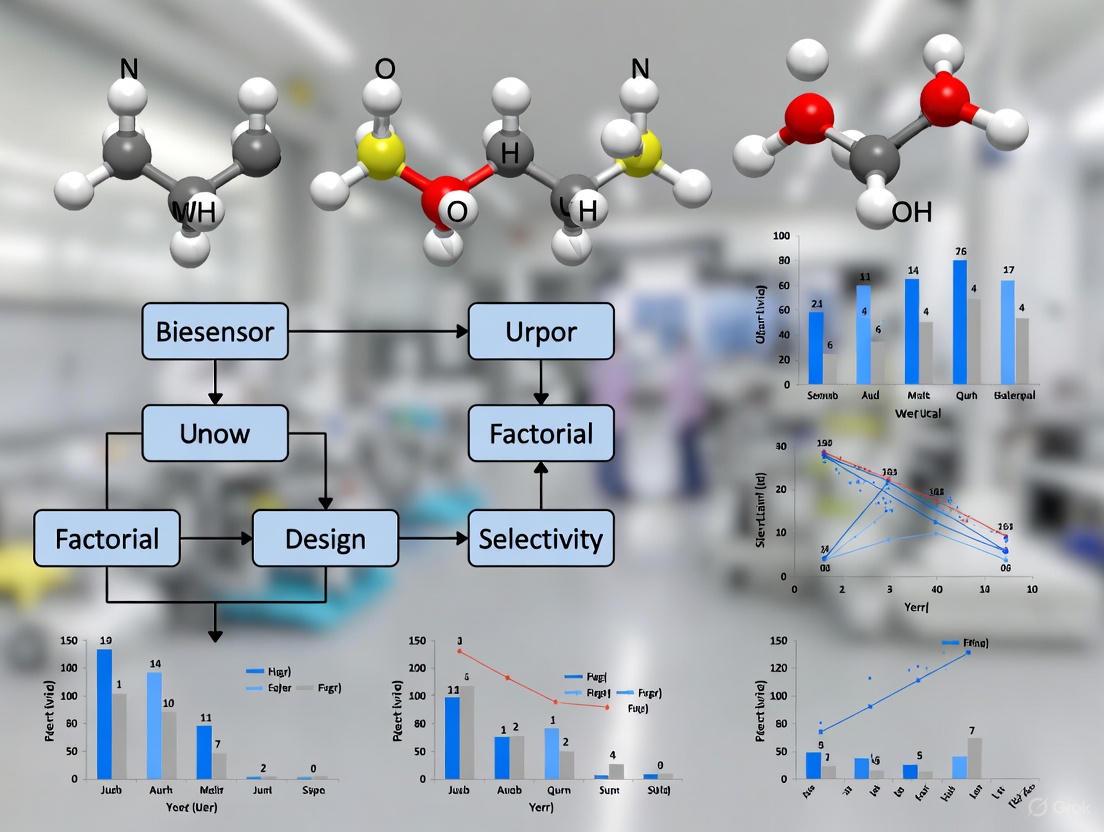

Systematic Optimization of Biosensor Selectivity: A Factorial Design Approach for Biomedical Research

Biosensor selectivity is a critical performance parameter for accurate diagnostics, drug development, and biomedical research.

Systematic Optimization of Biosensor Selectivity: A Factorial Design Approach for Biomedical Research

Abstract

Biosensor selectivity is a critical performance parameter for accurate diagnostics, drug development, and biomedical research. Traditional one-variable-at-a-time optimization often fails to identify complex interactions that undermine sensor performance in complex biological matrices. This article provides a comprehensive framework for troubleshooting biosensor selectivity issues using Design of Experiments (DoE), specifically factorial design. We explore the foundational sources of selectivity challenges, detail the methodological application of factorial designs for systematic optimization, present advanced troubleshooting strategies, and discuss validation through multi-mode sensing and comparative analysis. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, this guide aims to bridge the gap between laboratory biosensor development and reliable, real-world application.

Deconstructing Biosensor Selectivity: The Core Challenges in Complex Samples

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on Biosensor Selectivity

FAQ 1: What is the fundamental difference between selectivity and specificity in biosensing?

Answer: In biosensing, specificity refers to the ability of the biorecognition element (e.g., an antibody, enzyme, or aptamer) to bind exclusively to its intended target analyte. Selectivity, however, is a broader characteristic of the entire biosensor device. It describes the ability to detect the target analyte accurately within a complex sample matrix (like blood, urine, or saliva) without being influenced by other interfering compounds. A biosensor can have a highly specific bioreceptor but suffer from poor selectivity due to matrix effects that cause nonspecific binding or signal interference [1] [2].

FAQ 2: In a clinical serum sample, my biosensor signal is higher than expected. What are common causes?

Answer: An unexpectedly high signal in complex samples like serum is often due to interference from electroactive compounds or nonspecific adsorption (NSA). Common interferents in physiological fluids include:

- Electroactive species: Ascorbic acid, uric acid, and acetaminophen can be oxidized or reduced at the working electrode, contributing to the signal [1].

- Nonspecific Binding (Fouling): Other proteins, cells, or biomolecules in the sample can adsorb onto the sensor surface without involving the specific biorecognition event, leading to a false signal [3].

- Solution: Employ permselective membranes (e.g., Nafion or cellulose acetate) that block interferents based on charge or size, use antifouling surface chemistries, or integrate a "sentinel" sensor to subtract the background signal [1] [4].

FAQ 3: Our biosensor works perfectly in buffer but fails in real samples. How can we troubleshoot this?

Answer: This is a classic symptom of a selectivity issue. The following systematic approach is recommended:

- Identify Interferents: Analyze the sample composition to identify potential interferents (e.g., proteins, salts, drugs, or metabolites).

- Incorporate Controls: Use a sentinel sensor (an identical sensor without the biorecognition element) to quantify the signal contribution from the matrix itself [1].

- Optimize Surface Chemistry: Implement advanced antifouling coatings, such as polymer brushes (e.g., poly(oligo(ethylene glycol) methacrylate) - POEGMA), to physically prevent nonspecific binding [4].

- Systematic Optimization: Use chemometric tools like Design of Experiments (DoE) to systematically test and optimize multiple factors (e.g., pH, immobilization density, membrane thickness) that influence selectivity simultaneously [5].

FAQ 4: How can multi-mode biosensing strategies improve selectivity and reliability?

Answer: Triple-mode biosensors utilize three independent detection mechanisms (e.g., electrochemical, colorimetric, and fluorescence) on a single platform. This approach significantly enhances reliability through cross-validation. If an interferent affects one signal, the other two independent signals can confirm the true result, thereby reducing false positives and negatives. This is particularly powerful in complex matrices where single-mode sensors are prone to interference [6].

FAQ 5: What is the role of a "sentinel" or "blank" sensor, and how is its data used?

Answer: A sentinel sensor is a key tool for correcting non-specific signals. It is fabricated to be identical to the biosensor but lacks the active biorecognition element (often replaced by an inert protein like BSA). When exposed to the sample, it records signals from all non-specific interactions and electrochemical interferences. This "blank" signal is then electronically or digitally subtracted from the biosensor's total signal, leaving a corrected signal that is (ideally) due only to the target analyte [1].

Table 1: Common Interferents in Biological Matrices and Potential Solutions

| Interferent Category | Example Compounds | Impact on Biosensor | Potential Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electroactive Species | Ascorbic Acid, Uric Acid, Acetaminophen | Oxidized/Reduced at electrode, adding to signal | Permselective membranes (Nafion), Lowering applied potential [1] |

| Structural Analytes | Molecules similar to the target | Binding to bioreceptor, causing false positive | Use of more specific bioreceptors (e.g., aptamers), Mutant enzymes [1] |

| Proteins & Macromolecules | Albumin, Fibrinogen, Lysates | Nonspecific adsorption (fouling), blocking surface | Antifouling coatings (e.g., POEGMA), blocking agents [3] [4] |

| Enzyme Inhibitors/Activators | Heavy metals, Pesticides, Drugs | Altering enzyme activity, affecting signal | Sample pre-treatment, Use of coupled enzyme systems [1] |

Troubleshooting Guide: A Factorial Design Approach

Systematic optimization is superior to the traditional "one-variable-at-a-time" approach. Design of Experiments (DoE) is a powerful chemometric tool for this purpose, as it efficiently accounts for interactions between variables [5].

A factorial design involves conducting experiments where all possible combinations of factors and their levels are investigated. A 2k factorial design is a first-order design where k factors are studied at two levels (coded as -1 and +1). This is highly efficient for identifying which factors significantly impact your biosensor's selectivity and whether factors interact with each other [5].

For example, in optimizing a biosensor's selectivity, you might investigate these three factors:

- Factor A: Bioreceptor Immobilization Density

- Factor B: Permselective Membrane Thickness

- Factor C: Incubation pH

A 2^3 full factorial design would require only 8 experiments to study all main effects and their interactions.

Table 2: Experimental Matrix for a 2³ Full Factorial Design

| Test Number | A: Immobilization Density (Low/High) | B: Membrane Thickness (Thin/Thick) | C: pH (Acidic/Basic) | Measured Response (Selectivity Ratio) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | -1 (Low) | -1 (Thin) | -1 (Acidic) | ... |

| 2 | +1 (High) | -1 (Thin) | -1 (Acidic) | ... |

| 3 | -1 (Low) | +1 (Thick) | -1 (Acidic) | ... |

| 4 | +1 (High) | +1 (Thick) | -1 (Acidic) | ... |

| 5 | -1 (Low) | -1 (Thin) | +1 (Basic) | ... |

| 6 | +1 (High) | -1 (Thin) | +1 (Basic) | ... |

| 7 | -1 (Low) | +1 (Thick) | +1 (Basic) | ... |

| 8 | +1 (High) | +1 (Thick) | +1 (Basic) | ... |

The data from this matrix is used to build a mathematical model that predicts selectivity based on the factors, allowing you to find the optimal combination of settings [5].

Experimental Protocol: Using a Sentinel Sensor for Signal Correction

Objective: To quantify and correct for signals arising from nonspecific binding and electrochemical interferences in complex samples.

Materials:

- Functional biosensors

- "Sentinel" sensors (identical to biosensors but with bioreceptor replaced by BSA or no protein)

- Analyte standard in buffer

- Complex sample (e.g., diluted serum, urine) with and without spiked analyte

- Electrochemical or optical readout instrument

Procedure:

- Calibration: Calibrate both the functional biosensor and the sentinel sensor using the analyte standard in a clean buffer solution.

- Sample Measurement: Measure the complex sample (without spiked analyte) with both sensors. The sentinel sensor's signal (

S_sentinel) represents the interference. - Spiked Sample Measurement: Measure the complex sample with a known concentration of spiked analyte using both sensors.

- Data Calculation: The corrected, selectivity-enhanced signal for the target analyte is calculated as:

Corrected Signal = S_biosensor - S_sentinelwhereS_biosensoris the total signal from the functional biosensor in the spiked sample [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Troubleshooting Selectivity

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in Enhancing Selectivity |

|---|---|

| Permselective Membranes | Coating the transducer to prevent interfering species from reaching the electrode surface based on size, charge, or hydrophobicity (e.g., Nafion for cations) [1]. |

| Antifouling Polymers (e.g., POEGMA) | Forming a brush-like layer on the sensor surface that physically resists the nonspecific adsorption of proteins and other biomolecules [4]. |

| Enzymes (e.g., Ascorbate Oxidase) | Converting an electroactive interferent (e.g., Ascorbic Acid) into an electro-inactive molecule within the biosensor layer, eliminating its signal [1]. |

| Redox Mediators | Shuttling electrons to lower the operating potential of the biosensor, moving it to a "safer" window where fewer interferents are active [1] [2]. |

| Magnetic Beads with POEGMA Coating | Providing a high-surface-area, antifouling solid support for bioreceptors, enabling efficient capture and washing steps to minimize background noise [4]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the most common sources of interference in electrochemical biosensors? The most common interference sources are electroactive compounds, enzyme inhibitors, and biofouling [7] [8]. Electroactive compounds (e.g., ascorbic acid, uric acid, acetaminophen) oxidize or reduce at similar potentials as your target analyte, creating a false signal [8]. Enzyme inhibitors directly affect the biorecognition element's activity, reducing the catalytic rate and signal output [8]. Biofouling involves the non-specific adsorption of proteins, cells, or other macromolecules onto the sensor surface, which can block the active site and hinder analyte diffusion, leading to signal drift and reduced sensor lifetime [7].

FAQ 2: How can I improve the selectivity of my first-generation amperometric biosensor against electroactive interferents? For first-generation biosensors, which operate at high applied potentials, the following strategies are effective [7] [8]:

- Use of Permselective Membranes: Coat your electrode with membranes like Nafion (charge-based exclusion) or cellulose acetate (size-based exclusion) to prevent interferents from reaching the electrode surface [8].

- Employ a Sentinel Sensor: Use a control sensor that is identical to your biosensor but lacks the enzyme (e.g., immobilized with BSA). The signal from this sentinel sensor, which is due only to interferences, can be subtracted from your biosensor's total signal [8].

- Enzymatic Elimination of Interferents: Incorporate a second enzyme, such as ascorbate oxidase, which converts an electroactive interferent (ascorbic acid) into a non-electroactive product (dehydroascorbic acid) before it can reach the transducer [8].

FAQ 3: My biosensor signal is unstable in complex biological samples. Is this biofouling, and how can I prevent it? Signal drift and instability in complex matrices like blood or serum are classic signs of biofouling [7]. To mitigate this:

- Surface Modification with Anti-fouling Layers: Create a physical and chemical barrier using hydrophilic polymers (e.g., polyethylene glycol) or hydrogels that resist protein adsorption [7].

- Use of Nanomaterial Coatings: Certain nanomaterials, such as zwitterionic polymers or porous frameworks, can be engineered to have anti-fouling properties while maintaining sensor functionality [9].

- Optimize Surface Chemistry: Ensure your immobilization strategy creates a dense and uniform layer, leaving fewer sites for non-specific adsorption [10].

FAQ 4: How can a factorial design approach help me troubleshoot biosensor interference issues more efficiently?

Factorial designs are powerful for investigating multiple potential interference factors simultaneously [11]. Instead of testing one variable at a time (a slow and inefficient process), you can use a 2^k factorial design to test k factors (e.g., pH, temperature, interferent concentration) at two levels each. This approach allows you to:

- Identify Critical Interferents: Determine which factors have a statistically significant effect on your biosensor's signal.

- Discover Interactions: Uncover whether the effect of one interferent (e.g., ascorbic acid) depends on the level of another (e.g., uric acid).

- Systematically Optimize Solutions: Efficiently find the optimal levels of your control factors (e.g., membrane thickness, applied potential) to maximize selectivity and minimize interference [11].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing and Resolving Electrochemical Interference

Problem: High background current or inaccurate signal in complex samples despite a clean signal in buffer.

Symptoms:

- Non-linear response at low analyte concentrations.

- High signal in negative control samples.

- Poor correlation with standard analytical methods.

Step-by-Step Diagnosis:

- Run a Sentinel Control: Compare your biosensor response to that of a sentinel (enzyme-free) sensor in the same complex sample. A significant signal in the sentinel indicates direct electrochemical interference [8].

- Spike-and-Recovery Test: Spike a known concentration of your analyte into the sample. Low recovery suggests the presence of enzyme inhibitors or biofouling affecting the enzyme's activity or analyte diffusion [8].

- Vary the Applied Potential: If possible, characterize the interferent by running cyclic voltammetry on the sample to identify their oxidation/reduction potentials. Lowering the applied potential can sometimes minimize interference [7] [8].

Solutions to Implement:

- Apply a Permselective Membrane:

- Protocol (Nafion Coating):

- Dilute Nafion stock solution to 0.5-1% in a suitable solvent (e.g., alcohol/water mixture).

- Deposit a precise volume (e.g., 2-5 µL) onto the electrode surface.

- Allow to dry under ambient conditions for 15-30 minutes.

- Validate performance by testing in a solution containing both the target analyte and a known interferent (e.g., 0.1 mM ascorbic acid).

- Protocol (Nafion Coating):

- Switch to a Mediated (Second-Generation) Biosensor: Incorporate a redox mediator (e.g., ferrocene derivatives, ferricyanide) to shuttle electrons. This allows you to operate at a much lower, less interfering applied potential [8].

Guide 2: Addressing Enzyme Inhibition and Activity Loss

Problem: A gradual or sudden drop in biosensor sensitivity and slope.

Symptoms:

- Decreased signal amplitude over time or between calibrations.

- Increased response time.

- Signal does not return to baseline.

Step-by-Step Diagnosis:

- Check Enzyme Activity in Solution: Test the activity of your enzyme in a free solution assay using the sample matrix. This determines if the loss is due to inhibition or an immobilization issue.

- Analyze Calibration Curves: A change in

V_maxsuggests a loss of active enzyme or the presence of a non-competitive inhibitor. A change inK_msuggests a competitive inhibitor is present [8]. - Test with Different Enzyme Sources: Enzymes from different biological sources can have varying selectivity profiles. If an interferent is a substrate for one enzyme but not another, switching sources can resolve the issue [8].

Solutions to Implement:

- Use a Multi-Enzyme System:

- Protocol (Eliminating Ascorbic Acid Interference):

- Co-immobilize your primary enzyme (e.g., Glucose Oxidase) with Ascorbate Oxidase on the electrode.

- The Ascorbate Oxidase will convert ascorbic acid (interferent) to dehydroascorbic acid (non-interferent) before it can react at the electrode surface.

- Validate by demonstrating no signal change when ascorbic acid is added to a sample.

- Protocol (Eliminating Ascorbic Acid Interference):

- Employ a Multi-Sensor Array and Chemometrics:

- Develop a small array of biosensors with slightly different specificities (e.g., using enzymes from different sources or mutants).

- Expose the array to the sample and record the unique response pattern from each sensor.

- Use multivariate calibration models (e.g., Principal Component Analysis) to deconvolute the signal and quantify the target analyte in the presence of interferents [8].

Guide 3: Combating Biofouling in Complex Media

Problem: Signal drift and gradual loss of sensitivity during prolonged exposure to biological fluids (e.g., serum, whole blood).

Symptoms:

- Continuous baseline drift during measurement.

- Irreversible loss of sensitivity after exposure to complex samples.

- Reduced sensor lifespan.

Step-by-Step Diagnosis:

- Inspect the Sensor Surface: Use microscopy (e.g., SEM) after use to visually confirm the presence of an adsorbed fouling layer.

- Perform a Regeneration Test: Attempt to clean the surface with a gentle regeneration buffer (e.g., Glycine-HCl, pH 2.5). If the original signal is not restored, it suggests irreversible fouling.

- Monitor Real-Time Association: In a flow system, a slowly increasing baseline during sample injection is a key indicator of non-specific binding [10].

Solutions to Implement:

- Create an Anti-fouling Nanocomposite Layer:

- Protocol (BSA as a Blocking Agent):

- After immobilizing your biorecognition element, incubate the sensor surface with a 1% BSA solution for 30-60 minutes.

- Rinse thoroughly with buffer to remove unbound BSA.

- BSA molecules will occupy any remaining non-specific binding sites on the transducer surface.

- Test effectiveness by comparing baseline stability in serum before and after blocking.

- Protocol (BSA as a Blocking Agent):

- Surface Functionalization with Zwitterionic Materials:

- Modify your electrode surface with zwitterionic polymers (e.g., poly(carboxybetaine)). These create a super-hydrophilic surface that strongly binds water molecules, forming a physical and energetic barrier that prevents protein adhesion [7].

Table 1: Strategies for Mitigating Common Biosensor Interferences

| Interference Type | Example Compounds | Detection Impact | Recommended Solution | Key Experimental Validation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electroactive Compounds | Ascorbic Acid, Uric Acid, Acetaminophen [8] | False positive current; increased background [8] | Permselective membranes (Nafion, cellulose acetate); Sentinel sensors [8] | Signal recovery test in spiked serum; >90% signal retention [8] |

| Enzyme Inhibitors | Heavy metals (Arsenic, Mercury), Pesticides [8] [12] | Reduced signal amplitude; decreased sensitivity [8] | Use of multiple enzymes/isoforms; Mutant enzymes with altered selectivity [8] | Kinetic analysis (Km/Vmax shifts); IC50 determination for inhibitors [8] |

| Biofouling | Proteins, Lipids, Cells [7] | Signal drift; reduced sensitivity & lifespan [7] | Anti-fouling coatings (PEG, hydrogels); Nanostructured surfaces [7] [9] | Baseline stability in serum (>1 hour); >80% sensitivity after 5 weeks [9] |

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Selectivity Enhancement

| Reagent / Material | Function in Biosensor | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Nafion | Cation-exchange polymer membrane; blocks ascorbate and urate anions [8] | Inner membrane in implantable glucose sensors [8] |

| Manganese-doped ZIF-67 (Mn-ZIF-67) | Nanostructured porous platform; enhances electron transfer and allows antibody conjugation [9] | High-sensitivity detection of E. coli; enables selectivity in complex samples [9] |

| Ascorbate Oxidase | Enzyme that converts interfering ascorbate to non-electroactive dehydroascorbate [8] | Co-immobilized with oxidase enzymes (e.g., glucose oxidase) to eliminate ascorbic acid interference [8] |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | Blocking agent; occupies non-specific binding sites on sensor surface [8] [10] | Standard post-immobilization step to reduce biofouling in protein-based biosensors [10] |

| Transcription Factor (TF) ArsR | Genetically encoded sensing element; specifically binds heavy metal ions [12] | Engineered into microbial biosensors for detection of arsenic in environmental samples [12] |

Experimental Design and Workflow Visualizations

Troubleshooting with Factorial Design

Permselective Membrane Function

The Limitations of One-Variable-at-a-Time (OVAT) Optimization

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the fundamental weakness of the OVAT approach in optimizing biosensor selectivity? The primary weakness is that OVAT fails to detect interactions between factors. It optimizes one parameter while holding all others constant, which provides only a localized, partial understanding of the system. In biosensor development, parameters like pH, temperature, and biorecognition element density often interact; an optimal value for one can change depending on the settings of others. Consequently, OVAT is prone to finding a local optimum rather than the true global optimum, potentially leading to a biosensor with sub-par selectivity and sensitivity [13] [14].

FAQ 2: How can OVAT optimization lead to misleading conclusions about my biosensor's performance? Because OVAT does not account for factor interactions, the "optimal" conditions it identifies might only be optimal for that specific, narrow path of experimentation. A biosensor optimized via OVAT may show promising performance under controlled lab conditions but then fail in complex, real-world samples where interferents are present. This can lead to an overestimation of the biosensor's robustness and selectivity in its final application [13] [1].

FAQ 3: What are the practical consequences of using OVAT in terms of time and resources? Although OVAT appears simple, it is often inefficient and resource-intensive. For example, one study noted that optimizing six variables required 486 experiments with an OVAT strategy. In contrast, a Design of Experiments (DoE) approach achieved superior optimization in only 30 experiments. This represents a massive reduction in time, reagents, and costs without sacrificing—and often enhancing—the quality of the results [13].

FAQ 4: My OVAT-optimized biosensor has poor reproducibility. Could the optimization method be the cause? Yes. The failure of OVAT to find the true, robust optimum can directly impact reproducibility. If the biosensor operates at a local optimum near a steep performance cliff, minor, unavoidable variations in fabrication or assay conditions (e.g., temperature fluctuations, slight differences in reagent concentrations) can lead to significant performance changes and poor reproducibility between sensor batches [5].

Troubleshooting Common OVAT-Related Problems

Issue: Biosensor Signal is Unstable or Irreproducible

Potential Cause: The OVAT approach may have selected optimal conditions that are not robust, meaning the performance is highly sensitive to minor variations in factors that were not properly co-optimized.

Solution:

- Shift to a Screening DoE: Use a screening design like a Plackett-Burman design to efficiently identify which factors have the most significant impact on signal stability and reproducibility [13].

- Analyze for Interactions: The model from the DoE will reveal if interactions between factors (e.g., between immobilization pH and incubation time) are affecting stability. OVAT cannot provide this insight.

- Refine Optimal Conditions: Use the results of the screening design to perform a more focused optimization with a Response Surface Methodology (RSM), such as a Central Composite Design, to find a robust operating window [5].

Issue: Selectivity is Poor in Complex Samples

Potential Cause: OVAT optimization was likely performed using clean buffers, failing to account for how interferents in real samples (e.g., serum, food homogenates) interact with the biosensor's operational parameters.

Solution:

- Include Interference as a Factor: In your DoE, explicitly include the concentration of a known key interferent (e.g., ascorbic acid for electrochemical sensors) as an experimental factor [1].

- Use a Sentinel Sensor: Develop a "sentinel" or "dummy" sensor that lacks the specific biorecognition element. Use the DoE to model the signal from both the true biosensor and the sentinel sensor. The signal from the sentinel, which comes only from interferents, can be subtracted to yield a more selective response [1].

- Multi-Response Optimization: Use a DoE model that allows you to simultaneously optimize for two key responses: maximizing the target signal and minimizing the interferent signal.

Issue: The Optimization Process is Taking Too Long

Potential Cause: You are using an OVAT strategy for a system with more than a few variables. The number of experiments in OVAT grows rapidly with each additional variable, creating a "combinatorial explosion."

Solution:

- Adopt a Fractional Factorial Design: These designs allow you to study many factors simultaneously with a fraction of the experiments required for a full factorial design, dramatically accelerating the optimization process [14] [5].

- Use a D-Optimal Design: If some factors have more than two levels or the experimental space is constrained, a D-optimal design is an excellent choice to maximize information gain with a minimal number of experimental runs [13].

Quantitative Comparison: OVAT vs. Factorial Design

The table below summarizes a direct comparison between the OVAT and Factorial Design (DoE) approaches, based on documented case studies.

| Feature | One-Variable-at-a-Time (OVAT) | Factorial Design (DoE) |

|---|---|---|

| Experimental Efficiency | Low. A case with 6 variables required 486 experiments [13]. | High. The same 6-variable case was optimized with only 30 experiments [13]. |

| Handling of Factor Interactions | Cannot detect interactions, risking suboptimal results [13] [14]. | Explicitly models and quantifies interactions, finding a more robust optimum [13] [5]. |

| Quality of Final Optimum | Often finds a local optimum, leading to lower performance. A study showed a 5-fold worse LOD with OVAT [13]. | Finds a global, robust optimum. The same study achieved a 5-fold improvement in LOD with DoE [13]. |

| Risk of Misleading Results | High, as the perceived optimum is dependent on the starting point of other variables [14]. | Low, as it maps the entire experimental domain to provide a comprehensive understanding [5]. |

| Best Use Case | Very preliminary investigations with only one or two variables of interest. | The vast majority of research and development scenarios, especially with complex, multi-factor systems. |

Experimental Protocol: Implementing a Basic Factorial Design

This protocol provides a step-by-step methodology to replace an OVAT strategy with a simple 2-level factorial design for initial factor screening.

Objective: To efficiently identify the most critical factors affecting biosensor selectivity and their potential interactions.

Materials:

- Research Reagent Solutions: See the "Scientist's Toolkit" table below.

- Software: Statistical software package (e.g., JMP, Modde, R, Python with relevant libraries) or a spreadsheet for manual calculation.

Procedure:

- Define Factors and Ranges: Select the key variables (e.g., pH, ionic strength, probe concentration, incubation time) you would have tested with OVAT. Define a realistic "low" (-1) and "high" (+1) level for each factor based on prior knowledge or literature.

- Generate the Experimental Matrix: Use your software to create a design matrix for a full or fractional 2^k^ factorial design. This matrix specifies the exact conditions for each experimental run.

- Randomize and Execute: Run the experiments in a random order to avoid systematic bias. For each run, measure your key response(s), such as signal for the target analyte and signal for a known interferent.

- Model and Analyze:

- Input the response data into the software.

- Perform a multiple linear regression to fit a model that estimates the effect of each factor and their interactions.

- Analyze the Pareto chart or coefficient plot to identify which factors and interactions are statistically significant.

- Validate the Model: Perform a confirmation experiment at the conditions predicted by the model to be optimal to verify the results.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Biosensor Optimization |

|---|---|

| Permselective Membranes (e.g., Nafion, cellulose acetate) | Coating used to improve selectivity by repelling or blocking access of charged interferents (e.g., ascorbic acid, uric acid) to the electrode surface [1]. |

| Sentinel Sensor | A control sensor without the specific biorecognition element; its signal is subtracted from the biosensor's signal to correct for non-specific contributions and interference [1]. |

| Enzyme-based Scavengers (e.g., Ascorbate Oxidase) | An enzyme added to the sensing layer or solution to selectively convert an electrochemical interferent into a non-interfering species, thereby cleaning the signal [1]. |

| Redox Mediators | Molecules that shuttle electrons between the biorecognition element and the electrode, allowing operation at a lower, less interfering potential [1]. |

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymers | Synthetic polymer receptors that can be tailored for specific analytes, offering an alternative to biological recognition elements for challenging environments [15]. |

Workflow Visualization: From OVAT Problems to DoE Solutions

The diagram below illustrates the logical pathway for diagnosing OVAT-related issues and transitioning to a more effective DoE strategy.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide: Diagnosing and Resolving Signal Overestimation

Reported Problem: Biosensor is producing consistently higher readings than expected, particularly when testing complex biological samples like blood, sweat, or serum.

Potential Causes & Solutions:

Cause 1: Direct Oxidation of Electroactive Interferents. Common endogenous compounds like ascorbic acid (AA), uric acid (UA), and exogenous ones like acetaminophen (AP) are electroactive and can be directly oxidized at the working electrode, contributing extra current that is mistaken for the target analyte.

- Solution A: Apply a Permselective Membrane. Coat the biosensor with a charge-selective membrane like Nafion. As a cationic exchanger, Nafion repels negatively charged interferents like ascorbate and urate at physiological pH, while allowing neutral analytes (e.g., H₂O₂) to pass through [16] [17] [8].

- Solution B: Lower the Operating Potential. Transition from a first-generation biosensor (high potential) to a second-generation biosensor that uses a mediator (e.g., ferrocene derivatives). Mediators shuttle electrons at a much lower potential, minimizing the window where interferents are oxidized [1] [8].

- Solution C: Use an Enzyme-Based Interference Elimination Layer. Incorporate a secondary enzyme, such as ascorbate oxidase, which is immobilized in a layer before the primary sensing element. This layer pre-oxidizes ascorbic acid, eliminating its signal contribution before it reaches the transducer [18] [1] [8].

Cause 2: Incorrect Calibration in Complex Matrices. Calibrating the biosensor with simple buffer solutions may not account for the sample matrix's effect, leading to inaccurate readings.

- Solution: Use Standard Addition Method for Calibration. Perform calibration by spiking the sample matrix with known concentrations of the analyte. This method helps account for the background signal and matrix effects, providing a more accurate measurement [19].

Guide: Addressing Poor Selectivity in a New Biosensor Design

Reported Problem: A newly developed enzymatic biosensor lacks the required selectivity for its intended application in clinical diagnostics.

Systematic Optimization Approach using Factorial Design:

- Identify Key Factors: Select critical fabrication and operational variables that influence selectivity. Examples include:

- X1: Concentration of the permselective membrane (e.g., Nafion).

- X2: Applied detection potential.

- X3: Enzyme immobilization time [20].

- Define the Experimental Domain: Set a high (+1) and low (-1) level for each factor.

- Create an Experimental Matrix: Use a 2³ full factorial design to systematically test all combinations of these factor levels. This requires 8 experiments [20].

- Analyze the Results: The response (e.g., selectivity coefficient, signal-to-noise ratio) for each experiment is analyzed to determine which factors have a significant effect and if there are any interactions between them. For instance, the analysis might reveal that the membrane concentration and applied potential interact, meaning the optimal potential depends on the membrane thickness [20].

- Iterate and Refine: Based on the initial results, the experimental domain can be redefined (e.g., focusing on a narrower potential window) and a new design, such as a Central Composite Design, can be employed to model curvature and find the true optimum conditions [20].

The diagram below illustrates this iterative workflow for systematic biosensor optimization.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why are ascorbic acid, uric acid, and acetaminophen such common interferents in amperometric biosensors?

These compounds are electroactive and are readily oxidized at potentials similar to those used to detect the products of enzymatic reactions (like H₂O₂) in first-generation biosensors. In biological fluids, they are often present at significant concentrations, leading to a false positive current that overestimates the target analyte concentration [1] [8].

FAQ 2: What is the principle behind using a "sentinel" or "blank" sensor to correct for interferences?

A sentinel sensor is fabricated identically to the biosensor but lacks the specific biorecognition element (e.g., the enzyme is omitted or replaced with an inert protein like BSA). Any electroactive interferents present in the sample will produce a current at this sentinel sensor. This "interference current" can then be electronically subtracted from the total current measured by the functional biosensor, yielding a signal specific to the target analyte [1] [8].

FAQ 3: How does moving from a first-generation to a second-generation biosensor improve selectivity?

First-generation biosensors typically operate at high potentials (> +0.6 V vs. Ag/AgCl) to oxidize H₂O₂, a point where AA, UA, and AP are also oxidized. Second-generation biosensors use redox mediators that shuttle electrons from the enzyme's active site to the electrode at a much lower potential (often near 0 V). This lower potential window is outside the oxidation range of most common interferents, drastically reducing their impact [1] [8].

FAQ 4: Our research group is developing a novel biosensor. Why should we use a factorial design instead of testing one variable at a time (OVAT)?

The OVAT approach fails to capture interactions between variables. For example, the ideal operating potential for minimizing interferences might depend on the thickness of your permselective membrane. A factorial design systematically tests all factors simultaneously, revealing these critical interactions and leading to a more robust and optimally performing biosensor with fewer total experiments [20].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Detailed Protocol: Interference Elimination with an Ascorbate Oxidase Layer

This protocol details a method for eliminating ascorbic acid interference in a glucose oxidase (GOD)-based biosensor [18] [8].

Principle: Ascorbate oxidase (AAOx) is co-immobilized with glucose oxidase. AAOx catalyzes the conversion of ascorbic acid to dehydroascorbic acid, eliminating it before it can reach the electrode surface and cause interference.

Workflow:

Materials:

- Working electrode (e.g., Pt, Au, or screen-printed carbon)

- Glucose Oxidase (GOD) from Aspergillus niger

- Ascorbate Oxidase (AAOx) from Cucurbita species

- Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA)

- Glutaraldehyde solution (2.5% v/v)

- Nafion solution (e.g., 5% in lower aliphatic alcohols)

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS, 0.1 M, pH 7.4)

Step-by-Step Method:

- Electrode Preparation: Clean and polish the working electrode according to standard procedures.

- Enzyme Mixture Preparation: Prepare a mixture containing 2 mg/mL GOD, 1 mg/mL AAOx, and 10 mg/mL BSA in 10 μL of PBS. The BSA acts as a structural protein for the cross-linking matrix.

- Immobilization: Pipette 5 μL of the enzyme mixture onto the active area of the working electrode and allow it to dry at room temperature for 15 minutes.

- Cross-linking: Expose the electrode to glutaraldehyde vapor in a closed container for 30 minutes. This step creates a robust, cross-linked protein layer.

- Membrane Casting: To further block any remaining anionic interferents, cast 5 μL of Nafion solution onto the electrode surface and allow it to dry, forming a thin permselective film.

- Curing: Let the biosensor cure at 4°C for 24 hours before use to ensure stability.

Validation: Test the biosensor in PBS containing 5 mM glucose and 0.1 mM ascorbic acid. The response should be identical to the response in 5 mM glucose alone, confirming the elimination of the AA signal.

The table below summarizes various strategies to mitigate interference from ascorbic acid, uric acid, and acetaminophen.

Table 1: Comparison of Selectivity-Enhancement Strategies for Enzyme Biosensors

| Strategy | Mechanism | Key Advantage | Key Limitation | Reported Performance Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Permselective Membrane (e.g., Nafion) | Charge/size exclusion; repels anionic interferents [16] [17]. | Simple application, effective for charged species. | Can increase response time; may not block neutral species (e.g., acetaminophen). | ~90% rejection of ascorbate signal in glucose sensors [17]. |

| Mediator (2nd Gen Biosensor) | Lowers operating potential, outside oxidation window of most interferents [1] [8]. | Dramatically reduces interference from AA, UA, AP. | Requires design and immobilization of a stable mediator. | Glucose/interferent current ratio increased by >1000x [8]. |

| Enzyme-Based Elimination (e.g., AAOx) | Pre-oxidizes the interferent via a specific enzymatic reaction [18] [8]. | Highly specific and effective for a given interferent. | Adds complexity; only targets specific interferents (e.g., AAOx only works on AA). | "No interference" from AA in sweat Vitamin C sensor [18]. |

| Sentinel Sensor | Measures interferent signal directly for electronic subtraction [1] [8]. | Can correct for a wide range of non-specific signals. | Requires fabrication of a matched, inert sensor; adds to system complexity. | Effective for in vivo monitoring of multiple interferents [1]. |

| Multilayer Electrode (w/ HRP) | H₂O₂ generated by oxidase enzyme pre-oxidizes interferents in a horseradish peroxidase (HRP) layer [21]. | In-situ elimination without external reagents. | Requires careful design to prevent "wiring" of HRP, which can reduce signal. | Current from interferents decreased by a factor of 2500 [21]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Developing Selective Enzyme Biosensors

| Reagent / Material | Function in Biosensor Development | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Nafion | A perfluorosulfonated ionomer used as a permselective membrane to repel anionic interferents like ascorbate and urate [16] [17]. | Solution concentration and cast volume control film thickness, affecting selectivity and response time. |

| Glutaraldehyde | A cross-linking agent used to create a stable, insolubilized matrix for co-immobilizing enzymes and other proteins on the electrode surface [18]. | Vapor-phase cross-linking can provide more uniform layers than liquid-phase. |

| Ascorbate Oxidase (AAOx) | An enzyme used specifically to eliminate ascorbic acid interference by converting it to electroinactive dehydroascorbic acid [18] [8]. | Must be immobilized in a layer accessible to the interferent, often co-immobilized with the primary enzyme. |

| Potassium Ferricyanide / Ferrocene Derivatives | Common redox mediators used in second-generation biosensors to lower the operating potential and minimize interferent oxidation [17] [8]. | Mediators must have good stability, low toxicity, and should not leach from the sensor. |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | Used as an inert protein to form the bulk of a cross-linked enzyme layer and to fabricate sentinel sensors for background subtraction [1] [8]. | Provides a biocompatible environment for enzymes and helps control the density of active sites. |

| Cellulose Acetate | A polymer used as a size-exclusion membrane to block larger interfering molecules (e.g., proteins) and often used in combination with Nafion [8]. | Effective for improving biocompatibility and fouling resistance in implantable sensors. |

Leveraging Factorial Design for Systematic Biosensor Optimization

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on DoE Fundamentals

Q1: What is Design of Experiments (DoE), and why is it superior to the one-factor-at-a-time (OFAT) approach for optimizing biosensors?

A1: Design of Experiments (DoE) is a systematic, model-based approach used to study the effects of multiple input factors on a process or response simultaneously [22]. For biosensor development, this is superior to the one-factor-at-a-time (OFAT) method because OFAT cannot detect interactions between factors [22] [20]. For instance, the optimal pH for an enzyme-based biosensor might change depending on the temperature. OFAT experiments would miss this interaction, potentially leading to incorrect optimal conditions and a biosensor with sub-par selectivity and sensitivity. DoE efficiently uncovers these critical interactions, leading to a more robust and optimized sensor with fewer experimental runs [22] [23].

Q2: What are the core principles I must follow when setting up a DoE?

A2: Three core principles are essential for a valid DoE [24]:

- Randomization: The order in which you run your experimental trials should be random. This helps eliminate the influence of unknown or uncontrolled variables (e.g., ambient temperature fluctuations, reagent degradation) on your results.

- Replication: Repeating entire experimental runs helps you estimate the inherent variability (noise) in your process. This allows you to determine if the effects you observe from changing factors are statistically significant or just due to random chance.

- Blocking: This technique accounts for known sources of nuisance variation. For example, if you must perform your experiments over two days, you can use "Day" as a blocking factor. This separates the day-to-day variation from the effects of the factors you are actually studying, providing a clearer and more accurate picture.

Q3: Which common DoE designs are most useful for initial biosensor optimization?

A3: The choice of design depends on your goal. The most common and powerful designs for initial screening and optimization are [20]:

- Full Factorial Designs (2^k): These designs study all possible combinations of factors, each at two levels (e.g., high and low). A 2^k design is excellent for estimating the main effects of each factor and all their interaction effects. It is highly efficient but can become large as the number of factors (k) increases.

- Central Composite Designs (CCD): When you suspect a curved (quadratic) response surface, a CCD is ideal. It builds upon a factorial design by adding axial points and center points, allowing you to fit a second-order model. This is crucial for finding a true optimum, such as the maximum sensitivity or minimal interference for a biosensor.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common DoE Pitfalls in Biosensor Development

Problem 1: Inability to Reproduce Optimized Biosensor Performance

- Potential Cause: The initial DoE model was fitted using happenstance data or did not properly account for critical factor interactions, leading to a model that is not truly predictive [20].

- Solution: Ensure your model is built on causal data from a properly designed experiment, not retrospective data. Validate your model by running confirmation experiments at the predicted optimal settings. If performance is not reproducible, investigate potential factors you may have overlooked and include them in a new, iterative DoE round [20].

Problem 2: The Model Shows a Poor Fit or is Not Predictive

- Potential Cause: The relationship between the factors and the response (e.g., biosensor signal) may be curved, but you only used a first-order factorial design that cannot capture curvature [22] [20].

- Solution: Augment your initial factorial design with additional runs to create a Central Composite Design (CCD). This allows you to fit a second-order model and accurately map a response surface that may have a peak (maximum signal) or a valley (minimum interference) [20].

Problem 3: Confounded Factor Effects Leading to Misinterpretation

- Potential Cause: The experimental layout accidentally correlated two factors, making it impossible to tell which one is responsible for a change in the response [24]. For example, if all tests at high pH were also performed with Enzyme Type A, the effect of pH is confounded with the effect of the enzyme type.

- Solution: Always use a randomized experimental run order and a balanced design. In advanced designs, you can deliberately confound high-order interactions (which you assume are negligible) to reduce the number of required runs, but this should be done purposefully and with caution [24].

Key Experimental Factors and Protocols for Biosensor Optimization

The performance of a biosensor is governed by a multitude of interacting factors. The table below summarizes critical categories to consider in a DoE.

Table 1: Key Factor Categories for Biosensor DoE

| Factor Category | Examples | Typical Response(s) to Measure |

|---|---|---|

| Biorecognition Element | Enzyme source/concentration, antibody clone, aptamer sequence [1] [20] | Sensitivity, Selectivity, Limit of Detection (LOD) |

| Immobilization Matrix | Polymer type, nanomaterial concentration, cross-linker ratio [1] [20] | Signal stability, Reproducibility, Shelf-life |

| Transducer Interface | Electrode material, surface roughness, applied potential [1] [23] | Signal-to-Noise Ratio, Sensitivity |

| Sample & Environment | pH, ionic strength, temperature, presence of interferents [1] [22] | Selectivity, Accuracy, Robustness |

Protocol: A Step-by-Step Guide to a 2^3 Factorial Design for an Electrochemical Biosensor

This protocol outlines how to systematically investigate three critical factors.

Step 1: Define Factors and Levels. Select three factors and assign two levels each (a low "-1" and a high "+1").

- Factor A: Enzyme Immobilization Time (e.g., 30 min, 60 min)

- Factor B: pH of Measurement Buffer (e.g., 6.5, 7.5)

- Factor C: Applied Detection Potential (e.g., +0.5 V, +0.7 V)

Step 2: Create the Experimental Matrix. The 2^3 full factorial design requires 8 unique runs.

Table 2: Experimental Matrix and Hypothetical Results for Biosensor Signal (µA)

| Standard Order | Run Order (Randomized) | A: Time | B: pH | C: Potential | Signal (µA) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4 | -1 (30 min) | -1 (6.5) | -1 (0.5 V) | 1.2 |

| 2 | 7 | +1 (60 min) | -1 (6.5) | -1 (0.5 V) | 1.8 |

| 3 | 2 | -1 (30 min) | +1 (7.5) | -1 (0.5 V) | 1.5 |

| 4 | 8 | +1 (60 min) | +1 (7.5) | -1 (0.5 V) | 2.2 |

| 5 | 3 | -1 (30 min) | -1 (6.5) | +1 (0.7 V) | 1.7 |

| 6 | 5 | +1 (60 min) | -1 (6.5) | +1 (0.7 V) | 2.0 |

| 7 | 1 | -1 (30 min) | +1 (7.5) | +1 (0.7 V) | 1.0 |

| 8 | 6 | +1 (60 min) | +1 (7.5) | +1 (0.7 V) | 1.5 |

Step 3: Execute the Experiment. Perform the 8 runs in the randomized order to comply with the principle of randomization [24].

Step 4: Analyze the Data. Use statistical software to calculate the main effects and interaction effects. For example, the main effect of A (Time) is the average signal when Time is high minus the average when it is low: (1.8+2.2+2.0+1.5)/4 - (1.2+1.5+1.7+1.0)/4 = 1.875 - 1.35 = 0.525 µA. A significant Interaction Effect A*B would indicate that the optimal immobilization time depends on the pH.

Step 5: Model and Optimize.

Fit a statistical model (e.g., Signal = β₀ + β₁A + β₂B + β₃C + β₁₂AB...) and use it to predict the factor settings that maximize the signal or minimize interference [22] [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for DoE-Optimized Biosensor Development

| Reagent / Material | Function in Biosensor Development | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Permselective Membranes (e.g., Nafion, Cellulose Acetate) | Block interfering electroactive compounds (e.g., ascorbic acid, acetaminophen) from reaching the electrode surface, thereby improving selectivity [1]. | Used in implantable glucose biosensors to mitigate acetaminophen interference [1]. |

| Sentinel Sensor | A control sensor lacking the biorecognition element. Its signal, arising from non-specific interactions and interferents, is subtracted from the main biosensor's signal [1]. | Employed to differentiate the specific biosensor signal from the background matrix signal in complex samples [1]. |

| Redox Mediators / "Wired" Enzymes | Shuttle electrons between the enzyme's active site and the electrode, lowering the operating potential and reducing interference from other redox species [1]. | Central to second- and third-generation biosensors for achieving selective detection at low potentials [1]. |

| Nanomaterials (e.g., Graphene, Metal Nanoparticles) | Increase electrode surface area, enhance electron transfer, and improve bioreceptor immobilization, leading to higher sensitivity and lower limits of detection [1] [25]. | A graphene-based biosensor used a multilayer architecture to achieve a sensitivity of 1785 nm/RIU for breast cancer detection [25]. |

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

DoE Optimization Workflow

Factorial Design Inputs and Outputs

Core Concepts: Full Factorial Designs

A Full Factorial Design is a systematic experimental approach that simultaneously investigates the effects of multiple factors (independent variables) and their interactions on a response variable. It involves executing experimental runs for all possible combinations of the levels of each factor [26]. This method is particularly valuable in biosensor development, where multiple parameters can interdependently influence the sensor's selectivity and overall performance [5].

Key Terminology:

- Factors: The independent variables or parameters you control in an experiment (e.g., pH, temperature, enzyme concentration).

- Levels: The specific values or settings at which a factor is tested (e.g., for pH: 7.0 and 9.0).

- Runs/Trials: The individual experiments performed, each corresponding to one unique combination of factor levels.

- Interactions: When the effect of one factor on the response depends on the level of another factor.

- Replication: Repeating the same experimental run multiple times to estimate inherent variability and ensure reliability [26].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Scenarios & Solutions

| Problem Scenario | Underlying Issue | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Unpredictable Performance: Biosensor signal varies significantly between complex samples (e.g., blood vs. buffer). | Unaccounted-for interaction effects between fabrication or operational parameters. | Use a Full Factorial Design to systematically quantify how factors like immobilization pH and cross-linker concentration interact, revealing optimal, robust conditions [5]. |

| Low Signal-to-Noise: The biosensor's output is weak or obscured by background interference. | Key factors influencing signal transduction (e.g., mediator concentration, applied potential) are not optimized in concert. | Employ a 2-level Full Factorial to efficiently screen multiple factors simultaneously and identify which ones most significantly affect the signal-to-noise ratio [26] [1]. |

| Poor Selectivity: Biosensor responds to non-target interferents present in the sample matrix. | The biosensor design does not adequately block or discriminate against electroactive interferents (e.g., ascorbic acid, uric acid). | Investigate the interaction between permselective membrane composition and operating potential using a Full Factorial Design to find a combination that rejects interferents [1]. |

| Irreproducible Results: High variability between different sensor batches or experimental days. | Unknown sources of variability (e.g., incubation time, temperature fluctuations) are not controlled or understood. | Implement a Full Factorial Design with blocking to account for known nuisance variables (like different production batches) and identify critical factors affecting reproducibility [26]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Screening Critical Factors for a Biosensor's Selectivity

Objective: To identify which factors (pH, Enzyme Loading, and Interferent Concentration) and their interactions significantly impact a biosensor's selectivity index.

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Define Factors and Levels: Select three critical factors and assign two levels (a "low" and "high" value) to each, based on preliminary knowledge.

- Create Experimental Matrix: Construct a 2³ Full Factorial design matrix, which outlines the 8 unique experimental runs. The table below is an example of this matrix.

- Randomize and Execute: Randomize the order of the 8 runs to minimize the effect of confounding variables. Prepare biosensors and measure the response for both the target analyte and a primary interferent.

- Calculate Selectivity Index: For each run, calculate the response for the target analyte divided by the response for the interferent.

- Statistical Analysis: Input the selectivity index data into statistical software. Perform Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) to determine the significance of the main effects and interaction effects.

Full Factorial Design Matrix (2³) for Selectivity Screening:

| Standard Order | Run Order | pH | Enzyme Loading (mg/mL) | Interferent Conc. (µM) | Selectivity Index |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5 | 7.0 (-1) | 0.5 (-1) | 10 (-1) | ... |

| 2 | 2 | 9.0 (+1) | 0.5 (-1) | 10 (-1) | ... |

| 3 | 7 | 7.0 (-1) | 2.0 (+1) | 10 (-1) | ... |

| 4 | 3 | 9.0 (+1) | 2.0 (+1) | 10 (-1) | ... |

| 5 | 8 | 7.0 (-1) | 0.5 (-1) | 100 (+1) | ... |

| 6 | 1 | 9.0 (+1) | 0.5 (-1) | 100 (+1) | ... |

| 7 | 6 | 7.0 (-1) | 2.0 (+1) | 100 (+1) | ... |

| 8 | 4 | 9.0 (+1) | 2.0 (+1) | 100 (+1) | ... |

Protocol 2: Optimizing a Permselective Membrane Formulation

Objective: To model and optimize the composition of a permselective membrane (using factors like Nafion%, Chitosan%, and curing Time) to maximize rejection of an anionic interferent like Ascorbic Acid.

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Define the Mixture and Process Factors: Identify the membrane components (Nafion, Chitosan) and a key process variable (Curing Time). Note that mixture components must total 100%.

- Design the Experiment: Use a Mixed-Level Full Factorial Design. The mixture components can be varied at different ratios (e.g., 3 levels), while the process factor (time) is varied at 2 levels.

- Fabricate and Test: Fabricate membranes according to the design matrix. Test each membrane by measuring the biosensor's amperometric response to a standard ascorbic acid solution.

- Build a Regression Model: Use the data to build a regression model that predicts the % Interference based on the membrane formulation and curing time.

- Find Optimal Settings: Use the model to identify the factor level combination that minimizes the interferent signal.

Example Experimental Matrix for Membrane Optimization:

| Run | Nafion (%) | Chitosan (%) | Curing Time (min) | % Interference (Ascorbic Acid) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 30 | ... |

| 2 | 1.5 | 0.5 | 30 | ... |

| 3 | 0.5 | 1.5 | 30 | ... |

| 4 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 60 | ... |

| 5 | 1.5 | 0.5 | 60 | ... |

| 6 | 0.5 | 1.5 | 60 | ... |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Biosensor Development | Application in Selectivity Troubleshooting |

|---|---|---|

| Permselective Membranes (e.g., Nafion, Chitosan) | Creates a charge- or size-exclusion barrier on the electrode surface. | Selectively blocks access of interfering compounds (e.g., ascorbic acid, uric acid) to the transducer based on charge or size [1]. |

| Enzyme Inhibitors/Activators | Compounds that selectively decrease or increase an enzyme's catalytic activity. | Used in "sentinel" sensors or control experiments to confirm the origin of the signal and rule out non-specific inhibition or activation [1]. |

| Redox Mediators | Shuttles electrons between the enzyme's active site and the electrode surface. | Lowers the operating potential of the biosensor, minimizing the electrochemical oxidation/reduction of common interferents [1]. |

| "Sentinel" Sensor | A control sensor identical to the biosensor but lacking the specific biorecognition element (e.g., enzyme). | The signal from the sentinel sensor is subtracted from the biosensor's signal, correcting for signals arising from direct electrochemical interference [1]. |

| Cross-linkers (e.g., Glutaraldehyde) | Forms stable covalent bonds to immobilize biorecognition elements (enzymes, antibodies) onto the sensor surface. | Optimizing cross-linker concentration is critical; too little leads to enzyme leaching, too much can reduce activity and selectivity. A Full Factorial Design can find the optimal level in concert with other factors [5]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My Full Factorial experiment shows a significant interaction between two factors. What does this mean practically for my biosensor? A significant interaction means the effect of one factor depends on the level of the other. For example, the optimal enzyme loading for maximizing signal might be different at pH 7.0 than it is at pH 9.0. Ignoring this interaction and optimizing each factor independently would lead to a suboptimal biosensor design. The Full Factorial Design uniquely captures these complex relationships [26] [27].

Q2: When should I use a Full Factorial Design versus a simpler "one-factor-at-a-time" (OFAT) approach? Use a Full Factorial Design when you suspect interactions between factors, which is common in complex systems like biosensors. OFAT can miss these interactions and may lead to incorrect conclusions about the true optimum conditions. Full Factorial is more efficient, providing more information about the system with fewer total experiments than a comprehensive OFAT study [5] [27].

Q3: How do I handle a situation where running a full factorial is too expensive or time-consuming? If the number of factors is large (e.g., more than 4 or 5), a Full Factorial can become prohibitively large. In such cases, you can begin with a Fractional Factorial Design. This is a screened-down version that sacrifices the ability to measure some higher-order interactions but is highly efficient for identifying the most important main effects. You can then perform a full factorial on that smaller set of critical factors for final optimization [26] [5].

Q4: My biosensor needs to be highly specific to one molecule, but my enzyme has "class selectivity" and recognizes a group of similar molecules. How can a Full Factorial Design help? A Full Factorial Design can help optimize other aspects of the biosensor to enhance effective specificity. You can investigate factors like the type and thickness of permselective membranes, the use of multi-enzyme systems to eliminate common interferents, or the operating potential. By treating these as factors in your design, you can find a combination that maximizes the response to your target while minimizing the response to structurally similar compounds [1].

Visual Workflows and Diagrams

Factorial Design Workflow

Interaction Effect Plot

A guide to systematic optimization for resolving complex biosensor selectivity challenges.

When optimizing biosensors, traditional one-variable-at-a-time (OVAT) approaches often fail to detect critical interactions between factors. This guide explains how Central Composite and Mixture Designs overcome this limitation, enabling researchers to efficiently capture curvature and interaction effects in their experimental data for robust, optimized biosensor performance.

Key Differences: Experimental Design Types

| Design Type | Primary Use | Key Strength | Model Captured | Best for Biosensor Stage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full Factorial [5] | Screening | Identifies significant factors & their interactions | First-Order (Linear) | Early-stage factor screening |

| Central Composite (CCD) [5] | Optimization | Models curvature & identifies optimal conditions | Second-Order (Quadratic) | Final performance optimization |

| Mixture [5] | Formulation | Optimizes component proportions where the total is fixed | Specialized for mixtures | Biolayer/recognition element formulation |

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Model Fit or Inability to Capture Curvature

Problem: Your initial factorial design shows a poor fit, indicating that the relationship between your factors and the biosensor's response (e.g., selectivity, sensitivity) is not linear but curved [5].

Solution: Augment your experimental plan with a Central Composite Design (CCD).

Methodology: A CCD adds axial points and center points to an existing factorial design, allowing you to estimate quadratic terms [5].

- Identify Key Factors: Use your initial factorial design to select the 2-3 most critical factors affecting biosensor selectivity.

- Set Axial Points (α): The distance of the axial points from the center defines the design's geometry. A common value is α = 1.414 for a rotatable design with two factors.

- Replicate Center Points: Include 3-5 replicates at the center point to estimate pure error and check for model stability.

- Run Experiments & Analyze: Execute the augmented design and use regression analysis to fit a second-order model:

Y = b₀ + b₁X₁ + b₂X₂ + b₁₂X₁X₂ + b₁₁X₁² + b₂₂X₂²whereYis the response (e.g., selectivity index) andXare your factors [5].

Interpretation: A significant positive or negative value for a quadratic term (e.g., b₁₁) confirms the presence of curvature in your system.

Issue 2: Insignificant Curvature in Central Composite Design

Problem: The analysis of your CCD shows insignificant quadratic terms, suggesting a lack of curvature, yet the biosensor performance is still not optimal.

Solution: Verify the experimental domain and check for factor interactions.

Methodology:

- Check Domain Size: The range you selected for your factors might be too narrow to observe curvature. Widen the high and low levels for critical factors and repeat the CCD.

- Analyze Interaction Plots: Examine the interaction plots from your model. Significant factor interactions (e.g.,

X₁X₂) can sometimes mask or compensate for curvature effects. - Confirm Center Point: Ensure that replicates at the center point show consistent results. High variability can obscure the detection of curvature.

Issue 3: Optimizing Component Proportions in a Fixed-Total Mixture

Problem: You need to optimize the formulation of your biosensor's biolayer (e.g., the ratio of enzyme, stabilizer, and cross-linker), where the total must sum to 100% [5].

Solution: Employ a Mixture Design.

Methodology: In a mixture design, the proportion of each component is the key variable, and they are interdependent [5].

- Define Components and Constraints: List all components in your mixture. Set minimum and maximum practical constraints for each (e.g., Enzyme 10-30%, Stabilizer 20-40%, Cross-linker 40-60%).

- Choose Design Type: For 3-4 components, a simplex-lattice or simplex-centroid design is often appropriate.

- Run Experiments & Analyze: Prepare formulations according to the design and measure the response. The resulting model will show how the proportion of each component and their interactions affect biosensor performance.

- Find Optimal Formulation: Use the model's response surface and optimization functions in your statistical software to find the component proportions that maximize selectivity.

Issue 4: Biosensor Selectivity is Unstable in Complex Samples

Problem: Even after optimization, your biosensor shows variable selectivity when analyzing real-world, complex samples like serum or blood.

Solution: Use a triple-mode biosensing strategy for cross-validation during the optimization process [6].

Methodology:

- Design a Multi-Mode Assay: Develop a biosensor that provides three independent readouts (e.g., electrochemical, colorimetric, and fluorescence) for the same analyte [6].

- Apply DoE: Use a CCD to optimize experimental conditions, using the concordance between the three signals as a key response variable for robustness.

- Validate: The optimal conditions identified should provide consistent results across all three detection modes, significantly reducing false positives/negatives caused by matrix interference [6].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the main advantage of a Central Composite Design over a Full Factorial Design?

The primary advantage is the ability to capture curvature in the response surface. A Full Factorial Design can only model linear effects and interactions. A CCD adds axial points, allowing for the estimation of quadratic effects, which is essential for finding a true optimum (e.g., the ideal temperature and pH for maximum selectivity) [5].

When should I use a Mixture Design instead of a Central Composite Design?

Use a Mixture Design when your experimental factors are proportions of a mixture and their total must sum to a constant (typically 100%). A CCD is used for independent factors that can be controlled independently, like time, temperature, or concentration of a non-mixture component [5].

How many experiments are required for a Central Composite Design?

The number of experiments in a CCD is based on the formula: 2ᵏ (factorial points) + 2k (axial points) + c₀ (center points), where k is the number of factors. For 3 factors, this is 8 + 6 + ~5 = ~19 experiments. While this is more than a 2-level factorial, the information gained about curvature is invaluable for final optimization [5].

My mixture components are constrained (e.g., I cannot use less than 10% of component A). Can I still use a Mixture Design?

Yes. Modern statistical software packages easily handle constrained mixture designs. You define the upper and lower limits for each component, and the software generates an experimental plan within this feasible region, which is often an irregular polygon inside the standard simplex.

How can I validate my final optimized model from a CCD?

Validation is a critical step. After developing the model, run 2-3 additional confirmation experiments at the optimal conditions predicted by the model. If the measured responses from these new experiments closely match the model's predictions, your model is considered validated and robust.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Biosensor Development |

|---|---|

| Biolayer Components (Enzymes, Antibodies, Aptamers) | Serves as the biorecognition element that provides the sensor's core selectivity by binding to the target analyte [6]. |

| Cross-linkers (e.g., Glutaraldehyde, EDC-NHS) | Immobilizes the biorecognition element onto the transducer surface, a critical step for stability and performance [5]. |

| Blocking Agents (e.g., BSA, Casein) | Reduces non-specific binding on the sensor surface, a key factor in improving selectivity in complex matrices [6]. |

| Nanomaterials (e.g., Graphene, Metal Nanoparticles) | Enhances the electrochemical or optical signal, increases surface area for bioreceptor immobilization, and can improve sensitivity and stability [28]. |

| Buffer Solutions | Maintains optimal pH and ionic strength, crucial for preserving the activity of biological elements and ensuring reproducible assay conditions [5]. |

Experimental Protocol & Visualization

Workflow: From Screening to Optimization

Central Composite Design Structure

Mixture Design Space for Three Components

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on Experimental Design for Biosensor Optimization

1. Why should I use a factorial design instead of testing one factor at a time (OFAT) for my biosensor?

Testing one factor at a time (OFAT) is a common but limited approach. It fails to detect interactions between factors, which are common in complex biosensor systems. For example, the optimal concentration of an immobilization reagent might depend on the pH of the solution [29]. A factorial design varies all factors simultaneously in a structured way, allowing you to:

- Detect Interactions: Identify if the effect of one factor (e.g., antibody concentration) changes at different levels of another factor (e.g., incubation time) [5] [30].

- Improve Efficiency: Find an optimal set of conditions with fewer experiments than a comprehensive OFAT approach [29].

- Avoid Pseudo-Optima: OFAT can lead to local performance maxima, while factorial designs help locate the global optimum for your biosensor's response [29].

2. How do I select which factors and ranges to test in the initial screening design?

Factor selection should be based on prior knowledge of the biosensor system. Key factors often include:

- Bioreceptor Immobilization: Concentration of antibodies, enzymes, or aptamers; incubation time and temperature [30].

- Detection Conditions: pH, ionic strength of the buffer, and temperature during signal measurement [1].

- Transducer Interface: Composition of nanocomposite materials or concentration of electron mediators [31] [32]. For range-finding, start with a broad but realistic range based on literature or preliminary experiments. The ranges should be wide enough to provoke a measurable change in the biosensor's response (e.g., signal intensity or limit of detection) but not so wide that they cause system failure [5] [29].

3. My biosensor signal is unstable. Could this be related to my experimental setup and how I handle variables?

Yes, signal instability can often be traced to uncontrolled variables. Key considerations include:

- Temperature Fluctuations: Electrochemical and potentiometric signals are highly temperature-sensitive. A 5°C temperature discrepancy can alter a concentration reading by at least 4% [33]. Ensure your calibration standards and samples are at the same stable temperature.

- Calibration Protocol: Always use an interpolation method, calibrating with standards that bracket your expected sample concentration. Extrapolation is not acceptable for accurate measurements [33].

- Surface Preparation: Inconsistent sensor surface modification or bioreceptor immobilization leads to poor reproducibility. Follow a strict, optimized protocol for surface cleaning and functionalization [1].

4. How can I use experimental design to specifically improve biosensor selectivity?

Experimental design can systematically optimize parameters that minimize interference:

- Permselective Membranes: Use a factorial design to optimize the composition and thickness of membranes (e.g., Nafion) that block interfering electroactive compounds like ascorbic acid and acetaminophen [1]. Factors could include polymer concentration and cross-linker ratio.

- Sentinel Sensors: Incorporate a control sensor (lacking the specific bioreceptor) into your experimental design. The signal from this sentinel can be subtracted from the biosensor's signal to account for non-specific binding and matrix effects [1].

- Detection Potential: For electrochemical biosensors, a key factor is the applied detection potential. A DoE can help find the potential that maximizes the signal for your target analyte while minimizing the oxidation/reduction of interferents [1].

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Performing a Step-by-Step Full Factorial Design for a Sandwich ELISA This protocol, adapted from Hernández et al. (2023), outlines how to sequentially optimize a multi-step biosensor assay using full factorial designs [30].

- Principle: Break down the complex assay into individual steps (e.g., plate coating, detection). Optimize each step with a separate full factorial design, then incorporate the optimal conditions into the next stage of development [30].

- Procedure:

- Plate Coating: Conduct a 2⁵ full factorial design. Factors: capture antibody concentration, coating buffer type, incubation time, incubation temperature, and plate type. Response: assay signal at high and low antigen concentrations. Statistically analyze results to identify significant factors and their interactions. Select the optimal conditions for the next step [30].

- Detection Antibody Incubation: Using the optimized coating conditions, conduct a new factorial design for the detection step. Factors: detection antibody concentration and incubation time. Determine the optimal combination [30].

- Enzyme-Conjugate Incubation: With coating and detection fixed, run a factorial design for the conjugate step. Factors: conjugate concentration and incubation time. Find the optimum [30].

- Final Assay Validation: Combine all optimized conditions into a single protocol and validate the final performance, noting the improvement in metrics like the lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) [30].

Protocol 2: Two-Point Calibration of a Potentiometric Biosensor A correct calibration procedure is critical for generating reliable data in any optimization workflow [33] [34].

- Principle: To establish a relationship between the sensor's mV output and the logarithm of the analyte concentration by measuring two standard solutions [33].

- Procedure:

- Conditioning: Soak the ion-selective electrode in the high-concentration standard solution for 30 minutes to equilibrate the membrane. Do not let the sensor rest on the bottom of the container, and ensure no air bubbles are trapped [34].

- First Calibration Point: While the sensor is in the high standard, record the stable mV reading. Input the known concentration of the standard into your analyzer [34].

- Rinsing: Rinse the sensor tip thoroughly with distilled water and gently blot dry. Do not rinse with large volumes of water while the sensor is over a drain, as this can dilute the conditioning layer and damage the membrane.

- Second Calibration Point: Place the sensor into the low-concentration standard. Record the stable mV reading and input the standard's concentration [34].

- Verification: The analyzer will use these two points to calculate the sensor's slope. A slope of -56 ± 3 mV/decade at 25°C is typical for a monovalent ion with Nernstian behavior [34].

Data Presentation

Table 1: Summary of Common Transcription Factor-Based Biosensors for Heavy Metal Detection [12]

| Target | Transcription Factor (TF) | Origin | Dynamic Range & Detection Limit (DL) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hg(II) | MerR | E. coli, P. luminescens | Information varies by specific construct |

| As(III) | ArsR | E. coli | Information varies by specific construct |

| Cd(II), Zn(II) | ZntR | E. coli | Information varies by specific construct |

| Pb(II) | PbrR | Cupriavidus metallidurans | Information varies by specific construct |

| Chromate | ChrB | Cupriavidus metallidurans | Information varies by specific construct |

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Biosensor Development and Optimization

| Reagent / Material | Function in Biosensor Development |

|---|---|

| Nafion & Cellulose Acetate | Used to form permselective membranes that block anionic interferents (e.g., ascorbic acid, uric acid) in electrochemical biosensors [1]. |

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | Nanomaterials used to enhance electrode surface area, facilitate electron transfer, and serve as a platform for immobilizing bioreceptors [31] [32]. |

| Methylene Blue (MB) | A redox probe used in surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS) and electrochemical studies to evaluate the performance and enhancement of nanostructured sensor platforms [31]. |