Strategies to Overcome Sensitivity Loss in Enzyme-Based Biosensors: From Nanomaterials to AI Integration

Sensitivity loss remains a critical challenge impeding the reliability and widespread adoption of enzyme-based biosensors in clinical and pharmaceutical settings.

Strategies to Overcome Sensitivity Loss in Enzyme-Based Biosensors: From Nanomaterials to AI Integration

Abstract

Sensitivity loss remains a critical challenge impeding the reliability and widespread adoption of enzyme-based biosensors in clinical and pharmaceutical settings. This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the mechanisms behind signal degradation and presents a multi-faceted framework for enhancing biosensor performance. We explore foundational causes of sensitivity loss, including enzyme instability and matrix interference, and detail advanced methodological solutions such as nanomaterial integration and innovative immobilization techniques. The content further delivers practical troubleshooting protocols and comparative validation metrics for real-world applications. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes cutting-edge strategies to develop robust, high-fidelity biosensing platforms for precise diagnostic and therapeutic monitoring.

Understanding the Roots of Signal Degradation: Why Enzyme Biosensors Lose Sensitivity

Key Components and Working Principles of Enzyme-Based Biosensors

Enzyme-based biosensors are analytical devices that integrate a biological recognition element (an enzyme) with a physicochemical transducer to detect target analytes with high specificity and sensitivity [1] [2]. These devices leverage the catalytic action of enzymes, which accelerate chemical reactions of specific substrates even within complex mixtures like blood or fermentation broth [3]. The unique ability of enzymes to react only with specific substrates makes them indispensable tools across medical diagnostics, environmental monitoring, and food safety [1]. A prime example is the glucose sensor, which employs the enzyme glucose oxidase to manage diabetes by monitoring blood glucose levels [2] [3]. The central challenge in advancing this technology lies in effectively integrating molecular recognition with signal amplification while overcoming issues such as sensitivity loss, which can be addressed through innovations in material engineering and enzyme immobilization strategies [4].

Core Components and Working Principle

The functionality of enzyme-based biosensors rests on three essential components working in synergy: the biological recognition element (enzyme), the transducer, and the immobilization matrix [1].

Biological Recognition Element (Enzyme)

The enzyme serves as the biocatalyst that specifically recognizes and reacts with the target analyte (substrate) [1] [5]. Commonly used enzymes include:

- Glucose Oxidase (GOx): For glucose monitoring, it catalyzes the oxidation of β-D-glucose to gluconic acid and hydrogen peroxide [1] [3].

- Acetylcholinesterase (AChE): For pesticide detection, its inhibition by toxins forms the basis for detection [1].

- Lactate Oxidase (LOx): For lactate monitoring in sports medicine and critical care [1].

- Urease: For kidney function diagnostics, it catalyzes the hydrolysis of urea into ammonia and carbon dioxide [1].

Transducer

The transducer converts the biochemical reaction between the enzyme and substrate into a measurable quantifiable signal [1] [6]. Different transducer types are employed:

- Electrochemical: Measures electrical changes (current or voltage) from redox reactions [1]. Amperometric sensors detect current from the enzyme-mediated reaction [3].

- Optical: Measures changes in light properties (absorbance, fluorescence, luminescence) [1].

- Thermal: Measures the heat released or absorbed during the enzymatic reaction [1].

- Piezoelectric: Measures changes in mass on the sensor surface due to enzyme binding or conversion [1].

Immobilization Matrix

To ensure the enzyme remains stable, reusable, and in proximity to the transducer, it is immobilized using various techniques [1] [2]. Common methods include:

- Physical Adsorption: The enzyme is attached to a solid surface via weak forces.

- Covalent Bonding: The enzyme is chemically linked to the transducer surface.

- Entrapment: The enzyme is confined within a porous polymer matrix or gel [1] [2].

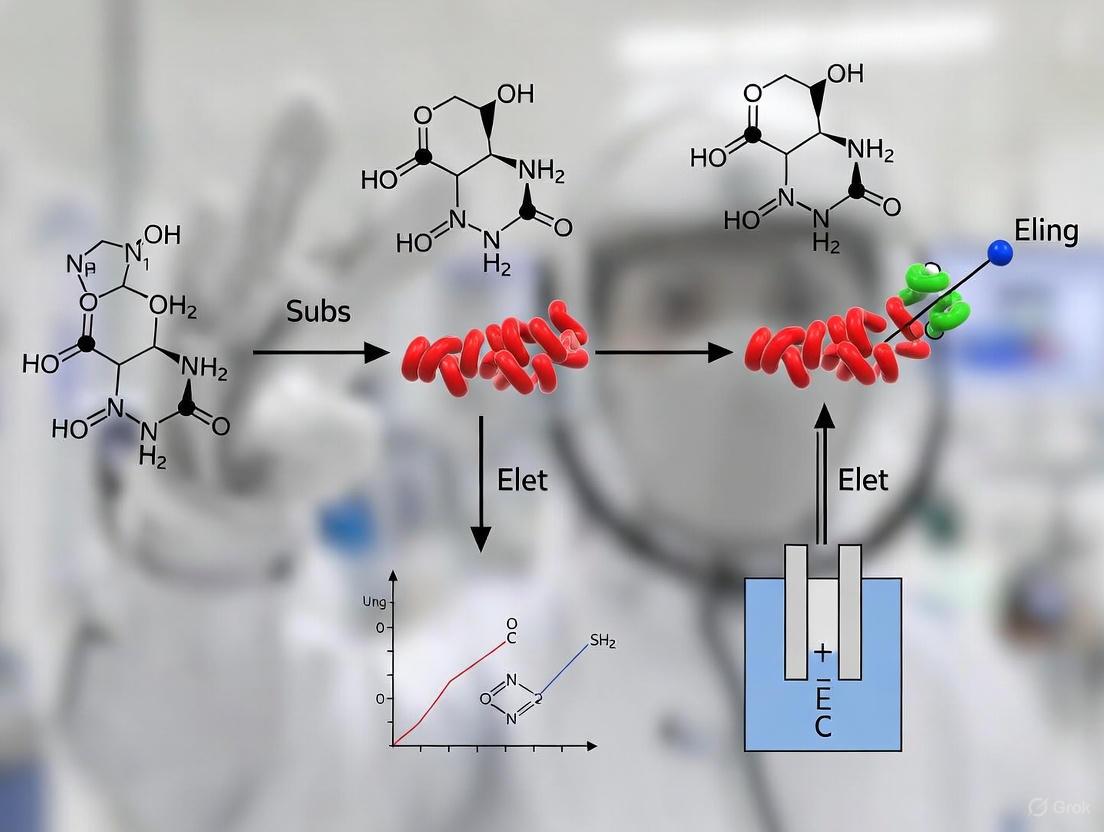

The following diagram illustrates the general working principle of an enzyme-based biosensor, from analyte recognition to signal output:

Biosensor signal pathway from recognition to output

Detailed Working Principle

The functional mechanism involves a specific enzyme-substrate interaction. When the target analyte comes into contact with the immobilized enzyme, a catalytic reaction occurs, producing or consuming specific molecules (e.g., hydrogen peroxide, oxygen, protons, electrons, heat, or light) [1]. For instance, in a glucose sensor using glucose oxidase, the reaction consumes oxygen and produces hydrogen peroxide [2]. This biochemical transformation causes a change in a physicochemical parameter (e.g., pH, redox potential, heat, mass, or light emission) [1]. The transducer detects this change and converts it into an electrical or optical signal proportional to the analyte concentration [1] [3]. In amperometric detection, the resulting current from the electrochemical reaction is measured over time, with the current increment correlating directly with the analyte concentration [7].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Researchers often encounter specific problems that lead to sensitivity loss and unreliable data. The following table addresses common issues, their causes, and solutions.

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low or No Signal Output [8] | Enzyme denaturation or inactivation. | Check enzyme storage conditions (-20°C), avoid freeze-thaw cycles, use fresh reagents, and verify expiration dates [9]. |

| Signal Drift/Instability [10] | Unstable reference electrode potential under current load. | Use a stable, separate reference electrode instead of a combined counter/pseudo-reference electrode to minimize potential shift [10]. |

| Incomplete Analyte Conversion [1] | Enzyme instability or leaching from the immobilization matrix. | Optimize the immobilization technique (covalent bonding or entrapment) to enhance enzyme stability and reusability [1] [2]. |

| Slow Response Time [1] | Poor mass transport of the analyte to the enzyme active site. | Use nanostructured materials (e.g., with high surface area and porosity) to facilitate efficient analyte diffusion [7]. |

| Low Sensitivity/High Detection Limit [4] | Limited enzyme loading and insufficient signal amplification. | Implement a multi-enzyme cascade system on a DNA-assembled scaffold to enhance substrate transfer and signal amplification [4]. |

| Interference from Sample Matrix [8] | Non-target substances in complex samples (e.g., blood) affecting selectivity. | Use additional protective membranes, sample pre-treatment, or more selective bioreceptors like DNAzymes or aptamers to overcome interferences [8]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the main reasons for sensitivity loss in enzyme-based biosensors over time? Sensitivity loss primarily stems from enzyme instability, where enzymes can denature under varying environmental conditions (pH, temperature) [1]. Other reasons include the gradual leaching of enzymes from the immobilization matrix, deactivation by inhibitors in the sample matrix, and fouling of the electrode surface, which reduces electron transfer efficiency [1] [8].

Q2: How can I improve the stability and lifespan of my enzyme biosensor? Advanced immobilization strategies are key. This includes covalent bonding of enzymes to the transducer surface or entrapment within stable polymers or nanomaterials [1]. Using engineered synthetic enzymes (nanozymes) that mimic natural enzyme activity while offering greater stability and resistance to denaturation can also significantly enhance operational lifespan [1].

Q3: Why is the selectivity of my biosensor poor in real sample matrices? Real samples like blood or wastewater contain abundant background species that can interfere with the enzyme's activity or be directly oxidized at the electrode, generating a false signal [8]. Improving selectivity can be achieved by incorporating protective, semi-permeable membranes, using purified samples, or developing receptors with higher specificity, such as functional nucleic acids (aptamers, DNAzymes) [8].

Q4: What are the best materials for transducers and electrodes? The choice depends on the application, but advanced functional materials are crucial. Carbon nanomaterials (graphene, carbon nanotubes), metal nanoparticles (gold, platinum), and conductive polymers are widely used due to their high electrical conductivity, large surface area, and ability to facilitate rapid electron transfer between the enzyme and the electrode [7].

Q5: How can I tune the dynamic range of my biosensor to match a specific detection threshold? Tuning the dynamic range is challenging as it is often limited by the inherent binding affinity of the enzyme [8]. However, strategies include modifying the enzyme concentration, using different immobilization matrices that affect substrate diffusion, or engineering the enzyme's binding site. For functional nucleic acid-based sensors, the sequence can be rationally designed to adjust affinity [8].

Advanced Protocols for Enhancing Performance

Protocol: Fabricating a Multi-Enzyme Cascade on a DNA Scaffold

This advanced protocol aims to overcome sensitivity limitations by creating a cooperative catalytic system [4].

Objective: To spatially organize multiple enzymes on a DNA nanostructure to enhance substrate channeling, improve catalytic throughput, and boost detection signal for low-abundance targets [4].

Materials:

- DNA Scaffold: A designed DNA origami structure (e.g., a 2D sheet or 3D tetrahedron) [4].

- Enzymes: Primary recognition enzyme (e.g., Glucose Oxidase) and secondary signaling enzyme (e.g., Horseradish Peroxidase).

- Crosslinkers: Chemical linkers (e.g., NHS-ester, maleimide) for covalent conjugation.

- Buffer: Immobilization buffer (e.g., 10 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4).

Methodology:

- Design and Synthesize: Design the DNA origami structure using a long single-stranded scaffold DNA and numerous short staple strands. Program specific staple strands to contain modified ends (e.g., thiol or amine groups) at precise locations [4].

- Purify: Purify the assembled DNA nanostructure using agarose gel electrophoresis or filtration to remove excess staples.

- Conjugate Enzymes: Activate the modified sites on the DNA scaffold with a heterobifunctional crosslinker. Incubate with the target enzymes to allow site-specific covalent conjugation. Control the molar ratio to ensure proper enzyme loading [4].

- Purify and Characterize: Remove unconjugated enzymes via size-exclusion chromatography. Confirm successful assembly and enzyme activity using techniques like transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and activity assays.

Logical Workflow: The following diagram outlines the experimental workflow for creating this advanced biosensing interface:

DNA scaffold multi-enzyme assembly workflow

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key materials and their functions for developing high-performance enzyme biosensors.

| Item | Function/Benefit |

|---|---|

| Glucose Oxidase (GOx) | Model enzyme for glucose detection; catalyzes glucose oxidation, producing H₂O₂ for amperometric detection [1] [3]. |

| DNA Origami Scaffold | Programmable nanostructure for precise, nanoscale co-immobilization of multiple enzymes, optimizing intermediate transfer [4]. |

| Nanozymes (Artificial Enzymes) | Engineered nanomaterials (e.g., metal oxides) with enzyme-like activity; offer superior stability and tunability over natural enzymes [1]. |

| Carbon Nanotubes/Graphene | Nanomaterial transducers with high conductivity and surface area, enhancing electron transfer and enzyme loading [1] [7]. |

| Covalent Immobilization Kits | Kits containing activated surfaces (e.g., gold, carbon) and crosslinkers for stable, oriented enzyme attachment, reducing leaching [1]. |

| Protective Membranes (e.g., Nafion) | Polymeric coatings that minimize surface fouling and reduce interference from electroactive species in complex samples [8] [7]. |

Understanding the key components and working principles of enzyme-based biosensors is fundamental to diagnosing and overcoming sensitivity loss. While challenges related to enzyme stability, signal transduction, and matrix interference persist, innovative solutions are available. Advanced material engineering, robust immobilization protocols, and novel architectures like DNA-scaffolded enzyme cascades provide a clear pathway toward developing the next generation of robust, sensitive, and reliable biosensors for critical applications in healthcare and environmental monitoring.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What are the most common causes of sensitivity loss in enzyme-based biosensors? The primary causes include the irreversible denaturation of the enzyme's three-dimensional structure due to temperature, pH fluctuations, or chemical inhibitors. Furthermore, enzyme activity can be reduced over time by fouling agents in biological samples, such as proteins and cells, which physically block the sensor surface [11] [12].

Why do my biosensors work perfectly in the lab but fail in complex biological fluids like blood or sweat? Biological fluids are complex matrices containing interferents like electrochemical species, metabolites, proteins, and cells that can foul the sensor surface or directly interfere with the signal transduction [11]. Pathological conditions can also alter the fluid's chemical composition or pH, further influencing enzyme activity and sensor performance [11].

How can I improve the long-term stability of my enzymatic biosensor? Advanced immobilization strategies are key. Using robust matrices like Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) for enzyme encapsulation has been shown to significantly enhance stability. For instance, one study demonstrated that a MOF-74/enzyme/Argdot composite retained over 94% of its current response after 60 days of storage [13]. Ensuring a surplus of enzyme activity to maintain a diffusion-controlled reaction is also critical for long-term function [12].

What is signal fouling and how can it be prevented? Signal fouling refers to the reduction in signal caused by the non-specific adsorption of proteins, macromolecules, or cells onto the biosensor's surface. This can block the access of the analyte to the enzyme or hinder electron transfer. Strategies to prevent it include using protective membranes like polyurethane, incorporating antifouling agents, and surface functionalization [11] [1].

Troubleshooting Guide: Diagnosing and Solving Sensitivity Loss

Problem: Gradual Decrease in Signal Output Over Time

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Recommended Solutions & Reagent Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Enzyme Denaturation/Leaching [12] [14] | - Test sensor activity in a fresh, standard analyte solution after storage.- Compare response pre- and post-exposure to operational conditions (e.g., temperature, pH). | - Advanced Immobilization: Use covalent bonding or biomimetic mineralization with MOFs (e.g., MOF-74) [13].- Stabilizing Additives: Co-immobilize with human serum albumin (HSA) and cross-link with glutaraldehyde (GDA) [12]. |

| Surface Fouling [11] | - Inspect sensor surface for visible deposits.- Test in a clean buffer vs. the complex sample matrix to isolate the fouling effect. | - Protective Membranes: Apply a diffusion-limiting membrane like polyurethane (PUR) [12].- Sample Pretreatment: Use filtration or extraction to remove foulants [11]. |

| Reversible Enzyme Inhibition [12] | - Implanted sensor sensitivity drops but recovers slowly after explantation and incubation in buffer. | - Design sensors with a large surplus of enzyme activity to overcome reversible inhibition [12]. |

Problem: Inaccurate Readings in Complex Biological Samples

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Recommended Solutions & Reagent Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Interferents [11] [1] | - Perform standard addition recovery experiments in the sample matrix.- Test for cross-reactivity with common metabolites. | - Use of Mediators/Nanozymes: Integrate redox mediators (e.g., Argdot carbon dots) to lower working voltage and reduce interference [13].- Protective Membranes: Use selective membranes to block interferents while allowing analyte passage [11]. |

| Environmental pH/Temperature Shift [11] [1] | - Measure the pH and temperature of the sample matrix and compare to sensor's optimal range. | - Robust Enzyme Selection: Use enzymes from thermophilic or extremophilic sources.- Sample Buffering: Adjust sample pH to the sensor's optimal range prior to measurement, if possible. |

Experimental Data and Protocols for Stability Enhancement

Quantitative Comparison of Immobilization Strategies

The following table summarizes performance data from recent studies on advanced enzyme stabilization techniques, providing a benchmark for your own research.

| Immobilization Strategy / Material | Key Component / Reagent | Reported Performance Improvement | Function of Reagent |

|---|---|---|---|

| MOF-74 Biomimetic Mineralization [13] | Arginine-derived carbon dots (Argdot) | Retained >94% response after 60 days; enhanced sensitivity for glucose, lactate, and xanthine. | Serves as a redox mediator and stabilizer, aiding in H₂O₂ catalysis at lower voltage. |

| Redox-Active MOF [14] | Engineered Metal-Organic Frameworks | Enabled highly efficient and stable long-term measurements; improved electron transfer. | Acts as a "molecular wire" for efficient electron exchange between the enzyme and electrode. |

| HSA-Glutaraldehyde Cross-linking [12] | Human Serum Albumin (HSA) & Glutaraldehyde (GDA) | Achieved functional stability over 600 days in vitro (in buffer). | Forms a stable, cross-linked protein matrix that protects the enzyme and prevents leaching. |

Featured Protocol: Enhancing Stability with MOF Biomimetic Mineralization

This protocol is adapted from research demonstrating high long-term stability for multi-analyte sensing [13].

Aim: To co-encapsulate enzymes (e.g., Glucose Oxidase, Lactate Oxidase, Xanthine Oxidase) with Argdot within a MOF-74 matrix to create a highly stable recognition layer.

Workflow:

Key Reagent Solutions & Functions:

- Boron‑nitrogen co-doped porous carbon nanospheres/ reduced graphene oxide (B,NMCNS/rGO): Serves as the sensing substrate, providing high conductivity, a large electrochemically active area, and abundant active sites [13].

- Arginine-derived carbon dots (Argdot): Functions as a peroxide mimetic and redox mediator, enabling the catalysis of H₂O₂ at a lower working voltage and stabilizing the enzyme structure [13].

- MOF-74 Matrix: The metal-organic framework provides a porous, protective cage around the enzymes via biomimetic mineralization, shielding them from harsh conditions and preventing leaching while allowing substrate diffusion [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

This table lists key materials used in the featured experiments to guide your reagent selection.

| Reagent / Material | Primary Function in Biosensor Development |

|---|---|

| Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) [13] [14] | Porous superlattice structures for encapsulating and protecting enzymes, enhancing stability and loading efficiency. |

| Carbon Nanotubes / Graphene Oxide [11] [13] | Nanomaterials used to modify electrodes, providing high surface area, excellent conductivity, and catalytic properties. |

| Redox Mediators (e.g., Argdot, Prussian Blue) [13] | Molecules that shuttle electrons between the enzyme's active site and the electrode, lowering the operating potential and reducing interference. |

| Human Serum Albumin (HSA) & Glutaraldehyde [12] | Used together to form a robust, cross-linked protein matrix for immobilizing enzymes on the sensor surface. |

| Polyurethane (PUR) & other Polymer Membranes [12] | Applied as a outer membrane to control analyte diffusion, reduce fouling, and extend the sensor's linear range. |

Impact of Complex Biological Matrices and Interfering Substances

This technical support center provides targeted troubleshooting guides and FAQs for researchers addressing sensitivity loss in enzyme-based biosensors due to complex biological matrices.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What are the primary causes of signal interference in complex samples? Signal interference often stems from matrix effects, where components in samples like serum, blood, or wastewater cause nonspecific adsorption (biofouling) on the sensor surface, limiting analyte access and altering the transducer's signal [15]. Furthermore, endogenous substances can exhibit cross-reactivity with the biorecognition element or cause competitive inhibition, reducing the assay's specificity and precision [15] [16].

Why does my biosensor perform well in buffers but fail in real biological samples? This is a common challenge. Under controlled buffer conditions, the biosensor operates in an ideal environment. Real biological matrices, however, contain a multitude of interfering molecules (e.g., proteins, lipids, salts) that can foul the sensor surface, interact with the analyte, or directly interfere with the enzyme's activity, leading to reduced sensitivity, specificity, and signal drift [15].

How can I improve the stability and reusability of my enzyme biosensor? Advanced enzyme immobilization techniques are key. Methods such as covalent bonding, entrapment in polymers or gels, and incorporation into nanostructured materials (e.g., graphene, carbon nanotubes, metal-organic frameworks) enhance enzyme stability, reusability, and consistent performance by securing the enzyme in close proximity to the transducer [1] [4].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Issues and Solutions

| Problem | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High Background Noise/Reduced Signal-to-Noise | Electronic noise (e.g., Thermal/Flicker noise); Non-specific adsorption of matrix proteins [17] | Use electrode materials with higher conductivity (e.g., novel carbon nanomaterials); Apply antifouling coatings (e.g., PEG, BSA-based composites) [17]. |

| Signal Drift and Loss of Sensitivity Over Time | Biofouling of the transducer surface; Degradation or instability of the immobilized enzyme [15] [1] | Implement innate antifouling materials (e.g., specific carbon nanomaterials); Optimize enzyme immobilization strategy to enhance operational stability [17] [1]. |

| Low Sensitivity and High Limit of Detection | Inefficient substrate transfer; Random enzyme orientation leading to low catalytic efficiency [4] | Employ DNA-assembled architectures for precise, nanoscale co-immobilization of enzymes to create efficient cascade systems and optimize substrate channeling [4]. |

| Loss of Specificity/False Positives | Cross-reactivity with non-target molecules in the matrix; Interference from electroactive substances in electrochemical detection [15] | Use more specific biorecognition elements (e.g., aptamers); Incorporate blocking agents (e.g., BSA) during surface preparation; Employ sample pre-treatment or filtration [15]. |

Advanced Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing Antifouling Coatings on Electrodes

This protocol details the application of a nanocomposite antifouling layer to minimize nonspecific binding from complex matrices like serum or saliva [17].

Key Research Reagent Solutions:

- BSA/prGOx/GA Nanocomposite: Serves as the foundational antifouling layer, physically blocking access to the electrode surface for non-target proteins.

- Polyethylene Glycol (PEG): A hydrophilic polymer used to create a hydration layer that repels biomolecules.

- Novel Carbon Nanomaterials: Materials with innate antifouling properties and high conductivity that can be used as the electrode base, eliminating the need for additional coatings and preventing signal reduction [17].

Procedure:

- Electrode Preparation: Clean and polish the base electrode (e.g., Gold, Glassy Carbon) according to standard electrochemical practices.

- Coating Application: Deposit the antifouling material. For a BSA-based layer, incubate the electrode in a 1-2% (w/v) BSA solution for 1 hour at room temperature. For carbon nanomaterial electrodes, the innate properties are often inherent to the material.

- Cross-linking (Optional): For BSA layers, treat with a 2.5% glutaraldehyde (GA) solution for 30 minutes to cross-link and stabilize the protein layer. Rinse thoroughly with buffer.

- Bioreceptor Immobilization: Immobilize your specific enzyme or biorecognition element on top of the established antifouling layer using your preferred method (e.g., EDC-NHS chemistry for covalent binding).

- Blocking: Incubate the functionalized sensor with a blocking agent (e.g., 1% BSA, casein) to cover any remaining reactive sites.

- Validation: Validate coating efficacy by testing sensor response in a pure buffer versus the target complex matrix (e.g., 10% serum) and comparing signal stability and background noise.

Protocol 2: Constructing a DNA-Assembled Multi-Enzyme Cascade

This protocol outlines the use of DNA nanotechnology (e.g., DNA origami) to spatially organize enzyme cascades, enhancing sensitivity and substrate channeling for detecting low-abundance analytes [4].

Key Research Reagent Solutions:

- DNA Origami Scaffold: A custom-designed, long single-stranded DNA (e.g., M13mp18) and complementary staple strands that self-assemble into a precise 2D or 3D nanostructure, providing addressable binding sites for enzymes.

- Enzyme-DNA Conjugates: Target enzymes chemically modified with short, unique DNA strands complementary to specific positions on the DNA origami.

- Biotin-Streptavidin System: A common affinity tool for purifying assembled complexes or for signal amplification in the final detection step.

Procedure:

- Design and Synthesis: Design a DNA origami structure that positions multiple enzymes (e.g., Glucose Oxidase and Horseradish Peroxidase) at a controlled nanoscale distance to facilitate intermediate transfer. Synthesize the structure by annealing the scaffold and staple strands.

- Enzyme Conjugation: Chemically conjugate the selected enzymes with their respective DNA linker strands via NHS-amine or maleimide-thiol chemistry.

- Hierarchical Assembly: Mix the purified DNA origami with the enzyme-DNA conjugates. The conjugates will hybridize to their specific locations on the origami via Watson-Crick base pairing, forming the precise multi-enzyme cascade.

- Immobilization on Transducer: Anchor the assembled DNA-enzyme architecture onto the biosensor transducer surface. This can be achieved by incorporating a thiol-modified anchor strand into the origami for gold surfaces, or a biotin anchor for streptavidin-coated surfaces.

- Performance Characterization: Characterize the cascade's performance by measuring kinetic parameters (e.g., catalytic efficiency, limit of detection) and compare it to a system with randomly immobilized enzymes.

Experimental Workflow and Signaling Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for troubleshooting and optimizing biosensor performance against matrix effects.

Biosensor Troubleshooting Workflow

Limitations of Operational Lifespans and Reusability

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Issues and Solutions

| Problem Area | Specific Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enzyme Stability | Gradual signal loss over time | Enzyme denaturation due to temperature, pH fluctuations, or proteolytic degradation [1] [18]. | Optimize immobilization protocol (e.g., covalent binding); use protective polymer matrices; incorporate enzyme stabilizers [19] [20]. |

| Sudden, complete failure | Leaching of enzymes from the sensor surface due to weak immobilization [18]. | Shift from adsorption to covalent bonding or entrapment methods; employ cross-linkers like glutaraldehyde [18] [20]. | |

| Sensor Surface & Immobilization | Inconsistent results between batches | Poor reproducibility in enzyme loading or uneven modification of the transducer surface [21]. | Standardize surface cleaning/activation protocols; use quantitative methods to measure enzyme loading [18]. |

| Signal drift during operation | Biofouling from non-specific adsorption (NSA) of proteins or other molecules in complex samples [22]. | Implement anti-fouling surface chemistries (e.g., PEGylation); use nanostructured materials to shield the recognition layer [22] [7]. | |

| Operational Performance | Reduced sensitivity (lower signal per analyte unit) | Conformational changes in immobilized enzyme reducing catalytic efficiency; passivation of electrode surface [1] [23]. | Engineer the enzyme's microenvironment with nanomaterials (e.g., MWCNTs, graphene) to facilitate electron transfer [20] [7]. |

| Extended response time | Diffusion barriers created by dense immobilization matrices or fouling layers [18]. | Use porous immobilization supports (e.g., metal-organic frameworks); ensure hydrogel matrices are not overly cross-linked [19] [7]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary factors that limit the operational lifespan of my enzyme-based biosensor? The core limitations are enzyme instability and immobilization failure. Enzymes can denature under operational conditions (e.g., variable temperature, pH), leading to a loss of catalytic activity [1]. Furthermore, if the immobilization method is weak (e.g., simple adsorption), enzymes can leach from the sensor surface, causing irreversible signal loss. Over time, biofouling from complex sample matrices (like blood or food) can also block the active site or electrode surface, reducing sensitivity and lifespan [22] [18].

Q2: How can I improve the reusability of my biosensor? The key to reusability is a robust immobilization strategy. Methods like covalent bonding and entrapment in stable polymers are superior to physical adsorption for preventing enzyme leaching [18]. Additionally, using nanomaterial carriers such as functionalized carbon nanotubes or graphene can enhance the enzyme's stability and allow the sensor to be regenerated and reused multiple times without significant performance decay [20]. One study reported an AChE-based sensor that maintained 98.5% reactivity after two weeks [20].

Q3: Why does my biosensor perform well in buffer but fail in real samples? This common issue is often due to matrix interference or biofouling. Real samples (e.g., serum, food homogenates) contain numerous interfering substances that can either non-specifically adsorb to the sensor surface (fouling) or directly interfere with the electron transfer process at the transducer [22] [21]. To overcome this, develop your sensor using real samples from the start and incorporate anti-fouling agents (e.g., bovine serum albumin, specific polymers) into your surface chemistry [22].

Q4: Are there standardized protocols for testing biosensor lifespan and reusability? While there is no single universal standard, a common practice is to evaluate operational stability and shelf-life. Test operational stability by performing repeated measurements with regeneration steps (e.g., washing with a gentle buffer) between assays and monitor the signal decay over cycles [18] [21]. For shelf-life, store the sensor under controlled conditions (often 4°C) and test its performance at regular intervals to determine how long it retains its activity [21].

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Protocol 1: Evaluating Operational Stability and Reusability

Objective: To quantitatively determine the number of times a biosensor can be reused before its signal drops below an acceptable threshold (e.g., 90% of initial response).

Materials:

- Fabricated biosensor

- Substrate/analyte solution at a known, fixed concentration (within linear range)

- Regeneration buffer (e.g., appropriate pH buffer)

- Electrochemical workstation or relevant transducer reader

Procedure:

- Initial Measurement: Record the sensor's signal (e.g., current for amperometry) in the presence of the analyte solution.

- Regeneration: Rinse the sensor thoroughly with the regeneration buffer to remove the reaction products and any unbound analyte. A gentle flow of buffer for 30-60 seconds is typically sufficient.

- Equilibration: Place the sensor in a clean buffer solution and allow the signal to stabilize to its baseline.

- Repeat: Repeat steps 1-3 for at least 10-20 cycles or until a significant loss of signal is observed.

- Data Analysis: Plot the normalized signal response (Signaln / Signalinitial) versus the cycle number. The operational lifespan can be reported as the number of cycles before the signal falls below a pre-defined percentage of its initial value.

Protocol 2: Covalent Immobilization of Enzymes using EDC/NHS Chemistry

Objective: To stably immobilize an enzyme onto a carboxylated surface (e.g., COOH-functionalized graphene or electrode) to enhance reusability.

Materials:

- Activation Solution: 50 mM MES buffer, pH 6.0, containing 20 mM EDC and 50 mM NHS [18].

- Enzyme Solution: The enzyme of interest dissolved in a compatible, mild buffer (e.g., 10 mM PBS, pH 7.4). Avoid amine-containing buffers like Tris.

- Blocking Solution: 1M Ethanolamine, pH 8.5, or 1% (w/v) Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA).

- Wash Buffers: Appropriate buffers at neutral pH.

Procedure:

- Surface Activation: Incubate the carboxylated sensor surface with the EDC/NHS activation solution for 30-60 minutes at room temperature. This step converts the carboxyl groups into amine-reactive NHS esters.

- Washing: Rinse the surface thoroughly with the MES buffer (pH 6.0) to remove excess EDC/NHS.

- Enzyme Coupling: Immediately incubate the activated surface with the enzyme solution for 2-4 hours at room temperature or overnight at 4°C. The primary amines (lysine residues) on the enzyme will form stable covalent bonds with the surface.

- Blocking: Rinse the sensor to remove unbound enzyme. Then, incubate with the ethanolamine or BSA solution for 1 hour to block any remaining reactive esters, which minimizes non-specific adsorption.

- Final Wash: Wash the biosensor with storage or assay buffer. The biosensor is now ready for testing or storage.

Visualization: Immobilization Strategy Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for selecting an enzyme immobilization strategy to address lifespan and reusability challenges.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Overcoming Lifespan & Reusability Limits | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| EDC & NHS | Cross-linkers for covalent immobilization of enzymes to surfaces containing carboxyl or amine groups. Creates stable bonds that prevent enzyme leaching [18]. | Must be used in amine-free buffers. Reaction efficiency depends on pH. |

| Glutaraldehyde | A homobifunctional cross-linker for creating extensive covalent networks between enzyme molecules and aminated surfaces [18]. | Can be harsh and lead to a significant loss of enzyme activity if not optimized. |

| Functionalized Nanomaterials (e.g., NH2-/COOH-MWCNTs) | Provide a high surface area for increased enzyme loading. Functional groups facilitate directed immobilization. Enhance electron transfer, boosting signal and stability [20] [7]. | Type of functionalization (-NH2, -COOH, -SH) must be matched to the enzyme and immobilization chemistry. |

| Nafion/Polymeric Membranes | Cation-selective polymer used to entrap enzymes and coat electrodes. Reduces fouling from anions and large molecules in complex samples [20]. | Can introduce diffusion barriers that may slow response time. |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | Used as a blocking agent to passivate unused binding sites on the sensor surface after immobilization, reducing non-specific adsorption (NSA) [18]. | A standard, low-cost reagent for improving selectivity in complex matrices. |

| Chitosan | A natural biopolymer used for enzyme entrapment due to its biocompatibility, mild gelling properties, and film-forming ability [20]. | Excellent for preserving enzyme activity but may suffer from swelling and mechanical instability. |

The Role of Substrate Diffusion and Immobilization Efficiency

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How does the enzyme immobilization method directly influence substrate diffusion and, consequently, biosensor sensitivity? The immobilization method critically influences the stability, orientation, and activity of the enzyme, which in turn governs how easily the substrate can diffuse to the enzyme's active site [24] [25]. Inefficient diffusion can create a barrier, leading to reduced sensitivity and a slower response time. Methods like covalent bonding and cross-linking provide stable attachment but can sometimes hinder diffusion or modify the enzyme's active site. In contrast, entrapment can protect the enzyme but may impose diffusion limitations if the matrix is too dense [24] [25].

Q2: What are the practical signs of substrate diffusion limitations in my experimental biosensor data? The primary signs include a slower response time, as the substrate takes longer to reach the enzyme; a lower-than-expected signal output (e.g., reduced current in amperometric sensors) because not all enzyme molecules are being efficiently utilized; and a non-linear response at higher substrate concentrations, where the reaction rate becomes limited by diffusion rather than the enzyme's intrinsic catalytic power [26].

Q3: Which immobilization strategy is best for maximizing sensitivity? There is no single "best" strategy, as the choice involves trade-offs. For maximum sensitivity, the goal is to preserve enzyme activity and ensure excellent substrate access. Site-specific affinity immobilization is often superior because it can orient the enzyme to keep its active site freely available [25]. Covalent immobilization on a nanostructured surface can also yield high sensitivity by providing a stable linkage and a high surface area for enzyme loading and substrate diffusion [25] [1]. Entrapment within porous matrices like Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) has more recently been shown to enhance stability with minimal activity loss, as demonstrated with AChE@Zn-MOF [27].

Q4: How can I quickly test whether my sensitivity loss is due to enzyme inactivation or diffusion problems? A simple diagnostic test is to compare the biosensor's response in a standard solution under stirred and unstirred conditions. If the signal increases significantly with stirring, it strongly indicates that the reaction is diffusion-limited. If the signal remains low regardless of stirring, the issue is more likely enzyme inactivation due to an unstable immobilization method or harsh environmental conditions [26].

Troubleshooting Guide: Addressing Sensitivity Loss

This guide helps diagnose and resolve common issues related to immobilization and diffusion that lead to sensitivity loss.

Table 1: Troubleshooting Sensitivity Loss in Enzyme Biosensors

| Problem & Observed Symptoms | Potential Root Cause | Recommended Solutions & Validation Experiments |

|---|---|---|

| Low Signal Output• Low current/absorbance• Poor sensitivity• High detection limit | Inactive or denatured enzyme: Immobilization process damaged the enzyme.Poor substrate diffusion: Dense polymer matrix or non-porous material blocks substrate access.Incorrect enzyme orientation: Active site is blocked or facing the transducer surface. | • Verify enzyme activity after immobilization with a standard solution assay [26].• Switch to a milder immobilization method (e.g., affinity-based for oriented binding) or a more porous support (e.g., MOFs, nanostructured materials) [27] [25].• Introduce a flexible spacer arm (e.g., PEG) during covalent immobilization to reduce steric hindrance [25]. |

| Slow Response Time• Long time to reach signal plateau• Sluggish kinetics | Severe substrate diffusion limitation: Substrate cannot quickly reach the enzyme layer. | • Optimize the thickness of the immobilization matrix; make it thinner [25].• Use a more porous or hydrogel-based material that facilitates faster diffusion [24].• Incorporate nanomaterials (e.g., carbon nanotubes, metal nanoparticles) to enhance electron transfer and potentially create more diffusion pathways [25] [1]. |

| Signal Instability & Drift• Signal decays rapidly during operation• Poor reproducibility between sensors | Enzyme leaching: Enzyme is not stably attached (common with simple adsorption).Fouling of the sensor surface: Non-specific adsorption of proteins or other molecules in the sample matrix blocks diffusion. | • Change to a more stable immobilization method like covalent bonding or cross-linking [24] [25].• Apply an anti-fouling coating (e.g., PEG, alginate) on top of the biosensor layer [28].• Pre-treat complex samples (e.g., filtration, dilution) to reduce interferents [9]. |

Experimental Protocols for Optimization

Protocol 1: Evaluating Immobilization Efficiency via Activity Assay

This protocol determines the percentage of active enzyme after the immobilization process.

- Prepare Reaction Mixture: In a cuvette, mix a known volume of your substrate solution (e.g., 100 μL of 10 mM glucose for Glucose Oxidase) with the appropriate buffer.

- Measure Initial Rate (Free Enzyme): Add a known amount (e.g., 0.1 mg) of free, non-immobilized enzyme to the cuvette. Immediately measure the initial rate of product formation (e.g., H₂O₂) spectrophotometrically or electrochemically. This is your reference activity (A_free).

- Measure Initial Rate (Immobilized Enzyme): Place your biosensor (with the immobilized enzyme) in an identical reaction mixture. Under the same conditions (stirred, if applicable), measure the initial rate of product formation. This is your immobilized activity (A_immob).

- Calculate Immobilization Efficiency:

- Immobilization Efficiency (%) = (Aimmob / Afree) × 100

- A value significantly below 100% indicates immobilization has compromised enzyme activity [26].

Protocol 2: Systematic Comparison of Immobilization Methods

This protocol provides a structured way to select the best immobilization method for your specific application.

- Surface Preparation: Divide your transducer surfaces (e.g., electrodes) into identical groups.

- Apply Methods: Apply different immobilization methods (Adsorption, Covalent, Entrapment, Affinity) to each group, following standardized protocols [24] [25].

- Benchmark Performance: Test all prepared biosensors using a standard analyte solution and record key performance parameters (KPIs) as shown in the table below.

- Analyze and Select: Compare the KPIs to identify the method that offers the best trade-off for your needs (e.g., highest sensitivity for diagnostic use, or best stability for environmental monitoring).

Table 2: Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) for Method Comparison

| Immobilization Method | Expected Relative Sensitivity | Expected Relative Stability | Key Advantage | Main Drawback |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adsorption | Moderate | Low | Simple and fast protocol [24] | Enzyme leaching over time [25] |

| Covalent Binding | High | High | Strong, stable attachment [24] | Risk of enzyme denaturation [24] |

| Entrapment | Moderate to Low | High | Protects enzyme from harsh environments [24] | Can severely limit substrate diffusion [24] |

| Affinity | High | High | Controlled, oriented binding [25] | Can be more complex and expensive [25] |

| Cross-linking | Variable | Very High | Creates a robust enzyme layer [24] | Can reduce activity due to rigidification [24] |

Visualization of Workflows and Relationships

Diagram 1: Immobilization Impact on Sensitivity

Diagram 2: Diagnostic Experimental Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Enhanced Immobilization

| Reagent / Material | Primary Function in Immobilization | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Glutaraldehyde (GTA) | A homobifunctional cross-linker that creates strong covalent bonds between enzyme molecules and/or with a support matrix [24]. | Creating a cross-linked enzyme aggregate (CLEA) on an electrode surface for high stability [24]. |

| Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) | Nanostructured, porous materials that entrap enzymes, stabilizing them and protecting their activity while allowing substrate diffusion [27]. | Immobilizing acetylcholinesterase (AChE) in Zn-MOF for a stable, sensitive pesticide biosensor [27]. |

| Aminated/Surfaced Supports | Transducer surfaces (e.g., gold, carbon) functionalized with amino (-NH₂) or other reactive groups for covalent enzyme attachment [25]. | Covalently binding the lysine residues of an enzyme to an electrode surface using EDC/NHS chemistry [25]. |

| Avidin/Biotin System | A high-affinity pairing for oriented immobilization; the enzyme is biotinylated and binds to an avidin-functionalized surface [25]. | Ensuring the active site of an antibody or enzyme faces the solution to maximize analyte binding [25]. |

| Nafion/Polymers | Cation-exchange polymers used for entrapment; can also repel interfering anions (e.g., ascorbate, urate) in biological samples [25]. | Entrapping glucose oxidase on an electrode for selective glucose sensing in blood serum [25]. |

| Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) | Nanomaterials that provide a high surface area for enzyme loading, enhance electron transfer, and can improve diffusion kinetics [25] [1]. | Modifying an electrode to boost the signal in an amperometric biosensor [1]. |

Advanced Engineering Solutions: Nanomaterials, Immobilization, and System Design

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on Sensitivity Loss

FAQ 1: Why does my enzyme biosensor suffer from a weak electrical signal and low sensitivity? This is often due to inefficient Electron Transfer (ET) between the enzyme's active site and the electrode surface. In many redox enzymes, the catalytic center is deeply buried within a protein shell, creating a physical barrier for electron flow. This can force reliance on slower, less efficient detection methods, such as measuring the consumption of oxygen or the production of hydrogen peroxide (first-generation), or using synthetic redox mediators (second-generation) [29]. Achieving Direct Electron Transfer (DET), where electrons move directly between the enzyme and electrode, is key to superior sensitivity but is challenging to establish [29] [30].

FAQ 2: My biosensor's signal drifts over time and loses stability. What could be the cause? A primary cause is the instability of the enzyme itself. Enzymes can denature (lose their functional structure) when exposed to non-physiological conditions like extreme pH, temperature, or organic solvents. Furthermore, they can slowly leach away from the electrode surface. Another factor is the fouling of the transducer surface by components in complex sample matrices (e.g., blood, fermentation broth), which insulates the electrode and degrades performance [21] [1].

FAQ 3: How can nanomaterials like graphene and CNTs specifically help prevent sensitivity loss? Nanomaterials act as a strategic interface to combat the root causes of sensitivity loss:

- Enhanced Electron Transfer: Graphene and CNTs possess exceptional electrical conductivity and a high surface area. They can "wire" themselves into the enzyme, facilitating more efficient DET and leading to a stronger, more robust signal [31] [32].

- Superior Enzyme Immobilization: Their large surface area provides more sites for stable enzyme attachment. Functional groups on these materials allow for strong covalent bonding or effective adsorption of enzymes, reducing leaching and maintaining a higher level of enzymatic activity over time [32] [33].

- Biocompatible Environment: These carbon-based nanomaterials provide a favorable environment that can help preserve the enzyme's native structure and bioactivity, thereby enhancing operational stability [32].

FAQ 4: What is the role of metal nanoparticles in improving biosensor performance? Metal nanoparticles like gold (AuNPs) and platinum (PtNPs) are frequently used to amplify the electrochemical signal. They are excellent catalysts for reactions that are central to biosensing. For instance, PtNPs can efficiently catalyze the reduction of hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂), a common byproduct of oxidase enzymes, allowing it to be detected at a lower and more selective potential, which reduces interference [33]. AuNPs also facilitate electron transfer and can be easily functionalized with enzymes via thiol groups [33].

Troubleshooting Guide: Addressing Common Experimental Issues

The table below summarizes common issues, their potential nanomaterial-based solutions, and the underlying mechanisms.

Table 1: Troubleshooting Guide for Sensitivity Loss in Enzyme-Based Biosensors

| Problem | Possible Cause | Nanomaterial Solution | Mechanism of Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low Signal & Sensitivity | Inefficient Electron Transfer (ET) | Use graphene, SWCNTs/MWCNTs, or gold nanoparticles [31] [32] [33]. | Facilitates Direct Electron Transfer (DET); provides high conductivity and large electroactive surface area [32] [29]. |

| Poor Stability & Signal Drift | Enzyme denaturation or leaching from the electrode. | Implement a robust immobilization matrix using graphene oxide or CNTs, often with cross-linkers like glutaraldehyde [31] [1]. | High surface area for increased enzyme loading; functional groups for strong covalent attachment, preserving enzyme activity [32]. |

| Slow Response Time | Long diffusion path for reactants/products. | Integrate a porous nanomaterial like a CNT network or a metal nanoparticle layer [31] [34]. | Creates a nano-structured, porous interface that shortens diffusion distance and accelerates mass transport [33]. |

| High Interference from Sample Matrix | Oxidation of interfering species (e.g., ascorbate, urate) at the working potential. | Modify the electrode with a charged nanocomposite or use catalytic nanoparticles like PtNPs [21] [33]. | Lowers the operational potential for H₂O₂ detection; Nafion-coated surfaces can repel negatively charged interferents. |

| Complex Analyte Detection | No single enzyme produces an easily detectable electroactive species for the target. | Develop a Multienzyme Cascade System (MCS) co-immobilized on nanomaterials [35]. | Enzymes work in sequence; the product of one reaction is the substrate for the next, amplifying the final measurable signal [35]. |

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials and Their Functions

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Nanomaterial-Enhanced Biosensors

| Reagent / Material | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Graphene Oxide (GO) & Reduced GO (rGO) | GO provides oxygen-containing groups for easy enzyme immobilization. rGO offers a balance of conductivity and functionality, ideal for electrochemical transducers [32]. |

| Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes (SWCNTs) | Their high aspect ratio and excellent conductivity make them ideal for creating a conductive network that wires enzymes to the electrode, promoting DET [31]. |

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | Biocompatible and easily functionalized with thiol chemistry, AuNPs enhance electron transfer and can be used to anchor enzymes and other biomolecules [33]. |

| Platinum Nanoparticles (PtNPs) | Primarily used for their superior electrocatalytic activity, especially for the reduction of H₂O₂, leading to signal amplification and lower detection potentials [33]. |

| Nafion | A perfluorosulfonate ionomer often used to form a protective membrane on the sensor surface. It repels negatively charged interferents and can help stabilize the nanomaterial layer [21]. |

| Glutaraldehyde | A common cross-linking agent used to form stable covalent bonds between amine groups on enzymes and functionalized nanomaterials, preventing enzyme leaching [1]. |

| Cellobiose Dehydrogenase (CDH) | An example of a model enzyme capable of DET. Its cytochrome domain allows for efficient electron tunneling to nanomaterials, making it a popular choice for fundamental DET studies [29]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Constructing a CNT-Based Glucose Biosensor

This protocol details the construction of a glucose biosensor using Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) to enhance sensitivity via a mediated electron transfer mechanism.

Objective: To fabricate a stable and sensitive amperometric glucose biosensor by co-immobilizing Glucose Oxidase (GOx) with CNTs and a redox mediator on a glassy carbon electrode.

Principle: GOx catalyzes the oxidation of glucose. CNTs enhance the electrode surface area and facilitate electron shuttling. The redox mediator (e.g., Ferrocene) efficiently shuttles electrons from the reduced enzyme (FADH₂) back to the oxidized form (FAD), and is subsequently detected at the electrode.

Materials:

- Enzyme: Glucose Oxidase (GOx) from Aspergillus niger.

- Nanomaterial: Carboxylated Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes (MWCNTs-COOH).

- Electrode: Glassy Carbon Electrode (GCE, 3 mm diameter).

- Redox Mediator: Ferrocene carboxylic acid.

- Cross-linker: Glutaraldehyde solution (2.5% v/v).

- Buffer: Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS, 0.1 M, pH 7.4).

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Electrode Pretreatment: Polish the GCE with 0.05 μm alumina slurry on a microcloth. Rinse thoroughly with deionized water and ethanol, then dry under a nitrogen stream.

- CNT Modification:

- Disperse 1 mg of MWCNTs-COOH in 1 mL of DMF by ultrasonication for 30 minutes to create a homogeneous suspension.

- Pipette 5 μL of this suspension onto the polished surface of the GCE.

- Allow the electrode to dry at room temperature, forming a uniform CNT film.

- Enzyme Immobilization:

- Prepare an immobilization mixture containing 2 μL of GOx (10 mg/mL in PBS), 1 μL of ferrocene carboxylic acid (10 mM), and 1 μL of glutaraldehyde (2.5%).

- Mix gently and pipette 4 μL of this mixture onto the CNT-modified GCE.

- Let it sit for 1 hour at 4°C for the cross-linking reaction to complete.

- Post-Assembly:

- Rinse the fabricated biosensor gently with PBS to remove any unbound enzyme or mediator.

- Store the biosensor in PBS at 4°C when not in use.

Calibration and Measurement:

- Use a standard three-electrode setup (biosensor as working electrode, Ag/AgCl reference, Pt wire counter).

- Apply a constant potential of +0.4 V vs. Ag/AgCl in a stirred PBS solution.

- Add successive aliquots of a standard glucose solution to the electrochemical cell.

- Measure the steady-state current response after each addition.

- Plot the current (μA) vs. glucose concentration (mM) to obtain the calibration curve.

Advanced Strategy: Multi-Enzyme Cascade System for Complex Analytes

For analytes where a single enzyme reaction is insufficient, a Multi-enzyme Cascade System (MCS) can be employed. The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for designing such a system to overcome detection limitations.

Example: Triglyceride Detection [35] A single enzyme cannot directly generate a signal from triglycerides. An MCS uses a sequence of enzymes where the product of one reaction becomes the substrate for the next, ultimately generating a detectable signal.

- Enzymes Used: Lipase, Glycerol Kinase (GK), Glycerol-3-Phosphate Oxidase (GPO).

- Cascade Reaction:

- Lipase hydrolyzes triglycerides to produce glycerol.

- GK phosphorylates glycerol (using ATP) to produce L-glycerol-3-phosphate.

- GPO oxidizes L-glycerol-3-phosphate to generate Hydrogen Peroxide (H₂O₂).

- Detection: The H₂O₂ is then electrochemically measured at a CNT- or metal nanoparticle-modified electrode. The nanomaterial platform is crucial for co-immobilizing all three enzymes in close proximity, ensuring efficient channeling of intermediates and minimizing diffusion losses, which dramatically enhances the overall sensitivity [35].

In the pursuit of high-performance enzyme-based biosensors, immobilization is not merely a convenient step but a critical determinant of analytical success. The core challenge in biosensor development lies in overcoming sensitivity loss, a frequent consequence of suboptimal enzyme integration with the transducer surface. When enzymes are improperly immobilized, the resulting biosensors often suffer from diminished catalytic activity, slowed electron transfer, and enzyme leaching, leading to signal drift and unreliable measurements. The three advanced techniques detailed in this guide—covalent bonding, entrapment, and cross-linking—each offer distinct pathways to stabilize the biological recognition element and preserve the signal integrity essential for sensitive detection. By understanding and troubleshooting these methods, researchers can systematically address the fundamental issues that undermine biosensor performance, paving the way for robust analytical devices in medical diagnostics, environmental monitoring, and drug development.

Core Principles and Strategic Selection

Covalent Bonding: This method involves forming strong, irreversible chemical bonds between functional groups on the enzyme surface (e.g., amino, carboxyl, thiol) and reactive groups on a support matrix [24] [36]. It provides exceptionally stable enzyme attachment, minimizing leaching into the solution, which is crucial for continuous biosensing applications and reagent conservation [37] [38]. A key consideration is that the covalent linkage must be formed without compromising the enzyme's active site to avoid significant activity loss [36].

Entrapment: Enzymes are physically confined within a porous polymer network or gel matrix, such as alginate, silica, or conductive polymers [24] [36]. The pores are sized to allow substrate and product molecules to diffuse freely while retaining the larger enzyme molecules. This method is less invasive and generally preserves enzyme activity well, as it avoids direct chemical modification of the enzyme [36] [38]. However, the diffusion barriers introduced by the matrix can slow response times and reduce apparent activity, particularly with high substrate concentrations [24].

Cross-linking: Enzymes are interconnected via bifunctional or multifunctional reagents (e.g., glutaraldehyde - GTA) to form large, stable aggregates [24] [37]. This can be done with or without a solid support. Cross-Linked Enzyme Aggregates (CLEAs) are a common carrier-free outcome of this technique. It creates a robust, three-dimensional enzyme network with high stability and operational lifetime [24]. The main challenge is that the cross-linking process can be harsh, potentially leading to conformational changes and a substantial drop in activity if not carefully controlled [24] [36].

Quantitative Technique Comparison

The table below summarizes the key performance characteristics and parameters of the three advanced immobilization techniques, providing a basis for informed selection.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Advanced Enzyme Immobilization Techniques

| Parameter | Covalent Bonding | Entrapment | Cross-Linking |

|---|---|---|---|

| Binding Force | Strong covalent bonds [24] | Physical confinement [24] | Covalent intermolecular bonds [24] |

| Stability | Very High [24] [37] | Moderate to High [36] | Very High [24] |

| Risk of Leaching | Very Low [37] | Low to Moderate (depends on pore size) [36] | Very Low [24] |

| Activity Retention | Variable (can be low due to active site involvement) [24] [36] | Typically High (no direct chemical modification) [36] [38] | Variable (can be low due to harsh reagents) [24] |

| Mass Transfer Limitation | Low | High (diffusion barrier) [24] [36] | Moderate |

| Typical Enzyme Loading | Controlled, often a monolayer [39] | High [36] | Very High [24] |

| Common Reagents/Supports | APTES, Glutaraldehyde, EDC/NHS, functionalized polymers/metal oxides [24] [40] | Alginate, polyacrylamide, sol-gel silica, conductive polymers [24] [36] | Glutaraldehyde (GTA) [24] [37] |

Troubleshooting Common Immobilization Problems

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why does my immobilized enzyme biosensor show a significantly lower signal (sensitivity) compared to the free enzyme in solution? This is a classic symptom of immobilization-induced sensitivity loss. The primary culprits are:

- Conformational Change: The enzyme's native structure is distorted by multipoint attachment (covalent bonding) or aggressive cross-linking, altering the active site [36].

- Mass Transfer Limitations: Especially in entrapment, the gel matrix can create a diffusion barrier, preventing the substrate from reaching the enzyme and the product from reaching the transducer quickly enough [24] [36].

- Steric Hindrance: The enzyme's active site may be oriented towards or blocked by the support material, preventing substrate access [36] [40].

Q2: How can I prevent my immobilized enzyme from detaching (leaching) from the sensor surface during operation? Leaching compromises the long-term stability and reusability of your biosensor.

- For Covalent Bonding: Ensure your support matrix is properly activated. Increase the density of reactive groups on the support and confirm the coupling chemistry is compatible with your buffer conditions (e.g., pH) [24] [37].

- For Entrapment: Optimize the polymer concentration and cross-linking density of the entrapping matrix. The pore size should be small enough to physically retain the enzyme while allowing for substrate diffusion [36].

- General Solution: A combination of techniques, such as mild adsorption followed by cross-linking, can create a more secure immobilization layer [37].

Q3: My cross-linked enzyme preparation has almost no activity. What went wrong? This indicates a loss of functional enzyme, typically due to over-cross-linking.

- Cause: Using an excessive concentration of cross-linker (like glutaraldehyde) or prolonged reaction time can lead to rigid, over-fixed aggregates where the active sites are destroyed or inaccessible [24].

- Solution: Systematically optimize the cross-linker-to-enzyme ratio and reaction time. Consider using milder cross-linking agents or adding inert proteins to "dilute" the mixture and create more space between enzyme molecules [24].

Q4: The response time of my biosensor is slow. How can I improve it? Slow response is often tied to mass transfer.

- Check Your Matrix: In entrapment systems, the polymer network may be too dense. Try using a more porous material or reducing the polymer concentration [36].

- Enzyme Distribution: Ensure the enzyme is immobilized in a thin, uniform layer close to the transducer surface. Thick, uneven layers increase the diffusion path [40].

- Nanomaterials: Integrate nanomaterials (e.g., carbon nanotubes, graphene, metal nanoparticles) into your support. They provide a high surface area, facilitating higher enzyme loading and improved electron transfer, which can speed up the response [7] [40].

Troubleshooting Guide Table

Table 2: Troubleshooting Guide for Common Immobilization Issues

| Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Low Activity/ Sensitivity | 1. Denaturation during immobilization [36]2. Active site blockage/steric hindrance [36]3. Diffusion limitations [24] | 1. Use milder immobilization conditions (shorter time, lower temperature).2. Employ a spacer arm (e.g., 6-aminocaproic acid) to distance enzyme from support [38].3. Use a more porous support or less dense gel matrix. |

| Enzyme Leaching | 1. Weak binding (inadequate covalent bonding) [37]2. Pores too large (entrapment) [36] | 1. Verify support activation; increase functional group density.2. Optimize polymerization conditions to decrease pore size; combine entrapment with mild cross-linking. |

| High Background Noise | 1. Non-specific adsorption of interferents [11]2. Over-oxidation of electrode | 1. Use a blocking agent (e.g., BSA, ethanolamine) after immobilization.2. Use a permselective membrane (e.g., Nafion) to exclude charged interferents [11]. |

| Poor Operational Stability | 1. Enzyme inactivation under operational conditions (pH, T)2. Leaching over time | 1. Choose an immobilization method that stabilizes the enzyme (e.g., multipoint covalent bonding) [24].2. Ensure robust attachment (covalent/cross-linking) and pre-incubate under operational conditions. |

| Slow Response Time | 1. Diffusion barriers in the matrix [24]2. Low electron transfer kinetics | 1. Use nanostructured materials to reduce diffusion path [7] [40].2. Incorporate redox mediators (2nd gen biosensors) or use direct electron transfer (3rd gen) strategies [24] [40]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Covalent Bonding on Aminated Silica Beads

This protocol describes a common method for creating a stable, covalently immobilized enzyme layer using an aminosilane-functionalized support and glutaraldehyde as a cross-linker.

Workflow: Covalent Immobilization

Materials:

- Support: Mesoporous silica beads (e.g., SBA-15, MCM-41) [40]

- Coupling Agent: (3-Aminopropyl)triethoxysilane (APTES)

- Cross-linker: Glutaraldehyde (GTA) solution, 2.5% (v/v) in buffer [24] [37]

- Enzyme: Your purified enzyme of interest (e.g., Glucose Oxidase)

- Buffer: 0.1 M phosphate buffer, pH 7.0-7.4 (unless specified otherwise for the enzyme)

- Quenching/Blocking Agents: Ethanolamine (1 M, pH 8.0), Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA, 1% w/v)

Step-by-Step Method:

- Support Activation (Amination):

- Place 100 mg of dry silica beads in a tube.

- Add 5 mL of a 2% (v/v) APTES solution in anhydrous toluene.

- Incubate at 70-80°C for 4-6 hours with gentle shaking or stirring.

- Wash thoroughly with toluene and ethanol to remove unbound silane, followed by drying under an inert gas or vacuum [40].

Glutaraldehyde Coupling:

Enzyme Immobilization:

- Add 5 mL of enzyme solution (1-5 mg/mL in 0.1 M phosphate buffer, pH 7.0) to the activated, washed beads.

- Incubate at 4°C for 12-16 hours (or at room temperature for 2-4 hours) with gentle mixing.

- Recover the beads by centrifugation and wash with buffer until the washings show no protein content (measured by Bradford assay or UV absorbance at 280 nm) to remove any unbound enzyme.

Quenching and Blocking:

- To block remaining aldehyde groups, incubate the immobilized enzyme with 1 M ethanolamine (pH 8.0) for 1 hour.

- Optionally, further block non-specific sites by treating with a 1% (w/v) BSA solution for 1 hour.

- Wash the final preparation thoroughly with buffer and store at 4°C in buffer until use [11].

Entrapment within Alginate-Polyacrylamide Hybrid Gel

This protocol outlines a gentle entrapment method suitable for enzymes that are sensitive to chemical modification.

Materials:

- Polymers: Sodium Alginate (2-4% w/v), Acrylamide/Bis-acrylamide solution.

- Cross-linker/Catalyst: Ammonium Persulfate (APS) and Tetramethylethylenediamine (TEMED).

- Enzyme: Your purified enzyme of interest.

- Buffer: 0.1 M phosphate or HEPES buffer, suitable for your enzyme.

- Gelling Solution: Calcium Chloride (CaCl₂, 100 mM).

Step-by-Step Method:

- Gel Precursor Preparation:

- Dissolve sodium alginate in buffer to make a 3% (w/v) solution. Gently heat if necessary to achieve complete dissolution. Let it cool to room temperature.

- Prepare a 30% (w/v) acrylamide/bis-acrylamide stock solution in buffer.

- Mix the alginate solution, acrylamide solution, and enzyme solution in a ratio of 7:2:1 (v/v/v). Keep the mixture on ice.

Polymerization and Gelling:

- Add APS and TEMED to the ice-cold mixture to initiate free-radical polymerization. Mix quickly but gently.

- Immediately pipet the mixture onto your electrode surface or as droplets into a stirred solution of 100 mM CaCl₂.

- The Ca²⁺ ions will cross-link the alginate, forming a stable gel bead or layer almost instantly, while the polyacrylamide network forms concurrently, reinforcing the structure.

- Allow the gel to stabilize for 30 minutes at room temperature.

Washing and Storage:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Advanced Enzyme Immobilization

| Reagent/ Material | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Glutaraldehyde (GTA) | Bifunctional cross-linker for covalent bonding and cross-linking. Reacts with primary amine groups [24] [37]. | Concentration and time must be optimized to prevent over-cross-linking and activity loss [24]. |

| APTES | Silane coupling agent used to introduce primary amine groups onto silica, metal oxide, and other hydroxylated surfaces [40]. | Requires anhydrous conditions for efficient silanization. |

| EDC / NHS | Carbodiimide cross-linker (EDC) used with N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) to activate carboxyl groups for coupling with primary amines, forming stable amide bonds [40]. | The EDC reaction is rapid, and the intermediate is unstable in water; NHS stabilizes it for higher coupling efficiency. |

| Sodium Alginate | Natural polysaccharide used for entrapment via ionotropic gelation with divalent cations like Ca²⁺ [36] [38]. | Mild, biocompatible method. Pore size and mechanical strength can be tuned by concentration and combining with other polymers. |

| Mesoporous Silica (e.g., SBA-15) | High-surface-area inorganic support for adsorption and covalent bonding [40]. | Pore size should be selected to match the enzyme dimensions for optimal loading and stability. |

| Carbon Nanotubes / Graphene | Nanostructured carbon materials used as conductive supports. Enhance electron transfer in electrochemical biosensors [7] [40]. | Requires functionalization (e.g., oxidation) to facilitate enzyme binding. Greatly improves biosensor sensitivity. |

| Polyacrylamide | Synthetic polymer used for entrapment via free-radical polymerization [36]. | Forms a highly tunable gel network. Acrylamide monomer is a neurotoxin and must be handled with care. |

Multienzyme Cascade Systems (MCS) for Amplified Signal and Specificity

Core Concepts: How MCS Enhance Biosensor Performance

Multienzyme Cascade Systems (MCS) integrate two or more enzymes in a specific sequence to overcome key limitations of single-enzyme biosensors. By creating a coordinated biocatalytic pathway, MCS significantly improve biosensor performance, particularly in overcoming sensitivity loss when detecting trace-level analytes in complex samples [41] [35].

The Core Mechanism In a typical cascade, the product generated by the first enzyme serves as the substrate for the next enzyme in the sequence. This creates an amplified, multi-step reaction on the sensor surface. For instance, a biosensor for triglycerides might sequentially employ lipase, glycerol kinase (GK), and glycerol-3-phosphate oxidase (GPO), as no single enzyme can both interact with the triglyceride and generate a measurable electrical signal [35]. This sequential processing overcomes substrate diffusion limits, minimizes loss of unstable intermediates, and enhances overall reaction efficiency and specificity compared to single-enzyme systems [35].

MCS Classification MCS are classified based on reaction pathways, which informs their design and application [35] [42]:

- Linear Cascades: A series of sequential reactions where the final product is measured.

- Orthogonal Cascades: Multiple reactions proceed independently but share a common cofactor or mediator.

- Parallel Cascades: Multiple substrates are detected simultaneously through different enzymatic pathways converging on a single signal.

- Cyclic Cascades: A cofactor or substrate is regenerated and reused within the cycle, improving sustainability and efficiency.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common MCS Challenges and Solutions

| Problem Area | Specific Issue | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity Loss | Low or diminished signal output over time. | Sub-optimal enzyme ratios [35], enzyme leaching from the sensor surface [43], inefficient electron transfer [41]. | Optimize molecular ratio and spatial organization of enzymes [35]. Use advanced nanomaterials (e.g., MOFs, COFs) for high-density, stable enzyme immobilization [41] [43]. |

| Signal Selectivity | Interference from electroactive substances in sample matrix (e.g., ascorbic acid, uric acid) [11]. | High operating potential required for H₂O₂ detection, non-specific reactions. | Employ second-generation biosensor principles using synthetic redox mediators (e.g., ferrocene) to lower operating potential [43]. Use permselective membranes to shield the electrode [11]. |

| System Stability & Reproducibility | Short sensor lifespan and inconsistent performance between batches. | Enzyme denaturation over time [43], inconsistent enzyme immobilization, deactivation by sample matrix components (e.g., H₂O₂) [44]. | Co-immobilize stabilizers or use nano-confinement within porous materials to protect enzyme structure [43] [42]. Implement enzyme engineering to improve inherent stability [35]. Add catalase to degrade harmful H₂O₂ byproducts [44]. |

| Cascade Efficiency | Low overall conversion yield, slow reaction kinetics. | Incompatible optimal conditions (pH, temp.) for different enzymes [35], mass transfer limitations of intermediates. | Fine-tune reaction buffer for a compromise condition that maintains activity for all enzymes [35]. Use computational modeling and multi-objective optimization to find optimal process parameters [45]. Design co-immobilization to minimize distance between enzymes for efficient substrate channeling [42]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How do I determine the optimal ratio of multiple enzymes in a cascade system? The optimal ratio is highly dependent on the specific enzymes and their kinetic parameters (e.g., Vmax, Km). A systematic approach is recommended: begin by testing different molecular ratios while keeping the total enzyme loading constant. The use of multi-objective dynamic optimization, a computational modeling technique, can be a valuable tool to predict the best compromises between key objectives like space-time yield, enzyme consumption, and cost, saving significant experimental time [35] [45].

Q2: What are the best strategies for co-immobilizing multiple enzymes while maintaining the activity of each? The key is selecting an immobilization strategy that provides a high surface area, biocompatible environment, and controlled enzyme orientation. Promising strategies include [41] [43] [42]:

- Porous Nanomaterials: Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs), Covalent Organic Frameworks (COFs), and mesoporous carbon offer ultrahigh surface areas and tunable pores for high-density, stable enzyme loading.

- Functionalized Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) and Graphene Oxide: These provide excellent electrical conductivity and can be functionalized with specific groups for covalent enzyme attachment.

- Enzyme-Scaffold Complexes: Using DNA origami or protein scaffolds allows for precise control over the spatial arrangement and distance between enzymes, facilitating efficient substrate channeling.

Q3: Our MCS biosensor performs well in buffer but loses sensitivity in complex biological samples like blood serum. How can this be addressed? This is a common challenge due to the "matrix effect," where proteins, cells, or other interferents in real samples foul the sensor surface or non-specifically interact with the enzymes. Solutions include [41] [11]:

- Sample Pre-treatment: Simple dilution, filtration, or extraction can reduce matrix complexity.

- Sensor Surface Engineering: Coating the sensor with a protective layer like bovine serum albumin (BSA) or a polymer membrane (e.g., Nafion) can block interferents while allowing the target analyte to pass through. The use of bulky stabilizing agents like BSA can also create steric hindrance, preventing large biomolecules from interacting with the sensor core [46].

- Mediator Selection: Using second-generation biosensor designs with selective redox mediators that operate at a lower potential can minimize the electrochemical oxidation of common interferents like ascorbic acid [43].

Q4: Can MCS be used to detect analytes for which no single, direct-reporting enzyme exists? Yes, this is one of the primary advantages of MCS. They significantly broaden the range of detectable analytes. The triglyceride sensor is a perfect example, combining lipase, GK, and GPO to create a detectable signal from an analyte that no single enzyme can handle [35]. Similarly, complex pathways can be designed to convert an initial analyte through several steps into a final, easily measurable product like H₂O₂ [42].

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Building a Lactate Biofuel Cell with a 3-Enzyme Cascade

This protocol details the construction of a bioanode for a lactate/O₂ biofuel cell (BFC) using a three-enzyme cascade, based on the work of Shitanda et al. [42]. This system demonstrates how MCS can be used for enhanced signal and power output.

Objective To fabricate a bioanode that fully oxidizes lactate through a cascade reaction involving Lactate Oxidase (LOx), Pyruvate Decarboxylase (PDC), and Aldehyde Dehydrogenase (ALDH), generating four electrons per lactate molecule and thereby increasing current density.

Materials and Reagents