Systematic Optimization of Biosensor Response Time Using Response Surface Methodology: A Guide for Biomedical Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on applying Response Surface Methodology (RSM) to optimize biosensor response time.

Systematic Optimization of Biosensor Response Time Using Response Surface Methodology: A Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on applying Response Surface Methodology (RSM) to optimize biosensor response time. It covers foundational principles, contrasting the limitations of traditional one-variable-at-a-time approaches with the efficiency of multivariate RSM designs like Central Composite Design (CCD) and Box-Behnken. The content details methodological steps for implementing RSM, from factor screening to model building, illustrated with case studies from electrochemical and optical biosensors. It further addresses troubleshooting common optimization challenges and presents frameworks for validating RSM models and comparing its performance against other optimization strategies, such as artificial neural networks. The goal is to equip scientists with a systematic framework to enhance biosensor kinetics for more effective point-of-care diagnostics and clinical testing.

Beyond One-Variable-at-a-Time: Foundational Principles of RSM for Biosensor Optimization

Core Concepts of Response Surface Methodology

Response Surface Methodology (RSM) is a collection of statistical and mathematical techniques for empirical model building and process optimization. The core objective is to model the relationship between several explanatory variables (factors) and one or more response variables to find the factor settings that optimize the response[s] [1] [2] [3].

This methodology was introduced by Box and Wilson in the 1950s and is particularly valuable when the functional relationship between the variables and the response is unknown or complex [1] [2]. It is widely applied in engineering, science, manufacturing, and notably, in the optimization of analytical methods and biosensors in chemical and pharmaceutical research [4] [5] [6].

RSM operates by using a sequence of designed experiments, often aiming to fit a polynomial model, most commonly a second-order (quadratic) model, which is easy to estimate and apply [1] [7]. The general form of a quadratic model for k independent variables is shown below, illustrating the components that account for linear, interaction, and curvature effects:

- Formula for a Quadratic Model:

Y = β₀ + ∑ᵢ βᵢ Xᵢ + ∑ᵢ ∑ⱼ βᵢⱼ Xᵢ Xⱼ + εY: The predicted response.β₀: The constant or intercept term.βᵢ: The coefficients for the linear terms.βᵢⱼ: The coefficients for the interaction terms.Xᵢ,Xⱼ: The independent variables (factors).ε: The random error term [4].

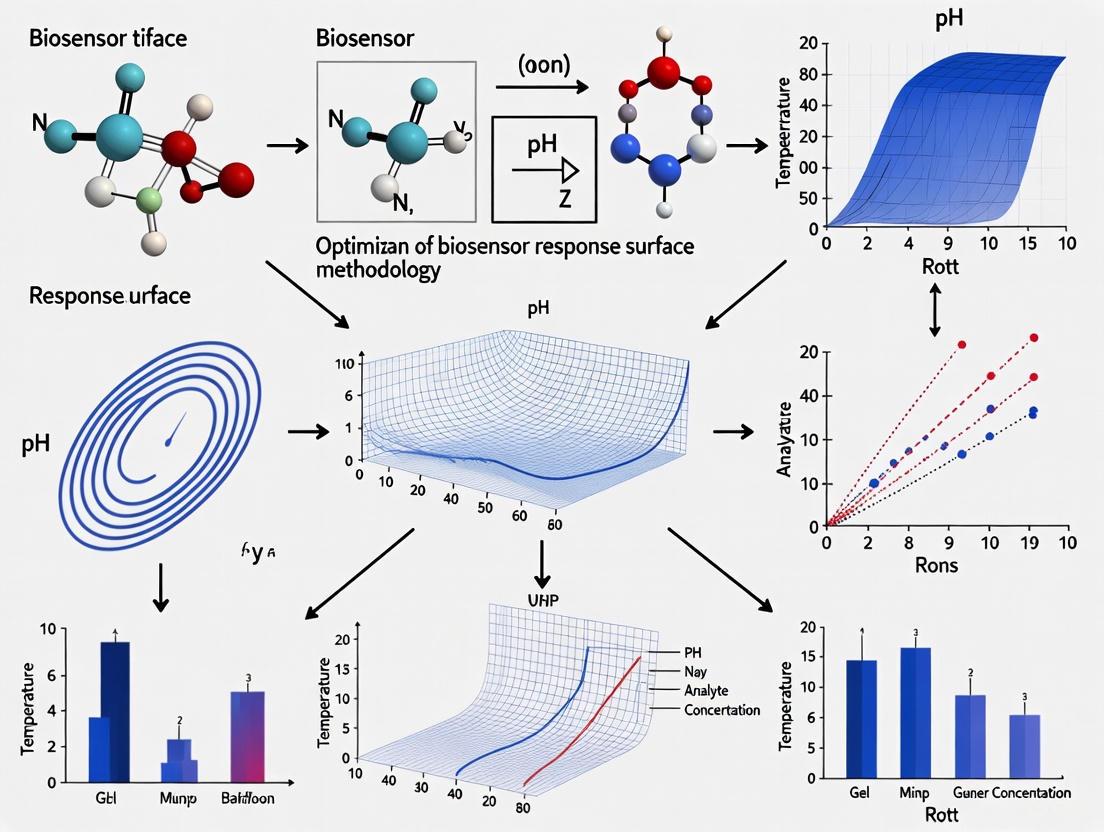

The following diagram illustrates the typical workflow for implementing RSM, from problem definition to validation.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting

Experimental Design

Q1: When should I use RSM instead of a simpler factorial design? Use RSM when you suspect curvature in your response surface and your goal is optimization (finding a maximum, minimum, or target value). Simple two-level factorial designs can only estimate linear effects. If the response is believed to have a peak or valley within the experimental region, RSM designs that include at least three levels for each continuous factor are necessary to model this curvature [3].

Q2: How do I choose between a Central Composite Design (CCD) and a Box-Behnken Design (BBD)? The choice depends on your experimental constraints and the region of interest. The table below summarizes the key differences.

- Table: Comparison of Common RSM Designs

| Feature | Central Composite Design (CCD) | Box-Behnken Design (BBD) |

|---|---|---|

| Runs | More runs; includes factorial, axial (star), and center points [4]. | Fewer runs for the same number of factors; uses combinations of midpoints of edges [4] [6]. |

| Experimental Region | Can explore a spherical or cuboidal region. The axial points may lie outside the factorial cube [4]. | Spherical region; all points lie within a hypersphere inscribed in the factorial cube. No corner points [4]. |

| When to Use | When you need to estimate curvature precisely and are willing to perform more runs. Useful when the region of interest includes extreme (corner) points [4]. | When performing experiments at the factorial extremes (corners) is impractical, expensive, or dangerous. Preferable when seeking efficiency with fewer runs [4] [6]. |

Q3: What is the most common mistake in planning an RSM experiment? A common mistake is an inappropriate screening of independent variables or an improper selection of levels [6]. Before embarking on an RSM study, it is crucial to clearly define the project's scope and objectives and use prior knowledge or screening designs to identify the factors that truly influence the response. Selecting levels that are too close together may not capture the curvature, while levels that are too far apart might make the quadratic model a poor approximation [4] [2].

Model Fitting and Analysis

Q4: My model has a high R-squared value, but the predictions are poor. What could be wrong? A high R-squared alone does not guarantee a good model. This issue often stems from model inadequacy. You should perform a lack-of-fit test and conduct residual analysis. A significant lack-of-fit indicates that the model (e.g., a quadratic polynomial) does not adequately describe the relationship in the data. Residual plots can reveal patterns that suggest the model is missing important terms or that there is non-constant variance [2] [7]. Always validate the model with confirmation runs at the predicted optimal conditions [2].

Q5: How do I handle multiple responses, like when optimizing for both high sensitivity and short response time in a biosensor? Optimizing multiple, potentially conflicting responses is a common challenge. Strategies include:

- Overlaid Contour Plots: Superimposing contour plots for each response to visually identify a region where all goals are simultaneously met [4] [3].

- Desirability Function Approach: This method converts each response into an individual desirability function (ranging from 0 to 1) and then combines them into a single composite desirability function that is maximized. This allows you to assign different importance levels to each response [4] [2].

Optimization and Validation

Q6: The optimization algorithm suggests factor settings that are impractical or unsafe to implement. How should I proceed? The mathematical optimum may lie outside practical operating limits. To address this, you should incorporate constraints into your optimization formulation. Most statistical software allows you to set lower and upper bounds for factors. You can use the models and contour plots to find a set of factor settings within your practical, safe, and economical operating window that still provides a near-optimal and robust response [4] [2].

Q7: After validation runs, the observed response at the predicted optimum is significantly different from the prediction. What are the next steps? This indicates that the model may not be a reliable predictor in that region. You should:

- Verify Experimental Error: Ensure the validation runs were conducted with the same precision as the original experiments.

- Check for Outliers: Re-examine your original data for any influential points.

- Iterate the Process: The optimal point from the first RSM study may guide you to a new region of interest. You may need to conduct a new RSM experiment centered around this new region to build a more accurate local model [2].

Practical Research Toolkit

Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists materials commonly used in experiments where RSM is applied for optimization, such as in biosensor development or analytical method optimization.

- Table: Essential Materials for Biosensor and Analytical Optimization Studies

| Item | Function/Description | Example from Research |

|---|---|---|

| Multi-walled Carbon Nanotubes (MWCNTs) | Used to modify electrode surfaces; enhance electrical conductivity and surface area [5]. | MWCNTs with an ionic liquid were used to modify a glassy carbon electrode for alkaline phosphatase detection [5]. |

| Ionic Liquids (IL) | Often used in composite materials to improve electrochemical stability and electron transfer kinetics [5]. | Combined with MWCNTs to create a modified electrode for a biosensor [5]. |

| Enzyme Substrates (e.g., pNPP) | A molecule that is acted upon by an enzyme. The reaction product generates a measurable signal (e.g., electrochemical, colorimetric) [5]. | para-Nitrophenylphosphate (pNPP) was used as the substrate for the enzyme alkaline phosphatase in a biosensor design [5]. |

| Electrochemical Probes (e.g., [Ru(NH₃)₅Cl]²⁺) | A redox-active molecule used to generate an amperometric signal in electrochemical biosensors [5]. | Used to detect the negative charges generated from the enzymatic hydrolysis of pNPP [5]. |

| Nanocomposite Adsorbents (e.g., Fe₃O₄/rGO/Ag) | Used in sample preparation for pollutant removal or pre-concentration of analytes; properties like magnetism allow for easy separation [8]. | Synthesized and used as an adsorbent for the removal of tetracycline and dyes from water; optimized using RSM [8]. |

| Britton-Robinson (BR) Buffer | A universal buffer solution used in electrochemistry to maintain a specific pH for the analyte's redox reaction [9]. | Used as the supporting electrolyte for the voltammetric determination of 2-nitrophenol [9]. |

Example Experimental Protocol: Optimizing Voltammetric Parameters

The following workflow details a published methodology for optimizing square wave voltammetry (SWV) parameters using RSM to detect an environmental pollutant [9]. This serves as a practical template for similar analytical optimizations.

Detailed Steps:

- Sensor Preparation: A glassy carbon (GC) electrode is modified, for example, via the electropolymerization of 2-amino nicotinamide (2-AN). The optimum number of deposition cycles is determined beforehand (e.g., 5 cycles) [9].

- Experimental Design: A Box-Behnken Design (BBD) is selected to optimize the three key SWV parameters: pulse amplitude, frequency, and potential step. This design efficiently requires a limited number of experimental runs [9].

- Data Collection and Modeling: The amperometric response (e.g., peak current) for a target analyte (e.g., 2-nitrophenol) is measured for each combination of parameters in the BBD matrix. The data is then used to build a predictive model. Advanced algorithms like Least Squares-Support Vector Machine (LS-SVM) or a standard quadratic polynomial can be employed for this purpose [5] [9].

- Optimization and Validation: The fitted model is used to pinpoint the combination of SWV parameters that predicts the maximum peak current (response). These optimal settings are then validated experimentally to confirm the predicted enhancement in sensor sensitivity [9].

This specific application resulted in a sensor with a wide linear range (9.9 nM - 52.5 μM and 52.5 μM - 603 μM) and a very low detection limit of 2.92 nM for 2-nitrophenol [9].

Limitations of One-Factor-at-a-Time (OFAT) Optimization in Complex Biosensor Systems

FAQs: Understanding OFAT and its Limitations

1. What is the fundamental weakness of the OFAT method in biosensor development? The primary weakness is that OFAT fails to account for interactions between factors. It optimizes one variable while keeping all others constant, which can lead to identifying a local optimum rather than the true, global best performance for the biosensor. It cannot detect when the effect of one factor (e.g., enzyme concentration) depends on the level of another (e.g., immobilization time) [10] [11].

2. How does OFAT impact the efficiency and cost of biosensor optimization? OFAT is an inefficient and resource-intensive process. It requires a significant number of experiments to explore each variable individually, leading to increased consumption of costly reagents, nanomaterials, and biorecognition elements (like enzymes or DNA probes), as well as substantial researcher time [10] [12].

3. My OFAT-optimized biosensor has unstable performance. Why might this be? This is a common consequence of un-detected factor interactions. An OFAT protocol may settle on a combination of conditions that is highly sensitive to minor variations in a factor that was not properly co-optimized, resulting in poor robustness and reproducibility [11].

4. Is there a scenario where using OFAT is acceptable? OFAT can be a preliminary tool for initial, rough estimates of factor ranges. However, for the final optimization of any complex biosensor system with multiple, potentially interacting variables, it is considered a suboptimal and outdated approach compared to multivariate methods [10].

Troubleshooting Guide: OFAT-Related Experimental Problems

Problem: Suboptimal Biosensor Performance After OFAT Optimization

Description: After a lengthy OFAT optimization process, the biosensor's sensitivity, detection limit, or response time does not meet expectations or is inferior to results reported in similar studies.

Possible Causes & Solutions:

- Cause 1: Unidentified Factor Interactions.

- Cause 2: The "Optimum" is Only Local.

- Solution: Abandon the OFAT results as a final answer. Use the knowledge gained from OFAT to define the initial factor ranges for a proper multivariate DoE, which is designed to explore the entire experimental domain globally [11].

Problem: Irreproducible Results Between Batches

Description: Biosensors fabricated based on OFAT-optimized conditions show high variability in performance from one production batch to another.

Possible Causes & Solutions:

- Cause: The Process is Not Robust.

- Solution: The OFAT method does not build a predictive model that accounts for how variations in one factor affect others. Implementing RSM creates a mathematical model that describes the response surface, allowing you to understand the process robustness and identify a "sweet spot" where performance is less sensitive to small, inevitable variations in manufacturing [11].

Case Studies: The Transition from OFAT to Multivariate Optimization

The following examples from recent literature demonstrate how moving beyond OFAT led to successful biosensor development.

Case Study 1: DNA Biosensor for Mycobacterium tuberculosis

- Challenge: Sensitive and specific detection of a tuberculosis DNA sequence.

- OFAT Limitation Overcome: The researchers explicitly stated that the conventional OFAT approach is incapable of investigating the combined effects of all factors and is time and resource-intensive [12].

- Multivariate Solution: They employed a Plackett-Burman design to screen 11 different factors and identify the most significant ones. This was followed by a Central Composite Design (CCD) under RSM to model the interactions and find the optimal conditions for probe concentration and immobilization time [12].

- Outcome: This systematic approach resulted in a biosensor with a wide detection range and a very low detection limit (0.141 nM) [12].

Case Study 2: Label-free DNA Nanobiosensor for Mycobacterium simiae

- Challenge: Creating the first diagnostic test for a specific Nontuberculous mycobacterium.

- OFAT Limitation Overcome: The authors noted that the conventional univariate (OFAT) method cannot evaluate the combined effect of variables and is time-consuming [13].

- Multivariate Solution: They used a Plackett-Burman screening design to select key factors from a large set, then applied RSM to optimize them. This allowed for a cost-effective and statistically sound optimization process [13].

- Outcome: The developed biosensor achieved an exceptionally low detection limit (1.40 fM) and high selectivity, demonstrating the power of a well-designed optimization strategy [13].

Comparative Data: OFAT vs. Multivariate Optimization

The table below summarizes the core limitations of the OFAT method and the corresponding advantages offered by multivariate optimization using Design of Experiments (DoE).

| OFAT Limitations | Multivariate DoE Advantages |

|---|---|

| Fails to detect interactions between factors [10]. | Models factor interactions to find a true global optimum [11]. |

| Inefficient, requiring many experiments for limited information [10]. | High efficiency, obtaining more information with fewer experiments [12] [13]. |

| Leads only to a local optimum, potentially missing the best performance [11]. | Maps the entire experimental domain to find the global optimum [11]. |

| Provides no predictive model of the system [11]. | Creates a mathematical model to predict performance within the factor space [11]. |

| Does not assess process robustness [11]. | Helps identify robust operating conditions that are less sensitive to noise [11]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

The following table lists key materials frequently used in the development and optimization of electrochemical biosensors, as cited in the research.

| Item | Function in Biosensor Development |

|---|---|

| Screen-Printed Electrodes (SPEs) | Disposable, portable electrode platforms often made of carbon, gold, or platinum. Serve as the solid support and transducer [14]. |

| Electroactive Polymers (e.g., Polypyrrole (PPy)) | Used to modify electrode surfaces. Enhance conductivity, provide a matrix for biomolecule entrapment, and improve stability [12]. |

| Nanomaterials (e.g., MWCNTs, Graphene Oxide, Au Nanoparticles) | Increase electrode surface area, enhance electron transfer, and act as immobilization matrices to significantly boost sensitivity [10] [12]. |

| Biorecognition Elements (e.g., Glucose Oxidase, DNA probes) | The core of the biosensor. Provides specificity to the target analyte (e.g., glucose, a specific DNA sequence) [10] [14] [12]. |

| Dendrimers (e.g., PAMAM) | Highly branched molecules with many functional groups. Used to amplify the electrochemical response and increase the amount of probe DNA that can be immobilized [13]. |

Experimental Workflow: From Problem to Optimized Biosensor

The diagram below outlines a logical pathway for diagnosing OFAT-related issues and implementing a superior multivariate optimization strategy.

Recommended Experimental Protocol: Implementing RSM with CCD

For researchers looking to replace OFAT, here is a generalized protocol based on the cited successful applications [14] [12] [13]:

- Factor Selection & Range Definition: Use prior knowledge or a screening design to select 2-4 critical factors (e.g., enzyme concentration, probe immobilization time, nanomaterial loading). Define a practical range (low and high level) for each.

- Design the Experiment: Create a Central Composite Design (CCD) matrix using statistical software (e.g., Minitab, Design-Expert). This design includes factorial points, axial points, and center points to efficiently fit a quadratic model.

- Run Experiments & Record Response: Fabricate biosensors and perform measurements according to the CCD matrix. Record your key response variable (e.g., sensitivity, peak current, detection limit).

- Model Fitting & Statistical Analysis: Input the data into the software to perform multiple least square regression. Use Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) to assess the model's significance and the importance of each term.

- Validation and Prediction: Use the software's optimization function to find the factor settings that predict the best performance. Conduct validation experiments at these predicted optimum conditions to confirm the model's accuracy.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is Response Surface Methodology (RSM) and when should I use it for biosensor optimization? Response Surface Methodology (RSM) is a collection of statistical, graphical, and mathematical techniques used to develop, improve, and optimize products and processes where the response of interest is influenced by several variables [4] [3]. You should use RSM when you need to find the factor settings that optimize your biosensor's response (e.g., maximize sensitivity, minimize response time) after you have identified the important factors through initial screening experiments [15] [3]. It is particularly useful when you suspect curvature in the response surface, meaning the optimum lies somewhere within the range of your factors, not just at their extremes [3].

2. My initial model shows a lack of fit. What does this indicate? A significant lack of fit in a first-order (linear) model often indicates that you have reached the vicinity of the optimum and that curvature is present in the system [15]. This is a key signal to move from initial factorial designs to a more elaborate RSM design, such as a Central Composite Design (CCD) or Box-Behnken Design (BBD), which can fit a second-order model and accurately map the optimal region [15] [16].

3. What is the difference between Central Composite Design (CCD) and Box-Behnken Design (BBD)? Both CCD and BBD are used to fit second-order models, but they differ in structure and application. A CCD contains a factorial or fractional factorial design, augmented with center points and axial (star) points, allowing it to estimate curvature [4] [15]. A BBD is an independent quadratic design where treatment combinations are at the midpoints of the edges of the process space and at the center; it does not contain an embedded factorial design and often requires fewer runs than a CCD for the same number of factors [4] [16]. The choice between them depends on your experimental region and resource constraints [16].

4. How do I handle optimizing multiple biosensor responses at once? When multiple responses (e.g., response time, sensitivity, and stability) need to be optimized simultaneously, the desirability function approach is very useful [15]. This method converts each response into an individual desirability function and then combines them into a single composite metric. This allows you to find a balanced setting for your factors that provides the most appropriate values for all responses, even if their individual optimums would lead to conflicting factor settings [15] [3].

Troubleshooting Guides

Poor Model Fit or Low Predictive Power

- Symptoms: Low R-squared or Adjusted R-squared values, significant lack of fit, poor agreement between predicted and actual values in validation experiments.

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- Insufficient Model Complexity: If the relationship between factors and the response is curved, a linear model will be inadequate. Solution: Use an RSM design (CCD or BBD) to fit a second-order (quadratic) model that can capture curvature [16] [3].

- Incorrect Factor Ranges: The experimental region may not encompass the true optimum. Solution: Use the method of steepest ascent/descent to sequentially move the experimental region toward the optimum before performing a detailed RSM study [15].

- Violated Model Assumptions: The statistical analysis assumes normality, independence, and constant variance of residuals. Solution: Perform residual analysis and consider transforming the response variable (e.g., logarithmic transformation) if diagnostics show violated assumptions [16].

Failure to Reach the Optimum

- Symptoms: The optimization process stalls, or the predicted optimum is at the edge of the experimental region.

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- Incorrect Search Direction: The path of steepest ascent/descent was miscalculated. Solution: Recalculate the path using the coefficients from the first-order model, ensuring the steps taken for each factor are proportional to their regression coefficients [15].

- Presence of Interactions or Curvature: The steepest ascent method assumes a linear, rising ridge. Solution: If the response stops improving, fit a new first-order model. If it shows lack of fit, you are near the optimum and should switch to an RSM design [15].

- Critical Factors Omitted: Important variables may not have been included in the experimental design. Solution: Return to the screening phase to ensure all influential factors have been identified [4] [16].

High Variability in Experimental Results

- Symptoms: Large confidence intervals for coefficient estimates, poor reproducibility of the optimal conditions.

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- Insufficient Replication: Experimental error is not well quantified. Solution: Include replicate runs, especially center points, to obtain a pure estimate of experimental error and check for model adequacy [4] [15].

- Uncontrolled External Factors: Environmental conditions or measurement techniques may not be standardized. Solution: Carefully control all non-experimental factors and randomize the run order of your experiments to avoid confounding [16].

The table below summarizes the core characteristics of the most common RSM designs to help you select the appropriate one for your biosensor optimization.

Table 1: Comparison of Common Response Surface Methodology Designs

| Design Type | Key Characteristics | Number of Runs (for k factors) | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Central Composite Design (CCD) [4] [15] [16] | Contains factorial points, center points, and axial (star) points. Can be rotatable. | Varies with type; e.g., a circumscribed CCD for 3 factors requires 16-20 runs. | The most general and widely used design for full RSM optimization; provides excellent overall coverage of the experimental region. |

| Box-Behnken Design (BBD) [4] [16] | Treats combinations at the midpoints of edges; requires only 3 levels per factor. Does not have axial points. | For k=3 factors: 13 runs (with 1 center point) [4]. | An efficient choice when looking to minimize the number of runs, especially when one-factor-at-a-time experiments are impractical at extreme (star) points. |

| 3-Level Full Factorial Design [16] | Every combination of all factors at all three levels. | 3k (e.g., for k=3, 27 runs). | Provides extensive data but becomes prohibitively large and expensive as the number of factors increases. |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key materials and their functions relevant to conducting a robust RSM study, particularly in a biochemical context like biosensor development.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for RSM Experiments

| Item | Function/Application in RSM |

|---|---|

| Carrier Agents (e.g., Maltodextrin) [17] | Used in process optimization to improve the yield and physical properties of spray-dried products (e.g., stabilizing sensitive bioactive compounds). |

| Buffering Agents (e.g., Phosphate, Acetate) [18] | Critical for maintaining consistent pH, a common continuous factor in biosensor and biochemical optimization studies. |

| Blocking Additives (e.g., BSA) [18] | Used to reduce non-specific binding on sensor surfaces, a key step in assay development and optimization for biosensors. |

| Non-ionic Surfactants (e.g., Tween 20) [18] | Added to running buffers to mitigate non-specific binding caused by hydrophobic interactions, improving data quality. |

| Sensor Chips (e.g., NTA, Carboxyl) [18] | The solid support for ligand immobilization; selecting the correct chemistry is fundamental to assay performance. |

RSM Workflow and Optimization Process

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for a typical RSM-based optimization project, from initial screening to final validation.

Diagram 1: RSM Optimization Workflow

Experimental Protocol: Central Composite Design for Biosensor Optimization

This protocol outlines the key steps for implementing a Central Composite Design (CCD) to optimize your biosensor's performance.

1. Identification of Inputs and Their Levels

- Based on prior screening experiments or literature, select the critical continuous factors (e.g., pH, temperature, ligand density) you wish to optimize [16].

- Define a feasible and relevant range for each factor (low and high levels). The center point will be the midpoint of this range [3].

2. Selection and Setup of the CCD

- Choose the type of CCD (e.g., circumscribed, face-centered) based on your experimental region and the desire for properties like rotatability [15] [16].

- Use statistical software to generate the run order, randomizing it to minimize the effects of uncontrolled variables.

- The standard CCD consists of three parts [4] [15]:

- Factorial Points: A full or fractional factorial design from the high and low levels.

- Center Points: Several replicates at the center of the design space to estimate pure error.

- Axial Points: Points located at a distance ±α from the center along each factor axis, while other factors are held at their center point.

3. Execution and Data Collection

- Execute the experiments precisely in the randomized order.

- For each run, meticulously record the response variable (e.g., biosensor response time, signal intensity).

4. Mathematical Modeling and Analysis

- Use multiple linear regression to fit a second-order polynomial model to the data [4] [16]. The model has the form: Y = β₀ + ∑βᵢXᵢ + ∑βᵢᵢXᵢ² + ∑βᵢⱼXᵢXⱼ + ε where Y is the predicted response, β₀ is the constant, βᵢ are linear coefficients, βᵢᵢ are quadratic coefficients, βᵢⱼ are interaction coefficients, and Xᵢ, Xⱼ are the factor levels [4].

- Analyze the variance (ANOVA) of the fitted model to check the significance of the model terms and the overall model adequacy (using R-squared, Adjusted R-squared, and lack-of-fit test) [16].

5. Optimization and Validation

- Use the fitted model to generate contour plots and 3D surface plots to visualize the relationship between factors and the response [4] [3].

- Use numerical optimization techniques or the desirability function approach to find the factor settings that produce the optimal response [15] [3].

- Conduct confirmation experiments at the predicted optimal conditions to validate the model's accuracy. Compare the observed response with the model's prediction [16].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the core advantage of using RSM over the traditional "one variable at a time" (OVAT) approach for optimizing my biosensor?

RSM's primary advantage is its ability to efficiently model complex interactions between multiple factors simultaneously, which the OVAT method misses entirely. While OVAT changes one parameter at a time while holding others constant, RSM uses structured experimental designs to vary all factors at once. This not only reveals how factors interact but also drastically reduces the number of experiments needed to find an optimum. For instance, one study optimized a paper-based electrochemical biosensor for miRNA detection: RSM found the optimum conditions with only 30 experiments, whereas the OVAT approach would have required 486 experiments [19].

Q2: My biosensor response is influenced by many variables. How does RSM help me identify which ones are most important?

RSM is often implemented in a sequential process. The first step typically involves screening designs, such as a Plackett-Burman (PB) design, to efficiently identify the factors that have significant effects on your response (e.g., biosensor sensitivity or response time). This allows you to filter out less important variables, saving time and resources for the subsequent optimization phase where you focus only on the critical few factors using more detailed RSM designs like Central Composite Design (CCD) [2] [12].

Q3: What kind of experimental designs are commonly used in RSM for biosensor development?

Two of the most prevalent designs are Central Composite Design (CCD) and Box-Behnken Design (BBD). Both are used to fit second-order (quadratic) models, which can capture curvature in the response surface—essential for finding a true optimum. The choice between them depends on your specific experimental constraints and the region of the factor space you wish to explore [2] [20] [21].

Q4: The model I get from RSM is an approximation. How can I check if it is reliable and accurate?

Model validation is a critical step in RSM. You can check your model's adequacy using several statistical methods provided by RSM software, including [2]:

- Analysis of Variance (ANOVA): To determine the statistical significance of the model and its terms.

- Lack-of-fit tests: To check if the model form is adequate.

- R-squared (R²) values: To see how much variation in the response is explained by the model.

- Residual analysis: To check the model's underlying assumptions.

- Confirmation runs: Conducting a small number of additional experiments at the predicted optimal conditions to verify the model's accuracy [2].

Troubleshooting Common RSM Challenges

Problem: Non-Specific Binding in Biosensor is Skimming My RSM Results

Scenario: You are using SPR technology to characterize binding kinetics as a response in your RSM study. You observe binding signals, but they may be inflated or inaccurate due to non-specific binding of the analyte to the sensor surface itself, rather than just the target ligand [22].

Solutions:

- Modify Running Buffer: Supplement your running buffer with additives like surfactants, Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA), dextran, or polyethylene glycol (PEG) to block non-specific sites [22].

- Optimize Reference Channel: Ensure your reference surface is appropriate. Test a high analyte concentration over a native or BSA-coated surface to check for non-specific binding to the reference [22].

- Change Sensor Chip Type: Switching to a different sensor chip chemistry (e.g., one with a different matrix or coating) can sometimes reduce non-specific interactions [22].

Problem: Inadequate Model or Failure to Locate an Optimum

Scenario: After analyzing your experimental data, the resulting model has a poor fit (low R²), or the predicted optimum seems unrealistic or is not found within your experimental region.

Solutions:

- Verify Factor Levels: Ensure your experimental range for factors is wide enough to capture the response variation, including any potential curvature. The optimum may lie outside your initial design space [23].

- Check for Transformation: Your response variable might require a mathematical transformation (e.g., log, square root) to meet the assumptions of the model.

- Iterate the Process: RSM is often an iterative methodology. If the initial experimental region is unsatisfactory, use the information gained to plan a new set of experiments in a more promising region of the factor space [2].

- Incorporate Prior Knowledge: Advanced techniques can use prior knowledge (e.g., the response is known to increase monotonically with a factor) to constrain the model during regression, leading to a more accurate and physically meaningful representation of the system [21].

Quantitative Data on RSM Efficiency

The table below summarizes data from real biosensor development studies, illustrating the dramatic reduction in experimental effort achieved by using RSM.

Table 1: Comparative Experimental Effort: RSM vs. OVAT Approach

| Biosensor Type / Target | Number of Variables | Estimated OVAT Experiments | RSM Experiments Actually Performed | RSM Design Used | Key Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paper-based electrochemical biosensor for miRNA-29c [19] | 6 | 486 | 30 | D-optimal | 5-fold improvement in detection limit |

| Electrochemical DNA biosensor for Mycobacterium tuberculosis [12] | Information missing | Information missing | Information missing | CCD & Plackett-Burman | Wide detection range (0.25–200.0 nM) with low LOD (0.141 nM) |

| Electrochemical sensor for heavy metal detection [19] | Information missing | Information missing | 13 | CCD | Detection limit improved from 12 nM to 1 nM |

Experimental Protocol: Optimizing a DNA Biosensor using RSM

This protocol is adapted from a study that developed a PCR-free electrochemical DNA biosensor for detecting Mycobacterium tuberculosis [12].

1. Define the Problem and Responses:

- Objective: Maximize the sensitivity (minimize the detection limit) of an electrochemical DNA biosensor.

- Response Variable (Y): The electrochemical signal (e.g., current from a redox indicator like Methylene Blue) after hybridization.

2. Screen and Select Factors:

- Use a Plackett-Burman (PB) screening design to identify which of many potential factors significantly affect the response. Factors can include [12]:

- Probe concentration

- Probe immobilization time

- Scan rate for electrodeposition of nanocomposite

- Target hybridization time

- Ionic strength/pH of the buffer

- Incubation temperature

3. Code Factor Levels and Select RSM Design:

- For the significant factors identified in Step 2, define high (+1) and low (-1) levels.

- Choose a Central Composite Design (CCD) to explore the factor space and fit a quadratic model. The CCD will define the specific combinations of factor levels for each experimental run [12].

4. Conduct Experiments and Develop the Model:

- Perform the hybridization assays according to the run order specified by the CCD.

- Measure the electrochemical response for each run.

- Use statistical software (e.g., Minitab, Design-Expert) to perform multiple regression analysis and fit a second-order polynomial model of the form [2] [21]:

Y = β₀ + β₁A + β₂B + β₃C + β₁₂AB + β₁₃AC + β₂₃BC + β₁₁A² + β₂₂B² + β₃₃C²(Where Y is the predicted response, A, B, C are the factors, and β are the coefficients.)

5. Model Validation and Optimization:

- Analyze the fitted model using ANOVA to check its significance.

- Use the model's response surfaces and contour plots to visually identify the optimal factor settings that yield the maximum signal.

- Perform confirmation experiments at the predicted optimal conditions to validate the model's accuracy [2].

Diagram: RSM Workflow for Biosensor Optimization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials

The table below lists essential materials used in RSM-optimized biosensor studies, along with their functions.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Biosensor Development

| Material / Reagent | Function in Biosensor Development | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes (MWCNTs) | Enhance electrical conductivity and provide a high surface-to-volume ratio for biomolecule immobilization, amplifying the electrochemical signal [12]. | Used in a nanocomposite with PPy and HAPNPs for tuberculosis detection [12]. |

| Polypyrrole (PPy) | An organic polymer that increases biocompatibility, conductivity, and chemical stability of the sensor surface while reducing toxicity [12]. | Part of the HAPNPs/PPy/MWCNTs nanocomposite [12]. |

| Hydroxyapatite Nanoparticles (HAPNPs) | A biomaterial used as a substrate for immobilizing biomolecules due to its excellent biocompatibility, non-toxicity, and multiple adsorption sites [12]. | Used to covalently attach the ssDNA probe in the M. tb biosensor [12]. |

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | Often used to modify electrode surfaces to improve electron transfer and provide a stable platform for functionalizing biomolecules like DNA or antibodies [19]. | A variable optimized in a D-optimal design for a paper-based miRNA biosensor [19]. |

| Central Composite Design (CCD) | A statistical experimental design that allows for efficient estimation of a second-order (quadratic) model, crucial for finding optimal conditions [2] [12]. | Applied to optimize probe immobilization and target hybridization parameters [12]. |

The Critical Link Between Biosensor Response Time and Clinical Utility

Response time is a critical performance parameter for biosensors, defined as the speed at which the biosensor reacts to changes in the concentration of the target analyte. In clinical and research settings, a slow response time can hinder controllability, introducing dangerous delays in processes ranging from real-time patient monitoring to high-throughput drug screening. For therapeutic applications, such as engineered cell-based therapies, dynamic regulation is even more critical, as genetic circuits must respond precisely to disease-relevant signals and control therapeutic output temporally [24].

Frequently Asked Questions on Response Time

Q1: What is considered a "good" response time for a clinical biosensor? The acceptable response time depends entirely on the clinical application. For continuous glucose monitoring, response times must be fast enough to detect rapid glycemic shifts, typically in the range of seconds to a few minutes. For detection of low-concentration analytes like specific proteins or miRNAs, the response time may be longer due to the kinetics of the binding reaction. The key is that the response time must be fast enough to enable clinical decision-making before the patient's condition changes significantly [24] [25].

Q2: Why has the response time of my biosensor suddenly increased? Increased response time can result from several factors:

- Biofouling: Accumulation of nonspecific proteins or cells on the sensor surface can create a diffusion barrier, slowing analyte access. This is particularly problematic in complex serum matrices [26].

- Sensor Degradation: Physical damage to the biorecognition element or transducer can impair binding efficiency and signal generation.

- Environmental Factors: Changes in temperature, pH, or ionic strength can alter binding kinetics and electron transfer rates in electrochemical biosensors. Regular calibration and appropriate surface regeneration protocols can help identify and mitigate these issues.

Q3: How can I reduce false results without sacrificing response time? Traditional approaches often create a trade-off between accuracy and speed. However, emerging methodologies that integrate machine learning with biosensor data can complement and improve biosensor accuracy and speed simultaneously. By analyzing the initial transient response of the biosensor rather than waiting for steady-state signals, these approaches can reduce both false results and time delays [25].

Q4: Can the choice of biorecognition element affect response time? Absolutely. Different biorecognition elements have characteristic binding kinetics:

- Antibodies: Typically have high specificity but may have slower binding kinetics (minutes to hours).

- Aptamers: Often have faster binding kinetics than antibodies (seconds to minutes).

- Peptides: Generally offer the fastest binding kinetics (seconds) and can be engineered for specific variants, as demonstrated in SARS-CoV-2 antibody detection platforms [26].

- Enzymes: Response depends on catalytic conversion rates, typically very fast (seconds).

Q5: How does Response Surface Methodology help optimize response time? Response Surface Methodology (RSM) is a statistical technique that models and optimizes multiple process parameters simultaneously. For biosensor optimization, RSM can identify optimal conditions that balance response time with other critical parameters like sensitivity and signal-to-noise ratio. For example, ChatGPT-4.0 recently assisted in determining an appropriate RSM design (face-centered central composite design) to optimize culture conditions for a diatom, demonstrating how AI can enhance this experimental approach [27].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Unacceptably Slow Response Time

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Suboptimal Biosensor Design

- Cause: Inefficient mass transfer of analyte to the sensing surface.

- Solution: Redesign the flow cell or microfluidic channels to enhance convective transport. Consider nanostructuring the surface to increase binding site density.

Non-optimized Binding Chemistry

- Cause: Poor orientation or density of biorecognition elements.

- Solution: Systematically vary immobilization conditions (pH, concentration, time) using RSM to find the optimal balance between density and activity.

Signal Processing Limitations

- Cause: Conventional data analysis waiting for steady-state response.

- Solution: Implement machine learning algorithms that can accurately predict final concentration from the initial transient response, potentially reducing required data acquisition time by 50% or more [25].

Problem: Inconsistent Response Times Between Sensor Replicates

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Manufacturing Variability

- Cause: Inconsistent fabrication of sensor surfaces or biorecognition element immobilization.

- Solution: Implement stricter quality control measures and use theory-guided feature engineering to identify and compensate for performance variances among different biosensors [25].

Environmental Fluctuations

- Cause: Uncontrolled temperature, pH, or flow rate variations.

- Solution: Implement environmental monitoring and control systems. Use RSM to quantify the effect of these parameters on response time and establish robust operating ranges.

Quantitative Data on Biosensor Response Time Factors

Table 1: Factors Affecting Biosensor Response Time and Optimization Strategies

| Factor | Impact on Response Time | Optimization Approach | Typical Optimization Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature | Increases kinetic rates; 2-3x faster per 10°C rise | RSM with temperature as variable | 20-37°C (biological systems) |

| Flow Rate | Enhances mass transfer; reduces stagnation layers | CFD modeling coupled with RSM | 5-100 μL/min (microfluidics) |

| Bioreceptor Density | Optimal range exists; too high causes steric hindrance | Immobilization chemistry optimization | 10¹²-10¹⁴ molecules/cm² |

| Sample Volume | Smaller volumes reach equilibrium faster | Microfluidic design optimization | 1-100 μL (point-of-care) |

| Surface Chemistry | Affects binding kinetics and nonspecific binding | SAM composition variation | Alkanethiol chain length C6-C16 |

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Biosensor Types by Typical Response Time

| Biosensor Type | Biorecognition Element | Typical Response Time | Best Clinical Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electrochemical | Enzymes, antibodies | Seconds to minutes | Continuous monitoring (e.g., glucose) |

| Optical (SPR) | Antibodies, peptides | Minutes | Label-free protein interaction studies |

| Piezoelectric | DNA, proteins | 10-30 minutes | miRNA detection, mass-sensitive applications |

| SERS-based | Peptides, aptamers | <5 minutes | Ultrasensitive pathogen detection [26] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Response Time Optimization Using Response Surface Methodology

Purpose: To systematically optimize biosensor response time while maintaining sensitivity and specificity.

Materials:

- Functionalized biosensors

- Target analyte solutions of known concentration

- Flow control system (e.g., syringe pump)

- Data acquisition system

- Statistical software (e.g., Minitab, R)

Methodology:

- Identify Critical Factors: Select 3-4 independent variables that potentially affect response time (e.g., temperature, flow rate, bioreceptor density, pH).

- Experimental Design: Implement a face-centered central composite design (FCCCD) as suggested in recent research [27]. This comprises factorial, axial, and center points.

- Response Measurement: For each experimental run, measure:

- Time to reach 90% of steady-state signal (Response Time)

- Signal magnitude at steady state (Sensitivity)

- Signal-to-noise ratio (Specificity indicator)

- Model Fitting: Fit the data to a quadratic model: Y = β₀ + β₁X₁ + β₂X₂ + β₃X₃ + β₁₁X₁² + β₂₂X₂² + β₃₃X₃² + β₁₂X₁X₂ + β₁₃X₁X₂ + β₂₃X₂X₃

- Optimization: Use response optimizer to find parameter settings that minimize response time while maintaining acceptable sensitivity and specificity.

- Validation: Conduct confirmation experiments at the predicted optimal conditions.

Protocol 2: Machine Learning-Enhanced Response Time Reduction

Purpose: To reduce effective response time through analysis of initial transient signals.

Materials:

- Cantilever, electrochemical, or optical biosensors

- Time-series data acquisition system

- Python with scikit-learn, TSFRESH packages

- Augmented dataset of biosensor dynamic responses [25]

Methodology:

- Data Collection: Collect dynamic biosensor responses (normalized signal change vs. time) across full concentration range.

- Data Augmentation: Address data sparsity using jittering, scaling, magnitude warping, and time warping techniques [25].

- Feature Engineering:

- Extract theory-based features from biosensor binding kinetics

- Generate additional features using TSFRESH algorithm

- Model Training: Train classification models (Random Forest, SVM) to predict analyte concentration from early transient response.

- Validation: Compare time to accurate classification using initial transient vs. full steady-state response.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Biosensor Response Time Optimization

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| 4-mercaptobenzoic acid (MBA) | Raman reporter molecule; forms self-assembled monolayers | SERS-based biosensors for antibody detection [26] |

| Gold nanoparticles (30nm) | Signal amplification; enhance electromagnetic field | Optical and electrochemical biosensors [26] |

| Synthetic peptides (e.g., P44) | Biorecognition elements with tunable kinetics | Variant-specific pathogen detection [26] |

| Carboxylated/aminated surfaces | Controlled immobilization of biorecognition elements | Optimal orientation for enhanced binding kinetics |

| Theory-guided feature sets | Machine learning inputs for early concentration prediction | Reducing effective response time by >50% [25] |

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

A Step-by-Step Methodology: Applying RSM to Accelerate Biosensor Response

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What are the most common factors that affect biosensor response time? The response time of a biosensor is primarily influenced by factors related to mass transport and the binding reaction kinetics. Key factors often include:

- Flow Conditions: The velocity and flow rate of the sample fluid. Slow flow can lead to thicker diffusion boundary layers, while very high flow may not allow sufficient time for analyte-binding reactions [28] [29].

- Sensor Geometry: The physical design of the sensing area, such as the arrangement (e.g., inline vs. staggered) and shape of micro-features like micropillar electrodes, can enhance surface area and induce fluid mixing, significantly improving response times [28].

- Analyte Concentration: The initial concentration of the target molecule in the sample influences how quickly the binding sites on the sensor surface are occupied [29].

- Binding Kinetics: The intrinsic rates of the association and dissociation between the analyte and the immobilized biorecognition element are fundamental [30].

2. How can I systematically identify the most critical factors for my biosensor optimization? Instead of testing one factor at a time, use a systematic approach like Design of Experiments (DoE). DoE is a chemometric tool that allows you to efficiently screen multiple factors simultaneously. It helps identify not only the individual effect of each factor but also how they interact with each other, which is often missed in traditional methods [31] [11]. For instance, a factorial design can be used as a first step to screen which factors (e.g., flow velocity, pillar spacing, analyte concentration) have a significant impact on your response variable (response time) [11].

3. I've identified key factors, but my response time model is inaccurate. What could be wrong? Your model might be failing to account for underlying physical or biochemical phenomena. For example:

- Molecular Rearrangement: The adsorption of biomolecules is sometimes followed by a change in their structure or orientation, a process known as rearrangement. This can alter the binding kinetics, leading to a two-step response that simple models cannot accurately describe [30].

- Inadequate Model Validation: The fitted model must be rigorously checked for accuracy. Use statistical validation like Analysis of Variance (ANOVA), lack-of-fit tests, and residual analysis to ensure the model is a good representation of the true process [2].

4. What is a major advantage of using Response Surface Methodology over one-factor-at-a-time experiments? The primary advantage is the ability to detect interactions between factors. In a one-factor-at-a-time approach, you might find a "best" level for one factor, but this level may not be optimal when another factor is changed. RSM, through its structured designs, can model these complex interactions and curvature in the response, leading to the identification of a true optimum [31] [11] [2].

5. How can I improve a biosensor's response time using passive fluid dynamics? Integrating micro-obstacles within the microfluidic channel is an effective passive method. Placing a strategically located obstacle, like a cylinder or a parallelepiped, deforms the fluid stream. This deformation enhances mixing, disrupts the diffusion boundary layer, and increases the transport of analytes to the sensing surface, thereby reducing the response time [28] [29]. One study showed that a staggered arrangement of micropillars can improve response time by 25% compared to an inline arrangement [28].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Slow Response Time During Association Phase A slow response time indicates that the analyte is taking too long to bind to the ligands on the sensor surface. This is often a mass transport limitation.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Thick Diffusion Boundary Layer | Check if response is faster at higher flow velocities. Visually inspect (via simulation or dye tests) for stagnant fluid regions above the sensor. | Introduce passive mixers (e.g., staggered micropillar arrays) into the flow channel to disrupt the boundary layer [28] [29]. |

| Sub-optimal Flow Velocity | Perform a DoE screening with flow velocity as a factor. Model the response to find if an optimum exists. | Systematically optimize the flow rate using RSM. The goal is to find a velocity that balances rapid analyte delivery with sufficient reaction time [28]. |

| Low Analyte Concentration | Verify the concentration of the prepared sample. Check if the signal increases proportionally with concentration in calibration tests. | Increase the analyte concentration if possible, or pre-concentrate the sample. Ensure the sensor's dynamic range is appropriate for the expected concentrations [29]. |

Problem: High Variability or Noise in Response Signal Fluctuations in the signal can mask the true binding response and affect the determination of response time.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Stochastic Binding/ Rearrangement | Analyze the power spectral density (PSD) of the signal noise. A model that includes rearrangement kinetics may better fit the data [30]. | Develop or use a more comprehensive noise model that accounts for processes like molecular rearrangement upon adsorption to correctly interpret signal fluctuations [30]. |

| Uncontrolled Experimental Conditions | Check for fluctuations in temperature, pressure, or flow rate from pumps and actuators. | Implement better environmental controls and use high-precision, calibrated equipment for fluid delivery. |

Problem: RSM Model Shows Poor Fit or Lack of Fit Your empirical model fails to adequately describe the relationship between your factors and the response time.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Important Factors Omitted | Use subject matter knowledge and literature review. Perform a factor screening DoE (e.g., Plackett-Burman) before a full RSM. | Re-specify the model by adding potentially critical factors identified in screening, such as specific geometric parameters (pillar diameter, spacing) or chemical conditions (pH, ionic strength) [28]. |

| Presence of Significant Curvature | Examine residual plots from a first-order model; a U-shaped pattern suggests curvature. | Move from a factorial design to a second-order RSM design like a Central Composite Design (CCD) or Box-Behnken Design, which can model curvature [2]. |

| Insufficient Data Points | Confirm the number of experimental runs meets the minimum required for the chosen model. | Augment the experimental design with additional runs, such as adding center points or axial points to a factorial design to create a CCD [11]. |

Critical Factors for Biosensor Response Time Optimization

The following table summarizes key factors that influence biosensor response time, as identified in experimental and numerical studies. These factors are critical to define in any optimization problem.

| Factor Category | Specific Factor | Influence on Response Time | Optimization Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fluid Flow & Transport | Flow Velocity / Rate | Directly affects mass transport; low velocity increases boundary layer thickness, very high velocity may reduce binding efficiency [28] [29]. | Use RSM to find optimum velocity; one study suggested a ratio of flow's inertia to viscous forces < 0.1 [28]. |

| Flow Confinement | Focusing the sample stream into a thin layer over the sensor increases local velocity and enhances binding rate [29]. | Optimize the ratio of sample flow to sheath flow rates. | |

| Sensor Geometry | Micropillar Arrangement | A staggered arrangement induces better mixing and can improve response time by ~25% compared to an inline arrangement [28]. | Compare different geometric configurations (inline, staggered) via simulation or DoE. |

| Obstacle Position | The location of a mixing obstacle relative to the sensor surface and inlet is critical for maximizing its disruptive effect on the boundary layer [29]. | Systematically vary the obstacle position (e.g., distance from inlet) in a DoE to find the optimal location. | |

| Binding Chemistry | Analyte Concentration | Higher concentrations generally lead to faster surface saturation and shorter association times, but may slow dissociation [29]. | Calibrate for the expected concentration range and consider it as a factor in the DoE if it is a variable. |

| Biomolecular Rearrangement | Post-adsorption changes in analyte structure can slow the overall response kinetics, leading to two-step binding behavior [30]. | Incorporate kinetic models that account for rearrangement (e.g., two-step kinetics) for accurate interpretation. |

Experimental Protocol: Optimizing Flow and Geometry with DoE

This protocol outlines how to use Response Surface Methodology to optimize flow and geometric factors for improved response time.

1. Define the Problem and Response Variable

- Objective: Minimize the response time of the biosensor.

- Response Variable: The time (in seconds) for the sensor's signal to reach 90% of its steady-state value upon introduction of the analyte.

2. Select and Code the Critical Factors Based on prior knowledge and screening, select two key factors for a CCD optimization. The factors are scaled to coded levels (-1, 0, +1).

- Factor A (Flow Velocity): For example, from 100 μm/s (-1) to 300 μm/s (+1), with a center point at 200 μm/s.

- Factor B (Obstacle Position): The distance of a mixing obstacle from the channel inlet, e.g., from 2 mm (-1) to 6 mm (+1), with a center point at 4 mm.

3. Select an Experimental Design and Conduct Runs

- Design: A Central Composite Design (CCD) is suitable for fitting a second-order (quadratic) model. A full CCD for two factors requires 13 experimental runs (4 factorial points, 4 axial points, and 5 center points for replication) [2].

- Execution: Set up your microfluidic biosensor system. For each run in the randomized experimental matrix, set the flow velocity and obstacle position to the specified levels, introduce the analyte, and record the response time.

4. Develop and Validate the Response Surface Model

- Model Development: Use statistical software to fit a second-order polynomial model to the data (e.g., Response Time = β₀ + β₁A + β₂B + β₁₁A² + β₂₂B² + β₁₂AB).

- Model Validation: Check the model's Analysis of Variance (ANOVA). Key metrics include a high R² value (e.g., >0.9) and a non-significant lack-of-fit p-value (e.g., >0.05) [2]. Perform confirmation runs at the predicted optimum settings to validate the model.

5. Optimize and Interpret the Results

- Use the software's optimization function to find the factor settings (A and B) that minimize the predicted response time.

- Examine the response surface contour plot to understand the relationship between the factors and to identify a robust operating region.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Response Time Optimization |

|---|---|

| COMSOL Multiphysics Software | A finite-element-based simulation platform used to numerically model the effects of geometry and flow on biosensor performance before physical prototyping, saving time and resources [28]. |

| Microfluidic Chips with Micropillar Arrays | Sensor substrates, often made of PDMS or gold, featuring engineered microstructures that increase surface area and disrupt laminar flow to enhance analyte transport [28]. |

| C-reactive Protein (CRP) / Immunoglobulin G (IgG) Pair | A well-characterized model analyte-ligand (antibody) system used in benchmark studies to test and optimize biosensor performance under controlled conditions [29]. |

| Design of Experiments (DoE) Software | Statistical software (e.g., JMP, Minitab, Design-Expert) used to create experimental designs, fit response surface models, and find optimal factor settings [31] [2]. |

RSM Workflow for Biosensor Optimization

The following diagram illustrates the iterative, multi-stage workflow for applying Response Surface Methodology to biosensor optimization.

For researchers optimizing biosensor response time, selecting the proper Response Surface Methodology (RSM) design is critical for efficiently modeling curvature and identifying optimal operating conditions. Central Composite Design (CCD) and Box-Behnken Design (BBD) are the two most widely used RSM designs for this purpose [32]. This guide will help you choose the right design and troubleshoot common issues.

CCD vs. BBD: A Quick Comparison

The table below summarizes the core characteristics of each design to help you make an initial selection.

| Feature | Central Composite Design (CCD) | Box-Behnken Design (BBD) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Structure | Built on a two-level factorial or fractional factorial design, augmented with axial (star) points and center points [32] [33]. | A three-level design based on combining two-level factorial designs with incomplete block designs; does not contain an embedded factorial matrix [32] [34]. |

| Factor Levels | Typically 5 levels per factor (for rotatable designs), but can be 3 with a face-centered design (α=1) [32] [33]. | Always 3 levels per factor [32]. |

| Experimental Points | Includes factorial points (corners), axial points (outside the cube), and center points [33]. | Points are located at the midpoints of the edges of the experimental space and at the center; no corner points [32] [34]. |

| Sequential Experimentation | Excellent. You can build on a previous factorial experiment by adding axial and center points [32] [33]. | Not suited. It is an "all-or-nothing" design that cannot naturally include prior factorial experiments [32] [33]. |

| Key Advantage | High flexibility and ideal for sequential learning when the process is not well understood [33]. | High efficiency and safety; avoids extreme factor combinations and is often less expensive to run [32] [33]. |

How to Choose: A Decision Guide

The following workflow diagram visualizes the key questions to ask when selecting between a CCD and a BBD for your biosensor optimization research.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Implementing a Central Composite Design (CCD)

A CCD is constructed from three distinct sets of experimental runs [35] [36]:

- Factorial Points: A full or fractional factorial design (2^k) that forms the "cube" of the design. These are the standard high (+1) and low (-1) settings.

- Axial (Star) Points: Points fixed axially at a distance α from the center of the design. This distance is defined for each factor and is used to estimate quadratic effects. The value of α can be chosen to achieve desired properties like rotatability. A common and practical choice is the face-centered design (α=1), which keeps all points within the original -1 to +1 range and requires only 3 factor levels [32].

- Center Points: Multiple replicate runs (typically 3-6) where all factors are set at their midpoint (coded 0). These are crucial for estimating pure experimental error and detecting curvature.

The total number of experiments (N) required for a CCD with k factors is: N = 2^k + 2k + n, where n is the number of center point replicates [35].

Workflow for Sequential Experimentation with CCD: This methodology is highly recommended for biosensor development where knowledge is built incrementally [37].

- Begin with a factorial design (full or fractional) to screen for significant factors affecting biosensor response time.

- Analyze the results. If curvature is suspected (e.g., from analysis of center points), augment the design by adding axial points.

- The combined set of runs (factorial + axial + center points) now constitutes a full CCD, allowing you to fit a highly accurate quadratic model for optimization.

Implementing a Box-Behnken Design (BBD)

A BBD is constructed differently, treating factors in separate blocks [34]:

- For a three-factor system, the design can be thought of as a set of two-factor full factorial designs (2^2), while the third factor is held constant at its center point.

- This process is rotated for all possible pairs of factors.

- Several center points are added to provide an estimate of error and model stability.

BBDs are noted for their run efficiency. For example, a 3-factor BBD requires only 15 experiments (including center points), while a comparable CCD requires 17-20 [33]. This efficiency becomes more pronounced with a higher number of factors.

Key Consideration for Biosensors: Because a BBD never includes experiments where all factors are at their extreme high or low settings simultaneously, it is exceptionally useful when testing such combinations could damage expensive biosensor components or produce unreliable data [32] [33].

Troubleshooting FAQs

1. I already ran a full factorial screening experiment. Can I use that data?

- Yes, if you choose a CCD. A major advantage of CCD is sequential experimentation. You can simply add the required axial points and additional center points to your existing factorial data to create a full response surface model [32] [33].

- No, if you choose a BBD. The BBD structure does not include a factorial design, so your previous data cannot be incorporated directly [32].

2. My model shows poor prediction capability. What went wrong?

- For CCD: Ensure your choice of α (alpha, the distance to axial points) is appropriate. A rotatable CCD (where α is calculated as (2^k)^0.25) provides constant prediction variance at all points equidistant from the center, leading to better prediction across the design space [32] [36]. If your experimental region is constrained, a face-centered CCD (α=1) might be a better, more practical choice.

- For both designs: Insufficient replication of center points is a common cause. Center points are essential for estimating pure error, which is used to test for model lack-of-fit. A minimum of 3-5 center points is generally recommended [36].

3. One of the optimum conditions suggested by the model is outside my safe operating zone. How can I prevent this?

- This is a key strength of the Box-Behnken Design. Since BBD does not include axial points that extend beyond the factorial cube or test all factors at their extreme settings simultaneously, all design points naturally fall within your defined safe operating zone [32] [33]. If you must use a CCD, opt for a face-centered design (α=1), which will keep all points within the -1 to +1 coded range, though you will still test the extreme corners [32].

4. I have more than 5 factors to optimize. The required runs are too high. What should I do?

- Neither CCD nor BBD is recommended for a high number of factors in RSM. The correct approach is to first use a screening design (like a fractional factorial or Plackett-Burman design) to identify the 3-5 most critical factors. Then, proceed with a CCD or BBD to optimize only those key factors [33] [35].

Research Reagent Solutions for Biosensor Optimization

When applying RSM to biosensor development, the key materials often revolve around the electrode and biorecognition elements [10].

| Material | Function in Biosensor Optimization |

|---|---|

| Glassy Carbon Electrode (GCE) | A common working electrode platform. Its surface is polished and modified to enhance electron transfer and provide a substrate for immobilization [10]. |

| Nanomaterials (e.g., Graphene Oxide, Carbon Nanotubes, Gold Nanoparticles) | Used to modify the electrode surface. They increase the effective surface area, improve electrocatalytic properties, and enhance the electron transfer rate, which can directly impact response time and sensitivity [10]. |

| Enzymes / Antibodies / Aptamers | The biorecognition elements. They are immobilized on the electrode to provide specificity to the target analyte. Their concentration, activity, and immobilization method are critical factors for optimization [10]. |

| Cross-linking Agents (e.g., Glutaraldehyde) | Used to create covalent bonds for immobilizing biorecognition elements onto the modified electrode surface, impacting biosensor stability and reproducibility [10]. |

| Self-Assembled Monolayer (SAM) Reagents | Used to create a highly ordered, thin organic film on electrode surfaces (especially gold), providing a well-defined platform for controlled immobilization of biomolecules [10]. |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Why is my biosensor's hybridization signal low or inconsistent, even when using the optimized parameters from my RSM model? Low hybridization signals often stem from suboptimal local conditions at the sensor surface that are not fully captured by the initial RSM model [38]. First, verify the ionic strength (NaCl concentration) of your hybridization buffer, as this is frequently the most significant factor affecting hybridization efficiency and signal intensity [38]. Second, check the pH of the buffer, as it can influence the charge state of the DNA backbone and the redox indicator [38]. Finally, ensure your hybridization time and temperature are strictly controlled, as these also significantly impact the process [38].

Q2: My RSM model suggests an optimum, but the experimental response is not reproducible. What could be wrong? Poor reproducibility usually points to inconsistencies in the biosensor fabrication process prior to hybridization [12] [10]. Key areas to troubleshoot include:

- Electrode Modification: Ensure uniform dispersion of nanomaterials like MWCNTs and consistent electrodeposition parameters for polymers like polypyrrole (PPy) across all electrodes [12].

- Probe Immobilization: The concentration of the DNA probe and its immobilization time are critical [12]. Use the same immobilization protocol for all sensors and confirm successful immobilization using techniques like Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) [38].

- RSM Model Validation: Confirm that your RSM model is statistically significant and that you are performing experiments at the optimum conditions with adequate replication to account for normal experimental variance [11].

Q3: The biosensor's detection limit is higher than predicted by the RSM optimization. How can I improve sensitivity? To enhance sensitivity, focus on the signal amplification strategy. Consider the following:

- Nanocomposite Performance: The synergistic effect of your nanocomposite (e.g., HAPNPs/PPY/MWCNTs) is crucial for signal amplification [12]. Verify the quality and proportion of these nanomaterials.

- Redox Indicator: The concentration and incubation time with the redox indicator (e.g., Methylene Blue) must be optimized, as this directly affects the current signal [12] [39].

- Advanced Modeling: If the basic RSM model is insufficient, consider applying constraints based on prior knowledge (e.g., a known monotonic relationship between probe concentration and signal) using advanced techniques like coefficient clipping to refine your model [21].

Q4: My biosensor lacks specificity and shows high response to non-complementary DNA sequences. What should I do? High non-specific binding is often related to the stringency of the hybridization conditions [38] [39].

- Increase Stringency: Introduce a washing step after hybridization with a buffer of lower ionic strength or at a slightly elevated temperature to disrupt weakly bound, non-specific sequences.

- Check Probe Design: Verify the specificity and uniqueness of your immobilized DNA probe sequence for the target.

- Optimize with RSM: Use RSM to explicitly optimize for selectivity by including the response to a non-complementary or mismatch DNA sequence as a secondary response variable to be minimized in your experimental design [38].

Troubleshooting Table: Common Experimental Issues and Solutions

| Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| High Background Signal | Non-specific adsorption of redox indicator; incomplete washing. | Optimize washing steps post-hybridization; include a blocking agent (e.g., BSA) on the sensor surface [38]. |

| Signal Drift Over Time | Instability of the nanocomposite film; degradation of the immobilized DNA probe. | Ensure stable electropolymerization of PPy [12]; store biosensors in appropriate buffer at 4°C [14]. |

| Poor Linear Range | Saturation of available probe sites on the electrode surface. | Use RSM to find the optimal probe concentration that offers a wide dynamic range without saturation at expected target concentrations [12]. |

| Large Error in RSM Model Prediction | High measurement noise; overlooked factor interactions. | Increase replicates at the center point of your experimental design to better estimate pure error; consider a more comprehensive design like Central Composite Design (CCD) to capture complex interactions [12] [11]. |

Experimental Protocols & Data

Detailed Protocol: RSM-Optimized Fabrication of an Electrochemical DNA Biosensor

This protocol is adapted from the work on detecting Mycobacterium tuberculosis, which utilized a HAPNPs/PPY/MWCNTs nanocomposite [12].

1. Electrode Pre-treatment:

- Polish a glassy carbon electrode (GCE) successively with alumina slurry (e.g., 1.0, 0.3, and 0.05 µm) on a microcloth.

- Rinse thoroughly with deionized water and then with ethanol.

- Perform electrochemical cleaning by cycling the potential in a 0.5 M H₂SO₄ solution until a stable cyclic voltammogram is obtained.

2. Nanocomposite Modification:

- Prepare a dispersion of MWCNTs in a suitable solvent (e.g., DMF).

- Drop-cast a specific volume of the MWCNTs dispersion onto the clean GCE surface and allow it to dry.

- Electropolymerize pyrrole onto the MWCNTs/GCE from a solution containing pyrrole monomer and a supporting electrolyte using Cyclic Voltammetry (CV).

- Immobilize Hydroxyapatite Nanoparticles (HAPNPs) onto the PPY/MWCNTs/GCE surface.

3. DNA Probe Immobilization:

- Covalently attach the amino-modified ssDNA probe to the HAPNPs/PPY/MWCNTs/GCE surface using a cross-linker like glutaraldehyde or EDC/NHS chemistry.

- Rinse the modified electrode to remove unbound probes.

4. DNA Hybridization and Detection:

- Incubate the biosensor with the sample containing the target DNA sequence under the RSM-optimized conditions (e.g., time, temperature, pH, ionic strength).

- After hybridization, rinse the electrode to remove unhybridized DNA.

- Incubate the biosensor with a Methylene Blue (MB) solution.

- Perform Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) to measure the reduction current of MB, which is inversely related to the amount of double-stranded DNA formed.

Quantitative Data from RSM-Optimized Biosensors

The table below summarizes performance data from various RSM-optimized electrochemical DNA biosensors, demonstrating the effectiveness of this approach.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of RSM-Optimized Electrochemical DNA Biosensors

| Target Analyte | Nanomaterial Used | Optimized Parameters (Examples) | Detection Limit | Linear Range | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis | HAPNPs/PPY/MWCNTs | Probe concentration, immobilization time, incubation time | 0.141 nM | 0.25 - 200.0 nM | [12] |

| Dengue Virus | SiNWs/AuNPs | pH, NaCl concentration, temperature, hybridization time | 10 pM (oligonucleotide) | Not Specified | [38] |

| Heavy Metal Ions (Bi³⁺, Al³⁺) | Pt/PPD/GOx | Enzyme concentration, flow rate, scan cycles | (Sensitivity optimized) | Wide working range | [14] |