Unraveling Signal Drift in Electrochemical Biosensors: From Fundamental Origins to Advanced Mitigation Strategies

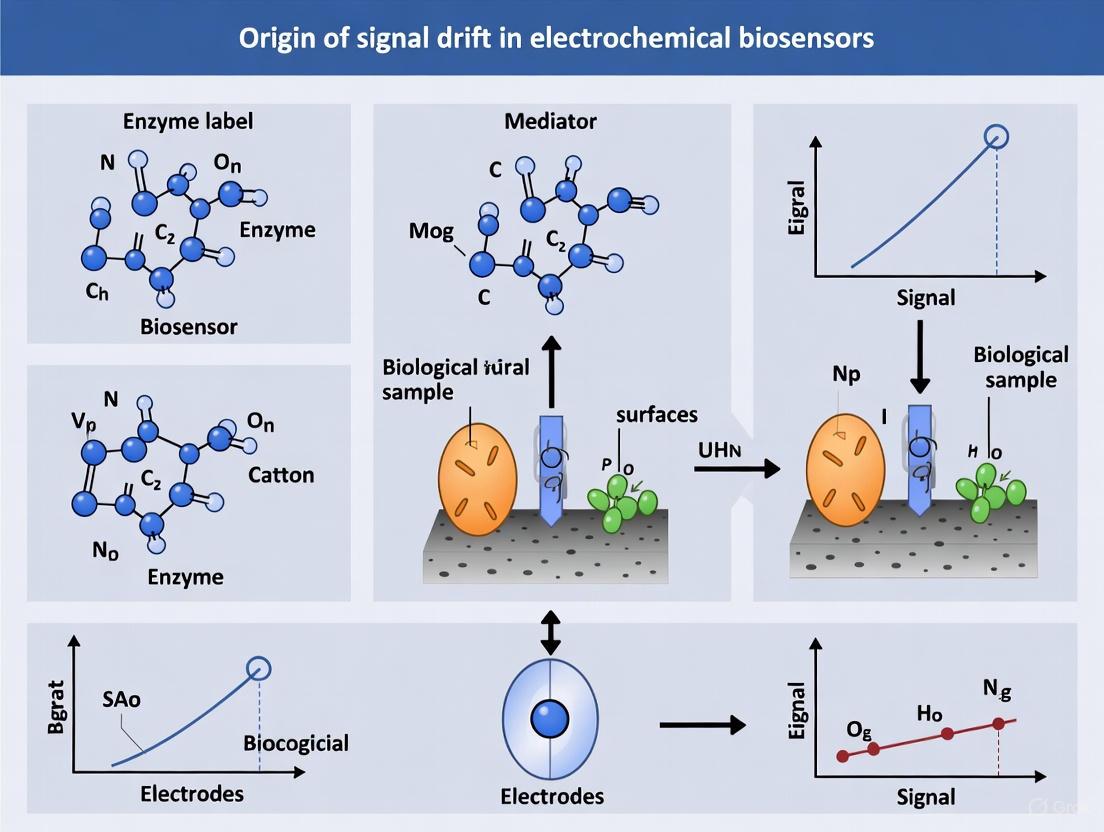

Signal drift presents a significant challenge to the reliability and long-term stability of electrochemical biosensors, hindering their translation from research to clinical and point-of-care applications.

Unraveling Signal Drift in Electrochemical Biosensors: From Fundamental Origins to Advanced Mitigation Strategies

Abstract

Signal drift presents a significant challenge to the reliability and long-term stability of electrochemical biosensors, hindering their translation from research to clinical and point-of-care applications. This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the origins and mechanisms of signal drift, exploring fundamental causes such as electrode fouling, monolayer desorption, and environmental fluctuations. It systematically reviews current methodological approaches for drift suppression, from material innovations to algorithmic corrections, and offers practical troubleshooting and optimization guidelines. Furthermore, it critically evaluates validation frameworks and comparative performance of different strategies, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a holistic resource to design robust, drift-resilient biosensing platforms for accurate in vivo and in vitro diagnostics.

The Core Mechanisms: Deconstructing the Fundamental Origins of Signal Drift

Electrochemical biosensors are powerful tools for therapeutic drug monitoring, in vivo sensing, and diagnostic applications. However, their deployment, particularly in complex biological environments, is hampered by signal drift, a phenomenon characterized by a gradual decrease in sensor signal over time. This instability primarily originates from two fundamental mechanisms: the desorption of self-assembled monolayers (SAMs) from electrode surfaces and the degradation of redox reporters. These processes constitute a significant challenge for the development of robust, long-term sensing platforms, especially for continuous monitoring applications in drug development and clinical settings. Research by [1] has systematically demonstrated that when challenged in biologically relevant conditions such as whole blood at 37°C, electrochemical biosensors exhibit biphasic signal loss. The initial, rapid exponential phase is dominated by biofouling, while the subsequent linear phase is primarily driven by electrochemical instabilities. Understanding and mitigating these specific degradation pathways is therefore critical for advancing the reliability and commercial viability of electrochemical biosensors.

Core Mechanisms of Instability

Self-Assembled Monolayer (SAM) Desorption

The SAM serves as the foundational layer that tethers biorecognition elements (e.g., aptamers, antibodies) to the electrode surface. Its instability directly compromises the sensor's integrity and function.

- Electrochemically Driven Desorption: The gold-thiolate bond, most commonly used for SAM formation, is susceptible to both reductive and oxidative desorption under applied potentials. Studies show that thiol-on-gold monolayers undergo reductive desorption at potentials below -0.5 V and oxidative desorption at potentials above ~1.0 V [1]. The stability of the SAM is therefore highly dependent on the electrochemical interrogation protocol. Research confirms that signal loss is minimal when the potential window is restricted to a narrow, stable region (e.g., -0.4 V to -0.2 V), whereas it increases significantly when the window encroaches on these desorption potentials [1].

- Impact of Molecular Structure on SAM Stability: The chemical structure of the thiol anchor profoundly influences packing density and monolayer stability.

- Anchor Geometry: Flexible trihexylthiol anchors (e.g., Letsinger-type) demonstrate superior stability compared to rigid adamantane-based trithiols or conventional monothiols. Sensors with flexible trithiol anchors retained 75% of their original signal after 50 days of storage in aqueous buffer, whereas those with monothiols or rigid trithiols suffered significant signal loss (>60%) under the same conditions [2].

- Chain Length: Longer alkane thiol chains (e.g., C11) form more stable and densely packed SAMs due to enhanced van der Waals interactions. However, this increased stability comes at the cost of higher electron transfer resistance, which can degrade sensor performance. Shorter chains (e.g., C6) offer a compromise between stability and electron transfer efficiency [3] [2].

Table 1: Factors Influencing SAM Stability and Their Impact on Sensor Performance

| Factor | Effect on Stability | Impact on Sensor Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Applied Potential | Outside stable window (-0.5 V to 1.0 V) causes rapid desorption [1] | Severe signal drift; dictates usable electrochemical techniques |

| Anchor Geometry | Flexible multidentate anchors (e.g., trithiols) enhance stability [2] | Greatly improved long-term and operational stability |

| Chain Length | Longer chains increase stability but impede electron transfer [3] [2] | Trade-off between sensor lifetime and signal strength/sensitivity |

| Surface Crystallinity | Pure gold surfaces ([111] orientation) promote denser SAM formation [3] | Improved reproducibility and reduced non-specific adsorption |

Redox Reporter Degradation

The redox reporter (e.g., Methylene Blue, ferrocene) is responsible for generating the electrochemical signal. Its degradation directly diminishes the sensor's output.

- Irreversible Redox Reactions: The reporter molecule can undergo irreversible side reactions during repeated electrochemical cycling, leading to its decomposition and a permanent loss of signal. The susceptibility to degradation is directly linked to its redox potential [1].

- Superior Stability of Methylene Blue: Among common reporters, Methylene Blue (MB) exhibits exceptional stability. This is attributed to its favorable redox potential (E⁰ = -0.25 V at pH 7.5), which falls within the narrow potential window where alkane-thiol-on-gold SAMs are also stable [1]. This synergy minimizes simultaneous SAM desorption and reporter degradation. Comparative studies have confirmed that MB-tagged peptides provide a much more stable background signal than those tagged with ferrocene, making MB the optimal choice for many biosensing applications [4].

- Reporter Position and Fouling: The placement of the redox reporter on the DNA or peptide backbone influences its vulnerability to signal loss from biofouling. When fouling occurs, it reduces the rate of electron transfer by physically impeding the reporter's approach to the electrode. Studies show that the rate and magnitude of this fouling-induced signal drift are strongly and monotonically dependent on the reporter's position [1].

Table 2: Comparison of Common Redox Reporters in Electrochemical Biosensors

| Redox Reporter | Redox Potential (Approx.) | Stability | Key Advantages / Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Methylene Blue (MB) | -0.25 V (vs. ref.) [1] | High | Stable within SAM-stable potential window; optimal for biological media [1] [4] |

| Ferrocene | > +0.3 V (vs. ref.) | Moderate/Low | Requires potentials that can promote SAM desorption [1] [4] |

| Inorganic Complexes | Variable | Variable | (e.g., ([Fe(CN)_6]^{3-/4-})) often used in solution-phase, can be sensitive to environment |

Experimental Analysis of Instability

To effectively study and quantify these instability mechanisms, researchers employ a suite of well-defined experimental protocols and analytical techniques.

Protocol for Quantifying SAM Desorption

This protocol is designed to isolate and measure signal loss originating from SAM desorption under electrochemical interrogation.

- Sensor Fabrication: Create a simplified, EAB-like proxy sensor by immobilizing a thiolated, single-stranded DNA sequence (lacking significant secondary structure to avoid confounding effects) modified with a redox reporter (e.g., Methylene Blue) onto a gold electrode. Backfill with 6-mercapto-1-hexanol (MCH) to form a mixed SAM [1] [2].

- Stability Testing in Benign Medium: Place the fabricated sensor in a controlled, non-biological medium such as phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at 37°C. The absence of biological components helps isolate electrochemical degradation mechanisms from biofouling [1].

- Electrochemical Interrogation: Subject the sensor to repeated square-wave voltammetry (SWV) scans over an extended period (e.g., 10+ hours). To test the impact of potential window, systematically vary the positive and negative limits of the SWV scan while monitoring the faradaic peak current [1].

- Data Analysis: The signal loss observed as a linear decrease over time in PBS is primarily attributed to electrochemically driven SAM desorption. The strong dependence of this loss on the potential window, particularly when exceeding the stable region, confirms the mechanism [1].

Protocol for Differentiating Fouling from Reporter Degradation

This methodology distinguishes signal loss from surface fouling versus the irreversible degradation of the redox reporter.

- Stability Testing in Complex Media: Challenge the sensor from Step 3.1 in a biologically relevant matrix such as undiluted whole blood at 37°C, using a narrow potential window to minimize electrochemical SAM desorption [1].

- Signal Analysis: Observe the signal drift profile. A biphasic loss—an initial exponential decay followed by a linear decrease—is typically observed. The exponential phase is attributed to blood-specific mechanisms [1].

- Fouling Reversibility Test: After a period of interrogation in blood (e.g., 2.5 hours), wash the electrode with a solubilizing agent like concentrated urea. Recovery of at least 80% of the initial signal indicates that the exponential drift phase is dominated by reversible fouling (e.g., protein adsorption) rather than irreversible enzymatic degradation of the DNA or reporter [1].

- Electron Transfer Kinetics Analysis: Monitor the square-wave voltammetry frequency at which maximum charge transfer occurs. A significant decrease in this frequency during the exponential drift phase indicates that fouling is reducing the electron transfer rate, consistent with a physical barrier on the surface [1].

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for deconvoluting the sources of signal drift, showing the decision pathway for identifying fouling versus degradation mechanisms.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Selecting appropriate materials is paramount for constructing stable and reliable electrochemical biosensors. The table below details key reagents and their optimal use cases for mitigating instabilities.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Mitigating Electrochemical Instabilities

| Reagent / Material | Function / Description | Rationale for Stability Enhancement |

|---|---|---|

| Flexible Trihexylthiol Anchor (e.g., Letsinger-type) [2] | Multidentate anchor for immobilizing DNA probes on gold surfaces. | Provides superior stability in aqueous storage and against thermal cycling compared to monothiols, due to multiple attachment points. |

| Methylene Blue (MB) [1] [4] | Redox reporter attached to the terminus of DNA or peptides. | Its redox potential lies within the SAM-stable window, minimizing simultaneous reporter degradation and SAM desorption during interrogation. |

| 6-Mercapto-1-hexanol (MCH) [3] [2] | Backfilling / blocking agent in mixed SAMs. | Dilutes the probe layer, reduces non-specific adsorption, and helps the biorecognition element adopt a functional conformation. |

| 2'O-methyl RNA / Spiegelmers [1] | Nuclease-resistant oligonucleotide backbone. | Used to confirm that signal loss is not primarily due to enzymatic degradation, helping to isolate fouling as the dominant mechanism. |

| PEG-based Dithiol [4] | Component of a Ternary SAM (T-SAM). | Improves analytical performance and minimizes non-specific protein adsorption, thereby reducing fouling-induced drift. |

| Pure [111] Gold Electrode [3] | Solid support with defined crystallinity. | Promotes denser and more uniform SAM formation compared to nanoparticle-coated or polycrystalline surfaces, enhancing baseline stability. |

The journey toward truly stable and long-lasting electrochemical biosensors requires a fundamental and mechanistic understanding of signal drift. This review has delineated the two primary culprits: the desorption of self-assembled monolayers and the degradation of redox reporters. The experimental evidence confirms that SAM desorption is an electrochemically driven process that can be managed by carefully selecting the interrogation potential and employing advanced anchoring chemistries like flexible trithiols. Concurrently, the choice of redox reporter is critical, with Methylene Blue emerging as the optimal candidate due to its favorable redox potential that aligns with SAM stability. Moving forward, rational design strategies that co-optimize the SAM anchor, the redox reporter, and the surface chemistry will be essential. The integration of novel, fouling-resistant monolayers, the exploration of gold-alkyne bonds as alternatives to thiols [3], and the development of even more robust reporter molecules represent the forefront of research aimed at suppressing these electrochemical instabilities. By systematically addressing these core issues, the path is cleared for the development of highly reliable biosensors capable of long-term, in vivo monitoring, thereby unlocking their full potential in drug development and personalized medicine.

Biological fouling, the non-specific adsorption of proteins and adhesion of cells to sensor surfaces, is a fundamental challenge that compromises the long-term stability and accuracy of electrochemical biosensors in complex biological environments. This phenomenon is a primary origin of signal drift, a key obstacle for in vivo monitoring and reliable in vitro diagnostics [1] [5]. Fouling occurs immediately upon exposure of a sensor to biological fluids such as blood or serum, leading to the formation of an impermeable layer on the electrode surface. This layer can increase background noise, screen the analyte's signal, and significantly degrade the sensor's sensitivity and reproducibility [6] [1]. For applications such as real-time, in vivo monitoring of drugs and biomarkers, even minor surface fouling can be disastrous, as it can completely obscure the already low signal of the target analyte [6] [7]. Understanding the mechanisms of protein adsorption and cell adhesion is therefore not merely a surface chemistry problem, but a critical requirement for designing next-generation robust biosensing platforms.

Fundamental Mechanisms of Biofouling

The Dynamics of Protein Adsorption

Protein adsorption is a dynamic, multi-step process initiating the fouling cascade. It involves reversible attachment, irreversible adsorption, and often subsequent conformational changes and denaturation of the protein on the surface [8]. This process can be simply described by the following kinetic model:

Paq + S ⇄ kads/kdes Ps → kd Pad

Where Paq is protein in the aqueous phase, S is a surface site, Ps is a reversibly adsorbed protein, and Pad is an irreversibly adsorbed, often denatured, protein [8]. The rate coefficients kads, kdes, and kd govern the kinetics of adsorption, desorption, and denaturation, respectively.

The interaction of proteins with a sensor surface is driven by non-covalent forces, including Van der Waals interactions, hydrogen bonding, electrostatics, and hydrophobic interactions [5]. A critical phenomenon in complex media is the Vroman effect, which describes the competitive displacement of abundant, high-mobility proteins (like albumin) over time by proteins that have higher surface affinity but lower mobility (such as fibrinogen) [5]. The final adsorbed protein layer is thus a result of a dynamic interplay of concentration, affinity, and mobility.

From Protein Adsorption to Cell Adhesion

The layer of adsorbed proteins directly dictates subsequent cell adhesion. Mammalian cell adhesion is controlled by the identity, density, conformation, and orientation of the adsorbed proteins [5]. For instance, as little as ~10 ng cm⁻² of adsorbed fibrinogen is sufficient for most mammalian cells to adhere [5]. Denaturation of non-adhesive proteins can increase surface hydrophobicity, promoting bacterial adhesion. Beyond the protein layer, material properties such as surface stiffness, roughness, and topography independently influence cell adhesion, signaling, and differentiation [5]. Bacterial adhesion, if left unchecked, can lead to biofilm formation—structured communities of bacterial cells enclosed in a self-produced extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) matrix. Biofilms are markedly more resistant to cleaning and antimicrobial agents than individual planktonic cells, making their prevention a paramount goal [9].

The Direct Link to Sensor Signal Drift

The fouling layer contributes to signal drift through several physical and electrochemical mechanisms [1]:

- Physical Barrier Effect: The accumulation of proteins, cells, and EPS creates a diffusion barrier, physically impeding the access of the target analyte to the electrode surface and the return of the redox reporter (e.g., methylene blue) to the electrode for electron transfer [1].

- Electron Transfer Inhibition: Fouling can drastically reduce the rate of electron transfer. Studies have shown that the electron transfer rate can decrease by a factor of three during the initial exponential drift phase in whole blood, directly reducing the Faradaic current [1].

- Electrochemical Instability: Electrochemical interrogation itself can accelerate fouling-induced degradation. The applied potential can drive the desorption of the self-assembled monolayers (SAMs) commonly used to functionalize gold electrodes, leading to a linear, continuous signal loss over time [1] [7]. This is particularly severe when potential windows encroach on the regions of reductive (below -0.5 V) or oxidative (above ~1 V) desorption of thiol-on-gold bonds [1].

The following diagram illustrates the sequential mechanisms leading from initial exposure to signal loss.

Quantitative Analysis of Fouling and its Impact

The impact of fouling is quantifiable, providing critical data for evaluating antifouling strategies. The table below summarizes key quantitative findings from fouling studies.

Table 1: Quantitative Impacts of Biofouling on Surfaces and Systems

| System / Surface | Fouling Condition | Quantitative Impact | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ship Hulls | Heavy marine fouling | Up to 40% increase in hydrodynamic resistance; 62.5% spike in fuel consumption. | [10] |

| Ship Hulls | Moderate fouling | 10-20% higher annual fuel costs; 2 knots loss in speed. | [10] |

| Electrochemical Sensor | Whole blood at 37°C | Biphasic signal loss: exponential drop over ~1.5h, followed by a linear decrease. | [1] |

| PEG Brush Surfaces | Protein adsorption | Defined as "ultralow fouling" at < 5 ng cm⁻² of irreversibly adsorbed protein. | [8] |

| Cell Adhesion | Fibrinogen-coated surface | As little as ~10 ng cm⁻² required for most mammalian cells to adhere. | [5] |

The effectiveness of antifouling strategies is also measured quantitatively, often by the reduction in adhesion forces.

Table 2: Measured Effectiveness of Antifouling Strategies

| Antifouling Strategy | Measurement Technique | Quantitative Outcome | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vanillin-modified PES Membrane | FluidFM Force Spectroscopy | Significant decrease in biofilm adhesion forces, work, and binding events. | [9] |

| Narrow Potential Window (-0.4V to -0.2V) | Electrochemical Interrogation in PBS | Only 5% signal loss after 1500 scans, vs. major loss with wider windows. | [1] |

| High-Performance Ship Coating | Fuel consumption analysis | Reduced fouling-related fuel consumption increase to ~5% per year, vs. 20% for standard coatings. | [10] |

Experimental Protocols for Fouling Analysis

Protocol: Single-Molecule TIRF Microscopy for Protein Adsorption Kinetics

This technique provides high spatiotemporal resolution of protein-surface interactions, revealing dynamics obscured by ensemble-averaging methods [8].

- Objective: To probe the dynamics of individual protein molecules (reversible/irreversible adsorption, desorption rates) on low-fouling surfaces in real time.

- Materials:

- Total Internal Reflection Fluorescence (TIRF) Microscope.

- Low-fouling surface sample (e.g., PEG brush, polyelectrolyte multilayer).

- Fluorescently labeled protein of interest (e.g., BSA, fibrinogen).

- Relevant buffer for the experiment.

- Procedure:

- Sample Mounting: Secure the surface sample in a flow cell on the microscope stage.

- Baseline Imaging: Introduce buffer alone and focus the objective to excite only the evanescent field (typically < 150 nm from the surface).

- Protein Introduction: Flush in a solution of fluorescently labeled protein at a very low concentration (to enable single-molecule detection).

- Real-Time Data Acquisition: Record video-rate microscopy of the surface. Individual protein molecules interacting with the surface will appear as discrete, diffraction-limited spots.

- Data Analysis: Use single-molecule localization and tracking software to:

- Count the number of adsorption events per unit area over time.

- Track the residence time of individual molecules on the surface.

- Calculate the adsorption rate coefficient (kads) and desorption rate coefficient (kdes).

- Key Consideration: The requirement for fluorescent labeling and low protein concentrations means this method is conducted under non-physiological conditions, complementing rather than replacing other techniques [8].

Protocol: FluidFM for Biofilm-Surface Adhesion Force Measurement

This novel method quantifies the adhesion forces of entire biofilms, offering more realistic data than single-cell probes [9].

- Objective: To directly measure the adhesion forces between a bacterial biofilm and a modified membrane surface.

- Materials:

- FluidFM instrument (combination of AFM and microfluidics).

- Microfluidic cantilevers with an aperture.

- COOH-functionalized polystyrene beads (~

- Procedure:

- Biofilm Probe Fabrication:

- Incubate COOH-functionalized beads with bacteria for 3 hours to allow biofilm growth.

- Aspirate a single biofilm-covered bead onto the aperture of a microfluidic cantilever by applying a negative pressure.

- Surface Preparation: Mount the test membrane (e.g., vanillin-modified PES) in the FluidFM liquid cell.

- Force Spectroscopy:

- Approach the biofilm probe to the membrane surface.

- Retract the probe at a constant speed while recording the cantilever deflection.

- Repeat the measurement across multiple locations on the surface.

- Data Analysis:

- Analyze the retraction force curves to extract:

- Adhesion Force: The maximum force required to detach the biofilm.

- Adhesion Work: The area under the retraction curve.

- Number of Adhesion Events: The number of discrete "jump-off" events in the curve, indicating bond ruptures.

- Analyze the retraction force curves to extract:

- Biofilm Probe Fabrication:

- Key Advantage: This method captures the complex contribution of the EPS matrix, showing that biofilm adhesion behavior is fundamentally different from that of single cells [9].

The workflow for this advanced technique is outlined below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Fouling Research

| Item | Function in Fouling Research | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) | Gold-standard polymer for creating low-fouling surfaces and brushes; resists protein adsorption via steric repulsion and hydration [8] [6]. | Grafting density and chain length are critical. Low-density brushes can be less effective. |

| Self-Assembled Monolayers (SAMs) | Well-defined organic surfaces formed on gold (e.g., from alkanethiols) to study fundamental interactions or as a platform for attaching antifouling molecules [1]. | Stability can be a limitation; susceptible to electrochemical desorption depending on applied potential. |

| Vanillin | A natural phenolic aldehyde used as an anti-biofouling coating; acts as a quorum-sensing inhibitor, reducing EPS production and biofilm formation [9]. | Offers a non-biocidal, "anti-virulence" mechanism of action. |

| Sol-Gel Silicate Layers | Porous, mechanically stable coatings for electrochemical sensors; act as a physical diffusion barrier to protect the electrode from foulants [6]. | Showed remarkable long-term stability, sustaining signal for 6 weeks in cell culture medium. |

| Syringaldazine | A redox mediator adsorbed onto electrode surfaces; used as a model catalyst to evaluate the protective effect of antifouling layers without adding external probes [6]. | Its rapid deterioration in complex media makes it an excellent indicator of coating efficacy. |

| COOH-functionalized Beads | Serve as carriers for growing biofilms for use in FluidFM adhesion force measurements [9]. | Provide a suitable surface for bacterial growth and biofilm formation. |

Biological fouling, initiated by protein adsorption and amplified by cell adhesion, remains a central problem in the development of stable, reliable electrochemical biosensors. It is a direct and major contributor to signal drift, limiting the in vivo lifespan and in vitro reproducibility of these devices. Combating this issue requires a multi-faceted approach: a deep understanding of the fundamental interaction mechanisms, the application of sophisticated characterization techniques like single-molecule TIRF and FluidFM that go beyond simple ensemble averages, and the rational design of advanced antifouling materials such as high-density polymer brushes, zwitterionic coatings, and non-fouling hydrogels. Future progress will hinge on the development of standardized testing protocols and the creation of robust, surface-modification strategies that can withstand the complex, dynamic, and harsh environment of real-world biological applications.

Electrochemical biosensors are powerful analytical tools that convert biological recognition events into quantifiable electrical signals, finding extensive applications in healthcare diagnostics, environmental monitoring, and food safety [11] [12]. A significant challenge in their practical deployment, however, lies in their susceptibility to signal drift induced by fluctuations in environmental and operational parameters such as temperature, pH, and ionic strength [13] [14]. This drift originates from the profound influence these stressors exert on both the biological recognition elements and the underlying physico-chemical transduction processes [15] [16].

The stability of a biosensor is critical for its commercial success and reliable operation, as it directly translates to longevity and measurement accuracy [15]. Biological elements like enzymes, antibodies, and aptamers are highly sensitive to their immediate environment. Temperature shifts can alter their conformational structure and reaction kinetics, pH variations can affect their charge state and catalytic activity, and changes in ionic strength can modulate binding affinities and electron transfer rates [13] [12] [14]. Simultaneously, these parameters directly affect electrochemical properties, including the conductivity of the solution, the double-layer capacitance at the electrode-solution interface, and the kinetics of Faradaic reactions [14]. Isolating the specific signal originating from the target analyte from the noise and drift caused by these extrinsic variables is therefore a fundamental pursuit in biosensor research and development [14]. This guide provides a technical examination of these stressors, detailing their mechanisms of action, methodologies for their systematic study, and strategies for their mitigation.

Mechanisms of Signal Interference

Environmental stressors induce signal drift through multiple, often interconnected, mechanisms that impact the biorecognition element, the transducer interface, and the sample matrix itself.

Impact of Temperature Fluctuations

Temperature is one of the most critical factors affecting biosensor performance. Its influence is multifaceted, altering the properties of the biological layer, the electrode kinetics, and the bulk solution.

- Biorecognition Element Dynamics: The activity of biological receptors, particularly enzymes, is intrinsically temperature-dependent. According to the Arrhenius equation, reaction rates typically increase with temperature, potentially enhancing sensitivity within an optimal range. However, excessive temperatures induce denaturation, an irreversible loss of tertiary structure and function, leading to permanent sensor degradation [15]. For instance, in hydrogel-based ionic strength sensors, temperature changes directly impact sensor characteristics like sensitivity, response time, and stability [13].

- Electrode and Solution Properties: Temperature changes affect the electrochemical cell's physics. A rise in temperature generally decreases the viscosity of the solution, increasing the diffusion coefficient of ions and redox species. This leads to higher mass transport rates and larger Faradaic currents. Furthermore, the standard rate constant of electron transfer for electrochemical reactions is itself temperature-dependent, following an Arrhenius-type relationship [14]. Studies on interdigitated microelectrodes (IDEs) have quantified this, showing a significant negative coefficient for temperature, where impedance decreases as temperature rises [14].

Impact of pH Shifts

The pH of the sample medium can drastically alter the charge state and functionality of the biological components and influence the electrochemical environment.

- Charge State of Biomolecules: Enzymes, antibodies, and aptamers possess specific ionic groups that can protonate or deprotonate. The isoelectric point (pI) of a protein defines the pH at which it has no net charge. Deviations from this pH can alter the molecule's three-dimensional structure, its binding affinity for the target analyte, and its catalytic efficiency. A shift in pH can render an aptamer's folded structure unstable, compromising its specificity and affinity [12].

- Electrochemical Reaction Kinetics: The pH directly governs the availability of protons in redox reactions. For many common redox couples (e.g., ferrocene/ferrocenium or reactions involving hydroquinone), the electron transfer kinetics are pH-sensitive. A classic example is in fermentation monitoring, where CO2 production lowers the pH, which in turn affects the impedance measurement independently of the chemical changes being tracked [14]. Research on IDE sensors has demonstrated a strong positive correlation between pH and impedance, with impedance increasing as the solution becomes more basic [14].

Impact of Ionic Strength Variations

The concentration of ions in a solution defines its ionic strength, which shapes the electrostatic environment around the biosensor interface.

- Shielding of Electrostatic Interactions: High ionic strength solutions contain a high concentration of counter-ions that can screen electrostatic charges. This shielding can disrupt the binding between a charged bioreceptor (e.g., a DNA aptamer) and its target, which often relies on complementary charge interactions [12].

- Modification of the Electrical Double Layer: At the electrode-electrolyte interface, a structured layer of ions forms, known as the electrical double layer (EDL). Its thickness, governed by the Debye length, is inversely proportional to the square root of the ionic strength. In high ionic strength solutions, the EDL is compressed, which can significantly alter the measured capacitance and electron transfer resistance, key parameters in electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) [14]. Hydrogel-based sensors are explicitly designed to swell or shrink in response to changes in ionic strength, converting this physical change into a measurable pressure signal [13].

Quantitative Analysis of Stressor Effects

A systematic, quantitative understanding of how each stressor impacts sensor output is essential for developing robust sensing platforms and correction algorithms. The following table summarizes key quantitative findings from experimental studies on these stressors.

Table 1: Quantitative Effects of Environmental Stressors on Biosensor Performance

| Stressor | Sensor Type / Application | Observed Impact | Quantified Effect / Model Coefficient | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature | Interdigitated Microelectrodes (IDEs) in wine | Impedance decreases with temperature increase. | Coefficient (β): -195.5 Ω/°C(in a multi-parameter model: Z(Ω) = ... -1.955·10²·T(°C) ...) | [14] |

| pH | Interdigitated Microelectrodes (IDEs) in wine | Impedance increases with pH increase. | Coefficient (β): +897.8 Ω/pH unit(in a multi-parameter model: Z(Ω) = ... +8.978·10²·pH ...) | [14] |

| Temperature | Hydrogel-based Ionic Strength Sensor | Affects sensor sensitivity, response time, and stability. | Sensor characteristics investigated as a function of temperature in vitro. | [13] |

| Ionic Strength | Hydrogel-based Biosensor | Hydrogel volume changes with ionic strength. | Volume change captured as a pressure signal in a confined cavity. | [13] |

The mathematical model developed for IDE sensors, which incorporates sensor geometry and operational frequency alongside environmental parameters, provides a powerful tool for quantifying the significance of each variable [14]. The general form of the model is:

Z(Ω) = Constant + β₁·dₑ + β₂·sₑ + β₃·Area + β₄·f(Hz) + β₅·T(°C) + β₆·pH

Where dₑ is electrode width, sₑ is electrode spacing, Area is the sensing area, and f is the measurement frequency. The magnitude and sign of the coefficients (β) directly quantify the effect of each parameter on the impedance. For example, the negative coefficient for temperature (β₅ = -195.5) confirms that impedance decreases with rising temperature, while the positive coefficient for pH (β₆ = +897.8) shows that impedance increases with pH [14].

Experimental Protocols for Stressor Analysis

To isolate and analyze the effects of environmental stressors, controlled experimental protocols are required. The following workflow provides a generalized methodology that can be adapted for specific biosensor platforms.

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for analyzing environmental stressors.

Protocol for Isolating Temperature Effects

This protocol outlines the steps to characterize the effect of temperature on a biosensor's signal independently of other variables.

Materials:

- Electrochemical Cell with Temperature Control: A jacketed cell connected to a thermostated water bath or a Peltier-controlled cell holder is essential for precise temperature regulation.

- Potentiostat/Galvanostat: An instrument capable of performing the intended electrochemical technique (e.g., amperometry, EIS).

- Buffer Solution: A well-buffered solution (e.g., 0.1 M phosphate buffer, pH 7.4) to ensure pH remains stable over the temperature range.

- Thermometer or Temperature Probe: For accurate and independent monitoring of the solution temperature.

Procedure:

- Sensor Preparation: Functionalize the electrode surface and immobilize the bioreceptor (e.g., enzyme, aptamer) according to the established protocol.

- Baseline Measurement: Place the sensor in the electrochemical cell with the buffer solution and a fixed concentration of the target analyte. Set the temperature to a reference point (e.g., 25°C) and allow the system to equilibrate for 10-15 minutes. Record the baseline signal (e.g., steady-state current or impedance spectrum).

- Temperature Variation: Systematically increase or decrease the temperature in increments (e.g., 5°C). At each new temperature, allow sufficient time for thermal equilibration before recording the signal.

- Data Analysis: Plot the sensor signal (e.g., current, charge transfer resistance Rct) against temperature. The data can be fitted to an appropriate model (e.g., Arrhenius plot for reaction rates, or a linear/polynomial model for impedance) to derive a temperature coefficient [14].

Protocol for Isolating pH Effects

This protocol describes how to evaluate the impact of pH shifts on biosensor performance.

Materials:

- Buffer Series: A set of buffers with identical ionic strength but different pH values (e.g., 0.1 M phosphate buffers for pH 6-8, 0.1 M acetate for lower pH, 0.1 M Tris for higher pH). The use of a background electrolyte like KNO₃ or NaCl can help maintain constant ionic strength across different buffers.

- pH Meter: A calibrated, high-precision pH meter is mandatory for verifying the actual pH of the solution in the cell.

Procedure:

- Sensor Preparation: As in the previous protocol.

- Buffer Introduction: Introduce the first buffer into the electrochemical cell. Add a fixed concentration of the target analyte.

- Signal Measurement: Measure the sensor signal at a constant temperature and stirring rate. Precisely record the pH of the solution.

- pH Cycling: Rinse the sensor and cell thoroughly with deionized water. Introduce the next buffer in the series with the same concentration of analyte and repeat the measurement. Continue this process across the desired pH range.

- Data Analysis: Plot the sensor signal versus pH to determine the optimal pH for maximum activity and the range over which the sensor operates reliably. This profile is crucial for understanding the sensor's limitations in samples with variable pH [14].

Protocol for Isolating Ionic Strength Effects

This protocol is designed to assess sensor performance against changes in background ionic strength.

Materials:

- Concentrated Salt Solution: A high-purity stock solution of an inert salt such as NaCl or KCl.

- Concentrated Buffer Solution: A buffer concentrate that, when diluted, will give the desired pH.

Procedure:

- Sensor Preparation: As above.

- Baseline in Low Ionic Strength: Prepare a solution with the target analyte in a low-ionic-strength buffer.

- Titration of Salt: While continuously measuring the sensor signal (e.g., via amperometry or EIS), add small, known volumes of the concentrated salt stock solution to the cell. Ensure thorough mixing after each addition.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the ionic strength for each addition. Plot the sensor signal (e.g., Rct from EIS, or current) against the square root of the ionic strength. A sharp change may indicate EDL compression or disruption of biorecognition binding events [13] [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Selecting appropriate materials and reagents is fundamental to constructing stable biosensor interfaces and conducting reliable stressor analysis.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Biosensor R&D

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | Electrode nanomodification; signal amplification carrier. | Excellent biocompatibility, high conductivity, large surface-to-volume ratio, facile functionalization with thiolated biomolecules [16] [17]. |

| Reduced Graphene Oxide (rGO) | Carbon nanomaterial for electrode modification. | High electrical conductivity, large specific surface area, good mechanical strength, enhances electron transfer [15] [17]. |

| Chitosan (CS) | Biopolymer for constructing biocompatible interfaces. | Excellent film-forming ability, biodegradability, biocompatibility, non-toxicity; often used with other nanomaterials (e.g., GO-CS) [16]. |

| Interdigitated Microelectrodes (IDEs) | Transducer platform for impedimetric sensing. | Enhanced signal sensitivity, suitable for monitoring adhesion, biofouling, and chemical changes in liquids [14]. |

| Poly(o-phenylenediamine) | Electropolymerized membrane for enzyme entrapment. | Used to create selective, low-fouling permselective membranes on electrode surfaces [15]. |

| Systematic Evolution of Ligands by Exponential Enrichment (SELEX) | Technology for generating specific DNA/RNA aptamers. | Produces stable nucleic acid bioreceptors with high affinity and specificity for targets, from ions to cells [12] [17]. |

Mitigation Strategies and Future Directions

Addressing the challenge of signal drift requires a multi-faceted approach that combines interface engineering, signal processing, and smart material design.

Interface Engineering with Advanced Materials: Using composite materials can significantly enhance interface stability. Nanomaterials like gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) and graphene oxide improve conductivity and provide a stable microenvironment for biomolecules [16] [17]. Polymers like chitosan offer biocompatible matrices that protect biological elements from harsh environmental conditions [16]. Bimetallic core-shell nanostructures have also shown improved stability and catalytic activity compared to their single-metal counterparts [16].

Mathematical Modeling and Signal Correction: As demonstrated with the IDE sensor model, developing a quantitative understanding of the influence of temperature and pH allows for software-based correction of the acquired signal [14]. The general form of the model is: Zcorrected = Zmeasured - [βT · (T - Tref) + βpH · (pH - pHref)] This approach effectively isolates the impedance change due to the target analyte from the drift caused by the extrinsic variables [14].

Microfluidic Integration and Automated Systems: Integrating biosensors into microfluidic platforms enables precise control over the sample environment, including temperature and flow conditions. Furthermore, the application of vibration and hydrodynamic flow in such systems has been shown to enhance sensor performance, lower the limit of detection, and pave the way for automated, high-throughput analysis, reducing environmental variability [11].

Exploration of Robust Bioreceptors: The search for more stable recognition elements is ongoing. Aptamers are generally more stable than antibodies over a range of temperatures and can be regenerated more easily [12] [17]. The development of thermostable enzymes or biomimetic catalysts (e.g., nanozymes) also offers a path toward sensors capable of operating in demanding environments [16].

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between the core environmental stressors, their mechanisms of action, and the corresponding mitigation strategies discussed.

Diagram 2: Stressor mechanisms and mitigation strategies.

The Impact of Electrode Potential and Scanning Parameters on Drift Kinetics

Signal drift, the undesired change in sensor output over time under constant conditions, presents a major obstacle to the long-term stability and reliability of electrochemical biosensors. This phenomenon is particularly critical in applications such as continuous molecular monitoring in vivo or in complex biological fluids, where sensor stability over many hours or days is required for effective patient management or drug development studies [1]. The drift kinetics are not merely a function of time but are intimately governed by the electrochemical interrogation parameters used during sensor operation. Electrode potential and scanning protocols directly influence the fundamental processes occurring at the electrode-electrolyte interface, either accelerating or mitigating the mechanisms that lead to signal degradation [1]. Understanding these relationships is paramount for designing robust biosensing systems with predictable longevity. This technical guide examines the origin of signal drift within the context of how operational electrochemical parameters impact the underlying degradation mechanisms, providing researchers with a framework for optimizing biosensor performance through controlled electrochemical protocols.

Fundamental Mechanisms of Signal Drift

Signal drift in electrochemical biosensors originates from multiple physical and chemical processes that can be categorized into two primary classes: electrochemically-driven degradation and biology-driven fouling.

Electrochemically-Driven Degradation

This category encompasses processes directly instigated by the electrical signals used to operate the sensor. A primary mechanism is the electrochemically driven desorption of the self-assembled monolayer (SAM) that typically anchors biorecognition elements (such as DNA aptamers or enzymes) to the electrode surface, often gold [1]. The stability of the gold-thiol bond, fundamental to these SAMs, is highly dependent on the applied electrode potential. Both reductive desorption at potentials below approximately -0.5 V and oxidative desorption at potentials above ~1.0 V can break this bond, leading to a loss of the sensing layer and a corresponding signal decrease [1]. A secondary electrochemical mechanism is the irreversible degradation of the redox reporter molecule (e.g., methylene blue) through side reactions that occur during its repeated cycling between oxidized and reduced states [1].

Biology-Driven Fouling and Degradation

When deployed in biological matrices like blood or interstitial fluid, sensors face additional challenges. Surface fouling involves the non-specific adsorption of proteins, cells, and other biomolecules to the electrode surface [1]. This fouling layer can hinder the diffusion of the redox reporter to the electrode surface, thereby reducing the electron transfer rate and the observed signal [1]. Furthermore, enzymatic degradation of biological recognition elements (e.g., nucleases cleaving DNA or RNA aptamers) contributes to the exponential signal loss phase often observed in complex media [1]. The interplay between these mechanisms dictates the overall drift profile, which often manifests as a biphasic signal loss: an initial rapid exponential decay followed by a slower, more linear decrease [1].

Impact of Electrode Potential on Drift Kinetics

The applied electrode potential is a critical parameter controlling the rate of signal drift, primarily through its effect on the stability of the electrode-sensing layer interface.

Potential Window and SAM Desorption

The voltage range, or potential window, scanned during electrochemical measurements is a major determinant of the sensor's operational lifespan. Research has demonstrated that the stability of thiol-on-gold monolayers is highly susceptible to extreme potentials. The table below summarizes the effect of the applied potential window on the observed signal drift, highlighting the existence of a "stability window" [1].

Table 1: Impact of Electrode Potential Window on Signal Drift

| Negative Potential Limit (V) | Positive Potential Limit (V) | Observed Drift Over 1500 Scans | Primary Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| -0.4 V | -0.2 V | ~5% signal loss | Minimal desorption |

| -0.4 V | 0.0 V | Low degradation rate | Onset of oxidative processes |

| -0.4 V | > +0.2 V | Significant signal loss | Oxidative desorption of SAM |

| < -0.4 V | -0.2 V | Significant signal loss | Reductive desorption of SAM |

Experiments reveal that a narrow potential window of -0.4 V to -0.2 V results in only 5% signal loss after 1500 scans, whereas expanding the window to include more extreme potentials dramatically increases the degradation rate [1]. This is because potentials beyond the threshold for reductive or oxidative desorption directly break the gold-thiol bonds [1].

Redox Reporter Stability

The choice and positioning of the redox reporter are also influenced by potential. Methylene blue (MB), with a formal potential (E⁰) of approximately -0.25 V vs. Ag/AgCl at pH 7.5, is notably stable because its redox activity falls within the narrow potential window where alkane-thiol-on-gold monolayers are most stable [1]. In contrast, reporters with redox potentials outside this stable window necessitate the use of destabilizing potentials, accelerating drift. Furthermore, the reporter's position within a DNA or protein scaffold influences its susceptibility to fouling, which is itself modulated by the applied electric fields [1].

Impact of Scanning Parameters on Drift Kinetics

Beyond the static potential limits, the dynamic parameters of the electrochemical scanning technique itself contribute to drift kinetics.

Scan Rate and Frequency

The scan rate in voltammetric techniques or the frequency in impedance spectroscopy determines how rapidly the interfacial structure is perturbed. While not explicitly quantified in the provided research, faster scanning generally subjects the SAM to more frequent structural stress and redox cycling, which can potentially accelerate fatigue and desorption over prolonged operation. However, higher frequencies in alternating current (AC) techniques like EIS can sometimes help isolate the faradaic process from slow fouling effects.

Continuous vs. Intermittent Interrogation

The duty cycle of electrochemical measurement is a significant factor. Studies show that pausing the electrochemical interrogation in a controlled environment (e.g., PBS buffer) can halt the signal degradation associated with the linear drift phase [1]. This indicates that the electrochemically-driven desorption is active only when a potential is being applied, providing a strategy to extend total sensor lifetime through intermittent measurement protocols rather than continuous operation.

Experimental Protocols for Drift Kinetics Characterization

A systematic approach is required to deconvolute the various contributions to signal drift. The following protocol offers a methodology for evaluating the impact of electrode potential and scanning parameters.

Protocol: Quantifying Potential-Dependent Drift

This experiment is designed to isolate the effect of the electrochemical potential window on SAM stability.

- Objective: To determine the rate of signal loss due to electrochemical desorption as a function of the applied potential window.

- Materials:

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), pH 7.4

- Custom-fabricated gold electrode sensor with a redox-labeled DNA SAM

- Potentiostat

Method:

- Sensor Preparation: Immobilize a thiolated DNA probe labeled with Methylene Blue (MB) onto a clean gold electrode to form a SAM. Rinse and stabilize in PBS.

- Baseline Measurement: Record a square-wave voltammogram (SWV) in PBS using a very stable, narrow potential window (e.g., -0.4 V to -0.2 V) to establish the initial signal.

- Stress Testing: Subject the sensor to a continuous sequence of SWV scans (e.g., 1000 scans) using the test potential window.

- Signal Monitoring: Periodically (e.g., every 100 scans) record a "probe" SWV scan using the stable baseline window to track the decay of the peak current without contributing significantly to the degradation.

- Data Analysis: Plot the normalized peak current from the probe scans versus the cumulative number of stress scans. Fit the data to determine the degradation rate constant for each tested potential window.

Key Analysis: Compare the degradation rates across different potential windows. A sharp increase in the degradation rate as the window expands beyond the stability thresholds provides a quantitative basis for selecting optimal operating parameters [1].

Protocol: Deconvoluting Fouling from Electrochemical Drift

This protocol characterizes the biological contribution to drift using blood as a challenging matrix.

- Objective: To distinguish signal loss from surface fouling and enzymatic degradation from purely electrochemical drift.

- Materials:

- Undiluted whole blood, heparinized

- PBS, pH 7.4

- Urea solution (concentrated, e.g., 6-8 M)

- Gold electrode sensors with MB-labeled DNA or enzyme-resistant RNA

- Method:

- Sensor Interrogation in Blood: Place the sensor in whole blood at 37°C. Interrogate continuously with SWV using a narrow, stable potential window to minimize electrochemical degradation.

- Signal Recording: Monitor the SWV peak current over time (e.g., 2-3 hours). Observe the characteristic biphasic drift.

- Fouling Recovery: After a significant exponential signal drop (e.g., 2.5 hours), wash the sensor with concentrated urea to solubilize and remove non-specifically adsorbed biomolecules.

- Signal Recovery Measurement: Re-measure the SWV signal in PBS. Recovery of >80% of the initial signal indicates that fouling, not permanent degradation, was the primary cause of the initial exponential drift [1].

- Control with Enzyme-Resistant Oligonucleotides: Repeat the experiment using a sensor fabricated with a nuclease-resistant backbone (e.g., 2'-O-methyl RNA). A persistent exponential drift phase suggests that fouling, rather than enzymatic cleavage, is the dominant biological mechanism [1].

Visualization of Drift Mechanisms and Experimental Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the core concepts and experimental workflows discussed in this guide.

Diagram 1: Signal drift mechanisms and controlling factors.

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for quantifying potential-dependent drift.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key materials and their specific functions in experiments focused on drift kinetics.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Drift Kinetics Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Rationale | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Gold Electrode | Standard substrate for forming stable thiol-based Self-Assembled Monolayers (SAMs). | Purity and surface roughness affect SAM uniformity and stability [18] [19]. |

| Alkane-Thiol SAM | Creates an ordered monolayer that minimizes non-specific adsorption and provides a scaffold for bioreceptors. | Chain length and terminal functional group influence packing density and stability [1]. |

| Methylene Blue-labeled DNA | Acts as a model EAB sensor; MB's redox potential falls within the stable window for gold-thiol SAMs [1]. | Reporter position on the DNA strand affects susceptibility to fouling-induced signal loss [1]. |

| 2'-O-Methyl RNA | Enzyme-resistant nucleic acid analog used to decouple enzymatic degradation from fouling effects [1]. | Confirms that exponential drift in blood is primarily due to fouling, not nuclease activity. |

| Ultra-Pure Buffer (PBS) | Provides a controlled, biologically inert medium for isolating electrochemical drift mechanisms [1]. | Absence of proteins and cells allows study of SAM desorption and reporter degradation alone. |

| Whole Blood | Complex biological matrix used as a proxy for in vivo conditions to study fouling and biological degradation [1]. | Contains proteins, cells, and enzymes that collectively contribute to the exponential drift phase. |

| Concentrated Urea | A chemical denaturant used to wash sensors; it solubilizes proteins, reversing fouling-based signal loss [1]. | Useful for quantifying the recoverable portion of signal drift, confirming fouling's role. |

The kinetics of signal drift in electrochemical biosensors are not an immutable property but a controllable variable dictated by the operational electrochemical parameters. This guide has established that the electrode potential window is a primary lever, with a clearly defined stability zone for thiol-on-gold chemistry that, when respected, can minimize electrochemically driven SAM desorption. Furthermore, the duty cycle of interrogation and the choice of redox reporter are critical secondary parameters. Mitigating drift requires a multi-pronged strategy: employing the narrowest possible potential window that encompasses the redox reaction of interest, using stable reporters like methylene blue, and considering intermittent measurement schemes for long-term monitoring. Future research will likely focus on engineering even more robust surface architectures, such as using non-thiol anchor chemistries with wider electrochemical stability windows, and developing advanced drift-correction algorithms that can dynamically adapt to changing sensor performance. A fundamental understanding of the impact of electrode potential and scanning parameters on drift kinetics, as detailed herein, is essential for transforming electrochemical biosensors from research tools into reliable, long-term monitoring solutions in biomedicine and drug development.

Electrochemical biosensors synergistically integrate the molecular recognition capabilities of biological elements with the sensitivity of electrochemical transducers, offering a powerful platform for detecting targets ranging from small molecules to whole cells [20]. A critical challenge impeding the reliable deployment of these biosensors, particularly for long-term monitoring in complex biological environments, is signal drift—the undesirable decrease in sensor signal over time. A primary origin of this drift is the degradation of the immobilized biorecognition elements, such as nucleic acids (e.g., aptamers) and peptides, by nucleases and proteases present in biological fluids [1]. This degradation compromises the structural integrity and function of the sensing interface, leading to a loss of signal fidelity. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical analysis of the mechanisms by which nuclease and protease activity induces signal drift, summarizes quantitative studies on degradation kinetics, outlines detailed experimental protocols for investigating these phenomena, and presents advanced strategies to engineer stable, degradation-resistant biosensing interfaces.

Mechanisms of Biomolecule Degradation and Signal Drift

Nuclease Degradation of DNA-Based Biorecognition Elements

Electrochemical aptamer-based (EAB) sensors, which utilize a redox-tagged DNA aptamer immobilized on a gold electrode, are highly susceptible to nuclease degradation. When deployed in biologically relevant conditions like whole blood at 37°C, the sensor signal exhibits a biphasic drift profile [1].

- Exponential Drift Phase: The initial, rapid signal loss occurs over approximately 1.5 hours and is primarily driven by biological mechanisms. Studies using enzyme-resistant oligonucleotides (2'-O-methyl RNA) have demonstrated that this phase persists despite nuclease resistance, pointing to biofouling as a dominant mechanism. Fouling by blood cells and proteins alters the dynamics of the redox reporter (e.g., methylene blue), reducing its electron transfer rate to the electrode by a factor of three [1].

- Linear Drift Phase: The subsequent, slower signal loss is electrochemically driven. Systematic investigation has linked this phase to the reductive and oxidative desorption of the alkane-thiolate self-assembled monolayer (SAM) from the gold electrode surface, a process triggered by the applied electrochemical potentials. By narrowing the potential window to -0.4 V to -0.2 V (vs. Ag/AgCl), this degradation phase was nearly eliminated, with only 5% signal loss observed after 1500 scans [1].

Protease Degradation of Peptide-Based Biorecognition Elements

Peptide-based biosensors detect protease activity by monitoring the cleavage of an electrode-bound, redox-tagged peptide substrate. Protease-induced cleavage severs the redox reporter from the electrode surface, causing a measurable drop in current [4] [21]. This same principle, while useful for detection, becomes a source of signal drift when non-specific proteolysis degrades the peptide biorecognition layer. The degradation kinetics can often be modeled using a heterogeneous Michaelis-Menten model, allowing for the extraction of kinetic parameters like kcat and KM [4] [22]. The stability of the peptide layer is influenced by its structure; for instance, designed arched peptides can exhibit enhanced resistance to proteolytic hydrolysis compared to linear peptides [23].

Quantitative Data on Degradation Kinetics

The following tables summarize key quantitative findings from research on the degradation of biorecognition elements and its impact on biosensor performance.

Table 1: Quantifying Signal Drift in Electrochemical Biosensors

| Drift Phase | Proposed Primary Mechanism | Experimental Evidence | Impact on Signal |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exponential (Initial 1.5 hrs) | Biofouling from blood components [1] | Signal loss persists with nuclease-resistant oligonucleotides; ~80% signal recovery after urea wash [1] | Rapid signal decrease; Electron transfer rate reduced 3-fold [1] |

| Linear (Long-term) | Electrochemically driven SAM desorption [1] | Drift rate highly dependent on applied potential window; minimized at -0.4 V to -0.2 V [1] | Slow, continuous signal decrease; Little change in electron transfer rate [1] |

Table 2: Enzymatic Degradation Kinetics of Biorecognition Elements

| Enzyme Target | Biorecognition Element | Redox Reporter | Kinetic Parameter (kcat/Km) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trypsin | Methylene blue-tagged peptide, T-SAM | Methylene Blue | Not specified (LOD: 250 pM) [4] | [4] |

| Cathepsin B | Ferrocene-appended tetrapeptide on VACNF NEA | Ferrocene | (4.3 ± 0.8) × 10⁴ M⁻¹s⁻¹ [22] | [22] |

| Legumain | Ferrocene-appended tetrapeptide on VACNF NEA | Ferrocene | (1.13 ± 0.38) × 10⁴ M⁻¹s⁻¹ [22] | [22] |

Experimental Protocols for Investigating Degradation

Protocol: Investigating Nuclease-Driven Signal Drift

This protocol is adapted from studies elucidating the mechanisms of EAB sensor drift [1].

- Sensor Fabrication:

- Substrate: Use gold disk working electrodes (e.g., 2 mm diameter).

- SAM Formation: Incubate electrodes in a 1 µM solution of alkane-thiolated DNA (e.g., a 37-base sequence without significant secondary structure) modified with a methylene blue (MB) redox reporter at the 3'-end. Incubate for 1 hour.

- Rinsing & Storage: Rinse thoroughly with deionized water and store in PBS buffer until use.

- Experimental Deployment & Drift Measurement:

- Electrochemical Setup: Use a standard three-electrode system (Ag/AgCl reference, Pt counter) and square wave voltammetry (SWV).

- Conditions: Challenge the sensors in two environments at 37°C:

- Complex Biofluid: Undiluted whole blood.

- Control: Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS).

- Data Acquisition: Record successive SWV scans over several hours (e.g., 10+ hours). The peak current of the MB signal is the primary metric.

- Mechanistic Interrogation:

- Fouling Test: After 2.5 hours in blood, wash sensors with concentrated urea (e.g., 6 M) and re-measure signal in PBS to assess recoverable signal loss.

- Nuclease Degradation Test: Repeat the deployment experiment using a sensor fabricated with a nuclease-resistant oligonucleotide (e.g., 2'-O-methyl RNA).

- Electrochemical Stress Test: In PBS, systematically vary the SWV potential window to identify regimes that minimize the linear drift phase.

Protocol: Measuring Protease Activity and Peptide Stability

This protocol is derived from electrochemical protease biosensor studies [4] [22].

- Sensor Fabrication:

- Electrode Platform: Use a gold electrode or a nanoelectrode array (e.g., Vertically Aligned Carbon Nanofiber NEA).

- Peptide Immobilization:

- Form a ternary self-assembled monolayer (T-SAM) on gold using a mixture of a thiolated peptide substrate (e.g., specific to trypsin, cathepsin B, or legumain) and a spacer molecule (e.g., a PEG-based dithiol) to minimize non-specific adsorption [4].

- For carbon surfaces, use covalent chemistry (e.g., EDC/sulfo-NHS) to attach the peptide.

- Redox Tagging: Ensure the immobilized peptide is labeled with a redox reporter (e.g., Methylene Blue or Ferrocene) at the distal end.

- Proteolysis Measurement:

- Baseline Acquisition: In the appropriate reaction buffer, perform square wave voltammetry (SWV) or AC voltammetry (ACV) to record the initial peak current.

- Enzyme Kinetics: Add a known concentration of the target protease to the electrochemical cell.

- Real-time Monitoring: Continuously record SWV/ACV scans over time (e.g., 30-60 minutes). The proteolytic cleavage and release of the redox reporter will manifest as a decrease in peak current.

- Data Analysis:

- Plot the normalized peak current versus time.

- Fit the kinetic data to a heterogeneous Michaelis-Menten model to extract the catalytic efficiency (kcat/KM) for the surface-attached peptide substrate [22].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Investigating and Mitigating Biomolecule Degradation

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Feature / Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Methylene Blue (MB) | Redox reporter for DNA and peptide-based sensors [4] [1]. | Its redox potential falls within the stable window of thiol-on-gold SAMs, minimizing electrochemical desorption [1]. |

| 2'-O-Methyl RNA | Nuclease-resistant oligonucleotide backbone [1]. | Used to isolate the contribution of nuclease degradation from fouling in drift studies [1]. |

| Phosphorothioate Aptamer (PS-Apt) | Nuclease-resistant biorecognition element [23]. | Replacement of non-bridging oxygen with sulfur in the phosphate backbone confers enhanced stability against nucleases [23]. |

| Arched Peptide (APEP) | Antifouling and protease-resistant peptide layer [23]. | An arched structure formed by immobilization at both ends enhances stability against proteolytic hydrolysis [23]. |

| Ternary SAM (T-SAM) | Mixed self-assembled monolayer on gold [4]. | Incorporates a PEG-based diluent (e.g., dithiol) to reduce steric hindrance, improve enzyme access, and minimize non-specific adsorption [4]. |

| Vertically Aligned Carbon Nanofiber (VACNF) NEA | Nanostructured electrode platform [22]. | High current density and fast electron transfer kinetics enable sensitive detection of low-activity proteases [22]. |

Visualization: Experimental Workflows and Mechanisms

Workflow for Deconvoluting Signal Drift Mechanisms

Mechanisms of Biomolecule Degradation on Sensor Surface

Understanding and mitigating biomolecule degradation is paramount for advancing the field of electrochemical biosensors, particularly for applications requiring long-term stability in vivo or in complex biological samples. The research demonstrates that signal drift originates from a complex interplay of electrochemical desorption, enzymatic degradation, and biofouling. Future research directions should focus on the synergistic integration of multiple stabilization strategies. This includes developing novel biorecognition elements with inherent stability (e.g., phosphorothioate aptamers, D-peptides), engineering robust antifouling matrices (e.g., arched peptides, hydrogels), and optimizing electrochemical protocols to minimize interfacial stress. Furthermore, the application of artificial intelligence for data interpretation and the development of wearable biosensing systems will demand even greater emphasis on interface stability. By systematically addressing the degradation pathways outlined in this guide, researchers can design next-generation biosensors with the reliability required for transformative impact in biomedical research, drug development, and clinical diagnostics.

Counteracting Drift: Methodological Innovations and Practical Applications

Signal drift, the undesirable degradation of sensor signal over time, presents a fundamental obstacle to the long-term, reliable operation of electrochemical biosensors in real-world applications. This phenomenon is particularly debilitating in contexts such as continuous therapeutic drug monitoring and in vivo biomarker sensing, where measurement stability over hours or days is essential [24] [1]. The origins of signal drift are multifaceted, primarily stemming from biofouling in complex biological environments, electrode passivation, desorption of molecular layers, and degradation of sensing elements [24] [1]. This technical guide examines three cornerstone material strategies—anti-fouling polymers, advanced nanocomposites, and stable self-assembled monolayers (SAMs)—developed to mitigate these mechanisms at their source. By enhancing the interfacial stability between the biosensor and its operational environment, these material solutions directly address the physicochemical origins of signal drift, thereby paving the way for robust, continuous sensing platforms suitable for clinical and point-of-care diagnostics.

Table 1: Core Mechanisms of Signal Drift and Corresponding Material Solutions

| Drift Mechanism | Impact on Sensor Performance | Proposed Material Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Biofouling [24] [1] | Non-specific adsorption of proteins, cells, or other biomolecules onto the electrode surface, causing signal suppression and noise. | Anti-fouling Polymer Coatings (e.g., Zwitterionic polymers, PEG) |

| SAM Desorption [2] [1] | Loss of the bioreceptor anchor layer from the electrode surface, leading to a continuous decrease in signal amplitude. | Stable Monolayer Architectures (e.g., Tri-thiol anchors, optimized potential windows) |

| Insufficient Signal & Poor Stability [25] | Low signal-to-noise ratio and inherent instability of nanostructured interfaces limit sensitivity and operational lifespan. | Conductive Nanocomposites (e.g., AuNPs@MXene, Nanoclay composites) |

| Enzymatic Degradation [1] | Cleavage of DNA or protein-based recognition elements in biological fluids, resulting in permanent signal loss. | Enzyme-Resistant Oligonucleotides (e.g., 2'O-methyl RNA) |

Anti-fouling Polymers: Creating a Bio-inert Interface

Biofouling from blood components and other biological matrices is a dominant source of the initial, rapid signal decay observed in electrochemical biosensors [1]. Anti-fouling polymers form a physical and chemical barrier that minimizes non-specific adsorption, thereby preserving the sensor's signal integrity.

Zwitterionic Poly(SBMA) Coating

Poly(sulfobetaine methacrylate) (poly(SBMA)) is a zwitterionic polymer that creates a super-hydrophilic surface through a tightly bound water layer. This layer forms a physical and thermodynamic barrier that energetically discourages the adhesion of biomolecules [24].

Experimental Protocol for SBMA@PDA Coating:

- Surface Priming: A polydopamine (PDA) layer is first deposited on the cleaned electrode surface. This is achieved by immersing the electrode in a weak alkaline solution (e.g., 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.5) containing dopamine hydrochloride (2 mg/mL) for 30-60 minutes. The PDA layer adheres to virtually any substrate and provides a versatile platform for subsequent grafting.

- Polymer Grafting: The PDA-coated electrode is then immersed in an aqueous solution of sulfobetaine methacrylate (SBMA) monomer (e.g., 0.5 - 1.0 M).

- Radical Polymerization: Polymerization is initiated, typically by adding ammonium persulfate (APS) as an initiator and heating the solution to 60-70°C for several hours. This process grafts the poly-SBMA brush onto the PDA-primed surface.

- Rinsing and Storage: The resulting SBMA@PDA-coated sensor is thoroughly rinsed with deionized water and stored in a buffer until use [24].

Performance Data: Sensors coated with this SBMA@PDA antifouling layer demonstrated high robustness to variations in pH, temperature, and mechanical stress. When integrated into a wearable microneedle patch for monitoring vancomycin in artificial interstitial fluid, the coating enabled stable and continuous detection, showcasing its potential for in vivo applications [24].

Poly(OEGMA) for Extended Debye Length

In transistor-based biosensors (BioFETs), the Debye screening effect in high-ionic-strength physiological fluids severely limits the detection of charged biomarkers. Poly(oligo(ethylene glycol) methyl ether methacrylate) (POEGMA) is a polymer brush that acts as a "Debye length extender."

- Mechanism: When grafted onto the sensor surface, the POEGMA brush establishes a Donnan equilibrium potential, which effectively pushes the electrical double layer further out from the sensor surface. This extends the sensing distance beyond the typical sub-nanometer range in 1X PBS, allowing for the detection of larger biomolecules like antibodies [26].

- Experimental Protocol:

- The sensor surface (e.g., a CNT-based transistor) is functionalized with an initiator for atom transfer radical polymerization (ATRP).

- The surface is then immersed in a solution containing the OEGMA monomer, and polymerization is carried out via surface-initiated ATRP to grow dense POEGMA brushes.

- Capture antibodies are subsequently printed into this polymer brush matrix, creating a sensing interface that operates effectively in undiluted biological fluids [26].

Diagram 1: SBMA@PDA coating workflow.

Nanocomposites: Enhancing Signal and Stability

Nanocomposites enhance the electrochemical properties of biosensor electrodes, providing a larger active surface area and improved conductivity, which directly translates to higher sensitivity and better signal stability.

AuNPs@MXene Nanocomposite

The combination of gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) with MXene (Ti₃C₂) creates a synergistic nanocomposite that significantly boosts sensor performance.

Experimental Protocol for AuNPs@MXene-Modified Electrode:

- MXene Preparation: MXene Ti₃C₂ is typically prepared by etching the aluminum layer from the MAX phase (Ti₃AlC₂) using hydrofluoric acid or a fluoride-containing salt and HCl, followed by delamination via sonication.

- Nanocomposite Synthesis: AuNPs are synthesized in situ on the MXene sheets. This can be done by mixing an aqueous dispersion of MXene with a solution of chloroauric acid (HAuCl₄). A reducing agent, such as sodium citrate or sodium borohydride, is added to reduce the Au³⁺ ions to metallic gold, nucleating AuNPs on the MXene surface.

- Electrode Modification: A drop-casting method is used where a controlled volume (e.g., 5-10 µL) of the AuNPs@MXene nanocomposite dispersion is deposited onto a polished gold electrode surface and allowed to dry, often under mild heating or in a vacuum desiccator [25].

Performance Data: This nanocomposite achieved an over thirty-fold increase in electroactive surface area compared to a bare gold electrode and a half-fold increase compared to an AuNPs-modified electrode. This massive increase directly enhances the analytical capability and signal stability of the sensor during continuous operation [25].

Functionalized Nanoclay Composites

Nanoclays, such as montmorillonite (MMT), are layered silicate materials. While they offer high ion exchange capacity and a modifiable layered structure, their poor conductivity is a limitation. Functionalization with conductive nanoparticles creates highly effective nanocomposites for electrode modification.

- Functionalization Modalities:

- Metal/Metal Oxide Incorporation: Silver (Ag), zinc oxide (ZnO), or bimetallic (Ag-Au) nanoparticles can be intercalated into the clay structure via ion exchange or mechanochemical methods [27].

- Organic Molecule Modification: Incorporation of organic compounds like carbon paste, polymers, or biomolecules such as Human Serum Albumin (HSA) can improve biocompatibility and binding capacity. For instance, HSA-modified nanoclay composites showed improved conductivity and were successfully applied in the detection of pharmaceuticals like efavirenz and zidovudine [27].

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Comparison of Nanocomposites

| Nanocomposite | Target Analyte | Key Performance Metric | Reported Enhancement |

|---|---|---|---|

| AuNPs@MXene [25] | Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) | Active Surface Area | >30x vs. bare Au electrode; 0.5x vs. AuNPs-only electrode |

| HSA-Modified Nanoclay/Ag-Au [27] | Efavirenz, Nevirapine, Zidovudine | Conductivity & Analytical Performance | Improved current response, good linearity, and acceptable detection limits |

| POEGMA-based D4-TFT [26] | General Biomarkers (Immunoassay) | Sensitivity in 1X PBS | Sub-femtomolar (aM) detection in undiluted ionic solution |

Stable Monolayers: Anchoring the Sensing Element

The self-assembled monolayer (SAM) is the foundational layer that anchors bioreceptors (e.g., DNA aptamers) to the gold electrode surface. Instability of this monolayer, leading to desorption, is a major source of signal drift [2] [1].

Trithiol versus Monothiol Anchors

Research has systematically compared the stability of different thiol-based anchors.

- Flexible Trihexylthiol Anchor (Letsinger-type): This anchor uses three thiol groups connected by a flexible backbone, providing multiple attachment points to the gold surface. This multi-point attachment dramatically improves stability compared to monothiols [2].

- Experimental Comparison: In a landmark study, E-DNA sensors fabricated with the flexible trithiol anchor retained 75% of their original signal after 50 days of storage in aqueous buffer. In contrast, sensors made with a conventional six-carbon monothiol or a rigid adamantane-based trithiol suffered significant signal loss (>60%) under the same conditions. The flexible trithiol anchors also exhibited excellent stability against temperature cycling and repeated electrochemical interrogation [2].

Optimizing Electrochemical Interrogation

The stability of thiol-on-gold monolayers is highly dependent on the electrochemical potential window applied during sensor operation.

- Mechanism Investigation: Studies have shown that signal drift in simpler, EAB-like proxies in PBS is primarily caused by electrochemically driven desorption of the SAM. This occurs when the applied potential triggers reductive desorption (at potentials below -0.4 V vs. Ag/AgCl) or oxidative desorption (at potentials above 0.0 V) [1].