Streamlining Biosensor Analysis: Advanced Strategies for Sample Pretreatment Simplification

This article addresses the critical challenge of complex sample preparation in biosensor applications, a significant bottleneck for their adoption in drug development, clinical diagnostics, and environmental monitoring.

Streamlining Biosensor Analysis: Advanced Strategies for Sample Pretreatment Simplification

Abstract

This article addresses the critical challenge of complex sample preparation in biosensor applications, a significant bottleneck for their adoption in drug development, clinical diagnostics, and environmental monitoring. It explores foundational principles, innovative methodological approaches, systematic optimization techniques, and rigorous validation strategies for simplifying pretreatment protocols. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, the content synthesizes current advancements to provide a comprehensive guide for developing faster, more cost-effective, and user-friendly biosensing systems suitable for point-of-care and resource-limited settings.

The Bottleneck of Biosensing: Why Sample Pretreatment is a Critical Barrier to Adoption

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs for Biosensor Research

Fundamental Concepts and Troubleshooting

This section addresses common conceptual and technical challenges researchers face when developing biosensors with simplified sample pretreatment.

FAQ: Why is my biosensor signal weak or unstable after simplifying the sample pretreatment protocol?

Answer: A weak or unstable signal often results from matrix interference or non-specific adsorption from complex sample matrices like blood, urine, or plant extracts. When you reduce pretreatment steps, more interfering substances (like proteins or lipids) may reach the sensor surface.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Check Bioreceptor Immobilization: Ensure your bioreceptor (antibody, aptamer, enzyme) is properly immobilized and remains active. Inadequate immobilization can lead to receptor leaching or denaturation. Use a reliable immobilization method, such as the streptavidin-biotin capturing method for nucleic acids, to ensure stability. [1]

- Introduce a Blocking Step: After immobilizing your bioreceptor, incubate the sensor surface with a blocking agent (e.g., BSA, casein) to cover any remaining active sites on the sensor chip and minimize non-specific binding. [1] [2]

- Optimize Wash Buffer: Increase the stringency of your wash buffers (e.g., by adding mild detergents like Tween-20) after sample introduction to remove weakly bound, non-specific molecules without disrupting the specific analyte-bioreceptor interaction. [2]

- Validate with Controls: Always run control experiments with samples lacking the analyte to quantify the level of non-specific binding and establish a baseline for your signal.

FAQ: How can I improve the specificity of my biosensor for my target analyte in a crude sample?

Answer: Specificity is paramount, especially when complex sample preparation is minimized. The issue likely lies in the choice of bioreceptor or the assay design.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Bioreceptor Selection: Consider using aptamers (single-stranded DNA or RNA). They can be selected for high affinity and specificity against a wide range of targets, including small molecules, and can often distinguish between closely related compounds. [2] [3] For example, engineered transcription factors like TtgR have been used to develop whole-cell biosensors with tailored specificity for bioactive compounds. [4]

- Assay Design: Implement a sandwich assay format if possible. This requires two distinct binding sites on the analyte, which significantly enhances specificity compared to a direct binding assay.

- Surface Engineering: Modify the sensor surface with self-assembled monolayers (SAMs) or other materials that create a hydrophilic and charge-neutral environment to reduce electrostatic and hydrophobic non-specific interactions. [5] [2]

FAQ: My biosensor's reproducibility is low between experimental runs. What could be the cause?

Answer: Poor reproducibility often stems from inconsistencies in the sensor surface or fluidic system.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Standardize Immobilization: Ensure the density and orientation of immobilized bioreceptors are consistent across all sensor chips. Using a covalent coupling chemistry with optimized and tightly controlled reaction times and concentrations is crucial. [1] [2]

- Calibrate the Instrument: Regularly perform calibration checks as per the manufacturer's instructions to ensure the transducer (e.g., optical or electrochemical) is functioning correctly.

- Control Flow Rate: In flow-based systems like SPR, variations in flow rate can affect binding kinetics. Maintain a constant, optimized flow rate during sample injection for all experiments. [1]

- Monitor Regeneration: If you regenerate your sensor surface for reuse, ensure the regeneration solution and conditions (contact time, flow rate) completely remove the bound analyte without damaging the immobilized bioreceptor. An incomplete or harsh regeneration will lead to decreasing activity over successive cycles. [1]

Experimental Protocols for Simplified Sample Analysis

This section provides detailed methodologies for key biosensor experiments that minimize sample pretreatment.

Protocol 1: Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) for RNA-Small Molecule Interaction Analysis

This protocol is ideal for studying interactions with nucleic acid targets, such as in drug discovery, with minimal sample purification. [1]

1. Objective: To quantitatively measure the affinity and kinetics of a small molecule binding to an immobilized RNA sequence using SPR, a label-free technique.

2. Research Reagent Solutions:

| Reagent/Material | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Biotinylated RNA | The target molecule immobilized on the sensor chip. |

| Streptavidin Sensor Chip | Surface for capturing biotinylated RNA. Provides a stable and uniform immobilization. |

| Running Buffer (e.g., HBS-EP) | Buffered solution to maintain pH and ionic strength; used for dilution and as a continuous flow buffer. |

| Small Molecule Analytes | The compounds being tested for binding to the RNA target. |

| Regeneration Solution (e.g., mild EDTA) | Solution to remove bound analyte from the immobilized RNA, regenerating the surface for a new experiment. |

3. Workflow:

4. Step-by-Step Procedure:

1. Prepare Sensor Surface: Prime the SPR instrument and streptavidin sensor chip with running buffer until a stable baseline is achieved. [1]

2. Immobilize RNA: Dilute the biotinylated RNA in running buffer and inject it over the streptavidin chip surface. A successful immobilization will show a sharp increase in resonance units (RU), followed by a stable plateau. [1]

3. Establish Baseline: Continue flowing running buffer to establish a stable baseline.

4. Inject Analyte: Prepare a dilution series of the small molecule analyte in running buffer. Inject each concentration over the RNA surface and a reference cell for a fixed period (e.g., 1-2 minutes). This is the association phase. [1]

5. Monitor Association: The SPR signal in RU will increase as molecules bind to the RNA.

6. Inject Running Buffer: Switch the flow back to running buffer alone. This begins the dissociation phase. [1]

7. Monitor Dissociation: The SPR signal will decrease as bound molecules dissociate from the RNA.

8. Regenerate Surface: Inject a regeneration solution (e.g., containing EDTA or high salt) for a short time to remove all bound analyte, returning the signal to the baseline. This allows for multiple cycles on the same RNA surface. [1]

9. Data Analysis: Use the SPR instrument's software to fit the association and dissociation sensorgrams to a binding model (e.g., 1:1 Langmuir). This will calculate the kinetic rate constants (association rate k_on, dissociation rate k_off) and the equilibrium dissociation constant (K_D). [1]

Protocol 2: Electrochemical Immunosensor for Protein Detection

This protocol is highly sensitive and suitable for point-of-care applications, often requiring minimal sample volume and preparation. [5]

1. Objective: To detect a specific protein antigen (e.g., carcinoembryonic antigen, CEA) using an amperometric immunosensor.

2. Research Reagent Solutions:

| Reagent/Material | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Capture Antibody | The primary antibody immobilized on the electrode, specific to the target antigen. |

| Enzyme-Labeled Secondary Antibody (e.g., HRP-labeled) | Binds to the captured antigen, providing an amplifying signal via enzyme catalysis. |

| Electrode (e.g., Screen-printed Carbon, Gold) | The transducer platform. |

| Electrochemical Redox Mediator (e.g., Thionine) | Shuttles electrons from the enzyme reaction to the electrode surface. |

| Enzyme Substrate (e.g., H₂O₂ for HRP) | The molecule converted by the enzyme to produce a measurable current change. |

3. Workflow:

4. Step-by-Step Procedure: 1. Electrode Modification: Clean the working electrode (e.g., glassy carbon). It can be modified with materials like carbon nanotubes or a self-assembled monolayer to enhance surface area and facilitate antibody immobilization. [5] 2. Immobilize Capture Antibody: Attach the specific capture antibody to the modified electrode surface. This can be done via covalent coupling (e.g., using EDC/NHS chemistry) or physical adsorption. [5] 3. Blocking: Incubate the electrode with a blocking agent (e.g., BSA) to cover any non-specific binding sites. 4. Incubate with Sample: Apply the sample containing the target antigen to the electrode and incubate to allow antigen-antibody binding. 5. Incubate with Secondary Antibody: Wash the electrode and then incubate it with the enzyme-labeled secondary antibody. 6. Amperometric Measurement: Place the electrode in a buffer solution containing the redox mediator and the enzyme substrate (e.g., H₂O₂ for HRP). Apply a constant potential and measure the resulting current. The enzyme catalyzes the reduction of H₂O₂, which is coupled to the electrochemical reaction of the mediator, producing a catalytic current proportional to the amount of captured antigen. [5] 7. Signal Quantification: Construct a calibration curve by plotting the measured current against the concentration of a known standard to quantify the antigen in unknown samples.

Advanced Support: Quantitative Data and Reagent Specifications

This section provides consolidated data and reagent information to aid in experimental design and troubleshooting.

Table 1: Comparison of Biosensor Transducers for Simplified Pretreatment

| Transducer Type | Key Advantage for Simplified Pretreatment | Typical Sensitivity | Example Application in Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electrochemical | Low-cost; miniaturized devices; small sample volumes. [5] | Nanomolar (nM) to picomolar (pM) range. [5] | Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) detection with screen-printed electrodes. [5] |

| Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) | Label-free, real-time monitoring of interactions; measures kinetics. [1] | High (e.g., K_D measurements from nM to pM). [1] | RNA-small molecule interaction studies for drug discovery. [1] |

| Fluorescence-Based | Very high sensitivity and multiplexing capability. | Picomolar (pM) to femtomolar (fM) range. | Rapid bacterial detection in milk using recombinase-aided amplification with test strips. [4] |

| Piezoelectric (QCM) | Mass-sensitive; useful for studying adhesion and adsorption. | Nanogram (ng) mass changes. | Not explicitly covered in results. |

| Whole-Cell Biosensors | Provides functional response (e.g., to bioactive compounds). | Varies with the cellular system. | Engineered TtgR-based biosensors for monitoring flavonoids. [4] |

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Biosensor Development

| Item | Critical Function | Technical Notes & Selection Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Bioreceptors | Molecular recognition element that confers specificity. | Aptamers: Offer high stability and tailorability. [2] Antibodies: High specificity but can be more expensive. [5] Engineered Proteins: (e.g., TtgR) can be genetically modified for tailored responses. [4] |

| Immobilization Matrix | Provides a stable interface between the bioreceptor and transducer. | Streptavidin-Biotin: Very common and reliable for nucleic acids and proteins. [1] Self-Assembled Monolayers (SAMs): Provide a well-defined, controllable surface chemistry on gold electrodes. [5] [2] Redox Polymers: Used in electrochemical sensors to "wire" enzymes to the electrode. [5] |

| Signal Generation System | Converts the binding event into a measurable signal. | Enzyme Labels (HRP, ALP): Provide signal amplification. [5] Redox Mediators (e.g., Ferrocene): Shuttle electrons in electrochemical sensors. [5] Fluorescent Dyes: For high-sensitivity optical detection. |

| Microfluidic Components | Controls and manipulates small fluid volumes, enabling automation. | Used to integrate sample preparation steps (like mixing or filtering) directly onto the sensor chip, reducing manual handling and simplifying the overall process. [2] [3] |

Sample pretreatment is a foundational step in the biosensing workflow, aimed at preparing a complex biological sample for accurate analysis. Its primary purpose is to isolate or make the target analyte accessible while removing substances that could interfere with the biosensor's function. Effective pretreatment directly determines the reliability of the final result by enhancing sensitivity (the ability to detect low analyte concentrations), specificity (the ability to distinguish the target from other substances), and reproducibility (the consistency of results across multiple tests) [6]. Neglecting this step can lead to false positives, false negatives, and unreliable data, ultimately compromising diagnostic or monitoring outcomes.

### FAQ: Troubleshooting Sample Pretreatment

1. My biosensor results are inconsistent between runs. Could sample preparation be the cause?

Yes, inconsistency is a classic sign of variable sample pretreatment. To address this:

- Standardize Protocols: Ensure that the sample collection method, storage time, and pretreatment steps (like dilution, filtration, or incubation time) are identical for every test [7].

- Check Buffer Conditions: Verify the pH, concentration, and expiration date of your buffer solutions. Degraded or incorrect buffers can alter the sample matrix and cause erratic results [7].

- Control Sample Temperature: Measure the sample temperature during preparation, as it can affect chemical reaction rates and the stability of biological components [7].

2. The sensitivity of my assay has dropped. What sample-related issues should I investigate?

A loss of sensitivity often indicates that interfering substances are blocking the biosensor's active site or that the target is being lost during preparation.

- Investigate Interfering Substances: Samples like saliva, blood, or food contain proteins, salts, and other components that can foul the sensor surface. Implement or optimize a filtration or centrifugation step to remove these interferents [8] [9].

- Avoid Sample Degradation: Ensure that target analytes (especially labile ones like RNA or some proteins) are not degrading during pretreatment. Reduce processing time and store samples at appropriate temperatures [7].

- Confirm Sensor Calibration: Regularly calibrate your sensor with standard solutions to ensure its inherent sensitivity has not changed [7].

3. How can I simplify sample pretreatment for point-of-care testing?

Simplification is a major research focus in biosensing. Successful strategies include:

- Using Innovative Design: A novel biosensor for detecting SARS-CoV-2 RNA from saliva uses a downward-facing electrode in a special cuvette. This design allows debris to settle away from the sensing surface by gravity, eliminating the need for filtration [8].

- Choosing Robust Biorecognition Elements: Opt for stable recognition elements like aptamers or engineered DNAzymes, which can function better in complex samples compared to some traditional antibodies or enzymes [9].

- Leveraging Integrated Systems: Explore biosensors that incorporate built-in microfluidic channels for automatic sample mixing and separation [6].

### Experimental Protocols: Key Pretreatment Methods

Protocol 1: Direct Detection from Unfiltered Saliva for an RNA Biosensor

This protocol demonstrates how a specific biosensor design can drastically simplify pretreatment [8].

- Principle: An electrochemical biosensor uses a specially designed cuvette with a downward-facing electrode. Gravity causes debris in saliva to settle away from the active sensing surface, preventing interference and eliminating the need for filtration or complex RNA extraction.

- Procedure:

- Sample Collection: Collect a fresh saliva sample from the participant.

- Sample Mixing: Mix the saliva sample with an equal volume of the provided assay buffer.

- Loading: Pipette the saliva-buffer mixture directly into the biosensor's cuvette. No filtration or centrifugation is performed.

- Measurement: Place the cuvette into the biosensor device and initiate the electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) measurement. The downward-facing electrode interacts with the clarified portion of the sample.

- Regeneration & Reuse: After measurement, clean the electrode surface according to the manufacturer's instructions (e.g., rinsing with a regeneration solution) to prepare for the next sample.

Protocol 2: General Sample Pretreatment for Complex Matrices

This is a generalized protocol for biosensors detecting targets in complex samples like blood, urine, or food homogenates.

- Principle: Using physical separation methods to remove particulates and interfering macromolecules that can cause matrix effects, thereby improving specificity and reproducibility [6] [9].

- Procedure:

- Homogenization: For solid or semi-solid samples (e.g., food, tissue), homogenize the sample in a suitable buffer to create a uniform liquid suspension.

- Centrifugation: Centrifuge the homogenized sample or a liquid sample (e.g., blood, urine) at a specified speed and duration to pellet insoluble debris, cells, or large particles.

- Filtration/Clarification: Pass the supernatant through a syringe filter (e.g., 0.22 µm or 0.45 µm pore size) to remove remaining fine particles and sterilize the sample if necessary.

- Dilution: Dilute the clarified sample in an appropriate buffer to bring the analyte concentration into the detection range of the biosensor and to reduce the concentration of potential interferents.

- pH Adjustment: If required, adjust the pH of the final sample solution to the optimal range for the biosensor's biorecognition element (e.g., antibody, enzyme).

### The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Sample Pretreatment

Table 1: Key reagents and materials used in sample pretreatment protocols, with their specific functions.

| Reagent/Material | Function in Pretreatment |

|---|---|

| Assay Buffer | Stabilizes the pH of the sample and provides the ideal ionic strength for the biosensor's operation [7]. |

| Filtration Membranes | Remove particulate matter, cells, and other insoluble contaminants that could foul the sensor surface [6]. |

| Centrifuge | Separates components of a sample based on density, pelleting debris and clarifying the supernatant for analysis [6]. |

| Hydrophobic Coating | Applied to sensor surfaces to prevent air bubble and salt crystal formation, which can interfere with measurements [8]. |

| Oligonucleotide Probes | Synthetic DNA/RNA sequences that specifically hybridize with the target; they are immobilized on the sensor as the recognition element [8]. |

Table 2: How different pretreatment steps influence key biosensor performance metrics.

| Pretreatment Step | Impact on Sensitivity | Impact on Specificity | Impact on Reproducibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Filtration/Centrifugation | Reduces signal suppression from interferents, improving the limit of detection [8]. | Removes substances that may bind non-specifically to the sensor surface [9]. | Provides a more consistent sample matrix from test to test [7]. |

| pH Buffering | Ensures optimal activity of enzymatic bioreceptors or DNA hybridization efficiency [7]. | Prevents denaturation of sensitive biorecognition elements, preserving their binding function [9]. | Maintains constant reaction conditions, leading to more predictable assay kinetics [7]. |

| Sample Dilution | Can reduce sensitivity if over-diluted, but can also minimize matrix effects that mask low-level signals. | Reduces the concentration of cross-reacting molecules, potentially increasing specificity. | Mitigates variability from highly heterogeneous sample compositions. |

| No Pretreatment (with design) | Maintained 100% sensitivity for SARS-CoV-2 RNA in saliva due to innovative cuvette design [8]. | Maintained 100% specificity by preventing debris from causing false signals [8]. | The reusable design and consistent method support high reproducibility [8]. |

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

This technical support center provides targeted guidance for researchers developing and using point-of-care (POC) biosensors with simplified or eliminated sample pretreatment. The content addresses common experimental challenges within the broader research context of streamlining sample preparation to enable decentralized diagnostics.

Troubleshooting Guide for Simplified Pretreatment Biosensors

The following table outlines common issues, their potential causes, and recommended solutions for biosensors designed with minimal pretreatment steps.

| Problem | Possible Root Cause | Recommended Solution | Underlying Principle |

|---|---|---|---|

| High Background Noise/ Low Signal-to-Noise Ratio | Non-specific binding of matrix components (e.g., proteins, cells) to the sensor surface. [10] | Incorporate a blocking step with agents like BSA or casein to passivate unused sensor surface areas. [11] | Blocking agents occupy non-specific binding sites, reducing interference from complex sample matrices without full purification. [11] |

| Low Sensitivity/ High Limit of Detection | Sensor is unable to concentrate the target from a raw, dilute sample. [12] | Integrate on-chip target accumulation methods, such as microfluidic trapping structures or magnetic bead-based capture. [12] | In-situ concentration increases the local density of the target analyte at the sensing zone, improving the detectable signal without pre-processing. [12] |

| Poor Reproducibility/ Inconsistent Results | Variable sample composition (e.g., viscosity, hematocrit) affects fluidics and binding kinetics in unprocessed samples. [10] [13] | 1. Include an internal standard or control. 2. Design microfluidic mixers (e.g., Z or S-shaped units) to ensure uniform antigen-antibody interaction. [12] | Standardization and controlled mixing mitigate the variable pre-analytical factors inherent in direct sample analysis. [13] [12] |

| Slow Assay Time | Inefficient mixing in miniaturized systems delays the reaction between the target and the biorecognition element. [12] | Optimize microfluidic channel design to include passive mixers that enhance reagent interaction without external equipment. [12] | Passive micro-mixers reduce diffusion distances and create chaotic advection, accelerating the binding reaction to achieve faster results. [12] |

| Sensor Fouling or Loss of Function | Biofouling from proteins or cells in untreated samples clogs microfluidic channels or coats the sensor surface. [10] | Use antifouling materials for the chip construction (e.g., specific surface coatings) or implement a pre-filtration membrane within the device. [10] | Physicochemical surface modifications prevent the non-specific adsorption of biomolecules, preserving sensor functionality and fluidic integrity. [10] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How can I validate that my simplified pretreatment biosensor is performing accurately against a standard laboratory method?

It is crucial to perform a cross-validation study. Run a set of clinical samples using your POC biosensor and compare the results with those obtained from the reference method used in a central laboratory. [10] Statistical analysis, such as calculating correlation coefficients (e.g., R²) and using Bland-Altman plots, should be employed to assess the agreement between the two methods. Furthermore, test the biosensor's performance with samples that contain potential interfering substances to confirm specificity. [14] [13]

Q2: What are the key stability challenges for single-use, disposable biosensors that require no sample prep, and how can I address them?

The primary challenge is shelf-stability, which relates to retaining the activity of biological recognition elements (e.g., enzymes, antibodies) over time. [10] Factors like temperature and humidity during storage are major influencers. To address this:

- Conduct rigorous real-time and accelerated stability studies to establish the product's shelf life.

- Optimize the formulation of the reagents, which may include the use of stabilizing sugars or proteins in the dry reagent layer.

- Ensure proper packaging with desiccants to control moisture. [10]

Q3: Our biochip uses a paper-based module for visual detection. How can we transition from a qualitative "yes/no" result to a semi-quantitative or quantitative readout?

You can integrate a smartphone-based readout system. Develop a mobile application that uses the smartphone's camera to capture an image of the colorimetric signal on the paper strip. The application can then analyze the color intensity or the size of the detection zone, which exhibits a dose-dependent correlation with the target concentration. [14] This approach has been successfully demonstrated for detecting biomarkers like creatinine and alkaline phosphatase, transforming a visual signal into quantifiable data. [14]

Experimental Protocol: Pretreatment-Free Microfluidic Biochip for Blood Typing

The following protocol is adapted from a recent study demonstrating a sensitive, accumulation pretreatment-free method for visual ABO/Rh blood typing. [12]

1. Objective To determine the ABO and Rh blood type directly from a liquid blood sample without any centrifugation, washing, or other pretreatment steps using a polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS)-based microfluidic biochip.

2. Research Reagent Solutions & Materials

| Item | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| PDMS-based Microfluidic Biochip | The core platform containing micro-mixers, a reaction chamber, and a biosensing channel for RBC accumulation and visualization. [12] |

| Anti-A, Anti-B, and Anti-D Antibodies | Specific antibodies that bind to A, B, and RhD antigens on red blood cells, respectively, triggering agglutination. [12] |

| EDTA-anticoagulated Whole Blood | The sample for testing, used directly without processing to separate red blood cells. [12] |

| Vacuum Pump | Provides uniform negative pressure to drive the sample and reagents through the microfluidic chip without complex pumping systems. [12] |

3. Step-by-Step Methodology

- Chip Preparation: Fabricate the PDMS microfluidic biochip using standard soft photolithography, ensuring it includes two continuous mixing units (Z and S shapes) at the entrance. [12]

- Sample and Reagent Loading: Pipette 10 µL of the whole blood sample and 10 µL of the corresponding antibody (e.g., Anti-A) into their designated inlets on the biochip. [12]

- On-Chip Mixing and Reaction: Activate the vacuum pump connected to the chip's outlet. The negative pressure draws the blood and antibody through the integrated mixing units, ensuring rapid and efficient interaction. The antigen-antibody reaction occurs in the reaction chamber. [12]

- Target Accumulation and Detection: The formed red blood cell clusters flow into the biosensing channel and are physically trapped, accumulating to form a visible bar. The result can be observed with the naked eye or under a microscope within 5 minutes. [12]

- Interpretation: The presence of a visible bar in the channel where a specific antibody was used indicates a positive reaction for that blood group antigen (e.g., a bar with Anti-A means the blood is type A).

This protocol highlights how strategic microfluidic design effectively replaces traditional, multi-step sample pretreatment.

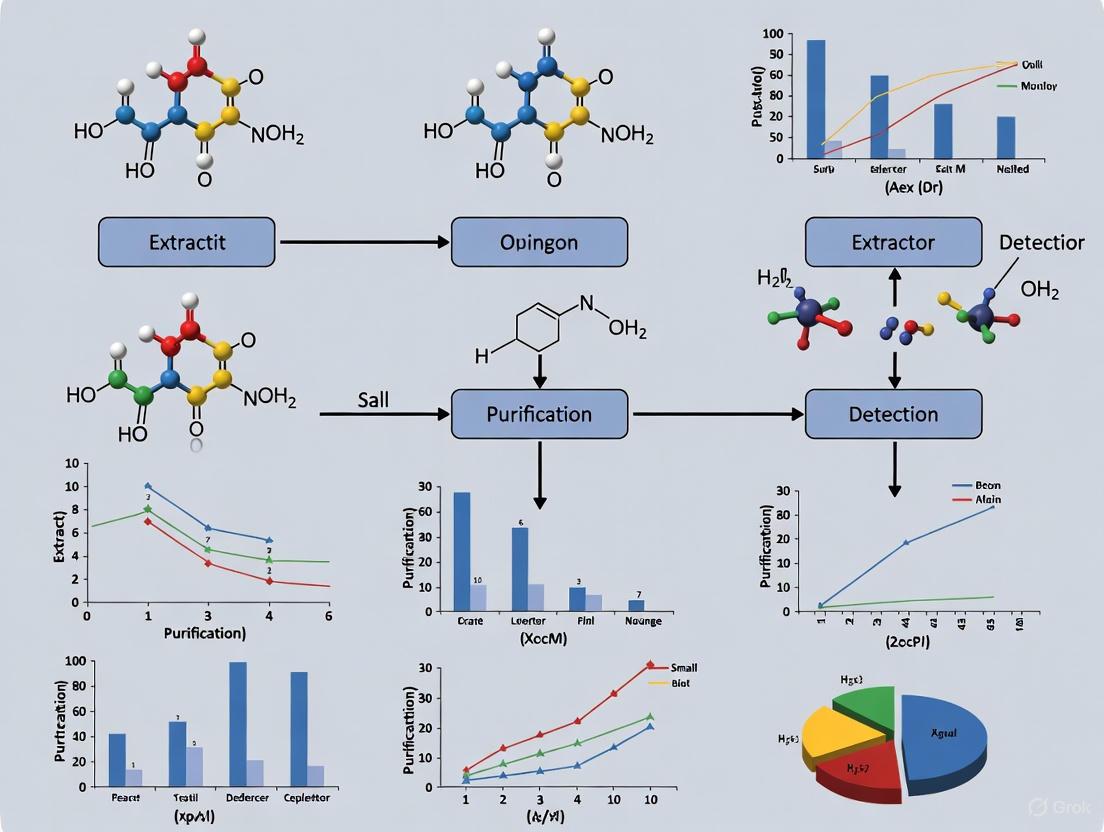

Visualization: Workflow of a Pretreatment-Free Biochip

The following diagram illustrates the operational workflow and key components of the microfluidic biochip used in the experimental protocol above.

Visualization: Key Strategies for Simplifying Sample Pretreatment

This diagram summarizes the core technical approaches, as discussed in the troubleshooting guide and FAQs, for overcoming the challenges of analyzing unprocessed samples.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the most significant challenges when using biosensors with complex samples like blood or urine? The primary challenge is the matrix effect, where components in the sample itself interfere with the biosensor's function, leading to inaccurate results. In clinical samples like serum and plasma, this can cause severe inhibition of the biosensor's signal. For example, in cell-free biosensor systems, serum and plasma can inhibit reporter production by over 98%, while urine can cause over 90% inhibition [15]. These effects stem from biomolecules like nucleases and proteases that degrade the sensor components, or from substances that quench the detection signal.

FAQ 2: Which types of samples typically cause the most interference? Among clinical samples, serum and plasma often show the strongest inhibitory effects. Research systematically evaluating cell-free systems found that serum and plasma almost completely impeded reporter production (>98% inhibition). Urine also showed strong inhibition (>90%), while saliva produced relatively less interference [15]. The variability between individual patient samples adds another layer of complexity, making consistent detection challenging.

FAQ 3: What are some common strategies to mitigate matrix effects? Common strategies include:

- Sample Pre-treatment: Simple processing steps like centrifugation or filtration to remove particulates or specific interfering components [15].

- Use of Inhibitors: Adding reagents like RNase inhibitors to the biosensor reaction mix to protect its components. Studies show RNase inhibitor can improve protein production in cell-free systems by about 70% in urine, 20% in serum, and 40% in plasma [15].

- Surface Engineering: Designing sensor surfaces with antifouling coatings to minimize non-specific binding from the sample matrix [16].

- Optimized Immobilization: Using robust methods to attach biological recognition elements (enzymes, antibodies) to the sensor to maintain their activity in complex environments [16].

FAQ 4: How can I improve the robustness of my biosensor against sample-to-sample variability? Improving the biosensor's core components can temper interpatient variability. For instance, developing new cell-free extracts that produce their own RNase inhibitor during preparation can reduce variability associated with matrix effects, particularly in plasma samples [15]. Furthermore, incorporating internal standards or controls into the assay design can help normalize results against variable matrix influences.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide: Addressing Signal Inhibition in Clinical Samples

Problem: Low or no signal output when testing blood, plasma, or urine samples, despite the sensor working perfectly with standard buffers.

Possible Causes & Solutions:

| Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Nuclease Degradation | Run a stability test of the biosensor's nucleic acid components (if any) in the sample. | Incorporate RNase or DNase inhibitors into the reaction buffer. Note that commercial inhibitor buffers containing glycerol can themselves be inhibitory; consider using extracts engineered to produce inhibitors natively [15]. |

| Protease Activity | Check for degradation of protein-based recognition elements (e.g., antibodies, enzymes) via gel electrophoresis. | Add protease inhibitors (bacterial or mammalian-specific). Note: studies found this less effective than nuclease inhibition for cell-free systems, so prioritize based on diagnostic results [15]. |

| Sample Complexity | Test a dilution series of the sample. If signal recovers with dilution, the matrix is too complex. | Dilute the sample if the analyte concentration allows. Implement a sample clean-up step such as solid-phase extraction (SPE) or centrifugation to remove interfering substances [15] [17]. |

Guide: Managing Non-Specific Binding and Fouling

Problem: High background signal or false positives, particularly in complex matrices like food extracts or environmental water.

Possible Causes & Solutions:

| Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Fouling of Sensor Surface | Inspect the sensor surface for adsorbed debris or films after exposure to the sample. | Use nanostructured materials or apply antifouling coatings (e.g., polydopamine, PEG) to the sensor surface to prevent non-specific adhesion [16] [18]. |

| Non-Specific Interactions | Test the biosensor with a sample that does not contain the target analyte. A signal change indicates non-specific binding. | Optimize blocking protocols during sensor fabrication using agents like BSA or casein. Include blocking agents or surfactants in the running buffer to reduce hydrophobic interactions [16]. |

Experimental Protocol: Evaluating Matrix Effects

This protocol provides a methodology to systematically assess the impact of various complex samples on biosensor performance, based on approaches used in recent research [15].

Objective: To quantify the inhibitory effect (matrix effect) of clinical, food, or environmental samples on a biosensor's signal output.

Materials:

- Biosensor system (e.g., cell-free expression system, electrochemical sensor, optical sensor).

- Reporter molecule (e.g., plasmid constitutively expressing sfGFP or luciferase for cell-free systems; redox mediator for electrochemical sensors).

- Test samples: Pooled or individual samples of serum, plasma, urine, saliva, food homogenate, or environmental water.

- Positive control: Buffer or solvent without any sample matrix.

- RNase inhibitor (if applicable).

- Microcentrifuge tubes and pipettes.

- Appropriate detection instrument (e.g., plate reader for fluorescence/luminescence, potentiostat for electrochemistry).

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: If necessary, perform minimal pre-processing. For blood, centrifuge to obtain serum or plasma. For environmental or food samples, filter or centrifuge to remove large particulates.

- Reaction Setup: Prepare the biosensor reaction mixture according to its standard protocol. For a quantitative test, divide the mixture into several aliquots.

- Positive Control: Add 90% reaction mix + 10% pure buffer.

- Test Samples: Add 90% reaction mix + 10% of the complex sample (e.g., serum, urine).

- Inhibitor Test (Optional): Add 90% reaction mix + 10% complex sample + a recommended amount of RNase inhibitor.

- Incubation and Measurement: Incubate the reactions under optimal conditions (e.g., 37°C for 30-120 minutes). Measure the signal output (e.g., fluorescence, luminescence, current) at the end of the reaction or in real-time.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the percentage of signal inhibition caused by the sample matrix using the formula:

% Inhibition = [1 - (Signal Sample / Signal Positive Control)] × 100%

Workflow Diagram for Matrix Effect Evaluation

Research Reagent Solutions

Essential materials and reagents for developing and troubleshooting biosensors for complex matrices.

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| RNase Inhibitor | Protects RNA-based biosensors from degradation in clinical samples. Critical for cell-free systems [15]. | Commercial buffers may contain glycerol, which can be inhibitory. Consider custom production or engineered extracts. |

| Nanomaterials (e.g., Graphene, CQDs) | Enhance sensor sensitivity and surface area. Used as substrates in SERS and electrochemical biosensors [18] [19]. | Require rigorous characterization. Functionalization is key to specificity. |

| Antifouling Coatings (e.g., Polydopamine) | Mimics mussel adhesion proteins to create surfaces that resist non-specific binding from complex samples [20] [16]. | Biocompatible and versatile for various transducer surfaces. |

| Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE) Sorbents | Miniaturized extraction to clean-up and pre-concentrate analytes from environmental or food samples [17]. | Reduces matrix complexity before analysis, improving biosensor accuracy. |

| Cell-Free TX-TL System | Abiotic, tunable biosensing platform for detecting a wide range of targets, from metabolites to nucleic acids [15]. | Lyophilizable for room-temperature storage; highly sensitive to matrix inhibitors. |

Diagram: Strategies to Mitigate Matrix Effects

Innovative Approaches for Simplified and Integrated Sample Preparation

This technical support center is designed for researchers developing integrated diagnostic platforms that minimize or eliminate complex sample pretreatment. The core thesis is that the synergy between paper-based microfluidic platforms and lyophilized (freeze-dried) reagents creates a powerful foundation for direct sample application, driving the next generation of accessible, point-of-care biosensors [21] [22]. Paper substrates leverage capillary action for fluid transport, eliminating the need for external pumps [23] [22]. When pre-loaded with lyophilized reagents, these devices can incorporate all necessary biochemical components for detection in a stable, ready-to-use format, significantly simplifying protocols and reducing user steps [21].

The following guides and FAQs address specific, practical challenges encountered when working with these integrated systems, providing targeted troubleshooting for researchers and drug development professionals.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: What are the primary causes of inconsistent fluid flow or failure to wick in my paper-based device?

Inconsistent wicking is a common issue that can compromise reagent rehydration and assay uniformity.

Potential Cause 1: Inhomogeneous Paper Substrate.

- Explanation: Paper is a fibrous material, and its homogeneity can vary between batches and manufacturers [23]. Inconsistencies in pore size and distribution can lead to erratic capillary flow.

- Troubleshooting: Sourcing paper with consistent quality is critical. Visually inspect the paper under a microscope for uniformity. Consider using nitrocellulose membranes, which are known for their consistent capillary action and are widely used in lateral flow assays [23] [22].

Potential Cause 2: Hydrophobic Barriers are Imperfect.

- Explanation: The wax or polymer barriers printed to define microfluidic channels can fail if they do not fully penetrate the paper thickness, allowing sample to leak between channels [23].

- Troubleshooting: Optimize the fabrication protocol. For wax printing, ensure the heating step (e.g., on a hotplate) is at a sufficient temperature and duration for the wax to melt and penetrate through the entire paper thickness.

Potential Cause 3: Incomplete or Uneven Rehydration of Lyophilized Reagents.

- Explanation: If a pellet of lyophilized reagent is not positioned correctly in the flow path, or if the flow is too fast/slow, the reagent may not fully dissolve, leading to poor assay performance.

- Troubleshooting: Redesign the device geometry to include a dedicated "rehydration chamber" that ensures the sample pool surrounds the reagent pellet before flowing forward. Test different sample volumes to ensure sufficient liquid for complete rehydration.

FAQ 2: Why is my assay sensitivity lower than expected after integrating lyophilized reagents?

A drop in sensitivity often points to issues with reagent stability or interaction during the lyophilization process.

Potential Cause 1: Damage to Bioreceptors During Lyophilization.

- Explanation: Enzymes, antibodies, or aptamers can lose activity if they are not protected during the freeze-drying process. The formation of ice crystals and subsequent dehydration can denature proteins [24].

- Troubleshooting: Incorporate lyoprotectants into your reagent mix before lyophilization. Common cryoprotectants (e.g., trehalose, sucrose) and lyoprotectants (e.g., polyvinylpyrrolidone) stabilize biomolecules by forming a glassy matrix that prevents denaturation. A matrix of trehalose is often highly effective.

Potential Cause 2: Inefficient Release from the Lyophilized Pellet.

- Explanation: Even if the reagent is stable, it may not be released efficiently into the flowing sample stream, reducing the effective concentration available for the detection reaction.

- Troubleshooting: Experiment with the formulation of the lyophilized pellet. Including soluble filler materials like mannitol or polyethylene glycol (PEG) can create a more porous pellet structure that dissolves more rapidly and completely.

Potential Cause 3: Non-specific Binding (NSB).

- Explanation: Lyophilized reagents can sometimes aggregate, increasing the potential for non-specific binding to the paper matrix, which sequesters them from the target analyte [24].

- Troubleshooting: Include blockers in both the paper pre-treatment and the reagent lyophilization buffer. Common blocking agents like bovine serum albumin (BSA), casein, or surfactants (e.g., Tween 20) can occupy non-specific sites on the paper and stabilize reagents.

FAQ 3: How can I reduce the occurrence of false positives or false negatives in my minimal-processing biosensor?

False results are a critical concern and can stem from multiple sources in an integrated system [24].

Potential Cause for False Positives: Contamination or Non-Specific Signal.

- Explanation: Contamination from amplicons in nucleic acid tests or cross-reactivity of antibodies with non-target molecules in a complex sample (like saliva or blood) can generate a signal in the absence of the target [24].

- Troubleshooting:

- For nucleic acid assays: Physically separate the amplification and detection zones within the paper device. Use uracil-DNA glycosylase (UDG) systems to carryover contamination.

- For immunoassays: Re-evaluate the specificity of your biorecognition elements (e.g., antibodies, aptamers). Perform cross-reactivity tests against likely interferents. Optimize the concentration of blockers in the system [24].

Potential Cause for False Negatives: Signal Inhibition or Hook Effect.

- Explanation: Complex sample matrices can contain components that inhibit enzymatic or binding reactions. In immunoassays, extremely high analyte concentrations (the "hook effect") can also lead to false negatives [24].

- Troubleshooting:

- Sample Inhibition: Dilute the sample in an appropriate buffer to dilute out inhibitors. Incorporate wash steps within the paper device design to remove inhibitors.

- Hook Effect: Perform an initial dilution series of any sample with a potentially high analyte concentration to rule out this effect. Use a two-site (sandwich) assay format that is less prone to the hook effect at very high concentrations.

Experimental Protocol: Developing an Integrated Paper-Based Biosensor with Lyophilized Reagents

The following methodology details the key steps for fabricating and testing a minimal-processing biosensor for pathogen detection, as referenced in recent literature [21] [25].

Device Fabrication: Wax Printing for Microfluidic Pads (μPADs)

- Objective: To create hydrophobic barriers on paper that define hydrophilic microfluidic channels and reaction zones.

- Materials: Whatman Grade 1 filter paper or nitrocellulose membrane, wax printer, hotplate or oven.

- Procedure:

- Design the microfluidic pattern using graphic design software (e.g., Adobe Illustrator, CorelDRAW). The design should include sample inlet, channels, reaction zones, and waste pads.

- Print the design onto the paper using the wax printer.

- Place the printed paper on a hotplate pre-heated to ~120-150°C for 1-2 minutes. The heat will melt the wax, causing it to penetrate through the paper and form a complete hydrophobic barrier.

- Allow the device to cool to room temperature before proceeding.

Reagent Preparation and Lyophilization

- Objective: To stabilize the assay reagents (e.g., enzymes, antibodies, primers) in a dry format within the paper device.

- Materials: Biorecognition elements (e.g., specific antibodies), reaction buffers, lyoprotectants (e.g., trehalose), freeze dryer.

- Procedure:

- Prepare the master mix containing all necessary reagents for the detection reaction (e.g., for an immunoassay: labeled detection antibody, substrate; for nucleic acid detection: primers, probes, nucleotides).

- Add a lyoprotectant solution to the master mix to a final concentration of 5-15% w/v.

- Pipette a precise volume (e.g., 1-5 µL) of the mixture onto the specific reaction zone of the pre-fabricated paper device.

- Immediately flash-freeze the device by placing it on a pre-cooled shelf in a freeze dryer or submerging it in a dry ice/ethanol bath.

- Lyophilize the devices under a vacuum for 12-24 hours until completely dry.

- Store the finished devices in a sealed pouch with desiccant at 4°C until use.

Assay Execution and Signal Detection

- Objective: To perform the diagnostic test by applying a minimally processed sample directly to the device.

- Materials: Liquid sample (e.g., saliva, buffer), timer, appropriate signal reader (e.g., smartphone camera, portable electrochemical reader, visual inspection).

- Procedure:

- Apply a predetermined volume of the liquid sample to the device's sample inlet.

- Allow the sample to wick through the device via capillary action. This will rehydrate the lyophilized reagents in the reaction zone, initiating the specific biochemical reaction (e.g., antigen-antibody binding, enzymatic amplification).

- Incubate the device for the optimized reaction time (typically 10-30 minutes).

- Measure the signal generated in the detection zone. This can be a colorimetric change measured by a smartphone camera app, a fluorescence signal, or an electrochemical current/impendance read by a portable potentiostat [25].

Data Presentation: Performance of Selected Paper-based Biosensors

The table below summarizes key performance metrics from recent research on paper-based biosensors relevant to minimal-processing platforms.

Table 1: Analytical Performance of Selected Paper-based Biosensors

| Target Analyte | Detection Mechanism | Assay Time | Limit of Detection (LOD) | Sample Matrix | Key Feature | Source (Conceptual) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Helicobacter pylori (CagA protein) | Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) | 15 min | 109.9 fg/mL | Patient Saliva | Non-invasive; monoclonal antibody-based; uses polypyrrole nanotubes. | [25] |

| Pseudomonas fluorescens | Recombinase Aid Amplification (RAA) with Lateral Flow Strip | ~90 min (total) | 37 CFU/mL (gyrB gene) | Milk | Dual-gene target; combined with PMAxx for live cell detection. | [4] |

| Listeria monocytogenes | Electrochemical Aptasensor | Not Specified | 4.5 CFU/mL | Food Samples | Aptamer-based; paper electrode functionalized with tungsten disulfide. | [22] |

| Food-borne Pathogens (General) | Lateral Flow Assay (LFA) | Minutes | Varies by target | Food Samples | Cost-effective, rapid response; visual readout. | [22] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

This table details key materials and their functions for developing the described integrated platforms.

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Integrated Biosensor Development

| Item | Function/Explanation | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Nitrocellulose Membrane | A paper-like substrate with high and consistent capillary action, ideal for creating defined flow paths in lateral flow assays. | Used as the main platform in pregnancy tests and other LFAs for immobilizing capture lines [23] [22]. |

| Lyoprotectants (e.g., Trehalose) | Disaccharides that form an amorphous glassy state upon lyophilization, protecting biomolecules from denaturation by stabilizing their native structure. | Added to enzyme or antibody solutions before freeze-drying onto paper to maintain long-term activity at room temperature [24]. |

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | Commonly used as labels for colorimetric detection. Their surface plasmon resonance causes a red color and can be conjugated to antibodies or oligonucleotides. | Serve as the visual signal generator in many lateral flow immunoassays [21]. |

| Recombinase Polymerase Amplification (RPA) Kit | An isothermal nucleic acid amplification technique that works at constant low temperature (37-42°C), eliminating the need for a thermal cycler. | Integrated with paper-based sensors for rapid, instrument-free pathogen DNA/RNA detection [21] [4]. |

| Carboxylated Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes (MWCNTs) | Nanomaterials used to modify electrode surfaces in electrochemical biosensors. They increase the electroactive surface area, enhancing signal strength and sensitivity. | Used on screen-printed carbon electrodes to improve the immobilization of antibodies and electron transfer in impedance-based detection [25]. |

Workflow and Troubleshooting Diagrams

Diagram 1: Biosensor Workflow and Failure Points. This diagram illustrates the ideal operational workflow of an integrated paper-based biosensor (top) and maps common experimental failure points to their corresponding troubleshooting solutions (bottom).

Nucleic Acid Aptamers and Engineered Proteins for Enhanced Specificity in Complex Samples

Key Challenges in Complex Sample Analysis

The table below summarizes the primary challenges and their impacts on biosensor performance.

| Challenge | Impact on Biosensor Performance | Common Complex Samples Where Observed |

|---|---|---|

| Matrix Interference [26] | Reduces sensitivity, causes nonspecific signals, and can lead to false positives/negatives. | Meat, vegetables, cheese brine, milk [26]. |

| Nuclease Degradation [27] | Shortens the functional half-life of nucleic acid aptamers, especially RNA, in biological fluids. | Serum, blood, plasma [27]. |

| Non-Specific Binding | Increases background noise, reduces signal-to-noise ratio, and lowers detection accuracy. | Blood, serum, food homogenates [26]. |

| Target Accessibility | Hinders the recognition element from binding to its target, reducing effective sensitivity. | Cellular lysates, viscous samples, samples with high particulate content. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: The sensitivity of my aptasensor drops significantly when testing real food samples compared to buffer. What is the primary cause and how can I fix it?

Answer: A significant sensitivity drop in complex food matrices is most commonly caused by matrix interference [26]. Fats, proteins, and pigments in food can foul the sensor surface or cause nonspecific binding, thereby reducing the assay's accuracy and sensitivity [26].

Solution: Implement a Filter-Assisted Sample Preparation (FASP) protocol. This simple and rapid preprocessing step can remove interfering food residues from the target bacteria.

- Procedure:

- Homogenize the solid food sample (e.g., 25 g of vegetable or meat) using a stomacher [26].

- Pass the homogenized sample through a double-filtration system.

- The filtered bacteria can then be resuspended in a clean buffer for analysis.

- Outcome: This method has been shown to enable the detection of pathogens like E. coli O157:H7, S. Typhimurium, and L. monocytogenes at concentrations as low as 10¹ CFU/mL in the final preprocessed solution, directly from various food matrices [26].

FAQ 2: My DNA/RNA aptamer is being degraded in biological samples, leading to inconsistent results. How can I improve its stability?

Answer: Nucleic acid aptamers, particularly RNA, are susceptible to degradation by nucleases present in biological fluids [27]. This reduces their half-life and effectiveness.

Solution: Consider the following strategies to enhance aptamer stability:

- Use Chemically Modified Nucleotides: Incorporate stable nucleotide analogs during or post-SELEX selection. For instance, the FDA-approved aptamer Pegaptanib uses 2'-fluoropyrimidine residues, which dramatically increase its resistance to nucleases [27].

- Terminal Modifications: Cap the 3'-end with an inverted dT nucleotide to block exonuclease activity [27].

- Peptide Nucleic Acid (PNA) Backbones: While not directly cited in the provided results, PNAs are a well-established technology in the field that confer extreme nuclease resistance and can be explored as an alternative recognition element.

FAQ 3: My biosensor suffers from high background noise due to non-specific adsorption of sample matrix components. How can I minimize this fouling?

Answer: Non-specific binding from sample matrices is a common issue that compromises sensor reusability and accuracy [28].

Solution: Engineer the sensor surface with stable antifouling nano-coatings.

- Procedure:

- Functionalize the transducer surface (e.g., a QCM chip) with a terpolymer brush nanocoating [28].

- Immobilize the aptamer receptor on this functionalized surface.

- Outcome: This approach has been demonstrated to create a reusable biosensor capable of withstanding 60 sequential injections of complex hamburger samples with only a minor shift in detection limit. It allows for direct detection of E. coli O157:H7 in food products like milk and hamburgers with a limit of detection as low as ~10² CFU/mL [28].

FAQ 4: The SELEX process for generating new aptamers is time-consuming and often fails for small-molecule targets. Are there more efficient selection methods?

Answer: Yes, conventional SELEX has limitations, but several advanced techniques improve efficiency and success rates [29].

Solution: Adopt modern SELEX variants tailored to your target:

- For Small Molecules: Use Capture SELEX. In this method, the oligonucleotide library is immobilized on a solid support. The small molecule targets are then passed through, and aptamers that bind are released into the supernatant. This method is advantageous for small targets with limited binding epitopes and can select for aptamers with structure-switching properties [29].

- For Faster, High-Efficiency Selection: Use Capillary Electrophoresis SELEX (CE-SELEX). This method separates aptamer-target complexes based on electrophoretic mobility, enabling highly efficient affinity maturation and often completing the selection in just 2-4 rounds [29].

- Leverage Computation: Employ In Silico-Enhanced SELEX, which uses machine learning and computational modeling to pre-screen libraries and predict high-affinity candidates, significantly reducing the number of required laboratory selection rounds [29].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Filter-Assisted Sample Preparation for Complex Food Matrices

This protocol is designed to separate pathogens from interfering substances in food, simplifying sample pretreatment for biosensors [26].

- Objective: To rapidly remove matrix interference from complex food samples for subsequent aptasensor analysis.

- Materials:

- Stomacher or homogenizer

- Vacuum pump

- Primary Filter: Glass fiber filter (GF/D)

- Secondary Filter: Cellulose acetate filter (0.45 μm pore size)

- Elution Buffer (e.g., phosphate-buffered saline)

- Method:

- Homogenization: Weigh 25 g of the food sample (e.g., lettuce, minced meat). Add to a sterile bag with an appropriate diluent (e.g., 225 mL of buffered peptone water) and homogenize in a stomacher for 1-2 minutes [26].

- Primary Filtration: Pour the homogenate through the primary glass fiber filter under vacuum. This step removes large particulate matter and fibers.

- Secondary Filtration: Pass the filtrate from step 2 through the secondary 0.45 μm cellulose acetate filter. This membrane will capture the target bacteria.

- Elution (Optional, depending on biosensor format): The bacteria can be eluted from the secondary filter by back-flushing with a small volume (e.g., 1-5 mL) of elution buffer. Alternatively, the filter itself can be integrated directly into the biosensor flow cell.

- Analysis: The eluted sample or the filter is now ready for analysis with the biosensor. The entire sample preparation process is completed in under 3 minutes [26].

Protocol 2: Magnetic Bead-Based SELEX for Protein Targets

This protocol outlines a robust method for selecting DNA aptamers against protein targets.

- Objective: To isolate high-affinity DNA aptamers against a specific protein target.

- Materials:

- His-tagged or biotinylated target protein

- Magnetic Beads (e.g., Ni-NTA beads for His-tagged proteins; Streptavidin beads for biotinylated proteins)

- Single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) library (random ~40-60 nt region flanked by constant primer regions)

- PCR reagents and thermocycler

- Binding/Washing Buffers

- Method:

- Immobilization: Incubate the purified target protein with the appropriate magnetic beads to form bead-target complexes [29].

- Incubation: Mix the ssDNA library with the bead-target complexes in binding buffer. Incubate with gentle rotation to allow aptamers to bind.

- Partitioning: Place the tube in a magnetic separator. Once clear, carefully remove and discard the supernatant containing unbound sequences.

- Washing: Wash the beads with binding buffer several times to remove weakly or non-specifically bound sequences.

- Elution: Elute the specifically bound aptamers from the target-bead complex. This can be achieved by heating or using a denaturing buffer.

- Amplification: Amplify the eluted pool using PCR. For DNA SELEX, the product is a double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) that must be converted back to ssDNA for the next round.

- Purification: Separate the ssDNA from the dsDNA PCR product (e.g., using strand-specific biotinylation and streptavidin bead separation).

- Counter-Selection: To improve specificity, perform a counter-selection round by incubating the enriched library with bare magnetic beads (without target) and collecting the unbound sequences. These are then used for the next positive selection round.

- Iteration: Repeat steps 2-8 for typically 8-15 rounds. The stringency can be increased in later rounds by reducing the amount of target protein or increasing the number of washes.

- Cloning and Sequencing: After the final round, clone and sequence the enriched pool to identify individual aptamer candidates for further characterization [29].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists essential materials and their functions for developing and working with aptamer-based biosensors.

| Item | Function/Benefit | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Magnetic Beads (Ni-NTA/Streptavidin) | Solid support for efficient partitioning of target-bound aptamers during the SELEX process [29]. | Immobilization of His-tagged or biotinylated protein targets for aptamer selection. |

| Cellulose Acetate Filter (0.45 μm) | Captures bacterial cells while allowing smaller matrix components to pass through, purifying the sample [26]. | Preprocessing of food samples (vegetables, meat) to isolate pathogens for detection. |

| Antifouling Terpolymer Coating | Prevents non-specific adsorption of proteins and other biomolecules onto the sensor surface, enhancing reliability and reusability [28]. | Coating QCM or SPR chips for direct analysis in complex media like blood or food homogenates. |

| Structure-Switching Aptamer | An aptamer that undergoes a conformational change upon target binding, which can be directly transduced into a signal, simplifying assay design [29]. | Label-free electrochemical or optical detection of small molecules (ATP, cocaine). |

| Nuclease-Modified Nucleotides (e.g., 2'-F) | Replaces natural ribonucleotides to dramatically increase the stability of RNA aptamers in biological fluids [27]. | Developing therapeutic aptamers or diagnostic sensors for use in serum or plasma. |

Workflow and System Diagrams

Diagram 1: Filter-assisted sample preparation workflow for complex food matrices. [26]

Diagram 2: Magnetic bead-based SELEX process for aptamer selection. [29]

Cell-free biosensing systems represent a paradigm shift in biosensor technology, moving beyond the constraints of living cells to create analytical tools that are both robust and exceptionally adaptable. By harnessing the core biochemical machinery of the cell—including transcription, translation, and metabolism—without the burden of maintaining viability, these systems open new frontiers for applications in environmental monitoring, medical diagnostics, and therapeutic development [30]. The fundamental advantage of this approach lies in its direct simplification of sample pretreatment. The elimination of cell walls and membranes, which typically act as barriers to analyte transport, allows for a more direct interaction between the sensing components and the target molecules in a sample [31]. This open reaction environment is a key facilitator for reducing preprocessing complexity.

The inherent flexibility of cell-free systems enables their deployment in formats that are incompatible with living cells, such as lyophilized (freeze-dried) reactions on paper-based platforms [30]. These shelf-stable, ready-to-use formats can be rehydrated with a raw sample, drastically cutting down on the need for complex sample preparation, specialized equipment, or technical expertise [32]. This is particularly valuable for point-of-care diagnostics in resource-limited settings and for the on-site detection of environmental contaminants [30]. This technical support center is designed to empower researchers in overcoming practical challenges associated with implementing these powerful systems, with a constant view towards streamlining the journey from sample to answer.

Troubleshooting Guide: Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My cell-free biosensor is producing a high background signal even in the absence of the target analyte. How can I reduce this noise?

- A: A high background signal is a common challenge that can stem from several sources. To address it, consider these strategies:

- Reformulate the Cell-Free System: The standard glutamate salts in cell-free reactions can be metabolically converted into background glutamine, generating false-positive signals. Replacing glutamate with alternative salts like aspartate, acetate, citrate, or sulfate can disrupt these pathways. Aspartate-based systems, in particular, have been shown to maintain high signal strength while reducing background to undetectable levels over several hours [32].

- Use Engineered Cell Extracts: Prepare your cell extract from genetically modified strains. For instance, using E. coli with knockouts of genes like

lacZ(for β-galactosidase) andglnA(for glutamine synthetase) can prevent the endogenous production of reporter proteins and background analytes [32]. - Add Metabolic Inhibitors: Incorporate inhibitors such as L-methionine sulfoximine (MSO), a competitive inhibitor of glutamine synthetase, to further suppress the endogenous generation of specific metabolites like glutamine [32].

Q2: I am getting no protein expression from my cell-free biosensor reaction. What are the primary causes?

- A: A complete lack of protein expression typically points to issues with core reaction components. Systematically check the following:

- DNA Template Quality and Quantity: Ensure your DNA template is pure and free from contaminants like ethanol, salts, or RNases. Do not use DNA purified from an agarose gel, as residual gel can inhibit the reaction. Verify the sequence for the correct ATG initiation codon and that it is in-frame. Use the recommended amount of DNA (e.g., 10–15 µg for a 2 mL reaction) and increase it for larger proteins [33].

- Reagent Integrity: Confirm that all reagents, especially the cell extract and energy sources, have been stored correctly and are not past their expiration date. Avoid multiple freeze-thaw cycles, as this can degrade activity [33].

- Reaction Conditions: The reaction must be incubated with shaking (e.g., in a thermomixer or shaking incubator), not in a static water bath. Verify that the incubation temperature is appropriate (typically 25-37°C) [33].

Q3: The yield of my target protein is low. How can I optimize it?

- A: To enhance protein yield, focus on reaction optimization and feeding strategies:

- Optimize Feeding Schedule: Instead of a single feeding step, implement multiple feeding steps with smaller volumes of feed buffer. For example, add 0.25 mL of feed buffer to a 1 mL sample every 45 minutes over 3 hours to continuously supply energy and substrates [33].

- Adjust Incubation Temperature: For large or complex proteins, reducing the incubation temperature to 25–30°C can help improve proper folding and stability, thereby increasing functional yield [33].

- Address Protein Solubility and Folding: Add mild detergents (e.g., up to 0.05% Triton-X-100) or molecular chaperones to the reaction mixture to promote solubility and correct folding of the synthesized protein [33].

Q4: My protein synthesis reaction produces multiple bands or smearing on an SDS-PAGE gel. What could be the cause?

- A: Truncated proteins or smearing are often signs of degradation or synthesis issues.

- Proteolysis and Degradation: Limit reaction incubation time and include protease inhibitors in the mixture. Ensure that your DNA template is intact, as degraded templates can lead to truncated products [33].

- Sample Preparation: Precipitate proteins with acetone prior to SDS-PAGE to remove interfering substances. Avoid overloading the gel with too much protein, and ensure that no residual ethanol was present in the reaction [33].

- Translation Issues: Internal initiation of translation can occur if the gene sequence contains multiple methionine codons or internal ribosome binding sites. Re-check your gene design and sequence [33].

Q5: How can I make my cell-free biosensor stable for storage and deployment in the field?

- A: For field deployment, stability is achieved through preservation and formatting.

- Lyophilization: Cell-free systems are highly amenable to lyophilization (freeze-drying). Lyophilized reactions can be stored at room temperature for extended periods and remain functional. They can be embedded on paper-based platforms and rehydrated with a liquid sample at the point of use, making them ideal for resource-limited settings [30] [32].

- Use of Stabilizing Materials: Integration with materials such as hydrogels or encapsulation in synthetic structures can further enhance the long-term stability of the biosensing components [30].

Experimental Protocols: Key Methodologies for Biosensor Development

Protocol: Developing a Zero-Background Glutamine Biosensor via CFPS Reformulation

This protocol details the creation of a cell-free glutamine biosensor with minimal background signal by replacing traditional glutamate salts with aspartate [32].

- Principle: Standard cell-free protein synthesis (CFPS) systems use high concentrations of glutamate, which can be enzymatically converted to glutamine by native enzymes in the cell extract, creating a high background. Replacing glutamate with aspartate severs this metabolic link, eliminating the background generation of glutamine and creating a sensor whose output is directly proportional to the exogenous glutamine added from the sample.

- Materials:

- Cell extract prepared from E. coli BL21-Star DE3 (ΔlacZ ΔglnA) strain.

- Plasmid DNA encoding a colorimetric reporter protein (e.g., β-galactosidase).

- Reaction Salts: Prepare 2M stock solutions of L-Aspartic acid, potassium hydroxide. For the traditional control, prepare L-Glutamic acid, potassium hydroxide.

- Energy Solution: 1M Magnesium glutamate (or aspartate), 0.5M Phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP), 0.1M ATP, 1M Ammonium glutamate (or aspartate).

- Amino Acid Mixture: A mix of all 20 amino acids, omitting glutamine.

- Detection substrate (e.g., chromogenic substrate for β-galactosidase).

Procedure:

- Prepare the Cell-Free Reaction Master Mix: For the experimental condition, combine the following components to create an aspartate-based system:

- Cell Extract: 30% (v/v) of the final reaction volume.

- Amino Acid Mixture (without Gln): 2 mM final concentration for each amino acid.

- Energy Solution: Formulated with aspartate salts instead of glutamate.

- Plasmid DNA: 10-15 µg per mL of final reaction volume.

- Nucleotides: 2 mM each of ATP, GTP, UTP, CTP.

- Polymerase: 1-1.5 µL of T7 RNA polymerase (50 U/µL) per 50 µL reaction.

- Other Cofactors: Include folinic acid, tRNA, and coenzyme A as needed for the specific CFPS system.

- Prepare a Glutamate-Based Control: Prepare a separate master mix identical to the above but using the traditional glutamate-based energy solution and salts.

- Initiate the Reaction: Aliquot the master mixes into separate tubes and add varying known concentrations of glutamine (e.g., 0 µM, 50 µM, 100 µM, 500 µM) to create a standard curve. Include a blank (no glutamine) for both systems to measure background.

- Incubate: Incubate the reactions at 30°C with shaking for 2-4 hours.

- Measure Output: At the end of the incubation, add the detection substrate and measure the colorimetric signal (e.g., absorbance). For the aspartate-based system, the signal in the 0 µM glutamine blank should be negligible, while a strong, concentration-dependent signal should be visible in the samples containing glutamine.

Protocol: Engineering a Transcription Factor-Based Biosensor for Heavy Metal Detection

This protocol outlines the use of allosteric transcription factors (aTFs) in a cell-free system to detect heavy metals like mercury (Hg²⁺) and lead (Pb²⁺) with high sensitivity [30].

- Principle: An allosteric transcription factor, such as MerR for mercury or PbrR for lead, is used. In the absence of the metal, the aTF binds to its specific DNA operator sequence, repressing transcription of a downstream reporter gene. Upon binding its target metal ion, the aTF undergoes a conformational change that activates transcription, leading to the production of a detectable reporter protein (e.g., fluorescent or colorimetric).

- Materials:

- Cell-free system (e.g., E. coli extract-based).

- Plasmid DNA containing the reporter gene under the control of a promoter with the aTF operator sequence.

- Purified aTF protein (or the gene encoding it can be included in the CFPS reaction).

- Standard solutions of target heavy metals (e.g., HgCl₂, Pb(NO₃)₂).

- Water samples for testing.

Procedure:

- Design and Cloning: Clone the genetic circuit into a plasmid: a promoter with the specific operator sequence (e.g., merOP or pbrOP) upstream of a reporter gene (e.g., GFP or luciferase).

- Set Up the Biosensing Reaction: In a tube, combine:

- Cell-free extract.

- The constructed plasmid DNA.

- All necessary components for CFPS (energy sources, amino acids, nucleotides).

- If not co-expressed, add the purified aTF protein.

- Sample Introduction: Add the environmental water sample (with minimal pretreatment, such as filtration or pH adjustment) or a standard metal solution to the reaction.

- Incubation and Detection: Incubate the reaction at 30°C for several hours. Measure the output signal (e.g., fluorescence or luminescence) over time. The signal intensity will be proportional to the concentration of the heavy metal in the sample. This system has achieved detection limits as low as 0.5 nM for Hg²⁺ and 0.1 nM for Pb²⁺ in real water samples [30].

Workflow and Pathway Diagrams

Cell-Free Biosensor Assembly Workflow

The diagram below illustrates the key steps in constructing and utilizing a typical cell-free biosensor, highlighting the simplified sample pretreatment.

Metabolic Pathway for Background Signal Elimination

This diagram contrasts the traditional and engineered metabolic pathways to show how background signal is eliminated in a glutamine biosensor.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The table below catalogs essential materials and their functions for developing and troubleshooting cell-free biosensing systems.

Table 1: Key Research Reagents for Cell-Free Biosensor Development

| Reagent / Material | Function / Purpose | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli S30 Extract | Provides the core transcriptional and translational machinery (ribosomes, factors, enzymes). | Use extracts from engineered strains (e.g., ΔglnA) to reduce background [32]. Avoid multiple freeze-thaw cycles. |

| T7 RNA Polymerase | Drives high-level transcription of the reporter gene from a T7 promoter. | Essential for systems using T7-promoter based plasmids; add externally to the reaction [33]. |

| Plasmid DNA Template | Encodes the genetic circuit (promoter, reporter gene, regulatory elements). | Must be pure, without ethanol/salt contamination. Do not use gel-purified DNA. Verify sequence and initiation codon [33]. |

| Energy Regeneration System | Supplies ATP and other NTPs for transcription/translation. | Traditional systems use glutamate salts. For low-background sensors, use aspartate, acetate, citrate, or sulfate salts [32]. |

| Amino Acid Mixture | Building blocks for protein synthesis (the reporter). | For analyte-limiting sensors, formulate the mixture to lack the target analyte (e.g., no glutamine) [32]. |

| Reporters (e.g., β-galactosidase, GFP, Luciferase) | Generates a measurable signal (color, fluorescence, light). | Choose based on detection equipment available and required sensitivity. Colorimetric is ideal for visual/POC tests [30] [32]. |

| Membrane Protein Reagents (e.g., MembraneMax) | Provides a lipid bilayer environment for folding and stabilizing membrane proteins. | The scaffold protein may appear as a ~28 kDa band on SDS-PAGE [33]. |

| Molecular Chaperones & Detergents | Aids in the proper folding of complex proteins, improving solubility and activity. | Add detergents like Triton-X-100 (up to 0.05%) or commercial chaperone mixes to the reaction [33]. |

| Inhibitors (e.g., L-methionine sulfoximine - MSO) | Suppresses specific enzymatic activity in the extract to reduce background noise. | MSO is a competitive inhibitor of glutamine synthetase [32]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the core advantage of an integrated Sample-In-Answer-Out system over traditional detection methods? Traditional methods for detecting pathogens or biomarkers, such as plate counts and PCR, often require multiple, separate steps including sample preparation, culture-based enumeration, and analysis. These processes can take between 24 to 72 hours and demand specialized equipment and trained personnel [26]. In contrast, integrated Sample-In-Answer-Out systems consolidate sample preprocessing, amplification, and detection into a single, automated device. This integration drastically reduces the total analysis time to under a few hours, minimizes the need for manual handling, and enables rapid, on-site testing without sophisticated laboratory infrastructure [34] [35].

Q2: My complex food samples often clog the filtration system. How can this be mitigated? Clogging is a common challenge when processing complex matrices like meats or vegetables, which contain fats, proteins, and fibers. A recommended solution is to implement a dual-filtration system. This involves using a primary filter with a larger pore size (e.g., glass fiber filter) to remove large food particles and debris, followed by a secondary filter (e.g., a 0.45 μm cellulose acetate membrane) to capture the target microorganisms [26]. This step-wise filtration prevents the rapid fouling of the fine secondary filter and ensures more consistent processing and higher recovery of the target bacteria from complex food matrices.

Q3: Why is my biosensor signal weak or inconsistent even after successful sample purification? Weak signals can stem from two primary issues: residual inhibitors or suboptimal biosensor operation. First, despite purification, trace amounts of inhibitors from the sample matrix may remain and interfere with the detection reaction. Ensuring the purification step is robust is critical [26] [36]. Second, you should verify the functional stability of the biosensor's biological components (e.g., antibodies or enzymes). Check that storage and operational conditions (like temperature and pH) are within the specified ranges. For optical biosensors, ensure that the sample is clear and that food pigments, which can quench fluorescence or absorb light, have been effectively removed [26] [37].