Architecture: Ensure the CNN is deep enough to learn complex features but use techniques like dropout layers to prevent overfitting to minor, irrelevant image artifacts. [29]

Optimize Immunoassay Chemistry:

- Increase the concentration of the blocking agent (e.g., BSA, casein) in the running buffer and on the nitrocellulose membrane to reduce non-specific binding. [1]

- Titrate the concentration of the capture antibody on the test line to find the optimal level that maximizes specificity.

Problem 3: Poor Dynamic Range in an ML-Enhanced Biosensor

Symptoms: The biosensor and its ML model fail to accurately quantify analyte concentrations across a wide range, either saturating too early or lacking sensitivity at low concentrations.

Investigation and Resolution Protocol:

Characterize the Raw Biosensor Response:

- Perform a dose-response experiment without the ML model. Plot the raw output signal (e.g., voltage, fluorescence intensity, FRET ratio) against the analyte concentration on a log scale. [33] This will reveal the intrinsic dynamic range of the biosensor hardware.

Select an Appropriate ML Algorithm:

- For extending quantification, use regression-type supervised learning algorithms (e.g., Random Forest regression, Support Vector Regression) that are trained to map the complex input signal to a continuous concentration output. [30] [29]

- Ensure your training dataset is evenly populated with samples across the entire desired concentration range, including the upper and lower limits.

Engineer the Biosensor's Dynamic Range:

- If the hardware itself is the limitation, consider re-engineering the biosensor. For genetic biosensors, this can involve tuning promoter strength, ribosome binding sites, or the ligand-binding domain of the bioreceptor to adjust the sensor's operational range. [33]

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Establishing a Training and Validation Dataset for ML Model Development

Purpose: To create a robust, high-quality dataset for training a machine learning model to recognize true biosensor signals and reject noise and false positives.

Reagents and Equipment:

- Functional biosensors (e.g., electrode strips, functionalized chips)

- Purified target analyte at known concentrations

- Negative control samples (blank buffer, sample matrix without analyte)

- Potential interfering substances relevant to the sample matrix

- Data acquisition system (potentiostat, fluorimeter, camera for colorimetric signals)

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a large set of samples (N > 100 is recommended for a good start). This set should include:

- A range of analyte concentrations spanning the expected dynamic range.

- Multiple replicates of negative controls.

- Samples containing common interferents at physiologically relevant concentrations.

- The exact number of samples required depends on the complexity of the task and the ML algorithm used.

Data Acquisition: For each sample, collect the raw signal output from your biosensor. For image-based sensors (e.g., LFAs), capture standardized images under consistent lighting conditions.

Data Labeling (for supervised learning): This is a critical step. Assign the "ground truth" label to each sample based on the known, prepared concentration, or a validated reference method. For example:

- Classification: Label as "Positive" or "Negative".

- Regression: Label with the exact concentration value.

Data Splitting: Randomly split the complete, labeled dataset into three distinct subsets [29]:

- Training Set (~60%): Used to train the ML model.

- Validation Set (~20%): Used to tune model hyperparameters and check for overfitting during training.

- Blind Test Set (~20%): Used only once for the final evaluation of the model's performance on unseen data.

Protocol 2: Validating an ML-Integrated Biosensor Using Upstream Regulators

Purpose: To rigorously test the specificity and dynamic response of a biosensor, particularly one reporting on dynamic cellular processes (e.g., GTPase activity), by co-expression with known activators and inhibitors. [32]

Reagents and Equipment:

- Cultured adherent cells (e.g., HEK293)

- DNA plasmids for:

- The biosensor itself

- A positive regulator (e.g., a constitutively active mutant or a guanine nucleotide exchange factor - GEF)

- A negative regulator (e.g., a dominant-negative mutant or a GTPase-activating protein - GAP)

- A non-functional control regulator

- 96-well microplate suitable for automated microscopy

- Automated fluorescence microscope

Methodology:

- Cell Transfection: Seed cells into a 96-well plate. Co-transfect the biosensor plasmid with a titration series of the regulator plasmids (positive, negative, and non-functional control). Keep the total DNA mass constant across wells using an empty vector. [32]

Image Acquisition: After an appropriate expression period, image the live cells using an automated microscope. Acquire images in the necessary channels (e.g., donor, FRET, and acceptor for a FRET biosensor).

Data Analysis:

- Calculate the biosensor's activity metric (e.g., FRET ratio) for each cell in each well.

- Plot the average biosensor activity against the mass of regulator DNA transfected.

- A valid and specific biosensor will show a strong, saturating increase in activity with the positive regulator, a decrease with the negative regulator, and no change with the non-functional control. [32]

Key Signaling Pathways and Workflows

Workflow of ML-Integrated Biosensor Data Analysis

This diagram illustrates the end-to-end pipeline for processing biosensor signals with machine learning, from raw data to actionable insights.

Data Preprocessing Pipeline for ML

This diagram details the critical data preprocessing steps required to prepare raw, noisy biosensor data for effective machine learning.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table lists key reagents and materials essential for developing and troubleshooting ML-integrated biosensor assays.

| Item | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Positive/Negative Regulator Plasmids | To saturate and validate biosensor response range by providing maximal activation/inhibition. [32] | Co-transfection in cell-based assays to generate ground truth data for model training. [32] |

| Donor-only & Acceptor-only Biosensor Constructs | To measure and correct for spectral bleed-through in FRET-based optical biosensors. [32] | Essential control for calibrating fluorescence measurements and improving signal quantification. |

| Non-functional Control Regulators | To test for non-specific effects of protein overexpression on the biosensor signal. [32] | Serves as a critical negative control to confirm biosensor specificity. |

| High-Quality Blocking Agents | To reduce non-specific binding of detection reagents or analytes to the sensor surface. [1] | Minimizing false positives in immunoassays and aptamer-based sensors (e.g., BSA, casein). |

| Stable Reference Analytes | To generate consistent, reliable calibration curves for model training. | Creating a labeled training dataset with known ground truth concentrations. |

| Nanomaterial-enhanced Transducers | To boost the primary signal and improve the signal-to-noise ratio before ML analysis. [5] [30] | Using porous gold or graphene in electrochemical sensors; Au-Ag nanostars in SERS platforms. [5] |

Developing Dual-Mode Biosensors for Self-Validation and Cross-Checking

Conventional single-mode biosensors, despite their promising advancements, face significant challenges including signal noise, environmental variability, cross-reactivity, and calibration difficulties in miniaturized devices, all of which compromise their accuracy and reliability [2]. These limitations can lead to false positive and false negative results, which have substantial implications in clinical diagnostics, food safety, and drug development [1].

Dual-mode biosensors represent a transformative approach by integrating two complementary detection techniques within a single platform. This design allows for internal cross-validation of data, significantly reducing false results while providing reliable measurements in complex biological matrices [2]. The convergence of multiple sensing modalities enhances measurement accuracy, expands analyte detection capabilities, and improves sensitivity compared to single-mode systems [34] [2].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs): Core Concepts

Q1: What fundamentally distinguishes a dual-mode biosensor from a single-mode one? A dual-mode biosensor integrates two distinct transduction mechanisms (e.g., optical and electrochemical) to generate two independent signals for the same analyte. The key distinction is not merely having two outputs, but using these outputs for cross-validation and complementary data generation, thereby enhancing reliability and reducing the risk of false positives/negatives that plague single-mode systems [2].

Q2: How does cross-validation within a single biosensor improve diagnostic certainty? Cross-validation provides an internal mechanism for the sensor to "check itself." For example, a positive result is only confirmed if both detection modes generate a positive signal. This process significantly reduces false results caused by non-specific binding, matrix interference, or instrument calibration errors. The result from each mode can be used for cross-validation, and only a doubly confirmed positive or negative result is considered dependable [34] [2].

Q3: What are the most promising modality combinations for dual-mode detection? Recent research highlights several powerful combinations:

- Colorimetric and Photothermal: Leverages the photothermal effect of nanoparticles for quantitative measurement alongside visual color changes [34].

- Fluorescent and Colorimetric: Uses different signal generation mechanisms (e.g., SYBR Green I for fluorescence and streptavidin-modified alkaline phosphatase for colorimetry) for cross-validating detection [35].

- Electrochemical and Optical: Combines the high sensitivity of electrochemical detection with the visual interpretation or fingerprinting capability of optical methods [2].

Q4: What are the primary translational challenges for commercializing dual-mode biosensors? Key challenges include increased system complexity and cost, multistep fabrication processes, potential signal interference between modalities, and the need for precise calibration between different detection systems. Additionally, navigating regulatory approval for combination devices and ensuring user-friendly operation present significant hurdles [2].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Issues

Signal Generation and Detection Issues

Problem: Inconsistent signals between the two detection modes.

- Potential Cause: Different optimal working conditions for each modality (e.g., buffer composition, pH, temperature).

- Solution: Systematically optimize the universal assay buffer by testing a range of pH and ionic strength conditions to find a compromise that maintains the activity of both recognition systems. Use a Design of Experiments (DoE) approach for efficient optimization.

- Prevention: During initial biosensor design, select modality pairs with compatible working requirements, such as CRISPR-Cas systems that can trigger both colorimetric and photothermal responses under the same conditions [34].

Problem: High background noise in one detection channel.

- Potential Cause: Non-specific adsorption of reagents or interference from complex sample matrices.

- Solution: Implement more stringent washing protocols and include blocking agents like BSA, casein, or specialized commercial blocking buffers. For sample analysis, incorporate purification steps or use sample dilution to reduce matrix effects.

- Verification: Test the biosensor with standard solutions in simple buffers versus spiked real samples to distinguish between assay and matrix-related issues [1].

Problem: One detection mode shows significantly lower sensitivity.

- Potential Cause: Improper ratio of shared recognition elements or incompatible signal amplification strategies.

- Solution: Titrate the concentration of common biorecognition elements (e.g., antibodies, CRISPR guide RNA) to find the optimal balance that supports both detection modalities. Consider adding a separate, non-interfering amplification step for the weaker signal.

- Example: In a CRISPR-dCas9 system, optimize the sgRNA concentration and the ratio of SYBR Green I to streptavidin-alkaline phosphatase to balance fluorescent and colorimetric signals [35].

Material and Fabrication Issues

Problem: Nanoparticle aggregation affecting both detection modalities.

- Potential Cause: Salt concentration in the assay buffer is too high, or improper functionalization of nanoparticle surfaces.

- Solution: When using gold nanoparticles (AuNPs), gradually introduce salt solutions or use buffers specifically designed to prevent aggregation. Ensure proper conjugation of probes to nanoparticles through characterization of conjugation efficiency via UV-Vis spectroscopy or gel electrophoresis.

- Prevention: Use surfactants or stabilizers in the nanoparticle storage solution, and characterize the hydrodynamic size and zeta potential of nanoparticles before assay implementation [34].

Problem: Poor reproducibility between different sensor batches.

- Potential Cause: Inconsistent fabrication procedures, particularly in manual modification steps.

- Solution: Standardize all fabrication steps with precise timing, temperature, and concentration controls. Implement rigorous quality control checks for each batch, including testing with positive and negative controls.

- Documentation: Maintain detailed Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) for all fabrication and modification steps, including environmental conditions [2].

Data Interpretation Issues

Problem: Discrepant results between the two detection modes.

- Potential Cause: Different limits of detection or dynamic ranges for each modality, or cross-reactivity with interfering substances.

- Solution: Pre-establish decision rules for discrepant results, such as repeating the assay or using a confirmatory method. Characterize the dynamic range and limit of detection for each modality independently before integrating them.

- Analysis: If one signal is positive and the other negative, consider whether the analyte concentration falls within the detectable range of both modalities [2].

Problem: Calibration drift in one detection system over time.

- Potential Cause: Instability of reagents, evaporation of solutions, or fouling of sensor surfaces.

- Solution: Implement regular calibration checks using fresh standard solutions. For long-term assays, use sealed systems to prevent evaporation, and incorporate internal controls to monitor signal stability.

- Validation: Include calibration standards at the beginning and end of each assay run to detect and correct for drift [1].

Performance Data and Technical Specifications

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Representative Dual-Mode Biosensors

| Target Analyte | Detection Modes | Limit of Detection (LOD) | Dynamic Range | Assay Time | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Salmonella spp. | Colorimetric & Photothermal | 1 CFU/mL | 1 - 108 CFU/mL | <60 min | [34] |

| S. typhimurium | Fluorescent & Colorimetric | 1 CFU/mL | 1 - 109 CFU/mL | ~90 min | [35] |

| BRCA-1 Protein | Electrochemical & Optical | 0.04 ng/mL | 0.05-20 ng/mL | ~30 min | [36] |

Table 2: Comparison of Biosensing Modalities for Dual-Mode Systems

| Transduction Method | Key Advantages | Common Limitations | Ideal Partner Modality |

|---|---|---|---|