Systematic Optimization with Design of Experiments (DoE) for Advanced Point-of-Care Biosensor Development

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on applying Design of Experiments (DoE) to overcome critical challenges in point-of-care (POC) biosensor development.

Systematic Optimization with Design of Experiments (DoE) for Advanced Point-of-Care Biosensor Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on applying Design of Experiments (DoE) to overcome critical challenges in point-of-care (POC) biosensor development. It covers foundational DoE principles as a powerful alternative to inefficient one-variable-at-a-time approaches, detailed methodologies for optimizing biosensor fabrication and performance, systematic troubleshooting to enhance robustness, and rigorous validation strategies for clinical translation. By synthesizing recent advances, this review demonstrates how structured, multivariate experimentation can significantly accelerate the creation of sensitive, reliable, and commercially viable POC diagnostic devices, ultimately bridging the gap between laboratory innovation and clinical application.

Foundations of DoE: A Paradigm Shift from Traditional Biosensor Optimization

In the field of point-of-care biosensor development, achieving optimal performance is critical for reliable diagnostics. Traditional one-variable-at-a-time (OVAT) experimentation has long been the standard approach, where researchers optimize a single parameter while holding all others constant. However, this method possesses fundamental limitations: it fails to capture interaction effects between variables, often leads to suboptimal conditions, and requires extensive experimental resources without providing a comprehensive understanding of the system. As biosensors increasingly target ultrasensitive detection of biomarkers at sub-femtomolar concentrations for early disease diagnosis, the limitations of OVAT become particularly pronounced, especially when enhancing signal-to-noise ratio, selectivity, and reproducibility [1] [2].

Design of Experiments (DoE) emerges as a powerful chemometric solution to these challenges. DoE is a systematic, model-based optimization approach that develops data-driven models connecting variations in input variables to sensor outputs. Unlike OVAT, DoE investigates all factors simultaneously across a predefined experimental domain, enabling researchers to identify not only individual variable effects but also crucial interaction effects that would otherwise remain undetected. This methodology has demonstrated significant value in optimizing various aspects of biosensor fabrication, including detection interface formulation, immobilization strategies for biorecognition elements, and detection conditions [1] [3]. For point-of-care biosensor development, where performance parameters such as limit of detection, dynamic range, and reproducibility are critical, DoE provides a structured framework for efficient optimization with reduced experimental effort.

Theoretical Foundations of Design of Experiments

Core Principles and Comparative Advantages

DoE operates on several fundamental principles that distinguish it from traditional OVAT approaches. First, it employs a predetermined experimental plan that explores the entire experimental domain simultaneously rather than sequentially. This a priori approach enables global knowledge of the system, allowing prediction of responses at any point within the experimental domain, including conditions not directly tested [1]. Second, DoE utilizes coded variables (typically -1 and +1) to normalize factors across different measurement scales, facilitating comparison of their effects regardless of original units.

The mathematical foundation of DoE typically involves constructing a model that describes the relationship between input variables and the response. For a simple two-factor system, this can be represented as:

Y = b₀ + b₁X₁ + b₂X₂ + b₁₂X₁X₂ [1]

Where Y is the predicted response, b₀ is the constant term, b₁ and b₂ are coefficients for the linear effects of factors X₁ and X₂, and b₁₂ represents their interaction effect. The coefficients are computed using least squares regression based on data collected across strategically designed experimental points.

Table 1: Comparison Between OVAT and DoE Approaches

| Aspect | One-Variable-at-a-Time (OVAT) | Design of Experiments (DoE) |

|---|---|---|

| Experimental Strategy | Sequential variation of single factors | Simultaneous variation of all factors |

| Interaction Detection | Cannot detect interactions between variables | Systematically identifies and quantifies interactions |

| Experimental Efficiency | Requires more experiments for same information | Maximizes information per experiment |

| Optimum Identification | May identify false or suboptimal conditions | Identifies true optimum considering all factor relationships |

| Model Development | No comprehensive model generated | Develops predictive mathematical model of the system |

| Resource Utilization | Higher experimental costs over full optimization | Reduced experimental effort and resource consumption |

Key DoE Methodologies in Biosensor Optimization

Several experimental designs have proven particularly valuable in biosensor development, each with specific applications and advantages:

Factorial Designs: The 2^k factorial design is a first-order orthogonal design requiring 2^k experiments, where k represents the number of variables being studied. In these designs, each factor is tested at two levels (coded as -1 and +1), which correspond to the selected range for each variable. From a geometric perspective, the experimental domain forms a square (2 factors), cube (3 factors), or hypercube (more than 3 factors) with responses recorded at each corner [1]. This design efficiently estimates main effects and interactions but cannot account for curvature in responses.

Central Composite Designs (CCD): When response curvature is anticipated, second-order models become necessary. CCD augments initial factorial designs with axial points and center points to estimate quadratic terms, thereby enhancing the predictive capability of the model [1] [3]. This design is particularly valuable in response surface methodology for identifying optimal conditions within the experimental domain.

Mixture Designs: These specialized designs apply when the total proportion of all components must equal 100%. In such cases, components cannot be varied independently, as changing one component necessarily changes the proportions of others [1]. This design is particularly relevant for optimizing biosensor formulations where multiple reagents or materials must combine to form a complete system.

Practical Implementation: DoE Protocol for Biosensor Optimization

Experimental Design and Setup

This protocol outlines the application of a full factorial design for optimizing a whole-cell biosensor responsive to protocatechuic acid (PCA), based on published research [4].

Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

Table 2: Essential Materials for Biosensor DoE Optimization

| Category | Specific Items | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Biological Components | Allosteric transcription factor (PcaV), Reporter gene (GFP), Constitutive promoter (PlacI), Repressible promoter (PPV) | Forms the core biosensor genetic circuit for stimulus-response detection |

| Molecular Biology Tools | Plasmid vectors, Restriction enzymes, Ligases, Bacterial transformation reagents | Enables genetic construction and modification of biosensor components |

| Host System | E. coli expression strains | Provides cellular machinery for biosensor operation and signal generation |

| Analytical Equipment | Flow injection analysis apparatus, Potentiostat, Microplate reader | Measures biosensor response signals (electrochemical, optical) |

| Chemical Reagents | Target analytes (e.g., PCA, ferulic acid), Buffer components, Substrates | Creates standardized conditions for biosensor testing and performance evaluation |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Define Optimization Objectives and Response Metrics: Identify critical biosensor performance parameters to optimize. These typically include:

- OFF-state output (leakiness): Should be minimized for accurate low-signal measurements

- ON-state output (reporter expression): Should be maximized for detection above background noise

- Dynamic range: Ratio of ON/OFF states; higher values improve signal-to-noise ratio

- Sensitivity: Ability to detect low analyte concentrations

- Sensing range: Spectrum of analyte concentrations over which the biosensor functions [4]

Select Factors and Experimental Ranges: Choose variables that may influence biosensor performance. For genetic biosensors, key factors often include:

- Promoter strengths for regulatory components (Preg)

- Promoter strengths for output elements (Pout)

- Ribosome binding site strengths (RBSout) Define appropriate ranges for each factor based on preliminary experiments or literature values [4].

Construct Experimental Matrix: For a 2^3 full factorial design (three factors at two levels each), create an experimental matrix specifying the conditions for each experimental run. The matrix will include 8 unique combinations plus center point replicates to estimate experimental error.

Implement Genetic Variants: Clone or assemble the genetic constructs corresponding to each experimental condition in the design matrix. Transform these constructs into the appropriate host organism (typically E. coli for bacterial biosensors).

Execute Randomized Experiments: Conduct biosensor performance characterization for all experimental conditions in random order to minimize systematic bias. For each construct:

- Grow cultures under standardized conditions

- Expose to a range of analyte concentrations

- Measure response outputs (e.g., fluorescence for GFP-based reporters)

- Record both basal (OFF-state) and induced (ON-state) expression levels

Data Collection and Analysis: Compile response metrics for each experimental condition. Calculate dynamic range (ON/OFF ratio) and other relevant performance parameters.

Table 3: Example DoE Results for PCA Biosensor Optimization [4]

| Construct | Preg | Pout | RBSout | OFF Signal | ON Signal | Dynamic Range (ON/OFF) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pD1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 593.9 ± 17.4 | 1035.5 ± 18.7 | 1.7 ± 0.08 |

| pD2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 397.9 ± 3.4 | 62070.6 ± 1042.1 | 156.0 ± 1.5 |

| pD3 | -1 | -1 | -1 | 28.9 ± 0.7 | 45.7 ± 4.7 | 1.6 ± 0.16 |

| pD4 | 1 | -1 | 0 | 479.8 ± 2.0 | 860.5 ± 15.1 | 1.8 ± 0.04 |

| pD5 | -1 | 1 | 0 | 1543.3 ± 46.2 | 5546.2 ± 101.7 | 3.6 ± 0.11 |

| pD6 | 0 | -1 | -1 | 16.3 ± 4.1 | 36.0 ± 5.4 | 2.2 ± 0.68 |

| pD7 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1282.1 ± 37.9 | 47138.5 ± 1702.8 | 36.8 ± 1.6 |

| pD8 | 1 | 0 | -1 | 41.0 ± 5.1 | 49.7 ± 2.9 | 1.2 ± 0.11 |

Data Analysis and Model Interpretation

Calculate Model Coefficients: Using the experimental responses, compute coefficients for the mathematical model relating factors to responses through multiple linear regression. The general form for a linear model with interactions is:

Y = β₀ + β₁X₁ + β₂X₂ + β₃X₃ + β₁₂X₁X₂ + β₁₃X₁X₃ + β₂₃X₂X₃

Where Y is the predicted response (e.g., dynamic range), β₀ is the intercept, β₁, β₂, β₃ are main effect coefficients, and β₁₂, β₁₃, β₂₃ are interaction coefficients.

Evaluate Model Significance: Assess the statistical significance of each coefficient using t-tests or analysis of variance (ANOVA). Remove non-significant terms (typically p > 0.05) to develop a simplified, more robust model.

Interpret Factor Effects:

- Main effects indicate how each individual factor influences the response

- Interaction effects reveal whether the effect of one factor depends on the level of another factor

- Positive coefficients indicate factors that increase the response when raised from low to high level

- Negative coefficients indicate factors that decrease the response when raised

Response Optimization: Identify factor level combinations that maximize desirable responses (e.g., dynamic range) while minimizing undesirable ones (e.g., leakiness). Response surface plots can visualize the relationship between factors and responses.

Model Validation: Confirm model predictions by conducting additional experiments at identified optimal conditions. Compare predicted and actual responses to validate model adequacy.

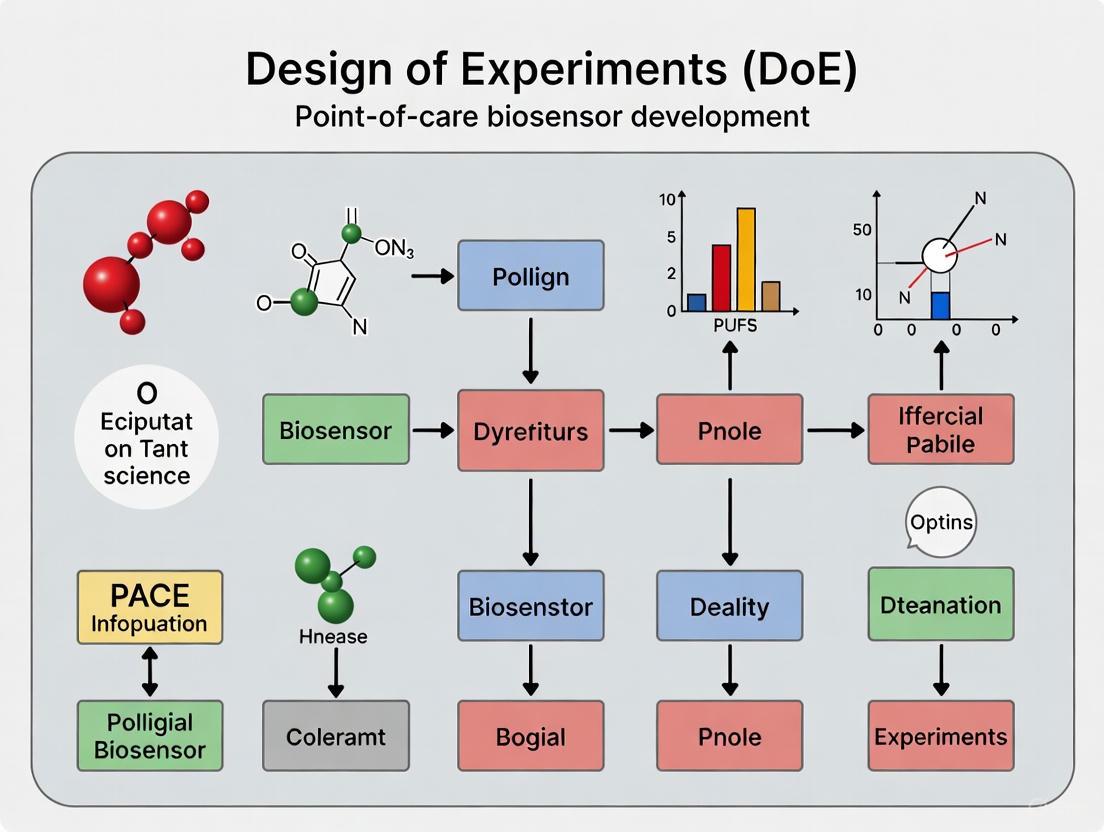

DoE Experimental Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the systematic, iterative nature of the DoE process in biosensor optimization:

Case Study: Successful Application in Electrochemical Biosensor Optimization

A compelling example of DoE application comes from the optimization of an electrochemical biosensor for heavy metal detection. Researchers employed response surface methodology based on a central composite design to optimize three critical factors: enzyme concentration (50-800 U·mL⁻¹), number of voltammetric cycles during biosensor preparation (10-30 cycles), and flow rate in the flow injection system (0.3-1 mL·min⁻¹) [3].

The experimental design consisted of 20 experiments incorporating factorial points, axial points, and center point replicates. Sensitivity of the Pt/PPD/GOx biosensor toward Bi³⁺ and Al³⁺ ions served as the response variable. Through systematic optimization via DoE, the researchers identified optimal conditions of 50 U·mL⁻¹ enzyme concentration, 30 scan cycles, and 0.3 mL·min⁻¹ flow rate. The resulting biosensor demonstrated significantly enhanced performance with high reproducibility (RSD = 0.72%) [3].

This case study highlights several advantages of DoE over traditional approaches. First, the researchers obtained a comprehensive understanding of factor interactions with minimal experimental effort. Second, the mathematical model generated provided predictive capabilities that were validated through confirmation experiments. Third, the systematic approach enabled identification of true optimal conditions rather than local optima that might have been identified through OVAT experimentation.

DoE represents a paradigm shift in biosensor optimization, moving from traditional one-variable-at-a-time approaches to systematic, multivariate experimentation. For point-of-care biosensor development, where performance requirements are stringent and development timelines are critical, DoE offers a structured framework for efficient optimization. The methodology enables researchers to not only identify optimal conditions but also develop fundamental understanding of factor interactions that govern biosensor performance.

As biosensing technologies advance toward increasingly complex multiplexed detection and miniaturized point-of-care platforms, the application of DoE will become increasingly vital. By embracing this powerful chemometric tool, researchers can accelerate the development of robust, high-performance biosensors suitable for clinical diagnostics and environmental monitoring, ultimately facilitating their reliable integration into practical healthcare applications.

In the field of point-of-care (POC) biosensor research, achieving optimal performance requires carefully balancing multiple interconnected parameters. Design of Experiments (DoE) provides a systematic, statistical framework for this optimization, moving beyond traditional one-factor-at-a-time (OFAT) approaches that fail to detect critical interactions between variables [5] [6]. DoE is defined as a branch of applied statistics that deals with planning, conducting, analyzing, and interpreting controlled tests to evaluate the factors that control the value of a parameter or group of parameters [5]. For biosensor development, this methodology enables researchers to efficiently identify key influences on sensor performance, optimize multiple responses simultaneously, and develop robust diagnostic assays suitable for clinical use [2].

The fundamental advantage of DoE lies in its ability to analyze interactions between factors—situations where the effect of one factor depends on the level of another [6]. This is particularly crucial in biosensor systems, where complex relationships between biological recognition elements, transducer materials, and detection conditions significantly impact overall performance [2]. As this application note will demonstrate through core concepts, illustrative case studies, and practical protocols, mastering DoE provides researchers with a powerful toolkit for accelerating the development of reliable, high-performance POC diagnostic devices.

Core DoE Concepts: Factors, Responses, and Interactions

Fundamental Principles and Terminology

At the heart of any DoE study are factors and responses. Factors are input variables that the experimenter controls or modifies, while responses are the output measures used to evaluate the experimental outcome [5] [7]. In biosensor development, factors might include material concentrations, incubation times, or temperature conditions, while typical responses include limit of detection (LOD), sensitivity, signal-to-noise ratio, and assay time [2].

The following table categorizes common factors and responses in POC biosensor optimization:

Table 1: Typical Factors and Responses in Biosensor DoE Studies

| Category | Parameter Type | Examples in Biosensor Development |

|---|---|---|

| Factors (Inputs) | Continuous | Temperature, pH, concentration of biorecognition elements, incubation time [2] [8] |

| Categorical | Type of immobilization method (covalent binding, physical adsorption), transducer material (gold, carbon), buffer system [2] | |

| Responses (Outputs) | Performance Metrics | Limit of Detection (LOD), sensitivity, specificity, signal-to-noise ratio [2] |

| Operational Metrics | Assay time, cost per test, shelf-life stability, reproducibility [9] |

Three foundational statistical principles govern properly designed experiments:

- Randomization: Performing experimental runs in a random sequence to minimize the effects of uncontrolled variables [5].

- Replication: Repeating experimental treatments to obtain an estimate of experimental error [5].

- Blocking: Restricting randomization by grouping experimental units to account for known sources of variability [5].

The Critical Importance of Analyzing Interactions

A primary limitation of the OFAT approach is its inability to detect interactions between factors [5] [6]. In an OFAT experiment, a researcher might optimize temperature while holding pH constant, then optimize pH while holding temperature constant, completely missing the possibility that the effect of temperature depends on the pH level [6].

In contrast, DoE methodologies systematically vary all factors simultaneously according to a predefined experimental matrix, enabling the detection and quantification of these interactions [2] [10]. The diagram below illustrates this fundamental conceptual difference between the two approaches:

In biosensor systems, interactions are common and often profound. For example, the optimal concentration of an enzyme like glucose oxidase may depend on the concentration of a mediator like ferrocene methanol, and vice versa [8]. Similarly, the effect of immobilization pH might depend on the temperature during the binding process. Failure to detect such interactions can lead to suboptimal performance and an incomplete understanding of the system [2].

Case Study: DoE in Optimizing a Glucose Biosensor

Experimental Background and Objectives

A recent study demonstrated the power of factorial DoE in optimizing the performance of a glucose biosensor based on glucose oxidase (GOx) immobilization with ferrocene methanol (Fc) and multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) [8]. The researchers aimed to maximize the amperometric response to glucose oxidation by finding the optimal combination of three key factors: GOx concentration, Fc concentration, and MWCNT concentration.

DoE Application and Results

The team employed a full factorial design with three factors, each investigated at two levels, requiring 2³ = 8 experimental runs [8]. This approach allowed them to estimate not only the main effects of each factor but also all possible two-way and three-way interactions. The experimental design and results are summarized below:

Table 2: Factorial Design for Glucose Biosensor Optimization [8]

| Run Order | GOx Concentration (mM mL⁻¹) | Fc Concentration (mg mL⁻¹) | MWCNT Concentration (mg mL⁻¹) | Amperometric Response (Normalized) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | -1 (5) | -1 (1) | -1 (5) | 64 |

| 2 | +1 (10) | -1 (1) | -1 (5) | 78 |

| 3 | -1 (5) | +1 (2) | -1 (5) | 71 |

| 4 | +1 (10) | +1 (2) | -1 (5) | 82 |

| 5 | -1 (5) | -1 (1) | +1 (15) | 80 |

| 6 | +1 (10) | -1 (1) | +1 (15) | 92 |

| 7 | -1 (5) | +1 (2) | +1 (15) | 85 |

| 8 | +1 (10) | +1 (2) | +1 (15) | 100 |

Statistical analysis of the results revealed that all three factors significantly influenced the biosensor response, with MWCNT concentration having the strongest effect [8]. Crucially, the analysis also identified a significant interaction between MWCNT and Fc concentrations—meaning the effect of Fc concentration depended on the level of MWCNTs, and vice versa [8]. This interaction would have been missed in a traditional OFAT approach.

The resulting model led to the identification of optimal conditions: 10 mM mL⁻¹ GOx, 2 mg mL⁻¹ Fc, and 15 mg mL⁻¹ MWCNT, which produced the greatest amperometric response for glucose oxidation [8].

Experimental Protocols for DoE Implementation

Generalized DoE Workflow for Biosensor Development

Implementing DoE effectively requires a structured workflow. The following protocol outlines a generalized approach that can be adapted for various biosensor optimization challenges:

Table 3: Generalized DoE Protocol for Biosensor Optimization

| Step | Action | Details and Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Problem Definition | Define clear objectives and responses. | Determine the primary goal (e.g., minimize LOD, maximize signal). Identify measurable responses and ensure measurement system reliability [5] [7]. |

| 2. Factor Selection | Identify potential factors and their ranges. | Brainstorm all possible influential factors using subject matter expertise and literature review. Select realistic high/low levels for each factor [5] [2]. |

| 3. Experimental Design | Choose appropriate design type. | For initial screening of many factors: fractional factorial [11]. For optimizing few critical factors: full factorial or Response Surface Methodology (RSM) [2] [11]. |

| 4. Experiment Execution | Run experiments according to design. | Randomize run order to minimize confounding effects. Control non-experimental variables carefully. Document any unexpected observations [5] [7]. |

| 5. Data Analysis | Analyze results statistically. | Use ANOVA to identify significant factors and interactions. Build a mathematical model relating factors to responses [2] [7]. |

| 6. Validation | Confirm optimized settings. | Perform confirmation runs at predicted optimal conditions to verify model accuracy and robustness [7]. |

Protocol for a Screening Design Using Fractional Factorial

For scenarios involving numerous potential factors (e.g., 5-10), a fractional factorial design is recommended for the initial screening phase [11]. The following workflow details this specific protocol:

Key Considerations:

- Aliasing: In fractional factorial designs, some effects are "aliased" (confounded) and cannot be distinguished. A Resolution V design ensures that no two-factor interactions are aliased with each other [11].

- Center Points: Adding 2-3 center points to the design helps detect curvature in the response, indicating whether factor levels need adjustment for subsequent optimization phases [11].

- Resource Allocation: Do not allocate more than 40% of available resources to this initial screening phase, saving the majority for subsequent optimization studies [2].

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of DoE in biosensor development requires both statistical knowledge and appropriate materials. The following table details key research reagent solutions commonly employed in these optimization studies:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Biosensor Development and Optimization

| Reagent/Material | Function in Biosensor Development | Example Application in DoE |

|---|---|---|

| Glucose Oxidase (GOx) | Model enzyme for biorecognition; catalyzes glucose oxidation [8] | Factor in optimizing enzymatic biosensor formulation [8] |

| Ferrocene Derivatives | Electron transfer mediators; enhance electrochemical signal [8] | Factor interacting with enzyme and nanomaterial concentrations [8] |

| Multi-walled Carbon Nanotubes (MWCNTs) | Nanomaterial transducer; increases electrode surface area and electron transfer [8] | Significant factor often showing strong main effects and interactions [8] |

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | Transducer material; provides high surface area for biomolecule immobilization [9] | Factor in optical and electrochemical biosensor optimization |

| Thiol-modified Aptamers | Biorecognition elements; offer stability and specificity [9] | Factor in optimizing surface functionalization for specific detection |

| Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) | Chip-based biosensor substrate; enables microfluidic design [12] | Categorical factor in device architecture optimization |

The systematic application of DoE provides biosensor researchers with a powerful framework for understanding complex systems, optimizing multiple performance parameters, and accelerating development timelines. By moving beyond one-factor-at-a-time approaches and explicitly measuring interactions between factors, DoE reveals insights that would otherwise remain hidden [2] [8]. The case study on glucose oxidase immobilization demonstrates how a relatively simple factorial design can identify not only critical factors but also significant interactions that directly impact biosensor performance [8].

As the demand for sophisticated POC diagnostics grows, embracing statistically rigorous development methodologies like DoE becomes increasingly essential. By implementing the protocols and principles outlined in this application note, researchers can develop more sensitive, robust, and reliable biosensors, ultimately contributing to improved healthcare outcomes through advanced diagnostic technologies.

The Critical Need for Systematic Optimization in POC Biosensors

Point-of-care (POC) biosensors represent a transformative approach in medical diagnostics, enabling rapid testing at or near the patient location. These devices provide critical advantages over traditional centralized laboratory testing, including faster treatment decisions, reduced costs, and improved accessibility in resource-limited settings [13]. The most significant feature of translational point-of-care technology is that testing can be performed quickly by clinical staff not trained in clinical laboratory sciences, providing results during patient consultations that directly inform treatment decisions [13].

Despite their potential, the transition of biosensors from laboratory prototypes to reliable POC devices faces significant challenges. Performance characteristics such as sensitivity, selectivity, and reproducibility must be rigorously optimized to meet clinical requirements [2]. Traditional optimization approaches that vary one parameter at a time (OFAT) are inefficient and often fail to identify optimal conditions, particularly when parameter interactions exist. These methods are robust and accurate but usually take a long time to implement, making them ineffective in emergencies and remote situations [13]. The systematic application of Design of Experiments (DoE) has emerged as a powerful chemometric tool to overcome these limitations, enabling efficient, statistically sound optimization of biosensor performance for POC applications [2].

The Case for Systematic Optimization in Biosensor Development

Limitations of Traditional Optimization Approaches

Conventional univariate optimization methods present several critical limitations for POC biosensor development:

- Inefficiency in resource utilization: OFAT approaches require numerous experimental runs, consuming valuable time, reagents, and materials [2].

- Failure to detect interactions: Univariate methods cannot account for interactions between factors, potentially leading to incorrect conclusions about optimal conditions [2].

- Localized optimization: These approaches typically identify locally optimal conditions rather than the global optimum across the entire experimental domain [2].

- Limited predictive capability: OFAT results do not enable prediction of biosensor performance under untested conditions [2].

These limitations are particularly problematic for POC biosensors, where performance requirements are stringent, and development timelines are often compressed.

Fundamental DoE Principles for Biosensor Optimization

Design of Experiments provides a structured, statistical framework for optimizing complex systems by simultaneously varying multiple factors. The methodology is based on several key principles:

- Factorial designs: Systematically explore all possible combinations of factors and levels to identify main effects and interactions [2].

- Response surface methodology: Models relationships between quantitative factors and responses to locate optimal conditions [14].

- Model building: Develops mathematical relationships between input variables and biosensor performance outputs [2].

The fundamental DoE workflow involves identifying potentially influential factors, establishing experimental ranges, executing a predetermined experimental plan, collecting response data, building mathematical models, and validating predictions [2].

Experimental Frameworks and Protocols

DoE-Guided Optimization of Electrochemical Biosensors

Electrochemical biosensors represent a prominent platform for POC diagnostics due to their potential for miniaturization, portability, and sensitivity. The systematic optimization of a microfluidic impedance biosensor for SARS-CoV-2 detection demonstrates the power of DoE in this context [15].

Experimental Protocol: DoE-Optimized SARS-CoV-2 Impedance Biosensor

Objective: Optimize operational parameters for sensitive detection of SARS-CoV-2 viral antigens using electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS).

Materials:

- Microfluidic impedance biosensor chip

- Portable potentiostat with EIS capability

- SARS-CoV-2 spike protein standards

- Specific antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 antigens

- Buffer solutions

- Clinical samples (nasopharyngeal swabs)

Methodology:

- Factor Identification: Identify critical factors influencing detection sensitivity through preliminary experiments (e.g., antibody concentration, incubation time, flow rate, applied potential).

- Experimental Design: Implement a Central Composite Design (CCD) to explore factor effects and interactions while minimizing experimental runs.

- Biosensor Functionalization: Immobilize capture antibodies on electrode surfaces using appropriate coupling chemistry.

- Sample Analysis: Process standards and clinical samples using the predetermined experimental conditions from the CCD matrix.

- Response Measurement: Quantify biosensor response through EIS, measuring changes in charge transfer resistance (Rct).

- Model Development: Build a mathematical model relating factors to biosensor response using regression analysis.

- Validation: Confirm model adequacy and optimize parameters for sensitive detection of SARS-CoV-2 in clinical samples.

Key Findings: The DoE-optimized biosensor achieved detection of SARS-CoV-2 antigens at fM concentration levels and successfully analyzed clinical samples with cycle threshold (Ct) values up to 27, demonstrating relevance for early infection detection [15].

Response Surface Methodology for Biosensor Optimization

Response Surface Methodology (RSM) provides powerful tools for modeling and optimizing biosensor systems when response surfaces exhibit curvature. A representative application involves optimizing an amperometric biosensor for heavy metal ion detection [14].

Experimental Protocol: RSM Optimization of Metal Ion Biosensor

Objective: Optimize preparation and operational parameters of a Pt/PPD/GOx (platinum/poly(o-phenylenediamine)/glucose oxidase) biosensor for detection of Bi³⁺ and Al³⁺ ions.

Materials:

- Screen-printed platinum electrodes

- Glucose oxidase (GOx) enzyme

- o-phenylenediamine monomer

- Metal ion standards (Bi³⁺, Al³⁺, Ni²⁺, Ag⁺)

- Acetate buffer (50 mM, pH 5.2)

- Flow injection analysis system with potentiostat

Methodology:

- Factor Selection: Identify three critical factors: enzyme concentration (50-800 U·mL⁻¹), number of electropolymerization cycles (10-30), and flow rate (0.3-1 mL·min⁻¹).

- Experimental Design: Implement a Central Composite Design (CCD) with 20 experiments including factorial points, axial points, and center points.

- Biosensor Preparation: Electropolymerize PPD/GOx films on platinum electrodes under conditions specified by the experimental design.

- Biosensor Characterization: Measure sensitivity (S, μA·mM⁻¹) toward Bi³⁺ and Al³⁺ ions as the response variable.

- Model Fitting: Develop second-order polynomial models relating factors to biosensor sensitivity.

- Optimization and Validation: Identify optimal conditions and experimentally verify predictions.

Optimized Parameters:

- Enzyme concentration: 50 U·mL⁻¹

- Electropolymerization cycles: 30

- Flow rate: 0.3 mL·min⁻¹

The optimized biosensor demonstrated high reproducibility (RSD = 0.72%) and was successfully applied to detect additional metal ions (Ni²⁺, Ag⁺) [14].

DoE for Transcription Factor-Based Biosensors

Genetic circuits based on allosteric transcription factors represent emerging biosensor platforms for environmental monitoring and industrial biotechnology. A recent study demonstrated DoE-guided optimization of a TphR-based terephthalate (TPA) biosensor [16].

Experimental Protocol: Tuning Genetic Biosensor Performance

Objective: Engineer TphR-based biosensors with tailored dynamic range, sensitivity, and output characteristics for TPA detection.

Materials:

- Bacterial expression strains

- TphR transcription factor variants

- Reporter plasmids with promoter/operator variants

- Terephthalate standards

- Flow cytometry or microplate reader for output measurement

Methodology:

- Promoter Engineering: Simultaneously engineer core promoter and operator regions to create diverse biosensor variants.

- Dual Refactoring Approach: Implement systematic variation of multiple genetic components to explore enhanced design space.

- Performance Characterization: Quantify biosensor responses (dynamic range, sensitivity, steepness) across TPA concentrations.

- Model Development: Build statistical models linking genetic design elements to performance characteristics.

- Application Testing: Validate optimized biosensors for primary screening of PET hydrolases and enzyme condition screening.

This DoE framework enabled efficient sampling of complex sequence-function relationships and development of tailored biosensors with enhanced performance characteristics for specific applications [16].

Implementation Framework and Best Practices

Structured Approach to DoE Implementation

Successful implementation of DoE for POC biosensor optimization follows a systematic workflow:

Systematic DoE Workflow for POC Biosensor Optimization

Key Performance Indicators for POC Biosensors

The systematic optimization of POC biosensors targets multiple critical performance parameters:

Table 1: Essential Performance Indicators for POC Biosensors

| Performance Indicator | Definition | Importance for POC Applications | Typical Target Values |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | Ability to detect low analyte concentrations | Early disease detection, low abundance biomarkers | Sub-femtomolar for proteins [2] |

| Selectivity | Discrimination against interfering species | Accurate detection in complex samples (blood, saliva) | Minimal cross-reactivity [17] |

| Response Time | Time to obtain measurable result | Rapid clinical decision-making | Minutes rather than hours [13] |

| Reproducibility | Consistency between devices and measurements | Reliable clinical interpretation | RSD <5-10% [14] |

| Limit of Detection (LOD) | Lowest detectable analyte concentration | Early disease detection | Dependent on clinical need [2] |

| Dynamic Range | Concentration range over which response is quantitative | Clinical relevance across physiological/pathological levels | 3-4 orders of magnitude [16] |

Research Reagent Solutions for DoE-Optimized Biosensors

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Biosensor Development and Optimization

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Biosensor Development |

|---|---|---|

| Biorecognition Elements | Glucose oxidase, antibodies, DNA probes, allosteric transcription factors [18] [16] | Target recognition and binding; determines specificity |

| Nanomaterials | Carbon nanotubes, graphene oxide, gold nanoparticles [19] | Signal enhancement, increased surface area, improved electron transfer |

| Transducer Materials | Screen-printed electrodes, piezoelectric crystals, optical fibers [18] | Conversion of biological recognition events into measurable signals |

| Immobilization Matrices | Photocrosslinkable polymers, self-assembled monolayers, hydrogels [14] [18] | Stabilization of biorecognition elements on transducer surface |

| Signal Reporting Systems | Fluorophores, redox mediators, enzymes [18] [19] | Generation of detectable signal proportional to analyte concentration |

The critical need for systematic optimization in POC biosensors is undeniable for translating laboratory prototypes into clinically viable diagnostic tools. Design of Experiments provides a powerful, statistically grounded framework for efficiently navigating complex multivariate optimization spaces, accounting for factor interactions, and developing predictive models that guide biosensor development. The illustrated experimental protocols and frameworks demonstrate successful application of DoE principles across diverse biosensor platforms, from electrochemical devices for SARS-CoV-2 detection to transcription factor-based systems for environmental monitoring. As the field advances toward increasingly sophisticated POC diagnostics, the adoption of systematic optimization approaches will be essential for developing reliable, sensitive, and reproducible biosensors that meet stringent clinical requirements and ultimately improve patient care through rapid, accurate diagnostics.

Design of Experiments (DoE) represents a powerful statistical approach for systematically optimizing complex processes, enabling researchers to efficiently explore multiple experimental factors simultaneously. Within point-of-care (PoC) biosensor development, DoE provides a structured methodology to overcome critical challenges in analytical performance, reproducibility, and manufacturing consistency [1]. Unlike traditional one-variable-at-a-time approaches that often miss critical factor interactions and require extensive experimental runs, DoE frameworks enable researchers to identify true optimal conditions with minimized resource investment while capturing the complex relationships between factors that govern biosensor performance [10].

The adoption of systematic optimization approaches is particularly crucial for PoC biosensors, which must satisfy stringent REASSURED criteria (Real-time connectivity, Ease of specimen collection, Affordable, Sensitive, Specific, User-friendly, Rapid and robust, Equipment-free, and Deliverable to end-users) to be viable in real-world settings [20]. This application note provides an overview of three fundamental DoE frameworks—factorial, definitive screening, and mixture designs—with specific protocols and applications tailored to PoC biosensor development research.

Fundamental DoE Frameworks for Biosensor Development

Factorial Designs

Theoretical Basis and Mathematical Foundation Factorial designs constitute first-order orthogonal designs that systematically investigate all possible combinations of factors and their levels. The 2^k factorial design, where k represents the number of factors, each examined at two levels (coded as -1 and +1), requires 2^k experimental runs [1]. The mathematical model for a two-factor factorial design includes main effects and their interaction term:

Y = b₀ + b₁X₁ + b₂X₂ + b₁₂X₁X₂ [1]

where Y represents the response, b₀ is the global average response, b₁ and b₂ are main effect coefficients, and b₁₂ is the two-factor interaction coefficient.

Table 1: Experimental Matrix for 2² Factorial Design

| Test Number | X₁ | X₂ | Response Y |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | -1 | -1 | Y₁ |

| 2 | +1 | -1 | Y₂ |

| 3 | -1 | +1 | Y₃ |

| 4 | +1 | +1 | Y₄ |

Application in Biosensor Development Full factorial designs are particularly valuable during initial biosensor development phases when investigating the effects of multiple factors such as probe concentration, immobilization time, temperature, and pH on critical performance parameters including sensitivity, specificity, and signal-to-noise ratio [1]. These designs efficiently identify not only main effects but also interaction effects between factors—for example, how the optimal probe concentration might depend on immobilization temperature—that would remain undetected using one-variable-at-a-time approaches [1] [10].

Definitive Screening Designs (DSD)

Theoretical Basis and Key Advantages Definitive screening designs represent advanced resolution IV designs that efficiently screen multiple factors while maintaining the ability to detect quadratic effects and some two-way interactions. DSDs require only 2k+1 or 2k+3 experimental runs (for even and odd numbers of factors, respectively), making them highly efficient for investigating processes with numerous potential factors [21] [22]. In these designs, main effects are not aliased with any two-way interactions, and square terms are not aliased with main effects, enabling researchers to detect curvature in responses while maintaining experimental efficiency [22].

Application in Biosensor Development DSD is particularly valuable when optimizing complex, multi-step biosensor systems where numerous factors may influence the final output. This approach has been successfully applied to optimize whole-cell biosensors by systematically modifying genetic components to enhance dynamic range, sensitivity, and signal output [4]. Similarly, DSD has proven effective for balancing reaction kinetics in one-pot CRISPR/Cas12a detection systems, enabling sensitive nucleic acid detection without spatial or temporal separation of amplification and detection steps [23].

Table 2: Comparison of Screening Design Characteristics

| Design Characteristic | Full Factorial | Resolution III | Definitive Screening |

|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum Runs (6 factors) | 64 | 7 | 13 |

| Main Effect Aliasing | None | With 2-way interactions | None |

| Quadratic Effect Detection | No | No | Yes |

| 2-Way Interaction Assessment | Full | Limited | Partial |

| Experimental Efficiency | Low | High | High |

Mixture Designs

Theoretical Basis and Mathematical Foundation Mixture designs address the unique constraint where the sum of all component proportions must equal 100%. This constraint differentiates them from standard factorial designs, as changing one component necessarily alters the proportions of others [1] [24]. These designs are essential for formulating biosensor materials where the composition of multiple components must be optimized, such as electrode materials, hydrogel matrices, or reagent mixtures for nucleic acid amplification [24].

The mathematical model for a mixture design incorporates these constraints, with the general form for a quadratic mixture model expressed as:

Y = ∑βᵢXᵢ + ∑∑βᵢⱼXᵢXⱼ where ∑Xᵢ = 1 [24]

Application in Biosensor Development In biosensor development, mixture designs have been applied to optimize electrode formulations by determining the ideal proportions of active materials, conductive additives, and binders to maximize electron transfer efficiency while maintaining stability [24]. Similarly, these designs optimize reagent mixtures for nucleic acid amplification in PoC devices, balancing enzymes, primers, nucleotides, and buffers to achieve maximal amplification efficiency and detection sensitivity [20].

Experimental Protocols for DoE Implementation

Protocol for Definitive Screening Design in Biosensor Optimization

Step 1: Experimental Definition and Range Finding

- Identify 5-7 continuous factors potentially influencing biosensor performance (e.g., probe concentration, immobilization time, hybridization temperature, buffer ionic strength, detection pH)

- Establish experimentally relevant ranges for each factor based on preliminary data or literature values

- Define 2-3 critical responses representing biosensor performance (e.g., limit of detection, signal-to-noise ratio, assay time)

Step 2: Experimental Design Generation

- Select a DSD template appropriate for the number of factors being investigated

- Utilize statistical software (JMP, Design-Expert, or Minitab) to generate the experimental matrix

- Include 3-5 center point replicates to estimate pure error and detect curvature

- Randomize run order to minimize confounding from systematic external factors

Step 3: Experimental Execution

- Prepare biosensor components according to the specified factor levels in the design matrix

- Execute experiments in randomized order to prevent bias

- Measure all defined responses for each experimental run

- Record any observational data that might explain anomalous results

Step 4: Data Analysis and Model Building

- Employ multiple linear regression to develop predictive models for each response

- Identify statistically significant factors (p < 0.05) using ANOVA

- Validate model assumptions through residual analysis

- Utilize model graphs to understand factor effects and identify optimization directions

Step 5: Optimization and Validation

- Determine optimal factor settings using desirability functions or optimization algorithms

- Conduct confirmation experiments at predicted optimal conditions

- Validate model adequacy by comparing predicted and observed responses [21] [23] [4]

Protocol for Mixture Design in Biosensor Formulation

Step 1: Component Selection and Constraint Definition

- Identify 3-5 components constituting the biosensor formulation (e.g., active material, conductive additive, binder for electrodes; or enzymes, buffers, cofactors for reagent mixtures)

- Define minimum and maximum percentage constraints for each component based on functional requirements

- Ensure the sum of all components equals 100%

Step 2: Experimental Design Generation

- Select an appropriate mixture design (simplex lattice, simplex centroid, or optimal combined design)

- Generate experimental runs that efficiently cover the constrained experimental space

- Include replicate measurements at critical formulations to estimate variance

Step 3: Formulation Preparation and Testing

- Prepare biosensor formulations according to the specified component proportions

- Fabricate biosensors using consistent processing parameters

- Measure critical performance responses (sensitivity, stability, reproducibility)

- Assess manufacturability characteristics where applicable

Step 4: Model Development and Optimization

- Develop mixture models relating component proportions to performance responses

- Create contour plots and trace plots to visualize component effects

- Identify the optimal formulation that balances multiple performance requirements

- Confirm optimal formulation through experimental validation [1] [24]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for DoE in Biosensor Development

| Reagent/Material | Function in Biosensor Development | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Probes | Target recognition elements | DNA/RNA probes for specific sequence detection [20] |

| Allosteric Transcription Factors | Synthetic biology recognition elements | Whole-cell biosensors for small molecule detection [4] |

| CRISPR/Cas12a Components | Nucleic acid recognition and signal amplification | One-pot detection systems [23] |

| Conductive Additives | Enhance electron transfer in electrochemical biosensors | Carbon black, carbon nanofibers in electrode formulations [24] |

| Cell-Free Protein Synthesis Systems | Provide enzymatic machinery without cell viability constraints | Point-of-care detection of metals, pathogens [25] |

| Polymer Binders | Immobilize recognition elements and maintain stability | PVDF, elastomers in electrode and membrane formulations [24] |

| Fluorescent Reporters | Generate detectable signal upon target recognition | GFP, luciferase in optical biosensors [4] [25] |

The strategic application of appropriate DoE frameworks—factorial, definitive screening, and mixture designs—significantly accelerates the development and optimization of PoC biosensors. By enabling efficient exploration of complex experimental spaces while capturing critical factor interactions, these methodologies facilitate the systematic optimization required to meet the stringent REASSURED criteria for practical biosensor implementation. As biosensing technologies evolve toward greater complexity and integration, the adoption of sophisticated DoE approaches will become increasingly essential for translating innovative detection principles into robust, deployable diagnostic solutions.

Implementing DoE: A Step-by-Step Methodology for Biosensor Enhancement

In the development of point-of-care (POC) biosensors, three analytical parameters form the fundamental triad that defines analytical performance: sensitivity, dynamic range, and limit of detection (LOD). These metrics collectively determine a biosensor's ability to accurately quantify biomarkers at clinically relevant concentrations, enabling early disease diagnosis and effective treatment monitoring. Within the framework of Design of Experiments (DoE), these parameters become the critical responses that guide systematic optimization of fabrication and operational variables [1]. The intense focus on achieving lower LODs has sometimes overshadowed other crucial aspects of biosensor functionality, though a balanced approach that aligns technical capabilities with practical clinical needs is essential for developing effective POC diagnostic tools [26].

This document provides a structured framework for defining, measuring, and optimizing these core performance metrics through systematic experimental design, specifically tailored for biosensors targeting POC applications.

Defining the Key Performance Metrics

Limit of Detection (LOD)

The LOD represents the lowest concentration of an analyte that can be reliably distinguished from zero. It is a crucial parameter for applications requiring early disease detection when biomarker concentrations are minimal. The LOD is formally defined as the analyte concentration corresponding to a signal three standard deviations (σ) above the mean of the blank (negative) sample [27]:

LOD = 3σ/S

where S is the sensitivity of the calibration curve. For example, in gastrointestinal cancer detection, biosensors have achieved LODs refined to the amol level for miRNA and even down to 3.46 aM for specific miRNAs like miR-21, enabling potential detection of early-stage tumors [28].

Sensitivity

Sensitivity refers to the change in output signal per unit change in analyte concentration. In electrochemical biosensors, this may be measured as the slope of the calibration curve (current vs. concentration), while in optical biosensors, it could reflect the refractive index shift per concentration unit [27]. High sensitivity ensures that small variations in analyte concentration produce measurable changes in the detector signal, which is particularly important for quantifying biomarkers present at low concentrations in complex biological matrices.

Dynamic Range

The dynamic range defines the span of analyte concentrations over which the biosensor provides a quantitatively reliable response, typically bounded by the LOD at the lower end and by signal saturation at the upper end. This range must encompass the clinically relevant concentrations of the target biomarker. For instance, a biosensor capable of detecting picomolar concentrations of a biomarker represents an impressive technical feat, but if the biomarker's clinical relevance occurs in the nanomolar range, such extreme sensitivity becomes redundant [26].

Table 1: Clinically Relevant Performance Metrics for Different Application Domains

| Application Domain | Typical LOD Requirement | Required Dynamic Range | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Infectious Disease Detection | Sufficient for early infection markers [27] | Must cover presymptomatic to acute phase concentrations [27] | Alignment with REASSURED criteria; speed often prioritizes extreme sensitivity [27] |

| Cancer Biomarker Detection | aM-fM for early detection [28] | 3-4 orders of magnitude for monitoring progression [28] | Must detect rare biomarkers in complex samples; multi-analyte detection often needed [26] |

| Therapeutic Drug Monitoring | Sufficient for pharmacokinetic profiles | Linear across therapeutic window | Emphasis on reproducibility and ease of use for repeated measurements [26] |

| Environmental Monitoring | ppt-ppb levels for contaminants | Wide range for source identification | Robustness against sample matrix effects is critical [26] |

The DoE Framework for Systematic Optimization

Design of Experiments (DoE) provides a powerful, systematic methodology for optimizing multiple performance metrics simultaneously while accounting for potential interactions between variables. This approach uses statistically designed experiments to build data-driven models that relate input variables (e.g., materials properties, fabrication parameters) to sensor outputs (e.g., LOD, sensitivity) [1].

The fundamental model for a 2^k factorial design, which is a first-order orthogonal design, can be represented as:

Y = b₀ + b₁X₁ + b₂X₂ + b₁₂X₁X₂

where Y is the response (e.g., LOD), X₁ and X₂ are the input variables, b₀ is the constant term, b₁ and b₂ are linear coefficients, and b₁₂ is the interaction term [1]. This model efficiently maps the experimental domain with minimal experimental effort.

Key DoE Strategies for Biosensor Optimization

Factorial Designs: These first-order designs (e.g., 2^k designs) are ideal for initial screening of important variables and their interactions. Each factor is tested at two levels (-1 and +1), providing a efficient way to identify which parameters most significantly affect the key performance metrics [1].

Response Surface Methodologies: Central composite designs and other second-order models capture nonlinear relationships and identify optimal conditions, essential for finding the balance between sometimes competing performance metrics [1].

Sequential Approach (4S Method): The 4S framework (START, SHIFT, SHARPEN, STOP) provides a structured pathway for optimization. This method was successfully applied to optimize a competitive lateral flow immunoassay for Aflatoxin B1, reducing the LOD from 0.1 ng/mL to 0.027 ng/mL while cutting antibody consumption by approximately fourfold [29].

The following diagram illustrates the strategic workflow for applying DoE in biosensor optimization:

Diagram 1: The 4S Sequential Framework for DoE

Experimental Protocols for Metric Characterization

Protocol for LOD and Sensitivity Determination

This protocol outlines the standardized procedure for establishing the limit of detection and sensitivity of an electrochemical biosensor.

Materials and Reagents:

- Purified target analyte in known concentrations

- Appropriate buffer for sample dilution

- Functionalized biosensor platform

- Reference electrodes (Ag/AgCl preferred)

- Electrochemical workstation

Procedure:

- Prepare a dilution series of the analyte spanning 3-5 orders of magnitude, ensuring concentrations bracket the expected LOD.

- Measure the biosensor response for each concentration in triplicate, randomizing the measurement order to minimize systematic error.

- Include at least five blank (zero analyte) measurements to establish the baseline signal.

- Plot the mean response against analyte concentration and fit with an appropriate regression model (linear, 4-parameter logistic, etc.).

- Calculate sensitivity as the slope of the linear portion of the calibration curve.

- Calculate LOD using the formula: LOD = 3.3 × (Standard Deviation of Blank) / Slope [27].

Data Interpretation: The linear range of the calibration curve defines the quantitative working range, while the slope represents the analytical sensitivity. The LOD should be validated by testing samples at this concentration to confirm the signal is distinguishable from the blank with 95% confidence.

Protocol for Dynamic Range Assessment

Procedure:

- Follow steps 1-3 from the LOD protocol, but extend the concentration range to include expected maximum physiological and supraphysiological levels.

- Identify the linear range where the coefficient of determination (R²) exceeds 0.99.

- Determine the upper limit of quantification (ULOQ) as the concentration where the signal deviates from linearity by >15% or where precision (RSD) exceeds 15%.

- The dynamic range spans from the LOD to the ULOQ.

Quality Control:

- Include quality control samples at low, medium, and high concentrations within the dynamic range in each experiment.

- The coefficient of variation for replicate measurements should not exceed 15% across the dynamic range.

Advanced Optimization Approaches

Balancing Conflicting Metrics Through DoE

A common challenge in biosensor optimization involves balancing the LOD with the dynamic range. Enhancing sensitivity to lower the LOD often comes at the expense of narrowing the dynamic range, particularly in affinity-based sensors where high-affinity receptors saturate at lower analyte concentrations [26]. DoE provides a systematic approach to finding the optimal compromise between these competing metrics by modeling their relationship to fabrication and operational parameters.

Table 2: DoE Applications in Optimizing Different Biosensor Types

| Biosensor Type | Key Optimization Variables | Performance Trade-offs | DoE Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electrochemical Immunosensor | Antibody concentration, incubation time, electrode surface area [30] | Sensitivity vs. assay time; LOD vs. dynamic range [26] | Full factorial design to screen variables, followed by central composite for optimization [1] |

| Lateral Flow Immunoassay | Antibody concentration, conjugate label type, membrane porosity [29] | Sensitivity vs. cost; reproducibility vs. simplicity [29] | 4S sequential design focusing on detector and competitor parameters [29] |

| Optical Biosensor (SPR/LSPR) | Substrate functionalization, receptor density, flow rate [1] | Sensitivity vs. specificity; LOD vs. nonspecific binding | Mixture design to optimize surface chemistry composition [1] |

| Capacitive Biosensor | Electrode geometry, dielectric thickness, receptor density [31] | Sensitivity vs. stability; LOD vs. response time | Response surface methodology to balance multiple performance criteria [32] |

Signal Amplification and Noise Reduction Strategies

Advanced signal amplification strategies can simultaneously improve LOD and sensitivity without compromising dynamic range:

Nanomaterial-Enhanced Sensing:

- Incorporate gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) or graphene-based composites to increase electroactive surface area and enhance electron transfer in electrochemical biosensors [27].

- Utilize quantum dots or metal-enhanced fluorescence to boost signal intensity in optical biosensors [33].

Enzyme-Based Amplification:

- Implement enzyme-catalyzed precipitation or cycling systems to amplify the detection signal, as demonstrated in solid-phase electrochemiluminescence sensors for glucose detection achieving μM LOD [33].

The following diagram illustrates an optimized biosensor development workflow integrating DoE and performance validation:

Diagram 2: DoE-Optimized Biosensor Development

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Biosensor Development and Optimization

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | Plasmonic reporters for colorimetric detection; electrode modifiers for enhanced electron transfer [27] [29] | Lateral flow immunoassays; electrochemical sensor surface modification [29] |

| Graphene & Carbon Nanotubes | High surface area electrodes; excellent electrical conductivity [27] | Field-effect transistors; electrode modification for nucleic acid sensing [33] |

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) | Artificial receptors with selective binding cavities [27] | Synthetic alternatives to antibodies in competitive assays [27] |

| Glucose Oxidase (GOx) | Model enzyme for catalytic biosensing [34] | Enzymatic glucose sensors; signal amplification systems [34] |

| Aptamers | Nucleic acid-based recognition elements selected via SELEX [34] | Detection of small molecules, proteins, and cells; stable alternative to antibodies [34] |

| Monoclonal Antibodies | High-specificity recognition elements for immunoassays [34] | Sandwich-type assays for protein biomarkers; competitive formats for small molecules [29] |

Optimizing biosensors for POC applications requires a balanced approach that prioritizes clinically significant performance metrics over purely technical achievements. The LOD paradox—where pushing for ultra-low detection limits may not translate to practical utility—highlights the need for context-specific optimization goals [26]. By implementing systematic DoE methodologies, researchers can efficiently navigate complex parameter spaces to develop biosensors that successfully balance sensitivity, dynamic range, and LOD with other essential characteristics such as cost-effectiveness, reproducibility, and user-friendliness required for real-world POC applications [26] [1].

Future directions in biosensor optimization will likely involve increased integration of artificial intelligence with DoE to handle increasingly complex multi-parameter systems, as well as a stronger emphasis on multiplexed detection systems that require balancing the performance metrics for multiple analytes simultaneously [34]. Through the systematic application of these principles and protocols, researchers can accelerate the development of robust, clinically valuable biosensors that effectively address unmet diagnostic needs.

The performance of point-of-care (POC) electrochemical biosensors is fundamentally governed by the precise control of three critical interdependent factors: bioreceptor immobilization, nanomaterial integration, and surface chemistry. Within the context of Design of Experiments (DoE) for biosensor development, optimizing these factors is paramount for achieving high sensitivity, specificity, and reproducibility. The immobilization of bioreceptors must ensure optimal density, orientation, and stability to maximize the capture of target analytes [35]. The integration of nanomaterials serves as a powerful strategy to enhance the electroactive surface area, improve electron transfer kinetics, and increase the loading capacity of bioreceptors [36] [37]. Finally, the underlying surface chemistry dictates the efficiency of both nanomaterial attachment and subsequent bioreceptor immobilization, while also playing a crucial role in minimizing non-specific binding through effective passivation strategies [35]. A DoE approach is exceptionally suited to navigate this complex, multi-parameter optimization landscape, as it systematically resolves factor interactions and identifies global optima with greater experimental efficiency than traditional one-variable-at-a-time (OVAT) methods [10]. This protocol provides detailed application notes and experimental methods for the systematic investigation and optimization of these key parameters.

Bioreceptor Immobilization Strategies

Covalent Immobilization on Gold Surfaces

Covalent immobilization via self-assembled monolayers (SAMs) on gold electrodes is one of the most prevalent and robust methods for attaching bioreceptors such as DNA, antibodies, or peptides.

Protocol: Thiol-Based Immobilization on Gold Electrodes

- Reagents: Thiolated bioreceptor (e.g., DNA probe or antibody), 6-mercapto-1-hexanol (MCH), absolute ethanol, phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4).

- Equipment: Gold working electrode (e.g., disk or screen-printed), electrochemical workstation, agitator.

- Procedure:

- Electrode Pretreatment: Clean the gold electrode by polishing with alumina slurry (0.05 µm) and sonicating in ethanol and deionized water for 5 minutes each. Perform electrochemical cycling in 0.5 M H₂SO₄ until a stable cyclic voltammogram is obtained.

- SAM Formation: Incubate the clean, dry gold electrode with a 1-10 µM solution of the thiolated bioreceptor in PBS for 1-4 hours at room temperature under gentle agitation.

- Surface Backfilling: Rinse the electrode thoroughly with PBS to remove physisorbed molecules. Subsequently, incubate in a 1 mM solution of MCH for 30-60 minutes. This critical step displaces non-specific adsorption and creates a well-ordered, passivated SAM that orientates the bioreceptor and reduces background signals [35].

- Rinsing and Storage: Rinse again with PBS and store in buffer at 4°C until use.

Optimization Notes: A DoE study can efficiently optimize key parameters such as bioreceptor concentration, immobilization time, and MCH backfilling time. The DoE model can identify significant interactions, for instance, where the optimal immobilization time is dependent on the bioreceptor concentration, to achieve maximal probe density and hybridization efficiency [10].

Streptavidin-Biotin Affinity Immobilization

The streptavidin-biotin interaction offers a highly specific, stable, and versatile method for immobilizing biotinylated bioreceptors.

Protocol: Affinity Immobilization on Streptavidin-Coated Surfaces

- Reagents: Biotinylated bioreceptor, streptavidin (or neutravidin/avidin), biotin solution, PBS.

- Equipment: Substrate (e.g., carbon or gold electrode), micro-pipettes.

- Procedure:

- Surface Functionalization: First, immobilize streptavidin onto the sensor surface. This can be achieved through physical adsorption (incubation for 1 hour) or covalent coupling (e.g., using EDC/NHS chemistry on carboxylated surfaces).

- Blocking: Incubate with a biotin solution (e.g., 0.1 mg/mL) for 15 minutes to block any unoccupied binding sites on the streptavidin.

- Bioreceptor Immobilization: Incubate the surface with the biotinylated bioreceptor (e.g., 0.1-1 µM in PBS) for 30-60 minutes. The strong non-covalent interaction (K_d ≈ 10⁻¹⁵ M) ensures stable attachment [36].

- Rinsing: Rinse gently with PBS to remove unbound receptor.

Optimization Notes: This method is notable for its ability to provide a controlled orientation of the bioreceptor, which can enhance accessibility to the analyte. DoE can be applied to optimize the concentration of immobilized streptavidin and the incubation time with the biotinylated bioreceptor to maximize binding capacity and assay sensitivity [17].

Table 1: Comparison of Bioreceptor Immobilization Methods

| Method | Mechanism | Advantages | Disadvantages | Common DoE Factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thiol-Gold (SAM) | Covalent Au-S bond | High stability, well-ordered monolayer | Requires thiol-modified bioreceptors | Bioreceptor concentration, time, backfilling agent & time [35] |

| Streptavidin-Biotin | Affinity interaction (Non-covalent) | Strong binding, controlled orientation, versatile | Multi-step process, requires biotinylation | Streptavidin density, incubation time, [36] [17] |

| Covalent (EDC/NHS) | Amide bond formation | Applicable to carbon & polymer surfaces | Can lead to random orientation | EDC/NHS ratio, pH, activation time [35] |

| Physical Adsorption | Electrostatic/ hydrophobic forces | Simple, no modification needed | Uncontrolled orientation, can be unstable | pH, ionic strength, incubation time [35] |

Nanomaterial Integration for Signal Enhancement

Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) for Enhanced Transduction

Gold nanoparticles are extensively used to amplify electrochemical signals due to their excellent conductivity, high surface-to-volume ratio, and facile functionalization.

Protocol: Functionalization of AuNPs with Bioreceptors

- Reagents: Citrate-capped AuNPs (e.g., 10-20 nm diameter), thiolated or aminomodified DNA probes, sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), PBS buffer.

- Equipment: Spectrophotometer, centrifuge, vortex mixer.

- Procedure:

- Functionalization: Add a concentrated solution of thiolated DNA probe to the AuNP solution. The final probe concentration should be sufficiently high to achieve dense surface coverage (e.g., 2-5 µM). Incubate for 16-24 hours.

- Aging and Cleaning: Add PBS and SDS to stabilize the NPs, and incubate for an additional 24-40 hours. Centrifuge the solution (e.g., at 14,000 rpm for 30 minutes) to remove excess unbound probes. Carefully remove the supernatant.

- Washing and Resuspension: Resuspend the red pellet in a clean buffer (e.g., with 0.1% SDS). Repeat the centrifugation and resuspension cycle 2-3 times.

- Characterization: Verify functionalization by measuring the UV-Vis absorption spectrum and observing a characteristic red-shift in the surface plasmon resonance peak [36].

Application in Biosensors: Functionalized AuNPs can be used as labels in sandwich assays. When the target analyte is captured, the AuNP catalyzes the reduction of H⁺ or the deposition of metals like silver, leading to a strong, quantifiable electrochemical signal [36].

Carbon Nanomaterials and Quantum Dots

Carbon nanotubes (CNTs), graphene, and quantum dots (QDs) offer unique electronic and structural properties for biosensing.

Protocol: Modification of Electrodes with Carbon Nanotubes

- Reagents: Carboxylated multi-walled or single-walled CNTs, N,N-Dimethylformamide (DMF) or water, chitosan solution (0.5-1% w/v in acetic acid).

- Equipment: Ultrasonic bath, micro-pipettes.

- Procedure:

- Dispersion: Disperse CNTs in DMF or deionized water at a concentration of 1 mg/mL. Sonicate for 30-60 minutes until a stable, black suspension forms without aggregates.

- Electrode Modification (Drop-Casting): Pipette a precise volume (e.g., 5-10 µL) of the CNT suspension onto the surface of the working electrode (e.g., glassy carbon or screen-printed carbon). Allow the solvent to evaporate under ambient conditions or with mild heating.

- Stabilization (Optional): To improve adhesion, a stabilizing agent like chitosan can be mixed with the CNT dispersion before drop-casting [37].

Optimization Notes: A key parameter is the concentration and dispersion quality of the nanomaterial, which directly affects the electroactive surface area and electron transfer kinetics. DoE is highly effective for modeling the non-linear relationship between nanomaterial loading and sensor sensitivity, identifying the optimal loading that maximizes signal without causing electrical shorts or excessive background [38].

Table 2: Key Nanomaterials and Their Functions in Biosensors

| Nanomaterial | Key Properties | Role in Biosensor | Example DoE Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | High conductivity, Surface Plasmon Resonance, facile bioconjugation | Signal amplification, Electron shuttle, Label for detection | Size, concentration, functionalization density [36] |

| Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) | High aspect ratio, excellent electrical conductivity, large surface area | Enhances electron transfer, platform for bioreceptor immobilization | Dispersion concentration, length/type (SW/MW), deposition method [37] |

| Quantum Dots (QDs) | Size-tunable fluorescence, high quantum yield | Electrochemiluminescence labels, photoelectrochemical sensing | Core/shell composition, size, surface coating [39] [37] |

| Graphene & Derivatives | High electrical and thermal conductivity, single-atom thickness | Transducer material, quencher in fluorescence assays | Number of layers, degree of oxidation (in rGO) [37] |

Surface Chemistry and Passivation Techniques

Controlling surface chemistry is critical not only for effective bioreceptor attachment but also for suppressing non-specific binding (NSB) of interferents, which is a major source of false positives and background noise in complex samples like blood or serum.

Protocol: Surface Passivation with Mixed Self-Assembled Monolayers (SAMs)

- Reagents: Thiolated bioreceptor, passivating thiol (e.g., 6-mercapto-1-hexanol, MCH), polyethylene glycol (PEG)-thiol, bovine serum albumin (BSA).

- Equipment: Gold electrode.

- Procedure:

- Co-immobilization: Prepare a mixed solution containing the thiolated bioreceptor and the passivating thiol (e.g., MCH) at a molar ratio optimized to balance probe density with passivation (e.g., 1:100 to 1:1000 bioreceptor:MCH). Incubate the gold electrode with this mixture for a defined time.

- Alternative: Sequential Method: As described in Section 2.1, immobilize the bioreceptor first, followed by backfilling with the passivating thiol. This often provides better control over probe orientation [35].

- Alternative Passivants: For non-gold surfaces or additional blocking, incubate the functionalized sensor with a solution of BSA (1-5% w/v) or casein for 30 minutes.

Optimization Notes: The choice and density of the passivating molecule are crucial. DoE can be used to screen different passivating agents (MCH, PEG-thiols of varying lengths, BSA) and their concentrations to find the combination that minimizes NSB while maintaining the activity of the immobilized bioreceptor. The effectiveness of passivation should be quantitatively tested against relevant negative controls [35] [17].

Design of Experiments (DoE) Framework for Systematic Optimization

Applying a DoE approach is fundamental for efficiently navigating the multi-factorial space of biosensor development, moving beyond the limitations of the traditional one-variable-at-a-time (OVAT) method [10].

Protocol: A Two-Stage DoE for Biosensor Optimization

- Stage 1: Factor Screening

- Objective: Identify which factors among many potential parameters (e.g., pH, ionic strength, bioreceptor concentration, nanomaterial loading, immobilization time, passivant concentration) have a significant impact on the critical responses (e.g., signal-to-noise ratio, %RCC (Radiochemical Conversion), specific activity).

- Design: Use a fractional factorial design (e.g., Resolution III or IV) to screen a large number of factors (e.g., 5-7) with a minimal number of experimental runs. This is highly efficient for eliminating non-influential factors [10].

- Stage 2: Response Surface Optimization

- Objective: Model the complex, non-linear relationships between the significant factors (identified in Stage 1) and the responses to find the optimal factor settings.

- Design: Employ a central composite design (CCD) or Box-Behnken design with a reduced set of factors (e.g., 2-4). These designs allow for the estimation of quadratic effects and the creation of a predictive model for the response surface [10] [38].

- Analysis: Use statistical software (e.g., JMP, Modde, R) to perform multiple linear regression (MLR) on the data. Analyze the model using Analysis of Variance (ANOVA), regression coefficients, and contour plots to understand factor interactions and locate the optimum [10].

Diagram 1: DoE optimization workflow for biosensor development.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Biosensor Development and Optimization

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Thiolated DNA/Probes | Bioreceptor for covalent immobilization on gold surfaces | Sequence-specific nucleic acid sensor development [35] |

| Biotinylated Antibodies | Bioreceptor for affinity-based immobilization | Immunosensor for protein targets (e.g., viral antigens) [36] [17] |

| Citrate-capped AuNPs | Nanomaterial platform for signal amplification | Functionalization with thiolated probes for enhanced electron transfer [36] |

| Carboxylated CNTs | Nanomaterial for electrode modification | Increasing electroactive surface area and wiring redox enzymes [37] |

| 6-Mercapto-1-hexanol (MCH) | Passivating agent for gold surfaces | Backfilling SAMs to reduce non-specific binding and orient probes [35] |